プエルトリコの音楽

The Misic of Puerto Rico

プエルトリコの音楽

The Misic of Puerto Rico

★プエルトリコの音楽は、多様な文化資源の異質かつダイナミックな産物と して発展してきた。プエルトリコの最も顕著な音楽源は、主にヨーロッパ、先住民、アフリカの影響を受けているが、プエルトリコ音楽の多くの側面はカリブ海 の他の地域の起源を反映している。今日のプエルトリコの音楽文化は、ボンバ、ダンザ、プレナといった 本質的にネイティブなジャンルから、サルサ、ラテント ラップ、レゲトンといった最近のハイブリッドなジャンルまで、幅広く豊かなバラエティで構成されている。広く考えれば、「プエルトリコ音楽」の領域は、当 然、米国、特にニューヨークに住む数百万人のプエルトリコ系住民の音楽文化で構成されるはずだ。サルサからラファエル・エルナンデスのボレロまで、彼らの 音楽はプエルトリコの音楽文化そのものと切り離すことはできない。

★プエルトリコ文化関係のサイト内リンク集:▶ヌヨリカン運動(NYでの文化運動)▶レゲ

トン︎▶カチカチ音楽(ハワイで開花したプエルトリコ音楽)︎︎▶クアトロ(楽器)︎▶メス

ティーソ︎︎▶︎アメリカにおける市民の概念▶︎︎レゲトンとデムボウ▶「教育される」ということが大嫌いだった僕(=あなた)との対話︎▶感覚のエスノグラフィー︎︎▶︎エクトル・ラボエ▶文化がもたらす美的機能▶︎遠隔地ナショナリズム▶パブロ・エスコバルとホアキン・エル・チャポ・グスマン︎︎▶︎エコ・ツーリズムと中央アメリカ▶︎︎ユナイティド・フルーツ▶︎ジュリアン・スチュワード▶︎︎ヨー・ヨー・ボイン!▶︎ラテ

ン・ヒップ・ポップ▶︎︎ラテントラップ▶チュイート・デ・バジャモン▶プエルトリコ調査関係リンク︎︎▶︎

| The Music of Puerto Rico has evolved as a heterogeneous and dynamic product of diverse cultural resources. The most conspicuous musical sources of Puerto Rico have primarily included European, Indigenous, and African influences, although many aspects of Puerto Rican music reflect origins elsewhere in the Caribbean. Puerto Rican music culture today comprises a wide and rich variety of genres, ranging from essentially native genres such as bomba, danza, and plena to more recent hybrid genres such as salsa, Latin trap and reggaeton. Broadly conceived, the realm of "Puerto Rican music" should naturally comprise the music culture of the millions of people of Puerto Rican descent who have lived in the United States, especially in New York City. Their music, from salsa to the boleros of Rafael Hernández, cannot be separated from the music culture of Puerto Rico itself. | プエルトリコの音楽は、多様な文化資源の異質かつダイナミックな産物と して発展してきた。プエルトリコの最も顕著な音楽源は、主にヨーロッパ、先住民、アフリカの影響を受けているが、プエルトリコ音楽の多くの側面はカリブ海 の他の地域の起源を反映している。今日のプエルトリコの音楽文化は、ボンバ、ダンザ、プレナといった本質的にネイティブなジャンルから、サルサ、ラテント ラップ、レゲトンといった最近のハイブリッドなジャンルまで、幅広く豊かなバラエティで構成されている。広く考えれば、「プエルトリコ音楽」の領域は、当 然、米国、特にニューヨークに住む数百万人のプエルトリコ系住民の音楽文化で構成されるはずだ。サルサからラファエル・エルナンデスのボレロまで、彼らの 音楽はプエルトリコの音楽文化そのものと切り離すことはできない。 |

| Traditional,

folk, and popular

music Early music The music culture in Puerto Rico during the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries is poorly documented. Certainly, it included Spanish church music, military band music, and diverse genres of dance music cultivated by the jíbaros and enslaved Africans and their descendants. While these later never constituted more than 11% of the island's population, they contributed to some of the island's most dynamic musical features becoming distinct indeed. In the 19th century Puerto Rican music begins to emerge into historical daylight, with notated genres like danza being naturally better documented than folk genres like jíbaro music and bomba y plena and seis. The African people of the island used drums made of carved hardwood covered with untreated rawhide on one side, commonly made from goatskin. A popular word derived from creole to describe this drum was shukbwa, which translates to 'trunk of tree' |

伝

統音楽、民族音楽、ポピュラー音楽【後述】 アーリーミュージック 16世紀、17世紀、18世紀のプエルトリコの音楽文化は、ほとんど記録されていない。確かに、スペインの教会音楽、軍楽隊の音楽、ジバロや奴隷にされた アフリカ人とその子孫が育てた多様なジャンルのダンスミュージックがあった。これらの音楽は島の人口の11%以上を占めることはなかったが、島の最もダイ ナミックな音楽的特徴が実際に明確なものとなるのに貢献した。 19世紀になると、プエルトリコの音楽は歴史に名を残すようになり、ジバロ音楽、ボンバ・イ・プレナ・セイスのような民俗音楽よりも、ダンザのような楽譜 のあるジャンルの方が、当然記録されている。 この島のアフリカの人々は、彫りの深い広葉樹の片面を未処理の生皮で覆った太鼓、一般的には山羊の皮で作られた太鼓を使っていた。このドラムを表すクレ オール語から派生した一般的な言葉はシュクブワで、「木の幹」と訳される。 |

| Folk music If the term "folk music" is taken to mean music genres that have flourished without elite support[clarification needed], and have evolved independently of the commercial mass media, the realm of Puerto Rican folk music would comprise the primarily Hispanic-derived jíbaro music, the Afro-Puerto Rican bomba, and the essentially "creole" plena. As these three genres evolved in Puerto Rico and are unique to that island[citation needed], they occupy a respected[neutrality is disputed] place in island culture, even if they are not currently as popular as contemporary music such as salsa or reggaeton. |

民俗音楽【後述】 民俗音楽」という用語が、エリートの支援なしに栄え[clearification needed]、商業的マスメディアとは無関係に発展してきた音楽ジャンルを意味するとすると、プエルトリコの民俗音楽の領域は、主にヒスパニック由来の ジバロ音楽、アフロプエルトリコのボンバ、本質的に「クロール」のプレナからなる。これら3つのジャンルはプエルトリコで発展したものであり、プエルトリ コ独自のものであるため[citation needed]、サルサやレゲトンなどの現代音楽ほどの人気はないにせよ、島の文化において尊敬に値する[中立性には異論がある]位置を占めている。 |

| Puerto

Rican Pop Much music in Puerto Rico falls outside the standard categories of "Latin music" and is better regarded as constituting varieties of "Latin world pop." This category includes, for example, Ricky Martin (who had a #1 Hot 100 hit in the U.S. with "Livin' La Vida Loca" in 1999), the boy-band Menudo (with its changing personnel of which Martin was once a member of), Los Chicos, Las Cheris, Salsa Kids and Chayanne. Famous singers include the Despacito singer Luis Fonsi. Also, singer and virtuoso guitarist Jose Feliciano born in Lares, Puerto Rico, became a world pop star in 1968 when his Latin-soul version of "Light My Fire" and the LP Feliciano! became great successes in the American and international rankings and allowed Feliciano to be the first Puerto Rican to win Grammy awards, during that year. Feliciano's "Feliz Navidad" remains one of the most popular Christmas songs. |

プ

エルトリコ・ポップ プエルトリコの多くの音楽は、標準的な "ラテン・ミュージック "のカテゴリーから外れており、"ラテン・ワールド・ポップ "の一種と見なした方がいいだろう。このカテゴリーには、例えば、リッキー・マーティン(1999年に「Livin' La Vida Loca」で全米ホット100の1位を獲得)、ボーイズ・バンドのメヌード(マーティンがかつて在籍していたボーイズ・バンドで、メンバーチェンジを繰り 返している)、ロス・チコス(Los Chicos)、ラス・チェリス(Las Cheris)、サルサ・キッズ(Salsa Kids)、チャヤンヌ(Chayanne)などが含まれる。有名な歌手としては、デスパシート(Despacito)のボーカル、ルイス・フォンシ (Luis Fonsi)がいる。また、プエルトリコのラレスで生まれたシンガーで名ギタリストのホセ・フェリシアーノは、1968年に「Light My Fire」のラテン・ソウル・バージョンとLP『フェリシアーノ!』がアメリカのみならず世界的なランキングで大成功を収め、その年にフェリシアーノはプ エルトリコ人として初めてグラミー賞を受賞した。フェリシアーノの "Feliz Navidad "は、今でも最も人気のあるクリスマス・ソングのひとつである。 |

| Reggaetón

and Dembow The roots of reggaetón lie in the 1980s by Puerto Rican rapper Vico C[citation needed]. In the early 1990s reggaeton coalesced as a more definitive genre, using the "Dem Bow" riddim derived from a Shabba Ranks song by that name, and further resembling Jamaican dancehall in its verses sung in simple tunes and stentorian style, and its emphasis—via lyrics, videos, and artist personas—on partying, dancing, boasting, "bling," and sexuality rather than weighty social commentary. While reggaeton may have commenced as a Spanish-language version of Jamaican dancehall, in the hands of performers like Tego Calderón, Daddy Yankee, Don Omar, and others, it soon acquired its distinctive flavor and today might be considered the most popular dance music in the Spanish Caribbean, surpassing even salsa.[8] Reggaetón is a genre of music, significantly blown up in Puerto Rico and across the world, that combines Latin rhythms, dancehall, and hip-hop and rap music. Reggaetón is frequently affiliated with “machismo” characteristics, strong or aggressive masculine pride. Since women have joined this genre of music they have been underrepresented and have been fighting to change its image.[9] This inevitably is causing controversy between what the genre was and what it is now. Reggaetón has transformed from being a musical expression with Jamaican and Panamanian roots to being “dembow” a newer style that has changed the game,[10] which is listened to mainly in the Dominican Republic. Despite its success, its constant reputation highlights sexuality in the dancing, its explicit lyrics that have women screaming sexualized phrases in the background, and the clothing women are presented in. In the '90s and early 2000s, Reggaetón had been targeted and censored in many Latin American countries for its ranchyness nature and truths[citation needed]. Censorship can be seen as the government's way of suppressing the people and ensuring that communication is not strong amongst the community[citation needed]. Since then, many women have joined Reggaetón in hopes of changing preconceptions. Many of them have paved the way and have successful careers such as Karol G, Natti Natasha, and others. Dembow has received notable population in Puerto Rico despite it originating from the Dominican Republic, with influences from Puerto Rico and Jamaica. When Shabba Ranks released the track "Dem Bow" in 1990, it did not take long for the dembow genre to form. The main elements of dembow music are its rhythm, which is somewhat reminiscent of reggaeton and dancehall music, but with a more constant rhythm and faster than reggaeton. Riddims were built from the song and the sound became a popular part of reggaeton. The rhythm and melodies in dembow music tends to be simple and repetitive.[11][12][13][14]  Ivy Queen Ivy Queen was born as Martha Ivelisse Pesante on March 4, 1972, in Añasco, Puerto Rico. After writing raps during her youth and competing in an underground nightclub called The Noise, it led to the beginning of her musical career. Many consider her the “Queen of Reggaeton.”[15] In the beginning of her career, it was very difficult for her to be taken seriously in the reggaeton industry because this genre of music is seen as misogynistic. Recently, there has been controversy regarding how big her female influence has been on the genre. Another reggaeton artist, Anuel AA, questioned her place as the “Queen of Reggaeton” since she had not had a hit in seven years.[16] He also insinuated that his girlfriend, Karol G, should be the queen of reggaeton. Ivy Queen responded saying her career paved the way for female artists to thrive in this genre.[17] In reaction to the comments made by her boyfriend Anuel AA, Karol G responded with a video, saying “For Becky G, Natti Natasha, Anitta, Ivy Queen and all the women who have shown me respect in all my social networks and interviews: I have had the honor of telling them in person how much I admire their work and careers, but we are all worthy of what we have because nobody has given anything to anyone.” She went on to say, “This is a crown, and nobody is not going to give it to them, for what they have done. I am not looking for a degree, I am only looking for the success of my career, as everyone is doing every day. Getting up for the dream. To my boyfriend, I just want to say thank you, because I know what you wanted to say. I am your queen and I am very happy that you see me that big because you do motivate me. All of us are going to do what we like and work for it.”[18] Ultimately, Ivy Queen would make amends with Anuel, and after finally meeting Karol G, Ivy would go on to feature on Karol's successful 2021 album “KG0516” on the multi-artist track “Leyendas” (‘Legends’). The track, also featuring Zion, Nicky Jam, and Wisin y Yandel, opens with Ivy Queen singing memorable parts of her biggest song to date, “Yo Quiero Bailar” (‘I want to dance’) before Karol joins in. Ivy Queen has been an influence on other women like Cardi B and Farina. Even men, such as Bad Bunny,[19] have listed her as an influence for their lyrics. Her ability to compete amongst men who dominated Reggaetón gave hope to other women who had similar interests in the music industry. Her influence and her dominance in the genre has helped other women be able to break through in the reggaetón scene and sparked a place for women's empowerment not only for Puerto Rican artist but for other Latinas who are newer to the game such as Karol G and Natti Natasha, leaving Ivy Queen to crown herself with the title “The Queen”.[20] Karol G is a Colombian reggaeton singer who has done collaborations with other reggaeton singers, such as J Balvin, Bad Bunny, and Maluma.[21] Throughout her career, Karol G has had troubles in the industry because reggaeton is a genre that is dominated by males. She recounts how when starting her career she noticed that there were not many opportunities for her in the genre because reggaeton was dominated by male artists.[22] In 2018, Karol G's single "Mi Cama" became very popular and she made a remix with J Balvin and Nicky Jam. The Mi cama remix appeared in the top 10 Hot Latin Songs and number 1 in Latin Airplay charts.[23] This year she has collaborated with Maluma on her song "Creeme" and with Anuel AA in the song "Culpables". The single, "Culpables" has been in the top 10 Hot Latin Songs for 2 consecutive weeks.[21] On May 3, 2019, Karol G was able to release her new album called Ocean.[24] Natti Natasha is a Dominican reggaeton singer who has also joined the reggaeton industry and has listed Ivy Queen as one of her influences for her music.[25] In 2017 she made a single called "Criminal" that features reggaeton artist, Ozuna. Her single "Criminal" became very popular on YouTube with more than has 1.5 billion views.[26] In 2018 Natti Natasha collaborated with RKM and Ken Y in their single "Tonta". She later also collaborated with Becky G in “Sin Pijama” which made it to the top 10 in Hot Latin songs, Latin Airplay, and Latin Pop Airplay charts.[27] After all the collaborations that Natti Natasha has done she was able to release her album called illumiNatti on February 15, 2019.[28] |

レ

ゲトンとデンボウ(→「レゲトン」「レゲトンとデムボウ」) レゲトンのルーツは1980年代のプエルトリコ人ラッパー、ヴィコC[要出典]にある。1990年代初頭、レゲトンはより明確なジャンルとしてまとまり、 シャバ・ランクス(Shabba Ranks)の曲から派生した「Dem Bow」リディムを使用し、シンプルな曲調とステントリアン・スタイルで歌われる詩はジャマイカのダンスホールにさらに似ており、歌詞、ビデオ、アーティ ストのペルソナは、重厚な社会的論評よりも、パーティー、ダンス、自慢、「ブリング」、セクシュアリティに重点を置いている。レゲトンはジャマイカのダン スホールのスペイン語版として始まったかもしれないが、テゴ・カルデロン、ダディ・ヤンキー、ドン・オマールなどのパフォーマーの手にかかると、すぐに独 特の風味を獲得し、今日ではサルサさえも凌ぐ、スペイン系カリブ海で最も人気のあるダンスミュージックと見なされるようになった[8]。 レゲトンは、ラテンのリズム、ダンスホール、ヒップホップやラップ・ミュージックを融合させた音楽のジャンルで、プエルトリコだけでなく、世界中で大ブー ムとなっている。レゲトンは "マチズモ "的な特徴、つまり男性的な強いプライドや攻撃的なプライドと結びついていることが多い。このジャンルの音楽に女性が加わって以来、彼女たちの存在感は薄 れ、そのイメージを変えようと闘ってきた[9]。このことは必然的に、このジャンルがかつてそうであったことと、現在そうであることの間に論争を引き起こ している。レゲトンは、ジャマイカやパナマにルーツを持つ音楽表現から、ドミニカ共和国を中心に聴かれている[10]、ゲームを変えた新しいスタイルの 「デムボウ」へと変貌を遂げた。その成功にもかかわらず、一定の評価を得ているのは、ダンスにおけるセクシュアリティ、女性が性的なフレーズを叫ぶ露骨な 歌詞、そして女性が着ている服装が強調されていることである。90年代から2000年代初頭にかけて、レゲトンはその牧畜的な性質と真実[要出典]のため に、多くのラテンアメリカ諸国で標的にされ、検閲された。検閲は、政府が民衆を抑圧し、コミュニティ間のコミュニケーションが強まらないようにするための 手段ともいえる[要出典]。それ以来、多くの女性が先入観を変えることを願ってレゲトンに参加した。彼女たちの多くは道を切り開き、カロルG、ナッティ・ ナターシャなどのような成功したキャリアを持っている。Dembowは、プエルトリコとジャマイカの影響を受けたドミニカ共和国発祥にもかかわらず、プエ ルトリコで注目すべき人口を獲得している。1990年にシャバ・ランクスがトラック「Dem Bow」をリリースすると、デンボウというジャンルが形成されるのに時間はかからなかった。デムボウ・ミュージックの主な要素はそのリズムで、レゲトンや ダンスホール・ミュージックを多少彷彿とさせるが、レゲトンよりも一定のリズムでより速い。曲からリディムが作られ、そのサウンドはレゲトンの人気パート となった。デムボウ・ミュージックのリズムとメロディーはシンプルで繰り返しが多い傾向にある[11][12][13][14]。  アイビー・クイーン アイビー・クイーンは1972年3月4日、プエルトリコのアニャスコでマーサ・イヴェリス・ペサンテとして生まれた。若い頃にラップを書き、ザ・ノイズと 呼ばれるアンダーグラウンドのナイトクラブで競い合ったことが、彼女の音楽活動の始まりとなった。多くの人が彼女を "レゲトンの女王 "と考えている[15]。キャリアの初期には、レゲトンというジャンルの音楽が女性差別的と見られていたため、彼女がレゲトン業界で真剣に受け入れられる ことは非常に難しかった。最近では、彼女の女性としての影響力がこのジャンルにどれほど大きなものであったかについて論争が起きている。もう一人のレゲト ンアーティスト、アニュエル・AAは、彼女が7年間ヒットを出していないことから、「レゲトンの女王」としての彼女の地位に疑問を呈した[16]。彼はま た、ガールフレンドのカロルGがレゲトンの女王になるべきだとほのめかした。アイビー・クイーンは、彼女のキャリアがこのジャンルで活躍する女性アーティ ストの道を開いたと反論した[17]。ボーイフレンドのアニュエルAAのコメントに反応して、カロルGはビデオでこう反論した。「ベッキーG、ナッティ・ ナターシャ、アニッタ、アイビー・クイーン、そして私のすべてのソーシャル・ネットワークやインタビューで私に敬意を示してくれたすべての女性のために: 彼女たちの仕事やキャリアにどれだけ敬意を表しているか、直接彼女たちに伝える光栄に浴した。これは王冠であり、誰も彼らに与えるつもりはない。私は学位 など求めていない。みんなが毎日しているように、自分のキャリアの成功だけを求めている。夢のために立ち上がる。ボーイフレンドには、ただありがとうと言 いたい。私はあなたの女王であり、あなたが私をそこまで大きく見てくれることがとても嬉しい。最終的に、アイビー・クイーンはアニュエルと仲直りし、カロ ルGと出会った後、アイビーはカロルの成功した2021年のアルバム『KG0516』のマルチ・アーティスト・トラック「Leyendas」 (「Legends」)でフィーチャーされることになった。ザイオン、ニッキー・ジャム、ウィシン・イ・ヤンデルも参加したこのトラックは、アイビー・ク イーンが、カロルが参加する前に、彼女のこれまでの最大の楽曲「Yo Quiero Bailar」(「踊りたい」)の印象的な部分を歌うところから始まる。 アイビー・クイーンは、カーディ・Bやファリーナといった他の女性たちにも影響を与えている。バッド・バニー[19]のような男性でさえ、歌詞に影響を受 けた人物として彼女を挙げている。レゲトンを支配する男性たちの中で競争する彼女の能力は、音楽業界で同じような関心を持つ他の女性たちに希望を与えた。 彼女の影響力とジャンルにおける優位性は、他の女性がレゲトン・シーンでブレイクするのを助け、プエルトリコ人アーティストだけでなく、カロルGやナッ ティ・ナターシャのようなこのゲームに新しいラテン系女性にも女性のエンパワーメントの場を巻き起こし、アイビー・クイーンは自らに「女王」の称号を戴く ことになった[20]。 カロルGはコロンビアのレゲトン・シンガーで、J・バルヴィン、バッド・バニー、マルマといった他のレゲトン・シンガーとコラボレートしている[21]。 レゲトンは男性優位のジャンルであるため、カロルGはキャリアを通して、業界で問題を抱えてきた。彼女は、キャリアをスタートさせたとき、レゲトンが男性 アーティストに支配されているため、このジャンルで自分にチャンスがあまりないことに気づいたと語っている[22]。 2018年、カロルGのシングル「Mi Cama」が大人気となり、J・バルヴィンとニッキー・ジャムとリミックスを制作。Mi camaのリミックスはHot Latin Songsのトップ10とLatin Airplayチャートの1位に登場した[23]。 今年、彼女はMalumaと "Creeme "で、Anuel AAと "Culpables "でコラボレーションした。シングル "Culpables "は2週連続でHot Latin Songsのトップ10にランクインしている[21]。 2019年5月3日、カロルGはニューアルバム『Ocean』をリリースすることができた[24]。 ナッティ・ナターシャはドミニカ共和国のレゲトン・シンガーで、レゲトン業界にも参加しており、彼女の音楽に影響を与えた一人としてアイビー・クイーンを 挙げている[25]。 2017年、彼女はレゲトン・アーティストのオズーナをフィーチャーした「Criminal」というシングルを作った。彼女のシングル "Criminal "はYouTubeで大人気となり、再生回数は15億回を超えた[26]。 2018年、ナッティ・ナターシャはRKMとKen Yとシングル "Tonta "でコラボ。彼女はその後、ホット・ラテン・ソング、ラテン・エアプレイ、ラテン・ポップ・エアプレイ・チャートのトップ10に入った「Sin Pijama」でベッキー・Gともコラボした[27]。 ナッティ・ナターシャが行ったすべてのコラボレーションの後、彼女は2019年2月15日にillumiNattiというアルバムをリリースすることがで きた[28]。 |

| Top

25 Puerto Ricans Rappers: 2023’s Best Rappers from Puerto Rico. 1. Bad Bunny 2. Daddy Yankee 3. Nengo Flow 4. Eladio Carrión 5. Cosculluela 6. Bryant Myers 7. Noriel 8. Darell 9. Miky Woodz 10. Residente 11. Jon Z 12. Almighty 13. Jamby El Favo 14. Brray 15. kevvo 16. Luar La L 17. Ele A el Dominio 18. Juanka 19. YOVNGCHIMI 20. Pusho 21. omar courtz 22. Omy De Oro 23. Tempo 24. Hozwal 25. ankhal |

プエルトリコ

のベスト・ラッパーたち、トップ25. 1. Bad Bunny 2. Daddy Yankee 3. Nengo Flow 4. Eladio Carrión 5. Cosculluela 6. Bryant Myers 7. Noriel 8. Darell 9. Miky Woodz 10. Residente 11. Jon Z 12. Almighty 13. Jamby El Favo 14. Brray 15. kevvo 16. Luar La L 17. Ele A el Dominio 18. Juanka 19. YOVNGCHIMI 20. Pusho 21. omar courtz 22. Omy De Oro 23. Tempo 24. Hozwal 25. ankhal |

| Caribbean influences Although bachata is very well-known to have originated in the Dominican Republic, it has received notable recognition in Puerto Rico due to its strong cultural ties with the Dominican Republic. One of the primary influences of early bachata includes Cuba's bolero and Puerto Rico's Jíbaro, along with others such as Cuban son, America's rock and blues, Mexico's ranchera and corrido and Dominican merengue[29][30][31] The appearance of Dominican styles of music such as bachata and merengue in reggaetón coincided with the arrival in Puerto Rico of the Dominican-born production team of Luny Tunes—although they are not solely credited for this development.[32] In 2000, they received an opportunity to work in the reggaeton studio of DJ Nelson. They began to produce a string of successful releases for reggaeton artists including Ivy Queen, Tego Calderón and Daddy Yankee.[32] "Pa' Que Retozen", one of the first songs to combine bachata and reggaeton appeared on Tego Calderón's highly acclaimed El Abayarde (2002). It features the unmistakable guitar sounds of Dominican bachata—although, it was not produced by Luny Tunes by DJ Joe.[32] Luny Tunes, however, on their debut studio album, Mas Flow (2003) included a hit by Calderón, "Métele Sazón". It exhibited bachata's signature guitar arpeggios as well as merengue's characteristic piano riffs.[32] After the initial success of these songs, other artists began to incorporate bachata with reggaeton. Artists such as Ivy Queen began releasing singles that featured bachata's signature guitar sound, slower romantic rhythm, and exaggerated emotional singing style.[32] This is reflected in the hits "Te He Querido, Te He Llorado" and "La Mala".[32] Daddy Yankee's "Lo Que Paso, Paso" and Don Omar's "Dile" also reflect this. A further use of bachata occurred in 2005 when producers began remixing existing reggaeton with bachata's characteristic guitar sounds marketing it as bachatón defining it as "bachata, but Puerto Rican style".[32] Artists from Puerto Rico and/or of Puerto Rican descent that have been known to experiment with bachata and/or bachatón includes Fufi Santori, Daddy Yankee, Ivy Queen, Don Omar, Ozuna, Nicky Jam, Myke Towers, Bad Bunny, Romeo Santos, Toby Love, Alejandra Feliz, Yolandita Monge, Sonya Cortés, Domenic Marte, Tego Calderón, Héctor el Father, Tito El Bambino, Wisin & Yandel, Angel & Khriz, Chayanne, Ricky Martin, amongst many others.[32][33][34] Bolero Although bolero has its origins in Cuba, it had already reached Puerto Rico in the 20th century where it was popularized on the island through the first radio stations in 1915 and was being both enjoyed as well as composed and performed by Puerto Ricans, including such outstanding figures as Rafael Hernández, Daniel Santos, Pedro Flores, Johnny Albino, Odilio González, Noel Estrada, José Feliciano, Trio Vegabajeño, and Tito Rodríguez, amongst many others. Similar to the bolero genre in Cuba, the bolero in Puerto Rico is usually combined with other genres of Cuban and Puerto Rican origin, such as bomba, danza, plena, jíbaro, guaracha, mambo, rumba, cha-cha-cha, and salsa. Merengue Although merengue is a type of music and dance that has its origins and also carries a very strong association with the Dominican Republic, it became widespread throughout Latin America and the United States, including Puerto Rico.[35][36] The choreography of the ballroom merengue is a basic side two-step, but with a difficult twist of the hip to the right, which makes it somewhat hard to perform. The two dance partners get into a vals, or waltz-like position. The couple then side steps, known as a Paso de la empalizada or "stick-fence step," followed by either a clockwise or counter-clockwise turn. During all of the dance steps of the ballroom merengue, the couple never separates. The second kind of merengue is called the Figure Meringue or Merengue de Figura. The performing couple makes individual turns without releasing the hands of the partner and still keeping the rhythm of the beat.[37] Popular merengue performers from Puerto Rico include Elvis Crespo, Olga Tañón, Gisselle, Manny Manuel, Grupo Mania, Limi-T 21, amongst many others.[38][39] Merenhouse, which is a subgenre of merengue that is formed by rapping and includes influences of hip-hop, dancehall, and latin house was formed in New York City in the late 1980s. Lisa M, who was the first major female Latin rapper that was born and raised in San Juan, Puerto Rico is often credited for making the first song in the merenhouse genre. Mostly credited on her second album No Lo Derrumbes, which was released in 1990.[40] Guaracha and Salsa  The timbales of Tito Puente on exhibit in the Musical Instruments Museum in Phoenix, AZ Salsa is another genre whose form derived from the Cuban/Puerto Rican melding of the genre, especially Cuban dance music of the 1950s—but which in the 1960s–70s became an international genre, cultivated with special zeal and excellence in Puerto Rico and by Puerto Ricans in New York City. Forms such as the Charanga were hugely popular with Puerto Ricans and Nuyoricans who, in effect, rescued this genre which had been stagnating and limited to only Cuba in the 1960s, giving it new life, new social significance, and many new stylistic innovations. Salsa is the name acquired by the modernized form of Cuban/Puerto Rican-style dance music that was cultivated and rearticulated starting in the late 1960s by Puerto Ricans in New York City and, subsequently, in Puerto Rico and elsewhere. While salsa soon became an international phenomenon, thriving in Colombia, Venezuela, and elsewhere, New York and Puerto Rico remained its two epicenters. Particularly prominent on the island were El Gran Combo, Sonora Ponceña, and Willie Rosario, as well as the more pop-oriented "salsa romántica" stars of the 1980s–90s. (For further information see the entry on "salsa music.") Other popular Nuyorican and Puerto Rican exposers of these genres have been Tito Puente, Tito Rodríguez (guaracha and bolero singer), pianists Eddie Palmieri, Richie Ray and Papo Lucca, conguero Ray Barreto, trombonist and singer Willie Colón, and singers La India, Andy Montañez, Bobby Cruz, Cheo Feliciano, Héctor Lavoe, Ismael Miranda, Ismael Rivera, Tito Nieves, Pete El Conde Rodríguez and Gilberto Santa Rosa. Reggae and Dancehall Puerto Rico has had its music scene for both reggae and dancehall artists, in addition to the local reggaetón genre, which had evolved in Puerto Rico primarily through reggae and dancehall influences from Panama and Jamaica.[41][42] Local artists and bands such as Cultura Profética, Millo Torres y El Tercer Planeta, and Gomba Jahbari have received notable recognition on the island, as well as other reggae and dancehall acts in Puerto Rico. Reggae in Puerto Rico uses elements such as intricate horn arrangements and chord progressions to distinguish it from other styles of reggae, most notably Jamaican reggae. It is also sung primarily in Spanish and/or English, although Puerto Rican reggae can also be sung in other languages as well. Their variation of reggae has also been influenced by other music genres such as salsa, which originated in Puerto Rico, and jazz music which came from the United States, as their local reggae and dancehall musicians like to experiment with other genres and combine them with their style of reggae. |

カリブ海の影響 バチャータがドミニカ共和国で生まれたことはよく知られているが、ドミニカ共和国との文化的な結びつきが強いため、プエルトリコでも注目されている。初期 のバチャータはキューバのボレロやプエルトリコのジバロ、キューバのソン、アメリカのロックやブルース、メキシコのランチェラやコリド、ドミニカのメレン ゲ[29][30][31]などの影響を受けている。レゲトンにバチャータやメレンゲのようなドミニカ風の音楽が登場したのは、ドミニカ出身のプロダク ション・チーム、ルニー・チューンズがプエルトリコに到着した時期と重なる。 [32]2000年、彼らはDJネルソンのレゲトン・スタジオで働く機会を得た。32]「Pa' Que Retozen」は、バチャータとレゲトンを組み合わせた最初の曲のひとつで、高い評価を得たテゴ・カルデロンの『El Abayarde』(2002年)に収録されている。この曲はドミニカン・バチャータの紛れもないギター・サウンドをフィーチャーしているが、DJジョー のルニー・テューンズによるプロデュースではなかった[32]。しかし、ルニー・テューンズはデビュー・スタジオ・アルバム『マス・フロー』(2003 年)に、カルデロンのヒット曲「メテレ・サゾン」を収録。この曲は、バチャータの特徴であるギターのアルペジオとメレンゲの特徴であるピアノのリフを表し ていた[32]。これらの曲の最初の成功の後、他のアーティストがバチャータをレゲトンに取り入れるようになった。アイビー・クイーンのようなアーティス トは、バチャータの特徴的なギターサウンド、ゆったりとしたロマンチックなリズム、大げさで感情的な歌い方をフィーチャーしたシングルをリリースし始めた [32]。これはヒット曲「Te He Querido, Te He Llorado」や「La Mala」に反映されている[32]。ダディ・ヤンキーの「Lo Que Paso, Paso」やドン・オマールの「Dile」もこれを反映している。2005年、プロデューサーたちが既存のレゲトンにバチャータの特徴的なギター・サウン ドをリミックスし始め、「バチャータだがプエルトリコ・スタイル」と定義するバチャトンとして売り出したことで、バチャータのさらなる使用が始まった [32]。 ロメオ・サントス、トビー・ラヴ、アレハンドラ・フェリス、ヨランディータ・モンゲ、ソーニャ・コルテス、ドメニック・マルテ、テゴ・カルデロン、エクト ル・エル・ファーザー、ティト・エル・バンビーノ、ウィシン&ヤンデル、エンジェル&クリズ、チャヤンヌ、リッキー・マーティンなど。 [32][33][34] ボレロ ボレロはキューバに起源を持つが、20世紀にはすでにプエルトリコに到達しており、1915年に最初のラジオ局を通じてプエルトリコに広まり、ラファエ ル・エルナンデス、ダニエル・サントス、ペドロ・フローレス、ジョニー・アルビーノ、オディリオ・ゴンサレス、ノエル・エストラーダ、ホセ・フェリシアー ノ、トリオ・ベガバジェーニョ、ティト・ロドリゲスなど、多くのプエルトリコ人がボレロを楽しみ、作曲し、演奏していた。キューバのボレロと同様に、プエ ルトリコのボレロもキューバやプエルトリコ発祥の他のジャンル、例えばボンバ、ダンツァ、プレナ、ジバロ、グアラチャ、マンボ、ルンバ、チャチャチャ、サ ルサなどと組み合わされるのが普通である。 メレンゲ メレンゲはドミニカ共和国を起源とする音楽とダンスの一種であり、ドミニカ共和国との結びつきも非常に強いが、プエルトリコを含むラテン・アメリカとアメ リカ全土に広まった[35][36]。社交ダンスのメレンゲの振り付けは基本的なサイド・ツー・ステップだが、腰を右にひねるのが難しく、やや演じにく い。2人のダンス・パートナーはバルス、つまりワルツのような体勢になる。その後、パソ・デ・ラ・エンパリザダ(棒柵ステップ)として知られるサイドス テップを踏み、時計回りまたは反時計回りにターンする。社交ダンスのメレンゲのステップの間、カップルが離れることはない。2つ目のメレンゲはフィギュ ア・メレンゲ(Merengue de Figura)と呼ばれる。プエルトリコ出身の人気メレンゲ・パフォーマーには、エルビス・クレスポ、オルガ・タニョン、ジセル、マニー・マヌエル、グ ルーポ・マニア、リミ-T 21などがいる[38][39]。メレンゲのサブジャンルで、ラップによって形成され、ヒップホップ、ダンスホール、ラテン・ハウスの影響を含むメレンゲ は、1980年代後半にニューヨークで形成された。プエルトリコのサン・フアンで生まれ育ったリサ・Mは、メレンゲ・ハウスというジャンルの最初の曲を 作った最初のメジャーな女性ラテン・ラッパーとしてよく知られている。主に1990年にリリースされた彼女のセカンド・アルバム『No Lo Derrumbes』にクレジットされている[40]。 グアラチャとサルサ  アリゾナ州フェニックスの楽器博物館に展示されているティト・プエンテのティンバレス サルサもまた、キューバとプエルトリコの融合、特に1950年代のキューバ・ダンス・ミュージックから派生したジャンルであるが、1960年代から70年 代にかけて、プエルトリコとニューヨークのプエルトリコ人によって特別な熱意と卓越性をもって育成され、国際的なジャンルとなった。チャランガのような形 式は、プエルトリコ人やヌヨリカンに絶大な人気を博し、彼らは事実上、1960年代にキューバだけに限定され停滞していたこのジャンルを救い出し、新たな 生命、新たな社会的意義、そして多くの新しいスタイルの革新を与えた。サルサとは、1960年代後半にニューヨークのプエルトリコ人たちによって始められ た、キューバ/プエルトリコ・スタイルの現代化されたダンス・ミュージックに付けられた名称であり、その後プエルトリコやその他の地域でも広まった。サル サはすぐに国際的な現象となり、コロンビアやベネズエラなどでも盛んになったが、ニューヨークとプエルトリコがその2つの中心であり続けた。特にプエルト リコでは、エル・グラン・コンボ、ソノーラ・ポンセーニャ、ウィリー・ロサリオや、1980年代から90年代にかけてのポップ志向の「サルサ・ロマンチ カ」スターたちが目立っていた。(詳しくは「サルサ音楽」の項目を参照)。 これらのジャンルで人気を博した他のヌヨリカン、プエルトリコ人シンガーには、ティト・プエンテ、ティト・ロドリゲス(グアラチャ、ボレロ・シンガー)、 ピアニストのエディ・パルミエリ、リッチー・レイ、パポ・ルッカ、コンゲーロのレイ・バレット トロンボーン奏者で歌手のウィリー・コロン、歌手のラ・インディア、アンディ・モンタニェス、ボビー・クルス、チェオ・フェリシアーノ、エクトル・ラボ エ、イスマエル・ミランダ、イスマエル・リベラ、ティト・ニエベス、ピート・エル・コンデ・ロドリゲス、ジルベルト・サンタ・ロサ。 レゲエとダンスホール プエルトリコには、主にパナマとジャマイカからのレゲエとダンスホールの影響によってプエルトリコで発展した地元のレゲエ・ジャンルに加えて、レゲエとダ ンスホールの両方のアーティストの音楽シーンがあった[41][42]。クルトゥラ・プロフェティカ、ミロ・トーレス・イ・エル・テルセル・プラネタ、ゴ ンバ・ジャハバリなどの地元のアーティストやバンドは、プエルトリコの他のレゲエやダンスホールのアーティストと同様に、島で注目すべき評価を得ている。 プエルトリコのレゲエは、複雑なホーン・アレンジやコード進行などの要素を用いて、他のスタイルのレゲエ(特にジャマイカン・レゲエ)と区別している。ま た、主にスペイン語や英語で歌われるが、プエルトリコのレゲエは他の言語でも歌われることがある。レゲエのバリエーションは、プエルトリコ発祥のサルサや アメリカ発祥のジャズといった他の音楽ジャンルからも影響を受けている。 |

El Cumbanchero - Rafael Hernández Marín, Piano |

●ラファエル・エルナンデスとクンバンチェロ |

| ●ホセ・フェリシアーノ |

|

| Héctor Juan Pérez Martínez (30

September 1946 – 29 June 1993) |

●エクト

ル・ラヴォ |

| ●サルサ |

|

| ●ヒップ・ホップ |

|

| ●レゲトン 「レゲトン(スペイン語: Reguetón、英語: Reggaeton)は、80年代から90年代にアメリカ合衆国のヒップホップの影響を受けたプエルトリコ人によって生み出された音楽である」 |

|

| ●レ

ゲトンとデムボウ(Reggaetón and Dembow) 「デ ムボウはドミニカの音楽ジャンル[1][2]で、ジャマイカのダンスホールで生まれたリディムに端を発する[3]。 1990年にシャバ・ランクスが「Dem Bow」をリリースすると、デムボウというジャンルが形成されるまで長くはかからなかった。この曲からリディムが作られ、そのサウンドはレゲトンの人気コ ンテンツとなった。その後、ドミニカ共和国でUNDERWORLD(スペイン語で「Bajo Mundo」)というサウンドが生まれた。それがニューヨークのストリートでヒットし、そこからラテンアメリカ全土へと広がっていった」 |

|

| ●ク

アトロ(楽器) |

|

| ●カチカチ音

楽 |

|

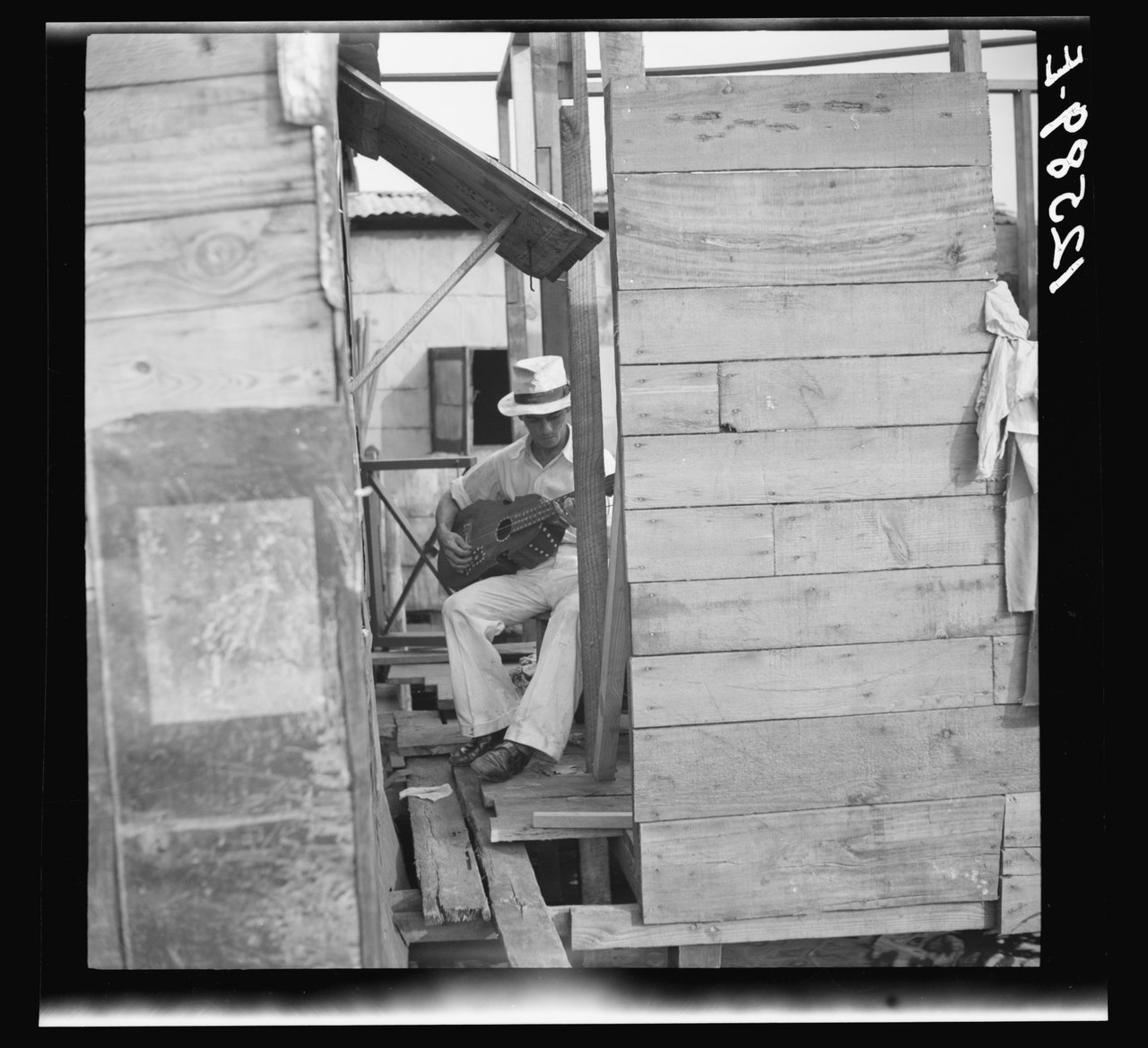

| Traditional, folk, and popular

music Jíbaro music  A Tiple Requinto (1880) from Puerto Rico Jíbaros are small farmers of mixed descent who constituted the overwhelming majority of the Puerto Rican population until the mid-twentieth century.[1] They are traditionally recognized as romantic icons of land cultivation, hard-working, self-sufficient, hospitable, and with an innate love of song and dance. Their instruments[2] were relatives of the Spanish vihuela, especially the cuatro — which evolved from four single strings to five pairs of double strings —[3] and the lesser known tiple.[4] A typical jíbaro group nowadays might feature a cuatro, guitar, and percussion instrument such as the güiro scraper and/or bongo. Lyrics to jíbaro music are generally in the décima form, consisting of ten octosyllabic lines in the rhyme scheme abba, accddc. Décima form derives from 16th century Spain. Although it has largely died out in that country (except the Canaries), it took root in various places in Latin America—especially Cuba and Puerto Rico—where it is sung in diverse styles. A sung décima might be pre-composed, derived from a publication by some literati, or ideally, improvised on the spot, especially in the form of a “controversia” in which two singer-poets trade witty insults or argue on some topic. In between the décimas, lively improvisations can be played on the cuatro. This music form is also known as "típica" as well as "trópica". The décimas are sung to stock melodies, with standardized cuatro accompaniment patterns. About twenty such song types are in common use. These are grouped into two broad categories, viz., seis (e.g., seis fajardeño, seis chorreao) and aguinaldo (e.g., aguinaldo orocoveño, aguinaldo cayeyano). Traditionally, the seis could accompany dancing, but this tradition has largely died out except in tourist shows and festivals. The aguinaldo is most characteristically sung during the Christmas season, when groups of revelers (parrandas) go from house to house, singing jíbaro songs and partying. The aguinaldo texts are generally not about Christmas, and also unlike Anglo-American Christmas carols, they are generally sung by a solo with the other revelers singing the chorus. In general, the Christmas season is a time when traditional music—both seis and aguinaldo—is most likely to be heard. Fortunately, many groups of Puerto Ricans are dedicated to preserving traditional music through continued practice. Jíbaro music came to be marketed on commercial recordings in the twentieth century, and singer-poets like Ramito (Flor Morales Ramos, 1915–90) are well documented. However, jíbaros themselves were becoming an endangered species, as agribusiness and urbanization have drastically reduced the numbers of small farmers on the island. Many jíbaro songs dealt accordingly with the vicissitudes of migration to New York. Jíbaro music has in general declined accordingly, although it retains its place in local culture, especially around Christmas time and special social gatherings, and there are many cuatro players, some of whom have cultivated prodigious virtuosity. HOMENAJE JIBARO 2007(1940-2007) |

伝

統音楽、民族音楽、ポピュラー音楽 プエルトリコのティプル・レキント(1880年) ヒバロとは、20世紀半ばまでプエルトリコの人口の圧倒的多数を占めていた混血の小農民のことである[1]。彼らは伝統的に、勤勉で自給自足、もてなしの 心を持ち、生まれつき歌と踊りを愛する、ロマンティックな開墾の象徴として認識されている。彼らの楽器[2]はスペインのビウエラの親戚であり、特に4本 の単弦から5対の複弦に進化したクアトロ[3]と、あまり知られていないティプル[4]である。今日、典型的なジバロ・グループは、クアトロ、ギター、グ イロ・スクレイパーやボンゴなどの打楽器を特徴とする。ジバロ音楽の歌詞は一般的にデシマ形式で、abba, accddcの韻律で10行の8音節からなる。デシマ形式は16世紀のスペインに由来する。スペインでは(カナリア諸島を除いて)ほとんど廃れてしまった が、ラテンアメリカ、特にキューバとプエルトリコの様々な場所で定着し、様々なスタイルで歌われている。歌われるデチマは、あらかじめ作曲されたもので あったり、文学者の出版物に由来するものであったり、理想的にはその場で即興で作られる。デシマの合間には、クアトロで生き生きとした即興演奏が行われる こともある。この音楽形式は、「típica(ティピカ)」、「trópica(トロピカ)」とも呼ばれる。 デチマは、標準化されたクアトロの伴奏パターンで、標準的なメロディに合わせて歌われる。このような歌は約20種類あり、一般的に使用されている。これら は2つの大きなカテゴリーに分類される。すなわち、seis(seis fajardeño、seis chorreaoなど)とaguinaldo(aguinaldo orocoveño、aguinaldo cayeyanoなど)である。伝統的に、セイスは踊りの伴奏として使われることもあったが、観光客向けのショーや祭りを除いて、その伝統はほとんど廃れ てしまった。アギナルドが最も特徴的に歌われるのはクリスマス・シーズンで、お祭り騒ぎをするグループ(パランダ)が家々を回り、ジバロの歌を歌いながら パーティーをする。アギナルドのテキストは一般的にクリスマスに関するものではなく、また、英米のクリスマス・キャロルとは異なり、ソロで歌われ、他のお 祭り騒ぎをする人たちがコーラスを歌うのが一般的である。一般的に、クリスマス・シーズンは、セイスもアギナルドも伝統的な音楽が最もよく聞かれる時期で ある。幸いなことに、多くのプエルトリコ人グループが、継続的な練習を通じて伝統音楽の保存に尽力している。 ヒバロの音楽は20世紀に商業用レコードで販売されるようになり、ラミート(フロール・モラレス・ラモス、1915~90年)のような歌手詩人もよく知ら れている。しかし、アグリビジネスと都市化によって島の小規模農家の数が激減したため、ヒバロ自体が絶滅危惧種になりつつあった。多くのジバロの歌は、そ れに応じてニューヨークへの移住の波乱を扱った。ヒバロの音楽は、特にクリスマスや特別な社交の場など、地元の文化の中でその地位を保ってはいるものの、 一般的にはそれに応じて衰退していった。 |

| Bomba

(Puerto Rico) Historical references indicate that by the decades around 1800 plantation slaves were cultivating a music and dance genre called bomba. By the mid-twentieth century, when it started to be recorded and filmed, bomba was performed in regional variants in various parts of the island, especially Loíza, Ponce, San Juan, and Mayagüez. It is not possible to reconstruct the history of bomba; various aspects reflect Congolese derivation, though some elements (as suggested by subgenre names like holandés) have come from elsewhere in the Caribbean. French Caribbean elements are particularly evident in the bomba style of Mayagüez, and striking choreographic parallels can be seen with the bélé of Martinique. All of these sources were blended into a unique sound that reflects the life of the Jibaro, the slaves, and the culture of Puerto Rico. In its call-and-response singing set to ostinato-based rhythms played on two or three squat drums (barriles), bomba resembles other neo-African genres in the Caribbean. Of clear African provenance is its format in which a single person emerges from an informal circle of singers to dance in front of the drummers, engaging the lead drummer in a sort of playful duel; after dancing for a while, that person is then replaced by another. While various such elements can be traced to origins in Africa or elsewhere, bomba must be regarded as a local Afro-Puerto Rican creation. Its rhythms (e.g. seis corrido, yubá, leró, etc.), dance moves, and song lyrics that sometimes mimic farm animals(in Spanish, with some French creole words in eastern Puerto Rico) collectively constitute a unique Puerto Rican genre. In the 1950s, the dance-band ensemble of Rafael Cortijo and Ismael Rivera performed several songs in they had labeled as "bombas"; although these bore some similarities to the sicá style of bomba, in their rhythms and horn arrangements they also borrowed noticeably from the Cuban dance music which had long been popular in the island. Giving rise to Charanga music. As of the 1980s, bomba had declined, although it was taught, in a somewhat formalized fashion, by the Cepeda family in Santurce, San Juan, and was still actively performed informally, though with much vigor, in the Loíza towns, home to the then Ayala family dynasty of bomberos. Bomba continues to survive there and has also experienced something of a revival, being cultivated by folkloric groups such as Son Del Batey, Los Rebuleadores de San Juan, Bomba Evolución, Abrane y La Tribu, and many more elsewhere on the island. In New York City with groups such as Los Pleneros de la 21,[5] members of La Casita de Chema, and Alma Moyo. In Chicago Buya, and Afro-Caribe have kept the tradition alive and evolving. In California Bomba Liberte, Grupo Aguacero, Bombalele, La Mixta Criolla, Herencia de los Carrillo, and Los Bomberas de la Bahia are all groups that have promoted and preserved the culture. Women have also played a role in its revival, as in the case of the all-female group Yaya, Legacy Woman, Los Bomberas de la Bahia, Grupo Bambula (Originally female group), and Ausuba in Puerto Rico. There has also been a strong commitment towards Bomba Fusion. Groups such as Los Pleneros de la 21, and Viento De Agua have contributed greatly towards fusing Bomba and Plena with Jazz and other Genres. Yerbabuena has brought a popular cross-over appeal. Abrante y La Tribu have made fusions with Hip Hop. Tambores Calientes, Machete Movement, and Ceiba have fused the genres with various forms of Rock and Roll. The Afro-Puerto Rican bombas, developed in the sugarcane haciendas of Loíza, the northeastern coastal areas, in Guayama and southern Puerto Rico, utilize barrel drums and tambourines, while the rural version uses stringed instruments to produce music, relating to the bongos. (1) “The bomba is danced in pairs, but there is no contact. The dancers each challenge the drums and musicians with their movements by approaching them and performing a series of fast steps called floretea piquetes, creating a rhythmic discourse. Unlike normal dance routines, the drummers are the ones who follow the performers and create a beat or rhythm based on their movements. Women who dance bomba often use dresses or scarves to enhance bodily movements.[6] Unlike normal dance terms, the instruments follow the performer. Like other such traditions, bomba is now well documented on sites like YouTube, and a few ethnographic documentary films. Bomba Puertorriqueña |

●ボンバ 歴史的文献によると、1800年頃の数十年間、プランテーションの奴隷たちがボンバと呼ばれる音楽とダンスのジャンルを育てていた。20世紀半ばになる と、ボンバは録音や映像化されるようになり、島の各地、特にロイザ、ポンセ、サンファン、マヤグェスで地域的なバリエーションが披露されるようになった。 ボンバの歴史を再構築することは不可能である。様々な側面がコンゴ由来であることを反映しているが、いくつかの要素(ホランデスなどのサブジャンル名から 示唆される)はカリブ海の他の地域からもたらされたものである。フランス領カリブ海の要素は、特にマヤグエスのボンバ・スタイルに顕著であり、マルティ ニークのベレとの顕著な振り付けの類似が見られる。これらのソースはすべて、ジバロの生活、奴隷、プエルトリコの文化を反映した独特のサウンドに融合され た。 2つまたは3つのスクワット・ドラム(バリレス)で演奏されるオスティナートを基調としたリズムに合わせてコール・アンド・レスポンスで歌うボンバは、カ リブ海の他のネオ・アフリカン・ジャンルに似ている。その形式は、歌い手の非公式な輪の中から一人が出てきて太鼓奏者の前で踊り、リード・ドラマーと一種 の遊びのような決闘をする。このような様々な要素は、アフリカやその他の地域に起源を求めることができるが、ボンバはアフロ・プエルトリコのローカルな創 作と見なさなければならない。そのリズム(seis corrido、yubá、leróなど)、ダンスの動き、時には農耕動物を模した歌詞(スペイン語で、プエルトリコ東部ではフランス語のクレオール語も ある)は、総体的にプエルトリコ独自のジャンルを構成している。 1950年代、ラファエル・コルティージョとイスマエル・リベラのダンス・バンド・アンサンブルは、彼らが「ボンバ」と名付けた数曲を演奏した。これら は、シカ・スタイルのボンバと似ている部分もあるが、リズムやホーンのアレンジにおいて、プエルトリコで長く親しまれてきたキューバのダンス音楽からの引 用も目立つ。チャランガ音楽の誕生 1980年代の時点で、ボンバは衰退していたが、サントゥルセ、サンフアンのセペダファミリーによって、いくぶん形式化された形で教えられ、当時のアヤラ 一家のボンバロ王朝の本拠地であったロイザの町では、依然として非公式に、しかし精力的に演奏されていた。ソン・デル・バテイ(Son Del Batey)、ロス・レブレアドーレス・デ・サン・フアン(Los Rebuleadores de San Juan)、ボンバ・エヴォルシオン(Bomba Evolución)、アブラネ・イ・ラ・トリブ(Abrane y La Tribu)などのフォークロア・グループや、島の他の場所でも多くのグループによって培われてきた。ニューヨークでは、ロス・プレネロス・デ・ラ21、 [5]ラ・カシータ・デ・ケマのメンバー、アルマ・モヨなどのグループ。シカゴではブヤやアフロ・カリベが伝統を守り、進化させている。カリフォルニアで は、Bomba Liberte、Grupo Aguacero、Bombalele、La Mixta Criolla、Herencia de los Carrillo、Los Bomberas de la Bahiaがこの文化を推進し、保存しているグループである。また、女性だけのグループ、ヤヤ、レガシー・ウーマン、ロス・ボンベラス・デ・ラ・バイア、 グルポ・バンブラ(元々は女性グループ)、プエルトリコのアウスバのように、女性もその復活に一役買ってきた。 また、ボンバ・フュージョンへの取り組みも盛んだ。ロス・プレネロス・デ・ラ21やビエント・デ・アグアといったグループは、ボンバやプレナをジャズや他 のジャンルと融合させることに大きく貢献してきた。イエルバブエナは、人気のあるクロスオーバーの魅力をもたらした。アブランテとラ・トリブはヒップホッ プとの融合を果たした。タンボレス・カリエンテス(Tambores Calientes)、マチェーテ・ムーヴメント(Machete Movement)、セイバ(Ceiba)は、これらのジャンルを様々な形態のロックンロールと融合させた。 アフロ・プエルトリコのボンバは、ロイザのサトウキビ農園、北東部の沿岸地域、グアヤマ、プエルトリコ南部で発展し、樽太鼓とタンバリンを使う。(1) 「ボンバは二人一組で踊るが、接触はない。踊り手はそれぞれ太鼓や音楽隊に近づき、フロレテア・ピケテスと呼ばれる一連の速いステップを踏むことで、リズ ムの言説を作り出し、その動きで太鼓や音楽隊に挑む。通常のダンス・ルーティンとは異なり、太鼓奏者はパフォーマーに付き従い、パフォーマーの動きに基づ いてビートまたはリズムを作る。ボンバを踊る女性は、ドレスやスカーフを使って身体の動きを強調することが多い[6]。通常のダンス用語とは異なり、楽器 はパフォーマーに従う。 他の伝統と同様、ボンバも現在ではYouTubeのようなサイトや、いくつかの民族ドキュメンタリー映画でよく記録されている。 プエルトリコのボンバ音楽が抵抗となる理由(日本語サブタイトル) |

Plena Puerto Rican Güiro Around 1900 plena emerged as a humble proletarian folk genre in the lower-class, largely Afro-Puerto Rican urban neighborhoods in San Juan, Ponce, and elsewhere. Plena subsequently came to occupy its niche in island music culture. In its quintessential form, plena is an informal, unpretentious, simple folk-song genre, in which alternating verses and refrains are sung to the accompaniment of round, often homemade frame drums called panderetas (like tambourines without jingles), perhaps supplemented by accordion, guitar, or whatever other instruments might be handy. An advantage of the percussion arrangement is its portability, contributing to the plena's spontaneous appearance at social gatherings. Other instruments commonly heard in plena music are the cuatro, the maracas, and accordions. The plena rhythm is a simple duple pattern, although a lead pandereta player might add lively syncopations. Plena melodies tend to have an unpretentious, "folksy" simplicity. Some early plena verses commented on barrio anecdotes, such as "Cortarón a Elena" (They stabbed Elena) or "Allí vienen las maquinas" (Here come the firetrucks). Many had a decidedly irreverent and satirical flavor, such as "Llegó el obispo" mocking a visiting bishop. Some plenas, such as "Cuando las mujeres quieren a los hombres" and "Santa María," are familiar throughout the island. In 1935 the essayist Tomás Blanco celebrated plena—rather than the outdated and elitist danza—as an expression of the island's fundamentally creole, Taino or mulatto racial and cultural character. Plenas are still commonly performed in various contexts; a group of friends attending a parade or festival may bring a few panderetas and burst into song, or new words will be fitted to the familiar tunes by protesting students or striking workers which have long been a regular form of protest from occupation and slavery. While enthusiasts might on occasion dance to a plena, plena is not characteristically oriented toward dance.  Old man playing the accordion in Old San Juan In the 1920s–30s plenas came to be commercially recorded, especially by Manuel "El Canario" Jimenez, who performed old and new songs, supplementing the traditional instruments with piano and horn arrangements. In the 1940s Cesar Concepción popularized a big-band version of plena, lending the genre a new prestige, to some extent at the expense of its proletarian vigor and sauciness. In the 1950s a newly invigorated plena emerged as performed by the smaller band of Rafael Cortijo and vocalist Ismael "Maelo" Rivera, attaining unprecedented popularity and modernizing the plena while recapturing its earthy vitality. Many of Cortijo's plenas present colorful and evocative vignettes of barrio life and lent a new sort of recognition to the dynamic contribution of Afro-Puerto Ricans to the island's culture (and especially music). This period represented the apogee of plena's popularity as a commercial popular music. Unfortunately, Rivera spent much of the 1960s in prison, and the group never regained its former vigor. Nevertheless, the extraordinarily massive turnout for Cortijo's funeral in 1981 reflected the beloved singer's enduring popularity. By then, however, plena's popularity had been replaced by that of salsa, although some revivalist groups, such as Plena Libre, continue to perform in their lively fashion, while "street" plena is also heard on various occasions. Los de La Isla - Los Pleneros de La Cresta |

●プレナ プエルトリコのグイロ 1900年頃、プレナはサンフアンやポンセなどの下層階級、主にアフロ・プエルトリカンの都市部で、 質素なプロレタリアのフォーク・ジャンルとして出現し た。プレナはその後、島の音楽文化のニッチを占めるようになった。その典型的な形として、プレナは、カジュアルで気取らない、シンプルな民謡のジャンル で、パンデレタ(ジングルのないタンバリンのようなもの)と呼ばれる丸い、しばしば手作りのフレームドラムの伴奏に合わせて、詩とリフレインを交互に歌い ます。パーカッションの配置の利点は持ち運びやすいことで、プレナが社交の場に自然に登場することに貢献している。プレナ音楽でよく耳にする他の楽器は、 クアトロ、マラカス、アコーディオンである。 プレナのリズムは単純な二重パターンだが、リードのパンデレタ奏者が軽快なシンコペーションを加えることもある。プレナのメロディーは、気取らない「民謡 的」な単純さを持つ傾向がある。初期のプレナの詩の中には、バリオの逸話を歌ったものがあり、例えば、"Cortarón a Elena"(エレナを刺した)や "Allí vienen las maquinas"(消防車が来た)などがある。また、「Llegó el obispo(オビスポの到着)」のように、来日した司教を揶揄するような、明らかに不遜で風刺的な趣向のものも多い。いくつかのプレナは、 "Cuando las mujeres quieren a los hombres "や "Santa María "のように、島中で親しまれている。1935年、エッセイストのトマス・ブランコは、時代遅れでエリート主義的なダンスではなく、島の基本的なクレオー ル、タイノー、または混血の人種的、文化的特徴を表現するものとして、プレナを賞賛した。パレードやお祭りに参加する友人たちがパンデレッタを数曲持って きて歌い出すこともあれば、占領や奴隷制度に対する抗議の定番であった学生やストライキに参加する労働者が、おなじみの曲に新しい言葉をつけて歌うことも ある。熱狂的なファンがプレナに合わせて踊ることもあるが、プレナは特徴的にダンス向きではない。  サンフアン旧市街でアコーディオンを演奏する老人 1920年代から30年代にかけて、プレナは商業的に録音されるようになり、特にマヌエル・"エル・カナリオ"・ヒメネスは、伝統的な楽器をピアノやホル ンのアレンジで補いながら、新旧の曲を演奏した。1940年代には、セザール・コンセプシオンがビッグバンド版のプレナを普及させ、このジャンルに新たな 名声を与えた。1950年代には、ラファエル・コルティージョとヴォーカリストのイスマエル・"マエロ"・リベラの小編成バンドによる、新たに活性化され たプレナが登場し、空前の人気を博すとともに、プレナの土俗的な活力を取り戻しながら現代化された。コルティージョのプレナの多くは、バリオの生活を彩り 豊かに描いたもので、島の文化(特に音楽)に対するアフロ・プエルトリカンのダイナミックな貢献が新たに認識されるようになった。この時期は、商業的なポ ピュラー音楽としてのプレナの人気の絶頂期であった。残念ながら、リベラは1960年代の大半を刑務所で過ごし、グループがかつての活気を取り戻すことは なかった。とはいえ、1981年に行われたコルティージョの葬儀には非常に多くの参列者が集まり、この最愛の歌手の不滅の人気を反映していた。しかし、そ のころには、プレナの人気はサルサに取って代わられていた。プレナ・リブレのような復活を遂げたグループが生き生きとした演奏を続けているほか、"スト リート "プレナもさまざまな場面で聴かれている。 他の伝統と同様に、ボンバも現在ではYouTubeなどのサイトや、いくつかの民族ドキュメンタリー映画でよく記録されています。 Los Pleneros de la 21 performs Somos Boricuas |

| Danza By the late 1700s, the country dance (French contredanse, Spanish contradanza) had come to thrive as a popular recreational dance, both in courtly and festive vernacular forms, throughout much of Europe, replacing dances such as the minuet. By 1800 a creolized form of the genre, called contradanza, was thriving in Cuba, and the genre also appears to have been extant, in similar vernacular forms, in Puerto Rico, Venezuela, and elsewhere, although documentation is scanty. By the 1850s, the Cuban contradanza—increasingly referred to as danza—was flourishing both as a salon piano piece, or as a dance-band item to accompany social dancing, in a style evolving from collective figure dancing (like a square dance) to independent couples dancing ballroom-style (like a waltz, but in duple rather than ternary rhythm). According to local chroniclers, in 1845 a ship arrived from Havana, bearing, among other things, a party of youths who popularized a new style of contradanza/danza, confusingly called "merengue." This style subsequently became wildly popular in Puerto Rico, to the extent that in 1848 it was banned by the priggish Spanish governor Juan de la Pezuela. This prohibition, however, does not seem to have had much lasting effect, and the newly invigorated genre—now more commonly referred to as "danza"—went on to flourish in distinctly local forms. As in Cuba, these forms included the pieces of music played by dance ensembles as well as sophisticated light-classical items for solo piano (some of which could subsequently be interpreted by dance bands). The danza as a solo piano idiom reached its greatest heights in the music of Manuel Gregorio Tavárez (1843–83), whose compositions have a grace and grandeur closely resembling the music of Chopin, his model. Achieving greater popularity were the numerous danzas of his follower, Juan Morel Campos (1857–96), a bandleader and extraordinarily prolific composer who, like Tavárez, died in his youthful prime (but not before having composed over 300 danzas). By Morel Campos' time, the Puerto Rican Danza had evolved into a form quite distinct from that of its Cuban (not to mention European) counterparts. Particularly distinctive was its form consisting of an initial paseo, followed by two or three sections (sometimes called "merengues"), which might feature an arpeggio-laden "obbligato" melody played on the tuba-like bombardino (euphonium). Many danzas achieved island-wide popularity, including the piece "La Borinqueña", which is the national anthem of Puerto Rico. Like other Caribbean creole genres such as the Cuban danzón, the danzas featured the insistent ostinato called "cinquillo" (roughly, ONE-two-THREE-FOUR-five-SIX-SEVEN-eight, repeated). The danza remained vital until the 1920s, but after that decade its appeal came to be limited to the Hispanophilic elite. The danzas of Morel Campos, Tavárez, José Quintón, and a few others are still performed and heard on various occasions, and a few more recent composers have penned their idiosyncratic forms of danzas, but the genre is no longer a popular social dance idiom. During the first part of the dancing danza, to the steady tempo of the music, the couples promenade around the room; during the second, with a lively rhythm, they dance in a closed ballroom position and the orchestra would begin by leading dancers in a "paseo," an elegant walk around the ballroom, allowing gentlemen to show off their lady's grace and beauty. This romantic introduction ended with a salute by the gentlemen and a curtsey from the ladies in reply. Then, the orchestra would strike up and the couples would dance freely around the ballroom to the rhythm of the music.[7] |

ダンス曲(舞曲) 1700年代後半には、メヌエットなどの舞曲に代わって、カントリーダンス(フランス語のコントルダンス、スペイン語のコントルダンザ)が、ヨーロッパ全 土で宮廷や祝祭のヴァナキュラー形式として、人気のレクリエーションダンスとして盛んになっていました。1800年頃には、このジャンルをクレオール化し たコントラダンザという形式がキューバで盛んになり、プエルトリコ、ベネズエラなどでも同様のヴァナキュラー形式で現存していたようだが、資料は乏しいも のだった。1850年代までに、キューバのコントラバンザは、サロンでのピアノ曲として、あるいは社交ダンスに伴うダンスバンドのアイテムとして、集団的 なフィギュアダンス(スクエアダンスのようなもの)から独立したカップルが踊る社交ダンス(ワルツのようだが3進法ではなく2進法)へと発展するスタイル で繁栄していた。1845年、ハバナから一隻の船が到着し、その船には、「メレンゲ」と紛らわしい名前で呼ばれる新しいスタイルのコントランサ/ダンザを 広めた若者たちの一団が乗っていたと、地元の年代記者は伝えている。その後、このスタイルはプエルトリコで大流行し、1848年には、気難しいスペイン総 督フアン・デ・ラ・ペズエラによって禁止されたほどである。しかし、この禁止令はそれほど長続きしなかったようで、新たに活性化したジャンルは、現在では 「ダンツァ」と呼ばれるようになり、その土地特有の形で繁栄していった。キューバと同様、ダンス・アンサンブルで演奏される曲や、ピアノ独奏のための洗練 されたライト・クラシックの曲(一部はダンス・バンドが解釈することもある)などがその形式である。ピアノ独奏のイディオムとしてのダンザは、マヌエル・ グレゴリオ・タバレス(1843-83)の音楽で最高の高みに達し、その曲は、彼のモデルであるショパンの音楽に近い優雅さと壮大さを備えている。タバレ ス同様、若くしてこの世を去ったが、300曲以上の舞曲を作曲し、バンドリーダーであり、非常に多作な作曲家でもあった。モレル・カンポスの時代には、プ エルトリコのダンサは、キューバやヨーロッパのダンサとは全く異なる形式へと進化していた。特に特徴的だったのは、最初のパセオに続く2~3つのセクショ ン(「メレンゲ」と呼ばれることもある)で、チューバのようなボンバルディーノ(ユーフォニアム)で演奏されるアルペジオを含む「オブリガート」メロディ を特徴とする形式であった。プエルトリコの国歌である「La Borinqueña」をはじめ、多くのダンスが島中で人気を博しています。キューバのダンソンのようなカリブ海のクレオールのジャンルと同様に、ダン ツァは「チンキージョ」(ONE-two-THREE-FOUR-5-SIX-SEVEN-8を繰り返す)というしつこいオスティナートを特徴とする。 1920年代まで活況を呈したが、それ以降、その魅力はイスパノフィルのエリートに限定されるようになった。モレル・カンポス、タバレス、ホセ・キントン など数人の作曲家のダンスは、今でも様々な場面で演奏され、耳にすることができますし、最近の作曲家の中には、独自の形式のダンスもあるが、このジャンル は、もはや社交ダンスのイディオムとしては人気がない。ダンス・ダンサの第1部では、安定したテンポの音楽に合わせて、カップルは部屋の中をプロムナード する。第2部では、活発なリズムで、彼らは閉じたボールルームの位置で踊り、オーケストラはまずダンサーを「パセオ」(ボールルームを優雅に歩き、男性が 女性の優雅さと美しさをアピールできる)に導く。このロマンティックな導入は、紳士が敬礼し、淑女がそれに応えて礼をすることで終わる。その後、オーケス トラの演奏が始まり、カップルは音楽のリズムに合わせて舞踏場を自由に踊り歩いた[7]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_Puerto_Rico |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

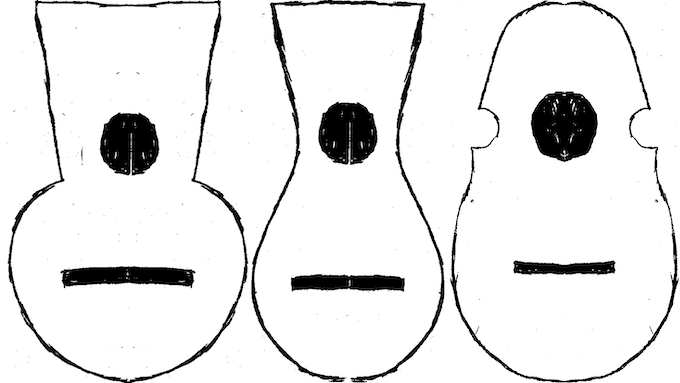

A modern Puerto rican

cuatro ; A plan of three cuatro body designs. From left to right, the

traditional cuatro antiguo design, the "Southern" soft waisted cuatro

antiguo, and the modern "aviolinado" cuatro

+++

Luis Fonsi - Despacito ft. Daddy Yankee; GERMAN ROSARIO- PELANDO MORCILLA

GERMAN ROSARIO, YOMO TORO- COSAS DE LA VIDA; Wally Rita Y Los Kauianos

FLOR MORALES RAMOS-

(RAMITO) EL DILUVIO UNIVERSAL

The cuatro is a family of Latin

American string instruments played in Puerto Rico, Venezuela and other

Latin American countries.

ロートレック:ボレロを踊る女(19世紀)——フランス

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Acknowledgement; This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 21K18363.

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆