Encyclopedia of Reggaeton

Standing

male figure, 400 BCE–200 CE, Late Formative, Xochipala

Encyclopedia of Reggaeton

Standing

male figure, 400 BCE–200 CE, Late Formative, Xochipala

「レゲトン(スペイン語: Reguetón、英語: Reggaeton)は、1980年代から90年代にアメリカ合衆国のヒップホップの影響を受け たプ エルトリコ人によって生み出された音楽である」。以下も同 様にウィキペディアのレゲトンからの収集物である。

レゲトンは、1990年代半ばにプエルト リコで生まれた音楽スタイルである。 ダンスホールから発展し、アメリカのヒップホップ、ラテンアメリカ、カリブ海の音楽から影響を受けている。ボーカルにはラップと歌があり、通常はス ペイン語(現在では世界の現地語)で歌う。レゲトンという言葉は、1994年にダ ディ・ヤンキーとDJプレイロがアルバム『プレイロ36』で、ヒップホップとレゲエのリズムにスペ イン語のラップと歌を合成したプエルトリコ発の新しいアンダーグラウンドジャンル[Boricua underground]を表すためにこの名前を使ったのが最初である。(しかし、 Fundéu BBVAやPuerto Rican Academy of the Spanish Languageなどの規定主義者は、スペイン語の伝統的な綴り方に近いreguetónという綴りを推奨している)。

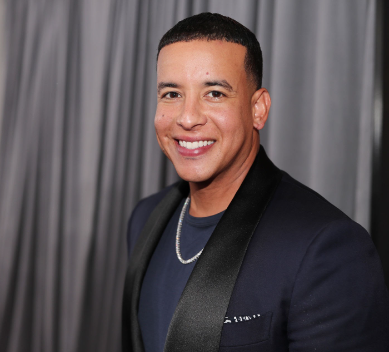

2004年にダディー・ヤンキー(Daddy Yankee;

Ramón Luis Ayala Rodríguez, b.1974)が、ガソリーナ(ガソリン)を発表し、世界的なヒットとなり、大流行した。

"Reggaeton (UK: /ˈrɛɡeɪtoʊn, ˌrɛɡeɪˈtɒn/,[1][2] US: /ˌrɛɡeɪˈtoʊn, ˌreɪɡ-/),[3][4] also known as reggaetón and reguetón[5] (Spanish: [reɣeˈton]), is a music style that originated in Puerto Rico during the mid-1990s.[6] It has evolved from dancehall and has been influenced by American hip hop, Latin American, and Caribbean music. Vocals include rapping and singing, typically in Spanish. The word reggaeton (formed from the word reggae plus the augmentative suffix -tón) was first used in 1994, when Daddy Yankee and DJ Playero used the name on the album Playero 36 to describe the new underground genre emerging from Puerto Rico that synthesized hip-hop and reggae rhythms with Spanish rapping and singing.[9] The spellings reggaeton and reggaetón are common, although prescriptivist sources such as the Fundéu BBVA and the Puerto Rican Academy of the Spanish Language recommend the spelling reguetón, as it conforms more closely with traditional Spanish spelling rules.[5][10]"- Reggaeton.

ヒップホップ音楽またはヒップホップ・ミュージックは、ラップ音楽としても知られ、以前はディスコ・ラップとして知られていたが、1970年代初頭にアフリカ系アメリカ人によってニューヨーク市のブロンクス地区で生まれた大 衆音楽のジャンルである。ヒップホップは、反ドラッグ、反暴力のジャンルとして生まれ、一方で、一般的にラップ、唱えられるリズミカルで韻を踏んだスピーチに 伴う様式化されたリズム音楽(通常はドラムビートを中心に構築)で構成されている。 テンプル大学のアフリカ系アメリカ研究者のアサンテ教授によると、「ヒップホップは黒人が自分たちのものとして明確に主張できるもの[17]」とある。 ヒップホップ文化の一部として発展し、4つの重要な様式的要素によって定義されるサブカルチャーである: MC/ラップ、DJ/ターンテーブルを使ったスクラッチ、ブレイクダンス、グラフィティアート[18] [19][20]などの要素があり、レコードからビートやベースラインをサンプリングしたり(あるいは合成したビートやサウンド)、リズムの良いビート ボックスもある(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hip_hop_music)。

レゲトンは、ラテンアメリカ世界のみならず、世界的レベルで膾炙

し、現地言語・現地文化化がすす

んでいる。

レゲトン研究については、こちらでサイト内リンク します (#Reggaeton_studies)

| It has evolved from

dancehall and has been influenced by American hip hop, Latin American,

and Caribbean music. Vocals include rapping and singing, typically in

Spanish. Reggaeton is regarded as one of the most popular music genres in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, including Puerto Rico, Panama, Dominican Republic, Cuba, Colombia, and Venezuela.[13] Over the 2010s, the genre has seen increased popularity across Latin America, as well as acceptance within mainstream Western music.[14] |

ダンスホールから発展し、アメリカのヒップホップ、ラテンアメリカ、カ

リブ海の音楽の影響を受けている。ボーカルにはラップと歌があり、通常はスペイン語で歌われる。 レゲトンはプエルトリコ、パナマ、ドミニカ共和国、キューバ、コロンビア、ベネズエラなどのスペイン語圏のカリブ海で最も人気のある音楽ジャンルの1つと みなされている[13] 2010年代にかけて、このジャンルはラテンアメリカ全体で人気が高まり、主流の西洋音楽の中でも受け入れられてきた[14]。 |

| Etymology The word reggaeton (formed from the word reggae plus the augmentative suffix -tón) was first used in 1988 when El General's representative Michael Ellis gave it that name to describe it as "reggae grande" (big reggae).[1] The spellings reggaeton and reggaetón are common, although prescriptivist sources such as the Fundéu BBVA and the Academia Puertorriqueña de la Lengua Española recommend the spelling reguetón, as it conforms more closely with traditional Spanish spelling rules.[9][15] |

語源 レゲトンという言葉(レゲエという言葉に補語の-tónを加えたもの)は、1988 年にエル・ジェネラルの代表マイケル・エリスが「レゲエ・グランデ」(大きなレゲエ)と表現してこの名前をつけたことから初めて使われるようになった[1]。 [1] レゲトンやレゲトンという表記が一般的だが、Fundéu BBVAやAcademia Puertorriqueña de la Lengua Españolaなどの規定主義者は、伝統的なスペイン語の表記規則により近いとしてレゲトンという表記を推奨している[9][15]。 |

| Often mistaken for reggae or

reggae en Español, reggaeton is a younger genre that originated in the

late-1980s in Panama and since then hasfrom become popularized by

Puerto Rican artists.[10][11][1] It had its origins in what was known

as Rap y reggae "underground" music, due to its circulation through

informal networks and performances at unofficial venues. DJ Playero and

DJ Nelson were inspired by hip hop and Dancehall to produce "riddims",

the first reggaeton tracks. As Caribbean and African-American music

gained momentum in Puerto Rico, reggae rap in Spanish marked the

beginning of the Boricua underground

and was a creative outlet for many

young people. This created an inconspicuous-yet-prominent underground

youth culture which sought to express itself. As a youth culture

existing on the fringes of society and the law, it has often been

criticized. The Puerto Rican police launched a campaign against

underground music by confiscating cassette tapes from music stores

under penal obscenity codes, levying fines and demonizing rappers in

the media.[17] Bootleg recordings and word of mouth became the primary

means of distribution for this music until 1998, when it coalesced into

modern reggaeton. The genre's popularity increased when it was

discovered by international audiences during the early 2000s.[18] The new genre, simply called "underground" and later "perreo", had explicit lyrics about drugs, violence, poverty, friendship, love and sex. These themes, depicting the troubles of inner-city life, can still be found in reggaeton. "Underground" music was recorded in marquesinas (or carports) by creators using second-hand recording equipment, mostly.[19] The cassettes were then sold or distributed on the streets from the trunk of a car.[19][17] Many of the recordings were made in small marquesinas[19] and at public "housing complexes such as Villa Kennedy, and Jurutungo".[20][17] Despite that, the quality of the cassettes was good enough to help increase their popularity among Puerto Rican youth. The availability and quality of the cassettes led to reggaeton's popularity, which crossed socioeconomic barriers in the Puerto Rican music scene. The most popular cassettes in the early 1990s were DJ Negro's The Noise I and II and DJ Playero's 37 and 38. Gerardo Cruet, who created the recordings, spread the genre from the marginalized residential areas into other sectors of society, particularly private schools. BAD BUNNY - YO PERREO SOLA | YHLQMDLG (Video Oficial) By the mid-1990s, "underground" cassettes were being sold in music stores. The genre caught on with middle-class youth, then found its way into the media. By this time, Puerto Rico had several clubs dedicated to the underground scene; Club Rappers in Carolina and PlayMakers in Puerto Nuevo were the most notable. Bobby "Digital" Dixon's "Dem Bow" production was played in clubs. Underground music was not originally intended to be club music. In South Florida, DJ Laz and Hugo Diaz of the Diaz Brothers were popularizing the genre from Palm Beach to Miami. Underground music in Puerto Rico was harshly criticized. In February 1995, there was a government-sponsored campaign against underground music and its cultural influence. Puerto Rican police raided six record stores in San Juan,[21] hundreds of cassettes were confiscated and fines imposed in accordance with Laws 112 and 117 against obscenity.[17] The Department of Education banned baggy clothing and underground music from schools.[22] For months after the raids local media demonized rappers, calling them "irresponsible corrupters of the public order."[17] In 1995, DJ Negro released The Noise 3 with a mockup label reading, "Non-explicit lyrics". The album had no cursing until the last song. It was a hit, and underground music continued to seep into the mainstream. Senator Velda González of the Popular Democratic Party and the media continued to view the movement as a social nuisance.[23] During the mid-1990s, the Puerto Rican police and National Guard confiscated reggaeton tapes and CDs to get "obscene" lyrics out of the hands of consumers.[24] Schools banned hip hop clothing and music to quell reggaeton's influence. In 2002, Senator González led public hearings to regulate the sexual "slackness" of reggaeton lyrics. Although the effort did not seem to negatively affect public opinion about reggaeton, it reflected the unease of the government and the upper social classes with what the music represented. Because of its often sexually-charged content and its roots in poor, urban communities, many middle- and upper-class Puerto Ricans found reggaeton threatening, "immoral, as well as artistically deficient, a threat to the social order, apolitical".[22] Despite the controversy, reggaeton slowly gained acceptance as part of Puerto Rican culture — helped, in part, by politicians including González who began to use reggaeton in election campaigns to appeal to younger voters in 2003.[22] Puerto Rican mainstream acceptance of reggaeton has grown and the genre has become part of popular culture, including a 2006 Pepsi commercial with Daddy Yankee[25] and PepsiCo's choice of Ivy Queen as musical spokesperson for Mountain Dew.[26][unreliable source?] Other examples of greater acceptance in Puerto Rico are religiously- and educationally-influenced lyrics; Reggae School is a rap album produced to teach math skills to children, similar to School House Rock.[27] Reggaeton expanded when other producers, such as DJ Nelson and DJ Eric, followed DJ Playero. During the 1990s, Ivy Queen's 1996 album En Mi Imperio, DJ Playero's Playero 37 (introducing Daddy Yankee) and The Noise: Underground, The Noise 5 and The Noise 6 were popular in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. Don Chezina, Tempo, Eddie Dee, Baby Rasta & Gringo and Lito & Polaco were also popular. The name "reggaeton" became prominent during the early 2000s, characterized by the dembow beat. It was coined in Puerto Rico to describe a unique fusion of Puerto Rican music.[18] Reggaeton is currently popular throughout Latin America. It increased in popularity with Latino youth in the United States when DJ Joe and DJ Blass worked with Plan B and Sir Speedy[28] on Reggaeton Sex, Sandunguero and Fatal Fantasy. REGGAETON SEX VOL.2 - DJ BLASS (2000) [CD COMPLETO][MUSIC ORIGINAL] |

レゲエと間違われることが多いが、レゲトンは1980年代後半にパナマで生まれ、その後、プエルトリコのアーティストによって広

められた若いジャンルである[10][11][1]。DJプレイロとDJネルソンはヒップホップとダンスホールに触発され、最初のレゲトン

のトラックである「リディム」を制作した。カリブ海やアフリカ系アメリカ人の音楽がプエルトリコで勢いを増す中、スペイン語によるレゲエ・ラップはボリク

ア・アンダーグラウンドの始まりとなり、多くの若者たちの創造力のはけ口となった。これは、目立たぬように、しかし目立つように、自己表現を求めるアン

ダーグラウンドの若者文化を作り上げたのである。社会と法のはざまに存在する若者文化として、それはしばしば批判されてきた。プエルトリコの警察は、刑法上の猥褻物陳列所からカセットテープを没収し、罰金を課し、メディ

アでラッパーを悪者扱いするなど、アンダーグラウンドミュージックに対するキャンペーンを開始した[17]。2000年代前半に国際的な聴

衆に発見されると、このジャンルの人気は高まった[18]。 単に "アンダーグラウンド "と呼ばれ、後に "ペレオ "と呼ばれるようになったこの新しいジャンルは、ドラッグ、暴力、貧困、友情、愛、セックスについての露骨な歌詞を持っていた。これらのテーマは、都心生 活の悩みを描いたもので、今でもレゲトンに見られる。「アンダーグラウンド "の音楽は、主に中古の録音機器を使ってクリエイターたちによってマルキーナ(またはカーポート)で録音された[19]。カセットはその後、車のトランク から路上で販売されたり、配布されたりした[19][17]。カセットの入手可能性とクオリティは、プエルトリコの音楽シーンにおいて社会経済的な障壁を 越えたレゲトンの人気につながった。1990年代初頭に最も人気があったカセットは、DJ Negroの『The Noise I and II』とDJ Playeroの『37 and 38』だった。これらの音源を制作したジェラルド・クルートは、このジャンルを疎外された居住区から社会の他のセクター、特に私立学校へと広めた。 DJ Playero 37 - Ragga Moofin Mix - Daddy Yankee 1990年代半ばには、「アンダーグラウンド」カセットが楽器店で売ら れるようになった。このジャンルは、中流階級の若者の間で流行し、その後、メディア にも登場するようになりました。この頃、プエルトリコにはアンダーグラウンド・シーン専門のクラブがいくつかあり、カロライナのクラブ・ラッパーズやプエ ルト・ヌエボのプレイメイカーズが最も有名であった。ボビー・"デジタル"・ディクソンの「Dem Bow」はクラブで演奏された。アンダーグラウンド・ミュージックは、もともとクラブ・ミュージックとして作られたものではない。南フロリダでは、DJ LazとDiaz BrothersのHugo Diazが、パームビーチからマイアミにかけてこのジャンルを広めていた。 プエルトリコのアンダーグラウンド・ミュージックは厳しく批判された。1995年2月、政府主催のアンダーグラウンドミュージックとその文化的影響力に対 するキャンペーンが行われた。プエルトリコ警察はサンフアンの6つのレコード店を襲撃し[21]、何百ものカセットテープが押収され、わいせつ防止法 112と117に基づき罰金を課した。 教育省はバギーカーとアンダーグラウンドミュージックを学校で禁止した[22]。襲撃から数ヶ月、地元メディアはラッパーを「無責任な公序の乱暴者」と悪 評した[17]。 1995年、DJ Negroは「Non-explicit lyrics」と書かれた模造のラベルを貼った『The Noise 3』をリリースした。このアルバムでは最後の曲まで罵倒はなかった。このアルバムはヒットし、アンダーグラウンド音楽はメインストリームに浸透し続けた。 民衆民主党のベルダ・ゴンサレス上院議員やメディアは、この運動を社会的な迷惑と見なし続けた[23]。 1990年代半ば、プエルトリコの警察と州兵は消費者の手から「卑猥な」歌詞を取り除くためにレゲトンのテープやCDを没収した[24]。 学校はレゲトンの影響を鎮めるためにヒップホップの服や音楽を禁止していた。2002年、ゴンサレス上院議員はレゲトンの歌詞の性的「弛緩」を規制するた めの公聴会を主導した。この取り組みはレゲトンに対する世論に悪影響を与えなかったようだが、レゲトンが表現する音楽に対する政府や上流社会の不安を反映 したものであった。しばしば性的に刺激的な内容であり、貧しい都市コミュニティに根ざしているため、多くの中流階級や上流階級のプエルトリコ人はレゲトンを「不道徳であり、芸術的にも欠陥があ り、社会秩序に対する脅威であり、非政治的」であると考えたのである[22]。 レゲトンはプエルトリコの文化の一部として徐々に受け入れられていった が、2003年に若い有権者にアピールするために選挙キャンペーンでレゲトンを使い始めたゴンサレスなどの政治家の助けもあった[22]。 プエルトリコではレゲトンを受け入れる傾向が強まり、このジャンルは大衆文化の一部になった。 [26][unreliable source?] その他、プエルトリコでより受け入れられた例として、宗教的、教育的影響を受けた歌詞がある。レゲエ・スクールは、スクールハウス・ロックに似た、子供た ちに数学のスキルを教えるために制作されたラップアルバムである[27] DJプレイロに続いてDJネルソンやDJエリックなど他のプロデューサーが登場するとレゲトンは拡大することになった。1990年代には、アイビー・ク イーンの1996年のアルバム『En Mi Imperio』、DJプレイロの『Playero 37』(ダディ・ヤンキーを紹介)、『The Noise』。Underground、The Noise 5、The Noise 6はプエルトリコとドミニカ共和国で人気を博しました。ドン・チェジーナ、テンポ、エディ・ディー、ベイビーラスタ&グリンゴ、リト&ポラコも人気があっ た。 2000年代前半には、デムボウビートを特徴とする「レゲトン」という 名称が目立つようになった。レゲトンは現在、ラテンアメリカ全域で人気がある。DJ ジョーとDJブラスがプランBやサー・スピーディ[28]と組んで『Reggaeton Sex』『Sandunguero』『Fatal Fantasy』を発表し、アメリカではラテン系の若者の間で人気が高まった。 DJ Blass - Intro - Soy El Sandunguero |

| 2004: Crossover In 2004, reggaeton became popular throughout the United States and Europe. Tego Calderón was receiving airplay in the U.S., and the music was popular among youth. Daddy Yankee's El Cangri.com became popular that year in the country, as did Héctor & Tito. Luny Tunes and Noriega's Mas Flow, Yaga & Mackie's Sonando Diferente, Tego Calderón's El Abayarde, Ivy Queen's Diva, Zion & Lennox's Motivando a la Yal and the Desafío compilation were also well-received. Rapper N.O.R.E. released a hit single, "Oye Mi Canto". Daddy Yankee released Barrio Fino and a hit single, "Gasolina", opening the door for reggaeton globally.[29] Tego Calderón recorded the singles "Pa' Que Retozen" and "Guasa Guasa". Don Omar was popular, particularly in Europe, with "Pobre Diabla" and "Dale Don Dale".[30] Other popular reggaeton artists include Tony Dize, Angel & Khriz, Nina Sky, Dyland & Lenny, RKM & Ken-Y, Julio Voltio, Calle 13, Héctor Delgado, Wisin & Yandel and Tito El Bambino. In late 2004 and early 2005, inspired by the success of "Gasolina", Shakira collaborated with Alejandro Sanz to record "La Tortura" and "La Tortura – Shaketon Remix" for her album, Fijación Oral Vol. 1, further popularizing reggaeton.[31] Four reggaeton songs were sung at the 2005 MTV Video Music Awards: by Don Omar ("Dile"), Tego Calderón, Daddy Yankee, and Shakira with Sanz – the first time any reggaeton song was performed on that stage. Musicians began to incorporate bachata into reggaeton,[32] with Ivy Queen releasing singles ("Te He Querido, Te He Llorado" and "La Mala") featuring bachata's signature guitar sound, slower, romantic rhythms and emotive singing style.[32] Daddy Yankee's "Lo Que Paso, Paso" and Don Omar's "Dile" are also bachata-influenced. In 2005 producers began to remix existing reggaeton music with bachata, marketing it as bachaton: "bachata, Puerto Rican style".[32] |

2004: クロスオーバー 2004年、レゲトンはアメリカやヨーロッパで人気を博した。アメリカではテゴ・カルデロンがエアプレイを受け、若者の間で音楽が人気を博していた。この 年、ダディ・ヤンキーのEl Cangri.comが同国で人気を博し、エクトル&ティトも人気を博した。ルニー・チューンズとノリエガの「Mas Flow」、ヤガ&マッキーの「Sonando Diferente」、テゴ・カルデロンの「El Abayarde」、アイビー・クイーンの「Diva」、シオン&レノックスの「Motivando a la Yal」と「Desafío」のコンピも評判になった。ラッパーのN.O.R.E.はヒットシングル "Oye Mi Canto "をリリースしました。ダディ・ヤンキーはBarrio Finoをリリースし、シングル「Gasolina」をヒットさせ、世界的にレゲトンの扉を開いた[2004-2004][29] テゴ・カルデロンはシングル「Pa' Que Retozen」と「Guasa Guasa」をレコーディングした。ドン・オマールは「Pobre Diabla」と「Dale Don Dale」で特にヨーロッパで人気があった[30] 他の人気レゲトンアーティストはトニー・ダイズ、エンジェル&クリズ、ニナ・スカイ、ダイランド&レニー、RKM&ケン-Y、フリオ・ボルチオ、カレ 13、エクトル・デルガド、ウィシン&ヤンデル、ティト・エ・バンビーノなどである。2004年末から2005年初めにかけて、「ガソリーナ」【YouTube】の成功に触 発されたシャキーラはアレハンドロ・サンスとコラボして、アルバム『フィジャシオン・オーラル Vol.1』に「ラ・トルチュラ」と「ラ・トルチュラ - シャケトン・リミックス」【YouTube】 を収録、レゲトンをさらに一般化させることとなった。 [31] 2005年のMTV Video Music Awardsでは、ドン・オマール(「Dile」)、テゴ・カルデロン、ダディ・ヤンキー、シャキーラの4曲が歌われ、レゲトンの曲がその舞台で披露され たのはこれが初めてであった。 ミュージシャンたちはバチャータをレゲトンに取り入れ始め[32]、アイビー・クイーンはバチャータの特徴であるギターサウンド、スローでロマンチックな リズム、感情的な歌い方を特徴とするシングル(「Te He Querido, Te He Llorado」と「La Mala」)をリリースした[32] 。ダディ・ヤンキーの「Lo Que Paso, Paso」とドン・オマールの「Dile」もバチャータの影響を受けたものである。2005年にはプロ デューサーが既存のレゲトン音楽をバチャータにリ ミックスし始め、バチャトン(「プエルトリコ風バチャータ」)として売り出した[32]。 |

| 2006–2017: Topping the charts In May 2006, Don Omar's King of Kings was the highest-ranking reggaeton LP to date on the U.S. charts, debuting atop the Top Latin Albums chart and peaking at number seven on the Billboard 200 chart. Omar's single, "Angelito", topped the Billboard Latin Rhythm Radio Chart.[33] He broke Britney Spears' in-store-appearance sales record at Downtown Disney's Virgin music store. In June 2007, Daddy Yankee's El Cartel III: The Big Boss set a first-week sales record for a reggaeton album, with 88,000 copies sold.[34] It topped the Top Latin Albums and Top Rap Albums charts, the first reggaeton album to do so on the latter. The album peaked at number nine on the Billboard 200, the second-highest reggaeton album on the mainstream chart.[35] The third-highest-ranking reggaeton album was Wisin & Yandel's Wisin vs. Yandel: Los Extraterrestres, which debuted at number 14 on the Billboard 200 and number one on the Top Latin Albums chart later in 2007.[36] In 2008 Daddy Yankee soundtrack to his film, Talento de Barrio, debuted at number 13 on the Billboard 200 chart. It peaked at number one on the Top Latin Albums chart, number three on Billboard's Top Soundtracks and number six on the Top Rap Albums chart.[35] In 2009, Wisin & Yandel's La Revolución debuted at number seven on the Billboard 200, number one on the Top Latin Albums and number three on the Top Rap Albums charts. By 2008, Reggaeton was the "biggest-selling genre of Latin music" and one of its artists, Tego Calderon, was using it to describe and encourage black pride.[37] |

2006-2017: チャート上位にランクイン 2006年5月、ドン・オマールの『キ ング・オブ・キングス』は、全米チャートでこれまでのレゲトンLPとしては最高位となり、トップ・ラテン・アルバ ム・チャートでデビューし、ビルボード200チャートでは7位を記録した。オマールのシングル「アンジェリート」はビルボード・ラテンリズ ム・ラジオ チャートで首位を獲得した[33]。ダウンタウン・ディズニーのヴァージン・ミュージック・ストアではブリトニー・スピアーズの店頭販売記録を塗り替え た。 2007年6月、ダディ・ヤンキーの『El Cartel III: The Big Boss』はレゲトンアルバムの初週売上記録となる88,000枚を売り上げた[34]。トップラテンアルバムとトップラップアルバムのチャートで首位を 獲得、後者はレゲトンのアルバムで初めてであった。ビルボード200では9位を記録し、メインストリームチャートで2番目に高いレゲトンアルバムとなった [35]。 3位のレゲトンアルバムはウィシン&ヤンデルの『Wisin vs. Yandel』であった。2008年、ダディ・ヤンキーの映画『タレント・デ・バリオ』のサウンドトラックがビルボード200チャートで13位に初登場し た[36]。2009年には、ウィシン&ヤンデルのLa Revoluciónがビルボード200で7位、トップラテンアルバムチャートで1位、トップラップアルバムチャートで3位を獲得した[35]。 2008年までにレゲトンは「ラテン音楽で最も売れているジャンル」となり、そのアーティストの一人であるテゴ・カルデロンは、ブラックプライドを表現し 奨励するためにレゲトンを使っていた[37]。 |

| 2017–present: "Despacito" effect In 2017, the music video for "Despacito" by Luis Fonsi featuring Daddy Yankee reached one billion views in less than three months. From January 2018 to November 2020, the music video was the most viewed YouTube video of all-time. With its 3.3 million certified sales plus track-equivalent streams, "Despacito" became one of the best-selling Latin singles in the United States. The success of the song and its remix version led Daddy Yankee to become the most listened-to artist worldwide on the streaming service Spotify on 9 July 2017, being the first Latin artist to do so.[38][39][40] He later became the fifth most listened-to male artist and the sixth overall of 2017 on Spotify.[41] In June 2017, "Despacito" was cited by Billboard's Leila Cobo as the song that renewed interest in the Latin music market from recording labels in the United States.[42] Julyssa Lopez of The Washington Post stated that the successes of "Despacito" and J Balvin's "Mi Gente" is "the beginning of a new Latin crossover era."[43] Stephanie Ho of Genius website wrote that "the successes of 'Despacito' and 'Mi Gente' could point to the beginning of a successful wave for Spanish-language music in the US."[44] Ho also stated that "as 'Despacito' proves, fans don't need to understand the language in order to enjoy the music", referring to the worldwide success of the song, including various non-Spanish-speaking countries.[44] "Te Boté" and the minimalist dembow In April 2018, "Te Boté" was released by Nio Garcia, Casper Magico, Darell, Ozuna, Bad Bunny and Nicky Jam. It reached number one on the Billboard Hot Latin Songs chart. It currently has over 1.8 billion views on YouTube.[45] Many artists began to mark strong commercial trends in a market dominated by mixing Latin trap and reggaeton followed by a new minimalist dembow rhythm. For example, songs such as "Adictiva" by Daddy Yankee and Anuel AA, "Asesina" by Brytiago and Darell, "Cuando Te Besé" by Becky G and Paulo Londra, "No Te Veo" by Casper Magico and many other songs have been made in this style.[46] [47] |

2017年〜現在 "デスパシート "効果 2017年、Luis Fonsi featuring Daddy Yankeeによる「Despacito」のミュージックビデオは、3ヶ月足らずで10億回再生を達成した 【2023年8月の時点で82億回】。2018年1月から2020年11月まで、同 ミュージックビデオはYouTubeの歴代最多再生回数を記録した。330万件の認定セールス+トラック換算のストリームにより、「Despacito」 は米国で最も売れたラテン系シングルの1つとなった。この曲とそのリミックス版の成功により、ダディ・ヤンキーは2017年7月9日にストリーミング・ サービスSpotifyで世界で最も聴かれているアーティストとなり、ラテン系アーティストとしては初めてそうなった[38][39][40]。 その後Spotifyで2017年に最も聴かれている男性アーティスト第5位、全体で第6位になった[41] 2017年6月にビルボードのレイラ・コボによって「Despacito」はアメリカの録音レーベルがラテン音楽市場に新たに興味を示した楽曲として引用 されている。 [42] ワシントン・ポストのジュリーサ・ロペスは、「Despacito」とJ・バルヴィンの「Mi Gente」の成功は「新しいラテンクロスオーバー時代の始まり」だと述べた[43] Geniusサイトのステファニー・ホーは、「『Despacito』と『Mi Gente』の成功はアメリカにおけるスペイン語音楽の成功の波の始まりを指し示すかもしれない」と記した。 "44]ホーはまた、「『デスパシート』が証明しているように、ファンは音楽を楽しむために言語を理解する必要はない」と述べ、スペイン語圏以外の様々な 国を含むこの曲の世界的な成功に言及した[44]。 "Te Boté "とミニマル・デムボウ 2018年4月、ニオ・ガルシア、キャスパー・マジコ、ダレル、オズナ、バッド・バニー、ニッキー・ジャムによってリリースされた「Te Boté(テ・ボテ)」。ビルボード・ホット・ラテン・ソングス・チャートで1位を獲得した。多くのアーティストが、ラテントラップとレゲトンをミックス し、新しいミニマルなデムボウのリズムが続く市場に、強い商業的傾向をマークし始めた[45]。例えば、ダディ・ヤンキーとアニュエルAAの 「Adictiva」、ブライティアゴとダレルの「Asesina」、ベッキーGとパウロ・ロンドラの「Cuando Te Besé」、カスパー・マジコの「No Te Veo」などの曲がこのスタイルで作られた[46] [47]。 |

| Rhythm The dembow riddim was created by Jamaican dancehall producers during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Dembow consists of a kick drum, kickdown drum, palito, snare drum, timbal, timballroll and (sometimes) a high-hat cymbal. Dembow's percussion pattern was influenced by dancehall and other West Indian music (soca, calypso and cadence); this gives dembow a pan-Caribbean flavor. Steely & Clevie, creators of the Poco Man Jam riddim, are usually credited with the creation of dembow.[40] At its heart is the 3+3+2 (tresillo) rhythm, complemented by a bass drum in 4/4 time.[41] The riddim was first highlighted by Shabba Ranks in "Dem Bow", from his 1991 album Just Reality. To this day, elements of the song's accompaniment track are found in over 80% of all reggaeton productions.[42] During the mid-1980s, dancehall music was revolutionized by the electronic keyboard and drum machine; subsequently, many dancehall producers used them to create different dancehall riddims. Dembow's role in reggaeton is a basic building block, a skeletal sketch in percussion. In Reggaeton 'dembow' also incorporates identical Jamaican riddims such as Bam Bam, Hot This Year, Poco Man Jam, Fever Pitch, Red Alert, Trailer Reloaded and Big Up riddims, and several samples are often used. Some reggaeton hits incorporate a lighter, electrified version of the riddim. Examples are "Pa' Que la Pases Bien" and "Quiero Bailar", which uses the Liquid riddim.[43] Since 2018 a new variation of the Dembow rhythm has emerged; Starting with Te Bote, a sharper minimalist Dembow has become a stable of Reggaeton production which has allowed for more syncopated rhythmic experiments.[44] [45] |

リズム(Rhythm) デムボウ・リディム【YouTube】 は、1980年代後半から1990年代前半にかけて、ジャマイカのダンスホール・プロデューサーたちによって作られた。 Dembowは、キックドラム、キックダウンドラム、パリトー、スネアドラム、ティンバール、ティンバロール、(時には)ハイハットシンバルで構成されて いる。Dembowのパーカッションパターンはダンスホールや他の西インド音楽(ソカ、カリプソ、ケイデンス)の影響を受けており、これがDembow に汎カリブ海的な風味を与えている。Poco Man Jamリディム【YouTube】の制作者である Steely & Clevieは通常、Dembowの誕生に貢献したとされている[40]。その中心は3+3+2(トレシーロ)のリズムで、4分の4拍子のバスドラムに よって補完されている[41]。 このリディムはシャバ・ランクスが1991年に発表したアルバム『Just Reality』に収録されている「Dem Bow」【Shabba Ranks - Dem Bow】で初めて取り上げられた。1980年代半ば、ダンスホール・ミュージックは電子キーボードとドラムマシンによって革命を起こ し、その後、多くのダ ンスホール・プロデューサーがそれらを使って様々なダンスホール・リディムを制作した[42]。レゲトンにおけるデムボウの役割は、パーカッションにおけ る基本的な構成要素、骨組みのスケッチである。 レゲトンにおける「Dembow」は、Bam Bam、Hot This Year、Poco Man Jam、Fever Pitch、Red Alert、Trailer Reloaded、Big Upといった同一のジャマイカのリディムも取り入れ、いくつかのサンプルもよく使われる。レゲトンのヒット曲の中には、リディムをより軽く、電化したもの を取り入れたものもある。例としては、リキッド・リディムを使った「Pa' Que la Pases Bien」や「Quiero Bailar」などがある[43]。2018年以降、Dembowリズムの新しいバリエーションが登場した。Te Boteから始まり、シャープなミニマルDembowがレゲトン制作の安定となり、よりシンコペーションなリズム実験が可能になった[44][45]。 |

| Lyrics

and themes Reggaeton lyrical structure resembles that of hip hop. Although most reggaeton artists recite their lyrics rapping (or resembling rapping) rather than singing, many alternate rapping and singing. Reggaeton uses traditional verse-chorus-bridge hip hop structure. Like hip hop, reggaeton songs have a hook which is repeated throughout the song. Latino ethnic identity is a common musical, lyrical and visual theme. Unlike hip-hop CDs, reggaeton discs generally do not have parental advisories. An exception is Daddy Yankee's Barrio Fino en Directo (Barrio Fino Live), whose live material (and with Snoop Dogg in "Gangsta Zone") were labeled explicit. Artists such as Alexis & Fido circumvent radio and television censorship by sexual innuendo and lyrics with double meanings. Some songs have raised concerns about their depiction of women.[46] Although reggaeton began as a mostly-male genre, the number of women artists has been a slowly increasing and include the "Queen of Reggaeton", Ivy Queen,[47] Mey Vidal, K-Narias, Adassa, La Sista and Glory. |

歌詞とテーマ レゲトンの歌詞の構成はヒップホップのそれに似ている。ほとんどのレゲ トンアーティストは歌ではなく、ラップ(またはラップに似たもの)で歌詞を朗読する が、多くはラップと歌を交互に繰り返す。レゲトンはヒップホップの伝統的な詩-コーラス-ブリッジの構造を使われている。ヒップホップのように、レゲトン の曲には曲中で繰り返されるフックがある。ラテンアメリカの民族的アイデンティティは、音楽的、歌詞的、視覚的な共通のテーマとなっている。 ヒップホップのCDとは異なり、レゲトンのディスクには一般的に保護者の注意書きがない。例外はダディ・ヤンキー(Daddy Yankee)のBarrio Fino en Directo (Barrio Fino Live)で、そのライブ音源(およびスヌープ・ドッグとの「Gangsta Zone」)は露骨なラベル付けがされている。アレクシス&ファイドのようなアーティストは、性的な風刺や二重の意味を持つ歌詞によって、ラジオやテレビ の検閲を回避している。レゲトンはほとんどが男性のジャンルとして始まったが、女性アーティストの数は徐々に増えており、「レゲトンの女王」アイビー・ク イーン、[47] メイ・ヴィダル、Kナリアス、アダッサ、ラ・シスタ、グローリーなどがいる。 |

| Sandungueo, or perreo, is a

dance associated with reggaeton which emerged during the early 1990s in

Puerto Rico. It focuses on grinding, with one partner facing the back

of the other (usually male behind female).[58] Another way of

describing this dance is "back-to-front", where the woman presses her

rear into the pelvis of her partner to create sexual stimulation. Since

traditional couple dancing is face-to-face (such as square dancing and

the waltz), reggaeton dancing initially shocked observers with its

sensuality but was featured in several music videos.[59] It is also

known as daggering, grinding or juking in the English-speaking areas of

the U.S.[60] |

サンドゥングエオ、またはペレオは、1990年代初頭にプエルトリコで

生まれたレゲトンに関連するダンスである。このダンスを別の言葉で表現すると「バック・トゥ・フロント」で、女性がパートナーの骨盤に自分の背中を押し付

けることで性的刺激を与える。伝統的なカップルダンスは対面式であるため(スクエアダンスやワルツなど)、レゲトンダンスは当初その官能性で観察者に

ショックを与えたが、いくつかの音楽ビデオで取り上げられた。 アメリカの英語圏ではダッガー、グラインド、ジュキングとも呼ばれる[60]。 |

| Popularity Latin America Over the past decade,[when?] reggaeton has received mainstream recognition in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, where the genre originated from, including Puerto Rico, Cuba, Panama, the Dominican Republic, Colombia and Venezuela, where it is now regarded as one of the most popular music genres. Reggaeton has also seen increased popularity in the wider Latin America region, including in El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Ecuador and Peru. In Cuba, reggaeton came to incorporate elements of traditional Cuban music, leading to the hybrid Cubaton. Two bands credited with popularizing Cubaton are Máxima Alerta (founded in 1999) and Cubanito 20.02. The former is notable for fusing Cubaton with other genres, such as son Cubano【YouTube】, conga【YouTube】, cumbia【YouTube】, salsa【YouTube - Celia Cruz】, merengue【YouTube - Juan Luis Guerra】【merengue tradicional】, and Cuban rumba【YouTube】, as well as styles and forms such as rap and ballads, whereas the latter's music is influenced more by Jamaican music.[61][62] The government of Cuba imposed restrictions on reggaeton in public places in 2012. In March 2019, the government went a step further; they banned the "aggressive, sexually explicit and obscene messages of reggaeton" from radio and television, as well as performances by street musicians.[63] CELSO PIÑA - REINA DE CUMBIAS (OFICIAL HD) The first name of reggaeton in Brazil was the Señores Cafetões group, who became known in 2007 with the track "Piriguete" - which at the time was mistakenly mistaken by Brazilians for hip hop and Brazilian funk because reggaeton was still a genre almost unknown in the country.[64] In Brazil, this musical genre only reached a reasonable popularity around the middle of the decade of 2010. The first great success of the genre in the country was the song "Yes or no" by Anitta with Maluma. One of the explanations for reggaeton has not reached the same level of popularity that exists in other Latin American countries is due to the fact that Brazil is a Portuguese-speaking country, which has historically led it to become more isolationist than other Latin American countries in the musical scene. The musical rhythm only became popular in the country when it reached other markets, like the American.[clarification needed] The genre is now overcoming the obstacle of language. Some of the biggest names in the Brazilian music market have partnered with artists from other Latin American countries and explored the rhythm. Anitta feat. Maluma - Sim Ou Não (Official Music Video) |

その人気 ラテンアメリカ 過去10年間で、レゲトンはプエルトリコ、キューバ、パナマ、ドミニカ 共和国、コロンビア、ベネズエラなど、このジャンルが生まれたスペイン語圏のカリブ 海地域で主流の認知を得ており、現在では最も人気のある音楽ジャンルの1つと見なされている(いつ?レゲトンはまた、エルサルバドル、ホンジュラス、グ アテマラ、ニカラグア、コスタリカ、メキシコ、アルゼンチン、チリ、ウルグアイ、エクアドル、ペルーなど、ラテンアメリカ地域でも人気が高まっている。 ︎▶︎メヒコにおけるラップ▶︎︎︎Reggaeton Mexicano 2023, YouTube▶︎Musica Reggaeton Panama 2023▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎ キューバでは、レゲトンがキューバの伝統音楽の要素を取り入れるように なり、ハイブリッド音楽のクバトンにつながった。クバトンを広めたとされるバンド は、1999年に結成されたMáxima AlertaとCubanito 20.02の2つです。前者はクバトンをソンクバーノ、コンガ、クンビア、サルサ、 メレンゲ、キューバンルンバなどの他ジャンルや、ラップやバラードなど のスタイルや形式と融合させることで注目されているが、後者の音楽はよりジャマイカ音楽の影響を受けている[61][62] キューバ政府は2012年に公共の場でのレゲトンに対して制限を課した。2019年3月、政府はさらに一歩踏み込み、ラジオやテレビから「レゲトンの攻撃 的で性的に露骨で卑猥なメッセージ」を禁止し、ストリートミュージシャンによる演奏も禁止した[63]。 ブラジルにおけるレゲトンの最初の名前はセニョーレス・カフェトインスというグループで、2007年に「Piriguete」という曲で知られるように なった。当時、レゲトンはブラジルではまだほとんど知られていないジャンルだったため、ブラジル人はヒップホップやブラジル・ファンクと間違えていた [64] ブラジルではこの音楽ジャンルは2010年の半ば頃にようやくそれなりの人気を獲得するようになった。このジャンルでの最初の大きな成功は、アニッタがマ ルマと組んだ曲「Yes or no」であった。レゲトンが他のラテンアメリカ諸国のような人気を博していない理由のひとつは、ブラジルがポルトガル語圏であり、歴史的に他のラテンアメ リカ諸国よりも音楽シーンで孤立主義的な傾向があることにある。この音楽リズムは、アメリカなど他の市場に出て初めて国内で人気を博した[要出典]。この ジャンルは現在、言語という障害を乗り越えつつある。ブラジルの音楽市場における大物の中には、他のラテンアメリカ諸国のアーティストと提携し、このリズ ムを探求している者もいる。  Colson, Jaime. Merengue, 1938 Óleo sobre cartón 52 x 68 cm. Piriguete - Señores |

| United States The New York-based rapper N.O.R.E., also known as Noreaga, produced Nina Sky's 2004 hit "Oye Mi Canto", which featured Tego Calderón and Daddy Yankee, and reggaeton became popular in the U.S.[65] Daddy Yankee then caught the attention of many hip-hop artists with his song "Gasolina",[65] and that year XM Radio introduced its reggaeton channel, Fuego (XM). Although XM Radio removed the channel in December 2007 from home and car receivers, it can still be streamed from the XM Satellite Radio website. Reggaeton is the foundation of a Latin-American commercial-radio term, hurban,[65] a combination of "Hispanic" and "urban" used to evoke the musical influences of hip hop and Latin American music. Reggaeton, which evolved from dancehall and reggae, and with influences from hip hop has helped Latin-Americans contribute to urban American culture and keep many aspects of their Hispanic heritage. The music relates to American socioeconomic issues, including gender and race, in common with hip hop.[65] Gasolina by Daddy Yankee Daddy Yankee ft. N.O.R.E. & Nina Sky |

アメリカ合衆国 ニューヨークを拠点とするラッパーN.O.R.E.(ノレアガとしても知られる)が、テゴ・カルデロンとダディ・ヤンキーが参加したニーナ・スカイの 2004年のヒット「Oye Mi Canto」を制作し、レゲトンが米国で人気を得た[65]。その後ダディ・ヤンキーの曲「ガソリナ」で多くのヒップホップ・アーティストに注目を集め、 同年XMラジオがレゲトン・チャンネルFuego(XM)を導入した[65]。XMラジオは2007年12月に家庭や車の受信機からこのチャンネルを削除 したが、XMサテライトラジオのウェブサイトからはまだストリーミングで聴くことができる。レゲトンはラテンアメリカの商業ラジオ用語であるハーバン [65]の基礎であり、「ヒスパニック」と「アーバン」の組み合わせは、ヒップホップとラテンアメリカ音楽の音楽的影響を想起させるために使われている。 ダンスホールとレゲエから発展し、ヒップホップの影響を受けたレゲトンは、ラテンアメリカ人がアメリカの都市文化に貢献し、ヒスパニックの遺産の多くの側 面を維持するのに役立っている。この音楽はヒップホップと共通して、ジェンダーや人種を含むアメリカの社会経済的な問題に関連している[65]。 |

| Europe Although reggaeton is less popular in Europe than it is in Latin America, it appeals to Latin American immigrants, especially in Spain.[66] A Spanish media custom, "La Canción del Verano" ("The Song of the Summer"), in which one or two songs define the season's mood, was the basis of the popularity of reggaeton songs such as "Baila Morena" by Héctor & Tito and Daddy Yankee's "Gasolina" in 2005. Aya Nakamura - Djadja (Clip officiel) |

ヨーロッパ レゲトンはヨーロッパではラテンアメリカほど人気がないが、特にスペインではラテンアメリカからの移民にアピールしている[66] スペインのメディア慣習である「La Canción del Verano」(「夏の歌」)は、1、2曲が季節の気分を決めるもので、2005年にエクトル&ティトの「Baila Morena」やダディ・ヤンキーの「Gasolina」といったレゲトン曲が流行する基礎となったと言われている。 ROSALÍA, J Balvin - Con Altura (Official Video) ft. El Guincho |

| Asia In the Philippines, reggaeton artists primarily use the Filipino language instead of Spanish or English. One example of a popular local reggaeton act is Zamboangueño duo Dos Fuertes, who had a dance hit in 2007 with "Tarat Tat", and who primarily uses the Chavacano language in their songs. TARAT TAT BY DOS FUERTES | ZUMBA | MARKY WITH TEAM BLADERS In 2020, Malaysian rapper Namewee released the single and music video "China Reggaeton" featuring Anthony Wong. It is the first time reggaeton was sung in the Chinese languagea of Mandarin and Hakka and accompanied by traditional Chinese instruments like the erhu, pipa and guzheng, creating a fusion of reggaeton and traditional Chinese musical styles.[67] |

アジア フィリピンでは、レゲトンのアーティストは主にスペイン語や英語の代わりにフィリピン語が使われる。地元で人気のあるレゲトンの例としては、2007年に 「Tarat Tat」でダンスヒットを飛ばしたザンボアンゲーニョのデュオDos Fuertesがあり、彼らは主にチャバカノ語を曲中で使っている。 2020年にはマレーシアのラッパーNameweeがAnthony Wongをフィーチャーしたシングルとミュージックビデオ「China Reggaeton」を発表した。レゲトンが初めて北京語や客家語の中国語で歌われ、二胡やピパ、古筝などの中国の伝統的な楽器を伴って、レゲトンと中国 の伝統的な音楽スタイルの融合を実現した[67]。 Namewee Ft. Anthony Perry【China Reggaeton】@亞洲通才 2020 Asian Polymath |

| Criticism Despite the great popularity of the genre as a whole, reggaeton has also attracted criticism due to its constant references to sexual and violent themes. Mexican singer-songwriter Aleks Syntek made a public post on social media complaining that such music was played on Mexico City's airport in the morning with children present.[68] By 2019, other singers who expressed dismay over the genre included vallenato singer Carlos Vives and Heroes Del Silencio singer Enrique Bunbury.[69] That same year, some activists stated that reggaeton music gives way to misogynistic and sadistic messages.[70] Some reggaeton singers have decided to counteract such accusations. One notable example is singer Flex, who in 2009 committed himself to singing songs with romance messages, a sub genre he dubbed “romantic style”.[71] |

批判 ジャンル全体としての大きな人気にもかかわらず、レゲトンは性的・暴力 的なテーマに常に言及していることから、批判も集めている。メキシコのシンガーソン グライターであるアレクス・シンテクは、そのような音楽がメキシコシティの空港で朝、子供たちがいる中で流れていることに不満を抱き、ソーシャルメディア に公開投稿した[68]。 2019年までに、このジャンルに対して不快感を示した他の歌手は、バレナート歌手のカルロス・ビベスとヒーローズ・デル・シレンシオ歌手のエンリケ・バ ンバリーを含む[69]。 同じ年に、いくつかの活動家は、レゲトン音楽が女性差別とサディスティックなメッセージへの道を開く、と述べている。[70]. レゲトンの歌手の中には、そのような非難に対抗することを決意した者もいる。1つの顕著な例は歌手のフレックスで、彼は2009年にロマンスメッセージの ある歌、彼が「ロマンチックスタイル」と名付けたサブジャンルを歌うことに専念した[71]。 |

| List

of reggaeton musicians Reggae en Español Panamanian reggaetón Dancehall Calypso Soca Latino poetry Nuyorican movement Kwaito |

レゲトンミュージシャンの一覧 スペイン語レゲエ パナマのレゲトン ダンスホール カリプソ ソーカ ラテン詩 ニュヨリカン運動 クワイト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reggaeton |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| The Nuyorican movement

is a cultural and intellectual movement involving poets, writers,

musicians and artists who are Puerto Rican or of Puerto Rican descent,

who live in or near New York City, and either call themselves or are

known as Nuyoricans.[1] It originated in the late 1960s and early 1970s

in neighborhoods such as Loisaida, East Harlem, Williamsburg, and the

South Bronx as a means to validate Puerto Rican experience in the

United States, particularly for poor and working-class people who

suffered from marginalization, ostracism, and discrimination. The term Nuyorican was originally used as an insult until leading artists such as Miguel Algarín reclaimed it and transformed its meaning. Key cultural organizations such as the Nuyorican Poets Café and Charas/El Bohio in the Lower East Side, the Puerto Rican Traveling Theater, Agüeybaná Bookstore, Mixta Gallery, Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural Center, El Museo del Barrio, and El Maestro were some of the institutional manifestations of this movement. The next generation of Nuyorican cultural hubs include PRdream.com, Camaradas El Barrio in Spanish Harlem. Social and political counterparts to those establishments in late 1960s and 70s New York include the Young Lords and the ASPIRA Association. |

ヌヨリカン運動とは、ニューヨーク市近郊に住むプエルトリコ人またはプ

エルトリコ系の詩人、作家、音楽家、芸術家が参加する文化・知的運動であり、ヌヨリカンと自称するか知られている[1]。 [1]

1960年代後半から1970年代前半にかけて、ロイセイダ、イーストハーレム、ウィリアムズバーグ、サウスブロンクスなどの地域で、特に疎外、排斥、差

別に苦しんでいた貧困層や労働階級の人々が、アメリカでのプエルトリコ人の経験を検証する手段として生まれた。 ヌヨリカンという言葉は、ミゲル・アルガリンのような代表的なアーティストがそれを取り戻し、その意味を変えるまでは、もともと侮辱の言葉として使われて いた。ローワーイーストサイドのヌヨリカンポエッツカフェやチャラス/エルボヒオ、プエルトリコトラベリングシアター、アグエイバナ書店、ミクスタギャラ リー、クレメンテソトベレス文化センター、エルムセオデルバリオ、エルマエストロなどの主要文化組織は、この運動を組織的に表現した例である。次世代のヌ ヨリカン文化の拠点としては、PRdream.com、スパニッシュ・ハーレムのCamaradas El Barrioなどがある。1960年代後半から70年代のニューヨークで、これらの施設に対応する社会的、政治的組織として、ヤング・ローズやアスピラ・ アソシエーションがある。 |

| Charas/El Bohio History Puerto Rico's history and culture in the Lower East Side, known to much of its Puerto Rican community as Loisaida, is long and extensive. From early 1400s to the end of the 1800s, Puerto Rico had slavery and was dutiful to the Spanish Crown. With granted autonomy from Spain in 1897, Puerto Rico was allowed to elect and print their own currency for a year as a territory. In 1898, The United States seized control over the territory. Being a sugar cane and coffee dependent nation allowed for the United States to intervene and rule Puerto Rico politically and economically, with no intention of giving Puerto Ricans citizenship. In 1910, the American government grew fearful of an uprising. In order to keep Puerto Rico under control from being independent, the United States imposed U.S. citizenship, never consulting the actual people who resided. Since the United States only allowed or the production of sugarcane the people started to go hungry, leaving them with no choice but to leave the island in search for a better life in the United States.[2] Puerto Ricans began migrate to places like New York City, specifically to Puerto Rican enclaves, such as the Lower East Side, San Juan Hill, and Spanish Harlem, creating a new identity, culture, and way of life. With the formation of neighborhoods and culture, arose a Latin American gem formerly the P.S. 64 school building.[3] The building was renamed Charas/El Bohio Community Center, repurposed, and appropriated into Puerto Rican immigrant life. CHARAS/El Bohio was a cultural center established in 1977. The center was built with the intention of revitalizing Loisaida,[4] to encourage Latino pride and community action, to preserve the neighborhood and protect those still living there. The building, formerly PS 64, was abandoned by the Department of Education and taken over and remodeled by Adopt-A-Building. Much of the funding to renovate the building was provided by federal grants or directly from the City. CHARAS moved into the building shortly after, followed by the El Bohio Corporation. CHARAS was the continuation of the Real Great Society, and was spearheaded by Chino Garcia and Armando Perez. Chino Garcia and Armando Perez were and are two of many founders and collaborators of CHARA/ El Bohio Community Center. More importantly they helped form many artists in the 1960s. They renovated classrooms into art studios and rehearsal rooms. This influenced the demographic of the Lower East Side profusely. The original organization was built in 1964 with the intention of helping youth gang members use their skills and ideals for positive use by encouraging business development and educational programs. CHARAS was also involved actively in urban ecology, developing many of the LES community gardens. El Bohio was more artistically based, hosting cultural performances and providing a space for Latino artists to showcase their work and celebrate Latino culture through the arts. |

シャラス/エル・ボヒオ 歴史 ローワーイーストサイドのプエルトリコ人コミュニティの多くにロイセイダと呼ばれるプエルトリコの歴史と文化は長く、広範囲に及んでいる。1400年代初 頭から1800年代の終わりまで、プエルトリコには奴隷制度があり、スペイン王室に忠実であった。1897年にスペインから自治権を与えられたプエルトリ コは、領土として1年間、自分たちで選挙し、通貨を印刷することが許可された。1898年、米国がこの領土を支配することになった。サトウキビとコーヒー に依存する国であったため、アメリカはプエルトリコに市民権を与えるつもりはなく、政治的、経済的に介入し、支配することを許した。1910年、アメリカ 政府は反乱の発生を恐れていた。アメリカはプエルトリコを独立させないようにコントロールするために、実際に住んでいる人たちに相談することなく、アメリ カの市民権を押し付けた。アメリカはサトウキビの生産しか認めなかったため、人々は飢え始め、アメリカでより良い生活を求めて島を離れるしかなかった [2]。 プエルトリコ人はニューヨークなどへ移住し始め、特にローワーイーストサイド、サンフアンヒル、スパニッシュハーレムなどのプエルトリコの飛び地に移り、 新しいアイデンティティ、文化、生活様式を作り出した。 地域と文化の形成に伴い、以前はP.S.64の校舎だったラテンアメリカの宝石が生まれた[3]。 この建物はCharas/El Bohio Community Centerと名前を変え、再利用され、プエルトリコ移民の生活に使われるようになった。チャラス/エル・ボヒオは1977年に設立された文化センターで ある。このセンターは、ロイセイダを活性化させ、ラテンアメリカ人のプライドとコミュニティ活動を奨励し、近隣を保護し、今もそこに住んでいる人々を守る ことを意図して建設された[4]。元PS64だった建物は、教育省に放棄され、アドプト・ア・ビルディングが引き継いで改築したものである。改築のための 資金の多くは、連邦政府の補助金や市から直接提供されたものです。CHARASが入居して間もなく、El Bohio Corporationが入居した。CHARASは、「真の偉大なる社会」を継承し、チノ・ガルシアとアーマンド・ペレスが中心となって活動していた。 チノ・ガルシアとアーマンド・ペレスは、CHARA/エル・ボヒオ・コミュニティ・センターの多くの創設者であり、また協力者でもある。さらに重要なこと は、彼らが1960年代に多くのアーティストの育成を助けたことです。彼らは教室をアートスタジオやリハーサルルームに改築した。これはローワーイースト サイドの人口統計に多大な影響を与えました。1964年に設立されたCHARASは、ギャングの若者たちが自分たちのスキルや理想をポジティブに使えるよ うに、ビジネス展開や教育プログラムを奨励することを意図している。CHARASはまた、LESのコミュニティガーデンの多くを開発するなど、都市生態系 に積極的に関与していた。エル・ボヒオはより芸術的な活動を行い、文化的なパフォーマンスを主催し、ラテン系アーティストに作品を展示する場を提供し、芸 術を通してラテン文化を賞賛していた。 |

| Conflicts and controversies Despite massive community efforts to save the building, CHARAS/El Bohio faced numerous obstacles presented by Mayor Giuliani[5] and Councilmember Antonio Pagán, which ultimately led to their losing of the building in the late 1990s to Gregg Singer, a developer who has been attempting to demolish the building and build high rise dorms for nearly 20 years. His efforts have been repeatedly halted by CB3, who made the building a NYC landmark shortly after he began to destroy moldings of almost a hundred years of age. The landmarking of PS 64 was an immediate reaction to the beginning of Singer's process of demolishing the building. The involvement of CB3 is especially significant, as the board grew involved after a number of Latin Kings went to them pleading for assistance in saving the building. The two groups formed an unlikely alliance in an attempt to preserve the space, and were together successful in saving it as a historic landmark, thus halting Singer's attempts at demolition and reconstruction.[6] PS 64 was home to a number of different organizations. Besides CHARAS (formerly the Real Great Society) and El Bohio, the building was also occupied by artists and activists who rented out studio space, an art gallery, numerous art programs and afterschool programs for students, and other artistic programs and organizations centered around music, dance, and theater. Many of the activists and artists involved in the creation and preservation of the cultural space were former or active gang members, specifically members of the Latin Kings and Queens, looking to work within their communities and foster positive change.[7] In April 1999, CHARAS cofounder Armando Perez was found murdered outside his wife's home in Queens[8] a death which many presume was gang related, though there was no evidence found to corroborate this theory. At the time of his death, Perez had been deeply involved in the fight to save PS 64 from Gregg Singer. |

葛藤と論争 建物を保存するための大規模なコミュニティの努力にもかかわらず、CHARAS/El Bohioはジュリアーニ市長[5]とアントニオ・パガン議員によって示された数々の障害に直面し、最終的に1990年代後半に建物を失い、20年近くも 建物を解体して高層寮を建設しようとしている開発者、グレッグ・シンガーの手に渡ったのである。シンガー氏は20年近く前から建物を壊して高層寮を建てよ うとしていたが、CB3によって何度も阻止され、彼が築100年近いモールディングを壊し始めた直後にニューヨークのランドマークとなった。PS64のラ ンドマーク化は、シンガーの建物取り壊し作業の開始に対する即時反応であった。特にCB3の関与は重要で、多くのラテン系の王が建物保存の援助を懇願した 後、CB3が関与するようになった。この2つのグループは、空間を保存するために思いもよらない同盟を結び、歴史的建造物として保存することに成功し、シ ンガーによる取り壊しと再建の試みを止めた[6]。CHARAS(旧Real Great Society)やEl Bohioのほか、スタジオスペース、アートギャラリー、学生向けの数多くのアートプログラムやアフタースクールプログラム、音楽、ダンス、演劇を中心と した芸術プログラムや組織を貸し出すアーティストや活動家たちがこの建物を利用していたのである。1999年4月、CHARASの共同創設者であるアーマ ンド・ペレスがクイーンズにある妻の家の外で殺害されているのが発見され[8]、多くの人がギャングとの関連性を推測したが、この説を裏付ける証拠は見つ かっていない。ペレスは死の間際、PS64をグレッグ・シンガーから救うための闘いに深く関わっていた。 |

| Present day In 2017, Mayor de Blasio announced that he would be buying back PS 64 from Singer, and making efforts to revert the building back to a community center. The likelihood of this occurring was immediately shot down by Singer, who made a statement following Mayor de Blasio's claiming he had no intention to sell the building.[9] How Mayor de Blasio will respond is not yet known. Though perhaps one of the more powerful political leaders, he was not the first to make public attempts to retrieve the building. Councilwoman Rosie Mendez has shown open opposition to Singer during her time as councilwoman, an attitude which is held by current city councilwoman Carlina Rivera. When Rivera's campaign was endorsed by the Villager, the author of the endorsement article discussed seeing Rivera as a teenager at a protest to save the community center when it was first lost.[10] She has been a continuous threat to Singer since. During Rivera's campaign, Singer distributed literature around the Lower East Side promoting three of Rivera's rival candidates, encouraging the community to vote for any candidate besides Rivera. Despite his efforts, he must now attempt to work with Rivera, as she poses one of his greatest obstacles. Although Singer originally proposed a demolition of the building and the development of a twenty-story dorm building, his proposals have continuously been rejected by Community Board 2, as the demolition of the building coincides with the policies for construction on a landmarked building. A more recent proposal produced by Singer shows the building in its original form, remodeled only slightly, but still acting as a dorm building for college students.[11] As of November 2017, community activists were advocating the city Department of Buildings to void the original sale of the building to Singer and to reacquire the building [12] |

現在の様子 2017年、デブラシオ市長はPS 64をシンガーから買い戻し、建物をコミュニティセンターに戻す努力をすることを発表しました。この実現の可能性は、デブラシオ市長の「建物を売るつもり はない」という主張を受けて声明を出したシンガーによって即座に打ち消された[9]。 デブラシオ市長がどう対応するかはまだわかっていない。おそらくより強力な政治指導者の一人であるデブラシオ市長は、建物を取り戻すための公的な試みを 行った最初の人物ではない。ロージー・メンデス議員は議員時代、シンガーに公然と反対する姿勢を示しており、その姿勢は現市議会議員のカルリナ・リベラも 同じである。リベラの選挙運動が『ビレッジャー』紙に支持されたとき、その支持記事の著者は、コミュニティセンターが最初に失われたとき、それを救うため の抗議活動で10代のリベラを見たことを話した[10]。 彼女は以来、シンガーに対する脅威でありつづけてきたのだ。リベラの選挙運動中、シンガーはリベラのライバル候補3人を宣伝する文献をローワーイーストサ イドで配布し、リベラ以外の候補に投票するよう地域住民に呼びかけた。しかし、リベラはシンガーにとって最大の障害であり、リベラと協力しなければならな い。シンガーは当初、この建物を取り壊し、20階建ての寮を建設することを提案したが、建物の取り壊しはランドマークとなる建物の建設方針と重なるため、 コミュニティボード2からは却下され続けている。シンガーが作成したより最近の提案では、建物は元の形のまま、わずかに改装されただけで、大学生のための 寮ビルとして機能している[11]。 2017年11月の時点で、コミュニティの活動家は、シンガーへの建物の元の売却を無効にして、建物を再取得するよう市建築局に提唱していた[12]。 |

| Literature and poetry The Nuyorican movement significantly influenced Puerto Rican literature, spurring themes such as cultural identity, civil rights, and discrimination.[13] The Nuyorican Poets Café, a non-profit organization in Alphabet City, Manhattan, founded by Miguel Piñero, Miguel Algarín, and Pedro Pietri. Prominent figures include poets Giannina Braschi, Willie Perdomo, Edwin Torres (poet), Nancy Mercado, and Sandra María Esteves. Later voices include Lemon Andersen, Emanuel Xavier, Mariposa (María Teresa Fernández) and Caridad de la Luz (La Bruja). Current organizations include The Acentos Foundation originally based in the Bronx, New York City which publishes poetry, fiction, memoir, interviews, translations, and artwork by emerging and established Latino/a writers and artists four times a year through The Acentos Review, and Capicu Cultural Showcase based in Brooklyn, New York City.[citation needed] |

文学と詩 ヌヨリカン運動はプエルトリコ文学に大きな影響を与え、文化的アイデンティティ、公民権、差別などのテーマに拍車をかけた[13]。 マンハッタンのアルファベットシティにある非営利団体ヌヨリカンポエッツカフェは、ミゲル・ピニェロ、ミゲル・アルガリン、ペドロ・ピエトリが設立した。 著名な人物としては、詩人のGiannina Braschi、Willie Perdomo、Edwin Torres(詩人)、Nancy Mercado、Sandra María Estevesらがいる。後に、レモン・アンデルセン、エマニュエル・シャビエル、マリポサ(マリア・テレサ・フェルナンデス)、カリダッド・デ・ラ・ル ス(ラ・ブルハ)などが登場する。現在、ニューヨーク市ブロンクスを拠点とするアセントス財団があり、アセントス・レビューを通じて、新進・ベテランのラ テンアメリカ系作家やアーティストによる詩、小説、回想録、インタビュー、翻訳、アートワークを年4回出版しているほか、ニューヨーク市ブルックリンにあ るカピック文化ショーケースがある[citation needed]. |

| Music Nuyorican music became popular in the 1960s with the recordings of Tito Puente's "Oye Como Va"[14][better source needed] and Ray Barretto's "El Watusi" and incorporated Spanglish lyrics.[15] Latin bands who had formerly played the imported styles of cha-cha-cha or charanga began to develop their own unique Nuyorican music style by adding flutes and violins to their orchestras. This new style came to be known as the Latin boogaloo. Some of the musicians who helped develop this unique music were Joe Cuba with "Bang Bang",[16] Richie Ray and Bobby Cruz with "Mr. Trumpet Man", and the brothers Charlie and Eddie Palmieri.[1] Subsequently, Nuyorican music has evolved into Latin rap, freestyle music, Latin house, salsa, Nuyorican soul and reggaeton. The development of the Nuyorican music can be seen in salsa and hip hop music. Musician and singer Willie Colón shows this diaspora in his salsa music by blending the sounds of the trombone, an instrument popular in the New York urban scene, and the cuatro, an instrument native to Puerto Rico and prevalent in salsa music. Furthermore, many salsa songs address this diaspora and relationship between the homeland, in this case, Puerto Rico and the migrant community, New York City.[1] Some see the positives and negatives in this exchange, but often the homeland questions the cultural authenticity of the migrants. In salsa music, the same occurs. The Puerto Ricans question the validity and authenticity of the music. Today, salsa music has expanded to incorporate the sounds of Africa, Cuba, and other Latin American countries, creating more of a salsa fusion. In addition, with the second and third generations of Nuyoricans, the new debated and diasporic sound is hip hop. With hip hop, Nuyoricans gave back to Puerto Rico with rappers like Vico C and Big Pun, who created music that people in both New York and Puerto Rico could relate to and identify with. Other notable Puerto Ricans who made contributions to hip-hop were DJ Disco Wiz, Prince Whipper Whip, DJ Charlie Chase, Tony Touch, DJ Johnny "Juice" Rosado (Public Enemy/producer), Tego Calderon, Fat Joe, Jim Jones, N.O.R.E., Joell Ortiz, and Lloyd Banks. Currently, groups like Circa '95 (PattyDukes & RephStar) are continuing the traditions as torchbearers of the Nuyorican hip hop movement. Thus the musical relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico has become a circular exchange and blended fusion, as embodied in the name Nuyorican.[1] |

音楽 ヌヨリカンミュージックは1960年代にティト・プエンテの「Oye Como Va」[14][出典] やレイ・バレットの「El Watusi」が録音され、スパングリッシュな歌詞を取り入れたことで人気を博した[15]。 輸入されたチャチャチャやチャランガを演奏していたラテン系バンドは、オーケストラにフルートやバイオリンを加え、独自のヌヨリカンミュージックのスタイ ルを確立し始める。この新しいスタイルは、ラテン・ブーガルーとして知られるようになった。このユニークな音楽の発展に貢献したミュージシャンには、「バ ンバン」のジョー・キューバ、「ミスター・トランペット・マン」のリッチー・レイとボビー・クルーズ、チャーリーとエディのパルミエリ兄弟などがいる [1]。 その後、ヌヨリカン音楽は、ラテンラップ、フリースタイルミュージック、 ラテンハウス、サルサ、ヌヨリカンソウルとレゲトンへと発展している。 ヌヨリカンミュージックの発展は、サルサやヒップホップミュージックに見ることができる。ミュージシャンで歌手のウィリー・コロンは、ニューヨークのアー バンシーンで人気のあるトロンボーンと、プエルトリコ原産でサルサ音楽に普及しているクアトロという楽器の音をブレンドして、サルサ音楽でこのディアスポ ラを示している。さらに、多くのサルサ曲は、このディアスポラと、故郷プエルトリコと移住者コミュニティであるニューヨークの関係を取り上げている [1]。この交流にはプラスもマイナスもあるが、しばしば故郷は移住者の文化の真正性を問う。サルサ音楽においても、同じことが起こる。プエルトリコ人 は、音楽の正当性と真正性を疑うのである。今日、サルサ音楽は、アフリカ、キューバ、その他のラテンアメリカの国々の音を取り入れ、よりサルサ・フュー ジョンとして広がりを見せている。さらに、2代目、3代目のヌヨリカンによって、新たに議論されるようになったディアスポラ的なサウンドがヒップホップで ある。ヒップホップでは、ヴィコCやビッグ・パンといったラッパーが、ニューヨークとプエルトリコの両方の人々が共感できる音楽を作り、ヌヨリカンはプエ ルトリコに恩返しをしたのである。ヒップホップに貢献したその他の著名なプエルトリコ人は、DJディスコ・ウィズ、プリンス・ウィッパー・ウィップ、DJ チャーリー・チェイス、トニー・タッチ、DJジョニー "ジュース "ロサード(パブリック・エネミー/プロデューサー)、テゴ・カルデロン、ファット・ジョー、ジム・ジョーンズ、N.O.R.E、ジョエル・オーティズ、 ロイド・バンクスなどです。現在では、Circa '95 (PattyDukes & RephStar) などのグループが、ヌヨリカン・ヒップホップ・ムーブメントの聖火ランナーとして伝統を受け継いでいる。このように、アメリカとプエルトリコの音楽的関係 は、ヌヨリカンという名前に体現されているように、循環的な交流と融合となっている[1]。 |

| Playwrights and theater companies Spanish-language Puerto Rican writers such as René Marqués who wrote about the immigrant experience can be considered as antecedents of Nuyorican movement. Marqués's best-known play The Oxcart (La Carreta) traces the life of a Puerto Rican family who moved from the countryside to San Juan and then to New York, only to realize that they would rather live a poor life in Puerto Rico than face discrimination in the United States.[17] Puerto Rican actress Míriam Colón founded The Puerto Rican Traveling Theatre in 1967 precisely after a successful run of The Oxcart.[18][19] Her company gives young actors the opportunity to participate in its productions. Some of PRTT's productions, such as Edward Gallardo's Simpson Street concern life in a New York's ghettos.[20][better source needed] Other theater companies include Pregones Theater, established in 1979 in the Bronx and currently directed by Rosalba Rolón, Alvan Colón-Lespier, and Jorge Merced.[21][22] Playwrights who pioneered the Nuyorican movement include Pedro Pietri, Miguel Piñero, Giannina Braschi, Jesús Papoleto Meléndez, and Tato Laviera. Piñero is the acclaimed playwright with Short Eyes, a drama about prison life which received a Tony Award nomination and won an Obie Award. Candido Tirado and Carmen Rivera, Obie Award-winner for her play La Gringa; and Judge Edwin Torres wrote Carlito's Way.[23][24] Currently, spaces such as B.A.A.D. (the Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance),[25] established in 1998 by the dancer and choreographer Arthur Aviles and the writer Charles Rice-González in the Hunts Point neighborhood of the Bronx, provide numerous Nuyorican, Latina/o, and queer of color artists and writers with a space to present and develop their work.[26] Other theater groups use the theaters at the Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural Center in Loisaida for their events.[27] |

劇作家と劇団 ヌヨリカン運動の先駆けとして、移民の体験を書いたレネ・マルケスなどのスペイン語圏のプエルトリコ人作家が挙げられる。マルケスの最もよく知られている 戯曲『牛車』(La Carreta)は、田舎からサンフアン、そしてニューヨークへと移り住んだプエルトリコ人家族が、アメリカで差別に遭うくらいならプエルトリコで貧しい 生活を送る方がましだと気づくまでの生活を描く[17]。 プエルトリコ人女優ミリアム・コロンが『牛車』の成功を受けて、1967年にまさにプエルトリコ旅行劇を設立した[18][19] 彼女の会社は若い俳優にその作品に参加する機会を提供している。エドワード・ガヤルドの『シンプソン・ストリート』など、PRTTの作品の中にはニュー ヨークのゲットーでの生活を描いたものもある[20][より良い出典を求める] その他の劇団には1979年にブロンクスに設立され、現在ロサルバ・ロロン、アルバン・コロン=レスピア、ホルヘ・メルセドが主宰するプレゴネス劇場もあ る[21][22]。 ヌヨリカン運動の先駆者である劇作家には、ペドロ・ピエトリ、ミゲル・ピニェロ、ジャンニナ・ブラスキ、ヘスス・パポレト・メレンデス、タト・ラヴィエラ が含まれる。ピニェーロは、トニー賞にノミネートされ、オビー賞を受賞した刑務所生活についてのドラマ「ショート・アイズ」で高い評価を得ている劇作家で す。カンディド・ティラドとカルメン・リベラは『La Gringa』でオビー賞を受賞し、エドウィン・トレス判事は『Carlito's Way』を執筆しています[23][24]。 現在,ブロンクスのハンツポイント地区にダンサー・振付家のアーサー・アヴィレスと作家のチャールズ・ライス=ゴンサレスが1998年に設立した B.A.A.D(the Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance)[25]などのスペースは,多くのヌヨリカン,ラテン/オ,有色人種の同性愛者のアーティストや作家に作品を発表・発展する場を提供している [26]他の劇団もロイシダ地区のクレメンテ・サト・ベレス文化センターのシアターをイベントのために使っている[27]. |

| Visual arts The Nuyorican movement has always included a strong visual arts component, including arts education. Pioneer Raphael Montañez Ortiz established El Museo del Barrio in 1969 as a way to promote Nuyorican art. Painters and print makers such as Rafael Tufiño, Fernando Salicrup, Marcos Dimas, and Nitza Tufiño established organizations such as Taller Boricua.[28] Writers and poets such as Sandra María Esteves and Nicholasa Mohr alternated and complemented their prose and lyrical compositions with visual images on paper. At other times, experimental artists such as Adál Maldonado (better known as Adál) collaborated with poets such as Pedro Pietri. During this time, the gay Chinese American painter Martin Wong collaborated with his lover Miguel Piñero; one of their collaborations is owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[29] In the 1970s and 1980s, graffiti-inspired Nuyorican artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat achieved great recognition for their work. Installation artists such as Antonio Martorell and Pepon Osorio create environments that bring together local aesthetic practices with political and social concerns. In 1992, Nuyorican artist Soraida Martinez created the art of Verdadism, a form of hard-edge abstraction where each painting is accompanied by a written social commentary. Born in Harlem in 1956 and also influenced by the 1960s social movements, the artist created a painting depicting the Nuyorican experience, “Between Two Islands, 1996.”[30] Since 1993, the Organization of Puerto Rican Artists (better known by its acronym O.P. Art) has opened a space for Puerto Rican visual artists in New York, particularly through its events at the Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural Center in the Lower East Side. More recently painters and muralists such as James De La Vega, Jorge Zeno, Miguel Luciano, Miguelangel Ruiz and Sofia Maldonado have continued to expand this tradition. Gallerists, curators, and museum directors such as Marvette Pérez, Yasmin Ramírez, Deborah Cullen, Susana Torruella Leval, Judith Escalona, Tanya Torres, and Chino Garcia have helped Puerto Rican and Nuyorican art gain more recognition. |

ビジュアルアート ヌヨリカンムーブメントは、芸術教育を含め、常にビジュアルアートの要素を強く含んでいる。先駆者であるラファエル・モンタニェス・オルティスは、ヌヨリ カンアートの普及のために1969年にエル・ムセオ・デル・バリオを設立しました。ラファエル・トゥフィニョ、フェルナンド・サリクラップ、マルコス・ ディマス、ニツァ・トゥフィニョといった画家や版画家は、タレール・ボリクアといった組織を設立した[28]。サンドラ・マリア・エステヴェスとニコラ サ・モールといった作家や詩人は、散文や叙情を紙上の視覚イメージと交代に補完していた。また、アダル・マルドナド(アダルとして知られる)のような実験 的なアーティストが、ペドロ・ピエトリのような詩人と共同作業を行ったこともあった。この時期、ゲイの中国系アメリカ人画家マーティン・ウォンは、恋人の ミゲル・ピニェロと共同制作し、彼らの共同作品のひとつはメトロポリタン美術館に所蔵されている[29]。1970年代と1980年代に、ジャン=ミシェ ル・バスキアなどのグラフィティに影響を受けたヌヨリカンのアーティストがその仕事で大きな評価を得た。アントニオ・マルトレルやペポン・オソリオのよう なインスタレーション・アーティストは、地元の美的習慣と政治的、社会的関心を一緒にした環境を作る。1992年、ヌヨリカンのアーティスト、ソライダ・ マルティネスは、ハードエッジな抽象画の一形態であるベルダディズムの芸術を創り出し、それぞれの絵に社会的な解説を書き添えた。1956年にハーレムで 生まれ、1960年代の社会運動にも影響を受けたこのアーティストは、ヌヨリカンの経験を描いた絵画「Between Two Islands, 1996」を制作した[30]。1993年から、プエルトリコ芸術家機構(O.P. Artという略称の方が有名)は、ニューヨークのプエルトリコの視覚芸術家のための場所を開き、特にローワーイーストサイドのクレメンテソトベレス文化セ ンターでのイベントを通してその場を提供している。 最近では、James De La Vega、Jorge Zeno、Miguel Luciano、Miguelangel Ruiz、Sofia Maldonadoなどの画家や壁画家がこの伝統を拡大し続けている。マーベット・ペレス、ヤスミン・ラミレス、デボラ・カレン、スサナ・トルエラ・レ ヴァル、ジュディス・エスカロナ、ターニャ・トーレス、チノ・ガルシアなどのギャラリスト、キュレーター、美術館館長は、プエルトリコやヌヨリカンの芸術 がより認知されるのに貢献している。 |

| Nuyorican writers and poets Miguel Algarín, co-founder of Nuyorican Poet's Cafe[31] Jack Agüeros Giannina Braschi, author of the postmodern classics Empire of Dreams, Yo-Yo Boing! and United States of Banana[32][33][34][35][36] Julia de Burgos, author of Puerto Rican poetry classic "Yo misma fui mi ruta"[37] Jesús Colón Victor Hernández Cruz Nelson Denis Sandra María Esteves Tato Laviera Felipe Luciano Jesús Papoleto Meléndez[38] Nancy Mercado Nicholasa Mohr Richie Narvaez[39][40] Pedro Pietri, co-founder of Nuyorican Poet's Café best known for "Puerto Rican Obituary," poet laureate of the Nuyorican movement[41] Miguel Piñero, dramatist best known for the play Short Eyes[42] Noel Quiñones Bimbo Rivas Abraham Rodriguez Bonafide Rojas[43][44] Esmeralda Santiago, author of When I Was Puerto Rican[45] Piri Thomas, author of Down These Mean Streets[46] Edwin Torres (judge), author of Carlito's Way J. L. Torres, author of The Accidental Native and Boricua Passport[47][48] Luz María Umpierre Edgardo Vega Yunqué (also Ed Vega), author of The Lamentable Journey of Omaha Bigelow into the Impenetrable Loisaida Jungle |

ヌエヨリカン系作家および詩人 ミゲル・アルガリン(Nuyorican Poet's Cafeの共同創設者)[31] ジャック・アグエロス ジャニナ・ブラスキ(ポストモダン古典『Empire of Dreams』、『Yo-Yo Boing!』、『United States of Banana』の著者)[32][33][34][35][36] プエルトリコの古典詩「Yo misma fui mi ruta」の著者、ジュリア・デ・ブルゴス[37] ヘスス・コロン ビクター・ヘルナンデス・クルス ネルソン・デニス サンドラ・マリア・エステベス タト・ラヴィエラ フェリペ・ルシアーノ ヘスス・パポレット・メレンデス[38] ナンシー・メルカード ニコラサ・モール リッチー・ナルバエス[39][40] ヌエヨリカン・ポエット・カフェの共同創設者で、「プエルトリコ人訃報」で最もよく知られ、ヌエヨリカン運動の桂冠詩人であるペドロ・ピエトリ[41] 劇作家で、戯曲『ショート・アイズ』で最もよく知られるミゲル・ピニェロ[42] ノエル・キニョネス ビンボ・リバス エイブラハム・ロドリゲス ボナファイド・ロハス[43][44] エスメラルダ・サンティアゴ、『When I Was Puerto Rican』の著者[45] ピリ・トーマス、『Down These Mean Streets』の著者[46] エドウィン・トーレス(判事)、『Carlito's Way』の著者 J. L. トーレス、『The Accidental Native』および『Boricua Passport』の著者[47][48] ルス・マリア・ウンピエル エドガルド・ベガ・ユンケ(別名エド・ベガ)、著書『オマハ・ビグローの不可解なロイサイダ密林への哀れな旅』 |

| In popular culture The life of Nuyorcan movement poet Miguel Piñero was portrayed in the 2001 Hollywood production Piñero, directed by Leon Ichaso and starring Benjamin Bratt in the title role. In the film, Piñero's love life, with both men and women, is depicted, including with his protégé Reinaldo Povod. The relationships are secondary to the life of the writer as an individual, as the movie shows a non-chronological portrayal of Piñero's development as both a poet and a person. The movie blends visual and audio segments shot in short, music/slam poetry videos with typical movie narratives to show Piñero's poetics in action.[49] |

大衆文化において ヌヨルカ運動の詩人ミゲル・ピニェーロの生涯は、2001年にハリウッドで制作された『ピニェーロ』(監督:レオン・イチャソ、主演:ベンジャミン・ブ ラット)で描かれている。この映画では、ピニェーロの男女の恋愛が描かれ、弟子のレイナルド・ポボドとの恋愛も描かれている。恋愛は二の次で、詩人とし て、人間としてのピニェーロの成長が非時系列的に描かれている。この映画は、ピニェーロの詩学を行動で示すために、音楽/スラム詩の短いビデオで撮影され た映像と音声セグメントを典型的な映画の物語と混ぜ合わせている[49]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuyorican_movement |

|

Daddy Yankee Ramón Luis Ayala Rodríguez (born February 3, 1977),[2][5][6] known professionally as Daddy Yankee, is a retired Puerto Rican rapper, singer, songwriter, and actor. He is also known as the "King of Reggaeton" by music critics and fans alike.[7] He is often cited as an influence by other Hispanic urban performers. Ayala was born in Río Piedras and was raised in the Villa Kennedy Housing Projects neighborhood.[8] He aspired to be a professional baseball player and tried out for the Seattle Mariners of Major League Baseball.[8] Before he could be officially signed, he was hit by a stray round from an AK-47 rifle while taking a break from a studio recording session with reggaeton artist DJ Playero.[8] Ayala spent roughly a year and a half recovering from the wound; the bullet was never removed from his hip, and he credits the shooting incident with allowing him to focus entirely on a music career.[8] In 2004, Daddy Yankee released his international hit single "Gasolina", which is credited with introducing reggaeton to audiences worldwide, and making the music genre a global phenomenon.[9] Since then, he has sold around 30 million records, making him one of the best-selling Latin music artists.[10][11] Daddy Yankee's album Barrio Fino made history when it became the top-selling Latin music album of the decade between 2000 and 2009.[12][13] In 2017, Daddy Yankee, in collaboration with Latin pop singer Luis Fonsi, released the hit single "Despacito". It became the first Spanish-language song to hit number one on the Billboard Hot 100 since "Macarena" in 1996.[14] The single gained global success. The video for "Despacito" on YouTube received its billionth view on April 20, 2017, and became the most-watched video on the platform. Its success led Daddy Yankee to become the most-listened artist worldwide on the streaming service Spotify in June 2017, the first Latin artist to do so.[15][16] In March 2022, Daddy Yankee announced that he would be retiring from music after the release of his seventh studio album Legendaddy and its supporting tour.[17] During his career, Daddy Yankee earned numerous accolades, including five Latin Grammy Awards, two Billboard Music Awards, 14 Billboard Latin Music Awards, two Latin American Music Awards, eight Lo Nuestro Awards, an MTV Video Music Award, and six ASCAP Awards. He also received a Puerto Rican Walk of Fame star, special awards by People en Español magazine, and the Presencia Latina at Harvard University. He was named by CNN as the "Most Influential Hispanic Artist" of 2009, and included in Time 100 in 2006.[18] |

ダディー・ヤンキー ラモン・ルイス・アヤラ・ロドリゲス(Ramón Luis Ayala Rodríguez、1977年2月3日生まれ)[2][5][6]は、プエルトリコ出身のラッパー、シンガー、ソングライター、俳優。彼はまた、音楽評 論家やファンから「レゲトンの帝王」として知られている[7]。 アヤラはリオ・ピエドラで生まれ、ヴィラ・ケネディ・ハウジング・プロジェクツで育った[8]。 [8]彼は正式に契約する前に、レゲトンアーティストのDJプレイエロとのスタジオレコーディングセッションの休憩中にAK-47ライフルの流れ弾に当 たった[8]。 2004年、ダディー・ヤンキーは世界的なヒットシングル 「Gasolina」をリリースし、レゲトンを世界中の聴衆に紹介し、この音楽ジャンルを世界的な現象にしたと言われている[9]。 それ以来、彼は約3000万枚のレコードを売り上げ、最も売れたラテン音楽アーティストの一人となった[10][11]。 ダディー・ヤンキーのアルバム「Barrio Fino」は、2000年から2009年の10年間で最も売れたラテン音楽アルバムとなり、歴史に名を刻んだ[12][13]。 2017年、ダディ・ヤンキーはラテンポップ歌手のルイス・フォンシと共同で、ヒットシングル「Despacito」をリリース。 このシングルは、1996年の「マカレナ」以来、ビルボード・ホット100で1位を獲得した初のスペイン語曲となった[14]。YouTubeでの 「Despacito」のビデオは、2017年4月20日に10億回目の再生回数を記録し、同プラットフォームで最も視聴されたビデオとなった。その成功 により、ダディ・ヤンキーは2017年6月、ストリーミングサービスSpotifyで世界で最も視聴されたアーティストとなり、ラテン系アーティストとし て初の快挙を成し遂げた[15][16]。 2022年3月、ダディ・ヤンキーは7枚目のスタジオアルバム『Legendaddy』とそのサポートツアーのリリースを最後に音楽活動を引退すると発表 した[17]。 Luis Fonsi - Despacito ft. Daddy Yankee ダディー・ヤンキーのキャリアは、5つのラテン・グラミー賞、2つのビルボード・ミュージック・アワード、14のビルボード・ラテン・ミュージック・ア ワード、2つのラテン・アメリカン・ミュージック・アワード、8つのロ・ヌエストロ・アワード、MTVビデオ・ミュージック・アワード、6つのASCAP アワードなど、数多くの賞を獲得。また、プエルトリコ・ウォーク・オブ・フェイムの星、ピープル・エン・エン・エスパニョール誌の特別賞、ハーバード大学 のプレゼンシア・ラティーナ賞も受賞。2009年にはCNNから「最も影響力のあるヒスパニック系アーティスト」に選ばれ、2006年にはTime 100に選出された[18]。 |

| Musical career 1994–1999: Career beginnings Often considered to be one of the pioneers within the reggaeton genre,[20] Ayala was originally going to become a professional baseball player but he was shot in the leg while taking a break from a studio recording session. The bullet was never removed and he credits this incident with allowing him to pursue a musical career. He first appeared on the 1994 DJ Playero's Mixtape, Playero 34, with the song "So' Persigueme, No Te Detengas".[citation needed] His first official studio project as a solo artist was No Mercy, which was released on April 2, 1995 through White Lion Records and BM Records in Puerto Rico.[4] Early in his career he attempted to imitate the rap style of Vico C. He went on to emulate other artists in the genre, including DJ Playero, DJ Nelson, and Tempo taking elements from their styles in order to develop an original style with the Dembow rhythm. In doing so, he eventually abandoned the traditional model of rap and became one of the first artists to perform reggaeton.[21] Throughout the 1990s, Daddy Yankee appeared in several of DJ Playero's underground mixtapes which were banned by the Puerto Rican government due to explicit lyrics; these songs would later be among the first reggaeton songs ever produced.[22] |

音楽活動 1994-1999: キャリアの始まり レゲトンというジャンルのパイオニアの一人とされるアヤラは[20]、当初はプロ野球選手になる予定だったが、スタジオでのレコーディングの休憩中に足を 撃たれた。弾丸は摘出されることはなく、彼はこの出来事が音楽の道に進むきっかけになったと信じている。1994年のDJプレイロのミックステープ『プレ イロ34』に「So' Persigueme, No Te Detengas」という曲で初登場した[要出典]。ソロアーティストとしての初の公式スタジオプロジェクトは、1995年4月2日にプエルトリコのホワ イト・ライオン・レコードとBMレコードからリリースされた『No Mercy』である。 [4]キャリアの初期、彼はヴィコCのラップ・スタイルを模倣しようとしたが、DJプレイエロ、DJネルソン、テンポなどこのジャンルの他のアーティスト を模倣し、彼らのスタイルから要素を取り入れ、デンボー・リズムを取り入れたオリジナル・スタイルを確立した。1990年代を通して、ダディ・ヤンキー は、露骨な歌詞のためにプエルトリコ政府によって禁止されたDJプレイロのアンダーグラウンドなミックステープのいくつかに登場した。 |

| 2000–2003: Early music and El

Cangri.com In 1997, Daddy Yankee collaborated with the rapper Nas, who was an inspiration for Ayala, in the song "The Profecy", for the album Boricua Guerrero. He released two compilation albums with original material: El Cartel (1997) and El Cartel II (2001). Both albums were successful in Puerto Rico, but not throughout Latin America. Between those years, Daddy Yankee released a total of nine music videos, including "Posición" featuring Alberto Stylee, "Tu Cuerpo en la Cama" featuring Nicky Jam, and "Muévete y Perrea". In 2000, Daddy Yankee formed an unofficial duo called "Los Cangris" with Nicky Jam and released several successful singles together. Yankee and Nicky Jam fell apart in 2004 due to personal issues and creative differences.[23][24] In 2012, Daddy Yankee and Nicky Jam reconciled and performed in various concerts together.[25] In 2002, El Cangri.com became Daddy Yankee's first album with international success, receiving coverage in the markets of New York City and Miami with hits including "Latigazo", "Son las Doce", "Guayando" and other songs like "Enciende", which talks about different social problems of the era, mentioning 9/11, corruption and religion. In 2003, Daddy Yankee released a compilation album named Los Homerun-es, which contains his first charted single ("Segurosqui"), five new songs and 12 remakes of DJ Playero's albums songs. that was later charted, "Seguroski", being his first charted single after six of them. In 2003, Daddy Yankee collaborated for the first time with the prestigious reggaeton producers Luny Tunes on the album Mas Flow, with his commercial success song "Cógela Que Va Sin Jockey" (a.k.a. "Métele con Candela"), and Mas Flow 2. |

2000-2003: 初期の音楽とEl Cangri.com 1997年、ダディ・ヤンキーはアルバム『Boricua Guerrero』の収録曲 "The Profecy "で、アヤラにインスピレーションを与えたラッパーのナスとコラボレート。オリジナル曲を含む2枚のコンピレーション・アルバムをリリース: El Cartel』(1997年)と『El Cartel II』(2001年)。両アルバムともプエルトリコでは成功を収めたが、ラテンアメリカ全域では成功しなかった。その間、ダディ・ヤンキーはアルベルト・ スティレをフィーチャリングした "Posición"、ニッキー・ジャムをフィーチャリングした "Tu Cuerpo en la Cama"、"Muévete y Perrea "など、合計9本のミュージックビデオを発表。2000年、ダディ・ヤンキーはニッキー・ジャムと非公式デュオ "ロス・カングリス "を結成し、数枚のシングルをリリースして成功を収めた。2004年、ヤンキーとニッキー・ジャムは個人的な問題やクリエイティブの違いにより、仲たがい した[23][24]。 2002年、El Cangri.comはダディー・ヤンキーの最初のアルバムとなり、国際的な成功を収め、"Latigazo"、"Son las Doce"、"Guayando "などのヒット曲や、9.11、汚職、宗教など、時代の様々な社会問題を歌った "Enciende "などの曲で、ニューヨークやマイアミの市場で報道された。2003年、ダディ・ヤンキーはコンピレーション・アルバム『Los Homerun-es』をリリース。このアルバムには、自身初のチャートイン・シングル("Segurosqui")、新曲5曲、DJプレイロのアルバム 曲のリメイク12曲が収録されている。2003年、ダディ・ヤンキーはレゲトンの名門プロデューサー、ルニー・チューンズとアルバム『マス・フロー』で初 めてコラボレーションし、商業的成功を収めた "Cógela Que Va Sin Jockey"(別名 "Métele con Candela")と『マス・フロー2』を発表。 |

| 2004–2006: Barrio Fino and

"Gasolina" Daddy Yankee's next album, Barrio Fino, was produced by Luny Tunes and DJ Nelson among others and released in July 2004 by El Cartel Records and VI Music. It was the most highly anticipated album in the reggaeton community.[26] Daddy Yankee had enjoyed salsa music since he was young, and this led him to include music of genres besides reggaeton in the album.[26] The most prominent of these cross-genre singles was "Melao", in which he performed with Andy Montañez.[26] The album was described as his most complete, and with it he intended to introduce combinations of reggaeton and other genres to the English-speaking market.[26] Barrio Fino was followed up by an international tour with performances in numerous countries including the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Honduras, Spain, Colombia, Argentina, Venezuela, and the United States.[26] The album has sold over 1.1 millions of copies in the United States alone, making it the seventh best-selling Latin album in the country according to Nielsen SoundScan. Also, It had sold over 2 million copies throughout Latin America and worldwide.[27][28][29] During this same time, Daddy Yankee was featured in N.O.R.E.'s single "Oye Mi Canto" which hit number 12 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart; a record for a reggaeton single at the time.[30] Other successful featured singles included "Mayor Que Yo" and "Los 12 Discípulos". In 2005, Daddy Yankee won several international awards, making him one of the most recognized reggaeton artists within the music industry.[31] The first award of the year was Lo Nuestro Awards within the "Album of the Year" category, which he received for Barrio Fino.[31] In this event he performed "Gasolina" in a performance that was described as "innovative".[31] Barrio Fino also won the "Reggaeton Album of the Year" award in the Latin Billboard that took place on April 28, 2005,[31] where he performed a mix of three of his songs in a duet with P. Diddy. The album was promoted throughout Latin America, the United States, and Europe, reaching certified gold in Japan.[citation needed] Due to the album's success, Daddy Yankee received promotional contracts with radio stations and soda companies, including Pepsi.[32] His hit single, "Gasolina", received the majority of votes cast for the second edition of Premios Juventud, in which it received eight nominations and won seven awards.[31] Daddy Yankee also made a live presentation during the award ceremony. "Gasolina" received nominations in the Latin Grammy and MTV Video Music Awards.[31] The commercial success of "Gasolina" in the United States led to the creation of a new radio format and a Billboard chart: Latin Rhythm Airplay.[12] According to Nestor Casonu, CEO of Casonu Strategic Management, "Daddy Yankee and 'Gasolina' triggered the explosion of urban Latin music worldwide".[12] The successful single, "Gasolina", was covered by artists from different music genres. This led to a controversy when "Los Lagos", a Mexican banda group, did a cover with the original beat but changed the song's lyrics.[33] The group's label had solicited the copyright permission to perform the single and translate it to a different music style, but did not receive consent to change the lyrics; legal action followed.[33] Speaking for the artist, Daddy Yankee's lawyer stated that having his song covered was an "honor, but it must be done the right way." On December 13, 2005, he released Barrio Fino en Directo, a live record and the follow-up of Barrio Fino. The album sold more than in 800,000 copies in the United States, becoming the 13th best-selling Latin album in the US according to Nielsen SoundScan and over 3 million of copies worldwide.[29] On April 30, 2006, Daddy Yankee was named one of the 100 most influential people by Time, which cited the 2 million copies of Barrio Fino sold, Daddy Yankee's $20 million contract with Interscope Records, and his Pepsi endorsement.[34] During this period, Daddy Yankee and William Omar Landrón (more commonly known by his artistic name Don Omar) were involved in a rivalry within the genre, dubbed "tiraera". The rivalry received significant press coverage despite being denied early on by both artists. It originated with a lyrical conflict between the artists begun by Daddy Yankee's comments in a remix single, where he criticized Landron's common usage of the nickname "King of Kings". Don Omar responded to this in a song titled "Ahora Son Mejor", in his album Los Rompediscotecas.[35] |

2004-2006: バリオ・フィノと "ガソリーナ" ダディ・ヤンキーの次のアルバム『Barrio Fino』は、ルニー・チューンズやDJネルソンらがプロデュースし、2004年7月にエル・カルテル・レコードとVIミュージックからリリースされた。 このアルバムはレゲトン・コミュニティで最も期待されたアルバムであった[26]。ダディー・ヤンキーは若い頃からサルサ・ミュージックを楽しんでいたた め、このアルバムにはレゲトン以外のジャンルの音楽を取り入れた[26]。これらのジャンルを超えたシングルの中で最も著名なのは、アンディー・モンタ ニェスと共演した「Melao」であった[26]。 [26]バリオ・フィノはその後、ドミニカ共和国、エクアドル、メキシコ、パナマ、ペルー、ホンジュラス、スペイン、コロンビア、アルゼンチン、ベネズエ ラ、アメリカを含む多くの国で公演を行う国際ツアーを行った[26]。ニールセン・サウンドスキャンによると、このアルバムはアメリカだけで110万枚以 上を売り上げ、同国で7番目に売れたラテン・アルバムとなった。また、ラテンアメリカ全土と世界中で200万枚以上を売り上げた[27][28] [29]。 同時期、ダディ・ヤンキーはN.O.R.Eのシングル "Oye Mi Canto "にフィーチャーされ、ビルボードホット100チャートで12位を記録。 2005年、ダディ・ヤンキーはいくつかの国際的な賞を受賞し、音楽業界で最も認められたレゲトン・アーティストの一人となった[31]。 [31]。2005年4月28日に開催されたラテン・ビルボードでも「レゲトン・アルバム・オブ・ザ・イヤー」を受賞し[31]、P.ディディとのデュ エットで3曲のミックスを披露した。このアルバムはラテンアメリカ、アメリカ、ヨーロッパでプロモーションされ、日本ではゴールド・ディスクに認定された [要出典]。このアルバムの成功により、ダディ・ヤンキーはラジオ局やペプシなどのソーダ会社とプロモーション契約を結んだ[32]。「ガソリーナ」はラ テン・グラミー賞とMTVビデオ・ミュージック・アワードにもノミネートされた[31]: カソヌ・ストラテジック・マネジメントのCEOであるネストル・カソヌによれば、「ダディ・ヤンキーと『ガソリーナ』は、世界中でアーバン・ラテンミュー ジックが爆発的にヒットするきっかけとなった」[12]。 ヒットしたシングル「ガソリーナ」は、さまざまなジャンルのアーティストにカバーされた。同グループのレーベルは、シングルを演奏し、別の音楽スタイルに 翻訳する著作権の許可を求めたが、歌詞を変更する同意は得られず、法的措置が取られた[33]。ダディ・ヤンキーの弁護士は、アーティストを代表して、自 分の曲をカバーされることは「名誉なことだが、正しい方法で行われなければならない」と述べた[33]。 2005年12月13日、彼は『Barrio Fino』に続くライブ盤『Barrio Fino en Directo』をリリース。このアルバムはアメリカで80万枚以上を売り上げ、ニールセン・サウンドスキャンによると、アメリカで13番目に売れたラテ ン・アルバムとなり、世界中で300万枚以上を売り上げた[29]。 2006年4月30日、ダディ・ヤンキーはタイム誌の「最も影響力のある100人」に選ばれ、同誌はバリオ・フィノの200万枚の売り上げ、ダディ・ヤン キーのインタースコープ・レコードとの2,000万ドルの契約、ペプシの推薦を挙げている[34]。 この時期、ダディ・ヤンキーとウィリアム・オマール・ランドロン(ドン・オマールという芸名の方が一般的)は、「ティラエラ」と呼ばれるジャンル内でのラ イバル関係にあった。この対立は、両アーティストによって否定されていたにもかかわらず、大きな報道を受けた。発端は、ダディ・ヤンキーのリミックス・シ ングルでの、ランドロンがよく使う「キング・オブ・キングス」というニックネームを批判する発言によるアーティスト間の歌詞の対立だった。ドン・オマール はアルバム『Los Rompediscotecas』に収録された「Ahora Son Mejor」という曲でこれに反論した[35]。 |

| 2007–2009: El Cartel: The Big

Boss and Talento de Barrio El Cartel: The Big Boss was released by Interscope on June 5, 2007. Daddy Yankee stated that the album marked a return to his hip-hop roots as opposed to being considered a strictly reggaeton album.[1] The album was produced in 2006, and included the participation of will.i.am, Scott Storch, Tainy Tunes, Neli, and personnel from Daddy Yankee's label. Singles were produced with Héctor el Father, Fergie, Nicole Scherzinger and Akon.[1] The first single from the album was titled "Impacto", and was released prior to the completion of the album. The album was promoted by a tour throughout the United States, which continued throughout Latin America.[1] He performed in Mexico, first in Monterrey, where 10,000 attended the concert, and later at San Luis Potosí coliseum, where the concert sold out, leaving hundreds of fans outside the building.[36] Daddy Yankee performed in Chile as well, and established a record for attendance in Ecuador.[37] He also performed in Bolivia, setting another record when 50,000 fans attended his Santa Cruz de la Sierra concert.[37] This show was later described as "the best show with the biggest attendance in history" and as "somehappy that his album had sold more than those of Juan Luis Guerra and Juanes, and that this was an "official proof that reggaeton's principal exponent defeated the rest of the genres".[38] Between 2007 and 2008, Daddy Yankee made several guest appearances in famous reggaeton compilation albums including Caribbean Connection, Echo Presenta: Invasión, Mas Flow: Los Benjamins, and 20 Number 1's Now.[39][40][41] He appeared on the 2008 Rockstar Games' video game Grand Theft Auto IV as the DJ of Radio San Juan Sounds, with spanglish lines. The radio includes reggaeton songs from Daddy Yankee's colleagues, like Wisin & Yandel, Héctor el Father, Tito El Bambino and Jowell & Randy. San Juan Sounds also featured Daddy Yankee's hit "Impacto". In July 2008, Daddy Yankee announced that as part of his work, he would produce a cover version of Thalía's song, "Ten Paciencia".[42] On August 17, 2008 his soundtrack album Talento De Barrio for the eponymous film was released. Prior to the album's release, Daddy Yankee scheduled several activities, including an in-store contract signing.[43] The album was awarded as Multi-Platinum by RIAA on April 17, 2009.[citation needed] On February 27, 2009, he performed at the Viña del Mar International Song Festival in Chile.[44] In this event, the artists receive awards based on the public's reaction. After performing "Rompe", "Llamado de emergencia", "Ella Me Levantó", "Gasolina", "Limpia Parabrisas" and "Lo Que Pasó, Pasó" over the course of two hours, Daddy Yankee received the "Silver Torch", "Gold Torch" and "Silver Seagull" recognitions.[44] On April 24, 2009, he received the Spirit of Hope Award as part of the Latin Billboard Music Awards ceremony.[45] The recognition is given to the artists that participate in their community or social efforts throughout the year. |

2007-2009: エル・カルテル