このページは「学際研究を継続させる要因とは何か」「ジュリアン・スチュワードと地域研究」 からの分枝である。ここでは、ジュリアン・スチュアード(スチュアート)の生涯について考える。

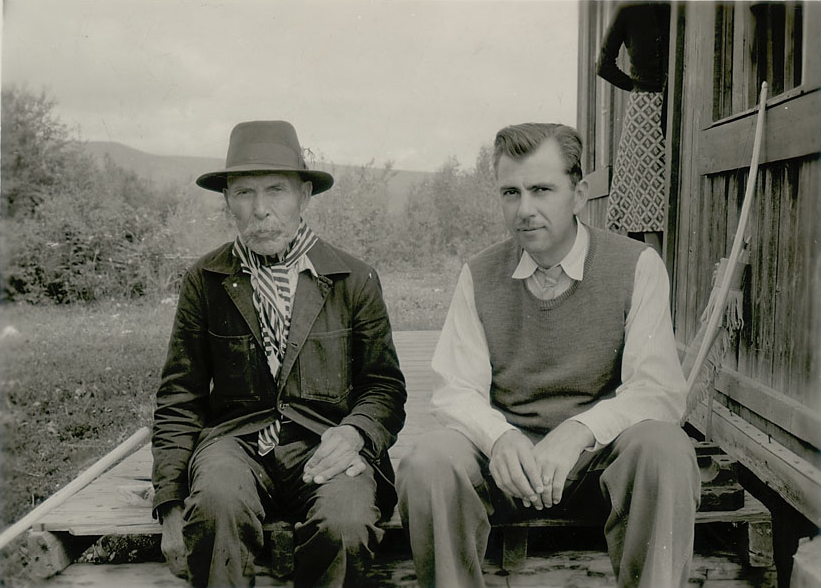

Unidentified Native

Man

(Carrier Indian) (possibly Steward's informant, Chief Louis Billy

Prince) and Julian Steward (1902–1972) ,

Outside Wood Building, 1940

| Julian Haynes

Steward

(January 31, 1902 – February 6, 1972) was an American anthropologist

known best for his role in developing "the concept and method" of

cultural ecology, as well as a scientific theory of culture change. Early life and education Steward was born in Washington, D.C., where he lived on Monroe Street, NW, and later, Macomb Street in Cleveland Park. At age 16, Steward left an unhappy childhood in Washington, D.C. to attend boarding school in Deep Springs Valley, California, in the Great Basin. Steward's experience at the newly established Deep Springs Preparatory School (which later became Deep Springs College), high in the White Mountains had a significant influence on his academic and career interests. Steward's "direct engagement" with the land (specifically, subsistence through irrigation and ranching) and the Northern Paiute Amerindians that lived there became a "catalyst" for his theory and method of cultural ecology. (Kerns 1999; Murphy 1977) As an undergraduate, Steward studied for a year at UC Berkeley, with two of his professors being Alfred Kroeber and Robert Lowie, after which he transferred to Cornell University, from which he graduated in 1925 with a B.Sc. in zoology. Although Cornell, like most universities at the time, did not have an anthropology department, its president, Livingston Farrand, had previously been a professor of anthropology at Columbia University. Farrand advised Steward to continue pursuing his interest (or, in Steward's words, his already chosen "life work") in anthropology at Berkeley (Kerns 2003:71–72). Steward studied as directed by Kroeber and Lowie—- and was taught by Oskar Schmieder in regional geography—- at Berkeley, where his dissertation The Ceremonial Buffoon of the American Indian, a Study of Ritualized Clowning and Role Reversals was accepted in 1929. |

ジュリアン・ヘインズ・スチュワード(Julian Haynes

Steward、1902年1月31日 -

1972年2月6日)は、文化生態学の「概念と方法」、および文化変化の科学的理論を開発したことで知られるアメリカの人類学者である。 生い立ちと教育 スチュワードはワシントンD.C.で生まれ、モンロー・ストリート(NW)、後にクリーブランド・パークのマコンブ・ストリートに住んだ。 16歳の時、スチュワードはワシントンD.C.での不幸な幼少期を離れ、大盆地にあるカリフォルニア州ディープスプリングス・バレーの寄宿学校に通った。 ホワイト・マウンテンの高地に新設されたディープ・スプリングス・プレパラトリー・スクール(後にディープ・スプリングス・カレッジとなる)での経験は、 スチュワードの学業とキャリアに大きな影響を与えた。スチュワードの土地(具体的には灌漑と牧場経営による自給自足)とそこに住むノーザン・パイユート・ アメリカンとの「直接的な関わり」は、彼の文化生態学の理論と手法の「きっかけ」となった。(Kerns 1999; Murphy 1977)。 学部時代、スチュワードはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校で1年間学び、アルフレッド・ クローバーとロバート・ローウィーの2人の教授に師事した。コー ネル大学には当時、ほとんどの大学と同様、人類学部がなかったが、学長のリビングストン・ファランドは以前、コロンビア大学で人類学の教授を務めていた。 ファーランドはスチュワードに、バークレー大学で人類学への関心(スチュワードの言葉を借りれば、すでに選択した「ライフワーク」)を追求し続けるよう助 言した(Kerns 2003:71-72)。スチュワードはクローバーとローイの指導のもとで学び、地域地理学ではオスカー・シュミーダーの指導を受けたが、バークレー校で は1929年に学位論文『The Ceremonial Buffoon of the American Indian, a Study of Ritualized Clowning and Role Reversals』が受理された。 |

| Career Steward later established an anthropology department at the University of Michigan, where he taught until 1930, when he was replaced by Leslie White, with whose model of "universal" cultural evolution he disagreed, although it became popular and gained the department fame and notoriety. In 1930 Steward relocated to the University of Utah, which appealed to him for its proximity to the Sierra Nevada, and nearby archaeological fieldwork opportunities in California, Nevada, Idaho, and Oregon. Steward's research interests mainly concerned "subsistence"—- the dynamic interaction of man, environment, technology, social structure, and the organization of work—- which Kroeber regarded as "eccentric", original, and innovative. (EthnoAdmin 2003) In 1931, Steward, needing money, began fieldwork on the Great Basin Shoshone for Kroeber's Culture Element Distribution (CED) survey; in 1935 he received an appointment to the Smithsonian's Bureau of American Ethnography (BAE), which published some of his most influential works. Among them: Basin-Plateau Aboriginal Sociopolitical Groups (1938), which "fully explicated" the paradigm of cultural ecology, and helped decrease the diffusionist emphasis of American anthropology. For eleven years Steward was an administrator of considerable influence, editing the Handbook of South American Indians. He also had a job with the Smithsonian Institution, where he initiateded the Institute for Social Anthropology in 1943. He also served on a committee to reorganize the American Anthropological Association and played a role in the creation of the National Science Foundation. He was also active in archaeological pursuits, successfully lobbying Congress to create the Committee for the Recovery of Archaeological Remains (the beginning of what is known presently as 'salvage archaeology') and worked with Gordon Willey to establish the Viru Valley project, an ambitious research program involved with Peru. Steward searched for cross-cultural regularities in an effort to discern principles of culture and culture change. His work explained variation in the complexity of social organization as being limited to within a range possibilities by the environment. In evolutionary terms, he described cultural ecology as "multi-linear", in contrast to the unilinear typological models popular during the 19th century, and Leslie White's "universal" model. Steward's most important theoretical contributions happened during his teaching years at Columbia (1946–53). Steward's most productive years theoretically were from 1946 to 1953, while teaching at Columbia University. During this time, Columbia had an influx of World War II veterans who were attending school due to the GI Bill. Steward quickly developed a coterie of students who would later have enormous influence in the history of anthropology, including Sidney Mintz, Eric Wolf, Roy Rappaport, Stanley Diamond, Robert Manners, Morton Fried, Robert F. Murphy, and influenced other scholars such as Marvin Harris. Many of these students participated with the Puerto Rico Project, yet another large-scale group research study that concerned modernization in Puerto Rico. Steward quit Columbia for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he directed the Anthropology Department and continued to teach until his retirement in 1968. There he began yet another large-scale study, a comparative analysis of modernization in eleven third world societies. The results of this research were published in three volumes entitled Contemporary Change in Traditional Societies. Steward died in 1972. |

経歴 その後、スチュワードはミシガン大学に人類学部を設立し、1930年まで教鞭をとったが、レスリー・ホワイトに後任として教鞭を取られた。1930年、ス チュワードはユタ大学に移り住んだ。ユタ大学はシエラネバダに近く、カリフォルニア、ネバダ、アイダホ、オレゴンでの考古学的フィールドワークの機会にも 恵まれていた。 スチュワードの研究対象は主に「生業」、つまり人間、環境、技術、社会構造、労働組織のダイナミックな相互作用に関するもので、クルーバーはこれを「風変 わり」で独創的、革新的と評価した(EthnoAdmin 2003)。(1931年、資金を必要としたスチュワードは、クルーバーの文化要素分布(CED)調査のために、グレート・ベイシン・ショショーネの フィールドワークを開始した。そのなかには次のようなものがある: Basin-Plateau Aboriginal Sociopolitical Groups』(1938年)は、文化生態学のパラダイムを「完全に説明」し、アメリカ人類学の拡散主義的強調を減少させるのに貢献した。 スチュワードは11年間、『Handbook of South American Indians(南米インディアン・ハンドブック)』を編集するなど、大きな影響力を持つ行政官であった。彼はスミソニアン協会でも仕事をし、1943年 には社会人類学研究所を設立した。また、アメリカ人類学会の再編成委員会の委員も務め、国民科学財団の創設にも一役買った。考古学の研究にも積極的で、議 会に働きかけて考古学的遺物回収委員会(現在「サルベージ考古学」として知られるものの始まり)の設立に成功し、ゴードン・ウィリーと協力してペルーに関 わる野心的な研究プログラムであるヴィル・ヴァレー・プロジェクトを立ち上げた。 スチュワードは、文化と文化の変化の原理を見極めようと、異文化間の規則性を探った。彼の研究は、社会組織の複雑さの変化は、環境による可能性の範囲内に 限定されると説明した。進化論的な用語で言えば、彼は文化生態学を「多直線的」なものとして説明し、19世紀に流行した一直線的な類型論的モデルやレス リーホワイトの「普遍的」モデルとは対照的であった。スチュワードの最も重要な理論的貢献は、コロンビア大学で教鞭をとっていた時期(1946-53年) に起こった。 スチュワードが理論的に最も生産的だったのは、コロンビア大学で教えていた1946年から1953年までの数年間である。この時期、コロンビア大学には第 二次世界大戦の退役軍人がGIビルによって学校に通っていた。スチュワードは、シドニー・ミンツ、エリック・ウルフ、ロイ・ラパポート、スタンリー・ダイ アモンド、ロバート・マナーズ、モートン・フリード、ロバート・F・マーフィーなど、後に人類学の歴史に多大な影響を与えることになる学生たちとすぐに同 好の士を作り、マーヴィン・ハリスなどの学者にも影響を与えた。これらの学生の多くは、プエルトリコの近代化に関する大規模なグループ研究であるプエルト リコ・プロジェクトに参加した。 スチュワードはコロンビア大学を辞め、イリノイ大学アーバナ・シャンペーン校に移り、人類学部を指導し、1968年に定年退職するまで教鞭をとった。そこ で彼は、第三世界の11の社会における近代化の比較分析という、さらに大規模な研究を開始した。この研究成果は、『伝統社会の現代的変化』と題された3冊 の本として出版された。スチュワードは1972年に死去した。 |

| Work and influence In addition to his role as a teacher and administrator, Steward is remembered most for his method and theory of cultural ecology. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, American anthropologists were suspicious of generalizations and often unwilling to generalize conclusions from the meticulously detailed monographs that they produced. Steward is notable for developing a more nomothetic, social-scientific style. His theory of "multilinear" cultural evolution examined the way in which societies adapted to their environment. This method was more nuanced than Leslie White's theory of "universal evolution", which was influenced by philosophers such as Lewis Henry Morgan. Steward's interest in the evolution of society also caused him to examine processes of modernization. He was one of the first anthropologists to examine the way in which national and local levels of society were related to one another. He questioned the possibility of creating a social theory which encompassed the entire evolution of humanity; yet, he also argued that anthropologists are not limited to description of specific, existing cultures. Steward believed it is possible to create theories analyzing typical, common culture, representative of specific eras or regions. As the decisive factors determining the development of a given culture, he indicated technology and economics, while noting that there are secondary factors, such as political systems, ideologies, and religions. These factors cause a given society to evolve in several ways at the same time. Steward initially emphasized ecosystems and physical environments, but soon became interested in how these environments could influence cultures (Clemmer 1999: ix). It was during Steward's teaching years at Columbia, which lasted until 1952, that he wrote arguably his most important theoretical contributions: "Cultural Causality and Law: A Trial Formulation of the Development of Early Civilizations (1949b), "Area Research: Theory and Practice" (1950), "Levels of Sociocultural Integration" (1951), "Evolution and Process (1953a), and "The Cultural Study of Contemporary Societies: Puerto Rico" (Steward and Manners 1953). Clemmer writes, "Altogether, the publications released between 1949 and 1953 represent nearly the entire gamut of Steward's broad range of interests: from cultural evolution, prehistory, and archaeology to the search for causality and cultural "laws" to area studies, the study of contemporary societies, and the relationship of local cultural systems to national ones (Clemmer 1999: xiv)." In regard to Steward's Great Basin work, Clemmer writes, " ... [his philosophy] might be characterized as a perspective that people are in large part defined by what they do for a living, can be seen in his growing interest in studying the transformation of slash-and-burn horticulturists into national proletariats in South America" (Clemmer 1999: xiv). Clemmer does mention two works that contradict his characteristic style and reveal a less familiar aspect to his work, which are "Aboriginal and Historic Groups of the Ute Indians of Utah: An Analysis and Native Components of the White River Ute Indians" (1963b) and "The Northern Paiute Indians" (Steward and Wheeler-Vogelin 1954; Clemmer 1999; xiv). |

仕事と影響力 スチュワードは、教師および管理者としての役割に加え、文化生態学の方法と理論で最もよく知られている。20世紀前半の30年間、アメリカの人類学者は一 般化することを疑い、綿密に書かれたモノグラフから結論を一般化することに消極的であった。スチュワードは、より能動的で社会科学的なスタイルを確立した ことで知られている。彼の「マルチリニア」文化進化論は、社会がどのように環境に適応していくかを考察したものである。この方法は、ルイス・ヘンリー・ モーガンなどの哲学者の影響を受けたレスリー・ホワイトの「普遍的進化」理論よりもニュアンスが強かった。社会の進化に関心を持ったスチュワードは、近代 化の過程についても研究した。彼は人類学者として初めて、国民レベルと地域レベルの社会が互いにどのように関連しているかを調べた。彼は、人類の進化全体 を包含する社会理論を創造する可能性に疑問を呈したが、人類学者は特定の既存文化の記述に限定されるものではないとも主張した。スチュワードは、特定の時 代や地域を代表する典型的な共通文化を分析する理論を作ることは可能だと考えていた。ある文化の発展を決定的に左右する要因として、彼は技術と経済を挙げ たが、政治体制、イデオロギー、宗教といった二次的な要因もあると指摘した。これらの要因によって、ある社会は同時にいくつかの進化を遂げることになる。 スチュワードは当初、生態系と物理的環境を重視していたが、やがてこれらの環境が文化にどのような影響を与えうるかに興味を持つようになった (Clemmer 1999: ix)。1952年までコロンビア大学で教鞭を執っていたスチュワードは、最も重要な理論的貢献をした: 「文化的因果性と法: 文化的因果性と法:初期文明の発展に関する試論」(1949b)、「地域研究:理論と実践」(1952)である: 理論と実践」(1950年)、「社会文化的統合の水準」(1951年)、「進化と過程」(1953a)、「現代社会の文化研究」(プエルトリコ)である: プエルトリコ』(Steward and Manners 1953)である。クレマーは、「1949年から1953年にかけて発表された出版物を総合すると、スチュワードの幅広い関心のほぼ全領域を表している。 文化進化、先史学、考古学から、因果関係や文化的「法則」の探求、地域研究、現代社会の研究、地域文化システムと国民文化システムとの関係まで (Clemmer 1999: xiv)」と書いている。 スチュワードのグレート・ベイスンの研究に関して、クレマーは次のように書いている。[彼の哲学は)人間は生活のために何をするかによってその大部分が規 定されるという視点として特徴づけられるかもしれないが、それは南米における焼畑園芸農民の国民的プロレタリアートへの変容を研究することに彼が関心を高 めていることからも見て取れる」(Clemmer 1999: xiv)。クレマーは、彼の特徴的なスタイルとは相反し、あまり馴染みのない側面を明らかにする2つの著作に言及している: An Analysis and Native Components of the White River Ute Indians「 (1963b)と 」The Northern Paiute Indians" (Steward and Wheeler-Vogelin 1954; Clemmer 1999; xiv)である。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_Steward |

1902

Steward was born in Washington, D.C., where he lived on Monroe Street, NW, and later, Macomb Street in Cleveland Park.(以下の情報はウィキペディアからの引用)

1918

At age 16, Steward left an unhappy childhood in Washington, D.C. to attend boarding school in Deep Springs Valley, California, in the Great Basin. Steward's experience at the newly established Deep Springs Preparatory School (which later became Deep Springs College), high in the White Mountains had a significant influence on his academic and career interests. Steward’s “direct engagement” with the land (specifically, subsistence through irrigation and ranching) and the Northern Paiute that lived there became a “catalyst” for his theory and method of cultural ecology. (Kerns 1999; Murphy 1977)

1921 U.C. Berkeley に進学。メンターは、A.L. Kroeber, R.H. Lowie, and Edward

Winslow Gifford. それにCarl O. Saur。

クローバーの思い出にはいつも、A.L. Kroeber is always wonderful, but... と書く。

1925 B.A. in Zoology, Cornell University

(1925)

As an undergraduate,

Steward studied for a year at Berkeley under Alfred Kroeber and Robert

Lowie, after which he transferred to Cornell University, from which he

graduated in 1925 with a B.Sc. in Zoology.

1928 M.A. in Anthropology, University of

California, Berkeley (1928)

1929 Ph.D. in Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley (1929)

Although Cornell, like most universities at the time, had no anthropology department, its president, Livingston Farrand, had previously held appointment as a professor of anthropology at Columbia University. Farrand advised Steward to continue pursuing his interest (or, in Steward's words, his already chosen "life work") in anthropology at Berkeley (Kerns 2003:71–72). Steward studied under Kroeber and Lowie—and was taught by Oskar Schmieder in regional geography—at Berkeley, where his dissertation The Ceremonial Buffoon of the American Indian, a Study of Ritualized Clowning and Role Reversals was accepted in 1929.

1930

Steward went on to establish an anthropology department at the University of Michigan, where he taught until 1930, when he was replaced by Leslie White, with whose model of "universal" cultural evolution he disagreed, although it went on to become popular and gained the department fame/notoriety. In 1930 Steward moved to the University of Utah, which appealed to him for its proximity to the Sierra Nevada, and nearby archaeological fieldwork opportunities in California, Nevada, Idaho, and Oregon./ Steward's research interests centered on "subsistence"—the dynamic interaction of man, environment, technology, social structure, and the organization of work—an approach Kroeber regarded as "eccentric", original, and innovative. (EthnoAdmin 2003) In 1931, Steward, pressed for money, began fieldwork on the Great Basin Shoshone under the auspices of Kroeber's Culture Element Distribution (CED) survey;

1930 最初の結婚:Dorothy

Nyswander (1894–1998) (married 1930–1932)

1933 二度目の結婚:Jane Cannon Steward

(1908–1988) (married 1933–1972) 彼女はモルモン教徒

1934

1935

in 1935 he received an appointment to the Smithsonian's Bureau of American Ethnography (BAE), which published some of his most influential works. Among them: Basin-Plateau Aboriginal Sociopolitical Groups (1938), which "fully explicated" the paradigm of cultural ecology, and marked a shift away from the diffusionist orientation of American anthropology.(--> Indian Reorganization Act, 1934)

文献:清水和久『アメリカ・インディアン』

(1971:88-93):当時のインディアン総務局/John

Collier (sociologist)1933-1945, of the Bureau

of Indian Affairs, BIA.

1943

For eleven years Steward became an administrator of considerable clout, editing the Handbook of South American Indians (1945-1950). He also took a position at the Smithsonian Institution, where he founded the Institute for Social Anthropology in 1943. He also served on a committee to reorganize the American Anthropological Association and played a role in the creation of the National Science Foundation. He was also active in archaeological pursuits, successfully lobbying Congress to create the Committee for the Recovery of Archaeological Remains (the beginning of what is known today as 'salvage archaeology') and worked with Gordon Willey to establish the Viru Valley project, an ambitious research program centered in Peru.

1946

「11月ルース・ベネディクトは『菊と刀』公刊しコ

ロンビア大学に復帰した。彼女は全米女性大学人協会の年間功労賞を受賞する。コロン

ビア大学の同僚(=かつての宿敵)リントンの後任としてJ・スチュアード(Julian Steward, 1902–1972)が赴任する」

1946-1953

Steward searched for cross-cultural regularities in an effort to discern laws of culture and culture change. His work explained variation in the complexity of social organization as being limited to within a range possibilities by the environment. In evolutionary terms, he located this view of cultural ecology as "multi-linear", in contrast to the unilinear typological models popular in the 19th century, and Leslie White's "universal" approach. Steward's most important theoretical contributions came during his teaching years at Columbia (1946–53)./ Steward's most theoretically productive years were from 1946–1953, while teaching at Columbia University. At this time, Columbia saw an influx of World War II veterans who were attending school thanks to the GI Bill. Steward quickly developed a coterie of students who would go on to have enormous influence in the history of anthropology, including Sidney Mintz, Eric Wolf, Roy Rappaport, Stanley Diamond, Robert Manners, Morton Fried, Robert F. Murphy, and influenced other scholars such as Marvin Harris. Many of these students participated in the Puerto Rico Project, yet another large-scale group research study that focused on modernization in Puerto Rico.

1947-1948 プエルトリコ研究(調査実施は1948年2月〜1949年8月) 1956年に報告書

1950 Area

Research: Theory and Practice. Bulletin No.63, New York:

Social Science Research Council.

1952 イリノイ大学教授(O・ルイス、J・マクレガー[John C. McGregor,])

1955 Theory of culture change : the methodology of multilinear evolution / Julian H. Steward, Urbana : University of Illinois Press , 1955

| 序論 |

|

| 概念と方法 |

1. 多系進化 |

| 2. 文化生態学の概念と方法 |

|

| 3. 社会文化的統合レベル |

|

| 4. 国民的社会文化制度 |

|

| 5. 土着アメリカにおける文化領域と文化タイプ |

|

| 実体的応用 |

6. 大盆地ショショニインディアン |

| 7. 父系バンド |

|

| 8. 複合狩猟バンド |

|

| 9. リネージからクランへ |

|

| 10. 生態学的応用の多様性 |

|

| 11. 複合社会の発展 |

|

| 12. 複雑な社会分析 |

1956 プエルトリコ研究:4つのサブカルチャー構造

| 伝統的小農民 |

| コーヒーアシエンダ |

| サトウキビプランテーション |

| 上流社会 |

1968

Steward left Columbia for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he chaired the Anthropology Department and continued to teach until his retirement in 1968. There he undertook yet another large-scale study, a comparative analysis of modernization in eleven third world societies. The results of this research were published in three volumes entitled Contemporary Change in Traditional Societies. Steward died in 1972.

1969 イリノイ大学引退

1972 2月6日死去。2日後に葬儀。

理論

| cultural ecology |

In addition to

his role as a teacher and administrator, Steward is most remembered for

his method and theory of cultural ecology. During the first three

decades of the twentieth century, American anthropology was suspicious

of generalizations and often unwilling to draw broader conclusions from

the meticulously detailed monographs that anthropologists produced.

Steward is notable for moving anthropology away from this more

particularist approach and developing a more nomothetic,

social-scientific direction. His theory of "multilinear" cultural

evolution examined the way in which societies adapted to their

environment. This approach was more nuanced than Leslie White's theory

of "universal evolution", which was influenced by thinkers such as

Lewis Henry Morgan. Steward's interest in the evolution of society also

led him to examine processes of modernization. He was one of the first

anthropologists to examine the way in which national and local levels

of society were related to one another. He questioned the possibility

of creating a social theory which encompassed the entire evolution of

humanity; yet, he also argued that anthropologists are not limited to

description of specific, existing cultures. Steward believed it is

possible to create theories analyzing typical, common culture,

representative of specific eras or regions. As the decisive factors

determining the development of a given culture, he pointed to

technology and economics, while noting that there are secondary

factors, such as political systems, ideologies, and religions. These

factors push the evolution of a given society in several directions at

the same time. |

| ecosystems and

physical environments |

Coming from a

scientific background, Steward initially focused on ecosystems and

physical environments, but soon took interest on how these environments

could influence cultures (Clemmer 1999: ix). It was during Steward's

teaching years at Columbia, which lasted until 1952, that he wrote

arguably his most important theoretical contributions: "Cultural

Causality and Law: A Trial Formulation of the Development of Early

Civilizations (1949b), "Area Research: Theory and Practice" (1950),

"Levels of Sociocultural Integration" (1951), "Evolution and Process

(1953a), and "The Cultural Study of Contemporary Societies: Puerto

Rico" (Steward and Manners 1953). Clemmer writes, "Altogether, the

publications released between 1949 and 1953 represent nearly the entire

gamut of Steward's broad range of interests: from cultural evolution,

prehistory, and archaeology to the search for causality and cultural

"laws" to area studies, the study of contemporary societies, and the

relationship of local cultural systems to national ones (Clemmer 1999:

xiv)." We can clearly see that Steward's diversity in subfields,

extensive and comprehensive field work and a profound intellect

coalesce in the form of a brilliant anthropologist. |

| Ute Indians and

Paiute Indians" |

In regard to

Steward's Great Basin work, Clemmer writes, " ... [his approach] might

be characterized as a perspective that people are in large part defined

by what they do for a living, can be seen in his growing interest in

studying the transformation of slash-and-burn horticulturists into

national proletariats in South America" (Clemmer 1999: xiv). Clemmer

does mention two works that contradict his characteristic style and

reveal a less familiar aspect to his work, which are "Aboriginal and

Historic Groups of the Ute Indians of Utah: An Analysis and Native

Components of the White River Ute Indians" (1963b) and "The Northern

Paiute Indians" (Steward and Wheeler-Vogelin 1954; Clemmer 1999; xiv). |

| Indian Reorganization Act, 1934 | The Indian

Reorganization Act (IRA) of June 18, 1934, or the Wheeler–Howard Act,

was U.S. federal legislation that dealt with the status of American

Indians in the United States. It was the centerpiece of what has been

often called the "Indian New Deal". The major goal was to reverse the

traditional goal of cultural assimilation of Native Americans into

American society and to strengthen, encourage and perpetuate the tribes

and their historic Native American cultures in the United States. |

●おまけ

「プエルトリコには人種差別がほとんど存在しないと

いう一般的な誤解に対抗して、ジェイ・キンズブルーナーの『純血でない』は、人種的偏見が長い間プエルトリコ社会に陰湿な影響を与えてきたことを明らかに

している。キンズブルーナーの研究は、19世紀のプエルトリコにおける人種的偏見の本質を探るために、アフリカ系の自由人(非白人とみなされながら奴隷制

の間は法的に自由だった人々)に焦点を当てるものである。19世紀の態度が20世紀のプエルトリコにもたらした結果を考察する中で、キンズブルナーは、人

種差別が有色人種の機会を制限し続けていることを示唆している。歴史的な観点からプエルトリコの人種的偏見を論じた後、キンズブルナーは居住形態、結婚、

出生、死亡、職業、家族と家庭の問題を説明し、自由な有色人種が人種主義によって政治的、社会的、経済的地位を低下させられた不利なコミュニティであるこ

とを実証している。プエルトリコの人種的偏見と差別の複雑さと矛盾を分析し、「陰の差別」の微妙さを説明し、米西戦争後のアメリカによる島の占領が人種関

係に及ぼした深刻な悪影響を検証している。プエルトリコの人種的平等の神話の背後を探る本書は、カリブ研究、プエルトリコ史、ラテンアメリカ研究の専門家

だけでなく、人種主義と差別の問題を研究するさまざまな分野の研究者にとっても興味深いものであるだろう。」Jay Kinsbruner, Not of Pure

Blood: The Free People of Color and Racial Prejudice in

Nineteenth-century Puerto Rico. Duke University Press, 1996.

リンク

- 地域科学・地域研究・国別研究・戦略情報・地政学︎▶︎民族誌=エスノグラフィー ▶︎︎Eggan,

Fred. Rewiew of "Area Research," by J.H. Steward, 1950 in Pdf file▶︎行動科学の歴史▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

文献

- Steward, Julian H. Theory of Culture Change. University of Illinois Press, 1990.

- Kerns, Virginia. 2003. Scenes From The High Desert: Julian Steward's Life and Theory.University of Illinois Press.

- Joseph Hanc , Julian Steward

and the Rise of Anthropological Theory, History of Anthropology

Newsletter, 1980

文献

- スチュワード、ジュリアン(Steward, Julian Haynes ) 1950 Area Research: Theory and Practice. Bulletin No.63, New York: Social Science Research Council.

- Julian H. Steward, Alfred Kroeber (1973) New York

: Columbia University Press.

- Geertz, Clifford. 1963. Agricultural

Involution: The Process of Ecological Change in Indonesia.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

- 池田光穂(2005)「「持続可能性」の意味:医療人類学からみた 保健医療プロジェクトの持続可能性に関する学際研究」『保健医療プロジェクトの持続可能性に関する学際研究』Pp.42-59、2004年度調査 報告書。

- ウィットフォーゲル『オリエンタル・デスポティズム――専制官僚国家の生成と崩壊』(湯浅赳男訳、新評論、1995年), Karl

August Wittfogel, Oriental Despotism; a Comparative Study of Total

Power Yale University Press, 1957

その他の情報

- スチュワードが、マッカーシー委員会時代にカール・ウィトフォーゲルの学問的擁護者になった話はよく知られている(20180517141537.pdf)with password