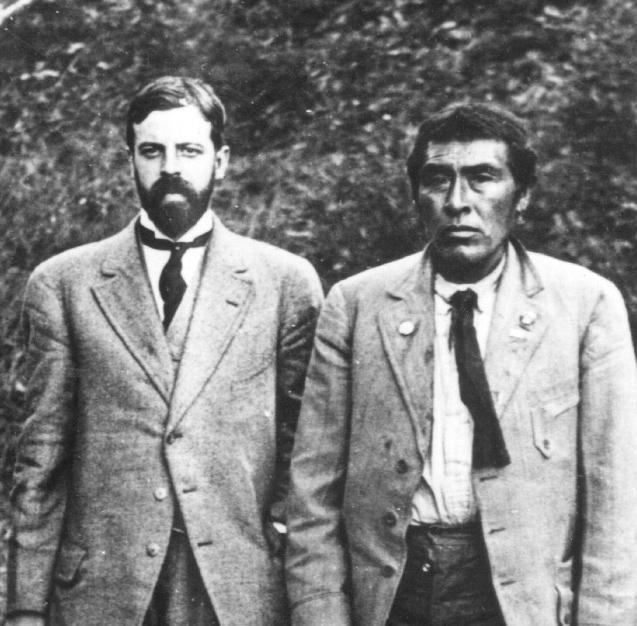

My web-page of Alfred Louis Kroeber, 1876-1960 is now moved to Alfred_Kroeber.html

Ishi c. 1861-1916, ひとりのヤヒ先住民はこちらです!!!

左:35歳のクロー

バー(Alfred Louis Kroeber, 1876-1960)と、右:イシ(推計 50歳;

ca.1861-1916)1911年撮影(ウィキコモンズ)

My web-page of Alfred Louis Kroeber, 1876-1960 is now moved to Alfred_Kroeber.html

Ishi c. 1861-1916, ひとりのヤヒ先住民はこちらです!!!

左:35歳のクロー

バー(Alfred Louis Kroeber, 1876-1960)と、右:イシ(推計 50歳;

ca.1861-1916)1911年撮影(ウィキコモンズ)