メスティーソ

Mestizo

A

casta painting of a Spanish man and an Indigenous woman with a

Mestizo child/ Mestizo, Mestiza, Mestizo Sample of a Peruvian casta

painting, showing intermarriage within a casta category.

★メスティーソと(Mestizo)は、ヨーロッパ人とアメリカ先 住民の祖先が混在する人を指す人種分類に使われる言葉である。ラテンアメリカなど特定の地域では、祖先がヨーロッパ人でなく ても文化的にヨーロッパ人である人を指すこともある。スペイン帝国時代に発展した混血のカスタの民族・人種区分として使われた言葉である。広義には メスティーソはヨーロッパ人と先住民の混血を意味するが、植民地時代には一定の意味を持たなかった[要出典]。 国勢調査、教区台帳、異端審問裁判などの公式文書では個人に対する正式なラベルであった。神父や王室関係者がメスティーソに分類した可能性もあるが、個人 も自 認のためにこの言葉を使った/使っている。

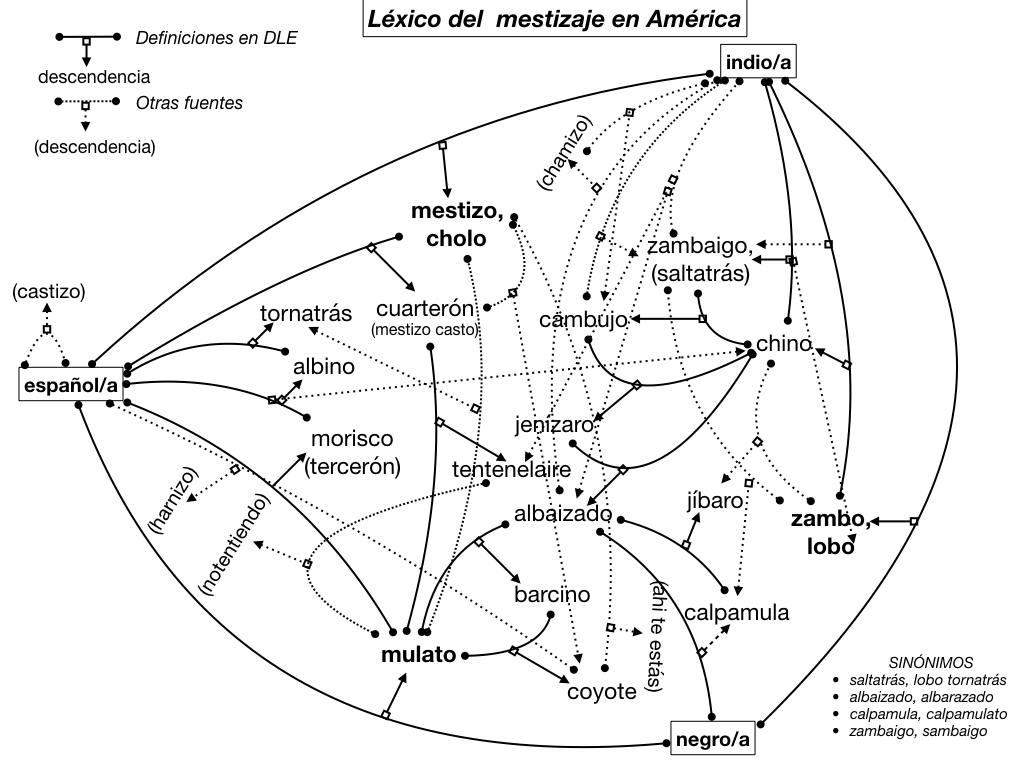

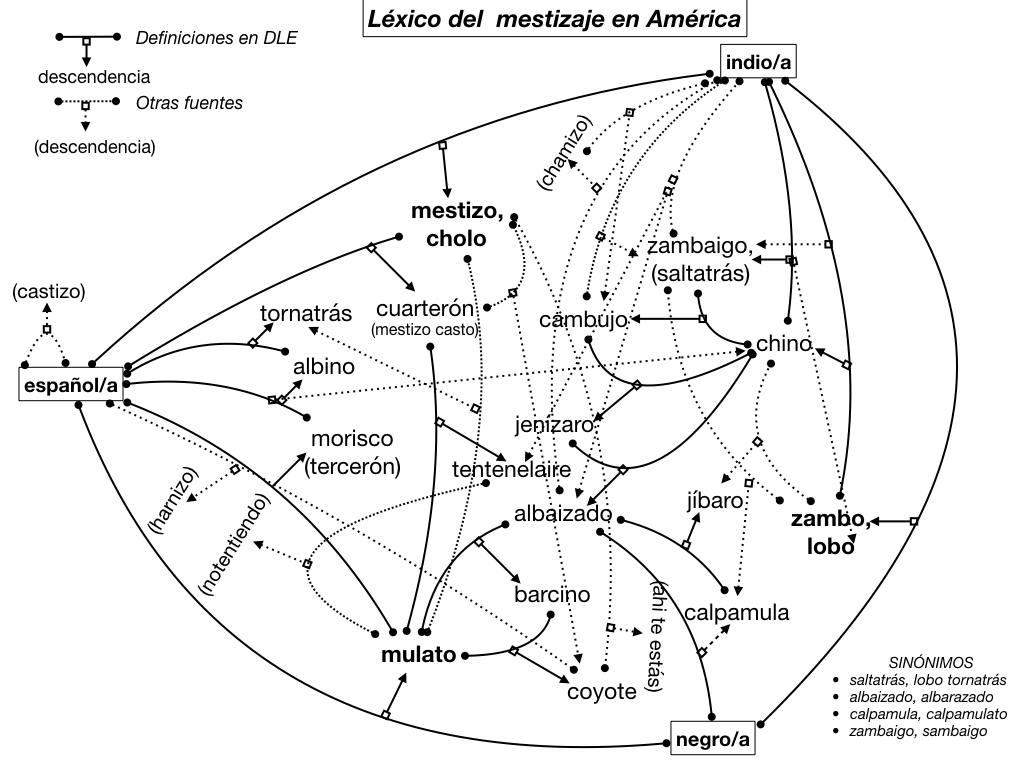

☆メスティーソを形成する要因が混交あるいは混血すなわちメスティサッヘである。混血 (mestizaje) とは、異なる民族的背景を持つ人々間の生物学的および文化的交雑の過程であり、これにより、人口において新たな社会的、文化的、遺伝的構成が生まれる。 [1][2] この概念は、そのような混血から生まれた人々を指す場合もあり、ラテンアメリカでは19世紀から20世紀にかけて、国家アイデンティティの基盤として推進 された。[3][4] スペインのアメリカ植民地のような植民地時代、メスティサージョは、人種的階層、キリスト教化、領土支配と関連した構造的な現象だった。その影響は地域の 状況によって異なり、統合、排除、白人化といった地域ごとの異なるパターンを生み出した。[4][5] メスティゾ化はフィリピン、カリブ海地域、南アフリカ、ブラジルなどの地域でも起こったが、ラテンアメリカでは、その人口の広さと、社会的統合と文化的ア イデンティティを促進する国民的議論の中心的な要素となっていることで際立っている。[3][6] これに対し、アメリカ合衆国では人種隔離政策が実施され、混血の人々が社会的に完全に受け入れられ、機関によって公式に認められることを妨げてきた。 [7]

| El mestizaje es el

proceso de cruce biológico y cultural entre personas de diferentes

orígenes étnicos, que da lugar a nuevas configuraciones sociales,

culturales y genéticas en las poblaciones.[1][2] Este concepto, que

también puede designar a las personas resultantes de dicha mezcla, ha

tenido especial importancia en América Latina, donde fue promovido como

base de identidad nacional durante los siglos xix y xx.[3][4] En contextos coloniales como el del Imperio español en América, el mestizaje fue un fenómeno estructural, relacionado con jerarquías raciales, procesos de evangelización y control territorial. Su impacto varió según las condiciones locales, dando lugar a patrones regionales distintos de integración, exclusión o blanqueamiento.[4][5] Aunque el mestizaje también ha ocurrido en regiones como Filipinas, el Caribe, Sudáfrica o Brasil, en América Latina destaca por su gran extensión demográfica y por ser parte central de discursos nacionales que promueven la integración social y la identidad cultural.[3][6] En contraste, en Estados Unidos se aplicó un modelo de segregación racial impidió que las personas de origen mixto fueran plenamente aceptadas socialmente y reconocidas oficialmente por las instituciones.[7] |

混血(mestizaje)とは、異なる民族的背

景を持つ人々間の生物学的および文化的交雑の過程であり、これにより、人口において新たな社会的、文化的、遺伝的構成が生まれる。[1][2]

この概念は、そのような混血から生まれた人々を指す場合もあり、ラテンアメリカでは19世紀から20世紀にかけて、国家アイデンティティの基盤として推進

された。[3][4] スペインのアメリカ植民地のような植民地時代、メスティサージョは、人種的階層、キリスト教化、領土支配と関連した構造的な現象だった。その影響は地域の 状況によって異なり、統合、排除、白人化といった地域ごとの異なるパターンを生み出した。[4][5] メスティゾ化はフィリピン、カリブ海地域、南アフリカ、ブラジルなどの地域でも起こったが、ラテンアメリカでは、その人口の広さと、社会的統合と文化的ア イデンティティを促進する国民的議論の中心的な要素となっていることで際立っている。[3][6] これに対し、アメリカ合衆国では人種隔離政策が実施され、混血の人々が社会的に完全に受け入れられ、機関によって公式に認められることを妨げてきた。 [7] |

| Mestizaje en África África ha tenido una larga historia de mezclarse con no africanos desde tiempos prehistóricos. El reflujo euroasiático que ocurrió en tiempos prehistóricos vio una gran migración desde el Levante que ingresó a la región y estos inmigrantes se mezclaron con los nativos africanos. Se pueden encontrar signos de esta migración entre las personas que habitan el Cuerno de África y Sudán. África en la Antigüedad también ha tenido una larga historia de mezclas interraciales con exploradores, comerciantes y soldados árabes y europeos que tenían relaciones sexuales con mujeres negras africanas y las tomaban como esposas.[8] Richard Francis Burton escribe, durante su expedición a África, sobre las relaciones entre mujeres negras y hombres blancos: "Las mujeres están bien dispuestas hacia los extraños de tez clara, aparentemente con el permiso de sus maridos". Hay varias poblaciones de raza mixta en toda África, en su mayoría como resultado de las relaciones interraciales entre hombres árabes y europeos y mujeres negras. En Sudáfrica, hay grandes comunidades mestizas como los mestizos y los griqua formados por colonos blancos que toman esposas nativas africanas. En Namibia existe una comunidad llamada Rehoboth Basters formada por el matrimonio interracial de hombres holandeses/alemanes y mujeres negras africanas.[9] En la antigua África portuguesa (ahora conocida como Angola, Mozambique y Cabo Verde), la mezcla racial entre portugueses blancos y africanos negros era bastante común, especialmente en Cabo Verde, donde la mayoría de la población es de ascendencia mixta. Ha habido algunos casos registrados de comerciantes y trabajadores chinos que tomaron esposas africanas en África, ya que muchos trabajadores chinos fueron empleados para construir ferrocarriles y otros proyectos de infraestructura en África. Estos grupos laborales estaban compuestos completamente por hombres y muy pocas mujeres chinas venían a África. En África occidental, especialmente en Nigeria, hay muchos casos de hombres no africanos que toman mujeres africanas. Muchos de sus descendientes han ganado posiciones destacadas en África. El teniente de vuelo Jerry John Rawlings, de padre escocés y madre ghanesa negra, fue nombrado presidente de Ghana. Jean Ping, hijo de un comerciante chino y madre gabonesa negra, se convirtió en vice primer ministro y ministro de Relaciones Exteriores de Gabón y fue presidente de la Comisión de la Unión Africana de 2009 a 2012. Los hombres indios, que durante mucho tiempo han sido comerciantes en el este de África, a veces se casan con mujeres africanas locales. El Imperio británico trajo muchos trabajadores indios a África Oriental para construir ferrocarriles en Uganda . Los indios finalmente poblaron Sudáfrica, Kenia, Uganda, Tanzania, Malaui, Ruanda, Zambia, Zimbabue y Zaire en pequeñas cantidades. Estas uniones interraciales eran en su mayoría matrimonios unilaterales entre hombres indios y mujeres de África Oriental.[10] En Reunión la mayoría de la población se define como mestiza. En los últimos 350 años, varios grupos étnicos (africanos, chinos, británicos, franceses, indios gujarati, indios tamiles) han llegado y se han asentado en la isla. Ha habido personas de raza mixta en la isla desde su primera habitación permanente en 1665. La población nativa de Kaf tiene una diversa gama de ascendencia que proviene de los pueblos coloniales indios, chinos y esclavos africanos traídos de países como Mozambique, Guinea, Senegal, Madagascar, Tanzania y Zambia a la isla.[11] En Madagascar hubo una mezcla frecuente entre las poblaciones de habla austronesia y bantú. Un gran número de los malgaches de hoy son el resultado de un mestizaje entre austronesios y africanos. Esto es más evidente en los mikeas, que también son la última población malgache conocida que todavía practica un estilo de vida de cazadores-recolectores. En el estudio de los malgaches, el ADN autosómico muestra el grupo étnico de los montañeses casi una mezcla uniforme de origen del Sudeste Asiático y bantú, mientras que el grupo étnico costero tiene una mezcla bantú mucho más alta en su ADN autosómico, lo que sugiere que son una mezcla de nuevos inmigrantes bantú y el grupo étnico montañés ya establecido. Las estimaciones de máxima verosimilitud favorecen un escenario en el que Madagascar fue colonizada hace aproximadamente 1200 años por un grupo muy pequeño de mujeres de aproximadamente 30. El pueblo malgache existió a través de matrimonios mixtos entre la pequeña población fundadora. También matrimonios mixtos entre hombres chinos trabajadores o hombres franceses colonos con las mujeres malgaches nativas no eran infrecuentes.[12][13] |

アフリカにおける混血 アフリカは、先史時代から非アフリカ人との混血の長い歴史を持っています。先史時代に起こったユーラシアからの逆流により、レバント地方からこの地域へ大 規模な移民が流入し、これらの移民はアフリカ先住民と混血しました。この移住の痕跡は、アフリカの角とスーダンに住む人々に見られる。古代アフリカも、ア ラブ人やヨーロッパ人の探検家、商人、兵士がアフリカの黒人女性と性関係を持ち、彼女たちを妻として迎えるという、長い人種間の混血の歴史がある。[8] リチャード・フランシス・バートンは、アフリカ探検中に、黒人女性と白人男性の関係について次のように記している。「女性は、夫たちの許可を得ているの か、色白の見知らぬ人に対して親しみやすい態度を示している」。アフリカ全土には、主にアラブ人やヨーロッパ人の男性と黒人女性との人種間の関係の結果と して、さまざまな人種混血の集団が存在する。南アフリカには、白人入植者がアフリカ出身の女性を妻としたメスティーソやグリクアといった大規模な混血コ ミュニティがある。ナミビアには、オランダ人/ドイツ人男性とアフリカ黒人女性の異人種間結婚によって形成された、レホボス・バスターズと呼ばれるコミュ ニティがある。[9] 旧ポルトガル領アフリカ(現在のアンゴラ、モザンビーク、カーボベルデ)では、白人ポルトガル人と黒人アフリカ人の間の人種的混血が非常に一般的で、特にカーボベルデでは、人口の大部分が混血の祖先を持つ人々で構成されている。 アフリカでは、鉄道やその他のインフラ建設プロジェクトに多くの中国人労働者が雇用されたため、アフリカ人女性を妻に迎えた中国人商人や労働者がいくつか記録されている。これらの労働者グループは完全に男性で構成されており、アフリカに来た中国人女性はごくわずかだった。 西アフリカ、特にナイジェリアでは、アフリカ人男性がアフリカ人女性を妻に迎えるケースが多く見られる。その子孫の多くはアフリカで重要な地位に就いてい る。スコットランド人の父とガーナ人の黒人女性の間に生まれたジェリー・ジョン・ローリングス空軍中尉は、ガーナの大統領に就任した。中国人の商人とガボ ン人の黒人女性の間に生まれたジャン・ピンは、ガボンの副首相兼外務大臣となり、2009年から2012年までアフリカ連合委員会の委員長を務めた。 東アフリカで長い間商人として活動してきたインド人男性は、現地のアフリカ人女性と結婚する場合もある。イギリス帝国は、ウガンダに鉄道を建設するため に、多くのインド人労働者を東アフリカに連れてきた。インド人は、最終的に南アフリカ、ケニア、ウガンダ、タンザニア、マラウイ、ルワンダ、ザンビア、ジ ンバブエ、ザイールに少人数で定住した。これらの異人種間の結婚は、ほとんどがインド人男性と東アフリカ人女性との一方的な結婚だった。 レユニオンでは、人口の大半がメスティーソ(混血)と定義されている。過去 350 年間に、さまざまな民族(アフリカ人、中国人、イギリス人、フランス人、グジャラート人、タミル人)がこの島に移住し、定住してきた。1665 年にこの島に最初の定住者が到着して以来、この島には人種的に混血の人々が住んでいる。カフの先住民は、インドの植民地民、中国人、モザンビーク、ギニ ア、セネガル、マダガスカル、タンザニア、ザンビアなどの国々から島に連れてこられたアフリカ人奴隷など、さまざまな祖先を持つ人々で構成されている。 [11] マダガスカルでは、オーストロネシア語族とバンツー語族の集団の間で頻繁に混血が起こった。現在のマダガスカル人の多くは、オーストロネシア人とアフリカ 人の混血の結果だ。これは、マダガスカルで最後に知られている狩猟採集民の生活様式を今も実践しているミケア族に最も顕著に見られる。マダガスカル人の研 究では、常染色体DNAは、山岳民族の民族グループが東南アジアとバンツーの起源がほぼ均等に混ざり合ったものであるのに対し、沿岸民族グループは常染色 体DNAにバンツーの混血がはるかに多く、バンツーの新規移民とすでに定着していた山岳民族の民族グループとの混血である可能性を示している。最尤推定値 は、マダガスカルが約1200年前に、約30人の非常に小さな女性グループによって植民地化されたというシナリオを支持している。マダガスカル人は、小さ な先住民集団間の混血結婚によって存続してきた。また、中国人の労働者やフランス人植民者男性とマダガスカルの先住民女性との混血結婚も珍しくなかった。 [12][13] |

| Mestizaje en Asia central Los asiáticos centrales descienden de una mezcla de varios pueblos, como los mongoles, los túrquicos y los iranios. La conquista mongola de Asia Central en el siglo xiii resultó en asesinatos masivos de la población de habla irania e indoeuropea de la región, y su cultura e idiomas fueron reemplazados por los de los pueblos turco-mongoles. La población sobreviviente restante se casó con invasores. La genética muestra una mezcla de ascendencia asiática oriental y caucásica en los individuos de Asia central.[14][15] |

中央アジアの混血 中央アジアの人々は、モンゴル人、テュルク人、イラン人など、さまざまな民族の混血だ。13世紀のモンゴルによる中央アジアの征服は、この地域のイラン語 およびインド・ヨーロッパ語を話す住民の大虐殺をもたらし、彼らの文化や言語は、テュルク・モンゴル人の文化や言語に取って代わられた。生き残った住民は 侵略者と結婚した。遺伝学的には、中央アジアの個人には東アジア系とコーカサス系の混血が見られる。[14][15] |

| Mestizaje en Hispanoamérica Artículo principal: Mestizaje en América  Une Chilienne prisonnière des Indiens des côtes de l'Araucanie, por el pintor francés Raimundo Monvoisin. Obra imaginada por el autor sobre la leyenda de Elisa Bravo, supuesta superviviente de un naufragio, cautiva de los mapuches. Términos empleados en la América colonial española para designar a los "mestizos", según el origen de sus ascendientes. Este proceso se ha definido como uno de transculturación, que ha definido la identidad latinoamericana. El proceso de mestizaje en América se originó con la llegada de los europeos al continente y subsecuentemente de los esclavos africanos que vinieron con ellos. En este encuentro de culturas surgieron varios tipos de mestizos:  Mestizo: mezcla de indígena y europeo (principalmente español). Numulita: primogénito del mestizo. Mulato: mezcla de negro y europeo. Morisco: mezcla de mulato y europeo. Cholo o coyote: mezcla de mestizo e indígena. Zambo: mezcla de negro e indígena. Castizo: mezcla de mestizo y español. Criollo: español nacido en los territorios americanos.[16] Chino: mezcla de indígena y europeo. El mestizaje ha sido uno de los temas fundamentales en los países americanos pero especialmente en América Latina. Esta característica de fusiones culturales, ha sido acogida en las últimas dos décadas para explicar el fenómeno de la pluralidad en Iberoamérica. Así mismo, esta misma ideología le ha dado fuerza a la teoría de que detrás de la percepción de la sociedad como producto del mestizaje existe un fenómeno enmascarado de racismo y exclusión. Este último punto se refleja en el hecho que estudios recientes tienden a llamar la atención sobre la necesidad de reformar el derecho para poder hacer frente a una realidad antes inexistente o ignorada: la pluralidad de la sociedad. La idea del mestizaje, según algunos estudiosos, ha sido utilizada por los gobiernos y las élites latinoamericanas para ocultar indicios de discriminación racial y racismo en el continente. Utilizando términos de Stanley Cohen, Ariel Dulitzky argumenta que existen tres tipos de formas en que se niegan la discriminación racial y el racismo en el continente: la negación literal, la negación interpretativa y la negación justificada. La primera de éstas se da cuando los gobiernos niegan que se dé cualquier tipo masivo de racismo y discriminación en sus países. Una forma clara de negación literal es mediante el uso de la idea de mestizaje. A través del discurso de igualdad de razas en el continente, la percepción de que todos pertenecemos a una sola etnia «mestiza» que tiene los mismos ancestros ayuda a reforzar la imagen de que no existe el racismo puesto que ni siquiera existen razas diferentes. Esta noción ayuda a reforzar la idea de la democracia e incluso a fomentar la consolidación de un nacionalismo que fortalece el estado, en el período republicano la idea de la raza única mestiza era un arma de defensa contra otros elementos que podían fragmentar los nuevos estados latinoamericanos por medio de esta se buscaba fortalecer los países emergentes al estilo de las naciones europeas. Sin embargo, esta visión de mestizaje ha adquirido, según Peter Wade, una imagen que se acerca más a aquella proyectada por la raza blanca y se ha intentado alienar a la raza indígena y aún en mayor medida a la negra. Aunque la noción de raza ya es un concepto anacrónico, Peter Wade tenía la idea de que en estas razas o grupos étnicos de no blancos y no mestizos, existiría un deseo de blanqueamiento mediante el mestizaje lo que les llevaría a un nuevo posicionamiento dentro del orden social. En esto se enfoca Peter Wade al hablar en especial de la raza negra cuando algunos buscan abrir un camino de abrir nuevas posibilidades para sus descendientes. Sin embargo, existe la noción contraria bajo la cual el mestizaje es evitado por una de las razas ya que esto es mal visto por los suyos, en el caso de alguien de raza negra esto podría ser considerado una traición para sus ancestros. Véase también: Conquista de América |

メスティゾ(混血)とラテンアメリカ 主な記事:メスティゾ(混血)とアメリカ  アラウカニア沿岸のインディアンに捕らわれたチリ人女性、フランス人画家ライムンド・モンヴォワザン作。船の難破で生き残り、マプチェ族に捕らえられたエリサ・ブラボーの伝説を、作者が想像して描いた作品。 スペイン植民地時代のアメリカで、祖先の出身地に応じて「メスティーソ」を指す用語。 この過程は、ラテンアメリカのアイデンティティを定義する「トランスカルチャー」と定義されている。アメリカ大陸における混血の過程は、ヨーロッパ人が大 陸に到着し、その後、彼らとともにアフリカからの奴隷が連れてこられたことから始まった。この文化の出会いから、さまざまなタイプのメスティーソが生まれ た。  メスティーソ:先住民とヨーロッパ人(主にスペイン人)の混血。 ヌムリタ:メスティーソの長子。 ムラート:黒人とヨーロッパ人の混血。 モリスコ:ムラートとヨーロッパ人の混血。 チョロまたはコヨーテ:メスティーソと先住民の混血。 ザンボ:黒人と先住民の混血。 カスティージョ:メスティーソとスペイン人の混血。 クリオージョ:アメリカ大陸で生まれたスペイン人。[16] チノ:先住民とヨーロッパ人の混血。 混血は、アメリカ諸国、特にラテンアメリカ諸国において重要なテーマのひとつだ。この文化の融合という特徴は、ここ 20 年ほど、イベロアメリカにおける多様性の現象を説明する上で受け入れられてきた。同様に、このイデオロギーは、社会が混血の産物であるという認識の背後に は、人種差別や排除という隠れた現象がある、という説を補強するものとなっている。この最後の点は、最近の研究が、これまで存在しなかった、あるいは無視 されていた現実、すなわち社会の多様性に対処するために、法律の改正の必要性を指摘していることに反映されている。 一部の学者によると、混血という概念は、ラテンアメリカの政府やエリート層によって、大陸における人種差別や人種主義の兆候を隠蔽するために利用されてき た。スタンリー・コーエンの用語を用いて、アリエル・デュリツキーは、大陸における人種差別と人種主義を否定する3つの形態がある、と主張している。1つ 目は、文字通りの否定、2つ目は解釈上の否定、3つ目は正当化された否定である。1つ目は、政府が自国において大規模な人種差別や人種主義が存在すること を否定する場合だ。 文字通りの否定の明確な例は、メスティーソ(混血)の概念の使用だ。大陸における人種の平等という言説を通じて、私たちは皆、同じ祖先を持つ単一の「メス ティーソ」という民族に属しているという認識が、人種差別は存在しないというイメージを強化するのに役立っている。この考えは、民主主義の概念を強化し、 国家を強化するナショナリズムの定着を促進する役割を果たしている。共和制時代、単一人種であるメスティーソの概念は、新しいラテンアメリカ諸国を分裂さ せる可能性のある要素に対する防衛手段であり、ヨーロッパ諸国のような新興国を強化するための手段だった。 しかし、ピーター・ウェイドによると、この混血の考え方は、白人種によって投影されたイメージに近づき、先住民、さらに黒人を疎外しようとする動きにつながった。 人種という概念はもはや時代遅れのものとなっているが、ピーター・ウェイドは、白人およびメスティーソではないこれらの人種や民族グループには、混血に よって白人化したいという願望があり、それが社会秩序の中で新たな地位の獲得につながるという考え方を持っていた。ピーター・ウェイドは、一部の人々が子 孫のために新しい可能性を切り開こうとしている中で、特に黒人種についてこの点に着目している。しかし、その反対の考えもあり、混血は、その人種の人たち から悪と見なされるため、ある人種によって避けられている。黒人種の場合、それは先祖に対する裏切りとみなされる可能性がある。 参照:アメリカ大陸の征服 |

| Mestizaje en España El mestizaje en España ha sido un fenómeno continuo a lo largo de su historia, resultado de su posición geográfica entre Europa, África y el Mediterráneo, su historia de invasiones y colonizaciones, así como su legado imperial y migratorio. El proceso ha abarcado tanto aspectos biológicos como culturales y lingüísticos. Historia temprana Desde la prehistoria, la península ibérica ha recibido influencias de múltiples pueblos. Durante el Neolítico, hubo contacto entre poblaciones del norte de África y del sur peninsular.[17] Posteriormente, la colonización por fenicios, griegos y cartagineses, seguida por la dominación romana (218 a. C.-siglo v d. C.), promovió una mezcla entre colonizadores y pueblos íberos, celtas y tartesios, consolidando una población hispanorromana mestiza. Con la llegada de los pueblos germánicos (visigodos, suevos) tras la caída de Roma, se produjo un nuevo ciclo de integración, aunque limitado por el reducido número de estos grupos invasores. Pluralismo étnico y religioso medieval La conquista islámica en el siglo viii transformó la composición étnica y religiosa del territorio. Durante casi ocho siglos, gran parte de la península formó parte de Al-Ándalus, donde convivieron musulmanes (árabes y bereberes), cristianos y judíos. El mestizaje se expresó en matrimonios mixtos, conversiones religiosas y transferencias culturales.[18] En 1393 se fundó en Sevilla la Cofradía de los Negritos, una hermandad religiosa formada por personas de origen africano, en su mayoría esclavizadas o libertas. Su existencia documenta la presencia organizada de población negra en la Castilla bajomedieval y su integración parcial en las estructuras sociales y eclesiásticas del momento. La cofradía, aún activa en la actualidad, constituye una de las instituciones más antiguas de su tipo en Europa.[19] La posterior Reconquista y las expulsiones de judíos (1492) y moriscos (1609-1614) redujeron formalmente la diversidad religiosa, pero estudios genéticos han demostrado que muchos descendientes permanecieron integrados en la sociedad cristiana.[20] Durante esta etapa, también se consolidó la presencia del pueblo gitano en la península ibérica, documentado desde el siglo xv. Aunque a menudo marginado, el pueblo gitano ha influido en la cultura española (especialmente en regiones como Andalucía, Extremadura y Cataluña) y ha formado parte de procesos de mestizaje a nivel local.[21] |

スペインの混血 スペインの混血は、その歴史を通じて継続的な現象であり、ヨーロッパ、アフリカ、地中海に囲まれた地理的位置、侵略と植民地化の歴史、そして帝国と移民の遺産の結果である。このプロセスは、生物学的側面だけでなく、文化的、言語的側面も包含している。 初期の歴史 先史時代から、イベリア半島は複数の民族の影響を受けてきた。新石器時代には、北アフリカと半島南部の住民が接触した。[17] その後、フェニキア人、ギリシャ人、カルタゴ人による植民地化、そしてローマ帝国の支配(紀元前218年~5世紀)により、植民者とイベリア人、ケルト 人、タルテシオ人との混血が進み、メスティーソと呼ばれるヒスパニック・ローマ人の人口が定着した。 ローマ帝国の崩壊後、ゲルマン民族(西ゴート族、スエビ族)が到来すると、新たな統合のサイクルが始まったが、これらの侵略者グループの数が少なかったため、その範囲は限定的だった。 中世の民族・宗教の多元主義 8世紀のイスラム征服は、この地域の民族的・宗教的構成を一変させた。約8世紀の間、半島の大部分はアル・アンダルスの一部となり、イスラム教徒(アラブ 人とベルベル人)、キリスト教徒、ユダヤ教徒が共存した。混血は、異民族間の結婚、宗教の改宗、文化の伝播という形で表れた。[18] 1393年、セビリアにコフラディア・デ・ロス・ネグリトス(黒人兄弟団)が設立された。これは、主に奴隷または解放奴隷であったアフリカ出身者によって 構成される宗教的兄弟団だ。その存在は、中世後期のカスティーリャに黒人集団が組織的に存在し、当時の社会・教会構造に部分的に統合されていたことを証明 している。この兄弟団は現在も活動を続けており、ヨーロッパで最も古い同種の機関のひとつだ。[19] その後のレコンキスタと、ユダヤ人(1492年)およびモリスコ(1609年~1614年)の追放により、宗教の多様性は形式的には減少したが、遺伝子研究により、多くの子孫がキリスト教社会に統合されたままだったことが明らかになっている。[20] この時代、15世紀から記録されているイベリア半島におけるジプシーの定住も定着しました。しばしば疎外されてきましたが、ジプシーはスペイン文化(特に アンダルシア、エストレマドゥーラ、カタルーニャなどの地域)に影響を与え、地域レベルでの混血の過程にも参加してきました。[21] |

| Edad Moderna y mestizaje ultramarino Durante el Imperio español (siglos xvi-xix), España fue también un receptor indirecto de mestizaje a través del retorno de colonos y esclavos liberados, especialmente en regiones como Andalucía y Canarias. En ciudades portuarias como Sevilla y Cádiz, hubo presencia de población de origen africano, tanto esclavizada como libre, que formó parte del entramado social urbano y contribuyó, en cierta medida, a los procesos de mestizaje local.[19]  Retrato de Juan de Pareja, esclavo manumiso de ascendencia africana y morisca, pintado por Diego Velázquez en 1650. Considerado un ejemplo histórico del mestizaje en la España del Siglo de Oro. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Nueva York). Las Islas Canarias fueron escenario de un proceso de mestizaje entre los aborígenes canarios, colonos europeos y población africana traída como mano de obra.[22] Durante los siglos xvi y xvii, se implantaron en la Monarquía Hispánica los llamados Estatutos de limpieza de sangre, un mecanismo de discriminación legal dirigido principalmente contra los judeoconversos —y, en menor medida, contra los moriscos—, conocidos como «cristianos nuevos». Estas normas exigían al aspirante a cargos eclesiásticos, militares, administrativos o educativos demostrar que descendía exclusivamente de cristianos viejos, sin ascendencia judía ni musulmana.[23] La adopción de estos estatutos por muchas instituciones limitó el ascenso social de estos grupos y reforzó una visión excluyente de la identidad cristiana que condicionó, durante siglos, las posibilidades de mestizaje y movilidad social en determinados ámbitos. En las Islas Baleares, el mestizaje tuvo expresiones singulares aunque limitadas. En Mallorca, surgió la comunidad de los chuetas (xuetes), descendientes de judeoconversos que fueron objeto de estigmatización social durante siglos, pese a su integración formal como cristianos.[24] En Menorca, el dominio británico durante el siglo xviii dejó una huella cultural, aunque el mestizaje biológico con la población británica fue escaso.[25] Durante este periodo también aparecen referencias documentadas a grupos seminómadas conocidos como mercheros o quinquis, de origen diverso (incluyendo posibles mezclas entre gitanos, moriscos y campesinos empobrecidos), que desarrollaron una cultura propia y una jerga particular conocida como quinqui.[26] |

近世と海外の混血 スペイン帝国時代(16~19世紀)、スペインは植民地からの帰還者や解放された奴隷を通じて、特にアンダルシアやカナリア諸島などの地域で、間接的に混 血の影響を受けた。セビリアやカディスなどの港湾都市には、奴隷や自由民としてアフリカ出身の住民が住んでおり、都市の社会構造の一部となり、ある程度、 現地の混血化に貢献した。  1650年にディエゴ・ベラスケスによって描かれた、アフリカとムーア人の血を引く解放奴隷、フアン・デ・パレハの肖像画。黄金時代のスペインにおける混血の歴史的な例とみなされている。(ニューヨーク、メトロポリタン美術館)。 カナリア諸島は、先住民であるカナリア人、ヨーロッパからの入植者、そして労働力として連れてこられたアフリカ人による混血の過程の舞台となった。[22] 16 世紀から 17 世紀にかけて、スペイン王国では、主にユダヤ教から改宗した人々(そして、程度は少ないが、モリスコも対象となった)を差別する法的措置である「純血法」 が導入された。これらの規則は、教会、軍隊、行政、教育機関の役職に就こうとする者に、ユダヤ人やイスラム教徒の血を一切持たない、純粋なキリスト教徒の 末裔であることを証明することを義務付けた。[23] 多くの機関がこれらの法令を採用したことで、これらの集団の社会的上昇が制限され、キリスト教徒のアイデンティティを排他的に捉える考え方が強まり、何世 紀にもわたって、特定の分野における混血や社会的流動の可能性を制限した。 バレアレス諸島では、混血は独特ながらも限定的な形で現れた。マヨルカ島では、ユダヤ教から改宗した人々の子孫であるチュエタス(xuetes)のコミュ ニティが生まれた。彼らは、キリスト教徒として正式に統合されたにもかかわらず、何世紀にもわたって社会的偏見の対象となった。[24] メノルカ島では、18世紀の英国の支配が文化的な痕跡を残したが、英国人との生物学的混血はごくわずかだった。[25] この期間には、多様な出身(ジプシー、モリスコ、貧困農民の混血を含む)の半遊牧民グループ「メルチェロス」または「キンキス」に関する記録も残っており、彼らは独自の文化と「キンキ」と呼ばれる特有の俗語を発展させた。[26] |

| Siglos xix-xx y migraciones reversas Durante los siglos xix y xx, cientos de miles de españoles emigraron a Hispanoamérica, especialmente desde regiones como Galicia, Asturias y Canarias. A lo largo de las generaciones, algunos de sus descendientes han regresado —y siguen regresando— a España, en muchos casos tras haber obtenido la nacionalidad española por vía legal, como nietos o bisnietos de emigrantes. Aunque no suelen contabilizarse como inmigrantes extranjeros, parte de estos retornos incluye personas con ascendencia mestiza, lo que ha podido aportar a la diversidad biológica en el país.[27][28] Situación contemporánea A partir de la segunda mitad de los años 1990, España se ha convertido en un país receptor de inmigración. Según el Instituto Nacional de Estadística, más del 15 % de la población residente en España es de origen extranjero (2024), procedente mayoritariamente de Iberoamérica, África y Europa del Este.[29] Este fenómeno ha generado nuevas dinámicas de mestizaje, tanto en grandes urbes como Madrid, Barcelona o Valencia; como en las ciudades fronterizas de Ceuta y Melilla, donde la coexistencia histórica de musulmanes, cristianos, judíos y comunidades bereberes ha configurado un entorno cultural, lingüístico y religioso diverso.[30] Las comunidades gitanas y mercheras siguen presentes en la sociedad española contemporánea, con situaciones diversas según la región. Si bien muchas familias están plenamente integradas, otras aún enfrentan barreras estructurales, pobreza y estigmatización. No obstante, tanto la cultura gitana como la memoria de los grupos marginados del pasado forman parte del patrimonio multicultural español. Un ejemplo destacado es el flamenco, expresión artística surgida en Andalucía con raíces mestizas, entre las que destaca la aportación gitana, junto con influencias moriscas, judías, africanas y populares andaluzas.[31][32] También se ha concedido el acceso a la nacionalidad española a descendientes de sefardíes —judíos expulsados de España en 1492—, en virtud de una ley aprobada en 2015 que reconoce ese vínculo histórico.[33] Cabe señalar que, a diferencia de otros países, en España no se recogen datos étnico-raciales en los censos oficiales ni en registros administrativos. Esta limitación se debe tanto a razones históricas como a la legislación vigente sobre protección de datos y no discriminación, que impide clasificar a la población por raza o etnia en registros públicos.[34] Genética de la población española Estudios recientes han confirmado la huella genética de múltiples migraciones. La población española actual presenta una base mayoritaria europea occidental, con aportes norteafricanos y del Próximo Oriente en proporciones variables según la región.[35] Los linajes africanos (haplogrupo E-M81, por ejemplo) son más frecuentes en Andalucía occidental y Canarias, reflejando siglos de contacto con África del Norte y el comercio atlántico.[36] Percepciones sociales La sociedad española actual debate activamente sobre la integración, el racismo y la identidad multicultural. Aunque el mestizaje biológico es cada vez más común entre generaciones jóvenes, persisten retos en materia de discriminación y reconocimiento de la diversidad étnica y cultural. Las comunidades históricas como los gitanos o los descendientes de mercheros a menudo enfrentan estos desafíos con una identidad doble: como parte del tejido nacional y, al mismo tiempo, herederos de una memoria de exclusión. |

19世紀から20世紀にかけての逆移民 19世紀から20世紀にかけて、何十万人ものスペイン人が、特にガリシア、アストゥリアス、カナリア諸島などの地域から、ヒスパニックアメリカ大陸へ移住 しました。何世代にもわたって、その子孫の一部はスペインに戻ってきており、その多くは移民の孫やひ孫として合法的にスペイン国籍を取得しています。彼ら は通常、外国人移民としてカウントされることはありませんが、この帰国者の中にはメスティーソ(混血)の人もおり、スペインの生物学的多様性に貢献してい ると考えられます。[27][28] 現在の状況 1990年代後半以降、スペインは移民の受け入れ国となった。国立統計局によると、スペインの居住者の15%以上は外国出身者(2024年)で、その大半はラテンアメリカ、アフリカ、東ヨーロッパ出身者だ。[29] この現象は、マドリード、バルセロナ、バレンシアなどの大都市だけでなく、セウタやメリリャなどの国境都市でも、イスラム教徒、キリスト教徒、ユダヤ教徒、ベルベル人コミュニティが歴史的に共存し、多様な文化、言語、宗教の環境を形成している。[30] ジプシーや行商人のコミュニティは、現代スペイン社会にも依然として存在しており、地域によって状況はさまざまだ。多くの家族は完全に社会に溶け込んでい るが、依然として構造的な障壁、貧困、差別と闘っている家族もいる。しかし、ジプシーの文化も、過去に疎外された集団の記憶も、スペインの多文化遺産の重 要な一部となっている。その顕著な例が、アンダルシアで生まれた芸術表現であるフラメンコだ。フラメンコは、メスティーソのルーツを持ち、ジプシーの貢献 が際立つほか、ムーア人、ユダヤ人、アフリカ人、そしてアンダルシアの民衆の影響も受けている。[31][32] また、1492年にスペインから追放されたセファルディム(ユダヤ人)の子孫には、その歴史的つながりを認める2015年に成立した法律により、スペイン国籍の取得が認められている。[33] 他の国とは異なり、スペインでは公式の人口調査や行政登録において、民族や人種に関するデータは収集されていない。この制限は、歴史的な理由と、公的記録 において人口を人種や民族によって分類することを禁じる、現行のデータ保護および差別禁止に関する法律によるものです。[34] スペインの人口の遺伝学 最近の研究では、複数の移住の遺伝的痕跡が確認されている。現在のスペインの人口は、主に西ヨーロッパ系で、地域によって北アフリカや中東系の割合が異なる。[35] アフリカ系の血統(例えば、ハプログループ E-M81)は、アンダルシア西部およびカナリア諸島で多く見られ、何世紀にもわたる北アフリカとの接触や大西洋貿易を反映している。[36] 社会的認識 現在のスペイン社会では、統合、人種差別、多文化のアイデンティティについて活発な議論が行われている。生物学的混血は若い世代の間でますます一般的に なっていますが、差別や民族的・文化的多様性の認識に関する課題は依然として残っています。ジプシーやメルチェロスの子孫などの歴史的なコミュニティは、 国家の構成員であると同時に、排除の記憶を継承する者としての二重のアイデンティティを抱え、こうした課題に直面しています。 |

| Mestizaje en Brasil A Redenção de Cam (1895): abuela negra, madre mulata, esposo e hijo blancos; esta pintura sintetiza una realidad en el blanqueamiento de la piel de la población brasileña (cuadro del pintor gallego Modesto Brocos y Gomes). Pocos países en el mundo pasaron por un mestizaje tan intenso como Brasil.[37] Los portugueses ya trajeron a Brasil varios siglos de integración genética y cultural entre grupos europeos, y ejemplo de ello son los pueblos celta, romano, germánicos, otros pueblos ibéricos y lusitano. A pesar de que los portugueses básicamente son un grupo europeo, siete siglos de convivencia con moros del norte de África así como con judíos, dejaron por cierto en ellos un importante legado genético y cultural. Y en Brasil, una parte importante de los colonizadores portugueses e ibéricos se mezcló con indios y con africanos, dando lugar a un proceso que resultó muy importante para la formación del futuro nuevo país en suelo americano. Al citado y a otros procesos, se sumó luego una fuerte inmigración desde otras regiones de Europa. Desde mediados del siglo xix hasta mediados del siglo xx, Brasil recibió cerca de cinco millones de inmigrantes europeos, en su mayoría portugueses, españoles, italianos y alemanes, sin contar otros grupos menores, pero significativos, como los estadounidenses, que llegaron a fundar pueblos (ejemplo: Americana, SP), japoneses, chinos, coreanos, paraguayos, peruanos, bolivianos, entre otros grupos. La suma de estos procesos dio por resultado la actual composición de la población brasileña, que sigue adelante con su tradición de misceginación. En 2008, 48 % de la población de Brasil se consideraba blanca, 44 % se identificaba como parda, y 7 % se consideraba negra.[38] Los indios brasileros no presentan relevantes diferencias genéticas entre sí, pues serían todos descendientes del primer grupo de cazadores asiáticos que llegaron a las Américas, hace 60 mil años atrás.[39] Pero en lo cultural, los aborígenes brasileros constituían una diversidad de naciones con lenguas y costumbres distintas. La llegada de los primeros portugueses, en su mayoría hombres, culminó en relaciones esporádicas y de concubinato con las indias. Y el 4 de abril de 1755, D. José, rey de Portugal, firmó un decreto autorizando el mestizaje de portugueses con indios.[40] Los africanos esclavizados en Brasil pertenecían a muchas diferentes etnias, aunque la mayor parte eran bantúes, originarios de Angola, Congo, y Mozambique. De todas maneras, en lugares como Bahía predominaron esclavos de Nigeria, Daomé, y Costa da Mina, especialmente durante el siglo xviii. Algunos esclavos islámicos habían sido alfabetizados en árabe, trayendo así a Brasil un rico y variado aporte cultural. A fines del siglo xix, el gobierno brasilero liberó a los esclavos, aunque sin darles adecuada asistencia social, y por varios motivos, incluyendo la necesidad de mano de obra y el deseo de "blanquear" a la población nacional, durante al menos un siglo se estimuló muy especialmente la inmigración europea. Había entre los gobernantes de Brasil de la época, la idea de que si inmigrantes europeos se casaban con pardos y negros, el resultado sería un paulatino "emblanquecimiento" de la población brasilera. La conocida pintura A Redenção de Cam,[41] obra hecha en 1895 por Modesto Brocos y Gómez, sintetiza la idea corriente de esa época: «A través del mestizaje con europeos, los brasileños se volverían de piel cada vez más blanca». |

ブラジルの混血 A Redenção de Cam(1895年):黒人の祖母、混血の母親、白人の夫と息子。この絵画は、ブラジル国民の肌の白化という現実を要約している(ガリシア出身の画家、モデスト・ブロコス・イ・ゴメスによる作品)。 ブラジルほど激しい混血を経験した国は、世界でもほとんどない[37]。 ポルトガル人は、ヨーロッパのさまざまな民族間の遺伝的・文化的統合を何世紀にもわたってブラジルにもたらした。その例としては、ケルト人、ローマ人、ゲ ルマン人、その他のイベリア人、ルシタニア人などが挙げられる。ポルトガル人は基本的にヨーロッパ人であるが、7世紀にわたる北アフリカのムーア人やユダ ヤ人との共生は、彼らに重要な遺伝的・文化的遺産を残した。そしてブラジルでは、ポルトガル人およびイベリア人の入植者の大部分が、インディオやアフリカ 人と混血し、アメリカ大陸に新しい国を形成するために非常に重要なプロセスを生み出した。 上記の過程に加え、その後、ヨーロッパの他の地域からも大規模な移民が流入した。19世紀半ばから20世紀半ばにかけて、ブラジルには約500万人のヨー ロッパ人移民が流入した。その大半はポルトガル人、スペイン人、イタリア人、ドイツ人だったが、アメリカ人、日本人、中国人、韓国人、パラグアイ人、ペ ルー人、ボリビア人など、少数ながら重要なグループも存在し、彼らは町を設立した(例:サンパウロ州のアメリカナ)。これらの過程の結果、現在のブラジル の人口構成が形成され、混血の伝統が引き継がれている。2008年、ブラジルの人口の48%は白人、44%は混血、7%は黒人であると自認していた [38]。 ブラジルの先住民は、6万年前にアメリカ大陸にやってきたアジアの最初の狩猟民の子孫であることから、遺伝的に大きな違いはない。しかし、文化面では、ブ ラジルの先住民は、さまざまな言語や習慣を持つ多様な民族で構成されていた。最初のポルトガル人(その大半は男性)の到着は、インディアスとの断続的な関 係や同棲関係に発展した。そして 1755 年 4 月 4 日、ポルトガルの王ジョゼは、ポルトガル人とインディオの混血を許可する法令に署名した。[40] ブラジルで奴隷として連れてこられたアフリカ人は、さまざまな民族に属していましたが、その大半はアンゴラ、コンゴ、モザンビーク出身のバンツー族でし た。いずれにせよ、バイアなどの地域では、特に18世紀には、ナイジェリア、ダオメ、コスタ・ダ・ミナ出身の奴隷が主流だった。一部のイスラム教徒の奴隷 はアラビア語を習得しており、ブラジルに豊かで多様な文化をもたらした。 19世紀末、ブラジル政府は奴隷を解放しましたが、十分な社会的支援は提供せず、労働力の必要性や国民を「白人化」したいという願望など、さまざまな理由 から、少なくとも1世紀以上にわたり、ヨーロッパからの移民を特に奨励しました。当時のブラジルの支配者たちは、ヨーロッパからの移民が混血や黒人と結婚 すれば、ブラジル国民が徐々に「白人化」するだろうと考えていた。1895年にモデスト・ブロコス・イ・ゴメスによって描かれた有名な絵画『A Redenção de Cam』[41]は、当時の一般的な考え方を要約している。「ヨーロッパ人との混血によって、ブラジル人はますます肌が白くなっていく」と。 |

| Mestizaje en América |

|

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mestizaje |

なお、以下の項目「メスティーソ」では、末尾にプエルトリコ人(Puerto Ricans)に関

する情報も含まれている。

| Mestizo

(/mɛsˈtiːzoʊ, mɪ-/;[5][6] Spanish: [mesˈtiso] (listen); fem. mestiza)

is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed

European and Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as

Latin America, it may also refer to people who are culturally European

even though their ancestors are not.[7] The term was used as an

ethnic/racial category for mixed-race castas that evolved during the

Spanish Empire. Although, broadly speaking, mestizo means someone of

mixed European/Indigenous heritage, the term did not have a fixed

meaning in the colonial period.[citation needed] It was a formal label

for individuals in official documents, such as censuses, parish

registers, Inquisition trials, and others. Priests and royal officials

might have classified persons as mestizos, but individuals also used

the term in self-identification.[8] The noun mestizaje, derived from the adjective mestizo, is a term for racial mixing that did not come into usage until the twentieth century; it was not a colonial-era term.[9] In the modern era, mestizaje is used by scholars such as Gloria Anzaldúa as a synonym for miscegenation, but with positive connotations.[10] In the modern era, particularly in Latin America, mestizo has become more of a cultural term, with the term Indigenous being reserved exclusively for people who have maintained a separate Indigenous ethnic and cultural identity, language, tribal affiliation, community engagement, etc. In late 19th- and early 20th-century Peru, for instance, mestizaje denoted those peoples with evidence of Euro-indigenous ethno-racial "descent" and access—usually monetary access, but not always—to secondary educational institutions. Similarly, well before the twentieth century, Euramerican "descent" did not necessarily denote Spanish American ancestry or solely Spanish American ancestry, especially in Andean regions re-infrastructured by Euramerican "modernities" and buffeted by mining labor practices. This conception changed by the 1920s, especially after the national advancement and cultural economics of indigenismo.[11] To avoid confusion with the original usage of the term mestizo, mixed people started to be referred to collectively as castas. In some Latin American countries, such as Mexico, the concept of the Mestizo became central to the formation of a new independent identity that was neither wholly Spanish nor wholly Indigenous. The word mestizo acquired another meaning in the 1930 census, being used by the government to refer to all Mexicans who did not speak Indigenous languages regardless of ancestry.[12][13] During the colonial era of Mexico, the category Mestizo was used rather flexibly to register births in local parishes and its use did not follow any strict genealogical pattern. With Mexican independence, in academic circles created by the "mestizaje" or "Cosmic Race" ideology, scholars asserted that Mestizos are the result of the mixing of all the races. After the Mexican Revolution the government, in its attempts to create an unified Mexican identity with no racial distinctions, adopted and actively promoted the "mestizaje" ideology.[12] |

メ

スティーゾ/メスティーソ(/mɛ,;[5][6] スペイン語: [mesʊ] (listen); fem.

mestiza)は、ヨーロッパ人とアメリカ先住民の祖先が混在する人を指す人種分類に使われる言葉である。ラテンアメリカなど特定の地域では、祖先が

ヨーロッパ人でなくても文化的にヨーロッパ人である人を指すこともある[7]。スペイン帝国時代に発展した混血のカスタの民族・人種区分として使われた言

葉である。広義にはメスティーソはヨーロッパ人と先住民の混血を意味するが、植民地時代には一定の意味を持たなかった[要出典]。

国勢調査、教区台帳、異端審問裁判などの公式文書では個人に対する正式なラベルであった。神父や王室関係者がメスチソに分類した可能性もあるが、個人も自

認のためにこの言葉を使った[8]。 形容詞mestizoから派生した名詞mestizajeは、20世紀になってから使われるようになった人種的混合の用語であり、植民地時代の用語ではな かった[9]。現代では、mestizajeはGloria Anzaldúaなどの学者によって、混血の同義語として、しかしポジティブな意味合いを持って使われている[10]。 現代では、特にラテンアメリカにおいて、メスティーソは文化的な用語として使われるようになり、先住民という用語は、先住民の民族的・文化的アイデンティ ティ、言語、部族の所属、コミュニティの関与などを個別に維持している人々だけに留保されている。例えば、19世紀末から20世紀初頭のペルーでは、メス ティサヘは、ヨーロッパ系先住民の民族・人種の「血統」を証明し、中等教育機関へのアクセス(通常は金銭的アクセスだが、常にそうとは限らない)を持つ人 々を示していた。同様に、20世紀以前は、ヨーロッパ人の「血統」は必ずしもスペイン系アメリカ人の血統を意味せず、特にヨーロッパ人の「近代化」によっ てインフラが整備され、鉱山労働の慣行にさらされたアンデス地域では、スペイン系アメリカ人の血統のみを意味するものであった。この概念は1920年代ま でに、特にインディヘニスモの国家的進歩と文化的経済の後、変化した[11]。 メスチーソという用語の本来の用法との混乱を避けるために、混血の人々はカスタと総称されるようになった。メキシコなど一部のラテンアメリカ諸国では、メ スティーソの概念は、完全にスペイン人でもなく、完全に先住民でもない、新しい独立したアイデンティティの形成の中心となった。メスティーソという言葉は 1930年の国勢調査で別の意味を持ち、祖先に関係なく先住民の言語を話さないすべてのメキシコ人を指す言葉として政府によって使われるようになった [12][13]。 メキシコの植民地時代には、メスティーソというカテゴリーは地元の教区で出生を登録するためにかなり柔軟に使われ、その使用は厳密な系図パターンに従うも のではなかった。メキシコ独立後、「メスチサヘ」または「宇宙民族」イデオロギーによって作られた学界で、学者達はメスチソはすべての人種が混ざり合った 結果であると主張しました。メキシコ革命後、政府は人種的な区別のない統一されたメキシコのアイデンティティを作ろうとして、「メスチザヘ」思想を採用 し、積極的に推進した[12]。 |

| Etymology The Spanish word mestizo is from Latin mixticius, meaning mixed.[14][15] Its usage was documented as early as 1275, to refer to the offspring of an Egyptian/Afro Hamite and a Semite/Afro Asiatic.[16] This term was first documented in English in 1582.[17] |

語源 スペイン語のメスティーソはラテン語のmixticiusに由来し、混合を意味する[14][15]。 この用語は1275年には、エジプト人・アフロ・ハマイトとセム人・アフロ・アジア人の子供を指すものとして記録されている。この用語が英語で初めて記録 されたのは1582年[16]であった。 |

| Cognates and related terms Mestizo (Spanish: [mesˈtiθo] or [mesˈtiso]), mestiço (Portuguese: [mɨʃˈtisu], [mesˈt(ʃ)isu] or [miʃˈt(ʃ)isu]), métis (French: [meˈtis] or [meˈti]), mestís (Catalan: [məsˈtis]), Mischling (German: [mɪʃˈlɪŋɡ]), meticcio (Italian: [meˈtittʃo]), mestiezen (Dutch: [mɛsˈtizə(n)]), mestee (Middle English: [məsˈtiː]), and mixed (English) are all cognates of the Latin word mixticius. The Portuguese cognate, mestiço, historically referred to any mixture of Portuguese and local populations in the Portuguese colonies. In colonial Brazil, most of the non-enslaved population was initially mestiço de indio, i.e. mixed Portuguese and Native Brazilian. There was no descent-based casta system, and children of upper-class Portuguese landlord males and enslaved females enjoyed privileges higher than those given to the lower classes, such as formal education. Such cases were not so common and the children of enslaved women tended not to be allowed to inherit property. This right of inheritance was generally given to children of free women, who tended to be legitimate offspring in cases of concubinage (this was a common practice in certain American Indian and African cultures). In the Portuguese-speaking world, the contemporary sense has been the closest to the historical usage from the Middle Ages. Because of important linguistic and historical differences, mestiço (mixed, mixed-ethnicity, miscegenation, etc.) is separated altogether from pardo (which refers to any kind of brown people) and caboclo (brown people originally of European–Indigenous American admixture, or assimilated Indigenous American). The term mestiços can also refer to fully African or East Asian in their full definition (thus not brown). One does not need to be a mestiço to be classified as pardo or caboclo. In Brazil specifically, at least in modern times, all non-Indigenous people are considered to be a single ethnicity (os brasileiros. Lines between ethnic groups are historically fluid); since the earliest years of the Brazilian colony, the mestiço ([mesˈt(ʃ)isu], Portuguese pronunciation: [meʃˈt(ʃ)isu], [miʃˈt(ʃ)isu]) group has been the most numerous among the free people. As explained above, the concept of mestiço should not be confused with mestizo as used in either the Spanish-speaking world or the English-speaking one. It does not relate to being of American Indian ancestry, and is not used interchangeably with pardo, literally "brown people." (There are mestiços among all major groups of the country: Indigenous, Asian, pardo, and African, and they likely constitute the majority in the three latter groups.) In English-speaking Canada, Canadian Métis (capitalized), as a loanword from French, refers to persons of mixed French or European and Indigenous ancestry, who were part of a particular ethnic group. French-speaking Canadians, when using the word métis, are referring to Canadian Métis ethnicity, and all persons of mixed Indigenous and European ancestry. Many were involved in the fur trade with Canadian First Nations peoples (especially Cree and Anishinaabeg). Over generations, they developed a separate culture of hunters and trappers, and were concentrated in the Red River Valley and speak the Michif language. In Saint Barthélemy, the term mestizo refers to people of mixed European (usually French) and East Asian ancestry. This reflects a different colonial era, when the French recruited East Asians as workers.[18] In the Spanish East Indies, which were Spain’s overseas possessions comprising the Captaincy-General of what is now the Philippines and other Pacific island nations ruled through the Viceroyalty of New Spain (today Mexico), the term mestizo was used to refer to a person with any foreign ancestry,[7] and in some islands usually shortened as Tisóy. In the Philippines, the word mestizo usually refers to a Filipino with combined Indigenous and European ancestry. Occasionally it is used for a Filipino with apparent Chinese ancestry, who will also be referred to as 'chinito'. The latter was officially listed as a "mestizo de sangley" in birth records of the 19th century, with 'sangley' referring to the Hokkienese word for business, 'seng-li'. |

同義語・関連語 メスティーソ(スペイン語:[mesˈtiθo] または [mesˈ])、メスティソ(ポルトガル語:[mɨ↪Ll283↩ˈ]、 [mesʃ isu] または [miʃ isu] )、メティス(フランス語: [meˈtis] または [meˈti] )、メスティ(カタラン: [məsˈtis]), ミッシュリング(ドイツ語: [Mˈtis]: [mɪʃˈlɪŋɡ]、mestiezen(オランダ語:[mɛˈ(n)])、mestee(中英:[mː])、mixed(英語)などは、ラテン語 mixticiusの同義語である。 ポルトガル語の同義語であるmestiçoは、歴史的にポルトガル植民地におけるポルトガル人と現地人の混血を指していた。植民地時代のブラジルでは、当 初、非奴隷民のほとんどがメスティソ・デ・インディオ、つまりポルトガル人とブラジル先住民の混血であった。また、血統に基づくカースト制度はなく、上流 階級のポルトガル人地主男性と奴隷女性の子どもは、正規の教育を受けるなど下層階級よりも高い特権を享受していた。このようなケースはそれほど多くなく、 奴隷女性の子どもには財産の相続が認められない傾向があった。この相続権は一般的に自由な女性の子どもに与えられており、妾腹の場合は嫡出子となる傾向が あった(これはアメリカ・インディアンやアフリカの一部の文化圏では一般的な慣習であった)。ポルトガル語圏では、現代の意味が中世からの歴史的用法に最 も近いとされている。言語的、歴史的に重要な違いがあるため、メスティソ(混血、混血、混血など)は、パルド(あらゆる種類の褐色人種を指す)やカボクロ (もともとヨーロッパ人とアメリカ先住民の混血の褐色人種、または同化したアメリカ先住民)と完全に分離されています。メスチソという言葉は、その完全な 定義において、完全にアフリカ人や東アジア人を指すこともある(したがって、褐色ではない)。メスチソでなくても、パルドやカボクロに分類されることもあ る。 特にブラジルでは、少なくとも現代においては、非先住民はすべて単一の民族(os brasileiros。 民族間の線引きは歴史的に流動的)であると考えられており、ブラジル植民地の初期から、メスティソ([mesˈ(↪Ll_283)isu], ポルトガル語発音: [meʃˈ, [miʃˈ]) のグループが自由民の中で最も多く存在した。以上のように、メスティーソという概念は、スペイン語圏や英語圏で使われるメスティーソと混同してはいけな い。また、アメリカンインディアンの血を引いていることとも関係なく、パルド(文字通り「褐色の人々」)と同じ意味で使われることもない。(この国のすべ ての主要な集団にメスチソが存在する。先住民、アジア人、パルド、アフリカ人など、この国のすべての主要な集団にメスチソがおり、後者の3つの集団では過 半数を占めていると思われる)。 英語圏のカナダでは、フランス語からの借用語であるカナディアン・メティス(大文字)は、フランス人またはヨーロッパ人と先住民の混血で、特定の民族集団 に属していた人たちを指す。フランス語圏のカナダ人がメティスという言葉を使う場合、カナダのメティス族、および先住民族とヨーロッパ人の混血の先祖を持 つすべての人を指します。カナダの先住民族(特にクリー族とアニシナベグ族)との毛皮貿易に携わっていた人が多くいます。何世代にもわたって、狩猟や罠猟 を行う独立した文化を発展させ、レッドリバーバレーに集中し、ミチフ語を話す。 サン・バルテルミー島では、メスティーソという言葉は、ヨーロッパ人(通常はフランス人)と東アジア人の祖先が混ざった人々を指します。これは、フランス が東アジア人を労働者として徴用した、異なる植民地時代を反映している[18]。 スペインの海外領であった東インド諸島では、現在のフィリピンやその他の太平洋諸島の国々が新スペイン総督府(現在のメキシコ)を通じて統治されており、 メスティーソという言葉はあらゆる外国の祖先を持つ人を指すのに使われ[7]、いくつかの島では通常ティソイと略されていた。フィリピンでは、メスティー ソという言葉は通常、先住民族とヨーロッパ人の祖先を併せ持つフィリピン人を指す。時折、明らかに中国系の祖先を持つフィリピン人に使われることもあり、 その場合は「チニート」とも呼ばれる。後者は19世紀の出生記録で公式に「メスティーソ・デ・サンレイ」と記載されており、「サンレイ」は福建語で商売を 意味する「センリ」に由来している。 |

| Mestizo as a colonial-era

category (Casta) |

|

| Mexico. Around 50-90% of Mexicans can be classified as "mestizos", meaning in modern Mexican usage that they identify fully neither with any European heritage nor with an Indigenous culture, but rather identify as having cultural traits incorporating both European and Indigenous elements. In Mexico, mestizo has become a blanket term which not only refers to mixed Mexicans but includes all Mexican citizens who do not speak Indigenous languages[12] even Asian Mexicans and Afro-Mexicans.[29] Sometimes, particularly outside of Mexico, the word "mestizo" is used with the meaning of Mexican persons with mixed Indigenous and European blood. This usage does not conform to the Mexican social reality where a person of pure Indigenous genetic heritage would be considered mestizo either by rejecting his Indigenous culture or by not speaking an Indigenous language,[30] and a person with none or very low percentage of Indigenous genetic heritage would be considered fully Indigenous either by speaking an Indigenous language or by identifying with a particular Indigenous cultural heritage.[31] In the Yucatán peninsula the word mestizo has a different meaning to the one used in the rest of Mexico, being used to refer to the Maya-speaking populations living in traditional communities, because during the caste war of the late 19th century those Maya who did not join the rebellion were classified as mestizos.[30] In Chiapas, the term Ladino is used instead of Mestizo.[32] Due to the extensiveness of the modern definition of mestizo, various publications offer different estimations of this group, some try to use a biological, racial perspective and calculate the mestizo population in contemporary Mexico as being around a half and two thirds of the population,[33] while others use the culture-based definition, and estimate the percentage of mestizos as high as 90%[12] of the Mexican population, several others mix-up both due lack of knowledge in regards to the modern definition and assert that mixed ethnicity Mexicans are as much as 93% of Mexico's population.[34] Paradoxically to its wide definition, the word mestizo has long been dropped of popular Mexican vocabulary, with the word even having pejorative connotations,[30] which further complicates attempts to quantify mestizos via self-identification. While for most of its history the concept of mestizo and mestizaje has been lauded by Mexico's intellectual circles, in recent times the concept has been target of criticism, with its detractors claiming that it delegitimizes the importance of ethnicity in Mexico under the idea of "(racism) not existing here (in Mexico), as everybody is mestizo."[35] In general, author Federico Navarrete concludes that Mexico introducing a real racial classification and accepting itself as a multicultural country opposed to a monolithic mestizo country would bring benefits to the Mexican society as a whole.[36] |

メキシコ メキシコ人の約50-90%は「メスティーソ」に分類される。現代のメキシコでは、ヨーロッパ人の遺産も先住民族の文化も完全に認めず、むしろヨーロッパ 人と先住民族の両方の要素を取り入れた文化的特徴を持つと認識することを意味する。メキシコでは、メスティーソは混血のメキシコ人を指すだけでなく、先住 民族の言語を話さないすべてのメキシコ国民[12]、さらにはアジア系メキシコ人やアフロメキシコ人も含む包括的な言葉になっている[29]。 特にメキシコ国外では、「メスティーソ」という言葉が、先住民族とヨーロッパ人の血が混じったメキシコ人の意味で使われることもある。この用法は、純粋な 先住民族の遺伝子を持つ者は、先住民族の文化を拒否するか、先住民族の言語を話さないことによってメスティーソとみなされ[30]、全くあるいは非常に低 い割合の先住民族の遺伝子を持つ者は、先住民族の言語を話すか特定の先住民族の文化遺産を持つことによって完全に先住民とみなされるメキシコの社会現実に 合致していない。 [31] ユカタン半島ではメスティーソという言葉はメキシコの他の地域で使われているものとは異なる意味を持ち、伝統的な共同体に住むマヤ語を話す人々を指すのに 使われている。これは19世紀後半のカースト戦争において、反乱に参加しなかったマヤ人はメスティーソとして分類されていたからである[30] チアパスではメスティーソではなくラジノという言葉が用いられている[32]。 メスティーソの現代的な定義の広さのために、様々な出版物がこのグループの異なる推定を提供している。あるものは生物学的、人種的な視点を使おうとし、現 代のメキシコのメスティーソ人口を人口の半分から3分の2程度であると計算し[33]、他のものは文化ベースの定義を使い、メキシコの人口の90% [12]と高いメスティーソ比率と推定し、他のいくつかのものは現代の定義に関する知識の不足から両方を混合し、メキシコの人口の93%と同じくらい混合 民族であると断定している。 [34] その広い定義とは逆説的に、メスティーソという言葉は長い間メキシコの一般的な語彙から外され、その言葉には蔑称的な意味合いさえある[30]。 メスティーソとメスチサヘの概念はその歴史の大半においてメキシコの知識人界で賞賛されてきたが、近年ではその概念は批判の対象となっており、「(人種差 別は)ここ(メキシコ)では存在しない、みんなメスティーソだから」という考えのもと、メキシコにおける民族の重要性を委縮させるとする論者もいる [35][36]。 「35] 一般的には、著者のフェデリコ・ナバレテは、メキシコが本当の人種分類を導入し、一枚岩のメスティーソの国に対して多文化国家として受け入れることは、メ キシコの社会全体に利益をもたらすと結論づけている[36]。 |

| Central America (Ladino people) The Ladino people are a mix of Mestizo or Hispanicized peoples[40] in Latin America, principally in Central America. The demonym Ladino is a Spanish word that derives from Latino. Ladino is an exonym dating to the colonial era to refer to those Spanish-speakers who were not colonial elites (Peninsulares and Criollos), or Indigenous peoples.[41] Guatemala (Demographics of Guatemala) The Ladino population in Guatemala is officially recognized as a distinct ethnic group, and the Ministry of Education of Guatemala uses the following definition: "The ladino population has been characterized as a heterogeneous population which expresses itself in the Spanish language as a maternal language, which possesses specific cultural traits of Hispanic origin mixed with indigenous cultural elements, and dresses in a style commonly considered as western."[3] The population censuses include the ladino population as one of the different ethnic groups in Guatemala.[4][5] In popular use, the term ladino commonly refers to non-indigenous Guatemalans, as well as mestizos and westernized Amerindians. The word was popularly thought to be derived from a mix of Latino and ladrón, the Spanish word for "thief", but is not necessarily or popularly considered a pejorative.[6] The word is actually derived from the old Spanish ladino (inherited from the same Latin root Latinus that the Spanish word Latino was later borrowed from), originally referring to those who spoke Romance languages in medieval times, and later also developing the separate meaning of "crafty" or "astute". In the Central American colonial context, it was first used refer to those Amerindians who came to speak only Spanish, and later included their mestizo descendants.[7] Ladino is sometimes used to refer to the mestizo middle class, or to the population of indigenous peoples who have attained some level of upward social mobility above the largely impoverished indigenous masses. This relates especially to achieving some material wealth and adopting a North American lifestyle. In many areas of Guatemala, it is used in a wider sense, meaning "any Guatemalan whose primary language is Spanish". Indigenist rhetoric sometimes uses ladino in the second sense, as a derogatory term for indigenous peoples who are seen as having betrayed their homes by becoming part of the middle class. Some may deny indigenous heritage to assimilate. "The 20th century K'iche Maya political activist, Rigoberta Menchú, born in 1959, used the term this way in her noted memoir, which many considered controversial. She illustrates the use of ladino both as a derogatory term, when discussing an indigenous person becoming mestizo/ladino, and in terms of the general mestizo community identifying as ladino as a kind of happiness. |

中央アメリカ(ラディーノ族) ラディーノ族は、主に中央アメリカのラテンアメリカに住むメスティーソまたはヒスパニック化した民族[40]の混血である。デモニムであるラディーノはラ ティーノから派生したスペイン語である。ラディーノは植民地時代の外来語で、植民地時代のエリート(ペニンシュラやクリオロス)でもなく、先住民でもない スペイン語話者に言及する[41]。 グアテマラ(グアテマラの人口統計学) グアテマラのラディーノ人口は、個別の民族集団として公式に認められており、グアテマラ教育省は以下のような定義を使っている。 "ラディーノ集団は、母国語としてのスペイン語で自己表現し、先住民の文化的要素と混在するヒスパニック系の特定の文化的特徴を持ち、一般に西洋とみなさ れるスタイルの服装をする異質な集団として特徴づけられている"[3]。 人口調査には、グアテマラの異なる民族集団の一つとしてラディーノ人口が含まれている[4][5]。 一般的に使われる場合、ラジノという言葉はグアテマラの非原住民、メスティーソ、西洋化したアメリンド人を指すのが普通である。この言葉はラティーノとス ペイン語で「泥棒」を意味するラドロンの混合語から派生したと一般に考えられていたが、必ずしも蔑称とは考えられていない[6]。 この言葉は実際には古いスペイン語のラディーノ(スペイン語のラティーノが後に借用したものと同じラテン語の語根から継承)に由来し、元々は中世にロマン ス語を話す人々を指していたが、後に「ずる賢い」「敏腕」という別の意味をも持つに至った。中米植民地時代には、スペイン語のみを話すようになったアメリ カ先住民を指す言葉として使われ、後にその子孫であるメスティーソも含まれるようになった[7]。 ラディーノはメスティーソの中産階級や、貧困にあえぐ先住民の中からある程度社会的な地位の向上を果たした人々を指す言葉として使われることもある。これ は特に物質的な豊かさを手に入れ、北米のライフスタイルを取り入れたことに関連する。グアテマラの多くの地域では、「スペイン語を母国語とするグアテマラ 人」を意味する広い意味で使われる。 土着主義者のレトリックでは、中産階級の一員となることで故郷を裏切ったと見なされる先住民に対する蔑称として、第二の意味でラディーノが使われることも ある。中には、同化するために先住民の遺産を否定する者もいるかもしれない。「20世紀のキチェ・マヤの政治活動家、リゴベルタ・メンチュ(1959年生 まれ)は、多くの人が物議を醸すと考えた著名な回想録の中でこの言葉を使った。彼女は、先住民がメスティーソ/ラディーノになることを論じる際に、蔑称と してのラディーノの使用と、一般のメスティーソコミュニティーが一種の幸福としてラディーノとして認識することの両方を説明しているのである。 |

| Mestizaje in Latin America: Race

and ethnicity in Latin America. Mestizaje ([mes.tiˈsa.xe]) is a term that came into usage in twentieth-century Latin America for racial mixing, not a colonial-era term.[9] In the modern era, it is used to denote the positive unity of race mixtures in modern Latin America. This ideological stance is in contrast to the term miscegenation, which usually has negative connotations.[54] The main ideological advocate of mestizaje was José Vasconcelos (1882–1959), the Mexican Minister of Education in the 1920s. The term was in circulation in Mexico in the late nineteenth century, along with similar terms, cruzamiento ("crossing") and mestización (process of "Mestizo-izing"). In Spanish America, the colonial-era system of castas sought to differentiate between individuals and groups on the basis of a hierarchical classification by ancestry, skin color, and status (calidad), giving separate labels to the perceived categorical differences and privileging whiteness. In contrast, the idea of modern mestizaje is the positive unity of a nation's citizenry based on racial mixture. "Mestizaje placed greater emphasis [than the casta system] on commonality and hybridity to engineer order and unity... [it] operated within the context of the nation-state and sought to derive meaning from Latin America's own internal experiences rather than the dictates and necessities of empire... ultimately [it] embraced racial mixture."[55] |

ラテンアメリカのメスティサヘ(Mestizaje in

Latin America)。ラテンアメリカの人種とエスニシティ メスティサヘ ([mes.tiˈsa.xe]) は、20世紀のラテンアメリカで人種混合に対して使われるようになった用語で、植民地時代の用語ではない。[9] 現代では、現代のラテンアメリカにおける人種混合が肯定的に統一することを表すために使われる。この思想的姿勢は、通常否定的な意味合いを持つ混血という 用語とは対照的である[54]。 メスティサヘの主な思想的提唱者は、1920年代にメキシコの教育大臣を務めたホセ・バスコンセロス(1882-1959)である。この言葉は、類似の言 葉であるcruzamiento(「横断」)やmestización(「メスティーソ化」のプロセス)と共に、19世紀後半にメキシコで流通していたも のである。スペイン領アメリカでは、植民地時代のカスタ(castas)制度が、家系、肌の色、身分(calidad)による階層的な分類に基づいて個人 や集団を区別しようとし、認識されたカテゴリー的な差異に別々のラベルを与え、白人性を特権化した。これに対して、現代のメスチサヘの考え方は、人種的混 血に基づく国家国民の積極的な団結である。「メスチサヘは、秩序と統一を実現するために、共通性と混血に(カスタ制度よりも)大きな重点を置いていた。 [国民国家の文脈の中で運営され、帝国の命令や必要性よりもむしろラテンアメリカ自身の内部の経験から意味を導き出そうとした...最終的に[それは]人 種的混合を受け入れた」[55]とある。] |

| Mestizos migrating to Europe Martín Cortés, son of the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and of the Nahuatl–Maya Indigenous Mexican interpreter Malinche, was one of the first documented Mestizos to arrive in Spain. His first trip occurred in 1528, when he accompanied his father, Hernán Cortés, who sought to have him legitimized by Pope Clement VII, the Pope of Rome from 1523 to 1534. There is also verified evidence of the grandchildren of Moctezuma II, Aztec emperor, whose royal descent the Spanish Crown acknowledged, willingly having set foot on European soil. Among these descendants are the Counts of Miravalle, and the Dukes of Moctezuma de Tultengo, who became part of the Spanish peerage and left many descendants in Europe.[64] The Counts of Miravalle, residing in Andalucía, Spain, demanded in 2003 that the government of Mexico recommence payment of the so-called 'Moctezuma pensions' it had cancelled in 1934. The Mestizo historian Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, son of Spanish conquistador Sebastián Garcilaso de la Vega and of the Inca princess Isabel Chimpo Oclloun arrived in Spain from Peru. He lived in the town of Montilla, Andalucía, where he died in 1616. The Mestizo children of Francisco Pizarro were also military leaders because of their famous father. Starting in the early 19th and throughout the 1980s, France and Sweden saw the arrival of hundreds of Chileans, many of whom fled Chile during the dictatorial government of Augusto Pinochet. |

ヨーロッパに移住するメスティーソたち スペインの征服者エルナン・コルテスとメキシコ先住民ナワト族マヤ族の通訳マリンチェの息子であるマルティン・コルテスは、スペインに到着した最初のメス ティーソの一人でした。1523年から1534年までローマのローマ教皇だったクレメンス7世から正統性を認められたコルテスは、1528年に父エルナ ン・コルテスに同行し、最初の渡航を果たしている。 また、スペイン王室が王家の血筋を認めたアステカ皇帝モクテスマ2世の孫が、進んでヨーロッパの地に足を踏み入れたという証拠も確認されている。これらの 子孫の中には、ミラバレー伯爵家とモクテスマ・デ・トルテンゴ公爵家があり、彼らはスペインの貴族となりヨーロッパに多くの子孫を残した[64] スペインのアンダルシアに住むミラバレー伯爵家は2003年にメキシコ政府に対して1934年に取り消したいわゆる「モクテスマ年金」を再び支払うよう要 求している。 スペインの征服者セバスチャン・ガルシラソ・デ・ラ・ベガとインカの王女イサベル・チンポ・オクルーンの息子でメスティーソの歴史家インカ・ガルシラソ・ デ・ラ・ベガはペルーからスペインに到着しました。彼はアンダルシアのモンティージャの町に住み、1616年にそこで死んだ。フランシスコ・ピサロのメス ティーソの子供たちも、有名な父の影響で軍事指導者となった。19世紀初頭から1980年代を通じて、フランスとスウェーデンには何百人ものチリ人がやっ てきた。その多くはアウグスト・ピノチェト(Augusto Pinochet)の独裁政権時代にチリから逃れた人たちである。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mestizo |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| Puerto

Ricans (Spanish: Puertorriqueños; or boricuas) are the people of Puerto

Rico, the inhabitants, and citizens of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico

and their descendants. (Demographics

of Puerto Rico) The culture held in common by most Puerto Ricans is referred to as a Western culture largely derived from the traditions of Spain, and more specifically Andalusia and the Canary Islands. Puerto Rico has also received immigration from other parts of Spain such as Catalonia as well as from other European countries such as France, Ireland, Italy and Germany. Puerto Rico has also been influenced by African culture, with many Puerto Ricans partially descended from Africans, though Afro-Puerto Ricans of unmixed African descent are only a significant minority. Also present in today's Puerto Ricans are traces (about 10-15%) of the aboriginal Taino natives that inhabited the island at the time of the European colonizers in 1493.[12][13] Recent studies in population genetics have concluded that Puerto Rican gene pool is on average predominantly European, with a significant Sub-Saharan African, North African Guanche, and Indigenous American substrate, the latter two originating in the aboriginal people of the Canary Islands and Puerto Rico's pre-Columbian Taíno inhabitants, respectively.[14][15][16][17] The population of Puerto Ricans and descendants is estimated to be between 8 and 10 million worldwide, with most living on the islands of Puerto Rico and in the United States mainland. Within the United States, Puerto Ricans are present in all states of the Union, and the states with the largest populations of Puerto Ricans relative to the national population of Puerto Ricans in the United States at large are the states of New York, Florida, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, with large populations also in Massachusetts, Connecticut, California, Illinois, and Texas.[18][19] For 2009,[20] the American Community Survey estimates give a total of 3,859,026 Puerto Ricans classified as "Native" Puerto Ricans. It also gives a total of 3,644,515 (91.9%) of the population being born in Puerto Rico and 201,310 (5.1%) born in the United States. The total population born outside Puerto Rico is 322,773 (8.1%). Of the 108,262 who were foreign born outside the United States (2.7% of Puerto Ricans), 92.9% were born in Latin America, 3.8% in Europe, 2.7% in Asia, 0.2% in Northern America, and 0.1% in Africa and Oceania each.[21] |

プエルトリコ人(スペイン語:Puertorriqueños;

or boricuas)は、プエルトリコの人々、プエルトリコ連邦の住民、市民、およびその子孫のことである。(プエルトリコの人口統計) 多くのプエルトリコ人に共通する文化は、スペイン、特にアンダルシアとカナリア諸島の伝統に由来する西洋文化と呼ばれる。プエルトリコには、カタルーニャ 地方などスペインの他の地域や、フランス、アイルランド、イタリア、ドイツなどヨーロッパの国々からも移民が来ています。プエルトリコはアフリカ文化の影 響も受けており、多くのプエルトリコ人は部分的にアフリカ人の子孫であるが、アフリカ人との混血でないアフロ・プエルトリコ人はかなりの少数派である。ま た、現在のプエルトリコ人には、1493年にヨーロッパ人が入植した時にこの島に住んでいた原住民タイノの痕跡(約10-15%)が残っている。 [12][13] 最近の集団遺伝学の研究では、プエルトリコ人の遺伝子プールは平均的にヨーロッパ人が多く、サハラ以南のアフリカ人、北アフリカのグアンシュ人、アメリカ 先住民の基盤があり、後者はそれぞれカナリア諸島の原住民とプエルトリコの先植民地のタイノ族に由来していると結論づけている[14][15][16] [17]。 プエルトリコ人とその子孫の人口は世界で800万人から1000万人と推定され、そのほとんどがプエルトリコの島々とアメリカ本土に住んでいる。アメリカ 合衆国内では、プエルトリコ人は連邦のすべての州に存在し、アメリカ合衆国全体のプエルトリコ人の人口に対してプエルトリコ人の人口が最も多い州は、 ニューヨーク、フロリダ、ニュージャージー、ペンシルベニアで、マサチューセッツ、コネチカット、カリフォルニア、イリノイ、テキサスにも大きな人口が存 在する[18][19]。 2009年、アメリカン・コミュニティ・サーベイの推計では、3,859,026人のプエルトリコ人が「先住民」として分類されている[20]。また、 3,644,515人(91.9%)がプエルトリコ生まれで、201,310人(5.1%)がアメリカ生まれであることも示されている。プエルトリコ以外 で生まれた人口の合計は322,773人(8.1%)である。アメリカ以外の外国生まれ108,262人(プエルトリコ人の2.7%)のうち、92.9% がラテンアメリカ、3.8%がヨーロッパ、2.7%がアジア、0.2%が北アメリカ、アフリカとオセアニアがそれぞれ0.1%である[21]。 |

| Race and origin history The first census by the United States in 1899 reported a population of 953,243 inhabitants, 61.8% of them classified as white, 31.9% as mixed, and 6.3% as black.[20] A strong European immigration wave and large importation of slaves from Africa helped increase the population of Puerto Rico sixfold during the 19th century. No major immigration wave occurred during the 20th century.[21] The federal Naturalization Act, signed into law on March 26, 1790, by President Washington stated that immigrants to the United States had to be White according to the definition under the British Common Law, which the United States inherited. The legal definition of Whiteness differed greatly from White Society's informal definition, thus Jews, Romani Peoples, Middle Eastern Peoples and those of the Indian Subcontinent were before 1917 classified as White for Immigration purposes but not considered White by the society at large. The Naturalization Act of 1870, passed during Reconstruction, allowed for peoples of African descent to become U.S. Citizens but it excluded other nonwhites. The U.S. Supreme Court in the case United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898) declared that all nonwhites who were born in the United States were eligible for citizenship via the Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment. U.S. Immigration Policy was first restricted toward Chinese with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Gentleman's Agreement of 1907 in which Japan voluntarily barred emigration to the United States and the Immigration Act of 1917 or the Asiatic Barred Zone which barred immigrants from all of the Middle East, the Steppes and the Orient, excluding the Philippines which was then a US Colony. European Jews and Romani, although of Asiatic Ancestry, were not affected by the Asiatic Barred Zone, as they held European Citizenship. The Johnson-Reed act of 1924 applied only to the Eastern Hemisphere. The Act imposed immigration quotas on Europe, which allowed for easy immigration from Northern and Western Europe, but almost excluded the Southern and Eastern European Nations. Africa and Asia were excluded altogether. The Western Hemisphere remained unrestricted to immigrate to the United States. Thus under the Immigration Act of 1924 all Hispanics and Caribbeans could immigrate to the United States, but a White family from Poland or Russia could not immigrate. Puerto Rican Citizenship was created under the Foraker Act, Pub.L. 56–191, 31 Stat. 77 but it wasn't until 1917 that Puerto Ricans were granted full American Citizenship under the Jones–Shafroth Act (Pub.L. 64–368, 39 Stat. 951). Puerto Ricans, excluding those of obvious African ancestry, were like most Hispanics formally classified as White under U.S. Law. Until 1950 the U.S. Bureau of the Census attempted to quantify the racial composition of the island's population, while experimenting with various racial taxonomies. In 1960 the census dropped the racial identification question for Puerto Rico but included it again in the year 2000. The only category that remained constant over time was white, even as other racial labels shifted greatly—from "colored" to "Black", "mulatto" and "other". Regardless of the precise terminology, the census reported that the bulk of the Puerto Rican population was white from 1899 to 2000.[16] In the late 1700s, Puerto Rico had laws like the Regla del Sacar or Gracias al Sacar where a person of mixed ancestry could be considered legally white so long as they could prove that at least one person per generation in the last four generations had also been legally white. Therefore, people of mixed ancestry with known white lineage were classified as white, the opposite of the "one-drop rule" in the United States.[22] According to the 1920 Puerto Rico census, 2,505 individuals immigrated to Puerto Rico between 1910 and 1920. Of these, 2,270 were classified as "white" in the 1920 census (1,205 from Spain, 280 from Venezuela, 180 from Cuba, and 135 from the Dominican Republic). During the same 10-year period, 7,873 Puerto Ricans emigrated to the U.S. Of these, 6,561 were listed as "white" on the U.S mainland census, 909 as "Spanish white" and 403 as "black".[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Puerto_Rico |

人種と出自の歴史 1899年のアメリカ合衆国による最初の国勢調査では、人口953,243人のうち61.8%が白人、31.9%が混血、6.3%が黒人に分類されたと報 告された[20]。 ヨーロッパからの強い移民の波とアフリカからの奴隷の大量輸入により、19世紀にはプエルトリコの人口は6倍になった。20世紀には大きな移民の波は起こ らなかった[21]。 1790年3月26日にワシントン大統領が署名した連邦帰化法は、アメリカ合衆国への移民は、アメリカ合衆国が継承したイギリスの慣習法における定義に 従った白人でなければならないとした。法律上の白人の定義は、白人社会の非公式な定義とは大きく異なっており、ユダヤ人、ロマ人、中東の人々、インド亜大 陸の人々は、1917年以前は移民法上の白人として分類されていたが、社会一般からは白人とは見なされていなかったのである。再建中の1870年に制定さ れた帰化法は、アフリカ系の人々がアメリカ市民になることを認めましたが、その他の非白人を除外していました。連邦最高裁判所は、United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898)という事件で、米国で生まれたすべての非白人は、修正14条の市民権条項によって市民権を得る資格があると宣言した。アメリカの移民政策は、 1882年の中国人排斥法、1907年の日本が自主的にアメリカへの移民を禁止した紳士協定、1917年の移民法(当時アメリカの植民地だったフィリピン を除く中東、ステップ、東洋からの移民を禁止するアジア禁止区域)で中国人に対して制限されたのが最初であった。ヨーロッパのユダヤ人やロマ人は、アジア 系とはいえ、ヨーロッパの市民権を持っていたので、アジア人禁制地帯の影響を受けなかった。1924年のジョンソン・リード法は、東半球にのみ適用され た。この法律はヨーロッパに移民割当を課し、北と西ヨーロッパからの移民を容易にしたが、南と東ヨーロッパ諸国はほとんど除外された。アフリカとアジアは 完全に除外された。西半球はアメリカへの移民を制限されないままであった。1924年の移民法では、ヒスパニック系とカリブ系は移民できたが、ポーランド やロシア出身の白人の家族は移民できなかった。プエルトリコの市民権はForaker Act, Pub.L. 56-191, 31 Stat. 77によって作られましたが、プエルトリコ人がJones-Shafroth Act (Pub.L. 64-368, 39 Stat. 951)によって完全にアメリカ市民権を与えられたのは1917年になってからのことです。プエルトリコ人は、明らかにアフリカ系の祖先を持つ人々を除い て、ほとんどのヒスパニック系住民と同様に、米国の法律では正式に白人に分類されていました。 1950年まで米国国勢調査局は、様々な人種分類を試しながら、島の人口の人種構成を定量化しようとしました。1960年、国勢調査はプエルトリコの人種 識別の質問をやめたが、2000年には再びこの質問を取り入れた。他の人種分類は、「有色人種」、「黒人」、「混血」、「その他」など大きく変化している にもかかわらず、唯一一定しているのは「白人」である。正確な用語はともかく、国勢調査では1899年から2000年までプエルトリコの人口の大部分は白 人であったと報告されている[16]。 1700年代後半、プエルトリコにはRegla del SacarやGracias al Sacarのような法律があり、過去4世代のうち1世代につき少なくとも1人が合法的に白人であったことを証明できれば、混血の祖先を持つ者は合法的に白 人と見なされることができた。そのため、白人の血筋がわかっている混血の人々は白人に分類され、アメリカにおける「ワンドロップ・ルール」の逆を行くもの であった[22]。 1920年のプエルトリコの国勢調査によると、1910年から1920年の間に2,505人がプエルトリコに移民している。このうち、1920年の国勢調 査で「白人」と分類されたのは2,270人(スペインから1,205人、ベネズエラから280人、キューバから180人、ドミニカ共和国から135人)で ある。このうち6,561人がアメリカ本土の国勢調査で「白人」、909人が「スペイン系白人」、403人が「黒人」として記載されている[23]。 |

De negro é india sale

lobo "from black man and Indian woman comes 'wolf' (Zambo)." (Pintura

de castas, ca. 1780), Unknown author, Mexico

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆