ラテンアメリカにおける人種概念

Notes

on

Race in Latin America

The

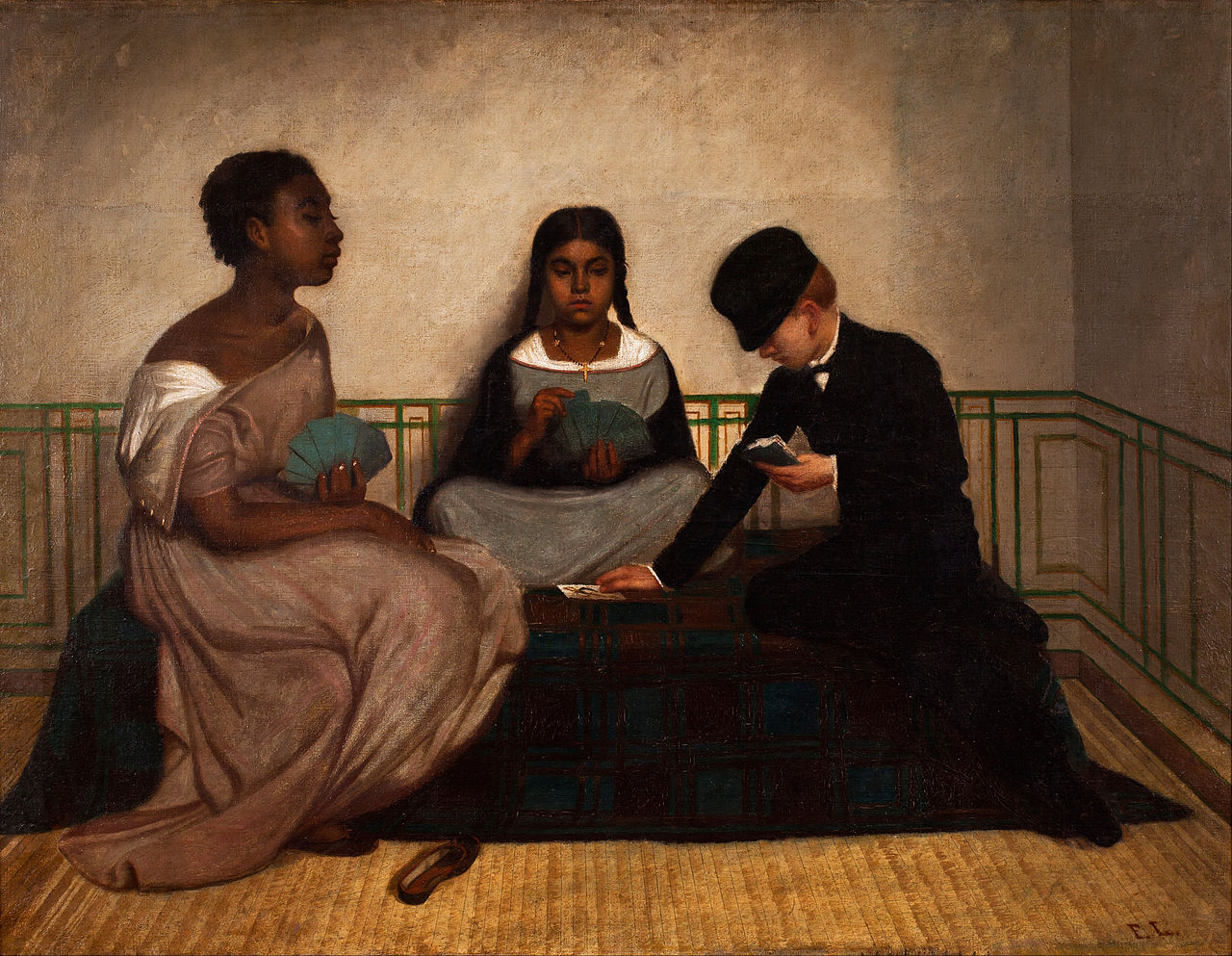

Three Races or Equality before the Law, ca. 1859, Francisco Laso,

Peru

★ラテンアメリカにおける人種概念をめぐるメモランダム

・人種主義は人間の種的分類概 念として19世紀を席 巻した生物学上の概念であり、20世紀にはその概念そのものが問題に伏されるものになり、21世紀には、人種が社会的構築物であるという合意であるという 認識にたどり着いた多様な変化の来歴がある(→「スペイン植民地におけるカースト制」)。

・ラテンアメリカで言われるインディヘナと︎メスティーソ(ラディーノ)の二元論を「混血」とい

う人種的比喩で理解すると本質的な二元論や日本で言われるような純粋な先住民(アイヌ)は存在しないという詭弁につながる.重要なことは[純な方向への]

インディオ化が支配者によりなされたことだ。

・ラテンアメリカにおける人種(raza, race)は、地理的変異、文化的変異、身体形質的変異を表現する用語として広く行き渡っている。その定義は曖昧で多様で、人種の概念がリジッドな北米に 比 べると、ラテンアメリカでは多様な人種的概念が横溢している。

・ラテンアメリカにおける、エスニシティの概念 (etnia, etnicidades)は、言語、文化的区分にもとづく人種のサブカテゴリーとして使われることもあるが、人種とエスニシティに関する人びとの区分は曖 昧である。

・ラテンアメリカにおける人種の概念は、植民地統治 においてヨーロッパから持ち込まれたものだが、現地社会での混血により、その関係が複雑に多様化してゆく。

・ラテンアメリカにおける、人種差別の二大マーカー は、先住民と黒人であり、社会階層の底辺の人びとをさす用語として機能している。

・人種がヨーロッパ言語に登場するのは16世紀初期 で、最初はリネージの意味で使われ、人種という用語が広く膾炙するようになったのは18世紀の終わり以降。他者表象として、奴隷制に使った「黒人」いう人 種で表現するのが今日の人種主義の嚆矢。

・イベリア半島では、レコンキスタ時代に、イスラム 教徒(ムーア人)を排斥し、その後に異端審問やユダヤ人の排斥運動が、キリスト教勢力のなかでおこる。宗教的排除は、キリスト教へ改宗という課題を伴って いたので、新たに改宗した「新キリスト教徒」として、以前からの「古くからのキリスト教徒」とを峻別した。改宗を、「血液を浄化する」(limpieza de sangre)というメタファーで表現した。血液や血は、イベリア半島における「家系の名誉」の概念と結びつけられた。

・人種概念の優劣を、身体性のメタファーで表現する ことはその後もつづく。例えば、奴隷制導入の時期以降に、先住民や黒人の乳母から授乳した際の母乳を、悪い母乳と呼んでいたという。

・人種の概念の洗練化は気候や天体の運行(占星術) が、その人間集団の外見・気質・知性を決定する要因と考えるようになってきた。その中でも、ヨーロッパの人びとが、新大陸での生活の適応することに強い関 心が持たれたが、新大陸の気候は文明人の心身の状態に悪影響を与えると考えられた。

・Jorge Cazares-Esguerra17世紀の歴史家は、アメリカの先住民の劣等性は揺るぎないものの、クリーオジョは熱帯の生活の中で適応した結果、それ ほど劣等化していないのは、彼らの血統がヨーロッパ由来だからだと、気候の悪影響よりも、血統の優秀性を強調した。クレオールは、それゆえ、先住民にも優 越し、また黒人奴隷にも優越しているという人種化された理論を展開した。

・リンネとブレーメンバッハの分類(18世紀後 半):白人、東方アジア人、黒人、アメリカ先住民、南西アジアおよび太平洋人

・ギュスタヴ・ル・ボン、ジョセフ・アルチュール・ ド・ゴビノーでは、ラテンアメリカの混血は(彼らの混血=人種劣等化の主張にもとづいて)「雑種の人種」の典型と見なされた。——ブラジル人、Nina Rodrigues は、チェザーレ・ロンブローゾの人種理論とを結びつけて、犯罪者に対しては、人種ごとに、異なった強度の処罰をおこなうべきと主張。

・このような人種差別論は、フランシス・ゴルドンの 優生学思想の普及で頂点に達する。優生学思想のタイプには2つあり、普及した地域も異なる:種の普遍性を説く「ハード」優生学(北米、英国)と、獲得形質 の遺伝を前提にした「ソフト」優生学(ないしは「新ラマルク派」優生学)(ラテンアメリカと東欧の大陸ヨーロッパ)にわかれる。いずれにせよ、1930年 代を境にしてナチス・ドイツ以外では覇権が急速に失われる(→「アメリカ合衆国の優 生学」)。

・1850年代には、ラテン人種(raza latina)という人種概念が登場。ラテンアメリカで軍事行動にでる北米のサクソン人種(Saxon race)に対抗して、ラテン人種の防衛を主張した、コロンビアのJose Maria Torres Caicedo が、詩作のなかで主張。パナマのJusto Arosemena, はヤンキー人種(la raza Yankee)がパナマ運河地帯でのさばることを批判。

・イスパノアメリカでは、コロンブスの上陸記念日を 「人種の日(El Día de la Raza)」と定めている:

El Día de la Raza se celebra el 12 de octubre en la mayor parte de Hispanoamérica, España y los Estados Unidos entre otros países. Fue creado a partir del siglo XX, inicialmente de forma espontánea y no oficial, para conmemorar una nueva identidad cultural, producto del encuentro y fusión entre los pueblos indígenas de América y los colonizadores españoles, además de la valorización del patrimonio cultural hispanoamericano. Aunque el nombre «Día de la Raza» es el más popular en la actualidad, el nombre oficial suele variar de un país a otro: en España es el Día de la Fiesta Nacional o Día de la Hispanidad, en Estados Unidos es Columbus Day o Día de Cristóbal Colón, en Chile y Perú se denomina Día del Encuentro de Dos Mundos, en Argentina recibe el nombre de Día del Respeto a la Diversidad Cultural. Por otra parte, algunos países han optado por reivindicar claramente las posiciones de los pueblos originaros y han decidido conmemorar en esta fecha el Día de la resistencia indígena. - El Día de la Raza

・しかしながら、現在では、この日は(新大陸の発見 の日を記念するよりも)人種・民族の多様性を祝う日になったり、現在では、征服への抵抗を記念すべき日への解釈されている——日本の建国記念日に似てい る?

・人種も民族も、ラテンアメリカの日常的用語法で は、人間集団の本質的差異を表現するものとして、それほど区分されるものとして使われていない。しかし、文化人類学ならびに先住民やマイノリティへの社会 活動家たちの影響で、人種よりも民族という用語法がより好んで使われる傾向にある。

・汎マヤ運動などでは(それぞれの言語集団の区別に よるグループ内で/あるいはそれらのグループの連合体で)マヤ民族の集団的統一性や文化の本質性が強調されるが、その際も、人種概念よりも民族概念を(よ り優先して)使われる。——政治的解放の言説が動員される時には、文化人類学/文化人類学者は、植民地科学/植民地主義者として分類され、反感を持たれる ことも事実だ。

・ブラジルは、沿岸部および内陸の農園労働で黒人奴 隷の比率が高いために、褐色(pardo)——スペイン語 marron——を、混血の伝統として表現することがある。

・北米のような「一滴のルール(one-drop rule)」のような原則はラテンアメリカでは通用せず、パーセントなどの「血液の分量/比率」で人種的特性を表現する。

・白人性は、19世紀後半から20 世紀初頭にヨーロッパからの移民が多い南部ブラジル、アルゼンチン、ウルグアイなどで、人種的にはより包摂するカテゴリーとして機能している。当然のこと に、自身がヨーロッパ起源の出自の認識がある人には、その白人性の優越の意識が強い。コスタリカやドミニカ共和国のような(相対的に)ヨーロッパからの移 民の比率がそれほど高くない国家にも、白人性を優越させる傾向がある。

・先のMarisol de la Cadena のインフォーマントたちの例のように、先住民かメスティーソという自己定義も(言語使用などのような帰属要件が制限されるようなケースを除いて——同時に 外部者が言語使用につよく拘われば排外主義的なレイシストと見なされる可能性すらある)容易に変化しうる可能性を残している。

・植民地期には、ムラートや、メスティーソは、エス パニョール(クリオーリョ)と結婚しようとした、それは貢納から逃れる手段であったが、同時に、血を清潔に(sangre limpia)をする手段でもあった。

・白人化することだけが、何らかの社会的身分を上げ

ることだけではなかった。先住民との婚姻を通して、メスティーソが先住民化することもあった。その場合は、カシーケの家族との姻戚関係になることで、カ

シーケの権力を簒奪することである。あるいは、トゥパック・アマル2世のように、メスティーソ出自の彼が、インカの王権の正統な継承者として振る舞うこと

で、先住民反乱のリーダーになることがある。

クレジット:(旧ページ名)「人種的カテゴリー再 考」ラテンアメリカにおける「人種概念」に関する研究ノート・メモである。

"Crypto-Judaism is the secret adherence to Judaism while publicly professing to be of another faith; practitioners are referred to as "crypto-Jews" (origin from Greek kryptos – κρυπτός, 'hidden'). The term is especially applied historically to Spanish Jews who outwardly professed Catholicism,[1][2][3][4][5] also known as Anusim or Marranos. The phenomenon is especially associated with renaissance Spain, following the Massacre of 1391 and the expulsion of the Jews in 1492.[6]" - Crypto-Judaism.

"Criptojudaísmo

es la adhesión confidencial al judaísmo mientras se declara

públicamente ser de otra fe. A las personas que practican

criptojudaísmo se les refiere como cripto-judíos o criptojudíos. El

término criptojudío también se utiliza para describir a descendientes

de judíos que todavía –en general en secreto– mantienen algunas

costumbres judías, a menudo mientras se adhieren a las otras

religiones, más comúnmente el cristianismo." - Criptojudaísmo.

★Race and ethnicity in Latin America(ラテンアメリカにおける人種と民族)

| There is no single

system of races or ethnicities that covers all modern Latin America,

and usage of labels may vary substantially. In Mexico, for example, the category mestizo[1] is not defined or applied the same as the corresponding category of mestiço in Brazil. In spite of these differences, the construction of race in Latin America can be contrasted with concepts of race and ethnicity in the United States. The ethno-racial composition of modern-day Latin American nations combines diverse Indigenous American populations, with influence from Iberian and other Western European colonizers, and equally diverse African groups brought to the Americas as slave labor, and also recent immigrant groups from all over the world. Racial categories in Latin America are often linked to both continental ancestry or mixture as inferred from phenotypical traits, but also to socio-economic status. Ethnicity is often constructed either as an amalgam national identity or as something reserved for the indigenous groups so that ethnic identity is something that members of indigenous groups have in addition to their national identity. Racial and ethnic discrimination is common in Latin America where socio-economic status generally correlates with perceived whiteness, while indigenous status and perceived African ancestry is generally correlated with poverty, and lack of opportunity and social status. |

現代のラテンアメリカ全体をカバーする単一の人種や民族のシステムは存

在せず、ラベルの使い方も大きく異なる場合がある。 例えばメキシコでは、メスティーソ[1]というカテゴリーは、ブラジルのメスティーソというカテゴリーと同じ定義や適用ではない。 こうした違いにもかかわらず、ラテンアメリカにおける人種の構築は、アメリカにおける人種や民族の概念と対比することができる。現代のラテンアメリカ諸国 の民族・人種構成は、イベリア半島をはじめとする西ヨーロッパの植民地からの影響を受けた多様なアメリカ先住民集団と、奴隷労働者としてアメリカ大陸に連 れてこられた同じく多様なアフリカ人集団、さらに世界各地からの最近の移民集団が組み合わさっている。 ラテンアメリカの人種カテゴリーは、表現型特徴から推測される大陸的な祖先や混血だけでなく、社会経済的な地位とも関連していることが多い。エスニシティ はしばしば、アマルガム的な国民的アイデンティティとして、あるいは先住民族にのみ許されたものとして構築され、民族的アイデンティティは先住民族の構成 員が国民的アイデンティティに加えて持つものである。 ラテンアメリカでは人種的・民族的差別が一般的であり、社会経済的地位は一般的に白人であると認識されることと相関するが、先住民族であることやアフリカ 系であると認識されることは一般的に貧困や機会不足、社会的地位の欠如と相関する。 |

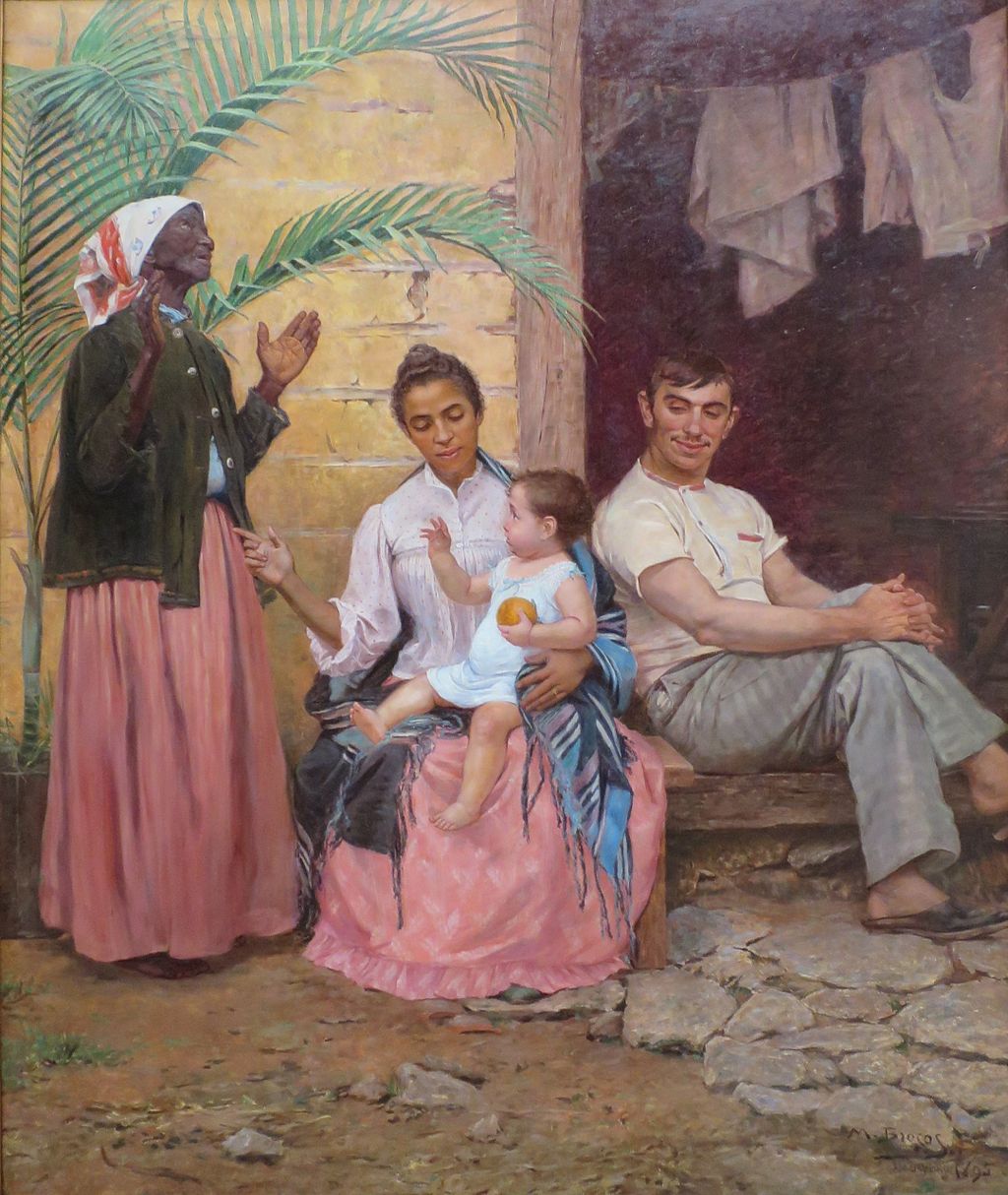

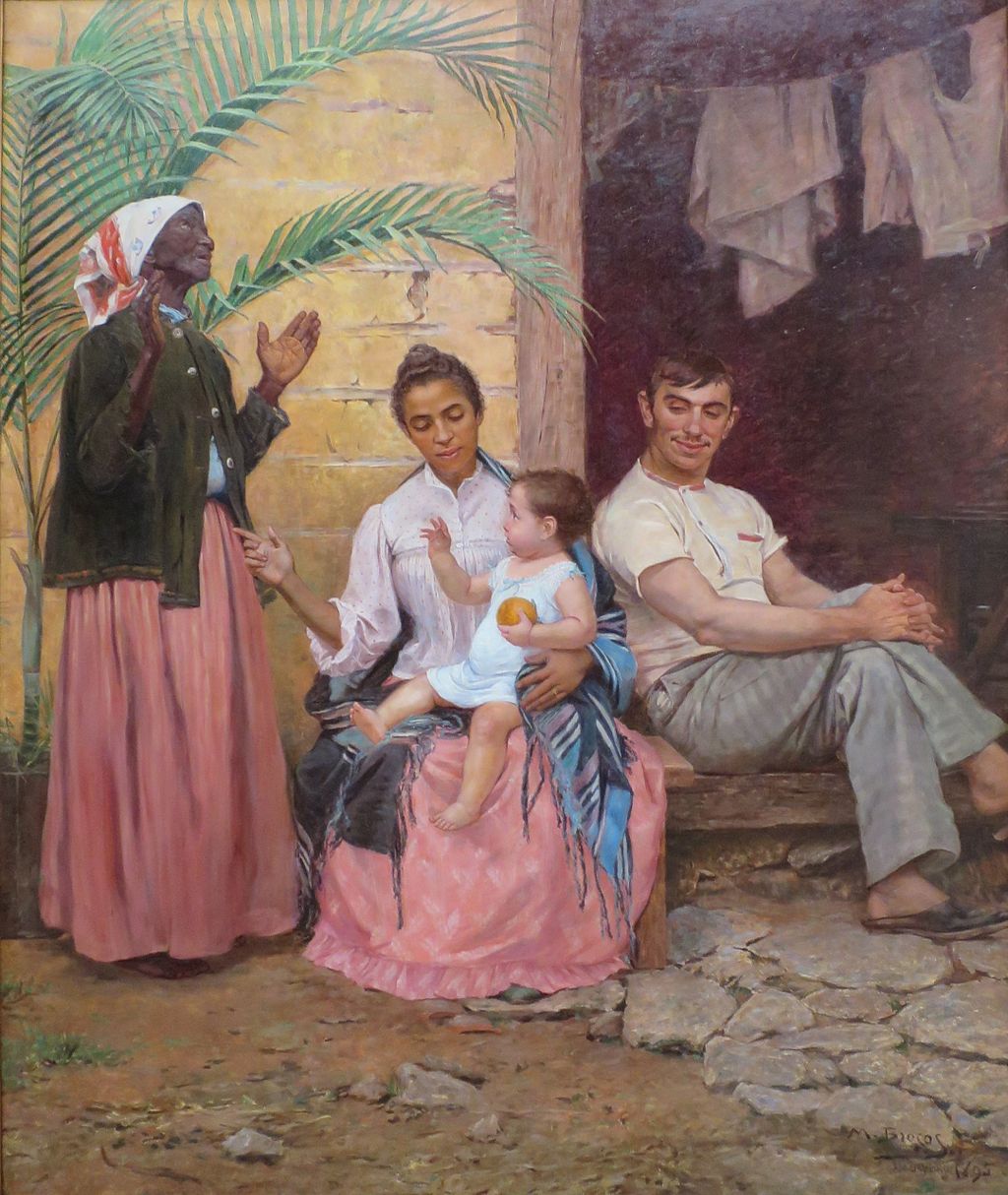

| Concepts of race and ethnicity Further information: La Raza and Limpieza de Sangre In Latin American concepts of race, physiological traits are often combined with social traits such as socio-economic status, so that a person is categorized not only according to physical phenotype but also social standing.[2][3] Ethnicity on the other hand is a system that classifies groups of people according to cultural, linguistic and historic criteria. An ethnic group is normally defined by having a degree of cultural and linguistic similarity and often an ideology of shared roots. Another difference between race and ethnicity is that race is usually conceptualized as a system of categorization where membership is limited to one category and is externally ascribed by other who are not members of that category without regards to the individuals own feeling of membership. Whereas ethnicity is often seen as a system of social organization where membership is established through mutual identification between a group and its members. The construction of race in Latin America is different from, for example, the model found in the United States, possibly because race mixing has been a common practice since the early colonial period, whereas in the United States it has generally been avoided or severely sanctioned.[4] Moreover, phenotypical appearance determines racial classification more than strict ancestry.[5] Blanqueamiento Main article: Blanqueamiento  A Redenção de Cam (Redemption of Ham), by Galician painter Modesto Brocos, 1895, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, Brazil. The painting depicts a black grandmother, mulatta mother, white father and their quadroon child, hence three generations of racial hypergamy through whitening. Blanqueamiento, or whitening, is a social, political, and economic practice used to "improve" the race (mejorar la raza) towards whiteness.[6] The term blanqueamiento is rooted in Latin America and is used more or less synonymous with racial whitening. However, blanqueamiento can be considered in both the symbolic and biological sense [7] Symbolically, blanqueamiento represents an ideology that emerged from legacies of European colonialism, described by Anibal Quijano's theory of coloniality of power, which caters to white dominance in social hierarchies [8] Biologically, blanqueamiento is the process of whitening by marrying a lighter skinned individual in order to produce lighter-skinned offspring.[8] Blanqueamiento was enacted in national policies of many Latin American countries, particularly Brazil, Venezuela and Cuba, at the turn of the 20th century.[9][10][11] In most cases, these policies promoted European immigration as a means to whiten the population.[12] Mestizaje Main article: Mestizaje An important phenomenon described for some parts of Latin America is "Whitening" or "Mestizaje" describing the policy of planned racial mixing with the purpose of minimizing the non-white part of the population.[13][14] This practice was possible as in these countries one is classified as white even with very few white phenotypical traits and it has meant that the percentages of people identifying as fully black or indigenous has increased over the course of the twentieth century as the mixed class expanded.[15][16] It has also meant that the racial categories have been fluid.[17][18][19][20] Unlike the United States where ancestry is used to define race, Latin American scholars came to agree by the 1970s that race in Latin America could not be understood as the “genetic composition of individuals” but instead “based upon a combination of cultural, social, and somatic considerations. In Latin America, a person's ancestry is quite irrelevant to racial classification. For example, full-blooded siblings can often be classified by different races (Harris 1964).[21][22] |

人種と民族の概念 さらに詳しい情報 ラ・ラサ(La Raza)とリムピエサ・デ・サングレ(Limpieza de Sangre) ラテンアメリカの人種概念では、生理学的形質が社会経済的地位などの社会的形質と組み合わされることが多く、身体的表現型だけでなく社会的地位によっても 分類される。民族集団は通常、文化的・言語的な類似性を持つことによって定義され、多くの場合、ルーツを共有するというイデオロギーを持つ。人種とエスニ シティのもう一つの違いは、人種は通常、一つのカテゴリーに限定され、そのカテゴリーのメンバーでない他の人々によって、個人のメンバーシップ意識とは無 関係に外的に帰属させられる、カテゴリー化のシステムとして概念化されていることである。一方、エスニシティはしばしば、集団とその構成員との間の相互同 一性によってメンバーシップが確立される社会組織のシステムと見なされる。 ラテンアメリカにおける人種の構築は、例えばアメリカ合衆国で見られるモデルとは異なっている。おそらく、人種混合が植民地時代初期から一般的に行われて きたのに対し、アメリカ合衆国では一般的に避けられるか、厳しく制裁されてきたからであろう[4]。さらに、厳密な祖先よりも表現型の外見が人種分類を決 定する[5]。 ブランキアミエント 主な記事 ブランキアミエント  ガリシア人画家モデスト・ブロコスの作品『ハムの贖罪』(1895年、ブラジル国立美術館蔵)。この絵には、黒人の祖母、ムラッタの母、白人の父、そして クアドルーン人の子供が描かれている。 ブランケアミエント(白色化)とは、白色化に向けて人種を「改善」(mejorar la raza)するために用いられる社会的、政治的、経済的実践である[6]。ブランケアミエントという用語はラテンアメリカに根ざしており、人種的白色化と 多かれ少なかれ同義語として用いられている。しかし、ブランケアミエントは象徴的な意味でも生物学的な意味でも考えることができる[7]。象徴的には、ブ ランケアミエントはヨーロッパ植民地主義の遺産から生まれたイデオロギーを表しており、アニバル・キハノの「権力の植民地性」理論によって説明され、社会 階層における白人の優位に配慮している[8]。生物学的には、ブランケアミエントとは、肌の白い子孫を残すために、肌の白い個体と結婚することによって美 白化するプロセスのことである[8]。 ブランキアミエントは、20世紀に入ってから多くのラテンアメリカ諸国、特にブラジル、ベネズエラ、キューバの国策として制定された[9][10] [11]。ほとんどの場合、これらの政策は人口を白くする手段としてヨーロッパからの移民を促進した[12]。 メスティサヘ 主な記事 メスティサヘ ラテンアメリカのいくつかの地域で説明される重要な現象は、人口の非白人部分を最小限に抑えることを目的とした計画的な人種混合政策を説明する「ホワイト ニング」または「メスティサヘ」である[13][14]。これらの国々では、白人の表現形質がほとんどなくても白人として分類されるため、この実践は可能 であった。 [15][16]それはまた、人種のカテゴリーが流動的であることを意味している。[17][18][19][20]祖先の血統が人種を定義するために使 用されるアメリカとは異なり、ラテンアメリカの学者たちは1970年代までに、ラテンアメリカにおける人種は「個人の遺伝的構成」として理解されるのでは なく、「文化的、社会的、身体的な考慮の組み合わせに基づく」ものであるという見解で一致するようになった。ラテンアメリカでは、祖先の血統は人種分類と はまったく無関係である。例えば、完全な血縁関係にある兄弟姉妹はしばしば異なる人種に分類されることがある(Harris 1964)[21][22]。 |

| North/Central America Mexico Main article: Mexicans § Ethnic groups Racial and ethnic ideologies  De negro é española sale mulato "from black man and Spanish woman comes mulatto." (Pintura de castas, ca. 1780), Unknown author, Mexico Very generally speaking ethno-racial relations can be arranged on an axis between the two extremes of European and Indigenous American cultural and biological heritage, this is a remnant of the colonial Spanish caste system which categorized individuals according to their perceived level of biological mixture between the two groups. Additionally the presence of considerable portions of the population with partly African and Asian heritage further complicates the situation. Even though it still arranges persons along the line between indigenous and European, in practice the classificatory system is no longer biologically based, but rather mixes socio-cultural traits with phenotypical traits, and classification is largely fluid, allowing individuals to move between categories and define their ethnic and racial identities situationally.[23][24] Generally, it can be said that in scholarship, as well as popular discourse, there has been a tendency of talking about indigenous peoples in terms of ethnicity, about Afro-minorities and white socio-economic privilege in terms of race, and about mestizos in terms of national identity. It is now however becoming recognized that processes of identity formation and social stratification in regards to all population groups in Mexico can be analyzed both in terms of race and of ethnicity. Racial and ethnical terms Mestizaje Main article: Mestizaje In Mexico in the post-revolutionary period, Mestizaje was a racial ideology that combined elements of the Euro-American ideologies of the racial superiority of the "white race" with the social reality of a postcolonial, multiracial setting. It promoted the use of planned miscegenation as a eugenic strategy designed (in their conception) to improve the overall quality of the population by multiplying white genetic material to the entire population. This ideology was very different from the way the eugenics debate was carried out in Europe and North America, where racial "purity" and anti-miscegenation legislation was the eugenic strategy of choice. The ideology of Mestizaje came from the long tradition of tolerance of racial mixing that existed in the Spanish colonies.[13] The ideology was also a part of the strategy of forging a national identity to serve as the basis of a modern nation state, and for this reason mestizaje also became a way of fusing disparate cultural identities into a single national ethnicity.[25][26] The ideology was influently worded by José Vasconcelos who in his La Raza Cósmica formulated a vision of how a "race of the future" would be created by mixing the mongoloid, negroid, and caucasian races. As the place where this mixing was already well underway, Mexico, and Latin America in general, was the center of the creation of this new and improved species of human beings, the mestizo. Mestizos The large majority of Mexicans classify themselves as "Mestizos", meaning that they neither identify fully with any indigenous culture or with a particular non-Mexican heritage, but rather identify as having cultural traits and heritage that is mixed by elements from indigenous and European traditions. By the deliberate efforts of post-revolutionary governments the "Mestizo identity" was constructed as the base of the modern Mexican national identity, through a process of cultural synthesis referred to as mestizaje. Mexican politicians and reformers such as José Vasconcelos and Manuel Gamio were instrumental in building a Mexican national identity on the concept of mestizaje (see the section below).[27][28] The term "Mestizo" is not in wide use in Mexican society today and has been dropped as a category in population censuses, it is however still used in social and cultural studies when referring to the non-indigenous part of the Mexican population. The word has somewhat pejorative connotations and most of the Mexican citizens who would be defined as mestizos in the sociological literature would probably self-identify primarily as Mexicans. In the Yucatán peninsula, the word Mestizo is even used about Maya speaking populations living in traditional communities, because during the Caste War of the late 19th century those Maya who did not join the rebellion were classified as mestizos.[29] In Chiapas the word "Ladino" is used instead of mestizo.[30] Sometimes, particularly outside of Mexico, the word "mestizo" is used with the meaning of a person with mixed indigenous and European blood. This usage does not conform to the Mexican social reality where, like in Brazil, a person of mostly indigenous genetic heritage would be considered Mestizo either by rejecting his indigenous culture or by not speaking an indigenous language,[29] and a person with a very low percentage of indigenous genetic heritage would be considered fully indigenous either by speaking an indigenous language or by identifying with a particular indigenous cultural heritage.[31] Additionally the categories carry additional meanings having to do with social class so that the term indigena or the more pejorative "indio" (Indian) is connected with ideas of low social class, poverty, rural background, superstition, being dominated by traditional values as opposed to reason. Commonly, instead of the term Mestizo, which also has a somewhat pejorative usage, the term "gente de razón" ("people of reason") is used and contrasted with "gente de costumbre" ("people of tradition"), cementing the status of indigeneity being connected to superstition and backwardness. For example, it has been observed that upwards social mobility is generally correlated with "whitening", if persons with indigenous biological and cultural roots rise to positions of power and prestige they tend to be viewed as more "white" than if they belonged to a lower social class.[31] Indigenous groups Prior to contact with Europeans the indigenous peoples of Mexico had not had any kind of shared identity.[32] Indigenous identity was constructed by the dominant Euro-Mestizo majority and imposed upon the indigenous people as a negatively defined identity, characterized by the lack of assimilation into modern Mexico. Indian identity therefore became socially stigmatizing.[33] Cultural policies in early post-revolutionary Mexico were paternalistic towards the indigenous people, with efforts designed to "help" indigenous peoples achieve the same level of progress as the rest of society, eventually assimilating indigenous peoples completely to Mestizo Mexican culture, working toward the goal of eventually solving the "indian problem" by transforming indigenous communities into mestizo communities .[34] The category of "indígena" (indigenous) is a modern term in Spanish America for those termed Indios ("Indians") in the colonial era. They can be defined narrowly according to linguistic criteria including only persons that speak one of Mexico's 62 indigenous languages, this is the categorization used by the National Mexican Institute of Statistics. It can also be defined broadly to include all persons who self-identify as having an indigenous cultural background, whether or not they speak the language of the indigenous group they identify with. This means that the percentage of the Mexican population defined as "indigenous" varies according to the definition applied, cultural activists have referred to the usage of the narrow definition of the term for census purposes as "statistical genocide".[35][36] |

北中米 メキシコ 主な記事 メキシコ人§民族グループ 人種的・民族的イデオロギー  De negro é española sale mulato「黒人男性とスペイン人女性から混血が生まれる。(1780年頃)作者不詳、メキシコ ごく一般的に言えば、民族・人種関係は、ヨーロッパ人とアメリカ先住民の文化的・生物学的遺産の両極端を軸に整理することができるが、これは植民地時代の スペインのカースト制度の名残であり、このカースト制度は、2つのグループの間の生物学的混血の認知度によって個人を分類していた。さらに、人口のかなり の部分がアフリカやアジアの血を受け継いでいることが、状況をさらに複雑にしている。今でも先住民族とヨーロッパ人という線に沿って個人を分類していると はいえ、実際には分類システムはもはや生物学的ベースではなく、むしろ社会文化的形質と表現型形質が混在しており、分類は大部分が流動的であるため、個人 はカテゴリー間を移動し、状況に応じて民族的・人種的アイデンティティを定義することができる[23][24]。 一般的に、学問においても一般的な言説においても、先住民については民族の観点から、アフロ・マイノリティと白人の社会経済的特権については人種の観点か ら、メスチゾについては国民的アイデンティティの観点から語られる傾向があるといえる。しかし、現在では、メキシコのすべての人口集団に関するアイデン ティティの形成過程と社会階層は、人種と民族の両方の観点から分析できることが認識されつつある。 人種と民族の用語 ︎メスティーソ 主な記事 メスチサヘ 革命後のメキシコにおいて、メスティサヘは、「白人種」の人種的優越性というヨーロッパ・アメリカのイデオロギーの要素と、ポストコロニアルの多人種とい う社会的現実を組み合わせた人種イデオロギーであった。このイデオロギーは、白人の遺伝物質を全人口に増殖させることによって、人口全体の質を向上させる ことを目的とした優生学的戦略として、計画的な混血を推進した。このイデオロギーは、人種の「純粋性」と混血防止法が優生戦略として選択されていたヨー ロッパや北米での優生学論争の進め方とは大きく異なっていた。メスティサヘのイデオロギーは、スペインの植民地に存在した人種混合に対する寛容さの長い伝 統から生まれた[13]。 このイデオロギーはまた、近代国民国家の基礎となる国民的アイデンティティを形成する戦略の一部でもあり、この理由からメスティサヘはまた、異質な文化的 アイデンティティを単一の国民的エスニシティに融合させる手段ともなった[25][26]。 このイデオロギーは、ホセ・ヴァスコンセロス(José Vasconcelos)が『La Raza Cósmica』の中で、モンゴロイド、ネグロイド、コーカソイドの混血によって「未来の人種」がどのように創造されるかというヴィジョンを提示したこと に影響を受けている。この混血がすでに進行していたメキシコ、そしてラテンアメリカ全般が、この新しい改良型人類、メスティーソを生み出す中心地となっ た。 ︎メスティーソ メキシコ人の大多数は、自らを「メスティーソ」と分類している。つまり、土着の文化や特定の非メキシコ的遺産を完全に自認しているわけではなく、むしろ、 土着の伝統とヨーロッパの伝統の要素が混ざり合った文化的特徴や遺産を持っていると自認しているのである。革命後の政府による意図的な努力によって、「メ スティーソのアイデンティティ」は、メスティーサヘと呼ばれる文化的統合のプロセスを通じて、現代のメキシコ国民アイデンティティの基盤として構築され た。ホセ・バスコンセロスやマヌエル・ガミオといったメキシコの政治家や改革者たちは、メスティサヘの概念に基づくメキシコの国民的アイデンティティの構 築に尽力した(以下のセクションを参照)[27][28]。 メスチーソ」という言葉は、今日のメキシコ社会ではあまり使われておらず、人口調査でもカテゴリーから外れている。しかし、社会学や文化研究において、メ キシコの人口の非先住民の部分を指すときにはまだ使われている。この言葉にはやや侮蔑的な意味合いがあり、社会学の文献でメスティーソと定義されているメ キシコ国民のほとんどは、おそらく主にメキシコ人であると自認しているだろう。ユカタン半島では、19世紀末のカースト戦争の際、反乱に参加しなかったマ ヤ人はメスティーソに分類されたため、伝統的な共同体に住むマヤ語を話す人々に対してさえメスティーソという言葉が使われる[29]。 特にメキシコ国外では、「メスティーソ」という言葉が先住民とヨーロッパ人の混血という意味で使われることがある。この用法は、ブラジルのように、先住民 の遺伝子をほとんど受け継いでいる人は、先住民の文化を拒絶するか、先住民の言語を話さないことでメスティーソとみなされ[29]、先住民の遺伝子の割合 が非常に低い人は、先住民の言語を話すか、特定の先住民の文化遺産を持つことで完全に先住民とみなされる[31]。 [31]さらに、このカテゴリーには社会階層に関連する意味も含まれており、インディヘナ(indigena)またはより侮蔑的な「インディオ (indio)」(インド人)という用語は、社会階層の低さ、貧困、農村出身、迷信、理性とは対照的な伝統的価値観に支配されているという考えと結びつい ている。一般的に、メスティーソ(Mestizo)というやや侮蔑的な用法の代わりに、「gente de razón」(「理性の人々」)という言葉が使われ、「gente de costumbre」(「伝統の人々」)と対比される。例えば、上方への社会的移動は一般的に「白人化」と相関していることが観察されており、先住民の生 物学的・文化的ルーツを持つ人物が権力や名声のある地位に就くと、より低い社会階級に属する場合よりも「白人」とみなされる傾向がある[31]。 先住民族 ヨーロッパ人との接触以前には、メキシコの先住民族はいかなる種類の共有アイデンティティも持っていなかった[32]。先住民族のアイデンティティは、支 配的な多数派であるヨーロッパ系メスティーソによって構築され、近代メキシコへの同化の欠如を特徴とする否定的に定義されたアイデンティティとして先住民 族に押し付けられた。革命後初期のメキシコにおける文化政策は先住民に対して父権的であり、先住民が他の社会と同じレベルの進歩を達成する「手助け」をす るための努力がなされ、最終的には先住民を完全にメスティーソのメキシコ文化に同化させ、最終的には先住民のコミュニティをメスティーソのコミュニティに 変えることで「インディアン問題」を解決するという目標に向かっていた[34]。 インディヘナ」(先住民)というカテゴリーは、植民地時代にインディオ(「インディオ」)と呼ばれていた人々のスペイン領アメリカにおける現代用語であ る。先住民は、メキシコの62の先住民言語のいずれかを話す人だけを含む言語的基準に従って狭く定義することができ、これはメキシコ国立統計研究所によっ て使用されている分類である。また、先住民族の文化的背景を持つことを自認するすべての人を含むという広義の定義も可能で、その場合、自認する先住民族の 言語を話すかどうかは問わない。つまり、「先住民」と定義されるメキシコ人口の割合は、適用される定義によって異なるということであり、文化活動家たち は、国勢調査の目的のために狭い定義でこの用語を使用することを「統計的ジェノサイド」と呼んでいる[35][36]。 |

| Central America Cuba In Cuba, people are defined as either “blanco” (white), “negro” (black) or “mulatto” (mixed African and European) Subdivisions for these include “Trigueño” which means a person of Mediterranean ancestry or phenotype. Someone who has dark hair, eyes and tan skin but is not indigenous, African nor Arab are described as “trigueño”. Another term is “prieto” which describes someone with a darker skin than “trigueño” but lighter than “negro”. “Habao” is a term used to describe European people with light afro hair or pale skin with African features. “Achinado” refers to anyone who has vaguely Asiatic eyes without being East Asian, while “chino” refers to anyone who is of East Asian ancestry. “blanquito” quite literally translates to the little white one and it just means anyone who is European with lighter features than that of a “trigueño”. |

中央アメリカ キューバ キューバでは、人々は「ブランコ」(白人)、「ネグロ」(黒人)、「ムラート」(アフリカ系とヨーロッパ系の混血)のいずれかに定義される。黒い髪、目、 日焼けした肌を持っているが、先住民でもアフリカ人でもアラブ人でもない人を「トリゲーニョ」と表現する。また、「tigueño 」よりも黒く、「negro 」よりも明るい肌を持つ人を表す 「prieto 」という言葉もある。 「ハバオ "は、明るいアフロヘアやアフリカの特徴を持つ色白の肌を持つヨーロッパ人を表す言葉である。「Achinado 「は、東アジア人でなくても、どことなくアジア的な目をしている人を指し、」chino "は、東アジアの先祖を持つ人を指す。ブランキート(blanquito)」は、直訳すると「小さな白い人」で、「トリゲーニョ(tigueño)」より も色白のヨーロッパ人を意味する。 |

| South America Brazil Main article: Race and ethnicity in Brazil Racial and ethnical ideologies Brazilians are made up of a mixed race of individuals with native Brazilian ancestry, Portuguese or other European,Asian and African descent. Racial and ethnical terms The five racial categories in which the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistic has for the population is Branco, Pardo, Preto, Amarelo, and Indigena. Furthermore, Brazil has three different systems for racial classification. These systems are dependent on a white to black spectrum. Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics First Racial System in the Brazilian Census: branco, pardo, preto, amarela, indigena. Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statisticts Second Racial System in the Brazilian Census: Inspired by a census of open ended question. Acquired similar but more specific racial terms. Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statisticts Third Racial System is the Black Movement: pardos and pretos and negros. Afro descendant is a term that is getting brought more to use by this movement. 【図表省略】 Colombia Main articles: Race and ethnicity in Colombia and Colombia Racial and ethnical ideologies Colombian government acknowledges three ethnic minority groups: Afro Colombians, Indigenous, and Romani. In difference, the non-ethnic population are mestizos and whites, who make up 86% of the Colombian population in the 2005 census. Mestizos and whites live in urban areas, mainly in the Andean highlands. Afro Colombians (Black, Zambo, and Mulattoes) are near the coastal areas and in Cauca and Magdalena rivers. Raizales inhabit Archipielago of San Andres and they keep their British influences through the practice of Protestantism, and English based creole language use. Racial and ethnical terms 【図表省略】 Indigenous groups The Indigenous American population in Colombia as of 2005 is 4.3 million people or 3.4% of the population. Despite a small population, this community has a large self-government within Colombian municipalities. In fact almost 25% of the country's land titles have been regained by the indigenous population. Ecuador Racial and ethnical ideologies Indigenous, Afro descendants, and Spanish descendants make up the ethno-racial groups in Ecuador. Ethnic identification is dependent on phenotypes though there is a tendency to identify as Mestizo.[37] El Hombre Ecuatoriano: "The Ecuadorian Man" Mejorar La Raza: "Improve the Race" There is a nationalization effort in Ecuador to homogenize the country's ethnicity. Nonetheless, a great focus on white supremacy can be seen behind this effort which is negates the effort of "inclusion" as per this nationalization effort. Racial and ethnic terms 【図表省略】 Indigenous groups The indigenous individuals of Ecuador are descendant of the Inca Empire. The Inca empire imposed their culture and Quechua language to diverse indigenous cultures that had already been in the Guayas river basin in the early 10th century BC. Another indigenous group within Ecuador are the Amazonians who are the most isolated. The "Levantamientos" Indigenous people uprising in response to disenfranchisement. The Levantamiento Indigena called for Ecuador to be classified as a plurination, agrarian redistribution, and validation of former indigenous lands. This all was through the formation of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador, CONAIE. List of indigenous nations represented by CONAIE: Highland Kichwa Eastern Amazonian Kichwa Achuar Cofan Huaorani Secoya Shuar Siona Zapara Awa Chachi Espera Mata Tsachila Wankavilka 【図表省略】 Peru Racial and ethnical ideologies The ethnic Peruvian structure is mestizos, indigenous Peruvian, white or Europeans, afro Peruvian, and Asian Peruvians. Ethnic groups or indigenous individuals are all treated as Peruvian.[38][better source needed] Racial and ethnical terms |

南米 ブラジル 主な記事 ブラジルの人種と民族 人種と民族のイデオロギー ブラジル人は、祖先がブラジル人、ポルトガル人、その他のヨーロッパ系、アジア系、アフリカ系の混血で構成されている。 人種と民族の用語 ブラジル地理統計院が人口を5つの人種に分類しており、ブランコ、パルド、プレト、アマレロ、インディヘナである。さらに、ブラジルには3つの異なる人種 分類システムがある。これらのシステムは、白人から黒人までのスペクトルに依存している。 ブラジル地理統計院 ブラジル国勢調査における最初の人種システム:ブランコ、パルド、プレト、アマレーラ、インディヘナ。 ブラジル地理統計院 ブラジル国勢調査における第二の人種制度: ブラジルの国勢調査における第二の人種制度。似たような、しかしより具体的な人種用語を獲得した。 ブラジル地理統計研究所の第3の人種システムは、黒人運動である。アフロの子孫という言葉は、この運動によって使われるようになった。 【図表省略】 コロンビア 主な記事 コロンビアの人種と民族、コロンビア 人種・民族イデオロギー コロンビア政府は3つの少数民族を認めている: アフリカ系コロンビア人、インディヘナ、ロマニである。それに対して、非民族はメスチソと白人で、2005年の国勢調査ではコロンビア人口の86%を占め る。 メスティーソと白人は主にアンデス高地の都市部に住んでいる。 アフロ系コロンビア人(黒人、ザンボ、ムラート)は、沿岸部やカウカ川、マグダレナ川周辺にいる。ライサレス人はサン・アンドレス群島に居住し、プロテス タントの実践や英語をベースとしたクレオール語の使用を通じて、イギリスの影響を受け続けている。 人種・民族用語 【図表省略】 先住民グループ 2005年現在、コロンビアのアメリカ先住民人口は430万人で、人口の3.4%である。人口が少ないにもかかわらず、このコミュニティはコロンビアの自 治体内で大きな自治権を持っている。実際、コロンビアの土地の25%近くが先住民によって取り戻されている。 エクアドル 人種的・民族的イデオロギー エクアドルでは、先住民、アフロ系、スペイン系が民族・人種グループを形成している。民族の識別は表現型に依存するが、メスティーソとして識別される傾向 がある[37]。 El Hombre Ecuatoriano:「エクアドル人男性」 Mejorar La Raza: 「人種を改善する」 エクアドルでは、国の民族性を均質化するための国営化の取り組みが行われている。それにもかかわらず、この努力の背後には白人至上主義に大きな焦点が当て られていることが見て取れ、この国有化の努力にあるような「包摂」の努力を否定している。 人種・民族用語 【図表省略】 先住民族 エクアドルの先住民は、インカ帝国の末裔である。インカ帝国は、紀元前10世紀初頭にすでにグアヤス川流域に存在していた多様な先住民文化に、彼らの文化 とケチュア語を押し付けた。エクアドルのもうひとつの先住民グループは、最も孤立しているアマゾン人である。 「レバンタミエントス」 先住民の権利剥奪に対する蜂起。レバンタミエント・インディヘナは、エクアドルを単一民族国家に分類し、農地再分配を行い、かつての先住民の土地を有効活 用することを求めた。これはすべて、エクアドル先住民族連合(CONAIE)の結成によるものであった。 CONAIEが代表する先住民族のリスト 高地キチュワ族 アマゾン東部キチュワ族 アチュア コファン フアオラニ セコヤ シュアール シオナ サパラ アワ チャチ エスペラ マタ ツァチラ ワンカビルカ 【図表省略】 ペルー 人種的・民族的イデオロギー ペルーの民族構成は、メスチソ、ペルー先住民、白人またはヨーロッパ人、アフロ・ペルー人、アジア系ペルー人である。民族グループや先住民はすべてペルー 人として扱われる[38][要出典]。 人種・民族用語 |

| Casta Ethnic groups in Latin America |

カスタ ラテンアメリカの民族グループ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Race_and_ethnicity_in_Latin_America |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆