カチカチ音楽

Cachi Cachi music, Kachi Kachi

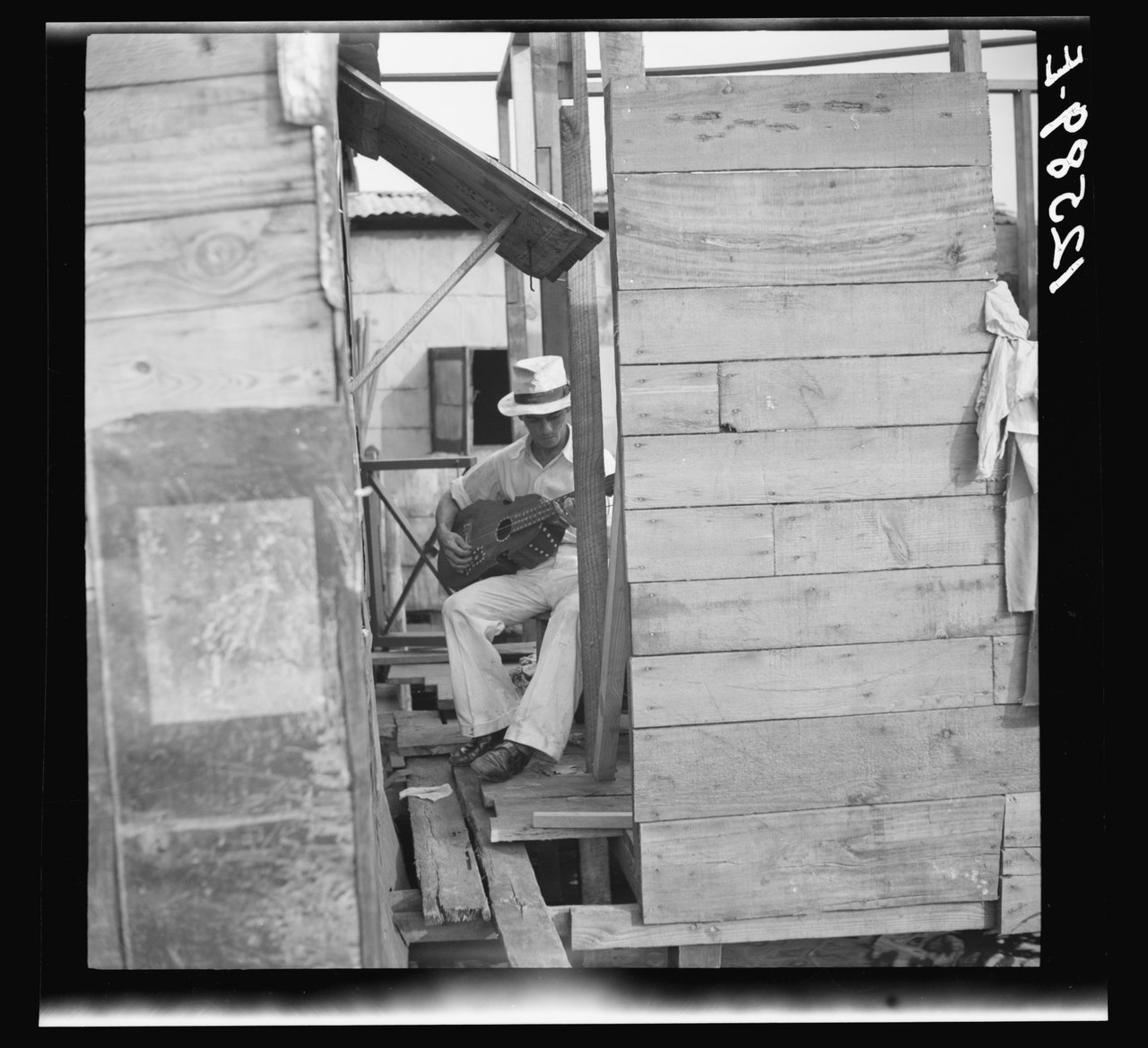

Wally Rita Y Los Kauaianos ; El Cuatro Puertorriqueño (1938): Guitar

player above the swamp water. The workers' quarter of Puerto de Tierra.

San Juan, Puerto Rico

カチカチ音楽

Cachi Cachi music, Kachi Kachi

Wally Rita Y Los Kauaianos ; El Cuatro Puertorriqueño (1938): Guitar

player above the swamp water. The workers' quarter of Puerto de Tierra.

San Juan, Puerto Rico

★カチカチ音楽(Cachi Cachi music)は、Kachi Kachi、Kachi-Kachi、Katchi-Katchiと も表記され、1901年にハワイに移住したプエルトリコ人が演奏する音楽を指す造語である。ハワイで見つけられるダンス音楽のバリエーション」であり、時 に非常に速く演奏される。「ハワイへの影響は、プエルトリコのヒバロスタイルの派生である四つ打ちのカチカチと呼ばれる音楽形態に今日まで残っている」。 ヒバロとはスペイン語で農夫のことであり、ハワイでプエルトリコ人は「よく働きよく遊ぶ」音楽で他のプランテーション労働者への負担を軽くしたと言われて いる。カチカチの名称は、サトウキビ労働に従事する日系移民のひとたちが、隣接して働くプエルトリコ人たちの音楽を表現した言葉に由来する、と言われる。

| Cachi Cachi music,

also spelled Kachi Kachi, Kachi-Kachi[1] and Katchi-Katchi,[2] is a

term that was coined to refer to music played by Puerto Ricans[3] in

Hawaii, after they migrated to Hawaii in 1901.[4] It is a "variation of dance music found in Hawaii"[5] which is, at times, played very fast.[6][7][3] The "influence on Hawai'i endures to this day in the musical form known as cachi cachi played on the quarto [sic] and derivative of the Puerto Rican jibaro style."[8] Jibaro means farmer in Spanish.[9] The Puerto Ricans in Hawaii "worked hard and played hard" and lightened the load for other plantation workers with their music.[4] In Hawaii, the Puerto Ricans played their music with six-string guitar, güiro, and the Puerto Rican cuatro.[10][11] Maracas and "palitos" sticks could be heard in the music around the 1930s.[12] More modern versions of the music may include the accordion and electric and percussion instruments such as conga drums.[13][10][14] |

カチカチ音楽は、カチカチ、カチカチ[1]、カチカチ[2]とも表記さ

れ、1901年にハワイに移住したプエルトリコ人[3]が演奏する音楽を指す造語である[4]。 ハワイで見つけられるダンス音楽のバリエーション」[5]であり、時に非常に速く演奏される[6][7][3]。「ハワイへの影響は、プエルトリコのジバ ロスタイルの派生である四つ打ちのカチカチと呼ばれる音楽形態に今日まで残っている」[8] ジバロとはスペイン語で農夫のことであり、ハワイでプエルトリコ人は「よく働きよく遊ぶ」音楽で他のプランテーション労働者への負担を軽くしたと言われて いる[9][4]。 ハワイでは、プエルトリコ人は6弦ギター、グイロ、プエルトリコのクアトロで 音楽を演奏していた[10][11] 1930年代頃にはマラカスや「パリトス」というスティックが音楽で聞かれるようになった[12]。 より現代的なバージョンでは、アコーディオンや電気、コンガドラムなどの打楽器が含まれることもある[13][10][14]。 |

| Etymology Cachi cachi music is what the people in Hawaii, who heard the Puerto Ricans playing their own music, called it. It needed a name and the people of Hawaii, specifically the Japanese plantation workers called it cachi cachi according to oral tradition- video recordings by Onetake2012 and research done by Ted Solis, an ethnomusicologist.[15][9][16] The Puerto Ricans, who only spoke Spanish and no English, worked alongside immigrants from the Philippines, China, but in one location their "camp" was next to the Japanese camp.[17][8] and when the Japanese heard their music, they said it sounded "scratchy".[18] The relationships between the Japanese and Puerto Ricans working on the plantations, didn't use to be good. They lived near one another and the Puerto Ricans felt disrespected when the Japanese walked around naked or almost naked for their baths. Sometimes fights would break out.[19] |

語源 カチカチ音楽は、プエルトリコ人が自分たちの音楽を演奏しているのを聞いたハワイの人たちがそう呼んだものである。ハワイの人々、特に日本人プランテー ション労働者は、口伝やOnetake2012によるビデオ録画、民族音楽学者のテッド・ソリスによる研究によって、カチカチと呼ぶようになった[15] [9][16]。 スペイン語しか話せず英語も話せないプエルトリコ人は、フィリピンや中国からの移民と一緒に働いていたが、ある場所では彼らの「キャンプ」は日本人キャン プの隣にあった[17][8]。そして日本人が彼らの音楽を聴くと、「スクラッチ」な音だと言った[18]。 プランテーションで働く日本人とプエルトリコ人の関係は、昔はあまり良くなかった。彼らは近くに住んでいたのであるが、日本人がお風呂に入るために裸かほ とんど裸で歩いているのを見て、プエルトリコ人は軽蔑の念を抱いた。時には喧嘩になることもあったという[19]。 |

| Current status In 1989, the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, a nonprofit established for recording music by small communities from around the world, made available an album called Puerto Rican music in Hawai'i containing 16 tracks.[20][5][21] The Library of Congress included the recording in its 1990 list of "outstanding recordings" of US folk music for meeting specific criteria including that the music emphasizes "root traditions over popular adaptations of traditional materials."[1] William Cumpiano, a master guitarmaker and his colleagues Wilfredo Echevarría and Juan Sotomayor researched, wrote, directed and produced a short documentary about the Hawaiian Puerto Ricans and their music which includes genres such as slack-key, décima, seís and aguinaldos. It was titled Un Canto en Otra Montaña or A Song From Another Mountain.[22] Sonny Morales, a resident of the Big Island of Hawaii, was "famous for making cuatros".[23] The young Auliʻi Cravalho, the voice of the Disney character, Moana, in the 2016 movie by the same name, talks about growing up with cachi cachi music. She was raised on the Big Island of Hawaii.[24] Willie K., an award-winning, Hawaiian musician from the island of Maui,[25][26] sings about it with lyrics "Cachi cachi music Makawao ...play the conga drum down in Lahaina".[6][27] |

現在の状況 1989年、世界中の小さなコミュニティの音楽を録音するために設立された非営利団体であるスミソニアン・フォークウェイズ・レコーディングスは、16曲 入りの『ハワイのプエルトリコ音楽』というアルバムを発売した[20][5][21]。議会図書館は、その音楽が「伝統資料の大衆迎合よりも根付いた伝 統」を強調しているなどの特定の基準を満たすとして、1990年に米国の民族音楽の「優れた録音」リストにこの録音を含めた[1]。 ギターの名手であるウィリアム・クンピアーノと、彼の同僚であるウィルフレド・エチェバリア、フアン・ソトマヨールは、スラックキー、デシマ、セイス、ア ギナルドスなどのジャンルを含むハワイ系プエルトリコ人とその音楽について研究、執筆、監督、制作したショートドキュメンタリーを発表した。タイトルは 『Un Canto en Otra Montaña』(別の山からの歌)である[22]。 ギターの名手であるウィリアム・クンピアーノと、彼の同僚であるウィルフレド・エチェバリア、フアン・ソトマヨールは、スラックキー、デシマ、セイス、ア ギナルドスなどのジャンルを含むハワイ系プエルトリコ人とその音楽について研究、執筆、監督、制作したショートドキュメンタリーを発表した。タイトルは 『Un Canto en Otra Montaña』(別の山からの歌)である[22]。 ハワイ島在住のソニー・モラレスは「クアトロを作ることで有名」であった[23]。 2016年の同名映画でディズニーキャラクター、モアナの声を担当した若き日のAuliʻi Cravalhoは、カチカチ音楽とともに発展してきたことを語っている。彼女はハワイ島で育ちました[24]。 マウイ島出身の受賞歴のあるハワイアンミュージシャン、ウィリーK[25][26]は「Cachi cachi music Makawao ...play the conga drum down in Lahaina」という歌詞でそのことを歌っている[6][27]。 |

| Artists; Some of the artists who

played or play a variety of Puerto Rican (cach cachi) music in

Hawaii:[20][28][9] Bobby Rodriguez Danny Rivera Darren Benitez[29][30] Eddie Rivera Ernest Rivera Eva Lopez[31] Glenn Ferreira[20] Juan Rodriguez Luciano Alvarez[9] Natalio Santiago[9] Peter Rivera Raymond Rodriguez Silva Rivera Tiny[7] Virginia Rodrigues[20] Willie K The following musicians are featured in the Puerto Rican Music of Hawaii CD by the Smithsonian Folkways.[21] August M. Rodrigues Bobby Castillo Bonaventura Torres Charles Figueroa El Leo George Ayala[15] Johnny Lopez Jorge Burgos Juan Cabrera Julio Rodrigues[31] Leroy Joseph Pinero Los Caminantes Los Guepos Mi Gente Quique Rosario The Latin Five The Latin Gentlemen Tommy Valentine |

アーティスト;ハワイでプエルトリコ音楽(カッチカチ)の様々な演奏をしていた、またはしているアーティストの一部:[20][28][9] ボビー・ロドリゲス ダニー・リベラ ダレン・ベニテス[29][30] エディ・リベラ アーネスト・リベラ エバ・ロペス[31] グレン・フェレイラ[20] フアン・ロドリゲス ルシアーノ・アルバレス[9] ナタリオ・サンティアゴ[9] ピーター・リベラ レイモンド・ロドリゲス シルバ・リベラ タイニー[7] バージニア・ロドリゲス[20] ウィリー・K スミソニアン・フォークウェイズによるCD『プエルトリカン・ミュージック・オブ・ハワイ』には、以下のミュージシャンが参加している。[21] オーガスト・M・ロドリゲス ボビー・カスティーヨ ボナベンチュラ・トーレス チャールズ・フィゲロア エル・レオ ジョージ・アヤラ[15] ジョニー・ロペス ホルヘ・ブルゴス フアン・カブレラ フリオ・ロドリゲス[31] リロイ・ジョセフ・ピネロ ロス・カミナンテス ロス・ゲポス ミ・ヘンテ キケ・ロザリオ ザ・ラテン・ファイヴ ザ・ラテン・ジェントルメン トミー・バレンタイン |

| Poncie Ponce Music of Hawaii Music of Puerto Rico Boogaloo Jibaro Puerto Rican immigration to Hawaii List of Puerto Ricans Puerto Rico History of Hawaii Gabby Pahinui |

ポンシエ・ポンセ ハワイの音楽 プエルトリコの音楽 ブーガルー ジバロ プエルトリコ人のハワイへの移住 プエルトリコ人の一覧 プエルトリコ ハワイの歴史 ギャビー・パヒヌイ |

| The Puerto

Rican cuatro (Spanish: cuatro puertorriqueño) is the national

instrument of Puerto Rico. It belongs to the lute family of string

instruments, and is guitar-like in function, but with a shape closer to

that of the violin. The word cuatro means "four", which was the total

number of strings of the earliest Puerto Rican instrument known by the

cuatro name.[1] The current cuatro has ten strings[1] in five courses, tuned, in fourths, from low to high B3 B2♦E4 E3♦A3 A3♦D4 D4♦G4 G4 (note that the bottom two pairs are in octaves, while the top three pairs are tuned in unison), and a scale length of 500-520 millimetres.[2] The cuatro is the most familiar of the three instruments which make up the Puerto Rican jíbaro orchestra (the cuatro, the tiple and the bordonúa).[citation needed] A cuatro player is called a cuatrista. This instrument has had its prominent performers like Andrés Jiménez, Edwin Colón Zayas, Yomo Toro, Iluminado Davila Medina and the maestro Maso Rivera.[citation needed] |

プエルトリコのクアトロ(スペイン語:cuatro

puertorriqueño)は、プエルトリコの民族楽器である。弦楽器のリュート科に属し、機能的にはギターに似ているが、形状はバイオリンに近い。

クアトロという言葉は「4」を意味し、クアトロの名で知られるプエルトリコ最古の楽器の弦の総数であった[1]。 現在のクアトロは5コース10弦[1]で、調弦は4分の1で低音から高音までB3 B2♦E4 E3♦A3 A3♦D4 D4♦G4 G4(下の2組はオクターブ、上の3組はユニゾンで調弦されているので注意)、スケール長は500~520ミリ[2]となっている。 クアトロは、プエルトリコのジバロ・オーケストラを構成する3つの楽器(クアトロ、ティプル、ボルドヌア)の中で最も親しまれている[citation needed]。 クアトロの演奏者はクアトリスタと呼ばれる。この楽器には、アンドレス・ヒメネス、エドウィン・コロン・サヤス、ヨモ・トロ、イルミナード・ダビラ・メ ディナ、巨匠マソ・リベラなどの著名な演奏家がいる[引用者注釈]。 |

| Very little is known about the

exact origin of the cuatro. However, most experts believe that the

cuatro has existed on the island in one form or another for about 400

years. The Spanish instrument that it is most closely related to is the

vihuela poblana (also known as the Medieval/Renaissance guitar), which

had four courses, two strings each for eight strings in total as well

as the Spanish Medieval/Renaissance four-course and the Spanish laúd,

particularly in the Canary Islands.[citation needed] There was a "cuatro antiguo" which had four single strings, then eight strings in four doubled courses, and then the modern cuatro with five double courses. Despite the name, however, the origins are not clear.[citation needed] |

クアトロの正確な起源については、ほとんど知られていない。しかし、ほ

とんどの専門家は、クアトロは約400年前から何らかの形でこの島に存在していたと考えている。最も近い関係にあるスペインの楽器は、4コース、各2弦、

合計8弦を持つヴィウエラポブラナ(中世/ルネサンスギターとも呼ばれる)、およびスペイン中世/ルネサンス4コース、特にカナリア諸島のスペインラウド

である[citation needed] 。 単弦4本の「クアトロ・アンティグオ」、4本の2重コースに8本の弦を張った「クアトロ」、そして5本の2重コースを持つ現代の「クアトロ」がある。しか し、その名前とは裏腹に、起源は明らかではない。[citation needed]。 |

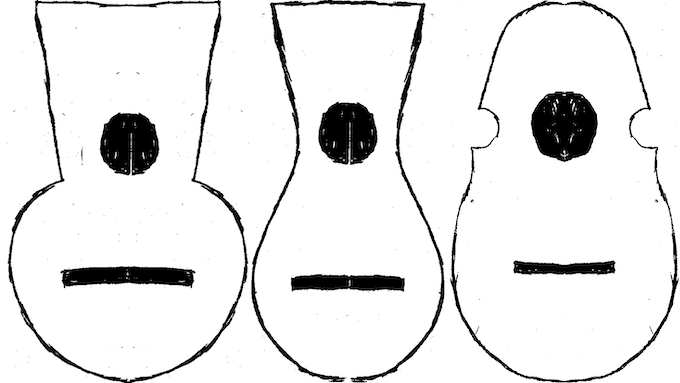

| Types of Puerto Rican cuatros There are three main types of cuatro: cuatro antiguo of four orders and four strings, the "Southern" cuatro of four orders and eight strings, and the cuatro "moderno" of five orders and ten strings.[citation needed] The four string cuatro antiguo: This is the original Puerto Rican cuatro. It was made from a single block of wood and used four gut strings. This instrument may have evolved from the vihuela poblana. It was used to mostly play jíbaro music. The eight-string "Southern" cuatro: This cuatro evolved from the old four-string cuatro. It was made like a guitar and had four pairs of steel strings. It was used to play salon genres like the mazurka, danza, waltz, polka, etc. The ten string cuatro "moderno": This cuatro evolved from the Baroque era ten string bandurria and laúd from Spain. It is made from a single block of wood and it has five pairs of steel strings. It is the most commonly used today and is used to play jíbaro music, salon genres, salsa, pop, rock, classical, jazz, and even American bluegrass and many more styles. |

プエルトリコのクアトロの種類 クアトロには大きく分けて、4オーダー4弦のクアトロ・アンティグオ、4オーダー8弦の「南部」クアトロ、5オーダー10弦のクアトロ・モデルノの3種類 がある[要出典]。 4弦のクアトロ・アンティグオです。プエルトリコのクアトロの原型である。1つの木の塊から作られ、4本のガット弦が使われていました。この楽器はビウエ ラポブラナから発展したものと思われる。主にジバロの演奏に使われた。8弦の「南部」クアトロ。このクアトロは、古い4弦クアトロから発展したものであ る。ギターのような形状で、4対のスチール弦を備えている。マズルカ、ダンツァ、ワルツ、ポルカなどのサロンのジャンルを演奏するのに使われた。10弦の クアトロ「モダノ」。バロック時代のスペインの10弦バンドゥリアやラウドから発展したクアトロ。スペインのバロック時代の10弦バンドゥリアやラウドか ら発展したクアトロで、1つの木の塊から作られ、5対のスチール弦が張られています。現在最もよく使われており、ジバロ音楽、サロンジャンル、サルサ、 ポップス、ロック、クラシック、ジャズ、さらにはアメリカのブルーグラスなど、さまざまなスタイルの演奏に使われる。 |

| Cuatro shapes, sizes and variants Sound Box designs The antiguo design: This box resembles a medieval keyhole, also known as cuatro cuadrao, or cuatro araña. This shape has been found on some old dotars and citolas. Four-string, eight-string and ten-string cuatros were made using this design. This was the very first design and it might be 400 years old. Sometimes some ten-string cuatros are still made with this design. The aviolinado design: This box resembles a violin. It is the most common shape used today. Eight string and ten-string cuatros were made using this design starting in the 19th century. The dos puntos design: This box looked like some old mandolinas made by Martin in the United States during the 20th century. However, it was first used in the 19th century in Yauco, Puerto Rico. Eight string cuatros were made using this design. The tulipán design: This box looked like the antiguo design but with no straight lines and all curves and thus resembled a tulip. Eight-string and ten-string cuatros were made using this design during the 1900s near Yauco and Ponce. The higuera design: This is the rarest design. This box was shaped like an organic oval. This was because the soundboxes were made from domed gourds instead of wood. Four-string cuatros were made using this design in the 19th century in Puerto Rico by enslaved Africans on the island. Now they are made with ten metal strings and often have designs carved onto their backs. Besides these, many other lesser-known and one-of-a-kind designs also exist. Variants In the 1950s, there was an effort to produce a "classical" ensemble of cuatros, with various-sized instruments taking on the role of the violins, violas, cellos, and double basses in a classical orchestra. To meet these roles cuatros of the aviolinado style were produced in four different sizes and tunings: Cuatro Soprano, Cuatro Alto, Cuatro Tradicional (the standard instrument, also called Cuatro Tenor), and Cuatro Bajo (Bass Cuatro): all have ten strings and are tuned in fourths. The project met with only limited success and today most of these variants are rare, with the cuatro tradicional surviving as the standard instrument.[3] There is also a Cuatro Lírico ("lyrical cuatro"), which is about the size of the Tenor, but has a deep jelly-bean shaped body; a Cuatro Sonero, which has fifteen strings in five courses of three strings each; and a Seis, which is a Cuatro Tradicional with an added two string course (usually a lower course), giving it a total of twelve strings in six courses.[4][5][6][7] |

クアトロの形状、サイズ、バリエーション サウンドボックスデザイン アンティグオのデザイン。中世の鍵穴に似たデザインで、「クアトロ・クアドラオ」「クアトロ・アラーニャ」とも呼ばれます。この形は、古いドターやシトラ で見つかっています。4弦、8弦、10弦のクアトロがこのデザインで使われました。これは最初のデザインであり、400年前のものかもしれない。今でも 10弦のクアトロがこのデザインで作られていることがあります。 アビオリナードのデザイン。アビオリナードデザイン:バイオリンに似た形の箱です。現在、最も一般的に使われている形です。19世紀以降、8弦や10弦の クアトロがこのデザインで作られるようになりました。 ドス・プントス(Dos puntos)デザイン。20世紀にアメリカのマーチン社で作られた古いマンドリンに似た箱です。しかし、この箱は19世紀にプエルトリコのヤウコで使わ れたのが最初である。8弦のクアトロがこのデザインで使われた。 トゥリパンのデザイン。アンティグオのデザインに似ているが、直線がなく曲線ばかりなので、チューリップのような箱。1900年代にヤウコやポンセで8弦 と10弦のクアトロが使われた。 ヒグエラのデザイン。最も希少なデザインです。このボックスは、有機的な楕円のような形をしています。これは、サウンドボックスが木の代わりにドーム型の 瓢箪で作られていたためです。4弦のクアトロは、19世紀にプエルトリコで、島の奴隷になったアフリカ人によってこのデザインで使われた。現在は10本の 金属弦で作られ、背中にデザインが彫られていることが多い。 このほかにも、あまり知られていない一点もののデザインも多く存在する。 バリエーション 1950年代、クラシックオーケストラのヴァイオリン、ヴィオラ、チェロ、コントラバスの役割を担うクアトロのアンサンブルを、さまざまなサイズの楽器で 実現しようとする試みがなされた。そのため、アビオリナードスタイルのクアトロは、4種類のサイズとチューニングで製作された。クアトロ・ソプラノ、クア トロ・アルト、クアトロ・トラディシオナル(標準楽器、クアトロ・テナーとも呼ばれる)、クアトロ・バホ(バス・クアトロ)の4種類で、いずれも10弦、 4分音符で調律されている。このプロジェクトは限られた成功しか収められず、現在ではこれらのバリエーションはほとんど存在せず、クアトロ・トラディシオ ナルが標準楽器として存続している[3]。 また、テナーとほぼ同じ大きさで、深いジェリービーンズ型のボディを持つクアトロ・リコ(「リリカル・クアトロ」)、3弦ずつ5コースで15弦のクアト ロ・ソネーロ、クアトロ・トラディショナルに2弦コース(通常は下コース)を加え、6コースで12弦とするセイスもある[4][5][6][7]。 |

| Cuatro orchestras of Puerto Rico The original cuatro orchestra was the orquesta jíbara which consisted of a various number of different string instruments: Puerto Rican Tiple Cuatro Tradicional Bordonúa At least two configurations of "classical" cuatro orchestra were formed in the 1950s and 1960s: Primero Cuatro Concertino Segundo Cuatro Concertino Cuatro Bajo Cuatro Rítmico Cuatro Tradicional Or: Cuatro Soprano Cuatro Tenor Cuatro Alto Cuatro Bajo As noted, most of the instrumental variants are now rare, as are these classical groupings. There have been, however, modern efforts to revive the orquesta jíbara.[citation needed] |

プエルトリコのクアトロ・オーケストラス クアトロオーケストラの原型は、様々な数の異なる弦楽器で構成されたオルケスタ・ジバラである。 プエルトリコのティプル クアトロ・トラディショナル(Cuatro Tradicional ボルドヌア 1950年代から1960年代にかけて、少なくとも2つの構成の「クラシック」クアトロ・オーケストラが結成されました。 プリメロ・クアトロ・コンチェルティーノ セグンド・キュアトロ・コンチェルティーノ クアトロ・バホ(Cuatro Bajo クアトロ・リトミカ(Cuatro Rítmico クアトロ・トラディショナル(Cuatro Tradicional または クアトロ・ソプラノ(Cuatro Soprano クアトロテナー クアトロアルト クアトロ・バホ(Cuatro Bajo 前述のように、ほとんどの楽器編成は、これらの古典的なグループと同様に、現在では珍しいものとなっています。しかし、現代ではオルケスタ・ジバラを復活 させようとする動きがある[citation needed]。 |

| The Puerto Rican Cuatro Project" William Cumpiano and Christina Sotomayor founded the Puerto Rican Cuatro Project, a non-profit organization dedicated to fostering the traditions that surround the national instrument of Puerto Rico, by means of gathering, promoting and preserving the cultural memories of Puerto Rican musical traditions, folkloric stringed instruments and musicians. The Cuatro Project is also dedicated to promoting and preserving the Puerto Rican décima verse form and the traditional song as created by its greatest troubadours, living and past.[8] Cumpiano, together with Sotomayor and Wilfredo Echevarría, wrote, directed and produced two DVD documentaries for The Cuatro Project. They are: OUR CUATRO Vol. 1, the first feature-length documentary about the cuatro and its music and OUR CUATRO Vol. 2: A Historic Concert. Cumpiano and cultural researcher David Morales produced another DVD documentary THE DÉCIMA BORINQUEÑA: An ancient poetic singing tradition, directed by Myriam Fuentes. The proceeds of these recordings were to be used for the research and documentation activities of the Puerto Rican Cuatro Project.[9] "Nuestro Cuatro: Volumen 1", The Puerto Ricans and their stringed instruments. An unprecedented documentary that reveals the emotional story of the development and the history of the music and stringed instruments traditions of Puerto Rico. "Nuestro Cuatro: Volumen 2", Un Concierto Histórico/A Historical Concert. The conclusion of the video documentary Nuestro Cuatro, a cultural and musical history of the Puerto Rican cuatro and Puerto Rico's stringed instruments. |

プエルトリカン・クアトロ・プロジェクト 「William CumpianoとChristina Sotomayorは、プエルトリコの音楽伝統、民俗弦楽器、音楽家の文化的記憶を収集、促進、保存することにより、プエルトリコの民族楽器を取り巻く伝 統を育むことを目的とした非営利団体、Puerto Rican Cuatro Projectを設立しました。また、クアトロ・プロジェクトは、プエルトリコのデシマ詩の形式と、生前および過去の偉大なトルバドゥールによって作られ た伝統的な歌の普及と保存に力を注いでいる[8]。 クアトロ・プロジェクトでは、ソトマヨール、ウィルフレド・エチェバリアとともに、2本のDVDドキュメンタリーの脚本・監督・制作を担当しました。それ らは クアトロとその音楽に関する初の長編ドキュメンタリー「OUR CUATRO Vol.1」と「OUR CUATRO Vol.2: A Historic Concert」です。また、クンパイアーノと文化研究者のデビッド・モラレスは、ミリアム・フエンテス監督によるDVDドキュメンタリー「THE DÉCIMA BORINQUEÑA: An ancient poetic singing tradition」を制作しました。これらの録音の収益は、プエルトリコ・クアトロ・プロジェクトの研究・記録活動に使われることになった[9]。 "Nuestro Cuatro: Volumen 1」プエルトリコ人とその弦楽器。プエルトリコの音楽と弦楽器の伝統の発展と歴史の感動的な物語を明らかにする、前代未聞のドキュメンタリーです。 "ヌエストロ・クアトロ Volumen 2", Un Concierto Histórico/A Historical Concert. プエルトリコのクアトロとプエルトリコの弦楽器の文化的・音楽的歴史を描いたビデオドキュメンタリー「Nuestro Cuatro」の完結編です。 |

| Use in popular music Jon Anderson used a cuatro on the Yes album Tormato,[10] although the sleeve-notes misdescribe the instrument as an Álvarez ten string guitar. Puerto Rican singer-songwriter Christian Nieves played a cuatro on the 2017 hit single "Despacito" by Luis Fonsi featuring Daddy Yankee;[11] the instrument, as strung for left-handed playing, appears at 3:32 of the song's official music video, which became the most-viewed video on YouTube on August 4, 2017.[12] Famous cuatro player (cuatrista) Yomo Toro. |

ポピュラー音楽での使われ方 ジョン・アンダーソンはYesのアルバム『Tormato』でクアトロを使われたが[10]、スリーブノートにはアルバレスの10弦ギターと誤記されてい る。プエルトリコのシンガーソングライターであるChristian Nievesは、Luis Fonsi featuring Daddy Yankeeによる2017年のヒットシングル「Despacito」でクアトロを演奏しており[11]、左手演奏用に弦を張った楽器は、同曲の公式 ミュージックビデオの3分32秒で登場しており、このビデオはYouTubeで最も視聴数の多いビデオとなった(2017年8月4日)[12]。 |

| El Cuatro (Spanish Wikipedia) Music of Puerto Rico Cuatro (Venezuela) |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Puerto_Rican_cuatro |

|

| The Music

of Puerto Rico has evolved as a heterogeneous and dynamic product

of diverse cultural resources. The most conspicuous musical sources of

Puerto Rico have primarily included European, Indigenous, and African

influences, although many aspects of Puerto Rican music reflect origins

elsewhere in the Caribbean. Puerto Rican music culture today comprises

a wide and rich variety of genres, ranging from essentially native

genres such as bomba, danza, and plena to more recent hybrid genres

such as salsa, Latin trap and reggaeton. Broadly conceived, the realm

of "Puerto Rican music" should naturally comprise the music culture of

the millions of people of Puerto Rican descent who have lived in the

United States, especially in New York City. Their music, from salsa to

the boleros of Rafael Hernández, cannot be separated from the music

culture of Puerto Rico itself. |

プエルトリコの音楽は、多様な文化資源の異質かつダイナミックな産物と

して発展してきた。プエルトリコの最も顕著な音楽源は、主にヨーロッパ、先住民、アフリカの影響を受けているが、プエルトリコ音楽の多くの側面はカリブ海

の他の地域の起源を反映している。今日のプエルトリコの音楽文化は、ボンバ、ダンザ、プレナといった本質的にネイティブなジャンルから、サルサ、ラテント

ラップ、レゲトンといった最近のハイブリッドなジャンルまで、幅広く豊かなバラエティで構成されている。広く考えれば、「プエルトリコ音楽」の領域は、当

然、米国、特にニューヨークに住む数百万人のプエルトリコ系住民の音楽文化で構成されるはずだ。サルサからラファエル・エルナンデスのボレロまで、彼らの

音楽はプエルトリコの音楽文化そのものと切り離すことはできない。 |

| Traditional, folk, and popular

music Early music The music culture in Puerto Rico during the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries is poorly documented. Certainly, it included Spanish church music, military band music, and diverse genres of dance music cultivated by the jíbaros and enslaved Africans and their descendants. While these later never constituted more than 11% of the island's population, they contributed to some of the island's most dynamic musical features becoming distinct indeed. In the 19th century Puerto Rican music begins to emerge into historical daylight, with notated genres like danza being naturally better documented than folk genres like jíbaro music and bomba y plena and seis. The African people of the island used drums made of carved hardwood covered with untreated rawhide on one side, commonly made from goatskin. A popular word derived from creole to describe this drum was shukbwa, which translates to 'trunk of tree' |

伝統音楽、民族音楽、ポピュラー音楽 アーリーミュージック 16世紀、17世紀、18世紀のプエルトリコの音楽文化は、ほとんど記録されていない。確かに、スペインの教会音楽、軍楽隊の音楽、ジバロや奴隷にされた アフリカ人とその子孫が育てた多様なジャンルのダンスミュージックがあった。これらの音楽は島の人口の11%以上を占めることはなかったが、島の最もダイ ナミックな音楽的特徴が実際に明確なものとなるのに貢献した。 19世紀になると、プエルトリコの音楽は歴史に名を残すようになり、ジバロ音楽、ボンバ・イ・プレナ・セイスのような民俗音楽よりも、ダンザのような楽譜 のあるジャンルの方が、当然記録されている。 この島のアフリカの人々は、彫りの深い広葉樹の片面を未処理の生皮で覆った太鼓、一般的には山羊の皮で作られた太鼓を使っていた。このドラムを表すクレ オール語から派生した一般的な言葉はシュクブワで、「木の幹」と訳される。 |

| Folk music If the term "folk music" is taken to mean music genres that have flourished without elite support[clarification needed], and have evolved independently of the commercial mass media, the realm of Puerto Rican folk music would comprise the primarily Hispanic-derived jíbaro music, the Afro-Puerto Rican bomba, and the essentially "creole" plena. As these three genres evolved in Puerto Rico and are unique to that island[citation needed], they occupy a respected[neutrality is disputed] place in island culture, even if they are not currently as popular as contemporary music such as salsa or reggaeton. |

民俗音楽 民俗音楽」という用語が、エリートの支援なしに栄え[clearification needed]、商業的マスメディアとは無関係に発展してきた音楽ジャンルを意味するとすると、プエルトリコの民俗音楽の領域は、主にヒスパニック由来の ジバロ音楽、アフロプエルトリコのボンバ、本質的に「クロール」のプレナからなる。これら3つのジャンルはプエルトリコで発展したものであり、プエルトリ コ独自のものであるため[citation needed]、サルサやレゲトンなどの現代音楽ほどの人気はないにせよ、島の文化において尊敬に値する[中立性には異論がある]位置を占めている。 |

| Jíbaro music Jíbaros are small farmers of mixed descent who constituted the overwhelming majority of the Puerto Rican population until the mid-twentieth century.[1] They are traditionally recognized as romantic icons of land cultivation, hard-working, self-sufficient, hospitable, and with an innate love of song and dance. Their instruments[2] were relatives of the Spanish vihuela, especially the cuatro — which evolved from four single strings to five pairs of double strings —[3] and the lesser known tiple.[4] A typical jíbaro group nowadays might feature a cuatro, guitar, and percussion instrument such as the güiro scraper and/or bongo. Lyrics to jíbaro music are generally in the décima form, consisting of ten octosyllabic lines in the rhyme scheme abba, accddc. Décima form derives from 16th century Spain. Although it has largely died out in that country (except the Canaries), it took root in various places in Latin America—especially Cuba and Puerto Rico—where it is sung in diverse styles. A sung décima might be pre-composed, derived from a publication by some literati, or ideally, improvised on the spot, especially in the form of a “controversia” in which two singer-poets trade witty insults or argue on some topic. In between the décimas, lively improvisations can be played on the cuatro. This music form is also known as "típica" as well as "trópica". The décimas are sung to stock melodies, with standardized cuatro accompaniment patterns. About twenty such song types are in common use. These are grouped into two broad categories, viz., seis (e.g., seis fajardeño, seis chorreao) and aguinaldo (e.g., aguinaldo orocoveño, aguinaldo cayeyano). Traditionally, the seis could accompany dancing, but this tradition has largely died out except in tourist shows and festivals. The aguinaldo is most characteristically sung during the Christmas season, when groups of revelers (parrandas) go from house to house, singing jíbaro songs and partying. The aguinaldo texts are generally not about Christmas, and also unlike Anglo-American Christmas carols, they are generally sung by a solo with the other revelers singing the chorus. In general, the Christmas season is a time when traditional music—both seis and aguinaldo—is most likely to be heard. Fortunately, many groups of Puerto Ricans are dedicated to preserving traditional music through continued practice. Jíbaro music came to be marketed on commercial recordings in the twentieth century, and singer-poets like Ramito (Flor Morales Ramos, 1915–90) are well documented. However, jíbaros themselves were becoming an endangered species, as agribusiness and urbanization have drastically reduced the numbers of small farmers on the island. Many jíbaro songs dealt accordingly with the vicissitudes of migration to New York. Jíbaro music has in general declined accordingly, although it retains its place in local culture, especially around Christmas time and special social gatherings, and there are many cuatro players, some of whom have cultivated prodigious virtuosity. |

ヒバロ音楽 ジバロは、20世紀半ばまでプエルトリコの人口の圧倒的多数を占めていた混血の小農民である[1]。彼らは伝統的に、勤勉で自給自足、もてなし好きで、生 来の歌と踊りを愛する、土地開拓のロマンあふれる象徴と認識されている。彼らの楽器[2]はスペインのビウエラの親戚で、特にクアトロ(4本の単弦から5 対の複弦に進化した)[3]とあまり知られていないティプル[4]がある。現在、ジバロのグループはクアトロ、ギター、グイロスクレイパーやボンゴなどの 打楽器を特徴とするかもしれません。ジバロ音楽の歌詞は一般的にデシマ形式であり、abba, accddcの韻律で10行の八音節からなる。デシマ形式は、16世紀のスペインに由来する。スペインではカナリア諸島を除いてほとんど廃れてしまった が、ラテンアメリカの各地、特にキューバとプエルトリコで定着し、さまざまなスタイルで歌われている。歌われるデシマは、あらかじめ作曲されたもの、文学 者の出版物に由来するもの、あるいは理想的にはその場で即興的に作られるもので、特に2人の歌い手詩人が気の利いた侮辱を交わしたり、何らかのテーマにつ いて議論する「論争」のような形がとられます。デシマの合間には、クアトロで生き生きとした即興演奏が行われることもある。この音楽形式は、 「trópica」だけでなく「típica」とも呼ばれます。 「デシマス」は、標準的なメロディーに、標準的なクアトロの伴奏パターンで歌われる。このような歌は約20種類あり、一般的に使われている。これらは大 きく分けて、セイス(セイス・ファジャルデーニョ、セイス・コレアオなど)とアギナルド(アギナルド・オロコベーニョ、アギナルド・カエヤノなど)の2種 類に分類される。伝統的に、セイスは踊りの伴奏として使われることもあったが、観光客向けのショーや祭りを除いては、その伝統はほとんどなくなっている。 アギナルドが最も特徴的に歌われるのは、クリスマスの時期で、お祭り好きのグループ(パランダ)が家々を回り、ジバロの歌を歌いながらパーティーをする。 アギナルドのテキストは一般にクリスマスに関するものではなく、また英米のクリスマスキャロルとは異なり、一般にソロで歌われ、他の酒宴の参加者がコーラ スを担当する。一般に、クリスマスシーズンは、セイとアギナルドの両方の伝統音楽が最もよく聴かれる時期である。幸いなことに、多くのプエルトリコ人グ ループが、継続的な練習によって伝統音楽を守ることに専念している。 ジバロ音楽は20世紀に入ると商業用レコードで販売されるようになり、ラミート(Flor Morales Ramos, 1915-90)のような歌手詩人もよく知られている。しかし、アグリビジネスと都市化によって島の小規模農家が激減したため、ジバロ自体が絶滅危惧種に なりつつあった。ジバロの歌の多くは、ニューヨークへの移住の波乱万丈をそれなりに扱っていた。ジバロの音楽は、一般的には衰退していったが、特にクリス マスの時期や特別な社交の場では、地元の文化の中でその地位を保っており、多くのクアトロ奏者がいて、その中には天才的な名人芸を身につけた人もいる。 |

| Bomba

(Puerto Rico) Historical references indicate that by the decades around 1800 plantation slaves were cultivating a music and dance genre called bomba. By the mid-twentieth century, when it started to be recorded and filmed, bomba was performed in regional variants in various parts of the island, especially Loíza, Ponce, San Juan, and Mayagüez. It is not possible to reconstruct the history of bomba; various aspects reflect Congolese derivation, though some elements (as suggested by subgenre names like holandés) have come from elsewhere in the Caribbean. French Caribbean elements are particularly evident in the bomba style of Mayagüez, and striking choreographic parallels can be seen with the bélé of Martinique. All of these sources were blended into a unique sound that reflects the life of the Jibaro, the slaves, and the culture of Puerto Rico. In its call-and-response singing set to ostinato-based rhythms played on two or three squat drums (barriles), bomba resembles other neo-African genres in the Caribbean. Of clear African provenance is its format in which a single person emerges from an informal circle of singers to dance in front of the drummers, engaging the lead drummer in a sort of playful duel; after dancing for a while, that person is then replaced by another. While various such elements can be traced to origins in Africa or elsewhere, bomba must be regarded as a local Afro-Puerto Rican creation. Its rhythms (e.g. seis corrido, yubá, leró, etc.), dance moves, and song lyrics that sometimes mimic farm animals(in Spanish, with some French creole words in eastern Puerto Rico) collectively constitute a unique Puerto Rican genre. In the 1950s, the dance-band ensemble of Rafael Cortijo and Ismael Rivera performed several songs in they had labeled as "bombas"; although these bore some similarities to the sicá style of bomba, in their rhythms and horn arrangements they also borrowed noticeably from the Cuban dance music which had long been popular in the island. Giving rise to Charanga music. As of the 1980s, bomba had declined, although it was taught, in a somewhat formalized fashion, by the Cepeda family in Santurce, San Juan, and was still actively performed informally, though with much vigor, in the Loíza towns, home to the then Ayala family dynasty of bomberos. Bomba continues to survive there and has also experienced something of a revival, being cultivated by folkloric groups such as Son Del Batey, Los Rebuleadores de San Juan, Bomba Evolución, Abrane y La Tribu, and many more elsewhere on the island. In New York City with groups such as Los Pleneros de la 21,[5] members of La Casita de Chema, and Alma Moyo. In Chicago Buya, and Afro-Caribe have kept the tradition alive and evolving. In California Bomba Liberte, Grupo Aguacero, Bombalele, La Mixta Criolla, Herencia de los Carrillo, and Los Bomberas de la Bahia are all groups that have promoted and preserved the culture. Women have also played a role in its revival, as in the case of the all-female group Yaya, Legacy Woman, Los Bomberas de la Bahia, Grupo Bambula (Originally female group), and Ausuba in Puerto Rico. There has also been a strong commitment towards Bomba Fusion. Groups such as Los Pleneros de la 21, and Viento De Agua have contributed greatly towards fusing Bomba and Plena with Jazz and other Genres. Yerbabuena has brought a popular cross-over appeal. Abrante y La Tribu have made fusions with Hip Hop. Tambores Calientes, Machete Movement, and Ceiba have fused the genres with various forms of Rock and Roll. The Afro-Puerto Rican bombas, developed in the sugarcane haciendas of Loíza, the northeastern coastal areas, in Guayama and southern Puerto Rico, utilize barrel drums and tambourines, while the rural version uses stringed instruments to produce music, relating to the bongos. (1) “The bomba is danced in pairs, but there is no contact. The dancers each challenge the drums and musicians with their movements by approaching them and performing a series of fast steps called floretea piquetes, creating a rhythmic discourse. Unlike normal dance routines, the drummers are the ones who follow the performers and create a beat or rhythm based on their movements. Women who dance bomba often use dresses or scarves to enhance bodily movements.[6] Unlike normal dance terms, the instruments follow the performer. Like other such traditions, bomba is now well documented on sites like YouTube, and a few ethnographic documentary films. |

ボンバ 歴史的な文献によると、1800年頃の数十年間、プランテーションの奴隷たちがボンバと呼ばれる音楽とダンスのジャンルを育てていたようです。20世紀半 ばになると、記録や映像が作られるようになり、ボンバは島の各地、特にロイザ、ポンセ、サンファン、マヤグェスで地域的なバリエーションで演奏されてい る。ボンバの歴史を再構築することは不可能である。様々な側面がコンゴ由来であることを反映しているが、いくつかの要素(ホランデスのようなサブジャンル 名で示唆される)はカリブ海の他の地域から来たものである。フランス領カリブ海の要素は、マヤグエスのボンバスタイルに特に顕著であり、マルティニークの ベレと顕著な振付上の類似性が見られる。これらのソースはすべて、ジバロの生活、奴隷、プエルトリコの文化を反映したユニークなサウンドにブレンドされ た。 2つまたは3つのスクワットドラム(バリレス)で演奏されるオスティナートに基づくリズムに合わせてコール&レスポンスで歌うボンバは、カリブ海の他のネ オアフリカのジャンルに似ている。アフリカに起源があることは明らかで、その形式は、歌い手の非公式な輪の中から一人が出てきて、ドラムの前で踊り、リー ド・ドラマーと遊びのような決闘をする。このような様々な要素は、アフリカやその他の地域に起源を求めることができるが、ボンバはアフロ・プエルトリコの ローカルな創作と見なさなければならない。そのリズム(seis corrido、yubá、leróなど)、ダンスの動き、時に農作物を模した歌詞(スペイン語、プエルトリコ東部ではフランス語のクレオール語もある) などは、プエルトリコ独自のジャンルを形成している。 1950年代、ラファエル・コルティージョとイスマエル・リベラのダンスバンドアンサンブルは、彼らが「ボンバ」と名付けた数曲を演奏した。これらは、シ カのスタイルのボンバに似ているが、リズムやホルンのアレンジは、この島で長く親しまれていたキューバのダンスミュージックから顕著に引用している。チャ ランガ音楽が誕生する 1980年代には、ボンバは衰退したが、サントゥルセ、サンフアンのセペダ家では、やや正式な形で教えられ、当時のアヤラ家のボンバロ家の本拠地であるロ イザの町では、非公式ながら活発に演奏されていた。ボンバはこの地で生き続け、また、Son Del Batey、Los Rebuleadores de San Juan、Bomba Evolución、Abrane y La Tribuなどのフォークロア・グループによって、島の他の場所で培われ、いくつかの復活を経験している。ニューヨークでは、Los Pleneros de la 21、[5] La Casita de Chemaのメンバー、Alma Moyoといったグループと。シカゴでは、ブヤ、アフロ・カリベが伝統を守り、進化させています。カリフォルニアでは、Bomba Liberte、Grupo Aguacero、Bombalele、La Mixta Criolla、Herencia de los Carrillo、Los Bomberas de la Bahiaなどが、文化の普及と保存に取り組んでいる。また、プエルトリコの女性グループ「ヤヤ」「レガシー・ウーマン」「ロス・ボンベラス・デ・ラ・バ イア」「グルポ・バンブラ(元々女性グループ)」「アウスバ」のように、女性がその復活に一役買っていることもある。 また、ボンバ・フュージョンへの取り組みも盛んである。Los Pleneros de la 21やViento De Aguaなどのグループは、ボンバやプレナをジャズや他のジャンルと融合させることに大きく貢献しました。Yerbabuenaは、人気のあるクロスオー バーの魅力をもたらしている。Abrante y La Tribuは、ヒップホップとの融合を実現した。タンボレス・カリエンテス、マチェーテ・ムーブメント、セイバは、これらのジャンルを様々な形態のロック ンロールと融合させた。 アフロ・プエルトリコのボンバは、ロイザのサトウキビ農園、北東部の海岸地域、グアヤマ、プエルトリコ南部で発展し、樽太鼓やタンバリンを使うが、地方で はボンゴに関連した弦楽器を使って音楽を奏でるものである。(1) 「ボンバは2人1組で踊られるが、接触はない。ダンサーはそれぞれ、ドラムやミュージシャンに近づいて、フロレテア・ピケテスと呼ばれる速いステップを連 発し、リズムの談話を作りながら、その動きに挑戦する。通常のダンスとは異なり、太鼓奏者はパフォーマーに追従し、その動きをもとに拍子やリズムを作り出 す存在である。ボンバを踊る女性は、ドレスやスカーフを使って身体の動きを強調することが多い[6]。通常のダンス用語とは異なり、楽器は演奏者に付いて いく。 他の伝統と同様に、ボンバも現在ではYouTubeなどのサイトや、いくつかの民族ドキュメンタリー映画でよく記録されています。 |

| Plena Around 1900 plena emerged as a humble proletarian folk genre in the lower-class, largely Afro-Puerto Rican urban neighborhoods in San Juan, Ponce, and elsewhere. Plena subsequently came to occupy its niche in island music culture. In its quintessential form, plena is an informal, unpretentious, simple folk-song genre, in which alternating verses and refrains are sung to the accompaniment of round, often homemade frame drums called panderetas (like tambourines without jingles), perhaps supplemented by accordion, guitar, or whatever other instruments might be handy. An advantage of the percussion arrangement is its portability, contributing to the plena's spontaneous appearance at social gatherings. Other instruments commonly heard in plena music are the cuatro, the maracas, and accordions. The plena rhythm is a simple duple pattern, although a lead pandereta player might add lively syncopations. Plena melodies tend to have an unpretentious, "folksy" simplicity. Some early plena verses commented on barrio anecdotes, such as "Cortarón a Elena" (They stabbed Elena) or "Allí vienen las maquinas" (Here come the firetrucks). Many had a decidedly irreverent and satirical flavor, such as "Llegó el obispo" mocking a visiting bishop. Some plenas, such as "Cuando las mujeres quieren a los hombres" and "Santa María," are familiar throughout the island. In 1935 the essayist Tomás Blanco celebrated plena—rather than the outdated and elitist danza—as an expression of the island's fundamentally creole, Taino or mulatto racial and cultural character. Plenas are still commonly performed in various contexts; a group of friends attending a parade or festival may bring a few panderetas and burst into song, or new words will be fitted to the familiar tunes by protesting students or striking workers which have long been a regular form of protest from occupation and slavery. While enthusiasts might on occasion dance to a plena, plena is not characteristically oriented toward dance. In the 1920s–30s plenas came to be commercially recorded, especially by Manuel "El Canario" Jimenez, who performed old and new songs, supplementing the traditional instruments with piano and horn arrangements. In the 1940s Cesar Concepción popularized a big-band version of plena, lending the genre a new prestige, to some extent at the expense of its proletarian vigor and sauciness. In the 1950s a newly invigorated plena emerged as performed by the smaller band of Rafael Cortijo and vocalist Ismael "Maelo" Rivera, attaining unprecedented popularity and modernizing the plena while recapturing its earthy vitality. Many of Cortijo's plenas present colorful and evocative vignettes of barrio life and lent a new sort of recognition to the dynamic contribution of Afro-Puerto Ricans to the island's culture (and especially music). This period represented the apogee of plena's popularity as a commercial popular music. Unfortunately, Rivera spent much of the 1960s in prison, and the group never regained its former vigor. Nevertheless, the extraordinarily massive turnout for Cortijo's funeral in 1981 reflected the beloved singer's enduring popularity. By then, however, plena's popularity had been replaced by that of salsa, although some revivalist groups, such as Plena Libre, continue to perform in their lively fashion, while "street" plena is also heard on various occasions. |

プレナ 1900年頃、プレナは、サンフアンやポンセなどの下層階級、主にアフロ・プエルトリカンの都市部で、質素なプロレタリアの民俗ジャンルとして出現しまし た。その後、プレナは島の音楽文化の中でそのニッチを占めるようになった。その典型的な形として、プレナは非公式で気取らないシンプルな民謡のジャンルで あり、パンデレタ(ジングルのないタンバリンのようなもの)と呼ばれる丸い、しばしば自家製のフレームドラムの伴奏に合わせて詩とリフレインを交互に歌 い、おそらくアコーディオンやギター、その他の手近な楽器で補足されることになる。打楽器は持ち運びが便利なため、社交の場などで自然に演奏されることが 多い。プレナでは、クアトロ、マラカス、アコーディオンなどの楽器がよく使われる。 プレナのリズムは単純な二重パターンであるが、リードのパンデレタ奏者は活発なシンコペーションを加えることがある。プレナのメロディーは、気取らない、 「庶民的」なシンプルさを持つ傾向がある。初期のプレナの詩は、「エレナを刺した」「消防車が来た」など、バリオの逸話を題材にしたものがある。また、 「Llegó el obispo」のように、来日した司教を揶揄するような、明らかに不遜で風刺の効いたものも多い。また、「Cuando las mujeres quieren a los hombres」や「Santa María」のように、島中で親しまれているプレナもある。1935年、エッセイストのトマス・ブランコは、時代遅れでエリート主義的なダンスではなく、 この島の基本的なクレオール、タイノ、マルチーズの人種と文化の特徴を表現するものとして、プレナを賞賛しました。パレードや祭りに参加する友人たちがパ ンデレタを持って来て歌い出したり、占領や奴隷制度への抗議として昔から行われてきた学生や労働者のストライキでおなじみの曲に新しい言葉が付けられたり と、プレナは今でも様々な文脈でよく演奏されています。愛好家がプレナに合わせて踊ることもあるが、プレナは特徴的に踊りを志向しているわけではない。 1920年代から30年代にかけて、プレナは商業的に録音されるようになり、特にマヌエル・エル・カナリオ・ヒメネスは、伝統的な楽器をピアノやホルンの アレンジで補いながら、古い曲や新しい曲を演奏した。1940年代には、セザール・コンセプシオンがプレナのビッグバンド版を普及させ、このジャンルに新 たな名声を与えたが、プロレタリアの活気や洒落た雰囲気はある程度犠牲になっていたようである。1950年代に入ると、ラファエル・コルティージョとイス マエル・マエロ・リベラの小編成バンドによるプレナが登場し、空前の人気を博し、プレナの土俗的な活力を取り戻しながら現代化されました。コルティージョ のプレナの多くは、バリオの生活を色鮮やかに表現しており、島の文化(特に音楽)に対するアフロ・プエルトリコ人のダイナミックな貢献が新たに認識される ようになった。この時期は、商業的なポピュラー音楽としてのプレナの人気の絶頂期であった。しかし、残念ながらリベラは1960年代の大半を刑務所で過ご し、グループはかつての活気を取り戻すことはなかった。しかし、1981年のコルティージョの葬儀には多くの参列者が集まり、この歌手の人気は衰えること がなかった。しかし、プレナ・リブレのような復活グループもあり、生き生きとした演奏が続けられ、また、「ストリート」プレナも様々な場面で聞かれる。 |

| Danza By the late 1700s, the country dance (French contredanse, Spanish contradanza) had come to thrive as a popular recreational dance, both in courtly and festive vernacular forms, throughout much of Europe, replacing dances such as the minuet. By 1800 a creolized form of the genre, called contradanza, was thriving in Cuba, and the genre also appears to have been extant, in similar vernacular forms, in Puerto Rico, Venezuela, and elsewhere, although documentation is scanty. By the 1850s, the Cuban contradanza—increasingly referred to as danza—was flourishing both as a salon piano piece, or as a dance-band item to accompany social dancing, in a style evolving from collective figure dancing (like a square dance) to independent couples dancing ballroom-style (like a waltz, but in duple rather than ternary rhythm). According to local chroniclers, in 1845 a ship arrived from Havana, bearing, among other things, a party of youths who popularized a new style of contradanza/danza, confusingly called "merengue." This style subsequently became wildly popular in Puerto Rico, to the extent that in 1848 it was banned by the priggish Spanish governor Juan de la Pezuela. This prohibition, however, does not seem to have had much lasting effect, and the newly invigorated genre—now more commonly referred to as "danza"—went on to flourish in distinctly local forms. As in Cuba, these forms included the pieces of music played by dance ensembles as well as sophisticated light-classical items for solo piano (some of which could subsequently be interpreted by dance bands). The danza as a solo piano idiom reached its greatest heights in the music of Manuel Gregorio Tavárez (1843–83), whose compositions have a grace and grandeur closely resembling the music of Chopin, his model. Achieving greater popularity were the numerous danzas of his follower, Juan Morel Campos (1857–96), a bandleader and extraordinarily prolific composer who, like Tavárez, died in his youthful prime (but not before having composed over 300 danzas). By Morel Campos' time, the Puerto Rican Danza had evolved into a form quite distinct from that of its Cuban (not to mention European) counterparts. Particularly distinctive was its form consisting of an initial paseo, followed by two or three sections (sometimes called "merengues"), which might feature an arpeggio-laden "obbligato" melody played on the tuba-like bombardino (euphonium). Many danzas achieved island-wide popularity, including the piece "La Borinqueña", which is the national anthem of Puerto Rico. Like other Caribbean creole genres such as the Cuban danzón, the danzas featured the insistent ostinato called "cinquillo" (roughly, ONE-two-THREE-FOUR-five-SIX-SEVEN-eight, repeated). The danza remained vital until the 1920s, but after that decade its appeal came to be limited to the Hispanophilic elite. The danzas of Morel Campos, Tavárez, José Quintón, and a few others are still performed and heard on various occasions, and a few more recent composers have penned their idiosyncratic forms of danzas, but the genre is no longer a popular social dance idiom. During the first part of the dancing danza, to the steady tempo of the music, the couples promenade around the room; during the second, with a lively rhythm, they dance in a closed ballroom position and the orchestra would begin by leading dancers in a "paseo," an elegant walk around the ballroom, allowing gentlemen to show off their lady's grace and beauty. This romantic introduction ended with a salute by the gentlemen and a curtsey from the ladies in reply. Then, the orchestra would strike up and the couples would dance freely around the ballroom to the rhythm of the music.[7] |

ダンス曲(舞曲) 1700年代後半には、メヌエットなどの舞曲に代わって、カントリーダンス(フランス語のコントルダンス、スペイン語のコントルダンザ)が、ヨーロッパ全 土で宮廷や祝祭のヴァナキュラー形式として、人気のレクリエーションダンスとして盛んになっていました。1800年頃には、このジャンルをクレオール化し たコントラダンザという形式がキューバで盛んになり、プエルトリコ、ベネズエラなどでも同様のヴァナキュラー形式で現存していたようだが、資料は乏しいも のだった。1850年代までに、キューバのコントラバンザは、サロンでのピアノ曲として、あるいは社交ダンスに伴うダンスバンドのアイテムとして、集団的 なフィギュアダンス(スクエアダンスのようなもの)から独立したカップルが踊る社交ダンス(ワルツのようだが3進法ではなく2進法)へと発展するスタイル で繁栄していた。1845年、ハバナから一隻の船が到着し、その船には、「メレンゲ」と紛らわしい名前で呼ばれる新しいスタイルのコントランサ/ダンザを 広めた若者たちの一団が乗っていたと、地元の年代記者は伝えている。その後、このスタイルはプエルトリコで大流行し、1848年には、気難しいスペイン総 督フアン・デ・ラ・ペズエラによって禁止されたほどである。しかし、この禁止令はそれほど長続きしなかったようで、新たに活性化したジャンルは、現在では 「ダンツァ」と呼ばれるようになり、その土地特有の形で繁栄していった。キューバと同様、ダンス・アンサンブルで演奏される曲や、ピアノ独奏のための洗練 されたライト・クラシックの曲(一部はダンス・バンドが解釈することもある)などがその形式である。ピアノ独奏のイディオムとしてのダンザは、マヌエル・ グレゴリオ・タバレス(1843-83)の音楽で最高の高みに達し、その曲は、彼のモデルであるショパンの音楽に近い優雅さと壮大さを備えている。タバレ ス同様、若くしてこの世を去ったが、300曲以上の舞曲を作曲し、バンドリーダーであり、非常に多作な作曲家でもあった。モレル・カンポスの時代には、プ エルトリコのダンサは、キューバやヨーロッパのダンサとは全く異なる形式へと進化していた。特に特徴的だったのは、最初のパセオに続く2~3つのセクショ ン(「メレンゲ」と呼ばれることもある)で、チューバのようなボンバルディーノ(ユーフォニアム)で演奏されるアルペジオを含む「オブリガート」メロディ を特徴とする形式であった。プエルトリコの国歌である「La Borinqueña」をはじめ、多くのダンスが島中で人気を博しています。キューバのダンソンのようなカリブ海のクレオールのジャンルと同様に、ダン ツァは「チンキージョ」(ONE-two-THREE-FOUR-5-SIX-SEVEN-8を繰り返す)というしつこいオスティナートを特徴とする。 1920年代まで活況を呈したが、それ以降、その魅力はイスパノフィルのエリートに限定されるようになった。モレル・カンポス、タバレス、ホセ・キントン など数人の作曲家のダンスは、今でも様々な場面で演奏され、耳にすることができますし、最近の作曲家の中には、独自の形式のダンスもあるが、このジャンル は、もはや社交ダンスのイディオムとしては人気がない。ダンス・ダンサの第1部では、安定したテンポの音楽に合わせて、カップルは部屋の中をプロムナード する。第2部では、活発なリズムで、彼らは閉じたボールルームの位置で踊り、オーケストラはまずダンサーを「パセオ」(ボールルームを優雅に歩き、男性が 女性の優雅さと美しさをアピールできる)に導く。このロマンティックな導入は、紳士が敬礼し、淑女がそれに応えて礼をすることで終わる。その後、オーケス トラの演奏が始まり、カップルは音楽のリズムに合わせて舞踏場を自由に踊り歩いた[7]。 |

| Puerto Rican pop Much music in Puerto Rico falls outside the standard categories of "Latin music" and is better regarded as constituting varieties of "Latin world pop." This category includes, for example, Ricky Martin (who had a #1 Hot 100 hit in the U.S. with "Livin' La Vida Loca" in 1999), the boy-band Menudo (with its changing personnel), Los Chicos, Las Cheris, Salsa Kids and Chayanne. Famous singers include the Despacito singer Luis Fonsi. Also, singer and virtuoso guitarist Jose Feliciano born in Lares, Puerto Rico, became a world pop star in 1968 when his Latin-soul version of "Light My Fire" and the LP Feliciano! became great successes in the American and international rankings and allowed Feliciano to be the first Puerto Rican to win Grammy awards, during that year. Feliciano's "Feliz Navidad" remains one of the most popular Christmas songs. |

プエルトリカンポップ プエルトリコの音楽の多くは、標準的な「ラテン音楽」のカテゴリーから外れており、「ラテン・ワールド・ポップ」の一種と見なすのが妥当である。このカテ ゴリーには、例えば、リッキー・マーティン(1999年に「Livin' La Vida Loca」で全米Hot100の1位を獲得)、ボーイズバンドのメヌード(メンバーは変更あり)、ロス・チコス、ラス・チェリス、サルサキッズ、チャヤン ヌが含まれます。有名な歌手としては、デスパシート(Despacito)のボーカル、ルイス・フォンシ(Luis Fonsi)がいます。また、プエルトリコのラレスで生まれた歌手で名ギタリストのホセ・フェリシアーノは、1968年にラテン・ソウル・バージョンの 「Light My Fire」とLP「Feliciano!」がアメリカや世界のランキングで大成功し、その年にプエルトリコ人として初めてグラミー賞を受賞し、世界のポッ プスターとなった。フェリシアーノの "Feliz Navidad "は、今でも最も人気のあるクリスマスソングの1つである。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_Puerto_Rico |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

A modern Puerto rican

cuatro ; A plan of three cuatro body designs. From left to right, the

traditional cuatro antiguo design, the "Southern" soft waisted cuatro

antiguo, and the modern "aviolinado" cuatro

+++

Luis Fonsi - Despacito ft. Daddy Yankee; GERMAN ROSARIO- PELANDO MORCILLA

GERMAN ROSARIO, YOMO TORO- COSAS DE LA VIDA; Wally Rita Y Los Kauianos

FLOR MORALES RAMOS-

(RAMITO) EL DILUVIO UNIVERSAL

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099