プレナ

Plena Puertorriquña

"Baile

De Loiza Aldea".

☆ プレナ(Plena)は プエルトリコ原産の音楽とダンスのジャンルである。 プレナというジャンルは1900年頃にプエルトリコのポンセにあるバリオ・サン・アントンで生まれた。プレナは、メキシコの コリドスと同様に、人々の間にメッセージを広めたため、下層階級ではしばしばピリオディコ・カンタード、または「歌われた新聞」と呼ばれた。

| Plena is a genre of

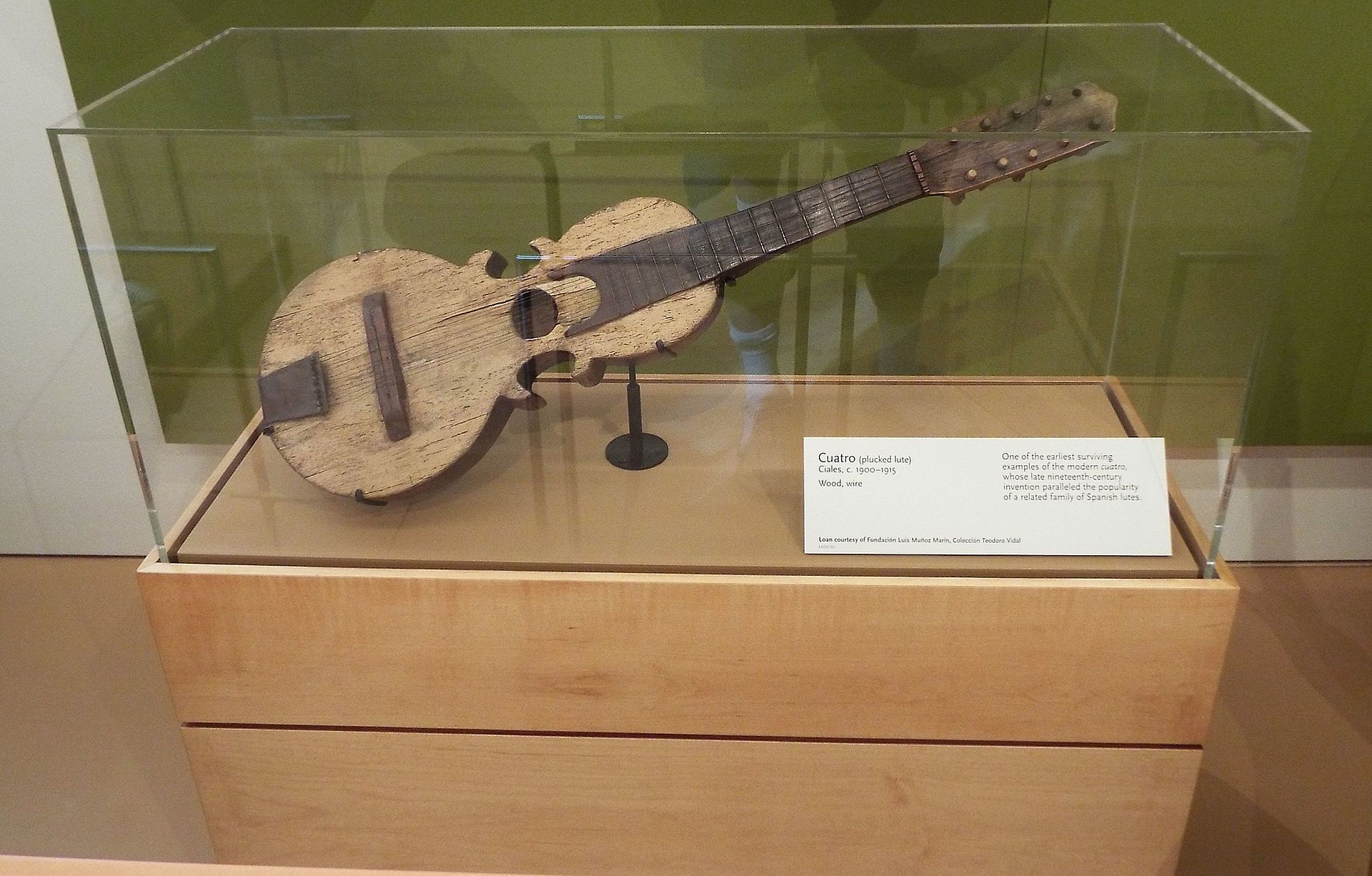

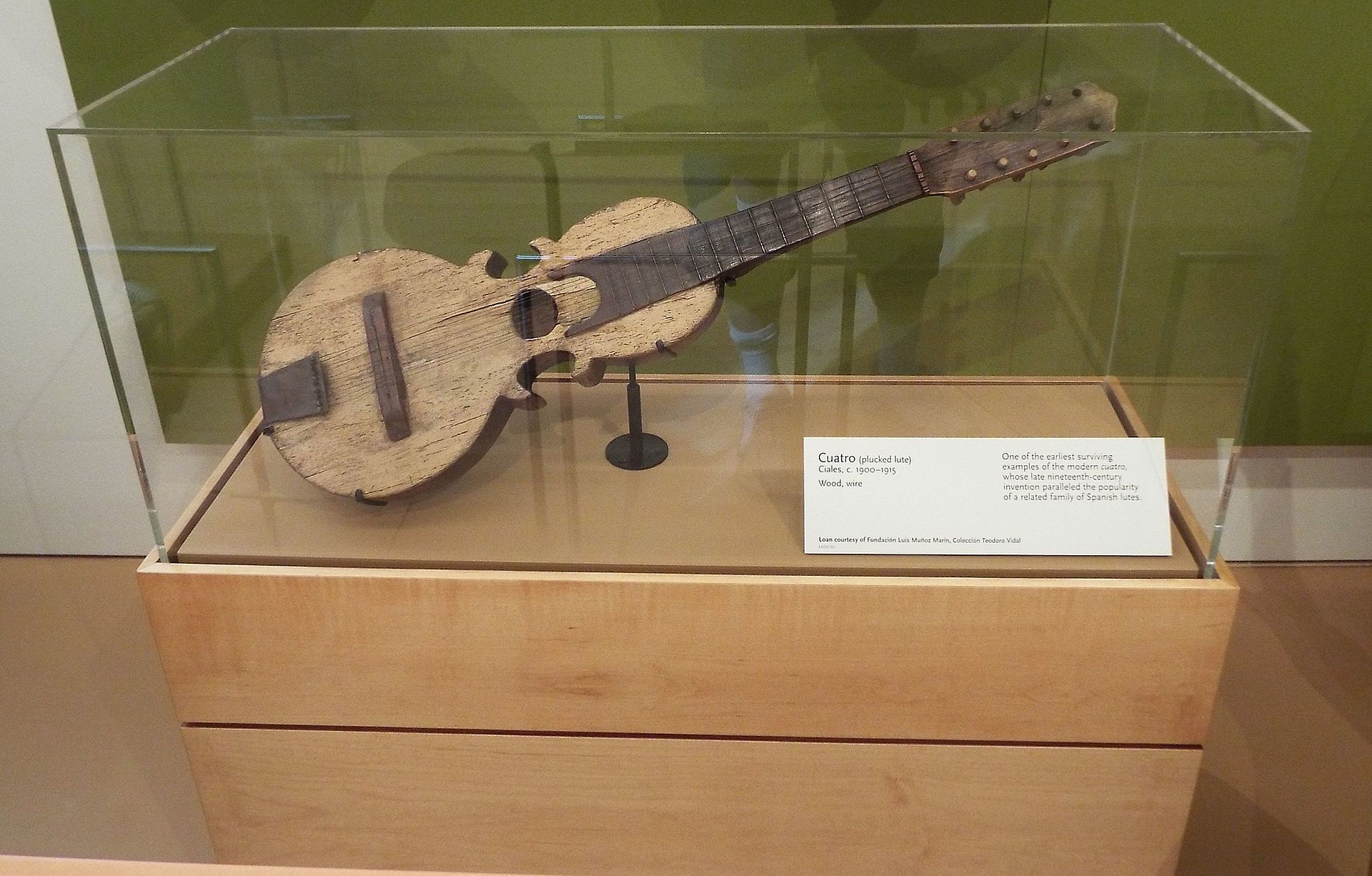

music and dance native to Puerto Rico.[1][2] Origins The plena genre originated in Barrio San Antón, Ponce, Puerto Rico,[3][4] around 1900.[5] It was influenced by the bomba style of music.[citation needed] Originally, sung texts were not associated with the plena, which was rendered by guitar, accordion and pandero, but eventually, in 1907,[citation needed] singing was added. Plena was often called the periodico cantado[citation needed] or "sung newspaper" for the lower classes because it spread messages among people, similar to the corridos in Mexico.  A Cuatro, (c. 1900 - 1915) from Ciales, Puerto Rico on exhibit in the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix. |

プレナは

プエルトリコ原産の音楽とダンスのジャンルである[1][2]。 起源[編集] プレナというジャンルは1900年頃にプエルトリコのポンセにあるバリオ・サン・アントンで生まれた[3][4][5] 。プレナは、メキシコの コリドスと同様に、人々の間にメッセージを広めたため、下層階級ではしばしばピリオディコ・カンタード[要出典]、または「歌われた新聞」と呼ば れた。  フェニックスの楽器博物館に展示されているプエルトリコ、シアレスの クアトロ(1900年〜1915年頃)。 |

| History The plena was a result of the mixing of the culturally diverse popular class, where their workplace, neighborhood, and life experiences met to create an expressive, satirical style of music.[6] It became a way for the working class to gain empowerment through parody. Due to originating in the lower social class, it was regarded by the upper class as "a menace to public order and private property" and was for many years associated with people of la vida alegre (the merry life), referring to prostitutes, dancers, alcoholics, and moral degenerates. Singing and dancing of the plena often happened in cafetines, bars that frequently doubled as brothels and where interracial socializing and sexual encounters were free to take place.[7] According to singers discussing the use of the plena, they stated it was song with lyrics that related to a current event. For example, if someone drowned or was killed, a plena would be written about it.[8] Tintorera del Mar,[9] Mataron a Elena, El Obispo de Ponce, and Matan a Bumbum[10] were some plenas which became wildly popular.[11] The eventual widespread acceptance of the plena can be attributed to the increased number of people joining the workforce, which led to a new demand for public leisure. It was still considered indecent by the upper class, who fought against its rising popularity. In December 1917, an ordinance was passed banning the dances from happening inside the city limits. It took another decade for the plena to gain widespread popularity throughout Puerto Rico and cross racial and cultural boundaries. Listening to plena at home and at neighborhood- or municipal-sanctioned celebrations became acceptable and was no longer considered morally tainted by "respectable" white upper class Ponceños. Eventually, with much whitewashing to make it more palatable to the masses, plena was embraced in earnest as a style of music that united Puerto Ricans. However, with the acceptance of the upper class, what began as a vitally important cultural identifier and personal expression of philosophy, community, and self to the lower class became an entertaining spectacle for the white upper class.[7] By the 1930s, the plena was accessible to all through the radio and record industries.[7] |

歴史[編集] プレナは、文化的に多様な庶民階級が混ざり合った結果生まれたもので、 彼らの職場、近隣、人生経験が出会い、表現力豊かで風刺的なスタイルの音楽を生み出した[6]。労働者階級がパロディを通じて力を得る手段となった。下層 社会で生まれたため、上流階級からは「公序良俗と私有財産を脅かすもの」とみなされ、長い間、娼婦、踊り子、アル中、道徳的堕落者を指すラ・ヴィダ・アレ グレ(陽気な生活)の人々と結びつけられていた。プレナの歌と踊りは、しばしば売春宿を兼ねたバーであり、異人種間の社交や性的な出会いが自由に行われて いたカフェティンでしばしば行われていた[7]。 プレナの用途について語る歌手によれば、彼らはプレナは時事的な出来事に関連した歌詞を持つ歌であると述べている。例えば、誰かが溺れたり殺されたりした 場合、それについてプレナが書かれる[8]。 プレナが最終的に広く受け入れられるようになったのは、労働人口が増加し、公共のレジャーに対する新たな需要が生まれたためと考えられる。しかし、上流階 級はプレナを猥褻なものとみなし、人気の高まりに反対した。1917年12月には、 市内での踊りを禁止する条例が制定された。プレナがプエルトリコ全土に広まり、人種や 文化の垣根を越えて人気を博すには、さらに10年かかった。 自宅や近所、あるいは市公認の祝賀行事でプレナを聴くことが受け入れられるようになり、「立派な」白人上流階級のポンセーニョたちからは、もはや道徳的に 汚れたものとは見なされなくなった。やがて、大衆に受け入れられやすくするために多くの白塗り加工が施され、プレナはプエルトリコ人を団結させる音楽のス タイルとして本格的に受け入れられるようになった。しかし、上流階級が受け入れたことで、下層階級にとって極めて重要な文化的識別子であり、哲学、コミュ ニティ、自己の個人的表現として始まったものが、白人上流階級にとっては娯楽的な見世物となった[7]。 1930年代までには、プレナはラジオや レコード産業を通じてすべての人がアクセスできるようになった[7]。 |

| Genre Plena music is generally folkloric in nature. The music's beat and rhythm are usually played using hand drums called panderetas, also known as panderos. The music is accompanied by a scrape gourd, the guiro. Panderetas resemble tambourines but without the jingles. These are handheld drums with stretched animal skins, usually goat skin, covering a round wooden frame. Three different sizes of pandereta are used in plena: the Seguidor (the largest of the three), the Punteador (the medium-sized drum), and the requinto. An advantage of this percussion arrangement is its portability, contributing to the plena's spontaneous appearance at social gatherings. Other instruments commonly heard in plena music are the cuatro, the maracas, and accordions.[12] The fundamental melody of the plena, as in all regional Puerto Rican music, has a decided Spanish strain; it is marked in the resemblance between the plena Santa María and a song composed in the Middle Ages by Alfonso the Wise, King of Spain. The lyrics of plena songs are usually octosyllabic and assonant. Following the universal custom the theme touches upon all phases of life—romance, politics, and current events. Generally, anything which appeals to the imagination of the people, such as the arrival of a personage, a crime, a bank moratorium, or a hurricane, can be the subject of plena music. |

ジャンル[編集] プレナ音楽は一般的に民俗音楽である。音楽のビートと リズムは通常、パンデレタ(パンデロスとも呼ばれる)と呼ばれる手太鼓を使って演奏される。音楽は擦弦楽器のギロによって伴奏される。パンデレタは タンバリンに似ているが、ジングルはない。手持ちの太鼓で、丸い木枠に動物の皮(通常はヤギの皮)が張られている。プレナでは3種類の大きさのパンデレタ が使われる:セギドール(3種類の中で最も大きい)、プンテアドール(中型の太鼓)、レキント。この打楽器配置の利点は持ち運びが容易なことで、社交の場 でのプレナの自発的な出現に貢献している。プレナ音楽でよく聴かれる他の楽器は、クアトロ、マラカス、アコーディオンである[12]。 プレナの基本的なメロディーは、プエルトリコの他の地域音楽と同様、明らかにスペイン的な系統を持っている。それは、プレナ「サンタ・マリア」とスペイン 王アルフォンソ賢王が中世に作曲した歌との類似性に顕著である。プレナの歌詞は、通常8音節で構成されている。普遍的な習慣に従い、テーマは恋愛、政治、 時事問題など人生のあらゆる局面に触れる。一般的に、人物の登場、犯罪、銀行取引停止、ハリケーンなど、人々の想像力に訴えるものであれば何でもプレナの 題材になりうる。 |

| Spread Plena is played throughout Puerto Rico especially during special occasions such as the Christmas season, and as the musical backdrop for civic protests, due to its traditional use as a vehicle for social commentary. When plena is played the audience often joins in the singing, clapping, and dancing. Plena is also enjoyed by the Puerto Rican diaspora outside of Puerto Rico. Pleneros de la 21, for example, traveled to Hawaii to perform for the Puerto Rican diaspora there which include descendants of Puerto Ricans who immigrated to Hawaii from Puerto Rico in the early 20th century.[13] 13: "Los Pleneros de la 21: Afro-Puerto Rican traditions". Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2020. |

普及[編集] プレナはプエルトリコ全土で演奏され、特にクリスマス・シーズンなどの特別な機会に演奏される。また、伝統的に社会批判の手段として使われてきたため、市民による抗議活動の音楽的背景としても使わ れる。プレナが演奏されると、聴衆も歌や手拍子、踊りに加わることが多い。プレナは、プエルトリコ以外のプエルトリコ人ディアスポラでも楽 しまれている。例えば、プレネロス・デ・ラ21は、20世紀初頭にプエルトリコからハワイに移住したプエルトリコ人の子孫を含むプエルトリコのディアスポ ラのためにハワイを訪れ、演奏した[13]。 |

| Composers As a folk genre, there have been many good composers, some well known in their day and into the present. Perhaps one of the genre's most celebrated composers and performers was Manuel Jiménez, known as 'El Canario'. Certainly, there were many others, including such greats as Ramito, Ismael Rivera, Mon Rivera (the junior), and Rafael Cortijo. In 2006, Tito Matos and Los Pleneros de la 21 received a Grammy nomination for their Para Todos Ustedes plena songs recording.[14] The genre has had a revival recently, as evident by the emergence of many plena bands (such as Plena Libre, Viento de agua and others) and its use in various songs, such as Ricky Martin's recent song "Pégate" and Ivy Queen's "Vamos A Celebrar". In 1953, Puerto Rican writer, Luis Palés Matos wrote Plena del Menéalo urging the Puerto Rican woman to move it and ends the plena with the line ¡Para que rabie el Tio Sam (to make "Uncle Sam" angry).[15] |

作曲家[編集] 民俗音楽のジャンルとして、多くの優れた作曲家が存在し、当時から現在に至るまで有名な作曲家もいる。このジャンルで最も有名な作曲家・演奏家の一人は、 「エル・カナリオ」として知られるマヌエル・ヒメネスだろう。確かに、ラミート、イスマエル・リベラ、モン・リベラ(ジュニア)、ラファエル・コルティー ジョといった偉大なミュージシャンは他にもたくさんいた。2006年、ティト・マトスとロス・プレネロス・デ・ラ21は、Para Todos Ustedesのプレナソングのレコーディングでグラミー賞にノミネートされた[14]。 このジャンルは最近復活を遂げ、プレナ・バンド(プレナ・リブレ、ビエント・デ・アグアなど)が数多く登場し、リッキー・マーティンの最近の曲 「Pégate」やアイビー・クイーンの「Vamos A Celebrar」など、様々な曲で使用されている。 1953年、プエルトリコの作家ルイス・パレス・マトスは、プエルトリコの女性にそれを動かすよう促すプレナ・デル・メネアロを書き、プレナの最後を ¡Paraque rabie el Tio Sam(「サムおじさん」を怒らせるために)というセリフで締めくくった[15]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plena |

|

| Around

1900 plena emerged as a humble proletarian folk genre in the

lower-class, largely Afro-Puerto Rican urban neighborhoods in San Juan,

Ponce, and elsewhere. Plena subsequently came to occupy its niche in

island music culture. In its quintessential form, plena is an informal,

unpretentious, simple folk-song genre, in which alternating verses and

refrains are sung to the accompaniment of round, often homemade frame

drums called panderetas (like tambourines without jingles), perhaps

supplemented by accordion, guitar, or whatever other instruments might

be handy. An advantage of the percussion arrangement is its

portability, contributing to the plena's spontaneous appearance at

social gatherings. Other instruments commonly heard in plena music are

the cuatro, the maracas, and accordions. The plena rhythm is a simple duple pattern, although a lead pandereta player might add lively syncopations. Plena melodies tend to have an unpretentious, "folksy" simplicity. Some early plena verses commented on barrio anecdotes, such as "Cortarón a Elena" (They stabbed Elena) or "Allí vienen las maquinas" (Here come the firetrucks). Many had a decidedly irreverent and satirical flavor, such as "Llegó el obispo" mocking a visiting bishop. Some plenas, such as "Cuando las mujeres quieren a los hombres" and "Santa María," are familiar throughout the island. In 1935 the essayist Tomás Blanco celebrated plena—rather than the outdated and elitist danza—as an expression of the island's fundamentally creole, Taino or mulatto racial and cultural character. Plenas are still commonly performed in various contexts; a group of friends attending a parade or festival may bring a few panderetas and burst into song, or new words will be fitted to the familiar tunes by protesting students or striking workers which have long been a regular form of protest from occupation and slavery. While enthusiasts might on occasion dance to a plena, plena is not characteristically oriented toward dance. In the 1920s–30s plenas came to be commercially recorded, especially by Manuel "El Canario" Jimenez, who performed old and new songs, supplementing the traditional instruments with piano and horn arrangements. In the 1940s Cesar Concepción popularized a big-band version of plena, lending the genre a new prestige, to some extent at the expense of its proletarian vigor and sauciness. In the 1950s a newly invigorated plena emerged as performed by the smaller band of Rafael Cortijo and vocalist Ismael "Maelo" Rivera, attaining unprecedented popularity and modernizing the plena while recapturing its earthy vitality. Many of Cortijo's plenas present colorful and evocative vignettes of barrio life and lent a new sort of recognition to the dynamic contribution of Afro-Puerto Ricans to the island's culture (and especially music). This period represented the apogee of plena's popularity as a commercial popular music. Unfortunately, Rivera spent much of the 1960s in prison, and the group never regained its former vigor. Nevertheless, the extraordinarily massive turnout for Cortijo's funeral in 1981 reflected the beloved singer's enduring popularity. By then, however, plena's popularity had been replaced by that of salsa, although some revivalist groups, such as Plena Libre, continue to perform in their lively fashion, while "street" plena is also heard on various occasions. |

1900年頃、プレナはサンフアン

やポンセなどの下層階級、主にアフロ・プエルトリカンの都市部で、質素なプロレタリアのフォーク・ジャンルとして出現し

た。プレナはその後、島の音楽文化のニッチを占めるようになった。その典型的な形として、プレナは、カジュアルで気取らない、シンプルな民謡のジャンル

で、パンデレタ(ジングルのないタンバリンのようなもの)と呼ばれる丸い、しばしば手作りのフレームドラムの伴奏に合わせて、詩とリフレインを交互に歌い

ます。パーカッションの配置の利点は持ち運びやすいことで、プレナが社交の場に自然に登場することに貢献している。プレナ音楽でよく耳にする他の楽器は、

クアトロ、マラカス、アコーディオンである。 プレナのリズムは単純な二重パターンだが、リードのパンデレタ奏者が軽快なシンコペーションを加えることもある。プレナのメロディーは、気取らない「民謡 的」な単純さを持つ傾向がある。初期のプレナの詩の中には、バリオの逸話を歌ったものがあり、例えば、"Cortarón a Elena"(エレナを刺した)や "Allí vienen las maquinas"(消防車が来た)などがある。また、「Llegó el obispo(オビスポの到着)」のように、来日した司教を揶揄するような、明らかに不遜で風刺的な趣向のものも多い。いくつかのプレナは、 "Cuando las mujeres quieren a los hombres "や "Santa María "のように、島中で親しまれている。1935年、エッセイストのトマス・ブランコは、時代遅れでエリート主義的なダンスではなく、島の基本的なクレオー ル、タイノー、または混血の人種的、文化的特徴を表現するものとして、プレナを賞賛した。パレードやお祭りに参加する友人たちがパンデレッタを数曲持って きて歌い出すこともあれば、占領や奴隷制度に対する抗議の定番であった学生やストライキに参加する労働者が、おなじみの曲に新しい言葉をつけて歌うことも ある。熱狂的なファンがプレナに合わせて踊ることもあるが、プレナは特徴的にダンス向きではない。 1920年代から30年代にかけて、プレナは商業的に録音されるようになり、特にマヌエル・"エル・カナリオ"・ヒメネスは、伝統的な楽器をピアノやホル ンのアレンジで補いながら、新旧の曲を演奏した。1940年代には、セザール・コンセプシオンがビッグバンド版のプレナを普及させ、このジャンルに新たな 名声を与えた。1950年代には、ラファエル・コルティージョとヴォーカリストのイスマエル・"マエロ"・リベラの小編成バンドによる、新たに活性化され たプレナが登場し、空前の人気を博すとともに、プレナの土俗的な活力を取り戻しながら現代化された。コルティージョのプレナの多くは、バリオの生活を彩り 豊かに描いたもので、島の文化(特に音楽)に対するアフロ・プエルトリカンのダイナミックな貢献が新たに認識されるようになった。この時期は、商業的なポ ピュラー音楽としてのプレナの人気の絶頂期であった。残念ながら、リベラは1960年代の大半を刑務所で過ごし、グループがかつての活気を取り戻すことは なかった。とはいえ、1981年に行われたコルティージョの葬儀には非常に多くの参列者が集まり、この最愛の歌手の不滅の人気を反映していた。しかし、そ のころには、プレナの人気はサルサに取って代わられていた。プレナ・リブレのような復活を遂げたグループが生き生きとした演奏を続けているほか、"スト リート "プレナもさまざまな場面で聴かれている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_Puerto_Rico |

https://navymule9.sakura.ne.jp/Puetorican_music.html |

Manuel Jimenez La Mala Suerte Del Pobre

La

Plena

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆