ユナイティド・フルーツ

United

Fruit Company

★Caricatura de la política del «Gran Garrote» (del inglés «Big Stick») del gobierno del presidente estadounidense Theodore Roosevelt, que mantuvo a todos los países del Caribe bajo un dominio férreo a fin de que la construcción del Canal de Panamá ocurriera sin problemas.【上掲挿絵:左】パナマ運河建設を円滑に進めるため、カリブ海諸国を厳しく管理したセオドア・ルーズベルト政権の「ビッグ・スティッ ク」政策を風刺したもの。【上掲挿絵:右】ニューオーリンズにおけるバナナの積み下ろし(Workers unload bananas in New Orleans in the 1920s) Library of Congress Catalog: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/agc1996002003/PP.

★[Industry]: Agriculture, [Predecessors] Boston Fruit Company, Tropical Trading & Transport.[Founded] March 30, 1899.[Defunct] June 30, 1970 (as United Fruit Company), August 1984 (as United Brands).[Fate] Merged with AMK to become United Brands Company. [Successor]Chiquita Brands International.

会社概要:[業種]:

農業、[前身]ボストン・フルーツ・カンパニー、トロピカル・トレーディング&トランスポート[設立]1899年3月30日[消滅]1970年6月30日

(United Fruit Companyとして)、1984年8月(United Brandsとして)[運命]AMKと合併しUnited

Brands Companyとなる。[後継]チキータ・ブランズ・インターナショナル。

| The

United Fruit Company (now Chiquita) was an American multinational

corporation that traded in tropical fruit (primarily bananas) grown on

Latin American plantations and sold in the United States and Europe.

The company was formed in 1899 from the merger of the Boston Fruit

Company with Minor C. Keith's banana-trading enterprises. It flourished

in the early and mid-20th century, and it came to control vast

territories and transportation networks in Central America, the

Caribbean coast of Colombia and the West Indies. Although it competed

with the Standard Fruit Company (later Dole Food Company) for dominance

in the international banana trade, it maintained a virtual monopoly in

certain regions, some of which came to be called banana republics –

such as Costa Rica, Honduras, and Guatemala.[1] United Fruit had a deep and long-lasting impact on the economic and political development of several Latin American countries. Critics often accused it of exploitative neocolonialism, and they described it as the archetypal example of the influence of a multinational corporation on the internal politics of the so-called banana republics. After a period of financial decline, United Fruit was merged with Eli M. Black's AMK in 1970 to become the United Brands Company. In 1984, Carl Lindner, Jr. transformed United Brands into the present-day Chiquita Brands International.  Entrance façade of the old United Fruit Building at 321 St. Charles Avenue, New Orleans, Louisiana |

ユ

ナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニー(現チキータ)は、中南米の農園で発展している熱帯果実(主にバナナ)を米国とヨーロッパで販売する米国の多国籍企業で

ある。1899年にボストン・フルーツ・カンパニーとマイナー・C・キースのバナナ貿易事業が合併して設立された。20世紀初頭から中盤にかけて隆盛を極

め、中米、コロンビア・カリブ海沿岸、西インド諸島の広大な領土と輸送網を支配するようになった。バナナの国際取引ではスタンダード・フルーツ社(後の

ドール・フード社)と覇権を争ったが、コスタリカ、ホンジュラス、グアテマラなどバナナ共和国と呼ばれるようになった一部の地域で事実上の独占を維持した

[1]。 ユナイテッド・フルーツは、ラテンアメリカのいくつかの国の経済的、政治的発展に深く、長期的な影響を及ぼした。批評家はしばしば、搾取的な新植民地主義 として非難し、いわゆるバナナ共和国の内政に多国籍企業が影響を与えた典型的な例と評した。ユナイテッド・フルーツは経営が悪化した後、1970年にイー ライ・M・ブラックのAMKと合併し、ユナイテッド・ブランズ・カンパニーとなった。1984年、カール・リンドナー・ジュニアがユナイテッド・ブランズ を現在のチキータ・ブランズ・インターナショナルに変身させた。  ルイジアナ州ニューオーリンズ、セント・チャールズ通り321番地にある旧ユナイテッド・フルーツ・ビルの入口ファサード |

| Early years In 1871, U.S. railroad entrepreneur Henry Meiggs signed a contract with the government of Costa Rica to build a railroad connecting the capital city of San José to the port of Limón in the Caribbean. Meiggs was assisted in the project by his young nephew, Minor C. Keith, who took over Meiggs's business concerns in Costa Rica after his death in 1877. Keith began experimenting with the planting of bananas as a cheap source of food for his workers.[2] When the Costa Rican government defaulted on its payments in 1882, Keith had to borrow £1.2 million from London banks and from private investors to continue the difficult engineering project.[2] In exchange for this and for renegotiating Costa Rica's own debt, in 1884, the administration of President Próspero Fernández Oreamuno agreed to give Keith 800,000 acres (3,200 km2) of tax-free land along the railroad, plus a 99-year lease on the operation of the train route. The railroad was completed in 1890, but the flow of passengers proved insufficient to finance Keith's debt. However, the sale of bananas grown in his lands and transported first by train to Limón, then by ship to the United States, proved very lucrative. Keith eventually came to dominate the banana trade in Central America and along the Caribbean coast of Colombia. |

創業期 1871年、米国の鉄道事業家ヘンリー・メイグスは、コスタリカ政府と首都サンホセとカリブ海のリモン港を結ぶ鉄道建設の契約を結んだ。1877年のメグ スの死後、コスタリカでのメグスの事業を引き継いだ甥のマイナー・C・キースは、このプロジェクトを支援した。キースは、労働者のための安価な食料源とし てバナナの栽培の実験を開始した[2]。 1882年にコスタリカ政府の支払いが滞ると、キースは困難なエンジニアリング・プロジェクトを継続するためにロンドンの銀行と個人投資家から120万ポ ンドを借りなければならなかった[2]。このこととコスタリカ自身の債務の再交渉の代わりに、1884年にプロスペロ・フェルナンデス・オレアムノ大統領 政権はキースに鉄道沿線の80万エーカー(3,200km2)の非課税土地と99年間の鉄道ルート運営に関する借用を与えることに同意した。1890年に 鉄道は完成したが、利用客は少なく、キースの負債を埋めるには十分ではなかった。しかし、彼の土地で発展しているバナナを列車でリモンまで運び、さらに船 でアメリカまで運ぶと、非常に大きな利益を生むことが分かった。キースはやがて、中米とコロンビアのカリブ海沿岸のバナナ貿易を支配するようになった。 |

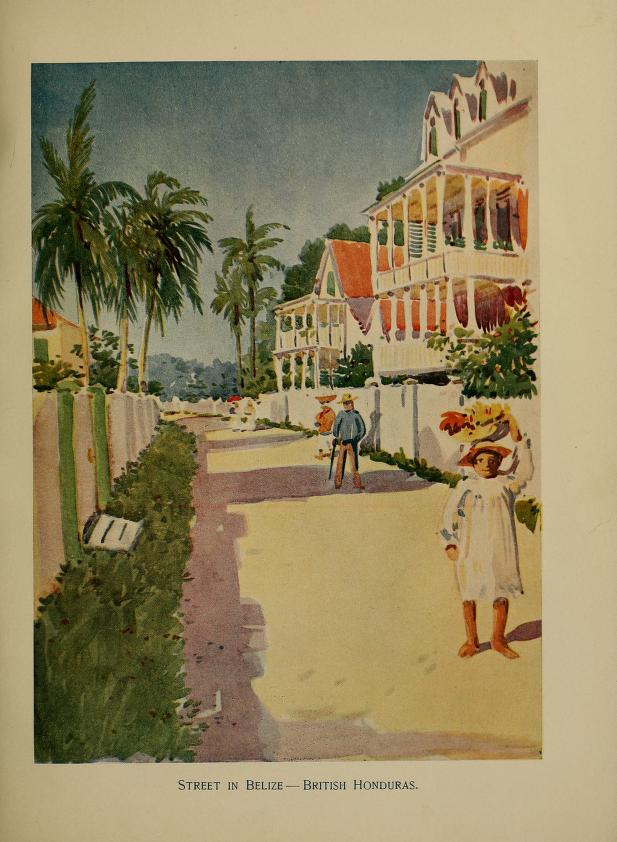

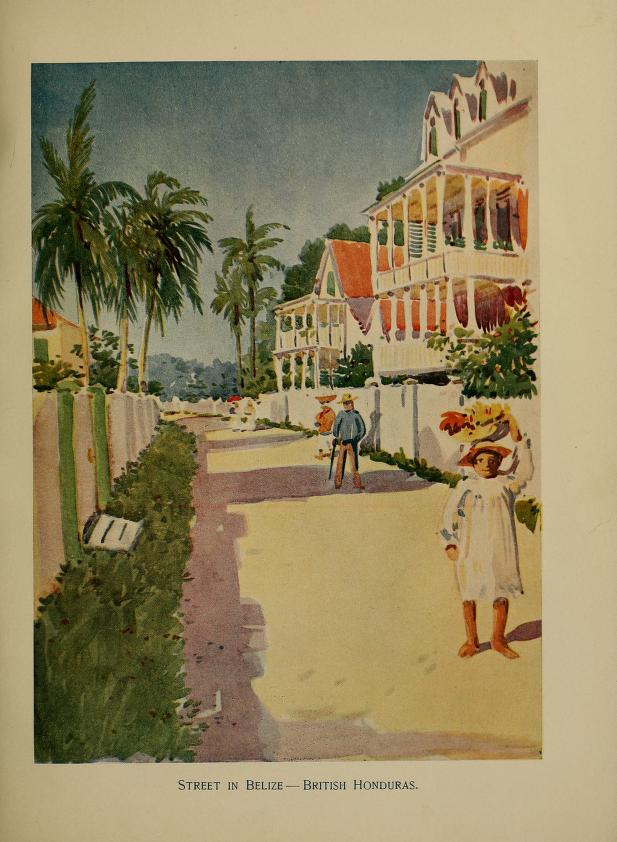

United Fruit (1899–1970) Banana company staff in Jamaica as part of United Fruit Company campaign to promote tourism  Docks of the United Fruit Company in New Orleans, 1922  An illustration from The Golden Caribbean, 1900 In 1899, Keith lost $1.5 million when Hoadley and Co., a New York City broker, went bankrupt.[2] He then traveled to Boston, Massachusetts, to participate in the merger of his banana trading company, Tropical Trading and Transport Company, with the rival Boston Fruit Company. Boston Fruit had been established by Lorenzo Dow Baker, a sailor who, in 1870, had bought his first bananas in Jamaica, and by Andrew W. Preston. Preston's lawyer, Bradley Palmer, had devised a scheme for the solution of the participants' cash flow problems and was in the process of implementing it. The merger formed the United Fruit Company, based in Boston, with Preston as president and Keith as vice-president. Palmer became a permanent member of the executive committee and for long periods of time the director. From a business point of view, Bradley Palmer was United Fruit. Preston brought to the partnership his plantations in the West Indies, a fleet of steamships, and his market in the U.S. Northeast. Keith brought his plantations and railroads in Central America and his market in the U.S. South and Southeast. At its founding, United Fruit was capitalized at $11.23 million. The company at Palmer's direction proceeded to buy, or buy a share in, 14 competitors, assuring them of 80% of the banana import business in the United States, then their main source of income. The company catapulted into financial success. Bradley Palmer overnight became a much-sought-after expert in business law, as well as a wealthy man. He later became a consultant to presidents and an adviser to Congress. In 1900, the United Fruit Company produced The Golden Caribbean: A Winter Visit to the Republics of Colombia, Costa Rica, Spanish Honduras, Belize and the Spanish Main – via Boston and New Orleans written and illustrated by Henry R. Blaney. The travel book featured landscapes and portraits of the inhabitants pertaining to the regions where the United Fruit Company possessed land. It also described the voyage of the United Fruit Company's steamer, and Blaney's descriptions and encounters of his travels.[3] In 1901, the government of Guatemala hired the United Fruit Company to manage the country's postal service, and in 1913 the United Fruit Company created the Tropical Radio and Telegraph Company. By 1930, it had absorbed more than 20 rival firms, acquiring a capital of $215 million and becoming the largest employer in Central America. In 1930, Sam Zemurray (nicknamed "Sam the Banana Man") sold his Cuyamel Fruit Company to United Fruit and retired from the fruit business. By then, the company held a major role in the national economies of several countries and eventually became a symbol of the exploitative export economy. This led to serious labor disputes by the Costa Rican peasants, involving more than 30 separate unions and 100,000 workers, in the 1934 Great Banana Strike, one of the most significant actions of the era by trade unions in Costa Rica.[4][5] By the 1930s the company owned 3.5 million acres (14,000 km2) of land in Central America and the Caribbean and was the single largest land owner in Guatemala. Such holdings gave it great power over the governments of small countries. That was one of the factors that led to the coining of the phrase "banana republic".[6] In 1933, concerned that the company was mismanaged and that its market value had plunged, Zemurray staged a hostile takeover. Zemurray moved the company's headquarters to New Orleans, Louisiana, where he was based. United Fruit went on to prosper under Zemurray's management;[7][8] Zemurray resigned as president of the company in 1951. In addition to many other labor actions, the company faced two major strikes of workers in South and Central America, in Colombia in 1928 and the Great Banana Strike of 1934 in Costa Rica.[9] The latter was an important step that would eventually lead to the formation of effective trade unions in Costa Rica since the company was required to sign a collective agreement with its workers in 1938.[10][11] Labor laws in most banana production countries began to be tightened in the 1930s.[12] United Fruit Company saw itself as being specifically targeted by the reforms, and often refused to negotiate with strikers, despite frequently being in violation of the new laws.[13][14] In 1952, the government of Guatemala began expropriating unused United Fruit Company land to landless peasants.[13] The company responded by intensively lobbying the U.S. government to intervene and mounting a misinformation campaign to portray the Guatemalan government as communist.[15] In 1954, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency deposed the democratically elected government of Guatemala, and installed a pro-business military dictatorship.[16] In 1967, it acquired the A&W Restaurants.[citation needed] United Brands (1970–1984) Corporate raider Eli M. Black bought 733,000 shares of United Fruit in 1968, becoming the company's largest shareholder. In June 1970, Black merged United Fruit with his own public company, AMK (owner of meat packer John Morrell), to create the United Brands Company. United Fruit had far less cash than Black had counted on, and Black's mismanagement led to United Brands becoming crippled with debt. The company's losses were exacerbated by Hurricane Fifi in 1974, which destroyed many banana plantations in Honduras. On February 3, 1975, Black committed suicide by jumping out of his office on the 44th floor of the Pan Am Building in New York City. Later that year, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission exposed a scheme by United Brands (dubbed Bananagate) to bribe Honduran President Oswaldo López Arellano with $1.25 million, plus the promise of another $1.25 million upon the reduction of certain export taxes. Trading in United Brands stock was halted, and López was ousted in a military coup.[citation needed] Chiquita Brands International Main article: Chiquita Brands International After Black's suicide, Cincinnati-based American Financial Group, one of billionaire Carl Lindner, Jr.'s companies, bought into United Brands. In August 1984, Lindner took control of the company and renamed it Chiquita Brands International. The headquarters was moved to Cincinnati in 1985. By 2019, the company's main offices left the United States and relocated to Switzerland.[citation needed] Throughout most of its history, United Fruit's main competitor was the Standard Fruit Company, now the Dole Food Company.[citation needed] |

ユナイテッド・フルーツ社(1899-1970) ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の観光促進キャンペーンの一環として、バナナ会社のスタッフがジャマイカを訪れた。  ニューオーリンズのユナイテッド・フルーツ社のドック(1922年)  『ゴールデン・カリビアン』(1900年)の挿絵 1899年、キースはニューヨークの仲介業者Hoadley and Co.が倒産し、150万ドルを失った[2]。 その後、マサチューセッツ州ボストンに渡り、自身のバナナ貿易会社Tropical Trading and Transport Companyとライバル会社のBoston Fruit Companyの合併に参加する。ボストン・フルーツ社は、1870年にジャマイカで初めてバナナを購入した船員のロレンゾ・ダウ・ベーカーと、アンド リュー・W・プレストンによって設立された会社であった。プレストンの弁護士ブラッドリー・パーマーは、両社の資金繰りの問題を解決するためのスキームを 考案し、実行に移しているところであった。この合併により、プレストンが社長、キースが副社長となり、ボストンを拠点とするユナイテッド・フルーツ社が設 立された。パーマーは、常任執行委員となり、長い間、取締役を務めた。ビジネス的には、ブラッドリー・パーマーがユナイテッド・フルーツ社であった。プレ ストンは、西インド諸島の農園と蒸気船の船団、そしてアメリカ北東部の市場をこの提携に持ち込んだ。キースは、中米の農園と鉄道、そしてアメリカ南部と南 東部の市場を持ち込んだ。創業時のユナイテッド・フルーツの資本金は1,123万ドルであった。パルマーの指示により、同社は14社の競合他社を買収、ま たはその株を購入し、当時の主な収入源であった米国でのバナナ輸入事業の80%を確保した。こうして、ブラッドレー・パーマーは、一夜にして、アメリカに おけるバナナ輸入の第一人者となった。ブラッドリー・パーマーは、一夜にしてビジネス法の専門家として注目され、大富豪となった。その後、彼は大統領のコ ンサルタントや議会の顧問を務めるようになった。 1900年、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社は『黄金のカリブ海:コロンビア、コスタリカ、スペイン領ホンジュラス、ベリーズ、スペイン領本島への冬の旅-ボス トン、ニューオーリンズを経由して』をヘンリー・R・ブレイニーによって執筆、挿絵も担当した。この旅行記には、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社が土地を所有し ていた地域の風景や住民の肖像画が掲載されていた。また、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の汽船の航海や、ブラニーの旅の描写や出会いも描かれていた[3]。 1901年、グアテマラ政府はユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニーに国内の郵便事業の運営を依頼し、1913年にはトロピカル・ラジオ&テレグラフ・カン パニーを設立した。1930年までに20社以上のライバル会社を吸収し、2億1500万ドルの資本金を得て、中米最大の雇用主となった。1930年、サ ム・ゼムレイ(愛称「バナナマン」)は、所有していたクヤメルフルーツ社をユナイテッド・フルーツ社に売却し、果物ビジネスから引退しました。その頃、同 社は数カ国の国民経済において大きな役割を担っており、やがて搾取的な輸出経済の象徴となった。このため、コスタリカの農民による深刻な労働争議が起こ り、30以上の別々の組合と10万人の労働者が参加し、1934年のバナナ大ストライキは、コスタリカの労働組合によるこの時代の最も重要な行動の1つで あった[4][5]。 1930年代までに、同社は中央アメリカとカリブ海に350万エーカー(14,000km2)の土地を所有し、グアテマラの単独で最大の土地所有者であっ た。グアテマラでは最大の土地所有者であった。このような土地所有は、小国の政府に対して大きな力を与えた。それが「バナナ共和国」という言葉を生んだ要 因の一つである[6]。 1933年、ゼムレイは、会社の経営がうまくいっておらず、市場価値が急落していることを懸念し、敵対的買収を敢行した。ゼムレイは、会社の本社をルイジ アナ州ニューオリンズに移した。ユナイテッド・フルーツはゼムレイの経営下で繁栄していった[7][8]。ゼムレイは1951年に社長を辞した。 他の多くの労働運動に加えて、同社は1928年のコロンビアと1934年のコスタリカのバナナ大ストライキという中南米の労働者の2つの大きなストライキ に直面した[9] 後者は、同社が1938年に労働者との労働協約を締結することが求められたため、コスタリカで効果的な労働組合を形成するに至る重要な段階であった [10][11]。 [10][11] ほとんどのバナナ生産国の労働法は1930年代に強化され始めた[12]。ユナイテッド・フルーツ社は自社が特に改革の標的とされていると考え、しばしば 新しい法律に違反していたにもかかわらず、ストライカーとの交渉を拒否していた[13][14]。 1952年、グアテマラ政府はユナイテッド・フルーツ社の未使用の土地を土地なし農民に収用し始めた[13]。 同社はこれに対し、アメリカ政府に介入するよう集中的に働きかけ、グアテマラ政府を共産主義と見なす誤報キャンペーンを展開した[15]。 1954年にアメリカ中央情報局は民主的に選ばれたグアテマラの政府を退け、親ビジネスの軍事独裁政権を設立した[16]。 1967年、A&Wレストランを買収[要出典]。 ユナイテッドブランド(1970〜1984年) 企業買収者イーライ・M・ブラックは、1968年にユナイテッド・フルーツの株式733,000株を購入し、同社の筆頭株主となった。1970年6月、ブ ラックはユナイテッド・フルーツ社を自身の上場企業であるAMK(食肉加工業者ジョン・モレルのオーナー)と合併させ、ユナイテッド・ブランズ社を設立し た。ユナイテッド・フルーツ社は、ブラック氏が想定していたよりもはるかに少ない資金しか持っておらず、ブラック氏の不手際によりユナイテッド・ブランズ 社は負債を抱え、破綻した。1974年のハリケーン「フィフィ」によって、ホンジュラスの多くのバナナ農園が破壊され、同社の損失はさらに悪化した。 1975年2月3日、ブラックはニューヨークのパンナムビルディング44階のオフィスから飛び降り自殺をした。同年末、米国証券取引委員会は、ホンジュラ スのオズワルド・ロペス・アレヤノ大統領に125万ドルを贈与し、さらに輸出税の軽減を条件に125万ドルを約束するというユナイテッド・ブランズの計画 (バナナゲートと呼ばれる)を暴露した。ユナイテッド・ブランズの株式の取引は停止され、ロペスは軍事クーデターで失脚した[要出典]。 チキータ・ブランズ・インターナショナル 主な記事 チキータ・ブランズ・インターナショナル Blackの自殺後、億万長者Carl Lindner, Jr.の会社の1つであるシンシナティに拠点を置くAmerican Financial GroupがUnited Brandsを買収した。1984年8月、リンドナーは同社の経営権を取得し、社名をチキータ・ブランズ・インターナショナルに変更した。1985年、本 社をシンシナティに移転。2019年には、同社の主要なオフィスは米国を離れ、スイスに移転した[citation needed]。 その歴史のほとんどを通じて、ユナイテッド・フルーツの主な競争相手はスタンダード・フルーツ・カンパニー(現在のドール・フード・カンパニー)であった [要出典]。 |

| Reputation The United Fruit Company was frequently accused of bribing government officials in exchange for preferential treatment, exploiting its workers, paying little by way of taxes to the governments of the countries where it operated, and working ruthlessly to consolidate monopolies. Latin American journalists sometimes referred to the company as el pulpo ("the octopus"),[17] and leftist parties in Central and South America encouraged the company's workers to strike. Criticism of the United Fruit Company became a staple of the discourse of the communist parties in several Latin American countries, where its activities were often interpreted as illustrating Vladimir Lenin's theory of capitalist imperialism. Major left-wing writers in Latin America, such as Carlos Luis Fallas of Costa Rica, Ramón Amaya Amador of Honduras, Miguel Ángel Asturias and Augusto Monterroso of Guatemala, Gabriel García Márquez of Colombia, Carmen Lyra of Costa Rica, and Pablo Neruda of Chile, denounced the company in their literature. The Fruit Company, Inc. reserved for itself the most succulent piece, the central coast of my own land, the delicate waist of America. It rechristened its territories 'Banana Republics', and over the sleeping dead, over the restless heroes who brought about the greatness, the liberty, and the flags, it established the comic opera: it abolished free will, gave out imperial crowns, encouraged envy, attracted the dictatorship of flies ... flies sticky with submissive blood and marmalade, drunken flies that buzz over the tombs of the people, circus flies, wise flies expert at tyranny. — Pablo Neruda, "La United Fruit Co." (1950) The business practices of United Fruit were also frequently criticized by journalists, politicians, and artists in the United States. Little Steven released a song in 1987 called "Bitter Fruit", with lyrics that referred to a hard life for a company "far away," and whose accompanying video depicted orange groves worked by peasants overseen by wealthy managers. The lyrics and scenery are generic, but United Fruit (or its successor Chiquita) was reputedly the target.[18] The integrity of John Foster Dulles' "anti-Communist" motives has been disputed, since Dulles and his law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell negotiated the land giveaways to the United Fruit Company in Guatemala and Honduras. John Foster Dulles' brother, Allen Dulles, who was head of the CIA under Eisenhower, also did legal work for United Fruit. The Dulles brothers and Sullivan & Cromwell were on the United Fruit payroll for thirty-eight years.[19][20] Recent research has uncovered the names of multiple other government officials who received benefits from United Fruit: John Foster Dulles, who represented United Fruit while he was a law partner at Sullivan & Cromwell – he negotiated that crucial United Fruit deal with Guatemalan officials in the 1930s – was Secretary of State under Eisenhower; his brother Allen, who did legal work for the company and sat on its board of directors, was head of the CIA under Eisenhower; Henry Cabot Lodge, who was America's ambassador to the UN, was a large owner of United Fruit stock; Ed Whitman, the United Fruit PR man, was married to Ann Whitman, Dwight Eisenhower's personal secretary. You could not see these connections until you could – and then you could not stop seeing them.[19][21] |

評判 ユナイテッド・フルーツ社は、優遇措置と引き換えに政府高官を買収し、労働者を搾取し、事業を行っている国の政府にほとんど税金を払わず、独占を強化する ために冷酷に働いているとよく非難されました。ラテンアメリカのジャーナリストは、この会社をel pulpo(「タコ」)と呼ぶこともあり[17]、中南米の左翼政党は、この会社の労働者にストライキを奨励しました。ユナイテッドフルーツ社の批判は、 ラテンアメリカのいくつかの国の共産党の談話の定番となり、その活動はしばしばウラジーミル・レーニンの資本主義帝国主義の理論を示すものとして解釈され た。コスタリカのカルロス・ルイス・ファラス、ホンジュラスのラモン・アマヤ・アマドル、グアテマラのミゲル・アンヘル・アストゥリアス、アウグスト・モ ンテロソ、コロンビアのガブリエル・ガルシア・マルケス、コスタリカのカルメン・リラ、チリのパブロ・ネルダなどラテンアメリカの主要な左翼作家は、その 文献で会社を糾弾している。 フルーツ社は、私の国の中央海岸、つまりアメリカの繊細な腰の部分という、最もジューシーな部分を自分たちのために確保した。そして、その領土を「バナナ 共和国」と改名し、眠れる死者の上に、偉大さ、自由、国旗をもたらした落ち着きのない英雄の上に、喜劇のオペラを作り上げた。自由意志を廃止し、帝冠を与 え、妬みを奨励し、ハエの独裁を引き寄せた... 服従した血とマーマレードでべとべとのハエ、人々の墓の上でうなる酔っ払いのハエ、サーカスのハエ、専制に長けた賢いハエ。 - パブロ・ネルーダ「ラ・ユナイテッド・フルーツ社」(1950年) ユナイテッド・フルーツのビジネス手法は、アメリカのジャーナリスト、政治家、アーティストからも頻繁に批判された。リトル・スティーブンは1987年に 「ビター・フルーツ」という曲を発表した。歌詞の内容は、「遠く離れた」会社の厳しい生活を指しており、そのビデオでは、裕福な経営者が監督する農民が働 くオレンジ畑が描かれていた。歌詞や風景は一般的なものだが、ユナイテッド・フルーツ(またはその後継のチキータ)がターゲットとされているとされる [18]。 ジョン・フォスター・ダレスの「反共産主義」の動機の完全性は、ダレスと彼の法律事務所サリバン&クロムウェルがグアテマラとホンジュラスのユナイテッ ド・フルーツ社への土地譲渡の交渉を行ったことから、論争になってきた。アイゼンハワー政権下でCIA長官を務めたジョン・フォスター・ダレスの弟、アレ ン・ダレスもユナイテッド・フルーツ社のために法律事務を行っていた。ダレス兄弟とサリバン&クロムウェルは、38年間ユナイテッド・フルーツの給与名簿 に載っていた[19][20]。 最近の調査で、ユナイテッド・フルーツから利益を受けた他の複数の政府関係者の名前が明らかになった。 ジョン・フォスター・ダレスは、サリバン&クロムウェル法律事務所のパートナーとしてユナイテッド・フルーツの代理人を務め、1930年代にグアテマラ当 局との重要な取引を交渉し、アイゼンハワー政権下で国務長官を務めました[19]。ユナイテッド・フルーツの広報担当者であるエド・ホイットマンは、ドワ イト・アイゼンハワーの個人秘書であったアン・ホイットマンと結婚していたのです。このようなつながりは、見えてくるまでわからなかった-そして、見えて きてからが本番だったのである[19][21]。 |

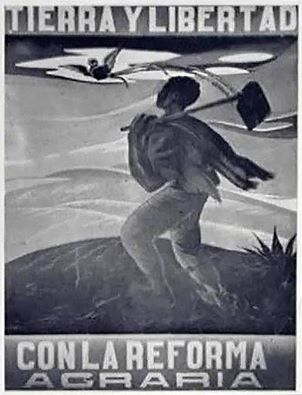

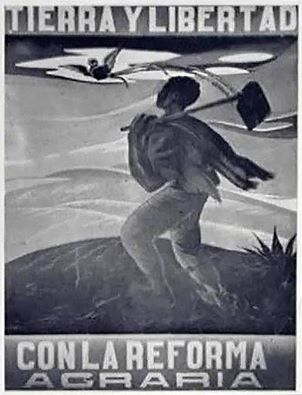

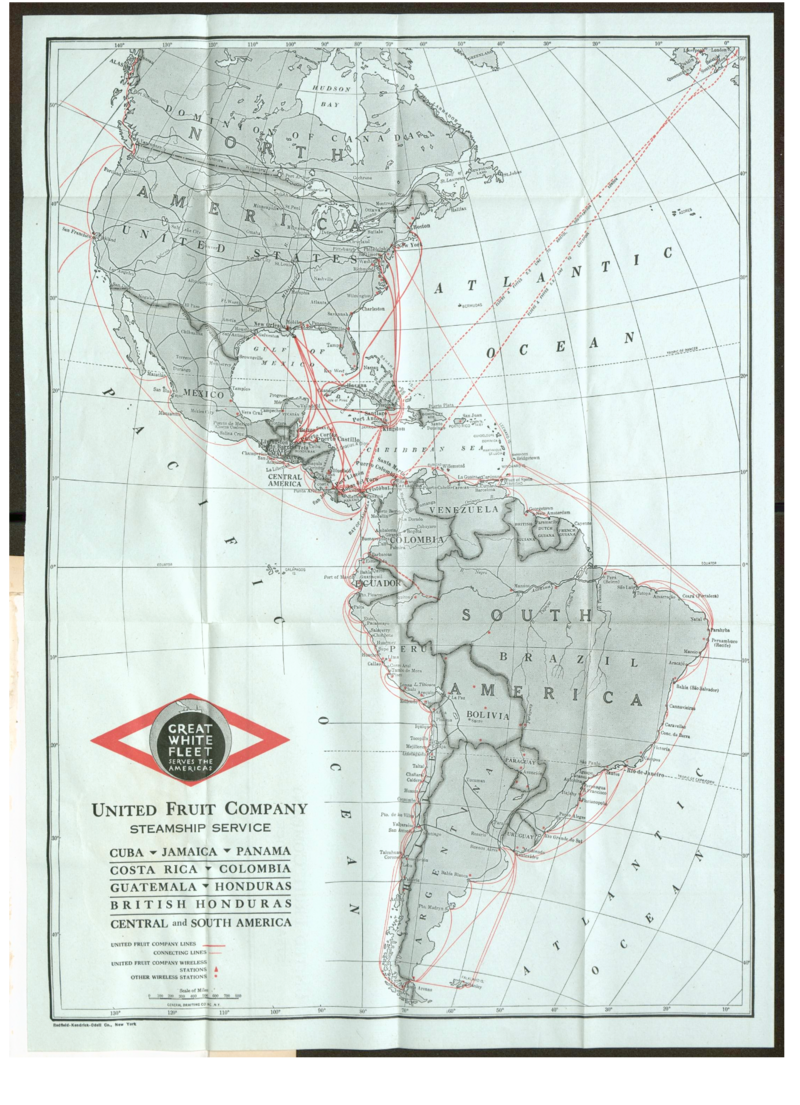

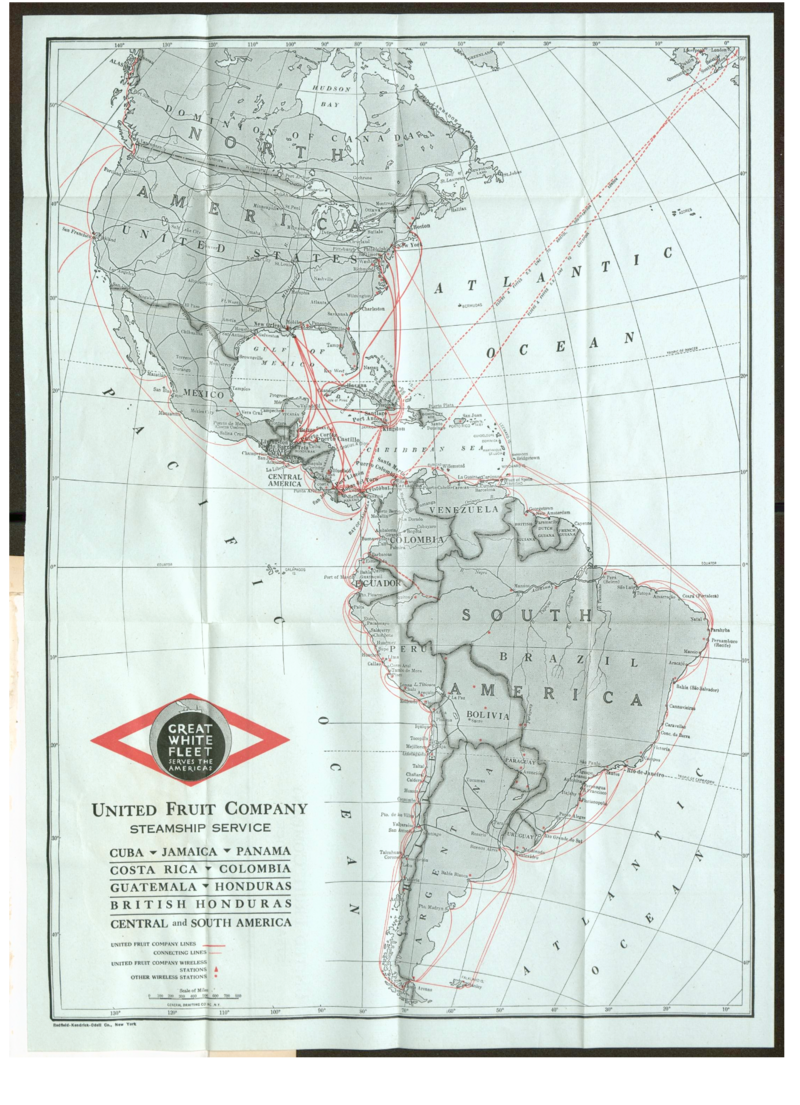

| History in Latin America The United Fruit Company (UFCO) owned huge tracts of land in the Caribbean lowlands. It also dominated regional transportation networks through its International Railways of Central America and its Great White Fleet of steamships. In addition, UFCO branched out in 1913 by creating the Tropical Radio and Telegraph Company. UFCO's policies of acquiring tax breaks and other benefits from host governments led to it building enclave economies in the regions, in which a company's investment is largely self-contained for its employees and overseas investors and the benefits of the export earnings are not shared with the host country.[22] One of the company's primary tactics for maintaining market dominance was to control the distribution of arable land. UFCO claimed that hurricanes, blight and other natural threats required them to hold extra land or reserve land. In practice, what this meant was that UFCO was able to prevent the government from distributing land to peasants who wanted a share of the banana trade. The fact that the UFCO relied so heavily on manipulating land use rights to maintain their market dominance had a number of long-term consequences for the region. For the company to maintain its unequal land holdings it often required government concessions. And this in turn meant that the company had to be politically involved in the region even though it was an American company. In fact, the heavy-handed involvement of the company in often-corrupt governments created the term "banana republic", which represents a servile dictatorship.[23] The term "Banana Republic" was coined by American writer O. Henry.[24] Environmental effects The United Fruit Company's entire process of creating a plantation to farming the banana and the effects of these practices created noticeable environmental degradation when it was a thriving company. Infrastructure built by the company was constructed by clearing out forests, filling in low, swampy areas, and installing sewage, drainage, and water systems. Ecosystems that existed on these lands were destroyed, devastating biodiversity.[25] With a loss in biodiversity, other natural processes within nature necessary for plant and animal survival are shut down.[26] Techniques used for farming were at fault for loss of biodiversity and harm to the land as well. To create farm land, the United Fruit Company would either clear forests (as mentioned) or would drain marshlands to reduce avian habitats and to create "good" soil for banana plant growth.[27] The most common practice in farming was called the "shifting plantation agriculture". This is done by using produced soil fertility and hydrological resources in the most intense manner, then relocating when yields fell and pathogens followed banana plants. Techniques like this destroy land and when the land is unusable for the company, then they move to other regions.[dubious – discuss] Guatemala Although UFCO sometimes promoted the development of the nations where it operated, its long-term effects on their economy and infrastructure were often devastating. In Central America, the Company built extensive railroads and ports, provided employment and transportation, and created numerous schools for the people who lived and worked on Company land. On the other hand, it allowed vast tracts of land under its ownership to remain uncultivated and, in Guatemala and elsewhere, it discouraged the government from building highways, which would have lessened the profitable transportation monopoly of the railroads under its control. UFCO also destroyed at least one of those railroads upon leaving its area of operation.[28]  When President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán attempted a redistribution of land, he was overthrown in the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état. In 1954, the Guatemalan government of Colonel Jacobo Árbenz, elected in 1950, was toppled by forces led by Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas[29] who invaded from Honduras. Commissioned by the Eisenhower administration, this military operation was armed, trained and organized by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency[30] (see Operation PBSuccess). The directors of United Fruit Company (UFCO) had lobbied to convince the Truman and Eisenhower administrations that Colonel Árbenz intended to align Guatemala with the Eastern Bloc. Besides the disputed issue of Árbenz's allegiance to communism, UFCO was being threatened by the Árbenz government's agrarian reform legislation and new Labor Code.[31] UFCO was the largest Guatemalan landowner and employer, and the Árbenz government's land reform program included the expropriation of 40% of UFCO land.[31] U.S. officials had little proof to back their claims of a growing communist threat in Guatemala;[32] however, the relationship between the Eisenhower administration and UFCO demonstrated the influence of corporate interest on U.S. foreign policy.[30] United States Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, an avowed opponent of communism, was also a member of the law firm, Sullivan and Cromwell, which had represented United Fruit.[33] His brother Allen Dulles, director of the CIA, was also a board member of United Fruit. United Fruit Company is the only company known to have a CIA cryptonym. The brother of the Assistant Secretary of State for InterAmerican Affairs, John Moors Cabot, had once been president of United Fruit. Ed Whitman, who was United Fruit's principal lobbyist, was married to President Eisenhower's personal secretary, Ann C. Whitman.[33] Many individuals who directly influenced U.S. policy towards Guatemala in the 1950s also had direct ties to UFCO.[31] After the overthrow of Árbenz, a military dictatorship was established under Carlos Castillo Armas. Soon after coming to power, the new government launched a concerted campaign against trade unionists, in which some of the most severe violence was directed at workers on the plantations of the United Fruit Company.[16] Despite UFCO's government connections and conflicts of interest, the overthrow of Árbenz failed to benefit the company. Its stock market value declined along with its profit margin. The Eisenhower administration proceeded with antitrust action against the company, which forced it to divest in 1958. In 1972, the company sold off the last of its Guatemalan holdings after over a decade of decline. Even as the Árbenz government was being overthrown, in 1954 a general strike against the company organized by workers in Honduras rapidly paralyzed that country, and, due to the United States' concern about the events in Guatemala, was settled more favorably for the workers in order for the United States to gain leverage for the Guatemala operation. Cuba Company holdings in Cuba, which included sugar mills in the Oriente region of the island, were expropriated by the 1959 revolutionary government led by Fidel Castro. By April 1960 Castro was accusing the company of aiding Cuban exiles and supporters of former leader Fulgencio Batista in initiating a seaborne invasion of Cuba directed from the United States.[34] Castro warned the U.S. that "Cuba is not another Guatemala" in one of many combative diplomatic exchanges before the U.S. organized the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion of 1961. |

ラテンアメリカの歴史 ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニー(UFCO)は、カリブ海の低地に広大な土地を所有していました。また、中米国際鉄道とグレート・ホワイト・フリート という蒸気船を保有し、地域の交通網を支配していた。さらに、1913年には、熱帯無線電信会社を設立し、事業を拡大した。UFCOは、投資先政府から税 制上の優遇措置やその他の利益を得る政策により、投資先企業の従業員と海外投資家がほぼ自己完結し、輸出収益の利益を投資先と共有しない飛び地経済を現地 に構築することになった[22]。 市場支配を維持するための同社の主要な戦術の一つは、耕作地の配分をコントロールすることであった。UFCOは、ハリケーン、疫病、その他の自然の脅威に よって、余分な土地や予備地を保有することが必要だと主張した。実際、これは UFCO がバナナ貿易の分け前を求める農民に政府が土地を分配するのを妨げたことを意味する。UFCO が市場支配を維持するために土地使用権の操作に大きく頼っていたことは、この地域に多くの 長期的影響を与えた。同社が不平等な土地保有を維持するためには、しばしば政府の利権が必要であった。そのため、アメリカ企業であるにもかかわらず、政治 的な関与が必要とされた。実際、しばしば腐敗した政府への会社の強引な関与は、隷属的独裁を表す「バナナ共和国」という言葉を生み出した[23]。「バナ ナ共和国」という言葉は、アメリカの作家O・ヘンリーによって作られたものである[24]。 環境への影響 ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニーは、プランテーションの創設からバナナの栽培までの全行程とその影響により、繁栄していた頃は顕著な環境破壊を生み出 していた。同社が建設したインフラは、森林を切り開き、低い湿地帯を埋め、下水、排水、給水システムを設置することで構築された。生物多様性が失われる と、植物や動物の生存に必要な自然界の他のプロセスも停止してしまった[26]。 農業に使われる技術も、生物多様性の喪失と土地への害の原因となっていました。農地を作るために、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社は森林を伐採するか(前述の通 り)、湿地帯の水を抜いて鳥類の生息地を減らし、バナナの生育に適した「良い」土壌を作った[27] 。農法で最もよく行われていたのは「焼畑農法」と呼ばれるものであった。これは生産された土壌の肥沃度と水文学的資源を最も激しく使い、収量が落ち、病原 菌がバナナ植物に付きまとうようになると移転するものである。このような技術は土地を破壊し、その土地が企業にとって使えなくなると、他の地域に移動する [dubious - discuss]。 グアテマラ UFCOは、時にはその国の発展を促すこともあったが、長期的にはその国の経済やインフラに壊滅的な影響を与えることも少なくなかった。中米では、鉄道や 港を建設し、雇用や交通を提供し、土地に住む人々や働く人々のために多くの学校をつくった。また、グアテマラなどでは、政府が高速道路を建設するのを妨害 し、支配下にある鉄道会社の独占的な輸送力を低下させた。また、UFCOは、その操業地域から離れる際に、少なくともこれらの鉄道の1つを破壊した [28]。  ハコボ・アルベンス・グスマン大統領が土地の再分配を試みたが、1954年のグアテマラ・クーデターで倒された。(ポスターは1952年) 1954年、1950年に選出されたハコボ・アルベンツ大佐のグアテマラ政府は、ホンジュラスから侵攻したカルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマス大佐[29] が率いる軍によって倒された。アイゼンハワー政権によって委託されたこの軍事作戦は、アメリカ中央情報局[30]によって武装、訓練、組織されていた (「PBSuccess作戦」を参照)。ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニー(UFCO)の取締役は、アルベンツ大佐がグアテマラと東欧諸国との同盟を意 図しているとトルーマン政権とアイゼンハワー政権に説得するように働きかけていた。アルベンスの共産主義への忠誠の問題に加えて、アルベンツ政府の農地改 革法案と新しい労働法によってUFCOは脅かされていた[31]。UFCOはグアテマラ最大の土地所有者兼雇用主で、アルベンツ政府の土地改革計画には UFCOの40%の土地収用が含まれていた[31]。しかし、アイゼンハワー政権とUFCOの関係は、アメリカの外交政策に企業の利害が影響を及ぼすこと を示した[30]。 共産主義の反対を公言していた国務長官ジョン・フォスター・ダレスは、ユナイテッドフルーツの代理人を務めていた法律事務所サリバン&クロムウェルのメン バーでもあった[33]。ユナイテッド・フルーツ社は、CIAの暗号名を持つ唯一の会社として知られている。米州担当国務次官補ジョン・ムーアス・キャ ボットの弟は、かつてユナイテッド・フルーツの社長であったことがある。ユナイテッド・フルーツの主要なロビイストであったエド・ホイットマンは、アイゼ ンハワー大統領の個人秘書アン・C・ホイットマンと結婚していた[33]。1950年代のアメリカの対グアテマラ政策に直接影響を与えた多くの人物も UFCOと直接的な関係をもっていた[31]。 アルベンスを打倒した後、カルロス・カスティーリョ・アルマスによる軍事独裁政権が樹立された。政権を握った直後、新政府は労働組合員に対する協調的な キャンペーンを開始し、その中で最も激しい暴力がユナイテッド・フルーツ社の農園で働く労働者に向けられた[16]。 UFCOの政府とのつながりや利益相反にもかかわらず、アルベンツの打倒は同社に利益をもたらすことができなかった。UFCOの株式市場価値は利益率とと もに低下した。アイゼンハワー政権は、同社に対して独占禁止法の適用を進め、1958年に同社は売却を余儀なくされた。そして、1972年、10年以上に わたって低迷していたグアテマラの全株式を売却した。 アルベス政権が倒されつつある1954年、ホンジュラスで労働者が組織した同社に対するゼネストが発生し、同国は急速に麻痺状態に陥ったが、グアテマラで の出来事を懸念した米国がグアテマラ事業を有利にするために労働者に有利に解決した。 キューバ 1959年、フィデル・カストロ率いる革命政府によって、オリエンテ地方の製糖工場を含むキューバでの同社の保有資産は収用された。1960年4月には、 カストロは、キューバ人亡命者やフルヘンシオ・バティスタの支持者が、アメリカからキューバへの海上侵攻を開始するのを手助けしていると非難した [34]。カストロは、アメリカが1961年のピッグス湾侵攻作戦を組織して失敗するまでの多くの外交対話の1つとして「キューバはもうひとつのグアテマ ラではない」とアメリカに対して警告している。 |

| Banana massacre One of the most notorious strikes by United Fruit workers broke out on 12 November 1928 near Santa Marta on the Caribbean coast of Colombia. On December 6, Colombian Army troops allegedly under the command of General Cortés Vargas opened fire on a crowd of strikers in the central square of Ciénaga. Estimates of the number of casualties vary from 47 to 3,000.[clarification needed] The military justified this action by claiming that the strike was subversive and its organizers were Communist revolutionaries. Congressman Jorge Eliécer Gaitán claimed that the army had acted under instructions from the United Fruit Company. The ensuing scandal contributed to President Miguel Abadía Méndez's Conservative Party being voted out of office in 1930, putting an end to 44 years of Conservative rule in Colombia. The first novel of Álvaro Cepeda Samudio, La Casa Grande, focuses on this event, and the author himself grew up in close proximity to the incident. The climax of García Márquez's novel One Hundred Years of Solitude is based on the events in Ciénaga. General Cortés Vargas issued the order to shoot, arguing later that he had done so because of information that US boats were poised to land troops on Colombian coasts to defend American personnel and the interests of the United Fruit Company. Vargas issued the order so the United States would not invade Colombia. The telegram from Bogotá Embassy to the U.S. Secretary of State, dated December 5, 1928, stated: "I have been following Santa Marta fruit strike through United Fruit Company representative here; also through Minister of Foreign Affairs who on Saturday told me government would send additional troops and would arrest all strike leaders and transport them to prison at Cartagena; that government would give adequate protection to American interests involved."[35] The telegram from Bogotá Embassy to Secretary of State, date December 7, 1928, stated: "Situation outside Santa Marta City unquestionably very serious: outside zone is in revolt; military who have orders 'not to spare ammunition' have already killed and wounded about fifty strikers. Government now talks of general offensive against strikers as soon as all troopships now on the way arrive early next week."[36] The dispatch from U.S. Bogotá Embassy to the U.S. Secretary of State, dated December 29, 1928, stated: "I have the honor to report that the legal advisor of the United Fruit Company here in Bogotá stated yesterday that the total number of strikers killed by the Colombian military authorities during the recent disturbance reached between five and six hundred; while the number of soldiers killed was one."[37] The dispatch from the U.S. embassy to the U.S. Secretary of State, dated January 16, 1929, stated: "I have the honor to report that the Bogotá representative of the United Fruit Company told me yesterday that the total number of strikers killed by the Colombian military exceeded one thousand."[38] The Banana massacre is said to be one of the main events that preceded the Bogotazo, the subsequent era of violence known as La Violencia, and the guerrillas who developed in the bipartisan National Front period, creating the ongoing armed conflict in Colombia.[citation needed] |

バナナの大虐殺 ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の労働者による最も悪名高いストライキの一つは、1928年11月12日にコロンビアのカリブ海沿岸のサンタマルタ付近で発生し た。12月6日、コルテス・バルガス将軍の指揮下にあるとされるコロンビア軍部隊が、シエナガ中央広場でストライキの群衆に発砲した。死傷者の数は47人 から3,000人と推定されている[clarification needed] 軍は、ストライキは破壊的であり、その主催者は共産主義革命家であると主張し、この行動を正当化した。ホルヘ・エリエセル・ガイタン下院議員は、軍はユナ イテッド・フルーツ社からの指示で行動したと主張した。このスキャンダルは、1930年にミゲル・アバディア・メンデス大統領の保守党を落選させ、コロン ビアにおける44年間の保守党支配に終止符を打つことになった。アルバロ・セペダ・サムーディオの処女作『ラ・カサ・グランデ』はこの事件を題材にしてお り、著者自身もこの事件のすぐ近くで育っている。ガルシア・マルケスの小説『百年の孤独』のクライマックスは、シエナガでの事件を題材にしている。 コルテス・バルガス将軍は、アメリカ人職員とユナイテッド・フルーツ社の利益を守るために、アメリカ軍の船がコロンビア沿岸に上陸する準備をしているとい う情報があったからだと、後に主張して、銃撃命令を発したのである。バルガスは、米国がコロンビアに侵攻しないようにこの命令を出したのである。 1928年12月5日付のボゴタ大使館からアメリカ国務長官への電報には、次のように記されている。 「私はサンタマルタの果物ストライキを、ここにいるユナイテッド・フルーツ社の代表を通して、また外務大臣を通して見てきたが、土曜日に政府は追加の軍隊 を送り、ストライキの指導者を全員逮捕し、カルタヘナの刑務所に移送すると言ってきた、政府は関係するアメリカの利益を十分に保護するだろう」[35]。 1928年12月7日付のボゴタ大使館から国務長官への電報には、次のように記されていた。 サンタマルタ市郊外の状況は疑いなく非常に深刻である。郊外は反乱状態にあり、「弾薬を惜しむな」という命令を受けた軍隊がすでに約50人のストライカー を殺傷している。政府は現在、来週初めに現在航行中のすべての軍艦が到着次第、ストライカーに対して総攻撃をかけると語っている」[36]。 1928年12月29日付のアメリカ・ボゴタ大使館からアメリカ国務長官への派遣状には、次のように記されている。 「ここボゴタのユナイテッド・フルーツ社の法律顧問が昨日、最近の騒乱の間にコロンビア軍当局によって殺されたストライカーの総数が500から600人に 達し、一方、殺された兵士の数は1人であると述べたことを報告する名誉がある」[37]。 1929年1月16日付のアメリカ大使館からアメリカ国務長官への派遣状には、こう書かれている。 "ユナイテッド・フルーツ社のボゴタ代表が昨日、コロンビア軍によって殺害されたストライカーの総数が1000人を超えたと私に告げたことを報告する光栄 に浴します"[38]。 バナナの虐殺は、ボゴタソ、その後のラ・ヴィオレンシアと呼ばれる暴力の時代、そして超党派の国民戦線時代に発展したゲリラに先行し、コロンビアで続く武 力紛争を生み出した主要事件の1つであると言われている[要出典]。 |

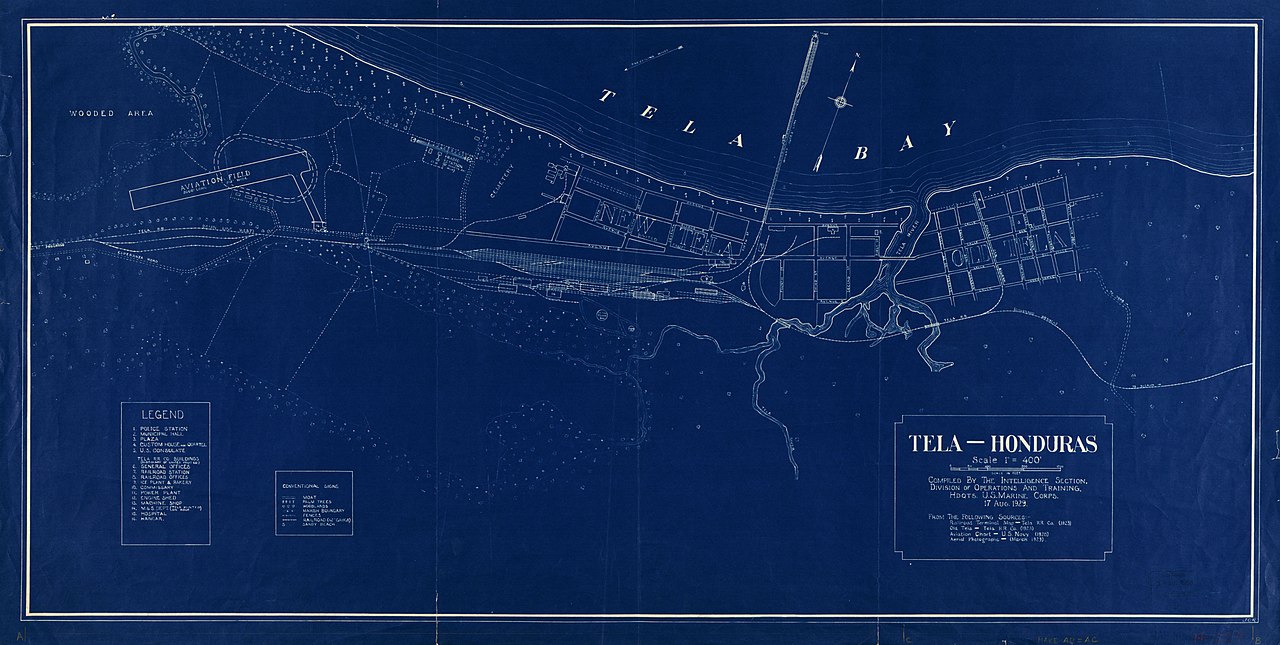

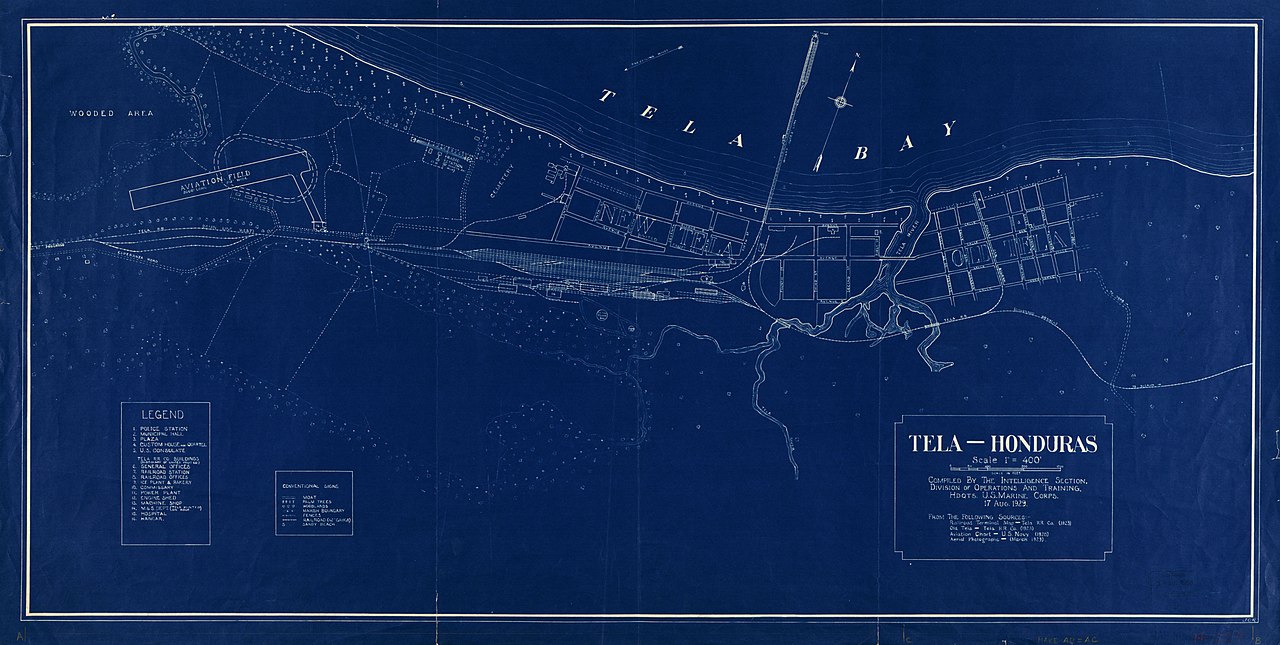

| The United Fruit Company in

Honduras Attempt at state capture  Main railroad station in La Ceiba, Honduras, in 1920 Following the Honduran declaration of independence in 1838 from the Central American Federation, Honduras was in a state of economic and political strife due to constant conflict with neighboring countries for territorial expansion[clarification needed] and control.[39] Liberal President Marco Aurelio Soto (1876–1883) saw instating the Agrarian Law of 1877 as a way to make Honduras more appealing to international companies looking to invest capital into a promising host export-driven economy. The Agrarian Law would grant international, multinational companies leniency in tax regulations along with other financial incentives.[40] Acquiring the first railroad concession from liberal President Miguel R. Dávila in 1910, the Vaccaro brothers and Company helped set the foundation on which the banana republic would struggle to balance and regulate the relationships between American capitalism and Honduran politics. Samuel Zemurray, a small-sized American banana entrepreneur, rose to be another contender looking to invest in the Honduran agricultural trade. In New Orleans, Zemurray found himself strategizing with the newly exiled General Manuel Bonilla (nationalist ex-president of Honduras 1903–1907, 1912–1913) and fomented a coup d'état against President Dávila. On Christmas Eve, December 1910, in clear opposition of the Dávila administration, Samuel Zemurray, U.S. General Lee Christmas, and Honduran General Manuel Bonilla boarded the yacht "Hornet", formerly known as the USS Hornet and recently purchased by Zemurray in New Orleans. With a gang of New Orleans mercenaries and plenty of arms and ammunition, they sailed to Roatan to attack, then seize the northern Honduran ports of Trujillo and La Ceiba.[41][42] Unbeknownst to Zemurray, he was being watched by the US Secret Service. Having captured the aging fort at Roatan, he quickly sold the Hornet to a Honduran straw buyer on the island to avoid falling foul of the Neutrality Act. After successfully attacking the port of Trujillo, the Hornet unexpectedly encountered the U.S. gunboat Tacoma, and was towed back to New Orleans. The nascent revolution continued apace, Zemurray's media contacts having spread the word in advance.[42] President Dávila was forced to step down, with Francisco Bertrand becoming interim president until General Bonilla handily won the November 1911 Honduran presidential elections. In 1912, General Bonilla quickly granted the second railroad concession to the newly incorporated Cuyamel Fruit Company owned by Zemurray. The period of some of these exclusive railroad land concessions was up to 99 years. The first railroad concession leased the national railroad of Honduras to the Vaccaro Bros. and Co. (once Standard Fruit Company and currently Dole Food Company). Zemurray granted his concession to the Tela Railroad Company—another division within his own company. Cuyamel Fruit Company's concession would also be awarded to the Tela Railroad Company. United Fruit Company (currently Chiquita Brands International) would partner with President Bonilla in the exchange of access and control of Honduran natural resources plus tax and financial incentives. In return, President Bonilla would receive cooperation, protection and a substantial amount of U.S. capital to build a progressive infrastructure in Honduras.[40] Banana multinational establishment and expansion  1929 map of the town of Tela The granting of land ownership in exchange for the railroad concession started the first official competitive market for bananas and giving birth to the banana republic. Cuyamel Fruit Company and the Vaccaro Bros. and Co. would become known as being multinational enterprises. Bringing western modernization and industrialization to the welcoming Honduran nation. All the while Honduran bureaucrats would continue to take away the indigenous communal lands to trade for capital investment contracts as well as neglect the fair rights of Honduran laborers. After the peak of the banana republic era, resistance eventually began to grown on the part of small-scale producers and production laborers, due to the exponential rate in growth of the wealth gap as well as the collusion between the profiting Honduran government officials and the U.S. fruit companies (United Fruit Co., Standard Fruit Co., Cuyamel Fruit Co.) versus the Honduran working and poor classes. Due to the exclusivity of the land concessions and lack of official ownership documentation, Honduran producers and experienced laborers were left with two options to regain these lands—dominio util or dominio pleno. Dominio util—meaning the land was intended to be developed for the greater good of the public with a possibility of being the granted "full private ownership" versus dominio pleno was the immediate granting of full private ownership with the right to sell.[41] Based on the 1898 Honduran agrarian law, without being sanctioned the right their communal lands, Honduran villages and towns could only regain these lands if granted by the Honduran government or in some cases it was permitted by U.S. companies, such as United Fruit Co., to create long-term contracts with independent producers on devastatingly diseased infested districts.[43] Even once granted land concessions, many were so severely contaminated with either the Panaman, moko, or sigatoka, that it would have to reduce the acreage used and the amount produced or changed the crop being produced. Additionally, accusations were reported of the Tela Railroad Company placing intense requirements, demanding exclusivity in distribution, and unjustly denying crops produced by small-scale farmers because they were deemed "inadequate". Compromise was attempted between small-scale fruit producers and the multinationals enterprises, but were never reached and resulted in local resistance.[40] The U.S. fruit corporations were choosing rural agriculture lands in Northern Honduras, specifically using the new railroad system for their proximity to major port cities of Puerto Cortes, Tela, La Ceiba, and Trujillo as the main access points of transport for shipments designated back to the United States and Europe. To get an understanding of the dramatic increase in amount of bananas being exported, firstly "in the Atlantida, the Vaccaro Brothers (Standard Fruit) oversaw the construction of 155 kilometers of railroad between 1910 and 1915...the expansion of the railroad led to a concomitant rise exports, from 2.7 million bunches in 1913 to 5.5 million in 1919."[41] Standard Fruit, Cuyamel, and the United Fruit Co. combined surpassed past profit performances, "In 1929 a record 29 million bunches left Honduran shores, a volume that exceeded the combined exports of Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Panama."[41] |

ホンジュラスにおけるユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニー 国家捕囚の試み  1920年、ホンジュラス、ラ・セイバの主要鉄道駅 1838年にホンジュラスが中米連邦から独立を宣言した後、ホンジュラスは領土の拡大[要確認]や支配をめぐって近隣諸国と絶えず対立し、経済的にも政治 的にも苦境に立たされていた[39]。自由主義のマルコ・オーレリオ・ソト大統領(1876-1883)は1877年の農業法を制定し、輸出主導の有望な 経済への資本投資を目指す国際企業にとってホンジュラスの魅力を増す方法として考えていた。農業法は、国際的な多国籍企業に他の財政的インセンティブとと もに税制上の優遇措置を与えるものであった[40] 。1910年に自由主義派の大統領ミゲル・R・ダビラから最初の鉄道利権を獲得したヴァカロ兄弟と会社は、バナナ共和国がアメリカの資本主義とホンジュラ スの政治の間の関係のバランスをとり規制しようと努力する基盤作りを手伝った。 アメリカの小規模なバナナ企業家であるサミュエル・ゼムレイは、ホンジュラスの農産物貿易に投資しようとするもう一人の候補者として台頭してきた。ゼムレ イはニューオーリンズで、亡命したばかりのマヌエル・ボニーヤ将軍(国粋主義者の元ホンジュラス大統領1903-1907、1912-1913)と戦略を 練り、ダビラ大統領に対するクーデターを画策する。1910年12月のクリスマスイブ、ダビラ政権に明確に反対するサミュエル・ゼムレイ、アメリカの リー・クリスマス将軍、ホンジュラスのマヌエル・ボニーヤ将軍は、かつてUSSホーネットとして知られ、ゼムレイがニューオーリンズで購入したばかりの ヨット「ホーネット」に乗船しました。ニューオーリンズの傭兵の一団と多くの武器と弾薬を携えて、彼らはロアタンに航海し、ホンジュラス北部のトルヒーヨ とラ・セイバの港を攻撃し、奪取した[41][42] ゼムレイには知らされていないが、彼は米国秘密情報部に監視されていたのであった。ロアタンの老朽化した砦を攻略した彼は、中立法に抵触するのを避けるた め、すぐにホーネットを島のホンジュラス人のわら買い手に売り渡した。トルヒーヨ港の攻略に成功したホーネット号は、思いがけずアメリカの砲艦タコマに遭 遇し、ニューオリンズに曳航されることになった。ダビラ大統領は退陣を余儀なくされ、フランシスコ・バートランドが臨時大統領となり、1911年11月の ホンジュラス大統領選挙でボニラ将軍が圧勝するまでの間、革命が続いた[42]。 1912年、ボニージャ将軍は、ゼムレイが所有する新しく法人化されたクヤメル果実会社に2つ目の鉄道利権をすぐに与えた。これらの独占的な鉄道用地の利 権の中には、最長で99年の期間を持つものもあった。最初の鉄道利権は、ホンジュラスの国鉄をヴァッカロ兄弟社(かつてのスタンダード・フルーツ社、現在 のドール・フード社)に貸与するものであった。ゼムレイは、自分の会社の別の部門であるテラ鉄道会社に租借権を与えた。クヤメルフルーツ社の利権もテラ鉄 道会社に譲渡されることになった。ユナイテッド・フルーツ社(現チキータ)は、ボニーヤ大統領と提携し、ホンジュラスの天然資源へのアクセスとコントロー ル、税制や金融面での優遇措置を交換することになった。その見返りとして、ボニーヤ大統領は、ホンジュラスに進歩的なインフラを構築するための協力と保 護、そして相当額のアメリカ資本を受け取ることになる[40]。 バナナ多国籍企業の設立と拡大  1929年テラ市地図 鉄道の利権と引き換えに土地所有権が与えられたことで、バナナの最初の公式な競争市場が始まり、バナナ共和国が誕生した。クヤメル・フルーツ・カンパニー とヴァッカロ・ブラザーズ・アンド・カンパニーは、後に多国籍企業として知られるようになる。ホンジュラスに西洋の近代化・工業化をもたらしたのです。そ の一方で、ホンジュラスの官僚たちは、資本投資契約と引き換えに先住民族の土地を取り上げ、ホンジュラス人労働者の公正な権利を無視し続けました。バナナ 共和国時代のピークを過ぎると、富の格差が指数関数的に拡大し、利益を得るホンジュラス政府高官と米国の果物会社(ユナイテッドフルーツ社、スタンダード フルーツ社、クヤメル社)が、ホンジュラスの労働者や貧困層と結託したため、小規模生産者や生産労働者の間で抵抗勢力が発展していました。 土地租界の独占性と公式な所有権証明書の欠如のため、ホンジュラスの生産者と熟練労働者は、これらの土地を取り戻すために2つの選択肢、ドミニオ・ユー ティかドミニオ・プレノを迫られた。ドミニオ・ユティルとは、その土地が公共の利益のために開発され、「完全な私有地」が認められる可能性があることを意 味し、ドミニオ・プレノとは、売却する権利を伴う完全な私有地が直ちに認められることを意味する[41]。1898年のホンジュラスの農地法に基づき、ホ ンジュラスの村や町は共同所有地の権利を認可されることなしに、ホンジュラス政府から認められるか、場合によってはユナイテッドフルーツなどの米国企業に よって許されるかによって、これらの土地は再取得された。また、パナマ、モコ、シガトカのいずれかにひどく汚染されていたため、使われる面積や生産量を減 らすか、生産する作物を変えなければならないこともあった。また、テラ鉄道会社が厳しい条件をつけ、独占的な流通を要求し、小規模農家の作物を「不適当」 と判断して不当に拒否しているとの告発があった。小規模な果物生産者と多国籍企業との間で妥協が試みられたが、実現には至らず、地元の抵抗につながった [40]。 米国の果実企業はホンジュラス北部の農村農地を選び、特にプエルト・コルテス、テラ、ラ・セイバ、トルヒーヨといった主要港に近い鉄道網を利用して、米国 や欧州に戻る出荷のための主要なアクセスポイントとして利用した。バナナの輸出量の激増を理解するために、まず「アトランティダでは、ヴァッカロ兄弟(ス タンダードフルーツ社)が 1910 年から 1915 年の間に 155km の鉄道建設を監督し、鉄道の拡張に伴い輸出量も増加し、1913 年には 270 万房であったのが、1915 年には 20 万房となり、バナナの輸出量も増加した。 スタンダード・フルーツ、クヤメル、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社を合わせると過去の利益実績を上回り、「1929年には2900万房を記録し、コロンビア、 コスタリカ、グアテマラ、パナマの輸出量の合計を上回った」[41]とされています。 |

| Social welfare programs for

employees of United Fruit Company U.S. food corporations, such as United Fruit established community services and facilitates for mass headquartered (production) divisions, settlements of banana plantations throughout their partnered host countries such in the Honduran cities of Puerto Cortes, El Progreso, La Ceiba, San Pedro Sula, Tela, and Trujillo.[citation needed]) Because of the strong likelihood of these communities being in extremely isolated rural agricultural areas, both American and Honduran workers were offered on-site community services similar to those found in other company towns, such as free, furnished housing (similar to barracks) for workers and their immediate family members, health care via hospitals/clinics/health units, education (2–6 years) for children/younger dependents/ other laborers, commissaries (grocery/retail), religious (United Fruit built on-site churches) and social activities, agricultural training at the Zamorano Pan-American Agricultural School, and cultural contributions such as the restoration of the Mayan city Zaculeu in Guatemala.[43] According to a 2022 study in Econometrica, the UFCo had a positive and persistent effect on living standards in Costa Rica, which had granted substantial land concessions to the company from 1899 to 1984. The reason is that the company invested heavily in local amenities, such as education and health care, in order to attract and maintain a sizable workforce.[44] Agriculture research and training  Early 20th-century Honduras agricultural brochure Samuel Zemurray employed agronomists, botanists, and horticulturists to aid in research studies for United Fruit in their time of crisis, as early as 1915 when the Panama disease first inhabited crops. Funding specialized studies to treat Panama disease and supporting the publishing of such findings throughout the 1920s–1930s, Zemurray has consistently been an advocate for agricultural research and education. This was first observed when Zemurray funded the first research station of Lancetilla in Tela, Honduras in 1926 and led by Dr. Wilson Popenoe. Zemurray also founded the Zamorano Pan-American Agricultural School (Escuela Agricola Panamericana) in 1941 with Dr. Popenoe as the head agronomist. There were certain requirements before a student could be accepted into the fully paid for 3-year program including additional expenses (room and board, clothing, food, stc), a few being a male between the ages of 18–21, 6 years of elementary education, plus an additional 2 years of secondary.[43] Zemurray, established a policy where, "The School is not for the training or improvement of the company's own personnel, but represents an outright and disinterested contribution to the improvement of agriculture in Spanish America...This was one way in which the United Fruit Company undertook to discharge its obligation of social responsibility in those countries in which it operates-and even to help others."[43] Zemurray was so intensely adamant in his policy, that students were not allowed to become employees at the United Fruit Company post graduation. |

ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の従業員向け社会福祉プログラム ユナイテッド・フルーツ社などの米国の食品会社は、ホンジュラスのプエルト・コルテス、エル・プログレソ、ラ・セイバ、サンペドロ・スラ、テラ、トルヒー ヨといった提携先のバナナ農園の集落や大量本部(生産)部門に対して地域サービスや便宜施設を設立しました。 [これらのコミュニティは極めて孤立した田舎の農業地帯にある可能性が高いため、アメリカ人とホンジュラス人の労働者は、労働者とその近親者のための無料 の家具付き住宅(バラックに似ている)など、他のカンパニータウンに見られるような現場でのコミュニティサービスを提供された。例えば、労働者とその家族 のための無料家具付き住居(バラックに類似)、病院/診療所/健康ユニットによる健康管理、子供/若い扶養家族/他の労働者のための教育(2~6年)、コ ミッサリー(食料品/小売)、宗教(ユナイテッド・フルーツ社は現地に教会を建設)および社会活動、ザモラノ・パンアメリカ農業学校での農業研修、グアテ マラのマヤ都市ザクレイの修復などの文化貢献があった[43]。 [43] Econometrica誌の2022年の研究によれば、UFCoは1899年から1984年まで同社にかなりの土地利権を与えていたコスタリカの生活水 準に肯定的かつ持続的な影響を及ぼしていた。その理由は、同社がかなりの労働力を引き付けて維持するために、教育や医療といった地元のアメニティに多額の 投資を行っていたからである[44]。 農学研究・研修  20世紀初頭のホンジュラスの農業パンフレット サミュエル・ゼムレイは、パナマ病が初めて農作物に発生した1915年から、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の危機に際して、農学者、植物学者、園芸家を雇用 し、調査研究を支援しました。1920年代から30年代にかけては、パナマ病治療のための専門的な研究に資金を提供し、その研究成果の出版を支援するな ど、ゼムレイは一貫して農業研究と教育の擁護者であった。これは、ゼムレイが1926年にホンジュラスのテラで、ウィルソン・ポペノエ博士が率いるランセ ティージャの最初の研究ステーションに資金を提供したときに初めて確認されたことです。 また、ゼムレイは1941年にザモラノ汎米農業学校(Escuela Agricola Panamericana)を設立し、ポペノエ博士を農学博士として指導しました。この学校は、18歳から21歳までの男性で、6年間の初等教育とさらに 2年間の中等教育が必要であった[43]。ゼムレイは、「この学校は、会社の職員の訓練や改善のためではなく、スペイン領アメリカにおける農業の改善に対 する明白かつ無関心な貢献である」という方針を確立している[44]。 これは、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社が、事業を展開している国々で社会的責任を果たすための一つの方法であり、他者を助けることでもある」[43] ゼムレイは、その方針に強く固執し、学生は卒業後ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の従業員になることは許されなかった。 |

| United fruit and labor challenges Invasive banana diseases Epidemic diseases would cyclically strike the banana enterprise in the form of Panama disease, black sigatoka, and Moko (Ralstonia solanacearum). Large investments of capital, resources, time, tactical practices, and extensive research would be necessary in search for a solution. The agriculture research facilities employed by United Fruit pioneered in the field of treatment with physical solutions such as controlling Panama disease via "flood fallowing" and chemical formulations such as the Bordeaux mixture spray. These forms of treatment and control would be rigorously applied by laborers on a daily basis and for long periods of time so that they would be as effective as possible. Potentially toxic chemicals were constantly exposed to workers such as copper(II) sulfate in Bordeaux spray (which is still used intensively today in organic and "bio" agriculture), 1,2-dibromo-3-chloropropane in Nemagon the treatment for Moko, or the sigatoka control process that began a chemical spray followed by an acid wash of bananas post-harvesting. The fungicidal treatments would cause workers to inhale fungicidal dust and come into direct skin contact with the chemicals without means of decontamination until the end of their workday.[43] These chemicals would be studied and proven to carry their own negative repercussions towards the laborers and land of these host nations. While the Panama disease was the first major challenging and aggressive epidemic, again United Fruit would be faced with an even more combative fungal disease, Black sigatoka, in 1935. Within a year, sigatoka plagued 80% of their Honduran crop and once again scientists would begin a search for a solution to this new epidemic.[43] By the end of 1937 production resumed to its normal level for United Fruit after the application of Bordeaux spray, but not without creating devastating blows to the banana production. "Between 1936–1937, the Tela Railroad Company banana output fell from 5.8 to 3.7 million bunches" and this did not include independent farmers who also suffered from the same epidemics, "export figures confirm the devastating effect of the pathogen on non-company growers: between 1937-1939 their exports plummeted from 1.7 million bunches to a mere 122,000 bunches".[40] Without any positive eradication of sigatoka from banana farms due to the tropical environment, the permanent fungicidal treatment was incorporated and promoted in every major banana enterprise, which would be reflective in the time, resources, labor, and allocation of expenses needed for rehabilitation. Labor health risks Both United Fruit Company production laborers and their fellow railroad workers from the Tela Railroad Company were not only at constant risk from long periods of chemical exposure in the intense tropical environment, but there was a possibility of contracting malaria/ yellow fever from mosquito bites, or inhale the airborne bacteria of tuberculosis from infected victims. In 1950, El Prision Verde ("The Green Prison"), written by Ramón Amaya Amador, a leading member of the Honduran Communist Party, exposed the injustices of working and living conditions on banana plantations with the story of Martin Samayoa, a former Bordeaux spray applicator. This literary piece is the personal account of everyday life, as an applicator, and the experienced as well as witnessed injustices pre/post-exposure to the toxic chemicals within these fungicidal treatments and insecticides. The Bordeaux spray in particular is a blue-green color and many sources referring to its usage usually bring to light the apparent identification of those susceptible to copper toxicity based on their appearance after working. For example, Pericos ("parakeets") was the nickname given to spray workers in Puerto Rico because of the blue-green coloring left on their clothing after a full day of spraying.[40] In 1969, there was only one documented case of vineyard workers being studied in Portugal as they worked with the Bordeaux spray whom all suffered similar health symptoms and biopsied to find blue-green residue within the victim's lungs.[40] Little evidence was collected in the 1930s–1960s by either the American or Honduran officials to address these acute, chronic, and deadly effects and illnesses warranted from the chemical exposure such as tuberculosis, long-term respiratory problems, weight loss, infertility, cancer, and death. Many laborers were discouraged to voice the pain caused from physical injustices that occurred from the chemicals penetrating their skin or by inhalation from fungicide fumes in long labor-intensive hours spraying the applications. Without any specialized health care[clarification needed][citation needed] targeted to cure these unabating ailments and little to no compensation of workers who did become gravely ill.[43] Bringing awareness to such matters especially against major powers such as United Fruit Co. amongst other multinational companies and the involved national governments would be feat for any single man/ woman to prove and demand for change. That is until the legalization of labor unionization and organized resistance. |

連合果実と労働力の課題 バナナの外来病害 パナマ病、黒シガトカ、モコ(Ralstonia solanacearum)といった流行病が周期的にバナナ企業を襲う。その解決策を探るには、資本、資源、時間、戦術、そして広範な研究への大きな投資 が必要である。ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の農業研究施設では、パナマ病に対する「洪水休耕」による物理的防除や、ボルドー液の散布などの化学的製剤による 防除の分野で先駆的な取り組みを行っている。 これらの治療や防除は、できるだけ効果を上げるために、労働者が毎日、長時間、厳しく行っていました。ボルドー液の硫酸銅(現在でも有機農業やバイオ農業 で盛んに使われている)、モコの処理剤ネマゴンの1,2-ジブロモ-3-クロロプロパン、収穫後のバナナに薬剤散布と酸洗いを行うシガトカ処理など、有毒 な薬剤が常に労働者にさらされることになったのです。これらの化学薬品は、労働者が殺菌性の粉塵を吸い込み、化学薬品と直接皮膚に接触し、労働時間の終わ りまで汚染除去の手段がない状態になる[43]。 これらの化学薬品は、これらの受け入れ国の労働者と土地に対して独自の負の反響をもたらすことが研究・証明された。 パナマ病は最初の大きな挑戦的で攻撃的な疫病であったが、ユナイテッド・フルーツは1935年にさらに闘争的な真菌病であるブラック・シガトカに直面する ことになる。シガトカは1年以内にホンジュラスの作物の80%を苦しめ、再び科学者がこの新しい疫病の解決策を探し始めることになった。 1937年末にはボルドー液を散布し、ユナイテッドフルーツの生産は通常レベルに戻ったが、バナナ生産に壊滅的な打撃を与えなかったわけではない。 「1936-1937 年の間に、テラ鉄道会社のバナナ生産量は 580 万房から 370 万房に減少し、これには 同じ疫病にかかった独立農家は含まれていない。 熱帯の環境からバナナ農園からシガトカを根絶することができないまま、すべての主要なバナナ企業で恒久的な殺菌処理が取り入れられ推進され、それは復旧に 必要な時間、資源、労働力、経費の配分に反映されることになった。 労働者の健康リスク ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の生産労働者も、テラ鉄道社の鉄道労働者も、熱帯の厳しい環境の中で長時間化学薬品にさらされる危険に常にさらされていただけで なく、蚊に刺されてマラリア・黄熱病に感染したり、感染者から空気中の結核菌を吸い込む可能性もありました。 1950年、ホンジュラス共産党の中心メンバーであったラモン・アマヤ・アマドールが書いた「エル・プリシオン・ヴェルデ」(「緑の刑務所」)は、元ボル ドーのスプレー塗布員マルティン・サマヨアを主人公に、バナナ農園の労働・生活条件の不当性を暴露している。この作品は、殺菌剤や殺虫剤に含まれる有毒な 化学物質にさらされる前と後の、塗布者としての日常生活と、経験した、あるいは目撃した不正の個人的な記録である。特にボルドーのスプレーは青緑色をして おり、その使用方法について言及している多くの資料では、作業後の外見から銅の毒性に弱い人を明らかに識別していることが浮き彫りになっている。例えば、 ペリコス(「インコ」)は、一日中散布した後に彼らの衣服に残る青緑色の着色のためにプエルトリコの散布労働者に与えられたニックネームだった[40]。 1969年に、ポルトガルで調査されたブドウ園労働者で、全員が同様の健康症状を起こし、生検で被害者の肺の中に青緑色の残留物を見つけたボルドーのスプ レーを使用した1件のみが記録されていた[40]。 1930年代から1960年代にかけて、結核、長期にわたる呼吸器障害、体重減少、不妊、癌、死亡など、化学物質への暴露がもたらす急性、慢性、致命的な 影響や病気について、アメリカやホンジュラスの当局が集めた証拠はほとんどありません。多くの労働者が、長い労働時間をかけて散布された殺菌剤の煙を吸い 込んだり、皮膚に化学物質が付着することで起こる身体的な不公平による苦痛を訴えることを躊躇していたのです。これらの衰えぬ病気を治すための専門的な医 療[要出典][要出典]もなく、重篤な病気になった労働者への補償もほとんどありません[43] こうした問題に意識を向けることは、特にユナイテッドフルーツ社などの多国籍企業や関係各国政府などの大国に対しては、どんな男性/女性にとっても証明し 変化を要求するのは至難の業でしょう。労働組合結成と組織的抵抗が合法化されるまではそうであった。 |

| Resistance and reformation Labor resistance, although was most progressive in the 1950s to the 1960s, there has been a consistent presence of abrasiveness towards multinational enterprises such as United Fruit. General Bonilla's choice to approve the concessions without demanding the establishment of fair labor rights and market price, nor enforce a comprise between small-scale fruit producers and the conglomerate of U.S. fruit enterprises would create the foundation in which strife would ensue from political, economic, and natural challenges. The first push for resistance began from the labor movement, leading into the Honduran government's turn towards nationalism, compliance with Honduran land and labor reformations (1954–1974)*, and the severance of U.S. multinational support in all host countries' governmental affairs (1974–1976)*.[45] As United Fruit battles with Honduran oppositions, they also fight similar battles with the other host Central American nations, let alone their own Great Depression and the rising threat of communism. Labor unionization From 1900 to 1945, the power and economic hegemony allotted to the American multinational corporations by host countries was designed to bring nations such as Honduras out of foreign debt and economic turmoil all the while decreasing the expenses of production, increasing the levels of efficiency and profit, and thriving in a tariff-free economic system. However, the growing demand for bananas surpassed the supply because of challenges such as invasive fruit diseases (Panama, sigtaoka, and moko) plus human illnesses from extreme working conditions (chemical toxicity and communicable diseases).[43] Laborers began to organize, protest, and expose the conditions in what they were suffering from at the location of their division. Small-scale fruit producers would also join the opposition to regain equality in the market economy and push for the redistribution of the taken communal lands sold to American multinational corporations. Referencing to the Honduran administrations from 1945 to 1954, business historian Marcelo Bucheli interpreted their acts of collusion and stated "The dictators helped United Fruit's business by creating a system with little or no social reform, and in return United Fruit helped them remain in power".[45] As the rise of dictatorship flourished under Tiburcio Carías Andino's national administration (1933–1949) and prevailed for 16 years until it was passed onto nationalist President Juan Manuel Gálvez (a former lawyer for the United Fruit Company). The General Strike of 1954 in Tela, Honduras was largest organized labor opposition against the United Fruit company. However, it did involve the laborers from United Fruit, Standard Fruit, along with industrial workers from San Pedro Sula. Honduran laborers were demanding fair pay, economic rights, checked national authority, and eradication of imperialist capitalism.[41] The total number of protesters was estimated at greater than 40,000.[46] On the 69th day, an agreement was made between United Fruit and the mass of protesters leading to the end of the General Strike. Under the administration of Galvez (1949–1954) strides were taken to put into effect the negotiated improvements of workers rights. Honduran laborers gained the right for shorter work days, paid holidays, limited employee responsibility for injuries, the improvement of employment regulation over women and children, and the legalization of unionization. In the summer of 1954 the strike ended, yet the demand for economic nationalism and social reform was just beginning to gain even more momentum going into the 1960s–1970s. Nationalist movement By legalizing unionization, the large mass of laborers were able to organize and act on the influences of nationalist movement, communist ideology, and becomes allies of the communist party. As like in the neighboring nation of Cuba and the rise communism led by Fidel Castro, the fight for nationalism spread to other Latin American nations and ultimately led to a regional revolution. Aid was given to these oppressed Latin American nations by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union[citation needed]. Americans struggled to maintain control and protect their capital investment while building tensions grew between America, the communist, and nationalist parties. The 1970s energy crisis was a period where petroleum production reached its peak, causing an inflation in price, leading to petroleum shortages, and a 10-year economic battle. Ultimately the United Fruit Company, among other multinational fruit enterprises, would attempt to recover capital lost due to the oil crisis through the Latin American nations. The United Fruit's plan for recovery would ensue by increasing taxation and reestablishing exclusivity contracts with small-scale farmers."The crisis forced local governments to realign themselves and follow protectionist policies" (Bulmer-Thomas, 1987).[45] The fight to not lose their control over Honduras and other sister host nations to communism failed, yet the nature of their relationship did change to where the national government had the higher authority and control. |

抵抗と改革 労働者の抵抗は、1950年代から1960年代にかけて最も進んだが、ユナイテッド・フルーツのような多国籍企業に対しては、一貫して擦り寄りの姿勢が見 られる。ボニーヤ将軍は、公正な労働権や市場価格の確立を要求することなく、また小規模の果物生産者と米国果実企業のコングロマリットとの間の協定を実施 することなく利権を承認することを選択し、政治、経済、自然の諸問題から争いを引き起こす基盤を作ることになりました。労働運動から始まった最初の抵抗運 動は、ホンジュラス政府のナショナリズムへの転向、ホンジュラスの土地・労働改革の遵守(1954-1974)*、すべてのホスト国の政府業務における米 国の多国籍企業の支援の断絶(1974-1976)*につながる[45]。ユナイテッドフルーツはホンジュラスの反対勢力と戦う一方で、他のホスト中米諸 国、さらには自国の大恐慌と共産主義の脅威の台頭に同様の戦いをしているのである。 労働組合結成 1900年から1945年まで、アメリカの多国籍企業がホスト国から与えられた権力と経済覇権は、ホンジュラスのような国を対外債務と経済の混乱から救 い、生産費を減らし、効率と利益のレベルを上げ、関税のない経済システムで繁栄させるために計画されたものだった。しかし、バナナの需要の高まりは、パナ マ、シガトカ、モコといった外来種の果実病や、化学毒性、感染症といった過酷な労働条件による人体への影響により、供給を上回るようになった[43]。 労働者たちは組織化され、抗議し、自分たちが分業先で苦しんでいる状況を暴露し始めた。小規模の果物生産者もまた、市場経済における平等性を取り戻すため に反対運動に参加し、アメリカの多国籍企業に売却された奪われた共同体土地の再分配を推し進めることになる。1945年から1954年までのホンジュラス 政権に言及し、経営史家のマルセロ・ブチェリは彼らの癒着行為を解釈し、「独裁者は社会改革がほとんどないシステムを作ることによってユナイテッドフルー ツのビジネスを助け、その代わりにユナイテッドフルーツは彼らの権力維持に貢献した」と述べた[45]。独裁の隆盛はティブルシオ・カリアス・アンディー ノの国政(1933-1949)下で栄え、民族主義のフアン・マヌエル・ガルベス大統領(元ユナイテッドフルーツ社の弁護士)に移るまでの16年間優位に 立った。 1954年にホンジュラスのテラで起こったゼネストは、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社に対する最大の組織的労働反対運動だった。しかし、このゼネストはユナイ テッド・フルーツ社、スタンダード・フルーツ社の労働者とサンペドロ・スーラの産業労働者を巻き込んだものであった。ホンジュラスの労働者は、公正な賃 金、経済的権利、国家権力のチェック、帝国主義資本主義の根絶を要求していた[41]。 69日目に、ゼネストの終了につながるユナイテッドフルーツと抗議者の集団の間で合意がなされた[46]。ガルベス政権(1949-1954)の下で、労 働者の権利の交渉による改善を実行に移すために前進がもたらされた。ホンジュラスの労働者は、労働時間の短縮、有給休暇、負傷に対する従業員の限定的な責 任、女性や子どもに関する雇用規制の改善、組合結成の合法化などの権利を獲得した。1954年夏、ストライキは終結しましたが、経済ナショナリズムと社会 改革の要求は、1960年代から1970年代にかけて、さらに勢いを増し始めたところだった。 ナショナリズム運動 組合結成を合法化することによって、大量の労働者が組織化され、民族主義運動、共産主義思想の影響を受けて行動し、共産党の味方になることができた。隣国 のキューバでフィデル・カストロを中心に共産主義が台頭したように、ナショナリズムの闘いは他のラテンアメリカ諸国にも広がり、最終的には地域革命を引き 起こした。このような抑圧されたラテンアメリカ諸国に対して、ソビエト連邦共産党から援助が行われた[citation needed]。アメリカは、アメリカ、共産主義者、民族主義者の間で建物の緊張が発展している間、支配を維持し、資本投資を守るために奮闘した。 1970年代のエネルギー危機は、石油の生産量がピークに達し、価格のインフレを引き起こし、石油不足に陥り、10年にわたる経済戦が繰り広げられた時期 である。この石油危機で失われた資本を、多国籍果実企業であるユナイテッド・フルーツ社は、ラテンアメリカ諸国を通じて回収しようとする。ホンジュラスを はじめとするホスト国の支配力を共産主義に奪われないための戦いは失敗したが、その関係は、国家政府がより高い権威と支配力を持つように変化していった [45]。 |

| End of the Honduran banana

republic era At the end of the 1970s energy crisis, Honduras was under the administration of Oswaldo Lopez Arellano after he seized control from President Ramon Villeda Morales. Trying to redistribute the taken lands of Honduras, President Arellano attempted to aid the Honduran people in regaining their economic independence but was stopped by President Ramón Ernesto Cruz Uclés in 1971. In 1960, the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was created and did not involve Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, and Colombia. Designed to strengthen the same nations that experienced extreme economic turmoil, the authority and control of foreign multinational companies, 1970s energy crisis, and the inflation of trade tariffs.[45] Through nullification of the concession contracts originally granted to the U.S. multinational companies, Latin American countries were able to further their plan for progress but were met with hostility from the U.S. companies. Later in 1974, President Arellano approved a new agrarian reform granting thousands of acres of expropriated lands from the United Fruit Company back to Honduran people. The worsened relations between the U.S. and the newly affirmed powers of the Latin American countries would bring all parties into the 1974 banana War. |

ホンジュラス・バナナ共和国時代の終焉 1970年代のエネルギー危機の末、ホンジュラスはラモン・ヴィレダ・モラレス大統領から政権を奪取したオズワルド・ロペス・アレヤノ政権の下にあった。 ホンジュラスの奪われた土地を再分配しようとしたアレジャーノ大統領は、ホンジュラス国民が経済的自立を取り戻すための支援を試みたが、1971年にラモ ン・エルネスト・クルス・ウクレス大統領に阻止された。1960年、石油輸出国機構(OPEC)が設立され、コスタリカ、グアテマラ、ホンジュラス、パナ マ、コロンビアは参加しなかった。極端な経済的混乱、外国の多国籍企業の権威と支配、1970年代のエネルギー危機、貿易関税のインフレを経験した同じ国 々を強化するために設計された[45] もともとアメリカの多国籍企業に与えられた利権契約の無効化を通じて、ラテンアメリカ諸国は進歩への計画を進めることができたが、アメリカ企業からの敵対 に直面することになった。その後1974年にアレジャーノ大統領は、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社から収用された数千エーカーの土地をホンジュラス国民に返還 する新たな農地改革を承認した。米国と新たに肯定されたラテンアメリカ諸国の関係悪化は、1974年のバナナ戦争にすべての当事国を巻き込むことになる。 |

| Aiding and abetting a terrorist

organization In March 2007 Chiquita Brands pleaded guilty in a United States Federal court to aiding and abetting a terrorist organization, when it admitted to the payment of more than $1.7 million to the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), a group that the United States has labeled a terrorist organization since 2001. Under a plea agreement, Chiquita Brands agreed to pay $25 million in restitution and damages to the families of victims of the AUC. The AUC had been paid to protect the company's interest in the region.[47] In addition to monetary payments, Chiquita has also been accused of smuggling weapons (3,000 AK-47s) to the AUC and in assisting the AUC in smuggling drugs to Europe.[48] Chiquita Brands admitted that they paid AUC operatives to silence union organizers and intimidate farmers into selling only to Chiquita. In the plea agreement, the Colombian government let Chiquita Brands keep the names of U.S. Citizens who brokered this agreement with the AUC secret, in exchange for relief to 390 families. Despite calls from Colombian authorities and human rights organizations to extradite the U.S. citizens responsible for war crimes and aiding a terrorist organization, the U.S. Department of Justice has refused to grant the request, citing 'conflicts of law'. As with other high-profile cases involving wrongdoing by American companies abroad, the U.S. State Department and the U.S. Department of Justice are very careful to hand over any American citizen to be tried under another country's legal system, so for the time being Chiquita Brands International avoided a catastrophic scandal, and instead walked away with a humiliating defeat in court and eight of its employees fired.[49] |

テロ組織への幇助 2007年3月、Chiquita Brandsは米国連邦裁判所において、2001年以来米国がテロ組織と認定しているコロンビア連合自衛隊(AUC)に対して170万ドル以上を支払った ことを認め、テロ組織幇助の罪を認めました。司法取引に基づき、チキータ・ブランズはAUCの犠牲者の家族に2500万ドルの返還と損害賠償を支払うこと に同意しました。AUCはこの地域における同社の権益を保護するために支払われたものであった[47]。 金銭的な支払いに加えて、チキータはAUCに武器(3000個のAK-47)を密輸し、AUCがヨーロッパに麻薬を密輸するのを支援したことでも告発され ています[48]。 チキータブランズは、組合組織者を黙らせ農民を脅迫してチキータにだけ販売するようにAUC工作員に金を支払ったことを認めました。司法取引では、コロン ビア政府はチキータ・ブランズに、390人の家族の救済と引き換えに、AUCとのこの契約を仲介したアメリカ市民の名前を秘密にしておくことを許可しまし た。 コロンビア当局や人権団体から、戦争犯罪とテロ組織幇助の責任を負う米国市民の身柄引き渡しを求められているにもかかわらず、米国司法省は「法の抵触」を 理由にその要請を拒否しています。海外のアメリカ企業による不正行為に関わる他の有名な事件と同様に、アメリカ国務省とアメリカ司法省は、他国の法制度の 下で裁かれるべきアメリカ国民を引き渡すことに非常に慎重であるため、当面はチキータ・ブランズ・インターナショナルは破滅的なスキャンダルを回避し、代 わりに法廷での屈辱的敗北と8人の従業員の解雇をもって立ち去ることができた[49]。 |

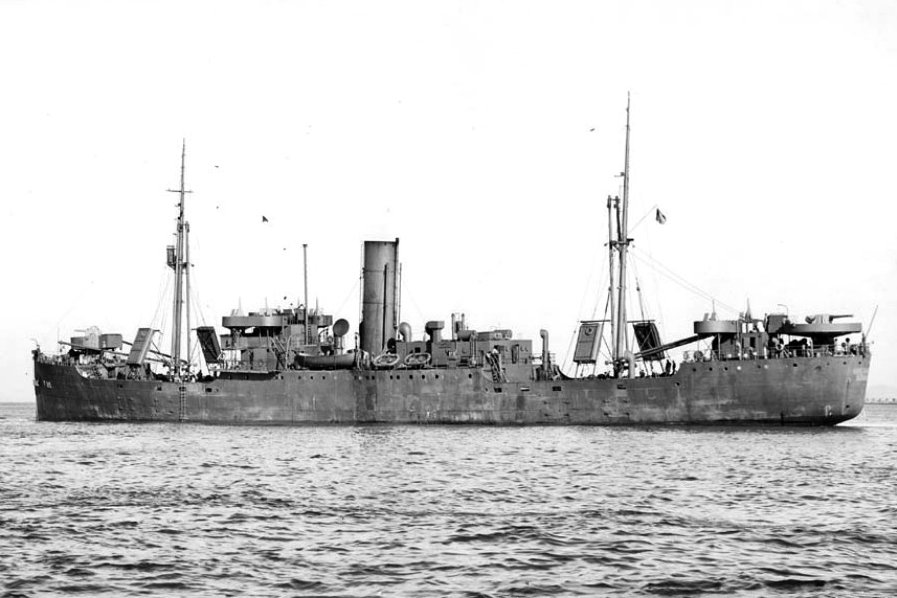

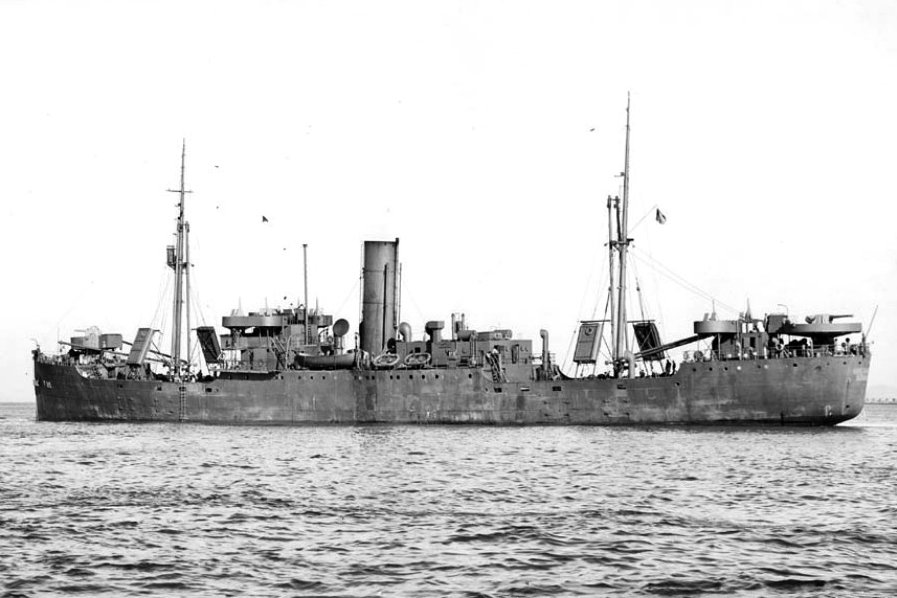

The Great White Fleet 1916 advertisement for the United Fruit Company steamship service  Routes of United Fruit Company steamship service (1924)  Dinner menu, T.E.S. Chiriqui, 1935  USS Taurus, which was built as San Benito in 1921, may have been the world's first turbo-electric merchant ship  SS Abangarez, a United Fruit banana boat, c. 1945 For over a century, United Fruit Company steamships carried bananas and passengers between Caribbean and United States seaports. These fast ships were initially designed to transport bananas but later included cargo liners with accommodations for fifty to one hundred passengers. Cruises of two to four weeks were instrumental in establishing Caribbean tourism. These banana boats were painted white to keep the temperature of the bananas lower by reflecting the tropical sun:[50] notes Admiral Dewey, Admiral Schley, Admiral Sampson and Admiral Farragut (1899) were United States Navy vessels declared surplus after the Spanish–American War. Each carried 53 passengers and 35,000 bunches of bananas.[51] Venus (1903) United Fruit Company's first refrigerated banana ship[51] San Jose, Limon and Esparta (1904) first banana reefers built to United Fruit design. San Jose and Esparta were sunk by U-boats in World War II.[51] Atenas (1909) class of 13 5,000-ton banana reefers built in Ireland[51] Tivives (1911) 4,596 GRT fruit carrier built by Workman, Clark & Company of Belfast, changed from British to United States registry 1914 when war broke out in Europe, served briefly as commissioned transport for U.S. Navy in World War I, and was again in service for World War II under U.S. Army charter then as War Shipping Administration transport. Torpedoed and sunk October 21, 1943 by German aircraft off Algeria in Convoy MKS-28.[52][53] Carrillo and Sixaola, sister ships of Tivives, both 1911, both U.S. Navy in WW I. Carrillo as ID-1406 and Sixaola as ID-2777/4524.[54][55] Both in WW II as United Fruit operated vessels for the War Shipping Administration. Carrillo survived to be scrapped 1948.[56] Sixaola was torpedoed and sunk 12 June 1942.[55][57] Pastores (1912) 7241-ton cruise liner became USS Pastores (AF-16)[58] Calamares (1913) 7,622-ton banana reefer became USS Calamares (AF-18)[58] Toloa (1917) 6,494-ton banana reefer[51] Ulua (1917) 6,494-ton banana reefer became USS Octans (AF-26)[58] San Benito (1921) 3,724-ton turbo-electric banana reefer became USS Taurus (AF-25)[58] Mayari and Choluteca (1921) 3,724-ton banana reefers[51] La Playa (1923) banana reefer[51] La Marea (1924) 3,689-ton diesel-electric banana reefer became Darien 4,281-ton turbo-electric banana reefer in about 1929–31[59] Telda, Iriona, Castilla and Tela (1927) banana reefers[51] Aztec (1929) banana reefer[51] Platano and Musa (1930) turbo-electric banana reefers[51] Talamanca (1931) 6,963-ton turbo-electric passenger and cargo liner became USS Talamanca (AF-15)[58] Jamaica (1931) 6,968-ton turbo-electric passenger and cargo liner became USS Ariel (AF-22)[58] Chiriqui (1931) 6,963-ton turbo-electric passenger and cargo liner became USS Tarazed (AF-13)[58] SS Antigua (1931) 6,982-ton Turbo-electric passenger and cargo liner providing two-week cruises of Cuba, Jamaica, Colombia, Honduras and the Panama Canal Zone.[51] Quirigua (1932) 6,982-ton turbo-electric passenger and cargo liner became USS Mizar (AF-12)[58] Veraqua (1932) 6,982-ton turbo-electric passenger and cargo liner became USS Merak (AF-21)[58] Oratava (1936) banana reefer[51] Comayagua, Junior, Metapan, Yaque and Fra Berlanga (1946) banana reefers[51] Manaqui (1946) bulk sugar ship[51] |

グレート・ホワイト・フリート 1916年、ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニーの蒸気船サービスの広告  ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の蒸気船航路(1924年)  ディナーメニュー、T.E.S.チリキ、1935年  1921年にサンベニートとして建造されたUSSタウルスは、世界初のターボ電気商船であった可能性がある。  ユナイテッド・フルーツのバナナボート、SSアバンガレス(1945年頃 1世紀以上にわたり、ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニーの蒸気船は、カリブ海と米国の港の間でバナナと乗客を運んできた。これらの高速船は、当初はバナ ナを輸送するために設計されたが、後に50人から100人の乗客を収容する貨物船も含まれるようになった。2~4週間のクルーズはカリブ海観光の確立に貢 献した。これらのバナナボートは、熱帯の太陽を反射してバナナの温度を低く保つために白く塗られていた[50]。 注釈 アドミラル・デューイ、アドミラル・シュリー、アドミラル・サンプソン、アドミラル・ファラガット(1899年)は、米西戦争後に余剰とされたアメリカ海軍の艦船だった。それぞれ53人の乗客と35,000房のバナナを積んでいた[51]。 Venus (1903) ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニー初の冷蔵バナナ船[51]。 San Jose、Limon、Esparta (1904) ユナイテッド・フルーツの設計で建造された最初のバナナ冷蔵船。サン・ホセとエスパルタは第二次世界大戦でUボートに撃沈された[51]。 アテナス (1909) アイルランドで建造された13隻の5,000トン級バナナ・リーファー[51]。 ティヴィヴス (1911) ベルファストのワークマン、クラーク&カンパニーが建造した4,596GRTの果物運搬船で、ヨーロッパで戦争が勃発した1914年にイギリスか らアメリカ籍に変更され、第一次世界大戦ではアメリカ海軍の委託輸送船として短期間就役し、第二次世界大戦ではアメリカ陸軍のチャーターで再び就役し、そ の後陸軍船舶管理局の輸送船となった。1943年10月21日、コンボイMKS-28でアルジェリア沖でドイツ軍機により魚雷攻撃を受けて沈没した [52][53]。 ティヴィヴの姉妹船であるカリージョとシクサオラは、ともに1911年、第一次世界大戦でアメリカ海軍のID-1406としてカリージョ、ID- 2777/4524としてシクサオラとして活躍した[54][55]。第二次世界大戦では、ともにユナイテッド・フルーツが陸軍船舶管理局のために運航す る船舶として活躍した。Carrilloは1948年にスクラップになるまで生き残った[56] Sixaolaは1942年6月12日に魚雷攻撃を受けて沈没した[55][57]。 Pastores (1912) 7241トン客船はUSS Pastores (AF-16)[58]となった。 カラマレス (1913) 7,622トンのバナナ冷凍船はUSSカラマレス(AF-18)[58]となった。 トロア (1917) 6,494トン バナナ冷凍船[51]。 ウルア (1917年) 6,494トンのバナナ・リーファーはUSS Octans (AF-26)[58]となった。 サンベニート (San Benito、1921年) 3,724トンのターボ・エレクトリック・バナナ・リーファーはUSSタウルス (AF-25)[58]となった。 MayariとCholuteca (1921) 3,724トンのバナナ冷凍船[51]。 ラ・プラヤ(1923年)バナナ・リーファー[51] La Marea (1924) 3,689トン ディーゼル電気式バナナ・リーファー 1929-31年頃にDarien 4,281トン ターボ電気式バナナ・リーファーとなる[59]。 Telda、Iriona、Castilla、Tela(1927年)のバナナ・リーファー[51]。 Aztec (1929) バナナ・リーファー[51]。 プラタノとムサ(1930年)ターボ電気式バナナ・リーファー[51]。 タラマンカ (Talamanca) (1931) 6,963トンのターボ電気旅客・貨物定期船がUSSタラマンカ (AF-15)[58] となる。 ジャマイカ(1931年)6,968トン・ターボ電気旅客・貨物定期船はUSSアリエル(AF-22)となった[58]。 チリキ(1931) 6,963トン ターボ電気旅客・貨物定期船 USS Tarazed (AF-13)[58]となる。 SS Antigua (1931) 6,982トンのターボ・エレクトリック客船・貨物船で、キューバ、ジャマイカ、コロンビア、ホンジュラス、パナマ運河地帯を2週間クルーズした[51]。 Quirigua (1932) 6,982トンのターボ・エレクトリック旅客・貨物定期船はUSS Mizar (AF-12)[58]となった。 ヴェラクア (Veraqua) (1932) 6,982トンのターボ電気旅客・貨物定期船はUSSメラク (AF-21)[58]となった。 オラタヴァ(1936年) バナナ冷凍船[51] Comayagua, Junior, Metapan, Yaque and Fra Berlanga (1946) バナナ・リーファー[51]。 マナキー(1946年)粗糖船[51] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Fruit_Company |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| Chiquita Brands International United Fruit Company strike (1913) Lancetilla Botanical Garden |

チキータ・ブランズ・インターナショナル ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニーのストライキ(1913年) ランセティージャ植物園 |

| Schoultz, Lars (1998). Beneath the United States. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674922761. |

The maritime flag of the United Fruit Company[

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆