音楽理論

Music theory

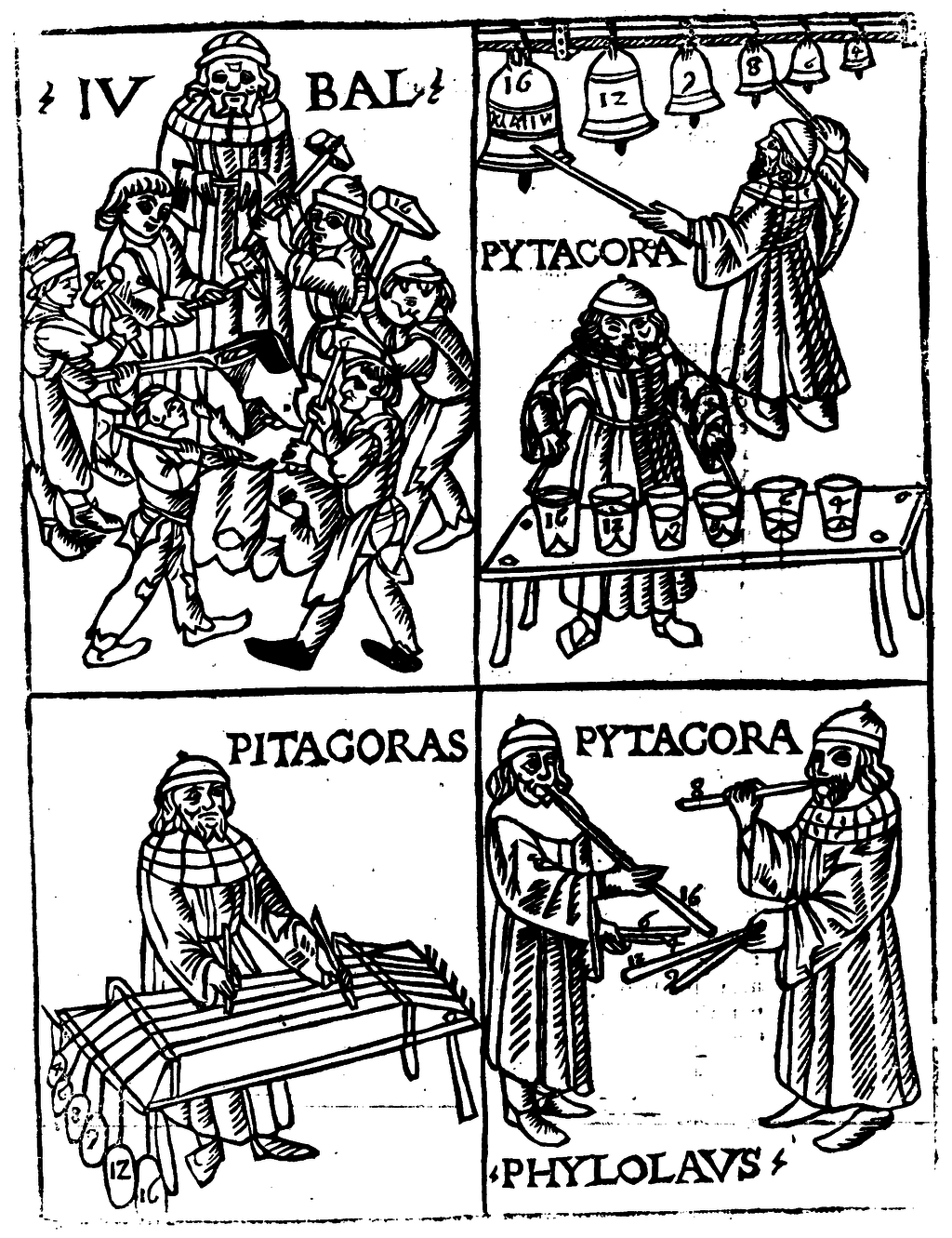

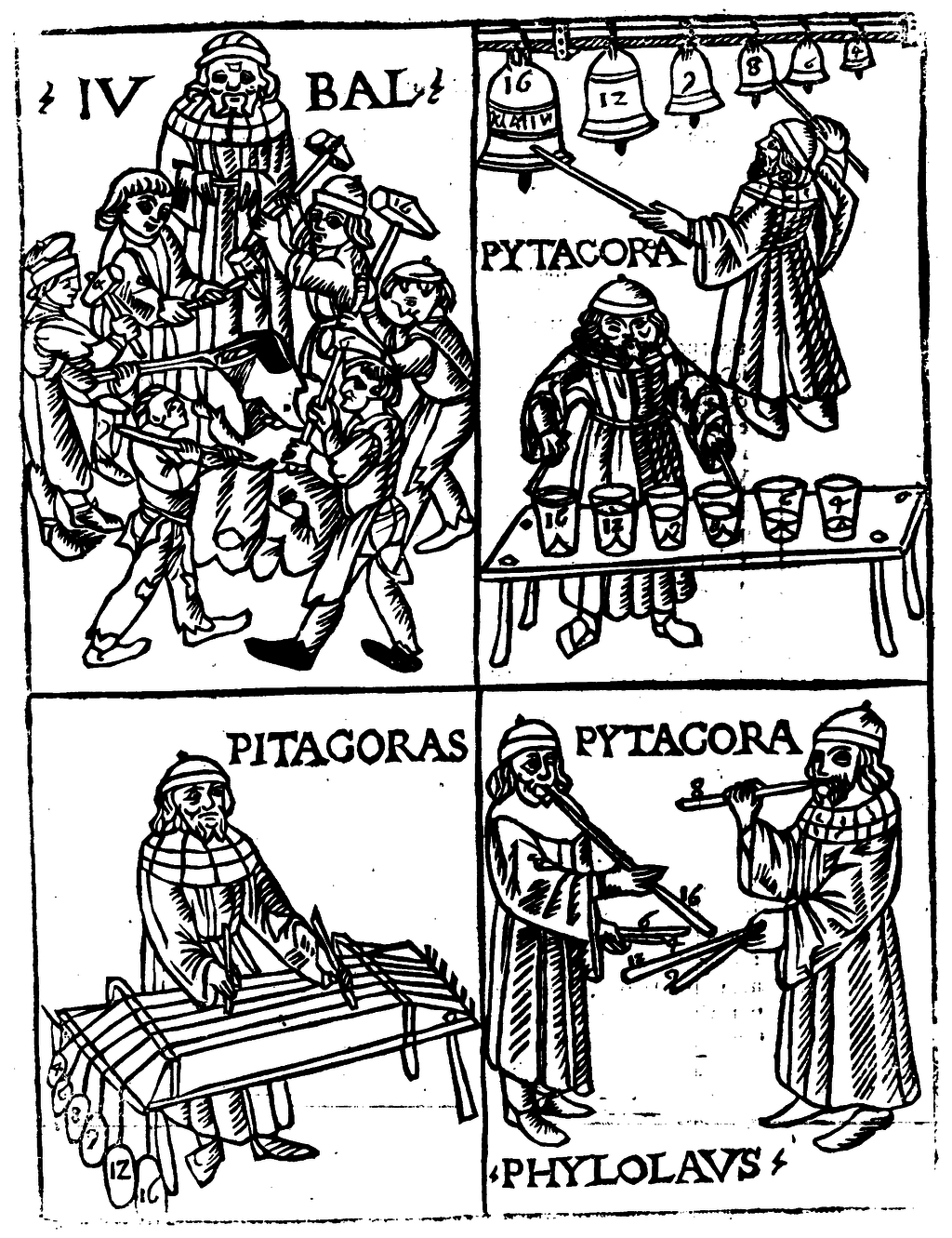

Jubal,

Pythagoras and Philolaus engaged in theoretical investigations, in a

woodcut from Franchinus Gaffurius, Theorica musicæ (1492)

☆ 音楽理論(Music theory)とは、音楽の実践と可能性を研究する学問である。オックスフォード・コンパニ オン・トゥ・ ミュージック』では、「音楽理論」という用語について、 相互に関連する3つの用法を説明している: 1つ目は、楽譜(調号、拍子記号、リズム表記)を理解するために必要な「初歩」、2つ目は、古代から現在に至るまでの音楽に関する学者の見解を学ぶこと、 3つ目は、「音楽における過程と一般原理を定義しようとする」音楽学のサブテーマである。音楽学的な理論へのアプローチは、「個々の作品や演奏ではなく、 それが構築される基本的な素材を出発点とするという点で、音楽分析とは異なる」Fallows, David (2011). "Theory". The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford Music Online.

【目次】

| Music

theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music.

The

Oxford Companion to Music describes three interrelated uses of the term

"music theory": The first is the "rudiments", that are needed to

understand music notation (key signatures, time signatures, and

rhythmic notation); the second is learning scholars' views on music

from antiquity to the present; the third is a sub-topic of musicology

that "seeks to define processes and general principles in music". The

musicological approach to theory differs from music analysis "in that

it takes as its starting-point not the individual work or performance

but the fundamental materials from which it is built."[1] Music theory is frequently concerned with describing how musicians and composers make music, including tuning systems and composition methods among other topics. Because of the ever-expanding conception of what constitutes music, a more inclusive definition could be the consideration of any sonic phenomena, including silence. This is not an absolute guideline, however; for example, the study of "music" in the Quadrivium liberal arts university curriculum, that was common in medieval Europe, was an abstract system of proportions that was carefully studied at a distance from actual musical practice.[n 1] But this medieval discipline became the basis for tuning systems in later centuries and is generally included in modern scholarship on the history of music theory.[n 2] Music theory as a practical discipline encompasses the methods and concepts that composers and other musicians use in creating and performing music. The development, preservation, and transmission of music theory in this sense may be found in oral and written music-making traditions, musical instruments, and other artifacts. For example, ancient instruments from prehistoric sites around the world reveal details about the music they produced and potentially something of the musical theory that might have been used by their makers. In ancient and living cultures around the world, the deep and long roots of music theory are visible in instruments, oral traditions, and current music-making. Many cultures have also considered music theory in more formal ways such as written treatises and music notation. Practical and scholarly traditions overlap, as many practical treatises about music place themselves within a tradition of other treatises, which are cited regularly just as scholarly writing cites earlier research. In modern academia, music theory is a subfield of musicology, the wider study of musical cultures and history. Music theory is often concerned with abstract musical aspects such as tuning and tonal systems, scales, consonance and dissonance, and rhythmic relationships. In addition, there is also a body of theory concerning practical aspects, such as the creation or the performance of music, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation, and electronic sound production.[3] A person who researches or teaches music theory is a music theorist. University study, typically to the MA or PhD level, is required to teach as a tenure-track music theorist in a US or Canadian university. Methods of analysis include mathematics, graphic analysis, and especially analysis enabled by western music notation. Comparative, descriptive, statistical, and other methods are also used. Music theory textbooks, especially in the United States of America, often include elements of musical acoustics, considerations of musical notation, and techniques of tonal composition (harmony and counterpoint), among other topics. |

音楽理論とは、音楽の実践と可能性

を研究する学問である。オックスフォード・コンパニオン・トゥ・ミュージック』では、「音楽理論」という用語について、相互に関連する3つの用法を説明し

ている:

1つ目は、楽譜(調号、拍子記号、リズム表記)を理解するために必要な「初歩」、2つ目は、古代から現在に至るまでの音楽に関する学者の見解を学ぶこと、

3つ目は、「音楽における過程と一般原理を定義しようとする」音楽学のサブテーマである。音楽学的な理論へのアプローチは、「個々の作品や演奏ではなく、

それが構築される基本的な素材を出発点とするという点で、音楽分析とは異なる」[1]。 音楽理論は、音楽家や作曲家がどのように音楽を作るかを説明することに関心がある。音楽を構成するものの概念が拡大し続けているため、より包括的な定義 は、静寂を含むあらゆる音の現象を考慮することである。しかし、これは絶対的なガイドラインではない。例えば、中世ヨーロッパで一般的であったクアドリ ヴィウム教養大学のカリキュラムにおける「音楽」の研究は、実際の音楽的実践から距離を置いて注意深く研究された比率の抽象的なシステムであった[n 1]。しかし、この中世の学問は、後の世紀における調律システムの基礎となり、音楽理論の歴史に関する現代の学問に一般的に含まれている[n 2]。 実践的な学問としての音楽理論は、作曲家やその他の音楽家が音楽を創作・演奏する際に用いる手法や概念を包含している。この意味での音楽理論の発展、保 存、伝達は、口承や文字による音楽制作の伝統、楽器、その他の遺物の中に見出すことができる。例えば、世界中の先史時代の遺跡から出土した古楽器からは、 その楽器から生み出された音楽の詳細や、製作者が使用していたであろう音楽理論が明らかになる可能性がある。世界中の古代文化や現存する文化において、音 楽理論の深く長いルーツは、楽器や口承伝承、現在の音楽制作の中に見ることができる。また、多くの文化では、書かれた論文や楽譜など、より正式な方法で音 楽理論を考察してきた。実践的な伝統と学術的な伝統は重なり合っており、音楽に関する多くの実践的な論考は、他の論考の伝統の中に位置づけられ、学術的な 文章が以前の研究を引用するのと同じように、定期的に引用されている。 現代の学術界では、音楽理論は音楽学の一分野であり、音楽文化や音楽史に関する広範な学問である。音楽理論は、調律や音律体系、音階、協和音と不協和音、 リズム関係など、抽象的な音楽的側面に関わることが多い。また、音楽の創作や演奏、オーケストレーション、装飾、即興演奏、電子音響制作など、実践的な側 面に関する理論も存在する[3]。アメリカやカナダの大学でテニュアトラックの音楽理論家として教えるためには、通常、修士号または博士号レベルの大学で の研究が必要である。分析の方法としては、数学、図形分析、特に西洋楽譜による分析があります。比較法、記述法、統計法、その他の方法も用いられます。音 楽理論の教科書には、特にアメリカでは、音楽音響学の要素、楽譜の考察、調性構成の技法(和声と対位法)などが含まれていることが多い。 |

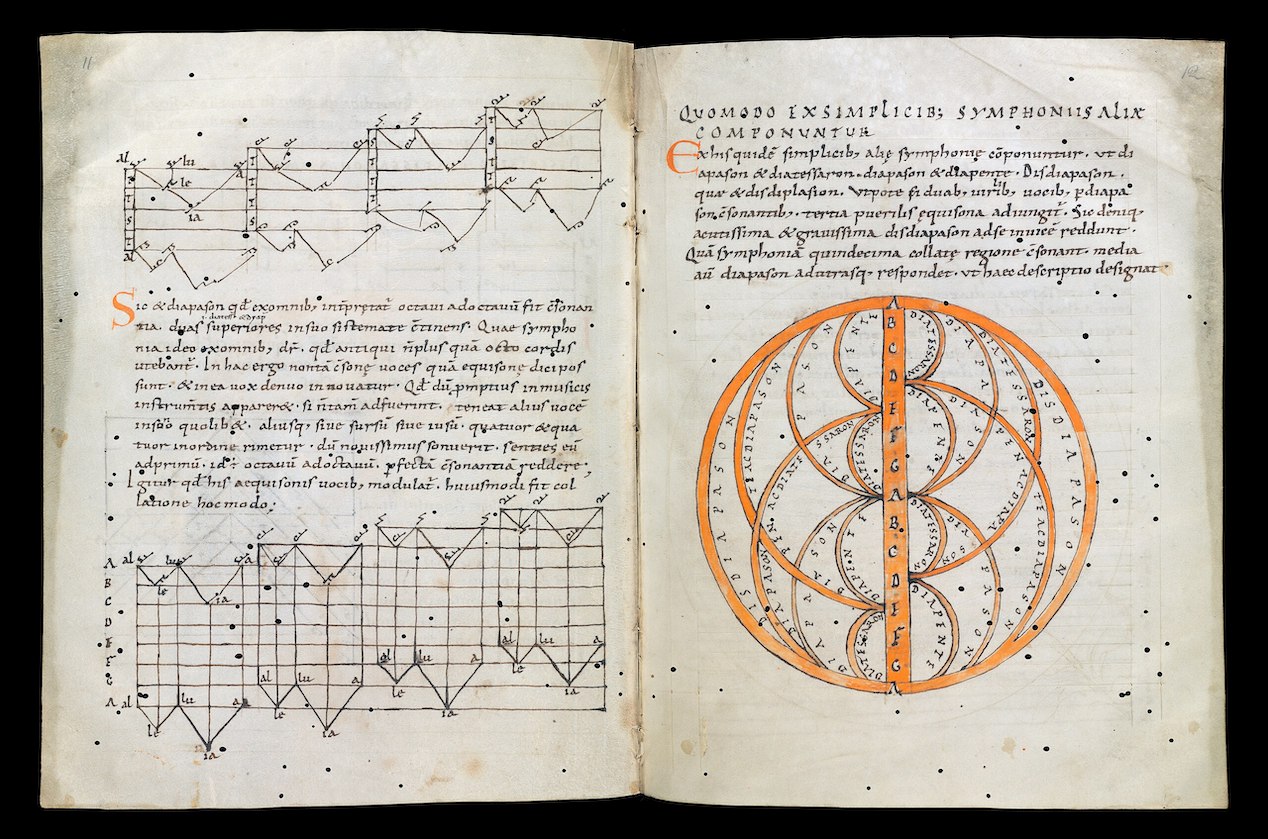

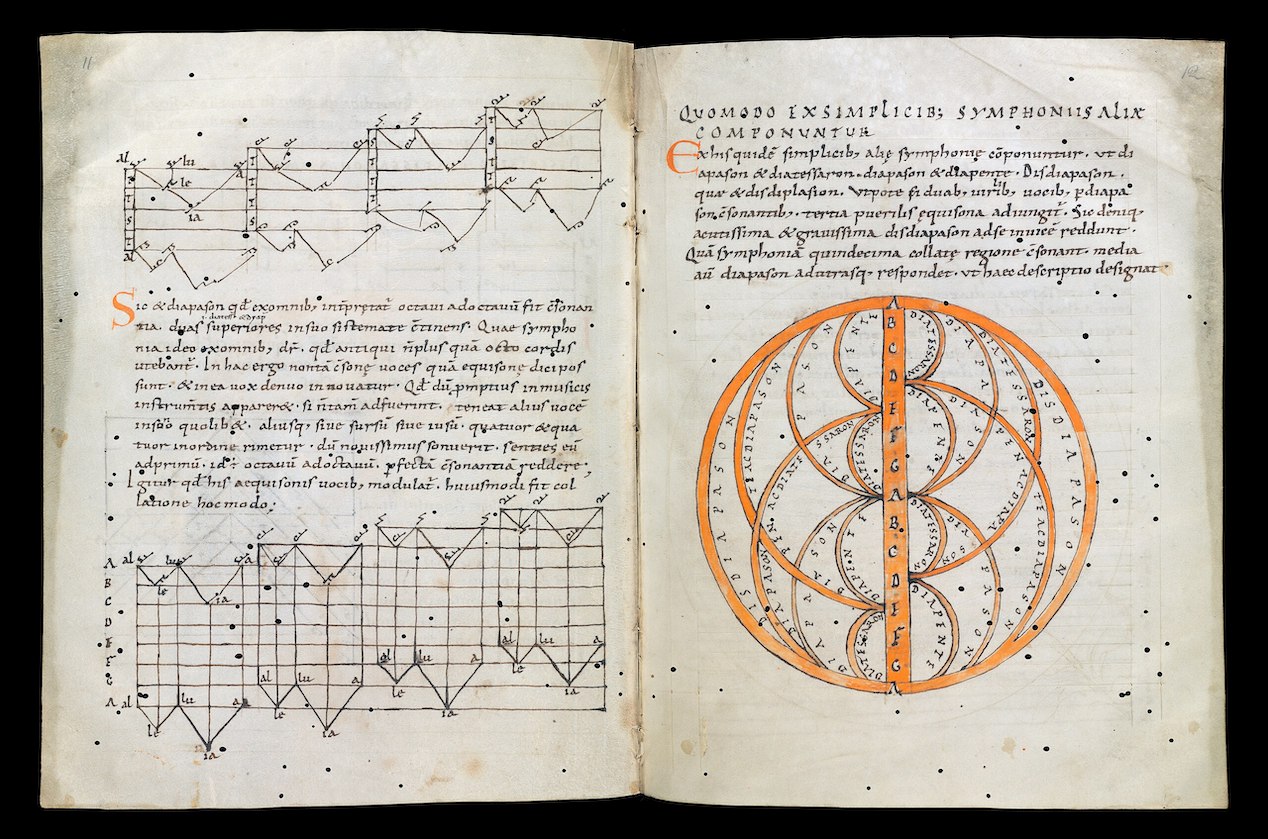

| History Further information: History of music Antiquity Further information: Ancient music Mesopotamia See also: Music of Mesopotamia Several surviving Sumerian and Akkadian clay tablets include musical information of a theoretical nature, mainly lists of intervals and tunings.[4] The scholar Sam Mirelman reports that the earliest of these texts dates from before 1500 BCE, a millennium earlier than surviving evidence from any other culture of comparable musical thought. Further, "All the Mesopotamian texts [about music] are united by the use of a terminology for music that, according to the approximate dating of the texts, was in use for over 1,000 years."[5] China See also: Music of China and Chinese musicology Much of Chinese music history and theory remains unclear.[6] Chinese theory starts from numbers, the main musical numbers being twelve, five and eight. Twelve refers to the number of pitches on which the scales can be constructed. The Lüshi chunqiu from about 239 BCE recalls the legend of Ling Lun. On order of the Yellow Emperor, Ling Lun collected twelve bamboo lengths with thick and even nodes. Blowing on one of these like a pipe, he found its sound agreeable and named it huangzhong, the "Yellow Bell." He then heard phoenixes singing. The male and female phoenix each sang six tones. Ling Lun cut his bamboo pipes to match the pitches of the phoenixes, producing twelve pitch pipes in two sets: six from the male phoenix and six from the female: these were called the lülü or later the shierlü.[7] Apart from technical and structural aspects, ancient Chinese music theory also discusses topics such as the nature and functions of music. The Yueji ("Record of music", c1st and 2nd centuries BCE), for example, manifests Confucian moral theories of understanding music in its social context. Studied and implemented by Confucian scholar-officials [...], these theories helped form a musical Confucianism that overshadowed but did not erase rival approaches. These include the assertion of Mozi (c. 468 – c. 376 BCE) that music wasted human and material resources, and Laozi's claim that the greatest music had no sounds. [...] Even the music of the qin zither, a genre closely affiliated with Confucian scholar-officials, includes many works with Daoist references, such as Tianfeng huanpei ("Heavenly Breeze and Sounds of Jade Pendants").[6] India See also: Music of India The Samaveda and Yajurveda (c. 1200 – 1000 BCE) are among the earliest testimonies of Indian music, but properly speaking, they contain no theory. The Natya Shastra, written between 200 BCE to 200 CE, discusses intervals (Śrutis), scales (Grāmas), consonances and dissonances, classes of melodic structure (Mūrchanās, modes?), melodic types (Jātis), instruments, etc.[8] Greece See also: Musical system of ancient Greece and List of music theorists § Antiquity Early preserved Greek writings on music theory include two types of works:[9] technical manuals describing the Greek musical system including notation, scales, consonance and dissonance, rhythm, and types of musical compositions; treatises on the way in which music reveals universal patterns of order leading to the highest levels of knowledge and understanding. Several names of theorists are known before these works, including Pythagoras (c. 570 ~ c. 495 bce), Philolaus (c. 470 ~ (c. 385 bce), Archytas (428–347 bce), and others. Works of the first type (technical manuals) include Anonymous (erroneously attributed to Euclid) (1989) [4th–3rd century bce]. Barker, Andrew (ed.). Κατατομή κανόνος [Division of the Canon]. Greek Musical Writings. Vol. 2: Harmonic and Acoustic Theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 191–208. English trans. Theon of Smyrna. Τωv κατά τό μαθηματικόν χρησίμων είς τήν Πλάτωνος άνάγνωσις [On the Mathematics Useful for Understanding Plato] (in Greek). 115–140 ce. Nicomachus of Gerasa. Άρμονικόν έγχειρίδιον [Manual of Harmonics]. 100–150 ce. Cleonides. Είσαγωγή άρμονική [Introduction to Harmonics] (in Greek). 2nd century ce. Gaudentius. Άρμονική είσαγωγή [Harmonic Introduction] (in Greek). 3rd or 4th century ce. Bacchius Geron. Είσαγωγή τέχνης μουσικής [Introduction to the Art of Music]. 4th century ce or later. Alypius of Alexandria. Είσαγωγή μουσική [Introduction to Music] (in Greek). 4th–5th century ce. More philosophical treatises of the second type include Aristoxenus. Άρμονικά στοιχεία [Harmonic Elements] (in Greek). 375~360 bce, before 320 bce. Aristoxenus. Ρυθμικά στοιχεία [Rhythmic Elements] (in Greek). Ptolemaios (Πτολεμαίος), Claudius. Άρμονικά [Harmonics] (in Greek). 127–148 ce. Porphyrius. Είς τά άρμονικά Πτολεμαίον ύπόμνημα [On Ptolemy's Harmonics] (in Greek). c. 232~233 – c. 305 ce. Post-classical See also: List of music theorists § Post-classical, and List of medieval music theorists China The pipa instrument carried with it a theory of musical modes that subsequently led to the Sui and Tang theory of 84 musical modes.[6] Arabic countries / Persian countries Medieval Arabic music theorists include:[n 3] Abū Yūsuf Ya'qūb al-Kindi (Bagdad, 873 CE), who uses the first twelve letters of the alphabet to describe the twelve frets on five strings of the oud, producing a chromatic scale of 25 degrees.[10] [Yaḥyā ibn] al-Munajjim (Baghdad, 856–912), author of Risāla fī al-mūsīqī ("Treatise on music", MS GB-Lbl Oriental 2361) which describes a Pythagorean tuning of the oud and a system of eight modes perhaps inspired by Ishaq al-Mawsili (767–850).[11] Abū n-Nașr Muḥammad al-Fārābi (Persia, 872? – Damas, 950 or 951 CE), author of Kitab al-Musiqa al-Kabir ("The Great Book of Music").[12] 'Ali ibn al-Husayn ul-Isfahānī (897–967), known as Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, author of Kitāb al-Aghānī ("The Book of Songs"). Abū 'Alī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd-Allāh ibn Sīnā, known as Avicenna (c. 980 – 1037), whose contribution to music theory consists mainly in Chapter 12 of the section on mathematics of his Kitab Al-Shifa ("The Book of Healing").[13] al-Ḥasan ibn Aḥmad ibn 'Ali al-Kātib, author of Kamāl adab al Ghinā' ("The Perfection of Musical Knowledge"), copied in 1225 (Istanbul, Topkapi Museum, Ms 1727).[14] Safi al-Din al-Urmawi (1216–1294 CE), author of the Kitabu al-Adwār ("Treatise of musical cycles") and ar-Risālah aš-Šarafiyyah ("Epistle to Šaraf").[15] Mubārak Šāh, commentator of Safi al-Din's Kitāb al-Adwār (British Museum, Ms 823).[16] Anon. LXI, Anonymous commentary on Safi al-Din's Kitāb al-Adwār.[17] Shams al-dῑn al-Saydᾱwῑ Al-Dhahabῑ (14th century CE (?)), music theorist. Author of Urjῡza fi'l-mῡsῑqᾱ ("A Didactic Poem on Music").[18] Europe The Latin treatise De institutione musica by the Roman philosopher Boethius (written c. 500, translated as Fundamentals of Music[2]) was a touchstone for other writings on music in medieval Europe. Boethius represented Classical authority on music during the Middle Ages, as the Greek writings on which he based his work were not read or translated by later Europeans until the 15th century.[19] This treatise carefully maintains distance from the actual practice of music, focusing mostly on the mathematical proportions involved in tuning systems and on the moral character of particular modes. Several centuries later, treatises began to appear which dealt with the actual composition of pieces of music in the plainchant tradition.[20] At the end of the ninth century, Hucbald worked towards more precise pitch notation for the neumes used to record plainchant. Guido d'Arezzo wrote a letter to Michael of Pomposa in 1028, entitled Epistola de ignoto cantu,[21] in which he introduced the practice of using syllables to describe notes and intervals. This was the source of the hexachordal solmization that was to be used until the end of the Middle Ages. Guido also wrote about emotional qualities of the modes, the phrase structure of plainchant, the temporal meaning of the neumes, etc.; his chapters on polyphony "come closer to describing and illustrating real music than any previous account" in the Western tradition.[19] During the thirteenth century, a new rhythm system called mensural notation grew out of an earlier, more limited method of notating rhythms in terms of fixed repetitive patterns, the so-called rhythmic modes, which were developed in France around 1200. An early form of mensural notation was first described and codified in the treatise Ars cantus mensurabilis ("The art of measured chant") by Franco of Cologne (c. 1280). Mensural notation used different note shapes to specify different durations, allowing scribes to capture rhythms which varied instead of repeating the same fixed pattern; it is a proportional notation, in the sense that each note value is equal to two or three times the shorter value, or half or a third of the longer value. This same notation, transformed through various extensions and improvements during the Renaissance, forms the basis for rhythmic notation in European classical music today. Modern Middle Eastern and Central Asian countries Bāqiyā Nāyinῑ (Uzbekistan, 17th century CE), Uzbek author and music theorist. Author of Zamzama e wahdat-i-mῡsῑqῑ ["The Chanting of Unity in Music"].[18] Baron Francois Rodolphe d'Erlanger (Tunis, Tunisia, 1910–1932 CE), French musicologist. Author of La musique arabe and Ta'rῑkh al-mῡsῑqᾱ al-arabiyya wa-usῡluha wa-tatawwurᾱtuha ["A History of Arabian Music, its principles and its Development"] D'Erlanger divulges that the Arabic music scale is derived from the Greek music scale, and that Arabic music is connected to certain features of Arabic culture, such as astrology.[18] Europe Renaissance Further information: List of music theorists § 15th and 16th centuries Baroque Further information: List of music theorists § 17th century Further information: List of music theorists § 18th century 1750–1900 As Western musical influence spread throughout the world in the 1800s, musicians adopted Western theory as an international standard—but other theoretical traditions in both textual and oral traditions remain in use. For example, the long and rich musical traditions unique to ancient and current cultures of Africa are primarily oral, but describe specific forms, genres, performance practices, tunings, and other aspects of music theory.[22][23] Sacred harp music uses a different kind of scale and theory in practice. The music focuses on the solfege "fa, sol, la" on the music scale. Sacred Harp also employs a different notation involving "shape notes", or notes that are shaped to correspond to a certain solfege syllable on the music scale. Sacred Harp music and its music theory originated with Reverend Thomas Symmes in 1720, where he developed a system for "singing by note" to help his church members with note accuracy.[24] Further information: List of music theorists § 19th century Contemporary See also: List of music theorists § 20th century, and List of music theorists § 21st century  Explanation of the diapason in a 10th-century manuscript of Musica enchiriadis |

歴史 さらに詳しい情報 音楽の歴史 古代 さらに詳しい情報 古代の音楽 メソポタミア 関連項目 メソポタミアの音楽 現存するシュメール語やアッカド語の粘土板には、主に音程や調弦のリストなど、理論的な音楽情報が含まれている[4]。学者のサム・ミレルマンは、これら のテキストのうち最も古いものは紀元前1500年以前のものであり、同等の音楽思想を持つ他の文化圏の現存する証拠よりも千年も早い、と報告している。さ らに、「(音楽に関する)メソポタミアのテキストはすべて、テキストのおおよその年代測定によれば、1,000年以上にわたって使用されていた音楽用語の 使用によって統一されている」[5]。 中国 以下も参照: 中国の音楽と中国音楽学 中国音楽の歴史と理論の多くは、いまだに不明な点が多い[6]。 中国の理論は数字から始まり、主な音楽的数字は12、5、8である。12は音階を構成できる音程の数を意味する。紀元前239年頃の『呂志春秋』には、凌 遅の伝説が記されている。黄帝の命により、凌遅は節が太く均等な竹を12本集めた。そのうちの1本をパイプのように吹いてみると、心地よい音がしたので、 黄鐘と名づけた。すると、鳳凰の鳴き声が聞こえてきた。雄と雌の鳳凰はそれぞれ6つの音色を歌った。霊倫は鳳凰の音程に合わせて竹管を切り、雄の鳳凰から 6本、雌の鳳凰から6本の計12本を2組にした。 技術的、構造的な側面とは別に、古代中国の音楽理論は音楽の性質や機能といったトピックについても論じている。例えば『岳記』(「楽記」、前1~2世紀 頃)には、音楽を社会的背景の中で理解するという儒教的な道徳理論が示されている。儒学者である官僚たちによって研究され、実践されたこれらの理論は、音 楽的儒教の形成に貢献し、対立するアプローチの影を落としたが、消し去ることはできなかった。例えば、音楽は人的・物的資源を浪費するという茂子(前 468年頃~前376年頃)の主張や、最高の音楽には音がないという老子の主張などである。(中略)儒教の士官と密接な関係にある秦琴の音楽でさえ、天風 煥平(「天風と玉佩の音」)のような道教を引用した作品を多く含んでいる[6]。 インド こちらも参照: インドの音楽 サマヴェーダ』と『ヤジュルヴェーダ』(前1200年頃~前1000年頃)は、インド音楽に関する最も古い文献のひとつであるが、正しくは理論的な内容は 含まれていない。紀元前200年から紀元後200年の間に書かれた『ナティヤ・シャストラ』では、音程(シュルティス)、音階(グラーマ)、協和音と不協 和音、旋律構造のクラス(ムルチャナー、モード?)、旋律のタイプ(ジャーティス)、楽器などについて論じている[8]。 ギリシャ 以下も参照: 古代ギリシアの音楽体系と音楽理論家のリスト§古代 ギリシア初期に残された音楽理論に関する著作には、以下の2種類がある[9]。 記譜法、音階、協和音と不協和音、リズム、楽曲の種類など、ギリシアの音楽体系を説明した技術書; 音楽が普遍的な秩序パターンを明らかにし、最高レベルの知識と理解へと導く方法に関する論文。 ピタゴラス(前570年頃~前495年頃)、フィロラオス(前470年頃~前385年頃)、アルキタス(前428年~前347年頃)など、これらの著作以 前に理論家の名前がいくつか知られている。 最初のタイプの作品(技術マニュアル)には以下のものがある。 匿名(ユークリッドの誤記とされる)(1989)[前4~3世紀] Barker, Andrew (ed.). Κατατομή κανόνος [Division of the Canon]. ギリシア音楽著作集. 第2巻:和声と音響理論. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 英語訳. Theon of Smyrna. Τωv κατά τό μαθηματικόν χρησίμων είς τήν Πλάτωνος άνάγνωσις [プラトンを理解するのに有用な数学について] (in Greek). 前115-140年 ゲラサのニコマコス Άρμονικόν έγχειρίδιον [調和学の手引書] 100-150 ce. クレオニデス Είσαγωγή άρμονική[調和学入門](ギリシャ語). 2世紀 Gaudentius. Άρμονική είσαγωγή[和声学入門](ギリシア語)。3~4世紀 バッキウス・ゲロン Είσαγωγή τέχνης μουσικής [音楽芸術入門]. 4世紀以降 アレクサンドリアのアリピウス Είσαγωγήμουσική[音楽入門](ギリシア語)。前4~5世紀 第二のタイプの哲学書には以下のものがある。 アリストクセヌス Άρμονικά στοιχεία [Harmonic Elements] (ギリシャ語)。前375~360年、前320年以前。 アリストクセヌス Ρυθμικά στοιχεία [Rhythmic Elements](ギリシア語)。 プトレマイオス(Πτολεμαίος)、クラウディウス。Άρμονικά [Harmonics] (ギリシア語). 127-148 ce. ポルフィリウス Είς τά άρμονικά Πτολεμαίον ύπόμνημα[プトレマイオスの調和論について](ギリシャ語). 古典期以降 以下も参照: 音楽理論家リスト§後古典派、中世音楽理論家リスト 中国 琵琶という楽器は、後に隋唐の84の音楽様式の理論につながる音楽様式の理論を携えていた[6]。 アラビア諸国/ペルシャ諸国 中世アラビアの音楽理論家は以下の通り[n 3]。 Abū Yūsuf Ya'qūb al-Kindi(バグダッド、CE 873年)は、アルファベットの最初の12文字を使ってウードの5本の弦の12のフレットを表現し、25度の半音階を生み出した[10]。 [Risāla fī al-mūsīqī(『音楽論』、MS GB-Lbl Oriental 2361)の著者である[11]。 Abū n-Nașr Muḥammad al-Fārābi(ペルシャ、872年? - ダマス、950年または951年)、Kitab al-Musiqa al-Kabir(『偉大なる音楽の書』)の著者[12]。 Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahaniとして知られる'Ali ibn al-Husayn ul-Isfahānī(897年-967年)、Kitāb al-Aghānī(『歌の書』)の著者。 アヴィセンナ(980年頃-1037年)として知られるアブー'アリー'アル-Ḥusayn ibn +Abd-Allāh ibn Sīnāは、音楽理論への貢献は主にKitab Al-Shifa(『治癒の書』)の数学の章の第12章にある[13]。 Al-Ḥasan ibn Aḥmad ibn 'Ali al-Kātib、『音楽知識の完成』(Kamāl adab al Ghinā')の著者、1225年写本(イスタンブール、トプカプ博物館、Ms 1727)[14]。 サフィ・アル=ディン・アル=ウルマウィー(1216-1294年)、『キタブ・アル=アドワール』(Kitabu al-Adwār)、『アル=リサーラ・アシュ=シャーラフィヤ』(ar-Risālah aš-Šarafiyyah)(『シャーラフへの手紙』)の著者[15]。 ムバーラク・シャー、サフィ・アル=ディンの『キターブ・アル=アドワール』(大英博物館、Ms.823)の注釈者[16]。 Anon. LXI, Safi al-Din's Kitāb al-Adwārの匿名の注釈書[17]。 Shams al-dῑ al-Saydwῑ Al-Dhahab_1(14世紀(?Urjῡza fi'l-mῡqῡ(『音楽についての教訓詩』)の著者[18]。 ヨーロッパ ローマの哲学者ボエティウスによるラテン語の論文『De institutione musica』(500年頃に書かれ、『音楽の基礎』[2]と訳されている)は、中世ヨーロッパにおける他の音楽に関する著作の試金石となった。ボエティ ウスは中世の音楽における古典的権威を代表する人物であり、彼の著作の基となったギリシア語の著作は15世紀になるまで後世のヨーロッパ人によって読まれ たり翻訳されたりすることはなかった[19]。この論考は実際の音楽の実践から慎重に距離を置き、調律法に関わる数学的な比率や特定のモードの道徳的な性 格に主に焦点を当てている。数世紀後、プレーンチャントの伝統に則った楽曲の実際の作曲を扱った論考が現れ始めた[20]。 9世紀末、フクバルドはプレーンチャントを記録するために使用されるノイムのために、より正確な音程表記を目指した。 グイド・ダレッツォは、1028年にポンポーザのミヒャエルに宛てた書簡『Epistola de ignoto cantu』[21]で、音符と音程を音節で表す方法を紹介した。これが、中世の終わりまで使用されることになった六和音ソルミゼーションの源となった。 グイドはまた、モードの情緒的特質、平叙歌のフレーズ構造、ノームの時間的意味などについても書いている。ポリフォニーに関する彼の章は、西洋の伝統にお ける「以前のどの記述よりも、実際の音楽の記述と説明に近い」ものであった[19]。 13世紀には、1200年頃にフランスで開発された、固定された反復パターン、いわゆるリズム・モードでリズムを記譜する、より初期の限定的な方法から、 メンソール記譜法と呼ばれる新しいリズム・システムが発展した。初期の記譜法は、ケルンのフランコ(1280年頃)の『Ars cantus mensurabilis』(「計量聖歌の技法」)に初めて記述され、体系化された。メンソラ記譜法は、異なる音符の形を使って異なる長さを指定するもの で、写字者は同じ固定したパターンを繰り返すのではなく、変化するリズムを捉えることができた。それぞれの音価は、短い音価の2倍または3倍、あるいは長 い音価の半分または3分の1に等しいという意味で、比例記譜法である。この同じ記譜法が、ルネサンス期にさまざまな拡張や改良を経て、今日のヨーロッパの クラシック音楽におけるリズム記譜法の基礎となっている。 近代 中東・中央アジア諸国 Bāqiyā Nāyinῑ(ウズベキスタン、17世紀)、ウズベキスタンの作家、音楽理論家。Zamzama e wahdat-i-mῡsῑ[「音楽における統一の詠唱」]の著者[18]。 Baron Francois Rodolphe d'Erlanger(チュニジア、チュニス、1910年-1932年)、フランスの音楽学者。La musique arabe』『Ta'rῑ al-mῡ al-arabiyya wa-usῡ wa-tatawwurDZtuha』(『アラブ音楽の歴史、その原理と発展』)の著者。 D'Erlangerは、アラビア音楽の音階はギリシア音楽の音階から派生したものであり、アラビア音楽は占星術のようなアラビア文化の特定の特徴と結び ついていると明かしている[18]。 ヨーロッパ ルネサンス さらなる情報 音楽理論家のリスト§15世紀と16世紀 バロック さらなる情報 音楽理論家リスト§17世紀 さらなる情報 音楽理論家リスト§18世紀 1750-1900 1800年代に西洋音楽の影響が世界中に広まるにつれ、音楽家たちは西洋の理論を国際的な基準として採用したが、テキストと口承の両方における他の理論的 伝統も依然として使用されている。例えば、アフリカの古代および現在の文化に特有の長く豊かな音楽的伝統は、主に口承によるものであるが、特定の形式、 ジャンル、演奏方法、調律、その他の音楽理論の側面について記述されている[22][23]。 聖なるハープ音楽は、実際には異なる種類の音階と理論を用いている。音楽は音階上のソルフェージュ「ファ、ソル、ラ」に重点を置いている。また、セイク リッド・ハープでは「シェイプ・ノート」、つまり音階上の特定のソルフェージュ音節に対応するようシェイプされた音符を含む異なる記譜法を採用している。 セイクリッド・ハープの音楽とその音楽理論は、1720年にトーマス・シンメス牧師によって創始され、彼は教会員の音符の正確さを助けるために「音符で歌 う」システムを開発した[24]。 さらなる情報 音楽理論家のリスト§19世紀 現代 以下も参照: 音楽理論家リスト§20世紀、音楽理論家リスト§21世紀  10世紀の写本『Musica enchiriadis』における音域の説明 |

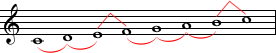

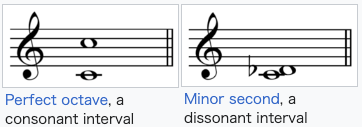

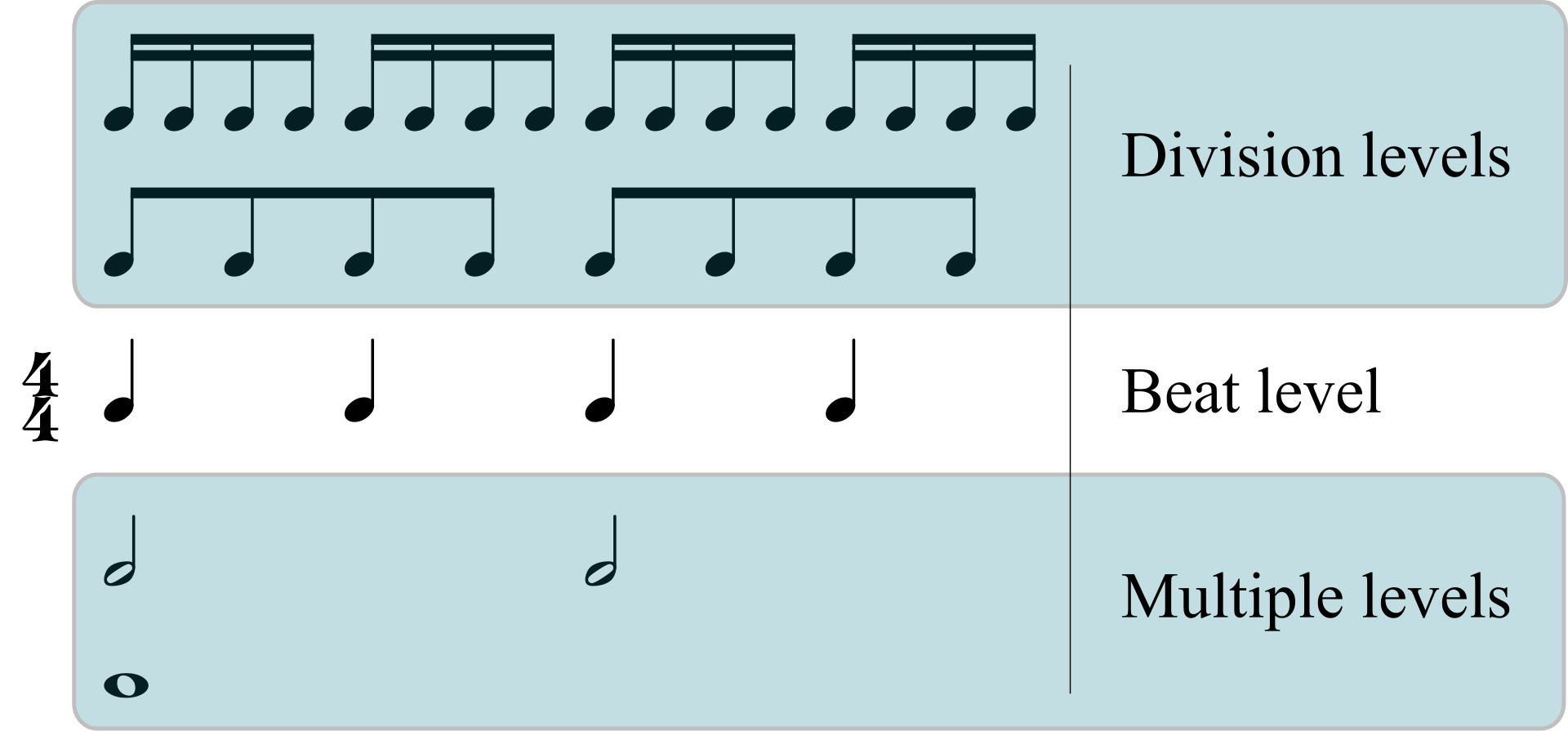

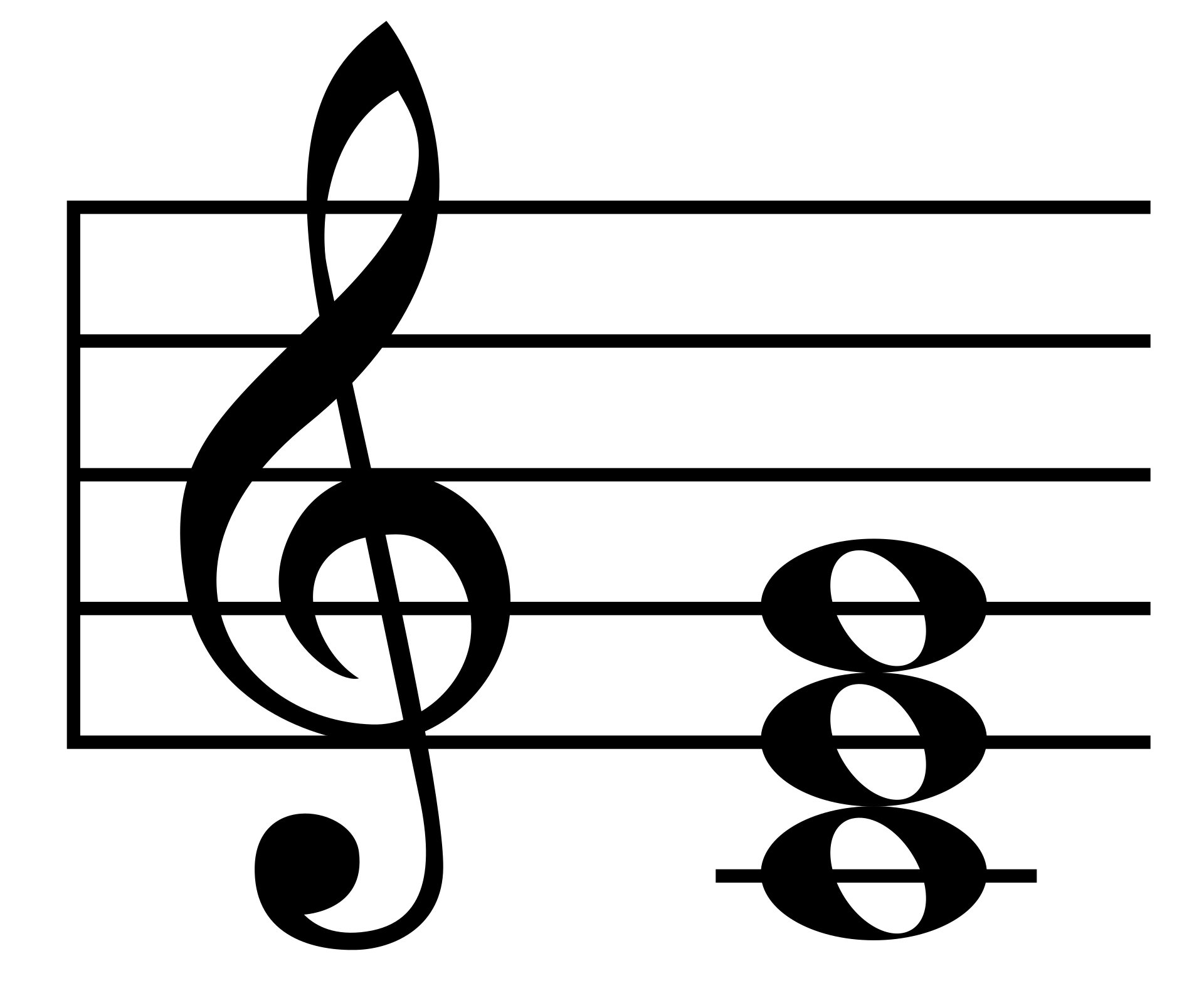

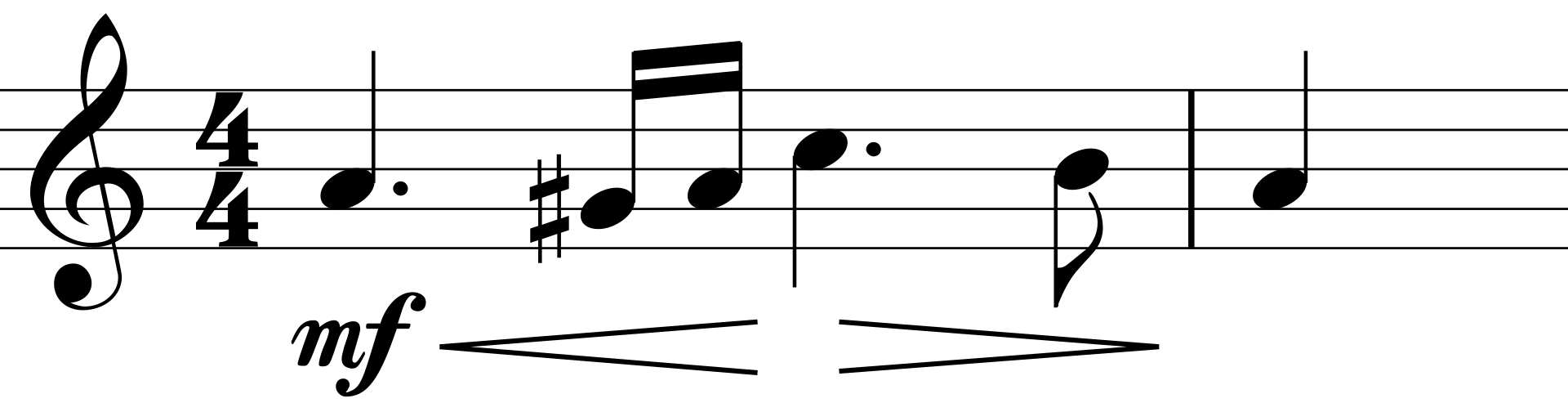

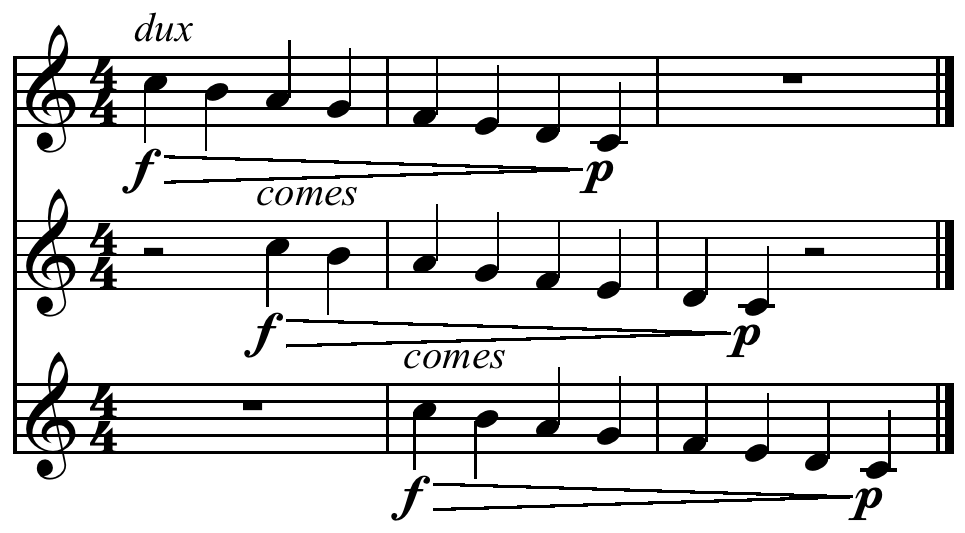

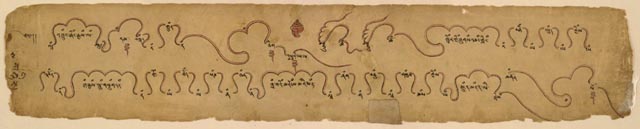

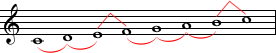

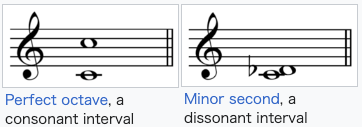

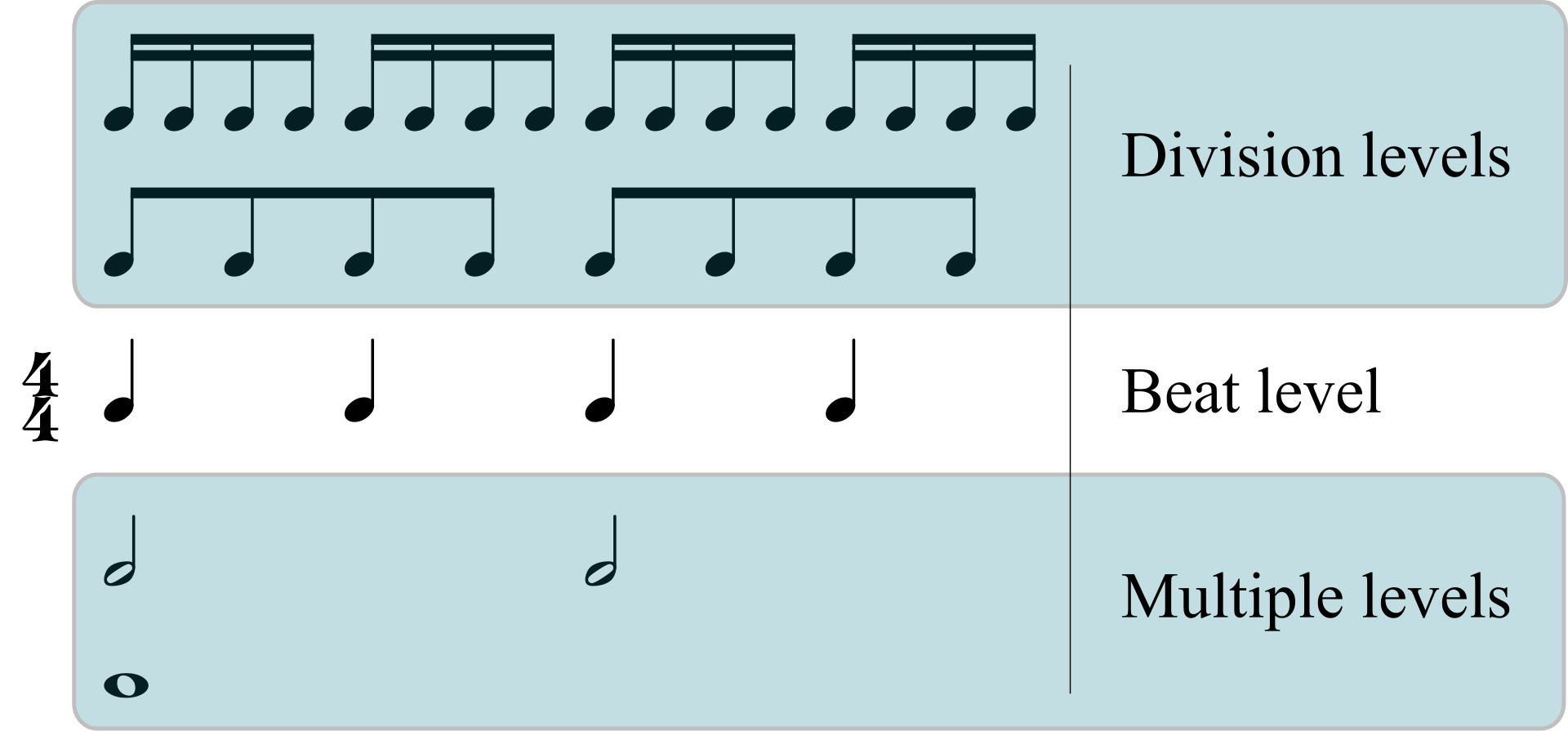

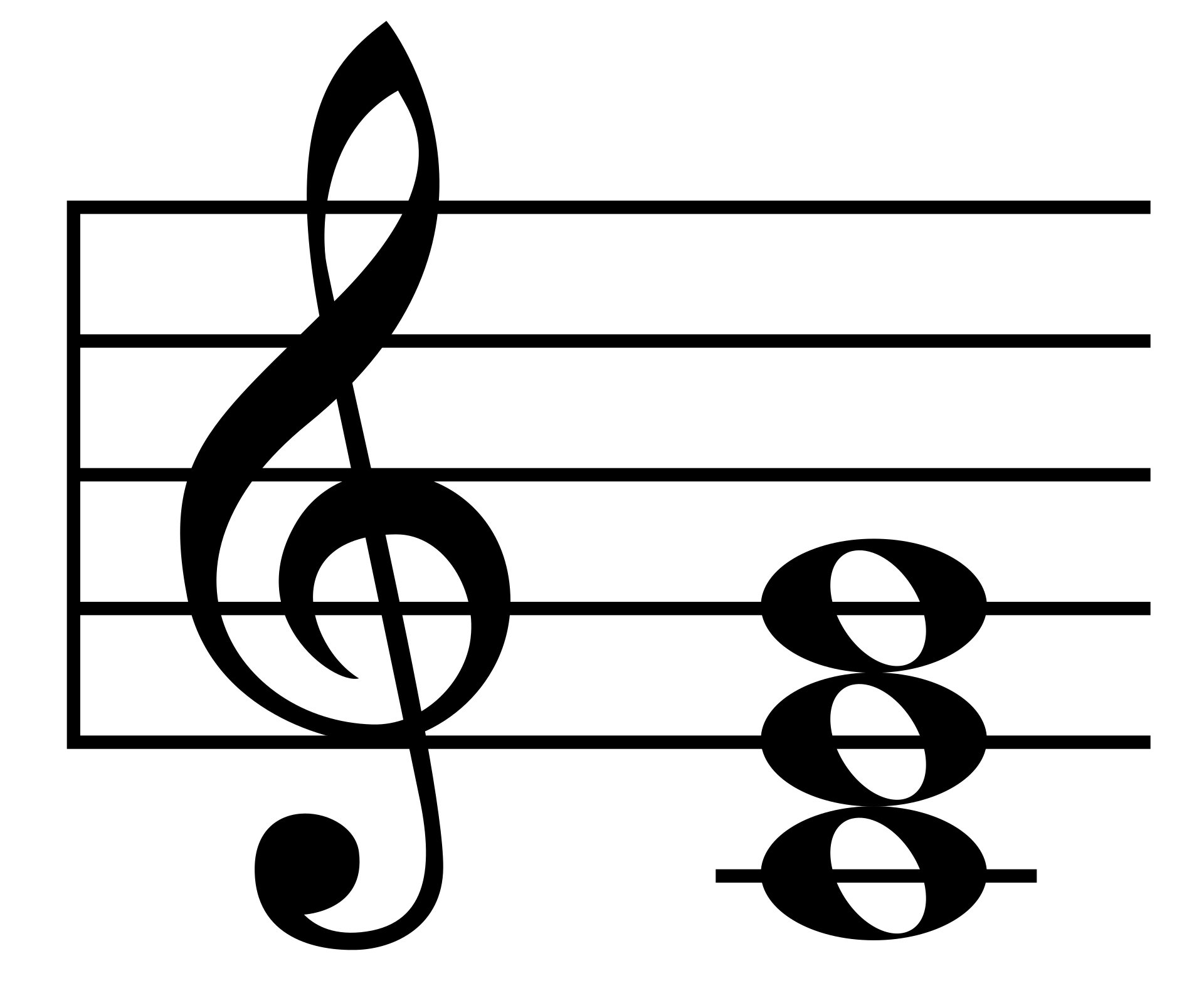

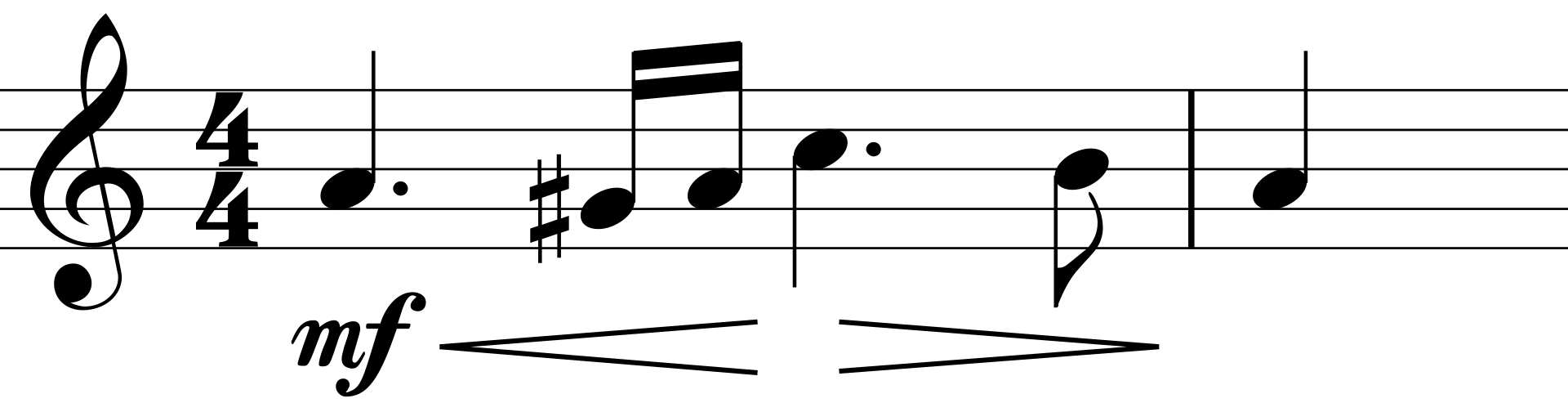

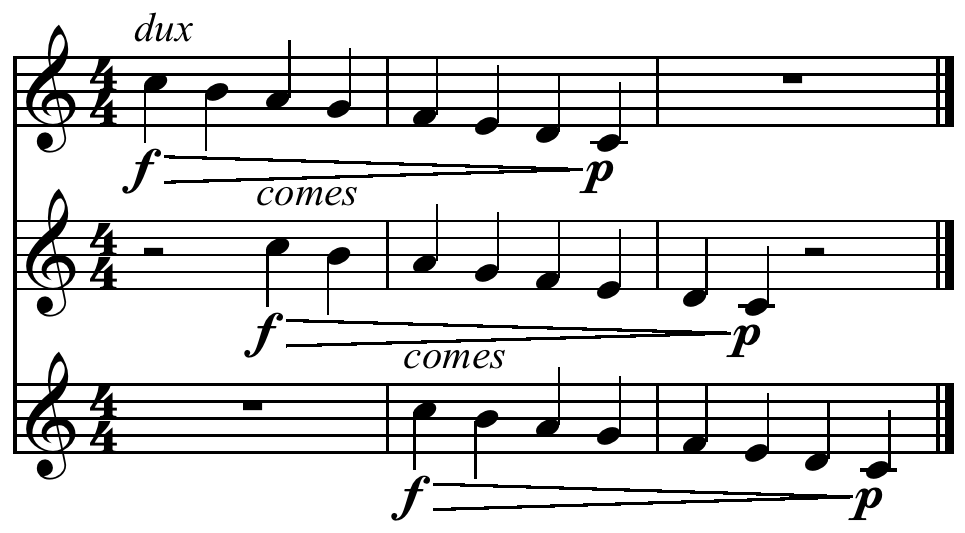

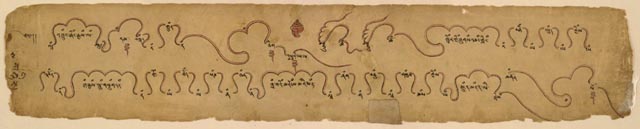

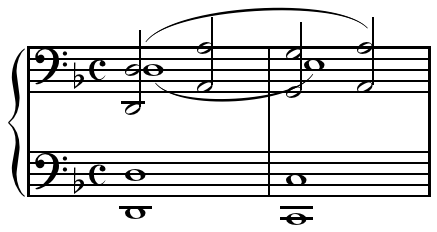

| Fundamentals of music Main article: Aspect of music Music is composed of aural phenomena; "music theory" considers how those phenomena apply in music. Music theory considers melody, rhythm, counterpoint, harmony, form, tonal systems, scales, tuning, intervals, consonance, dissonance, durational proportions, the acoustics of pitch systems, composition, performance, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation, electronic sound production, etc.[25] Pitch Main article: Pitch (music) Middle C (261.626 Hz) Duration: 0 seconds.0:00 Pitch is the lowness or highness of a tone, for example the difference between middle C and a higher C. The frequency of the sound waves producing a pitch can be measured precisely, but the perception of pitch is more complex because single notes from natural sources are usually a complex mix of many frequencies. Accordingly, theorists often describe pitch as a subjective sensation rather than an objective measurement of sound.[26] Specific frequencies are often assigned letter names. Today most orchestras assign concert A (the A above middle C on the piano) to the frequency of 440 Hz. This assignment is somewhat arbitrary; for example, in 1859 France, the same A was tuned to 435 Hz. Such differences can have a noticeable effect on the timbre of instruments and other phenomena. Thus, in historically informed performance of older music, tuning is often set to match the tuning used in the period when it was written. Additionally, many cultures do not attempt to standardize pitch, often considering that it should be allowed to vary depending on genre, style, mood, etc. The difference in pitch between two notes is called an interval. The most basic interval is the unison, which is simply two notes of the same pitch. The octave interval is two pitches that are either double or half the frequency of one another. The unique characteristics of octaves gave rise to the concept of pitch class: pitches of the same letter name that occur in different octaves may be grouped into a single "class" by ignoring the difference in octave. For example, a high C and a low C are members of the same pitch class—the class that contains all C's. [27] Musical tuning systems, or temperaments, determine the precise size of intervals. Tuning systems vary widely within and between world cultures. In Western culture, there have long been several competing tuning systems, all with different qualities. Internationally, the system known as equal temperament is most commonly used today because it is considered the most satisfactory compromise that allows instruments of fixed tuning (e.g. the piano) to sound acceptably in tune in all keys. Scales and modes Main articles: Musical scale and Musical mode  A pattern of whole and half steps in the Ionian mode or major scale on C Duration: 0 seconds.0:00 Notes can be arranged in a variety of scales and modes. Western music theory generally divides the octave into a series of twelve pitches, called a chromatic scale, within which the interval between adjacent tones is called a semitone, or half step. Selecting tones from this set of 12 and arranging them in patterns of semitones and whole tones creates other scales.[28] The most commonly encountered scales are the seven-toned major, the harmonic minor, the melodic minor, and the natural minor. Other examples of scales are the octatonic scale and the pentatonic or five-tone scale, which is common in folk music and blues. Non-Western cultures often use scales that do not correspond with an equally divided twelve-tone division of the octave. For example, classical Ottoman, Persian, Indian and Arabic musical systems often make use of multiples of quarter tones (half the size of a semitone, as the name indicates), for instance in 'neutral' seconds (three quarter tones) or 'neutral' thirds (seven quarter tones)—they do not normally use the quarter tone itself as a direct interval.[28] In traditional Western notation, the scale used for a composition is usually indicated by a key signature at the beginning to designate the pitches that make up that scale. As the music progresses, the pitches used may change and introduce a different scale. Music can be transposed from one scale to another for various purposes, often to accommodate the range of a vocalist. Such transposition raises or lowers the overall pitch range, but preserves the intervallic relationships of the original scale. For example, transposition from the key of C major to D major raises all pitches of the scale of C major equally by a whole tone. Since the interval relationships remain unchanged, transposition may be unnoticed by a listener, however other qualities may change noticeably because transposition changes the relationship of the overall pitch range compared to the range of the instruments or voices that perform the music. This often affects the music's overall sound, as well as having technical implications for the performers.[29] The interrelationship of the keys most commonly used in Western tonal music is conveniently shown by the circle of fifths. Unique key signatures are also sometimes devised for a particular composition. During the Baroque period, emotional associations with specific keys, known as the doctrine of the affections, were an important topic in music theory, but the unique tonal colorings of keys that gave rise to that doctrine were largely erased with the adoption of equal temperament. However, many musicians continue to feel that certain keys are more appropriate to certain emotions than others. Indian classical music theory continues to strongly associate keys with emotional states, times of day, and other extra-musical concepts and notably, does not employ equal temperament. Consonance and dissonance  Main article: Consonance and dissonance A consonance Perfect octave, a consonant interval Duration: 7 seconds.0:07 A dissonance Minor second, a dissonant interval Duration: 0 seconds.0:00 Consonance and dissonance are subjective qualities of the sonority of intervals that vary widely in different cultures and over the ages. Consonance (or concord) is the quality of an interval or chord that seems stable and complete in itself. Dissonance (or discord) is the opposite in that it feels incomplete and "wants to" resolve to a consonant interval. Dissonant intervals seem to clash. Consonant intervals seem to sound comfortable together. Commonly, perfect fourths, fifths, and octaves and all major and minor thirds and sixths are considered consonant. All others are dissonant to a greater or lesser degree.[30] Context and many other aspects can affect apparent dissonance and consonance. For example, in a Debussy prelude, a major second may sound stable and consonant, while the same interval may sound dissonant in a Bach fugue. In the Common practice era, the perfect fourth is considered dissonant when not supported by a lower third or fifth. Since the early 20th century, Arnold Schoenberg's concept of "emancipated" dissonance, in which traditionally dissonant intervals can be treated as "higher," more remote consonances, has become more widely accepted.[30] Rhythm Main article: Rhythm  Metric levels: beat level shown in middle with division levels above and multiple levels below Rhythm is produced by the sequential arrangement of sounds and silences in time. Meter measures music in regular pulse groupings, called measures or bars. The time signature or meter signature specifies how many beats are in a measure, and which value of written note is counted or felt as a single beat. Through increased stress, or variations in duration or articulation, particular tones may be accented. There are conventions in most musical traditions for regular and hierarchical accentuation of beats to reinforce a given meter. Syncopated rhythms contradict those conventions by accenting unexpected parts of the beat.[31] Playing simultaneous rhythms in more than one time signature is called polyrhythm.[32] In recent years, rhythm and meter have become an important area of research among music scholars. The most highly cited of these recent scholars are Maury Yeston,[33] Fred Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff,[34] Jonathan Kramer,[35] and Justin London.[36] Melody Main article: Melody "Pop Goes the Weasel" melody[37] Duration: 12 seconds.0:12 A melody is a group of musical sounds in agreeable succession or arrangement.[38] Because melody is such a prominent aspect in so much music, its construction and other qualities are a primary interest of music theory. The basic elements of melody are pitch, duration, rhythm, and tempo. The tones of a melody are usually drawn from pitch systems such as scales or modes. Melody may consist, to increasing degree, of the figure, motive, semi-phrase, antecedent and consequent phrase, and period or sentence. The period may be considered the complete melody, however some examples combine two periods, or use other combinations of constituents to create larger form melodies.[39] Chord Main article: Chord (music)  C major triad represented in staff notation. Playⓘ in just intonation Playⓘ in Equal temperament Playⓘ in 1/4-comma meantone Playⓘ in Young temperament Playⓘ in Pythagorean tuning A chord, in music, is any harmonic set of three or more notes that is heard as if sounding simultaneously.[40]: pp. 67, 359 [41]: p. 63 These need not actually be played together: arpeggios and broken chords may, for many practical and theoretical purposes, constitute chords. Chords and sequences of chords are frequently used in modern Western, West African,[42] and Oceanian[43] music, whereas they are absent from the music of many other parts of the world.[44]: p. 15 The most frequently encountered chords are triads, so called because they consist of three distinct notes: further notes may be added to give seventh chords, extended chords, or added tone chords. The most common chords are the major and minor triads and then the augmented and diminished triads. The descriptions major, minor, augmented, and diminished are sometimes referred to collectively as chordal quality. Chords are also commonly classed by their root note—so, for instance, the chord C major may be described as a triad of major quality built on the note C. Chords may also be classified by inversion, the order in which the notes are stacked. A series of chords is called a chord progression. Although any chord may in principle be followed by any other chord, certain patterns of chords have been accepted as establishing key in common-practice harmony. To describe this, chords are numbered, using Roman numerals (upward from the key-note),[45] per their diatonic function. Common ways of notating or representing chords[46] in western music other than conventional staff notation include Roman numerals, figured bass (much used in the Baroque era), chord letters (sometimes used in modern musicology), and various systems of chord charts typically found in the lead sheets used in popular music to lay out the sequence of chords so that the musician may play accompaniment chords or improvise a solo. Harmony Main article: Harmony  Barbershop quartets, such as this US Navy group, sing 4-part pieces, made up of a melody line (normally the second-highest voice, called the "lead") and 3 harmony parts. In music, harmony is the use of simultaneous pitches (tones, notes), or chords.[44]: p. 15 The study of harmony involves chords and their construction and chord progressions and the principles of connection that govern them.[47] Harmony is often said to refer to the "vertical" aspect of music, as distinguished from melodic line, or the "horizontal" aspect.[48] Counterpoint, which refers to the interweaving of melodic lines, and polyphony, which refers to the relationship of separate independent voices, is thus sometimes distinguished from harmony.[49] In popular and jazz harmony, chords are named by their root plus various terms and characters indicating their qualities. For example, a lead sheet may indicate chords such as C major, D minor, and G dominant seventh. In many types of music, notably Baroque, Romantic, modern, and jazz, chords are often augmented with "tensions". A tension is an additional chord member that creates a relatively dissonant interval in relation to the bass. It is part of a chord, but is not one of the chord tones (1 3 5 7). Typically, in the classical common practice period a dissonant chord (chord with tension) "resolves" to a consonant chord. Harmonization usually sounds pleasant to the ear when there is a balance between the consonant and dissonant sounds. In simple words, that occurs when there is a balance between "tense" and "relaxed" moments.[50][unreliable source?] Timbre Main article: Timbre  Spectrogram of the first second of an E9 chord played on a Fender Stratocaster guitar with noiseless pickups. Below is the E9 chord audio: Duration: 13 seconds.0:13 Timbre, sometimes called "color", or "tone color," is the principal phenomenon that allows us to distinguish one instrument from another when both play at the same pitch and volume, a quality of a voice or instrument often described in terms like bright, dull, shrill, etc. It is of considerable interest in music theory, especially because it is one component of music that has as yet, no standardized nomenclature. It has been called "... the psychoacoustician's multidimensional waste-basket category for everything that cannot be labeled pitch or loudness,"[51] but can be accurately described and analyzed by Fourier analysis and other methods[52] because it results from the combination of all sound frequencies, attack and release envelopes, and other qualities that a tone comprises. Timbre is principally determined by two things: (1) the relative balance of overtones produced by a given instrument due its construction (e.g. shape, material), and (2) the envelope of the sound (including changes in the overtone structure over time). Timbre varies widely between different instruments, voices, and to lesser degree, between instruments of the same type due to variations in their construction, and significantly, the performer's technique. The timbre of most instruments can be changed by employing different techniques while playing. For example, the timbre of a trumpet changes when a mute is inserted into the bell, the player changes their embouchure, or volume.[citation needed] A voice can change its timbre by the way the performer manipulates their vocal apparatus, (e.g. the shape of the vocal cavity or mouth). Musical notation frequently specifies alteration in timbre by changes in sounding technique, volume, accent, and other means. These are indicated variously by symbolic and verbal instruction. For example, the word dolce (sweetly) indicates a non-specific, but commonly understood soft and "sweet" timbre. Sul tasto instructs a string player to bow near or over the fingerboard to produce a less brilliant sound. Cuivre instructs a brass player to produce a forced and stridently brassy sound. Accent symbols like marcato (^) and dynamic indications (pp) can also indicate changes in timbre.[53] Dynamics This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Main article: Dynamics (music)  Illustration of hairpins in musical notation In music, "dynamics" normally refers to variations of intensity or volume, as may be measured by physicists and audio engineers in decibels or phons. In music notation, however, dynamics are not treated as absolute values, but as relative ones. Because they are usually measured subjectively, there are factors besides amplitude that affect the performance or perception of intensity, such as timbre, vibrato, and articulation. The conventional indications of dynamics are abbreviations for Italian words like forte (f) for loud and piano (p) for soft. These two basic notations are modified by indications including mezzo piano (mp) for moderately soft (literally "half soft") and mezzo forte (mf) for moderately loud, sforzando or sforzato (sfz) for a surging or "pushed" attack, or fortepiano (fp) for a loud attack with a sudden decrease to a soft level. The full span of these markings usually range from a nearly inaudible pianissississimo (pppp) to a loud-as-possible fortissississimo (ffff). Greater extremes of pppppp and fffff and nuances such as p+ or più piano are sometimes found. Other systems of indicating volume are also used in both notation and analysis: dB (decibels), numerical scales, colored or different sized notes, words in languages other than Italian, and symbols such as those for progressively increasing volume (crescendo) or decreasing volume (diminuendo or decrescendo), often called "hairpins" when indicated with diverging or converging lines as shown in the graphic above. Articulation This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Main article: Articulation (music)  Examples of articulation marks. From left to right: staccato, staccatissimo, martellato, accent, tenuto. Articulation is the way the performer sounds notes. For example, staccato is the shortening of duration compared to the written note value, legato performs the notes in a smoothly joined sequence with no separation. Articulation is often described rather than quantified, therefore there is room to interpret how to execute precisely each articulation. For example, staccato is often referred to as "separated" or "detached" rather than having a defined or numbered amount by which to reduce the notated duration. Violin players use a variety of techniques to perform different qualities of staccato. The manner in which a performer decides to execute a given articulation is usually based on the context of the piece or phrase, but many articulation symbols and verbal instructions depend on the instrument and musical period (e.g. viol, wind; classical, baroque; etc.). There is a set of articulations that most instruments and voices perform in common. They are—from long to short: legato (smooth, connected); tenuto (pressed or played to full notated duration); marcato (accented and detached); staccato ("separated", "detached"); martelé (heavily accented or "hammered").[contradictory] Many of these can be combined to create certain "in-between" articulations. For example, portato is the combination of tenuto and staccato. Some instruments have unique methods by which to produce sounds, such as spiccato for bowed strings, where the bow bounces off the string. Texture Main article: Musical texture  Introduction to Sousa's "Washington Post March," mm. 1–7 features octave doubling [54] and a homorhythmic texture Duration: 0 seconds.0:00 In music, texture is how the melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic materials are combined in a composition, thus determining the overall quality of the sound in a piece. Texture is often described in regard to the density, or thickness, and range, or width, between lowest and highest pitches, in relative terms as well as more specifically distinguished according to the number of voices, or parts, and the relationship between these voices. For example, a thick texture contains many "layers" of instruments. One of these layers could be a string section, or another brass. The thickness also is affected by the number and the richness of the instruments playing the piece. The thickness varies from light to thick. A lightly textured piece will have light, sparse scoring. A thickly or heavily textured piece will be scored for many instruments. A piece's texture may be affected by the number and character of parts playing at once, the timbre of the instruments or voices playing these parts and the harmony, tempo, and rhythms used.[55] The types categorized by number and relationship of parts are analyzed and determined through the labeling of primary textural elements: primary melody, secondary melody, parallel supporting melody, static support, harmonic support, rhythmic support, and harmonic and rhythmic support.[56][incomplete short citation] Common types included monophonic texture (a single melodic voice, such as a piece for solo soprano or solo flute), biphonic texture (two melodic voices, such as a duo for bassoon and flute in which the bassoon plays a drone note and the flute plays the melody), polyphonic texture and homophonic texture (chords accompanying a melody).[citation needed] Form or structure  A musical canon. Encyclopaedia Britannica calls a "canon" both a compositional technique and a musical form.[57] Main article: Musical form The term musical form (or musical architecture) refers to the overall structure or plan of a piece of music, and it describes the layout of a composition as divided into sections.[58] In the tenth edition of The Oxford Companion to Music, Percy Scholes defines musical form as "a series of strategies designed to find a successful mean between the opposite extremes of unrelieved repetition and unrelieved alteration."[59] According to Richard Middleton, musical form is "the shape or structure of the work." He describes it through difference: the distance moved from a repeat; the latter being the smallest difference. Difference is quantitative and qualitative: how far, and of what type, different. In many cases, form depends on statement and restatement, unity and variety, and contrast and connection.[60] Expression Main article: Musical expression  A violinist performing Musical expression is the art of playing or singing music with emotional communication. The elements of music that comprise expression include dynamic indications, such as forte or piano, phrasing, differing qualities of timbre and articulation, color, intensity, energy and excitement. All of these devices can be incorporated by the performer. A performer aims to elicit responses of sympathetic feeling in the audience, and to excite, calm or otherwise sway the audience's physical and emotional responses. Musical expression is sometimes thought to be produced by a combination of other parameters, and sometimes described as a transcendent quality that is more than the sum of measurable quantities such as pitch or duration. Expression on instruments can be closely related to the role of the breath in singing, and the voice's natural ability to express feelings, sentiment and deep emotions.[clarification needed] Whether these can somehow be categorized is perhaps the realm of academics, who view expression as an element of musical performance that embodies a consistently recognizable emotion, ideally causing a sympathetic emotional response in its listeners.[61] The emotional content of musical expression is distinct from the emotional content of specific sounds (e.g., a startlingly-loud 'bang') and of learned associations (e.g., a national anthem), but can rarely be completely separated from its context.[citation needed] The components of musical expression continue to be the subject of extensive and unresolved dispute.[62][63][64][65][66][67] Notation Main articles: Musical notation and Sheet music  Tibetan musical score from the 19th century Musical notation is the written or symbolized representation of music. This is most often achieved by the use of commonly understood graphic symbols and written verbal instructions and their abbreviations. There are many systems of music notation from different cultures and different ages. Traditional Western notation evolved during the Middle Ages and remains an area of experimentation and innovation.[68] In the 2000s, computer file formats have become important as well.[69] Spoken language and hand signs are also used to symbolically represent music, primarily in teaching. In standard Western music notation, tones are represented graphically by symbols (notes) placed on a staff or staves, the vertical axis corresponding to pitch and the horizontal axis corresponding to time. Note head shapes, stems, flags, ties and dots are used to indicate duration. Additional symbols indicate keys, dynamics, accents, rests, etc. Verbal instructions from the conductor are often used to indicate tempo, technique, and other aspects. In Western music, a range of different music notation systems are used. In Western Classical music, conductors use printed scores that show all of the instruments' parts and orchestra members read parts with their musical lines written out. In popular styles of music, much less of the music may be notated. A rock band may go into a recording session with just a handwritten chord chart indicating the song's chord progression using chord names (e.g., C major, D minor, G7, etc.). All of the chord voicings, rhythms and accompaniment figures are improvised by the band members. |

音楽の基礎 主な記事 音楽の側面 音楽は聴覚的な現象から構成されている。音楽理論では、旋律、リズム、対位法、和声、形式、調性、音階、調律、音程、協和、不協和音、持続時間の比率、音 高システムの音響学、作曲、演奏、管弦楽法、装飾法、即興演奏、電子音響制作などを考察する[25]。 音程 主な記事 ピッチ(音楽) ミドルC (261.626 Hz) 演奏時間 0秒0:00 ピッチとは音色の低さまたは高さのことで、例えばミドルCと高音Cの差のことである。ピッチを生み出す音波の周波数は正確に測定できるが、自然音源からの 単一音は通常多くの周波数が複雑に混ざり合っているため、ピッチの知覚はより複雑である。したがって、理論家はしばしば音程を音の客観的な測定ではなく、 主観的な感覚として表現する[26]。 特定の周波数には、しばしば文字の名前が付けられます。今日、ほとんどのオーケストラは、コンサートA(ピアノのミドルCの上のA)を440Hzの周波数 に割り当てている。例えば、1859年のフランスでは、同じAが435Hzにチューニングされていた。このような違いは、楽器の音色やその他の現象に顕著 な影響を与える。そのため、古い音楽を歴史的な情報に基づき演奏する場合、チューニングはしばしば、その音楽が書かれた時代に使われていたチューニングに 合わせて設定されます。さらに、多くの文化では音程を標準化しようとせず、ジャンルやスタイル、気分などによって変化することを許容すべきだと考えること が多い。 2つの音符の音程差は音程と呼ばれます。最も基本的な音程はユニゾンで、これは単に同じ音程の2つの音です。オクターブ音程は、2倍または半分の周波数を 持つ2つの音程である。オクターブのユニークな特徴から、ピッチ・クラスという概念が生まれました。異なるオクターブに出現する同じ文字名の音程は、オク ターブの違いを無視して、ひとつの「クラス」にグループ化されることがあります。例えば、高いCと低いCは同じピッチ・クラス(すべてのCを含むクラス) のメンバーです。[27] 音楽の調律システム、または音律は、音程の正確な大きさを決定します。チューニング・システムは、世界の文化の中でも文化の間でも大きく異なります。西洋 文化では、長い間、いくつかのチューニング・システムが競合しており、そのすべてが異なる性質を持つ。国際的には、等音律として知られるシステムが今日最 も一般的に使用されています。これは、固定調律の楽器(例えばピアノ)が、すべての調性において許容範囲内で調律された音を出すことを可能にする、最も満 足のいく妥協点と考えられているからです。 音階とモード 主な記事 音階とモード  イオニアン・モードにおける全音階と半音階のパターン。 演奏時間 0秒0:00 音符は様々な音階やモードにアレンジすることができる。西洋の音楽理論では、一般的にオクターブを半音階と呼ばれる12の音に分割し、その中で隣り合う音 の間隔を半音または半音階と呼びます。この12のセットから音を選び、半音と全音のパターンに並べることで、他の音階が作られる[28]。 最もよく使われるスケールは、7音のメジャー、ハーモニック・マイナー、メロディック・マイナー、ナチュラル・マイナーです。その他の音階の例としては、 オクタトニックスケール、ペンタトニックまたは5音音階があり、これらは民族音楽やブルースでよく使われる。非西洋文化圏では、オクターブを等分した12 音に対応しない音階を使うことが多い。例えば、古典的なオスマン、ペルシャ、インド、アラビアの音楽システムでは、「ニュートラル」セカンド(3つの4分 音符)や「ニュートラル」サード(7つの4分音符)など、4分音符の倍数(名前が示すように半音の半分の大きさ)を使うことが多く、通常、4分音符そのも のを直接的な音程として使うことはありません[28]。 伝統的な西洋の記譜法では、作曲に使用される音階は通常、その音階を構成する音程を指定するための調号によって最初に示されます。音楽が進むにつれて、使 用されるピッチが変わり、異なるスケールが導入されることがある。音楽は様々な目的のために、ある音階から別の音階に移調することができ、多くの場合、声 楽家の音域に合わせるために移調されます。このような移調は、全体の音域を上げたり下げたりしますが、元の音階の音間関係は維持します。例えば、ハ長調か らニ長調に移調すると、ハ長調の音階のすべての音程が等しく全音上がります。音程関係は変わらないので、移調は聴き手には気づかれないかもしれませんが、 移調によって、音楽を演奏する楽器や声楽の音域と比較して、全体的な音域の関係が変わるため、他の性質が顕著に変化することがあります。このことはしばし ば音楽全体の響きに影響を与えるだけでなく、演奏家にとっても技術的な意味を持つ[29]。 西洋の調性音楽で最も一般的に使用される調の相互関係は、五度圏によって簡便に示されている。また、特定の作曲のために独自の調号が考案されることもあ る。バロック時代には、情念の教義として知られる特定の調に対する感情的な連想が音楽理論の重要なトピックであったが、その教義を生み出した調の独特な音 色は、平均律の採用によってほとんど消えてしまった。しかし、多くの音楽家は、特定の調が他の調よりも特定の感情に適していると感じ続けている。インド古 典音楽理論では、キーと感情の状態、時間帯、その他の音楽外の概念を強く関連付け続けており、特に平均律は採用していない。 共振と不協和音  主な記事 子音と不協和音 子音 完全オクターブ、協和音程 演奏時間 7秒0:07 不協和音 短二度、不協和音の音程 演奏時間 0秒.0:00 コンソナンス(和声)とディスコナンス(不協和音)は、異なる文化や時代によって大きく異なる音程の主観的な性質である。共振(または和音)とは、それ自 体が安定し、完全であるように見える音程や和音の質のことです。不協和音(ディスコード)とはその逆で、不完全で、子音的な音程に「解決したい」と感じる ものです。不協和音はぶつかり合うように聞こえる。子音の音程は、一緒にいると心地よく聞こえる。一般的に、完全四度、五度、オクターブ、すべての長三 度、短三度、六度は子音とみなされます。それ以外は大なり小なり不協和音である[30]。 文脈や他の多くの側面が、見かけ上の不協和音や子音に影響を与えることがある。例えば、ドビュッシーの前奏曲では、長2が安定した子音に聞こえるかもしれ ないが、バッハのフーガでは同じ音程が不協和音に聞こえるかもしれない。一般的な練習曲の時代には、完全4番は下位の3番や5番によってサポートされてい ない場合、不協和音とみなされます。20世紀初頭以降、アーノルド・シェーンベルクの「解放された」不協和音という概念が広く受け入れられるようになっ た。 リズム 主な記事 リズム  メトリック・レベル:真ん中にビート・レベル、その上に分割レベル、その下に複数のレベル リズムは、時間内の音と沈黙の連続的な配置によって生み出される。メートル法は、小節または小節と呼ばれる規則的な脈拍のまとまりで音楽を測定する。拍子 記号や拍子記号は、1小節にいくつの拍があるか、どの音価の書かれた音を1拍と数えるかを指定します。 強弱をつけたり、持続時間やアーティキュレーションを変化させたりすることで、特定の音色にアクセントをつけることができます。ほとんどの音楽の伝統に は、与えられた音律を強化するために、規則的かつ階層的に拍を強調する慣例があります。シンコペーション・リズムは、拍の予期せぬ部分にアクセントをつけ ることで、そのような慣例に反している[31]。2つ以上の拍子記号で同時にリズムを演奏することは、ポリリズムと呼ばれる[32]。 近年、リズムとメーターは音楽学者の間で重要な研究分野となっている。これらの最近の学者の中で最も引用が多いのは、モーリー・イェストン、[33]フ レッド・レルダールとレイ・ジャッケンドフ、[34]ジョナサン・クレイマー、[35]ジャスティン・ロンドンである[36]。 メロディ 主な記事 メロディ "Pop Goes the Weasel "のメロディ[37]。 演奏時間 12秒0:12 メロディは多くの音楽において非常に重要な要素であるため、その構成やその他の性質は音楽理論の主要な関心事である。 メロディの基本的な要素は、音程、持続時間、リズム、テンポである。旋律の音は通常、音階やモードなどの音程体系から引き出されます。旋律は、数字、動 機、半音階、先行詞と後続詞、そしてピリオド(文)で構成されます。ピリオドは完全な旋律と見なされることもあるが、2つのピリオドを組み合わせたり、他 の構成要素の組み合わせを使ってより大きな形式の旋律を作る例もある[39]。 和音 主な記事 和音 (音楽)  五線譜で表されたハ長調の三和音。 ジャスト・イントネーションでのプレイⓘ。 平均律で弾くⓘ. 1/4コンマ平均律で弾くⓘ. ヤング音律で演奏ⓘする ピタゴラス音律で ⓘ 弾く 和音(わおん)とは、音楽において、同時に鳴っているように聴こえる3つ以上の音の和声的な集合のことである[40]: pp.67, 359 [41]: p.63 これらは実際に一緒に演奏される必要はない。和音と和音列は、現代の西洋音楽、西アフリカ音楽[42]、オセアニア音楽[43]で頻繁に使用されている が、世界の他の多くの地域の音楽では使用されていない[44]。 最も頻繁に遭遇する和音は三和音であり、3つの異なる音から構成されていることからそう呼ばれている。最も一般的な和音は、長三和音と短三和音、そして補 三和音と減三和音です。メジャー、マイナー、オーギュメンテッド、ディミニッシュという表現は、和音質と総称されることもあります。また、和音は一般的に 根音によって分類されます。例えば、Cメジャーという和音は、C音を基音とする長調のトライアドと表現されます。 一連のコードはコード進行と呼ばれます。どの和音にも原則として他の和音が続くことができますが、一般的なハーモニーでは、特定のパターンの和音がキーを 確立するものとして受け入れられています。これを説明するために、和音はダイアトニックの機能ごとにローマ数字(キー・ノートから上方)を使って番号付け されます[45]。従来の五線譜以外の西洋音楽におけるコードの一般的な表記法[46]には、ローマ数字、フィギュアド・バス(バロック時代に多く用いら れた)、コード・レター(現代音楽学で用いられることもある)、ポピュラー音楽のリード・シートによく見られるコード・チャートの様々なシステムがあり、 ミュージシャンが伴奏コードを演奏したり、ソロを即興で演奏したりできるようにコードの順序を並べている。 ハーモニー 主な記事 ハーモニー  この米海軍のグループのようなバーバーショップ・カルテットは、メロディー・ライン(通常は「リード」と呼ばれる2番目に高い声)と3つのハーモニー・ パートからなる4部構成の曲を歌う。 音楽においてハーモニーとは、同時に音程(トーン、音符)、または和音を使用することである[44]。 [和声はしばしば音楽の「垂直」な側面を指すと言われ、旋律線、すなわち「水平」な側面とは区別される[48]。旋律線の織り成しを指す対位法や、別々の 独立した声部の関係を指すポリフォニーは、このように和声と区別されることがある[49]。 ポピュラー和声やジャズ和声では、和音はそのルートとその性質を示す様々な用語や文字によって命名される。例えば、リードシートにはCメジャー、Dマイ ナー、Gドミナントセブンスなどのコードが記載されている。多くのタイプの音楽、特にバロック、ロマン派、モダン、ジャズでは、コードはしばしば「テン ション」で補強されます。テンションとは、ベースに対して比較的不協和な音程を作り出す、追加のコードメンバーのことです。和音の一部ではあるが、和音 (1 3 5 7)のひとつではない。通常、クラシックの一般的な練習期間では、不協和音(緊張を伴う和音)は子音和音に「解決」される。和声は通常、子音と不協和音の バランスがとれているときに耳に心地よく響く。簡単に言えば、それは「緊張」と「弛緩」のバランスがとれているときに起こります[50][信頼できない ソース?] 音色 主な記事 音色  ノイズレス・ピックアップを搭載したフェンダー・ストラトキャスター・ギターで演奏されたE9コードの最初の1秒のスペクトログラム。以下はE9コードの 音声: 再生時間: 13秒0:13 音色は「カラー」、「トーン・カラー」と呼ばれることもあり、ある楽器が同じ音程と音量で演奏されたときに、その楽器を他の楽器と区別するための主要な現 象です。この現象は音楽理論において非常に興味深いものであり、特に音楽の構成要素のひとつでありながら、まだ標準化された命名法がないためです。音色 は、音の周波数、アタック・エンベロープとリリース・エンベロープ、および音色が構成するその他の特性の組み合わせから生じるため、「...ピッチやラウ ドネスとラベル付けすることができないすべてのもののための、音響心理学者の多次元的なゴミ箱カテゴリー」[51]と呼ばれていますが、フーリエ解析やそ の他の方法[52]によって正確に記述および分析することができます。 音色は、主に次の2つによって決まります:(1)楽器の構造(形状や材質など)に起因する、与えられた楽器によって生成される倍音の相対的なバランス、 (2)音の包絡線(時間経過による倍音構造の変化を含む)。音色は楽器や声楽によって大きく異なりますが、同じ種類の楽器でも、その構造や演奏者のテク ニックによって大きく異なります。ほとんどの楽器の音色は、演奏中に異なるテクニックを用いることで変えることができます。例えば、トランペットの音色 は、ミュートをベルに挿入したり、奏者がアンブシュアを変えたり、音量を変えたりすることで変化する[要出典]。 声楽は、演奏者が発声器官(声腔や口の形など)をどのように操作するかによって音色を変えることができます。楽譜には、発音技法、音量、アクセントなどの 変化による音色の変化が頻繁に記されています。これらは記号や言葉による指示によって様々に示される。例えば、dolce(甘く)という単語は、具体的で はないが、一般的に理解されている柔らかく「甘い」音色を示す。Sul tasto(スル・タスト)は、弦楽器奏者に対して、指板の近くや指板の上で弓を引くように指示し、輝きの少ない音を出すように指示する。Cuivre は、金管楽器奏者に対して、強引で力強くブラッシーな音を出すように指示する。マルカート(^)やダイナミック指示(pp)のようなアクセント記号も音色 の変化を示すことがある[53]。 ダイナミクス このセクションには引用元がありません。信頼できるソースの引用を追加して、このセクションの改善にご協力ください。ソースのないものは、異議を唱えら れ、削除されることがあります。(2015年7月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 主な記事 ダイナミクス(音楽)  楽譜におけるヘアピンの図 音楽において「ダイナミクス」は通常、物理学者やオーディオエンジニアがデシベルやフォンで測定するような強度や音量の変化を指します。しかし楽譜では、 ダイナミクスは絶対値としてではなく、相対値として扱われます。ダイナミクスは通常主観的に測定されるため、演奏や強弱の知覚に影響を与える要素は振幅以 外にもあり、例えば音色、ビブラート、アーティキュレーションなどがあります。 従来のダイナミクスの表記は、大音量を表すf(フォルテ)や小音量を表すp(ピアノ)といったイタリア語の略語でした。この2つの基本的な表記は、中程度 の柔らかさ(文字通り「半分の柔らかさ」)を表すメゾ・ピアノ(mp)や中程度の大きさを表すメゾ・フォルテ(mf)、波打つようなアタックや「押され る」アタックを表すスフォルツァンド(sforzando)またはスフォルツァート(sforzato)(sfz)、大きなアタックと突然の柔らかさへの 減少を表すフォルテピアノ(fortepiano)(fp)などの表記によって変更されます。これらの記号は通常、ほとんど聞こえないピアニッシッシッシ モ(ppppp)から、可能な限り大きなフォルテッシッシッシモ(ffff)まで、全範囲に及びます。 pppppとffffffの両極端や、p+やpiù pianoのようなニュアンスが見られることもある。音量を示す他のシステムとしては、dB(デシベル)、数値スケール、色付き音符や異なる大きさの音 符、イタリア語以外の言語の単語、徐々に音量を上げる(クレッシェンド)または音量を下げる(ディミヌエンドまたはデクレッシェンド)記号などがあり、上 の図のように発散または収束する線で示される場合は、しばしば「ヘアピン」と呼ばれます。 アーティキュレーション このセクションは、出典を引用していません。信頼できるソースの引用を追加して、このセクションの改善にご協力ください。ソースのないものは、異議申し立 てがなされ、削除されることがあります。(2015年7月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 主な記事 アーティキュレーション(音楽)  アーティキュレーション記号の例。左からスタッカート、スタッカティッシモ、マルテラート、アクセント、テヌート。 アーティキュレーションとは、演奏者が音を鳴らす方法のこと。例えば、スタッカートは書かれた音価に比べて音符の長さが短くなること、レガートは音符が分 離することなく滑らかに連続すること。アーティキュレーションは数値化されるのではなく、記述されることが多いため、それぞれのアーティキュレーションを どのように正確に実行するかを解釈する余地がある。 例えば、スタッカートは、表記された持続時間を短縮するための定義や数値があるのではなく、「分離」や「離鍵」と呼ばれることが多い。ヴァイオリン奏者 は、さまざまな質のスタッカートを演奏するために、さまざまなテクニックを使います。演奏者がどのようなアーティキュレーションを使用するかは、通常、曲 やフレーズの文脈に基づいて決定されますが、多くのアーティキュレーション記号や言語による指示は、楽器や音楽時代(例:ヴァイオリン、管楽器、古典派、 バロック派など)によって異なります。 ほとんどの楽器や声楽に共通するアーティキュレーションがあります。長いものから短いものまで、レガート(滑らかな、つながった)、テヌート(押された、 または譜面どおりの長さで演奏された)、マルカート(アクセントのついた、離された)、スタッカート(「離された」、「離された」)、マルテレ(激しいア クセントのついた、または「打たれた」)です。例えば、ポルタートはテヌートとスタッカートの組み合わせである。楽器によっては、弓を使った弦楽器のス ピッカートなど、弓が弦に当たって跳ね返るような独特の音の出し方をするものもある。 テクスチャー 主な記事 音楽の質感  スーザの「ワシントン・ポスト・マーチ」の序奏、mm. 1-7ではオクターヴの倍音[54]とホモリズムのテクスチュアが特徴的である。 演奏時間 0秒0:00 音楽においてテクスチャーとは、旋律、リズム、和声の素材が作曲の中でどのように組み合わされているかということであり、それによって曲の全体的な響きの 質が決まります。テクスチュアはしばしば、最低音と最高音の間の密度(厚み)、音域(幅)に関して相対的に説明されるほか、声部(パート)の数とこれらの 声部間の関係によってより具体的に区別されます。例えば、厚みのあるテクスチャーは、多くの楽器の "層 "を含んでいる。これらの層の1つは弦楽器セクションかもしれないし、別の金管楽器かもしれない。 厚みもまた、その曲を演奏する楽器の数と豊かさに影響される。厚みは軽いものから厚いものまで様々です。軽いテクスチャーの曲は、軽く、まばらなスコアリ ングが施される。テクスチャーの厚い曲は、多くの楽器のために採譜されます。曲のテクスチュアは、一度に演奏されるパートの数と性格、これらのパートを演 奏する楽器や声部の音色、使用される和声、テンポ、リズムによって影響を受けることがある[55]。パートの数と関係によって分類されるタイプは、主要な テクスチュアの要素である主旋律、副旋律、旋律を支える並列旋律、静的な支え、和声的な支え、リズム的な支え、和声とリズムの支えというラベリングを通し て分析され、決定される[56][不完全な短い引用]。 一般的なタイプとしては、モノフォニック・テクスチュア(独唱ソプラノや独奏フルートのための曲のような単一の旋律声部)、バイフォニック・テクスチュア (ファゴットとフルートのためのデュオで、ファゴットがドローン音を、フルートが旋律を演奏するような2つの旋律声部)、ポリフォニック・テクスチュア、 ホモフォニック・テクスチュア(旋律を伴う和音)がある[要出典]。 形式または構造  音楽のカノン。ブリタニカ百科事典は「カノン」を作曲技法と音楽形式の両方と呼んでいる[57]。 主な記事 音楽形式 音楽形式(または音楽建築)という用語は、楽曲の全体的な構造または計画を指し、セクションに分割された楽曲のレイアウトを表す[58]。 パーシー・ショールズは『オックスフォード・コンパニオン・トゥ・ミュージック』第10版で、音楽形式を「緩和されない反復と緩和されない変化という正反 対の両極端の間に成功した平均を見出すためにデザインされた一連の戦略」と定義している[59]。彼はそれを、繰り返しから移動した距離である「差」に よって表現している。差異とは量的なものであり、また質的なものでもある。多くの場合、形式は陳述と再陳述、統一と多様性、対照と接続によって決まる [60]。 表現 主な記事 音楽表現  演奏するヴァイオリニスト 音楽表現とは、音楽を演奏したり歌ったりする際に、感情的なコミュニケーションを図ることである。表現を構成する音楽の要素には、フォルテやピアノなどの 動的指示、フレージング、音色やアーティキュレーションの質の違い、色彩、強弱、エネルギー、興奮などがある。演奏者は、これらの要素をすべて取り入れる ことができる。演奏家は、聴衆の共感を呼び起こし、聴衆の身体的・感情的反応を興奮させたり、落ち着かせたり、あるいは揺さぶったりすることを目的として いる。音楽表現は、他のパラメーターの組み合わせによって生み出されると考えられることもあり、音程や持続時間といった測定可能な量の総和を超える超越的 な質として表現されることもある。 楽器における表現は、歌唱における息の役割や、感情、情感、深い情動を表現する声の自然な能力と密接に関連することがある[clarification needed]。これらを何らかの形で分類できるかどうかは、おそらく学者の領域であり、彼らは表現を、一貫して認識可能な情動を体現し、理想的には聴き 手に共感的な情動反応を引き起こす、音楽演奏の要素と見なしている[61]。音楽表現の情動的内容は、特定の音(例えば、 音楽表現の感情的内容は、特定の音(例えば、驚くほど大きな「バン」という音)や学習された連想(例えば、国歌)の感情的内容とは異なるが、その文脈から 完全に切り離されることはほとんどない[要出典]。 音楽表現の構成要素は、広範かつ未解決の論争の対象であり続けている[62][63][64][65][66][67]。 記譜法 主な記事 楽譜と楽譜  19世紀のチベット楽譜 楽譜とは、音楽を文字や記号で表したものである。一般的に理解されている図形記号や、言葉による指示やその略語を使用することで実現されることが多い。楽 譜には、さまざまな文化や時代から多くのシステムがあります。伝統的な西洋の記譜法は中世に発展し、今でも実験と革新の分野である[68]。2000年代 には、コンピュータのファイル形式も重要になってきた[69]。 標準的な西洋音楽の記譜法では、音は五線譜や五線譜の上に置かれた記号(音符)によって図式化され、縦軸が音高、横軸が時間に対応する。音符の頭の形、ス テム、フラッグ、タイ、ドットは、持続時間を示すために使われます。その他の記号は、調、強弱、アクセント、休符などを表します。指揮者の口頭指示は、テ ンポや奏法などを示すのによく使われます。 西洋音楽では、さまざまな記譜法が使われています。西洋クラシック音楽では、指揮者はすべての楽器のパートが書かれた印刷された楽譜を使い、オーケストラ のメンバーは譜面に書かれたパート譜を読みます。ポピュラー音楽のスタイルでは、楽譜に記譜される部分はもっと少ないかもしれない。ロックバンドは、コー ドネーム(Cメジャー、Dマイナー、G7など)で曲のコード進行を示した手書きのコード表だけを持ってレコーディングに臨むこともある。コード・ヴォイシ ング、リズム、伴奏の数字はすべてバンド・メンバーが即興で作る。 |

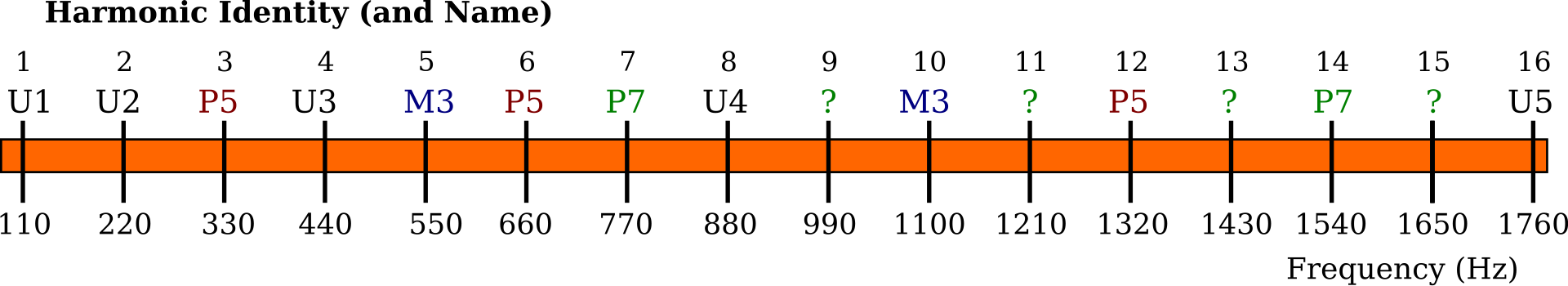

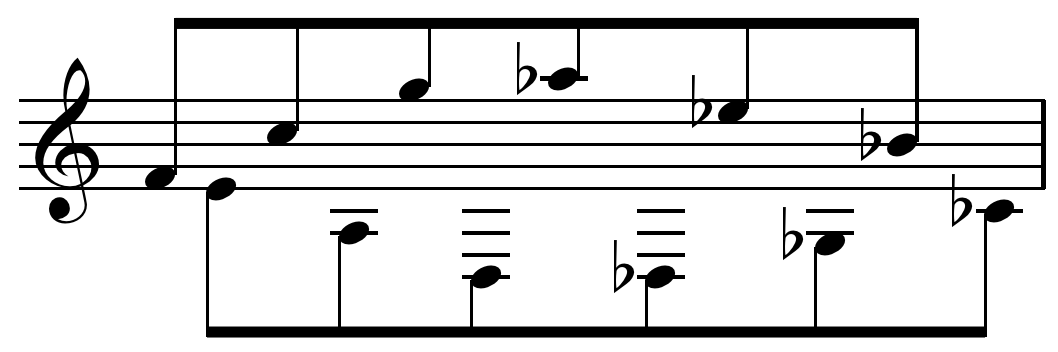

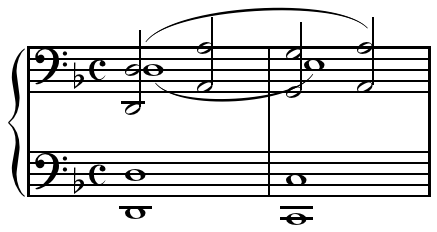

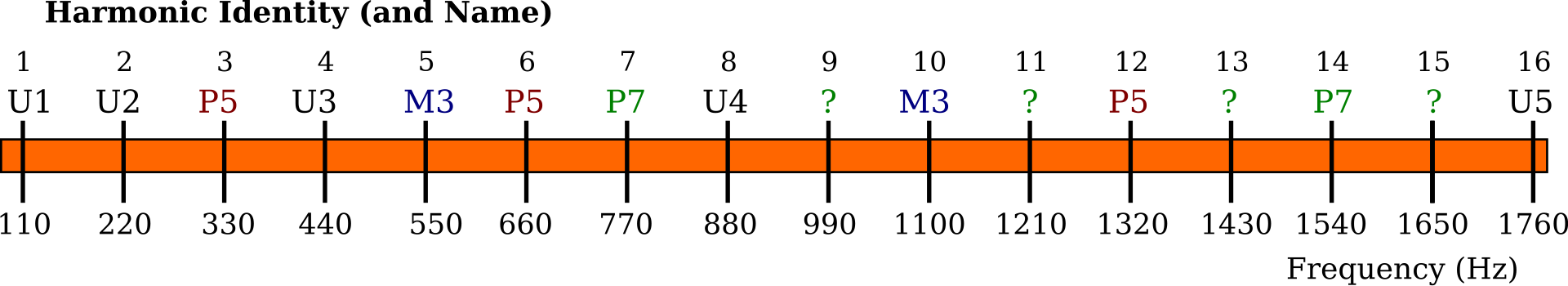

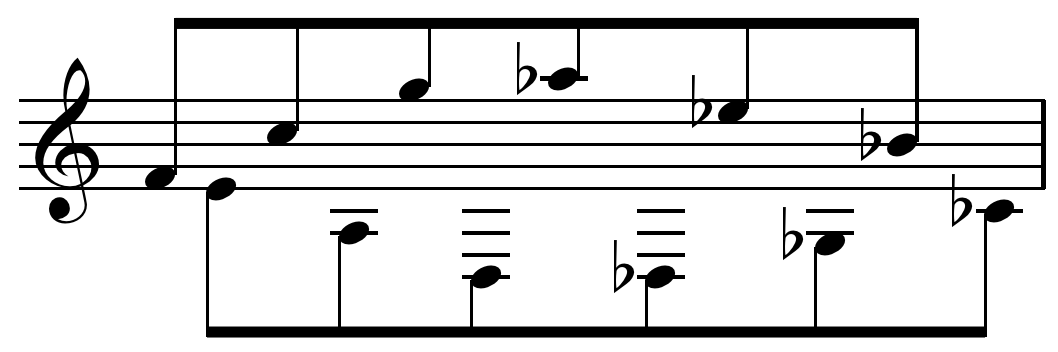

| As academic discipline The scholarly study of music theory in the twentieth century has a number of different subfields, each of which takes a different perspective on what are the primary phenomenon of interest and the most useful methods for investigation. Analysis Main articles: Musical analysis, Schenkerian analysis, and Transformational theory  Typically a given work is analyzed by more than one person and different or divergent analyses are created. For instance, the first two bars of the prelude to Claude Debussy's Pelléas et Melisande are analyzed differently by Leibowitz, Laloy, van Appledorn, and Christ. Leibowitz analyses this succession harmonically as D minor:I–VII–V, ignoring melodic motion, Laloy analyses the succession as D:I–V, seeing the G in the second measure as an ornament, and both van Appledorn and Christ analyse the succession as D:I–VII. Playⓘ Musical analysis is the attempt to answer the question how does this music work? The method employed to answer this question, and indeed exactly what is meant by the question, differs from analyst to analyst, and according to the purpose of the analysis. According to Ian Bent, "analysis, as a pursuit in its own right, came to be established only in the late 19th century; its emergence as an approach and method can be traced back to the 1750s. However, it existed as a scholarly tool, albeit an auxiliary one, from the Middle Ages onwards."[70][incomplete short citation] Adolf Bernhard Marx was influential in formalising concepts about composition and music understanding towards the second half of the 19th century. The principle of analysis has been variously criticized, especially by composers, such as Edgard Varèse's claim that, "to explain by means of [analysis] is to decompose, to mutilate the spirit of a work".[71] Schenkerian analysis is a method of musical analysis of tonal music based on the theories of Heinrich Schenker (1868–1935). The goal of a Schenkerian analysis is to interpret the underlying structure of a tonal work and to help reading the score according to that structure. The theory's basic tenets can be viewed as a way of defining tonality in music. A Schenkerian analysis of a passage of music shows hierarchical relationships among its pitches, and draws conclusions about the structure of the passage from this hierarchy. The analysis makes use of a specialized symbolic form of musical notation that Schenker devised to demonstrate various techniques of elaboration. The most fundamental concept of Schenker's theory of tonality may be that of tonal space.[72] The intervals between the notes of the tonic triad form a tonal space that is filled with passing and neighbour notes, producing new triads and new tonal spaces, open for further elaborations until the surface of the work (the score) is reached. Although Schenker himself usually presents his analyses in the generative direction, starting from the fundamental structure (Ursatz) to reach the score, the practice of Schenkerian analysis more often is reductive, starting from the score and showing how it can be reduced to its fundamental structure. The graph of the Ursatz is arrhythmic, as is a strict-counterpoint cantus firmus exercise.[73] Even at intermediate levels of the reduction, rhythmic notation (open and closed noteheads, beams and flags) shows not rhythm but the hierarchical relationships between the pitch-events. Schenkerian analysis is subjective. There is no mechanical procedure involved and the analysis reflects the musical intuitions of the analyst.[74] The analysis represents a way of hearing (and reading) a piece of music. Transformational theory is a branch of music theory developed by David Lewin in the 1980s, and formally introduced in his 1987 work, Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations. The theory, which models musical transformations as elements of a mathematical group, can be used to analyze both tonal and atonal music. The goal of transformational theory is to change the focus from musical objects—such as the "C major chord" or "G major chord"—to relations between objects. Thus, instead of saying that a C major chord is followed by G major, a transformational theorist might say that the first chord has been "transformed" into the second by the "Dominant operation." (Symbolically, one might write "Dominant(C major) = G major.") While traditional musical set theory focuses on the makeup of musical objects, transformational theory focuses on the intervals or types of musical motion that can occur. According to Lewin's description of this change in emphasis, "[The transformational] attitude does not ask for some observed measure of extension between reified 'points'; rather it asks: 'If I am at s and wish to get to t, what characteristic gesture should I perform in order to arrive there?'"[75] Music perception and cognition Further information: Music psychology, Fred Lerdahl, and Ray Jackendoff Music psychology or the psychology of music may be regarded as a branch of both psychology and musicology. It aims to explain and understand musical behavior and experience, including the processes through which music is perceived, created, responded to, and incorporated into everyday life.[76][77] Modern music psychology is primarily empirical; its knowledge tends to advance on the basis of interpretations of data collected by systematic observation of and interaction with human participants. Music psychology is a field of research with practical relevance for many areas, including music performance, composition, education, criticism, and therapy, as well as investigations of human aptitude, skill, intelligence, creativity, and social behavior. Music psychology can shed light on non-psychological aspects of musicology and musical practice. For example, it contributes to music theory through investigations of the perception and computational modelling of musical structures such as melody, harmony, tonality, rhythm, meter, and form. Research in music history can benefit from systematic study of the history of musical syntax, or from psychological analyses of composers and compositions in relation to perceptual, affective, and social responses to their music. Genre and technique Main articles: Music genre and Musical technique  A Classical piano trio is a group that plays chamber music, including sonatas. The term "piano trio" also refers to works composed for such a group. A music genre is a conventional category that identifies some pieces of music as belonging to a shared tradition or set of conventions.[78] It is to be distinguished from musical form and musical style, although in practice these terms are sometimes used interchangeably.[79][failed verification] Music can be divided into different genres in many different ways. The artistic nature of music means that these classifications are often subjective and controversial, and some genres may overlap. There are even varying academic definitions of the term genre itself. In his book Form in Tonal Music, Douglass M. Green distinguishes between genre and form. He lists madrigal, motet, canzona, ricercar, and dance as examples of genres from the Renaissance period. To further clarify the meaning of genre, Green writes, "Beethoven's Op. 61 and Mendelssohn's Op. 64 are identical in genre—both are violin concertos—but different in form. However, Mozart's Rondo for Piano, K. 511, and the Agnus Dei from his Mass, K. 317 are quite different in genre but happen to be similar in form."[80] Some, like Peter van der Merwe, treat the terms genre and style as the same, saying that genre should be defined as pieces of music that came from the same style or "basic musical language."[81] Others, such as Allan F. Moore, state that genre and style are two separate terms, and that secondary characteristics such as subject matter can also differentiate between genres.[82] A music genre or subgenre may also be defined by the musical techniques, the style, the cultural context, and the content and spirit of the themes. Geographical origin is sometimes used to identify a music genre, though a single geographical category will often include a wide variety of subgenres. Timothy Laurie argues that "since the early 1980s, genre has graduated from being a subset of popular music studies to being an almost ubiquitous framework for constituting and evaluating musical research objects".[83] Musical technique is the ability of instrumental and vocal musicians to exert optimal control of their instruments or vocal cords to produce precise musical effects. Improving technique generally entails practicing exercises that improve muscular sensitivity and agility. To improve technique, musicians often practice fundamental patterns of notes such as the natural, minor, major, and chromatic scales, minor and major triads, dominant and diminished sevenths, formula patterns and arpeggios. For example, triads and sevenths teach how to play chords with accuracy and speed. Scales teach how to move quickly and gracefully from one note to another (usually by step). Arpeggios teach how to play broken chords over larger intervals. Many of these components of music are found in compositions, for example, a scale is a very common element of classical and romantic era compositions.[citation needed] Heinrich Schenker argued that musical technique's "most striking and distinctive characteristic" is repetition.[84] Works known as études (meaning "study") are also frequently used for the improvement of technique. Mathematics Main article: Music and mathematics Music theorists sometimes use mathematics to understand music, and although music has no axiomatic foundation in modern mathematics, mathematics is "the basis of sound" and sound itself "in its musical aspects... exhibits a remarkable array of number properties", simply because nature itself "is amazingly mathematical".[85] The attempt to structure and communicate new ways of composing and hearing music has led to musical applications of set theory, abstract algebra and number theory. Some composers have incorporated the golden ratio and Fibonacci numbers into their work.[86][87] There is a long history of examining the relationships between music and mathematics. Though ancient Chinese, Egyptians and Mesopotamians are known to have studied the mathematical principles of sound,[88] the Pythagoreans (in particular Philolaus and Archytas)[89] of ancient Greece were the first researchers known to have investigated the expression of musical scales in terms of numerical ratios.  The first 16 harmonics, their names and frequencies, showing the exponential nature of the octave and the simple fractional nature of non-octave harmonics In the modern era, musical set theory uses the language of mathematical set theory in an elementary way to organize musical objects and describe their relationships. To analyze the structure of a piece of (typically atonal) music using musical set theory, one usually starts with a set of tones, which could form motives or chords. By applying simple operations such as transposition and inversion, one can discover deep structures in the music. Operations such as transposition and inversion are called isometries because they preserve the intervals between tones in a set. Expanding on the methods of musical set theory, some theorists have used abstract algebra to analyze music. For example, the pitch classes in an equally tempered octave form an abelian group with 12 elements. It is possible to describe just intonation in terms of a free abelian group.[90] Serial composition and set theory  Tone row from Alban Berg's Lyric Suite, movement I Duration: 0 seconds.0:00 Further information: Serialism, Set theory (music), Arnold Schoenberg, Milton Babbitt, David Lewin, and Allen Forte In music theory, serialism is a method or technique of composition that uses a series of values to manipulate different musical elements. Serialism began primarily with Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, though his contemporaries were also working to establish serialism as one example of post-tonal thinking. Twelve-tone technique orders the twelve notes of the chromatic scale, forming a row or series and providing a unifying basis for a composition's melody, harmony, structural progressions, and variations. Other types of serialism also work with sets, collections of objects, but not necessarily with fixed-order series, and extend the technique to other musical dimensions (often called "parameters"), such as duration, dynamics, and timbre. The idea of serialism is also applied in various ways in the visual arts, design, and architecture[91] "Integral serialism" or "total serialism" is the use of series for aspects such as duration, dynamics, and register as well as pitch. [92] Other terms, used especially in Europe to distinguish post-World War II serial music from twelve-tone music and its American extensions, are "general serialism" and "multiple serialism".[93] Musical set theory provides concepts for categorizing musical objects and describing their relationships. Many of the notions were first elaborated by Howard Hanson (1960) in connection with tonal music, and then mostly developed in connection with atonal music by theorists such as Allen Forte (1973), drawing on the work in twelve-tone theory of Milton Babbitt. The concepts of set theory are very general and can be applied to tonal and atonal styles in any equally tempered tuning system, and to some extent more generally than that.[citation needed] One branch of musical set theory deals with collections (sets and permutations) of pitches and pitch classes (pitch-class set theory), which may be ordered or unordered, and can be related by musical operations such as transposition, inversion, and complementation. The methods of musical set theory are sometimes applied to the analysis of rhythm as well.[citation needed] Musical semiotics Further information: Music semiology and Jean-Jacques Nattiez  Semiotician Roman Jakobson Music semiology (semiotics) is the study of signs as they pertain to music on a variety of levels. Following Roman Jakobson, Kofi Agawu adopts the idea of musical semiosis being introversive or extroversive—that is, musical signs within a text and without.[citation needed] "Topics", or various musical conventions (such as horn calls, dance forms, and styles), have been treated suggestively by Agawu, among others.[citation needed] The notion of gesture is beginning to play a large role in musico-semiotic enquiry.[citation needed] "There are strong arguments that music inhabits a semiological realm which, on both ontogenetic and phylogenetic levels, has developmental priority over verbal language."[94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101][incomplete short citation][clarification needed] Writers on music semiology include Kofi Agawu (on topical theory,[citation needed] Heinrich Schenker,[102][103] Robert Hatten (on topic, gesture)[citation needed], Raymond Monelle (on topic, musical meaning)[citation needed], Jean-Jacques Nattiez (on introversive taxonomic analysis and ethnomusicological applications)[citation needed], Anthony Newcomb (on narrativity)[citation needed], and Eero Tarasti[citation needed]. Roland Barthes, himself a semiotician and skilled amateur pianist, wrote about music in Image-Music-Text,[full citation needed] The Responsibilities of Form,[full citation needed] and Eiffel Tower,[full citation needed] though he did not consider music to be a semiotic system[citation needed]. Signs, meanings in music, happen essentially through the connotations of sounds, and through the social construction, appropriation and amplification of certain meanings associated with these connotations. The work of Philip Tagg (Ten Little Tunes,[full citation needed] Fernando the Flute,[full citation needed] Music's Meanings[full citation needed]) provides one of the most complete and systematic analysis of the relation between musical structures and connotations in western and especially popular, television and film music. The work of Leonard B. Meyer in Style and Music[full citation needed] theorizes the relationship between ideologies and musical structures and the phenomena of style change, and focuses on romanticism as a case study. Education and careers  Columbia University music theorist Pat Carpenter in an undated photo Music theory in the practical sense has been a part of education at conservatories and music schools for centuries, but the status music theory currently has within academic institutions is relatively recent. In the 1970s, few universities had dedicated music theory programs, many music theorists had been trained as composers or historians, and there was a belief among theorists that the teaching of music theory was inadequate and that the subject was not properly recognised as a scholarly discipline in its own right.[104] A growing number of scholars began promoting the idea that music theory should be taught by theorists, rather than composers, performers or music historians.[104] This led to the founding of the Society for Music Theory in the United States in 1977. In Europe, the French Société d'Analyse musicale was founded in 1985. It called the First European Conference of Music Analysis for 1989, which resulted in the foundation of the Société belge d'Analyse musicale in Belgium and the Gruppo analisi e teoria musicale in Italy the same year, the Society for Music Analysis in the UK in 1991, the Vereniging voor Muziektheorie in the Netherlands in 1999 and the Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie in Germany in 2000.[105] They were later followed by the Russian Society for Music Theory in 2013, the Polish Society for Music Analysis in 2015 and the Sociedad de Análisis y Teoría Musical in Spain in 2020, and others are in construction. These societies coordinate the publication of music theory scholarship and support the professional development of music theory researchers. As part of their initial training, music theorists will typically complete a B.Mus or a B.A. in music (or a related field) and in many cases an M.A. in music theory. Some individuals apply directly from a bachelor's degree to a PhD, and in these cases, they may not receive an M.A. In the 2010s, given the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of university graduate programs, some applicants for music theory PhD programs may have academic training both in music and outside of music (e.g., a student may apply with a B.Mus. and a Masters in Music Composition or Philosophy of Music). Most music theorists work as instructors, lecturers or professors in colleges, universities or conservatories. The job market for tenure-track professor positions is very competitive: with an average of around 25 tenure-track positions advertised per year in the past decade, 80–100 PhD graduates are produced each year (according to the Survey of Earned Doctorates) who compete not only with each other for those positions but with job seekers that received PhD's in previous years who are still searching for a tenure-track job. Applicants must hold a completed PhD or the equivalent degree (or expect to receive one within a year of being hired—called an "ABD", for "All But Dissertation" stage) and (for more senior positions) have a strong record of publishing in peer-reviewed journals. Some PhD-holding music theorists are only able to find insecure positions as sessional lecturers. The job tasks of a music theorist are the same as those of a professor in any other humanities discipline: teaching undergraduate and/or graduate classes in this area of specialization and, in many cases some general courses (such as Music appreciation or Introduction to Music Theory), conducting research in this area of expertise, publishing research articles in peer-reviewed journals, authoring book chapters, books or textbooks, traveling to conferences to present papers and learn about research in the field, and, if the program includes a graduate school, supervising M.A. and PhD students and giving them guidance on the preparation of their theses and dissertations. Some music theory professors may take on senior administrative positions in their institution, such as Dean or Chair of the School of Music. |