音楽の起源

The origins of music

☆ 以下の記述は「進化音楽学(Evolutionary musicology)」からのインポートである。この分野における音楽の起源にはつぎの3つの起源仮説がある。1)二足歩行仮説、2)音楽言語仮説、3)音楽進化のAVIDモデル[視聴覚威嚇ディスプレイ仮説]。

| The origins of music See also: Prehistoric music, Music archaeology, and Cognitive neuroscience of music Like the origin of language, the origin of music has been a topic for speculation and debate for centuries. Leading theories include Darwin's theory of partner choice (women choose male partners based on musical displays), the idea that human musical behaviors are primarily based on behaviors of other animals (see zoomusicology), the idea that music emerged because it promotes social cohesion, the idea that music emerged because it helps children acquire verbal, social, and motor skills, and the idea that musical sound and movement patterns, and links between music, religion and spirituality, originated in prenatal psychology and mother-infant attachment. Two major topics for any subfield of evolutionary psychology are the adaptive function (if any) and phylogenetic history of the mechanism or behavior of interest including when music arose in human ancestry and from what ancestral traits it developed. Current debate addresses each of these. One part of the adaptive function question is whether music constitutes an evolutionary adaptation or exaptation (i.e. by-product of evolution). Steven Pinker, in his book How the Mind Works, for example, argues that music is merely "auditory cheesecake"—it was evolutionarily adaptive to have a preference for fat and sugar but cheesecake did not play a role in that selection process. This view has been directly countered by numerous music researchers.[3][4][5] Adaptation, on the other hand, is highlighted in hypotheses such as the one by Edward Hagen and Gregory Bryant which posits that human music evolved from animal territorial signals, eventually becoming a method of signaling a group's social cohesion to other groups for the purposes of making beneficial multi-group alliances.[6][7] |

音楽の起源 こちらも参照: 先史時代の音楽、音楽考古学、音楽の認知神経科学 言語の起源と同様に、音楽の起源も何世紀にもわたって憶測と議論の対象となってきた。代表的な説としては、ダーウィンのパートナー選択説(女性は音楽的表 現に基づいて男性のパートナーを選ぶ)、人間の音楽的行動は主に他の動物の行動に基づいているという考え(zoomusicologyを参照)、音楽は社 会的結束を促進するため生まれたという考え、音楽は子供が言語的、社会的、運動的スキルを習得するのに役立つため生まれたという考え、音楽の音や動きのパ ターン、音楽と宗教やスピリチュアリティの関連性は、出生前の心理学や母子愛着に由来するという考えなどがある。 進化心理学のどのサブフィールドにとっても、2つの主要なトピックは、ヒトの祖先において音楽がいつ発生し、どのような祖先形質から発達したのかなど、関 心のあるメカニズムや行動の適応機能(もしあるとすれば)と系統発生史である。現在の議論は、これらのそれぞれについて取り組んでいる。 適応機能の問題の一つは、音楽が進化的適応なのか、それとも外適応(進化の副産物)なのかということである。例えば、スティーブン・ピンカーはその著書 『How the Mind Works』の中で、音楽は単なる「聴覚的チーズケーキ」であると論じている--脂肪と砂糖を好むことは進化的に適応的であったが、チーズケーキはその淘 汰過程で役割を果たさなかったのだ。この見解には、多くの音楽研究者が真っ向から反論している[3][4][5]。 一方、適応は、エドワード・ハーゲンやグレゴリー・ブライアントによる仮説のように、人間の音楽は動物の縄張り信号から進化し、最終的には有益な複数集団の同盟を結ぶ目的で、集団の社会的結束を他の集団に示す方法になったという仮説で強調されている[6][7]。 |

| The bipedalism hypothesis The evolutionary switch to bipedalism may have influenced the origins of music.[8] The background is that noise of locomotion and ventilation may mask critical auditory information. Human locomotion is likely to produce more predictable sounds than those of non-human primates. Predictable locomotion sounds may have improved our capacity of entrainment to external rhythms and to feel the beat in music. A sense of rhythm could aid the brain in distinguishing among sounds arising from discrete sources and also help individuals to synchronize their movements with one another. Synchronization of group movement may improve perception by providing periods of relative silence and by facilitating auditory processing.[9][10] The adaptive value of such skills to early human ancestors may have been keener detection of prey or stalkers and enhanced communication. Thus, bipedal walking may have influenced the development of entrainment in humans and thereby the evolution of rhythmic abilities. Primitive hominids lived and moved around in small groups. The noise generated by the locomotion of two or more individuals can result in a complicated mix of footsteps, breathing, movements against vegetation, echoes, etc. The ability to perceive differences in pitch, rhythm, and harmonies, i.e. "musicality", could help the brain to distinguish among sounds arising from discrete sources, and also help the individual to synchronize movements with the group. Endurance and an interest in listening might, for the same reasons, have been associated with survival advantages eventually resulting in adaptive selection for rhythmic and musical abilities and reinforcement of such abilities. Listening to music seems to stimulate release of dopamine. Rhythmic group locomotion combined with attentive listening in nature may have resulted in reinforcement through dopamine release. A primarily survival-based behavior may eventually have attained similarities to dance and music, due to such reinforcement mechanisms . Since music may facilitate social cohesion, improve group effort, reduce conflict, facilitate perceptual and motor skill development, and improve trans-generational communication,[11] music-like behavior may at some stage have become incorporated into human culture. Another proposed adaptive function is creating intra-group bonding. In this aspect it has been seen as complementary to language by creating strong positive emotions while not having a specific message people may disagree on. Music's ability to cause entrainment (synchronization of behavior of different organisms by a regular beat) has also been pointed out. A different explanation is that signaling fitness and creativity by the producer or performer to attract mates. Still another is that music may have developed from human mother-infant auditory interactions (motherese) since humans have a very long period of infant and child development, infants can perceive musical features, and some infant-mother auditory interaction have resemblances to music.[12] Part of the problem in the debate is that music, like any complex cognitive function, is not a holistic entity but rather modular[13]—perception and production of rhythm, melodies, harmony and other musical parameters may thus involve multiple cognitive functions with possibly quite distinct evolutionary histories.[14] |

二足歩行仮説 二足歩行への進化的転換が音楽の起源に影響を与えた可能性がある[8]。その背景には、運動や換気の騒音が重要な聴覚情報を覆い隠してしまう可能性がある ことがある。ヒトの運動音は、ヒト以外の霊長類の運動音よりも予測しやすい。予測可能な運動音は、外部のリズムに同調し、音楽のビートを感じる能力を向上 させたかもしれない。リズムの感覚は、脳が別々の音源から発生する音を区別するのを助けるかもしれないし、個体が互いに動きを同期させるのを助けるかもし れない。集団運動の同期化は、相対的な静寂の時間を提供し、聴覚処理を促進することによって知覚を向上させる可能性がある[9][10]。初期の人類の祖 先にとって、このようなスキルの適応的価値は、獲物やストーカーをより早く発見し、コミュニケーションを強化することであったかもしれない。このように、 二足歩行はヒトにおける同調性の発達、ひいてはリズム能力の進化に影響を与えた可能性がある。原始ヒト科動物は小さな集団で生活し、動き回っていた。2人 以上の個体の運動によって発生する騒音は、足音、呼吸、草木にぶつかる動き、反響音などが複雑に混ざり合う。ピッチ、リズム、ハーモニーの違い、すなわち 「音楽性」を知覚する能力は、脳が別々の音源から発生する音を区別するのに役立ち、また個体が集団と動きを同期させるのにも役立つだろう。同じ理由から、 持久力と聴くことへの興味は、やがてリズムや音楽的能力の適応淘汰やそのような能力の強化につながり、生存に有利に働いたのかもしれない。音楽を聴くこと は、ドーパミンの放出を刺激するようだ。リズミカルな集団運動と自然界における注意深い聴き取りが組み合わさることで、ドーパミン放出による強化がもたら されたのかもしれない。主に生存に基づく行動は、このような強化メカニズムによって、やがてダンスや音楽と類似性を獲得したのかもしれない。音楽は社会的 結合を促進し、集団の努力を向上させ、争いを減らし、知覚や運動技能の発達を促し、世代を超えたコミュニケーションを改善する可能性があるため[11]、 音楽に似た行動はある段階で人間の文化に組み込まれたのかもしれない。 もう1つの適応的機能として提案されているのは、集団内の絆をつくることである。この点で、音楽は強い肯定的な感情を生み出す一方で、人々の意見が分かれ るような特定のメッセージを持たず、言語を補完するものと考えられてきた。音楽が同調(規則的なビートによって異なる生物の行動を同期させること)を引き 起こす能力も指摘されている。別の説明では、製作者や演奏者が仲間を引きつけるために、体力や創造性を示すというものもある。さらにもうひとつは、ヒトの 乳幼児期は非常に長く、乳幼児は音楽の特徴を知覚することができ、乳幼児と母親の聴覚的相互作用には音楽に似たものがあることから、音楽はヒトの母親と乳 幼児の聴覚的相互作用(モテレス)から発達したのではないかというものである[12]。 この議論における問題の一つは、音楽が他の複雑な認知機能と同様に、全体的な実体ではなく、むしろモジュール化されているということである[13]-リズ ム、メロディ、ハーモニー、その他の音楽パラメータの知覚と生成は、したがって、おそらくは全く異なる進化の歴史を持つ複数の認知機能に関与している可能 性がある[14]。 |

| The Musilanguage hypothesis "Musilanguage [pdf]" is a term coined by Steven Brown to describe his hypothesis of the ancestral human traits that evolved into language and musical abilities. It is both a model of musical and linguistic evolution and a term coined to describe a certain stage in that evolution. Brown argues that both music and human language have origins in a "musilanguage" stage of evolution and that the structural features shared by music and language are not the results of mere chance parallelism, nor are they a function of one system emerging from the other. This model argues that "music emphasizes sound as emotive meaning and language emphasizes sound as referential meaning."[15] The musilanguage model is a structural model of music evolution, meaning that it views music's acoustic properties as effects of homologous precursor functions. This can be contrasted with functional models of music evolution, which view music's innate physical properties to be determined by its adaptive roles. The musilanguage evolutionary stage is argued to exhibit three properties found in both music and language: lexical tone, combinatorial phrase formation, and expressive phrasing mechanisms. Many of these ideas have their roots in existing phonological theory in linguistics, but Brown argues that phonological theory has largely neglected the strong mechanistic parallels between melody, phrasing, and rhythm in speech and music. Lexical tone refers to the pitch of speech as a vehicle for semantic meaning. The importance of pitch to conveying musical ideas is well-known, but the linguistic importance of pitch is less obvious. Tonal languages such as Thai and Cantonese, wherein the lexical meaning of a sound depends heavily on its pitch relative to other sounds, are seen as evolutionary artifacts of musilanguage. Non-tonal, or "intonation" languages, which do not depend heavily on pitch for lexical meaning, are seen as evolutionary late-comers that have discarded their dependence on tone. Intermediate states, known as pitch accent languages, which exhibit some lexical dependence on tone, but also depend heavily on intonation, are exemplified by Japanese, Swedish, and Serbo-Croatian. Combinatorial formation refers to the ability to form small phrases from different tonal elements. These phrases must be able to exhibit melodic, rhythmic, and semantic variation, and must be able to combine with other phrases to create global melodic formulas capable of conveying emotive meaning. Examples in modern speech would be the rules for arranging letters to form words and then words to form sentences. In music, the notes of different scales are combined according to their own unique rules to form larger musical ideas. Expressive phrasing is the device by which expressive emphasis can be added to the phrases, both at a local (in the sense of individual units) and global (in the sense of phrases) level. There are numerous ways this can occur in both speech and music that exhibit interesting parallels. For instance, the increase in the amplitude of a sound being played by an instrument accents that sound much the same way that an increase in amplitude can emphasize a particular point in speech. Similarly, speaking very rapidly often creates a frenzied effect that mirrors that of a fast and agitated musical passage. |

音楽言語仮説 「ミューシランゲージ(Musilanguage [pdf])」 とは、スティーヴン・ブラウンが言語と音楽能力に進化した人類の祖先形質に関する仮説を説明するために作った造語である。これは音楽と言語の進化のモデル であると同時に、進化のある段階を表す造語でもある。ブラウンは、音楽も人間の言語も進化の「音楽言語」段階に起源を持ち、音楽と言語に共通する構造的特 徴は、単なる偶然の並列性の結果でも、一方のシステムが他方のシステムから生まれた機能でもないと主張している。このモデルは、「音楽は音を感情的な意味 として強調し、言語は音を参照的な意味として強調する」と主張している[15]。音楽言語モデルは音楽進化の構造モデルであり、音楽の音響特性を同種の前 駆体機能の効果とみなすことを意味している。これは、音楽の生得的な物理的特性がその適応的役割によって決定されるとみなす音楽進化の機能モデルと対照的 である。 音楽言語の進化段階は、音楽と言語の両方に見られる3つの特性、すなわち語彙的な音調、組み合わせ的なフレーズ形成、表現的なフレージング機構を示すと主 張されている。これらのアイデアの多くは、言語学における既存の音韻論的理論にルーツがあるが、ブラウンは、音韻論的理論は、音声と音楽におけるメロ ディ、フレージング、リズムの間の強力なメカニズム的類似性をほとんど無視してきたと主張する。 レキシカル・トーンとは、意味的な伝達手段としての音声のピッチのことである。音楽的なアイデアを伝えるための音程の重要性はよく知られているが、言語学 的な音程の重要性はあまり知られていない。タイ語や広東語のような調性言語は、音の語彙的意味が他の音との相対的なピッチに大きく依存するため、音楽言語 の進化的人工物とみなされている。非音調言語、すなわち「イントネーション」言語は、語彙的意味を音高に大きく依存しない言語であり、音高への依存を捨て た進化的後発言語とみなされる。日本語、スウェーデン語、セルボ・クロアチア語などがその例である。 組み合わせ形成とは、異なる調性要素から小さなフレーズを形成する能力のことである。これらのフレーズは、旋律的、リズム的、意味的な変化を示すことがで きなければならず、また、他のフレーズと組み合わせて、感情的な意味を伝えることのできる大域的な旋律公式を作り出すことができなければなりません。現代 の音声における例としては、文字を並べて単語を作り、単語を並べて文章を作るルールがある。音楽では、異なる音階の音符が独自のルールに従って組み合わさ れ、より大きな音楽的アイデアを形成する。 表現力豊かなフレージングとは、局所的(個々の単位という意味)にも全体的(フレーズという意味)にも、フレーズに表現上の強調を加えることができる装置 である。スピーチでも音楽でも、興味深い類似性を示す数多くの方法がある。例えば、楽器が演奏する音の振幅が大きくなると、その音にアクセントがつきます が、これは、振幅が大きくなると、スピーチの特定のポイントが強調されるのと同じことです。同様に、非常に速く話すと、しばしば熱狂的な効果が生まれ、そ れは速く煽動的な音楽のパッセージを反映する。 |

| AVID model of music evolution Joseph Jordania has suggested that music (as well as several other universal elements of contemporary human culture, including dance and body painting) was part of a predator control system used by early hominids. He suggested that rhythmic loud singing and drumming, together with the threatening rhythmic body movements and body painting, was the core element of the ancient "Audio-Visual Intimidating Display" (AVID).[16] AVID was also a key factor in putting the hominid group into a specific altered state of consciousness which he calls "battle trance" where they would not feel fear and pain and would be religiously dedicated to group interests. Jordania suggested that listening and dancing to the sounds of loud rhythmic rock music, used in many contemporary combat units before the combat missions is directly related to this.[17] Apart from the defense from predators, Jordania suggested that this system was the core strategy to obtain food via confrontational, or aggressive scavenging. It is theorized that humming could have played an important role in the early human (hominid) evolution as contact calls. Many social animals produce seemingly haphazard and indistinctive sounds (like chicken cluck) when they are going about their everyday business (foraging, feeding). These sounds have two functions: (1) to let group members know that they are among kin and there is no danger, and (2) in case of the appearance of any signs of danger (suspicious sounds, movements in a forest), the animal that notices danger first, stops moving, stops producing sounds, remains silent and looks in the direction of the danger sign. Other animals quickly follow suit and very soon all the group is silent and is scanning the environment for the possible danger. Charles Darwin was the first to notice this phenomenon, having observed it among wild horses and cattle.[18] Jordania suggested that for humans, as for many social animals, silence can be a sign of danger, and that's why gentle humming and musical sounds relax humans (see the use of gentle music in music therapy, lullabies). |

音楽進化のAVIDモデル ジョセフ・ジョルダニアは、音楽は(ダンスやボディペインティングなど、現代人の文化に普遍的に見られる他のいくつかの要素と同様に)、初期のヒト科動物 が使用していた捕食者制御システムの一部であったと示唆している。彼は、リズミカルな大音量の歌や太鼓が、威嚇的なリズミカルな体の動きやボディペイン ティングとともに、古代の「視聴覚威嚇ディスプレイ」(AVID)の中核要素であったと示唆した[16]。AVIDはまた、ヒト科の集団を、恐怖や痛みを 感じず、集団の利益に宗教的に献身する「戦闘トランス」と彼が呼ぶ特定の変性意識状態にするための重要な要素でもあった。ジョルダニアは、戦闘任務の前に 現代の戦闘部隊の多くで使用されている、大音量でリズミカルなロック・ミュージックを聴いたり踊ったりすることが、これに直接関係していることを示唆した [17]。捕食者からの防衛とは別に、ジョルダニアはこのシステムが、対立的、あるいは攻撃的な漁獲によって食料を得るための中核戦略であったことを示唆 した。 ハミングは、初期の人類(ヒト科)の進化において、コンタクトコールとして重要な役割を果たした可能性があると理論化されている。多くの社会的動物は、日 常の仕事(採食や給餌)をするときに、一見行き当たりばったりで区別のつかない鳴き声(ニワトリの鳴き声のような)を出す。これらの鳴き声には2つの機能 がある:(1)群れのメンバーに、自分たちが親類の中にいて危険がないことを知らせる。(2)危険の兆候(不審な鳴き声、森の中の動き)が現れた場合、最 初に危険に気づいた動物は動きを止め、鳴き声を出すのを止め、黙ったまま危険の兆候の方向を見る。他の動物もすぐにそれに倣い、すぐにすべての群れが沈黙 し、危険の可能性がないか環境をスキャンする。チャールズ・ダーウィンは、野生の馬や牛の間でこの現象を観察し、初めてこの現象に気づいた[18]。ジョ ルダニアは、多くの社会的動物と同様に、人間にとっても静寂は危険の兆候である可能性があり、だからこそ穏やかなハミングや音楽的な音が人間をリラックス させるのだと示唆した(音楽療法における穏やかな音楽の使用、子守唄を参照)。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolutionary_musicology |

Prehistoric music -- 先史時代の音楽

| Prehistoric music

(previously called primitive music) is a term in the history of music

for all music produced in preliterate cultures (prehistory), beginning

somewhere in very late geological history. Prehistoric music is

followed by ancient music in different parts of the world, but still

exists in isolated areas. However, it is more common to refer to the

"prehistoric" music which still survives as folk, indigenous or

traditional music. Prehistoric music is studied alongside other periods

within music archaeology.[citation needed] Findings from Paleolithic archaeology sites suggest that prehistoric people used carving and piercing tools to create instruments. Archeologists have found Paleolithic flutes carved from bones in which lateral holes have been pierced. The disputed Divje Babe flute, a perforated cave bear femur, is at least 40,000 years old. Instruments such as the seven-holed flute and various types of stringed instruments, such as the Ravanahatha, have been recovered from the Indus Valley civilization archaeological sites.[1] India has one of the oldest musical traditions in the world—references to Indian classical music (marga) are found in the Vedas, ancient Hindu scriptures.[2] |

先史時代の音楽(以前は原始音楽と呼ばれていた)とは、文字の発明以前

の文化(先史時代)において、地質学的に非常に古い時代に始まった音楽の総称である。先史時代の音楽は、世界の異なる地域では古代音楽に引き継がれたが、

現在でも孤立した地域では存在している。しかし、現在でも民族音楽、土着音楽、伝統音楽として生き残っている「先史時代の」音楽という表現の方が一般的で

ある。先史時代の音楽は、音楽考古学の他の時代とともに研究されている。 旧石器時代の遺跡から得られた発見は、先史時代の人間が楽器を作るために彫刻や穿孔の道具を使用していたことを示唆している。考古学者は、横穴が穿孔され た骨から作られた旧石器時代のフルートを発見している。論争の的となっているディヴィエ・バーベのフルートは、穴の開いた穴熊の大腿骨であり、少なくとも 4万年前のものである。7孔の笛や、ラヴァナハタなどの弦楽器の数々がインダス文明の遺跡から発見されている。[1] インドには世界最古の音楽の伝統がある。インド古典音楽(マルガ)に関する記述は、ヴェーダという古代ヒンドゥー教の聖典にも見られる。[2] |

| Origins of prehistoric instruments Many languages traditionally have terms for music that include dance, religion, or cult.[citation needed] The context in which prehistoric music took place has also become a subject of study and debate, as the sound made by music in prehistory would have been somewhat different depending on the acoustics present. Some cultures include sound mimesis within their music; often, this feature is related to shamanistic beliefs or practice.[3][4] It may also serve entertainment[5][6] or practical functions, for example in hunting scenarios.[5] It is likely that the first musical instrument was the human voice itself, which can make a vast array of sounds, from singing, humming and whistling through to clicking, coughing and yawning.[7] The oldest known Neanderthal hyoid bone with the modern human form has been dated to be 60,000 years old,[8] predating the oldest known Paleolithic bone flute by some 20,000 years,[9] but the true chronology may date back much further. Theoretically, music may have existed prior to the Paleolithic era. Anthropological and archaeological research suggest that music first arose when stone tools first began to be used by hominins.[citation needed] The noises produced by work, such as pounding seed and roots into a meal, are a likely source of rhythm created by early humans. The first rhythm instruments or percussion instruments most likely involved the clapping of hands, stones hit together, or other things that are useful to create rhythm. There are bone flutes and pipes which are unambiguously paleolithic. Additionally, pierced phalanges (usually interpreted as "phalangeal whistles"), bullroarers, and rasps have also been discovered. The latter musical finds date back as far as the Paleolithic era, although there is some ambiguity over archaeological finds which can be variously interpreted as either musical or non-musical instruments/tools.[10] Another possible origin of music is motherese, the vocal-gestural communication between mothers and infants. This form of communication involves melodic, rhythmic and movement patterns as well as the communication of intention and meaning, and in this sense is similar to music.[11] Geoffrey Miller suggests musical displays play a role in "demonstrating fitness to mate." Based on the ideas of honest signal and the handicap principle, Miller suggested that music and dancing, as energetically costly activities, demonstrated the physical and psychological prowess of the singing and dancing individual.[12] Similarly, communal singing occurs among both sexes in cooperatively breeding songbirds of Australia and Africa, such as magpies[13] and white-browed sparrow-weavers.[14] |

先史時代の楽器の起源 多くの言語には、伝統的に、舞踊、宗教、またはカルトを含む音楽を表す用語がある。[要出典] 先史時代の音楽が演奏された状況も研究と議論の対象となっている。先史時代の音楽が奏でる音は、その当時の音響効果によって多少異なるはずだからだ。一部 の文化では、音楽に音の模倣を取り入れている。この特徴は、しばしばシャーマニズムの信仰や実践と関連している。[3][4] また、娯楽[5][6]や実用的な機能、例えば狩猟の場面などでも役立つことがある。[5] 最初の楽器は人間の声そのものであった可能性が高い。人間の声は、歌ったり、鼻歌を歌ったり、口笛を吹いたり、さらには、カチカチと音を立てたり、咳をし たり、あくびをしたりと、実にさまざまな音を出すことができる。 [7] 現生人類の形をした最古のネアンデルタール人の舌骨は、6万年前のものであることが判明しているが、[8] 現生人類の最古の骨笛は、その2万年前のものであることが判明している。[9] しかし、実際の年代はさらに遡る可能性がある。 理論的には、音楽は旧石器時代以前から存在していた可能性がある。人類学や考古学の研究によると、音楽はヒト属が石器を使い始めたときに初めて生まれたと いう。[要出典] 種子や根を叩いて粉にするといった作業で発生する音は、初期の人類が作り出したリズムの源である可能性が高い。最初の打楽器や打楽器は、おそらく手拍子や 石をぶつけ合うなど、リズムを作り出すのに役立つものであった。骨笛や骨管は、疑いなく旧石器時代の楽器である。さらに、穿孔された指骨(通常「指骨笛」 と解釈される)、牛追い笛、やすりも発見されている。後者の楽器は旧石器時代まで遡るが、考古学的発見には、楽器または非楽器/道具として様々な解釈がで きるものもあり、曖昧な部分もある。 音楽の起源として考えられるもう一つの可能性は、母親と乳児の間の音声による身振りコミュニケーションである「マザーリーズ」である。このコミュニケー ションの形態には、旋律、リズム、動きのパターン、そして意図や意味の伝達が含まれており、この点において音楽と類似している。 ジェフリー・ミラーは、音楽的な表現は「交尾の適性を示す」役割を果たしていると示唆している。正直なシグナルとハンディキャップ原理の考えに基づき、ミ ラーは、音楽やダンスはエネルギーを消費する活動であるため、歌ったり踊ったりする個人の身体的・心理的な能力の高さを示すものだと示唆した。[12] 同様に、オーストラリアやアフリカの鳴禽類では、カササギ[13]や眉白スズメモドキ[14]など、協力して繁殖する鳥類の両性間で集団での歌がみられ る。 |

| Archaeoacoustic methodology This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The field of archaeoacoustics uses acoustic techniques to explore prehistoric sounds, soundscapes, and instruments; it has included the study of ringing rocks and lithophones, of the acoustics of ritual sites such as chamber tombs and stone circles, and the exploration of prehistoric instruments using acoustic testing. Such work has included acoustic field tests to capture and analyze the impulse response of archaeological sites; acoustic tests of lithophones or 'rock gongs'; and reconstructions of soundscapes as experimental archaeology. |

考古音響学の方法論 この節には出典が全く示されていない。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。出典のない項目は、削除される場合があります。 (2021年10月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 考古音響学の分野では、音響技術を用いて先史時代の音、サウンドスケープ、楽器を研究している。これには、鳴り石や石琴、横穴墓や環状列石などの儀式の場 の音響、音響試験を用いた先史時代の楽器の探索の研究が含まれている。このような作業には、考古学遺跡のインパルス応答を捉え分析するための音響フィール ドテスト、リトフォン(岩琴)の音響テスト、実験考古学としてのサウンドスケープの再構成などが含まれている。 |

| Africa Egypt Main article: Music of Egypt In prehistoric Egypt, music and chanting were commonly used in magic and rituals. The ancient Egyptians credited the goddess Bat with the invention of music. The cult of Bat was eventually syncretised into that of Hathor because both were depicted as cows. Hathor's music was believed to have been used by Osiris as part of his effort to civilise the world. The lion-goddess Bastet was also considered a goddess of music. Rhythms during this time were unvaried and music served to create rhythm. Small shells were used as whistles.[15]: 26–30 During the predynastic period of Egyptian history, funerary chants continued to play an important role in Egyptian religion and were accompanied by clappers or a flute. Despite the lack of physical evidence in some cases, Egyptologists theorise that the development of certain instruments known of the Old Kingdom period, such as the end-blown flute, took place during this time.[15]: 33–34 Libya  Entrance of Haua Fteah Excavations in 1969 found a 90-115,000 year old bone flute fragment in the Haua Fteah cave in Libya. It has one manmade punctured hole, which resembles similar bone flutes found in Europe and the Mediterranean. The exact species the bone comes from is unknown, but it seems to have come from a large bird.[16] Southern Africa The peoples of Southern Africa in the South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Zambia region used bone, clay, and metal for creating instruments, as idiophones and aerophones were the two types of instruments that were made. Spinning disks, bone tubes, and a bullroarer were found in the Southern and Western Capes of South Africa that date back from 2525±85 BP - 1732 AD. There were also many more bone tubes found in the Matjes River which may have been used for flutes, trumpets, whistles, bells, and mbira keys.[17] Numerous mbira keys were found in Zimbabwe that date back to 210±90 BP - Later Iron Age.[17] |

アフリカ エジプト 詳細は「エジプトの音楽」を参照 先史時代のエジプトでは、音楽や詠唱は呪術や儀式で一般的に用いられていた。古代エジプト人は、音楽の発明をバト神の功績であると考えていた。バト神の信 仰は、両者が牛として描かれていたことから、最終的にはハトホル神の信仰と融合した。ハトホル神の音楽は、オシリスが世界を文明化する努力の一環として用 いられたと考えられていた。獅子の女神バステトも音楽の女神と考えられていた。この時代の音楽のリズムは変化に乏しく、音楽はリズムを生み出すために用い られた。小さな貝殻が笛として用いられた。[15]: 26–30 エジプトの歴史における王朝以前の時代には、葬祭の歌はエジプトの宗教において重要な役割を果たし続け、拍子木や笛が伴奏として用いられた。物的証拠が欠 如しているケースもあるが、エジプト学者は、古王国時代に知られるようになった特定の楽器、例えば、吹き口を口にくわえて吹く笛などの発展は、この時代に 起こったと推測している。[15]: 33–34 リビア  ハワ・フテアの入り口 1969年の発掘調査で、リビアのハウア・フテア洞窟から9万~11万5千年前の骨製のフルートの断片が発見された。 穴が1つ開けられており、ヨーロッパや地中海で発見された同様の骨製フルートに似ている。 骨の正確な種は不明だが、大型の鳥の骨である可能性が高い。 南部アフリカ 南アフリカ、ジンバブエ、ザンビア地域に住む南アフリカの人々は、楽器の製作に骨、粘土、金属を使用していた。 回転盤、骨の管、牛追い笛が、紀元前2525年±85年から西暦1732年まで遡る南アフリカの南西ケープで発見されている。また、マティエス川では、フ ルート、トランペット、笛、鐘、ムビラの鍵盤に使用された可能性のある骨製の管が多数発見されている。[17] ジンバブエでは、紀元前210年±90年(後期鉄器時代)にさかのぼるムビラの鍵盤が多数発見されている。[17] |

| Asia China In 1986, several gudi (lit. "bone flutes") were found in Jiahu in Henan Province, China. They date to about 7000 BCE. They have between six and nine holes each and were made from the hollow bones of the red-crowned crane. At the time of discovery, one was found to be still playable. This playable bone flute is capable of using both the five- or seven-note Xia Zhi scale and the six-note Qing Shang scale of the ancient Chinese musical system.[18] India India has the oldest musical traditions in the world. References to Indian classical music (marga) are found in the Vedas, ancient scriptures of the Hindu tradition.[2] Instruments such as the seven-holed flute and various types of stringed instruments have been recovered from the Indus Valley Civilisation archaeological sites.[19] Palestine  The 7 bone flutes found in Eynan-Mallaha The peoples of Israel had prehistoric bones that were specifically aerophones. Several of these bones were excavated at Eynan-Mallaha and date back to 10,730 and 9760 cal BC. Smaller bird bones were preferred to bigger ones due to the difference in sound, although they are more difficult to play as a result of their size.[20] The pitch of the tone the flutes produce are believed to mimic the call of several birds. It is likely that the flute was used for music and dance rather than hunting, since it is limited by the small range of birds imitated. It is common for birds to be used as an inspiration for music such as the Sun Dance of the Plains Indians in which dancers used whistles to mimic eagles, or the Kaluli people who wore rainforest birds' feathers as ornaments.[20] Vietnam Two deer antlers were discovered in the Go O Chua site of southern Vietnam which were used as stringed instruments, they are dated to be at minimum 2,000 years old. One discovered in 1997, and the other in 2008. The instrument has a single string which was attached on both ends of the antler, with the burr of the antler forming a bridge.[21] The instrument is similar in form to a Đàn brố, or a K'ni. These are the first stringed instruments archaeologically discovered in Vietnam.[21] Several lithophones were also found across the country which would have been laid down on strings with wooden or bamboo frames and struck to make noise.[21] |

アジア 中国 1986年、中国・河南省のジャフで数本の骨笛(文字通り「骨のフルート」)が発見された。それらは紀元前7000年頃のものである。それぞれ6~9個の 穴があり、タンチョウの骨をくりぬいて作られている。発見当時、そのうちの1本はまだ演奏可能な状態であった。この演奏可能な骨笛は、古代中国の音楽シス テムである夏至五音または七音音階と清商六音音階の両方を使用することができる。[18] インド インドは世界最古の音楽の伝統を持つ国である。インド古典音楽(マルガ)に関する言及は、ヒンドゥー教の伝統における古代の聖典であるヴェーダに見られる。[2] 7孔の笛やさまざまな弦楽器などの楽器は、インダス文明の遺跡から発見されている。[19] パレスチナ  エヤナン・マッラで発見された7本の骨笛 イスラエルの人々は、特に気鳴楽器である先史時代の骨を持っていた。これらの骨の一部は、エヤン・マッラーで発掘され、紀元前10,730年から9760 年までさかのぼる。大きな骨よりも小さな鳥の骨が好まれたのは、音の違いによるものだが、そのサイズから演奏はより困難であった。[20] フルートが奏でる音の高さは、いくつかの鳥の鳴き声を模倣したものと考えられている。模倣された鳥の鳴き声の範囲が限られていることから、フルートは狩猟 よりも音楽や舞踊に使用されていた可能性が高い。平原インディアンのサンダンスのように、踊り手がホイッスルでワシの鳴き声を真似るような音楽のインスピ レーションとして鳥が使われることは一般的である。また、熱帯雨林の鳥の羽を装飾品として身につけるカルリ族もいる。[20] ベトナム ベトナム南部のゴ・オ・チュア遺跡で、弦楽器として使われた2つの鹿の角が発見された。その年代は少なくとも2000年前のものである。1997年に発見 されたものと、2008年に発見されたものがある。この楽器は、鹿の角の両端に弦が取り付けられており、角の突起部分がこまとして機能する仕組みになって いる。この楽器は、ベトナムで考古学的に発見された弦楽器としては初めてのものである。 また、木や竹の枠に弦を張り、叩いて音を出す石琴も国内各地で発見されている。[21] |

| Australia Main article: Indigenous music of Australia  Performance of Aboriginal song and dance in the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander music includes the music of Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders. Music has formed an integral part of the social, cultural and ceremonial observances of these people, down through the millennia of their individual and collective histories to the present day, and has existed for 40,000 years.[22][23][24][25] The traditional forms include many aspects of performance and musical instrumentation which are unique to particular regions or Indigenous Australian groups; there are equally elements of musical tradition which are common or widespread through much of the Australian continent, and even beyond. The culture of the Torres Strait Islanders is related to that of adjacent parts of New Guinea and so their music is also related. Music is a vital part of Indigenous Australians' cultural maintenance.[26] Traditional instruments Didgeridoo  Buskers playing didgeridoos at Fremantle Markets, 2009 Main article: Didgeridoo A didgeridoo is a type of musical instrument that, according to western musicological classification, falls into the category of aerophone. It is one of the oldest instruments to date. It consists of a long tube, without finger holes, through which the player blows. It is sometimes fitted with a mouthpiece of beeswax. Didgeridoos are traditionally made of eucalyptus, but contemporary materials such as PVC piping are used. In traditional situations it is played only by men, usually as an accompaniment to ceremonial or recreational singing, or, much more rarely, as a solo instrument. Skilled players use the technique of circular breathing to achieve a continuous sound, and also employ techniques for inducing multiple harmonic resonances. Traditionally the instrument was not widespread around the country, but was only used by Aboriginal groups in the most northerly areas.[citation needed] Clapsticks Main article: Clapstick A clapstick is a type of musical instrument that, according to western musicological classification, falls into the category of percussion. Unlike drumsticks, which are generally used to strike a drum, clapsticks are intended for striking one stick on another, and people as well. They are of oval shape with paintings of snakes, lizards, birds and more. Gum leaf Used as a hand-held free reed instrument. Bullroarer Main article: Bullroarer A bullroarer consists of a weighted airfoil (a rectangular thin slat of wood about 15 cm (6 in) to 60 cm (24 in) long and about 1.25 cm (0.5 in) to 5 cm (2 in) wide) attached to a long cord. Typically, the wood slat is trimmed down to a sharp edge around the edges, and serrations along the length of the wooden slat may or may not be used, depending on the cultural traditions of the region in question. Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article "Bullroarer". The cord is given a slight initial twist, and the roarer is then swung in a large circle in a horizontal plane, or in a smaller circle in a vertical plane. The aerodynamics of the roarer will keep it spinning about its axis even after the initial twist has unwound. The cord winds fully first in one direction and then the other, alternating. It makes a characteristic roaring vibrato sound with notable sound modulations occurring from the rotation of the roarer along its longitudinal axis, and the choice of whether a shorter or longer length of cord is used to spin the bullroarer. By modifying the expansiveness of its circuit and the speed given it, and by changing the plane in which the bullroarer is whirled from horizontal to vertical or vice versa, the modulation of the sound produced can be controlled, making the coding of information possible. Audio/visual demonstration Sound modulation by changing orbital plane. The low-frequency component of the sound travels extremely long distances, clearly audible over many miles on a quiet night. The use of bullroarers has also been documented in ancient Greece, Britain, Ireland, Scandinavia, Mali, New Zealand, and the Americas (see Bullroarer). Banks Island Eskimos were still using bullroarers circa 1963 (59-year-old "Susie" being documented scaring off four polar bears armed with only three seal hooks and vocals.[27] Aleut, Eskimo and Inuit used bullroarers occasionally as a children's toy or musical instruments, but preferred drums and rattles.[28] |

オーストラリア 詳細は「オーストラリアの先住民音楽」を参照  シドニーのオーストラリア国立海洋博物館でのアボリジニの歌と踊りのパフォーマンス オーストラリアのアボリジニとトレス海峡諸島民の音楽は、オーストラリアのアボリジニとトレス海峡諸島民の音楽である。音楽は、これらの人々の社会、文 化、儀式の重要な一部であり、個人および集団の歴史を通じて、現在に至るまで数千年にわたって存在してきた。 [22][23][24][25] 伝統的な形式には、特定の地域やオーストラリア先住民グループに特有のパフォーマンスや楽器演奏の多くの側面が含まれている。また、オーストラリア大陸の 大部分、さらにはその外でも共通または広く普及している音楽の伝統の要素もある。トレス海峡諸島民の文化は、ニューギニアの隣接地域と関連しているため、 彼らの音楽も関連している。音楽は、オーストラリア先住民の文化維持に欠かせない要素である。 伝統楽器 ディジュリドゥ  フリーマントル・マーケットでディジュリドゥを演奏するストリートミュージシャン(2009年) 詳細は「ディジュリドゥ」を参照 ディジュリドゥは、西洋音楽学の分類では気鳴楽器に分類される種類の楽器である。現存する楽器としては最も古いもののひとつである。指孔のない長い管から なり、演奏者はその管を吹く。蜜蝋のマウスピースが取り付けられることもある。伝統的にはユーカリの木から作られてきたが、現代ではポリ塩化ビニル管など の素材も用いられる。伝統的な状況では、男性のみが演奏し、通常は儀式や娯楽の歌の伴奏として、あるいは、はるかにまれにソロ楽器として演奏される。熟練 した奏者は、連続した音を出すために循環呼吸のテクニックを用い、また、複数の倍音共鳴を誘発するテクニックも用いる。伝統的に、この楽器は国内で広く普 及しておらず、最も北部の地域のアボリジニグループのみが使用していた。 拍子木 詳細は「クラップスティック」を参照 クラップスティックは、西洋音楽の分類では打楽器に分類される楽器の一種である。一般的にドラムを叩くために使用されるドラムスティックとは異なり、ク ラップスティックは2本のスティックを打ち合わせたり、人や物を叩いたりするために使用される。楕円形をしており、蛇やトカゲ、鳥などの絵が描かれてい る。 ガムリーフ 手持ちのフリーリード楽器として使用される。 ブルローラー 詳細は「ブルローラー」を参照 ブルローラーは、重りのついた翼形材(長さ15cm(6インチ)から60cm(24インチ)、幅1.25cm(0.5インチ)から5cm(2インチ)の細 長い木片)が長い紐に取り付けられたもの。通常、木製のスラットは周囲が鋭く削られ、また、木製のスラットの長さに沿ってギザギザが付いている場合と付い ていない場合があるが、これは当該地域の文化伝統によって異なる。 ウィキソースには、1911年のブリタニカ百科事典の記事「ブルロアー」のテキストがある。 ロープには最初にわずかな捻りが加えられ、その後、ローラーは水平面で大きな円を描くように、あるいは垂直面で小さな円を描くように振られる。ローラーの 空力特性により、最初の捻りが解けてもローラーは軸を中心に回転し続ける。ロープは、まず一方方向に完全に巻き取られ、その後、もう一方方向に完全に巻き 取られる。 これは、ブルローラーの長さを短くするか長くするか、また、ブルローラーを回転させる際に縦軸に沿ってローラーが回転することによって生じる顕著な音の変 調により、特徴的な轟くようなビブラート音を奏でる。その回路の広がりと与えられる速度を変更し、また、牛の角笛を回す平面を水平から垂直、またはその逆 に変えることで、発生する音の変調を制御でき、情報の符号化が可能になる。 視聴覚デモンストレーション 軌道平面の変更による音の変調。 音の低周波成分は非常に長い距離を伝わり、静かな夜には何マイルも離れた場所でもはっきりと聞こえる。 古代ギリシャ、イギリス、アイルランド、スカンジナビア、マリ、ニュージーランド、南北アメリカ大陸でも、ブルローラーの使用が記録されている(「ブル ローラー」を参照)。1963年頃には、バンクス島のエスキモーがまだブルローラーを使用していた(59歳の「スージー」は、たった3本の銛と声だけで4 頭のホッキョクグマを追い払ったことが記録されている。[27] アリュート族、エスキモー、イヌイットは、ブルローラーを子供のおもちゃや楽器として時折使用していたが、太鼓やガラガラを好んだ。[28] |

| Europe Austria and Hungary Clay bells were found in Austria and Hungary which date to the early neolithic period. One is from the Starčevo site in Gellénháza, Hungary, and the other is from the Brunn site located on the outskirts of Vienna which was excavated in 1999. Unlike modern bells these bells lack a clapper. They were suspended by string and most likely struck with wooden sticks or animal bones.[29] Both bells were recreated and played, but neither were loud enough to be used as instruments, which might be why they were destroyed and thrown away.[29] France A one-of-a-kind Upper Paleolithic era Seashell Horn was discovered in the Marsoulas cave in 1931, which is made of a Charonia lampus shell. Dating back to the early Magdalenian period, it was modified to be played as a wind instrument by blowing air through the mouthpiece located at the apex. There are engravings on the inside of the lip, while unclear what the engravings represent, it is clear that they were intentional.[30] Germany  Aurignacian flute made from a vulture bone, Geissenklösterle (Swabia), which is about 35,000 years old In 2008, archaeologists discovered a bone flute in the Hohle Fels cave near Ulm, Germany.[31][32][33] The five-holed flute has a V-shaped mouthpiece and is made from a vulture wing bone. The researchers involved in the discovery officially published their findings in the journal Nature in June 2009. It is one of several similar instruments found in the area, which date to around 42,000 years ago, making this the oldest confirmed finds of any musical instruments in history.[34] The Hohle Fels flute was found next to the Venus of Hohle Fels and a short distance from the oldest known human carving.[35] On announcing the discovery, scientists suggested that the "finds demonstrate the presence of a well-established musical tradition at the time when modern humans colonized Europe".[31] Scientists have also suggested that the discovery of the flute may help to explain why early humans survived, while Neanderthals became extinct.[34] Greece This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Cycladic statues of a double flute player (foreground) and a harpist (background) Further information: Music of ancient Greece and Cycladic culture On the island of Keros (Κέρος), two marble statues from the late Neolithic culture called Early Cycladic culture (2900–2000 BCE) were discovered together in a single grave in the 19th century. They depict a standing double flute player and a sitting musician playing a triangular-shaped lyre or harp. The harpist is approximately 23 cm (9 in) high and dates to around 2700–2500 BCE. He expresses concentration and intense feelings and tilts his head up to the light. The meaning of these and many other figures is not known; perhaps they were used to ward off evil spirits, had religious significance, served as toys, or depicted figures from mythology. Ireland The oldest known wooden pipes were discovered in Wicklow, Ireland, in the winter of 2003, carbon-dated at around 2167±30 BCE. A wood-lined pit contained a group of six flutes made from yew wood, between 30 and 50 cm (12 and 20 in) long, tapered at one end, but without any finger holes. They may once have been strapped together.[36] Slovakia A clay egg-shaped rattle, bottle-shaped rattles, and pan pipes made of bone were all discovered in Slovakia. They are dated back to 300-800 AD, during the Migration Period. Music culture in Slovakia had not formed until the 9th century while these instruments go back to 4-6th century AD, so while they cannot be connected to Slovak culture they prove that music had existed in this region at that time.[37] They may have been used for ceremonies, rituals, or cults for dancing and singing to ward off evil spirits or call to the gods for help.[37] Slovenia  Divje Babe flute The oldest flute ever discovered may be the so-called Divje Babe flute, found in the Cerkno Hills, Slovenia in 1995, though this is disputed.[38] The item in question is a fragment of the femur of a juvenile cave bear, and has been dated to about 43,000 years ago.[39][40] However, whether it is truly a musical instrument or simply a carnivore-chewed bone is a matter of ongoing debate.[38] In 2012, some flutes that were discovered years earlier in the Geißenklösterle cave received a new high-resolution carbon-dating examination yielding an age of 42,000 to 43,000 years.[41] |

ヨーロッパ オーストリアとハンガリー オーストリアとハンガリーでは、新石器時代初期の粘土製の鐘が発見されている。ひとつはハンガリーのゲレェンハーズァにあるスターチェヴォ遺跡から、もう ひとつは1999年に発掘されたウィーン郊外にあるブルン遺跡から出土している。現代の鐘とは異なり、これらの鐘には舌がなかった。これらは紐で吊るされ ており、おそらく木の棒や動物の骨で叩いていたと考えられている。[29] 両方の鐘は再現され演奏されたが、楽器として使用するには音量が十分ではなく、それが破壊され捨てられた理由かもしれない。[29] フランス 1931年にマルスーラ洞窟で発見された、世界に一つしかない旧石器時代の貝製ホーンは、チャロニア・ランプス貝でできている。マドレーヌ文化の初期にさ かのぼるこの楽器は、先端の吹き口から息を吹き込んで吹く管楽器として改造されていた。唇の内側に彫刻が施されているが、その意味は不明である。しかし、 意図的に施されたものであることは明らかである。 ドイツ  ハゲタカの骨で作られたオーリニャック文化期のフルート(ガイセンクロスターレ、シュヴァーベン、約3万5千年前 2008年、ドイツのウルム近郊のホーレ・フェルス洞窟で、考古学者が骨製のフルートを発見した。[31][32][33] 5つの穴が開けられたフルートはV字型の吹き口があり、ハゲタカの翼の骨から作られている。この発見に関わった研究者は、2009年6月に学術誌『ネイ チャー』に正式に調査結果を発表した。このフルートは、この地域で発見された数点の同様の楽器のうちの1つであり、年代は約4万2千年前と推定されてい る。これは、歴史上確認されている楽器としては最古のものである。ホーレ・フェルスのフルートは、ホーレ・フェルスのヴィーナスの隣で発見され、現存する 最古の人類の彫刻からわずかな距離にあった。 [35] 発見が発表された際、科学者たちは「この発見は、現生人類がヨーロッパに定住した当時、確立された音楽の伝統が存在していたことを示す」と指摘した。 [31] また、科学者たちはフルートの発見が、ネアンデルタール人が絶滅する一方で初期の人類がなぜ生き残ったのかを解明する手掛かりになる可能性を示唆してい る。[34] ギリシャ この節には出典が全く示されていない。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。出典の無い項目は削除されることがあります。 (2017年9月) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  キクラデス文明の二本フルート奏者(手前)とハープ奏者(奥)の像 詳細は「古代ギリシアの音楽」および「キクラデス文明」を参照 ケロス島(Κέρος)では、新石器時代後期の文化である初期キクラデス文化(紀元前2900年~2000年)の2体の大理石像が、19世紀に1つの墓か ら一緒に発見された。 2体の像は、立っているダブルフルート奏者と、座っている三角形の竪琴またはハープを弾く音楽家を表している。ハープ奏者の像は高さ約23cm(9イン チ)で、紀元前2700年から2500年頃のものとされる。集中力と激しい感情を表し、光の方へ頭を傾けている。これらの像やその他の多くの像の意味は不 明である。おそらく、悪霊を追い払うために使われたか、宗教的な意味があったか、おもちゃとして使われたか、あるいは神話の登場人物を描いたものであった か、と考えられている。 アイルランド 2003年の冬、アイルランドのウィックローで発見された最古の木製パイプは、放射性炭素年代測定法により紀元前2167年±30年頃のものであることが 判明した。木で囲まれた穴には、イチイの木でできた6本のフルートが収められていた。長さは30~50cm(12~20インチ)で、片方の先が細くなって おり、指穴はなかった。かつてはこれらが紐で繋がれていた可能性がある。[36] スロバキア 粘土製の卵形のガラガラ、瓶形のガラガラ、骨製のパンパイプがスロバキアで発見されている。これらは紀元300年から800年頃の民族移動時代のものであ る。スロバキアの音楽文化が形成されるのは9世紀になってからであるが、これらの楽器は西暦4世紀から6世紀にまで遡るため、スロバキア文化と直接結びつ けることはできないものの、当時この地域に音楽が存在していたことは証明されている。[37] これらの楽器は、悪霊を追い払ったり、神に助けを求めたりするための儀式や祭礼、あるいは踊りや歌の儀式に使用されていた可能性がある。[37] スロベニア  ディヴィエ・バーベのフルート これまで発見された最古のフルートは、1995年にスロベニアのツェルクノ丘陵で発見された、いわゆるディヴィエ・バーベのフルートである可能性がある が、これは議論の余地がある。[38] 問題の品は、幼いホラアナグマの大腿骨の断片であり、約4万3千年前のものであるとされている。 [39][40] しかし、それが本当に楽器であるのか、あるいは単に肉食動物が噛んだ骨であるのかについては、現在も議論が続いている。[38] 2012年には、ガイゼンクロイステレ洞窟で数年前に発見されたフルートが、新たに高解像度の炭素年代測定検査を受け、42,000年から43,000年 前のものであることが判明した。[41] |

| The Americas Canada Main article: Music of Canada For thousands of years, Canada has been inhabited by Indigenous Peoples from a variety of different cultures and of several major linguistic groupings. Each of the Indigenous communities had (and have) their own unique musical traditions. Chanting – singing is widely popular, with many of its performers also using a variety of musical instruments.[42] They used the materials at hand to make their instruments for thousands of years before Europeans immigrated to the new world.[43] They made gourds and animal horns into rattles which were elaborately carved and beautifully painted.[44] In woodland areas, they made horns of birchbark along with drumsticks of carved antlers and wood.[43] Drums were generally made of carved wood and animal hides.[45] These musical instruments provide the background for songs and dances.[45] |

南北アメリカ カナダ 詳細は「カナダの音楽」を参照 カナダには数千年にわたり、さまざまな異なる文化や主要な言語グループに属する先住民が居住してきた。先住民の各コミュニティには、それぞれ独自の音楽の 伝統があった(そして今もある)。歌うこと(チャンティング)は広く人気があり、多くのパフォーマーはさまざまな楽器も使用している。[42] ヨーロッパ人が新世界に移住する何千年も前から、彼らは手近にある材料を使って楽器を作っていた。 [43] 彼らは、ひょうたんや動物の角を精巧に彫刻し、美しい彩色を施したラトル(ガラガラ)を作った。[44] 森林地帯では、白樺の樹皮で角を作り、角や木を彫刻してドラムスティックを作った。[43] ドラムは一般的に、彫刻を施した木や動物の皮で作られた。[45] これらの楽器は歌や踊りの背景となる。[45] |

| Ancient music Behavioral modernity Neuroscience of music Evolutionary musicology International Study Group on Music Archaeology Onomatopoeia Origin of language Origins of religion Prehistoric art Sound symbolism |

古代音楽 行動の近代性 音楽の神経科学 進化音楽学 音楽考古学に関する国際研究グループ オノマトペ 言語の起源 宗教の起源 先史時代の芸術 音の象徴 |

| References Deschênes, Bruno (2002). "Inuit Throat-Singing". Musical Traditions. The Magazine for Traditional Music Throughout the World. Diószegi, Vilmos (1960). Sámánok nyomában Szibéria földjén. Egy néprajzi kutatóút története. Terebess Ázsia E-Tár (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó. This book has been translated to English: Diószegi, Vilmos (1968). Tracing shamans in Siberia. The story of an ethnographical research expedition. Translated from Hungarian by Anita Rajkay Babó. Oosterhout: Anthropological Publications. Hoppál, Mihály (2006). "Music in Shamanic Healing" (PDF). In Gerhard Kilger (ed.). Macht Musik. Musik als Glück und Nutzen für das Leben. Köln: Wienand Verlag. ISBN 3-87909-865-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2007. Nattiez, Jean Jacques (2014). Inuit Games and Songs • Chants et Jeux des Inuit. Musiques & musiciens du monde • Musics & musicians of the world. Montreal: Research Group in Musical Semiotics, Faculty of Music, University of Montreal. OCLC 892647446. These songs are available online from the ethnopoetics website curated by Jerome Rothenberg. Mithen, Steven (2006). The Singing Neanderthals: the Origins of Music, Language, Mind and Body. Sorce Keller, M. (1984). "Origini della musica". In Basso, Alberto (ed.). Dizionario Enciclopedico Universale della Musica e dei Musicisti (in Italian). Vol. III. Torino: UTET. pp. 494–500. Parncutt, R (2009). "Prenatal and infant conditioning, the mother schema, and the origins of music and religion" (PDF). Musicae Scientiae. 13 (2, supplemental): 119–150. doi:10.1177/1029864909013002071. S2CID 143590098. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-05. Hagen, EH and; Hammerstein P (2009). "Did Neanderthals and other early humans sing? Seeking the biological roots of music in the loud calls of primates, lions, hyenas, and wolves" (PDF). Musicae Scientiae. 13: 291–320. doi:10.1177/1029864909013002131. S2CID 39481097. Further reading Ellen Hickmann, Anne D. Kilmer and Ricardo Eichmann, (ed.) Studies in Music Archaeology III, 2001, VML Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH., Germany ISBN 3-89646-640-2 Engel, Carl, The Music of the Most Ancient Nations, Wm. Reeves, 1929. Haik Vantoura, Suzanne (1976). The Music of the Bible Revealed ISBN 978-2-249-27102-1 Morley, Iain (2013). The Prehistory of Music: Human Evolution, Archaeology, and the Origins of Musicality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923408-0. Nettl, Bruno (1956). Music in Primitive Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-59000-7. Sachs, Curt, The Rise of Music in the Ancient World, East and West, W.W. Norton, 1943. Sachs, Curt, The Wellsprings of Music, McGraw-Hill, 1965. Smith, Hermann, The World's Earliest Music, Wm. Reeves, 1904. Wallin, Nils; Merker, Björn; Brown, Steven, eds. (2000). The Origins of Music. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-73143-0. |

参考文献 デシェーヌ、ブルーノ(2002年)。「イヌイットの喉歌」。Musical Traditions。世界の伝統音楽に関する雑誌。 ディオセギ、ヴィルモシュ(1960年)。「シャーマンの足跡を追って。シベリアの大地で。民族誌学的研究の歴史。Terebess Ázsia E-Tár(ハンガリー語)。ブダペスト:Magvető Könyvkiadó。 この本は英語に翻訳されている:Diószegi, Vilmos (1968). Tracing shamans in Siberia. The story of an ethnographical research expedition. Translated from Hungarian by Anita Rajkay Babó. Oosterhout: Anthropological Publications. ホッパル・ミハーイ(2006年)。「シャーマニック・ヒーリングにおける音楽」(PDF)。ゲルハルト・キルガー編『Macht Musik. Musik als Glück und Nutzen für das Leben.』ケルン:ヴィーナント出版社。ISBN 3-87909-865-4。2007年10月8日、オリジナル(PDF)よりアーカイブ。 Nattiez, Jean Jacques (2014). Inuit Games and Songs • Chants et Jeux des Inuit. Musiques & musiciens du monde • Musics & musicians of the world. Montreal: Research Group in Musical Semiotics, Faculty of Music, University of Montreal. OCLC 892647446. これらの歌は、ジェローム・ローゼンバーグが管理するエスノポエティックスのウェブサイトからオンラインで入手できる。 ミズン、スティーブン(2006年)。『歌うネアンデルタール人:音楽、言語、心、身体の起源』。 ソースケラー、M.(1984年)。「音楽の起源」。バッソ、アルベルト(編)『音楽と音楽家のための百科事典』。第3巻。トリノ:UTET。494-500ページ。 Parncutt, R (2009). 「Prenatal and infant conditioning, the mother schema, and the origins of music and religion」 (PDF). Musicae Scientiae. 13 (2, supplemental): 119–150. doi:10.1177/1029864909013002071. S2CID 143590098. 2011年6月5日オリジナル(PDF)よりアーカイブ。 ハーゲン、EHおよび、ハンマーシュタインP(2009年)。「ネアンデルタール人と他の初期の人類は歌ったのか? 霊長類、ライオン、ハイエナ、オオカミの大きな鳴き声に音楽の生物学的ルーツを求める」(PDF)。Musicae Scientiae. 13: 291–320. doi:10.1177/1029864909013002131. S2CID 39481097. 参考文献 エレン・ヒックマン、アン・D・キルマー、リカルド・アイヒマン(編)『音楽考古学研究第3巻』2001年、VML Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH.、ドイツ、ISBN 3-89646-640-2 エンゲル、カール『最も古代の国民の音楽』W. リーブス、1929年 ヘイク・ヴァントゥーラ、スザンヌ(1976年)。『聖書の音楽が明らかにするもの』ISBN 978-2-249-27102-1 モーリー、イアン(2013年)。『音楽の前史:人類の進化、考古学、音楽性の起源』オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-923408-0. ネトル、ブルーノ(1956年)。『原始文化における音楽』ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-674-59000-7。 サックス、カート、『古代世界における音楽の興隆』東洋と西洋、W.W. Norton、1943年。 サックス、カート、『音楽の源泉』McGraw-Hill、1965年。 スミス、ヘルマン、『世界最古の音楽』、Wm. Reeves、1904年。 Wallin, Nils; Merker, Björn; Brown, Steven, eds. (2000). 『音楽の起源』。ケンブリッジ:MIT Press。ISBN 978-0-262-73143-0。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prehistoric_music |

*Music archaeology - 音楽考古学

Performers in procession, Bonampak temple room 1.770AD

| Music

archaeology is an interdisciplinary field of study that combines

musicology and archaeology. As it includes the study of music from

various cultures, it is often considered to be a subfield of

ethnomusicology. Archaeomusicology refers to the study of the

musicology of the antiquity. It is the anglo-saxon version of music

archaeology. Archaeomusicology is uniquely dedicated to the study of

ancient musical systems, metrology and organology of the ancient Near

and Middle East. |

音

楽考古学は、音楽学と考古学を組み合わせた学際的な研究分野である。さまざまな文化における音楽の研究を含むため、民族音楽学のサブ分野であると見なされ

ることが多い。 考古音楽学は古代の音楽学の研究を指す。 音楽考古学の英語圏版である。

考古音楽学は、古代の音楽システム、計量学、古代の中近東の楽器学の研究に特化している。 |

| Definitions According to music archaeologist Adje Both, "In its broadest sense, music archaeology is the study of the phenomenon of past musical behaviours and sounds."[2] Music archaeologists often combine methods from musicology and archaeology. A theoretical and methodological foundation has yet to be established, and remains one of the main areas of interest for the international community of researchers.[3] Research goals in the field include the study of artifacts relevant to the reconstruction of ancient music, such as sound-producing devices, representations of musical scenes, and textual evidence. The archaeological analysis and documentation of such artifacts, including their dating, description, and analysis of their origin and cultural context, can improve understanding of the usage of an instrument and can sometimes enable reconstruction of functional replicas. Textual study may involve the investigation of early musical notations and literary sources. The field has also expanded to include neurophysiological, biological, and psychological research examining the prerequisites for music production in humans. |

定義 音楽考古学者のAdje Bothによると、「音楽考古学とは、最も広い意味では、過去の音楽的行動や音の現象を研究する学問である」[2]。音楽考古学者は、音楽学と考古学の手 法を組み合わせることが多い。理論的・方法論的な基盤はまだ確立されておらず、国際的な研究者のコミュニティにとっての主要な関心事のひとつとなってい る。 この分野における研究目標には、古代音楽の復元に関連する人工物の研究が含まれ、音を発生させる装置、音楽の場面を表したもの、テキストによる証拠などが 挙げられる。 このような人工物の年代、記述、起源や文化的背景の分析を含む考古学的分析や文書化は、楽器の使用方法の理解を深め、時には機能的なレプリカの復元を可能 にする。 文献研究には、初期の楽譜や文学的資料の調査が含まれる場合がある。 この分野はさらに拡大し、人間における音楽制作の前提条件を調べる神経生理学、生物学、心理学の研究も含まれるようになった。 |

| History One of the first attempts to join the two distinct disciplines of musicology and archaeology took place at the conference of the International Musicological Society at Berkeley in 1977 where for the first time the term archaeomusicology was mentioned. One of the round tables was designated "Music and Archaeology", to which were invited specialists to discuss the musical remains of ancient cultures: Bathia Bayer (Israel), Charles Boilès (Mexico), Ellen Hickmann (Egypt), David Liang (China), Cajsa S. Lund (Sweden). The main stimulus for this session was the sensational discovery of an ancient Mesopotamian musical system by Anne D. Kilmer, an Assyriologist in Berkeley. On the basis of this discovery, excavated from Ugarit, she was able to advance a decipherment and transcription into Western notation of a late Bronze Age hymn in the Hurrian language, which contained notation based on the Mesopotamian system. Prior to the conference a replica of a Sumerian lyre had been made, with the help of musicologist Richard L. Crocker (Berkeley) and instrument maker Robert Brown, and Kilmer's version of the Hurrian hymn had been recorded and released, accompanied by a carefully prepared commentary, as Sounds from Silence: Recent Discoveries in Ancient Near Eastern Music (LP with information booklet, Bit Enki Publications, Berkeley, 1976). At the round table in Berkeley, Kilmer explained their method of reconstruction and demonstrated the resulting sound. This was the starting point of the ICTM Study Group on Music Archaeology, officially founded within the International Council for Traditional Music (ICTM) in Seoul/Korea in 1981, and recognized by the ICTM in New York in 1983 following its first meeting on current music-archaeological research in Cambridge/UK in 1982. The ICTM Study Group on Music Archaeology went on to hold international conferences in Stockholm (1984), Hannover/Wolfenbüttel (1986), Saint Germain-en-Laye (1990), Liège (1992), Istanbul (1993), Jerusalem (1994/1995, together with the ICTM-Study Group for Iconography), and Limassol, Cyprus (1996). These meetings resulted in comprehensive conference reports. The International Study Group on Music Archaeology (ISGMA) has been founded by Ellen Hickmann and Ricardo Eichmann in 1998. The Study Group emerged from the ICTM Study Group on Music Archaeology with the objective to obtain closer cooperation with archaeologists. Since then, the ISGMA has worked continuously with the German Archaeological Institute, Berlin (DAI, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Berlin). A new series called "Studien zur Musikarchäologie" was created as a sub-series of "Orient-Archäologie" to present the conference reports of the ISGMA, and to integrate music-archaeological monographs independent of the Study Group's meetings; it is published by the Orient Department of the DAI through the Verlag Marie Leidorf. Between 1998 and 2004, conferences of ISGMA were held every two years at Michaelstein Monastery, Music Academy of Sachsen-Anhalt (Kloster Michaelstein, Landesmusikakademie Sachsen-Anhalt), sponsored by the German Research Foundation (DFG, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft). In close cooperation with the Department for Ethnomusicology at the Ethnological Museum of Berlin (Ethnologisches Museum Berlin, SMB SPK, Abteilung Musikethnologie, Medien-Technik und Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv), the 5th and 6th Symposium of the ISGMA were held in 2006 respectively in 2008 at the Ethnological Museum of Berlin. In friendly cooperation with the Tianjin Conservatory of Music, the 7th Symposium of the ISGMA was held in Tianjin, China, in 2010. The 8th Symposium of the ISGMA (2012) was also held in China, in Suzhou and Beijing; three more symposiums have been held since then, with Germany and China continuing to alternate as hosts. The ICTM Study Group on Music Archaeology continued to develop separately and hold its own events, although a number of researchers remained involved in both groups. After a couple of years of inactivity, Julia L. J. Sanchez re-established the Study Group in 2003 on the initiative of Anthony Seeger, beginning with meetings in Los Angeles, California (2003), and Wilmington, North Carolina (2006). These were followed by a joint-conference in New York (2009), the 11th of the Study Group since its foundation in 1981 (also the 12th Conference of the Research Center for Music Iconography). The 12th conference was then held in Valladolid, Spain (2011), which was the largest meeting of the ICTM Study Group to date, followed by the 13th Symposium of the Study Group held in Guatemala in 2013. Also in 2013, a new print series was launched, Publications of the ICTM Study Group on Music Archaeology, published through Ekho Verlag. ICONEA, International Council of Archaeomusicological Researches held its first conference at the British Museum in December 2008. ICONEA was founded by Irving Finkel and Richard Dumbrill. It was then affiliated to the Institute of Musical Research of the School of Advanced Study of the University of London but now is dedicated to publishing books, articles and videos about archaeomusicology. On 27 May 2011, a public concert under the banner of Palaeophonics, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Beyond Text programme and the University of Edinburgh Campaign, took place at the George Square Theatre in Edinburgh. The event showcased the outcomes of collaborative research and creative practice by archaeologists, composers, filmmakers, and performers from across Europe and the Americas. Whilst inspired and driven by research in music archaeology, Palaeophonics represents the emergence of a new, possibly significant, development within the field and within musicology which approaches the subject through the production and performance of new sound- and music-based multi-media creative works instead of through direct representation and reproduction. Described by some observers as "experimental" and "avant-garde", the event provoked mixed feedback from a public audience of around 250 people. In 2013, the European Music Archaeology Project (EMAP) was funded by the EU funding programme EACEA, for a period of five years. The project developed a touring exhibition on ancient music in Europe and an elaborate concert and event program.[4][5] |

歴史 音楽学と考古学という2つの異なる学問分野を結びつける最初の試みの一つは、1977年にバークレーで開催された国際音楽学会議において行われ、そこで初 めて「考古音楽学」という用語が使用された。円卓会議のひとつが「音楽と考古学」と名付けられ、古代文化の音楽的遺産について議論するために、バティア・ バイエル(イスラエル)、チャールズ・ボワレス(メキシコ)、エレン・ヒックマン(エジプト)、デビッド・リャン(中国)、カイサ・S・ルンド(スウェー デン)といった専門家が招かれた。このセッションの主なきっかけとなったのは、バークレーのアッシリア学者アン・D・キルマーによる古代メソポタミアの音 楽システムのセンセーショナルな発見であった。この発見に基づき、彼女はウガリットから発掘されたヒッタイト語による青銅器時代後期の賛美歌の解読と西洋 音譜への転記を進めることができた。この賛美歌にはメソポタミアの音譜に基づく音符が含まれていた。会議に先立ち、音楽学者のリチャード・L・クロッカー 氏(バークレー)と楽器製作者のロバート・ブラウン氏の協力によりシュメールの竪琴のレプリカが作られ、キルマー氏によるヒッタイト語の賛美歌の録音が、 入念に準備された解説とともに『Sounds from Silence: Recent Discoveries in Ancient Near Eastern Music』(LP、情報冊子付き、Bit Enki Publications、バークレー、1976年)として発表された。バークレーでの円卓会議で、キルマーは復元の手法を説明し、その結果として得られ た音を披露した。これが、1981年に韓国ソウルで正式に設立された国際伝統音楽評議会(ICTM)内の音楽考古学に関する研究グループの始まりであり、 1982年に英国ケンブリッジで音楽考古学の最新の研究について話し合う最初の会合が開催された後、1983年にニューヨークのICTMで認められた。 音楽考古学に関するICTM研究グループは、その後もストックホルム(1984年)、ハノーファー/ヴォルフェンビュッテル(1986年)、サン・ジェル マン・アン・レー(1990年)、リエージュ(1992年)、イスタンブール(1993年)、エルサレム(1994年/1995年、ICTM図像学研究グ ループとの合同開催)、 およびキプロス、リマソール(1996年)。これらの会議は、包括的な会議報告書という結果をもたらした。 国際音楽考古学研究グループ(ISGMA)は、1998年にエレン・ヒックマンとリカルド・アイヒマンによって設立された。この研究グループは、音楽考古 学に関する国際音楽研究会議(ICTM)から独立し、考古学者とのより緊密な協力関係を築くことを目的として設立された。それ以来、ISGMAはベルリン のドイツ考古学研究所(DAI、Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Berlin)と継続的に協力している。「音楽考古学研究」と名付けられた新しいシリーズは、「オリエント考古学」のサブシリーズとして創刊され、 ISGMAの会議報告を発表し、研究グループの会議とは別に音楽考古学の単行本を統合することを目的としている。このシリーズは、DAIのオリエント部門 がVerlag Marie Leidorfを通じて出版している。1998年から2004年にかけて、ISGMAの会議は、ドイツ研究振興協会(DFG、Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft)の支援を受け、ザクセン=アンハルト音楽アカデミーのミヒャエルシュタイン修道院(Kloster Michaelstein, Landesmusikakademie Sachsen-Anhalt)で2年ごとに開催された。 ベルリン民族学博物館(Ethnologisches Museum Berlin, SMB SPK, Abteilung Musikethnologie, Medien-Technik und Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv)の民族音楽学部門との緊密な協力により、ISGMAの第5回および第6回シンポジウムは、それぞれ2006年と 2008年にベルリン民族学博物館で開催された。天津音楽学院との友好的な協力により、ISGMAの第7回シンポジウムは2010年に中国・天津で開催さ れた。ISGMAの第8回シンポジウム(2012年)も中国で開催され、蘇州と北京で開かれた。それ以来、さらに3回のシンポジウムが開催され、ドイツと 中国が交互に主催を務めている。 音楽考古学に関するICTM研究グループは独自に発展を続け、独自のイベントを開催したが、多くの研究者が両方のグループに関与し続けた。活動休止の時期 を経て、ジュリア・L・J・サンチェスは2003年にアンソニー・シーガーの主導により研究グループを再設立し、カリフォルニア州ロサンゼルス(2003 年)とノースカロライナ州ウィルミントン(2006年)で会議を開催した。これに続いて、ニューヨークで合同会議(2009年)が開催された。これは、 1981年の設立以来、研究グループとしては11回目(音楽図像学研究センターとしては12回目)の会議であった。第12回会議はスペインのバリャドリッ ドで開催され(2011年)、これは現在まででICTM研究グループ最大の会議となった。その後、2013年にグアテマラで開催された研究グループの第 13回シンポジウムが続いた。また2013年には、エコー・ヴェラグ社から出版された「音楽考古学に関するICTM研究グループの出版物」という新しい印 刷シリーズが開始された。 ICONEA(国際考古音楽学協議会)は、2008年12月に大英博物館で第1回会議を開催した。ICONEAは、アーヴィング・フィンケルとリチャー ド・ダンブリルによって設立された。当初はロンドン大学高等研究所音楽研究所の関連組織であったが、現在は考古音楽学に関する書籍、論文、ビデオの出版に 専念している。 2011年5月27日、英国人文科学研究会議(AHRC)の「Beyond Text」プログラムおよびエディンバラ大学のキャンペーンによる資金援助を受け、パレオフォニックスの旗印のもと、エディンバラのジョージ・スクエア・ シアターで公開コンサートが開催された。このイベントでは、ヨーロッパおよび南北アメリカから集まった考古学者、作曲家、映画制作者、演奏家による共同研 究と創造的実践の成果が披露された。音楽考古学の研究からインスピレーションを得て推進された「古楽音学」は、この分野および音楽学における新たな、そし て重要な展開の始まりを象徴するものであり、音や音楽をベースとした新しいマルチメディア作品の制作やパフォーマンスを通じて、主題にアプローチするもの である。一部の観客からは「実験的」あるいは「前衛的」と評されたこのイベントは、約250人の観客からさまざまな反応を引き出した。 2013年には、欧州音楽考古学プロジェクト(EMAP)がEUの助成プログラムEACEAから5年間の助成を受けた。このプロジェクトでは、ヨーロッパの古代音楽に関する巡回展と、綿密に計画されたコンサートやイベントプログラムが開発された。[4][5] |

| Approaches Music archaeology is an interdisciplinary field with multifaceted approaches,[6] falling under the cross section of experimental archaeology and musicology research.[7] Music archaeology research aims to understand past musical behaviors; this may be done through methods such as recreating past musical performances, or reconstructing musical instruments from the past. A common research approach for an interdisciplinary field is to develop a collaborative research team with diverse specialists who can offer varying perspectives on data and findings. Music archaeology research teams are frequently composed of musicologists and archaeologists. In addition, specialists such as psychologists, organologists, biologists, chemists, and historians can be key in understanding past musical behaviors.[8] For example, a human physiologist can help provide useful insight on singing and tonal capabilities when analysing excavated human remains.[9] In pursuit of achieving accurate results, it is important that all sources of information and data, regardless of how they are reported or recorded, are treated equally. The information obtained from various scientific approaches can deepen the interpretation of past musical behaviors, sound artefacts, and acoustic spaces.[10] Archaeological researchers date and classify findings from digs to better understand past behaviors; both dating and classifying are equally important when interpreting data.[11] |

アプローチ 音楽考古学は、多角的なアプローチを採る学際的な分野であり、実験考古学と音楽学の研究の交差点に位置する。音楽考古学の研究は、過去の音楽的行動を理解することを目的としている。これは、過去の音楽パフォーマンスの再現や、過去の楽器の復元などの方法によって行われる。 学際的な分野における一般的な研究アプローチは、データや調査結果に対して多様な視点を提供できる多様な専門家による共同研究チームを結成することであ る。音楽考古学の研究チームは、音楽学者と考古学者で構成されることが多い。さらに、心理学者、器官学者、生物学者、化学者、歴史家などの専門家は、過去 の音楽的行動を理解する上で重要な役割を果たす可能性がある。[8] 例えば、発掘された人骨を分析する際には、人間の生理学者が歌や音色に関する有益な洞察を提供できる可能性がある。[9] 正確な結果を得るためには、報告や記録の方法に関わらず、あらゆる情報源やデータが平等に扱われることが重要である。さまざまな科学的アプローチから得ら れた情報は、過去の音楽的行動、音響遺物、音響空間の解釈を深めることができる。[10] 考古学研究者は、発掘調査で得られた発見物の年代と分類を行い、過去の行動をより深く理解しようとしている。年代と分類は、データの解釈においてどちらも 同様に重要である。[11] |

| Notable music archaeologists Graeme Lawson Ellen Hickmann[12] Cajsa Lund[13] Irving Finkel Richard Dumbrill https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Dumbrill_(musicologist) Bo Lawergren[14] Anne D. Kilmer Ricardo Eichmann Arnd Adje Both [1] Stefan Hagel [2] Peter Holmes [3] John C. Franklin [4] |

著名な音楽考古学者 グレーム・ローソン エレン・ヒックマン[12] カイサ・ルンド[13] アーヴィング・フィンケル リチャード・ダンブリルhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Dumbrill_(音楽学者) ボー・ローエルグレン[14] アン・D・キルマー リカルド・アイヒマン アンド・アジェ・ボス[1] ステファン・ハーゲル[2] ピーター・ホームズ[3] ジョン・C・フランクリン [4] |

| Networks The ICTM Study Group on Music Archaeology was founded in the early 1980s.[15] In 2013, the book series Publications of the ICTM Study Group on Music Archaeology was launched. The International Study Group on Music Archaeology (ISGMA)[16] was founded in 1998. The study group is hosted at the Orient Department of the German Archaeological Institute Berlin (DAI, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Orient-Abteilung) and the Department for Ethnomusicology at the Ethnological Museum Berlin (Ethnologisches Museum Berlin, SMB SPK, Abteilung Musikethnologie, Medien-Technik und Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv). MOISA: The International Society for the Study of Greek and Roman Music and its Cultural Heritage is a non-profit association incorporated in Italy in 2007 for the preservation, interpretation, and valorization of ancient Greek and Roman music and musical theory, as well as its cultural heritage to the present day.[17] The Acoustics and Music of British Prehistory Research Network was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, led by Rupert Till and Chris Scarre, as well as Professor Jian Kang of Sheffield University's Department of Architecture. The network maintains a list of researchers working in the field, as well as links to many other relevant sites.[18] |

ネットワーク ICTM音楽考古学研究グループは1980年代初頭に設立された。[15] 2013年には、ICTM音楽考古学研究グループの出版シリーズが開始された。 国際音楽考古学研究グループ(ISGMA)[16] は1998年に設立された。この研究グループは、ベルリン・ドイツ考古学研究所(DAI、ドイツ考古学研究所、オリエント部門)とベルリン民族学博物館 (SMB SPK、ベルリン民族学博物館、音楽民族学部門、メディア・技術・ベルリン・フォノグラム・アーカイブ)の民族音楽学部門が主催している。 MOISA:ギリシャ・ローマ音楽とその文化遺産の研究のための国際学会は、古代ギリシャ・ローマの音楽と音楽理論の保存、解釈、価値向上、およびそれらの文化遺産を今日まで伝えていくことを目的として、2007年にイタリアで設立された非営利団体である。 先史時代の英国の音響と音楽研究ネットワークは、ルパート・ティルとクリス・スカー、シェフィールド大学建築学部のジャン・カン教授が主導し、人文科学研 究評議会と工学・物理科学研究評議会から資金提供を受けている。このネットワークは、この分野で研究活動を行っている研究者のリストを管理しているほか、 関連する多くのサイトへのリンクも提供している。[18] |

Man playing traditional Music bow. one of the oldest stringed instruments. |

伝統音楽の弓奏楽器を演奏する男性。最も古い弦楽器のひとつ。 |

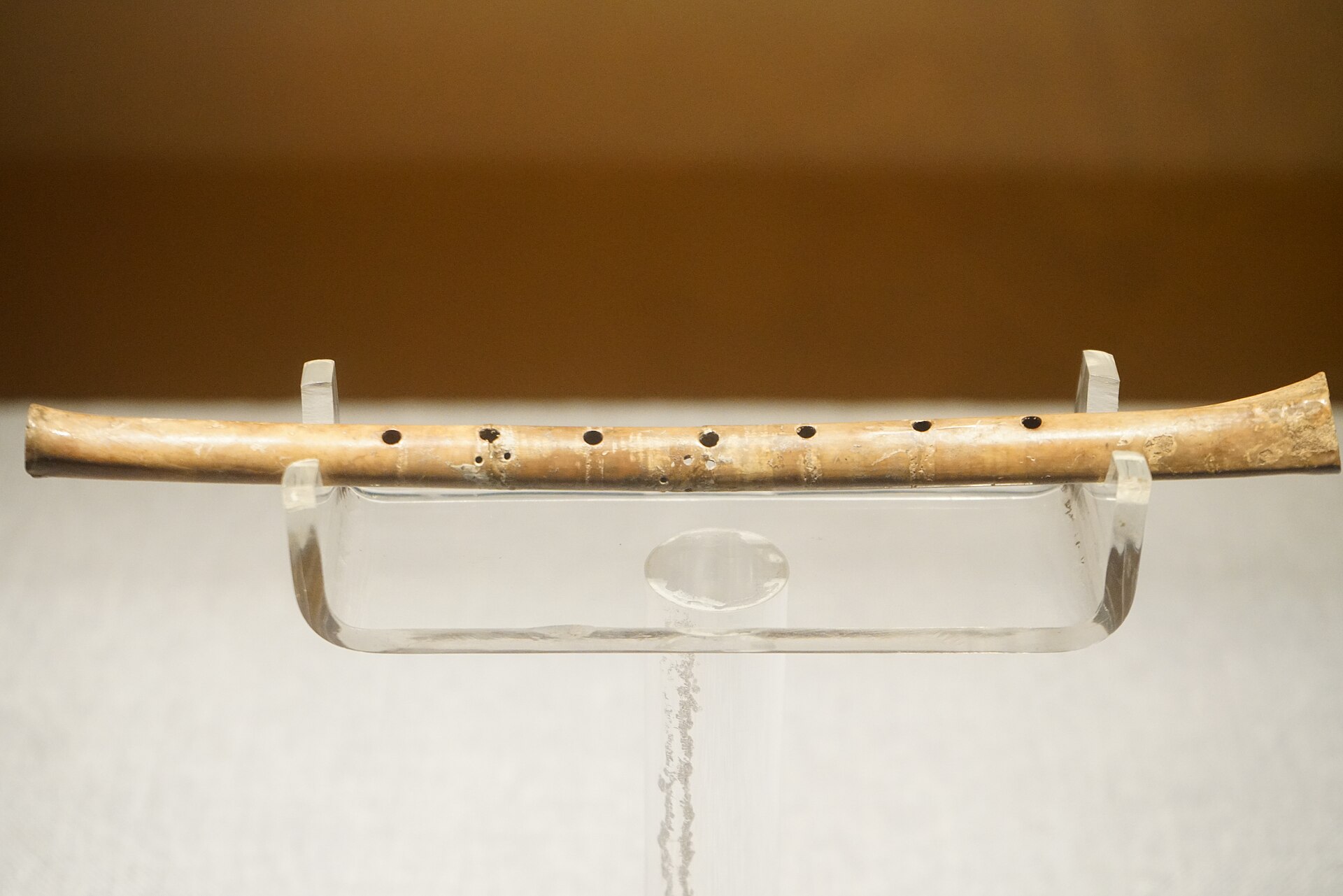

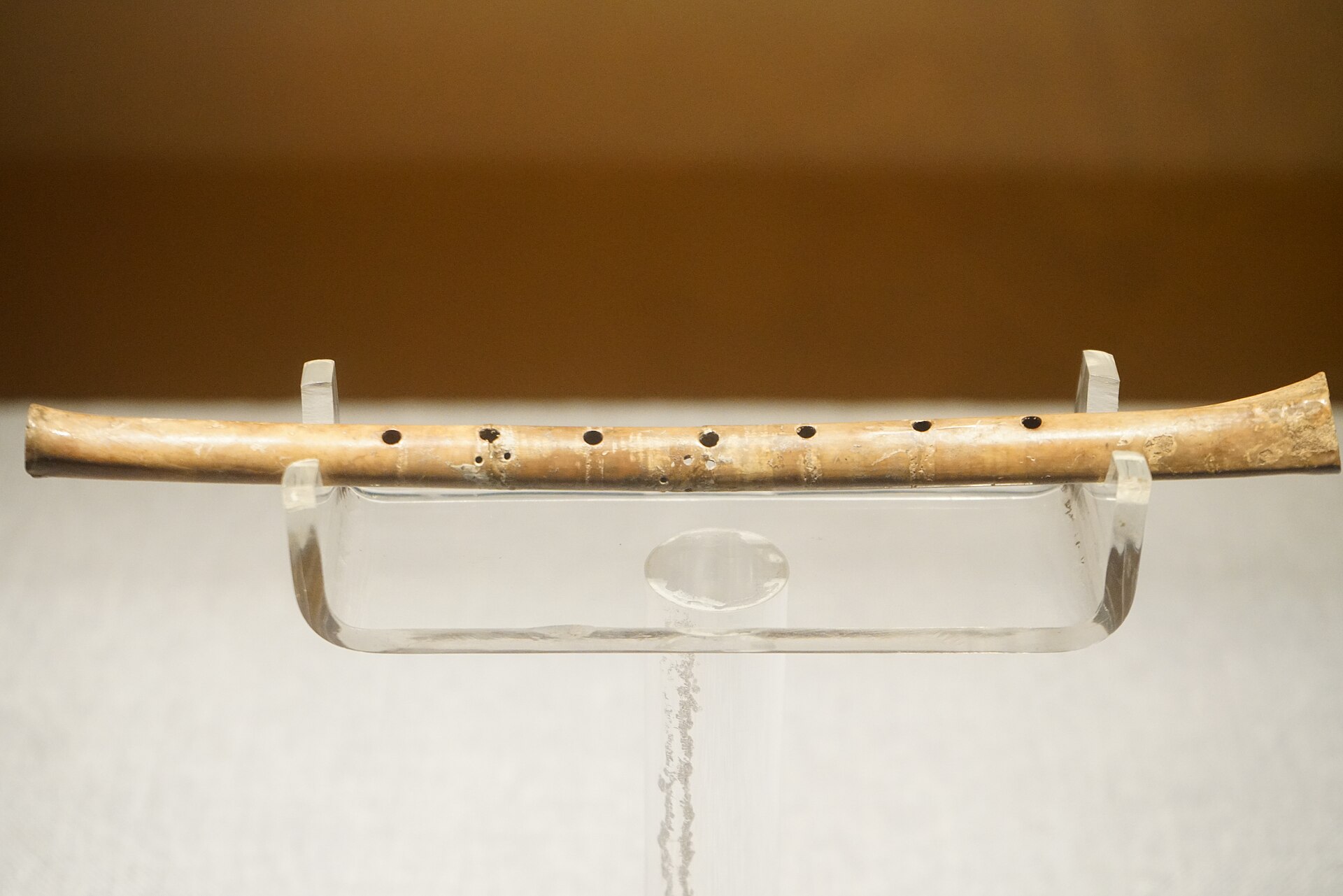

Bone Flutes are some of the oldest remaining musical instruments. |

骨笛は現存する最古の楽器のひとつである。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_archaeology |

****

| 33 |

|

****

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆