音楽と時間性

Music and Time in der-Welt-Musik

池田光穂

☆ 7音階で構成される古典的西洋「音楽」の3つの要素とは、メロディ(melody; 旋律)、リズム(rhytm)、ハーモニー(harmony)からなるという。これらの音楽の要素に、時間性と いう概念が関わっている。まず、メロディは、継起的時間の推移のなかで決められた音階が移動し時間に沿った音階がそのメロディを定義している。リズムは、 時間の進行のなかの単位(小節 bar in small sections)における拍(beat, music beat)から構成されるものである。そして、ハーモニー(和声;music harmony)は、継起的時間の流れではなく、その時点での中心音(tonal centre)に調性(tonality)をもつ別の音が従属的に関わっていることをさす。調性は、18世紀および19世紀のヨーロッパの芸術音楽の中心 的語法であり、それを調性機能(harmonic function)[機能和声理論; Funktionstheorie]と呼ばれる。

★最後の、ハーモニー(和声;music harmony)は、7音階でなくても、5音階やその他の(7音階からみた時の)「特殊な」音階——教会旋法(Gregorian mode)—— によっても中心音性があれば調性をもつこととなる。しかしながら、(古典的で保守的な)西洋音楽理論では、これらのより汎用性の高いものを、狭義の調性 (tonality)と区別して旋法性(modality)と呼ぶ。したがって、旋法性(modality)は、非時間概念優先であったハーモニーにおけ る狭義の調性(tonality)から、再度、時間性を取り戻して、メロディ(melody; 旋律)、リズム(rhytm)、ハーモニー(harmony)という3つの概念をつかって、音楽が時間性の中でどのような存在様式をもつのかを明らかにす る突破口を切り開いた。

☆ 教会旋法(グレゴリアン・モード)は、8世紀から9世紀頃以来、少なくとも16世紀頃まで西洋音楽理論の基礎であったが、機能和声の発達によって長調・短 調の組織に取って代わられた。しかし機能和声がすべての音楽性を解析できるわけでなく、また、限定された歴史性・地域性のなかでの維持的な流行にすぎな い。そのため、19世紀末以降、新たな音楽の可能性の追求の中で教会旋法(Gregorian mode)がしばしば用いられるにいたり、上記で述べたように、ハーモニーにおける時間性の概念を取り戻したと言えよう。

★以

上をまとめると:「音楽(music)とは、形式、和声(ハーモニー)、旋律(メロディ)、リズム、またはその他の表現的な内容の何らかの組み合わせを作

り出すための音の配置である。音楽の定義は 文化によって異なるが、音楽はすべての人間社会の側面であり、文化的普遍である。

音楽の創作は一般的に作曲、即興、演奏に分けられるが、このテーマ自体は学問、批評、哲学、心理学、治療の文脈にまで及ぶ。音楽は、人間の声を含

む膨大な種類の楽器を用いて演奏されたり即興されたりすることがあり、そのためその極めて多様な創造性の機会がしばしば評価される」(→音楽・ミュージック)

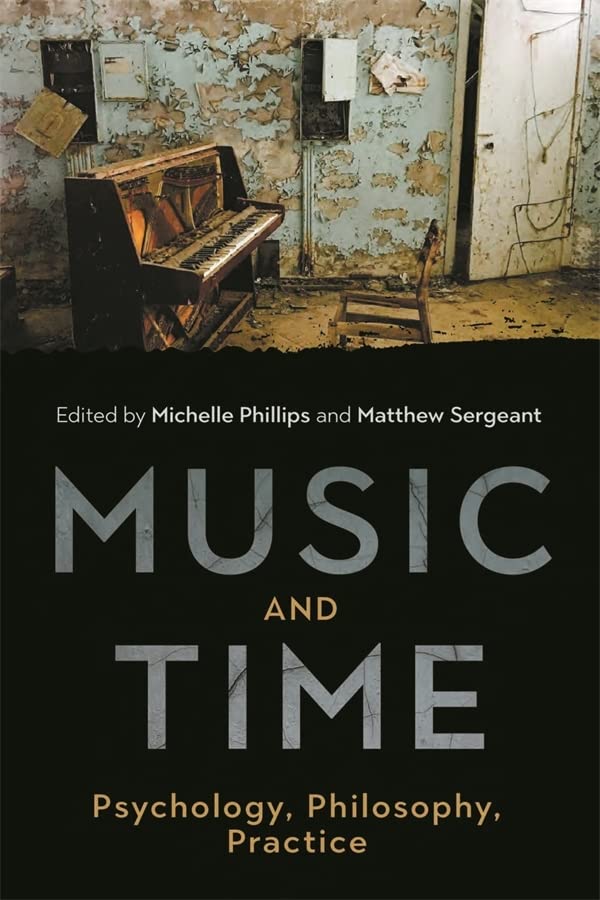

| Music and Time Psychology, Philosophy, Practice Edited by Michelle Phillips and Matthew Sergeant |

|

Introduction IntroductionMatthew Sergeant and Michelle Phillips Part I. Experiences 1. Music Listening and the Perception of Time: The LEMI Model Michelle Phillips 2. The Remembrance of Things to Be: An Approach to Memory, Repetition, and Cyclical Structures Bryn Harrison 3. An Overview of the Psychology of Time Perception Luke A. Jones 4. The Perceptual Present and the Philosophical Puzzle of Musical Experience Abigail Connor and Joel Smith Part II. Enactments 5. Ensemble Timing in String Quartets Alan Wing, Maria Witek, Ryan Stables, and Adrian Bradbury 6. Midway Ambiguities: Disorientation and Interpretation in Long-Duration Music Philip Thomas 7. Live Coding as a Theatre of Agency and a Factory of Time Alejandro Franco Briones Part III. Meanings 8. Comparing Temporal Fictions in Tonality and Triadic Post-Tonality: Chopin's Fourth Ballade as a Link Between the Ages Jason Noble 9. Nothing Really Changes': Material Processes in and as Timein hearmleoþ-gieddunga Lauren Redhead 10. Music, Time, and Society Matthew Sergeant Conclusion: Multiplicity, Fluidity, Fragility Michelle Phillips and Matthew Sergeant Bibliography Index |

はじめに はじめにマシュー・サージェント、ミシェル・フィリップス 第一部 経験 1. 音楽鑑賞と時間の知覚:LEMIモデル ミシェル・フィリップス 2. あるべきものの記憶:記憶、反復、循環構造へのアプローチ ブリン・ハリソン 3. 時間知覚の心理学の概観 ルーク・ジョーンズ 4. 知覚的現在と音楽経験の哲学的パズル アビゲイル・コナー、ジョエル・スミス パート II. 演技 5. 弦楽四重奏におけるアンサンブルのタイミング アラン・ウィング、マリア・ウィテック、ライアン・ステイブルズ、エイドリアン・ブラッドベリー 6. 中途半端な曖昧さ: 長時間の音楽における見当識の喪失と解釈 フィリップ・トーマス 7. エージェンシーの劇場と時間の工場としてのライブコーディング アレハンドロ・フランコ・ブリオネス パート III. 意味 8. 調性と三和音的ポスト調性における時間的虚構の比較: 時代をつなぐものとしてのショパンのバラード第4番 ジェイソン・ノーブル 9. 「本当に変わるものなど何もない」: 時間における、そして時間としての物質的プロセス ローレン・レッドヘッド 10. 音楽、時間、社会 マシュー・サージェント 結論 多重性、流動性、脆弱性 ミシェル・フィリップス、マシュー・サージェント 参考文献 索引 |

| MICHELLE PHILLIPS is a music

psychologist and a Senior Lecturer at the Royal Northern College of

Music. MATTHEW SERGEANT is a composer and researcher and Reader in Music at Bath Spa University. |

|

| https://boydellandbrewer.com/9781783277087/music-and-time/ |

|

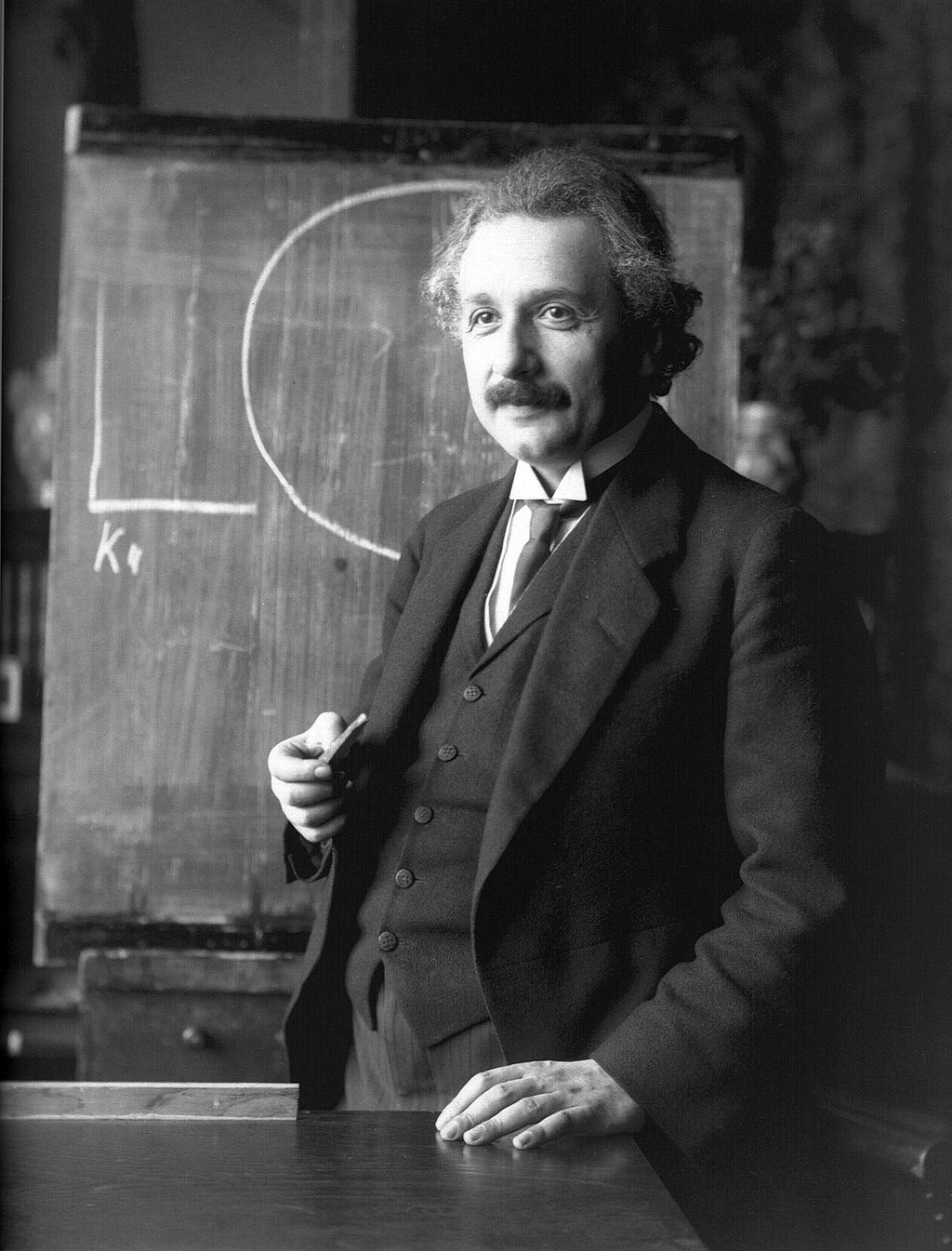

| メタファーとしての「音楽における時間」から「物理学における」へについて(思考実験) |

|

| In theoretical physics, the

problem of time is a conceptual conflict between general relativity and

quantum mechanics in that quantum mechanics regards the flow of time as

universal and absolute, whereas general relativity regards the flow of

time as malleable and relative.[1][2] This problem raises the question

of what time really is in a physical sense and whether it is truly a

real, distinct phenomenon. It also involves the related question of why

time seems to flow in a single direction, despite the fact that no

known physical laws at the microscopic level seem to require a single

direction.[3] |

理論物理学において、時間の問題は一般相対性理論と量子力学の間の概念

的な対立である。量子力学は時間の流れを普遍的で絶対的なものとみなしているのに対し、一般相対性理論は時間の流れを可鍛性で相対的なものとみなしてい

る。また、ミクロなレベルでは単一の方向を必要とするような物理法則は知られていないにもかかわらず、なぜ時間は単一の方向に流れているように見えるのか

という関連した問題も含んでいる[3]。 |

Time in quantum mechanics Time in quantum mechanicsIn classical mechanics, a special status is assigned to time in the sense that it is treated as a classical background parameter, external to the system itself. This special role is seen in the standard formulation of quantum mechanics. It is regarded as part of a priori given classical background with a well defined value. The classical treatment of time is intertwined with the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, and, thus, with the conceptual foundations of quantum theory: all measurements of observables are made at certain instants of time and probabilities are only assigned to such measurements. Overturning of absolute time in general relativity Though classically spacetime appears to be an absolute background, within general relativity time is no longer a background parameter, but must be considered on equal footing with space, and time and space evolve together as spacetime. Gravity is a manifestation of spacetime geometry, and spacetime is not fixed, but dynamic, as evidenced by phenomena such as gravitational waves. |

量子力学における時間 量子力学における時間古典力学では、時間には特別な地位が与えられており、それは古典的な背景パラメータとして扱われ、システム自体の外部にある。この特別な役割は、量子力学 の標準的な定式化にも見られる。時間は、先験的に与えられた古典的背景の一部とみなされ、その値は明確に定義されている。時間の古典的な扱いは、量子力学 のコペンハーゲン解釈、ひいては量子論の概念的基礎と絡み合っている:観測値の測定はすべて時間のある瞬間に行われ、確率はそのような測定にのみ割り当て られる。 一般相対性理論における絶対時間の逆転 古典的には、時空は絶対的な背景であるように見えるが、一般相対性理論では、時間はもはや背景パラメータではなく、空間と同等に考えなければならず、時間 と空間は時空として一緒に進化する。重力は時空幾何学の現れであり、重力波などの現象が示すように、時空は固定されたものではなく、動的なものである。 |

| Proposed solutions to the problem of time The quantum concept of time first emerged from early research on quantum gravity, in particular from the work of Bryce DeWitt in the 1960s:[4], which resulted in the Wheeler–DeWitt equation. "Other times are just special cases of other universes." In other words, time is an entanglement phenomenon, which places all equal clock readings (of correctly prepared clocks – or of any objects usable as clocks) into the same history. This was first understood by physicists Don Page and William Wootters in 1983.[5] They made a proposal to address the problem of time in systems like general relativity called conditional probabilities interpretation.[6] It consists in promoting all variables to quantum operators, one of them as a clock, and asking conditional probability questions with respect to other variables. They arrived at a solution based on the quantum phenomenon of entanglement. Page and Wootters showed how quantum entanglement can be used to measure time.[7] In 2013, at the Istituto Nazionale di Ricerca Metrologica (INRIM) in Turin, Italy, Ekaterina Moreva, together with Giorgio Brida, Marco Gramegna, Vittorio Giovannetti, Lorenzo Maccone, and Marco Genovese performed the first experimental test of Page and Wootters' ideas. They confirmed that time is an emergent phenomenon for internal observers but absent for external observers of the universe just as the Wheeler–DeWitt equation predicts.[8][9][10] Consistent discretizations approach developed by Jorge Pullin and Rodolfo Gambini have no constraints. These are lattice approximation techniques for quantum gravity. In the canonical approach if one discretizes the constraints and equations of motion, the resulting discrete equations are inconsistent: they cannot be solved simultaneously. To address this problem one uses a technique based on discretizing the action of the theory and working with the discrete equations of motion. These are automatically guaranteed to be consistent. Most of the hard conceptual questions of quantum gravity are related to the presence of constraints in the theory. Consistent discretized theories are free of these conceptual problems and can be straightforwardly quantized, providing a solution to the problem of time. It is a bit more subtle than this. Although without constraints and having "general evolution", the latter is only in terms of a discrete parameter that isn't physically accessible. The way out is addressed in a way similar to the Page–Wooters approach. The idea is to pick one of the physical variables to be a clock and asks relational questions. These ideas, where the clock is also quantum mechanical, have actually led to a new interpretation of quantum mechanics — the Montevideo interpretation of quantum mechanics.[11][12] This new interpretation solves the problems of the use of environmental decoherence as a solution to the problem of measurement in quantum mechanics by invoking fundamental limitations, due to the quantum mechanical nature of clocks, in the process of measurement in quantum mechanics. These limitations are very natural in the context of generally covariant theories as quantum gravity where the clock must be taken as one of the degrees of freedom of the system itself. They have also put forward this fundamental decoherence as a way to resolve the black hole information paradox.[13][14] In certain circumstances, a matter field is used to de-parametrize the theory and introduce a physical Hamiltonian. This generates physical time evolution, not a constraint. Reduced phase space quantization constraints are solved first then quantized. This approach was considered for some time to be impossible as it seems to require first finding the general solution to Einstein's equations. However, with use of ideas involved in Dittrich's approximation scheme (built on ideas of Rovelli) a way to explicitly implement, at least in principle, a reduced phase space quantization was made viable.[15] Avshalom Elitzur and Shahar Dolev argue that quantum mechanical experiments such as the Quantum Liar[16] provide evidence of inconsistent histories, and that spacetime itself may therefore be subject to change affecting entire histories.[17] Elitzur and Dolev also believe that an objective passage of time and relativity can be reconciled, and that it would resolve many of the issues with the block universe and the conflict between relativity and quantum mechanics.[18] One solution to the problem of time proposed by Lee Smolin is that there exists a "thick present" of events, in which two events in the present can be causally related to each other, but in contrast to the block universe view of time in which all time exists eternally.[19] Marina Cortês and Lee Smolin argue that certain classes of discrete dynamical systems demonstrate time asymmetry and irreversibility, which is consistent with an objective passage of time.[20] |

時間の問題に対する解決策の提案 時間の量子概念は、量子重力に関する初期の研究、特に1960年代のブライス・デウィットの研究から生まれた[4]。 "他の時間は他の宇宙の特殊なケースに過ぎない"。 言い換えれば、時間とはもつれ現象であり、(正しく準備された時計、あるいは時計として使用可能なあらゆる物体の)すべての等しい時計の読み取り値を同じ 歴史に置くものである。このことは、1983年に物理学者のドン・ペイジとウィリアム・ウーターズによって初めて理解された[5]。彼らは、一般相対性理 論のようなシステムにおける時間の問題に対処するために、条件付き確率解釈と呼ばれる提案を行った[6]。これは、すべての変数を量子作用素に昇格させ、 そのうちの1つを時計に見立てて、他の変数に関して条件付き確率を問うというものである。彼らはエンタングルメントという量子現象に基づく解決策にたどり 着いた。PageとWoottersは、量子もつれを時間計測に利用できることを示した[7]。 2013年、イタリアのトリノにある国立計量標準研究所(INRIM)で、エカテリーナ・モレヴァはジョルジョ・ブリーダ、マルコ・グラメーニャ、ヴィッ トリオ・ジョヴァネッティ、ロレンツォ・マッコーネ、マルコ・ジェノヴェーゼとともに、ペイジとウーターズのアイデアの最初の実験的テストを行った。彼ら は,Wheeler-DeWitt方程式が予言するように,時間は内部観測者にとっては創発的な現象であるが,宇宙の外部観測者にとっては存在しないこと を確認した[8][9][10]。 Jorge PullinとRodolfo Gambiniによって開発された整合離散化アプローチには制約がない。これらは量子重力に対する格子近似の手法である。カノニカルアプローチでは、拘束 条件と運動方程式を離散化すると、得られる離散方程式は矛盾する。この問題に対処するために、理論の作用を離散化し、離散運動方程式を扱う技術を用いる。 この離散方程式は自動的に矛盾しないことが保証される。量子重力に関する難しい概念の問題のほとんどは、理論における制約の存在に関連している。矛盾のな い離散化された理論は、このような概念的な問題から解放され、素直に量子化することができる。これより少し微妙なことがある。制約がなく「一般的な進化」 を持つとはいえ、後者は物理的にアクセスできない離散的なパラメーターの観点でしかない。出口は、ペイジ・ウーターズ・アプローチに似た方法で対処され る。物理変数の一つを時計として選び、関係性のある質問をするというものだ。時計も量子力学的であるというこれらの考え方は、実際に量子力学の新しい解釈 である量子力学のモンテビデオ解釈[11][12]につながっている。この新しい解釈は、量子力学における測定のプロセスにおいて、時計の量子力学的性質 に起因する基本的な制限を呼び出すことによって、量子力学における測定の問題の解決策として環境デコヒーレンスを使用することの問題を解決している。この ような制限は、量子重力のような一般に共変的な理論の文脈では非常に自然なことであり、そこでは時計はシステム自体の自由度の1つと見なされなければなら ない。彼らはまた、ブラックホール情報のパラドックスを解決する方法として、この基本的なデコヒーレンスを提唱している[13][14]。ある状況下で は、理論を非パラメトリック化し、物理的ハミルトニアンを導入するために物質場が使われる。これにより、制約ではなく物理的な時間発展が生じる。 位相空間の量子化制約がまず解かれ、それから量子化される。このアプローチは、まずアインシュタイン方程式の一般解を求める必要があるため、しばらくは不 可能だと考えられていた。しかし,Dittrichの近似スキーム(Rovelliのアイデアに基づいて作られた)のアイデアを使うことで,少なくとも原 理的には,位相空間の量子化を明示的に実装する方法が実現可能になった[15]。 Avshalom ElitzurとShahar Dolevは、Quantum Liar[16]のような量子力学的実験が矛盾した歴史の証拠を提供し、それゆえ時空それ自体が歴史全体に影響を与える変化を受ける可能性があると論じて いる[17]。ElitzurとDolevはまた、客観的な時間の経過と相対性理論は調和可能であり、ブロック宇宙や相対性理論と量子力学の対立に関する 問題の多くを解決できると考えている[18]。 リー・スモリンによって提案された時間の問題に対する1つの解決策は、事象の「厚い現在」が存在し、その現在における2つの事象は互いに因果関係を持つこ とができるが、すべての時間が永遠に存在するブロック宇宙的な時間の見方とは対照的であるというものである[19]。 マリナ・コルテスとリー・スモリンは、離散力学系のある種のクラスが時間の非対称性と不可逆性を示すと主張しており、これは客観的な時間の経過と矛盾しな い[20]。 |

| Weyl time in scale-invariant quantum gravity Motivated by the Immirzi ambiguity in loop quantum gravity and the near conformal invariance of the standard model of elementary particles,[21] Charles Wang and co-workers have argued that the problem of time may be related to an underlying scale invariance of gravity-matter systems.[22][23][24] Scale invariance has also been proposed to resolve the hierarchy problem of fundamental couplings.[25] As a global continuous symmetry, scale invariance generates a conversed Weyl current[22][23] according to Noether’s theorem. In scale-invariant cosmological models, this Weyl current naturally gives rise to a harmonic time.[26] In the context of loop quantum gravity, Charles Wang et al suggest that scale invariance may lead to the existence of a quantized time.[22] |

スケール不変量子重力におけるウェイル時間 ループ量子重力におけるイミルジ曖昧性と素粒子の標準模型のほぼ共形不変性に動機づけられ[21],Charles Wangとその共同研究者は,時間の問題が重力物質系の根底にあるスケール不変性に関係しているかもしれないと主張している[22][23][24]。 [22][23][24]。スケール不変性は、基本的結合の階層問題を解決するためにも提案されている。ループ量子重力の文脈では、Charles Wangらがスケール不変性が量子化された時間の存在につながる可能性を示唆している[22]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Problem_of_time |

|

| The specious present

is the time duration wherein one's perceptions are considered to be in

the present. Time perception studies the sense of time, which differs

from other senses since time cannot be directly perceived but must be

reconstructed by the brain. Description The term was coined by E. Robert Kelly,[2] better known under the pseudonym "E. R. Clay".[3] The relation of experience to time has not been profoundly studied. Its objects are given as being of the present, but the part of time referred to by the datum is a very different thing from the conterminous of the past and future which philosophy denotes by the name Present. The present to which the datum refers is really a part of the past—a recent past—delusively given as being a time that intervenes between the past and the future. Let it be named the specious present, and let the past, that is given as being the past, be known as the obvious past. All the notes of a bar of a song seem to the listener to be contained in the present. All the changes of place of a meteor seem to the beholder to be contained in the present. At the instant of the termination of such series, no part of the time measured by them seems to be a past. Time, then, considered relatively to human apprehension, consists of four parts, viz., the obvious past, the specious present, the real present, and the future. Omitting the specious present, it consists of three ... nonentities—the past, which does not exist, the future, which does not exist, and their conterminous, the present; the faculty from which it proceeds lies to us in the fiction of the specious present.[1] The concept was further developed by philosopher William James.[3] James defined the specious present to be "the prototype of all conceived times... the short duration of which we are immediately and incessantly sensible". C. D. Broad in "Scientific Thought" (1930) further elaborated on the concept of the specious present, and considered that the Specious Present may be considered as the temporal equivalent of a sensory datum. Finally, the claim of what precisely is being affirmed, in affirming the 'existence' of the specious present, is difficult to clarify. Philosophical theories of time do not usually interpret time to be in any unique way a production of human phenomenology, and the claim that we have some faculty by which we are aware of successive states of consciousness is trivially true.[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Specious_present |

空間的現在とは、自分の知覚が現在にあるとみなされる時間のことである。時間知覚は時間の感覚を研究するもので、他の感覚とは異なり、時間は直接知覚することができず、脳によって再構築される必要がある。 解説 この言葉は、「E.R.クレイ」というペンネームで知られるE.ロバート・ケリーによって作られた[2]。 経験と時間との関係は深く研究されてこなかった。その対象は現在のものとして与えられているが、データム(単数のデータ)によって参照される時間の部分 は、哲学が「現在」という名で示す過去と未来の連続体とはまったく異なるものである。データムが指す現在とは、実際には過去の一部分であり、過去と未来の 間に介在する時間として錯誤的に与えられた最近の過去である。それを「偽りの現在」と名付け、過去であるとして与えられた過去を「明白な過去」と呼ぼう。 歌の1小節の音符はすべて、聴き手には現在に含まれているように見える。流星の場所の変化はすべて、見る者には現在に含まれているように見える。このよう な一連の流れが終わる瞬間には、それによって計測された時間のどの部分も過去には見えない。つまり、時間は4つの部分、すなわち明白な過去、まやかしの現 在、現実の現在、そして未来からなる。偽りの現在を省くと、それは3つの......実体のないもの、すなわち存在しない過去、存在しない未来、そしてそ れらの集合体である現在からなる。 この概念は哲学者のウィリアム・ジェームズによってさらに発展した[3]。ジェームズは推測された現在を「すべての時間の原型......我々が即座に絶 え間なく感知している短い持続時間」と定義した。C.D.ブロードは『科学的思考』(1930年)の中で、思弁的現在という概念をさらに詳しく説明し、思 弁的現在とは感覚的データの時間的等価物であると考えた。 最後に、思弁的な現在の「存在」を肯定することによって、いったい何が肯定されるのか、という主張の解明は難しい。哲学的な時間論は通常、時間を人間の現 象学の産物として独自の方法で解釈することはなく、私たちが連続する意識状態を認識する何らかの能力を持っているという主張は些細なことである[4]。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆