持続あるいはベルクソン的時間

Duration and/or Bergsonian Time

☆ アンリ・ベルクソンは時間は数学や科学からは逃れられるという結論に達した。個人にとって、時間は速くなったり遅くなったりするが、科学にとっては変わらな い。それゆえベルクソンは、人間の内面的な生を探求することにしたのである。それは想像力の単純な直観によってのみ把握することができる

Duration (French: la

durée) is a theory of time and consciousness posited by the French

philosopher Henri Bergson. Bergson sought to improve upon inadequacies

he perceived in the philosophy of Herbert Spencer, due, he believed, to

Spencer's lack of comprehension of mechanics, which led Bergson to the

conclusion that time eluded mathematics and science.[1] Bergson became

aware that the moment one attempted to measure a moment, it would be

gone: one measures an immobile, complete line, whereas time is mobile

and incomplete. For the individual, time may speed up or slow down,

whereas, for science, it would remain the same. Hence Bergson decided

to explore the inner life of man, which is a kind of duration, neither

a unity nor a quantitative multiplicity.[1] Duration is ineffable and

can only be shown indirectly through images that can never reveal a

complete picture. It can only be grasped through a simple intuition of

the imagination.[2] Duration (French: la

durée) is a theory of time and consciousness posited by the French

philosopher Henri Bergson. Bergson sought to improve upon inadequacies

he perceived in the philosophy of Herbert Spencer, due, he believed, to

Spencer's lack of comprehension of mechanics, which led Bergson to the

conclusion that time eluded mathematics and science.[1] Bergson became

aware that the moment one attempted to measure a moment, it would be

gone: one measures an immobile, complete line, whereas time is mobile

and incomplete. For the individual, time may speed up or slow down,

whereas, for science, it would remain the same. Hence Bergson decided

to explore the inner life of man, which is a kind of duration, neither

a unity nor a quantitative multiplicity.[1] Duration is ineffable and

can only be shown indirectly through images that can never reveal a

complete picture. It can only be grasped through a simple intuition of

the imagination.[2]Bergson first introduced his notion of duration in his essay Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness. It is used as a defense of free will in a response to Immanuel Kant, who believed free will was only possible outside time and space.[3] |

持

続=デュレーション(フランス語:la

durée)は、フランスの哲学者アンリ・ベルクソンによって提唱された時間と意識の理論である。ベルクソンは、ハーバート・スペンサーの哲学に見られる

不十分な点を改善しようと努めたが、その原因はスペンサーが力学を理解していなかったことにあると考え、ベルクソンは時間は数学や科学からは逃れられると

いう結論に達した[1]。個人にとって、時間は速くなったり遅くなったりするが、科学にとっては変わらない。それゆえベルクソンは、人間の内面的な生を探

求することにしたのである。それは想像力の単純な直観によってのみ把握することができる[2]。 持

続=デュレーション(フランス語:la

durée)は、フランスの哲学者アンリ・ベルクソンによって提唱された時間と意識の理論である。ベルクソンは、ハーバート・スペンサーの哲学に見られる

不十分な点を改善しようと努めたが、その原因はスペンサーが力学を理解していなかったことにあると考え、ベルクソンは時間は数学や科学からは逃れられると

いう結論に達した[1]。個人にとって、時間は速くなったり遅くなったりするが、科学にとっては変わらない。それゆえベルクソンは、人間の内面的な生を探

求することにしたのである。それは想像力の単純な直観によってのみ把握することができる[2]。ベルクソンは『時間と自由意志』というエッセイの中で、持続時間という概念を初めて紹介した: 意識の即物的データに関する試論』(An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness)である。自由意志は時間と空間の外でのみ可能であると考えたイマヌエル・カントに対する反論として、自由意志を擁護するため に使用された[3]。 |

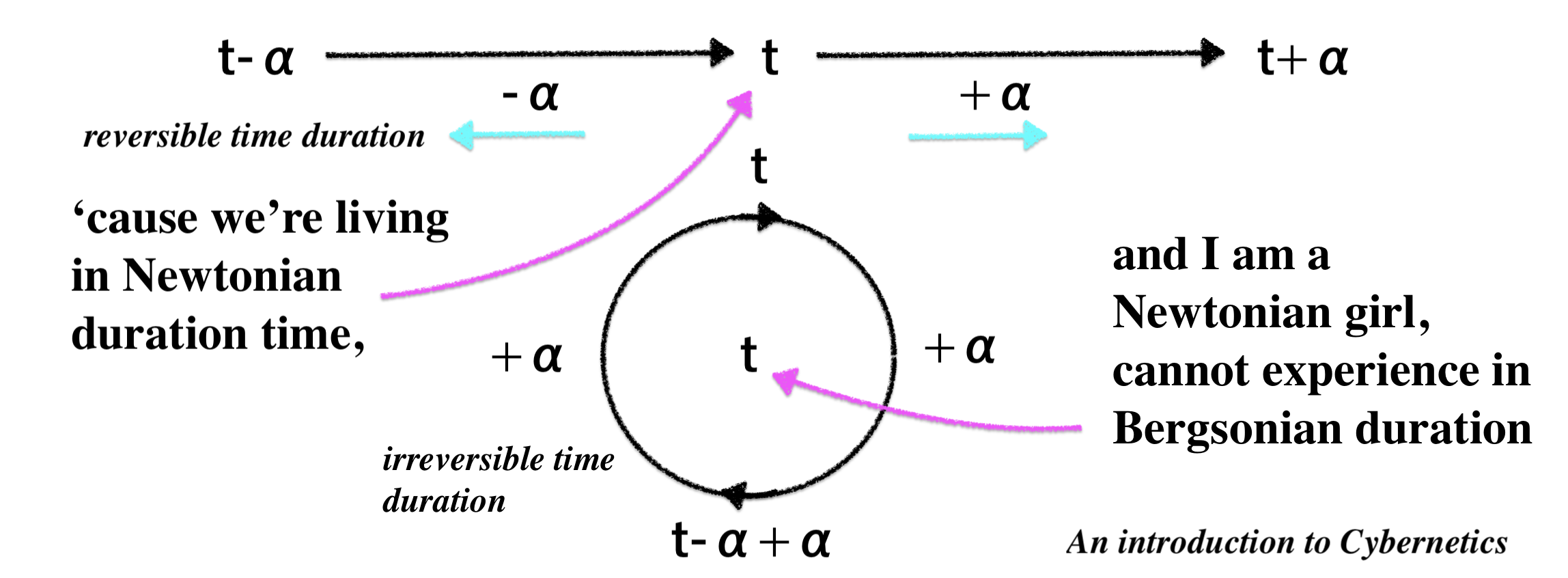

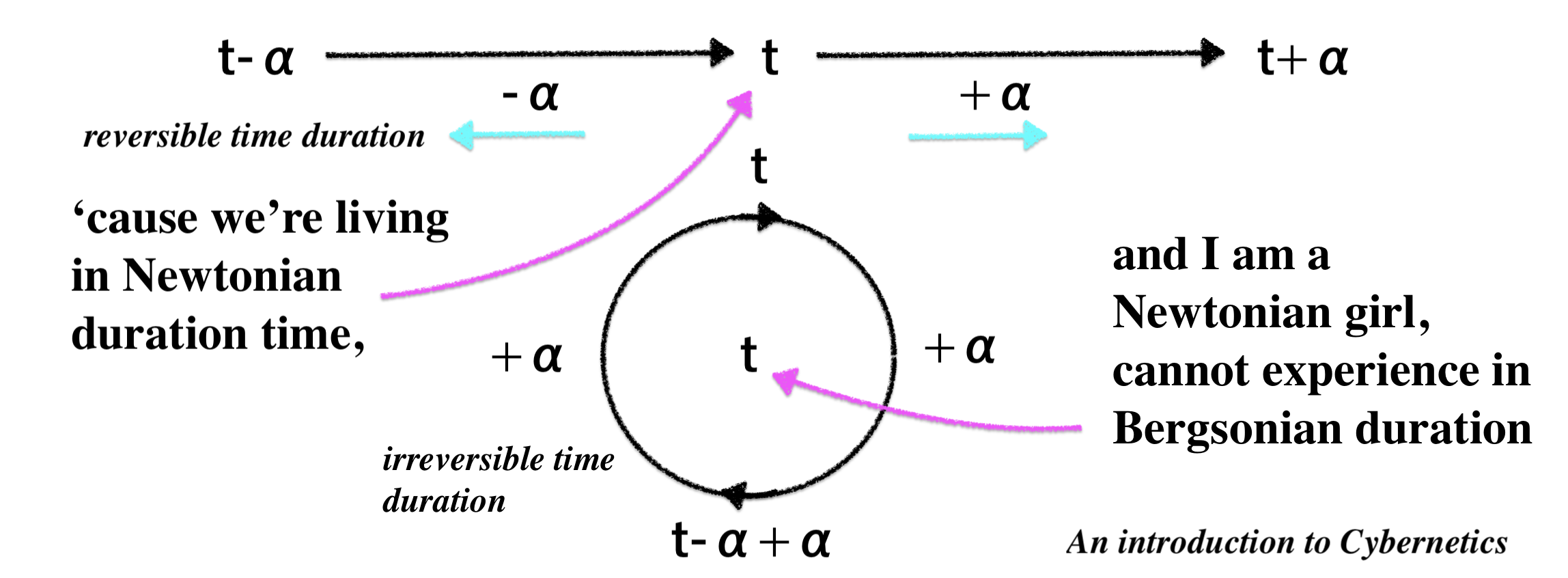

Responses to Kant and Zeno Immanuel Kant, who believed free will was only a pragmatic belief. Zeno of Elea believed reality was an uncreated and indestructible immobile whole.[4] He formulated four paradoxes to present mobility as an impossibility. We can never, he said, move past a single point because each point is infinitely divisible, and it is impossible to cross an infinite space.[5] But to Bergson, the problem only arises when mobility and time, that is, duration, are mistaken for the spatial line that underlies them. Time and mobility are mistakenly treated as things, not progressions. They are treated retrospectively as a thing's spatial trajectory, which can be divided ad infinitum, whereas they are, in fact, an indivisible whole.[6] Bergson's response to Kant is that free will is possible within a duration within which time resides. Free will is not really a problem but merely a common confusion among philosophers caused by the immobile time of science.[7] To measure duration (durée), it must be translated into the immobile, spatial time (temps) of science, a translation of the unextended into the extended. It is through this translation that the problem of free will arises. Since space is a homogeneous, quantitative multiplicity, as opposed to what Bergson calls a heterogenous, qualitative multiplicity,[8] duration becomes juxtaposed and converted into a succession of distinct parts, one coming after the other and therefore "caused" by one another. Nothing within a duration can be the cause of anything else within it. Hence determinism, the belief everything is determined by a prior cause, is an impossibility. One must accept time as it really is through placing oneself within duration where freedom can be identified and experienced as pure mobility.[9] |

カントとゼノンへの反論 自由意志はプラグマティックな信念に過ぎないと考えていたイマニュエル・カント。 エレアのゼノンは、現実は創造されず、破壊されない不動の全体であると信じていた。なぜなら各点は無限に分割可能であり、無限の空間を横切ることは不可能 だからである[5]。しかしベルクソンに言わせれば、問題は移動性と時間、すなわち持続時間が、それらの根底にある空間的な線と取り違えられたときにのみ 生じる。時間と移動性は、進行ではなく、物事として誤って扱われる。それらは事物の空間的な軌跡として遡及的に扱われ、それは無限に分割することができる が、実際には不可分の全体である[6]。 カントに対するベルクソンの回答は、自由意志は時間が存在する持続時間の中で可能であるというものである。自由意志は実際には問題ではなく、科学における 不動の時間によって引き起こされる哲学者たちの共通の混乱に過ぎない。この翻訳によって自由意志の問題が生じる。空間は、ベルクソンが異質で質的な多様性 と呼ぶものとは対照的に、均質で量的な多様性である[8]。持続時間の中にあるものは、その中にある他のものの原因にはなりえない。従って、決定論、つま り、すべてが事前の原因によって決定されると考えることは不可能である。人は、自由を識別し、純粋な可動性として経験することができる持続時間の中に身を 置くことによって、時間をありのままに受け入れなければならない[9]。 |

Images of duration The

first is of two spools, one unrolling to represent the continuous flow

of ageing as one feels oneself moving toward the end of one's

life-span, the other rolling up to represent the continuous growth of

memory which, for Bergson, equals consciousness. No two successive

moments are identical, for the one will always contain the memory left

by the other. A person with no memory might experience two identical

moments but, Bergson says, that person's consciousness would thus be in

a constant state of death and rebirth, which he identifies with

unconsciousness.[10] The image of two spools, however, is of a

homogeneous and commensurable thread, whereas, according to Bergson, no

two moments can be the same, hence duration is heterogeneous. The

first is of two spools, one unrolling to represent the continuous flow

of ageing as one feels oneself moving toward the end of one's

life-span, the other rolling up to represent the continuous growth of

memory which, for Bergson, equals consciousness. No two successive

moments are identical, for the one will always contain the memory left

by the other. A person with no memory might experience two identical

moments but, Bergson says, that person's consciousness would thus be in

a constant state of death and rebirth, which he identifies with

unconsciousness.[10] The image of two spools, however, is of a

homogeneous and commensurable thread, whereas, according to Bergson, no

two moments can be the same, hence duration is heterogeneous.Bergson then presents the image of a spectrum of a thousand gradually changing shades with a line of feeling running through them, being both affected by and maintaining each of the shades. Yet even this image is inaccurate and incomplete, for it represents duration as a fixed and complete spectrum with all the shades spatially juxtaposed, whereas duration is incomplete and continuously growing, its states not beginning or ending but intermingling.[10][11] Instead, let us imagine an infinitely small piece of elastic, contracted, if that were possible, to a mathematical point. Let us draw it out gradually in such a way as to bring out of the point a line which will grow progressively longer. Let us fix our attention not on the line as line, but on the action which traces it. Let us consider that this action, in spite of its duration, is indivisible if one supposes that it goes on without stopping; that, if we intercalate a stop in it, we make two actions of it instead of one and that each of these actions will then be the indivisible of which we speak; that it is not the moving act itself which is never indivisible, but the motionless line it lays down beneath it like a track in space. Let us take our mind off the space subtending the movement and concentrate solely on the movement itself, on the act of tension or extension, in short, on pure mobility. This time we shall have a more exact image of our development in duration. — Henri Bergson, The Creative Mind: An Introduction to Metaphysics, pages 164 to 165. Even this image is incomplete, because the wealth of colouring is forgotten when it is invoked.[10] But as the three images illustrate, it can be stated that duration is qualitative, unextended, multiple yet a unity, mobile and continuously interpenetrating itself. Yet these concepts put side-by-side can never adequately represent duration itself; The truth is we change without ceasing...there is no essential difference between passing from one state to another and persisting in the same state. If the state which "remains the same" is more varied than we think, [then] on the other hand the passing of one state to another resembles—more than we imagine—a single state being prolonged: the transition is continuous. Just because we close our eyes to the unceasing variation of every physical state, we are obliged when the change has become so formidable as to force itself on our attention, to speak as if a new state were placed alongside the previous one. Of this new state we assume that it remains unvarying in its turn and so on endlessly.[12] Because a qualitative multiplicity is heterogeneous and yet interpenetrating, it cannot be adequately represented by a symbol; indeed, for Bergson, a qualitative multiplicity is inexpressible. Thus, to grasp duration, one must reverse habitual modes of thought and place oneself within duration by intuition.[2] |

持続時間のイメージ 一

方は、自分の寿命が尽きようとしているのを感じながら、歳を重ねるという絶え間ない流れを表し、もう一方は、ベルクソンにとって意識に等しい記憶の絶え間

ない成長を表している。連続する2つの瞬間が同じであることはなく、一方は常に他方が残した記憶を含んでいるからである。しかし、ベルクソンによれば、2

つの糸巻きのイメージは均質で共有可能な糸のイメージであり、一方、2つの瞬間が同じであることはあり得ず、それゆえ、持続時間は不均質である。 一

方は、自分の寿命が尽きようとしているのを感じながら、歳を重ねるという絶え間ない流れを表し、もう一方は、ベルクソンにとって意識に等しい記憶の絶え間

ない成長を表している。連続する2つの瞬間が同じであることはなく、一方は常に他方が残した記憶を含んでいるからである。しかし、ベルクソンによれば、2

つの糸巻きのイメージは均質で共有可能な糸のイメージであり、一方、2つの瞬間が同じであることはあり得ず、それゆえ、持続時間は不均質である。ベルクソンは次に、徐々に変化する千の色合いのスペクトルのイメージを提示する。しかし、このイメージでさえも不正確で不完全である。というのも、このイ メージは持続時間を、すべての陰影が空間的に並置された固定された完全なスペクトルとして表しているからである。 その代わりに、可能であれば数学的な点まで収縮させた、無限に小さなゴムの断片を想像してみよう。その点から徐々に長くなる線を引き出すような方法で、そ の線を徐々に引き出してみよう。線としてではなく、線をなぞる作用に注意を向けよう。この作用は、その持続時間にもかかわらず、止まることなく続いている と仮定すれば、不可分であることを考えよう。この作用に停止を挟むと、1つの作用ではなく2つの作用となり、これらの作用のそれぞれが、われわれの言う不 可分となる。動きの下にある空間から目を離し、動きそのもの、つまり張力や伸張の行為、要するに純粋な運動性だけに集中しよう。そうすれば、持続時間にお けるわれわれの発展について、より正確なイメージを持つことができるだろう。 - アンリ・ベルクソン、『創造する心』: 形而上学入門』164-165ページ。 しかし、この3つのイメージが示すように、持続時間は質的であり、延長されず、複数でありながら単一であり、移動可能であり、継続的にそれ自身を相互貫入 している。しかし、これらの概念を並べても、持続時間そのものを適切に表すことはできない; ある状態から別の状態に移行することと、同じ状態を維持することに本質的な違いはない。もし「変わらない」状態が私たちが考えている以上に変化に富んでい るとすれば、[その一方で]ある状態から別の状態への移行は、私たちが想像している以上に、ひとつの状態が長く続くことに似ている。あらゆる物理的状態が 絶え間なく変化していることに目をつぶっているために、私たちは、変化が手ごわくなって注意を向けざるを得なくなったとき、あたかも新しい状態が前の状態 と並べられたかのように話さざるを得なくなる。この新しい状態について、私たちはそれが変化することなく延々と続くと仮定する[12]。 質的な多重性は異質であり、しかも相互に浸透しているので、記号によって適切に表現することはできない。したがって、持続性を把握するためには、習慣的な 思考様式を逆転させ、直観によって持続性の中に身を置かなければならない[2]。 |

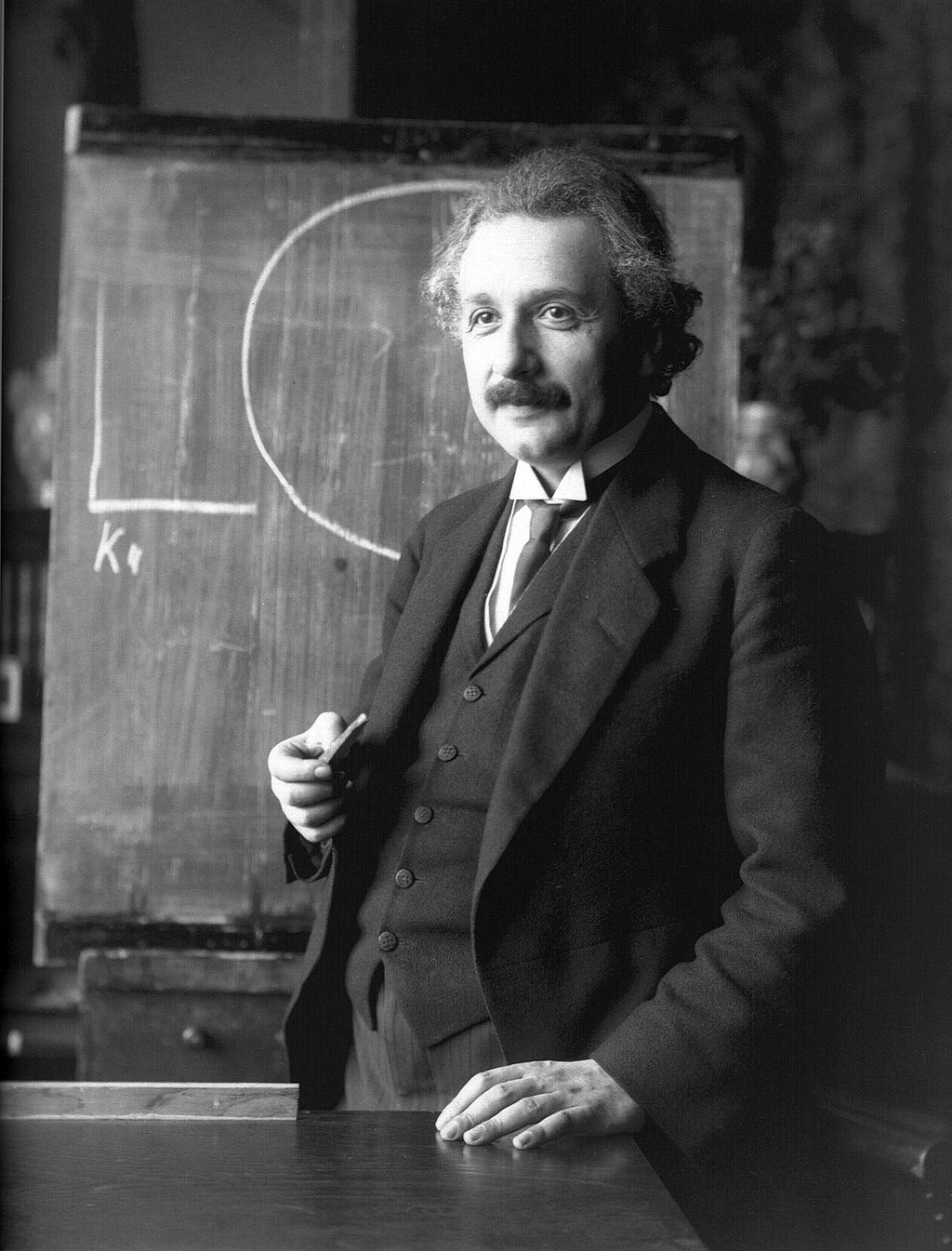

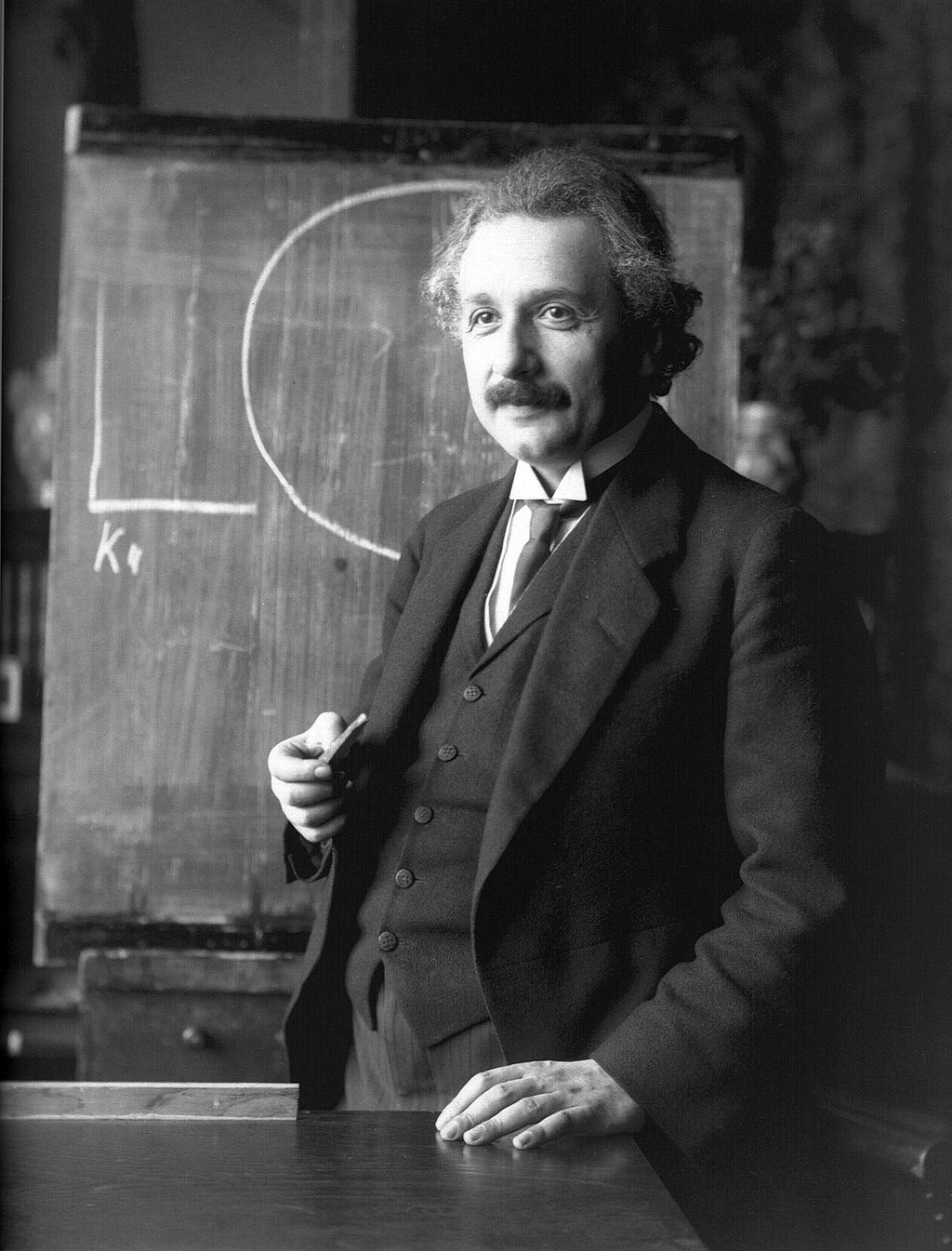

| Influence on Gilles Deleuze Gilles Deleuze was profoundly influenced by Bergson's theory of duration, particularly in his work Cinema 1: The Movement Image in which he described cinema as providing people with continuity of movement (duration) rather than still images strewn together.[13] Physics and Bergson's ideas  Albert Einstein in 1921 Bergson had a correspondence with physicist Albert Einstein in 1922 and a debate over Einstein's theory of relativity and its implications.[14] For Bergson, the primary disagreement was over metaphysical and epistemological claims made by the theory of relativity, rather than a dispute about scientific evidence for or against the theory. Bergson famously stated of the theory that it is "a metaphysics grafted upon science, it is not science".[15] |

ジル・ドゥルーズへの影響 ジル・ドゥルーズはベルクソンの持続時間の理論に大きな影響を受けており、特に彼の作品『シネマ1:運動のイメージ』では、映画は静止画を並べたものでは なく、動きの連続性(持続時間)を人々に提供するものだと述べている[13]。 物理学とベルクソンの思想  1921年、アルベルト・アインシュタイン 1922年、ベルクソンは物理学者アルベルト・アインシュタインと文通し、アインシュタインの相対性理論とその意味するところをめぐって議論を交わした [14]。ベルクソンにとって主な意見の相違は、相対性理論に対する科学的証拠についての論争というよりも、相対性理論が主張する形而上学的、認識論的な 主張をめぐるものであった。ベルクソンはこの理論について「科学の上に接ぎ木された形而上学であり、科学ではない」と述べたことで有名である[15]。 |

| Loop quantum

gravity Problem of time Specious present Uncertainty principle |

ループ量

子重力 時間の問題 擬似現在 不確定性原理 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆