時間についての簡潔な歴史

時間についての簡潔な歴史

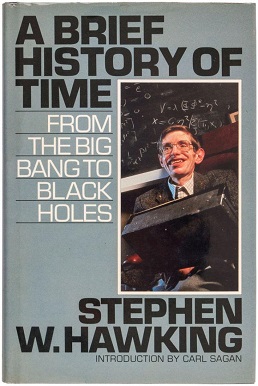

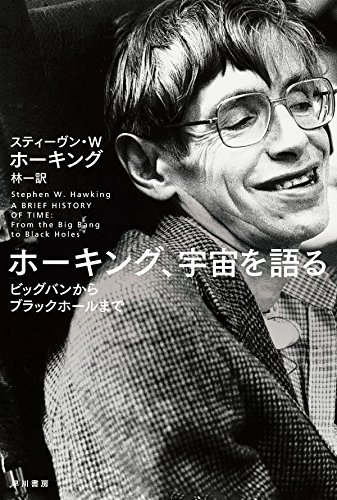

◎ A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes by Stephen Hawking, 1942-2018

★トーマス・ハートッホ(2025:

292)によると、スティーヴン・ホーキング自身がのちにこの本(「時間についての簡潔な歴史」)は「間違った視点から書いていた」と述懐している。その

間違った視点とは、神の視点であり、宇宙とその波動関数を、どうにかして外から見ているように叙述したことだという。ハートッホは「時間は存在しない」とか、ビッグバンとともに時間ははじまったので、超越論的な時間の存在は否定している。

| A Brief

History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes is a book on

theoretical cosmology by English physicist Stephen Hawking.[1] It was

first published in 1988. Hawking wrote the book for readers who had no

prior knowledge of physics. In A Brief History of Time, Hawking writes in non-technical terms about the structure, origin, development and eventual fate of the Universe, which is the object of study of astronomy and modern physics. He talks about basic concepts like space and time, basic building blocks that make up the Universe (such as quarks) and the fundamental forces that govern it (such as gravity). He writes about cosmological phenomena such as the Big Bang and black holes. He discusses two major theories, general relativity and quantum mechanics, that modern scientists use to describe the Universe. Finally, he talks about the search for a unifying theory that describes everything in the Universe in a coherent manner. The book became a bestseller and sold more than 25 million copies.[2] |

A Brief History of

Time(ア・ブリーフ・ヒストリー・オブ・タイム)。From the Big Bang to Black

Holesは、イギリスの物理学者スティーヴン・ホーキングによる理論的宇宙論に関する書籍である[1]。

1988年に初版が発行された。ホーキング博士は、物理学の予備知識のない読者に向けてこの本を書いた。 ホーキング博士は、天文学や現代物理学の研究対象である宇宙の構造、起源、発展、最終的な運命について、専門用語を使わずに書いている。空間や時間といっ た基本的な概念、宇宙を構成する基本的な構成要素(クォークなど)、宇宙を支配する基本的な力(重力など)について語られている。ビッグバンやブラック ホールなどの宇宙論的現象について書いています。一般相対性理論と量子力学という、現代の科学者が宇宙を記述するために用いている2つの主要な理論につい て論じる。そして最後に、宇宙のすべてを首尾一貫して記述する統一理論の探求について語る。 この本はベストセラーとなり、2,500万部以上売れた[2]。 |

| Publication Early in 1983, Hawking first approached Simon Mitton, the editor in charge of astronomy books at Cambridge University Press, with his ideas for a popular book on cosmology. Mitton was doubtful about all the equations in the draft manuscript, which he felt would put off the buyers in airport bookshops that Hawking wished to reach. With some difficulty, he persuaded Hawking to drop all but one equation.[3] The author himself notes in the book's acknowledgements that he was warned that for every equation in the book, the readership would be halved, hence it includes only a single equation: {\displaystyle E=mc^{2}}E = mc^2. The book does employ a number of complex models, diagrams, and other illustrations to detail some of the concepts that it explores. |

出版物 1983年の初め、ホーキング博士はケンブリッジ大学出版局で天文学の本を担当していた編集者のサイモン・ミトンに、宇宙論についての一般向けの本の構想 を持ちかけた。ミットンは、原稿に書かれているすべての方程式に疑問を持ち、ホーキング博士がアプローチしたい空港の書店の購買者を遠ざけるのではないか と考えた。著者自身は、この本の謝辞の中で、方程式を一つ入れるごとに読者が半減すると警告されたので、一つの方程式しか入れていない、と書いている [3]。{E=mc^{2}}E = mc^2. この本では、複雑なモデル、図、その他の図版を数多く用いて、探求する概念のいくつかを詳しく説明している。 |

| In A Brief History of Time,

Stephen Hawking attempts to explain a range of subjects in cosmology,

including the Big Bang, black holes and light cones, to the

non-specialist reader. His main goal is to give an overview of the

subject, but he also attempts to explain some complex mathematics. In

the 1996 edition of the book and subsequent editions, Hawking discusses

the possibility of time travel and wormholes and explores the

possibility of having a Universe without a quantum singularity at the

beginning of time. The 2017 edition of the book contained twelve

chapters, whose contents are summarized below. |

スティーブン・ホーキング博士は、『A Brief History

of

Time』の中で、ビッグバン、ブラックホール、ライトコーンなど、宇宙論におけるさまざまなテーマを、専門家ではない読者に説明することを試みている。

彼の主な目的は、このテーマの概要を説明することであるが、複雑な数学の説明も試みている。1996年版以降では、ホーキング博士はタイムトラベルやワー

ムホールの可能性を論じ、時間の始まりに量子特異点がない宇宙が存在する可能性を探っている。2017年版には12章が収録されており、その内容は以下の

ようにまとめられている。 |

| Chapter 1: Our Picture of the

Univers |

1. われわれの宇宙観 |

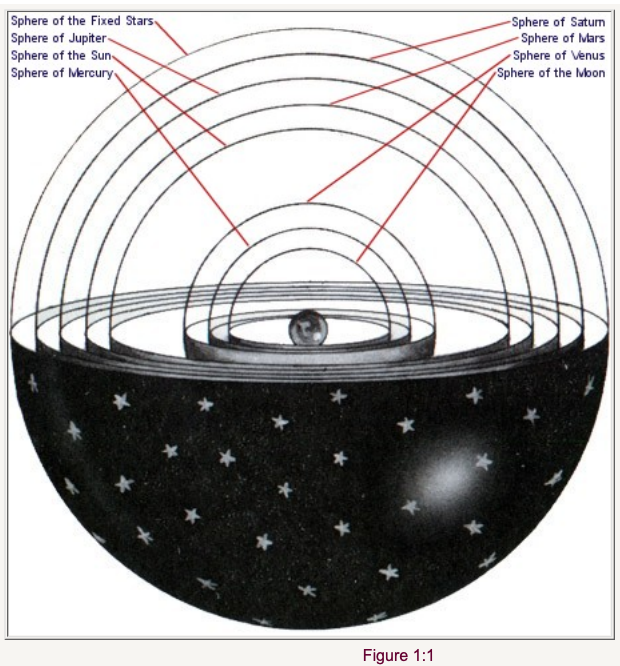

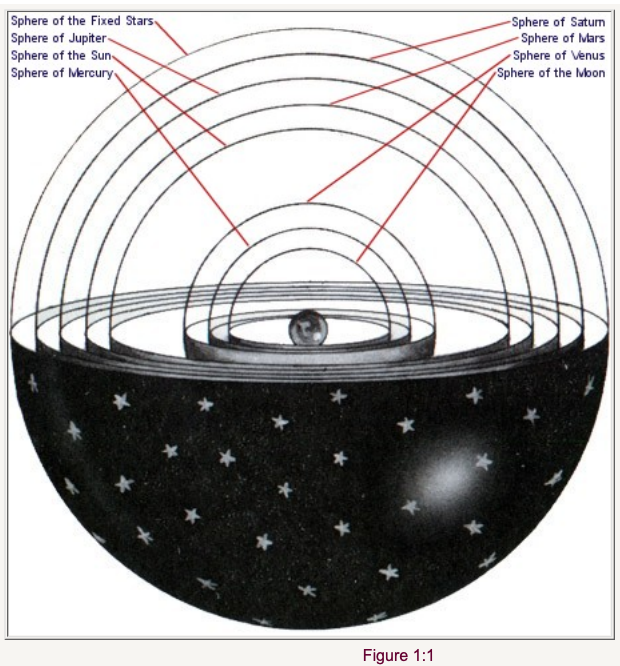

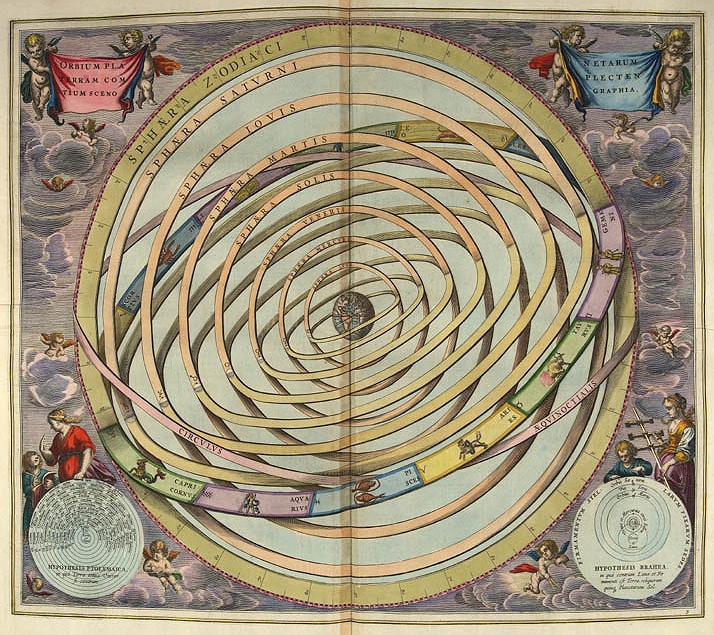

In the first chapter, Hawking discusses the history of astronomical studies, particularly ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle's conclusions about spherical Earth and a circular geocentric model of the Universe, later elaborated upon by the second-century Greek astronomer Ptolemy. Hawking then depicts the rejection of the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic model and the gradual development of the currently accepted heliocentric model of the Solar System in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, first proposed by the Polish priest Nicholas Copernicus in 1514, validated a century later by Italian scientist Galileo Galilei and German scientist Johannes Kepler (who proposed an elliptical orbit model instead of a circular one), and further supported mathematically by English scientist Isaac Newton in his 1687 book on gravity, Principia Mathematica. In this chapter, Hawking also covers how the topic of the origin of the Universe and time was studied and debated over the centuries: the perennial existence of the Universe hypothesised by Aristotle and other early philosophers was opposed by St. Augustine and other theologians' belief in its creation at a specific time in the past, where time is a concept that was born with the creation of the Universe. In the modern age, German philosopher Immanuel Kant argued again that time had no beginning. In 1929, American astronomer Edwin Hubble's discovery of the expanding Universe implied that between ten and twenty billion years ago, the entire Universe was contained in one singular extremely dense place. This discovery brought the concept of the beginning of the Universe within the province of science. Currently scientists use Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity and quantum mechanics to partially describe the workings of the Universe, while still looking for a complete Grand Unified Theory that would describe everything in the Universe.  |

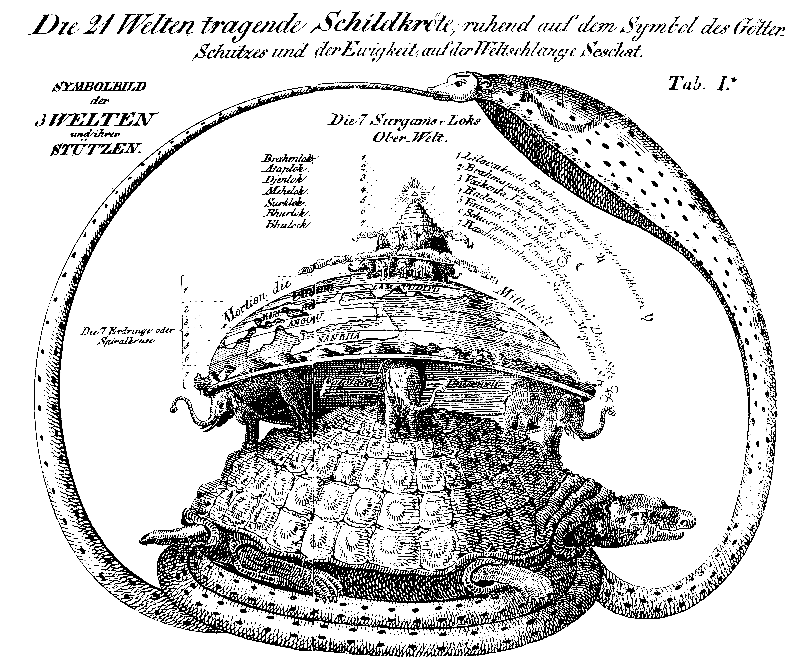

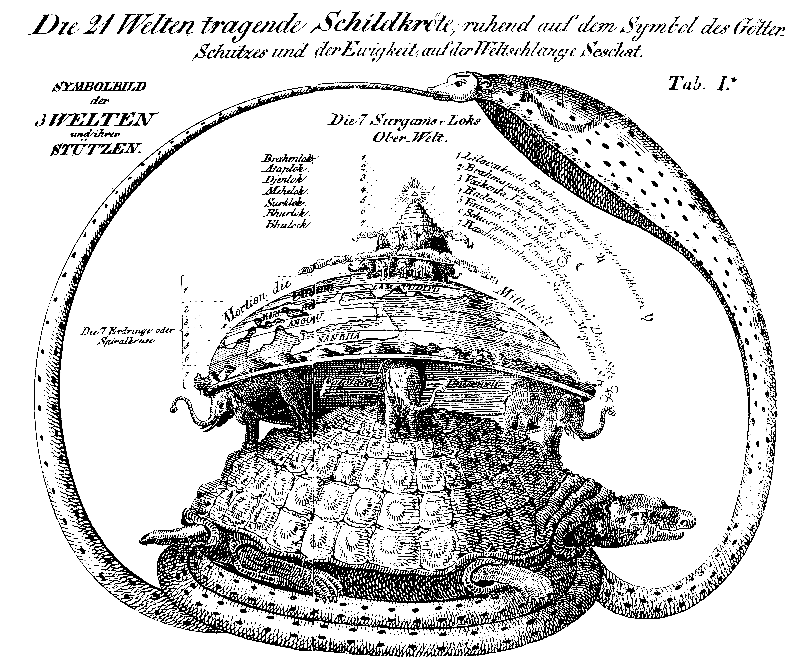

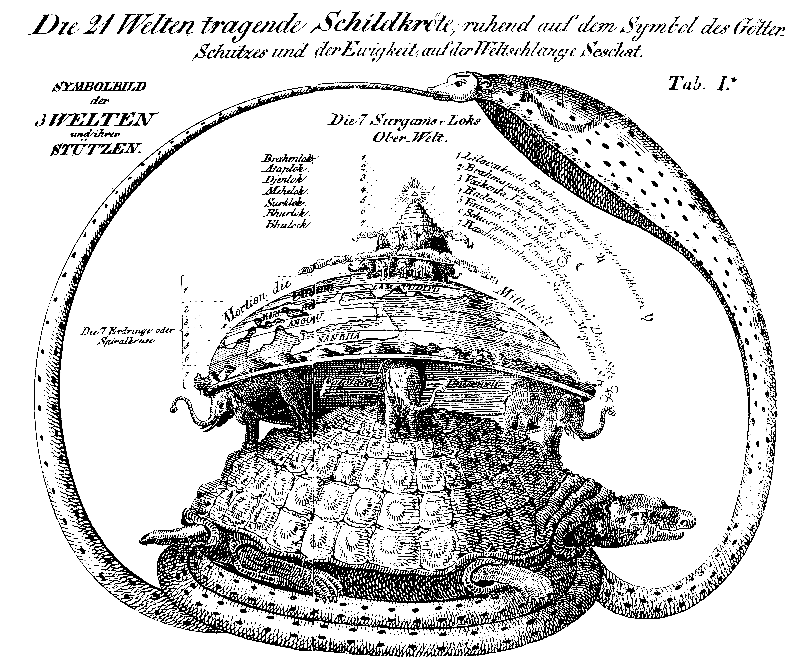

第1章では、天文研究の歴史、特に古代ギリシャの哲学者アリストテレス による球状の地球と円形の地動説の結論について、後に2世紀のギリシャの天文学者プトレマイオスが精緻な記述を行ったことについて述べている。その後、ア リストテレスやプトレマイオスのモデルが否定され、現在受け入れられている太陽系の天動説モデルが16、17、18世紀に徐々に発展していく様子が描かれ ている。その100年後、イタリアの科学者ガリレオ・ガリレイとドイツの科学者ヨハネス・ケプラー(円軌道ではなく楕円軌道を提案)が検証し、さらにイギ リスの科学者アイザック・ニュートンが1687年に重力に関する著書『プリンキピア・マテマティカ』で数学的に支持した。 この章では、宇宙と時間の起源が何世紀にもわたって研究され、議論されてきたことも取り上げています。アリストテレスなど初期の哲学者が仮定した宇宙の永 続的な存在に対し、聖アウグスティヌスなど神学者は過去の特定の時期に宇宙が創造されたと考え、時間は宇宙の創造とともに生まれた概念であるとして反論し ている。近代に入ると、ドイツの哲学者イマニュエル・カントが再び「時間には始まりがない」と主張した。1929年、アメリカの天文学者エドウィン・ハッ ブルは、宇宙の膨張を発見し、100億年から200億年前には、宇宙全体が極めて密度の高い一カ所に収まっていたことを示唆した。この発見により、宇宙の 始まりという概念が科学の領域に入ってきた。現在、科学者はアルバート・アインシュタインの一般相対性理論と量子力学を用いて宇宙の仕組みを部分的に説明 しているが、宇宙のすべてを説明する大統一理論の完成はまだ先である。  プトレマイオスモデル(恒星の天球の外側に天国と地獄が想定されていて教会にとっては都合のよいモデル)邦訳 20ページ |

| Chapter 2: Space and Time |

2. 空間と時間 |

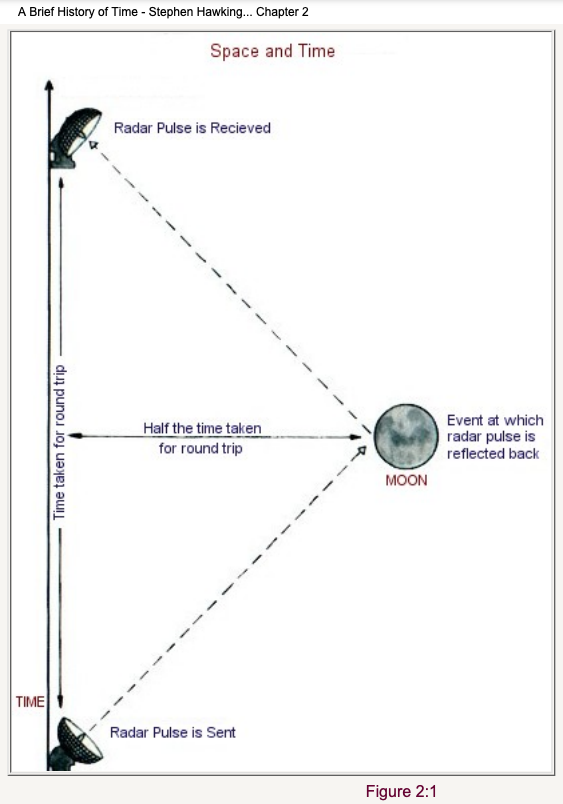

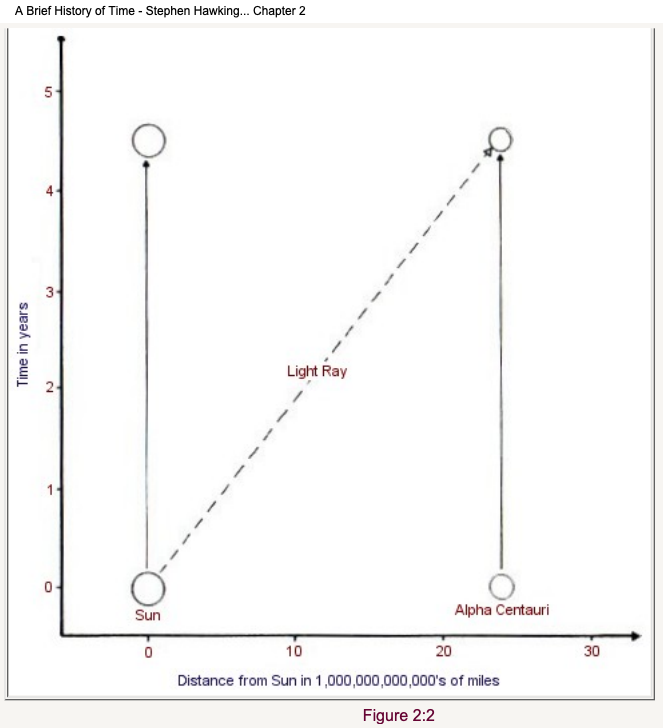

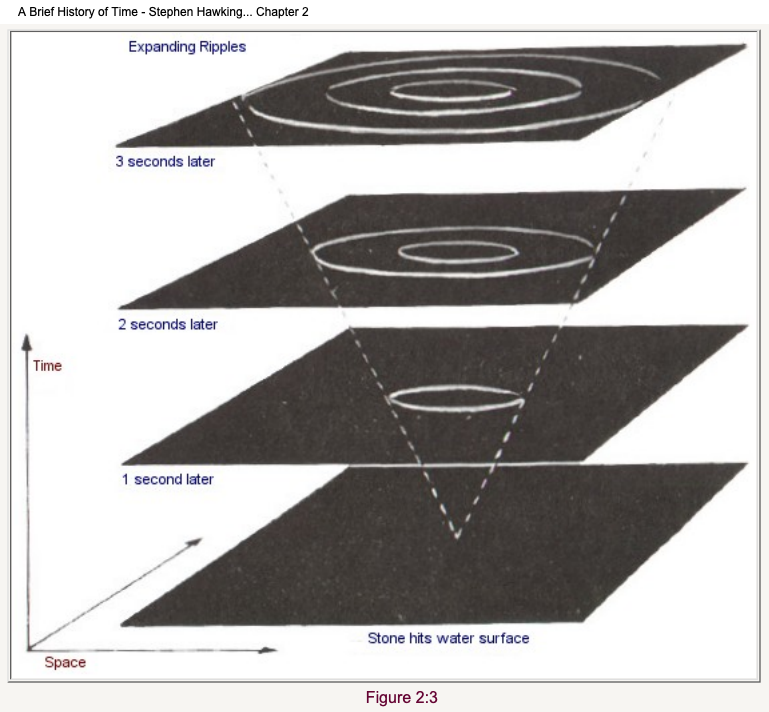

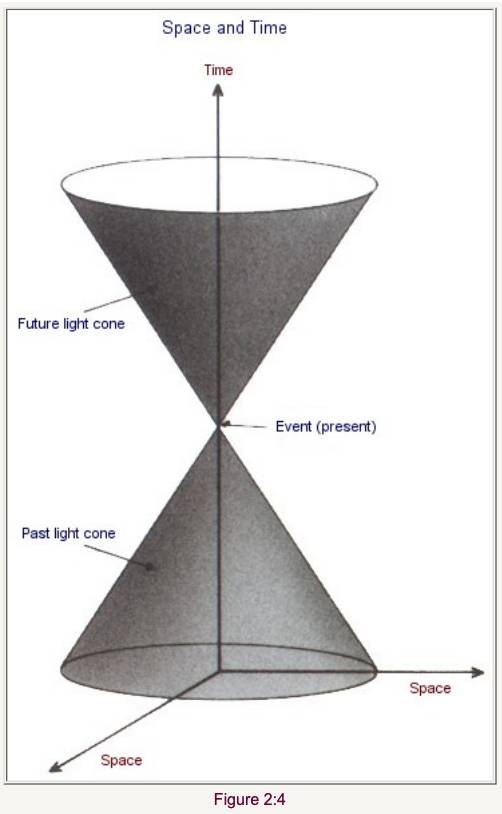

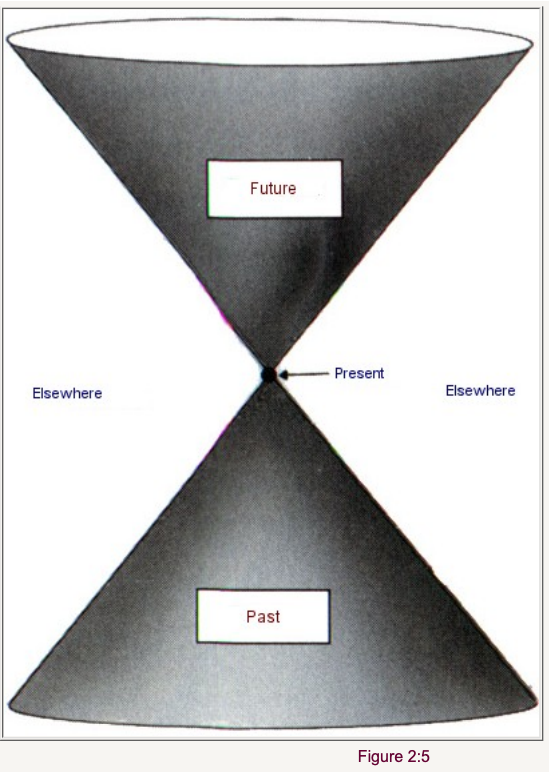

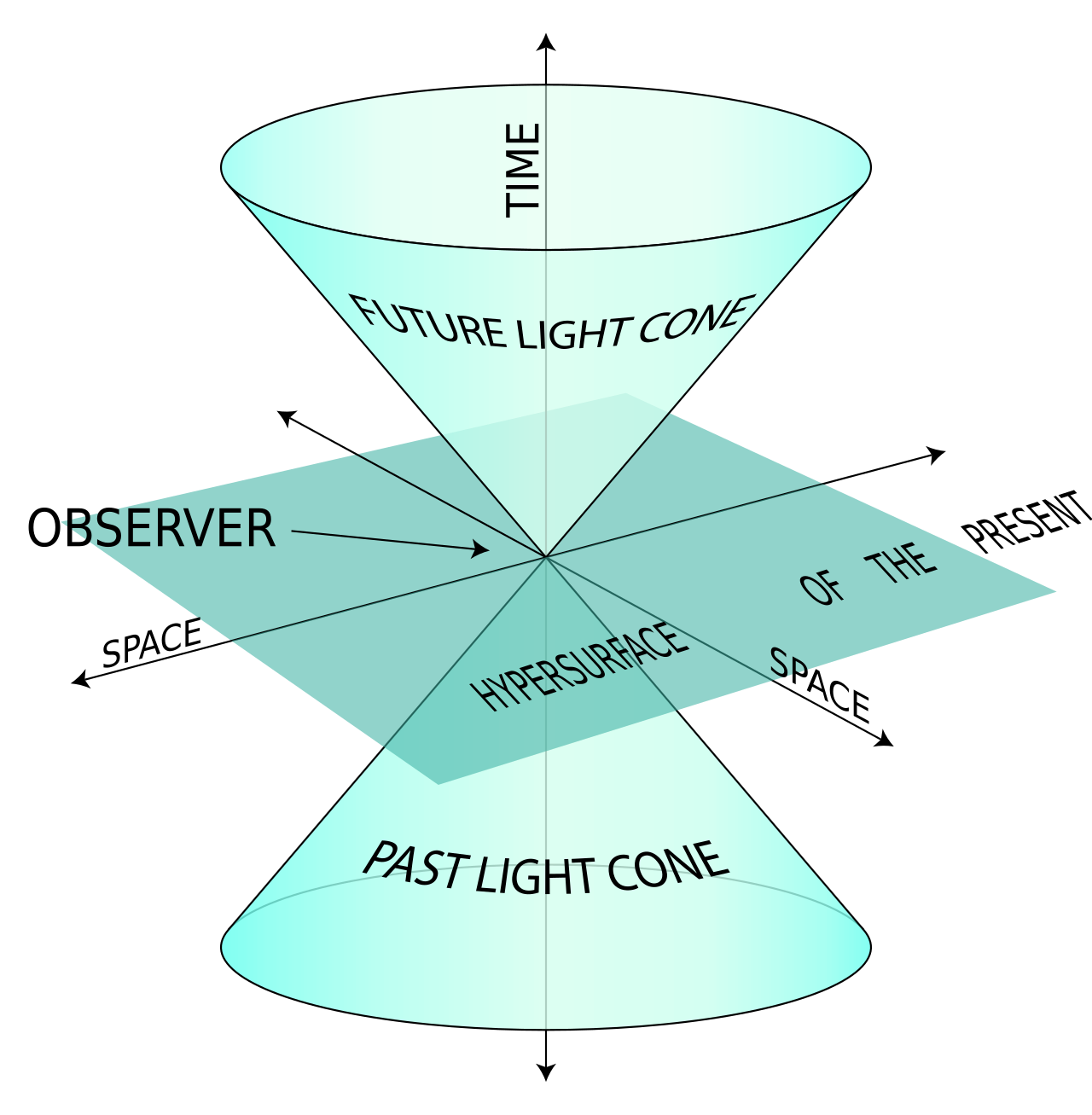

In this chapter, Hawking

describes the development of scientific thought regarding the nature of

space and time. He first describes the Aristotelian idea that the

naturally preferred state of a body is to be at rest, and which can

only be moved by force, implying that heavier objects will fall faster.

However, Italian scientist Galileo Galilei experimentally proved

Aristotle's theory wrong with by observing the motion of objects of

different weights and concluding that all objects would fall at the

same rate. This eventually led to English scientist Isaac Newton's laws

of motion and gravity. However, Newton's laws implied that there is no

such thing as absolute state of rest or absolute space as believed by

Aristotle: whether an object is 'at rest' or 'in motion' depends on the

inertial frame of reference of the observer.       Hawking then describes Aristotle and Newton's belief in absolute time, i.e. time can be measured accurately regardless of the state of motion of the observer. However, Hawking writes that this commonsense notion does not work at or near the speed of light. He mentions Danish scientist Ole Rømer's discovery that light travels at a very high but finite speed through his observations of Jupiter and one of its moons Io as well as British scientist James Clerk Maxwell's equations on electromagnetism which showed that light travels in waves moving at a fixed speed. Since the notion of absolute rest was abandoned in Newtonian mechanics, Maxwell and many other physicists argued that light must travel through a hypothetical fluid called aether, its speed being relative to that of aether. This was later disproved by the Michelson–Morley experiment, showing that the speed of light always remains constant regardless of the motion of the observer. Einstein and Henri Poincaré later argued that there is no need for aether to explain the motion of light, assuming that there is no absolute time. The special theory of relativity is based on this, arguing that light travels with a finite speed no matter what the speed of the observer is. Mass and energy are related by the famous equation {\displaystyle E=mc^{2}}E = mc^2, which explains that an infinite amount of energy is needed for any object with mass to travel at the speed of light(3×10⁸m/s). A new way of defining a metre using speed of light was developed. "Events" can also be described by using light cones, a spacetime graphical representation that restricts what events are allowed and what are not based on the past and the future light cones. A 4-dimensional spacetime is also described, in which 'space' and 'time' are intrinsically linked. The motion of an object through space inevitably impacts the way in which it experiences time. Einstein's general theory of relativity explains how the path of a ray of light is affected by 'gravity', which according to Einstein is an illusion caused by the warping of spacetime, in contrast to Newton's view which described gravity as a force which matter exerts on other matter. In spacetime curvature, light always travels in a straight path in the 4-dimensional "spacetime", but may appear to curve in 3-dimensional space due to gravitational effects. These straight-line paths are geodesics. The twin paradox, a thought experiment in special relativity involving identical twins, considers that twins can age differently if they move at different speeds relative to each other, or even if they lived in different locations with unequal spacetime curvature. Special relativity is based upon arenas of space and time where events take place, whereas general relativity is dynamic where force could change spacetime curvature and which gives rise to a dynamic, expanding Universe. Hawking and Roger Penrose worked upon this and later proved using general relativity that if the Universe had a beginning a finite time ago in the past, then it also might end at a finite time from now into the future. |

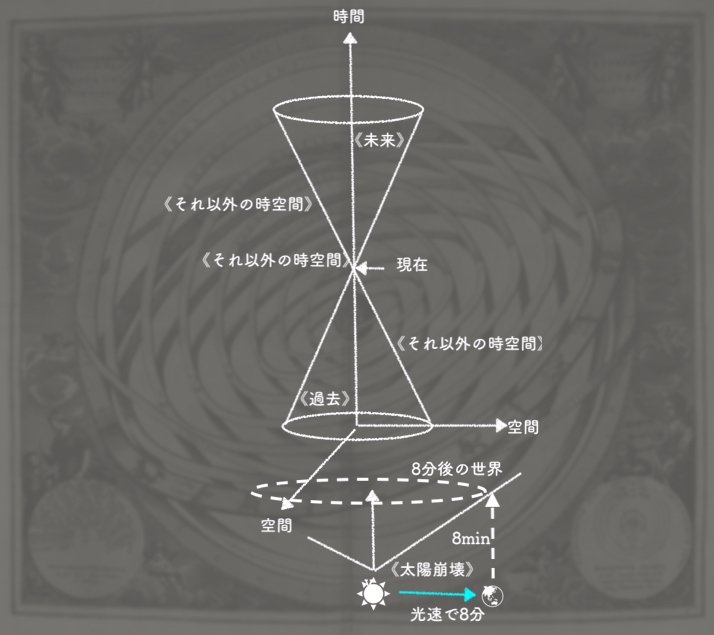

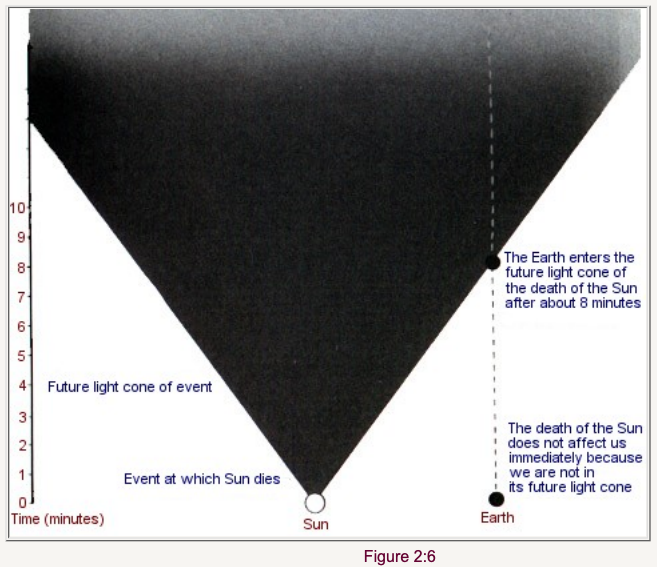

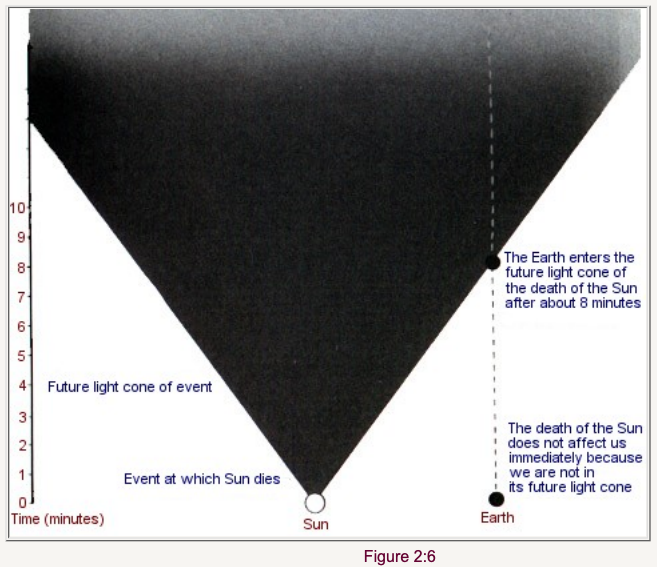

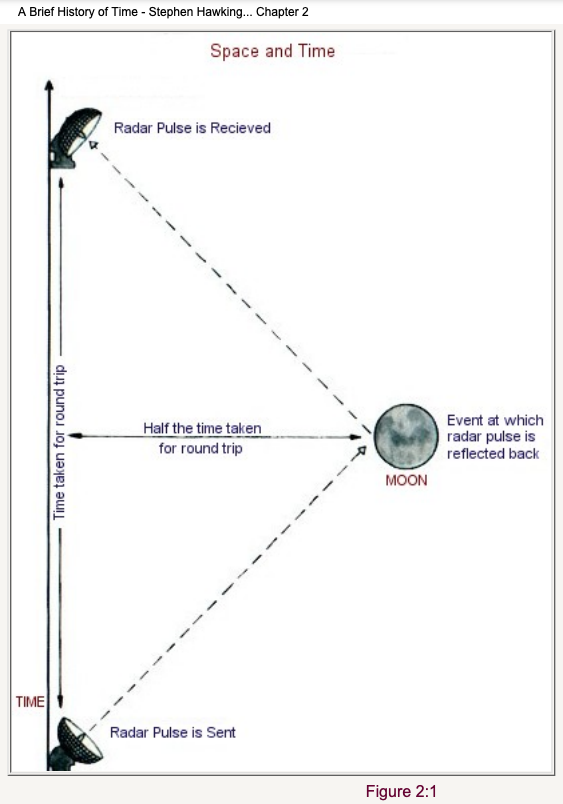

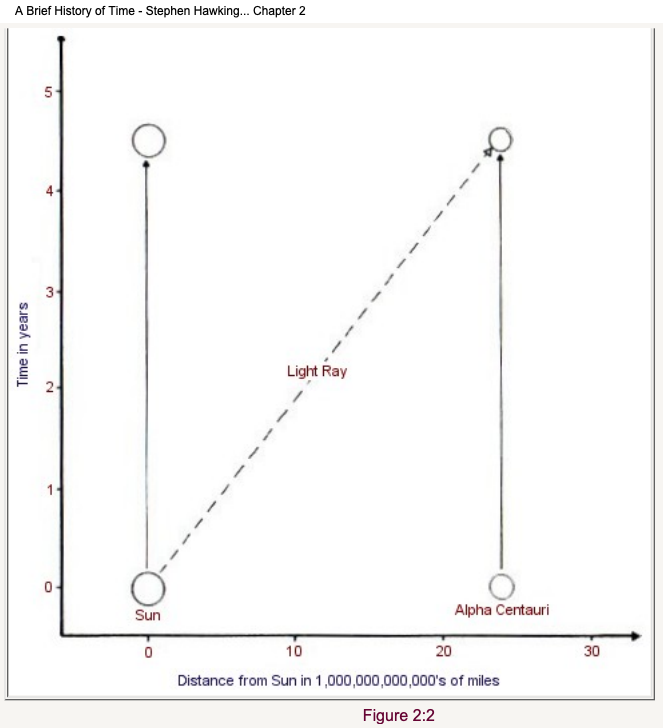

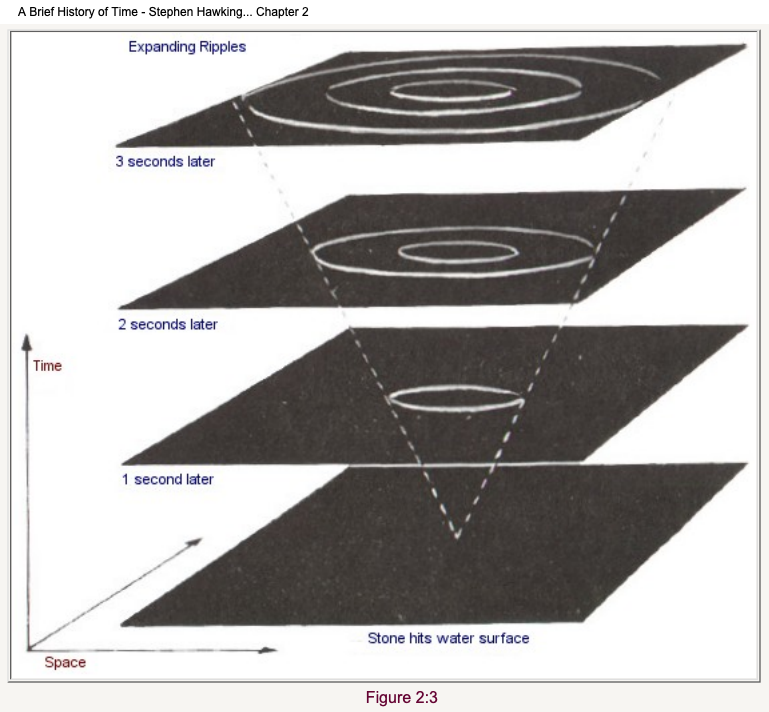

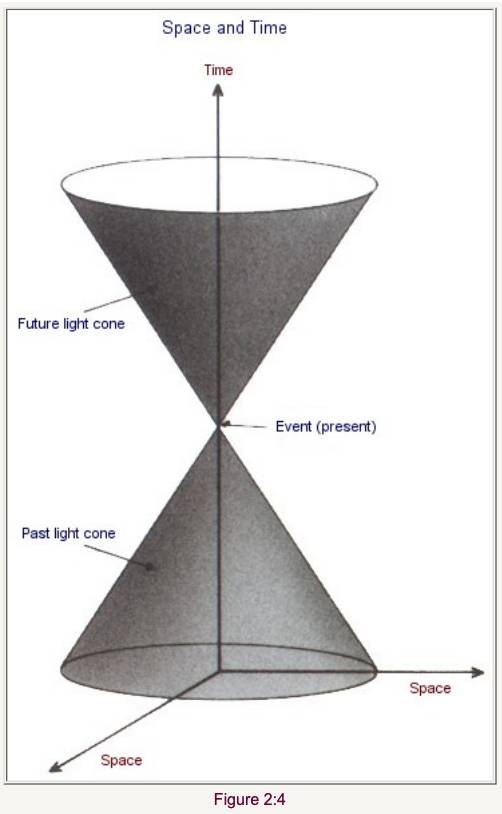

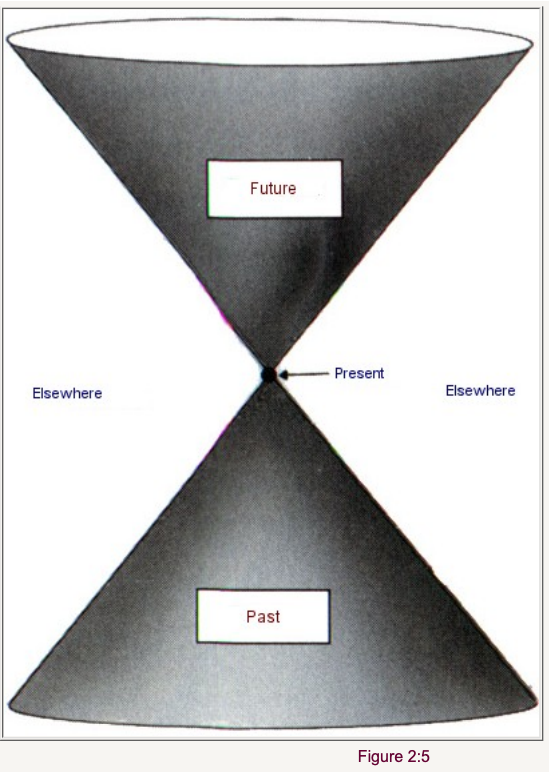

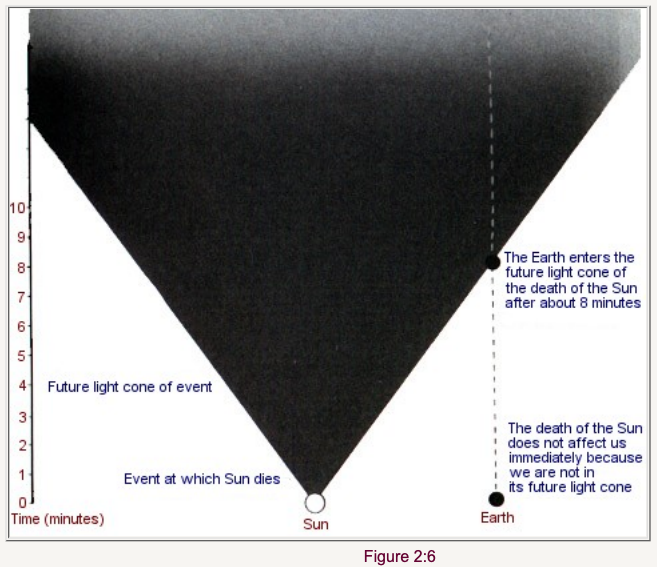

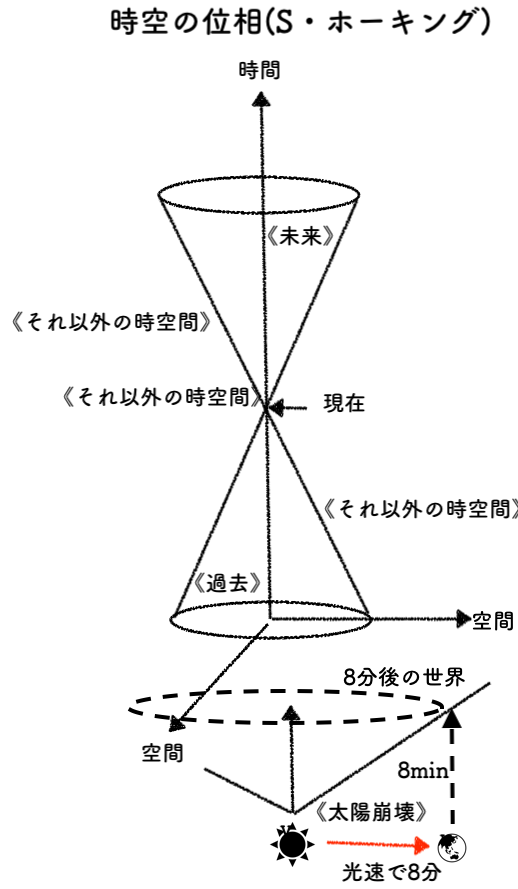

この章でホーキング博士は、空間と時間の性質に関する科学的思考の発展

について述べている。まず、アリストテレスの「物体は静止しているのが最も好ましい状態であり、力によってのみ動かすことができる」という考え方について

説明し、「重い物ほど速く落ちる」と暗に示している。しかし、イタリアの科学者ガリレオ・ガリレイは、重さの異なる物体の運動を観察し、すべての物体は同

じ速度で落下すると結論づけ、アリストテレスの理論が誤りであることを実験的に証明したのである。これが、イギリスの科学者アイザック・ニュートンの「運

動と重力の法則」につながっていく。しかし、ニュートンの法則は、アリストテレスが信じていたような絶対的な静止状態や絶対的な空間というものは存在せ

ず、物体が「静止」しているか「運動」しているかは観察者の慣性フレームに依存することを暗示していたのだ。 時間と空間の関係をパースペクティヴィズムという方法で表現する——電波望遠鏡による計測(邦訳 47ページ)  遠方にある星(ケンタウルス座アルファ星)に太陽の光がとどく時間と実際の距離の関係(邦訳 50ページ)——これはマクスウェルの方程式よる。  水面に石を投げ入れた時に広がる波紋を立体的に構成すると円錐になる。これは、時間と距離の関係を三次元(=水面の波紋という2次元モデルと時間という1 次元モデルからなる3次元モデル)で表現する方法になる(邦訳 51-52ページ)  現在は2つの三角錐の交点にある。水面の波紋という2次元モデルと時間という1次元モデルからなる3次元モデルが構成される。下の円錐は過去光円錐とい い、上のものは未来光円錐という。  Pという時点の現在の出来事は、下の《過去》という過去の光円錐の中でおこったことの結果であり、それ以外の時空間である他所(elsewhereで表 示)とは完全に無関係である。言い方を変えると、過去の円錐のなかでおこったことのすべてがわかれば、現在のPで何がおこったのかがわかるはずである。ま た、他所で何がおこっていたとしてもPには何の影響も与えない。いま仮に太陽が消滅したとしても、我々は何の影響も今は受けない。地球でその影響が生じる のは8分後である。次の図につづく  太陽の質量は時空を曲げておりそれにより地球は四次元時空の中ではまっすぐな軌道を辿っているのに三次元では円軌道を描いているように我々には見える (ホーキング) 初版では、2.7と2.8,2.9の図はない 次にホーキングは、アリストテレスとニュートンが信じていた絶対時間、つまり観察者の運動状態に関係なく時間は正確に測定できるということについて述べて いる。しかし、この常識的な考え方は、光速やその近辺では通用しないとホーキングは書いている。ホーキング博士は、デンマークの科学者ローマーが木星とそ の衛星イオを観測して光が非常に高速だが有限の速度で伝わることを発見したことや、イギリスの科学者マクスウェルが電磁気学の方程式で光が一定の速度で伝 わる波であることを示したことに触れている。ニュートン力学では絶対安静の概念が捨てられたため、マクスウェルをはじめとする多くの物理学者は、光はエー テルという仮想の流体の中を進むはずで、その速度はエーテルの速度に対する相対速度であると主張した。これは、後にマイケルソン=モーリーの実験によって 反証され、光の速度は観測者の運動に関係なく常に一定であることが示された。その後、アインシュタインとアンリ・ポアンカレは、絶対時間は存在しないとし て、光の運動を説明するためにエーテルは不要であると主張した。特殊相対性理論はこれに基づいており、観測者の速度がどうであれ、光は有限の速度で進むと 主張している。 質量とエネルギーは、E=mc^{2}E = mc^2という有名な式で表され、質量のある物体が光速(3×10⁸m/s)で進むためには、無限のエネルギーが必要であると説明されています。光速を利 用した新しいメートルの定義方法が開発された。また、「事象」はライトコーンという時空図で表現することができ、過去と未来のライトコーンを基準にして、 許される事象と許されない事象を制限することができる。また、「空間」と「時間」が本質的に結びついている4次元の時空も記述される。空間を通過する物体 の運動は、必然的に時間を経験する方法に影響を与える。 アインシュタインの一般相対性理論では、光線の進路が「重力」によってどのように影響を受けるかを説明している。アインシュタインによれば、重力は時空の ゆがみによって生じる錯覚であり、ニュートンの考え方が、物質が他の物質に対して及ぼす力として記述されているのとは対照的である。時空のゆがみでは、光 は4次元の「時空」内では常に直進するが、3次元空間では重力の影響により曲がって見えることがある。この直進経路が測地線である。一卵性双生児の思考実 験である「双子のパラドックス」では、双子が互いに異なる速度で移動した場合、あるいは、時空の曲率が等しくない異なる場所に住んでいた場合にも、異なる 年齢をとることができると考えられている。特殊相対性理論が、事象が起こる空間と時間に基づくのに対し、一般相対性理論は、力が時空間の曲率を変えること ができる動的なものであり、ダイナミックに膨張する宇宙を生み出すものである。ホーキング博士とペンローズ博士は、一般相対性理論を用いて、宇宙が有限時 間前の過去に始まり、有限時間後の未来に終わる可能性があることを証明した。 |

| Chapter 3: The Expanding Universe |

3. 拡張する宇宙 |

| In this chapter, Hawking first

describes how physicists and astronomers calculated the relative

distance of stars from the Earth. In the 18th century, Sir William

Herschel confirmed the positions and distances of many stars in the

night sky. In 1924, Edwin Hubble discovered a method to measure the

distance using the brightness of Cepheid variable stars as viewed from

Earth. The luminosity, brightness, and distance of these stars are

related by a simple mathematical formula. Using all these, he

calculated distances of nine different galaxies. We live in a fairly

typical spiral galaxy, containing vast numbers of stars. The stars are very far away from us, so we can only observe their one characteristic feature, their light. When this light is passed through a prism, it gives rise to a spectrum. Every star has its own spectrum, and since each element has its own unique spectra, we can measure a star's light spectra to know its chemical composition. We use thermal spectra of the stars to know their temperature. In 1920, when scientists were examining spectra of different galaxies, they found that some of the characteristic lines of the star spectrum were shifted towards the red end of the spectrum. The implications of this phenomenon were given by the Doppler effect, and it was clear that many galaxies were moving away from us. It was assumed that, since some galaxies are red shifted, some galaxies would also be blue shifted. However, redshifted galaxies far outnumbered blueshifted galaxies. Hubble found that the amount of redshift is directly proportional to relative distance. From this, he determined that the Universe is expanding and had had a beginning. Despite this, the concept of a static Universe persisted into the 20th century. Einstein was so sure of a static Universe that he developed the 'cosmological constant' and introduced 'anti-gravity' forces to allow a universe of infinite age to exist. Moreover, many astronomers also tried to avoid the implications of general relativity and stuck with their static Universe, with one especially notable exception, the Russian physicist Alexander Friedmann. Friedmann made two very simple assumptions: the Universe is identical wherever we are, i.e. homogeneity, and that it is identical in every direction that we look in, i.e. isotropy. His results showed that the Universe is non-static. His assumptions were later proved when two physicists at Bell Labs, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, found unexpected microwave radiation not only from the one particular part of the sky but from everywhere and by nearly the same amount. Thus Friedmann's first assumption was proved to be true. At around the same time, Robert H. Dicke and Jim Peebles were also working on microwave radiation. They argued that they should be able to see the glow of the early Universe as background microwave radiation. Wilson and Penzias had already done this, so they were awarded with the Nobel Prize in 1978. In addition, our place in the Universe is not exceptional, so we should see the Universe as approximately the same from any other part of space, which supports Friedmann's second assumption. His work remained largely unknown until similar models were made by Howard Robertson and Arthur Walker. Friedmann's model gave rise to three different types of models for the evolution of the Universe. First, the Universe would expand for a given amount of time, and if the expansion rate is less than the density of the Universe (leading to gravitational attraction), it would ultimately lead to the collapse of the Universe at a later stage. Secondly, the Universe would expand, and at some time, if the expansion rate and the density of the Universe became equal, it would expand slowly and stop, leading to a somewhat static Universe. Thirdly, the Universe would continue to expand forever, if the density of the Universe is less than the critical amount required to balance the expansion rate of the Universe. The first model depicts the space of the Universe to be curved inwards. In the second model, the space would lead to a flat structure, and the third model results in negative 'saddle shaped' curvature. Even if we calculate, the current expansion rate is more than the critical density of the Universe including the dark matter and all the stellar masses. The first model included the beginning of the Universe as a Big Bang from a space of infinite density and zero volume known as 'singularity', a point where the general theory of relativity (Friedmann's solutions are based in it) also breaks down. This concept of the beginning of time (proposed by the Belgian Catholic priest Georges Lemaître) seemed originally to be motivated by religious beliefs, because of its support of the biblical claim of the universe having a beginning in time instead of being eternal.[4] So a new theory was introduced, the "steady state theory" by Hermann Bondi, Thomas Gold, and Fred Hoyle, to compete with the Big Bang theory. Its predictions also matched with the current Universe structure. But the fact that radio wave sources near us are far fewer than from the distant Universe, and there were numerous more radio sources than at present, resulted in the failure of this theory and universal acceptance of the Big Bang Theory. Evgeny Lifshitz and Isaak Markovich Khalatnikov also tried to find an alternative to the Big Bang theory but also failed. Roger Penrose used light cones and general relativity to prove that a collapsing star could result in a region of zero size and infinite density and curvature called a Black Hole. Hawking and Penrose proved together that the Universe should have arisen from a singularity, which Hawking himself disproved once quantum effects are taken into account. |

この章ではまず、物理学者や天文学者がどのように地球から星の相対距離

を計算したかを説明します。18世紀、ウィリアム・ハーシェル卿は夜空に輝く多くの星の位置と距離を確認した。1924年、エドウィン・ハッブルは、地球

から見たケフェウス座変光星の明るさを利用して距離を測定する方法を発見した。これらの星の光度、明るさ、距離は、簡単な数式で関係づけられている。これ

らをすべて使って、彼は9つの銀河の距離を計算した。私たちが住んでいるのは、典型的な渦巻き型銀河で、そこにはたくさんの星がある。 星々は私たちからとても遠くにあるため、私たちが観察できるのは星々の光という特徴だけである。この光をプリズムに通すと、スペクトルになります。星には それぞれ固有のスペクトルがあり、元素ごとに固有のスペクトルがあるため、星の光のスペクトルを測定することで化学組成を知ることができる。星の温度を知 るためには、星の熱スペクトルを使います。1920年、科学者たちがさまざまな銀河のスペクトルを調べていたところ、星のスペクトルの特徴的な線の一部が 赤方面にシフトしていることを発見した。この現象の意味するところは、ドップラー効果によって与えられ、多くの銀河が我々から遠ざかっていることが明らか になったのである。 赤方偏移した銀河があるのだから、青方偏移した銀河もあるはずだと考えられていた。しかし、赤方偏移した銀河は、青方偏移した銀河よりもはるかに数が多 い。ハッブルは、赤方偏移の量が相対距離に正比例することを発見した。このことから、ハッブルは宇宙が膨張していること、そして宇宙には始まりがあること を突き止めた。にもかかわらず、「宇宙は静止している」という考え方は20世紀まで続いた。アインシュタインは、静的な宇宙を確信していたので、「宇宙定 数」を開発し、「反重力」の力を導入して、無限の年齢の宇宙が存在するようにした。さらに、多くの天文学者も一般相対性理論が意味するところを避けて、静 的な宇宙に固執しようとした。特に顕著な例外が、ロシアの物理学者アレクサンダー・フリードマンである。 フリードマンは、宇宙はどこにいても同じである(均質性)、そしてどの方向を見ても同じである(等方性)という、非常に単純な2つの仮定をした。彼の結果 は、宇宙が非静止的であることを示した。その後、ベル研究所の2人の物理学者、アルノ・ペンジアスとロバート・ウィルソンが、予期せぬマイクロ波放射を、 空のある特定の部分からだけでなく、あらゆる場所から、しかもほぼ同じ量だけ発見し、彼の仮定は証明された。フリードマンの最初の仮説が正しかったことが 証明されたのである。 同じ頃、ロバート・H・ディックとジム・ピーブルスもマイクロ波放射の研究をしていた。彼らは、初期宇宙の輝きを背景マイクロ波放射として見ることができ るはずだと主張した。ウィルソンとペンジアスは、すでにこれを実現していたので、1978年にノーベル賞を受賞しました。また、宇宙における我々の位置は 例外的なものではないので、宇宙のどの場所からもほぼ同じように見えるはずであり、これはフリードマンの2番目の仮定を支持するものである。彼の研究は、 ハワード・ロバートソンやアーサー・ウォーカーによって同様のモデルが作られるまで、ほとんど知られていなかった。 フリードマンのモデルから、宇宙の進化について3種類のモデルが生まれた。第一に、宇宙はある時間だけ膨張し、膨張率が宇宙の密度より小さい場合(重力引 力が生じる)、最終的に後の段階で宇宙が崩壊するというものである。第二に、宇宙は膨張し、ある時期に膨張率と宇宙の密度が等しくなれば、ゆっくりと膨張 して停止し、やや静的な宇宙となる。3つ目は、宇宙の密度が、宇宙の膨張率と釣り合うために必要な臨界量以下であれば、宇宙は永遠に膨張し続けるというも のです。 1つ目のモデルでは、宇宙の空間は内側に湾曲しているように描かれています。2番目のモデルでは、空間は平坦な構造になり、3番目のモデルでは、負の「鞍 型」曲率になる。計算しても、現在の膨張率は、暗黒物質とすべての恒星質量を含めた宇宙の臨界密度より大きい。最初のモデルは、宇宙の始まりが「特異点」 と呼ばれる密度無限、体積ゼロの空間からのビッグバンであり、一般相対性理論(フリードマンの解が基になっている)も破綻する地点である。 この「時間の始まり」の概念(ベルギーのカトリック司祭ジョルジュ・ルメートルが提唱)は、宇宙は永遠ではなく時間の始まりがあるという聖書の主張を支持 するもので、もともと宗教観が背景にあったようだ[4]。そこで、ビッグバン理論に対抗して、ヘルマン・ボンディ、トーマス・ゴールド、フレッド・ホイル による「定常論」という新しい理論も導入されることになる。その予測は、現在の宇宙構造とも一致した。しかし、我々の近くにある電波源は遠い宇宙から来た ものに比べて圧倒的に少なく、現在よりも多数の電波源があったことから、この説は失敗に終わり、ビッグバン理論が普遍的に受け入れられることになった。エ フゲニー・リフシッツとイサーク・マルコヴィッチ・ハラトニコフもビッグバン理論に代わるものを探そうとしたが、これも失敗した。 ロジャー・ペンローズは、光円錐と一般相対性理論を用いて、崩壊する星がブラックホールと呼ばれる大きさゼロ、密度と曲率無限大の領域になることを証明し ました。ホーキング博士とペンローズは、宇宙は特異点から発生したはずだと証明しましたが、量子効果を考慮するとホーキング博士自身が反証している。 |

| Chapter 4: The Uncertainty

Principle |

4. 不確定性原理 |

| In this chapter, Hawking first

discusses nineteenth-century French mathematician Laplace's strong

belief in scientific determinism, where scientific laws will eventually

be able to accurately predict the future of the Universe. Then he

discusses the theory of infinite radiation of stars according to the

calculations of British scientists Lord Rayleigh and James Jeans, which

was later revised in 1900 by German scientist Max Planck who suggested

that energy must radiate in small, finite packets called quanta. Hawking then discusses the uncertainty principle formulated by German scientist Werner Heisenberg, according to which the speed and the position of a particle cannot be precisely known due to Planck's quantum hypothesis: increasing the accuracy in measuring its speed will decrease the certainty of its position and vice versa. This disproved Laplace's idea of a completely deterministic theory of the universe. Hawking then describes the eventual development of quantum mechanics by Heisenberg, Austrian physicist Erwin Schroedinger and English physicist Paul Dirac in the 1920s, a theory which introduced an irreducible element of unpredictability into science, and despite German scientist Albert Einstein's strong objections, it has been proven to be very successful in describing the universe except for gravity and large-scale structures. Hawking then discusses how Heisenberg's uncertainty principle implies the wave–particle duality behaviour of light (and particles in general). He then describes the phenomenon of interference where multiple light waves interfere with each other to give rise to a single light wave with properties different from those of the component waves, as well as the interference within particles, exemplified by the two-slit experiment. Hawking writes how interference refined our understanding of the structure of atoms, the building blocks of matter. While Danish scientist Niels Bohr's theory only partially solved the problem of collapsing electrons, quantum mechanics completely resolved it. According to Hawking, American scientist Richard Feynman's sum over histories is a nice way of visualizing the wave-particle duality. Finally, Hawking mentions that Einstein's general theory of relativity is a classical, non-quantum theory which ignores the uncertainty principle and that it has to be reconciled with quantum theory in situations where gravity is very strong, such as black holes and the Big Bang. |

この章でホーキング博士は、まず19世紀のフランスの数学者ラプラスが

唱えた、科学的法則がやがて宇宙の未来を正確に予測できるようになるという科学的決定論への強い信仰について論じている。その後、イギリスの科学者レイ

リー卿とジェームス・ジーンズの計算による星の無限放射説が、1900年にドイツの科学者マックス・プランクによって修正され、エネルギーは量子という小

さな有限のパケットで放射されなければならないと示唆したことについて述べている。 プランクの量子論は、粒子の速度と位置を正確に知ることはできないというもので、速度の測定精度を上げると位置の確実性が下がり、その逆もまた然りであ る。これは、ラプラスの考えていた完全な決定論的宇宙論を否定するものだった。ホーキングは次に、1920年代にハイゼンベルク、オーストリアの物理学者 エルヴィン・シュレーディンガー、イギリスの物理学者ポール・ディラックが最終的に開発した量子力学について説明する。この理論は科学に予測不可能な要素 を導入し、ドイツの科学者アルベルト・アインシュタインの強い反対にもかかわらず、重力と大規模構造以外の宇宙の記述に非常に成功していることが証明され ている。 次にホーキング博士は、ハイゼンベルクの不確定性原理が、光(および粒子一般)の波動-粒子二重性挙動をどのように含意しているかを論じている。 そして、複数の光波が互いに干渉して、それぞれの光波とは異なる性質を持つ1つの光波を生み出す干渉現象や、2スリット実験に代表される粒子内の干渉につ いて説明する。ホーキング博士は、干渉が物質の構成要素である原子の構造に関する我々の理解をいかに深めたかについて書いている。デンマークの科学者ニー ルス・ボーアの理論は、電子の崩壊の問題を部分的に解決しただけだったが、量子力学はこの問題を完全に解決した。ホーキング博士によると、アメリカの科学 者リチャード・ファインマンが唱えた「歴史の和」は、波動と粒子の二重性を視覚化する良い方法だという。最後にホーキング博士は、アインシュタインの一般 相対性理論は不確定性原理を無視した古典的な非量子論であり、ブラックホールやビッグバンのような重力が非常に強い状況では量子論と折り合いをつけなけれ ばならないことに触れている。 |

| Chapter 5: Elementary Particles

and Forces of Nature |

5. 素粒子と自然力 |

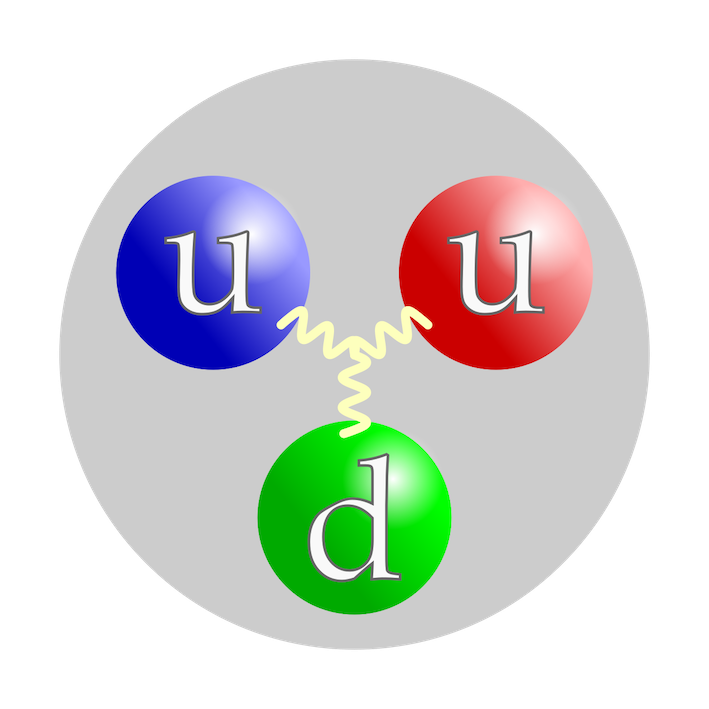

| In this chapter, Hawking traces

the history of investigation about the nature of matter: Aristotle's

four elements, Democritus's notion of indivisible atoms, John Dalton's

ideas about atoms combining to form molecules, J. J. Thomson's

discovery of electrons inside atoms, Ernest Rutherford's discovery of

atomic nucleus and protons, James Chadwick's discovery of neutrons and

finally Murray Gell-Mann's work on even smaller quarks which make up

protons and neutrons. Hawking then discusses the six different

"flavors" (up, down, strange, charm, bottom, and top) and three

different "colors" of quarks (red, green, and blue). Later in the

chapter he discusses anti-quarks, which are outnumbered by quarks due

to the expansion and cooling of the Universe. Hawking then discusses the spin property of particles, which determines what a particle looks like from different directions. Hawking then discusses two groups of particles in the Universe based on their spin: fermions and bosons. Fermions, with a spin of 1/2, follow the Pauli exclusion principle, which states that they cannot share the same quantum state (for example, two "spin up" protons cannot occupy the same location in space). Without this rule, complex structures could not exist. Bosons or the force-carrying particles, with a spin of 0, 1, or 2, do not follow the exclusion principle. Hawking then gives the examples of virtual gravitons and virtual photons. Virtual gravitons, with a spin of 2, carry the force of gravity. Virtual photons, with a spin of 1, carry the electromagnetic force. Hawking then discusses the weak nuclear force (responsible for radioactivity and affecting mainly fermions) and the strong nuclear force carried by the particle gluon, which binds quarks together into hadrons, usually neutrons and protons, and also binds neutrons and protons together into atomic nuclei. Hawking then writes about the phenomenon called color confinement which prevents the discovery of quarks and gluons on their own (except at extremely high temperature) as they remain confined within hadrons. Hawking writes that at extremely high temperature, the electromagnetic force and weak nuclear force behave as a single electroweak force, giving rise to the speculation that at even higher temperatures, the electroweak force and strong nuclear force would also behave as a single force. Theories which attempt to describe the behaviour of this "combined" force are called Grand Unified Theories, which may help us explain many of the mysteries of physics that scientists have yet to solve. |

この章では、ホーキング博士が物質の性質に関する研究の歴史をたどって

いる。アリストテレスの4つの元素、デモクリトスの分割できない原子の概念、ジョン・ダルトンの原子が結合して分子を形成するという考え、J・J・トムソ

ンの原子内部の電子の発見、アーネスト・ラザフォードの原子核と陽子の発見、ジェームズ・チャドウィックの中性子の発見、そしてマレー・ゲルマンの陽子と

中性子を構成するさらに小さなクォークの研究である。そしてホーキング博士は、6種類の「フレーバー」(アップ、ダウン、ストレンジ、チャーム、ボトム、

トップ)と3種類の「色」(レッド、グリーン、ブルー)のクォークについて論じている。この章の後半では、宇宙の膨張と冷却によってクォークより数が少な

くなった反クォークについて論じている。 次にホーキングは、粒子のスピンの性質について説明します。スピンは、粒子がさまざまな方向からどのように見えるかを決定するものである。ホーキング博士 は、スピンに基づいて宇宙に存在する2つの粒子グループ、フェルミオンとボゾンについて説明する。スピンが1/2のフェルミオンは、パウリの排他律に従 い、同じ量子状態を共有することはできない(例えば、2つの「スピンアップ」陽子は空間内で同じ場所を占めることはできない)。この法則がなければ、複雑 な構造は存在できない。 スピンが0、1、2のボソンや力を伝える粒子は、排他律に従わない。次にホーキング博士は、仮想重力子と仮想光子の例を挙げる。仮想重力子はスピン2であ り、重力の力を伝える。仮想重力子はスピン2、仮想光子はスピン1で、電磁気力を発生させる。ホーキングは次に、弱い核力(放射能の原因であり、主にフェ ルミオンが影響を受ける)と、グルオンという粒子が担う強い核力について論じ、グルオンはクォーク同士を結びつけてハドロン(通常は中性子と陽子)にし、 中性子と陽子を結びつけて原子核にする、と述べています。そしてホーキングは、クォークとグルーオンがハドロン内に閉じ込められたままであるため、(極め て高温の場合を除き)クォークとグルーオンが単独で発見されない色拘束と呼ばれる現象について書いている。 ホーキング博士は、超高温では電磁気力と弱い核力が一つの電気弱い力として振る舞うことを書き、さらに高温では電気弱い力と強い核力が一つの力として振る 舞うのではないかという推測を生み出している。この「合力」の振る舞いを記述しようとする理論は大統一理論と呼ばれ、科学者がまだ解決できていない物理学 の謎の多くを説明するのに役立つと考えられている。 |

| Chapter 6: Black Holes |

6. ブラックホール |

| In this chapter, Hawking

discusses black holes, regions of spacetime where extremely strong

gravity prevents everything, including light, from escaping from within

them. Hawking describes how most black holes are formed during the

collapse of massive stars (at least 25 times heavier than the Sun)

approaching end of life. He writes about the event horizon, the black

hole's boundary from which no particle can escape to the rest of

spacetime. Hawking then discusses non-rotating black holes with

spherical symmetry and rotating ones with axisymmetry. Hawking then

describes how astronomers discover a black hole not directly, but

indirectly, by observing with special telescopes the powerful X-rays

emitted when it consumes a star. Hawking ends the chapter by mentioning

his famous bet made in 1974 with American physicist Kip Thorne in which

Hawking argued that black holes did not exist. Hawking lost the bet as

new evidence proved that Cygnus X-1 was indeed a black hole. |

この章では、ホーキング博士はブラックホールについて論じている。ブ

ラックホールとは、極めて強い重力によって、光を含むすべてのものがその内部から脱出できない時空の領域である。ホーキング博士は、ほとんどのブラック

ホールが、寿命が尽きた大質量星(少なくとも太陽の25倍の重さ)が崩壊する際に形成されることを説明している。彼は、ブラックホールの境界である事象の

地平線について書き、そこから時空の残りの部分に逃げることのできない粒子について述べている。次にホーキング博士は、球対称性を持つ非回転ブラックホー

ルと、軸対称性を持つ回転ブラックホールについて説明する。そして、天文学者がブラックホールを直接ではなく、ブラックホールが星を飲み込んだときに放出

される強力なX線を特殊な望遠鏡で観測することによって間接的に発見する方法について説明する。最後に、ホーキング博士は1974年にアメリカの物理学者

キップ・ソーンと行った有名な賭けについて触れ、ブラックホールは存在しないと主張したことを明らかにする。ホーキング博士はこの賭けに敗れ、新たな証拠

によって「はくちょう座X-1」が本当にブラックホールであることが証明された。 |

| Chapter 7: Black Holes Ain't So

Black |

7. ブラックホールはそんなにブラックじゃない |

| This chapter discusses an aspect

of black hole behaviour that Stephen Hawking discovered in the 1970s.

According to earlier theories, black holes can only become larger, and

never smaller, because nothing which enters a black hole can come out.

However, in 1974, Hawking published a new theory which argued that

black holes can "leak" radiation. He imagined what might happen if a

pair of virtual particles appeared near the edge of a black hole.

Virtual particles briefly 'borrow' energy from spacetime itself, then

annihilate with each other, returning the borrowed energy and ceasing

to exist. However, at the edge of a black hole, one virtual particle

might be trapped by the black hole while the other escapes. Because of

the second law of thermodynamics, particles are 'forbidden' from taking

energy from the vacuum. Thus, the particle takes energy from the black

hole instead of from the vacuum, and escape from the black hole as

Hawking radiation. According to Hawking, black holes must very slowly shrink over time and eventually "evaporate" because of this radiation, rather than continue existing forever as scientists had previously believed. |

この章では、スティーブン・ホーキング博士が1970年代に発見したブ

ラックホールのふるまいの一面について説明する。それまでの理論では、ブラックホールは大きくなることしかできず、小さくなることはないとされていた。し

かし、1974年、ホーキング博士は、ブラックホールは放射線を「漏らす」ことができるとする新しい理論を発表した。ホーキング博士は、ブラックホールの

縁に仮想粒子のペアが出現したらどうなるかを想像した。仮想粒子は、時空から一瞬エネルギーを借りて、互いに消滅し、借りたエネルギーを返して消滅する。

しかし、ブラックホールの縁では、一方の仮想粒子はブラックホールに捕らえられ、もう一方の仮想粒子は逃げてしまうかもしれない。熱力学の第二法則によ

り、粒子は真空からエネルギーを取り込むことが「禁止」されている。そのため、粒子は真空からではなく、ブラックホールからエネルギーを取り込み、ホーキ

ング放射としてブラックホールから脱出する。 ホーキング博士によると、ブラックホールは、それまで科学者が信じていたように永遠に存在し続けるのではなく、この放射のために、時間の経過と共に非常に ゆっくりと縮小し、最終的には「蒸発」しなければならないそうである。 |

| Chapter 8: The Origin and Fate

of the Universe |

8. 宇宙のはじまりと終わり |

| The beginning and the end of the

universe are discussed in this chapter. Most scientists agree that the Universe began in an expansion called the "Big Bang". At the start of the Big Bang, the Universe had an extremely high temperature, which prevented the formation of complex structures like stars, or even very simple ones like atoms. During the Big Bang, a phenomenon called "inflation" took place, in which the Universe briefly expanded ("inflated") to a much larger size. Inflation explains some characteristics of the Universe that had previously greatly confused researchers. After inflation, the universe continued to expand at a slower pace. It became much colder, eventually allowing for the formation of such structures. Hawking also discusses how the Universe might have appeared differently if it grew in size slower or faster than it actually has. For example, if the Universe expanded too slowly, it would collapse, and there would not be enough time for life to form. If the Universe expanded too quickly, it would have become almost empty. Hawking argues in favor of the controversial "eternal inflation hypothesis", suggesting that our Universe is only one of countless universes with different laws of physics, most of which would be inhospitable to life. The concept of quantum gravity is also discussed in this chapter. |

この章では、宇宙の始まりと終わりについて説明する。 ほとんどの科学者は、宇宙は「ビッグバン」と呼ばれる膨張で始まったと認めている。ビッグバン当初、宇宙は非常に高温であったため、星のような複雑な構造 物はおろか、原子のような非常に単純な構造物さえも形成されなかった。ビッグバンでは、宇宙が一時的に大きく膨張する「インフレーション」と呼ばれる現象 が起こった。インフレーションは、これまで研究者を大いに混乱させていた宇宙の特徴を説明するものである。インフレーションの後、宇宙はゆっくりとした ペースで膨張を続けた。そして、宇宙はより低温になり、最終的にこのような構造の形成が可能になった。 さらにホーキング博士は、宇宙が実際の大きさよりも遅く、あるいは速く膨張した場合、どのように違った姿を見せたかについても論じている。例えば、宇宙の 膨張が遅すぎれば、宇宙は崩壊し、生命が誕生するのに十分な時間がない。また、宇宙の膨張が速すぎれば、宇宙はほとんど空っぽになってしまう。ホーキング 博士は「永遠のインフレーション仮説」を支持し、我々の宇宙は異なる物理法則を持つ無数の宇宙の一つに過ぎず、そのほとんどは生命を寄せ付けないだろうと 主張している。 この章では、量子重力の概念についても論じている。 |

| Chapter 9: The Arrow of Time |

9. 時間の矢 |

| In this chapter Hawking talks

about why "real time", as Hawking calls time as humans observe and

experience it (in contrast to "imaginary time", which Hawking claims is

inherent to the laws of science) seems to have a certain direction,

notably from the past towards the future. Hawking then discusses three

"arrows of time" which, in his view, give time this property. Hawking's

first arrow of time is the thermodynamic arrow of time: the direction

in which entropy (which Hawking calls disorder) increases. According to

Hawking, this is why we never see the broken pieces of a cup gather

themselves together to form a whole cup. Hawking's second arrow is the

psychological arrow of time, whereby our subjective sense of time seems

to flow in one direction, which is why we remember the past and not the

future. Hawking claims that our brain measures time in a way where

disorder increases in the direction of time – we never observe it

working in the opposite direction. In other words, he claims that the

psychological arrow of time is intertwined with the thermodynamic arrow

of time. Hawking's third and final arrow of time is the cosmological

arrow of time: the direction of time in which the Universe is expanding

rather than contracting. According to Hawking, during a contraction

phase of the universe, the thermodynamic and cosmological arrows of

time would not agree. Hawking then claims that the "no boundary proposal" for the universe implies that the universe will expand for some time before contracting back again. He goes on to argue that the no boundary proposal is what drives entropy and that it predicts the existence of a well-defined thermodynamic arrow of time if and only if the universe is expanding, as it implies that the universe must have started in a smooth and ordered state that must grow toward disorder as time advances. He argues that, because of the no boundary proposal, a contracting universe would not have a well-defined thermodynamic arrow and therefore only a Universe which is in an expansion phase can support intelligent life. Using the weak anthropic principle, Hawking goes on to argue that the thermodynamic arrow must agree with the cosmological arrow in order for either to be observed by intelligent life. This, in Hawking's view, is why humans experience these three arrows of time going in the same direction. |

この章でホーキングは、人間が観察し経験する時間をホーキングが「現実

の時間」と呼ぶのに対し、ホーキングが科学の法則に内在すると主張する「空想の時間」は、特に過去から未来に向かって一定の方向を持つように見える理由に

ついて述べている。そして、ホーキングは、時間にこの性質を与える3つの「時間の矢」について論じている。ホーキング博士の考える最初の時間の矢は、熱力

学的な時間の矢で、エントロピー(ホーキング博士はこれを無秩序と呼んでいる)が増大する方向である。ホーキング博士によれば、壊れたコップの破片が集

まって全体のコップになるのを見ることがないのはこのためである。ホーキング博士の第二の矢は、時間の心理的な矢であり、私たちの主観的な時間感覚は一方

向に流れているように見えるため、私たちは過去のことは覚えているが、未来のことは覚えていない。ホーキング博士は、脳は時間の流れにそって無秩序に時間

が増えるように時間を測定しており、その逆方向の働きは観察されないと主張している。つまり、心理学的な時間の矢印は、熱力学的な時間の矢印と絡み合って

いるのだ。ホーキング博士の主張する3つ目の時間の矢は、宇宙論的時間の矢であり、宇宙が収縮する方向ではなく、膨張する方向の時間である。ホーキング博

士によれば、宇宙が収縮している段階では、熱力学的な時間の矢と宇宙論的な時間の矢は一致しないという。 そしてホーキング博士は、宇宙の「無境界提案」は、宇宙が再び収縮する前にしばらく膨張することを意味していると主張する。さらに、無境界提案は、宇宙が 膨張している場合にのみ、エントロピーを促進し、熱力学的に明確な時間の矢の存在を予言するものであると主張する。彼は、無境界の提案により、収縮する宇 宙は明確な熱力学的矢印を持たず、したがって、膨張段階にある宇宙のみが知的生命を維持できると主張している。さらにホーキング博士は、弱い人間原理を用 いて、知的生命体が観測できるためには、熱力学的な矢印と宇宙論的な矢印が一致しなければならないと主張する。これが、人間がこれら3つの時間の矢を同じ 方向に感じる理由だとホーキングは考えている。 |

| Chapter 10: Wormholes and Time

Travel |

10. ワームホールと時間旅行 |

| In this chapter, Hawking

discusses whether it is possible to time travel, i.e., travel into the

future or the past. He shows how physicists have attempted to devise

possible methods by humans with advanced technology may be able to

travel faster than the speed of light, or travel backwards in time, and

these concepts have become mainstays of science fiction. Einstein–Rosen

bridges were proposed early in the history of general relativity

research. These "wormholes" would appear identical to black holes from

the outside, but matter which entered would be relocated to a different

location in spacetime, potentially in a distant region of space, or

even backwards in time. However, later research demonstrated that such

a wormhole, even if possible for it to form in the first place, would

not allow any material to pass through before turning back into a

regular black hole. The only way that a wormhole could theoretically

remain open, and thus allow faster-than-light travel or time travel,

would require the existence of exotic matter with negative energy

density, which violates the energy conditions of general relativity. As

such, almost all physicists agree that faster-than-light travel and

travel backwards in time are not possible. Hawking also describes his own "chronology protection conjecture", which provides a more formal explanation for why faster-than-light and backwards time travel are almost certainly impossible. |

この章でホーキング博士は、タイムトラベル、つまり未来や過去に移動す

ることが可能かどうかを論じている。彼は、物理学者たちが、高度な技術を持つ人間が光速よりも速く移動したり、時間を逆行したりする方法を考案しようと試

みてきたことを示し、これらのコンセプトがSFの主役になっていることを説明する。アインシュタイン・ローゼンブリッジは、一般相対性理論の研究の初期に

提案されたものである。この「ワームホール」は、外からはブラックホールと同じように見えるが、入り込んだ物質は時空の異なる場所に移動し、遠い宇宙空間

や時間をさかのぼる可能性があるというものである。しかし、その後の研究によって、このようなワームホールは、たとえ形成が可能であったとしても、物質を

通過させることができず、通常のブラックホールに戻ってしまうことが明らかにされた。ワームホールが理論的に開いていて、光よりも速い速度での移動や時間

旅行ができるためには、負のエネルギー密度を持つエキゾチックな物質の存在が必要で、これは一般相対性理論のエネルギー条件に違反する。そのため、光速移

動や時間遡行は不可能であるというのが、ほぼすべての物理学者の一致した意見である。 ホーキング博士はまた、彼自身の「年表保護仮説」についても述べており、光よりも速い時間旅行や時間逆行がほぼ確実に不可能である理由を、より公式に説明 している。 |

| Chapter 11: The Unification of

Physics |

11. 物理学の統一理論 |

| Quantum field theory (QFT) and

general relativity (GR) describe the physics of the Universe with

astounding accuracy within their own domains of applicability. However,

these two theories contradict each other. For example, the uncertainty

principle of QFT is incompatible with GR. This contradiction, and the

fact that QFT and GR do not fully explain observed phenomena, have led

physicists to search for a theory of "quantum gravity" that is both

internally consistent and explains observed phenomena just as well as

or better than existing theories do. Hawking is cautiously optimistic that such a unified theory of the Universe may be found soon, in spite of significant challenges. At the time the book was written, "superstring theory" had emerged as the most popular theory of quantum gravity, but this theory and related string theories were still incomplete and had yet to be proven in spite of significant effort (this remains the case as of 2021). String theory proposes that particles behave like one-dimensional "strings", rather than as dimensionless particles as they do in QFT. These strings "vibrate" in many dimensions. Instead of 3 dimensions as in QFT or 4 dimensions as in GR, superstring theory requires a total of 10 dimensions. The nature of the six "hyperspace" dimensions required by superstring theory are difficult if not impossible to study, leaving countless theoretical string theory landscapes which each describe a universe with different properties. Without a means to narrow the scope of possibilities, it is likely impossible to find practical applications for string theory. Alternative theories of quantum gravity, such as loop quantum gravity, similarly suffer from a lack of evidence and difficulty to study. Hawking thus proposes three possibilities: 1) there exists a complete unified theory that we will eventually find; 2) the overlapping characteristics of different landscapes will allow us to gradually explain physics more accurately with time and 3) there is no ultimate theory. The third possibility has been sidestepped by acknowledging the limits set by the uncertainty principle. The second possibility describes what has been happening in physical sciences so far, with increasingly accurate partial theories. Hawking believes that such refinement has a limit and that by studying the very early stages of the Universe in a laboratory setting, a complete theory of Quantum Gravity will be found in the 21st century allowing physicists to solve many of the currently unsolved problems in physics. |

量子場の理論(QFT)と一般相対性理論(GR)は、それぞれの適用領

域において、宇宙の物理を驚くほど正確に記述している。しかし、この2つの理論は互いに矛盾している。例えば、QFTの不確定性原理はGRと相容れない。

この矛盾と、QFTやGRが観測される現象を十分に説明できないことから、物理学者は、内部的に矛盾がなく、かつ既存の理論と同等かそれ以上に観測現象を

説明できる「量子重力」理論を探し求めているのである。 ホーキング博士は、大きな課題があるにもかかわらず、このような宇宙の統一理論がすぐに見つかるかもしれないと、慎重に楽観視している。この本が書かれた 当時、量子重力の理論として「超弦理論」が最も有力視されていたが、この理論と関連する弦理論はまだ不完全で、多大な努力にもかかわらず証明されていな かった(これは2021年現在も同様である)。弦理論は、粒子がQFTのような無次元粒子としてではなく、1次元の「弦」のように振る舞うことを提唱して いる。この弦は、多次元で「振動」する。QFTのような3次元、GRのような4次元ではなく、超弦理論は合計10次元を必要とする。超弦理論が必要とする 6つの「超空間」次元の性質は、研究不可能ではないにしても困難であり、それぞれが異なる性質を持つ宇宙を記述する無数の理論的弦理論の風景が残されてい る。このような可能性の幅を狭める手段がなければ、超ひも理論の実用化は不可能であろう。 ループ量子重力のような量子重力の代替理論も同様に、証拠がなく研究が困難である。 そこで、ホーキング博士は3つの可能性を提唱している。1)完全な統一理論が存在し、いずれ見つかる、2)異なる風景の特徴が重なり合うことで、時間とと もに徐々に物理をより正確に説明できるようになる、3)究極の理論は存在しない、というものだ。3番目の可能性は、不確定性原理が設定した限界を認めるこ とで回避されてきた。2番目の可能性は、物理科学においてこれまで起こってきたことを説明するもので、部分的な理論の精度を高めていくものである。 ホーキング博士は、このような精緻化には限界があり、宇宙のごく初期の段階を実験室で研究することによって、21世紀には量子重力の完全な理論が見つか り、現在物理学で解決されていない多くの問題を物理学者が解決できるようになるだろうと考えている。 |

| 12. Conclusion |

12. 結論 |

| In this final chapter, Hawking

summarises the efforts made by humans through their history to

understand the Universe and their place in it: starting from the belief

in anthropomorphic spirits controlling nature, followed by the

recognition of regular patterns in nature, and finally with the

scientific advancement in recent centuries, the inner workings of the

universe have become far better understood. He recalls the suggestion

of the nineteenth-century French mathematician Laplace that the

Universe's structure and evolution could eventually be precisely

explained by a set of laws whose origin is left in God's domain.

However, Hawking states that the uncertainty principle introduced by

the quantum theory in the twentieth century has set limits to the

predictive accuracy of future laws to be discovered. Hawking comments that historically, the study of cosmology (the study of the origin, evolution, and end of Earth and the Universe as a whole) has been primarily motivated by a search for philosophical and religious insights, for instance, to better understand the nature of God, or even whether God exists at all. However, for Hawking, most scientists today who work on these theories approach them with mathematical calculation and empirical observation, rather than asking such philosophical questions. In his mind, the increasingly technical nature of these theories have caused modern cosmology to become increasingly divorced from philosophical discussion. Hawking nonetheless expresses hope that one day everybody would talk about these theories in order to understand the true origin and nature of the Universe, and accomplish "the ultimate triumph of human reasoning". |

自然を支配する擬人化された精霊への信仰に始まり、自然界の規則的なパ

ターンの認識、そして近年の科学の進歩により、宇宙の内部構造ははるかによく理解されるようになった。ホーキング博士は、19世紀のフランスの数学者ラプ

ラスが、宇宙の構造と進化は最終的には神の領域に委ねられた一連の法則によって正確に説明できると示唆したことを想起している。しかし、ホーキング博士

は、20世紀に量子論によって導入された不確定性原理により、将来発見される法則の予測精度には限界があると述べている。 ホーキングは、歴史的に宇宙論(地球や宇宙全体の起源、進化、終焉を研究する学問)は、哲学的・宗教的洞察を求めること、例えば、神の本質、あるいは神が 存在するかどうかをより良く理解することが主な動機であったとコメントしている。しかし、ホーキング博士によれば、今日、これらの理論に取り組む科学者の 多くは、そのような哲学的な問いかけよりも、数学的計算や実証的観察によってアプローチしているという。ホーキング博士の考えでは、これらの理論の技術的 な性質が強くなるにつれて、現代の宇宙論は哲学的な議論からますます遠ざかっているのだという。しかし、ホーキング博士は、いつの日か誰もがこれらの理論 について語り、宇宙の真の起源と本質を理解し、「人間の理性の究極の勝利」を達成する日が来ることを望んでいる。 |

| 1988: The first edition included

an introduction by Carl Sagan that tells the following story: Sagan was

in London for a scientific conference in 1974, and between sessions he

wandered into a different room, where a larger meeting was taking

place. "I realized that I was watching an ancient ceremony: the

investiture of new fellows into the Royal Society, one of the most

ancient scholarly organizations on the planet. In the front row, a

young man in a wheelchair was, very slowly, signing his name in a book

that bore on its earliest pages the signature of Isaac Newton ...

Stephen Hawking was a legend even then." In his introduction, Sagan

goes on to add that Hawking is the "worthy successor" to Newton and

Paul Dirac, both former Lucasian Professors of Mathematics.[5] The introduction was removed after the first edition, as it was copyrighted by Sagan, rather than by Hawking or the publisher, and the publisher did not have the right to reprint it in perpetuity. Hawking wrote his own introduction for later editions. 1994, A brief history of time – An interactive adventure. A CD-Rom with interactive video material created by S. W. Hawking, Jim Mervis, and Robit Hairman (available for Windows 95, Windows 98, Windows ME, and Windows XP).[6] 1996, Illustrated, updated and expanded edition: This hardcover edition contained full-color illustrations and photographs to help further explain the text, as well as the addition of topics that were not included in the original book. 1998, Tenth-anniversary edition: It features the same text as the one published in 1996, but was also released in paperback and has only a few diagrams included. ISBN 0553109537 2005, A Briefer History of Time: a collaboration with Leonard Mlodinow of an abridged version of the original book. It was updated again to address new issues that had arisen due to further scientific development. ISBN 0-553-80436-7 |

1988

年:初版にはカール・セーガンによる次のような紹介文が含まれていた。「1974年、セーガンはロンドンで開催された科学会議に出席していた。会議の合間

に、セーガンは異なる部屋に入り、そこではより大きな会議が行われていた。「私は自分が古代の儀式を見ていることに気づいた。地球上で最も古い学術団体の

ひとつである英国王立協会への新会員の任命式である。最前列には車椅子に乗った若い男性が座り、非常にゆっくりと、アイザック・ニュートンの署名が載って

いる本のページに自分の名前をサインしていた。スティーブン・ホーキングは当時すでに伝説的な人物だった。」

サガンは序文で、ホーキング博士はニュートンとポール・ディラックという2人の元ルーカス数学教授の「正当な後継者」であると付け加えている。 この序文は初版の後に削除された。なぜなら、著作権はホーキングや出版社ではなくサガンに帰属しており、出版社には永久に再版する権利がなかったからであ る。ホーキングは後の版のために、自ら序文を書いた。 1994年、『ホーキング、マーヴィス、ヘアマンによるインタラクティブな冒険の時間』。S.W.ホーキング、ジム・マーヴィス、ロビット・ヘアマンによ るインタラクティブなビデオ素材を収録したCD-ROM(Windows 95、Windows 98、Windows ME、Windows XP対応)。[6] 1996年、イラスト入り、改訂・増補版:このハードカバー版には、本文の説明を補足するフルカラーのイラストや写真が掲載され、また、初版には含まれて いなかったトピックも追加された。 1998年、10周年記念版:1996年に出版されたものと同じテキストが掲載されているが、ペーパーバック版も発売され、図表はわずかしか含まれていな い。ISBN 0553109537 2005年、『ホーキング、宇宙を語る:時を語る』:レナード・モドロノフとの共著で、原作の要約版。科学のさらなる進歩により生じた新たな問題に対処す るため、再び改訂された。ISBN 0-553-80436-7 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Brief_History_of_Time |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

★The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time, 1973

The Large Scale Structure of Space–Time, 1973

| The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time

is a 1973 treatise on the theoretical physics of spacetime by the

physicist Stephen Hawking and the mathematician George Ellis.[1] It is

intended for specialists in general relativity rather than newcomers.[2] |

『時空の大規模構造』は、物理学者スティーヴン・ホーキングと数学者ジョージ・エリスによる時空の理論物理学に関する1973年の論文である。[1] これは一般相対性理論の専門家向けであり、初心者向けではない。[2] |

| Background In the mid-1970s, advances in the technologies of astronomical observations – radio, infrared, and X-ray astronomy – opened up the Universe of exploration. New tools became necessary. In this book, Hawking and Ellis attempt to establish the axiomatic foundation for the geometry of four-dimensional spacetime as described by Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity and to derive its physical consequences for singularities, horizons, and causality. Whereas the tools for studying Euclidean geometry were a straightedge and a compass, those needed to investigate curved spacetime are test particles and light rays.[3] According to the mathematical physicist John Baez from the University of California, Riverside, The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time was "the first book to provide a detailed description of the revolutionary topological methods introduced by Penrose and Hawking in the early seventies."[4] Hawking co-wrote the book with Ellis, while he was postdoctoral fellow at the University of Cambridge. In his 1988 book A Brief History of Time, he describes The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time as "highly technical" and unreadable for the layperson. The book, now considered a classic, has also appeared in paperback format and has been reprinted many times.a A fiftieth anniversary edition was published by Cambridge University Press in February 2023.[5] |

背景 1970年代半ば、電波天文学、赤外線天文学、X線天文学といった天文観測技術の進歩が、探求すべき宇宙の扉を開いた。新たな道具が必要となった。本書に おいてホーキングとエリスは、アルバート・アインシュタインの一般相対性理論が記述する四次元時空の幾何学に対する公理的基礎を確立し、特異点、事象の地 平線、因果性に関する物理的帰結を導出しようとする。ユークリッド幾何学を研究する道具が定規とコンパスであったのに対し、曲がりくねった時空を調査する ために必要なのは試験粒子と光線である。[3] カリフォルニア大学リバーサイド校の数学物理学者ジョン・ベイズによれば、『時空の大規模構造』は「1970年代初頭にペンローズとホーキングが導入した 革新的な位相幾何学的手法を詳細に解説した最初の書籍」であったという。[4] ホーキングはケンブリッジ大学の博士研究員時代にエリスと共著で本書を執筆した。1988年の著書『時間の本質』において、彼は『時空の大規模構造』を「高度に専門的」であり、一般人には読めない書物だと述べている。 現在では古典と評される本書は、ペーパーバック版も刊行され、何度も再版されている。a 2023年2月にはケンブリッジ大学出版局より50周年記念版が刊行された。[5] |

| Table of contents Preface 1. The Role of Gravity 2. Differential Geometry 3. General Relativity 4. The Physical Significance of Curvature 5. Exact Solutions 6. Causal Structure 7. The Cauchy Problem in General Relativity 8. Space-time Singularities 9. Gravitational Collapse and Black Holes 10. The Initial Singularity of the Universe Appendix A: Translation of An Essay by P. S. Laplace Appendix B: Spherically Symmetric Solutions of Birkhoff's Theorem. References Notation Index |

目次 序文 1. 重力の役割 2. 微分幾何学 3. 一般相対性理論 4. 曲率の物理的意義 5. 正確解 6. 因果構造 7. 一般相対性理論におけるコーシー問題 8. 時空特異点 9. 重力崩壊とブラックホール 10. 宇宙の初期特異点 付録A: P. S. ラプラスによる論文の翻訳 付録B: バーコフの定理の球対称解 参考文献 記号 索引 |

| Assessment Mathematician Nicholas Michael John Woodhouse at the University of Oxford considered this book to be an authoritative treatise that could become a classic. He observed that the authors begin with axioms of geometry and physics then derive the consequences in a rigorous fashion. Various well-known exact solutions to Einstein's field equations and their physical meaning are explored. In particular, Hawking and Ellis show that singularities and black holes arise in a large class of plausible solutions. He warned that although this book is self-contained, it is more suitable for specialists rather than new students as it is heavy-going and contains no exercises. He noted that despite the authors' attempt at a rigorous treatment, certain technical terms, such as Lie groups, are used but never explained, and that modern coordinate-free methods are introduced, but not used effectively.[6] Theoretical physicist Rainer Sachs from the University of California, Berkeley, observed that The Large-Scale Structure of Space-Time was published within just a few years as Gravitation and Cosmology by Steven Weinberg and Gravitation by Charles Misner, Kip Thorne, and John Archibald Wheeler. He believed these three books can supplement each other and lead students to the forefront of research. Whereas Hawking and Ellis employ global analysis extensively but say relatively little about perturbative methods, the other two books neglect global analysis and cover in great detail perturbations. He believed Hawking and Ellis did a great job summarizing recent developments in the field (as of 1974) and that the intended audience is a doctoral student (or higher) with a strong mathematical background and prior exposure to general relativity. He argued that the core of the books consists of two chapters, Chapter 4 on the significance of spacetime curvature and Chapter 6 on causal structure, and that the most interesting application is the penultimate chapter on black holes. He noted that mathematical arguments are at times difficult to follow and suggested Techniques of Differential Topology in Relativity by Roger Penrose for reference. He also noticed a small number of errors, though none affect the general conclusions drawn by the authors. He thought that this book is a "model" presentation on the interplay between mathematics and physics that could become highly influential in the future.[7] Theoretical physicist John Archibald Wheeler of Princeton University recommended this book to anyone interested in the implications of general relativity for cosmology, the singularity theorems, and the physics of black holes, presented in an almost Euclidean fashion, though he acknowledged that this is not a textbook due to its lack of examples and exercises. He praised its 62 illustrative diagrams.[3] |

評価 オックスフォード大学の数学者ニコラス・マイケル・ジョン・ウッドハウスは、この本を権威ある論文であり、古典となり得るものと考えていた。彼は、著者た ちが幾何学と物理学の公理から始め、厳密な方法で結果を導き出していると指摘した。アインシュタインの場の方程式に対する様々なよく知られた正確な解とそ の物理的意味が探求されている。特にホーキングとエリスは、特異点やブラックホールが広範な妥当な解のクラスにおいて生じうることを示した。彼は警告し た。本書は自足的ではあるが、難解で演習問題を含まないため、新規の学生よりも専門家向けであると。著者が厳密な扱いを試みたにもかかわらず、リー群など の専門用語が説明なく使用され、現代的な座標不依存手法が導入されつつも効果的に活用されていない点を指摘した。[6] カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の理論物理学者ライナー・サックスは、『時空の大規模構造』が出版されてからわずか数年で、スティーブン・ワインバーグの 『重力と宇宙論』、チャールズ・ミスナー、キップ・ソーン、ジョン・アーチボルド・ウィーラーの『重力』が刊行されたと指摘した。彼はこれら三冊が互いに 補完し合い、学生を研究の最前線へと導けると確信していた。ホーキングとエリスはグローバル解析を多用する一方、摂動論的手法については比較的触れていな い。他方、他の二冊はグローバル解析を軽視し、摂動論を詳細に扱っている。彼はホーキングとエリスが(1974年時点での)分野の近年の進展を要約する上 で優れた仕事をしたと評価し、対象読者は数学的素養が強く一般相対論の予備知識を持つ博士課程学生(あるいはそれ以上)であると指摘した。彼は、本書の核 心は第4章「時空曲率の意義」と第6章「因果構造」の二章で構成され、最も興味深い応用例は最終章の一つ前のブラックホールに関する章だと主張した。数学 的議論が時に理解しにくい点に言及し、参考書としてロジャー・ペンローズの『相対論における微分位相幾何学の手法』を推奨した。また、少数の誤りを指摘し たが、いずれも著者の導いた結論全体に影響を与えるものではないと述べた。彼は本書を数学と物理学の相互作用に関する「模範的な」提示であり、将来的に非 常に影響力を持つ可能性があると考えた。[7] プリンストン大学の理論物理学者ジョン・アーチボルド・ウィーラーは、一般相対性理論が宇宙論、特異点定理、ブラックホールの物理学に与える影響に興味が ある者なら誰でもこの本を推奨した。内容はほぼユークリッド的な手法で提示されているが、例題や演習問題が不足しているため教科書ではないと認めた。彼は 62点の図解を称賛した。[3] |

| Mathematics of general relativity List of books on general relativity |

一般相対性理論の数学 一般相対性理論に関する書籍一覧 |

| Hawking, S. W.; Ellis, G.

F. R. (1973). The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time. Cambridge

University Press. ISBN 0-521-09906-4. |

ホーキング, S. W.; エリス, G. F. R. (1973). 『時空の大規模構造』. ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 0-521-09906-4. |

| References 01. Gibbons, G. W.; Shellard, E. P. S.; Rankin, S. J. (23 October 2003). The Future of Theoretical Physics and Cosmology: Celebrating Stephen Hawking's Contributions to Physics. Cambridge University Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-521-82081-3. McEvoy, J. P.; Zarate, Oscar (1995). Introducing Stephen Hawking. Totem Books. ISBN 978-1-874-16625-2. Wheeler, John A. (March–April 1975). "The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time by S. W. Hawking and G. F. R.Ellis". Review. American Scientist. 62 (2). Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society: 218. JSTOR 27845370. Baez, John; Hillman, Chris (October 1998). "Guide to Relativity Books". Department of Physics, University of California, Riverside. Retrieved August 25, 2019. 05. Hawking, Stephen (2023). The large scale structure of space-time. George F. R. Ellis, Abhay Ashtekar (50th anniversary ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-1-009-25316-1. OCLC 1347434162. Woodhouse, Nicholas (1974). "The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time". Physics Bulletin. 25 (6): 238. doi:10.1088/0031-9112/25/6/029. 07. Sachs, Rainer (April 1974). "The Large Scale Structure of Space–Time". Physics Today. 27 (4). American Institute of Physics: 91–3. Bibcode:1974PhT....27d..91H. doi:10.1063/1.3128542. S2CID 121949888. |

参考文献 01. ギボンズ, G. W.; シェラード, E. P. S.; ランキン, S. J. (2003年10月23日). 『理論物理学と宇宙論の未来:スティーブン・ホーキングの物理学への貢献を称えて』. ケンブリッジ大学出版局. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-521-82081-3. McEvoy, J. P.; Zarate, Oscar (1995). 『スティーブン・ホーキング入門』. トーテム・ブックス. ISBN 978-1-874-16625-2. Wheeler, John A. (1975年3月–4月). 「S. W. ホーキングとG. F. R. エリスによる時空の大規模構造」. 書評。アメリカン・サイエンティスト。62 (2)。シグマ・カイ、科学研究名誉協会:218。JSTOR 27845370。 バエズ、ジョン;ヒルマン、クリス(1998年10月)。「相対性理論書籍ガイド」。カリフォルニア大学リバーサイド校物理学部。2019年8月25日取得。 05. Hawking, Stephen (2023). 『時空の大規模構造』. George F. R. Ellis, Abhay Ashtekar (50周年記念版). 英国ケンブリッジ. ISBN 978-1-009-25316-1. OCLC 1347434162. ウッドハウス、ニコラス(1974)。「時空の大規模構造」。物理学紀要。25 (6): 238。doi:10.1088/0031-9112/25/6/029。 07. サックス、ライナー(1974年4月)。「時空の大規模構造」. フィジックス・トゥデイ. 27 (4). アメリカ物理学会: 91–3. Bibcode:1974PhT....27d..91H. doi:10.1063/1.3128542. S2CID 121949888. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Large_Scale_Structure_of_Space-Time |

| Chapter 1: Our

Picture of the Universe |

Ptolemy's Earth-centric

model about the location of the planets, stars, and Sun Ptolemy's Earth-centric

model about the location of the planets, stars, and Sun |

| Chapter 2: Space and Time |

|

| Chapter 3: The Expanding Universe |

|

| Chapter 4: The Uncertainty

Principle |

ホ

ログラフィック原理「スティーヴン・ホーキングはブラックホールの集団の事象の地平面の総計は常に時間とともに増加することを示した。その地平面は光的な

測地線によって定義される境界である。すなわち、それはちょうどぎりぎり脱出することのできないこれらの光線である。もし周辺の測地線がそれぞれに向かっ

て動き始めるとそれらは最終的には衝突する。その衝突地点ではそれらの延長はブラックホールの内部となる。そのため測地線は常にお互い離れるように動いて

おり、その境界、つまりその地平面の面積を生成する測地線の数は常に増加する。ホーキングの結果は熱力学第二法則(エントロピー増大の法則)とのアナロ

ジーでブラックホール熱力学の第二法則と呼ばれる。しかし当初は彼はこのアナロジーをあまり真面目にはとらえていなかった」https://x.gd/BY5VA |

| Chapter 5: Elementary Particles

and Forces of Nature |

|

| Chapter 6: Black Holes |

|

| Chapter 7: Hawking Radiation |

A proton consists of three

quarks, which are different colours due to colour confinement. |

| Chapter 8: The Origin and Fate

of the Universe |

|

| Chapter 9: The Arrow of Time |

|

| Chapter 10: Wormholes and Time

Travel |

|

| Chapter 11: The Unification of

Physics |

|

| Chapter 12: Conclusion |

| Absolute zero | 絶対零度 |

Absolute zero: The lowest

possible temperature, at which substances contain no heat energy. |

| Acceleration | 加速 | Acceleration: The rate at which

the speed of an object is changing. |

| Anthropic principle | 人間原理 |

Anthropic principle:

We see the universe the way it is because if it were different we would

not be here toobserve it. もし宇宙が異なっていたら、私たちはここで宇宙を観察していることは不可能だという理屈のこと。 |

| Antiparticle | 反粒子 |

Antiparticle: Each type of

matter particle has a corresponding antiparticle. When a particle

collides with itsantiparticle, they annihilate, leaving only energy. |

| Atom | Atom: The basic unit of ordinary

matter, made up of a tiny nucleus (consisting of protons and neutrons)

surrounded by orbiting electrons. |

|

| Big bang | Big bang: The singularity at the

beginning of the universe. |

|

| Big crunch | Big crunch: The singularity at

the end of the universe. |

|

| Black hole | Black hole: A region of

space-time from which nothing, not even light, can escape, because

gravity is so strong. |

|

| Casimir effect | カシミー

ル効果 |

Casimir effect: The attractive

pressure between two flat, parallel metal plates placed very near to

each other in a vacuum. The pressure is due to a reduction in the usual

number of virtual particles in the space between the plates. 非常に小さい距離を隔てて設置された二枚の平面金属板が真空中で互いに引き合う現象を、静的カシミール効果という。また、二枚の金属板を振動させると光子 が生じる。これを動的カシミール効果という。 |

| Chandrasekhar limit | Chandrasekhar limit: The maximum

possible mass of a stable cold star, above which it must collapse into

a black hole. |

|

| Conservation of energy | Conservation of energy: The law

of science that states that energy (or its equivalent in mass) can

neither be created nor destroyed. |

|

| Coordinates | Coordinates: Numbers that

specify the position of a point in space and time. |

|

| Cosmological constant | Cosmological constant: A

mathematical device used by Einstein to give space-time an inbuilt

tendency to expand. |

|

| Cosmology | Cosmology: The study of the

universe as a whole. |

|

| Dark matter | Dark matter: Matter in galaxies,

clusters, and possibly between clusters, that can not be observed

directly but can be detected by its gravitational effect. As much as 90

percent of the mass of the universe may be in the form of dark matter. |

|

| Duality | Duality: A correspondence

between apparently different theories that lead to the same physical

results. |

|

| Einstein-Rosen bridge | Einstein-Rosen bridge: A thin

tube of space-time linking two black holes. Also see Wormhole. |

|

| Electric charge | Electric charge: A property of a

particle by which it may repel (or attract) other particles that have a

charge ofsimilar (or opposite) sign. |

|

| Electromagnetic force: | Electromagnetic force: The force

that arises between particles with electric charge; the second

strongest of the four fundamental forces. |

|

| Electron | Electron: A particle with negative electric charge that orbits the nucleus of an atom. | |

| Electroweak unification energy | Electroweak unification energy:

The energy (around 100 GeV) above which the distinction between the

electromagnetic force and the weak force disappears. |

|

| Elementary particle | Elementary particle: A particle

that, it is believed, cannot be subdivided. |

|

| Event | Event: A point in space-time,

specified by its time and place. |

|

| Event horizon | Event horizon: The boundary of a

black hole. |

|

| Exclusion principle | Exclusion principle: The idea

that two identical spin-1/2 particles cannot have (within the limits

set by the uncertainty principle) both the same position and the same

velocity. |

|

| Field | Field: Something that exists

throughout space and time, as opposed to a particle that exists at only

one point at a time. |

|

| Frequency | Frequency: For a wave, the

number of complete cycles per second. |

|

| Gamma rays | Gamma rays: Electromagnetic rays

of very short wavelength, produced in radio-active decay or by

collisions of elementary particles. |

|

| General relativity | 一般相対性 |

General relativity: Einstein’s

theory based on the idea that the laws of science should be the same

for all observers, no matter how they are moving. It explains the force

of gravity in terms of the curvature of a four-dimensional space-time. |

| Geodesic | 測地線(ジオデシック) |

Geodesic: The shortest (or

longest) path between two points. |

| Grand unification energy | Grand unification energy: The

energy above which, it is believed, the electro-magnetic force, weak

force, and strong force become indistinguishable from each other. |

|

| Grand unified theory (GUT) | 大統一理論 |

Grand unified theory (GUT): A

theory which unifies the electromagnetic, strong, and weak forces. |

| Light cone | Light cone: A surface in

space-time that marks out the possible directions for light rays

passing through a given event. |

|

| Light-second (light-year) | Light-second (light-year): The

distance traveled by light in one second (year). |

|

| Magnetic field | Magnetic field: The field

responsible for magnetic forces, now incorporated along with the

electric field, into the electromagnetic field. |

|

| Mass | Mass: The quantity of matter in

a body; its inertia, or resistance to acceleration. |

|

| Microwave background radiation | Microwave background radiation: The radiation from the glowing of the hot early universe, now so greatly red-shifted that it appears not as light but as microwaves (radio waves with a wavelength of a few centimeters).Also see COBE, on page 145. | |

| Naked singularity | 裸の特異点 |

Naked singularity: A space-time

singularity not surrounded by a black hole. |

| Neutrino | Neutrino: An extremely light

(possibly massless) particle that is affected only by the weak force

and gravity. |

|

| Neutron | Neutron: An uncharged particle,

very similar to the proton, which accounts for roughly half the

particles in an atomic nucleus. |

|

| Neutron star | Neutron star: A cold star,

supported by the exclusion principle repulsion between neutrons. |

|

| No boundary condition | No boundary condition: The idea

that the universe is finite but has no boundary (in imaginary time). |

|

| Nuclear fusion | Nuclear fusion: The process by

which two nuclei collide and coalesce to form a single, heavier nucleus. |

|

| Nucleus | Nucleus: The central part of an

atom, consisting only of protons and neutrons, held together by the

strongforce. |

|

| Particle accelerator | Particle accelerator: A machine

that, using electromagnets, can accelerate moving charged particles,

giving them more energy. |

|

| Phase | Phase: For a wave, the position

in its cycle at a specified time: a measure of whether it is at a

crest, a trough, or somewhere in between. |

|

| Photon | Photon: A quantum of light. |

|

| Planck’s quantum principle | プランクの量子原理 |

Planck’s quantum principle: The

idea that light (or any other classical waves) can be emitted or

absorbed only in discrete quanta, whose energy is proportional to their

wavelength. |

| Positron | Positron: The (positively

charged) antiparticle of the electron. |

|

| Primordial black hole | 原初ブラックホール |

Primordial black hole: A black

hole created in the very early universe. |

| Proportional | Proportional: ‘X is proportional

to Y’ means that when Y is multiplied by any number, so is X. ‘X is

inversely proportional to Y’ means that when Y is multiplied by any

number, X is divided by that number. |

|

| Proton | Proton: A positively charged

particle, very similar to the neutron, that accounts for roughly half

the particles in the nucleus of most atoms. |

|

| Pulsar | Pulsar: A rotating neutron star

that emits regular pulses of radio waves. |

|

| Quantum | Quantum: The indivisible unit in

which waves may be emitted or absorbed. |

|

| Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) | 量子色力学(QCD) |

Quantum chromodynamics (QCD):

The theory that describes the interactions of quarks and gluons. |

| Quantum mechanics | Quantum mechanics: The theory

developed from Planck’s quantum principle and Heisenberg’s uncertainty

principle. |

|

| Quark | Quark: A (charged) elementary

particle that feels the strong force. Protons and neutrons are each

composed of three quarks. |

|

| Radar | レーダー |

Radar: A system using pulsed

radio waves to detect the position of objects by measuring the time it

takes a single pulse to reach the object and be reflected back. |

| Radioactivity | Radioactivity: The spontaneous

breakdown of one type of atomic nucleus into another. |

|

| Red shift | 赤方偏移 |

Red shift: The reddening of

light from a star that is moving away from us, due to the Doppler

effect. |

| Singularity | 特異点 |

Singularity: A point in

space-time at which the space-time curvature becomes infinite. |

| Singularity theorem | 特異点定理 |

Singularity theorem: A theorem

that shows that a singularity must exist under certain circumstances –

in particular, that the universe must have started with a singularity. |

| Space-time | 時空 |

Space-time: The four-dimensional

space whose points are events. 時空:四次元空間でそのなかの点が出来事(イベント)であるもの |

| Spatial dimension | Spatial dimension: Any of the

three dimensions that are spacelike – that is, any except the time

dimension. |

|

| Special relativity | 特殊相対性 |

Special relativity: Einstein’s

theory based on the idea that the laws of science should be the same

for all observers, no matter how they are moving, in the absence of

gravitational phenomena. |

| Spectrum | Spectrum: The component

frequencies that make up a wave. The visible part of the sun’s spectrum

can be seen in a rainbow. |

|

| Spin | Spin: An internal property of

elementary particles, related to, but not identical to, the everyday

concept of spin. |

|

| Stationary state | Stationary state: One that is

not changing with time: a sphere spinning at a constant rate is

stationary because it looks identical at any given instant. |

|

| String theory | String theory: A theory of

physics in which particles are described as waves on strings. Strings

have length but no other dimension. |

|

| Strong force | Strong force: The strongest of

the four fundamental forces, with the shortest range of all. It holds

the quarks together within protons and neutrons, and holds the protons

and neutrons together to form atoms. |

|

| Uncertainty principle | Uncertainty principle: The

principle, formulated by Heisenberg, that one can never be exactly sure

of both the position and the velocity of a particle; the more

accurately one knows the one, the less accurately one can know the

other. |

|

| Virtual particle | Virtual particle: In quantum

mechanics, a particle that can never be directly detected, but whose

existence does have measurable effects. |

|

| Wave/particle duality | Wave/particle duality: The

concept in quantum mechanics that there is no distinction between waves

and particles; particles may sometimes behave like waves, and waves

like particles. |

|

| Wavelength | Wavelength: For a wave, the

distance between two adjacent troughs or two adjacent crests. |

|

| Weak force | 弱い力(核力) |

Weak force: The second weakest

of the four fundamental forces, with a very short range. It affects all

matter particles, but not force-carrying particles. |

| Weight | 重量 |

Weight: The force exerted on a

body by a gravitational field. It is proportional to, but not the same

as, its mass. |

| White dwarf | 白色矮星 |

White dwarf: A stable cold star,

supported by the exclusion principle repulsion between electrons. |

| Wormhole | ワームホール |

Wormhole: A thin tube of

space-time connecting distant regions of the universe. Wormholes might

also link to parallel or baby universes and could provide the

possibility of time travel. |

| Imaginary time | 虚時間(虚数で表現される時間) |

Imaginary time: Time measured using imaginary numbers. |

A Brief

History of Time, 1988

| The

Large Scale Structure of Space–Time

is a 1973 treatise on the theoretical physics of spacetime by the

physicist Stephen Hawking and the mathematician George Ellis.[1] It is

intended for specialists in general relativity rather than newcomers.[2] |

『時空の大規模構造』は、物理学者スティーヴン・ホーキングと数学者

ジョージ・エリスによる時空の理論物理学に関する1973年の論文である。[1]

この書は一般相対性理論の専門家を対象としており、初心者向けではない。[2] |

| Background In the mid-1970s, advances in the technologies of astronomical observations – radio, infrared, and X-ray astronomy – opened up the Universe of exploration. New tools became necessary. In this book, Hawking and Ellis attempt to establish the axiomatic foundation for the geometry of four-dimensional spacetime as described by Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity and to derive its physical consequences for singularities, horizons, and causality. Whereas the tools for studying Euclidean geometry were a straightedge and a compass, those needed to investigate curved spacetime are test particles and light rays.[3] According to the mathematical physicist John Baez from the University of California, Riverside, The Large Scale Structure of Space–Time was "the first book to provide a detailed description of the revolutionary topological methods introduced by Penrose and Hawking in the early seventies."[4] Hawking co-wrote the book with Ellis, while he was postdoctoral fellow at the University of Cambridge. In his 1988 book A Brief History of Time, he describes The Large Scale Structure of Space–Time as "highly technical" and unreadable for the layperson. The book, now considered a classic, has also appeared in paperback format and has been reprinted many times.a A fiftieth anniversary edition was published by Cambridge University Press in February 2023.[5] |

背景 1970年代半ば、電波天文学、赤外線天文学、X線天文学といった天文観測技術の進歩が、探求すべき宇宙の扉を開いた。新たな道具が必要となった。本書に おいてホーキングとエリスは、アルバート・アインシュタインの一般相対性理論が記述する四次元時空の幾何学に対する公理的基礎を確立し、特異点・事象の地 平線・因果性に関する物理的帰結を導出しようとする。ユークリッド幾何学を研究する道具が定規とコンパスであったのに対し、曲がりくねった時空を調査する ために必要なのは試験粒子と光線である。[3] カリフォルニア大学リバーサイド校の数学物理学者ジョン・ベイズによれば、『時空の大規模構造』は「70年代初頭にペンローズとホーキングが導入した革命 的な位相幾何学的手法を詳細に解説した最初の書籍」であった。[4] ホーキングはケンブリッジ大学の博士研究員時代にエリスと共著で本書を執筆した。1988年の著書『時間についての簡潔な歴史』で、彼は『時空の大規模構 造』を「高度に技術的」で一般人には読めない本だと述べている。 現在では古典とみなされるこの本は、ペーパーバック版も出版され、何度も再版されている。a 2023年2月にはケンブリッジ大学出版局より50周年記念版が刊行された。[5] |

| Table of contents Preface 1. The Role of Gravity 2. Differential Geometry 3. General Relativity 4. The Physical Significance of Curvature 5. Exact Solutions 6. Causal Structure 7. The Cauchy Problem in General Relativity 8. Space–time Singularities 9. Gravitational Collapse and Black Holes 10. The Initial Singularity of the Universe Appendix A: Translation of An Essay by P. S. Laplace Appendix B: Spherically Symmetric Solutions of Birkhoff's Theorem. References Notation Index |

目次 序文 1. 重力の役割 2. 微分幾何学 3. 一般相対性理論 4. 曲率の物理的意義 5. 正確解 6. 因果構造 7. 一般相対性理論におけるコーシー問題 8. 時空特異点 9. 重力崩壊とブラックホール 10. 宇宙の初期特異点 付録A: P. S. ラプラスによる論文の翻訳 付録B: バーコフの定理の球対称解 参考文献 記号 索引 |

| Assessment Mathematician Nicholas Michael John Woodhouse at the University of Oxford considered this book to be an authoritative treatise that could become a classic. He observed that the authors begin with axioms of geometry and physics then derive the consequences in a rigorous fashion. Various well-known exact solutions to Einstein's field equations and their physical meaning are explored. In particular, Hawking and Ellis show that singularities and black holes arise in a large class of plausible solutions. He warned that although this book is self-contained, it is more suitable for specialists rather than new students as it is heavy-going and contains no exercises. He noted that despite the authors' attempt at a rigorous treatment, certain technical terms, such as Lie groups, are used but never explained, and that modern coordinate-free methods are introduced, but not used effectively.[6] Theoretical physicist Rainer Sachs from the University of California, Berkeley, observed that The Large-Scale Structure of Space–Time was published within just a few years as Gravitation and Cosmology by Steven Weinberg and Gravitation by Charles Misner, Kip Thorne, and John Archibald Wheeler. He believed these three books can supplement each other and lead students to the forefront of research. Whereas Hawking and Ellis employ global analysis extensively but say relatively little about perturbative methods, the other two books neglect global analysis and cover in great detail perturbations. He believed Hawking and Ellis did a great job summarizing recent developments in the field (as of 1974) and that the intended audience is a doctoral student (or higher) with a strong mathematical background and prior exposure to general relativity. He argued that the core of the books consists of two chapters, Chapter 4 on the significance of spacetime curvature and Chapter 6 on causal structure, and that the most interesting application is the penultimate chapter on black holes. He noted that mathematical arguments are at times difficult to follow and suggested Techniques of Differential Topology in Relativity by Roger Penrose for reference. He also noticed a small number of errors, though none affect the general conclusions drawn by the authors. He thought that this book is a "model" presentation on the interplay between mathematics and physics that could become highly influential in the future.[7] Theoretical physicist John Archibald Wheeler of Princeton University recommended this book to anyone interested in the implications of general relativity for cosmology, the singularity theorems, and the physics of black holes, presented in an almost Euclidean fashion, though he acknowledged that this is not a textbook due to its lack of examples and exercises. He praised its 62 illustrative diagrams.[3] |