人間原理

Anthropic principle

☆

宇宙論や科学哲学において、人間原理は観測選択効果とも呼ばれ、宇宙について可能な観測の範囲は、そもそも観測者を育てることができるタイプの宇宙でのみ

観測が可能であるという事実によって制限されるという命題である。人間原理の支持者は、宇宙が知的生命体を受け入れるのに必要な年齢と基本物理定数を持つ

理由を、人間原理で説明できると主張する。もしどちらかが大きく異なっていたら、誰も観測を行うことはできなかっただろう。人間原理は、測定された特定の

物理定数が、他の恣意的な値ではなく、なぜそのような値をとるのかという疑問を解決するためや、宇宙が生命の存在のために細かく調整されているように見え

るという認識を説明するために使われてきた。

人間原理にはさまざまな定式化がある。哲学者のニック・ボストロムは30を数えるが、

その根底にある原理は、宇宙論的主張の種類によって「弱い」ものと「強い」ものに分けられる[1]。

| In cosmology and

philosophy of science, the anthropic principle, also known as the

observation selection effect, is the proposition that the range of

possible observations that could be made about the universe is limited

by the fact that observations are only possible in the type of universe

that is capable of developing observers in the first place. Proponents

of the anthropic principle argue that it explains why the universe has

the age and the fundamental physical constants necessary to accommodate

intelligent life. If either had been significantly different, no one

would have been around to make observations. Anthropic reasoning has

been used to address the question as to why certain measured physical

constants take the values that they do, rather than some other

arbitrary values, and to explain a perception that the universe appears

to be finely tuned for the existence of life. There are many different formulations of the anthropic principle. Philosopher Nick Bostrom counts thirty, but the underlying principles can be divided into "weak" and "strong" forms, depending on the types of cosmological claims they entail.[1] |

宇宙論や科学哲学において、人間原理は観測選択効果とも呼ばれ、宇宙に

ついて可能な観測の範囲は、そもそも観測者を育てることができるタイプの宇宙でのみ観測が可能であるという事実によって制限されるという命題である。人間

原理の支持者は、宇宙が知的生命体を受け入れるのに必要な年齢と基本物理定数を持つ理由を、人間原理で説明できると主張する。もしどちらかが大きく異なっ

ていたら、誰も観測を行うことはできなかっただろう。人間原理は、測定された特定の物理定数が、他の恣意的な値ではなく、なぜそのような値をとるのかとい

う疑問を解決するためや、宇宙が生命の存在のために細かく調整されているように見えるという認識を説明するために使われてきた。 人間原理にはさまざまな定式化がある。哲学者のニック・ボストロムは30を数えるが、 その根底にある原理は、宇宙論的主張の種類によって「弱い」ものと 「強い」ものに分けられる[1]。 |

| Definition and basis The principle was formulated as a response to a series of observations that the laws of nature and parameters of the universe have values that are consistent with conditions for life as it is known rather than values that would not be consistent with life on Earth. The anthropic principle states that this is an a posteriori necessity, because if life were impossible, no living entity would be there to observe it, and thus it would not be known. That is, it must be possible to observe some universe, and hence, the laws and constants of any such universe must accommodate that possibility. The term anthropic in "anthropic principle" has been argued[2] to be a misnomer.[note 1] While singling out the currently observable kind of carbon-based life, none of the finely tuned phenomena require human life or some kind of carbon chauvinism.[3][4] Any form of life or any form of heavy atom, stone, star, or galaxy would do; nothing specifically human or anthropic is involved.[5] The anthropic principle has given rise to some confusion and controversy, partly because the phrase has been applied to several distinct ideas. All versions of the principle have been accused of discouraging the search for a deeper physical understanding of the universe. Critics of the weak anthropic principle point out that its lack of falsifiability entails that it is non-scientific and therefore inherently not useful. Stronger variants of the anthropic principle which are not tautologies can still make claims considered controversial by some; these would be contingent upon empirical verification.[clarification needed] |

定義と根拠 この原理は、自然法則や宇宙のパラメータは、地球上の生命と一致しない値ではなく、知られているような生命の条件と一致する値を持っているという一連の観 察への応答として定式化された。人間原理では、これはア・ポステリオリな必然であるとしている。生命が不可能であれば、それを観察する生命体は存在せず、 したがって生命を知ることもできないからである。つまり、ある宇宙を観測することは可能でなければならず、したがって、そのような宇宙の法則と定数はその 可能性に対応しなければならない。 人間原理」の人間的という用語は誤用であると主張されている[2]。現在観測可能な炭素ベースの生命を特別視しているが、細かく調整された現象のどれも が、人間の生命やある種の炭素排他主義を必要としない[3][4]。どのような形の生命でも、どのような形の重い原子、石、星、銀河でもよく、特に人間や 人間的なものは関係ない[5]。 人間原理はいくつかの混乱と論争を引き起こしてきた。人間原理のすべてのバージョンは、宇宙のより深い物理的理解の探求を妨げると非難されてきた。弱い人 間原理を批判する人々は、人間原理には反証可能性がないため、非科学的であり、本質的に有用ではないと指摘する。トートロジーでない人間原理の強い変形 は、一部の人々によって論争的とみなされる主張を行うことができる[clarification needed]。 |

| Anthropic observations Main article: Fine-tuned universe In 1961, Robert Dicke noted that the age of the universe, as seen by living observers, cannot be random.[6] Instead, biological factors constrain the universe to be more or less in a "golden age", neither too young nor too old.[7] If the universe was one tenth as old as its present age, there would not have been sufficient time to build up appreciable levels of metallicity (levels of elements besides hydrogen and helium) especially carbon, by nucleosynthesis. Small rocky planets did not yet exist. If the universe were 10 times older than it actually is, most stars would be too old to remain on the main sequence and would have turned into white dwarfs, aside from the dimmest red dwarfs, and stable planetary systems would have already come to an end. Thus, Dicke explained the coincidence between large dimensionless numbers constructed from the constants of physics and the age of the universe, a coincidence that inspired Dirac's varying-G theory. Dicke later reasoned that the density of matter in the universe must be almost exactly the critical density needed to prevent the Big Crunch (the "Dicke coincidences" argument). The most recent measurements may suggest that the observed density of baryonic matter, and some theoretical predictions of the amount of dark matter, account for about 30% of this critical density, with the rest contributed by a cosmological constant. Steven Weinberg[8] gave an anthropic explanation for this fact: he noted that the cosmological constant has a remarkably low value, some 120 orders of magnitude smaller than the value particle physics predicts (this has been described as the "worst prediction in physics").[9] However, if the cosmological constant were only several orders of magnitude larger than its observed value, the universe would suffer catastrophic inflation, which would preclude the formation of stars, and hence life. The observed values of the dimensionless physical constants (such as the fine-structure constant) governing the four fundamental interactions are balanced as if fine-tuned to permit the formation of commonly found matter and subsequently the emergence of life.[10] A slight increase in the strong interaction (up to 50% for some authors[11]) would bind the dineutron and the diproton and convert all hydrogen in the early universe to helium;[12] likewise, an increase in the weak interaction also would convert all hydrogen to helium. Water, as well as sufficiently long-lived stable stars, both essential for the emergence of life as it is known, would not exist.[13] More generally, small changes in the relative strengths of the four fundamental interactions can greatly affect the universe's age, structure, and capacity for life. |

人間的観察 主な記事 微調整された宇宙 1961年、ロバート・ディッケは、生きている観測者が見ている宇宙の年齢がランダムであるはずがないと指摘した[6]。 その代わり、生物学的な要因によって、宇宙は若すぎず、古すぎず、多かれ少なかれ「黄金時代」にあることが制約されている[7]。 もし宇宙が現在の年齢の10分の1であったとしたら、核合成によって相当なレベルの金属量(水素とヘリウム以外の元素のレベル)、特に炭素を蓄積するのに 十分な時間はなかっただろう。小さな岩石惑星はまだ存在していなかった。もし宇宙が実際の10倍古かったら、ほとんどの星は主系列に留まるには古すぎて、 最も暗い赤色矮星は別として、白色矮星になっていただろうし、安定した惑星系はすでに終焉を迎えていただろう。こうしてディッケは、物理学の定数から構成 される大きな無次元数と宇宙の年齢が一致することを説明した。 ディッケは後に、宇宙の物質密度はビッグクランチを防ぐために必要な臨界密度とほぼ同じでなければならないと推論した(「ディッケの偶然の一致」論)。最 新の測定結果は、観測されたバリオン物質の密度と、暗黒物質の量に関するいくつかの理論的予測は、この臨界密度の約30%を占め、残りは宇宙定数によるも のであることを示唆していると考えられる。スティーブン・ワインバーグ[8]は、この事実に対して人間学的な説明を行った。彼は、宇宙定数の値が著しく低 く、素粒子物理学が予測する値よりも120桁ほど小さいと指摘した(これは「物理学における最悪の予測」と表現されている)[9]。 4つの基本的な相互作用を支配する無次元物理定数(微細構造定数など)の観測値は、一般的に見られる物質の形成と、それに続く生命の出現を可能にするよう に微調整されているかのようにバランスが取れている[10]。強い相互作用がわずかに増加(著者によっては最大50%[11])すれば、二中性子と二陽子 が結合し、初期宇宙のすべての水素がヘリウムに変わるだろう[12]。より一般的には、4つの基本的相互作用の相対的な強さのわずかな変化は、宇宙の年 齢、構造、生命の能力に大きな影響を与える可能性がある。 |

| Origin The phrase "anthropic principle" first appeared in Brandon Carter's contribution to a 1973 Kraków symposium. Carter, a theoretical astrophysicist, articulated the anthropic principle in reaction to the Copernican principle, which states that humans do not occupy a privileged position in the Universe. Carter said: "Although our situation is not necessarily central, it is inevitably privileged to some extent."[14] Specifically, Carter disagreed with using the Copernican principle to justify the Perfect Cosmological Principle, which states that all large regions and times in the universe must be statistically identical. The latter principle underlies the steady-state theory, which had recently been falsified by the 1965 discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation. This discovery was unequivocal evidence that the universe has changed radically over time (for example, via the Big Bang).[citation needed] Carter defined two forms of the anthropic principle, a "weak" one which referred only to anthropic selection of privileged spacetime locations in the universe, and a more controversial "strong" form that addressed the values of the fundamental constants of physics. Roger Penrose explained the weak form as follows: The argument can be used to explain why the conditions happen to be just right for the existence of (intelligent) life on the Earth at the present time. For if they were not just right, then we should not have found ourselves to be here now, but somewhere else, at some other appropriate time. This principle was used very effectively by Brandon Carter and Robert Dicke to resolve an issue that had puzzled physicists for a good many years. The issue concerned various striking numerical relations that are observed to hold between the physical constants (the gravitational constant, the mass of the proton, the age of the universe, etc.). A puzzling aspect of this was that some of the relations hold only at the present epoch in the Earth's history, so we appear, coincidentally, to be living at a very special time (give or take a few million years!). This was later explained, by Carter and Dicke, by the fact that this epoch coincided with the lifetime of what are called main-sequence stars, such as the Sun. At any other epoch, the argument ran, there would be no intelligent life around to measure the physical constants in question—so the coincidence had to hold, simply because there would be intelligent life around only at the particular time that the coincidence did hold! — The Emperor's New Mind, chapter 10 One reason this is plausible, is that there are many other places and times in which humans could have evolved. But when applying the strong principle, there is only one universe, with one set of fundamental parameters. Thus, Carter offers two possibilities: First, humans can use their own existence to make "predictions" about the parameters. But second, "as a last resort", humans can convert these predictions into explanations by assuming that there is more than one universe, in fact a large and possibly infinite collection of universes, something that is now called the multiverse ("world ensemble" was Carter's term), in which the parameters (and perhaps the laws of physics) vary across universes. The strong principle then becomes an example of a selection effect, analogous to the weak principle. Postulating a multiverse is a radical step that could provide at least a partial insight, seemingly out of the reach of normal science, regarding why the fundamental laws of physics take the particular form we observe and not another. Since Carter's 1973 paper, the term anthropic principle has been extended to cover a number of ideas that differ in important ways from his. Particular confusion was caused by the 1986 book The Anthropic Cosmological Principle by John D. Barrow and Frank Tipler,[15] which distinguished between a "weak" and "strong" anthropic principle in a way different from Carter's, as discussed in the next section. Carter was not the first to invoke some form of the anthropic principle. The evolutionary biologist Alfred Russel Wallace anticipated the anthropic principle as long ago as 1904: "Such a vast and complex universe as that which we know exists around us, may have been absolutely required [...] in order to produce a world that should be precisely adapted in every detail for the orderly development of life culminating in man."[16] In 1957, Robert Dicke wrote: "The age of the Universe 'now' is not random but conditioned by biological factors [...] [changes in the values of the fundamental constants of physics] would preclude the existence of man to consider the problem."[17] Ludwig Boltzmann may have been one of the first in modern science to use anthropic reasoning. Prior to knowledge of the Big Bang, Boltzmann's thermodynamic concepts painted a picture of a universe that had inexplicably low entropy. Boltzmann suggested several explanations, one of which relied on fluctuations that could produce pockets of low entropy or Boltzmann universes. While most of the universe is featureless in this model, to Boltzmann, it is unremarkable that humanity happens to inhabit a Boltzmann universe, as that is the only place that could develop and support intelligent life.[18][19] |

起源 『人間原理」という言葉は、ブランドン・カーターが1973年のクラクフ・シンポジウムに寄稿した中で初めて登場した。理論天体物理学者であったカーター は、人間は宇宙において特権的な地位を占めていないとするコペルニクス的原理に対して、人間原理を明確に打ち出した。カーターは言う: 「特に、カーターはコペルニクス的原理を用いて、宇宙のすべての大きな領域と時間は統計的に同一でなければならないとする完全宇宙論的原理を正当化するこ とに反対した。後者の原理は定常状態の理論の根底にあるもので、1965年に宇宙マイクロ波背景放射が発見されたことによって、定常状態の理論が否定され たばかりであった。この発見は、宇宙が(例えばビッグバンを介して)時間の経過とともに根本的に変化してきたという明白な証拠であった[要出典]。 カーターは人間原理の2つの形式を定義した。宇宙の特権的な時空位置の人間的選択のみに言及する「弱い」形式と、物理学の基本定数の値に対処する、より論争の的となる「強い」形式である。 ロジャー・ペンローズは、弱い形式について次のように説明している: この議論は、現在の地球上に(知的)生命体が存在するための条件が、なぜ偶然にもちょうど良いのかを説明するために使うことができる。もしその条件が適切 でなければ、我々は今ここにいるのではなく、どこか他の適切な時期にここにいるはずだからである。この原理は、ブランドン・カーターとロバート・ディッケ によって、物理学者を長年困惑させてきた問題を解決するために非常に効果的に使われた。この問題は、物理定数(重力定数、陽子の質量、宇宙の年齢など)の 間に成り立つことが観測されている、さまざまな印象的な数値関係に関するものであった。この問題の不可解な点は、いくつかの関係が地球の歴史における現在 のエポックにおいてのみ成り立つことで、偶然にも、我々は非常に特殊な時代(数百万年かどうかは別として!)に生きているように見えることであった。これ は後にカジェ(番街)とディッケによって、このエポックが太陽のような主系列星と呼ばれる星の寿命と一致するという事実によって説明された。それ以外の時 代には、問題の物理定数を測定する知的生命体は存在しないのだから、偶然の一致が成立するのは、偶然の一致が成立する個別主義の時代だけである! - 天皇の新しい心』第10章 これがもっともらしい理由のひとつは、人類が進化できた場所や時間は他にもたくさんあるからだ。しかし、強者の原理を適用すると、宇宙は一つしかなく、基 本的なパラメーターも一つしかない。そこでカーターは2つの可能性を提示する: 第一に、人類は自分たちの存在を利用して、パラメータに関する「予測」を行うことができる。第二に、「最後の手段 」として、人間は、複数の宇宙が存在すると仮定することによって、これらの予測を説明へと変換することができる。実際には、現在では多元宇宙 (「world ensemble 」がカージェの用語)と呼ばれているような、大規模かつ無限の宇宙の集まりが存在し、パラメータ(そしておそらく物理法則)は宇宙間で異なっていると仮定 することができる。強い原理は、弱い原理に類似した選択効果の一例となる。多宇宙を仮定することは急進的な一歩であり、物理学の基本法則がなぜ我々が観測 している特定の形式をとり、他の形式をとらないのかについて、通常の科学では到達できないような、少なくとも部分的な洞察を与える可能性がある。 カーターの1973年の論文以来、人間原理という用語は、カーターの論文とは重要な点で異なる多くの考え方をカバーするために拡張されてきた。特に混乱を 招いたのは、1986年に出版されたジョン・D・バローとフランク・ティプラーによる『The Anthropic Cosmological Principle(人間宇宙原理)』[15]であり、次節で議論するように、カーターとは異なる方法で「弱い」人間原理と「強い」人間原理を区別してい た。 ある種の人間原理を唱えたのはカーターが初めてではない。進化生物学者アルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレスは、1904年も前に人間原理を予見していた: 私たちの周りに存在するような広大で複雑な宇宙は、人間を頂点とする生命の秩序ある発展のために、あらゆる細部において正確に適応されるべき世界を生み出 すために、絶対に必要であったかもしれない」[16][17] 1957年、ロバート・ディッケは次のように書いている:「宇宙の 「現在 」の年齢はランダムではなく、生物学的要因によって条件づけられている。 ルートヴィヒ・ボルツマンは、人間原理を用いた近代科学の最初の一人であったかもしれない。ビッグバンの知識が生まれる前、ボルツマンの熱力学的概念は、 不可解なほどエントロピーの低い宇宙を描いていた。ボルツマンはいくつかの説明を提案したが、そのうちのひとつは、低エントロピーのポケットやボルツマン 宇宙を生み出すゆらぎに依存していた。このモデルでは宇宙の大部分は特徴を持たないが、ボルツマンにとっては、人類がたまたまボルツマン宇宙に住んでいる ことは驚くべきことではなく、それこそが知的生命体を発展させ、維持することができる唯一の場所だからである[18][19]。 |

| Variants According to Brandon Carter, the weak anthropic principle (WAP) states that "... our location in the universe is necessarily privileged to the extent of being compatible with our existence as observers."[14] For Carter, "location" refers to our location in time and space. Carter goes on to define the strong anthropic principle (SAP) as the idea that: The universe (and hence the fundamental parameters on which it depends) must be such as to admit the creation of observers within it at some stage. To paraphrase Descartes, cogito ergo mundus talis est. The Latin tag (which means, "I think, therefore the world is such [as it is]") makes it clear that "must" indicates a deduction from the fact of our existence; the statement is thus a truism. In their 1986 book, The anthropic cosmological principle, John Barrow and Frank Tipler depart from Carter and define the WAP and SAP differently.[20][21] According to Barrow and Tipler, the WAP is the idea that:[22]: 16 The observed values of all physical and cosmological quantities are not equally probable but they take on values restricted by the requirement that there exist sites where carbon-based life can evolve and by the requirements that the universe be old enough for it to have already done so. Unlike Carter, they restrict the principle to "carbon-based life" rather than just "observers". A more important difference is that they apply the WAP to the fundamental physical constants, such as the fine-structure constant, the number of spacetime dimensions, and the cosmological constant—topics that fall under Carter's SAP. According to Barrow and Tipler, the SAP states that "the Universe must have those properties which allow life to develop within it at some stage in its history."[22]: 21 While this looks very similar to Carter's SAP, the "must" is an imperative, as shown by the following three possible elaborations of the SAP, each proposed by Barrow and Tipler:[23] "There exists one possible Universe 'designed' with the goal of generating and sustaining 'observers'." This can be seen as simply the classic design argument restated in the garb of contemporary cosmology. It implies that the purpose of the universe is to give rise to intelligent life, with the laws of nature and their fundamental physical constants set to ensure that life emerges and evolves. "Observers are necessary to bring the Universe into being." Barrow and Tipler believe that this is a valid conclusion from quantum mechanics, as John Archibald Wheeler has suggested, especially via his idea that information is the fundamental reality and his participatory anthropic principle (PAP) which is an interpretation of quantum mechanics associated with the ideas of Eugene Wigner. (See: It from bit) "An ensemble of other different universes is necessary for the existence of our Universe." By contrast, Carter merely says that an ensemble of universes is necessary for the SAP to count as an explanation. Philosophers John Leslie[24] and Nick Bostrom[19] reject the Barrow and Tipler SAP as a fundamental misreading of Carter. For Bostrom, Carter's anthropic principle just warns us to make allowance for "anthropic bias"—that is, the bias created by anthropic selection effects (which Bostrom calls "observation" selection effects)—the necessity for observers to exist in order to get a result. He writes: Many "anthropic principles" are simply confused. Some, especially those drawing inspiration from Brandon Carter's seminal papers, are sound, but... they are too weak to do any real scientific work. In particular, I argue that existing methodology does not permit any observational consequences to be derived from contemporary cosmological theories, though these theories quite plainly can be and are being tested empirically by astronomers. What is needed to bridge this methodological gap is a more adequate formulation of how observation selection effects are to be taken into account. Bostrom defines a concept called the "strong self-sampling assumption" (SSSA), the idea that "each observer-moment should reason as if it were randomly selected from the class of all observer-moments in its reference class." Analyzing an observer's experience into a sequence of "observer-moments" like this helps avoid certain paradoxes, but the main ambiguity is the selection of the appropriate "reference class". For Carter's WAP, this might correspond to all real or potential observer-moments in our universe. As for his SAP, this might correspond to all in the multiverse. Bostrom's mathematical development shows that choosing too broad or too narrow a reference class leads to counter-intuitive results, but he is not able to prescribe an ideal choice. According to Jürgen Schmidhuber, the anthropic principle essentially just says that the conditional probability of finding yourself in a universe compatible with your existence is always one. It does not allow for any additional nontrivial predictions such as "gravity won't change tomorrow". To gain more predictive power, additional assumptions on the prior distribution of alternative universes are necessary.[26][27] Playwright and novelist Michael Frayn describes a form of the strong anthropic principle in his 2006 book The Human Touch, which explores what he characterises as "the central oddity of the Universe":[28] It's this simple paradox. The Universe is very old and very large. Humankind, by comparison, is only a tiny disturbance in one small corner of it--and a very recent one. Yet the Universe is only very large and very old because we are here to say it is... And yet, of course, we all know perfectly well that it is what it is whether we are here or not. |

変種 ブランドン・カーターによると、弱い人間原理(WAP)は「...宇宙における我々の位置は、観測者としての我々の存在と両立する範囲において、必然的に特権的である」と述べている[14]。カーターはさらに、強い人間原理(SAP)を次のように定義している: 宇宙(ひいては宇宙が依存する基本的なパラメータ)は、ある段階でその中に観測者が生まれることを認めるようなものでなければならない。デカルトの言葉を借りれば、cogito ergo mundus talis estである。 このラテン語のタグ(「私は考える、だから世界はそのようなものである」という意味)は、「そうでなければならない」が私たちの存在という事実からの演繹であることを明らかにしている。 ジョン・バローとフランク・ティプラーは1986年の著書『The anthropic cosmological principle』において、カーターとは異なり、WAPとSAPを異なる形で定義している[20][21]: 16 すべての物理量と宇宙量の観測値は等しくあり得るわけではないが、炭素ベースの生命が進化できる場所が存在するという条件と、宇宙がすでに進化しているのに十分古いという条件によって制限された値をとる。 カーターとは異なり、彼らは原理を「観測者」だけでなく「炭素ベースの生命」に限定している。さらに異なる点は、カーターのSAPに該当する、微細構造定数、時空間次元数、宇宙定数などの基本物理定数にWAPを適用していることである。 バローとティプラーによれば、SAPは「宇宙は、その歴史のある段階において、生命がその中で発展することを可能にするような性質を持たなければならな い」と述べている[22]: 21 これはカーターのSAPと非常によく似ているが、バローとティプラーによって提案されたSAPの次の3つの可能性によって示されるように、「持たなければ ならない」は命令である[23]。 「観察者 」を生成し維持することを目標に 「設計された 」可能性のある宇宙が一つ存在する" これは単に古典的な設計論を現代の宇宙論の衣をまとって再定義したものと見ることができる。宇宙の目的は知的生命体を誕生させることであり、自然法則とその基本的な物理定数は、生命が誕生し進化するように設定されている。 「宇宙を誕生させるためには、観測者が必要である。 バローとティプラーは、ジョン・アーチボルド・ウィーラーが示唆したように、これは量子力学から導かれる妥当な結論であると信じている。特に、情報こそが 基本的な現実であるという彼の考えや、ユージン・ウィグナーの考えに関連した量子力学の解釈である参加型人間原理(PAP)を通じて。(参照:It from bit) 「我々の宇宙が存在するためには、異なる宇宙の集合体が必要である。 これに対してカーターは、SAPが説明として数えられるためには、宇宙のアンサンブルが必要だと言っているに過ぎない。 哲学者のジョン・レスリー[24]とニック・ボストロム[19]は、バローとティプラーのSAPをカーターの根本的な誤読として否定している。ボストロム にとって、カージェ(番街)の人間原理は「人間的バイアス」、つまり人間的選択効果(ボストロムは「観測」選択効果と呼んでいる)によって生じるバイア ス、つまり結果を得るために観測者が存在する必要性を許容するように警告しているだけである。彼はこう書いている: 多くの 「人間原理 」は単に混乱しているだけである。特にブランドン・カーターの代表的な論文からヒントを得たものは健全であるが、...本当の科学的研究を行うには弱すぎ る。特に、天文学者によって実証的に検証され、検証されつつあるにもかかわらず、既存の方法論では、現代の宇宙論から観測的な結果を導き出すことはできな いと私は主張する。この方法論的ギャップを埋めるために必要なのは、観測による選択効果をどのように考慮するかという、より適切な定式化である。 カジェ(番街)は「強自己サンプリング仮定」(SSSA)と呼ばれる概念を定義しているが、これは「各観測者-瞬間は、あたかもその参照クラスの全観測者 -瞬間のクラスからランダムに選択されたかのように推論すべきである」という考え方である。このように観察者の経験を「観察者-瞬間」の連続に分析するこ とは、ある種のパラドックスを回避するのに役立つが、主な曖昧さは適切な「参照クラス」の選択にある。カーターのWAPの場合、これは我々の宇宙における すべての現実的または潜在的な観察者モーメントに相当するかもしれない。カーターのSAPの場合は、多元宇宙におけるすべてに対応するかもしれない。ボス トロムの数学的展開は、参照クラスを広すぎても狭すぎても直感に反する結果になることを示しているが、理想的な選択を規定することはできない。 ユルゲン・シュミッドフーバーによれば、人間原理は本質的に、自分の存在と適合する宇宙に自分が存在する条件付き確率は常に1であるというだけである。こ の原理は、「明日重力が変化することはない」というような、自明でない予測を可能にするものではない。より多くの予測力を得るためには、代替的な宇宙の事 前分布に関する追加的な仮定が必要である[26][27]。 劇作家であり小説家であるマイケル・フレインは、2006年に出版した著書『The Human Touch』において、強い人間原理の一形態について述べている。 それはこの単純なパラドックスである。宇宙は非常に古く、非常に大きい。それに比べて人類は、その片隅にある小さな擾乱に過ぎない。しかし、宇宙が非常に 大きく、非常に古いのは、私たちがここにいるからに他ならない。そしてもちろん、私たちは皆、私たちがここにいようがいまいが、宇宙がそういうものである ことをよく知っている。 |

| Character of anthropic reasoning Carter chose to focus on a tautological aspect of his ideas, which has resulted in much confusion. In fact, anthropic reasoning interests scientists because of something that is only implicit in the above formal definitions, namely that humans should give serious consideration to there being other universes with different values of the "fundamental parameters"—that is, the dimensionless physical constants and initial conditions for the Big Bang. Carter and others have argued that life would not be possible in most such universes. In other words, the universe humans live in is fine tuned to permit life. Collins & Hawking (1973) characterized Carter's then-unpublished big idea as the postulate that "there is not one universe but a whole infinite ensemble of universes with all possible initial conditions".[29] If this is granted, the anthropic principle provides a plausible explanation for the fine tuning of our universe: the "typical" universe is not fine-tuned, but given enough universes, a small fraction will be capable of supporting intelligent life. Ours must be one of these, and so the observed fine tuning should be no cause for wonder. Although philosophers have discussed related concepts for centuries, in the early 1970s the only genuine physical theory yielding a multiverse of sorts was the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. This would allow variation in initial conditions, but not in the truly fundamental constants. Since that time a number of mechanisms for producing a multiverse have been suggested: see the review by Max Tegmark.[30] An important development in the 1980s was the combination of inflation theory with the hypothesis that some parameters are determined by symmetry breaking in the early universe, which allows parameters previously thought of as "fundamental constants" to vary over very large distances, thus eroding the distinction between Carter's weak and strong principles. At the beginning of the 21st century, the string landscape emerged as a mechanism for varying essentially all the constants, including the number of spatial dimensions.[note 2] The anthropic idea that fundamental parameters are selected from a multitude of different possibilities (each actual in some universe or other) contrasts with the traditional hope of physicists for a theory of everything having no free parameters. As Albert Einstein said: "What really interests me is whether God had any choice in the creation of the world." In 2002, some proponents of the leading candidate for a "theory of everything", string theory, proclaimed "the end of the anthropic principle"[31] since there would be no free parameters to select. In 2003, however, Leonard Susskind stated: "... it seems plausible that the landscape is unimaginably large and diverse. This is the behavior that gives credence to the anthropic principle."[32] The modern form of a design argument is put forth by intelligent design. Proponents of intelligent design often cite the fine-tuning observations that (in part) preceded the formulation of the anthropic principle by Carter as a proof of an intelligent designer. Opponents of intelligent design are not limited to those who hypothesize that other universes exist; they may also argue, anti-anthropically, that the universe is less fine-tuned than often claimed, or that accepting fine tuning as a brute fact is less astonishing than the idea of an intelligent creator. Furthermore, even accepting fine tuning, Sober (2005)[33] and Ikeda and Jefferys,[34][35] argue that the anthropic principle as conventionally stated actually undermines intelligent design. Paul Davies's book The Goldilocks Enigma (2006) reviews the current state of the fine-tuning debate in detail, and concludes by enumerating the following responses to that debate:[7]: 261–267 1. The absurd universe: Our universe just happens to be the way it is. 2. The unique universe: There is a deep underlying unity in physics that necessitates the Universe being the way it is. A Theory of Everything will explain why the various features of the Universe must have exactly the values that have been recorded. 3. The multiverse: Multiple universes exist, having all possible combinations of characteristics, and humans inevitably find themselves within a universe that allows us to exist. 4. Intelligent design: A creator designed the Universe with the purpose of supporting complexity and the emergence of intelligence. 5. The life principle: There is an underlying principle that constrains the Universe to evolve towards life and mind. 6. The self-explaining universe: A closed explanatory or causal loop: "perhaps only universes with a capacity for consciousness can exist". This is Wheeler's participatory anthropic principle (PAP). 7. The fake universe: Humans live inside a virtual reality simulation. Omitted here is Lee Smolin's model of cosmological natural selection, also known as fecund universes, which proposes that universes have "offspring" that are more plentiful if they resemble our universe. Also see Gardner (2005).[36] Clearly each of these hypotheses resolve some aspects of the puzzle, while leaving others unanswered. Followers of Carter would admit only option 3 as an anthropic explanation, whereas 3 through 6 are covered by different versions of Barrow and Tipler's SAP (which would also include 7 if it is considered a variant of 4, as in Tipler 1994). The anthropic principle, at least as Carter conceived it, can be applied on scales much smaller than the whole universe. For example, Carter (1983)[37] inverted the usual line of reasoning and pointed out that when interpreting the evolutionary record, one must take into account cosmological and astrophysical considerations. With this in mind, Carter concluded that given the best estimates of the age of the universe, the evolutionary chain culminating in Homo sapiens probably admits only one or two low probability links. |

人間的推論の特徴 カーターは、自分の考えのトートロジー的な側面に焦点を当てることを選んだため、多くの混乱を招いた。実際、人間性推論が科学者たちの関心を集めているの は、上記の形式的な定義では暗黙の了解となっていること、つまり、「基本パラメータ」、つまりビッグバンの無次元物理定数や初期条件の値が異なる別の宇宙 が存在することを、人類は真剣に考慮すべきだという点にある。カーターらは、そのような宇宙ではほとんどの場合、生命は存在し得ないと主張している。言い 換えれば、人類が住んでいる宇宙は、生命が存在できるように微調整されているのである。コリンズとホーキング(1973年)は、当時未発表だったカーター のビッグアイデアを、「宇宙は一つではなく、ありとあらゆる初期条件を持つ宇宙の無限のアンサンブル全体が存在する」という仮定として特徴づけた [29]。これが認められれば、人間原理は我々の宇宙の微調整についてもっともらしい説明を提供することになる。しかし、十分な数の宇宙があれば、知的生 命体を維持できる宇宙はごく一部であるはずだ。 哲学者たちは何世紀にもわたって関連する概念について議論してきたが、1970年代初頭には、ある種の多元宇宙をもたらす唯一の本格的な物理理論は、量子 力学の多世界解釈であった。この解釈では、初期条件の変化は許容されるが、真に基本的な定数は変化しない。1980年代の重要な発展は、インフレーション 理論と、いくつかのパラメータは初期宇宙における対称性の破れによって決定されるという仮説の組み合わせであった。21世紀初頭には、空間次元数を含む本 質的にすべての定数を変化させるメカニズムとして、超ひも理論が登場した[注釈 2]。 基本的なパラメータは、マルチチュードの異なる可能性(それぞれどこかの宇宙か他の宇宙で実際に存在するもの)から選択されるという人間原理的な考え方 は、自由なパラメータを持たない万物の理論に対する物理学者の伝統的な希望とは対照的である。アルベルト・アインシュタインは言った: 「私が本当に興味があるのは、神が世界の創造において何らかの選択をしたのかどうかということだ」。2002年、「万物の理論」の最有力候補である超ひも 理論の一部の支持者は、選択すべき自由パラメータが存在しないことから、「人間原理の終焉」[31]を宣言した。しかし2003年、レナード・サスキンド は次のように述べている: 「風景が想像を絶するほど大きく多様であることは、もっともらしい。これは人間原理に信憑性を与える振る舞いである」[32]。 現代的な形のデザイン論は、インテリジェント・デザインによって提唱されている。インテリジェント・デザインの支持者は、知的設計者の証明として、カー ターによる人間原理の定式化に(部分的に)先行したファインチューニング観測をしばしば引用する。インテリジェント・デザインの反対派は、他の宇宙が存在 するという仮説を立てる人たちに限らず、反人類的に、宇宙はしばしば主張されるよりもファインチューニングされていないと主張したり、ファインチューニン グを厳然たる事実として受け入れることは、知的創造主の考えよりも驚くべきことではないと主張したりする。さらに、ファインチューニングを受け入れたとし ても、Sober(2005年)[33]やIkeda and Jefferys, [34][35]は、従来から言われている人間原理はインテリジェントデザインを実際に弱体化させると論じている。 Paul Daviesの著書The Goldilocks Enigma (2006)は、ファインチューニングの議論の現状を詳細にレビューし、その議論に対する以下の回答を列挙して締めくくっている[7]: 261-267 1. 不条理な宇宙: 我々の宇宙はたまたまそうなっているだけである。 2. ユニークな宇宙: 物理学の根底には、宇宙がそうでなければならない深い統一性がある。万物理論では、宇宙の様々な特徴が、記録された値を正確に持たなければならない理由を説明する。 3. 多元宇宙: 複数の宇宙が存在し、あらゆる特徴の組み合わせが可能であり、人類は必然的に、我々が存在できる宇宙の中に身を置くことになる。 4. インテリジェント・デザイン: 創造主が、複雑さと知性の出現をサポートする目的で宇宙を設計した。 5. 生命原理:宇宙が生命と精神に向かって進化するよう制約する根本原理がある。 6. 自己説明的な宇宙: 説明や因果のループが閉じている: 「おそらく意識の能力を持つ宇宙だけが存在できる」。これはホイーラーの参加型人間原理(PAP)である。 7. 偽の宇宙: 人間は仮想現実のシミュレーションの中に住んでいる。 ここでは省略するが、リー・スモリンの宇宙論的自然淘汰のモデル(fecund universesとも呼ばれる)は、宇宙は「子孫」を持ち、それが我々の宇宙と似ていればより多く存在すると提唱している。また、Gardner (2005)も参照されたい[36]。 これらの仮説のそれぞれが、パズルのある側面を解決する一方で、他の側面については未解決のままにしていることは明らかである。カーターの信奉者は、人間 原理的説明として3の選択肢のみを認めるだろうが、3から6はバローとティプラーのSAPの異なるバージョンによってカバーされている(ティプラー 1994のように4の変形と見なされる場合は、7も含まれる)。 人間原理は、少なくともカーターが考えたように、宇宙全体よりもはるかに小さなスケールで適用することができる。例えば、カーター(1983)[37]は 通常の推論を逆転させ、進化の記録を解釈する際には宇宙論的・天体物理学的な考察を考慮に入れなければならないと指摘した。このことを念頭に置いて、カー ターは、宇宙の年齢に関する最良の推定値を考えると、ホモ・サピエンスに至る進化の連鎖は、おそらく1つか2つの確率の低いリンクしか認めないと結論づけ た。 |

| Observational evidence No possible observational evidence bears on Carter's WAP, as it is merely advice to the scientist and asserts nothing debatable. The obvious test of Barrow's SAP, which says that the universe is "required" to support life, is to find evidence of life in universes other than ours. Any other universe is, by most definitions, unobservable (otherwise it would be included in our portion of this universe[undue weight? – discuss]). Thus, in principle Barrow's SAP cannot be falsified by observing a universe in which an observer cannot exist. Philosopher John Leslie[38] states that the Carter SAP (with multiverse) predicts the following: - Physical theory will evolve so as to strengthen the hypothesis that early phase transitions occur probabilistically rather than deterministically, in which case there will be no deep physical reason for the values of fundamental constants; - Various theories for generating multiple universes will prove robust; - Evidence that the universe is fine tuned will continue to accumulate; - No life with a non-carbon chemistry will be discovered; - Mathematical studies of galaxy formation will confirm that it is sensitive to the rate of expansion of the universe. Hogan[39] has emphasised that it would be very strange if all fundamental constants were strictly determined, since this would leave us with no ready explanation for apparent fine tuning. In fact, humans might have to resort to something akin to Barrow and Tipler's SAP: there would be no option for such a universe not to support life. Probabilistic predictions of parameter values can be made given: 1. a particular multiverse with a "measure", i.e. a well defined "density of universes" (so, for parameter X, one can calculate the prior probability P(X0) dX that X is in the range X0 < X < X0 + dX), and 2. an estimate of the number of observers in each universe, N(X) (e.g., this might be taken as proportional to the number of stars in the universe). The probability of observing value X is then proportional to N(X) P(X). A generic feature of an analysis of this nature is that the expected values of the fundamental physical constants should not be "over-tuned", i.e. if there is some perfectly tuned predicted value (e.g. zero), the observed value need be no closer to that predicted value than what is required to make life possible. The small but finite value of the cosmological constant can be regarded as a successful prediction in this sense. One thing that would not count as evidence for the anthropic principle is evidence that the Earth or the Solar System occupied a privileged position in the universe, in violation of the Copernican principle (for possible counterevidence to this principle, see Copernican principle), unless there was some reason to think that that position was a necessary condition for our existence as observers. |

観測的証拠 カーターのWAPは科学者へのアドバイスに過ぎず、議論の余地のあることは何も主張していないため、観測可能な証拠は何もない。宇宙が生命を維持するため に「必要である」とするバローのSAPの明らかなテストは、我々の宇宙以外の宇宙で生命の証拠を見つけることである。それ以外の宇宙は、ほとんどの定義に よれば、観測不可能である(そうでなければ、この宇宙の我々の部分に含まれるはずである[過度の重み付け? - 議論])。したがって、原理的には、観測者が存在し得ない宇宙を観測することによって、バローのSAPを反証することはできない。 哲学者のジョン・レスリー[38]は、カーターSAP(多元宇宙を含む)は次のように予測していると述べている: - 物理理論は、初期の相転移は決定論的ではなく確率論的に起こるという仮説を強化するように進化し、その場合、基本定数の値には深い物理的理由は存在しなくなる; - その場合、基本定数の値に深い物理的理由はなくなる。複数の宇宙を生成するためのさまざまな理論が強固であることが証明される; - 宇宙が微調整されているという証拠は蓄積され続けるだろう; - 炭素以外の化学的性質を持つ生命は発見されない; - 銀河形成の数学的研究により、銀河形成が宇宙の膨張率に敏感であることが確認される。 ホーガン[39]は、もしすべての基本定数が厳密に決定されているとしたら、それは非常に奇妙なことだと強調している。実際、人類はバローとティプラーのSAPのようなものに頼らざるを得ないかもしれない。 このような宇宙では、生命を維持しないという選択肢はないだろう。パラメータ値の確率的予測は、次のような条件で行うことができる: 1. 「尺度 」を持つ個別主義的な多元宇宙、すなわち、明確に定義された 「宇宙の密度」(したがって、パラメータXについて、XがX0 < X < X0 + dXの範囲にある事前確率P(X0) dXを計算できる)、および2. 2.各宇宙の観測者数N(X)の推定値(例えば、これは宇宙の星の数に比例すると考えられる)。 値Xを観測する確率は、N(X) P(X)に比例する。このような性質を持つ分析の一般的な特徴は、基本物理定数の期待値が「オーバーチューニング」されてはならないということである。つ まり、完全に調整された予測値(例えばゼロ)がある場合、観測される値は、生命を可能にするために必要な値よりも、その予測値に近づく必要はないというこ とである。宇宙定数の小さいが有限の値は、この意味で成功した予言とみなすことができる。 コペルニクス的原理(この原理に対する反証の可能性については、コペルニクス的原理を参照)に反して、地球や太陽系が宇宙の中で特権的な位置を占めているという証拠が、人間原理の証拠とみなされることはない。 |

| Applications of the principle The nucleosynthesis of carbon-12 Fred Hoyle may have invoked anthropic reasoning to predict an astrophysical phenomenon. He is said to have reasoned, from the prevalence on Earth of life forms whose chemistry was based on carbon-12 nuclei, that there must be an undiscovered resonance in the carbon-12 nucleus facilitating its synthesis in stellar interiors via the triple-alpha process. He then calculated the energy of this undiscovered resonance to be 7.6 million electronvolts.[40][41] Willie Fowler's research group soon found this resonance, and its measured energy was close to Hoyle's prediction. However, in 2010 Helge Kragh argued that Hoyle did not use anthropic reasoning in making his prediction, since he made his prediction in 1953 and anthropic reasoning did not come into prominence until 1980. He called this an "anthropic myth", saying that Hoyle and others made an after-the-fact connection between carbon and life decades after the discovery of the resonance. An investigation of the historical circumstances of the prediction and its subsequent experimental confirmation shows that Hoyle and his contemporaries did not associate the level in the carbon nucleus with life at all.[42] |

原理の応用 炭素12の核合成 フレッド・ホイルは、天体物理学的な現象を予測するために、人間原理を利用したのかもしれない。彼は、地球上に炭素12原子核を化学的基礎とする生命体が 多く存在することから、炭素12原子核には未発見の共鳴が存在し、トリプルアルファ過程を経て恒星内部で合成されるに違いないと推論したと言われている。 そして彼は、この未発見の共鳴のエネルギーを760万電子ボルトと計算した[40][41]。ウィリー・ファウラーの研究グループはすぐにこの共鳴を発見 し、その測定されたエネルギーはホイルの予測に近かった。 しかしながら、2010年にヘルゲ・クラグは、ホイルが予測を行ったのは1953年であり、人間論的推論が注目されるようになったのは1980年であるこ とから、ホイルは予測を行う際に人間論的推論を用いていないと主張した。彼はこれを 「人間神話 」と呼び、ホイルらは共鳴の発見から何十年も経ってから、炭素と生命を事後的に結びつけたと述べた。 この予言とその後の実験的確証の歴史的経緯を調査すると、ホイルと彼の同時代の研究者たちは、炭素原子核の準位と生命を全く関連付けていなかったことがわかる[42]。 |

| Cosmic inflation Main article: Cosmic inflation Don Page criticized the entire theory of cosmic inflation as follows.[43] He emphasized that initial conditions that made possible a thermodynamic arrow of time in a universe with a Big Bang origin, must include the assumption that at the initial singularity, the entropy of the universe was low and therefore extremely improbable. Paul Davies rebutted this criticism by invoking an inflationary version of the anthropic principle.[44] While Davies accepted the premise that the initial state of the visible universe (which filled a microscopic amount of space before inflating) had to possess a very low entropy value—due to random quantum fluctuations—to account for the observed thermodynamic arrow of time, he deemed this fact an advantage for the theory. That the tiny patch of space from which our observable universe grew had to be extremely orderly, to allow the post-inflation universe to have an arrow of time, makes it unnecessary to adopt any "ad hoc" hypotheses about the initial entropy state, hypotheses other Big Bang theories require. |

宇宙のインフレーション(膨張) 主な記事 宇宙のインフレーション ドン・ペイジは、宇宙インフレーションの理論全体を次のように批判した[43]。 彼は、ビッグバン起源の宇宙で熱力学的な時間の矢を可能にする初期条件には、最初の特異点では宇宙のエントロピーが低く、したがって極めてあり得ないとい う仮定が含まれていなければならないと強調した。ポール・デイヴィスは、インフレーション版の人間原理を持ち出して、この批判に反論した[44]。デイ ヴィスは、観測された熱力学的な時間の矢を説明するためには、目に見える宇宙の初期状態(膨張する前に微視的な空間を満たしていた)が、ランダムな量子揺 らぎのために非常に低いエントロピー値を持たなければならないという前提を受け入れたが、この事実は理論にとって有利であると考えた。インフレーション後 の宇宙が時間の矢印を持つためには、私たちの観測可能な宇宙が成長した微小な空間が極めて整然としていなければならなかった。 |

| String theory Main article: String theory landscape String theory predicts a large number of possible universes, called the "backgrounds" or "vacua". The set of these vacua is often called the "multiverse" or "anthropic landscape" or "string landscape". Leonard Susskind has argued that the existence of a large number of vacua puts anthropic reasoning on firm ground: only universes whose properties are such as to allow observers to exist are observed, while a possibly much larger set of universes lacking such properties go unnoticed.[32] Steven Weinberg[45] believes the anthropic principle may be appropriated by cosmologists committed to nontheism, and refers to that principle as a "turning point" in modern science because applying it to the string landscape "may explain how the constants of nature that we observe can take values suitable for life without being fine-tuned by a benevolent creator". Others—most notably David Gross but also Luboš Motl, Peter Woit, and Lee Smolin—argue that this is not predictive. Max Tegmark,[46] Mario Livio, and Martin Rees[47] argue that only some aspects of a physical theory need be observable and/or testable for the theory to be accepted, and that many well-accepted theories are far from completely testable at present. Jürgen Schmidhuber (2000–2002) points out that Ray Solomonoff's theory of universal inductive inference and its extensions already provide a framework for maximizing our confidence in any theory, given a limited sequence of physical observations, and some prior distribution on the set of possible explanations of the universe. Zhi-Wei Wang and Samuel L. Braunstein proved that life's existence in the universe depends on various fundamental constants. It suggests that without a complete understanding of these constants, one might incorrectly perceive the universe as being intelligently designed for life. This perspective challenges the view that our universe is unique in its ability to support life.[48] |

ストリング理論(弦理論) 主な記事 超ひも理論の風景 弦理論では、「背景」または「ヴァキュア」と呼ばれる多数の可能な宇宙を予言する。これらのヴァキュアの集合は、しばしば「多元宇宙」、「人間景観」、 「弦の景観」と呼ばれる。レナード・サスキンドは、多数のヴァキュアが存在することで、人間論的推論が揺るぎないものになると主張している。 スティーブン・ワインバーグ[45]は、人間原理が非神論に傾倒する宇宙論者によって流用されるかもしれないと考えており、この原理を弦の風景に適用する ことで「慈悲深い創造主によって微調整されることなく、我々が観測している自然の定数が生命に適した値を取ることができる方法を説明できるかもしれない」 という理由から、この原理を現代科学の「転換点」と呼んでいる。他の研究者、特にデビッド・グロス(David Gross)、ルボシュ・モトル(Luboš Motl)、ピーター・ヴォイト(Peter Woit)、リー・スモリン(Lee Smolin)らは、これは予言的ではないと主張している。マックス・テグマーク、[46] マリオ・リビオ、マーティン・リース[47]は、理論が受け入れられるためには、物理理論のいくつかの側面だけが観測可能であり、検証可能である必要があ ると主張している。 Jürgen Schmidhuber (2000-2002)は、Ray Solomonoffの普遍的帰納推論の理論とその拡張が、限定された一連の物理的観測と、宇宙の説明の可能性の集合に関する事前分布が与えられた場合 に、どのような理論に対する信頼性を格律するための枠組みをすでに提供していることを指摘している。 王志偉とサミュエル・L・ブラウンシュタインは、宇宙における生命の存在が様々な基本定数に依存していることを証明した。これらの定数を完全に理解しなけ れば、宇宙が生命のために知的に設計されていると誤って認識する可能性があることを示唆している。この視点は、我々の宇宙が生命を維持する能力においてユ ニークであるという見解に挑戦するものである[48]。 |

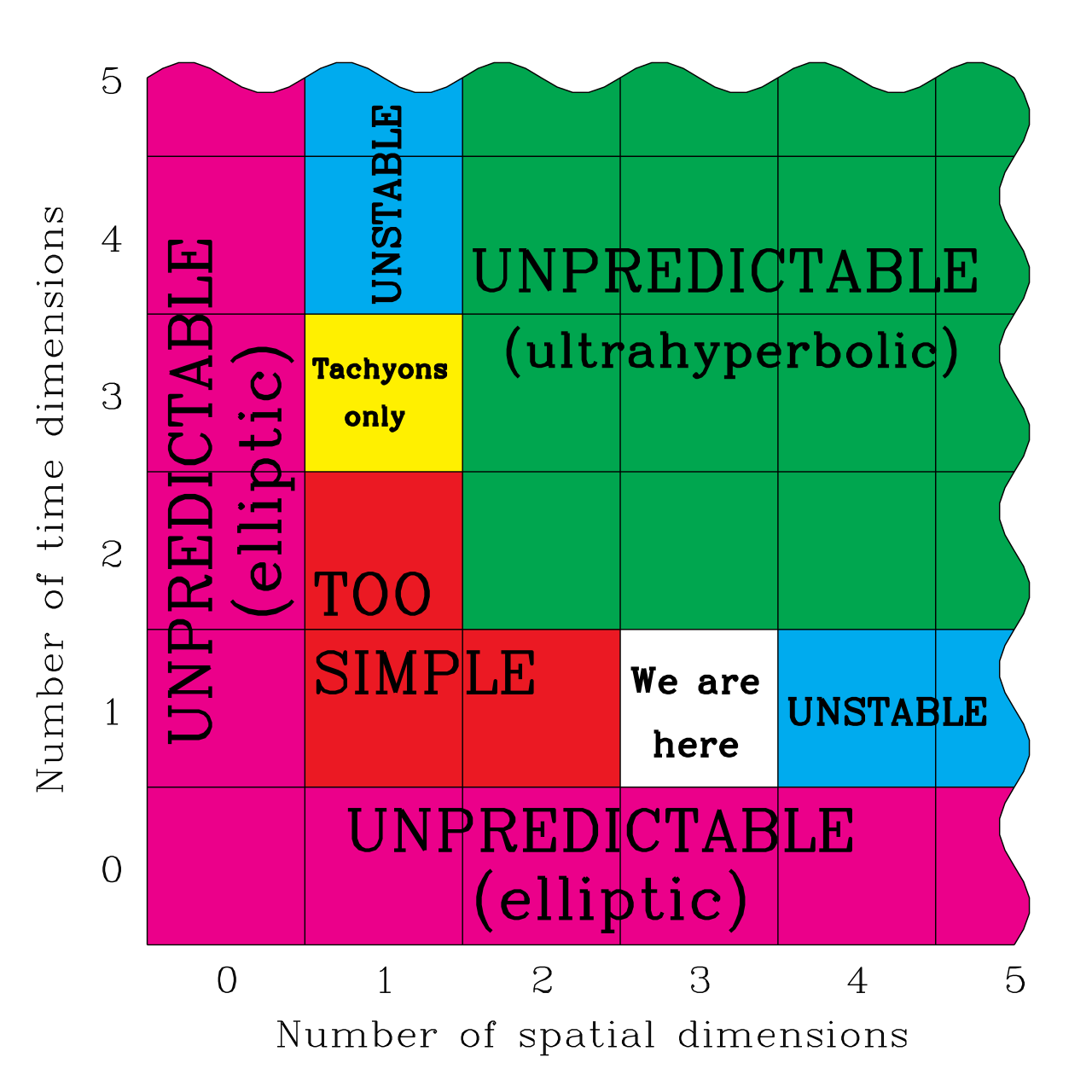

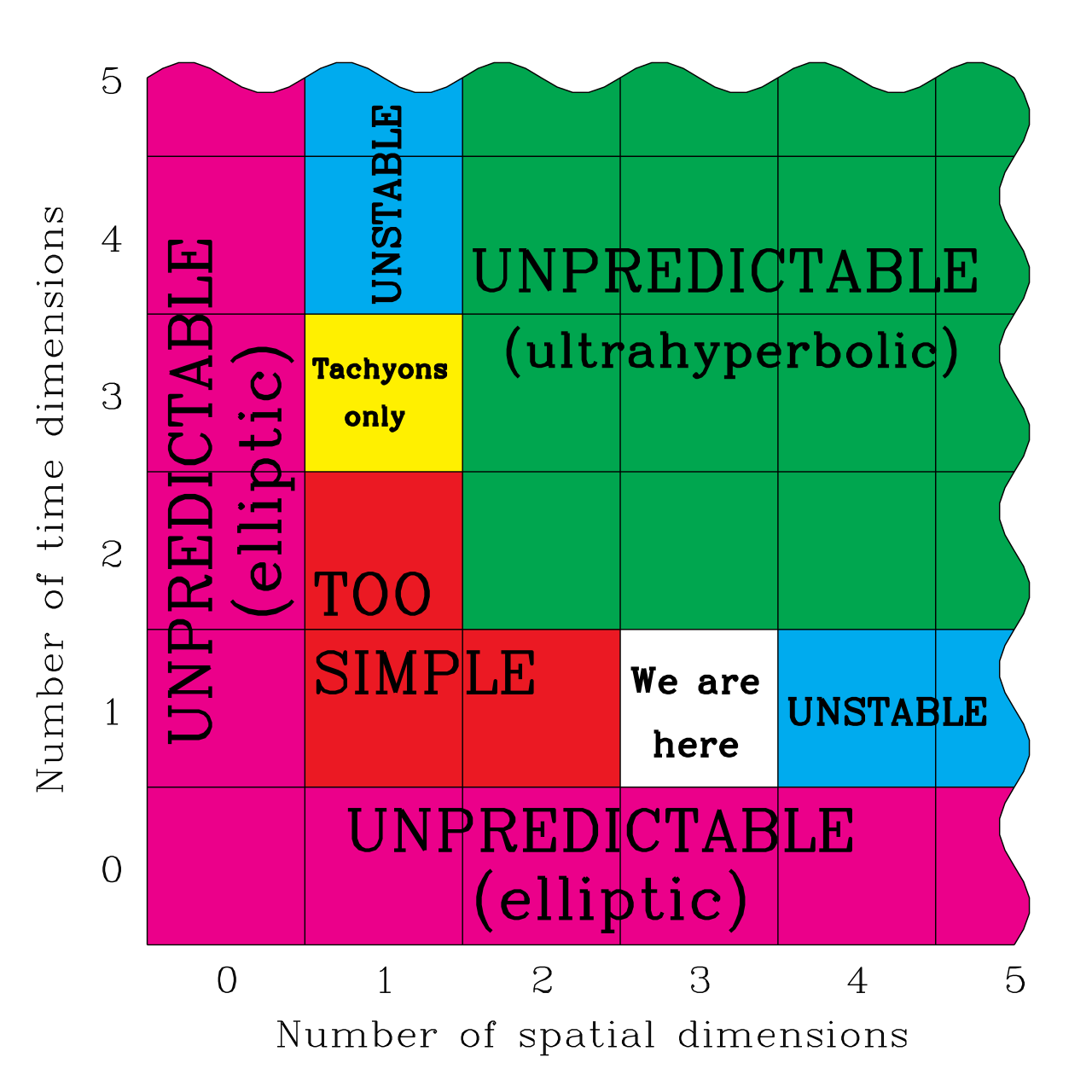

Dimensions of spacetime Properties of (n + m)-dimensional spacetimes[49] There are two kinds of dimensions: spatial (bidirectional) and temporal (unidirectional).[50] Let the number of spatial dimensions be N and the number of temporal dimensions be T. That N = 3 and T = 1, setting aside the compactified dimensions invoked by string theory and undetectable to date, can be explained by appealing to the physical consequences of letting N differ from 3 and T differ from 1. The argument is often of an anthropic character and possibly the first of its kind, albeit before the complete concept came into vogue. The implicit notion that the dimensionality of the universe is special is first attributed to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who in the Discourse on Metaphysics suggested that the world is "the one which is at the same time the simplest in hypothesis and the richest in phenomena".[51] Immanuel Kant argued that 3-dimensional space was a consequence of the inverse square law of universal gravitation. While Kant's argument is historically important, John D. Barrow said that it "gets the punch-line back to front: it is the three-dimensionality of space that explains why we see inverse-square force laws in Nature, not vice-versa" (Barrow 2002:204).[note 3] In 1920, Paul Ehrenfest showed that if there is only a single time dimension and more than three spatial dimensions, the orbit of a planet about its Sun cannot remain stable. The same is true of a star's orbit around the center of its galaxy.[52] Ehrenfest also showed that if there are an even number of spatial dimensions, then the different parts of a wave impulse will travel at different speeds. If there are 5+2k {\displaystyle 5+2k} spatial dimensions, where k is a positive whole number, then wave impulses become distorted. In 1922, Hermann Weyl claimed that Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism can be expressed in terms of an action only for a four-dimensional manifold.[53] Finally, Tangherlini showed in 1963 that when there are more than three spatial dimensions, electron orbitals around nuclei cannot be stable; electrons would either fall into the nucleus or disperse.[54] Max Tegmark expands on the preceding argument in the following anthropic manner.[55] If T differs from 1, the behavior of physical systems could not be predicted reliably from knowledge of the relevant partial differential equations. In such a universe, intelligent life capable of manipulating technology could not emerge. Moreover, if T > 1, Tegmark maintains that protons and electrons would be unstable and could decay into particles having greater mass than themselves. (This is not a problem if the particles have a sufficiently low temperature.)[55] Lastly, if N < 3, gravitation of any kind becomes problematic, and the universe would probably be too simple to contain observers. For example, when N < 3, nerves cannot cross without intersecting.[55] Hence anthropic and other arguments rule out all cases except N = 3 and T = 1, which describes the world around us. On the other hand, in view of creating black holes from an ideal monatomic gas under its self-gravity, Wei-Xiang Feng showed that (3 + 1)-dimensional spacetime is the marginal dimensionality. Moreover, it is the unique dimensionality that can afford a "stable" gas sphere with a "positive" cosmological constant. However, a self-gravitating gas cannot be stably bound if the mass sphere is larger than ~1021 solar masses, due to the small positivity of the cosmological constant observed.[56] In 2019, James Scargill argued that complex life may be possible with two spatial dimensions. According to Scargill, a purely scalar theory of gravity may enable a local gravitational force, and 2D networks may be sufficient for complex neural networks.[57][58] |

時空の次元 (n+m)次元時空の性質[49]。 空間的次元(双方向性)と時間的次元(単方向性)の2種類の次元がある[50]。N = 3とT = 1であることは、超ひも理論によって呼び出され、今日まで検出されていないコンパクト化された次元はさておき、Nを3から異ならせ、Tを1から異ならせる ことの物理的帰結に訴えることによって説明することができる。 宇宙の次元性が特別であるという暗黙の概念は、ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツが『形而上学言説』の中で、世界は「仮説において最も単純であ ると同時に現象において最も豊かなもの」であると示唆したことに端を発している[51]。イマニュエル・カントは、3次元空間は万有引力の逆2乗則の結果 であると主張した。カントの議論は歴史的に重要であるが、ジョン・D・バローは、「オチを前に戻している:自然界で逆2乗の力の法則を見る理由を説明する のは空間の3次元性であって、その逆ではない」と述べている(Barrow 2002:204)[注 3]。 1920年、ポール・エーレンフェストは、時間次元が1つしかなく、空間次元が3つ以上ある場合、太陽を回る惑星の軌道は安定を保てないことを示した。同 じことが、銀河の中心を回る星の軌道にも当てはまる[52]。エーレンフェストはまた、空間次元が偶数個ある場合、波のインパルスの異なる部分が異なる速 度で伝わることも示した。空間次元の数が偶数であれば、波のインパルスの異なる部分は異なる速度で進む。 5+2k {\displaystyle 5+2k}{k は正の整数であり、そのとき波のインパルスは歪む。1922年、ヘルマン・ヴァイルは、マクスウェルの電磁気学理論は4次元の多様体についてのみ作用で表 すことができると主張した[53]。最後に、タンガーリーニは1963年に、空間次元が3つ以上ある場合、原子核の周りの電子軌道は安定にならないことを 示した。 マックス・テグマルクは、先の議論を次のような人間論的な方法で展開している[55]。Tが1から異なる場合、関連する偏微分方程式の知識から物理系の振 る舞いを確実に予測することはできない。そのような宇宙では、テクノロジーを操作できる知的生命体は出現できない。さらに、もしT > 1であれば、陽子と電子は不安定になり、崩壊して自分より質量の大きな粒子になる可能性があるとテグマークは主張している。(これは、粒子の温度が十分に 低ければ問題にはならない)[55]。最後に、N < 3の場合、あらゆる種類の重力が問題になり、宇宙はおそらく観測者を含むには単純すぎるだろう。例えば、N < 3の場合、神経は交わることなく交差することはできない[55]。それゆえ、人間論や他の議論は、N = 3とT = 1以外のすべてのケースを除外する。 一方、理想的な単原子ガスから自己重力下でブラックホールを作るという観点から、Wei-Xiang Fengは、(3 + 1)次元時空が境界次元であることを示した。さらに、それは「正」の宇宙論的定数を持つ「安定な」ガス球を与えることができる唯一の次元性である。しか し,観測される宇宙定数の正値が小さいため,質量球が~1021太陽質量より大きいと,自己重力ガスは安定に束縛されない[56]。 2019年、ジェームズ・スカーギルは、複雑な生命は2つの空間次元で可能かもしれないと主張した。スカーギルによれば、重力の純粋なスカラー理論は局所 的な重力力を可能にするかもしれず、2次元ネットワークは複雑な神経ネットワークにとって十分かもしれない[57][58]。 |

| Metaphysical interpretations Some of the metaphysical disputes and speculations include, for example, attempts to back Pierre Teilhard de Chardin's earlier interpretation of the universe as being Christ centered (compare Omega Point), expressing a creatio evolutiva instead the elder notion of creatio continua.[59] From a strictly secular, humanist perspective, it allows as well to put human beings back in the center, an anthropogenic shift in cosmology.[59] Karl W. Giberson[60] has laconically stated that What emerges is the suggestion that cosmology may at last be in possession of some raw material for a postmodern creation myth. — Karl W. Giberson William Sims Bainbridge disagreed with de Chardin's optimism about a future Omega point at the end of history, arguing that logically, humans are trapped at the Omicron point, in the middle of the Greek alphabet rather than advancing to the end, because the universe does not need to have any characteristics that would support our further technical progress, if the anthropic principle merely requires it to be suitable for our evolution to this point.[61] |

形而上学的解釈 形而上学的な論争や思索の中には、例えば、ピエール・テイヤール・ド・シャルダンの、キリストを中心とする宇宙という以前の解釈(オメガ・ポイントを参照)を支持しようとする試みがあり、長年の創造連続体という概念の代わりに創造進化論を表現している[59]。 そこから見えてくるのは、宇宙論がついにポストモダンの創造神話の素材を手に入れたのではないかという示唆である。 - カール・W・ギバーソン ウィリアム・シムズ・ベインブリッジは、歴史の終わりにおける将来のオメガ点についてのド・シャルダンの楽観論に同意せず、論理的には、人類はオミクロン点、ギリシア語のアルファベットの真ん中に捕らわれているのであって、終わりまで進んでいるのではないと主張している。 |

| The Anthropic Cosmological Principle A thorough extant study of the anthropic principle is the book The Anthropic Cosmological Principle by John D. Barrow, a cosmologist, and Frank J. Tipler, a cosmologist and mathematical physicist. This book sets out in detail the many known anthropic coincidences and constraints, including many found by its authors. While the book is primarily a work of theoretical astrophysics, it also touches on quantum physics, chemistry, and earth science. An entire chapter argues that Homo sapiens is, with high probability, the only intelligent species in the Milky Way. The book begins with an extensive review of many topics in the history of ideas the authors deem relevant to the anthropic principle, because the authors believe that principle has important antecedents in the notions of teleology and intelligent design. They discuss the writings of Fichte, Hegel, Bergson, and Alfred North Whitehead, and the Omega Point cosmology of Teilhard de Chardin. Barrow and Tipler carefully distinguish teleological reasoning from eutaxiological reasoning; the former asserts that order must have a consequent purpose; the latter asserts more modestly that order must have a planned cause. They attribute this important but nearly always overlooked distinction to an obscure 1883 book by L. E. Hicks.[62] Seeing little sense in a principle requiring intelligent life to emerge while remaining indifferent to the possibility of its eventual extinction, Barrow and Tipler propose the final anthropic principle (FAP): Intelligent information-processing must come into existence in the universe, and, once it comes into existence, it will never die out.[63] Barrow and Tipler submit that the FAP is both a valid physical statement and "closely connected with moral values". FAP places strong constraints on the structure of the universe, constraints developed further in Tipler's The Physics of Immortality.[64] One such constraint is that the universe must end in a Big Crunch, which seems unlikely in view of the tentative conclusions drawn since 1998 about dark energy, based on observations of very distant supernovas. In his review[65] of Barrow and Tipler, Martin Gardner ridiculed the FAP by quoting the last two sentences of their book as defining a completely ridiculous anthropic principle (CRAP): At the instant the Omega Point is reached, life will have gained control of all matter and forces not only in a single universe, but in all universes whose existence is logically possible; life will have spread into all spatial regions in all universes which could logically exist, and will have stored an infinite amount of information, including all bits of knowledge that it is logically possible to know. And this is the end.[66] |

人間宇宙原理 現存する人間原理の徹底的な研究は、宇宙学者のジョン・D・バローと宇宙学者で数理物理学者のフランク・J・ティプラーによる『人間宇宙原理』である。こ の本には、著者らによって発見されたものも含め、多くの既知の人間学的偶然と制約が詳細に述べられている。本書は主に理論宇宙物理学の著作であるが、量子 物理学、化学、地球科学にも触れている。章全体を通して、ホモ・サピエンスが高い確率で天の川銀河に存在する唯一の知的種であると論じている。 本書は、人間原理に関連すると著者らが考える思想史の多くのトピックの広範なレビューから始まる。著者らは、人間原理が目的論やインテリジェント・デザイ ンの概念に重要な先例を持つと考えるからである。フィヒテ、ヘーゲル、ベルクソン、アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドの著作や、テイヤール・ド・シャ ルダンのオメガポイント宇宙論について論じている。バローとティプラーは、目的論的推論とユータクソロジー的推論を注意深く区別している。前者は秩序には 結果的な目的がなければならないと主張し、後者は秩序には計画された原因がなければならないと控えめに主張する。前者は秩序には結果的な目的がなければな らないと主張し、後者はもっと控えめに、秩序には計画された原因がなければならないと主張しているのである[62]。 バローとティプラーは、知的生命体が出現することを要求する一方で、その生命体が最終的に絶滅する可能性については無関心であり続けるという原理にはほとんど意味がないと考え、最終的人間原理(FAP)を提案している。 バローとティプラーは、FAPは有効な物理的言明であると同時に「道徳的価値と密接に関連している」と提唱している。FAPは宇宙の構造に強い制約を課し ており、その制約はティプラーの『不死の物理学』でさらに発展している[64]。そのような制約の一つは、宇宙はビッグクランチで終わらなければならない というものであるが、1998年以降、非常に遠方の超新星の観測に基づいてダークエネルギーについて暫定的な結論が導かれていることからすると、それはあ りそうにない。 マーティン・ガードナーはバローとティプラーの書評[65]の中で、彼らの著書の最後の2つの文章を引用して、FAPを完全に馬鹿げた人間原理(CRAP)を定義していると揶揄している: オメガ・ポイントに到達した瞬間に、生命は一つの宇宙だけでなく、論理的に存在可能なすべての宇宙において、すべての物質と力を支配するようになり、論理 的に存在可能なすべての宇宙において、生命はすべての空間領域に広がり、論理的に知ることが可能なすべての知識を含む無限の情報を蓄えるようになる。そし て、これが終わりである。 |

| Reception and controversies Carter has frequently expressed regret for his own choice of the word "anthropic", because it conveys the misleading impression that the principle involves humans in particular, to the exclusion of non-human intelligence more broadly.[67] Others[68] have criticised the word "principle" as being too grandiose to describe straightforward applications of selection effects. A common criticism of Carter's SAP is that it is an easy deus ex machina that discourages searches for physical explanations. To quote Penrose again: "It tends to be invoked by theorists whenever they do not have a good enough theory to explain the observed facts."[69] Carter's SAP and Barrow and Tipler's WAP have been dismissed as truisms or trivial tautologies—that is, statements true solely by virtue of their logical form and not because a substantive claim is made and supported by observation of reality. As such, they are criticized as an elaborate way of saying, "If things were different, they would be different",[citation needed] which is a valid statement, but does not make a claim of some factual alternative over another. Critics of the Barrow and Tipler SAP claim that it is neither testable nor falsifiable, and thus is not a scientific statement but rather a philosophical one. The same criticism has been leveled against the hypothesis of a multiverse, although some argue[70] that it does make falsifiable predictions. A modified version of this criticism is that humanity understands so little about the emergence of life, especially intelligent life, that it is effectively impossible to calculate the number of observers in each universe. Also, the prior distribution of universes as a function of the fundamental constants is easily modified to get any desired result.[71] Many criticisms focus on versions of the strong anthropic principle, such as Barrow and Tipler's anthropic cosmological principle, which are teleological notions that tend to describe the existence of life as a necessary prerequisite for the observable constants of physics. Similarly, Stephen Jay Gould,[72][73] Michael Shermer,[74] and others claim that the stronger versions of the anthropic principle seem to reverse known causes and effects. Gould compared the claim that the universe is fine-tuned for the benefit of our kind of life to saying that sausages were made long and narrow so that they could fit into modern hotdog buns, or saying that ships had been invented to house barnacles.[citation needed] These critics cite the vast physical, fossil, genetic, and other biological evidence consistent with life having been fine-tuned through natural selection to adapt to the physical and geophysical environment in which life exists. Life appears to have adapted to the universe, and not vice versa. Some applications of the anthropic principle have been criticized as an argument by lack of imagination, for tacitly assuming that carbon compounds and water are the only possible chemistry of life (sometimes called "carbon chauvinism"; see also alternative biochemistry).[75] The range of fundamental physical constants consistent with the evolution of carbon-based life may also be wider than those who advocate a fine-tuned universe have argued.[76] For instance, Harnik et al.[77] propose a Weakless Universe in which the weak nuclear force is eliminated. They show that this has no significant effect on the other fundamental interactions, provided some adjustments are made in how those interactions work. However, if some of the fine-tuned details of our universe were violated, that would rule out complex structures of any kind—stars, planets, galaxies, etc. Lee Smolin has offered a theory designed to improve on the lack of imagination that has been ascribed to anthropic principles. He puts forth his fecund universes theory, which assumes universes have "offspring" through the creation of black holes whose offspring universes have values of physical constants that depend on those of the mother universe.[78] The philosophers of cosmology John Earman,[79] Ernan McMullin,[80] and Jesús Mosterín contend that "in its weak version, the anthropic principle is a mere tautology, which does not allow us to explain anything or to predict anything that we did not already know. In its strong version, it is a gratuitous speculation".[81] A further criticism by Mosterín concerns the flawed "anthropic" inference from the assumption of an infinity of worlds to the existence of one like ours: The suggestion that an infinity of objects characterized by certain numbers or properties implies the existence among them of objects with any combination of those numbers or characteristics [...] is mistaken. An infinity does not imply at all that any arrangement is present or repeated. [...] The assumption that all possible worlds are realized in an infinite universe is equivalent to the assertion that any infinite set of numbers contains all numbers (or at least all Gödel numbers of the [defining] sequences), which is obviously false. |

受容と論争 カーターは「人間原理」という言葉を自ら選択したことについて、しばしば後悔の念を表明している。なぜなら、「人間原理」という言葉は、人間以外の知性をより広く排除して、特に人間に関わる原理であるという誤解を招く印象を与えるからである[67]。 カーターのSAPに対する一般的な批判は、それが安易なデウス・エクス・マキナであり、物理的説明の探求を妨げるというものである。再びペンローズの言葉 を引用しよう: 「観察された事実を説明するのに十分な理論を持っていないときはいつでも、理論家によって呼び出される傾向がある」[69]。 カーターのSAPやバローとティプラーのWAPは、真理主義や些細な同語反復として否定されてきた。つまり、本質的な主張がなされ、現実の観察によって裏 付けられたからではなく、論理的な形式によってのみ真であるという記述である。つまり、論理的な形式によってのみ真実であり、現実の観察によって裏付けら れた実質的な主張がなされているわけではないということである。そのため、「もし物事が異なっていたら、それらは異なっていただろう」[要出典]という言 い方の精巧な方法として批判される。 バローとティプラーSAPを批判する人々は、バローとティプラーSAPは検証可能でも反証可能でもないため、科学的な声明ではなく、むしろ哲学的な声明で あると主張している。同じ批判が多宇宙の仮説に対してもなされているが、反証可能な予言をしていると主張する者もいる[70]。この批判の修正版は、人類 は生命、特に知的生命の出現についてほとんど理解していないため、各宇宙の観測者の数を計算することは事実上不可能であるというものである。また、基本定 数の関数としての宇宙の事前分布は、望む結果を得るために簡単に修正できる[71]。 多くの批判は、バローやティプラーの人間宇宙原理のような、強い人間原理のバージョンに焦点を当てている。これは、物理学の観測可能な定数の必要条件とし て生命の存在を記述する傾向がある目的論的な概念である。同様に、スティーヴン・ジェイ・グールド[72][73]、マイケル・シャーマー[74]等は、 人間原理のより強力なバージョンは、既知の因果を逆転させているように見えると主張している。グールドは、宇宙が我々のような生命のために微調整されてい るという主張を、ソーセージが現代のホットドッグのパンに入るように細長く作られたと言ったり、フジツボを収容するために船が発明されたと言ったりするこ とに例えている。生命は宇宙に適応したように見えるが、その逆ではない。 人間原理の応用の中には、炭素化合物と水が生命の唯一の可能な化学的性質であると暗黙のうちに仮定しているため、想像力の欠如による議論として批判される ものもある(「炭素排他主義」と呼ばれることもある。彼らは、他の基本的な相互作用がどのように働くかを調整すれば、他の基本的な相互作用に大きな影響を 与えないことを示している。しかし、もし我々の宇宙のファインチューニングの詳細が侵害された場合、星、惑星、銀河などの複雑な構造を否定することにな る。 リー・スモリンは、人間原理が持つ想像力の欠如を改善するための理論を提唱した。彼は、ブラックホールの生成によって宇宙が「子孫」を持つと仮定する従属 宇宙理論を提唱しており、その子孫の宇宙は、母なる宇宙の物理定数に依存した物理定数の値を持つと仮定している[78]。 宇宙論の哲学者であるジョン・イアーマン[79]、エルナン・マクマリン[80]、ヘスス・モステリンは、「弱いバージョンでは、人間原理は単なるトート ロジーであり、我々がまだ知らなかったことを説明することも予測することもできない。強いバージョンでは、それは無償の推測である」[81] モステリンによる更なる批判は、無限の世界の仮定から我々のような世界の存在への欠陥のある「人間的」推論に関するものである: ある数や特性によって特徴づけられた物体が無限に存在すれば、その中にそれらの数や特性の任意の組み合わせを持つ物体が存在することになるという提案は間 違っている。無限大は、どのような配置も存在したり繰り返されたりすることをまったく意味しない。[無限の宇宙ではすべての可能世界が実現されるという仮 定は、無限の数集合がすべての数(あるいは少なくとも[定義]数列のすべてのゲーデル数)を含むという主張と等価であるが、これは明らかに誤りである。 |

| Anthropocentrism – Belief that humans are the most important beings in existence Arthur Schopenhauer – German philosopher (1788–1860) (an immediate precursor of the idea) Big Bounce – Model for the origin of the universe Copernican principle – Principle that humans are not privileged observers of the universe Doomsday argument – Doomsday scenario on human births Fermi paradox – Discrepancy of the lack of evidence for alien life despite its apparent likelihood Goldilocks principle – Analogy for optimal conditions Great Filter – Hypothesis of barriers to forming interstellar civilizations Infinite monkey theorem – Counterintuitive result in probability Inverse gambler's fallacy – Formal fallacy of Bayesian inference Mathematical universe hypothesis – Cosmological theory Measure problem (cosmology) – Concept in cosmology Mediocrity principle – Philosophical concept Metaphysical naturalism – Philosophical worldview rejecting anything supernatural Neocatastrophism – Hypothesis for lack of detected aliens Fine-tuned universe – Hypothesis about life in the universe Quark mass and congeniality to life – Costa Rican physicist (work of Alejandro Jenkins) Rare Earth hypothesis – Hypothesis that complex extraterrestrial life is improbable and extremely rare Sleeping Beauty problem – Mathematical problem Triple-alpha process – Nuclear fusion reaction Why there is anything at all – Metaphysical concept Vertiginous question – Philosophical argument by Benj Hellie |

人間中心主義 - 人間が存在する中で最も重要な存在であるという信念 アルトゥール・ショーペンハウアー - ドイツの哲学者(1788-1860)(この思想の直接的な先駆者である) ビッグ・バウンス - 宇宙の起源のモデル コペルニクス的原理 - 人間は宇宙の特権的観測者ではないという原理 終末論 - 人類誕生に関する終末シナリオ フェルミのパラドックス - 異星人が存在する可能性が高いにもかかわらず、その証拠がないという矛盾 ゴルディロックスの原理 - 最適条件のアナロジー グレートフィルター - 星間文明を形成する障壁の仮説 無限猿の定理 - 確率における直観に反する結果 逆ギャンブラーの誤謬 - ベイズ推論の形式的誤謬 数学的宇宙仮説 - 宇宙論 測度問題(宇宙論) - 宇宙論における概念 中庸の原理 - 哲学的概念 形而上学的自然主義 - 超自然的なものを否定する哲学的世界観 ネオカタストロフィズム - 宇宙人が検出されないことの仮説 Fine-tuned universe(微調整された宇宙) - 宇宙における生命に関する仮説 クォークの質量と生命への適合性 - コスタリカの物理学者(アレハンドロ・ジェンキンスの研究) レアアース仮説 - 複雑な地球外生命体はあり得なく、極めて稀であるという仮説 眠れる森の美女問題 - 数学的問題 トリプルアルファ過程 - 核融合反応 なぜ何かが存在するのか - 形而上学的概念 垂直問題 - ベンジ・ヘリーによる哲学的議論 |

| Notes & Footnotes |

|

| References Barrow, John D.; Tipler, Frank J. (1986). The Anthropic Cosmological Principle (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-282147-8. LCCN 87028148. Bostrom, N. (2002), Anthropic bias: Observation selection effects in science and philosophy, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-93858-7 5 chapters available online. Archived 2006-08-26 at the Wayback Machine Cirkovic, M. M. (2002). "On the first anthropic argument in astrobiology". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 91 (4): 243–254. arXiv:astro-ph/0306185. Bibcode:2002EM&P...91..243C. doi:10.1023/A:1026266630823. S2CID 17341587. Cirkovic, M. M. (2004). "The anthropic principle and the duration of the cosmological past". Astronomical and Astrophysical Transactions. 23 (6): 567–597. arXiv:astro-ph/0505005. Bibcode:2004A&AT...23..567C. doi:10.1080/10556790412331335327. S2CID 6068309. Conway Morris, Simon (2003). Life's solution: Inevitable humans in a lonely Universe. Cambridge University Press. Craig, William Lane (1987). "Critical review of The anthropic cosmological principle". International Philosophical Quarterly. 27 (4): 437–47. doi:10.5840/ipq198727433. Hawking, Stephen W. (1988). A brief history of time. New York: Bantam books. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-553-34614-5. Stenger, Victor J. (July–August 1999). "Anthropic Design: Does the Cosmos Show Evidence of Purpose?". The Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 23, no. 4. pp. 40–43. Mosterín, Jesús (2005). "Anthropic explanations in cosmology". In P. Háyek, L. Valdés and D. Westerstahl (ed.), Logic, methodology and philosophy of science, Proceedings of the 12th international congress of the LMPS. London: King's college publications, pp. 441–473. ISBN 1-904987-21-4. Taylor; Stuart Ross (1998). Destiny or chance: Our Solar System and its place in the cosmos. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78521-1. Tegmark, Max (1997). "On the dimensionality of spacetime". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 14 (4): L69 – L75. arXiv:gr-qc/9702052. Bibcode:1997CQGra..14L..69T. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/14/4/002. S2CID 15694111. A simple anthropic argument for why there are 3 spatial and 1 temporal dimensions. Tipler, F. J. (2003). "Intelligent life in cosmology". International Journal of Astrobiology. 2 (2): 141–48. arXiv:0704.0058. Bibcode:2003IJAsB...2..141T. doi:10.1017/S1473550403001526. S2CID 119283361. Walker, M. A. & Cirkovic, M. M. (2006). "Anthropic reasoning, naturalism and the contemporary design argument". International Studies in the Philosophy of Science. 20 (3): 285–307. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.212.2588. doi:10.1080/02698590600960945. S2CID 8804703. Shows that some of the common criticisms of anthropic principle based on its relationship with numerology or the theological design argument are wrong. Ward, P. D. & Brownlee, D. (2000). Rare Earth: Why complex life is uncommon in the Universe. Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-98701-9. Vilenkin, Alex (2006). Many worlds in one: The search for other universes. Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-9523-0. |

参考文献 バロー, ジョン D.; ティプラー, フランク J. (1986). 人間宇宙論的原理(第1版). オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-282147-8. LCCN 87028148. Bostrom, N. (2002), Anthropic bias: Observation selection effects in science and philosophy, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-93858-7 5 chapters available online. Archived 2006-08-26 at the Wayback Machine Cirkovic, M. M. (2002). 「宇宙生物学における最初の人間論的議論について」. 地球、月、惑星。91 (4): 243–254. arXiv:astro-ph/0306185. Bibcode:2002EM&P...91..243C. doi:10.1023/A:1026266630823. s2cid 17341587. Cirkovic, M. M. (2004). 「The anthropic principle and the duration of the cosmological past". Astronomical and Astrophysical Transactions. 23 (6): 567–597. arXiv:astro-ph/0505005. Bibcode:2004A&AT...23..567C. doi:10.1080/10556790412331335327. S2CID 6068309. Conway Morris, Simon (2003). 生命の解決策: Life's solution: Inevitable humans in a lonely Universe. Cambridge University Press. Craig, William Lane (1987). 「Critical review of The anthropic cosmological principle". International Philosophical Quarterly. 27 (4): 437–47. doi:10.5840/ipq198727433. ホーキング博士 (1988). A brief history of time. ニューヨーク: p. 174. ISBN 978-0-553-34614-5. Stenger, Victor J. (July-August 1999). 「人間的デザイン: 宇宙は目的の証拠を示しているか?". The Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 23, no. 4. 40-43. Mosterín, Jesús (2005). 「宇宙論における人間的説明". P. Háyek, L. Valdés and D. Westerstahl (ed.), Logic, methodology and philosophy of science, Proceedings of the 12th international congress of the LMPS. London: キングス・カレッジ出版、441-473頁。ISBN 1-904987-21-4. Taylor; Stuart Ross (1998). 運命か偶然か: 太陽系と宇宙におけるその位置. ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-521-78521-1. Tegmark, Max (1997). 「時空の次元性について". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 14 (4): arXiv:gr-qc/9702052。Bibcode:1997CQGra..14L..69T. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/14/4/002. s2cid 15694111. なぜ3つの空間次元と1つの時間次元が存在するのか? Tipler, F. J. (2003). 「宇宙論における知的生命". International Journal of Astrobiology. 2 (2): 141-48. arXiv:0704.0058. Bibcode:2003IJAsB...2..141T. doi:10.1017/S1473550403001526. s2cid 119283361. Walker, M. A. & Cirkovic, M. M. (2006). 「人間的推論、自然主義、現代のデザイン論争」。International Studies in the Philosophy of Science. 20 (3): 285-307. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.212.2588. doi:10.1080/02698590600960945. S2CID 8804703. 数秘術や神学的設計論との関係に基づく人間原理に対する一般的な批判のいくつかは間違っていることを示す。 Ward, P. D. & Brownlee, D. (2000). 希少な地球: なぜ複雑な生命は宇宙では珍しいのか?Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-98701-9. Vilenkin, Alex (2006). Many worlds in one: The search for other universes. Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-9523-0. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthropic_principle |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099