世界音楽のミュージッキング

World

Musicking

★

世界音楽化・世界音楽のミュージッキング(world

musicking)とは、世界のさまざまな音楽の集合体から、スタイル=様式を流用(appropriation)し、自分たちが直面している「文化」

の文脈(=コンテンツ、内容)のなかに押し戻す行為のことを言う。世界音楽化という言葉を概念を理解するために、その合成語を、音楽化と世

界音楽という2

つの用語の歴史をたどる必要がある(→音楽人類学・民族音楽学)。

☆音楽化(ミュージッキング, Musicking)は、クリストファー・スモールが、同名の書物により、1998年に提唱したことばである。ミュージッキングは、演奏、リスニング、リ ハーサル、作曲など、音楽演奏に関わるあらゆる活動(ウィキショナリー)の ことであるが、とりわけ重要なことは、これまで音楽は演奏中心、あるいは演奏者中心で考えられてきたが、そこに、聴取者が音楽を消費するというアクション が込められていることである。これは、21世紀の世界音楽(world music)という市場を支えている大きな原動力であり、そのような、多くの聴取者がいるからこそ、演奏家や作曲家が、聴取者のことを考えて古典的な ミュージッキングを実践したことが、より、幅のひろい活動に代わり、音楽というものが、まさに、人類の共通の文化として、確立したからなのである。

☆ 他方、世界音楽(ワールドミュージック, world music)は、インドネシアを専門とする民族音楽学者ロバート・E・ブラウンによる造語であるが、これは彼が勤めていたウェ ズリアン大学で、授業の一貫として、世界のさまざまな伝統音楽の演奏家を集めて、かつコンサートをしたために「世界のさまざまな伝統音楽の集合体」という 意味を込めたものだった。この場合の、世界音楽には、世界の中心あるいは盟主として自負する西洋のクラシック音楽や西洋現代音楽などは含まれない。(現在 イリノイ大学には"Robert E. Brown Center for World Music︎"がある)。

★ しかし、ここでいう世界音楽化という用語における世界音楽は、そのような、狭量な意味を持たせない。ここでの世界音楽とは、むしろ、ロバート・ブラウン(Robert E. Brown)の 「世界のさまざまな伝統音楽の集合体」という古典的な定義を、改良して「世界のさま ざまな音楽の集合体」 という意味として捉える。そして、芸術としての音楽の内容について、議論するのではなく、むしろ、先に、形式や様式の、インターネットの世界におけるリア ルタイムにおける世界流通という現象に目を向ける。音楽という芸術を、内容ではなく、形式として世界音楽化という現象に注目するのは、スーザン・ソンタグの『反解釈』の議論からそのアイディアを流用した からである(→ソンタグ「様式=スタイルについて」)。

☆ 世界音楽化について研究すると、どのようなことをいうのであろうか?例えば、レゲトンのラテ ンアメリカ域内ならびにグローバルな流通の実態を考えるために、レコードやCD時代に嚆矢をもつ世界音楽化(world musicking - これはChristopher Small, 1998 から作った申請者による造語)がインターネットの普及で、リアルタイムで世界の若者(z世代)に文化の自由な流用を可能にした実態の文化研究(文化人類 学や文化社会学)が必要なこと、である。

★

ク

リストファー・スモールさんのミュージッキングは、「演奏すること、聴くこと、リハーサルや練習をすること、演奏のための素材を提供すること(いわゆる作

曲)、あるいは踊ること。時には、当日券を取る人、ピアノやドラムを移動させる屈強な男たち、楽器をセッティングしサウンドチェックを行うローディー、皆

が去った後を掃除する清掃員まで、その意味を拡大することもあるだろう。彼らもまた、音楽演奏というイベントの本質に貢献しているのだ」というけど、彼

の、著作は、そのミュージキングをクラシック音楽でやっていることが不満です。世界音楽(ロバート・ブラウンの造語)という概念を導入して、ミュージキン

グの世界音楽化が、僕は必要だと思う。

| ★Any activity

involving or related to music performance, such as performing,

listening, rehearsing, or composing. |

演奏、リスニング、リハーサル、作曲など、音楽演奏に関わるあらゆる活

動(ウィキショナリー)。 |

Musicking MusickingIn his book of the same title (Musicking, 1998), Small argues for introducing a new word to the English dictionary – that of musicking (from the verb to music), meaning any activity involving or related to music performance. According to his own definition, To music is to take part, in any capacity, in a musical performance, whether by performing, by listening, by rehearsing or practicing, by providing material for performance (what is called composing), or by dancing. We might at times even extend its meaning to what the person is doing who takes the tickets at the door or the hefty men who shift the piano and the drums or the roadies who set up the instruments and carry out the sound checks or the cleaners who clean up after everyone else has gone. They, too, are all contributing to the nature of the event that is a musical performance.[3] In expanding his ideas presented in his earlier book (Music, Society, Education, 1977), Small continues to demonstrate that musicking is an active way in which we relate to the rest of the world. The act of musicking establishes in the place where it is happening a set of relationships, and it is in those relationships that the meaning of the act lies. They are to be found not only between those organized sounds which are conventionally thought of as being the stuff of musical meaning but also between the people who are taking part, in whatever capacity, in the performance; and they model, or stand as metaphor for, ideal relationships as the participants in the performance imagine them to be: relationships between person and person, between individual and society, between humanity and the natural world and even perhaps the supernatural world.[4] Another book by Small is Music of the Common Tongue: Survival and Celebration in African American Music (1987), he discusses Africans and Europeans and the Making of Music. His main highlights were 1. Characteristics of African social life and 2. Europeans and the effects of slavery. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Small |

ミュージッキング ミュージッキングスモールは同タイトルの著書(『Musicking』1998年)の中で、英語辞書に新しい単語を導入することを主張している。彼自身の定義によれば 「演奏すること、聴くこと、リハーサルや練習をすること、演奏のための素材を提供す ること(いわゆる作曲)、あるいは踊ること。時には、当日券を取る人、ピアノやドラムを移動させる屈強な男たち、楽器をセッティングしサウンドチェックを 行うローディー、皆が去った後を掃除する清掃員まで、その意味を拡大することもあるだろう。彼らもまた、音楽演奏というイベントの本質に貢献しているのだ」[3]。 スモールは、以前の著書(Music, Society, Education, 1977)で提示した考えを発展させながら、音楽を演奏することが、私たちが他の世界と関わるための能動的な方法であることを示し続けている。 「音楽を奏でるという行為は、それが行われている場所に一連の関係を築 き、その関係の中にこそその行為の意味がある。そしてそれは、演奏の参加者が想像するような理想的な関係、すなわち人と人との関係、個人と社会との関係、 人類と自然界との関係、そしておそらくは超自然的な世界との関係をモデル化する、あるいはそのメタファーとして成り立つのである」[4]。 スモールによるもう一冊の本は、『共通語の音楽』(Music of the Common Tongue)である: アフリカ系アメリカ人の音楽における生存と祝祭』(1987年)で、彼はアフリカ人とヨーロッパ人、そして音楽の作り方について論じている。彼の主なハイ ライトは、1. アフリカの社会生活の特徴、2. ヨーロッパ人と奴隷制の影響。 [3] Small, Christopher (1998). Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Hanover: University Press of New England. pp. 9. ISBN 978-0-8195-2257-3. [4] ibid. p.13 |

Robert E. Brown, 1927-2005 World music is an English phrase for styles of music from non-Western countries, including quasi-traditional, intercultural, and traditional music. World music's inclusive nature and elasticity as a musical category pose obstacles to a universal definition, but its ethic of interest in the culturally exotic is encapsulated in Roots magazine's description of the genre as "local music from out there".[1][2] This music that does not follow "North American or British pop and folk traditions"[3] was given the term "world music" by music industries in Europe and North America.[4] The term was popularized in the 1980s as a marketing category for non-Western traditional music.[5][6] It has grown to include subgenres such as ethnic fusion (Clannad, Ry Cooder, Enya, etc.)[7] and worldbeat.[8][9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_music |

ロバート・E・ブラウン ワー ルド・ミュージックとは、非西洋諸国の音楽スタイルを指す英語表現で、準伝統音楽、異文化間音楽、伝統音楽などが含まれる。ワールド・ミュージックの包括 的な性質と、音楽のカテゴリーとしての弾力性は、普遍的な定義の障害となっているが、文化的にエキゾチックなものへの関心というその倫理観は、『ルーツ』 誌がこのジャンルを「向こうのローカル・ミュージック」と表現したことに集約されている[1][2]。 この「北米やイギリスのポップやフォークの伝統」[3]に従わない音楽は、ヨーロッパや北米の音楽業界によって「ワールド・ミュージック」という用語が与 えられた[4]。 この用語は、非西洋の伝統音楽のマーケティング・カテゴリーとして1980年代に広まった[5][6]。 エスニック・フュージョン(クラナド、ライ・クーダー、エンヤなど)[7]やワールドビート[8][9]といったサブジャンルを含むまでに成長した。 |

| The term "world music,"

meaning folk music from around the world, has been credited to

ethnomusicologist Robert E. Brown,

who coined it in the early 1960s at Wesleyan University in Connecticut,

where he developed undergraduate through doctoral programs in the

discipline. To enhance the learning process (John Hill), he invited

more than a dozen visiting performers from Africa and Asia and began a

world music concert series.[1][2] The term became current in the 1980s as a marketing/classificatory device in the media and the music industry.[3] There are several conflicting definitions for world music. One is that it consists of "all the music in the world", though such a broad definition renders the term virtually meaningless.[4][5] The term also is taken as a classification of music that combines Western popular music styles with one of many genres of non-Western music that are also described as folk music or ethnic music. However, world music is not exclusively traditional folk music. It may include cutting edge pop music styles as well. Succinctly, it can be described as "local music from out there",[6] or "someone else's local music".[7] It is a very nebulous term with an increasing number of genres that fall under the umbrella of world music to capture musical trends of combined ethnic style and texture, including Western elements. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_music_(term) |

世

界各地の民族音楽を意味する「ワールドミュージック」という言葉は、民族音楽学者ロバート・E・ブラウンが1960年代初頭にコネチカット州のウェズリア

ン大学で考案したものとされている。学習プロセス(ジョン・ヒル)を強化するため、彼はアフリカやアジアから10人以上の客演演奏家を招き、ワールド・

ミュージック・コンサート・シリーズを始めた[1][2]。(現在イリノイ大学には"Robert E. Brown Center for World Music︎"

がある) ワールドミュージックという言葉は、1980年代にメディアや音楽業界 におけるマーケティング/分類装置として広まった[3]。1つは「世界中の全ての音楽」から成るというものだが、そのような広範な定義はこの用語を事実上 無意味なものにしている[4][5]。 この用語はまた、西洋のポピュラー音楽のスタイルと、民族音楽や民族音楽とも表現される非西洋音楽の多くのジャンルのうちの1つを組み合わせた音楽の分類 としても捉えられている。しかし、ワールドミュージックは伝統的な民族音楽だけを指すわけではない。最先端のポップミュージックスタイルも含まれる。簡潔に言えば、「向こうのローカルな音楽」[6]、または「他人のローカルな音楽」[7]と表 現することができる。非常に曖昧な用語であり、西洋の要素を含む民族的なスタイルと質感を組み合わせた音楽的傾向を捉えるために、ワールド ミュージックの傘下に入るジャンルが増えている。 |

| The Western impact on world music : change, adaptation, and survival / Bruno Nett. New York : Schirmer Books. - London : Collier Macmillan , c1985 | 世界音楽の時代 / ブルーノ・ネトル著 ; 細川周平訳,

勁草書房 , 1989. |

| Musicking : the meanings of

performing and listening, Christopher Small |

ミュージッキング : 音楽は〈行為〉である,

クリストファー・スモール著 ; 野澤豊一, 西島千尋訳. 水声社 2023 内容説明 音楽は“作品”ではない、“実践”なのだ!“音楽”から“ミュージッキング”へ―既成概念を根底から転倒させ、わたしたちを“音の現場”へといざなう画期 的な評論、待望の全訳。 目次 プレリュード 音楽と音楽すること 第1章 聴くための場所 第2章 コンサートとは現代的な出来事である 第3章 見知らぬ者同士が出来事を共有する インターリュード1 身ぶりの言語 第4章 切り離された世界 第5章 うやうやしいお辞儀 第6章 死んだ作曲家たちを呼び起こす インターリュード2 すべての芸術の母 第7章 総譜とパート譜 第8章 ハーモニー、天国のようなハーモニー インターリュード3 社会的に構築された意味 第9章 劇場のわざ 第10章 関係を表現する音楽のドラマ 第11章 秩序のヴィジョン 第12章 コンサート・ホールではいったい何が起こっているのか? 第13章 孤独なフルート吹き ポストリュード これは良いパフオーマンスだったのだろうか?そしてそのことをあなたはどうやってわかるのだろうか? |

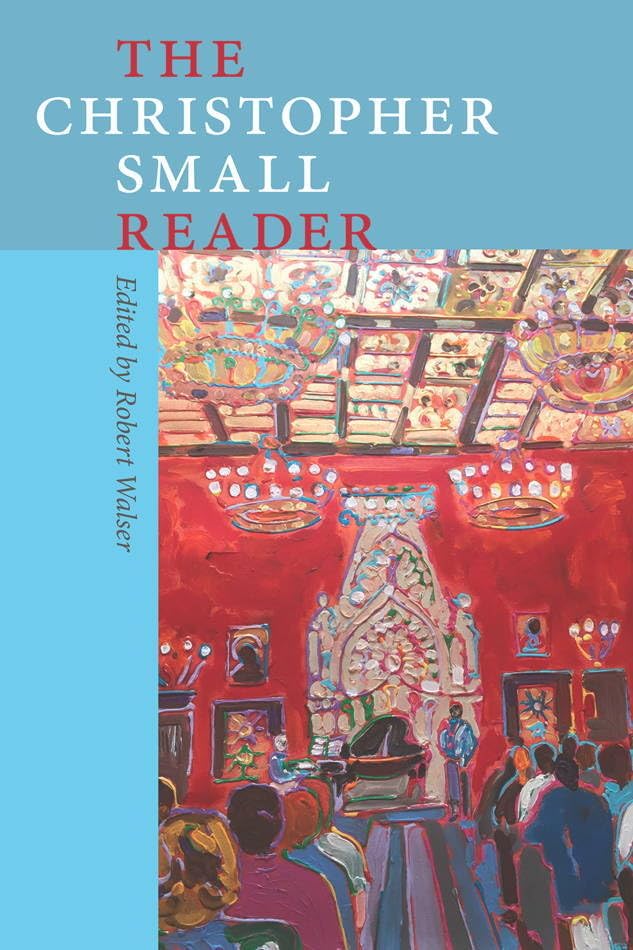

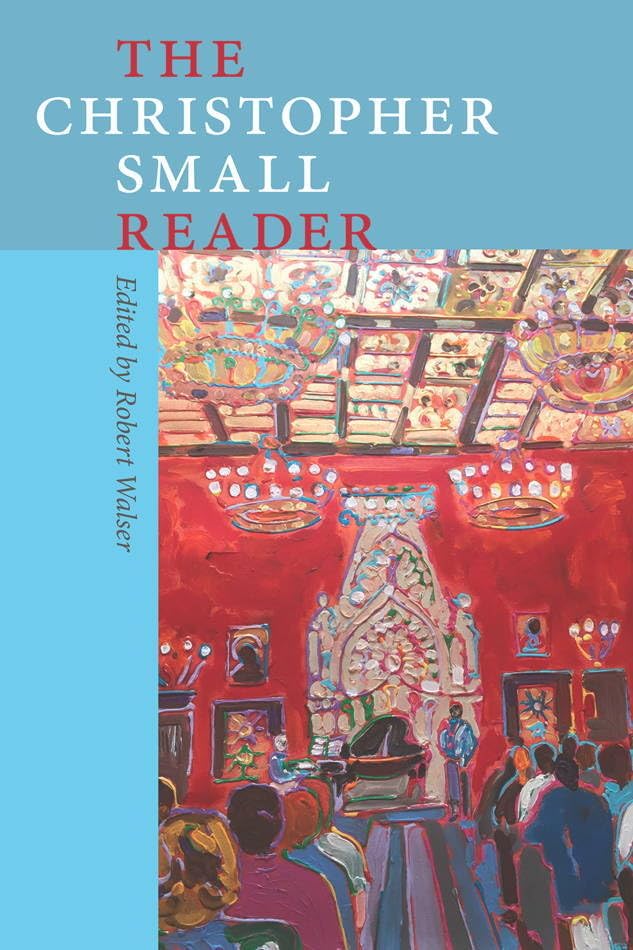

| The

Christopher Small Reader By Robert Walser Wesleyan University Press Copyright © 2016 The Estate of Christopher Small All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-8195-7640-8 Contents Editor's Introduction by Robert Walser, vii, Autobiography (2004; rev. 2008), 1, Introduction to Music, Society, Education (1977), 15, A Different Drummer — American Music: From Music, Society, Education (1977), 20, Introduction to Music of the Common Tongue (1987), 50, Styles of Encounter III — Jazz: From Music of the Common Tongue (1987), 62, Whose Music Do We Teach, Anyway? (1990), 87, Introduction to Musicking: Prelude: Music and Musicking (1998), 95, A Solitary Flute Player: From Musicking (1977), 114, Interview by Robert Christgau (2000), 120, The Sardana and Its Meanings (2003), 150, Why Doesn't the Whole World Love Chamber Music? (2001), 153, Creative Reunderstandings (2005), 173, Rock Concert (2002), 186, Exploring, Affirming, Celebrating — and Teaching (2003), 189, Deep and Crisp and Even (2008), 200, Six Aphorisms and Five Commentaries (2007), 207, Afterword: On Music Education (2009), 217, Pelicans (2009), 227, Afterword by Susan McClary: Remembering Neville Braithwaite, 230, Acknowledgments, 233, Index, 235, CHAPTER 1 Introduction to Music, Society, Education (1977) It is generally acknowledged that the musical tradition of post-Renaissance Europe and her offshoots is one of the most brilliant and astonishing cultural phenomena of human history. In its range and power it is perhaps to be matched by only one other intellectual achievement — the science of post-Renaissance Europe. It is understandable, therefore, if those of us who are its heirs (which includes not only the Americas and many late and present colonies of Europe but also by now a large portion of the non-western world as well) are inclined to find in the European musical tradition the norm and ideal for all musical experience, just as they find in the attitudes of western science the paradigm for the acquisition of all knowledge, and to view all other musical cultures as at best exotic and odd. It is in fact precisely this inbuilt certainty of the superiority of European culture to all others that has given Europeans, and latterly their American heirs, the confidence to undertake the cultural colonization of the world and the imposition of European values and habits of thought on the whole human race. We should not, however, allow the brilliance of the western musical tradition to blind us to its limitations and even areas of downright impoverishment. We may be reluctant to think of our musical life, with its great symphony orchestras, its Bach, its Beethoven, its mighty concert halls and opera houses, as in any way impoverished, and yet we must admit that we have nothing to compare with the rhythmic sophistication of Indian, or what we are inclined to dismiss as "primitive" African music, that our ears are deaf to the subtleties of pitch inflection of Indian raga or Byzantine church music, that the cultivation of bel canto as the ideal of the singing voice has shut us off from all but a very small part of the human voice's sound possibilities or expressive potential, such as are part of the everyday resources of a Balkan folk singer or an Eskimo, and that the smooth mellifluous sound of the romantic symphony orchestra drowns out the fascinating buzzes and distortions cultivated alike by African and medieval European musicians. It is only comparatively recently that Europeans have developed sufficient interest in these and other musical cultures to hear in them anything more than quaintness or cacophony; we were in the position of the fish in Albert Einstein's metaphor, not aware of the water because it knows nothing of any other medium. Today, partly through our increasing knowledge of other musical cultures, we have the opportunity to become aware of our own tradition as a medium surrounding and supporting us and shaping our perceptions and attitudes as the needs of hydrodynamics shape the fish's body; this book is in part an attempt to examine the western musical tradition through this experience as well as in itself, to see it through the mirror of these other musics as it were from the outside, and in so doing to learn something of the inner unspoken nature of western culture as a whole. We shall try to look beneath the surface of the music, beneath the "message," if any, which the composer consciously intended (and even the fact that a message is intended may be in itself significant), to its basic technical means, its assumptions, which we usually accept unawares, on such matters as the nature of sound, the manner of listening, the passing of time, as well as its social situation and relations, to see what lies hidden there. For it is in the arts of our, or indeed of any, culture, that we see not only a metaphor for, but also a way of transcending, its otherwise unspoken and unexamined assumptions. Art can reveal to us new modes of perception and feeling, which jolt us out of our habitual ways; it can make us aware of possibilities of alternative societies whose existence is not yet. Many writers and critics have undertaken, in the visual and plastic arts and in literature, to make plain the social implications of their chosen arts; it is to me perpetually surprising that so few writers have made any comparable attempt in music, whose criticism and appreciation exists for the most part in a social vacuum. Perhaps it is the lack of explicit subject matter in music that frightens people off. I make the attempt here with much trepidation, but feel it imperative, not merely for the sake of constructing yet another aesthetic of music (though even to do this in a way that takes note of the musical experience of other cultures would be a worthwhile project) but because of what I believe to be the importance and urgency from the social and especially the educational point of view of what I have learnt from my explorations. In following these explorations in this book the reader will notice that I occasionally return to the same point more than once; I must ask the reader to regard these repetitions not as signs of simple garrulousness but rather as nodal points in that network structure which my argument resembles more than it resembles a straight logic-line. The explorer (to introduce a metaphor which will become familiar) in a strange territory may cross and re-cross the same point many times, but will come towards it from a different direction each time as he traverses the terrain, and, if he is lucky, will each time obtain a new point of view. And if I appear to leave the subject and introduce irrelevancies I must ask the reader to trust me eventually to make relationships plain. I shall begin my investigation with an exposition of what I see as the principal characteristics of western classical music, and of the conventions, both social and technical, of that music. I shall try to show how both western classical music and western science speak of very deep-rooted states of mind in Europeans, states of mind which have brought us to our present uncomfortable, if not downright dangerous condition in our relations with one another and with nature. I shall suggest that education, or rather schooling, as at present conceived in our society has worked to perpetuate those states of mind by which we see nature as a mere object for use, products as all-important regardless of the process by which they are obtained, and knowledge as an abstraction, existing "out there," independent of the experience of the knower, the three notions being linked by an intricate web of cause and effect. In holding up some other musical cultures to the reader's attention I shall try to show that different aesthetics of music are possible that can stand as metaphors for quite different world views, for different systems of relationships within society and nature from our own. I shall describe the various attempts, in the music of our century, to frame a critique of our present society and its world view, while a brief survey of music in the United States will show that that country possesses a culture which is not only more remote from Europe than we imagine but has also long contained within it the vision of a potential society which is perhaps stronger and more radical than anything in European culture. And finally, I shall attempt to show how the new vision of art revealed can serve as a model for a new vision of education, and possibly of society. I have based my investigations upon two postulates: first, that art is more than the production of beautiful, or even expressive, objects (including sound-objects such as symphonies and concertos) for others to contemplate and admire, but is essentially a process, by which we explore our inner and outer environments and learn to live in them. The artist, whether he is Beethoven struggling to bring a symphony into being, Michelangelo wresting his forms from the marble, the devoted gardener laying out his garden or the child making his highly formalized portraits of the important people and things in his life, is exploring his environment, and his responses to it, no less than is a scientist in his laboratory; he is ordering his perceptions and making a model of reality, both present and potential. If he is a sufficiently gifted artist his art will help others do the same. Art is thus, notwithstanding its devaluation in post-Renaissance society, as vital an activity as science, and in fact reaches into areas of activity that science cannot touch. The second postulate is that the nature of these means of exploration, of science and of art, their techniques and attitudes, is a sure pointer to the nature and the preoccupations of the society that gave them birth. We shall find that our culture is presently undergoing a transformation as profound as that which took place in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries which we call the Renaissance, and that this transformation, like the Renaissance, is taking place not just on the level of conscious opinions and concepts but, more importantly, on that of perception and the often unconscious habits of thought on which we base our everyday speech and action. And since it is perception and the subconscious that are the concern of art, it is the methods of art rather than of science which can provide a model and a guide for the new conceptual universe towards which we are moving. It is a grave but common error to think of the aims of art and of science as identical, or complementary, or even much in tune with each other. Art and science, it is true, are both means of exploration, but the intention, the method and the kind of reality they explore are very different. This is not simply the Cartesian split between matter and mind (we must indeed start from the assumption that they are identical); it is rather that the aim of art is to enable us to live in the world, while that of science is to enable us to master it. It is for this reason that I insist on the supreme importance of the art-process and the relative unimportance of the art-object; the essential tool of art is the unrepeatable experience. With science it is the finished product that counts, the theory, the hypothesis, the objectified knowledge; we obtain it by whatever means we can, and the tool is the repeatable experiment. Art is knowledge as experience, the structuring and ordering of feeling and perception, while science is abstract knowledge divorced as completely as possible from experience, a body of facts and concepts existing outside of and independently of the knower. Both are valid human activities, but since the Renaissance we have allowed the attitudes and values of science to predominate over those of art, to the detriment of the quality of our experience. Our schools, for example, concern themselves almost exclusively with abstract knowledge, which pupils are expected to absorb immediately and regurgitate on demand. The pupils may or may not wish, or be able, to absorb the knowledge, but the one lesson that all do learn is that they can be consumers, not producers, of knowledge, and that the only knowledge that has validity is that which comes to them through the school system. They are taught much about the world, but their experience of it, apart from the hermetic world of classroom and playground, is seriously impaired. And so, too, of our culture as a whole. We know more about the world, and experience it less, than perhaps any previous generation in history; so, too, musicology has made available to us more knowledge about music than ever before, and yet our experience of it is greatly diluted by being mediated through the knowledge of experts. We become afraid of the encounter with new musical experience, where knowledge and expertise are no guide and only the subjective experience honestly felt can serve, and retreat into the safe past, where we know what to expect and connoisseurship is paramount. This book will suggest that artistic activity, properly understood, can provide not only a way out of this impasse in musical appreciation, in itself an unimportant matter, but also an approach to the restructuring of education and even perhaps of our society. Simply because the artist sets his own goals and works with his whole self — reason, intuition, the most ruthless self-criticism and realistic assessment of a situation, freely, without external compulsion and with love — art is a model for what work could be were it freely and lovingly undertaken rather than, as it is for most today, forced, monotonous and boring. The spectacular changes which western art has undergone in our century are metaphors for changes that are still only latent in our culture. They show, however, that there are in fact forces within the matrix of society that are favorable to these changes, which could bring about our liberation from the scientific and technocratic domination of our lives, from the pointless and repetitious labor that passes for work for most people, and, for our children, from the scars inflicted by our present schools, well-intentioned though they may be, on all those, successful and unsuccessful alike, who pass through them. CHAPTER 2 A Different Drummer — American Music From Music, Society, Education (1977) It is a characteristic of tonal-harmonic music that it requires a high degree of subordination of the individual elements of the music to the total effect. Not only is the progress of each individual voice required to conform to the progression of chords, but also each individual note or chord is meaningless in itself, gaining significance only within the context of the total design, much as the authoritarian or totalitarian state requires the subordination of the interests of its individual citizens to its purposes. It is therefore interesting to see in the music of those British colonies, which become the United States of America, a disintegration of tonal functional harmony taking place long before such a process became detectable in Europe, and it is not too fanciful to view this as one expression of the ideal of individual liberty on which the United States was founded, an ideal that, however meagerly realized or even betrayed during the course of its history, has never quite disappeared. The colonists who arrived in New England in the early seventeenth century had left behind the last days of a golden age of English musical culture. Many were, in the words of the first Governor of the New England colonies, "very expert in music," and although the Pilgrims and Puritans favored sacred over secular music, they had no objection to secular instrumental music, and even dance, as long as decorum was preserved. However, the Mayflower and her successors had little room for any but the most essential cargo, and only the smallest and hardiest musical instruments could be accommodated — certainly nothing so bulky and liable to damage as a virginal or organ. So far as is known, the early colonists could and did enjoy only music that was simple and functional, that is, social music and worship music. As far as the former is concerned, we do know that there were instruments around, though what they played is unclear — possibly from English collections like those of Thomas Ravenscroft, and later John Playford. Secular song was not unknown, not only in the Anglo-Celtic ballads, which belonged to the ancient oral rather than to the literate tradition, and which in America proved extremely durable, but also songs from the various collections that had crossed the Atlantic with them. Worship music, on the other hand, meant almost exclusively the singing of the psalms in metrical translation, a practice that was not unknown in England even in the Established Church. This may seem a limited repertoire, but there are after all a hundred and fifty psalms, many of which are very long, and their emotional range is very wide. The version favored by the early colonists was that of Henry Ainsworth, who used a variety of poetic meters and provided no less than thirty-nine different tunes, which were printed at the back of the book in the form of single lines of melody. Dissatisfaction was, however, early expressed by the Puritan divines, who alleged that faithfulness to the literal word of God was too often sacrificed to literary grace, and in 1640 a new metrical translation was made by a committee and published — the first book to be printed in the New England colony. The translations were made into only six metrical schemes, mostly in four-line stanzas, so that the same tune could be used for several psalms, and the number of tunes that needed to be learnt was kept to a minimum. The new psalm book was adopted, after much disputation, throughout the New England colonies by the end of the seventeenth century; under the name of Bay Psalm Book it ran through innumerable editions over the next century. It was not until the ninth edition, of 1698, that tunes were provided — a mere thirteen — to which the psalms could be sung. Irving Lowens makes a valuable comment on the American culture of this period: The story of the arts in seventeenth century New England is the tale of a people trying to plant in the New World the very vines whose fruit they had enjoyed in the Old, while, at the same time, it is the chronicle of the subconscious development of a totally different civilization. The seventeenth-century history of the Bay Psalm Book is a case in point, for although the psalm-tunes may superficially appear nothing more than a parochial utilization of certain music sung in the mother country, a mysterious qualitative change took place when they were sung on different soil. Here, they proved to be the seed from which a new, uniquely American music was later to flower. (Continues...) Excerpted from The Christopher Small Reader by Robert Walser . Copyright © 2016 The Estate of Christopher Small. Excerpted by permission of Wesleyan University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. |

クリストファー・スモール読本 ロバート・ウォルザー著 ウェズリアン大学出版 著作権 © 2016 クリストファー・スモールの遺産 無断複写・転載を禁じます。 ISBN: 978-0-8195-7640-8 目次 ロバート・ヴァルザーによる編集者序文、vii、 自伝(2004年、2008年改訂版), 1、 音楽・社会・教育入門』(1977年)、15、 異なるドラマー-アメリカの音楽 音楽、社会、教育』(1977年)20より、 共通語の音楽入門』(1987年)、50、 出会いのスタイルIII-ジャズ: 共通語の音楽から』(1987年)62、 私たちは誰の音楽を教えているのか?(1990), 87, 音楽入門: 前奏曲: 音楽とミュ-ジッキング』(1998年)95、 孤独なフルート奏者 1977)、114、 ロバート・クリストガウによるインタビュー(2000年)、120、 サーダナとその意味』(2003年)、150、 なぜ全世界は室内楽を愛さないのか?(2001), 153, 創造的理解」(2005年)、173、 ロック・コンサート(2002年)、186 探求し、肯定し、祝福し、そして教える(2003年)、189、 ディープ・アンド・クリスプ・アンド・イーブン」(2008年)、200、 6つの格言と5つの解説(2007年)、207、 あとがき: 音楽教育について』(2009年)、217、 ペリカンズ』(2009年)、227、 スーザン・マクラリーによるあとがき: ネヴィル・ブレイスウェイトを偲ぶ、230、 謝辞、233、 索引、235 第1章 序章 音楽、社会、教育 (1977) ルネサンス以後のヨーロッパとその分派の音楽の伝統が、人類史上最も輝かしく驚くべき文化現象のひとつであることは、一般に認められている。ルネサンス期 以降のヨーロッパにおける科学は、その範囲と力において、おそらく他のひとつの知的業績に匹敵するものであろう。それゆえ、その継承者である私たち(アメ リカ大陸やヨーロッパの後期および現在の植民地の多くだけでなく、今では非西洋世界の大部分も含まれる)が、ヨーロッパの音楽の伝統にあらゆる音楽体験の 規範と理想を見いだし、西洋科学の姿勢にあらゆる知識習得のパラダイムを見いだすように、他のすべての音楽文化をせいぜいエキゾチックで奇妙なものとみな す傾向があるとすれば、それは理解できる。ヨーロッパ人、そして後にその後継者となるアメリカ人に、世界を文化的に植民地化し、ヨーロッパの価値観や思考 習慣を全人類に押し付けるという自信を与えたのは、実は、ヨーロッパ文化が他のすべての文化より優れているという、まさにこの内蔵された確信なのである。 しかし、西洋音楽の伝統の素晴らしさに目を奪われ、その限界や、貧しさに目を奪われてはならない。偉大な交響楽団、バッハ、ベートーヴェン、巨大なコン サートホールやオペラハウスを擁する私たちの音楽生活を、貧しくなったとは考えたくないかもしれないが、インドの洗練されたリズムや、私たちが「原始的」 と切り捨てたくなるようなアフリカの音楽と比較するものがないこと、インドのラーガやビザンチンの教会音楽の微妙な音程の抑揚に私たちの耳が聞こえないこ とは認めなければならない、 歌声の理想としてのベルカントの育成が、バルカン半島の民謡歌手やエスキモーが日常的に持っているような、人間の声の可能性や表現力のごく一部を除いて、 私たちを遠ざけていること、ロマン派交響楽団の滑らかで芳醇な響きが、アフリカや中世ヨーロッパの音楽家が同様に培ってきた魅力的なざわめきや歪みをかき 消してしまっていること。 アルベルト・アインシュタインの比喩にある魚のようなもので、他の媒体を知らないために水の存在に気づかないのだ。今日、他の音楽文化についての知識が増 えたこともあり、私たちは、流体力学の必要性が魚の体を形作るように、私たちを取り囲み、支え、私たちの知覚や態度を形作る媒体としての自分たちの伝統を 意識する機会を得ている。本書は、西洋音楽の伝統を、それ自体としてだけでなく、このような経験を通して検証し、他の音楽という鏡を通して、いわば外側か ら見る試みでもある。音楽の表面の下、作曲家が意識的に意図した「メッセージ」があるとすればその下(メッセージが意図されているという事実自体が重要で ある場合もある)、その基本的な技術的手段、音の性質、聴き方、時間の流れ、社会的状況や関係といった事柄について、私たちが通常無意識のうちに受け入れ ているその前提に目を向け、そこに何が隠されているかを見ようとする。 というのも、私たちの文化、いや、あらゆる文化の芸術の中にこそ、私たちは、そうでなければ語られることのない、また吟味されることのない前提のメタ ファーを見るだけでなく、それを超越する方法を見ることができるからである。芸術は、私たちを習慣的な方法から揺り動かす新しい知覚や感情の様式を明らか にすることができる。多くの作家や批評家が、視覚芸術や造形芸術、そして文学において、自らが選んだ芸術の社会的意味を明らかにしようとしてきた。おそら く、音楽には明確な主題がないことが、人々を怖がらせているのだろう。この試みは、単に音楽の美学を構築するためではなく(他の文化圏の音楽体験に留意し てこれを行うことでさえ、価値あるプロジェクトになるだろうが)、私の探求から学んだことが社会的、特に教育的観点から重要であり、緊急であると信じてい るからである。本書でこのような探索を追っていくと、読者は私が時折同じポイントに何度も戻っていることに気づくだろう。読者には、このような繰り返し を、単なる戯言の兆候としてではなく、むしろ私の議論が直線的な論理線に似ている以上に似ているネットワーク構造における結節点として捉えていただくよう お願いしなければならない。見知らぬ土地の探検家(馴染みのある比喩を紹介しよう)は、同じ地点を何度も横切ったり横断したりするが、地形を横断するたび に異なる方向からその地点に向かい、運がよければそのたびに新しい視点を得ることができる。そして、もし私が主題から離れ、無関係なことを持ち込んでいる ように見えたとしても、読者には、いずれ私が関係を明らかにすることを信じていただかなければならない。 私は、西洋のクラシック音楽の主な特徴と、その音楽の社会的・技術的な慣習について説明することから調査を始めることにする。西洋のクラシック音楽と西洋 の科学が、いかにヨーロッパ人の非常に根深い心の状態を物語っているかを明らかにしようと思う。私たちの社会で現在考えられているような教育、いや学校教 育は、自然を単なる使用対象として、生産物をそれが得られる過程に関係なくすべて重要なものとして、知識を抽象的なものとして、知る者の経験とは無関係に 「そこに」存在するものとしてとらえ、この3つの観念が原因と結果の複雑な網の目によって結びついている、このような心の状態を永続させるように働いてき たことを指摘したい。他の音楽文化をいくつか取り上げて読者の注意を喚起することで、私たちとはまったく異なる世界観、社会や自然における異なる関係性の システムのメタファーとして成り立つ、異なる音楽の美学が可能であることを示そうと思う。また、アメリカの音楽を簡単に調査することで、この国が、私たち が想像している以上にヨーロッパからかけ離れた文化を持っているだけでなく、おそらくヨーロッパ文化のどんなものよりも強く先鋭的な、潜在的な社会のヴィ ジョンを長い間内包してきたことを示すだろう。そして最後に、明らかにされた芸術の新しいビジョンが、教育の新しいビジョン、ひいては社会の新しいビジョ ンのモデルとなりうることを示そうと思う。 第一に、芸術とは、他人が観賞したり賞賛したりするための美しい、あるいは表現力豊かなオブジェ(交響曲や協奏曲のような音のオブジェも含む)を作り出す こと以上のものであり、本質的には、私たちが自分の内的・外的環境を探求し、その中で生きることを学ぶプロセスである、ということだ。ベートーヴェンが交 響曲を生み出そうと奮闘しているときであれ、ミケランジェロが大理石から形を引き出そうとしているときであれ、献身的な庭師が庭を整備しているときであ れ、子供が自分の人生における重要な人々や物事の高度に形式化された肖像画を描いているときであれ、芸術家は、研究室にいる科学者に劣らず、自分の環境と それに対する自分の反応を探求している。もし彼が十分な才能を持った芸術家であれば、彼の芸術は他の人々が同じことをするのを助けるだろう。このように、 ルネサンス以降の社会で芸術が軽んじられているにもかかわらず、芸術は科学と同じくらい重要な活動であり、事実、科学が触れることのできない活動領域にま で及んでいる。第二の仮定は、科学と芸術の探求手段、その技術や態度の性質は、それらを生み出した社会の性質や関心事を確実に指し示すものである、という ものである。ルネサンスと呼ばれる15世紀から16世紀にかけて起こったような深遠な変容を、私たちの文化が現在進行形で経験していること、そしてこの変 容は、ルネサンスと同様に、意識的な意見や概念のレベルだけでなく、より重要なこととして、私たちが日常的な言動の基盤としている知覚や、しばしば無意識 的な思考の習慣のレベルでも起こっていることに気づくだろう。そして、知覚と潜在意識こそが芸術の関心事である以上、私たちが向かっている新しい概念的宇 宙のモデルや指針を提供できるのは、科学よりもむしろ芸術の手法なのである。 芸術と科学の目的が同一であるとか、相補的であるとか、あるいは互いに調和していると考えるのは、重大だがありがちな誤りである。芸術と科学はどちらも探 求の手段であることは事実だが、その意図、方法、探求する現実の種類はまったく異なる。これは単にデカルト的な物質と心の分裂ではなく(実際、私たちは両 者が同一であるという前提から出発しなければならない)、むしろ芸術の目的は私たちが世界の中で生きることを可能にすることであり、科学の目的は私たちが 世界を支配することを可能にすることなのである。芸術の本質的な道具は、再現不可能な経験である。科学の場合、重要なのは完成品であり、理論であり、仮説 であり、客観化された知識である。芸術は経験としての知識であり、感情や知覚の構造化と秩序化である。一方、科学は経験から可能な限り完全に切り離された 抽象的知識であり、知る者の外部に、またそれとは無関係に存在する事実と概念の体である。しかしルネサンス以来、私たちは科学の姿勢や価値観が芸術のそれ よりも優位に立つことを許してきた。 例えば、私たちの学校では、ほとんど抽象的な知識だけに関心が向けられ、生徒たちはその知識を即座に吸収し、要求に応じて復唱することが期待されている。 生徒がその知識を吸収することを望むか望まないか、あるいはできるかできないかは別として、すべての生徒が学ぶ教訓は、自分たちは知識の生産者ではなく消 費者になりうるということ、そして有効な知識は学校制度を通じてもたらされるものだけだということである。彼らは世界について多くのことを教えられるが、 教室と遊び場という密閉された世界から離れた世界についての経験は、著しく損なわれている。私たちの文化全体についても同様である。音楽学は、かつてない ほど多くの音楽に関する知識を私たちに提供するようになったが、専門家の知識を媒介にすることで、私たちの音楽体験は大きく損なわれている。私たちは、知 識や専門知識が何の指針にもならず、素直に感じた主観的な経験だけが役立つような、新しい音楽的経験との出会いを恐れるようになり、何を期待すればいいの かがわかり、目利きが最優先される安全な過去に引きこもるようになる。 本書は、芸術活動を正しく理解することで、音楽鑑賞におけるこの行き詰まりから抜け出す道が開けるだけでなく、それ自体が重要ではない問題であるが、教 育、そしておそらくは社会の再構築へのアプローチにもなることを示唆する。芸術家が自ら目標を設定し、理性、直感、最も冷酷な自己批判、現実的な状況判断 など、自己のすべてを駆使して、自由に、外的な強制を受けずに、愛情をもって取り組むからである。西洋美術が今世紀に経験した壮大な変化は、私たちの文化 にまだ潜在的にしかない変化のメタファーである。この変化は、私たちの生活における科学技術支配からの解放、ほとんどの人々にとって仕事と見なされている 無意味で反復的な労働からの解放、そして私たちの子供たちにとっては、たとえ善意であったとしても、現在の学校によって、成功した者も失敗した者も、そこ を通るすべての人々に負わされた傷跡からの解放をもたらす可能性がある。 第2章 異なるドラマー-アメリカの音楽 音楽、社会、教育 (1977) 調性和声音楽の特徴として、音楽の個々の要素が全体的な効果に高度に従属することが要求される。各声部の進行が和音の進行に合わせることを要求されるだけ でなく、個々の音符や和音はそれ自体無意味であり、全体的なデザインの文脈の中でのみ意味を持つ。したがって、ヨーロッパでそのようなプロセスが検出され るようになるずっと前に、調性機能和声の崩壊が起こっていたことを、アメリカ合衆国となるイギリスの植民地の音楽に見るのは興味深いことである。 17世紀初頭にニューイングランドに到着した入植者たちは、イギリス音楽文化の黄金時代の末期を残していた。ピルグリムやピューリタンたちは、世俗音楽よ りも聖楽を好んだが、礼儀が守られる限り、世俗の器楽やダンスにさえ異論はなかった。しかし、メイフラワー号とその後継船には、最も必要な貨物以外はほと んど入れるスペースがなく、収容できるのは最も小さくて丈夫な楽器だけだった。知られている限りでは、初期の入植者たちはシンプルで機能的な音楽、つまり 社交音楽と礼拝音楽しか楽しめなかったし、実際に楽しんでいた。前者に関しては、楽器があったことは分かっているが、何を演奏していたのかは不明である。 おそらく、トーマス・レイヴェンスクロフトや後のジョン・プレイフォードのようなイギリス人のコレクションによると思われる。世俗的な歌は、アングロ・ケ ルトのバラッドだけでなく、文字よりもむしろ古代の口承の伝統に属し、アメリカでは非常に長持ちすることが証明されたバラッドや、彼らとともに大西洋を 渡った様々なコレクションからの歌など、未知のものではなかった。一方、礼拝用の音楽は、ほとんどもっぱら詩篇の挽歌を歌うことを意味した。これは限られ たレパートリーに見えるかもしれないが、詩篇は150編もあり、その多くは非常に長く、感情の幅も広い。初期の入植者たちに好まれたのはヘンリー・エイン ズワースの詩編で、彼はさまざまな詩的音律を用い、39種類以上の曲を提供した。ピューリタンの神学者たちは、神の言葉への忠実さが文学的な優美さのため に犠牲にされすぎていると主張し、1640年に委員会によって新しい計量訳が作られ、ニューイングランド植民地で印刷された最初の本として出版された。 訳詩は6つの韻律に分けられ、ほとんどが4行のスタンザで、同じ曲が複数の詩篇に使われるようになり、覚えるべき曲の数は最小限に抑えられた。この新しい 詩篇集は、多くの論争の末、17世紀末までにニューイングランド植民地全域で採用された。1698年の第9版まで、詩篇を歌えるような曲(わずか13曲) が提供されることはなかった。 アーヴィング・ローウェンズは、この時代のアメリカ文化について貴重なコメントを残している: 17世紀のニューイングランドにおける芸術の物語は、旧世界でその果実を享受していたブドウの木を新世界に植えようとする人々の物語であると同時に、まっ たく異なる文明の無意識的な発展の記録でもある。17世紀のベイ詩篇集の歴史は、その一例である。詩篇の曲は、表面的には母国で歌われている特定の音楽を 地方的に利用したものに過ぎないように見えるかもしれないが、異なる土壌で歌われると、不思議な質的変化が起こった。ここで、それらは後に新しい、アメリ カ独自の音楽を開花させる種であることが証明されたのである。 続く より抜粋 クリストファー・スモール読本 著 ロバート・ウォルザー . 著作権 © 2016 The Estate of Christopher Small. ウェズリアン大学出版局の許可を得て抜粋。 無断転載を禁じます。この抜粋のいかなる部分も、出版社からの書面による許可なく複製または転載することを禁じます。 抜粋は、ダイヤル・ア・ブック社より、当ウェブサイト訪問者の個人的な使用のためにのみ提供されています。 |

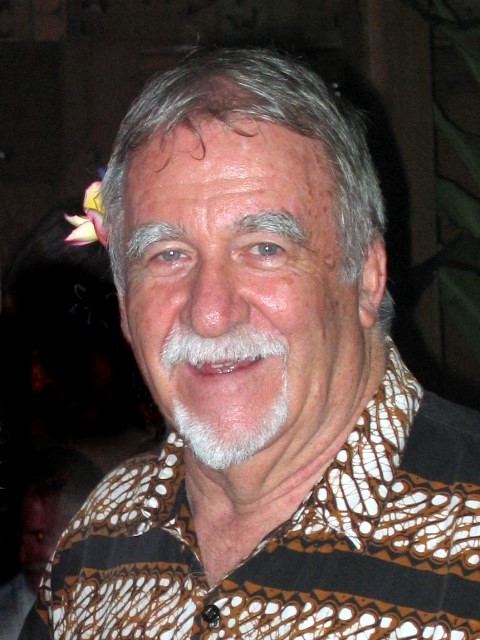

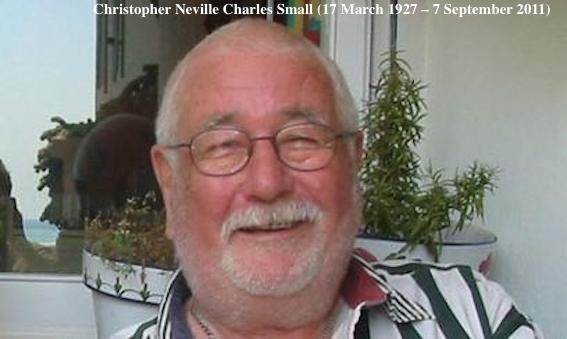

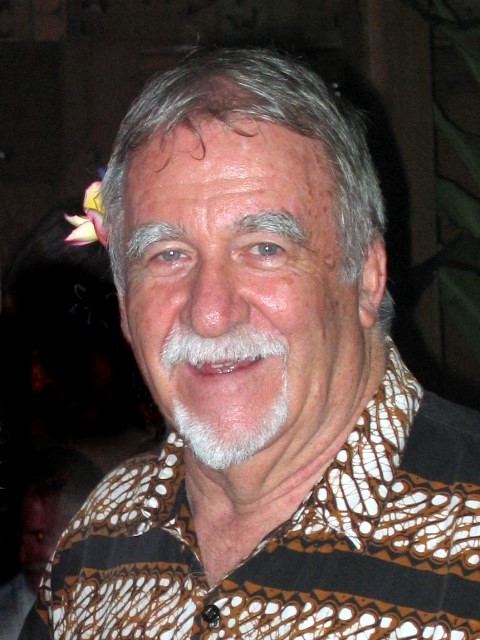

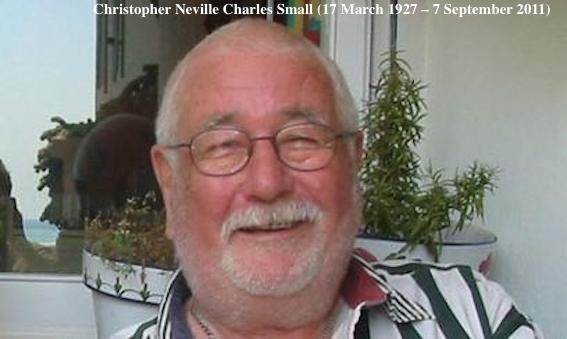

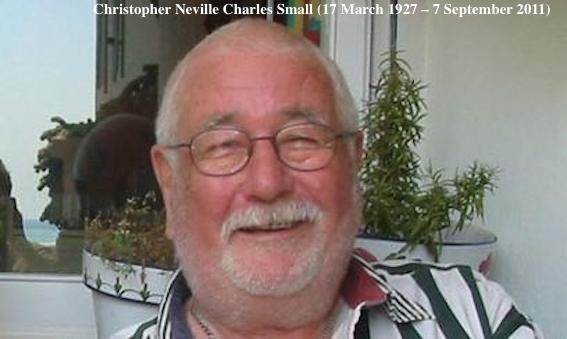

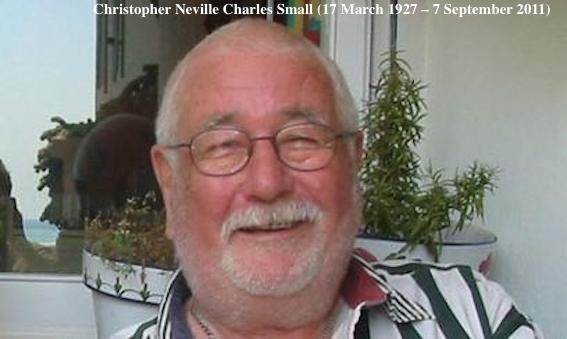

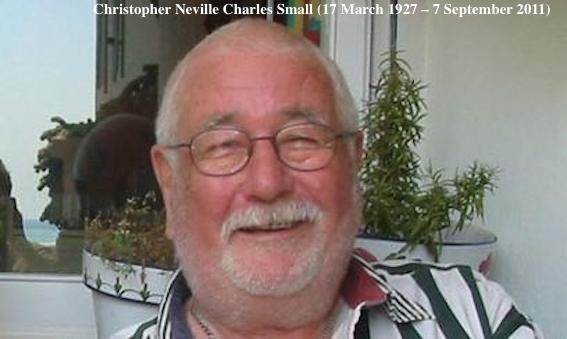

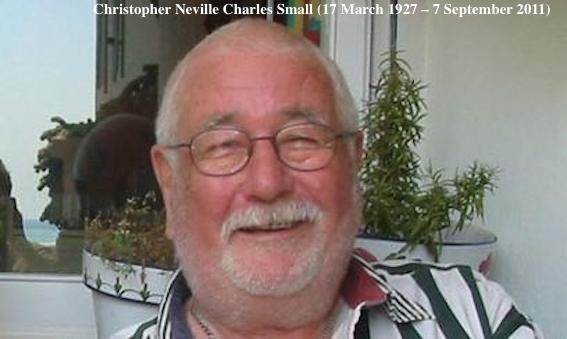

Christopher

Neville Charles Small (17 March 1927 – 7 September 2011) was a New

Zealand-born musician, educator, lecturer, and author of many

influential books and articles in the fields of musicology,

sociomusicology and ethnomusicology. He coined the term musicking, to

highlight music as a process (verb) and not an object (noun.)[1] Christopher

Neville Charles Small (17 March 1927 – 7 September 2011) was a New

Zealand-born musician, educator, lecturer, and author of many

influential books and articles in the fields of musicology,

sociomusicology and ethnomusicology. He coined the term musicking, to

highlight music as a process (verb) and not an object (noun.)[1]Biography Small was born in Palmerston North, New Zealand, to a dentist and former schoolteacher, and was the youngest of three children.[2] His early school education took place at the Terrace End and Russell Street Primary Schools (1932–39), Palmerston North Boys' High School (1940–41) and Wanganui Collegiate School (1942–44). Between 1945 and 1952 he attended the University of Otago and then Victoria University College. He taught at Horowhenua College (at the same time working at Morrow Productions Ltd making educational animated films) from 1953 to 1958, and at Waihi College from 1959 to 1960.[3] In 1960, he was awarded a New Zealand government bursary and he spent 1961 travelling in the United Kingdom, before studying composition in London with Priaulx Rainier, where he also had contact with Bernard Rands, Luigi Nono and Witold Lutoslawski. After his studies he stayed in England, where he taught at schools, including Anstey College of Education in Birmingham. He became senior lecturer in music at Ealing College of Higher Education in London (1971–86) and he also taught at Dartington College of Arts in 1979. Between 1977 and 1986 he was adjunct professor of the history of music at Syracuse University London Centre, and a tutor in music to the summer school of the BEd course of Sussex University between 1981 and 1984.[2][4] Smalls retired from teaching in 1986 and moved to Sitges, Spain, where he lived with his partner Neville Braithwaite (a Jamaican-born dancer, singer, and youth worker) whom he married in 2006. During his time in Spain, Small conducted Catalan choirs and was visited regularly by people from both Europe and the USA, who admired his work. In the USA his ideas have been supported by prominent musicologists such as Charles Keil, Robert Walser, Susan McClary and The Village Voice rock critic Robert Christgau.[2] Neville Braithwaite died in 2006, and Small died in 2011. He is survived by his sister, Rosemary.[2] During his lifetime he published a number of books, and articles in journals such as Music in Education, Tempo, The Musical Times, Music and Letters, and Musical America. He lectured in many educational institutions in the United Kingdom, Norway and the United States, contributed with papers to organisations such as the Composers' Guild of Great Britain (1984), the Association of Improvising Musicians (1985), Music Educators National Conference (Hartford, Connecticut, 1985; Washington DC, 1989) and the Society for Ethnomusicology (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1988). Small took part in the series Sounds Different, broadcast by BBC-TV2 (July 1982), and wrote This Is Who We Are, a three-programme broadcast on BBC Radio 3 (March 1988) about Afro-American music.[4] Musicking In his book of the same title (Musicking, 1998), Small argues for introducing a new word to the English dictionary – that of musicking (from the verb to music), meaning any activity involving or related to music performance. According to his own definition, To music is to take part, in any capacity, in a musical performance, whether by performing, by listening, by rehearsing or practicing, by providing material for performance (what is called composing), or by dancing. We might at times even extend its meaning to what the person is doing who takes the tickets at the door or the hefty men who shift the piano and the drums or the roadies who set up the instruments and carry out the sound checks or the cleaners who clean up after everyone else has gone. They, too, are all contributing to the nature of the event that is a musical performance.[5] In expanding his ideas presented in his earlier book (Music, Society, Education, 1977), Small continues to demonstrate that musicking is an active way in which we relate to the rest of the world. The act of musicking establishes in the place where it is happening a set of relationships, and it is in those relationships that the meaning of the act lies. They are to be found not only between those organized sounds which are conventionally thought of as being the stuff of musical meaning but also between the people who are taking part, in whatever capacity, in the performance; and they model, or stand as metaphor for, ideal relationships as the participants in the performance imagine them to be: relationships between person and person, between individual and society, between humanity and the natural world and even perhaps the supernatural world.[6] Works Bibliography Music, Society, Education (1977) Schoenberg (1977) Music of the Common Tongue: Survival and Celebration in African American Music (1987) Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening (1998) Compositions Actions for Chorus – Some Maori Place Names for large chorus (1974) Black Cat for school percussion ensemble and voices (1968) Children of the Mist, a ballet in two acts for orchestra (1960) Concert Piece for orchestra (1963) High Country Stockman, orchestral music for film (1952) Suite from Children of the Mist, for orchestra (1960) TB, for film (1955) The Story of Soil, music for film (1954) Trees, music for film (1952) Various Songs and Solo Piano Pieces for students and friends (1980) What on Earth is Happening music for film (1958)[4] Christopher Small Collection In 1997, Christopher Small retired in Sitges and donated his personal library to the University of Girona. The collection is of outstanding quality and unique in the context of Catalan universities. Most of its nearly 500 volumes are centered around music and cover ethnomusicology, musical sociology, and popular music - especially afroamerican genres like jazz, blues, soul. etc. |

ク

リストファー・ネヴィル・チャールズ・スモール(Christopher Neville Charles Small、1927年3月17日 -

2011年9月7日)は、ニュージーランド生まれの音楽家、教育者、講師であり、音楽学、社会音楽学、民族音楽学の分野で多くの影響力のある著書や論文の

著者である。彼は音楽を目的語(名詞)ではなく、過程(動詞)として強調するためにミュジッキングという言葉を作った[1]。 ク

リストファー・ネヴィル・チャールズ・スモール(Christopher Neville Charles Small、1927年3月17日 -

2011年9月7日)は、ニュージーランド生まれの音楽家、教育者、講師であり、音楽学、社会音楽学、民族音楽学の分野で多くの影響力のある著書や論文の

著者である。彼は音楽を目的語(名詞)ではなく、過程(動詞)として強調するためにミュジッキングという言葉を作った[1]。経歴 スモールはニュージーランドのパーマストン・ノースで歯科医と元教師の間に生まれ、3人兄弟の末っ子だった[2]。 初期の学校教育はテラス・エンド小学校とラッセル・ストリート小学校(1932-39年)、パーマストン・ノース・ボーイズ・ハイスクール(1940- 41年)、ワンガヌイ・カレッジ・スクール(1942-44年)で行われた。1945年から1952年までオタゴ大学、その後ビクトリア・ユニバーシ ティー・カレッジに通う。1953年から1958年までホロウェヌア・カレッジで(同時にモロー・プロダクションズ社で教育用アニメーション映画の制作に 携わる)、1959年から1960年までワイヒ・カレッジで教鞭をとる[3]。 1960年にはニュージーランド政府から奨学金を授与され、1961年にはイギリスを旅行し、その後ロンドンでプリオール・レーニエに作曲を師事、バー ナード・ランズ、ルイジ・ノーノ、ヴィトルド・ルトスワフスキらとも交流した。留学後はイギリスに留まり、バーミンガムのアンスティ教育大学などで教鞭を とった。1971年から86年までロンドンのイーリング高等教育カレッジで音楽の上級講師を務め、1979年にはダーティントン・カレッジ・オブ・アーツ でも教鞭をとった。1977年から1986年にかけては、シラキュース大学ロンドンセンターで音楽史の非常勤教授を務め、1981年から1984年にかけ ては、サセックス大学のBEdコースのサマースクールで音楽のチューターを務めた[2][4]。 スモールは1986年に教職を退き、スペインのシッチェスに移り住み、2006年に結婚したパートナーのネヴィル・ブレイスウェイト(ジャマイカ生まれの ダンサー、歌手、ユースワーカー)と暮らした。スペイン滞在中、スモールはカタルーニャの合唱団を指揮し、彼の作品を賞賛するヨーロッパとアメリカの人々 が定期的に訪れていた。アメリカでは、チャールズ・ケイル、ロバート・ウォルザー、スーザン・マクラリー、『ヴィレッジ・ヴォイス』誌のロック評論家ロ バート・クリストガウといった著名な音楽学者たちが彼の考えを支持している[2]。 ネヴィル・ブレイスウェイトは2006年に、スモールは2011年に死去。妹のローズマリーがいる[2]。 生前は多くの本を出版し、『Music in Education』、『Tempo』、『The Musical Times』、『Music and Letters』、『Musical America』などの雑誌に記事を掲載。イギリス、ノルウェー、アメリカの多くの教育機関で講義を行い、英国作曲家協会(1984年)、即興演奏家協会 (1985年)、音楽教育者全国会議(コネチカット州ハートフォード、1985年、ワシントンDC、1989年)、民族音楽学会(マサチューセッツ州ケン ブリッジ、1988年)などの組織に論文を寄稿した。 スモールは、BBC-TV2で放送されたシリーズ『Sounds Different』(1982年7月)に参加し、BBCラジオ3で放送されたアフロ・アメリカン音楽についての3番組『This Is Who We Are』(1988年3月)を執筆した[4]。 音楽活動 スモールは同タイトルの著書(Musicking, 1998)の中で、英語辞書に新しい単語を導入することを主張している。彼自身の定義によれば 演奏すること、聴くこと、リハーサルや練習をすること、演奏のための素材を提供すること(いわゆる作曲)、あるいは踊ること。時には、当日券を取る人、ピ アノやドラムを移動させる屈強な男たち、楽器をセッティングしサウンドチェックを行うローディー、皆が去った後を掃除する清掃員まで、その意味を拡大する こともあるだろう。彼らもまた、音楽演奏というイベントの本質に貢献しているのだ[5]。 スモールは、以前の著書(Music, Society, Education, 1977)で提示した考えを発展させながら、音楽を演奏することが、私たちが世界の他の部分と関わるための能動的な方法であることを示し続けている。 音楽を奏でるという行為は、それが行われている場所に一連の関係を築き、その関係の中にこそその行為の意味がある。そしてそれは、演奏の参加者が想像する ような理想的な関係、すなわち人と人との関係、個人と社会との関係、人類と自然界との関係、そしておそらくは超自然的な世界との関係をモデル化し、あるい はそのメタファーとして成り立っているのである[6]。 作品 書誌 音楽、社会、教育(1977年) シェーンベルク(1977年) 共通の舌の音楽: アフリカ系アメリカ人音楽における生存と祝祭(1987年) 音楽すること: 演奏することと聴くことの意味(1998年) 作曲作品 合唱のための行動-大合唱のためのいくつかのマオリの地名 (1974) 学校打楽器アンサンブルと声楽のための『Black Cat』(1968年) オーケストラのための2幕バレエ「霧の子供たち」 (1960) オーケストラのためのコンサート・ピース(1963) 映画のための管弦楽曲「ハイ・カントリー・ストックマン」(1952) 組曲「霧の子供たち」(管弦楽のための)(1960 TB、映画のための音楽(1955) 土の物語」映画音楽(1954) 映画音楽「木」(1952) 生徒と友人のための様々な歌とピアノ独奏曲(1980年) いったい何が起こっているのか 映画のための音楽(1958)[4] クリストファー・スモール・コレクション 1997年、クリストファー・スモールはシッチェスで引退し、個人蔵書をジローナ大学に寄贈した。このコレクションは、カタルーニャの大学の中でも非常に 質が高く、ユニークなものである。約500冊の蔵書の大半は音楽を中心としたもので、民族音楽学、音楽社会学、ポピュラー音楽、特にジャズ、ブルース、ソ ウルなどのアフロアメリカンのジャンルを網羅している。 |

日 本が、世界音楽化について、遅れているのは、日本のデジタル化の遅れそのものであるという主張すらある(山口哲一 Online)

★ ブルーノ・ネトル『ワールド・ミュージックに対する西洋の衝撃』の見出し

| 序 |

||

| アプローチ |

1. 4つの時代 |

|

| 2. 最初の出会い |

||

| 3. 変わらない音楽 |

||

| 4. 概念 |

||

| 5. 反応 |

||

| 実例 | 6. パウワウ |

|

| 7. 和声 |

||

| 8. 2つの都市 |

||

| 9. 互換性 |

||

| 10. ヴァイオリン |

||

| 11. ピアノ(スティーヴン・ホワイティング) |

||

| 12. しるし(徴し) |

||

| 13. オーケストラ |

||

| 14. ヴィクトローラ |

||

| 15. 楽譜 |

||

| 16. 移民 |

||

| 17. 音楽学校 |

||

| 18. 街路 |

||

| 19. コンサート |

||

| 20. 「ポップ」 |

||

| 21. ジュジュ(クリストファー・ウォーターマン) |

||

| 22. 国民的音楽(ポール・ウォルバース) |

||

| 23. 旧時代の宗教 |

||

| 24. 土着化 |

||

| 25. 新時代の宗教 |

||

| 26. 改革者 |

||

| 27. アメリカ人たち |

||

| 28. 旗手 |

||

| 29. 訪問者 |

||

| 30. 民族音楽学者 212 |

||

| 31. 意見 |

||

| 32. 国宝 |

||

| 33. 会議 |

||

| 34. マクーマ(ウィリアム・ベルツナー) |

||

| 35. マーフール |

||

| 36. ダックスダンス(ヴィクトリア・J・リンゼイ=レヴァイン) |

||

| 37. 協奏曲 |

||

| 規則性 |

38. 偶然の一致 |

|

| 39. 地域 |

||

| 40. 諸傾向 |

||

文

献

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099