ヌエバ・カンシオン

Nueva

canción, 新しい歌

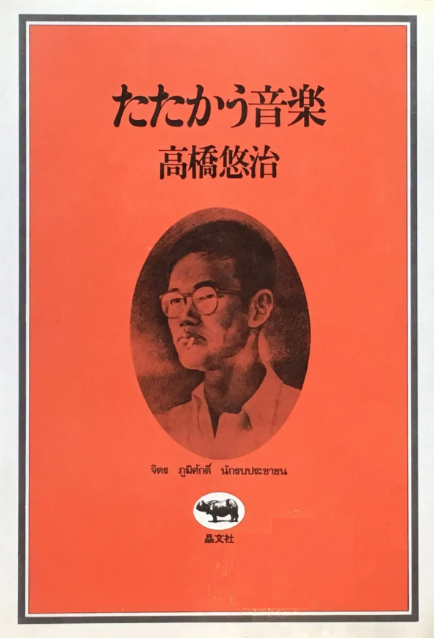

高

橋悠治『たたかう音楽』晶文社、1978年/ Victor Jara - El Derecho de Vivir en Paz

(Álbum completo)

☆ ヌ エバ・カンシオン(Nueva canción「新しい歌」)は、ラテンアメリカとイベリア半島における左翼的な社会運動と音楽ジャンルで、民謡風のスタイルと社会的な歌詞が特徴であ る。ヌエバ・カンシオンは、1970年代から1980年代にかけてポルトガル、スペ イン、ラテンアメリカで起こった民主化運動の社会的動乱において重要な 役割を果たしたと広く認識されており、この地域の社会主義組織の間で人気を博した。

★

「ボリビア、エクアドル、チリ、コロンビア、ペルー、ベネズエラの一部の

フォークロア音楽を含む。アンデス音楽はラテンアメリカ全土で程度の差こそあれ人気があり、農村部や先住民の間で中核をなしている。1970年代のヌエ

バ・カンシオン運動は、ラテンアメリカ全土でこのジャンルを復活させ、無名であった場所や忘れられていた場所にもたらした。ヌエバ・カンシオン(スペイン

語で「新しい歌」の意)は、ラテンアメリ

カやイベリア半島の民俗音楽、民俗に影響を受けた音楽、社会的にコミットした音楽の中の運動でありジャンルである。その発展と役割は、北米における第二次

フォーク音楽復興と似ている面がある。これには、伝統的な民俗音楽からこの新しいジャンルが進化したことも含まれ、英語のジャンル用語が一般的に適用され

ないことを除けば、本質的には現代民俗音楽である。ヌエバ・カンシオンは、1970年代から1980年代にかけてのポルトガル、スペイン、ラテンアメリカ

の社会的動乱において、強力な役割を果たしたと認識されている。ヌエバ・カンシオンは、1960年代にチリで「ヌエバ・カンシオン・チレーナ」として登場

した。その後間もなく、スペインやラテンアメリカでもこの音楽スタイルが登場し、似たような名前で知られるようになった。ヌエバ・カンシオンは、伝統的な

ラテンアメリカの民族音楽を一新し、その政治的な歌詞によって、革命運動、ラテンアメリカ新左翼、解放の神学、ヒッピー、人権運動とすぐに結びついた。ラ

テン・アメリカ全土で大きな人気を博し、スペイン語ロックの先駆けともなった」民俗音楽・フォーク

ミュージック)。

| ★Nueva canción

(European Spanish: [ˈnweβa kanˈθjon], American Spanish: [ˈnweβa

kanˈsjon]; 'new song') is a left-wing social movement and musical genre

in Latin America and the Iberian peninsula, characterized by

folk-inspired styles and socially committed lyrics. Nueva canción is

widely recognized to have played a profound role in the pro-democracy

social upheavals in Portugal, Spain and Latin America during the 1970s

and 1980s, and was popular amongst socialist organizations in the

region. Songs reflecting conflict have a long history in Spanish, and in Latin America were particularly associated with the "corrido" songs of Mexico's War of Independence after 1810, and the early 20th century years of Revolution. Nueva canción then surfaced almost simultaneously during the 1960s in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Spain. The musical style emerged shortly afterwards in other areas of Latin America where it came to be known under similar names. Nueva canción renewed traditional Latin American folk music, and was soon associated with revolutionary movements, the Latin American New Left, liberation theology, hippie and human rights movements due to political lyrics. It would gain great popularity throughout Latin America, and left an imprint on several other genres like rock en español, cumbia and Andean music. Nueva canción musicians often faced censorship, exile, torture, death, or forceful disappearances by the wave of right-wing military dictatorships that swept across Latin America and the Iberian peninsula in the Cold War era, e.g. in Francoist Spain, Pinochet's Chile, Salazar's Portugal and Videla and Galtieri's Argentina. Due to their strongly political messages, some nueva canción songs have been used in later political campaigns, for example the Orange Revolution, which used Violeta Parra's "Gracias a la Vida". Nueva canción has become part of Latin American and Iberian musical tradition, but is no longer a mainstream genre, and has given way to other genres, particularly rock en español. |

ヌエバ・カンシオン(Nueva

canción「新しい歌」)は、ラテンアメリカとイベリア半島における左翼的な社会運動と音楽ジャンルで、民謡風のスタイルと社会的な歌詞が特徴であ

る。ヌエバ・カンシオンは、1970年代から1980年代にかけてポルトガル、スペイン、ラテンアメリカで起こった民主化運動の社会的動乱において重要な

役割を果たしたと広く認識されており、この地域の社会主義組織の間で人気を博した。 紛争を反映した歌はスペイン語では長い歴史があり、ラテンアメリカでは特に、1810年以降のメキシコ独立戦争や20世紀初頭の革命期の「コリド」の歌に 関連していた。その後、ヌエバ・カンシオンは1960年代にアルゼンチン、チリ、ウルグアイ、スペインでほぼ同時に台頭した。この音楽スタイルは、その後 まもなくラテンアメリカの他の地域でも出現し、同じような名前で知られるようになった。ヌエバ・カンシオンは、ラテンアメリカの伝統的な民族音楽を刷新 し、政治的な歌詞から、革命運動、ラテンアメリカ新左翼、解放の神学、ヒッピー、人権運動とすぐに結びついた。ラテンアメリカ全土で大きな人気を博し、 ロック・エン・スペイン語、クンビア、アンデス音楽など他のジャンルにも影響を残した。 ヌエバ・カンシオンの音楽家たちは、冷戦時代にラテンアメリカとイベリア半島を席巻した右派軍事独裁政権(フランコ主義スペイン、ピノチェト政権チリ、サ ラザール政権ポルトガル、ビデラ政権アルゼンチン、ガルティエリ政権など)による検閲、追放、拷問、死、強制失踪にしばしば直面した。 ヌエバ・カンシオンの曲の中には、その強い政治的メッセージから、後の政治キャンペーンに使われたものもある。例えば、オレンジ革命ではヴィオレタ・パラ の「Gracias a la Vida」が使われた。ヌエバ・カンシオンはラテンアメリカやイベリア音楽の伝統の一部となったが、もはや主流ジャンルではなく、他のジャンル、特にスペ イン語のロックに道を譲った。 |

| Characteristics "Nueva canción" is a type of music which is committed to social good. Its musical and lyrical vernacular is rooted in the popular classes and often uses a popularly understood style of satire to advocate for sociopolitical change.[1] The movement reacted against the dominance of American and European music in Latin America at the time by assuming an anti-imperial stance that was markedly less focused on the visual spectacle of commercial music and more focused on social and political messages.[2] It characteristically talks about poverty, empowerment, imperialism, democracy, human rights, religion, and the Latin American identity. Nueva canción draws heavily upon Andean music, música negra, Spanish music, Cuban music and other Latin American folklore. Most songs feature the guitar, and often the quena, zampoña, charango or cajón. The lyrics are typically in Spanish, with some indigenous or local words mixed in, and frequently utilize the poetic forms of copla and décima. Nueva canción was explicitly related to leftist politics, advancing leftist ideals and flourishing within the structure of the Communist Party in Latin America. Cuban cultural organization Casa de las Américas hosted many notable gatherings of nueva canción musicians, including the 1967 Encuentro de la Canción Protesta.[3] Songs of conflict in Spanish have a very long history, with elements to be found in the "fronterizos", songs concerning the Reconquest of Spain from the Moors in the 15th century. More immediately, some of the roots of nueva canción may be seen in the Mexican "corrido", which took on a strongly political flavour during the War of Independence c. 1810, and then the Revolution after 1910. The modern nueva canción developed in the historical context of the "folklore boom" that occurred in Latin America in the 1950s. Chilean Violeta Parra and Argentine Atahualpa Yupanqui were two transitional figures as their mastery of folk music and personal involvement in leftist political organizations aided the eventual union of the two in Nueva canción. The movement was also aided by legislation like Juan Perón's Decreto 3371/1949 de Protección de la Música Nacional and Law No. 14,226, which required that half of the music played on the radio or performed live be of national origin.[2] National manifestations of nueva canción began occurring in the late 1950s. The earliest were in Chile and Spain, where the movement promoted Catalan language and culture.[4] The music quickly spread to Argentina and throughout Latin America during the 1960s and 1970s. Various national movements used their own terminology; however, the term "nueva canción" was adopted at the 1967 Encuentro de la Canción Protesta and has thereafter been used as an all-encompassing term.[2] Though Nueva canción is often considered a Pan-Latino phenomenon, national manifestations were varied and reacted to local political and cultural contexts. |

特徴 「ヌエバ・カンシオン」は、社会的な善にコミットするタイプの音楽である。この運動は、当時のラテンアメリカにおけるアメリカやヨーロッパの音楽の支配に 反発し、商業音楽の視覚的なスペクタクルに著しく重きを置かず、社会的、政治的なメッセージに重きを置く反帝国的な姿勢を取ることによって行われた [2]。特徴的なのは、貧困、エンパワーメント、帝国主義、民主主義、人権、宗教、ラテンアメリカのアイデンティティについて語ることである。 ヌエバ・カンシオンは、アンデス音楽、ムジカ・ネグラ、スペイン音楽、キューバ音楽、その他のラテンアメリカのフォークロアを多用している。ほとんどの曲 はギターをフィーチャーしており、ケーナ、サンポーニャ、チャランゴ、カホンなどがよく使われる。歌詞は一般的にスペイン語だが、土着語やその土地の言葉 も混じっており、コプラやデシマという詩的形式が頻繁に使われる。 ヌエバ・カンシオンは左翼政治と明確に関係し、左翼の理想を推進し、ラテンアメリカの共産党の構造の中で繁栄した。キューバの文化団体カサ・デ・ラス・ア メリカスは、1967年のEncuentro de la Canción Protestaを含め、ヌエバ・カンシオンのミュージシャンによる多くの注目すべき集会を主催した[3]。 スペイン語の紛争の歌の歴史は非常に古く、15世紀のムーア人からのスペインのレコンキスタ(征服)に関する歌である「フロンテリソス」にその要素が見ら れる。より身近なところでは、ヌエバ・カンシオンのルーツは、1810年頃の独立戦争、そして1910年以降の革命で政治色が強くなったメキシコの "コリド "に見られる。現代のヌエバ・カンシオンは、1950年代にラテンアメリカで起こった「フォルクローレ・ブーム」という歴史的背景の中で発展した。チリの ビオレタ・パラとアルゼンチンのアタフアルパ・ユパンキはその過渡期の人物であり、彼らの民俗音楽の熟達と左派政治組織への個人的関与が、最終的に両者が ヌエバ・カンシオンに融合する一助となった。この運動はまた、フアン・ペロンの国家音楽保護法第3371/1949号や法律第14,226号のような法律 にも助けられた。 ヌエバ・カンシオンの全国的な流行は1950年代後半に始まった。ヌエバ・カンシオンは1960年代から1970年代にかけて、アルゼンチンやラテンアメ リカ全体に急速に広まった。様々な国の運動が独自の用語を使用したが、「ヌエバ・カンシオン」という用語は1967年のプロテスト・カンセンで採用され、 以後包括的な用語として使用されるようになった[2]。ヌエバ・カンシオンはしばしば汎ラテンアメリカ的な現象と見なされるが、各国での発現は様々であ り、地域の政治的・文化的文脈に反応した。 |

Nueva Canción Chilena Violeta Parra, one of the most recognized figures

of the Nueva Canción Chilena Violeta Parra, one of the most recognized figures

of the Nueva Canción ChilenaSince 1952 Violeta Parra, together with her children, gathered a total of 3,000 songs of peasant origin,[5] and also released a book known as "Cantos Folklóricos Chilenos" (Chilean Folk Songs).[6] And in addition Violeta's children Isabel and Ángel founded the cultural center Peña de los Parra,[7] an organization that functioned as an organizing center for leftist political activism, and welcomed almost all of the major figures associated with early Nueva Canción, including Chileans: Patricio Manns, Víctor Jara, Rolando Alarcón, Payo Grondona, Patricio Castillo, Sergio Ortega, Homero Caro, Tito Fernández, and Kiko Álvarez, as well as non-Chilean musicians, such as Atahualpa Yupanqui from Argentina and Paco Ibañéz of Spain.[8] Nueva Canción Chilena moved out of small gathering places like Peña de los Parra in 1968 when the Communist Youth Party of Chile pressed 1000 copies of the album Por Vietnam by Quilapayún to raise funds for the band's travel to the International Youth Festival in Bulgaria. The copies sold out unexpectedly, a strong demonstration of the popular demand for this new music. In response, La Jota (Juventudes Comunistas) created Discoteca de Canto Popular (DICAP), a socially-conscious record label[9] that grew in its five years of operation from a 4,000 record operation in 1968 to pressing over 240,000 records in 1973.[10] DICAP united the various groups of young people wishing to spread Nueva Cancion at a time when U.S. music dominated chiefly commercial radio fare. "DICAP was a key counterhegemonic institution that broke through the censorship and silence imposed by the conservative cultural entities of the elite."[11] In 1969 the Universidad Cátolica in Santiago hosted the Primer Festival de la Nueva Canción Chilena.[12] Salvador Allende's 1970 presidential campaign was a major turning point in the history of Nueva Canción Chilena. Many artists became involved in the campaign; songs like "Venceremos" by Víctor Jara were widely used in Allende rallies. After Allende's election, nueva canción artists were utilized as a pro-Allende public relations machine inside and outside of Chile.[13] By 1971, groups like Inti-Illimani and Quilapayún were receiving financial support from the Allende government.[14] In 1973, the United States/CIA-backed[15] right-wing military coup overthrew Allende's democratic government, bombing the presidential palace. Pinochet's forces then rounded up 5,000 civilians into a soccer stadium for interrogation, torture, and execution.[16] Victor Jara was beaten, tortured, and his wrists were broken,[17] after several days he was executed and shot 44 times. His wife Joan Jara writes, "where his belly ought to have been was a gory, gaping void".[18] Because of his popularity and fame in the music world, Jara is the most well-known victim of a regime that killed or "disappeared" at least 3,065 people and tortured more than 38,000, bringing the number of victims to 40,018.[19] Other musicians, such as Patricio Manns and groups Inti-Illimani and Quilapayún, found safety outside the country. Under Augusto Pinochet nueva canción recordings were seized, burned, and banned from the airwaves and record stores. The military government exiled and imprisoned artists and went as far as to ban many traditional Andean instruments in order to suppress the nueva canción movement.[20] This period in Chilean history is known as the "Apagón Cultural" (Cultural Blackout).[12] By late 1975, artists had begun to circumvent these restrictions through so-called "Andean Baroque" ensembles that performed standards of the Western classical repertoire on indigenous South American instruments. These performances took place in the politically neutral environments of churches, community centers, and the few remaining peñas. For this reason, and because of the novelty of the concept, these performances were allowed to continue without government interference. Performers gradually grew bolder, incorporating some of old nueva canción repertoire, though carefully avoiding overtly political topics. Artists began calling this music "Canto Nuevo", a term selected to both reference and distance the new movement from the former nueva canción. Because of the precarious political circumstances in which it existed, canto nuevo is notable for its use of highly metaphorical language, allowing songs to evade censors by disguising political messages beneath layers of symbolism. Live performances often included spoken introductions or interludes that provided insight into the song's real meaning.[12] As the 1980s arrived, advances in recording technology allowed supporters to informally exchange cassettes outside of the governmental control. An economic crisis forced Chilean television stations to hire cheaper Chilean performers rather than international stars for broadcast bookings, while a relaxation in government restrictions allowed canto nuevo performers to participate in several major popular music festivals. Increasing public recognition of the movement facilitated the gathering of its participants at events such as the Congreso de Artistas y Trabajadores (Conference of Artists and Workers) in 1983. The canto nuevo repertoire began to diversify, incorporating cosmopolitan influences such as electronic instruments, classical harmonies, and jazz influences.[12] Though the genre is not especially active today, the legacy of figures like Violeta Parra is enormous. Parra's music continues to be recorded by contemporary artists and her song "Gracias a la Vida" was recorded by supergroup Artists for Chile in an effort to raise relief funds in the wake of the 2010 Chilean earthquake. The protests that began in October 2019 have showed a strong resurgence of Nueva Canción as curfewed residents began performing the music of Violeta Parra and Victor Jara [21] and soon major artists began adapting and writing politically motivated music backing the protests and critical of the Piñera government.[22] Violeta Parra "Miren como sonríen" |

ヌエバ・カンシオン・チレーナ ヌエバ・カンシオン・チレーナで最も知られた人物の一人、ビオレタ・パラ ヌエバ・カンシオン・チレーナで最も知られた人物の一人、ビオレタ・パラ1952年以来、ヴィオレタ・パラは子供たちとともに、農民由来の歌を合計3,000曲集め[5]、『Cantos Folklóricos Chilenos(チリの民謡)』として知られる本も発表した[6]。 さらに、ヴィオレタの子供たちイサベルとアンヘルは、文化センター「ペーニャ・デ・ロス・パーラ」[7]を設立した。この組織は、左翼政治活動の組織化セ ンターとして機能し、チリ人を含む初期のヌエバ・カンシオンに関わる主要人物のほとんどすべてを迎え入れた: パトリシオ・マンズ、ビクトル・ハラ、ロランド・アラルコン、パヨ・グロンドーナ、パトリシオ・カスティージョ、セルヒオ・オルテガ、ホメロ・カロ、ティ ト・フェルナンデス、キコ・アルバレスといったチリ人ミュージシャンや、アルゼンチンのアタワルパ・ユパンキ、スペインのパコ・イバニェスといったチリ人 以外のミュージシャンを含む。 ヌエバ・カンシオン・チレーナは、1968年にペーニャ・デ・ロス・パラのような小さな集会所から移動し、チリの共産主義青年党が、ブルガリアの国際青年 フェスティバルへのバンドの旅費を調達するために、キラパユンのアルバム『Por Vietnam』を1000枚プレスした。このアルバムは予想に反して完売し、この新しい音楽に対する大衆の強い需要が示された。これに呼応して、ラ・ ジョータ(フヴェントゥデス・コムニスタス)は、社会意識の高いレコードレーベルであるディスコテカ・デ・カント・ポピュラー(DICAP)を設立し [9]、1968年には4,000枚だったレコードを、1973年には24万枚以上のレコードをプレスするまでに成長させた。「DICAPは、エリートの 保守的な文化団体によって課された検閲と沈黙を打ち破る、重要な反ヘゲモニー的機関であった」[11]。 1969年、サンティアゴのカトリカ大学はヌエバ・カンシオン・チレーナの初フェスティバルを主催した[12]。サルバドール・アジェンデの1970年の 大統領選挙運動は、ヌエバ・カンシオン・チレーナの歴史における大きな転機となった。ビクトル・ハラの「Venceremos」のような曲は、アジェンデ の集会で広く使われた。アジェンデの当選後、ヌエバ・カンシオンのアーティストたちはチリ内外で親アジェンデの広報機関として利用された[13]。 1971年までに、インティ・イリマニやキラパユンのようなグループはアジェンデ政府から財政的支援を受けていた[14]。 1973年、アメリカ/CIAの支援を受けた[15]右派の軍事クーデターがアジェンデの民主政権を打倒し、大統領官邸を空爆した。ビクトル・ハラは殴ら れ、拷問を受け、手首を折られ[17]、数日後に44発の銃弾を浴び処刑された。彼の妻ジョアン・ジャラは、「彼の腹があったはずの場所には、血まみれ の、ぽっかりと空いた空洞があった」と書いている[18]。音楽界における彼の人気と名声のため、ハラは、少なくとも3,065人を殺害または「失踪」さ せ、38,000人以上を拷問し、犠牲者の数を40,018人にした政権の最もよく知られた犠牲者である[19]。パトリシオ・マンズやグループ「イン ティ・イリマニ」、「キラパユン」などの他のミュージシャンは、国外に安全な場所を見つけた。アウグスト・ピノチェト政権下では、ヌエバ・カンシオンのレ コードは押収、焼却され、電波やレコード店から追放された。軍事政権はアーティストを追放、投獄し、ヌエバ・カンシオン運動を抑圧するためにアンデスの伝 統楽器の多くを禁止するまでに至った[20]。チリの歴史におけるこの時期は、「アパゴン・カルチュラル」(文化的ブラックアウト)として知られている [12]。 1975年後半になると、アーティストたちはいわゆる「アンデス・バロック」と呼ばれるアンサンブルを通じて、こうした規制を回避するようになった。これ らの演奏は、教会や公民館、わずかに残ったペーニャといった政治的に中立な環境で行われた。そのため、またそのコンセプトが斬新であったため、これらの演 奏は政府の干渉を受けることなく続けられた。演奏家たちは次第に大胆になり、あからさまな政治的トピックは慎重に避けながらも、古いヌエバ・カンシオンの レパートリーを取り入れるようになった。アーティストたちはこの音楽を "カント・ヌエボ "と呼ぶようになった。この言葉は、かつてのヌエバ・カンシオンから新しいムーブメントを参照し、距離を置くために選ばれたものである。カント・ヌエボ は、その不安定な政治的状況ゆえに、非常に比喩的な言葉を使うことで注目され、政治的なメッセージを何層もの象徴の下に隠すことで、検閲を逃れることがで きた。ライブ・パフォーマンスではしばしば、曲の本当の意味を理解するためのイントロや間奏が話し言葉で演奏された[12]。 1980年代に入ると、録音技術の進歩により、支持者たちは政府の管理外で非公式にカセットを交換することができるようになった。経済危機により、チリの テレビ局は放送ブッキングのために国際的なスターではなく、安価なチリ人演奏家を雇わざるを得なくなり、一方で政府の規制緩和により、カント・ヌエボの演 奏家はいくつかの主要なポピュラー音楽祭に参加することができるようになった。カント・ヌエボ運動に対する社会的認知が高まったことで、1983年に開催 された「芸術家と労働者の会議(Congreso de Artistas y Trabajadores)」などのイベントに参加者が集まりやすくなった。カント・ヌエボのレパートリーは多様化し始め、電子楽器、クラシックのハーモ ニー、ジャズの影響など、国際的な影響を取り入れた[12]。 このジャンルは今日、特に活発に活動しているわけではないが、ヴィオレタ・パラのような人物の遺産は非常に大きい。パラの音楽は現代のアーティストたちに よってレコーディングされ続けており、彼女の曲「Gracias a la Vida」は、2010年のチリ地震を受け、救援金を募るためにスーパーグループ「Artists for Chile」によってレコーディングされた。2019年10月に始まった抗議デモでは、外出禁止令を受けた住民たちがヴィオレタ・パラとビクトル・ハラの 音楽を演奏し始め[21]、やがてメジャーなアーティストたちが抗議デモを支持し、ピニェラ政権に批判的な政治的動機の音楽を翻案し、書き始めたことか ら、ヌエバ・カンシオンの強い復活が見られた[22]。 |

Argentina:

Nuevo Cancionero (New Songbook) Argentina:

Nuevo Cancionero (New Songbook)In Argentina, the movement was founded under the name Nuevo Cancionero and formally codified on 11 February 1963 when fourteen artists met in Mendoza, Argentina to sign the Manifiesto Fundacional de Nuevo Cancionero. Present were both musical artists and poet writers. The Argentine movement especially was a musico-literal. Writers like Armando Tejada Gomez were highly influential and made substantial contributions to the movement in the form of original poetry. The Manifesto's introduction places the roots of Nuevo Cancionero in the rediscovery of folk music and indigenous traditions to the work of folklorists Atahualpa Yupanqui and Buenaventura Luna and the internal urban migration that brought rural Argentines to the capital of Buenos Aires. The body of the document outlines the goal of the movement: the development of a national song that overcome the dominance of tango-folklore in Argentine national music and the rejection of pure commercialism. Instead Nuevo Cancionero sought to embrace of institutions that encouraged critical thinking and the open exchange of ideas.[23] Nuevo Cancionero's most famous proponent was Mercedes Sosa. Her success at the 1965 Cosquin Folklore Festival introduced Nuevo Cancionero to new levels of public exposure after Argentine folk powerhouse Jorge Cafrune singled her out on stage as a budding talent.[24] In 1967, Sosa completed her first international tour in the United States and Europe.[25] Other notable Nuevo Cancionero artists of this time included Tito Francia, Víctor Heredia, and César Isella, who left the folk music group Los Fronterizos to pursue a solo career. In 1969 he set the poetry of Armando Tejada Gomez to produce "Canción para todos", an anthem later designated by UNESCO the hymn of Latin America.[26] Nuevo cancionero artists were among the approximately 30,000 victims of forced disappearances under Argentina's 1976–1983 military dictatorship.[27] Additional censorship, intimidation, and persecution forced many artists into exile where they had more freedom to publicize and criticize the events unfolding in Latin America. Sosa, for example, participated in the first Amnesty International concert in London in 1979, and also performed in Israel, Canada, Colombia, and Brazil while continuing to record.[28] After the fall of the dictatorship in 1983, Argentine artists returned and performed massive comeback concerts that regularly filled sports areas and public parks with tens of thousands of people.[29] Influences from time spent in exile abroad were clear through sample of instruments like the harmonica, drum set, bass guitar, electric keyboard, brass ensembles, backup singers, string instruments (especially double bass and violin), and stylistic and harmonic influences from the soundscapes of classical, jazz, pop, rock, and punk. Collaborations became increasingly common, especially between proponents of Nuevo Cancionero and the ideologically similar Rock Nacional. Nuevo Cancionero artists became symbols of a triumphant national identity. When Mercedes Sosa died, millions flooded the streets as her body lay in official state in the National Cathedral, an honor reserved for only the most prominent of national icons.[30] While the community of musicians actively composing in the Nuevo Cancionero tradition is small, recordings and covers of Nuevo Cancionero classics remain popular in Argentina. Mercedes Sosa - Todo Cambia (Videoclip) |

アルゼンチン:ヌエボ・カンシオネーロ(新曲集) アルゼンチン:ヌエボ・カンシオネーロ(新曲集)1963年2月11日、アルゼンチンのメンドーサで14人のアーティストが集まり、「Manifiesto Fundacional de Nuevo Cancionero」に署名した。参加者は音楽アーティストと詩人作家の両方であった。特にアルゼンチンのムーブメントは音楽文学的だった。アルマン ド・テハダ・ゴメスのような作家は大きな影響力を持ち、独創的な詩という形で運動に大きく貢献した。マニフェストの序章では、ヌエボ・カンシオネーロの ルーツを、民俗学者アタハルパ・ユパンキとブエナベントゥラ・ルナの仕事による民俗音楽と先住民の伝統の再発見、そしてアルゼンチンの農村から首都ブエノ スアイレスへの都市内移住に置いている。この文書の本文には、アルゼンチン国民音楽におけるタンゴ・フォルクローレの支配を克服し、純粋な商業主義を否定 する国民的な歌の開発という運動の目標が概説されている。その代わりにヌエボ・カンシオネーロは、批判的思考と開かれた意見交換を奨励する制度を受け入れ ることを求めた[23]。 ヌエボ・カンシオネーロの最も有名な提唱者はメルセデス・ソーサだった。1965年のコスキン・フォルクローレ・フェスティバルでの彼女の成功は、アルゼ ンチン・フォークの大御所ホルヘ・カフルネがステージ上で彼女を新進の才能として取り上げたことで、ヌエボ・カンシオネーロが新たなレベルで世間に知られ るきっかけとなった[24]。1969年、彼はアルマンド・テハダ・ゴメスの詩に曲をつけ、後にユネスコによってラテン・アメリカの賛美歌に指定された "Canción para todos "を生み出した[26]。 ヌエボ・カンシオネーロのアーティストたちは、1976年から1983年のアルゼンチンの軍事独裁政権下で強制失踪させられた約3万人の犠牲者の一人で あった[27]。さらなる検閲、脅迫、迫害により、多くのアーティストたちは、ラテンアメリカで繰り広げられる出来事をより自由に公表し、批判するために 亡命せざるを得なくなった。例えばソサは、1979年にロンドンで開催された第1回アムネスティ・インターナショナル・コンサートに参加し、レコーディン グを続けながらイスラエル、カナダ、コロンビア、ブラジルでも公演を行った[28]。 1983年の独裁政権崩壊後、アルゼンチンのアーティストたちは復帰し、定期的にスポーツエリアや公共の公園を数万人で埋め尽くす大規模なカムバック・コ ンサートを行った[29]。ハーモニカ、ドラムセット、ベースギター、エレクトリック・キーボード、ブラス・アンサンブル、バックシンガー、弦楽器(特に コントラバスやヴァイオリン)、クラシック、ジャズ、ポップス、ロック、パンクのサウンドスケープからの様式やハーモニーの影響など、海外に亡命していた 時からの影響は、サンプリングを通して明らかになった。特にヌエボ・カンシオネーロの支持者と、イデオロギー的に類似したロック・ナシオナルの間では、コ ラボレーションがますます一般的になった。 ヌエボ・カンシオネロのアーティストたちは、国民的アイデンティティの勝利の象徴となった。メルセデス・ソーサが亡くなったとき、彼女の遺体が国立大聖堂 に安置されると、何百万人もの人々が通りに押し寄せたが、これは最も著名な国家的アイコンのみに許された栄誉であった[30]。ヌエボ・カンシオネーロの 伝統に則って積極的に作曲するミュージシャンのコミュニティは小規模であるが、ヌエボ・カンシオネーロの名曲のレコーディングやカヴァーは、アルゼンチン で依然として人気がある。 |

| Cuba: Nueva Trova (New Trova) Of the regional manifestations of nueva canción, nueva trova is distinct because of its function within and support from the Castro government. While nueva canción in other countries primarily functioned in opposition to existing regimes, nueva trova emerged after the Cuban Revolution and enjoyed various degrees of state support throughout the late twentieth century. Nueva trova has its roots in the traditional trova, but differs from it because its content is, in the widest sense, political. It combines traditional folk music idioms with 'progressive' and often politicized lyrics that concentrate on socialism, injustice, sexism, colonialism, racism and similar 'serious' issues.[31] Occasional examples of non-political styles in the nueva trova movement can also be found, for example, Liuba María Hevia, whose lyrics are focused on more traditional subjects such as love and solitude albeit in a highly poetical style. Later nueva trova musicians were also influenced by rock and pop of that time. Silvio Rodríguez and Pablo Milanés became the most important exponents of the style. Carlos Puebla and Joseíto Fernández were long-time trova singers who added their weight to the new regime, but of the two only Puebla wrote special pro-revolution songs.[32] The Castro administration gave plenty of support to musicians willing to write and sing anti-U.S. imperialism or pro-revolution songs, an asset in an era when many traditional musicians were finding it difficult or impossible to earn a living. In 1967 the Casa de las Américas in Havana held a Festival de la canción de protesta (protest songs). Much of the effort was spent applauding anti-U.S. expressions. Tania Castellanos, a filín singer and author, wrote "¡Por Ángela!" in support of US political activist Angela Davis. César Portillo de la Luz wrote "Oh, valeroso Viet Nam".[33] Institutions like the Grupo de Experimentación Sonora del ICAIC (GES) while not directly working in nueva trova, provided valuable musical training to amateur Cuban artists. |

キューバ ヌエバ・トロバ(新トロバ) ヌエバ・カンシオンの地域的な表れの中で、ヌエバ・トロバは、カストロ政権内での機能とその支援という点で際立っている。他の国のヌエバ・カンシオンが主 に既存の政権に対抗する形で機能していたのに対し、ヌエバ・トロバはキューバ革命後に登場し、20世紀後半を通じてさまざまな程度の国家支援を享受した。 ヌエバ・トロヴァは伝統的なトロヴァにルーツを持つが、その内容が広い意味で政治的である点が異なる。伝統的な民俗音楽のイディオムと、社会主義、不正 義、性差別、植民地主義、人種差別、および同様の「深刻な」問題に焦点を当てた「進歩的」でしばしば政治化された歌詞が組み合わされている。後のヌエバ・ トローバのミュージシャンたちは、当時のロックやポップスにも影響を受けている。 シルビオ・ロドリゲスとパブロ・ミラネスは、このスタイルの最も重要な表現者となった。カルロス・プエブラとホセイト・フェルナンデスは、新体制に重きを 置いた長年のトローバ歌手だったが、2人のうちプエブラだけが特別に革命支持の歌を書いた[32]。 カストロ政権は、多くの伝統的な音楽家が生計を立てることが困難か不可能であった時代には貴重な財産であった、反米帝国主義や親革命の歌を歌ってくれる音 楽家たちに多くの支援を与えた。1967年、ハバナのカサ・デ・ラス・アメリカスは、プロテスト・ソング・フェスティバルを開催した。労力の多くは、反米 表現への拍手に費やされた。フィリピン人歌手であり作家でもあるタニア・カステジャーノスは、米国の政治活動家アンジェラ・デイヴィスを支持して "アンジェラのために!"を書いた。セサル・ポルティージョ・デ・ラ・ルスは「おお、ヴェトナムよ」を書いた[33]。ICAICのソノラ実験グループ (GES)のような機関は、ヌエバ・トローバには直接取り組んでいなかったが、アマチュアのキューバ人アーティストに貴重な音楽的訓練を提供した。 |

| Spain and Catalonia: Nova Cançó The Nova Cançó was an artistic movement of the late 1950s that promoted Catalan music in Francoist Spain. The movement sought to normalize use of the Catalan language after public use of the language was forbidden when Catalonia fell in the Spanish Civil War. Artists used the Catalan language to assert Catalan identity in popular music and denounce the injustices of the Franco regime. Musically, it had roots in the French Chanson.[34] In 1957, the writer Josep Maria Espinàs gave lectures on the French singer-songwriter Georges Brassens, whom he called "the troubadour of our times." Espinàs had begun to translate some of Brassens' songs into Catalan. In 1958, two EPs of songs in Catalan were released: Hermanas Serrano cantan en catalán los éxitos internacionales ("The Serrano Sisters Sing International Hits in Catalan")[35] and José Guardiola: canta en catalán los éxitos internationales. They are now considered the first recordings of modern music in the Catalan language.[36] These singers, as well as others such as Font Sellabona and Rudy Ventura, form a prelude to the Nova Cançó.[37] At the suggestion of Josep Benet i de Joan and Maurici Serrahima, a group composed of Jaume Armengol, Lluís Serrahima and Miquel Porter started composing Catalan songs.[37] In 1959, after an article by Lluís Serrahima, titled "Ens calen cançons d’ara" ("We need songs for today"), was published in Germinàbit, more authors and singers were attracted to the movement.[37] Miquel Porter, Josep Maria Espinàs and Remei Margarit founded the group Els Setze Jutges (The Sixteen Judges, in Catalan). Their first concert, although still not with this name, was on 19 December 1961, in Barcelona. Their first performance with the name of Els Setze Jutges was in Premià de Mar in 1962.[34] New singers joined the group in the following years, until the number of sixteen (Setze), like Delfí Abella and Francesc Pi de la Serra.[34] The first Nova Cançó records appeared in 1962, and many musical bands, vocal groups, singer-songwriters, and interpreters picked up the trend.[34] In 1963, a professional Catalan artist, Salomé, and a Valencian, Raimon, were awarded the first prize of the Fifth Mediterranean Song Festival with the song "Se’n va anar" ("[She] left").[38] Other important participants in the movement included Guillem d'Efak and Núria Feliu, who received the Spanish Critics' Award in 1966, or other new members of Els Setze Jutges.[34] Some of them were even well known abroad. Apart from Raimon, other former members of Els Setze Jutges continued their careers successfully, including Guillermina Motta, Francesc Pi de la Serra, Maria del Mar Bonet, Lluís Llach and Joan Manuel Serrat. Other significant figures appeared somewhat later, like the Valencian Ovidi Montllor. |

スペインとカタルーニャ ノバ・カンソン ノヴァ・カンソーは1950年代後半の芸術運動で、フランコ体制下のスペインでカタルーニャ音楽を広めた。この運動は、スペイン内戦でカタルーニャが陥落 した際、カタルーニャ語の公の場での使用が禁止されたため、カタルーニャ語の使用を正常化しようとするものだった。アーティストたちはカタルーニャ語を用 いてポピュラー音楽でカタルーニャのアイデンティティを主張し、フランコ政権の不正を糾弾した。音楽的にはフランスのシャンソンにルーツがある[34]。 1957年、作家のジョゼップ・マリア・エスピナスは、フランスのシンガーソングライター、ジョルジュ・ブラッサンスについて講義を行った。エスピナス は、ブラッサンスの歌の一部をカタルーニャ語に翻訳し始めていた。1958年、カタルーニャ語の歌を収録した2枚のEPがリリースされた: Hermanas Serrano cantan en catalán los éxitos internacionales(セラーノ姉妹がカタルーニャ語で世界のヒット曲を歌う)[35]とJosé Guardiola: canta en catalán los éxitos internationales(ホセ・グアルディオラがカタルーニャ語で世界のヒット曲を歌う)である。これらの歌手をはじめ、フォント・セラボナやル ディ・ヴェントゥーラは、ノヴァ・カンソーの前奏曲となった[37]。 ジョセップ・ベネ・イ・デ・ジョアンとマウリシ・セラヒマの提案により、ジャウマ・アルメンゴル、リュイス・セラヒマ、ミケル・ポーターからなるグループ がカタルーニャ語の歌の作曲を始める。 [ミケル・ポーター、ジョセップ・マリア・エスピナス、レメイ・マルガリットの3人は、カタルーニャ語で「16人の裁判官」と呼ばれるグループを結成。最 初のコンサートは1961年12月19日、バルセロナで行われた。エルス・セッツェ・ジュッジスという名前での初公演は、1962年のプレミア・デ・マー ル(Premià de Mar)であった[34]。その後、デルフィ・アベラ(Delfí Abella)やフランセスク・ピ・デ・ラ・セッラ(Francesc Pi de la Serra)など、16人(セッツェ)になるまで、新たな歌手がグループに加わった[34]。 1963年には、プロのカタルーニャ人アーティストであるサロメとバレンシア人のライモンが、"Se'n va anar"(「彼女は去った」)という曲で第5回地中海歌謡祭の最優秀賞を受賞した[38]。この運動における他の重要な参加者には、1966年にスペイ ン批評家賞を受賞したギエム・デファクとヌリア・フェリウ、あるいはエルス・セッツェ・ユッジの他の新メンバーがいた[34]。ライモン以外にも、ギジェ ルミーナ・モッタ、フランセスク・ピ・デ・ラ・セッラ、マリア・デル・マール・ボネ、リュイス・ルラッチ、ジョアン・マヌエル・セラットなど、エルス・ セッツェ・ジュッジの元メンバーは順調にキャリアを重ねた。その他、バレンシアのオビディ・モンテロールのように、やや遅れて登場した重要人物もいる。 |

| Nicaragua Nicaragua nueva canción (Nueva canción nicaragüense) musicians are attributed with transmitting social and political messages, and aiding in the ideological mobilisation of the populace during the Sandinista revolution. Carlos Mejía Godoy y Los de Palacagüina were probably the best known proponents of this style.[1] |

ニカラグア ニカラグアのヌエバ・カンシオン(Nueva canción nicaragüense)の音楽家たちは、社会的・政治的メッセージを発信し、サンディニスタ革命時の民衆のイデオロギー的動員を助けたとされている。 カルロス・メヒア・ゴドイとロス・デ・パラカグイナは、おそらくこのスタイルの最も有名な提唱者である[1]。 |

| List of

socialist songs |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nueva_canci%C3%B3n |

|

Ejercito Popular Sandinista

Carlos

Mejía Godoy - "No Pasarán"

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099