民俗音楽・フォークミュージック

Béla Bartók using a gramaphone

to record folk songs sung by Slovak peasants.

☆ フォーク・ミュージック(民俗音楽)は、伝統的なフォーク・ミュージック(民俗音楽)と、20世 紀のフォーク復興期にそこから発展した現代的なジャンルを含む音楽ジャンルとしての「フォーク・ミュージック」がある。民俗音楽の中にはワールドミュージックと呼ばれるものもある(さらに日本語では「流行歌」もフォークミュージックの範疇に入れてもいいだろう)。伝統的な 民俗音楽はいくつかの方法で定義されている。口頭で伝えられる音楽、作曲者不明の音楽、伝統的な楽器で演奏される音楽、文化的または国民的アイデンティ ティに関する音楽、世代間で変化する音楽(民俗的過程)、民衆のフォークロアに関連する音楽、または長期間にわたって慣習によって演奏される音楽などであ る。商業的なスタイルや古典的なスタイルと対比されてきた。この用語は19世紀に生まれたが、フォーク・ミュージックはそれだけにとどまらない。 20世紀半ばから、伝統的な民俗音楽(フォーク・ミュージック)から新しい形のポピュラー民俗音楽(ポピュラーミュージックや「流行歌」など)が発展した。この過程と時期は(第二次)フォーク・リバイバルと呼ばれ、1960年 代に頂点に達した。この音楽形態は、それ以前のフォーク形態と区別するために、コンテンポラリー・フォーク・ミュージックまたはフォーク・リバイバ ル・ミュージックと呼ばれることがある。小規模で同様のリバイバルは世界の他の場所でも他の時期に起こっているが、フォーク・ミュージックという用 語は通常、それらのリバイバルの間に生み出された新しい音楽には適用されていない。この種のフォーク・ミュージックには、フォーク・ロック、フォーク・メ タルなどのフュージョン・ジャンルも含まれる。コンテンポラリー・フォーク・ミュージックは、伝統的なフォーク・ミュージックとは一般的に異なるジャンル であるが、米国英語では同じ名前を持ち、伝統的なフォーク・ミュージックと同じ演奏者や会場で演奏されることが多い。

★以下の日本語邦訳では、DeepLで翻訳しているために、フォーク・ミュージックと民俗音楽という表現が混在しているが、同じものとみなしてよい。なぜなら、上に解説したように「伝統的なフォーク・ミュージック(民俗音楽)」と「20世 紀のフォーク復興期にそこから発展した現代的なジャンルを含む音楽ジャンルとしての『フォーク・ミュージック』」は、同じ伝統を共有し、また、民衆=フォークに親しむように、進化適応を遂げてきたので、それらを厳密に分ける音楽理論上の線引きは不可能である。

| Folk

music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the

contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century

folk revival. Some types of folk music may be called world music.

Traditional folk music has been defined in several ways: as music

transmitted orally, music with unknown composers, music that is played

on traditional instruments, music about cultural or national identity,

music that changes between generations (folk process), music associated

with a people's folklore, or music performed by custom over a long

period of time. It has been contrasted with commercial and classical

styles. The term originated in the 19th century, but folk music extends

beyond that. Starting in the mid-20th century, a new form of popular folk music evolved from traditional folk music. This process and period is called the (second) folk revival and reached a zenith in the 1960s. This form of music is sometimes called contemporary folk music or folk revival music to distinguish it from earlier folk forms.[1] Smaller, similar revivals have occurred elsewhere in the world at other times, but the term folk music has typically not been applied to the new music created during those revivals. This type of folk music also includes fusion genres such as folk rock, folk metal, and others. While contemporary folk music is a genre generally distinct from traditional folk music, in U.S. English it shares the same name, and it often shares the same performers and venues as traditional folk music. |

フォーク・ミュージック(民俗音楽)は、伝統的なフォーク・ミュージック(民俗音楽)と、20世

紀のフォーク復興期にそこから発展した現代的なジャンルを含む音楽ジャンルとしての「フォーク・ミュージック」がある。民俗音楽の中にはワールドミュージックと呼ばれるものもある(さらに日本語では「流行歌」もフォークミュージックの範疇に入れてもいいだろう)。伝統的な

民俗音楽はいくつかの方法で定義されている。口頭で伝えられる音楽、作曲者不明の音楽、伝統的な楽器で演奏される音楽、文化的または国民的アイデンティ

ティに関する音楽、世代間で変化する音楽(民俗的過程)、民衆のフォークロアに関連する音楽、または長期間にわたって慣習によって演奏される音楽などであ

る。商業的なスタイルや古典的なスタイルと対比されてきた。この用語は19世紀に生まれたが、フォーク・ミュージックはそれだけにとどまらない。 20世紀半ばから、伝統的な民俗音楽(フォーク・ミュージック)から新しい形のポピュラー民俗音楽(ポピュラーミュージックや「流行歌」など)が発展した。この過程と時期は(第二次)フォーク・リバイバルと呼ばれ、1960年 代に頂点に達した。この音楽形態は、それ以前のフォーク形態と区別するために、コンテンポラリー・フォーク・ミュージックまたはフォーク・リバイバ ル・ミュージックと呼ばれることがある。小規模で同様のリバイバルは世界の他の場所でも他の時期に起こっているが、フォーク・ミュージックという用 語は通常、それらのリバイバルの間に生み出された新しい音楽には適用されていない。この種のフォーク・ミュージックには、フォーク・ロック、フォーク・メ タルなどのフュージョン・ジャンルも含まれる。コンテンポラリー・フォーク・ミュージックは、伝統的なフォーク・ミュージックとは一般的に異なるジャンル であるが、米語では同じ名前を持ち、伝統的なフォーク・ミュージックと同じ演奏者や会場で演奏されることが多い。 |

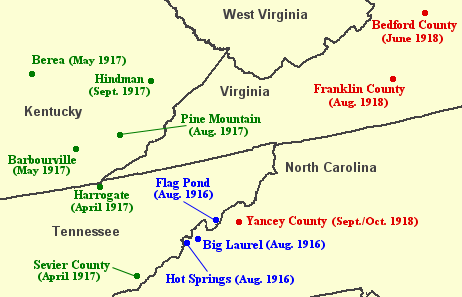

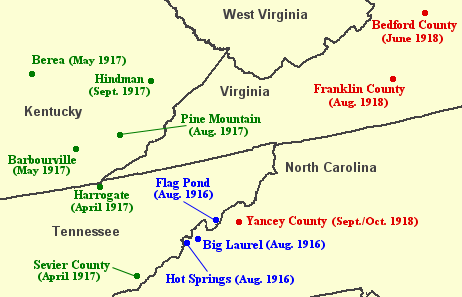

| Traditional folk music Definition The terms folk music, folk song, and folk dance are comparatively recent expressions. They are extensions of the term folklore, which was coined in 1846 by the English antiquarian William Thoms to describe "the traditions, customs, and superstitions of the uncultured classes".[2] The term further derives from the German expression volk, in the sense of "the people as a whole" as applied to popular and national music by Johann Gottfried Herder and the German Romantics over half a century earlier.[3] Though it is understood that folk music is the music of the people, observers find a more precise definition to be elusive.[4][5] Some do not even agree that the term folk music should be used.[4] Folk music may tend to have certain characteristics[2] but it cannot clearly be differentiated in purely musical terms. One meaning often given is that of "old songs, with no known composers,"[6] another is that of music that has been submitted to an evolutionary "process of oral transmission.... the fashioning and re-fashioning of the music by the community that give it its folk character."[7] Such definitions depend upon "(cultural) processes rather than abstract musical types...", upon "continuity and oral transmission...seen as characterizing one side of a cultural dichotomy, the other side of which is found not only in the lower layers of feudal, capitalist and some oriental societies but also in 'primitive' societies and in parts of 'popular cultures'".[8] One widely used definition is simply "Folk music is what the people sing."[9] For Scholes,[2] as well as for Cecil Sharp and Béla Bartók,[10] there was a sense of the music of the country as distinct from that of the town. Folk music was already, "...seen as the authentic expression of a way of life now past or about to disappear (or in some cases, to be preserved or somehow revived),"[11] particularly in "a community uninfluenced by art music"[7] and by commercial and printed song. Lloyd rejected this in favor of a simple distinction of economic class[10] yet for him, true folk music was, in Charles Seeger's words, "associated with a lower class"[12] in culturally and socially stratified societies. In these terms, folk music may be seen as part of a "schema comprising four musical types: 'primitive' or 'tribal'; 'elite' or 'art'; 'folk'; and 'popular'."[13] Music in this genre is also often called traditional music. Although the term is usually only descriptive, in some cases people use it as the name of a genre. For example, the Grammy Award previously used the terms "traditional music" and "traditional folk" for folk music that is not contemporary folk music.[14] Folk music may include most indigenous music.[4] Characteristics  Viljandi Folk Music Festival held annually within the castle ruins in Viljandi, Estonia. From a historical perspective, traditional folk music had these characteristics:[12] It was transmitted through an oral tradition. Before the 20th century, ordinary people were usually illiterate; they acquired songs by memorizing them. Primarily, this was not mediated by books or recorded or transmitted media. Singers may extend their repertoire using broadsheets or song books, but these secondary enhancements are of the same character as the primary songs experienced in the flesh. The music was often related to national culture. It was culturally particular; from a particular region or culture. In the context of an immigrant group, folk music acquires an extra dimension for social cohesion. It is particularly conspicuous in immigrant societies, where Greek Australians, Somali Americans, Punjabi Canadians, and others strive to emphasize their differences from the mainstream. They learn songs and dances that originate in the countries their grandparents came from. They commemorate historical and personal events. On certain days of the year, including such holidays as Christmas, Easter, and May Day, particular songs celebrate the yearly cycle. Birthdays, weddings, and funerals may also be noted with songs, dances and special costumes. Religious festivals often have a folk music component. Choral music at these events brings children and non-professional singers to participate in a public arena, giving an emotional bonding that is unrelated to the aesthetic qualities of the music. The songs have been performed, by custom, over a long period of time, usually several generations. As a side-effect, the following characteristics are sometimes present: There is no copyright on the songs. Hundreds of folk songs from the 19th century have known authors but have continued in oral tradition to the point where they are considered traditional for purposes of music publishing. This has become much less frequent since the 1940s. Today, almost every folk song that is recorded is credited with an arranger. Fusion of cultures: Because cultures interact and change over time, traditional songs evolving over time may incorporate and reflect influences from disparate cultures. The relevant factors may include instrumentation, tunings, voicings, phrasing, subject matter, and even production methods. Tune In folk music, a tune is a short instrumental piece, a melody, often with repeating sections, and usually played a number of times.[15] A collection of tunes with structural similarities is known as a tune-family. America's Musical Landscape says "the most common form for tunes in folk music is AABB, also known as binary form."[16][page needed] In some traditions, tunes may be strung together in medleys or "sets."[17] Origins  Indians always distinguished between classical and folk music, though in the past even classical Indian music used to rely on the unwritten transmission of repertoire. Indian Nepali folk musician Navneet Aditya Waiba Navneet Aditya Waiba (Nepali:नवनित अादित्य वाइवा) is an Indian singer who primarily sings in Nepali-language and the daughter of the late Hira Devi Waiba, the pioneer of Nepali folk music. Throughout most of human prehistory and history, listening to recorded music was not possible.[18][19] Music was made by common people during both their work and leisure, as well as during religious activities. The work of economic production was often manual and communal.[20] Manual labor often included singing by the workers, which served several practical purposes.[21] It reduced the boredom of repetitive tasks, it kept the rhythm during synchronized pushes and pulls, and it set the pace of many activities such as planting, weeding, reaping, threshing, weaving, and milling. In leisure time, singing and playing musical instruments were common forms of entertainment and history-telling—even more common than today when electrically enabled technologies and widespread literacy make other forms of entertainment and information-sharing competitive.[22] Some believe that folk music originated as art music that was changed and probably debased by oral transmission while reflecting the character of the society that produced it.[2] In many societies, especially preliterate ones, the cultural transmission of folk music requires learning by ear, although notation has evolved in some cultures.[23] Different cultures may have different notions concerning a division between "folk" music on the one hand and of "art" and "court" music on the other. In the proliferation of popular music genres, some traditional folk music became also referred to as "World music" or "Roots music".[24] The English term "folklore", to describe traditional folk music and dance, entered the vocabulary of many continental European nations, each of which had its folk-song collectors and revivalists.[2] The distinction between "authentic" folk and national and popular song in general has always been loose, particularly in America and Germany[2] – for example, popular songwriters such as Stephen Foster could be termed "folk" in America.[2][25] The International Folk Music Council definition allows that the term can also apply to music that, "...has originated with an individual composer and has subsequently been absorbed into the unwritten, living tradition of a community. But the term does not cover a song, dance, or tune that has been taken over ready-made and remains unchanged."[26] The post–World War II folk revival in America and in Britain started a new genre, Contemporary Folk Music, and brought an additional meaning to the term "folk music": newly composed songs, fixed in form and by known authors, which imitated some form of traditional music. The popularity of "contemporary folk" recordings caused the appearance of the category "Folk" in the Grammy Awards of 1959;[27] in 1970 the term was dropped in favor of "Best Ethnic or Traditional Recording (including Traditional Blues)",[28] while 1987 brought a distinction between "Best Traditional Folk Recording" and "Best Contemporary Folk Recording".[29] After that, they had a "Traditional music" category that subsequently evolved into others. The term "folk", by the start of the 21st century, could cover singer-songwriters, such as Donovan[30] from Scotland and American Bob Dylan,[31] who emerged in the 1960s and much more. This completed a process to where "folk music" no longer meant only traditional folk music.[6] Subject matter Armenian traditional music Assyrian folk music Three Hours Of Assyrian Folk Music Assyrians playing a zurna and a davul, instruments typically used for Assyrian folk music and dance. Traditional folk music often includes sung words, although folk instrumental music occurs commonly in dance music traditions. Narrative verse looms large in the traditional folk music of many cultures.[32][33] This encompasses such forms as traditional epic poetry, much of which was meant originally for oral performance, sometimes accompanied by instruments.[34][35] Many epic poems of various cultures were pieced together from shorter pieces of traditional narrative verse, which explains their episodic structure, repetitive elements, and their frequent in medias res plot developments. Other forms of traditional narrative verse relate the outcomes of battles or lament tragedies or natural disasters.[36] Sometimes, as in the triumphant Song of Deborah[37] found in the Biblical Book of Judges, these songs celebrate victory. Laments for lost battles and wars, and the lives lost in them, are equally prominent in many traditions; these laments keep alive the cause for which the battle was fought.[38][39] The narratives of traditional songs often also remember folk heroes such as John Henry[40][41] or Robin Hood.[42] Some traditional song narratives recall supernatural events or mysterious deaths.[43] Hymns and other forms of religious music are often of traditional and unknown origin.[44] Western musical notation was originally created to preserve the lines of Gregorian chant, which before its invention was taught as an oral tradition in monastic communities.[45][46] Traditional songs such as Green grow the rushes, O present religious lore in a mnemonic form, as do Western Christmas carols and similar traditional songs.[47] Work songs frequently feature call and response structures and are designed to enable the laborers who sing them to coordinate their efforts in accordance with the rhythms of the songs.[48] They are frequently, but not invariably, composed. In the American armed forces, a lively oral tradition preserves jody calls ("Duckworth chants") which are sung while soldiers are on the march.[49] Professional sailors made similar use of a large body of sea shanties.[50][51] Love poetry, often of a tragic or regretful nature, prominently figures in many folk traditions.[52] Nursery rhymes and nonsense verse used to amuse or quiet children also are frequent subjects of traditional songs.[53] Folk song transformations and variations See also: List of folk music traditions This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Korean traditional musicians Music transmitted by word of mouth through a community, in time, develops many variants, since this transmission cannot produce word-for-word and note-for-note accuracy. In addition, folk singers may choose to modify the songs they hear. For example, the words of "I'm a Man You Don't Meet Every Day" (Roud 975) were written down in a broadside in the 18th century, and seem to have an Irish origin.[54] In 1958 the song was recorded in Canada (My Name is Pat and I'm Proud of That). Scottish traveler Jeannie Robertson from Aberdeen, made the next recorded version in 1961. She has changed it to make reference to "Jock Stewart", one of her relatives, and there are no Irish references. In 1976 Scottish artist Archie Fisher deliberately altered the song to remove the reference to a dog being shot. In 1985 The Pogues took it full circle by restoring the Irish references.[original research?] Because variants proliferate naturally, there is generally no "authoritative" version of song. Researchers in traditional songs have encountered countless versions of the Barbara Allen ballad throughout the English-speaking world, and these versions often differ greatly from each other. The original is not known; many versions can lay an equal claim to authenticity. Influential folklorist Cecil Sharp felt that these competing variants of a traditional song would undergo a process of improvement akin to biological natural selection: only those new variants that were the most appealing to ordinary singers would be picked up by others and transmitted onward in time. Thus, over time we would expect each traditional song to become more aesthetically appealing, due to incremental community improvement. Literary interest in the popular ballad form dates back at least to Thomas Percy and William Wordsworth. English Elizabethan and Stuart composers had often evolved their music from folk themes, the classical suite was based upon stylised folk-dances, and Joseph Haydn's use of folk melodies is noted. But the emergence of the term "folk" coincided with an "outburst of national feeling all over Europe" that was particularly strong at the edges of Europe, where national identity was most asserted. Nationalist composers emerged in Central Europe, Russia, Scandinavia, Spain and Britain: the music of Dvořák, Smetana, Grieg, Rimsky-Korsakov, Brahms, Liszt, de Falla, Wagner, Sibelius, Vaughan Williams, Bartók, and many others drew upon folk melodies.[citation needed] Regional forms Naxi traditional musicians  The Steinegger brothers, traditional fifers of Grundlsee, Styria, 1880 While the loss of traditional folk music in the face of the rise of popular music is a worldwide phenomenon,[55] it is not one occurring at a uniform rate throughout the world.[56] The process is most advanced "where industrialization and commercialisation of culture are most advanced"[57] but also occurs more gradually even in settings of lower technological advancement. However, the loss of traditional music is slowed in nations or regions where traditional folk music is a badge of cultural or national identity.[citation needed] Early folk music, fieldwork and scholarship Much of what is known about folk music prior to the development of audio recording technology in the 19th century comes from fieldwork and writings of scholars, collectors and proponents.[58] 19th-century Europe Starting in the 19th century, academics and amateur scholars, taking note of the musical traditions being lost, initiated various efforts to preserve the music of the people.[59] One such effort was the collection by Francis James Child in the late 19th century of the texts of over three hundred ballads in the English and Scots traditions (called the Child Ballads), some of which predated the 16th century.[9] Contemporaneously with Child, the Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould and later Cecil Sharp worked to preserve a great body of English rural traditional song, music and dance, under the aegis of what became and remains the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS).[60] Sharp campaigned with some success to have English traditional songs (in his own heavily edited and expurgated versions) to be taught to school children in hopes of reviving and prolonging the popularity of those songs.[61][62] Throughout the 1960s and early to mid-1970s, American scholar Bertrand Harris Bronson published an exhaustive four-volume collection of the then-known variations of both the texts and tunes associated with what came to be known as the Child Canon.[63] He also advanced some significant theories concerning the workings of oral-aural tradition.[64] Similar activity was also under way in other countries. One of the most extensive was perhaps the work done in Riga by Krisjanis Barons, who between the years 1894 and 1915 published six volumes that included the texts of 217,996 Latvian folk songs, the Latvju dainas.[65] In Norway the work of collectors such as Ludvig Mathias Lindeman was extensively used by Edvard Grieg in his Lyric Pieces for piano and in other works, which became immensely popular.[66] Around this time, composers of classical music developed a strong interest in collecting traditional songs, and a number of composers carried out their own field work on traditional music. These included Percy Grainger[67] and Ralph Vaughan Williams[68] in England and Béla Bartók[69] in Hungary. These composers, like many of their predecessors, both made arrangements of folk songs and incorporated traditional material into original classical compositions.[70][71] North America  Locations in Southern and Central Appalachia visited by the British folklorist Cecil Sharp in 1916 (blue), 1917 (green), and 1918 (red). Sharp sought "old world" English and Scottish ballads passed down to the region's inhabitants from their British ancestors. He collected hundreds of such ballads, the most productive areas being the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina and the Cumberland Mountains of Kentucky. The advent of audio recording technology provided folklorists with a revolutionary tool to preserve vanishing musical forms.[72] The earliest American folk music scholars were with the American Folklore Society (AFS), which emerged in the late 1800s.[73] Their studies expanded to include Native American music, but still treated folk music as a historical item preserved in isolated societies as well.[74] In North America, during the 1930s and 1940s, the Library of Congress worked through the offices of traditional music collectors Robert Winslow Gordon,[75] Alan Lomax[76][77][78] and others to capture as much North American field material as possible.[79] John Lomax (the father of Alan Lomax) was the first prominent scholar to study distinctly American folk music such as that of cowboys and southern blacks. His first major published work was in 1911, Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads.[80] and was arguably the most prominent US folk music scholar of his time, notably during the beginnings of the folk music revival in the 1930s and early 1940s. Cecil Sharp also worked in America, recording the traditional songs of the Appalachian Mountains in 1916–1918 in collaboration with Maud Karpeles and Olive Dame Campbell and is considered the first major scholar covering American folk music.[81] Campbell and Sharp are represented under other names by actors in the modern movie Songcatcher.[82] One strong theme amongst folk scholars in the early decades of the 20th century was regionalism,[83] the analysis of the diversity of folk music (and related cultures) based on regions of the US rather than based on a given song's historical roots.[84][85] Later, a dynamic of class and circumstances was added to this.[86] The most prominent regionalists were literary figures with a particular interest in folklore.[87][88] Carl Sandburg often traveled the U.S. as a writer and a poet.[89] He also collected songs in his travels and, in 1927, published them in the book The American Songbag.[90] Rachel Donaldson, a historian who worked for Vanderbilt, later stated this about The American Songbird in her analysis of the folk music revival. "In his collections of folk songs, Sandburg added a class dynamic to popular understandings of American folk music. This was the final element of the foundation upon which the early folk music revivalists constructed their own view of Americanism. Sandburg's working-class Americans joined with the ethnically, racially, and regionally diverse citizens that other scholars, public intellectuals, and folklorists celebrated their own definitions of the American folk, definitions that the folk revivalists used in constructing their own understanding of American folk music, and an overarching American identity".[91] Prior to the 1930s, the study of folk music was primarily the province of scholars and collectors. The 1930s saw the beginnings of larger scale themes, commonalities, and linkages in folk music developing in the populace and practitioners as well, often related to the Great Depression.[92] Regionalism and cultural pluralism grew as influences and themes. During this time folk music began to become enmeshed with political and social activism themes and movements.[92] Two related developments were the U.S. Communist Party's interest in folk music as a way to reach and influence Americans,[93] and politically active prominent folk musicians and scholars seeing communism as a possible better system, through the lens of the Great Depression.[94] Woody Guthrie exemplifies songwriters and artists with such an outlook.[95] Folk music festivals proliferated during the 1930s.[96] President Franklin Roosevelt was a fan of folk music, hosted folk concerts at the White House, and often patronized folk festivals.[97] One prominent festival was Sarah Gertrude Knott's National Folk Festival, established in St. Louis, Missouri in 1934.[98] Under the sponsorship of the Washington Post, the festival was held in Washington, DC at Constitution Hall from 1937 to 1942.[99] The folk music movement, festivals, and the wartime effort were seen as forces for social goods such as democracy, cultural pluralism, and the removal of culture and race-based barriers.[100] Barbara Allen Duration: 2 minutes and 40 seconds.2:40 Barbara Allen, a traditional English language folk ballad, sung by Hule "Queen" Hines of Florida to John Lomax in 1939 The American folk music revivalists of the 1930s approached folk music in different ways.[101] Three primary schools of thought emerged: "Traditionalists" (e.g. Sarah Gertrude Knott and John Lomax) emphasized the preservation of songs as artifacts of deceased cultures. "Functional" folklorists (e.g. Botkin and Alan Lomax) maintained that songs only retain relevance when used by those cultures which retain the traditions which birthed those songs. "Left-wing" folk revivalists (e.g. Charles Seeger and Lawrence Gellert) emphasized music's role "in 'people's' struggles for social and political rights".[101] By the end of the 1930s these and others had turned American folk music into a social movement.[101] Sometimes folk musicians became scholars and advocates themselves. For example, Jean Ritchie (1922–2015) was the youngest child of a large family from Viper, Kentucky that had preserved many of the old Appalachian traditional songs.[102] Ritchie, living in a time when the Appalachians had opened up to outside influence, was university educated and ultimately moved to New York City, where she made a number of classic recordings of the family repertoire and published an important compilation of these songs.[103] In January 2012, the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, with the Association for Cultural Equity, announced that they would release Lomax's vast archive of 1946 and later recording in digital form. Lomax spent the last 20 years of his life working on an Interactive Multimedia educational computer project he called the Global Jukebox, which included 5,000 hours of sound recordings, 400,000 feet of film, 3,000 videotapes, and 5,000 photographs.[104] As of March 2012, this has been accomplished. Approximately 17,400 of Lomax's recordings from 1946 and later have been made available free online.[105][106] This material from Alan Lomax's independent archive, begun in 1946, which has been digitized and offered by the Association for Cultural Equity, is "distinct from the thousands of earlier recordings on acetate and aluminum discs he made from 1933 to 1942 under the auspices of the Library of Congress. This earlier collection—which includes the famous Jelly Roll Morton, Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, and Muddy Waters sessions, as well as Lomax's prodigious collections made in Haiti and Eastern Kentucky (1937) — is the provenance of the American Folklife Center"[105] at the library of Congress. |

伝統的フォーク・ミュージック 定義 フォークミュージック、フォークソング、フォークダンスという用語は比較的最近の表現である。これらはフォークロアという用語の拡張であり、フォークロア は1846年にイギリスの古美術家ウィリアム・トムズによって「教養のない階級の伝統、風習、迷信」を表すために作られたものである[2]。この用語はさ らに、半世紀以上前にヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダーとドイツ・ロマン派によってポピュラー音楽および国民音楽に適用された、「全体としての民衆」とい う意味でのドイツ語のvolkという表現に由来する[3]。 [3] フォーク・ミュージックは民衆の音楽であると理解されているが、観察者たちはより正確な定義がつかみにくいと感じている[4][5]。 民俗音楽という用語が使用されるべきでないという意見さえある[4]。しばしば与えられる意味の1つは、「作曲者が知られていない古い歌」[6]であり、 もう1つは、進化的な「口承による伝達の過程......共同体による音楽の形成と再形成......それが民俗的性格を与える」[7]に供されてきた音 楽である。 このような定義は「抽象的な音楽の型よりもむしろ(文化的な)過程...」、「連続性と口承...文化的な二分法の一方を特徴づけるものと見なされ、その 他方は封建社会、資本主義社会、および一部の東洋社会の下層部だけでなく、「原始」社会や「大衆文化」の一部にも見られる」[8]。 スコールズ[2]にとっても、セシル・シャープやベーラ・バルトーク[10]にとっても、田舎の音楽は町の音楽とは異なるという感覚があった。特に「芸術 音楽の影響を受けていない」[7]、「商業的で印刷された歌謡曲の影響を受けていないコミュニティ」[11]では、民俗音楽はすでに「......もはや 過去のもの、あるいは消え去ろうとしている(あるいは場合によっては保存されるべき、あるいは何とかして復活させるべき)生活様式の正真正銘の表現とみな されていた」[11]。ロイドは経済階級という単純な区別を支持してこれを否定したが[10]、彼にとって真のフォーク音楽とは、チャールズ・シーガーの 言葉を借りれば、文化的・社会的に階層化された社会における「下層階級と結びついた」ものであった[12]。このような観点からすると、民俗音楽は「『原 始的』または『部族的』、『エリート』または『芸術』、『民俗』、そして『ポピュラー』という4つの音楽タイプからなるスキーマ」の一部とみなすことがで きる[13]。 このジャンルの音楽はしばしば伝統音楽とも呼ばれる。この言葉は通常、説明的なものに過ぎないが、ジャンル名として使われる場合もある。例えば、グラミー 賞では以前、現代のフォーク・ミュージックではないフォーク・ミュージックに対して「トラディショナル・ミュージック」や「トラディショナル・フォーク」 という用語が使われていた[14]。 特徴  エストニア、ヴィルヤンディの城跡内で毎年開催されるヴィルヤンディ民族音楽祭。 歴史的観点から見ると、伝統的な民族音楽には以下のような特徴がある[12]。 口承によって伝承された。20世紀以前は、一般の人々はたいてい読み書きができなかった。主に、書物や記録・伝達メディアを介することはなかった。歌い手 はブロードシートや歌集を使ってレパートリーを増やすこともあるが、こうした二次的な強化は、生身で経験する一次的な歌と同じ性格のものである。 音楽はしばしば国の文化に関連していた。それは文化的に特殊なもので、特定の地域や文化のものである。移民集団の文脈では、フォーク・ミュージックは社会的結束のために 特別な次元を獲得する。ギリシャ系オーストラリア人、ソマリア系アメリカ人、パンジャブ系カナダ人などが主流との違いを強調しようと努力する移民社会で は、特に顕著である。彼らは祖父母の出身国で生まれた歌や踊りを学ぶ。 彼らは歴史的、個人的な出来事を記念する。クリスマス、イースター、メーデーといった祝祭日を含む1年の特定の日には、特定の歌が1年のサイクルを祝う。 誕生日、結婚式、葬式なども、歌や踊り、特別な衣装で祝われることがある。宗教的なお祭りには、しばしば民族音楽の要素が含まれる。こうした行事での合唱 は、子供たちやプロではない歌手が公共の場に参加することで、音楽の美的特質とは無関係に感情的な結びつきを与える。 このような歌は、慣習によって、長い期間、通常は数世代にわたって演奏されてきた。 副次的な効果として、次のような特徴が見られることがある: 歌には著作権がない。19世紀に作られた何百もの民謡は、作者はわかっているものの、音楽出版の目的上伝統的なものとみなされるまでに口承が続いてきた。 1940年代以降、このようなことはあまり見られなくなった。今日では、レコーディングされるほとんどすべてのフォークソングに編曲者がクレジットされて いる。 文化の融合: 文化は時間の経過とともに相互に影響し合い、変化していくものであるため、時代とともに進化する伝統的な歌には、異なる文化からの影響が取り入れられ、反 映されることがある。関連する要素には、楽器編成、チューニング、ヴォイシング、フレージング、主題、さらには制作方法などが含まれる。 曲 フォーク・ミュージックでは、曲は短い器楽曲、旋律であり、しばしば繰り返し部分を持ち、通常は何度も演奏される[15]。構造的な類似性を持つ曲の集まりは、チューン ファミリーとして知られている。America's Musical Landscapeは「民族音楽における曲の最も一般的な形式はAABBであり、バイナリ形式としても知られている」と述べている[16][要出典]。 いくつかの伝統では、曲はメドレーや「セット」で繋げられることがある[17]。 起源  インド人は常に古典音楽と民俗音楽を区別していたが、かつてはインドの古典音楽でさえ、レパートリーの不文律による伝達に頼っていた。 インド・ネパールの民族音楽家ナヴニート・アディティヤ・ワイバ ナヴニート・アディティヤ・ワイバ(ネパール語:नवनित्य वाइदित्य)は、主にネパール語で歌うインドの歌手であり、ネパール民族音楽の先駆者である故ヒラ・デヴィ・ワイバの娘である。 人類の先史時代と歴史の大半を通じて、録音された音楽を聴くことは不可能であった[18][19]。経済生産の仕事はしばしば手作業であり、共同作業で あった[20]。手作業にはしばしば労働者による歌唱が含まれていたが、これはいくつかの実用的な目的を果たしていた[21]。反復作業の退屈さを軽減 し、押し引きの同調時にリズムを保ち、植え付け、草取り、刈り入れ、脱穀、機織り、製粉といった多くの活動のペースを設定するものであった。余暇には、 歌ったり楽器を演奏したりすることが、娯楽や歴史を語るための一般的な形態であった。電気的に可能になった技術や広範な識字率が他の形態の娯楽や情報共有 を競争力のあるものにしている今日よりも、さらに一般的であった[22]。 フォーク・ミュージックは、それを生み出した社会の性格を反映しつつ、口承によって変化し、おそらくは堕落した芸術音楽として生まれたと考える人もいる[2]。多くの社 会、特に文字を持たない社会では、フォーク・ミュージックの文化的伝達は耳で学ぶことを必要とするが、一部の文化では記譜法が発展してきた[23]。文化が異なれば、一 方では「民俗」音楽、他方では「芸術」や「宮廷」音楽の区分に関する考え方も異なるかもしれない。ポピュラー音楽のジャンルが拡散する中で、伝統的な民族 音楽の一部は「ワールドミュージック」や「ルーツミュージック」とも呼ばれるようになった[24]。 伝統的なフォーク・ミュージックと民俗舞踊を表す英語の「フォークロア(folklore)」という用語は、ヨーロッパ大陸の多くの国々の語彙に入り込み、それぞれの国 には民謡のコレクターやリバイバリストが存在した[2]。一般的に「本物の」フォークと国民的歌謡やポピュラー歌謡の区別は、特にアメリカとドイツでは常 に緩かった[2]。 [2][25]。国際フォーク音楽協議会の定義では、この用語は「...個人の作曲家に端を発し、その後ある共同体の書かれざる生きた伝統に吸収された」 音楽にも適用できるとしている。しかし、この用語は、既成のものを引き継いでそのままになっている歌、踊り、曲は対象としていない」[26]。 第二次世界大戦後のアメリカとイギリスにおけるフォーク復興は、コンテンポラリー・フォーク・ミュージックという新しいジャンルを生み出し、「フォーク・ ミュージック」という用語に新たな意味をもたらした。コンテンポラリー・フォーク」録音の人気は、1959年のグラミー賞における「フォーク」部門の登場 を引き起こした[27]。1970年にはこの用語は廃止され、「最優秀エスニックまたはトラディショナル・レコーディング(トラディショナル・ブルースを 含む)」[28]が選ばれ、1987年には「最優秀トラディショナル・フォーク・レコーディング」と「最優秀コンテンポラリー・フォーク・レコーディン グ」が区別されるようになった[29]。21世紀に入ると、「フォーク」という言葉は、1960年代に登場したスコットランドのドノヴァン[30]やアメ リカのボブ・ディラン[31]などのシンガー・ソングライターをカバーするようになった。これによって「フォーク・ミュージック」がもはや伝統的なフォー ク・ミュージックだけを意味するものではなくなったというプロセスが完成した[6]。 主題 アルメニアの伝統音楽 アッシリアの民族音楽 アッシリアのフォーク・ミュージック アッシリアの民族音楽と舞踊によく使われる楽器、ズルナとダヴルを演奏するアッシリア人。 伝統的なフォーク・ミュージックにはしばしば歌詩が含まれるが、舞踊音楽の伝統では民俗器楽が一般的である。多くの文化の伝統的なフォーク・ミュージックには物語詩が大きく関わってい る[32][33]。これには伝統的な叙事詩のような形式が含まれ、その多くは元来口演のためのもので、楽器を伴うこともあった[34][35]。伝統的 な物語詩の他の形式は、戦いの結果や悲劇や自然災害を嘆くものである[36]。 時には、聖書の士師記にあるデボラの歌[37]のように、勝利を祝う歌もある。失われた戦いや戦争、そしてそこで失われた命に対する嘆きも同様に多くの伝 統において顕著であり、これらの嘆きは戦いが戦われた大義を生かすものである[38][39]。伝統的な歌の語りは、しばしばジョン・ヘンリー[40] [41]やロビン・フッド[42]のような民間の英雄を想起させる。 讃美歌やその他の形態の宗教音楽は、伝統的で起源が不明であることが多い[44]。西洋の楽譜はもともとグレゴリオ聖歌の行を保存するために作られたもの であり、グレゴリオ聖歌が発明される前は修道院の共同体で口承として教えられていた[45][46]。Green grow the rushes, Oのような伝統的な歌は、西洋のクリスマスキャロルや同様の伝統的な歌と同様に、宗教的な伝承をニモニック形式で提示している[47]。 労働歌はコールアンドレスポンス構造を特徴とすることが多く、それを歌う労働者が歌のリズムに従って自分の努力を調整できるように設計されている [48]。アメリカの軍隊では、兵士が行軍している間に歌われるジョディ・コール(「ダックワースの詠唱」)が生き生きとした口承の伝統として残っている [49]。プロの水兵は、大量のシーシャンティ[50][51]を同様に利用していた。 多くの民謡の中には、しばしば悲劇的または後悔的な性質の愛の詩が顕著に登場する[52]。 民謡の変形と変奏 以下も参照のこと: 民謡の伝統一覧 このセクションの検証には追加の引用が必要です。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力ください。ソースの ないものは異議申し立てされ、削除されることがあります。(2022年10月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 韓国の伝統音楽家 地域社会で口伝えで伝えられる音楽は、一字一句、一音一音を正確に伝えることができないため、やがて多くの変種が生まれる。加えて、民謡の歌い手たちは、 自分たちが聞いた歌に手を加えることもある。 例えば、「I'm a Man You Don't Meet Every Day」(Roud 975)の歌詞は、18世紀に広辞苑に書き留められたもので、アイルランドに起源を持つと思われる[54]。 1958年、この歌はカナダで録音された(『My Name is Pat and I'm Proud of That』)。アバディーン出身のスコットランド人旅行家ジーニー・ロバートソンは、1961年に次の録音バージョンを作った。彼女は自分の親戚のひとり である「ジョック・スチュワート」に言及するように変更し、アイルランド人への言及はない。1976年、スコットランドのアーティスト、アーチー・フィッ シャーは、撃たれる犬への言及を削除するために意図的に曲を変更した。1985年、ポーグスはアイルランドへの言及を復活させ、この曲を完成させた。 変種は自然に増殖するため、一般に歌には「権威ある」バージョンは存在しない。伝統歌謡の研究者たちは、英語圏でバーバラ・アレン・バラッドの無数のバー ジョンに出会ってきたが、これらのバージョンはしばしば互いに大きく異なっている。オリジナルは不明であり、多くのバージョンが同じように真正性を主張し ている。 影響力のある民俗学者のセシル・シャープは、伝統的な歌のこうした競合する変種は、生物学的な自然淘汰に似た改良の過程を経るだろうと考えた。つまり、一 般的な歌い手にとって最も魅力的な新しい変種だけが、他の歌い手にも受け継がれ、やがて広まっていくのである。 ポピュラー・バラッドという形式に対する文学者の関心は、少なくともトーマス・パーシーとウィリアム・ワーズワースにまで遡る。イギリスのエリザベス朝や スチュアート朝の作曲家たちは、しばしば民俗的なテーマから音楽を発展させており、古典組曲は様式化された民俗舞曲に基づいていた。しかし、「民俗」とい う用語の出現は、「ヨーロッパ全土における民族感情の爆発」と時を同じくしており、特に民族的アイデンティティが最も主張されたヨーロッパの端のほうで強 かった。中央ヨーロッパ、ロシア、スカンジナビア、スペイン、イギリスではナショナリストの作曲家が登場し、ドヴォルザーク、スメタナ、グリーグ、リムス キー=コルサコフ、ブラームス、リスト、デ・ファリャ、ワーグナー、シベリウス、ヴォーン・ウィリアムズ、バルトーク、その他多くの作曲家の音楽が民俗旋 律を利用している[要出典]。 地域の形態 ナシ族の伝統音楽家  シュタイアーマルク州グルンドルゼーの伝統的フィンガー、シュタイネガー兄弟(1880年 ポピュラー音楽の台頭に直面して伝統的なフォーク・ミュージックが失われていくのは世界的な現象であるが[55]、それは世界中で一様な速度で起こっている現象ではない [56]。このプロセスは「文化の工業化と商業化が最も進んでいるところ」で最も進んでいるが[57]、技術的進歩が低い環境においてもより徐々に起こっ ている。しかし、伝統的な民族音楽が文化的または国民的アイデンティティのバッジとなっている国や地域では、伝統音楽の喪失は緩やかになる[要出典]。 初期のフォーク・ミュージック、フィールドワーク、および学術研究 19世紀に録音技術が開発される以前のフォーク・ミュージックについて知られていることの多くは、フィールドワークと学者、収集家、支持者の著述によるものである [58]。 19世紀のヨーロッパ 19世紀に入ると、失われつつある音楽の伝統に注目した学者やアマチュア研究者たちが、民衆の音楽を保存するための様々な取り組みを開始した[59]。そ のような取り組みの一つが、19世紀後半にフランシス・ジェイムズ・チャイルド(Francis James Child)によって行われた、イングランドとスコットランドに伝わる300以上のバラッドのテキスト(チャイルド・バラッドと呼ばれる)の収集であり、 そのうちのいくつかは16世紀以前のものであった[9]。 チャイルドと同時期に、牧師のサビーヌ・バーリング=グールドと後のセシル・シャープは、イングリッシュ・フォークダンス・ソング協会(EFDSS)の庇 護のもとで、イギリスの農村の伝統的な歌、音楽、ダンスの膨大な数の保存に努めていた[60]。 [61] [62] アメリカの学者バートランド・ハリス・ブロンソンは、1960年代から1970年代初頭から半ばにかけて、チャイルド・カノンとして知られるようになった ものに関連するテキストと曲の両方について、当時知られていたバリエーションを網羅した4巻のコレクションを出版した[63]。 彼はまた、口承-聴覚の伝統の仕組みに関するいくつかの重要な理論を提唱した[64]。 同様の活動は他の国々でも行われていた。最も広範な活動のひとつは、おそらくクリスヤニス・バロンズ(Krisjanis Barons)によるリガでの活動であり、彼は1894年から1915年にかけてラトヴィア民謡217,996曲のテキストを含む6巻の歌集『ラト ヴィュ・ダイナス(Latvju dainas)』を出版した[65]。ノルウェーでは、ルドヴィク・マティアス・リンデマン(Ludvig Mathias Lindeman)などの収集家の活動が、エドヴァルド・グリーグ(Edvard Grieg)のピアノのための抒情小曲集やその他の作品に広く利用され、絶大な人気を博した[66]。 この頃(19世紀末から20世紀初頭)、クラシック音楽の作曲家たちは 伝統的な歌曲の収集に強い関心を抱くようになり、多くの作曲家たちが伝統音楽のフィールドワークを行った。その中に は、イギリスのパーシー・グレインジャー[67]やラルフ・ヴォーン・ウィリアムズ[68]、ハンガリーのベーラ・バルトーク[69]が含まれる。これら の作曲家は、多くの先達と同様に、民謡の編曲を行い、また伝統的な素材をオリジナルのクラシック楽曲に取り入れた[70][71]。 北米  イギリスの民俗学者セシル・シャープが1916年(青)、1917年(緑)、1918年(赤)に訪れたアパラチア南部および中央部の場所。シャープはイギ リス人の祖先からこの地域の住民に受け継がれた「旧世界」のイギリスやスコットランドのバラッドを探した。彼はそのようなバラッドを何百と集めたが、最も 収穫が多かったのはノースカロライナのブルーリッジ山脈とケンタッキーのカンバーランド山脈だった。 録音技術の出現は、消えつつある音楽形式を保存する画期的な手段を民俗学者に提供した[72]。最も初期のアメリカの民俗音楽学者は、1800年代後半に 誕生したアメリカ民俗学協会(AFS)に属していた[73]。 [北米では1930年代から1940年代にかけて、米国議会図書館が伝統音楽収集家のロバート・ウィンズロー・ゴードン(Robert Winslow Gordon)[75]、アラン・ローマックス(Alan Lomax)[76][77][78]らの事務所を通じて、北米の現地資料を可能な限り収集することに取り組んだ[79]。 ジョン・ローマックス(アラン・ローマックスの父)は、カウボーイや南部の黒人など、はっきりとしたアメリカの民族音楽を研究した最初の著名な学者であ る。彼の最初の主要な出版物は1911年の『Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads』であり[80]、特に1930年代から1940年代初頭にかけてのフォーク音楽リバイバルの始まりにおいて、当時最も著名な米国のフォー ク音楽研究者であったことは間違いない。セシル・シャープもまたアメリカで活動し、1916年から1918年にかけてモード・カーペレスやオリーヴ・デイ ム・キャンベルと共同でアパラチア山脈の伝統的な歌を録音しており、アメリカフォーク・ミュージックを網羅した最初の主要な学者とみなされている[81]。 20世紀初頭のフォーク研究者の間で強いテーマとなっていたのは地域主義であり[83]、ある曲の歴史的ルーツに基づくのではなく、米国の地域に基づく フォーク音楽(および関連文化)の多様性の分析であった[84][85]。後に、これに階級や境遇のダイナミズムが加わった[86]。 [87][88]カール・サンドバーグは作家として、また詩人としてしばしばアメリカを旅していた[89]。 彼はまた旅先で歌を収集し、1927年にそれらを『アメリカン・ソングバッグ』(The American Songbag)という本にまとめて出版した[90]。ヴァンダービルトに勤務していた歴史家レイチェル・ドナルドソンは後にフォーク音楽復興についての 分析の中で『アメリカン・ソングバッグ』についてこのように述べている。「サンドバーグはその民謡集において、アメリカ民謡に対する大衆の理解に階級的な ダイナミズムを加えた。これは、初期のフォーク音楽リバイバリストたちが自らのアメリカニズム観を構築する土台となる最後の要素であった。サンドバーグの 労働者階級のアメリカ人は、民族的、人種的、地域的に多様な市民と一緒になって、他の学者、公共知識人、民俗学者がアメリカ民俗の独自の定義、民俗復興主 義者たちがアメリカフォーク・ミュージックの独自の理解を構築する際に用いた定義、包括的なアメリカのアイデンティティを謳歌した」[91]。 1930年代以前は、フォーク音楽の研究は主に学者や収集家の領域であった。1930年代には、民衆や実践家の間でも、フォーク・ミュージックにおけるより大規模なテー マ、共通点、連関が生まれ始めたが、これはしばしば世界恐慌と関連していた。この時期、フォーク音楽は政治的・社会的活動主義のテーマや運動と絡み合い始 めた[92]。関連する二つの展開として、アメリカ共産党がアメリカ人に手を差し伸べ影響を与える方法としてフォーク音楽に関心を持ったこと[93]、政 治的に活動的な著名フォーク・ミュージシャンや学者が大恐慌というレンズを通して共産主義をより良いシステムの可能性があると考えたこと[94]が挙げら れる。 フランクリン・ルーズベルト大統領はフォーク音楽のファンであり、ホワイトハウスでフォーク・コンサートを主催し、フォーク・フェスティバルをしばしば後 援していた[97]。 [ワシントン・ポスト紙の後援のもと、このフェスティバルは1937年から1942年までワシントンDCのコンスティテューション・ホールで開催された [99]。フォーク音楽運動、フェスティバル、そして戦時中の取り組みは、民主主義、文化的多元主義、文化や人種に基づく障壁の撤廃といった社会的財産の ための力と見なされた[100]。 バーバ ラ・アレン 再生時間:2分40秒.2:40 バーバラ・アレン、フロリダのヒュール "クイーン "ハインズが1939年にジョン・ローマックスに歌わせた伝統的な英語のフォーク・バラード 1930年代のアメリカのフォーク音楽復興主義者たちは、さまざまな方法でフォーク音楽にアプローチした[101]。 3つの主要な学派が生まれた: 「伝統主義者」(サラ・ガートルード・ノット(Sarah Gertrude Knott)やジョン・ローマックス(John Lomax)など)は、亡くなった文化の芸術品としての歌の保存を強調した。「機能的」フォークロリスト(BotkinやAlan Lomaxなど)は、歌は、その歌を生み出した伝統を保持する文化によって使用される場合にのみ関連性を保つと主張した。左翼」フォーク復興主義者 (チャールズ・シーガーやローレンス・ゲラートなど)は、「社会的権利や政治的権利を求める『民衆』の闘争における」音楽の役割を強調した[101]。 1930年代末までに、こうした人々やその他の人々はアメリカのフォーク音楽を社会運動に変えた[101]。 フォーク・ミュージシャン自身が学者や提唱者になることもあった。例えば、ジーン・リッチー(1922-2015)はケンタッキー州バイパーの大家族の 末っ子で、アパラチア地方の古い伝統的な歌の多くを保存していた[102]。アパラチア地方が外部の影響に開放された時代に生きたリッチーは大学教育を受 け、最終的にはニューヨークに移り住み、そこで家族のレパートリーの数々の名盤を録音し、これらの歌の重要な編集物を出版した[103]。 2012年1月、米国議会図書館のアメリカン・フォークライフ・センターは、Association for Cultural Equityとともに、1946年以降の録音からなるローマックスの膨大なアーカイブをデジタル形式で公開すると発表した。ローマックスは人生の最後の 20年間を、彼が「グローバル・ジュークボックス」と呼ぶ、5,000時間の録音、400,000フィートのフィルム、3,000本のビデオテープ、 5,000枚の写真を含むインタラクティブ・マルチメディア教育コンピューター・プロジェクトに費やした[104]。1946年以降のアラン・ローマック スの録音のうち、約17,400件がオンラインで無料公開されている[105][106]。1946年に開始されたアラン・ローマックスの独立したアーカ イヴからデジタル化され、Association for Cultural Equityによって提供されているこの資料は、「1933年から1942年にかけて議会図書館の後援のもとで行われた、アセテートとアルミディスクによ る数千の以前の録音とは異なるもの」である。この初期のコレクションには、有名なジェリー・ロール・モートン、ウディ・ガスリー、リード・ベリー、マ ディ・ウォーターズのセッションや、ハイチと東ケンタッキー(1937年)で行われたローマックスの膨大なコレクションが含まれており、米国議会図書館の American Folklife Centerが所蔵している」[105]。 |

| National and regional forms Africa Main article: Music of Africa  The African lamellophone, thumb piano or mbira Africa is a vast continent[107] and its regions and nations have distinct musical traditions.[108][109] The music of North Africa for the most part has a different history from Sub-Saharan African music traditions.[110] The music and dance forms of the African diaspora, including African American music and many Caribbean genres like soca, calypso and Zouk; and Latin American music genres like the samba, Cuban rumba, salsa; and other clave (rhythm)-based genres, were founded to varying degrees on the music of African slaves, which has in turn influenced African popular music.[111][112] Asia See also: Tamang Selo, Iranian folk music, and Indian folk music Paban Das Baul Paban Das Baul (born 1961) is a noted Baul singer and musician from India, who also plays a dubki, a small tambourine and sometimes an ektara as an accompaniment. He is known for pioneering traditional Baul music on the international music scene and for establishing a genre of folk-fusion music. Many Asian civilizations distinguish between art/court/classical styles and "folk" music.[113][114] For example, the late Alam Lohar is an example of a South Asian singer who was classified as a folk singer.[115] Khunung Eshei/Khuland Eshei is an ancient folk song from India, a country of Asia, of Meiteis of Manipur, that is an example of Asian folk music, and how they put it into its own genre.[116] Folk music of China Further information: Music of China § Folk music, Shijing, and Yuefu Archaeological discoveries date Chinese folk music back 7000 years;[117] it is largely based on the pentatonic scale.[118] Han traditional weddings and funerals usually include a form of oboe called a suona,[119] and apercussive ensembles called a chuigushou.[120] Ensembles consisting of mouth organs (sheng), shawms (suona), flutes (dizi) and percussion instruments (especially yunluo gongs) are popular in northern villages;[121] their music is descended from the imperial temple music of Beijing, Xi'an, Wutai shan and Tianjin. Xi'an drum music, consisting of wind and percussive instruments,[122] is popular around Xi'an, and has received some commercial popularity outside of China.[123] Another important instrument is the sheng, a type of Chinese pipe, an ancient instrument that is ancestor of all Western free reed instruments, such as the accordion.[124] Parades led by Western-type brass bands are common, often competing in volume with a shawm/chuigushou band. In southern Fujian and Taiwan, Nanyin or Nanguan is a genre of traditional ballads.[125] They are sung by a woman accompanied by a xiao and a pipa, as well as other traditional instruments.[126] The music is generally sorrowful and typically deals with love-stricken people.[127][128] Further south, in Shantou, Hakka and Chaozhou, zheng ensembles are popular.[129] Sizhu ensembles use flutes and bowed or plucked string instruments to make harmonious and melodious music that has become popular in the West among some listeners.[130] These are popular in Nanjing and Hangzhou, as well as elsewhere along the southern Yangtze area.[131] Jiangnan Sizhu (silk and bamboo music from Jiangnan) is a style of instrumental music, often played by amateur musicians in tea houses in Shanghai.[132] Guangdong Music or Cantonese Music is instrumental music from Guangzhou and surrounding areas.[133] The music from this region influenced Yueju (Cantonese Opera) music,[134] which would later grow popular during the self-described "Golden Age" of China under the PRC.[135] Folk songs have been recorded since ancient times in China. The term Yuefu was used for a broad range of songs such as ballads, laments, folk songs, love songs, and songs performed at court.[136] China is a vast country, with a multiplicity of linguistic and geographic regions. Folk songs are categorized by geographic region, language type, ethnicity, social function (e.g. work song, ritual song, courting song) and musical type. Modern anthologies collected by Chinese folklorists distinguish between traditional songs, revolutionary songs, and newly-invented songs.[137] The songs of northwest China are known as "flower songs" (hua'er), a reference to beautiful women, while in the past they were notorious for their erotic content.[138] The village "mountain songs" (shan'ge) of Jiangsu province were also well-known for their amorous themes.[139][140] Other regional song traditions include the "strummed lyrics" (tanci) of the Lower Yangtze Delta, the Cantonese Wooden Fish tradition (muyu or muk-yu) and the Drum Songs (guci) of north China.[141] In the twenty-first century many cherished Chinese folk songs have been inscribed in the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[142] In the process, songs once seen as vulgar are now being reconstructed as romantic courtship songs.[143] Regional song competitions, popular in many communities, have promoted professional folk singing as a career, with some individual folk singers having gained national prominence.[144] Traditional folk music of Sri Lanka Main article: Music of Sri Lanka The art, music and dance of Sri Lanka derive from the elements of nature, and have been enjoyed and developed in the Buddhist environment.[145] The music is of several types and uses only a few types of instruments.[146] The folk songs and poems were used in social gatherings to work together. The Indian influenced classical music has grown to be unique.[147][148][149][150] The traditional drama, music and songs of Sinhala Light Music are typically Sri Lankan.[151] The temple paintings and carvings feature birds, elephants, wild animals, flowers, and trees, and the Traditional 18 Dances display the dancing of birds and animals.[152] For example: Mayura Wannama – The dance of the peacock[153][154] Hanuma Wannama – The dance of the monkey[155] Gajaga Wannama – The dance of the elephant Musical types include: Local drama music includes Kolam[156] and Nadagam types.[157] Kolam music is based on low country tunes primarily to accompany mask dance in exorcism rituals.[158][159] It is considered less developed/evolved, true to the folk tradition and a preserving of a more ancient artform.[160] It is limited to approximately 3–4 notes and is used by the ordinary people for pleasure and entertainment.[161] Nadagam music is a more developed form of drama influenced from South Indian street drama which was introduced by some south Indian artists. Phillippu Singho from Negombo in 1824 performed "Harishchandra Nadagama" in Hnguranketha which was originally written in the Telingu language. Later "Maname",[162] "Sanda kinduru"[163] and others were introduced. Don Bastian of Dehiwala introduced Noorthy firstly by looking at Indian dramas and then John de Silva developed it as did Ramayanaya in 1886.[164] Sinhala light music is currently the most popular type of music in Sri Lanka and enriched with the influence of folk music, kolam music, nadagam music, noorthy music, film music, classical music, Western music, and others.[165] Some artists visited India to learn music and later started introducing light music. Ananda Samarakone was the pioneer of this[166][167] and also composed the national anthem.[168] The classical Sinhalese orchestra consists of five categories of instruments, but among the percussion instruments, the drum is essential for dance.[169] The vibrant beat of the rhythm of the drums form the basic of the dance.[170] The dancers' feet bounce off the floor and they leap and swirl in patterns that reflect the complex rhythms of the drum beat. This drum beat may seem simple on the first hearing but it takes a long time to master the intricate rhythms and variations, which the drummer sometimes can bring to a crescendo of intensity. There are six common types of drums falling within 3 styles (one-faced, two-faced, and flat-faced):[171][172] The typical Sinhala Dance is identified as the Kandyan dance and the Gatabera drum is indispensable to this dance.[173] Yak-bera is the demon drum or the drum used in low country dance in which the dancers wear masks and perform devil dancing, which has become a highly developed form of art.[174] The Daula is a barrel-shaped drum, and it was used as a companion drum with a Thammattama in the past, to keep strict time with the beat.[175] The Thammattama is a flat, two-faced drum. The drummer strikes the drum on the two surfaces on top with sticks, unlike the others where you drum on the sides. This is a companion drum to the aforementioned Dawula.[176] A small double-headed hand drum is used to accompany songs. It is primarily heard in the poetry dances like vannam.[clarification needed] The Rabana is a flat-faced circular drum and comes in several sizes.[177] The large Rabana - called the Banku Rabana - has to be placed on the floor like a circular short-legged table and several people (traditionally women) can sit around it and beat on it with both hands.[178] This is used in festivals such as the Sinhalese New Year and ceremonies such as weddings.[179] The resounding beat of the Rabana symbolizes the joyous moods of the occasion. The small Rabana is a form of mobile drum beat since the player carries it wherever the person goes.[180] Other instruments include: The Thalampata – 2 small cymbals joined by a string.[181] The wind section, is dominated by an instrument akin to the clarinet.[clarification needed] This is not normally used for dances. This is important to note because the Sinhalese dance is not set to music as the western world knows it; rhythm is king. The flutes of metal such as silver & brass produce shrill music to accompany Kandyan Dances, while the plaintive strains of music of the reed flute may pierce the air in devil-dancing. The conch-shell (Hakgediya) is another form of a natural instrument, and the player blows it to announce the opening of ceremonies of grandeur.[182] The Ravanahatha (ravanhatta, rawanhattha, ravanastron or ravana hasta veena) is a bowed fiddle that was once popular in Western India.[183][184] It is believed to have originated among the Hela civilisation of Sri Lanka in the time of King Ravana.[185] The bowl is made of cut coconut shell, the mouth of which is covered with goat hide. A dandi, made of bamboo, is attached to this shell.[185] The principal strings are two: one of steel and the other of a set of horsehair. The long bow has jingle bells[186][187] Australia See also: Australian folk music and Indigenous music of Australia Folk song traditions were taken to Australia by early settlers from England, Scotland and Ireland and gained particular foothold in the rural outback.[188][189] The rhyming songs, poems and tales written in the form of bush ballads often relate to the itinerant and rebellious spirit of Australia in The Bush, and the authors and performers are often referred to as bush bards.[190] The 19th century was the golden age of bush ballads.[191] Several collectors have catalogued the songs including John Meredith whose recording in the 1950s became the basis of the collection in the National Library of Australia.[190] The songs tell personal stories of life in the wide open country of Australia.[192][193] Typical subjects include mining, raising and droving cattle, sheep shearing, wanderings, war stories, the 1891 Australian shearers' strike, class conflicts between the landless working class and the squatters (landowners), and outlaws such as Ned Kelly, as well as love interests and more modern fare such as trucking.[194] The most famous bush ballad is "Waltzing Matilda", which has been called "the unofficial national anthem of Australia".[195] Indigenous Australian music includes the music of Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders, who are collectively called Indigenous Australians;[196] it incorporates a variety of distinctive traditional music styles practiced by Indigenous Australian peoples, as well as a range of contemporary musical styles of and fusion with European traditions as interpreted and performed by indigenous Australian artists.[197] Music has formed an integral part of the social, cultural and ceremonial observances of these peoples, down through the millennia of their individual and collective histories to the present day.[198][199] The traditional forms include many aspects of performance and musical instruments unique to particular regions or Indigenous Australian groups.[200] Equal elements of musical tradition are common through much of the Australian continent, and even beyond.[201] The culture of the Torres Strait Islanders is related to that of adjacent parts of New Guinea and so their music is also related. Music is a vital part of Indigenous Australians' cultural maintenance.[202] Europe See also: English folk music, French folk music, German folk music, Greek folk music, Italian folk music, and Music of Spain Battlefield Band in concert 2006 Battlefield Band were a Scottish traditional music group. Founded in Glasgow in 1969, they have released over 30 albums and undergone many changes of lineup. As of 2010, none of the original founders remain in the band. Celtic traditional music See also: Folk music of Ireland and Folk music of Scotland Celtic music is a term used by artists, record companies, music stores and music magazines to describe a broad grouping of musical genres that evolved out of the folk musical traditions of the Celtic peoples.[203] These traditions include Irish, Scottish, Manx, Cornish, Welsh, and Breton traditions.[204] Asturian and Galician music is often included, though there is no significant research showing that this has any close musical relationship.[205][206] Brittany's Folk revival began in the 1950s with the "bagadoù" and the "kan-ha-diskan" before growing to world fame through Alan Stivell's work since the mid-1960s.[207] In Ireland, The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem (although its members were all Irish-born, the group became famous while based in New York's Greenwich Village[208]), The Dubliners,[209] Clannad,[210] Planxty,[211] The Chieftains,[212][213] The Pogues,[214] The Corrs,[215] The Irish Rovers,[216] and a variety of other folk bands have done much over the past few decades to revitalise and re-popularise Irish traditional music.[217] These bands were rooted, to a greater or lesser extent, in a tradition of Irish music and benefited from the efforts of artists such as Seamus Ennis and Peter Kennedy.[207] In Scotland, The Corries,[218] Silly Wizard,[219][220] Capercaillie,[221] Runrig,[222] Jackie Leven,[223] Julie Fowlis,[224] Karine Polwart,[225] Alasdair Roberts,[226][227] Dick Gaughan,[228] Wolfstone,[229] Boys of the Lough,[230] and The Silencers[231] have kept Scottish folk vibrant and fresh by mixing traditional Scottish and Gaelic folk songs with more contemporary genres.[232] These artists have also been commercially successful in continental Europe and North America.[233] There is an emerging wealth of talent in the Scottish traditional music scene, with bands such as Mànran,[234] Skipinnish,[235] Barluath[236] and Breabach[237] and solo artists such as Patsy Reid,[238] Robyn Stapleton[239] and Mischa MacPherson[240] gaining a lot of success in recent years.[241] Central and Eastern Europe See also: Music of Belarus, Hungarian folk music, Music of Moldova, Russian folk music, Ukrainian folk music, Music of Slovenia, and Czech folklore During the Eastern Bloc era, national folk dancing was actively promoted by the state.[242] Dance troupes from Russia and Poland toured non-communist Europe from about 1937 to 1990.[243] The Red Army Choir recorded many albums, becoming the most popular military band.[244] Eastern Europe is also the origin of the Jewish Klezmer tradition.[245] Duration: 2 minutes and 4 seconds.2:04 Ľubomír Párička playing bagpipes, Slovakia The polka is a central European dance and also a genre of dance music familiar throughout Europe and the Americas. It originated in the middle of the 19th century in Bohemia.[246] Polka is still a popular genre of folk music in many European countries and is performed by folk artists in Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Czech Republic, Netherlands, Croatia, Slovenia, Germany, Hungary, Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Ukraine, Belarus, Russia and Slovakia.[247] Local varieties of this dance are also found in the Nordic countries, United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Latin America (especially Mexico), and in the United States. German Volkslieder perpetuated by Liederhandschriften manuscripts like Carmina Burana[248] date back to medieval Minnesang and Meistersinger traditions.[249] Those folk songs revived in the late 18th century period of German Romanticism,[250] first promoted by Johann Gottfried Herder[251][252] and other advocates of the Enlightenment,[253] later compiled by Achim von Arnim[254] and Clemens Brentano (Des Knaben Wunderhorn)[255] as well as by Ludwig Uhland.[256] The Volksmusik and folk dances genre, especially in the Alpine regions of Bavaria, Austria, Switzerland (Kuhreihen) and South Tyrol, up to today has lingered in rustic communities against the backdrop of industrialisation[257]—Low German shanties or the Wienerlied[258] (Schrammelmusik) being notable exceptions. Slovene folk music in Upper Carniola and Styria also originated from the Alpine traditions, like the prolific Lojze Slak Ensemble.[259] Traditional Volksmusik is not to be confused with commercial Volkstümliche Musik, which is a derivation of that.[260] The Hungarian group Muzsikás played numerous American tours[261] and participated in the Hollywood movie The English Patient[262] while the singer Márta Sebestyén worked with the band Deep Forest.[263] The Hungarian táncház movement, started in the 1970s, involves strong cooperation between musicology experts and enthusiastic amateurs.[264] However, traditional Hungarian folk music and folk culture barely survived in some rural areas of Hungary, and it has also begun to disappear among the ethnic Hungarians in Transylvania. The táncház movement revived broader folk traditions of music, dance, and costume together and created a new kind of music club.[265] The movement spread to ethnic Hungarian communities elsewhere in the world.[265] Balkan music Main article: Balkan music See also: Balkan folk music and Romani music  The Mystery of the Bulgarian Voices Balkan folk music was influenced by the mingling of Balkan ethnic groups in the period of the Ottoman Empire.[266] It comprises the music of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Montenegro, Serbia, Romania, North Macedonia, Albania, some of the historical states of Yugoslavia or Serbia and Montenegro and geographical regions such as Thrace.[267] Some music is characterised by complex rhythm.[268] A notable act is the Mystery of the Bulgarian Voices, which won the Grammy Award for Best Traditional Folk Recording at the 32nd annual ceremony.[269][270] An important part of the whole Balkan folk music is the music of the local Romani ethnic minority, which is called tallava and brass band music.[271][272] Nordic folk music  Latvian men's folk ensemble Vilki, performing at the festival of Baltic crafts and warfare Apuolė 854 in Apuolė, August 2009 Main article: Nordic folk music See also: Traditional Nordic dance music, Joik, Nyckelharpa, and Baltic psaltery Nordic folk music includes a number of traditions in Northern European, especially Scandinavian, countries. The Nordic countries are generally taken to include Iceland, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Greenland.[273] Sometimes it is taken to include the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.[274] Maria Gasolina - Dooyo Maria Gasolina oli suomalainen, pääasiassa brasilialaista populaarimusiikkia suomeksi esittävä yhtye, joka oli perustettu Helsingissä vuonna 2001. Yhtyeeltä ilmestyi neljä pitkäsoittoa, Se jokin vuonna 2006, Mä olen sun vuonna 2008, Aina uusi aalto vuonna 2010 ja Pitkää siltaa vuonna 2017. Mä olen sun -levyn singleraita ”Kaipuusamba” valittiin Radio Helsingin kuulijoiden vuoden 2008 kesähitiksi. The many regions of the Nordic countries share certain traditions, many of which have diverged significantly, like Psalmodicon of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway.[275] It is possible to group together the Baltic states (or, sometimes, only Estonia) and parts of northwest Russia as sharing cultural similarities,[276] although the relationship has gone cold in recent years.[277] Contrast with Norway, Sweden, Denmark and the Atlantic islands of Iceland and the Faroe Islands, which share virtually no similarities of that kind. Greenland's Inuit culture has its own unique musical traditions.[278] Finland shares many cultural similarities with both the Baltic nations and the Scandinavian nations. The Sami of Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia have their own unique culture, with ties to the neighboring cultures.[279] Swedish folk music is a genre of music based largely on folkloric collection work that began in the early 19th century in Sweden.[280] The primary instrument of Swedish folk music is the fiddle.[281] Another common instrument, unique to Swedish traditions, is the nyckelharpa.[282] Most Swedish instrumental folk music is dance music; the signature music and dance form within Swedish folk music is the polska.[283] Vocal and instrumental traditions in Sweden have tended to share tunes historically, though they have been performed separately.[284] Beginning with the folk music revival of the 1970s, vocalists and instrumentalists have also begun to perform together in folk music ensembles. |

国と地域の形態 アフリカ 主な記事 アフリカの音楽  アフリカのラメロフォン、親指ピアノ、ムビラ アフリカは広大な大陸[107]であり、その地域や国々は独自の音楽的伝統を持っている[108][109]。ほとんどの場合、北アフリカの音楽はサハラ 以南のアフリカ音楽の伝統とは異なる歴史を持っている[110]。 アフリカン・アメリカン・ミュージックやソカ、カリプソ、ズークといったカリブ海の多くのジャンル、サンバ、キューバン・ルンバ、サルサ、その他のクラー ベ(リズム)をベースとしたジャンルといったラテンアメリカの音楽ジャンルを含むアフリカン・ディアスポラの音楽とダンスの形態は、程度の差こそあれアフ リカ人奴隷の音楽を基盤としており、それがアフリカのポピュラー音楽に影響を与えている[111][112]。 アジア 以下も参照: タマンセロ、イランのフォーク・ミュージック、インドのフォーク・ミュージック パバン・ダス・バウル パバン・ダス・バウル(1961年生まれ)は、インド出身の著名なバウル・シンガー/ミュージシャンで、伴奏としてドゥブキ、小型タンバリン、時にはエク タラも演奏する。国際的な音楽シーンにおいて伝統的なバウル音楽を開拓し、フォーク・フュージョン音楽のジャンルを確立したことで知られる。 多くのアジア文明は芸術/宮廷/クラシック様式と「民俗」音楽を区別している[113][114]。 例えば、故アラム・ロハールは民俗歌手に分類された南アジアの歌手の一例である[115]。 Khunung Eshei/Khuland Esheiは、アジアの国であるインド、マニプールのメイテイ族の古代の民謡であり、アジアのフォーク・ミュージックの一例であり、彼らがそれを独自のジャンルに押し上 げた例である[116]。 中国のフォーク・ミュージック さらに詳しい情報 中国の音楽§民間音楽、詩経、越譜 考古学的発見により、中国の民族音楽は7000年前にさかのぼる[117]。 漢民族の伝統的な冠婚葬祭には通常、嗩吶(スオナ)と呼ばれるオーボエの一種[119]と、楚鼓笙(チュイグショウ)と呼ばれる打楽器による合奏が含まれ る[120]。西安の太鼓音楽は管楽器と打楽器で構成され[122]、西安周辺で人気があり、中国国外でも商業的な人気を得ている[123]。もうひとつ の重要な楽器は笙で、中国のパイプの一種である。 福建省南部および台湾では、南京または南竿は伝統的なバラードのジャンルである[125]。 [127][128]さらに南の汕頭、客家、潮州では、鄭合奏が盛んである[129]。 [江南四竹(江南の絹と竹の音楽)は器楽音楽の一種で、上海の茶館でアマチュアの音楽家によって演奏されることが多い。 [132]広東音楽または広東音楽は広州とその周辺地域の器楽音楽である[133]。この地域の音楽は越州(広東オペラ)音楽に影響を与え[134]、後 に中華人民共和国のもとで中国の自称「黄金時代」に人気を博すことになる[135]。 中国では古くから民謡が記録されている。粤笛という用語は、バラード、哀歌、民謡、恋歌、宮廷で演奏される歌など幅広い歌に使われていた[136]。民謡 は、地理的地域、言語の種類、民族、社会的機能(仕事歌、儀礼歌、求愛歌など)、音楽の種類によって分類される。中国の民俗学者が収集した現代のアンソロ ジーでは、伝統的な歌、革命的な歌、新しく発明された歌に区別されている[137]。中国西北部の歌は「花歌」(hua'er)として知られているが、こ れは美しい女性への言及であり、かつてはエロティックな内容で悪名高かった。 [138]江蘇省の村の「山の歌」(shan'ge)もまた、その情愛をテーマにしたものでよく知られている[139][140]。その他の地域の歌の伝 統には、長江デルタ下流の「打ち鳴らし歌詞」(tanci)、広東の木魚の伝統(muyuまたはmuk-yu)、華北の太鼓の歌(guci)などがある [141]。 21世紀には、多くの大切にされてきた中国の民謡がユネスコの人類無形文化遺産代表リストに登録された[142]。その過程で、かつては低俗なものと見な されていた歌が、現在ではロマンチックな求愛の歌として再構築されている[143]。 スリランカの伝統民謡 主な記事 スリランカの音楽 スリランカの芸術、音楽、舞踊は自然の要素に由来しており、仏教的な環境の中で享受され発展してきた[145]。音楽にはいくつかの種類があり、数種類の 楽器しか使用しない[146]。インドの影響を受けた古典音楽は独特なものに成長した[147][148][149][150]。 シンハラ軽音楽の伝統的な演劇、音楽、歌は典型的なスリランカのものである[151]。寺院の絵画や彫刻には鳥、象、野生動物、花、木が描かれ、伝統的な 18の踊りには鳥や動物の踊りが描かれている: マユラ・ワンナマ-孔雀の踊り[153][154]。 ハヌマ・ワンナマ-猿の踊り[155]。 ガジャガ・ワンナーマ-象の踊り 音楽の種類は以下の通り: 地方劇音楽にはコラム[156]型とナダガム型がある[157]。コラム音楽は、主に悪魔払いの儀式における仮面舞踊の伴奏のための低音域のカントリー・ チューンに基づく[158][159]。 ナダガム音楽は、南インドのストリートドラマの影響を受けてより発展した形態であり、南インドのアーティストたちによって紹介された。1824年、ネゴン ボのフィリプ・シンホは、テリング語で書かれた『ハリシュチャンドラ・ナダガマ』をフングランケタ(Hnguranketha)で上演した。後に「マナ メ」[162]、「サンダ・キンドゥル」[163]などが紹介された。デヒワラのドン・バスティアンは、まずインドのドラマを見てノールティを導入し、そ の後ジョン・デ・シルヴァが1886年にラーマーヤナヤと同様に発展させた[164]。 シンハラ軽音楽は現在スリランカで最も人気のあるタイプの音楽であり、民族音楽、コーラム音楽、ナーダガム音楽、ノールティ音楽、映画音楽、クラシック音 楽、西洋音楽などの影響を受けて豊かになっている[165]。音楽を学ぶためにインドを訪れ、後に軽音楽を紹介し始めたアーティストもいる。アナンダ・サ マラコーネはその先駆者であり[166][167]、国歌も作曲した[168]。 古典シンハラ・オーケストラは5つのカテゴリーの楽器で構成されているが、打楽器の中でも太鼓は舞踊に不可欠である[169]。 太鼓のリズムの躍動的なビートが舞踊の基本を形成している[170]。 踊り手の足は床を跳ね、太鼓のビートの複雑なリズムを反映したパターンで跳躍したり旋回したりする。このドラム・ビートは、最初に聞いたときは単純に思え るかもしれないが、複雑なリズムとバリエーションをマスターするには長い時間がかかり、ドラマーは時にその激しさをクレッシェンドさせることもある。3つ のスタイル(一面、二面、平面)に分類される6種類の一般的な太鼓がある[171][172]。 典型的なシンハラ舞踊はカンディアン・ダンスと呼ばれ、ガタベーラ太鼓はこの舞踊に不可欠である[173]。 ヤク・ベーラは悪魔の太鼓、あるいは踊り手が仮面をつけて悪魔の踊りを演じるロー・カントリー・ダンスで使われる太鼓であり、高度に発達した芸術形式と なっている[174]。 ダウラは樽型の太鼓で、かつてはタンマッタマとともに、拍子を厳密に合わせるための伴奏太鼓として使用されていた[175]。 タンマッタマは平らな二面太鼓である。ドラマーは、側面で叩く他の太鼓とは異なり、上面の2つの面をスティックで叩く。これは前述のDawulaの仲間で ある[176]。 小型の双頭のハンドドラムは歌の伴奏に使われる。主にバンナムのような詩の踊りで聞かれる[要出典]。 ラバナは平らな面を持つ円形の太鼓で、いくつかのサイズがある[177]。大きなラバナ(バンクー・ラバナと呼ばれる)は、円形の短い脚のテーブルのよう に床に置かなければならず、数人(伝統的には女性)がその周りに座って両手で叩くことができる[178]。小型のラバナは、演奏者がどこへ行くにも持ち運 ぶことができるため、移動太鼓の一種である[180]。 その他の楽器は以下の通り: タランパタ - 2つの小さなシンバルを弦でつないだもの[181]。 管楽器セクションは、クラリネットに似た楽器によって支配されている。というのも、シンハラ舞踊は西洋世界が知っているような音楽に合わせたものではな く、リズムが王様だからである。 銀や真鍮のような金属製のフルートは、カンディヤ舞踊の伴奏にけたたましい音楽を奏でます。法螺貝(ハクゲディヤ)も自然楽器の一種で、奏者は壮大な儀式 の開会を告げるためにこれを吹く[182]。 ラヴァナハッタ(ravanhatta、rawanhattha、ravanastronまたはravana hasta veena)は、かつて西インドで流行した弓を使ったバイオリンである[183][184]。主弦は2本で、1本は鋼鉄、もう1本は馬の毛である [185]。長い弓にはジングルベルが付いている[186][187]。 オーストラリア 以下も参照のこと: オーストラリアのフォーク・ミュージックおよびオーストラリアの先住民音楽 フォークソングの伝統は、イングランド、スコットランド、アイルランドからの初期の入植者たちによってオーストラリアに持ち込まれ、特にアウトバックの農 村地帯に定着しました[188][189]。ブッシュ・バラッドという形式で書かれた韻を踏んだ歌、詩、物語は、しばしば「ブッシュの中のオーストラリ ア」の遍歴と反骨精神に関連しており、作者や演奏者はしばしばブッシュ吟遊詩人と呼ばれます。 [190]19世紀はブッシュ・バラッドの黄金時代であった[191]。ジョン・メレディス(John Meredith)が1950年代に録音したものがオーストラリア国立図書館のコレクションの基礎となった[190]。 典型的な題材としては、鉱業、牧畜、羊の毛刈り、放浪、戦争の話、1891年のオーストラリアの毛刈り労働者のストライキ、土地を持たない労働者階級とス クワッター(地主)との階級闘争、ネッド・ケリーのような無法者、さらに恋愛やトラック運送業などより現代的なものなどがある[192][193]。 [194]最も有名なブッシュ・バラードは「Waltzing Matilda」で、「オーストラリアの非公式国歌」と呼ばれている[195]。 オーストラリア先住民音楽には、オーストラリア先住民族と総称されるアボリジニとトレス海峡諸島民の音楽が含まれる[196]。この音楽には、オーストラ リア先住民族が実践してきた様々な特徴的な伝統音楽スタイルと、オーストラリア先住民族のアーティストが解釈・演奏する様々な現代音楽スタイルやヨーロッ パの伝統音楽との融合が組み込まれている。 [197]音楽は、これらの民族の社会的、文化的、儀式的な行事の不可欠な一部を形成しており、数千年にわたる彼らの個人的、集団的な歴史を経て今日に 至っている[198][199]。伝統的な形式には、特定の地域やオーストラリア先住民グループ特有の演奏や楽器の多くの側面が含まれる[200]。音楽 はオーストラリア先住民の文化維持に欠かせないものである[202]。 ヨーロッパ 以下も参照のこと: イングランドのフォーク・ミュージック、フランスのフォーク・ミュージック、ドイツのフォーク・ミュージック、ギリシャのフォーク・ミュージック、イタリアのフォーク・ミュージック、スペインの音楽 バトルフィールド・バンドのコンサート2006 バトルフィールド・バンドはスコットランドの伝統音楽グループ。1969年にグラスゴーで結成され、これまでに30枚以上のアルバムをリリース。2010 年現在、オリジナルメンバーは一人もバンドに残っていない。 ケルトの伝統音楽 以下も参照: アイルランドの民族音楽およびスコットランドの民族音楽 ケルト音楽は、アーティスト、レコード会社、楽器店、音楽雑誌によって、ケルト民族の民族音楽の伝統から発展した幅広い音楽ジャンルのグループを表すため に使われる用語である[203]。これらの伝統には、アイルランド、スコットランド、マンクス、コーニッシュ、ウェールズ、ブルトンの伝統が含まれる。 [204] アストゥリアスやガリシアの音楽も含まれることが多いが、これが音楽的に密接な関係があることを示す重要な研究はない[205][206]。 ブルターニュのフォーク復興は1950年代に「バガドゥー」や「カン=ハ=ディスカン」によって始まり、その後1960年代半ば以降のアラン・スティヴェ ルの活動によって世界的に有名になった[207]。 アイルランドでは、クランシー・ブラザーズとトミー・マケム(メンバーは全員アイルランド出身だが、ニューヨークのグリニッジ・ヴィレッジを拠点に活動し ている間に有名になった[208])、ダブリナーズ、[209] クラナド、[210] プランクティ、[211] ザ・チーフタンズ、[212][213] ザ・ポーグス、[214] ザ・コーズ、[215] ザ・アイリッシュ・ローヴァーズ、[216] その他さまざまなフォーク・バンドが、過去数十年にわたってアイルランドの伝統音楽を活性化し、再人気を得るために多くのことを行ってきた。 [217]。これらのバンドは多かれ少なかれアイルランド音楽の伝統に根ざしており、シェイマス・アニスやピーター・ケネディといったアーティストの努力 の恩恵を受けている[207]。 スコットランドでは、The Corries、[218] Silly Wizard、[219][220] Capercaillie、[221] Runrig、[222] Jackie Leven、[223] Julie Fowlis、[224] Karine Polwart、[225] Alasdair Roberts、[226][227] Dick Gaughan、 [228] ウルフストーン、[229] ボーイズ・オブ・ザ・ラフ、[230] ザ・サイレンサーズ[231]は、伝統的なスコットランドやゲールのフォークソングをより現代的なジャンルとミックスすることによって、スコットランド・ フォークの活気と新鮮さを保ってきた。 [これらのアーティストはヨーロッパ大陸や北米でも商業的に成功を収めている[233]。スコットランドの伝統音楽シーンには才能豊かなアーティストが台 頭してきており、Mànran、[234] Skipinnish、[235] Barluath[236]、Breabach[237]といったバンドや、Patsy Reid、[238] Robyn Stapleton[239]、Mischa MacPherson[240]といったソロ・アーティストが近年多くの成功を収めている[241]。 中東欧 以下も参照: ベラルーシの音楽、ハンガリーの民族音楽、モルドヴァの音楽、ロシアの民族音楽、ウクライナの民族音楽、スロヴェニアの音楽、チェコのフォークロア 東欧圏時代には、民族舞踊が国家によって積極的に奨励された[242]。ロシアとポーランドの舞踊団は、1937年頃から1990年頃まで非共産主義ヨー ロッパを巡回した[243]。 演奏時間: 2分4秒.2:04 バグパイプを演奏するĽubomír Párička(スロヴァキア ポルカは中央ヨーロッパのダンスであり、ヨーロッパとアメリカ大陸で親しまれているダンス音楽のジャンルでもある。ポーランド、ラトヴィア、リトアニア、 チェコ共和国、オランダ、クロアチア、スロヴェニア、ドイツ、ハンガリー、オーストリア、スイス、イタリア、ウクライナ、ベラルーシ、ロシア、スロヴァキ アでは、フォーク・アーティストたちによって踊られている。 カルミナ・ブラーナ[248]のようなリートハンドシュリフテンの写本によって広まったドイツの民謡は、中世のミンネザングやマイスタージンガーの伝統に さかのぼる[249]。それらの民謡は、18世紀後半のドイツ・ロマン主義[250]の時代に復活し、ヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダー[251] [252]をはじめとする啓蒙主義の提唱者たちによって最初に推進され[253]、後にアヒム・フォン・アルニム[254]やクレメンス・ブレンターノ (Des Knaben Wunderhorn)[255]、ルートヴィヒ・ウーランドによって編纂された[256]。 特にバイエルン、オーストリア、スイス(クーライヘン)、および南チロルのアルプス地方におけるフォルクスムジークと民俗舞曲のジャンルは、今日に至るま で工業化を背景に素朴な地域社会に残っている[257]-低地ドイツのシャンティやヴィーネルリート[258](シュランメルムジーク)は特筆すべき例外 である。上カルニオラとシュタイアーマルク州のスロヴェニアフォーク・ミュージックも、多作なロイツェ・スラック・アンサンブルのようにアルプスの伝統に由来する [259]。伝統的なフォルクスムジークは、その派生である商業的なフォルクスシュトゥムジークと混同されるべきではない[260]。 ハンガリーのグループであるムズィカーシュは数多くのアメリカ・ツアーに参加し[261]、ハリウッド映画『イングリッシュ・ペイシェント』にも参加した [262]。タンチャーズ運動は、音楽、舞踊、衣装といったより広範な民俗伝統を共に復活させ、新しい種類の音楽クラブを作り上げた[265]。この運動 は世界の他の地域のハンガリー系民族のコミュニティにも広まった[265]。 バルカン音楽 主な記事 バルカン音楽 以下も参照: バルカン民族音楽、ロマーニ音楽  ブルガリアの声の謎 ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナ、ブルガリア、クロアチア、ギリシャ、モンテネグロ、セルビア、ルーマニア、北マケドニア、アルバニア、ユーゴスラビアやセルビ ア・モンテネグロの歴史的国家の一部、トラキアなどの地理的地域の音楽から成る[266]。 特筆すべきは、第32回グラミー賞で最優秀トラディショナル・フォーク・レコーディング賞を受賞した「ブルガリアの声の神秘」である[269] [270]。 バルカン民族音楽全体の重要な部分は、タラヴァやブラスバンド音楽と呼ばれる地元の少数民族ロマニの音楽である[271][272]。 北欧の民族音楽  2009年8月、アプオレ(Apuolė)で開催されたバルト工芸と戦火の祭典「Apuolė 854」で演奏するラトビアの男性フォーク・アンサンブル、ヴィルキ(Vilki)。 主な記事 北欧の民族音楽 以下も参照のこと: 北欧の伝統舞踊音楽、ヨイク、ニッケルハルパ、バルトのプサルテリ 北欧の民族音楽には、北欧、特にスカンディナヴィア諸国の数多くの伝統が含まれる。北欧諸国は一般的に、アイスランド、ノルウェー、フィンランド、ス ウェーデン、デンマーク、グリーンランドを含むと考えられている[273]。エストニア、ラトヴィア、リトアニアのバルト三国を含むと考えられることもあ る[274]。 Maria Gasolina - Dooyo 「マリア・ガソリーナは、主にブラジルのポピュラー音楽をフィンランド語で演奏するフィンランドのバンドで、2001年にヘルシンキで結成された。 2006年に『Se jokin』、2008年に『Mä olen sun』、2010年に『Aina uusi aalto』、2017年に『Pitkää siltaa』という4枚のロング・アルバムをリリース。 Mä olen sun』からのシングル「Kaipuusamba」は、ラジオ・ヘルシンキのリスナーによって2008年の夏のヒット曲に選ばれた。」 北欧諸国の多くの地域は特定の伝統を共有しているが、その多くはデンマーク、スウェーデン、ノルウェーのプサルモディコンのように大きく分岐している [275]。バルト三国(あるいはエストニアのみという場合もある)とロシア北西部の一部を文化的な類似性を共有する地域としてまとめることは可能である が[276]、その関係は近年冷え込んでいる[277]。ノルウェー、スウェーデン、デンマーク、大西洋に浮かぶアイスランドとフェロー諸島は、その種の 類似性を事実上共有していないのとは対照的である。グリーンランドのイヌイット文化には独自の音楽的伝統がある[278]。フィンランドはバルト諸国やス カンジナビア諸国と多くの文化的類似点を共有している。スウェーデン、ノルウェー、フィンランド、ロシアのサーミ人は、近隣の文化とのつながりを持ちなが ら独自の文化を持っている[279]。 スウェーデンフォーク・ミュージックは、主に19世紀初頭にスウェーデンで始まった民俗的な収集作業に基づく音楽のジャンルである[280]。スウェーデンフォーク・ミュージックの主 な楽器はフィドルである[281]。スウェーデンの伝統に特有のもう1つの一般的な楽器はニッケルハルパである[282]。スウェーデンの器楽フォーク・ミュージックの ほとんどは舞踊音楽であり、スウェーデンフォーク・ミュージックにおける特徴的な音楽および舞踊形式はポルスカである。 [スウェーデンの声楽と器楽の伝統は、歴史的には曲を共有する傾向があるが、別々に演奏されることもあった[284]。 1970年代のフォーク・ミュージックの復興に始まり、声楽家と器楽家はフォーク・ミュージックのアンサンブルで共演するようにもなった。 |