ソンタグ「反解釈」ノート

On

Susan Sontag's Against

Interpretation

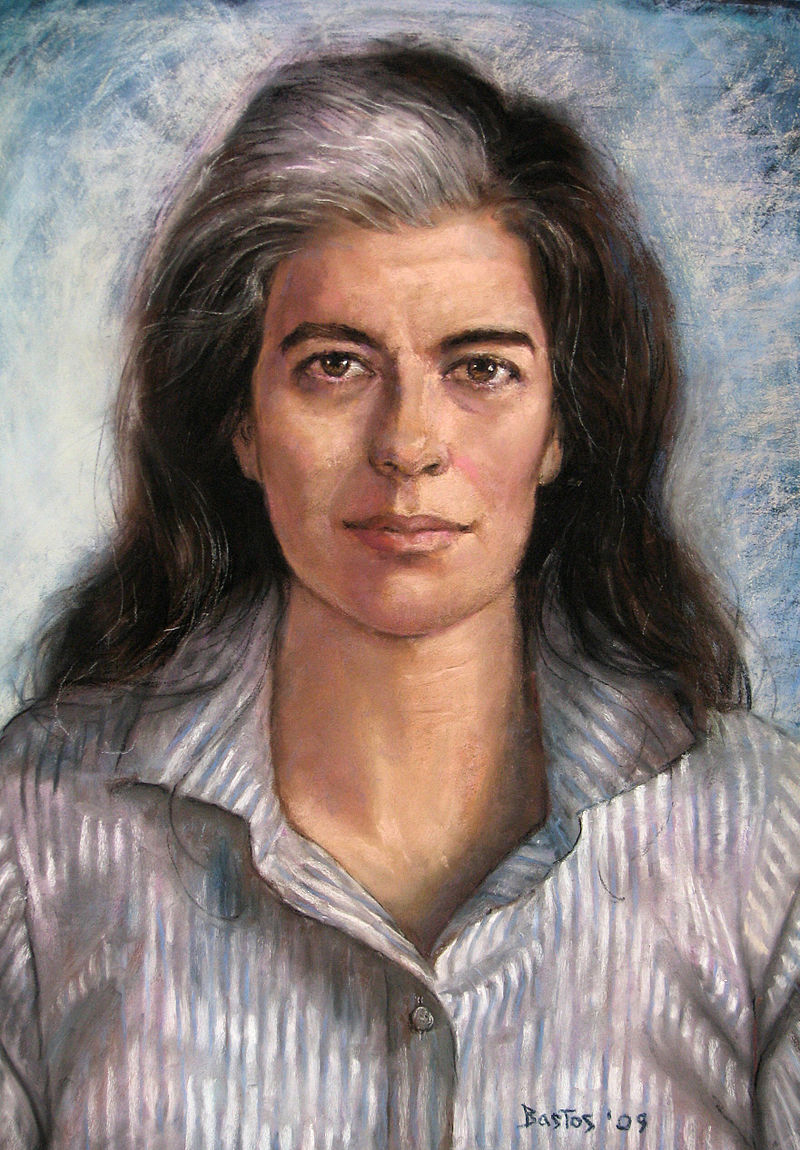

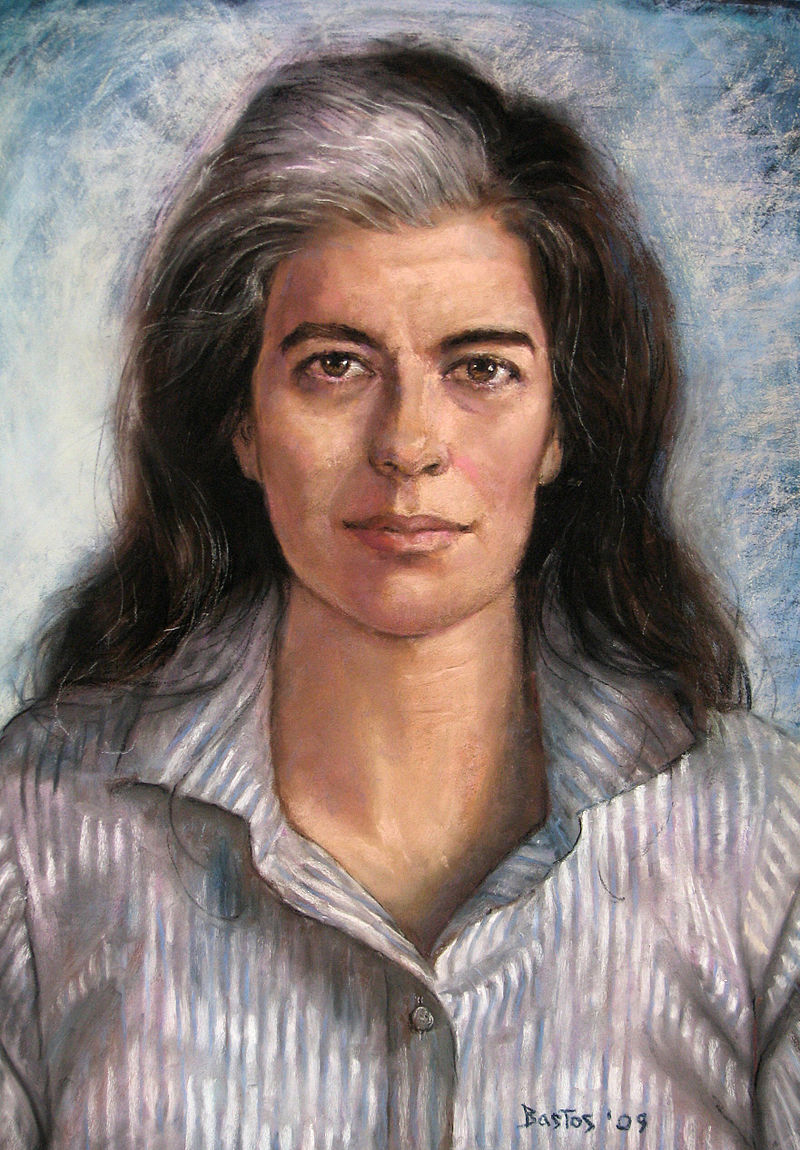

Pastel portrait of Susan Sontag

commissioned by the Gay & Lesbian Review for the 2009 May-June cover

★「都市環境のなかでわれわれの五感を襲っている雑多な味覚や嗅覚や

視覚に加うるに、各人に提供される芸術作品の極端な増加を考えてみるがいい。われわれの

文化の基盤は過剰、生産過剰にある。その結果、われわれの感覚的経験は着実に鋭敏さを失

いつつある。現代生活の物質的充満や人口過密など、あらゆる条件が力を合わせて、われわ

れの感覚的能力を鈍らせようとする。だから、今日批評家の任務は、われわれの感覚、われ

われの能力(別の時代の感覚や能力でなく)の置かれている状況に照らして、評価されなけ

ればならないのである」(33)——スーザン・ソンタグ

エピグラム:Content is a glimpse of something, an encounter like a flash. It’s very tiny—very tiny, content. WILLEM DE KOONING, in an interview It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible. OSCAR WILDE, in a letter

内容とは何ものかの片鱗であり、つかのまの出会いに過ぎぬ。ちっぽけな、まもとにちっぽけな 代物だよ、内容ってやつは(ウィレム・デ・クーニン)/浅はかな人間に限って自分は外見で判断しないという。世界の神秘は目に見えないものではなく、目に 見えるもののなかにある(オスカー・ワイルド)(→ソンタグ「様式=スタイル について」)

| 節番号 |

パラ |

||

| The earliest experience of art

must have been that it was incantatory,

magical; art was an instrument of ritual. (Cf. the paintings in the

caves at

Lascaux, Altamira, Niaux, La Pasiega, etc.) The earliest theory of art,

that

of the Greek philosophers, proposed that art was mimesis, imitation of

reality. |

1 |

1 |

・芸術模倣(ミメシス)説 芸術は儀式の道具であった。(ラスコー、アルタミラ、ニアウ、ラ・パシエガなどの洞窟に描かれた絵を参照)最古の芸術理論であるギリシア哲学者たちは、芸 術とはミメーシス(模倣)であり、現実の模倣であると提唱した。 |

| It is at this point that the

peculiar question of the value of art arose. For the mimetic theory, by

its very terms, challenges art to justify itself. |

2 |

・芸術の存在理由 この時点で、芸術の価値という独特の問題が生じた。というのも、模倣論は、その言葉そのものからして、芸術がそれ自身を正当化することに挑戦しているから である。 |

|

| Plato, who proposed the theory,

seems to have done so in order to

rule that the value of art is dubious. Since he considered ordinary

material

things as themselves mimetic objects, imitations of transcendent forms

or

structures, even the best painting of a bed would be only an “imitation

of

an imitation.” For Plato, art was not particularly useful (the painting

of a

bed is no good to sleep on nor, in the strict sense, true. And

Aristotle’s

arguments in defense of art do not really challenge Plato’s view that

all

art is an elaborate trompe l’oeil, and therefore a lie. But he does

dispute

Plato’s idea that art is useless. Lie or no, art has a certain value

according

to Aristotle because it is a form of therapy. Art is useful, after all,

Aristotle

counters, medicinally useful in that it arouses and purges dangerous

emotions. |

3 |

こ

の理論を提唱したプラトンは、芸術の価値は疑わしいと断定するためにそうしたようだ。プラトンは、通常の物質的なものはそれ自体模倣的なものであり、超越

的な形態や構造の模倣であると考えたため、たとえ最高のベッドの絵であっても、それは "模倣の模倣

"に過ぎなかった。プラトンにとって、芸術は特に有用なものではなかった(ベッドの絵は寝ても意味がないし、厳密な意味では真実でもない)。そして、芸術

を擁護するアリストテレスの議論は、すべての芸術は精巧なだまし絵であり、したがって嘘であるというプラトンの見解に異議を唱えるものではない。しかし、

芸術は役に立たないというプラトンの考えには異議を唱えている。嘘であろうとなかろうと、アリストテレスによれば芸術には一定の価値がある。結局のとこ

ろ、芸術は有用であり、危険な感情を喚起し浄化するという点で薬として有用なのだ、とアリストテレスは反論する。 |

|

| In Plato and Aristotle, the

mimetic theory of art goes hand in hand

with the assumption that art is always figurative. But advocates of the

mimetic theory need not close their eyes to decorative and abstract

art.

The fallacy that art is necessarily a “realism” can be modified or

scrapped

without ever moving outside the problems delimited by the mimetic

theory. |

4 |

・プラトンからアリストテレスへ プラトンやアリストテレスにおいて、芸術の模倣論は、芸術は常に具象的であるという仮定と密接に結びついている。しかし、模倣理論の提唱者が装飾芸術や抽 象芸術に目をつぶる必要はない。芸術は必然的に「写実主義」であるという誤謬は、模倣理論によって区切られた問題の外に出ることなく、修正することも廃絶 することもできるのだ。 |

|

| The fact is, all Western

consciousness of and reflection upon art have

remained within the confines staked out by the Greek theory of art as

mimesis or representation. It is through this theory that art as such—

above and beyond given works of art—becomes problematic, in need of

defense. And it is the defense of art which gives birth to the odd

vision by

which something we have learned to call “form” is separated off from

something we have learned to call “content,” and to the

well-intentioned

move which makes content essential and form accessory. |

5 |

事

実、西洋の芸術に対する意識と考察はすべて、ギリシアの「模倣」あるいは「表象」としての芸術理論が定めた枠内にとどまっている。この理論によって、芸術

は、与えられた芸術作品以上に、防衛を必要とする問題となる。そして、私たちが「形」と呼ぶことを学んだものを「内容」と呼ぶことを学んだものから切り離

すという奇妙なビジョンや、内容を本質的なものとし、形を付属的なものとする善意の動きを生み出すのは、芸術の防衛なのである。 |

|

| Even in modern times, when most

artists and critics have discarded

the theory of art as representation of an outer reality in favor of the

theory

of art as subjective expression, the main feature of the mimetic theory

persists. Whether we conceive of the work of art on the model of a

picture

(art as a picture of reality) or on the model of a statement (art as

the

statement of the artist), content still comes first. The content may

have

changed. It may now be less figurative, less lucidly realistic. But it

is still

assumed that a work of art is its content. Or, as it’s usually put

today, that

a work of art by definition says something. (“What X is saying is…,”

“What X is trying to say is…,” “What X said is…” etc., etc.) |

6 |

ほ

とんどの芸術家や批評家が、外的現実の表現としての芸術論を捨て、主観的表現としての芸術論を支持するようになった現代においても、模倣論の主要な特徴は

存続している。芸術作品を絵画のモデル(現実の絵画としての芸術)として考えようが、陳述のモデル(芸術家の陳述としての芸術)として考えようが、内容が

第一であることに変わりはない。その内容は変わっているかもしれない。その内容は、より具象的でなく、より明晰に写実的でなくなっているかもしれない。し

かし、芸術作品とはその内容であることに変わりはない。あるいは、今日一般的に言われているように、芸術作品は定義上、何かを語っている。(Xが言ってい

ることは...」「Xが言おうとしていることは...」「Xが言ったことは...」等々)。 |

|

| None of us can ever retrieve

that innocence before all theory when art

knew no need to justify itself, when one did not ask of a work of art

what

it said because one knew (or thought one knew) what it did. From now to

the end of consciousness, we are stuck with the task of defending art.

We

can only quarrel with one or another means of defense. Indeed, we have

an obligation to overthrow any means of defending and justifying art

which becomes particularly obtuse or onerous or insensitive to

contemporary needs and practice. |

2 |

7 |

・芸術の無垢概念からの自由 ・芸術擁護論からの離脱の必要性 芸術が自己を正当化する必要を知らなかった時代、芸術が何をするものかを知っていた(あるいは知っていると思っていた)ために、芸術作品に何を語るかを問 わなかった時代、あらゆる理論以前のあの無邪気さを、私たちの誰もが取り戻すことはできない。今から意識の終わりまで、私たちは芸術を擁護する作業に追わ れる。私たちは、どちらか一方の防衛手段で争うしかない。実際、私たちは、現代のニーズや実践に対して特に鈍感になったり、負担になったり、鈍感になった りした、芸術を擁護し正当化する手段を打倒する義務がある。 |

| This is the case, today, with the very idea of content itself. Whatever it may have been in the past, the idea of content is today mainly a hindrance, a nuisance, a subtle or not so subtle philistinism. | 8 |

・コンテンツ批判 今日、コンテンツという考え方そのものがそうである。過去にはどうであったにせよ、今日、コンテンツという考え方は、主に邪魔であり、厄介であり、微妙 な、あるいはそうでない俗物主義である。 |

|

| Though the actual developments in many arts may seem to be leading us away from the idea that a work of art is primarily its content, the idea still exerts an extraordinary hegemony. I want to suggest that this is because the idea is now perpetuated in the guise of a certain way of encountering works of art thoroughly ingrained among most people who take any of the arts seriously. What the overemphasis on the idea of content entails is the perennial, never consummated project of interpretation. And, conversely, it is the habit of approaching works of art in order to interpret them that sustains the fancy that there really is such a thing as the content of a work of art. | 9 |

多

くの芸術における実際の発展は、芸術作品がその内容を第一義とする考え方から私たちを遠ざけているように見えるかもしれないが、この考え方はいまだに並外

れたヘゲモニーを発揮している。その理由は、芸術を真摯に受け止める多くの人々の間に、この考え方が、芸術作品との出会い方という名目で浸透しているから

である。内容という概念を過度に強調することが意味するのは、解釈という永遠の、決して完成されることのないプロジェクトである。そして逆に、解釈するた

めに芸術作品に近づく習慣こそが、芸術作品の内容などというものが本当に存在するという空想を支えているのである。 |

|

| Of course, I don’t mean

interpretation in the broadest sense, the sense in

which Nietzsche (rightly) says, “There are no facts, only

interpretations.”

By interpretation, I mean here a conscious act of the mind which

illustrates a certain code, certain “rules” of interpretation. Directed

to art,

interpretation means plucking a set of elements (the X, the Y, the Z,

and

so forth) from the whole work. The task of interpretation is virtually

one

of translation. The interpreter says, Look, don’t you see that X is

really—

or, really means—A? That Y is really B? That Z is really C? |

3 |

10 |

もちろん、私は広義の解釈という意味ではなく、ニーチェが(正しくは)"事実は存在せず、解釈のみが存在する "と言っているような意味での解釈である。解釈とは、ある種のコード、解釈の「ルール」を示す心の意識的な行為を意味する。芸術の解釈とは、作品全体から 一連の要素(X、Y、Zなど)を抜き出すことである。解釈の仕事は事実上、翻訳のひとつである。通訳は言う。「いいですか、Xは本当は......いや、 本当はAという意味なんですよ。Yは本当はBなんだよ。Zは本当にCなのか? |

| What situation could prompt this

curious project for transforming a

text? History gives us the materials for an answer. Interpretation

first

appears in the culture of late classical antiquity, when the power and

credibility of myth had been broken by the “realistic” view of the

world

introduced by scientific enlightenment. Once the question that haunts

post-mythic consciousness—that of the seemliness of religious symbols—

had been asked, the ancient texts were, in their pristine form, no

longer

acceptable. Then interpretation was summoned, to reconcile the ancient

texts to “modern” demands. Thus, the Stoics, to accord with their view

that the gods had to be moral, allegorized away the rude features of

Zeus

and his boisterous clan in Homer’s epics. What Homer really designated

by the adultery of Zeus with Leto, they explained, was the union

between

power and wisdom. In the same vein, Philo of Alexandria interpreted the

literal historical narratives of the Hebrew Bible as spiritual

paradigms.

The story of the exodus from Egypt, the wandering in the desert for

forty

years, and the entry into the promised land, said Philo, was really an

allegory of the individual soul’s emancipation, tribulations, and final

deliverance. Interpretation thus presupposes a discrepancy between the

clear meaning of the text and the demands of (later) readers. It seeks

to

resolve that discrepancy. The situation is that for some reason a text

has

become unacceptable; yet it cannot be discarded. Interpretation is a

radical strategy for conserving an old text, which is thought too

precious

to repudiate, by revamping it. The interpreter, without actually

erasing or

rewriting the text, is altering it. But he can’t admit to doing this.

He claims

to be only making it intelligible, by disclosing its true meaning.

However

far the interpreters alter the text (another notorious example is the

Rabbinic and Christian “spiritual” interpretations of the clearly

erotic Song of Songs), they must claim to be reading off a sense that

is already

there. |

11 |

・雅歌の精神的な解釈 ・フィロンのタナハ解釈 どのような状況が、このような不思議なテキストの変換プロジェクトを促したのだろうか?歴史はその答えの材料を与えてくれる。解釈は、神話の力と信頼性 が、科学的啓蒙によってもたらされた「現実的」な世界観によって打ち破られた、古典古代後期の文化に初めて登場する。神話以後の意識につきまとう疑問、つ まり宗教的シンボルの見かけの良し悪しが問われるようになると、古代のテキストは原始的な形ではもはや受け入れられなくなった。そこで、古代のテキストを "現代的 "な要求に調和させるために、解釈が召喚された。こうしてストア派は、神々は道徳的でなければならないという彼らの見解に合致させるために、ホメロスの叙 事詩に登場するゼウスとその騒々しい一族の無礼な特徴を寓意化した。ホメロスがゼウスとレトの姦淫によって本当に指定したのは、力と知恵の結合であると彼 らは説明した。同じように、アレクサンドリアのフィロは、ヘブライ語聖書の文字通りの歴史物語を霊的なパラダイムとして解釈した。エジプトからの脱出、 40年間の砂漠での放浪、そして約束の地への入城の物語は、実際には個人の魂の解放、苦難、そして最終的な解放の寓話であるとフィロは言った。このよう に、解釈は、テキストの明確な意味と(後の)読者の要求との間に矛盾があることを前提とする。その食い違いを解消しようとするのである。あるテキストが何 らかの理由で受け入れられなくなったという状況である。解釈とは、否定するにはあまりにも貴重と思われる古いテキストを、刷新することによって保存するた めの急進的な戦略である。解釈者は、実際にテキストを消去したり書き換えたりすることなく、それを改変しているのである。しかし、彼はそれを認めることは できない。真の意味を明らかにすることで、理解しやすくしているだけだと主張する。どんなに解釈者がテキストを改変しようとも(もう一つの悪名高い例は、 明らかにエロチックな「雅歌」のラビ派やキリスト教の「霊的」解釈である)、彼らはすでにそこにある意味を読み取っていると主張しなければならない。 |

|

| Interpretation in our own time,

however, is even more complex. For

the contemporary zeal for the project of interpretation is often

prompted

not by piety toward the troublesome text (which may conceal an

aggression), but by an open aggressiveness, an overt contempt for

appearances. The old style of interpretation was insistent, but

respectful;

it erected another meaning on top of the literal one. The modern style

of

interpretation excavates, and as it excavates, destroys; it digs

“behind” the

text, to find a sub-text which is the true one. The most celebrated and

influential modern doctrines, those of Marx and Freud, actually amount

to elaborate systems of hermeneutics, aggressive and impious theories

of

interpretation. All observable phenomena are bracketed, in Freud’s

phrase, as manifest content. This manifest content must be probed and

pushed aside to find the true meaning—the latent content beneath. For

Marx, social events like revolutions and wars; for Freud, the events of

individual lives (like neurotic symptoms and slips of the tongue) as

well

as texts (like a dream or a work of art)—all are treated as occasions

for

interpretation. According to Marx and Freud, these events only seem to

be intelligible. Actually, they have no meaning without interpretation.

To

understand is to interpret. And to interpret is to restate the

phenomenon,

in effect to find an equivalent for it. |

12 |

・マルクスとフロイト しかし、現代における解釈はさらに複雑である。というのも、解釈というプロジェクトに対する現代の熱意は、しばしば、厄介なテキストに対する敬虔さ(これ は攻撃性を隠しているかもしれない)ではなく、公然たる攻撃性、外見に対するあからさまな軽蔑によって促されているからである。旧来の解釈は、文字通りの 意味の上に別の意味を重ねるものであった。現代的な解釈のスタイルは掘り起こし、掘り起こすと同時に破壊する。テキストの「背後」を掘り起こし、真実のサ ブテキストを見つけるのだ。最も有名で影響力のある近代の教義、マルクスやフロイトの教義は、実は精巧な解釈学の体系であり、攻撃的で不敬な解釈理論であ る。観察可能な現象はすべて、フロイトの言葉を借りれば「顕在的内容」として括られる。この顕在的な内容は、真の意味、つまりその下にある潜在的な内容を 見出すために、探られ、脇に押しやられなければならない。マルクスにとっては、革命や戦争のような社会的出来事であり、フロイトにとっては、個人の生活上 の出来事(神経症状や舌の滑りのようなもの)やテキスト(夢や芸術作品のようなもの)である。マルクスとフロイトによれば、これらの出来事は理解できるよ うに見えるだけである。実際には、解釈なしには意味を持たない。理解するとは解釈することである。そして解釈とは、現象を再定義することであり、事実上、 現象に相当するものを見つけることである。 |

|

| Thus, interpretation is not (as

most people assume) an absolute value,

a gesture of mind situated in some timeless realm of capabilities.

Interpretation must itself be evaluated, within a historical view of

human

consciousness. In some cultural contexts, interpretation is a

liberating act.

It is a means of revising, of transvaluing, of escaping the dead past.

In other cultural contexts, it is reactionary, impertinent, cowardly,

stifling. |

13 |

・解釈行為の人間化 したがって、解釈は(多くの人が思い込んでいるような)絶対的な価値や、ある時間を超越した能力の領域に位置する心のしぐさではない。解釈は、人間の意識 の歴史観の中で、それ自体が評価されなければならない。ある文化的文脈においては、解釈は解放的な行為である。それは、死んだ過去から逃れるための、価値 を変える手段である。他の文化的文脈においては、解釈は反動的であり、不遜であり、臆病であり、息苦しいものである。 |

|

| Today is such a time, when the

project of interpretation is largely

reactionary, stifling. Like the fumes of the automobile and of heavy

industry which befoul the urban atmosphere, the effusion of

interpretations of art today poisons our sensibilities. In a culture

whose

already classical dilemma is the hypertrophy of the intellect at the

expense of energy and sensual capability, interpretation is the revenge

of

the intellect upon art. |

4 |

14 |

現

代はそのような時代であり、解釈というプロジェクトが大きく反動的で、息苦しい。都市の大気を汚染する自動車や重工業の煙のように、今日の芸術解釈の噴出

は私たちの感性を毒する。エネルギーと感覚的能力を犠牲にして知性を肥大化させるという、すでに古典的なジレンマを抱える文化において、解釈は芸術に対す

る知性の復讐である。 |

| Even more. It is the revenge of

the intellect upon the world. To

interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world—in order to set up a

shadow world of “meanings.” It is to turn the world into this world.

(“This world”! As if there were any other.) |

15 |

・解釈とは世界に対する知性の復讐 それ以上だ。それは世界に対する知性の復讐である。解釈するということは、世界を貧しくすることであり、枯渇させることである。それは世界をこの世界に変 えることである。(この世界」! 他に何かあるかのように)。 |

|

| The world, our world, is depleted, impoverished enough. Away with all duplicates of it, until we again experience more immediately what we have. | 16 |

世界は、私たちの世界は、十分に枯渇し、貧しくなっている。私たちが今

持っているものを、もっとすぐに経験できるようになるまで。 |

|

| In most modern instances,

interpretation amounts to the philistine refusal

to leave the work of art alone. Real art has the capacity to make us

nervous. By reducing the work of art to its content and then

interpreting

that, one tames the work of art. Interpretation makes art manageable,

comformable. |

5(p.23) |

17 |

・本物の芸術は我々を不安にする 現代のほとんどの場合、解釈は芸術作品を放っておくことを拒否する俗物 的な行為に等しい。本物の芸術は私たちを緊張させる力を持っている。芸術作品をその内容に還元し、それを解釈することによって、人は芸術作品を手なずける ことができる。解釈は芸術を扱いやすく、適合可能なものにする。 |

| This philistinism of

interpretation is more rife in literature than in any

other art. For decades now, literary critics have understood it to be

their

task to translate the elements of the poem or play or novel or story

into

something else. Sometimes a writer will be so uneasy before the naked

power of his art that he will install within the work itself—albeit

with a

little shyness, a touch of the good taste of irony—the clear and

explicit

interpretation of it. Thomas Mann is an example of such an

overcooperative author. In the case of more stubborn authors, the

critic is

only too happy to perform the job. |

18 |

こ

のような解釈の俗物主義は、他のどの芸術よりも文学に蔓延している。もう何十年も前から、文芸批評家は詩や戯曲や小説や物語の要素を何か別のものに翻訳す

ることが自分たちの仕事だと理解してきた。時には、作家が自分の芸術の赤裸々な力を前にして不安になり、少し恥ずかしがりながら、皮肉というセンスを交え

て、作品そのものの中に、その芸術の明確で露骨な解釈をインストールすることもある。トーマス・マンは、そのような過協力的な作家の一例である。もっと頑

固な作家の場合、批評家はその仕事を喜んで引き受ける。 |

|

| The work of Kafka, for example,

has been subjected to a mass

ravishment by no less than three armies of interpreters. Those who read

Kafka as a social allegory see case studies of the frustrations and

insanity

of modern bureaucracy and its ultimate issuance in the totalitarian

state.

Those who read Kafka as a psychoanalytic allegory see desperate

revelations of Kafka’s fear of his father, his castration anxieties,

his sense

of his own impotence, his thralldom to his dreams. Those who read Kafka

as a religious allegory explain that K. in The Castle is trying to gain

access

to heaven, that Joseph K. in The Trial is being judged by the

inexorable

and mysterious justice of God…. Another oeuvre that has attracted

interpreters like leeches is that of Samuel Beckett. Beckett’s delicate

dramas of the withdrawn consciousness—pared down to essentials, cut

off, often represented as physically immobilized—are read as a

statement

about modern man’s alienation from meaning or from God, or as an

allegory of psychopathology. |

19 |

・カフカ作品に対する3つのレイプ 例えば、カフカの作品は、3つ以上の解釈者たちによって大量に破壊されてきた。カフカを社会的寓話として読む者は、近代官僚制の挫折と狂気、そして全体主 義国家におけるその究極の発行の事例研究を見る。精神分析的寓話としてカフカを読む者は、カフカの父親への恐怖、去勢の不安、自らの無力感、夢への執着な どの絶望的な暴露を見る。カフカを宗教的寓話として読む人は、『城』のKは天国へのアクセスを得ようとしている、『裁判』のヨーゼフ・Kは神のどうしよう もなく神秘的な正義によって裁かれている......と説明する。サミュエル・ベケットの作品もまた、ヒルのように解釈者を惹きつけてきた。ベケットの引 きこもり意識のデリケートなドラマは、本質を突かれ、断ち切られ、しばしば肉体的に固定化されたものとして表現され、現代人の意味や神からの疎外について の声明として、あるいは精神病理学の寓意として読まれる。 |

|

| Proust, Joyce, Faulkner, Rilke,

Lawrence, Gide…one could go on

citing author after author; the list is endless of those around whom

thick

encrustations of interpretation have taken hold. But it should be noted

that interpretation is not simply the compliment that mediocrity pays

to

genius. It is, indeed, the modern way of understanding something, and

is

applied to works of every quality. Thus, in the notes that Elia Kazan

published on his production of A Streetcar Named Desire, it becomes

clear

that, in order to direct the play, Kazan had to discover that Stanley

Kowalski represented the sensual and vengeful barbarism that was

engulfing our culture, while Blanche Du Bois was Western civilization,

poetry, delicate apparel, dim lighting, refined feelings and all,

though a

little the worse for wear to be sure. Tennessee Williams’ forceful

psychological melodrama now became intelligible: it was about

something, about the decline of Western civilization. Apparently, were

it

to go on being a play about a handsome brute named Stanley Kowalski

and a faded mangy belle named Blanche Du Bois, it would not be

manageable. |

20 |

プ

ルースト、ジョイス、フォークナー、リルケ、ロレンス、ギド......次から次へと作家を挙げればきりがない。しかし、解釈とは、単に凡庸な者が天才に

贈る賛辞ではないことに留意すべきである。実際、解釈とは何かを理解する現代的な方法であり、あらゆる質の作品に適用される。エリア・カザンが発表した

『欲望という名の電車』の演出ノートには、カザンがこの戯曲を演出するために、スタンリー・コワルスキーが我々の文化を飲み込んでいる官能的で復讐に燃え

る野蛮さを表現しているのに対し、ブランシュ・デュボワは西洋文明、詩、繊細な服装、薄暗い照明、洗練された感情など、確かに少しは悪くなってはいるが、

すべてを表現していることを発見しなければならなかったことが明らかにされている。テネシー・ウィリアムズの力強い心理的メロドラマが理解できるように

なった。スタンリー・コワルスキーという名のハンサムな野獣とブランシュ・デュボアという名の色あせた淫乱な美女が繰り広げる戯曲である。 |

|

| It doesn’t matter whether

artists intend, or don’t intend, for their works to

be interpreted. Perhaps Tennessee Williams thinks Streetcar is about

what

Kazan thinks it to be about. It may be that Cocteau in The Blood of a

Poet

and in Orpheus wanted the elaborate readings which have been given

these films, in terms of Freudian symbolism and social critique. But

the

merit of these works certainly lies elsewhere than in their “meanings.”

Indeed, it is precisely to the extent that Williams’ plays and

Cocteau’s

films do suggest these portentous meanings that they are defective,

false,

contrived, lacking in conviction. |

6 |

21 |

芸

術家が自分の作品の解釈を意図するかしないかは問題ではない。おそらくテネシー・ウィリアムズは、『ストリートカー』がカザンの考える通りの作品だと考え

ているのだろう。詩人の血』や『オルフェウス』のコクトーは、フロイト的象徴主義や社会批評の観点から、これらの作品に与えられているような精巧な読解を

望んでいたのかもしれない。しかし、これらの作品の長所は、その "意味

"よりも別のところにあることは確かだ。実際、ウィリアムズの戯曲やコクトーの映画が、このような寓意的な意味を示唆する程度においてこそ、それらは欠陥

品であり、偽りであり、作為的であり、説得力に欠けるのである。 |

| From interviews, it appears that

Resnais and Robbe-Grillet

consciously designed Last Year at Marienbad to accommodate a

multiplicity of equally plausible interpretations. But the temptation

to

interpret Marienbad should be resisted. What matters in Marienbad is

the

pure, untranslatable, sensuous immediacy of some of its images, and its

rigorous if narrow solutions to certain problems of cinematic form. |

22 |

イ

ンタビューによれば、レネとロブ=グリエは『去年マリエンバートで』は、等しくもっともらしい複数の解釈に対応できるように意識的にデザインしたようだ。

しかし、『マリエンバッド』を解釈しようとする誘惑には抗うべきである。マリエンバッド』で重要なのは、いくつかのイメージの純粋で、翻訳不可能で、感覚

的な即時性であり、映画形式のある種の問題に対する、狭いながらも厳格な解決策である。 |

|

| Again, Ingmar Bergman may have

meant the tank rumbling down

the empty night street in The Silence as a phallic symbol. But if he

did, it

was a foolish thought. (“Never trust the teller, trust the tale,” said

Lawrence.) Taken as a brute object, as an immediate sensory equivalent

for the mysterious abrupt armored happenings going on inside the hotel,

that sequence with the tank is the most striking moment in the film.

Those

who reach for a Freudian interpretation of the tank are only expressing

their lack of response to what is there on the screen. |

23 |

・語り手を信用するな、物語を信用せよ(26) 繰り返すが、イングマール・ベルイマンは、『沈黙』の誰もいない夜道をゴロゴロと走る戦車を男根の象徴として言いたかったのかもしれない。しかし、もしそ うだとしたら、それは愚かな考えである。(ホテル内部で起こっている謎めいた突然の装甲ハプニングの感覚的な等価物としてとらえれば、戦車のシークエンス はこの映画で最も印象的な瞬間である。戦車をフロイト流に解釈しようとする人は、スクリーンに映し出されたものに対する反応の欠如を表現しているに過ぎな い。 |

|

| It is always the case that

interpretation of this type indicates a

dissatisfaction (conscious or unconscious) with the work, a wish to

replace it by something else. |

24 |

こ

の種の解釈は常に、作品に対する(意識的あるいは無意識的な)不満や、他の何かに置き換えたいという願望を示すものである。 |

|

| Interpretation, based on the

highly dubious theory that a work of art

is composed of items of content, violates art. It makes art into an

article

for use, for arrangement into a mental scheme of categories. |

25 |

芸

術作品は内容物から構成されるという極めて疑わしい理論に基づく解釈は、芸術を侵害する。それは、芸術を使用するための物品にし、カテゴリーという精神的

スキームにアレンジするためのものである。 |

|

| Interpretation does not, of

course, always prevail. In fact, a great deal of

today’s art may be understood as motivated by a flight from

interpretation. To avoid interpretation, art may become parody. Or it

may

become abstract. Or it may become (“merely”) decorative. Or it may

become non-art. |

7 |

26 |

も

ちろん、常に解釈が優先されるわけではない。実際、今日の芸術の多くは、解釈からの逃避に突き動かされていると理解できるかもしれない。解釈を避けるため

に、芸術はパロディになるかもしれない。抽象的になることもある。あるいは(「単に」)装飾的になるかもしれない。あるいは、非芸術になるかもしれない。 |

| The flight from interpretation

seems particularly a feature of modern

painting. Abstract painting is the attempt to have, in the ordinary

sense,

no content; since there is no content, there can be no interpretation.

Pop

Art works by the opposite means to the same result; using a content so

blatant, so “what it is,” it, too, ends by being uninterpretable. |

27 |

・現代絵画と解釈 解釈からの逃避は、特に現代絵画の特徴であるように思える。抽象絵画は、通常の意味で内容を持たない試みである。内容がない以上、解釈もありえない。ポッ プ・アートは、同じ結果を得るために逆の手段を使っている。あまりにあからさまな内容、つまり「ありのままのもの」を使っているため、それもまた解釈不可 能で終わる。 |

|

| A great deal of modern poetry as

well, starting from the great

experiments of French poetry (including the movement that is

misleadingly called Symbolism) to put silence into poems and to

reinstate

the magic of the word, has escaped from the rough grip of

interpretation.

The most recent revolution in contemporary taste in poetry—the

revolution that has deposed Eliot and elevated Pound—represents a

turning away from content in poetry in the old sense, an impatience

with

what made modern poetry prey to the zeal of interpreters. |

28 |

フ

ランス詩の偉大な実験(象徴主義と誤解を招く呼び方をされている運動を含む)から始まった、詩の中に沈黙を入れ、言葉の魔力を復活させようとする現代詩の

多くも、解釈の荒々しい掌握から逃れてきた。エリオットを退位させ、パウンドを昇格させた革命である。最近の現代詩の嗜好の革命は、古い意味での詩の内容

からの転向、つまり、現代詩を解釈者の熱意の餌食にしているものへの焦りを表している。 |

|

| I am speaking mainly of the

situation in America, of course.

Interpretation runs rampant here in those arts with a feeble and

negligible

avant-garde: fiction and the drama. Most American novelists and

playwrights are really either journalists or gentlemen sociologists and

psychologists. They are writing the literary equivalent of program

music.

And so rudimentary, uninspired, and stagnant has been the sense of what

might be done with form in fiction and drama that even when the content

isn’t simply information, news, it is still peculiarly visible,

handier, more

exposed. To the extent that novels and plays (in America), unlike

poetry

and painting and music, don’t reflect any interesting concern with

changes in their form, these arts remain prone to assault by

interpretation. |

29 |

・小説と演劇 もちろん、私は主にアメリカの状況について話している。前衛芸術が弱く、無視できるような芸術である小説や演劇では、解釈が横行している。アメリカの小説 家や劇作家のほとんどは、ジャーナリストか紳士的な社会学者や心理学者である。彼らは、プログラム音楽と同等の文学を書いているのだ。そして、小説や戯曲 の形式によって何ができるのかという感覚が、あまりにも初歩的で、刺激に欠け、停滞しているため、内容が単なる情報やニュースでない場合でも、独特の目に つきやすく、手軽で、露出度の高いものになっている。アメリカの)小説や戯曲が、詩や絵画や音楽と違って、その形式の変化に対する興味深い関心を反映しな い分、これらの芸術は解釈によって攻撃されやすいままなのだ。 |

|

| But programmatic

avant-gardism—which has meant, mostly,

experiments with form at the expense of content—is not the only defense

against the infestation of art by interpretations. At least, I hope

not. For

this would be to commit art to being perpetually on the run. (It also

perpetuates the very distinction between form and content which is,

ultimately, an illusion.) Ideally, it is possible to elude the

interpreters in

another way, by making works of art whose surface is so unified and

clean, whose momentum is so rapid, whose address is so direct that the

work can be…just what it is. Is this possible now? It does happen in

films,

I believe. This is why cinema is the most alive, the most exciting, the

most

important of all art forms right now. Perhaps the way one tells how

alive

a particular art form is, is by the latitude it gives for making

mistakes in it,and still being good. For example, a few of the films of

Bergman—though

crammed with lame messages about the modern spirit, thereby inviting

interpretations—still triumph over the pretentious intentions of their

director. In Winter Light and The Silence, the beauty and visual

sophistication of the images subvert before our eyes the callow

pseudointellectuality

of the story and some of the dialogue. (The most

remarkable instance of this sort of discrepancy is the work of D. W.

Griffith.) In good films, there is always a directness that entirely

frees us

from the itch to interpret. Many old Hollywood films, like those of

Cukor,

Walsh, Hawks, and countless other directors, have this liberating

antisymbolic

quality, no less than the best work of the new European

directors, like Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player and Jules and Jim,

Godard’s

Breathless and Vivre Sa Vie, Antonioni’s L’Avventura, and Olmi’s The

Fiancés. |

30 |

し

かし、プログラム主義的なアヴァンギャルド主義は、そのほとんどが、内容を犠牲にした形の実験であり、解釈による芸術の蔓延に対する唯一の防御策ではな

い。少なくとも、私はそうであってほしくない。というのも、そうすることは、芸術が永遠に逃げ続けることを約束することになるからだ。(それはまた、究極

的には幻想である形式と内容の区別そのものを永続させることでもある)。理想的なのは、別の方法で解釈者から逃れることである。作品の表面が非常に統一さ

れ、きれいで、勢いがあり、直接的で、作品が...ありのままでいられるような作品を作ることである。今、それは可能なのだろうか?映画では可能だと思

う。だからこそ映画は今、あらゆる芸術の中で最も生き生きとしていて、最もエキサイティングで、最も重要なのだ。おそらく、ある芸術形式がどれほど生きて

いるかを知る方法は、その芸術形式において間違いを犯しても、なお良い作品であることを許容するかどうかということだろう。例えば、ベルイマンのいくつか

の映画は、現代精神についてのいい加減なメッセージを詰め込み、それによって解釈の幅を広げているが、それでも監督の気取った意図に打ち勝っている。冬の

光』や『沈黙』では、映像の美しさと洗練されたビジュアルが、ストーリーや台詞の一部の無愛想な似非インテリぶりを目の前で覆す。(この種の矛盾の最も顕

著な例は、D・W・グリフィスの作品である)。優れた映画には常に、解釈するかゆみから私たちを完全に解放してくれる率直さがある。キューカー、ウォル

シュ、ホークス、その他無数の監督の作品のように、多くの古いハリウッド映画は、トリュフォーの『ピアノ弾きを撃て』や『ジュールとジム』、ゴダールの

『息もできない』や『ヴィーヴル・サ・ヴィー』、アントニオーニの『L'Avventura』、オルミの『婚約者たち』といったヨーロッパの新しい監督の

最高傑作に劣らず、この解放的な反記号的質を持っている。 |

|

| The fact that films have not

been overrun by interpreters is in part

due simply to the newness of cinema as an art. It also owes to the

happy

accident that films for such a long time were just movies; in other

words,

that they were understood to be part of mass, as opposed to high,

culture,

and were left alone by most people with minds. Then, too, there is

always

something other than content in the cinema to grab hold of, for those

who

want to analyze. For the cinema, unlike the novel, possesses a

vocabulary

of forms—the explicit, complex, and discussable technology of camera

movements, cutting, and composition of the frame that goes into the

making of a film. |

31 |

映

画が解釈者によって蹂躙されなかったのは、単に芸術としての映画の新しさによるところが大きい。

言い換えれば、映画は大衆文化の一部であり、ハイカルチャーとは対照的なものであると理解され、心を持つほとんどの人々から放っておかれたのである。つま

り、映画は大衆文化の一部であり、高尚な文化とは対照的なものだと理解され、心ある人々のほとんどから放っておかれていたのである。映画には、小説とは異なり、形式という語彙がある。それは、カメラの動き、カット割り、フレー

ムの構成など、映画製作に関わる明示的で複雑な、議論可能な技術である。 |

|

| What kind of criticism, of

commentary on the arts, is desirable today? For

I am not saying that works of art are ineffable, that they cannot be

described or paraphrased. They can be. The question is how. What would

criticism look like that would serve the work of art, not usurp its

place? |

8 |

32 |

・作品を簒奪する批評ではなく、作品に奉仕する批評 今日、どのような批評、芸術の解説が望まれているのだろうか?私は、芸術作品が不可解なものであり、描写や言い換えができないものだと言っているのではな い。それは可能だ。問題はその方法だ。芸術作品に奉仕し、その座を奪うことのない批評とはどのようなものだろうか? |

| What is needed, first, is more

attention to form in art. If excessive

stress on content provokes the arrogance of interpretation, more

extended

and more thorough descriptions of form would silence. What is needed is

a vocabulary—a descriptive, rather than prescriptive, vocabulary—for

forms.* The best criticism, and it is uncommon, is of this sort that

dissolves considerations of content into those of form. On film, drama,

and painting respectively, I can think of Erwin Panofsky’s essay,

“Style

and Medium in the Motion Pictures,” Northrop Frye’s essay “A

Conspectus of Dramatic Genres,” Pierre Francastel’s essay “The

Destruction of a Plastic Space.” Roland Barthes’ book On Racine and his

two essays on Robbe-Grillet are examples of formal analysis applied to

the work of a single author. (The best essays in Erich Auerbach’s

Mimesis,

like “The Scar of Odysseus,” are also of this type.) An example of

formal

analysis applied simultaneously to genre and author is Walter

Benjamin’s

essay, “The Story Teller: Reflections on the Works of Nicolai Leskov.” * One of the difficulties is that our idea of form is spatial (the Greek metaphors for form are all derived from notions of space). This is why we have a more ready vocabulary of forms for the spatial than for the temporal arts. The exception among the temporal arts, of course, is the drama; perhaps this is because the drama is a narrative (i.e., temporal) form that extends itself visually and pictorially, upon a stage…. What we don’t have yet is a poetics of the novel, any clear notion of the forms of narration. Perhaps film criticism will be the occasion of a breakthrough here, since films are primarily a visual form, yet they are also a subdivision of literature. |

33 |

まず必要なのは、芸術における形にもっと注意を払うことだ。内容への過度なこだわりが解釈の傲慢さを引き起こす

のであれば、形式に関するより広範で徹底的な記述は沈黙をもたらすだろう。最良の批評とは、この種のものであり、内容に関する考察を形式に関する考察に溶

け込ませるものである。

映画、演劇、絵画それぞれについて、私はエルヴィン・パノフスキーのエッセイ『映画における様式と媒体』、ノースロップ・フライのエッセイ『ドラマティッ

ク・ジャンルの考察』、ピエール・フランカステルのエッセイ『可塑的空間の破壊』を思い浮かべることができる。ロラン・バルトの『ラシーヌについて』とロ

ブ=グレに関する2つのエッセイは、一人の作家の作品に形式分析を適用した例である。(エーリッヒ・アウエルバッハの『ミメーシス』における最高のエッセ

イ、「オデュッセウスの傷跡」などもこのタイプである)。形式分析をジャンルと作者に同時に適用した例としては、ヴァルター・ベンヤミンのエッセイ『物語

の語り手』がある: ニコライ・レスコフの作品についての考察』である。 * 困難のひとつは、私たちの考える形式が空間的なものであることだ(形式に関するギリシャ語の比喩は、すべて空間の概念に由来する)。そのため私たちは、時 間芸術よりも空間芸術のほうが、よりすぐれた形の語彙を持っている。もちろん、時間芸術の例外はドラマである。おそらくこれは、ドラマが視覚的・絵画的に 舞台上に展開する物語(すなわち時間)形式だからであろう......。私たちがまだ持っていないのは、小説の詩学であり、語りの形式についての明確な概 念である。映画は主に視覚的な形式でありながら、文学の一分野でもあるからだ。 |

|

| Equally valuable would be acts

of criticism which would supply a

really accurate, sharp, loving description of the appearance of a work

of

art. This seems even harder to do than formal analysis. Some of Manny

Farber’s film criticism, Dorothy Van Ghent’s essay “The Dickens World:

A View from Todgers’,” Randall Jarrell’s essay on Walt Whitman are

among the rare examples of what I mean. These are essays which reveal

the sensuous surface of art without mucking about in it. |

34 |

同

様に価値があるのは、芸術作品の外観を本当に正確に、鋭く、愛情を持って描写する批評行為だろう。これは形式的な分析以上に難しいことのように思える。マ

ニー・ファーバーの映画批評、ドロシー・ヴァン・ゲントのエッセイ「ディケンズの世界:

トジャーズからの眺め」、ウォルト・ホイットマンに関するランドール・ジャレルのエッセイなどは、私が言いたいことの希有な例である。これらのエッセイ

は、芸術の官能的な表層を、詮索することなく明らかにしている。 |

|

| Transparence is the highest,

most liberating value in art-and in criticismtoday.

Transparence means experiencing the luminousness of the thing in

itself, of things being what they are. This is the greatness of, for

example,

the films of Bresson and Ozu and Renoir’s The Rules of the Game. |

9 |

35 |

・透明 透明性は、今日の芸術、そして批評において最も高く、最も解放的な価値である。透明性とは、事物そのもの、事物のありのままの輝きを体験することである。 これこそが、例えばブレッソンや小津の映画、ルノワールの『ゲームの規則』の偉大さである。 |

| Once upon a time (say, for

Dante), it must have been a revolutionary

and creative move to design works of art so that they might be

experienced on several levels. Now it is not. It reinforces the

principle of

redundancy that is the principal affliction of modem life. |

36 |

かつて(例えばダンテの場合)、芸術作品をいくつかのレベルで体験でき

るようにデザインすることは、革命的で創造的な動きだったに違いない。今はそうではない。それは、現代生活の主な悩みである冗長性の原則を強化するもの

だ。 |

|

| Once upon a time (a time when

high art was scarce), it must have

been a revolutionary and creative move to interpret works of art. Now

it

is not. What we decidedly do not need now is further to assimilate Art

into Thought, or (worse yet) Art into Culture. |

37 |

昔々(高い芸術が少なかった時代)、芸術作品を解釈することは革命的で

創造的な動きだったに違いない。今はそうではない。今、私たちに必要なのは、芸術を思想に、あるいは(さらに悪いことに)芸術を文化に同化させることでは

あるまい。 |

|

| Interpretation takes the sensory

experience of the work of art for

granted, and proceeds from there. This cannot be taken for granted,

now.

Think of the sheer multiplication of works of art available to every

one of

us, superadded to the conflicting tastes and odors and sights of the

urban

environment that bombard our senses. Ours is a culture based on excess,

on overproduction; the result is a steady loss of sharpness in our

sensory

experience. All the conditions of modem life-its material plenitude,

its sheer crowdedness-conjoin to dull our sensory faculties. And it is

in the

light of the condition of our senses, our capacities (rather than those

of

another age), that the task of the critic must be assessed. |

38 |

・「都市環境のなかでわれわれの五感を襲っている雑多な味覚や嗅覚や

視覚に加うるに、各人に提供される芸術作品の極端な増加を考えてみるがいい。われわれの

文化の基盤は過剰、生産過剰にある。その結果、われわれの感覚的経験は着実に鋭敏さを失

いつつある。現代生活の物質的充満や人口過密など、あらゆる条件が力を合わせて、われわ

れの感覚的能力を鈍らせようとする。だから、今日批評家の任務は、われわれの感覚、われ

われの能力(別の時代の感覚や能力でなく)の置かれている状況に照らして、評価されなけ

ればならないのである」(33) |

|

| What

is important now is to

recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel

more. |

39 |

今

大切なのは、感覚を取り戻すことだ。もっと見ること、もっと聞くこと、もっと感じることを学ばなければならない。 |

|

| Our task is not to find the

maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more

content out of the work than is already there. Our task is to cut back

content so that we can see the thing at all. |

40 |

私たちの仕事は、芸術作品から最大限の内容を探し出すことではないし、

ましてや作品からすでにある以上の内容を絞り出すことでもない。私たちの仕事は、その作品を見ることができるように、内容を削ぎ落とすことなのだ。 |

|

| The aim of all commentary on art

now should be to make works of

art-and, by analogy, our own experience-more, rather than less, real to

us.

The function of criticism should be to show how it is what it is, even

that it

is what it is, rather than to show what it means. |

41 |

今、

すべての芸術批評の目的は、芸術作品を、そしてその類推によって、私たち自身の経験を、私たちにとってより現実的なものにすることであるべきだ。批評の機

能は、それが何を意味するのかを示すことよりも、それがどのようなものであるかを示すこと、さらにはそれがどのようなものであるかを示すことであるべきな

のだ。 |

|

| In place of a hermeneutics we

need an erotics of art. |

10 |

42 |

・解釈学の代わりに、われわれは官能美学(エロティクス)を必要として

いる——In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art. (1964) |

++

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099