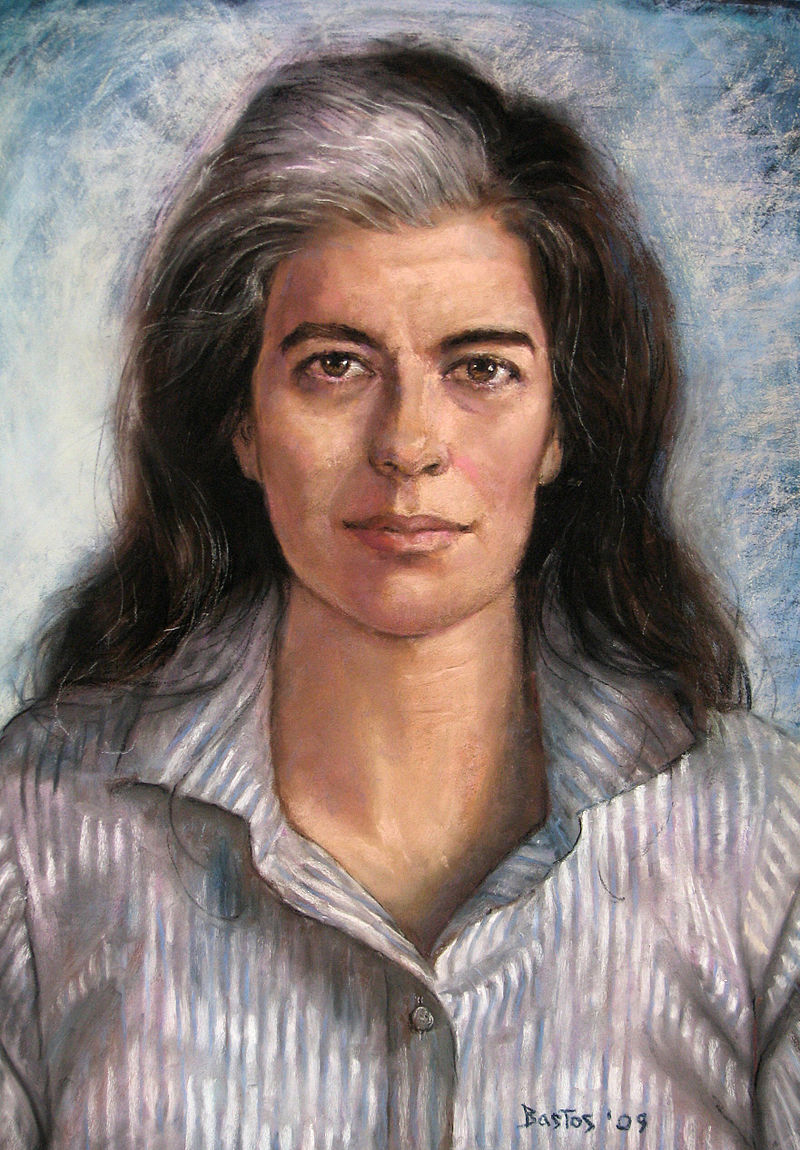

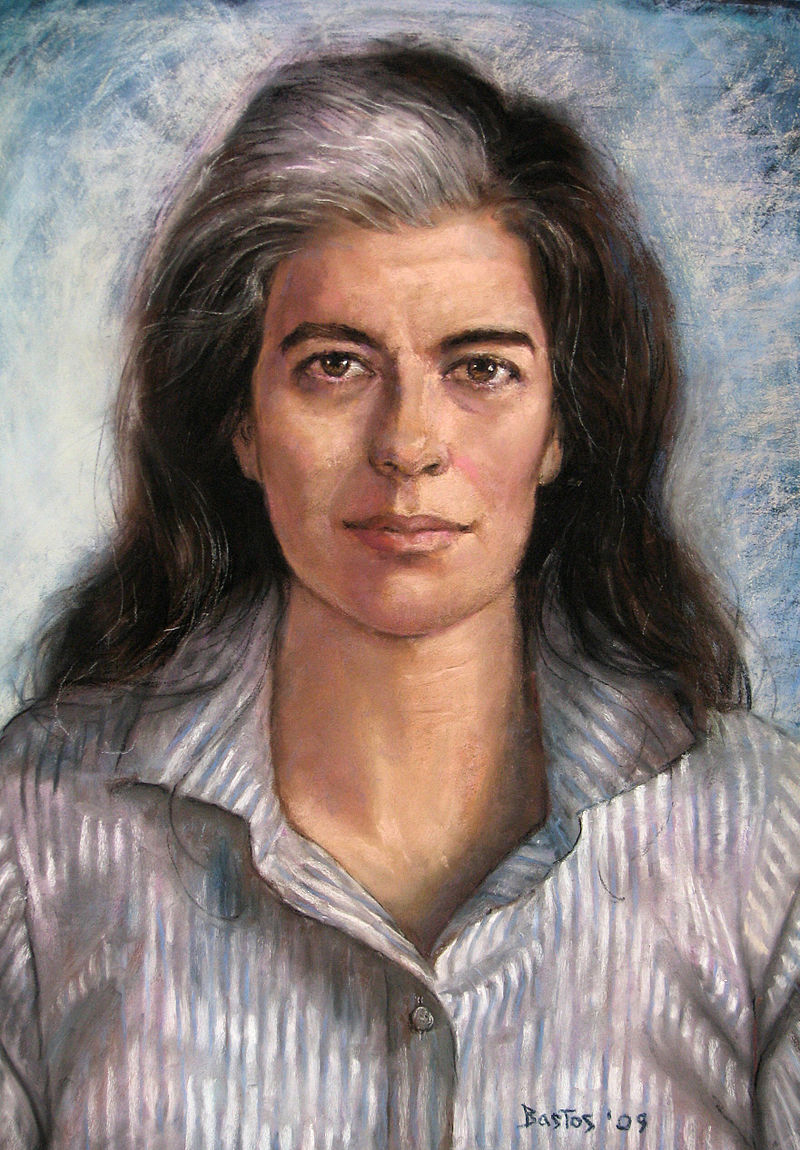

Pastel

portrait of Susan Sontag commissioned by the Gay & Lesbian Review

for the 2009 May-June cover

ソンタグ『エイズとその隠喩』ノート

Pastel

portrait of Susan Sontag commissioned by the Gay & Lesbian Review

for the 2009 May-June cover

表題:ソンタグ『エイズとその隠喩』ノート:スーザン・ソンタグ年譜(Susan Sontag, 1933-2004)

S・ソンタグ『エイズとその隠喩』ノート

(ページは:富山太佳夫訳,みすず書房,1990[1989]による)

"Susan Sontag (/ˈsɒntæɡ/; January 16, 1933 – December 28, 2004) was an American writer, film-maker, teacher, political activist.[2] She published her first major work, the essay "Notes on 'Camp'", in 1964. Her best-known works include On Photography, Against Interpretation, Styles of Radical Will, The Way We Live Now, Illness as Metaphor, Regarding the Pain of Others, The Volcano Lover, and In America.Sontag was active in writing and speaking about, or travelling to, areas of conflict, including during the Vietnam War and the Siege of Sarajevo. She wrote extensively about photography, culture and media, AIDS and illness, human rights, and communism and leftist ideology. Although her essays and speeches sometimes drew controversy,[3] she has been described as "one of the most influential critics of her generation."[4]" - Susan Sontag, 1933-2004

”Illness as Metaphor is a 1978 work of critical theory by Susan Sontag, in which she challenges the victim-blaming in the language that is often used to describe diseases and the people affected by them. Teasing out the similarities between public perspectives on cancer (the paradigmatic disease of the 20th century before the appearance of AIDS), and tuberculosis (the symbolic illness of the 19th century), Sontag showed that both diseases were popularly associated with personal psychological traits. In particular, she said that the metaphors and terms used to describe both syndromes lead to an association between repressed passion and the physical disease itself. She wrote about the peculiar reversal that "With the modern diseases (once TB, now cancer), the romantic idea that the disease expresses the character is invariably extended to assert that the character causes the disease–because it has not expressed itself. Passion moves inward, striking and blighting the deepest cellular recesses." Sontag said that the clearest and most truthful way of thinking about diseases is without recourse to metaphor. She believed that wrapping disease in metaphors discouraged, silenced, and shamed patients. Some other writers have disagreed with her, saying that metaphors and other symbolic language help some affected people form meaning out of their experiences.[1]”- Wiki, Illness as Metaphor.

Synopsis -”Illness as Metaphor served as a way for Susan Sontag to express her opinions on the use of metaphors in order to refer to illnesses, with her main focuses being tuberculosis and cancer. The book contrasts the view points and metaphors associated with each disease. At one point, tuberculosis was seen as a creative disease, leading to healthy people wanting to look as if they were ill with the disease. However, lack of improvement from tuberculosis was usually seen as lack of passion in the individual. Tuberculosis was even seen as a sign of punishment by some religions, such as Christianity, leading the afflicted to believe that they deserved their ailment.[2] Sontag then made the comparison between the metaphors used to describe tuberculosis and cancer, with cancer being seen in the 1970s as a disease that afflicted people who lacked passion and sensuality, and those who repressed their feelings. Sontag wrote that multiple studies found a link between depression and cancer, which she argued was just a sign of the times and not a reason for the disease, since in previous times physicians found that cancer patients suffered from hyperactivity and hypersensitivity, which were signs of their times.[2] In the last chapter, Sontag argued that society's disease metaphors cause patients to feel as if society were against them. Her final argument was that metaphors are not useful for patients, since metaphors make patients feel as if their illness was due to their feelings, rather than lack of effective treatment.[2] The most effective way of thinking about illness would be to avoid metaphorical thinking, and to focus on only the physical components and treatment.[3]”- Wiki, Illness as Metaphor

+

社会を「統制のとれた肉体」と見ること:「社会を肉体にたとえるのは、社会を家族にたとえること以上に、権威主義的な秩序づけを、不変、不可避のものに見

せてしまう」(7)

ウイルヒョウの細胞=生命の基本単位::細胞=自由国家のメタファー

ルクレチウスの主張=病気と健康をメタファーでとらえることへの反発(9)

ルクレチウス『事物の本質について』㈽:124ー35において、健康=「調和」(→音楽から借用されたメタファー)に対して批判を加えて、メ タファーは 音楽家に変えすべきものと、詩に詠んだ。

肉体のメタファー:統制のとれた社会、神殿(聖パウロ)、肉体=工場説、肉体=砦説など(10)。

医学における軍事的隠喩の多用(12)

キャンペーン(13):平原:合戦場//戦闘・戦役・従軍

外来からの侵入に対して免疫が「防衛機構」を発揮する

化学療法が癌を「攻撃する」

「総力戦」(14ー5):「かっては病気に闘いをいどんだのは医者であったが、今では社会全体である。」(14)

前著『隠喩としての病い』の執筆動機:癌というスティグマと闘う(16-)

ただし、癌にかかるのは、昔ほどのスティグマでもなくなった(21)

「隠喩と神話はひとを殺す」(19)

癌が米国で告知されるようになったこと:癌は恐ろしい病気ではなくなった:「真実を告げない」ことで訴訟されることを恐れた医師たちの態度変容

そして「どの社会も、悪とみなされる病気をひとつは必要としている」(22)

2.

3.

エイズは定義構築次第の産物だ 40-1

死刑判決としてのHIV感染

エイズの蓋然性をもった者が、即エイズとされてしまう。

HIV陽性者への抑圧

キャリアーの入国を拒否する国は多い

結局、医学検査の進歩による「ラディカルな病気概念の拡張」は、本人の生物学的な死以前に「社会的な死」(早すぎる死)を生みだしたのだ。これ は、近代医 学による権力的支配の誕生以前の状態に患者を引き戻してしまう。

「(エイズは‥‥)近代以前の病気体験をいくらか復権させてしまうのだ。」48ー9

(→例えば:ブードゥー・デスを想像すればよい)

エイズ検査の問題点 51

「‥‥今日では、診てもらうとは検査を受けるということである」51

「検査を受けて有罪判決の危惧を振り切るのを、先々差別とかそれよりもひどい事態をもたらしかねないリストに載せられはしないかという不安か ら、あるいは 宿命論(そんなことをして何の役に立つの?)からしぶる人が多い所以である。」p.51

→このことを「社会医学者」は真剣に考えているだろうか?

(ソンタグの迷信排斥の近代主義者の側面はp.53の一連の行をみよ)

4.

顔と肉体のアイデンティティ?の分離に関するソンタグの緒論 57ー60

顔と肉体の分離は、ヨーロッパのキリスト教的伝統に由来する(???)

諸聖人のイコン:肉体の廃虚と、苦痛も恐れもとどめない顔

唯一の例外は受難のキリストである:苦痛に歪むキリスト顔:「人の子であり、神の子であるキリストのみが顔に苦痛を浮かべるのだ。受難とはそう いうもので ある。」p.58

病気による顔の崩壊は、人格の崩壊を映し出すことを含意する p.59

病気のミアスマ説と文芸的想像力の問題 60ー62

「体質」の処遇の変遷 62

㈰体質の病弱性は、19世紀の心理学というジャンル(ゲットー)に閉じこめられてゆく。

㈪心理学の科学としての市民権の獲得

㈫体質概念が医学に再び帰還してゆく:あるいは心理学において洗練されたその考え方が医学にも影響(侵食?)してゆく

エイズは(今のところ)心理学の次元では取り扱われない 63

5.

エイズのアフリカ起源(神話)に対する対抗神話「CIA説」76

エイズ:㈰疫病の外来性、㈪疫病の原因としての道徳の腐敗 78

19世紀初頭英国の道徳と病い

貧民=不健康者への病いとしての疫病79

「疫病の隠喩は、社会の危機に即決の審判を下すさいの必需品」である。p.82

カレル・チャペック『白い疫病』1937:ファシズム:疫病83ー86

カミユ『ペスト』:ペストの機能:生にその真摯さを取り戻す死を招く86

6.

検疫隔離の効果のなさ(→象徴的暴力が現実のものになることの無根拠性)p.120

エイズ問題は南北問題であるp.122

特権的な国の人々の不安125

人類の1/4が死滅することは、たいしたことのない問題か?

S・J・グールドのコメントをめぐって 127-8

●ソンタグの強調点 p.140-1

軍事的メタファーからの退却

公共の福祉の医療モデルへの警戒、なぜなら権威主義支配を強化するから。

全体ではない、侵略を受けているのではない、病人は敵ではない、肉体は戦場ではない、などいう軍事的メタファー(隠喩)の批判(→ルクレチウス の批判を、 言葉を替えて繰り返すのである)。

● Susan Sontag, 1933-2004 年譜(情報はおもにウィキペディア日本語「スーザン・ソンタグ」による)

1933 父ジャック・ローゼンブラット(Jack Rosenblatt)と母ミルドレッド・ヤコブセン(Mildred Jacobsen)の間に東欧ユダヤ系移民のアメリカ人としてニューヨーク市で誕生した。

1938 父親は中国で毛皮の貿易会社を経営していたが結核で死去した

1945 母は同じ東欧ユダヤ系のネイサン・ソンタグ(Nathan Sontag)と親密関係になった。正式には結婚はしなかったが、スーザンとその妹のジュディスはその義父のソンタグ姓を名乗るようになった。

n.d ソンタグはアリゾナ州ツーソンで育ち、後に、ロサンゼルスに越し

1948 ノースハリウッド高等学校を卒業、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校で学び始める

n.d. シカゴ大学に転校し、学士号を得て卒業

1950 17歳で、シカゴにいる間、10日間の熱烈な求婚を受けて、ソンタグはフィリップ・リーフと結婚

ca. 1952 シカゴ大学卒業、ハーバード大学、オックスフォード大学のセント・アンズ・カレッジ、パリ大学の大学院では哲学、文学、神学を専攻

1958 フィリップ・リーフと8年間の結婚生活を経て、1958年に離婚した

1966 『反解釈 』Against Interpretationを処女出版(ちくま学芸文庫, 1996)。写真家ピーター・ヒュージャーが撮影した印象的なカバー写真は、ソンタグが"the Dark Lady of American Letters"としての名声を得るのを後押しした。

1969 『ハノイで考えたこと』邦高忠二訳 晶文社 1969年

1970 『死の装具』斎藤数衛訳 早川書房 1970年。小説

1974 『ラディカルな意志のスタイル』川口喬一訳 晶文社

1976 『アントナン・アルトー論』岩崎力訳 コーベブックス、1976

1979 『写真論』近藤耕人訳 晶文社 1979年

1981 『わたしエトセトラ』行方昭夫訳 新潮社 1981年 小説

1982 『隠喩としての病い』冨山太佳夫訳 みすず書房 1982年、『土星の徴しの下に』冨山太佳夫訳 晶文社

1989 写真家のアニー・リーボヴィッツと交際

1990 『エイズとその隠喩』冨山太佳夫訳 みすず書房

1992 『隠喩としての病い エイズとその隠喩』みすず書房

1998 『アルトーへのアプローチ』岩崎力訳 みすず書房

2001 『火山に恋して』冨山太佳夫訳 みすず書房 2001年 歴史小説

2002 『この時代に想う テロへの眼差し』木幡和枝訳 NTT出版

2003 『他者の苦痛へのまなざし』北條文緒訳 みすず書房

2004 『良心の領界』木幡和枝訳 NTT出版

2004 12月28日、骨髄異形成症候群の合併症から急性骨髄性白血病を併発し、ニューヨークで死去。71歳。遺体はパリ・モンパルナスの共同墓地に埋葬。

2009 『エッセイ集 1 文学・映画・絵画 書くこと、ロラン・バルトについて』冨山太佳夫訳 みすず書房;『同じ時のなかで』木幡和枝訳 NTT出版 2009年

2009 デイヴィッド・リーフ『死の海を泳いで スーザン・ソンタグ最後の日々』(上岡伸雄訳、岩波書店、2009年)

2010 『私は生まれなおしている 日記とノート1947-1963』デイヴィッド・リーフ編 木幡和枝訳 河出書房新社

2012 『エッセイ集 2 写真・演劇・文学 サラエボで、ゴドーを待ちながら』冨山太佳夫訳 みすず書房; 『夢の賜物』木幡和枝訳 河出書房新社 2012 小説

2013-2014 『こころは体につられて 日記とノート 1964-1980 (上・下)』デイヴィッド・リーフ編 木幡和枝訳 河出書房新社

2016 『イン・アメリカ』木幡和枝訳 河出書房新社 2016 小説

リンク

文献

その他の情報