★IT WOULD be hard to

find any reputable literary critic today who would care to be caught

defending as

an idea the old antithesis of style versus content. On this issue a

pious consensus prevails. Everyone

is quick to avow that style and content are indissoluble, that the

strongly individual style of each

important writer is an organic aspect of his work and never something

merely “decorative.”

In the practice of criticism, though, the old antithesis lives

on,

virtually unassailed. Most of the

same critics who disclaim, in passing, the notion that style is an

accessory to content maintain the

duality whenever they apply themselves to particular works of

literature. It is not so easy, after all, to

get unstuck from a distinction that practically holds together the

fabric of critical discourse, and

serves to perpetuate certain intellectual aims and vested interests

which themselves remain

unchallenged and would be difficult to surrender without a fully

articulated working replacement at

hand.

|

1.

今日、評判の良い文芸評論家で、「スタイル」対「内容」という古いアンチテーゼを思想として擁護している人を見つけるのは難しいだろう。この問題に関して

は、敬虔なコンセンサスが優勢である。文体と内容は不可分であり、各重要な作家の強く個性的な文体は、その作品の有機的な側面であって、決して単なる

"装飾 "的なものではない、と誰もがすぐに公言する。

しかし、批評の実践においては、古いアンチテーゼはほとんど揺るがされることなく生き続けている。文体が内容の付属物であるという考え方を一応否定する批

評家のほとんどは、特定の文学作品に当てはめるたびに、その二重性を維持している。結局のところ、批評的言説の布石を実質的に支え、特定の知的目的や既得

権益を永続させるのに役立っているこの区別から解き放たれるのは、そう簡単なことではない。

|

In fact, to talk about the style

of a particular novel or poem at all as a “style,” without implying,

whether one wishes to or not, that style is merely decorative,

accessory, is extremely hard. Merely by

employing the notion, one is almost bound to invoke, albeit implicitly,

an antithesis between style and

something else. Many critics appear not to realize this. They think

themselves sufficiently protected

by a theoretical disclaimer on the vulgar filtering-off of style from

content, all the while their

judgments continue to reinforce precisely what they are, in theory,

eager to deny.

|

3.

実際、特定の小説や詩のスタイルを「スタイル」として語ることは、望むと望まざるとにかかわらず、スタイルが単なる装飾的なもの、アクセサリーであること

を暗示することなく、極めて困難なことである。この概念を用いるだけで、スタイルとそれ以外の何かとの間のアンチテーゼを、暗黙のうちにとはいえ、呼び起

こすことになる。多くの批評家はこのことに気づいていないように見える。彼らは、スタイルと内容との間の低俗なフィルタリングに関する理論的な免責事項に

よって自分たちが十分に守られていると思っているが、その一方で、自分たちの判断は、理論的には否定しようと躍起になっていることをまさに補強し続けてい

るのである。

|

One way in which the old duality

lives on in the practice of criticism, in concrete judgments, is the

frequency with which quite admirable works of art are defended as good

although what is miscalled

their style is acknowledged to be crude or careless. Another is the

frequency with which a very

complex style is regarded with a barely concealed ambivalence.

Contemporary writers and other

artists with a style that is intricate, hermetic, demanding—not to

speak of “beautiful”—get their ration

of unstinting praise. Still, it is clear that such a style is often

felt to be a form of insincerity: evidence

of the artist’s intrusion upon his materials, which should be allowed

to deliver themselves in a pure

state.

|

4.

批評の実践、具体的な判断において、古い二元性が生きている一つの方法は、非常に立派な芸術作品が、その作風が粗雑であるとか無頓着であると誤解されてい

るにもかかわらず、良い作品であると擁護される頻度である。もうひとつは、非常に複雑な作風が、かろうじて隠された両義性をもって評価される頻度である。

現代の作家やその他の芸術家たちは、「美しい」とまでは言わないが、複雑で、隠微で、要求の多い作風を持ち、惜しみない賞賛を浴びている。しかし、そのよ

うな作風がしばしば不誠実さの一形態と感じられるのは明らかである。純粋な状態で自らを表現させるべき素材に、芸術家が介入している証拠なのだ。

|

Whitman, in the preface to the

1855 edition of Leaves of Grass, expresses the disavowal of

“style” which is, in most arts since the last century, a standard ploy

for ushering in a new stylistic

vocabulary. “The greatest poet has less a marked style and is more the

free channel of himself,” that

great and very mannered poet contends. “He says to his art, I will not

be meddlesome, I will not have

in my writing any elegance or effect or originality to hang in the way

between me and the rest like

curtains. I will have nothing hang in the way, not the richest

curtains. What I tell I tell for precisely

what it is.”

|

ホイットマンは『草の葉』1855年版の序文で、前世紀以降のほとんど

の芸術において、新しい文体=スタイルの語彙を導入するための標準的な策略である「文体」の否定を表明している。「最も偉大な詩人は、際立ったスタイルを

持たず、むしろ自分自身の自由なチャンネルを持っている。「彼は自分の芸術に対してこう言うのだ、私はお節介を焼かない、私の文章には、カーテンのように

私と他者との間に邪魔になるようなエレガンスや効果や独創性を持ち込まない、と。カーテンのように邪魔になるものは何もない。私が語ることは、それが何で

あるかを正確に伝えるものだ」。

|

Of course, as everyone knows or

claims to know, there is no neutral, absolutely transparent style.

Sartre has shown, in his excellent review of The Stranger, how the

celebrated “white style” of

Camus’ novel—impersonal, expository, lucid, flat—is itself the vehicle

of Meursault’s image of the

world (as made up of absurd, fortuitous moments). What Roland Barthes

calls “the zero degree of

writing” is, precisely by being anti-metaphorical and dehumanized, as

selective and artificial as any

traditional style of writing. Nevertheless, the notion of a style-less,

transparent art is one of the most

tenacious fantasies of modern culture. Artists and critics pretend to

believe that it is no more possible

to get the artifice out of art than it is for a person to lose his

personality. Yet the aspiration lingers—a

permanent dissent from modern art, with its dizzying velocity of style

changes.

|

もちろん、誰もが知っているように、あるいは知っていると主張するよう

に、中立的で絶対的に透明なスタイルなど存在しない。サルトルは『見

知らぬ人』の優れた批評の中で、カミュの小説の有名な「白い文体」-非人間的で、説明的で、明晰で、平坦な-が、それ自体、(不条理で偶然の瞬間からな

る)ムルソーの世界像の乗り物であることを示した。ロラン・バルトが「ゼロ度の文章」と呼ぶものは、まさに反喩的で非人間的であることによって、伝統的な

文体と同様に選択的で人工的なものである。にもかかわらず、スタイルのない透明な芸

術という概念は、現代文化の最も粘り強い幻想のひとつである。芸術家や批評家たちは、芸術から作為を取り除くことは、人が人格を失うこと以

上に不可能だと信じているふりをする。しかし、この願望は、めまぐるしいスピードでスタイルが変化していく現代美術に対する永久的な反抗なのである。

|

To speak of style is one way of

speaking about the totality of a work of art. Like all discourse about

totalities, talk of style must rely on metaphors. And metaphors mislead.

|

スタイルについて語ることは、芸術作品の全体性について語る一つの方法である。全体性についてのあらゆる言説と同様、スタイルについての話もメタファーに頼らざるを得ない。そしてメタファーは誤解を招く。

|

Take, for instance, Whitman’s

very material metaphor. By likening style to a curtain, he has of

course confused style with decoration and for this would be speedily

faulted by most critics. To

conceive of style as a decorative encumbrance on the matter of the work

suggests that the curtain

could be parted and the matter revealed; or, to vary the metaphor

slightly, that the curtain could be

rendered transparent. But this is not the only erroneous implication of

the metaphor. What the

metaphor also suggests is that style is a matter of more or less

(quantity), thick or thin (density). And,

though less obviously so, this is just as wrong as the fancy that an

artist possesses the genuine option

to have or not to have a style. Style is not quantitative, any more

than it is superadded. A more

complex stylistic convention—say, one taking prose further away from

the diction and cadences of

ordinary speech—does not mean that the work has “more” style.

|

例

えば、ホイットマンの非常に物質的な比喩を考えてみよう。スタイルをカーテンに喩えたホイットマンは,もちろんスタイルを装飾と混同している。作風を作品

の本質を覆い隠す装飾と考えることは,カーテンを裂いて本質を明らかにすること,あるいは比喩を少し変えて,カーテンを透明にすることを示唆している。し

かし、この比喩の誤りはこれだけではない。この比喩が示唆しているのは、スタイルとは多いか少ないか(量)、厚いか薄いか(密度)の問題であるということ

だ。そして、あまり明らかではないが、これはアーティストがスタイルを持つか持たないかという真の選択肢を持っているという空想と同じくらい間違ってい

る。スタイルは量的なものではない。より複雑な文体の慣例、例えば、散文が通常の会話の語法や文調から離れていることは、その作品が「より」文体があるこ

とを意味しない。

|

Indeed, practically all

metaphors for style amount to placing matter on the inside, style on

the

outside. It would be more to the point to reverse the metaphor. The

matter, the subject, is on the

outside; the style is on the inside. As Cocteau writes: “Decorative

style has never existed. Style is the

soul, and unfortunately with us the soul assumes the form of the body.”

Even if one were to define

style as the manner of our appearing, this by no means necessarily

entails an opposition between a

style that one assumes and one’s “true” being. In fact, such a

disjunction is extremely rare. In almost

every case, our manner of appearing is our manner of being. The mask is

the face.

|

実

際、スタイルに関するほとんどすべての比喩は、物質を内側に、スタイルを外側に置くことに等しい。喩えを逆にした方がより的を得ている。物質、つまり主題

は外側にあり、スタイルは内側にある。コクトーが書いているように、「装飾的なスタイルは存在しない。スタイルとは魂であり、残念なことに、魂は肉体の形

をとる。仮に、スタイルを私たちの外見のあり方として定義するとしても、それは必ずしも、自分のスタイルと自分の「真の」存在との対立を意味するものでは

ない。実際、そのような矛盾は極めて稀である。ほとんどすべての場合において、私たちの出現の仕方は私たちの存在の仕方なのである。マスクは顔である。

|

I should make clear, however,

that what I have been saying about dangerous metaphors doesn’t

rule out the use of limited and concrete metaphors to describe the

impact of a particular style. It

seems harmless to speak of a style, drawing from the crude terminology

used to render physical

sensations, as being “loud” or “heavy” or “dull” or “tasteless” or,

employing the image of an

argument, as “inconsistent.”

|

し

かし、私が危険なメタファーについて述べてきたことは、特定のスタイルのインパクトを表現するために、限定的で具体的なメタファーを使用することを排除す

るものではないことを明確にしておかなければならない。身体感覚を表現するのに使われる粗雑な用語を用いて、あるスタイルを "うるさい "とか

"重い "とか "鈍い "とか "不味い "とか、あるいは議論のイメージを使って "矛盾している "などと言うのは無害に思える。

|

The antipathy to “style” is

always an antipathy to a given style. There

are no style-less works of

art,

only works of art belonging to different, more or less complex

stylistic traditions and conventions.

This means that the notion of style, generically considered, has a

specific, historical meaning. It is

not only that styles belong to a time and a place; and that our

perception of the style of a given work

of art is always charged with an awareness of the work’s historicity,

its place in a chronology.

|

11.

「スタイル」に対する反感は、常に与えられたスタイルに対する反感である。スタイル

のない芸術作品など存在せず、異なる、多かれ少なかれ複雑なスタイルの伝統や慣習に属する芸術作品があるだけである。つまり、スタイルという概念は、一般

的に考えれば、特定の歴史的意味を持つということだ。スタイルがある時代と場所に属するということだけでなく、ある芸術作品のスタイルに対する私たちの認

識は、常にその作品の歴史性、年表における位置づけを意識しているのである。

|

Further: the visibility of

styles is itself a product of historical consciousness. Were it not for

departures from, or experimentation with, previous artistic norms which

are known to us, we could

never recognize the profile of a new style. Still further: the very

notion of “style” needs to be

approached historically. Awareness of style as a problematic and

isolable element in a work of art

has emerged in the audience for art only at certain historical

moments—as a front behind which other

issues, ultimately ethical and political, are being debated. The notion

of “having a style” is one of the

solutions that has arisen, intermittently since the Renaissance, to the

crises that have threatened old

ideas of truth, of moral rectitude, and also of naturalness.

|

さ

らに、スタイルの可視性は、それ自体が歴史意識の産物である。私たちが知っている以前の芸術的規範からの逸脱や実験がなければ、新しいスタイルの輪郭を認

識することはできない。さらに言えば、「スタイル」という概念そのものを歴史的に捉える必要がある。芸術作品における問題であり、分離可能な要素としての

スタイルに対する意識は、ある歴史的瞬間においてのみ、芸術を鑑賞する人々の間に生まれた。様式を持つ」という概念は、ルネサンス以降、真理や道徳的な正

しさ、そして自然さといった古い観念を脅かす危機に対して、断続的に生じてきた解決策のひとつである。

|

But suppose all this is

admitted. That all representation is incarnated in a given style (easy

to say).

That there is, therefore, strictly speaking, no such thing as realism,

except as, itself, a special stylistic

convention (a little harder). Still, there are styles and styles.

Everyone is acquainted with movements

in art—two examples: Mannerist painting of the late 16th and early 17th

centuries, Art Nouveau in

painting, architecture, furniture, and domestic objects—which do more

than simply have “a style.”

Artists such as Parmigianino, Pontormo, Rosso, Bronzino, such as Gaudí,

Guimard, Beardsley, and

Tiffany, in some obvious way cultivate style. They seem to be

preoccupied with stylistic questions

and indeed to place the accent less on what they are saying than on the

manner of saying it.

|

し

かし、仮にこれがすべて認められたとしよう。すべての表現は、あるスタイルに化身している(言うのは簡単だ)。したがって、厳密に言えば、リアリズムなど

というものは存在しない。それでも、スタイルや様式は存在する。芸術におけるムーブメントを誰もが知っている:

16世紀末から17世紀初頭のマニエリスム絵画、絵画、建築、家具、家庭用品におけるアール・ヌーヴォーなどだ。パルミジャニーノ、ポントルモ、ロッソ、

ブロンズィーノ、ガウディ、ギマール、ビアズリー、ティファニーなどの芸術家たちは、明らかにスタイルを培っている。彼らは様式的な問題に夢中になってい

るように見えるし、実際、何を言っているかよりも、それを言う方法にアクセントを置いている。

|

To deal with art of this type,

which seems to demand the distinction I have been urging be

abandoned, a term such as “stylization” or its equivalent is needed.

“Stylization” is what is present in

a work of art precisely when an artist does make the by no means

inevitable distinction between

matter and manner, theme and form. When that happens, when style and

subject are so distinguished,

that is, played off against each other, one can legitimately speak of

subjects being treated (or

mistreated) in a certain style. Creative mistreatment is more the rule.

For when the material of art is

conceived of as “subject-matter,” it is also experienced as capable of

being exhausted. And as

subjects are understood to be fairly far along in this process of

exhaustion, they become available to

further and further stylization.

|

こ

のようなタイプの芸術を扱うには、「様式化」あるいはそれに相当する用語が必要である。「様式化」とは、芸術家が問題と作法、主題と形式を、決して避けら

れないわけではないが区別しているときにこそ、芸術作品に現れるものである。そのような場合、スタイルと主題が区別される、つまり、互いを打ち消し合うよ

うな場合、主題があるスタイルで扱われる(あるいは不当な扱いを受ける)ということを正当に語ることができる。創造的な虐待はむしろルールである。という

のも、芸術の素材が「主題」として考えられるとき、それはまた、使い果たされうるものとして経験されるからである。そして、題材がこの枯渇のプロセスのか

なり先まで進んでいると理解されるにつれて、さらなる様式化が可能になる。

|

Compare, for example, certain

silent movies of Sternberg (Salvation Hunters, Underworld, The

Docks of New York) with the six American movies he made in the 1930s

with Marlene Dietrich. The

best of the early Sternberg films have pronounced stylistic features, a

very sophisticated aesthetic

surface. But we do not feel about the narrative of the sailor and the

prostitute in The Docks of New

York as we do about the adventures of the Dietrich character in Blonde

Venus or The Scarlet

Empress, that it is an exercise in style. What informs these later

films of Sternberg’s is an ironic

attitude toward the subject-matter (romantic love, the femme fatale), a

judgment on the subject-matter

as interesting only so far as it is transformed by exaggeration, in a

word, stylized.… Cubist painting,

or the sculpture of Giacometti, would not be an example of

“stylization” as distinguished from “style”

in art; however extensive the distortions of the human face and figure,

these are not present to make

the face and figure interesting. But the paintings of Crivelli and

Georges de La Tour are examples of

what I mean.

|

例

えば、スタンバーグのある種のサイレント映画(『救世の狩人』、『暗黒街』、『ニューヨークの波止場』)と、彼がマレーネ・ディートリッヒと1930年代

に撮った6本のアメリカ映画とを比べてみよう。初期のスタンバーグ映画の最高傑作は、際立った文体的特徴、非常に洗練された美的表面を持っている。しか

し、『ブロンド・ヴィーナス』や『スカーレット・エンプレス』のディートリッヒの冒険のように、『ニューヨークの波止場』の船乗りと娼婦の物語を、スタイ

ルの練習だとは感じない。キュビズムの絵画やジャコメッティの彫刻は、芸術における「様式」と区別される「様式化」の例ではない。しかし、クリヴェッリや

ジョルジュ・ド・ラ・トゥールの絵画は、私が言いたいことの例である。

|

“Stylization” in a work of art,

as distinct from style, reflects an ambivalence (affection

contradicted by contempt, obsession contradicted by irony) toward the

subject-matter. This

ambivalence is handled by maintaining, through the rhetorical overlay

that is stylization, a special

distance from the subject. But the common result is that either the

work of art is excessively narrow

and repetitive, or else the different parts seem unhinged, dissociated.

(A good example of the latter is

the relation between the visually brilliant denouement of Orson Welles’

The Lady from Shanghai and

the rest of the film.) No doubt, in a culture pledged to the utility

(particularly the moral utility) of art,

burdened with a useless need to fence off solemn art from arts which

provide amusement, the

eccentricities of stylized art supply a valid and valuable

satisfaction. I have described these

satisfactions in another essay, under the name of “camp” taste. Yet, it

is evident that stylized art,

palpably an art of excess, lacking harmoniousness, can never be of the

very greatest kind.

|

芸術作品における "様式化

"は、様式とは異なるものとして、主題に対する両義性(軽蔑と矛盾する愛情、皮肉と矛盾する執着)を反映している。この両義性は、様式化という修辞的な上

塗りによって、主題との特別な距離を保つことで処理される。しかし、その結果、芸術作品は過度に狭く反復的なものになるか、あるいは異なる部分がバラバラ

になり、解離したように見える。(後者の好例は、オーソン・ウェルズの『上海から来た女』の視覚的に見事な結末と、それ以外の部分との関係である)。芸術

の有用性(特に道徳的有用性)に誓いを立て、厳粛な芸術と娯楽を提供する芸術を隔てる無用な必要性を背負わされた文化において、様式化された芸術の奇抜さが有効で貴重な満足感を与えているのは間違いない。こ

のような満足感については、別のエッセイで「キャンプ」趣味という名で述べた。しかし、様式化された芸術は、明らかに過剰な芸術であり、調和を欠いてい

る。

|

What haunts all contemporary use

of the notion of style is the putative opposition between form and

content. How is one to exorcise the feeling that “style,” which

functions like the notion of form,

subverts content? One thing seems certain. No affirmation of the

organic relation between style and

content will really carry conviction—or guide critics who make this

affirmation to the recasting of

their specific discourse—until the notion of content is put in its

place.

|

ス

タイルという概念の現代的な使われ方につきまとうのは、形式と内容の対立である。形式という概念と同じように機能する「スタイル」が、内容を破壊してしま

うという感覚をどのように払拭すればいいのだろうか?ひとつ確かなことがある。スタイルとコンテンツの間の有機的な関係を肯定することは、コンテンツとい

う概念がその場所に置かれない限り、本当に説得力を持つことはないだろうし、この肯定をする批評家たちを具体的な言説の再構築へと導くこともないだろう。

|

Most critics would agree that a

work of art does not “contain” a certain amount of content (or

function—as in the case of architecture) embellished by “style.” But

few address themselves to the

positive consequences of what they seem to have agreed to. What is

“content”? Or, more precisely,

what is left of the notion of content when we have transcended the

antithesis of style (or form) and

content? Part of the answer lies in the fact that for a work of art to

have “content” is, in itself, a rather

special stylistic convention. The great task which remains to critical

theory is to examine in detail the

formal function of subject-matter.

|

ほとんどの批評家は、芸術作品が "スタイル "によって装飾された一定の内容(建築の場合は機能)を "含まない "ことに同意するだろう。しかし、彼らが同意しているように見えることの肯定的な帰結に言及する人はほとんどいない。「コ

ンテンツ」とは何か?より正確には、スタイル(あるいは形式)と内容のアンチテーゼを超越したとき、内容という概念には何が残るのだろうか?その答えの一

端は、芸術作品が「内容」を持つこと自体が、かなり特殊な様式的慣習であるという事実にある。批評理論に残された大きな課題は、主題の形式的機能を詳細に

検討することである。

|

Until this function is

acknowledged and properly explored, it is inevitable that critics will

go on

treating works of art as “statements.” (Less so, of course, in those

arts which are abstract or have

largely gone abstract, like music and painting and the dance. In these

arts, the critics have not solved

the problem; it has been taken from them.) Of course, a work of art can

be considered as a statement,

that is, as the answer to a question. On the most elementary level,

Goya’s portrait of the Duke of

Wellington may be examined as the answer to the question: what did

Wellington look like? Anna

Karenina may be treated as an investigation of the problems of love,

marriage, and adultery. Though

the issue of the adequacy of artistic representation to life has pretty

much been abandoned in, for

example, painting, such adequacy continues to constitute a powerful

standard of judgment in most

appraisals of serious novels, plays, and films. In critical theory, the

notion is quite old. At least since

Diderot, the main tradition of criticism in all the arts, appealing to

such apparently dissimilar criteria

as verisimilitude and moral correctness, in effect treats the work of

art as a statement being made in

the form of a work of art.

|

19.

この機能が認められ、適切に探求されるまでは、批評家が芸術作品を "ステートメント

"として扱い続けることは避けられない。(もちろん、音楽、絵画、舞踊のように抽象的な芸術、あるいはその大部分が抽象化された芸術においてはそうではな

い。これらの芸術では、批評家は問題を解決していない。)

もちろん、芸術作品はステートメントとして、つまり質問に対する答えとして考えることもできる。最も初歩的なレベルでは、ゴヤのウェリントン公爵の肖像画

は、「ウェリントンはどのような人物だったのか?アンナ・カレーニナ』は、恋愛、結婚、不倫の問題の調査として扱われるかもしれない。絵画などでは、芸術

的な表現が人生に対して適切であるかどうかという問題はほとんど放棄されているが、シリアスな小説、戯曲、映画の評価においては、その適切さが依然として

強力な判断基準となっている。批評理論においては、この考え方はかなり古い。少なくともディドロ以来、あらゆる芸術における批評の主な伝統は、真実性(verisimilitude)

と道徳的正しさという一見異質な基準に訴えかけながら、事実上、芸術作品を、芸術作品という形でなされる声明として扱ってきた。

|

To treat works of art in this

fashion is not wholly irrelevant. But it is, obviously, putting art to

use

—for such purposes as inquiring into the history of ideas, diagnosing

contemporary culture, or

creating social solidarity. Such a treatment has little to do with what

actually happens when a person

possessing some training and aesthetic sensibility looks at a work of

art appropriately. A work of art

encountered as a work of art is an experience, not a statement or an

answer to a question. Art is not

only about something; it is something. A work of art is a thing in the

world, not just a text or

commentary on the world.

|

芸

術作品をこのように扱うことは、まったく無関係というわけではない。しかし、それは明らかに芸術を利用することであり、思想史の探求、現代文化の診断、社

会的連帯の創出といった目的のために利用することである。このような扱いは、ある程度の訓練と美的感覚を持った人間が芸術作品を適切に鑑賞したときに実際

に起こることとはほとんど関係がない。芸術作品として出会った作品は経験であり、ステートメントや質問に対する答えではない。芸術とは何かについてだけあ

るのではなく、何かである。芸術作品とは、単なる文章や解説ではなく、世界に存在するものなのだ。

|

I am not saying that a work of

art creates a world which is entirely self-referring. Of course,

works of art (with the important exception of music) refer to the real

world—to our knowledge, to

our experience, to our values. They present information and

evaluations. But their distinctive feature

is that they give rise not to conceptual knowledge (which is the

distinctive feature of discursive or

scientific knowledge—e.g., philosophy, sociology, psychology, history)

but to something like an

excitation, a phenomenon of commitment, judgment in a state of

thralldom or captivation. Which is to

say that the knowledge we gain through art is an experience of the form

or style of knowing

something, rather than a knowledge of something (like a fact or a moral

judgment) in itself.

This explains the preeminence of the value of expressiveness in works

of art; and how the value

of expressiveness—that is, of style—rightly takes precedence over

content (when content is, falsely,

isolated from style). The satisfactions of Paradise Lost for us do not

lie in its views on God and man,

but in the superior kinds of energy, vitality, expressiveness which are

incarnated in the poem.

Hence, too, the peculiar dependence of a work of art, however

expressive, upon the cooperation

of the person having the experience, for one may see what is “said” but

remain unmoved, either

through dullness or distraction. Art is seduction, not rape. A work of

art proposes a type of

experience designed to manifest the quality of imperiousness. But art

cannot seduce without the

complicity of the experiencing subject.

|

私は、芸術作品が完全に自己言及的な世界を創造すると言っているのでは

ない。もちろん、芸術作品は(音楽という重要な例外を除いて)現実の世界、つまり私

たちの知識、経験、価値観を参照している。それらは情報や評価を提示する。しかし、その特徴は、概念的な知識(哲学、社会学、心理学、歴史学など)ではな

く、興奮やコミットメントの現象、虜囚状態における判断のようなものを生み出すことである。つまり、私たちが芸術を通して得る知識は、何か(事実や道徳的

判断のような)それ自体についての知識ではなく、何かを知るための形式やスタイルの経験なのである。

23.

このことは、芸術作品における表現力の価値の優位性を説明するものであり、表現力の価値、つまりスタイルの価値が、(コンテンツがスタイルから誤って切り

離された場合)コンテンツに優先することを説明するものである。失楽園』が私たちを満足させるのは、その神と人間についての見解にあるのではなく、この詩

に込められた優れた種類のエネルギー、活力、表現力にあるのだ。それゆえ、どんなに表現力豊かな芸術作品であっても、それを体験する人の協力に依存するの

である。芸術は誘惑であり、強姦ではない。芸術作品は、不遜さの質を顕在化させるためにデザインされた一種の経験を提案する。しかし、芸術は、体験する主

体の共犯なしには誘惑できない。

|

Inevitably, critics who regard

works of art as statements will be wary of “style,” even as they pay

lip

service to “imagination.” All that imagination really means for them,

anyway, is the supersensitive

rendering of “reality.” It is this “reality” snared by the work of art

that they continue to focus on,

rather than on the extent to which a work of art engages the mind in

certain transformations.

But when the metaphor of the work of art as a statement loses its

authority, the ambivalence

toward “style” should dissolve; for this ambivalence mirrors the

presumed tension between the

statement and the manner in which it is stated.

|

芸術作品をステートメントとみなす批評家たちは、"イマジネーション

"にリップサービスをしながらも、必然的に "スタイル "を警戒する。いずれにせよ、彼らにとっての想像力とは、"現実

"を超感覚的に描写することなのだ。彼らが注目し続けるのは、芸術作品によって捕らえられた "現実

"であり、むしろ芸術作品が心をどの程度変容させるかということなのだ。

しかし、声明としての芸術作品というメタファーがその権威を失ったとき、「スタイル」に対するアンビバレンスは解消されるはずである。このアンビバレンス

は、声明とそれを述べる方法との間に推定される緊張を映し出すからである。

|

In the end, however, attitudes

toward style cannot be reformed merely by appealing to the

“appropriate” (as opposed to utilitarian) way of looking at works of

art. The ambivalence toward

style is not rooted in simple error—it would then be quite easy to

uproot—but in a passion, the

passion of an entire culture. This passion is to protect and defend

values traditionally conceived of as

lying “outside” art, namely truth and morality, but which remain in

perpetual danger of being

compromised by art. Behind the ambivalence toward style is, ultimately,

the historic Western

confusion about the relation between art and morality, the aesthetic

and the ethical.

|

しかし、結局のところ、芸術作品の「適切な」(功利主義的な見方とは対

照的な)見方を訴えるだけでは、スタイルに対する態度を改めることはできない。スタイルに対するアンビバレンスは、単純な誤りに根ざしているのではなく、

文化全体の情熱に根ざしているのだ。その情熱とは、伝統的に芸術の「外」にあると考えられてきた価値、すなわち真理と道徳を守り抜くことである。スタイル

に対するアンビバレンスの背後には、結局のところ、芸術と道徳、美的なものと倫理的なものとの関係についての歴史的な西洋の混乱がある。

|

For the problem of art versus

morality is a pseudo-problem. The distinction itself is a trap; its

continued plausibility rests on not putting the ethical into question,

but only the aesthetic. To argue on

these grounds at all, seeking to defend the autonomy of the aesthetic

(and I have, rather uneasily, done

so myself), is already to grant something that should not be

granted—namely, that there exist two

independent sorts of response, the aesthetic and the ethical, which vie

for our loyalty when we

experience a work of art. As if during the experience one really had to

choose between responsible

and humane conduct, on the one hand, and the pleasurable stimulation of

consciousness, on the other!

Of course, we never have a purely aesthetic response to works of

art—neither to a play or a

novel, with its depicting of human beings choosing and acting, nor,

though it is less obvious, to a

painting by Jackson Pollock or a Greek vase. (Ruskin has written

acutely about the moral aspects of

the formal properties of painting.) But neither would it be appropriate

for us to make a moral

response to something in a work of art in the same sense that we do to

an act in real life. I would

undoubtedly be indignant if someone I knew murdered his wife and got

away with it (psychologically,

legally), but I can hardly become indignant, as many critics seem to

be, when the hero of Norman

Mailer’s An American Dream murders his wife and goes unpunished.

Divine, Darling, and the others

in Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers are not real people whom we are

being asked to decide whether

to invite into our living rooms; they are figures in an imaginary

landscape. The point may seem

obvious, but the prevalence of genteel-moralistic judgments in

contemporary literary (and film)

criticism makes it worth repeating a number of times.

|

というのも、芸術か道徳かという問題は疑似問題だからだ。その区別自体

が罠であり、その区別が妥当であり続けるかどうかは、倫理的なものを問題にせず、美的なものだけを問題にするかどうかにかかっている。美学的なものの自律

性を擁護しようとして、このような根拠に基づいて議論することは(私自身、かなり不安ではあるが、そうしてきた)、すでに認めてはならないことを認めてい

ることになる。つまり、美学的なものと倫理的なものという2種類の独立した反応が存在し、私たちが芸術作品を体験するときに、その2種類の反応が私たちの

忠誠を争うということだ。あたかも、体験中に、一方では責任ある人道的な行為、他方では快楽的な意識刺激のどちらかを選ばなければならないかのように!

28.

もちろん、私たちは芸術作品に対して純粋に美的な反応を示すことはない。人間が選択し行動する姿を描いた戯曲や小説に対しても、あまり目立たないがジャク

ソン・ポロックの絵画やギリシャの壺に対してもそうである(ラスキンは絵画の形式的特性が道徳的側面に及ぼす影響について鋭く書いている)。しかし、現実

の生活における行為と同じような意味で、芸術作品の何かに対して道徳的な反応を示すことは、どちらも適切ではないだろう。しかし、多くの批評家がそうであ

るように、ノーマン・メーラーの『アメリカン・ドリーム』の主人公が妻を殺害し、罰せられずにいることに憤慨することはできない。ジュネの『花のノートル

ダム』に登場するディヴァインやダーリン、その他の人々は、私たちが居間に招き入れるかどうかの判断を求められている実在の人物ではない。この指摘は自明

のことのように思えるかもしれないが、現代の文芸(および映画)批評には、上品で道徳的な判断が蔓延しているため、何度でも繰り返す価値がある。

|

For most people, as Ortega y

Gasset has pointed out in The Dehumanization of Art, aesthetic

pleasure is a state of mind essentially indistinguishable from their

ordinary responses. By art, they

understand a means through which they are brought in contact with

interesting human affairs. When

they grieve and rejoice at human destinies in a play or film or novel,

it is not really different from

grieving and rejoicing over such events in real life—except that the

experience of human destinies in

art contains less ambivalence, it is relatively disinterested, and it

is free from painful consequences.

The experience is also, in a certain measure, more intense; for when

suffering and pleasure are

experienced vicariously, people can afford to be avid. But, as Ortega

argues, “a preoccupation with

the human content of the work [of art] is in principle incompatible

with aesthetic judgment.”2

Ortega is entirely correct, in my opinion. But I would not care to

leave the matter where he does,

which tacitly isolates aesthetic from moral response. Art is connected

with morality, I should argue.

One way that it is so connected is that art may yield moral pleasure;

but the moral pleasure peculiar

to art is not the pleasure of approving of acts or disapproving of

them. The moral pleasure in art, as

well as the moral service that art performs, consists in the

intelligent gratification of consciousness.

|

オルテガ・イ・ガセットが『芸術の非人間化』の中で指摘しているよう

に、ほとんどの人にとって、美的快楽とは、通常の反応と本質的に区別できない心の状態である。芸術とは、興味深い人間的な出来事と接触するための手段であ

る。演劇や映画や小説の中の人間の運命に悲しんだり喜んだりするのは、現実の生活の中でそのような出来事に悲しんだり喜んだりするのとあまり変わらない。

苦しみや喜びを身をもって体験することで、人はより熱心になれるからだ。しかし、オルテガが主張するように、「作品(芸術)の人間的内容へのこだわりは、

美的判断とは原理的に相容れない」2。しかし私は、美的判断と道徳的判断とを暗黙のうちに切り離してしまうオルテガの立場を、そのままにしておくことには

抵抗がある。芸術は道徳と結びついている。しかし、芸術に特有の道徳

的快楽とは、行為を肯定したり否定したりする快楽ではない。芸術における道徳的快楽は、芸術が果たす道徳的奉仕と同様に、意識の知的満足にある。

|

What “morality” means is a

habitual or chronic type of behavior (including feelings and acts).

Morality is a code of acts, and of judgments and sentiments by which we

reinforce our habits of

acting in a certain way, which prescribe a standard for behaving or

trying to behave toward other

human beings generally (that is, to all who are acknowledged to be

human) as if we were inspired by

love. Needless to say, love is something we feel in truth for just a

few individual human beings,

among those who are known to us in reality and in our imagination.…

Morality is a form of acting and

not a particular repertoire of choices.

|

道徳」が意味するのは、習慣的あるいは慢性的な行動(感情や行為を含

む)である。道徳とは行為の規範であり、私たちがある種の方法で行動する習慣を強化する判断や感情の規範であり、それはあたかも私たちが愛に感化されたか

のように、他の人間一般(つまり、人間であると認められるすべての人)に対してふるまう、あるいはふるまおうとする基準を規定するものである。言うまでも

なく、愛とは、現実と想像の中で私たちに知られている人間のうち、ほんの少数の個々の人間に対して私たちが真実に感じるものである......。道徳とは

行動の一形態であり、特定の選択のレパートリーではない。

|

If morality is so understood—as

one of the achievements of human will, dictating to itself a mode

of acting and being in the world—it becomes clear that no generic

antagonism exists between the

form of consciousness, aimed at action, which is morality, and the

nourishment of consciousness,

which is aesthetic experience. Only when works of art are reduced to

statements which propose a

specific content, and when morality is identified with a particular

morality (and any particular

morality has its dross, those elements which are no more than a defense

of limited social interests and

class values)—only then can a work of art be thought to undermine

morality. Indeed, only then can the

full distinction between the aesthetic and the ethical be made.

|

道徳を人間の意志の成果の一つとして理解し、世界における行動様式と存在様式を自らに指示するのであれば、道徳である行動を目的とした意識の形態と、美的経験である意識の糧との間には、一般的な拮抗関係が存在しないことが明らかになる。芸術作品が特定の内容を提示する声明に還元され、道徳が特定の道徳と同一視されるとき(そして、どのような特定の道徳にも、限られた社会的利益や階級的価値を擁護する以外の何ものでもない要素という夾雑物がある)、初めて芸術作品が道徳を損なうと考えることができる。美学的なものと倫理的なものを完全に区別することができるのは、そのときだけなのだ。

|

But if we understand morality in

the singular, as a generic decision on the part of consciousness,

then it appears that our response to art is “moral” insofar as it is,

precisely, the enlivening of our

sensibility and consciousness. For it is sensibility that nourishes our

capacity for moral choice, and

prompts our readiness to act, assuming that we do choose, which is a

prerequisite for calling an act

moral, and are not just blindly and unreflectively obeying. Art

performs this “moral” task because the

qualities which are intrinsic to the aesthetic experience

(disinterestedness, contemplativeness,

attentiveness, the awakening of the feelings) and to the aesthetic

object (grace, intelligence,

expressiveness, energy, sensuousness) are also fundamental constituents

of a moral response to life.

|

33. しかし、もし私たちが、道徳を単数的なもの、つまり意識の側に

おける一般的な決定として理解するならば、芸術に対する私たちの反応は、それがまさに私たちの感性と意識を活気づけるものである限りにおいて、「道徳的」

であるように思われる。というのも、私たちの道徳的な選択能力を養い、私たちの行動の準備を促すのは感性だからである。美的体験に内在する特質(無関心、

観照性、注意深さ、感情の覚醒)や美的対象に内在する特質(優美さ、知性、表現力、エネルギー、官能性)は、人生に対する道徳的反応の基本的構成要素でも

あるからだ。 |

In art, “content” is, as it

were, the pretext, the goal, the lure which engages consciousness in

essentially formal processes of transformation.

|

アートにおいて「コンテンツ=内容」とは、いわば、本質的に形式的な変

容のプロセスに意識を巻き込むための口実であり、目標であり、誘惑である。

|

This is how we can, in good

conscience, cherish works of art which, considered in terms of

“content,” are morally objectionable to us. (The difficulty is of the

same order as that involved in

appreciating works of art, such as The Divine Comedy, whose premises

are intellectually alien.) To

call Leni Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will and The Olympiad

masterpieces is not to gloss over

Nazi propaganda with aesthetic lenience. The Nazi propaganda is there.

But something else is there,

too, which we reject at our loss. Because they project the complex

movements of intelligence and

grace and sensuousness, these two films of Riefenstahl (unique among

works of Nazi artists)

transcend the categories of propaganda or even reportage. And we find

ourselves—to be sure, rather

uncomfortably—seeing “Hitler” and not Hitler, the “1936 Olympics” and

not the 1936 Olympics.

Through Riefenstahl’s genius as a film-maker, the “content” has—let us

even assume, against her

intentions—come to play a purely formal role.

|

このように、"内容 "という観点から考えると、道徳的に好ましくない芸術作品を、良心の呵責をもって大切にすることができるのである。(この困難は、『神曲』のような、その前提が知的に異質な芸術作品を鑑賞するのと同程度のものである)。レニ・リーフェンシュタールの『意志の勝利』や『オリンピアード』を傑作と呼ぶことは、ナチスのプロパガンダを美的な寛容さでごまかすことではない。ナチスのプロパガンダはそこにある。しかし、それ以外のものもそこにあり、私たちはそれを拒絶している。知

性と気品と官能の複雑な動きを映し出すリーフェンシュタールのこの2作品(ナチスの芸術家の作品の中では異色)は、プロパガンダやルポルタージュの範疇さ

えも超越している。そして私たちは、「ヒトラー」であってヒトラーではなく、「1936年オリンピック」であって1936年オリンピックではなく、

「1936年オリンピック」を見ていることに気づく。リーフェンシュタールの映画作家としての天才によって、"内容 "は、彼女の意図に反して、純粋に形式的な役割を果たすようになった。

|

A work of art, so far as it is a

work of art, cannot—whatever the artist’s personal intentions—

advocate anything at all. The greatest artists attain a sublime

neutrality. Think of Homer and

Shakespeare, from whom generations of scholars and critics have vainly

labored to extract particular

“views” about human nature, morality, and society.

|

芸術作品は、それが芸術作品である限り、芸術家の個人的意図がどうであれ、何かを主張することはできない。最も偉大な芸術家たちは、崇高な中立性を獲得している。ホメロスやシェイクスピアを思い浮かべてほしい。彼らから何世代もの学者や批評家たちが、人間の本質、道徳、社会についての特定の「見解」を引き出そうと無駄な努力を重ねてきた。

|

Again, take the case of

Genet—though here, there is additional evidence for the point I am

trying

to make, because the artist’s intentions are known. Genet, in his

writings, may seem to be asking us to

approve of cruelty, treacherousness, licentiousness, and murder. But so

far as he is making a work of

art, Genet is not advocating anything at all. He is recording,

devouring, transfiguring his experience.

In Genet’s books, as it happens, this very process itself is his

explicit subject; his books are not only

works of art but works about art. However, even when (as is usually the

case) this process is not in

the foreground of the artist’s demonstration, it is still this, the

processing of experience, to which we

owe our attention. It is immaterial that Genet’s characters might repel

us in real life. So would most

of the characters in King Lear. The interest of Genet lies in the

manner whereby his “subject” is

annihilated by the serenity and intelligence of his imagination.

|

ここでもまた、ジュネのケースを考えてみよう。ジュネはその著作の中で、残酷さ、裏切り、放縦、殺人を肯定するよう求めているように見えるかもしれない。しかし、芸術作品を作っている限り、ジュネは何も主張していない。彼は自分の経験を記録し、むさぼり、変容させているのだ。ジュ

ネの本では、偶然にも、このプロセスそのものが彼の明確な主題となっている。しかし、(通常そうであるように)このプロセスが作家の実演の前景にないとき

でさえ、私たちが注意を払わなければならないのは、やはりこのプロセス、すなわち経験の処理なのである。ジュネの登場人物が、現実の生活で私たちの反感を

買うかもしれないことは重要ではない。『リア王』の登場人物のほとんどがそうだろう。ジュネの面白さは、彼の「主題」が彼の想像力の静けさと知性によって

消滅させられる方法にある。

|

Approving or disapproving

morally of what a work of art “says” is just as extraneous as

becoming sexually excited by a work of art. (Both are, of course, very

common.) And the reasons

urged against the propriety and relevance of one apply as well to the

other. Indeed, in this notion of

the annihilation of the subject we have perhaps the only serious

criterion for distinguishing between

erotic literature or films or paintings which are art and those which

(for want of a better word) one

has to call pornography. Pornography has a “content” and is designed to

make us connect (with

disgust, desire) with that content. It is a substitute for life. But

art does not excite; or, if it does, the

excitation is appeased, within the terms of the aesthetic experience.

All great art induces

contemplation, a dynamic contemplation. However much the reader or

listener or spectator is aroused

by a provisional identification of what is in the work of art with real

life, his ultimate reaction—so

far as he is reacting to the work as a work of art—must be detached,

restful, contemplative,

emotionally free, beyond indignation and approval. It is interesting

that Genet has recently said that he

now thinks that if his books arouse readers sexually, “they’re badly

written, because the poetic

emotion should be so strong that no reader is moved sexually. Insofar

as my books are pornographic, I

don’t reject them. I simply say that I lacked grace.”

|

芸術作品が「何を言っているのか」を道徳的に賛否することは、芸術作品

に性的興奮を覚えることと同様に、余計なお世話である。(もちろん、どちらもごく一般的なことだ)そして、一方の妥当性や関連性を否定する理由は、他方に

も当てはまる。実際、この「主体の消滅」という考え方には、芸術であるエロティックな文学や映画や絵画と、(言葉は悪いが)ポルノと呼ばなければならない

ものを区別する、おそらく唯一の重大な基準がある。ポルノには「内容」があり、その内容と私たちを(嫌悪や欲望をもって)結びつけさせるようにデザインさ

れている。それは人生の代用品である。しかし、芸術は興奮させない。あるいは、興奮させるとしても、美的体験の条件の範囲内で、興奮を鎮める。偉大な芸術

はすべて、動的な瞑想を誘発する。読者や聴衆や観客が、芸術作品にあるものを現実の生活と仮に同一視することによってどれほど興奮したとしても、彼の最終

的な反応は、芸術作品として作品に反応している限りにおいて、憤りや賛意を超えて、離隔的で、安らかで、瞑想的で、感情的に自由でなければならない。最近

ジュネが、「自分の本が読者を性的に興奮させるなら、それはひどい作品だと思う、と語っているのは興味深い。私の本がポルノ的である限り、私はそれを否定

しない。単に "恩寵(=資質)が足りなかった "と言うだけだ」。

|

A

work of art may contain all

sorts of information and offer instruction in new (and sometimes

commendable) attitudes. We may learn about medieval theology and

Florentine history from Dante;

we may have our first experience of passionate melancholy from Chopin;

we may become convinced

of the barbarity of war by Goya and of the inhumanity of capital

punishment by An American Tragedy.

But so far as we deal with these works as works of art, the

gratification they impart is of another

order. It is an experience of the qualities or forms of human

consciousness.

|

芸

術作品にはさまざまな情報が含まれ、新たな(そして時には称賛に値する)姿勢を教えてくれるかもしれない。ダンテから中世の神学やフィレンツェの歴史を学

び、ショパンから情熱的なメランコリーを初めて体験し、ゴヤから戦争の野蛮さを、『アメリカの悲劇』から死刑の非人道性を確信するかもしれない。しかし、

これらの作品を芸術作品として扱う限り、それらが与える満足感は別の次元のものである。それは、人間の意識の特質や形態を体験することである。

|

The objection that this approach

reduces art to mere “formalism” must not be allowed to stand.

(That word should be reserved for those works of art which mechanically

perpetuate outmoded or

depleted aesthetic formulas.) An approach which considers works of art

as living, autonomous

models of consciousness will seem objectionable only so long as we

refuse to surrender the shallow

distinction of form and content. For the sense in which a work of art

has no content is no different

from the sense in which the world has no content. Both are. Both need

no justification; nor could they

possibly have any.

|

このアプローチが芸術を単なる「形式主義=フォルマリズム」に貶めると

いう反論は、決して許してはならない。(この言葉は、時代遅れの、あるいは枯渇した美的定型を機械的に永続させるような芸術作品に対してのみ使われるべき

ものである)。芸術作品を生きた、自律的な意識のモデルとして考えるアプローチは、形式と内容という浅薄な区別を放棄することを拒む限り、異論があるよう

に思われるだろう。芸術作品に内容がないという意味は、世界に内容がないという意味と何ら変わらないからだ。どちらもそうなのだ。どちらも正当化する必要

はない。

|

The hyperdevelopment of style

in, for example, Mannerist painting and Art Nouveau, is an emphatic

form of experiencing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon. But only a

particularly emphatic form,

which arises in reaction to an oppressively dogmatic style of realism.

All style—that is, all art—

proclaims this. And the world is,

ultimately, an aesthetic phenomenon.

|

41

例えば、マニエリスム絵画やアール・ヌーヴォーにおける様式の超展開は、世界を美的現象として経験することの強調された形式である。しかし、それは特に強

調された形式であり、リアリズムという抑圧的で独断的な様式への反動として生まれたものである。すべてのスタイル、すなわちすべての芸術は、このことを宣

言している。そして、世界は究極的には美的現象なのだ。

|

That is to say, the world (all

there is) cannot, ultimately, be justified. Justification is an

operation

of the mind which can be performed only when we consider one part of

the world in relation to

another—not when we consider all there is.

|

つまり、世界(そこに存在するすべて)を究極的に正当化することはできない。正当化とは心の働きであり、世界のある部分を別の部分との関係において考察するときにのみ可能なのであって、世界のすべてを考察するときには不可能なのである。

|

The work of art, so far as we

give ourselves to it, exercises a total or absolute claim on us. The

purpose of art is not as an auxiliary to truth, either particular and

historical or eternal. “If art is

anything,” as Robbe-Grillet has written, “it is everything; in which

case it must be self-sufficient, and

there can be nothing beyond it.”

|

43.

芸術作品は、私たちがそれに身を委ねる限りにおいて、私たちに全面的あるいは絶対的な要求を行使する。芸術の目的は、特定の歴史的な真理や永遠の真理を補

助することではない。「ロブ=グリエが書いているように、「芸術が何かであるとすれば、それはすべてである。そして、その場合、それは自給自足でなければ

ならない」。

|

But this position is easily

caricatured, for we live in the world, and it is in the world that

objects

of art are made and enjoyed. The claim that I have been making for the

autonomy of the work of art—

its freedom to “mean” nothing—does not rule out consideration of the

effect or impact or function of

art, once it be granted that in this functioning of the art object as

art object the divorce between the

aesthetic and the ethical is meaningless.

|

し

かし、この立場は戯画化されやすい。なぜなら、私たちは世界に生きており、芸術の対象が作られ、享受されるのも世界だからである。私がこれまで主張してき

た芸術作品の自律性、つまり何も「意味しない」自由は、芸術の効果や影響や機能についての考察を排除するものではない。

|

I have several times applied to

the work of art the metaphor of a mode of nourishment. To become

involved with a work of art entails, to be sure, the experience of

detaching oneself from the world.

But the work of art itself is also a vibrant, magical, and exemplary

object which returns us to the

world in some way more open and enriched.

|

私

は何度か、芸術作品に「栄養補給」という比喩を使ったことがある。芸術作品に関わることは、確かに、世界から自分を切り離す経験を伴う。しかし、芸術作品

そのものは、私たちをより開放的で豊かな世界へと戻してくれる、生き生きとした、魔法のような、模範的な対象でもある。

|

Raymond Bayer has written: “What

each and every aesthetic object imposes upon us, in appropriate

rhythms, is a unique and singular formula for the flow of our energy.…

Every work of art embodies a

principle of proceeding, of stopping, of scanning; an image of energy

or relaxation, the imprint of a

caressing or destroying hand which is [the artist’s] alone.” We can

call this the physiognomy of the

work, or its rhythm, or, as I would rather do, its style. Of course,

when we employ the notion of style

historically, to group works of art into schools and periods, we tend

to efface the individuality of

styles. But this is not our experience when we encounter a work of art

from an aesthetic (as opposed

to a conceptual) point of view. Then, so far as the work is successful

and still has the power to

communicate with us, we experience only the individuality and

contingency of the style.

|

レ

イモンド・ベイヤーはこう書いている:

「すべての芸術作品は、進行、停止、走査の原理を体現している。エネルギーや弛緩のイメージ、撫でる手や破壊する手の刻印は、(芸術家)だけのものであ

る。私たちはこれを作品の人相と呼ぶこともできるし、リズムと呼ぶこともできる。もちろん、芸術作品を流派や時代に分類するために歴史的に様式という概念

を用いると、私たちは様式の個性を消し去る傾向がある。しかし、(概念的な視点ではなく)美的な視点から芸術作品に出会ったときには、このようなことは起

こらない。そして、その作品が成功し、なおかつ私たちとコミュニケーションする力を持っている限り、私たちはスタイルの個性と偶発性だけを経験することに

なる。

|

It is the same with our own

lives. If we see them from the outside, as the influence and popular

dissemination of the social sciences and psychiatry has persuaded more

and more people to do, we

view ourselves as instances of generalities, and in so doing become

profoundly and painfully

alienated from our own experience and our humanity.

|

そ

れは私たち自身の人生も同じだ。社会科学や精神医学の影響と普及が、ますます多くの人々にそうさせるように説得しているように、私たちが外からそれらを見

るとすれば、私たちは自分自身を一般論の一例として見ることになり、そうすることで、自分自身の経験や人間性から深く痛く疎外されることになる。

|

As William Earle has recently

noted, if Hamlet is “about” anything, it is about Hamlet, his

particular situation, not about the human condition. A work of art is a

kind of showing or recording or

witnessing which gives palpable form to consciousness; its object is to

make something singular

explicit. So far as it is true that we cannot judge (morally,

conceptually) unless we generalize, then it

is also true that the experience of works of art, and what is

represented in works of art, transcends

judgment—though the work itself may be judged as art. Isn’t this just

what we recognize as a feature

of the greatest art, like the Iliad and the novels of Tolstoy and the

plays of Shakespeare? That such art

overrides our petty judgments, our facile labelling of persons and acts

as good or bad? And that this

can happen is all to the good. (There is even a gain for the cause of

morality in it.)

|

ウィ

リアム・アールが最近指摘したように、『ハムレット』が何か "について

"描かれているとすれば、それはハムレットと彼の特殊な状況についてであって、人間の条件についてではない。芸術作品とは、意識に具体的な形を与える一種

のショーであり、記録であり、目撃である。一般化しない限り、(道徳的、概念的に)判断することはできないというのが真実である限り、芸術作品の経験や芸

術作品に表現されるものは、判断を超越しているというのも真実である。これは、イーリアスやトルストイの小説、シェイクスピアの戯曲のような偉大な芸術の

特徴として、私たちが認識していることにほかならないのではないだろうか?そのような芸術は、私たちの些細な判断や、人物や行為に安易に善悪のレッテルを

貼ることを覆すのではないだろうか?そして、このようなことが起こり得ることは、すべて良いことなのだ。(道徳という大義名分を得ることさえあるのだか

ら)。

|

For morality, unlike art, is

ultimately justified by its utility: that it makes, or is supposed to

make,

life more humane and livable for us all. But consciousness—what used to

be called, rather

tendentiously, the faculty of contemplation—can be, and is, wider and

more various than action. It has

its nourishment, art and speculative thought, activities which can be

described either as self-justifying

or in no need of justification. What a work of art does is to make us

see or comprehend something

singular, not judge or generalize. This

act of comprehension

accompanied by voluptuousness is the

only valid end, and sole sufficient justification, of a work of art.

|

49.

というのも、道徳は芸術とは異なり、究極的にはその有用性によって正当化されるからである。しかし、意識は、かつてはどちらかといえば傾向的に「観照の能

力」と呼ばれていたものであり、行動よりも広く多様なものである。芸術や思索という、自己正当化とも正当化の必要もない活動によって養われる。芸術作品が

することは、何かを判断したり一般化したりするのではなく、特異なものを見たり理解したりさせることである。官能性(voluptuousness)を伴うこの理解行為こそが、芸術作品の唯一の有効な目的であり、唯一の十分な正当性なのであ

る。

|

Perhaps the best way of

clarifying the nature of our experience of works of art, and the

relation

between art and the rest of human feeling and doing, is to invoke the

notion of will. It is a useful

notion because will is not just a particular posture of consciousness,

energized consciousness. It is

also an attitude toward the world, of a subject toward the world.

|

芸

術作品に対する私たちの体験の本質、そして芸術と人間の感情や行為との関係を明

確にする最善の方法は、意志という概念を呼び起こすことだろう。意志とは、単に意識の特定の姿勢や、エネルギーを与えられた意識というだけではないから

だ。それはまた、世界に対する、世界に対する主体の態度でもある。

|

The complex kind of willing that

is embodied, and communicated, in a work of art both abolishes

the world and encounters it in an extraordinary intense and specialized

way. This double aspect of the

will in art is succinctly expressed by Bayer when he says: “Each work

of art gives us the schematized

and disengaged memory of a volition.” Insofar as it is schematized,

disengaged, a memory, the willing

involved in art sets itself at a distance from the world.

|

芸

術作品に具現化され、伝達される複雑な種類の意志は、世界を廃絶すると同時に、並はずれて強烈で特殊な方法で世界と出会う。芸術における意志のこの二重の

側面は、バイエルによって簡潔に表現されている。それが図式化され、切り離され、記憶である限りにおいて、芸術に関わる意志は自らを世界と距離を置く。

|

All of which harkens back to

Nietzsche’s famous statement in The Birth of Tragedy: “Art is not an

imitation of nature but its metaphysical supplement, raised up beside

it in order to overcome it.”

All works of art are founded on a certain distance from the lived

reality which is represented.

This “distance” is, by definition, inhuman or impersonal to a certain

degree; for in order to appear to

us as art, the work must restrict sentimental intervention and

emotional participation, which are

functions of “closeness.” It is the degree and manipulating of this

distance, the conventions of

distance, which constitute the style of the work. In the final

analysis, “style” is art. And art is nothing

more or less than various modes of stylized, dehumanized representation.

|

52. これらはすべて、『悲劇の誕生』におけるニーチェの有名な発言

を思い起こさせる: 「芸術は自然を模倣するものではなく、自然を克服するために自然の傍らに立ち上がる、形而上学的な補完物である」。

53. すべての芸術作品は、表現される現実との一定の距離の上に成り立っている。この "距離

"は、定義上、非人間的あるいは非個性的なものである。私たちに芸術として見えるためには、作品は "近さ

"の機能である感傷的な介入や感情的な参加を制限しなければならない。作品のスタイルを構成するのは、この距離の程度と操作、距離の慣習である。最終的

に、「スタイル」とは芸術である。そして、芸術とは、様式化され、非人間化されたさまざまな表現様式以上でも以下でもない。

|

But this view—expounded by

Ortega y Gasset, among others—can easily be misinterpreted, since

it seems to suggest that art, so far as it approaches its own norm, is

a kind of irrelevant, impotent toy.

Ortega himself greatly contributes to such a misinterpretation by

omitting the various dialectics

between self and world involved in the experiencing of works of art.

Ortega focuses too exclusively

on the notion of the work of art as a certain kind of object, with its

own, spiritually aristocratic,

standards for being savored. A work of art is first of all an object,

not an imitation; and it is true that

all great art is founded on distance, on artificiality, on style, on

what Ortega calls dehumanization. But

the notion of distance (and of dehumanization, as well) is misleading,

unless one adds that the

movement is not just away from but toward the world. The overcoming or

transcending of the world

in art is also a way of encountering the world, and of training or

educating the will to be in the world.

It would seem that Ortega and even Robbe-Grillet, a more recent

exponent of the same position, are

still not wholly free of the spell of the notion of “content.” For, in

order to limit the human content of

art, and to fend off tired ideologies like humanism or socialist

realism which would put art in the

service of some moral or social idea, they feel required to ignore or

scant the function of art. But art

does not become function-less when it is seen to be, in the last

analysis, content-less. For all the

persuasiveness of Ortega’s and Robbe-Grillet’s defense of the formal

nature of art, the specter of

banished “content” continues to lurk around the edges of their

argument, giving to “form” a defiantly

anemic, salutarily eviscerated look.

|

54.

しかし、オルテガ・イ・ガセットらによって説かれたこの見解は、芸術が自らの規範に近づく限り、無関係で無力な玩具のようなものだと示唆しているように思

われるため、誤解されやすい。オルテガ自身、芸術作品の体験に関わる自己と世界の間のさまざまな弁証法を省くことで、このような誤解に大きく加担してい

る。オルテガは、芸術作品を、ある種の対象として、それ自身の、精神的に貴族的な、味わうための基準を持つものとしてとらえすぎている。そして、すべての

偉大な芸術が、距離、人工性、様式、オルテガの言う非人間性に基づいていることは事実である。しかし、距離という概念(そして非人間化という概念も同様)

は、その運動が世界から離れるだけでなく、世界へ向かうものであることを付け加えない限り、誤解を招く。芸術における世界の克服や超越は、世界と出会うこ

とでもあり、世界に存在しようとする意志を訓練したり教育したりすることでもある。オルテガや、同じ立場をより最近提唱したロブ=グリエでさえも、"内容

"という概念の呪縛から完全に解き放たれているわけではないようだ。というのも、芸術の人間的内容を限定し、ヒューマニズムや社会主義リアリズムのよう

な、芸術を道徳的あるいは社会的思想のために役立てようとする疲弊したイデオロギーを退けるために、彼らは芸術の機能を無視するか、あるいは乏しくする必

要があると感じているからである。しかし、最終的に無内容であることがわかれば、芸術が無機能になるわけではない。オルテガとロブ=グリエが芸術の形式的

本質を擁護することには説得力があるが、彼らの主張の端々には、追放された「内容」の亡霊が潜み続けている。

|

The argument will never be

complete until “form” or “style” can be thought of without that

banished specter, without a feeling of loss. Valéry’s daring

inversion—“Literature. What is ‘form’

for anyone else is ‘content’ for me”—scarcely does the trick. It

is

hard to think oneself out of a

distinction so habitual and apparently self-evident. One can do so only

by adopting a different, more

organic, theoretical vantage point—such as the notion of will. What is

wanted of such a vantage point

is that it do justice to the twin aspects of art: as object and as

function, as artifice and as living form

of consciousness, as the overcoming or supplementing of reality and as

the making explicit of forms

of encountering reality, as autonomous individual creation and as

dependent historical phenomenon.

|

55.

「形式」や「スタイル」が、その追放された亡霊なしに、喪失感なしに考えられるようになるまでは、議論は決して完結しない。ヴァレリーの大胆な反転、すな

わち「文学。他の誰にとっても「形式」であるものが、私にとっては「内容」なのだ」

は、そのトリックをほとんど成し遂げていない。これほど習慣的で自明な区別から自分を解き放つのは難しい。そうするためには、意志の概念のような、より有

機的で理論的な視点を採用するしかない。このような視点に求められるのは、芸術の二つの側面を正しく理解することである。対象としてであると同時に機能と

して、人工物としてであると同時に意識の生きた形として、現実の克服や補完としてであると同時に現実との出会いの形を明示するものとして、自律的な個人の

創造としてであると同時に依存的な歴史的現象としてである。

|

Art is the objectifying of the

will in a thing or performance, and the provoking or arousing of the

will.

From the point of view of the artist, it is the objectifying of a

volition; from the point of view of the

spectator, it is the creation of an imaginary décor for the will.

|

56.

芸術とは、物事やパフォーマンスにおいて意志を対象化することであり、意志を刺激したり喚起したりすることである。芸術家から見れば、それは意志の対象化

であり、観客から見れば、それは意志のための想像上の装飾の創造である。

|

Indeed, the entire history of

the various arts could be rewritten as the history of different

attitudes

toward the will. Nietzsche and Spengler wrote pioneer studies on this

theme. A valuable recent

attempt is to be found in a book by Jean Starobinski, The Invention of

Liberty, mainly devoted to 18th

century painting and architecture. Starobinski examines the art of this

period in terms of the new ideas

of self-mastery and of mastery of the world, as embodying new relations

between the self and the

world. Art is seen as the naming of emotions. Emotions, longings,

aspirations, by thus being named,

are virtually invented and certainly promulgated by art: for example,

the “sentimental solitude”

provoked by the gardens that were laid out in the 18th century and by

much-admired ruins.

Thus, it should be clear that the account of the autonomy of art I have

been outlining, in which I

have characterized art as an imaginary landscape or décor of the will,

not only does not preclude but

rather invites the examination of works of art as historically

specifiable phenomena.

The intricate stylistic convolutions of modern art, for example, are

clearly a function of the

unprecedented technical extension of the human will by technology, and

the devastating commitment

of human will to a novel form of social and psychological order, one

based on incessant change. But

it also remains to be said that the very possibility of the explosion

of technology, of the contemporary

disruptions of self and society, depends on the attitudes toward the

will which are partly invented and

disseminated by works of art at a certain historical moment, and then

come to appear as a “realistic”

reading of a perennial human nature.

|

57.

実際、さまざまな芸術の歴史はすべて、意志に対するさまざまな態度の歴史として書き直すことができる。ニーチェとシュペングラーはこのテーマについて先駆

的な研究を行った。最近の貴重な試みは、ジャン・スタロビンスキーの著書『自由の発明』(The Invention of

Liberty)に見られる。スタロビンスキーは、この時代の芸術を、自己の支配と世界の支配という新しい観念の観点から、自己と世界との新しい関係を体

現するものとして考察している。芸術は感情の命名とみなされる。感情、憧れ、願望は、こうして名づけられることによって、事実上、芸術によって発明され、

確かに広められた。たとえば、18世紀に整備された庭園や、多くの賞賛を浴びた廃墟が引き起こす「感傷的な孤独」。

58.

このように、私がこれまで述べてきた芸術の自律性に関する説明は、芸術を想像上の風景や意志の装飾として特徴づけるものであり、歴史的に特定可能な現象と

しての芸術作品の考察を排除するものではないばかりか、むしろそれを促すものであることは明らかであろう。

59.

例えば、現代美術の複雑な文体の錯綜は、テクノロジーによる人間の意志の前例のない技術的拡張と、絶え間ない変化に基づく社会的・心理的秩序の新形態への

人間の意志の破滅的なコミットメントの機能であることは明らかである。しかし、テクノロジーの爆発、自己と社会の現代的破壊の可能性そのものが、ある歴史

的瞬間に芸術作品によって部分的に発明され、広められた意志に対する態度によって左右され、その後、普遍的な人間の本質を「現実的」に読み解くものとして

現れるようになることもまた、忘れてはならない。

|

Style is the principle of

decision in a work of art, the signature of the artist’s will. And as

the human will is capable of an indefinite number of stances, there are

an indefinite number of possible styles for works of art..

|

60

スタイルとは、芸術作品における決定原理であり、芸術家の意志の署名である。そして、人間の意志が不特定多数のスタンスを取ることができるように、芸術作

品には不特定多数の可能なスタイルが存在する。

|

Seen from the outside, that is,

historically, stylistic decisions can always be correlated with some

historical development—like the invention of writing or of movable

type, the invention or

transformation of musical instruments, the availability of new

materials to the sculptor or architect.

But this approach, however sound and valuable, of necessity sees

matters grossly; it treats of

“periods” and “traditions” and “schools.”

|

外

から見れば、つまり歴史的に見れば、文体の決定は常に、文字や活字の発明、楽器の発明や変形、彫刻家や建築家が新しい材料を利用できるようになったことな

ど、何らかの歴史的発展と関連づけることができる。しかし、このアプローチは、どんなに健全で貴重なものであったとしても、必然的に問題を大雑把に見るこ

とになる。

|

Seen from the inside, that is,

when one examines an individual work of art and tries to account for

its value and effect, every stylistic decision contains an element of

arbitrariness, however much it

may seem justifiable propter hoc. If art is the supreme game which the

will plays with itself, “style”

consists of the set of rules by which this game is played. And the

rules are always, finally, an

artificial and arbitrary limit, whether they are rules of form (like

terza rima or the twelve-tone row

or frontality) or the presence of a certain “content.” The role of the

arbitrary and unjustifiable in art

has never been sufficiently acknowledged. Ever since the enterprise of

criticism began with

Aristotle’s Poetics, critics have been beguiled into emphasizing the

necessary in art. (When Aristotle

said that poetry was more philosophical than history, he was justified

insofar as he wanted to rescue

poetry, that is, the arts, from being conceived as a type of factual,

particular, descriptive statement.

But what he said was misleading insofar as it suggests that art

supplies something like what

philosophy gives us: an argument. The metaphor of the work of art as an

“argument,” with premises

and entailments, has informed most criticism since.) Usually critics

who want to praise a work of art

feel compelled to demonstrate that each part is justified, that it

could not be other than it is. And every

artist, when it comes to his own work, remembering the role of chance,

fatigue, external distractions,

knows what the critic says to be a lie, knows that it could well have

been otherwise. The sense of

inevitability that a great work of art projects is not made up of the

inevitability or necessity of its

parts, but of the whole.

|

62.(p.45)

内側から見れば、つまり、個々の芸術作品を吟味し、その価値と効果を説明しようとすれば、様式的な決定は、それがどんなにその場しのぎで正当化できるよう

に見えても、恣意的な要素を含んでいる。芸術が、意志が自分自身と繰り広げる至高のゲームであるとすれば、「様式」とは、このゲームが行われる際のルール

セットからなるものである。そしてそのルールは、(テルツァ・リマや十二音列や正面性のような)形式のルールであれ、ある "内容

"の存在であれ、最終的には常に人為的で恣意的な制限である。芸術における恣意的で正当化できないものの役割は、これまで十分に認められてこなかった。批

評がアリストテレスの『詩学』から始まって以来、批評家は芸術において必要なものを強調するように誘導されてきた。(アリストテレスが「詩は歴史よりも哲

学的である」と言ったのは、詩を、つまり芸術を、事実的な、特定の、記述的な記述の一種としてとらえることから救おうとしたのである。しかし、彼の発言

は、芸術が哲学が私たちに与えてくれるようなもの、つまり論証を与えてくれるものだと示唆している限りにおいて、誤解を招きかねないものであった。芸術作

品を、前提条件と帰結を持つ「論証」として喩えることは、それ以来、ほとんどの批評に影響を与えている。)

通常、芸術作品を賞賛したい批評家は、それぞれの部分が正当であること、それ以外にはありえないことを証明しなければならないと感じる。そしてすべての芸

術家は、自分の作品に関して言えば、偶然や疲労、外的な気晴らしの役割を思い出しながら、批評家の言うことが嘘であることを知っている。偉大な芸術作品が

映し出す必然性は、部分の必然性や必然性ではなく、全体の必然性によって成り立っている。

|

In other words, what is

inevitable in a work of art is the style. To the extent that a work

seems right,

just, unimaginable otherwise (without loss or damage), what we are

responding to is a quality of its

style. The most attractive works of art are those which give us

the

illusion that the artist had no

alternatives, so wholly centered is he in his style. Compare that which

is forced, labored, synthetic in

the construction of Madame Bovary and of Ulysses with the ease and

harmony of such equally

ambitious works as Les Liaisons Dangereuses and Kafka’s Metamorphosis.

The first two books I

have mentioned are great indeed. But

the greatest art seems secreted,

not constructed.

|

63. 言い換えれば、芸術作品において必然的なものはスタイルである。作品が正しく、正当で、それ以外では(損失や

損害がなく)想像できないと思える程度まで、私たちが反応しているのは、そのスタイルの質なのだ。最も魅力的な芸術作品とは、芸術家が自分

のスタイルに完全に集中しているため、他に選択肢がなかったかのような錯覚を与える作品である。『ボヴァリー夫人』や『ユリシーズ』の構成に見られる強引

さ、労苦、合成的なものと、『レ・リエゾン・ダンジェローズ』やカフカの『変身』のような同じように野心的な作品の容易さと調和を比べてみてほしい。最初

に挙げた2冊は確かに素晴らしい。しかし、最も偉大な芸術は、構築されたものではな

く、秘匿されたものである。

|

For an artist’s style to have

this quality of authority, assurance, seamlessness, inevitability does

not, of course, alone put his work at the very highest level of

achievement. Radiguet’s two novels have it as well as Bach.

|

ある芸術家の作風がこのような権威、保証、継ぎ目のなさ、必然性を持っているからといって、もちろんそれだけでその作品が最高レベルの業績に位置づけられるわけではない。ラディゲの2つの小説は、バッハと同様にそれを備えている。

|

The difference that I have drawn

between “style” and “stylization” might be analogous to the difference

between will and willfulness.

|

私が描いた「スタイル」と「スタイル化」の違いは、意志と意思の違いに似ているかもしれない。

|

An artist’s style is, from a

technical point of view, nothing other than the particular idiom in

which he

deploys the forms of his art. It is for this reason that the problems

raised by the concept of “style”

overlap with those raised by the concept of “form,” and their solutions

will have much in common.

For instance, one function of style is identical with, because it is

simply a more individual

specification of, that important function of form pointed out by

Coleridge and Valéry: to preserve the

works of the mind against oblivion. This function is easily

demonstrated in the rhythmical, sometimes

rhyming, character of all primitive, oral literatures. Rhythm and

rhyme, and the more complex formal

resources of poetry such as meter, symmetry of figures, antitheses, are

the means that words afford for

creating a memory of themselves before material signs (writing) are

invented; hence everything that

an archaic culture wishes to commit to memory is put in poetic form.

“The form of a work,” as Valéry

puts it, “is the sum of its perceptible characteristics, whose physical

action compels recognition and

tends to resist all those varying causes of dissolution which threaten

the expressions of thought,

whether it be inattention, forgetfulness, or even the objections that

may arise against it in the mind.”

Thus, form—in its specific idiom, style—is a plan of sensory

imprinting, the vehicle for the

transaction between immediate sensuous impression and memory (be it

individual or cultural). This

mnemonic function explains why every style depends on, and can be

analyzed in terms of, some

principle of repetition or redundancy.

|

66.

アーティストのスタイルとは、技術的な観点から言えば、彼が自分の芸術の形式を展開する特定のイディオムにほかならない。だからこそ、「スタイル」という

概念が提起する問題は、「形式=フォーム」という概念が提起する問題と重なり合い、その解決策には共通点が多いのである。

たとえば、文体の機能のひとつは、コールリッジやヴァレリーが指摘した形式の重要な機能、すなわち心の作品を忘却から守ることと同じであり、より個別的な

仕様に過ぎないからである。この機能は、すべての原始的な口承文芸のリズミカルな、時には韻を踏んだという特徴に容易に示されている。リズムと韻、そして

詩のより複雑な形式的資源であるメートル法、図形の対称性、反語は、物質的な記号(文字)が発明される前に、言葉そのものを記憶に残すための手段である。

「ヴァレリーが言うように、"作品の形式とは、その知覚可能な特徴の総体であり、その物理的な作用は認識を強制し、不注意であれ、忘れっぽさであれ、ある

いは心の中に生じる反論であれ、思考の表現を脅かすあらゆるさまざまな溶解の原因に抵抗する傾向がある"。このように、形式は、その特定の慣用句であるス

タイルにおいて、感覚的刷り込みの計画であり、即時的な感覚的印象と記憶(それが個人的なものであれ、文化的なものであれ)の間の取引のための手段なので

ある。このニモニック機能は、なぜあらゆるスタイルが反復や冗長性の原則に依存し、その観点から分析できるのかを説明する。

|

It also explains the

difficulties of the contemporary period of the arts. Today styles do

not develop

slowly and succeed each other gradually, over long periods of time

which allow the audience for art

to assimilate fully the principles of repetition on which the work of

art is built; but instead succeed

one another so rapidly as to seem to give their audiences no breathing

space to prepare. For, if one

does not perceive how a work repeats itself, the work is, almost

literally, not perceptible and

therefore, at the same time, not intelligible. It is the perception of

repetitions that makes a work of art

intelligible. Until one has grasped, not the “content,” but the

principles of (and balance between)

variety and redundancy in Merce Cunningham’s “Winterbranch” or a

chamber concerto by Charles

Wuoronin or Burrough’s Naked Lunch or the “black” paintings of Ad

Reinhardt, these works are

bound to appear boring or ugly or confusing, or all three.

|

69. それはまた、芸術の現代における困難も説明している。今日の様式は、長い時間をかけてゆっくりと発展し、徐々に継承されるものではなく、芸術作品の

土台となっている反復の原理を、芸術を鑑賞する観客が完全に吸収できるようなものではない。というのも、ある作品がどのように繰り返されるかを知覚しなければ、その作品はほとんど文字ど

おり知覚できず、したがって同時に理解できないからである。芸術作品を理解可能なものにするのは、繰り返しの知覚である。マース・カニング

ハムの「ウィンターブランチ」、チャールズ・ウーローニンの室内楽協奏曲、バロウの「裸のランチ」、アド・ラインハルトの「黒い」絵画など、「内容」では

なく、多様性と冗長性の原理(とそのバランス)を理解しない限り、これらの作品は退屈に見えるか、醜く見えるか、混乱して見えるか、あるいはその3つに見

えるに違いない。

|

Style has other functions

besides that of being, in the extended sense that I have just

indicated, a mnemonic device.

|

スタイルには、今述べたような拡張的な意味での記憶のデバイスとしての

機能以外にも、他の機能がある。

|

For instance, every style

embodies an epistemological decision, an interpretation of how and

what we perceive. This is easiest to see in the contemporary,

self-conscious period of the arts, though

it is no less true of all art. Thus, the style of Robbe-Grillet’s

novels expresses a perfectly valid, if

narrow, insight into relationships between persons and things: namely,

that persons are also things

and that things are not persons. Robbe-Grillet’s behavioristic

treatment of persons and refusal to

“anthropomorphize” things amount to a stylistic decision—to give an

exact account of the visual and

topographic properties of things; to exclude, virtually, sense

modalities other than sight, perhaps

because the language that exists to describe them is less exact and

less neutral. The circular repetitive

style of Gertrude Stein’s Melanctha expresses her interest in the

dilution of immediate awareness by

memory and anticipation, what she calls “association,” which is

obscured in language by the system

of the tenses. Stein’s insistence on the presentness of experience is

identical with her decision to keep

to the present tense, to choose commonplace short words and repeat

groups of them incessantly, to

use an extremely loose syntax and abjure most punctuation. Every style

is a means of insisting on

something.

|

71. 例えば、どのスタイルも認識論的な決定、つまり私たちがどのように、そして何を認識するかについての解

釈を体現している。このことは、現代的で自意識的な芸術の時代において最もわかりやすいが、すべての芸術に当てはまることでもある。した

がって、ロブ=グリエの小説の文体は、狭いながらも、人と物との関係についての完全に妥当な洞察、すなわち、人もまた物であり、物は人ではないという洞察

を表現している。ロブ=グリエの人物に対する行動主義的な扱いと、事物を「擬人化」することの拒否は、文体上の決断に等しい。事物の視覚的・地形的特性を

正確に説明し、視覚以外の感覚モダリティを事実上排除するのは、おそらく、それらを記述するために存在する言語が、より正確で中立的でないためであろう。

ガートルード・スタインの『Melanctha』の循環反復文体は、彼女が「連想」と呼ぶ、記憶と予期による即時意識の希薄化に対する関心を表現してい

る。スタインの経験の現在性への主張は、現在時制を守り、ありふれた短い単語を選び、そのグループを絶え間なく繰り返し、極めてゆるい構文を使い、句読点

をほとんど使わないという決定と同じである。どんなスタイルも、何かを主張するため

の手段なのだ。

|

It will be seen that stylistic

decisions, by focusing our attention on some things, are also a

narrowing of our attention, a refusal to allow us to see others. But

the greater interestingness of one

work of art over another does not rest on the greater number of things

the stylistic decisions in that

work allow us to attend to, but rather on the intensity and authority

and wisdom of that attention,

however narrow its focus.

|

様式的な決定が、私たちの注意をあるものに集中させることによって、私

たちの注意を狭め、他のものを見ることを拒むものでもあることがわかるだろう。しかし、ある芸術作品が他の作品より面白いかどうかは、その作品における文

体の決定が私たちに注意を向けさせるものの数が多いかどうかにかかっているのではなく、その注意の強度と権威と知恵にかかっているのである。

|

In the strictest sense, all the

contents of consciousness are ineffable. Even the simplest sensation

is, in

its totality, indescribable. Every work of art, therefore, needs to be

understood not only as something

rendered, but also as a certain handling of the ineffable. In the

greatest art, one is always aware of

things that cannot be said (rules of “decorum”), of the contradiction

between expression and the

presence of the inexpressible. Stylistic devices are also techniques of

avoidance. The most potent

elements in a work of art are, often, its silences.

|

73.

厳密な意味では、意識の内容はすべて筆舌に尽くしがたい。最も単純な感覚でさえ、その全体性において、筆舌に尽くしがたい。したがって、あらゆる芸術作品

は、単に表現されたものとしてだけでなく、言葉にできないものを扱うものとして理解される必要がある。最も偉大な芸術においては、人は常に言うことのでき

ないこと(「礼儀作法」のルール)、表現と言い表せないものの存在との間の矛盾を意識している。文体の工夫は、回避のテクニックでもある。芸術作品における最も強力な要素は、しばしばその沈黙である。

|

What I have said about style has

been directed mainly to clearing up certain misconceptions about

works of art and how to talk about them. But it remains to be said that

style is a notion that applies to

any experience (whenever we talk about its form or qualities). And just

as many works of art which

have a potent claim on our interest are impure or mixed with respect to

the standard I have been

proposing, so many items in our experience which could not be classed

as works of art possess some

of the qualities of art objects. Whenever

speech or movement or behavior or objects exhibit a certain

deviation from the most direct, useful, insensible mode of expression

or being in the world, we may

look at them as having a “style,” and being both autonomous and

exemplary. [1965]

|

74.

私がスタイルについて述べてきたことは、主に芸術作品とその語り方に関するある種の誤解を解くことに向けられてきた。しかし、スタイルとは(その形式や特

質について語るときはいつでも)どんな経験にも当てはまる概念であることは言うまでもない。そして、私たちの興味を強く惹きつける多くの芸術作品が、私が

提案した基準からすると不純であったり、混ざり合っていたりするのと同じように、私たちの経験の中には、芸術作品として分類されることのない多くのもの

が、芸術作品の特質をいくつか持っている。話し方や動作や行動や物体が、世の中で最

も直接的で、有用で、無感覚な表現様式や存在様式からある種の逸脱を示すときはいつでも、私たちはそれらを「スタイル」を持ち、自律的であると同時に模範

的であるとみなすことができる。

|

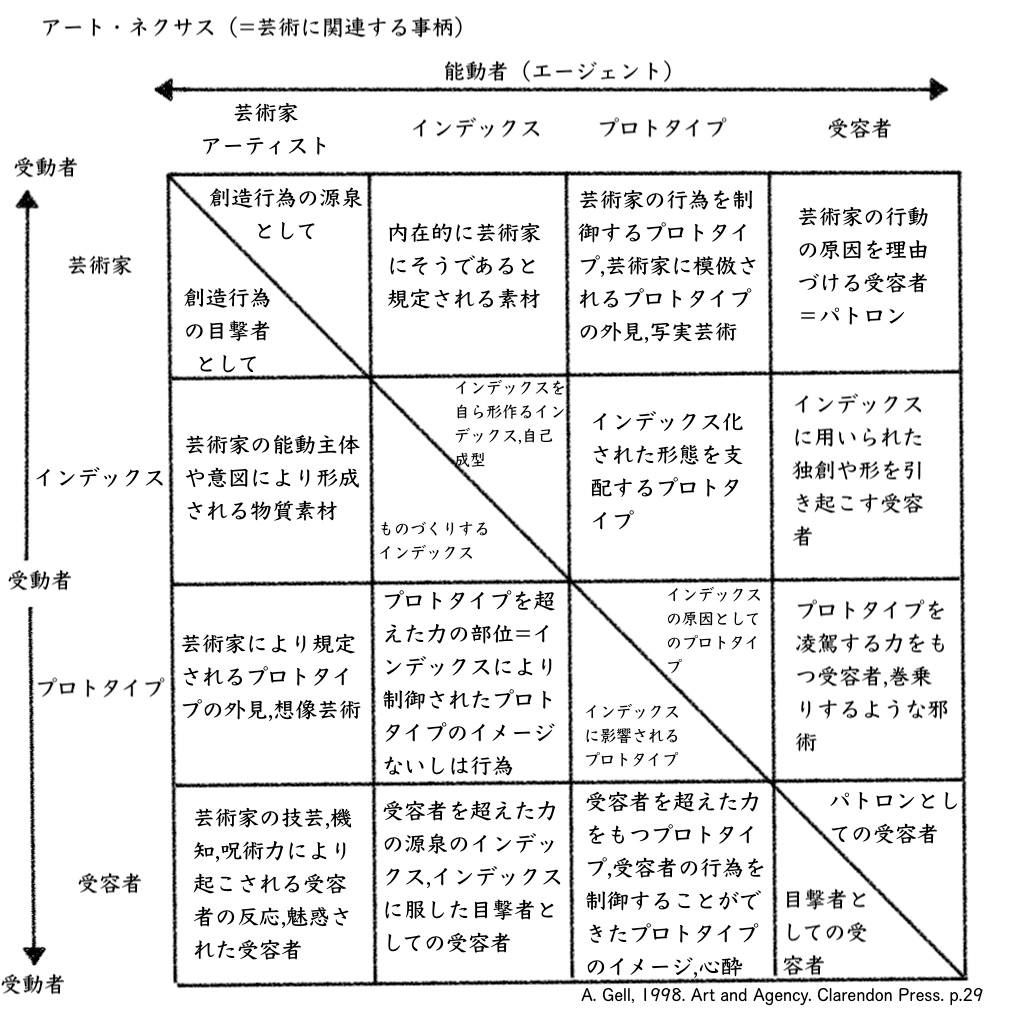

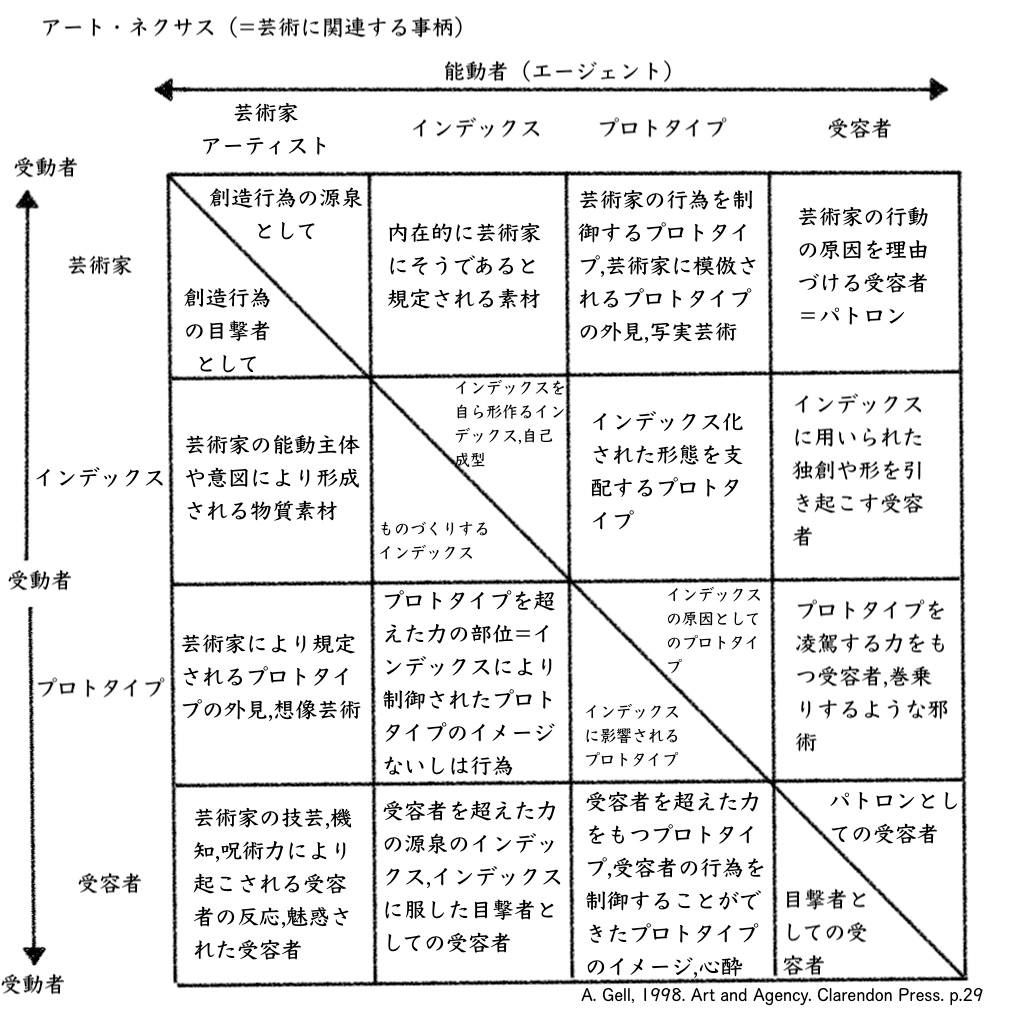

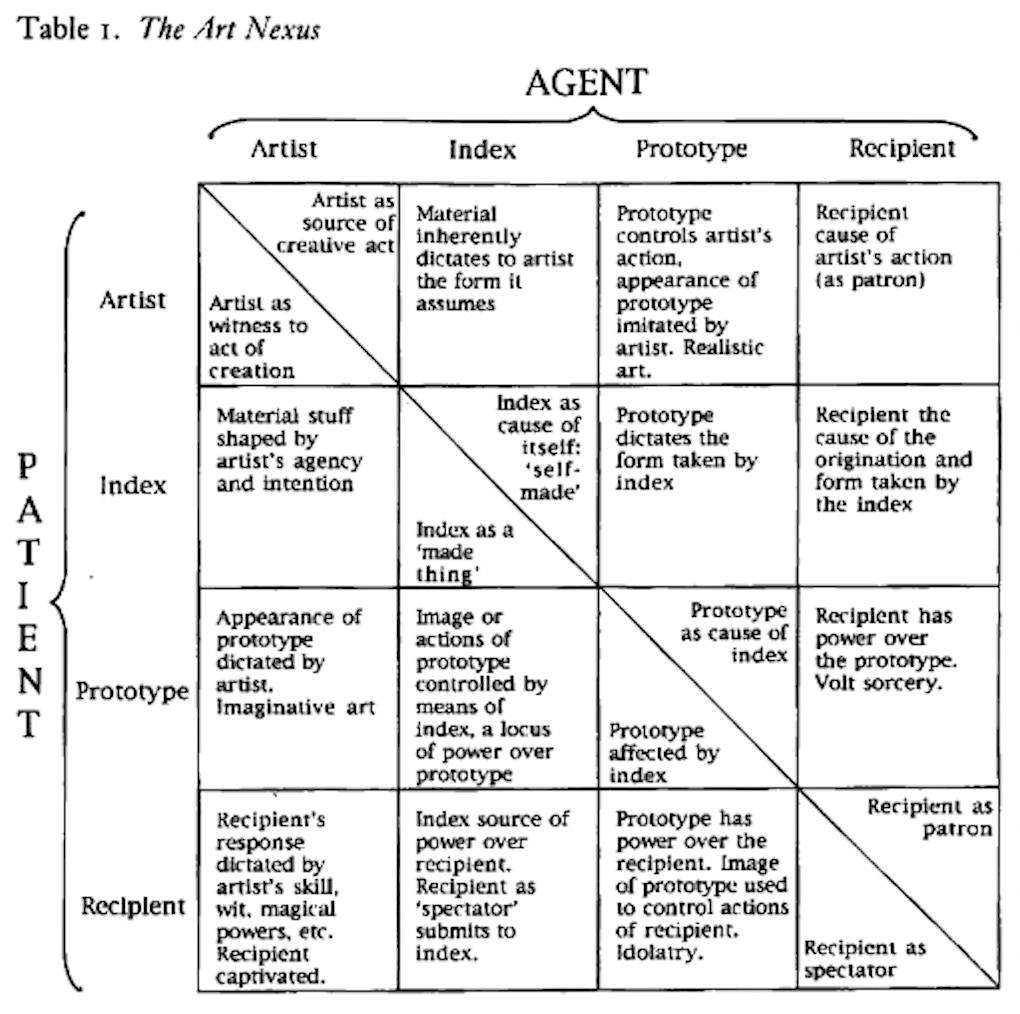

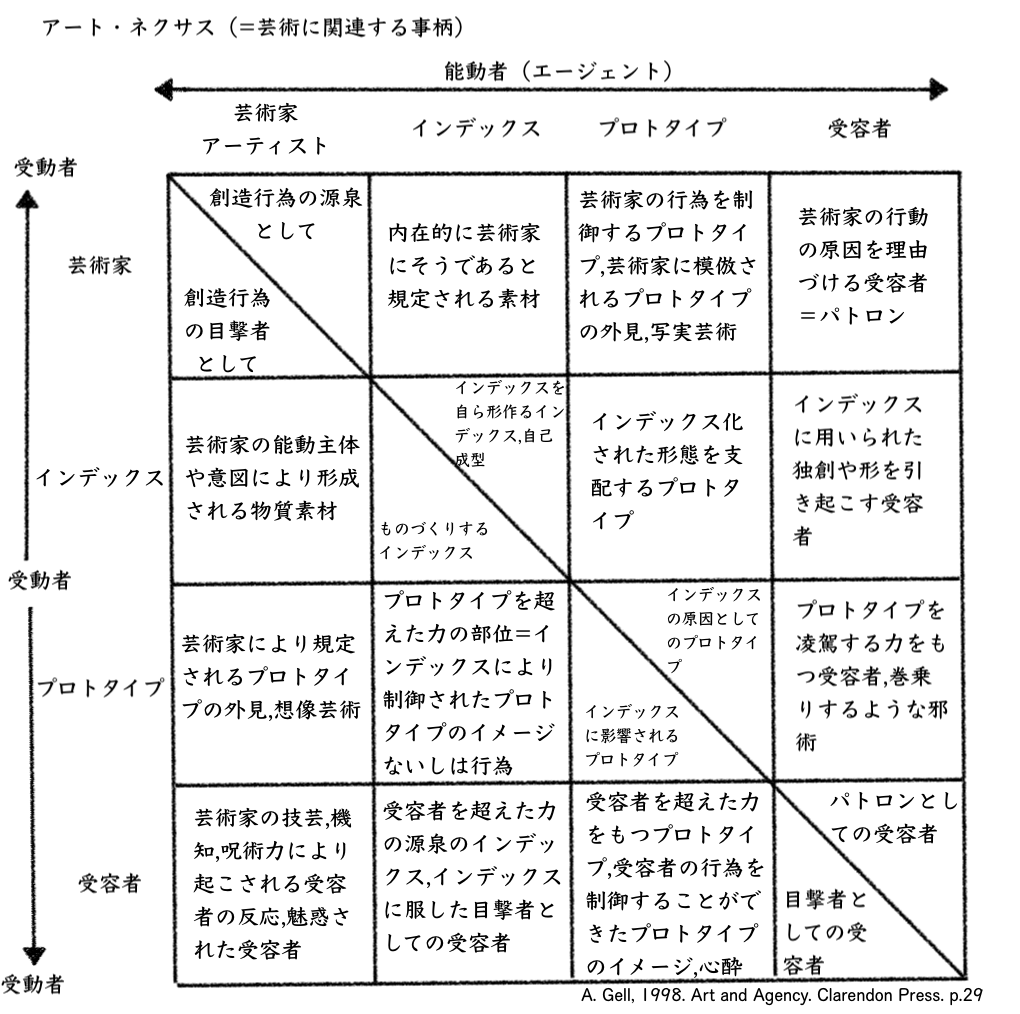

Art and agency : an anthropological theory / Alfred Gell, Oxford : Clarendon Press , 1998

|

Art and agency : an anthropological theory / Alfred Gell, Oxford : Clarendon Press , 1998

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|