The imagination of

disaster

THE typical science fiction film has a form as predictable as a

Western, and is made up of elements

which, to a practiced eye, are as classic as the saloon brawl, the

blonde schoolteacher from the East,

and the gun duel on the deserted main street.

One model scenario proceeds through five phases.

(1) The arrival of the thing. (Emergence of the monsters, landing of

the alien spaceship, etc.) This

is usually witnessed or suspected by just one person, a young scientist

on a field trip. Nobody, neither

his neighbors nor his colleagues, will believe him for some time. The

hero is not married, but has a

sympathetic though also incredulous girl friend.

(2) Confirmation of the hero’s report by a host of witnesses to a great

act of destruction. (If the

invaders are beings from another planet, a fruitless attempt to parley

with them and get them to leave

peacefully.) The local police are summoned to deal with the situation

and massacred.

(3) In the capital of the country, conferences between scientists and

the military take place, with

the hero lecturing before a chart, map, or blackboard. A national

emergency is declared. Reports of

further destruction. Authorities from other countries arrive in black

limousines. All international

tensions are suspended in view of the planetary emergency. This stage

often includes a rapid montage

of news broadcasts in various languages, a meeting at the UN, and more

conferences between the

military and the scientists. Plans are made for destroying the enemy.

(4) Further atrocities. At some point the hero’s girl friend is in

grave danger. Massive counterattacks

by international forces, with brilliant displays of rocketry, rays, and

other advanced weapons,

are all unsuccessful. Enormous military casualties, usually by

incineration. Cities are destroyed

and/or evacuated. There is an obligatory scene here of panicked crowds

stampeding along a highway

or a big bridge, being waved on by numerous policemen who, if the film

is Japanese, are

immaculately white-gloved, preternaturally calm, and call out in dubbed

English, “Keep moving.

There is no need to be alarmed.”

(5) More conferences, whose motif is: “They must be vulnerable to

something.” Throughout the

hero has been working in his lab to this end. The final strategy, upon

which all hopes depend, is

drawn up; the ultimate weapon—often a super-powerful, as yet untested,

nuclear device—is mounted.

Countdown. Final repulse of the monster or invaders. Mutual

congratulations, while the hero and girl

friend embrace cheek to cheek and scan the skies sturdily. “But have we

seen the last of them?”

|

災害の想像力

典型的なSF映画は、西部劇のように予測可能な形式を持ち、酒場の喧嘩、東部から来たブロンドの女教師、さびれた大通りでの銃撃戦など、慣れた目には古典

的と思える要素で構成されている。

1つのモデルシナリオは5つの段階を経て進行する。

(1)

アレの登場。(怪物の出現、宇宙船の着陸など)これは通常、遠足に来ている若い科学者一人だけが目撃したり、疑ったりするものである。隣人も同僚も誰も、

しばらくは彼のことを信じてくれない。主人公は結婚していないが、同情的ではあるが信じられないような女友達がいる。

(2)

大破壊の目撃者が多数いて、主人公の報告を確認する。(侵略者が他の惑星からの存在である場合、彼らと交渉して平和的に去ってもらおうとする試みは実を結

ばない。) 地元警察は事態に対処するために召集され、虐殺される。

(3)

首都では科学者と軍部の会議が行われ、主人公は図表や地図、黒板などを前に講義をする。国家非常事態が宣言される。さらなる破壊の報告。他国の当局が黒い

リムジンで到着する。惑星の緊急事態を考慮して、すべての国際的緊張が停止される。この段階には、さまざまな言語でのニュース放送、国連での会議、軍と科

学者の会議などの急速なモンタージュが含まれることが多い。敵を破壊するための計画が立てられる。

(4)さらなる残虐行為

いつしか主人公の女友達に重大な危機が訪れる。国際軍の大規模な反撃は、ロケット弾や光線などの最新兵器を駆使して行われるが、すべて失敗に終わる。莫大

な軍人の犠牲者、通常は焼却処分。都市は破壊され、避難する。パニックに陥った群衆がハイウェイや大きな橋の上で、大勢の警官に手を振られ、もしこの映画

が日本のものなら、完璧な白い手袋をして、極めて冷静に、英語の吹き替えで、「Keep

moving(立ち止まらないで)」と呼びかけているシーンが、ここにはお決まりのようにある。警戒する必要はありません。"と吹き替えで呼びかける。

(5)より多くの会議。そのモチーフは、"彼らは何かに対して脆弱であるに違いない

"である。主人公はずっと、この目的のために研究室で働いているのです。すべての望みがかかっている最終戦略が描かれ、最終兵器(多くの場合、まだ実験さ

れていない超強力な核兵器)が搭載される。カウントダウン。怪物や侵略者を最終的に撃退する。ヒーローとガールフレンドは頬を寄せ合いながら、互いの祝福

を受け、力強く空を見上げる。「しかし、我々は彼らの最後を見たのだろうか?

|

The film I have just described

should be in color and on a wide screen. Another typical scenario,

which follows, is simpler and suited to black-and-white films with a

lower budget. It has four phases.

(1) The hero (usually, but not always, a scientist) and his girl

friend, or his wife and two children,

are disporting themselves in some innocent ultra-normal middle-class

surroundings—their house in a

small town, or on vacation (camping, boating). Suddenly, someone starts

behaving strangely; or some

innocent form of vegetation becomes monstrously enlarged and

ambulatory. If a character is pictured

driving an automobile, something gruesome looms up in the middle of the

road. If it is night, strange

lights hurtle across the sky.

(2) After following the thing’s tracks, or determining that It is

radioactive, or poking around a

huge crater—in short, conducting some sort of crude investigation—the

hero tries to warn the local

authorities, without effect; nobody believes anything is amiss. The

hero knows better. If the thing is

tangible, the house is elaborately barricaded. If the invading alien is

an invisible parasite, a doctor or

friend is called in, who is himself rather quickly killed or “taken

possession of” by the thing.

(3) The advice of whoever further is consulted proves useless.

Meanwhile, It continues to claim

other victims in the town, which remains implausibly isolated from the

rest of the world. General

helplessness.

(4) One of two possibilities. Either the hero prepares to do battle

alone, accidentally discovers

the thing’s one vulnerable point, and destroys it. Or, he somehow

manages to get out of town and

succeeds in laying his case before competent authorities. They, along

the lines of the first script but

abridged, deploy a complex technology which (after initial setbacks)

finally prevails against the

invaders.

|

今説明した映画は、カラーで、ワイドスクリーンとされなければならな

い。もうひとつの典型的なシナリオは、次のようなもので、もっとシンプルで、低予算のモノクロ映画に向いている。これは、4つの段階からなる。

(1)

主人公(通常は科学者)とその女友達、あるいは妻と二人の子供が、小さな町の自宅や休暇(キャンプや船旅)で、何の変哲もない超普通の中流階級の環境でく

つろいでいる。突然、誰かが奇妙な行動を始めたり、無邪気な植物が巨大化し、歩き回るようになったりする。自動車を運転している場面では、道路の真ん中に

ぞっとするようなものが現れる。夜であれば、奇妙な光が空を横切る。

(2)その足跡をたどったり、それが放射能を帯びていると判断したり、巨大なクレーターをつついたり、要するに何らかの下調べをした後、主人公は地元当局

に警告しようとするが、効果はなく、誰も何も異常があるとは思っていない。主人公はよく分かっている。もし、目に見えるものであれば、家は入念にバリケー

ドで囲われる。侵入してきたエイリアンが目に見えない寄生虫であれば、医者や友人を呼ぶが、彼自身はすぐに殺されるか、そのモノに「取り憑かれる」ことに

なる。

(3) さらに誰に相談しても無駄であることがわかる。一方、世界と隔絶されたこの町では、Itは他の犠牲者を出し続けている。一般的な無力感。

(4)

2つの可能性のうちの1つ。主人公が一人で戦う準備をし、偶然にもそいつの弱点を発見し、破壊してしまうか。あるいは、どうにかして街を脱出し、当局の前

で自分の主張を通すことに成功する。彼らは、最初の脚本を要約したような複雑なテクノロジーを展開し、(最初の失敗の後)最終的に侵略者に打ち勝つのであ

る。

|

Another version of the second

script opens with the scientist-hero in his laboratory, which is

located

in the basement or on the grounds of his tasteful, prosperous house.

Through his experiments, he

unwittingly causes a frightful metamorphosis in some class of plants or

animals which turn

carnivorous and go on a rampage. Or else, his experiments have caused

him to be injured (sometimes

irrevocably) or “invaded” himself. Perhaps he has been experimenting

with radiation, or has built a

machine to communicate with beings from other planets or transport him

to other places or times.

Another version of the first script involves the discovery of some

fundamental alteration in the

conditions of existence of our planet, brought about by nuclear

testing, which will lead to the

extinction in a few months of all human life. For example: the

temperature of the earth is becoming

too high or too low to support life, or the earth is cracking in two,

or it is gradually being blanketed

by lethal fallout.

A third script, somewhat but not altogether different from the first

two, concerns a journey through

space—to the moon, or some other planet. What the space-voyagers

discover commonly is that the

alien terrain is in a state of dire emergency, itself threatened by

extra-planetary invaders or nearing

extinction through the practice of nuclear warfare. The terminal dramas

of the first and second scripts

are played out there, to which is added the problem of getting away

from the doomed and/or hostile

planet and back to Earth.

|

もう一つのバージョンは、科学者の主人公が、趣味の良い豊かな家の地下

や敷地内にある実験室にいるところから始まる。彼は実験を通して、知らず知らずのうちに、ある種の植物や動物に恐ろしい変態を引き起こし、肉食になって暴

れまわる。あるいは、彼の実験によって、彼自身が怪我をしたり(時には取り返しのつかないことに)、「侵略」されたりしている。もしかしたら、彼は放射線

の実験をしていたかもしれないし、他の惑星の生物と通信したり、他の場所や時間に転送するための機械を作っていたかもしれない。

最初の脚本の別のバージョンでは、核実験によってもたらされた地球の存在条件の根本的な変化が発見され、それによって数ヵ月後にすべての人類が滅亡すると

いうものだ。例えば、地球の温度が生命維持に必要なほど高くなったり低くなったり、地球が2つに割れたり、致死的な放射性降下物で徐々に覆われたりするの

である。

3つ目の脚本は、最初の2つとは多少異なるが、月や他の惑星への宇宙の旅に関するものである。宇宙を旅する者たちが共通して発見するのは、異星人の地形

が、惑星外からの侵略者に脅かされているか、核戦争によって絶滅寸前の悲惨な状態にあるということである。第1作と第2作の終盤のドラマがそこで展開さ

れ、そこに運命の星や敵対する星から離れ、地球に戻るという問題が加わってくる。

|

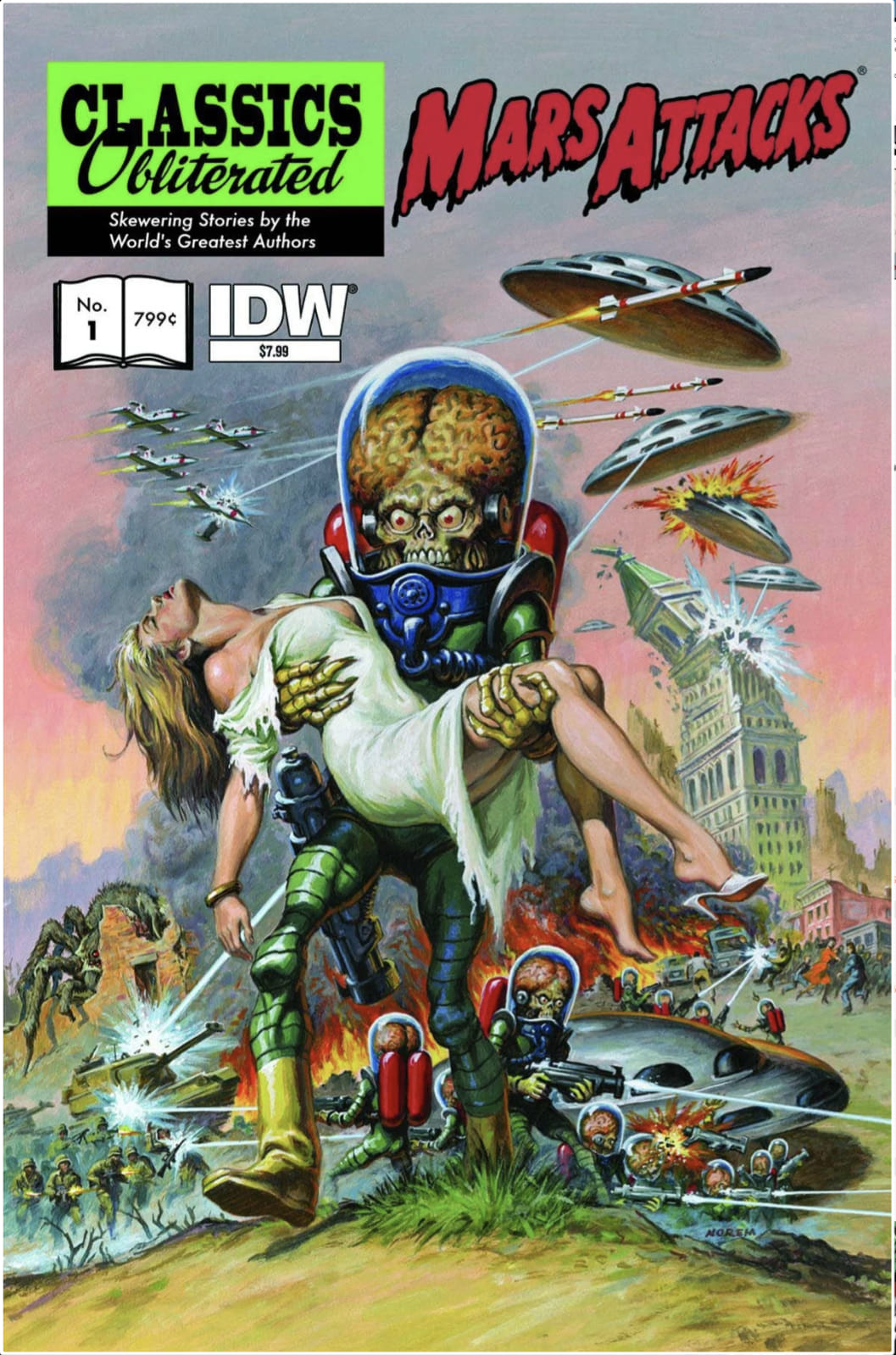

I am aware, of course, that

there are thousands of science fiction novels (their heyday was the

late

1940s), not to mention the transcriptions of science fiction themes

which, more and more, provide the

principal subject-matter of comic books. But I propose to discuss

science fiction films (the present

period began in 1950 and continues, considerably abated, to this day)

as an independent subgenre,

without reference to other media—and, most particularly, without

reference to the novels from which,

in many cases, they were adapted. For, while novel and film may share

the same plot, the fundamental

difference between the resources of the novel and the film makes them

quite dissimilar.

Certainly, compared with the science fiction novels, their film

counterparts have unique strengths,

one of which is the immediate representation of the extraordinary:

physical deformity and mutation,

missile and rocket combat, toppling skyscrapers. The movies are,

naturally, weak just where the

science fiction novels (some of them) are strong—on science. But in

place of an intellectual workout,

they can supply something the novels can never provide—sensuous

elaboration. In the films it is by

means of images and sounds, not words that have to be translated by the

imagination, that one can

participate in the fantasy of living through one’s own death and more,

the death of cities, the

destruction of humanity itself.

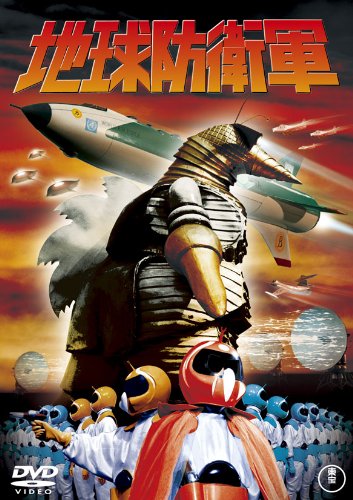

Science fiction films are not about science. They are about disaster,

which is one of the oldest

subjects of art. In science fiction films disaster is rarely viewed

intensively; it is always extensive. It

is a matter of quantity and ingenuity. If you will, it is a question of

scale. But the scale, particularly in

the wide-screen color films (of which the ones by the Japanese director

Inoshiro Honda and the

American director George Pal are technically the most convincing and

visually the most exciting),

does raise the matter to another level.

Thus, the science fiction film (like that of a very different

contemporary genre, the Happening) is

concerned with the aesthetics of destruction, with the peculiar

beauties to be found in wreaking

havoc, making a mess. And it is in the imagery of destruction that the

core of a good science fiction

film lies. Hence, the disadvantage of the cheap film—in which the

monster appears or the rocket

lands in a small dull-looking town. (Hollywood budget needs usually

dictate that the town be in the

Arizona or California desert. In The Thing From Another World [1951]

the rather sleazy and

confined set is supposed to be an encampment near the North Pole.)

Still, good black-and-white

science fiction films have been made. But a bigger budget, which

usually means color, allows a much

greater play back and forth among several model environments. There is

the populous city. There is

the lavish but ascetic interior of the spaceship—either the invaders’

or ours—replete with

streamlined chromium fixtures and dials and machines whose complexity

is indicated by the number

of colored lights they flash and strange noises they emit. There is the

laboratory crowded with

formidable boxes and scientific apparatus. There is a comparatively

old-fashioned-looking

conference room, where the scientists unfurl charts to explain the

desperate state of things to the

military. And each of these standard locales or backgrounds is subject

to two modalities—intact and

destroyed. We may, if we are lucky, be treated to a panorama of melting

tanks, flying bodies, crashing

walls, awesome craters and fissures in the earth, plummeting

spacecraft, colorful deadly rays; and to

a symphony of screams, weird electronic signals, the noisiest military

hardware going, and the leaden

tones of the laconic denizens of alien planets and their subjugated

earthlings.

Certain of the primitive gratifications of science fiction films—for

instance, the depiction of urban

disaster on a colossally magnified scale—are shared with other types of

films. Visually there is little

difference between mass havoc as represented in the old horror and

monster films and what we find

in science fiction films, except (again) scale. In the old monster

films, the monster always headed for

the great city, where he had to do a fair bit of rampaging, hurling

busses off bridges, crumpling trains

in his bare hands, toppling buildings, and so forth. The archetype is

King Kong, in Schoedsack and

Cooper’s great film of 1933, running amok, first in the native village

(trampling babies, a bit of

footage excised from most prints), then in New York. This is really no

different in spirit from the

scene in Inoshiro Honda’s Rodan (1957) in which two giant reptiles—with

a wingspan of 500 feet

and supersonic speeds—by flapping their wings whip up a cyclone that

blows most of Tokyo to

smithereens. Or the destruction of half of Japan by the gigantic robot

with the great incinerating ray

that shoots forth from his eyes, at the beginning of Honda’s The

Mysterians (1959). Or, the

devastation by the rays from a fleet of flying saucers of New York,

Paris, and Tokyo, in Battle in

Outer Space (1960). Or, the inundation of New York in When Worlds

Collide (1951). Or, the end of

London in 1966 depicted in George Pal’s The Time Machine (1960).

Neither do these sequences

differ in aesthetic intention from the destruction scenes in the big

sword, sandal, and orgy color

spectaculars set in Biblical and Roman times—the end of Sodom in

Aldrich’s Sodom and Gomorrah,

of Gaza in De Mille’s Samson and Delilah, of Rhodes in The Colossus of

Rhodes, and of Rome in a

dozen Nero movies. Griffith began it with the Babylon sequence in

Intolerance, and to this day there

is nothing like the thrill of watching all those expensive sets come

tumbling down.

In other respects as well, the science fiction films of the 1950s take

up familiar themes. The

famous 1930s movie serials and comics of the adventures of Flash Gordon

and Buck Rogers, as well

as the more recent spate of comic book super-heroes with

extraterrestrial origins (the most famous is

Superman, a foundling from the planet Krypton, currently described as

having been exploded by a

nuclear blast), share motifs with more recent science fiction movies.

But there is an important

difference. The old science fiction films, and most of the comics,

still have an essentially innocent

relation to disaster. Mainly they offer new versions of the oldest

romance of all—of the strong

invulnerable hero with a mysterious lineage come to do battle on behalf

of good and against evil.

Recent science fiction films have a decided grimness, bolstered by

their much greater degree of

visual credibility, which contrasts strongly with the older films.

Modern historical reality has greatly

enlarged the imagination of disaster, and the protagonists—perhaps by

the very nature of what is

visited upon them—no longer seem wholly innocent.

The lure of such generalized disaster as a fantasy is that it releases

one from normal obligations.

The trump card of the end-of-the-world movies—like The Day the Earth

Caught Fire (1962)—is

that great scene with New York or London or Tokyo discovered empty, its

entire population

annihilated. Or, as in The World, The Flesh, and The Devil (1957), the

whole movie can be devoted

to the fantasy of occupying the deserted metropolis and starting all

over again, a world Robinson

Crusoe.

Another kind of satisfaction these films supply is extreme moral

simplification—that is to say, a

morally acceptable fantasy where one can give outlet to cruel or at

least amoral feelings. In this

respect, science fiction films partly overlap with horror films. This

is the undeniable pleasure we

derive from looking at freaks, beings excluded from the category of the

human. The sense of

superiority over the freak conjoined in varying proportions with the

titillation of fear and aversion

makes it possible for moral scruples to be lifted, for cruelty to be

enjoyed. The same thing happens in

science fiction films. In the figure of the monster from outer space,

the freakish, the ugly, and the

predatory all converge—and provide a fantasy target for righteous

bellicosity to discharge itself, and

for the aesthetic enjoyment of suffering and disaster. Science fiction

films are one of the purest forms

of spectacle; that is, we are rarely inside anyone’s feelings. (An

exception is Jack Arnold’s The

Incredible Shrinking Man [1957].) We are merely spectators; we watch.

But in science fiction films, unlike horror films, there is not much

horror. Suspense, shocks,

surprises are mostly abjured in favor of a steady, inexorable plot.

Science fiction films invite a

dispassionate, aesthetic view of destruction and violence—a

technological view. Things, objects,

machinery play a major role in these films. A greater range of ethical

values is embodied in the décor

of these films than in the people. Things, rather than the helpless

humans, are the locus of values

because we experience them, rather than people, as the sources of

power. According to science

fiction films, man is naked without his artifacts. They stand for

different values, they are potent, they

are what get destroyed, and they are the indispensable tools for the

repulse of the alien invaders or

the repair of the damaged environment.

|

も

ちろん、何千ものSF小説(全盛期は1940年代後半)があることは承知しているし、SFのテーマを書き写したものが、ますますコミックの主要な題材と

なっていることも言うまでもない。しかし私は、SF映画(現在の時代は1950年に始まり、かなり衰えながらも今日まで続いている)を、他のメディアを参

照することなく、とりわけ、多くの場合映画化された小説を参照することなく、独立したサブジャンルとして論じることを提案する。というのも、小説と映画は

同じプロットを共有しているかもしれないが、小説と映画のリソースの根本的な違いによって、両者はまったく異なっているからだ。

確かに、SF小説に比べれば、映画には独特の強みがある。そのひとつが、肉体の奇形や突然変異、ミサイルやロケットによる戦闘、高層ビルの倒壊など、非日

常を即座に表現することだ。SF小説(の一部)が科学に強いだけに、当然、映画は弱い。しかし、知的トレーニングの代わりに、小説では決して提供できない

もの、つまり官能的な精巧さを提供することができる。映画では、想像力によって翻訳されなければならない言葉ではなく、映像や音によって、自分自身の死

や、都市の死、人類そのものの滅亡を生き抜くファンタジーに参加することができるのだ。

SF映画は科学についてではない。災害がテーマであり、それは芸術の最も古い主題のひとつである。SF映画では、災害が集中的に扱われることはほとんどな

い。それは量と工夫の問題である。言うなれば、スケールの問題である。しかし、特にワイドスクリーンのカラー映画(日本の本多猪四郎監督やアメリカの

ジョージ・パル監督の作品は、技術的に最も説得力があり、視覚的に最もエキサイティングである)では、そのスケールが問題を別のレベルに引き上げている。

このように、SF映画は(現代の全く異なるジャンルである『ハプニング』のように)破壊の美学、大混乱を引き起こし、混乱させることに見出される独特の美

学に関心を寄せている。そして、優れたSF映画の核心は破壊のイメージにある。それゆえ、怪物が現れたり、ロケットが退屈そうな小さな町に着陸したりする

ような安っぽい映画には不利なのだ。(ハリウッドの予算の都合上、その町はアリゾナかカリフォルニアの砂漠にあるのが普通だ)。別世界からのもの』

[1951]では、かなりみすぼらしく窮屈なセットは北極付近の野営地とされている)。それでも、優れたモノクロSF映画は作られてきた。しかし、より大

きな予算、つまり通常はカラーにすることで、いくつかのモデル環境の間を行ったり来たりすることが可能になる。人口の多い都市がある。豪華だが禁欲的な宇

宙船の内部(侵略者側か我々側か)には、流線型のクロム製の備品やダイヤル、点滅するカラーライトの数や発する奇妙な音で複雑さがわかる機械がある。実験

室には手ごわい箱や科学機器がひしめいている。比較的古風に見える会議室があり、そこでは科学者たちがチャートを広げて軍に絶望的な状況を説明している。

そして、これらの標準的な場所や背景は、それぞれ2つの様相を呈している。運がよければ、溶解するタンク、飛散する死体、墜落する壁、地球のすごいクレー

ターや亀裂、急降下する宇宙船、色とりどりの殺人光線などのパノラマや、悲鳴、奇妙な電子信号、最も騒々しい軍用ハードウェア、異星人の惑星の住人や服従

させられた地球人の無口な声などのシンフォニーを見ることができる。

SF映画のある種の原始的な満足感、たとえば、巨大に拡大されたスケールでの都市災害の描写は、他のタイプの映画と共通している。昔のホラー映画や怪獣映

画で表現された大混乱と、SF映画で見られる大混乱は、(やはり)スケールを除けば、視覚的にはほとんど違いがない。昔の怪獣映画では、怪獣はいつも大都

会を目指し、バスを橋から投げ落としたり、列車を素手で潰したり、ビルを倒したりと、かなりの暴れっぷりを見せなければならなかった。その原型は、

1933年に製作されたショーサックとクーパーの大作に登場するキングコングであり、最初は原住民の村で(赤ん坊を踏みつけ、ほとんどのプリントから少し

映像が削除されている)、次にニューヨークで大暴れする。これは、本多猪四郎監督の『ロダン』(1957年)で、2匹の巨大な爬虫類(翼を広げると500

フィートもあり、超音速を出す)が羽ばたくことによってサイクロンを巻き起こし、東京の大部分を粉々に吹き飛ばすシーンと、精神的にはまったく変わらな

い。あるいは、本多監督の『ミステリアン』(1959年)の冒頭で、目から大きな焼却光線を放つ巨大ロボットによって日本の半分が破壊される。あるいは、

『宇宙戦艦ヤマト』(1960)の、空飛ぶ円盤の艦隊が放つ光線によるニューヨーク、パリ、東京の壊滅。あるいは、『世界がぶつかる時』(1951年)に

おけるニューヨークの水没。あるいは、ジョージ・パルの『タイムマシン』(1960年)で描かれる1966年のロンドンの終末である。アルドリッチ監督の

『ソドムとゴモラ』におけるソドムの滅亡、デ・ミルの『サムソンとデリラ』におけるガザの滅亡、『ロードス島の巨像』におけるロードス島の滅亡、十数本の

ネロ映画におけるローマの滅亡などである。グリフィスは『イントレランス』のバビロンのシークエンスでそれを始めたが、今日に至るまで、高価なセットが崩

れ落ちるのを見るスリルほど素晴らしいものはない。

他の点でも、1950年代のSF映画はおなじみのテーマを取り上げている。フラッシュ・ゴードンやバック・ロジャースの冒険を描いた1930年代の有名な

連続映画やコミックはもちろん、最近では地球外からやってきたスーパーヒーローたち(最も有名なのはスーパーマンだが、クリプトン星からやってきた拾われ

子で、現在は核爆発で爆発したとされている)を描いたコミックも、最近のSF映画とモチーフを共有している。しかし、重要な違いがある。古いSF映画やコ

ミックのほとんどは、いまだに災害に対して本質的に無邪気な関係を持っている。主に、神秘的な血筋を持つ不死身の強いヒーローが、善のために、悪と戦うた

めにやってくるという、最も古いロマンスの新しいバージョンを提供している。最近のSF映画には、映像的な信頼性の高さに後押しされた重苦しさがあり、古

い映画とは強いコントラストをなしている。現代の歴史的現実は、災害に対する想像力を大きく膨らませ、主人公たちは、おそらくは彼らに降りかかる出来事の

性質上、もはや完全に無邪気とは思えない。

このようなファンタジーとしての一般化された災害の魅力は、通常の義務から解放されることである。地球が燃える日』(1962年)のような世界の終わりを

描いた映画の切り札は、ニューヨークやロンドンや東京が空っぽになり、全人口が消滅しているのを発見するシーンである。あるいは、『世界、肉、そして悪

魔』(1957年)のように、映画全体が、砂漠化した大都市を占領し、ロビンソン・クルーソーの世界から再出発するというファンタジーに費やされることも

ある。

つまり、残酷な、あるいは少なくとも非道徳的な感情を吐き出すことができる、道徳的に受け入れられるファンタジーである。この点で、SF映画はホラー映画

と重なる部分がある。これは、人間というカテゴリーから排除された存在であるフリークスを見ることから得られる紛れもない快楽である。フリークに対する優

越感が、恐怖や嫌悪の刺激とさまざまな割合で結びついて、道徳的な疑念を解き放ち、残酷さを楽しむことを可能にする。同じことがSF映画でも起こる。宇宙

からやってきた怪物の姿の中に、奇怪なもの、醜いもの、捕食するもの、そのすべてが収束し、正義の好戦性を発散させ、苦しみや災難を美的に楽しむための

ファンタジーの標的を提供する。SF映画は最も純粋なスペクタクルのひとつである。(例外はジャック・アーノルドの『The Incredible

Shrinking Man』[1957年]である)私たちは単なる観客であり、見ているだけである。

しかしSF映画では、ホラー映画と違って、恐怖はあまりない。サスペンス、ショック、サプライズはほとんど排除され、安定した、どうしようもない筋書きが

優先される。SF映画は、破壊と暴力に対する冷静で美的な見方、つまり技術的な見方を誘う。これらの映画では、モノ、物体、機械が重要な役割を果たす。こ

れらの映画の装飾品には、人間よりも幅広い倫理観が具現化されている。無力な人間ではなくモノが価値観の拠り所となるのは、私たちが人間ではなくモノを力

の源として経験するからである。SF映画によれば、人間は人工物なしには裸である。それらは異なる価値を表し、力を持ち、破壊されるものであり、異星人の

侵略を撃退したり、破壊された環境を修復したりするための不可欠な道具なのだ。

|

The science fiction films are

strongly moralistic. The standard message is the one about the proper,

or

humane, use of science, versus the mad, obsessional use of science.

This message the science fiction

films share in common with the classic horror films of the 1930s, like

Frankenstein, The Mummy,

Island of Lost Souls, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. (Georges Franju’s

brilliant Les Yeux Sans Visage

[1959], called here The Horror Chamber of Doctor Faustus, is a more

recent example.) In the horror

films, we have the mad or obsessed or misguided scientist who pursues

his experiments against good

advice to the contrary, creates a monster or monsters, and is himself

destroyed—often recognizing his

folly himself, and dying in the successful effort to destroy his own

creation. One science fiction

equivalent of this is the scientist, usually a member of a team, who

defects to the planetary invaders

because “their” science is more advanced than “ours.”

This is the case in The Mysterians, and, true to form, the renegade

sees his error in the end, and

from within the Mysterian space ship destroys it and himself. In This

Island Earth (1955), the

inhabitants of the beleaguered planet Metaluna propose to conquer

earth, but their project is foiled by

a Metalunan scientist named Exeter who, having lived on earth a while

and learned to love Mozart,

cannot abide such viciousness. Exeter plunges his spaceship into the

ocean after returning a

glamorous pair (male and female) of American physicists to earth.

Metaluna dies. In The Fly (1958),

the hero, engrossed in his basement-laboratory experiments on a

matter-transmitting machine, uses

himself as a subject, exchanges head and one arm with a housefly which

had accidentally gotten into

the machine, becomes a monster, and with his last shred of human will

destroys his laboratory and

orders his wife to kill him. His discovery, for the good of mankind, is

lost.

Being a clearly labeled species of intellectual, scientists in science

fiction films are always liable

to crack up or go off the deep end. In Conquest of Space (1955), the

scientist-commander of an

international expedition to Mars suddenly acquires scruples about the

blasphemy involved in the

undertaking, and begins reading the Bible mid-journey instead of

attending to his duties. The

commander’s son, who is his junior officer and always addresses his

father as “General,” is forced to

kill the old man when he tries to prevent the ship from landing on

Mars. In this film, both sides of the

ambivalence toward scientists are given voice. Generally, for a

scientific enterprise to be treated

entirely sympathetically in these films, it needs the certificate of

utility. Science, viewed without

ambivalence, means an efficacious response to danger. Disinterested

intellectual curiosity rarely

appears in any form other than caricature, as a maniacal dementia that

cuts one off from normal human

relations. But this suspicion is usually directed at the scientist

rather than his work. The creative

scientist may become a martyr to his own discovery, through an accident

or by pushing things too far.

But the implication remains that other men, less imaginative—in short,

technicians—could have

administered the same discovery better and more safely. The most

ingrained contemporary mistrust of

the intellect is visited, in these movies, upon the

scientist-as-intellectual.

The message that the scientist is one who releases forces which, if not

controlled for good, could

destroy man himself seems innocuous enough. One of the oldest images of

the scientist is

Shakespeare’s Prospero, the overdetached scholar forcibly retired from

society to a desert island,

only partly in control of the magic forces in which he dabbles. Equally

classic is the figure of the

scientist as satanist (Doctor Faustus, and stories of Poe and

Hawthorne). Science is magic, and man

has always known that there is black magic as well as white. But it is

not enough to remark that

contemporary attitudes—as reflected in science fiction films—remain

ambivalent, that the scientist is

treated as both satanist and savior. The proportions have changed,

because of the new context in

which the old admiration and fear of the scientist are located. For his

sphere of influence is no longer

local, himself or his immediate community. It is planetary, cosmic.

|

SF

映画は強く道徳的である。標準的なメッセージは、科学の正しい使い方、つまり人道的な使い方と、科学の狂気的で強迫観念的な使い方についてのものだ。この

メッセージは、『フランケンシュタイン』、『ミイラ』、『魂の島』、『ジキル博士とハイド氏』といった1930年代の古典的ホラー映画と共通している。

(ジョルジュ・フランジュの素晴らしい『Les Yeux Sans

Visage』[1959]は、ここでは『ファウストゥス博士の恐怖部屋』と呼ばれている。)

ホラー映画では、狂気の、あるいは取り憑かれた、あるいは誤った科学者が、それとは正反対の適切な助言に反して実験を進め、怪物やモンスターを生み出し、

自らも破壊される。SFでこれに相当するのが、科学者(通常はチームのメンバー)で、「彼らの 」科学が 「我々の

」科学より進んでいるという理由で惑星侵略者に亡命するケースだ。

これは『ミステリアン』でのケースであり、忠実に言えば、反逆者は最後に自分の過ちに気づき、ミステリアン宇宙船の中から宇宙船と自分自身を破壊する。こ

の島の地球』(1955年)では、窮地に陥った惑星メタルーナの住民が地球征服を提案するが、メタルーナの科学者エクセターによって計画は頓挫する。エク

セターは、アメリカ人物理学者の華やかなペア(男女)を地球に帰還させた後、宇宙船を海に投げ込む。メタルーナは死ぬ。ザ・フライ』(1958年)では、

地下の実験室で物質透過装置の実験に没頭していた主人公が、自分自身を被験者として、誤って装置の中に入り込んだイエバエと頭と片腕を交換し、怪物と化

し、人間としての最後の意志のかけらで実験室を破壊し、妻に自分を殺すよう命じる。人類のための彼の発見は失われた。

知識人という明確なレッテルを貼られた種であるため、SF映画に登場する科学者たちは、常にクラッキングを起こしたり、深みにはまったりしがちだ。宇宙征

服』(1955年)では、火星への国際探検隊を率いる科学者が、突然、この計画に含まれる神への冒涜に疑念を抱くようになり、任務の代わりに旅の途中で聖

書を読み始める。指揮官の息子は下士官であり、常に父親を「将軍」と呼ぶが、船が火星に着陸するのを阻止しようとしたため、老人を殺さざるを得なくなる。

この映画では、科学者に対するアンビバレンスの両側面が語られている。一般的に、このような映画で科学事業が完全に同情的に扱われるには、実用性の証明が

必要である。科学が両価性なしに見られるということは、危険に対する効果的な対応を意味する。利害関係のない知的好奇心が、通常の人間関係から人を切り離

すマニアックな痴呆として、戯画以外の形で登場することはめったにない。しかし、このような疑念は通常、その仕事よりも科学者に向けられる。創造的な科学

者は、事故や行き過ぎた努力によって、自らの発見に殉じるかもしれない。しかし、想像力に乏しい他の人間、つまり技術者であれば、同じ発見をよりうまく、

より安全に実施できたはずだという含意は残る。知性に対する現代人の最も根強い不信は、このような映画の中で、知識人としての科学者に向けられる。

科学者は、善のために制御しなければ人間そのものを破壊しかねない力を解放する存在であるというメッセージは、一見無害に見える。科学者の最も古いイメー

ジのひとつは、シェイクスピアのプロスペローである。社会から強制的に無人島に追いやられた学者で、自分が手を染める魔法の力を部分的にしか制御できな

い。同様に古典的なのは、悪魔崇拝者としての科学者の姿である(『ファウストゥス博士』、ポーやホーソーンの物語)。科学は魔術であり、人間は常に白魔術

と黒魔術があることを知っていた。しかし、SF映画に反映されているように、現代の態度が両義的なままであること、科学者が悪魔崇拝者であると同時に救世

主として扱われていることを指摘するだけでは十分ではない。科学者に対するかつての称賛と恐怖が、新たな文脈の中で位置づけられるようになったからだ。彼

の影響範囲は、もはや彼自身や彼の身近なコミュニティといったローカルなものではない。それは惑星的、宇宙的なものである。

|

One gets the feeling,

particularly in the Japanese films but not only there, that a mass

trauma exists

over the use of nuclear weapons and the possibility of future nuclear

wars. Most of the science fiction

films bear witness to this trauma, and, in a way, attempt to exorcise

it.

The accidental awakening of the super-destructive monster who has slept

in the earth since

prehistory is, often, an obvious metaphor for the Bomb. But there are

many explicit references as

well. In The Mysterians, a probe ship from the planet Mysteroid has

landed on earth, near Tokyo.

Nuclear warfare having been practiced on Mysteroid for centuries (their

civilization is “more

advanced than ours”), ninety percent of those now born on the planet

have to be destroyed at birth,

because of defects caused by the huge amounts of Strontium 90 in their

diet. The Mysterians have

come to earth to marry earth women, and possibly to take over our

relatively uncontaminated

planet … In The Incredible Shrinking Man, the John Doe hero is the

victim of a gust of radiation

which blows over the water, while he is out boating with his wife; the

radiation causes him to grow

smaller and smaller, until at the end of the movie he steps through the

fine mesh of a window screen

to become “the infinitely small.” … In Rodan, a horde of monstrous

carnivorous prehistoric insects,

and finally a pair of giant flying reptiles (the prehistoric

Archeopteryx), are hatched from dormant

eggs in the depths of a mine shaft by the impact of nuclear test

explosions, and go on to destroy a good

part of the world before they are felled by the molten lava of a

volcanic eruption.… In the English

film, The Day the Earth Caught Fire, two simultaneous hydrogen bomb

tests by the United States and

Russia change by 11 degrees the tilt of the earth on its axis and alter

the earth’s orbit so that it begins

to approach the sun.

Radiation casualties—ultimately, the conception of the whole world as a

casualty of nuclear

testing and nuclear warfare—is the most ominous of all the notions with

which science fiction films

deal. Universes become expendable. Worlds become contaminated, burnt

out, exhausted, obsolete. In

Rocketship X-M (1950) explorers from the earth land on Mars, where they

learn that atomic warfare

has destroyed Martian civilization. In George Pal’s The War of the

Worlds (1953), reddish spindly

alligator-skinned creatures from Mars invade the earth because their

planet is becoming too cold to

be inhabitable. In This Island Earth, also American, the planet

Metaluna, whose population has long

ago been driven underground by warfare, is dying under the missile

attacks of an enemy planet.

Stocks of uranium, which power the force field shielding Metaluna, have

been used up; and an

unsuccessful expedition is sent to earth to enlist earth scientists to

devise new sources for nuclear

power. In Joseph Losey’s The Damned (1961), nine icy-cold radioactive

children are being reared

by a fanatical scientist in a dark cave on the English coast to be the

only survivors of the inevitable

nuclear Armageddon.

|

特に日本映画においてだが、それだけではなく、核兵器の使用と将来の核

戦争の可能性に対して、大衆のトラウマが存在しているように感じられる。ほとんどのSF映画は、このトラウマを目撃し、ある意味でそれを祓おうとしてい

る。

先史時代から地球に眠っていた超破壊的な怪物が偶然目覚めるというのは、しばしば原爆の明らかな隠喩である。しかし、露骨な隠喩も多い。ミステリアン』で

は、惑星ミステロイドからの探査船が東京近郊の地球に着陸した。ミステロイド星では何世紀にもわたって核戦争が行われており(彼らの文明は

「我々より進んでいる」)、現在この星で生まれた人々の90%は、食事に含まれる大量のストロンチウム90によって引き起こされる欠陥のために、生まれた

時点で破壊されなければならない。ミステリアンたちは地球人女性と結婚するために地球にやってきており、比較的汚染されていないこの惑星を乗っ取ろうとし

ているのかもしれない......『インクレディブル・シュリンキング・マン』では、ジョン・ドウの主人公が妻とボートで出かけているときに、海上に吹き

荒れた突風放射線の犠牲となる。放射線によって彼はどんどん小さくなっていき、映画の最後には窓の網戸の細かい網目を通り抜けて 「限りなく小さく

」なってしまう。...『ローダン』では、怪物のような肉食の先史時代の昆虫の大群、そして最後には巨大な空飛ぶ爬虫類のペア(先史時代のアルケオプテリ

クス)が、核実験の爆発の衝撃で鉱山坑道の奥深くに眠っていた卵から孵化し、火山噴火の溶岩で倒れる前に世界のかなりの部分を破壊しに行く。 ...

英国の映画『The Day the Earth Caught

Fire』では、アメリカとロシアによる2回同時の水爆実験によって、地軸の傾きが11度変わり、地球の軌道が変化して太陽に近づき始める。

放射線の犠牲者、つまるところ、全世界が核実験と核戦争の犠牲者であるという概念は、SF映画が扱うあらゆる概念の中で最も不吉なものである。宇宙は消耗

品となる。世界は汚染され、燃え尽き、疲弊し、時代遅れになる。ロケットシップX-M』(1950年)では、地球の探検家が火星に降り立ち、そこで原子戦

争が火星文明を破壊したことを知る。ジョージ・パルの『The War of the

Worlds』(1953年)では、火星からやってきた赤くてひょろひょろとしたワニのような肌の生物が、自分たちの星が寒すぎて住めなくなったという理

由で地球を侵略する。同じくアメリカの『この島の地球』では、人口が戦火で地下に追いやられて久しい惑星メタルーナが、敵星のミサイル攻撃で滅びようとし

ている。メタルーナをシールドするフォースフィールドの動力源であるウランの在庫は使い果たされ、新たな原子力源を開発するため、地球の科学者たちに協力

を求めるため、失敗した探検隊が地球に送られる。ジョセフ・ロージー監督の『ダムド』(1961年)では、氷のように冷たい9人の放射能に汚染された子供

たちが、イギリスの海岸にある暗い洞窟で狂信的な科学者によって育てられている。

|

There is a vast amount of

wishful thinking in science fiction films, some of it touching, some of

it

depressing. Again and again, one detects the hunger for a “good war,”

which poses no moral

problems, admits of no moral qualifications. The imagery of science

fiction films will satisfy the most

bellicose addict of war films, for a lot of the satisfactions of war

films pass, untransformed, into

science fiction films. Examples: the dogfights between earth “fighter

rockets” and alien spacecraft in

the Battle in Outer Space (1960); the escalating firepower in the

successive assaults upon the

invaders in The Mysterians, which Dan Talbot correctly described as a

non-stop holocaust; the

spectacular bombardment of the underground fortress of Metaluna in This

Island Earth.

Yet at the same time the bellicosity of science fiction films is neatly

channeled into the yearning

for peace, or for at least peaceful coexistence. Some scientist

generally takes sententious note of the

fact that it took the planetary invasion to make the warring nations of

the earth come to their senses

and suspend their own conflicts. One of the main themes of many science

fiction films—the color

ones usually, because they have the budget and resources to develop the

military spectacle—is this

UN fantasy, a fantasy of united warfare. (The same wishful UN theme

cropped up in a recent

spectacular which is not science fiction, Fifty-Five Days in Peking

[1963]. There, topically enough,

the Chinese, the Boxers, play the role of Martian invaders who unite

the earthmen, in this case the

United States, England, Russia, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan.) A

great enough disaster cancels

all enmities and calls upon the utmost concentration of earth

resources.

Science—technology—is conceived of as the great unifier. Thus the

science fiction films also

project a Utopian fantasy. In the classic models of Utopian

thinking—Plato’s Republic, Campanella’s

City of the Sun, More’s Utopia, Swift’s land of the Houyhnhnms,

Voltaire’s Eldorado—society had

worked out a perfect consensus. In these societies reasonableness had

achieved an unbreakable

supremacy over the emotions. Since no disagreement or social conflict

was intellectually plausible,

none was possible. As in Melville’s Typee, “they all think the same.”

The universal rule of reason

meant universal agreement. It is interesting, too, that societies in

which reason was pictured as totally

ascendant were also traditionally pictured as having an ascetic or

materially frugal and economically

simple mode of life. But in the Utopian world community projected by

science fiction films, totally

pacified and ruled by scientific consensus, the demand for simplicity

of material existence would be

absurd.

|

SF

映画には、感動的なものもあれば憂鬱なものもある。何度も何度も、道徳的な問題もなく、道徳的な資格も認められない「良い戦争」への渇望が感じられる。

SF映画のイメージは、戦争映画の最も好戦的な中毒者を満足させるだろう。なぜなら、戦争映画の満足感の多くは、そのままSF映画に受け継がれるからだ。

例えば、『宇宙での戦い』(1960)における地球の「戦闘機ロケット」と異星人の宇宙船とのドッグファイト、ダン・タルボットが正しくノンストップ・ホ

ロコーストと表現した『ミステリアン』における侵略者への連続攻撃におけるエスカレートする火力、『この島の地球』におけるメタルーナの地下要塞への壮絶

な砲撃などである。

しかし同時に、SF映画の好戦性は、平和への憧れ、あるいは少なくとも平和的共存への憧れへとうまく誘導されている。ある科学者は一般に、地球上で争って

いる国々が正気を取り戻し、自分たちの争いを中断させるためには、惑星の侵略が必要だったという事実を感傷的に受け止めている。多くのSF映画の主要テー

マのひとつは、軍事的スペクタクルを展開する予算と資源があるため、通常はカラー映画である。(SFではないが、最近のスペクタクル映画『北京五十五日』

[1963年]にも、同じような願望的国連テーマが登場する)。そこでは、中国人の義和団が火星の侵略者の役割を演じ、地球人(この場合はアメリカ、イギ

リス、ロシア、フランス、ドイツ、イタリア、日本)を団結させるのだ)。大きな災害がすべての敵意を消し去り、地球の資源を最大限に集中させる。

科学技術は偉大な統合者として考えられている。このように、SF映画はユートピア的なファンタジーをも映し出す。ユートピア思想の古典的モデル-プラトン

の『共和国』、カンパネラの『太陽の都』、モアの『ユートピア』、スウィフトの『ホウ族の国』、ヴォルテールの『エルドラド』-では、社会は完璧なコンセ

ンサスを得ていた。これらの社会では、理性は感情に対してゆるぎない覇権を握っていた。意見の不一致や社会的対立は、知的にもっともらしくもなく、何一つ

起こりえなかった。メルヴィルの『タイピー』にあるように、「彼らはみな同じことを考えている」。理性の普遍的なルールは、普遍的な合意を意味した。理性

が完全に優位に立つ社会が、伝統的に禁欲的、あるいは物質的に質素で経済的に単純な生活様式を持つ社会として描かれてきたことも興味深い。しかし、SF映

画が映し出す、完全に平和化され、科学的合意に支配されたユートピア的な世界共同体では、物質的存在の簡素化を求めるのは不合理である。

|

Yet alongside the hopeful

fantasy of moral simplification and international unity embodied in the

science fiction films lurk the deepest anxieties about contemporary

existence. I don’t mean only the

very real trauma of the Bomb—that it has been used, that there are

enough now to kill everyone on

earth many times over, that those new bombs may very well be used.

Besides these new anxieties

about physical disaster, the prospect of universal mutilation and even

annihilation, the science fiction

films reflect powerful anxieties about the condition of the individual

psyche.

For science fiction films may also be described as a popular mythology

for the contemporary

negative imagination about the impersonal. The other-world creatures

that seek to take “us” over are

an “it,” not a “they.” The planetary invaders are usually zombie-like.

Their movements are either

cool, mechanical, or lumbering, blobby. But it amounts to the same

thing. If they are non-human in

form, they proceed with an absolutely regular, unalterable movement

(unalterable save by

destruction). If they are human in form—dressed in space suits,

etc.—then they obey the most rigid

military discipline, and display no personal characteristics

whatsoever. And it is this regime of

emotionlessness, of impersonality, of regimentation, which they will

impose on the earth if they are

successful. “No more love, no more beauty, no more pain,” boasts a

converted earthling in The

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). The half-earthling, half-alien

children in The Children of the

Damned (1960) are absolutely emotionless, move as a group and

understand each others’ thoughts,

and are all prodigious intellects. They are the wave of the future, man

in his next stage of

development.

These alien invaders practice a crime which is worse than murder. They

do not simply kill the

person. They obliterate him. In The War of the Worlds, the ray which

issues from the rocket ship

disintegrates all persons and objects in its path, leaving no trace of

them but a light ash. In Honda’s

The H-Man (1959), the creeping blob melts all flesh with which it comes

in contact. If the blob,

which looks like a huge hunk of red Jello and can crawl across floors

and up and down walls, so

much as touches your bare foot, all that is left of you is a heap of

clothes on the floor. (A more

articulated, size-multiplying blob is the villain in the English film

The Creeping Unknown [1956].) In

another version of this fantasy, the body is preserved but the person

is entirely reconstituted as the

automatized servant or agent of the alien powers. This is, of course,

the vampire fantasy in new dress.

The person is really dead, but he doesn’t know it. He is “undead,” he

has become an “unperson.” It

happens to a whole California town in The Invasion of the Body

Snatchers, to several earth

scientists in This Island Earth, and to assorted innocents in It Came

From Outer Space, Attack of the

Puppet People (1958), and The Brain Eaters (1958). As the victim always

backs away from the

vampire’s horrifying embrace, so in science fiction films the person

always fights being “taken over”;

he wants to retain his humanity. But once the deed has been done, the

victim is eminently satisfied

with his condition. He has not been converted from human amiability to

monstrous “animal” bloodlust

(a metaphoric exaggeration of sexual desire), as in the old vampire

fantasy. No, he has simply

become far more efficient—the very model of technocratic man, purged of

emotions, volitionless,

tranquil, obedient to all orders. (The dark secret behind human nature

used to be the upsurge of the

animal—as in King Kong. The threat to man, his availability to

dehumanization, lay in his own

animality. Now the danger is understood as residing in man’s ability to

be turned into a machine.)

The rule, of course, is that this horrible and irremediable form of

murder can strike anyone in the

film except the hero. The hero and his family, while greatly

threatened, always escape this fate and by

the end of the film the invaders have been repulsed or destroyed. I

know of only one exception, The

Day That Mars Invaded Earth (1963), in which after all the standard

struggles the scientist-hero, his

wife, and their two children are “taken over” by the alien invaders—and

that’s that. (The last minutes

of the film show them being incinerated by the Martians’ rays and their

ash silhouettes flushed down

their empty swimming pool, while their simulacra drive off in the

family car.) Another variant but

upbeat switch on the rule occurs in The Creation of the Humanoids

(1964), where the hero discovers

at the end of the film that he, too, has been turned into a metal

robot, complete with highly efficient

and virtually indestructible mechanical insides, although he didn’t

know it and detected no difference

in himself. He learns, however, that he will shortly be upgraded into a

“humanoid” having all the

properties of a real man.

Of all the standard motifs of science fiction films, this theme of

dehumanization is perhaps the

most fascinating. For, as I have indicated, it is scarcely a

black-and-white situation, as in the old

vampire films. The attitude of the science fiction films toward

depersonalization is mixed. On the one

hand, they deplore it as the ultimate horror. On the other hand,

certain characteristics of the

dehumanized invaders, modulated and disguised—such as the ascendancy of

reason over feelings, the

idealization of teamwork and the consensus-creating activities of

science, a marked degree of moral

simplification—are precisely traits of the savior-scientist. It is

interesting that when the scientist in

these films is treated negatively, it is usually done through the

portrayal of an individual scientist who

holes up in his laboratory and neglects his fiancée or his loving wife

and children, obsessed by his

daring and dangerous experiments. The scientist as a loyal member of a

team, and therefore

considerably less individualized, is treated quite respectfully.

There is absolutely no social criticism, of even the most implicit

kind, in science fiction films. No

criticism, for example, of the conditions of our society which create

the impersonality and

dehumanization which science fiction fantasies displace onto the

influence of an alien It. Also, the

notion of science as a social activity, interlocking with social and

political interests, is

unacknowledged. Science is simply either adventure (for good or evil)

or a technical response to

danger. And, typically, when the fear of science is paramount—when

science is conceived of as

black magic rather than white—the evil has no attribution beyond that

of the perverse will of an

individual scientist. In science fiction films the antithesis of black

magic and white is drawn as a split

between technology, which is beneficent, and the errant individual will

of a lone intellectual.

Thus, science fiction films can be looked at as thematically central

allegory, replete with standard

modern attitudes. The theme of depersonalization (being “taken over”)

which I have been talking

about is a new allegory reflecting the age-old awareness of man that,

sane, he is always perilously

close to insanity and unreason. But there is something more here than

just a recent, popular image

which expresses man’s perennial, but largely unconscious, anxiety about

his sanity. The image

derives most of its power from a supplementary and historical anxiety,

also not experienced

consciously by most people, about the depersonalizing conditions of

modern urban life. Similarly, it

is not enough to note that science fiction allegories are one of the

new myths about—that is, one of the

ways of accommodating to and negating—the perennial human anxiety about

death. (Myths of heaven

and hell, and of ghosts, had the same function.) For, again, there is a

historically specifiable twist

which intensifies the anxiety. I mean, the trauma suffered by everyone

in the middle of the 20th

century when it became clear that, from now on to the end of human

history, every person would

spend his individual life under the threat not only of individual

death, which is certain, but of

something almost insupportable psychologically—collective incineration

and extinction which could

come at any time, virtually without warning.

From a psychological point of view, the imagination of disaster does

not greatly differ from one

period in history to another. But from a political and moral point of

view, it does. The expectation of

the apocalypse may be the occasion for a radical disaffiliation from

society, as when thousands of

Eastern European Jews in the 17th century, hearing that Sabbatai Zevi

had been proclaimed the

Messiah and that the end of the world was imminent, gave up their homes

and businesses and began

the trek to Palestine. But people take the news of their doom in

diverse ways. It is reported that in

1945 the populace of Berlin received without great agitation the news

that Hitler had decided to kill

them all, before the Allies arrived, because they had not been worthy

enough to win the war. We are,

alas, more in the position of the Berliners of 1945 than of the Jews of

17th century Eastern Europe;

and our response is closer to theirs, too. What I am suggesting is that

the imagery of disaster in

science fiction is above all the emblem of an inadequate response. I

don’t mean to bear down on the

films for this. They themselves are only a sampling, stripped of

sophistication, of the inadequacy of

most people’s response to the unassimilable terrors that infect their

consciousness. The interest of the

films, aside from their considerable amount of cinematic charm,

consists in this intersection between

a naïve and largely debased commercial art product and the most

profound dilemmas of the

contemporary situation.

|

し

かし、SF映画が体現する道徳の単純化と国際的団結という希望に満ちたファンタジーの傍らには、現代の存在に対する深い不安が潜んでいる。それは、原爆が

使用されたこと、地球上のすべての人を何度も殺すのに十分な数の原爆が存在すること、新たな原爆が使用されるかもしれないということである。このような物

理的な災害に対する新たな不安、普遍的な切断や消滅さえも予感させる不安のほかに、SF映画は個人の精神の状態に対する強力な不安を映し出している。

SF映画はまた、非人間的なものに対する現代の否定的な想像力のための大衆的な神話と言えるかもしれない。私たち」を乗っ取ろうとする異世界の生物は、

「彼ら 」ではなく 「それ

」である。惑星の侵略者はたいていゾンビのようだ。彼らの動きはクールで機械的か、あるいはゴツゴツとした塊のようだ。しかし、それは同じことだ。もし彼

らの姿が人間でないなら、彼らはまったく規則正しく、変更不可能な動きで進む(破壊されなければ変更不可能)。もし彼らが人間の姿をしていて、宇宙服など

に身を包んでいるのなら、彼らは最も厳格な軍規に従い、個人的な特徴はまったく示さない。もし彼らが成功すれば、この無感情、無個性、統制の体制を地球に

押し付けることになる。もう愛も美も痛みもない」と『ボディ・スナッチャーズの侵略』(1956年)で改心した地球人は自慢する。呪われた子供たち』

(1960年)に登場する半地球人、半エイリアンの子供たちは、まったく感情を持たず、集団で動き、互いの考えを理解し、全員が天才的な知性を持ってい

る。彼らは未来の波であり、次の発展段階にある人間なのだ。

このエイリアンの侵略者たちは、殺人よりもひどい犯罪を行っている。彼らは単に人を殺すのではない。抹殺するのだ。世界大戦』では、ロケット船から発射さ

れた光線は、その進路上にあるすべての人間や物体を崩壊させ、痕跡を残さず軽い灰にする。本多監督の『Hマン』(1959年)では、忍び寄るブロブが接触

したすべての肉を溶かす。巨大な赤いゼリーの塊のようで、床を這い、壁を上り下りすることができるブロブが素足に触れただけで、残されるのは床に散らばっ

た衣服だけである(もっと明瞭で、サイズが増殖するブロブは、イギリス映画『クリーピング・アンノウン』[1956]の悪役である)。このファンタジーの

別のバージョンでは、身体は保存されているが、人間は完全に異能者の自動化された手下や代理人として再構成されている。これはもちろん、新たな装いをした

吸血鬼ファンタジーである。本人は本当に死んでいるのだが、それに気づいていない。彼は 「アンデッド 」であり、「非人間

」になっているのだ。それは、『ボディ・スナッチャーズの侵略』ではカリフォルニアの町全体に、『この島の地球』では数人の地球科学者に、『宇宙から来

た』、『パペット・ピープルの攻撃』(1958年)、『ブレイン・イーター』(1958年)では罪のない人々に起こる。被害者が常に吸血鬼の恐ろしい抱擁

から後ずさりするように、SF映画では人間は常に「乗っ取られる」ことに抵抗する。しかし、ひとたびその行為が行われると、被害者は自分の状態に満足す

る。旧来のヴァンパイア・ファンタジーのように、人間的な愛らしさから怪物的な「動物的」血への渇望(性的欲望の誇張の隠喩)へと変貌したわけではない。

感情を排除し、意思を持たず、静謐で、あらゆる命令に従順である。(人間の本性に潜む暗い秘密は、かつてはキングコングに見られるような動物性の高揚で

あった。人間にとっての脅威、人間性を奪う可能性は、人間自身の動物性にあった。今、その危険は、人間が機械に変えられる能力にあると理解されている)。

もちろん、この恐ろしい、救いようのない殺人形態は、映画の中では主人公以外の誰をも襲う可能性があるというルールである。主人公とその家族は、大きな脅

威にさらされながらも、常にこの運命から逃れ、映画の終わりには侵略者は撃退されるか破壊されている。私が知っている唯一の例外は、『火星が地球を侵略し

た日』(1963年)で、お決まりの苦闘の末、科学者である主人公とその妻、そして2人の子供がエイリアンの侵略者に 「乗っ取られ

」てしまう。(映画の最後の数分間は、火星人の光線によって焼却され、灰のシルエットが空のプールに流され、彼らのシミュラクラは家族の車で走り去る。)

ヒューマノイドの創造』(1964年)では、主人公が映画の最後で、自分もまた金属製のロボットに改造され、非常に効率的で事実上破壊不可能な機械内部を

備えていることを発見する。しかし彼は、間もなく本物の人間のあらゆる特性を備えた「ヒューマノイド」にアップグレードされることを知る。

SF映画の定番モチーフの中でも、この非人間化というテーマは最も魅力的だろう。というのも、これまで述べてきたように、このテーマは、昔の吸血鬼映画の

ように、白か黒かという状況ではないからだ。非人間化に対するSF映画の態度は複雑である。一方では、究極の恐怖として嫌悪している。その一方で、非人間

化された侵略者のある種の特徴は、感情よりも理性が優位に立つこと、チームワークや科学の合意形成活動を理想化すること、道徳的な単純化が顕著であること

など、調整され、偽装されているが、まさに救世主科学者の特徴である。興味深いことに、これらの映画で科学者が否定的に扱われる場合、たいていは研究室に

閉じこもり、大胆で危険な実験に取り憑かれ、婚約者や愛する妻子をないがしろにする科学者個人の描写を通して行われる。チームの忠実な一員としての科学者

は、それゆえ個人性がかなり希薄だが、かなり丁重に扱われる。

SF映画には、暗黙的な社会批判さえまったくない。例えば、SFファンタジーが異星人「イット」の影響に置き換えている非人間性や非人間性を生み出してい

る私たちの社会の状況に対する批判はない。また、社会的・政治的利害と連動する社会活動としての科学という概念も認識されていない。科学とは、(善悪を問

わず)単に冒険であるか、危険に対する技術的な対応である。そして一般的に、科学への恐怖が最優先されるとき、つまり科学が白魔術ではなく黒魔術のように

考えられるとき、悪は科学者個人の倒錯した意志を超える帰結を持たない。SF映画では、黒魔術と白魔術のアンチテーゼは、有益なテクノロジーと、孤独な知

識人の誤った個人的意志との分裂として描かれる。

このように、SF映画はテーマ的に中心的な寓話として見ることができ、標準的な現代的態度がふんだんに盛り込まれている。これまで述べてきた脱人格化

(「乗っ取られる」)というテーマは、正気であっても常に狂気や理不尽に近づきつつあるという人間の古くからの自覚を反映した新しい寓話である。しかし、

ここには、人間の正気に対する長年にわたる、しかしほとんど無意識のうちに抱いている不安を表現する、最近の一般的なイメージ以上の何かがある。このイ

メージは、現代都市生活の非人間的な状況に対する、補足的で歴史的な不安からその力を得ている。同様に、SFの寓話は、死に対する人間の永続的な不安に対

応し、それを否定する方法のひとつである。(天国と地獄の神話や幽霊の神話も、同じような機能を果たしていた)

繰り返すが、その不安を強める歴史的に特定可能なねじれがあるからだ。つまり、20世紀半ば、これから人類の歴史が終わるまで、すべての人が個人の死とい

う確実なものだけでなく、集団的な焼却や絶滅という心理的にほとんど耐え難いものの脅威にさらされながら個人の人生を過ごすことになることが明らかになっ

たとき、誰もが受けたトラウマである。

心理学的な観点から見れば、災害に対する想像力は、歴史の時代によって大きな違いはない。しかし、政治的、道徳的な観点からは、そうである。たとえば、

17世紀に何千人もの東ヨーロッパのユダヤ人が、サバタイ・ゼビがメシアと宣言され、世界の終わりが迫っていると聞き、家や会社を手放してパレスチナへの

旅を始めたように、終末の予感は社会からの過激な離反のきっかけになるかもしれない。しかし、人々は破滅の知らせをさまざまな形で受け止めている。

1945年、ベルリンの民衆は、ヒトラーは連合国が到着する前に、戦争に勝利するのに十分な価値がなかったという理由で、自分たちを皆殺しにすることを決

めたというニュースを、大きな動揺もなく受け取ったと伝えられている。残念ながら、私たちは17世紀の東ヨーロッパのユダヤ人よりも、1945年のベルリ

ン市民の立場にいる。私が言いたいのは、SFにおける災害のイメージは、何よりも不十分な対応の象徴であるということだ。このことで映画を非難するつもり

はない。映画そのものは、彼らの意識に伝染する同化できない恐怖に対する、多くの人々の反応の不十分さを、洗練を排したサンプリングに過ぎないのだ。この

映画の面白さは、その映画的な魅力もさることながら、ナイーブでほとんど堕落した商業的な芸術作品と、現代の状況における最も深遠なジレンマとの交差にあ

る。

|

Ours is indeed an age of

extremity. For we live under continual threat of two equally fearful,

but

seemingly opposed, destinies: unremitting banality and inconceivable

terror. It is fantasy, served out

in large rations by the popular arts, which allows most people to cope

with these twin specters. For

one job that fantasy can do is to lift us out of the unbearably humdrum

and to distract us from terrors

—real or anticipated—by an escape into exotic, dangerous situations

which have last-minute happy

endings. But another of the things that fantasy can do is to normalize

what is psychologically

unbearable, thereby inuring us to it. In one case, fantasy beautifies

the world. In the other, it

neutralizes it.

The fantasy in science fiction films does both jobs. The films reflect

world-wide anxieties, and

they serve to allay them. They inculcate a strange apathy concerning

the processes of radiation,

contamination, and destruction which I for one find haunting and

depressing. The naïve level of the

films neatly tempers the sense of otherness, of alien-ness, with the

grossly familiar. In particular, the

dialogue of most science fiction films, which is of a monumental but

often touching banality, makes

them wonderfully, unintentionally funny. Lines like “Come quickly,

there’s a monster in my bathtub,”

“We must do something about this,” “Wait, Professor. There’s someone on

the telephone,” “But that’s

incredible,” and the old American stand-by, “I hope it works!” are

hilarious in the context of

picturesque and deafening holocaust. Yet the films also contain

something that is painful and in deadly

earnest.

There is a sense in which all these movies are in complicity with the

abhorrent. They neutralize it,

as I have said. It is no more, perhaps, than the way all art draws its

audience into a circle of

complicity with the thing represented. But in these films we have to do

with things which are (quite

literally) unthinkable. Here, “thinking about the unthinkable”—not in

the way of Herman Kahn, as a

subject for calculation, but as a subject for fantasy—becomes, however

inadvertently, itself a

somewhat questionable act from a moral point of view. The films

perpetuate clichés about identity,

volition, power, knowledge, happiness, social consensus, guilt,

responsibility which are, to say the

least, not serviceable in our present extremity. But collective

nightmares cannot be banished by

demonstrating that they are, intellectually and morally, fallacious.

This nightmare—the one reflected,

in various registers, in the science fiction films—is too close to our

reality.

[1965]

|

現

代はまさに極限の時代である。絶え間なく続く平凡さと、想像を絶する恐怖である。多くの人々がこの2つの恐怖に対処できるのは、大衆芸術によって大量に配

給されるファンタジーのおかげである。ファンタジーができることのひとつは、私たちを耐え難いほど平凡な日常から解き放ち、土壇場でハッピーエンドを迎え

るエキゾチックで危険な状況へと逃避させることで、恐怖--現実のものであれ、予期されたものであれ--から目をそらさせることである。しかし、ファンタ

ジーができることのもうひとつは、心理的に耐え難いものを正常化し、それによって私たちをそれに慣れさせることである。ファンタジーは世界を美化する。も

うひとつは、世界を中和することだ。

SF映画におけるファンタジーは、その両方の役割を担っている。映画は世界全体の不安を反映し、それを和らげる役割を果たす。放射線、汚染、破壊のプロセ

スに対する奇妙な無関心を植え付け、私はそれが心を痛め、憂鬱になる。映画のナイーブなレベルは、異質なもの、異質なものという感覚を、ひどく親しみやす

いものとうまく和らげている。特に、ほとんどのSF映画の台詞は記念碑的でありながら、しばしば感動的な平凡さであり、それが映画を素晴らしく、思わず笑

えるものにしている。早く来て、私のバスタブに怪物がいる」「これを何とかしなければ」「待って、教授。電話口に誰かいる」、「でも信じられない」、そし

てアメリカ人の定番である「うまくいくといいね!」といったセリフは、絵に描いたような、耳をつんざくようなホロコーストの文脈の中では愉快である。しか

し、この映画には痛々しく、深刻なものも含まれている。

これらの映画はすべて、忌まわしいものと共謀しているようなところがある。これまで述べてきたように、彼らはそれを中和している。それはおそらく、あらゆ

る芸術が観客を、表現されたものとの共犯関係の輪の中に引き込むのと同じことだ。しかし、これらの映画では、(文字通り)考えられないものを扱わなければ

ならない。ここでは、「考えられないことについて考えること」--ハーマン・カーンのように、計算の対象としてではなく、空想の対象として--は、たとえ

不注意であったとしても、それ自体が道徳的観点から見ていささか疑わしい行為となる。映画は、アイデンティティ、意志、権力、知識、幸福、社会的コンセン

サス、罪悪感、責任などに関する決まり文句を永続させる。しかし、集団的な悪夢は、それが知的にも道徳的にも誤りであることを示すだけでは、追い払うこと

はできない。この悪夢は、SF映画にさまざまな形で反映されているものだが、私たちの現実にあまりにも近い。

|

|

|

|

|

■「『地球防衛軍』(本多猪四郎監督、1957——引

用者)がこの例で、最後になって離脱者が過ちを知って内部からミステリアンの宇宙

船を自分もろとも破壊する。『宇宙水爆戦争』(1955)では、包囲されたメタルーナ星の住人たちが地球制服を図るが、しばらく地球で暮らしてモーツアル

トを好きになり、そのような非道な行為に耐えられないエクセターという名前のメタルーナの科学者のために、この計画は挫折する。エクセターは一組の魅惑的

な(男と女の)アメリカの物理学者を地球に戻したあと、自分の宇宙船を大洋に墜落させる。『蠅 The

Fly』(1958)の主人公は、地下の実験室で物体交換機の実験に夢中になって、自分を実験材料にし、たまたま機械に飛び込んできた家蠅と頭と片腕を交

換し、怪物になるが、わずかに残った人間の意志をふりしぼって実験室を破壊し、自分を殺すように妻に命ずる。彼の発見は、人間の幸福のために、失われてし

まう」(p.242)。

■「『地球防衛軍』(本多猪四郎監督、1957——引

用者)がこの例で、最後になって離脱者が過ちを知って内部からミステリアンの宇宙

船を自分もろとも破壊する。『宇宙水爆戦争』(1955)では、包囲されたメタルーナ星の住人たちが地球制服を図るが、しばらく地球で暮らしてモーツアル

トを好きになり、そのような非道な行為に耐えられないエクセターという名前のメタルーナの科学者のために、この計画は挫折する。エクセターは一組の魅惑的

な(男と女の)アメリカの物理学者を地球に戻したあと、自分の宇宙船を大洋に墜落させる。『蠅 The

Fly』(1958)の主人公は、地下の実験室で物体交換機の実験に夢中になって、自分を実験材料にし、たまたま機械に飛び込んできた家蠅と頭と片腕を交

換し、怪物になるが、わずかに残った人間の意志をふりしぼって実験室を破壊し、自分を殺すように妻に命ずる。彼の発見は、人間の幸福のために、失われてし

まう」(p.242)。 户塚

伸兒さん、ありがとう!! (2022年クリスマス)

户塚

伸兒さん、ありがとう!! (2022年クリスマス)

☆

☆