ブルーノ・ネトル

Bruno Nettl (14 March 1930 – 15 January

2020)

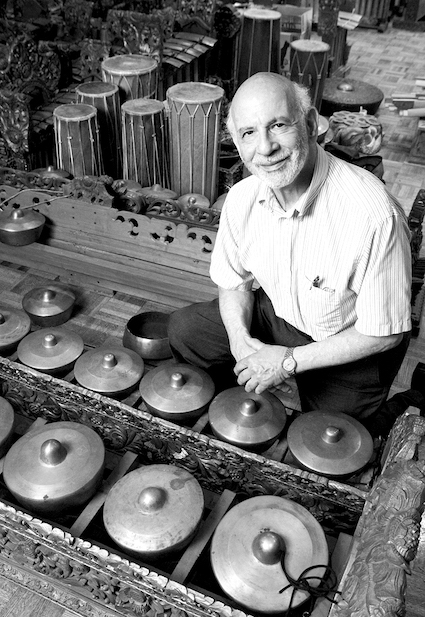

☆ ブルーノ・ネトル(Bruno Nettl、1930年3月14日 - 2020年1月15日)は、民族音楽学(ethnomusicology)を学問として定義する上で中心となった民族音楽学者である。 民族音楽や伝統音楽、特にアメリカ先住民の音楽、イランの音楽、学問としての民族音楽学に関する多くのトピックに焦点を当てて研究していた。

| Bruno Nettl (14

March 1930 – 15 January 2020) Bruno Nettl (14 March 1930 – 15 January 2020) was an ethnomusicologist who was central in defining ethnomusicology as a discipline.[1][2] His research focused on folk and traditional music, specifically Native American music the music of Iran and numerous topics surrounding ethnomusicology as a discipline.[3] |

ブルーノ・ネトル(Bruno Nettl、1930年3月14日

- 2020年1月15日) ブルーノ・ネトル(Bruno Nettl、1930年3月14日 - 2020年1月15日)は、民族音楽学(ethnomusicology)を学問として定義する上で中心となった民族音楽学者である。 民族音楽や伝統音楽、特にアメリカ先住民の音楽、イランの音楽、学問としての民族音楽学に関する多くのトピックに焦点を当てて研究していた。 |

| Bruno Nettl (1930-2020) was born

in Prague, Czechoslovakia in 1930, and he was the son of Paul and

Gertrude (Hutter) Nettl, who both had musical backgrounds.[4] In 1939,

Nettl and his family, which was of Jewish heritage, moved to the US to

escape the Holocaust, which caused several deaths within his

family.[5][6] He studied at Indiana University with George Herzog[7]

and the University of Michigan and taught from 1964 at the University

of Illinois, where he eventually was named Professor Emeritus of Music

and Anthropology. Nettl met his wife, Wanda Maria White, while he was a

student at Indiana University and the couple married in 1952.[8] Bruno

and Wanda had two children, Rebecca and Gloria.[9] The Nettl’s were a

connected family, as his daughters continued living in Champaign even

in their adult lives, and Bruno was said to be a devoted father and

husband who cherished every moment with his family.[10] He continued to

teach part-time until his death. Nettl introduced and expanded the

ethnomusicology department at the University of Illinois, making it

among the national leaders in ethnomusicology.[11] Nettl was known to

have pride in the accomplishments of his students, many of whom went on

to teach at leading national universities.[12] Active principally in

the field of ethnomusicology, he did field research with Native

American peoples (1960s and 1980s, see Blackfoot music), in Iran (1966,

1968–69, 1972, 1974), and in South India (1981–82). He served as

president of the Society for Ethnomusicology and as editor of its

journal, Ethnomusicology. Nettl held honorary doctorates from the

University of Illinois, Carleton College, Kenyon College, and the

University of Chicago. He was a recipient of the Fumio Koizumi Prize

for ethnomusicology, and was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts

and Sciences. Nettl was named the 2014 Charles Homer Haskins Prize

Lecturer by the American Council of Learned Societies. In the course of

his long career as a scholar and as a professor, he was the teacher of

many of the most visible ethnomusicologists active today in the

international scene, including Philip Bohlman, Christopher Waterman,

Marcello Sorce Keller, and Victoria Lindsay Levine. The Sousa Archives

and Center for American Music holds the Bruno Nettl Papers, 1966–1988,

which consists of administrative and personal correspondence while

Nettl was a professor and head of the Musicology Division for the

University of Illinois School of Music.[13][14][15] |

ブ

ルーノ・ネトルは、1930年、チェコスロバキアのプラハに生まれ、ポール・ネトルとガートルード(ハッター)・ネトルの息子で、ともに音楽家であった。

1939年、ユダヤ人の血を引く家族とともに、家族内で数人の死者を出したホロコーストから逃れるためにアメリカに渡った[5][6]。

インディアナ大学でジョージ・ヘルツォーク[7]、ミシガン大学で学び、1964年からイリノイ大学で教え、ついには音楽と人類学の名誉教授に就任した。

ネトルはインディアナ大学在学中に妻のワンダ・マリア・ホワイトと出会い、1952年に結婚した[8]

。ブルーノとワンダの間にはレベッカとグロリアという2人の子供がいた[9]

。ネトル一家は、娘たちが成人してもシャンペーンに住み、またブルーノは家族との時間を大切にする父親、夫だったといわれ、つながりを持つことができた

[10]

。ネットルはイリノイ大学の民族音楽学部門を導入・拡大し、民族音楽学で全米をリードする存在となった[11]。ネットルは教え子たちの成果に誇りを持っ

ており、多くの教え子が国立大学の一流校で教えるようになったことでも知られている[12]。

[主に民族音楽学の分野で活躍し、アメリカ先住民(1960年代と1980年代、ブラックフット音楽を参照)、イラン(1966、1968-69、

1972、1974)、南インド(1981-82)で現地調査を行った。)

民族音楽学会の会長、同学会誌『民族音楽学』の編集長を務めた。イリノイ大学、カールトンカレッジ、ケニオンカレッジ、シカゴ大学から名誉博士号を授与さ

れた。民族音楽学で小泉文夫賞を受賞し、アメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローでもある。ネトルは、米国学協会協議会から2014年チャールズ・ホー

マー・ハスキンズ賞の講師に指名された。学者として、また教授としての長いキャリアの中で、フィリップ・ボールマン、クリストファー・ウォーターマン、マ

ルチェロ・ソース・ケラー、ヴィクトリア・リンゼイ・レヴィンなど、現在国際的に活躍する多くの著名な民族音楽学者の師となった。Sousa

Archives and Center for American Musicが所蔵するBruno Nettl Papers,

1966-1988は、Nettlがイリノイ大学音楽学部教授および音楽学部長であったときの事務的および個人的な書簡から構成されている[13]

[14][15]。 |

| The Study of Ethnomusicology,

initially published in 1983, provides comprehensive discourse of

ethnomusicology and is widely considered some of Nettl’s best work.[16]

The book’s first edition included 29 chapters discussing the ins and

outs of ethnomusicology, which Nettl expanded to 31 chapters in 2005,

and 33 chapters in 2015.[17] The work includes an array of riveting

discussions surrounding ethnomusicology, including defining the

practice, the topic of universals, fieldwork, and the effects of music

on different cultures and demographics.[18] Nettl discusses fieldwork throughout his book, as seen in Chapter 10, “Come Back and See Me Next Tuesday: Essentials of Fieldwork,” and Chapter 11, “You Will Never Understand This Music: Insiders and Outsiders.”[19] Chapter 10 provides an insight into Nettl’s fieldwork, as the chapter opens by detailing Nettl’s interactions with a Native American called Joe.[20] Nettl had to do a series of favors for Joe before earning the right to interview him, demonstrating the importance of earning one’s trust while conducting fieldwork.[21] Next, Nettl used this anecdote as a base to dive deeper into fieldwork, stating how every ethnomusicologist has a unique approach to fieldwork, fieldwork can be a private matter for some ethnomusicologists, and understanding cultural dynamics and building relationships plays a tremendous role in the success of one’s fieldwork.[22] He also explained how three kinds of data should be gathered in fieldwork: texts, structures, and “the imponderabilia of everyday life."[23] This chapter also extensively investigated the history of fieldwork in ethnomusicology.[24] In this section, Nettl showed how fieldwork and research have become more unified, how ethnomusicologists became more willing to immerse themselves into a field, and how the increased accessibility of travel evolved fieldwork.[25] The chapter concluded by detailing the best ways to identify an informant within the field and how to best extract information from him or her.[26] Meanwhile, Chapter 11 concentrates on a somewhat controversial ethnomusicological topic: insiders and outsiders.[27] The chapter begins by explaining how natives to a culture tend not to appreciate foreign, especially Western, ethnomusicologists entering their domain and making claims about their music and cultures.[28] Nettl also elaborated on how some ethnomusicologists struggle to ingratiate themselves into a field and how some view music systems as “untranslatable.”[29] Nettl then articulated three common problems with outsider ethnomusicologists:[30] • They are only focused on comparing foreign traditions to their own. • They want to use their own approaches to non-Western music. • They generalize categories of music too easily. The chapter then transitioned to examining insiders.[31] Nettl stated that colonialism could lead to confusion when determining whom an insider is and debated whether insiders should help ethnomusicologists without compensation.[32] The chapter concluded by outlining the best way to conduct fieldwork.[33] Fieldwork is most effective when insiders and outsiders have mutual respect and understanding.[34] It is also essential for outsiders to enter a field with an open mind and engage in their research as a “participant.”[35] |

1983年に出版された『The Study of

Ethnomusicology』は、民族音楽学の包括的な言説を提供し、ネトルの最高傑作と広く考えられている[16]。この本の初版は、民族音楽学の

内実を論じる29章を含み、2005年に31章、2015年に33章に拡張された。 [17]

この作品には、実践の定義、普遍性の話題、フィールドワーク、異なる文化や人口動態に対する音楽の効果など、民族音楽学をめぐる興味深い議論が数多く含ま

れている[18]。 ネトルは、第10章「Come Back and See Me Next Tuesday」や第11章「You Will Never Understand This Music: Insiders and Outsiders」に見られるように、本書を通じてフィールドワークを論じている[19]。第10章では、冒頭でジョーというネイティブ・アメリカンと の交流が描かれており、ネットルのフィールドワークへの洞察を与えている[20]。 次に、ネットルはこの逸話をもとに、フィールドワークについて深く掘り下げ、民族音楽学者にはそれぞれフィールドワークに対するユニークなアプローチがあ ること、フィールドワークは民族音楽学者によってはプライベートな問題であること、文化の力学を理解し人間関係を構築することがフィールドワークの成功に 多大な役割を果たすことを述べている[21] 。 また、フィールドワークでは、テキスト、構造物、「日常生活の不可思議なもの」という3種類のデータを収集すべきことを説明した[23]。本章では、民族 音楽学におけるフィールドワークの歴史も広く調査した[24]。 [この章では、フィールドワークと研究がどのように一体化していったのか、民族音楽学者がどのようにフィールドに没頭することを望むようになったのか、旅 行へのアクセス性の向上がどのようにフィールドワークを進化させていったのかが示されている[25]。 この章の最後では、フィールド内でインフォーマントを特定する最善の方法と、彼または彼女から情報を引き出す最善の方法が詳述されている[26]。 一方、第11章では、やや議論の多い民族音楽学のトピックであるインサイダーとアウトサイダーに焦点を当てている[27]。この章では、まず、ある文化の 出身者が、外国、特に西洋の民族音楽学者が自分たちの領域に入り、自分たちの音楽と文化について主張することを認めない傾向にあることを説明している [28]。 [また、ネットルは、ある民族音楽学者がいかにそのフィールドに恩を着せるのに苦労しているか、そして、いかに音楽システムを「翻訳不可能なもの」として 見ているかについても詳しく説明している[29]。そして、ネットルはアウトサイダーの民族音楽学者に共通する三つの問題を明示している[30]。 外国の伝統と自国の伝統とを比較することだけに集中している。 非西洋音楽に対して独自のアプローチを使いたがる。 音楽のカテゴリーを安易に一般化しすぎる。 そして、インサイダー(=民族音楽学者たち自身へ)の考察に移行した[31]。ネトルは、インサイダーが誰であるかを決定する際に植民地主義が混乱を招く 可能性があると述べ、インサイダーは報酬なしで民族音楽学者を助けるべきかどうかを議論した[32]。本章は、フィールドワークを行う最善の方法について 概説して締めくくられている。インサイダーとアウトサイダーが相互に尊敬と理解を持つとき、フィールドワークは最も有効である[34]。またアウトサイ ダーにとってオープンマインドを持って現場に入り、「参加者」として調査に従事することが重要である[35]。 |

| Nettl’s contributions to

ethnomusicology have been cited in publications throughout the field

and he has undoubtedly influenced the work of other scholars. For

example, Nettl’s work is mentioned extensively in Stephen Amico’s “‘We

Are All Musicologists Now’; or, the End of Ethnomusicology,” a piece

that criticized several aspects of ethnomusicology.[36] Amico first

used Nettl’s “Contemplating Ethnomusicology: What Have We Learned” to

point out that the world’s music has become an “unholy mix” and that

the consensus did not find this alarming.[37] Amico also cited this

piece to make the point that ethnomusicological research is losing its

authenticity.[38] Finally, Amico disagreed with a point from Nettl’s

Elephant: On the History of Ethnomusicology, which was that

ethnomusicologists had yet to figure out their profession’s goals and

central questions.[39] Another scholar who benefitted from Nettl’s

contributions was Anna Schultz. In her essay “Still an

Ethnomusicologist (for Now),” she cited Nettl’s Elephant numerous times

to make the point that musicology and musicologists were imperative in

shaping what we now know as ethnomusicology.[40] Additionally,

Australian ethnomusicologist Clint Bracknell heavily utilized the 1983

and 2005 publications of The Study of Ethnomusicology to make numerous

claims about the emergence of non-Western voices in ethnomusicology in

his work, “‘Say You’re a Nyungarmusicologist’: Indigenous Research and

Endangered Song.”[41] |

ネットルの民族音楽学への貢献は、この分野のあらゆる出版物に引用され

ており、彼が他の学者の研究に影響を与えたことは間違いない。例えば、スティーブン・アミコの「『We Are All Musicologists

Now』; or, the End of

Ethnomusicology」は、民族音楽学のいくつかの側面を批判した作品であり、ネットルの研究は広く言及されている[36]。アミコはまずネッ

トルの「民族音楽学について考えてみよう。また、アミコはこの作品を引用して、民族音楽学的研究がその真正性を失いつつあるという指摘をしている

[38]。最後に、アミコはネットルの『象』からの指摘に反対している。また、ネットルの貢献から恩恵を受けた研究者として、アンナ・シュルツがいる。

シュルツは、「(今のところは)まだ民族音楽学者」というエッセイの中で、音楽学と音楽学者が現在の民族音楽学というものを形成する上で不可欠な存在であ

ることを主張し、ネトルのエレファントを何度も引用している[40]。

[さらに、オーストラリアの民族音楽学者クリント・ブラックネルは、1983年と2005年に出版された『民族音楽学研究』を大いに利用し、「『ニョンガ

ル音楽学者』と言え」という著作で、民族音楽学における非西洋人の声の出現について多くの主張を行っている。先住民の研究と絶滅の危機に瀕した歌」

[41]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruno_Nettl 音楽人類学・民族音楽学 |

★ ブルーノ・ネトル『ワールド・ミュージックに対する西洋の衝撃』の見出し

| 序 |

||

| アプローチ |

1. 4つの時代 |

|

| 2. 最初の出会い |

||

| 3. 変わらない音楽 |

||

| 4. 概念 |

||

| 5. 反応 |

||

| 実例 | 6. パウワウ |

|

| 7. 和声 |

||

| 8. 2つの都市 |

||

| 9. 互換性 |

||

| 10. ヴァイオリン |

||

| 11. ピアノ(スティーヴン・ホワイティング) |

||

| 12. しるし(徴し) |

||

| 13. オーケストラ |

||

| 14. ヴィクトローラ |

||

| 15. 楽譜 |

||

| 16. 移民 |

||

| 17. 音楽学校 |

||

| 18. 街路 |

||

| 19. コンサート |

||

| 20. 「ポップ」 |

||

| 21. ジュジュ(クリストファー・ウォーターマン) |

||

| 22. 国民的音楽(ポール・ウォルバース) |

||

| 23. 旧時代の宗教 |

||

| 24. 土着化 |

||

| 25. 新時代の宗教 |

||

| 26. 改革者 |

||

| 27. アメリカ人たち |

||

| 28. 旗手 |

||

| 29. 訪問者 |

||

| 30. 民族音楽学者 212 |

||

| 31. 意見 |

||

| 32. 国宝 |

||

| 33. 会議 |

||

| 34. マクーマ(ウィリアム・ベルツナー) |

||

| 35. マーフール |

||

| 36. ダックスダンス(ヴィクトリア・J・リンゼイ=レヴァイン) |

||

| 37. 協奏曲 |

||

| 規則性 |

38. 偶然の一致 |

|

| 39. 地域 |

||

| 40. 諸傾向 |

||

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆