スチュアート・ホール

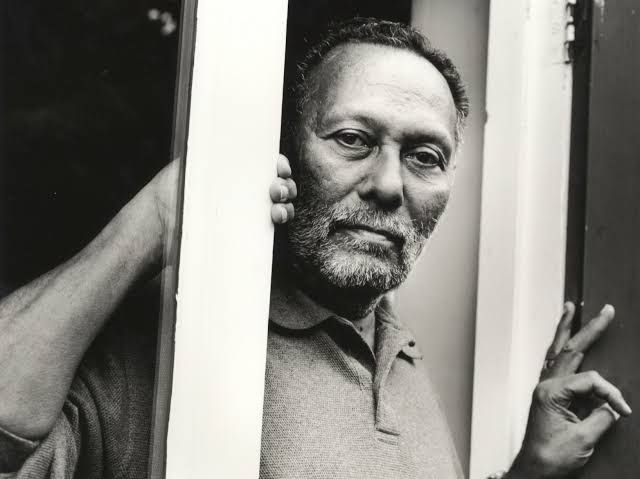

Stuart Hall, 1932-2014

☆

スチュアート・ヘンリー・マクフェイル・ホール(Stuart Henry McPhail Hall、1932年2月3日 -

2014年2月10日)は、ジャマイカ生まれのイギリスのマルクス主義社会学者、文化理論家、政治活動家である。ホールは、リチャード・ホガート、レイモ

ンド・ウィリアムズとともに、英国文化研究(British Cultural

Studies)またはバーミンガム学派文化研究(Birmingham School of Cultural

Studies)として知られる学派の創設者の一人である[2]。

1950年代、ホールは影響力のある雑誌『ニュー・レフト・レビュー』の創刊者であった。1964年、ホガートの招きでバーミンガム大学の現代文化研究セ

ンター(CCCS)に加わる。ホールは1968年にホガートからCCCSの所長代行を引き継ぎ、1972年に所長となり、1979年まで在籍した[3]。

同センター在籍中、人種やジェンダーを扱うカルチュラル・スタディーズの範囲を拡大する役割を果たし、ミシェル・フーコーのようなフランスの理論家の仕事

から派生した新しい考え方を取り入れる手助けをしたと評価されている[4]。

ホールは1979年にセンターを去り、オープン大学の社会学教授となった[5]。

1995年から1997年まで英国社会学会の会長を務めた[5]。ジョン・アコムフラやアイザック・ジュリアンといった映画監督も彼をヒーローの一人とし

て見ている[10]。

ホールはユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンのフェミニストでイギリス近現代史の教授であるキャサリン・ホールと結婚し、2人の子供をもうけた[3]。

ホールの死後、スチュアート・ホールは「過去60年間で最も影響力のある知識人の一人」と評された[11]。

スチュアート・ホール財団は2015年に彼の家族、友人、同僚によって設立され、「スチュアート・ホールの精神を受け継ぎ、創造的なパートナーシップを築

くために協力し合い、人種的に公正でより平等な未来に向けて共に考え、活動する」ことを目的としている[12]。

| Stuart

Henry McPhail Hall (3 February 1932 – 10 February 2014) was a

Jamaican-born British Marxist sociologist, cultural theorist, and

political activist. Hall — along with Richard Hoggart and Raymond

Williams — was one of the founding figures of the school of thought

known as British Cultural Studies or the Birmingham School of Cultural

Studies.[2] In the 1950s Hall was a founder of the influential journal New Left Review. At Hoggart's invitation, he joined the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) at the University of Birmingham in 1964. Hall took over from Hoggart as acting director of the CCCS in 1968, became its director in 1972, and remained there until 1979.[3] While at the centre, Hall is credited with playing a role in expanding the scope of cultural studies to deal with race and gender, and with helping to incorporate new ideas derived from the work of French theorists such as Michel Foucault.[4] Hall left the centre in 1979 to become a professor of sociology[5] at the Open University.[6] He was President of the British Sociological Association from 1995 to 1997.[5] He retired from the Open University in 1997[7] and was professor emeritus there until his death.[8] British newspaper The Observer called him "one of the country's leading cultural theorists".[9] Hall was also involved in the Black Arts Movement. Movie directors such as John Akomfrah and Isaac Julien also see him as one of their heroes.[10] Hall was married to Catherine Hall, a feminist professor of modern British history at University College London, with whom he had two children.[3] After his death, Stuart Hall was described as "one of the most influential intellectuals of the last sixty years".[11] The Stuart Hall Foundation was established in 2015 by his family, friends and colleagues to "work collaboratively to forge creative partnerships in the spirit of Stuart Hall; thinking together and working towards a racially just and more equal future."[12] |

スチュアート・ヘンリー・マクフェイル・ホール(Stuart

Henry McPhail Hall、1932年2月3日 -

2014年2月10日)は、ジャマイカ生まれのイギリスのマルクス主義社会学者、文化理論家、政治活動家である。ホールは、リチャード・ホガート、レイモ

ンド・ウィリアムズとともに、英国文化研究(British Cultural

Studies)またはバーミンガム学派文化研究(Birmingham School of Cultural

Studies)として知られる学派の創設者の一人である[2]。 1950年代、ホールは影響力のある雑誌『ニュー・レフト・レビュー』の創刊者であった。1964年、ホガートの招きでバーミンガム大学の現代文化研究セ ンター(CCCS)に加わる。ホールは1968年にホガートからCCCSの所長代行を引き継ぎ、1972年に所長となり、1979年まで在籍した[3]。 同センター在籍中、人種やジェンダーを扱うカルチュラル・スタディーズの範囲を拡大する役割を果たし、ミシェル・フーコーのようなフランスの理論家の仕事 から派生した新しい考え方を取り入れる手助けをしたと評価されている[4]。 ホールは1979年にセンターを去り、オープン大学の社会学教授となった[5]。 1995年から1997年まで英国社会学会の会長を務めた[5]。ジョン・アコムフラやアイザック・ジュリアンといった映画監督も彼をヒーローの一人とし て見ている[10]。 ホールはユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンのフェミニストでイギリス近現代史の教授であるキャサリン・ホールと結婚し、2人の子供をもうけた[3]。 ホールの死後、スチュアート・ホールは「過去60年間で最も影響力のある知識人の一人」と評された[11]。 スチュアート・ホール財団は2015年に彼の家族、友人、同僚によって設立され、「スチュアート・ホールの精神を受け継ぎ、創造的なパートナーシップを築 くために協力し合い、人種的に公正でより平等な未来に向けて共に考え、活動する」ことを目的としている[12]。 |

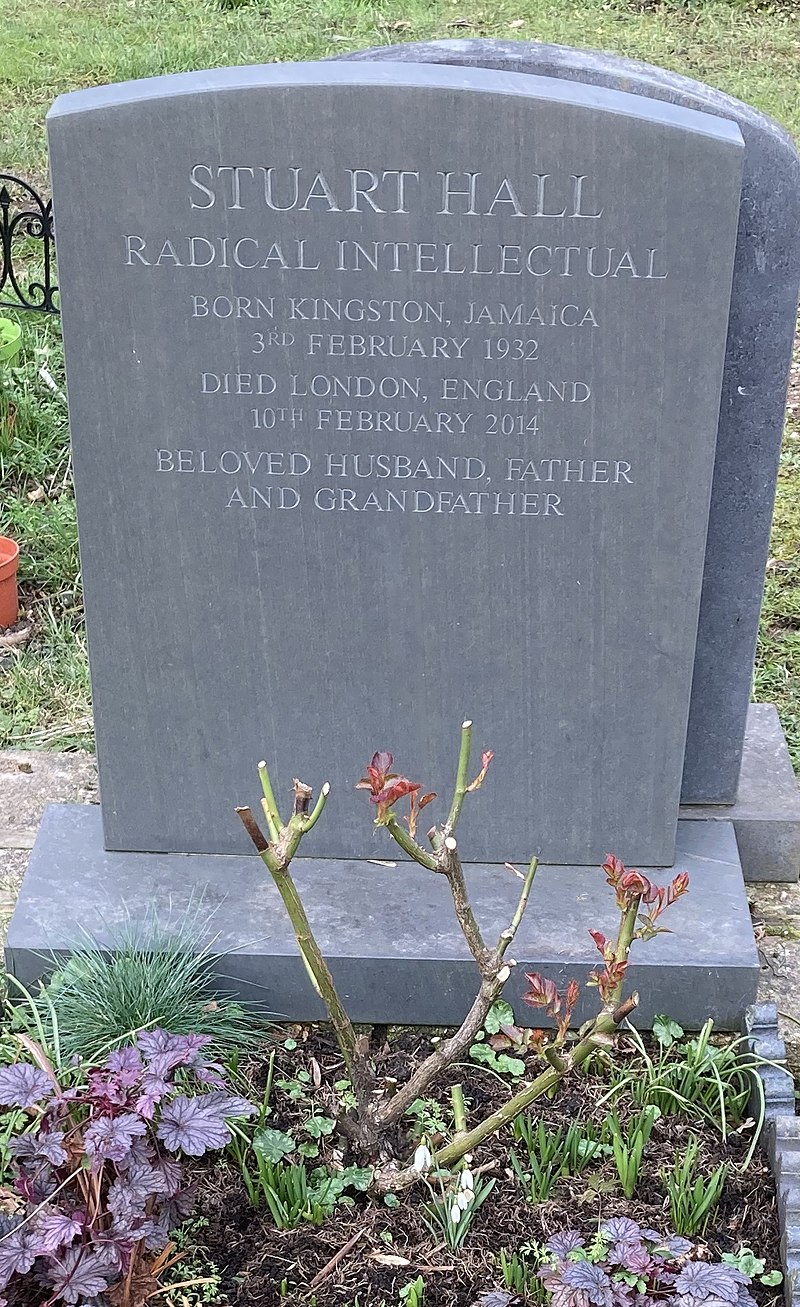

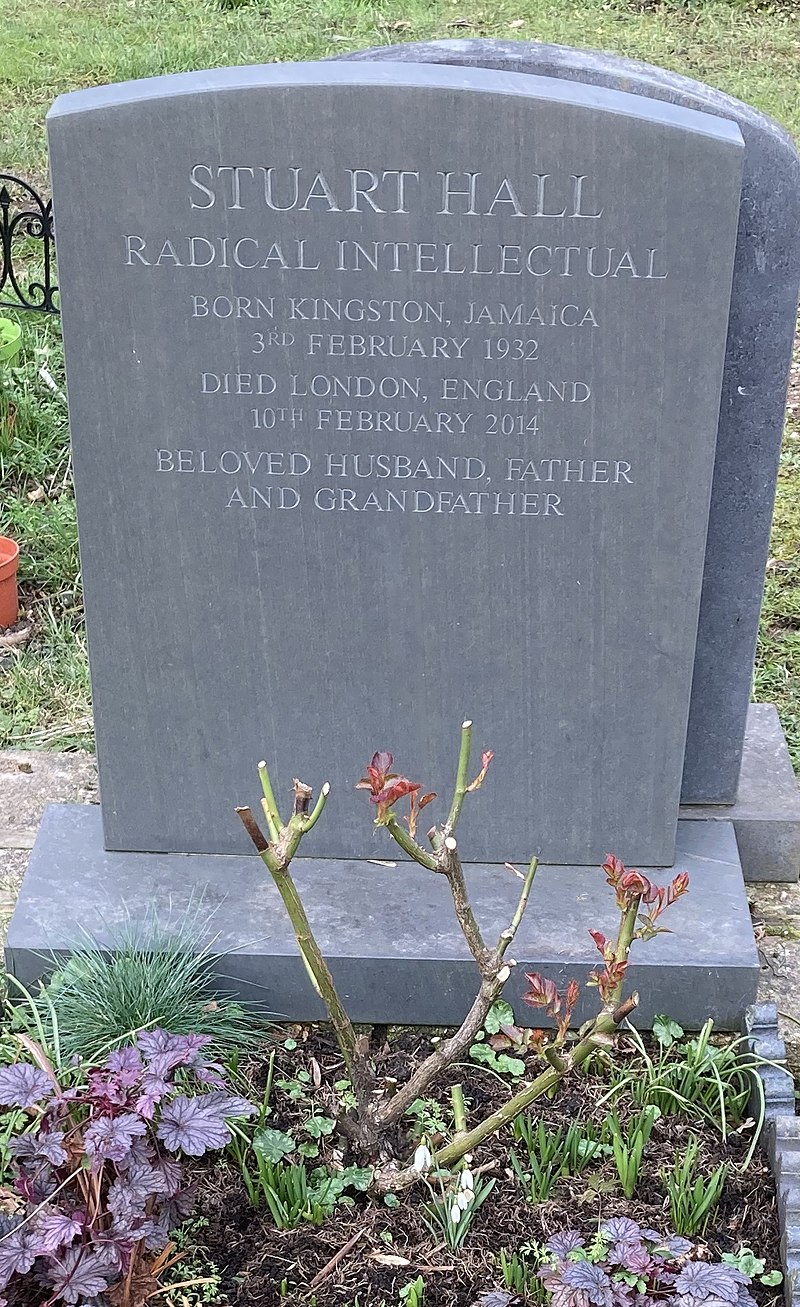

| Biography Stuart Henry McPhail Hall was born on 3 February 1932 in Kingston, Colony of Jamaica, into a middle-class family. His parents were Herman McPhail Hall and Jessie Merle Hopwood. Herman's direct ancestors were English, living in Jamaica for several centuries, tracing back to the Kingston tavern-keeper John Hall (1722–1797) and his Dutch wife Allegonda Boom.[13] Hall's direct paternal ancestors were implicated in the trans-Atlantic slave trade and slavery in Jamaica, being associated with the Grecian Regale Plantation, Saint Andrew Parish. Hall's mother was descended through her mother from John Rock Grosset, a local pro-slavery Tory member of Parliament.[14] According to the 1820 Jamaica Almanac, Stuart's great-great-great grandfather John Herman Hall owned 20 enslaved Black African people.[15] His ancestors were Portuguese, Jews, English, Africans and Indians.[9][16][17] As a teen he had been baptized in an Evangelical Youth Group.[18] He attended the all-male Jamaica College, one of the island’s elite establishments, receiving an education modeled after the British school system.[19] In an interview, Hall describes himself as a "bright, promising scholar" in these years and his formal education as "a very 'classical' education; very good but in very formal academic terms." With the help of sympathetic teachers, he expanded his education to include "T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Freud, Marx, Lenin and some of the surrounding literature and modern poetry", as well as "Caribbean literature".[20] Hall's later works reveal that growing up in the pigmentocracy of the colonial West Indies, where he was of darker skin than much of his family, had a profound effect on his views.[21] In 1951, Hall won a Rhodes Scholarship to Merton College at the University of Oxford, where he studied English and obtained a Master of Arts degree,[22][23] becoming part of the Windrush generation, the first large-scale emigration of West Indians, as that community was then known. He originally intended to do graduate work on the medieval poem Piers Plowman, reading it through the lens of contemporary literary criticism, but was dissuaded by his language professor, J. R. R. Tolkien, who told him "in a pained tone that this was not the point of the exercise."[24][25] Hall began a doctorate on Henry James at Oxford but, galvanised particularly by the 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary (which saw many thousands of members leave the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and look for alternatives to previous orthodoxies) and the Suez Crisis, abandoned this in 1957[23] or 1958[19] to focus on his political work. In 1957, he joined the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and it was on a CND march that he met his future wife.[5] From 1958 to 1960, Hall worked as a teacher in a London secondary modern school[26] and in adult education, and in 1964 married Catherine Hall, concluding around this time that he was unlikely to return permanently to the Caribbean.[23]  Hall's grave in Highgate Cemetery (east side) After working on the Universities and Left Review during his time at Oxford, Hall joined E. P. Thompson, Raymond Williams and others to merge it with The New Reasoner journal, launching the New Left Review in 1960, with Hall as the founding editor.[19][27] In 1958, the same group, with Raphael Samuel, launched the Partisan Coffee House in Soho as a meeting place for left-wingers.[28] Hall left the board of the New Left Review in 1961[29] or 1962.[30] Hall's academic career took off in 1964 after he co-wrote with Paddy Whannel of the British Film Institute "one of the first books to make the case for the serious study of film as entertainment", The Popular Arts.[31] As a direct result, Richard Hoggart invited Hall to join the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham, initially as a research fellow at Hoggart's own expense.[30] In 1968, Hall became director of the centre.[32] He wrote a number of influential articles in the years that followed, including Situating Marx: Evaluations and Departures (1972) and Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse (1973) and The Great Moving Right Show (for Marxism Today), in which he famously coined the term ‘Thatcherism’. He also contributed to the book Policing the Crisis (1978) and coedited the influential Resistance Through Rituals (1975). Shortly before Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister in 1979, Hall and Maggie Steed presented "It Ain't Half Racist Mum", an Open Door programme made by the Campaign Against Racism in the Media (CARM), which tackled racial stereotypes and contemporary British attitudes to immigration.[33] After his appointment as a professor of sociology at the Open University (OU) that year, Hall published further influential books, including The Hard Road to Renewal (1988), Formations of Modernity (1992), Questions of Cultural Identity (1996) and Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (1997). Through the 1970s and 1980s, Hall was closely associated with the journal Marxism Today;[34] in 1995, he was a founding editor of Soundings: A Journal of Politics and Culture.[35] He spoke internationally on Cultural Studies, including a series of lectures in 1983 at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign that were recorded and would decades later form the basis of the 2016 book Cultural Studies 1983: A Theoretical History (edited by Jennifer Slack and Lawrence Grossberg).[36] Hall was the founding chair of Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts) and the photography organization Autograph ABP (the Association of Black Photographers).[37] Hall retired from the Open University in 1997. He was elected fellow of the British Academy in 2005 and received the European Cultural Foundation's Princess Margriet Award in 2008.[3] He died on 10 February 2014, from complications following kidney failure, a week after his 82nd birthday. By the time of his death, he was widely known as the "godfather of multiculturalism".[3][38][39][40] His memoir, Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands (co-authored with Bill Schwarz), was posthumously published in 2017, based on hours of interviews conducted with Hall over many years.[41] Hall was buried on the eastern side of Highgate Cemetery,[42] where in 2022 an audio artwork by Trevor Mathison explored his legacy.[43][44] Entitled The Conversation Continues: We Are Still Listening, the 40-minute soundscape was "a re-examination of the lives and histories of those laid to rest at Highgate Cemetery in the context of contemporary anti-racism movements."[45][46] |

略歴 スチュアート・ヘンリー・マクファイル・ホールは1932年2月3日、ジャマイカ植民地のキングストンで中流階級の家庭に生まれた。両親はハーマン・マク フェイル・ホールとジェシー・マール・ホップウッドである。ハーマンの直接の先祖はイギリス人で、キングストンの居酒屋経営者ジョン・ホール(1722- 1797)とオランダ人の妻アレゴンダ・ブームに遡り、数世紀にわたってジャマイカに住んでいた[13]。ホールの直接の父方の先祖は大西洋横断奴隷貿易 とジャマイカの奴隷制度に関与しており、セント・アンドリュー教区のグレシアン・レゲール農園に関係していた。1820年の『ジャマイカ年鑑』によると、 スチュアートの曽祖父ジョン・ハーマン・ホールは20人のアフリカ系黒人を奴隷として所有していた[15]。 彼の祖先はポルトガル人、ユダヤ人、イギリス人、アフリカ人、インディアンであった[9][16][17]。 10代の頃、彼は福音派のユース・グループで洗礼を受けた[18]。彼は島のエリート教育機関のひとつである、男ばかりのジャマイカ・カレッジに通い、イ ギリスの学校制度に倣った教育を受けた[19]。親身になってくれる教師の助けもあって、彼は「T・S・エリオット、ジェイムズ・ジョイス、フロイト、マ ルクス、レーニン、そして周辺の文学や現代詩」、さらには「カリブ海文学」へと教育の幅を広げていった[20]。ホールの後年の著作を読むと、植民地時代 の西インド諸島の有色人種社会で育ち、家族の多くよりも肌が黒かったことが、彼の考え方に大きな影響を与えたことがわかる[21]。 1951年、ホールはローズ奨学金を得てオックスフォード大学のマートン・カレッジで英語を学び、修士号を取得した[22][23]。彼は当初、中世の詩 『ピアーズ・プラウマン』を現代の文芸批評のレンズを通して読み解き、大学院で研究するつもりだったが、国語の教授であったJ・R・R・トールキンに、 「これは研究の目的ではない」と言われ、思いとどまった。 「24][25]ホールはオックスフォード大学でヘンリー・ジェイムズに関する博士号を取得し始めたが、特に1956年のソ連によるハンガリー侵攻(この 侵攻によって何千人もの党員がイギリス共産党(CPGB)を脱退し、それまでの正統主義に代わるものを探すことになった)とスエズ危機によって奮起し、 1957年[23]か1958年[19]にこれを断念して政治活動に専念した。1958年から1960年まで、ホールはロンドンの中等近代学校[26]と 成人教育の教師として働き、1964年にキャサリン・ホールと結婚した。  ハイゲート墓地にあるホールの墓(東側) オックスフォード大学在学中に『ユニバーシティーズ・アンド・レフト・レヴュー』誌の編集に携わった後、ホールはE・P・トンプソン、レイモンド・ウィリ アムズらとともに『ニュー・リーズナー』誌と統合し、ホールを創刊編集長として1960年に『ニュー・レフト・レヴュー』誌を創刊した[19][27]。 1958年には同じグループがラファエル・サミュエルとともに左翼主義者の集会所としてソーホーに『パルチザン・コーヒー・ハウス』を立ち上げた [28]。 1964年に英国映画協会のパディ・ワネルと「娯楽としての映画を真剣に研究することを主張した最初の本のひとつ」である『ポピュラー・アーツ』を共著し た後、ホールの学術的キャリアは飛躍した[31]。その直接的な結果として、リチャード・ホガートはホールをバーミンガム大学の現代文化研究センターに招 き、当初はホガートの自費で研究員として参加させた[30]: 評価と出発』(1972年)、『テレビ言説における符号化と復号化』(1973年)、『The Great Moving Right Show』(『今日のマルクス主義』所収)などがある。また、『Policing the Crisis』(1978年)にも寄稿し、影響力のある『Resistance Through Rituals』(1975年)を共同編集した。 1979年にマーガレット・サッチャーが首相に就任する直前、ホールとマギー・スティードは「メディアにおける人種主義反対キャンペーン(CARM)」が 制作したオープンドア番組『It Ain't Half Racist Mum』を発表し、人種的ステレオタイプと移民に対する現代のイギリス人の態度に取り組んだ。 [33]同年、オープンユニバーシティ(OU)の社会学教授に任命されたホールは、『The Hard Road to Renewal』(1988年)、『Formations of Modernity』(1992年)、『Questions of Cultural Identity』(1996年)、『Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices』(1997年)など、影響力のある著作をさらに出版した。1970年代から1980年代にかけて、ホールは雑誌『マルクス主義トゥデ イ』と密接な関係にあった[34]: A Journal of Politics and Culture』の創刊編集者を務めた[35]。 1983年にイリノイ大学アーバナ・シャンペーン校で行われた一連の講義は録音され、数十年後に2016年に出版された『カルチュラル・スタディーズ 1983』の基礎となった: A Theoretical History』(ジェニファー・スラック、ローレンス・グロスバーグ編)の基礎となった[36]。 ホールはイニヴァ(Institute of International Visual Arts)と写真団体オートグラフABP(the Association of Black Photographers)の創設委員長であった[37]。 1997年にオープンユニバーシティを退職。2005年に英国アカデミーのフェローに選出され、2008年にはヨーロッパ文化財団のプリンセス・マルグ リート賞を受賞した[3]。2014年2月10日、82歳の誕生日の1週間後に腎不全の合併症のため死去。死の直前まで、彼は「多文化主義のゴッドファー ザー」として広く知られていた[3][38][39][40]: A Life Between Two Islands』(ビル・シュワルツとの共著)が2017年に死後出版されたが、これは長年にわたってホールに行った何時間ものインタビューに基づいてい る[41]。 ホールはハイゲート墓地の東側に埋葬され[42]、2022年にはトレヴァー・マティソンによるオーディオ・アートワークが彼の遺産を探求した[43] [44]: We Are Still Listening』と題された40分間のサウンドスケープは、「現代の反人種主義運動の文脈の中で、ハイゲート墓地に眠る人々の人生と歴史を再検証す る」ものだった[45][46]。 |

| Ideas Hall's work covers issues of hegemony and cultural studies, taking a post-Gramscian stance. He regards language-use as operating within a framework of power, institutions and politics/economics. This view presents people as producers and consumers of culture at the same time. (Hegemony, in Gramscian theory, refers to the socio-cultural production more of "consent" and "coercion".) For Hall, culture was not something to simply appreciate or study, but a "critical site of social action and intervention, where power relations are both established and potentially unsettled".[47] Hall became one of the main proponents of reception theory, and developed the theory of encoding and decoding. This approach to textual analysis focuses on the scope for negotiation and opposition on the part of the audience. This means that the audience does not simply passively accept a text—social control. Crime statistics, in Hall's view, are often manipulated for political and economic purposes. Moral panics (e.g. over mugging) could thereby be ignited in order to create public support for the need to "police the crisis". The media play a central role in the "social production of news" in order to reap the rewards of lurid crime stories.[48] In his 2006 essay "Reconstruction Work: Images of Postwar Black Settlement", Hall also interrogates questions of historical memory and visuality in relation to photography as a colonial technology. According to Hall, understanding and writing about the history of black migration and settlement in Britain during the postwar era requires a careful and critical examination of the limited historical archive, and photographic evidence proves itself invaluable. However, photographic images are often perceived as more objective than other representations, which is dangerous. In his view, one must critically examine who produced these images, what purpose they serve, and how they further their agenda (e.g., what has been deliberately included and excluded in the frame). For example, in the context of postwar Britain, photographic images such as those displayed in the Picture Post article "Thirty Thousand Colour Problems" construct black migration, blackness in Britain, as "the problem".[49] They construct miscegenation as "the centre of the problem", as "the problem of the problem", as "the core issue".[49] Hall's political influence extended to the Labour Party, perhaps related to the influential articles he wrote for the CPGB's theoretical journal Marxism Today (MT) that challenged the left's views of markets and general organisational and political conservatism. This discourse had a profound impact on the Labour Party under both Neil Kinnock and Tony Blair, although Hall later decried New Labour as operating on "terrain defined by Thatcherism".[39] |

アイデア ホールの研究はヘゲモニーとカルチュラル・スタディーズの問題を扱っており、ポスト・グラムシアン的なスタンスをとっている。彼は、言語使用は権力、制 度、政治/経済の枠組みの中で作動していると考えている。この見解では、人々は文化の生産者であると同時に消費者でもある。(グラムシアン理論におけるヘ ゲモニーとは、「同意」と「強制」による社会文化生産を指す)。ホールにとって、文化は単に鑑賞したり研究したりするものではなく、「権力関係が確立され ると同時に潜在的に動揺させられる、社会的行為と介入の重要な場」であった[47]。 ホールは受容理論の主要な支持者の一人となり、エンコードとデコードの理論を発展させた。このテキスト分析へのアプローチは、観客側の交渉と対立の余地に 焦点を当てる。つまり、観客はテキスト=社会的統制を単に受動的に受け入れるわけではないということだ。ホールの見解では、犯罪統計はしばしば政治的・経 済的目的のために操作される。それによって、(強盗などの)モラル・パニックに火をつけ、「危機を取り締まる」必要性に対する大衆の支持を作り出すことが できる。メディアは「ニュースの社会的生産」において中心的な役割を果たし、薄気味悪い犯罪記事から報酬を得るのである[48]。 2006年のエッセイ「復興作業:戦後の黒人居住地のイメージ」においても、ホールは植民地技術としての写真に関連して、歴史的記憶と視覚性の問題を問う ている。ホールによれば、戦後のイギリスにおける黒人の移住と定住の歴史を理解し、それについて書くには、限られた歴史的アーカイブを注意深く批判的に検 証することが必要であり、写真の証拠はそれ自体が貴重である。しかし、写真画像は他の表現よりも客観的であると思われがちだが、それは危険である。彼の見 解では、誰がこれらの画像を制作したのか、どのような目的を果たすものなのか、そしてどのように彼らの意図を推し進めるものなのか(例えば、フレームに意 図的に何が含まれ、何が除外されたのか)を批判的に検証しなければならない。例えば、戦後のイギリスという文脈において、ピクチャー・ポストの記事「3万 色の問題」に掲載されたような写真画像は、黒人の移住、イギリスにおける黒人を「問題」として構築している[49]。彼らは混血を「問題の中心」、「問題 の問題」、「核心的な問題」として構築している[49]。 ホールの政治的影響力は労働党にまで及んでいたが、それはおそらく彼がCPGBの理論誌『Marxism Today』(MT)に寄稿した、左派の市場観や一般的な組織的・政治的保守主義に異議を唱える影響力のある記事に関連していた。この言説はニール・キ ノックとトニー・ブレアの両政権下の労働党に大きな影響を与えたが、ホールは後に新労働党が「サッチャリズムによって定義された地形」の上で活動している と批判している[39]。 |

| Encoding and decoding model Main article: Reception theory Hall presented his encoding and decoding philosophy in various publications and at several oral events across his career. The first was in "Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse" (1973), a paper he wrote for the Council of Europe Colloquy on "Training in the Critical Readings of Television Language" organised by the Council and the Centre for Mass Communication Research at the University of Leicester. It was produced for students at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, which Paddy Scannell explains: "largely accounts for the provisional feel of the text and its 'incompleteness'".[50] In 1974 the paper was presented at a symposium on Broadcasters and the Audience in Venice. Hall also presented his encoding and decoding model in "Encoding/Decoding" in Culture, Media, Language in 1980. The time difference between Hall's first publication on encoding and decoding in 1973 and his 1980 publication is highlighted by several critics. Of particular note is Hall's transition from the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies to the Open University.[50] Hall had a major influence on cultural studies, and many of the terms his texts set forth continue to be used in the field. His 1973 text is viewed as a turning point in Hall's research toward structuralism and provides insight into some of the main theoretical developments he explored at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Hall takes a semiotic approach and builds on the work of Roland Barthes and Umberto Eco.[51] The essay takes up and challenges longheld assumptions about how media messages are produced, circulated and consumed, proposing a new theory of communication.[52] "The 'object' of production practices and structures in television is the production of a message: that is, a sign-vehicle or rather sign-vehicles of a specific kind organized, like any other form of communication or language, through the operation of codes, within the syntagmatic chains of a discourse."[53] According to Hall, a message "must be perceived as meaningful discourse and meaningfully de-coded" before it has an "effect", a "use", or satisfies a "need".[54] There are four codes of the encoding/decoding model of communication. The first way of encoding is the dominant (i.e. hegemonic) code. This is the code the encoder expects the decoder to recognize and decode. "When the viewer takes the connoted meaning ... full and straight ... and decodes the message in terms of the reference-code in which it has been coded, ... [it operates] inside the dominant code."[55] The second way of encoding is the professional code. It operates in tandem with the dominant code. "It serves to reproduce the dominant definitions precisely by bracketing the hegemonic quality, and operating with professional codings which relate to such questions as visual quality, news and presentational values, televisual quality, 'professionalism' etc."[55] The third way of encoding is the negotiated code. "It acknowledges the legitimacy of the hegemonic definitions to make the grand significations, while, at a more restricted, situational level, it makes its own ground-rules, it operates with 'exceptions' to the rule."[56] The fourth way of encoding is the oppositional code, also known as the globally contrary code. "It is possible for a viewer perfectly to understand both the literal and connotative inflection given to an event, but to determine to decode the message in a globally contrary way."[57] "Before this message can have an 'effect' (however defined), or satisfy a 'need' or be put to a 'use', it must first be perceived as a meaningful discourse and meaningfully de-coded."[54] Hall challenged all four components of the mass communications model. He argues that (i) meaning is not simply fixed or determined by the sender; (ii) the message is never transparent; and (iii) the audience is not a passive recipient of meaning.[52] For example, a documentary film on asylum seekers that aims to provide a sympathetic account of their plight does not guarantee that audiences will feel sympathetic. Despite being realistic and recounting facts, the documentary must still communicate through a sign system (the aural-visual signs of TV) that simultaneously distorts the producers' intentions and evokes contradictory feelings in the audience.[52] Distortion is built into the system, rather than being a "failure" of the producer or viewer. There is a "lack of fit", Hall argues, "between the two sides in the communicative exchange"—that is, between the moment of the production of the message ("encoding") and the moment of its reception ("decoding").[52] In "Encoding/decoding", Hall suggests media messages accrue common-sense status in part through their performative nature. Through the repeated performance, staging or telling of the narrative of "9/11" (as an example; there are others like it), a culturally specific interpretation becomes not only plausible and universal but elevated to "common sense".[52] |

符号化・復号化モデル 主な記事 受信理論 ホールは自身のエンコードとデコードの哲学を、さまざまな出版物や、キャリアを通じたいくつかの口頭イベントで発表した。最初のものは、欧州評議会とレス ター大学のマス・コミュニケーション研究センターが主催した「テレビ言語の批判的読解の訓練」に関する欧州評議会コロキー(Council of Europe Colloquy)のために書いた論文「テレビ言説におけるエンコードとデコード」(1973年)である。これは現代文化研究センターの学生向けに制作さ れたもので、パディ・スキャネルはこう説明している: 「1974年、この論文はヴェニスで開催された放送局と視聴者に関するシンポジウムで発表された。ホールはまた、1980年に『Culture, Media, Language』の「Encoding/Decoding」で彼のエンコードとデコードのモデルを発表した。ホールがエンコードとデコードについて最初 に発表した1973年と、1980年の発表との時差は、何人かの批評家によって強調されている。特に注目すべきは、ホールが現代文化研究センターから放送 大学に移ったことである[50]。 ホールはカルチュラル・スタディーズに大きな影響を及ぼし、彼のテキストが提示した用語の多くはこの分野で使われ続けている。彼の1973年のテキスト は、構造主義に向かうホールの研究のターニングポイントとみなされており、彼が現代カルチュラル・スタディーズ・センターで探求した主な理論的展開のいく つかを洞察している。 ホールは記号論的なアプローチをとり、ロラン・バルトとウンベルト・エーコの研究を土台にしている。このエッセイでは、メディア・メッセージがどのように 生産され、流通し、消費されるかについて長年信じられてきた仮定を取り上げ、それに挑戦し、コミュニケーションの新しい理論を提唱している。 [52]「テレビにおける生産の実践と構造の『対象』は、メッセージの生産である。つまり、他のコミュニケーションや言語の形式と同様に、言説の統語的連 鎖のなかで、コードの操作を通じて組織された、特定の種類の記号-乗り物、あるいはむしろ記号-乗り物である」[53]。 ホールによれば、メッセージは「効果」、「使用」、「必要性」を満たす前に、「意味のある言説として認識され、意味のある脱コード化されなければならな い」[54]。コミュニケーションの符号化/脱コード化モデルには4つのコードがある。最初の符号化の方法は支配的な(すなわち覇権的な)符号である。こ れは、エンコーダーがデコーダーに認識され、デコードされることを期待するコードである。視聴者が含蓄された意味を......完全かつストレートに受け 止め、......コード化された参照コードの観点からメッセージを解読するとき、......」。[それは支配的なコードの内部で作動する。それは支配 的なコードと連動して作動する。覇権的な質を括弧で囲み、視覚的な質、ニュースやプレゼンテーションの価値、テレビの質、「プロフェッショナリズム 」などの問題に関連する専門的なコード化によって、支配的な定義を正確に再現する役割を果たす。覇権的な定義の正当性を認めながら、より限定された状況的 なレベルでは、独自のルールを作り、ルールに対する 「例外 」とともに行動する。このメッセージが(どのように定義されようとも)「効果」を持ったり、「必要性」を満たしたり、「使用」されたりする前に、このメッ セージはまず意味のある言説として知覚され、意味のあるデコードをされなければならない。 ホールはマス・コミュニケーション・モデルの4つの構成要素すべてに異議を唱えている。彼は、(i)意味は送り手によって単純に固定されたり決定されたり するものではない、(ii)メッセージは決して透明なものではない、(iii)観客は意味の受動的な受信者ではない、と主張している[52]。例えば、亡 命希望者のドキュメンタリー映画は、彼らの苦境について同情的な説明を提供することを目的としているが、観客が同情的な気持ちになることを保証するもので はない。ドキュメンタリーは、現実的であり、事実を語っているにもかかわらず、制作者の意図を歪め、観客に矛盾した感情を呼び起こすようなサインシステム (テレビの聴覚・視覚的サイン)を通じてコミュニケーションを行わなければならない[52]。 歪みは、制作者や視聴者の「失敗」ではなく、システムに組み込まれている。つまり、メッセージの制作(「エンコード」)の瞬間とその受信(「デコード」) の瞬間の間にあるのである。9.11」の物語(一例として。このようなものは他にもある)を繰り返し演じたり、演出したり、語ったりすることを通して、文 化的に特異な解釈は、もっともらしく、普遍的であるだけでなく、「常識」へと昇華される[52]。 |

| Views on cultural identity and the African diaspora In his influential 1996 essay "Cultural Identity and Diaspora", Hall presents two different definitions of cultural identity. In the first definition, cultural identity is "a sort of collective 'one true self' ... which many people with a shared history and ancestry hold in common."[58] In this view, cultural identity provides a "stable, unchanging and continuous frame of reference and meaning" through the ebb and flow of historical change.[58] This allows the tracing back the origins of descendants and reflecting on the historical experiences of ancestors as a shared truth.[59] Therefore, blacks living in the diaspora need only "unearth" their African past to discover their true cultural identity.[59] While Hall appreciates the good effects this first view of cultural identity has had in the postcolonial world, he proposes a second definition of cultural identity that he views as superior. Hall's second definition of cultural identity "recognises that, as well as the many points of similarity, there are also critical points of deep and significant difference which constitute 'what we really are'; or rather – since history has intervened – 'what we have become'."[60] In this view, cultural identity is not a fixed essence rooted in the past. Instead, cultural identities "undergo constant transformation" throughout history as they are "subject to the continuous 'play' of history, culture, and power".[60] Thus Hall defines cultural identities as "the names we give to the different ways we are positioned by, and position ourselves within, the narratives of the past."[60] This view of cultural identity was more challenging than the previous due to its dive into deep differences, but nonetheless it showed the mixture of the African diaspora. In other words, for Hall cultural identity is "not an essence but a positioning".[61] |

文化的アイデンティティとアフリカン・ディアスポラについての見解 1996年の影響力のあるエッセイ『文化的アイデンティティとディアスポラ』において、ホールは文化的アイデンティティの2つの異なる定義を提示している。 最初の定義では、文化的アイデンティティとは「歴史と祖先を共有する多くの人々が共通して保持する、ある種の集団的な『一つの真の自己』...」である [58]。この見解では、文化的アイデンティティは歴史的変化の浮き沈みを通じて「安定した、不変の、継続的な参照と意味の枠」を提供する[58]。これ によって、子孫の出自を遡ったり、祖先の歴史的経験を共有の真実として振り返ったりすることが可能になる。 [したがって、ディアスポラに住む黒人は、自分たちの真の文化的アイデンティティを発見するためにアフリカの過去を「発掘」するだけでよいのである [59]。ホールは、この文化的アイデンティティの第一の見解がポストコロニアル世界でもたらした良い効果を評価する一方で、文化的アイデンティティの第 二の定義を提唱しており、その方が優れていると考えている。 ホールの文化的アイデンティティの第二の定義は、「多くの類似点と同様に、『われわれが本当は何であるか』を構成する深く重要な相違点も存在することを認 識する。その代わりに、文化的アイデンティティは「歴史、文化、権力の継続的な『戯れ』の対象となる」ため、歴史を通じて「絶え間ない変容を遂げる」ので ある[60]。したがって、ホールは文化的アイデンティティを「過去の物語によって位置づけられ、過去の物語のなかで自分自身を位置づけるさまざまな方法 に私たちが与える名前」[60]と定義している。言い換えれば、ホールにとっての文化的アイデンティティとは「本質ではなく、位置づけ」なのである [61]。 |

| Presences Hall describes Caribbean identity in terms of three distinct "presences": the African, the European, and the American.[62] Taking the terms from Aimé Césaire and Léopold Senghor, he describes the three presences: "Présence Africaine", "Présence Européenne", and "Présence Americaine".[62] "Présence Africaine" is the "unspeakable 'presence' in Caribbean culture".[62] According to Hall, the African presence, though repressed by slavery and colonialism, is in fact hiding in plain sight in every aspect of Caribbean society and culture, including language, religion, the arts, and music. For many black people living in the diaspora, Africa becomes an "imagined community" to which they feel a sense of belonging.[59] However, Hall points out, there is no going back to the Africa that existed before slavery, because Africa too has changed. Secondly, Hall describes the European presence in Caribbean cultural identity as the legacy of colonialism, racism, power and exclusion. Unlike the "Présence Africaine", the European presence is not unspoken even though many would like to be separated from the history of the oppressor. But Hall argues that Caribbeans and diasporic peoples must acknowledge how the European presence has also become an inextricable part of their own identities.[59] Lastly, Hall describes the American presence as the "ground, place, territory" where people and cultures from around the world collided.[63] It is, as Hall puts it, "where the fateful/fatal encounter was staged between Africa and the West", and also where the displacement of the natives occurred.[63] |

存在 ホールはカリブ海のアイデンティティを、アフリカ人、ヨーロッパ人、アメリカ人という3つの異なる「プレゼンス」の観点から説明している: アフリカ的存在」、「ヨーロッパ的存在」、「アメリカ的存在」である[62]。「アフリカ的存在」は、「カリブ海文化における語ることのできない『存 在』」である[62]。ホールによれば、アフリカ的存在は、奴隷制と植民地主義によって抑圧されてはいるが、実際には、言語、宗教、芸術、音楽など、カリ ブ海の社会と文化のあらゆる側面に見え隠れしている。ディアスポラに住む多くの黒人にとって、アフリカは帰属意識を感じる「想像上の共同体」となっている [59]。 しかしホールは、アフリカも変化してしまったため、奴隷制度以前のアフリカに戻ることはできないと指摘する。第二に、ホールはカリブ海の文化的アイデン ティティにおけるヨーロッパの存在を、植民地主義、人種主義、権力、排除の遺産であると述べている。プレザンス・アフリケーヌ」とは異なり、ヨーロッパ人 の存在は、多くの人が抑圧者の歴史から切り離されたいと思っていても、語られることはない。しかしホールは、カリブ人やディアスポラの人々は、ヨーロッパ のプレゼンスがいかに彼ら自身のアイデンティティの抜き差しならない一部にもなっているかを認めなければならないと主張している[59]。最後に、ホール はアメリカのプレゼンスについて、世界中の人々と文化が衝突した「地面、場所、領土」であると述べている[63]。ホールが言うように、そこは「アフリカ と西洋の運命的/宿命的な出会いが演出された場所」であり、また原住民の移動が起こった場所でもある[63]。 |

| Diasporic identity Because diasporic cultural identity in the Caribbean and throughout the world is a mixture of all these different presences, Hall advocated a "conception of 'identity' that lives with and through, not despite, difference; by hybridity".[64] According to Hall, black people living in diaspora are constantly reinventing themselves and their identities by mixing, hybridizing, and "creolizing" influences from Africa, Europe, and the rest of the world in their everyday lives and cultural practices.[65] Therefore, there is no one-size-fits-all cultural identity for diasporic people, but rather a multiplicity of different cultural identities that share both important similarities and important differences, all of which should be respected.[59] |

ディアスポラ的アイデンティティ カリブ海地域および世界全体におけるディアスポラの文化的アイデンティティは、これらすべての異なる存在の混合物であるため、ホールは「差異にもかかわら ずではなく、差異とともに生き、差異を通じて生きる『アイデンティティ』の概念;混血によって」[64]を提唱した。ホールによれば、ディアスポラに生き る黒人は、日常生活や文化的実践のなかでアフリカ、ヨーロッパ、およびその他の地域からの影響をミヘ、混血、および「クレオール化」することによって、自 分自身と自分たちのアイデンティティを常に再発明している。 [したがって、ディアスポラの人々にとって画一的な文化的アイデンティティは存在せず、むしろ重要な類似点と重要な相違点の両方を共有する多種多様な異な る文化的アイデンティティが存在し、それらはすべて尊重されるべきである[59]。 |

| Difference and differance In "Cultural Identity and Diaspora", Hall sheds light on the topic of difference within black identity. He first acknowledges the oneness in the black diaspora and how this unity is at the core of blackness and the black experience. He expresses how this has a unifying effect on the diaspora, giving way to movements such as negritude and the pan-African political project. Hall also acknowledges the deep-rooted "difference" within the diaspora as well. This difference was created by destructive nature of the transatlantic slave trade and the resulting generations of slavery. He describes this difference as what constitutes "what we really are", or the true nature of the diaspora.[59] The duality of such an identity, that expresses deep unity but clear uniqueness and internal distinctness provokes a question out of Hall: "How, then, to describe this play of 'difference' within identity?"[66] Hall's answer is "Différance". The use of the "a" in the word unsettles us from our initial and common interpretation of it, and was originally introduced by Jacques Derrida. This modification of the word difference conveys the separation between spatial and temporal difference, and more adequately encapsulates the nuances of the diaspora. |

差異と相違 文化的アイデンティティとディアスポラ』の中で、ホールは黒人アイデンティティの中の差異というトピックに光を当てている。彼はまず、黒人のディアスポラ における一体性を認め、この一体性が黒人と黒人の経験の核心であることを示す。このことがいかにディアスポラに統一的な影響を与え、ネグリチュードや汎ア フリカ政治プロジェクトといった運動につながるかを表現している。ホールはまた、ディアスポラ内部にも根深い「差異」があることも認めている。この違い は、大西洋横断奴隷貿易の破壊的な性質と、その結果生じた奴隷の世代によって生み出された。彼はこの差異を、「われわれの本当の姿」、すなわちディアスポ ラの本質を構成するものと表現している[59]。このようなアイデンティティの二重性は、深い統一性を表現しながらも、明確な独自性と内部的な区別を示す ものであり、ホールに疑問を投げかける: では、アイデンティティの内部におけるこの「差延」の戯れをどのように表現すればよいのだろうか」[66] ホールの答えは「差延」である。この言葉の「a」の使用は、私たちの最初の、そして一般的な解釈から私たちを動揺させるものであり、もともとはジャック・ デリダによって導入されたものである。この「差異」という言葉の修飾は、空間的差異と時間的差異の分離を伝え、ディアスポラのニュアンスをより適切に表現 している。 |

| Global policy Hall was one of the signatories of the agreement to convene a convention for drafting a world constitution.[67][68] As a result, for the first time in human history, a World Constituent Assembly convened to draft and adopt the Constitution for the Federation of Earth.[69] |

世界政策 ホールは、世界憲法を起草するための大会を招集する協定の署名者の一人であった[67][68]。 その結果、人類史上初めて、地球連邦の憲法を起草・採択するための世界憲法制定議会が招集された[69]。 |

| Legacy The Stuart Hall Library, Iniva's specialist arts and culture reference library, currently located in Pimlico, London, and founded in 2007, is named after Stuart Hall, who was the chair of the board of Iniva for many years. In November 2014, a week-long celebration of Stuart Hall's achievements was held at the University of London's Goldsmiths College, where on 28 November the new Academic Building was renamed in his honour, as the Professor Stuart Hall building (PSH).[70][71] The establishment of the Stuart Hall Foundation in his memory and to continue his life's work was announced in December 2014.[72] The Foundation is "committed to public education, addressing urgent questions of race and inequality in culture and society through talks and events, and building a growing network of Stuart Hall Foundation scholars and artists in residence."[12] In May 2016, Housmans bookshop sold Hall's private library. 3,000 books were donated to Housmans by Hall's widow Catherine Hall.[73] Artist Claudette Johnson completed a portrait of Hall in 2023. Commissioned by Merton College, the portrait hangs in the Hall at Merton alongside other Fellows and Wardens.[74] Film Hall was a presenter of a seven-part television series entitled Redemption Song — made by Barraclough Carey Productions, and transmitted on BBC2, between 30 June and 12 August 1991 — in which he examined the elements that make up the Caribbean, looking at the turbulent history of the islands and interviewing people who live there today.[75] The series episodes were as follows: "Shades of Freedom" (11/08/1991) "Following Fidel" (04/08/1991) "Worlds Apart" (28 July 1991) "La Grande Illusion" (21 July 1991) "Paradise Lost" (14 July 1991) "Out of Africa" (7 July 1991) "Iron in the Soul" (30 June 1991) Hall's lectures have been turned into several videos distributed by the Media Education Foundation: Race, the Floating Signifier (1997). Representation & the Media (1997). The Origins of Cultural Studies (2006). Mike Dibb produced a film based on a long interview between journalist Maya Jaggi and Stuart Hall called Personally Speaking (2009).[76][77] Hall is the subject of two films directed by John Akomfrah, entitled The Unfinished Conversation (2012) and The Stuart Hall Project (2013). The first film was shown (26 October 2013 – 23 March 2014) at Tate Britain, Millbank, London,[78] while the second is now available on DVD.[79] The Stuart Hall Project was composed of clips drawn from more than 100 hours of archival footage of Hall, woven together over the music of jazz artist Miles Davis, who was an inspiration to both Hall and Akomfrah.[80] The film's structure is composed of multiple strands. There is a chronological grounding in historical events, such as the Suez Crisis, the Vietnam War, and the Hungarian Uprising of 1956, along with reflections by Hall on his experiences as an immigrant from the Caribbean to Britain. Another historical event vital to the film was the 1958 Notting Hill race riots occasioned by attacks on black people in the area; these protests showed the presence of a black community within England. When discussing the Caribbean, Hall discusses the idea of hybridity and he states that the Caribbean is the home of hybridity. There are also voiceovers and interviews offered without a specific temporal grounding in the film that nonetheless give the viewer greater insights into Hall and his philosophy. Along with the voiceovers and interviews, embedded in the film are also Hall's personal achievements; this is extremely rare, as there are no traditional archives of those Caribbean peoples moulded by the Middle Passage experience. The film can be viewed as a more pointedly focused take on the Windrush generation, those who migrated from the Caribbean to Britain in the years immediately following the World War II. Hall, himself a member of this generation, focused on the racial discrimination faced by the Windrush generation, contrasting the idealized perceptions among West Indian immigrants of Britain versus the harsher reality they encountered when arriving in the "mother country".[81] A central theme in the film is diasporic belonging. Hall confronted his own identity within both British and Caribbean communities, and at one point in the film he remarks: "Britain is my home, but I am not English." IMDb summarises the film as "a roller coaster ride through the upheavals, struggles and turning points that made the 20th century the century of campaigning, and of global political and cultural change."[82] In August 2012, Professor Sut Jhally conducted an interview with Hall that touched on a number of themes and issues in cultural studies.[83] Book McRobbie, Angela (2016). Stuart Hall, Cultural Studies and the Rise of Black and Asian British Art. McRobbie has also written an article in tribute to Hall: "Times with Stuart". OpenDemocracy. 14 February 2014. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014. Scott, David (2017). Stuart Hall's Voice: Intimations of an Ethics of Receptive Generosity. Durham: Duke University Press. |

レガシー 現在ロンドンのピムリコにあり、2007年に設立されたイニヴァの芸術文化専門レファレンス・ライブラリーであるスチュアート・ホール・ライブラリーは、長年イニヴァの理事長を務めたスチュアート・ホールにちなんで命名された。 2014年11月には、スチュアート・ホールの功績を称える1週間の祝賀会がロンドン大学ゴールドスミス・カレッジで開催され、11月28日には新アカデミック棟が彼に敬意を表してスチュアート・ホール教授棟(PSH)と改名された[70][71]。 彼を偲び、彼の生涯の仕事を継続するためのスチュアート・ホール財団の設立が2014年12月に発表された[72]。 同財団は「公教育に尽力し、講演やイベントを通じて文化や社会における人種や不平等に関する緊急の問題に取り組み、スチュアート・ホール財団の学者やアー ティスト・イン・レジデンスのネットワークを拡大する」[12]。 2016年5月、Housmans書店はホールの私設図書館を売却した。3,000冊の本がホールの未亡人キャサリン・ホールによってHousmansに寄贈された[73]。 画家のクローデット・ジョンソンは2023年にホールの肖像画を完成させた。マートン・カレッジの依頼で、肖像画は他のフェローやウォーデンと共にマートンのホールに飾られている[74]。 映画 ホールは、1991年6月30日から8月12日にかけてBBC2で放映された、Barraclough Carey Productions制作の『Redemption Song』と題された7部構成のテレビシリーズでプレゼンターを務め、カリブ海を構成する要素を検証し、島々の激動の歴史に目を向け、現在そこに住む人々 にインタビューを行った[75]。シリーズのエピソードは以下の通り: 「自由の陰影」(11/08/1991) 「フィデルを追って」(1991年08月04日) 「別世界」(1991年7月28日) 「ラ・グランド・イリュージョン」(1991年7月21日) 「失楽園」(1991年7月14日) 「アウト・オブ・アフリカ」(1991年7月7日) 「魂の鉄」(1991年6月30日) ホールの講演は、メディア教育財団によっていくつかのビデオにまとめられ、配布されている: 人種、浮遊する記号」(1997年) 表象とメディア(1997年) カルチュラル・スタディーズの起源」(2006年)。 マイク・ディブは、ジャーナリスト、マヤ・ジャッジとスチュアート・ホールのロングインタビューに基づく映画『Personally Speaking』(2009年)を制作した[76][77]。 ホールは、『The Unfinished Conversation』(2012年)と『The Stuart Hall Project』(2013年)というジョン・アコムフラ監督の2本の映画の題材となっている。1作目はロンドンのミルバンクにあるテート・ブリテンで上 映(2013年10月26日~2014年3月23日)され[78]、2作目はDVDが発売されている[79]。 スチュアート・ホール・プロジェクト』は、ホールとアコムフラーの両者にインスピレーションを与えたジャズ・アーティスト、マイルス・デイヴィスの音楽に乗せて、100時間を超えるホールのアーカイブ映像から抽出されたクリップで構成された[80]。 この映画の構成は、複数の筋から成っている。スエズ危機、ベトナム戦争、1956年のハンガリー蜂起といった歴史的な出来事と、カリブ海諸国から英国に移 民したホールによる内省が、時系列に沿って描かれている。この映画にとってもうひとつ重要な歴史的出来事は、1958年にノッティング・ヒルで起こった人 種暴動である。カリブ海について論じる際、ホールは混血のアイデアについて論じ、カリブ海は混血の本場であると述べている。また、この映画では、特定の時 間的根拠を持たないナレーションやインタビューが提供されているが、それにもかかわらず、ホールと彼の哲学についてのより深い洞察を観客に与えている。ナ レーションやインタビューとともに、ホールの個人的な業績も映画に埋め込まれている。中航路の経験によって形成されたカリブ海の人々に関する伝統的なアー カイブが存在しないため、これは極めて珍しいことである。 この映画は、第二次世界大戦直後の数年間にカリブ海諸国から英国に移住したウィンドラッシュ世代に、より焦点を絞った作品として見ることができる。自身も この世代の一員であるホールは、ウィンドラッシュ世代が直面した人種差別に焦点を当て、西インド系移民の間で理想化されたイギリスに対する認識と、彼らが 「祖国」に到着したときに遭遇した厳しい現実とを対比させている[81]。 この映画の中心的なテーマは、ディアスポラへの帰属である。ホールは、イギリスとカリブ海のコミュニティの両方における自身のアイデンティティに直面し、映画のある場面で、「イギリスは私の故郷だが、私はイギリス人ではない」と発言する。 IMDbはこの映画を「20世紀を運動の世紀、そして世界的な政治的・文化的変化の世紀とした激動、闘争、転換点をジェットコースターのように駆け抜ける」と要約している[82]。 2012年8月、サット・ジャリー教授はホールへのインタビューを行い、カルチュラル・スタディーズにおける多くのテーマや問題に触れている[83]。 著書 McRobbie, Angela (2016). Stuart Hall, Cultural Studies and the Rise of Black and Asian British Art. マクロビーはホールへの追悼記事も書いている: 「スチュアートとの時間」。OpenDemocracy. 14 February 2014. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. 2014年6月30日取得。 Scott, David (2017). Stuart Hall's Voice: Intimations of an Ethics of Receptive Generosity. Durham: Duke University Press. |

| Personal life Hall was married to the feminist historian Catherine Hall.[14] |

私生活 ホールはフェミニストの歴史家キャサリン・ホールと結婚していた[14]。 |

| Publications This is not a complete list: 1960s Hall, Stuart (March–April 1960). "Crosland territory". New Left Review. I (2): 2–4. Hall, Stuart (January–February 1961). "Student journals". New Left Review. I (7): 50–51. Hall, Stuart (March–April 1961). "The new frontier". New Left Review. I (8): 47–48. Hall, Stuart; Anderson, Perry (July–August 1961). "Politics of the common market". New Left Review. I (10): 1–15. Hall, Stuart; Whannell, Paddy (1964). The Popular Arts. London: Hutchinson Educational. OCLC 2915886. Hall, Stuart (1968). The Hippies: an American "moment". Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. OCLC 12360725. 1970s Hall, Stuart (1971). Deviancy, Politics and the Media. Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Hall, Stuart (1971). "Life and Death of Picture Post", Cambridge Review, vol. 92, no. 2201. Hall, Stuart; P. Walton (1972). Situating Marx: Evaluations and Departures. London: Human Context Books. Hall, Stuart (1972). "The Social Eye of Picture Post", Working Papers in Cultural Studies, no. 2, pp. 71–120. Hall, Stuart (1973). Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse. Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Hall, Stuart (1973). A ‘Reading’ of Marx's 1857 Introduction to the Grundrisse. Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Hall, Stuart (1974). "Marx's Notes on Method: A ‘Reading’ of the ‘1857 Introduction’", Working Papers in Cultural Studies, no. 6, pp. 132–171. Hall, Stuart; T. Jefferson (1976), Resistance Through Rituals, Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain. London: HarperCollinsAcademic. Hall, Stuart (1977). "Journalism of the air under review". Journalism Studies Review. 1 (1): 43–45. Hall, Stuart; C. Critcher; T. Jefferson; J. Clarke; B. Roberts (1978), Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order. London: Macmillan. London: Macmillan Press. ISBN 0-333-22061-7 (paperback); ISBN 0-333-22060-9 (hardback). Hall, Stuart (January 1979). "The great moving right show". Marxism Today. Amiel and Melburn Collections: 14–20. 1980s Hall, Stuart (1980). "Encoding / Decoding." In: S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, and P. Willis (eds). Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972–79. London: Hutchinson, pp. 128–138. Hall, Stuart (1980). "Cultural Studies: two paradigms". Media, Culture & Society. 2 (1): 57–72. doi:10.1177/016344378000200106. S2CID 143637900. Hall, Stuart (1980). "Race, Articulation and Societies Structured in Dominance." In: UNESCO (ed). Sociological Theories: Race and Colonialism. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 305–345. Hall, Stuart (1981). "Notes on Deconstructing the Popular". In: People's History and Socialist Theory. London: Routledge. Hall, Stuart; P. Scraton (1981). "Law, Class and Control". In: M. Fitzgerald, G. McLennan & J. Pawson (eds). Crime and Society, London: RKP. Hall, Stuart (1988). The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left. London: Verso Books. Hall, Stuart (June 1986). "Gramsci's relevance for the study of race and ethnicity". Journal of Communication Inquiry. 10 (2): 5–27. doi:10.1177/019685998601000202. S2CID 53782. Hall, Stuart (June 1986). "The problem of ideology-Marxism without guarantees". Journal of Communication Inquiry. 10 (2): 28–44. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1033.1130. doi:10.1177/019685998601000203. S2CID 144448154. Hall, Stuart; Jacques, Martin (July 1986). "People aid: a new politics sweeps the land". Marxism Today. Amiel and Melburn Collections: 10–14. Hall, Stuart (1989). "Ethnicity: Identity and Difference". Radical America 23 (4): 9–20. Available online. 1990s Hall, Stuart; Held, David; McGrew, Anthony (1992). Modernity and its futures. Cambridge: Polity Press in association with the Open University. ISBN 9780745609669. Hall, Stuart (1992), "The question of cultural identity", in Hall, Stuart; Held, David; McGrew, Anthony (eds.), Modernity and its futures, Cambridge: Polity Press in association with the Open University, pp. 274–316, ISBN 9780745609669. Hall, Stuart (Summer 1996). "Who dares, fails". Soundings, Issue: Heroes and Heroines. 3. Lawrence and Wishart. Hall, Stuart (1997). Representation: cultural representations and signifying practices. London Thousand Oaks, California: Sage in association with the Open University. ISBN 9780761954323. Hall, Stuart (1997), "The local and the global: globalization and ethnicity", in McClintock, Anne; Mufti, Aamir; Shohat, Ella (eds.), Dangerous liaisons: gender, nation, and postcolonial perspectives, Minnesota, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 173–187, ISBN 9780816626496. Hall, Stuart (January–February 1997). "Raphael Samuel: 1934-96". New Left Review. I (221). Available online. 2000s Hall, Stuart (2001), "Foucault: Power, knowledge and discourse", in Wetherell, Margaret; Taylor, Stephanie; Yates, Simeon J. (eds.), Discourse Theory and Practice: a reader, D843 Course: Discourse Analysis, London Thousand Oaks California: SAGE in association with the Open University, pp. 72–80, ISBN 9780761971566. 2010s Hall, Stuart (2011). "The neo-liberal revolution". Cultural Studies. 25 (6): 705–728. doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.619886. S2CID 143653421. Hall, Stuart; Evans, Jessica; Nixon, Sean (2013) [1997]. Representation (2nd ed.). London: Sage in association with The Open University. ISBN 9781849205634. Hall, Stuart (2016). Cultural Studies 1983: A Theoretical History. Slack, Jennifer, and Lawrence Grossberg (eds), Duke University Press. ISBN 0822362635. Hall, Stuart (2017). Selected Political Writings: The Great Moving Right Show and other essays. London: Lawrence & Wishart. ISBN 9781910448656. Hall, Stuart (with Bill Schwarz) (2017). Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands. London: Allen Lane; Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822363873. 2020s Selected Writings on Marxism (2021), Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 978-1-4780-0034-1. Selected Writings on Race and Difference (2021), Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 978-1478011668. |

出版物 これは完全なリストではない: 1960s Hall, Stuart (1960年3月-4月). 「Crosland territory」. New Left Review. I (2): 2-4. Hall, Stuart (January-February 1961). 「学生雑誌」。New Left Review. I (7): 50-51. Hall, Stuart (March-April 1961). 「The new frontier」. New Left Review. I (8): 47-48. Hall, Stuart; Anderson, Perry (July-August 1961). 「共通市場の政治」。New Left Review. I (10): 1-15. Hall, Stuart; Whannell, Paddy (1964). The Popular Arts. London: Hutchinson Educational. OCLC 2915886. Hall, Stuart (1968). The Hippies: an American 「moment」. バーミンガム: 現代文化研究センター。OCLC 12360725. 1970s ホール、スチュアート (1971). 逸脱、政治、メディア. バーミンガム: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Hall, Stuart (1971). ピクチャー・ポストの生と死」『ケンブリッジ・レビュー』92巻2201号。 Hall, Stuart; P. Walton (1972). マルクスを位置づける: 評価と出発. London: Human Context Books. Hall, Stuart (1972). ピクチャー・ポストの社会的眼差し」『文化研究ワーキング・ペーパー』第2号、71-120頁。 Hall, Stuart (1973). テレビ言説における符号化と復号化. バーミンガム: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Hall, Stuart (1973). マルクスの1857年の『グルンドリッセ』序説を「読む」。バーミンガム: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Hall, Stuart (1974). 「Marx's Notes on Method: 1857年序説』の『読解』」『カルチュラル・スタディーズ研究論文集』第6号、132-171頁。 Hall, Stuart; T. Jefferson (1976), Resistance Through Rituals, Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain. London: HarperCollinsAcademic. Hall, Stuart (1977). 「Journalism of the air under review」. Journalism Studies Review. 1 (1): 43-45. Hall, Stuart; C. Critcher; T. Jefferson; J. Clarke; B. Roberts (1978), Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order. ロンドン: マクミラン。ロンドン: マクミラン・プレス. ISBN 0-333-22061-7(ペーパーバック); ISBN 0-333-22060-9(ハードカバー)。 Hall, Stuart (January 1979). 「The great moving right show」. Marxism Today. Amiel and Melburn Collections: 14-20. 1980s Hall, Stuart (1980). 「エンコード/デコード」. In: S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, and P. Willis (eds). Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972-79. London: Hutchinson, pp. Hall, Stuart (1980). 「カルチュラル・スタディーズ:二つのパラダイム」。Media, Culture & Society. 2 (1): 57–72. doi:10.1177/016344378000200106. s2cid 143637900. Hall, Stuart (1980). 「Race, Articulation and Societies Structured in Dominance.」. In: UNESCO (ed). Sociological Theories: 人種と植民地主義. パリ: UNESCO. 305-345. Hall, Stuart (1981). 「大衆の脱構築に関するノート」. In: People's History and Socialist Theory. London: Routledge. Hall, Stuart; P. Scraton (1981). 「法、階級、統制」。In: M. Fitzgerald, G. McLennan & J. Pawson (eds). 犯罪と社会、ロンドン: RKP. Hall, Stuart (1988). The Hard Road to Renewal: サッチャリズムと左翼の危機. ロンドン: Verso Books. Hall, Stuart (June 1986). 「Gramsci's relevance for the study of race and ethnicity」. Journal of Communication Inquiry. 10 (2): 5–27. doi:10.1177/019685998601000202. S2CID 53782. Hall, Stuart (June 1986). 「イデオロギーの問題-保証なきマルクス主義」. Journal of Communication Inquiry. 10 (2): 28-44. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1033.1130. doi:10.1177/019685998601000203. S2CID 144448154. Hall, Stuart; Jacques, Martin (July 1986). 「People Aid: a new politics sweeps the land」. Marxism Today. Amiel and Melburn Collections: 10-14. Hall, Stuart (1989). 「Ethnicity: Identity and Difference」. Radical America 23 (4): 9-20. オンラインで入手可能。 1990s Hall, Stuart; Held, David; McGrew, Anthony (1992). Modernity and its futures. ケンブリッジ: Polity Press in association with the Open University. ISBN 9780745609669. Hall, Stuart (1992), 「The question of cultural identity」, in Hall, Stuart; Held, David; McGrew, Anthony (eds.), Modernity and its futures, Cambridge: Polity Press in association with the Open University, pp.274-316, ISBN 9780745609669. Hall, Stuart (Summer 1996). 「Who dares, fails」. Soundings, Issue: Heroes and Heroines. 3. Lawrence and Wishart. Hall, Stuart (1997). 表象:文化的表象と意味づけの実践. London Thousand Oaks, California: Sage in association with the Open University. ISBN 9780761954323. Hall, Stuart (1997), 「The local and the global: globalization and ethnicity」, in McClintock, Anne; Mufti, Aamir; Shohat, Ella (eds.), Dangerous liaisons: gender, nation, and postcolonial perspectives, Minnesota, Minneapolis: ミネソタ大学出版局、173-187頁、ISBN 9780816626496。 Hall, Stuart (January-February 1997). 「Raphael Samuel: 1934-96」. New Left Review. I (221). オンラインで入手可能。 2000s Hall, Stuart (2001), "Foucault: Power, knowledge and discourse」, Wetherell, Margaret; Taylor, Stephanie; Yates, Simeon J. (eds.), Discourse Theory and Practice: a reader, D843 Course: 談話分析、ロンドン・サウザンドオークス・カリフォルニア: SAGE in association with the Open University, pp.72-80, ISBN 9780761971566. 2010s Hall, Stuart (2011). 「新自由主義革命」. Cultural Studies. 25 (6): 705–728. doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.619886. s2cid 143653421. Hall, Stuart; Evans, Jessica; Nixon, Sean (2013) [1997]. Representation (2nd ed.). London: Sage in association with The Open University. ISBN 9781849205634. Hall, Stuart (2016). Cultural Studies 1983: A Theoretical History. Slack, Jennifer, and Lawrence Grossberg (eds), Duke University Press. ISBN 0822362635. Hall, Stuart (2017). Selected Political Writings: The Great Moving Right Show and other essays. London: Lawrence & Wishart. ISBN 9781910448656. Hall, Stuart (with Bill Schwarz) (2017). Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands. London: Allen Lane; Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822363873。 2020s Selected Writings on Marxism (2021), Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 978-1-4780-0034-1. Selected Writings on Race and Difference (2021), Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 978-1478011668. |

| Articulation (sociology) Musgrave Medal Bill Schwarz |

アーティキュレーション(社会学) マスグレイブ・メダル ビル・シュワルツ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stuart_Hall_(cultural_theorist) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆