持続可能性・サステナビリティ

Sustainability

☆ 持続可能性とは、人々が長期にわたって地球上で共存していくための社会的目標である。この用語の定義には異論があり、文献、文脈、時代によって異なってい る[2][1]。持続可能性には通常、環境、経済、社会という3つの側面(または柱)がある[1]。持続可能性という考え方は、世界レベル、国民レベル、 組織レベル、個人レベルでの意思決定を導くことができる[5]。関連する概念に持続可能な開発というものがあり、この2つの用語は同じ意味で使われること が多い[6]: 「持続可能性は、長期的な目標(すなわち、より持続可能な世界)と考えられることが多いが、持続可能な開発は、それを達成するための多くのプロセスや経路 を指す」[7]。 持続可能性の経済的側面をめぐる詳細については議論がある[1] 。例えば、「万人のための福祉と繁栄」という考え方と環境保全との間には常に緊張関係があり[8][1]、トレードオフが必要である。経済成長と環境破壊 を切り離す方法を見つけることが望まれる[9]。これは、経済成長しながらも、単位生産量あたりの資源使用量を減らすことを意味する[10]。これを行う のは難しい[11][12]。一部の専門家は、そのようなデカップリングが必要な規模で起こっているという証拠はないと述べている[13]。 環境、社会、経済を対象とした指標は開発されているが、持続可能性の指標に決まった定義はない[15]。また、フェアトレードやオーガニックのような持続 可能性の基準や認証制度も含まれる。また、企業の持続可能性報告やトリプルボトムライン会計などの指標や会計システムも含まれる。 持続可能性の移行を達成するためには、持続可能性に対する多くの障壁に対処する必要がある[5]: 34 [16] 自然とその複雑性から生じる障壁もあれば、持続可能性の概念から外在する障壁もある。例えば、各国の支配的な制度的枠組みに起因するものがある。 持続可能性のグローバルな問題は、グローバルな解決策を必要とするため、取り組むのが難しい。国連やWTOのような既存のグローバルな組織は、現在のグ ローバルな規制を実施する上で非効率であると考えられている。その理由の一つは、適切な制裁メカニズムがないことである[5]: 135-145 持続可能性のための行動源は政府だけではない。例えば、ビジネスグループは、持続可能なビジネスを求めて、エコロジーへの関心を経済活動に統合しようとし ている[17][18]。宗教指導者は、自然への配慮と環境の安定の必要性を強調している。個人もまた、より持続可能な生活を送ることができる[5]。 持続可能性という考え方を批判する人々もいる。批判の一点は、この概念が曖昧で流行語に過ぎないということである[19][1]。もうひとつは、持続可能 性が不可能な目標かもしれないということである[20]。専門家の中には、「生物物理学的な惑星の境界を越えることなく、国民が必要とするものを提供して いる国はない」と指摘する者もいる[21]: 11

| Sustainability is a

social goal for people to co-exist on Earth over a long period of time.

Definitions of this term are disputed and have varied with literature,

context, and time.[2][1] Sustainability usually has three dimensions

(or pillars): environmental, economic, and social.[1] Many definitions

emphasize the environmental dimension.[3][4] This can include

addressing key environmental problems, including climate change and

biodiversity loss. The idea of sustainability can guide decisions at

the global, national, organizational, and individual levels.[5] A

related concept is that of sustainable development, and the terms are

often used to mean the same thing.[6] UNESCO distinguishes the two like

this: "Sustainability is often thought of as a long-term goal (i.e. a

more sustainable world), while sustainable development refers to the

many processes and pathways to achieve it."[7] Details around the economic dimension of sustainability are controversial.[1] Scholars have discussed this under the concept of weak and strong sustainability. For example, there will always be tension between the ideas of "welfare and prosperity for all" and environmental conservation,[8][1] so trade-offs are necessary. It would be desirable to find ways that separate economic growth from harming the environment.[9] This means using fewer resources per unit of output even while growing the economy.[10] This decoupling reduces the environmental impact of economic growth, such as pollution. Doing this is difficult.[11][12] Some experts say there is no evidence that such a decoupling is happening at the required scale.[13] It is challenging to measure sustainability as the concept is complex, contextual, and dynamic.[14] Indicators have been developed to cover the environment, society, or the economy but there is no fixed definition of sustainability indicators.[15] The metrics are evolving and include indicators, benchmarks and audits. They include sustainability standards and certification systems like Fairtrade and Organic. They also involve indices and accounting systems such as corporate sustainability reporting and Triple Bottom Line accounting. It is necessary to address many barriers to sustainability to achieve a sustainability transition.[5]: 34 [16] Some barriers arise from nature and its complexity while others are extrinsic to the concept of sustainability. For example, they can result from the dominant institutional frameworks in countries. Global issues of sustainability are difficult to tackle as they need global solutions. Existing global organizations such as the UN and WTO are seen as inefficient in enforcing current global regulations. One reason for this is the lack of suitable sanctioning mechanisms.[5]: 135–145 Governments are not the only sources of action for sustainability. For example, business groups have tried to integrate ecological concerns with economic activity, seeking sustainable business.[17][18] Religious leaders have stressed the need for caring for nature and environmental stability. Individuals can also live more sustainably.[5] Some people have criticized the idea of sustainability. One point of criticism is that the concept is vague and only a buzzword.[19][1] Another is that sustainability might be an impossible goal.[20] Some experts have pointed out that "no country is delivering what its citizens need without transgressing the biophysical planetary boundaries".[21]: 11 |

持続可能性とは、人々が長期にわたって地球上で共存していくための社会

的目標である。この用語の定義には異論があり、文献、文脈、時代によって異なっている[2][1]。持続可能性には通常、環境、経済、社会という3つの側

面(または柱)がある[1]。持続可能性という考え方は、世界レベル、国民レベル、組織レベル、個人レベルでの意思決定を導くことができる[5]。関連す

る概念に持続可能な開発というものがあり、この2つの用語は同じ意味で使われることが多い[6]:

「持続可能性は、長期的な目標(すなわち、より持続可能な世界)と考えられることが多いが、持続可能な開発は、それを達成するための多くのプロセスや経路

を指す」[7]。 持続可能性の経済的側面をめぐる詳細については議論がある[1] 。例えば、「万人のための福祉と繁栄」という考え方と環境保全との間には常に緊張関係があり[8][1]、トレードオフが必要である。経済成長と環境破壊 を切り離す方法を見つけることが望まれる[9]。これは、経済成長しながらも、単位生産量あたりの資源使用量を減らすことを意味する[10]。これを行う のは難しい[11][12]。一部の専門家は、そのようなデカップリングが必要な規模で起こっているという証拠はないと述べている[13]。 環境、社会、経済を対象とした指標は開発されているが、持続可能性の指標に決まった定義はない[15]。また、フェアトレードやオーガニックのような持続 可能性の基準や認証制度も含まれる。また、企業の持続可能性報告やトリプルボトムライン会計などの指標や会計システムも含まれる。 持続可能性の移行を達成するためには、持続可能性に対する多くの障壁に対処する必要がある[5]: 34 [16] 自然とその複雑性から生じる障壁もあれば、持続可能性の概念から外在する障壁もある。例えば、各国の支配的な制度的枠組みに起因するものがある。 持続可能性のグローバルな問題は、グローバルな解決策を必要とするため、取り組むのが難しい。国連やWTOのような既存のグローバルな組織は、現在のグ ローバルな規制を実施する上で非効率であると考えられている。その理由の一つは、適切な制裁メカニズムがないことである[5]: 135-145 持続可能性のための行動源は政府だけではない。例えば、ビジネスグループは、持続可能なビジネスを求めて、エコロジーへの関心を経済活動に統合しようとし ている[17][18]。宗教指導者は、自然への配慮と環境の安定の必要性を強調している。個人もまた、より持続可能な生活を送ることができる[5]。 持続可能性という考え方を批判する人々もいる。批判の一点は、この概念が曖昧で流行語に過ぎないということである[19][1]。もうひとつは、持続可能 性が不可能な目標かもしれないということである[20]。専門家の中には、「生物物理学的な惑星の境界を越えることなく、国民が必要とするものを提供して いる国はない」と指摘する者もいる[21]: 11 |

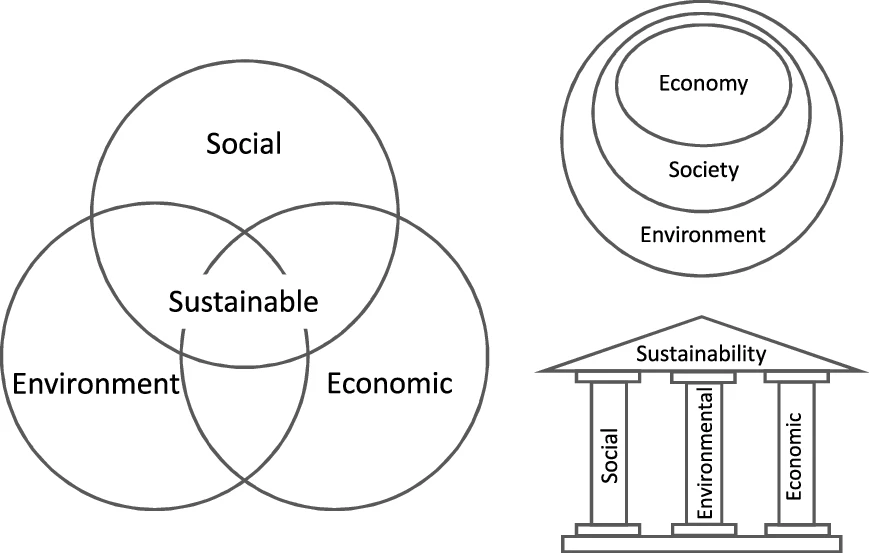

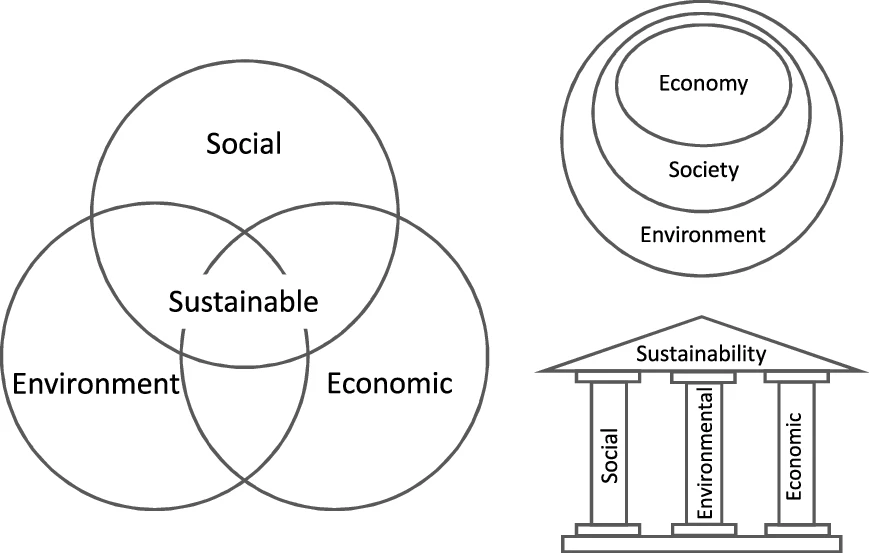

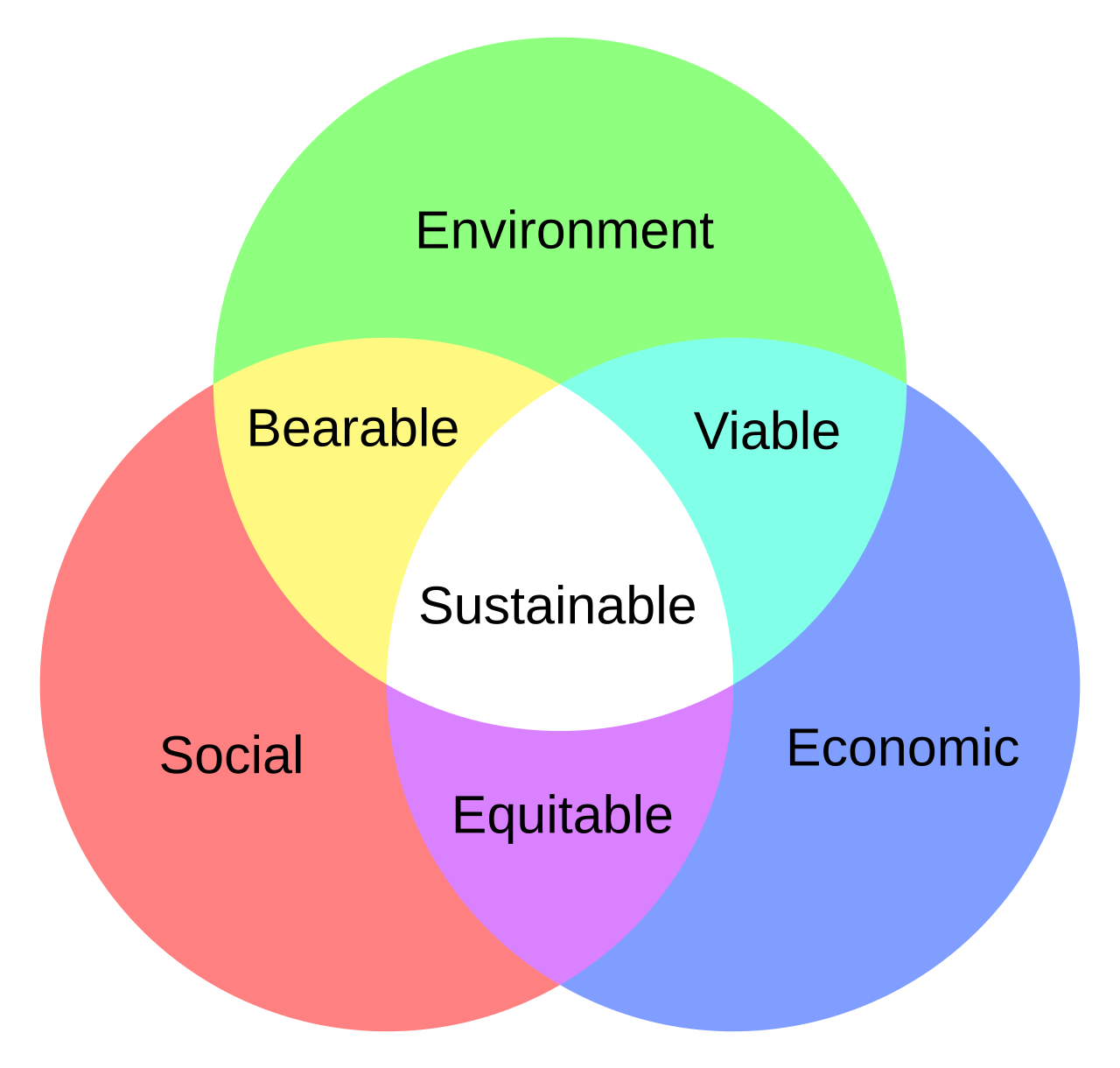

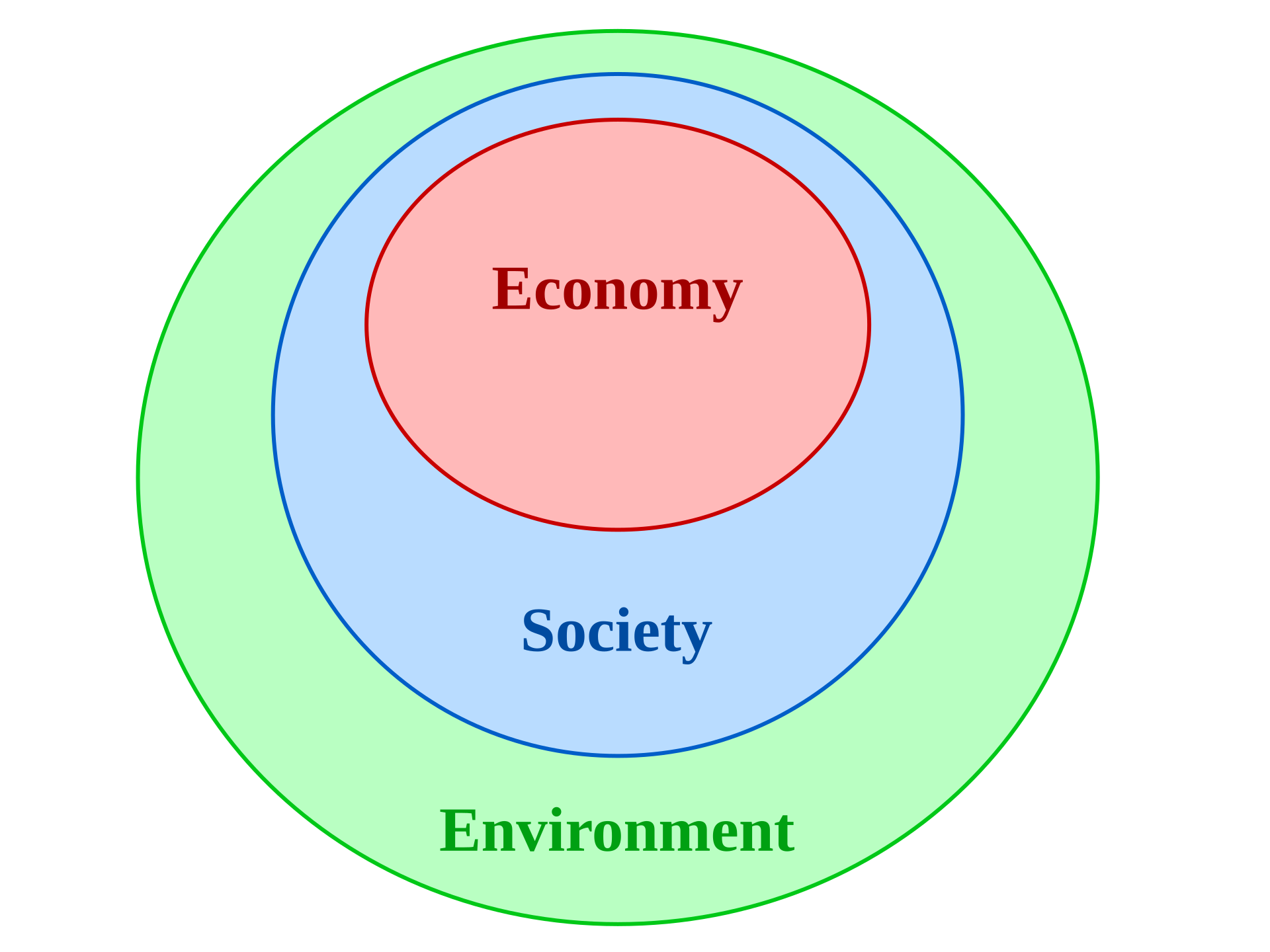

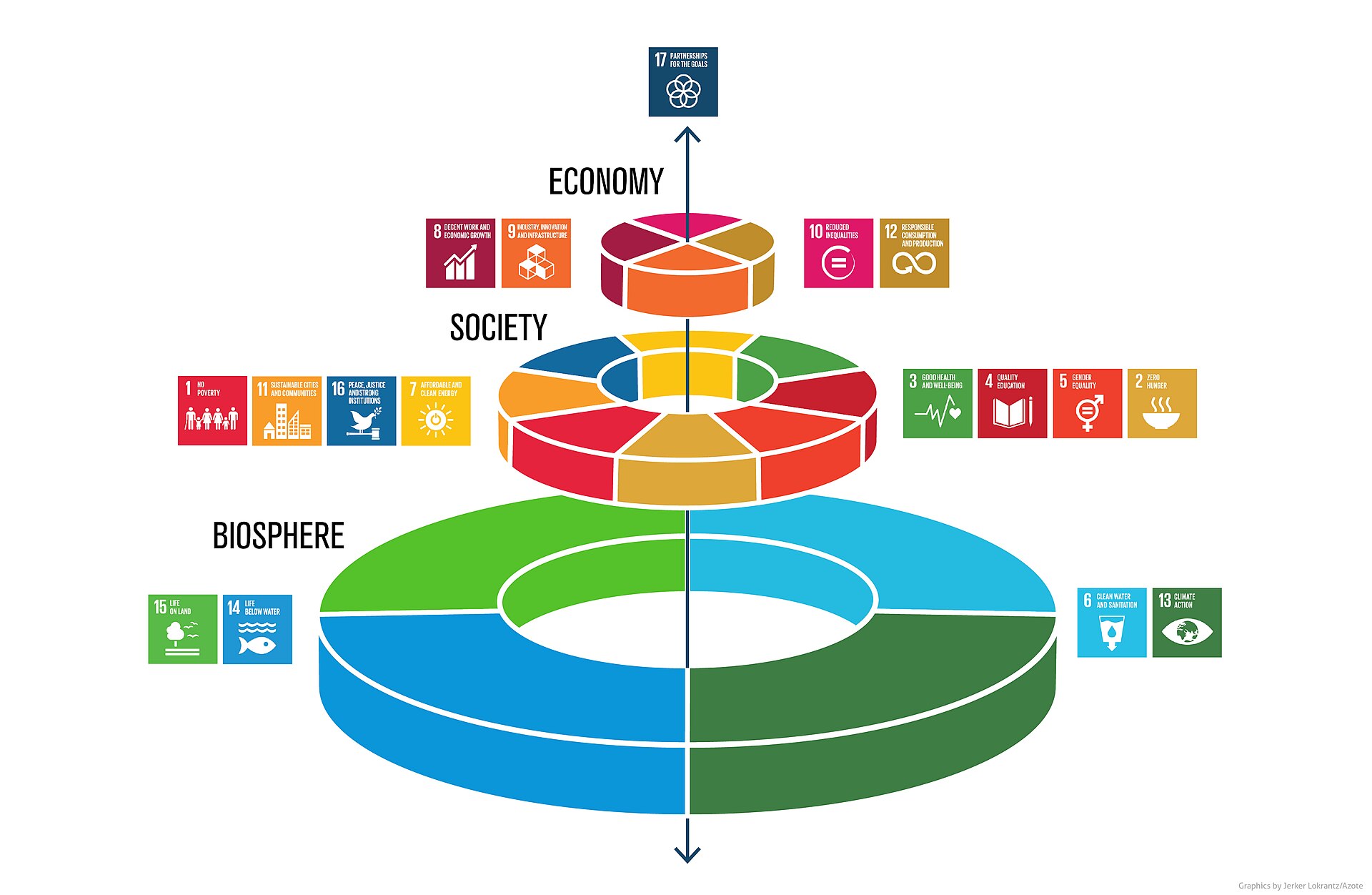

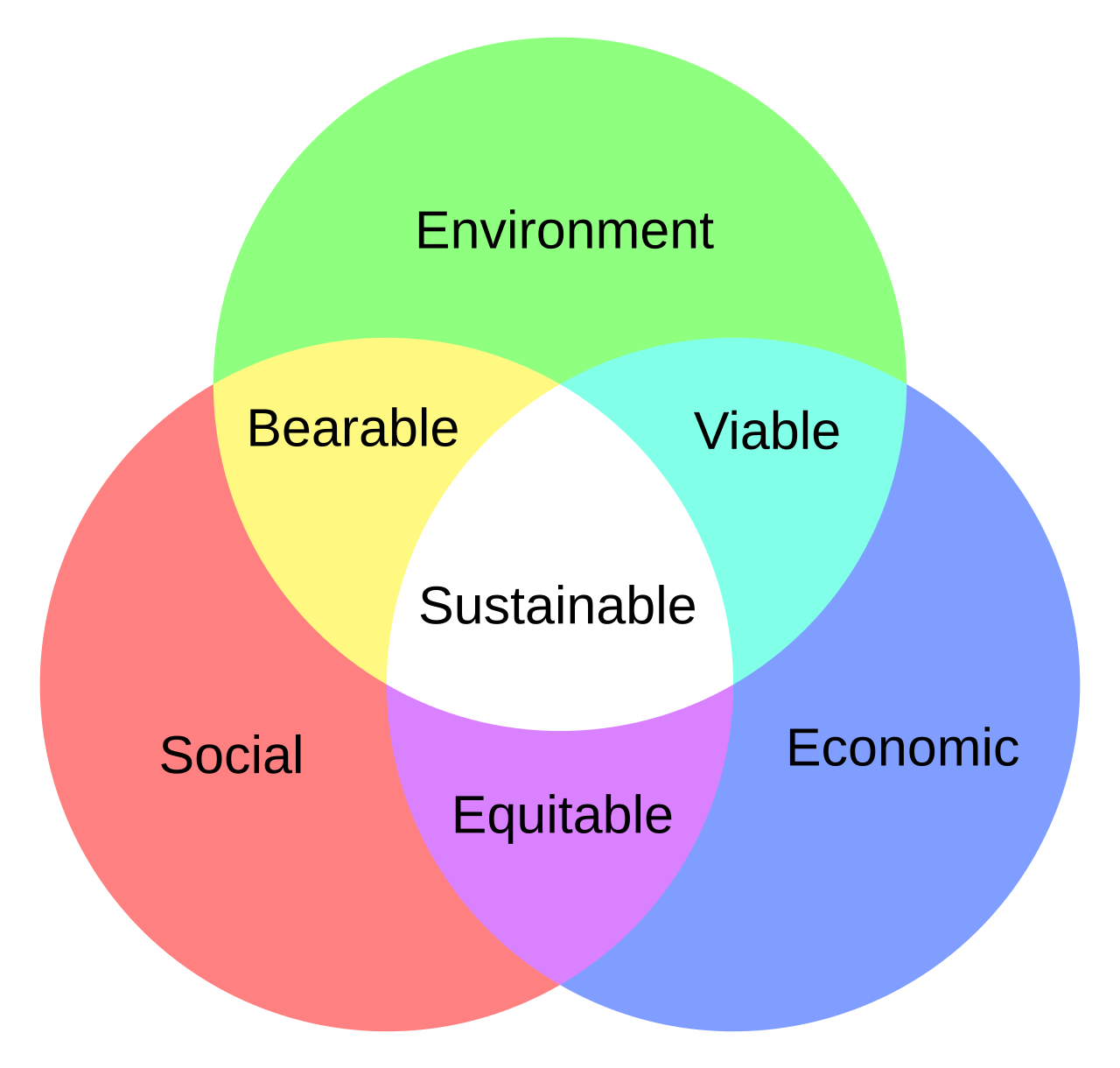

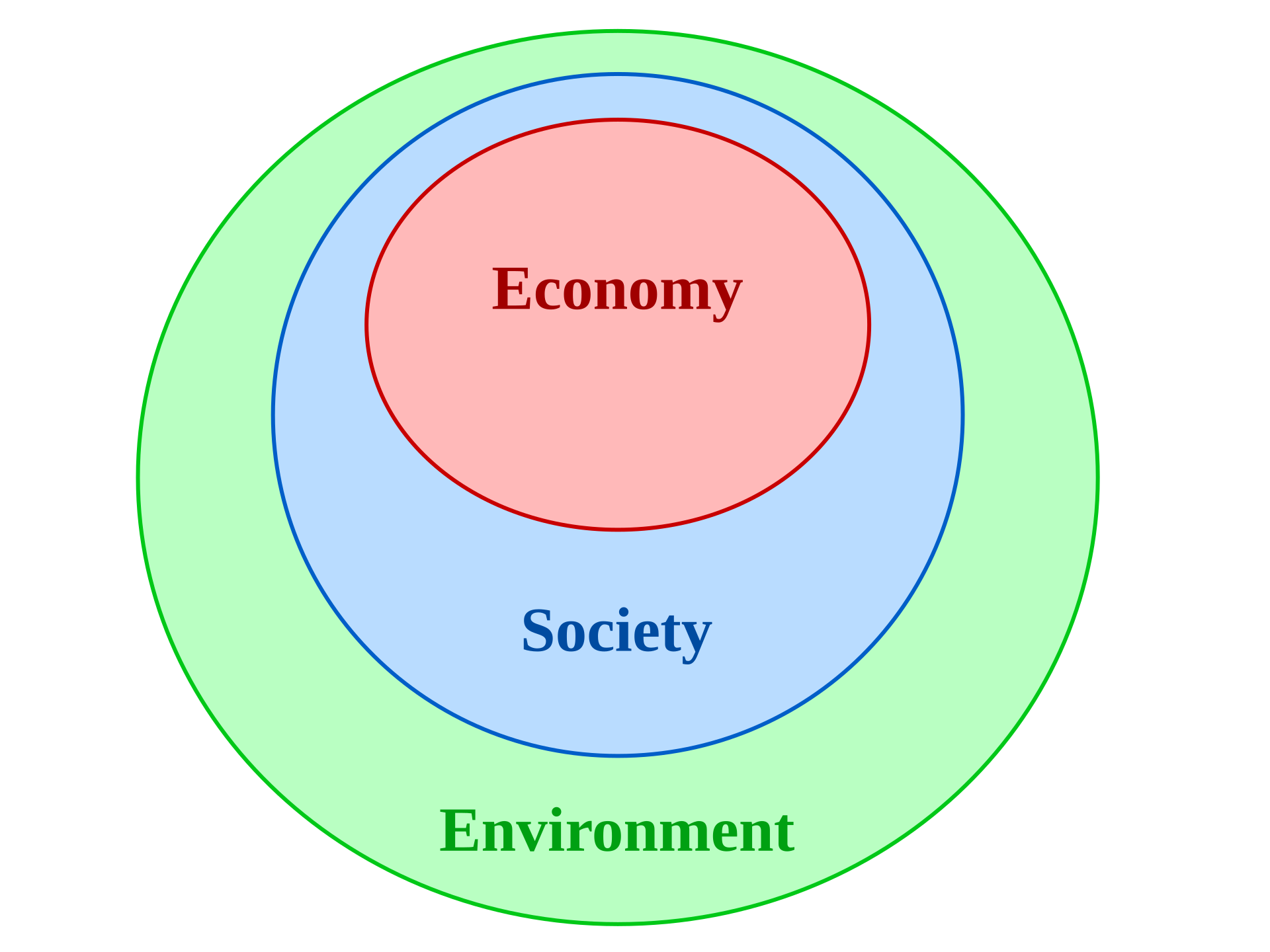

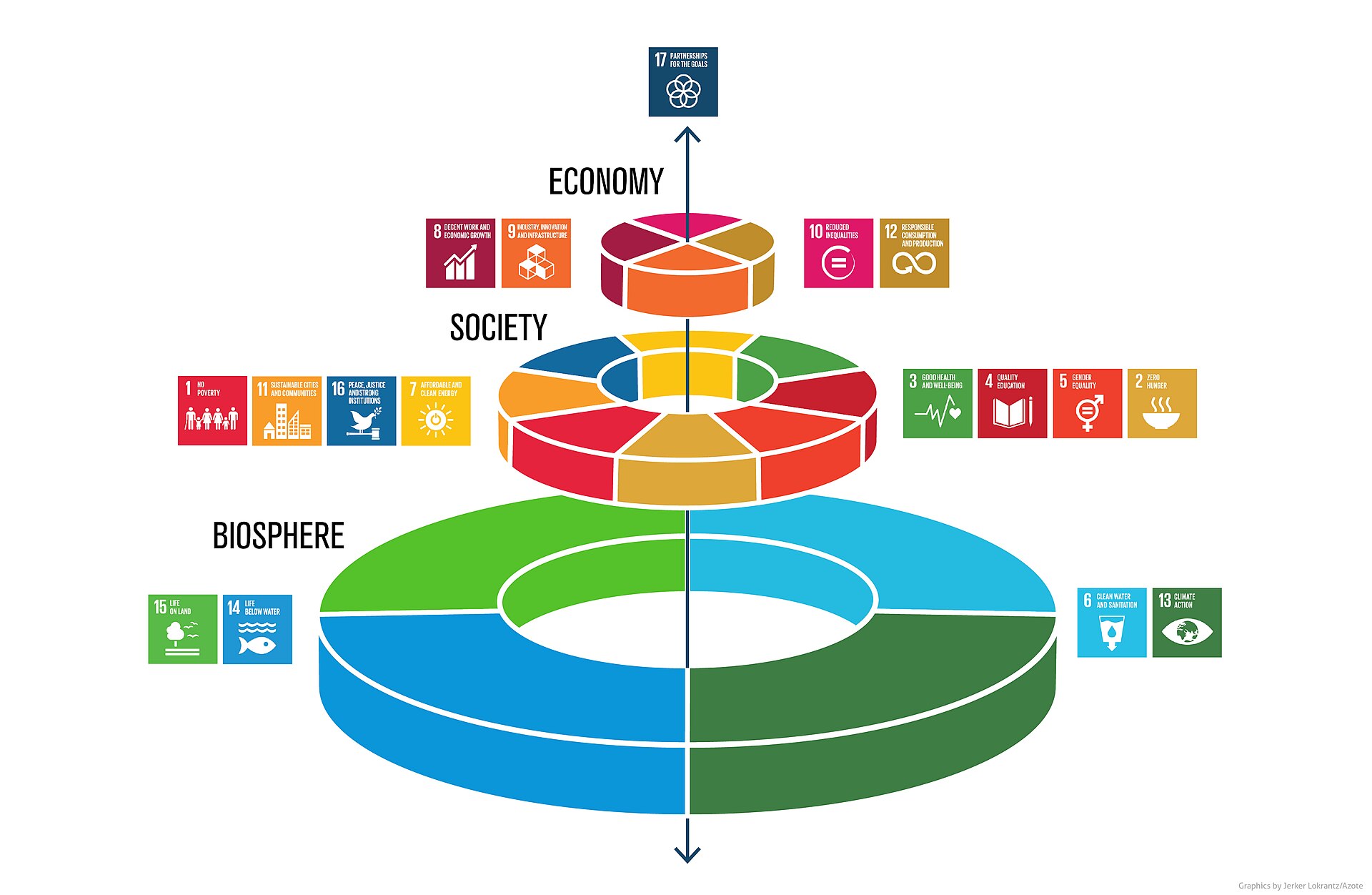

Three visual representations of sustainability and its three dimensions: the left image shows sustainability as three intersecting circles. In the top right, it is a nested approach. In the bottom right it is three pillars.[1] The schematic with the nested ellipses emphasizes a hierarchy of the dimensions, putting environment as the foundation for the other two. |

持続可能性とその3つの次元を視覚的に表現した3つの図:左の図は、持続可能性を3つの交差する円として示している。右上の図は、入れ子のアプローチであ る。右下は3本の柱である[1]。楕円が入れ子になっている図式は、次元の階層性を強調しており、環境を他の2つの土台としている。 |

| Definitions Current usage Sustainability is regarded as a "normative concept".[5][22][23][2] This means it is based on what people value or find desirable: "The quest for sustainability involves connecting what is known through scientific study to applications in pursuit of what people want for the future."[23] The 1983 UN Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Commission) had a big influence on the use of the term sustainability today. The commission's 1987 Brundtland Report provided a definition of sustainable development. The report, Our Common Future, defines it as development that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs".[24][25] The report helped bring sustainability into the mainstream of policy discussions. It also popularized the concept of sustainable development.[1] Some other key concepts to illustrate the meaning of sustainability include:[23] It may be a fuzzy concept but in a positive sense: the goals are more important than the approaches or means applied; It connects with other essential concepts such as resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability. Choices matter: "it is not possible to sustain everything, everywhere, forever"; Scale matters in both space and time, and place matters; Limits exist (see planetary boundaries). In everyday usage, sustainability often focuses on the environmental dimension.[citation needed] Specific definitions Scholars say that a single specific definition of sustainability may never be possible. But the concept is still useful.[2][23] There have been attempts to define it, for example: "Sustainability can be defined as the capacity to maintain or improve the state and availability of desirable materials or conditions over the long term."[23] "Sustainability [is] the long-term viability of a community, set of social institutions, or societal practice. In general, sustainability is understood as a form of intergenerational ethics in which the environmental and economic actions taken by present persons do not diminish the opportunities of future persons to enjoy similar levels of wealth, utility, or welfare."[6] "Sustainability means meeting our own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. In addition to natural resources, we also need social and economic resources. Sustainability is not just environmentalism. Embedded in most definitions of sustainability we also find concerns for social equity and economic development."[26] Some definitions focus on the environmental dimension. The Oxford Dictionary of English defines sustainability as: "the property of being environmentally sustainable; the degree to which a process or enterprise is able to be maintained or continued while avoiding the long-term depletion of natural resources".[27] Historical usage Further information: Sustainable development § Development of the concept The term sustainability is derived from the Latin word sustinere. "To sustain" can mean to maintain, support, uphold, or endure.[28][29] So sustainability is the ability to continue over a long period of time. In the past, sustainability referred to environmental sustainability. It meant using natural resources so that people in the future could continue to rely on them in the long term.[30][31] The concept of sustainability, or Nachhaltigkeit in German, goes back to Hans Carl von Carlowitz (1645–1714), and applied to forestry. The term for this now would be sustainable forest management.[32] He used this term to mean the long-term responsible use of a natural resource. In his 1713 work Silvicultura oeconomica,[33] he wrote that "the highest art/science/industriousness [...] will consist in such a conservation and replanting of timber that there can be a continuous, ongoing and sustainable use".[34] The shift in use of "sustainability" from preservation of forests (for future wood production) to broader preservation of environmental resources (to sustain the world for future generations) traces to a 1972 book by Ernst Basler, based on a series of lectures at M.I.T.[35] The idea itself goes back a very long time: Communities have always worried about the capacity of their environment to sustain them in the long term. Many ancient cultures, traditional societies, and indigenous peoples have restricted the use of natural resources.[36] Comparison to sustainable development Further information: Sustainable development The terms sustainability and sustainable development are closely related. In fact, they are often used to mean the same thing.[6] Both terms are linked with the "three dimensions of sustainability" concept.[1] One distinction is that sustainability is a general concept, while sustainable development can be a policy or organizing principle. Scholars say sustainability is a broader concept because sustainable development focuses mainly on human well-being.[23] Sustainable development has two linked goals. It aims to meet human development goals. It also aims to enable natural systems to provide the natural resources and ecosystem services needed for economies and society. The concept of sustainable development has come to focus on economic development, social development and environmental protection for future generations.[citation needed] |

定義 現在の用法 持続可能性は「規範的概念」[5][22][23][2]であると考えられている: 「持続可能性の追求は、科学的な研究によって知られていることを、人々が未来に望むことを追求する応用に結びつけることを含む」[23]。 1983年の国連環境開発委員会(ブルントラント委員会)は、今日の持続可能性という用語の使用に大きな影響を与えた。同委員会の1987年のブルントラ ント報告書は、持続可能な開発の定義を提示した。この報告書『Our Common Future』では、持続可能な開発とは「将来の世代が自らのニーズを満たす能力を損なうことなく、現在のニーズを満たす」開発であると定義している [24][25]。また、持続可能な開発という概念も一般化した[1]。 持続可能性の意味を説明する他の重要な概念には、以下が含まれる[23]。 曖昧な概念かもしれないが、肯定的な意味では、適用されるアプローチや手段よりも目標が重要である; レジリエンス、適応能力、脆弱性など、他の本質的な概念と結びついている。 選択は重要である: 「すべてを、どこでも、永遠に維持することは不可能である」; 空間的にも時間的にも規模が重要であり、場所も重要である; 限界は存在する(惑星境界を参照)。 日常的な用法では、持続可能性はしばしば環境側面に焦点を当てる[要出典]。 具体的な定義 学者によれば、持続可能性の具体的な定義をひとつにまとめることは不可能である。しかし、この概念は依然として有用である: 「持続可能性とは、望ましい物質や状態の状態や利用可能性を長期的に維持または改善する能力として定義することができる」[23]。 「持続可能性とは、コミュニティ、一連の社会制度、または社会的慣行の長期的な存続可能性のことである。一般に、持続可能性とは、現在の人がとる環境的・ 経済的行動が、将来の人が同程度の富、効用、福祉を享受する機会を減少させないという世代間倫理の一形態として理解される"[6]。 「持続可能性とは、将来の世代が自らのニーズを満たす能力を損なうことなく、我々自身のニーズを満たすことを意味する。天然資源に加えて、社会的・経済的 資源も必要である。持続可能性とは、単なる環境保護主義ではない。持続可能性の定義の多くには、社会的公正と経済発展への懸念も含まれている」[26]。 環境側面に焦点を当てた定義もある。オックスフォード英語辞典は、持続可能性を次のように定義している: 「環境的に持続可能であるという性質。あるプロセスや企業が、天然資源の長期的な枯渇を回避しながら維持または継続できる度合い」[27]。 歴史的用法 さらなる情報 持続可能な開発§概念の発展 持続可能性という言葉は、ラテン語のsustinereに由来する。「持続可能性とは、長期にわたって継続する能力のことである[28][29]。 かつて持続可能性とは、環境の持続可能性を指していた。持続可能性(ドイツ語ではNachhaltigkeit)の概念は、ハンス・カール・フォン・カル ロヴィッツ(1645-1714)に遡り、林業に適用された。彼はこの言葉を、天然資源の長期的な責任ある利用という意味で使った。1713年の著作 『Silvicultura oeconomica』[33]では、「最高の芸術/科学/産業は、継続的、継続的かつ持続可能な利用ができるような木材の保全と植え替えからなる」と書 いている[34]。「持続可能性」の用法が森林の保全(将来の木材生産のため)からより広範な環境資源の保全(将来の世代のために世界を維持するため)へ と変化したのは、MITでの一連の講義に基づくエルンスト・バスラーによる1972年の著書[35]に遡る。 この考え方自体は非常に古くからある: コミュニティは常に、長期的に自分たちを維持できる環境の能力を心配してきた。多くの古代文化、伝統社会、先住民は、天然資源の利用を制限してきた[36]。 持続可能な開発との比較 さらなる情報 持続可能な開発 持続可能性と持続可能な開発という言葉は密接に関連している。実際、両者は同じ意味で使われることが多い[6]。どちらの用語も、「持続可能性の3つの側 面」という概念と結びついている[1]。学者たちは、持続可能な開発は主に人間の幸福に焦点を当てているため、持続可能性の方がより広範な概念であると述 べている[23]。 持続可能な開発には、2つの関連した目標がある。人間の開発目標を達成することである。また、自然システムが経済や社会に必要な天然資源や生態系サービス を提供できるようにすることも目的としている。持続可能な開発という概念は、経済発展、社会発展、将来の世代のための環境保護に焦点を当てるようになった [要出典]。 |

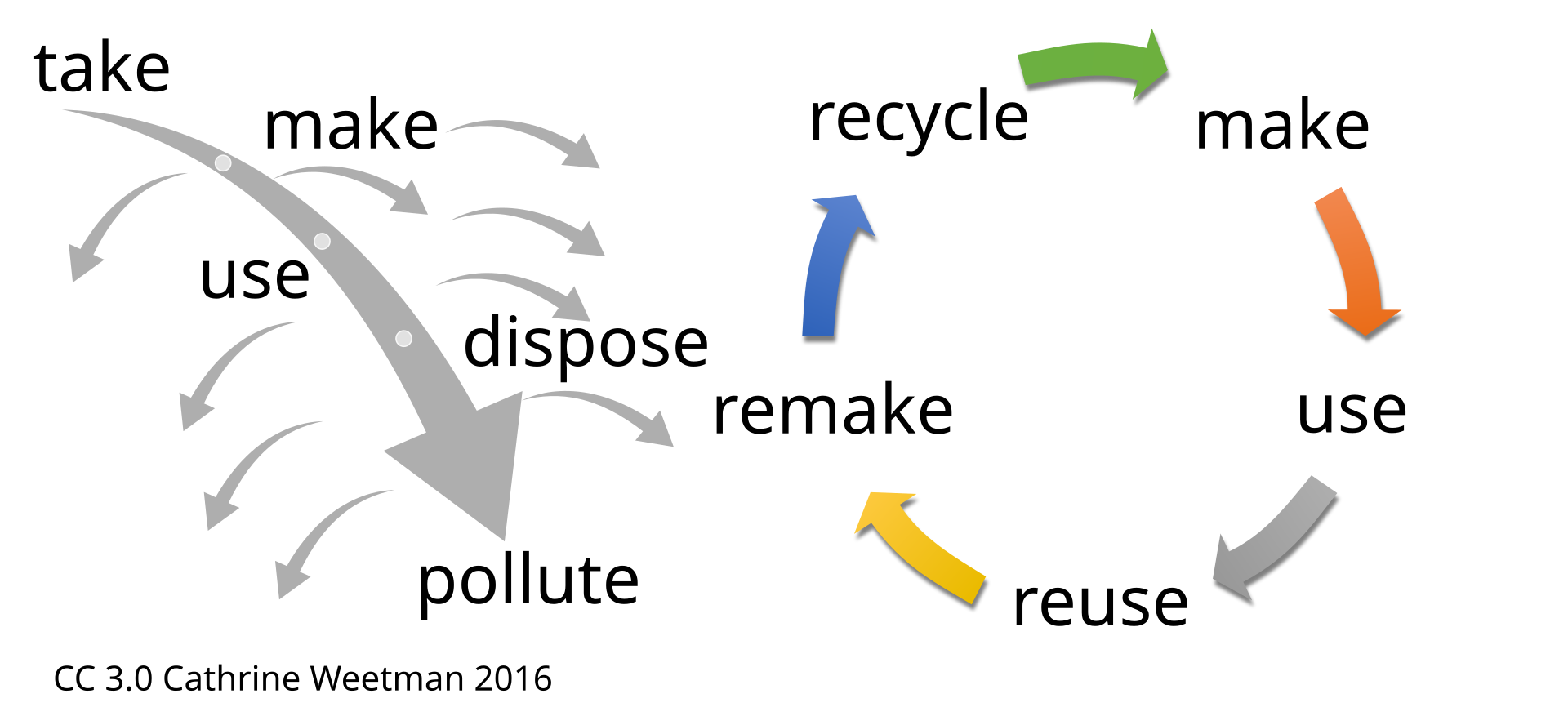

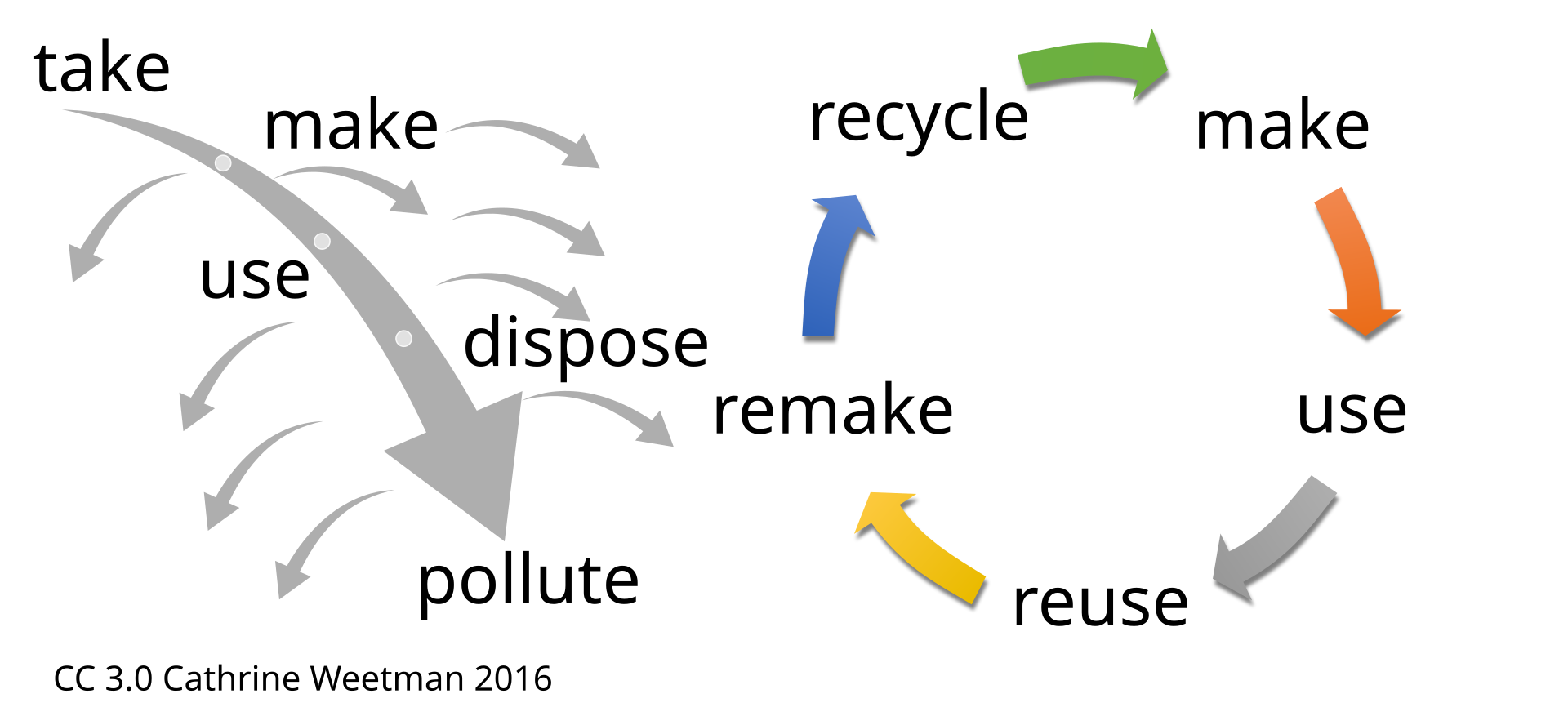

| Dimensions Development of three dimensions  Sustainability Venn diagram, where sustainability is thought of as the area where the three dimensions overlap Scholars usually distinguish three different areas of sustainability. These are the environmental, the social, and the economic. Several terms are in use for this concept. Authors may speak of three pillars, dimensions, components, aspects,[37] perspectives, factors, or goals. All mean the same thing in this context.[1] The three dimensions paradigm has few theoretical foundations.[1] The popular three intersecting circles, or Venn diagram, representing sustainability first appeared in a 1987 article by the economist Edward Barbier.[1][38] Scholars rarely question the distinction itself. The idea of sustainability with three dimensions is a dominant interpretation in the literature.[1] In the Brundtland Report, the environment and development are inseparable and go together in the search for sustainability. It described sustainable development as a global concept linking environmental and social issues. It added sustainable development is important for both developing countries and industrialized countries: The 'environment' is where we all live; and 'development' is what we all do in attempting to improve our lot within that abode. The two are inseparable. [...] We came to see that a new development path was required, one that sustained human progress not just in a few pieces for a few years, but for the entire planet into the distant future. Thus 'sustainable development' becomes a goal not just for the 'developing' nations, but for industrial ones as well. — Our Common Future (also known as the Brundtland Report), [24]: Foreword and Section I.1.10 The Rio Declaration from 1992 is seen as "the foundational instrument in the move towards sustainability".[39]: 29 It includes specific references to ecosystem integrity.[39]: 31 The plan associated with carrying out the Rio Declaration also discusses sustainability in this way. The plan, Agenda 21, talks about economic, social, and environmental dimensions:[40]: 8.6 Countries could develop systems for monitoring and evaluation of progress towards achieving sustainable development by adopting indicators that measure changes across economic, social and environmental dimensions. — United Nations Conference on Environment & Development – Earth Summit (1992), [40]: 8.6 Agenda 2030 from 2015 also viewed sustainability in this way. It sees the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with their 169 targets as balancing "the three dimensions of sustainable development, the economic, social and environmental".[41] Hierarchy  The diagram with three nested ellipses indicates a hierarchy between the three dimensions of sustainability: both economy and society are constrained by environmental limits[42]  The wedding cake model for the sustainable development goals is similar to the nested ellipses diagram, where the environmental dimension or system is the basis for the other two dimensions.[43] Scholars have discussed how to rank the three dimensions of sustainability. Many publications state that the environmental dimension is the most important.[3][4] (Planetary integrity or ecological integrity are other terms for the environmental dimension.) Protecting ecological integrity is the core of sustainability according to many experts.[4] If this is the case then its environmental dimension sets limits to economic and social development.[4] The diagram with three nested ellipses is one way of showing the three dimensions of sustainability together with a hierarchy: It gives the environmental dimension a special status. In this diagram, the environment includes society, and society includes economic conditions. Thus it stresses a hierarchy. Another model shows the three dimensions in a similar way: In this SDG wedding cake model, the economy is a smaller subset of the societal system. And the societal system in turn is a smaller subset of the biosphere system.[43] In 2022 an assessment examined the political impacts of the Sustainable Development Goals. The assessment found that the "integrity of the earth's life-support systems" was essential for sustainability.[3]: 140 The authors said that "the SDGs fail to recognize that planetary, people and prosperity concerns are all part of one earth system, and that the protection of planetary integrity should not be a means to an end, but an end in itself".[3]: 147 The aspect of environmental protection is not an explicit priority for the SDGs. This causes problems as it could encourage countries to give the environment less weight in their developmental plans.[3]: 144 The authors state that "sustainability on a planetary scale is only achievable under an overarching Planetary Integrity Goal that recognizes the biophysical limits of the planet".[3]: 161 Other frameworks bypass the compartmentalization of sustainability into separate dimensions completely.[1] Environmental sustainability Further information: Human impact on the environment The environmental dimension is central to the overall concept of sustainability. People became more and more aware of environmental pollution in the 1960s and 1970s. This led to discussions on sustainability and sustainable development. This process began in the 1970s with concern for environmental issues. These included natural ecosystems or natural resources and the human environment. It later extended to all systems that support life on Earth, including human society.[44]: 31 Reducing these negative impacts on the environment would improve environmental sustainability.[44][45] Environmental pollution is not a new phenomenon. But it has been only a local or regional concern for most of human history. Awareness of global environmental issues increased in the 20th century.[44]: 5 [46] The harmful effects and global spread of pesticides like DDT came under scrutiny in the 1960s.[47] In the 1970s it emerged that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were depleting the ozone layer. This led to the de facto ban of CFCs with the Montreal Protocol in 1987.[5]: 146 In the early 20th century, Arrhenius discussed the effect of greenhouse gases on the climate (see also: history of climate change science).[48] Climate change due to human activity became an academic and political topic several decades later. This led to the establishment of the IPCC in 1988 and the UNFCCC in 1992. In 1972, the UN Conference on the Human Environment took place. It was the first UN conference on environmental issues. It stated it was important to protect and improve the human environment.[49]: 3 It emphasized the need to protect wildlife and natural habitats:[49]: 4 The natural resources of the earth, including the air, water, land, flora and fauna and [...] natural ecosystems must be safeguarded for the benefit of present and future generations through careful planning or management, as appropriate. — UN Conference on the Human Environment, [49]: p.4., Principle 2 In 2000, the UN launched eight Millennium Development Goals. The aim was for the global community to achieve them by 2015. Goal 7 was to "ensure environmental sustainability". But this goal did not mention the concepts of social or economic sustainability.[1] Specific problems often dominate public discussion of the environmental dimension of sustainability: In the 21st century these problems have included climate change, biodiversity and pollution. Other global problems are loss of ecosystem services, land degradation, environmental impacts of animal agriculture and air and water pollution, including marine plastic pollution and ocean acidification.[50][51] Many people worry about human impacts on the environment. These include impacts on the atmosphere, land, and water resources.[44]: 21 Human activities now have an impact on Earth's geology and ecosystems. This led Paul Crutzen to call the current geological epoch the Anthropocene.[52] Economic sustainability  A circular economy can improve aspects of economic sustainability (left: the 'take, make, waste' linear approach; right: the circular economy approach). The economic dimension of sustainability is controversial.[1] This is because the term development within sustainable development can be interpreted in different ways. Some may take it to mean only economic development and growth. This can promote an economic system that is bad for the environment.[53][54][55] Others focus more on the trade-offs between environmental conservation and achieving welfare goals for basic needs (food, water, health, and shelter).[8] Economic development can indeed reduce hunger or energy poverty. This is especially the case in the least developed countries. That is why Sustainable Development Goal 8 calls for economic growth to drive social progress and well-being. Its first target is for: "at least 7 per cent GDP growth per annum in the least developed countries".[56] However, the challenge is to expand economic activities while reducing their environmental impact.[10]: 8 In other words, humanity will have to find ways how societal progress (potentially by economic development) can be reached without excess strain on the environment. The Brundtland report says poverty causes environmental problems. Poverty also results from them. So addressing environmental problems requires understanding the factors behind world poverty and inequality.[24]: Section I.1.8 The report demands a new development path for sustained human progress. It highlights that this is a goal for both developing and industrialized nations.[24]: Section I.1.10 UNEP and UNDP launched the Poverty-Environment Initiative in 2005 which has three goals. These are reducing extreme poverty, greenhouse gas emissions, and net natural asset loss. This guide to structural reform will enable countries to achieve the SDGs.[57][58]: 11 It should also show how to address the trade-offs between ecological footprint and economic development.[5]: 82 Social sustainability  Social justice is just one part of social sustainability. The social dimension of sustainability is not well defined.[59][60][61] One definition states that a society is sustainable in social terms if people do not face structural obstacles in key areas. These key areas are health, influence, competence, impartiality and meaning-making.[62] Some scholars place social issues at the very center of discussions.[63] They suggest that all the domains of sustainability are social. These include ecological, economic, political, and cultural sustainability. These domains all depend on the relationship between the social and the natural. The ecological domain is defined as human embeddedness in the environment. From this perspective, social sustainability encompasses all human activities.[64] It goes beyond the intersection of economics, the environment, and the social.[65] There are many broad strategies for more sustainable social systems. They include improved education and the political empowerment of women. This is especially the case in developing countries. They include greater regard for social justice. This involves equity between rich and poor both within and between countries. And it includes intergenerational equity.[66] Providing more social safety nets to vulnerable populations would contribute to social sustainability.[67]: 11 A society with a high degree of social sustainability would lead to livable communities with a good quality of life (being fair, diverse, connected and democratic).[68] Indigenous communities might have a focus on particular aspects of sustainability, for example spiritual aspects, community-based governance and an emphasis on place and locality.[69] Proposed additional dimensions Some experts have proposed further dimensions. These could cover institutional, cultural, political, and technical dimensions.[1] Cultural sustainability Further information: Cultural sustainability Some scholars have argued for a fourth dimension. They say the traditional three dimensions do not reflect the complexity of contemporary society.[70] For example, Agenda 21 for culture and the United Cities and Local Governments argue that sustainable development should include a solid cultural policy. They also advocate for a cultural dimension in all public policies. Another example was the Circles of Sustainability approach, which included cultural sustainability.[71] |

ディメンション 3つの次元の展開  持続可能性のベン図では、持続可能性は3つの次元が重なる領域と考えられている。 学者は通常、持続可能性を3つの異なる領域に分類している。環境、社会、経済の3つである。この概念にはいくつかの用語が使われている。著者は、3つの 柱、次元、構成要素、側面、視点、要因、または目標について語ることがある[37]。この文脈では、すべてが同じことを意味する[1]。3つの次元のパラ ダイムには理論的な基礎がほとんどない[1]。 持続可能性を表す一般的な3つの交差する円、またはベン図は、経済学者エドワード・バービエによる1987年の論文で初めて登場した[1][38]。 学者がこの区別自体に疑問を呈することはほとんどない。3つの次元を持つ持続可能性という考え方は、文献の中で支配的な解釈である[1]。 ブルントラント報告書では、環境と開発は切り離せないものであり、持続可能性を追求する上で一体であるとしている。ブルントラント報告書では、持続可能な 開発は、環境問題と社会問題を結びつける世界的な概念であるとしている。また、持続可能な開発は、発展途上国と先進国の双方にとって重要であると付け加え た: 環境』とは、私たち全員が住む場所であり、『開発』とは、その住まいの中で私たちの地位を向上させるために私たち全員が行うことである。この2つは切って も切れない関係にある。[私たちは、人類の進歩を数年の間だけでなく、遠い将来まで地球全体で持続させるような、新たな発展の道が必要だと考えるように なった。こうして「持続可能な開発」は、「発展途上」国民だけでなく、先進工業国の目標にもなった。 - Our Common Future』(ブルントラント報告書としても知られる)[24]: 序文とセクションI.1.10 1992年のリオ宣言は、「持続可能性に向けた動きの基礎となる文書」[39]: 29とみなされており、生態系の完全性に関する具体的な言及が含まれている[39]: 31: 31 リオ宣言の実施に関連する計画も、このように持続可能性を論じている。この計画「アジェンダ21」は、経済、社会、環境の各側面について述べている [40]:8.6。 各国は、経済、社会、環境の各側面における変化を測定する指標を採用することにより、持続可能な開発の達成に向けた進捗状況を監視・評価するシステムを開発することができる。 - 国連環境開発会議-地球サミット(1992年)、[40]: 8.6 2015年からのアジェンダ2030も、持続可能性をこのように捉えている。169のターゲットを持つ17の持続可能な開発目標(SDGs)は、「持続可能な開発の3つの次元、経済、社会、環境」のバランスをとるものであると捉えている[41]。 階層  3つの楕円が入れ子になっている図は、持続可能性の3つの次元の間に階層があることを示している。  持続可能な開発目標のウエディング・ケーキ・モデルは、入れ子になった楕円の図に似ており、環境の次元やシステムが他の2つの次元の基礎となっている[43]。 学者たちは、持続可能性の3つの次元をどのようにランク付けするか議論してきた。多くの出版物は、環境の次元が最も重要であると述べている[3][4] (Planetary IntegrityまたはEcological Integrityは、環境の次元を表す他の用語である)。 多くの専門家によれば、生態系の完全性を守ることが持続可能性の核心である[4]。 そうであるならば、環境次元は経済的・社会的発展の限界を設定することになる[4]。 3つの楕円が入れ子になっている図は、持続可能性の3つの次元を階層とともに示す1つの方法である: この図では、環境の次元に特別な地位を与えている。この図では、環境には社会が含まれ、社会には経済状況が含まれる。この図では、環境は社会を含み、社会 は経済状況を含む。 もう一つのモデルは、3つの次元を同様の方法で示している: このSDGsのウェディングケーキモデルでは、経済は社会システムの小さなサブセットである。そして社会システムは、生物圏システムのより小さなサブセットである。 2022年、ある評価が持続可能な開発目標の政治的影響を調査した。その評価では、「地球の生命維持システムの完全性」が持続可能性にとって不可欠である ことが明らかにされた[3]: 140 著者は、「SDGsは、惑星、人間、繁栄の懸念がすべて1つの地球システムの一部であることを認識しておらず、惑星の完全性の保護は手段ではなく、それ自 体が目的であるべきである」と述べている[3]: 147 環境保護の側面は、SDGsの明確な優先事項ではない。このことは、各国が開発計画において環境の比重を低くすることを助長しかねないという問題を引き起 こす[3]: 144 著者は、「惑星規模での持続可能性は、地球の生物物理学的限界を認識する包括的な惑星完全性目標の下でのみ達成可能である」と述べている[3]: 161 他の枠組みは、持続可能性を個別の次元に区分することを完全に回避している[1]。 環境の持続可能性 さらなる情報 人間が環境に与える影響 環境という側面は、持続可能性という概念全体の中心をなすものである。1960年代から1970年代にかけて、環境汚染に対する人々の意識が高まった。そ の結果、持続可能性と持続可能な開発についての議論が始まった。このプロセスは1970年代に環境問題への関心から始まった。その中には、自然の生態系や 天然資源、そして人間環境も含まれていた。その後、それは人間社会を含む、地球上の生命を支えるすべてのシステムにまで拡大した[44]: 31 こうした環境への悪影響を減らすことは、環境の持続可能性を向上させることになる[44][45]。 環境汚染は新しい現象ではない。しかし、人類の歴史の大部分において、環境汚染は地域的または局所的な問題でしかなかった。地球環境問題に対する意識が高 まったのは20世紀に入ってからである[44]: 5[46]。1960年代には、DDTのような農薬の有害な影響と世界的な広がりがクローズアップされ た[47]。1970年代には、フロン(CFCs)がオゾン層を破壊していることが明らかになった。このため、1987年のモントリオール議定書によって フロンが事実上禁止された[5]: 146 20世紀初頭、アレニウスは温室効果ガスが気候に及ぼす影響について議論した(気候変動科学の歴史も参照)[48]。その結果、1988年にIPCCが設立され、1992年にUNFCCCが設立された。 1972年、国連人間環境会議が開催された。これは環境問題に関する最初の国連会議であった。同会議は、人間環境を保護し改善することが重要であると述べた[49]: 3 野生生物と自然の生息地を保護する必要性を強調した[49]: 4 大気、水、土地、動植物、[...]自然生態系を含む地球の天然資源は、現在および将来の世代の利益のために、必要に応じて慎重な計画または管理を通じて保護されなければならない。 - 国連人間環境会議、[49]:4ページ、原則2 2000年、国連は8つのミレニアム開発目標を打ち出した。その目的は、2015年までにそれらを達成することであった。目標7は「環境の持続可能性の確保」であった。しかし、この目標には社会的、経済的持続可能性という概念は言及されていなかった[1]。 持続可能性の環境的側面に関する公的な議論では、しばしば特定の問題が支配的である: 21世紀には、気候変動、生物多様性、公害などの問題があった。21世紀には、気候変動、生物多様性、汚染などがこうした問題に含まれている。その他の世 界的な問題としては、生態系サービスの喪失、土地の劣化、畜産業が環境に与える影響、海洋プラスチック汚染や海洋酸性化を含む大気汚染や水質汚染などがあ る[50][51]。これには大気、土地、水資源への影響が含まれる。 人間の活動は現在、地球の地質や生態系に影響を与えている。このことから、ポール・クルッツェンは現在の地質学的エポックを「人新世」と呼んだ[52]。 経済的持続可能性  循環型経済は、経済的持続可能性の側面を改善することができる(左:「取る、作る、無駄にする」直線的アプローチ、右:循環型経済アプローチ)。 持続可能性の経済的側面については議論がある[1]。 持続可能な開発における開発という用語は、さまざまな解釈が可能だからである。経済的な発展と成長だけを意味すると考える人もいるだろう。また、環境保全 と基本的ニーズ(食料、水、健康、住居)に対する福祉目標の達成との間のトレードオフに重点を置く人もいる[8]。 経済発展は、確かに飢餓やエネルギー貧困を減らすことができる。これは特に後発開発途上国において顕著である。だからこそ、持続可能な開発目標8は、社会 的進歩と福祉を推進するための経済成長を求めているのである。その最初の目標は以下の通りである: 「しかし、課題は、環境への影響を抑えながら経済活動を拡大することである。 ブルントラント報告書は、貧困が環境問題を引き起こすと述べている。貧困は環境問題の結果でもある。したがって、環境問題に取り組むには、世界の貧困と不 平等の背後にある要因を理解する必要がある[24]: セクションI.1.8 報告書は、人類の持続的進歩のための新たな開発路線を要求している。これは開発途上国と先進国の双方にとっての目標であることを強調している[24]: 第I.1.10節 国連環境計画(UNEP)と国連開発計画(UNDP)は、2005年に「貧困・環境イニシアティブ」を立ち上げ、3つの目標を掲げている。極度の貧困の削 減、温室効果ガスの排出削減、自然資産の正味損失の削減である。この構造改革ガイドは、各国がSDGsを達成することを可能にする[57][58]: 11 また、エコロジカル・フットプリントと経済発展の間のトレードオフにどのように対処するかを示すべきである。 社会の持続可能性  社会正義は、社会的持続可能性の一部分に過ぎない。 持続可能性の社会的側面は十分に定義されていない[59][60][61]。ある定義では、人々が主要な分野において構造的な障害に直面しなければ、その 社会は社会的に持続可能であるとしている。これらの重要な領域とは、健康、影響力、能力、公平性、意味形成である[62]。 社会問題を議論の中心に据える学者もいる[63]。彼らは、持続可能性のすべての領域が社会的であると示唆している。これらの領域には、生態学的持続可能 性、経済的持続可能性、政治的持続可能性、文化的持続可能性が含まれる。これらの領域はすべて、社会と自然の関係に依存している。生態学的領域は、環境に 組み込まれた人間として定義される。この観点から、社会的持続可能性は、すべての人間活動を包含する[64]。経済、環境、社会が交差する領域を超えてい る[65]。 より持続可能な社会システムのための広範な戦略は数多くある。その中には、教育の改善や女性の政治的エンパワーメントも含まれる。これは特に発展途上国に おけるケースである。社会正義をより重視することも含まれる。これには、国内および国家間の貧富の公平が含まれる。また、世代間の公平性も含まれる [66]。社会的弱者により多くの社会的セーフティ・ネットを提供することは、社会の持続可能性に貢献するだろう[67]: 11 社会的持続可能性の高い社会は、生活の質の高い(公平で、多様で、つながりがあり、民主的な)住みやすいコミュニティをもたらすであろう[68]。 先住民のコミュニティは、持続可能性の特定の側面、例えば、精神的な側面、コミュニティを基盤とした統治、場所と地域性の重視などに重点を置くかもしれない[69]。 さらなる次元の提案 さらなる次元を提案する専門家もいる。これらは、制度的、文化的、政治的、技術的な次元をカバーすることができる[1]。 文化的持続可能性 さらなる情報 文化的持続可能性 第4の次元を主張する学者もいる。彼らは、従来の3つの次元は現代社会の複雑性を反映していないと述べている[70]。例えば、文化のためのアジェンダ 21や都市と地方自治体の連合は、持続可能な開発には確固たる文化政策が含まれるべきだと主張している。彼らはまた、すべての公共政策に文化的な側面を取 り入れることを提唱している。もうひとつの例は、文化の持続可能性を含む「持続可能性の輪」アプローチである[71]。 |

| Interactions between dimensions Environmental and economic dimensions Further information: Weak and strong sustainability See also: Sustainable city People often debate the relationship between the environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability.[72] In academia, this is discussed under the term weak and strong sustainability. In that model, the weak sustainability concept states that capital made by humans could replace most of the natural capital.[73][72] Natural capital is a way of describing environmental resources. People may refer to it as nature. An example for this is the use of environmental technologies to reduce pollution.[74] The opposite concept in that model is strong sustainability. This assumes that nature provides functions that technology cannot replace.[75] Thus, strong sustainability acknowledges the need to preserve ecological integrity.[5]: 19 The loss of those functions makes it impossible to recover or repair many resources and ecosystem services. Biodiversity, along with pollination and fertile soils, are examples. Others are clean air, clean water, and regulation of climate systems. Weak sustainability has come under criticism. It may be popular with governments and business but does not ensure the preservation of the earth's ecological integrity.[76] This is why the environmental dimension is so important.[4] The World Economic Forum illustrated this in 2020. It found that $44 trillion of economic value generation depends on nature. This value, more than half of the world's GDP, is thus vulnerable to nature loss.[77]: 8 Three large economic sectors are highly dependent on nature: construction, agriculture, and food and beverages. Nature loss results from many factors. They include land use change, sea use change and climate change. Other examples are natural resource use, pollution, and invasive alien species.[77]: 11 Trade-offs Trade-offs between different dimensions of sustainability are a common topic for debate. Balancing the environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability is difficult. This is because there is often disagreement about the relative importance of each. To resolve this, there is a need to integrate, balance, and reconcile the dimensions.[1] For example, humans can choose to make ecological integrity a priority or to compromise it.[4] Some even argue the Sustainable Development Goals are unrealistic. Their aim of universal human well-being conflicts with the physical limits of Earth and its ecosystems.[21]: 41 |

次元間の相互作用 環境的・経済的側面 さらに詳しい情報 弱い持続可能性と強い持続可能性 以下も参照のこと: 持続可能な都市 持続可能性の環境的側面と経済的側面の関係について、人々はしばしば議論する[72]。学界では、これを弱い持続可能性と強い持続可能性という用語で議論 している。このモデルでは、弱い持続可能性の概念は、人間によって作られた資本が自然資本のほとんどに取って代わる可能性があると述べている[73] [72]。人々はそれを自然と呼ぶこともある。その例として、汚染を削減するための環境技術の利用が挙げられる[74]。 そのモデルにおける反対の概念は、強力な持続可能性である。これは、技術では代替できない機能を自然が提供することを前提としている[75]。したがっ て、強い持続可能性は、生態系の完全性を維持する必要性を認めている[5]: 19 このような機能が失われると、多くの資源や生態系サービスの回復や修復が不可能になる。受粉や肥沃な土壌とともに、生物多様性がその例である。その他に も、きれいな空気、きれいな水、気候システムの調整などがある。 脆弱な持続可能性には批判もある。政府や企業には好評かもしれないが、地球の生態学的完全性の保全は保証されていない[76]。 世界経済フォーラムは、2020年にこのことを説明した。同フォーラムは、44兆ドルの経済的価値の創出が自然に依存していることを明らかにした。この価 値は世界のGDPの半分以上であるため、自然損失に対して脆弱である[77]。建設、農業、食品・飲料の3つの大きな経済部門は、自然への依存度が高い。 自然損失は、多くの要因から生じる。土地利用の変化、海洋利用の変化、気候変動などである。その他の例としては、天然資源の利用、汚染、侵略的外来種など がある[77]: 11 トレードオフ 持続可能性の異なる次元間のトレードオフは、よく議論されるテーマである。持続可能性の環境的、社会的、経済的側面のバランスをとることは難しい。なぜな ら、それぞれの相対的な重要性について意見が分かれることが多いからである。これを解決するためには、各次元を統合し、バランスをとり、調和させる必要が ある[1]。例えば、人間は生態系の完全性を優先するか、妥協するかを選択することができる[4]。 持続可能な開発目標は非現実的だと主張する人さえいる。人間の普遍的な幸福を目指すその目標は、地球とその生態系の物理的限界と相反しているのである[21]: 41 |

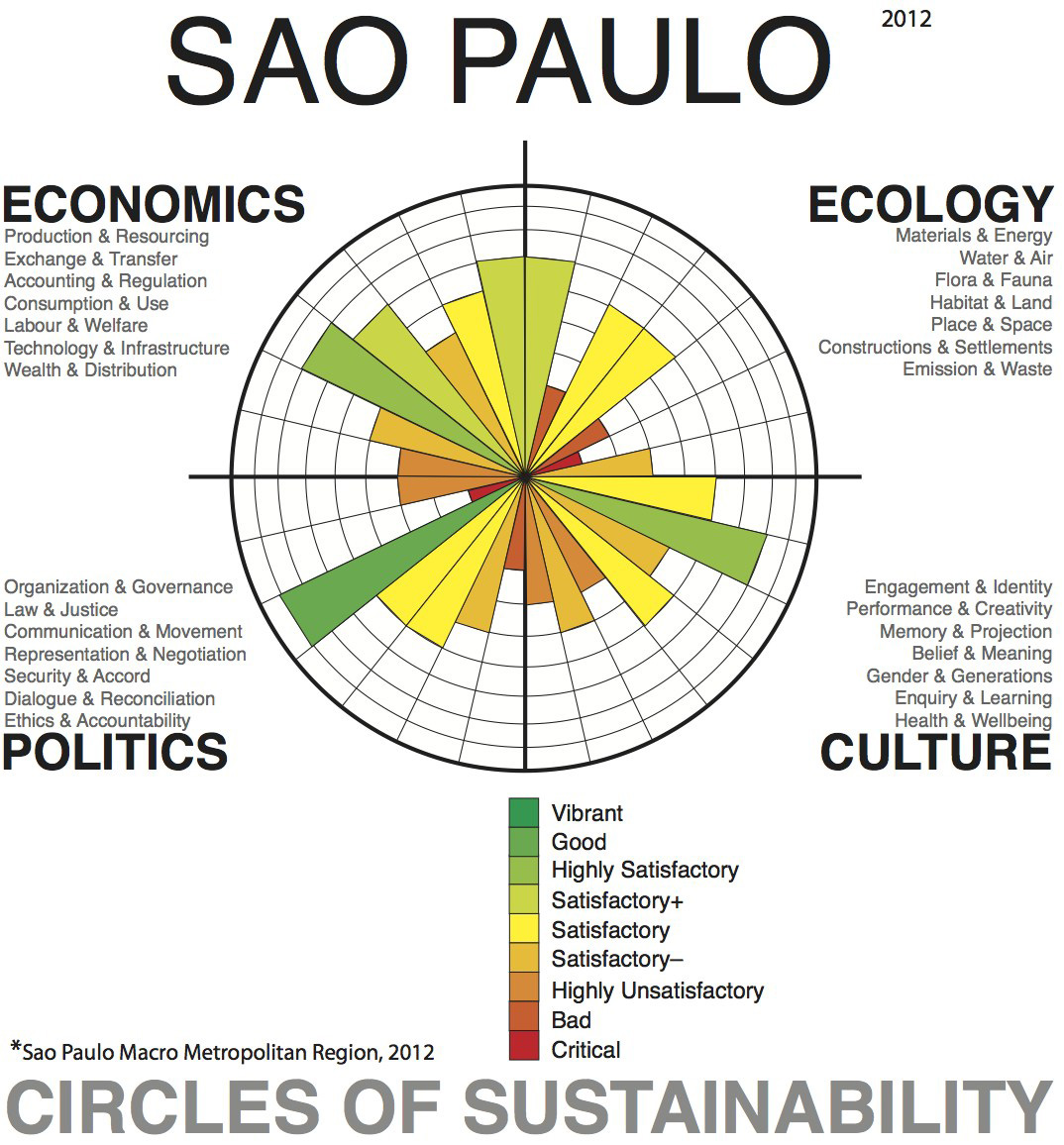

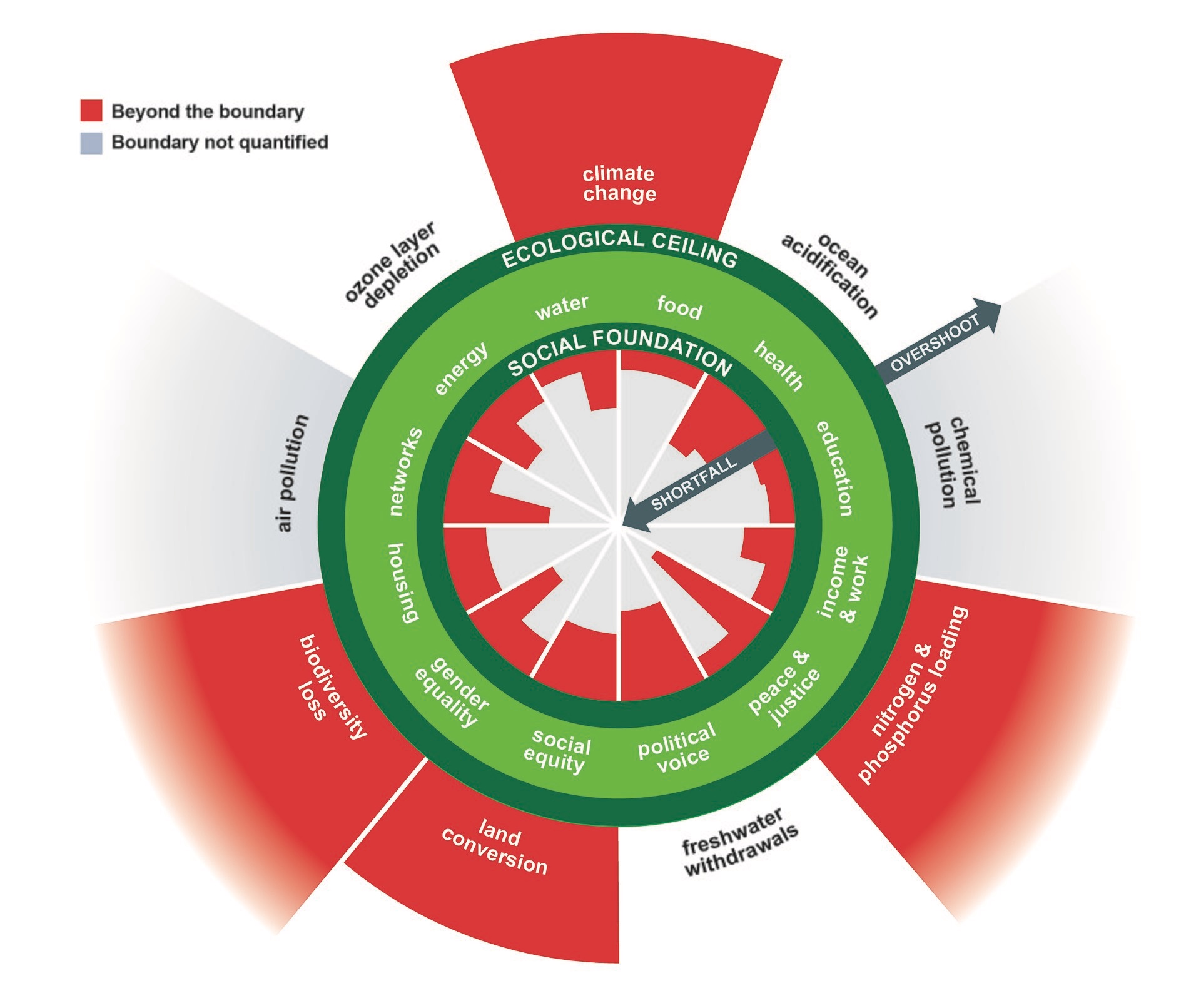

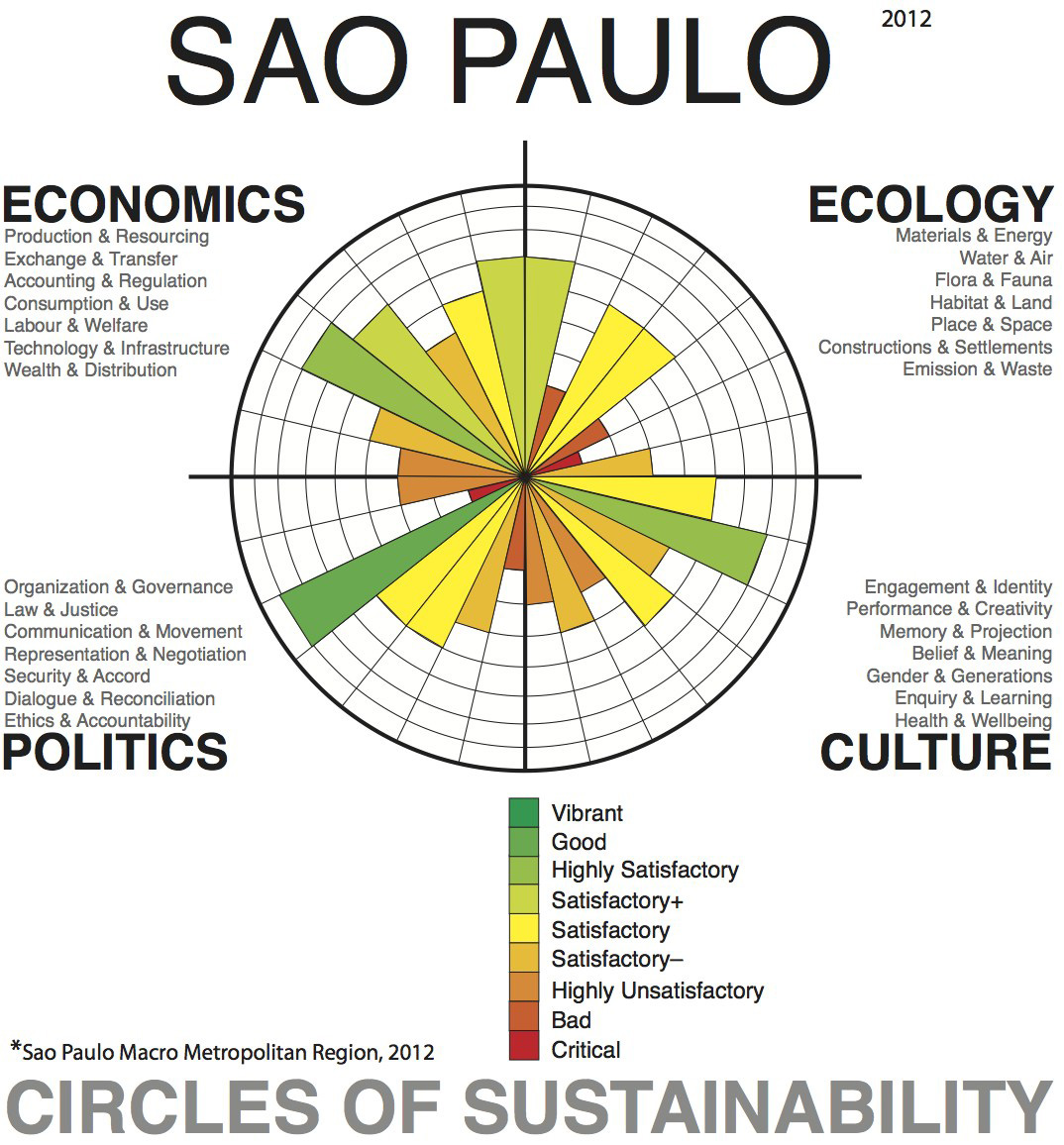

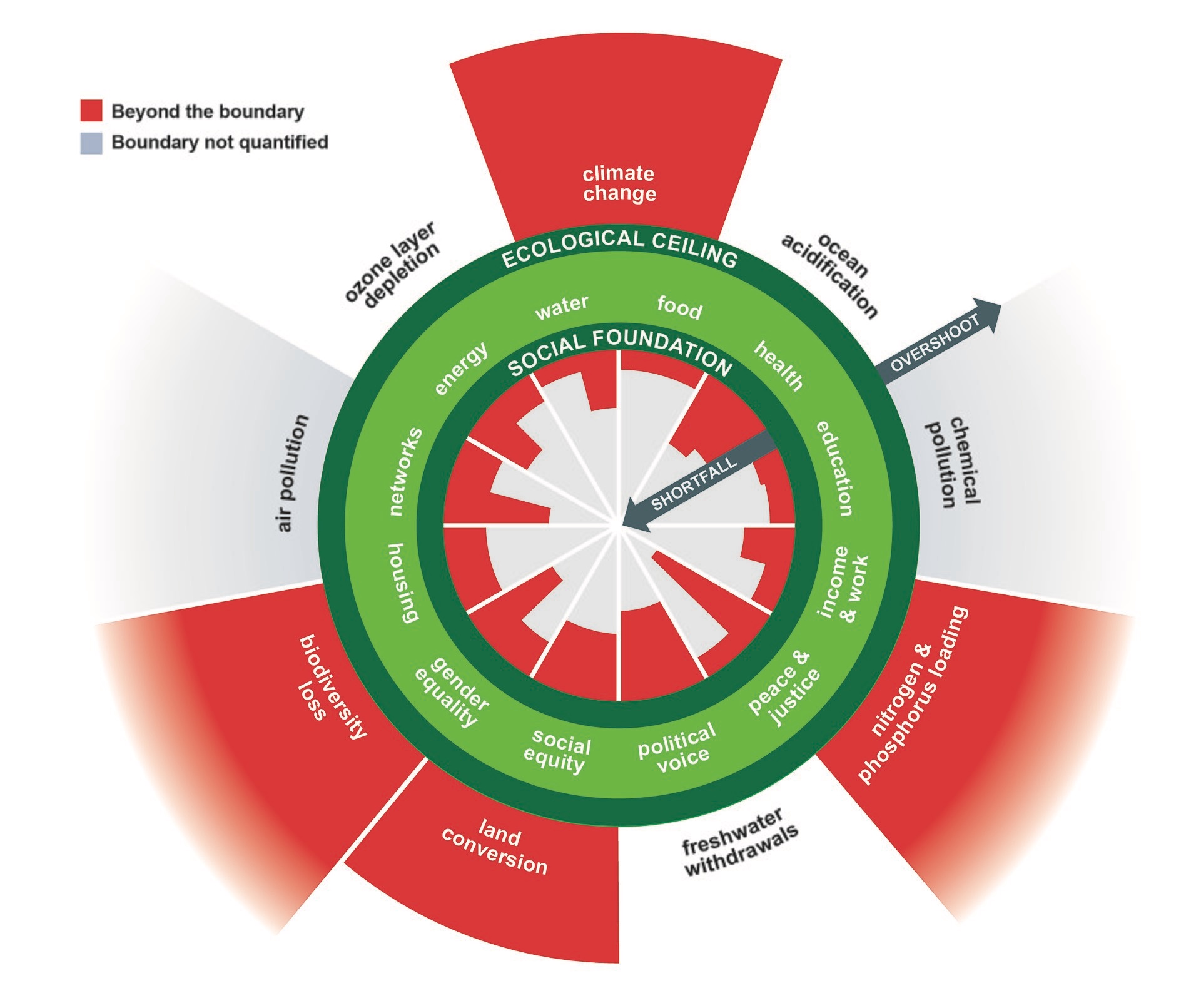

| Measurement tools Further information: Sustainability metrics and indices  Urban sustainability analysis of the greater urban area of the city of São Paulo using the 'Circles of Sustainability' method of the UN and Metropolis Association[78] This section is an excerpt from Sustainability measurement.[edit] Sustainability measurement is a set of frameworks or indicators used to measure how sustainable something is. This includes processes, products, services and businesses. Sustainability is dijfjfbfn to quantify.[79] It may even be impossible to measure as there is no fixed definition.[80] To measure sustainability, frameworks and indicators consider environmental, social and economic domains. The metrics vary by use case and are still evolving. They include indicators, benchmarks and audits. They include sustainability standards and certification systems like Fairtrade and Organic. They also involve indices and accounting. They can include assessment, appraisal[81] and other reporting systems. The metrics are used over a wide range of spatial and temporal scales.[82][80] For organizations, sustainability measures include corporate sustainability reporting and Triple Bottom Line accounting.[79] For countries, they include estimates of the quality of sustainability governance or quality of life measures, or environmental assessments like the Environmental Sustainability Index and Environmental Performance Index. Some methods let us track sustainable development.[83][84] These include the UN Human Development Index and ecological footprints. Environmental impacts of humans Further information: Planetary boundaries and Ecological footprint There are several methods to measure or describe human impacts on Earth. They include the ecological footprint, ecological debt, carrying capacity, and sustainable yield. The idea of planetary boundaries is that there are limits to the carrying capacity of the Earth. It is important not to cross these thresholds to prevent irreversible harm to the Earth.[85][86] These planetary boundaries involve several environmental issues. These include climate change and biodiversity loss. They also include types of pollution. These are biogeochemical (nitrogen and phosphorus), ocean acidification, land use, freshwater, ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosols, and chemical pollution.[85][87] (Since 2015 some experts refer to biodiversity loss as change in biosphere integrity. They refer to chemical pollution as introduction of novel entities.) The IPAT formula measures the environmental impact of humans. It emerged in the 1970s. It states this impact is proportional to human population, affluence and technology.[88] This implies various ways to increase environmental sustainability. One would be human population control. Another would be to reduce consumption and affluence[89] such as energy consumption. Another would be to develop innovative or green technologies such as renewable energy. In other words, there are two broad aims. The first would be to have fewer consumers. The second would be to have less environmental footprint per consumer. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment from 2005 measured 24 ecosystem services. It concluded that only four have improved over the last 50 years. It found 15 are in serious decline and five are in a precarious condition.[90]: 6–19 Economic costs  The doughnut model, with indicators to what extent the ecological ceilings are overshot and social foundations are not met yet Experts in environmental economics have calculated the cost of using public natural resources. One project calculated the damage to ecosystems and biodiversity loss. This was the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity project from 2007 to 2011.[91] An entity that creates environmental and social costs often does not pay for them. The market price also does not reflect those costs. In the end, government policy is usually required to resolve this problem.[92] Decision-making can take future costs and benefits into account. The tool for this is the social discount rate. The bigger the concern for future generations, the lower the social discount rate should be.[93] Another approach is to put an economic value on ecosystem services. This allows us to assess environmental damage against perceived short-term welfare benefits. One calculation is that, "for every dollar spent on ecosystem restoration, between three and 75 dollars of economic benefits from ecosystem goods and services can be expected".[94] In recent years, economist Kate Raworth has developed the concept of doughnut economics. This aims to integrate social and environmental sustainability into economic thinking. The social dimension acts as a minimum standard to which a society should aspire. The carrying capacity of the planet acts an outer limit.[95] |

測定ツール さらに詳しい情報 持続可能性の測定基準と指標  国連とメトロポリス協会の「サークルズ・オブ・サステナビリティ」手法を用いたサンパウロ市の大都市圏の都市持続可能性分析[78]。 このセクションは、持続可能性の測定[編集]からの抜粋である。 持続可能性測定とは、何かがどの程度持続可能であるかを測定するために使用される一連のフレームワークまたは指標である。これには、プロセス、製品、サービス、ビジネスが含まれる。持続可能性とは、定量化することである[79]。 持続可能性を測定するために、フレームワークや指標は環境、社会、経済の領域を考慮する。指標はユースケースによって異なり、現在も進化を続けている。指 標、ベンチマーク、監査が含まれる。また、フェアトレードやオーガニックのような持続可能性の基準や認証制度も含まれる。また、指標や会計も含まれる。評 価、鑑定[81]、その他の報告システムも含まれる。組織の場合、持続可能性の尺度には、企業の持続可能性報告書やトリプルボトムライン会計[79]が含 まれ、国の場合、持続可能性ガバナンスの質の推定や生活の質の尺度、あるいは環境持続可能性指数や環境パフォーマンティ指数のような環境評価が含まれる。 国連人間開発指数やエコロジカル・フットプリントなど、持続可能な開発を追跡できる手法もある[83][84]。 人間が環境に与える影響 さらなる情報 惑星境界とエコロジカル・フットプリント 人類が地球に与える影響を測定したり表現したりする方法はいくつかある。エコロジカル・フットプリント、エコロジカル・デット、環境収容力、持続可能な収 穫量などである。惑星間境界の考え方は、地球の環境収容力には限界があるというものである。地球への不可逆的な危害を防ぐためには、これらの閾値を超えな いことが重要である。気候変動や生物多様性の損失などがそれである。また、汚染の種類も含まれる。これらは、生物地球化学的(窒素とリン)、海洋酸性化、 土地利用、淡水、オゾン層破壊、大気エアロゾル、化学汚染である[85][87](2015年以降、生物多様性の損失を生物圏の完全性の変化と呼ぶ専門家 もいる)。2015年以降、一部の専門家は、生物多様性の損失を生物圏の完全性の変化と呼んでいる[85][87]。 IPAT式は、人間が環境に与える影響を測定するものである。これは1970年代に登場した。この影響は、人間の人口、豊かさ、技術に比例するとしている [88]。これは、環境の持続可能性を高めるためのさまざまな方法を示唆している。ひとつは人間の人口抑制である。もうひとつは、エネルギー消費などの消 費や豊かさ[89]を削減することである。もうひとつは、再生可能エネルギーなどの革新的な技術やグリーンな技術を開発することである。つまり、2つの大 きな目的がある。ひとつは、消費者を減らすことである。もうひとつは、消費者一人当たりの環境フットプリントを減らすことである。 2005年のミレニアム生態系評価では、24の生態系サービスが測定された。その結果、過去50年間で改善したのはわずか4つだけであると結論づけられた。また、15が深刻な衰退状態にあり、5が不安定な状態にあることがわかった[90]。 経済的コスト  ドーナツ・モデルは、生態系の上限がどの程度超過し、社会的基盤がどの程度満たされていないかを示す指標である。 環境経済学の専門家は、公共の自然資源を利用するコストを計算している。あるプロジェクトでは、生態系へのダメージと生物多様性の損失を計算した。2007年から2011年までの「生態系と生物多様性の経済学」プロジェクトである[91]。 環境コストや社会コストを生み出す主体は、多くの場合、そのコストを支払わない。市場価格もまた、そうしたコストを反映していない。結局、この問題を解決するためには、政府の政策が必要になることが多い[92]。 意思決定では、将来のコストと便益を考慮することができる。そのためのツールが社会的割引率である。将来の世代に対する懸念が大きいほど、社会的割引率は 低くなるはずである[93]。もう一つのアプローチは、生態系サービスに経済的価値をつけることである。これによって、環境破壊を、短期的な厚生便益と比 較して評価することができる。ある計算では、「生態系の回復に1ドル費やすごとに、生態系の財やサービスから3~75ドルの経済的便益が期待できる」とさ れている[94]。 近年、経済学者のケイト・ローワースは、ドーナツ経済学という概念を開発した。これは、社会と環境の持続可能性を経済的思考に統合することを目的としている。社会的側面は、社会が目指すべき最低限の基準として機能する。地球の環境収容力は外的限界の役割を果たす。 |

| Barriers There are many reasons why sustainability is so difficult to achieve. These reasons have the name sustainability barriers.[5][16] Before addressing these barriers it is important to analyze and understand them.[5]: 34 Some barriers arise from nature and its complexity ("everything is related").[23] Others arise from the human condition. One example is the value-action gap. This reflects the fact that people often do not act according to their convictions. Experts describe these barriers as intrinsic to the concept of sustainability.[96]: 81 Other barriers are extrinsic to the concept of sustainability. This means it is possible to overcome them. One way would be to put a price tag on the consumption of public goods.[96]: 84 Some extrinsic barriers relate to the nature of dominant institutional frameworks. Examples would be where market mechanisms fail for public goods. Existing societies, economies, and cultures encourage increased consumption. There is a structural imperative for growth in competitive market economies. This inhibits necessary societal change.[89] Furthermore, there are several barriers related to the difficulties of implementing sustainability policies. There are trade-offs between the goals of environmental policies and economic development. Environmental goals include nature conservation. Development may focus on poverty reduction.[16][5]: 65 There are also trade-offs between short-term profit and long-term viability.[96]: 65 Political pressures generally favor the short term over the long term. So they form a barrier to actions oriented toward improving sustainability.[96]: 86 Barriers to sustainability may also reflect current trends. These could include consumerism and short-termism.[96]: 86 |

障壁 持続可能性の実現が困難な理由は数多くある。これらの障壁に取り組む前に、障壁を分析し理解することが重要である[5][16]: 34 いくつかの障壁は、自然とその複雑性(「すべては関連している」)から生じる[23]。一例として、価値と行動のギャップがある。これは、人がしばしば信 念に従って行動しないという事実を反映している。専門家は、こうした障壁を持続可能性の概念に内在するものと表現している[96]: 81。 その他の障壁は、持続可能性の概念に外在するものである。つまり、それらを克服することは可能である。一つの方法は、公共財の消費に値札をつけることであ る[96]: 84 外在的な障壁の中には、支配的な制度的枠組みの性質に関係するものもある。例えば、市場メカニズムが公共財のために機能しない場合である。既存の社会、経 済、文化は、消費の拡大を奨励している。競争的な市場経済には、成長を求める構造的な要請がある。このことが、必要な社会の変化を阻害している[89]。 さらに、持続可能性政策を実施することの難しさに関連するいくつかの障壁がある。環境政策の目標と経済発展の間にはトレードオフがある。環境目標には自然 保護が含まれる。また、短期的な利益と長期的な存続可能性との間にもトレードオフがある。そのため、政治的圧力は、持続可能性の向上を目指した行動に対す る障壁となる[96]: 86。 持続可能性に対する障壁は、現在の傾向を反映している場合もある。これには消費主義や短期主義が含まれる[96]: 86。 |

| Transitions Components and characteristics The European Environment Agency defines a sustainability transition as "a fundamental and wide-ranging transformation of a socio-technical system towards a more sustainable configuration that helps alleviate persistent problems such as climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss or resource scarcities."[97]: 152 The concept of sustainability transitions is like the concept of energy transitions.[98] One expert argues a sustainability transition must be "supported by a new kind of culture, a new kind of collaboration, [and] a new kind of leadership".[99] It requires a large investment in "new and greener capital goods, while simultaneously shifting capital away from unsustainable systems".[21]: 107 It prefers these to unsustainable options.[21]: 101 In 2024 an interdisciplinary group of experts including Chip Fletcher, William J. Ripple, Phoebe Barnard, Kamanamaikalani Beamer, Christopher Field, David Karl, David King, Michael E. Mann and Naomi Oreskes published the academic paper "Earth at Risk". They made an extensive review of existing scientific literature, placing the blame for the ecological crisis on "imperialism, extractive capitalism, and a surging population" and proposed a paradigm shift that replaces it with a socio-economic model prioritizing sustainability, resilience, justice, kinship with nature, and communal well-being. They described many ways in which the transition to a sustainable future can be achieved.[100] A sustainability transition requires major change in societies. They must change their fundamental values and organizing principles.[44]: 15 These new values would emphasize "the quality of life and material sufficiency, human solidarity and global equity, and affinity with nature and environmental sustainability".[44]: 15 A transition may only work if far-reaching lifestyle changes accompany technological advances.[89] Scientists have pointed out that: "Sustainability transitions come about in diverse ways, and all require civil-society pressure and evidence-based advocacy, political leadership, and a solid understanding of policy instruments, markets, and other drivers."[51] There are four possible overlapping processes of transformation. They each have different political dynamics. Technology, markets, government, or citizens can lead these processes.[22] Principles It is possible to divide action principles to make societies more sustainable into four types. These are nature-related, personal, society-related and systems-related principles.[5]: 206 Nature-related principles: decarbonize; reduce human environmental impact by efficiency, sufficiency and consistency; be net-positive – build up environmental and societal capital; prefer local, seasonal, plant-based and labor-intensive; polluter-pays principle; precautionary principle; and appreciate and celebrate the beauty of nature. Personal principles: practise contemplation, apply policies with caution, celebrate frugality. Society-related principles: grant the least privileged the greatest support; seek mutual understanding, trust and many wins; strengthen social cohesion and collaboration; engage stakeholders; foster education – share knowledge and collaborate. Systems-related principles: apply systems thinking; foster diversity; make what is relevant to the public more transparent; maintain or increase option diversity. Example steps There are many approaches that people can take to transition to environmental sustainability. These include maintaining ecosystem services, protecting and co-creating common resources, reducing food waste, and promoting dietary shifts towards plant-based foods.[101] Another is reducing population growth by cutting fertility rates. Others are promoting new green technologies, and adopting renewable energy sources while phasing out subsidies to fossil fuels.[51] In 2017 scientists published an update to the 1992 World Scientists' Warning to Humanity. It showed how to move towards environmental sustainability. It proposed steps in three areas:[51] Reduced consumption: reducing food waste, promoting dietary shifts towards mostly plant-based foods. Reducing the number of consumers: further reducing fertility rates and thus population growth. Technology and nature conservation: there are several related approaches. One is to maintain nature's ecosystem services. Another is promote new green technologies. Another is changing energy use. One aspect of this is to adopt renewable energy sources. At the same time it is necessary to end subsidies to energy production through fossil fuels. Agenda 2030 for the Sustainable Development Goals  United Nations Sustainable Development Goals In 2015, the United Nations agreed the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Their official name is Agenda 2030 for the Sustainable Development Goals. The UN described this programme as a very ambitious and transformational vision. It said the SDGs were of unprecedented scope and significance.[41]: 3/35 The UN said: "We are determined to take the bold and transformative steps which are urgently needed to shift the world on to a sustainable and resilient path."[41] The 17 goals and targets lay out transformative steps. For example, the SDGs aim to protect the future of planet Earth. The UN pledged to "protect the planet from degradation, including through sustainable consumption and production, sustainably managing its natural resources and taking urgent action on climate change, so that it can support the needs of the present and future generations".[41] |

トランジション 構成要素と特徴 欧州環境庁は、持続可能性の移行を「気候変動、汚染、生物多様性の損失、資源不足といった持続的な問題の緩和に役立つ、より持続可能な構成に向けた社会技 術システムの根本的かつ広範な変革」と定義している[97]: 152 持続可能性の移行という概念は、エネルギーの移行という概念に似ている[98]。 ある専門家は、持続可能性の移行は「新しい種類の文化、新しい種類の協働、(そして)新しい種類のリーダーシップに支えられ」なければならないと主張して いる[99]。 持続可能性の移行には、「新しく環境に優しい資本財への大規模な投資が必要であり、同時に資本を持続不可能なシステムからシフトさせる」必要がある [21]: 107 持続可能でない選択肢よりも、こうした選択肢を好むのである[21]: 101 2024年、チップ・フレッチャー、ウィリアム・J・リップル、フィービー・バーナード、カマナマイカラニ・ビーマー、クリストファー・フィールド、デ ビッド・カール、デビッド・キング、マイケル・E・マン、ナオミ・オレスケスを含む学際的な専門家グループが、学術論文「Earth at Risk」を発表した。彼らは既存の科学文献を幅広くレビューし、生態系危機の責任を「帝国主義、採取資本主義、急増する人口」に求め、それを持続可能 性、回復力、正義、自然との親和性、共同体の幸福を優先する社会経済モデルに置き換えるパラダイムシフトを提案した。彼らは、持続可能な未来への移行を達 成するための多くの方法を説明した[100]。 持続可能性への移行は、社会における大きな変化を必要とする。社会は基本的な価値観や組織原理を変えなければならない: 15 こうした新しい価値観は、「生活の質と物質的充足、人間の連帯とグローバルな公平性、自然との親和性と環境の持続可能性」を強調するものである[44]: 15 移行がうまくいくのは、技術の進歩に伴ってライフスタイルが大きく変化した場合に限られるかもしれない[89]。 科学者たちは次のように指摘している: 「持続可能性の移行は多様な方法でもたらされ、そのすべてに市民社会の圧力と証拠に基づくアドボカシー、政治的リーダーシップ、政策手段、市場、その他の推進要因に関する確かな理解が必要である」[51]。 変革のプロセスには、4つの重複する可能性がある。これらはそれぞれ、異なる政治力学を有している。テクノロジー、市場、政府、または市民が、これらのプロセスを主導することができる[22]。 原則 社会をより持続可能なものにするための行動原則を4つのタイプに分けることができる。すなわち、自然関連原則、個人関連原則、社会関連原則、システム関連原則である[5]。 自然関連の原則:脱炭素化、効率性、充足性、一貫性による人間の環境への影響の低減、ネット・ポジティブであること、つまり環境資本と社会資本を構築する こと、地元産、季節産、植物性、労働集約的なものを好むこと、汚染者負担の原則、予防原則、自然の美しさを評価し讃えること。 個人的原則:思索を実践し、慎重に政策を適用し、質素倹約を称える。 社会関連の原則:最も恵まれない人々に最大の支援を与え、相互理解、信頼、多くの勝利を求め、社会的結束と協力を強化し、利害関係者を関与させ、教育を促進し、知識を共有し、協力する。 システム関連の原則:システム思考を適用する;多様性を育成する;国民に関連するものをより透明化する;選択肢の多様性を維持または増加させる。 ステップ例 環境の持続可能性に移行するために、人々が取り得るアプローチは数多くある。例えば、生態系サービスの維持、共有資源の保護と共創、食品廃棄物の削減、植 物性食品への食生活のシフトの促進などが挙げられる[101]。その他にも、新しいグリーン・テクノロジーを推進し、化石燃料への補助金を段階的に廃止す る一方で、再生可能なエネルギー源を採用することである[51]。 2017年、科学者たちは1992年の『世界科学者の人類への警告』の最新版を発表した。それは、環境の持続可能性に向かう方法を示したものである。それは以下の3つの分野でのステップを提案している[51]。 消費の削減:食品廃棄物を減らし、主に植物由来の食品への食生活のシフトを促進する。 消費者の数を減らす:出生率をさらに低下させ、人口増加を抑える。 技術と自然保護:関連するアプローチがいくつかある。ひとつは自然の生態系サービスを維持することである。もうひとつは、新しいグリーン・テクノロジーを 推進することである。もうひとつはエネルギー利用の変化である。そのひとつが再生可能エネルギーの導入である。同時に、化石燃料によるエネルギー生産への 補助金を廃止することも必要である。 持続可能な開発目標アジェンダ2030  国連の持続可能な開発目標 2015年、国連は持続可能な開発目標(SDGs)に合意した。正式名称は「持続可能な開発目標のためのアジェンダ2030」である。国連はこのプログラ ムを非常に野心的で変革的なビジョンであると説明した。SDGsは前例のない範囲と意義を持つものだと述べている[41]: 3/35 国連はこう述べている: 「私たちは、世界を持続可能で強靭な道へとシフトさせるために緊急に必要とされる、大胆で変革的なステップを踏むことを決意している」[41]。 17のゴールとターゲットは、変革的なステップを打ち出している。例えば、SDGsは地球の未来を守ることを目指している。国連は、「持続可能な消費と生 産、天然資源の持続可能な管理、気候変動に対する緊急の行動などを通じて、地球を劣化から守り、現在と将来の世代のニーズを支えることができるようにす る」ことを約束した[41]。 |

| Options for overcoming barriers Further information: Sustainable development § Pathways Issues around economic growth Further information: Eco-economic decoupling, Degrowth, and Steady-state economy Eco-economic decoupling is an idea to resolve tradeoffs between economic growth and environmental conservation. The idea is to "decouple environmental bads from economic goods as a path towards sustainability".[11] This would mean "using less resources per unit of economic output and reducing the environmental impact of any resources that are used or economic activities that are undertaken".[10]: 8 The intensity of pollutants emitted makes it possible to measure pressure on the environment. This in turn makes it possible to measure decoupling. This involves following changes in the emission intensity associated with economic output.[10] Examples of absolute long-term decoupling are rare. But some industrialized countries have decoupled GDP growth from production- and consumption-based CO2 emissions.[102] Yet, even in this example, decoupling alone is not enough. It is necessary to accompany it with "sufficiency-oriented strategies and strict enforcement of absolute reduction targets".[102]: 1 One study in 2020 found no evidence of necessary decoupling. This was a meta-analysis of 180 scientific studies. It found that there is "no evidence of the kind of decoupling needed for ecological sustainability" and that "in the absence of robust evidence, the goal of decoupling rests partly on faith".[11] Some experts have questioned the possibilities for decoupling and thus the feasibility of green growth.[12] Some have argued that decoupling on its own will not be enough to reduce environmental pressures. They say it would need to include the issue of economic growth.[12] There are several reasons why adequate decoupling is currently not taking place. These are rising energy expenditure, rebound effects, problem shifting, the underestimated impact of services, the limited potential of recycling, insufficient and inappropriate technological change, and cost-shifting.[12] The decoupling of economic growth from environmental deterioration is difficult. This is because the entity that causes environmental and social costs does not generally pay for them. So the market price does not express such costs.[92] For example, the cost of packaging into the price of a product. may factor in the cost of packaging. But it may omit the cost of disposing of that packaging. Economics describes such factors as externalities, in this case a negative externality.[103] Usually, it is up to government action or local governance to deal with externalities.[104] There are various ways to incorporate environmental and social costs and benefits into economic activities. Examples include: taxing the activity (the polluter pays); subsidizing activities with positive effects (rewarding stewardship); and outlawing particular levels of damaging practices (legal limits on pollution).[92] Government action and local governance A textbook on natural resources and environmental economics stated in 2011: "Nobody who has seriously studied the issues believes that the economy's relationship to the natural environment can be left entirely to market forces."[105]: 15 This means natural resources will be over-exploited and destroyed in the long run without government action. Elinor Ostrom (winner of the 2009Nobel economics prize) expanded on this. She stated that local governance (or self-governance) can be a third option besides the market or the national government.[106] She studied how people in small, local communities manage shared natural resources.[107] She showed that communities using natural resources can establish rules their for use and maintenance. These are resources such as pastures, fishing waters, and forests. This leads to both economic and ecological sustainability.[106] Successful self-governance needs groups with frequent communication among participants. In this case, groups can manage the usage of common goods without overexploitation.[5]: 117 Based on Ostrom's work, some have argued that: "Common-pool resources today are overcultivated because the different agents do not know each other and cannot directly communicate with one another."[5]: 117 Global governance  Launch of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) Chapter Indonesia Questions of global concern are difficult to tackle. That is because global issues need global solutions. But existing global organizations (UN, WTO, and others) do not have sufficient means.[5]: 135 For example, they lack sanctioning mechanisms to enforce existing global regulations.[5]: 136 Some institutions do not enjoy universal acceptance. An example is the International Criminal Court. Their agendas are not aligned (for example UNEP, UNDP, and WTO) And some accuse them of nepotism and mismanagement.[5]: 135–145 Multilateral international agreements, treaties, and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) face further challenges. These result in barriers to sustainability. Often these arrangements rely on voluntary commitments. An example is Nationally Determined Contributions for climate action. There can be a lack of enforcement of existing national or international regulation. And there can be gaps in regulation for international actors such as multi-national enterprises. Critics of some global organizations say they lack legitimacy and democracy. Institutions facing such criticism include the WTO, IMF, World Bank, UNFCCC, G7, G8 and OECD.[5]: 135 |

障害を克服するための選択肢 さらなる情報 持続可能な開発 経済成長をめぐる問題 さらなる情報 環境経済デカップリング、脱成長、定常経済 環境経済的デカップリングとは、経済成長と環境保全のトレードオフを解決するための考え方である。この考え方は、「持続可能性に向けた道筋として、経済財 から環境悪を切り離す」ことである[11]。これは、「経済生産高単位当たりの資源使用量を減らし、使用される資源や実施される経済活動が環境に与える影 響を減らす」ことを意味する[10]。その結果、デカップリングを測定することが可能になる。これには、経済生産高に関連する排出強度の変化を追跡するこ とが含まれる[10]。絶対的な長期デカップリングの例はまれである。しかし、先進国の中には、GDP成長と生産・消費ベースのCO2排出量をデカップリ ングしている国もある[102]。十分性志向の戦略と絶対的削減目標の厳格な実施」を伴うことが必要である[102]: 1 2020年に行われたある研究では、必要なデカップリングの証拠は見つからなかった。これは180の科学的研究のメタ分析である。この研究では、「生態系 の持続可能性に必要なデカップリングの証拠はない」とし、「確固とした証拠がない以上、デカップリングという目標は部分的には信仰にかかっている」とした [11]。 一部の専門家は、デカップリングの可能性、ひいてはグリーン成長の実現可能性に疑問を呈している[12]。彼らは、デカップリングには経済成長の問題を含 める必要があると言う[12]。現在、適切なデカップリングが行われていない理由はいくつかある。それらは、エネルギー支出の増加、リバウンド効果、問題 の転嫁、サービスの影響の過小評価、リサイクルの限られた可能性、不十分かつ不適切な技術革新、コスト転嫁などである[12]。 経済成長と環境悪化の切り離しは困難である。というのも、環境コストや社会コストを発生させる主体は、一般にそのコストを支払わないからである。そのた め、市場価格はそのようなコストを表現していない[92]。例えば、製品の価格に包装のコストを反映させることはできる。しかし、その包装を廃棄するコス トは省かれることがある。経済学では、このような要因を外部性(この場合は負の外部性)と表現する[103]。通常、外部性に対処するのは政府の行動や地 域のガバナンスに任されている[104]。 環境的・社会的コストと便益を経済活動に組み込むには、さまざまな方法がある。例えば、活動に課税する(汚染者負担)、プラスの効果をもたらす活動に補助 金を出す(スチュワードシップに報いる)、特定のレベルの有害な行為を違法化する(汚染の法的制限)などがある[92]。 政府の行動と地方自治 天然資源と環境経済学の教科書は2011年にこう述べている: 「この問題を真面目に研究した人の中で、経済と自然環境の関係を完全に市場原理に委ねることができると考えている人はいない」[105]: 15 つまり、天然資源は長期的には、政府が行動を起こさなければ過剰に開発され、破壊されてしまうということだ。 エリナー・オストロム(2009年ノーベル経済学賞受賞者)はこれをさらに発展させた。エリノア・オストロム(2009年ノーベル経済学賞受賞者)は、市 場や国民政府以外の第三の選択肢として、ローカル・ガバナンス(またはセルフ・ガバナンス)があり得ると述べている[106]。彼女は、小規模な地域コ ミュニティの人々が、共有する天然資源をどのように管理しているかを研究した[107]。それらは牧草地、漁場、森林などの資源である。これは、経済的に も生態学的にも持続可能なものである。この場合、集団は過剰な搾取をすることなく共有財の利用を管理することができる[5]: 117 オストロムの研究に基づき、次のように主張する者がいる: 「今日、共有資源が過剰に耕作されているのは、さまざまな主体が互いを知らず、直接コミュニケーションできないからである」[5]: 117 グローバル・ガバナンス  国連持続可能な開発ソリューション・ネットワーク(SDSN)インドネシア支部の発足 地球規模の問題に取り組むのは難しい。それは、グローバルな問題にはグローバルな解決策が必要だからである。しかし、既存のグローバル組織(国連、 WTO、その他)には十分な手段がない[5]: 135 例えば、既存のグローバルな規制を実施するための制裁メカニズムが欠如している[5]: 136 制度によっては、普遍的な受容を得られていないものもある。その一例が国際刑事裁判所である。また、縁故主義や不始末を非難する者もいる[5]: 135 -145 多国間の国際協定、条約、政府間組織(IGO)は、さらなる課題に直面している。これらは、持続可能性に対する障壁となる。多くの場合、これらの取り決め は自発的な約束に依存している。例えば、気候変動対策のための国民決定拠出金である。既存の国民的または国際的な規制の施行が不十分な場合もある。また、 多国籍企業のような国際的なアクターに対する規制にもギャップがある。グローバル組織の中には、正当性と民主主義を欠いていると批判するものもある。こう した批判に直面している組織には、WTO、IMF、世界銀行、UNFCCC、G7、G8、OECDなどがある[5]: 135 |

| Responses by nongovernmental stakeholders Businesses See also: Environmental, social, and corporate governance  The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) seal for wood products is meant to indicate sustainable production of wood (in a forest in Germany). Sustainable business practices integrate ecological concerns with social and economic ones.[17][18] One accounting framework for this approach uses the phrase "people, planet, and profit". The name of this approach is the triple bottom line. The circular economy is a related concept. Its goal is to decouple environmental pressure from economic growth.[108][109] Growing attention towards sustainability has led to the formation of many organizations. These include the Sustainability Consortium of the Society for Organizational Learning,[110] the Sustainable Business Institute,[111] and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development.[112] Supply chain sustainability looks at the environmental and human impacts of products in the supply chain. It considers how they move from raw materials sourcing to production, storage, and delivery, and every transportation link on the way.[113] Religious communities Further information: Religion and environmentalism Religious leaders have stressed the importance of caring for nature and environmental sustainability. In 2015 over 150 leaders from various faiths issued a joint statement to the UN Climate Summit in Paris 2015.[114] They reiterated a statement made in the Interfaith Summit in New York in 2014: As representatives from different faith and religious traditions, we stand together to express deep concern for the consequences of climate change on the earth and its people, all entrusted, as our faiths reveal, to our common care. Climate change is indeed a threat to life, a precious gift we have received and that we need to care for.[115] Individuals Further information: Sustainable living Individuals can also live in a more sustainable way. They can change their lifestyles, practise ethical consumerism, and embrace frugality.[5]: 236 These sustainable living approaches can also make cities more sustainable. They do this by altering the built environment.[116] Such approaches include sustainable transport, sustainable architecture, and zero emission housing. Research can identify the main issues to focus on. These include flying, meat and dairy products, car driving, and household sufficiency. Research can show how to create cultures of sufficiency, care, solidarity, and simplicity.[89] Some young people are using activism, litigation, and on-the-ground efforts to advance sustainability. This is particularly the case in the area of climate action.[67]: 60 |

非政府関係者の反応 事業内容 こちらも参照のこと: 環境、社会、コーポレート・ガバナンス  木材製品のFSC(Forest Stewardship Council:森林管理協議会)シールは、(ドイツの森林における)持続可能な木材生産を示すものである。 持続可能なビジネス慣行は、生態学的な関心事を社会的・経済的な関心事と統合するものである[17][18]。このアプローチを示す会計上の枠組みのひと つに、「人・地球・利益」という言葉がある。このアプローチの名称はトリプルボトムラインである。循環型経済は、関連する概念である。その目標は、経済成 長から環境圧力を切り離すことである[108][109]。 持続可能性への関心が高まるにつれ、多くの組織が設立された。その中には、Society for Organizational Learningのサステナビリティ・コンソーシアム[110]、Sustainable Business Institute[111]、World Business Council for Sustainable Development(持続可能な開発のための世界経済人会議)[112]などがある。サプライチェーンの持続可能性は、サプライチェーンにおける製品 の環境と人間への影響を検討するものであり、原材料の調達から生産、保管、配送、そしてその途中のあらゆる輸送経路を考慮する[113]。 宗教団体 さらに詳しい情報 宗教と環境保護主義 宗教指導者たちは、自然への配慮と環境の持続可能性の重要性を強調してきた。2015年、さまざまな宗教の150人以上の指導者が、パリで開催された国連 気候サミット2015に向けて共同声明を発表した[114]。彼らは、2014年にニューヨークで開催された宗教間サミットでの声明を繰り返した: 異なる信仰と宗教的伝統の代表者として、私たちは共に立ち上がり、私たちの信仰が明らかにするように、私たちの共通の配慮に委ねられている地球とそこに住 む人々に対する気候変動の結果に対する深い懸念を表明する。気候変動は、まさに生命に対する脅威であり、私たちが受け取った貴重な贈り物であり、私たちが 大切にしなければならないものである[115]。 個人 さらに詳しい情報 持続可能な生活 個人もまた、より持続可能な方法で生活することができる。ライフスタイルを変え、倫理的な消費生活を実践し、倹約を受け入れることができる[5]。こうし たアプローチには、持続可能な輸送、持続可能な建築、ゼロ・エミッション住宅などがある。調査によって、焦点を当てるべき主な問題を特定することができ る。これには、飛行機、肉や乳製品、車の運転、家計の充足などが含まれる。研究によって、充足、配慮、連帯、簡素化の文化を創造する方法を示すことができ る[89]。 持続可能性を推進するために、活動主義、訴訟、現場での取り組 みを利用する若者もいる。これは特に気候変動対策にお いて顕著である[67]。 |

| Assessments and reactions Impossible to reach Scholars have criticized the concepts of sustainability and sustainable development from different angles. One was Dennis Meadows, one of the authors of the first report to the Club of Rome, called "The Limits to Growth". He argued many people deceive themselves by using the Brundtland definition of sustainability.[53] This is because the needs of the present generation are actually not met today. Instead, economic activities to meet present needs will shrink the options of future generations.[117][5]: 27 Another criticism is that the paradigm of sustainability is no longer suitable as a guide for transformation. This is because societies are "socially and ecologically self-destructive consumer societies".[118] Some scholars have even proclaimed the end of the concept of sustainability. This is because humans now have a significant impact on Earth's climate system and ecosystems.[20] It might become impossible to pursue sustainability because of these complex, radical, and dynamic issues.[20] Others have called sustainability a utopian ideal: "We need to keep sustainability as an ideal; an ideal which we might never reach, which might be utopian, but still a necessary one."[5]: 5 Vagueness The term is often hijacked and thus can lose its meaning. People use it for all sorts of things, such as saving the planet to recycling your rubbish.[27] A specific definition may never be possible. This is because sustainability is a concept that provides a normative structure. That describes what human society regards as good or desirable.[2] But some argue that while sustainability is vague and contested it is not meaningless.[2] Although lacking in a singular definition, this concept is still useful. Scholars have argued that its fuzziness can actually be liberating. This is because it means that "the basic goal of sustainability (maintaining or improving desirable conditions [...]) can be pursued with more flexibility".[23] Confusion and greenwashing Sustainability has a reputation as a buzzword.[1] People may use the terms sustainability and sustainable development in ways that are different to how they are usually understood. This can result in confusion and mistrust. So a clear explanation of how the terms are being used in a particular situation is important.[23] Greenwashing is a practice of deceptive marketing. It is when a company or organization provides misleading information about the sustainability of a product, policy, or other activity.[67]: 26 [119] Investors are wary of this issue as it exposes them to risk.[120] The reliability of eco-labels is also doubtful in some cases.[121] Ecolabelling is a voluntary method of environmental performance certification and labelling for food and consumer products. The most credible eco-labels are those developed with close participation from all relevant stakeholders.[122] |

評価と反応 到達不可能 学者たちは、持続可能性や持続可能な開発という概念をさまざまな角度から批判してきた。その一人が、ローマクラブへの最初の報告書『成長の限界』の著者の 一人であるデニス・メドウズである。彼は、多くの人々がブルントラントの持続可能性の定義を使うことによって、自分自身を欺いていると主張した[53]。 なぜなら、現在の世代のニーズは実際には満たされていないからである。それどころか、現在のニーズを満たすための経済活動は、将来の世代の選択肢を狭めて しまう。[117][5]: 27 もうひとつの批判は、持続可能性というパラダイムは、変革の指針としてはもはや適切ではないというものである。なぜなら、社会は「社会的にも生態学的にも 自己破壊的な消費社会」だからである[118]。 持続可能性という概念の終焉を宣言する学者さえいる。このような複雑で、過激で、ダイナミックな問題のために、持続可能性を追求することは不可能になるかもしれない[20]。持続可能性をユートピア的な理想と呼ぶ学者もいる: 5 曖昧さ この言葉はしばしば乗っ取られ、その意味を失うことがある。人々はこの言葉を、地球を守るとか、ゴミをリサイクルするとか、あらゆることに使っている [27]。というのも、持続可能性は規範構造を提供する概念だからである。それは、人間社会が良いとみなすもの、あるいは望ましいとみなすものを記述する ものである[2]。 しかし、持続可能性が曖昧で論争が多いとはいえ、意味がないわけではないという意見もある[2]。学者たちは、その曖昧さがかえって解放につながると主張 している。それは、「持続可能性の基本的な目標(望ましい状態を維持または改善すること[...])をより柔軟に追求することができる」ことを意味するか らである[23]。 混乱とグリーンウォッシング 持続可能性は、流行語としての評判がある[1]。人々は、持続可能性や持続可能な開発という用語を、それらが通常理解される方法とは異なる方法で使用する ことがある。その結果、混乱や不信が生じることがある。そのため、特定の状況で用語がどのように使用されているかを明確に説明することが重要である [23]。 グリーンウォッシングとは、欺瞞的なマーケティングの実践である。企業や組織が製品や政策、その他の活動の持続可能性について誤解を招くような情報を提供 することである[67]: 26 [119] 投資家はリスクにさらされることになるため、この問題を警戒している[120] エコラベルの信頼性も疑わしいケースがある[121] エコラベルは、食品や消費者製品の環境性能の認証とラベリングの自主的な方法である。最も信頼できるエコラベルは、関連するすべての利害関係者が密接に参 加して開発されたものである[122]。 |

| List of sustainability topics Outline of sustainability |

持続可能性トピック一覧 サステナビリティの概要 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sustainability |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆