戦 術

Tactic

☆ 戦術(tactic)とは、短期的な目標を達成することを目的とした概念的な行動または一連の短い行動のことである([T]actics are the actual means used to gain an objective.)。この行動は、1つまたは複数の具体的なタスクとして実施することができる。この用語は、ビジネス、抗議行動、軍事、諜報、法執行の文脈、およびチェス、スポーツ、その他の競争的な活動で一般的に使用されている。[1](→「戦略」)

★軍事戦術(Military tactics)は、戦場またはその周辺で戦闘部隊を組織し、運用する技芸(アート)である。これには、密接に関連する4つの戦場機能の適用が含まれる。すなわち、動的また は火力、機動性、保護または安全保障、および衝撃行動である。戦術は、指揮統制や後方支援とは異なる独立した機能である。現代の軍事科学において、戦術は 戦争遂行の3つのレベルのうち最も低いレベルであり、上位のレベルは戦略的レベルと作戦的レベルである。歴史を通じて、4つの戦術的機能の間のバランスは 変化し続けてきた。これは主に軍事技術の応用に基づいている。これにより、一定期間、1つまたは複数の戦術的機能が優位となり、通常は戦場に展開される関 連する戦闘部隊(歩兵、砲兵、騎兵、戦車など)の優位性が伴う。

| A tactic

is a conceptual action or short series of actions with the aim of

achieving a short-term goal. This action can be implemented as one or

more specific tasks. The term is commonly used in business, by protest

groups, in military, espionage, and law enforcement contexts, as well

as in chess, sports or other competitive activities.[1] |

戦

術とは、短期的な目標を達成することを目的とした概念的な行動または一連の短い行動のことである。この行動は、1つまたは複数の具体的なタスクとして実施

することができる。この用語は、ビジネス、抗議行動、軍事、諜報、法執行の文脈、およびチェス、スポーツ、その他の競争的な活動で一般的に使用されてい

る。[1] |

| Etymology The word originates from the Ancient Greek adjective τακτικός (taktikos), meaning that which pertains to ordinance. The related Ancient Greek noun is τάγμα (tagma), meaning ordinance, command.[2] Both words root in the verb τάσσω (tasso), meaning draw up in order, station, appoint |

語源 この単語は、古代ギリシャ語の形容詞「τακτικός(taktikos)」に由来し、「規則に関する」という意味がある。関連する古代ギリシャ語の名 詞は「τάγμα(tagma)」で、「規則、命令」という意味がある。[2] どちらの単語も、動詞「τάσσω(tasso)」に由来し、「整列させる、配置する、任命する」という意味がある。 |

| Distinction from strategy A strategy is a set of guidelines used to achieve an overall objective, whereas tactics are the specific actions aimed at adhering to those guidelines.[3] |

戦略との違い 戦略とは、全体的な目標を達成するために用いられる一連の指針のことです。一方、戦術とは、その指針に従うために講じる具体的な行動のことです。[3] |

| Military usage In military usage, a military tactic is used by a military unit of no larger than a division to implement a specific mission and achieve a specific objective, or to advance toward a specific target.[4] The terms tactic and strategy are often confused: tactics are the actual means used to gain an objective, while strategy is the overall campaign plan, which may involve complex operational patterns, activity, and decision-making that govern tactical execution. The United States Department of Defense Dictionary of Military Terms defines the tactical level as "the level of war at which battles and engagements are planned and executed to accomplish military objectives assigned to tactical units or task forces. Activities at this level focus on the ordered arrangement and maneuver of combat elements in relation to each other and to the enemy to achieve combat objectives."[5] If, for example, the overall goal is to win a war against another country, one strategy might be to undermine the other nation's ability to wage war by preemptively annihilating their military forces. The tactics involved might describe specific actions taken in specific locations, like surprise attacks on military facilities, missile attacks on offensive weapon stockpiles, and the specific techniques involved in accomplishing such objectives.[original research?] |

軍事用途 軍事用途では、軍事戦術(下記で説明)は、特定の任務を遂行し、特定の目標を達成するため、あるいは特定の目標に向かって前進するために、師団以下の規模の軍事部隊によって用いられる。[4] 戦術と戦略という用語はしばしば混同される。戦術は目標を達成するために実際に用いられる手段であり、戦略は、戦術の実行を支配する複雑な作戦パターン、活動、意思決定を含む、全体的な作戦計画である。米国国防総省の軍事用語辞典では、戦術レベルを「戦術部隊または任務部隊に割り当てられた軍事目標を達成するために、戦闘や交戦が計画され実行される戦争のレベル」と定義している。このレベルでの活動は、戦闘目標を達成するために、戦闘要素を互いに、および敵に対して秩序立てて配置し、機動させることに焦点を当てている。[5] 例えば、全体的な目標が他国との戦争に勝利することである場合、1 つの戦略としては、他国の軍事力を先制的に破壊して、戦争遂行能力を低下させるという方法がある。これに伴う戦術としては、軍事施設への奇襲攻撃、攻撃用 兵器の備蓄施設へのミサイル攻撃、およびそのような目標を達成するための具体的な手法などが挙げられる。[独自研究?] |

| Chess tactics Political tactics Protest tactics Strategy Tactical bombing Tactical wargame |

チェスの戦術 政治の戦術 抗議の戦術 戦略 戦術爆撃 戦術的戦争ゲーム |

| 1. Wragg, David W. (1973). A Dictionary of Aviation (first ed.). Osprey. p. 259. ISBN 9780850451634. 2. ""ΛΟΓΕΙΟΝ - τάγμα"". Retrieved 25 February 2024. 3. "The Difference between Strategy and Tactics". web-strategist.com. Retrieved 30 November 2016. 4. Reznichenko, Vasiliy G. (2019). Tactics—A Component Part of Military Art. In The Soviet Art Of War (first ed.). Routledge. p. 235-239. ISBN 9780429314681. 5. Dictionary of Military Terms Archived February 11, 2005, at the Wayback Machine Copy on the Joint Chiefs of Staff site |

1. Wragg, David W. (1973). A Dictionary of Aviation (第 1 版). Osprey. p. 259. ISBN 9780850451634. 2. 「ΛΟΓΕΙΟΝ - τάγμα」. 2024年2月25日取得。 3. 「戦略と戦術の違い」。web-strategist.com。2016年11月30日取得。 4. Reznichenko, Vasiliy G. (2019). Tactics—A Component Part of Military Art. In The Soviet Art Of War (初版). Routledge. p. 235-239. ISBN 9780429314681. 5. 軍事用語辞典 2005年2月11日、ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ 統合参謀本部サイトに掲載のコピー |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tactic_(method) |

|

| Military tactics

encompasses the art of organizing and employing fighting forces on or

near the battlefield. They involve the application of four battlefield

functions which are closely related – kinetic or firepower, mobility,

protection or security, and shock action. Tactics are a separate

function from command and control and logistics. In contemporary

military science, tactics are the lowest of three levels of

warfighting, the higher levels being the strategic and operational

levels. Throughout history, there has been a shifting balance between

the four tactical functions, generally based on the application of

military technology, which has led to one or more of the tactical

functions being dominant for a period of time, usually accompanied by

the dominance of an associated fighting arm deployed on the

battlefield, such as infantry, artillery, cavalry or tanks.[1] |

軍事戦術は、戦場またはその周辺で戦闘部隊を組織し、運用する技芸(アート)で

ある。これには、密接に関連する4つの戦場機能の適用が含まれる。すなわち、動的または火力、機動性、保護または安全保障、および衝撃行動である。戦術

は、指揮統制や後方支援とは異なる独立した機能である。現代の軍事科学において、戦術は戦争遂行の3つのレベルのうち最も低いレベルであり、上位のレベル

は戦略的レベルと作戦的レベルである。歴史を通じて、4つの戦術的機能の間のバランスは変化し続けてきた。これは主に軍事技術の応用に基づいている。これ

により、一定期間、1つまたは複数の戦術的機能が優位となり、通常は戦場に展開される関連する戦闘部隊(歩兵、砲兵、騎兵、戦車など)の優位性が伴う。

[1] |

| Tactical functions Kinetic or firepower Beginning with the use of melee and missile weapons such as clubs and spears, the kinetic or firepower function of tactics has developed along with technological advances so that the emphasis has shifted over time from the close-range melee and missile weapons to longer-range projectile weapons. Kinetic effects were generally delivered by the sword, spear, javelin and bow until the introduction of artillery by the Romans. Until the mid 19th century, the value of infantry-delivered missile firepower was not high, meaning that the result of a given battle was rarely decided by infantry firepower alone, often relying on artillery to deliver significant kinetic effects. The development of disciplined volley fire, delivered at close range, began to improve the hitting power of infantry, and compensated in part for the limited range, poor accuracy and low rate of fire of early muskets. Advances in technology, particularly the introduction of the rifled musket, used in the Crimean War and American Civil War, meant flatter trajectories and improved accuracy at greater ranges, along with higher casualties. The resulting increase in defensive firepower meant infantry attacks without artillery support became increasingly difficult. Firepower also became crucial to fixing an enemy in place to allow a decisive strike. Machine guns added significantly to infantry firepower at the turn of the 20th century, and the mobile firepower provided by tanks, self-propelled artillery and military aircraft rose significantly in the century that followed. Along with infantry weapons, tanks and other armoured vehicles, self-propelled artillery, guided weapons and aircraft provide the firepower of modern armies.[2] |

戦術的機能 運動エネルギーまたは火力 棍棒や槍などの近接武器や投射武器の使用から始まり、戦術の運動エネルギーまたは火力機能は技術進歩と共に発展し、近接戦闘用の近接武器や投射武器から、 より長射程の投射武器へと重点が移っていった。運動エネルギーは、ローマ人が砲兵を導入するまで、主に剣、槍、ジャベリン、弓によって発揮されていた。 19世紀半ばまで、歩兵が使用する射撃火力の価値は高くなく、特定の戦いの結果は歩兵の火力 alone で決まることは稀で、しばしば大砲が重要な動的効果を付与する役割を果たしていた。規律ある連射射撃の近距離での実施は、歩兵の命中率を向上させ、初期の マスケット銃の射程の短さ、精度不足、発射速度の低さを一部補うようになった。技術の進歩、特にクリミア戦争やアメリカ南北戦争で使用されたライフル銃の 導入により、弾道が平坦になり、遠距離での精度が向上し、死傷者数も増加した。その結果、防御側の火力が強化され、砲兵の支援のない歩兵の攻撃はますます 困難になった。また、決定的な一撃を与えるために敵をその場に釘付けにするためにも、火力は極めて重要になった。20世紀初頭には機関銃が歩兵の火力に大 きく貢献し、その後100年間で戦車、自走砲、軍用航空機による移動可能な火力が飛躍的に向上した。現代軍の火力は、歩兵武器に加え、戦車を含む装甲車 両、自走砲、誘導兵器、航空機によって構成されている。[2] |

| Mobility Mobility, which determines how quickly a fighting force can move, was for most of human history limited by the speed of a soldier on foot, even when supplies were carried by beasts of burden. With this restriction, most armies could not travel more than 32 kilometres (20 mi) per day, unless travelling on rivers. Only small elements of a force such as cavalry or specially trained light troops could exceed this limit. This restriction on tactical mobility remained until the latter years of World War I when the advent of the tank improved mobility sufficiently to allow decisive tactical manoeuvre. Despite this advance, full tactical mobility was not achieved until World War II when armoured and motorised formations achieved remarkable successes. However, large elements of the armies of World War II remained reliant on horse-drawn transport, which limited tactical mobility within the overall force. Tactical mobility can be limited by the use of field obstacles, often created by military engineers.[3] |

機動性 戦闘部隊の移動速度を決定する機動性は、人類の歴史の大部分において、兵士が徒歩で移動できる速度によって制限されていた。これは、荷物を運ぶために家畜 を使用していた時代でも同様だった。この制限により、ほとんどの軍隊は、川を移動する場合を除き、1 日に 32 キロメートル(20 マイル)以上移動することはできなかった。騎兵や特別訓練を受けた軽装部隊のような小規模な部隊のみがこの制限を超えることができた。この戦術的機動性の 制限は、第一次世界大戦後期に戦車の登場により機動性が十分に改善され、決定的な戦術的機動が可能になるまで続いた。この進歩にもかかわらず、完全な戦術 的機動性は第二次世界大戦まで実現されなかった。第二次世界大戦では、装甲部隊と機械化部隊が著しい成功を収めたが、第二次世界大戦の軍隊の大部分は馬車 に依存しており、全体としての戦術的機動性を制限していた。戦術的機動性は、軍事工兵によって作成されることが多い野戦障害物の使用によって制限されるこ とがある。[3] |

| Protection and security Personal armour has been worn since the classical period to provide a measure of individual protection, which was also extended to include barding of the mount. The limitations of armour have always been weight and bulk, and its consequent effects on mobility as well as human and animal endurance. By the 18th and 19th centuries, personal armour had been largely discarded, until the re-introduction of helmets during World War I in response to the firepower of artillery. Armoured fighting vehicles proliferated during World War II, and after that war, body armour returned for the infantry, particularly in Western armies. Fortifications, which have been used since ancient times, provide collective protection, and modern examples include entrenchments, roadblocks, barbed wire and minefields. Like obstacles, fortifications are often created by military engineers.[3] |

保護と安全 個人用防具は、個人を保護するための手段として、古代から着用されており、その対象は馬具にも拡大した。防具の欠点は、その重量と体積であり、その結果、 機動性や人間や動物の耐久力に影響を与えることだった。18 世紀から 19 世紀にかけて、個人用防具は、ほとんど使用されなくなったが、第一次世界大戦中に、大砲の火力の強化に対応するため、ヘルメットが再導入された。第二次世 界大戦中に装甲戦闘車両が普及し、その後、特に西側諸国の軍隊で、歩兵用の防弾チョッキが復活した。古代から使用されてきた要塞は、集団の保護の役割を果 たしており、現代の例としては、塹壕、道路封鎖、有刺鉄線、地雷原などが挙げられる。障害物と同様に、要塞も多くの場合、軍事技術者によって建設される。 |

| Shock action Shock action is as much a psychological function of tactics as a physical one, and can be significantly enhanced by the use of surprise. It has been provided by charging infantry, and as well as by chariots, war elephants, cavalry and armoured vehicles which provide momentum to an assault. It has also been used in a defensive way, for example by the drenching flights of arrows from English longbowmen at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 which caused the horses of the French knights to panic. During early modern warfare, the use of the tactical formations of columns and lines had a greater effect than the firepower of the formations alone. During the early stages of World War II, the combined effects of German machine gun and tank gun firepower, enhanced by accurate indirect fire and air attack, often broke up Allied units before their assault commenced, or caused them to falter due to casualties among key unit leaders. In both the early modern and World War II examples, the cumulative psychological shock effect on the enemy was often greater than the actual casualties incurred.[4] |

衝撃行動 衝撃行動は、物理的な機能と同じくらい戦術の心理的な機能でもあり、驚きを利用することで大幅に強化することができる。これは、突撃する歩兵、戦車、戦 象、騎兵、装甲車両など、攻撃に勢いを与えるものによって実現されてきた。防御的な用途としても用いられ、例えば1415年のアジャンクールの戦いで、イ ングランドのロングボウ兵が放った矢の雨により、フランス騎士団の馬がパニックに陥った事例がある。近世の戦争では、戦列や列の戦術的編成の効果が、編成 自体の火力よりも大きな役割を果たした。第二次世界大戦初期には、ドイツ軍の機関銃と戦車砲の火力が、正確な間接射撃と空襲によって強化され、連合軍の部 隊が攻撃を開始する前に崩壊したり、重要な指揮官の戦死により戦意を喪失したりするケースが多かった。近現代と第二次世界大戦の例ともに、敵に与えた累積 的な心理的衝撃は、実際の戦死者の数よりも大きかった。[4] |

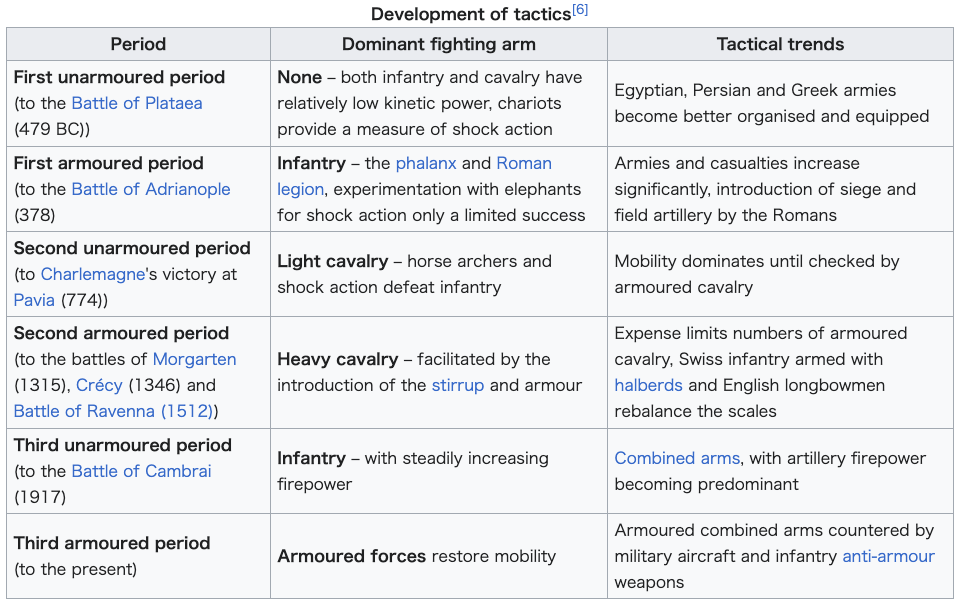

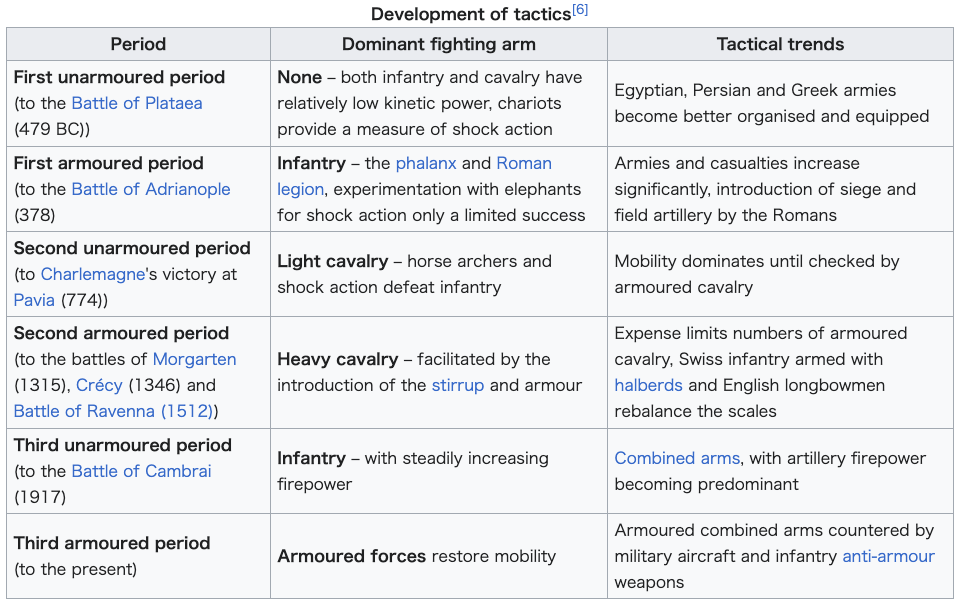

| Development over time The development of tactics has involved a shifting balance between the four tactical functions since ancient times, and changes in firepower and mobility have been fundamental to these changes. Various models have been proposed to explain the interaction between the tactical functions and the dominance of individual fighting arms during different periods. J. F. C. Fuller proposed three "tactical cycles" in each of the classical and Christian eras. For the latter epoch, he proposed a "shock" cycle between 650 and 1450, a "shock and projectile" cycle 1450–1850, and a "projectile" cycle from 1850, with respect to the Western and North American warfare.[5] During World War II, Tom Wintringham proposed six chronological periods, which alternate the dominance between unarmoured and armoured forces and highlight tactical trends in each period.[1]  Massed volley fire by archers brought infantry firepower to the fore in Japanese warfare in the second half of the 13th century, preceding the rise of the English longbowman.[7] The mobility and shock action of the Oirat Mongol army at the Battle of Tumu in 1449 demonstrated that cavalry could still defeat a large infantry force.[8] In both the European and Oriental traditions of warfare, the advent of gunpowder during the late Medieval and Early Modern periods created a relentless shift to infantry firepower becoming "a decisive, if not dominant" arm on the battlefield,[9] exemplified by the significant impact of massed arquebusiers at the Battle of Nagashino in 1575.[10] |

時間の経過に伴う発展 戦術の発展は、古代から 4 つの戦術的機能のバランス変化を伴い、その変化には火力の変化や機動力の変化が大きな役割を果たしてきた。異なる時代における戦術的機能間の相互作用や、 個々の武器の優位性を説明するさまざまなモデルが提案されている。J. F. C. フルラーは、古典時代とキリスト教時代にそれぞれ3つの「戦術サイクル」を提唱した。後者の時代については、西欧と北米の戦争を基準に、650年から 1450年までの「衝撃」サイクル、1450年から1850年までの「衝撃と投射」サイクル、1850年以降の「投射」サイクルを提案した。[5] 第二次世界大戦中、トム・ウィントリングハムは、装甲のない部隊と装甲部隊の優位性が交互に繰り返され、各時代の戦術的傾向を強調する6つの年代区分を提 案した。[1]  13世紀後半の日本の戦争において、弓兵の集中射撃は歩兵の火力を前面に押し出し、イングランドのロングボウマンの台頭を先駆けた。[7] 1449年のトゥム戦におけるオイラト・モンゴル軍の機動性と衝撃的な攻撃は、騎兵が依然として大規模な歩兵部隊を破る能力を有することを示した。[8] ヨーロッパと東洋の戦争伝統の両方で、中世後期から近世にかけて火薬の登場は、戦場において歩兵の火力が「決定的、あるいは支配的な」武器へと移行する不 可避な変化をもたらした。[9] 1575年の長篠の戦いで大量の火縄銃兵が与えた大きな影響が、その典型的な例だ。[10] |

| Combined arms tactics The synchronisation of the various fighting arms to achieve the tactical mission is known as combined arms tactics. One method of measuring tactical effectiveness is the extent to which the arms, including military aviation, are integrated on the battlefield. A key principle of effective combined arms tactics is that for maximum potential to be achieved, all elements of combined arms teams need the same level of mobility, and sufficient firepower and protection. The history of the development of combined arms tactics has been dogged by costly and painful lessons. For example, while German commanders in World War II clearly understood from the outset the key principle of combined arms tactics outlined above, British commanders were late to this realisation. Successful combined arms tactics require the fighting arms to train alongside each other and to be familiar with each other's capabilities.[11] |

複合武器戦術 戦術的任務を達成するために、さまざまな戦闘部隊を同期させることを複合武器戦術と呼ぶ。戦術的有効性を測定する方法のひとつは、軍事航空を含む各部隊が 戦場でどの程度統合されているかだ。効果的な複合武器戦術の重要な原則は、最大の潜在能力を発揮するためには、複合武器チームのすべての要素が同レベルの 機動性、十分な火力、および保護を備えている必要があるということだ。連合作戦の戦術の発展の歴史は、高価で痛ましい教訓に悩まされてきた。例えば、第二 次世界大戦中のドイツの指揮官は、上記の連合作戦の戦術の重要な原則を当初から明確に理解していたが、イギリスの指揮官はこれに気づくのが遅れた。連合作 戦の戦術を成功させるには、戦闘部隊が互いに訓練を積み、互いの能力に精通している必要がある。[11] |

| Impact of air power Beginning in the latter stages of World War I, airpower has brought a significant change to military tactics. World War II saw the development of close air support which greatly enhanced the effect of ground forces with the use of aerial firepower and improved tactical reconnaissance and the interdiction of hostile air power. It also made possible the supply of ground forces by air, achieved by the British during the Burma Campaign but unsuccessful for the Germans at the Battle of Stalingrad. Following World War II, rotary-wing aircraft had a significant impact on firepower and mobility, comprising a fighting arm in its own right in many armies. Aircraft, particularly those operating at low or medium altitudes, remain vulnerable to ground-based air defence systems as well as other aircraft.[11] Parachute and glider operations and rotary-wing aircraft have provided significant mobility to ground forces but the reduced mobility, protection and firepower of troops delivered by air once landed has limited the tactical utility of such vertical envelopment or air assault operations. This was demonstrated during Operation Market Garden in September 1944, and during the Vietnam War, in the latter case despite the additional firepower provided by helicopter gunships and the ability quickly to remove casualties, provided by aeromedical evacuation.[12] |

空軍の影響 第一次世界大戦の後半から、空軍は軍事戦術に大きな変化をもたらした。第二次世界大戦では、空中火力と戦術偵察の向上、敵の空軍力の阻止により、地上部隊 の効果を大幅に高める近接航空支援が開発された。また、イギリス軍がビルマ戦線で達成したが、ドイツ軍はスターリングラードの戦いで失敗した、地上部隊へ の空輸も可能になった。第二次世界大戦後、回転翼航空機は火力と機動性に大きな影響を与え、多くの軍隊で独立した戦闘部隊を構成するようになった。航空 機、特に低高度または中高度で飛行する航空機は、地上防空システムや他の航空機に対して依然として脆弱である[11]。 パラシュートとグライダーの作戦、および回転翼航空機は地上部隊に大きな機動性を提供したが、空輸された部隊の着陸後の機動性、防護力、火力の低下は、垂 直包囲作戦や空挺作戦の戦術的有用性を制限してきた。これは1944年9月のマーケット・ガーデン作戦で示され、ベトナム戦争でも同様だった。後者の場 合、ヘリコプター攻撃機による追加の火力と、航空医療搬送による負傷者の迅速な撤収能力が提供されたにもかかわらず、その制約が明らかになった。[12] |

Concept German World War I observation post disguised as a tree. Military tactics answer the questions of how best to deploy and employ forces on a small scale.[13] Some practices have not changed since the dawn of warfare: assault, ambushes, skirmishing, turning flanks, reconnaissance, creating and using obstacles and defenses, etc. Using ground to best advantage has not changed much either. Heights, rivers, swamps, passes, choke points, and natural cover, can all be used in multiple ways. Before the nineteenth century, many military tactics were confined to battlefield concerns: how to maneuver units during combat in open terrain. Nowadays, specialized tactics exist for many situations, for example for securing a room in a building. Technological changes can render existing tactics obsolete, and sociological changes can shift the goals and methods of warfare, requiring new tactics. Tactics define how soldiers are armed and trained. Thus technology and society influence the development of types of soldiers or warriors through history: Greek hoplite, Roman legionary, medieval knight, Turk-Mongol horse archer, Chinese crossbowman, or an air cavalry trooper. Each – constrained by his weaponry, logistics and social conditioning – would use a battlefield differently, but would usually seek the same outcomes from their use of tactics. The First World War forced great changes in tactics as advances in technology rendered prior tactics useless.[14] "Gray-zone" tactics are also becoming more widely used. These include "everything from strong-arm diplomacy and economic coercion, to media manipulation and cyberattacks, to use of paramilitaries and proxy forces". The title "gray-zone" comes from the ambiguity between defense vs. offense, as well as the ambiguity between peace-keeping vs. war effort.[15] |

コンセプト 第一次世界大戦のドイツ軍観測所を木に偽装したもの。 軍事戦術は、小規模な部隊をどのように配置し、運用するのが最善かという問題に対応する。[13] 戦争の黎明期から変わっていない戦術もある。攻撃、待ち伏せ、小競り合い、側面攻撃、偵察、障害物や防御施設の構築と活用などだ。地形を最大限に活用する という点でも、それほど大きな変化はない。高地、川、湿地、峠、要衝、自然の遮蔽物などは、多目的に利用可能だ。19世紀以前、多くの軍事戦術は戦場での 問題に限定されていた:開けた地形での戦闘中に部隊を機動させる方法。現在では、建物の部屋を確保するなどの多くの状況に対応した専門的な戦術が存在して いる。 技術的な変化は既存の戦術を陳腐化させ、社会的な変化は戦争の目的や方法を変化させ、新たな戦術を必要とさせる。戦術は兵士の武装や訓練方法を定義する。 したがって、技術と社会は歴史を通じて兵士や戦士の種類の発展に影響を与える:ギリシャのホプリテ、ローマのレギオナーレ、中世の騎士、トルコ・モンゴル の騎馬弓兵、中国のクロスボウ兵、または空挺騎兵など。それぞれは、武器、兵站、社会的条件によって制約を受け、戦場の戦い方は異なるが、戦術の使用に よって通常は同じ結果を求めます。第一次世界大戦では、技術の進歩によって従来の戦術が役に立たなくなったため、戦術に大きな変化が余儀なくされました [14]。 「グレーゾーン」戦術もますます広く使用されるようになっている。これには「強硬な外交や経済的圧迫から、メディア操作やサイバー攻撃、準軍事組織や代理 勢力の利用まで」が含まれる。「グレーゾーン」という名称は、防御と攻撃の曖昧さ、および平和維持と戦争努力の曖昧さから来ている。[15] |

| List of military tactics Combat arms |

軍事戦術の一覧 戦闘兵器 |

| Bibliography Haskew, Michael; Jorgensen, Christer; McNab, Chris; Niderost, Eric; Rice, Rob S. (2008). Fighting Techniques of the Oriental World 1200-1860: Equipment, Combat Skills and Tactics. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books. ISBN 978-1-905704-96-5. Holmes, Richard; Strachan, Hew; Bellamy, Chris; Bicheno, Hugh (2001). The Oxford Companion to Military History. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866209-9. Johnson, Rob; Whitby, Michael; France, John (2010). How to win on the battlefield : 25 key tactics to outwit, outflank, and outfight the enemy. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-25161-4. Muhm, Gerhard. "German Tactics in the Italian Campaign". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2007. Gerhard Muhm : La Tattica nella campagna d’Italia, in LINEA GOTICA AVAMPOSTO DEI BALCANI, (Hrsg.) Amedeo Montemaggi - Edizioni Civitas, Roma 1993. |

参考文献 Haskew, Michael; Jorgensen, Christer; McNab, Chris; Niderost, Eric; Rice, Rob S. (2008). Fighting Techniques of the Oriental World 1200-1860: Equipment, Combat Skills and Tactics. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books. ISBN 978-1-905704-96-5. Holmes, Richard; Strachan, Hew; Bellamy, Chris; Bicheno, Hugh (2001). The Oxford Companion to Military History. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866209-9. ジョンソン、ロブ;ホイットビー、マイケル;フランス、ジョン(2010)。戦場で勝つ方法:敵を裏切り、包囲し、打ち負かす 25 の重要な戦術。テムズ&ハドソン。ISBN 978-0-500-25161-4。 ムーム、ゲルハルト。「イタリア戦線におけるドイツの戦術」。2007年9月27日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2007年9月27日に取得。 ゲルハルト・ムーム:La Tattica nella campagna d’Italia、LINEA GOTICA AVAMPOSTO DEI BALCANI(編)、アメデオ・モンテマッジ、エディツィオーニ・チヴィタス、ローマ、1993年。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_tactics |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆