戦 略

Strategy

☆ 戦略(ギリシア語 στρατηγία stratēgia、Strategy「部隊長の技術;将軍の役職、指揮、将軍職」に由来)とは、不確実な状況下で1つまたは複数の長期的または全体的な目標を達成 するための一般的な計画である。軍事戦術、攻城術、兵站などを含むいくつかの技能のサブセットを含む「将軍の技術」という意味で、この用語は東ロー マ用語で紀元前6世紀に使用されるようになり、西洋の現地語に翻訳されたのは18世紀になってからである。それ以降20世紀まで、「戦略」という言葉は、 敵味方双方が相互作用する軍事紛争において、「意志の弁証法において、武力による威嚇や実際の使用を含む政治的目的を追求しようとする包括的な方法」を示 すようになった。

| Strategy

(from Greek στρατηγία stratēgia, "art of troop leader; office of

general, command, generalship"[1]) is a general plan to achieve one or

more long-term or overall goals under conditions of uncertainty.[2] In

the sense of the "art of the general", which included several subsets

of skills including military tactics, siegecraft, logistics etc., the

term came into use in the 6th century C.E. in Eastern Roman

terminology, and was translated into Western vernacular languages only

in the 18th century. From then until the 20th century, the word

"strategy" came to denote "a comprehensive way to try to pursue

political ends, including the threat or actual use of force, in a

dialectic of wills" in a military conflict, in which both adversaries

interact.[3] Strategy is important because the resources available to achieve goals are usually limited. Strategy generally involves setting goals and priorities, determining actions to achieve the goals, and mobilizing resources to execute the actions.[4] A strategy describes how the ends (goals) will be achieved by the means (resources).[5] Strategy can be intended or can emerge as a pattern of activity as the organization adapts to its environment or competes.[4] It involves activities such as strategic planning and strategic thinking.[6] Henry Mintzberg from McGill University defined strategy as a pattern in a stream of decisions to contrast with a view of strategy as planning,[7] while Henrik von Scheel defines the essence of strategy as the activities to deliver a unique mix of value – choosing to perform activities differently or to perform different activities than rivals.[8] while Max McKeown (2011) argues that "strategy is about shaping the future" and is the human attempt to get to "desirable ends with available means". Vladimir Kvint defines strategy as "a system of finding, formulating, and developing a doctrine that will ensure long-term success if followed faithfully."[9] |

戦

略(ギリシア語 στρατηγία

stratēgia、「部隊長の技術;将軍の役職、指揮、将軍職」[1]に由来)とは、不確実な状況下で1つまたは複数の長期的または全体的な目標を達成

するための一般的な計画である[2]。軍事戦術、攻城術、兵站などを含むいくつかの技能のサブセットを含む「将軍の技術」という意味で、この用語は東ロー

マ用語で紀元前6世紀に使用されるようになり、西洋の現地語に翻訳されたのは18世紀になってからである。それ以降20世紀まで、「戦略」という言葉は、

敵味方双方が相互作用する軍事紛争において、「意志の弁証法において、武力による威嚇や実際の使用を含む政治的目的を追求しようとする包括的な方法」を示

すようになった[3]。 目標を達成するために利用できる資源は通常限られているため、戦略は重要である。戦略は一般的に、目標と優先順位の設定、目標を達成するための行動の決 定、行動を実行するための資源の動員を含む[4]。戦略は、目的(目標)が手段(資源)によってどのように達成されるかを記述する[5]。 マギル大学のヘンリー・ミンツバーグは、戦略を計画として捉える見方とは対照的に、戦略を意思決定の流れの中のパターンとして定義しており[7]、ヘン リック・フォン・シールは、戦略の本質をユニークな価値のミックスを提供するための活動、つまりライバルとは異なる活動を行うこと、あるいはライバルとは 異なる活動を行うことを選択することであると定義している[8]。マックス・マッキューン(2011)は、「戦略とは未来を形作ること」であり、「利用可 能な手段を用いて望ましい目的」に到達しようとする人間の試みであると論じている。ウラジミール・クヴィントは戦略を「忠実に従えば長期的な成功を確実に するような教義を発見し、策定し、発展させるシステム」と定義している[9]。 |

| Military theory Main article: Military strategy Subordinating the political point of view to the military would be absurd, for it is policy that has created war...Policy is the guiding intelligence, and war only the instrument, not vice-versa. — On War by Carl von Clausewitz In military theory, strategy is "the utilization during both peace and war, of all of the nation's forces, through large scale, long-range planning and development, to ensure security and victory" (Random House Dictionary).[7] The father of Western modern strategic study, Carl von Clausewitz, defined military strategy as "the employment of battles to gain the end of war." B. H. Liddell Hart's definition put less emphasis on battles, defining strategy as "the art of distributing and applying military means to fulfill the ends of policy".[10] Hence, both gave the pre-eminence to political aims over military goals. U.S. Naval War College instructor Andrew Wilson defined strategy as the "process by which political purpose is translated into military action."[11] Lawrence Freedman defined strategy as the "art of creating power."[12] Eastern military philosophy dates back much further, with examples such as The Art of War by Sun Tzu dated around 500 B.C.[13] Counterterrorism Strategy Because counterterrorism involves the synchronized efforts of numerous competing bureaucratic entities, national governments frequently create overarching counterterrorism strategies at the national level.[14] A national counterterrorism strategy is a government's plan to use the instruments of national power to neutralize terrorists, their organizations, and their networks in order to render them incapable of using violence to instill fear and to coerce the government or its citizens to react in accordance with the terrorists' goals.[14] The United States has had several such strategies in the past, including the United States National Strategy for Counterterrorism (2018);[15] the Obama-era National Strategy for Counterterrorism (2011); and the National Strategy for Combatting Terrorism (2003). There have also been a number of ancillary or supporting plans, such as the 2014 Strategy to Counter the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, and the 2016 Strategic Implementation Plan for Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the United States.[14] Similarly, the United Kingdom's counterterrorism strategy, CONTEST, seeks "to reduce the risk to the UK and its citizens and interests overseas from terrorism, so that people can go about their lives freely and with confidence."[16] |

軍事理論 主な記事 軍事戦略 政治的視点を軍事に従属させることは不合理である。なぜなら、戦争を生み出したのは政策だからである......政策は指導的知性であり、戦争は道具にすぎず、その逆ではない。 ——カール・フォン・クラウゼヴィッツ著『戦争について』 軍事理論において戦略とは、「平和時と戦争時の両方において、安全保障と勝利を確保するために、大規模で長期的な計画と開発を通じて、国家の全兵力を活用すること」(ランダムハウス辞典)である[7]。 西洋近代戦略学の父、カール・フォン・クラウゼヴィッツは、軍事戦略を 「戦争の終結を得るための戦闘の活用 」と定義した。B.H.リデル・ハートの定義は戦闘をあまり重視せず、戦略を「政策の目的を達成するために軍事的手段を配分し適用する技術」と定義した [10]。したがって、両者とも軍事的目標よりも政治的目的を優先させた。アメリカ海軍大学のアンドリュー・ウィルソン教官は戦略を「政治的目的が軍事行 動に変換されるプロセス」と定義し[11]、ローレンス・フリードマンは戦略を「権力を創造する技術」と定義した[12]。 東洋の軍事哲学の歴史はもっと古く、紀元前500年頃の孫子の兵法などがその例である[13]。 対テロ戦略 テロ対策は多数の競合する官僚組織の同調した努力を伴うため、国家政府は国家レベルで包括的なテロ対策戦略を策定することが多い[14]。国家テロ対策戦 略とは、テロリスト、その組織、そのネットワークを無力化するために国家権力の手段を用いる政府の計画であり、テロリストが恐怖を植え付けるために暴力を 行使することを不可能にし、テロリストの目標に従って政府や国民が反応するよう強制するためのものである。 [14]米国は過去に、対テロ国家戦略(2018年)、[15]オバマ政権時代の対テロ国家戦略(2011年)、対テロ国家戦略(2003年)など、いく つかのそのような戦略を持っていた。また、2014年の「イラクとレバントのイスラム国に対抗する戦略」や、2016年の「米国における暴力的過激主義を 防止するために地域のパートナーを強化するための戦略的実施計画」など、補助的あるいは支援的な計画も数多く存在する[14]。同様に、英国のテロ対策戦 略であるCONTESTは、「テロリズムによる英国およびその国民、海外の利益に対するリスクを低減し、人々が自由に安心して生活できるようにする」こと を目指している[16]。 |

| Management theory Main article: Strategic management The essence of formulating competitive strategy is relating a company to its environment. — Michael Porter[17] Modern business strategy emerged as a field of study and practice in the 1960s; prior to that time, the words "strategy" and "competition" rarely appeared in the most prominent management literature.[18][19] Alfred Chandler wrote in 1962 that: "Strategy is the determination of the basic long-term goals of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals."[20] Michael Porter defined strategy in 1980 as the "...broad formula for how a business is going to compete, what its goals should be, and what policies will be needed to carry out those goals" and the "...combination of the ends (goals) for which the firm is striving and the means (policies) by which it is seeking to get there."[17] Definition Henry Mintzberg described five definitions of strategy in 1998: 1. Strategy as plan – a directed course of action to achieve an intended set of goals; similar to the strategic planning concept; 2. Strategy as pattern – a consistent pattern of past behavior, with a strategy realized over time rather than planned or intended. Where the realized pattern was different from the intent, he referred to the strategy as emergent; 3. Strategy as position – locating brands, products, or companies within the market, based on the conceptual framework of consumers or other stakeholders; a strategy determined primarily by factors outside the firm; 4. Strategy as ploy – a specific maneuver intended to outwit a competitor; and 5. Strategy as perspective – executing strategy based on a "theory of the business" or natural extension of the mindset or ideological perspective of the organization.[21] Complexity theorists define strategy as the unfolding of the internal and external aspects of the organization that results in actions in a socio-economic context.[22][23][24] Strategic Problem This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please help improve it to make it understandable to non-experts, without removing the technical details. (December 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The concept of strategic problem elucidates the dynamic interplay between competitive warfare and harmonious cooperation among agents within fluctuating markets. Crouch delves into this domain, emphasizing the sustenance of dynamic relationships. While embracing the notion of cooperation, the author accentuates the primacy of market structure preceding strategy, in turn preceding organizational structure. Hence, the author's perspectives align closely with definitions that regard strategy as a valuable position, as articulated by Porter and Mintzberg.[25][26][27] In contrast, Burnett adopt a prescriptive viewpoint, defining strategy as a plan formulated through methodology. According to Burnett, the strategic problem encompasses six tasks: goal formulation, environmental analysis, strategy formulation, strategy evaluation, strategy implementation, and strategic control.[28] Mukherji and Hurtado indicates a bifurcation in defining the strategic problem. The literature commonly highlights two aspects: the challenge of categorizing the environment and emphasizing the organization's primary responses to the established context. These aspects, as identified by the authors, encapsulate the three dimensions originally proposed by Ansoff and Hayes, which evolved to encompass internal and external issues arising from the situation, the processes involved in resolving these issues, and their constituting variables.[29] From a complexity perspective, the strategic problem intertwines invariably with governance within complex, interconnected systems, both internally and within the external milieu. In Terra and Passador's conceptualization, the strategic problem is rooted in the interrelations among subsystems, human agents, and environmental elements within organizations seen as complex sociotechnical systems consisting of symbiotic relationships among subsystems, originating from the configurations of the organization's internal social system and the responses it generates to ensure its own identity. This model accentuates the intricate nature of these interconnections, highlighting the challenge for strategists to comprehend and navigate the complex interactions between internal structures and external responses.[30][23] Complexity Theory This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please help improve it to make it understandable to non-experts, without removing the technical details. (December 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Complexity science, as articulated by R. D. Stacey, represents a conceptual framework capable of harmonizing emergent and deliberate strategies. Within complexity approaches, the term "strategy" is intricately linked to action but contrasts programmed action. Complexity theorists view programs merely as predetermined sequences effective in highly ordered and less chaotic environments. Conversely, strategy emerges from a simultaneous examination of determined conditions (order) and uncertainties (disorder) that drive action. Complexity theory posits that strategy involves execution, encompasses control and emergence, scrutinizes both internal and external organizational aspects, and can take the form of maneuvers or any other act or process.[31][23][30] The works of Stacey stand as pioneering efforts in applying complexity principles to the field of strategy. This author applied self-organization and chaos principles to describe strategy, organizational change dynamics, and learning. Their propositions advocate for strategy approached through choices and the evolutionary process of competitive selection. In this context, corrections of anomalies occur through actions involving negative feedback, while innovation and continuous change stem from actions guided by positive feedback.[32][31][33] Dynamically, complexity in strategic management can be elucidated through the model of "Symbiotic Dynamics" by Terra and Passador.[23][34] This model conceives the social organization of production as an interplay between two distinct systems existing in a symbiotic relationship while interconnected with the external environment. The organization's social network acts as a self-referential entity controlling the organization's life, while its technical structure resembles a purposeful "machine" supplying the social system by processing resources. These intertwined structures exchange disturbances and residues while interacting with the external world through their openness. Essentially, as the organization produces itself, it also hetero-produces, surviving through energy and resource flows across its subsystems.[23][34] This dynamic has strategic implications, governing organizational dynamics through a set of attraction basins establishing operational and regenerative capabilities. Hence, one of the primary roles of strategists is to identify "human attractors" and assess their impacts on organizational dynamics. According to the theory of Symbiotic Dynamics, both leaders and the technical system can act as attractors, directly influencing organizational dynamics and responses to external disruptions. Terra and Passador further assert that while producing, organizations contribute to environmental entropy, potentially leading to abrupt ruptures and collapses within their subsystems, even within the organizations themselves. Given this issue, the authors conclude that organizations intervening to maintain the environment's stability within suitable parameters for survival tend to exhibit greater longevity.[23][34] The theory of Symbiotic Dynamics posits that organizations must acknowledge their impact on the external environment (markets, society, and the environment) and act systematically to reduce their degradation while adapting to the demands arising from these interactions. To achieve this, organizations need to incorporate all interconnected systems into their decision-making processes, enabling the envisioning of complex socio-economic systems where they integrate in a stable and sustainable manner. This blend of proactivity and reactivity is fundamental to ensure the survival of the organization itself. [23] Components Professor Richard P. Rumelt described strategy as a type of problem solving in 2011. He wrote that good strategy has an underlying structure he called a kernel. The kernel has three parts: 1) A diagnosis that defines or explains the nature of the challenge; 2) A guiding policy for dealing with the challenge; and 3) Coherent actions designed to carry out the guiding policy.[35] President Kennedy illustrated these three elements of strategy in his Cuban Missile Crisis Address to the Nation of 22 October 1962: Diagnosis: "This Government, as promised, has maintained the closest surveillance of the Soviet military buildup on the island of Cuba. Within the past week, unmistakable evidence has established the fact that a series of offensive missile sites are now in preparation on that imprisoned island. The purpose of these bases can be none other than to provide a nuclear strike capability against the Western Hemisphere." Guiding Policy: "Our unswerving objective, therefore, must be to prevent the use of these missiles against this or any other country, and to secure their withdrawal or elimination from the Western Hemisphere." Action Plans: First among seven numbered steps was the following: "To halt this offensive buildup a strict quarantine on all offensive military equipment under shipment to Cuba is being initiated. All ships of any kind bound for Cuba from whatever nation or port will, if found to contain cargoes of offensive weapons, be turned back."[36] Rumelt wrote in 2011 that three important aspects of strategy include "premeditation, the anticipation of others' behavior, and the purposeful design of coordinated actions." He described strategy as solving a design problem, with trade-offs among various elements that must be arranged, adjusted and coordinated, rather than a plan or choice.[35] Formulation and implementation Strategy typically involves two major processes: formulation and implementation. Formulation involves analyzing the environment or situation, making a diagnosis, and developing guiding policies. It includes such activities as strategic planning and strategic thinking. Implementation refers to the action plans taken to achieve the goals established by the guiding policy.[6][35] Bruce Henderson wrote in 1981 that: "Strategy depends upon the ability to foresee future consequences of present initiatives." He wrote that the basic requirements for strategy development include, among other factors: 1) extensive knowledge about the environment, market and competitors; 2) ability to examine this knowledge as an interactive dynamic system; and 3) the imagination and logic to choose between specific alternatives. Henderson wrote that strategy was valuable because of: "finite resources, uncertainty about an adversary's capability and intentions; the irreversible commitment of resources; necessity of coordinating action over time and distance; uncertainty about control of the initiative; and the nature of adversaries' mutual perceptions of each other."[37] |

マネジメント理論 主な記事 戦略的マネジメント 競争戦略策定の本質は、企業をその環境に関連付けることである。 - マイケル・ポーター[17] それ以前は、最も著名な経営学の文献に「戦略」や「競争」という言葉が登場することはほとんどなかった[18][19]。アルフレッド・チャンドラーは 1962年に次のように書いている: 「戦略とは、企業の基本的な長期目標の決定であり、これらの目標を遂行するために必要な行動方針の採用と資源の配分である」[20]。マイケル・ポーター は1980年に戦略を「...企業がどのように競争しようとしているのか、その目標はどうあるべきなのか、それらの目標を遂行するためにどのような政策が 必要なのかについての大まかな公式」であり、「...企業が目指している目的(目標)と、そこに到達しようとする手段(政策)の組み合わせ」と定義してい る[17]。 定義 ヘンリーミンツバーグは1998年に戦略の5つの定義を記述した: 1. 計画としての戦略 - 意図された一連の目標を達成するための指示された行動のコース; 戦略的計画の概念に類似している; 2. パターンとしての戦略-過去の行動の一貫したパターン。実現されたパターンが意図と異なる場合、彼は戦略を創発的と呼んだ; 3. ポジションとしての戦略 - 消費者または他の利害関係者の概念的枠組みに基づいて、ブランド、製品、または企業を市場内に位置づけること; 4. 策略としての戦略 - 競争相手を出し抜くことを意図した具体的な作戦。 5. 視点としての戦略-「ビジネスの理論」、あるいは組織の考え方やイデオロギー的視点の自然な延長に基づいて戦略を実行すること[21]。 複雑性理論家は、戦略を、社会経済的コンテクストにおける行動をもたらす組織の内部と外部の側面の展開として定義している[22][23][24]。 戦略的問題 このセクションは、ほとんどの読者には専門的すぎて理解できないかもしれません。技術的な詳細を削除することなく、非専門家にも理解できるように改善することにご協力ください。(2023年12月) (このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 戦略的問題という概念は、変動する市場において、エージェント間の競争的抗争と調和的協力の間のダイナミックな相互作用を解明するものである。クラウチは この領域を掘り下げ、ダイナミックな関係を維持することを強調している。著者は協力という概念を受け入れながら、戦略に先立つ市場構造、ひいては組織構造 に先立つ市場構造の優位性を強調している。したがって、著者の視点は、ポーターやミンツバーグが明確にしたように、戦略を価値あるポジションとみなす定義 と密接に一致している[25][26][27]。 対照的に、バーネットは、戦略を方法論を通じて策定された計画として定義する、規定的な視点を採用している。バーネットによれば、戦略問題は、目標策定、環境分析、戦略策定、戦略評価、戦略実行、戦略統制の6つのタスクを包含している[28]。 MukherjiとHurtadoは、戦略的問題の定義における分岐を示している。この文献では、環境を分類するという課題と、確立された文脈に対する組 織の主要な反応を強調するという2つの側面が共通して強調されている。これらの側面は、著者によって識別されるように、状況、これらの問題の解決に関与す るプロセス、およびそれらの構成変数から生じる内部および外部の問題を包含するように発展したAnsoffおよびHayesによって最初に提案された3つ の次元を包含する[29]。 複雑性の観点からは、戦略的問題は、内部及び外部環境の両方において、複雑で相互接続されたシステム内のガバナンスと常に絡み合っている。Terraと Passadorの概念化では、戦略的問題は、サブシステム間の共生関係からなる複雑な社会技術システムとみなされる組織内のサブシステム、人的主体、環 境要素の相互関係に根ざしており、組織の内部社会システムの構成と、組織自身のアイデンティティを確保するために組織が生み出す反応に由来する。このモデ ルは、これらの相互関係の複雑な性質を強調し、内部構造と外部対応との間の複雑な相互作用を理解し、ナビゲートするという戦略家の課題を浮き彫りにしてい る[30][23]。 複雑性理論 このセクションは、ほとんどの読者には専門的すぎて理解できないかもしれません。技術的な詳細を削除することなく、非専門家にも理解できるよう、改善にご協力ください。(2023年12月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) R.D.ステイシーによって明らかにされた複雑性科学は、創発的戦略と意図的戦略を調和させることができる概念的枠組みを表している。複雑性のアプローチ では、「戦略」という用語は行動と密接に結びついているが、プログラムされた行動とは対照的である。複雑性理論家は、プログラムを、高度に秩序化され、あ まり混沌としていない環境において有効な、あらかじめ決められたシーケンスとしか見ていない。逆に、戦略は、行動を促す決定された条件(秩序)と不確実性 (無秩序)を同時に検討することから生まれる。複雑性理論は、戦略は実行を含み、制御と創発を包含し、内部と外部の組織的側面の両方を精査し、作戦やその 他の行為やプロセスの形をとることができると仮定している[31][23][30]。 Staceyの著作は、複雑性の原理を戦略の分野に適用した先駆的な取り組みである。この著者は自己組織化とカオスの原理を戦略、組織変革のダイナミク ス、学習を説明するために適用した。彼らの命題は、選択と競争淘汰の進化プロセスを通じてアプローチする戦略を提唱している。この文脈では、異常の修正は 負のフィードバックを伴う行動を通じて起こるが、革新と継続的な変化は正のフィードバックによって導かれる行動から生じる[32][31][33]。 動的には、戦略的マネジメントにおける複雑性は、TerraとPassadorによる「Symbiotic Dynamics」のモデルを通じて解明することができる[23][34]。このモデルは、生産の社会的組織を、外部環境と相互接続しながら共生関係にあ る2つの異なるシステム間の相互作用として考えている。組織の社会的ネットワークは、組織の生命を制御する自己言及的な実体として機能し、一方、その技術 的構造は、リソースを処理することによって社会システムに供給する、目的を持った「機械」に似ている。これらの絡み合った構造は、その開放性によって外界 と相互作用しながら、外乱と残滓を交換する。本質的に、組織が自らを生産するとき、組織はまた、そのサブシステムを横断するエネルギーと資源の流れを通じ て生き残りながら、異質な生産も行っている[23][34]。 このダイナミズムは戦略的な意味合いを持ち、運用能力と再生能力を確立する一連のアトラクション・ベースを通じて組織のダイナミクスを支配する。したがっ て、戦略家の主要な役割の1つは、「人的アトラクター」を特定し、それらが組織のダイナミクスに及ぼす影響を評価することである。共生ダイナミクスの理論 によると、リーダーと技術システムの両方がアトラクターとして機能し、組織のダイナミクスと外部の混乱への対応に直接影響を与えることができる。 TerraとPassadorはさらに、生産する一方で、組織は環境エントロピーを助長し、組織自体の内部でさえも、サブシステム内の突然の断裂や崩壊に つながる可能性があると主張している。この問題を考慮すると、著者らは、生存に適したパラメータの範囲内で環境の安定性を維持するために介入する組織は、 より長寿を示す傾向があると結論付けている[23][34]。 共生ダイナミクスの理論は、組織が外部環境(市場、社会、環境)に与える影響を認識し、これらの相互作用から生じる要求に適応しながら、その劣化を軽減す るために組織的に行動しなければならないことを提起している。これを達成するために、組織は相互接続されたすべてのシステムを意思決定プロセスに組み込む 必要があり、安定した持続可能な方法で統合された複雑な社会経済システムを構想することが可能になる。このような積極性と反応性の融合は、組織自体の存続 を確保するための基本である。[23] 構成要素 リチャード・P・ルメルト教授は2011年、戦略を問題解決の一種であると説明した。ルメルト教授は、優れた戦略にはカーネルと呼ばれる基礎構造があると 述べている。カーネルには3つの部分がある:1) 課題の本質を定義または説明する診断、2) 課題に対処するための指導方針、3) 指導方針を実行するために設計された首尾一貫した行動である: 診断:「本政府は約束通り、キューバ島におけるソ連の軍備増強を最も厳しく監視してきた。この1週間のうちに、まぎれもない証拠によって、キューバ島では 現在、一連の攻撃用ミサイル基地が準備中であるという事実が立証された。これらの基地の目的は、西半球に対する核攻撃能力を提供することにほかならな い。」 政策の指針 「従って、我々の揺るぎない目的は、この国、あるいは他のいかなる国に対しても、これらのミサイルの使用を阻止し、西半球からの撤退、あるいは廃絶を確実にすることでなければならない」 行動計画: 7つのステップのうち、最初のステップは次のようなものだった: 「この攻撃的増強を阻止するため、キューバに輸送中のすべての攻撃的軍事装備の厳重な検疫を開始する。どのような国や港からキューバに向かう船であれ、攻 撃的兵器の積荷が見つかった場合は、すべて引き返させる」[36]。 ルメルトは2011年に、戦略の3つの重要な側面には、「計画性、他者の行動の予測、そして意図的に設計された協調行動 」が含まれると書いている。彼は戦略を、計画や選択というよりもむしろ、配置され、調整され、調整されなければならない様々な要素間のトレードオフを伴 う、設計上の問題を解決することであると表現している[35]。 策定と実施 戦略には通常、策定と実行という2つの大きなプロセスがある。策定には、環境や状況を分析し、診断を下し、指導方針を策定することが含まれる。これには、 戦略計画や戦略的思考などの活動が含まれる。実施は指導方針によって確立される目的を達成するために取られる行動計画を示す[6][35]。 ブルース・ヘンダーソンは1981年に次のように書いている: 「戦略は、現在の取り組みが将来もたらす結果を予見する能力にかかっている。彼は、戦略策定のための基本的な要件には、とりわけ次のようなものが含まれる と書いている: 1)環境、市場、競争相手に関する広範な知識、2)この知識を相互作用的な動的システムとして検討する能力、3)特定の選択肢の中から選択する想像力と論 理。ヘンダーソンは、戦略が価値あるものである理由を次のように書いている: 「資源が有限であること、敵の能力と意図に関する不確実性、資源の不可逆的な投入、時間と距離にわたって行動を調整する必要性、主導権の支配に関する不確 実性、敵対者の互いに対する認識の性質」[37]。 |

| Game theory Main article: Strategy (game theory) In game theory, a player's strategy is any of the options that the player would choose in a specific setting. Any optimal outcomes they receive depend not only on their actions but also, the actions of other players.[38] |

ゲーム理論 主な記事 戦略(ゲーム理論) ゲーム理論において、プレイヤーの戦略とは特定の状況下でプレイヤーが選択する選択肢のことである。プレイヤーが受け取る最適な結果は、プレイヤーの行動だけでなく、他のプレイヤーの行動にも依存する[38]。 |

| Concept Driven Strategy Consultant Odds algorithm (Odds strategy) Sports strategy Strategy game Strategic management Strategy pattern Strategic planning Strategic voting Strategist Strategy Markup Language Tactic (method) Time management U.S. Army Strategist |

コンセプト・ドリブン・ストラテジー コンサルタント オッズアルゴリズム(オッズ戦略) スポーツ戦略 戦略ゲーム 戦略マネジメント 戦略パターン 戦略プランニング 戦略投票 ストラテジスト 戦略マークアップ言語 戦術(方法) 時間管理 米陸軍ストラテジスト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strategy |

|

| Military strategy

is a set of ideas implemented by military organizations to pursue

desired strategic goals.[1] Derived from the Greek word strategos, the

term strategy, when first used during the 18th century,[2] was seen in

its narrow sense as the "art of the general",[3] or "the art of

arrangement" of troops.[4] and deals with the planning and conduct of

campaigns. The father of Western modern strategic studies, Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831), defined military strategy as "the employment of battles to gain the end of war."[5] B. H. Liddell Hart's definition put less emphasis on battles, defining strategy as "the art of distributing and applying military means to fulfill the ends of policy".[6] Hence, both gave the preeminence to political aims over military goals. Sun Tzu (544–496 BC) is often considered as the father of Eastern military strategy and greatly influenced Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese historical and modern war tactics.[7] The Art of War by Sun Tzu grew in popularity and saw practical use in Western society as well. It continues to influence many competitive endeavors in Asia, Europe, and America including culture, politics,[8][9] and business,[10] as well as modern warfare. The Eastern military strategy differs from the Western by focusing more on asymmetric warfare and deception.[7] Chanakya's Arthashastra has been an important strategic and political compendium in Indian and Asian history as well.[11] |

軍

事戦略とは、軍事組織が望ましい戦略目標を達成するために実施する一連の考えのことである[1]。

ギリシャ語の「ストラテゴス」に由来する「戦略」という用語は、18 世紀に初めて使用された当時[2] は、狭義の「将軍の術」[3]

または「軍隊の配置の術」[4] と解釈され、作戦の計画と実施を扱っていた。 西洋の現代戦略研究の父とされるカール・フォン・クラウゼヴィッツ(1780–1831)は、軍事戦略を「戦争の目的を達成するための戦闘の活用」と定義 した。[5] B. H. リデル・ハートは、戦闘への重点を弱め、戦略を「政策の目的を達成するために軍事手段を配分し適用する技術」と定義した。[6] したがって、両者は政治的目的を軍事目標よりも優先させた。 孫子(紀元前544–496)は、東洋の軍事戦略の父とされ、中国、日本、韓国、ベトナムの歴史的および現代の戦術に大きな影響を与えた。[7] 孫子の『孫子』は人気を博し、西洋社会でも実践的に活用された。この本は、文化、政治[8][9]、ビジネス[10]、そして現代の戦争など、アジア、 ヨーロッパ、アメリカにおける多くの競争的な取り組みに影響を与え続けている。東洋の軍事戦略は、非対称戦争と欺瞞に重点を置いている点で西洋の軍事戦略 とは異なります[7]。チャナキャの『アルタシャストラ』は、インドおよびアジアの歴史においても重要な戦略的・政治的要約書となっている[11]。 |

| Military

strategy is the planning and execution of the contest between groups of

armed adversaries. It is a subdiscipline of warfare and of foreign

policy, and a principal tool to secure national interests. Its

perspective is larger than military tactics, which involve the

disposition and maneuver of units on a particular sea or

battlefield,[12] but less broad than grand strategy (or "national

strategy"), which is the overarching strategy of the largest of

organizations such as the nation state, confederation, or international

alliance and involves using diplomatic, informational, military and

economic resources. Military strategy involves using military resources

such as people, equipment, and information against the opponent's

resources to gain supremacy or reduce the opponent's will to fight,

developed through the precepts of military science.[13] NATO's definition of strategy is "presenting the manner in which military power should be developed and applied to achieve national objectives or those of a group of nations."[14] Field Marshal Viscount Alanbrooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff and co-chairman of the Anglo-US Combined Chiefs of Staff Committee for most of the Second World War, described the art of military strategy as: "to derive from the [policy] aim a series of military objectives to be achieved: to assess these objectives as to the military requirements they create, and the preconditions which the achievement of each is likely to necessitate: to measure available and potential resources against the requirements and to chart from this process a coherent pattern of priorities and a rational course of action."[15] Field-Marshal Montgomery summed it up thus "Strategy is the art of distributing and applying military means, such as armed forces and supplies, to fulfill the ends of policy. Tactics means the dispositions for, and control of, military forces and techniques in actual fighting. Put more shortly: strategy is the art of the conduct of war, tactics the art of fighting."[16] |

軍事戦略とは、武装した敵対者間の

争いの計画と実行のことだ。これは、戦争および外交政策の一分野であり、国益を確保するための主要な手段だ。その視点は、特定の海域や戦場における部隊の

配置や機動を含む軍事戦術よりも広範ですが[12]、国家、連合、国際同盟などの最大規模の組織における包括的な戦略であり、外交、情報、軍事、経済的な

資源の活用を含む大戦略(または「国家戦略」)よりも狭義です。軍事戦略とは、軍事科学の教義に基づいて、敵の資源に対して、人員、装備、情報などの軍事

資源を用いて、優位性を確保したり、敵の戦闘意志を弱めたりすることだ[13]。 NATO の戦略の定義は、「国家または国家の集団の目標を達成するために、軍事力をどのように開発し、適用すべきかを提示すること」[14] である。第二次世界大戦中の大部分において、帝国参謀総長および英米統合参謀本部共同議長を務めたアランブルック元帥は、軍事戦略の芸術を次のように説明 している。「政策目標から達成すべき一連の軍事目標を導き出すこと:これらの目標が創出する軍事要件を評価し、各目標の達成が必然的に必要とする前提条件 を特定すること:利用可能な資源と潜在的な資源を要件と照合し、このプロセスから一貫した優先順位のパターンと合理的な行動方針を策定すること。」 [15] モンゴメリー元帥は次のように要約している。「戦略とは、政策の目的を達成するために、軍隊や物資などの軍事手段を配分し、適用する芸術である。戦術と は、実際の戦闘における軍事力と技術の配置および統制を意味する。より簡潔に言えば、戦略は戦争の指揮の芸術であり、戦術は戦闘の芸術である。」[16] |

| Background Military strategy in the 19th century was still viewed as one of a trivium of "arts" or "sciences" that govern the conduct of warfare; the others being tactics, the execution of plans and maneuvering of forces in battle, and logistics, the maintenance of an army. The view had prevailed since the Roman times, and the borderline between strategy and tactics at this time was blurred, and sometimes categorization of a decision is a matter of almost personal opinion. Carnot, during the French Revolutionary Wars thought it simply involved concentration of troops.[17] As French statesman Georges Clemenceau said, "War is too important a business to be left to soldiers." This gave rise to the concept of the grand strategy[18] which encompasses the management of the resources of an entire nation in the conduct of warfare. On this issue Clausewitz stated that a successful military strategy may be a means to an end, but it is not an end in itself.[19] |

背景 19 世紀の軍事戦略は、依然として、戦争の遂行を支配する「芸術」または「科学」の 3 つの分野のうちの 1 つとみなされていました。他の 2 つは、戦術(計画の実行と戦闘における部隊の操縦)と兵站(軍隊の維持)でした。この見方はローマ時代から主流であり、当時、戦略と戦術の境界は曖昧で、 決定の分類は、ほとんど個人的な見解によるものもあった。フランス革命戦争中のカルノーは、戦略とは単に軍隊の集中であると考えていた[17]。 フランスの政治家ジョルジュ・クレマンソーは、「戦争は、兵士たちに任せるにはあまりにも重要な事業である」と述べた。これにより、戦争遂行における国民 全体の資源の管理を含む大戦略[18] の概念が生まれた。この問題について、クラウゼヴィッツは、軍事戦略の成功は目的を達成するための手段であるかもしれないが、それ自体が目的ではないと述 べた[19]。 |

Principles Military stratagem in the Maneuver against the Romans by Cimbri and Teutons circa 100 B.C. Many military strategists have attempted to encapsulate a successful strategy in a set of principles. Sun Tzu defined 13 principles in his The Art of War while Napoleon listed 115 maxims. American Civil War General Nathan Bedford Forrest had only one: to "[get] there first with the most men".[20] The concepts given as essential in the United States Army Field Manual of Military Operations (FM 3–0) are:[21] Objective type (direct every military operation towards a clearly defined, decisive, and attainable objective) Offensive type (seize, retain, and exploit the initiative) Mass Type (concentrate combat power at the decisive place and time) Economy of force type (allocate minimum essential combat power to secondary efforts) Maneuver type (place the enemy in a disadvantageous position through the flexible application of combat power) Unity of command type (for every objective, ensure unity of effort under one responsible commander) Security type (never permit the enemy to acquire an unexpected advantage) Surprise type (strike the enemy at a time, at a place, or in a manner for which they are unprepared) Simplicity type (prepare clear, uncomplicated plans and clear, concise orders to ensure thorough understanding) According to Greene and Armstrong, some planners assert adhering to the fundamental principles guarantees victory, while others claim war is unpredictable and the strategist must be flexible. Others argue predictability could be increased if the protagonists were to view the situation from the other sides in a conflict.[22] |

原則 紀元前100年頃のキンブリ族とテウトン族によるローマ人に対する作戦における軍事戦略 多くの軍事戦略家は、成功する戦略を一連の原則にまとめようとしてきました。孫子は『孫子』で 13 の原則を定義し、ナポレオンは 115 の格律を列挙しました。アメリカ南北戦争の将軍、ネイサン・ベドフォード・フォレストは、たった 1 つの原則、「最も多くの兵力を率いて、最初にその場に到着する」を掲げていました[20]。米国陸軍軍事作戦フィールドマニュアル(FM 3–0)で必須とされている概念は、次のとおりです[21]。 目的のタイプ(すべての軍事作戦を、明確に定義され、決定的で達成可能な目的 towards に向ける) 攻撃のタイプ(主導権を掌握し、維持し、活用する) 集中のタイプ(決定的な場所と時間に戦闘力を集中させる) 力の経済性のタイプ(二次的な努力には最小限の戦闘力を割り当てる) 機動のタイプ(戦闘力の柔軟な適用により、敵を不利な位置に置く) 指揮統一型(すべての目標について、1 人の責任ある指揮官の下での行動の統一を確保する 安全型(敵に予期せぬ優位性を決して与えない 奇襲型(敵が準備していない時間、場所、方法で敵を攻撃する 単純型(明確で複雑でない計画と、明確で簡潔な命令を用意し、徹底した理解を確保する グリーンとアームストロングによると、一部の計画者は、基本原則を順守すれば勝利が保証されると主張し、一方、戦争は予測不可能であり、戦略家は柔軟でな ければならないと主張する者もいる。また、紛争の当事者が相手側の立場から状況を見れば、予測可能性が高まると主張する者もいる[22]。 |

| Development Antiquity The principles of military strategy emerged at least as far back as 500 BC in the works of Sun Tzu and Chanakya. The campaigns of Alexander the Great, Chandragupta Maurya, Hannibal, Qin Shi Huang, Julius Caesar, Zhuge Liang, Khalid ibn al-Walid and, in particular, Cyrus the Great demonstrate strategic planning and movement. Early strategies included the strategy of annihilation, exhaustion, attrition warfare, scorched earth action, blockade, guerrilla campaign, deception and feint. Ingenuity and adeptness were limited only by imagination, accord, and technology. Strategists continually exploited ever-advancing technology. The word "strategy" itself derives from the Greek "στρατηγία" (strategia), "office of general, command, generalship",[23] in turn from "στρατηγός" (strategos), "leader or commander of an army, general",[24] a compound of "στρατός" (stratos), "army, host" + "ἀγός" (agos), "leader, chief",[25] in turn from "ἄγω" (ago), "to lead".[26] Middle Ages Through maneuver and continuous assault, Chinese, Persian, Arab and Eastern European armies were stressed by the Mongols until they collapsed, and were then annihilated in pursuit and encirclement.[27] Early Modern era In 1520 Niccolò Machiavelli's Dell'arte della guerra (Art of War) dealt with the relationship between civil and military matters and the formation of grand strategy. In the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden demonstrated advanced operational strategy that led to his victories on the soil of the Holy Roman Empire. It was not until the 18th century that military strategy was subjected to serious study in Europe. The word was first used in German as "Strategie" in a translation of Leo VI's Tactica in 1777 by Johann von Bourscheid. From then onwards, the use of the word spread throughout the West.[28] |

発展 古代 軍事戦略の原則は、少なくとも紀元前 500 年に孫子やチャナキャの著作で登場している。アレクサンダー大王、チャンドラグプタ・マウリヤ、ハンニバル、秦の始皇帝、ジュリアス・シーザー、諸葛亮、 ハリド・イブン・アル・ワリード、そして特にキュロス大王の戦いは、戦略的計画と動きを実証している。 初期の戦略には、全滅、消耗、消耗戦、焦土作戦、封鎖、ゲリラ戦、欺瞞、陽動作戦などがあった。創意工夫と熟練は、想像力、協調性、技術によってのみ制限 されていた。戦略家は、進歩し続ける技術を絶えず活用していた。「戦略」という言葉自体は、ギリシャ語の「στρατηγία」(ストラテギア)、「将軍 の職、指揮、将軍職」[23]に由来し、さらに「στρατηγός」(ストラテゴス)、「軍隊の指導者または指揮官、将軍」[24]に由来し、これは 「στρατός」(ストラトス)、「軍隊、敵軍」と「ἀγός」 (アゴス)、「指導者、首長」[25]、これは「ἄγω」(アゴ)、「導く」から派生したものだ。 中世 中国、ペルシャ、アラブ、東ヨーロッパの軍隊は、モンゴル軍による機動戦と連続的な攻撃によって疲弊し、最終的に崩壊し、追撃と包囲によって全滅した。 近世 1520年、ニコロ・マキャヴェッリは『戦争の技法』(Dell'arte della guerra)で、民政と軍事の関係、大戦略の形成について論じた。30年戦争(1618-1648)では、スウェーデンのグスタフ2世アドルフが、神聖 ローマ帝国の領土で勝利を収めるための高度な作戦戦略を示した。ヨーロッパで軍事戦略が真剣に研究されるようになったのは、18 世紀に入ってからのことだった。この言葉は、1777 年にヨハン・フォン・ブルシャイトがレオ 6 世の『戦術』を翻訳した際に、ドイツ語で「Strategie」として初めて使用された。それ以降、この言葉の使用は西洋全体に広まった[28]。 |

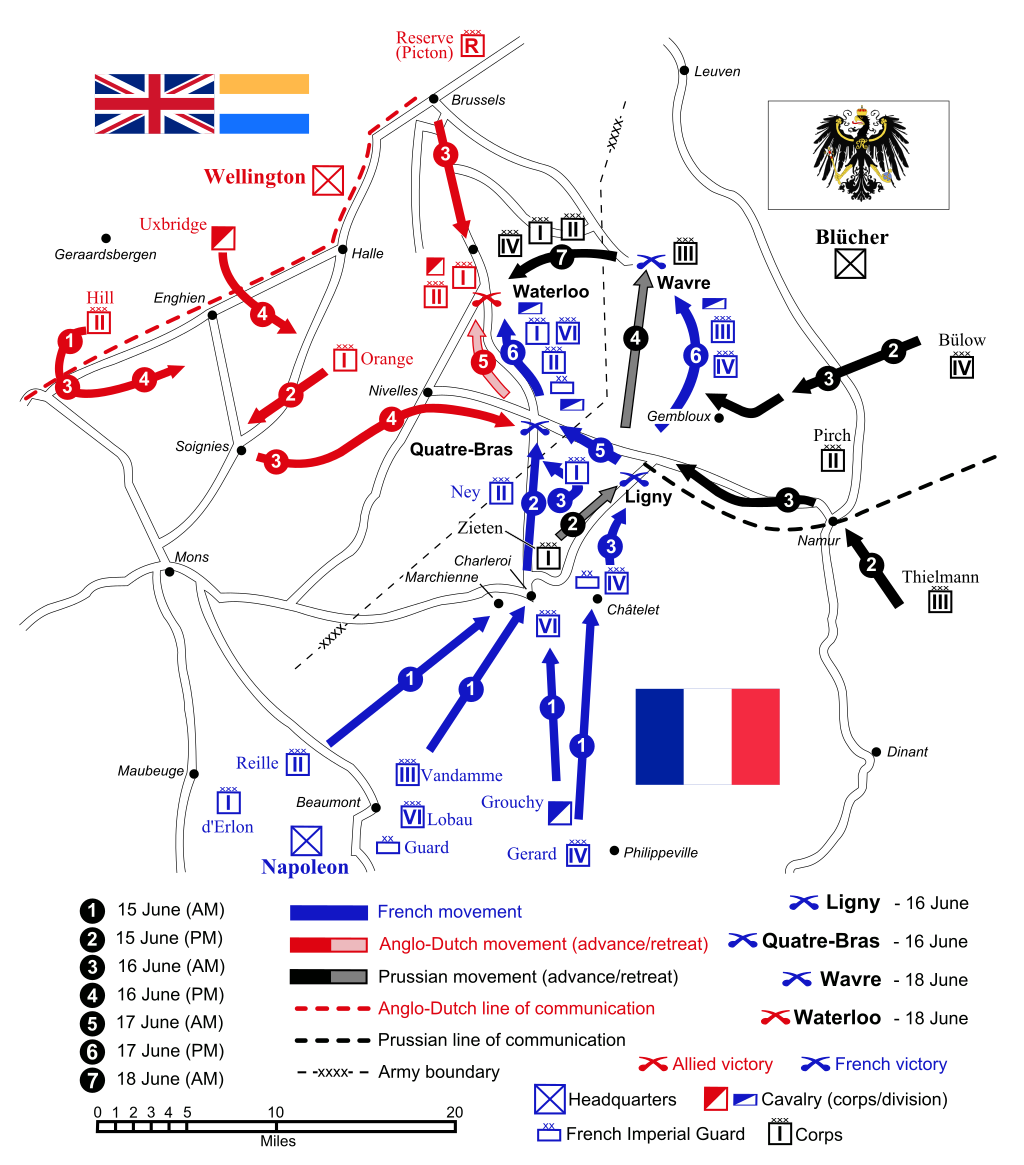

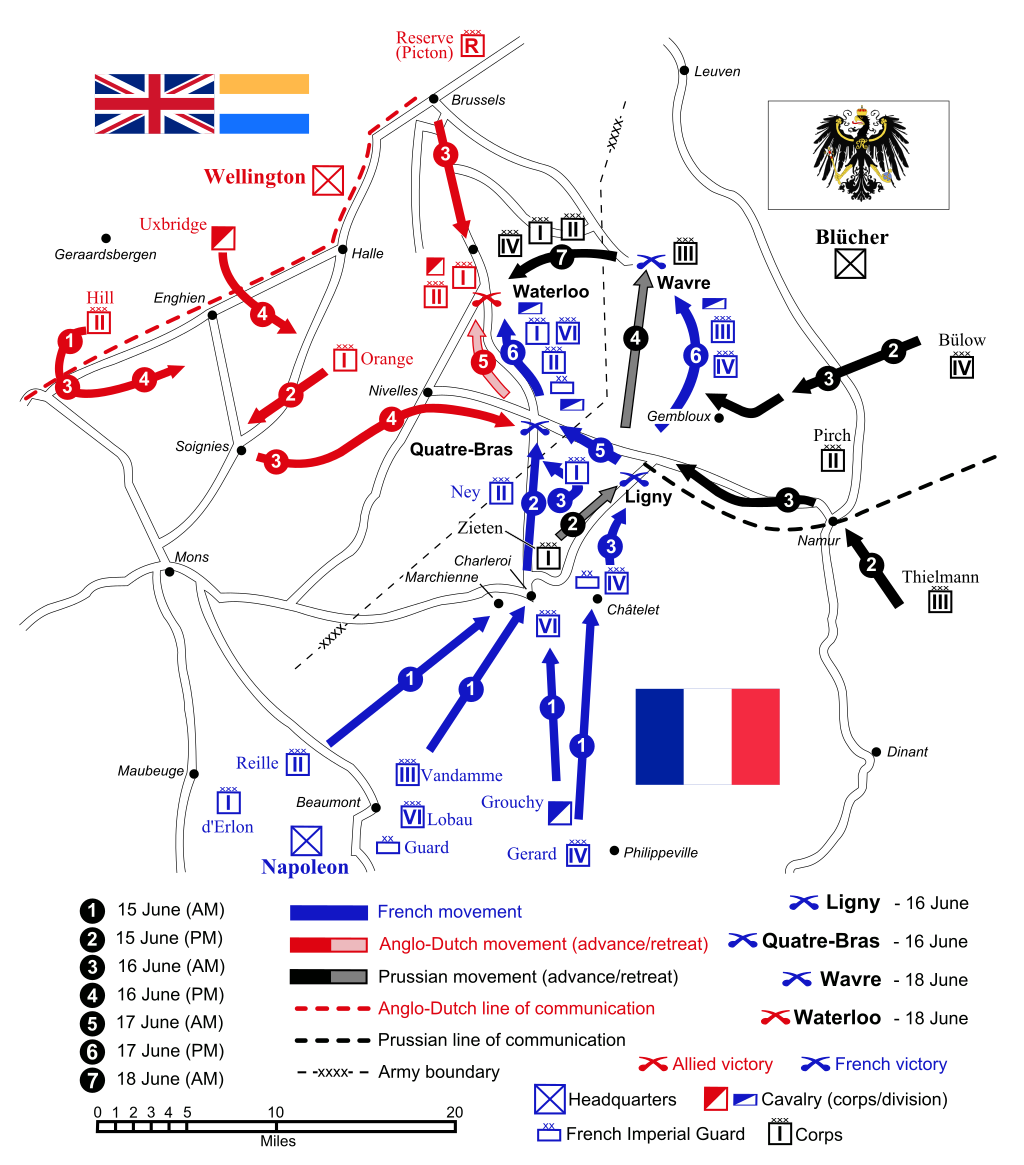

| Napoleonic See also: Napoleonic wars Waterloo  Map of the Waterloo campaign  19th century musketeers from Wellington at Waterloo by Robert Alexander Hillingford, 18 June 1815 See also: Waterloo Campaign Clausewitz and Jomini  Carl von Clausewitz Clausewitz's On War has become a famous reference[29][30] for strategy, dealing with political, as well as military, leadership,[31] his most famous assertion being: "War is not merely a political act, but also a real political instrument, a continuation of policy by other means." Clausewitz saw war first and foremost as a political act, and thus maintained that the purpose of all strategy was to achieve the political goal that the state was seeking to accomplish. As such, Clausewitz famously argued that war was the "continuation of politics by other means".[32] Clausewitz and Jomini are widely read by US military personnel.[33] World War I Main article: World War I Interwar Technological change had an enormous effect on strategy, but little effect on leadership. The use of telegraph and later radio, along with improved transport, enabled the rapid movement of large numbers of men. One of Germany's key enablers in mobile warfare was the use of radios, where these were put into every tank. However, the number of men that one officer could effectively control had, if anything, declined. The increases in the size of the armies led to an increase in the number of officers. Although the officer ranks in the US Army did swell, in the German army the ratio of officers to total men remained steady.[34] |

ナポレオン 参照:ナポレオン戦争 ウォータールー  ウォータールーの戦いの地図  1815年6月18日、ロバート・アレクサンダー・ヒリングフォードによる、ウォータールーのウェリントン軍所属の19世紀の銃兵たち 参照:ウォータールーの戦い クラウゼヴィッツとジョミニ  カール・フォン・クラウゼヴィッツ クラウゼヴィッツの『戦争論』は、政治、軍事、リーダーシップに関する戦略の有名な参考書となっている[29][30]。彼の最も有名な主張は次のとおりだ。 「戦争は単なる政治行為ではなく、他の手段による政策の継続である、真の意味での政治手段である。 クラウゼヴィッツは、戦争を何よりもまず政治的行為と捉え、したがって、あらゆる戦略の目的は、国家が達成しようとしている政治的目的を達成することにあ ると主張した。そのため、クラウゼヴィッツは、戦争は「他の手段による政治の継続」であると主張し、その主張は有名になった[32]。クラウゼヴィッツと ジョミニは、米軍の将校たちに広く読まれている[33]。 第一次世界大戦 主な記事:第一次世界大戦 戦間期 技術革新は戦略に大きな影響を与えたが、リーダーシップにはほとんど影響を与えなかった。電信と後の無線の普及、および輸送手段の改善により、大量の兵士 の迅速な移動が可能になった。ドイツの機動戦における重要な要因の一つは無線の活用で、これらはすべての戦車に搭載された。しかし、1人の将校が効果的に 指揮できる兵士の数は、むしろ減少した。軍隊の規模拡大に伴い、将校の数も増加した。アメリカ陸軍では将校の数が急増したが、ドイツ陸軍では将校と兵士の 比率はおおむね一定だった。[34] |

| World War II Interwar Germany had as its main strategic goals the reestablishment of Germany as a European great power[35] and the complete annulment of the Versailles treaty of 1919. After Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party took power in 1933, Germany's political goals also included the accumulation of Lebensraum ("Living space") for the Germanic "race" and the elimination of communism as a political rival to Nazism. The destruction of European Jewry, while not strictly a strategic objective, was a political goal of the Nazi regime linked to the vision of a German-dominated Europe, and especially to the Generalplan Ost for a depopulated east[36] which Germany could colonize. Cold War Soviet strategy in the Cold War was dominated by the desire to prevent, at all costs, the recurrence of an invasion of Russian soil. The Soviet Union nominally adopted a policy of no first use, which in fact was a posture of launch on warning.[37] Other than that, the USSR adapted to some degree to the prevailing changes in the NATO strategic policies that are divided by periods as: [38] Strategy of massive retaliation (1950s) (Russian: стратегия массированного возмездия) Strategy of flexible reaction (1960s) (Russian: стратегия гибкого реагирования) Strategies of realistic threat and containment (1970s) (Russian: стратегия реалистического устрашения или сдерживания) Strategy of direct confrontation (1980s) (Russian: стратегия прямого противоборства) one of the elements of which became the new highly effective high-precision targeting weapons. Strategic Defense Initiative (also known as "Star Wars") during its 1980s development (Russian: стратегическая оборонная инициатива – СОИ) which became a core part of the strategic doctrine based on Defense containment. All-out nuclear World War III between NATO and the Warsaw Pact did not take place. The United States recently (April 2010) acknowledged a new approach to its nuclear policy which describes the weapons' purpose as "primarily" or "fundamentally" to deter or respond to a nuclear attack.[39] |

第二次世界大戦 戦間期のドイツは、ヨーロッパの大国としてのドイツの復活[35] と、1919年のヴェルサイユ条約の完全破棄を主な戦略目標としていた。1933年にアドルフ・ヒトラーとナチス党が政権を握った後、ドイツの政治目標に は、ゲルマン人種のための「生存空間」の確保と、ナチズムの政治的ライバルである共産主義の排除も加わった。ヨーロッパのユダヤ人の絶滅は、厳密には戦略 的目標ではなかったが、ナチス政権の政治目標の一つであり、ドイツ支配下のヨーロッパのビジョン、特にドイツが植民地化できる人口削減された東欧地域を想 定した「一般東部計画」[36]と密接に関連していた。 冷戦 冷戦期のソビエト戦略は、ロシア領土への侵攻の再発を何としても防ぐという願望に支配されていた。ソビエト連邦は名目上「先制不使用」政策を採用したが、 実際には警告発令後の発射姿勢だった[37]。それ以外では、ソビエト連邦はNATOの戦略政策の変化に一定程度適応し、その変化は時期別に次のように分 類される: [38 大量報復戦略(1950年代)(ロシア語:стратегия массированного возмездия) 柔軟な反応戦略(1960年代)(ロシア語:стратегия гибкого реагирования) 現実的な脅威と封じ込め戦略(1970年代)(ロシア語:стратегия реалистического устрашения или сдерживания) 直接対決戦略(1980年代)(ロシア語:стратегия прямого противоборства) その要素の一つが、新たな高精度誘導兵器となった。 戦略的防衛イニシアチブ(通称「スターウォーズ」) 1980年代の開発段階(ロシア語:стратегическая оборонная инициатива – СОИ) 防衛封じ込めを基盤とする戦略的教義の核心部分となった。 NATOとワルシャワ条約機構の間で全面的な核戦争(第三次世界大戦)は発生しなかった。アメリカ合衆国は最近(2010年4月)、核政策の新たなアプローチを承認し、核兵器の目的を「主に」または「根本的に」核攻撃の抑止または対応と定義した。[39] |

| Post–Cold War See also: Asymmetric warfare and Network-centric warfare Strategy in the post Cold War is shaped by the global geopolitical situation: a number of potent powers in a multipolar array which has arguably come to be dominated by the hyperpower status of the United States.[40] Parties to conflict which see themselves as vastly or temporarily inferior may adopt a strategy of "hunkering down" – witness Iraq in 1991[41] or Yugoslavia in 1999.[42] The major militaries of today are usually built to fight the "last war" (previous war) and hence have huge armored and conventionally configured infantry formations backed up by air forces and navies designed to support or prepare for these forces.[43] Netwar A main point in asymmetric warfare is the nature of paramilitary organizations such as Al-Qaeda which are involved in guerrilla military actions but which are not traditional organizations with a central authority defining their military and political strategies. Organizations such as Al-Qaeda may exist as a sparse network of groups lacking central coordination, making them more difficult to confront following standard strategic approaches. This new field of strategic thinking is tackled by what is now defined as netwar.[44] |

冷戦後 関連項目:非対称戦争、ネットワーク中心の戦争 冷戦後の戦略は、世界的な地政学的状況によって形作られている。すなわち、多極的な勢力構造の中で、複数の強力な勢力が存在し、その中では、米国が超大国としての地位を確立しているといえる状況だ[40]。 自身を圧倒的にまたは一時的に劣勢と見なす紛争当事者は、「籠城」戦略を採用する可能性がある。1991年のイラク[41]や1999年のユーゴスラビア[42]がその例だ。 現在の主要な軍隊は通常、「最後の戦争」(前回の戦争)を戦うために構築されており、そのため、空軍や海軍によって支援または準備される、巨大な装甲部隊や伝統的な編成の歩兵部隊を保有している。[43] ネット戦争 非対称戦争の主要なポイントは、アルカイダのような準軍事組織の性質にある。これらの組織はゲリラ軍事行動に関与しているが、軍事的・政治的戦略を定義す る中央権威を持つ伝統的な組織ではない。アルカイダのような組織は、中央の調整を欠く疎なネットワークとして存在するため、標準的な戦略的アプローチでは 対応が困難だ。この新たな戦略的思考の分野は、現在「ネットウォー」として定義されている。[44] |

| General Strategy Grand strategy Naval strategy Operational mobility Military doctrine Principles of war Military tactics List of military tactics List of military strategies and concepts List of military writers List of military strategy books Roerich Pact Examples of military strategies Schlieffen Plan Mutual assured destruction Blitzkrieg Shock and awe Fabian strategy Progressive war Related topics Asymmetric warfare Basic Strategic Art Program Battleplan (documentary TV series) Force multiplication Strategic bombing Strategic depth U.S. Army Strategist War termination |

一般 戦略 大戦略 海軍戦略 作戦機動性 軍事学 戦争の原則 軍事戦術 軍事戦術の一覧 軍事戦略および概念の一覧 軍事作家の一覧 軍事戦略書の一覧 ルーリッヒ協定 軍事戦略の例 シュリーフェン計画 相互確証破壊 電撃戦 衝撃と畏怖 ファビアン戦略 漸進戦争 関連 非対称戦争 基本戦略芸術プログラム バトルプラン(ドキュメンタリーTVシリーズ) 戦力倍増 戦略爆撃 戦略的深度 アメリカ陸軍戦略家 戦争終結 |

| Bibliography Brands, Hal, ed. The New Makers of Modern Strategy: From the Ancient World to the Digital Age (2023) excerpt, 46 essays by experts on ideas of famous strategists; 1200 pp Carpenter, Stanley D. M., Military Leadership in the British Civil Wars, 1642–1651: The Genius of This Age, Routledge, 2005. Chaliand, Gérard, The Art of War in World History: From Antiquity to the Nuclear Age, University of California Press, 1994. Gartner, Scott Sigmund, Strategic Assessment in War, Yale University Press, 1999. Heuser, Beatrice, The Evolution of Strategy: Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge University Press, 2010), ISBN 978-0-521-19968-1. Matloff, Maurice, (ed.), American Military History: 1775–1902, volume 1, Combined Books, 1996. May, Timothy. The Mongol Art of War: Chinggis Khan and the Mongol Military System. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword, 2007. ISBN 978-1844154760. Wilden, Anthony, Man and Woman, War and Peace: The Strategist's Companion, Routledge, 1987. |

参考文献 Brands, Hal, ed. The New Makers of Modern Strategy: From the Ancient World to the Digital Age (2023) 抜粋、著名な戦略家の思想に関する専門家による 46 編の論文、1200 ページ Carpenter, Stanley D. M., Military Leadership in the British Civil Wars, 1642–1651: The Genius of This Age, Routledge, 2005. チャリアンド、ジェラール、『世界史における戦争の芸術:古代から核時代まで』、カリフォルニア大学出版局、1994年。 ガートナー、スコット・シグムンド、『戦争における戦略的評価』、エール大学出版局、1999年。 ヒューザー、ベアトリス、『戦略の進化:古代から現代までの戦争の思考』(ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2010年)、ISBN 978-0-521-19968-1。 マトロフ、モーリス(編)、『アメリカ軍事史:1775-1902』、第1巻、Combined Books、1996年。 メイ、ティモシー。『モンゴルの戦争芸術:チンギス・ハンとモンゴル軍事システム』。バーンズリー、イギリス:ペン&ソード、2007年。ISBN 978-1844154760。 ワイルデン、アンソニー、『男と女、戦争と平和:戦略家のコンパニオン』、ルートレッジ、1987年。 |

| The US Army War College

Strategic Studies Institute publishes several dozen papers and books

yearly focusing on current and future military strategy and policy,

national security, and global and regional strategic issues. Most

publications are relevant to the International strategic community,

both academically and militarily. All are freely available to the

public in PDF format. The organization was founded by General Dwight D.

Eisenhower after World War II. Black, Jeremy, Introduction to Global Military History: 1775 to the Present Day, Routledge Press, 2005. D'Aguilar, G.C., Napoleon's Military Maxims, free ebook, Napoleon's Military Maxims. Freedman, Lawrence. Strategy: A History (2013) excerpt Holt, Thaddeus, The Deceivers: Allied Military Deception in the Second World War, Simon and Schuster, June, 2004, hardcover, 1184 pages, ISBN 0-7432-5042-7. Tomes, Robert R., US Defense Strategy from Vietnam to Operation Iraqi Freedom: Military Innovation and the New American Way of War, 1973–2003, Routledge Press, 2007. |

米国陸軍戦争大学戦略研究所は、現在および将来の軍事戦略と政策、国家

安全保障、世界および地域の戦略的問題に焦点を当てた数十の論文や書籍を毎年発行している。ほとんどの出版物は、学術的および軍事的の両面から、国際戦略

コミュニティに関連している。これらはすべて、PDF

形式で一般に無料で公開されている。この組織は、第二次世界大戦後にドワイト・D・アイゼンハワー将軍によって設立された。 ブラック、ジェレミー、『世界軍事史入門:1775 年から現在まで』、Routledge Press、2005 年。 D'Aguilar、G.C.、『ナポレオンの軍事格律』、無料電子書籍、『ナポレオンの軍事格律』。 フリードマン、ローレンス。『戦略:その歴史』(2013 年)抜粋 ホルト、サデウス、『欺瞞者たち: 第二次世界大戦における連合軍の軍事欺瞞、サイモン・アンド・シュスター、2004 年 6 月、ハードカバー、1184 ページ、ISBN 0-7432-5042-7。 トムズ、ロバート R.、ベトナムからイラク自由作戦までの米国の防衛戦略:軍事革新と新しいアメリカの戦争方法、1973 年~2003 年、ラウトレッジ・プレス、2007 年。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_strategy |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆