タイーノ族

Taíno, タイノ族

Statue of Agüeybaná II, El Bravo, at the Monument to Agüeybaná II, El Bravo, Park, at the intersection of the Ponce Bypass and the Ave. Hostos, Playa neighborhood, Ponce, Puerto Rico

ア

グエイバナ2世の像、エル・ブラボ、アグエイバナ2世の記念碑、公園、ホストス通りとポンセバイパス通りの交差点、プエルトリコ、ポンセ、プラヤ地区

☆

タイノ族とは、カリブ海の歴史的な先住民族を指す用語であり、その文化は今日、子孫やタイノ族復興派のコミュニティによって受け継がれている。[2]

[3][4]

大アンティル諸島の先住民族は、1836年に人類学者コンスタンティン・サミュエル・ラフィネスクが作った造語であるため、自分たちをタイノ族とは呼ばな

かった。[2]

大アンティル諸島の先住民族は、アイランド・アラワク族と呼ばれることもある。15世紀後半にヨーロッパ人が接触した当時、彼らは現在のキューバ、ドミニ

カ共和国、ジャマイカ、ハイチ、プエルトリコ、バハマ、および小アンティル諸島北部のほとんどの地域に主に居住していた。タイノ族のルカヤン支族は、

1492年10月12日にクリストファー・コロンブスがバハマ諸島で遭遇した最初の新世界の人々であった。タイノ族は歴史的にアラワク語族の言語を話して

いた。GranberryとVescelius(2004年)は、タイノ語には2つの種類があることを認識しており、プエルトリコとイスパニョーラ島の大

部分で話されていた「古典タイノ語」と、バハマ、キューバの大部分、イスパニョーラ島西部、ジャマイカで話されていた「シボネイ・タイノ語」である。彼ら

は、首長が統治する農業社会で、定住し、母系制の親族制度と相続制度のもとで暮らしていた。タイノ族の宗教はゼミスの崇拝を中心としていた。

一部の文化人類学者や歴史家は、タイノ族は数世紀前にすでに絶滅していたと主張している。[7][8][9]

あるいは、彼らは徐々にアフリカやスペインの文化と共通のアイデンティティに融合していったという説もある。[10]

しかし、今日では多くの人々がタイノ族であると自認し、あるいはタイノ族の血を引いていると主張している。特にプエルトリコ人、キューバ人、ドミニカ人の

国民の間で顕著である。[11][1 2]

多くのプエルトリコ人、キューバ人、ドミニカ人はカリブ海先住民のミトコンドリアDNAを持っており、直接の女性系を通じてタイノ族の血筋を受け継いでい

ることを示している。[13][14]

一部のコミュニティでは、タイノ族の古い文化遺産が途切れることなく受け継がれており、秘密裏に継承されている場合もあるが、タイノ族の文化を生活に取り

入れようとする復興主義のコミュニティもある。[9][15]

| Outline Taíno is a term referring to a historic Indigenous people of the Caribbean, whose culture has been continued today by their descendants and Taíno revivalist communities.[2][3][4] Indigenous people in the Greater Antilles did not refer to themselves as Taínos, as the term was coined by the anthropologist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque in 1836.[2] The Indigenous peoples of the Greater Antilles are sometimes referred to as Island Arawaks. At the time of European contact in the late 15th century, they were the principal inhabitants of most of what is now Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Haiti, Puerto Rico, the Bahamas, and the northern Lesser Antilles. The Lucayan branch of the Taíno were the first New World peoples encountered by Christopher Columbus, in the Bahama Archipelago on October 12, 1492. The Taíno historically spoke an Arawakan language. Granberry and Vescelius (2004) recognized two varieties of the Taino language, "Classical Taino", spoken in Puerto Rico and most of Hispaniola, and "Ciboney Taino", spoken in the Bahamas, most of Cuba, western Hispaniola, and Jamaica.[5] They lived in agricultural societies ruled by caciques with fixed settlements and a matrilineal system of kinship and inheritance. Taíno religion centered on the worship of zemis.[6] Some anthropologists and historians have argued that the Taíno were no longer extant centuries ago,[7][8][9] or that they gradually merged into a common identity with African and Hispanic cultures.[10] However, many people today identify as Taíno or have Taíno descent, most notably in subsections of the Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Dominican nationalities.[11][12] Many Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Dominicans have Caribbean-Indigenous mitochondrial DNA, suggesting Taíno descent through the direct female line.[13][14] While some communities describe an unbroken cultural heritage passed down from the old Taíno peoples, often in secret, others are revivalist communities who seek to incorporate Taíno culture into their lives.[9][15] |

概要 タイノ族とは、カリブ海の歴史的な先住民族を指す用語であり、その文化 は今日、子孫やタイノ族復興派のコミュニティによって受け継がれている。[2][3][4] 大アンティル諸島の先住民族は、1836年に人類学者コンスタンティン・サミュエル・ラフィネスクが作った造語であるため、自分たちをタイノ族とは呼ばな かった。[2] 大アンティル諸島の先住民族は、アイランド・アラワク族と呼ばれることもある。15世紀後半にヨーロッパ人が接触した当時、彼らは現在のキューバ、ドミニ カ共和国、ジャマイカ、ハイチ、プエルトリコ、バハマ、および小アンティル諸島北部のほとんどの地域に主に居住していた。タイノ族のルカヤン支族は、 1492年10月12日にクリストファー・コロンブスがバハマ諸島で遭遇した最初の新世界の人々であった。タイノ族は歴史的にアラワク語族の言語を話して いた。GranberryとVescelius(2004年)は、タイノ語には2つの種類があることを認識しており、プエルトリコとイスパニョーラ島の大 部分で話されていた「古典タイノ語」と、バハマ、キューバの大部分、イスパニョーラ島西部、ジャマイカで話されていた「シボネイ・タイノ語」である。彼ら は、首長が統治する農業社会で、定住し、母系制の親族制度と相続制度のもとで暮らしていた。タイノ族の宗教はゼミスの崇拝を中心としていた。 一部の文化人類学者や歴史家は、タイノ族は数世紀前にすでに絶滅していたと主張している。[7][8][9] あるいは、彼らは徐々にアフリカやスペインの文化と共通のアイデンティティに融合していったという説もある。[10] しかし、今日では多くの人々がタイノ族であると自認し、あるいはタイノ族の血を引いていると主張している。特にプエルトリコ人、キューバ人、ドミニカ人の 国民の間で顕著である。[11][1 2] 多くのプエルトリコ人、キューバ人、ドミニカ人はカリブ海先住民のミトコンドリアDNAを持っており、直接の女性系を通じてタイノ族の血筋を受け継いでい ることを示している。[13][14] 一部のコミュニティでは、タイノ族の古い文化遺産が途切れることなく受け継がれており、秘密裏に継承されている場合もあるが、タイノ族の文化を生活に取り 入れようとする復興主義のコミュニティもある。[9][15] |

Terminology Reconstruction of a Taíno village in El Chorro de Maíta, Cuba Scholars have faced difficulties researching the native inhabitants of the Caribbean islands to which Columbus voyaged in 1492, since European accounts cannot be read as objective evidence of a native Caribbean social reality.[16] The people who inhabited most of the Greater Antilles when Europeans arrived have been called Taínos, a term coined by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque in 1836.[2] Taíno is not a universally accepted denomination—it was not the name this people called themselves originally, and there is still uncertainty about their attributes and the boundaries of the territory they occupied.[17] The term nitaino or nitayno, from which Taíno derived, referred to an elite social class, not to an ethnic group. No 16th-century Spanish documents use this word to refer to the tribal affiliation or ethnicity of the natives of the Greater Antilles. The word tayno or taíno, with the meaning "good" or "prudent", was mentioned twice in an account of Columbus's second voyage by his physician, Diego Álvarez Chanca, while in Guadeloupe. José R. Oliver writes that the Natives of Borinquén, who had been captured by the Caribs of Guadeloupe and who wanted to escape on Spanish ships to return home to Puerto Rico, used the term to indicate that they were the "good men", as opposed to the Caribs.[2] According to Peter Hulme, most translators appear to agree that the word taíno was used by Columbus's sailors, not by the islanders who greeted them, although there is room for interpretation. The sailors may have been saying the only word they knew in a native Caribbean tongue, or perhaps they were indicating to the "commoners" on the shore that they were taíno, i.e., important people, from elsewhere and thus entitled to deference. If taíno was being used here to denote ethnicity, then it was used by the Spanish sailors to indicate that they were "not Carib", and gives no evidence of self-identification by the native people.[17] According to José Barreiro, a direct translation of the word Taíno signified "men of the good".[18] The Taíno people, or Taíno culture, have been classified by some authorities as belonging to the Arawak peoples. Their language is considered to have belonged to the Arawak language family, the languages of which were historically present throughout the Caribbean, and much of Central and South America. In 1871, early ethnohistorian Daniel Garrison Brinton referred to the Taíno people as the Island Arawak, expressing their connection to the continental peoples.[19] Since then, numerous scholars and writers have referred to the Indigenous group as Arawaks or Island Arawaks. However, contemporary scholars (such as Irving Rouse and Basil Reid) concluded that the Taíno developed a distinct language and culture from the Arawak of South America.[20][page needed][21] Taíno and Arawak have been used with numerous and contradictory meanings by writers, travelers, historians, linguists, and anthropologists. Often they were used interchangeably: Taíno was applied to the Greater Antillean natives only, but could include the Bahamian or the Leeward Islands natives, excluding the Puerto Rican and Leeward nations. Similarly, Island Taíno has been used to refer only to those living in the Windward Islands, or to the northern Caribbean inhabitants, as well as to the Indigenous population of all the Caribbean islands. Many modern historians, linguists, and anthropologists now hold that the term Taíno should refer to all the Taíno/Arawak nations except the Caribs, who are not seen as belonging to the same people. Linguists continue to debate whether the Carib language was an Arawakan dialect or a Creole language. They also speculate that it was an independent language isolate, with an Arawakan pidgin used for communication purposes with other peoples, as in trading. Rouse classifies all inhabitants of the Greater Antilles as Taíno (except the western tip of Cuba and small pockets of Hispaniola), as well as those of the Lucayan Archipelago and the northern Lesser Antilles. He subdivides the Taíno into three main groups: Classic Taíno, from most of Hispaniola and all of Puerto Rico; Western Taíno, or sub-Taíno, from Jamaica, most of Cuba, and the Lucayan archipelago; and Eastern Taíno, from the Virgin Islands to Montserrat.[22] Modern groups with Caribbean-Indigenous heritage have reclaimed the exonym Taíno as a self-descriptor, although terms such as Neo-Taino or Indio are also used.[23][14] |

用語 キューバのエル・チョロ・デ・マイタにあるタイノ族の村の復元 1492年にコロンブスが航海したカリブ海諸島の先住民について研究することは、学者にとって困難を伴う。なぜなら、ヨーロッパ人の記録は、カリブ海諸島 の社会の実情を客観的に示す証拠として読むことができないからである。[16] ヨーロッパ人が到着した当時、大アンティル諸島の大部分に居住していた人々はタイノ族と呼ばれてきた 。この名称は、1836年にコンスタンティン・サミュエル・ラフィネスケが作った造語である。[2] タイノ族という名称は、一般的に受け入れられているわけではない。この名称は、もともとこの民族が自分たちを呼んでいた名称ではないし、彼らの属性や彼ら が占領していた領土の境界についても、依然として不明な点がある。[17] タイノ族の語源となったnitainoまたはnitaynoという用語は、エリート階級を指すものであり、民族を指すものではない。16世紀のスペインの 文書には、この語が大アンティル諸島先住民の部族や民族を指して使われたものは見当たらない。「善良」または「思慮深い」という意味の「タイノ」または 「タイノ」という語は、コロンブスの2回目の航海の際に、グアドループに滞在していたコロンブスの主治医ディエゴ・アルバレス・チャンカによって2度言及 されている。ホセ・R・オリバーは、グアデループのカリブ人に捕らえられ、スペイン船でプエルトリコに帰国しようとしていたボリンケンの先住民たちが、カ リブ人に対して自分たちは「善良な人間」であることを示すためにこの言葉を使ったと書いている。 ピーター・ハルムによると、解釈の余地はあるものの、ほとんどの翻訳者は、タイノという言葉は、彼らを迎えた島民ではなく、コロンブスの船乗りが使ったと いう点で一致しているようだ。船乗りが知っていた唯一のカリブの原住民の言葉を使っていたのかもしれないし、あるいは、海岸にいた「平民」に対して、自分 たちはタイノ、つまり、自分たちは他所から来た重要な人物であり、敬意を払われるべき存在であると示していたのかもしれない。もしここで「タイノ」という 言葉が民族性を示すために使われているのであれば、スペイン人船員たちは自分たちが「カリブ人ではない」ことを示すために使っていたことになり、先住民が 自らをそう呼んでいたという証拠は何も見当たらない。[17] ホセ・バレイロによると、タイノという言葉の直訳は「善良な人々」を意味する。[18] タイノ族またはタイノ文化は、一部の権威者によってアラワク族に属すると分類されている。彼らの言語はアラワク語族に属すると考えられており、その言語は 歴史的にカリブ海全域、および中南米の大部分に存在していた。 1871年、初期の民族歴史学者ダニエル・ギャリソン・ブリントンはタイノ族を「島アラワク人」と呼び、大陸の民族とのつながりを表現した。[19] それ以来、多数の学者や作家が先住民族グループをアラワク人または島アラワク人と呼んできた。しかし、現代の学者(アーヴィング・ラウスやバジル・リード など)は、タイノ族は南アメリカのアラワク族とは異なる独自の言語と文化を発展させていたと結論づけている。[20][要ページ番号][21] タイノ族とアラワク族という名称は、作家、旅行者、歴史家、言語学者、人類学者によって、数多く、かつ矛盾する意味で使用されてきた。 しばしば、両者は交換可能に使用されてきた。「タイノ族」は大アンティル諸島の原住民のみを指す場合もあれば、バハマ諸島や風下諸島の原住民を含み、プエ ルトリコや風下諸国を除く場合もあった。同様に、「島嶼タイノ族」は風上諸島のみに居住する人々、あるいはカリブ海北部の住民、あるいはカリブ海諸島の先 住民全体を指す場合にも用いられた。 現在では、多くの現代の歴史家、言語学者、人類学者が、タイノ族という用語は、同じ民族とは見なされないカリブ族を除く、すべてのタイノ族/アラワク族の 国民を指すべきであると考えている。言語学者の間では、カリブ族の言語がアラワク語の方言であったのか、あるいはクレオール語であったのかについて、現在 も議論が続いている。また、彼らは、カリブ族の言語は独立した孤立言語であり、貿易など他の民族とのコミュニケーションの手段としてアラワク語のピジン語 が使われていたのではないかとも推測している。 ラウスは、大アンティル諸島の全住民(キューバの西端とハイチ島のごく一部を除く)をタイノ族とし、さらにルカヤン諸島と小アンティル諸島北部の住民もタ イノ族としている。彼はタイノ族をさらに3つの主要グループに細分化している。古典的タイノ族は、イスパニオラ島の大部分とプエルトリコ全土に居住。西部 タイノ族または亜タイノ族は、ジャマイカ、キューバの大部分、およびルカヤン諸島に居住。東部タイノ族は、バージン諸島からモントセラト島に居住。 カリブ海先住民の血を引く現代のグループは、自称を表す言葉として外来語の「タイノ族」を復活させたが、ネオ・タイノ族やインディオなどの用語も使用されている。[23][14] |

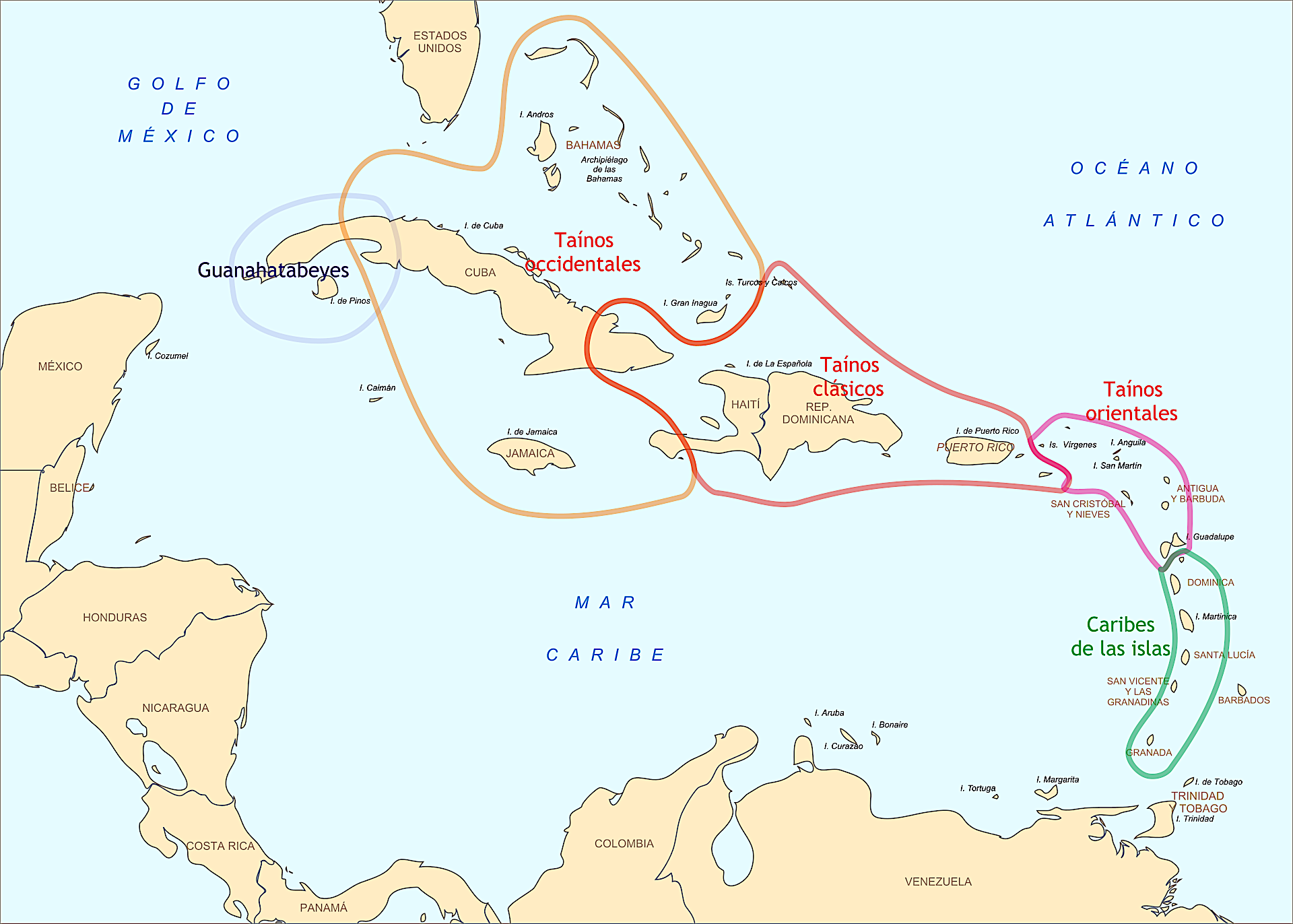

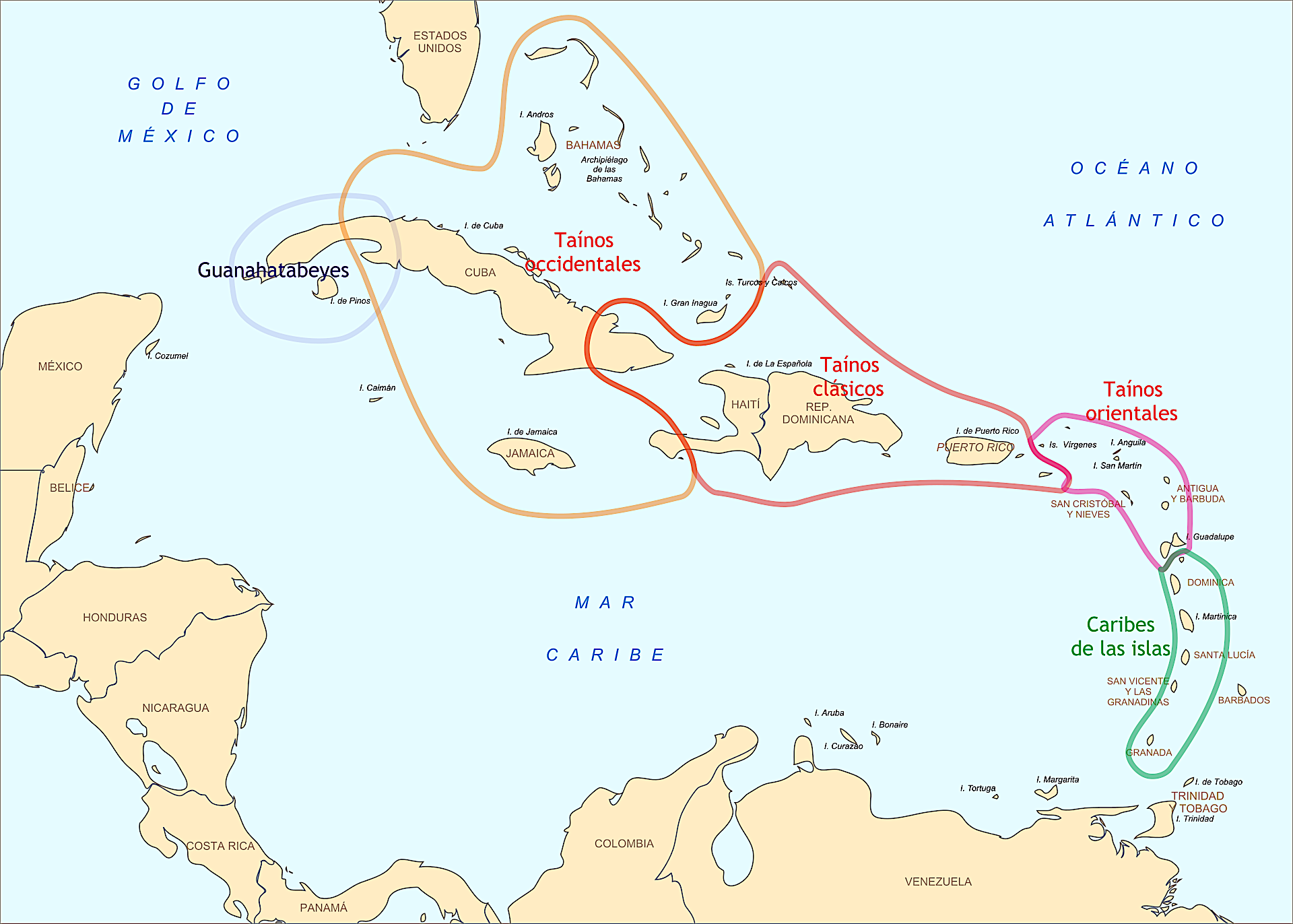

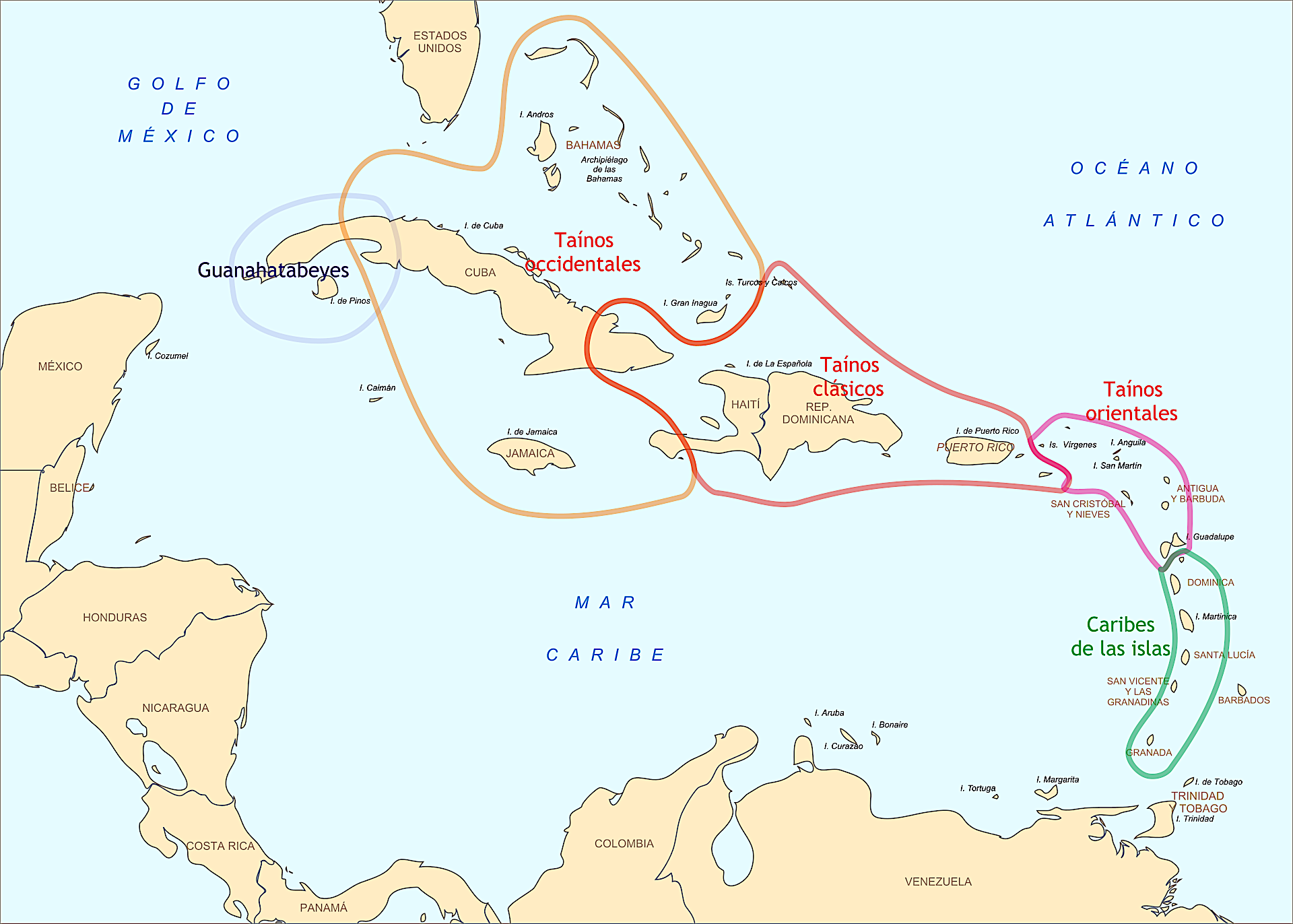

Origins The Guanahatabey region in relation to Taíno and Island Carib groups Two schools of thought have emerged regarding the origin of the Indigenous Caribbean people. One group of scholars contends that the Taíno's ancestors were Arawak speakers from the center of the Amazon Basin, as indicated by linguistic, cultural, and ceramic evidence. They migrated to the Orinoco Valley on the north coast, before reaching the Caribbean by way of what is now Venezuela into Trinidad, migrating along the Lesser Antilles to Cuba and the Bahamas. Evidence that supports the theory includes the tracing of the ancestral cultures of these people to the Orinoco Valley and their languages to the Amazon Basin.[24][25][26] The alternate theory, known as the circum-Caribbean theory, contends that the Taíno's ancestors diffused from the Colombian Andes. Julian H. Steward, who originated this concept, suggests a migration from the Andes to the Caribbean and a parallel migration into Central America and the Guianas, Venezuela, and the Amazon Basin of South America.[24] Taíno culture as documented is believed to have developed in the Caribbean. The Taíno creation story says they emerged from caves in a sacred mountain on present-day Hispaniola.[27] In Puerto Rico, 21st-century studies have shown that a high proportion of people have Amerindian mtDNA. Of the two major haplotypes found, one does not exist in the Taíno ancestral group, so other Native people are also among the genetic ancestors.[25][28] DNA studies changed some of the traditional beliefs about pre-Columbian Indigenous history. According to National Geographic, "studies confirm that a wave of pottery-making farmers—known as Ceramic Age people—set out in canoes from the north-eastern coast of South America starting some 2,500 years ago and island-hopped across the Caribbean. They were not, however, the first colonizers. On many islands, they encountered foraging people who arrived some 6,000 or 7,000 years ago...The ceramicists, who are related to today's Arawak-speaking peoples, supplanted the earlier foraging inhabitants—presumably through disease or violence—as they settled new islands."[29] |

起源 グアナハタベイ地方とタイノ族および島嶼カリブ族グループとの関係 カリブ先住民の起源については、2つの学説が提唱されている。 一方の学説では、タイノ族の祖先はアマゾン盆地の中央部から来たアラワク語話者であったと主張している。その根拠として、言語学的、文化学的、陶器の証拠 が挙げられている。彼らは、現在のベネズエラを経由してトリニダードに到達する前に、北岸のオリノコ渓谷に移住し、小アンティル諸島に沿ってキューバやバ ハマ諸島へと移動した。この説を裏付ける証拠としては、これらの人々の祖先の文化がオリノコ渓谷にまで遡ることや、彼らの言語がアマゾン流域にまで遡るこ とが挙げられる。 代替説として知られる「環カリブ海地域説」では、タイノ族の祖先はコロンビアのアンデス地方から拡散したと主張している。この概念を提唱したジュリアン・ H・スチュワートは、アンデスからカリブ海への移住と、それに並行する中米、ギアナ、ベネズエラ、南米のアマゾン盆地への移住を示唆している。 文書化されているタイノ族の文化は、カリブ海地域で発展したと考えられている。タイノ族の創世神話によると、彼らは現在のイスパニョーラ島の聖なる山にあ る洞窟から現れたとされている。[27] プエルトリコでは、21世紀の研究により、アメリカインディアンのミトコンドリアDNAを持つ人の割合が高いことが明らかになっている。 発見された2つの主要ハプロタイプの1つはタイノ族の祖先グループには存在しないため、他の先住民も遺伝的な祖先の1つである。[25][28] DNA研究により、コロンブス到来以前の先住民の歴史に関する従来の考え方が一部変更された。ナショナル・ジオグラフィック誌によると、「研究により、陶 器を作る農民の一団が、約2500年前に南米北東部の海岸からカヌーで出発し、カリブ海の島々を渡っていったことが確認された。しかし、彼らは最初の入植 者ではなかった。多くの島々で、彼らは6,000年か7,000年前に到着した狩猟採集民と遭遇した...今日のアラワク語族と関係のある陶器職人たち は、おそらく病気や暴力によって、それ以前の狩猟採集民を追いやり、新たな島々に定住した。」[29] |

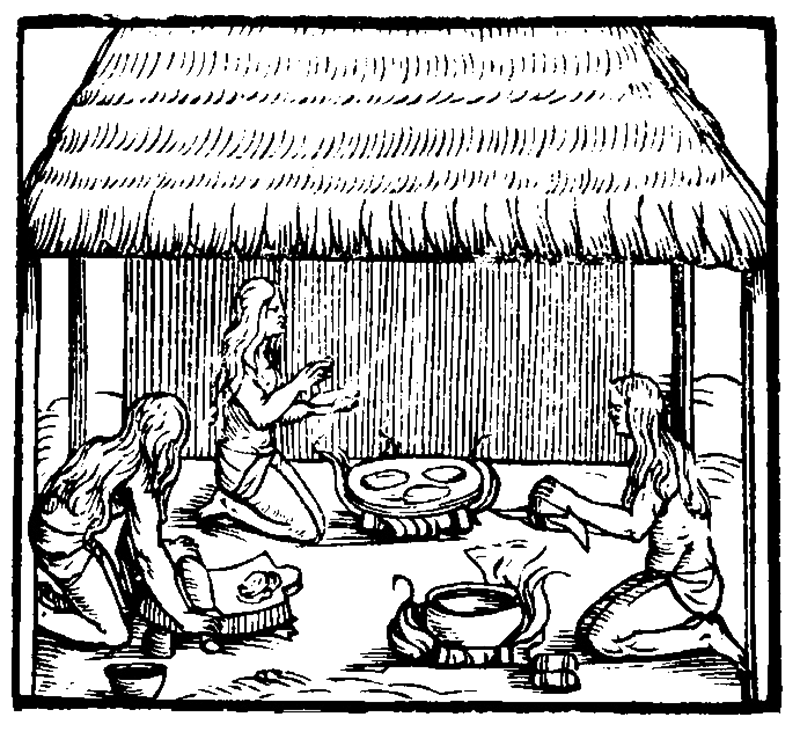

Culture Some Taíno women are preparing cassava bread in 1565: grating yuca roots into paste, shaping the bread, and cooking it on a fire-heated burén  Dujo, a wooden ceremonial chair crafted by Taínos Taíno society was divided into two classes: naborias (commoners) and nitaínos (nobles). They were governed by male and female chiefs known as caciques, who inherited their position through their mother's noble line. (This was a matrilineal kinship system, with social status passed through the female lines.) The nitaínos functioned as sub-caciques in villages, overseeing the work of naborias. Caciques were advised by priests/healers known as bohíques. Caciques enjoyed the privilege of wearing golden pendants called guanín, living in square bohíos, instead of the round ones of ordinary villagers, and sitting on wooden stools to be above the guests they received.[30] Bohíques were extolled for their healing powers and ability to speak with deities. They were consulted and granted the Taíno permission to engage in important tasks.[citation needed] The Taíno had a matrilineal system of kinship, descent, and inheritance. Spanish accounts of the rules of succession for a chief are not consistent, and the rules of succession may have changed as a result of the disruptions to Taíno society that followed the Spanish intrusion. Two early chroniclers, Bartolomé de las Casas and Peter Martyr d'Anghiera, reported that a chief was succeeded by a son of a sister. Las Casas was not specific as to which son of a sister would succeed, but d'Anghiera stated that the order of succession was the oldest son of the oldest sister, then the oldest son of the next oldest sister.[31] Post-marital residence was avunculocal, meaning a newly married couple lived in the household of the maternal uncle. He was more important in the lives of his niece's children than their biological father; the uncle introduced the boys to men's societies in his sister and his family's clan. Some Taíno practiced polygamy. Men might have multiple wives. Ramón Pané, a Catholic friar who traveled with Columbus on his second voyage and was tasked with learning the Indigenous people's language and customs, wrote in the 16th century that caciques tended to have two or three spouses and the principal ones had as many as 10, 15, or 20.[32][33] The Taíno women were skilled in agriculture, which the people depended on. The men also fished and hunted, making fishing nets and ropes from cotton and palm. Their dugout canoes (kanoa) were of various sizes and could hold from 2 to 150 people; an average-sized canoe would hold 15–20. They used bows and arrows for hunting and developed the use of poisons on their arrowheads.[citation needed] Taíno women commonly wore their hair with bangs in front and longer in the back, and they occasionally wore gold jewelry, paint, and/or shells. Taíno men and unmarried women usually went naked. After marriage, women wore a small cotton apron, called a nagua.[34] The Taíno lived in settlements called yucayeques, which varied in size depending on the location. Those in Puerto Rico and Hispaniola were the largest and those in the Bahamas were the smallest. In the center of a typical village was a central plaza, used for various social activities, such as games, festivals, religious rituals, and public ceremonies. These plazas had many shapes, including oval, rectangular, narrow, and elongated. Ceremonies where the deeds of the ancestors were celebrated, called areitos, were performed here.[35] Often, the general population lived in large circular buildings (bohios), constructed with wooden poles, woven straw, and palm leaves. These houses, built surrounding the central plaza, could hold 10–15 families each.[36][full citation needed] The cacique and their family lived in rectangular buildings (caney) of similar construction, with wooden porches. Taíno home furnishings included cotton hammocks (hamaca), sleeping and sitting mats made of palms, wooden chairs (dujo or duho) with woven seats and platforms, and cradles for children. |

文化 1565年、キャッサバパンを準備するタイノ族の女性たち:ユカの根をすりおろしてペースト状にし、パンを成形し、火で熱したブレネで調理する。  タイノ族が作った木製の儀式用椅子、ドゥホ タイノ社会は、ナボリア(平民)とニタイノス(貴族)の2つの階級に分かれていた。彼らは、カシケとして知られる男女の首長によって統治されていた。カシ ケは、母親の貴族の家系を通じてその地位を継承した。(これは母系親族制度であり、社会的地位は女性家系を通じて受け継がれた。)ニタイノスは村の副カシ ケとして、ナボリアの仕事を監督していた。カシケは、ボヒケと呼ばれる司祭や治療師の助言を受けていた。カシケは、グアニンと呼ばれる黄金のペンダントを 身につける特権があり、一般の村人の丸いボヒオではなく四角いボヒオに住み、来客を迎える際には木製のスツールに座って来客より高い位置にいた。[30] ボヒオは、その治癒能力と神と会話する能力で称賛されていた。彼らは相談を受け、重要な任務に従事するタイノ族の許可を与えられた。[要出典] タイノ族は母系制の親族制度、血統、相続制度を持っていた。スペイン人による首長の継承に関する規則の記述は一致しておらず、スペイン人の侵入後にタイノ 族社会が混乱した結果、継承の規則が変更された可能性がある。初期の年代記編者であるバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスとペドロ・マルティル・ダ・アンジェイ ラは、首長は姉妹の息子が継承すると報告している。ラス・カサスは、姉妹のどの息子が後継者となるかについては明確にしていないが、ダンジェラは、長女の 長男、次女の長男の順に継承されると述べている。[31] 結婚後の住居は母方の叔父の家であり、これは母方叔父の家系に住むことを意味する。彼は、姪の子供たちにとって実の父親よりも重要な存在であり、叔父は、 妹と自分の一族の氏族における男子社会に少年たちを紹介した。一部のタイノ族は一夫多妻制を実践していた。男性は複数の妻を持つことがあった。コロンブス の2度目の航海に同行し、先住民の言語と習慣を学ぶことを任務としていたカトリック修道士のラモン・パネは、16世紀に、首長は2人か3人の配偶者を持つ 傾向があり、主な配偶者は10人、15人、あるいは20人いたと書いている。 タイノ族の女性は農業に長けており、人々はそれに依存していた。男性も漁や狩猟を行い、綿やヤシから漁網やロープを作っていた。彼らの丸木舟(カノア)は 様々な大きさがあり、2人乗りから150人乗りまであった。平均的な大きさのカノアには15人から20人が乗ることができた。彼らは弓矢で狩猟を行い、矢 じりに毒を使うことを開発した。 タイノ族の女性は前髪を残して後ろ髪を長く伸ばすのが一般的で、金製の装飾品や顔料、貝殻を身に付けることもあった。タイノ族の男性と未婚の女性は通常裸であった。結婚後は女性はナグアと呼ばれる小さな木綿のエプロンを身に付けた。 タイノ族はユカイケと呼ばれる集落に住んでいたが、その規模は場所によって異なっていた。プエルトリコとイスパニョーラ島にあるものは最大規模で、バハマ にあるものは最小規模であった。典型的な村の中心には中央広場があり、ゲーム、祭り、宗教儀式、公的式典など、さまざまな社会的活動に使用されていた。こ れらの広場は、楕円形、長方形、狭いもの、細長いものなど、さまざまな形状をしていた。先祖の功績を祝う儀式は、アリートと呼ばれる式典としてここで執り 行われた。 一般住民は、木の柱や藁、ヤシの葉で造られた大きな円形の建物(ボイオス)に住んでいた。中央広場を取り囲むように建てられたこれらの家屋は、それぞれ 10~15家族が住めるようになっていた。[36][要出典] カシケとその家族は、同様の構造で木製のベランダを備えた長方形の建物(カニー)に住んでいた。タイノ族の家屋には、綿のハンモック(ハマカ)、ヤシの繊 維でできた寝具や座布団、座面と台が編み込まれた木製の椅子(ドゥホまたはドゥホ)、そして子供用の揺りかごがあった。 |

Caguana Ceremonial ball court (batey) in Puerto Rico, outlined with stones The Taíno played a ceremonial ball game called batey. Opposing teams had 10 to 30 players per team and used a solid rubber ball. Normally, the teams were composed of men, but occasionally women played the game as well.[37] The Classic Taíno played in the village's center plaza or on especially designed rectangular ball courts called batey. Games on the batey are believed to have been used for conflict resolution between communities. The most elaborate ball courts are found at chiefdom boundaries.[35] Often, chiefs made wagers on the possible outcome of a game.[37] Taíno spoke an Arawakan language and used an early form of proto-writing in the form of petroglyph,[38] as found in Taíno archeological sites in the West Indies.[39] Some words they used, such as barbacoa ("barbecue"), hamaca ("hammock"), kanoa ("canoe"), tabaco ("tobacco"), sabana (savanna), and juracán ("hurricane"), have been incorporated into other languages.[40] For warfare, the men made wooden war clubs, which they called macanas. It was about one inch thick and was similar to the coco macaque. The Taínos decorated and applied war paint to their face to appear fierce toward their enemies. They ingested substances at religious ceremonies and invoked zemis.[41] |

プエルトリコのカグアナ儀式用球技場(バテイ)は石で輪郭が描かれている。 タイノ族はバテイと呼ばれる儀式用の球技を行っていた。対戦するチームは1チームあたり10人から30人の選手で構成され、硬いゴム製のボールを使用し た。通常、チームは男性で構成されていたが、時には女性もプレーした。[37] 古典期のタイノ族は、村の中心広場や、バテイと呼ばれる特別に設計された長方形の球技場でプレーした。バテイでのゲームは、コミュニティ間の紛争解決のた めに使われたと考えられている。最も精巧な球技場は首長国の境界線上に存在している。[35] しばしば、首長はゲームの結果を賭けた。[37] タイノ族はアラワク語族の言語を話し、西インド諸島のタイノ族の遺跡で発見されているように、岩絵という原初的な文字の初期の形を使用していた。 彼らが使用していた言葉のなかには、バルバコア(「バーベキュー」)、ハマカ(「ハンモック」)、カノア(「カヌー」)、タバコ(「タバコ」)、サバナ(「サバンナ」)、フラカン(「ハリケーン」)など、他の言語に取り入れられたものもある。 戦いのために、男性たちは木製の戦闘用棍棒を作った。彼らはそれをマカナと呼んだ。それは約1インチの厚さで、ココヤシの果実の殻に似ていた。 タイノ族は敵に対して獰猛に見せるために、顔を装飾し、戦いの化粧をした。彼らは宗教儀式で物質を摂取し、ゼミスを呼び起こした。[41] |

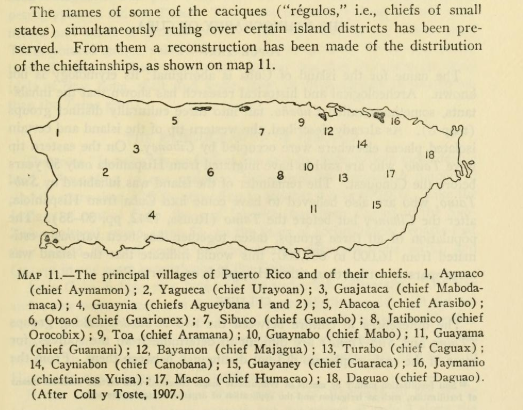

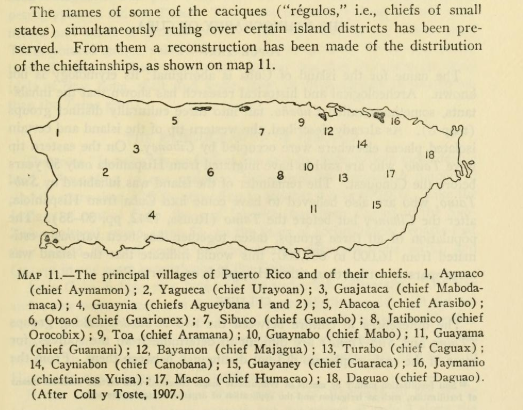

Cacicazgo/society Cayetano Coll y Toste's 1901 map of Puerto Rico caciques[42] The Taíno were the most culturally advanced of the Arawak group to settle in what is now Puerto Rico.[43] Individuals and kinship groups that previously had some prestige and rank in the tribe began to occupy the hierarchical position that would give way to the cacicazgo.[44] The Taíno founded settlements around villages and organized their chiefdoms, or cacicazgos, into a confederation.[45] The Taíno society, as described by the Spanish chroniclers, was composed of four social classes: the cacique, the nitaínos, the bohíques, and the naborias.[44] According to archeological evidence, the Taíno islands were able to support a high number of people for approximately 1,500 years.[46] Every individual living in the Taíno society had a task to do. The Taíno believed that everyone living on their islands should eat properly.[46] They followed a very efficient nature harvesting and agricultural production system.[46] Either people were hunting, searching for food, or doing other productive tasks.[46] Tribal groups settled in villages under a chieftain, known as cacique, or cacica if the ruler was a woman. Many women whom the Spaniards called cacicas were not always rulers in their own right, but were mistakenly acknowledged as such because they were the wives of caciques.[citation needed] Chiefs were chosen from the nitaínos and generally obtained power from their maternal line. A male ruler was more likely to be succeeded by his sister's children than his own unless their mother's lineage allowed them to succeed in their own right.[47] The chiefs had both temporal and spiritual functions. They were expected to ensure the welfare of the tribe and to protect it from harm from both natural and supernatural forces.[48] They were also expected to direct and manage the food production process. The cacique's power came from the number of villages he controlled and was based on a network of alliances related to family, matrimonial, and ceremonial ties. According to an early 20th-century Smithsonian study, these alliances showed the unity of the Indigenous communities in a territory;[49] they would band together as a defensive strategy to face external threats, such as the attacks by the Caribs on communities in Puerto Rico.[50] The practice of polygamy enabled the cacique to have women and create family alliances in different localities, thus extending his power. As a symbol of his status, the cacique carried a guanín of South American origin, made of an alloy of gold and copper. This symbolized the first Taíno mythical cacique Anacacuya, whose name means "star of the center", or "central spirit". In addition to the guanín, the cacique used other artifacts and adornments to serve to identify his role. Some examples are tunics of cotton and rare feathers, crowns, and masks or "guaizas" of cotton with feathers; colored stones, shells, or gold; cotton woven belts; and necklaces of snail beads or stones, with small masks of gold or other material.[44] |

カシカスゴ(カシーケ=首長)制度 Cayetano Coll y Tosteの1901年のプエルトリコの地図 caciques[42] タイノ族は、現在のプエルトリコに定住したアラワク族の中でも最も文化的に進んでいた。[43] それまで部族内で一定の威信と地位を持っていた個人や親族集団が、カシカサゴの地位につながる階層的な地位を占めるようになった。[44] タイノ族は村の周辺に集落を築き、その首長国、すなわちカシカサゴを連合国家として組織した。[45] スペイン人年代記編者による描写によると、タイノ社会は首長、ニタイノス、ボヒケス、ナボリアスの4つの社会階級から構成されていた。[44] 考古学的証拠によると、タイノ諸島は約1500年にわたって多くの人々を養うことができた。[46] タイノ社会に暮らす人々は皆、何らかの役割を担っていた。タイノ族は、自分たちの島に住む人々は皆、きちんと食事をとるべきだと信じていた。[46] 彼らは非常に効率的な自然の収穫と農業生産システムに従っていた。[46] 人々は狩猟をしたり、食料を探したり、その他の生産的な作業に従事していた。[46] 部族集団は、酋長(カシケ、女性の場合はカシカ)のもとに集落を形成して暮らしていた。スペイン人がカシカと呼んだ多くの女性たちは、必ずしも自分自身で 統治者であったわけではないが、カシケの妻であったために誤ってそのように認められていた。[要出典] 酋長はニタイノの中から選ばれ、一般的に母方の家系から権力を得ていた。男性の統治者が自分の子供ではなく姉妹の子供に後を継がせる可能性は、母親の血統 が彼ら自身の後継者となることを許さない限り、より高かった。[47] 首長には世俗的な機能と精神的な機能の両方があった。彼らは部族の福利を確保し、自然および超自然的な力による危害から部族を守ることが期待されていた。 [48] また、食糧生産のプロセスを指揮し管理することも期待されていた。カシケの権力は、彼が支配する村の数に由来し、家族、婚姻、儀式のつながりに関する同盟 のネットワークに基づいている。20世紀初頭のスミソニアン協会の研究によると、これらの同盟は、領土内の先住民コミュニティの結束を示している。 [49] 彼らは、プエルトリコのコミュニティに対するカリブ族の攻撃などの外部からの脅威に直面した際には、防御戦略として団結した。[50] 首長は一夫多妻制を実践することで、異なる地域社会の女性たちと家族同盟を築き、その権力を拡大することができた。首長の地位の象徴として、首長は南米起 源のグアニンを身につけていた。これは金と銅の合金でできており、タイノ族の最初の神話上の首長であるアナカクヤ(「中心の星」、または「中心の精神」を 意味する)を象徴するものだった。カシキは、グアニン以外にも、自身の役割を示すための他の工芸品や装飾品を使用していた。例えば、綿織物や珍しい羽根の チュニック、王冠、綿織物に羽根をあしらったマスクや「グアイアス」、色石や貝殻、あるいは金、綿織物のベルト、巻貝のビーズや石のネックレス、金やその 他の素材でできた小さなマスクなどである。 |

Cacicazgos of Hispaniola Under the cacique, social organization was composed of two tiers: The nitaínos at the top and the naborias at the bottom.[43] The nitaínos were considered the nobles of the tribes. They were made up of warriors and the family of the cacique.[51] Advisors who assisted in operational matters such as assigning and supervising communal work, planting and harvesting crops, and keeping peace among the village's inhabitants, were selected from among the nitaínos.[52] The naborias were the more numerous working peasants of the lower class.[51] The bohíques were priests who represented religious beliefs.[51] Bohíques dealt with negotiating with angry or indifferent gods as the accepted lords of the spiritual world. The bohíques were expected to communicate with the gods, soothe them when they were angry, and intercede on the tribe's behalf. It was their duty to cure the sick, heal the wounded, and interpret the will of the gods in ways that would satisfy the expectations of the tribe. Before carrying out these functions, the bohíques performed certain cleansing and purifying rituals, such as fasting for several days and inhaling sacred tobacco snuff.[48] |

イスパニョーラ島の首長たち 首長の下の社会組織は2つの階層から構成されていた。上層はニタイーノ、下層はナボリアである。[43] ニタイーノは部族の貴族とみなされていた。彼らは戦士と酋長の家族で構成されていた。[51] 共同作業の割り当てや監督、農作物の植え付けや収穫、村の住民間の平和維持など、運営上の問題を支援するアドバイザーは、ニタイノスの中から選ばれた。 [52] ナボリアは、より数が多い下層階級の労働農民であった。[51] ボヒークは、宗教的信念を代表する司祭であった。[51] ボヒークは、怒り狂うか無関心な神々と交渉し、精神世界の支配者として認められていた。ボヒークは神々と交信し、神々が怒っているときはそれを鎮め、部族 のために仲裁することが期待されていた。病気を治し、負傷者を癒し、部族の期待に沿う形で神々の意志を解釈することは、彼らの義務であった。これらの職務 を遂行する前に、ボヒークたちは数日間の断食や神聖なタバコの粉末を吸引するなどの浄化と清めの儀式を行った。[48] |

Food and agriculture Cassava, starchy (yuca) roots, the Taínos' main crop Taíno staples included vegetables, fruit, meat, and fish. Though there were no large animals native to the Caribbean, they captured and ate small animals such as hutias, other mammals, earthworms, lizards, turtles, and birds. Manatees were speared and fish were caught in nets, speared, trapped in weirs, or caught with hook and line. Wild parrots were decoyed with domesticated birds, and iguanas were taken from trees and other vegetation. The Taíno stored live animals until they were ready to be consumed: fish and turtles were stored in weirs, hutias and dogs were stored in corrals.[53]  Piedra Escrita on River Saliente in Jayuya, Puerto Rico The Taíno people became very skilled fishermen. One method used was to hook a remora, also known as a suckerfish, to a line secured to a canoe and wait for the fish to attach itself to a larger fish or even a sea turtle. Once this happened, someone would dive into the water to retrieve the catch. Another method used by the Taínos involved shredding the stems and roots of poisonous senna plants and throwing them into nearby streams or rivers. After eating the bait, the fish would be stunned and ready for collection. These practices did not render fish inedible. The Taíno also collected mussels and oysters in exposed mangrove roots found in shallow waters.[54] Some young boys hunted waterfowl from flocks that "darkened the sun", according to Christopher Columbus.[46] Taíno groups located on islands that had experienced relatively high development, such as Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, and Jamaica, relied more on agriculture (farming and other jobs) than did groups living elsewhere. Fields for important root crops, such as the staple crop yuca, were prepared by heaping up mounds of soil, called conucos. This improved soil drainage and fertility as well as delayed erosion while allowing for the longer storage of crops in the ground. Less important crops such as corn were cultivated in clearings made using the slash-and-burn technique. Typically, conucos were three feet high, nine feet in circumference, and were arranged in rows.[55] The primary root crop was yuca or cassava, a woody shrub cultivated for its edible and starchy tuberous root. It was planted using a coa, a kind of hoe made completely from wood. Women processed the poisonous variety of cassava by squeezing it to extract its toxic juices. Roots were then ground into flour for bread. Batata (sweet potato) was the next most important root crop.[55] Tobacco was grown by pre-Columbian peoples in the Americas for centuries before 1492. Christopher Columbus in his journal described how Indigenous people used tobacco by lighting dried herbs wrapped in a leaf and inhaling the smoke.[56] Tobacco, derived from the Taino word "tabaco", was used in medicine and in religious rituals. The Taino people utilized dried tobacco leaves, which they smoked using pipes and cigars. Alternatively, they finely crushed the leaves and inhaled them through a hollow tube. The natives employed uncomplicated yet efficient tools for planting and caring for their crops. Their primary tool was a planting stick, referred to as a "coa" among the Taino, which measured around five feet in length and featured a sharp point that had been hardened through fire.[57][58] Contrary to mainland practices, corn was not ground into flour and baked into bread, but was cooked and eaten off the cob. Corn bread becomes moldy faster than cassava bread in the high humidity of the Caribbean. Corn also was used to make an alcoholic beverage known as chicha.[59] The Taíno grew squash, beans, peppers, peanuts, and pineapples. Tobacco, calabashes (bottle gourds), and cotton were grown around the houses. Other fruits and vegetables, such as palm nuts, guavas, and Zamia roots, were collected from the wild.[55] |

食料と農業 キャッサバ、デンプン質の(ユカ)根、タイノ族の主要作物 タイノ族の主食は、野菜、果物、肉、魚であった。カリブ海に大型の動物は生息していなかったが、フクイナなどの哺乳類、ミミズ、トカゲ、亀、鳥などの小動 物を捕獲して食べていた。マナティーは槍で突き、魚は網で捕まえたり、槍で突いたり、堰で捕まえたり、釣り糸で捕まえたりした。野生のオウムは飼いならさ れた鳥で誘き寄せ、イグアナは木やその他の植物から捕まえた。タイノ族は、魚や亀は堰で、フウチョウモドキやイヌは囲いで、食用に適するまで生きた動物を 保管した。  プエルトリコ、ハユヤのサリエンテ川にある「ピエドラ・エスクリタ」 タイノ族は非常に熟練した漁師であった。その方法の一つは、カヌーに固定した糸にコバンザメ(吸盤魚とも呼ばれる)を引っ掛けて、その魚がより大きな魚や ウミガメに吸い付くのを待つというものだった。そうなったら、誰かが水中に潜って獲物を捕まえる。タイノ族が用いた別の方法では、毒のあるセンナの茎や根 を細かく刻んで、近くの小川や川に投げ込んだ。魚が餌を食べると、魚は気絶し、捕獲できるようになる。これらの慣習によって魚が食べられなくなることはな かった。タイノ族はまた、浅瀬の露出したマングローブの根に生息する二枚貝や牡蠣も採集していた。[54] クリストファー・コロンブスによると、少年の中には「太陽を覆い隠す」ほどの水鳥の群れを狩る者もいたという。[46] プエルトリコ、イスパニョーラ島、ジャマイカなど、比較的開発が進んでいた島々に住んでいたタイノ族は、他の地域に住んでいたグループよりも農業(農耕や その他の仕事)に頼っていた。主食であるキャッサバなどの重要な根菜類の畑は、conucosと呼ばれる土のマウンドを積み上げて準備した。これにより、 土壌の排水性と肥沃度が改善され、浸食が遅延すると同時に、作物を地中に長く保存することが可能となった。トウモロコシなどのあまり重要でない作物は、焼 き畑農業の手法で開墾された土地で栽培された。通常、コヌコスは高さ3フィート、周囲9フィートで、列状に配置されていた。[55] 主な根菜は、食用でデンプン質の塊根を栽培する木質の低木であるユカまたはキャッサバであった。これは、木製の鍬の一種であるコーアを使って植えられた。 女性たちは、有毒のキャッサバの品種を絞ってその有毒の汁を抽出して加工した。根はパン用の小麦粉に挽かれた。バタタ(サツマイモ)は、次に重要な根菜で あった。 コロンブスがアメリカ大陸を発見する何世紀も前から、アメリカ大陸の先住民たちはタバコを栽培していた。クリストファー・コロンブスは日記の中で、先住民 たちが乾燥させた葉を巻いたものを火で炙り、煙を吸うことでタバコを利用していたことを記している。[56] タバコはタイノ族の言葉「タバコ」に由来し、医療や宗教儀式に用いられていた。タイノ族の人々は乾燥させたタバコの葉を利用し、パイプや葉巻でそれを吸っ ていた。あるいは、葉を細かく砕いて中空の管から吸い込んでいた。先住民たちは、作物の植え付けや手入れに、単純だが効率的な道具を使用していた。主な道 具は「コア」と呼ばれる長さ約150センチの植え付け用の棒で、先端は火で焼いて硬く尖らせてあった。 本土の慣習とは異なり、トウモロコシは粉にしてパンに焼くのではなく、調理して実の部分をそのまま食べていた。トウモロコシパンはカリブ海の高温多湿の気 候ではキャッサバパンよりも早くカビが生える。トウモロコシはまた、チチャ(chicha)と呼ばれるアルコール飲料の原料としても用いられた。[59] タイノ族はカボチャ、豆、唐辛子、落花生、パイナップルを栽培した。 タバコ、ヒョウタン、綿花は家の周囲で栽培された。 ヤシの実、グアバ、ザミアの根などの他の果物や野菜は野生から採取された。[55] |

Spirituality Taíno zemí sculpture Walters Art Museum Taíno spirituality centered on the worship of zemis (spirits or ancestors). Major Taíno zemis included Atabey and her son, Yúcahu. Atabey was thought to be the zemi of the moon, fresh waters, and fertility. Other names for her included Atabei, Atabeyra, Atabex, and Guimazoa.[citation needed] The Taínos of Kiskeya (Hispaniola) called her son, "Yúcahu|Yucahú Bagua Maorocotí", which meant "White Yuca, great and powerful as the sea and the mountains". He was considered the spirit of cassava, the zemi of cassava – the Taínos' main crop – and the sea.[citation needed] Guabancex was the non-nurturing aspect of the zemi Atabey who was believed to have control over natural disasters. She is identified as the goddess of hurricanes or as the zemi of storms. Guabancex had twin sons: Guataubá, a messenger who created hurricane winds, and Coatrisquie, who created floodwaters.[60] Iguanaboína was the goddess of good weather. She also had twin sons: Boinayel, the messenger of rain, and Marohu, the spirit of clear skies.[61] Minor Taíno zemis are related to the growing of cassava, the process of life, creation, and death. Baibrama was a minor zemi worshiped for his assistance in growing cassava and curing people of its poisonous juice. Boinayel and his twin brother Márohu were the zemis of rain and fair weather, respectively.[62] Maquetaurie Guayaba or Maketaori Guayaba was the zemi of Coaybay or Coabey, the land of the dead. Opiyelguabirán', a dog-shaped zemi, watched over the dead. Deminán Caracaracol, a male cultural hero from whom the Taíno believed themselves to be descended, was worshipped as a zemí.[62] Macocael was a cultural hero worshipped as a zemi, who had failed to guard the mountain from which human beings arose. He was punished by being turned into stone, or a bird, a frog, or a reptile, depending on the interpretation of the myth.[63]  Zemí, a physical object housing a zemi, spirit or ancestor Lombards Museum Zemí was also the name the people gave to physical representations of Zemis, which could be objects or drawings. They took many forms and were made of many materials and were found in a variety of settings. The majority of zemís were crafted from wood, but stone, bone, shell, pottery, and cotton were used as well.[64] Zemí petroglyphs were carved on rocks in streams, ball courts, and stalagmites in caves, such as the zemi carved into a stalagmite in a cave in La Patana, Cuba.[65] Cemí pictographs were found on secular objects such as pottery, and tattoos. Yucahú, the zemi of cassava, was represented with a three-pointed zemí, which could be found in conucos to increase the yield of cassava. Wood and stone zemís have been found in caves in Hispaniola and Jamaica.[66] Cemís are sometimes represented by toads, turtles, fish, snakes, and various abstract and human-like faces.[citation needed]  Cohoba Spoon, 1200–1500 Brooklyn Museum  Rock petroglyph overlaid with chalk in the Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Center in Utuado, Puerto Rico Some zemís were accompanied by small tables or trays, which are believed to be a receptacle for hallucinogenic snuff called cohoba, prepared from the beans of a species of Piptadenia tree. These trays have been found with ornately carved snuff tubes. Before certain ceremonies, Taínos would purify themselves, either by inducing vomiting (with a swallowing stick) or by fasting.[67] After communal bread was served, first to the zemí, then to the cacique, and then to the common people, the people would sing the village epic to the accompaniment of maraca and other instruments.[citation needed] One Taíno oral tradition explains that the Sun and Moon came out of caves. Another story tells of the first people, who once lived in caves and only came out at night because it was believed that the Sun would transform them; a sentry became a giant stone at the mouth of the cave, and others became birds or trees. The Taíno believed they were descended from the union of the cultural hero Deminán Caracaracol and a female turtle (who was born of the former's back after being afflicted with a blister).[citation needed] The origin of the oceans is described in the story of a huge flood that occurred when the great spirit Yaya murdered his son Yayael (who was about to murder his father). The father put his son's bones into a gourd or calabash. When the bones turned into fish, the gourd broke, an accident caused by Deminán Caracaracol, and all the water of the world came pouring out.[citation needed] Taínos believed that Jupias, the souls of the dead, would go to Coaybay, the underworld, and there they rest by day. At night they would assume the form of bats and eat the guava fruit.[citation needed] |

スピリチュアリティ タイノ族のゼミス(精霊または祖先)彫刻 ウォルターズ美術館 タイノ族のスピリチュアリティは、ゼミス(精霊または祖先)の崇拝を中心としていた。タイノ族の主要なゼミスには、アタベイと彼女の息子ユカグがいた。ア タベイは、月、淡水、豊穣のゼミスと考えられていた。彼女の別名には、Atabei、Atabeyra、Atabex、Guimazoaなどがある。[要 出典] イスパニョーラ島のキスケージャ(Kiskeya)のタイノ族は、息子のことを「Yúcahu|Yucahú Bagua Maorocotí」と呼んだ。これは「白いユッカ、海や山のように偉大で力強い」という意味である。彼はキャッサバの精霊、すなわちタイノ族の主要作物 であるキャッサバの精霊であり、海の精霊であると考えられていた。 グアバンセクスは、自然災害を支配すると考えられていたアタベイの非育成的な側面であった。彼女はハリケーンの女神、あるいは嵐の精霊として認識されてい る。グアバンセクスには双子の息子がいた。ハリケーンの風を起こす使者グアタウバと、洪水を起こすコアトリスキーである。 イグアナボイナは、好天の女神であった。彼女にも双子の息子がいた。雨の使者ボイナイエルと、澄み切った空の精霊マロフである。 マイナー・タイノ族のゼミは、キャッサバの栽培と、生命の誕生、創造、死に関係している。バイブラマは、キャッサバの栽培を手助けし、その毒汁から人々を癒すことで崇拝されていたマイナー・ゼミであった。ボイナエルと双子の兄弟マロフは、それぞれ雨と晴天のゼミであった。 マケタウリ・グアヤバまたはマケタウリ・グアヤバは、死者の国であるコアイバイまたはコアベイのゼミであった。オピエルグアビランは犬の姿をしたゼミで、 死者の世話をしていた。デミナン・カラカラコルは、タイノ族が自分たちの祖先であると信じていた男性の文化英雄であり、ゼミとして崇拝されていた。 [62] マコセルは、人間が生まれた山を守れなかった文化英雄であり、ゼミとして崇拝されていた。彼は石や鳥、カエル、爬虫類に変えられて罰せられたが、その解釈 は神話によって異なる。[63]  ゼミ、ゼミ、精霊や祖先を収容する物理的な物体 ロンバード博物館 ゼミはまた、人々がゼミの物理的な表現に与えた名称でもあり、それは物体や絵画である可能性があった。それらは様々な形態をとり、様々な素材でできてお り、様々な環境で発見されている。ゼミの大部分は木でできていたが、石、骨、貝殻、陶器、綿なども使用されていた。ゼミの岩絵は、小川の岩、球技場、洞窟 の石筍に刻まれていた 、キューバのラ・パタナにある洞窟の石筍に刻まれたゼミなどがある。[65] ゼミの絵文字は、陶器や入れ墨などの世俗的な物にも見られる。キャッサバのゼミは、3つの突起を持つゼミで表現され、キャッサバの収穫量を増やすためにコ ンウコに置かれていた。 木材や石のゼミは、イスパニョーラ島やジャマイカの洞窟で発見されている。[66] ゼミは、ヒキガエル、カメ、魚、ヘビ、および様々な抽象的な顔や人間の顔で表現されることもある。[要出典]  コホバ・スプーン、1200年~1500年 ブルックリン美術館  プエルトリコ、ウトゥアドのカグアナ先住民儀式センターにあるチョークで覆われた岩絵(ペトログリフ) ゼミの一部には、小さなテーブルやトレイが添えられており、これらはピプタデニア属の豆から作られたコホバと呼ばれる幻覚作用のある嗅ぎタバコを入れる入 れ物であったと考えられている。これらのトレイには、凝った彫刻が施された嗅ぎタバコ用の管が置かれていた。特定の儀式の前には、タイノ族は嘔吐(嚥下棒 を使用)または断食によって身を清めた。[67] 共同のパンが、まずゼミに、次にカシキに、そして一般民衆に供された後、人々はマラカスやその他の楽器の伴奏に合わせて村の叙事詩を歌った。[要出典] タイノ族の口承伝承のひとつによると、太陽と月は洞窟から出てきたと説明されている。別の話では、かつて洞窟に住んでいた最初の人間たちは、太陽が彼らを 変えてしまうと信じられていたため、夜だけ外に出ていたという。見張り番は洞窟の入り口で巨大な石となり、他の者は鳥や木になった。タイノ族は、文化の英 雄デミナン・カラカラコルと、水ぶくれを患った後に背中から生まれたメスの亀との間に生まれた子孫であると信じていた。[要出典] 海の起源は、偉大な精霊ヤヤが息子ヤヤエル(父親を殺そうとしていた)を殺害した際に起こった大洪水の物語で説明されている。父親は息子の骨をひょうたん に入れた。骨が魚に変わったとき、デミナン・カラカラコルによる事故でひょうたんが割れ、世界の水がすべて流れ出てしまった。 タイノ族は、死者の魂であるJupiasは、冥界であるCoaybayに行き、そこで昼間は休むと信じていた。夜になると彼らはコウモリの姿になり、グアバの実を食べる。[要出典] |

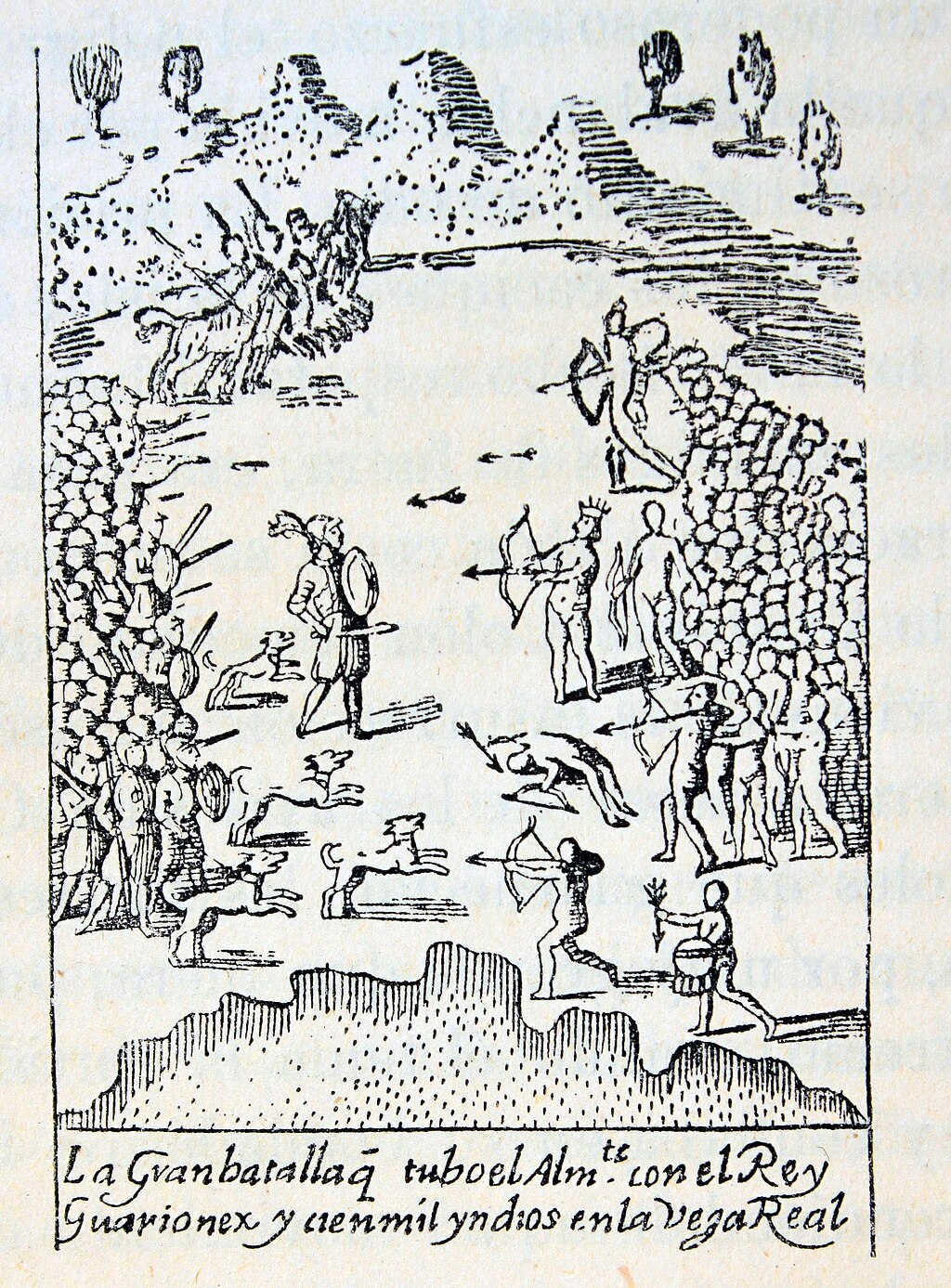

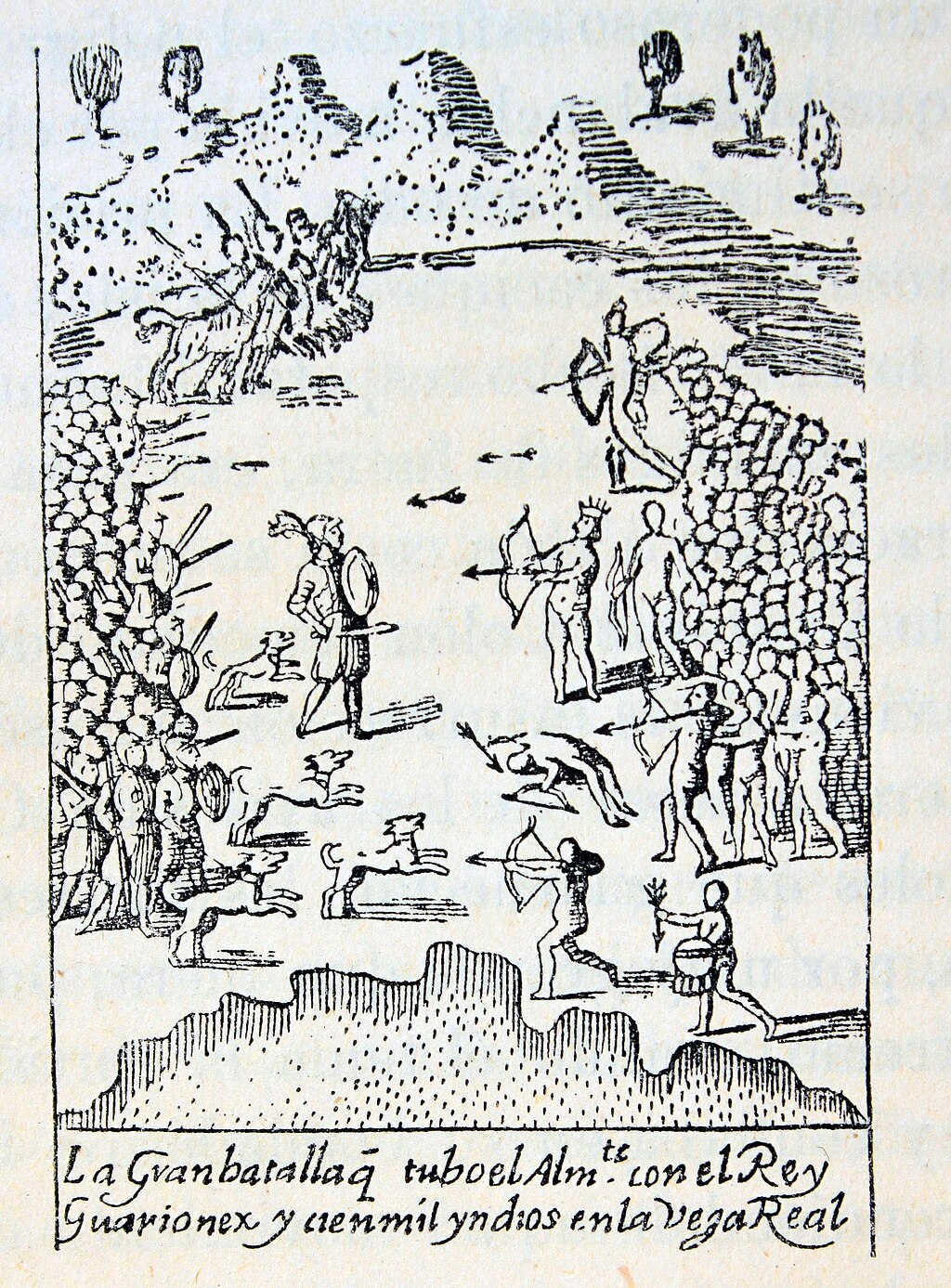

Spanish and Taíno Battle of Vega Real Columbus and the crew of his ship were the first Europeans to encounter the Taíno people, as they landed in The Bahamas on October 12, 1492. After their first interaction, Columbus described the Taínos as a physically tall, well-proportioned people, with noble and kind personalities. In his diary, Columbus wrote: They traded with us and gave us everything they had, with good will ... they took great delight in pleasing us ... They are very gentle and without knowledge of what is evil; nor do they murder or steal...Your highness may believe that in all the world there can be no better people ... They love their neighbors as themselves, and they have the sweetest talk in the world, and are gentle and always laughing.[68] At this time, the neighbors of the Taíno were the Guanahatabeys in the western tip of Cuba, the Island-Caribs in the Lesser Antilles from Guadeloupe to Grenada, and the Calusa and Ais nations of Florida. Guanahaní was the Taíno name for the island that Columbus renamed San Salvador (Spanish for "Holy Savior"). Columbus erroneously called the Taíno "Indians", a reference that has grown to encompass all the Indigenous peoples of the Western Hemisphere. A group of about 24 Taíno people were abducted and forced to accompany Columbus on his 1494 return voyage to Spain.[69] On Columbus' second voyage in 1493, he began to demand tribute from the Taíno in Hispaniola. According to Kirkpatrick Sale, each adult over 14 years of age was expected to deliver a hawks bell full of gold every three months, or when this was lacking, twenty-five pounds of spun cotton. If this tribute was not brought, the Spanish cut off the hands of the Taíno and left them to bleed to death[70] These savage, cruel practices inspired many revolts by the Taíno and campaigns against the Spanish—some being successful, some not. In 1511, Antonio de Montesinos, a Dominican missionary in Hispaniola, became the first European to publicly denounce the abduction and enslavement of the Indigenous peoples of the island and the Encomienda system.[71] In 1511, several caciques in Puerto Rico, such as Agüeybaná II, Arasibo, Hayuya, Jumacao, Urayoán, Guarionex, and Orocobix, allied with the Carib and tried to oust the Spaniards. The revolt was suppressed by the Indio-Spanish forces of Governor Juan Ponce de León.[72] Hatuey, a Taíno chieftain who had fled from Hispaniola to Cuba with 400 natives to unite the Cuban natives, was burned at the stake on February 2, 1512. In Hispaniola, a Taíno chieftain named Enriquillo mobilized more than 3,000 Taíno in a successful rebellion in the 1520s. These Taíno were accorded land and a charter from the royal administration. Despite the small Spanish military presence in the region, they often used diplomatic divisions and, with help from powerful native allies, controlled most of the region.[73][74] In "exchange" for a seasonal salary, and religious and language education, the Taíno were forced to work for Spanish and erroneously-labeled "Indian" landowners. This system of labor was part of the encomienda.[75] |

スペイン人とタイノ族 ベガ・レアルの戦い コロンブスと乗組員たちは、1492年10月12日にバハマ諸島に上陸した最初のヨーロッパ人であり、タイノ族と遭遇した。初めての遭遇の後、コロンブスはタイノ族を「体格が良く、均整のとれた人々で、気高く親切な性格」と描写した。 コロンブスは日記にこう記している。 彼らは我々と交易を行い、持っているものをすべて快く与えてくれた。彼らは我々を喜ばせることに大きな喜びを感じていた。彼らはとても穏やかで、悪を知ら ず、殺人も窃盗もしない。殿下は、世界にはこれほど素晴らしい人々はいないと信じておられるだろう。彼らは隣人を自分自身のように愛し、世界で最も甘い言 葉で語りかけ、穏やかで、いつも笑っている。 当時、タイノ族の隣人として知られていたのは、キューバの西端に暮らすグアナハタベ族、グアドループ島からグレナダ島までの小アンティル諸島に暮らす島カ リブ族、そしてフロリダのカルーサ族とアイス族であった。グアナハナは、コロンブスがサン・サルバドル(スペイン語で「聖なる救世主」の意)と改名した島 のタイノ族名であった。コロンブスはタイノ族を「インディアン」と呼んだが、この呼称は後に西半球の先住民全体を指すようになった。1494年、コロンブ スがスペインへの帰路に24人ほどのタイノ族を拉致し、同行させた。 1493年のコロンブスの2度目の航海では、コロンブスはイスパニョーラ島のタイノ族に貢ぎ物を要求し始めた。カークパトリック・セイルによると、14歳 以上の成人は3か月ごとに鷹の鈴いっぱいの金、またはそれが不足している場合は紡いだ綿25ポンドを納めることが期待されていた。この貢ぎ物がもたらされ なければ、スペイン人はタイノ族の手を切り落とし、そのまま失血死させた[70]。このような野蛮で残酷な行為は、タイノ族による多くの反乱とスペイン人 に対するキャンペーンを招いた。そのうちのいくつかは成功し、いくつかは成功しなかった。 1511年には、イスパニョーラ島のドミニコ会宣教師アントニオ・デ・モンテシーノスが、同島の先住民の拉致と奴隷化、およびエンコミエンダ制度を公然と非難した最初のヨーロッパ人となった。 1511年、プエルトリコのいくつかの首長国、例えばアグエイバナ2世、アライシボ、ハユヤ、フマカオ、ウラヨン、グアリオネクス、オロコビックスなどが カリブ族と同盟を結び、スペイン人の追放を試みた。この反乱は、フアン・ポンセ・デ・レオン総督のインディオ・スペイン軍によって鎮圧された。[72] ハスエーイは、イスパニョーラ島からキューバ島に400人の原住民を連れて逃れ、キューバ島の原住民をまとめようとしたタイノ族の族長であったが、 1512年2月2日に火あぶりの刑に処された。 イスパニョーラ島では、エンリケーヨ(Enriquillo)という名のタイノ族の族長が3,000人以上のタイノ族を動員し、1520年代に反乱を成功 させた。これらのタイノ族には土地と王政からの憲章が与えられた。スペイン軍の駐留が少なかったにもかかわらず、彼らは外交的な分裂を巧みに利用し、有力 な先住民の同盟者の助けを借りて、その地域の大部分を支配した。[73][74] 季節ごとの給与、宗教教育、言語教育と引き換えに、タイノ族はスペイン人や、誤って「インディアン」と称された土地所有者たちのために働かされた。この労 働システムは、エンコミエンダの一部であった。[75] |

Women Cacique (Chief) Taína, Indigenous of the island of Hispaniola Taíno society was based on a matrilineal system and descent was traced through the mother. Women lived in village groups containing their children. The men lived separately. As a result, Taíno women had extensive control over their lives and their fellow villagers.[76] The Taínos told Columbus that another Indigenous tribe, Caribs, were fierce warriors, who made frequent raids on the Taínos, often capturing the women.[77][78] Taíno women played an important role in intercultural interaction between Spaniards and the Taíno people. When Taíno men were away fighting against intervention from other groups, women assumed the roles of primary food producers or ritual specialists.[79] Women appeared to have participated in all levels of the Taíno political hierarchy, occupying roles as high up as being cazicas.[80] Potentially, this meant Taíno women could make important choices for the village and could assign tasks to tribe members.[81] There is evidence that suggests that the women who were the wealthiest among the tribe collected crafted goods that they would then use for trade or as gifts.[citation needed] In contrast to the significant autonomy granted to women in Taíno society, Taíno women were taken by Spaniards as hostages to be used during negotiations. Some sources report that Taíno women became so-called commodities for Spaniards to trade, seen by some as the beginning of a period of more regular Spanish abduction and systemic rape of Taíno women.[82] |

女性 カシケ(首長) タイナ(タイノの女性形)、イスパニオラ島先住民 タイノ社会は母系制を基盤としており、血統は母親を通じてたどられた。女性たちは子供たちとともに村のグループで暮らしていた。男性たちは別に暮らしてい た。そのため、タイノ族の女性たちは自分たちの生活や村人たちに対して広範な支配力を有していた。[76] タイノ族は、コロンブスに、別の先住民部族であるカリブ族は獰猛な戦士であり、タイノ族を頻繁に襲撃し、しばしば女性を捕虜にしていたと伝えた。[77] [78] タイノ族の女性は、スペイン人とタイノ族の間の異文化交流において重要な役割を果たしていた。タイノ族の男性が他の部族との戦いに出かけている間、女性た ちは食料生産や儀式の専門家として重要な役割を担っていた。[79] 女性たちはタイノ族の政治的階層のあらゆるレベルに参加しており、カシカ(cazica)として高い地位に就いていた。[80] このことは、タイノ族の女性が村にとって重要な選択を行い、部族のメンバーに仕事を割り当てることができた可能性を示唆している。[81] 部族の中で最も裕福な女性たちが工芸品を集め、それを貿易や贈り物として使用していたことを示す証拠がある。[要出典] タイノ社会において女性に与えられた大きな自治権とは対照的に、タイノの女性たちはスペイン人によって人質として捕らえられ、交渉の道具として利用され た。一部の資料によると、タイノの女性たちはスペイン人にとって、いわゆる交易品となり、スペイン人によるタイノの女性たちに対する誘拐と組織的なレイプ がより日常的に行われるようになった始まりと見なされている。[82] |

| Genocide and depopulation Main article: Taíno genocide Further information: Paper genocide § Taíno and indigenous peoples of the Caribbean Early population estimates of Hispaniola, thought to have likely been the most populous island inhabited by Taínos, range from 10,000 to 1,000,000 people.[83] The maximum estimates for Jamaica and Puerto Rico are 600,000 people.[22] A 2020 genetic analysis estimated the population to be no more than a few tens of thousands of people.[84][85] Spanish priest and defender of the Taíno, Bartolomé de las Casas (who had lived in Santo Domingo), wrote in his 1561 multi-volume History of the Indies:[86] There were 60,000 people living on this island [when I arrived in 1508], including the Indians; so that from 1494 to 1508, over three million people had perished from war, slavery and the mines. Who in future generations will believe this? Researchers today doubt Las Casas' figures for the pre-contact levels of the Taíno population, considering them an exaggeration.[87] For example, Karen Anderson Córdova estimates a maximum of 500,000 people inhabiting the island.[88] The encomienda system forced many Taíno to work in the fields and mines in so-called exchange for Spanish protection,[89] education, and a seasonal salary.[90] Under the pretense of searching for gold and other materials,[91] many Spaniards took advantage of the regions now under the control of the anaborios and Spanish encomenderos to exploit the native population by seizing their land and wealth. Historian David Stannard characterizes the encomienda as a genocidal system that "had driven many millions of native peoples in Central and South America to early and agonizing deaths."[92] It would take some time before the Taíno revolted against their oppressors—both Native and Spanish alike—and many military campaigns before Emperor Charles V eradicated the encomienda system as a form of enslavement.[93][94] Disease played a significant role in the destruction of the Indigenous population, but forced labor was also one of the chief reasons behind the depopulation of the Taíno.[95] The first man to introduce this forced labor among the Taínos was the leader of the European colonization of Puerto Rico, Ponce de León.[95] Such forced labor eventually led to the Taíno rebellions, to which the Spaniards responded with violent military expeditions known as cabalgadas.[citation needed] The purpose of the military expeditions was to capture the Indigenous people.[citation needed] This violence by the Spaniards was a reason why there was a decline in the Taíno population since it forced many of them to emigrate to other islands and the mainland.[96] In thirty years, between 80% and 90% of the Taíno population died.[97][95] Because of the increased number of people (Spanish) on the island, there was a higher demand for food. Taíno cultivation was converted to Spanish methods. In hopes of frustrating the Spanish, some Taínos refused to plant or harvest their crops. The supply of food became so low in 1495 and 1496 that some 50,000 died from famine.[98] Historians have determined that the massive decline was due more to infectious disease outbreaks than any warfare or direct attacks.[99][100] By 1507, their numbers had shrunk to 60,000. Scholars believe that epidemic disease (smallpox, influenza, measles, and typhus) was an overwhelming cause of the population decline of the Indigenous people,[101] and also attributed a "large number of Taíno deaths...to the continuing bondage systems" that existed.[102][103] Academics, such as historian Andrés Reséndez of the University of California, Davis, assert that disease alone does not explain the destruction of Indigenous populations of Hispaniola. While the populations of Europe rebounded following the devastating population decline associated with the Black Death, there was no such rebound for the Indigenous populations of the Caribbean. He concludes that, even though the Spanish were aware of deadly diseases such as smallpox, there is no mention of them in the New World until 1519, meaning perhaps they did not spread as fast as initially believed, and that, unlike Europeans, the Indigenous populations were subjected to enslavement, exploitation, and forced labor in gold and silver mines on an enormous scale.[104] Reséndez says that "slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the Indigenous people of the Caribbean.[105] Anthropologist Jason Hickel estimates that the lethal forced labor in these mines killed a third of the Indigenous people there every six months.[106] |

大量虐殺と人口減少 詳細は「タイノ族の大量虐殺」を参照 さらに詳しい情報: 紙の大量虐殺 § タイノ族とカリブ海の先住民 タイノ族が最も多く居住していたと考えられているイスパニョーラ島の初期の人口推定値は、1万人から100万人である。[83] ジャマイカとプエルトリコの最大推定値は60万人である。[22] 2020年の遺伝子解析では、人口は数万人に過ぎないと推定されている。[84][85] スペイン人の司祭でタイノ族の擁護者であったバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス(サント・ドミンゴ在住)は、1561年に出版された『インド史』の複数巻本で 次のように書いている。 私が1508年に到着したとき、この島にはインディアンを含め6万人が暮らしていた。つまり、1494年から1508年の間に、戦争、奴隷、鉱山労働によって300万人以上が命を落としたことになる。将来の世代で、これを信じる人がいるだろうか? 今日、研究者たちはラス・カサスの主張する先住民人口を疑っており、誇張されていると考えている。[87] たとえば、カレン・アンダーソン・コルドバは、最大でも50万人が島に住んでいたと推定している。[88] エンコミエンダ制度により、多くの先住民はスペイン人の保護、[89] 教育、季節ごとの給与と引き換えに、 スペインの保護[89]、教育、季節ごとの給与と引き換えに、いわゆる労働を強いられた。[90] 金やその他の資源の探索を口実に、[91] 多くのスペイン人が、アナボリオスやスペイン人エンコミエンダの支配下にある地域を利用して、先住民の土地や財産を奪い、彼らを搾取した。歴史家のデビッ ド・スタナードは、このエンコミエンダ制度を「何百万人もの中米と南米の先住民を早すぎる苦痛に満ちた死へと追い込んだ」大量虐殺のシステムと評してい る。[92] タイノ族が先住民とスペイン人の両方による抑圧者に対して反乱を起こし、エンコミエンダ制度を奴隷制度の一形態として皇帝カール5世が根絶するまでに、多 くの軍事行動とタイノ族の反乱が起こるまでにはしばらくの時間を要した。[93][94] 先住民の人口減少には、伝染病が大きな役割を果たしたが、強制労働もタイノ族の人口減少の主な理由のひとつであった。[95] タイノ族に初めて強制労働を導入したのは、プエルトリコのヨーロッパ人による植民地化の指導者であった、ポンセ・デ・レオンであった。[95] このような強制労働は、最終的にタイノ族の反乱につながった これに対してスペイン人は、カバルガダ(cabalgadas)として知られる暴力的な軍事遠征で応じた。[要出典] 軍事遠征の目的は先住民の捕獲であった。[要出典] スペイン人によるこの暴力行為が、多くのタイノ族を他の島々や本土への移住を余儀なくさせたため、タイノ族の人口が減少した理由である。[96] 30年の間に、タイノ族の人口の80%から90%が死亡した。[97][95] 島にスペイン人が増えたため、食糧の需要が高まった。タイノ族の耕作はスペイン式に転換された。スペイン人を困らせることを期待して、一部のタイノ族は作 物の植え付けや収穫を拒否した。1495年と1496年には食糧供給が極端に不足し、5万人が飢餓で死亡した。[98] 歴史家は、この大幅な人口減少は、戦争や直接攻撃よりも感染症の流行によるものだと結論づけている。[99][100] 1507年までに、人口は6万人にまで減少した。学者たちは、先住民の人口減少の圧倒的な原因は伝染病(天然痘、インフルエンザ、麻疹、チフス)であった と考えている。また、「多数のタイノ族の死は... 継続的な奴隷制度」のせいであると主張している。[102][103] カリフォルニア大学デービス校の歴史学者アンドレス・レセンデスなどの学者は、疾病だけではイスパニョーラ島の先住民の人口減少を説明できないと主張して いる。ヨーロッパでは、ペストによる壊滅的な人口減少の後、人口が回復した一方で、カリブ海地域では先住民の人口は回復しなかった。彼は、スペイン人が天 然痘などの致死性の高い病気を認識していたにもかかわらず、1519年まで新大陸での言及が一切ないことから、当初考えられていたほど急速に広まらなかっ た可能性があると結論づけている。また、ヨーロッパ人と異なり、先住民は奴隷化、搾取、金銀鉱山での強制労働に 。[104] レスエンデスは、「奴隷制度が先住民の主要な死因となっている」と述べている。[105] 人類学者のジェイソン・ヒッケルは、これらの鉱山における過酷な強制労働により、先住民の3分の1が半年ごとに死亡していると推定している。[106] |

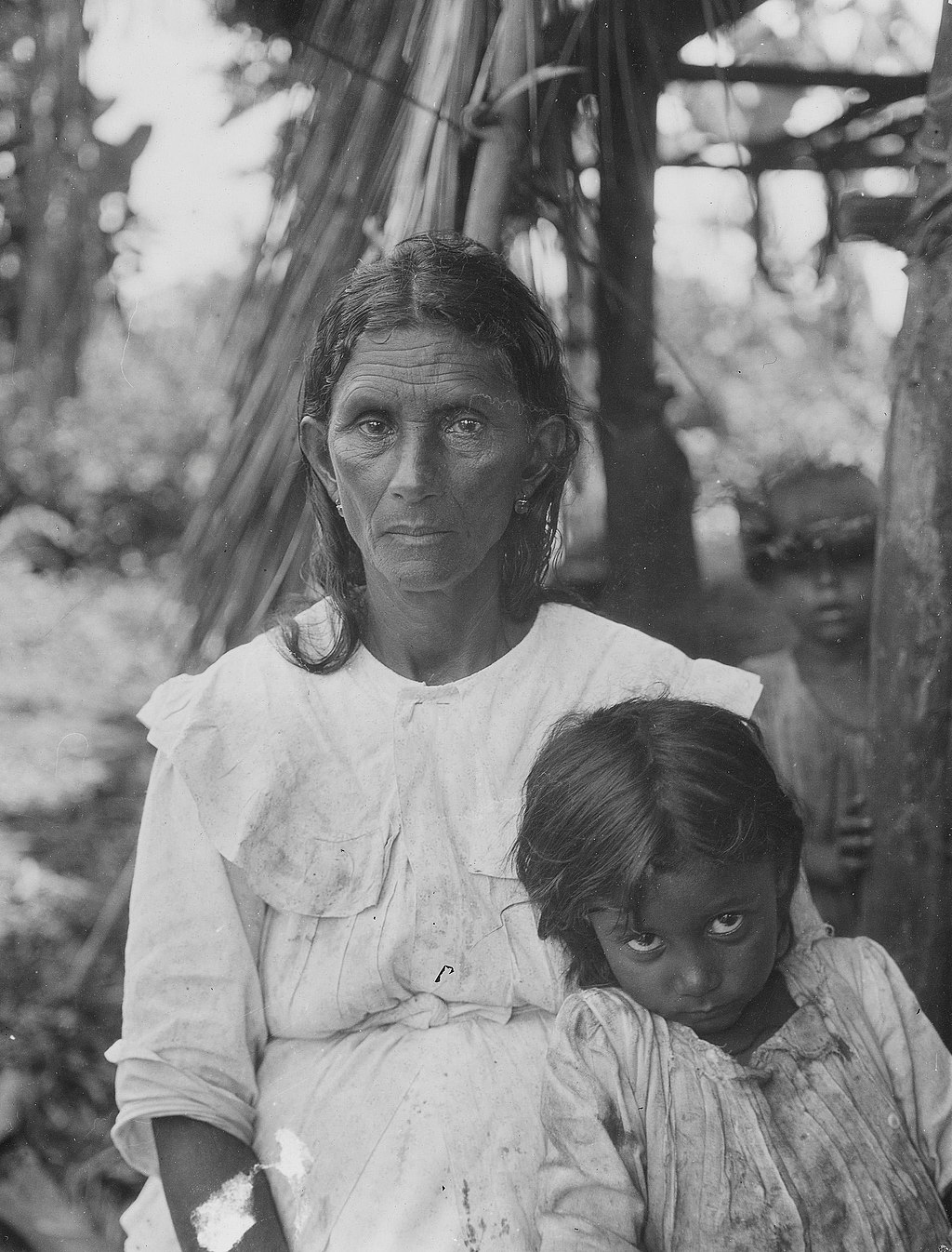

Taíno culture today Native woman (probably Luisa Gainsa) with a girl in Baracoa, Cuba, in 1919 Histories of the Caribbean traditionally describe the Taíno as extinct, due to being killed off by disease, slavery, and war with the Spaniards. Contemporary scholarship is more ambivalent, accepting that some degree of Taíno cultural heritage survives in the Caribbean, though many disagree on the extent and meaning of this.[107][108][109] Many Caribbean people also have a degree of Indigenous descent, usually on the maternal side.[84][87][110] Present-day peoples with Caribbean Indigenous heritage may identify as Taíno, Taíno descendants, or other localised terms, and often come from rural mestizo communities such as the jíbaro.[111][112] Although Taíno was originally an exonym, contemporary descendants of the Taínos have begun to reclaim the name and publicly assert a shared Taíno Caribbean-Indigenous identity.[113][114][115] They typically describe traditions that have been passed on in secret to evade enslavement or persecution.[112] Groups advocating this point of view are sometimes known as Neo-Taínos—though this is not usually a term they use to describe themselves—and are also established in the Puerto Rican communities located in New Jersey and New York. A few Taíno groups are pushing not only for recognition but respect for their cultural assets.[116] Scholars who remain sceptical that Taíno culture survived in recognizable form point to the process of mestizaje or creolisation as evidence of the modern Taíno's actual origins. Most Taíno descendants argue that this is evidence for their continued survival, rather than evidence against it, since creolization allowed their culture and identity to persist while evolving and adapting.[116] According to Antonio Curet, this part of the modern Taíno argument is frequently ignored by sceptical scholars, even though, as he believes, creolization itself "does not disprove the claims of indigenous survival". Curet suggests, however, that modern Taíno views about creolization may downplay the contribution of European and especially African heritage, and that this may be seen as anti-African sentiment.[116] Other scholars, such as Pedro Ferbel-Azcarate, dispute this, suggesting that Taíno identities are part of an ongoing process of resisting a Eurocentric mestizo identity which already ignores both African and Indigenous heritage.[117] Despite the recorded extinction of the Taíno across the Caribbean, historian Ranald Woodaman says the survival of the Taíno is supported by "the enduring (though not unchanged) presence of Native genes, culture, knowledge and identity among the descendants of the Taíno peoples of the region". He also notes the Indigenous and African heritage of communities such as the Maroons, and how these remained distinct from the larger populations while honouring their Taíno predecessors.[118] Taíno-derived customs and identities can be found especially among marginalised rural populations on the Caribbean islands such of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica and Puerto Rico.[119][120][121] |

今日のタイノ文化 1919年、キューバのバラコアで少女と写る先住民の女性(おそらくルイサ・ゲインサ) カリブ海地域の歴史では、タイノ族はスペイン人との戦争や病気、奴隷制度によって絶滅したと伝統的に説明されている。現代の学術研究では、見解が分かれて おり、ある程度のタイノ文化遺産がカリブ海地域に生き残っていることを認めているが、その範囲や意味については多くの異論がある。[107][108] [109] カリブ海地域の多くの人々は、通常は母方の先住民の血筋を引いている。[84][87][110] カリブ海地域の先住民の遺産を持つ現代の人々は、 タイノ族、タイノ族の子孫、あるいはその他の地域限定の名称を名乗ることがあり、しばしばヒバロのような農村部の混血コミュニティ出身である。[111] [112] タイノ族は元来は外来語であったが、現代のタイノ族の子孫たちはその名称を取り戻し、タイノ族としてのカリブ海先住民としてのアイデンティティを公に主張 し始めている。[11 彼らは通常、奴隷化や迫害を避けるために秘密裏に受け継がれてきた伝統について語る。[112] この見解を支持するグループは、自らを「ネオ・タイノ」と呼ぶこともあるが、これは通常、彼らが自らを表現する際に使用する用語ではない。また、ニュー ジャージー州やニューヨーク州にあるプエルトリコ人コミュニティにも存在している。少数のタイノ族グループは、自分たちの文化遺産の認知だけでなく、敬意 も求めている。[116] タイノ族の文化が認識できる形で生き残ったという説に懐疑的な学者たちは、メスティサ(混血)化またはクレオール化の過程を、現代のタイノ族の実際の起源 を示す証拠として挙げている。ほとんどのタイノ族の子孫は、クレオール化によって彼らの文化とアイデンティティが存続し、進化し、適応することが可能に なったため、これは彼らの生存の証拠であり、生存の否定の証拠ではないと主張している。[116] アントニオ・キュレットによると、懐疑的な学者たちは、現代のタイノ族の主張のこの部分を頻繁に無視しているが、彼自身は、クレオール化自体は「先住民の 生存の主張を否定するものではない」と考えている。しかし、キュレットは、現代のタイノ族のクレオール化に関する見解は、ヨーロッパ、特にアフリカの遺産 の貢献を軽視している可能性があり、これは反アフリカ感情と見なされる可能性があると示唆している。[116] ペドロ・フェルベル=アスカラテなどの他の学者はこれに異論を唱え、タイノ族のアイデンティティは、すでにアフリカと先住民の遺産の両方を無視している ヨーロッパ中心主義のメスティーソのアイデンティティに抵抗する継続的なプロセスの一部であると示唆している。[117] カリブ海全域でタイノ族が絶滅したという記録があるにもかかわらず、歴史家のラナルド・ウッドマンは、「この地域のタイノ族の子孫の間には、ネイティブの 遺伝子、文化、知識、アイデンティティが(変化はしているものの)今もなお根強く残っている」ことがタイノ族の生存を裏付けていると述べている。また、彼 は、マローン族などのコミュニティにおける先住民とアフリカの遺産、そして彼らがタイノ人の先人たちを敬いながらも、より大きな人口集団とは異なる存在で あり続けたことを指摘している。[118] タイノ族由来の習慣やアイデンティティは、キューバ、ドミニカ共和国、ジャマイカ、プエルトリコなどのカリブ海諸島の周縁化された農村地域の人々を中心に みられる。[119][120][121] |

| Cuba In isolated parts of eastern Cuba (including areas near El Caney,[122] Yateras and Baracoa), there are Indigenous communities who have maintained their Taíno identities and cultural practices into the 21st century.[119][123][109] Reports of Indigenous communities surviving in the east of Cuba date at least as far back as the 19th century, from sources as varied as anthropologists, missionaries, military officials and tourists.[124] Abolitionist and British consul to Cuba David Turnbull, who visited the island in the 1830s, said the inhabitants of Guanabacoa, El Caney and Jiguaní had Indigenous heritage, and recorded Spanish stories of Taíno who had migrated to "the Yucatan and the Floridas".[122] In the 1840s, José de la Torre reportedly saw 50 "pure blooded" Taíno dancing at El Caney and researcher Miguel Rodríguez Ferrer reportedly found various Taíno families living in the footholds of the Sierra Maestra mountains. In the 1880s, author Maturin M. Ballou, a sceptic of Taíno survival, said there were reports of an Arawak-Taíno village living near the copper mines "northwest of Santiago de Cuba",[122] and Nicolas Fort y Roldan described encountering the "almost extinct race lucaya", and their settlements in El Caney and Yateras. In the 1890s, author and photographer José de Olivares documented nomadic Indigenous Cubans whom he identified as "the last remnants of that interesting and sorely persecuted race".[125] Most famously, Cuban national icon and poet José Martí reported the aid of "los Indios de Garrido" during the 1895 war of independence.[125] In the early 20th century, scientist B. E. Fernow reported "twenty-eight families" of mixed Indigenous people still living in isolated settlements in the foothills of the Sierra Maestro mountains,[125] and archaeologist Stewart Culin noted the presence of "full-blooded" Indians near Yateras and Baracoa. The former group had apparently migrated from Santo Domingo; the latter group comprised 800 local Indigenous people, largely from three families: Gainsa, Azahares, and Rojas. Culin also met a Taíno man named José Almenares Argüello, or "Almenares", who said the town of El Caney had once been reserved only for Indians. In 1908 and 1909, explorer Sir Harry Johnston shared reports of "pure-blood" Taínos and recounted seeing mestizos who were "almost as pure breeds" in eastern Cuba, some of whom lived on former "reservations". He distinguished these from the general populace of 1.2 million Spanish Cubans who had various degrees of mixed "Amerindian-Arawak" heritage. Others such as Jesse W. Fewkes and Mark Raymond Harrington reported similar findings, including an additional settlement near Jaruco. Later, between the 1910s and 1920s, archaeologist J. A. Cosculluela discovered Indigenous families in the Zapata swamps, and apparently corroborated their lineage by visiting the local cemetery. In the 1940s, archaeologist Irving Rouse reported the existence of "pure blooded" Taíno or "Indios de las orillas" at Camagüey.[125] Historian Pichardo Moya, in his address to the Cuban Academy of History in 1945, criticized "the widely accepted opinion" that the Indigenous Cubans were "practically exterminated". He blamed this viewpoint on nationalistic histories that overlooked evidence of "Indian" heritage. Anthropologist and geneticist Reginald Ruggles Gates also reported many "Indian descent people" and people who were "pure Indians", especially women, noting Indigenous families with the surnames Gainsa, Ramírez and Rojas. When anthropologists Manuel Rivero de la Calle and Milan Pospisil analysed Cuba's Indigenous communities, they suggested those in the east were likely of Taíno heritage, rather than from the newer Yucatecan Mayan community living in the west.[126] There are also Indigenous communities who migrated to Cuba from Florida and other parts of the mainland, who in some cases intermarried with local Taíno communities.[127] Jason M. Yaremko says there are many organised communities of Amerindians currently living in Cuba, many of whom have an Arawak-Taíno identity, and that a number of these are even "pure bloods". He suggests that Euro-American views from the 18th century onward, which saw race and Indigeneity in terms of essentialism and "primordiality", insisted on "narratives of disappearance" for Indigenous peoples and imposed upon them alternate identities as "white, black, or mulatto". In his view, Eurocentric perspectives saw the decline of the Indigenous peoples—whether through extinction or dilution—as the inevitable conclusion of the "heroic saga of civilization". Subsequent attempts to promote a singular Cuban national identity which transcended race and ethnicity, he says, may have "suffocated" more complex identities for the sake of "national unity", impacting both Afro-Cubans and Amerindian Cubans. But he says this Amerindian identity has nevertheless persisted in Cuba, "whether as 'Indios' in pueblos indios, as individuals in cities and towns, or together in vibrant, if 'invisible' (until recently), rural communities like Yateras". He also suggests that, although the oral histories are "compelling", to address controversies over modern Cuban Taíno identities, this heritage could be "corroborated and reinforced by fieldwork conducted, to begin with, in documentary records contained in Cuba’s former 'Indian towns' and parishes, among other repositories in the country".[128] |

キューバ キューバ東部の孤立した地域(エル・カネー[122]、ヤテラス、バラコア近郊を含む)には、21世紀に入ってもタイノ族としてのアイデンティティと文化 を維持している先住民コミュニティが存在している。[119][123][109] キューバ東部に先住民コミュニティが生存しているという報告は、少なくとも 人類学者、宣教師、軍人、観光客など、さまざまな情報源から、少なくとも19世紀まで遡る。[124] 1830年代にキューバを訪れた奴隷制度廃止論者でキューバ駐在のイギリス領事のデイヴィッド・ターンブルは、グアナバコア、エル・カニー、ヒグアニの住 民が先住民の血を引いていると述べ、 「ユカタン半島とフロリダ半島」に移住したタイノ族のスペイン語による物語を記録した。[122] 1840年代には、ホセ・デ・ラ・トーレがエル・カネイで50人の「純血」タイノ族が踊っているのを目撃したと伝えられ、また、研究者ミゲル・ロドリゲ ス・フェレールはシエラ・マエストラ山脈のふもとに暮らすさまざまなタイノ族の家族を発見したと伝えられている。1880年代には、タイノ族の生存を懐疑 的に見ていた作家マチュリン・M・バロウが、「サンティアゴ・デ・クーバの北西」にある銅鉱山の近くにアラワク族とタイノ族の村が存在するという報告が あったと述べている[122]。また、ニコラス・フォート・イ・ロルダンは「ほぼ絶滅したルカイ族」と遭遇し、彼らがエル・カニーとヤテラスに居住してい ることを記述している。1890年代には、作家であり写真家でもあるホセ・デ・オリヴァレスが、彼が「興味深く、ひどく迫害された種族の最後の生き残り」 と特定した、放浪のキューバ先住民を記録した。[125] 最も有名なのは、キューバ国民の象徴であり詩人でもあるホセ・マルティが、1895年の独立戦争中に「ガリード族」が支援したことを報告したことである。 [125] 20世紀初頭には、科学者のB. E. フェルナウが、シエラ・マエストロ山脈のふもとの孤立した集落に、混血のインディアン「28家族」が今も暮らしていることを報告している。また、考古学者 のスチュワート・カリンは、ヤテラスとバラコアの近くに「純血」のインディアンの存在を指摘した。前者のグループは、どうやらサント・ドミンゴから移住し てきたようである。後者のグループは、ゲインサ、アサハレス、ロハスの3つの家族を中心に、800人の地元先住民で構成されていた。また、クリンはホセ・ アルメナーレス・アルグエヨ、または「アルメナーレス」という名のタイノ族の男性にも会った。アルメナーレスは、かつてエル・カニーの町はインディアン専 用であったと語った。1908年と1909年には、探検家のハリー・ジョンストン卿が「純血」タイノ族の報告を共有し、キューバ東部で「ほぼ純血種」の混 血種を目撃したことを語った。その中にはかつての「保留地」に住む者もいた。彼は、これらの人々を「アメリカインディアン-アラワク族」の混血の度合いが 異なる120万人のスペイン系キューバ人一般住民と区別した。ジェシー・W・フークスやマーク・レイモンド・ハリントンといった他の研究者も、ジャルコ近 郊の集落など、同様の発見を報告している。その後、1910年代から1920年代にかけて、考古学者のJ. A. コスクジョエラがサパタ湿地帯の先住民家族を発見し、地元の墓地を訪れることで彼らの血統を裏付けたようだ。1940年代には、考古学者アーヴィング・ラ ウスがカマグエイに「純血」のタイノ族または「インディオス・デ・ラス・オリジャス」が存在することを報告した。[125] 歴史家ピチャルド・モヤは、1945年にキューバ歴史アカデミーで行った講演で、先住民キューバ人が「事実上絶滅した」という「広く受け入れられている意 見」を批判した。彼は、この見解を「インディアン」の遺産の証拠を見落としている民族主義的な歴史観のせいだと非難した。人類学者で遺伝学者のレジナル ド・ラグルズ・ゲーツもまた、多くの「インディアン系の人々」と「純粋なインディアン」の人々、特に女性について報告し、ゲインサ、ラミレス、ロハスなど の姓を持つ先住民の家族について言及した。人類学者のマヌエル・リベロ・デ・ラ・カジェとミラン・ポスピシルがキューバの先住民コミュニティを分析したと ころ、東部に住む人々は、西部に住む比較的新しいユカテク族マヤ人コミュニティではなく、タイノ族の血を引いている可能性が高いと指摘している。 [126] また、フロリダや本土の他の地域からキューバに移住した先住民コミュニティも存在し、その一部は地元のタイノ族コミュニティと混血している。[127] ジェイソン・M・ヤレムコは、現在キューバに居住するアメリカインディアンの組織化されたコミュニティは多く、その多くはアラワク族・タイノ族としてのア イデンティティを持ち、その中には「純血」の人々もいると述べている。彼は、18世紀以降のヨーロッパ・アメリカ人の見解は、人種や土着性を本質主義や 「原始性」の観点から捉え、土着民族に対して「消滅の物語」を主張し、「白人、黒人、混血」といった別のアイデンティティを押し付けてきたと指摘してい る。彼の考えでは、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な視点では、先住民の衰退は絶滅であれ希薄化であれ、「文明の英雄叙事詩」の必然的な帰結と見なされていた。 その後、人種や民族性を超越した単一のキューバ国民としてのアイデンティティを推進しようとする試みは、「国民の団結」のために、より複雑なアイデンティ ティを「窒息」させ、アフリカ系キューバ人とアメリカ先住民の両方に影響を与えた可能性がある、と彼は言う。しかし、この先住民としてのアイデンティティ はキューバで根強く残っていると彼は言う。「インディオの村で『インディオ』として、都市や町で個人として、あるいは、イアテラのような活気のある(最近 まで)『目に見えない』農村共同体で共に暮らすことで」である。また、口承の歴史は「説得力がある」が、現代のキューバにおけるタイノ族のアイデンティ ティをめぐる論争に対処するには、この遺産は「まず第一に、キューバの旧『インディアンタウン』や教区に含まれる文書記録、および国内のその他の保管場所 で実施された現地調査によって裏付けられ、強化される可能性がある」と示唆している。[128] |

| Dominican Republic Frank Moya Pons, a Dominican historian, documented that Spanish colonists intermarried with Taíno women. Over time, some of their mixed-race descendants intermarried with Africans, creating a tripartite Creole culture. Census records from the year 1514 reveal that 40% of Spanish men on the island of Hispaniola had Taíno wives.[129] Nevertheless, Spanish documents declared the Taíno to be extinct in the 16th century, as early as 1550.[130] Despite this, scholars note that contemporary rural Dominicans retain elements of Taíno culture including linguistic features, agricultural practices, food ways, medicine, fishing practices, technology, architecture, oral history, and religious views, even though such cultural traits may be considered backward in the cities.[108] Among these rural communities, some families and individuals also identify as Taíno.[9] |

ドミニカ共和国 ドミニカ共和国の歴史家フランク・モヤ・ポンスは、スペイン人入植者とタイノ族の女性との婚姻関係を記録している。 時が経つにつれ、混血の子孫の一部はアフリカ人と婚姻関係を結び、3つの文化が融合したクレオール文化が生まれた。1514年の国勢調査記録によると、イ スパニオラ島にいたスペイン人男性の40%がタイノ族の女性を妻としていたことが明らかになっている。[129] それにもかかわらず、スペインの文書では、16世紀にはタイノ族はすでに絶滅していたと宣言されており、早いものでは1550年には絶滅していたとされて いる。[130] それにもかかわらず、学者たちは、現代のドミニカ共和国の農村地域では、言語、農業、食生活、医療、漁業、技術、建築、口承、宗教観など、タイノ文化の要 素が残っていると指摘している。都市部ではこうした文化的な特徴は時代遅れとみなされる可能性があるが、[108] これらの農村地域では、一部の家族や個人がタイノ族であることを表明している。[9] |

| Jamaica Evidence suggests that some Taíno women and African men intermarried and lived in relatively isolated Maroon communities in the interior of the islands, where they developed into a mixed-race population who were relatively independent of Spanish authorities.[131] For instance, when the colony of Jamaica was under the rule of Spain (known then as the colony of Santiago), both Taíno men and women fled to the Bastidas Mountains (currently known as the Blue Mountains), where they intermingled with escaped enslaved Africans. They were among the ancestors of the Jamaican Maroons of the east, including those communities led by Juan de Bolas and Juan de Serras. The Maroons of Moore Town claim descent from the Taíno.[131] |

ジャマイカ 証拠によると、一部のタイノ族の女性とアフリカ系男性が結婚し、島の奥地にある比較的孤立したマローン共同社会で暮らしていた。そこでは、スペイン当局か ら比較的独立した混血の人口が発展していた。[131] たとえば、 ジャマイカ植民地がスペインの支配下にあった時代(当時はサンティアゴ植民地と呼ばれていた)、タイノ族の男女はバスティダス山脈(現在のブルー・マウン テンズ)に逃げ込み、逃亡した奴隷のアフリカ人と混血した。彼らは、フアン・デ・ボラスとフアン・デ・セラスが率いるコミュニティを含む、東部のジャマイ カ・マローンの祖先となった。ムーアタウンのマローンは、タイノ族の子孫であると主張している。[131] |

| United States, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands Indigenous peoples are recorded later in Puerto Rico than on many other Caribbean islands. The Puerto Rican census of 1777 listed 1,756 indios, while the 1787 census listed 2,032. It is not clear, however, exactly which groups were counted as indios at the time and how accurate the census data was—some indios may have remained hidden or lived in isolated and remote communities to avoid enslavement or worse.[132] Puerto Rican historian Loida Figueroa has suggested that all native Puerto Ricans were considered Indian until the beginning of the 19th century, when they were subsequently labelled pardos by Governor don Toribio Montes, who struggled to fit the multiethnic non-whites into American racial categories. Oral histories collected by Juan Manuel Delgado in 1977 also support the idea that "Indians" were widespread until the 19th century.[133] By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Puerto Rico was subjected to various attempts at Americanization, including through educational institutions.[134][135] This often included learning English and Spanish, and being required to wear Anglo-American clothing.[136] Some Puerto Rican children were sent to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the flagship among American Indian boarding schools,[134][137][135] including children with Taíno heritage.[107] Despite this, there is widespread recognition that Taíno customs and culture have survived in some form in Puerto Rico, where these customs are celebrated as a part of Puerto Rico's creole identity.[138][139] At the 2010 U.S. census, 1,098 people in Puerto Rico identified as "Puerto Rican Indian", 1,410 identified as "Spanish American Indian", and 9,399 identified as "Taíno". In total, 35,856 Puerto Ricans identified as Indigenous.[140] A consistent explanation given by modern Taíno/Boricuas for their survival is that their families lived, at least for a time, close to the mountainous interior of the island, which they call Las Indieras ("the place of the Indians"). Anthropologist Sherina Feliciano-Santos says these areas typically have an increased prevalence of Indigenous foods, customs and vocabulary than elsewhere.[141] People with Indigenous heritage in Puerto Rico may call themselves Boricua, after the Indigenous word for the island, as well as or instead of Taíno. Local Taíno/Boricua groups have also begun attempts to reconstruct a distinct Taíno language, called Taíney, often extrapolating from other Arawakan languages and using a modified version of the Latin alphabet.[142] The Guainía Taíno Tribe has been recognized as a tribe by the governor of the US Virgin Islands.[143] |

アメリカ合衆国、プエルトリコ、米領バージン諸島 プエルトリコでは、他の多くのカリブ海諸島よりも遅れて先住民が記録されている。1777年のプエルトリコ国勢調査では1,756人のインディオが、 1787年の国勢調査では2,032人がリストアップされた。しかし、当時どのグループがインディオとして数えられたのか、また国勢調査のデータがどの程 度正確であったのかは明らかになっていない。一部のインディオは、奴隷化やそれ以上の扱いを受けることを避けるために、身を隠したり、孤立した遠隔地で暮 らしていた可能性もある。[132] プエルトリコの歴史家ロイーダ・ フィゲロアは、19世紀初頭まではプエルトリコの原住民はすべてインディアンとみなされていたが、多民族の非白人たちをアメリカの民族カテゴリーに当ては めるのに苦労したドン・トリビオ・モンテス知事によって、彼らはその後パードと呼ばれるようになったと示唆している。1977年にフアン・マヌエル・デル ガドが収集した口述歴史も、「インディアン」が19世紀まで広く存在していたという考えを裏付けている。 19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて、プエルトリコは教育機関などを通じて、さまざまなアメリカ化の試みにさらされた。[134][135] これには、英語とスペイン語の学習や、アングロ・アメリカ風の服装の着用が義務付けられることがよくあった。[136] プエルトリコ人の子供たちの中には、カーライル・インディアン・インダストリアル・スクール( アメリカインディアンの寄宿学校の代表格であるカーライル・インディアン・インダストリアル・スクールには、タイノ族の血を引く子供たちも含まれていた。 [107] にもかかわらず、タイノ族の風習や文化はプエルトリコのどこかで生き残っているという認識が広まっている。これらの風習はプエルトリコのクレオールとして のアイデンティティの一部として祝われている。[138][139] 2010年の国勢調査では、プエルトリコの1,098人が「プエルトリコ・インディアン」と、1,410人が「スペイン系アメリカ・インディアン」と、 9,399人が「タイノ」と回答した。合計すると、先住民として自らを識別するプエルトリコ人は35,856人に上る。[140] 現代のタイノ族/ボリクア族が自分たちの生存について一貫して説明しているのは、彼らの家族は少なくとも一時的には島の山岳地帯の近くに住んでいたという ことである。彼らはその地域をラス・インディエラス(「インディアンの地」)と呼んでいる。人類学者のシェリーナ・フェリシアーノ=サントスは、これらの 地域では一般的に、他の地域よりも先住民の食文化、習慣、語彙が広く浸透していると述べている。 プエルトリコの先住民の血を引く人々は、先住民の言葉でプエルトリコを意味する「ボリクア」を、先住民の言葉である「タイノ」と同様に、あるいは「タイ ノ」の代わりに、自分たちの名称として用いることがある。地元のタイノ族/ボリクア族のグループは、他のアラワク語族の言語から推測し、ラテン文字の修正 版を使用して、タイニーと呼ばれる独特のタイノ語の再構築を試みている。 グアイニア・タイノ族は、アメリカ領ヴァージン諸島の知事から部族として認定されている。[143] |

| Taíno revivalist communities See also: Pedro Guanikeyu Torres As of 2006, there were a couple of dozen activist Taíno descendant organizations from Florida to Puerto Rico and California to New York with growing memberships numbering in the thousands. These efforts are known as the Taíno restoration, a revival movement for Taíno culture that seeks to revive and reclaim Taíno heritage, as well as official recognition of the survival of the Taíno people.[144][145] Historian Ranald Woodaman describes the modern Taíno movement as "a declaration of Native survival through mestizaje (genetic and cultural mixing over time), reclamation and revival".[146] In Puerto Rico, the history of the Taíno is being taught in schools, where children learn about the Taíno culture and identity through dance, costumes, and crafts. Martínez Cruzado, a geneticist at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez said celebrating and learning about their Taíno roots is helping Puerto Ricans feel connected.[147] Scholar Yolanda Martínez-San Miguel sees the development of a Neo-Taíno movement in Puerto Rico as a useful counter to the domination of the island by the United States and the Spanish legacies of island society. She also notes that "what could be seen as a useless anachronistic reinvention of a 'Boricua coqui' identity can also be conceived as a productive example of Spivak's 'strategic essentialism'".[108] Scholar Gabriel Haslip-Viera suggests that the Taíno revival movements which emerged among marginalised Puerto Rican communities, especially from the 1980s and 1990s, are a response to US racism and Reaganism, which produced hostile political and socioeconomic conditions in the Caribbean.[148] |

タイノ族復興派コミュニティ 関連項目:ペドロ・グアニケユ・トレス 2006年現在、フロリダからプエルトリコ、カリフォルニアからニューヨークまで、数十のタイノ族の子孫による活動家団体があり、会員数は数千に上ってい る。これらの取り組みは「タイノ復興」として知られ、タイノ文化の復興運動であり、タイノの遺産を復活させ、取り戻すことを目指すもので、タイノ族の生存 を公式に認めることも目的としている。[144][145] 歴史家のラナルド・ウッドマンは、現代のタイノ族の運動を「メスティソ(混血)化(遺伝的および文化的な長年の混合)によるネイティブの生存の宣言、取り 戻し、復活」と表現している。[146] プエルトリコでは、学校でタイノ族の歴史が教えられており、子供たちはダンス、衣装、工芸品などを通してタイノ族の文化やアイデンティティについて学んで いる。 プエルトリコ大学マヤグエス校の遺伝学者マルティネス・クルサードは、タイノ族のルーツを祝ったり学んだりすることは、プエルトリコ人が自分たちに繋がり を感じることにつながっていると述べている。 学者のヨランダ・マルティネス=サンミゲルは、プエルトリコにおけるネオ・タイノ運動の発展は、米国によるプエルトリコ支配とスペインの社会遺産に対する 有効な対抗手段であると見ている。また、「『ボリクア・ココイ』としてのアイデンティティを時代錯誤的に無駄に再発明していると見なされることも、スピ ヴァクの『戦略的本質主義』の生産的な例として考えられる」とも指摘している。[108] 学者のガブリエル・ハスリップ=ヴィエラは 、1980年代から1990年代にかけて特に周辺化されたプエルトリコ人コミュニティの間で台頭したタイノ族復興運動は、カリブ海地域に敵対的な政治的・ 社会経済的条件を生み出した米国の人種主義とレーガノミクスへの反応であると示唆している。[148] |

| DNA of Taíno descendants In 2018, a DNA study mapped the genome of a tooth belonging to an 8th- to 10th–century "ancient Taíno" woman from the Bahamas.[149] The research team compared the genome to 104 Puerto Ricans who participated in the 1000 Genomes Project (2008), who had 10 to 15 percent Indigenous American ancestry. The results suggested they were more "closely related to the ancient Bahamian genome" than to any other Indigenous American group.[149][110] Although most do not identify as such, DNA evidence suggests that a large proportion of the current populations of the Greater Antilles have Taíno ancestry, with 61% of Puerto Ricans, up to 30% of Dominicans, and 33% of Cubans having mitochondrial DNA of Indigenous origin. Some groups have, however, reportedly maintained Taíno or indio customs to some degree.[9] Sixteen autosomal studies of peoples in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean and its diaspora (mostly Puerto Ricans) have shown that between 10% and 20% of their DNA is Indigenous. Some individuals have slightly higher scores, and others have lower scores or no indigenous DNA at all.[150] A recent study of a population in eastern Puerto Rico, where the majority of persons tested claimed Taíno ancestry and pedigree, showed that they had 61% mtDNA (distant maternal ancestry) from Indigenous peoples and 0% Y-chromosome DNA (distant paternal ancestry) from the Indigenous people. This suggests part of the Creole population descends from unions between Taíno women and European or African men.[151] |

タイノ族の子孫のDNA 2018年、バハマ諸島出身の8世紀から10世紀の「古代タイノ族」の女性に属する歯のゲノムを、DNA研究によりマッピングした。[149] 研究チームは、ゲノムを1000 Genomes Project(2008年)に参加した10~15%の先住民アメリカ人の血筋を持つ104人のプエルトリコ人と比較した。その結果、彼らは他のどのアメ リカ先住民グループよりも「古代バハマ人のゲノムと密接な関係」にあることが示唆された。[149][110] ほとんどの人はそう認識していないが、DNAの証拠から、大アンティル諸島の現在の人口の大部分がタイノ族の血筋を引いていることが示唆されている。プエ ルトリコ人の61%、ドミニカ人の最大30%、キューバ人の33%が、先住民起源のミトコンドリアDNAを持っている。しかし、一部のグループは、ある程 度タイノ族やインディオの風習を維持していると報告されている。 スペイン語圏カリブ海地域とそのディアスポラ(主にプエルトリコ人)の人々を対象とした16の常染色体研究では、彼らのDNAの10%から20%が先住民 由来であることが示されている。一部の個人はやや高い数値を示し、また、数値が低い、あるいは先住民のDNAが全く見られない人もいる。[150] プエルトリコ東部の住民を対象とした最近の研究では、調査対象者の大半がタイノ族の血筋を主張しているが、彼らは先住民のミトコンドリアDNA(遠い母系 祖先)を61%持ち、Y染色体DNA(遠い父系祖先)は0%であることが分かった。このことから、クレオール人の一部はタイノ族の女性とヨーロッパ人また はアフリカ人の男性との間の子孫であることが示唆される。[151] |

| Ciboney Garifuna Hupia, spirit of the dead Indigenismo Indigenismo in Mexico Indigenous Amerindian genetics List of Taínos Palapa (structure) Pomier Caves Tibes Indigenous Ceremonial Center Yamaye(→Jamaica) |

シボニー ガリフナ族 フピア、死者の霊 インディヘニスム メキシコにおけるインディヘニスム 先住民アメリカインディアン遺伝学 タイノ族の一覧 パラパ(建造物) ポミエ洞窟 ティベス先住民儀式センター ヤマーイ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ta%C3%ADno |

★タイノ(タイーノ)への虐殺行為(The Taíno genocide)

[Plate p.10. Conquistadors attacking a village of Indians. Scene of hangings and stake.] [Call number: BNF C43324]. / / A 16th-century illustration by Flemish Protestant Theodor de Bry for Las Casas' Brevisima relación de la destrucción de las Indias, depicting Spanish atrocities during the conquest of Hispaniola. Bartolome wrote: "They erected certain Gibbets, large, but low made, so that their feet almost reached the ground, every one of which was so ordered as to bear Thirteen Persons in Honour and Reverence (as they said blasphemously) of our Redeemer and his Twelve Apostles, under which they made a Fire to burn them to Ashes whilst hanging on them"

[プ

レート p.10. インディアンの村を襲うコンキスタドールたち。絞首刑と火あぶりの場面。] [請求記号:BNF C43324] / /

ラス・カサス著『インディアスの破壊についての簡潔な報告』のためにフランドル人のプロテスタント、テオドール・デ・ブリが描いた16世紀の挿絵。イスパ

ニョーラ征服時のスペイン人の残虐行為を描いている。バルトロメは次のように書いている。「彼らは、背の低い大きな絞首台を建て、その足が地面にほぼ届く

ようにした。その絞首台には、救い主と12使徒の(彼らが冒涜的に呼ぶところの)13の尊い人格を象徴するものを掲げ、その下で火を燃やし、吊るしたまま

灰にするよう命じた」

| The Taíno genocide

was committed against the Taíno Indigenous people by the Spanish during

their colonization of the Caribbean during the 16th century.[3] The

population of the Taíno before the arrival of the Spanish Empire on the

island of Quisqueya or Ayití in 1492,[4]which Christopher Columbus

baptized as Hispaniola, is estimated at between 10,000 and

1,000,000.[3][5] The Spanish subjected them to slavery, massacres and

other violent treatment after the last Taíno chief was deposed in 1504.

By 1514, the population had reportedly been reduced to just 32,000

Taíno,[3] by 1565, the number was reported at 200, and by 1802, they

were declared extinct by the Spanish colonial authorities. However,

descendants of the Taíno continue to live and their disappearance from

records was part of a fictional story created by the Spanish Empire