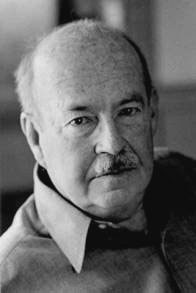

タルコット・パーソンズ

Talcott

Parsons, 1902-1979

タルコット・パーソンズ

Talcott

Parsons, 1902-1979

★タルコット・パーソンズ(Talcott Parsons、1902年12月13日 - 1979年5月8日)は、古典派の伝統を持つアメリカの社会学者で、彼の社会行動論と構造的機能主義で最もよく知られている人物である。経済学で博士号を 取得後、1927年から1929年までハーバード大学の教員を務めた。1930年に彼はハーバード大学の新しい社会学部の最初の教授の一人とな り、その後、ハーバード大学の社会関係学部の設立に貢献している(→「タルコット・パーソンズの理論」)。

| Talcott Parsons

(December 13, 1902 – May 8, 1979) was an American sociologist of the

classical tradition, best known for his social action theory and

structural functionalism. Parsons is considered one of the most

influential figures in sociology in the 20th century.[17] After earning

a PhD in economics, he served on the faculty at Harvard University from

1927 to 1929. In 1930, he was among the first professors in its new

sociology department.[18] Later, he was instrumental in the

establishment of the Department of Social Relations at Harvard. Based on empirical data, Parsons' social action theory was the first broad, systematic, and generalizable theory of social systems developed in the United States and Europe.[19] Some of Parsons' largest contributions to sociology in the English-speaking world were his translations of Max Weber's work and his analyses of works by Max Weber, Émile Durkheim, and Vilfredo Pareto. Their work heavily influenced Parsons' view and was the foundation for his social action theory. Parsons viewed voluntaristic action through the lens of the cultural values and social structures that constrain choices and ultimately determine all social actions, as opposed to actions that are determined based on internal psychological processes.[19] Although Parsons is generally considered a structural functionalist, towards the end of his career, in 1975, he published an article that stated that "functional" and "structural functionalist" were inappropriate ways to describe the character of his theory.[20] From the 1970s, a new generation of sociologists criticized Parsons' theories as socially conservative and his writings as unnecessarily complex. Sociology courses have placed less emphasis on his theories than at the peak of his popularity (from the 1940s to the 1970s). However, there has been a recent resurgence of interest in his ideas.[18] Parsons was a strong advocate for the professionalization of sociology and its expansion in American academia. He was elected president of the American Sociological Association in 1949 and served as its secretary from 1960 to 1965. |

タルコット・パーソンズ

(Talcott

Parsons、1902年12月13日 -

1979年5月8日)は、古典派の伝統を持つアメリカの社会学者で、彼の社会行動論と構造的機能主義で最もよく知られている人物である。経済学で博士号を

取得後、1927年から1929年までハーバード大学の教員を務めた[17]。1930年に彼はハーバード大学の新しい社会学部の最初の教授の一人とな

り、その後、ハーバード大学の社会関係学部の設立に貢献した[18]。 経験的データに基づいたパーソンズの社会行動理論は、アメリカやヨーロッパで開発された社会システムの最初の幅広く体系的で一般化可能な理論であった [19]。英語圏の社会学に対するパーソンズの最大の貢献はマックス・ウェーバーの作品の翻訳とマックス・ウェーバー、エミール・デュルケーム、ヴィルフ レド・パレトの作品の分析であった。彼らの研究は、パーソンズの見解に大きな影響を与え、彼の社会的行為論の基礎となった。パーソンズは内的な心理的プロ セスに基づいて決定される行動とは対照的に、選択を制約し、最終的にすべての社会的行動を決定する文化的価値と社会構造のレンズを通して自発的な行動を捉 えていた[19]。 パーソンズは一般的に構造的機能主義者と考えられているが、彼のキャリアの終わり頃、1975年に彼は「機能的」や「構造的機能主義者」が彼の理論の特徴 を表すのに不適切な方法であると述べている論文を発表している[20]。 1970年代から、社会学者の新しい世代はパーソンズの理論を社会的に保守的であると批判し、彼の著作を不必要に複雑であると批判していた。社会学のコー スは、彼の人気のピーク時(1940年代から1970年代まで)よりも彼の理論に重点を置いていない。しかし、最近になって彼の思想に対する関心が復活し ている[18]。 パーソンズは社会学の専門化とアメリカのアカデミズムにおけるその拡大の強い擁護者であった。彼は1949年にアメリカ社会学会の会長に選出され、 1960年から1965年まで同学会の幹事を務めていた。 |

| Early life He was born on December 13, 1902, in Colorado Springs, Colorado. He was the son of Edward Smith Parsons (1863–1943) and Mary Augusta Ingersoll (1863–1949). His father had attended Yale Divinity School, was ordained as a Congregationalist minister, and served first as a minister for a pioneer community in Greeley, Colorado. At the time of Parsons' birth, his father was a professor in English and vice-president at Colorado College. During his Congregational ministry in Greeley, Edward had become sympathetic to the Social Gospel movement but tended to view it from a higher theological position and was hostile to the ideology of socialism.[21] Also, both he and Talcott would be familiar with the theology of Jonathan Edwards. The father would later become the president of Marietta College in Ohio. Parsons' family is one of the oldest families in American history. His ancestors were some of the first to arrive from England in the first half of the 17th century.[22] The family's heritage had two separate and independently developed Parsons lines, both to the early days of American history deeper into British history. On his father's side, the family could be traced back to the Parsons of York, Maine. On his mother's side, the Ingersoll line was connected with Edwards and from Edwards on would be a new, independent Parsons line because Edwards' eldest daughter, Sarah, married Elihu Parsons on June 11, 1750. |

幼少期 1902年12月13日、コロラド州コロラドスプリングスで生まれた。エドワード・スミス・パーソンズ(1863-1943)とメアリー・オーガスタ・イ ンガーソル(1863-1949)の息子である。父はエール大学神学部で学び、会衆派牧師に叙階され、コロラド州グリーリーの開拓者コミュニティの牧師と して活躍した。パーソンズが生まれた当時、父親はコロラド大学の英語教授と副学長を務めていた。グリーリーでの会衆派牧師時代、エドワードは社会福音運動 に共感していたが、より高い神学的立場から見る傾向があり、社会主義の思想に敵対していた[21]。 また、彼とタルコットは共にジョナサン・エドワーズの神学に親しむことになった。父親は後にオハイオ州のマリエッタ・カレッジの学長となる。 パーソンズの家系は、アメリカ史の中で最も古い家系の一つである。彼の祖先は、17世紀前半にイギリスから最初にやってきた人々である[22]。この一族 の遺産には、アメリカの歴史の初期にイギリスの歴史に深く入り込んだ、2つの別々の、独立して発展したパーソンズの家系があった。父方はメイン州ヨークの パーソンズ家に遡ることができる。母方のインガソルの系統はエドワーズにつながり、エドワーズから先は、1750年6月11日にエドワーズの長女サラがエ リフ・パーソンズと結婚したため、新たに独立したパーソンズの系統となる。 |

| Education Amherst College As an undergraduate, Parsons studied biology and philosophy at Amherst College and received his BA in 1924. Amherst College had become the Parsons' family college by tradition; his father and his uncle Frank had attended it, as had his elder brother, Charles Edward. Initially, Parsons was attracted to a career in medicine, as he was inspired by his elder brother[23]: 826 so he studied a great deal of biology and spent a summer working at the Oceanographic Institution at Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Parsons' biology professors at Amherst were Otto C. Glaser and Henry Plough. Gently mocked as "Little Talcott, the gilded cherub," Parsons became one of the student leaders at Amherst. Parsons also took courses with Walton Hale Hamilton and the philosopher Clarence Edwin Ayres, both known as "institutional economists". Hamilton, in particular, drew Parsons toward social science.[23]: 826 They exposed him to literature by authors such as Thorstein Veblen, John Dewey, and William Graham Sumner. Parsons also took a course with George Brown in the philosophy of Immanuel Kant and a course in modern German philosophy with Otto Manthey-Zorn, who was a great interpreter of Kant. Parsons showed from early on, a great interest in the topic of philosophy, which most likely was an echo of his father's great interest in theology in which tradition he had been profoundly socialized, a position unlike with his professors'. Two term papers that Parsons wrote as a student for Clarence E. Ayres's class in Philosophy III at Amherst have survived. They are referred to as the Amherst Papers and have been of strong interest to Parsons scholars. The first was written on December 19, 1922, "The Theory of Human Behavior in its Individual and Social Aspects."[24] The second was written on March 27, 1923, "A Behavioristic Conception of the Nature of Morals".[25] The papers reveal Parsons' early interest in social evolution.[26] The Amherst Papers also reveal that Parsons did not agree with his professors since he wrote in his Amherst papers that technological development and moral progress are two structurally-independent empirical processes. London School of Economics After Amherst, he studied at the London School of Economics for a year, where he was exposed to the work of Bronisław Malinowski, R. H. Tawney, L. T. Hobhouse, and Harold Laski.[23]: 826 During his days at LSE, he made friends with E. E. Evans-Pritchard, Meyer Fortes, and Raymond Firth, who all participated in the Malinowski seminar. Also, he made a close personal friendship with Arthur and Eveline M. Burns. At the LSE he met Helen Bancroft Walker, a young American, and they married on April 30, 1927. The couple had three children: Anne, Charles, and Susan and eventually four grandchildren. Walker's father was born in Canada but had moved to the Boston area and later become an American citizen. |

教育内容 アマースト大学 1924年、パーソンズはアマースト大学で生物学と哲学を学び、学士号を取得した。アマースト大学は、パーソンズ家の伝統的な大学であり、父と叔父のフラ ンク、兄のチャールズ・エドワードが在籍していた。パーソンズは当初、兄の影響で医学の道に惹かれていた[23]: 826 ので、生物学を大いに学び、夏にはマサチューセッツ州ウッズホールの海洋研究所で働いた。 アマースト大学でパーソンズの生物学の教授を務めたのは、オットー・C・グレーザーとヘンリー・プラウであった。パーソンズは、「金ぴかのケルビム、小さ なタルコット」と揶揄されながらも、アマースト大学の学生指導者の一人となった。また、パーソンズは、「制度経済学者」として知られるウォルトン・ヘイ ル・ハミルトンや哲学者のクラレンス・エドウィン・エアーズの講義も受けた。特にハミルトンはパーソンズを社会科学に向かわせた[23]: 826 彼らは、トースタイン・ヴェブレン、ジョン・デューイ、ウィリアム・グラハム・サムナーといった著者の文献に彼を触れさせた。また、パーソンズは、ジョー ジ・ブラウンからイマニュエル・カントの哲学の講義を受け、オットー・マンテイ=ゾーンから現代ドイツ哲学の講義を受けた。パーソンズは早くから哲学に強 い関心を抱いていたが、それは、神学に強い関心を抱いていた父親の影響であったようで、その伝統の中で、教授陣とは異なる立場で深く社会性を身につけた。 パーソンズが学生時代にアマースト大学のクラレンス・E・エアズの哲学IIIの授業で書いた2つの論文も残っている。これらはアマースト・ペーパーズと呼 ばれ、パーソンズ研究者の強い関心を集めている。また、アマースト論文では、技術的発展と道徳的進歩は構造的に独立した経験的過程であると書いており、 パーソンズが教授と意見が合わなかったことも明らかにされている[26]。 ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス アマーストの後、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスに1年間留学し、マリノフ スキー、R. H. トーニー、L. T. ホブハウス、ハロルド・ラスキらの研究に触れる[23]: 826 LSE時代には、マリノフスキーのセミナーに参加したE. E. エバンス=プリチャード、メイヤー・フォータス、レイモンド・フィースと友人になり、また、アーサー・バーンズ、エヴリン・M・バーンズとも親交を深め た。また、アーサー・バーンズやエヴリン・M・バーンズとも個人的に親交を深めた。 LSEでは、若いアメリカ人のヘレン・バンクロフト・ウォーカーと出会い、1927年4月30日に結婚した。1927年4月30日に結婚し、3人の子供を もうけた。アン、チャールズ、スーザンの3人の子供と、4人の孫が生まれた。ウォーカーの父親はカナダ出身だが、ボストン近郊に移り住み、後にアメリカ国 籍を取得した。 |

| University of Heidelberg In June, Parsons went on to the University of Heidelberg, where he received his PhD in sociology and economics in 1927. At Heidelberg, he worked with Alfred Weber, Max Weber's brother; Edgar Salin, his dissertation adviser; Emil Lederer; and Karl Mannheim. He was examined on Kant's Critique of Pure Reason by the philosopher Karl Jaspers.[27] At Heidelberg, Parsons was also examined by Willy Andreas on the French Revolution. Parsons wrote his Dr. Phil. thesis on The Concept of Capitalism in the Recent German Literature, with his main focus on the work of Werner Sombart and Weber. It was clear from his discussion that he rejected Sombart's quasi-idealistic views and supported Weber's attempt to strike a balance between historicism, idealism and neo-Kantianism. The most crucial encounter for Parsons at Heidelberg was with the work of Max Weber about whom he had never heard before. Weber became tremendously important for Parsons because his upbringing with a liberal but strongly-religious father had made the question of the role of culture and religion in the basic processes of world history a persistent puzzle in his mind. Weber was the first scholar who truly provided Parsons with a compelling theoretical "answer" to the question, so Parsons became totally absorbed in reading Weber. Parsons decided to translate Weber's work into English and approached Marianne Weber, Weber's widow. Parsons would eventually translate several of Weber's works into English.[28][29] His time in Heidelberg had him invited by Marianne Weber to "sociological teas", which were study group meetings that she held in the library room of her and Max's old apartment. One scholar that Parsons met at Heidelberg who shared his enthusiasm for Weber was Alexander von Schelting. Parsons later wrote a review article on von Schelting's book on Weber.[30] Generally, Parsons read extensively in religious literature, especially works focusing on the sociology of religion. One scholar who became especially important for Parsons was Ernst D. Troeltsch (1865–1923). Parsons also read widely on Calvinism. His reading included the work of Emile Doumerque,[31] Eugéne Choisy, and Henri Hauser. |

ハイデルベルク大学 6月、パーソンズはハイデルベルク大学に進学し、1927年に社会学と経済学の博士号を取得した。ハイデルベルクでは、マックス・ウェーバーの弟アルフレッド・ウェーバー、学位論文の指導者エ ドガー・サリン、エミール・レーデラー、カール・マンハイムらと研究した。ハイデルベルクでは、カントの『純粋理性批判』について哲学者のカール・ヤス パースの審査を受けた[27]。また、フランス革命についてウィリー・アンドレアスの審査を受けた。パーソンズは、博士論文を「最近のドイ ツ文学における資本主義の概念」について執筆し、主にヴェルナー・ゾンバートとヴェーバーの作品に焦点を当てた。ソンバートの準理想主義的な考え方を否定 し、歴史主義、観念論、新カント主義とのバランスをとろうとするウェーバーの考え方を支持したことは、彼の議論から明らかであった。 ハイデルベルクでのパーソンズにとって最も重要な出会いは、それまで聞 いたこともなかったマックス・ウェーバーの仕事との出会いであった。自由主義者でありながら宗教心の強い父親のもとで育ったパーソンズにとって、世界史の 基本的過程における文化や宗教の役割の問題は、彼の心の中にある持続的なパズルであったからである。ウェーバーは、その問いに真に説得力のある理論的な 「答え」を与えてくれた最初の学者であり、パーソンズはウェーバーを読むことに没頭するようになった。 パーソンズは、ウェーバーの著作を英語に翻訳することを決意し、ウェー バーの未亡人であるマリアンヌ・ウェーバーに声をかけた。パーソンズは最終的にウェーバーの著作のいくつかを英語に翻訳することになる[28][29]。 ハイデルベルクでの時間は、マリアンヌ・ウェーバーから「社会学茶会」に招待されることになった。これは、彼女とマックスの古いアパートの図書館室で彼女 が開いていた研究会の会合だった。ハイデルベルクで出会った学者のうち、ウェーバーへの熱意を共有したのがアレクサンダー・フォン・シェルティングであっ た。パーソンズは、後にフォン・シェルティングのヴェーバーに関する本のレビュー記事を書いている[30]。一般的にパーソンズは、宗教文献、特に宗教社 会学に焦点を当てた著作を広く読んでいた。パーソンズにとって特に重要となった学者の一人がエルンスト・D・トロエルシュ(1865-1923)であっ た。パーソンズはまた、カルヴァン主義についても広く読んでいる。エミール・ドゥメルク、ウジェーヌ・ショワジー、アンリ・ハウザーの著作を読んでいた[31]。 |

| Early academic career Harvard Economics Department In 1927, after a year of teaching at Amherst (1926–1927), Parsons entered Harvard, as an instructor in the Economics Department,[32] where he followed F. W. Taussig's lectures on economist Alfred Marshall and became friends with the economist historian Edwin Gay, the founder of Harvard Business School. Parsons also became a close associate of Joseph Schumpeter and followed his course General Economics. Parsons was at odds with some of the trends in Harvard's department which then went in a highly-technical and a mathematical direction. He looked for other options at Harvard and gave courses in "Social Ethics" and in the "Sociology of Religion". Although he entered Harvard through the Economics Department, his activities and his basic intellectual interest propelled him toward sociology. However, no Sociology Department existed during his first years at Harvard. Harvard Sociology Department The chance for a shift to sociology came in 1930, when Harvard's Sociology Department was created[33] under Russian scholar Pitirim Sorokin. Sorokin, who had fled the Russian Revolution from Russia in 1923, was given the opportunity to establish the department. Parsons became one of the new department's two instructors, along with Carl Joslyn. Parsons established close ties with biochemist and sociologist Lawrence Joseph Henderson, who took a personal interest in Parsons' career at Harvard. Parsons became part of L. J. Henderson's famous Pareto study group, in which some of the most important[citation needed] intellectuals at Harvard participated, including Crane Brinton, George C. Homans, and Charles P. Curtis. Parsons wrote an article on Pareto's theory[34] and later explained that he had adopted the concept of "social system" from reading Pareto. Parsons also made strong connections with two other influential intellectuals with whom he corresponded for years: economist Frank H. Knight and Chester Barnard, one of the most dynamic businessmen of the US. The relationship between Parsons and Sorokin quickly turned sour. A pattern of personal tensions was aggravated by Sorokin's deep dislike for American civilization, which he regarded as a sensate culture that was in decline. Sorokin's writings became increasingly anti-scientistic in his later years, widening the gulf between his work and Parsons' and turning the increasingly positivistic American sociology community against him. Sorokin also tended to belittle all sociology tendencies that differed from his own writings, and by 1934 was quite unpopular at Harvard. Some of Parsons' students in the department of sociology were people such as Robin Williams Jr., Robert K. Merton, Kingsley Davis, Wilbert Moore, Edward C. Devereux, Logan Wilson, Nicholas Demereth, John Riley Jr., and Mathilda White Riley. Later cohorts of students included Harry Johnson, Bernard Barber, Marion Levy and Jesse R. Pitts. Parsons established, at the students' request, a little, informal study group which met year after year in Adams' house. Toward the end of Parsons' career, German systems theorist Niklas Luhmann also attended his lectures. In 1932, Parsons bought a farmhouse near the small town of Acworth, but Parsons often, in his writing, referred to it as "the farmhouse in Alstead". The farmhouse was not big and impressive; indeed, it was a very humble structure with almost no modern utilities. Still, it became central to Parsons' life, and many of his most important works were written in its peace and quiet. In the spring of 1933, Susan Kingsbury, a pioneer of women's rights in America, offered Parsons a position at Bryn Mawr College; however, Parsons declined the offer because, as he wrote to Kingsbury, "neither salary nor rank is really definitely above what I enjoy here".[35] In the academic year of 1939–1940 Parsons and Schumpeter conducted an informal faculty seminar at Harvard, which discussed the concept of rationality. Among the participants were D. V. McGranahan, Abram Bergson, Wassily Leontief, Gottfried Haberler, and Paul Sweezy. Schumpeter contributed the essay "Rationality in Economics", and Parsons submitted the paper "The Role of Rationality in Social Action" for a general discussion.[36] Schumpeter suggested that he and Parsons should write or edit a book together on rationality, but the project never materialized. Neoclassical economics vs. institutionalists In the discussion between neoclassical economics and the institutionalists, which was one of the conflicts that prevailed within the field of economics in the 1920s and early 1930s, Parsons attempted to walk a very fine line. He was very critical about neoclassical theory, an attitude he maintained throughout his life and that is reflected in his critique of Milton Friedman and Gary Becker. He was opposed to the utilitarian bias within the neoclassical approach and could not embrace them fully. However, he agreed partly on their theoretical and methodological style of approach, which should be distinguished from its substance. He was thus unable to accept the institutionalist solution. In a 1975 interview, Parsons recalled a conversation with Schumpeter on the institutionalist methodological position: "An economist like Schumpeter, by contrast, would absolutely have none of that. I remember talking to him about the problem and .. I think Schumpeter was right. If economics had gone that way [like the institutionalists] it would have had to become a primarily empirical discipline, largely descriptive, and without theoretical focus. That's the way the 'institutionalists' went, and of course Mitchell was affiliated with that movement."[37] Anti-Nazism Parsons returned to Germany in the summer of 1930 and became an eyewitness to the feverish atmosphere in Weimar Germany during which the Nazi Party rose to power. Parsons received constant reports about the rise of Nazism through his friend, Edward Y. Hartshorne, who was traveling there. Parsons began, in the late 1930s, to warn the American public about the Nazi threat, but he had little success, as a poll showed that 91 percent of the country opposed the Second World War.[38] Most of the US thought also that the country should have stayed out of the First World War and that the Nazis were, regardless of what they did in Germany or even Europe, no threat to the US. Many Americans even sympathized with Germany, as many had ancestry from there, and the latter both was strongly anticommunist and had gotten itself out of the Great Depression while the US was still suffering from it. One of the first articles that Parsons wrote was "New Dark Age Seen If Nazis Should Win". He was one of the key initiators of the Harvard Defense Committee, aimed at rallying the American public against the Nazis. Parsons' voice sounded again and again over Boston's local radio stations, and he also spoke against Nazism during a dramatic meeting at Harvard, which was disturbed by antiwar activists. Together with graduate student Charles O. Porter, Parsons rallied graduate students at Harvard for the war effort. (Porter later became a Democratic US Representative for Oregon.) During the war, Parsons conducted a special study group at Harvard, which analyzed what its members considered the causes of Nazism, and leading experts on that topic participated. Second World War In the spring of 1941, a discussion group on Japan began to meet at Harvard. The group's five core members were Parsons, John K. Fairbank, Edwin O. Reischauer, William M. McGovern, and Marion Levy Jr. A few others occasionally joined the group, including Ai-Li Sung and Edward Y. Hartshorne. The group arose out of a strong desire to understand the country whose power in the East had grown tremendously and had allied itself with Germany, but, as Levy frankly admitted, "Reischauer was the only one who knew anything about Japan."[39] Parsons, however, was eager to learn more about it and was "concerned with general implications." Shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Parsons wrote in a letter to Arthur Upham Pope (1881–1969) that the importance of studies of Japan certainly had intensified.[40] In 1942, Parsons worked on arranging a major study of occupied countries with Bartholomew Landheer of the Netherlands Information Office in New York.[41] Parsons had mobilized Georges Gurvitch, Conrad Arnsberg, Dr. Safranek and Theodore Abel to participate,[42] but it never materialized for lack of funding. In early 1942, Parsons unsuccessfully approached Hartshorne, who had joined the Psychology Division of the Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI) in Washington to interest his agency in the research project. In February 1943, Parsons became the deputy director of the Harvard School of Overseas Administration, which educated administrators to "run" the occupied territories in Germany and the Pacific Ocean. The task of finding relevant literature on both Europe and Asia was mindboggling and occupied a fair amount of Parsons' time. One scholar Parsons came to know was Karl August Wittfogel and they discussed Weber. On China, Parsons received fundamental information from Chinese scholar Ai-Li Sung Chin and her husband, Robert Chin. Another Chinese scholar Parsons worked closely with in this period was Hsiao-Tung Fei (or Fei Xiaotong) (1910–2005), who had studied at the London School of Economics and was an expert on the social structure of the Chinese village. Intellectual exchanges Parsons met Alfred Schütz during the rationality seminar, which he conducted together with Schumpeter, at Harvard in the spring of 1940. Schutz had been close to Edmund Husserl and was deeply embedded in the latter's phenomenological philosophy.[43] Schutz was born in Vienna but moved to the US in 1939, and for years, he worked on the project of developing a phenomenological sociology, primarily based on an attempt to find some point between Husserl's method and Weber's sociology.[44] Parsons had asked Schutz to give a presentation at the rationality seminar, which he did on April 13, 1940, and Parsons and Schutz had lunch together afterward. Schutz was fascinated with Parsons' theory, which he regarded as the state-of-the-art social theory, and wrote an evaluation of Parsons' theory that he kindly asked Parsons to comment. That led to a short but intensive correspondence, which generally revealed that the gap between Schutz's sociologized phenomenology and Parsons' concept of voluntaristic action was far too great.[45] From Parsons' point of view, Schutz's position was too speculative and subjectivist, and tended to reduce social processes to the articulation of a Lebenswelt consciousness. For Parsons, the defining edge of human life was action as a catalyst for historical change, and it was essential for sociology, as a science, to pay strong attention to the subjective element of action, but it should never become completely absorbed in it since the purpose of a science was to explain causal relationships, by covering laws or by other types of explanatory devices. Schutz's basic argument was that sociology cannot ground itself and that epistemology was not a luxury but a necessity for the social scientist. Parsons agreed but stressed the pragmatic need to demarcate science and philosophy and insisted moreover that the grounding of a conceptual scheme for empirical theory construction cannot aim at absolute solutions but needs to take a sensible stock-taking of the epistemological balance at each point in time. However, the two men shared many basic assumptions about the nature of social theory, which has kept the debate simmering ever since.[46][47] By request from Ilse Schutz, after her husband's death, Parsons gave, on July 23, 1971, permission to publish the correspondence between him and Schutz. Parsons also wrote "A 1974 Retrospective Perspective" to the correspondence, which characterized his position as a "Kantian point of view" and found that Schutz's strong dependence on Husserl's "phenomenological reduction" would make it very difficult to reach the kind of "conceptual scheme" that Parsons found essential for theory-building in social sciences.[48] Between 1940 and 1944, Parsons and Eric Voegelin (1901–1985) exchanged intellectual views through correspondence.[49][50][51] Parsons had probably met Voegelin in 1938 and 1939, when Voegelin held a temporary instructor appointment at Harvard. The bouncing point for their conversation was Parsons' manuscript on anti-Semitism and other materials that he had sent to Voegelin. Discussion touched on the nature of capitalism, the rise of the West, and the origin of Nazism. The key to the discussion was the implication of Weber's interpretation of Protestant ethics and the impact of Calvinism on modern history. Although the two scholars agreed on many fundamental characteristics about Calvinism, their understanding of its historical impact was quite different. Generally, Voegelin regarded Calvinism as essentially a dangerous totalitarian ideology; Parsons argued that its current features were temporary and that the functional implications of its long-term, emerging value-l system had revolutionary and not only "negative" impact on the general rise of the institutions of modernity. The two scholars also discussed Parsons' debate with Schütz and especially why Parsons had ended his encounter with Schutz. Parsons found that Schutz, rather than attempting to build social science theory, tended to get consumed in philosophical detours. Parsons wrote to Voegelin: "Possibly one of my troubles in my discussion with Schuetz lies in the fact that by cultural heritage I am a Calvinist. I do not want to be a philosopher – I shy away from the philosophical problems underlying my scientific work. By the same token I don't think he wants to be a scientist as I understand the term until he has settled all the underlying philosophical difficulties. If the physicists of the 17th century had been Schuetzes there might well have been no Newtonian system."[52] In 1942, Stuart C. Dodd published a major work, Dimensions of Society,[53] which attempted to build a general theory of society on the foundation of a mathematical and quantitative systematization of social sciences. Dodd advanced a particular approach, known as an "S-theory". Parsons discussed Dodd's theoretical outline in a review article the same year.[54] Parsons acknowledged Dodd's contribution to be an exceedingly formidable work but argued against its premises as a general paradigm for the social sciences. Parsons generally argued that Dodd's "S-theory", which included the so-called "social distance" scheme of Bogardus, was unable to construct a sufficiently sensitive and systematized theoretical matrix, compared with the "traditional" approach, which has developed around the lines of Weber, Pareto, Émile Durkheim, Sigmund Freud, William Isaac Thomas, and other important agents of an action-system approach with a clearer dialogue with the cultural and motivational dimensions of human interaction. In April 1944, Parsons participated in a conference, "On Germany after the War", of psychoanalytical oriented psychiatrists and a few social scientists to analyze the causes of Nazism and to discuss the principles for the coming occupation.[55] During the conference, Parsons opposed what he found to be Lawrence S. Kubie's reductionism. Kubie was a psychoanalyst, who strongly argued that the German national character was completely "destructive" and that it would be necessary for a special agency of the United Nations to control the German educational system directly. Parsons and many others at the conference were strongly opposed to Kubie's idea. Parsons argued that it would fail and suggested that Kubie was viewing the question of Germans' reorientation "too exclusively in psychiatric terms". Parsons was also against the extremely harsh Morgenthau Plan, published in September 1944. After the conference, Parsons wrote an article, "The Problem of Controlled Institutional Change", against the plan.[56] Parsons participated as a part-time adviser to the Foreign Economic Administration Agency between March and October 1945 to discuss postwar reparations and deindustrialization.[57][58] Parsons was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1945.[59] Taking charge at Harvard Parsons' situation at Harvard University changed significantly in early 1944, when he received a good offer from Northwestern University. Harvard reacted to the offer by appointing Parsons as the chairman of the department, promoting him to the rank of full professor and accepting the process of reorganization, which led to the establishment of the new department of Social Relations. Parsons' letter to Dean Paul Buck, on April 3, 1944, reveals the high point of this moment.[60] Because of the new development at Harvard, Parsons chose to decline an offer from William Langer to join the Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency. Langer proposed for Parsons to follow the American army in its march into Germany and to function as a political adviser to the administration of the occupied territories. Late in 1944, under the auspices of the Cambridge Community Council, Parsons directed a project together with Elizabeth Schlesinger. They investigated ethnic and racial tensions in the Boston area between students from Radcliffe College and Wellesley College. This study was a reaction to an upsurge of anti-Semitism in the Boston area, which began in late 1943 and continued into 1944.[61] At the end of November 1946, the Social Research Council (SSRC) asked Parsons to write a comprehensive report of the topic of how the social sciences could contribute to the understanding of the modern world. The background was a controversy over whether the social sciences should be incorporated into the National Science Foundation. Parsons' report was in form of a large memorandum, "Social Science: A Basic National Resource", which became publicly available in July 1948 and remains a powerful historical statement about how he saw the role of modern social sciences.[62] |

初期の学問的キャリア ハーバード大学 経済学部 1927年、アマースト大学で1年間教えた後(1926-1927)、パーソンズはハーバード大学の経済学部の講師として入学し、F・W・タウシグの経済 学者アルフレッド・マーシャルに関する講義を受け、経済学者の歴史学者でハーバードビジネススクールの創設者のエドウィン・ゲイと友人になった[32]。 パーソンズはまた、ヨーゼフ・シュンペーターの側近となり、彼の講義「一般経済学」を受講した。パーソンズは、高度に技術的、数学的な方向に進んでいった ハーバード大学の学部の動向と対立していた。彼は、ハーバード大学に他の選択肢を求め、「社会倫理学」や「宗教社会学」の講義を行った。経済学部からハー バード大学に入ったものの、彼の活動や基本的な知的関心は、社会学へと駆り立てた。しかし、ハーバード大学での最初の数年間は、社会学部は存在しなかっ た。 ハーバード大学社会学部 社会学への転換のチャンスは、1930年にロシア人学者ピティリム・ソローキンの下でハーバード大学の社会学部が創設されたときに訪れた[33]。ソロー キンは1923年にロシアからロシア革命を逃れてきており、学科設立の機会を与えられていた。パーソンズは、カール・ジョスリンとともに新学科の2人の教 官のひとりとなった。パーソンズは、生化学者で社会学者のローレンス・ジョセフ・ヘ ンダーソンと親密な関係を築き、彼はパーソンズのハーバード大学でのキャリアに個人的に関心を寄せていた。このグループには、クレイン・ブリントン、 ジョージ・C・ホーマンス、チャールズ・P・カーティスなど、ハーバード大学で最も重要な知識人たちが参加していた[citation needed]。パーソンズはパレートの理論に関する論文を書き[34]、後にパレートを読んで「社会システム」の概念を取り入れたと説明している。また パーソンズは、経済学者のフランク・H・ナイトやアメリカで最もダイナミックな実業 家の一人であるチェスター・バーナードという、長年にわたって文通を続けた有力な知識人たちとも強い結びつきをもっていた。パーソンズとソ ローキンの関係は、すぐに険悪になった。パーソンズとソローキンの関係は急速に悪化し、ソローキンがアメリカ文明を深く嫌い、アメリカ文明は衰退しつつあ る感覚的な文化だと考えていたこともあり、個人的な緊張が高まり、パーソンズとソローキンの関係は悪化した。晩年、ソローキンの著作はますます反科学的な ものとなり、パーソンズとの溝を深め、実証主義的なアメリカ社会学界を敵に回すことになった。ソローキンはまた、彼自身の著作と異なるすべての社会学の傾 向を軽んじる傾向があり、1934年までにハーバード大学でかなり不人気となった。 パーソンズの社会学部の学生には、ロビン・ウィリアム・ジュニア、ロバート・K・マートン、キングスレー・デイヴィス、ウィルバート・ムーア、エドワー ド・C・デヴリュー、ローガン・ウィルソン、ニコラス・デミアス、ジョン・ライリー・ジュニア、マチルダ・ホワイト・ライリーといった人たちがいる。その 後、ハリー・ジョンソン、バーナード・バーバー、マリオン・レヴィ、ジェシー・R・ピッツらが入学している。パーソンズは、学生たちの要望で、毎年アダム ズの家で会合を持つ小さな非公式の研究会を設立した。パーソンズのキャリアの終わりには、ドイツのシステム理論家ニクラス・ルーマンも彼の講義を受講して いた。 1932年、パーソンズはアクワースという小さな町の近くに農家を購入したが、パーソンズは執筆の際、しばしばそれを「アルステッドの農家」と呼んでい る。その農家は、大きく印象的なものではなかった。実際、近代的な設備はほとんどなく、非常に質素な建物であった。それでも、この農家はパーソンズの生活 の中心となり、彼の最も重要な作品の多くは、この平穏で静かな場所で書かれた。 1933年の春、アメリカにおける女性の権利の先駆者であるスーザン・キングスベリーはパーソンズにブリンマー大学での地位を提供したが、パーソンズはキ ングスベリーに書いたように、「給与も地位も私がここで楽しむものよりも本当に間違いなく上」なのでその申し出を辞退している[35]。 1939年から1940年にかけて、パーソンズとシュンペーターはハーバード大学で非公式な教授セミナーを行い、合理性の概念について議論していた。参加 者にはD. V. McGranahan、Abram Bergson、Wassily Leontief、Gottfried Haberler、Paul Sweezyが含まれていた。シュンペーターは「経済学における合理性」を、パーソンズは「社会的行為における合理性の役割」という論文を提出し、総合討 論に参加した[36]。 新古典派経済学と制度学派の比較 1920年代から1930年代初頭にかけて経済学の分野で起こった対立の一つである新古典派経済学と制度派の議論において、パーソンズは非常に微妙なライ ンを歩もうとした。彼は新古典派理論に対して非常に批判的であり、その姿勢は生涯を通じて維持され、ミルトン・フリードマンやゲイリー・ベッカーに対する 批判にも反映されている。彼は、新古典派アプローチの中にある功利主義的なバイアスに反対しており、彼らを完全に受け入れることはできなかった。しかし、 その実質とは区別されるべき、彼らの理論的・方法論的なアプローチのスタイルについては、部分的に同意していた。そのため、彼は制度学派の解決策を受け入 れることができなかった。パーソンズは、1975年のインタビューのなかで、制度主義の方法論の立場について、シュンペーターとの会話を回想している。 「シュンペーターのような経済学者は、それとは対照的に、まったくそのようなことはしないでしょう。私は彼とこの問題について話したことを覚えています。 もし経済学が(制度学派のように)そのような方向に進んでいたら、主に経験的な学問にならざるを得ず、大部分は記述的で、理論的な焦点を持たないものに なったでしょう。それが「制度派」の行き方であり、もちろんミッチェルはその運動に加わっていた」[37]。 反ナチズム パーソンズは1930年の夏にドイツに戻り、ナチス党が権力を握ったワイマール・ドイツの熱狂的な雰囲気を目撃することになる。パーソンズは、現地に出張 していた友人のエドワード・Y・ハーツホーンを通じて、ナチズムの台頭について絶えず報告を受けていた。パーソンズは1930年代後半にナチスの脅威についてアメリカ国民に警告を与え始めたが、 91%の国民が第二次世界大戦に反対しているという世論調査があるように、ほとんど成功はしなかった[38]。 また、第一次世界大戦には参戦すべきではなかった、ナチスはドイツやヨーロッパで何をしようが、アメリカにとって何の脅威にもならない、とほとんどのアメ リカ人が思っていた。アメリカ人の多くはドイツに先祖を持ち、ドイツは反共産主義が 強く、アメリカがまだ大恐慌に苦しんでいる間に自国を立ち直らせたので、ドイツに同情的でさえあった。 パーソンズが最初に書いた論文の1つに「もしナチスが勝利したら、新しい暗黒時代がやってくる」というのがある。彼は、アメリカ国民をナチスに反対させる ための「ハーバード・ディフェンス委員会」の主要な発起人の一人であった。ハーバード大学では、反戦運動家たちの妨害にあいながらも、ナチズムに反対する 劇的な集会が開かれ、パーソンズの声はボストンの地元ラジオ局から幾度となく流れた。大学院生のチャールズ・O・ポーターとともに、ハーバード大学の大学 院生を戦争支援のために結集させた。(戦時中、ハーバード大学では、ナチズムの原因を分析する特別研究会が開かれ、第一線の専門家が参加した。 第二次世界大戦 1941年春、ハーバード大学で日本に関する討論会が始まった。パーソンズ、ジョン・K・フェアバンク、エドウィン・O・ライシャワー、ウィリアム・M・ マクガバン、マリオン・レヴィ・ジュニアの五人が中心メンバーで、他に宋愛麗、エドワード・Y・ハートソーンらが時折参加していた。東洋の国力が驚異的に 発展し、ドイツと同盟を結んだこの国を理解したいという強い願いから生まれたが、レヴィが率直に認めたように、「日本について知っているのはライシャワー だけだった」[39]。 しかしパーソンズはもっと知りたがり、「一般的意味合いに関心があった」という。 日本が真珠湾を攻撃した直後、パーソンズはアーサー・ウファム・ポープ(1881-1969)に宛てた手紙の中で、日本研究の重要性が確かに強まったと書 いている[40]。 1942年にパーソンズはニューヨークのオランダ情報局のバーソロミュー・ランドヒアと共に占領下の国々に関する大規模な研究の手配に取り組んでいた [41]。 パーソンズはジョルジュ・グルヴィッチ、コンラッド・アーンスバーグ、サフラネック博士、セオドア・アベルを参加に動員していたが、資金不足で実現するこ とはなかった[42]。1942年初頭、パーソンズはワシントンの情報調整官事務所(COI)の心理学部門に加わったハーツホーンに、彼の機関に研究プロ ジェクトに関心を持たせるようアプローチしたが、失敗に終わっている。1943年2月、パーソンズは、ドイツと太平洋の占領地を「運営」する管理者を教育 するハーバード大学海外管理学部の副部長に就任していた。ヨーロッパとアジアの両方について関連する文献を見つける作業は気の遠くなるようなもので、パー ソンズの時間のかなりの部分を占めた。パーソンズが知り合った学者にカール・アウグスト・ヴィットフォーゲルがおり、彼らはヴェーバーについて議論した。 中国については、中国の学者であるアイリ・ソン・チンとその夫ロバート・チンから基本的な情報を得た。また、この時期にパーソンズが親交を深めた中国人学 者として、ロンドン大学経済学校で学び、中国村落の社会構造の専門家であった飛暁東(または飛暁東)(1910-2005年)がいる。 知的交流 パーソンズは、1940年の春にハーバード大学でシュンペーターとともに行った合理性セミナーでアルフレッド・シュッツと出会った。シュッツはエドムン ド・フッサールと親交があり、後者の現象学的哲学に深く入り込んでいた[43] ウィーンで生まれたシュッツは1939年にアメリカに移住し、長年にわたって現象学的社会学の開発プロジェクトに取り組み、主にフッサールの方法とウェー バーの社会学の間のある点を見つける試みに基づいていた[44] パーソンズはシュッツに合理性セミナーで発表するよう依頼しており、彼は1940年4月13日にそれを行って、その後パーソンズとシュッツは一緒に昼食を 取ったという。シュッツは、社会理論の最先端とされるパーソンズの理論に魅了され、パーソンズの理論に対する評価を書き、パーソンズに親切にもコメントを 求めている。その結果、短いながらも集中的な書簡が交わされ、シュッツの社会学化された現象学とパーソンズの自発的行為という概念の間のギャップがあまり にも大きいことが概ね明らかになった[45]。 パーソンズの立場からは、シュッツの立場はあまりにも推測的かつ主観的で、社会過程をレーベンスヴェルト意識の調合に還元する傾向があったとされる。パー ソンズにとって、人間生活の決定的な端緒は歴史的変化の触媒としての行動であり、科学としての社会学は行動の主観的要素に強い関心を払うことが不可欠で あったが、科学の目的は因果関係を、法則を網羅したり他の種類の説明装置によって説明することにあるので、決してそれに完全に没頭してはならなかった。 シュッツの基本的な主張は、社会学は自らを根拠づけることができず、認識論は贅沢品ではなく、社会科学者にとって必要なものであるということであった。 パーソンズもこれに同意していたが、科学と哲学を区別する現実的な必要性を強調し、さらに、経験的理論構築のための概念的スキームの根拠は絶対的解を目指 すものではなく、各時点における認識論的バランスの賢明な棚卸しが必要であると主張していた。しかし、二人は社会理論の本質について多くの基本的な前提を 共有しており、そのことが以後も議論を沸騰させている[46][47] 夫の死後、イルゼ・シューズからの要請により、パーソンズは1971年7月23日にシュッツとの間の書簡を公開する許可を得ている。またパーソンズはこの 書簡に対して「1974年の回顧的視点」を書き、その中で自分の立場を「カント的視点」として特徴づけ、フッサールの「現象学的還元」に強く依存する シュッツの姿勢は、パーソンズが社会科学の理論構築に不可欠とする「概念図」に達することを非常に困難にしていることを見出していた[48]。 1940年から1944年にかけて、パーソンズとエリック・ヴェーゲリン(1901-1985)は、書簡を通じて知的見解を交換した[49][50] [51] パーソンズは、ヴェーゲリンがハーバード大学の臨時講師を務めていた1938年と1939年に、おそらくヴェーゲリンと会っていた。パーソンズが反ユダヤ 主義に関する原稿やその他の資料をヴォーゲリンに送ったことが、二人の会話のきっかけとなった。議論は、資本主義の本質、西洋の台頭、ナチズムの起源に及 んだ。特に重要だったのは、ヴェーバーのプロテスタント倫理観の解釈と、カルヴァン主義が近代史に与えた影響についてであった。二人の学者は、カルヴァン 主義に関する多くの基本的な特徴については同意していたが、その歴史的影響についての理解はかなり異なっていた。一般に、ヴェーゲリンはカルヴァン主義を 本質的に危険な全体主義思想とみなしていたが、パーソンズは、その現在の特徴は一時的なものであり、その長期的で新興の価値体系が持つ機能的意味は、近代 の制度全般の台頭に「負の」影響のみならず革命的な影響を与えたと主張している。 また二人の学者は、パーソンズとシュッツとの論争、特にパーソンズがシュッツとの出会いを終えた理由について議論した。パーソンズは、シュッツが社会科学 理論を構築しようとするよりも、むしろ哲学的な回り道をする傾向にあることを見つけたのである。パーソンズはヴェーゲリンに次のように書いている。「おそ らく、シュッツとの議論における私の悩みの一つは、文化的遺産として私がカルヴァン主義者であるという事実にあるのだろう。私は哲学者にはなりたくありま せん。自分の科学的研究の根底にある哲学的な問題から遠ざかるのです。同じことですが、彼は、哲学的な問題を解決しない限り、私の理解する科学者にはなり たがらないと思います。もし17世紀の物理学者がシュエッツであったなら、ニュートン・システムは存在しなかったかもしれない」[52]。 1942年、スチュアート・C・ドッドは主要な著作である『社会の次元』[53]を発表し、社会科学の数学的・数量的体系化を基礎として社会の一般理論を 構築しようと試みていた。ドッドは「S理論」として知られる特定のアプローチを進めていた。パーソンズは同年のレビュー論文でドッドの理論的アウトライン を論じており、ドッドの貢献が非常に手ごわい仕事であると認めているが、社会科学の一般的パラダイムとしてのその前提に対して異議を唱えている[54]。 パーソンズは一般的に、ボガードスのいわゆる「社会的距離」スキームを含むドッドの「S理論」は、ウェーバー、パレート、エミール・デュルケーム、ジーク ムント・フロイト、ウィリアム・アイザック・トーマス、そして人間の相互作用の文化と動機の次元との明確な対話と行動システムアプローチの他の重要なエー ジェントのラインの周りに発展した「従来の」アプローチと比較して、十分に敏感で系統だった理論マトリックスを構築できなかったと主張している。 1944年4月、パーソンズは精神分析を志向する精神科医と少数の社会科学者による「戦後のドイツについて」という会議に参加し、ナチズムの原因を分析 し、来るべき占領のための原則を議論していた[55]。 この会議でパーソンズは、ローレンス・S・キュービーの還元主義に見つけたものに反対した。キュービーは精神分析医で、ドイツの国民性は完全に「破壊的」 であり、国連の特別機関がドイツの教育制度を直接管理することが必要であると強く主張した。パーソンズをはじめ、この会議に出席していた多くの人々は、ク ビーの考えに強く反対していた。パーソンズは、この案は失敗すると主張し、クビーはドイツ人の方向転換の問題を「あまりにも精神医学的な観点からしか見て いない」と指摘した。パーソンズは、1944年9月に発表された極めて厳しいモーゲンソー計画にも反対していた。会議の後、パーソンズはこの計画に反対す る論文「制御された制度変更の問題」を書いている[56]。 パーソンズは1945年3月から10月にかけて対外経済行政庁の非常勤顧問として参加し、戦後賠償と脱工業化について議論している[57][58]。 パーソンズは1945年にアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された[59]。 ハーバード大学で指揮をとる パーソンズのハーバード大学での状況は、1944年初めにノースウェスタン大学から良いオファーを受け、大きく変化した。ハーバード大学では、パーソンズ を学科長に任命し、正教授に昇進させ、社会関係学科の新設という組織改編のプロセスを受け入れることで、このオファーに対応した。1944年4月3日、 パーソンズが学長ポール・バックに宛てた手紙には、この時の高揚感が表れている[60] ハーバード大学での新しい展開のため、パーソンズは、ウィリアム・ランガーからの中央情報局の前身である戦略サービス局への誘いを断ることを選択する。ラ ンガーは、パーソンズにアメリカ軍のドイツ進軍に同行し、占領地行政の政治顧問として機能させることを提案した。1944年末、パーソンズはケンブリッジ 地域評議会の支援のもと、エリザベス・シュレジンジャーとともにあるプロジェクトを指揮した。1944年末、パーソンズは、エリザベス・シュレシンジャー (Elizabeth Schlesinger)と共に、ケンブリッジ地域評議会の支援のもと、ボストン周辺のラドクリフ大学、ウェルズリー大学の学生間の民族・人種間の緊張を 調査するプロジェクトを指揮した。1946年11月末、社会調査評議会(SSRC)はパーソンズに、社会科学が現代世界の理解にどのように貢献できるかと いうテーマについて包括的な報告書を書くよう要請する。背景には、社会科学を全米科学財団に編入すべきかどうかという論争があった。 パーソンズの報告は、「社会科学」という大きなメモの形をとっていた。これは1948年7月に公開され、彼が現代の社会科学の役割をどのように考えていた かを示す強力な歴史的発言として残っている[62]。 |

| Postwar Russian Research Center Parsons became a member of the Executive Committee of the new Russian Research Center at Harvard in 1948, which had Parsons' close friend and colleague, Clyde Kluckhohn, as its director. Parsons went to Allied-occupied Germany in the summer of 1948, was a contact person for the RRC, and was interested in the Russian refugees who were stranded in Germany. He happened to interview in Germany a few members of the Vlasov Army, a Russian Liberation Army that had collaborated with the Germans during the war.[63] The movement was named after Andrey Vlasov, a Soviet general captured by the Germans in June 1942. The Vlasov movement's ideology was a hybrid of elements and has been called "communism without Stalin", but in the Prague Manifesto (1944), it had moved toward the framework of a constitutional liberal state.[64] In Germany in the summer of 1948 Parsons wrote several letters to Kluckhohn to report on his investigations. Anticommunism Parsons' fight against communism was a natural extension of his fight against fascism in the 1930s and the 1940s. For Parsons, communism and fascism were two aspects of the same problem; his article "A Tentative Outline of American Values", published posthumously in 1989,[65] called both collectivistic types "empirical finalism", which he believed was a secular "mirror" of religious types of "salvationalism". In contrast, Parsons highlighted that American values generally were based on the principle of "instrumental activism", which he believed was the outcome of Puritanism as a historical process. It represented what Parsons called "worldly asceticism" and represented the absolute opposite of empirical finalism. One can thus understand Parsons' statement late in life that the greatest threat to humanity is every type of "fundamentalism".[66] By the term empirical finalism, he implied the type of claim assessed by cultural and ideological actors about the correct or "final" ends of particular patterns of value orientation in the actual historical world (such as the notion of "a truly just society"), which was absolutist and "indisputable" in its manner of declaration and in its function as a belief system. A typical example would be the Jacobins' behavior during the French Revolution. Parsons' rejection of communist and fascist totalitarianism was theoretically and intellectually an integral part of his theory of world history, and he tended to regard the European Reformation as the most crucial event in "modern" world history. Like Weber,[67] he tended to highlight the crucial impact of Calvinist religiosity in the socio-political and socio-economic processes that followed.[68] He maintained it reached its most radical form in England in the 17th century and in effect gave birth to the special cultural mode that has characterized the American value system and history ever since. The Calvinist faith system, authoritarian in the beginning, eventually released in its accidental long-term institutional effects a fundamental democratic revolution in the world.[69] Parsons maintained that the revolution was steadily unfolding, as part of an interpenetration of Puritan values in the world at large.[70] American exceptionalism Parsons defended American exceptionalism and argued that, because of a variety of historical circumstances, the impact of the Reformation had reached a certain intensity in British history. Puritan, essentially Calvinist, value patterns had become institutionalized in Britain's internal situation. The outcome was that Puritan radicalism was reflected in the religious radicalism of the Puritan sects, in the poetry of John Milton, in the English Civil War, and in the process leading to the Glorious Revolution of 1688. It was the radical fling of the Puritan Revolution that provided settlers in early 17th-century Colonial America, and the Puritans who settled in America represented radical views on individuality, egalitarianism, skepticism toward state power, and the zeal of the religious calling. The settlers established something unique in the world that was under the religious zeal of Calvinist values. Therefore, a new kind of nation was born, the character of which became clear by the time of the American Revolution and in the US constitution,[71] and its dynamics were later studied by Alexis de Tocqueville.[72] The French Revolution was a failed attempt to copy the American model. Although America has changed in its social composition since 1787, Parsons maintained that it preserves the basic revolutionary Calvinist value pattern. That has been further revealed in the pluralist and highly individualized America, with its thick, network-oriented civil society, which is of crucial importance to its success and these factors have provided it with its historical lead in the process of industrialization. Parsons maintained that this has continued to place it in the leading position in the world, but as a historical process and not in "the nature of things". Parsons viewed the "highly special feature of the modern Western social world" as "dependent on the peculiar circumstances of its history, and not the necessary universal result of social development as a whole".[73] Defender of modernity In contrast to some "radicals", Parsons was a defender of modernity.[74] He believed that modern civilization, with its technology and its constantly evolving institutions, was ultimately strong, vibrant, and essentially progressive. He acknowledged that the future had no inherent guarantees, but as sociologists Robert Holton and Bryan Turner said that Parsons was not nostalgic[75] and that he did not believe in the past as a lost "golden age" but that he maintained that modernity generally had improved conditions, admittedly often in troublesome and painful ways but usually positively. He had faith in humanity's potential but not naïvely. When asked at the Brown Seminary in 1973 if he was optimistic about the future, he answered, "Oh, I think I'm basically optimistic about the human prospects in the long run." Parsons pointed out that he had been a student at Heidelberg at the height of the vogue of Oswald Spengler, author of The Decline of the West, "and he didn't give the West more than 50 years of continuing vitality after the time he wrote.... Well, its more than 50 years later now, and I don't think the West has just simply declined. He was wrong in thinking it was the end."[76] Harvard Department of Social Relations At Harvard, Parsons was instrumental in forming the Department of Social Relations, an interdisciplinary venture among sociology, anthropology, and psychology. The new department was officially created in January 1946 with him as the chairman and with prominent figures at the faculty, such as Stouffer, Kluckhohn, Henry Murray and Gordon Allport. An appointment for Hartshorne was considered but he was killed in Germany by an unknown gunman as he was driving on the highway. His position went instead to George C. Homans. The new department was galvanized by Parsons' idea of creating a theoretical and institutional base for a unified social science. Parsons also became strongly interested in systems theory and cybernetics and began to adopt their basic ideas and concepts to the realm of social science, giving special attention to the work of Norbert Wiener (1894–1964). Some of the students who arrived at the Department of Social Relations in the years after the Second World War were David Aberle, Gardner Lindzey, Harold Garfinkel, David G. Hays, Benton Johnson, Marian Johnson, Kaspar Naegele, James Olds, Albert Cohen, Norman Birnbaum, Robin Murphy Williams, Jackson Toby, Robert N. Bellah, Joseph Kahl, Joseph Berger, Morris Zelditch, Renée Fox, Tom O'Dea, Ezra Vogel, Clifford Geertz, Joseph Elder, Theodore Mills, Mark Field, Edward Laumann, and Francis Sutton. Renée Fox, who arrived at Harvard in 1949, would become a very close friend of the Parsons family. Joseph Berger, who also arrived at Harvard in 1949 after finishing his BA from Brooklyn College, would become Parsons' research assistant from 1952 to 1953 and would get involved in his research projects with Robert F. Bales. According to Parsons' own account, it was during his conversations with Elton Mayo (1880–1949) that he realized it was necessary for him to take a serious look at the work of Freud. In the fall of 1938, Parsons began to offer a series of non-credit evening courses on Freud. As time passed, Parsons developed a strong interest in psychoanalysis. He volunteered to participate in nontherapeutic training at the Boston Psychoanalytic Institute, where he began a didactic analysis with Grete Bibring in September 1946. Insight into psychoanalysis is significantly reflected in his later work, especially reflected in The Social System and his general writing on psychological issues and on the theory of socialization. That influence was also to some extent apparent in his empirical analysis of fascism during the war. Wolfgang Köhler's study of the mentality of apes and Kurt Koffka's ideas of Gestalt psychology also received Parsons' attention. The Social System and Toward a General Theory of Action During the late 1940s and the early 1950s, he worked very hard on producing some major theoretical statements. In 1951, Parsons published two major theoretical works, The Social System[77] and Toward a General Theory of Action.[78] The latter work, which was coauthored with Edward Tolman, Edward Shils and several others, was the outcome of the so-called Carnegie Seminar at Harvard University, which had taken place in the period of September 1949 and January 1950.[79] The former work was Parsons' first major attempt to present his basic outline of a general theory of society since The Structure of Social Action (1937). He discusses the basic methodological and metatheoretical principles for such a theory. He attempts to present a general social system theory that is built systematically from most basic premises and so he featured the idea of an interaction situation based on need-dispositions and facilitated through the basic concepts of cognitive, cathectic, and evaluative orientation. The work also became known for introducing his famous pattern variables, which in reality represented choices distributed along a Gemeinschaft vs. Gesellschaft axis. The details of Parsons' thought about the outline of the social system went through a rapid series of changes in the following years, but the basics remained. During the early 1950s, the idea of the AGIL model took place in Parsons's mind gradually. According to Parsons, its key idea was sparked during his work with Bales on motivational processes in small groups.[80] Parsons carried the idea into the major work that he co-authored with a student, Neil Smelser, which was published in 1956 as Economy and Society.[81] Within this work, the first rudimentary model of the AGIL scheme was presented. It reorganized the basic concepts of the pattern variables in a new way and presented the solution within a system-theoretical approach by using the idea of a cybernetic hierarchy as an organizing principle. The real innovation in the model was the concept of the "latent function" or the pattern maintenance function, which became the crucial key to the whole cybernetic hierarchy. During its theoretical development, Parsons showed a persistent interest in symbolism. An important statement is Parsons' "The Theory of Symbolism in Relation to Action".[82] The article was stimulated by a series of informal discussion group meetings, which Parsons and several other colleagues in the spring of 1951 had conducted with philosopher and semiotician Charles W. Morris.[83] His interest in symbolism went hand in hand with his interest in Freud's theory and "The Superego and the Theory of Social Systems", written in May 1951 for a meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. The paper can be regarded as the main statement of his own interpretation of Freud,[84] but also as a statement of how Parsons tried to use Freud's pattern of symbolization to structure the theory of social system and eventually to codify the cybernetic hierarchy of the AGIL system within the parameter of a system of symbolic differentiation. His discussion of Freud also contains several layers of criticism that reveal that Parsons' use of Freud was selective rather than orthodox. In particular, he claimed that Freud had "introduced an unreal separation between the superego and the ego". Subscriber to systems theory Parsons was an early subscriber to systems theory. He had early been fascinated by the writings of Walter B. Cannon and his concept of homeostasis[85] as well as the writings of French physiologist Claude Bernard.[86] His interest in systems theory had been further stimulated by his contract with L.J. Henderson. Parsons called the concept of "system" for an indispensable master concept in the work of building theoretical paradigms for social sciences.[87] From 1952 to 1957, Parsons participated in an ongoing Conference on System Theory under the chairmanship of Roy R. Grinker, Sr., in Chicago. Parsons came into contact with several prominent intellectuals of the time and was particularly impressed by the ideas of social insect biologist Alfred Emerson. Parsons was especially compelled by Emerson's idea that, in the sociocultural world, the functional equivalent of the gene was that of the "symbol". Parsons also participated in two of the meetings of the famous Macy Conferences on systems theory and on issues that are now classified as cognitive science, which took place in New York from 1946 to 1953 and included scientists like John von Neumann. Parsons read widely on systems theory at the time, especially works of Norbert Wiener[88] and William Ross Ashby,[89] who were also among the core participants in the conferences. Around the same time, Parsons also benefited from conversations with political scientist Karl Deutsch on systems theory. In one conference, the Fourth Conference of the problems of consciousness in March 1953 at Princeton and sponsored by the Macy Foundation, Parsons would give a presentation on "Conscious and Symbolic Processes" and embark on an intensive group discussion which included exchange with child psychologist Jean Piaget.[90] Among the other participants were Mary A.B. Brazier, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, Nathaniel Kleitman, Margaret Mead and Gregory Zilboorg. Parsons would defend the thesis that consciousness is essentially a social action phenomenon, not primarily a "biological" one. During the conference, Parsons criticized Piaget for not sufficiently separating cultural factors from a physiologistic concept of "energy". McCarthy era During the McCarthy era, on April 1, 1952, J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, received a personal letter from an informant who reported on communist activities at Harvard. During a later interview, the informant claimed that "Parsons... was probably the leader of an inner group" of communist sympathizers at Harvard. The informant reported that the old department under Sorokin had been conservative and had "loyal Americans of good character" but that the new Department of Social Relations had turned into a decisive left-wing place as a result of "Parsons's manipulations and machinations". On October 27, 1952, Hoover authorized the Boston FBI to initiate a security-type investigation on Parsons. In February 1954, a colleague, Stouffer, wrote to Parsons in England to inform him that Stouffer had been denied access to classified documents and that part of the stated reason was that Stouffer knew communists, including Parsons, "who was a member of the Communist Party".[91] Parsons immediately wrote an affidavit in defense of Stouffer, and he also defended himself against the charges that were in the affidavit: "This allegation is so preposterous that I cannot understand how any reasonable person could come to the conclusion that I was a member of the Communist Party or ever had been."[92] In a personal letter to Stouffer, Parsons wrote, "I will fight for you against this evil with everything there is in me: I am in it with you to the death." The charges against Parsons resulted in Parsons being unable to participate in a UNESCO conference, and it was not until January 1955 that he was acquitted of the charges. Family, Socialization and Interaction Process Since the late 1930s, Parsons had continued to show great interest in psychology and in psychoanalysis. In the academic year of 1955–1956, he taught a seminar at Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute entitled "Sociology and Psychoanalysis". In 1956, he published a major work, Family, Socialization and Interaction Process,[93] which explored the way in which psychology and psychoanalysis bounce into the theories of motivation and socialization, as well into the question of kinship, which for Parsons established the fundamental axis for that subsystem he later would call "the social community". It contained articles written by Parsons and articles written in collaboration with Robert F. Bales, James Olds, Morris Zelditch Jr., and Philip E. Slater. The work included a theory of personality as well as studies of role differentiation. The strongest intellectual stimulus that Parsons most likely got then was from brain researcher James Olds, one of the founders of neuroscience and whose 1955 book on learning and motivation was strongly influenced from his conversations with Parsons.[94] Some of the ideas in the book had been submitted by Parsons in an intellectual brainstorm in an informal "work group" which he had organized with Joseph Berger, William Caudill, Frank E. Jones, Kaspar D. Naegele, Theodore M. Mills, Bengt G. Rundblad, and others. Albert J. Reiss from Vanderbilt University had submitted his critical commentary. In the mid-1950s, Parsons also had extensive discussions with Olds about the motivational structure of psychosomatic problems, and at this time Parsons' concept of psychosomatic problems was strongly influenced by readings and direct conversations with Franz Alexander (a psychoanalyst, originally associated with the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute, who was a pioneer of psychosomatic medicine), Grinker and John Spiegel.[95] In 1955, François Bourricaud was preparing a reader of some of Parsons' work for a French audience, and Parsons wrote a preface for the book Au lecteur français (To the French Reader); it also went over Bourricaud's introduction very carefully. In his correspondence with Bourricaud, Parsons insisted that he did not necessarily treat values as the only, let alone "the primary empirical reference point" of the action system since so many other factors were also involved in the actual historical pattern of an action situation.[96] Center of Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences Parsons spent 1957 to 1958 at the Center of Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences in Palo Alto, California, where he met for the first time Kenneth Burke; Burke's flamboyant, explosive temperament made a great impression on Parsons, and the two men became close friends.[97] Parsons explained in a letter the impression Burke had left on him: "The big thing to me is that Burke more than anyone else has helped me to fill a major gap in my own theoretical interests, in the field of the analysis of expressive symbolism." Another scholar whom Parsons met at the Center of Advanced Studies in the Behavioral Sciences at Palo Alto was Alfred L. Kroeber, the "dean of American anthropologists". Kroeber, who had received his PhD at Columbia and who had worked with the Arapaho Indians, was about 81 when Parsons met him. Parsons had the greatest admiration for Kroeber and called him "my favorite elder statesman". In Palo Alto, Kroeber suggested to Parsons that they write a joint statement to clarify the distinction between cultural and social systems, then the subject of endless debates. In October 1958, Parsons and Kroeber published their joint statement in a short article, "The Concept of Culture and the Social System", which became highly influential.[98] Parsons and Kroeber declared that it is important both to keep a clear distinction between the two concepts and to avoid a methodology by which either would be reduced to the other. |

戦後 ロシア研究センター パーソンズは、1948年にハーバード大学に新設されたロシア研究センターの執行委員会のメンバーとなり、パーソンズの親友で同僚のクライド・クラック ホーンを所長とした。パーソンズは、1948年夏、連合国占領下のドイツに行き、RRCの窓口となり、ドイツに取り残されたロシア難民に関心を持った。彼 はドイツで、戦時中にドイツに協力したロシア解放軍であるヴラソフ軍のメンバー数人に偶然インタビューした[63]。この運動は、1942年6月にドイツ 軍に捕らえられたソ連の将軍アンドレイ・ヴラソフにちなんで名づけられた。ヴラソフ運動のイデオロギーは要素の混成であり、「スターリン抜きの共産主義」 と呼ばれていたが、プラハ宣言(1944年)において、立憲自由主義国家の枠組みに向かっていた[64]。 1948年の夏、ドイツでパーソンズは自分の調査について報告するためにクルックホーンに何通かの手紙を書いている。 反共産主義 パーソンズの共産主義に対する戦いは、1930年代から1940年代にかけてのファシズムに対する戦いの自然な延長線上にあるものであった。パーソンズに とって、共産主義とファシズムは同じ問題の二つの側面であった。1989年に死後に出版された彼の論文「A Tentative Outline of American Values」[65]は、両方の集団主義のタイプを「経験的最終主義」と呼び、それは「救済主義」の宗教的タイプの世俗的「ミラー」であると彼は信じて いた。これに対して、パーソンズはアメリカの価値観が一般的に「道具的活動主義」の原理に基づいていることを強調し、それは歴史的プロセスとしてのピュー リタニズムの結果であると信じていた。それは、パーソンズが「世俗的禁欲主義」と呼ぶものであり、経験的最終主義の絶対的な対極にあるものであった。した がって、晩年のパーソンズの人類に対する最大の脅威はあらゆるタイプの「原理主義」であるという発言を理解することができる[66] 経験的最終主義という用語によって、彼は実際の歴史的世界における特定の価値志向のパターンの正しいまたは「最終」な結末について文化的・思想的行為者に よって評価されるタイプの主張(例えば「真に公正な社会」の概念)を意味しており、その宣言方法と信念体系としての機能において絶対主義で「議論の余地も なかった」ものであった。その典型が、フランス革命時のジャコバン派の行動であろう。パーソンズの共産主義やファシストの全体主義に対する拒絶は理論的に も知性的にも彼の世界史の理論の不可欠な部分であり、ヨーロッパの宗教改革を「近代」世界史における最も決定的な出来事と見なす傾向があった。ウェーバー のように[67]、彼はその後の社会政治的・社会経済的プロセスにおけるカルヴァン派の宗教性の決定的な影響を強調する傾向があった。 68] 彼はそれが17世紀にイングランドで最もラディカルな形に達し、それ以来、アメリカの価値体系と歴史を特徴付ける特別な文化様式を事実上誕生させることに なったと主張していた。カルヴァン主義の信仰制度は当初は権威主義的であったが、最終的にはその偶然的な長期的制度的効果において世界における根本的な民 主主義革命を解放した[69]。 パーソンズはその革命が世界全体におけるピューリタンの価値の相互浸透の一部として着実に展開されていると主張していた[70]。 アメリカの例外主義 パーソンズは、アメリカの例外主義を擁護し、さまざまな歴史的経緯から、宗教改革の影響がイギリスの歴史において一定の強度を持つに至ったと主張した。 ピューリタン、つまり本質的にはカルヴァン派の価値観が、イギリスの内情に制度化されていたのである。その結果、ピューリタンの急進主義は、ピューリタン 諸派の宗教的急進主義、ジョン・ミルトンの詩、イギリス内戦、そして1688年の栄光革命に至る過程に反映されることになったのである。17世紀初頭の植 民地時代のアメリカに入植者をもたらしたのは、ピューリタン革命の過激なフライングであり、アメリカに入植したピューリタンは、個性、平等主義、国家権力 への懐疑、宗教的使命の熱意などに関する過激な意見を代表するものであった。入植者たちは、カルヴァン主義的価値観の宗教的熱意のもとに、世界で唯一無二 のものを築き上げた。 したがって、新しい種類の国家が誕生し、その性格はアメリカ革命の時代までに、そしてアメリカ憲法において明らかになり[71]、そのダイナミクスは後に アレクシス・ド・トクヴィルによって研究された[72]。 フランス革命はアメリカモデルをコピーする試みとしては失敗していた。アメリカは1787年以降その社会的構成が変化したが、パーソンズは基本的な革命的 カルヴァン主義者の価値観パターンを保持していると主張していた。それはさらに、多元的で高度に個人化されたアメリカ、その成功にとって極めて重要なネッ トワーク指向の厚い市民社会、そしてこれらの要因が産業化の過程において歴史的なリードをもたらしたということに現れている。 パーソンズは、これが世界の主導的地位を占め続けてきたが、それは歴史的なプロセスとしてであり、「物事の本質」ではないと主張している。パーソンズは 「近代西洋社会世界の極めて特殊な特徴」を「その歴史の特殊な状況に依存しており、全体として社会発展の必要な普遍的な結果ではない」と見なしていた [73]。 近代の擁護者 一部の「急進派」とは対照的に、パーソンズは近代の擁護者であった[74]。 彼はそのテクノロジーと絶えず進化する制度を持つ近代文明が究極的に強く、活気に満ちており、本質的に進歩的であると信じていた。彼は未来が固有の保証を 持たないことを認めていたが、社会学者のロバート・ホルトンとブライアン・ターナーが言っていたように、パーソンズはノスタルジックではなく[75]、失 われた「黄金時代」として過去を信じるのではなく、近代が一般的に状況を改善しており、確かにしばしば厄介で痛みを伴う方法ではあったが通常はポジティブ であったと主張していた。彼は、人類の可能性を信じていたが、決してナイーブではなかった。1973年にブラウン神学校で、将来について楽観的かどうか尋 ねられたとき、彼は「ああ、私は基本的に長い目で見れば、人間の見通しについて楽観的だと思う」と答えている。パーソンズは、『西洋の衰退』の著者である オズワルド・スペングラーの流行の絶頂期にハイデルベルクの学生だったことを指摘し、「彼は執筆後50年以上西洋の生命力が続くとは思っていなかっ た......」と述べている。その50年後の今、私は西洋が単に衰退したとは思わない。彼はそれが終わりであると考えたのは間違いであった」[76]。 ハーバード大学社会関係学部 ハーバード大学では、パーソンズは社会学、人類学、心理学の学際的なベンチャーである社会関係学部の形成に貢献した。この新しい学科は、彼を委員長とし、 ストゥファー、クラックホーン、ヘンリー・マーレイ、ゴードン・オールポートといった著名な教授陣とともに、1946年1月に正式に創設された。ハーツ ホーンの就任も検討されたが、彼はドイツで高速道路を運転中に何者かに殺害された。ハーツホーンの代わりに、ジョージ・C・ホーマンス(George C. Homans)が就任した。新しい学科は、統一された社会科学のための理論的、制度的基盤を作ろうというパーソンズの考えによって活気づいた。パーソンズ はまた、システム論やサイバネティックスに強い関心を持ち、それらの基本的な考え方や概念を社会科学の領域に取り入れるようになり、特にノーバート・ ウィーナー(1894-1964)の研究に注目した。 第二次世界大戦後の数年間に社会関係学科に着任した学生には、デビッド・アベール、ガードナー・リンゼイ、ハロルド・ガーフィンケル、デビッド・G・ヘイ ズ、ベントン ジョンソン、マリアン ジョンソン、カスパー ネゲール、ジェームズ オールズ、アルバート コーヘン、ノーマン バーンバウム、ロビン マーフィー ウィリアムズ、ジャクソン トビー、ロバート N. ベラ、ジョセフ・カール、ジョセフ・バーガー、モリス・ゼルディッチ、レネー・フォックス、トム・オディア、エズラ・ヴォーゲル、クリフォード・ギアツ、 ジョセフ・エルダー、セオドア・ミルズ、マーク・フィールド、エドワード・ラウマン、フランシス・サットンなど。 1949年にハーバード大学に着任したルネ・フォックスは、パーソンズ一家と非常に親しい友人となる。同じく1949年にブルックリン・カレッジを卒業し てハーバードに来たジョセフ・バーガーは、1952年から1953年にかけてパーソンズの研究助手となり、ロバート・F・ベールズとともに彼の研究プロ ジェクトに関わることになる。 パーソンズ自身の説明によれば、エルトン・メイヨー(1880-1949)との会話の中で、フロイトの仕事を本格的に見直す必要があることを悟ったとい う。1938年秋、パーソンズはフロイトに関する一連のノンクレジット夜間講座を開講しはじめた。時が経つにつれ、パーソンズは精神分析に強い関心を抱く ようになった。彼は、ボストン精神分析研究所での非治療的トレーニングに参加することを志願し、1946年9月からグレーテ・ビブリングのもとで教則的な 分析を始めた。精神分析への洞察は、その後の彼の作品に大きく反映されており、特に『社会システム』や心理学的問題や社会化の理論に関する一般的な著作に 反映されている。その影響は、戦時中のファシズムに関する彼の実証的な分析にもある程度現れている。また、ウォルフガング・ケーラーの類人猿のメンタリ ティに関する研究やクルト・コフカのゲシュタルト心理学の考え方もパーソンズの関心を集めた。 社会システムと行為の一般理論に向けて 1940年代後半から1950年代前半にかけて、彼はいくつかの主要な理論的記述を生み出すことに懸命に取り組んでいた。1951年にパーソンズは『社会 システム』[77]と『行為の一般理論』[78]という2つの主要な理論的著作を発表した。後者はエドワード・トルマンやエドワード・シルス、その他数人 と共著した作品で、ハーバード大学におけるいわゆるカーネギーセミナー(1949年9月から50年1月の期間に行われた)の結果だった[79] 前者はパーソンズの最初の大きな試みで、社会に関する一般理論の基本概要を『社会行為の構造』(1937)以来提示したものであった。彼はそのような理論 のための基本的な方法論的およびメタ理論的な原理を論じている。彼は、最も基本的な前提から体系的に構築された一般的な社会システム理論の提示を試みてお り、そのために、欲求-性向に基づき、認知的、緊張的、評価的志向性の基本概念によって促進される相互作用状況という考えを取り上げたのである。また、こ の作品は、現実にはゲマインシャフト対ゲゼルシャフトという軸で分布する選択肢を表す有名なパターン変数を導入したことでも知られている。 社会システムの輪郭に関するパーソンズの思想の細部は、その後、急速に変化していったが、基本的な部分は残っていた。1950年代前半には、AGILモデ ルの構想がパーソンズの頭の中で徐々に進行していった。パーソンズによれば、その重要なアイデアはベールズと一緒に小集団における動機づけのプロセスにつ いて研究していた時に閃いたものであった[80]。 パーソンズはこのアイデアを学生のニール・スメルサーと共著で1956年に『経済と社会』として出版された大著に持ち込んだ[81]。この著作の中で AGILスキームの最初の初歩的モデルが提示されている。それはパターン変数の基本的な概念を新しい方法で再編成し、組織化原理としてサイバネティックな 階層の考え方を使うことによってシステム理論的なアプローチで解決策を提示したものであった。このモデルにおける真の革新は、「潜在機能」またはパターン 維持機能の概念であり、これがサイバネティック階層全体の重要な鍵となった。 その理論的展開の中で、パーソンズは象徴主義に根強い関心を示していた。重要な記述はパーソンズの「行動と関連した象徴主義の理論」である[82]。この 論文は1951年の春にパーソンズと他の数人の同僚が哲学者であり記号学者であるチャールズ・W・モリスと行った一連の非公式なディスカッショングループ 会議によって刺激されていた[83]。象徴主義に対する彼の関心はフロイトの理論に対する関心と手を携えて、アメリカ精神医学会での会議のために1951 年5月に書かれた「スーパーエゴと社会システムの理論」にも及んでいる。この論文は彼自身のフロイトの解釈の主な記述とみなすことができるが[84]、同 時にパーソンズがフロイトの象徴化のパターンを使って社会システムの理論を構成し、最終的にAGILシステムのサイバネティックな階層を象徴分化のシステ ムのパラメータの中でコード化しようとしたことを述べているものでもある。また、彼のフロイトに関する議論には、パーソンズのフロイトの使い方が正統的と いうよりは選択的であったことを明らかにする批判が幾重にも含まれている。特に、彼はフロイトが「超自我と自我の間に非現実的な分離を導入した」と主張し ている。 システム論への加入者 パーソンズはシステム理論の初期の購読者であった。彼は早くからウォルター・B・キャノンの著作や彼のホメオスタシス[85]の概念、またフランスの生理 学者クロード・ベルナールの著作に魅了されていた[86] システム理論に対する彼の関心はL・J・ヘンダーソンとの契約によってさらに刺激されることとなった。パーソンズは社会科学の理論的パラダイムを構築する 作業において、「システム」の概念を不可欠なマスターコンセプトと呼んでいた[87]。1952年から1957年にかけて、パーソンズはシカゴでロイ・ R・グリンカー・シニアの議長の下で行われていたシステム理論に関するカンファレンスに参加している。 パーソンズは当時の著名な知識人たちと接触し、特に社会昆虫生物学者アルフレッド・エマーソンの思想に感銘を受けていた。特に、社会文化的な世界では、遺 伝子の機能的な等価物は「シンボル」であるというエマーソンの考え方に強い印象を受けた。またパーソンズは、1946年から1953年にかけてニューヨー クで開催された、システム理論や現在認知科学として分類されている問題についての有名なメイシー会議のうち2つの会議に参加し、ジョン・フォン・ノイマン のような科学者も参加している。パーソンズは当時システム理論について広く読んでおり、特に会議の中心的参加者でもあったノーバート・ウィーナー[88] やウィリアム・ロス・アシュビー[89]の著作を読んでいる。また同じ頃、パーソンズは政治学者のカール・ドイッチュとシステム理論について会話すること で利益を得ていた。1953年3月にプリンストンで開催されたメイシー財団が主催する第4回意識問題会議では、パーソンズは「意識と象徴のプロセス」につ いてプレゼンテーションを行い、児童心理学者のジャン・ピアジェとの交流を含む集中的なグループ討議に乗り出すことになる[90]。 他の参加者には、メアリー・A・B・ブラジール、フリーダ・フロム・ライヒマン、ナサニエル・クライトマン、マーガレット・ミード、グレゴリー・ジルボー グがいた。パーソンズは、意識は本質的に社会的行為現象であり、主として「生物学的」なものではないというテーゼを擁護することになる。この会議の中で パーソンズは、ピアジェが文化的要因を生理的な「エネルギー」の概念から十分に切り離していないと批判している。 マッカーシー時代 マッカーシー時代、1952年4月1日、連邦捜査局長官J・エドガー・フーバーは、ハーバード大学での共産主義者の活動について報告した情報提供者から私 信を受け取った。この情報提供者は、その後のインタビューで、「パーソンズは、おそらくハーバード大学の共産主義者の内部グループのリーダーであった」と 主張している。情報提供者は、ソローキン率いる旧学部は保守的で「性格の良い忠実なアメリカ人」がいたが、新しい社会関係学部は「パーソンズの操作と策 略」の結果、決定的な左翼の場所に変わってしまったと報告している。1952年10月27日、フーバーはボストンFBIにパーソンズに対する保安型調査を 開始することを許可した。1954年2月、同僚のストゥファーはイギリスのパーソンズに手紙を出し、ストゥファーが機密文書へのアクセスを拒否されたこ と、その理由の一部としてストゥファーはパーソンズを含む共産党員と知り合いであったことを伝えた[91]。 パーソンズは、すぐにストゥッファーを擁護する宣誓供述書を書き、宣誓供述書にあった容疑に対しても自己弁護をした。「この疑惑はあまりにもばかげたもの で、私が共産党員であった、あるいはかつてそうであったという結論に合理的な人が達することができるのか理解できない」[92] パーソンズはストウファーへの私信で、「私はこの悪に対してあなたのために私の中にあるすべてをかけて戦います。私は死ぬまであなたと共にあります "と書いている。パーソンズに対する告発によって、パーソンズはユネスコの会議に参加することができなくなり、無罪となったのは1955年1月になってか らであった。 家族、社会化、相互作用の過程 1930年代後半から、パーソンズは心理学と精神分析に大きな関心を示し続けていた。1955年から1956年にかけては、ボストン精神分析協会で「社会 学と精神分析」と題するセミナーを開催している。1956年に彼は主要な著作である『家族、社会化、相互作用過程』を出版し[93]、心理学と精神分析が 動機づけと社会化の理論に、そしてパーソンズにとって後に彼が「社会共同体」と呼ぶことになるサブシステムの基本軸を確立した親族の問題にどのように影響 を及ぼすかを探求していた。 パーソンズの論文と、ロバート・F・ベールズ、ジェームズ・オールズ、モリス・ゼルディッチ・ジュニア、フィリップ・E・スレーターとの共同執筆による論 文が収録されている。その中には、パーソナリティの理論や役割分化の研究などが含まれていた。パーソンズが当時受けた最も強い知的刺激は、神経科学の創始 者の一人である脳研究者のジェームズ・オールズからであり、彼の1955年の学習と動機づけに関する著書はパーソンズとの会話から強い影響を受けている [94]。この本のアイデアの一部は、パーソンズがジョセフ・バーガー、ウィリアム・コーディル、フランクEジョーンズ、カスパーDナゲレ、テオドアMミ ルズ、ベントGランドブラッドらと組織した非公式の「ワークグループ」で知的ブレインストームをしながら提出したものであった。ヴァンダービルト大学のア ルバート・J・ライス(Albert J. Reiss)は、批判的な解説を寄せていた。 1950年代半ばには、パーソンズもオールズと心身症の問題の動機構造について幅広く議論しており、この頃のパーソンズの心身症の概念は、フランツ・アレ クサンダー(元々はベルリン精神分析研究所に所属する精神分析医で、心身医学の先駆者)、グリンカー、ジョン・シュピーゲルを読んだり直接会話することに よって強く影響を受けていた[95]。 1955年、フランソワ・ブールリコーはフランスの読者向けにパーソンズの著作の一部の読本を準備しており、パーソンズは『Au lecteur français(フランスの読者へ)』の序文を書いており、ブールリコーの序文も非常に慎重に検討されている。パーソンズはブリコーとの書簡の中で、行 動状況の実際の歴史的パターンには他の多くの要素も関与しているため、必ずしも価値を行動システムの唯一、ましてや「主要な経験的基準点」として扱ってい るわけではないと主張している[96]。 行動科学高等研究センター パーソンズは1957年から1958年にかけてカリフォルニア州パロアルトにある行動科学高等研究センターで過ごし、そこで初めてケネス・バークと出会 う。バークの華やかで爆発的な気質はパーソンズに大きな印象を与え、二人は親しい友人となった[97]。パーソンズはバークが彼に残した印象を手紙で説明 している。「私にとって重要なことは、バークが他の誰よりも、私の理論的関心事である表現的象徴の分析という分野における大きなギャップを埋める手助けを してくれたということです」[97]。 パーソンズがパロアルトの行動科学高等研究センターで出会ったもう一人の学者は、「アメリカの人類学者の長」であるアルフレッド・L・クローバーであっ た。コロンビア大学で博士号を取得し、アラパホ・インディアンとともに研究していたクローバーは、パーソンズが会った時、81歳くらいだった。パーソンズ はクローバーに最大の敬意を払い、「私の好きな長老」と呼んでいた。 パロアルトで、クローバーはパーソンズに文化システムと社会システムの区別を明確にするための共同声明を書くことを提案したが、当時は果てしない議論の対 象になっていた。1958年10月、パーソンズとクルーバーは共同声明を「文化の概念と社会システム」という短い論文として発表し、大きな影響力を持つこ とになった[98]。パーソンズとクルーバーは、2つの概念を明確に区別しておくことと、どちらかをもう一方に還元してしまう方法論を避けることが重要で あるとしている。 |