『ニグロの家族:国家行動のための事例研究』

The Negro Family: The Case For National

Action, 1965, by Daniel Patrick Moynihan

☆ 『ニグロの家族』 一般に「モイニハン報告」として知られるThe Negro Family: The Case For National Action, 1965.は、 リンドン・B・ジョンソン大統領の下で労働次官補を務め、後に上院議員になったアメリカの学者ダニエル・パトリック・モイニハンが1965年に書いた、ア メリカにおける黒人の貧困に関する報告書である。モイニハンは、黒人の母子家庭の増加は、仕事の不足が原因ではなく、ゲットー文化の破壊的な脈絡が原因で あると主張した。ダニエル・パトリック・モイニハン(Daniel Patrick Moynihan、1927年3月16日 - 2003年3月26日)は、アメリカの政治家、外交官。民主党に所属し、リチャード・ニクソン大統領の顧問を務めた後、1977年から2001年まで ニューヨーク州選出の上院議員を務めた。

★

『ニグロの家族:国家行動のための事例研究』(The Negro

Family: The Case For National Action, 1965)

| Daniel

Patrick Moynihan (March 16, 1927 – March 26, 2003) was an American

politician and diplomat. A member of the Democratic Party, he

represented New York in the United States Senate from 1977 until 2001

after serving as an adviser to President Richard Nixon. Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Moynihan moved at a young age to New York City. Following a stint in the navy, he earned a Ph.D. in history from Tufts University. He worked on the staff of New York Governor W. Averell Harriman before joining President John F. Kennedy's administration in 1961. He served as an Assistant Secretary of Labor under Presidents Kennedy and President Lyndon B. Johnson, devoting much of his time to the War on Poverty. In 1965, he published the controversial Moynihan Report. Moynihan left the Johnson administration in 1965 and became a professor at Harvard University. In 1969, he accepted Nixon's offer to serve as an Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy, and he was elevated to the position of Counselor to the President later that year. He left the administration at the end of 1970, and accepted appointment as United States Ambassador to India in 1973. He accepted President Gerald Ford's appointment to the position of United States Ambassador to the United Nations in 1975, holding that position until early 1976; later that year he won election to the Senate. Moynihan served as Chairman of the Senate Environment Committee from 1992 to 1993 and as Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee from 1993 to 1995. He also led the Moynihan Secrecy Commission, which studied the regulation of classified information. He emerged as a strong critic of President Ronald Reagan's foreign policy and opposed President Bill Clinton's health care plan. He frequently broke with liberal positions, but opposed welfare reform in the 1990s. He also voted against the Defense of Marriage Act, the North American Free Trade Agreement, and the Congressional authorization for the Gulf War. He was tied with Jacob K. Javits as the longest-serving Senator from the state of New York until they were both surpassed by Chuck Schumer in 2023. |

ダニエル・パトリック・モイニハン(Daniel Patrick

Moynihan、1927年3月16日 -

2003年3月26日)は、アメリカの政治家、外交官。民主党に所属し、リチャード・ニクソン大統領の顧問を務めた後、1977年から2001年まで

ニューヨーク州選出の上院議員を務めた。 オクラホマ州タルサで生まれ、若くしてニューヨークに移住。海軍勤務を経て、タフツ大学で歴史学の博士号を取得。ニューヨーク州知事W・アヴェレル・ハリ マンのスタッフを経て、1961年にジョン・F・ケネディ大統領の政権に参加。ケネディ大統領とリンドン・B・ジョンソン大統領の下で労働次官補を務め、 貧困との戦いに多くの時間を割いた。1965年には、物議を醸す「モイニハン・レポート」を発表。1965年にジョンソン政権を去り、ハーバード大学教授 に就任。 1969年、ニクソンの国内政策担当大統領補佐官就任の申し出を受け、同年末に大統領補佐官に昇格。1970年末に政権を去り、1973年に駐インド米国 大使に任命された。1975年にはジェラルド・フォード大統領から国連大使に任命され、1976年初めまで同職を務めた。 1992年から1993年まで上院環境委員会委員長、1993年から1995年まで上院財政委員会委員長を務めた。また、機密情報の規制を研究するモイニ ハン秘密委員会を率いた。ロナルド・レーガン大統領の外交政策を強く批判し、ビル・クリントン大統領の医療保険制度に反対した。リベラルな立場を崩すこと も多かったが、1990年代には福祉改革に反対した。結婚防衛法、北米自由貿易協定、湾岸戦争の議会承認にも反対票を投じた。2023年にチャック・ シューマーに抜かれるまで、ジェイコブ・K・ジャビッツと並んでニューヨーク州選出の上院議員としては最長在職。 |

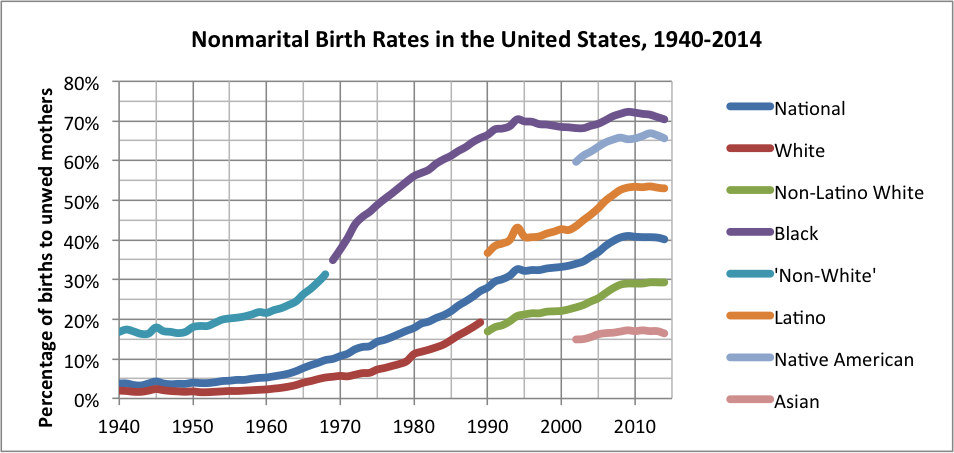

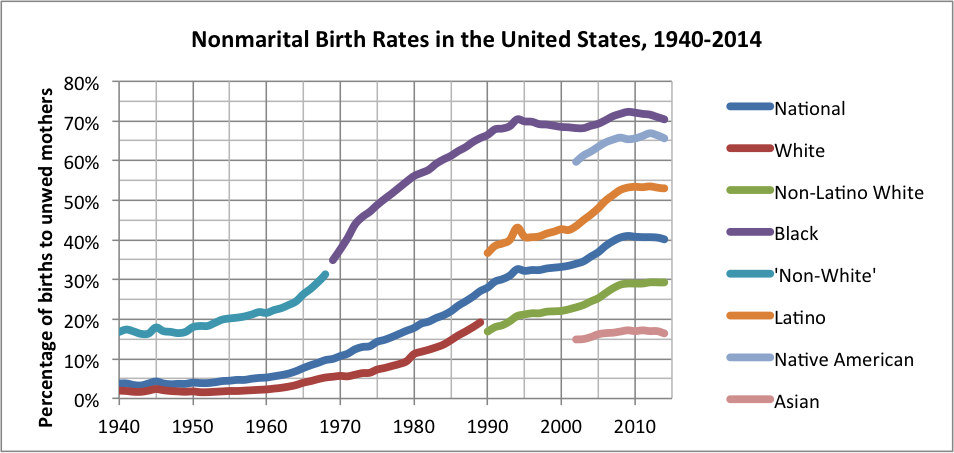

| The Negro

Family: The Case For National Action, 1965 The Negro Family: The Case For National Action, commonly known as the Moynihan Report, was a 1965 report on black poverty in the United States written by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, an American scholar serving as Assistant Secretary of Labor under President Lyndon B. Johnson and later to become a US Senator. Moynihan argued that the rise in black single-mother families was caused not by a lack of jobs, but by a destructive vein in ghetto culture, which could be traced to slavery times and continued discrimination in the American South under Jim Crow. Black sociologist E. Franklin Frazier had introduced that idea in the 1930s, but Moynihan was considered one of the first academics to defy conventional social-science wisdom about the structure of poverty. As he wrote later, "The work began in the most orthodox setting, the US Department of Labor, to establish at some level of statistical conciseness what 'everyone knew': that economic conditions determine social conditions. Whereupon, it turned out that what everyone knew was evidently not so."[1] The report concluded that the high rate of families headed by single mothers would greatly hinder progress of blacks toward economic and political equality. The Moynihan Report was criticized by liberals at the time of publication, and its conclusions remain controversial. Background While writing The Negro Family: The Case For National Action, Moynihan was employed in a political appointee position at the US Department of Labor, hired to help develop policy for the Johnson administration in its War on Poverty. In the course of analyzing statistics related to black poverty, Moynihan noticed something unusual:[2] Rates of black male unemployment and welfare enrollment, instead of running parallel as they always had, started to diverge in 1962 in a way that would come to be called "Moynihan's scissors."[3] When Moynihan published his report in 1965, the out-of-wedlock birthrate among blacks was 25 percent, much higher than that of whites.[4] Contents In the introduction to his report, Moynihan said that "the gap between the Negro and most other groups in American society is widening."[5] He also said that the collapse of the nuclear family in the black lower class would preserve the gap between possibilities for Negroes and other groups and favor other ethnic groups. He acknowledged the continued existence of racism and discrimination within society, despite the victories that blacks had won by civil rights legislation.[5] Moynihan concluded, "The steady expansion of welfare programs can be taken as a measure of the steady disintegration of the Negro family structure over the past generation in the United States."[6] More than 30 years later, S. Craig Watkins described Moynihan's conclusions: Representing: Hip Hop Culture and the Production of Black Cinema (1998): The report concluded that the structure of family life in the black community constituted a 'tangle of pathology... capable of perpetuating itself without assistance from the white world,' and that 'at the heart of the deterioration of the fabric of Negro society is the deterioration of the Negro family. It is the fundamental source of the weakness of the Negro community at the present time.' Also, the report argued that the matriarchal structure of black culture weakened the ability of black men to function as authority figures. That particular notion of black familial life has become a widespread, if not dominant, paradigm for comprehending the social and economic disintegration of late 20th-century black urban life.[7] Influence The Moynihan Report generated considerable controversy and has had long-lasting and important influence. Writing to Lyndon Johnson, Moynihan argued that without access to jobs and the means to contribute meaningful support to a family, black men would become systematically alienated from their roles as husbands and fathers, which would cause rates of divorce, child abandonment and out-of-wedlock births to skyrocket in the black community (a trend that had already begun by the mid-1960s), leading to vast increases in the numbers of households headed by females.[8] Moynihan made a contemporaneous argument for programs for jobs, vocational training, and educational programs for the black community. Modern scholars of the 21st century, including Douglas Massey, believe that the report was one of the more influential in the construction of the War on Poverty.[citation needed] In 2009 historian Sam Tanenhaus wrote that Moynihan's fights with the New Left over the report were a signal that Great Society liberalism had political challengers both from the right and from the left.[9] Reception and following debate From the time of its publication, the report has been sharply attacked by black and civil rights leaders as examples of white patronizing, cultural bias, or racism. At various times, the report has been condemned or dismissed by the NAACP and other civil rights groups and leaders such as Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton. Critics accused Moynihan of relying on stereotypes of the black family and black men, implying that blacks had inferior academic performance, portrayed crime and pathology as endemic to the black community and failing to recognize that cultural bias and racism in standardized tests had contributed to apparent lower achievement by blacks in school.[10] The report was criticized for threatening to undermine the place of civil rights on the national agenda, leaving "a vacuum that could be filled with a politics that blamed Blacks for their own troubles."[11] In 1987, Hortense Spillers, a black feminist academic, criticized the Moynihan Report on semantic grounds for its use of "matriarchy" and "patriarchy" when he described the African-American family. She argues that the terminology used to define white families cannot be used to define African-American families because of the way slavery has affected the African-American family.[12] Scholar Roderick Ferguson traced the effects of the Moynihan Report in his book Aberrations in Black, noting that black nationalists disagreed with the report's suggestion that the state provide black men with masculinity, but agreed that men needed to take back the role of the patriarch. Ferguson argued that the Moynihan Report generated hegemonic discourses about minority communities and nationalist sentiments in the Black community.[13] Ferguson uses the discourse of the Moynihan Report to inform his Queer of Color Critique, which attempts to resist national discourse while acknowledging a simultaneity of oppression through coalition building. African-American libertarian economist and writer Walter E. Williams has praised the report for its findings. He has also said, "The solutions to the major problems that confront many black people won't be found in the political arena, especially not in Washington or state capitols."[6] Thomas Sowell, an African-American libertarian economist as well, has also praised the Moynihan Report on several occasions. His 1982 book Race and Economics mentions Moynihan's report, and in 1998 he asserted that the report "may have been the last honest government report on race."[14] In 2015 Sowell argued that time had proved correct Moynihan's core idea that African-American poverty was less a result of racism and more a result of single-parent families: "One key fact that keeps getting ignored is that the poverty rate among black married couples has been in single digits every year since 1994."[15] Political commentator Heather Mac Donald wrote for National Review in 2008, "Conservatives of all stripes routinely praise Daniel Patrick Moynihan's prescience for warning in 1965 that the breakdown of the black family threatened the achievement of racial equality. They rightly blast those liberals who denounced Moynihan's report."[16] Sociologist Stephen Steinberg argued in 2011 that the Moynihan report was condemned "because it threatened to derail the Black liberation movement."[11] Attempting to divert responsibility Main article: Blaming the victim Psychologist William Ryan coined the phrase "blaming the victim" in his 1971 book Blaming the Victim,[17] specifically as a critique of the Moynihan report. He said that it was an attempt to divert responsibility for poverty from social structural factors to the behaviors and cultural patterns of the poor.[18] Feminist critique Some feminists[who?] argue the Moynihan Report presents a "male-centric" view of social problems.[citation needed] They believe that Moynihan failed to take into account basic rational incentives for marriage,[citation needed] and that he did not acknowledge that women had historically engaged in marriage in part out of need for material resources, as adequate wages were otherwise denied by cultural traditions excluding women from most jobs outside the home. With the expansion of welfare in the US in the mid to late 20th century, women gained better access to government resources intended to reduce family and child poverty.[19] Women also increasingly gained access to the workplace.[20] As a result, more women were able to subsist independently when men had difficulty finding work.[21][22] Counter-response  Out-of-wedlock birth rates by race in the United States from 1940–2014. Rate for African Americans is the purple line. Data is from the National Vital Statistics System Reports published by the CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Note: Prior to 1969, African American illegitimacy was included along with other minority groups as "Non-White."[23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39] Declaring Moynihan "prophetic," Ken Auletta, in his 1982 The Underclass, proclaimed that "one cannot talk about poverty in America, or about the underclass, without talking about the weakening family structure of the poor." Both the Baltimore Sun and the New York Times ran a series on the black family in 1983, followed by a 1985 Newsweek article called "Moynihan: I Told You So." In 1986, CBS aired the documentary The Vanishing Family, hosted by Bill Moyers, a onetime aide to President Johnson, which affirmed Moynihan's findings.[3] In a 2001 interview with PBS, Moynihan said: My view is we had stumbled onto a major social change in the circumstances of post-modern society. It was not long ago in this past century that an anthropologist working in London – a very famous man at the time, Malinowski – postulated what he called the first rule of anthropology: That in all known societies, all male children have an acknowledged male parent. That's what we found out everywhere… And well, maybe it's not true anymore. Human societies change.[40] By the time of that interview, rates of the number of children born to single mothers had gone up in the white and Hispanic working classes as well. In November 2016, the Current Population Survey of the United States Census Bureau reported that 69 percent of children under the age of 18 lived with two parents, which was a decline from 88 percent in 1960, while the percentage of U.S. children under 18 living with one parent increased from 9 percent (8 percent with mothers, 1 percent with fathers) to 27 percent (23 percent with mothers, 4 percent with fathers).[41] |

The Negro

Family: The Case For National Action, 1965 『ニグロの家族』 一般に「モイニハン報告」として知られるThe Negro Family: The Case For National Action, 1965.は、リンドン・B・ジョンソン大統領の下で労働次官補を務め、後に上院議 員になったアメリカの学者ダニエル・パトリック・モイニハンが1965年に書いた、アメリカにおける黒人の貧困に関する報告書である。モイニハンは、黒人 の母子家庭の増加は、仕事の不足が原因ではなく、ゲットー文化の破壊的な脈絡が原因であると主張した。 黒人社会学者のE・フランクリン・フレイジャーは1930年代にこの考えを導入していたが、モイニハンは貧困の構造について従来の社会科学の常識を覆した 最初の学者の一人とみなされていた。経済状況が社会状況を決定するという『誰もが知っている』ことを、統計的にある程度簡潔に立証するために、アメリカ労 働省という最もオーソドックスな場所で仕事が始まった。その結果、誰もが知っていたことが明らかにそうではなかったことが判明した」[1]。報告書は、シ ングルマザー世帯の割合が高いことが、黒人の経済的・政治的平等への前進を大きく妨げると結論づけた。モイニハン報告書は、発表当時リベラル派から批判を 浴び、その結論は今でも論争の的となっている。 背景 モイニハンは『The Negro Family: The Case For National Action』を執筆中、モイニハンは労働省の政治任用職に就いており、ジョンソン政権の「貧困との戦い」における政策立案を支援するために雇われた。黒 人の貧困に関する統計を分析する過程で、モイニハンはある異変に気づいた[2]。黒人男性の失業率と生活保護受給率は、これまでと同じように平行して推移 していたのではなく、1962年に「モイニハンのハサミ」と呼ばれるようになるような形で乖離し始めたのである[3]。 モイニハンが報告書を発表した1965年当時、黒人の婚外子率は25%で、白人のそれをはるかに上回っていた[4]。 内容 報告書の序文で、モイニハンは「アメリカ社会における黒人と他のほとんどの集団との間の格差は拡大している」と述べ[5]、また黒人の下層階級における核 家族の崩壊は、黒人と他の集団との可能性の格差を維持し、他の民族集団に有利に働くだろうと述べた。彼は、黒人が公民権法によって勝ち取った勝利にもかか わらず、社会の中に人種差別と差別が存在し続けていることを認めた[5]。 モイニハンは、「福祉プログラムの着実な拡大は、米国における過去何世代にもわたる黒人の家族構造の着実な崩壊の指標として捉えることができる」と結論づ けた[6]。 30年以上後、S.クレイグ・ワトキンスはモイニハンの結論をこう述べている: 表象する: Hip Hop Culture and the Production of Black Cinema』(1998年): 報告書は、黒人社会における家族生活の構造が「病理のもつれ......白人世界からの援助なしにそれ自体を永続させることができる」ものであり、「黒人 社会の構造の悪化の中心は、黒人家族の悪化である」と結論づけた。それは、現在の黒人社会の弱さの根本的な原因である」。また報告書は、黒人文化の母系制 構造が、黒人男性の権威者としての能力を弱めていると主張した。黒人の家族生活に関するこの特定の概念は、支配的ではないにせよ、20世紀後半の黒人都市 生活の社会的・経済的崩壊を理解するためのパラダイムとして広まった[7]。 影響力 モイニハン・レポートは大きな論争を巻き起こし、長期にわたって重要な影響を及ぼした。モイニハンは、リンドン・ジョンソンに宛てた文書で、黒人男性が仕 事を得られず、家族に有意義な支援を提供する手段がなければ、黒人男性は夫や父親としての役割から組織的に疎外されるようになり、その結果、黒人社会では 離婚、育児放棄、婚外子の割合が急増し(この傾向は1960年代半ばまでにすでに始まっていた)、女性が世帯主を務める世帯の数が大幅に増加すると主張し た[8]。 モイニハンは同時期に、黒人コミュニティのための雇用、職業訓練、教育プログラムのためのプログラムを主張した。ダグラス・マッセイを含む21世紀の現代 の研究者たちは、この報告書が「貧困との戦い」の構築に大きな影響を与えたと考えている[要出典]。 2009年、歴史家のサム・タネンハウスは、報告書をめぐるモイニハンと新左翼との戦いは、大いなる社会のリベラリズムが右からも左からも政治的挑戦者を 得たことを示すものであったと書いている[9]。 反響とその後の議論 この報告書は発表当初から、黒人や公民権運動の指導者たちから、白人贔屓、文化的偏見、人種差別の例として激しく攻撃されてきた。NAACPをはじめとす る公民権団体や、ジェシー・ジャクソンやアル・シャープトンといった指導者たちは、さまざまな場面でこの報告書を非難したり、否定したりした。批評家たち は、モイニハンが黒人家族や黒人男性のステレオタイプに頼り、黒人の学業成績が劣っているとほのめかし、犯罪や病理を黒人社会の風土病のように描き、標準 化テストにおける文化的偏見や人種差別が黒人の学業成績の見かけ上の低さの一因になっていることを認識していないと非難した[10]。 報告書は、国家的課題における公民権の位置を弱体化させ、「自分たちの問題を黒人になすりつける政治で埋められる空白」を残す恐れがあると批判された [11]。 1987年、黒人フェミニストの学者であるホーテンス・スピラーズは、モイニハン報告書がアフリカ系アメリカ人の家族について説明する際に「母系制」と 「家父長制」を用いているとして、意味論的な理由から批判した。彼女は、奴隷制度がアフリカ系アメリカ人の家族に与えた影響のため、白人の家族を定義する ために使われた用語をアフリカ系アメリカ人の家族を定義するために使うことはできないと主張している[12]。 学者のロデリック・ファーガソンは、著書『Aberrations in Black』の中でモイニハン報告の影響を辿り、黒人ナショナリストたちは、国家が黒人男性に男らしさを与えるという報告書の提案には同意しなかったが、 男性が家長の役割を取り戻す必要があることには同意したと述べている。ファーガソンは、モイニハン報告がマイノリティ・コミュニティに関する覇権的な言説 と黒人コミュニティにおける民族主義的な感情を生み出したと主張した[13]。ファーガソンは、モイニハン報告の言説を『クィア・オブ・カラー批評』に用 いており、それは、連合構築を通じて抑圧の同時性を認めつつ、国家的な言説に抵抗しようとするものである。 アフリカ系アメリカ人のリバタリアン経済学者で作家のウォルター・E・ウィリアムズは、この報告書の発見を称賛している。彼はまた、「多くの黒人が直面し ている大きな問題の解決策は、政治の場、特にワシントンや州都では見つからないだろう」とも述べている[6]。同じくアフリカ系アメリカ人のリバタリアン 経済学者であるトーマス・ソウェルも、何度かモイニハン報告を賞賛している。彼の1982年の著書『人種と経済学』はモイニハンの報告書に言及しており、 1998年には、この報告書は「人種に関する最後の正直な政府報告書であったかもしれない」と主張している[14][15] 2015年、ソーウェルは、アフリカ系アメリカ人の貧困は人種差別の結果というよりも、片親家庭の結果であるというモイニハンの核心的な考え方が正しいこ とは時間が証明したと主張した: 「無視され続けている一つの重要な事実は、1994年以来、黒人夫婦の貧困率が毎年一桁台であるということだ」[15]。 政治評論家のヘザー・マク・ドナルドは、2008年に『ナショナル・レビュー』誌にこう書いている。「あらゆる立場の保守派は、1965年に黒人家族の崩 壊が人種平等の達成を脅かすと警告したダニエル・パトリック・モイニハンの先見の明を、日常的に称賛している。彼らはモイニハンの報告書を非難したリベラ ル派を当然非難する」[16]。 社会学者のスティーブン・スタインバーグは2011年に、モイニハン報告が非難されたのは「黒人解放運動を脱線させる恐れがあったからだ」と主張している [11]。 責任転嫁の試み 主な記事 被害者のせいにする 心理学者のウィリアム・ライアンは、1971年に出版した著書『Blaming the Victim』[17]の中で、特にモイニハン報告書に対する批判として、「被害者を非難する」という言葉を作った。彼は、それは貧困の責任を社会構造的 要因から貧困層の行動や文化的パターンに逸らそうとする試みであると述べた[18]。 フェミニスト批判 一部のフェミニスト[who?]は、モイニハン報告が社会問題に対する「男性中心的」な見方を示していると主張している[citation needed]。彼らは、モイニハンが結婚に対する基本的な合理的インセンティブを考慮に入れておらず[citation needed]、女性が歴史的に物質的資源の必要性から結婚に従事してきたことを認めていないと考えている[citation needed]。20世紀半ばから後半にかけてアメリカでは福祉が拡大し、女性は家庭や子どもの貧困を減らすことを目的とした政府の資源をより利用しやす くなった[19]。 また、女性が職場にアクセスする機会も増えていった[20]。その結果、男性が仕事を見つけることが困難なときに、より多くの女性が自立して生活できるよ うになった[21][22]。 反動  1940年から2014年までのアメリカにおける人種別の婚外子出生率。アフリカ系アメリカ人の割合は紫色の線。データはCDC National Center for Health Statistics発行のNational Vital Statistics System Reportsより。注:1969年以前は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の非嫡出子は他のマイノリティ・グループとともに「非白人」として含まれていた[23] [24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39]。 モイニハンを「予言的」であると宣言したケン・オーレッタは、1982年の『The Underclass』において、「貧困層の家族構成の弱体化について語ることなしに、アメリカの貧困について、あるいはアンダークラスについて語ること はできない」と宣言した。ボルチモア・サン紙とニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、1983年に黒人家族に関するシリーズを掲載し、1985年にはニューズ ウィーク誌が "Moynihan: I Told You So "と題する記事を掲載した。1986年、CBSは、ジョンソン大統領の側近だったビル・モイヤーズが司会を務めるドキュメンタリー『The Vanishing Family』を放映し、モイニハンの調査結果を肯定した[3]。 2001年のPBSのインタビューで、モイニハンはこう語っている: 私の考えでは、ポストモダン社会という状況の中で、私たちは大きな社会変化に出くわしたのです。ロンドンで活動していた人類学者、当時はとても有名だった マリノフスキーが、人類学の第一法則と呼ぶものを提唱したのは、この100年前のことだった: 既知のすべての社会では、すべての男の子どもには認知された男親がいる。そして、それはもう真実ではないのかもしれない。人間の社会は変化するのです」 [40]。 そのインタビューの時点までに、シングルマザーから生まれた子どもの数の割合は、白人やヒスパニックの労働者階級でも上昇していた。2016年11月、米 国国勢調査局の人口動態調査によると、18歳未満の子どもの69%が両親と二人暮らしをしており、これは1960年の88%から減少している一方で、片親 と暮らす米国の18歳未満の子どもの割合は9%(母親と8%、父親と1%)から27%(母親と23%、父親と4%)に増加している[41]。 |

| African-American family structure Black matriarchy Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study Is Marriage for White People? William Julius Wilson |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆