ダニエル・パトリック・モイニハン

Daniel Patrick Moynihan (March 16, 1927 –

March 26, 2003)

☆ ダニエル・パトリック・モイニハン(Daniel Patrick Moynihan、1927年3月16日 - 2003年3月26日)は、アメリカの政治家、外交官。民主党に所属し、リチャード・ニクソン大統領の顧問を務めた後、1977年から2001年まで ニューヨーク州選出の上院議員を務めた。

★『ニグロの家族:国家行動のための事例研究』(The Negro Family: The Case For National Action, 1965)

| Daniel

Patrick Moynihan (March 16, 1927 – March 26, 2003) was an American

politician and diplomat. A member of the Democratic Party, he

represented New York in the United States Senate from 1977 until 2001

after serving as an adviser to President Richard Nixon. Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Moynihan moved at a young age to New York City. Following a stint in the navy, he earned a Ph.D. in history from Tufts University. He worked on the staff of New York Governor W. Averell Harriman before joining President John F. Kennedy's administration in 1961. He served as an Assistant Secretary of Labor under Presidents Kennedy and President Lyndon B. Johnson, devoting much of his time to the War on Poverty. In 1965, he published the controversial Moynihan Report. Moynihan left the Johnson administration in 1965 and became a professor at Harvard University. In 1969, he accepted Nixon's offer to serve as an Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy, and he was elevated to the position of Counselor to the President later that year. He left the administration at the end of 1970, and accepted appointment as United States Ambassador to India in 1973. He accepted President Gerald Ford's appointment to the position of United States Ambassador to the United Nations in 1975, holding that position until early 1976; later that year he won election to the Senate. Moynihan served as Chairman of the Senate Environment Committee from 1992 to 1993 and as Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee from 1993 to 1995. He also led the Moynihan Secrecy Commission, which studied the regulation of classified information. He emerged as a strong critic of President Ronald Reagan's foreign policy and opposed President Bill Clinton's health care plan. He frequently broke with liberal positions, but opposed welfare reform in the 1990s. He also voted against the Defense of Marriage Act, the North American Free Trade Agreement, and the Congressional authorization for the Gulf War. He was tied with Jacob K. Javits as the longest-serving Senator from the state of New York until they were both surpassed by Chuck Schumer in 2023. |

ダ

ニエル・パトリック・モイニハン(Daniel Patrick Moynihan、1927年3月16日 -

2003年3月26日)は、アメリカの政治家、外交官。民主党に所属し、リチャード・ニクソン大統領の顧問を務めた後、1977年から2001年まで

ニューヨーク州選出の上院議員を務めた。 オクラホマ州タルサで生まれ、若くしてニューヨークに移住。海軍勤務を経て、タフツ大学で歴史学の博士号を取得。ニューヨーク州知事W・アヴェレル・ハリ マンのスタッフを経て、1961年にジョン・F・ケネディ大統領の政権に参加。ケネディ大統領とリンドン・B・ジョンソン大統領の下で労働次官補を務め、 貧困との戦いに多くの時間を割いた。1965年には、物議を醸す「モイニハン・レポート」を発表。1965年にジョンソン政権を去り、ハーバード大学教授 に就任。 1969年、ニクソンの国内政策担当大統領補佐官就任の申し出を受け、同年末に大統領補佐官に昇格。1970年末に政権を去り、1973年に駐インド米国 大使に任命された。1975年にはジェラルド・フォード大統領から国連大使に任命され、1976年初めまで同職を務めた。 1992年から1993年まで上院環境委員会委員長、1993年から1995年まで上院財政委員会委員長を務めた。また、機密情報の規制を研究するモイニ ハン秘密委員会を率いた。ロナルド・レーガン大統領の外交政策を強く批判し、ビル・クリントン大統領の医療保険制度に反対した。リベラルな立場を崩すこと も多かったが、1990年代には福祉改革に反対した。結婚防衛法、北米自由貿易協定、湾岸戦争の議会承認にも反対票を投じた。2023年にチャック・ シューマーに抜かれるまで、ジェイコブ・K・ジャビッツと並んでニューヨーク州選出の上院議員としては最長在職。 |

| The Negro Family: The Case For National Action, 1965 The Negro Family: The Case For National Action, commonly known as the Moynihan Report, was a 1965 report on black poverty in the United States written by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, an American scholar serving as Assistant Secretary of Labor under President Lyndon B. Johnson and later to become a US Senator. Moynihan argued that the rise in black single-mother families was caused not by a lack of jobs, but by a destructive vein in ghetto culture, which could be traced to slavery times and continued discrimination in the American South under Jim Crow. Black sociologist E. Franklin Frazier had introduced that idea in the 1930s, but Moynihan was considered one of the first academics to defy conventional social-science wisdom about the structure of poverty. As he wrote later, "The work began in the most orthodox setting, the US Department of Labor, to establish at some level of statistical conciseness what 'everyone knew': that economic conditions determine social conditions. Whereupon, it turned out that what everyone knew was evidently not so."[1] The report concluded that the high rate of families headed by single mothers would greatly hinder progress of blacks toward economic and political equality. The Moynihan Report was criticized by liberals at the time of publication, and its conclusions remain controversial. Background While writing The Negro Family: The Case For National Action, Moynihan was employed in a political appointee position at the US Department of Labor, hired to help develop policy for the Johnson administration in its War on Poverty. In the course of analyzing statistics related to black poverty, Moynihan noticed something unusual:[2] Rates of black male unemployment and welfare enrollment, instead of running parallel as they always had, started to diverge in 1962 in a way that would come to be called "Moynihan's scissors."[3] When Moynihan published his report in 1965, the out-of-wedlock birthrate among blacks was 25 percent, much higher than that of whites.[4] Contents In the introduction to his report, Moynihan said that "the gap between the Negro and most other groups in American society is widening."[5] He also said that the collapse of the nuclear family in the black lower class would preserve the gap between possibilities for Negroes and other groups and favor other ethnic groups. He acknowledged the continued existence of racism and discrimination within society, despite the victories that blacks had won by civil rights legislation.[5] Moynihan concluded, "The steady expansion of welfare programs can be taken as a measure of the steady disintegration of the Negro family structure over the past generation in the United States."[6] More than 30 years later, S. Craig Watkins described Moynihan's conclusions: Representing: Hip Hop Culture and the Production of Black Cinema (1998): The report concluded that the structure of family life in the black community constituted a 'tangle of pathology... capable of perpetuating itself without assistance from the white world,' and that 'at the heart of the deterioration of the fabric of Negro society is the deterioration of the Negro family. It is the fundamental source of the weakness of the Negro community at the present time.' Also, the report argued that the matriarchal structure of black culture weakened the ability of black men to function as authority figures. That particular notion of black familial life has become a widespread, if not dominant, paradigm for comprehending the social and economic disintegration of late 20th-century black urban life.[7] Influence The Moynihan Report generated considerable controversy and has had long-lasting and important influence. Writing to Lyndon Johnson, Moynihan argued that without access to jobs and the means to contribute meaningful support to a family, black men would become systematically alienated from their roles as husbands and fathers, which would cause rates of divorce, child abandonment and out-of-wedlock births to skyrocket in the black community (a trend that had already begun by the mid-1960s), leading to vast increases in the numbers of households headed by females.[8] Moynihan made a contemporaneous argument for programs for jobs, vocational training, and educational programs for the black community. Modern scholars of the 21st century, including Douglas Massey, believe that the report was one of the more influential in the construction of the War on Poverty.[citation needed] In 2009 historian Sam Tanenhaus wrote that Moynihan's fights with the New Left over the report were a signal that Great Society liberalism had political challengers both from the right and from the left.[9] Reception and following debate From the time of its publication, the report has been sharply attacked by black and civil rights leaders as examples of white patronizing, cultural bias, or racism. At various times, the report has been condemned or dismissed by the NAACP and other civil rights groups and leaders such as Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton. Critics accused Moynihan of relying on stereotypes of the black family and black men, implying that blacks had inferior academic performance, portrayed crime and pathology as endemic to the black community and failing to recognize that cultural bias and racism in standardized tests had contributed to apparent lower achievement by blacks in school.[10] The report was criticized for threatening to undermine the place of civil rights on the national agenda, leaving "a vacuum that could be filled with a politics that blamed Blacks for their own troubles."[11] In 1987, Hortense Spillers, a black feminist academic, criticized the Moynihan Report on semantic grounds for its use of "matriarchy" and "patriarchy" when he described the African-American family. She argues that the terminology used to define white families cannot be used to define African-American families because of the way slavery has affected the African-American family.[12] Scholar Roderick Ferguson traced the effects of the Moynihan Report in his book Aberrations in Black, noting that black nationalists disagreed with the report's suggestion that the state provide black men with masculinity, but agreed that men needed to take back the role of the patriarch. Ferguson argued that the Moynihan Report generated hegemonic discourses about minority communities and nationalist sentiments in the Black community.[13] Ferguson uses the discourse of the Moynihan Report to inform his Queer of Color Critique, which attempts to resist national discourse while acknowledging a simultaneity of oppression through coalition building. African-American libertarian economist and writer Walter E. Williams has praised the report for its findings. He has also said, "The solutions to the major problems that confront many black people won't be found in the political arena, especially not in Washington or state capitols."[6] Thomas Sowell, an African-American libertarian economist as well, has also praised the Moynihan Report on several occasions. His 1982 book Race and Economics mentions Moynihan's report, and in 1998 he asserted that the report "may have been the last honest government report on race."[14] In 2015 Sowell argued that time had proved correct Moynihan's core idea that African-American poverty was less a result of racism and more a result of single-parent families: "One key fact that keeps getting ignored is that the poverty rate among black married couples has been in single digits every year since 1994."[15] Political commentator Heather Mac Donald wrote for National Review in 2008, "Conservatives of all stripes routinely praise Daniel Patrick Moynihan's prescience for warning in 1965 that the breakdown of the black family threatened the achievement of racial equality. They rightly blast those liberals who denounced Moynihan's report."[16] Sociologist Stephen Steinberg argued in 2011 that the Moynihan report was condemned "because it threatened to derail the Black liberation movement."[11] Attempting to divert responsibility Main article: Blaming the victim Psychologist William Ryan coined the phrase "blaming the victim" in his 1971 book Blaming the Victim,[17] specifically as a critique of the Moynihan report. He said that it was an attempt to divert responsibility for poverty from social structural factors to the behaviors and cultural patterns of the poor.[18] Feminist critique Some feminists[who?] argue the Moynihan Report presents a "male-centric" view of social problems.[citation needed] They believe that Moynihan failed to take into account basic rational incentives for marriage,[citation needed] and that he did not acknowledge that women had historically engaged in marriage in part out of need for material resources, as adequate wages were otherwise denied by cultural traditions excluding women from most jobs outside the home. With the expansion of welfare in the US in the mid to late 20th century, women gained better access to government resources intended to reduce family and child poverty.[19] Women also increasingly gained access to the workplace.[20] As a result, more women were able to subsist independently when men had difficulty finding work.[21][22] Counter-response Out-of-wedlock birth rates by race in the United States from 1940–2014. Rate for African Americans is the purple line. Data is from the National Vital Statistics System Reports published by the CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Note: Prior to 1969, African American illegitimacy was included along with other minority groups as "Non-White."[23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39] Declaring Moynihan "prophetic," Ken Auletta, in his 1982 The Underclass, proclaimed that "one cannot talk about poverty in America, or about the underclass, without talking about the weakening family structure of the poor." Both the Baltimore Sun and the New York Times ran a series on the black family in 1983, followed by a 1985 Newsweek article called "Moynihan: I Told You So." In 1986, CBS aired the documentary The Vanishing Family, hosted by Bill Moyers, a onetime aide to President Johnson, which affirmed Moynihan's findings.[3] In a 2001 interview with PBS, Moynihan said: My view is we had stumbled onto a major social change in the circumstances of post-modern society. It was not long ago in this past century that an anthropologist working in London – a very famous man at the time, Malinowski – postulated what he called the first rule of anthropology: That in all known societies, all male children have an acknowledged male parent. That's what we found out everywhere… And well, maybe it's not true anymore. Human societies change.[40] By the time of that interview, rates of the number of children born to single mothers had gone up in the white and Hispanic working classes as well. In November 2016, the Current Population Survey of the United States Census Bureau reported that 69 percent of children under the age of 18 lived with two parents, which was a decline from 88 percent in 1960, while the percentage of U.S. children under 18 living with one parent increased from 9 percent (8 percent with mothers, 1 percent with fathers) to 27 percent (23 percent with mothers, 4 percent with fathers).[41] |

『ニグロの家族:国家行動のための事例研究』 『ニグロの家族』 一般に「モイニハン報告」として知られるThe Negro Family: The Case For National Action, 1965.は、リンドン・B・ジョンソン大統領の下で労働次官補を務め、後に上院議員になったアメリカの学者ダニエル・パトリック・モイニハンが 1965年に書いた、アメリカにおける黒人の貧困に関する報告書である。モイニハンは、黒人の母子家庭の増加は、仕事の不足が原因ではなく、ゲットー文化 の破壊的な脈絡が原因であると主張した。 黒人社会学者のE・フランクリン・フレイジャーは1930年代にこの考えを導入していたが、モイニハンは貧困の構造について従来の社会科学の常識を覆した 最初の学者の一人とみなされていた。経済状況が社会状況を決定するという『誰もが知っている』ことを、統計的にある程度簡潔に立証するために、アメリカ労 働省という最もオーソドックスな場所で仕事が始まった。その結果、誰もが知っていたことが明らかにそうではなかったことが判明した」[1]。報告書は、シ ングルマザー世帯の割合が高いことが、黒人の経済的・政治的平等への前進を大きく妨げると結論づけた。モイニハン報告書は、発表当時リベラル派から批判を 浴び、その結論は今でも論争の的となっている。 背景 モイニハンは『The Negro Family: The Case For National Action』を執筆中、モイニハンは労働省の政治任用職に就いており、ジョンソン政権の「貧困との戦い」における政策立案を支援するために雇われた。黒 人の貧困に関する統計を分析する過程で、モイニハンはある異変に気づいた[2]。黒人男性の失業率と生活保護受給率は、これまでと同じように平行して推移 していたのではなく、1962年に「モイニハンのハサミ」と呼ばれるようになるような形で乖離し始めたのである[3]。 モイニハンが報告書を発表した1965年当時、黒人の婚外子率は25%で、白人のそれをはるかに上回っていた[4]。 内容 報告書の序文で、モイニハンは「アメリカ社会における黒人と他のほとんどの集団との間の格差は拡大している」と述べ[5]、また黒人の下層階級における核 家族の崩壊は、黒人と他の集団との可能性の格差を維持し、他の民族集団に有利に働くだろうと述べた。彼は、黒人が公民権法によって勝ち取った勝利にもかか わらず、社会の中に人種差別と差別が存在し続けていることを認めた[5]。 モイニハンは、「福祉プログラムの着実な拡大は、米国における過去何世代にもわたる黒人の家族構造の着実な崩壊の指標として捉えることができる」と結論づけた[6]。 30年以上後、S.クレイグ・ワトキンスはモイニハンの結論をこう述べている: 表象する: Hip Hop Culture and the Production of Black Cinema』(1998年): 報告書は、黒人社会における家族生活の構造が「病理のもつれ......白人世界からの援助なしにそれ自体を永続させることができる」ものであり、「黒人 社会の構造の悪化の中心は、黒人家族の悪化である」と結論づけた。それは、現在の黒人社会の弱さの根本的な原因である」。また報告書は、黒人文化の母系制 構造が、黒人男性の権威者としての能力を弱めていると主張した。黒人の家族生活に関するこの特定の概念は、支配的ではないにせよ、20世紀後半の黒人都市 生活の社会的・経済的崩壊を理解するためのパラダイムとして広まった[7]。 影響力 モイニハン・レポートは大きな論争を巻き起こし、長期にわたって重要な影響を及ぼした。モイニハンは、リンドン・ジョンソンに宛てた文書で、黒人男性が仕 事を得られず、家族に有意義な支援を提供する手段がなければ、黒人男性は夫や父親としての役割から組織的に疎外されるようになり、その結果、黒人社会では 離婚、育児放棄、婚外子の割合が急増し(この傾向は1960年代半ばまでにすでに始まっていた)、女性が世帯主を務める世帯の数が大幅に増加すると主張し た[8]。 モイニハンは同時期に、黒人コミュニティのための雇用、職業訓練、教育プログラムのためのプログラムを主張した。ダグラス・マッセイを含む21世紀の現代の研究者たちは、この報告書が「貧困との戦い」の構築に大きな影響を与えたと考えている[要出典]。 2009年、歴史家のサム・タネンハウスは、報告書をめぐるモイニハンと新左翼との戦いは、大いなる社会のリベラリズムが右からも左からも政治的挑戦者を得たことを示すものであったと書いている[9]。 反響とその後の議論 この報告書は発表当初から、黒人や公民権運動の指導者たちから、白人贔屓、文化的偏見、人種差別の例として激しく攻撃されてきた。NAACPをはじめとす る公民権団体や、ジェシー・ジャクソンやアル・シャープトンといった指導者たちは、さまざまな場面でこの報告書を非難したり、否定したりした。批評家たち は、モイニハンが黒人家族や黒人男性のステレオタイプに頼り、黒人の学業成績が劣っているとほのめかし、犯罪や病理を黒人社会の風土病のように描き、標準 化テストにおける文化的偏見や人種差別が黒人の学業成績の見かけ上の低さの一因になっていることを認識していないと非難した[10]。 報告書は、国家的課題における公民権の位置を弱体化させ、「自分たちの問題を黒人になすりつける政治で埋められる空白」を残す恐れがあると批判された [11]。 1987年、黒人フェミニストの学者であるホーテンス・スピラーズは、モイニハン報告書がアフリカ系アメリカ人の家族について説明する際に「母系制」と 「家父長制」を用いているとして、意味論的な理由から批判した。彼女は、奴隷制度がアフリカ系アメリカ人の家族に与えた影響のため、白人の家族を定義する ために使われた用語をアフリカ系アメリカ人の家族を定義するために使うことはできないと主張している[12]。 学者のロデリック・ファーガソンは、著書『Aberrations in Black』の中でモイニハン報告の影響を辿り、黒人ナショナリストたちは、国家が黒人男性に男らしさを与えるという報告書の提案には同意しなかったが、 男性が家長の役割を取り戻す必要があることには同意したと述べている。ファーガソンは、モイニハン報告がマイノリティ・コミュニティに関する覇権的な言説 と黒人コミュニティにおける民族主義的な感情を生み出したと主張した[13]。ファーガソンは、モイニハン報告の言説を『クィア・オブ・カラー批評』に用 いており、それは、連合構築を通じて抑圧の同時性を認めつつ、国家的な言説に抵抗しようとするものである。 アフリカ系アメリカ人のリバタリアン経済学者で作家のウォルター・E・ウィリアムズは、この報告書の発見を称賛している。彼はまた、「多くの黒人が直面し ている大きな問題の解決策は、政治の場、特にワシントンや州都では見つからないだろう」とも述べている[6]。同じくアフリカ系アメリカ人のリバタリアン 経済学者であるトーマス・ソウェルも、何度かモイニハン報告を賞賛している。彼の1982年の著書『人種と経済学』はモイニハンの報告書に言及しており、 1998年には、この報告書は「人種に関する最後の正直な政府報告書であったかもしれない」と主張している[14][15] 2015年、ソーウェルは、アフリカ系アメリカ人の貧困は人種差別の結果というよりも、片親家庭の結果であるというモイニハンの核心的な考え方が正しいこ とは時間が証明したと主張した: 「無視され続けている一つの重要な事実は、1994年以来、黒人夫婦の貧困率が毎年一桁台であるということだ」[15]。 政治評論家のヘザー・マク・ドナルドは、2008年に『ナショナル・レビュー』誌にこう書いている。「あらゆる立場の保守派は、1965年に黒人家族の崩 壊が人種平等の達成を脅かすと警告したダニエル・パトリック・モイニハンの先見の明を、日常的に称賛している。彼らはモイニハンの報告書を非難したリベラ ル派を当然非難する」[16]。 社会学者のスティーブン・スタインバーグは2011年に、モイニハン報告が非難されたのは「黒人解放運動を脱線させる恐れがあったからだ」と主張している[11]。 責任転嫁の試み 主な記事 被害者のせいにする(→「犠牲者非難」) 心理学者のウィリアム・ライアンは、1971年に出版した著書『Blaming the Victim』[17]の中で、特にモイニハン報告書に対する批判として、「被害者を非難する」という言葉を作った。彼は、それは貧困の責任を社会構造的 要因から貧困層の行動や文化的パターンに逸らそうとする試みであると述べた[18]。 フェミニスト批判 一部のフェミニスト[who?]は、モイニハン報告が社会問題に対する「男性中心的」な見方を示していると主張している[citation needed]。彼らは、モイニハンが結婚に対する基本的な合理的インセンティブを考慮に入れておらず[citation needed]、女性が歴史的に物質的資源の必要性から結婚に従事してきたことを認めていないと考えている[citation needed]。20世紀半ばから後半にかけてアメリカでは福祉が拡大し、女性は家庭や子どもの貧困を減らすことを目的とした政府の資源をより利用しやす くなった[19]。 また、女性が職場にアクセスする機会も増えていった[20]。その結果、男性が仕事を見つけることが困難なときに、より多くの女性が自立して生活できるよ うになった[21][22]。 反動 1940年から2014年までのアメリカにおける人種別の婚外子出生率。アフリカ系アメリカ人の割合は紫色の線。データはCDC National Center for Health Statistics発行のNational Vital Statistics System Reportsより。注:1969年以前は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の非嫡出子は他のマイノリティ・グループとともに「非白人」として含まれていた[23] [24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39]。 モイニハンを「予言的」であると宣言したケン・オーレッタは、1982年の『The Underclass』において、「貧困層の家族構成の弱体化について語ることなしに、アメリカの貧困について、あるいはアンダークラスについて語ること はできない」と宣言した。ボルチモア・サン紙とニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、1983年に黒人家族に関するシリーズを掲載し、1985年にはニューズ ウィーク誌が "Moynihan: I Told You So "と題する記事を掲載した。1986年、CBSは、ジョンソン大統領の側近だったビル・モイヤーズが司会を務めるドキュメンタリー『The Vanishing Family』を放映し、モイニハンの調査結果を肯定した[3]。 2001年のPBSのインタビューで、モイニハンはこう語っている: 私の考えでは、ポストモダン社会という状況の中で、私たちは大きな社会変化に出くわしたのです。ロンドンで活動していた人類学者、当時はとても有名だった マリノフスキーが、人類学の第一法則と呼ぶものを提唱したのは、この100年前のことだった: 既知のすべての社会では、すべての男の子どもには認知された男親がいる。そして、それはもう真実ではないのかもしれない。人間の社会は変化するのです」 [40]。 そのインタビューの時点までに、シングルマザーから生まれた子どもの数の割合は、白人やヒスパニックの労働者階級でも上昇していた。2016年11月、米 国国勢調査局の人口動態調査によると、18歳未満の子どもの69%が両親と二人暮らしをしており、これは1960年の88%から減少している一方で、片親 と暮らす米国の18歳未満の子どもの割合は9%(母親と8%、父親と1%)から27%(母親と23%、父親と4%)に増加している[41]。 |

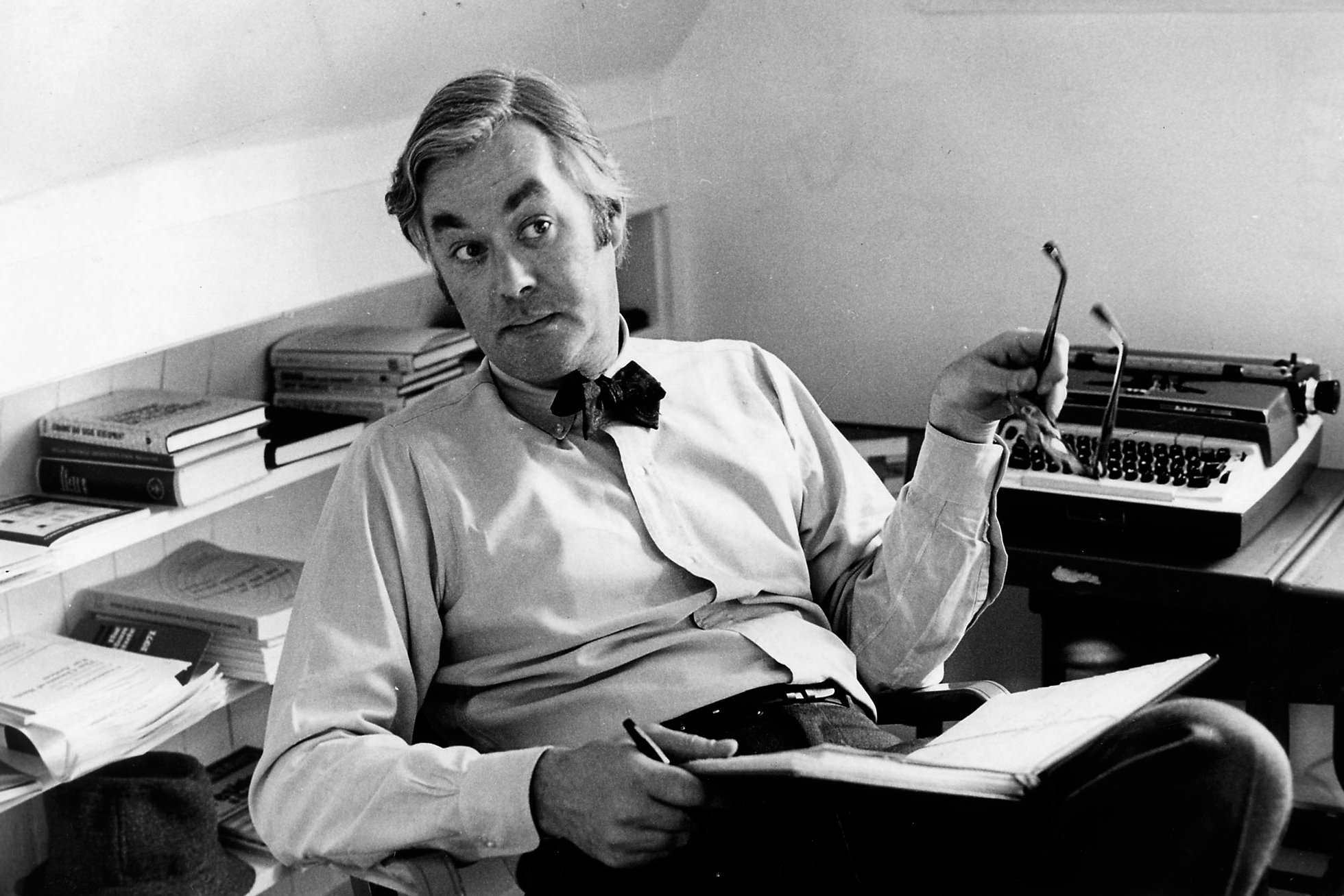

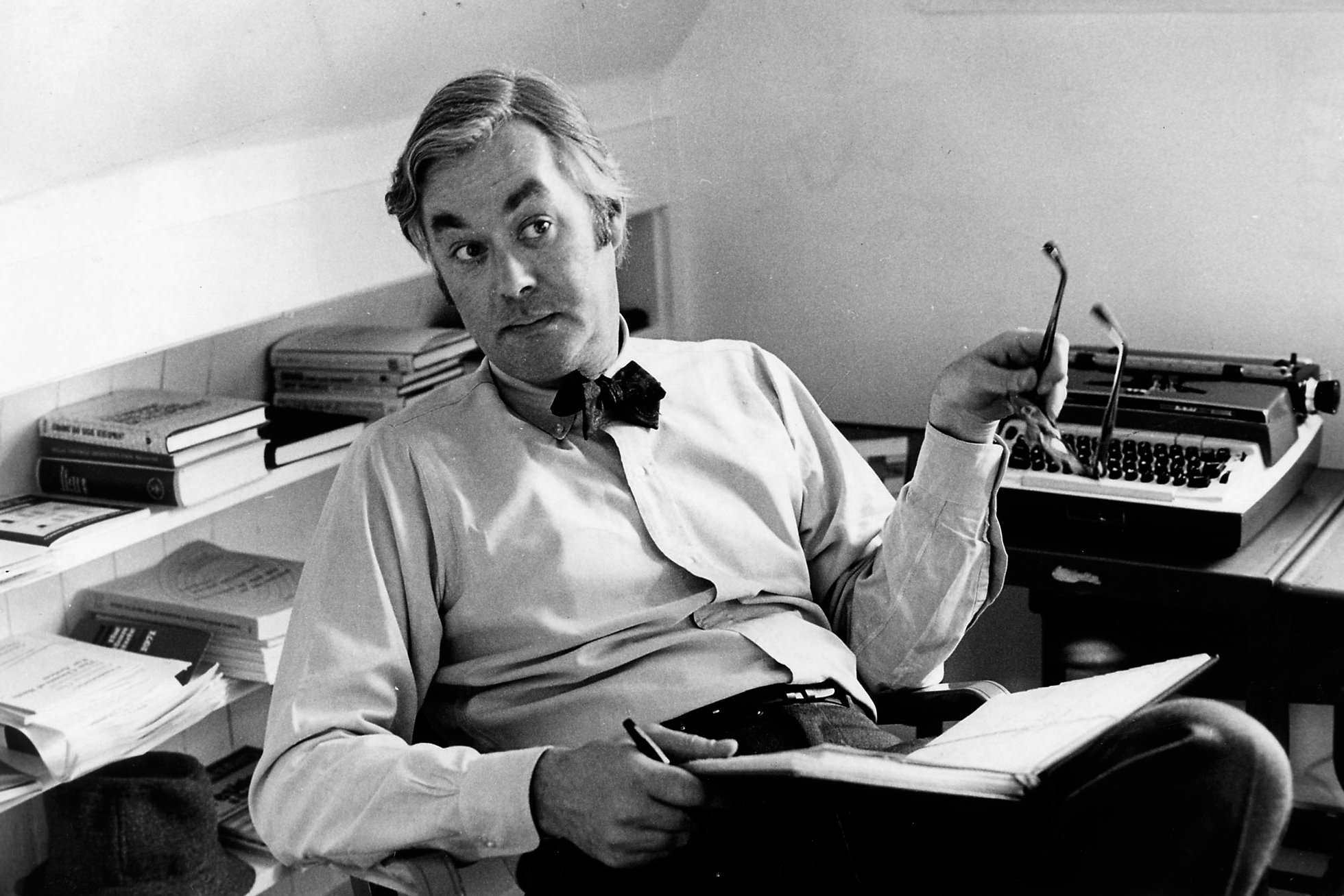

| Early life and education Moynihan was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the son of Margaret Ann (née Phipps), a homemaker, and John Henry Moynihan, a reporter for a daily newspaper in Tulsa but originally from Indiana.[1][2] He moved at the age of six with his Irish Catholic family to New York City. Brought up in the working class neighborhood of Hell's Kitchen,[3] he shined shoes and attended various public, private, and parochial schools, ultimately graduating from Benjamin Franklin High School in East Harlem. He was a parishioner of St. Raphael's Church, where he also cast his first vote.[4] He and his brother, Michael Willard Moynihan, spent most of their childhood summers at their grandfather's farm in Bluffton, Indiana. Moynihan briefly worked as a longshoreman before entering the City College of New York (CCNY), which at that time provided free higher education to city residents. Following a year at CCNY, Moynihan joined the United States Navy in 1944. He was assigned to the V-12 Navy College Training Program at Middlebury College from 1944 to 1945 and then enrolled as a Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps student at Tufts University, where he received an undergraduate degree in naval science in 1946. He completed active service as Gunnery officer of the USS Quirinus at the rank of lieutenant (junior grade) in 1947. Moynihan then returned to Tufts, where he completed a second undergraduate degree in sociology[5] cum laude in 1948 and earned an MA from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy in 1949. After failing the Foreign Service Officer exam, he continued his doctoral studies at the Fletcher School as a Fulbright fellow at the London School of Economics from 1950 to 1953. During this period, Moynihan struggled with writer's block and began to fashion himself as a "dandy", cultivating "a taste for Savile Row suits, rococo conversational riffs and Churchillian oratory" even as he maintained that "nothing and no one at LSE ever disposed me to be anything but a New York Democrat who had some friends who worked on the docks and drank beer after work." He also worked for two years as a civilian employee at RAF South Ruislip.[6] He ultimately received his PhD in history from Tufts (with a dissertation on the relationship between the United States and the International Labour Organization) from the Fletcher School in 1961 while serving as an assistant professor of political science and director of a government research project centered around Averell Harriman's papers at Syracuse University's Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs.[7][8] Political career and return to academia Moynihan's political career started in the 1950s, when he served as a member of New York Governor Averell Harriman's staff in a variety of positions (including speechwriter and acting secretary to the governor). He met his future wife, Elizabeth (Liz) Brennan, who also worked on Harriman's staff.[9] This period ended following Harriman's loss to Nelson Rockefeller in the 1958 general election. Moynihan returned to academia, serving as a lecturer for brief periods at Russell Sage College (1957–1958) and the Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations (1959) before taking a tenure-track position at Syracuse University (1959–1961). During this period, Moynihan was a delegate to the 1960 Democratic National Convention as part of John F. Kennedy's delegate pool. Kennedy and Johnson administrations This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Daniel Patrick Moynihan" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Moynihan first served in the Kennedy administration as special (1961–1962) and executive (1962–1963) assistant to Labor Secretaries Arthur J. Goldberg and W. Willard Wirtz. In 1962, he authored the directive "Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture", which discouraged use of an official style for federal buildings, and has been credited with enabling "a wide ranging set of innovative public building projects" in subsequent decades, including the San Francisco Federal Building and the United States Courthouse in Austin, Texas.[10] He was then appointed as Assistant Secretary of Labor for Policy, Planning and Research, serving from 1963 to 1965 under Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. In this capacity, he did not have operational responsibilities. He devoted his time to trying to formulate national policy for what would become the War on Poverty. His small staff included Ralph Nader. They took inspiration from historian Stanley Elkins's Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life (1959). Elkins essentially contended that slavery had made black Americans dependent on the dominant society, and that such dependence still existed a century later after the American Civil War. Moynihan and his staff believed that government must go beyond simply ensuring that members of minority groups have the same rights as the majority and must also "act affirmatively" in order to counter the problem of historic discrimination. Moynihan's research of Labor Department data demonstrated that even as fewer people were unemployed, more people were joining the welfare rolls. These recipients were families with children but only one parent (almost invariably the mother). The laws at that time permitted such families to receive welfare payments in certain parts of the United States. Controversy over the War on Poverty Moynihan issued his research in 1965 under the title The Negro Family: The Case For National Action, now commonly known as The Moynihan Report. Moynihan's report[11] fueled a debate over the proper course for government to take with regard to the economic underclass, especially blacks. Critics on the left attacked it as "blaming the victim",[12] a slogan coined by psychologist William Ryan.[13] Some suggested that Moynihan was propagating the views of racists[14] because much of the press coverage of the report focused on the discussion of children being born out of wedlock. Despite Moynihan's warnings, the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program included rules for payments only if no "Man [was] in the house."[15][16] Critics of the program's structure, including Moynihan, said that the nation was paying poor women to throw their husbands out of the house. After the 1994 Republican sweep of Congress, Moynihan agreed that correction was needed for a welfare system that possibly encouraged women to raise their children without fathers: "The Republicans are saying we have a hell of a problem, and we do."[17] Local New York City politics and ongoing academic career By the 1964 presidential election, Moynihan was recognized as a political ally of Robert F. Kennedy. For this reason he was not favored by then-President Johnson, and he left the Johnson Administration in 1965.[citation needed] He ran for office in the Democratic Party primary for the presidency of the New York City Council, a position now known as the New York City Public Advocate. However, he was defeated by Queens District Attorney Frank D. O'Connor.[citation needed] Throughout this transitional period, Moynihan maintained an academic affiliation as a fellow at Wesleyan University's Center for Advanced Studies from 1964 to 1967. In 1966, he was appointed to the faculties of Harvard University's Graduate School of Education and Graduate School of Public Administration as a full professor of education and urban politics. After commencing a second extended leave because of his public service in 1973, his faculty line was transferred to the university's Department of Government, where he remained until 1977. From 1966 to 1969, he also held a secondary administrative appointment as director of the Harvard–MIT Joint Center for Urban Studies.[8] With turmoil and riots in the United States, Moynihan, "a national board member of ADA incensed at the radicalism of the current anti-war and Black Power movements", decided to "call for a formal alliance between liberals and conservatives",[18] and wrote that the next administration would have to be able to unite the nation again. Nixon administration Moynihan in 1969 Connecting with President-elect Richard Nixon in 1968, Moynihan joined the Executive Office of the President in January 1969 as Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy and executive secretary of the Council of Urban Affairs (later the Urban Affairs Council), a forerunner of the Domestic Policy Council envisaged as an analog to the United States National Security Council. As one of the few people in Nixon's inner circle who had done academic research related to social policies, he was very influential in the early months of the administration. However, his disdain for "traditional budget-conscious positions" (including his proposed Family Assistance Plan, a "negative income tax or guaranteed minimum income" for families that met work requirements or demonstrated that they were seeking work which ultimately stalled in the Senate despite prefiguring the later Supplemental Security Income program) led to frequent clashes (belying their unwavering mutual respect) with Nixon's principal domestic policy advisor, conservative economist and Cabinet-rank Counselor to the President Arthur F. Burns.[19] While formulating the Family Assistance Plan proposal, Moynihan conducted significant discussions concerning a Basic Income Guarantee with Russell B. Long and Louis O. Kelso. Although Moynihan was promoted to Counselor to the President for Urban Affairs with Cabinet rank shortly after Burns was nominated by Nixon to serve as Chair of the Federal Reserve in October 1969, it was concurrently announced that Moynihan would be returning to Harvard (a stipulation of his leave from the university) at the end of 1970. Operational oversight of the Urban Affairs Council was given to Moynihan's nominal successor as Domestic Policy Assistant, former White House Counsel John Ehrlichman. This decision was instigated by White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman,[20] a close friend of Ehrlichman since college and his main patron in the administration. Haldeman's maneuvering situated Moynihan in a more peripheral context as the administration's "resident thinker" on domestic affairs for the duration of his service.[21] In 1969, on Nixon's initiative, NATO tried to establish a third civil column, establishing a hub of research and initiatives in the civil area, dealing as well with environmental topics.[22] Moynihan[22] named acid rain and the greenhouse effect as suitable international challenges to be dealt by NATO. NATO was chosen, since the organization had suitable expertise in the field, as well as experience with international research coordination. The German government was skeptical and saw the initiative as an attempt by the US to regain international terrain after the lost Vietnam War. The topics gained momentum in civil conferences and institutions.[22] In 1970, Moynihan wrote a memo to President Nixon saying, "The time may have come when the issue of race could benefit from a period of 'benign neglect'. The subject has been too much talked about. The forum has been too much taken over to hysterics, paranoids, and boodlers on all sides. We need a period in which Negro progress continues and racial rhetoric fades."[23] Moynihan regretted that, as he saw it, critics misinterpreted his memo as advocating that the government should neglect minorities.[24] |

生い立ちと教育 モイニハンはオクラホマ州タルサで、専業主婦だったマーガレット・アン(旧姓フィップス)と、タルサの日刊紙の記者でインディアナ州出身のジョン・ヘン リー・モイニハンの息子として生まれた[1][2]。ヘルズ・キッチンの労働者階級地区で育ち[3]、靴磨きをしながらさまざまな公立、私立、教区の学校 に通い、最終的にイースト・ハーレムのベンジャミン・フランクリン高校を卒業。弟のマイケル・ウィラード・モイニハンと共に、幼少期の夏のほとんどをイン ディアナ州ブラフトンにある祖父の農場で過ごした。モイニハンは、港湾労働者として短期間働いた後、当時ニューヨーク市民に無料で高等教育を提供していた シティ・カレッジ・オブ・ニューヨーク(CCNY)に入学。 CCNYで1年間学んだ後、1944年にアメリカ海軍に入隊。1944年から1945年までミドルベリー大学のV-12海軍大学訓練プログラムに配属さ れ、その後タフツ大学の海軍予備役将校訓練部隊の学生として入学し、1946年に海軍科学の学士号を取得した。1947年、USSクィリナスの砲術士官と して中尉の階級で現役を終えた。その後、タフツ大学に戻り、1948年に優秀な成績で社会学[5]の2つ目の学士号を取得し、1949年にフレッチャー法 外交大学院で修士号を取得した。 外交官試験に落ちた後、1950年から1953年までフルブライト研究員としてロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスに留学し、フレッチャー・スクール で博士課程の研究を続けた。この時期、モイニハンは作家のブロックと闘い、「ダンディ」なファッションを身につけ、「サヴィル・ロウのスーツ、ロココ調の 会話、チャーチリアンな演説を好む」ようになった。また、サウス・ルイスリップ空軍で民間人として2年間働いた[6]。 最終的には、シラキュース大学マックスウェル・スクール・オブ・シチズンシップ・アンド・パブリック・アフェアーズで政治学の助教授とアヴェレル・ハリマ ンの論文を中心とした政府研究プロジェクトのディレクターを務めながら、1961年にフレッチャー・スクールで歴史学の博士号(米国と国際労働機関の関係 に関する論文)を取得した[7][8]。 政治家としてのキャリアと学界への復帰 モイニハンの政治家としてのキャリアは1950年代に始まり、ニューヨーク州知事アヴェレル・ハリマンのスタッフとしてさまざまな役職(スピーチライター や知事秘書代理など)を務めた。後に妻となるエリザベス(リズ)・ブレナンと出会い、彼女もまたハリマンのスタッフとして働いていた[9]。 1958年の総選挙でハリマンがネルソン・ロックフェラーに敗れたため、この時期は終わった。モイニハンは学界に戻り、ラッセル・セージ・カレッジ (1957-1958年)とコーネル大学産業労働関係学部(1959年)で短期間講師を務めた後、シラキュース大学でテニュアトラックの職に就いた (1959-1961年)。この間、モイニハンは、ジョン・F・ケネディの代表団の一員として、1960年の民主党全国大会の代表を務めた。 ケネディ政権とジョンソン政権 このセクションは検証のために追加の引用が必要です。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力ください。ソースのないものは、異議申し立てがなされ、削除されることがあります。 出典を探す 「Daniel Patrick Moynihan" - news - newspapers - books - scholar - JSTOR (June 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) ケネディ政権のアーサー・J・ゴールドバーグ労働長官とW・ウィラード・ワーツ労働長官の特別補佐官(1961-1962年)および行政補佐官(1962 -1963年)を務めた。1962年、彼は「連邦建築の指導原則」という指令書を作成し、連邦政府の建物に公式様式を使用することを奨励した。その後数十 年間、サンフランシスコ連邦ビルやテキサス州オースティンの合衆国裁判所など、「幅広い革新的な公共建築プロジェクト」を可能にしたと評価されている [10]。 その後、政策・計画・調査担当の労働次官補に任命され、ケネディとリンドン・B・ジョンソンの下で1963年から1965年まで務めた。この職務では、業 務上の責任は持たなかった。彼は、後に「貧困との戦い」となることになる国家政策の策定に時間を割いた。彼の小さなスタッフにはラルフ・ネーダーもいた。 彼らは歴史家スタンリー・エルキンスの『奴隷制』からインスピレーションを得た: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life』(1959年)からヒントを得た。エルキンズは本質的に、奴隷制度がアメリカ黒人を支配社会に依存させ、南北戦争後100年経った今もなお、そ のような依存が存在すると主張していた。モイニハンと彼のスタッフは、政府は単にマイノリティ・グループのメンバーがマジョリティと同じ権利を持つことを 保証するだけでなく、歴史的差別の問題に対抗するために「積極的に行動」しなければならないと考えた。 モイニハンが労働省のデータを調査したところ、失業者が減る一方で、生活保護受給者が増えていることがわかった。これらの受給者は、子どもはいるが親は片 方だけ(ほとんどが母親)という家庭であった。当時の法律では、このような家庭でも生活保護を受けられるようになっていた。 対貧困戦争をめぐる論争 モイニハンは1965年に、『The Negro Family: The Case For National Action』というタイトルで発表した。モイニハンの報告書[11]は、経済的な下層階級、特に黒人に対して政府がとるべき適切な方針をめぐる議論を 煽った。左派の批評家たちは、この報告書を心理学者ウィリアム・ライアンによって作られたスローガンである「被害者を非難するもの」[12]として攻撃し た[13]。この報告書に関する報道の多くが婚外子についての議論に焦点を当てていたため、モイニハンは人種差別主義者の見解を広めていると指摘する者も いた[14]。モイニハンの警告にもかかわらず、扶養児童のいる家庭への援助(AFDC)プログラムには、「男性が家にいない」場合にのみ支給される規則 が含まれていた[15][16]。モイニハンを含むプログラムの構造に対する批評家たちは、国家が夫を家から追い出すために貧しい女性に金を払っていると 述べた。 1994年に共和党が議会を席巻した後、モイニハンは、父親なしで子供を育てることを女性に奨励している可能性のある福祉制度には是正が必要であることに同意した: 「共和党は、私たちにはとんでもない問題があると言っているが、実際にそうなのだ」[17]。 地元ニューヨークの政治と継続的な学問的キャリア 1964年の大統領選挙まで、モイニハンはロバート・F・ケネディの政治的盟友として認識されていた。そのため、当時のジョンソン大統領からは寵愛を受け ず、1965年にジョンソン政権を去った[要出典]。民主党の予備選挙で、ニューヨーク市議会議長(現在はニューヨーク市公述人として知られる)に立候 補。しかし、クイーンズ地区検事フランク・D・オコナーに敗れた[要出典]。 この過渡期を通じて、モイニハンは1964年から1967年までウェズリアン大学高等研究センターのフェローとして学術的な活動を続けた。1966年、 ハーバード大学教育大学院および行政大学院の教育学および都市政治学の正教授に任命された。1973年に公務のため2度目の長期休暇に入った後、教授職は 同大学行政学部に移され、1977年まで在籍した。1966年から1969年にかけては、ハーバード大学・ミット大学合同都市研究センター長という副次的 な管理職も兼任した[8]。米国内の混乱と暴動に伴い、「現在の反戦運動とブラックパワー運動の急進性に憤慨したADAの全国理事」であったモイニハン は、「リベラル派と保守派の正式な同盟を呼びかける」ことを決意し[18]、次の政権は再び国民を団結させることができなければならないと書いた。 ニクソン政権 1969年のモイニハン 1968年にリチャード・ニクソン次期大統領とつながったモイニハンは、1969年1月、国内政策担当大統領補佐官兼都市問題評議会(後の都市問題評議 会)事務局長として大統領府に入った。ニクソンの側近で社会政策に関連する学術的研究を行った数少ない人物の一人として、政権初期に大きな影響力を持っ た。しかし、「伝統的な予算重視の立場」(彼が提案した家族扶助計画、就労要件を満たすか、就労を希望していることを証明した家族に対する「負の所得税ま たは最低所得保証」、後の補助的保障所得(Supplemental Security Income)プログラムの先駆けとなったにもかかわらず、最終的には上院で行き詰まった)を軽んじたため、ニクソンの主要な国内政策顧問であり、保守派 エコノミストで閣僚級の大統領顧問であったアーサー・F・バーンズ(Arthur F. Burns)とは(揺るぎない相互尊敬の念とは裏腹に)たびたび衝突することになった[19]。 家族扶助計画案を策定する一方で、モイニハンはラッセル・B・ロングやルイス・O・ケルソと基本所得保障に関する重要な議論を行った。 1969年10月にバーンズがニクソンから連邦準備制度理事会議長に指名された直後、モイニハンは内閣官房都市問題担当大統領顧問に昇進したが、同時に、 モイニハンが1970年末にハーバード大学に復学することが発表された(大学休学の規定)。都市問題評議会の運営監督は、モイニハンの国内政策補佐官とし ての名目上の後任、ジョン・エーリクマン元ホワイトハウス顧問に委ねられた。この決定は、大学時代からエーリックマンと親交があり、政権内でも彼の主要な 後援者であった、ホワイトハウスの首席補佐官H・R・ホールドマン[20]によって扇動された。このホールドマンの策略によって、モイニハンは在任中、内 政問題における政権の「専属思想家」として、より周辺的な立場に置かれることになった[21]。 モイニハン[22]は、酸性雨と温室効果をNATOが扱うにふさわしい国際的課題として挙げた。NATOが選ばれたのは、NATOがこの分野で適切な専門 知識を持ち、国際的な研究調整の経験もあったからである。ドイツ政府は懐疑的で、このイニシアチブを、ベトナム戦争で敗れたアメリカが国際的な地歩を取り 戻すための試みと見なした。このトピックは市民会議や機関で盛り上がった[22]。 1970年、モイニハンはニクソン大統領に宛てたメモにこう書いた。この話題はあまりにも多く語られてきた。ヒステリックで偏執狂的で、あらゆる立場の ブードラーたちに、このフォーラムはあまりにも占領されてきた。われわれには、黒人の進歩が続き、人種的レトリックが薄れる時期が必要である」[23]。 モイニハンは、彼のメモが、政府がマイノリティを無視すべきだと提唱していると批評家たちが誤解したことを遺憾に思っていた[24]。 |

| U.S. Ambassador Following the October 1969 reorganization of the White House domestic policy staff, Moynihan was offered the position of United States Ambassador to the United Nations (then held by career Foreign Service Officer Charles Woodruff Yost) by Nixon on November 17, 1969; after initially accepting the president's offer, he decided to remain in Washington when the Family Assistance Plan stalled in the Senate Finance Committee.[25] On November 24, 1970, he refused a second offer from Nixon due to potential familial strain and ongoing financial problems; depression stemming from the repudiation of the Family Assistance Plan by liberal Democrats; and the inability to effect change due to static policy directives in the position, which he considered to be a tertiary role behind Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs Henry Kissinger and United States Secretary of State William P. Rogers.[25] Instead, he commuted from Harvard as a part-time member of the United States delegation during the ambassadorship of George H. W. Bush.[25] In 1973, Moynihan (who was circumspect toward the administration's "tilt" to Pakistan) accepted Nixon's offer to serve as United States Ambassador to India, where he would remain until 1975. The relationship between the two countries was at a low point following the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. Ambassador Moynihan was alarmed that two great democracies were cast as antagonists, and set out to fix things. He proposed that part of the burdensome debt be written off, part used to pay for U.S. embassy expenses in India, and the remaining converted into Indian rupees to fund an Indo-US cultural and educational exchange program that lasted for a quarter century. On February 18, 1974, he presented to the Government of India a check for 16,640,000,000 rupees, then equivalent to $2,046,700,000, which was the greatest amount paid by a single check in the history of banking.[26] The "Rupee Deal" is logged in the Guinness Book of World Records for the world's largest check,[27] presented to India's Secretary of Economic Affairs. [28] In June 1975, Moynihan accepted his third offer to serve as United States Ambassador to the United Nations, a position (including a rotation as President of the United Nations Security Council) that he would only hold until February 1976. Under President Gerald Ford, Ambassador Moynihan took a hardline anti-communist stance, in line with the agenda of the White House at the time. He was also a strong supporter of Israel,[29] condemning UN Resolution 3379, which declared Zionism to be a form of racism.[30] Moynihan's wife Liz later recalled being approached in the UN galleries by Palestine Liberation Organization Permanent Observer Zuhdi Labib Terzi during the controversy. He made a remark of which she later did not remember the exact phrasing, but rendered it approximately as 'you must have mixed feelings about remembering events in New Delhi', which she and biographer Gil Troy interpreted as a threatening reference to a failed assassination plan against her husband two years earlier.[31] But the American public responded enthusiastically to his moral outrage over the resolution; his condemnation of the "Zionism is Racism" resolution brought him celebrity status and helped him win a US Senate seat a year later.[32] Moynihan opposed the resolution because he thought it was completely false and perverse. Also, his years in New York sensitized him on a pragmatic issue: "resolution against Zionism not only affected Israel but every Zionist people, which included the majority of American Jews", which became clear when that community promoted a touristic boycott against Mexico as a consequence of its vote for the approval of the Resolution.[33] In his book, Moynihan's Moment, Gil Troy posits that Moynihan's 1975 UN speech opposing the resolution was the key moment of his political career.[34] Perhaps the most controversial action of Moynihan's career was his response, as Ambassador to the UN, to the Indonesian invasion of East Timor in 1975. Gerald Ford considered Indonesia, then under a military dictatorship, a key ally against Communism, which was influential in East Timor. Moynihan ensured that the UN Security Council took no action against the larger nation's annexation of a small country. The Indonesian invasion caused the deaths of 100,000–200,000 Timorese through violence, illness, and hunger.[35][36] In his memoir, Moynihan wrote: The United States wished things to turn out as they did, and worked to bring this about. The Department of State desired that the United Nations prove utterly ineffective in whatever measures it undertook. This task was given to me, and I carried it forward with no inconsiderable success.[37] Later, he said he had defended a "shameless" Cold War policy toward East Timor.[38] Moynihan's thinking began to change during his tenure at the UN. In his 1993 book on nationalism, Pandaemonium, he wrote that as time progressed, he began to view the Soviet Union in less ideological terms. He regarded it less as an expansionist, imperialist Marxist state, and more as a weak realist state in decline. He believed it was most motivated by self-preservation. This view would influence his thinking in subsequent years, when he became an outspoken proponent of the then-unpopular view that the Soviet Union was a failed state headed for implosion. Nevertheless, Moynihan's tenure at the UN marked the beginnings of a more bellicose, neoconservative American foreign policy that turned away from Kissinger's unabashedly covert, détente-driven realpolitik.[39] Although it was never substantiated, Moynihan initially believed that Kissinger directed Ivor Richard, Baron Richard (then British Ambassador to the United Nations) to publicly denounce his actions as "Wyatt Earp" diplomacy. Demoralized, Moynihan resigned from what he would subsequently characterize as an "abbreviated posting" in February 1976. In Pandaemonium, Moynihan expounded upon this decision, maintaining that he was "something of an embarrassment to my own government, and fairly soon left before I was fired." United States Senator from New York (1977–2001) In November 1976, Moynihan was elected to the U.S. Senate from the State of New York, defeating U.S. Representative Bella Abzug, former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark, New York City Council President Paul O'Dwyer and businessman Abraham Hirschfeld in the Democratic primary, and Conservative Party incumbent James L. Buckley in the general election. He also was nominated by the Liberal Party of New York.[40] Shortly after election, Moynihan analyzed the State of New York's budget to determine whether it was paying out more in federal taxes than it received in spending. Finding that it was, he produced a yearly report known as the Fisc (from the French[41]). Moynihan's strong support for Israel while UN Ambassador inspired support for him among the state's large Jewish population.[42] In an August 7, 1978 speech to the Senate, following the jailing of M. A. Farber, Moynihan stated the possibility of Congress having to become involved with securing press freedom and that the Senate should be aware of the issue's seriousness.[43] Moynihan's strong advocacy for New York's interests in the Senate, buttressed by the Fisc reports and recalling his strong advocacy for US positions in the UN, did at least on one occasion allow his advocacy to escalate into a physical attack. Senator Kit Bond, nearing retirement in 2010, recalled with some embarrassment in a conversation on civility in political discourse that Moynihan had once "slugged [Bond] on the Senate floor after Bond denounced an earmark Moynihan had slipped into a highway appropriations bill. Some months later Moynihan apologized, and the two occasionally would relax in Moynihan's office after a long day to discuss their shared interest in urban renewal over a glass of port."[44] Moynihan continued to be interested in foreign policy as a Senator, sitting on the Select Committee on Intelligence. His strongly anti-Soviet views became far more moderate when he emerged as a critic of the Reagan administration's hawkish tilt in the late Cold War, as exemplified by its support for the Contras in Nicaragua. Moynihan argued there was no active Soviet-backed conspiracy in Latin America, or anywhere. He suggested the Soviets were suffering from massive internal problems, such as rising ethnic nationalism and a collapsing economy. In a December 21, 1986, editorial in The New York Times, Moynihan predicted the replacement on the world stage of Communist expansion with ethnic conflicts. He criticized the administration's "consuming obsession with the expansion of Communism – which is not in fact going on." In a September 8, 1990 letter to Erwin Griswold, Moynihan wrote: "I have one purpose left in life; or at least in the Senate. It is to try to sort out what would be involved in reconstituting the American government in the aftermath of the [C]old [W]ar. Huge changes took place, some of which we hardly notice."[45] In 1981 he and fellow Irish-American politicians Senator Ted Kennedy and Speaker of the House Tip O'Neill co-founded the Friends of Ireland, a bipartisan organization of Senators and Representatives who opposed the ongoing sectarian violence and aimed to promote peace and reconciliation in Northern Ireland.[citation needed] Moynihan introduced Section 1706 of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which cost certain professionals (like computer programmers, engineers, draftspersons, and designers) who depended on intermediary agencies (consulting firms) a self-employed tax status option, but other professionals (like accountants and lawyers) continued to enjoy Section 530 exemptions from payroll taxes. This change in the tax code was expected to offset the tax revenue losses of other legislation that Moynihan proposed to change the law of foreign taxes of Americans working abroad.[46] Joseph Stack, who flew his airplane into a building housing IRS offices on February 18, 2010, posted a suicide note that, among many factors, mentioned the Section 1706 change to the Internal Revenue Code.[47][48] As a key Environment and Public Works Committee member, Moynihan gave vital support and guidance to William K. Reilly, who served under President George H. W. Bush as Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency.[49] External videos video icon Tribute to Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Wilson International Center for Scholars, March 17, 1997 (part one), C-SPAN video icon Tribute to Moynihan at the Wilson Center, March 17, 1997 (part two), C-SPAN video icon Panel discussion on Moynihan's life and career, held at the Museum of the City of New York, October 18, 2010, C-SPAN Early in his career in the Senate, Moynihan had expressed his annoyance with adamantly pro-choice, pro woman groups petitioning him and others on the issue of abortion. He challenged them saying, "you women are ruining the Democratic Party with your insistence on abortion." Moynihan broke with orthodox liberal positions of his party on numerous occasions. As chairman of the Senate Finance Committee in the 1990s, he strongly opposed President Bill Clinton's proposal to expand health care coverage to all Americans. Seeking to focus the debate over health insurance on the financing of health care, Moynihan garnered controversy by stating that "there is no health care crisis in this country."[50] On other issues though, he was much more progressive. He voted against the death penalty; the flag desecration amendment;[51] the balanced budget amendment, the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act; the Defense of Marriage Act; the Communications Decency Act; and the North American Free Trade Agreement. He was critical of proposals to replace the progressive income tax with a flat tax.[citation needed] Moynihan also voted against authorization of the Gulf War.[52] Despite his earlier writings on the negative effects of the welfare state, he ended by voting against welfare reform in 1996, a bill that removed unemployment benefits. He was sharply critical of the bill and certain Democrats who crossed party lines to support it.[53] |

米国大使 1969年10月のホワイトハウス国内政策スタッフの再編成後、モイニハンは1969年11月17日、ニクソンから国連大使(当時は外務官僚のチャール ズ・ウッドラフ・ヨストが務めていた)の職をオファーされた。当初は大統領のオファーを受け入れたが、家族支援計画が上院財政委員会で行き詰まったため、 ワシントンに留まることを決めた。 25]1970年11月24日、彼は家族への負担と継続的な財政問題、リベラルな民主党議員による家族扶助計画の否認からくる不況、キッシンジャー大統領 補佐官(国家安全保障問題担当)とウィリアム・P・ロジャース国務長官に次ぐ三次的な役割であるこの役職での固定的な政策指示のために変化をもたらすこと ができないことを理由に、ニクソンからの2度目のオファーを拒否した[25]。その代わり、ジョージ・H・W・ブッシュの大使在任中は、米国代表団の非常 勤メンバーとしてハーバード大学から通学していた[25]。 1973年、モイニハンは(パキスタンに対する政権の「傾斜」に慎重であった)ニクソンの申し出を受け入れ、駐インド米国大使として1975年まで在任し た。1971年の印パ戦争後、両国関係は低迷していた。モイニハン大使は、2つの偉大な民主主義国家が敵対関係にあることを憂慮し、事態の収拾に乗り出し た。彼は、重荷となっていた債務の一部を帳消しにし、一部は在インド米国大使館の経費に充て、残りはインド・ルピーに換えて、四半世紀にわたって続いた印 米文化・教育交流プログラムに充てることを提案した。1974年2月18日、彼はインド政府に当時2,046,700,000ドルに相当する 16,640,000,000ルピーの小切手を提示した。[28] 1975年6月、モイニハンは3度目となる国連大使就任のオファーを受けるが、この地位は1976年2月までしか続かなかった(国連安全保障理事会議長の 交代を含む)。ジェラルド・フォード大統領の下、モイニハン大使は当時のホワイトハウスの方針に沿って、強硬な反共姿勢をとった。彼はまたイスラエルの強 力な支持者でもあり[29]、シオニズムを人種差別の一形態であると宣言した国連決議3379を非難した[30]。モイニハンの妻リズは後に、論争中にパ レスチナ解放機構常任オブザーバーのズフディ・ラビブ・テルジに国連ギャラリーで声をかけられたことを回想している。彼は後に、正確な言い回しは覚えてい ないが、おおよそ「ニューデリーでの出来事を思い出して複雑な気持ちになっているに違いない」と発言し、彼女と伝記作家のギル・トロイは、2年前に失敗し た夫に対する暗殺計画への脅迫的な言及だと解釈した[31]。 [モイニハンがこの決議に反対したのは、それが完全に虚偽で曲解されたものだと考えたからである[32]。また、ニューヨークで過ごした年月は、彼に現実 的な問題を意識させた: 「シオニズムに反対する決議は、イスラエルだけでなく、アメリカのユダヤ人の大多数を含むすべてのシオニストの人々に影響を与えた」のであり、このこと は、そのコミュニティが決議案承認への投票の結果としてメキシコに対する観光ボイコットを推進したときに明らかになった[33]。 モイニハンのキャリアの中でおそらく最も物議を醸したのは、1975年のインドネシアによる東ティモール侵攻に対する国連大使としての彼の対応であった。 ジェラルド・フォードは、当時軍事独裁政権下にあったインドネシアを、東ティモールに影響力を持つ共産主義に対抗する重要な同盟国と考えていた。モイニハ ンは、国連安全保障理事会が、大国による小国の併合に対して何の行動も起こさないようにした。インドネシアの侵攻は、暴力、病気、飢餓によって10万 ~20万人の東ティモール人を死に至らしめた[35][36]: 米国は、事態がこのようになることを望み、そうなるように努力した。国務省は、国連がどのような措置を講じようとも、まったく効果がないことを証明することを望んだ。この任務は私に与えられ、私はそれを遂行し、少なからぬ成功を収めた[37]。 後に彼は、東ティモールに対する「恥知らずな」冷戦政策を擁護してきたと語っている[38]。 モイニハンの考え方は、国連在任中に変わり始めた。1993年に出版したナショナリズムに関する著書『パンダエモニウム(Pandaemonium)』の 中で、モイニハンは、時が経つにつれて、ソ連をイデオロギー的な観点から見ることが少なくなっていったと書いている。ソ連を拡張主義的、帝国主義的なマル クス主義国家としてではなく、衰退しつつある弱い現実主義国家としてとらえたのである。彼は、ソ連が最も意欲的なのは自存自衛であると考えていた。この見 解は、ソ連は崩壊に向かう破綻国家であるという当時は不評であった見解の率直な支持者となったモイニハンのその後の考え方に影響を与えることになる。 とはいえ、モイニハンの国連在任中は、より好戦的で新保守主義的なアメリカ外交の始まりであり、キッシンジャーの臆面もない秘密主義、デタント主導の現実 政治から目を背けたものであった[39]。 実証されたことはなかったが、モイニハンは当初、キッシンジャーがアイボア・リチャード男爵(当時のイギリス国連大使)に自分の行動を「ワイアット・アー プ」外交として公に非難するよう指示したと考えていた。意気消沈したモイニハンは、1976年2月、後に彼が「略式の赴任」と表現することになる辞任をし た。パンダモニウム』の中で、モイニハンはこの決断について、「自分自身の政府に対する恥さらしのようなもので、解雇される前にすぐに辞めた」と述べてい る。 ニューヨーク州選出上院議員(1977年-2001年) 1976年11月、モイニハンはニューヨーク州選出の連邦上院議員に選出され、民主党の予備選挙でベラ・アブズグ下院議員、ラムゼー・クラーク元司法長 官、ポール・オドワイヤーニューヨーク市議会議長、実業家のエイブラハム・ハーシュフェルドを破り、総選挙では保守党現職のジェームズ・L・バックリーを 破った。当選直後、モイニハンはニューヨーク州の予算を分析し、連邦税の支払いが支出を上回っていないかどうかを調べた。その結果、彼は「フィスク」(フ ランス語[41])として知られる年次報告書を作成した。国連大使時代のモイニハンのイスラエルへの強い支持は、同州の多くのユダヤ系住民の間での彼への 支持を刺激した[42]。 1978年8月7日、M・A・ファーバーが投獄された後の上院での演説で、モイニハンは議会が報道の自由の確保に関与しなければならない可能性を述べ、上院はこの問題の深刻さを認識すべきだと述べた[43]。 上院におけるモイニハンのニューヨークの利益のための強力な擁護は、フィスクの報告書に後押しされ、国連における米国の立場のための強力な擁護を思い起こ させるものであったが、少なくとも一度、その擁護が物理的な攻撃にエスカレートすることがあった。2010年に引退を間近に控えたキット・ボンド上院議員 は、政治的言説の礼節に関する会話の中で、モイニハンが「モイニハンが高速道路充当法案に紛れ込ませた耳目をボンドが糾弾した後、上院議場で(ボンドを) 殴った」ことがあったと、少し恥ずかしそうに回想した。数カ月後、モイニハンは謝罪し、2人は長い一日の後にモイニハンのオフィスでくつろぎ、ポートワイ ンを飲みながら都市再生への共通の関心について語り合うこともあった」[44]。 モイニハンは上院議員になっても外交政策に関心を持ち続け、情報特別委員会の委員を務めた。ニカラグアのコントラへの支援に代表されるように、冷戦後期に おけるレーガン政権のタカ派的な姿勢を批判する立場になると、彼の反ソ的な考え方ははるかに穏健なものとなった。モイニハンは、ラテンアメリカでもどこで も、ソ連が支援する陰謀など存在しないと主張した。彼は、ソビエトは民族ナショナリズムの高まりや経済の崩壊といった大規模な内部問題に苦しんでいると示 唆した。1986年12月21日付のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の社説で、モイニハンは、共産主義の拡大が世界の舞台で民族紛争に取って代わると予測した。 モイニハンは、政権の「共産主義の拡大への執着-それは実際には進行していない-」を批判した。1990年9月8日、アーウィン・グリスウォルドに宛てた 手紙の中で、モイニハンはこう書いている。それは、旧大戦後のアメリカ政府を再建するために何が必要かを整理することです。1981年、彼は同じアイルラ ンド系アメリカ人の政治家であるテッド・ケネディ上院議員、ティップ・オニール下院議長とともに、現在も続く宗派間の暴力に反対し、北アイルランドの和平 と和解を促進することを目的とした上院議員と下院議員による超党派組織「アイルランドの友」を共同設立した[要出典]。 モイニハンは1986年税制改革法第1706条を導入し、仲介機関(コンサルティング会社)に依存する特定の専門家(コンピュータ・プログラマー、エンジ ニア、製図技師、デザイナーなど)には自営業という税制上の選択肢を与えたが、その他の専門家(会計士や弁護士など)には引き続き530条による給与税免 除が適用された。この税法の変更は、モイニハンが海外で働くアメリカ人の外国税に関する法律を変更するために提案した他の法案による税収減を相殺すること が期待されていた[46]。2010年2月18日に国税庁の事務所があるビルに飛行機で突っ込んだジョセフ・スタックは、多くの要因の中で、内国歳入法の 1706条変更に言及した遺書を投稿した[47][48]。 環境・公共事業委員会の主要メンバーとして、モイニハンはジョージ・H・W・ブッシュ大統領の下で環境保護庁長官を務めたウィリアム・K・ライリーに重要な支援と指導を行った[49]。 外部ビデオ video icon ダニエル・パトリック・モイニハン上院議員へのトリビュート、ウィルソン国際学術センター、1997年3月17日(前編)、C-SPAN video icon 1997年3月17日、ウィルソン・センターでのモイニハンへの賛辞(後編)、C-SPAN video icon モイニハンの生涯とキャリアに関するパネルディスカッション、ニューヨーク市博物館にて、2010年10月18日、C-SPAN モイニハンは上院議員としてのキャリアの初期に、中絶問題に関して断固としてプロ・チョイス、プロ・ウーマンのグループが彼や他の人々に陳情することに苛立ちを表明していた。彼は、「あなた方女性は、中絶に固執して民主党をダメにしている」と、彼女たちを挑発した。 モイニハンは党の正統派リベラルの立場を何度も破った。1990年代には上院財政委員会の委員長として、ビル・クリントン大統領が提案したすべてのアメリ カ人に医療保険を拡大するという提案に強く反対した。健康保険をめぐる議論を医療財政に集中させようとしたモイニハンは、「この国に医療危機は存在しな い」と発言して物議を醸した[50]。 しかし他の問題については、彼はより進歩的であった。死刑制度、国旗冒涜修正案[51]、均衡予算修正案、私募証券訴訟改革法、結婚防衛法、通信品位法、 北米自由貿易協定に反対票を投じた。モイニハンはまた、湾岸戦争の承認に反対票を投じた[52]。福祉国家の弊害に関する以前の著作にもかかわらず、彼は 1996年の福祉改革(失業手当を廃止する法案)に反対票を投じた。この法案と、党派を超えてこの法案を支持した特定の民主党議員を厳しく批判した [53]。 |

| Public speaker Moynihan was a popular public speaker with a distinctly patrician style. He spoke with a slight stutter, which led him to draw out vowels. Linguist Geoffrey Nunberg compared his speaking style to that of William F. Buckley, Jr.[54] Commission on Government Secrecy Main article: Moynihan Commission on Government Secrecy This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Daniel Patrick Moynihan" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) In the post-Cold War era, the 103rd Congress enacted legislation directing an inquiry into the uses of government secrecy. Moynihan chaired the commission, which studied and made recommendations on the "culture of secrecy" that pervaded the United States government and its intelligence community for 80 years, beginning with the Espionage Act of 1917, and made recommendations on the statutory regulation of classified information. The commission's findings and recommendations were presented to the President in 1997. As part of the effort, Moynihan secured release from the Federal Bureau of Investigation of its classified Venona file. This file documents the FBI's joint counterintelligence investigation, with the United States Signals Intelligence Service, into Soviet espionage within the United States. Much of the information had been collected and classified as secret information for over 50 years. After release of the information, Moynihan authored Secrecy: The American Experience[55] where he discussed the impact government secrecy has had on the domestic politics of America for the past half century, and how myths and suspicion created an unnecessary partisan chasm. Personal life Moynihan married Elizabeth Brennan in 1955. The couple had three children, Tim, Maura, and John, and were married until Moynihan's death at Washington Hospital Center on March 26, 2003, from complications of a ruptured appendix, ten days after his 76th birthday.[56] Moynihan was criticized after reportedly making offensive comments towards a woman of Jamaican descent at Vassar College in early 1990.[57] During a question-and-answer session, Moynihan told Folami Grey, an official at the Dutchess County Youth Bureau, "If you don't like it in this country, why don't you pack your bags and go back where you came from". This incident caused a protest in which 100 students took over the college's main administration building in response to his comments. |

演説家 モイニハンは、独特のパトリシアン・スタイルで人気のある演説家だった。少し吃音があり、母音を引きずるように話す。言語学者のジェフリー・ナンバーグは、彼の話し方をウィリアム・F・バックリーJr.と比較した[54]。 政府機密委員会 主な記事 政府機密に関するモイニハン委員会 このセクションでは、検証のために追加の引用が必要です。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力ください。ソースのないものは異議申し立てがなされ、削除されることがあります。 出典を探す 「ダニエル・パトリック・モイニハン" - ニュース - 新聞 - 書籍 - 学術雑誌 - JSTOR (June 2021) (このテンプレートメッセージの削除方法と削除時期を知る) 冷戦後、第103回連邦議会は政府機密の使用に関する調査を指示する法案を制定した。モイニハンが委員長を務めたこの委員会は、1917年のスパイ防止法 に始まる80年間、米国政府とその情報機関に浸透していた「秘密文化」について調査し、機密情報の法的規制について勧告を行った。 委員会の調査結果と勧告は1997年に大統領に提出された。その一環として、モイニハンは連邦捜査局から機密情報ヴェノナ・ファイルの公開を取り付けた。 このファイルは、米国内のソ連のスパイ活動について、FBIが米国通信情報局と共同で防諜調査を行ったことを記録したものである。情報の多くは50年以上 にわたって収集され、秘密情報として分類されていた。 情報公開後、モイニハンは『Secrecy: The American Experience』[55]を執筆し、政府の秘密が過去半世紀にわたってアメリカの国内政治に与えた影響と、神話と疑惑がいかに不必要な党派間の溝を生み出したかを論じた。 私生活 モイニハンは1955年にエリザベス・ブレナンと結婚。夫妻にはティム、モーラ、ジョンの3人の子供がおり、モイニハンが76歳の誕生日を迎えて10日後の2003年3月26日、盲腸破裂の合併症によりワシントン病院センターで死去するまで結婚生活を送った[56]。 モイニハンは1990年初頭、ヴァッサー大学でジャマイカ系の女性に対して攻撃的な発言をしたと報じられ、批判を浴びた[57]。 質疑応答の際、モイニハンはダッチェス郡青少年局の職員フォラミ・グレイに「この国が嫌なら、荷物をまとめて元の場所に帰ったらどうだ」と言った。この発 言に対し、100人の学生が大学の管理棟を占拠する抗議デモが起こった。 |

| Death Moynihan died March 26, 2003, due to complications of a ruptured appendix.[58] Career as scholar As a public intellectual, Moynihan published articles on urban ethnic politics and on the problems of the poor in cities of the Northeast in numerous publications, including Commentary and The Public Interest. Moynihan coined the term "professionalization of reform", by which the government bureaucracy thinks up problems for government to solve rather than simply responding to problems identified elsewhere.[59] In 1983, he was awarded the Hubert H. Humphrey Award given by the American Political Science Association "in recognition of notable public service by a political scientist."[60] He wrote 19 books, leading his personal friend, columnist and former professor George F. Will, to remark that Moynihan "wrote more books than most senators have read." After retiring from the Senate, he rejoined the faculty of the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University, where he began his academic career in 1959.[61] Moynihan's scholarly accomplishments led Michael Barone, writing in The Almanac of American Politics to describe the senator as "the nation's best thinker among politicians since Lincoln and its best politician among thinkers since Jefferson."[62] Moynihan's 1993 article, "Defining Deviancy Down",[63] was notably controversial.[64][65] Writer and historian Kenneth Weisbrode describes Moynihan's book Pandaemonium as uncommonly prescient.[66] Selected books Beyond the Melting Pot, an influential study of American ethnicity, which he co-authored with Nathan Glazer (1963) The Negro Family: The Case For National Action, known as the Moynihan Report (1965) Maximum Feasible Misunderstanding: Community Action in the War on Poverty (1969) ISBN 0-02-922000-9 Violent Crimes (1970) ISBN 0-8076-6053-1 Coping: Essays on the Practice of Government (1973) ISBN 0-394-48324-3 The Politics of a Guaranteed Income: The Nixon Administration and the Family Assistance Plan (1973) ISBN 0-394-46354-4. Business and Society in Change (1975) OCLC 1440432 A Dangerous Place coauthor Suzanne Garment, (1978) ISBN 0-316-58699-4 Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year, 1980 (1980) ISBN 1-56554-516-8 Family and Nation: The Godkin Lectures (1986) ISBN 0-15-630140-7 Came the Revolution (1988) On the Law of Nations (1990) ISBN 0-674-63576-0 Pandaemonium: Ethnicity in International Politics (1994) ISBN 0-19-827946-9 Miles to Go: A Personal History of Social Policy (1996) ISBN 0-674-57441-9 Secrecy: The American Experience (1998) ISBN 0-300-08079-4 Future of the Family (2003) ISBN 0-87154-628-0 Awards and honors In 1966, Moynihan was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[67] In 1968, Moynihan was elected to the American Philosophical Society[68] The 5th Annual Heinz Award in Public Policy (1999)[69] Honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Tufts, his alma mater. 1989 Honor Award from the National Building Museum[70] In 1989, Moynihan received the U.S. Senator John Heinz Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards.[71] On August 9, 2000, he was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Clinton.[72] In 1992, he was awarded the Laetare Medal by the University of Notre Dame, considered the most prestigious award for American Catholics.[73] In 1994 the U.S. Navy Memorial Foundation awarded Moynihan its Lone Sailor Award for his naval service and subsequent government service. Honors The Moynihan Train Hall, which opened in January 2021, is named for him. It expanded New York Penn Station with a new concourse for Long Island Rail Road and Amtrak passengers in the adjacent, renovated James Farley Post Office building.[74] Moynihan had long championed the project, which is modeled after the original Penn Station; he had shined shoes in the original station as a boy during the Great Depression. During his latter years in the Senate, Moynihan had to secure federal approvals and financing for the project.[75] In 2005, the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs of Syracuse University renamed its Global Affairs Institute as the Moynihan Institute of Global Affairs.[76] The federal district courthouse in Manhattan's Foley Square was named in his honor. |

死去 2003年3月26日、盲腸破裂の合併症により死去[58]。 学者としてのキャリア 公共知識人として、モイニハンは『Commentary』や『The Public Interest』など数多くの出版物に、都市の民族政治や北東部の都市における貧困層の問題に関する論文を発表した。 モイニハンは「改革の専門化」という言葉を生み出したが、この言葉では、政府官僚機構が、他の場所で特定された問題に単に対応するのではなく、政府が解決すべき問題を考え出すというものである[59]。 1983年には、アメリカ政治学会から「政治学者による顕著な公共奉仕を称えて」贈られるヒューバート・H・ハンフリー賞を受賞した[60]。19冊の著 作があり、個人的な友人であるコラムニストで元教授のジョージ・F・ウィルは、モイニハンについて「ほとんどの上院議員が読んだことのある本よりも多くの 本を書いた」と評した。上院議員を引退した後、シラキュース大学のマックスウェル・スクール・オブ・シチズンシップ・アンド・パブリック・アフェアーズの 教授陣に復帰し、1959年から学問的キャリアをスタートさせた[61]。 モイニハンの学問的業績により、マイケル・バローンは『アメリカ政治年鑑』でこの上院議員を「政治家としてはリンカーン以来、思想家としてはジェファーソ ン以来、国家最高の思想家」[62]と評している。1993年のモイニハンの論文「Defining Deviancy Down」[63]は特に物議を醸した[64][65]。作家で歴史家のケネス・ワイズブロードは、モイニハンの著書『Pandaemonium』を類ま れな先見の明があると評している[66]。 主な著書 ネイサン・グレイザーと共著したアメリカのエスニシティに関する影響力のある研究書『Beyond the Melting Pot』(1963年) The Negro Family: モイニハン・レポートとして知られる『The Case For National Action』(1965年) 最大限の誤解: 貧困との戦いにおけるコミュニティ活動(1969年)ISBN 0-02-922000-9 暴力犯罪 (1970) ISBN 0-8076-6053-1 コーピング 政府の実践に関するエッセイ (1973) ISBN 0-394-48324-3 所得保障の政治学: ニクソン政権と家族扶助計画 (1973) ISBN 0-394-46354-4. 変化するビジネスと社会 (1975) OCLC 1440432 危険な場所 共著 スザンヌ・ガーメント (1978) ISBN 0-316-58699-4 ベスト・エディトリアル・カートゥーン・オブ・ザ・イヤー, 1980 (1980) ISBN 1-56554-516-8 家族と国家 ゴドキン講義 (1986) ISBN 0-15-630140-7 革命の到来 (1988) 国際法について (1990) ISBN 0-674-63576-0 パンダエモニウム 国際政治におけるエスニシティ (1994) ISBN 0-19-827946-9 Miles to Go: 社会政策の個人史 (1996) ISBN 0-674-57441-9 秘密主義: アメリカの経験 (1998) ISBN 0-300-08079-4 家族の未来 (2003) ISBN 0-87154-628-0 受賞と栄誉 1966年、モイニハンはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーに選出される[67]。 1968年、モイニハンはアメリカ哲学協会に選出される[68]。 第5回ハインツ賞公共政策部門受賞(1999年)[69]。 母校タフツ大学から名誉法学博士号を授与。 1989年、国立建築博物館から名誉賞[70]。 1989年、モイニハンはジェファーソン・アワードが毎年授与する、被選挙権者または任命権者による最も偉大な公共サービスに贈られるジョン・ハインツ賞(U.S. Senator John Heinz Award)を受賞[71]。 2000年8月9日、クリントン大統領から大統領自由勲章を授与された[72]。 1992年、ノートルダム大学から、アメリカのカトリック教徒にとって最も権威ある賞とされるレーターレ・メダルを授与される[73]。 1994年、米海軍記念財団は、モイニハンの海軍勤務とその後の政府勤務に対して「孤高の船乗り賞」を授与。 栄誉 2021年1月にオープンしたモイニハン・トレイン・ホールは彼の名にちなんで命名された。モイニハンは以前からこのプロジェクトを支持しており、そのモ デルとなっているのはオリジナルのペン・ステーションである。上院議員の晩年、モイニハンはこのプロジェクトのために連邦政府の承認と融資を確保しなけれ ばならなかった[75]。 2005年、シラキュース大学マックスウェル・スクール・オブ・シチズンシップ・アンド・パブリック・アフェアーズは、グローバル・アフェアーズ・インスティテュートをモイニハン・インスティテュート・オブ・グローバル・アフェアーズと改称した[76]。 マンハッタンのフォーリー・スクエアにある連邦地方裁判所は、モイニハンにちなんで命名された。 |

| Quotes "I don't think there's any point in being Irish if you don't know that the world is going to break your heart eventually. I guess that we thought we had a little more time." – Reacting to the assassination of John F. Kennedy, November 1963[77] "No one is innocent after the experience of governing. But not everyone is guilty." – The Politics of a Guaranteed Income, 1973[78] "Secrecy is for losers. For people who do not know how important the information really is." – Secrecy: The American Experience, 1998[79] The quote also adds, "The Soviet Union realized this too late. Openness is now a singular, and singularly American, advantage." "The issue of race could benefit from a period of benign neglect." – Memo to President Richard Nixon[80] "Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts." – Column on January 18, 1983 The Washington Post. Based on an earlier quote by James R. Schlesinger.[81] (In response to the question: "Why should I work if I am going to just end up emptying slop jars?") "That's a complaint you hear mostly from people who don't empty slop jars. This country has a lot of people who do exactly that for a living. And they do it well. It's not pleasant work, but it's a living. And it has to be done. Somebody has to go around and empty all those bed pans. And it's perfectly honorable work. There's nothing the matter with doing it. Indeed, there is a lot that is right about doing it, as any hospital patient will tell you."[82] "Food growing is the first thing you do when you come down out of the trees. The question is, how come the United States can grow food and you can't?" – speaking to Third World countries about global famine[83] "The central conservative truth is that it is culture, not politics, that determines the success of a society. The central liberal truth is that politics can change a culture and save it from itself."[84][85] "Truman left the Presidency thinking that Whittaker Chambers, Elizabeth Bentley were nuts, crackpots, scoundrels, and I think you could say that a fissure began in American political life that's never really closed. It reverberates, and I can say more about it. But in the main, American liberalism—Arthur Schlesinger, one of the conspicuous examples—got it wrong. We were on the side of the people who denied this, and a president who could have changed his rhetoric, explained it, told the American people, didn't know the facts, they were secret, and they were kept from him." – Secrecy: The American Experience, October 1998[86] |

引用 「アイルランド人である意味はないと思う。私たちにはもう少し時間があると思っていたのでしょう。" - ジョン・F・ケネディ暗殺への反応、1963年11月[77]。 「統治を経験した後に無罪になる人はいない。しかし、誰もが有罪というわけではない。 - 所得保証の政治学』1973年[78](The Politics of a Guaranteed Income, 1973) 「秘密主義は敗者のためのものだ。その情報が本当にどれほど重要かを知らない人々のためのものだ。 - 秘密主義: アメリカの経験』1998年[79] ソ連はこのことに気づくのが遅すぎた。オープンであることは、いまやアメリカ独自の、特異な利点である。 "人種問題は、ある期間温和な無視から利益を得ることができる。" - リチャード・ニクソン大統領へのメモ[80]。 「誰もが自分の意見を持つ権利はあるが、自分の事実を持つ権利はない。 - 1983年1月18日付ワシントン・ポスト紙コラム。ジェームズ・R・シュレジンジャーによる以前の引用に基づく[81]。 (質問に対して: 「ドロ瓶を空にするだけなら、なぜ働かなければならないのか?) 「それは、ドロ瓶を空にしない人々から多く聞かれる不満だ。この国には、まさにそれを生業としている人々がたくさんいる。そして彼らはよくやっている。楽 しい仕事ではないけれど、生活のためだ。そして、やらなければならない。誰かがベッドパンを空にして回らなければならない。そして、それは完全に名誉ある 仕事だ。何も問題はない。入院患者なら誰でも言うだろう。 「食料栽培は、木から下りてきて最初にすることである。問題は、なぜアメリカは食料を栽培できて、あなた方はできないのか、ということです」。 - 世界的な飢饉について第三世界諸国に向かって語る[83]。 「保守派の中心的な真理は、社会の成功を決めるのは政治ではなく文化であるということだ。リベラルの中心的な真理は、政治が文化を変え、文化をそれ自体から救うことができるということである」[84][85]。 「トルーマンは、ウィテカー・チェンバーズやエリザベス・ベントレーは気違いだ、変人だ、悪党だと思いながら大統領の座を去った。その亀裂は今もなお続い ており、私はそれについてもっと語ることができる。しかし大筋では、アメリカのリベラリズムは間違っていた。私たちはこの問題を否定する側の人間であり、 暴言を改め、説明し、米国民に伝えることができたはずの大統領が、事実を知らなかった。 - 秘密: アメリカの経験』1998年10月号[86] |

| Benign neglect "Benign neglect" redirects here. Not to be confused with Salutary neglect. Benign neglect is a policy proposed in 1969 by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who was then on President Richard Nixon's staff as an urban affairs adviser. While serving in this capacity, he sent Nixon a memo that suggested, "The time may have come when the issue of race could benefit from a period of 'benign neglect.' The subject has been too much talked about. The forum has been too much taken over to hysterics, paranoids, and boodlers on all sides. We need a period in which Negro progress continues and racial rhetoric fades."[7] The policy was designed to ease tensions after the Civil Rights Movement of the late 1960s. Moynihan was particularly troubled by the speeches of Vice-President Spiro Agnew. However, the policy was widely seen as the municipal disinvestment to abandon urban neighborhoods]], particularly ones with a majority-black population, as Moynihan's statements and writings appeared to encourage, for instance, fire departments engaging in triage to avoid a supposedly-futile war against arson.[2] |

良性のネグレクト "良性のネグレクト "はここにリダイレクトされる。救済的ネグレクトと混同しないように。 ベニグネグレクトとは、1969年にダニエル・パトリック・モイニハンが提唱した政策である。モイニハンはこの職務に就いていたとき、ニクソン大統領にメ モを送り、「人種問題は "良性の無視 "の期間から恩恵を受ける時が来たかもしれない」と提案した。この話題はあまりにも多く語られてきた。ヒステリックで偏執的で、各方面から非難を浴びるよ うな議論の場になっている。われわれは、黒人の進歩が続き、人種的なレトリックが薄れていく時期が必要なのだ」[7]。この政策は、1960年代後半の公 民権運動後の緊張を緩和するために立案された。モイニハンは特にスピロ・アグニュー副大統領の演説に悩まされていた。しかし、モイニハンの発言や著作は、 例えば、放火に対する本来は無駄な戦いを避けるためにトリアージに従事する消防署を奨励するように見えたため、この政策は、特に黒人が多数を占める都市近 隣]]を放棄するための自治体の非投資として広く見られた[2]。 |

| Salutary neglect. In American history, salutary neglect was the 18th-century policy of the British Crown of avoiding the strict enforcement of parliamentary laws, especially trade laws, as long as British colonies remained loyal to the government and contributed to the economic growth of their parent country, England and then, after the Acts of Union 1707, Great Britain. The term was first used in 1775 by Edmund Burke. Until the late 17th century, mercantilist ideas were gaining force in England and giving general shape to trade policy through a series of Navigation Acts. From the collapse of the centralized Dominion of New England in 1689 to 1763, salutary neglect was in effect. Afterwards, Britain began to try to enforce stricter rules and more direct management, which included the disallowment of laws to go into effect that were passed in colonial legislatures.[1] This eventually led to the American Revolutionary War.[2][3] Origins The colonies had a certain level of autonomy early on. During the establishment of the Dominion of New England, which was implemented in part to enforce the Navigation Acts, administration was centralized, and the colonies were presided over by the very unpopular Edmund Andros. After the Glorious Revolution, the 1689 Boston revolt,[2] and the removal of Andros, the colonies could return to an informal state of local ruling bodies insulated by certain boundaries from England.[4] The policy was later formalised by Robert Walpole after he took the position of Lord Commissioner of the Treasury in 1721 and worked with Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle. In an effort to increase tax income, Walpole relaxed the enforcement of trade laws and decreased regulations on the grounds that “if no restrictions were placed on the colonies, they would flourish”.[2] Walpole did not believe in enforcing the Navigation Acts, which had been established under Oliver Cromwell and Charles II and required goods traded between Britain and its colonies to be carried on English ships as part of the larger economic strategy of mercantilism.[2][3] The policy went unnamed until the term was coined in Edmund Burke's "Speech on Conciliation with America," which was given in the House of Commons on March 22 1775. The speech praised the governance of the British America, which, "through a wise and salutary neglect," had achieved great commercial success:[5][6] When I know that the colonies in general owe little or nothing to any care of ours, and that they are not squeezed into this happy form by the constraints of watchful and suspicious government, but that, through a wise and salutary neglect, a generous nature has been suffered to take her own way to perfection; when I reflect upon these effects, when I see how profitable they have been to us, I feel all the pride of power sink, and all presumption in the wisdom of human contrivances melt and die away within me.[7] Effects The policy succeeded in increasing money flow from the colonies to Britain. The lack of enforcement of trading laws meant American merchants profited from illegal trading with French possessions in the Caribbean from which Britain prospered, in turn, as American merchants purchased more British goods.[5] The laissez-faire nature of the policy led to the colonies being de facto independent. The policy helped develop a sense of independence and self-sufficiency and enabled colonial assemblies to wield significant power over the royally-appointed governors through their control of colony finances.[2] Additionally, Walpole's willingness to fill the unpopular colonial offices with friends and political allies led to an ineffective king's authority overseas.[5][3] West Indies The practice of a high degree of local autonomy was not limited to British colonies on the North American mainland. The island colonies in the Caribbean also enjoyed autonomy in their local legislatures.[8][9] End of policy From 1763, Britain began to try to enforce stricter rules and more direct management, which were driven in part by the outcome of the Seven Years' War in which Britain had gained large swathes of new territory in North America at the Treaty of Paris. The war meant that Britain had accrued large debts, and it was decided to deploy troops in the colonies to defend them from the continued threats from France.[2] British Prime Minister George Grenville thus proposed additional taxes to supplement the Navigation Acts that known as the Grenville Acts: the Sugar Act 1764, the Currency Act 1764, and the Stamp Act 1765 all aimed at increasing authority in and revenue from the colonies. These were unpopular in the colonies and led to the Stamp Act riots in August 1765 and the Boston Massacre in March 1770. The Grenville Acts, as well as the Intolerable Acts, were defining factors that led to the American Revolutionary War.[2] Deliberateness of policy To what extent "salutary neglect" constituted an actual neglect of colonial affairs, as the name suggests, or a conscious policy of the British government is controversial among historians, and it also varies with national perspective. Americans may side with Burke on the "salutary" effect of the policy by emphasizing the economic and social development of the colonies, but from a British imperial perspective it was a momentous failure, and debate remains as to its true social, economic, and political effects. The Board of Trade, which enforced mercantilist legislation in the United Kingdom, was too weak to enforce its own laws until 1748. Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle, became the relevant Secretary of State in 1724 but took time to learn the duties of his office, and even then, he was not firm in his action, which caused the historian James Henretta to blame salutary neglect on "administrative inefficiency, financial stringency, and political incompetence."[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salutary_neglect |

救済的ネグレクト アメリカ史では、18世紀にイギリス王室が行った政策で、イギリスの植民地が政府に忠誠を誓い、母国であるイギリス、そして1707年の連合法以降はイギ リスの経済成長に貢献する限り、議会法、特に通商法の厳格な執行を避けるというものであった。この言葉は1775年にエドモンド・バークによって初めて使 われた。 17世紀後半まで、イングランドでは重商主義的な考え方が力を持ち、一連の航海法を通じて貿易政策に一般的な形を与えていた。1689年に中央集権的な ニューイングランド藩が崩壊してから1763年までは、塩漬け放置が有効であった。その後、イギリスは植民地議会で可決された法律の発効を認めないなど、 より厳格な規則とより直接的な管理を実施しようとし始めた[1]。これが最終的にアメリカ独立戦争へとつながった[2][3]。 起源 植民地は早くから一定の自治権を持っていた。航海法の施行もあってニューイングランド・ドミニオンが設立された時期には、行政は中央集権化され、植民地は 不人気なエドマンド・アンドロスによって統治されていた。栄光革命、1689年のボストンの反乱[2]、アンドロスの解任の後、植民地はイングランドから 一定の境界線によって隔離された地方統治機関の非公式な状態に戻ることができた[4]。この政策は後に、ロバート・ウォルポールが1721年に財務長官の 職に就き、第1代ニューカッスル公トマス・ペラム=ホールズと協力した後に正式に決定された。税収を増やすために、ウォルポールは「植民地に制限を加えな ければ、植民地は繁栄する」という理由で貿易法の施行を緩和し、規制を減らした[2]。 ウォルポールは、オリヴァー・クロムウェルとチャールズ2世の下で制定され、重商主義の大きな経済戦略の一環としてイギリスと植民地との間で取引される商品をイギリス船で運ぶことを義務付けていた航海法の施行を信じていなかった[2][3]。 この政策は、1775年3月22日にエドマンド・バークが下院で行った「アメリカとの和解に関する演説」の中で造語として使われるまで、名前も知られてい なかった。この演説では、「賢明かつ有益な怠慢によって」大きな商業的成功を収めたイギリス領アメリカの統治を称賛していた[5][6]。 一般に植民地は、われわれのいかなる配慮にもほとんど、あるいはまったく負うところがなく、注意深く疑惑に満ちた政府の制約によってこの幸福な形に押し込 められたのではなく、賢明かつ有益な怠慢によって、寛大な自然が自らの道を歩んで完成に至るようにさせられたのだということを知るとき、このような効果が われわれにとってどれほど有益であったかを考えるとき、権力の誇りはすべて沈み、人間の知恵に対する僭越はすべて溶けて消え去るのを感じる[7]」。 効果 この政策は、植民地からイギリスへの資金流入を増加させることに成功した。貿易法の施行がなかったため、アメリカの商人たちはカリブ海のフランス領との違 法な取引で利益を得ており、アメリカの商人たちはイギリスの商品をより多く購入したため、イギリスは逆に繁栄した[5]。 自由放任主義が植民地の事実上の独立につながった。この政策によって独立自給の意識が芽生え、植民地議会は植民地の財政を管理することで王室が任命した総督に対して大きな権力を行使することが可能となった[2]。 さらに、ウォルポールは不人気な植民地の官職を友人や政治的同盟者で埋めようとしたため、海外では王の権威が効果的でなかった[5][3]。 西インド諸島 高度な地方自治の実践は、北米本土のイギリス植民地に限ったことではなかった。カリブ海の島嶼植民地も地方議会の自治を享受していた[8][9]。 政策の終了 1763年以降、イギリスはより厳格な規則とより直接的な管理を実施しようとし始めたが、その背景には、イギリスがパリ条約で北アメリカの広大な新領土を 獲得した七年戦争の結果もあった。この戦争によってイギリスは多額の負債を抱え、フランスからの継続的な脅威から植民地を守るために、植民地に軍隊を配備 することが決定された[2]。 1764年砂糖法、1764年通貨法、1765年印紙法は、いずれも植民地における権限と収入を増加させることを目的としたものであった。これらは植民地 では不評で、1765年8月の印紙税暴動や1770年3月のボストン大虐殺につながった。グレンヴィル法と忍容できない法は、アメリカ独立戦争を引き起こ す決定的な要因となった[2]。 政策の意図性 救済的怠慢」が、その名が示すように植民地問題に対する実際の怠慢であったのか、あるいはイギリス政府の意識的な政策であったのかについては、歴史家の間 でも論争があり、また国の立場によっても異なる。アメリカ人は、植民地の経済的・社会的発展を強調することで、この政策の「有益な」効果についてバークの 側に立つかもしれないが、イギリス帝国の視点から見れば、これは重大な失敗であり、その真の社会的・経済的・政治的効果については議論が残っている。 イギリスで重商主義的な法律を施行した貿易委員会は、1748年まで自国の法律を施行するにはあまりに弱体であった。第1代ニューカッスル公トマス・ペラ ム=ホレスは、1724年に関連する国務長官に就任したが、職務を学ぶのに時間がかかり、その上、行動もしっかりしていなかったため、歴史家ジェームズ・ ヘンレッタは、「行政の無能、財政の厳しさ、政治的無能」のせいで、俸給制の怠慢を非難した[2]。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆