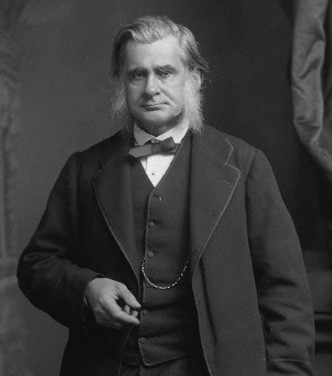

トマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー

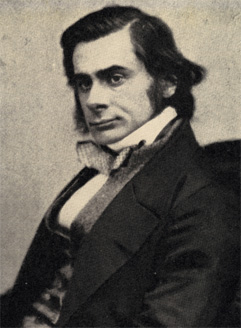

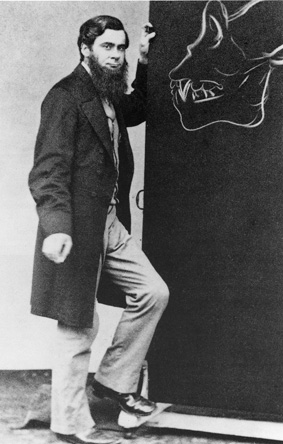

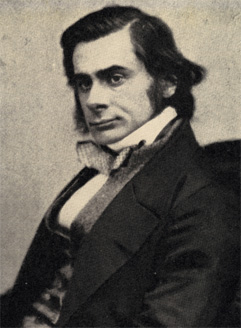

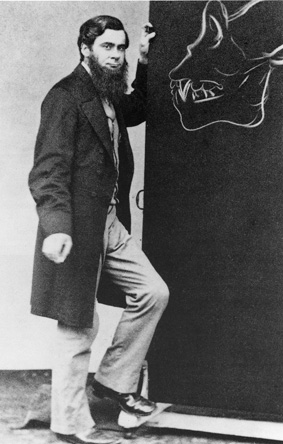

Thomas Henry Huxley, 1825-1895

☆ トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー(Thomas Henry Huxley PC FRS HonFRSE FLS、1825年5月4日 - 1895年6月29日)は、比較解剖学を専門としたイギリスの生物学者、人類学者である。チャールズ・ダーウィンの進化論を提唱し、「ダーウィンのブル ドッグ」として知られるようになった。 ハクスリーが1860年にオックスフォードで行った有名なサミュエル・ウィルバーフォースとの進化論論争に関する話は、進化論が広く受け入れられるように なった重要な瞬間であり、彼自身のキャリアにおいても重要な出来事であったが、現存する論争に関する話は後世の捏造であると考える歴史家もいる。ウィル バーフォースの指導を受けたのはリチャード・オーウェンで、ハクスリーもまた、人類が類人猿に近縁であるかどうかについて議論した。 ハクスリーは、漸進主義などダーウィンの考えのいくつかを受け入れるのに時間がかかり、自然淘汰については決めかねていたが、にもかかわらず、ダーウィン を公の場で心から支持した。イギリスにおける科学教育の発展に大きく貢献し、宗教的伝統の極端なバージョンと闘った。ハクスリーは1869年に「不可知 論」という言葉を創作し、1889年にはそれを発展させ、何が知りうることで、何が知りえないかという観点から、主張の本質を構成した。 ハクスリーは正規の学校教育をほとんど受けず、事実上独学で学んだ。無脊椎動物を研究し、それまでほとんど理解されていなかったグループ間の関係を明らか にした。その後、彼は脊椎動物、特に類人猿と人間の関係に取り組んだ。アルケオプテリクスとコンプソグナトゥスを比較した後、彼は鳥類は小型肉食恐竜から 進化したと結論づけた。 この優れた解剖学的業績は、進化論を支持する彼の精力的かつ論争的な活動や、科学教育に関する彼の広範な公的活動の影に隠れがちであったが、これらはいず れもイギリスやその他の地域の社会に大きな影響を与えた。ハクスリーの1893年のロマネス講義「進化と倫理」は、中国において非常に大きな影響力を持 ち、ハクスリーの講義の中国語訳は、ダーウィンの『種の起源』の中国語訳を変えたほどである。

★ハクスリーは人種主義者だったか?(論争)

| Racism debate In October 2021, a history group reviewing colonial links told Imperial College London that, because Huxley "might now be called racist", it should remove a bust of him and rename its Huxley Building. The group of 21 academics had been launched in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 to address Imperial's "links to the British Empire" and build a "fully inclusive organisation". It reported that Huxley's paper Emancipation – Black and White "espouses a racial hierarchy of intelligence" that helped feed ideas around eugenics, which "falls far short of Imperial's modern values", and that his theories "might now be called 'racist' in as much as he used racial divisions and hierarchical categorisation in his attempt to understand their origins in his studies of human evolution". Imperial's provost Ian Walmsley responded that Imperial would "confront, not cover up, uncomfortable or awkward aspects of our past" and this was "very much not a 'cancel culture' approach". Students would be consulted before management decided on any action to be taken.[166] A critical response by Nick Matzke said that Huxley was a public, longstanding abolitionist who wrote "the most complete demonstration of the specific diversity of the types of mankind will nowise constrain science to spread her ægis over their [slaveholders'] atrocities" and "the North is justified in any expenditure of blood or of money, which shall eradicate a system hopelessly inconsistent with the moral elevation, the political freedom, or the economical progress of the American people";[167] a major opponent of the racist position of polygenism, as well as the position that some human races were transitional (in 1867 Huxley said "there was no shade of justification for the assertion that any existing modification of mankind now known was to be considered as an intermediate form between man and the animals next below him in the scale of the fauna of the world"); a vehement opponent of the scientific racist James Hunt; and a political radical who believed in granting equal rights and the vote to both Black people and women.[168] |

人種差別論争 2021年10月、植民地とのつながりを検討する歴史グループがインペリアル・カレッジ・ロンドンに、ハクスリーは「人種差別主義者と呼ばれるかもしれな い」ので、彼の胸像を撤去し、ハクスリー・ビルディングの名称を変更すべきだと伝えた。21人の学者からなるこのグループは、インペリアルの「大英帝国と のつながり」に対処し、「完全に包括的な組織」を構築するために、2020年の「ブラック・ライブズ・マター」抗議をきっかけに発足した。同誌は、ハクス リーの論文『奴隷解放-白と黒』は「人種による知能の階層を主張」し、優生学にまつわるアイデアの糧となったが、それは「インペリアルの現代的価値観には ほど遠い」ものであり、彼の理論は「人類進化の研究において、その起源を理解しようとする試みに人種的区分と階層的分類を用いたという点で、現在では『人 種差別主義者』と呼ばれるかもしれない」と報じた。インペリアルのイアン・ウォルムズリー学長は、インペリアルは「過去の不快な面や厄介な面を隠蔽するの ではなく、直視する」と答え、これは「"キャンセル・カルチャー "的なアプローチではない」と述べた。経営陣が取るべき行動を決定する前に、学生に相談することになる[166]。 ニック・マツケによる批判的な回答は、ハクスリーは公然の長年の奴隷廃止論者であり、「人類のタイプの特異な多様性の最も完全な証明は、科学が彼ら(奴隷 所有者)の残虐行為の上にægisを広げることを束縛することはないだろう」、「北部は、アメリカ国民の道徳的向上、政治的自由、経済的進歩と絶望的に矛 盾するシステムを根絶するために、血や金を費やすことは正当化される」と書いていると述べている[167]; [ハクスリーは1867年に「現在知られている人類のどのような変化も、世界の動物相の尺度において、人間と彼の次に下に位置する動物との間の中間的な形 態とみなされるべきものであるという主張には、正当な根拠がまったくない」と述べている)、科学的人種差別主義者ジェームズ・ハントに激しく反対し、黒人 と女性の両方に平等な権利と選挙権を与えることを信じた政治的急進主義者であった。 [168] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Henry_Huxley |

★ハクスリーの伝記

| Thomas Henry Huxley

PC FRS HonFRSE FLS (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist

and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has

become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's

theory of evolution.[2] The stories regarding Huxley's famous 1860 Oxford evolution debate with Samuel Wilberforce were a key moment in the wider acceptance of evolution and in his own career, although some historians think that the surviving story of the debate is a later fabrication.[3] Huxley had been planning to leave Oxford on the previous day, but, after an encounter with Robert Chambers, the author of Vestiges, he changed his mind and decided to join the debate. Wilberforce was coached by Richard Owen, against whom Huxley also debated about whether humans were closely related to apes. Huxley was slow to accept some of Darwin's ideas, such as gradualism, and was undecided about natural selection, but despite this, he was wholehearted in his public support of Darwin. Instrumental in developing scientific education in Britain, he fought against the more extreme versions of religious tradition. Huxley coined the term "agnosticism" in 1869 and elaborated on it in 1889 to frame the nature of claims in terms of what is knowable and what is not. Huxley had little formal schooling and was virtually self-taught. He became perhaps the finest comparative anatomist of the later 19th century.[4] He worked on invertebrates, clarifying relationships between groups previously little understood. Later, he worked on vertebrates, especially on the relationship between apes and humans. After comparing Archaeopteryx with Compsognathus, he concluded that birds evolved from small carnivorous dinosaurs, a view now held by modern biologists. The tendency has been for this fine anatomical work to be overshadowed by his energetic and controversial activity in favour of evolution, and by his extensive public work on scientific education, both of which had significant effects on society in Britain and elsewhere.[5][6] Huxley's 1893 Romanes Lecture, "Evolution and Ethics", is exceedingly influential in China; the Chinese translation of Huxley's lecture even transformed the Chinese translation of Darwin's Origin of Species.[7] |

トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー(Thomas Henry

Huxley PC FRS HonFRSE FLS、1825年5月4日 -

1895年6月29日)は、比較解剖学を専門としたイギリスの生物学者、人類学者である。チャールズ・ダーウィンの進化論を提唱し、「ダーウィンのブル

ドッグ」として知られるようになった[2]。 ハクスリーが1860年にオックスフォードで行った有名なサミュエル・ウィルバーフォースとの進化論論争に関する話は、進化論が広く受け入れられるように なった重要な瞬間であり、彼自身のキャリアにおいても重要な出来事であったが、現存する論争に関する話は後世の捏造であると考える歴史家もいる。ウィル バーフォースの指導を受けたのはリチャード・オーウェンで、ハクスリーもまた、人類が類人猿に近縁であるかどうかについて議論した。 ハクスリーは、漸進主義などダーウィンの考えのいくつかを受け入れるのに時間がかかり、自然淘汰については決めかねていたが、にもかかわらず、ダーウィン を公の場で心から支持した。イギリスにおける科学教育の発展に大きく貢献し、宗教的伝統の極端なバージョンと闘った。ハクスリーは1869年に「不可知 論」という言葉を創作し、1889年にはそれを発展させ、何が知りうることで、何が知りえないかという観点から、主張の本質を構成した。 ハクスリーは正規の学校教育をほとんど受けず、事実上独学で学んだ。無脊椎動物を研究し、それまでほとんど理解されていなかったグループ間の関係を明らか にした。その後、彼は脊椎動物、特に類人猿と人間の関係に取り組んだ。アルケオプテリクスとコンプソグナトゥスを比較した後、彼は鳥類は小型肉食恐竜から 進化したと結論づけた。 この優れた解剖学的業績は、進化論を支持する彼の精力的かつ論争的な活動や、科学教育に関する彼の広範な公的活動の影に隠れがちであったが、これらはいず れもイギリスやその他の地域の社会に大きな影響を与えた[5][6]。 ハクスリーの1893年のロマネス講義「進化と倫理」は、中国において非常に大きな影響力を持ち、ハクスリーの講義の中国語訳は、ダーウィンの『種の起 源』の中国語訳を変えたほどである[7]。 |

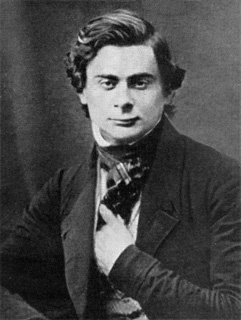

| Early life This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. See Wikipedia's guide to writing better articles for suggestions. (June 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Thomas Henry Huxley" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Thomas Henry Huxley was born in Ealing, then a village in Middlesex. He was the second youngest of eight children[8] of George Huxley and Rachel Withers. His parents were members of the Church of England, but he sympathized with nonconformists.[9] Like some other British scientists of the nineteenth century such as Alfred Russel Wallace, Huxley was brought up in a literate middle-class family which had fallen on hard times. His father was a mathematics teacher at Great Ealing School until it closed,[10] putting the family into financial difficulties. As a result, Thomas left school at the age of 10, after only two years of formal schooling.[11] Despite this lack of formal schooling, Huxley was determined to educate himself. He became one of the great autodidacts of the nineteenth century. At first he read Thomas Carlyle, James Hutton's Geology, and Hamilton's Logic. In his teens, he taught himself German, eventually becoming fluent and used by Charles Darwin as a translator of scientific material in German. He learned Latin, and enough Greek to read Aristotle in the original.[12]  Huxley, aged 21 Later on, as a young adult, he made himself an expert, first teaching himself about invertebrates, and later on vertebrates. He did many of the illustrations for his publications on marine invertebrates. In his later debates and writing on science and religion, his grasp of theology was better than many of his clerical opponents.[13][14] He was apprenticed for short periods to several medical practitioners: at 13 to his brother-in-law John Cooke in Coventry, who passed him on to Thomas Chandler, notable for his experiments using mesmerism for medical purposes. Chandler's practice was in London's Rotherhithe amidst the squalor endured by the Dickensian poor.[15] Afterward, another brother-in-law took him on: John Salt, his eldest sister's husband. Now aged 16, Huxley entered Sydenham College (behind University College Hospital), a cut-price anatomy school. All this time Huxley continued his programme of reading, which more than made up for his lack of formal schooling. A year later, buoyed by excellent results and a silver medal prize in the Apothecaries' yearly competition, Huxley was admitted to study at Charing Cross Hospital, where he obtained a small scholarship. At Charing Cross, he was taught by Thomas Wharton Jones, Professor of Ophthalmic Medicine and Surgery at University College London. Jones had been Robert Knox's assistant when Knox bought cadavers from Burke and Hare.[16] The young Wharton Jones, who acted as go-between, was exonerated of crime, but thought it best to leave Scotland. In 1845, under Wharton Jones' guidance, Huxley published his first scientific paper demonstrating the existence of a hitherto unrecognised layer in the inner sheath of hairs, a layer that has been known since as Huxley's layer. Later in life, Huxley organised a pension for his old mentor. At twenty he passed his First M.B. examination at the University of London, winning the gold medal for anatomy and physiology. However, he did not present himself for the final (Second M.B.) exams and consequently did not qualify for a university degree. His apprenticeships and exam results formed a sufficient basis for his application to the Royal Navy.[13][14] |

初期の人生 このセクションの論調や文体は、ウィキペディアで使用されている百科事典的な論調を反映していないかもしれない。よりよい記事の書き方についてはウィキペ ディアのガイドを参照のこと。(2022年6月) (このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) このセクションには検証のための追加引用が必要である。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきた い。ソースのないものは、異議申し立てされ、削除される可能性がある。 出典を探す 「Thomas Henry Huxley" - news - newspapers - books - scholar - JSTOR (June 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーは、当時ミドルセックス州の村であったイーリングに生まれた。ジョージ・ハクスリーとレイチェル・ウィザーズの8人兄弟の 次男[8]であった。アルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレスなど、19世紀のイギリスの科学者たちと同様、ハクスリーは苦境に陥った中流家庭で育った。父親は グレート・イーリング・スクールの数学教師であったが、その学校が閉鎖され、一家は経済的に困窮した[10]。その結果、トーマスは10歳で学校を去り、 2年間しか正式な学校教育を受けなかった[11]。 このように正式な学校教育を受けていないにもかかわらず、ハクスリーは自分自身を教育する決意を固めた。彼は19世紀の偉大な独学者の一人となった。最初 はトマス・カーライル、ジェームズ・ハットンの『地質学』、ハミルトンの『論理学』を読んだ。10代には独学でドイツ語を学び、最終的には流暢に話せるよ うになり、チャールズ・ダーウィンにドイツ語の科学資料の翻訳者として起用された。ラテン語と、アリストテレスを原文で読むのに十分なギリシャ語も学んだ [12]。  ハクスリー、21歳 その後、ハクスリーは専門家として、まず無脊椎動物について、後に脊椎動物について独学で学んだ。海洋無脊椎動物に関する出版物の挿絵の多くは彼が描いた ものである。後の科学と宗教に関する議論や執筆において、彼の神学に対する理解力は、多くの聖職者たちよりも優れていた[13][14]。 13歳のとき、コヴェントリーの義弟ジョン・クックに弟子入りし、医学のために催眠術を使った実験で有名なトーマス・チャンドラーのもとで修行した。チャ ンドラーの診療所はロンドンのロザーヒテにあり、ディケンズ時代の貧困層が耐え忍んでいた汚さの中にあった[15]: 長姉の夫であるジョン・ソルトである。16歳になったハクスリーは、シデナム・カレッジ(ユニバーシティ・カレッジ病院の裏手)に入学した。この間もハク スリーは読書を続け、正規の学校教育を受けていないことを補って余りあった。 1年後、優秀な成績とアポセカリーズ・イヤー・コンペティションでの銀賞受賞に後押しされ、ハクスリーはチャリング・クロス病院に入学し、少額の奨学金を 得た。チャリング・クロスでは、ユニバーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンの眼科医学・外科学教授、トーマス・ウォートン・ジョーンズに教えを受けた。ジョーン ズは、ノックスがバーク・アンド・ヘア社から死体を買い取ったときのロバート・ノックスの助手であった[16]。仲立ちを務めた若きウォートン・ジョーン ズは無罪放免となったが、スコットランドを去るのが最善と考えた。1845年、ハクスリーはウォートン・ジョーンズの指導の下、毛髪の内鞘にこれまで認識 されていなかった層が存在することを証明する最初の科学論文を発表した。後年、ハクスリーは年老いた恩師のために年金を用意した。 20歳の時、彼はロンドン大学の第一回M.B.試験に合格し、解剖学と生理学で金メダルを獲得した。しかし、最終試験(第二次試験)には出なかったため、 大学の学位を得ることはできなかった。見習い期間と試験の結果は、イギリス海軍への志願に十分な根拠となった[13][14]。 |

| Voyage of the Rattlesnake Aged 20, Huxley was too young to apply to the Royal College of Surgeons for a licence to practise, yet he was "deep in debt".[17] So, at a friend's suggestion, he applied for an appointment in the Royal Navy. He had references on character and certificates showing the time spent on his apprenticeship and on requirements such as dissection and pharmacy. William Burnett, the Physician General of the Navy, interviewed him and arranged for the College of Surgeons to test his competence (by means of a viva voce).[citation needed]  HMS Rattlesnake by the ship's artist Oswald Brierly Finally, Huxley was made Assistant Surgeon ('surgeon's mate', but in practice marine naturalist) to HMS Rattlesnake, about to set sail on a voyage of discovery and surveying to New Guinea and Australia. The Rattlesnake left England on 3 December 1846 and, once it arrived in the southern hemisphere, Huxley devoted his time to the study of marine invertebrates.[18] He began to send details of his discoveries back to England, where publication was arranged by Edward Forbes FRS (who had also been a pupil of Knox). Both before and after the voyage Forbes was something of a mentor to Huxley.[citation needed] Huxley's paper "On the anatomy and the affinities of the family of Medusae" was published in 1849 by the Royal Society in its Philosophical Transactions. Huxley united the Hydroid and Sertularian polyps with the Medusae to form a class to which he subsequently gave the name of Hydrozoa. The connection he made was that all the members of the class consisted of two cell layers, enclosing a central cavity or stomach. This is characteristic of the phylum now called the Cnidaria. He compared this feature to the serous and mucous structures of embryos of higher animals. When at last he got a grant from the Royal Society for the printing of plates, Huxley was able to summarise this work in The Oceanic Hydrozoa, published by the Ray Society in 1859.[19][20]  Australian woman: Pencil drawing by Huxley The value of Huxley's work was recognised and, on returning to England in 1850, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the following year, at the age of twenty-six, he not only received the Royal Society Medal but was also elected to the Council. He met Joseph Dalton Hooker and John Tyndall,[21] who remained his lifelong friends. The Admiralty retained him as a nominal assistant-surgeon, so he might work on the specimens he collected and the observations he made during the voyage of the Rattlesnake. He solved the problem of Appendicularia, whose place in the animal kingdom Johannes Peter Müller had found himself wholly unable to assign. It and the Ascidians are both, as Huxley showed, tunicates, today regarded as a sister group to the vertebrates in the phylum Chordata.[22] Other papers on the morphology of the cephalopods and on brachiopods and rotifers are also noteworthy.[13][14][23] |

ガラガラヘビの航海 20歳のハクスリーは、王立外科大学に開業免許を申請するには若すぎた。彼は、人柄に関する推薦状と、見習い期間と解剖や薬学などの必要な勉強に費やした 時間を示す証明書を持っていた。海軍軍医総監のウィリアム・バーネットは彼と面接し、外科医大学が彼の能力を(viva voceによって)テストするよう手配した[要出典]。  艦内画家オズワルド・ブライアリーが描いたHMSガラガラヘビ号? 最終的にハクスリーは、ニューギニアとオーストラリアへの発見と測量の航海に出航しようとしていたHMSラトルスネークの外科医助手(「外科医の航海 士」、実際には海洋博物学者)に任命された。1846年12月3日、ラトルスネーク号はイギリスを出航し、南半球に到着すると、ハクスリーは海洋無脊椎動 物の研究に没頭した[18]。彼は発見の詳細をイギリスに送り始め、エドワード・フォーブスFRS(ノックスの弟子でもあった)が出版を手配した。航海の 前も後も、フォーブスはハクスリーの師匠のような存在であった[要出典]。 ハクスリーの論文「メデュサエ科の解剖学的特徴と関連性について」は、1849年に王立協会によって『Philosophical Transactions』に掲載された。ハクスリーは、ヒドロ虫とセルチュラーポリープをメデュサエに統合し、ヒドロ虫綱と命名した。ハクスリーがヒド ロゾアと命名したのは、ヒドロゾアの仲間はすべて2つの細胞層からなり、中央の空洞あるいは胃を囲んでいるという点である。これは現在刺胞動物と呼ばれて いる門の特徴である。彼はこの特徴を、高等動物の胚の漿液構造や粘液構造と比較した。ついに王立協会から版画印刷のための助成金を得たハクスリーは、 1859年にレイ協会から出版された『The Oceanic Hydrozoa(海洋性ヒドロゾア)』にこの研究をまとめることができた[19][20]。  オーストラリアの女性: ハクスリーによる鉛筆画 ハクスリーの研究の価値は認められ、1850年にイギリスに帰国すると、王立協会のフェローに選出された。翌年、26歳の彼は王立協会メダルを受賞しただ けでなく、評議会のメンバーにも選ばれた。ジョセフ・ダルトン・フッカーとジョン・ティンダル[21]に出会い、生涯の友人となる。ガラガラヘビ号の航海 中に収集した標本や観察結果に取り組むため、提督は彼を名目上の外科助手として雇用した。彼は、ヨハネス・ピーター・ミュラーが動物界における位置づけを 決めかねていたアペンディキュラ(Appendicularia)の問題を解決した。頭足類の形態に関する論文、腕足類とワムシに関する論文も注目に値す る[13][14][23]。 |

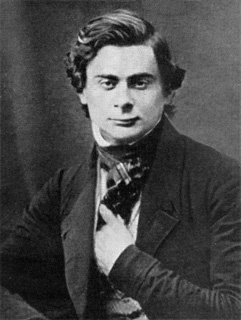

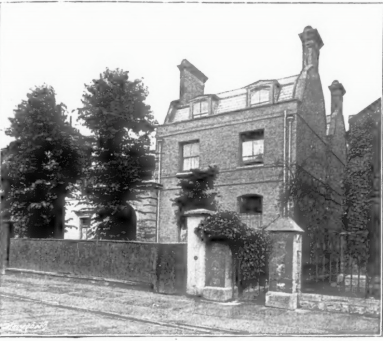

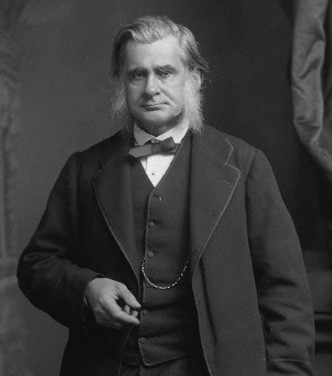

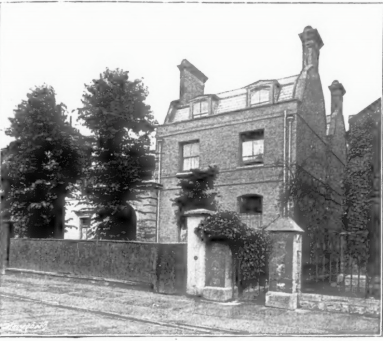

| Later life Following a lecture at the Royal Institution on 30 April 1852 Huxley indicated that it remained difficult to earn a living as a scientist alone. This was demonstrated in a letter written on 3 May 1852, where he states "Science in England does everything—but PAY. You may earn praise but not pudding".[24] However, Huxley effectively resigned from the navy by refusing to return to active service, and in July 1854 he became professor of natural history at the Royal School of Mines and naturalist to the British Geological Survey in the following year. In addition, he was Fullerian Professor at the Royal Institution 1855–1858 and 1865–1867; Hunterian Professor at the Royal College of Surgeons 1863–1869; president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science 1869–1870; president of the Quekett Microscopical Club 1878; president of the Royal Society 1883–1885; Inspector of Fisheries 1881–1885; and president of the Marine Biological Association 1884–1890.[14] He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society in 1869.[25] The thirty-one years during which Huxley occupied the chair of natural history at the Royal School of Mines included work on vertebrate palaeontology and on many projects to advance the place of science in British life. Huxley retired in 1885, after a bout of depressive illness which started in 1884. He resigned the presidency of the Royal Society in mid-term, the Inspectorship of Fisheries, and his chair (as soon as he decently could) and took six months' leave. His pension was £1200 a year.[26]  4 Marlborough Place, London Huxley's London home, in which he wrote many of his works, was at 4 Marlborough Place, St John's Wood. The house was extended in the early 1870s to include a large drawing and dining room at which he held informal Sunday gatherings.[27] In 1890, he moved from London to Eastbourne, where he had purchased land in the Staveley Road upon which a house was built, 'Hodeslea', under the supervision of his son-in-law F. Waller.[27] Here Huxley edited the nine volumes of his Collected Essays. In 1894 he heard of Eugene Dubois' discovery in Java of the remains of Pithecanthropus erectus (now known as Homo erectus).  Hodeslea, Staveley Road, Eastbourne He died of a heart attack (after contracting influenza and pneumonia) in 1895 in Eastbourne, and was buried in London at East Finchley Cemetery. No invitations were sent out but two hundred people turned up for the funeral; they included Joseph Dalton Hooker, William Henry Flower, Mulford B. Foster, Edwin Lankester, Joseph Lister, and apparently Henry James. The family plot had been purchased upon the death of his eldest son Noel, who died of scarlet fever in 1860; Huxley's wife Henrietta Anne née Heathorn and son Noel are also buried there.[28]  Huxley's grave in East Finchley Cemetery in north London Family Huxley and his wife had five daughters and three sons: Noel Huxley (1856–1860), died aged 3.[29][30] Jessie Oriana Huxley (1856–1927), married architect Fred Waller in 1877. Marian Huxley (1859–1887), married artist John Collier in 1879. Leonard Huxley (1860–1933), married Julia Arnold. Rachel Huxley (1862–1934), married civil engineer Alfred Eckersley in 1884. Henrietta (Nettie) Huxley (1863–1940), married Harold Roller, travelled Europe as a singer. Henry Huxley (1865–1946), became a fashionable general practitioner in London. Ethel Huxley (1866–1941) married artist John Collier (widower of sister) in 1889. Public duties and awards From 1870 onwards, Huxley was to some extent drawn away from scientific research by the claims of public duty. He served on eight Royal Commissions, from 1862 to 1884. From 1871 to 1880 he was a Secretary of the Royal Society and from 1883 to 1885 he was president. He was president of the Geological Society from 1868 to 1870. In 1870, he was president of the British Association at Liverpool and, in the same year was elected a member of the newly constituted London School Board. He was president of the Quekett Microscopical Club from 1877 to 1879. He was the leading person amongst those who reformed the Royal Society, persuaded government about science, and established scientific education in British schools and universities.[31] He was awarded the highest honours then open to British men of science. The Royal Society, who had elected him as Fellow when he was 25 (1851), awarded him the Royal Medal the next year (1852), a year before Charles Darwin got the same award. He was the youngest biologist to receive such recognition. Then later in life he received the Copley Medal in 1888 and the Darwin Medal in 1894; the Geological Society awarded him the Wollaston Medal in 1876; the Linnean Society awarded him the Linnean Medal in 1890. There were many other elections and appointments to eminent scientific bodies; these and his many academic awards are listed in the Life and Letters. He turned down many other appointments, notably the Linacre chair in zoology at Oxford and the Mastership of University College, Oxford.[32] Huxley  by Bassano c. 1883 In 1873 the King of Sweden made Huxley, Hooker and Tyndall Knights of the Order of the Polar Star: they could wear the insignia but not use the title in Britain.[33] Huxley collected many honorary memberships of foreign societies, academic awards and honorary doctorates from Britain and Germany. He also became a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1892.[34] In 1916, a street in the Bronx, New York was named in his honor (Huxley Avenue).[35] As recognition of his many public services, he was appointed Privy Councillor in 1892. Despite his many achievements, he was given no award by the British state until late in life. In this, he did better than Darwin, who got no award of any kind from the state. (Darwin's proposed knighthood was vetoed by ecclesiastical advisers, including Wilberforce.)[36] Perhaps Huxley had commented too often on his dislike of honours, or perhaps his many assaults on the traditional beliefs of organised religion made enemies in the establishment – he had vigorous debates in print with Benjamin Disraeli, William Ewart Gladstone, and Arthur Balfour, and his relationship with Lord Salisbury was less than tranquil.[14][37] Huxley was for about thirty years evolution's most effective advocate, and for some Huxley was "the premier advocate of science in the nineteenth century [for] the whole English-speaking world".[38] Though he had many admirers and disciples, his retirement and later death left British zoology somewhat bereft of leadership. He had, directly or indirectly, guided the careers and appointments of the next generation. Huxley thought he was "the only man who can carry out my work": The deaths of Balfour and W.K. Clifford were "the greatest losses to science in our time".[14] Vertebrate palaeontology The first half of Huxley's career as a palaeontologist is marked by a rather strange predilection for 'persistent types', in which he seemed to argue that evolutionary advancement (in the sense of major new groups of animals and plants) was rare or absent in the Phanerozoic. In the same vein, he tended to push the origin of major groups such as birds and mammals back into the Palaeozoic era, and to claim that no order of plants had ever gone extinct.[39] Much paper has been consumed by historians of science ruminating on this strange and somewhat unclear idea.[40] Huxley was wrong to pitch the loss of orders in the Phanerozoic as low as 7%, and he did not estimate the number of new orders which evolved. Persistent types sat rather uncomfortably next to Darwin's more fluid ideas; despite his intelligence, it took Huxley a surprisingly long time to appreciate some of the implications of evolution. However, gradually Huxley moved away from this conservative style of thinking as his understanding of palaeontology, and the discipline itself, developed.[citation needed] Huxley's detailed anatomical work was, as always, first-rate and productive. His work on fossil fish shows his distinctive approach: Whereas pre-Darwinian naturalists collected, identified, and classified, Huxley worked mainly to reveal the evolutionary relationships between groups.[citation needed]  Huxley by Wirgman a drawing in pencil (1882) The lobe-finned fish (such as coelacanths and lungfish) have paired appendages whose internal skeleton is attached to the shoulder or pelvis by a single bone, the humerus or femur. His interest in these fish brought him close to the origin of tetrapods, one of the most important areas of vertebrate palaeontology.[41][42][43] The study of fossil reptiles led to his demonstrating the fundamental affinity of birds and reptiles, which he united under the title of Sauropsida. His papers on Archaeopteryx and the origin of birds were of great interest then and still are.[23][44][45] Apart from his interest in persuading the world that man was a primate and had descended from the same stock as the apes, Huxley did little work on mammals, with one exception. On his tour of America Huxley was shown the remarkable series of fossil horses, discovered by O. C. Marsh, in Yale's Peabody Museum.[46][47] An Easterner, Marsh was America's first professor of palaeontology, but also one who had come west into hostile Indian territory in search of fossils, hunted buffalo, and met Red Cloud (in 1874).[48](pp 52, 141–160) Funded by his uncle George Peabody, Marsh had made some remarkable discoveries: the huge Cretaceous aquatic bird Hesperornis, and the dinosaur footprints along the Connecticut River were worth the trip by themselves, but the horse fossils were really special. After a week with Marsh and his fossils, Huxley wrote excitedly, "The collection of fossils is the most wonderful thing I ever saw."[48](p 203)  Huxley's sketch of then hypothetical five-toed Eohippus being ridden by "Eohomo" The collection at that time went from the small four-toed forest-dwelling Orohippus from the Eocene through three-toed species such as Miohippus to species more like the modern horse. By looking at their teeth he could see that, as the size grew larger and the toes reduced, the teeth changed from those of a browser to those of a grazer. All such changes could be explained by a general alteration in habitat from forest to grassland.[citation needed] And, it is now known, that is what did happen over large areas of North America from the Eocene to the Pleistocene: The ultimate causative agent was global temperature reduction (see Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum). The modern account of the evolution of the horse has many other members, and the overall appearance of the tree of descent is more like a bush than a straight line. The horse series also strongly suggested that the process was gradual, and that the origin of the modern horse lay in North America, not in Eurasia. If so, then something must have happened to horses in North America, since none were there when Europeans arrived. The experience with Marsh was enough for Huxley to give credence to Darwin's gradualism, and to introduce the story of the horse into his lecture series.[citation needed][48](p 204) Marsh's and Huxley's conclusions were initially quite different. However, Marsh carefully showed Huxley his complete sequence of fossils. As Marsh put it, Huxley "then informed me that all this was new to him and that my facts demonstrated the evolution of the horse beyond question, and for the first time indicated the direct line of descent of an existing animal. With the generosity of true greatness, he gave up his own opinions in the face of new truth, and took my conclusions as the basis of his famous New York lecture on the horse."[48](p 204) |

その後の人生 1852年4月30日の王立研究所での講演の後、ハクスリーは、科学者として一人で生計を立てるのは依然として困難であると指摘した。このことは、 1852年5月3日に書かれた手紙の中で、「イギリスの科学は何でもするが、ペイはしない。しかし、ハクスリーは現役復帰を拒否して海軍を事実上辞職し、 1854年7月に王立鉱山学校の博物学教授となり、翌年には英国地質調査所の博物学者となった。さらに、1855年から1858年と1865年から 1867年には王立研究所のフラー教授、1863年から1869年には王立外科医学校のハンター教授、1869年から1870年には英国科学振興協会の会 長、1878年にはケケット顕微鏡クラブの会長、1883年から1885年には王立協会の会長、1881年から1885年には漁業検査官、1884年から 1890年には海洋生物学会の会長を務めた[14]。 ハクスリーが王立水雷学校の自然史講座の教授を務めていた31年間は、脊椎動物の古生物学や、イギリス生活における科学の地位を向上させるための多くのプ ロジェクトに取り組んでいた。ハクスリーは1884年からうつ病を患い、1885年に引退した。王立協会の会長職、漁業検査官、そして自分の椅子を(でき る限り早く)辞任し、6ヶ月の休暇をとった。年金は年間1200ポンドだった[26]。  ロンドン、マールボロ・プレイス4番地 ハクスリーが多くの作品を執筆したロンドンの家は、セント・ジョンズ・ウッドのマルボロ・プレイス4番地であった。この家は1870年代初頭に増築され、 大きな応接間とダイニングルームが設けられた。 1890年、ハクスリーはロンドンからイーストボーンに移り、ステーブリー通りに土地を購入し、義理の息子であるF・ウォーラーの監督のもと、「ホデスレ ア」という家を建てた[27]。1894年、彼はユージン・デュボアがジャワ島でピテカントロプス・エレクトス(現在のホモ・エレクトス)の遺骨を発見し たことを知った。  イーストボーン、ステーブリー・ロードのホデスレア 1895年、イーストボーンで心臓発作(インフルエンザと肺炎の後)で死去し、ロンドンのイースト・フィンチリー墓地に埋葬された。葬儀には招待状は出さ れなかったが、ジョセフ・ダルトン・フッカー、ウィリアム・ヘンリー・フラワー、マルフォード・B・フォスター、エドウィン・ランケスター、ジョセフ・リ スター、そしてヘンリー・ジェイムズら200人が集まった。ハクスリーの妻ヘンリエッタ・アン(旧姓ヒースホーン)と息子ノエルもそこに埋葬されている [28]。  ロンドン北部のイースト・フィンチリー墓地にあるハクスリーの墓 家族 ハクスリー夫妻には5人の娘と3人の息子がいた: ノエル・ハックスレー(1856-1860)、3歳で死去[29][30]。 ジェシー・オリアナ・ハックスレー(1856-1927)、1877年に建築家のフレッド・ウォーラーと結婚。 マリアン・ハクスリー(1859-1887)、1879年に画家のジョン・コリアーと結婚。 レナード・ハックスレー(1860-1933)、ジュリア・アーノルドと結婚。 レイチェル・ハックスレー(1862-1934)、1884年に土木技師のアルフレッド・エッカースリーと結婚。 ヘンリエッタ(ネッティ)・ハクスリー(1863-1940)、ハロルド・ローラーと結婚、歌手としてヨーロッパを旅する。 ヘンリー・ハクスリー(1865-1946)、ロンドンでファッショナブルな開業医となる。 エセル・ハックスレー(1866-1941)は、1889年に画家のジョン・コリアー(姉の男やもめ)と結婚した。 公務と受賞歴 1870年以降、ハクスリーは公務のために科学研究からある程度遠ざかっていた。1862年から1884年まで、8つの王室委員会の委員を務めた。 1871年から1880年までは王立協会の幹事を務め、1883年から1885年までは会長を務めた。1868年から1870年まで地質学会の会長を務め た。1870年にはリバプールで英国協会の会長を務め、同年、新設されたロンドン教育委員会の委員に選出された。1877年から1879年まで、ケケット 顕微鏡クラブの会長を務めた。王立協会を改革し、科学について政府を説得し、イギリスの学校と大学における科学教育を確立した人々の中で、彼は第一人者で あった[31]。 彼は、当時イギリスの科学者に与えられていた最高の栄誉を授与された。彼が25歳のとき(1851年)にフェローに選出された王立協会は、翌年(1852 年)、チャールズ・ダーウィンが同賞を受賞する1年前に、彼にロイヤル・メダルを授与した。チャールズ・ダーウィンが同賞を受賞する1年前である。その 後、1888年にはコプリー賞を、1894年にはダーウィン賞を、1876年には地質学会からウォラストン・メダルを、1890年にはリンネ学会からリン ネ・メダルを授与された。その他にも多くの著名な科学団体に選出され、任命された。これらと彼の多くの学術賞は『Life and Letters』に掲載されている。ハクスリーは、オックスフォード大学リナクル動物学講座やオックスフォード大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジのマスター シップをはじめ、多くの昇進を辞退した[32]。 ハクスリー  1883年頃、バッサーノによる 1873年、スウェーデン国王は、ハクスリー、フッカー、ティンダルを北極星騎士団に任命した。また、1892年にはオランダ王立芸術科学アカデミーの外 国人会員となった[34]。1916年、ニューヨークのブロンクスにある通りがハクスリーにちなんで命名された(ハクスリー通り)[35]。 1892年、多くの公共事業への貢献が認められ、枢密顧問官に任命された。 多くの業績を残したにもかかわらず、彼は晩年までイギリス国家から何の賞も与えられなかった。この点では、国家から何の賞も授与されなかったダーウィンよ りも優れていた。(ダーウィンが提案した爵位は、ウィルバーフォースを含む教会顧問によって拒否された)[36]。おそらくハクスリーは、名誉を嫌うあま りに頻繁にコメントしていたか、あるいは、組織宗教の伝統的な信念に対する彼の多くの攻撃は、体制側に敵を作ったのかもしれない。 ハクスリーは約30年間、進化論の最も効果的な擁護者であり、何人かの人々にとってハクスリーは「19世紀における(英語圏全体にとっての)科学の最高の 擁護者」であった[38]。 彼には多くの崇拝者と弟子がいたが、彼の引退とその後の死によって、イギリスの動物学は指導者不在となった。彼は直接的にも間接的にも、次世代のキャリア と人事を導いていた。ハクスリーは、彼を「私の仕事を遂行できる唯一の男」だと考えていた: バルフォアとW.K.クリフォードの死は、「現代における科学の最大の損失」であった[14]。 脊椎動物古生物学 ハクスリーの古生物学者としてのキャリアの前半は、「持続型」に対する奇妙な嗜好が特徴的であった。同じように、彼は鳥類や哺乳類などの主要なグループの 起源を古生代まで遡らせる傾向があり、絶滅した植物の目もないと主張した[39]。 この奇妙でやや不明瞭な考えを反芻する科学史家たちによって、多くの紙面が費やされてきた。永続的な型は、ダーウィンのより流動的な考え方の隣で、むしろ 居心地悪く座っていた。彼の知性にもかかわらず、ハクスリーは進化の意味合いのいくつかを理解するのに驚くほど長い時間を要した。しかし、ハクスリーは古 生物学とその学問分野自体への理解が深まるにつれて、次第にこの保守的な思考スタイルから脱却していった[要出典]。 ハクスリーの詳細な解剖学的研究は、いつものように一流で生産的であった。化石魚類に関する彼の研究は、彼の独特なアプローチを示している: ダーウィン以前の博物学者が化石を収集し、同定し、分類したのに対し、ハクスリーは主にグループ間の進化的関係を明らかにすることに取り組んだ。  ウィルグマンによるハクスリー 鉛筆画(1882年) 葉鰭魚類(シーラカンスや肺魚など)は対になった付属器官を持ち、その内部骨格は上腕骨または大腿骨という単一の骨によって肩または骨盤に取り付けられて いる。彼はこれらの魚類に興味を持ち、脊椎動物古生物学の最も重要な分野の一つである四肢動物の起源に近づいた[41][42][43]。 爬虫類の化石の研究によって、彼は鳥類と爬虫類の基本的な親和性を実証し、それらをSauropsidaというタイトルで統一した。始祖鳥と鳥類の起源に 関する彼の論文は、当時も現在も大きな関心を集めている[23][44][45]。 人間が霊長類であり、類人猿と同じ系統の子孫であることを世間に説得することに関心を寄せていたことを除けば、ハクスリーは哺乳類に関する研究をほとんど 行わなかった。東部出身のマーシュは、アメリカ初の古生物学の教授であると同時に、化石を求めて敵対的なインディアンの領土に入り、バッファローを狩り、 レッド・クラウド(1874年)に出会った人物でもあった。 [叔父のジョージ・ピーボディから資金援助を受けていたマーシュは、白亜紀の巨大な水鳥ヘスペロルニスやコネチカット川沿いの恐竜の足跡など、それだけで も行く価値があったが、馬の化石は本当に特別だった。マーシュと彼の化石と1週間過ごした後、ハクスリーは興奮気味に「化石のコレクションは私が今まで見 た中で最も素晴らしいものだ」と書いている[48](p203)。  ハクスリーが描いた、"エオホモ "に乗られる5本指のエオヒップスのスケッチ(仮定のもの 当時のコレクションは、始新世の小さな4本足の森に住むオロヒップスから、ミオヒップスのような3本足の種を経て、現代の馬に近い種まであった。彼らの歯 を見ると、サイズが大きくなり、足指が小さくなるにつれて、歯がブラウザーのものから放牧者のものへと変化していることがわかった。このような変化はすべ て、生息地が森林から草原へと一般的に変化したことで説明できる: 最終的な原因は、地球全体の気温の低下であった(暁新世-更新世熱極大期を参照)。現代の馬の進化に関する記述には、他にも多くのメンバーがおり、全体的 な系統樹の姿は直線というよりは藪のようである。 馬の系列はまた、その過程が緩やかであり、現代の馬の起源はユーラシア大陸ではなく北アメリカにあることを強く示唆していた。もしそうなら、ヨーロッパ人 が到着したときには馬はいなかったのだから、北アメリカの馬に何かが起こったに違いない。マーシュとの経験は、ハクスリーにとって、ダーウィンの漸進主義 に信憑性を与えるのに十分なものであり、馬の話を彼の講義シリーズに導入するのに十分なものであった[要出典][48](p204)。 マーシュとハクスリーの結論は当初全く異なっていた。しかし、マーシュはハクスリーに化石の完全な配列を注意深く示した。マーシュの言葉を借りれば、ハク スリーは「そのとき、このことは彼にとってすべて初めてのことであり、私の事実が馬の進化を疑う余地なく実証し、現存する動物の直系の子孫を初めて示した のだ」と告げた。真の偉人としての寛大さをもって、彼は新たな真実に直面して自分の意見を放棄し、私の結論を馬に関する有名なニューヨーク講演の基礎とし た」[48](p204) |

| Support of Darwin See also: Reactions to On the Origin of Species  The frontispiece to Huxley's Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature (1863) compares ape and human skeletons. The gibbon (left) is double size. Huxley was originally not persuaded by "development theory", as evolution was once called. This can be seen in his savage review[49] of Robert Chambers' Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, a book which contained some quite pertinent arguments in favour of evolution. Huxley had also rejected Lamarck's theory of transmutation, on the basis that there was insufficient evidence to support it. All this scepticism was brought together in a lecture to the Royal Institution,[50] which made Darwin anxious enough to set about an effort to change young Huxley's mind. It was the kind of thing Darwin did with his closest scientific friends, but he must have had some particular intuition about Huxley, who was by all accounts a most impressive person even as a young man.[51][52] Huxley was therefore one of the small group who knew about Darwin's ideas before they were published (the group included Joseph Dalton Hooker and Charles Lyell). The first publication by Darwin of his ideas came when Wallace sent Darwin his famous paper on natural selection, which was presented by Lyell and Hooker to the Linnean Society in 1858 alongside excerpts from Darwin's notebook and a Darwin letter to Asa Gray.[53][54] Huxley's famous response to the idea of natural selection was "How extremely stupid not to have thought of that!"[55] However, he never conclusively made up his mind about whether natural selection was the main method for evolution, though he did admit it was a hypothesis which was a good working basis. Logically speaking, the prior question was whether evolution had taken place at all. It is to this question that much of Darwin's On the Origin of Species was devoted. Its publication in 1859 completely convinced Huxley of evolution and it was this and no doubt his admiration of Darwin's way of amassing and using evidence that formed the basis of his support for Darwin in the debates that followed the book's publication. Huxley's support started with his anonymous favourable review of the Origin in the Times for 26 December 1859,[56] and continued with articles in several periodicals, and in a lecture at the Royal Institution in February 1860.[57] At the same time, Richard Owen, whilst writing an extremely hostile anonymous review of the Origin in the Edinburgh Review,[58] also primed Samuel Wilberforce who wrote one in the Quarterly Review, running to 17,000 words.[59] The authorship of this latter review was not known for sure until Wilberforce's son wrote his biography. So it can be said that, just as Darwin groomed Huxley, so Owen groomed Wilberforce; and both the proxies fought public battles on behalf of their principals as much as themselves. Though we do not know the exact words of the Oxford debate, we do know what Huxley thought of the review in the Quarterly:  Caricature of Huxley by Carlo Pellegrini in Vanity Fair 1871 Since Lord Brougham assailed Dr Young, the world has seen no such specimen of the insolence of a shallow pretender to a Master in Science as this remarkable production, in which one of the most exact of observers, most cautious of reasoners, and most candid of expositors, of this or any other age, is held up to scorn as a "flighty" person, who endeavours "to prop up his utterly rotten fabric of guess and speculation," and whose "mode of dealing with nature" is reprobated as "utterly dishonourable to Natural Science." If I confine my retrospect of the reception of the Origin of Species to a twelvemonth, or thereabouts, from the time of its publication, I do not recollect anything quite so foolish and unmannerly as the Quarterly Review article...[60][61] Since his death, Huxley has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog", taken to refer to his pluck and courage in debate, and to his perceived role in protecting the older man. The sobriquet appears to be Huxley's own invention, although of unknown date,[62] and it was not current in his lifetime.[63] While the second half of Darwin's life was lived mainly within his family, the younger and combative Huxley operated mainly out in the world at large. A letter from Huxley to Ernst Haeckel (2 November 1871) states: "The dogs have been snapping at [Darwin's] heels too much of late." Debate with Wilberforce Main article: 1860 Oxford evolution debate Famously, Huxley responded to Wilberforce in the debate at the British Association meeting, on Saturday 30 June 1860 at the Oxford University Museum. Huxley's presence there had been encouraged on the previous evening when he met Robert Chambers, the Scottish publisher and author of Vestiges, who was walking the streets of Oxford in a dispirited state, and begged for assistance. The debate followed the presentation of a paper by John William Draper, and was chaired by Darwin's former botany tutor John Stevens Henslow. Darwin's theory was opposed by the Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce, and those supporting Darwin included Huxley and their mutual friends Hooker and Lubbock. The platform featured Brodie and Professor Beale, and Robert FitzRoy, who had been captain of HMS Beagle during Darwin's voyage, spoke against Darwin.[64] Wilberforce had a track record against evolution as far back as the previous Oxford B.A. meeting in 1847 when he attacked Chambers' Vestiges. For the more challenging task of opposing the Origin, and the implication that man descended from apes, he had been assiduously coached by Richard Owen—Owen stayed with him the night before the debate.[65] On the day, Wilberforce repeated some of the arguments from his Quarterly Review article (written but not yet published), then ventured onto slippery ground. His famous jibe at Huxley (as to whether Huxley was descended from an ape on his mother's side or his father's side) was probably unplanned, and certainly unwise. Huxley's reply to the effect that he would rather be descended from an ape than a man who misused his great talents to suppress debate—the exact wording is not certain—was widely recounted in pamphlets and a spoof play.[citation needed] The letters of Alfred Newton include one to his brother giving an eyewitness account of the debate, and written less than a month afterwards.[66] Other eyewitnesses, with one or two exceptions (Hooker especially thought he had made the best points), give similar accounts, at varying dates after the event.[67] The general view was and still is that Huxley got much the better of the exchange, though Wilberforce himself thought he had done quite well. In the absence of a verbatim report, differing perceptions are difficult to judge fairly; Huxley wrote a detailed account for Darwin, a letter which does not survive; however, a letter to his friend Frederick Daniel Dyster does survive with an account just three months after the event.[68][69][70][71][72][73] One effect of the debate was to hugely increase Huxley's visibility amongst educated people, through the accounts in newspapers and periodicals. Another consequence was to alert him to the importance of public debate: a lesson he never forgot. A third effect was to serve notice that Darwinian ideas could not be easily dismissed: on the contrary, they would be vigorously defended against orthodox authority.[74][75] A fourth effect was to promote professionalism in science, with its implied need for scientific education. A fifth consequence was indirect: as Wilberforce had feared, a defence of evolution did undermine literal belief in the Old Testament, especially the Book of Genesis. Many of the liberal clergy at the meeting were quite pleased with the outcome of the debate; they were supporters, perhaps, of the controversial Essays and Reviews. Thus, both on the side of science and on that of religion, the debate was important and its outcome significant.[76] (see also below) That Huxley and Wilberforce remained on courteous terms after the debate (and able to work together on projects such as the Metropolitan Board of Education) says something about both men, whereas Huxley and Owen were never reconciled.[citation needed] Man's place in nature See also: Man's Place in Nature For nearly a decade his work was directed mainly to the relationship of man to the apes. This led him directly into a clash with Richard Owen, a man widely disliked for his behaviour whilst also being admired for his capability. The struggle was to culminate in some severe defeats for Owen. Huxley's Croonian Lecture, delivered before the Royal Society in 1858 on The Theory of the Vertebrate Skull was the start. In this, he rejected Owen's theory that the bones of the skull and the spine were homologous, an opinion previously held by Goethe and Lorenz Oken.[77]  Huxley at 32 From 1860 to 1863 Huxley developed his ideas, presenting them in lectures to working men, students and the general public, followed by publication. Also in 1862 a series of talks to working men was printed lecture by lecture as pamphlets, later bound up as a little green book; the first copies went on sale in December.[78] Other lectures grew into Huxley's most famous work Evidence as to Man's place in Nature (1863) where he addressed the key issues long before Charles Darwin published his Descent of Man in 1871.[citation needed] Although Darwin did not publish his Descent of Man until 1871, the general debate on this topic had started years before (there was even a precursor debate in the 18th century between Monboddo and Buffon). Darwin had dropped a hint when, in the conclusion to the Origin, he wrote: "In the distant future... light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history".[79] Not so distant, as it turned out. A key event had already occurred in 1857 when Richard Owen presented (to the Linnean Society) his theory that man was marked off from all other mammals by possessing features of the brain peculiar to the genus Homo. Having reached this opinion, Owen separated man from all other mammals in a subclass of its own.[80] No other biologist held such an extreme view. Darwin reacted "Man...as distinct from a chimpanzee [as] an ape from a platypus... I cannot swallow that!"[81] Neither could Huxley, who was able to demonstrate that Owen's idea was completely wrong.  Huxley c.1870; sketch is a gorilla skull The subject was raised at the 1860 BA Oxford meeting, when Huxley flatly contradicted Owen, and promised a later demonstration of the facts. In fact, a number of demonstrations were held in London and the provinces. In 1862 at the Cambridge meeting of the B.A. Huxley's friend William Flower gave a public dissection to show that the same structures (the posterior horn of the lateral ventricle and hippocampus minor) were indeed present in apes. The debate was widely publicised, and parodied as the Great Hippocampus Question. It was seen as one of Owen's greatest blunders, revealing Huxley as not only dangerous in debate but also a better anatomist.[citation needed] Owen conceded that there was something that could be called a hippocampus minor in the apes, but stated that it was much less developed and that such a presence did not detract from the overall distinction of simple brain size.[82] Huxley's ideas on this topic were summed up in January 1861 in the first issue (new series) of his own journal, the Natural History Review: "the most violent scientific paper he had ever composed".[53] This paper was reprinted in 1863 as chapter 2 of Man's Place in Nature, with an addendum giving his account of the Owen/Huxley controversy about the ape brain.[83] In his Collected Essays this addendum was removed.[citation needed] The extended argument on the ape brain, partly in debate and partly in print, backed by dissections and demonstrations, was a landmark in Huxley's career. It was highly important in asserting his dominance of comparative anatomy, and in the long run more influential in establishing evolution amongst biologists than was the debate with Wilberforce. It also marked the start of Owen's decline in the esteem of his fellow biologists.[citation needed] The following was written by Huxley to Rolleston before the BA meeting in 1861: "My dear Rolleston... The obstinate reiteration of erroneous assertions can only be nullified by as persistent an appeal to facts; and I greatly regret that my engagements do not permit me to be present at the British Association in order to assist personally at what, I believe, will be the seventh public demonstration during the past twelve months of the untruth of the three assertions, that the posterior lobe of the cerebrum, the posterior cornu of the lateral ventricle, and the hippocampus minor, are peculiar to man and do not exist in the apes. I shall be obliged if you will read this letter to the Section" Yours faithfully, Thos. H. Huxley.[84] During those years there was also work on human fossil anatomy and anthropology. In 1862 he examined the Neanderthal skull-cap, which had been discovered in 1857. It was the first pre-sapiens discovery of a fossil man, and it was immediately clear to him that the brain case was surprisingly large.[85] Huxley also started to dabble in physical anthropology, and classified the human races into nine categories, along with placing them under four general categorisations as Australoid, Negroid, Xanthochroic and Mongoloid. Such classifications depended mainly on physical appearance and certain anatomical characteristics.[86][87] Natural selection Huxley was certainly not slavish in his dealings with Darwin. As shown in every biography, they had quite different and rather complementary characters. Important also, Darwin was a field naturalist, but Huxley was an anatomist, so there was a difference in their experience of nature. Lastly, Darwin's views on science were different from Huxley's views. For Darwin, natural selection was the best way to explain evolution because it explained a huge range of natural history facts and observations: it solved problems. Huxley, on the other hand, was an empiricist who trusted what he could see, and some things were not easily seen. With this in mind, one can appreciate the debate between them, Darwin writing his letters, Huxley never going quite so far as to say he thought Darwin was right.[citation needed] Huxley's reservations on natural selection were of the type "until selection and breeding can be seen to give rise to varieties which are infertile with each other, natural selection cannot be proved".[88][89] Huxley's position on selection was agnostic; yet he gave no credence to any other theory. Despite this concern about evidence, Huxley saw that if evolution came about through variation, reproduction and selection then other things would also be subject to the same pressures. This included ideas because they are invented, imitated and selected by humans: ‘The struggle for existence holds as much in the intellectual as in the physical world. A theory is a species of thinking, and its right to exist is coextensive with its power of resisting extinction by its rivals.’[90] This is the same idea as meme theory put forward by Richard Dawkins in 1976.[91] Darwin's part in the discussion came mostly in letters, as was his wont, along the lines: "The empirical evidence you call for is both impossible in practical terms, and in any event unnecessary. It's the same as asking to see every step in the transformation (or the splitting) of one species into another. My way so many issues are clarified and problems solved; no other theory does nearly so well".[92] Huxley's reservation, as Helena Cronin has so aptly remarked, was contagious: "it spread itself for years among all kinds of doubters of Darwinism".[93] One reason for this doubt was that comparative anatomy could address the question of descent, but not the question of mechanism.[94] Pallbearer Huxley was a pallbearer at the funeral of Charles Darwin on 26 April 1882.[95] |

ダーウィンの支持 こちらも参照のこと: 種の起源』への反応  ハクスリーの『Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature』(1863年)の扉絵は、類人猿と人間の骨格を比較している。テナガザル(左)は2倍の大きさである。 ハクスリーはもともと、かつて進化論と呼ばれていた「発生理論」には説得力がなかった。このことは、ロバート・チェンバースの『創造の自然史の名残り』 (Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation)という、進化論を支持する極めて適切な論点を含む書物に対する、彼の残酷な批評[49]に見ることができる。ハクスリーはまた、ラマル クの転成説を、それを支持する証拠が不十分であるという理由で否定していた。こうした懐疑論はすべて王立研究所での講義にまとめられ[50]、ダーウィン は若いハクスリーの考えを変える努力を始めるほど不安になった。それはダーウィンが最も親しい科学者の友人と行うようなことであったが、ハクスリーについ ては特別な直感があったに違いない。 したがって、ハクスリーは、ダーウィンの考えが出版される前にそれを知っていた少数のグループの一人であった(そのグループには、ジョセフ・ダルトン・ フッカーやチャールズ・ライエルも含まれていた)。ウォーレスが自然淘汰に関する有名な論文をダーウィンに送り、ライエルとフッカーが1858年にリンネ 学会でダーウィンのノートからの抜粋やダーウィンがエイサ・グレイに宛てた手紙とともに発表したのが、ダーウィンによる彼の思想の最初の発表であった [53]。 [53][54]自然淘汰の考えに対するハクスリーの有名な反応は、「それを考えなかったとは、なんと愚かなことか!」であった[55]。しかし、自然淘 汰が進化の主要な方法であるかどうかについて、彼は決定的な決心をすることはなかった。 論理的に言えば、それ以前の問題は、進化が全く行われなかったかどうかであった。ダーウィンの『種の起源』の大部分はこの問題に費やされた。1859年に 出版された『種の起源』によって、ハクスリーは進化論を完全に確信し、ダーウィンの証拠の集め方と使い方に感心したことが、この本の出版後の論争でダー ウィンを支持する基礎となったことは間違いない。 ハクスリーの支持は、1859年12月26日付の『タイムズ』紙に匿名で掲載された『オリジン』に対する好意的な批評に始まり[56]、いくつかの定期刊 行物に掲載された記事や1860年2月の王立研究所での講演でも続いた。 [57] 同時に、リチャード・オーウェンは『エジンバラ・レヴュー』誌に『起源』に対する極めて敵対的な匿名の批評を書く一方で[58]、サミュエル・ウィルバー フォースにも呼び水を与え、ウィルバーフォースは『クォータリー・レビュー』誌に17,000語に及ぶ批評を書いた[59]。つまり、ダーウィンがハクス リーを育てたように、オウエンがウィルバーフォースを育てたのである。オックスフォードでの討論の正確な言葉はわからないが、ハクスリーが『季刊』の批評 をどう思ったかはわかっている:  カルロ・ペレグリーニによるハクスリーの風刺画 カルロ・ペッレグリーニによる『ヴァニティ・フェア』誌の風刺画(1871年 ブロアム卿がヤング博士を非難して以来、世界は、科学の巨匠を気取る浅はかな者の横柄さを、この驚くべき作品ほど見せつけられたことはない、 この時代でも他のどの時代でも、最も正確な観察者であり、最も慎重な推論者であり、最も率直な解説者の一人が、「空想家」として軽蔑の対象とされ、「自分 の全く腐った推測と憶測の織物を支えようと」努力し、その「自然との付き合い方」は「自然科学にとって全く不名誉なもの」として非難されている。 " 私が『種の起源』の受容を、その出版から12ヶ月かそこらに限定して回顧するならば、季刊誌レビューの記事ほど愚かで礼儀知らずなものは記憶にない... [60][61]。 彼の死後、ハクスリーは「ダーウィンのブルドッグ」として知られるようになったが、これは討論における彼の気概と勇気、そして先輩を守る役割を果たしたと 認識されていることを指している。この呼称はハクスリー自身の創作であるようだが、年代は不明であり[62]、彼の存命中には使われていなかった [63]。 ダーウィンの人生の後半は主に家族の中で生活していたが、若く闘争的なハクスリーは主に世間一般で活動していた。ハクスリーからエルンスト・ヘッケルへの 手紙(1871年11月2日)にはこう書かれている: 「ダーウィンの)かかとを犬どもはここんとこ、やたらと叩いてくる」(1871年11月2日)とある。 ウィルバーフォースとの論争 主な記事 1860年オックスフォード進化論論争 有名なことに、ハクスリーは1860年6月30日(土)にオックスフォード大学博物館で開催された英国学会の討論会でウィルバーフォースに反論した。ハク スリーは、前日の夕方、オックスフォードの街を憂鬱そうに歩いていたスコットランドの出版社で『ヴェスティジェス』の著者ロバート・チェンバースに出会 い、援助を懇願した。討論会は、ジョン・ウィリアム・ドレイパーの論文発表に続いて行われ、ダーウィンの元植物学講師ジョン・スティーブンス・ヘンズロー が司会を務めた。ダーウィンの理論に反対したのはオックスフォード司教のサミュエル・ウィルバーフォースで、ダーウィンを支持したのはハクスリーや共通の 友人であるフッカーとラボックだった。壇上ではブロディとビール教授が演説し、ダーウィンの航海中にHMSビーグル号の船長であったロバート・フィッツロ イがダーウィンに反対する演説を行った[64]。 ウィルバーフォースは、1847年に開催された前回のオックスフォードB.A.会議で、チェンバーズの『遺物』を攻撃して、進化論に反対した実績があっ た。彼は、『起源』に反対し、人間が類人猿の子孫であることを示唆するという、より困難な課題に対して、リチャード・オーウェン(Richard Owen-Owen)から熱心な指導を受けていた。ハクスリーに対する有名な揶揄(ハクスリーが猿の血を引いているのは母方か父方かという質問)は、おそ らく無計画なものであり、賢明でなかったことは確かである。ハクスリーは、自分の偉大な才能を悪用して議論を抑圧する人間よりも、むしろ猿の子孫でありた いという趣旨の返事をしたが、正確な表現は定かではなく、パンフレットやなりすまし劇で広く語り継がれた[要出典]。 アルフレッド・ニュートンの手紙の中には、弟に宛てたものがあり、討論の目撃談を語っている。ハクスリーはダーウィンのために詳細な説明を書いたが、その 手紙は現存していない。しかし、友人のフレデリック・ダニエル・ダイスターに宛てた手紙には、その出来事からわずか3ヶ月後の説明が残されている[68] [69][70][71][72][73]。 この討論会の一つの効果は、新聞や定期刊行物に掲載された記事を通じて、教養のある人々の間でハクスリーの知名度が大いに高まったことであった。もう一つ の効果は、公開討論の重要性をハクスリーに認識させたことである。第三の効果は、ダーウィンの考えを簡単に否定することはできない、それどころか、正統派 の権威に対して精力的に擁護されることになるということを知らしめることであった[74][75]。ウィルバーフォースが恐れていたように、進化論の擁護 は旧約聖書、特に創世記に対する文字通りの信仰を損なうものであった。会合に出席していたリベラルな聖職者の多くは、この討論の結果に大いに満足した。彼 らは、おそらく論争の的となった『エッセイと評論』の支持者であったのだろう。このように、科学の側にとっても宗教の側にとっても、この議論は重要であ り、その結果は重要であった[76](以下も参照)。 ハクスリーとウィルバーフォースが論争後も友好的な関係を保っていたこと(メトロポリタン教育委員会などのプロジェクトで協力することができたこと)は、 ハクスリーとオウエンが和解することがなかったのとは対照的に、両人について何かを物語っている[要出典]。 自然における人間の位置 こちらも参照のこと: 自然における人間の位置 この10年近く、ハクスリーは主に人間と類人猿の関係について研究していた。そのため、リチャード・オウエンと衝突することになる。オウエンは、その能力 で賞賛される一方で、その行動で広く嫌われていた人物である。この争いは、オーウェンの大敗という結末を迎えることになる。ハクスリーが1858年に王立 協会で行った「脊椎動物の頭蓋の理論」に関するクルニアン講演がその始まりだった。この講義で彼は、ゲーテやローレンツ・オーケンが以前から持っていた、 頭蓋骨と脊椎の骨は相同であるというオーウェンの説を否定した[77]。  32歳のハクスリー 1860年から1863年にかけて、ハクスリーは自分の考えを発展させ、社会人、学生、一般大衆を対象とした講義を行い、その後出版に至った。また 1862年には、労働者を対象とした一連の講演が、講演ごとに小冊子として印刷され、後に小さな緑色の本として製本された。 ダーウィンが『人間下降論』を出版したのは1871年のことだが、このテーマに関する一般的な議論はその何年も前から始まっていた(18世紀には、モンボ ドとビュフォンの間で先駆的な議論が行われていた)。ダーウィンは『起源』の結びで、「遠い将来......人間の起源とその歴史に光が当てられるだろ う」と書いて、ヒントを与えていた[79]。1857年、リチャード・オーウェンが、人間はホモ属に特有の脳の特徴を持っていることによって、他のすべて の哺乳類から区別されているという説を(リンネ学会に)発表したとき、重要な出来事がすでに起こっていた。このような極端な見解を持つ生物学者は他にいな かった。ダーウィンは「人間は...チンパンジーと[カモノハシと猿のように]区別される...。ハクスリーも、オーウェンの考えが完全に間違っているこ とを証明することができた。  1870年頃のハクスリー。スケッチはゴリラの頭蓋骨である。 この話題は1860年のBAオックスフォードの会合で取り上げられ、ハクスリーはオーウェンに真っ向から反論し、後日事実を実証することを約束した。実 際、ロンドンや地方で多くのデモンストレーションが行われた。1862年、ハクスリーの友人であるウィリアム・フラワーは、ケンブリッジのBA会議で公開 解剖を行い、類人猿にも同じ構造(側脳室後角と小海馬)が確かに存在することを示した。この論争は広く知られるところとなり、「海馬の大問題」としてパロ ディ化された。これはオーウェンの最大の失策の一つと見なされ、ハクスリーが議論において危険であるだけでなく、優れた解剖学者であることを明らかにした [citation needed]。 オーウェンは類人猿に小海馬と呼べるものがあることは認めたが、それははるかに発達しておらず、そのような存在は単純な脳の大きさの全体的な区別を損なう ものではないと述べた[82]。 このトピックに関するハクスリーの考えは、1861年1月、彼自身の雑誌『自然史評論』の創刊号(新シリーズ)にまとめられている: この論文は1863年に『自然における人間の位置』の第2章として再版され、猿の脳に関するオーウェンとハクスリーの論争についての説明が補遺された [83]。 猿の脳について、一部は討論で、一部は印刷物で、解剖と実証に裏打ちされた広範な議論は、ハクスリーのキャリアにおける画期的なものであった。比較解剖学 の優位性を主張する上で非常に重要であり、長期的にはウィルバーフォースとの論争よりも生物学者の間で進化論を確立する上で影響力があった。また、この論 争がきっかけとなり、オウエンは生物学者仲間からの尊敬を失っていった[要出典]。 1861年のBA会合の前に、ハクスリーがロレストンに宛てた手紙に次のようなものがある: 「親愛なるロレストン... 大脳の後葉、側脳室の後円錐部、小海馬は人間に特有であり、類人猿には存在しないという3つの主張が真実でないことを、過去12ヶ月の間に7回目になると 思うのだが、それを個人的に証明するために、私は英国協会に出席することができないことを非常に残念に思っている。この手紙をセクションに読んでいただけ れば幸いである。 この数年間は、ヒトの化石解剖学と人類学の研究も行っていた。1862年、彼は1857年に発見されたネアンデルタール人の頭蓋を調査した。ハクスリーは また、身体人類学にも手を出し始め、人類を9つのカテゴリーに分類し、オーストラロイド、ネグロイド、ザントクロイド、モンゴロイドという4つの一般的な カテゴリーに分類した。このような分類は、主に外見と特定の解剖学的特徴によるものであった[86][87]。 自然淘汰 ハクスリーはダーウィンに隷属的ではなかった。あらゆる伝記に示されているように、二人はまったく異なる、むしろ相補的な性格を持っていた。また重要なこ とは、ダーウィンはフィールド・ナチュラリストであったが、ハクスリーは解剖学者であったため、彼らの自然体験には違いがあった。最後に、ダーウィンの科 学観はハクスリーのそれとは異なっていた。ダーウィンにとって、自然淘汰は進化を説明する最良の方法であり、それは膨大な自然史的事実や観察を説明できる からである。一方、ハクスリーは経験主義者であり、目に見えるものを信頼した。ダーウィンは手紙を書き、ハクスリーはダーウィンが正しいと思うとは決して 言わなかった。 自然淘汰に関するハクスリーの留保は、「淘汰と品種改良が互いに不稔な品種を生み出すことがわかるまでは、自然淘汰は証明できない」というタイプのもので あった[88][89]。証拠に対するこのような懸念にもかかわらず、ハクスリーは、もし進化が変異、繁殖、淘汰によってもたらされるのであれば、他のも のも同じ圧力を受けるだろうと考えた。物理的な世界と同じように、知的な世界でも存在への闘争が行われている。理論とは思考の一種であり、その存在の権利 は、ライバルによる絶滅に抵抗する力と同程度である」[90] 。 ダーウィンがこの議論に参加したのは、彼の常套手段であったように、ほとんどが手紙によるものであった: 「あなたが求める実証的証拠は、現実的には不可能であり、いずれにせよ不必要である。それは、ある種が別の種に変化する(あるいは分裂する)すべての段階 を見ることを求めるのと同じだ。私のやり方で多くの問題が解明され、問題が解決される。これほどうまくいく理論は他にない」[92]。 ヘレナ・クローニンが的確に述べているように、ハクスリーの留保は伝染し、「ダーウィニズムを疑うあらゆる人々の間に何年にもわたって広がっていった」 [93]。この疑念の理由のひとつは、比較解剖学は子孫の問題には対処できても、メカニズムの問題には対処できないということであった[94]。 喪主 ハクスリーは1882年4月26日に行われたチャールズ・ダーウィンの葬儀で喪主を務めた[95]。 |

| The X Club Main article: X Club In November 1864, Huxley succeeded in launching a dining club, the X Club, composed of like-minded people working to advance the cause of science; not surprisingly, the club consisted of most of his closest friends. There were nine members, who decided at their first meeting that there should be no more. The members were: Huxley, John Tyndall, J. D. Hooker, John Lubbock (banker, biologist and neighbour of Darwin), Herbert Spencer (social philosopher and sub-editor of the Economist), William Spottiswoode (mathematician and the Queen's Printer), Thomas Hirst (Professor of Physics at University College London), Edward Frankland (the new Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution) and George Busk, zoologist and palaeontologist (formerly surgeon for HMS Dreadnought). All except Spencer were Fellows of the Royal Society. Tyndall was a particularly close friend; for many years they met regularly and discussed issues of the day. On more than one occasion Huxley joined Tyndall in the latter's trips into the Alps and helped with his investigations in glaciology.[96][97][98]  From the portrait of A. Legros There were also some quite significant X-Club satellites such as William Flower and George Rolleston, (Huxley protegés), and liberal clergyman Arthur Stanley, the Dean of Westminster. Guests such as Charles Darwin and Hermann von Helmholtz were entertained from time to time.[99] They would dine early on first Thursdays at a hotel, planning what to do; high on the agenda was to change the way the Royal Society Council did business. It was no coincidence that the Council met later that same evening. The first item for the Xs was to get the Copley Medal for Darwin, which they managed after quite a struggle. The next step was to acquire a journal to spread their ideas. This was the weekly Reader, which they bought, revamped and redirected. Huxley had already become part-owner of the Natural History Review[100] bolstered by the support of Lubbock, Rolleston, Busk and Carpenter (X-clubbers and satellites). The journal was switched to pro-Darwinian lines and relaunched in January 1861. After a stream of good articles the NHR failed after four years; but it had helped at a critical time for the establishment of evolution. The Reader also failed, despite its broader appeal which included art and literature as well as science. The periodical market was quite crowded at the time, but most probably the critical factor was Huxley's time; he was simply over-committed, and could not afford to hire full-time editors. This occurred often in his life: Huxley took on too many ventures, and was not as astute as Darwin at getting others to do work for him. However, the experience gained with the Reader was put to good use when the X Club put their weight behind the founding of Nature in 1869. This time no mistakes were made: above all, there was a permanent editor (though not full-time), Norman Lockyer, who served until 1919, a year before his death. In 1925, to celebrate his centenary, Nature issued a supplement devoted to Huxley.[101] The peak of the X Club's influence was from 1873 to 1885 as Hooker, Spottiswoode and Huxley were Presidents of the Royal Society in succession. Spencer resigned in 1889 after a dispute with Huxley over state support for science.[102] After 1892 it was just an excuse for the surviving members to meet. Hooker died in 1911, and Lubbock (now Lord Avebury) was the last surviving member. Huxley was also an active member of the Metaphysical Society, which ran from 1869 to 1880.[103] It was formed around a nucleus of clergy and expanded to include all kinds of opinions. Tyndall and Huxley later joined The Club (founded by Dr. Johnson) when they could be sure that Owen would not turn up.[104] |

Xクラブ 主な記事 Xクラブ 1864年11月、ハクスリーは科学の進歩のために志を同じくする人々で構成されるXクラブというダイニング・クラブを立ち上げることに成功した。クラブ には9人の会員がいたが、最初の会合で、これ以上の会員を増やすべきでないと決定した。メンバーは以下の通りである: ハクスリー、ジョン・ティンダル、J.D.フッカー、ジョン・ラボック(銀行家、生物学者、ダーウィンの隣人)、ハーバート・スペンサー(社会哲学者、エ コノミスト誌副編集長)、ウィリアム・スポティスウッド(数学者、クイーンズ・プリンター)、トーマス・ハースト(ユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドン 物理学教授)、エドワード・フランクランド(王立研究所の新しい化学教授)、ジョージ・ブスク(動物学者、古生物学者、元HMSドレッドノート号の外科 医)である。スペンサーを除く全員が王立協会のフェローだった。ティンダルは特に親しい友人であり、何年もの間、彼らは定期的に会い、その時々の問題につ いて話し合った。ハクスリーはティンダルのアルプス旅行に同行し、氷河学の研究を手伝ったこともあった[96][97][98]。  A.レグロの肖像画より また、ウィリアム・フラワーやジョージ・ロレストン(ハクスリーの弟子)、ウェストミンスターの学部長であるリベラルな聖職者アーサー・スタンリーなど、 Xクラブの衛星として非常に重要な人物もいた。チャールズ・ダーウィンやヘルマン・フォン・ヘルムホルツのようなゲストも時々もてなされた[99]。 彼らは第一木曜日の早い時間にホテルで食事をし、何をすべきかを計画した。その日の夜、王立協会の評議会が開かれたのは偶然ではなかった。Xsの最初の課 題は、ダーウィンにコプリー・メダルを与えることだった。 次のステップは、自分たちの考えを広めるための雑誌を手に入れることだった。それが『週刊リーダー』誌であり、彼らはこれを購入し、刷新し、方向転換し た。ハクスリーはすでに、ラボック、ロレストン、バスク、カーペンター(Xクラブとその衛星)の支援を受けて、『自然史評論』誌[100]の一部所有者と なっていた。雑誌はダーウィン支持路線に転換され、1861年1月に再創刊された。NHRは優れた論文を次々と発表したが、4年後に失敗に終わった。しか し、進化論の確立にとって重要な時期にこの雑誌は役立っていた。リーダー』もまた、科学だけでなく芸術や文学を含む幅広いアピールがあったにもかかわら ず、失敗に終わった。当時の定期刊行物市場はかなり混雑していたが、おそらく決定的な要因はハクスリーの時間にあった。ハクスリーは多くの事業を引き受け すぎており、ダーウィンほど他人に仕事を依頼することに長けていなかった。 しかし、『リーダー』誌で得た経験は、1869年にXクラブが『ネイチャー』誌の創刊に力を注いだときに活かされた。何よりも、ノーマン・ロッキヤーとい う常任編集者が(専任ではなかったが)おり、彼は亡くなる前年の1919年まで務めた。1925年、ハクスリーの生誕100周年を記念して、『ネイ チャー』誌はハクスリー特集を組んだ[101]。 Xクラブの影響力のピークは1873年から1885年で、フッカー、スポティスウッド、ハクスリーが相次いで王立協会の会長を務めた。スペンサーは 1889年、科学への国家支援をめぐってハックスレーと対立し、辞任した[102]。フッカーは1911年に死去し、ラボック(現エイブベリー卿)が最後 の存命会員となった。 ハクスリーはまた、1869年から1880年まで活動していた形而上学協会のメンバーでもあった。ティンダルとハクスリーはその後、オウエンが現れないと 確信できるようになると、ザ・クラブ(ジョンソン博士が創設)に参加した[104]。 |

| Educational influence When Huxley himself was young there were virtually no degrees in British universities in the biological sciences and few courses. Most biologists of his day either were self-taught or took medical degrees. When he retired there were established chairs in biological disciplines in most universities, and a broad consensus on the curricula to be followed. Huxley was the single most influential person in this transformation. School of Mines and Zoology In the early 1870s, the Royal School of Mines moved to new quarters in South Kensington; ultimately it would become one of the constituent parts of Imperial College London. The move gave Huxley the chance to give more prominence to laboratory work in biology teaching, an idea suggested by practice in German universities.[31] In the main, the method was based on the use of carefully chosen types, and depended on the dissection of anatomy, supplemented by microscopy, museum specimens and some elementary physiology at the hands of Foster. The typical day would start with Huxley lecturing at 9 am, followed by a program of laboratory work supervised by his demonstrators.[105] Huxley's demonstrators were picked men—all became leaders of biology in Britain in later life, spreading Huxley's ideas as well as their own. Michael Foster became Professor of Physiology at Cambridge; Ray Lankester became Jodrell Professor of Zoology at University College London (1875–91), Professor of Comparative Anatomy at Oxford (1891–98) and Director of the Natural History Museum (1898–1907); S.H. Vines became Professor of Botany at Cambridge; W.T. Thiselton-Dyer became Hooker's successor at Kew (he was already Hooker's son-in-law!); T. Jeffery Parker became Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy at University College, Cardiff; and William Rutherford[106] became the Professor of Physiology at Edinburgh. William Flower, Conservator to the Hunterian Museum, and THH's assistant in many dissections, became Sir William Flower, Hunterian Professor of Comparative Anatomy and, later, Director of the Natural History Museum.[37] It's a remarkable list of disciples, especially when contrasted with Owen who, in a longer professional life than Huxley, left no disciples at all. "No one fact tells so strongly against Owen... as that he has never reared one pupil or follower".[107]  Photograph of Huxley (c. 1890) Huxley's courses for students were so much narrower than the man himself that many were bewildered by the contrast: "The teaching of zoology by use of selected animal types has come in for much criticism";[108] Looking back in 1914 to his time as a student, Sir Arthur Shipley said "Darwin's later works all dealt with living organisms, yet our obsession was with the dead, with bodies preserved, and cut into the most refined slices".[109] E.W MacBride said "Huxley... would persist in looking at animals as material structures and not as living, active beings; in a word... he was a necrologist.[110] To put it simply, Huxley preferred to teach what he had actually seen with his own eyes. This largely morphological program of comparative anatomy remained at the core of most biological education for a hundred years until the advent of cell and molecular biology and interest in evolutionary ecology forced a fundamental rethink. It is an interesting fact that the methods of the field naturalists who led the way in developing the theory of evolution (Darwin, Wallace, Fritz Müller, Henry Bates) were scarcely represented at all in Huxley's program. Ecological investigation of life in its environment was virtually non-existent, and theory, evolutionary or otherwise, was at a discount. Michael Ruse finds no mention of evolution or Darwinism in any of the exams set by Huxley, and confirms the lecture content based on two complete sets of lecture notes.[111] Since Darwin, Wallace and Bates did not hold teaching posts at any stage of their adult careers (and Műller never returned from Brazil) the imbalance in Huxley's program went uncorrected. It is surely strange that Huxley's courses did not contain an account of the evidence collected by those naturalists of life in the tropics; evidence which they had found so convincing, and which caused their views on evolution by natural selection to be so similar. Adrian Desmond suggests that "[biology] had to be simple, synthetic and assimilable [because] it was to train teachers and had no other heuristic function".[112] That must be part of the reason; indeed it does help to explain the stultifying nature of much school biology. But zoology as taught at all levels became far too much the product of one man. Huxley was comfortable with comparative anatomy, at which he was the greatest master of the day. He was not an all-round naturalist like Darwin, who had shown clearly enough how to weave together detailed factual information and subtle arguments across the vast web of life. Huxley chose, in his teaching (and to some extent in his research) to take a more straightforward course, concentrating on his personal strengths. Schools and the Bible Huxley was also a major influence in the direction taken by British schools: in November 1870, he was elected to the London School Board in its first elections.[113] In primary schooling, he advocated a wide range of disciplines, similar to what is taught today: reading, writing, arithmetic, art, science, music, etc. In secondary education he recommended two years of basic liberal studies followed by two years of some upper-division work, focusing on a more specific area of study. A practical example of the latter is his famous 1868 lecture On a Piece of Chalk which was first published as an essay in Macmillan's Magazine in London later that year.[114] The piece reconstructs the geological history of Britain from a simple piece of chalk and demonstrates science as "organized common sense". Huxley supported the reading of the Bible in schools. This may seem out of step with his agnostic convictions, but he believed that the Bible's significant moral teachings and superb use of language were relevant to English life. "I do not advocate burning your ship to get rid of the cockroaches".[115] However, what Huxley proposed was to create an edited version of the Bible, shorn of "shortcomings and errors... statements to which men of science absolutely and entirely demur... These tender children [should] not be taught that which you do not yourselves believe".[116][117] The Board voted against his idea, but it also voted against the idea that public money should be used to support students attending church schools. Vigorous debates took place on such points, and the debates were minuted in detail. Huxley said "I will never be a party to enabling the State to sweep the children of this country into denominational schools".[118][119] The Act of Parliament which founded board schools permitted the reading of the Bible but did not permit any denominational doctrine to be taught. It may be right to see Huxley's life and work as contributing to the secularisation of British society which gradually occurred over the following century. Ernst Mayr said "It can hardly be doubted that [biology] has helped to undermine traditional beliefs and value systems"[120]—and Huxley more than anyone else was responsible for this trend in Britain. Some modern Christian apologists consider Huxley the father of antitheism, though he himself maintained that he was an agnostic, not an atheist. He was, however, a lifelong and determined opponent of almost all organised religion throughout his life, especially the "Roman Church ... carefully calculated for the destruction of all that is highest in the moral nature, in the intellectual freedom, and in the political freedom of mankind".[119][121] In the same line of thought, in an article in Popular Science, Huxley used the expression "the so-called Christianity of Catholicism", explaining: "I say 'so-called' not by way of offence, but as a protest against the monstrous assumption that Catholic Christianity is explicitly or implicitly contained in any trust-worthy record of the teaching of Jesus of Nazareth."[122] Originally coining the term in 1869, Huxley elaborated on "agnosticism" in 1889 to frame the nature of claims in terms of what is knowable and what is not. Huxley states Agnosticism, in fact, is not a creed, but a method, the essence of which lies in the rigorous application of a single principle... the fundamental axiom of modern science... In matters of the intellect, follow your reason as far as it will take you, without regard to any other consideration... In matters of the intellect, do not pretend that conclusions are certain which are not demonstrated or demonstrable.[123] Use of that term has continued to the present day (see Thomas Henry Huxley and agnosticism).[124] Much of Huxley's agnosticism is influenced by Kantian views on human perception and the ability to rely on rational evidence rather than belief systems.[125] In 1893, during preparation for the second Romanes Lecture, Huxley expressed his disappointment at the shortcomings of 'liberal' theology, describing its doctrines as 'popular illusions', and the teachings they replaced 'faulty as they are, appear to me to be vastly nearer the truth'.[126] Vladimir Lenin remarked that for Huxley "agnosticism serves as a fig-leaf for materialism".[127] (See also the Debate with Wilberforce above.) Adult education  Thomas Henry Huxley, c. 1885, from a carte de visite  Method and results, 1893 Huxley's interest in education went still further than school and university classrooms; he made a great effort to reach interested adults of all kinds: after all, he himself was largely self-educated. There were his lecture courses for working men, many of which were published afterwards, and there was the use he made of journalism, partly to earn money but mostly to reach out to the literate public. For most of his adult life, he wrote for periodicals—the Westminster Review, the Saturday Review, the Reader, the Pall Mall Gazette, Macmillan's Magazine, the Contemporary Review. Germany was still ahead in formal science education, but interested people in Victorian Britain could use their initiative and find out what was going on by reading periodicals and using the lending libraries.[128][129] In 1868 Huxley became Principal of the South London Working Men's College in Blackfriars Road. The moving spirit was a portmanteau worker, Wm. Rossiter, who did most of the work; the funds were put up mainly by F.D. Maurice's Christian Socialists.[130][131] At sixpence for a course and a penny for a lecture by Huxley, this was some bargain; and so was the free library organised by the college, an idea which was widely copied. Huxley thought, and said, that the men who attended were as good as any country squire.[132] The technique of printing his more popular lectures in periodicals which were sold to the general public was extremely effective. A good example was "The Physical Basis of Life", a lecture given in Edinburgh on 8 November 1868. Its theme—that vital action is nothing more than "the result of the molecular forces of the protoplasm which displays it"—shocked the audience, though that was nothing compared to the uproar when it was published in the Fortnightly Review for February 1869. John Morley, the editor, said "No article that had appeared in any periodical for a generation had caused such a sensation".[133] The issue was reprinted seven times and protoplasm became a household word; Punch added 'Professor Protoplasm' to his other soubriquets. The topic had been stimulated by Huxley seeing the cytoplasmic streaming in plant cells, which is indeed a sensational sight. For these audiences, Huxley's claim that this activity should not be explained by words such as vitality, but by the working of its constituent chemicals, was surprising and shocking. Today we would perhaps emphasise the extraordinary structural arrangement of those chemicals as the key to understanding what cells do, but little of that was known in the nineteenth century. When the Archbishop of York thought this 'new philosophy' was based on Auguste Comte's positivism, Huxley corrected him: "Comte's philosophy [is just] Catholicism minus Christianity" (Huxley 1893 vol 1 of Collected Essays Methods & Results 156). A later version was "[positivism is] sheer Popery with M. Comte in the chair of St Peter, and with the names of the saints changed". (lecture on The scientific aspects of positivism Huxley 1870 Lay Sermons, Addresses and Reviews p. 149). Huxley's dismissal of positivism damaged it so severely that Comte's ideas withered in Britain. |

教育の影響 ハクスリー自身が若い頃、イギリスの大学には生物科学の学位はほとんどなく、コースもほとんどなかった。当時の生物学者のほとんどは独学か医学の学位を 取っていた。彼が引退したときには、ほとんどの大学で生物学分野の講座が開設され、従うべきカリキュラムについても幅広いコンセンサスが得られていた。ハ クスリーは、この変革に最も影響を与えた唯一の人物であった。 鉱山学と動物学 1870年代初頭、王立鉱山学校はサウスケンジントンの新しい宿舎に移転した。最終的には、インペリアル・カレッジ・ロンドンの構成要素のひとつとなる。 この移転により、ハクスリーは、ドイツの大学での実践にヒントを得て、生物学の教育において実験室での実習を重視するようになった。 典型的な一日は、午前9時にハクスリーの講義が始まり、その後、デモンストレーターが監督する実験室のプログラムが続くというものであった[105]。ハ クスリーのデモンストレーターは選りすぐりの人物であり、全員が後年、英国における生物学の指導者となり、ハクスリーの思想と自らの思想を広めた。マイケ ル・フォスターはケンブリッジ大学の生理学教授となり、レイ・ランケスターはロンドン大学のジョドレル動物学教授(1875-91)、オックスフォード大 学の比較解剖学教授(1891-98)、自然史博物館の館長(1898-1907)となった。ヴァインズはケンブリッジの植物学教授となり、W.T.ティ ゼルトン・ダイヤーはキューでフッカーの後継者となった(彼はすでにフッカーの娘婿だった!)。T.ジェフェリー・パーカーはカーディフのユニヴァーシ ティ・カレッジで動物学と比較解剖学の教授となり、ウィリアム・ラザフォード[106]はエディンバラの生理学教授となった。ウィリアム・フラワーはハン ター博物館の保存係で、THHの助手として多くの解剖に携わったが、ハンター博物館の比較解剖学教授であるサー・ウィリアム・フラワーとなり、後に自然史 博物館の館長となった[37]。「オウエンが弟子や追随者を一人も育てなかったことほど、オウエンに不利な事実はない」[107]。  ハクスリーの写真(1890年頃) ハクスリーの学生向け講座は、ハクスリー自身よりもはるかに狭いものであったため、そのコントラストに戸惑う者も多かった: 「1914年、アーサー・シプリー卿は学生時代を振り返って、「ダーウィンの後の著作はすべて生きた生物を扱っていた。 [E.W.マクブライドは、「ハクスリーは...動物を生きた活動的な存在としてではなく、物質的な構造として見ることに固執した。 細胞生物学と分子生物学が登場し、進化生態学への関心が根本的な再考を迫るまで、このような形態学的な比較解剖学プログラムが、100年にわたりほとんど の生物学教育の中核であり続けた。進化論の発展をリードしたフィールド・ナチュラリストたち(ダーウィン、ウォレス、フリッツ・ミュラー、ヘンリー・ベイ ツ)の手法が、ハクスリーのプログラムにはまったくといっていいほど含まれていなかったことは興味深い事実である。環境における生命の生態学的調査は事実 上存在せず、進化論であろうとなかろうと、理論は軽視されていた。マイケル・リューズは、ハクスリーが設定した試験のどれにも進化論やダーウィニズムにつ いての言及がないことを発見し、講義ノートの2つの完全なセットに基づいて講義内容を確認している[111]。 ダーウィン、ウォーレス、ベイツの3人は、社会人になってから教壇に立つことはなかったため(ミューラーもブラジルから帰国することはなかった)、ハクス リーのプログラムの不均衡は修正されることはなかった。ハクスリーの講座に、これらの博物学者が収集した熱帯の生物に関する証拠についての説明がなかった のは確かに奇妙である。エイドリアン・デズモンドは、「(生物学は)単純で、合成的で、同化しやすいものでなけ ればならなかったが、それは教師を養成するためのものであり、それ以外に発見的な機能を持たな かったからである」と指摘している。しかし、あらゆるレベルで教えられる動物学は、あまりにも一人の人間の産物になってしまった。 ハクスリーは比較解剖学を得意としており、その分野では当代随一の巨匠であった。彼はダーウィンのような万能の博物学者ではなかった。ダーウィンは、膨大 な生命の網の目を通して、詳細な事実情報と微妙な議論を織り交ぜる方法を十分に明らかにしていた。ハクスリーは、教育において(そして研究においても)、 個人的な強みに集中し、より率直な道を選んだのである。 学校と聖書 ハクスリーはイギリスの学校の方向性にも大きな影響を与えた。1870年11月、彼はロンドン教育委員会の最初の選挙で選出された[113]。初等教育で は、今日教えられているのと同様に、読み書き、算数、美術、科学、音楽など、幅広い分野を教えることを提唱した。中等教育では、2年間の基本的な教養教育 の後、2年間はより特定の分野に焦点を当てた高等教育を行うことを推奨した。後者の実践的な例としては、1868年の有名な講義『一片のチョークについ て』がある。この講義は、同年末にロンドンの『マクミランズ・マガジン』にエッセイとして発表された[114] 。 ハクスリーは学校で聖書を読むことを支持した。これは不可知論者であった彼の信念とはかけ離れているように見えるかもしれないが、彼は聖書の重要な道徳的 教えと優れた言葉の使い方がイギリス人の生活に関連していると信じていた。「しかし、ハクスリーが提案したのは、「欠点や誤り......科学者が絶対的 かつ完全に反対するような記述......」を取り除いた聖書の編集版を作ることであった。この優しい子供たちに、あなた方自身が信じていないことを教え るべきではない」[116][117]。理事会は彼のアイデアに反対票を投じたが、教会学校に通う生徒を支援するために公金を使うべきだというアイデアに も反対票を投じた。このような点について活発な討論が行われ、討論は詳細に記録された。ハクスリーは、「私は、国家がこの国の子供たちを宗派の学校に押し 込めることに加担するつもりはない」と述べている[118][119]。理事会学校を設立した議会法は、聖書の朗読を許可していたが、宗派の教義を教える ことは許可していなかった。 ハクスリーの人生と仕事は、その後の1世紀にわたって徐々に起こったイギリス社会の世俗化に貢献したと見るのが正しいかもしれない。エルンスト・マイヤー は「(生物学が)伝統的な信念や価値体系を弱体化させる一助となったことは疑う余地がない」と述べている[120]。現代のキリスト教弁証主義者の中に は、ハクスリーを反神論の父とみなす者もいるが、彼自身は無神論者ではなく不可知論者であると主張していた。しかし、彼は生涯を通じて、ほとんどすべての 組織化された宗教、特に「ローマ教会......人類の道徳的本性、知的自由、政治的自由において最高であるものすべてを破壊するために注意深く計算され たもの」[119][121]に断固として反対していた。同じ思想路線で、『ポピュラー・サイエンス』誌の記事の中で、ハクスリーは「カトリックのいわゆ るキリスト教」という表現を使い、こう説明している: 私が "いわゆる "と言ったのは、悪気があってではなく、カトリックのキリスト教が、ナザレのイエスの教えに関する信頼に値する記録の中に、明示的にも暗黙的にも含まれて いるという、とんでもない思い込みに対する抗議としてである」[122]。 ハクスリーは1869年に「不可知論」という言葉を創作したが、1889年に「不可知論」をさらに発展させ、何が知りうることで、何が知りえないことなの かという観点から、主張の本質を組み立てている。ハクスリーは次のように述べている。 不可知論とは、実は信条ではなく、一つの方法であり、その本質は、一つの原則...近代科学の基本公理...を厳格に適用することにある。知性の問題にお いては、他のいかなる考慮もせず、理性があなたを連れて行く限り、あなたの理性に従いなさい...。知性の問題においては、実証されていない、あるいは実 証可能でない結論が確かであるかのようなふりをしてはならない[123]。 この用語の使用は現在まで続いている(トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーと不可知論を参照)[124]。ハクスリーの不可知論の多くは、人間の知覚と、信念 体系ではなく合理的な証拠に頼る能力に関するカント派の見解に影響を受けている[125]。 1893年、第2回ロマネス講義の準備中に、ハクスリーは「自由主義」神学の欠点に失望を表明し、その教義を「大衆の幻想」と表現し、それらが取って代 わった教えは「欠点はあるが、私にははるかに真理に近いように見える」と述べている[126]。 ウラジーミル・レーニンは、ハクスリーにとって「不可知論は唯物論のためのイチジクの葉の役割を果たす」と発言している[127](上記のウィルバー フォースとの討論も参照)。 成人教育  トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー、1885年頃、訪問記録より  方法と結果、1893年 ハクスリーの教育への関心は、学校や大学の教室の中だけにとどまらず、あらゆる種類の関心のある大人たちにまで及んだ。社会人向けの講義もあり、その多く は後に出版された。また、ジャーナリズムを利用したこともあった。ウェストミンスター・レビュー』、『サタデー・レビュー』、『リーダー』、『ポール・ モール・ガゼット』、『マクミラン・マガジン』、『コンテンポラリー・レビュー』などである。正式な科学教育においてはドイツがまだ先を行っていたが、 ヴィクトリア朝時代のイギリスでは、興味を持った人々は定期刊行物を読んだり、貸し出し図書館を利用したりすることで、自発的に何が起こっているのかを知 ることができた[128][129]。 1868年、ハクスリーはブラックフライアーズ・ロードにあるサウス・ロンドン・ワーキングメンズ・カレッジの校長に就任した。ハクスリーは、1868 年、ブラックフライヤーズ・ロードにあるサウス・ロンドン労働者カレッジの校長に就任した。このカレッジを動かしていたのは、ほとんどの仕事をこなしたポ ルトマン労働者のWm.ロシターであり、資金は主にF.D.モーリスのキリスト教社会主義者によって集められた[130][131]。ハクスリーは、大学 に通う人たちはどんな田舎の従者にも劣らないと考え、そう言った[132]。 一般大衆に販売される定期刊行物に、より人気のある講義を印刷するという手法は非常に効果的であった。その好例が、1868年11月8日にエジンバラで行 われた講義「生命の物理的基礎」である。そのテーマ、すなわち生命活動は「それを表示する原形質の分子力の結果」にほかならないというもので、聴衆に衝撃 を与えたが、それが1869年2月の『フォートナイトリー・レヴュー』誌に掲載されたときの騒動に比べれば大したことはなかった。編集者のジョン・モー リーは、「一世代にわたって、どの定期刊行物に掲載された記事でも、これほどのセンセーションを巻き起こしたものはなかった」と述べている[133]。こ の号は7回再版され、原形質は一般的な言葉となった。 この話題は、ハクスリーが植物細胞内の細胞質の流れを見たことに端を発していたが、それは実にセンセーショナルな光景であった。これらの聴衆にとって、こ の活動は生命力などという言葉で説明されるべきではなく、構成する化学物質の働きによって説明されるべきだというハクスリーの主張は、驚きと衝撃を与える ものだった。今日なら、細胞の働きを理解する鍵として、それらの化学物質の並外れた構造的配置を強調するだろうが、19世紀にはそのようなことはほとんど 知られていなかった。 ヨーク大司教がこの「新しい哲学」をオーギュスト・コントの実証主義に基づいていると考えたとき、ハクスリーは彼を訂正した: 「コントの哲学は、カトリシズムからキリスト教を除いたものにすぎない」(Huxley 1893 vol. 1 of Collected Essays Methods & Results 156)。後のバージョンでは、「(実証主義は)聖ペテロの椅子にコントを座らせ、聖人の名前を変えただけの、まったくの教皇主義である」 (positivism is sheer Popery with M. Comte in the chair of St Peter, with the names of the saints)となった。(実証主義の科学的側面に関する講義 Huxley 1870 Lay Sermons, Addresses and Reviews p. 149)。ハクスリーが実証主義を否定したことで、実証主義は深刻なダメージを受け、コントの思想は英国で枯れてしまった。 |