論理哲学論考

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

☆ 『論理哲学論考』(Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, TLP)は、オーストリアの哲学者ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインが生前に出版した唯一の哲学書である。このプロジェクトは、言語と現実の関係を明ら かにし、科学の限界を定義するという幅広い目標を掲げていた[1]。ウィトゲンシュタインは、第一次世界大戦中の兵士であった時に『Tractatus』 のノートを書き、1918年の夏の休暇中に完成させた。1921年にドイツ語で『論理哲学論考』(Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung)として出版された。1922年には、英語訳とラテン語の題名とともに出版された。この題名は、G.E.ムーアがバルーク・スピノザ の『神学政治学綱要』(Tractatus Theologico-Politicus、1670年)へのオマージュとして提案したものである。 簡潔な文体で書かれ、論証はほとんどなく、525の宣言文で構成され、階層的に番号が振られている。 哲学者たちの間では、この著作は20世紀における最も重要な哲学的著作の一つとして認識されており、ルドルフ・カーナップやフリードリヒ・ウェイスマン、 バートランド・ラッセルの論文『論理的原子論の哲学』など、主にウィーン・サークルの論理実証主義哲学者たちに大きな影響を与えた。 ウィトゲンシュタインの晩年の著作、特に死後に出版された『哲学的考察』は、『論考』の多くの思想を批判している。しかし、ウィトゲンシュタインの思考に は、後世の著作における『哲学探究』への批判にもかかわらず、共通項を見出す要素がある。実際、「初期」と「後期」のウィトゲンシュタインという伝説的な 対比は、Pears (1987)やHilmy (1987)などの学者によって反論されている。例えば、ウィトゲンシュタインの中心的な問題において、「使用」としての「意味」に関連する、しかし無視 されている連続性の側面がある。使用としての意味」に関する彼の初期と後期の著作をつなぐのは、ある語句の直接的な結果に対する彼の訴えであり、それは例 えば、彼が言語を「微積分学」として語ることに反映されている。これらの箇所は、ウィトゲンシュタインの「使用としての意味」観にとって極めて重要である にもかかわらず、学術文献では広く無視されてきた。これらの箇所の中心性と重要性は、「Tractatusから後の著作へ、そして戻る-Nachlass からの新たな示唆」(de Queiroz 2023)で行われているように、ヴィトゲンシュタインのNachlaßを新たに検討することによって裏付けられ、増強される。

☆ドイツ語版ウィキペディアの解説

| Der Tractatus logico-philosophicus

oder kurz Tractatus (ursprünglicher deutscher Titel:

Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung) ist das erste Hauptwerk des

österreichischen Philosophen Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951). Das Werk wurde während des Ersten Weltkriegs geschrieben und 1918 vollendet. Es erschien mit Unterstützung von Bertrand Russell zunächst 1921 in Wilhelm Ostwalds Annalen der Naturphilosophie. Diese von Wittgenstein nicht gegengelesene Fassung enthielt grobe Fehler. Eine korrigierte, zweisprachige Ausgabe (deutsch/englisch) erschien 1922 bei Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. in London in der Reihe International Library of Psychology, Philosophy and Scientific Method und gilt als die offizielle Fassung. Die englische Übersetzung stammte von C. K. Ogden und Frank Ramsey. Eine zweite zweisprachige Ausgabe erschien 1933. 1929 legte Wittgenstein den Tractatus (der lateinische, an Spinozas Tractatus theologico-politicus erinnernde Titel geht auf G. E. Moore zurück) als Doktorarbeit am Trinity College der Universität Cambridge vor.[1] Wie im Titel des Buches angedeutet, enthält es zum einen eine logische Theorie, zum anderen legt Wittgenstein darin eine philosophische Methode dar. „Das Buch will also dem Denken eine Grenze ziehen, oder vielmehr – nicht dem Denken, sondern dem Ausdruck der Gedanken: Denn um dem Denken eine Grenze zu ziehen, müßten wir beide Seiten dieser Grenze denken können.“ (Vorwort). Wittgensteins Hauptanliegen ist es, die Philosophie von Unsinn und Verwirrung zu bereinigen, denn „[d]ie meisten Sätze und Fragen, welche über philosophische Dinge geschrieben worden sind, sind nicht falsch, sondern unsinnig. Wir können daher Fragen dieser Art überhaupt nicht beantworten, sondern nur ihre Unsinnigkeit feststellen. Die meisten Fragen und Sätze der Philosophen beruhen darauf, dass wir unsere Sprachlogik nicht verstehen.“ (4.003) „Im Einzelnen“ erhebt Wittgenstein „überhaupt nicht den Anspruch auf Neuheit; und darum gebe ich auch keine Quellen an, weil es mir gleichgültig ist, ob das, was ich gedacht habe, vor mir schon ein anderer gedacht hat.“ (Vorwort) Wittgenstein folgt im Tractatus dem Modus mathematicus, der damals vor allem den analytischen Philosophen angebracht erschien (Frege, Russell, Whitehead, Schlick u. a.). Knapp gefasste, präzise Definitionen von Begriffen und logische Folgerungen, aber auch die Einführung von formalen Notationen aus der mathematischen Logik geben dem Text den Anschein größtmöglicher Allgemeinheit und Endgültigkeit. Das auffallende Nummerierungssystem der einzelnen Sätze und Absätze soll nach Aussage Wittgensteins das logische Gewicht der Sätze andeuten. Ebendieses Nummerierungssystem, das auf Wittgenstein zurückgeht, hat in der akademischen Welt großen Anklang und Verbreitung erfahren. Wittgenstein definiert in der Umgangssprache gebräuchliche Termini wie Satz, Tatsache, Sachverhalt oder auch Welt im Tractatus genau und entwirft mit ihnen eine Bedeutungs- und Sprachtheorie. Wittgenstein widmete sein Erstlingswerk Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus seinem Freund und Lebensgefährten David Pinsent zum Gedenken.[2] |

『論理哲学論考』は、オーストリアの哲学者ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン(1889-1951)の最初の著作である。 第一次世界大戦中に執筆され、1918年に完成した。1921年、バートランド・ラッセルの協力を得て、ヴィルヘルム・オストヴァルトの『自然哲学論文 集』に初めて掲載された。この版はウィトゲンシュタインによって校正されておらず、重大な誤りを含んでいた。1922年、ロンドンのケーガン・ポール、ト レンチ、トラブナー社から、心理学、哲学、科学的方法の国際図書館シリーズとして、ドイツ語と英語の対訳版が出版され、これが公式版とされている。英訳は C.K.オグデンとフランク・ラムゼイによるものである。1929年、ウィトゲンシュタインはケンブリッジ大学トリニティ・カレッジの博士論文として 『Tractatus』(スピノザの『Tractatus theologico-politicus』を彷彿とさせるラテン語のタイトルはG・E・ムーアに遡る)を発表した[1]。 本書のタイトルが示すように、本書は一方に論理理論、他方に哲学的方法を含んでいる。「思考の下に線を引くためには、この線の両側から考えることができな ければならないからである。(序文)。ウィトゲンシュタインの主な関心事は、哲学からナンセンスと混乱を一掃することである。「哲学的物自体について書か れた命題や問いの大半は、偽りではなく、ナンセンスである。したがって、私たちはこの種の問いに答えることはできないが、その無意味さを立証することだけ はできる。哲学者の質問や命題のほとんどは、私たちが言語の論理を理解していないという事実に基づいている。" (4.003) 「詳細には」、ウィトゲンシュタインは 「新規性をまったく主張しない。」「だから私はいかなる出典も引用しないのである。」「私が考えたことが、私より前に他の誰かによってすでに考えられていたかどうかを気にしないからである。」 序文 ウィトゲンシュタインは『論考』において、当時分析哲学者(フレーゲ、ラッセル、ホワイトヘッド、シュリックなど)に特にふさわしいと思われていた数学的 モダスに従っている。概念と論理的結論の簡潔で正確な定義と、数理論理学からの形式的な記法の導入は、テキストに最大限の一般性と最終性を与えている。 ウィトゲンシュタインによれば、個々の文章や段落に顕著な番号付けがされているのは、文章の論理的重みを示すためである。まさにウィトゲンシュタインにま でさかのぼるこの番号付けシステムが、学問の世界で非常に人気があり、広まっているのである。ウィトゲンシュタインは『論考』の中で、文、事実、事実の問 題、世界といった一般的な口語用語を正確に定義し、それらを用いて意味と言語の理論を展開している。 ウィトゲンシュタインは最初の著作『論理哲学論考』を友人であり仲間であったデイヴィッド・ピンセントに捧げている[2]。 |

| Inhalt Abschnitte 1–3 Welt und Wirklichkeit Bei der Beschreibung von Welt und Wirklichkeit greift Wittgenstein auf folgende Termini zurück: Tatsache, Sachverhalt, Gegenstand, Form, logischer Raum. Folgende Sätze seien zur Erklärung dieser Begriffe herangezogen: „Die Welt ist die Gesamtheit der Tatsachen, nicht der Dinge.“ (1.1) „Was der Fall ist, die Tatsache, ist das Bestehen von Sachverhalten.“ (2) „Der Sachverhalt ist eine Verbindung von Gegenständen (Sachen, Dingen).“ (2.01) „Das Bestehen und Nichtbestehen von Sachverhalten ist die Wirklichkeit.“ (2.06) „Die Art und Weise, wie die Gegenstände im Sachverhalt zusammenhängen, ist die Struktur des Sachverhaltes.“ (2.032) „Die Form ist die Möglichkeit der Struktur.“ (2.033) Die Welt ist nach Wittgenstein keine Liste sie ausmachender Dinge oder Gegenstände, sondern erscheint in deren Verbindung (Anordnung): Dieselben Dinge können in verschiedenster Weise verbunden sein und bilden so verschiedene Sachverhalte. Etwa kann eine Halskette im Schaufenster liegen, den Hals einer Frau zieren oder Gegenstand einer Versteigerung sein. In jedem der drei Beispielfälle ist die Halskette in unterschiedlicher Weise mit den Dingen um sie verbunden und dadurch Bestandteil eines anderen Sachverhaltes. Nicht alle diese Sachverhalte können gleichzeitig bestehen, sondern immer nur einer auf Kosten der anderen, und ebendies ist die Wirklichkeit: der eine tatsächlich bestehende und die deswegen nichtbestehenden Sachverhalte. Alle überhaupt möglichen Sachverhalte aber, in die ein Ding oder Gegenstand eintreten kann, sind dessen Form (2.0141). Die Halskette ist ein veranschaulichendes Bild, denn was Wittgensteins „Dinge“ (oder „Gegenstände“) eigentlich sind, ist im Tractatus nicht genau spezifiziert. Wittgenstein stellt lediglich die Forderung auf, dass sie „einfach“ und atomar (also selber „nicht zusammengesetzt“, keine Sachverhalte) sein müssen (vgl. 2.02, 2.021). Alle bestehenden und nichtbestehenden Sachverhalte zusammengenommen bilden die Wirklichkeit. „Die gesamte Wirklichkeit ist die Welt.“ (2.063). Ontologisch sind die Ausgangspunkte seiner Philosophie nur die real existierenden Sachverhalte, sie sind für Wittgenstein das, was der Fall ist. Tatsachen sind bestehende Sachverhalte, die aus mehreren Gegenständen zusammengesetzt sind. Der Sachverhalt ist eine Verbindung von Gegenständen (Sachen, Dingen). Charakterisiert werden kann ein Gegenstand in einem Verständnis, in einer solchen Sprache der äußeren Beziehungen allein dadurch, dass man die möglichen Beziehungen angibt, in die dieser Gegenstand zu anderen Gegenständen treten kann. Hierzu ein Analogon: „Die Welt“[3] ist gleichsam ein Kartenspiel. Wittgensteins Ontologie wird zum Verständnis mit einem Pokerspiel gleichgesetzt. Dann ist die Gesamtheit der Karten in einem Blatt[4], die ein Spieler auf der Hand hält, ein bestehender Sachverhalt, eine „Tatsache“. Alle am Spiel beteiligten Pokerhände wären dann die „Gesamtheit der Tatsachen“, sie repräsentieren gemeinsam eine Welt, was für eine Spielsituation „der Fall ist“. Jede Karte der Pokerkarten vertritt für sich genommen einen „Gegenstand“. Die Karten haben nur als Verbindung einen Wert. In diesem Sinne müssen wir uns auch die „Gegenstände“ (Karte) stets „in ihrer Verbindung mit anderen Gegenständen“ denken. Die „Gegenstände“ (Karten) selbst ändern sich nicht, was sich ändert, ist die Verbindung, der Sachverhalt (das Kartenblatt). Nicht besetzte Spielerpositionen, an denen keine Karten (Gegenstände) liegen, können als nicht bestehende Sachverhalte angesehen werden.[5] |

目次 セクション1-3 世界と現実 ウィトゲンシュタインは、世界と現実を説明する際、次のような用語を使う:事実、事実の問題、対象、形式、論理空間。これらの用語を説明するために、次の文章が使われる: 「世界は事実の総体であり、物自体ではない。(1.1) 「事実とは、事実の存在である。(2) 「事実とは、物(事物、物自体)のつながりである。」 (2.01) 「事実の存在と非存在が現実である」(2.06) (2.06) 「事実の対象がどのようにつながっているかが、事実の構造である」 (2.06) (2.032) 「形は構造の可能性である。」 (2.033) (2.033) ウィトゲンシュタインによれば、世界はそれを構成する物や物体の羅列ではなく、それらのつながり(配置)の中に現れる: 同じ物自体でも、最も多様な方法で接続することができ、それによって異なる事実を形成する。例えば、ネックレスが店のウィンドウに飾られていたり、女性の 首を飾っていたり、オークションの対象になっていたりする。この3つの例では、ネックレスはそれぞれ異なる方法で周囲の物自体につながっており、したがっ て異なる状況の一部となっている。これらすべての事実が同時に存在することはありえないが、他の事実を犠牲にして1つの事実だけが存在する。しかし、物自 体や物体が入り込みうるすべての可能な状態が、その形なのである(2.0141)。 ウィトゲンシュタインの「物自体」(あるいは「対象」)が実際には何であるかは、『論考』では正確に規定されていないからである。ウィトゲンシュタイン は、それらが「単純」で原子的でなければならない(すなわち、それ自身「構成されていない」、事実ではない)という要件を述べているに過ぎない (2.02, 2.021参照)。存在する事実も存在しない事実もすべて一緒になって現実を形成する。「現実の全体が世界である。(2.063). 存在論的には、彼の哲学の出発点は、実際に存在する事実のみであり、ウィトゲンシュタインにとって、事実とは何かということである。事実とは、いくつかの 対象から構成される既存の状態である。事実とは、対象(物、事物)の組み合わせである。ある物体は、この物体が他の物体と結ぶことのできる可能な関係を規 定するだけで、理解において、このような外的関係の言語において、特徴づけることができる。例えるなら、「世界」[3]はトランプのパックのようなもので ある。ウィトゲンシュタインの存在論はポーカーゲームに例えられる。そして、あるプレイヤーが持っている手札[4]のカードの総体は、既存の状態であり、 「事実」である。そして、ゲームに関わるすべてのポーカーの手札が「事実の総体」となり、それらが一緒になって、ゲームの状況にとって「ある場合」である 世界を表すことになる。ポーカー・カードの一枚一枚は、それ自体が「物体」を表している。カードは組み合わせとしての価値しか持たない。この意味で、私た ちは常に「物」(カード)を「他の物との関連において」考えなければならない。モノ」(カード)そのものは変化しないが、変化するのは「つながり」であ り、「事実」(手札)なのである。カード(モノ)が存在しないプレイヤーポジションは、存在しない事実とみなすことができる[5]。 |

Analogie zum Pokerspiel: Jede Karte vertritt einen „Gegenstand“. Das, was der Spieler (siehe Abbildung) in der Hand hält, ist ein „bestehender Sachverhalt“, eine „Tatsache“. Die (nicht abgebildeten) Mitspieler sind die „Gesamtheit der Tatsachen“. Dabei müssen die „Gegenstände“ (Karten) stets „in ihrer Verbindung mit anderen Gegenständen“ gesehen werden. Bild, Gedanke, Satz, Elementarsatz Nach solch einführender Ontologie kommt Wittgenstein zu dem Thema, das ihn vorrangig interessiert: Sprache und deren Bedeutung. Er vertritt eine realistische Bedeutungstheorie, d. h. Sätze (Wittgenstein beschränkt sich auf deskriptive Sätze; Fragesätze, Aufforderungssätze usw. werden nicht behandelt.) werden wahr durch etwas ihnen als Welt Entsprechendes. Indem wir denken, stellen wir uns (laut 2.1) Tatsachen in „Bildern“ vor, in denen sich „Gedanken“ konstellieren (3). Was Wittgenstein hier mit „Bild“ meint, wird klarer, wenn man es sich als Gebilde oder auch Mosaik vorstellt, als etwas Zusammengesetztes. Durch den sprachlichen „Satz“ wird diese Zusammensetzung „sinnlich wahrnehmbar“ (3.1). Der Bezug zur Wirklichkeit liegt für Wittgenstein in der gleichen Zusammensetzung oder Struktur von Tatsache-Bild-Gedanke-Satz. Tatsachen zerfallen in Sachverhalte (2), Sachverhalte in Gegenstände (2.01) – in der Sprache stehen für die Gegenstände dann „Namen“ (3.22), den Sachverhalten entsprechen „Elementarsätze“ (4.21 & 4.0311), den Tatsachen „Sätze“, die folglich aus Elementarsätzen zusammengesetzt sind (5). Tatsächliche „Laut- oder Schriftzeichen“ (Wörter) bilden – im Vernehmen des von ihnen vorgestellten Gedankens – „mögliche Sachlagen“ (3.11) in der Vorstellung des Denkers (2.221). Da „Tatsache“ immer „bestehende Verbindung“ meint, muss auch ihr Vorstellen oder Denken sowie dessen Ausdruck im sprachlichen Satz zusammengesetzt (zerlegbar) sein. Wie der Sachverhalt aus einfachen Gegenständen oder „Dingen“, so ist der ihn ausdrückende Elementarsatz aus (Ding-)„Namen“ zusammengesetzt (3.202); deren „Konfiguration“ aber „im Satzzeichen entsprechen die Konfigurationen der Gegenstände in […] Sachlage(n).“ (3.21; „Satzzeichen“ ist hier nicht im Sinne von Interpunktion gemeint, sondern: „Das Zeichen, durch welches wir den Gedanken ausdrücken, nenne ich das Satzzeichen.“) Der „Name bedeutet den Gegenstand. Der Gegenstand ist seine Bedeutung“ (3.203). Jeder Gegenstand hat seinen Namen, der – wie sein Gegenstand im Sachverhalt – nur mit anderen im Elementarsatz Sinn ergibt. Es müssen Namen, um Gedanken einzugeben, Elementarsätze konfigurieren. Immer entspricht deren Namen-„Mosaik“ dem eines Sachverhalts (der von ihnen vertretenen Gegenstände); besteht dieser, wird sein Elementarsatz dadurch wahr (2.222). Wahrheit entspringt somit der Gleichheit zweier Muster: von Tatsache (bestehendem Sachverhalt) und Satz. |

ポーカーゲームに例えるなら、それぞれのカードは「オブジェクト」を表している。プレイヤー(イラスト参照)が手にしているのは「現存する状況」であり、 「事実」である。他のプレイヤー(図示せず)は「事実の総体」である。物」(カード)は常に「他の物との関連において」見なければならない。 イメージ、思考、文、素文 このような入門的な存在論の後、ウィトゲンシュタインは、彼の主たる関心事である「言語とその意味」の話題に入る。つまり、文(ウィトゲンシュタインは自らを記述文に限定しており、疑問文や命題などは扱っていない)は、世界としてそれに対応する何かを通して真となる。 思考することによって、私たちは(2.1によれば)「思考」が組み合わされた「イメージ」の中に事実を想像する(3)。ヴィトゲンシュタインがここで言う 「イメージ」とは、それを構造あるいはモザイクとして、構成されたものとして想像すれば、より明確になる。言語的な「文」を通して、この構成は「感覚的に 知覚可能」なものとなる(3.1)。ウィトゲンシュタインにとって、現実への言及は、事実-イメージ-思考-文という同じ構図や構造の中にある。 事実は事実に分解され(2)、事実は対象に分解される(2.01)-言語においては、対象は「名前」に対応し(3.22)、事実は「初等命題」に対応し(4.21 & 4.0311)、事実は「命題」に対応し、結果的に初等命題から構成される(5)。 実際の「表音記号」や「文字記号」(言葉)は、思考者の想像力の中で、それが表象する思考の知覚において、「可能な事実状況」(3.11)を形成する (2.221)。事実」はつねに「現存するつながり」を意味するのだから、言語文に表現されるだけでなく、その構想や思考もまた構成されなければならない (分解可能でなければならない)。事実が単純な物または「物自体」から構成されるように、それを表現する初等命題は(物)「名」から構成される (3.202)。しかし、それらの「構成」は、「命題記号の中で、[...]事実状況(複数)における物の構成に対応する」(3.21;「句読点」)。 (3.21;「句読点」はここでは句読点の意味ではなく、「思考を表現する記号を、私は句読点と呼ぶ」)。 名前は対象を意味する。対象はその意味である」(3.203)。すべての対象には名前があり、それは事実における対象のように、初等的命題における他者と の関係においてのみ意味をなす。思考に入るためには、名前は初等命題を構成しなければならない。その名前「モザイク」は、常にある状態(それが表す対象) のそれに対応する。これが存在すれば、その素命題は真となる(2.222)。こうして真理は、事実(現存する状態)と命題という二つのパターンの等質性か ら生じる。 |

| Abschnitt 4 Sagen und Zeigen, Grenzen der Sprache In Satz 4.0312 formuliert Wittgenstein seine zentrale These: „Mein Grundgedanke ist, daß die ‚logischen Konstanten‘ nicht vertreten. Daß sich die Logik der Tatsachen nicht vertreten läßt.“ Zeichenketten wie „und“, „oder“, „nicht“, „wenn … dann“ sind mit anderen Worten keine Namen im Sinne des Tractatus: Sie stehen nicht für Dinge, „vertreten“ nichts, ermöglichen höchstens die Vertretung. Denken lässt sich nach Wittgenstein nur, was konfiguriert ist, nicht aber „Konfiguration“ an sich, unabhängig von Konfiguriertem, logisch Gebildetem: „Der Satz kann die logische Form nicht darstellen, sie spiegelt sich in ihm. Was sich in der Sprache spiegelt, kann sie nicht darstellen. Was sich in der Sprache ausdrückt, können wir nicht durch sie ausdrücken. Der Satz zeigt die logische Form der Wirklichkeit. Er weist sie auf.“ (4.121) Wittgenstein steht hier im expliziten Gegensatz zu Bertrand Russell. Dass logische Konstanten wie „und“, „oder“, „wenn … dann“ nicht für etwas stehen, zeigt sich auch daran, dass sie ohne weiteres ineinander überführt, letztlich alle durch den Sheffer-Strich dargestellt werden können (vgl. 3.3441). Darüber hinaus verfängt Wittgensteins Ontologie: Wenn die komplexe Sachlage, die durch (die Elementarsätze) ‚a‘ und ‚b‘ ausgedrückt wird, besteht, die Elementarsätze also wahr sind, dann weil a und b bestehen. Es ist nicht nötig, wie Russell annahm, darüber hinaus auch noch eine Relation zwischen den Sachverhalten „und“ (und „Bekanntschaft“ damit) konstatieren zu müssen.[6] Die Logik, also die Struktur einer Tatsache, ihre Form, nennt Wittgenstein die „Grenze“ der Welt (vgl. 5.61), somit auch die Grenze des Beschreibbaren. In Sachen Logik lässt sich nichts Überprüfbares darstellen: „So kann man z. B. nicht sagen ‚Es gibt Gegenstände‘, wie man etwa sagt: ‚Es gibt Bücher‘. Und ebenso wenig: ‚Es gibt 100 Gegenstände‘, oder ‚Es gibt ℵ 0 {\displaystyle \aleph _{0}} Gegenstände‘. […] Wo immer das Wort ‚Gegenstand‘ […] richtig gebraucht wird, wird es in der Begriffsschrift durch den variablen Namen ausgedrückt. […] Wo immer es anders, also als eigentliches Begriffswort gebraucht wird, entstehen unsinnige Scheinsätze.“ (vgl. 4.1272) Der Satz „zeigt“ seinen Sinn (vgl. 4.022) in der Verbindung seiner Elementarsätze, ist deren „Wahrheitsfunktion“ (vgl. 5). Deswegen kann es keine sinnvollen Sätze über das geben, was Sätze ausmacht: Verbindungen; denn jeder solcher Sätze müsste, um Sinn zu haben, schon gerechtfertigt sein durch das, was er eigentlich erst feststellen will: die Logik von etwas, wozu er, als sinnvoller Satz, von vornherein gehören muss. „Wir können nichts Unlogisches denken, weil wir sonst unlogisch denken müssten.“ (3.03) |

第4節 言うことと示すこと、言語の限界 ウィトゲンシュタインは命題4.0312の中で、「私の基本的な考えは、『論理的定数』は表現できないということである。事実の論理は表現できないという ことである」。つまり、「and」、「or」、『not』、「if ... then 」といった文字列は、『論考』の意味での名前ではない。それらは物自体を表すものではなく、何かを「表象」するものでもなく、せいぜい表象を可能にするも のである。ウィトゲンシュタインによれば、構成されたものを考えることができるだけであって、構成されたもの、論理的に形成されたものとは無関係に、「構 成」そのものを考えることはできない。言語に反映されたものは、それを表現することはできない。言語で表現されるものは、言語を通して表現することはでき ない。文は現実の論理的形式を示す。それはそれを示している。" (4.121)ここでウィトゲンシュタインはバートランド・ラッセルと明確に対立している。そして」、「あるいは」、「もし......ならば」といった 論理定数が何かを表しているのではないという事実は、それらが容易に互いに変換することができ、最終的にはすべてシェファー・ダッシュで表すことができる という事実によっても示されている(3.3441参照)。さらに、ウィトゲンシュタインの存在論は、(素命題である)「a」と「b」によって表現される複 雑な事実状況が存在する、すなわち素命題が真であるならば、それはaとbが存在するからである、ということを捉えている。ラッセルが想定したように、事実 の間の関係「と」(とそれらとの「知」)をも述べなければならない必要はない[6]。 ウィトゲンシュタインは論理学、すなわち事実の構造、その形式を世界の「限界」と呼び(5.61参照)、したがって記述可能なものの限界でもある。例え ば、『本がある』と言うのと同じように、『物がある』とは言えない。例えば、『本がある』と同じように『物がある』とは言えない。 ℵ 0 {と言うこともできない。objects'である。[object'という単語が正しく使われている場合、概念スクリプトでは変数名で表現される。 [......それが別の形で、つまり実際の概念的な言葉として使われる場合には、無意味な幻想的文章が生じる。" (cf. 4.1272) (cf. 4.1272) 命題がその意味を「示す」(4.022参照)のは、その素命題の接続においてであり、その「真理関数」(5参照)である。それゆえ、命題を構成するもの、 すなわち接続について意味のある命題は存在しえない。なぜなら、そのような命題はすべて、意味を持つためには、そもそも、それが実際に確立したいもの、す なわち、意味のある命題として、それが最初から属していなければならない何かの論理によって、すでに正当化されなければならないからである。「そうでなけ れば、非論理的に考えなければならなくなるからである。(3.03) |

| Sinnvolle und sinnlose Sätze Wittgenstein unterscheidet drei Arten von Sätzen: sinnvolle, sinnlose und unsinnige. Ein sinnvoller Satz ist ein Satz, der einen Sachverhalt oder eine Tatsache abbildet; sein Sinn besteht in den vorgestellten Verhältnissen: „Man kann geradezu sagen: statt, dieser Satz hat diesen und diesen Sinn; dieser Satz stellt diese und diese Sachlage dar.“ (vgl. 4.031) Ein sinnloser Satz ist entweder tautologisch (etwa: „Es regnet oder es regnet nicht.“) oder – umgekehrt – kontradiktorisch („Olaf ist ein verheirateter Junggeselle“ oder „Sie zeichnet ein fünfseitiges Viereck“); er ist kein Bild einer Tatsache, hat also keinen Sinn, „die Tautologie lässt der Wirklichkeit den ganzen – unendlichen – logischen Raum; die Kontradiktion erfüllt den ganzen logischen Raum und lässt der Wirklichkeit keinen Punkt.“ (4.463) |

意味のある文と意味のない文 ウィトゲンシュタインは、意味のある文、意味のない文、無意味な文の3種類を区別している。意味のある文とは、ある状態や事実を描写する文であり、その意 味は提示された関係にある。(cf.4.031)意味のない文は、同語反復的(たとえば、「雨が降っている、あるいは降っていない」)か、あるいは逆に矛 盾的(「オラフは結婚している独身である」あるいは「彼女は五角形を描く」)である。(4.463) |

| Abschnitte 5–6 Unsinnige Sätze Als unsinnig bezeichnet der Tractatus alle Sätze, die weder sinnvoll noch sinnlos sind. Ein Satz wie etwa „Was ich hiermit schreibe, ist falsch“, der sich nur auf sich selbst und auf nichts außer ihm in der Welt bezieht (eine Anspielung auf das Paradoxon des Epimenides), erlangt infolgedessen nie Bedeutung. Ein Satz wird unsinnig, wenn einem seiner Bestandteile, Namen oder Elementarsatz, keine Bedeutung, kein von ihm unterschiedenes Sachliches, das er (seinerseits nur) abbildet, gegenübersteht (5.4733): „Der Name bedeutet den Gegenstand. Der Gegenstand ist seine Bedeutung“ (3.203). So ergibt z. B. auch „Liebe deinen nächsten wie dich selbst“ einen „Unsinn“, da es in diesem Satz auf etwas ankommt, das nicht von der Wirklichkeit abhängt. „Es ist klar, daß sich die Ethik nicht aussprechen läßt.“ (6.421) Ethische Sätze sind Vorschriften; das Sosein kann sie verletzen (nicht mit ihnen übereinstimmen), ohne dass sie dadurch inhaltlich einbüßen. Sätze, auf deren Geltung die Wirklichkeit keinen Einfluss hat, sind nach Auffassung des Tractatus „Unsinn“. Das trifft nicht nur auf ethische, sondern auch auf philosophische Sätze, letztlich den Tractatus selber zu: „Meine Sätze erläutern dadurch, dass sie der, welcher mich versteht, am Ende als unsinnig erkennt …“ (6.54). Philosophische Sätze stellen mit anderen Worten nichts Diesseitiges vor; denn „alles Geschehen und Sosein ist zufällig.“ Die philosophische Fassung dessen aber, was „es nicht-zufällig macht“, beschreibt etwas, das „nicht in der Welt liegen“ kann; „denn sonst wäre dies wieder zufällig. Es muß außerhalb der Welt liegen“ (6.41). Sinn können aber – nach dem Gebrauch, den der Tractatus von diesem Wort macht – nur Sachverhalte oder aus ihnen zusammengesetzte Tatsachen in der Welt ergeben. |

セクション5-6 無意味な文章 Tractatus』では、意味のない文も無意味な文も、すべて無意味な文としている。私がここに書いていることは偽りである」というような文は、それ自 身だけを指しており、世界の他の何ものをも指していない(エピメニデスのパラドックスへの言及)ので、意味を獲得することはない。命題は、その構成要素の 一つである名前あるいは初等命題が、いかなる意味とも、それとは異なる事実的な何ものとも対比されず、それが(ひいては)表象するのみであれば、無意味な ものとなる(5.4733): 「名前は対象を意味する。対象はその意味である」(3.203)。したがって、たとえば「隣人を自分のように愛せよ」も、この文は現実に依存しないものを 指しているのだから、「ナンセンス」に帰結する。「倫理が表現できないことは明らかである。(6.421)倫理的命題は規則であり、そのようなものは、そ の内容を失うことなく、それに違反する(それに反対する)ことができる。Tractatus』によれば、現実が妥当性に影響を及ぼさない命題は「ナンセン ス」である。これは倫理的な命題だけでなく、哲学的な命題にも当てはまり、究極的には『論語』そのものにも当てはまる。(6.54). 言い換えれば、哲学的命題はこの世の何ものでもない。「すべての出来事とそのようなものは偶然である 」からである。しかし、「偶発的でないことを偶発的にする」ものの哲学的バージョンは、「この世に存在しえない」ものを描写している。そうでなければ、こ れはまた偶然的なものとなってしまうからである」(6.41)。しかし、『トラクタトゥス』のこの言葉の用法によれば、世界において意味を持ちうるのは、 事実か、事実によって構成される事実だけである。 |

Die allgemeine Satzform |

Die allgemeine Satzform(省略:原文参照) |

| Psychologie Was die Inhalte menschlichen Bewusstseins angeht, stellt 5.542 fest: „Es ist aber klar, dass ‚A glaubt, dass p‘, ‚A denkt, dass p‘, ‚A sagt, dass p‘ von der Form ‚„p“ sagt p‘ sind: Und hier handelt es sich nicht um eine Zuordnung von einer Tatsache und einem Gegenstand, sondern um die Zuordnung von Tatsachen durch Zuordnung ihrer Gegenstände.“ – Psychologische Begriffe wie „Glauben“, „Denken“, „Vorstellen“, „Träumen“, „der und der Meinung-sein“ usf. kennzeichnen mit anderen Worten nichts aus einer „Tatsache“ (gemeint hier: die Seele als das, was „glaubt“, „träumt“ oder „denkt“) und einem ihr zugeordneten Gegenstand (gemeint: der Glaubens-, Vorstellungs- oder Trauminhalt „p“) Zusammengesetztes, sondern beziehen sich allein auf objektive, d. h. in Sätze übertragbare, „innere Bilder“ (aus Gegenständen zusammengesetzte Sachverhalte oder Tatsachen). Sie können nichts darüber hinausgehend Seelisches, das Vorgestellte Überbietendes (wesentlich von ihm Verschiedenes), zum Gegenstand haben. Denn wäre die Seele eine Tatsache wie ihr Inhalt, müsste auch sie abbildbar, mithin aus Gegenständen oder Sachverhalten zusammengesetzt, sein. „Eine zusammengesetzte Seele“ aber „wäre […] keine Seele mehr“ (5.5421), denn sie könnte in diesem Fall wie alles Zusammengesetzte zerlegt oder zerstört werden, sterben; die Seele ist aber (nach Platon) einfach, also nicht zusammengesetzt, daher unsterblich. Woraus für Wittgenstein folgt: „Das denkende, vorstellende Subjekt gibt es nicht“ (5.631) – in demselben Sinne etwa, in dem es Ethik oder Ästhetik nicht wie (raumeinnehmende, zusammengesetzte und zählbare) Bäume oder Häuser „gibt“. Unser Gemüt, indem es das eine oder andere tatsächlich vorstellt, wird doch nicht davon bedingt, kann auch nicht daraus bestimmt werden. Eine Grenze verläuft für Wittgenstein daher nicht zwischen Innenwelt und Außenwelt, die beide in ihrer sprachlichen Verfasstheit auf derselben Ebene liegen, sondern zwischen Sinn und Unsinn: dem, was sich vorstellen lässt, und dem, was eine Nichtvorstellung von einer Vorstellung unterscheidet. |

心理学 人間の意識の内容に関して、5.542は次のように述べている:「しかし、『A believes that p』、『A thinks that p』、『A says that p』が『「p」 says p』という形式であることは明らかである: そしてここでは、事実と対象の割り当てを扱っているのではなく、その対象を割り当てることによる事実の割り当てを扱っているのである。" - 信じる」、「考える」、「想像する」、「夢を見る」、「意見を持つ」などの心理学用語は、言い換えれば、事実を特徴づけるものではない。つまり、「事実」 (ここでは、「信じる」、「夢見る」、「考える」ものとしての魂のこと)と、それに割り当てられた対象(信念、想像、夢の内容「p」のこと)からなるもの を特徴づけるのではなく、客観的な「内的イメージ」(対象からなる事実や状況)、つまり文章に翻訳できるものだけを指すのである。それらは、魂を超えたも の、想像を超えたもの(魂とは本質的に異なるもの)を対象として持つことはできない。というのも、もし魂がその内容のような事実であるならば、それもまた 表象可能なもの、つまり対象や事実で構成されたものでなければならないからである。しかし、「複合的な魂」(5.5421)は、「もはや魂ではなくなる」 (5.5421)。なぜなら、この場合、魂は分解されたり破壊されたりする可能性があり、複合的なすべてのもののように死ぬ可能性があるからである。この ことから、ウィトゲンシュタインは次のように考える: 「思考し、想像する主体は存在しない」(5.631) - 例えば、倫理学や美学が(空間を占有し、複合的で可算的な)木や家のように「存在」しないのと同じ意味で。私たちの心は、どちらか一方を実際に想像するこ とによって、それによって条件づけられたり、決定されたりすることはない。したがって、ウィトゲンシュタインにとって、内的世界と外的世界(両者は言語的 構成において同じレベルにある)の間に境界があるのではなく、センスとナンセンスの間に境界があるのである。 |

| Ethik und Mystik Wittgenstein schrieb im Oktober 1919 an Ludwig von Ficker, dass der Sinn des Tractatus ein ethischer sei, und dass es als zweiteiliges Werk anzusehen ist, dessen ethischer Teil nicht geschrieben worden ist, weil er nur Unsinn sein würde. Zur Ethik schreibt er im Tractatus: „Darum kann es auch keine Sätze der Ethik geben. Sätze können nichts Höheres ausdrücken.“ (6.42) Ein Satz kann nicht formulieren, was ihn trägt, und daher „Welt“ immer nur darstellen, nicht aber an- oder einklagen. Ebenfalls kommt Wittgenstein auf Gott, Solipsismus und Mystik zu sprechen, so schreibt er: „Nicht wie die Welt ist, ist das Mystische, sondern dass sie ist.“ (6.44) Dieses Mysterium kann überhaupt nicht mit Sätzen erklärt werden (vgl. 6.522), da diese nur vorstellen, was möglich ist, nicht aber, warum es möglich ist. |

倫理と神秘主義 1919年10月、ウィトゲンシュタインはルートヴィヒ・フォン・フィッカーに宛てて、『Tractatus』の意味は倫理的なものであり、倫理的な部分 はナンセンスにしかならないので書かれなかった二部構成の作品とみなすべきだと書いた。倫理学について、彼は『Tractatus』の中で次のように書い ている。命題は高次のものを表現することはできない」(6.42)。(6.42)命題はそれを支えているものを定式化することはできず、したがって「世 界」を表現することはできても、それを非難したり嘆いたりすることはできない。ウィトゲンシュタインはまた、神、独在論、神秘主義を取り上げ、「世界がど のようにあるかが神秘的なのではなく、世界がどのようにあるかが神秘的なのである」(6.44)と書いている。(6.44)この神秘は、命題ではまったく 説明できない(6.522参照)。命題は、可能なことを提示するだけで、なぜ可能なのかを提示しないからである。 |

| Die Leiteranalogie Gegen Ende des Buches entlehnt Wittgenstein Arthur Schopenhauer eine Analogie: Er vergleicht den Tractatus mit einer Leiter, welche „weggeworfen“ werden müsse, nachdem man auf ihr „hinaufgestiegen“ sei. Wenn Philosophie im Fassen der Voraussetzung von Wahr und Falsch besteht, kann sie sich selbst weder auf das eine noch das andere berufen, ist sozusagen „nicht von dieser Welt“. „Meine Sätze erläutern dadurch, daß sie der, welcher mich versteht, am Ende als unsinnig erkennt, wenn er durch sie – auf ihnen – über sie hinausgestiegen ist.“ (6.54) |

梯子のアナロジー ウィトゲンシュタインは、本書の最後の方で、アーサー・ショーペンハウアーから梯子のアナロジーを借りている。哲学が真と偽の前提を把握することにあると すれば、哲学は一方にも他方にも言及することができず、いわば「この世のものではない」のである。「私の命題は、私を理解する者が、その命題を通して、つ まりその命題の上に登ってきたときに、最終的にそれを無意味なものとして認識するという事実によって説明される。(6.54) |

| Abschnitt 7 Der letzte Abschnitt des Tractatus besteht lediglich aus einem prägnanten und vielzitierten Satz: „Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen.“ Womit nicht gemeint ist, dass bestimmte Wahrheiten besser unerwähnt bleiben, sondern dass das, was Sprechen oder Denken ermöglicht, nicht dessen Gegenstand sein kann – wodurch philosophische Rede schlechthin in Frage steht. |

第7節 語れないものは沈黙しなければならない。これは、ある真理は語らない方がよいという意味ではなく、語ることや考えることを可能にするものは、その主題ではありえないという意味である。 |

Interpretation und Auswirkungen des Tractatus |

トラクタトゥスの解釈と効果 |

| Wittgenstein selbst glaubte mit

dem Tractatus alle philosophischen Probleme gelöst zu haben und zog

sich darum konsequenterweise, zumindest für einige Jahre, aus der

Philosophie zurück. Derweil erlangte das Werk v. a. das Interesse des Wiener Kreises, darunter das Rudolf Carnaps und Moritz Schlicks. Die Gruppe verbrachte mehrere Monate damit, das Werk Satz für Satz durchzuarbeiten, und schließlich überredete Schlick Wittgenstein, mit dem Kreis das Werk zu diskutieren. Während Carnap lobte, dass das Werk wichtige Einsichten vermittele, bemängelte er die letzten Sätze des Tractatus. Wittgenstein sagte daraufhin Schlick, dass er sich nicht vorstellen könne, dass Carnap die Absicht und den Sinn des Tractatus derart missverstanden habe. Neuere Interpretationen bringen den Tractatus mit Søren Kierkegaard in Verbindung, den Wittgenstein sehr bewunderte. Kierkegaard war überzeugt, dass sich bestimmte Dinge nicht in der Alltagssprache ausdrücken lassen könnten, und dass sie indirekt manifestiert werden müssten. Als Vertreter der neueren Tractatus-Interpretationen argumentieren zum Beispiel Cora Diamond und der US-amerikanische Philosoph James F. Conant (* 1958), Wittgensteins Sätze müssten tatsächlich als unsinnig aufgefasst werden, und die Grundintention des Tractatus bestünde tatsächlich darin zu zeigen, dass der Versuch, eine Grenze zwischen Sinn und Unsinn zu ziehen, selbst wieder in Unsinn endet. Ein deutschsprachiges Buch, in welchem diese Interpretation des Tractatus dargelegt wird, ist Wittgensteins Leiter von Logi Gunnarsson. Neben dem erheblichen Einfluss, den der Tractatus auf die (insbesondere analytische) Philosophie des 20. Jahrhunderts hatte, lassen sich auch Einflüsse auf die nicht-philosophische Literatur und Kunst nachweisen. In dem Roman Nervöse Fische von Heinrich Steinfest beispielsweise ist der Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus gewissermaßen die Bibel der Hauptperson, des Chefinspektors Lukastik. Umberto Eco zitiert in seinem Roman Der Name der Rose Satz 6.54 in mittelhochdeutscher Übersetzung: „Er muoz gelîchesame die leiter abewerfen, sô er an ir ufgestigen“. Der finnische Jazz-Komponist und Schriftsteller Mauri Antero Numminen und der österreichische Komponist Balduin Sulzer haben sogar versucht, den Tractatus zu vertonen: der eine parodistisch und nur die Hauptsätze zitierend, der andere sehr viel ernster und im Rückgriff auf die – auch von Wittgenstein geschätzte – „Wiener Schule“. |

ウィトゲンシュタイン自身は、『問題集』によってすべての哲学的問題を解決したと考え、少なくとも数年間は哲学から身を引いた。 一方、この著作は、ルドルフ・カルナップやモーリッツ・シュリックを含むウィーン・サークルの関心を特に集めた。シュリックは最終的に、ウィトゲンシュタ インにこの作品についてサークルで議論するよう説得した。カルナップは重要な洞察が得られたと作品を賞賛したが、彼は『Tractatus』の最後の文章 を批判した。ウィトゲンシュタインはシュリックに、カルナップが『試論』の意図と意味をこれほど誤解していたとは想像できないと言った。 最近の解釈では、ウィトゲンシュタインが敬愛していたセーレン・キェルケゴールとの関連が指摘されている。キルケゴールは、ある物自体は日常的な言語では 表現できず、間接的に表現されなければならないと確信していた。例えば、コーラ・ダイヤモンドやアメリカの哲学者ジェイムズ・F・コナン(※1958年) は、『論考』の最近の解釈の代表として、ウィトゲンシュタインの文章は実際にはナンセンスなものとして理解されなければならず、『論考』の基本的な意図 は、意味とナンセンスの間に線を引こうとする試み自体がナンセンスそのものに終わることを示すことにあると主張している。このような『論考』の解釈を示し たドイツ語の本に、ロジ・グンナルソン著『ウィトゲンシュタインのライター』がある。 20世紀の(特に分析)哲学に大きな影響を与えた『哲学論考』に加え、哲学以外の文学や芸術にも影響を与えた証拠がある。例えば、ハインリッヒ・シュタイ ンフェストの小説『ナーヴァス・フィッシュ』では、『論理哲学論考』が主人公の主任警部ルカスティックのバイブルとなっている。小説『薔薇の名前』の中 で、ウンベルト・エーコは中高ドイツ語訳6.54を引用している。フィンランドのジャズ作曲家で作家のマウリ・アンテロ・ヌンミネンとオーストリアの作曲 家バルドゥイン・スルツァーは、『Tractatus』を音楽化しようと試みている。 |

| Literatur Mirko Gemmel: Die Kritische Wiener Moderne. Ethik und Ästhetik. Karl Kraus, Adolf Loos, Ludwig Wittgenstein. Parerga, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-937262-20-2 (zur Bedeutung der Ethik im Tractatus). Gerd Graßhoff und Timm Lampert: Ludwig Wittgensteins Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung. Entstehungsgeschichte und Herausgabe der Typoskripte und Korrekturexemplare. Springer, Wien 2004. ISBN 978-3-211-83782-5 (http://www.springer.com/philosophy/book/978-3-211-83782-5) Alexander Maslow: Eine Untersuchung in Wittgensteins „Tractatus“. Aus dem Englischen von Jürgen Koller. Turia + Kant, Wien/Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-85132-830-1. Radmila Schweitzer: Ludwig Wittgenstein: die Tractatus Odyssee. Begleitpublikation zur Ausstellung, Wittgenstein Initiative Wien 2018. Ludwig Wittgenstein: Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung, Tractatus logico-philosophicus. Kritische Edition. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1998. ISBN 3-518-28959-4 Ludwig Wittgenstein: Tractatus logico-philosophicus, Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2003. ISBN 3-518-10012-2 Ludwig Wittgenstein: Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung, W. Ostwald (Hrsg.), Annalen der Naturphilosophie, Band 14, 1921, S. 185–262 (https://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/receive/jportal_jparticle_00326119). Sehr erhellend können Wittgensteins Tagebücher aus der Zeit von 1914 bis 1916 sein, in denen viele Formulierungen aus dem Tractatus weniger knapp vorweggenommen werden. Um den Tractatus mit Gewinn lesen zu können, erscheint es außerdem sinnvoll, sich vor der Lektüre mit den Grundzügen der Logik bekannt zu machen. |

文献 ミルコ・ゲンメル:批判的ウィーン・モダニズム。倫理と美学。カール・クラウス、アドルフ・ロース、ルートヴィヒ・ヴィトゲンシュタイン。Parerga, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-937262-20-2 (『論考』における倫理の意義について)。 Gerd Graßhoff and Timm Lampert: Ludwig Wittgenstein's Logical-Philosophical Treatise. 邦訳は、『ウィトゲンシュタイン論理哲学論考』(岩波書店、2004年)。Springer, Vienna 2004. ISBN 978-3-211-83782-5 (http://www.springer.com/philosophy/book/978-3-211-83782-5) アレクサンダー・マズロー:ウィトゲンシュタイン『哲学論考』の研究。ユルゲン・コラー著。Turia + Kant, Vienna/Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-85132-830-1. Radmila Schweitzer: Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Tractatus Odyssey. 展覧会に付随する出版物、Wittgenstein Initiative Vienna 2018。 ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン:論理哲学論考『論理哲学論考』。批評版。Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1998. ISBN 3-518-28959-4. Ludwig Wittgenstein: 『論理哲学論考』, Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2003. ISBN 3-518-10012-2 Ludwig Wittgenstein: Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung, W. Ostwald (ed.), Annalen der Naturphilosophie, vol. 14, 1921, pp. 185-262 (https://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/receive/jportal_jparticle_00326119). ウィトゲンシュタインの『1914年から1916年』までの日記には、『Tractatus』からの多くの定式化があまり簡潔でなく予想されており、非常 に示唆に富んでいる。Tractatusを有益に読むためには、それを読む前に論理学の主要な特徴に慣れておくことが賢明であると思われる。 |

| Einführungswerke G. E. M. Anscombe: An Introduction to Wittgenstein's Tractatus, Hutchinson, London, 1959. Weitere verbesserte Ausgaben. Elizabeth Anscombe: Eine Einführung in Wittgensteins „Tractatus“. Themen in der Philosophie Wittgensteins. Aus dem Englischen von Jürgen Koller. Turia + Kant, Wien/Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-85132-833-2. Max Black: A Companion to Wittgenstein's Tractatus, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 1964. Ernst Michael Lange: Ludwig Wittgenstein: 'Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung' , UTB-Schöning, Paderborn, 1996. Online (LPAEINLonline-1.pdf) Christian Mann: Wovon man schweigen muß: Wittgenstein über die Grundlagen von Logik und Mathematik. Turia & Kant, Wien 1994. ISBN 3-85132-073-5 (PDF) Howard O. Mounce Wittgenstein's Tractatus. An Introduction. Blackwell, Oxford 1990, ISBN 0-631-12556-6 (Einführung für College-Studenten) Howard O. Mounce: Wittgensteins „Tractatus“. Eine Einführung. Aus dem Englischen von Jürgen Koller. Turia + Kant, Wien/Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-85132-832-5. George Pitcher: Die Philosophie Wittgensteins. Eine kritische Einführung in den Tractatus und die Spätschriften. Alber, Freiburg im Breisgau/München 1967, ISBN 3-495-47159-6. Claus-Artur Scheier: Wittgensteins Kristall. Ein Satzkommentar zur 'Logisch-philosophischen Abhandlung', Alber, Freiburg / München 1991. ISBN 3-495-47678-4 Erik Stenius: Wittgenstein’s Tractatus; An Exposition of Its Main Lines of Thought. Basil Blackwell & Cornell University Press, Oxford & Ithaca, New York 1960. ISBN 0-631-06070-7 (Dt.: Wittgensteins Tractatus. Eine kritische Darlegung seiner Hauptgedanken. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1969.) Holm Tetens: Wittgensteins „Tractatus“. Ein Kommentar. Reclam, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-15-018624-4. |

作品紹介 G. E. M. Anscombe: An Introduction to Wittgenstein's Tractatus, Hutchinson, London, 1959. 改訂版もある。 Elizabeth Anscombe: An Introduction to Wittgenstein's 「Tractatus」, Hutchinson, London, 1959. ウィトゲンシュタイン哲学のテーマ。ユルゲン・コラー訳。Turia + Kant, Vienna/Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-85132-833-2. Max Black: A Companion to Wittgenstein's Tractatus, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 1964. Ernst Michael Lange: Ludwig Wittgenstein: 『Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung』, UTB-Schöning, Paderborn, 1996. オンライン (LPAEINLonline-1.pdf). クリスチャン・マン:Whereof one must be silent: 論理学と数学の基礎についてのヴィトゲンシュタイン。Turia & Kant, Vienna 1994 ISBN 3-85132-073-5 (PDF) ハワード・O・マウンス ウィトゲンシュタイン『論考』。序論。Blackwell, Oxford 1990, ISBN 0-631-12556-6 (大学生向け入門書) ハワード・O・マウンス ウィトゲンシュタイン『試論』。入門書。ユルゲン・コラー訳。Turia + Kant, Vienna/Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-85132-832-5. George Pitcher: The Philosophy of Wittgenstein. 論考と後期著作への批判的入門書。Alber, Freiburg im Breisgau/Munich 1967, ISBN 3-495-47159-6. Claus-Artur Scheier: Wittgenstein's Crystal. Ein Satzkommentar zur 『Logisch-philosophischen Abhandlung』, Alber, Freiburg / Munich 1991, ISBN 3-495-47678-4. Erik Stenius: Wittgenstein's Tractatus; An Exposition of Its Main Lines of Thought. Basil Blackwell & Cornell University Press, Oxford & Ithaca, New York 1960. ISBN 0-631-06070-7 (英文:Wittgenstein's Tractatus. 彼の主要な思想の批判的解説。Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1969)。 Holm Tetens: Wittgenstein's 「Tractatus」. 解説。Reclam, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-15-018624-4. |

| 1. Ludwig Wittgenstein:

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung. First

published by Kegan Paul (London), 1922. Side-by-side edition, Version

0.59 (MAY 12, 2021), containing the original German, alongside both the

Ogden/Ramsey, and Pears/McGuinness English translations.

(writing.upenn.edu) 2. Peter Louis Galison, Alex Roland: Atmospheric Flight in the Twentieth Century. Springer, 2000, ISBN 0-7923-6037-0, S. 360 (google.co.uk). 3. Joachim Schulte: Wittgenstein. Eine Einführung. (= 8564 Universal-Bibliothek) Reclam, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-15-008564-0, S. 67–69 4. so enthält das Französisches Blatt folgende Farben: Kreuz oder französisch Trèfle, Pik oder französisch Pique, herz oder französisch Cœur, Karo oder französisch Carreau. Jede Karte, des 52 Karten starken Kartenspiels, vertritt einen (wittgensteinschen) „Gegenstand“. 5. Jan-Benedikt Kersting, Jan-Philipp Schütze, Tobias Schmohl: Was der Fall ist: Was der Fall ist: Der Aufbau der Welt Der Aufbau der Welt. Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, 2007 [1] auf ruhr-uni-bochum.de, hier Versuch einer Analogie 6. Joachim Schulte: Wittgenstein. Eine Einführung. (= 8564 Universal-Bibliothek) Reclam, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 978-3-15-019386-0, S. 81–85 |

1. ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン:『論理哲学論考』

Logisch-philosophische

Abhandlung。1922年にケガン・ポール(ロンドン)から初版発行。ドイツ語原文と、オグデン/ラムゼイ、ピアーズ/マクギネスによる英語訳を

併記した並列版、バージョン 0.59(2021年5月12日)。(writing.upenn.edu) 2. ピーター・ルイス・ガリソン、アレックス・ローランド:『20 世紀の大気飛行』。スプリンガー、2000 年、ISBN 0-7923-6037-0、360 ページ (google.co.uk)。 3. ヨアヒム・シュルテ:『ウィトゲンシュタイン。Eine Einführung. (= 8564 Universal-Bibliothek) レクラム、シュトゥットガルト 1989、ISBN 3-15-008564-0、67–69 ページ 4. フランス語版では、カードの色は次のとおりだ:クロイツ(フランス語で「トレフ」)、ピック(フランス語で「ピケ」)、ハート(フランス語で「クー ル」)、ダイヤ(フランス語で「カレ」)。52枚のカードからなるカードゲームの各カードは、ウィトゲンシュタインの「対象」を表している。 5. ヤン=ベネディクト・ケルスティン、ヤン=フィリップ・シュッツェ、トビアス・シュモール:事実は何であるか:事実は何であるか:世界の構造。エバーハル ト・カール・トゥービンゲン大学、2007年 [1] ruhr-uni-bochum.de、ここでの類推の試み 6. ヨアヒム・シュルテ:ウィトゲンシュタイン。入門。(= 8564 ユニバーサル・ビブリオテーク)レクラム、シュトゥットガルト 1989年、ISBN 978-3-15-019386-0、81–85ページ |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tractatus_logico-philosophicus |

★英語版ウィキペディアの解説

| The Tractatus

Logico-Philosophicus (widely abbreviated and cited as TLP) is the only

book-length philosophical work by the Austrian philosopher Ludwig

Wittgenstein that was published during his lifetime. The project had a

broad goal: to identify the relationship between language and reality,

and to define the limits of science.[1] Wittgenstein wrote the notes

for the Tractatus while he was a soldier during World War I and

completed it during a military leave in the summer of 1918. It was

originally published in German in 1921 as Logisch-Philosophische

Abhandlung (Logical-Philosophical Treatise). In 1922 it was published

together with an English translation and a Latin title, which was

suggested by G. E. Moore as homage to Baruch Spinoza's Tractatus

Theologico-Politicus (1670). The Tractatus is written in an austere and succinct literary style, containing almost no arguments as such, but consists of 525 declarative statements altogether, which are hierarchically numbered. The Tractatus is recognized by philosophers as one of the most significant philosophical works of the twentieth century and was influential chiefly amongst the logical positivist philosophers of the Vienna Circle, such as Rudolf Carnap and Friedrich Waismann and Bertrand Russell's article "The Philosophy of Logical Atomism". Wittgenstein's later works, notably the posthumously published Philosophical Investigations, criticised many of his ideas in the Tractatus. There are, however, elements to see a common thread in Wittgenstein's thinking, in spite of those criticisms of the Tractatus in later writings. Indeed, the legendary contrast between 'early' and 'late' Wittgenstein has been countered by such scholars as Pears (1987) and Hilmy (1987). For example, a relevant, yet neglected aspect of continuity in Wittgenstein's central issues concerns 'meaning' as 'use'. Connecting his early and later writings on 'meaning as use' is his appeal to direct consequences of a term or phrase, reflected e.g. in his speaking of language as a 'calculus'. These passages are rather crucial to Wittgenstein's view of 'meaning as use', though they have been widely neglected in scholarly literature. The centrality and importance of these passages are corroborated and augmented by renewed examination of Wittgenstein's Nachlaß, as is done in "From Tractatus to Later Writings and Back – New Implications from the Nachlass" (de Queiroz 2023). |

『論理哲学論考』(Tractatus

Logico-Philosophicus,

TLP)は、オーストリアの哲学者ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインが生前に出版した唯一の哲学書である。このプロジェクトは、言語と現実の関係を明ら

かにし、科学の限界を定義するという幅広い目標を掲げていた[1]。ウィトゲンシュタインは、第一次世界大戦中の兵士であった時に『Tractatus』

のノートを書き、1918年の夏の休暇中に完成させた。1921年にドイツ語で『論理哲学論考』(Logisch-Philosophische

Abhandlung)として出版された。1922年には、英語訳とラテン語の題名とともに出版された。この題名は、G.E.ムーアがバルーク・スピノザ

の『神学政治学綱要』(Tractatus Theologico-Politicus、1670年)へのオマージュとして提案したものである。 簡潔な文体で書かれ、論証はほとんどなく、525の宣言文で構成され、階層的に番号が振られている。 哲学者たちの間では、この著作は20世紀における最も重要な哲学的著作の一つとして認識されており、ルドルフ・カーナップやフリードリヒ・ウェイスマン、 バートランド・ラッセルの論文『論理的原子論の哲学』など、主にウィーン・サークルの論理実証主義哲学者たちに大きな影響を与えた。 ウィトゲンシュタインの晩年の著作、特に死後に出版された『哲学探究』は、『論考』の多くの思想を批判している。しかし、ウィトゲンシュタインの思考に は、後世の著作における『論理哲学論考』への批判にもかかわらず、共通項を見出す要素がある。実際、「初期」と「後期」のウィトゲンシュタインという伝説的な 対比は、Pears (1987)やHilmy (1987)などの学者によって反論されている。例えば、ウィトゲンシュタインの中心的な問題において、「使用」としての「意味」に関連する、しかし無視 されている連続性の側面がある。使用としての意味」に関する彼の初期と後期の著作をつなぐのは、ある語句の直接的な結果に対する彼の訴えであり、それは例 えば、彼が言語を「微積分学」として語ることに反映されている。これらの箇所は、ウィトゲンシュタインの「使用としての意味」観にとって極めて重要である にもかかわらず、学術文献では広く無視されてきた。これらの箇所の中心性と重要性は、「Tractatusから後の著作へ、そして戻る-Nachlass からの新たな示唆」(de Queiroz 2023)で行われているように、ヴィトゲンシュタインのNachlaßを新たに検討することによって裏付けられ、増強される。 |

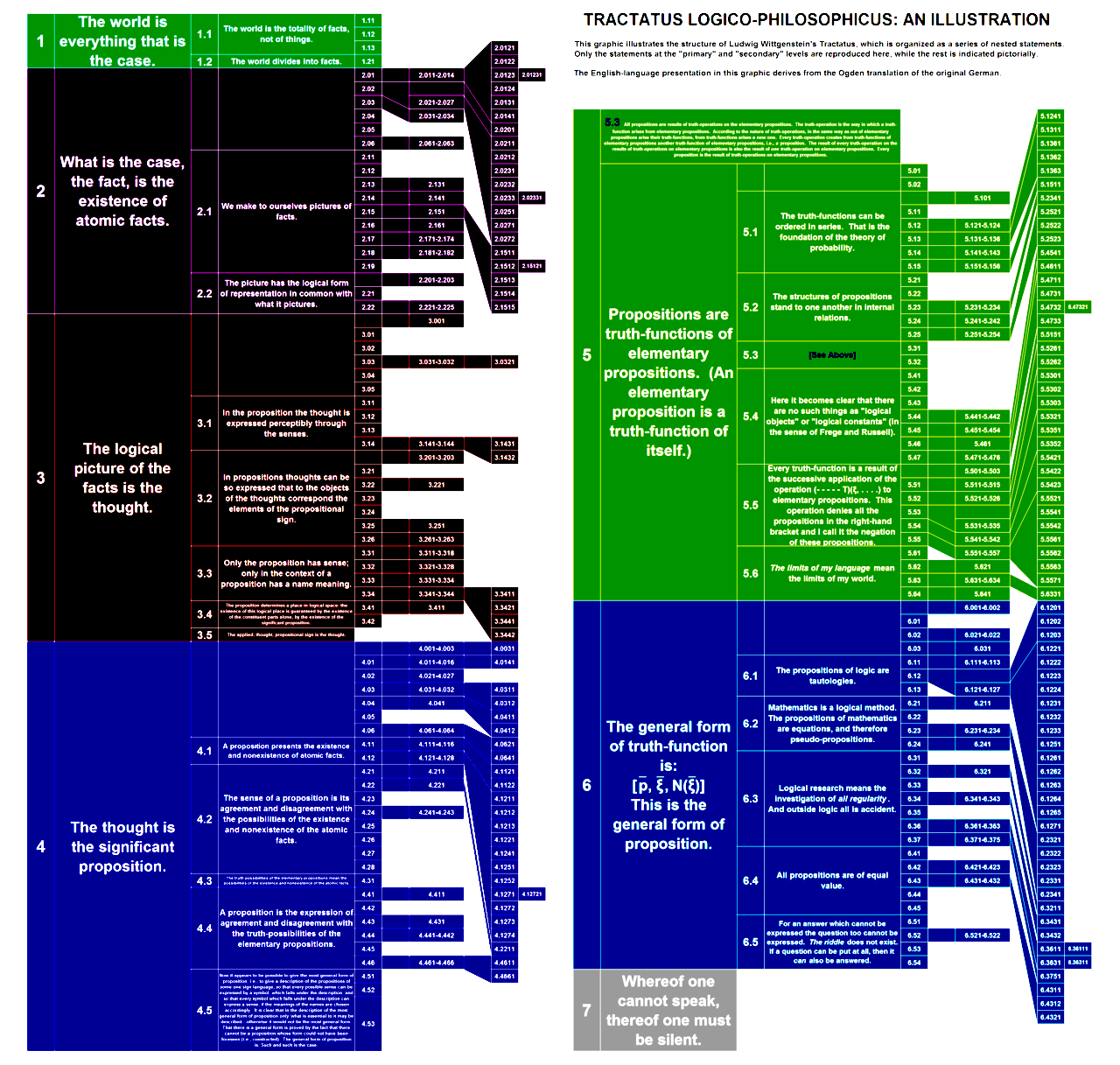

| Description and context The Tractatus employs an austere and succinct literary style. The work contains almost no arguments as such, but rather consists of declarative statements, or passages, that are meant to be self-evident. The statements are hierarchically numbered, with seven basic propositions at the primary level (numbered 1–7), with each sub-level being a comment on or elaboration of the statement at the next higher level (e.g., 1, 1.1, 1.11, 1.12, 1.13). In all, the Tractatus comprises 525 numbered statements. The Tractatus is recognized by philosophers as a significant philosophical work of the twentieth century and was influential chiefly amongst the logical positivist philosophers of the Vienna Circle, such as Rudolf Carnap and Friedrich Waismann. Bertrand Russell's article "The Philosophy of Logical Atomism" is presented as a working out of ideas that he had learned from Wittgenstein.[2] |

解説と背景 『トラクタトゥス』は簡潔な文体を用いている。論証はほとんどなく、自明であることを示す宣言的な文章で構成されている。記述には階層的な番号が振られて おり、7つの基本的な命題が第一階層(1~7の番号)にあり、それぞれの下位階層は、次の上位階層の記述に対するコメント、またはその精緻化である(例え ば、1、1.1、1.11、1.12、1.13)。全部で525の章からなる。 Tractatus』は20世紀の重要な哲学的著作として哲学者たちに認識されており、主にルドルフ・カルナップやフリードリヒ・ウェイスマンといった ウィーン・サークルの論理実証主義哲学者たちに影響を与えた。バートランド・ラッセルの論文「論理的原子論の哲学」は、彼がウィトゲンシュタインから学ん だアイデアの実践として提示されている[2]。 |

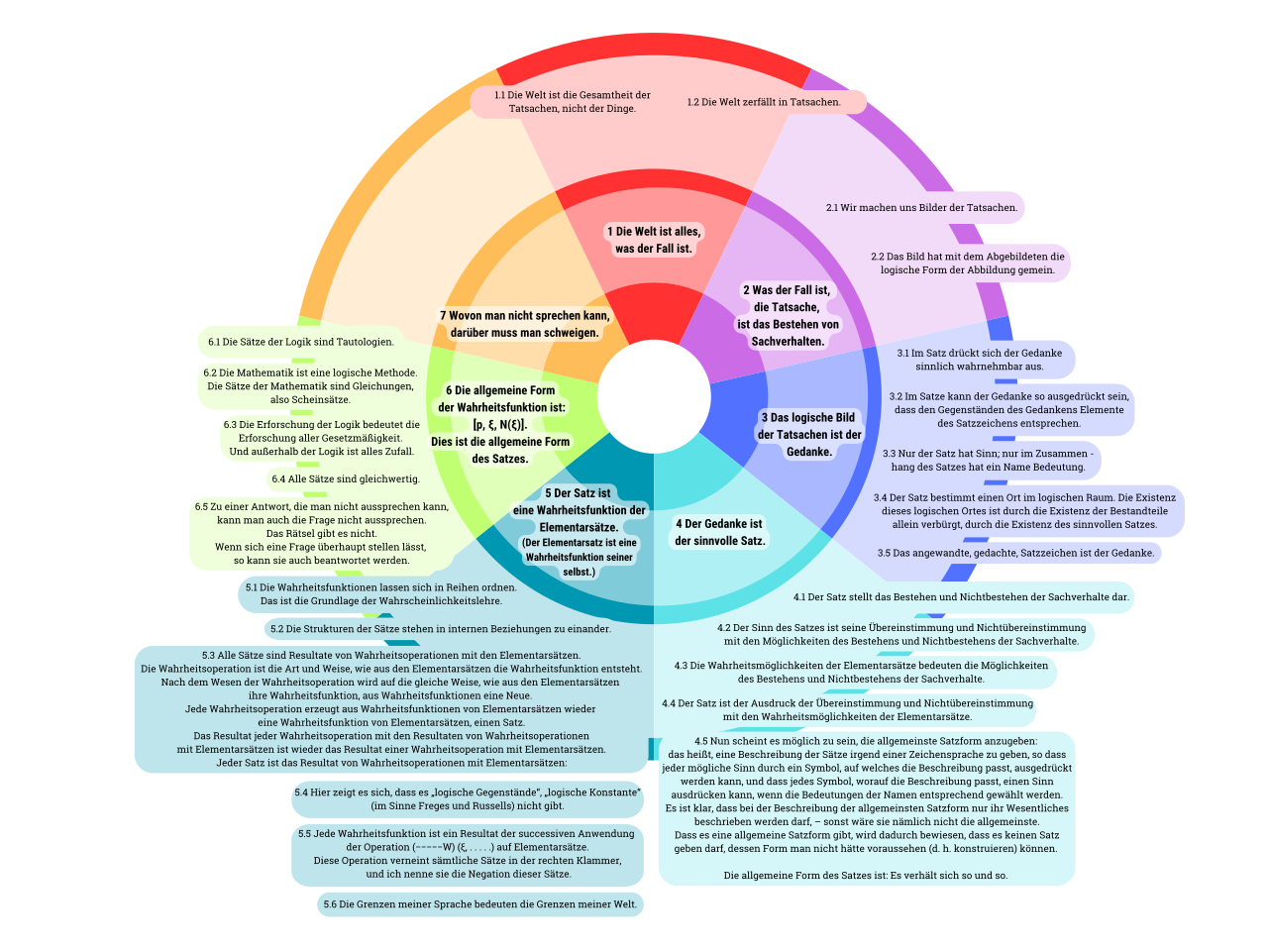

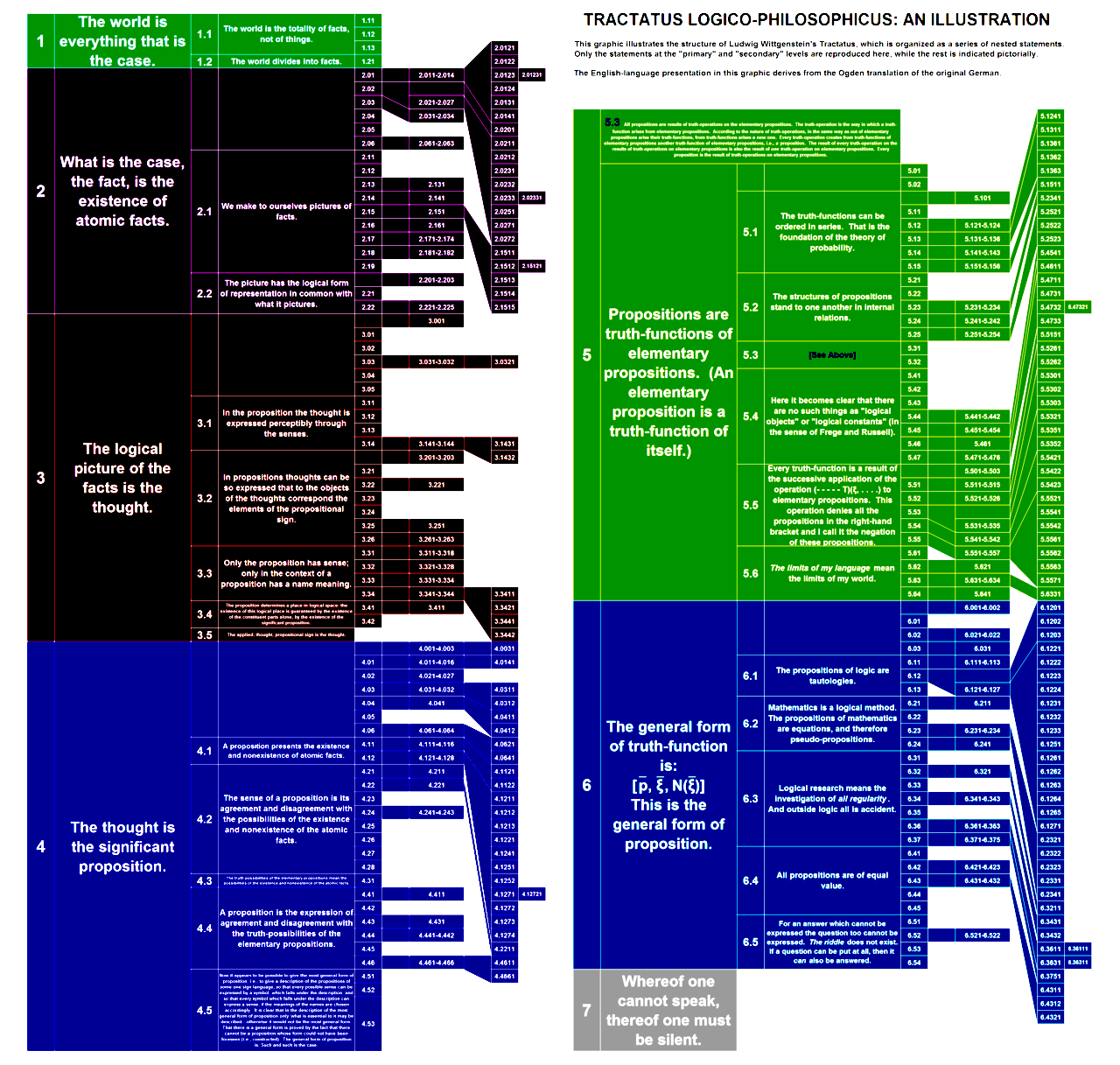

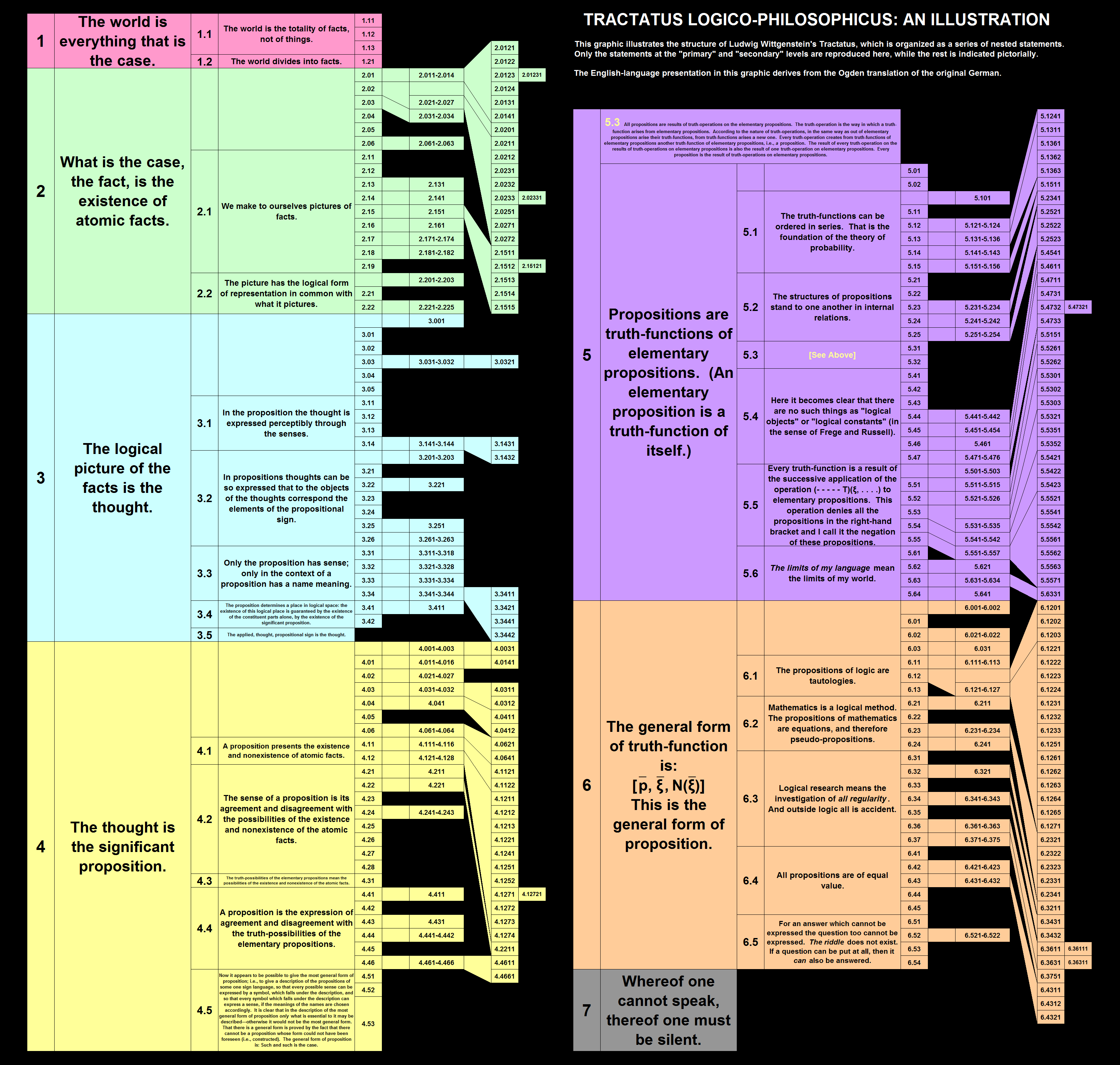

|

Illustration

of the structure of the Tractatus. Only primary and secondary

statements are reproduced, while the structure of the rest is indicated

pictorially. Tractatusの構造を示す図。一次的記述と二次的記述のみが再現され、それ以外の部分の構造は絵で示されている。 |

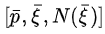

| Main theses Illustration of the structure of the Tractatus. Only primary and secondary statements are reproduced, while the structure of the rest is indicated pictorially. There are seven main propositions in the text. These are: The world is everything that is the case. What is the case (a fact) is the existence of states of affairs. A logical picture of facts is a thought. A thought is a proposition with a sense. A proposition is a truth-function of elementary propositions. (An elementary proposition is a truth-function of itself.) The general form of a proposition is the general form of a truth function, which is: This is the general form of a proposition. Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent. Proposition 1 The first chapter is very brief:  1 The world is all that is the case. 1.1 The world is the totality of facts, not of things. 1.11 The world is determined by the facts, and by their being all the facts. 1.12 For the totality of facts determines what is the case, and also whatever is not the case. 1.13 The facts in logical space are the world. 1.2 The world divides into facts. 1.21 Each item can be the case or not the case while everything else remains the same. This, along with the beginning of two, can be taken to be the relevant parts of Wittgenstein's metaphysical view that he will use to support his picture theory of language. Propositions 2 and 3 These sections concern Wittgenstein's view that the sensible, changing world we perceive does not consist of substance but of facts. Proposition two begins with a discussion of objects, form and substance. 2 What is the case—a fact—is the existence of states of affairs. 2.01 A state of affairs (a state of things) is a combination of objects (things). This epistemic notion is further clarified by a discussion of objects or things as metaphysical substances. 2.0141 The possibility of its occurrence in atomic facts is the form of an object. 2.02 Objects are simple. ... 2.021 Objects make up the substance of the world. That is why they cannot be composite. His use of the word "composite" in 2.021 can be taken to mean a combination of form and matter, in the Platonic sense. The notion of a static unchanging Form and its identity with Substance represents the metaphysical view that has come to be held as an assumption by the vast majority of the Western philosophical tradition since Plato and Aristotle, as it was something they agreed on. "[W]hat is called a form or a substance is not generated."[3] (Z.8 1033b13) The opposing view states that unalterable Form does not exist, or at least if there is such a thing, it contains an ever changing, relative substance in a constant state of flux. Although this view was held by Greeks like Heraclitus, it has existed only on the fringe of the Western tradition since then. It is commonly known now only in "Eastern" metaphysical views where the primary concept of substance is Qi, or something similar, which persists through and beyond any given Form. The former view is shown to be held by Wittgenstein in what follows: 2.024 The substance is what subsists independently of what is the case. 2.025 It is form and content. ... 2.026 There must be objects, if the world is to have unalterable form. 2.027 Objects, the unalterable, and the substantial are one and the same. 2.0271 Objects are what is unalterable and substantial; their configuration is what is changing and unstable. Although Wittgenstein largely disregarded Aristotle (Ray Monk's biography suggests that he never read Aristotle at all) it seems that they shared some anti-Platonist views on the universal/particular issue regarding primary substances. He attacks universals explicitly in his Blue Book. "The idea of a general concept being a common property of its particular instances connects up with other primitive, too simple, ideas of the structure of language. It is comparable to the idea that properties are ingredients of the things which have the properties; e.g. that beauty is an ingredient of all beautiful things as alcohol is of beer and wine, and that we therefore could have pure beauty, unadulterated by anything that is beautiful."[4] And Aristotle agrees: "The universal cannot be a substance in the manner in which an essence is",[3] (Z.13 1038b17) as he begins to draw the line and drift away from the concepts of universal Forms held by his teacher Plato. The concept of Essence, taken alone is a potentiality, and its combination with matter is its actuality. "First, the substance of a thing is peculiar to it and does not belong to any other thing"[3] (Z.13 1038b10), i.e. not universal and we know this is essence. This concept of form/substance/essence, which we have now collapsed into one, being presented as potential is also, apparently, held by Wittgenstein: 2.033 Form is the possibility of structure. 2.034 The structure of a fact consists of the structures of states of affairs. 2.04 The totality of existing states of affairs is the world. ... 2.063 The sum-total of reality is the world. Here ends what Wittgenstein deems to be the relevant points of his metaphysical view and he begins in 2.1 to use said view to support his Picture Theory of Language. "The Tractatus's notion of substance is the modal analogue of Immanuel Kant's temporal notion. Whereas for Kant, substance is that which 'persists' (i.e., exists at all times), for Wittgenstein it is that which, figuratively speaking, 'persists' through a 'space' of possible worlds."[5] Whether the Aristotelian notions of substance came to Wittgenstein via Kant, or via Bertrand Russell, or even whether Wittgenstein arrived at his notions intuitively, one cannot but see them. The further thesis of 2. and 3. and their subsidiary propositions is Wittgenstein's picture theory of language. This can be summed up as follows: The world consists of a totality of interconnected atomic facts, and propositions make "pictures" of the world. In order for a picture to represent a certain fact it must, in some way, possess the same logical structure as the fact. The picture is a standard of reality. In this way, linguistic expression can be seen as a form of geometric projection, where language is the changing form of projection but the logical structure of the expression is the unchanging geometric relationship. We cannot say with language what is common in the structures, rather it must be shown, because any language we use will also rely on this relationship, and so we cannot step out of our language with language. Propositions 4.N to 5.N The 4s are significant as they contain some of Wittgenstein's most explicit statements concerning the nature of philosophy and the distinction between what can be said and what can only be shown. It is here, for instance, that he first distinguishes between material and grammatical propositions, noting: 4.003 Most of the propositions and questions to be found in philosophical works are not false but nonsensical. Consequently we cannot give any answer to questions of this kind, but can only point out that they are nonsensical. Most of the propositions and questions of philosophers arise from our failure to understand the logic of our language. (They belong to the same class as the question whether the good is more or less identical than the beautiful.) And it is not surprising that the deepest problems are in fact not problems at all. A philosophical treatise attempts to say something where nothing can properly be said. It is predicated upon the idea that philosophy should be pursued in a way analogous to the natural sciences; that philosophers are looking to construct true theories. This sense of philosophy does not coincide with Wittgenstein's conception of philosophy. 4.1 Propositions represent the existence and non-existence of states of affairs. 4.11 The totality of true propositions is the whole of natural science (or the whole corpus of the natural sciences). 4.111 Philosophy is not one of the natural sciences. (The word "philosophy" must mean something whose place is above or below the natural sciences, not beside them.) 4.112 Philosophy aims at the logical clarification of thoughts. Philosophy is not a body of doctrine but an activity. A philosophical work consists essentially of elucidations. Philosophy does not result in "philosophical propositions", but rather in the clarification of propositions. Without philosophy thoughts are, as it were, cloudy and indistinct: its task is to make them clear and to give them sharp boundaries. ... 4.113 Philosophy sets limits to the much disputed sphere of natural science. 4.114 It must set limits to what can be thought; and, in doing so, to what cannot be thought. It must set limits to what cannot be thought by working outwards through what can be thought. 4.115 It will signify what cannot be said, by presenting clearly what can be said. Wittgenstein is to be credited with the popularization of truth tables (4.31) and truth conditions (4.431) which now constitute the standard semantic analysis of first-order sentential logic.[6][7] The philosophical significance of such a method for Wittgenstein was that it alleviated a confusion, namely the idea that logical inferences are justified by rules. If an argument form is valid, the conjunction of the premises will be logically equivalent to the conclusion and this can be clearly seen in a truth table; it is displayed. The concept of tautology is thus central to Wittgenstein's Tractarian account of logical consequence, which is strictly deductive. 5.13 When the truth of one proposition follows from the truth of others, we can see this from the structure of the propositions. 5.131 If the truth of one proposition follows from the truth of others, this finds expression in relations in which the forms of the propositions stand to one another: nor is it necessary for us to set up these relations between them, by combining them with one another in a single proposition; on the contrary, the relations are internal, and their existence is an immediate result of the existence of the propositions. ... 5.132 If p follows from q, I can make an inference from q to p, deduce p from q. The nature of the inference can be gathered only from the two propositions. They themselves are the only possible justification of the inference. "Laws of inference", which are supposed to justify inferences, as in the works of Frege and Russell, have no sense, and would be superfluous. Proposition 6.N At the beginning of Proposition 6, Wittgenstein postulates the essential form of all sentences. He uses the notation  , where  stands for all atomic propositions,  stands for any subset of propositions, and  stands for the negation of all propositions making up  Proposition 6 says that any logical sentence can be derived from a series of NOR operations on the totality of atomic propositions. Wittgenstein drew from Henry M. Sheffer's logical theorem making that statement in the context of the propositional calculus. Wittgenstein's N-operator is a broader infinitary analogue of the Sheffer stroke, which applied to a set of propositions produces a proposition that is equivalent to the denial of every member of that set. Wittgenstein shows that this operator can cope with the whole of predicate logic with identity, defining the quantifiers at 5.52, and showing how identity would then be handled at 5.53–5.532. The subsidiaries of 6. contain more philosophical reflections on logic, connecting to ideas of knowledge, thought, and the a priori and transcendental. The final passages argue that logic and mathematics express only tautologies and are transcendental, i.e. they lie outside of the metaphysical subject's world. In turn, a logically "ideal" language cannot supply meaning, it can only reflect the world, and so, sentences in a logical language cannot remain meaningful if they are not merely reflections of the facts. From Propositions 6.4–6.54, the Tractatus shifts its focus from primarily logical considerations to what may be considered more traditionally philosophical foci (God, ethics, meta-ethics, death, the will) and, less traditionally along with these, the mystical. The philosophy of language presented in the Tractatus attempts to demonstrate just what the limits of language are – to delineate precisely what can and cannot be sensically said. Among the sensibly sayable for Wittgenstein are the propositions of natural science, and to the nonsensical, or unsayable, those subjects associated with philosophy traditionally – ethics and metaphysics, for instance.[8] Curiously, on this score, the penultimate proposition of the Tractatus, proposition 6.54, states that once one understands the propositions of the Tractatus, he will recognize that they are senseless, and that they must be thrown away. Proposition 6.54, then, presents a difficult interpretative problem. If the so-called 'picture theory' of meaning is correct, and it is impossible to represent logical form, then the theory, by trying to say something about how language and the world must be for there to be meaning, is self-undermining. This is to say that the 'picture theory' of meaning itself requires that something be said about the logical form sentences must share with reality for meaning to be possible.[9] This requires doing precisely what the 'picture theory' of meaning precludes. It would appear, then, that the metaphysics and the philosophy of language endorsed by the Tractatus give rise to a paradox: for the Tractatus to be true, it will necessarily have to be nonsense by self-application; but for this self-application to render the propositions of the Tractatus nonsense (in the Tractarian sense), then the Tractatus must be true.[10] There are three primarily dialectical approaches to solving this paradox[9] 1) the traditionalist, or Ineffable-Truths View;[10] 2) the resolute, 'new Wittgenstein', or Not-All-Nonsense View;[10] 3) the No-Truths-At-All View.[10] The traditionalist approach to resolving this paradox is to hold that Wittgenstein accepted that philosophical statements could not be made, but that nevertheless, by appealing to the distinction between saying and showing, that these truths can be communicated by showing.[10] On the resolute reading, some of the propositions of the Tractatus are withheld from self-application, they are not themselves nonsense, but point out the nonsensical nature of the Tractatus. This view often appeals to the so-called 'frame' of the Tractatus, comprising the preface and propositions 6.54.[9] The No-Truths-At-All View states that Wittgenstein held the propositions of the Tractatus to be ambiguously both true and nonsensical, at once. While the propositions could not be, by self-application of the attendant philosophy of the Tractatus, true (or even sensical), it was only the philosophy of the Tractatus itself that could render them so. This is presumably what made Wittgenstein compelled to accept the philosophy of the Tractatus as specially having solved the problems of philosophy. It is the philosophy of the Tractatus, alone, that can solve the problems. Indeed, the philosophy of the Tractatus is for Wittgenstein, on this view, problematic only when applied to itself.[10] At the end of the text Wittgenstein uses an analogy from Arthur Schopenhauer and compares the book to a ladder that must be thrown away after it has been climbed. Proposition 7 As the last line in the book, proposition 7 has no supplementary propositions. It ends the book with the proposition "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent" (German: Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen). Picture theory A prominent view set out in the Tractatus is the picture theory, sometimes called the picture theory of language. The picture theory is a proposed explanation of the capacity of language and thought to represent the world.[11]: p44 Although something need not be a proposition to represent something in the world, Wittgenstein was largely concerned with the way propositions function as representations.[11] According to the theory, propositions can "picture" the world as being a certain way, and thus accurately represent it either truly or falsely.[11] If someone thinks the proposition, "There is a tree in the yard", then that proposition accurately pictures the world if and only if there is a tree in the yard.[11]: p53 One aspect of pictures which Wittgenstein finds particularly illuminating in comparison with language is the fact that we can directly see in the picture what situation it depicts without knowing if the situation actually obtains. This allows Wittgenstein to explain how false propositions can have meaning (a problem which Russell struggled with for many years): just as we can see directly from the picture the situation which it depicts without knowing if it in fact obtains, analogously, when we understand a proposition we grasp its truth conditions or its sense, that is, we know what the world must be like if it is true, without knowing if it is in fact true (TLP 4.024, 4.431).[12] It is believed that Wittgenstein was inspired for this theory by the way that traffic courts in Paris reenact automobile accidents.[13]: p35 A toy car is a representation of a real car, a toy truck is a representation of a real truck, and dolls are representations of people. In order to convey to a judge what happened in an automobile accident, someone in the courtroom might place the toy cars in a position like the position the real cars were in, and move them in the ways that the real cars moved. In this way, the elements of the picture (the toy cars) are in spatial relation to one another, and this relation itself pictures the spatial relation between the real cars in the automobile accident.[11]: p45 Pictures have what Wittgenstein calls Form der Abbildung or pictorial form, which they share with what they depict. This means that all the logically possible arrangements of the pictorial elements in the picture correspond to the possibilities of arranging the things which they depict in reality.[14] Thus if the model for car A stands to the left of the model for car B, it depicts that the cars in the world stand in the same way relative to each other. This picturing relation, Wittgenstein believed, was our key to understanding the relationship a proposition holds to the world.[11] Although language differs from pictures in lacking direct pictorial mode of representation (e.g., it does not use colors and shapes to represent colors and shapes), still Wittgenstein believed that propositions are logical pictures of the world by virtue of sharing logical form with the reality which they represent (TLP 2.18–2.2). And that, he thought, explains how we can understand a proposition without its meaning having been explained to us (TLP 4.02); we can directly see in the proposition what it represents as we see in the picture the situation which it depicts just by virtue of knowing its method of depiction: propositions show their sense (TLP 4.022).[15] However, Wittgenstein claimed that pictures cannot represent their own logical form, they cannot say what they have in common with reality but can only show it (TLP 4.12–4.121). If representation consist in depicting an arrangement of elements in logical space, then logical space itself cannot be depicted since it is itself not an arrangement of anything; rather logical form is a feature of an arrangement of objects and thus it can be properly expressed (that is depicted) in language by an analogous arrangement of the relevant signs in sentences (which contain the same possibilities of combination as prescribed by logical syntax), hence logical form can only be shown by presenting the logical relations between different sentences.[16][12] Wittgenstein's conception of representation as picturing also allows him to derive two striking claims: that no proposition can be known a priori – there are no apriori truths (TLP 3.05), and that there is only logical necessity (TLP 6.37). Since all propositions, by virtue of being pictures, have sense independently of anything being the case in reality, we cannot see from the proposition alone whether it is true (as would be the case if it could be known apriori), but we must compare it to reality in order to know that it is true (TLP 4.031 "In the proposition a state of affairs is, as it were, put together for the sake of experiment"). And for similar reasons, no proposition is necessarily true except in the limiting case of tautologies, which Wittgenstein say lack sense (TLP 4.461). If a proposition pictures a state of affairs in virtue of being a picture in logical space, then a non-logical or metaphysical "necessary truth" would be a state of affairs which is satisfied by any possible arrangement of objects (since it is true for any possible state of affairs), but this means that the would-be necessary proposition would not depict anything as being so but will be true no matter what the world is actually like; but if that's the case, then the proposition cannot say anything about the world or describe any fact in it – it would not be correlated with any particular state of affairs, just like a tautology (TLP 6.37).[17][18] Logical atomism  The Tractatus was first published in Annalen der Naturphilosophie (1921) Although Wittgenstein did not use the term himself, his metaphysical view throughout the Tractatus is commonly referred to as logical atomism. While his logical atomism resembles that of Bertrand Russell, the two views are not strictly the same.[11]: p58 Russell's theory of descriptions is a way of logically analyzing sentences containing definite descriptions without presupposing the existence of an object satisfying the description. According to the theory, a statement like "There is a man to my left" should be analyzed into: "There is some x such that x is a man and x is to my left, and for any y, if y is a man and y is to my left, y is identical to x". If the statement is true, x refers to the man to my left.[19] Whereas Russell believed the names (like x) in his theory should refer to things we can know directly by virtue of acquaintance, Wittgenstein did not believe that there are any epistemic constraints on logical analyses: the simple objects are whatever is contained in the elementary propositions which cannot be logically analyzed any further.[11]: p63 By objects, Wittgenstein did not mean physical objects in the world, but the absolute base of logical analysis, that can be combined but not divided (TLP 2.02–2.0201).[11] According to Wittgenstein's logico-atomistic metaphysical system, objects each have a "nature", which is their capacity to combine with other objects. When combined, objects form "states of affairs". A state of affairs that obtains is a "fact". Facts make up the entirety of the world; they are logically independent of one another, as are states of affairs. That is, the existence of one state of affairs (or fact) does not allow us to infer whether another state of affairs (or fact) exists or does not exist.[11]: pp58–59 Within states of affairs, objects are in particular relations to one another.[11]: p59 This is analogous to the spatial relations between toy cars discussed above. The structure of states of affairs comes from the arrangement of their constituent objects (TLP 2.032), and such arrangement is essential to their intelligibility, just as the toy cars must be arranged in a certain way in order to picture the automobile accident.[11] A fact might be thought of as the obtaining state of affairs that Madison is in Wisconsin, and a possible (but not obtaining) state of affairs might be Madison's being in Utah. These states of affairs are made up of certain arrangements of objects (TLP 2.023). However, Wittgenstein does not specify what objects are. Madison, Wisconsin, and Utah cannot be atomic objects: they are themselves composed of numerous facts.[11] Instead, Wittgenstein believed objects to be the things in the world that would correlate to the smallest parts of a logically analyzed language, such as names like x. Our language is not sufficiently (i.e., not completely) analyzed for such a correlation, so one cannot say what an object is.[11]: p60 We can, however, talk about them as "indestructible" and "common to all possible worlds".[11] Wittgenstein believed that the philosopher's job is to discover the structure of language through analysis.[13]: p38 Anthony Kenny provides a useful analogy for understanding Wittgenstein's logical atomism: a slightly modified game of chess.[11]: pp60–61 Just like objects in states of affairs, the chess pieces alone do not constitute the game—their arrangements, together with the pieces (objects) themselves, determine the state of affairs.[11] Through Kenny's chess analogy, we can see the relationship between Wittgenstein's logical atomism and his picture theory of representation.[11]: p61 For the sake of this analogy, the chess pieces are objects, they and their positions constitute states of affairs and therefore facts, and the totality of facts is the entire particular game of chess.[11] We can communicate such a game of chess in the exact way that Wittgenstein says a proposition represents the world.[11] We might say "WR/KR1" to communicate a white rook's being on the square commonly labeled as king's rook 1. Or, to be more thorough, we might make such a report for every piece's position.[11] The logical form of our reports must be the same logical form of the chess pieces and their arrangement on the board in order to be meaningful. Our communication about the chess game must have as many possibilities for constituents and their arrangement as the game itself.[11] Kenny points out that such logical form need not strictly resemble the chess game. The logical form can be had by the bouncing of a ball (for example, twenty bounces might communicate a white rook's being on the king's rook 1 square). One can bounce a ball as many times as one wishes, which means that the ball's bouncing has "logical multiplicity", and can therefore share the logical form of the game.[11]: p62 A motionless ball cannot communicate this same information, as it does not have logical multiplicity.[11] Distinction between saying and showing According to traditional reading of the Tractatus, Wittgenstein's views about logic and language led him to believe that some features of language and reality cannot be expressed in senseful language but only "shown" by the form of certain expressions. Thus for example, according to the picture theory, when a proposition is thought or expressed, the proposition represents reality (truly or falsely) by virtue of sharing some features with that reality in common. However, those features themselves are something Wittgenstein claimed we could not say anything about, because we cannot describe the relationship that pictures bear to what they depict, but only show it via fact-stating propositions (TLP 4.121). Thus we cannot say that there is a correspondence between language and reality; the correspondence itself can only be shown,[11]: p56 since our language is not capable of describing its own logical structure.[13]: p47 However, on the more recent "resolute" interpretation of the Tractatus (see below), the remarks on "showing" were not in fact an attempt by Wittgenstein to gesture at the existence of some ineffable features of language or reality, but rather, as Cora Diamond and James Conant have argued,[20] the distinction was meant to draw a sharp contrast between logic and descriptive discourse. On their reading, Wittgenstein indeed meant that some things are shown when we reflect on the logic of our language, but what is shown is not that something is the case, as if we could somehow think it (and thus understand what Wittgenstein tries to show us) but for some reason we just could not say it. As Diamond and Conant explain:[20] Speaking and thinking are different from activities the practical mastery of which has no logical side; and they differ from activities like physics the practical mastery of which involves the mastery of content specific to the activity. On Wittgenstein's view ... linguistic mastery does not, as such, depend on even an inexplicit mastery of some sort of content. ... The logical articulation of the activity itself can be brought more clearly into view, without that involving our coming to awareness that anything. When we speak about the activity of philosophical clarification, grammar may impose on us the use of 'that'-clauses and 'what'-constructions in the descriptions we give of the results of the activity. But, one could say, the final 'throwing away of the ladder' involves the recognition that that grammar of 'what'-ness has been pervasively misleading us, even as we read through the Tractatus. To achieve the relevant sort of increasingly refined awareness of the logic of our language is not to grasp a content of any sort. Similarly, Michael Kremer suggested that Wittgenstein's distinction between saying and showing could be compared with Gilbert Ryle's famous distinction between "knowing that" and "knowing how".[21] Just as practical knowledge or skill (such as riding a bike) is not reducible to propositional knowledge according to Ryle, Wittgenstein also thought that the mastery of the logic of our language is a unique practical skill that does not involve any sort of propositional "knowing that", but rather is reflected in our ability to operate with senseful sentences and grasping their internal logical relations. |