タスキーギ梅毒研究

Tuskegee Syphilis Study, 1932–1972

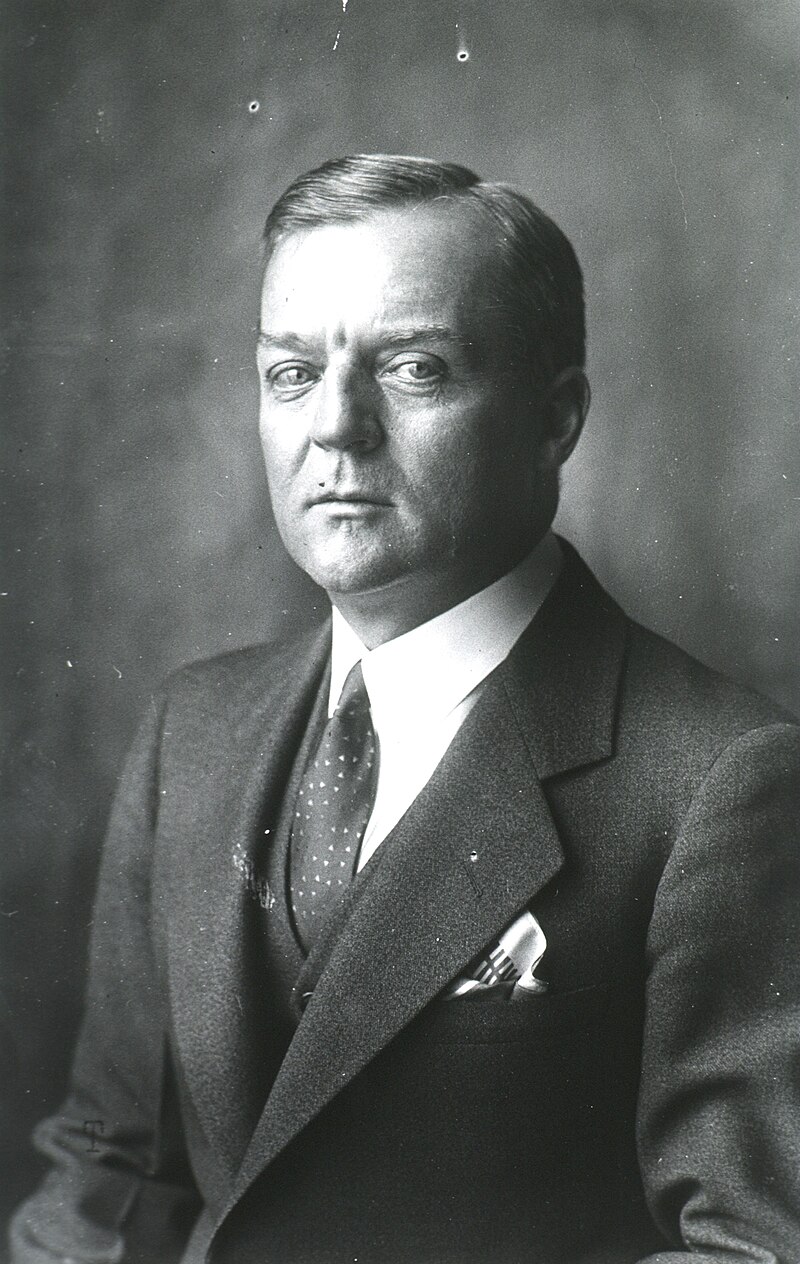

タ スキギー梅毒研究の被験者から採血するジョン・カトラー博士

☆

黒人男性における未治療梅毒のタスキーギ研究[1](非公式にはタスキーギ実験またはタスキーギ梅毒研究とも呼ばれる)は、米国公衆衛生局(PHS)と疾

病対策予防センター(CDC)が1932年から1972年にかけて、梅毒に罹患した約400人のアフリカ系アメリカ人男性のグループに対して実施した研究

である[2][3]。

[研究の目的は、未治療の場合の病気の影響を観察することであったが、研究の終わりには、医学の進歩により完全に治療可能な病気になっていた。被験者たち

は実験の内容を知らされておらず、その結果100人以上が死亡した。

公衆衛生局は1932年、アラバマ州の歴史的黒人大学であるタスキーギー大学(当時はタスキーギー研究所)と共同で研究を開始した。この研究では、アラバ

マ州メーコン郡の貧しいアフリカ系アメリカ人の小作人600人が登録された[4]。このうち399人が潜伏梅毒に罹患しており、対照群として感染していな

い男性201人が登録された[3]。研究に参加するインセンティブとして、男性には無料の医療が約束された。男性たちは、他の方法では受けられなかった医

療と精神的ケアの両方を受けたが[5]、PHSに騙され、梅毒の診断を知らされず[10]、「悪血」の治療として、偽のプラセボ、効果のない方法、診断方

法を提供された[11]。

男性たちは当初、この実験は6ヶ月しか続かないと聞かされていたが、40年まで延長された[3]。治療のための資金が失われた後、男性たちには治療が行わ

れないことを知らせないまま研究が続けられた。1947年には、ペニシリンという抗生物質が広く入手できるようになり、梅毒の標準的な治療法となっていた

にもかかわらず、感染した男性の誰もペニシリンによる治療を受けなかった[12]。

この研究は、1972年にマスコミにリークされた結果、同年11月16日に終了するまで、多くの公衆衛生局の監督下で続けられた[13]。それまでに、

28人の患者が梅毒で直接死亡し、100人が梅毒に関連した合併症で死亡し、40人の患者の妻が梅毒に感染し、19人の子供が先天梅毒で生まれた

[14]。

40年にわたるタスキギー研究は、倫理基準に対する重大な違反であり[12]、「間違いなく米国史上最も悪名高い生物医学研究」[15]として引用されて

いる。OHRPは、米国保健社会福祉省(HHS)内でこの責任を管理している[16]。その暴露は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の医学と米国政府に対する不信の

重要な原因ともなっている[15]。

1997年、ビル・クリントン大統領は、米国を代表して、この研究の被害者に正式に謝罪し、恥ずべき人種差別的なものであったと述べた[17]。「しか

し、沈黙を終わらせることはできる。あなた方の目を見つめ、アメリカ国民を代表して、合衆国政府が行ったことは恥ずべきことであり、申し訳ないとようやく

言うことができる」[17][18]。

| The

Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male[1] (informally

referred to as the Tuskegee Experiment or Tuskegee Syphilis Study) was

a study conducted between 1932 and 1972 by the United States Public

Health Service (PHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) on a group of nearly 400 African American men with

syphilis.[2][3] The purpose of the study was to observe the effects of

the disease when untreated, though by the end of the study medical

advancements meant it was entirely treatable. The men were not informed

of the nature of the experiment, and more than 100 died as a result. The Public Health Service started the study in 1932 in collaboration with Tuskegee University (then the Tuskegee Institute), a historically Black college in Alabama. In the study, investigators enrolled 600 impoverished African-American sharecroppers from Macon County, Alabama.[4] Of these men, 399 had latent syphilis, with a control group of 201 men who were not infected.[3] As an incentive for participation in the study, the men were promised free medical care. While the men were provided with both medical and mental care that they otherwise would not have received,[5] they were deceived by the PHS, who never informed them of their syphilis diagnosis[10] and provided disguised placebos, ineffective methods, and diagnostic procedures as treatment for "bad blood".[11] The men were initially told that the experiment was only going to last six months, but it was extended to 40 years.[3] After funding for treatment was lost, the study was continued without informing the men that they would never be treated. None of the infected men were treated with penicillin despite the fact that, by 1947, the antibiotic was widely available and had become the standard treatment for syphilis.[12] The study continued, under numerous Public Health Service supervisors, until 1972, when a leak to the press resulted in its termination on November 16 of that year.[13] By then, 28 patients had died directly from syphilis, 100 died from complications related to syphilis, 40 of the patients' wives were infected with syphilis, and 19 children were born with congenital syphilis.[14] The 40-year Tuskegee Study was a major violation of ethical standards[12] and has been cited as "arguably the most infamous biomedical research study in U.S. history."[15] Its revelation led to the 1979 Belmont Report and to the establishment of the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP)[16] and federal laws and regulations requiring institutional review boards for the protection of human subjects in studies. The OHRP manages this responsibility within the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).[16] Its revelation has also been an important cause of distrust in medical science and the US government amongst African Americans.[15] In 1997, President Bill Clinton formally apologized on behalf of the United States to victims of the study, calling it shameful and racist.[17] "What was done cannot be undone, but we can end the silence," he said. "We can stop turning our heads away. We can look at you in the eye, and finally say, on behalf of the American people, what the United States government did was shameful and I am sorry."[17][18] |

黒人男性における未治療梅毒のタスキーギ研究[1](非公式にはタス

キーギ実験またはタスキーギ梅毒研究とも呼ばれる)は、米国公衆衛生局(PHS)と疾病対策予防センター(CDC)が1932年から1972年にかけて、

梅毒に罹患した約400人のアフリカ系アメリカ人男性のグループに対して実施した研究である[2][3]。

[研究の目的は、未治療の場合の病気の影響を観察することであったが、研究の終わりには、医学の進歩により完全に治療可能な病気になっていた。被験者たち

は実験の内容を知らされておらず、その結果100人以上が死亡した。 公衆衛生局は1932年、アラバマ州の歴史的黒人大学であるタスキーギー大学(当時はタスキーギー研究所)と共同で研究を開始した。この研究では、アラバ マ州メーコン郡の貧しいアフリカ系アメリカ人の小作人600人が登録された[4]。このうち399人が潜伏梅毒に罹患しており、対照群として感染していな い男性201人が登録された[3]。研究に参加するインセンティブとして、男性には無料の医療が約束された。男性たちは、他の方法では受けられなかった医 療と精神的ケアの両方を受けたが[5]、PHSに騙され、梅毒の診断を知らされず[10]、「悪血」の治療として、偽のプラセボ、効果のない方法、診断方 法を提供された[11]。 男性たちは当初、この実験は6ヶ月しか続かないと聞かされていたが、40年まで延長された[3]。治療のための資金が失われた後、男性たちには治療が行わ れないことを知らせないまま研究が続けられた。1947年には、ペニシリンという抗生物質が広く入手できるようになり、梅毒の標準的な治療法となっていた にもかかわらず、感染した男性の誰もペニシリンによる治療を受けなかった[12]。 この研究は、1972年にマスコミにリークされた結果、同年11月16日に終了するまで、多くの公衆衛生局の監督下で続けられた[13]。それまでに、 28人の患者が梅毒で直接死亡し、100人が梅毒に関連した合併症で死亡し、40人の患者の妻が梅毒に感染し、19人の子供が先天梅毒で生まれた [14]。 40年にわたるタスキギー研究は、倫理基準に対する重大な違反であり[12]、「間違いなく米国史上最も悪名高い生物医学研究」[15]として引用されて いる。OHRPは、米国保健社会福祉省(HHS)内でこの責任を管理している[16]。その暴露は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の医学と米国政府に対する不信の 重要な原因ともなっている[15]。 1997年、ビル・クリントン大統領は、米国を代表して、この研究の被害者に正式に謝罪し、恥ずべき人種差別的なものであったと述べた[17]。「しか し、沈黙を終わらせることはできる。あなた方の目を見つめ、アメリカ国民を代表して、合衆国政府が行ったことは恥ずべきことであり、申し訳ないとようやく 言うことができる」[17][18]。 |

| History Study details  Subject blood draw, c. 1953 In 1928, the "Oslo Study of Untreated Syphilis" had reported on the pathologic manifestations of untreated syphilis in several hundred white males. This study was a retrospective study since investigators pieced together information from the histories of patients who had already contracted syphilis but remained untreated for some time.[19] The U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee group decided to build on the Oslo work and perform a prospective study to complement it.[2] The U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee began as a 6-month descriptive epidemiological study of the range of pathology associated with syphilis in the population of Macon County. The researchers involved with the study reasoned that they were not harming the men involved in the study, under the presumption that they were unlikely to ever receive treatment.[4] At that time, it was believed that the effects of syphilis depended on the race of those affected. Physicians believed that syphilis had a more pronounced effect on African-Americans' cardiovascular systems than on their central nervous systems.[16] Investigators enrolled in the study a total of 600 impoverished, African-American sharecroppers.[4] Of these men, 399 had latent syphilis, with a control group of 201 men who were not infected.[3] As an incentive for participation in the study, the men were promised free medical care, but were deceived by the PHS, who never informed subjects of their diagnosis, despite the risk of infecting others, and the fact that the disease could lead to blindness, deafness, mental illness, heart disease, bone deterioration, the collapse of the central nervous system, and death.[6][7][8][9] Instead, the men were told that they were being treated for "bad blood", a colloquialism that described various conditions such as syphilis, anemia, and fatigue. The collection of illnesses the term included was a leading cause of death within the southern African-American community.[3] At the study's commencement, major medical textbooks had recommended that all syphilis be treated, as the consequences were quite severe. At that time, treatment included arsenic-based compounds such as arsphenamine (branded as the "606" formula).[2] Initially, subjects were studied for six to eight months and then treated with contemporary methods, including Salvarsan ("606"), mercurial ointments, and bismuth, which were mildly effective and highly toxic.[4] Additionally, men in the study were administered disguised placebos, ineffective methods, and diagnostic procedures, which were misrepresented as treatments.[11] Throughout, participants remained ignorant of the study clinicians' true purpose, which was to observe the natural course of untreated syphilis.[4] Study clinicians could have chosen to treat all syphilitic subjects and close the study, or split off a control group for testing with penicillin. Instead, they continued the study without treating any participants; they withheld treatment and information about penicillin from the subjects. In addition, scientists prevented participants from accessing syphilis treatment programs available to other residents in the area.[20] The researchers reasoned that the knowledge gained would benefit humankind; however, it was determined afterward that the doctors did harm their subjects by depriving them of appropriate treatment once it had been discovered. The study was characterized as "the longest non-therapeutic experiment on human beings in medical history."[21] To ensure that the men would show up for the possibly dangerous, painful, diagnostic, and non-therapeutic spinal taps, doctors sent participants a misleading letter titled "Last Chance for Special Free Treatment".[2] The U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee published its first clinical data in 1934 and issued its first major report in 1936. This was before the discovery of penicillin as a safe and effective treatment for syphilis. The study was not secret, since reports and data sets were published to the medical community throughout its duration.[4] During World War II, 256 of the infected subjects registered for the draft and were consequently diagnosed as having syphilis at military induction centers and ordered to obtain treatment for syphilis before they could be taken into the armed services.[22][23] PHS researchers prevented these men from getting treatment, thus depriving them of chances for a cure. Vonderlehr argued, "this study is of great importance from a scientific standpoint. It represents one of the last opportunities which the science of medicine will have to conduct an investigation of this kind. ... [Study] Doctor [Murray] Smith ... asked that these men be excluded from the list of draftees needing treatment. ... in order to make it possible to continue this study on an effective basis."[23] Later, Smith, a local PHS representative involved in the study, wrote to Vonderlehr to ask what should be done with patients who had tested negative for syphilis at the time of enrollment in the study and were being used as control subjects but had later tested positive when registering for the draft: "So far, we are keeping the known positive patients from getting treatment. Is a control case of any value to the study, if he has contracted syphilis? Shall we withhold treatment from the control case who has developed syphilis?"[23] Vonderlehr replied that such cases "have lost their value to the study. There is no reason why these patients should not be given appropriate treatment unless you hear from Doctor Austin V. Deibert who is in direct charge of the study".[23] By 1947, penicillin had become standard therapy for syphilis. The U.S. government sponsored several public health programs to form "rapid treatment centers" to eradicate the disease. When campaigns to eradicate venereal disease came to Macon County, study researchers prevented their subjects from participating.[22] Although some of the men in the study received arsenical or penicillin treatments elsewhere, for most of them this did not amount to "adequate therapy".[24]  Subjects talking with study coordinator, Nurse Eunice Rivers, c. 1970 By the end of the study in 1972, only 74 of the test subjects were still alive.[9] Of the original 399 men, 28 had died of syphilis, 100 died of related complications, 40 of their wives had been infected, and 19 of their children were born with congenital syphilis.[14]  Researcher collecting a blood sample as part of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study The revelation in 1972 of study failures by whistleblower Peter Buxtun led to major changes in U.S. law and regulation concerning the protection of participants in clinical studies. Studies now require informed consent,[25] communication of diagnosis and accurate reporting of test results.[26] |

沿革 研究の詳細  被験者の採血、1953年頃 1928年、「Oslo Study of Untreated Syphilis 」が数百人の白人男性における未治療梅毒の病理学的症状について報告した。この研究は、すでに梅毒に罹患していたがしばらくの間未治療のままであった患者 の病歴から情報をつなぎ合わせたものであったため、後ろ向き研究であった[19]。 タスキギーの米国公衆衛生局梅毒研究グループは、オスロの研究を基に、それを補完する前向き研究を行うことを決定した[2]。タスキギーの米国公衆衛生局 梅毒研究は、メーコン郡の集団における梅毒に関連する病理の範囲に関する6ヵ月間の記述疫学研究として始まった。当時、梅毒の影響は罹患者の人種によって 異なると考えられていた。医師たちは、梅毒は中枢神経系よりもアフリカ系アメリカ人の心臓血管系により顕著な影響を及ぼすと考えていた[16]。 研究者たちは、合計600人の貧しいアフリカ系アメリカ人の小作農をこの研究に登録した[4]。 [3] 研究に参加するインセンティブとして、男性たちは無料の医療を約束されたが、PHSにだまされた。PHSは、他人に感染させる危険性があり、この病気が失 明、難聴、精神疾患、心臓疾患、骨の劣化、中枢神経系の崩壊、死につながる可能性があるという事実にもかかわらず、被験者に自分の診断を知らせなかったの である。 [6][7][8][9]その代わりに、男性たちは、梅毒、貧血、疲労などのさまざまな状態を表す口語表現である「悪い血」の治療を受けていると告げられ た。この言葉が含む病気のコレクションは、南部のアフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティにおける主要な死因であった[3]。 この研究が始まった当時、主要な医学教科書は、梅毒はかなり深刻な結果をもたらすため、すべての梅毒を治療することを推奨していた。当時、治療には、アル スフェナミン(「606」処方としてブランド化されている)などのヒ素ベースの化合物が含まれていた[2]。当初、被験者は6~8ヵ月間研究され、その 後、サルバルサン(「606」)、水銀軟膏、ビスマスなどの現代的な方法で治療されたが、これらは効果が穏やかで毒性が強かった[4]。さらに、研究対象 の男性には、治療と偽って偽装されたプラセボ、効果のない方法、診断手順が投与された[11]。 参加者は、未治療の梅毒の自然経過を観察するという研究臨床家の真の目的を知らないままであった[4]。研究臨床家は、すべての梅毒患者を治療して研究を 終了するか、対照群を分けてペニシリンによる試験を行うこともできた。その代わりに、彼らは参加者を治療することなく研究を継続し、治療とペニシリンに関 する情報を被験者から隠した。さらに科学者たちは、参加者がその地域の他の住民が利用できる梅毒治療プログラムを利用できないようにした[20]。研究者 たちは、得られた知識は人類のためになると考えたが、梅毒が発見された後、医師たちは適切な治療を被験者から奪い、被験者に害を与えたことが後に判明し た。この研究は、「医学史上最も長い非治療的な人体実験」[21]として特徴づけられた。 危険で、痛みを伴い、診断的で、非治療的である可能性のある脊髄穿刺に、被験者が確実に出頭するように、医師たちは「特別無料治療の最後のチャンス」と題した誤解を招くような手紙を被験者に送った[2]。 タスキギーでの米国公衆衛生局梅毒研究は、1934年に最初の臨床データを発表し、1936年に最初の主要な報告書を発表した。これは、梅毒の安全で効果 的な治療法としてペニシリンが発見される前のことである。研究期間中、報告書とデータセットが医学界に公表されたため、研究は秘密ではなかった[4]。 第二次世界大戦中、256人の感染者が徴兵のために登録され、その結果、軍の誘導センターで梅毒であると診断され、兵役に就く前に梅毒の治療を受けるよう に命じられた[22][23]。PHSの研究者たちは、これらの男性が治療を受けるのを阻止し、治療の機会を奪った。フォンデラーは、「この研究は科学的 見地から非常に重要である。医学がこの種の調査を行うことができる最後の機会の一つである。... [マレー・スミス医師は、......この人たちを治療が必要な徴兵者のリストから除外するよう求めた。この研究を効果的に継続できるようにするためであ る」[23]。 その後、この研究に関与していた地元のPHS代表スミスからフォンデラーに手紙が届き、研究登録時に梅毒検査で陰性と判定され、対照被験者として使用され ていたが、後に徴兵登録時に陽性と判定された患者をどうすべきか尋ねた: 「今のところ、陽性とわかっている患者には治療を受けさせないようにしている。もし梅毒に感染していたら、その対照例は研究にとって価値があるのだろう か?梅毒に罹患した対照例から治療を差し控えなければならないのだろうか?この研究を直接担当しているオースティン・V・ダイバート医師から連絡がない限 り、これらの患者に適切な治療を施すべきではない理由はない」[23]。 1947年までに、ペニシリンは梅毒の標準治療となっていた。米国政府は、この病気を根絶するために「迅速治療センター」を設立するいくつかの公衆衛生プ ログラムを後援した。性病撲滅キャンペーンがメーコン郡で行われるようになったとき、研究者は被験者の参加を阻止した[22]。 研究に参加した男性の中には、他の場所でヒ素やペニシリンの治療を受けた者もいたが、彼らの大部分にとって、これは「適切な治療」とは言えなかった [24]。  研究コーディネーターのユニス・リバース看護師と話す被験者たち(1970年頃) 当初の399人の男性のうち、28人が梅毒で死亡し、100人が関連合併症で死亡し、40人の妻が感染し、19人の子供が先天梅毒で生まれた[14]。  タスキーギ梅毒研究の一環として血液サンプルを採取する研究者 1972年、内部告発者ピーター・バクスタンによる研究の失敗の暴露は、臨床研究の参加者の保護に関する米国の法律と規制に大きな変化をもたらした。現在 では、インフォームド・コンセント、[25]診断の伝達、検査結果の正確な報告が研究において義務付けられている[26]。 |

| Study clinicians The venereal disease section of the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) formed a study group in 1932 at its national headquarters in Washington, D.C. Taliaferro Clark, head of the USPHS, is credited with founding it. His initial goal was to follow untreated syphilis in a group of African-American men for six months to one year, and then follow up with a treatment phase.[4][21] When the Rosenwald Fund withdrew its financial support, a treatment program was deemed too expensive.[19] Clark, however, decided to continue the study, interested in determining whether syphilis had a different effect on African-Americans than it did on Caucasians. A regressive study of untreated syphilis in white males had been conducted in Oslo, Norway, and could provide the basis for comparison.[19][27] The prevailing belief at the time was white people were more likely to develop neurosyphilis and that black people were more likely to sustain cardiovascular damage. Clark resigned before the study was extended beyond its original length.[28] Although Clark is usually assigned blame for conceiving the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, Thomas Parran Jr. also helped develop a non-treatment study in Macon County, Alabama. As the Health Commissioner of New York State (and former head of the PHS Venereal Disease Division), Parran was asked by the Rosenwald Fund to assess their serological survey of syphilis and demonstration projects in five Southern states.[29] Among his conclusions was the recommendation that: "If one wished to study the natural history of syphilis in the African American race uninfluenced by treatment, this county (Macon) would be an ideal location for such a study."[30] Oliver C. Wenger was the director of the regional PHS Venereal Disease Clinic in Hot Springs, Arkansas. He and his staff took the lead in developing study procedures. Wenger continued to advise and assist the study when it was adapted as a long-term, no-treatment observational study after funding for treatment was lost.[31] Raymond A. Vonderlehr was appointed on-site director of the research program and developed the policies that shaped the long-term follow-up section of the project. His method of gaining the "consent" of the subjects for spinal taps (to look for signs of neurosyphilis) was by advertising this diagnostic test as a "special free treatment".[4] He also met with local black doctors and asked them to deny treatment to participants in the Tuskegee Study. Vonderlehr retired as head of the venereal disease section in 1943, shortly after penicillin was proven to cure syphilis.[2] Several African-American health workers and educators associated with the Tuskegee Institute played a critical role in the study's progress. The extent to which they knew about the full scope of the study is not clear in all cases.[4] Robert Russa Moton, then president of Tuskegee Institute, and Eugene Dibble, head of the Institute's John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital, both lent their endorsement and institutional resources to the government study.[32] Nurse Eunice Rivers, who had trained at Tuskegee Institute and worked at its hospital, was recruited at the start of the study to be the main point of contact with the participants.[4] Rivers played a crucial role in the study because she served as the direct link to the regional African-American community. Vonderlehr considered her participation to be the key to gaining the trust of the subjects and promoting their participation.[33] As a part of "Miss Rivers' Lodge", participants would receive free physical examinations at Tuskegee University, free rides to and from the clinic, hot meals on examination days, and free treatment for minor ailments. Rivers was also key in convincing families to sign autopsy agreements in return for funeral benefits. As the study became long-term, Rivers became the chief person who provided continuity to the participants. She was the only study staff person to work with participants for the full 40 years.[4] |

臨床医の研究 米国公衆衛生局(PHS)の性病部門は、1932年にワシントンの国民本部で研究グループを結成した。彼の当初の目標は、アフリカ系アメリカ人男性グルー プの未治療梅毒を6ヵ月から1年間追跡調査し、その後、治療段階で追跡調査することであった[4][21]。 ローゼンワルド基金が財政支援を取りやめたため、治療プログラムは費用がかかりすぎるとみなされた[19]。 しかし、クラークは、梅毒がアフリカ系アメリカ人に及ぼす影響が白人とは異なるかどうかを調べることに関心を持ち、研究を継続することにした。白人男性に おける未治療梅毒の退行性研究がノルウェーのオスロで実施されており、比較の基礎となりうるものであった[19][27]。当時の通説では、白人は神経梅 毒を発症しやすく、黒人は心血管系の障害を受けやすいとされていた。クラークは研究が当初の期間を超えて延長される前に辞任した[28]。 クラークは通常、タスキギーでの米国公衆衛生局梅毒研究の発案者としての責任を負わされているが、トーマス・パラン・ジュニアもアラバマ州メーコン郡での 非治療研究の開発に貢献した。ニューヨーク州の保健長官(PHS性病部門の元責任者)であったパランは、ローゼンウォルド基金から、梅毒の血清学的調査と 南部5州における実証プロジェクトの評価を依頼された: 「治療の影響を受けていないアフリカ系アメリカ人における梅毒の自然史を研究したいのであれば、この郡(メーコン)はそのような研究にとって理想的な場所 であろう」[30]。 オリバー・C・ウェンガーは、アーカンソー州ホットスプリングスにある地域PHS性病診療所の所長であった。彼と彼のスタッフは、研究手順の開発を主導し た。ウェンガーは、治療のための資金が途絶えた後、この研究が長期無治療観察研究として適応された際にも、引き続き助言を行い、研究を支援した[31]。 Raymond A. Vonderlehrが研究プログラムの現場責任者に任命され、プロジェクトの長期追跡調査セクションを形成する方針を策定した。脊髄穿刺(神経梅毒の徴 候を探すため)に対する被験者の「同意」を得るための彼の方法は、この診断テストを「特別な無料治療」として宣伝することであった[4]。彼はまた、地元 の黒人医師と会い、タスキギー研究参加者の治療を拒否するよう依頼した。ヴォンダーラーは、ペニシリンが梅毒を治癒することが証明された直後の1943年 に性病課長を退いた[2]。 タスキギー研究所に関連するアフリカ系アメリカ人の医療従事者や教育者の何人かは、研究の進展に重要な役割を果たした。彼らが研究の全容をどの程度知って いたかは、すべての場合において明らかではない。タスキギー研究所(Tuskegee Institute)の当時の総長であったロバート・ラッサ・モトン(Robert Russa Moton)と、同研究所のジョン・A・アンドリュー記念病院(John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital)の院長であったユージン・ディブル(Eugene Dibble)は、ともに政府の研究に賛同し、組織的な資源を提供した[32]。 タスキギー研究所で研修を受け、その病院に勤務していた看護師のユニス・リバーズは、参加者との主な接点として研究の開始時に採用された[4]。リバーズ は、地域のアフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティとの直接的なつながりを担っていたため、この研究で重要な役割を果たした。ミス・リバーズ・ロッジ」の一員と して、参加者はタスキギー大学での無料健康診断、診療所への無料送迎、検査日の温かい食事、軽い病気の無料治療を受けることができた。リバーズはまた、葬 儀の給付と引き換えに剖検同意書に署名するよう家族を説得する上で重要な役割を果たした。研究が長期化するにつれ、リバーズは参加者に継続性を提供する チーフとなった。彼女は、40年間ずっと参加者と共に働いた唯一の研究スタッフであった[4]。 |

Raymond A. Vonderlehr (medical doctor) |

Eugene Dibble (medical doctor) |

Eunice Rivers (nurse) |

Oliver Wenger |

Study termination Peter Buxtun, a PHS venereal disease investigator, the whistleblower  Group of Tuskegee Experiment test subjects Several men employed by the PHS, namely Austin V. Deibert and Albert P. Iskrant, expressed criticism of the study, primarily on the grounds of poor scientific practice.[4] The first dissenter against the study who was not involved in the PHS was Count Gibson, an associate professor at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond. He expressed his ethical concerns to PHS's Sidney Olansky in 1955.[4] Another dissenter was Irwin Schatz, a young Chicago doctor only four years out of medical school. In 1965, Schatz read an article about the study in a medical journal and wrote a letter directly to the study's authors confronting them with a declaration of brazen unethical practice.[34] His letter, read by Anne R. Yobs, one of the study's authors, was immediately ignored and filed away with a brief memo that no reply would be sent.[4] In 1966, Peter Buxtun, a PHS venereal-disease investigator in San Francisco, sent a letter to the national director of the Division of Venereal Diseases expressing his concerns about the ethics and morality of the extended U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee.[35] The CDC, which by then controlled the study, reaffirmed the need to continue the study until completion; i.e. until all subjects had died and been autopsied. To bolster its position, the CDC received unequivocal support for the continuation of the study, both from local chapters of the National Medical Association (representing African-American physicians) and the American Medical Association (AMA).[4] In 1968, William Carter Jenkins, an African-American statistician in the PHS and part of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), founded and edited The Drum, a newsletter devoted to ending racial discrimination in HEW. In The Drum, Jenkins called for an end to the study.[36] He did not succeed; it is not clear who read his work. Buxtun finally went to the press in the early 1970s. The story broke first in the Washington Star on July 25, 1972, reported by Jean Heller of the Associated Press.[8] It became front-page news in the New York Times the following day. Senator Edward Kennedy called Congressional hearings, at which Buxtun and HEW officials testified. As a result of public outcry, the CDC and PHS appointed an ad hoc advisory panel to review the study.[6] The panel found that the men agreed to certain terms of the experiment, such as examination and treatment. However, they were not informed of the study's actual purpose.[3] The panel then determined that the study was medically unjustified and ordered its termination.[citation needed] In 1974, as part of the settlement of a class action lawsuit filed by the NAACP on behalf of study participants and their descendants, the U.S. government paid $10 million ($51.8 million in 2019) and agreed to provide free medical treatment to surviving participants and surviving family members infected as a consequence of the study. Congress created a commission empowered to write regulations to deter such abuses from occurring in the future.[3] A collection of materials compiled to investigate the study is held at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland.[37] |

研究打ち切り ピーター・バクスタン、PHSの性病研究者、内部告発者  タスキギー実験被験者グループ PHSに雇用されていたオースティン・V・ダイバート(Austin V. Deibert)とアルバート・P・イスクラント(Albert P. Iskrant)は、主に科学的実践が不十分であるという理由で、この研究に対する批判を表明した[4]。 PHSに関与していない最初の研究反対者は、リッチモンドにあるバージニア医科大学の准教授、カウント・ギブソン(Count Gibson)であった。彼は1955年にPHSのシドニー・オランスキーに倫理的懸念を表明した[4]。 もう一人の反対論者は、医学部を卒業してわずか4年目の若いシカゴの医師、アーウィン・シャッツであった。1965年、シャッツは医学雑誌でこの研究に関する記事を読み、この研究の著者たちに直接手紙を書き、倫理に反する行為を堂々と宣言するよう突きつけた。 1966年、サンフランシスコのPHS性病研究者ピーター・バクスタン(Peter Buxtun)は、性病部門の国民局長に書簡を送り、タスキギーにおける米国公衆衛生局の梅毒研究の延長の倫理と道徳について懸念を表明した。その立場を 強化するために、CDCは国民医師会(アフリカ系アメリカ人医師を代表する)の地方支部とアメリカ医師会(AMA)の両方から、研究の継続に対する明確な 支持を得た[4]。 1968年、保健教育福祉省(HEW)の一部であるPHSのアフリカ系アメリカ人統計学者ウィリアム・カーター・ジェンキンスは、HEWにおける人種差別 をなくすことに専念するニュースレター『ドラム』を創刊し、編集した。ジェンキンズは『ドラム』誌で調査の中止を訴えたが[36]、成功はしなかった。 バクスタンは1970年代初頭にようやく報道された。このニュースは1972年7月25日付の『ワシントン・スター』紙で最初に報道され、AP通信のジー ン・ヘラーが報じた[8]。エドワード・ケネディ上院議員は議会の公聴会を招集し、バクスタンやHEWの職員が証言した。世論の反発を受け、CDCと PHSはこの研究を再検討するためのアドホック諮問委員会を任命した[6]。委員会は、男性たちが検査や治療といった実験の一定の条件に同意したことを認 めた。しかし、彼らは研究の実際の目的については知らされていなかった。[3] その後、委員会は研究が医学的に不当であると判断し、その中止を命じた[要出典]。 1974年、NAACPが研究参加者とその子孫を代表して起こした集団訴訟の和解の一環として、米国政府は1000万ドル(2019年は5180万ドル) を支払い、研究の結果として感染した生存参加者と生存家族に無料で治療を提供することに同意した。議会は、今後このような虐待が起こることを抑止するため の規制を作成する権限を与えられた委員会を設立した[3]。 この研究を調査するために編纂された資料集は、メリーランド州ベセスダの国立医学図書館に所蔵されている[37]。 |

Aftermath Charlie Pollard, survivor  Herman Shaw, survivor In 1974, Congress passed the National Research Act and created a commission to study and write regulations governing studies involving human participants. Within the United States Department of Health and Human Services, the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) was established to oversee clinical trials. Now studies require informed consent,[25] communication of diagnosis and accurate reporting of test results.[26] Institutional review boards (IRBs), including laypeople, are established in scientific research groups and hospitals to review study protocols, protect patient interests, and ensure that participants are fully informed. In 1994, a multi-disciplinary symposium was held on the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee: Doing Bad in the Name of Good?: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Its Legacy at the University of Virginia. Following that, interested parties formed the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee to develop ideas that had arisen at the symposium, chaired by Vanessa Northington Gamble. It issued its final report in May 1996, having been established at a meeting on January 18–19 of that year.[38] The Committee had two related goals:[38] President Bill Clinton should publicly apologize to the survivors and their community for past government wrongdoing related to the study due to the harm done to the Macon County community and Tuskegee University, and the fears of government and medical abuse the study created among African Americans. No apology had yet been issued at the time.[38] The Committee and relevant federal agencies should develop a strategy to redress the damages, specifically recommending the creation of a center at Tuskegee University for public education about the study, "training programs for health care providers", and a center for the study of ethics in scientific research.[38] A year later on May 16, 1997, Bill Clinton formally apologized and held a ceremony at the White House for surviving Tuskegee study participants. He said: What was done cannot be undone. But we can end the silence. We can stop turning our heads away. We can look at you in the eye and finally say on behalf of the American people, what the United States government did was shameful, and I am sorry... To our African American citizens, I am sorry that your federal government orchestrated a study so clearly racist.[39] Five of the eight study survivors attended the White House ceremony.[40] The presidential apology led to progress in addressing the second goal of the Legacy Committee. The federal government contributed to establishing the National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care at Tuskegee, which officially opened in 1999 to explore issues that underlie research and medical care of African Americans and other under-served people.[41] In 2009, the Legacy Museum opened in the Bioethics Center, to honor the hundreds of participants of the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the African American Male.[38][42] In June 2022, the Milbank Memorial Fund apologized to descendants of the study's victims for its the role in the study.[43] Study participants The five survivors who attended the White House ceremony in 1997 were Charlie Pollard, Herman Shaw, Carter Howard, Fred Simmons, and Frederick Moss. The remaining three survivors had family members attend the ceremony in their name. Sam Doner was represented by his daughter, Gwendolyn Cox; Ernest Hendon by his brother, North Hendon; and George Key by his grandson, Christopher Monroe.[40] The last man who was a participant in the study died in 2004. Charlie Pollard appealed to civil rights attorney Fred D. Gray, who also attended the White House ceremony, for help when he learned the true nature of the study he had been participating in for years. In 1973, Pollard v. United States resulted in a $10 million settlement.[4] Another participant of the study was Freddie Lee Tyson, a sharecropper who helped build Moton Field, where the legendary "Tuskegee Airmen" learned to fly during World War II.[7] |

余波 チャーリー・ポラード、生存者  ハーマン・ショー、生存者 1974年、国民研究法が可決され、研究委員会が設置され、ヒトが参加する研究を管理する規則が制定された。米国保健社会福祉省の中に、臨床試験を監督す るための人間研究保護局(OHRP)が設立された。現在では、インフォームド・コンセント、[25] 診断結果の伝達、検査結果の正確な報告などが義務付けられている[26]。科学研究グループや病院には、一般市民を含む施設審査委員会(IRB)が設置さ れ、研究プロトコルの審査、患者の利益保護、参加者への十分な情報提供を徹底している。 1994年には、タスキギーにおけるアメリカ公衆衛生局の梅毒研究に関して、学際的なシンポジウムが開催された: 善の名の下に悪を行うのか?The Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Its Legacy)がヴァージニア大学で開催された。その後、関係者はシンポジウムで出たアイデアを発展させるため、ヴァネッサ・ノーティントン・ギャンブル を委員長とする「タスキギー梅毒研究遺産委員会」を結成した。同委員会は、同年1月18日から19日にかけての会議で設立され、1996年5月に最終報告 書を発表した[38]。 同委員会には、次の2つの関連する目標があった[38]。 ビル・クリントン大統領は、メーコン郡コミュニティとタスキーギ大学に与えた被害と、この研究がアフリカ系アメリカ人の間に引き起こした政府と医学の乱用 に対する恐怖のために、この研究に関連した過去の政府の不正行為について、生存者とそのコミュニティに公式に謝罪すべきである。当時はまだ謝罪は発表され ていなかった[38]。 委員会と連邦政府関連機関は、損害を是正するための戦略を立てるべきであり、具体的には、タスキギー大学に研究についての一般向け教育のためのセンター、「医療提供者のための研修プログラム」、科学研究における倫理の研究のためのセンターの設立を提言した[38]。 1年後の1997年5月16日、ビル・クリントンは正式に謝罪し、ホワイトハウスで生存しているタスキギー研究参加者のための式典を開いた。彼は言った: 行われたことは取り返しがつかない。しかし、沈黙を終わらせることはできる。しかし、沈黙を終わらせることはできる。アメリカ国民を代表して、アメリカ政 府が行ったことは恥ずべきことであり、申し訳なかった。アフリカ系アメリカ人の皆さん、あなた方の連邦政府が、明らかに人種差別的な研究を画策したことを お詫びします」[39]。 8人の研究生存者のうち5人がホワイトハウスの式典に出席した[40]。 大統領による謝罪は、レガシー委員会の第二の目標への取り組みに進展をもたらした。国民政府は、研究と医療における生命倫理のための国立センターをタスキ ギーに設立することに貢献し、アフリカ系アメリカ人やその他の恵まれない人々の研究と医療の根底にある問題を探求するために、1999年に正式にオープン した[41]。 2009年、アフリカ系アメリカ人男性の未治療梅毒に関するタスキギー研究の数百人の参加者を記念して、生命倫理センター内にレガシー博物館がオープンした[38][42]。 2022年6月、ミルバンク記念基金は、研究での役割について研究犠牲者の子孫に謝罪した[43]。 研究参加者 1997年にホワイトハウスの式典に出席した生存者は、チャーリー・ポラード、ハーマン・ショー、カーター・ハワード、フレッド・シモンズ、フレデリッ ク・モスの5人であった。残りの3人の生存者は、家族が自分の名前で式典に出席した。サム・ドナーは娘のグウェンドリン・コックス、アーネスト・ヘンドン は弟のノース・ヘンドン、ジョージ・キーは孫のクリストファー・モンローが代理出席した[40]。 チャーリー・ポラードは、自分が長年参加してきた研究の本質を知ったとき、ホワイトハウスの式典にも出席した公民権弁護士フレッド・D・グレイに助けを求めた。1973年、ポラード対アメリカは1,000万ドルの和解に至った[4]。 研究のもう一人の参加者はフレディ・リー・タイソンで、第二次世界大戦中に伝説的な「タスキーギ・エアメン」が飛行を学んだモトン・フィールドの建設を手伝った小作人だった[7]。 |

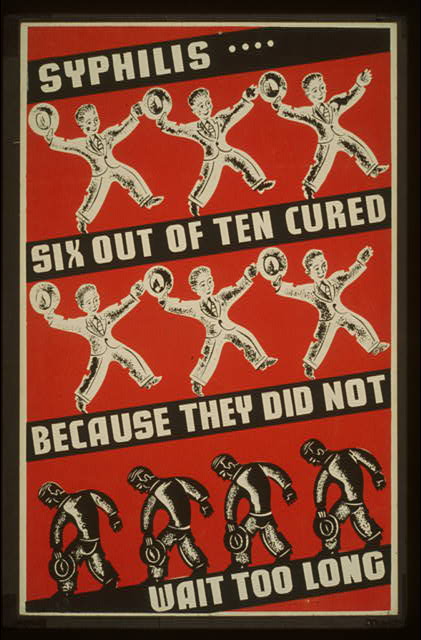

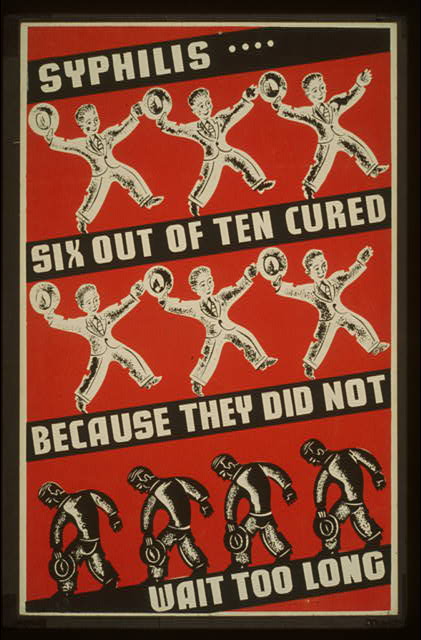

Legacy Depression-era U.S. poster advocating early syphilis treatment. Although treatments were available, participants in the study did not receive them. Scientific failings Aside from a study of racial differences, one of the main goals that researchers in the study wanted to accomplish was to determine the extent to which treatment for syphilis was necessary and at what point in the progression of the disease it should be treated. For this reason, the study emphasized observation of individuals with late latent syphilis.[2][4] However, despite clinicians' attempts to justify the study as necessary for science, the study itself was not conducted in a scientifically viable way. Because participants were treated with mercury rubs, injections of neoarsphenamine, protiodide, Salvarsan, and bismuth, the study did not follow subjects whose syphilis was untreated, however minimally effective these treatments may have been.[2][4] Austin V. Deibert of the PHS recognized that since the study's main goal had been compromised in this way, the results would be meaningless and impossible to manipulate statistically. Even the toxic treatments that were available before the availability of penicillin, according to Deibert, could "greatly lower, if not prevent, late syphilitic cardiovascular disease ... [while] increas[ing] the incidence of neuro-recurrence and other forms of relapse."[4] Despite their effectiveness, these treatments were never prescribed to the participants.[4] Racism Further information: Medical racism in the United States The conception which lay behind the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee in 1932, in which 100% of its participants were poor, rural African-American men with very limited access to health information, reflects the racial attitudes in the U.S. at that time. The clinicians who led the study assumed that African-Americans were particularly susceptible to venereal diseases because of their race, and they assumed that the study's participants were not interested in receiving medical treatment.[2][44] Taliaferro Clark said, "The rather low intelligence of the Negro population, depressed economic conditions, and the common promiscuous sex relations not only contribute to the spread of syphilis but the prevailing indifference with regards to treatment."[44] In reality, the promise of medical treatment, usually reserved only for emergencies among the rural black population of Macon County, Alabama, was what secured subjects' cooperation in the study.[2] Public trust The revelations of mistreatment under the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee are believed to have significantly damaged the trust of the black community toward public health efforts in the United States.[45][46] Observers believe that the abuses of the study may have contributed to the reluctance of many poor black people to seek routine preventive care.[46][47] A 1999 survey showed that 80% of African-American men wrongly believed the men in the study had been injected with syphilis.[15] While the final report of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee noted that the study had contributed to fears among the African American community of abuse and exploitation by government officials and medical professionals,[38] medical mistreatment of African Americans and resulting mistrust predates the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.[48] Vanessa Northington Gamble, who had chaired the committee, addressed this in a seminal article published in 1997[49] after President Clinton's apology. She argued that while the Tuskegee Syphilis Study contributed to African Americans' continuing mistrust of the biomedical community, the study was not the most important reason. She called attention to a broader historical and social context that had already negatively influenced community attitudes, including countless prior medical injustices before the study's start in 1932. These dated back to the antebellum period, when slaves had been used for unethical and harmful experiments including tests of endurance against and remedies for heatstroke and experimental gynecological surgeries without anesthesia. African Americans' graves were robbed to provide cadavers for dissection, a practice that continued, along with other abuses, after the American Civil War.[48] A 2016 paper by Marcella Alsan and Marianne Wanamaker found "that the historical disclosure of the [Tuskegee experiment] in 1972 is correlated with increases in medical mistrust and mortality and decreases in both outpatient and inpatient physician interactions for older black men. Our estimates imply life expectancy at age 45 for black men fell by up to 1.4 years in response to the disclosure, accounting for approximately 35% of the 1980 life expectancy gap between black and white men."[46] Studies that have investigated the willingness of black Americans to participate in medical studies have not drawn consistent conclusions related to the willingness and participation in studies by racial minorities.[50] The Tuskegee Legacy Project Questionnaire found that, even though black Americans are four times more likely to know about the syphilis trials than are whites, they are two to three times more willing to participate in biomedical studies.[51][4] Some of the factors that continue to limit the credibility of these few studies is how awareness differs significantly across studies. For instance, it appears that the rates of awareness differ as a function of the method of assessment. Study participants who reported awareness of the Tuskegee syphilis study are often misinformed about the results and issues, and awareness of the study is not reliably associated with unwillingness to participate in scientific research.[15][51][52][53] Distrust of the government, in part formed through the study, contributed to persistent rumors during the 1980s in the black community that the government was responsible for the HIV/AIDS crisis by having deliberately introduced the virus to the black community as some kind of experiment.[54] In February 1992 on ABC's Prime Time Live, journalist Jay Schadler interviewed Dr. Sidney Olansky, Public Health Services director of the study from 1950 to 1957. When asked about the lies that were told to the study subjects, Olansky said, "The fact that they were illiterate was helpful, too, because they couldn't read the newspapers. If they were not, as things moved on they might have been reading newspapers and seen what was going on."[33] On January 3, 2019, a United States federal judge stated that Johns Hopkins University, Bristol-Myers Squibb and the Rockefeller Foundation must face a $1 billion lawsuit for their roles in a similar experiment affecting Guatemalans.[55] In 2001, a court compared the Kennedy Krieger Institute's Lead-Based Paint Abatement and Repair and Maintenance Study to the Tuskegee experiments.[56] Some African Americans have been hesitant to get vaccinated against COVID-19 due to the Tuskegee experiments.[57] In September 2021, the right-wing group America's Frontline Doctors, which has promoted COVID-19 conspiracy theories and misinformation, filed a lawsuit against New York City, claiming that its vaccine passport health orders were inherently discriminatory against African Americans due to the "historical context".[58] |

遺産 梅毒の早期治療を提唱した大恐慌時代の米国のポスター。治療は可能であったが、この研究の参加者は治療を受けなかった。 科学的失敗 人種差の研究はさておき、この研究の研究者たちが達成したかった主な目的の一つは、梅毒の治療がどの程度必要で、病気の進行のどの時点で治療すべきかを明 らかにすることであった。このため、この研究では後期潜伏梅毒患者の観察が重視された[2][4]。しかし、臨床医がこの研究を科学のために必要なものと して正当化しようとしたにもかかわらず、研究自体は科学的に実行可能な方法で行われたわけではなかった。参加者は水銀擦過、ネオアルスフェナミン、プロチ オダイド、サルバルサン、ビスマスの注射による治療を受けていたため、これらの治療が最小限の効果であったとしても、梅毒が未治療であった被験者を追跡す ることはなかった[2][4]。 PHSのオースティン・V・ダイベルトは、このように研究の主目的が損なわれている以上、結果は無意味であり、統計的に操作することは不可能であると認識 していた。Deibertによれば、ペニシリンが利用可能になる前に利用可能であった毒性治療でさえ、「梅毒性心血管病の後期を予防しないまでも、大幅に 低下させることができた。[その有効性にもかかわらず、これらの治療法が参加者に処方されることはなかった。 人種主義 さらに詳しい情報 米国における医療人種主義 1932年にタスキギーで行われた米国公衆衛生局の梅毒研究の背景にあった考え方は、参加者の100%が健康情報へのアクセスが非常に限られている貧しい 農村部のアフリカ系アメリカ人男性であったというもので、当時の米国の人種意識を反映している。この研究を主導した臨床医は、アフリカ系アメリカ人は人種 的に特に性病にかかりやすいと想定し、この研究の参加者は医療を受けることに関心がないと想定していた[2][44]。 タリアフェロ・クラークは、「黒人集団の知能がかなり低いこと、経済状況が不況であること、乱れた性関係が一般的であることが、梅毒の蔓延だけでなく、治 療に対する一般的な無関心にも寄与している」と述べている[44]。実際には、アラバマ州メーコン郡の農村の黒人集団の間では、通常は緊急の場合にしか予 約されていない医療処置の約束が、被験者の研究への協力を確保するものであった[2]。 社会的信頼 タスキギーにおける米国公衆衛生局の梅毒研究のもとでの虐待の暴露は、米国における公衆衛生の取り組みに対する黒人コミュニティの信頼を著しく損ねたと考 えられている[45][46]。観察者たちは、この研究の虐待が、多くの貧しい黒人が定期的な予防医療を受けようとしないことの一因になったかもしれない と考えている[46][47]。 1999年の調査では、アフリカ系アメリカ人男性の80%が、この研究に参加した男性が梅毒を注射されたと誤解していることが示された[15]。 タスキーギ梅毒研究遺産委員会の最終報告書は、この研究がアフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティの政府高官や医療専門家による虐待や搾取に対する恐怖を助長し たことを指摘しているが[38]、アフリカ系アメリカ人に対する医療上の不当な扱いとその結果としての不信感は、タスキーギ梅毒研究よりも以前からあった [48]。 委員会の委員長であったヴァネッサ・ノーティントン・ギャンブルは、クリントン大統領の謝罪後の1997年に発表された重要な論文[49]でこのことを取 り上げている。彼女は、タスキーギ梅毒研究がアフリカ系アメリカ人の生物医学界に対する継続的な不信の一因ではあるが、研究が最も重要な理由ではないと主 張した。彼女は、1932年に研究が開始される以前から、数え切れないほどの医療上の不公正があったことを含め、すでに地域社会の態度に悪影響を及ぼして いた、より広範な歴史的・社会的背景に注意を喚起した。それらは前世紀にさかのぼり、熱射病に対する耐久テストや治療法、麻酔なしの実験的婦人科手術な ど、非倫理的で有害な実験に奴隷が使われていた。アフリカ系アメリカ人の墓は解剖用の死体を提供するために強奪され、この慣習は他の虐待とともにアメリカ 南北戦争後も続いた[48]。 Marcella AlsanとMarianne Wanamakerによる2016年の論文では、「1972年に[タスキーギ実験]が歴史的に公表されたことは、高齢の黒人男性における医療不信と死亡率 の増加、および外来患者および入院患者の医師との交流の減少と相関している。われわれの推計によれば、黒人男性の45歳時点での平均余命は、情報公開に反 応して最大で1.4年低下し、1980年の黒人男性と白人男性の平均余命差の約35%を占めた」[46]。 アメリカ黒人の医学研究への参加意欲を調査した研究では、人種的マイノリティの研究への意欲と参加に関連する一貫した結論は得られていない[50]。タス キギー・レガシー・プロジェクトの質問票では、アメリカ黒人は白人に比べて梅毒の臨床試験について知っている可能性が4倍高いにもかかわらず、生物医学研 究への参加意欲は2~3倍高いという結果が出ている[51][4]。これらの数少ない研究の信頼性を制限し続けている要因のいくつかは、認知度が研究に よって大きく異なることである。例えば、認知率は評価方法によって異なるようである。タスキーギ梅毒研究の認知を報告した研究参加者は、その結果や問題点 について誤った情報を得ていることが多く、研究の認知は科学研究への不本意な参加とは確実に関連していない[15][51][52][53]。 政府に対する不信感は、この研究を通じて形成されたこともあり、1980年代に黒人コミュニティでは、政府が何らかの実験として意図的に黒人コミュニティ にウイルスを持ち込んだことがHIV/AIDS危機の原因であるという噂が根強く流れた[54]。 1992年2月、ABCの『Prime Time Live』で、ジャーナリストのジェイ・シャドラーは、1950年から1957年までこの研究の公衆衛生局長であったシドニー・オランスキー博士にインタ ビューした。被験者についた嘘について聞かれたオランスキーは、「彼らが新聞を読めなかったので、文盲だったことも役に立った。もしそうでなかったら、事 態が進むにつれて、彼らは新聞を読み、何が起こっているのか見ていたかもしれない」[33]。 2019年1月3日、米国の連邦判事は、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学、ブリストル・マイヤーズ・スクイブ、ロックフェラー財団は、グアテマラ人に影響を与え た同様の実験における役割について、10億ドルの訴訟に直面しなければならないと述べた[55]。 2001年、裁判所は、ケネディ・クリーガー研究所の鉛ベースの塗料の減量と補修・メンテナンス研究をタスキーギ実験と比較した[56]。 アフリカ系アメリカ人のなかには、タスキギー実験のためにCOVID-19の予防接種を受けることをためらう者もいる[57]。 2021年9月、COVID-19の陰謀論や誤った情報を宣伝してきた右翼団体America's Frontline Doctorsは、ニューヨーク市に対して、そのワクチン・パスポートの保健命令は「歴史的背景」によってアフリカ系アメリカ人に対して本質的に差別的で あるとして訴訟を起こした[58]。 |

| Ethical implications The U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee highlighted issues in race and science.[59] The aftershocks of this study, and other human experiments in the United States, led to the establishment of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research and the National Research Act.[16] The latter requires the establishment of institutional review boards (IRBs) at institutions receiving federal support (such as grants, cooperative agreements, or contracts). Foreign consent procedures can be substituted which offer similar protections and must be submitted to the Federal Register unless a statute or Executive Order requires otherwise.[16] In the period following World War II, the revelation of the Holocaust and related Nazi medical abuses brought about changes in international law. Western allies formulated the Nuremberg Code to protect the rights of research subjects. In 1964, the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki specified that experiments involving human beings needed the "informed consent" of participants.[60] In spite of these events, the protocols of the study were not re-evaluated according to the new standards, even though whether or not the study should continue was re-evaluated several times (including in 1969 by the CDC). U.S. government officials and medical professionals kept silent and the study did not end until 1972, nearly three decades after the Nuremberg trials.[11] Writer James Jones said that the physicians were fixated on African-American sexuality. They believed that African-Americans willingly had sexual relations with infected persons (although no one had been told his diagnosis).[61] Due to the lack of information, the participants were manipulated into continuing the study without full knowledge of their role or their choices.[62] Since the late 20th century, IRBs established in association with clinical studies requirements that all involved in the study be willing and voluntary participants.[63] The Tuskegee University Legacy Museum has on display a check issued by the United States government on behalf of Dan Carlis to Lloyd Clements, Jr., a descendant of one of the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee participants.[64] Lloyd Clements, Jr.'s great-grandfather Dan Carlis and two of his uncles, Ludie Clements and Sylvester Carlis, were in the study. Original legal paperwork for Sylvester Carlis related to the study is on display at the museum as well. Lloyd Clements, Jr. has worked with noted historian Susan Reverby concerning his family's involvement with the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee.[64] |

倫理的意味合い タスキーギにおける米国公衆衛生局の梅毒研究は、人種と科学における問題を浮き彫りにした[59]。この研究の余波、および米国における他の人体実験の余 波は、生物医学的および行動学的研究の被験者保護のための国家委員会および国家研究法[16]の設立につながった。後者は、連邦政府の支援(助成金、協力 協定、契約など)を受けている機関に、機関内審査委員会(IRB)の設置を義務付けている。法令または行政命令で別段の定めがない限り、同様の保護を提供 し、連邦官報に提出しなければならない外国の同意手続きで代用することができる[16]。 第二次世界大戦後、ホロコーストとそれに関連するナチスの医療虐待が明らかになり、国際法に変化がもたらされた。西側同盟国は、研究被験者の権利を保護す るためにニュルンベルク綱領を策定した。1964年、世界医師会のヘルシンキ宣言は、人間を対象とする実験には参加者の「インフォームド・コンセント」が 必要であると規定した[60]。このような出来事にもかかわらず、研究を継続すべきかどうかが何度か再評価されたにもかかわらず(CDCによる1969年 を含む)、研究のプロトコルは新しい基準に従って再評価されることはなかった。アメリカ政府高官と医療関係者は沈黙を守り、研究はニュルンベルク裁判から 30年近く経った1972年まで終了しなかった[11]。 作家のジェームズ・ジョーンズは、医師たちはアフリカ系アメリカ人のセクシュアリティに固執していたと述べている。彼らは、アフリカ系アメリカ人は進んで 感染者と性的関係を持ったと信じていた(誰も自分の診断を聞かされていなかったが)[61]。 情報が不足していたため、参加者は自分の役割や選択について十分に知ることなく、研究を続けるように操られていた[62]。 20世紀後半以降、臨床研究に関連して設立されたIRBは、研究に関与するすべての人が自発的かつ自発的な参加者であることを要求している[63]。 タスキーギ大学レガシー博物館には、米国公衆衛生局のタスキーギ梅毒研究参加者の一人の子孫であるロイド・クレメンツ・ジュニアに、ダン・カーリスに代 わって米国政府が発行した小切手が展示されている[64]。シルヴェスター・カーリスの書斎に関する法的書類の原本も博物館に展示されている。ロイド・ク レメンツ・ジュニアは、タスキギーにおけるアメリカ公衆衛生局の梅毒研究と彼の家族の関わりについて、著名な歴史家スーザン・リヴァービーと協力している [64]。 |

| Society and culture Comics Truth: Red, White, and Black (published January–July 2003) is a seven-issue Marvel comic book series inspired by the Tuskegee trials. Written as a prequel to the Captain America series, Truth: Red, White, and Black explores the exploitation of certain races for scientific research, as in the Tuskegee syphilis trials.[51] Theater David Feldshuh's stage play Miss Evers' Boys (1992), based on the history of the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, was a runner-up for the 1992 Pulitzer Prize in drama.[65] Music The lyrics of Gil Scott-Heron's 33-second song, "Tuskeegee #626", featured on the Bridges (1977) LP, details and condemns the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. Frank Zappa's 1984 album Thing Fish was heavily inspired by the events of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Avant-garde metal band Zeal & Ardor's song "Tuskegee", from the 2020 EP Wake of a Nation, is about the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Jazz musician Don Byron's 1992 album Tuskegee Experiments was inspired by the study. Atlanta rapper JID juxtaposes his life to the Tuskegee Experiment in his 2021 song "Skegee".[66] Television The 1992 Secret History series documentary "Bad Blood" is about the experiment.[67] Miss Evers' Boys (1997), a TV adaptation of David Feldshuh's eponymous 1992 stage play, was nominated for 11 Emmy Awards[68] and won in four categories.[69] Video production Medical Racism: The New Apartheid (2021) exploits the Tuskegee trials to promote COVID-19 misinformation.[70][71][72][73] |

社会と文化 コミック 真実 赤・白・黒』(2003年1月~7月刊行)は、タスキギー裁判に着想を得たマーベルコミックの7号シリーズである。キャプテン・アメリカ』シリーズの前日 譚として書かれた: 赤・白・黒」は、タスキーギ梅毒裁判のように、科学研究のために特定の人種が搾取されることを探求している[51]。 演劇 デヴィッド・フェルドシューの舞台劇『Miss Evers' Boys』(1992年)は、タスキーギにおけるアメリカ公衆衛生局の梅毒研究の歴史に基づいており、1992年のピューリッツァー賞演劇部門の次点となった[65]。 音楽 ギル・スコット・ヘロンの33秒の曲「Tuskeegee #626」の歌詞は、LP『Bridges』(1977年)に収録され、タスキーギでのアメリカ公衆衛生局梅毒研究の詳細と非難を歌っている。 フランク・ザッパの1984年のアルバム『Thing Fish』は、タスキギー梅毒研究の出来事に大きくインスパイアされている。 アヴァンギャルド・メタル・バンド、Zeal & Ardorの2020年のEP『Wake of a Nation』収録曲「Tuskegee」は、タスキーギ梅毒研究についての曲である。 ジャズ・ミュージシャンのドン・バイロンが1992年に発表したアルバム『Tuskegee Experiments』は、この研究にインスパイアされたものだ。 アトランタのラッパーJIDは、2021年の曲「Skegee」で自身の人生をタスキーギ実験と重ね合わせている[66]。 テレビ 1992年の『シークレット・ヒストリー』シリーズのドキュメンタリー『バッド・ブラッド』は、この実験を題材にしている[67]。 デヴィッド・フェルドシューの1992年の同名の舞台劇をテレビ化した『Miss Evers' Boys』(1997年)は、エミー賞11部門にノミネートされ[68]、4部門で受賞した[69]。 ビデオ制作 医療人種主義: 新しいアパルトヘイト』(2021年)は、COVID-19の誤った情報を宣伝するためにタスキギー裁判を悪用している[70][71][72][73]。 |

| Declaration of Geneva Eugenics in the United States Kennedy Krieger Institute's Lead-Based Paint Abatement and Repair and Maintenance Study Guatemala syphilis experiments Human experimentation in North Korea Human subject research International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Bill Jenkins (epidemiologist) Medical Apartheid Operation Whitecoat Project 4.1 Race and health in the United States Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church Unethical human experimentation Unit 731 World Medical Association |

ジュネーブ宣言 アメリカにおける優生学 ケネディクリーガー研究所の鉛ベースペイントの除去および補修・メンテナンス研究 グアテマラ梅毒実験(→グアテマラ人への梅毒感染実験) 北朝鮮における人体実験 人体実験 ヒト用医薬品の登録に関する技術的要件の調和に関する国際会議 ビル・ジェンキンス(疫学者) 医療アパルトヘイト ホワイトコート作戦 プロジェクト4.1 米国における人種と健康 シャイロ宣教バプテスト教会 非倫理的な人体実験 ユニット731 世界医師会 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tuskegee_Syphilis_Study |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆