ユニヴァーサル・ヘルス・ケア

Universal health care

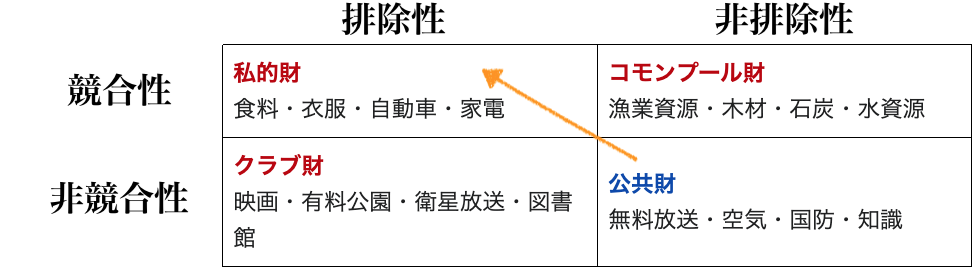

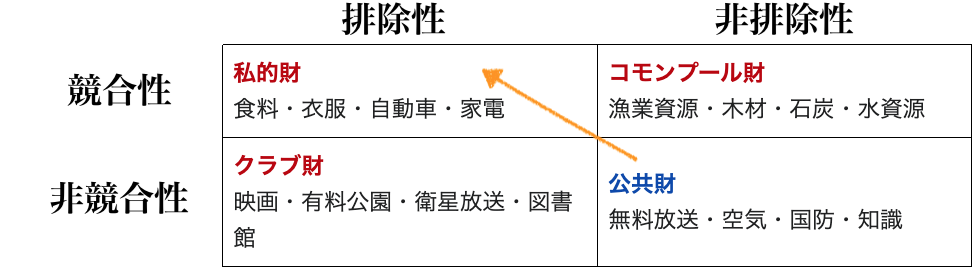

私的財・コモンプール財・クラブ財・公共財「ヘルス・ガバナンス」より

☆ ユニバーサル・ヘルスケア(Universal health care; ユニバーサル・ヘルス・カバレッジ、ユニバーサル・カバレッジ、ユニバーサル・ケアとも呼ばれる)とは、特定の国や地域のすべての住民が医療を受けられる ことが保証された医療制度のことである。一般に、すべての住民、または自力で医療サービスを受ける余裕のない住民にのみ、医療サービスまたはそれを受ける 手段を提供することを中心に組織され、健康アウトカムを改善することを最終目標としている。 国民皆保険は、すべての症例やすべての人に保険が適用されることを意味するのではなく、すべての人が経済的な困難を伴うことなく、必要なときに必要な場所 で医療を受けられることを意味する。国民皆保険制度には、政府が資金を拠出するものもあれば、国民全員が民間の医療保険に加入することを要件とするものも ある。世界保健機関(WHO)は、国民が経済的な苦境に陥ることなく医療サービスを受けられる状況としている。 WHOのマーガレット・チャン事務局長(当時)は、ユニバーサル・ヘルス・カバレッジを「公衆衛生が提供できる唯一で最も強力な概念」であると述べてい る。 持続可能な開発目標の一環として、国連加盟国は2030年までに世界的なユニバーサル・ヘルス・カバレッジを目指すことに合意している。したがって、 SDGsの目標にユニバーサル・ヘルス・カバレッジ(UHC)が含まれていることは、WHOが繰り返し支持していることと関連している可能性がある。

Universal health care by country (2010)

| Universal health care (also called

universal health coverage, universal coverage, or universal care) is a

health care system in which all residents of a particular country or

region are assured access to health care. It is generally organized

around providing either all residents or only those who cannot afford

on their own, with either health services or the means to acquire them,

with the end goal of improving health outcomes.[1] Universal healthcare does not imply coverage for all cases and for all people – only that all people have access to healthcare when and where needed without financial hardship. Some universal healthcare systems are government-funded, while others are based on a requirement that all citizens purchase private health insurance. Universal healthcare can be determined by three critical dimensions: who is covered, what services are covered, and how much of the cost is covered.[1] It is described by the World Health Organization as a situation where citizens can access health services without incurring financial hardship.[2] Then-Director General of the WHO Margaret Chan described universal health coverage as the "single most powerful concept that public health has to offer" since it unifies "services and delivers them in a comprehensive and integrated way".[3] One of the goals with universal healthcare is to create a system of protection which provides equality of opportunity for people to enjoy the highest possible level of health.[4] Critics say that universal healthcare leads to longer wait times and worse quality healthcare.[5] As part of Sustainable Development Goals, United Nations member states have agreed to work toward worldwide universal health coverage by 2030.[6][better source needed] Therefore, the inclusion of the universal health coverage (UHC) within the SDGs targets can be related to the reiterated endorsements operated by the WHO.[7]  |

ユニバーサル・ヘルスケア(ユニバーサル・ヘルス・カバレッジ、ユニ

バーサル・カバレッジ、ユニバーサル・ケアとも呼ばれる)とは、特定の国や地域のすべての住民が医療を受けられることが保証された医療制度のことである。

一般に、すべての住民、または自力で医療サービスを受ける余裕のない住民にのみ、医療サービスまたはそれを受ける手段を提供することを中心に組織され、健

康アウトカムを改善することを最終目標としている[1]。 国民皆保険は、すべての症例やすべての人に保険が適用されることを意味するのではなく、すべての人が経済的な困難を伴うことなく、必要なときに必要な場所 で医療を受けられることを意味する。国民皆保険制度には、政府が資金を拠出するものもあれば、国民全員が民間の医療保険に加入することを要件とするものも ある。世界保健機関(WHO)は、国民が経済的な苦境に陥ることなく医療サービスを受けられる状況としている[1]。 [2] WHOのマーガレット・チャン事務局長(当時)は、ユニバーサル・ヘルス・カバレッジを「公衆衛生が提供できる唯一で最も強力な概念」であると述べてい る。 持続可能な開発目標の一環として、国連加盟国は2030年までに世界的なユニバーサル・ヘルス・カバレッジを目指すことに合意している[6][要出典]。 したがって、SDGsの目標にユニバーサル・ヘルス・カバレッジ(UHC)が含まれていることは、WHOが繰り返し支持していることと関連している可能性 がある[7]。  |

| The

first move towards a national health insurance system was launched in

Germany in 1883, with the Sickness Insurance Law. Industrial employers

were mandated to provide injury and illness insurance for their

low-wage workers, and the system was funded and administered by

employees and employers through "sick funds", which were drawn from

deductions in workers' wages and from employers' contributions. This

social health insurance model, named the Bismarck Model after Prussian

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, was the first form of universal care in

modern times.[10] Other countries soon began to follow suit. In the

United Kingdom, the National Insurance Act 1911 provided coverage for

primary care (but not specialist or hospital care) for wage earners,

covering about one-third of the population. The Russian Empire

established a similar system in 1912, and other industrialized

countries began following suit. By the 1930s, similar systems existed

in virtually all of Western and Central Europe. Japan introduced an

employee health insurance law in 1927, expanding further upon it in

1935 and 1940. Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, a fully public

and centralized health care system was established in Soviet Russia in

1920.[11][12] However, it was not a truly universal system at that

point, as rural residents were not covered. In New Zealand, a universal health care system was created in a series of steps, from 1938 to 1941.[13][14] In Australia, the state of Queensland introduced a free public hospital system in 1946. Following World War II, universal health care systems began to be set up around the world. On July 5, 1948, the United Kingdom launched its universal National Health Service. Universal health care was next introduced in the Nordic countries of Sweden (1955),[15] Iceland (1956),[16] Norway (1956),[17] Denmark (1961)[18] and Finland (1964).[19] Universal health insurance was introduced in Japan in 1961, and in Canada through stages, starting with the province of Saskatchewan in 1962, followed by the rest of Canada from 1968 to 1972.[13][20] A public healthcare system was introduced in Egypt following the Egyptian revolution of 1952. Centralized public healthcare systems were set up in the Eastern bloc countries. The Soviet Union extended universal health care to its rural residents in 1969.[13][21] Kuwait and Bahrain introduced their universal healthcare systems in 1950 and 1957 respectively (prior to independence).[22] Italy introduced its Servizio Sanitario Nazionale (National Health Service) in 1978. Universal health insurance was implemented in Australia in 1975 with the Medibank, which led to universal coverage under the current Medicare system from 1984.[citation needed] From the 1970s to the 2000s, Western European countries began introducing universal coverage, most of them building upon previous health insurance programs to cover the whole population. For example, France built upon its 1928 national health insurance system, with subsequent legislation covering a larger and larger percentage of the population, until the remaining 1% of the population that was uninsured received coverage in 2000.[23][24] Single payer healthcare systems were introduced in Finland (1972), Portugal (1979), Cyprus (1980), Spain (1986) and Iceland (1990). Switzerland introduced a universal healthcare system based on an insurance mandate in 1994.[25][22] In addition, universal health coverage was introduced in some Asian countries, including South Korea (1989), Taiwan (1995), Singapore (1993), Israel (1995) and Thailand (2001). Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia retained and reformed its universal health care system,[26] as did other now-independent former Soviet republics and Eastern bloc countries. Beyond the 1990s, many countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa and the Asia-Pacific region, including developing countries, took steps to bring their populations under universal health coverage, including China which has the largest universal health care system in the world[27] and Brazil's SUS[28] which improved coverage up to 80% of the population.[29] India introduced a tax-payer funded decentralised universal healthcare system that helped reduce mortality rates drastically and improved healthcare infrastructure across the country dramatically.[30] A 2012 study examined progress being made by these countries, focusing on nine in particular: Ghana, Rwanda, Nigeria, Mali, Kenya, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam.[31][32] Currently, most industrialized countries and many developing countries operate some form of publicly funded health care with universal coverage as the goal. According to the National Academy of Medicine and others, the United States is the only wealthy, industrialized nation that does not provide universal health care. The only forms of government-provided healthcare available are Medicare (for elderly patients as well as people with disabilities), Medicaid (for low-income people),[33][34] the Military Health System (active, reserve, and retired military personnel and dependants), and the Indian Health Service (members of federally recognized Native American tribes). |

国

民健康保険制度に向けた最初の動きは、1883年にドイツで始まった「疾病保険法」である。産業雇用主は低賃金労働者に傷害・疾病保険を提供することが義

務づけられ、この制度は労働者の賃金控除と雇用主の拠出金で賄われる「疾病基金」を通じて、従業員と雇用主によって積立・運営された。この社会的健康保険

モデルは、プロイセンのオットー・フォン・ビスマルク首相にちなんでビスマルク・モデルと名付けられ、近代初の国民皆保険制度となった[10]。イギリス

では、1911年に国民保険法が制定され、賃金労働者のプライマリーケア(専門医や病院でのケアは対象外)に保険が適用され、人口の約3分の1がカバーさ

れた。ロシア帝国も1912年に同様の制度を設立し、他の先進国も追随し始めた。1930年代までには、西欧と中欧のほぼ全土に同様の制度が存在するよう

になった。日本では1927年に被用者保険法が導入され、1935年と1940年にはさらに拡大された。1917年のロシア革命後、ソビエトロシアでは

1920年に完全に公的で中央集権的な医療制度が確立された[11][12]が、農村部の住民は対象外であったため、その時点では真の国民皆保険制度では

なかった。 ニュージーランドでは、国民皆保険制度が1938年から1941年までの一連のステップで創設された[13][14]。オーストラリアでは、クイーンズランド州が1946年に無料の公立病院制度を導入した。 第二次世界大戦後、世界各地で国民皆保険制度が整備され始めた。1948年7月5日、イギリスは国民皆保険制度を開始した。次に、北欧のスウェーデン (1955年)[15]、アイスランド(1956年)[16]、ノルウェー(1956年)[17]、デンマーク(1961年)[18]、フィンランド (1964年)で国民皆保険制度が導入された[19]。日本では1961年に国民皆保険制度が導入され、カナダでは1962年にサスカチュワン州を皮切り に、1968年から1972年までカナダ全土で段階的に導入された[13][20]。1952年のエジプト革命後、エジプトで公的医療制度が導入された。 東欧圏諸国では、中央集権的な公的医療制度が設立された。クウェートとバーレーンはそれぞれ1950年と1957年(独立前)に国民皆保険制度を導入した [22]。イタリアは1978年に国民保健サービス(Servizio Sanitario Nazionale)を導入した。オーストラリアでは、1975年にメディバンクによって国民皆保険が導入され、1984年からは現在のメディケア制度に よる国民皆保険につながった[要出典]。 1970年代から2000年代にかけて、西欧諸国は国民皆保険を導入し始めたが、そのほとんどは、それまでの健康保険制度を基礎にして、全人口をカバーす るようにしたものであった。例えば、フランスは、1928年の国民健康保険制度を基礎として、その後の法律によって、より多くの人口の割合をカバーするよ うになり、2000年には、無保険であった人口の残りの1%が保険適用を受けるまでになった[23][24]。フィンランド(1972年)、ポルトガル (1979年)、キプロス(1980年)、スペイン(1986年)、アイスランド(1990年)では、単一支払い医療制度が導入された。スイスは1994 年に保険義務に基づく国民皆保険制度を導入した[25][22]。さらに、韓国(1989年)、台湾(1995年)、シンガポール(1993年)、イスラ エル(1995年)、タイ(2001年)など、アジアのいくつかの国では国民皆保険制度が導入された。 ソビエト連邦崩壊後、ロシアは国民皆保険制度を維持・改革し[26]、他の現在独立した旧ソビエト共和国や東欧圏諸国も同様であった。 1990年代以降、発展途上国を含むラテンアメリカ、カリブ海諸国、アフリカ、アジア太平洋地域の多くの国々が、世界最大の国民皆保険制度を有する中国 [27]や、国民の80%まで保険適用率を向上させたブラジルのSUS[28]など、国民を国民皆保険制度の下に置くための措置を講じた[29]: ガーナ、ルワンダ、ナイジェリア、マリ、ケニア、インドネシア、フィリピン、ベトナムの9カ国である[31][32]。 現在、ほとんどの先進国と多くの発展途上国は、国民皆保険を目標に、何らかの形で公的資金による医療を運営している。全米医学アカデミーなどによると、米 国は裕福な先進国で唯一、国民皆保険を提供していない。政府が提供する医療は、メディケア(高齢者と障害者向け)、メディケイド(低所得者向け)[33] [34]、軍保健制度(現役、予備軍、退役軍人とその扶養家族)、インディアン保健サービス(連邦公認のアメリカ先住民部族のメンバー)だけである。 |

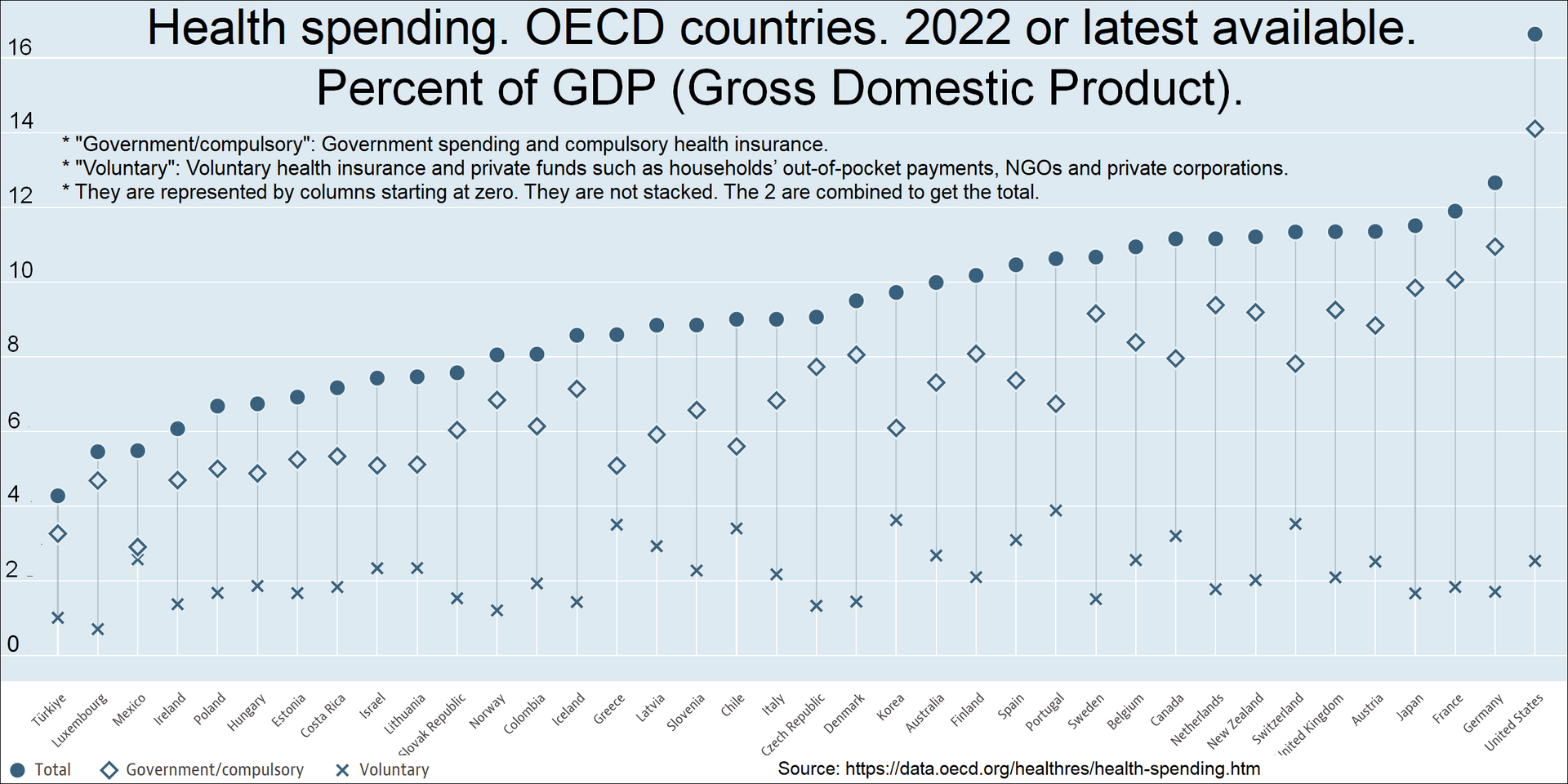

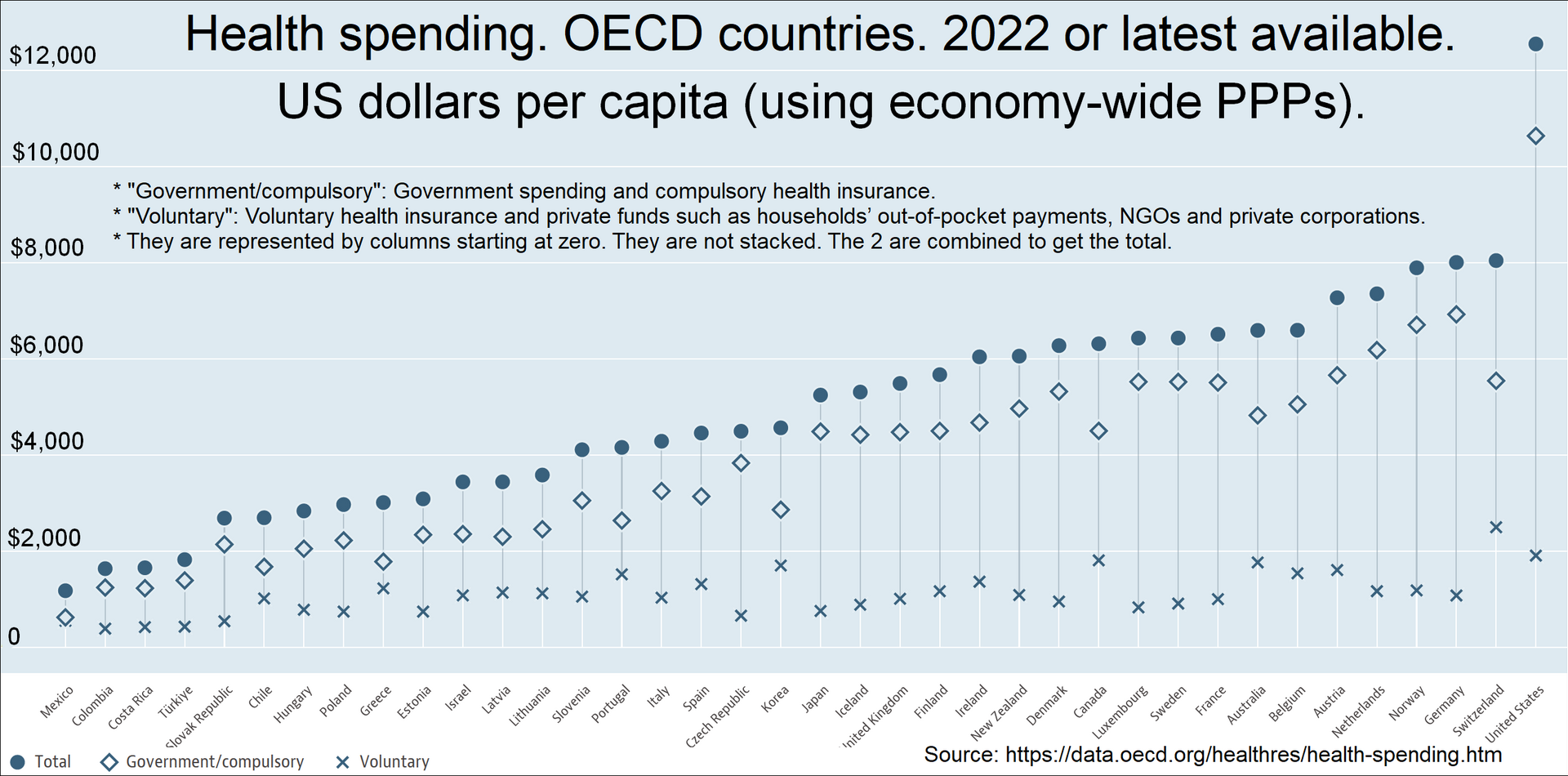

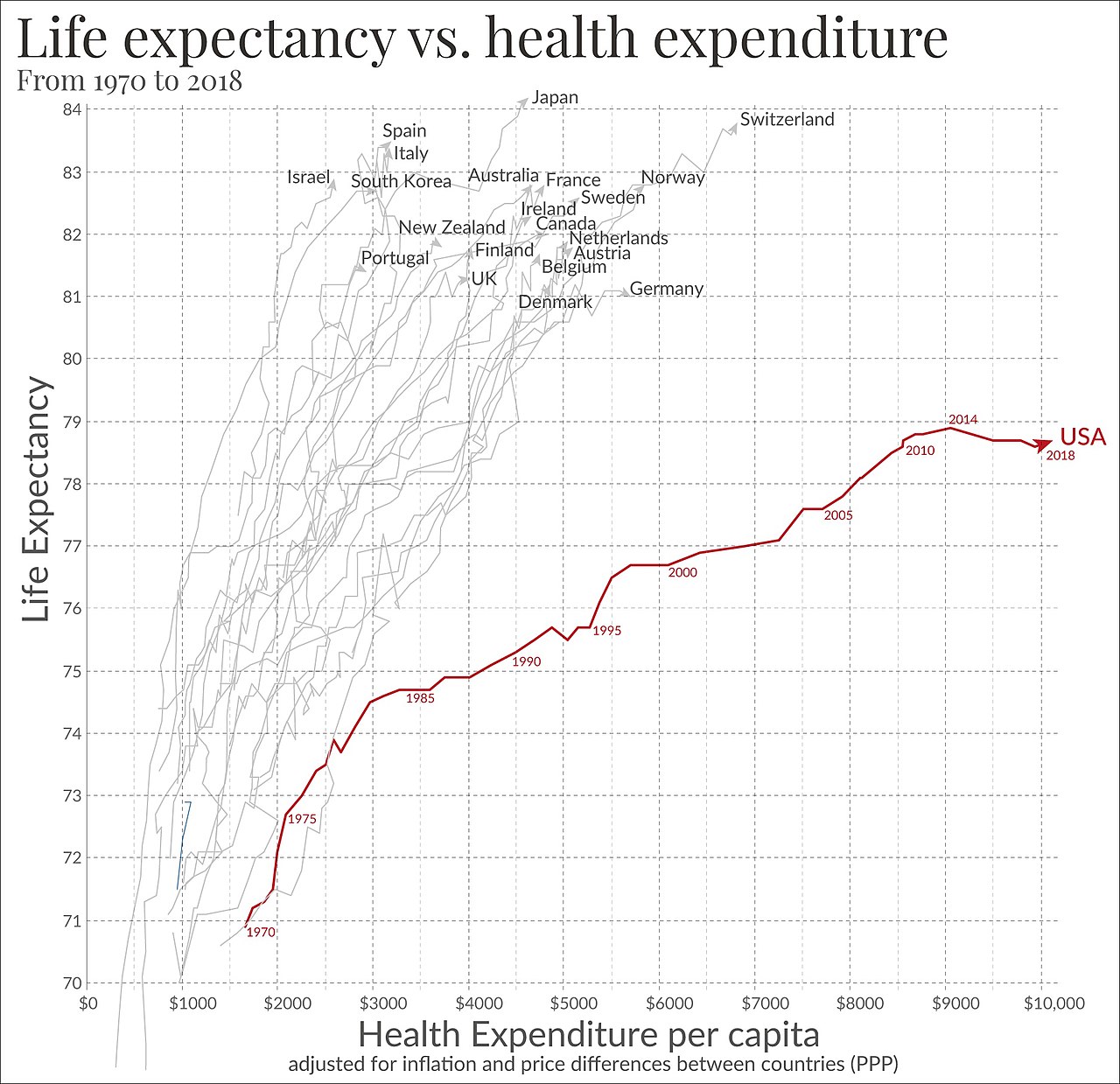

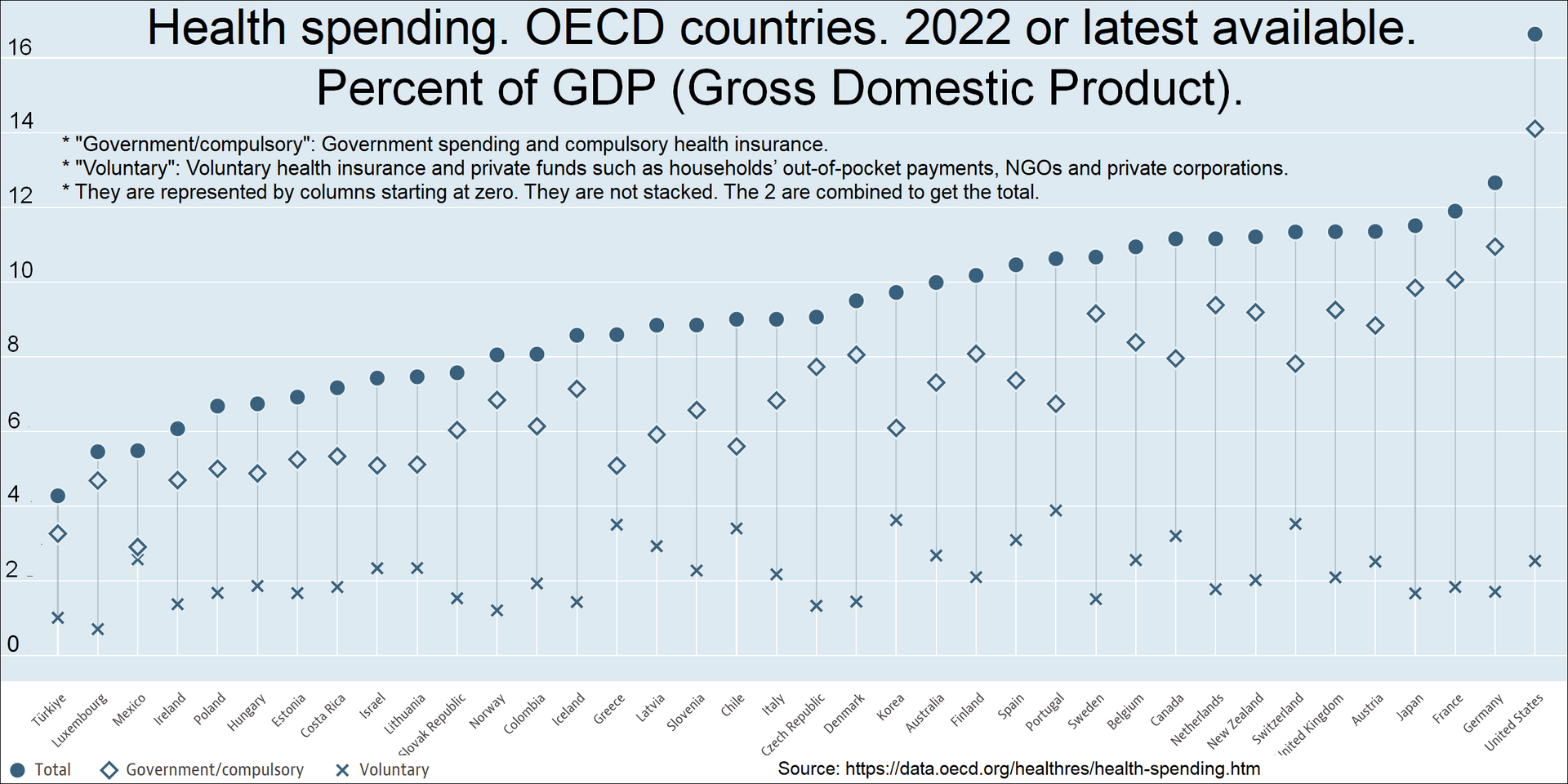

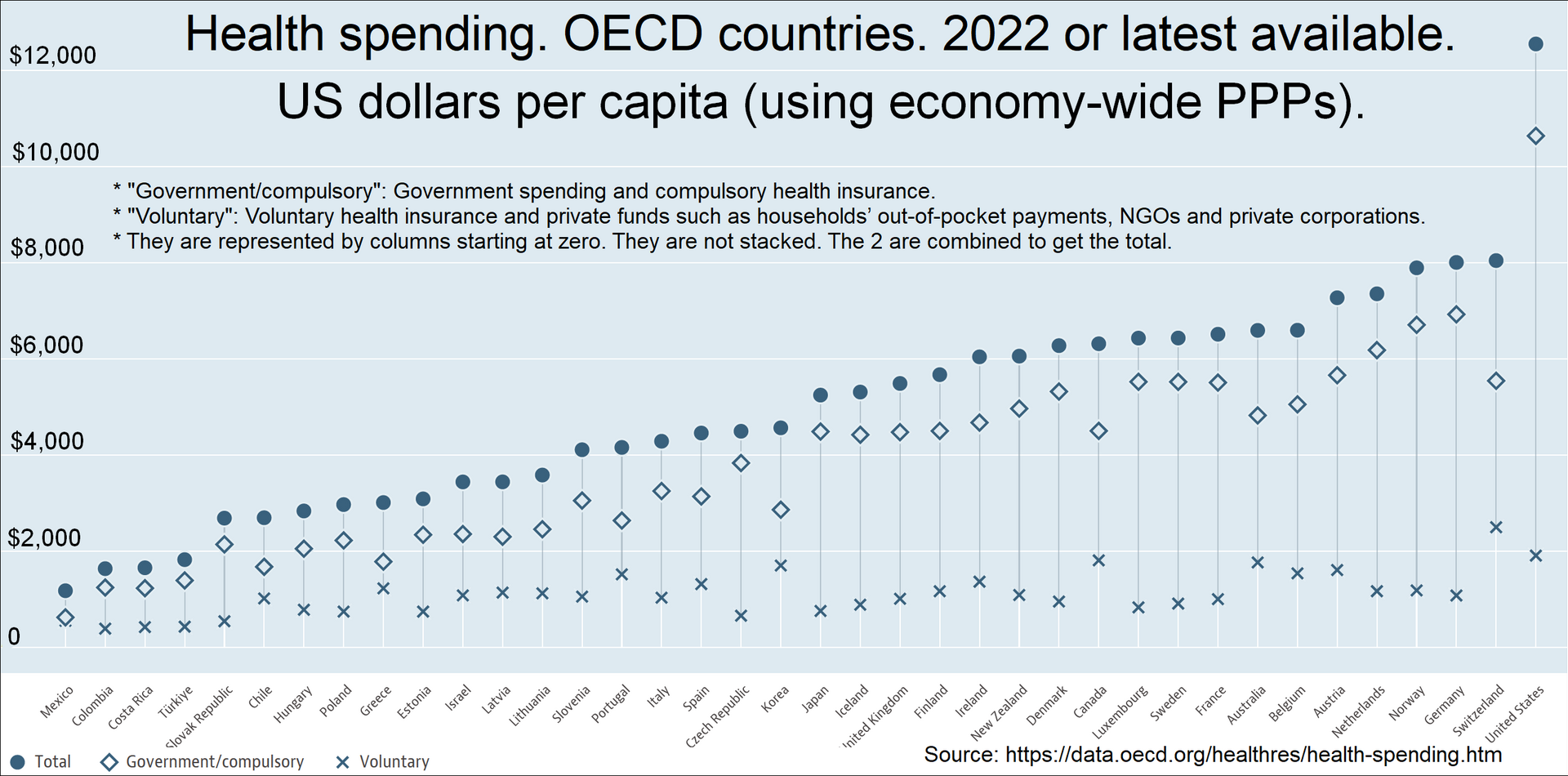

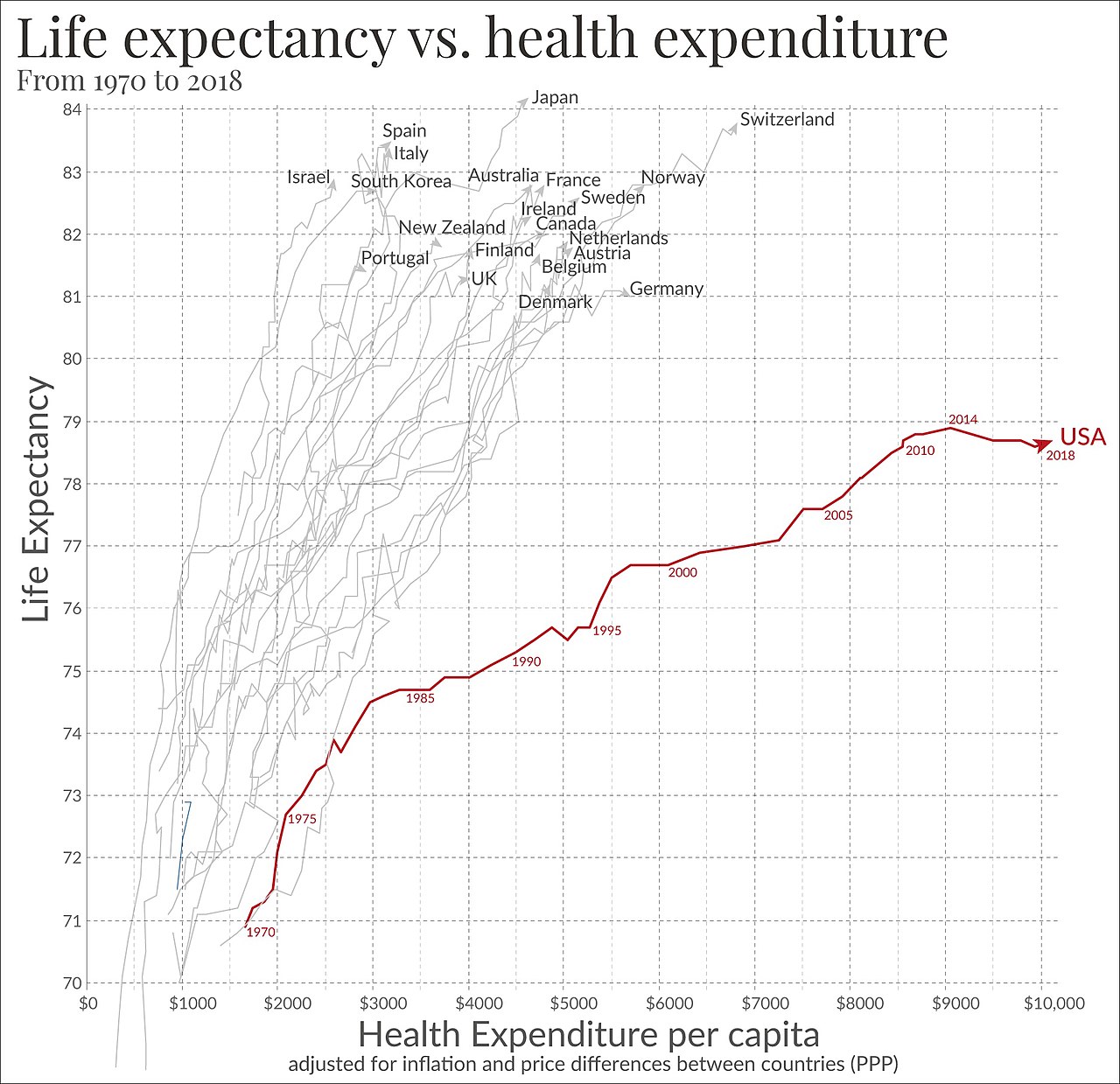

| Funding models See also: Health care economics  Health spending by country. Percent of GDP (Gross domestic product). For example: 11.2% for Canada in 2022. 16.6% for the United States in 2022.[35]  Total healthcare cost per person. Public and private spending. US dollars PPP. For example: $6,319 for Canada in 2022. $12,555 for the US in 2022.[35]  Life expectancy vs healthcare spending of rich OECD countries. US average of $10,447 in 2018.[36] Universal health care in most countries has been achieved by a mixed model of funding. General taxation revenue is the primary source of funding, but in many countries it is supplemented by specific charge (which may be charged to the individual or an employer) or with the option of private payments (by direct or optional insurance) for services beyond those covered by the public system. Almost all European systems are financed through a mix of public and private contributions.[37] Most universal health care systems are funded primarily by tax revenue (as in Portugal,[37] India, Spain, Denmark and Sweden). Some nations, such as Germany, France,[38] and Japan,[39] employ a multi-payer system in which health care is funded by private and public contributions. However, much of the non-government funding comes from contributions from employers and employees to regulated non-profit sickness funds. Contributions are compulsory and defined according to law. A distinction is also made between municipal and national healthcare funding. For example, one model is that the bulk of the healthcare is funded by the municipality, specialty healthcare is provided and possibly funded by a larger entity, such as a municipal co-operation board or the state, and medications are paid for by a state agency. A paper by Sherry A. Glied from Columbia University found that universal health care systems are modestly redistributive and that the progressivity of health care financing has limited implications for overall income inequality.[40] Compulsory insurance Main article: National health insurance This is usually enforced via legislation requiring residents to purchase insurance, but sometimes the government provides the insurance. Sometimes there may be a choice of multiple public and private funds providing a standard service (as in Germany) or sometimes just a single public fund (as in the Canadian provinces). Healthcare in Switzerland is based on compulsory insurance.[41][42] In some European countries where private insurance and universal health care coexist, such as Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands, the problem of adverse selection is overcome by using a risk compensation pool to equalize, as far as possible, the risks between funds. Thus, a fund with a predominantly healthy, younger population has to pay into a compensation pool and a fund with an older and predominantly less healthy population would receive funds from the pool. In this way, sickness funds compete on price and there is no advantage in eliminating people with higher risks because they are compensated for by means of risk-adjusted capitation payments. Funds are not allowed to pick and choose their policyholders or deny coverage, but they compete mainly on price and service. In some countries, the basic coverage level is set by the government and cannot be modified.[43] The Republic of Ireland at one time had a "community rating" system by VHI, effectively a single-payer or common risk pool. The government later opened VHI to competition, but without a compensation pool. That resulted in foreign insurance companies entering the Irish market and offering much less expensive health insurance to relatively healthy segments of the market, which then made higher profits at VHI's expense. The government later reintroduced community rating by a pooling arrangement and at least one main major insurance company, BUPA, withdrew from the Irish market.[citation needed] In Poland, people are obliged to pay a percentage of the average monthly wage to the state, even if they are covered by private insurance.[44] People working under a employment contract pay a percentage of their wage, while entrepreneurs pay a fixed rate, based on the average national wage. Unemployed people are insured by the labor office. Among the potential solutions posited by economists are single-payer systems as well as other methods of ensuring that health insurance is universal, such as by requiring all citizens to purchase insurance or by limiting the ability of insurance companies to deny insurance to individuals or vary price between individuals.[45][46] Single-payer Main article: Single-payer healthcare Single-payer health care is a system in which the government, rather than private insurers, pays for all health care costs.[47] Single-payer systems may contract for healthcare services from private organizations, or own and employ healthcare resources and personnel (as was the case in England before the introduction of the Health and Social Care Act). In some instances, such as Italy and Spain, both these realities may exist at the same time.[10] "Single-payer" thus describes only the funding mechanism and refers to health care financed by a single public body from a single fund and does not specify the type of delivery or for whom doctors work. Although the fund holder is usually the state, some forms of single-payer use a mixed public-private system.[citation needed] Tax-based financing In tax-based financing, individuals contribute to the provision of health services through various taxes. These are typically pooled across the whole population unless local governments raise and retain tax revenues. Some countries (notably Spain, the United Kingdom, Ireland, New Zealand, Italy, Brazil, Portugal, India and the Nordic countries) choose to fund public health care directly from taxation alone. Other countries with insurance-based systems effectively meet the cost of insuring those unable to insure themselves via social security arrangements funded from taxation, either by directly paying their medical bills or by paying for insurance premiums for those affected.[citation needed] Social health insurance In a social health insurance system, contributions from workers, the self-employed, enterprises and governments are pooled into single or multiple funds on a compulsory basis. This is based on risk pooling.[48] The social health insurance model is also referred to as the Bismarck Model, after Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who introduced the first universal health care system in Germany in the 19th century.[49] The funds typically contract with a mix of public and private providers for the provision of a specified benefit package. Preventive and public health care may be provided by these funds or responsibility kept solely by the Ministry of Health. Within social health insurance, a number of functions may be executed by parastatal or non-governmental sickness funds, or in a few cases, by private health insurance companies. Social health insurance is used in a number of Western European countries and increasingly in Eastern Europe as well as in Israel and Japan.[50] Private insurance In private health insurance, premiums are paid directly from employers, associations, individuals and families to insurance companies, which pool risks across their membership base. Private insurance includes policies sold by commercial for-profit firms, non-profit companies and community health insurers. Generally, private insurance is voluntary in contrast to social insurance programs, which tend to be compulsory.[51] In some countries with universal coverage, private insurance often excludes certain health conditions that are expensive and the state health care system can provide coverage. For example, in the United Kingdom, one of the largest private health care providers is BUPA, which has a long list of general exclusions even in its highest coverage policy,[52] most of which are routinely provided by the National Health Service. In the Netherlands, which has regulated competition for its main insurance system (but is subject to a budget cap), insurers must cover a basic package for all enrollees, but may choose which additional services they offer in supplementary plans; which most people possess [citation needed]. The Planning Commission of India has also suggested that the country should embrace insurance to achieve universal health coverage.[53] General tax revenue is currently used to meet the essential health requirements of all people. Community-based health insurance A particular form of private health insurance that has often emerged, if financial risk protection mechanisms have only a limited impact, is community-based health insurance.[54] Individual members of a specific community pay to a collective health fund which they can draw from when they need medical care. Contributions are not risk-related and there is generally a high level of community involvement in the running of these plans. Community-based health insurance generally only play a limited role in helping countries move towards universal health coverage. Challenges includes inequitable access by the poorest[55] that health service utilization of members generally increase after enrollment.[54] |

資金調達モデル こちらも参照のこと: 医療経済  国別の医療支出。GDP(国内総生産)に占める割合。例:2022年のカナダは11.2%。2022年の米国は16.6%[35]。  1人当たりの総医療費。公的支出と民間支出。米ドルPPP。例:2022年のカナダは6,319ドル。2022年の米国は12,555ドル[35]。  OECD加盟国の平均寿命と医療費の比較。2018年の米国平均10,447ドル[36]。 ほとんどの国の国民皆保険は、混合型の財源モデルによって達成されてきた。一般的な税収が主な財源であるが、多くの国では、公的制度でカバーされる範囲を 超えるサービスについては、特定料金(個人または雇用主に請求される場合もある)または民間支払い(直接または任意保険による)のオプションによって補完 されている。ほとんどの国民皆保険制度は、主に税収によって賄われている(ポルトガル、[37]インド、スペイン、デンマーク、スウェーデンなど)。ドイ ツ、フランス[38]、日本[39]のように、医療費を民間負担と公的負担で賄う多額負担制度を採用している国もある。しかし、政府以外の資金の多くは、 規制された非営利の疾病基金への雇用者と被雇用者からの拠出金である。拠出は強制であり、法律で定められている。また、自治体の医療費助成と国の医療費助 成は区別されている。例えば、医療費の大部分は自治体が賄い、専門的な医療は自治体の協力委員会や国などの大きな組織が提供し、場合によっては資金を提供 する。コロンビア大学のSherry A. Gliedの論文によると、国民皆保険制度は緩やかな再分配であり、医療財政の進歩性が全体的な所得格差に及ぼす影響は限定的であるとしている[40]。 強制保険 主な記事 国民健康保険 強制保険は通常、住民に保険加入を義務付ける法律によって施行されるが、政府が保険を提供することもある。標準的なサービスを提供する複数の公的・私的基 金から選択できる場合もあれば(ドイツのように)、単一の公的基金のみの場合もある(カナダの州のように)。スイスの医療は強制保険に基づいている [41][42]。 ドイツ、ベルギー、オランダなど、民間保険と国民皆保険が共存しているヨーロッパのいくつかの国では、逆選択の問題は、リスク補償プールを利用して、基金 間のリスクを可能な限り均等化することで克服されている。従って、健康で若年層が多い基金は補償プールに払い込まなければならず、高齢で健康でない層が多 い基金はプールから資金を受け取ることになる。このように、疾病基金は価格競争を行い、リスクの高い人々を排除するメリットはない。なぜなら、リスク調整 後の人頭分担金によって補償されるからである。基金は契約者を選んだり、保障を拒否したりすることは許されないが、主に価格とサービスで競争する。国に よっては、基本的な保障水準が政府によって定められ、変更できないところもある[43]。 アイルランド共和国では、一時期、VHIによる「地域格付け」制度があり、事実上、単一支払者または共通のリスクプールであった。政府は後にVHIを競争 に開放したが、補償プールはなかった。その結果、外国の保険会社がアイルランド市場に参入し、市場の比較的健康な層にはるかに安価な医療保険を提供し、 VHIの負担で高い利益を上げることになった。その後、政府はプーリング方式によるコミュニティ・レーティングを再導入し、少なくとも主要大手保険会社 BUPAはアイルランド市場から撤退した[要出典]。 ポーランドでは、民間保険に加入している場合でも、平均月給の一定割合を国に支払う義務がある[44]。失業者は労働局によって保険に加入する。 経済学者によって提起された潜在的な解決策の中には、すべての国民に保険への加入を義務付ける、あるいは保険会社が個人に対して保険を拒否したり、個人間 で価格を変えたりする能力を制限するなど、健康保険の普遍性を保証する他の方法と同様に、一人払いの制度がある[45][46]。 単一負担 主な記事 単一負担医療 単者負担医療とは、民間保険会社ではなく、政府が医療費の全額を負担する制度である[47]。単者負担医療制度は、民間団体と医療サービスを契約する場合 もあれば、医療資源や医療従事者を所有し雇用する場合もある(医療・社会保障法導入前のイギリスのケース)。イタリアやスペインのように、これら両方の実 態が同時に存在する場合もある[10]。したがって、「単一支払い」は、資金調達の仕組みのみを説明するものであり、単一の公的機関が単一の基金から資金 を調達する医療を指し、医療提供の種類や医師が誰のために働くかを特定するものではない。基金の保有者は通常国家であるが、単一支払い制度の中には官民混 合システムを用いる形態もある[要出典]。 税方式 税に基づく財政では、個人が様々な税金を通じて医療サービスの提供に拠出する。地方政府が税収を調達して保持しない限り、これらの税金は通常、全人口に プールされる。一部の国(特にスペイン、イギリス、アイルランド、ニュージーランド、イタリア、ブラジル、ポルトガル、インド、北欧諸国)は、税だけで直 接公的医療を賄うことを選択している。保険制度のある他の国では、医療費を直接支払ったり、保険料を負担したりすることで、税金を財源とする社会保障制度 によって、自分で保険に加入できない人の保険料を効果的に賄っている[要出典]。 社会医療保険 社会健康保険制度では、労働者、自営業者、企業、政府からの拠出金は、強制的に単一または複数の基金にプールされる。これはリスク・プーリングに基づいて いる[48]。社会的健康保険モデルは、19世紀にドイツで初の国民皆保険制度を導入したオットー・フォン・ビスマルク首相にちなんで、ビスマルク・モデ ルとも呼ばれる[49]。基金は通常、特定の給付パッケージの提供について、公的および民間の事業者と契約する。予防医療と公的医療は、これらの基金に よって提供されることもあれば、保健省が単独で責任を負うこともある。社会健康保険の中では、多くの機能が、準政府機関や非政府の疾病基金によって、ある いは少数のケースでは民間の健康保険会社によって実行されることがある。社会健康保険は、西欧諸国の多くで利用されており、東欧やイスラエル、日本でも利 用されるようになってきている[50]。 民間保険 民間医療保険では、保険料は雇用主、団体、個人、家族から保険会社に直接支払われ、保険会社は加入者全体のリスクをプールする。民間保険には、営利企業、 非営利企業、地域医療保険会社が販売する保険が含まれる。一般に、強制的な傾向がある社会保険制度とは対照的に、民間保険は任意加入である[51]。 国民皆保険制度のある一部の国では、民間保険は、高額な特定の健康状態を除外することが多く、国の医療制度が保障を提供することができる。例えば、イギリ スでは、最大の民間医療提供者のひとつがBUPAであり、BUPAは、その最も高い保障の方針においてさえ、一般的な除外事項の長いリストを持っており [52]、そのほとんどは、国民保健サービスによって日常的に提供されているものである。主な保険制度に競争規制を設けているオランダでは(ただし予算上 限がある)、保険者はすべての加入者に基本パッケージをカバーしなければならないが、補足プランで提供する追加サービスを選択することができ、ほとんどの 人が加入している[要出典]。 インド計画委員会も、国民皆保険を達成するために保険を導入すべきであると提案している[53]。 地域ベースの医療保険 財政的なリスク保護メカニズムが限定的な影響しか及ぼさない場合、しばしば出現してきた民間医療保険の特殊な形態は、地域ベースの医療保険である [54]。拠出金はリスクに関連しておらず、一般に、こうした制度の運営にはコミュニティが高いレベルで関与している。地域ベースの医療保険は、一般に、 各国が国民皆保険制度を目指す上で限られた役割しか果たさない。課題としては、最貧困層による不公平なアクセス[55]、加入者の医療サービス利用が一般 に加入後に増加することなどが挙げられる[54]。 |

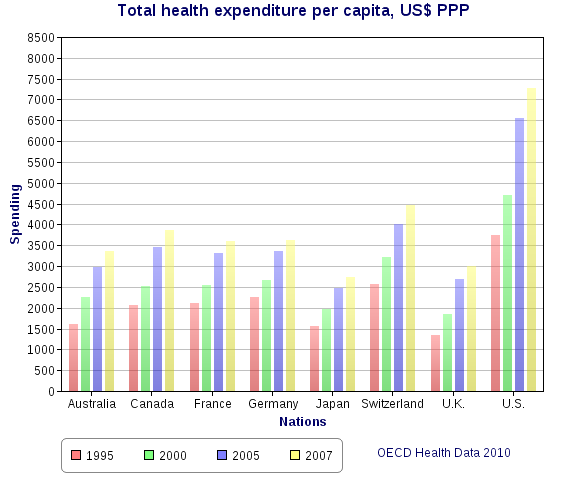

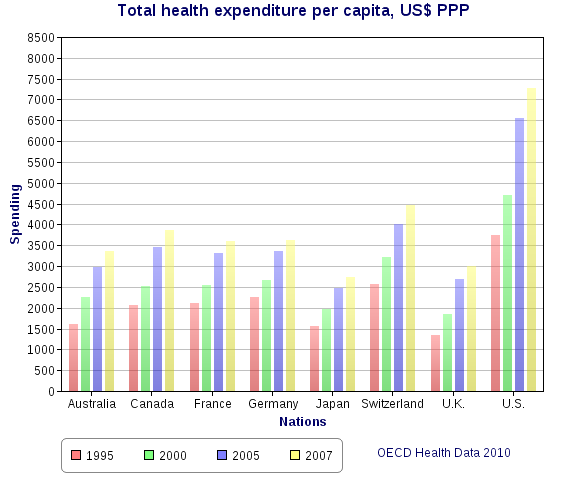

| Implementation and comparisons For a more comprehensive list, see List of countries with universal health care. See also: Health system and Health care systems by country  Health spending per capita, in US$ purchasing power parity-adjusted, among various OECD countries. For later data see List of countries by total health expenditure per capita. Universal health care systems vary according to the degree of government involvement in providing care or health insurance. In some countries, such as Canada, the UK, Spain, Italy, Australia, and the Nordic countries, the government has a high degree of involvement in the commissioning or delivery of health care services and access is based on residence rights, not on the purchase of insurance. Others have a much more pluralistic delivery system, based on obligatory health with contributory insurance rates related to salaries or income and usually funded by employers and beneficiaries jointly.[citation needed] Sometimes, the health funds are derived from a mixture of insurance premiums, salary-related mandatory contributions by employees or employers to regulated sickness funds, and by government taxes. These insurance based systems tend to reimburse private or public medical providers, often at heavily regulated rates, through mutual or publicly owned medical insurers. A few countries, such as the Netherlands and Switzerland, operate via privately owned but heavily regulated private insurers, which are not allowed to make a profit from the mandatory element of insurance but can profit by selling supplemental insurance.[citation needed] Universal health care is a broad concept that has been implemented in several ways. The common denominator for all such programs is some form of government action aimed at extending access to health care as widely as possible and setting minimum standards. Most implement universal health care through legislation, regulation, and taxation. Legislation and regulation direct what care must be provided, to whom, and on what basis. Usually, some costs are borne by the patient at the time of consumption, but the bulk of costs come from a combination of compulsory insurance and tax revenues. Some programs are paid for entirely out of tax revenues. In others, tax revenues are used either to fund insurance for the very poor or for those needing long-term chronic care. A critical concept in the delivery of universal healthcare is that of population healthcare. This is a way of organizing the delivery, and allocating resources, of healthcare (and potentially social care) based on populations in a given geography with a common need (such as asthma, end of life, urgent care). Rather than focus on institutions such as hospitals, primary care, community care etc. the system focuses on the population with a common as a whole. This includes people currently being treated, and those that are not being treated but should be (i.e. where there is health inequity). This approach encourages integrated care and a more effective use of resources.[56] The United Kingdom National Audit Office in 2003 published an international comparison of ten different health care systems in ten developed countries, nine universal systems against one non-universal system (the United States), and their relative costs and key health outcomes.[57] A wider international comparison of 16 countries, each with universal health care, was published by the World Health Organization in 2004.[58] In some cases, government involvement also includes directly managing the health care system, but many countries use mixed public-private systems to deliver universal health care. |

実施と比較 より包括的なリストは、国民皆保険制度のある国のリストを参照のこと。 こちらも参照のこと: 医療制度および国別医療制度  OECD加盟国の1人当たり医療費(購買力平価調整後、米ドル)。それ以降のデータについては、一人当たり総医療費国別リストを参照のこと。 国民皆保険制度は、医療や健康保険の提供に対する政府の関与の度合いによって異なる。カナダ、英国、スペイン、イタリア、オーストラリア、北欧諸国のよう に、政府が医療サービスの委託や提供に高度に関与し、保険加入ではなく居住権に基づいてアクセスする国もある。その他は、より多元的な医療提供体制をとっ ており、給与や所得に関連した拠出保険料率による義務的な医療に基づき、通常は雇用者と受給者が共同で資金を拠出している[要出典]。 健康資金は、保険料、規制された疾病基金への従業員または雇用主による給与に関連した強制拠出金、および政府税金の混合から得られることもある。これらの 保険制度は、相互または公営の医療保険会社を通じて、しばしば厳しく規制された料率で、民間または公的医療提供者に払い戻される傾向がある。オランダやス イスのように、民営だが厳しく規制された民間保険会社を通じて運営されている国もいくつかある。民間保険会社は、強制的な保険要素から利益を得ることは認 められていないが、補助的な保険を販売することで利益を得ることができる[要出典]。 国民皆保険は幅広い概念であり、いくつかの方法で実施されてきた。このようなプログラムに共通するのは、医療へのアクセスを可能な限り拡大し、最低限の基 準を設定することを目的とした、何らかの形の政府の行動である。その多くは、法律、規制、税制を通じて国民皆保険制度を実施している。法律と規制は、どの ような医療を、誰に、どのような基準で提供しなければならないかを指示する。通常、一部の費用は患者が消費時に負担するが、費用の大部分は強制保険と税収 の組み合わせで賄われる。全額が税収で賄われる制度もある。その他のプログラムでは、税収は極貧層や長期の慢性期医療を必要とする人々のための保険に充て られる。 国民皆保険の実現において重要な概念は、人口医療である。これは、共通のニーズ(喘息、終末期医療、緊急医療など)を持つ特定の地域の住民に基づき、医療 (および潜在的な社会的ケア)の提供と資源配分を組織化する方法である。このシステムは、病院、プライマリーケア、コミュニティケアなどの機関に焦点を当 てるのではなく、共通のニーズを持つ集団全体に焦点を当てる。これには、現在治療を受けている人々や、治療を受けていないが治療を受けるべき人々(つまり 健康格差のある人々)も含まれる。このアプローチは、統合ケアと資源のより効果的な利用を促すものである[56]。 2003年にイギリスの国家監査院は、先進10カ国の10種類の医療制度(9つの普遍的制度と1つの非普遍的制度(米国))の国際比較と、それらの相対的 な費用と主要な健康アウトカムの比較を発表した[57]。2004年には世界保健機関(WHO)によって、それぞれ国民皆保険制度を持つ16カ国の、より 広範な国際比較が発表された[58]。 場合によっては、政府の関与には医療制度を直接管理することも含まれるが、多くの国では国民皆保険制度を実現するために官民混合制度を用いている。 |

| Overview of Health Coverage Reports The 2023 report from the WHO and the World Bank indicates that the advancement towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC) by the year 2030 has not progressed since 2015. The UHC Service Coverage Index (SCI) has remained constant at a score of 68 from 2019 to 2021. It is reported that catastrophic out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenditures have impacted over 1 billion individuals globally. Additionally, in the year 2019, it was found that 2 billion people experienced financial difficulties due to health expenses, with ongoing, significant disparities in coverage. The report suggests several strategies to mitigate these challenges: it calls for the acceleration of essential health services, sustained attention to infectious disease management, improvement in health workforce and infrastructure, the elimination of financial barriers to care, an increase in pre-paid and pooled health financing, policy initiatives to curtail OOP expenses, a focus on primary healthcare to reinforce overall health systems, and the fortification of collaborative efforts to achieve UHC. These measures aim to increase health service coverage by an additional 477 million individuals by the year 2023 and to continue progress towards covering an extra billion people by the 2030 deadline.[59][60] |

医療保険制度報告書の概要 WHOと世界銀行による2023年報告書によると、2030年までのユニバーサル・ヘルス・カバレッジ(UHC)に向けた前進は2015年以降進んでいな い。UHCサービスカバレッジ指数(SCI)は、2019年から2021年まで68点で一定している。壊滅的な医療費支出が、世界で10億人以上に影響を 及ぼしていると報告されている。さらに、2019年には、20億人が医療費による経済的困難を経験し、保険適用に継続的で著しい格差があることが判明し た。報告書は、これらの課題を軽減するためのいくつかの戦略を提案している。必須保健サービスの加速化、感染症管理への持続的な関心、保健医療人材とイン フラの改善、医療への経済的障壁の排除、前払いおよびプール型医療資金の増加、OOP費用を抑制するための政策イニシアティブ、保健システム全体を強化す るためのプライマリ・ヘルスケアへの重点化、UHC達成に向けた協力的な取り組みの強化などである。これらの措置は、2023年までに医療サービスの適用 範囲をさらに4億7,700万人拡大し、2030年の期限までにさらに10億人をカバーするための進展を継続することを目的としている[59][60]。 |

| Criticism and support This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (June 2022) This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2022) Critics of universal healthcare say that it leads to longer wait times and a decrease in the quality of healthcare.[5] Critics of implementing universal healthcare in the United States say that it would require healthy people to pay for the medical care of unhealthy people, which they say goes against the American values of individual choice and personal responsibility; it would raise healthcare expenditures due to the high cost of implementation that the United States government supposedly cannot pay; and represents unnecessary government overreach into the lives of American citizens, healthcare, the health insurance industry, and employers' rights to choose what health coverage they want to offer to their employees.[5] Most contemporary studies posit that a single payer universal healthcare system would benefit the United States. According to a 2020 study published in The Lancet, the proposed Medicare for All Act would save 68,000 lives and $450 billion in national healthcare expenditure annually.[61] A 2022 study published in the PNAS found that a single-payer universal healthcare system would have saved 212,000 lives and averted over $100 billion in medical costs during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States in 2020 alone.[62] |

批判とサポート このセクションには複数の問題がある。改善の手助けをするか、トークページでこれらの問題について議論してほしい。(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) このセクションの例や視点は、このテーマに関する世界的な見解を表しているとは限らない。(2022年6月) このセクションは拡張が必要である。追加することで手助けできる。(2022年9月) 国民皆保険の批判者は、国民皆保険は待ち時間の長期化と医療の質の低下につながると言う。 [5] 米国で国民皆保険制度を導入することへの批判者は、健康な人が不健康な人の医療費を負担しなければならなくなり、それは個人の選択と個人の責任という米国 の価値観に反すると言う。 現代の研究のほとんどは、単一負担の国民皆保険制度が米国に利益をもたらすとしている。ランセット』誌に掲載された2020年の研究によれば、提案されて いる「万人のための医療保障法(Medicare for All Act)」は、年間68,000人の命を救い、4,500億ドルの国民医療費を節約することになる[61]。 PNAS』誌に掲載された2022年の研究によれば、2020年に米国でCOVID-19が大流行した際、一人払いの国民皆保険制度があれば、それだけで 212,000人の命を救い、1,000億ドル以上の医療費を回避できたという[62]。 |

| Acronyms in healthcare Cultural competence in health care Euro Health Consumer Index Global health Health care Health promotion Health law Health insurance cooperative Health spending as a percent of GDP by country (gross domestic product) Healthcare reform debate in the United States List of countries by health insurance coverage List of countries by total health expenditure per capita List of countries with universal health care National health insurance Primary healthcare Public health Publicly funded health care Right to health Single-payer healthcare Socialized medicine Two-tier healthcare Universal Health Coverage Day |

医療における略語 医療における文化的能力 ユーロ健康消費者指数 グローバルヘルス ヘルスケア 健康増進 健康法 健康保険組合 国別医療費の対GDP比(国内総生産) 米国における医療制度改革の議論 健康保険適用国別リスト 国民一人当たりの総医療費国別リスト 国民皆保険国一覧 国民健康保険 プライマリーヘルスケア 公的医療 公的医療費 健康への権利 単一支払い医療 社会化医療 二層医療 国民皆保険の日 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_health_care |

|

☆

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆