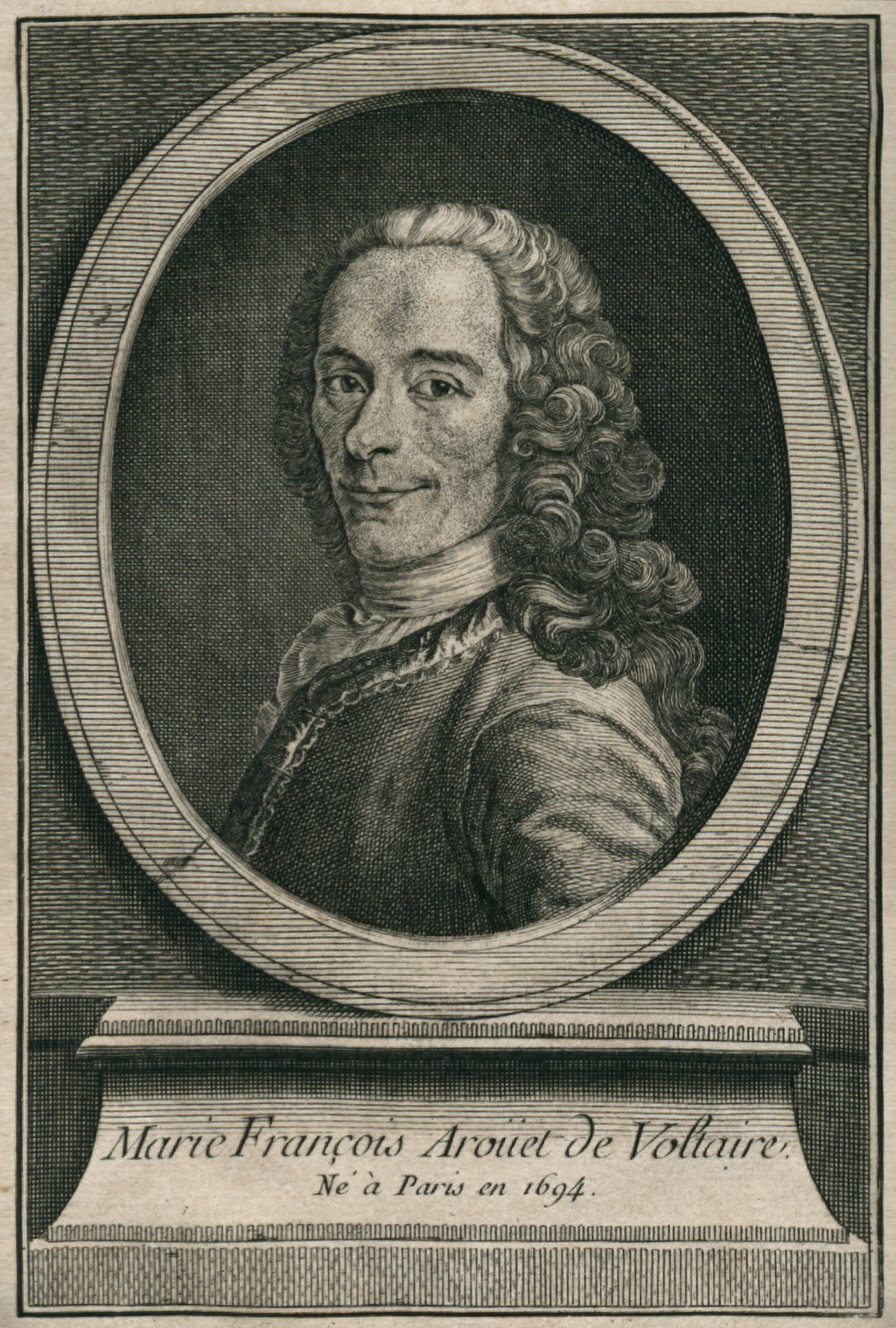

ヴォルテール

François-Marie Arouet, M. de Voltaire, 1694-1778

☆

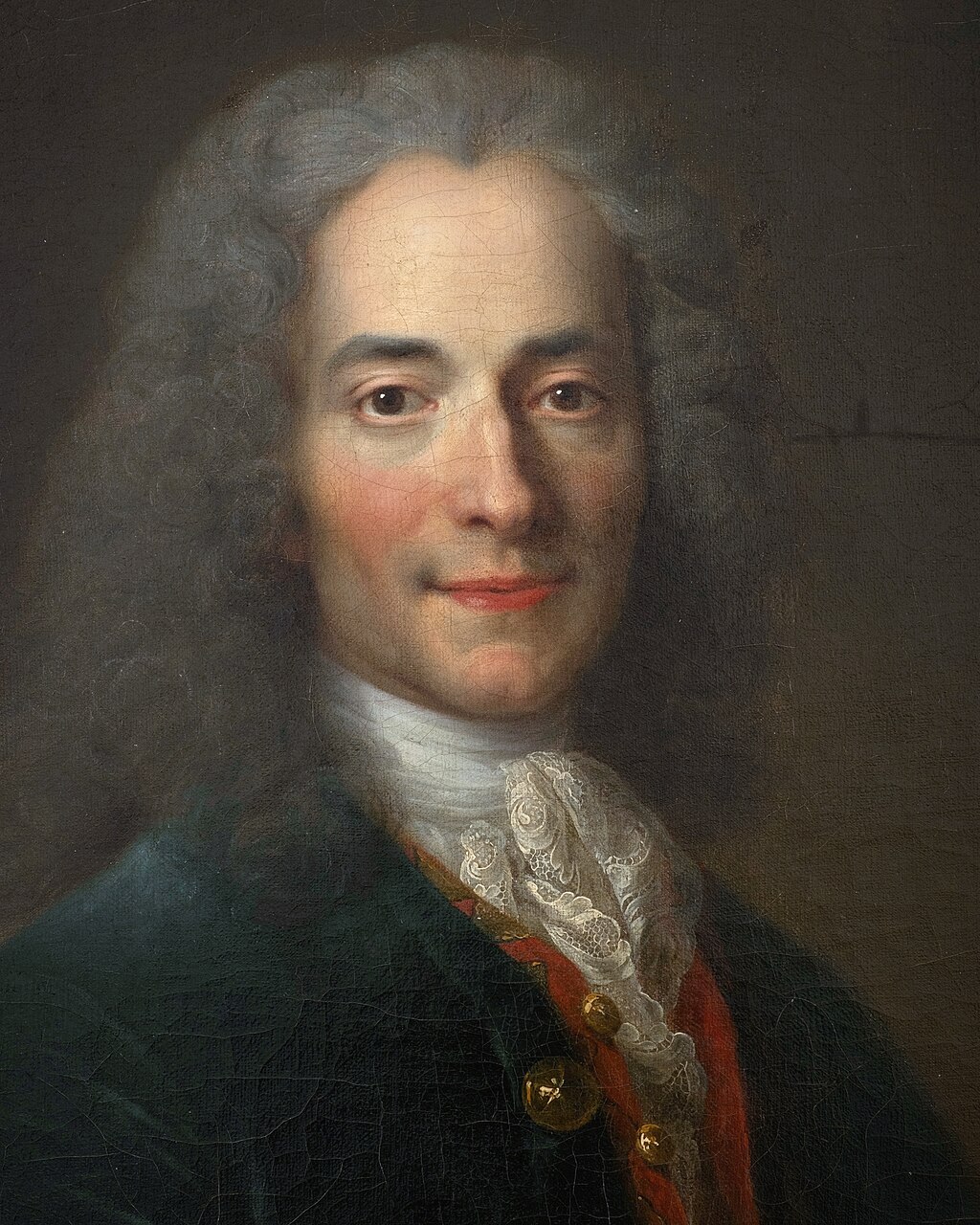

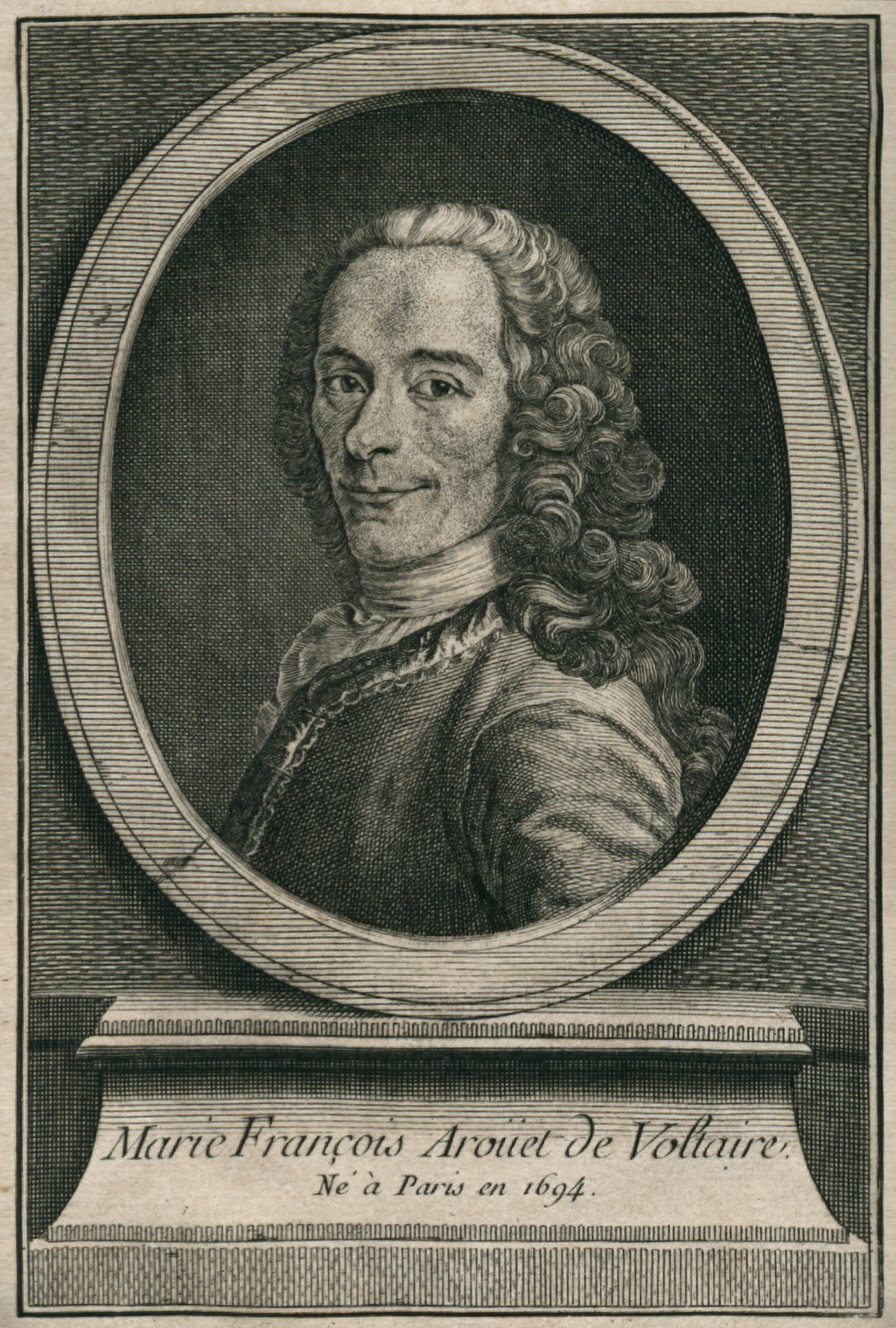

フランソワ=マリー・アルウエ(フランス語発音: [fʁɑ̃swa maʁi aʁwɛ]、1694年11月21日 -

1778年5月30日)、筆名M.ド・ヴォルテール(/vɒlˈ tɛər, voʊl-/,[2][3][4] US also

/vɔːl-/;[5][6] French:

[vɔltɛːʁ])は、フランスの啓蒙主義の作家、哲学者(フィロソフ)、風刺作家、歴史家である。機知に富み、キリスト教(特にローマ・カトリック教

会)や奴隷制度に対する痛烈な批判で知られたヴォルテールは、言論の自由、信教の自由、政教分離を唱えた。

ヴォルテールは多才で多作な作家であり、戯曲、詩、小説、随筆、歴史、さらには科学的な解説書など、ほぼすべての文学形式の作品を残している。

彼が書いた手紙は2万通以上、著書やパンフレットは2千点に上る。[7]

ヴォルテールは、国際的に著名となり商業的成功を収めた最初の作家の一人である。

彼は市民的自由の擁護者として率直な発言を繰り返し、カトリックのフランス王政の厳しい検閲法による絶え間ない危険に晒されていた。彼は、不寛容や宗教的

教義、さらには当時のフランスの制度を痛烈に風刺した論争を繰り広げた。彼の最も有名な作品であり、最高傑作である『カンディード』は、当時の多くの出来

事、思想家、哲学を論評し、批判し、嘲笑した小説であり、とりわけゴットフリート・ライプニッツと、彼が唱えた「我々の世界は必然的に『あり得べき世界の

中で最も良い世界』である」という信念を風刺したものである。[8][9]

| François-Marie

Arouet (French: [fʁɑ̃swa maʁi aʁwɛ]; 21 November 1694 – 30 May 1778),

known by his nom de plume M. de Voltaire (/vɒlˈtɛər, voʊl-/,[2][3][4]

US also /vɔːl-/;[5][6] French: [vɔltɛːʁ]), was a French Enlightenment

writer, philosopher (philosophe), satirist, and historian. Famous for

his wit and his criticism of Christianity (especially of the Roman

Catholic Church) and of slavery, Voltaire was an advocate of freedom of

speech, freedom of religion, and separation of church and state. Voltaire was a versatile and prolific writer, producing works in almost every literary form, including plays, poems, novels, essays, histories, and even scientific expositions. He wrote more than 20,000 letters and 2,000 books and pamphlets.[7] Voltaire was one of the first authors to become renowned and commercially successful internationally. He was an outspoken advocate of civil liberties and was at constant risk from the strict censorship laws of the Catholic French monarchy. His polemics witheringly satirized intolerance and religious dogma, as well as the French institutions of his day. His best-known work and magnum opus, Candide, is a novella that comments on, criticizes, and ridicules many events, thinkers and philosophies of his time, most notably Gottfried Leibniz and his belief that our world is of necessity the "best of all possible worlds".[8][9] |

フランソワ=マリー・アルウエ(フランス語発音: [fʁɑ̃swa

maʁi aʁwɛ]、1694年11月21日 - 1778年5月30日)、筆名M.ド・ヴォルテール(/vɒlˈ tɛər,

voʊl-/,[2][3][4] US also /vɔːl-/;[5][6] French:

[vɔltɛːʁ])は、フランスの啓蒙主義の作家、哲学者(フィロソフ)、風刺作家、歴史家である。機知に富み、キリスト教(特にローマ・カトリック教

会)や奴隷制度に対する痛烈な批判で知られたヴォルテールは、言論の自由、信教の自由、政教分離を唱えた。 ヴォルテールは多才で多作な作家であり、戯曲、詩、小説、随筆、歴史、さらには科学的な解説書など、ほぼすべての文学形式の作品を残している。 彼が書いた手紙は2万通以上、著書やパンフレットは2千点に上る。[7] ヴォルテールは、国際的に著名となり商業的成功を収めた最初の作家の一人である。 彼は市民的自由の擁護者として率直な発言を繰り返し、カトリックのフランス王政の厳しい検閲法による絶え間ない危険に晒されていた。彼は、不寛容や宗教的 教義、さらには当時のフランスの制度を痛烈に風刺した論争を繰り広げた。彼の最も有名な作品であり、最高傑作である『カンディード』は、当時の多くの出来 事、思想家、哲学を論評し、批判し、嘲笑した小説であり、とりわけゴットフリート・ライプニッツと、彼が唱えた「我々の世界は必然的に『あり得べき世界の 中で最も良い世界』である」という信念を風刺したものである。[8][9] |

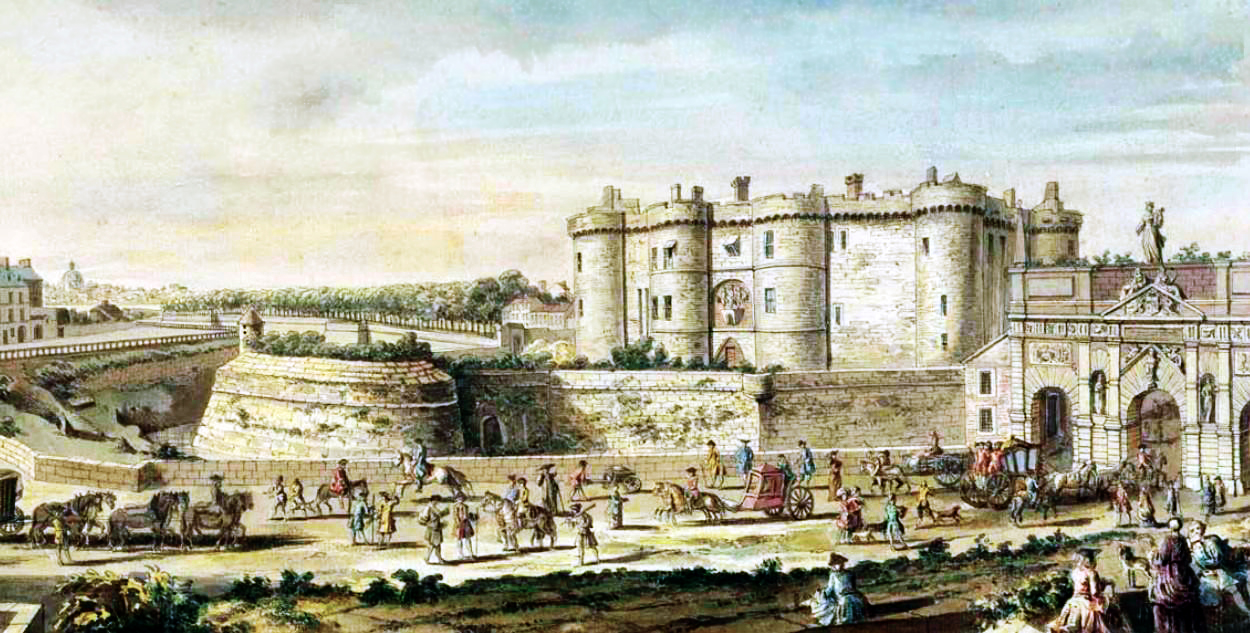

| Early life François-Marie Arouet was born in Paris, the youngest of the five children of François Arouet, a lawyer who was a minor treasury official, and his wife, Marie Marguerite Daumard, whose family was on the lowest rank of the French nobility.[10] Some speculation surrounds Voltaire's date of birth, because he claimed he was born on 20 February 1694 as the illegitimate son of a nobleman, Guérin de Rochebrune or Roquebrune.[11] Two of his older brothers—Armand-François and Robert—died in infancy, and his surviving brother Armand and sister Marguerite-Catherine were nine and seven years older, respectively.[12] Nicknamed "Zozo" by his family, Voltaire was baptized on 22 November 1694, with François de Castagnère, abbé de Châteauneuf [fr], and Marie Daumard, the wife of his mother's cousin, standing as godparents.[13] He was educated by the Jesuits at the Collège Louis-le-Grand (1704–1711), where he was taught Latin, theology, and rhetoric;[14] later in life he became fluent in Italian, Spanish, and English.[15] By the time he left school, Voltaire had decided he wanted to be a writer, against the wishes of his father, who wanted him to become a lawyer.[16] Voltaire, pretending to work in Paris as an assistant to a notary, spent much of his time writing poetry. When his father found out, he sent Voltaire to study law, this time in Caen, Normandy. But the young man continued to write, producing essays and historical studies. Voltaire's wit made him popular among some of the aristocratic families with whom he mixed. In 1713, his father obtained a job for him as a secretary to the new French ambassador in the Netherlands, the marquis de Châteauneuf [fr], the brother of Voltaire's godfather.[17] At The Hague, Voltaire fell in love with a French Protestant refugee named Catherine Olympe Dunoyer (known as 'Pimpette').[17] Their affair, considered scandalous, was discovered by de Châteauneuf and Voltaire was forced to return to France by the end of the year.[18]  Voltaire was imprisoned in the Bastille from 16 May 1717 to 15 April 1718 in a windowless cell with ten-foot-thick walls.[19] Most of Voltaire's early life revolved around Paris. From early on, Voltaire had trouble with the authorities for critiques of the government. As a result, he was twice sentenced to prison and once to temporary exile to England. One satirical verse, in which Voltaire accused the Régent of incest with his daughter, resulted in an eleven-month imprisonment in the Bastille.[20] The Comédie-Française had agreed in January 1717 to stage his debut play, Œdipe, and it opened in mid-November 1718, seven months after his release.[21] Its immediate critical and financial success established his reputation.[22] Both the Régent and King George I of Great Britain presented Voltaire with medals as a mark of their appreciation.[23] Voltaire mainly argued for religious tolerance and freedom of thought. He campaigned to eradicate priestly and aristo-monarchical authority, and supported a constitutional monarchy that protects people's rights.[24][25] Name Arouet adopted the name Voltaire in 1718, following his incarceration at the Bastille. Its origin is unclear. It is an anagram of AROVET LI, the Latinized spelling of his surname, Arouet, and the initial letters of le jeune ("the young").[26] According to a family tradition among the descendants of his sister, he was known as le petit volontaire ("determined little thing") as a child, and he resurrected a variant of the name in his adult life.[27] The name also reverses the syllables of Airvault, his family's home town in the Poitou region.[28] Richard Holmes[29] supports the anagrammatic derivation of the name, but adds that a writer such as Voltaire would have intended it to also convey connotations of speed and daring. These come from associations with words such as voltige (acrobatics on a trapeze or horse), volte-face (a spinning about to face one's enemies), and volatile (originally, any winged creature). "Arouet" was not a noble name fit for his growing reputation, especially given that name's resonance with à rouer ("to be beaten up") and roué (a débauché). In a letter to Jean-Baptiste Rousseau in March 1719, Voltaire concludes by asking that, if Rousseau wishes to send him a return letter, he do so by addressing it to Monsieur de Voltaire. A postscript explains: "J'ai été si malheureux sous le nom d'Arouet que j'en ai pris un autre surtout pour n'être plus confondu avec le poète Roi", ("I was so unhappy under the name of Arouet that I have taken another, primarily so as to cease to be confused with the poet Roi.")[30] This probably refers to Adenes le Roi, and the 'oi' diphthong was then pronounced like modern 'ouai', so the similarity to 'Arouet' is clear, and thus, it could well have been part of his rationale. Voltaire is known also to have used at least 178 separate pen names during his lifetime.[31] |

幼少期 フランソワ=マリー・アルーは、財務省の少額事務官であった弁護士フランソワ・アルーとその妻で、フランス貴族の最下層階級に属する家柄であったマリー・ マルグリット・ドーマールの5人の子供たちのうちの末っ子としてパリで生まれた。[10] ヴォルテールは、1694年2月20日に貴族のゲラン・ド・ロシュブルン(またはロクブルン)の庶子として生まれたと主張していたため、ヴォルテールの生 年月日についてはいくつかの推測がある 貴族のゲラン・ド・ロシュブルンまたはロクブルンの非嫡出子として生まれたと主張しているためである。[11] 彼の兄のうち2人、アルマン=フランソワとロベールは幼児期に死亡し、存命していた兄アルマンと妹マルグリット=カトリーヌはそれぞれ9歳と7歳年上だっ た。[12] 家族から「ゾゾ」という愛称で呼ばれていたヴォルテールは、1694年11月22日に洗礼を受けた。洗礼者は、フランソワ・ド・カスタニェール、 フランソワ・ド・カスタニェールと、母親の従兄弟の妻であるマリー・ドーマルが名付け親となった。[13] 彼はコレージュ・ルイ=ル=グラン(1704年-1711年)でイエズス会によって教育を受け、そこでラテン語、神学、修辞学を学んだ。[14] 後にイタリア語、スペイン語、英語に堪能となった。[15] 学校を去る頃には、ヴォルテールは父親の希望に反して、作家になりたいと決心していた。父親は息子に弁護士になってほしかったのだ。[16] パリで公証人の助手として働くふりをしながら、ヴォルテールは詩作に多くの時間を費やした。父親がそれを知ると、今度はノルマンディーのカーンで法律を学 ばせた。しかし、青年は執筆を続け、随筆や歴史研究を著した。 ヴォルテールの機知は、彼が交流した貴族の一部の間で彼を人気者にした。 1713年、父親は彼にオランダの新フランス大使、シャトールヌフ侯爵(fr)の秘書の職を得させた。シャトールヌフ侯爵はヴォルテールの名付け親の兄弟 であった。[17] ハーグで、ヴォルテールは フランス人プロテスタントの亡命者、カトリーヌ・オリンプ・デュノワイエ(通称「ピムペット」)と恋に落ちた。[17] ふたりの関係はスキャンダラスとみなされ、ド・シャトールヌフに知られてしまい、ヴォルテールは年末までにフランスに帰国せざるを得なくなった。[18]  ヴォルテールは1717年5月16日から1718年4月15日まで、窓のない厚さ3メートルの壁の独房に投獄された。 ヴォルテールの初期の人生のほとんどはパリを中心に展開した。ヴォルテールは早い時期から政府批判によって当局とトラブルを起こしていた。その結果、彼は 2度投獄され、1度イングランドに一時的に追放された。摂政が娘と近親相姦関係にあるとヴォルテールが告発した風刺詩の一件により、ヴォルテールはバス ティーユに11ヶ月間投獄された。[20] 1717年1月、コメディ・フランセーズはヴォルテールのデビュー作『オイディプス』の上演に同意し、 1718年11月中旬に公開され、釈放から7ヶ月後であった。[21] その作品はすぐに批評的にも商業的にも成功を収め、ヴォルテールの名声を確立した。[22] 摂政とイギリス王ジョージ1世は、ヴォルテールに感謝の印としてメダルを贈った。[23] ヴォルテールは主に宗教的寛容と思想の自由を主張した。聖職者と貴族君主の権威を根絶する運動を行い、人民の権利を守る立憲君主制を支持した。 名前 アローエは、バスティーユに投獄された後、1718年にヴォルテールという名前を採用した。その由来は不明である。これは、ラテン語表記の名字アローエ (AROVET LI)とle jeune(「若い」)の頭文字を組み合わせたアナグラムである。[26] 妹の子孫の間で語り継がれてきた家族の言い伝えによると、彼は子供の頃、le petit 子供の頃は「意志の強い小さなもの」という意味のle petit volontaire(小さな意志の強いもの)と呼ばれていた。そして、成人してからこの名前の変形を復活させた。[27] この名前はまた、ポワトゥー地方にある彼の家族の故郷、エアヴォー(Airvault)の音節を逆にしたものにもなっている。[28] リチャード・ホームズは、この名前の語源がアナグラムであることを支持しているが、ヴォルテールのような作家であれば、この名前には「スピード」や「大胆 さ」といった意味合いも込められているはずだと付け加えている。これらは、voltige(空中ブランコや馬上での曲芸)、volte-face(敵に向 かってくるくる回って向き直ること)、volatile(もともとは翼のある生き物)といった言葉との関連から来ている。「アルーエ」という名前は、彼の 名声の高まりにふさわしい高貴な名前ではなかった。特に、この名前は「殴られる」という意味の「ア・ルーエ」や放蕩者の「ルーエ」という言葉と響きが似て いる。 1719年3月、ジャン=バティスト・ルソーに宛てた手紙の最後に、ヴォルテールは、ルソーが返事を送る場合は「ムッシュー・ド・ヴォルテール」宛てにし てほしいと頼んでいる。追伸には次のように書かれている。「私はArouetという名前でとても不幸だったので、特に詩人の王と混同されないように別の名 前を名乗ることにした」と説明している。詩人ロワと混同されることがなくなるように」[30] これはおそらくAdenes le Roiを指しており、oiの二重母音は当時、現代のouaiのように発音されていたため、「Arouet」との類似性は明らかであり、したがって、それは 彼の理論的根拠の一部であった可能性が高い。ヴォルテールは生涯に少なくとも178の別名を使用していたことでも知られている。[31] |

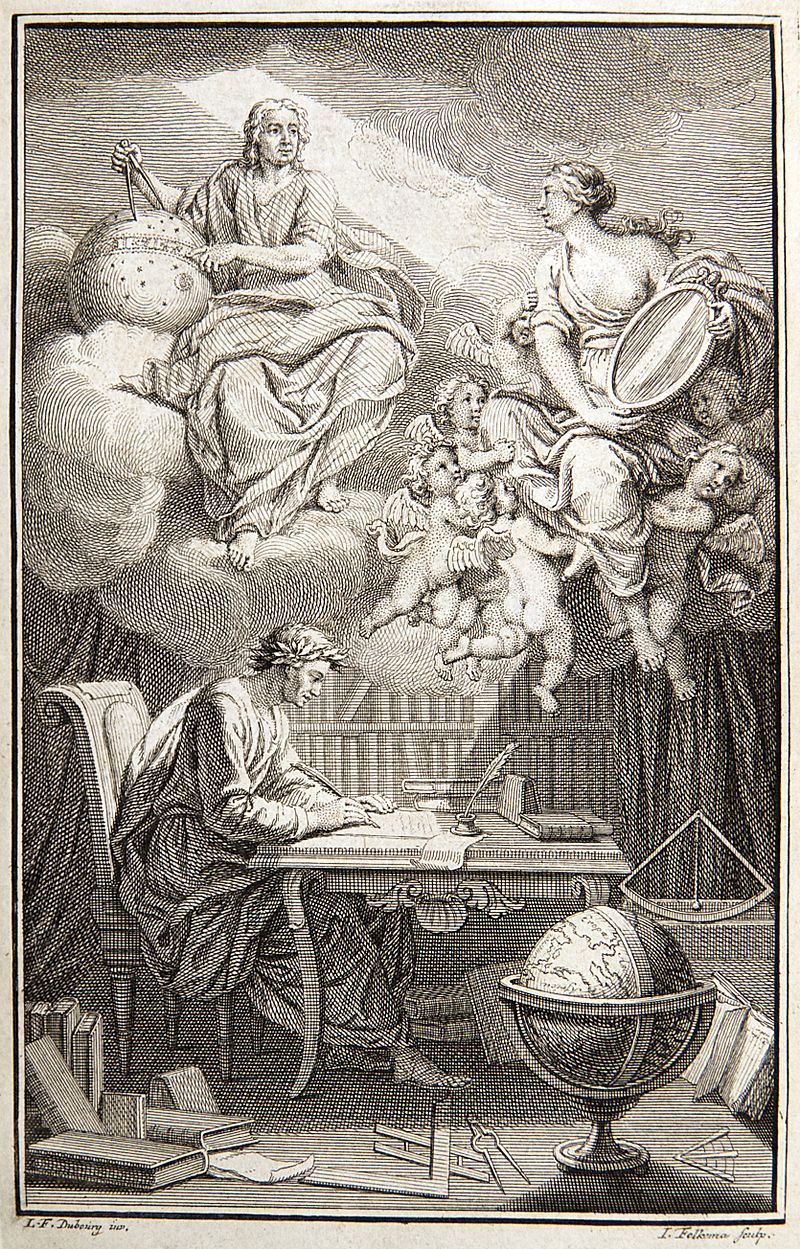

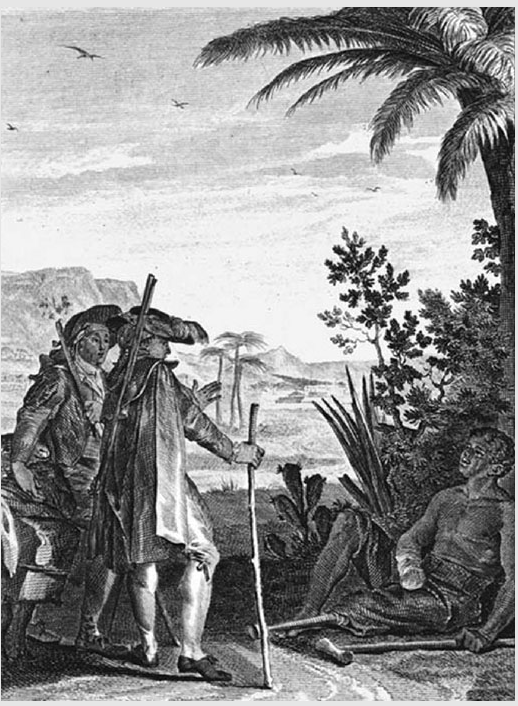

| Career Early fiction Voltaire's next play, Artémire, set in ancient Macedonia, opened on 15 February 1720. It was a flop and only fragments of the text survive.[32] He instead turned to an epic poem about Henry IV of France that he had begun in early 1717.[33] Denied a licence to publish, in August 1722 Voltaire headed north to find a publisher outside France. On the journey, he was accompanied by his mistress, Marie-Marguerite de Rupelmonde, a young widow.[34] At Brussels, Voltaire and Rousseau met up for a few days, before Voltaire and his mistress continued northwards. A publisher was eventually secured in The Hague.[35] In the Netherlands, Voltaire was struck and impressed by the openness and tolerance of Dutch society.[36] On his return to France, he secured a second publisher in Rouen, who agreed to publish La Henriade clandestinely.[37] After Voltaire's recovery from a month-long smallpox infection in November 1723, the first copies were smuggled into Paris and distributed.[38] While the poem was an instant success, Voltaire's new play, Mariamne, was a failure when it first opened in March 1724.[39] Heavily reworked, it opened at the Comédie-Française in April 1725 to a much-improved reception.[39] It was among the entertainments provided at the wedding of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska in September 1725.[39] Great Britain In early 1726, the aristocratic chevalier de Rohan-Chabot taunted Voltaire about his change of name, and Voltaire retorted that his name would win the esteem of the world, while Rohan would sully his own.[40] The furious Rohan arranged for his thugs to beat up Voltaire a few days later.[41] Seeking redress, Voltaire challenged Rohan to a duel, but the powerful Rohan family arranged for Voltaire to be arrested and imprisoned without trial in the Bastille on 17 April 1726.[42][43] Fearing indefinite imprisonment, Voltaire asked to be exiled to England as an alternative punishment, which the French authorities accepted.[44] On 2 May, he was escorted from the Bastille to Calais and embarked for Britain.[45]  Elémens de la philosophie de Neuton, 1738 In England, Voltaire lived largely in Wandsworth, with acquaintances including Everard Fawkener.[46] From December 1727 to June 1728 he lodged at Maiden Lane, Covent Garden, now commemorated by a plaque, to be nearer to his British publisher.[47] Voltaire circulated throughout English high society, meeting Alexander Pope, John Gay, Jonathan Swift, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, and many other members of the nobility and royalty.[48] Voltaire's exile in Great Britain greatly influenced his thinking. He was intrigued by Britain's constitutional monarchy in contrast to French absolutism, and by the country's greater freedom of speech and religion.[49] He was influenced by the writers of the time, and developed an interest in English literature, especially Shakespeare, who was still little known in continental Europe.[50] Despite pointing out Shakespeare's deviations from neoclassical standards, Voltaire saw him as an example for French drama, which, though more polished, lacked on-stage action. Later, however, as Shakespeare's influence began growing in France, Voltaire tried to set a contrary example with his own plays, decrying what he considered Shakespeare's barbarities. Voltaire may have been present at the funeral of Isaac Newton,[a] and met Newton's niece Catherine Conduitt.[47] In 1727, Voltaire published two essays in English, Upon the Civil Wars of France, Extracted from Curious Manuscripts and Upon Epic Poetry of the European Nations, from Homer Down to Milton.[47] He also published a letter about the Quakers after attending one of their services.[51] After two and a half years in exile, Voltaire returned to France, and after a few months in Dieppe, the authorities permitted him to return to Paris.[52] At a dinner, French mathematician Charles Marie de La Condamine proposed buying up the lottery that was organized by the French government to pay off its debts, and Voltaire joined the consortium, earning perhaps a million livres.[53] He invested the money cleverly and on this basis managed to convince the Court of Finances of his responsible conduct, allowing him to take control of a trust fund inherited from his father. He was now indisputably rich.[54][55] Further success followed in 1732 with his play Zaïre, which when published in 1733 carried a dedication to Fawkener praising English liberty and commerce.[56] He published his admiring essays on British government, literature, religion, and science in Letters Concerning the English Nation (London, 1733).[57] In 1734, they were published in Rouen as Lettres philosophiques, causing a huge scandal.[58][b] Published without approval of the royal censor, the essays lauded British constitutional monarchy as more developed and more respectful of human rights than its French counterpart, particularly regarding religious tolerance. The book was publicly burnt and banned, and Voltaire was again forced to flee Paris.[24] Château de Cirey  In the frontispiece to Voltaire's book on Newton's philosophy, Émilie du Châtelet appears as Voltaire's muse, reflecting Newton's heavenly insights down to Voltaire.[59] In 1733, Voltaire met Émilie du Châtelet (Marquise du Châtelet), a mathematician and married mother of three, who was 12 years his junior and with whom he was to have an affair for 16 years.[60] To avoid arrest after the publication of Lettres, Voltaire took refuge at her husband's château at Cirey on the borders of Champagne and Lorraine.[61] Voltaire paid for the building's renovation,[62] and Émilie's husband sometimes stayed at the château with his wife and her lover.[63] The intellectual paramours collected around 21,000 books, an enormous number for the time.[64] Together, they studied these books and performed scientific experiments at Cirey, including an attempt to determine the nature of fire.[65] Having learned from his previous brushes with the authorities, Voltaire began his habit of avoiding open confrontation with the authorities and denying any awkward responsibility.[66] He continued to write plays, such as Mérope (or La Mérope française) and began his long researches into science and history. Again, a main source of inspiration for Voltaire were the years of his British exile, during which he had been strongly influenced by Newton's works. Voltaire strongly believed in Newton's theories; he performed experiments in optics at Cirey,[67] and was one of the promulgators of the famous story of Newton's inspiration from the falling apple, which he had learned from Newton's niece in London and first mentioned in his Letters.[47]  Pastel by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1735 In the fall of 1735, Voltaire was visited by Francesco Algarotti, who was preparing a book about Newton in Italian.[68] Partly inspired by the visit, the Marquise translated Newton's Latin Principia into French, which remained the definitive French version into the 21st century.[24] Both she and Voltaire were also curious about the philosophy of Gottfried Leibniz, a contemporary and rival of Newton. While Voltaire remained a firm Newtonian, the Marquise adopted certain aspects of Leibniz's critiques.[24][69] Voltaire's own book Elements of the Philosophy of Newton made the great scientist accessible to a far greater public, and the Marquise wrote a celebratory review in the Journal des savants.[24][70] Voltaire's work was instrumental in bringing about general acceptance of Newton's optical and gravitational theories in France, in contrast to the theories of Descartes.[24][71] Voltaire and the Marquise also studied history, particularly the great contributors to civilization. Voltaire's second essay in English had been "Essay upon the Civil Wars in France". It was followed by La Henriade, an epic poem on the French King Henri IV, glorifying his attempt to end the Catholic-Protestant massacres with the Edict of Nantes, which established religious toleration. There followed a historical novel on King Charles XII of Sweden. These, along with his Letters on the English, mark the beginning of Voltaire's open criticism of intolerance and established religions.[citation needed] Voltaire and the Marquise also explored philosophy, particularly metaphysical questions concerning the existence of God and the soul. Voltaire and the Marquise analyzed the Bible and concluded that much of its content was dubious.[72] Voltaire's critical views on religion led to his belief in separation of church and state and religious freedom, ideas that he had formed after his stay in England. In August 1736, Frederick the Great, then Crown Prince of Prussia and a great admirer of Voltaire, initiated a correspondence with him.[73] That December, Voltaire moved to Holland for two months and became acquainted with the scientists Herman Boerhaave and Willem 's Gravesande.[74] From mid-1739 to mid-1740 Voltaire lived largely in Brussels, at first with the Marquise, who was unsuccessfully attempting to pursue a 60-year-old family legal case regarding the ownership of two estates in Limburg.[75] In July 1740, he traveled to the Hague on behalf of Frederick in an attempt to dissuade a dubious publisher, van Duren, from printing without permission Frederick's Anti-Machiavel.[76] In September Voltaire and Frederick (now King) met for the first time in Moyland Castle near Cleves and in November Voltaire was Frederick's guest in Berlin for two weeks,[77] followed by a meeting in September 1742 at Aix-la-Chapelle.[78] Voltaire was sent to Frederick's court in 1743 by the French government as an envoy and spy to gauge Frederick's military intentions in the War of the Austrian Succession.[79] Though deeply committed to the Marquise, Voltaire by 1744 found life at her château confining. On a visit to Paris that year, he found a new love—his niece. At first, his attraction to Marie Louise Mignot was clearly sexual, as evidenced by his letters to her (only discovered in 1957).[80][81] Much later, they lived together, perhaps platonically, and remained together until Voltaire's death. Meanwhile, the Marquise also took a lover, the Marquis de Saint-Lambert.[82] Prussia  Die Tafelrunde by Adolph von Menzel: guests of Frederick the Great at Sanssouci, including members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences and Voltaire (third from left) After the death of the Marquise in childbirth in September 1749, Voltaire briefly returned to Paris and in mid-1750 moved to Prussia at the invitation of Frederick the Great.[83] The Prussian king (with the permission of Louis XV) made him a chamberlain in his household, appointed him to the Order of Merit, and gave him a salary of 20,000 French livres a year.[84] He had rooms at Sanssouci and Charlottenburg Palace.[85] Life went well for Voltaire at first,[86] and in 1751 he completed Micromégas, a piece of science fiction involving ambassadors from another planet witnessing the follies of humankind.[87] However, his relationship with Frederick began to deteriorate after he was accused of theft and forgery by a Jewish financier, Abraham Hirschel, who had invested in Saxon government bonds on behalf of Voltaire at a time when Frederick was involved in sensitive diplomatic negotiations with Saxony.[88] He encountered other difficulties: an argument with Maupertuis, the president of the Berlin Academy of Science and a former rival for Émilie's affections, provoked Voltaire's Diatribe du docteur Akakia ("Diatribe of Doctor Akakia"), which satirized some of Maupertuis's theories and his persecutions of a mutual acquaintance, Johann Samuel König. This greatly angered Frederick, who ordered all copies of the document burned.[89] On 1 January 1752, Voltaire offered to resign as chamberlain and return his insignia of the Order of Merit; at first, Frederick refused until eventually permitting Voltaire to leave in March.[90] On a slow journey back to France, Voltaire stayed at Leipzig and Gotha for a month each, and Kassel for two weeks, arriving at Frankfurt on 31 May. The following morning, he was detained at an inn by Frederick's agents, who held him in the city for over three weeks while Voltaire and Frederick argued by letter over the return of a satirical book of poetry Frederick had lent to Voltaire. Marie Louise joined him on 9 June. She and her uncle only left Frankfurt in July after she had defended herself from the unwanted advances of one of Frederick's agents, and Voltaire's luggage had been ransacked and valuable items taken.[91] Voltaire's attempts to vilify Frederick for his agents' actions at Frankfurt were largely unsuccessful, including his Mémoires pour Servir à la Vie de M. de Voltaire, published posthumously, in which he also explicitly made mention of Frederick's homosexuality, when he described how the king regularly invited pages, young cadets or lieutenants from his regiment to have coffee with him and then withdrew with the favourite for a quickie.[92][93] However, the correspondence between them continued, and though they never met in person again, after the Seven Years' War they largely reconciled.[94] Geneva and Ferney  Voltaire's château at Ferney, France Voltaire's slow progress toward Paris continued through Mainz, Mannheim, Strasbourg, and Colmar,[95] but in January 1754 Louis XV banned him from Paris,[96] and he turned for Geneva, near which he bought a large estate (Les Délices) in early 1755.[97] Though he was received openly at first, the law in Geneva, which banned theatrical performances, and the publication of The Maid of Orleans against his will soured his relationship with Calvinist Genevans.[98] In late 1758, he bought an even larger estate at Ferney, on the French side of the Franco-Swiss border.[99] The town would adopt his name, calling itself Ferney-Voltaire, and this became its official name in 1878.[100] Early in 1759, Voltaire completed and published Candide, ou l'Optimisme (Candide, or Optimism). This satire on Leibniz's philosophy of optimistic determinism remains Voltaire's best-known work. He would stay in Ferney for most of the remaining 20 years of his life, frequently entertaining distinguished guests, such as James Boswell (who recorded their conversations in his journal and memoranda),[101] Adam Smith, Giacomo Casanova, and Edward Gibbon. In 1764, he published one of his best-known philosophical works, the Dictionnaire philosophique, a series of articles mainly on Christian history and dogmas, a few of which were originally written in Berlin.[43] From 1762, as an unmatched intellectual celebrity, he began to champion unjustly persecuted individuals, most famously the Huguenot merchant Jean Calas.[43] Calas had been tortured to death in 1763, supposedly because he had murdered his eldest son for wanting to convert to Catholicism. His possessions were confiscated, and his two daughters were taken from his widow and forced into Catholic convents. Voltaire, seeing this as a clear case of religious persecution, managed to overturn the conviction in 1765.[102] Voltaire was initiated into Freemasonry a little over a month before his death. On 4 April 1778, he attended la Loge des Neuf Sœurs in Paris, and became an Entered Apprentice Freemason. According to some sources, "Benjamin Franklin ... urged Voltaire to become a freemason; and Voltaire agreed, perhaps only to please Franklin."[103][104][105] However, Franklin was merely a visitor at the time Voltaire was initiated, the two only met a month before Voltaire's death, and their interactions with each other were brief.[106]  House in Paris where Voltaire died |

キャリア 初期の小説 古代マケドニアを舞台にしたヴォルテールの次の戯曲『アルテミラ』は、1720年2月15日に初演された。これは失敗作であり、テキストの断片のみが現存 している。[32] 代わりに、1717年初頭に書き始めたフランスのアンリ4世を題材にした叙事詩に着手した。[33] 出版許可が下りなかったため、1722年8月、ヴォルテールはフランス国外の出版社を探すために北に向かった。その旅には、彼の愛人である若い未亡人、マ リー=マルグリット・ド・ルーペルモンデが同行した。 ブリュッセルで、ヴォルテールとルソーは数日間を共に過ごし、その後ヴォルテールと愛人は北に向かって旅を続けた。最終的にハーグで出版社が確保された。 [35] オランダで、ヴォルテールはオランダ社会の開放性と寛容さに感銘を受けた。[36] フランスに戻ると、ルーアンで2番目の出版社を確保し、その出版社は『ラ・アンリエット』を秘密裏に出版することに同意した。[37] 1723年11月に1か月間続いた天然痘の感染から回復すると、最初のコピーがパリに密輸され、配布された。[38] この詩はたちまち成功を収めたが、ヴォルテールの新作戯曲『マリアンヌ』は1724年3月の初演時には失敗に終わった。[39] その後大幅に改稿され、1725年4月にコメディ・フランセーズで上演され、好評を博した。[39] 1725年9月のルイ15世とマリー・レクザンスカの結婚式では、余興のひとつとして上演された。[39] イギリス 1726年初頭、貴族のシュヴァリエ・ド・ロアン=シャボーは、ヴォルテールが改名したことを嘲笑し、ヴォルテールは、自分の名前は世間の尊敬を勝ち取る だろうが、ロアンは自分の評判を落とすだろうと反論した。[40] 激怒したロアンは、数日後、自分の暴漢たちにヴォルテールを暴行させた。[41] ヴォルテールは、ロアンに決闘を申し込んだが、 しかし、権力を持つロアン家は、1726年4月17日にヴォルテールを逮捕させ、裁判なしでバスチーユに投獄させた。[42][43] 無期限の投獄を恐れたヴォルテールは、代替の刑としてイギリスへの追放を求めた。フランス当局はこれを認めた。[44] 5月2日、ヴォルテールはバスチーユからカレーまで護送され、イギリスに向けて出航した。[45]  『ニュートンの哲学の諸原理』、1738年 イギリスでは、ヴォルテールは主にワンドワースに住み、エヴァラード・フォークナー(Everard Fawkener)などの知人たちと交流した。[46] 1727年12月から1728年6月までは、イギリスの出版社に近いコヴェント・ガーデン(Maiden Lane)に滞在し、 。ヴォルテールは英国の上流社会で広く知られており、アレクサンダー・ポープ、ジョン・ゲイ、ジョナサン・スウィフト、メアリー・ワードリー・モンタ ギュー夫人、マールバラ公爵夫人サラなど、多くの貴族や王族と面識があった。彼は、フランスの絶対王政とは対照的なイギリスの立憲君主制に興味をそそら れ、また、同国の言論や宗教の自由にも強く惹かれた。[49] 彼は同時代の作家たちから影響を受け、特に シェイクスピアは、当時まだヨーロッパ大陸ではほとんど知られていなかった。[50] ヴォルテールは、シェイクスピアが新古典主義の基準から逸脱していると指摘していたが、シェイクスピアをフランス演劇の模範とみなしていた。フランス演劇 は洗練されているものの、舞台上のアクションに欠けていたからだ。しかし、その後シェイクスピアの影響がフランスで広まり始めると、ヴォルテールはシェイ クスピアの蛮行とみなしたものを非難し、自身の戯曲で対抗しようとした。ヴォルテールはアイザック・ニュートンの葬儀に参列し[a]、ニュートンの姪であ るキャサリン・コンデュイットにも会った可能性がある[47]。1727年、ヴォルテールは『フランス内戦について』と『ホメーロスからミルトンまでの ヨーロッパ諸国民の叙事詩について』の2つのエッセイを英語で出版した[47]。また、クエーカー教徒の礼拝に出席した後、クエーカー教徒に関する手紙も 出版した[51]。 2年半の亡命生活の後、ヴォルテールはフランスに戻った。ディエップに数ヶ月滞在した後、当局はパリへの帰還を許可した。ディナーの席で、フランスの数学 者シャルル・マリー・ド・ラ・コンダミーヌが、フランス政府が負債返済のために開催した宝くじを買い占めることを提案し 政府が負債を返済するために開催した宝くじの購入を提案し、ヴォルテールもその共同事業に参加し、おそらく100万リーヴルを手に入れた。[53] 彼はその資金を賢く運用し、その実績を基に財務院を説得して、父親から相続した信託資金の管理権を手に入れた。彼は今や疑いなく裕福であった。[54] [55] 1732年には、彼の戯曲『ザイール』が成功を収め、1733年に出版された際には、フォークナーに献辞が捧げられ、英国の自由と商業が称賛された。 [56] 彼は、英国政府、文学、宗教、科学に関する賞賛に満ちたエッセイを『英国国民論』(ロンドン、1733年)で発表した。 33年)を出版した。[57] 1734年には、この著作は『哲学書簡』としてルーアンで出版され、大きなスキャンダルを引き起こした。[58][b] 王室検閲官の承認を得ずに出版されたこの著作では、イギリスの立憲君主制が、特に宗教的寛容の点において、フランスよりも発展しており、人権を尊重してい ると賞賛していた。この本は公開で焼却され、発禁処分となり、ヴォルテールは再びパリを離れることを余儀なくされた。[24] シュリー城  ニュートンの哲学に関するヴォルテールの著書の口絵には、ニュートンの天啓をヴォルテールに伝えるヴォルテールのミューズとしてエミリ・デュ・シャトレが描かれている。 1733年、ヴォルテールはエミリー・デュ・シャトレ(シャトレ侯爵夫人)と出会った。彼女は数学者であり、3児の母でもあった。12歳年下の彼女とヴォ ルテールは16年間関係を続けることになる。『手紙』の出版後に逮捕を免れるため、ヴォルテールはシャンパーニュとロレーヌの境界にあるシレの彼女の夫の 城に身を寄せた。 61] ヴォルテールは建物の改修費用を負担し、[62] エミリーの夫は妻とその愛人とともに城に滞在することもあった。[63] 知的な情人の二人は、当時としては膨大な21,000冊もの書籍を集めた。[64] 二人はこれらの書籍を研究し、シレで科学実験を行った。その中には、火の性質を解明しようとする試みも含まれていた。[65] 当局とのこれまでの衝突から学んだヴォルテールは、当局との正面からの対決を避け、厄介な責任を一切否定する習慣を身につけた。[66] 彼は『メローペ』(または『フランス版メローペ』)などの戯曲を書き続け、科学と歴史に関する長年の研究を始めた。この時も、ヴォルテールにとっての主な インスピレーションの源は、英国亡命時代の数年間であり、その間、彼はニュートンの著作から強い影響を受けていた。ヴォルテールはニュートンの理論を強く 信じており、シレで光学実験を行っていた[67]。また、ニュートンがリンゴの落下からひらめきを得たという有名な話の普及者の一人であり、この話はロン ドンでニュートンの姪から聞いたもので、手紙の中で初めて言及したものである[47]。  モーリス・カンタン・ド・ラ・トゥールによるパステル画、1735年 1735年の秋、ヴォルテールのもとにフランチェスコ・アルガロッティが訪れた。アルガロッティはニュートンに関する本をイタリア語で執筆中であった。 [68] その訪問に触発されたこともあり、侯爵夫人はニュートンのラテン語の著書『プリンキピア』をフランス語に翻訳した。このフランス語版は21世紀まで決定版 であり続けた。[24] 彼女とヴォルテールは、ニュートンの同時代人でライバルであったゴットフリート・ライプニッツの哲学にも興味を持っていた。ヴォルテールはあくまでも ニュートン主義者であったが、侯爵夫人はライプニッツの批判のいくつかの側面を取り入れた。[24][69] ヴォルテール自身の著書『ニュートンの哲学の諸要素』は、偉大な科学者をより多くの人々に身近なものにした。侯爵夫人は 『学芸誌』に祝辞を書いた。[24][70] ヴォルテールの功績により、デカルトの理論とは対照的に、ニュートンの光学理論と万有引力理論がフランスで広く受け入れられるようになった。[24] [71] ヴォルテールと侯爵夫人は歴史、特に文明への偉大な貢献者について研究した。ヴォルテールの2作目の英語論文は「フランス内戦についての試論」であった。 その後、フランス王アンリ4世を題材とした叙事詩『ラ・アンリアード』が続き、ナントの勅令によってカトリックとプロテスタントの虐殺を終わらせようとし た彼の試みを称賛し、宗教的寛容を確立した。その後、スウェーデンの国王カール12世を題材にした歴史小説が続いた。これらは『英人論』とともに、ヴォル テールが不寛容と既成宗教を公然と批判し始めたことを示す。ヴォルテールとマリー・ド・メディシスは、特に神と魂の存在に関する形而上学的な疑問につい て、哲学を探求した。ヴォルテールとマリー=ジョゼフは聖書を分析し、その内容の多くは疑わしいと結論付けた。[72] ヴォルテールの宗教に対する批判的な見解は、彼がイギリスに滞在した後に形成した、政教分離と信教の自由という信念につながった。 1736年8月、当時プロイセン王太子で、ヴォルテールを敬愛していたフリードリヒ大王は、彼との文通を始めた。[73] その12月、ヴォルテールは2ヶ月間オランダに滞在し、科学者のヘルマン・ボエルハーフェとウィレム・ス・グラーヴェンザンドと知り合った。[74] 1739年半ばから1740年半ばにかけて、ヴォルテールは主にブリュッセルに住み、最初は侯爵夫人と 、彼女はリンブルフ州にある2つの土地の所有権をめぐる60年前からの家族の訴訟を不成功に終わらせようとしていた。[75] 1740年7月、彼はフレデリックの代理としてハーグを訪れ、フレデリックの『アンチ・マキアヴェリ』を無断で出版しようとしていた疑わしい出版社のファ ン・ドゥーレンを説得しようとした。[76] 9月、ヴォルテールとフレデリック(現国王)は 9月にヴォルテールとフリードリヒ(このときすでに王)は、クレーフェにほど近いモイランド城で初めて会い、11月にはヴォルテールはベルリンで2週間フ リードリヒの客として滞在した。[77] それに続いて1742年9月には、アーヘンで会合が持たれた。[78] 1743年、ヴォルテールはフランス政府から特使およびスパイとしてフリードリヒの宮廷に派遣され、オーストリア継承戦争におけるフリードリヒの軍事的意 図を探った。[79] 侯爵夫人に深く献身していたものの、1744年にはヴォルテールは彼女の城での生活に閉塞感を抱いていた。その年、パリを訪れた際に、彼は新しい愛を見つ けた。それは姪だった。当初、マリー・ルイーズ・ミニョへの彼の魅力は明らかに性的なものであった。それは彼女への手紙(1957年に発見された)によっ て証明されている。[80][81] その後、彼らは一緒に暮らし、おそらくはプラトニックな関係であったが、ヴォルテールが亡くなるまで一緒に暮らした。その間、侯爵夫人はサン=ランベール 侯爵という恋人もいた。 プロイセン  アドルフ・フォン・メンツェルの『晩餐会』:サンスーシ宮殿におけるフリードリヒ大王の客たち、プロイセン科学アカデミーのメンバーとヴォルテール(左から3人目) 1749年9月に出産中に侯爵夫人が死去すると、ヴォルテールは一時的にパリに戻り、1750年半ばにフリードリヒ大王の招きに応じてプロイセンに移っ た。[83] プロイセン王(ルイ15世の許可を得て)は彼を宮廷侍従に任命し、功労勲章を授け、 功労勲章を授与し、年俸2万リーヴルの給与を与えた。[84] 彼はサンスーシ宮殿とシャルロッテンブルク宮殿に部屋を与えられた。[85] 当初は順調な生活を送っていたヴォルテールだが、1751年には、 別の惑星から来た大使が人類の愚行を目撃するという内容である。[87] しかし、フリードリヒとの関係は悪化し始めた。ユダヤ人の金融業者アブラハム・ヒルシェルが、ヴォルテールのためにザクセンの国債に投資していた時期に、 ヴォルテールが窃盗と偽造の容疑で告発されたためである。フリードリヒはザクセンとの微妙な外交交渉に関わっていた。[88] 彼は他にも困難に直面した。ベルリン科学アカデミーの総裁であり、かつてエミリーの愛情を巡ってのライバルであったモーペルテュイとの口論が、モーペル テュイの理論や、彼が共通の知人であるヨハン・サミュエル・ケーニヒを迫害したことの一部を風刺した『アカイア博士の暴言』をヴォルテールに書かせた。こ れに激怒したフリードリヒは、その文書のすべてのコピーを焼却するよう命じた。[89] 1752年1月1日、ヴォルテールは侍従を辞任し、功労勲章の記章を返還することを申し出た。当初、フリードリヒは拒否したが、最終的には3月にヴォル テールを出国させた。[90] フランスへの長い帰路の途中、ヴォルテールはライプツィヒとゴータに1か月ずつ、カッセルに2週間滞在し、5月31日にフランクフルトに到着した。翌朝、 彼はフリードリヒのエージェントたちによって宿屋に足止めされ、3週間以上も街に留め置かれた。その間、フリードリヒがヴォルテールに貸した風刺詩集の返 却をめぐって、ヴォルテールとフリードリヒが手紙で口論を繰り広げていた。マリー・ルイーズは6月9日に合流した。彼女と叔父は、フリードリヒのエージェ ントの一人から望ましくないアプローチを受けた後、ヴォルテールの荷物が漁られ貴重品が持ち去られた後、7月にようやくフランクフルトを離れた。 ヴォルテールは、フランクフルトでの側近たちの行動を理由にフリードリヒを中傷しようとしたが、その試みはほとんど成功しなかった。死後に出版された 『ヴォルテール伝』でも、彼はフリードリヒの同性愛について明確に言及しており、王が定期的に近衛兵の小姓や若い士官を 、若い士官候補生や連隊の副官を定期的に招いて一緒にコーヒーを飲み、その後お気に入りの相手と2人きりで外出していたことを説明している。[92] [93] しかし、2人の間の文通は続き、その後2度と直接会うことはなかったが、七年戦争の後、2人はほぼ和解した。[94] ジュネーヴとフェルネー  ヴォルテールのシャトー(フランス、フェルネー) ヴォルテールはマインツ、マンハイム、ストラスブール、コルマールとゆっくりとパリに向かって進み続けたが[95]、1754年1月、ルイ15世は彼をパ リから追放した[96]。そして、彼はジュネーヴに向かい、1755年初頭にその近くに広大な土地(レ・デリス)を購入した[97]。当初は公然と迎え入 れられたものの、演劇公演を禁止するジュネーヴの法律や、 また、彼の意に反して『オルレアン公女』の出版が許可されたことで、カルヴァン派のジュネーヴ市民との関係は悪化した。[98] 1758年の終わり頃、ヴォルテールはフランスとスイスの国境沿いにある、さらに広大なフェルネーの土地を購入した。[99] この町はヴォルテールの名を取り、フェルネー=ヴォルテールと名乗るようになり、1878年には正式名称となった。[100] 1759年初頭、ヴォルテールは『カンディード、あるいはオプティミズム(Candide, ou l'Optimisme)』を完成させ、出版した。この作品は、ライプニッツの楽観的決定論哲学を風刺したもので、ヴォルテールのもっとも有名な作品であ る。彼は残りの20年間のほとんどをフェルネーで過ごし、ジェイムズ・ボズウェル(彼らの会話を日記や覚書に記録した人物である)[101]、アダム・ス ミス、ジャコモ・カサノヴァ、エドワード・ギボンといった著名な来客を頻繁に歓待した。1764年には、彼の最も有名な哲学作品のひとつである『哲学事 典』を出版した。この作品は、主にキリスト教の歴史と教義に関する一連の記事であり、そのうちのいくつかはベルリンで執筆されたものである。 1762年以降、比類なき知識人として、不当に迫害された人々、特にユグノーの商人ジャン・カラスを擁護し始めた。カラスは1763年に拷問の末に死亡し たが、その理由は、カトリックへの改宗を望む長男を殺害したためとされている。カラスは財産を没収され、2人の娘は未亡人から引き離されてカトリックの修 道院に入れられた。ヴォルテールはこれを明らかな宗教迫害事件と見なし、1765年に有罪判決を覆すことに成功した。 ヴォルテールは死の1か月余り前にフリーメイソンに入会した。1778年4月4日、彼はパリの「ラ・ローグ・デ・ヌフ・スール」に出席し、フリーメイソン の見習いとなった。一部の情報源によると、「ベンジャミン・フランクリンはヴォルテールにフリーメイソンになるよう強く勧め、ヴォルテールはフランクリン を喜ばせるために同意した」という。[103][104][105] しかし、フランクリンはヴォルテールが入会した際には単なる訪問者にすぎず、2人が会ったのはヴォルテールが死ぬ1か月前だけで、彼らの交流は短期間だっ た。[106]  ヴォルテールが亡くなったパリの家 |

Death and burial Jean-Antoine Houdon, Voltaire, 1778, National Gallery of Art In February 1778, Voltaire returned to Paris for the first time in over 25 years, partly to see the opening of his latest tragedy, Irene.[107] The five-day journey was too much for the 83-year-old, and he believed he was about to die on 28 February, writing "I die adoring God, loving my friends, not hating my enemies, and detesting superstition." However, he recovered, and in March he saw a performance of Irene, where he was treated by the audience as a returning hero.[43] He soon became ill again and died on 30 May 1778. The accounts of his deathbed have been numerous and varying, and it has not been possible to establish the details of what precisely occurred. His enemies related that he repented and accepted the last rites from a Catholic priest, or that he died in agony of body and soul, while his adherents told of his defiance to his last breath.[108] According to one story of his last words, when the priest urged him to renounce Satan, he replied, "This is no time to make new enemies."[109] Because of his well-known criticism of the Church, which he had refused to retract before his death, Voltaire was denied a Christian burial in Paris,[110] but friends and relations managed to bury his body secretly at the Abbey of Scellières [fr] in Champagne, where Marie Louise's brother was abbé.[111] His heart and brain were embalmed separately.[112]  Voltaire's tomb in the Paris Panthéon  Tomb of Voltaire in the Pantheon in Paris On 11 July 1791, the National Assembly of France, regarding Voltaire as a forerunner of the French Revolution, had his remains brought back to Paris and enshrined in the Panthéon.[113][c] An estimated million people attended the procession, which stretched throughout Paris. There was an elaborate ceremony, including music composed for the event by André Grétry.[116] |

死と埋葬 ジャン・アントワーヌ・ウードン、ヴォルテール、1778年、ナショナル・ギャラリー・オブ・アート 1778年2月、ヴォルテールは25年ぶりにパリに戻った。その目的の一つは、自身の最新作である悲劇『イレーネ』の初演を見るためであった。[107] 83歳だったヴォルテールにとって5日間の旅は過酷すぎた。2月28日、ヴォルテールは「私は神を崇め、友人を愛し、敵を憎まず、迷信を嫌悪して死を迎え るだろう」と書き残している。しかし、彼は回復し、3月には『アイリーン』の公演を観劇し、観客から英雄として迎えられた。 間もなく再び病に倒れ、1778年5月30日に死去した。彼の臨終についての証言は数多くあり、内容も様々であるため、正確に何が起こったのかを特定する ことはできない。彼の敵対者たちは、彼が悔い改め、カトリックの司祭から最後の儀式を受けたと語った。あるいは、彼は肉体と精神の苦痛にさいなまれながら 死んだと語った。一方、彼の信奉者たちは、彼が最後の息を引き取るまで抵抗を続けたと語った。[108] 彼の最期の言葉についての話の一つによると、司祭が彼にサタンを棄てるよう促したところ、彼は「今は新たな敵を作る時ではない」と答えたという。 [109] 教会に対する批判で知られていたヴォルテールは、生前その撤回を拒んでいたため、パリでのキリスト教式の埋葬は認められなかったが、友人や親族の手でシャンパーニュ地方にあるセリエール修道院に密かに埋葬された。同修道院の院長はマリー・ルイーズの兄が務めていた。  パリのパンテオンにあるヴォルテールの墓  パリのパンテオンにあるヴォルテールの墓 1791年7月11日、フランス国民公会はヴォルテールをフランス革命の先駆者と見なし、彼の遺骸をパリに運び、パンテオンに安置した。[113][c] パリ全体に広がったその行列には、100万人もの人々が参加したと推定されている。アンドレ・グレトリがこのイベントのために作曲した音楽を含む、手の込 んだ式典が行われた。[116] |

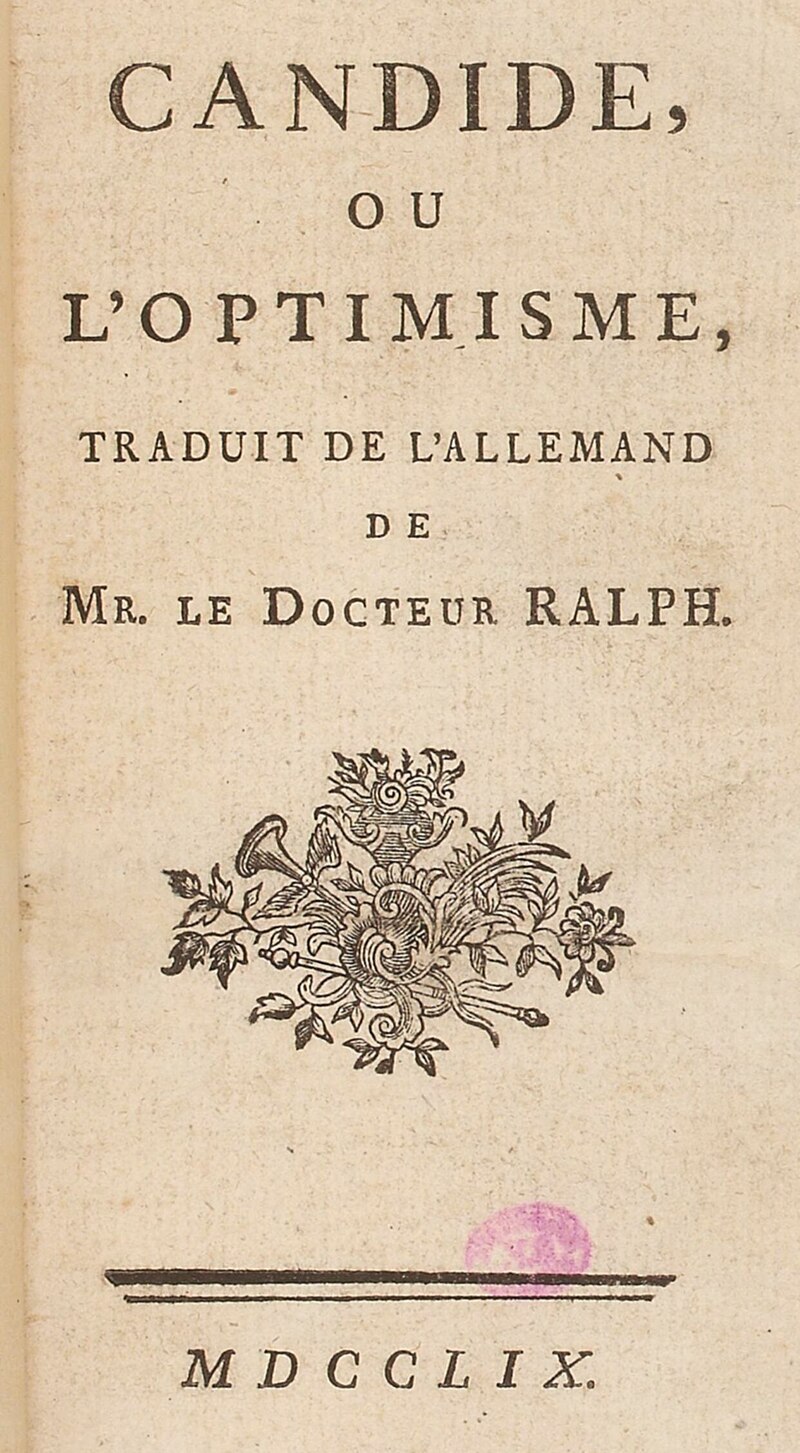

| Writings History Voltaire had an enormous influence on the development of historiography through his demonstration of fresh new ways to look at the past. Guillaume de Syon argues: Voltaire recast historiography in both factual and analytical terms. Not only did he reject traditional biographies and accounts that claim the work of supernatural forces, but he went so far as to suggest that earlier historiography was rife with falsified evidence and required new investigations at the source. Such an outlook was not unique in that the scientific spirit that 18th-century intellectuals perceived themselves as invested with. A rationalistic approach was key to rewriting history.[117] Voltaire's best-known histories are History of Charles XII (1731), The Age of Louis XIV (1751), and his Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the Nations (1756). He broke from the tradition of narrating diplomatic and military events, and emphasized customs, social history and achievements in the arts and sciences. The Essay on Customs traced the progress of world civilization in a universal context, rejecting both nationalism and the traditional Christian frame of reference. Influenced by Bossuet's Discourse on Universal History (1682), he was the first scholar to attempt seriously a history of the world, eliminating theological frameworks, and emphasizing economics, culture and political history. He treated Europe as a whole rather than a collection of nations. He was the first to emphasize the debt of medieval culture to Middle Eastern civilization, but otherwise was weak on the Middle Ages. Although he repeatedly warned against political bias on the part of the historian, he did not miss many opportunities to expose the intolerance and frauds of the church over the ages. Voltaire advised scholars that anything contradicting the normal course of nature was not to be believed. Although he found evil in the historical record, he fervently believed reason and expanding literacy would lead to progress. Voltaire explains his view of historiography in his article on "History" in Diderot's Encyclopédie: "One demands of modern historians more details, better ascertained facts, precise dates, more attention to customs, laws, mores, commerce, finance, agriculture, population." Voltaire's histories imposed the values of the Enlightenment on the past, but at the same time he helped free historiography from antiquarianism, Eurocentrism, religious intolerance and a concentration on great men, diplomacy, and warfare.[118][119] Yale professor Peter Gay says Voltaire wrote "very good history", citing his "scrupulous concern for truths", "careful sifting of evidence", "intelligent selection of what is important", "keen sense of drama", and "grasp of the fact that a whole civilization is a unit of study".[120] Poetry From an early age, Voltaire displayed a talent for writing verse, and his first published work was poetry. He wrote two book-long epic poems, including the first ever written in French, the Henriade, and later, The Maid of Orleans, besides many other smaller pieces.[citation needed] The Henriade was written in imitation of Virgil, using the alexandrine couplet reformed and rendered monotonous for modern readers but it was a huge success in the 18th and early 19th century, with sixty-five editions and translations into several languages. The epic poem transformed French King Henry IV into a national hero for his attempts at instituting tolerance with his Edict of Nantes. La Pucelle, on the other hand, is a burlesque on the legend of Joan of Arc. Prose  Title page of Voltaire's Candide, 1759 Many of Voltaire's prose works and romances, usually composed as pamphlets, were written as polemics. Candide attacks the passivity inspired by Leibniz's philosophy of optimism through the character Pangloss's frequent refrain that, because God created it, this is of necessity the "best of all possible worlds". L'Homme aux quarante ecus (The Man of Forty Pieces of Silver) addresses social and political ways of the time; Zadig and others, the received forms of moral and metaphysical orthodoxy; and some were written to deride the Bible. In these works, Voltaire's ironic style, free of exaggeration, is apparent, particularly the restraint and simplicity of the verbal treatment.[121] Candide in particular is the best example of his style. Voltaire also has—in common with Jonathan Swift—the distinction of paving the way for science fiction's philosophical irony, particularly in his Micromégas and the vignette "Plato's Dream" (1756).  Voltaire at Frederick the Great's Sanssouci, by Pierre Charles Baquoy In general, his criticism and miscellaneous writing show a similar style to Voltaire's other works. Almost all of his more substantive works, whether in verse or prose, are preceded by prefaces of one sort or another, which are models of his caustic yet conversational tone. In a vast variety of nondescript pamphlets and writings, he displays his skills at journalism. In pure literary criticism his principal work is the Commentaire sur Corneille, although he wrote many more similar works—sometimes (as in his Life and Notices of Molière) independently and sometimes as part of his Siècles.[122] Voltaire's works, especially his private letters, frequently urge the reader: "écrasez l'infâme", or "crush the infamous".[123] The phrase refers to contemporaneous abuses of power by royal and religious authorities, and the superstition and intolerance fomented by the clergy.[124] He had seen and felt these effects in his own exiles, the burnings of his books and those of many others, and in the atrocious persecution of Jean Calas and François-Jean de la Barre.[125] He stated in one of his most famous quotes that "Superstition sets the whole world in flames; philosophy quenches them" (La superstition met le monde entier en flammes; la philosophie les éteint).[126] The most oft-cited Voltaire quotation is apocryphal. He is incorrectly credited with writing, "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it." These were not his words, but rather those of Evelyn Beatrice Hall, written under the pseudonym S. G. Tallentyre in her 1906 biographical book The Friends of Voltaire. Hall intended to summarize in her own words Voltaire's attitude towards Claude Adrien Helvétius and his controversial book De l'esprit, but her first-person expression was mistaken for an actual quotation from Voltaire. Her interpretation does capture the spirit of Voltaire's attitude towards Helvétius; it had been said Hall's summary was inspired by a quotation found in a 1770 Voltaire letter to an Abbot le Riche, in which he was reported to have said, "I detest what you write, but I would give my life to make it possible for you to continue to write."[127] Nevertheless, scholars believe there must have again been misinterpretation, as the letter does not seem to contain any such quote.[d] Voltaire's first major philosophical work in his battle against "l'infâme" was the Traité sur la tolérance (Treatise on Tolerance), exposing the Calas affair, along with the tolerance exercised by other faiths and in other eras (for example, by the Jews, the Romans, the Greeks and the Chinese). Then, in his Dictionnaire philosophique, containing such articles as "Abraham", "Genesis", "Church Council", he wrote about what he perceived as the human origins of dogmas and beliefs, as well as inhuman behavior of religious and political institutions in shedding blood over the quarrels of competing sects. Amongst other targets, Voltaire criticized France's colonial policy in North America, dismissing the vast territory of New France as "a few acres of snow" ("quelques arpents de neige"). Letters Voltaire also engaged in an enormous amount of private correspondence during his life, totalling over 20,000 letters. Theodore Besterman's collected edition of these letters, completed only in 1964, fills 102 volumes.[128] One historian called the letters "a feast not only of wit and eloquence but of warm friendship, humane feeling, and incisive thought."[129] In Voltaire's correspondence with Catherine the Great he derided democracy. He wrote, "Almost nothing great has ever been done in the world except by the genius and firmness of a single man combating the prejudices of the multitude."[130] |

著作 歴史 過去を新しい視点で見る方法を示したことで、ヴォルテールは歴史学の発展に多大な影響を与えた。ギヨーム・ド・シオンは次のように主張している。 ヴォルテールは史学を事実と分析の両面から再構築した。彼は超自然的な力の働きを主張する伝統的な伝記や記録を拒絶しただけでなく、それ以前の史学は偽り の証拠に満ちており、新たな調査を必要としているとまで主張した。このような見解は、18世紀の知識人が自らに備わっていると認識していた科学的思考に特 有なものではなかった。合理主義的アプローチが歴史の書き換えの鍵であった。[117] ヴォルテールが最もよく知られている歴史書は、『カール12世の歴史』(1731年)、『ルイ14世の時代』(1751年)、そして『諸国民の慣習と精神 についての試論』(1756年)である。彼は、外交や軍事の出来事を叙述するという伝統から脱却し、慣習、社会史、芸術や科学の業績を強調した。『慣習 論』では、世界文明の進歩を普遍的な文脈で追跡し、ナショナリズムと伝統的なキリスト教の参照枠組みの両方を否定した。ボシュエの『普遍史論』(1682 年)の影響を受け、彼は神学的な枠組みを排除し、経済、文化、政治史を重視した世界史を本格的に試みた最初の学者となった。彼はヨーロッパを国民の集合体 ではなく、ひとつのまとまりとして扱った。彼は、中世文化が中東文明に負うところの大きさを初めて強調したが、それ以外の中世については理解が浅かった。 彼は歴史家が政治的偏見を持つことに対して繰り返し警告を発したが、教会の不寛容や不正を暴く機会を逃すことはあまりなかった。ヴォルテールは、自然の通 常の経過に反するものは信じるべきではないと学者たちに助言した。彼は歴史記録の中に悪を見出したが、理性と識字率の向上が発展につながると強く信じてい た。 ヴォルテールは、ディドロの『百科全書』の「歴史」に関する記事の中で、歴史学に対する自身の考えを次のように説明している。「現代の歴史家には、より詳 細な情報、より正確に確認された事実、正確な年代、風習、法律、慣習、商業、金融、農業、人口などへのより深い関心が求められる。」 ヴォルテールの歴史は啓蒙主義の価値観を過去に押し付けたが、同時に、歴史学を古物学、西欧中心主義、宗教的偏狭さ、偉人や外交、戦争への偏重から解放す るのに役立った。[118][119] イェール大学のピーター・ゲイ教授は、ヴォルテールは 「非常に優れた歴史」を書いたと述べ、その理由として「真実に対する細心の注意」、「証拠の慎重な選別」、「重要なものの賢明な選択」、「鋭いドラマ感 覚」、「文明全体が研究の対象となるという事実の把握」を挙げている。[120] 詩 ヴォルテールは幼い頃から詩作の才能を発揮し、最初に出版された作品は詩であった。彼は2冊の長編叙事詩を著し、その中にはフランス語で書かれた最初の作品である『アンリエット』や、後に『オルレアン公女』も含まれている。また、他にも多くの短編作品がある。 『アンリ4世』は、ヴィルジルの模倣として書かれたもので、アレクサンドランの韻文を改変し、現代の読者向けに単調なものに仕上げたが、18世紀から19 世紀初頭にかけて大成功を収め、65版が出版され、数か国語に翻訳された。この叙事詩は、ナントの勅令によって寛容を定めようとしたフランス王アンリ4世 を国民的英雄へと変貌させた。一方、『ラ・ピュセル』はジャンヌ・ダルク伝説のパロディである。 散文  ヴォルテールの『カンディード』のタイトルページ、1759年 ヴォルテールの散文作品やロマンスの多くは、通常パンフレットとして書かれたもので、論争を目的として書かれた。『カンディード』は、パンゴロスの「神が 創造したのだから、これは必然的に『ありうべき世界の中で最も良い世界』である」という頻繁に繰り返されるセリフを通して、ライプニッツの楽観主義哲学に 影響された受動性を攻撃している。『四十年の銀貨を持つ男』(L'Homme aux quarante ecus)は当時の社会や政治の在り方を、また『ザディグとその他』(Zadig and others)は道徳や形而上学の正統派の受け入れられた形式を扱っており、また聖書を嘲笑するために書かれた作品もある。これらの作品では、ヴォルテー ルの皮肉な文体が顕著であり、特に言葉の扱いにおける抑制と簡素さが際立っている。特に『カンディード』は、彼の文体を最もよく表している作品である。 ヴォルテールはまた、ジョナサン・スウィフトと共通して、特に『ミクロメガス』や挿話「プラトンの夢」(1756年)において、SFの哲学的皮肉の道を開 いたという点でも際立っている。  フリードリヒ大王のサンスーシ宮殿にて、ピエール・シャルル・バコワ作 一般的に、彼の批評や雑文は、ヴォルテールの他の作品と同様のスタイルを示している。詩であれ散文であれ、彼のより本格的な作品のほとんどすべてには、何 らかの序文が先行しており、それは辛辣でありながらも会話調のトーンの模範となっている。ありふれたパンフレットや著作の数々において、彼はジャーナリズ ムの才を発揮している。純粋な文学批評の分野では、『コルネイユ論評』が彼の主要な著作であるが、同様の著作は他にも数多くあり、時には(『モリエール 伝』のように)単独で、時には『世紀』の一部として書かれた。 ヴォルテールの作品、特に彼の私的な手紙は、しばしば「écrasez l'infâme(悪名高きものを打ち砕け)」と読者に呼びかけている。[123] このフレーズは、王や宗教当局による権力の乱用、および聖職者たちによって煽られた迷信と不寛容を指している。[124] 彼は、自身の亡命生活や、自身の著作や他の多くの著作の焼却、 、ジャン・カラスとフランソワ=ジャン・ド・ラ・バールに対する残虐な迫害の中で見て感じていた。[125] 彼は最も有名な引用句のひとつで、「迷信は全世界を炎上させる。哲学はそれを鎮火する」と述べている。[126] 最もよく引用されるヴォルテールの言葉は、偽書である。「私はあなたの意見に反対だが、それを言う権利は死守する」という言葉を書いたのはヴォルテールで あると誤って考えられているが、 これは彼の言葉ではなく、1906年に出版された伝記『ヴォルテールの友人たち』の中で、S. G. Tallentyreというペンネームで書かれた、Evelyn Beatrice Hallの言葉である。Hallは、クロード・アドリアン・ヘルヴェティウスと彼の物議を醸した著書『精神について』に対するヴォルテールの態度を、自分 の言葉で要約しようとしたが、彼女の一人称表現がヴォルテールの実際の引用文と誤解された。彼女の解釈は、ヴォルテールがヘルヴェティウスに対して抱いて いた態度の精神を捉えている。ホールの要約は、1770年にヴォルテールがリッシュ修道院長に宛てた手紙の中の引用から着想を得たものだと言われている。 その手紙の中でヴォルテールは、 「私はあなたが書くものを嫌悪しているが、あなたが書き続けることができるように、私は自分の命を捧げよう」と述べたと伝えられている。[127] しかし、学者たちは、その手紙にはそのような引用は含まれていないようであるため、またしても誤解があったに違いないと考えている。[d] ヴォルテールが「不道徳な者」との戦いにおいて最初に著した主要な哲学書は『寛容についての論考』であり、カルヴァン派の事件を暴露し、他の宗教や時代に おける寛容さ(例えば、ユダヤ人、ローマ人、ギリシア人、中国人による)を論じている。そして、彼の著書『哲学辞典』には、「アブラハム」、「創世記」、 「教会会議」などの項目があり、彼は、教義や信仰の人間的な起源、および宗派間の争いによって血を流す宗教的・政治的機関の非人間的な行動について書い た。そのほかにも、ヴォルテールは北米におけるフランスの植民地政策を批判し、広大なヌーベルフランスを「雪に覆われた数エーカーの土地」と切り捨てた。 手紙 ヴォルテールは生涯にわたって膨大な数の私信も交わしており、その数は2万通を超える。セオドア・ベスターマンの全集は1964年に完成したが、その巻数 は102巻に及ぶ。ある歴史家は、これらの手紙を「機知と雄弁さだけでなく、温かい友情、人間的な思いやり、鋭い洞察に満ちたもの」と呼んでいる。 ヴォルテールは、エカチェリーナ2世との書簡の中で、民主主義を嘲笑した。「世界において偉大なことを成し遂げたものは、ほとんど皆無である。それは、大衆の偏見と戦う一人の男の天才と不屈の精神によるもの以外にはない」と彼は書いた。[130] |

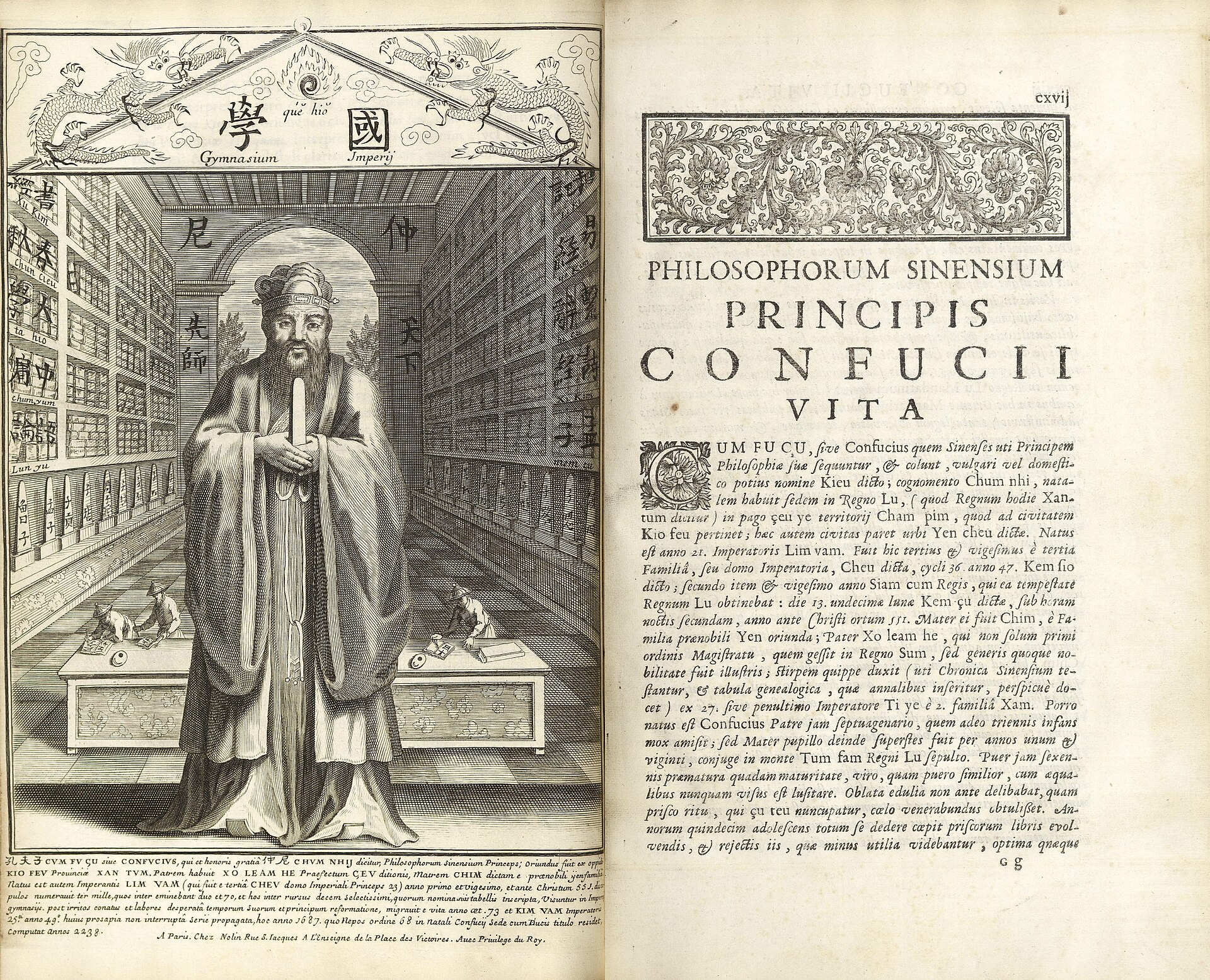

Religious and philosophical views Voltaire at 70; engraving from 1843 edition of his Philosophical Dictionary Like other key Enlightenment thinkers, Voltaire was a deist.[131] He challenged orthodoxy by asking: "What is faith? Is it to believe that which is evident? No. It is perfectly evident to my mind that there exists a necessary, eternal, supreme, and intelligent being. This is no matter of faith, but of reason."[132][133] In a 1763 essay, Voltaire supported the toleration of other religions and ethnicities: "It does not require great art, or magnificently trained eloquence, to prove that Christians should tolerate each other. I, however, am going further: I say that we should regard all men as our brothers. What? The Turk my brother? The Chinaman my brother? The Jew? The Siam? Yes, without doubt; are we not all children of the same father and creatures of the same God?"[134] In one of his many denunciations of priests of every religious sect, Voltaire describes them as those who "rise from an incestuous bed, manufacture a hundred versions of God, then eat and drink God, then piss and shit God."[135] Christianity Historians have described Voltaire's description of the history of Christianity as "propagandistic".[136] His Dictionnaire philosophique is responsible for the myth that the early Church had fifty gospels before settling on the standard canonical four as well as propagating the myth that the canon of the New Testament was decided at the First Council of Nicaea. Voltaire is partially responsible for the misattribution of the expression Credo quia absurdum to the Church Fathers.[137] Furthermore, despite the death of Hypatia being the result of finding herself in the crossfires of a mob (likely Christian) during a political feud in 4th-century Alexandria, Voltaire promoted the theory that she was stripped naked and murdered by the minions of the bishop Cyril of Alexandria, concluding by stating that "when one finds a beautiful woman completely naked, it is not for the purpose of massacring her." Voltaire meant for this argument to bolster one of his anti-Catholic tracts.[138] In a letter to Frederick the Great, dated 5 January 1767, he wrote about Christianity: La nôtre [religion] est sans contredit la plus ridicule, la plus absurde, et la plus sanguinaire qui ait jamais infecté le monde.[139] "Ours [i.e., the Christian religion] is assuredly the most ridiculous, the most absurd and the most bloody religion which has ever infected this world. Your Majesty will do the human race an eternal service by extirpating this infamous superstition, I do not say among the rabble, who are not worthy of being enlightened and who are apt for every yoke; I say among honest people, among men who think, among those who wish to think. ... My one regret in dying is that I cannot aid you in this noble enterprise, the finest and most respectable which the human mind can point out."[140][141] In La bible enfin expliquée, he expressed the following attitude to lay reading of the Bible: It is characteristic of fanatics who read the holy scriptures to tell themselves: God killed, so I must kill; Abraham lied, Jacob deceived, Rachel stole: so I must steal, deceive, lie. But, wretch, you are neither Rachel, nor Jacob, nor Abraham, nor God; you are just a mad fool, and the popes who forbade the reading of the Bible were extremely wise.[142] Voltaire's opinion of the Bible was mixed. Although influenced by Socinian works such as the Bibliotheca Fratrum Polonorum, Voltaire's skeptical attitude to the Bible separated him from Unitarian theologians like Fausto Sozzini or even Biblical-political writers like John Locke.[143] His statements on religion also brought down on him the fury of the Jesuits and in particular Claude-Adrien Nonnotte.[144][145][146][147] This did not hinder his religious practice, though it did win for him a bad reputation in certain religious circles. The deeply Christian Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote to his father the year of Voltaire's death, saying, "The arch-scoundrel Voltaire has finally kicked the bucket ..."[148] Voltaire was later deemed to influence Edward Gibbon in claiming that Christianity was a contributor to the fall of the Roman Empire in his book The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: As Christianity advances, disasters befall the [Roman] empire—arts, science, literature, decay—barbarism and all its revolting concomitants are made to seem the consequences of its decisive triumph—and the unwary reader is conducted, with matchless dexterity, to the desired conclusion—the abominable Manicheism of Candide, and, in fact, of all the productions of Voltaire's historic school—viz., "that instead of being a merciful, ameliorating, and benignant visitation, the religion of Christians would rather seem to be a scourge sent on man by the author of all evil."[149] However, Voltaire also acknowledged the self-sacrifice of Christians. He wrote: "Perhaps there is nothing greater on earth than the sacrifice of youth and beauty, often of high birth, made by the gentle sex in order to work in hospitals for the relief of human misery, the sight of which is so revolting to our delicacy. Peoples separated from the Roman religion have imitated but imperfectly so generous a charity."[150] Yet, according to Daniel-Rops, Voltaire's "hatred of religion increased with the passage of years. The attack, launched at first against clericalism and theocracy, ended in a furious assault upon Holy Scripture, the dogmas of the Church, and even upon the person of Jesus Christ Himself, who [he] depicted now as a degenerate."[151] Voltaire's reasoning may be summed up in his well-known saying, "Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities." Judaism According to Orthodox rabbi Joseph Telushkin, the most significant Enlightenment hostility against Judaism was found in Voltaire;[152] 30 of the 118 articles in his Dictionnaire philosophique dealt with Jews or Judaism, describing them in consistently negative ways.[153][154] For example, in Voltaire's A Philosophical Dictionary, he wrote of Jews: "In short, we find in them only an ignorant and barbarous people, who have long united the most sordid avarice with the most detestable superstition and the most invincible hatred for every people by whom they are tolerated and enriched."[155] Telushkin states that Voltaire did not limit his attack to aspects of Judaism that Christianity used as a foundation, repeatedly making it clear that he despised Jews.[152] On the other hand, Peter Gay, a contemporary authority on the Enlightenment,[152] points to Voltaire's remarks (for instance, that the Jews were more tolerant than the Christians) in the Traité sur la tolérance and surmises that "Voltaire struck at the Jews to strike at Christianity". Whatever anti-semitism Voltaire may have felt, Gay suggests, derived from negative personal experience.[156] Arthur Hertzberg, a Conservative Rabbi, claims that Gay's second suggestion is untenable, as Voltaire himself denied its validity when he remarked that he had "forgotten about much larger bankruptcies through Christians".[clarification needed][157] However, Bertram Schwarzbach's far more detailed studies of Voltaire's dealings with Jewish people throughout his life concluded that he was anti-biblical, not anti-semitic. His remarks on the Jews and their "superstitions" were essentially no different from his remarks on Christians.[158] Voltaire said of the Jews that they "have surpassed all nations in impertinent fables, in bad conduct and in barbarism. You deserve to be punished, for this is your destiny."[159][160][161] He further said, "They are, all of them, born with raging fanaticism in their hearts, just as the Bretons and the Germans are born with blond hair. I would not be in the least bit surprised if these people would not some day become deadly to the human race."[162][163][164] Some authors link Voltaire's anti-Judaism to his polygenism. According to Joxe Azurmendi this anti-Judaism has a relative importance in Voltaire's philosophy of history. However, Voltaire's anti-Judaism influenced later authors like Ernest Renan.[165] Voltaire did have a Jewish friend, Daniel de Fonseca, whom he esteemed highly, and proclaimed him as "the only philosopher, perhaps, among the Jews of his time".[166] Voltaire condemned the persecution of Jews on several occasions, including in Henriade, and he never advocated violence or attacks against them.[155][167] According to the historian Will Durant, Voltaire praised the simplicity, sobriety, regularity, and industry of Jews, but subsequently became strongly anti-Semitic after some personal financial transactions and quarrels with Jewish financiers. In his Essai sur les moeurs Voltaire denounced the ancient Hebrews in strong language. The anti-Semitic passages in Voltaire's Dictionnaire philosophique were criticized by Isaac De Pinto in 1762. Subsequently, Voltaire agreed with the criticism of the anti-Semitic passages and stated that De Pinto's letter convinced him that there are "highly intelligent and cultivated people" among the Jews and that he had been "wrong to attribute to a whole nation the vices of some individuals";[168] he also promised to revise the objectionable passages for forthcoming editions of the Dictionnaire philosophique, but he failed to do so.[168] Islam Voltaire's views about Islam were generally negative, and he found its holy book, the Quran, to be ignorant of the laws of physics.[169] In a 1740 letter to Frederick the Great, Voltaire ascribes to Muhammad a brutality that "is assuredly nothing any man can excuse" and suggests that his following stemmed from superstition; Voltaire continued, "But that a camel-merchant should stir up insurrection in his village; that in league with some miserable followers he persuades them that he talks with the angel Gabriel; that he boasts of having been carried to heaven, where he received in part this unintelligible book, each page of which makes common sense shudder; that, to pay homage to this book, he delivers his country to iron and flame; that he cuts the throats of fathers and kidnaps daughters; that he gives to the defeated the choice of his religion or death: this is assuredly nothing any man can excuse, at least if he was not born a Turk, or if superstition has not extinguished all natural light in him."[170] In 1748, after having read Henri de Boulainvilliers and George Sale,[171] he wrote again about Mohammed and Islam in "De l'Alcoran et de Mahomet" ("On the Quran and on Mohammed"). In this essay, Voltaire maintained that Mohammed was a "sublime charlatan".[e] Drawing on complementary information in Herbelot's "Oriental Library", Voltaire, according to René Pomeau, adjudged the Quran, with its "contradictions, ... absurdities, ... anachronisms", to be "rhapsody, without connection, without order, and without art".[172][173][174][175] Thus he "henceforward conceded"[175] that "if his book was bad for our times and for us, it was very good for his contemporaries, and his religion even more so. It must be admitted that he removed almost all of Asia from idolatry" and that "it was difficult for such a simple and wise religion, taught by a man who was constantly victorious, could hardly fail to subjugate a portion of the earth." He considered that "its civil laws are good; its dogma is admirable which it has in common with ours" but that "his means are shocking; deception and murder".[176] In his Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations (published 1756), Voltaire deals with the history of Europe before Charlemagne to the dawn of the age of Louis XIV, and that of the colonies and the East. As a historian, he devoted several chapters to Islam,[177][178][179] Voltaire highlighted the Arabian, Turkish courts, and conducts.[175][180][181] Here he called Mohammed a "poet", and stated that he was not an illiterate.[182] As a "legislator", he "changed the face of part of Europe [and] one half of Asia."[183][184][185] In chapter VI, Voltaire finds similarities between Arabs and ancient Hebrews, that they both kept running to battle in the name of God, and sharing a passion for the spoils of war.[186] Voltaire continues that, "It is to be believed that Mohammed, like all enthusiasts, violently struck by his ideas, first presented them in good faith, strengthened them with fantasy, fooled himself in fooling others, and supported through necessary deceptions a doctrine which he considered good."[187][188] He thus compares "the genius of the Arab people" with "the genius of the ancient Romans".[189] According to Malise Ruthven, as Voltaire learned more about Islam his opinion of the faith became more positive.[190] As a result, his play Mahomet inspired Goethe, who was attracted to Islam, to write a drama on this theme, though he completed only the poem "Mahomets-Gesang" ("Mahomet's Singing").[191] Drama Mahomet Main article: Mahomet (play) The tragedy Fanaticism, or Mahomet the Prophet (French: Le fanatisme, ou Mahomet le Prophete) was written in 1736 by Voltaire. The play is a study of religious fanaticism and self-serving manipulation. The character Muhammad orders the murder of his critics.[192] Voltaire described the play as "written in opposition to the founder of a false and barbarous sect."[193] Voltaire described Muhammad as an "impostor", a "false prophet", a "fanatic" and a "hypocrite".[194][195] Defending the play, Voltaire said that he "tried to show in it into what horrible excesses fanaticism, led by an impostor, can plunge weak minds".[196] When Voltaire wrote in 1742 to César de Missy, he described Muhammad as deceitful.[197][198] In his play, Muhammad is "whatever trickery can invent that is most atrocious and whatever fanaticism can accomplish that is most horrifying. Mahomet here is nothing other than Tartuffe with armies at his command."[199][200] After later having judged that he had made Muhammad in his play "somewhat nastier than he really was",[201] Voltaire claimed that Muhammad stole the idea of an angel weighing both men and women from Zoroastrians, who are often referred to as "Magi". Voltaire continued about Islam, saying: Nothing is more terrible than a people who, having nothing to lose, fight in the united spirit of rapine and of religion.[202] In a 1745 letter recommending the play to Pope Benedict XIV, Voltaire described Muhammad as "the founder of a false and barbarous sect" and "a false prophet". Voltaire wrote: "Your holiness will pardon the liberty taken by one of the lowest of the faithful, though a zealous admirer of virtue, of submitting to the head of the true religion this performance, written in opposition to the founder of a false and barbarous sect. To whom could I with more propriety inscribe a satire on the cruelty and errors of a false prophet, than to the vicar and representative of a God of truth and mercy?"[203][204] His view was modified slightly for Essai sur les Moeurs et l'Esprit des Nations, although it remained negative.[135][205][206][207] In 1751, Voltaire performed his play Mohamet once again, with great success.[208] Hinduism Commenting on the sacred texts of the Hindus, the Vedas, Voltaire observed: The Veda was the most precious gift for which the West had ever been indebted to the East.[209] He regarded Hindus as "a peaceful and innocent people, equally incapable of hurting others or of defending themselves."[210] Voltaire was himself a supporter of animal rights and was a vegetarian.[211] He used the antiquity of Hinduism to land what he saw as a devastating blow to the Bible's claims and acknowledged that the Hindus' treatment of animals showed a shaming alternative to the immorality of European imperialists.[212] Confucianism  Life and Works of Confucius, by Prospero Intorcetta, 1687 Works attributed to Confucius were translated into European languages through the agency of Jesuit missionaries stationed in China.[f] Matteo Ricci was among the earliest to report on the teachings of Confucius, and father Prospero Intorcetta wrote about the life and works of Confucius in Latin in 1687.[213] Translations of Confucian texts influenced European thinkers of the period,[214] particularly among the Deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who hoped to improve European morals and institutions by the serene doctrines of the East.[213][215] Voltaire shared these hopes,[216][217] seeing Confucian rationalism as an alternative to Christian dogma.[218] He praised Confucian ethics and politics, portraying the sociopolitical hierarchy of China as a model for Europe.[218] Confucius has no interest in falsehood; he did not pretend to be prophet; he claimed no inspiration; he taught no new religion; he used no delusions; flattered not the emperor under whom he lived... — Voltaire[218] With the translation of Confucian texts during the Enlightenment, the concept of a meritocracy reached intellectuals in the West, who saw it as an alternative to the traditional Ancien Régime of Europe.[219] Voltaire wrote favourably of the idea, claiming that the Chinese had "perfected moral science" and advocating an economic and political system after the Chinese model.[219] |

宗教的および哲学的見解 70歳のヴォルテール、1843年版『哲学辞典』の版画 他の主要な啓蒙思想家と同様に、ヴォルテールは理神論者であった。[131] 彼は「信仰とは何か? 明白なことを信じることなのか? いいや、私の考えでは、必要不可欠で永遠かつ至高の知的存在が存在することは明白である。これは信仰の問題ではなく、理性の問題である」[132] [133] 1763年のエッセイで、ヴォルテールは他の宗教や民族の寛容を支持した。「キリスト教徒がお互いを寛容にすべきであることを証明するには、優れた芸術や 見事な修練を積んだ雄弁は必要ない。しかし、私はさらに先を行く。私は、すべての人間を兄弟としてみなすべきだと主張する。トルコ人が私の兄弟?中国人は 兄弟か?ユダヤ人は?シャム人は?もちろんそうだ。我々は皆、同じ父の子供であり、同じ神の創造物ではないか。」[134] あらゆる宗派の聖職者を非難する中で、ヴォルテールは彼らを「近親相姦のベッドから生まれ、神の100のバージョンを作り出し、神を食い、飲み、神を小便や大便にする者」と表現している。[135] キリスト教 歴史家はヴォルテールのキリスト教史の記述を「プロパガンダ的」と評している。[136] 彼の著書『哲学辞典』は、初期の教会が標準的な正典の4福音書に定着する前に50の福音書を持っていたという神話を生み出した。また、新約聖書の正典はニ カイア公会議で決定されたという神話も広めた。ヴォルテールは、表現「クレド・キア・アブスルド(「私は不合理なことを信じる」の意)」が教父たちに帰せ られているという誤りを一部招いた責任がある。[137] さらに、ヒュパティアの死因は、4世紀のアレクサンドリアにおける政治的対立のさなか、暴徒(おそらくキリスト教徒)の銃撃戦に巻き込まれたことによるも のだったにもかかわらず、 ヴォルテールは、彼女はアレクサンドリアの司教シリルの手下たちによって裸にされ殺害されたという説を唱え、「美しい女性が完全に裸にされているのを見つ けたとしても、それは彼女を虐殺する目的ではない」と結論づけた。ヴォルテールは、この議論を自身の反カトリックの論文を補強するものとして意図してい た。[138] 1767年1月5日付のフリードリヒ大王への手紙の中で、彼はキリスト教について次のように書いている。 「我々の宗教は疑いなく、世界に蔓延した宗教の中で最も滑稽で、最も不合理で、最も血なまぐさいものである。」[139] 「我々(すなわちキリスト教)の宗教は、間違いなく、この世界に蔓延した宗教の中で最もばかげた、最も不合理な、最も血なまぐさい宗教である。陛下は、こ の悪名高い迷信を根絶することで、人類に永遠の奉仕をなされるだろう。私が言っているのは、教化されるに値せず、あらゆる束縛に適した下層民ではなく、正 直な人々、考える人々、考えたいと願う人々についてである。... 私が死ぬ際に唯一後悔することは、この崇高な事業、人間の精神が指し示す最も素晴らしく、最も尊敬に値する事業において、あなた方を支援できないこと だ。」[140][141] 『聖書最終解明』において、彼は聖書の素読に対する次のような態度を示した。 聖典を読む狂信者たちが自分に言い聞かせるのは、神が殺したのだから私も殺さねばならない、アブラハムは嘘をつき、ヤコブは人を欺き、ラケルは盗みを働い た。だから私も盗み、人を欺き、嘘をつかねばならない、というものだ。しかし、哀れな人間よ、君はラケルでもヤコブでもアブラハムでも神でもない。君はた だの狂った愚か者であり、聖書の読書を禁じた教皇たちは極めて賢明だったのだ。 ヴォルテールの聖書に対する意見は複雑であった。『ポーランド同胞図書』などのソシニアン作品の影響を受けながらも、聖書に対する懐疑的な態度から、ヴォ ルテールはファウスト・ソッツィーニのようなユニテリアン神学者や、ジョン・ロックのような聖書政治的な作家からも距離を置いた。[143] 宗教に関する彼の主張は、 イエズス会、特にクロード=アドリアン・ノノットの激しい怒りを買った。[144][145][146][147] しかし、これは彼の宗教的実践を妨げるものではなく、特定の宗教界で彼に悪い評判をもたらしただけだった。敬虔なキリスト教徒であったヴォルフガング・ア マデウス・モーツァルトは、ヴォルテールの死の年に父親に宛てた手紙で「極悪人ヴォルテールがついに死んだ」と書き送っている。[148] ヴォルテールは、エドワード・ギボンが著書『ローマ帝国衰亡史』でキリスト教がローマ帝国の衰退の一因であると主張する上で影響を与えたと考えられてい る。 キリスト教の進展に伴い、ローマ帝国には災難が降りかかる。芸術、科学、文学は衰退し、野蛮主義とそれに付随するあらゆる嫌悪すべきものが、キリスト教の 決定的な勝利の結果であるかのように描かれる。そして、油断した読者は、比類ない巧妙さで、望ましい結論へと導かれる。すなわち、 カンディードの、そして事実、ヴォルテールの歴史的学派のすべての作品に見られる忌まわしい人間中心主義、すなわち、「キリスト教は慈悲深く、改善をもた らし、慈悲深いものではなく、むしろ、あらゆる悪の根源である者が人間に与えた災厄であるように見える」[149] しかし、ヴォルテールはキリスト教徒の自己犠牲も認めていた。彼はこう書いている。「おそらく、この世で最も尊いものは、優しき性(女性)が、人間の苦悩 を和らげるために病院で働くために捧げる、若さと美しさ、そしてしばしば高貴な生まれであることの犠牲に勝るものはない。ローマの宗教から離れた民族は、 その慈善を不完全ながら模倣した。」[150] しかし、ダニエル・ロップによると、ヴォルテールの「宗教への憎悪は年月とともに増していった。当初は聖職者階級と神政に対する攻撃であったが、聖書、教 会の教義、さらにはイエス・キリスト自身に対する激しい攻撃へと発展し、ヴォルテールはイエスを退廃した人物として描いた」[151] ヴォルテールの論理は、よく知られた彼の格言に集約されている。「不合理なことを信じ込ませることができる者は、残虐行為を犯させられる」 ユダヤ教 正統派ラビのジョセフ・テラスキンによると、啓蒙主義者たちのユダヤ教に対する敵意はヴォルテールに最も顕著に表れていたという。[152] 彼の著書『哲学辞典』の118の項目中30項目がユダヤ人やユダヤ教についてのものであり、一貫して否定的な表現でそれらを描写していた。[153] [154] 例えば、ヴォルテールの著書『哲学辞典』では、ユダヤ人について次のように書いている。「要するに、彼らの中に見出されるのは無知で野蛮な民だけである。 彼らは長い間、最も卑しい強欲と最も忌まわしい迷信、そして彼らを許容し富ませてくれるあらゆる民族に対する最も揺るぎない憎悪とを結びつけてきたのだ」 [155] テルーシキンは、ヴォルテールはキリスト教が基盤としていたユダヤ教の側面だけに攻撃を限定したわけではなく、繰り返しユダヤ人を軽蔑していることを明ら かにしていたと述べている。 一方、啓蒙主義の権威であるピーター・ゲイは、ヴォルテールの『寛容論』における発言(例えば、ユダヤ人はキリスト教徒よりも寛容であるというような)を 指摘し、「ヴォルテールはキリスト教を攻撃するためにユダヤ人を攻撃した」と推測している。ヴォルテールが反ユダヤ主義の感情を抱いていたとしても、それ は個人的な否定的な経験に由来するものだとゲイは示唆している。 保守派のラビであるアーサー・ヘルツバーグは、ゲイの2つ目の指摘は成り立たないとし、ヴォルテール自身が「キリスト教徒によるはるかに大きな破綻につい ては忘れてしまった」と述べたことで、その妥当性を否定していると主張している。[要出典][157] しかし、ヴォルテールが生涯を通じてユダヤ人に対して取った行動について、バートラム・シュヴァルツバッハがはるかに詳細に研究した結果、彼は反ユダヤ主 義ではなく、反聖書主義者であったと結論づけている。彼がユダヤ人について述べたことや彼らの「迷信」に関する発言は、キリスト教徒に関する発言と本質的 には変わらない。 ヴォルテールはユダヤ人について、「彼らは不遜な寓話、悪行、野蛮さにおいて、あらゆる国民を凌駕している。汝らは罰せられるに値する。なぜなら、それが 汝らの運命なのだから」[159][160][161] さらに彼はこうも述べている。「彼らは皆、生まれつき狂信的な心を持っている。ちょうどブルトン人やドイツ人が金髪で生まれてくるように。もし彼らがいつ か人類にとって致命的な存在とならないとしても、私は少しも驚かないだろう」[162][163][164] 一部の著者は、ヴォルテールの反ユダヤ主義を多起源説と関連付けている。ジョクセ・アズルメンディによると、この反ユダヤ主義はヴォルテールの歴史哲学に おいて相対的に重要な位置を占めている。しかし、ヴォルテールの反ユダヤ主義は、後の作家であるエルネスト・ルナンなどに影響を与えた。 ヴォルテールにはダニエル・ド・フォンセカというユダヤ人の友人がおり、ヴォルテールは彼を高く評価し、「おそらく同時代のユダヤ人の中では唯一の哲学者」と称した。 ヴォルテールは『アンリエット』を含め、何度かユダヤ人迫害を非難しており、彼らに対する暴力や攻撃を擁護したことは一度もなかった。[155] [167] 歴史家のウィル・デュラントによると、ヴォルテールはユダヤ人の質素、節制、勤勉さを称賛していたが、その後、ユダヤ人金融業者との個人的な金銭取引や口 論を経て、強烈な反ユダヤ主義者となった。著書『エセー・シュル・レ・ムール』の中で、ヴォルテールは古代ヘブライ人を強い言葉で非難した。ヴォルテール の著書『哲学辞典』の反ユダヤ主義的な箇所は、1762年にアイザック・デ・ピントによって批判された。その後、ヴォルテールは反ユダヤ主義的な箇所に対 する批判に同意し、デ・ピントの書簡によって「ユダヤ人の中にも非常に聡明で教養のある人々がいる」ことを確信し、「一部の個人の悪徳を国民全体に帰属さ せるのは誤りであった」と述べた[168]。また、今後出版される『哲学辞典』の版では問題のある箇所を修正すると約束したが、結局は実現しなかった [168]。 イスラム教 ヴォルテールのイスラム教に対する見方は概して否定的であり、その聖典であるコーランは物理学の法則を知らないと彼は考えていた。[169] 1740年にフリードリヒ大王に宛てた手紙の中で、ヴォルテールはムハンマドの残虐性を「どんな人間でも弁解の余地のないもの」と断じ 」と述べ、彼の信奉は迷信から生じたものだと示唆した。さらにヴォルテールは、「しかし、ラクダ商人である彼が自分の村で反乱を煽り立てたこと、哀れな信 奉者たちと結託して、自分は天使ガブリエルと話していると彼らを説得したこと、自分は天国に運ばれ、そこでこの理解不能な書物の一部を受け取ったと自慢し たこと、 この書物に敬意を表するために、彼は自国を鉄と炎に委ねる。父親の喉を切り裂き、娘を誘拐する。敗者には、自らの宗教か死の選択を迫る。少なくとも、トル コ人として生まれなかった場合、あるいは迷信によって彼の中の自然な光がすべて消え去らなかった場合は、これは確かにどんな人間も弁解できないことであ る。」[170] 1748年、アンリ・ド・ブーランヴィリエとジョージ・セールの著作を読んだ後、ヴォルテールは再び『コーランとマホメットについて』の中で、モハメッド とイスラム教について書いた。この論文でヴォルテールは、ムハンマドは「崇高なペテン師」であると主張した。[e] ルネ・ポモーによると、ヴォルテールはエルベロの『東洋図書館』の補足情報を参考にし、その「矛盾、... 不条理、... 時代錯誤」を理由にコーランを「狂気じみた 、関連性も秩序も芸術性もない」と評した。[172][173][174][175] こうして彼は「今後は認める」[175]ことになり、「もし彼の著書が我々の時代や我々にとって有害であるならば、それは彼の同時代人にとっては非常に有 益であり、彼の宗教はさらに有益である。彼はアジアのほとんどを偶像崇拝から救ったことは認めねばならない」し、「常に勝利を収めていた人物が教える、シ ンプルかつ賢明な宗教が、地球の一部を征服できなかったはずがない」と彼は考えた。「その市民法は良い。その教義は、我々のものと共通する部分があり、称 賛に値する」が、「彼の手段は衝撃的だ。欺瞞と殺人だ」と彼は考えた。[176] 著書『諸国民の気風と精神についての試論』(1756年)において、ヴォルテールはシャルルマーニュ以前のヨーロッパの歴史からルイ14世の時代、そして 植民地と東洋の夜明けまでを扱っている。歴史家として、彼はイスラム教に数章を割いている。[177][178][179] ヴォルテールはアラビアとトルコの宮廷や風習を強調している。[175][180][181] ここで彼はムハンマドを「詩人」と呼び、彼が文盲ではなかったと述べている。[182] 「立法者」として、彼は「 ヨーロッパの一部とアジアの半分を覆い変えた」と述べている。[183][184][185] 第6章において、ヴォルテールはアラブ人と古代ヘブライ人の類似点を見出し、両者とも神の名のもとに戦場に走り続け、戦利品に対する情熱を共有していたと 述べている。[186] ヴォルテールはさらに次のように続けている。「 熱狂的な信者たちと同様に、自分の考えに強く心を動かされ、まず誠意をもってそれを提示し、空想でそれを補強し、他人を欺くことで自分自身を欺き、そし て、自分が正しいと考える教義を、必要な欺瞞によって支えたと信じられている」[187][188] 彼はこうして、「アラブ人の天才」を「古代ローマ人の天才」と比較している。[189] マリス・ラズヴェンによると、ヴォルテールはイスラム教について学ぶにつれ、その信仰に対する見解をより肯定的なものにしていったという。[190] その結果、彼の戯曲『マホメット』は、イスラム教に惹かれていたゲーテにインスピレーションを与え、このテーマで戯曲を書かせた。ただし、ゲーテが完成さ せたのは詩『マホメットの歌』(Mahomets-Gesang)のみであった。[191] 戯曲『マホメット』 詳細は「マホメット(戯曲)」を参照 狂信、あるいは預言者マホメット(仏語:Le fanatisme, ou Mahomet le Prophete)は、1736年にヴォルテールによって書かれた悲劇である。この劇は宗教的狂信と自己中心的な操作についての研究である。ムハンマドの キャラクターは、彼を批判する者たちの殺害を命じる。[192] ヴォルテールはこの劇を「偽りの野蛮な宗派の創始者に反対して書かれた」と表現した。[193] ヴォルテールはムハンマドを「詐欺師」、「偽預言者」、「狂信者」、「偽善者」と表現した。[194][195] この劇を擁護するヴォルテールは、「この劇で、 詐欺師に導かれた狂信主義が、弱い精神をどれほど恐ろしい過ちへと導くかを示そうとした」と述べた。[196] 1742年にセザール・ド・ミッシーに宛てた手紙の中で、ヴォルテールはムハンマドを欺瞞的と評した。[197][198] 彼の劇の中で、ムハンマドは「最も残虐な策略を編み出し、狂信主義が達成し得る最も恐ろしいことを成し遂げる人物である。ここで描かれるマホメットは、軍 隊を従えるタルチュフ以外の何者でもない」[199][200] その後、この劇で描いたムハンマドは「実際の人物よりもいくらか悪く描きすぎた」と判断したヴォルテールは、男女を天秤にかける天使のアイデアをムハンマ ドがゾロアスター教徒から盗んだと主張した。ゾロアスター教徒はしばしば「マギ」と呼ばれている。ヴォルテールはイスラム教について次のように述べた。 失うものなど何もない人々が、略奪と宗教の精神をひとつにして戦うことほど恐ろしいものはない。 1745年にローマ教皇ベネディクト14世にこの劇を推薦する手紙の中で、ヴォルテールはムハンマドを「偽りの野蛮な宗派の創始者」であり「偽りの預言 者」であると表現した。ヴォルテールは次のように書いている。「神聖なる教皇閣下は、熱心な美徳の崇拝者でありながら、偽りの野蛮な宗派の創始者に反対す る内容で書かれたこの劇を真の宗教の指導者に献上するという、信仰心の最も低い者の行動を許してくださるでしょう。偽りの預言者の残虐性と誤りを風刺する 作品を、真実と慈悲の神の代理者と代表者に捧げるのに、これ以上の適任者がいるだろうか?」[203][204] 彼の見解は『諸国民の性質と精神に関する試論』では若干修正されたが しかし、否定的な見解は変わらなかった。[135][205][206][207] 1751年、ヴォルテールは再び戯曲『モハメット』を上演し、大成功を収めた。[208] ヒンドゥー教 ヒンドゥー教の聖典ヴェーダについて、ヴォルテールは次のように述べている。 ヴェーダは西洋が東洋に負う最も貴重な贈り物である。 彼はヒンドゥー教徒を「平和的で無邪気な人々であり、他人を傷つけることも、自分自身を守ることもできない」とみなしていた。[210] ヴォルテール自身は動物愛護の支持者であり、菜食主義者であった。[211] 彼はヒンドゥー教の古さを武器に、聖書の主張に壊滅的な打撃を与えると考え、ヒンドゥー教徒の動物に対する扱いは、ヨーロッパの帝国主義者の不道徳さに対 する恥ずべき代案であると認めていた。[212] 儒教  プロスペロ・イントルチェッタ著『孔子の生涯と業績』、1687年 孔子の著作とされる作品は、中国に派遣されていたイエズス会の宣教師の仲介により、ヨーロッパの言語に翻訳された。[f] マテオ・リッチは、孔子の教えについて報告した最も初期の人物の一人であり、プロスペロ・イントルチェッタ神父は1687年にラテン語で孔子の生涯と業績 について著述した。[213] 儒教のテキストの翻訳は当時のヨーロッパの思想家に影響を与え、特に、東洋の穏やかな教義によってヨーロッパの道徳や制度を改善することを望む自然神論者 や啓蒙主義の他の哲学グループの間で影響を与えた。儒教の合理主義をキリスト教の教義の代替案と見なし、これらの希望を共有していた。[216] [217] 彼は儒教の倫理と政治を賞賛し、中国の社会政治的階層をヨーロッパのモデルとして描いた。[218] 孔子は虚偽には興味を持たず、預言者であるかのように振る舞うこともなく、霊感があるとも主張せず、新しい宗教を教えることもなく、妄想を用いることもなく、自分が仕える皇帝を媚びることもなかった... —ヴォルテール[218] 啓蒙主義の時代に儒教のテキストが翻訳されたことで、能力主義の概念が西洋の知識人の間に広まり、それはヨーロッパの伝統的なアンシャンレジーム(旧体 制)に代わるものとして受け止められた。[219] ヴォルテールは、その考えを好意的に受け止め、中国人は「道徳科学を完成」させたとし、中国をモデルとした経済・政治体制を提唱した。[219] |

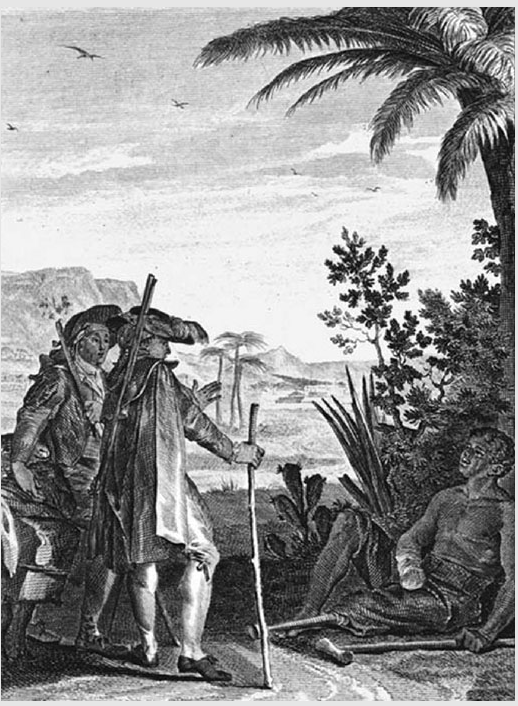

Views on race and slavery An illustration of a scene from Candide where the protagonist encounters a slave in French Guiana Voltaire rejected the biblical Adam and Eve story and was a polygenist who speculated that each race had entirely separate origins.[220][221] According to William Cohen, like most other polygenists, Voltaire believed that because of their different origins, Black Africans did not entirely share the natural humanity of white Europeans.[222] According to David Allen Harvey, Voltaire often invoked racial differences as a means to attack religious orthodoxy, and the Biblical account of creation.[223] Other historians, instead, have suggested that Voltaire's support for polygenism was more heavily encouraged by his investments in the French Compagnie des Indes and other colonial enterprises that engaged in the slave trade.[224][225][226] His most famous remark on slavery is found in Candide, where the hero is horrified to learn "at what price we eat sugar in Europe" after coming across a slave in French Guiana who has been mutilated for escaping, who opines that, if all human beings have common origins as the Bible taught, it makes them cousins, concluding that "no one could treat their relatives more horribly". Elsewhere, he wrote caustically about "whites and Christians [who] proceed to purchase negroes cheaply, in order to sell them dear in America". Voltaire has been accused of supporting the slave trade as per a letter attributed to him,[227][228][229] although it has been suggested that this letter is a forgery "since no satisfying source attests to the letter's existence."[230] In his Philosophical Dictionary, Voltaire endorses Montesquieu's criticism of the slave trade: "Montesquieu was almost always in error with the learned, because he was not learned, but he was almost always right against the fanatics and the promoters of slavery."[231] Zeev Sternhell argues that despite his shortcomings, Voltaire was a forerunner of liberal pluralism in his approach to history and non-European cultures.[232] Voltaire wrote, "We have slandered the Chinese because their metaphysics is not the same as ours ... This great misunderstanding about Chinese rituals has come about because we have judged their usages by ours, for we carry the prejudices of our contentious spirit to the end of the world."[232] In speaking of Persia, he condemned Europe's "ignorant audacity" and "ignorant credulity". When writing about India, he declares, "It is time for us to give up the shameful habit of slandering all sects and insulting all nations!"[232] In Essai sur les mœurs et l'esprit des nations, he defended the integrity of the Native Americans and wrote favorably of the Inca Empire.[233] |

人種と奴隷制に関する見解 主人公が仏領ギアナで奴隷に出会う場面を描いた『カンディード』の一挿話 ヴォルテールは聖書のアダムとイブの物語を否定し、各人種はそれぞれ完全に独立した起源を持つと推測した多系統説論者であった。[220][221] ウィリアム・コーエンによると、他の多系統説論者のほとんどと同様に、ヴォルテールは、起源が異なるため、黒人アフリカ人は白人ヨーロッパ人の持つ自然な 人間性を完全に共有していないと信じていた。[222] デビッド・アレン・ハーヴェイによると、ヴォルテールは しばしば人種間の相違を、宗教的正統派や聖書の天地創造説を攻撃する手段として引き合いに出していた。[223] 他の歴史家は、ヴォルテールが多様説を支持したのは、フランス・インド会社や奴隷貿易に従事するその他の植民地事業への投資が大きな影響を与えたためであ ると示唆している。[224][225][226] 奴隷制に関する彼の最も有名な発言は、主人公がフランス領ギアナで逃亡中に身体を損傷した奴隷に出会い、その奴隷が「聖書が教えるように、もし全ての人間 が共通の起源を持つのであれば、彼らは従兄弟同士になる。そして、「自分の親族をこれほどまでにひどく扱うことはできない」と結論づけている。また、別の 箇所では「アメリカで高値で売るために、安く黒人を購入する白人やキリスト教徒」について痛烈に批判している。ヴォルテールは、彼に帰属される手紙の内容 から奴隷貿易を支持していると非難されているが[227][228][229]、この手紙は「手紙の存在を証明する納得のいく情報源がないため」偽造であ るという指摘もある[230]。 ヴォルテールは『哲学辞典』の中で、モンテスキューの奴隷貿易批判を支持している。「モンテスキューは学識のある人々に対してはほとんど常に誤っていた。 なぜなら、彼自身は学識がなかったからだ。しかし、狂信者や奴隷制の推進者に対しては、ほとんど常に正しかった」[231] ゼーブ・スターンヘルは、ヴォルテールには欠点があったものの、歴史や非ヨーロッパ文化に対するアプローチにおいて、リベラルな多元主義の先駆者であった と主張している。[232] ヴォルテールは次のように書いている。「我々は中国人を中傷してきた。なぜなら、彼らの形而上学は我々と同じではないからだ... 中国人の儀式に関するこの大きな誤解は、我々が彼らの慣習を我々自身の慣習で判断したために生じた。我々は、争いを好む精神の偏見を世界の果てまで持ち続 けているからだ」[232] ペルシャについて語る際、彼はヨーロッパの「無知な大胆さ」と「無知な盲信」を非難した。インドについて書いているとき、彼は「あらゆる宗派を中傷し、あ らゆる国民を侮辱するという恥ずべき習慣を、私たちもそろそろやめるべき時が来た!」と宣言している。[232] 『諸国民の風俗と精神に関する試論』では、彼はアメリカ・インディアンの高潔さを擁護し、インカ帝国について好意的に書いている。[233] |