カンディードまたはカンディド

Candide, il faut cultiver notre jardin

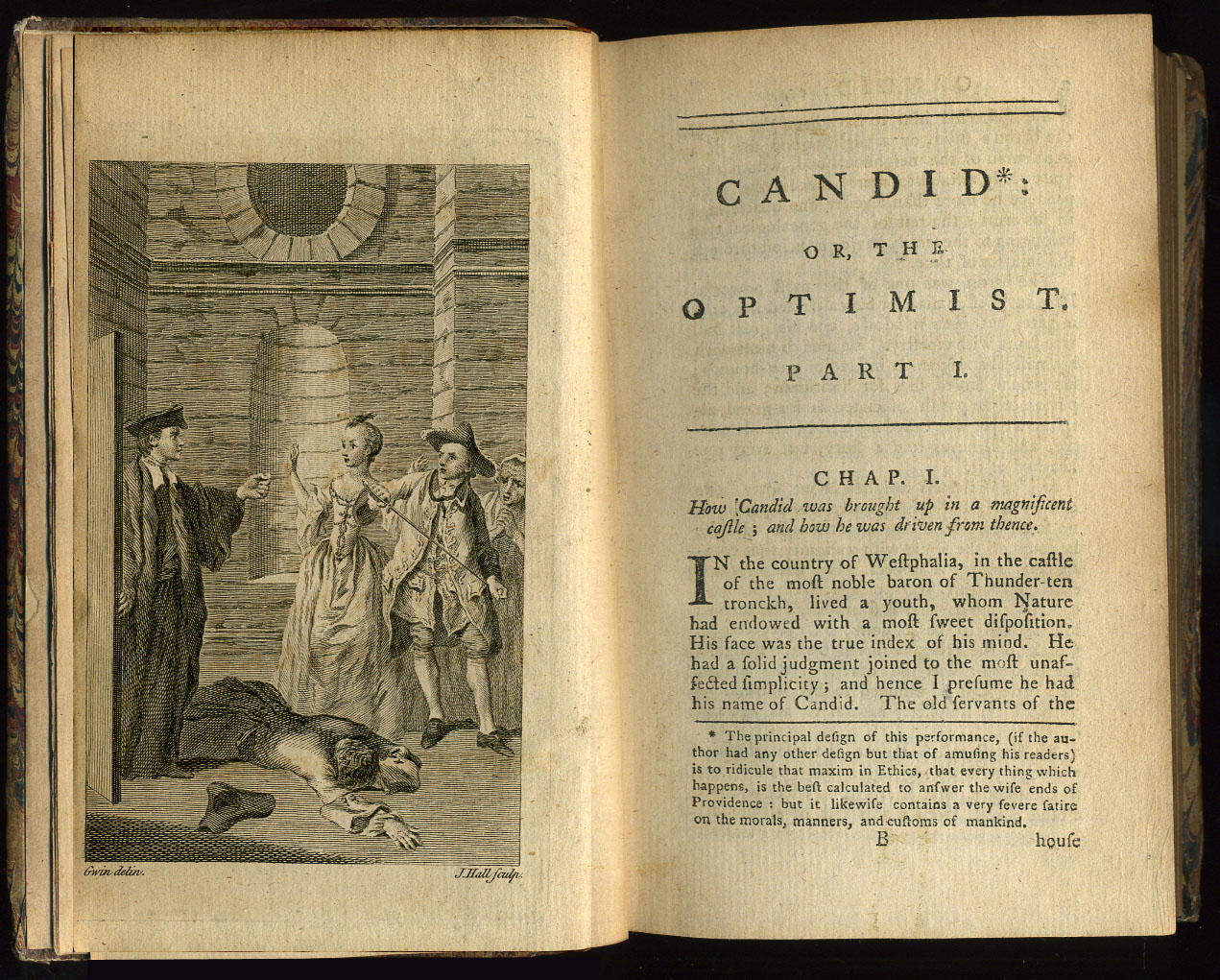

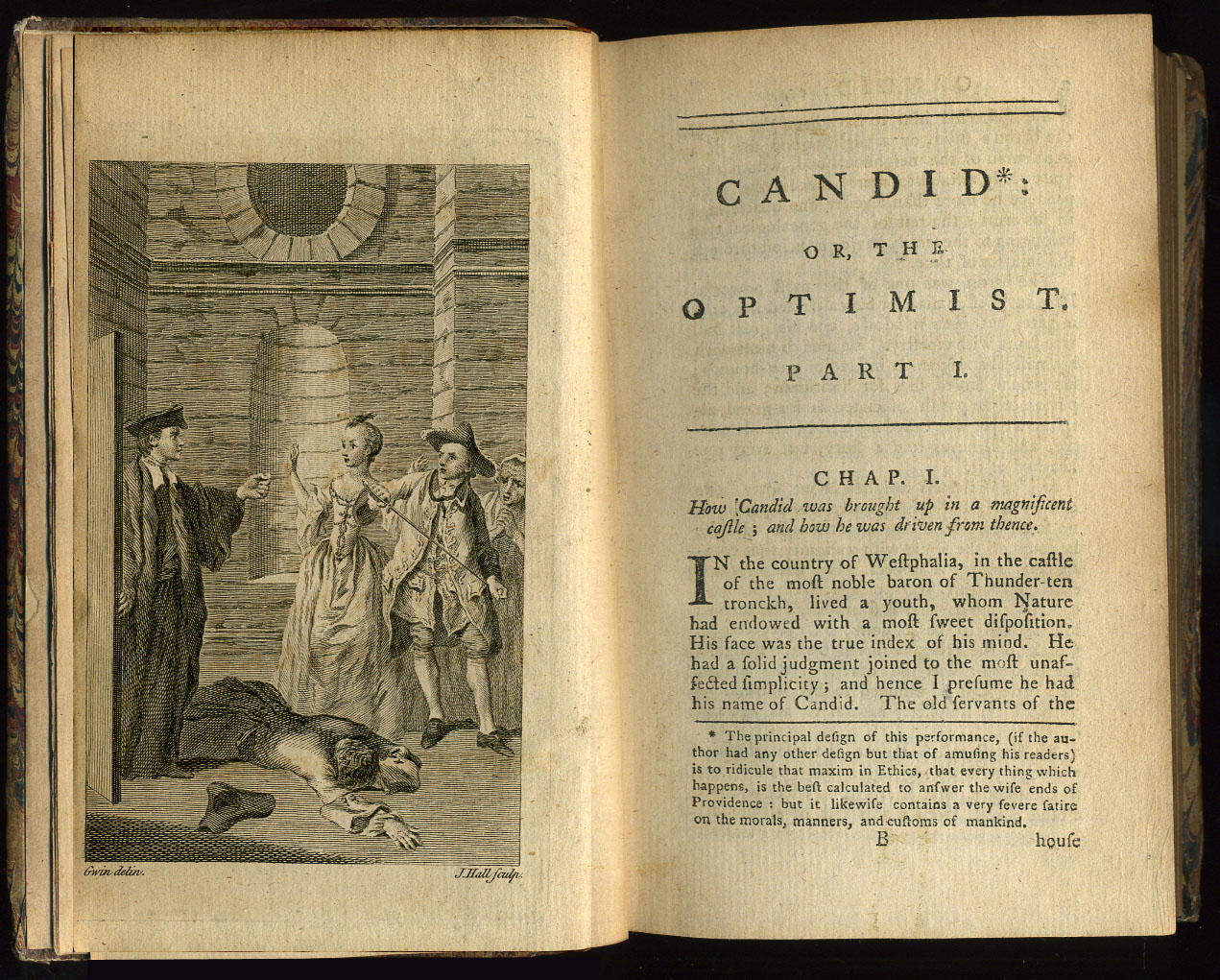

The title-page of the 1759 edition published by Cramer in Geneva, which reads, "Candide, or Optimism, translated from the German by Dr. Ralph."

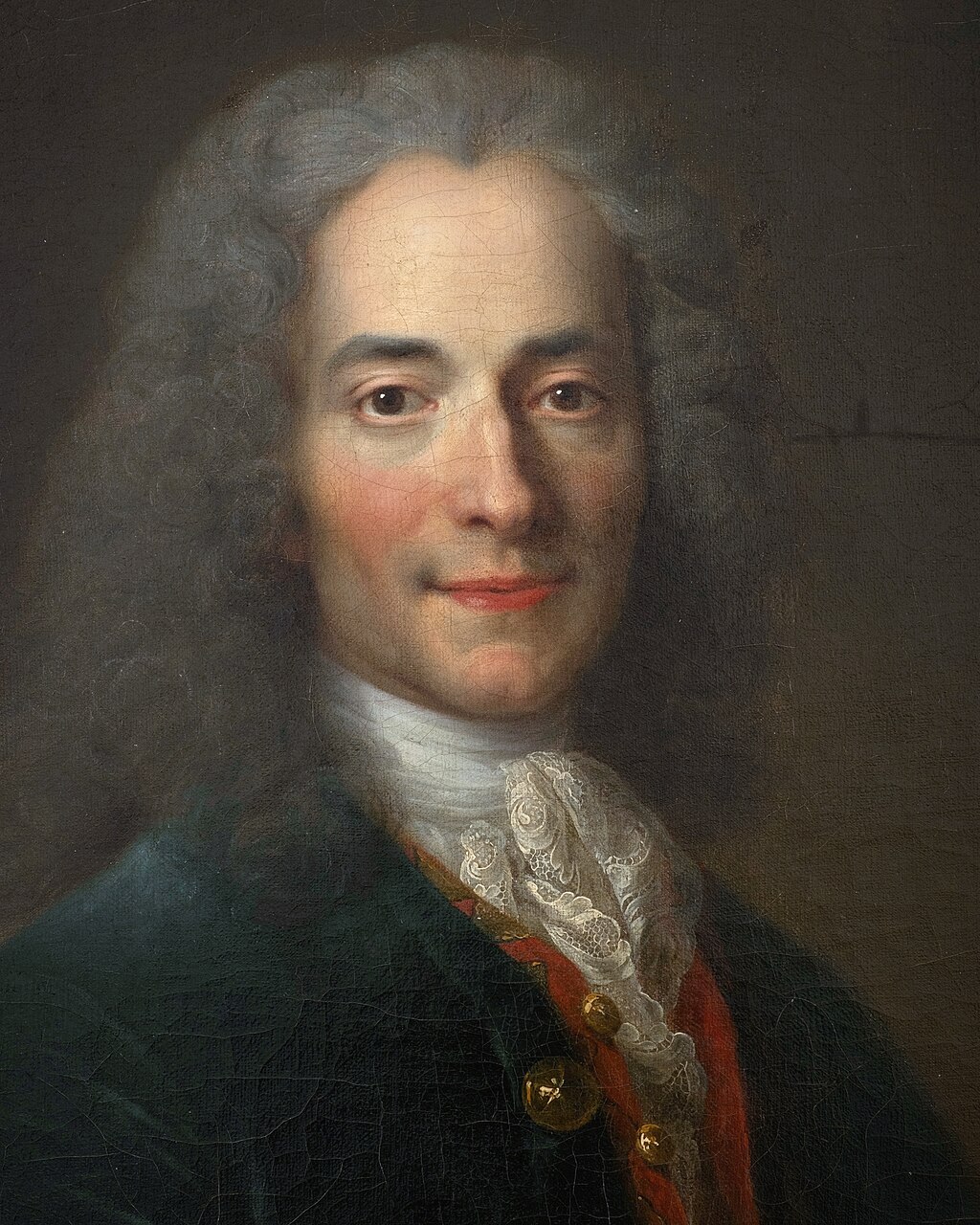

Engraving

of Voltaire published as the frontispiece to an 1843 edition of his

Dictionnaire philosophique

☆

『カンディード、あるいはある楽観主義者』(Candide, ou

l'Optimisme)は、啓蒙時代の哲学者であるヴォルテール[6]が書いたフランスの風刺小説で、1759年に出版された。この小説は広く翻訳され

ており、英語版のタ

イトルは『Candide: or, All for the Best』(1759年)、『Candide: or, The

Optimist』(1762年)、『Candide』

この作品は、エデンの園のような楽園で保護された生活を送っていた青年カンディードが、師であるパングロス教授からライプニッツ的な楽観主義を教え込ま

れるところから始まる。ヴォルテールは『カンディード』の最後を、ライプニッツ的楽観主義を真っ向から否定するわけではないにせよ、パングロスの

マントラである「すべては最善のためにある」というライプニッツ的マントラの代わりに、「われわれは庭を耕さねばならない」という深く実践的な教訓を提唱

して締めくくる。

☆

『カンディード、あるいはある楽観主義者』(Candide, ou

l'Optimisme)は、啓蒙時代の哲学者であるヴォルテール[6]が書いたフランスの風刺小説で、1759年に出版された。この小説は広く翻訳され

ており、英語版のタ

イトルは『Candide: or, All for the Best』(1759年)、『Candide: or, The

Optimist』(1762年)、『Candide』

この作品は、エデンの園のような楽園で保護された生活を送っていた青年カンディードが、師であるパングロス教授からライプニッツ的な楽観主義を教え込ま

れるところから始まる。ヴォルテールは『カンディード』の最後を、ライプニッツ的楽観主義を真っ向から否定するわけではないにせよ、パングロスの

マントラである「すべては最善のためにある」というライプニッツ的マントラの代わりに、「われわれは庭を耕さねばならない」という深く実践的な教訓を提唱

して締めくくる。

ヴォルテール:"Cela est bien dit, mais il faut cultiver notre

jardin"――「お説はごもっと も、なにはともあれ、われわれは自分の畑を耕さねばならぬ」

そうすることで、私は、

“Je ne suis pas d’accord avec ce que vous dites, mais je défendrai

jusqu’à la mort votre droit de le dire”――「私はあなたの意見には反対だ、だがあなたがそれを主張

する権利は命をかけて守る」

と、主張することができるのだ。

du

docteur Ralph, Candide, ou L'optimisme, traduit de l'allemand de Mr. le

docteur Ralph, 1759

| Candide, ou l'Optimisme

(/kɒnˈdiːd/ kon-DEED,[5] French: [kɑ̃did] ⓘ) is a French satire written

by Voltaire, a philosopher of the Age of Enlightenment,[6] first

published in 1759. The novella has been widely translated, with English

versions titled Candide: or, All for the Best (1759); Candide: or, The

Optimist (1762); and Candide: Optimism (1947).[7] It begins with a

young man, Candide, who is living a sheltered life in an Edenic

paradise and being indoctrinated with Leibnizian optimism by his

mentor, Professor Pangloss.[8] The work describes the abrupt cessation

of this lifestyle, followed by Candide's slow and painful

disillusionment as he witnesses and experiences great hardships in the

world. Voltaire concludes Candide with, if not rejecting Leibnizian

optimism outright, advocating a deeply practical precept, "we must

cultivate our garden", in lieu of the Leibnizian mantra of Pangloss,

"all is for the best" in the "best of all possible worlds". Candide is characterized by its tone as well as by its erratic, fantastical, and fast-moving plot. A picaresque novel with a story similar to that of a more serious coming-of-age narrative (bildungsroman), it parodies many adventure and romance clichés, the struggles of which are caricatured in a tone that is bitter and matter-of-fact. Still, the events discussed are often based on historical happenings, such as the Seven Years' War and the 1755 Lisbon earthquake.[9] As philosophers of Voltaire's day contended with the problem of evil, so does Candide in this short theological novel, albeit more directly and humorously. Voltaire ridicules religion, theologians, governments, armies, philosophies, and philosophers. Through Candide, he assaults Leibniz and his optimism.[10][11] Candide has enjoyed both great success and great scandal. Immediately after its secretive publication, the book was widely banned because it contained religious blasphemy, political sedition, and intellectual hostility hidden under a thin veil of naivety.[10] However, with its sharp wit and insightful portrayal of the human condition, the novel has since inspired many later authors and artists to mimic and adapt it. Today, Candide is considered Voltaire's magnum opus[10] and is often listed as part of the Western canon. It is among the most frequently taught works of French literature.[12] The British poet and literary critic Martin Seymour-Smith listed Candide as one of the 100 most influential books ever written. |

『カ

ンディード、あるいはある楽観主義者』(Candide, ou l'Optimisme, /kɒdiːd/ kon-DEED, [5]

French: [kɒdid]

̃̈)は、啓蒙時代の哲学者であるヴォルテール[6]が書いたフランスの風刺小説で、1759年に出版された。この小説は広く翻訳されており、英語版のタ

イトルは『Candide: or, All for the Best』(1759年)、『Candide: or, The

Optimist』(1762年)、『Candide:

この作品は、エデンの園のような楽園で保護された生活を送っていた青年カンディードが、師であるパングロス教授からライプニッツ的な楽観主義を教え込ま

れるところから始まる[8]。ヴォルテールは『カンディード』の最後を、ライプニッツ的楽観主義を真っ向から否定するわけではないにせよ、パングロスの

マントラである「すべては最善のためにある」というライプニッツ的マントラの代わりに、「われわれは庭を耕さねばならない」という深く実践的な教訓を提唱

して締めくくる。 『カンディード』の特徴は、その調子だけでなく、不規則で空想的で展開の速いプロットにもある。より深刻な青春小説(ビルドゥングスロマン)に似たストー リーを持つピカレスク小説で、冒険やロマンスの決まり文句をパロディにしており、その苦闘は辛辣で事実に即した口調で戯画化されている。ヴォルテールと同 時代の哲学者たちが悪の問題と闘っていたように、この短い神学小説でもキャンディードは、より直接的かつユーモラスに悪の問題を論じている。ヴォルテール は宗教、神学者、政府、軍隊、哲学、哲学者を嘲笑する。キャンディード』を通して、彼はライプニッツとその楽観主義を攻撃している[10][11]。 『カンディード』は大きな成功とスキャンダルの両方を享受した。秘密裏に出版された直後は、宗教的冒涜、政治的扇動、素朴さの薄いベールに隠された知的敵 意が含まれているとして、広く発禁処分を受けた[10]。しかし、鋭いウィットと洞察に満ちた人間の状態の描写により、この小説はその後多くの後世の作家 や芸術家に模倣や翻案を促すことになった。今日、『キャンディード』はヴォルテールの大作とされ[10]、しばしば西洋の正典の一部として挙げられてい る。イギリスの詩人で文芸評論家のマーティン・シーモア=スミスは、『カンディード』を「これまでに書かれた本の中で最も影響力のある100冊」のひとつ に挙げている[12]。 |

| Historical and literary

background A number of historical events inspired Voltaire to write Candide, most notably the publication of Leibniz's "Monadology" (a short metaphysical treatise), the Seven Years' War, and the 1755 Lisbon earthquake. Both of the latter catastrophes are frequently referred to in Candide and are cited by scholars as reasons for its composition.[13] The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, tsunami, and resulting fires of All Saints' Day had a strong influence on theologians of the day and on Voltaire, who was himself disillusioned by them. The earthquake had an especially large effect on the contemporary doctrine of optimism, a philosophical system founded on the theodicy of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, which insisted on God's benevolence in spite of such events. This concept is often put in the form, "all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds" (French: Tout est pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles). Philosophers had trouble fitting the horrors of this earthquake into their optimistic world view.[14]  This 1755 copper engraving shows the ruins of Lisbon in flames and a tsunami overwhelming the ships in the harbour. Voltaire actively rejected Leibnizian optimism after the natural disaster, convinced that if this were the best possible world, it should surely be better than it is.[15] In both Candide and Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne ("Poem on the Lisbon Disaster"), Voltaire attacks this optimist belief.[14] He makes use of the Lisbon earthquake in both Candide and his Poème to argue this point, sarcastically describing the catastrophe as one of the most horrible disasters "in the best of all possible worlds".[16] Immediately after the earthquake, unreliable rumours circulated around Europe, sometimes overestimating the severity of the event. Ira Wade, a noted expert on Voltaire and Candide, has analyzed which sources Voltaire might have referenced in learning of the event. Wade speculates that Voltaire's primary source for information on the Lisbon earthquake was the 1755 work Relation historique du Tremblement de Terre survenu à Lisbonne by Ange Goudar.[17] Apart from such events, contemporaneous stereotypes of the German personality may have been a source of inspiration for the text, as they were for Simplicius Simplicissimus,[18] a 1669 satirical picaresque novel written by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen and inspired by the Thirty Years' War. The protagonist of this novel, who was supposed to embody stereotypically German characteristics, is quite similar to the protagonist of Candide.[2] These stereotypes, according to Voltaire biographer Alfred Owen Aldridge, include "extreme credulousness or sentimental simplicity", two of Candide's and Simplicius's defining qualities. Aldridge writes, "Since Voltaire admitted familiarity with fifteenth-century German authors who used a bold and buffoonish style, it is quite possible that he knew Simplicissimus as well."[2] A satirical and parodic precursor of Candide, Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) is one of Candide's closest literary relatives. This satire tells the story of "a gullible ingenue", Gulliver, who (like Candide) travels to several "remote nations" and is hardened by the many misfortunes which befall him. As evidenced by similarities between the two books, Voltaire probably drew upon Gulliver's Travels for inspiration while writing Candide.[19] Other probable sources of inspiration for Candide are Télémaque (1699) by François Fénelon and Cosmopolite (1753) by Louis-Charles Fougeret de Monbron. Candide's parody of the bildungsroman is probably based on Télémaque, which includes the prototypical parody of the tutor on whom Pangloss may have been partly based. Likewise, Monbron's protagonist undergoes a disillusioning series of travels similar to those of Candide.[2][20][21] |

歴史的・文学的背景 ライプニッツの『モナドロジー』(形而上学の小論文)の出版、七年戦争、1755年のリスボン地震などである。1755年のリスボン地震、津波、その結果 起こった万聖節の大火は、当時の神学者たちやヴォルテールに強い影響を与え、ヴォルテール自身もそれに幻滅していた。この地震は、ゴットフリート・ヴィル ヘルム・ライプニッツの神義論に基づく哲学体系である楽観主義の教義に特に大きな影響を及ぼし、このような出来事にもかかわらず神の博愛を主張した。この 概念は、しばしば「すべての可能な世界の中で最善のものはすべて最善である」(フランス語:Tout est pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles)という形で表現される。哲学者たちは、この地震の恐怖を楽観的な世界観に当てはめることに苦労した[14]。  この1755年の銅版画には、炎に包まれたリスボンの廃墟と、港の船を圧倒する津波が描かれている。 ヴォルテールは、この自然災害の後、ライプニッツ的な楽観主義を積極的に否定し、この世界が可能な限り最良のものであるならば、きっと今よりも良くなって いるはずだと確信した[15]。『カンディード』と『リスボン震災詩』の両方で、ヴォルテールはこの楽観主義者の信念を攻撃している。 [14]彼は『カンディード』と『リスボンの災難についての詩』の両方でリスボン地震を題材にしてこの点を主張し、この大災害を「可能な限り最良の世界に おける」最も恐ろしい災害のひとつであると皮肉った[16]。ヴォルテールと『カンディード』の専門家として知られるアイラ・ウェイドは、ヴォルテールが この出来事を知る際に参考にしたであろう情報源を分析している。ウェイドは、リスボン地震に関するヴォルテールの主な情報源は、1755年に出版されたア ンジュ・グーダールの『Relation historique du Tremblement de Terre survenu à Lisbonne』であると推測している[17]。 そのような出来事とは別に、同時代のドイツ人の性格に関するステレオタイプが、ハンス・ヤコブ・クリストフェル・フォン・グリメルスハウゼンが30年戦争 に触発されて書いた1669年の風刺ピカレスク小説『Simplicius Simplicissimus』[18]のインスピレーションの源となったかもしれない。ヴォルテールの伝記作家アルフレッド・オーウェン・アルドリッジ によれば、このステレオタイプには、カンディードとシンプリシムスの特徴的な性質である「極端な信心深さや感傷的な単純さ」が含まれる。アルドリッジは 「ヴォルテールは大胆で滑稽な文体を使う15世紀のドイツ人作家に親しんでいたことを認めているので、シンプリシウスも知っていた可能性は十分にある」と 書いている[2]。 『カンディード』の風刺的でパロディ的な先駆けであるジョナサン・スウィフトの『ガリバー旅行記』(1726年)は、『カンディード』に最も近い文学的親 戚の一人である。この風刺小説は、「騙されやすい純情な少女」ガリバーが、(カンディードと同じように)いくつかの「辺境の国」を旅し、彼に降りかかる多 くの不幸によって心を固めていく物語である。この2冊の本が似ていることからわかるように、ヴォルテールは『カンディード』を書く際に『ガリバー旅行記』 からインスピレーションを得たと思われる[19]。『カンディード』のインスピレーションの源となったと思われる他の作品には、フランソワ・フェネロンの 『Télémaque』(1699年)とルイ=シャルル・フジェレ・ド・モンブロンの『Cosmopolite』(1753年)がある。カンディード』の ビルドゥングスロマンのパロディは、おそらく『Télémaque』に基づいており、その中には『パングロス』のモデルとなった家庭教師のパロディの原型 が含まれている。同様に、モンブロンの主人公は『カンディード』と似たような幻滅的な旅の連続を経験する[2][20][21]。 |

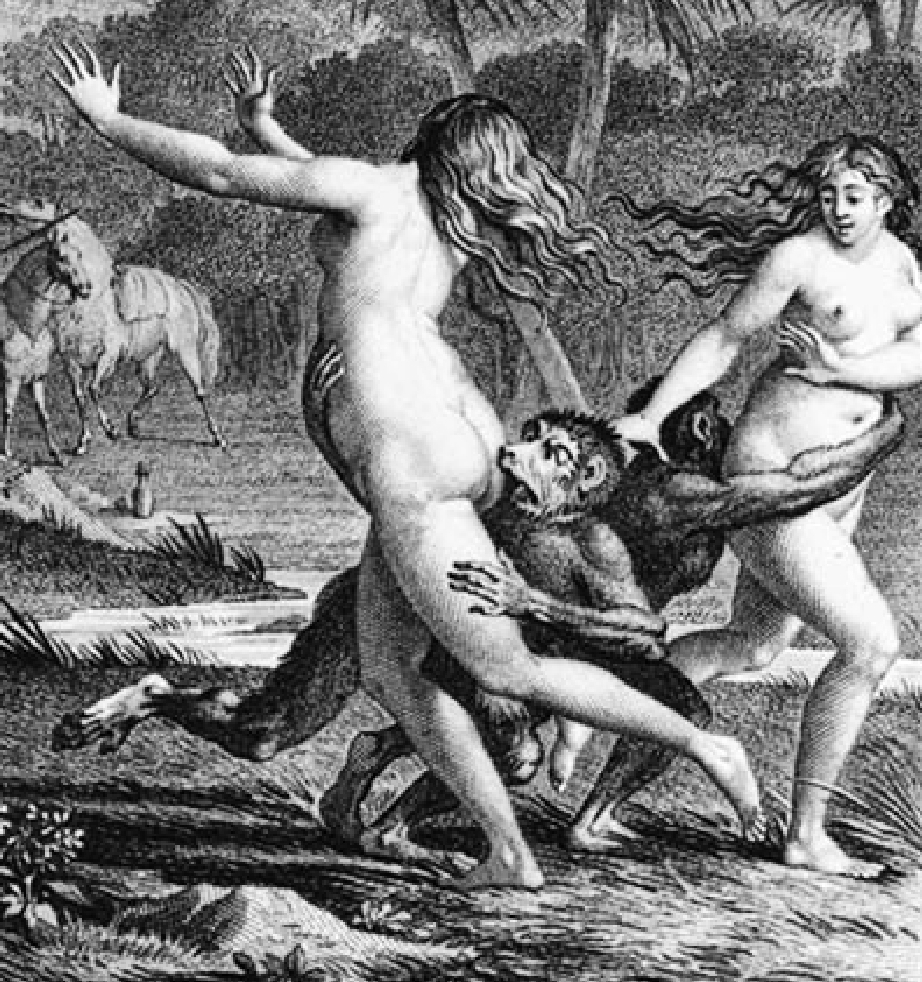

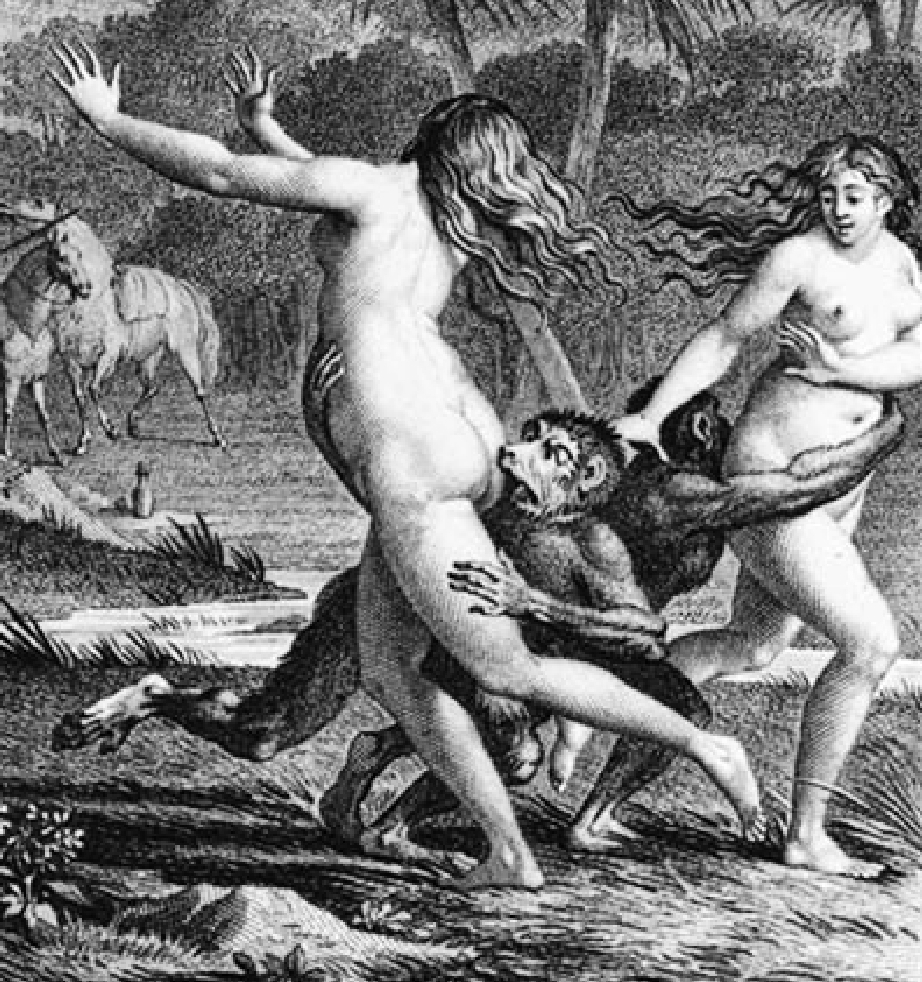

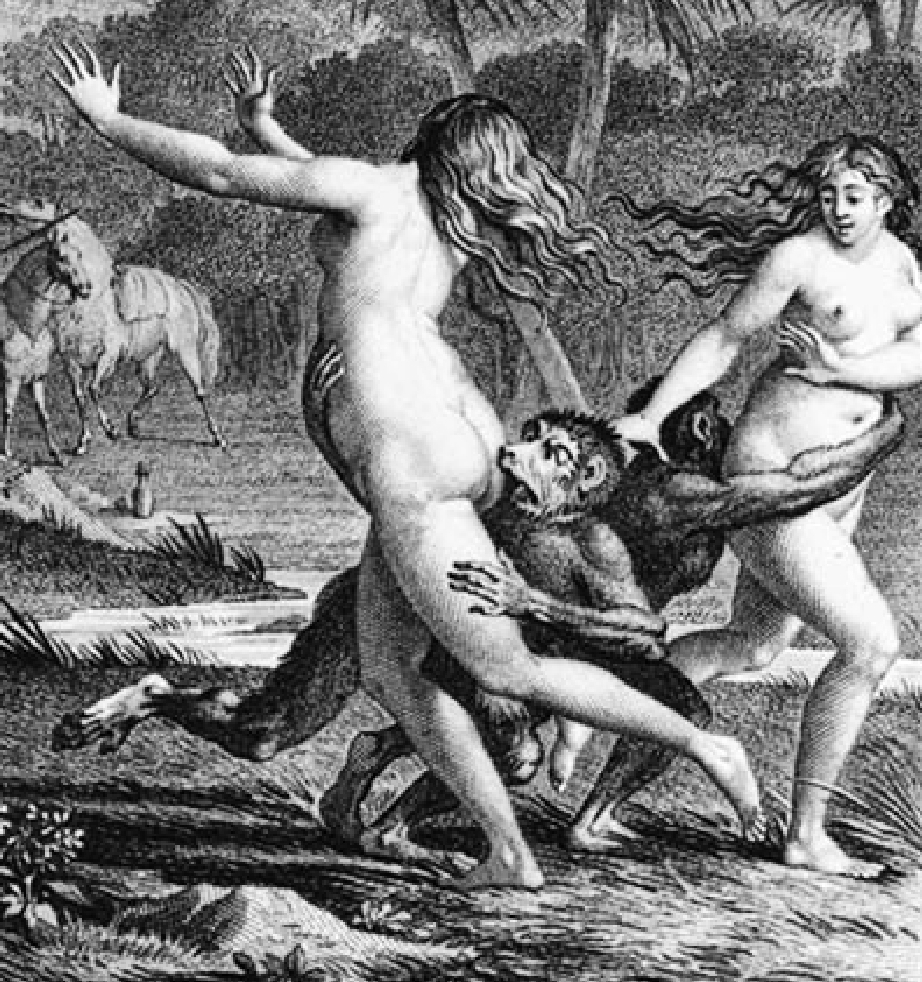

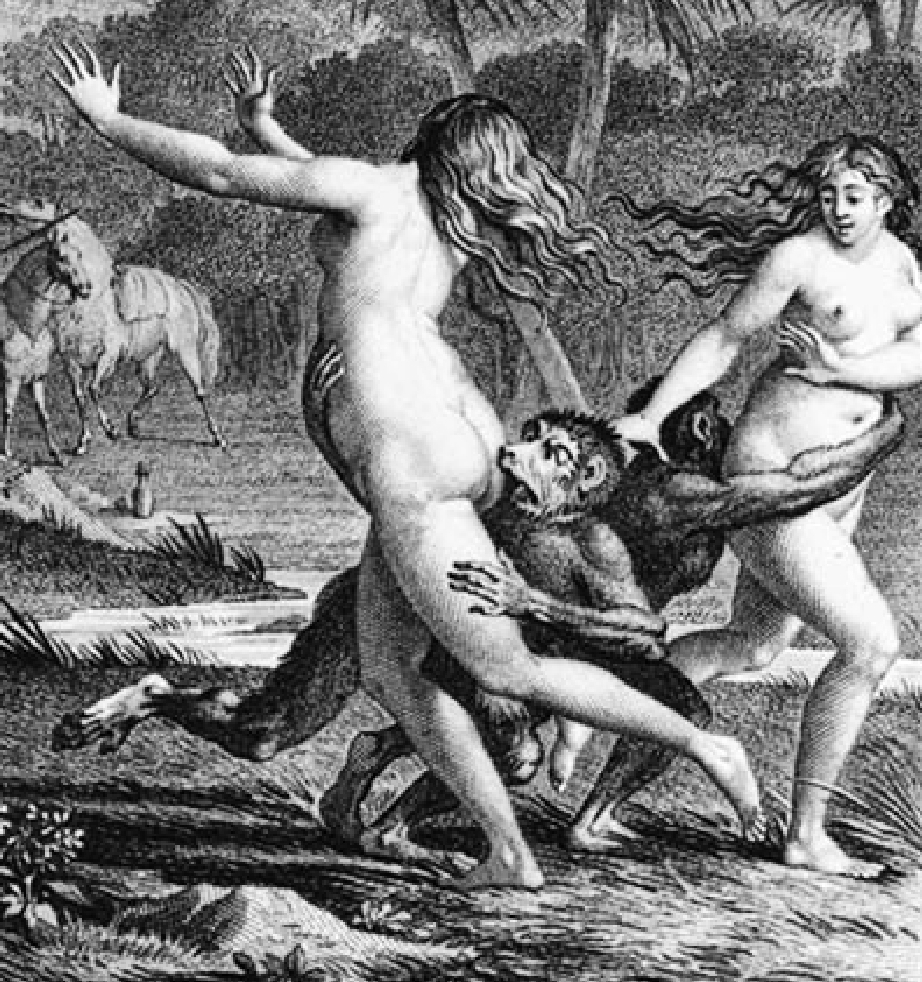

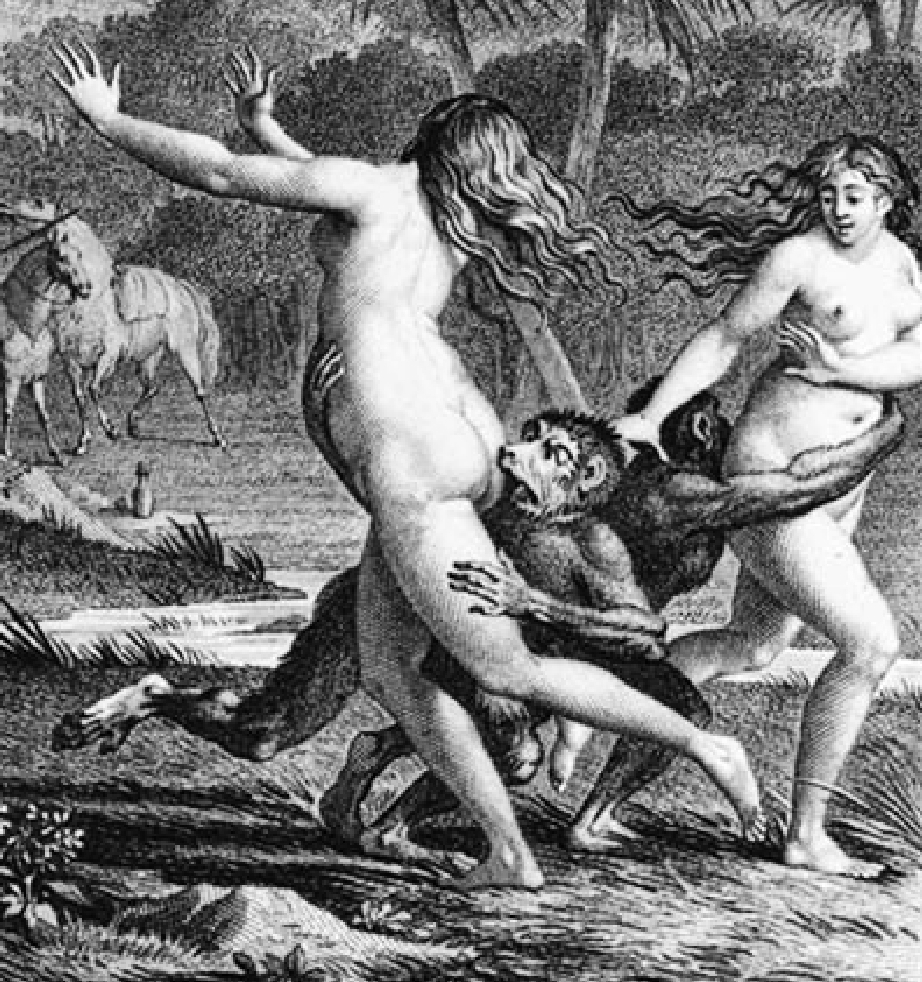

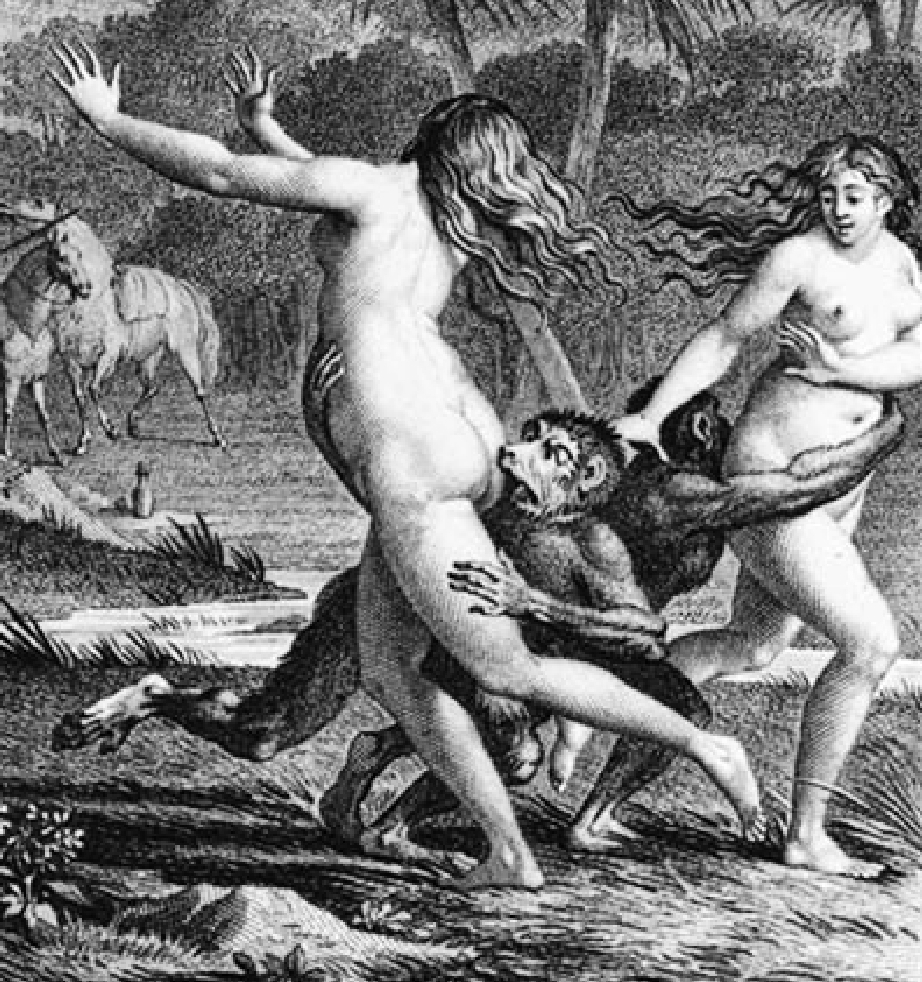

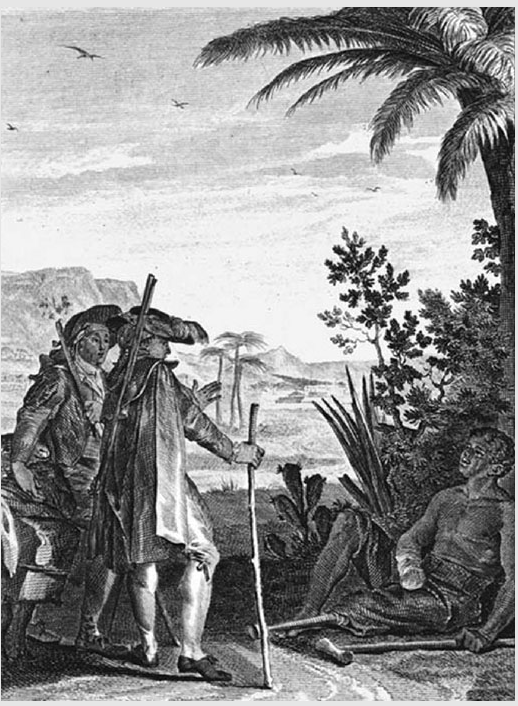

| Creation Born François-Marie Arouet, Voltaire (1694–1778), by the time of the Lisbon earthquake, was already a well-established author, known for his satirical wit. He had been made a member of the Académie Française in 1746. He was a deist, a strong proponent of religious freedom, and a critic of tyrannical governments. Candide became part of his large, diverse body of philosophical, political, and artistic works expressing these views.[22][23] More specifically, it was a model for the eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century novels called the contes philosophiques. This genre, of which Voltaire was one of the founders, included previous works of his such as Zadig and Micromegas.[24][25][26] Engraving of Voltaire published as the frontispiece to an 1843 edition of his Dictionnaire philosophique  It is unknown exactly when Voltaire wrote Candide,[27] but scholars estimate that it was primarily composed in late 1758 and begun as early as 1757.[28] Voltaire is believed to have written a portion of it while living at Les Délices near Geneva and also while visiting Charles Théodore, the Elector-Palatinate, at Schwetzingen for three weeks in the summer of 1758. Despite solid evidence for these claims, a popular legend persists that Voltaire wrote Candide in three days. This idea is probably based on a misreading of the 1885 work La Vie intime de Voltaire aux Délices et à Ferney by Lucien Perey (real name: Clara Adèle Luce Herpin) and Gaston Maugras.[29][30] The evidence indicates strongly that Voltaire did not rush or improvise Candide, but worked on it over a significant period of time, possibly even a whole year. Candide is mature and carefully developed, not impromptu, as the intentionally choppy plot and the aforementioned myth might suggest.[31] There is only one extant manuscript of Candide that was written before the work's 1759 publication; it was discovered in 1956 by Wade and since named the La Vallière Manuscript. It is believed to have been sent, chapter by chapter, by Voltaire to the Duke and Duchess La Vallière in the autumn of 1758.[4] The manuscript was sold to the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal in the late eighteenth century, where it remained undiscovered for almost two hundred years.[32] The La Vallière Manuscript, the most original and authentic of all surviving copies of Candide, was probably dictated by Voltaire to his secretary, Jean-Louis Wagnière, then edited directly.[29][33] In addition to this manuscript, there is believed to have been another, one copied by Wagnière for the Elector Charles-Théodore, who hosted Voltaire during the summer of 1758. The existence of this copy was first postulated by Norman L. Torrey in 1929. If it exists, it remains undiscovered.[29][34] Voltaire published Candide simultaneously in five countries no later than 15 January 1759, although the exact date is uncertain.[4][35] Seventeen versions of Candide from 1759, in the original French, are known today, and there has been great controversy over which is the earliest.[4] More versions were published in other languages: Candide was translated once into Italian and thrice into English that same year.[3] The complicated science of calculating the relative publication dates of all of the versions of Candide is described at length in Wade's article "The First Edition of Candide: A Problem of Identification". The publication process was extremely secretive, probably the "most clandestine work of the century", because of the book's obviously illicit and irreverent content.[36] The greatest number of copies of Candide were published concurrently in Geneva by Cramer, in Amsterdam by Marc-Michel Rey, in London by Jean Nourse, and in Paris by Lambert.[36]  1803 illustration of the two monkeys chasing their lovers. Candide shoots the monkeys, thinking they are attacking the women. Candide underwent one major revision after its initial publication, in addition to some minor ones. In 1761, a version of Candide was published that included, along with several minor changes, a major addition by Voltaire to the twenty-second chapter, a section that had been thought weak by the Duke of Vallière.[37] The English title of this edition was Candide, or Optimism, Translated from the German of Dr. Ralph. With the additions found in the Doctor's pocket when he died at Minden, in the Year of Grace 1759.[38] The last edition of Candide authorised by Voltaire was the one included in Cramer's 1775 edition of his complete works, known as l'édition encadrée, in reference to the border or frame around each page.[39][40] Voltaire strongly opposed the inclusion of illustrations in his works, as he stated in a 1778 letter to the writer and publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke: Je crois que des Estampes seraient fort inutiles. Ces colifichets n'ont jamais été admis dans les éditions de Cicéron, de Virgile et d'Horace. (I believe that these illustrations would be quite useless. These baubles have never been allowed in the works of Cicero, Virgil and Horace.)[41] Despite this protest, two sets of illustrations for Candide were produced by the French artist Jean-Michel Moreau le Jeune. The first version was done, at Moreau's own expense, in 1787 and included in Kehl's publication of that year, Oeuvres Complètes de Voltaire.[42] Four images were drawn by Moreau for this edition and were engraved by Pierre-Charles Baquoy.[43] The second version, in 1803, consisted of seven drawings by Moreau which were transposed by multiple engravers.[44] The twentieth-century modern artist Paul Klee stated that it was while reading Candide that he discovered his own artistic style. Klee illustrated the work, and his drawings were published in a 1920 version edited by Kurt Wolff.[45] |

創造 フランソワ=マリー・アルーエに生まれたヴォルテール(1694-1778)は、リスボン地震の頃にはすでに風刺的なウィットで知られる著名な作家になっ ていた。1746年にはアカデミー・フランセーズの会員となっていた。彼は神学者であり、信教の自由を強く支持し、専制的な政府を批判した。カンディー ド』は、哲学的、政治的、芸術的にこれらの見解を表現した、彼の大規模で多様な作品群の一部となった[22][23]。より具体的には、18世紀から19 世紀初頭にかけての、哲学小説と呼ばれる小説のモデルとなった。ヴォルテールが創始者の一人であるこのジャンルには、『ザディグ』や『ミクロメガス』と いった彼の過去の作品も含まれていた[24][25][26]。  1843年版『哲学辞典』の扉絵として掲載されたヴォルテールのエングレーヴィング。 ヴォルテールが『カンディード』を執筆した正確な時期は不明であるが[27]、学者たちは、主に1758年後半に執筆され、1757年には執筆が始まって いたと推定している[28]。こうした主張には確かな証拠があるにもかかわらず、ヴォルテールは『カンディード』を3日で書いたという俗説が根強く残って いる。この考えはおそらく、ルシアン・ペレイ(本名:クララ・アデル・ルーチェ・エルパン)とガストン・モーグラスによる1885年の著作『La Vie intime de Voltaire aux Délices et à Ferney』の誤読に基づいている。カンディード』は、意図的にちぐはぐなプロットや前述の神話が示唆するように、即興的なものではなく、成熟した、注 意深く練られた作品である[31]。 現存する『カンディード』の写本は、1759年の出版以前に書かれたもので、1956年にウェイドによって発見され、ラ・ヴァリエール写本と名付けられ た。この写本は、1758年の秋にヴォルテールからラ・ヴァリエール公爵夫妻に章ごとに送られたと考えられている。 [32] ラ・ヴァリエール写本は、現存する『カンディード』の写本の中で最もオリジナルで真正なものであり、おそらくヴォルテールが秘書のジャン=ルイ・ワニエー ルに口述したものを直接編集したものであろう[29][33]。この写本の他に、1758年の夏にヴォルテールをもてなした選帝侯シャルル=テオドールの ためにワニエールが書写したものがあったと考えられている。この写本の存在は、1929年にノーマン・L・トーレイによって初めて提唱された。現存すると しても未発見のままである[29][34]。 ヴォルテールは『カンディード』を遅くとも1759年1月15日までに5カ国で同時に出版したが、正確な日付は不明である[4][35]。 1759年に出版された『カンディード』の原文フランス語版は現在17種類知られており、どれが最古のものであるかについては大きな論争がある[4]: カンディード』は同年、イタリア語に1度、英語に3度翻訳された[3]。『カンディード』の全版の相対的な出版年代を計算する複雑な科学については、ウェ イドの論文「『カンディード』の初版本: A Problem of Identification "に詳しく書かれている。カンディード』の出版過程は極めて秘密主義的であり、おそらく「今世紀で最も秘密主義的な仕事」であったと思われる。  1803年、恋人を追いかける二匹の猿の挿絵。カンディードは猿が女性を襲っていると思い、猿を撃つ。 カンディード』は最初の出版後、1度大きな改稿が行われ、さらに小さな改稿も行われた。1761年、『カンディード』の改訂版が出版され、いくつかの小さ な変更とともに、ヴァリエール公爵が弱いと考えていた第22章にヴォルテールによる大きな加筆が加えられた[37]。ヴォルテールによって公認された『カ ンディード』の最後の版は、1775年にクラマーによって出版された『カンディード』全集に収録されたものであり、各ページを囲む枠にちなんで l'édition encadréeとして知られている[39][40]。 ヴォルテールは自分の作品に挿絵を入れることに強く反対しており、1778年に作家で出版者のシャルル・ジョゼフ・パンクーケに宛てた手紙の中でこう述べ ている: エスタンプ(挿絵)は全く無意味である。これらの挿絵は、シセロン版、ヴァージル版、ホレス版では、これまで一度も認められていない。(これらの挿絵は全 く役に立たないだろうと思う。キケロ、ヴァージル、ホラーチェの作品にこれらのつまらないものが許されたことは一度もない)[41]。 この抗議にもかかわらず、『カンディード』の挿絵はフランスの画家ジャン=ミシェル・モロー・ル・ジューヌによって2セット制作された。最初の版は 1787年にモローの私費で制作され、その年のケールの出版物『Oeuvres Complètes de Voltaire』に収録された[42]。この版のためにモローが描いた4枚の絵はピエール=シャルル・バコワによってエングレーヴィングされた [43]。クレーはこの作品の挿絵を描き、彼の絵はクルト・ヴォルフが編集した1920年版として出版された[45]。 |

| List of characters Main characters Candide: The title character. The illegitimate son of the sister of the Baron of Thunder-ten-Tronckh. In love with Cunégonde. Cunégonde: The daughter of the Baron of Thunder-ten-Tronckh. In love with Candide. Professor Pangloss: The royal educator of the court of the baron. Described as "the greatest philosopher of the Holy Roman Empire". The Old Woman: Cunégonde's maid while she is the mistress of Don Issachar and the Grand Inquisitor of Portugal. Flees with Candide and Cunégonde to the New World. Illegitimate daughter of Pope Urban X. Cacambo: Born from a Mestizo father and an Indigenous mother. Lived half his life in Spain and half in Latin America. Candide's valet while in America. Martin: Dutch amateur philosopher and Manichaean. Meets Candide in Suriname, travels with him afterwards. The Baron of Thunder-ten-Tronckh: Brother of Cunégonde. Is seemingly killed by the Bulgarians, but becomes a Jesuit in Paraguay. Disapproves of Candide and Cunégonde's marriage. Secondary characters The baron and baroness of Thunder-ten-Tronckh: Father and mother of Cunégonde and the second baron. Both slain by the Bulgars. The king of the Bulgars: Frederick II Jacques the Anabaptist: Dutch manufacturer who takes Candide in after his escape from the Prussian Army. Drowns in the port of Lisbon after saving a sailor's life. Don Issachar: Jewish banker in Portugal. Cunégonde becomes his mistress, shared with the Grand Inquisitor of Portugal. Killed by Candide. The Grand Inquisitor of Portugal: Sentences Candide and Pangloss at the auto-da-fé. Cunégonde is his mistress jointly with Don Issachar. Killed by Candide. Don Fernando d'Ibarra y Figueroa y Mascarenes y Lampourdos y Souza: Spanish governor of Buenos Aires. Wants Cunégonde as a mistress. The king of El Dorado, who helps Candide and Cacambo out of El Dorado, lets them pick gold from the grounds, and makes them rich. Mynheer Vanderdendur: Dutch ship captain/pirate and slave holder. Offers to take Candide from America to France for 30,000 gold coins, but then departs without him, stealing most of his riches. Dies after his ship sinks. The abbot of Périgord: Befriends Candide and Martin in the hopes of scamming them. Tries to have them arrested. The marchioness of Parolignac: Parisian wench who takes an elaborate title. The scholar: One of the guests of the "marchioness". Argues with Candide about art. Paquette: A chambermaid from Thunder-ten-Tronckh who gave Pangloss syphilis after getting it herself from her Franciscan confessor. After the slaying by the Bulgars, works as a prostitute in Venice and becomes entangled with Friar Giroflée. Friar Giroflée: Theatine friar. In love with the prostitute Paquette. Signor Pococurante: A Venetian noble. Candide and Martin visit his estate, where he discusses his disdain of most of the canon of great art. In an inn in Venice, Candide and Martin dine with six men who turn out to be deposed monarchs: Ahmed III Ivan VI of Russia Charles Edward Stuart Augustus III of Poland Stanisław Leszczyński Theodore of Corsica |

登場人物一覧 主な登場人物 カンディード︎▶︎ 主人公。サンダー・テン・トロンク男爵の妹の隠し子。キュネゴンドに恋している。 クネゴンド (クネゴンデ・キュネゴンド)▶︎サンダー・テン・トロンク男爵の娘。カンディードに恋している。 パングロス教授▶︎ 男爵の宮廷教育係。「神聖ローマ帝国最大の哲学者」と評される。 老女(老婆): キュネゴンドがドン・イッサシャールとポルトガルの大審問官の愛人である間の女中。カンディード、クネゴンドとともに新大陸へ逃れる。教皇ウルバン10世 の嫡女。 カカンボ▶︎メスティーソの父と先住民の母の間に生まれる。人生の半分をスペイン、半分をラテンアメリカで過ごす。アメリカ滞在中はカンディードの付き 人。 マーティン▶︎オランダのアマチュア哲学者でマニ教信者。スリナムでカンディードと出会い、その後共に旅をする。 サンダー・テン・トロンク男爵▶︎ キュネゴンドの弟。ブルガリア人に殺されたかに見えたが、パラグアイでイエズス会士となる。カンディードとキュネゴンドの結婚に反対。 二次的登場人物 サンダー・テン・トロンク男爵夫妻▶︎ クネゴンドと2番目の男爵の父と母。二人ともブルガルに殺される。 ブルガールの王▶︎フリードリヒ2世 洗礼者ジャック▶︎プロイセン軍から逃亡したカンディードを引き取ったオランダの製造業者。船員の命を救った後、リスボンの港で溺死する。 ドン・イッサカル▶︎ポルトガルのユダヤ人銀行家。キュネゴンドを愛人とし、ポルトガルの大審問官と共有する。カンディードに殺される。 ポルトガル大審問官▶︎ カンディードとパングロスをオート・ダ・フェで処刑。キュネゴンドはドン・イッサシャルと共同で彼の愛人となる。カンディードに殺される。 ドン・フェルナンド・ディバラ・イ・フィゲロア・イ・マスカレーネス・イ・ランポウドス・イ・スーザ▶︎ スペインのブエノスアイレス総督。クネゴンドを愛人に欲しがる。 エルドラドの王▶︎カンディードとカカンボをエルドラドから助け出し、敷地内の金を採らせて金持ちにする。 マインヒア・ヴァンダーデンドゥール▶︎ オランダ人の船長/海賊/奴隷所有者。金貨3万枚でキャンディドをアメリカからフランスに連れて行くと申し出るが、キャンディドを置いて出港し、富の大半 を盗む。船が沈没して死亡。 ペリゴール大修道院長▶︎カンディードとマルタンに近づき、詐欺を働く。二人を逮捕させようとする。 パロリニャックの侯爵夫人▶︎凝った爵位を名乗るパリの女官。 学者▶︎ 侯爵夫人」の客の一人。カンディードと芸術について議論する。 パケット▶︎ フランシスコ会修道士から梅毒をうつされ、パングロスに梅毒をうつしたサンダー・テン・トロンクの侍女。ブルガール人に殺された後、ヴェネツィアで娼婦と して働き、ジロフレ修道士に絡まれる。 ジロフレ修道士▶︎ 演劇修道士。娼婦パケットと恋に落ちる。 ポコクランテ修道士▶︎ヴェネツィアの貴族。カンディードとマルタンが彼の屋敷を訪れ、偉大な芸術の規範のほとんどを軽んじていることを話す。 ヴェニスの宿屋で、カンディードとマルティンは、退位した君主であることが判明した6人の男たちと食事をする: アハメド3世▶︎ ロシアのイヴァン6世▶︎ チャールズ・エドワード・スチュアート▶︎ ポーランドのアウグスト3世▶︎ スタニスワフ・レシチンスキ▶︎ コルシカ王テオドール▶︎ |

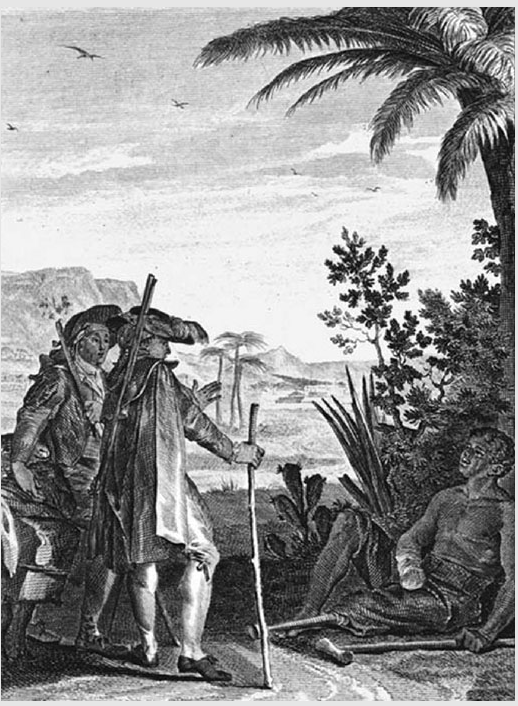

| Synopsis Candide contains thirty episodic chapters, which may be grouped into two main schemes: one consists of two divisions, separated by the protagonist's hiatus in El Dorado; the other consists of three parts, each defined by its geographical setting. By the former scheme, the first half of Candide constitutes the rising action and the last part the resolution. This view is supported by the strong theme of travel and quest, reminiscent of adventure and picaresque novels, which tend to employ such a dramatic structure.[46] By the latter scheme, the thirty chapters may be grouped into three parts each comprising ten chapters and defined by locale: I–X are set in Europe, XI–XX are set in the Americas, and XXI–XXX are set in Europe and the Ottoman Empire.[47][48] The plot summary that follows uses this second format and includes Voltaire's additions of 1761. Chapters I–X The tale of Candide begins in the castle of the Baron Thunder-ten-Tronckh in Westphalia, home to the Baron's daughter, Lady Cunégonde; his bastard nephew, Candide; a tutor, Pangloss; a chambermaid, Paquette; and the rest of the Baron's family. The protagonist, Candide, is romantically attracted to Cunégonde. He is a young man of "the most unaffected simplicity" (l'esprit le plus simple), whose face is "the true index of his mind" (sa physionomie annonçait son âme).[2] Dr. Pangloss, professor of "métaphysico-théologo-cosmolonigologie" (English: "metaphysico-theologo-cosmolonigology") and self-proclaimed optimist, teaches his pupils that they live in the "best of all possible worlds" and that "all is for the best".  Frontispiece and first page of chapter one of an early English translation by T. Smollett (et al.) of Voltaire's Candide, London, printed for J. Newbery (et al.), 1762. All is well in the castle until Cunégonde sees Pangloss sexually engaged with Paquette in some bushes. Encouraged by this show of affection, Cunégonde drops her handkerchief next to Candide, enticing him to kiss her. For this infraction, Candide is evicted from the castle, at which point he is captured by Bulgar (Prussian) recruiters and coerced into military service, where he is flogged, nearly executed, and forced to participate in a major battle between the Bulgars and the Avars (an allegory representing the Prussians and the French). Candide eventually escapes the army and makes his way to Holland where he is given aid by Jacques, an Anabaptist, who strengthens Candide's optimism. Soon after, Candide finds his master Pangloss, now a beggar with syphilis. Pangloss reveals he was infected with this disease by Paquette and shocks Candide by relating how Castle Thunder-ten-Tronckh was destroyed by Bulgars, that Cunégonde and her whole family were killed, and that Cunégonde was raped before her death. Pangloss is cured of his illness by Jacques, losing one eye and one ear in the process, and the three set sail to Lisbon. In Lisbon's harbor, they are overtaken by a vicious storm which destroys the boat. Jacques attempts to save a sailor, and in the process is thrown overboard.[49] The sailor makes no move to help the drowning Jacques, and Candide is in a state of despair until Pangloss explains to him that Lisbon harbor was created in order for Jacques to drown. Only Pangloss, Candide, and the "brutish sailor" who let Jacques drown[50] survive the wreck and reach Lisbon, which is promptly hit by an earthquake, tsunami, and fire that kill tens of thousands. The sailor leaves in order to loot the rubble while Candide, injured and begging for help, is lectured on the optimistic view of the situation by Pangloss. The next day, Pangloss discusses his optimistic philosophy with a member of the Portuguese Inquisition, and he and Candide are arrested for heresy, set to be tortured and killed in an "auto-da-fé" set up to appease God and prevent another disaster. Candide is flogged and sees Pangloss hanged, but another earthquake intervenes and he escapes. He is approached by an old woman,[51] who leads him to a house where Lady Cunégonde waits, alive. Candide is surprised: Pangloss had told him that Cunégonde had been raped and disemboweled. She had been, but Cunégonde points out that people survive such things. However, her rescuer sold her to a Jewish merchant, Don Issachar, who was then threatened by a corrupt Grand Inquisitor into sharing her (Don Issachar gets Cunégonde on Mondays, Wednesdays, and the sabbath day). Her owners arrive, find her with another man, and Candide kills them both. Candide and the two women flee the city, heading to the Americas.[52] Along the way, Cunégonde falls into self-pity, complaining of all the misfortunes that have befallen her. Chapters XI–XX The old woman reciprocates by revealing her own tragic life: born the daughter of Pope Urban X and the Princess of Palestrina, she was kidnapped and enslaved by Barbary pirates, witnessed violent civil wars in Morocco under the bloodthirsty king Moulay Ismaïl (during which her mother was drawn and quartered), suffered constant hunger, nearly died from a plague in Algiers, and had a buttock cut off to feed starving Janissaries during the Russian capture of Azov. After traversing all the Russian Empire, she eventually became a servant of Don Issachar and met Cunégonde. The trio arrives in Buenos Aires, where Governor Don Fernando d'Ibarra y Figueroa y Mascarenes y Lampourdos y Souza asks to marry Cunégonde. Just then, an alcalde (a Spanish magistrate) arrives, pursuing Candide for killing the Grand Inquisitor. Leaving the women behind, Candide flees to Paraguay with his practical and heretofore unmentioned manservant, Cacambo.  1787 illustration of Candide and Cacambo meeting a maimed slave from a sugarcane mill near Suriname. At a border post on the way to Paraguay, Cacambo and Candide speak to the commandant, who turns out to be Cunégonde's unnamed brother. He explains that after his family was slaughtered, the Jesuits' preparation for his burial revived him, and he has since joined the order.[52] When Candide proclaims he intends to marry Cunégonde, her brother attacks him, and Candide runs him through with his rapier. After lamenting all the people (mainly priests) he has killed, he and Cacambo flee. In their flight, Candide and Cacambo come across two naked women being chased and bitten by a pair of monkeys. Candide, seeking to protect the women, shoots and kills the monkeys, but is informed by Cacambo that the monkeys and women were probably lovers.  Cacambo and Candide are captured by Oreillons, or Orejones; members of the Inca nobility who widened the lobes of their ears, and are depicted here as the fictional inhabitants of the area. Mistaking Candide for a Jesuit by his robes, the Oreillons prepare to cook Candide and Cacambo; however, Cacambo convinces the Oreillons that Candide killed a Jesuit to procure the robe. Cacambo and Candide are released and travel for a month on foot and then down a river by canoe, living on fruits and berries.[53] After a few more adventures, Candide and Cacambo wander into El Dorado, a geographically isolated utopia where the streets are covered with precious stones, there exist no priests, and all of the king's jokes are funny.[54] Candide and Cacambo stay a month in El Dorado, but Candide is still in pain without Cunégonde, and expresses to the king his wish to leave. The king points out that this is a foolish idea, but generously helps them do so. The pair continue their journey, now accompanied by one hundred red pack sheep carrying provisions and incredible sums of money, which they slowly lose or have stolen over the next few adventures. Candide and Cacambo eventually reach Suriname where they split up: Cacambo travels to Buenos Aires to retrieve Lady Cunégonde, while Candide prepares to travel to Europe to await the two. Candide's remaining sheep are stolen, and Candide is fined heavily by a Dutch magistrate for petulance over the theft. Before leaving Suriname, Candide feels in need of companionship, so he interviews a number of local men who have been through various ill-fortunes and settles on a man named Martin. Chapters XXI–XXX This companion, Martin, is a Manichaean scholar based on the real-life pessimist Pierre Bayle, who was a chief opponent of Leibniz.[55] For the remainder of the voyage, Martin and Candide argue about philosophy, Martin painting the entire world as occupied by fools. Candide, however, remains an optimist at heart, since it is all he knows. After a detour to Bordeaux and Paris, they arrive in England and see an admiral (based on Admiral Byng) being shot for not killing enough of the enemy. Martin explains that Britain finds it necessary to shoot an admiral from time to time "pour encourager les autres" (to encourage the others).[56]  Candide, horrified, arranges for them to leave Britain immediately. Upon their arrival in Venice, Candide and Martin meet Paquette, the chambermaid who infected Pangloss with his syphilis. She is now a prostitute, and is spending her time with a Theatine monk, Brother Giroflée. Although both appear happy on the surface, they reveal their despair: Paquette has led a miserable existence as a sexual object since she was forced to become a prostitute, and the monk detests the religious order in which he was indoctrinated. Candide gives two thousand piastres to Paquette and one thousand to Brother Giroflée. Candide and Martin visit the Lord Pococurante, a noble Venetian. That evening, Cacambo—now a slave—arrives and informs Candide that Cunégonde is in Constantinople. Prior to their departure, Candide and Martin dine with six strangers who had come for the Carnival of Venice. These strangers are revealed to be dethroned kings: the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed III, Emperor Ivan VI of Russia, Charles Edward Stuart (an unsuccessful pretender to the English throne), Augustus III of Poland (deprived, at the time of writing, of his reign in the Electorate of Saxony due to the Seven Years' War), Stanisław Leszczyński, and Theodore of Corsica. On the way to Constantinople, Cacambo reveals that Cunégonde—now horribly ugly—currently washes dishes on the banks of the Propontis as a slave for a fugitive Transylvanian prince by the name of Rákóczi. After arriving at the Bosphorus, they board a galley where, to Candide's surprise, he finds Pangloss and Cunégonde's brother among the rowers. Candide buys their freedom and further passage at steep prices.[52] They both relate how they survived, but despite the horrors he has been through, Pangloss's optimism remains unshaken: "I still hold to my original opinions, because, after all, I'm a philosopher, and it wouldn't be proper for me to recant, since Leibniz cannot be wrong, and since pre-established harmony is the most beautiful thing in the world, along with the plenum and subtle matter."[57] Candide, the baron, Pangloss, Martin, and Cacambo arrive at the banks of the Propontis, where they rejoin Cunégonde and the old woman. Cunégonde has indeed become hideously ugly, but Candide nevertheless buys their freedom and marries Cunégonde to spite her brother, who forbids Cunégonde from marrying anyone but a baron of the Empire (he is secretly sold back into slavery). Paquette and Brother Giroflée—having squandered their three thousand piastres—are reconciled with Candide on a small farm (une petite métairie) which he just bought with the last of his finances. One day, the protagonists seek out a dervish known as a great philosopher of the land. Candide asks him why Man is made to suffer so, and what they all ought to do. The dervish responds by asking rhetorically why Candide is concerned about the existence of evil and good. The dervish describes human beings as mice on a ship sent by a king to Egypt; their comfort does not matter to the king. The dervish then slams his door on the group. Returning to their farm, Candide, Pangloss, and Martin meet a Turk whose philosophy is to devote his life only to simple work and not concern himself with external affairs. He and his four children cultivate a small area of land, and the work keeps them "free of three great evils: boredom, vice, and poverty."[58] Candide, Pangloss, Martin, Cunégonde, Paquette, Cacambo, the old woman, and Brother Giroflée all set to work on this "commendable plan" (louable dessein) on their farm, each exercising his or her own talents. Candide ignores Pangloss's insistence that all turned out for the best by necessity, instead telling him "we must cultivate our garden" (il faut cultiver notre jardin).[58] |

あらすじ 1つは、主人公がエルドラドで中断することによって区切られた2つの部分からなり、もう1つは、それぞれが地理的な設定によって定義された3つの部分から なる。前者の方式では、『カンディード』の前半が起承転結、後半が決着となる。この考え方は、冒険小説やピカレスク小説を彷彿とさせる、旅と探求という強 いテーマによって支持されている: I-X章はヨーロッパ、XI-XX章はアメリカ大陸、XXI-XXX章はヨーロッパとオスマン帝国が舞台である。 1)I-X章はヨーロッパ 2)XI-XX章はアメリカ大陸 3)XXI-XXX章はヨーロッパとオスマン帝国 1)第I章から第X章 『カンディード』の物語は、男爵の娘クネゴンド夫人、私生児の甥カンディード、家庭教師のパングロス、客室係(女中)のパケット、男爵一家が住むヴェスト ファーレ ンのサンダー・テン・トロンク男爵の城から始まる。主人公のカンディードはクネゴンドに恋心を抱く。カンディードは、「最も素朴な」青年であり、その顔 は「彼の心の真の指標」である[2]。métaphysico-théologo-cosmolonigologie"(英語では "métaphysico-theologo-cosmolonigologie")の教授であり、楽観主義者を自称するパングロスは、弟子たちに、自分 たちは "あらゆる可能な世界の中で最良の世界 "に生きており、"すべては最良のためにある "と教えている。  ヴォルテールの『カンディード』のT.スモレット(他)による初期の英訳版(ロンドン、J.ニューベリー(他)のために印刷、1762年)の扉絵と第1章 の最初のページ。 クネゴンドは、パングロスが茂みの中でパケットとセックスしているのを目撃する。この愛情表現に勇気づけられたクネゴンドは、ハンカチをカンディード の隣に落としてキスを誘う。この違反のために、カンディードは城から追い出され、ブルガール(プロイセン)の勧誘員に捕まって兵役を強要され、鞭打たれ、 処刑されそうになり、ブルガールとアヴァール(プロイセンとフランスを表す寓意)の大きな戦いに参加させられる。やがて軍を脱走したカンディードはオラン ダに向かい、そこでアナバプティストのジャックに助けられ、カンディードの楽観主義を強める。やがてカンディードは、梅毒で乞食となった師パングロスを見 つける。パングロスは、自分がパケットから梅毒をうつされたことを明かし、サンダー・テン・トロンク城がブルガリに破壊されたこと、キュネゴンドとその家 族が皆殺しにされたこと、クネゴンドが死ぬ前にレイプされたことを語り、カンディードを震え上がらせる。パングロスはジャックに病気を治してもらうが、 その過程で片目と片耳を失い、3人はリスボンに向けて出航する。 1)カンディード 2)パングロス 3)ジャック リスボンの港で激しい嵐に見舞われ、船は破壊される。船員は溺れるジャックを助けようとはせず、カンディードは絶望の淵に立たされるが、パングロスがリス ボン港はジャックを溺れさせるために造られたと説明する。パングロスとカンディード、そしてジャックを溺れさせた「残忍な船乗り」[50]だけが難破船か ら生き残り、リスボンにたどり着く。船員は瓦礫を略奪するために立ち去り、カンディードは怪我をして助けを求めていたが、パングロスに楽観的な見方を説教 される。 翌日、パングロスはポルトガルの異端審問官と彼の楽観的な哲学について話し合い、彼とカンディードは異端として逮捕され、拷問にかけられ、神の怒りを鎮 め、再び災害が起こるのを防ぐために設けられた「オート・ダ・フェ」で殺されることになる。カンディードは鞭打たれ、パングロスが絞首刑になるのを目撃す るが、再び地震が起こり、彼は逃げ出す。彼は老婆に声をかけられ[51]、クネゴンドが生きて待っている屋敷に案内される。カンディードは驚く: パングロスはクネゴンドがレイプされ、内臓を抜かれたと言っていたのだ。パングロスは、クネゴンドが強姦され、内臓を抜かれたと話していたのだ。しか し、クネゴンドはユダヤ人の商人ドン・イッサシャルに売られ、ドン・イッサシャルは悪徳大審問官に脅されてクネゴンドを分けてもらうことになる(ド ン・イッサシャルはクネゴンドを月、水、安息日に手に入れる)。彼女の所有者が現れ、彼女が他の男と一緒にいるのを見つけ、カンディードは二人を殺す。 カンディードと二人の女は街を逃げ出し、アメリカ大陸に向かう[52]。道中、クネゴンドは自分に降りかかったすべての不幸を訴え、自己憐憫に陥る。 2)第XI-XX章 教皇ウルバン10世とパレストリーナ王女の娘として生まれた彼女は、バーバリーの海賊に誘拐され奴隷にされ、血に飢えたムーレイ・イスマイール王のもとモ ロッコで激しい内戦を目撃し(その際に母親は四つ裂きにされた)、絶え間ない飢えに苦しみ、アルジェでは疫病で死にかけ、ロシアによるアゾフ占領の際には 飢えたジャニサリに食べさせるために臀部を切り落とされた。ロシア帝国全土を渡り歩いた彼女は、やがてドン・イッサシャルの下僕となり、クネゴンドと出 会う。 3人はブエノスアイレスに到着し、総督ドン・フェルナンド・ディバラ・イ・フィゲロア・イ・マスカレーネス・イ・ランポウドス・イ・スーザがクネゴンドと の結婚を申し込む。そこへ、大審問官を殺したとしてカンディードを追うアルカルデ(スペインの判事)がやって来る。カンディードは女たちを置き去りにし て、実用的でこれまで語られることのなかった下男のカカンボとともにパラグアイに逃亡する。  1787年、カンディードとカカンボがスリナム近郊のサトウキビ工場で手足の不自由な奴隷と出会う挿絵。 パラグアイに向かう途中の国境で、カカンボとカンディードは司令官と話すが、彼はクネゴンドの名も知らぬ兄であることが判明する。カンディードがクネゴン ドと結婚すると宣言すると、彼女の兄はカンディードを襲い、カンディードはレイピアで兄を打ち抜く。自分が殺したすべての人々(主に司祭)を嘆いた後、彼 とカカンボは逃げる。逃げる途中、カンディードとカカンボは2匹の猿に追いかけられ噛まれている2人の裸の女性に出くわす。カンディードは女性たちを守ろ うと猿を撃ち殺すが、カカンボから猿と女性は恋人同士だったのだろうと知らされる。  カカンボとカンディードはオレヨン(オレホネス)に捕らえられる。オレヨンはインカの貴族で、耳の小葉を広げた人々であり、ここではこの地域の架空の住民 として描かれている。カンディードをイエズス会士と勘違いしたオレヨンたちは、カンディードとカカンボを料理しようとするが、カカンボはカンディードがイ エズス会士を殺して衣を手に入れたとオレヨンたちを説得する。カカンボとカンディードは釈放され、徒歩とカヌーによる川下りで1ヶ月間旅をし、果物や木の 実で生活する[53]。 カンディドとカカンボはさらにいくつかの冒険をした後、エルドラドに迷い込む。エルドラドは地理的に隔離されたユートピアで、街路は宝石で覆われ、司祭は 存在せず、王の冗談はすべて面白い[54]。カンディドとカカンボはエルドラドに1ヶ月滞在するが、カンディドはクネゴンドがいないことにまだ苦痛を感じ ており、王に去りたいと申し出る。王はそれは愚かな考えだと指摘するが、寛大にも二人を助ける。二人は、食料と信じられないほどの大金を積んだ100頭の 赤い羊を従えて旅を続けるが、その後数回の冒険の間に、羊は徐々に失ったり盗まれたりする。 カンディードとカカンボはやがてスリナムに到着し、そこで別れる: カカンボはクネゴンデを取り戻すためにブエノスアイレスに向かい、 カンディードは2人を待つためにヨーロッパに向かう準備をする。 カンディードの残り の羊が盗まれ、 カンディードはオランダの判事から罰金を科される。スリナムを去る前に、カンディードは仲間が必要だと感じ、さまざまな不運を経験した地元 の男たちに話を聞き、マルタンという男に落ち着く。 3)XXI章からXXX章 このマルタンという伴侶は、ライプニッツの最大の敵であった実在の悲観主義者ピエール・バイユをモデルにしたマニ教の学者である[55]。航海の残りの期 間、マルタンとカンディードは哲学について議論し、マルタンが全世界を愚か者で占められていると描く。しかし、カンディードは、自分が知っているのはそれ しかないのだからと、根っからの楽観主義者であり続ける。ボルドーとパリに寄り道した後、イギリスに到着した二人は、敵を十分に殺さなかったという理由で 撃たれている提督(バイング提督がモデル)を見る。マーティンは、イギリスは時々提督を射殺する必要があることを "pour encourager les autres"(他の提督を励ますため)と説明する[56]。  ヴェネツィアに到着したカンディードとマルティンは、パングロスに梅毒をうつした客室係のパ ケットに出会う。彼女は現在娼婦で、テアティーヌ派の修道士ブラザー・ジロフレと過ごしている。二人とも表面的には幸せそうに見えるが、絶望を露わにして いる: パケットは娼婦にさせられて以来、性の対象として惨めな生活を送っており、修道士は自分が教え込まれた修道会を嫌悪している。カンディドはパケットに2千 ピアストル、ジロフレ修道士に1千ピアストルを贈る。 カンディードとマルタンは、高貴なヴェネツィア人ポコクランテ公を訪ねる。その夜、奴隷となったカカンボが到着し、キュネゴンドがコンスタンチノープルに いるとカンディードに知らせる。出発に先立ち、カンディードとマルティンは、ヴェニスの謝肉祭にやってきた6人の見知らぬ人々と食事をする。彼らはオスマ ン・トルコのスルタン、アフメド3世、ロシア皇帝イヴァン6世、チャールズ・エドワード・スチュアート(イギリス王位簒奪に失敗)、ポーランドのアウグス ト3世(執筆当時、七年戦争のためザクセン選帝侯国での統治権を剥奪された)、スタニスワフ・レシチンスキ、コルシカのテオドールであった。 コンスタンチノープルに向かう途中、カカンボは、クネゴンデが今は恐ろしいほど醜く、逃亡中のトランシルヴァニア王子ラーコチの奴隷としてプロポンティス 河岸で皿洗いをしていることを明かす。ボスポラス海峡に到着後、彼らはガレー船に乗り込むが、カンディードは驚いたことに、漕ぎ手の中にパングロスとキュ ネゴンドの兄を見つける。カンディードは二人の自由とさらなる航路を高値で買い取る[52]。二人は自分たちがどのように生き延びたかを語るが、恐怖を経 験したにもかかわらず、パングロスの楽観主義は揺るがない: 「というのも、結局のところ、私は哲学者であり、ライプニッツが間違っているはずはないし、あらかじめ確立された調和は、プレナムや微妙な物質と並んで、 この世で最も美しいものだからだ」[57]。 カンディード、男爵、パングロス、マルタン、カカンボはプロポンティス川のほとりに到着し、そこでクネゴンドと老婆と再会する。クネゴンドは確かに醜く なっていたが、それでもカンディードは二人の自由を買い取り、キュネゴンドに帝国の男爵以外との結婚を禁じた彼女の兄を恨んでクネゴンドと結婚する(彼 は密かに奴隷として売り戻される)。パケットとジロフレ兄は、3千ピエを浪費してしまったカンディードと、彼が最後の財産で買ったばかりの小さな農場 (une petite métairie)で和解する。 ある日、主人公たちはこの土地の偉大な哲学者として知られるダーヴィッシュを探す。カンディードは彼に、なぜ人間はこんなにも苦しまなければならないの か、人間はどうあるべきか、と問う。それに対してダー ヴィッシュは、なぜカンディードは悪と善の存在にこだわるのかと修辞的に問う。ダーヴィッシュは、人 間を王がエジプトに送る船のネズミのようなものだと表現する。そして一行に向かってドアを閉める。農場に戻ったカンディード、パングロス、 マーティンは、 単純労働にのみ人生を捧げ、対外的なことには関心を持たないという哲学を持つトルコ人に出会う。カンディード、パングロス、マルタン、クネゴンド、パ ケット、カカンボ、老女、そしてジロフレ兄は、この「称賛に値する計画」(louable dessein)のために、それぞれの才能を発揮して農場で働く。カンディードは、すべては必然的に最善になったというパングロスの主張を無視し、代わり に「私たちは庭を耕さなければならない」(il faut cultiver notre jardin)と告げる[58]。 |

| Style As Voltaire himself described it, the purpose of Candide was to "bring amusement to a small number of men of wit".[2] The author achieves this goal by combining wit with a parody of the classic adventure-romance plot. Candide is confronted with horrible events described in painstaking detail so often that it becomes humorous. Literary theorist Frances K. Barasch described Voltaire's matter-of-fact narrative as treating topics such as mass death "as coolly as a weather report".[59] The fast-paced and improbable plot—in which characters narrowly escape death repeatedly, for instance—allows for compounding tragedies to befall the same characters over and over again.[60] In the end, Candide is primarily, as described by Voltaire's biographer Ian Davidson, "short, light, rapid and humorous".[10][61] Behind the playful façade of Candide which has amused so many, there lies very harsh criticism of contemporary European civilization which angered many others. European governments such as France, Prussia, Portugal and England are each attacked ruthlessly by the author: the French and Prussians for the Seven Years' War, the Portuguese for their Inquisition, and the British for the execution of John Byng. Organised religion, too, is harshly treated in Candide. For example, Voltaire mocks the Jesuit order of the Roman Catholic Church. Aldridge provides a characteristic example of such anti-clerical passages for which the work was banned: while in Paraguay, Cacambo remarks, "[The Jesuits] are masters of everything, and the people have no money at all …". Here, Voltaire suggests the Christian mission in Paraguay is taking advantage of the local population. Voltaire depicts the Jesuits holding the indigenous peoples as slaves while they claim to be helping them.[62][63] Satire The main method of Candide's satire is to contrast ironically great tragedy and comedy.[10] The story does not invent or exaggerate evils of the world—it displays real ones starkly, allowing Voltaire to simplify subtle philosophies and cultural traditions, highlighting their flaws.[60] Thus Candide derides optimism, for instance, with a deluge of horrible, historical (or at least plausible) events with no apparent redeeming qualities.[2][59] A simple example of the satire of Candide is seen in the treatment of the historic event witnessed by Candide and Martin in Portsmouth harbour. There, the duo spy an anonymous admiral, supposed to represent John Byng, being executed for failing to properly engage a French fleet. The admiral is blindfolded and shot on the deck of his own ship, merely "to encourage the others" (French: pour encourager les autres, an expression Voltaire is credited with originating). This depiction of military punishment trivializes Byng's death. The dry, pithy explanation "to encourage the others" thus satirises a serious historical event in characteristically Voltairian fashion. For its classic wit, this phrase has become one of the more often quoted from Candide.[10][64] Voltaire depicts the worst of the world and his pathetic hero's desperate effort to fit it into an optimistic outlook. Almost all of Candide is a discussion of various forms of evil: its characters rarely find even temporary respite. There is at least one notable exception: the episode of El Dorado, a fantastic village in which the inhabitants are simply rational, and their society is just and reasonable. The positivity of El Dorado may be contrasted with the pessimistic attitude of most of the book. Even in this case, the bliss of El Dorado is fleeting: Candide soon leaves the village to seek Cunégonde, whom he eventually marries only out of a sense of obligation.[2][59] Another element of the satire focuses on what William F. Bottiglia, author of many published works on Candide, calls the "sentimental foibles of the age" and Voltaire's attack on them.[65] Flaws in European culture are highlighted as Candide parodies adventure and romance clichés, mimicking the style of a picaresque novel.[65][66] A number of archetypal characters thus have recognisable manifestations in Voltaire's work: Candide is supposed to be the drifting rogue of low social class, Cunégonde the sex interest, Pangloss the knowledgeable mentor, and Cacambo the skillful valet.[2] As the plot unfolds, readers find that Candide is no rogue, Cunégonde becomes ugly and Pangloss is a stubborn fool. The characters of Candide are unrealistic, two-dimensional, mechanical, and even marionette-like; they are simplistic and stereotypical.[67] As the initially naïve protagonist eventually comes to a mature conclusion—however noncommittal—the novella is a bildungsroman, if not a very serious one.[2][68] Garden motif Gardens are thought by many critics to play a critical symbolic role in Candide. The first location commonly identified as a garden is the castle of the Baron, from which Candide and Cunégonde are evicted much in the same fashion as Adam and Eve are evicted from the Garden of Eden in the Book of Genesis. Cyclically, the main characters of Candide conclude the novel in a garden of their own making, one which might represent celestial paradise. The third most prominent "garden" is El Dorado, which may be a false Eden.[69] Other possibly symbolic gardens include the Jesuit pavilion, the garden of Pococurante, Cacambo's garden, and the Turk's garden.[70] These gardens are probably references to the Garden of Eden, but it has also been proposed, by Bottiglia, for example, that the gardens refer also to the Encyclopédie, and that Candide's conclusion to cultivate "his garden" symbolises Voltaire's great support for this endeavour. Candide and his companions, as they find themselves at the end of the novella, are in a very similar position to Voltaire's tightly knit philosophical circle which supported the Encyclopédie: the main characters of Candide live in seclusion to "cultivate [their] garden", just as Voltaire suggested his colleagues leave society to write. In addition, there is evidence in the epistolary correspondence of Voltaire that he had elsewhere used the metaphor of gardening to describe writing the Encyclopédie.[70] Another interpretative possibility is that Candide cultivating "his garden" suggests his engaging in only necessary occupations, such as feeding oneself and fighting boredom. This is analogous to Voltaire's own view on gardening: he was himself a gardener at his estates in Les Délices and Ferney, and he often wrote in his correspondence that gardening was an important pastime of his own, it being an extraordinarily effective way to keep busy.[71][72][73] |

スタイル ヴォルテール自身が述べているように、『カンディード』の目的は「少数の機知に富んだ人々に娯楽をもたらす」ことであった[2]。著者は、機知と古典的な 冒険ロマンの筋立てのパロディを組み合わせることによって、この目的を達成している。カンディードは、ユーモラスになるほど頻繁に、細部まで丹念に描写さ れた恐ろしい出来事に直面する。文学理論家のフランシス・K・バラシュは、ヴォルテールの淡々とした語り口は、大量死のような話題を「天気予報のように冷 静に」扱っていると評している[59]。テンポが速く、ありえないプロット-たとえば、登場人物が何度も辛うじて死を免れる-は、同じ登場人物に何度も悲 劇が降りかかることを可能にしている[60]。 結局のところ、『カンディード』は、ヴォルテールの伝記作家イアン・デイヴィッドソンが評するように、「短く、軽く、速く、ユーモラス」である[10] [61]。 多くの人を楽しませた『カンディード』の遊び心に満ちた表情の裏には、現代ヨーロッパ文明に対する非常に厳しい批判があり、多くの人を怒らせた。フランス とプロイセンは七年戦争、ポルトガルは異端審問、イギリスはジョン・バイングの処刑などである。組織化された宗教もまた、『カンディード』では厳しく扱わ れている。例えば、ヴォルテールはローマ・カトリック教会のイエズス会を馬鹿にしている。パラグアイで、カカンボは「(イエズス会は)あらゆるものの支配 者であり、民衆はまったく金を持っていない......」と述べている。ここでヴォルテールは、パラグアイにおけるキリスト教宣教が地元住民を利用してい ることを示唆している。ヴォルテールは、イエズス会が先住民を助けていると主張する一方で、先住民を奴隷として拘束していることを描いている[62] [63]。 風刺 カンディード』の風刺の主な手法は、皮肉たっぷりに偉大な悲劇と喜劇を対比させることである[10]。この物語は、世の中の悪を作り出したり誇張したりす るのではなく、現実の悪を鮮明に表示することで、ヴォルテールは微妙な哲学や文化的伝統を単純化し、それらの欠点を強調することができる[60]。こうし て『カンディード』は、例えば、明らかに救いのない、恐ろしい歴史的(あるいは少なくとももっともらしい)出来事の洪水によって楽観主義を嘲笑する[2] [59]。 『カンディード』の風刺の単純な例は、カンディードとマーティンがポーツマス港で目撃した歴史的出来事の扱いに見られる。二人はそこで、ジョン・バングを 代 表すると思われる匿名の提督が、フランス艦隊との交戦に失敗した罪で処刑されるのを目撃する。提督は目隠しをされ、自分の船の甲板で撃たれるが、それは単 に「他の者を励ますため」(フランス語:pour encourageger les autres、この表現はヴォルテールが創始したとされている)であった。この軍事的処罰の描写は、ビングの死を矮小化している。他人を励ますため」とい う辛口で軽妙な説明は、このように、ヴォルテールらしいやり方で、重大な歴史的出来事を風刺している。その古典的な機知から、このフレーズは『カンディー ド』からよく引用されるようになった[10][64]。 ヴォルテールは、世の中の最悪の事態と、それを楽観的な見通しにはめ込もうとする哀れな主人公の必死の努力を描いている。カンディード』のほとんどすべて が、さまざまな形の悪についての議論であり、登場人物たちが一時的な安息すら見出すことはめったにない。少なくとも一つの顕著な例外がある。エルドラドの エピソードで、その幻想的な村の住民は単純に理性的であり、その社会は公正で合理的である。エルドラドの前向きさは、本書の大半の悲観的な態度と対照的か もしれない。この場合でも、エルドラドの至福はつかの間である: カンディードはすぐに村を出てクネゴンドを探すが、彼女とは結局、義務感から結婚しただけである[2][59]。 この風刺のもう一つの要素は、『カンディード』に関する多くの出版物の著者であるウィリアム・F・ボッティリアが「時代の感傷的な欠点」と呼ぶものと、そ れに対するヴォルテールの攻撃に焦点を当てている[65]。 カンディード』は冒険とロマンスの決まり文句をパロディ化し、ピカレスク小説のスタイルを模倣することで、ヨーロッパ文化の欠陥が強調されている[65] [66]: カンディードは社会的地位の低い流れ者のならず者、キュネゴンドは性欲の対象、パングロスは博識な指導者、カカンボは腕利きの付き人ということになってい る[2]。筋書きが展開するにつれ、読者はカンディードがならず者ではなく、キュネゴンドは醜くなり、パングロスは頑固な愚か者であることに気づく。カン ディード』の登場人物は非現実的で、二次元的で、機械的で、マリオネットのようでさえある。 庭園のモチーフ 多くの批評家によって、庭は『カンディード』において重要な象徴的役割を果たすと考えられている。一般的に庭とされる最初の場所は男爵の城であり、そこか らカンディードとキュネゴンドは、創世記でアダムとイヴがエデンの園から追い出されるのと同じように追い出される。循環的に、『カンディード』の主人公た ちは、天上の楽園を象徴するような、自分たちが作った庭で小説を締めくくる。三番目に目立つ「庭」はエルドラドで、これは偽のエデンかもしれない [69]。その他に象徴的と思われる庭には、イエズス会の館、ポコクランテの庭、カカンボの庭、トルコ人の庭などがある[70]。 これらの庭園はおそらくエデンの園を指しているのだろうが、例えばボッティリアは、庭園は百科全書も指しており、カンディードが「自分の庭」を耕すという 結論を出したのは、ヴォルテールがこの努力を大いに支援したことを象徴している、とも提唱している。カンディードとその仲間たちは、この小説の最後で、百 科全書を支えたヴォルテールの緊密な哲学サークルと非常に似た立場にいる。ヴォルテールが同僚たちに執筆のために社交界を離れることを勧めたように、『カ ンディード』の主人公たちも「(自分の)庭を耕す」ために隠遁生活を送るのである。さらに、ヴォルテールの書簡の中には、彼が百科全書執筆を表現するため に、他の場所でも園芸の比喩を使っていたという証拠がある[70]。もう一つの解釈の可能性は、カンディードが「自分の庭」を耕すということは、彼が自分 自身を養い、退屈と闘うといった必要な仕事だけに従事することを示唆しているということである。ヴォルテール自身、レ・デリスとフェルニーの邸宅で庭師を しており、書簡の中でしばしば、ガーデニングは自分にとって重要な娯楽であり、忙しくするための非常に効果的な方法であると書いている[71][72] [73]。 |

| Philosophy Optimism Candide satirises various philosophical and religious theories that Voltaire had previously criticised. Primary among these is Leibnizian optimism (sometimes called Panglossianism after its fictional proponent), which Voltaire ridicules with descriptions of seemingly endless calamity.[10] Voltaire demonstrates a variety of irredeemable evils in the world, leading many critics to contend that Voltaire's treatment of evil—specifically the theological problem of its existence—is the focus of the work.[74] Heavily referenced in the text are the Lisbon earthquake, disease, and the sinking of ships in storms. Also, war, thievery, and murder—evils of human design—are explored as extensively in Candide as are environmental ills. Bottiglia notes Voltaire is "comprehensive" in his enumeration of the world's evils. He is unrelenting in attacking Leibnizian optimism.[75] Fundamental to Voltaire's attack is Candide's tutor Pangloss, a self-proclaimed follower of Leibniz and a teacher of his doctrine. Ridicule of Pangloss's theories thus ridicules Leibniz himself, and Pangloss's reasoning is silly at best. For example, Pangloss's first teachings of the narrative absurdly mix up cause and effect: Il est démontré, disait-il, que les choses ne peuvent être autrement; car tout étant fait pour une fin, tout est nécessairement pour la meilleure fin. Remarquez bien que les nez ont été faits pour porter des lunettes; aussi avons-nous des lunettes. It is demonstrable that things cannot be otherwise than as they are; for as all things have been created for some end, they must necessarily be created for the best end. Observe, for instance, the nose is formed for spectacles, therefore we wear spectacles.[76] Following such flawed reasoning even more doggedly than Candide, Pangloss defends optimism. Whatever their horrendous fortune, Pangloss reiterates "all is for the best" ("Tout est pour le mieux") and proceeds to "justify" the evil event's occurrence. A characteristic example of such theodicy is found in Pangloss's explanation of why it is good that syphilis exists: c'était une chose indispensable dans le meilleur des mondes, un ingrédient nécessaire; car si Colomb n'avait pas attrapé dans une île de l'Amérique cette maladie qui empoisonne la source de la génération, qui souvent même empêche la génération, et qui est évidemment l'opposé du grand but de la nature, nous n'aurions ni le chocolat ni la cochenille; it was a thing unavoidable, a necessary ingredient in the best of worlds; for if Columbus had not caught in an island in America this disease, which contaminates the source of generation, and frequently impedes propagation itself, and is evidently opposed to the great end of nature, we should have had neither chocolate nor cochineal.[50] Candide, the impressionable and incompetent student of Pangloss, often tries to justify evil, fails, invokes his mentor and eventually despairs. It is by these failures that Candide is painfully cured (as Voltaire would see it) of his optimism. This critique of Voltaire's seems to be directed almost exclusively at Leibnizian optimism. Candide does not ridicule Voltaire's contemporary Alexander Pope, a later optimist of slightly different convictions. Candide does not discuss Pope's optimistic principle that "all is right", but Leibniz's that states, "this is the best of all possible worlds". However subtle the difference between the two, Candide is unambiguous as to which is its subject. Some critics conjecture that Voltaire meant to spare Pope this ridicule out of respect, although Voltaire's Poème may have been written as a more direct response to Pope's theories. This work is similar to Candide in subject matter, but very different from it in style: the Poème embodies a more serious philosophical argument than Candide.[77] Conclusion The conclusion of the novel, in which Candide finally dismisses his tutor's optimism, leaves unresolved what philosophy the protagonist is to accept in its stead. This element of Candide has been written about voluminously, perhaps above all others. The conclusion is enigmatic and its analysis is contentious.[78] Voltaire develops no formal, systematic philosophy for the characters to adopt.[79] The conclusion of the novel may be thought of not as a philosophical alternative to optimism, but as a prescribed practical outlook (though what it prescribes is in dispute). Many critics have concluded that one minor character or another is portrayed as having the right philosophy. For instance, a number believe that Martin is treated sympathetically, and that his character holds Voltaire's ideal philosophy—pessimism. Others disagree, citing Voltaire's negative descriptions of Martin's principles and the conclusion of the work in which Martin plays little part.[80] Within debates attempting to decipher the conclusion of Candide lies another primary Candide debate. This one concerns the degree to which Voltaire was advocating a pessimistic philosophy, by which Candide and his companions give up hope for a better world. Critics argue that the group's reclusion on the farm signifies Candide and his companions' loss of hope for the rest of the human race. This view is to be compared to a reading that presents Voltaire as advocating a melioristic philosophy and a precept committing the travellers to improving the world through metaphorical gardening. This debate, and others, focuses on the question of whether or not Voltaire was prescribing passive retreat from society, or active industrious contribution to it.[81] Inside vs. outside interpretations Separate from the debate about the text's conclusion is the "inside/outside" controversy. This argument centers on the matter of whether or not Voltaire was actually prescribing anything. Roy Wolper, professor emeritus of English, argues in a revolutionary 1969 paper that Candide does not necessarily speak for its author; that the work should be viewed as a narrative independent of Voltaire's history; and that its message is entirely (or mostly) inside it. This point of view, the "inside", specifically rejects attempts to find Voltaire's "voice" in the many characters of Candide and his other works. Indeed, writers have seen Voltaire as speaking through at least Candide, Martin, and the Turk. Wolper argues that Candide should be read with a minimum of speculation as to its meaning in Voltaire's personal life. His article ushered in a new era of Voltaire studies, causing many scholars to look at the novel differently.[82][83] Critics such as Lester Crocker, Henry Stavan, and Vivienne Mylne find too many similarities between Candide's point of view and that of Voltaire to accept the "inside" view; they support the "outside" interpretation. They believe that Candide's final decision is the same as Voltaire's, and see a strong connection between the development of the protagonist and his author.[84] Some scholars who support the "outside" view also believe that the isolationist philosophy of the Old Turk closely mirrors that of Voltaire. Others see a strong parallel between Candide's gardening at the conclusion and the gardening of the author.[85] Martine Darmon Meyer argues that the "inside" view fails to see the satirical work in context, and that denying that Candide is primarily a mockery of optimism (a matter of historical context) is a "very basic betrayal of the text".[86][87] |

哲学 楽観主義 『カンディード』は、それまでヴォルテールが批判してきたさまざまな哲学的・宗教的理論を風刺している。ヴォルテールは、世の中に存在する様々な救いよう の ない悪を示しており、多くの批評家は、ヴォルテールの悪の扱い、特に悪の存在に関する神学的な問題がこの作品の焦点であると主張する[74]。また、『カ ンディード』では、戦争、泥棒、殺人といった、人間が作り出した悪も、環境問題と同様に広範囲にわたって探求されている。ボッティリアは、ヴォルテールは 世界の悪を「包括的に」列挙していると指摘する。彼はライプニッツ的楽観主義を容赦なく攻撃する[75]。 ヴォルテールの攻撃の基本は、ライプニッツの信奉者を自称し、彼の教義を教えるカンディードの家庭教師パングロスにある。パングロスの理論を嘲笑すること は、ライプニッツ自身を嘲笑することになる。例えば、パングロスの最初の教えは、原因と結果を無茶苦茶に混同している: すべてのことはある結末のためにあるのであって、すべてのことはよりよい結末のために必要なのである。nezがlunetteを運ぶために作られたことを よく思い出してほしい。 なぜなら、すべてのものが何らかの目的のために創造されたように、必然的に最良の目的のために創造されなければならないからである。たとえば、鼻は眼鏡の ために形成されたのであり、したがって我々は眼鏡をかけるのである[76]。 このような欠陥のある推論に、カンディード以上に執拗に従いながら、パングロスは楽観主義を擁護する。パングロスは「すべては最善のためにある」 ("Tout est pour le mieux")と繰り返し、自分たちの恐ろしい運命がどのようなものであったとしても、その悪い出来事の発生を「正当化」しようとする。このような神学の 特徴的な例は、梅毒が存在することがなぜ良いことなのかについてのパングロスの説明に見られる: もしコロンブがアメリ カのある島で、そのような悪疫に罹患していなければ、その悪疫は遺伝の根源を絶つものであり、またしばしば遺伝を阻害するものであり、しかも自然の大義に 反するものであったろう; もしコロンブスがアメリカのある島で、生成の源を汚染し、しばしば伝播そのものを妨げ、明らかに自然の大いなる目的に反するこの病気を発見しなかったら、 チョコレートもコチニールもなかっただろう[50]。 パングロスの弟子であるカンディードは、多感で無能であるがゆえに、しばしば悪を正当化しようとし、失敗し、師を呼び、ついには絶望する。このような失敗 によって、カンディードは(ヴォルテールに言わせれば)楽観主義を苦しまぎれに治していくのである。 ヴォルテールのこの批評は、ほとんどライプニッツ的楽観主義にのみ向けられているように思われる。カンディード』は、ヴォルテールと同世代のアレクサン ダー・ポープを嘲笑していない。カンディード』が論じているのは、ポープの「すべては正しい」という楽観主義ではなく、ライプニッツの「これはあらゆる可 能な世界の中で最良のものである」という楽観主義である。両者の違いがいかに微妙であろうとも、『カンディード』の主題がどちらであるかは明白である。 ヴォルテールはポープへの敬意から、このような揶揄を避けたかったのだろうと推測する批評家もいるが、ヴォルテールの詩はポープの理論に対するより直接的 な応答として書かれたのかもしれない。この作品は主題において『カンディード』に似ているが、文体において『カンディード』とは大きく異なっており、『詩 編』は『カンディード』よりもまじめな哲学的議論を体現している[77]。 結末 カンディードが家庭教師の楽観主義を最終的に否定する小説の結末は、主人公がその代わりにどのような哲学を受け入れるべきかを未解決のままにしている。 『カ ンディード』のこの要素については、おそらく他のどの作品よりも多く書かれている。結論は謎めいており、その分析は論争を呼んでいる[78]。 ヴォルテールは、登場人物たちが採用すべき正式で体系的な哲学を展開していない[79]。この小説の結論は、楽観主義に対する哲学的な代替案としてではな く、規定された実践的な展望として考えられるかもしれない(ただし、それが何を規定しているかは議論の余地がある)。多くの批評家は、ある脇役や別の人物 が正しい哲学を持っていると結論付けている。例えば、マルタンが同情的に扱われ、彼のキャラクターがヴォルテールの理想的な哲学-悲観主義-を持っている と考える者も少なくない。また、マルタンの主義主張に対するヴォルテールの否定的な描写や、マルタンがほとんど活躍しない作品の結末を引き合いに出して、 反対する者もいる[80]。 『カンディード』の結論を読み解こうとする議論の中には、『カンディード』のもう一つの主要な論争がある。この議論は、ヴォルテールがどの程度悲観的な哲 学 を提唱しているのか、つまりカンディードとその仲間たちがよりよい世界への希望を捨てているのか、という点に関わるものである。批評家たちは、一行が農場 に閉じこもるのは、カンディードと仲間たちが他の人類に対する希望を失ったことを意味すると主張する。この見解は、ヴォルテールがメリオリスティックな哲 学を提唱し、隠喩的な園芸を通じて世界を改善することを旅人に約束する戒律を提唱しているとする読み方と比較される。この議論やその他の議論は、ヴォル テールが社会からの消極的な後退を処方していたのか、それとも社会への積極的な勤勉な貢献を処方していたのかという問題に焦点を当てている[81]。 内的解釈と外的解釈 本文の結論に関する議論とは別に、「内部/外部」論争がある。この論争の中心は、ヴォルテールが実際に何かを処方していたかどうかという問題である。ロ イ・ウォルパー名誉教授(英語)は1969年の革命的な論文で、『カンディード』は必ずしも作者を代弁しているわけではない、この作品はヴォルテールの歴 史から独立した物語として見るべきであり、そのメッセージはすべて(あるいはほとんど)ヴォルテールの内部にある、と主張している。この "内側 "という視点は、特に『カンディード』や他の作品に登場する多くの人物の中にヴォルテールの "声 "を見出そうとする試みを否定する。実際、作家たちは少なくともカンディード、マルタン、トルコ人を通してヴォルテールが語っていると見てきた。ヴォル パーは、『カンディード』はヴォルテールの私生活における意味について、最小限の推測で読まれるべきであると主張する。彼の論文はヴォルテール研究の新時 代の到来を告げ、多くの学者がこの小説を違った角度から見るきっかけとなった[82][83]。 レスター・クロッカー、ヘンリー・スタヴァン、ヴィヴィアン・マイルンといった批評家たちは、カンディードの視点とヴォルテールの視点にはあまりにも多く の類似点があるため、「内面的」な見方を受け入れず、「外面的」な解釈を支持している。彼らは、カンディードの最終的な決断はヴォルテールと同じであり、 主人公の成長と作者の間には強いつながりがあると考える[84]。マルティーヌ・ダルモン・メイヤーは、「内面的」な見方は風刺作品を文脈の中で見ること に失敗しており、『カンディード』が主に楽観主義を嘲笑するもの(歴史的文脈の問題)であることを否定することは「テクストに対する非常に基本的な裏切 り」であると論じている[86][87]。 |

| Reception De roman, Voltaire en a fait un, lequel est le résumé de toutes ses œuvres ... Toute son intelligence était une machine de guerre. Et ce qui me le fait chérir, c'est le dégoût que m'inspirent les voltairiens, des gens qui rient sur les grandes choses! Est-ce qu'il riait, lui? Il grinçait ... — Flaubert, Correspondance, éd. Conard, II, 348; III, 219[88] Voltaire made, with this novel, a résumé of all his works ... His whole intelligence was a war machine. And what makes me cherish it is the disgust which has been inspired in me by the Voltairians, people who laugh about the important things! Was he laughing? Voltaire? He was screeching ... — Flaubert, Correspondance, éd. Conard, II, 348; III, 219[88] Though Voltaire did not openly admit to having written the controversial Candide until 1768 (until then he signed with a pseudonym: "Monsieur le docteur Ralph", or "Doctor Ralph"[89]), his authorship of the work was hardly disputed.[90][a] Immediately after publication, the work and its author were denounced by both secular and religious authorities, because the book openly derides government and church alike. It was because of such polemics that Omer-Louis-François Joly de Fleury, who was Advocate General to the Parisian parliament when Candide was published, found parts of Candide to be "contrary to religion and morals".[90] Despite much official indictment, soon after its publication, Candide's irreverent prose was being quoted. "Let us eat a Jesuit", for instance, became a popular phrase for its reference to a humorous passage in Candide.[92] By the end of February 1759, the Grand Council of Geneva and the administrators of Paris had banned Candide.[4] Candide nevertheless succeeded in selling twenty thousand to thirty thousand copies by the end of the year in more than twenty editions, making it a best seller. The Duke de La Vallière speculated near the end of January 1759 that Candide might have been the fastest-selling book ever.[90] In 1762, Candide was listed in the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the Roman Catholic Church's list of prohibited books.[4] Bannings of Candide lasted into the twentieth century in the United States, where it has long been considered a seminal work of Western literature. At least once, Candide was temporarily barred from entering America: in February 1929, a US customs official in Boston prevented a number of copies of the book, deemed "obscene",[93] from reaching a Harvard University French class. Candide was admitted in August of the same year; however by that time the class was over.[93] In an interview soon after Candide's detention, the official who confiscated the book explained the office's decision to ban it, "But about 'Candide,' I'll tell you. For years we've been letting that book get by. There were so many different editions, all sizes and kinds, some illustrated and some plain, that we figured the book must be all right. Then one of us happened to read it. It's a filthy book".[94][95][96] |

レセプション ヴォルテールは、その全作品の要約である「一篇」を書いた。彼の知性はすべて戦争機械であった。それは、私がヴォルタイアンを奮い立たせ、壮大な出来事に 歓喜する人々を鼓舞している、その歓喜なのだ!それは何ですか?ニヤニヤして... - Flaubert, Correspondance, ed. Conard, II, 348; III, 219[88]. ヴォルテールはこの小説で、彼の全作品の履歴書を作った......。彼の全知性は戦争機械であった。私がこの小説を大切にしているのは、ヴォルテール主 義者たち、つまり、重要なことを笑い飛ばす人々によって、私の中に触発された嫌悪感である!彼は笑っていたのか?ヴォルテール?彼は金切り声をあげてい た... - Flaubert, Correspondance, éd. Conard, II, 348; III, 219[88]. ヴォルテールは1768年まで論争の的となった『カンディード』を書いたことを公には認めなかったが(それまでは「ラルフ医師」というペンネームで署名し ていた[89])。 出版直後から、この作品とその著者は世俗と宗教の両方の権威から非難された。カンディード』が出版された当時、パリ議会の法務官であったオメル=ルイ=フ ランソワ・ジョリー・ド・フルーリーは、『カンディード』の一部が「宗教と道徳に反している」と指摘した[90]。 多くの公式の非難にもかかわらず、『カンディード』の出版後すぐに、その不遜な散文が引用されるようになった。1759年2月末までに、ジュネーヴの大評 議会とパリの行政官は『カンディード』を出版禁止にした[4]。 それでも『カンディード』は20以上の版で年末までに2万部から3万部を売り上げるベストセラーとなった。1762年、『カンディード』はローマ・カト リック教会の禁書目録であるIndex Librorum Prohibitorumに掲載された[4]。 『カンディード』の発禁処分は20世紀まで続き、アメリカでは長い間、西洋文学の代表作とみなされてきた。少なくとも一度、『カンディード』は一時的にア メリカへの入国を禁止されたことがある。1929年2月、ボストンの税関職員が、ハーバード大学のフランス語の授業で、「わいせつ」[93]とみなされた この本のコピーが何冊も手に入るのを阻止した。カンディード』は同年8月に出版が許可されたが、その時点で授業は終了していた[93]。『カンディード』 が拘留された直後のインタビューで、この本を没収した職員は、この本を出版禁止にした当局の決定について次のように説明している。何年もの間、私たちはあ の本を放置してきました。大小さまざまな版があり、挿絵入りのものもあれば無地のものもあった。ある時、私たちの一人がたまたまその本を読んだ。不潔な本 だ」[94][95][96]。 |

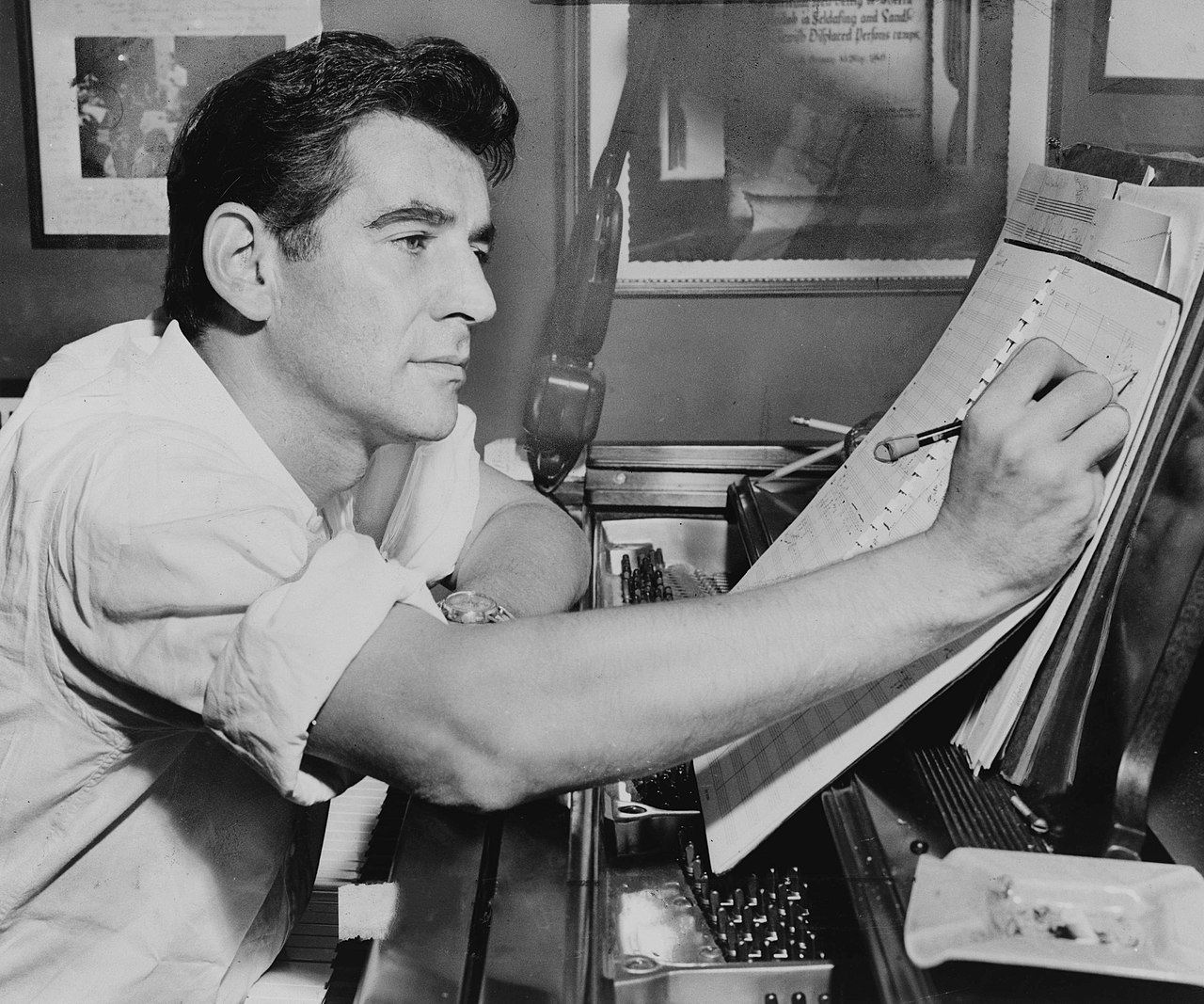

| Legacy Candide is the most widely read of Voltaire's many works,[63] and it is considered one of the great achievements of Western literature.[11] William F. Bottiglia opines, "The physical size of Candide, as well as Voltaire's attitude toward his fiction, precludes the achievement of artistic dimension through plenitude, autonomous '3D' vitality, emotional resonance, or poetic exaltation. Candide, then, cannot in quantity or quality, measure up to the supreme classics" such as the works of Homer or Shakespeare, Sophocles, Chaucer, Dante, Cervantes, Fielding, Goethe, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Racine, or Molière.[97] Bottiglia instead calls it a miniature classic; but others have been more forgiving of its size.[11][97] As the only work of Voltaire which has remained popular up to the present day,[98] Candide is listed in Harold Bloom's The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. It is included in the Encyclopædia Britannica collection Great Books of the Western World.[99] Candide has influenced modern writers of black humour such as Céline, Joseph Heller, John Barth, Thomas Pynchon, Kurt Vonnegut, and Terry Southern. Its parody and picaresque methods have become favourites of black humorists.[100] Charles Brockden Brown, an early American novelist, may have been directly affected by Voltaire, whose work he knew well. Mark Kamrath, professor of English, describes the strength of the connection between Candide and Brown's Edgar Huntly; or, Memoirs of a Sleep-Walker (1799): "An unusually large number of parallels...crop up in the two novels, particularly in terms of characters and plot." For instance, the protagonists of both novels are romantically involved with a recently orphaned young woman. Furthermore, in both works the brothers of the female lovers are Jesuits, and each is murdered (although under different circumstances).[101] Some twentieth-century novels that may have been influenced by Candide are some dystopian science-fiction works. Armand Mattelart, a French critic, sees Candide in Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, and Yevgeny Zamyatin's We, three canonical works of the genre. Specifically, Mattelart writes that in each of these works, there exist references to Candide's popularisation of the phrase "the best of all possible worlds". He cites as evidence, for example, that the French version of Brave New World was entitled Le Meilleur des mondes (lit. '"The best of worlds"').[102] Readers of Candide often compare it with certain works of the modern genre the Theatre of the Absurd. Haydn Mason, a Voltaire scholar, sees in Candide a few similarities to this brand of literature. For instance, he notes commonalities of Candide and Waiting for Godot (1952). In both of these works, and in a similar manner, friendship provides emotional support for characters when they are confronted with harshness of their existences.[103] However, Mason qualifies, "the conte must not be seen as a forerunner of the 'absurd' in modern fiction. Candide's world has many ridiculous and meaningless elements, but human beings are not totally deprived of the ability to make sense out of it."[104] John Pilling, biographer of Beckett, does state that Candide was an early and powerful influence on Beckett's thinking.[105] Rosa Luxemburg, in the aftermath of the First World War, remarked upon re-reading Candide: "Before the war, I would have thought this wicked compilation of all human misery a caricature. Now it strikes me as altogether realistic."[106] The American alternative rock band Bloodhound Gang refer to Candide in their song "Take the Long Way Home", from the American edition of their 1999 album Hooray for Boobies. Derivative works In 1760, one year after Voltaire published Candide, a sequel was published with the name Candide, ou l'optimisme, seconde partie.[107] This work is attributed both to Thorel de Campigneulles, a writer unknown today, and Henri Joseph Du Laurens, who is suspected of having habitually plagiarised Voltaire.[108] The story continues in this sequel with Candide having new adventures in the Ottoman Empire, Persia, and Denmark. Part II has potential use in studies of the popular and literary receptions of Candide, but is almost certainly apocryphal.[107] In total, by the year 1803, at least ten imitations of Candide or continuations of its story were published by authors other than Voltaire.[90] Candide was adapted for the radio anthology program On Stage in 1953. Richard Chandlee wrote the script; Elliott Lewis, Cathy Lewis, Edgar Barrier, Byron Kane, Jack Kruschen, Howard McNear, Larry Thor, Martha Wentworth, and Ben Wright performed.[109]  Leonard Bernstein in 1955 The operetta Candide was originally conceived by playwright Lillian Hellman, as a play with incidental music. Leonard Bernstein, the American composer and conductor who wrote the music, was so excited about the project that he convinced Hellman to do it as a "comic operetta".[110] Many lyricists worked on the show, including James Agee, Dorothy Parker, John Latouche, Richard Wilbur, Leonard and Felicia Bernstein, and Hellman. Hershy Kay orchestrated all the pieces except for the overture, which Bernstein did himself.[111] Candide first opened on Broadway as a musical on 1 December 1956. The premier production was directed by Tyrone Guthrie and conducted by Samuel Krachmalnick.[111] While this production was a box office flop, the music was highly praised, and an original cast album was made. The album gradually became a cult hit, but Hellman's libretto was criticised as being too serious an adaptation of Voltaire's novel.[112] Candide has been revised and reworked several times. The first New York revival, directed by Hal Prince, featured an entirely new libretto by Hugh Wheeler and additional lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. Bernstein revised the work again in 1987 with the collaboration of John Mauceri and John Wells. After Bernstein's death, further revised productions of the musical were performed in versions prepared by Trevor Nunn and John Caird in 1999, and Mary Zimmerman in 2010. Candido, ovvero un sogno fatto in Sicilia [it] (1977) or simply Candido is a book by Leonardo Sciascia. It was at least partly based on Voltaire's Candide, although the actual influence of Candide on Candido is a hotly debated topic. A number of theories on the matter have been proposed. Proponents of one say that Candido is very similar to Candide, only with a happy ending; supporters of another claim that Voltaire provided Sciascia with only a starting point from which to work, that the two books are quite distinct.[113][114] The BBC produced a television adaptation in 1973, with Ian Ogilvy as Candide, Emrys James as Dr. Pangloss, and Frank Finlay as Voltaire himself, acting as the narrator.[115] Nedim Gürsel wrote his 2001 novel Le voyage de Candide à Istanbul about a minor passage in Candide during which its protagonist meets Ahmed III, the deposed Turkish sultan. This chance meeting on a ship from Venice to Istanbul is the setting of Gürsel's book.[116] Terry Southern, in writing his popular novel Candy with Mason Hoffenberg adapted Candide for a modern audience and changed the protagonist from male to female. Candy deals with the rejection of a sort of optimism which the author sees in women's magazines of the modern era; Candy also parodies pornography and popular psychology. This adaptation of Candide was adapted for the cinema by director Christian Marquand in 1968.[117] In addition to the above, Candide was made into a number of minor films and theatrical adaptations throughout the twentieth century. For a list of these, see Voltaire: Candide ou L'Optimisme et autres contes (1989) with preface and commentaries by Pierre Malandain.[118] In May 2009, a play titled Optimism, based on Candide, opened at the CUB Malthouse Theatre in Melbourne. It followed the basic story of Candide, incorporating anachronisms, music, and stand up comedy from comedian Frank Woodley. It toured Australia and played at the Edinburgh International Festival.[119] In 2010, the Icelandic writer Óttar M. Norðfjörð published a rewriting and modernisation of Candide, titled Örvitinn; eða hugsjónamaðurinn. |

遺産 『カンディード』は、ヴォルテールの数ある作品の中で最も広く読まれており[63]、西洋文学の偉大な業績のひとつとみなされている[11]。ウィリア ム・ F・ボッティリアは、「『カンディード』の物理的な大きさと、ヴォルテールの小説に対する態度は、豊かさ、自律的な "3次元的 "活力、感情的共鳴、詩的高揚による芸術的次元の達成を妨げている。カンディード』は、量的にも質的にも、ホメロスやシェイクスピア、ソフォクレス、 チョーサー、ダンテ、セルバンテス、フィールディング、ゲーテ、ドストエフスキー、トルストイ、ラシーヌ、モリエールといった「至高の古典」には及ばな い。 [97]ボッティリアは代わりにこれを古典のミニチュアと呼ぶが、他の人々はその大きさに寛容である[11][97]。 今日まで人気を保っているヴォルテールの唯一の作品として[98]、『カンディード』はハロルド・ブルームの『西洋のカノン:時代の書物と学派』に掲載さ れている。カンディードは、セリーヌ、ジョセフ・ヘラー、ジョン・バース、トマス・ピンチョン、カート・ヴォネガット、テリー・サザンといった現代のブ ラックユーモア作家に影響を与えている。そのパロディとピカレスク的手法はブラックユーモア作家のお気に入りとなっている[100]。 初期のアメリカ人小説家であるチャールズ・ブロックデン・ブラウンは、彼がよく知るヴォルテールの作品から直接影響を受けたかもしれない。英語学のマー ク・カムラス教授は、『カンディード』とブラウンの『エドガー・ハントリー、あるいはある夢遊病者の回想』(1799年)とのつながりの強さについてこう 述べている: 「この2つの小説には、特に登場人物やプロットにおいて、非常に多くの類似点が見られる。例えば、両方の小説の主人公は、最近孤児になった若い女性と恋愛 関係にある。さらに、両作品とも恋人である女性の兄弟はイエズス会士であり、それぞれが(状況は異なるが)殺害されている[101]。 カンディード』に影響を受けたと思われる20世紀の小説には、ディストピア的なSF作品がある。フランスの批評家であるアルマン・マテラールは、カン ディードをオルダス・ハクスリーの『ブレイブ・ニュー・ワールド』、ジョージ・オーウェルの『ナインティーン188-フォー』、エフゲニー・ザミャーチン の『われら』の中に見ている。具体的には、マテラート氏は、これらの作品のそれぞれに、カンディードが広めた "the best of all possible worlds "という言葉への言及が存在すると書いている。例えば、『ブレイブ・ニュー・ワールド』のフランス語版のタイトルが『Le Meilleur des mondes』であったことを証拠として挙げている[102]。 『カンディード』の読者はしばしば、この作品を近代的ジャンルである「不条理劇場」のある作品と比較する。ヴォルテールの研究者であるヘイドン・メイソン は、『カンディード』にこの文学との類似点をいくつか見出している。例えば、彼は『カンディード』と『ゴドーを待ちながら』(1952年)の共通点を指摘 している。しかしメイソンは、「『カンディード』を、現代小説における『不条理』の先駆けとして見てはならない。ベケットの伝記作家であるジョン・ピリン グは、『カンディード』がベケットの思考に早くから強い影響を与えたと述べている。 ローザ・ルクセンブルクは、第一次世界大戦の後、『カンディード』を再読してこう述べている: 「戦争が始まる前なら、この邪悪な人間の不幸の集大成を戯画だと思っただろう。今となっては、まったく現実的な作品だと思う」[106]。 アメリカのオルタナティヴ・ロックバンド、ブラッドハウンド・ギャングは、1999年のアルバム『Hooray for Boobies』のアメリカ盤に収録されている「Take the Long Way Home」という曲の中で、『カンディード』に言及している。 派生作品 ヴォルテールが『カンディード』を出版した1年後の1760年、続編が『カンディード』(Candide, ou l'optimisme, seconde partie)という名前で出版された[107]。この作品は、今日では無名の作家であるソレル・ド・カンピニュレス(Thorel de Campigneulles)と、常習的にヴォルテールを盗用したと疑われているアンリ・ジョゼフ・デュ・ローランス(Henri Joseph Du Laurens)によるものとされている[108]。第II部は『カンディード』の大衆的・文学的受容の研究において利用される可能性があるが、ほぼ間違 いなく偽書である[107]。 1803年までに、ヴォルテール以外の作家によって、少なくとも10の『カンディード』の模倣や物語の続きが出版された[90]。 カンディード』は1953年にラジオのアンソロジー番組『オン・ステージ』のために脚色された。リチャード・チャンドリーが脚本を書き、エリオット・ルイ ス、キャシー・ルイス、エドガー・バリアー、バイロン・ケイン、ジャック・クルシェン、ハワード・マクニアー、ラリー・ソー、マーサ・ウェントワース、ベ ン・ライトが出演した[109]。  1955年のレナード・バーンスタイン オペレッタ『カンディード』は、もともと劇作家リリアン・ヘルマンによって、付随音楽付きの戯曲として構想された。音楽を担当したアメリカの作曲家兼指揮 者のレナード・バーンスタインは、このプロジェクトに非常に興奮し、「コミック・オペレッタ」として上演するようヘルマンを説得した[110]。ジェーム ズ・エイジ、ドロシー・パーカー、ジョン・ラトゥーシュ、リチャード・ウィルバー、レナード&フェリシア・バーンスタイン、ヘルマンなど、多くの作詞家が 上演に携わった。ハーシー・ケイは、序曲を除く全曲のオーケストレーションを担当し、バーンスタインはそれを自ら手がけた[111]。初演の演出はタイロ ン・ガスリー、指揮はサミュエル・クラクマルニックだった[111]。このプロダクションは興行的には失敗だったが、音楽は高く評価され、オリジナル・ キャスト・アルバムが制作された。このアルバムは次第にカルト的なヒットとなったが、ヘルマンの台本はヴォルテールの小説の脚色としては深刻すぎると批判 された[112]。ハル・プリンスが演出した最初のニューヨークでの再演では、ヒュー・ウィーラーによる全く新しい台本とスティーヴン・ソンドハイムによ る歌詞が追加された。バーンスタインは、ジョン・マウセリとジョン・ウェルズの協力を得て、1987年に再び作品を改訂した。バーンスタインの死後、 1999年にはトレヴァー・ナンとジョン・ケアードが、2010年にはメアリー・ジマーマンがこのミュージカルの改訂版を上演した。 Candido, ovvero un sogno fatto in Sicilia [it]』(1977)は、レオナルド・スキアシアの著書。少なくとも部分的にはヴォルテールの『カンディード』を下敷きにしているが、『カンディード』 が実際に『カンディード』に与えた影響については、熱い議論が交わされている。この問題については多くの説が提唱されている。ある説の支持者は、『カン ディード』は『カンディード』と非常によく似ているが、ハッピーエンドであるだけだと言い、別の説の支持者は、ヴォルテールはスキアシアに出発点を与えた だけで、2冊の本はまったく別物だと主張する[113][114]。 BBCは1973年にカンディードをイアン・オグルヴィ、パングロス博士をエムリス・ジェイムズ、ヴォルテール自身をフランク・フィンレイがナレーターを 務めるテレビドラマを制作した[115]。 ネディム・ギュセルは2001年、『カンディード』の小さな一節を題材にした小説『Le voyage de Candide à Istanbul』を書き、その中で主人公はトルコの退位したスルタン、アフメッド3世と出会う。このヴェネツィアからイスタンブールへの船上での偶然の 出会いが、ギュセルの本の舞台である[116]。テリー・サザンは、メイソン・ホッフェンバーグと人気小説『キャンディ』を執筆する際に、『カンディー ド』を現代の読者向けに脚色し、主人公を男性から女性に変えた。キャンディ』は、作者が現代の女性誌に見られるある種の楽観主義への拒絶を扱っており、ポ ルノや大衆心理学のパロディでもある。この『カンディード』の映画化は、1968年にクリスチャン・マルカン監督によって行われた[117]。 上記以外にも、『カンディード』は20世紀を通じて多くのマイナーな映画や舞台で翻案された。これらのリストについては、「ヴォルテール」を参照: Candide ou L'Optimisme et autres contes』(1989年、ピエール・マランダンによる序文と解説付き)を参照[118]。 2009年5月、メルボルンのCUB Malthouse Theatreで、『カンディード』を題材にした『Optimism』と題された演劇が上演された。カンディード』の基本的なストーリーに沿って、アナク ロニズム、音楽、コメディアンのフランク・ウッドリーによるスタンドアップコメディが盛り込まれた。2010年、アイスランドの作家オッタル・M・ノルズ フィョルズは、『カンディード』を現代風に書き直した『Örvitinn; eða hugsjónamaðurinn』を出版した。 |

| Candide ou l'optimisme au XXe

siècle (film, 1960) List of French-language authors Cannibalism in popular culture Pollyanna |

カンディード、二十世紀の楽観主義(映画、1960年) フランス語の作家一覧 大衆文化におけるカニバリズム ポリアンナ |

| Will Durant in The Age of

Voltaire: It was published early in 1759 as Candide, ou l'optimisme, purportedly "translated from the German of Dr. Ralph, with additions found in the pocket of the Doctor when he died at Minden." The Great Council of Geneva almost at once (March 5) ordered it to be burned. Of course Voltaire denied his authorship: "people must have lost their senses," he wrote to a friendly pastor in Geneva, "to attribute to me that pack of nonsense. I have, thank God, better occupations." But France was unanimous: no other man could have written Candide. Here was that deceptively simple, smoothly flowing, lightly prancing, impishly ironic prose that only he could write; here and there a little obscenity, a little scatology; everywhere a playful, darting, lethal irreverence; if the style is the man, this had to be Voltaire.[91] |

ウィル・デュラントは『ヴォルテールの時代』の中でこう述

べている: 1759年初頭、「ラルフ博士のドイツ語から翻訳され、博士がミンデンで死去したときにポケットから発見された加筆を加えた」とされる『カンディード』 (Candide, ou l'optimisme)として出版された。ジュネーブの大評議会は、ほとんどすぐに(3月5日)、この本の焼却を命じた。もちろん、ヴォルテールは自分 の著作であることを否定した: 「人々は正気を失っているに違いない」と彼はジュネーブの友好的な牧師に書き送った。私は神に感謝し、より良い職業を持っている"。しかし、フランス中の 意見は一致していた。ここには、彼にしか書けない、欺瞞に満ちたほど単純で、なめらかに流れ、軽やかに跳ね回り、不気味に皮肉った散文があり、あちこちに ちょっとした猥雑さ、スカトロジーがあり、いたるところに遊び心にあふれた、飛び抜けた、致命的な不遜さがある。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Candide |

+★Candide:

The shocking passages, Why is Voltaire's Candide controversial?

| Voltaire’s Candide,

or Optimism (1759), is a story of a young man who believed in his

tutor’s rosy worldview that “all is for the best.” Throughout the book,

he’s on a pursuit to find the girl he loves, while facing off a litany

of challenges which bring him against the worst humanity could offer.

Read below the thought-provoking passages from one of the most

controversial novels ever written. |

ヴォルテールの『カンディード、あるいは楽天主義』(1759年)は、

すべては最善であるという家庭教師の楽観的な世界観を信じた青年の物語である。この本全体を通して、彼は愛する女性を見つけるために奔走するが、その一方

で、人間が持つ最悪の側面を露わにする数々の試練に直面する。最も物議を醸した小説のひとつから、考えさせられる文章を以下に抜粋する。 |

| The German region of Westphalia