戦時移転住局

War Relocation Authority, WRA

The

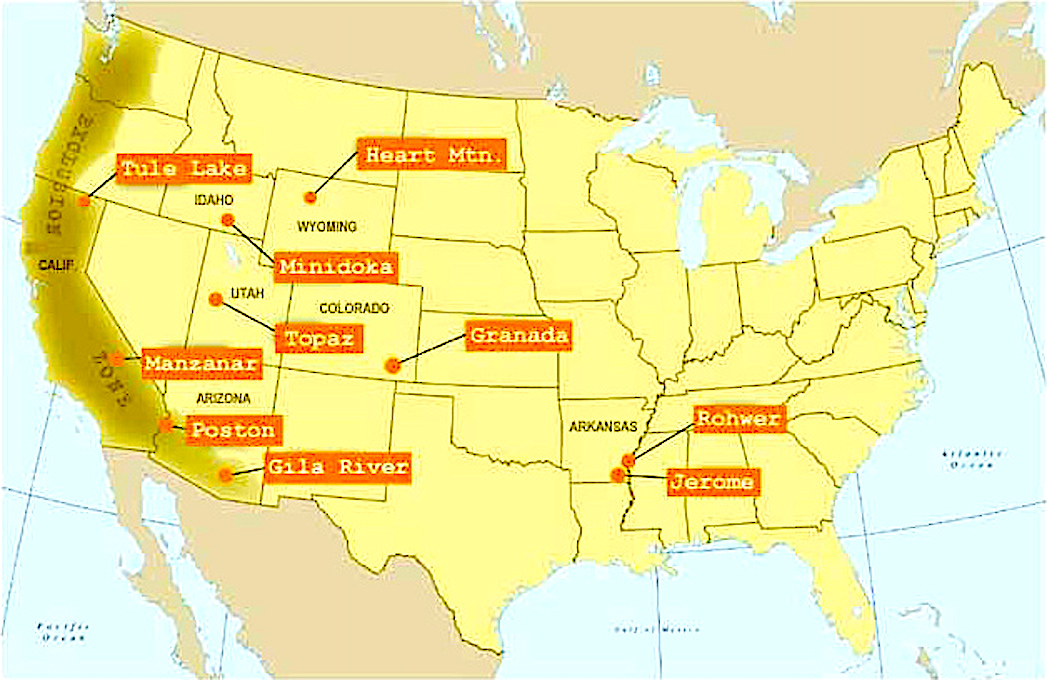

War Relocation Authority operated ten Japanese-American internment

camps in remote areas of the United States during World War II.

☆ 戦時転住局/戦時移転住局(WRA)は、第二次世界大戦中に日系アメリカ人の強制収容を担当するために設立された米国政府機関である。また、ニューヨーク 州オスウィーゴのフォート・オンタリオ緊急避難民収容所を運営した。これは、ヨーロッパからの難民のために米国で唯一設置された難民キャンプであった。 [1] 同機関は、1942年3月18日にフランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領が発令した行政命令9102号により設立され、ハリー・S・トルーマン大統領の命 令により1946年6月26日に廃止された。[2]

| The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was

a United States government agency established to handle the internment

of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort

Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was the

only refugee camp set up in the United States for refugees from

Europe.[1] The agency was created by Executive Order 9102 on March 18,

1942, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and was terminated June 26,

1946, by order of President Harry S. Truman.[2] |

戦時転住局/戦時移転住局(WRA) は、第二次世界大戦中に日系アメリカ人の強制収容を担当するために設立された米国政府機関である。また、ニューヨーク州オスウィーゴのフォート・オンタリ オ緊急避難民収容所を運営した。これは、ヨーロッパからの難民のために米国で唯一設置された難民キャンプであった。[1] 同機関は、1942年3月18日にフランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領が発令した行政命令9102号により設立され、ハリー・S・トルーマン大統領の命 令により1946年6月26日に廃止された。[2] |

ormation Hayward, California, May 8, 1942. Two children of the Mochida family who, with their parents, are awaiting an evacuation bus. The youngster on the right holds a sandwich given to her by one of a group of women who were present from a local church. The family unit is kept intact during evacuation and at War Relocation Authority centers where evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed for the duration. (Photo by Dorothea Lange). After the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing military commanders to create zones from which certain persons could be excluded if they posed a threat to national security. Many people of Japanese ancestry were also suspected of espionage after the Pearl Harbor attack. Military Areas 1 and 2 were created soon after, encompassing all of California and parts of Washington, Oregon, and Arizona, and subsequent civilian exclusion orders informed Japanese Americans residing in these zones they would be scheduled for "evacuation." The executive order also applied to Alaska as well, bringing the entire United States West Coast as off-limits to Japanese nationals and Americans of Japanese descent.[3] On March 18, 1942, the WRA was formed via Executive Order 9102. It was in many ways a direct successor to the Works Projects Administration (WPA) and the efforts of both overlapped and intermingled for quite some time. From March until November, the WPA spent more on internment than any other agency including the Army and was on the scene with removal and relocation even before Executive Order 9192. Beginning on March 11, for example, Rex L. Nicholson, the WPA's regional director, managed the first “Reception and Induction” centers. Another WPA veteran, Clayton E. Triggs, was the administrator the Manzanar Relocation Center, a facility which, according to one insider, was “manned just about 100% by the WPA.” Drawing on his background in New Deal road construction, Triggs installed such familiar concentration camp features as guard towers and spotlights. As the WPA wound down in late 1942 and early 1943, many of its employees moved over seamlessly to the WRA.[4] Milton S. Eisenhower was the WRA's original director. Eisenhower was a proponent of Roosevelt's New Deal and disapproved of the idea of mass internment.[5]: 57 Early on he had tried, unsuccessfully, to limit the internment to adult men, allowing women and children to remain free, and he pushed to keep WRA policy in line with the original idea of making the camps similar to subsistence homesteads in the rural interior of the country.[6] This, along with proposals for helping Japanese Americans resettle in labor-starved farming communities outside the exclusion zone, was met with opposition from the governors of these interior states, who worried about security issues and claimed it was "politically infeasible," at a meeting in Salt Lake City in April 1942.[5]: 56–57 Shortly before the meeting Eisenhower wrote to his former boss, Secretary of Agriculture Claude Wickard, and said, "when the war is over and we consider calmly this unprecedented migration of 120,000 people, we as Americans are going to regret the unavoidable injustices that we may have done".[5]: 57 Disappointed, Eisenhower was director of the WRA for only ninety days, resigning June 18, 1942. However, during his tenure with the WRA he raised wages for interned Japanese Americans, worked with the Japanese American Citizens League to establish an internee advisory council, initiated a student leave program for college-age Nisei, and petitioned Congress to create programs for postwar rehabilitation. He also pushed Roosevelt to make a public statement in support of loyal Nisei and attempted to enlist the Federal Reserve Bank to protect the property left behind by displaced Japanese Americans, but was unable to overcome opposition to these proposals.[6][5]: 57–58 Eisenhower was replaced by Dillon S. Myer, who would run the WRA until its dissolution at the end of the war. Japanese Americans had already been removed from their West Coast homes and placed in temporary "assembly centers" (run by a separate military body, the Wartime Civilian Control Administration [WCCA]) over the spring of 1942; Myer's primary responsibility upon taking the position was to continue with the planning and construction of the more permanent replacements for the camps run by the WCCA.[7] |

編成 1942年5月8日、カリフォルニア州ヘイワード。 両親とともに避難バスを待つ持田家の子供たち。右の子供は、地元の教会から来ていた女性グループの一人から受け取ったサンドイッチを持っている。 家族単位での避難は維持され、日系人避難民が収容される戦争移住局のセンターでもそれは変わらなかった。 (ドロシア・ラング撮影)。 1941年12月の真珠湾攻撃の後、フランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領は、国家の安全保障を脅かす可能性がある特定の人々を排除できる区域を軍司令官 が設定することを認める大統領令9066を発令した。真珠湾攻撃の後、多くの日系人もスパイ容疑をかけられた。その後すぐに、軍事地域1および2がカリ フォルニア州全域とワシントン州、オレゴン州、アリゾナ州の一部に設定され、これらの地域に住む日系アメリカ人に対して、後に「退去」が予定されているこ とが通知された。この大統領令はアラスカにも適用され、米国西海岸全体が日本人および日系アメリカ人の立ち入り禁止区域となった。 1942年3月18日、大統領令9102号により、WRAが設立された。WRAは、多くの点で公共事業促進局(WPA)の直接的な後継であり、両者の努力 はしばらくの間重複し、混在していた。3月から11月にかけて、WPAは陸軍を含むどの機関よりも多くの費用を収容所に費やし、大統領令9192号が発令 される前から、立ち退きと移転の現場に立ち会っていた。例えば、3月11日より、WPAの地域ディレクターであったレックス・L・ニコルソンは、最初の 「収容および入所」センターの管理を行った。マンザナール強制収容所の管理者であったWPAのベテラン、クレイトン・E・トリッグスは、内部関係者の証言 によると、「ほぼ100%がWPAの職員で占められていた」施設である。ニューディール政策による道路建設の経験を生かし、トリッグスは監視塔やスポット ライトなど、強制収容所でおなじみの設備を導入した。1942年末から1943年初頭にかけてWPAが縮小されると、その職員の多くがWRAにスムーズに 移籍した。 ミルトン・S・アイゼンハワーがWRAの初代局長となった。アイゼンハワーはルーズベルトのニューディール政策の支持者であり、集団抑留の考えには反対で あった。[5]:57 彼は早い段階で、抑留対象を成人男性に限定し、女性と子供は自由の身のままでいられるようにしようと試みたが、これは失敗に終わった。また、WRAの方針 を、収容所を国内の農村部の自給自足的な入植地に似たものにするという当初の考えに沿ったものに保つよう強く主張した 。[6] これは、日系アメリカ人の再定住を労働力不足の排除区域外の農村地域で支援するという提案とともに、1942年4月にソルトレークシティで行われた会議 で、治安上の懸念から「政治的に実現不可能」であると主張した内陸部の州知事たちから反対を受けた。[5]: 56–57 その会議の直前にアイゼンハワーはかつての上司であるクロード・ウィッカード農務長官に手紙を書き、「戦争が終わり、12万人という前例のない大規模な移 住を冷静に振り返ったとき、アメリカ人として、避けられなかった不正義を悔いることになるだろう」と述べた。[5]: 57 失望したアイゼンハワーは、WRAの所長をわずか90日間務めただけで、1942年6月18日に辞任した。しかし、WRA在任中には、抑留された日系アメ リカ人の賃金を引き上げ、日系市民協会と協力して抑留者諮問委員会を設立し、大学生の二世を対象とした学生休学制度を導入し、戦後の再定住プログラムを創 設するよう議会に請願した。また、ルーズベルト大統領に忠誠な二世を支持する声明を発表するよう働きかけ、連邦準備銀行に立ち退きを余儀なくされた日系ア メリカ人の残した財産の保護を依頼したが、これらの提案に対する反対意見を覆すことはできなかった。[6][5]: 57-58 アイゼンハワーはディロン・S・マイヤーに交代し、終戦までWRAを運営することになった。 日系アメリカ人はすでに1942年の春までに西海岸の自宅から立ち退きを命じられ、臨時の「集合センター」(戦時民間管理庁(WCCA)という別の軍機関 が運営)に入れられていた。マイヤーが就任した際の主な責務は、WCCAが運営する収容所の代わりとなるより恒久的な施設の建設計画を継続することだっ た。[7] |

| Life in the camps A homemade planter and a doily beside a service portrait, a prayer, and a letter home. One of the few ways to earn permission to leave the camps was to enter military service. Life in a WRA camp was difficult. Those fortunate enough to find a job worked long hours, usually in agricultural jobs. Resistance to camp guards and escape attempts were a low priority for most of the Japanese Americans held in the camps. Residents were more often concerned with the problems of day-to-day life: improving their often shoddily-constructed living quarters, getting an education, and, in some cases, preparing for eventual release. Many of those who were employed, particularly those with responsible or absorbing jobs, made these jobs the focus of their lives. However, the pay rate was deliberately set far lower than what inmates would have received outside camp, an administrative response to widespread rumors that Japanese Americans were receiving special treatment while the larger public suffered from wartime shortages. Non-skilled labor earned $14/month while doctors and dentists made a paltry $19/month.[7] Many found consolation in religion, and both Christian and Buddhist services were held regularly. Others concentrated on hobbies or sought self-improvement by taking adult classes, ranging from Americanization and American history and government to vocational courses in secretarial skills and bookkeeping, and cultural courses in such things as ikebana, Japanese flower arrangement. The young people spent much of their time in recreational pursuits: news of sports, theatrics, and dances fills the pages of the camp newspaper.[5]: 70–71 Living space was minimal. Families lived in army-style barracks partitioned into "apartments" with walls that usually did not reach the ceiling. These "apartments" were, at the largest, twenty by twenty-four feet (6.1 by 7.3 m) and were expected to house a family of six. In April 1943, the Topaz camp averaged 114 square feet (10.6 m2) (roughly six by nineteen feet [1.8 by 5.8 m]) per person.[5]: 67 Each inmate ate at one of several common mess halls, assigned by block. At the Army-run camps that housed dissidents and other "troublemakers", it was estimated that it cost 38.19 cents per day ($7.00 in present-day terms[9]) to feed each person. The WRA spent slightly more, capping per-person costs to 50 cents a day ($9.00 in present-day terms[9]) (again, to counteract rumors of "coddling" the inmates), but most people were able to supplement their diets with food grown in camp.[7][5]: 67 The WRA allowed Japanese Americans to establish a form of self-governance, with elected inmate leaders working under administration supervisors to help run the camps. This allowed inmates to keep busy and have some say in their day-to-day life; however, it also served the WRA mission of "Americanizing" the inmates so that they could be assimilated into white communities after the war. The "enemy alien" Issei were excluded from running for office, and inmates and community analysts argued that the WRA pulled the strings on important issues, leaving only the most basic and inconsequential decisions to Nisei leaders.[7] |

収容所での生活 サービス用ポートレート、祈りの品、そして故郷への手紙のそばに置かれた手作りのプランターとドイリー。収容所から出る許可を得る数少ない方法のひとつが、軍務に就くことだった。 WRAの収容所での生活は困難を極めた。仕事に就くことができた幸運な人々は、長時間労働を強いられ、その多くは農業関係の仕事であった。収容所の警備員 への抵抗や脱走未遂は、収容されていた日系アメリカ人の大半にとっては優先度の低い問題であった。収容されていた人々は、粗末に建てられたことが多い居住 区の改善、教育の確保、そして場合によっては、最終的な釈放に備えることなど、日々の生活の問題により関心を寄せていた。仕事に就いていた人々、特に責任 のある仕事ややりがいのある仕事に就いていた人々は、その仕事を生活の中心に据えていた。しかし、賃金は意図的に収容所外で受給できるはずの額よりもはる かに低く設定されていた。これは、日系アメリカ人が戦時中の物資不足に苦しむ国民のなかで特別扱いされているという噂が広がっていたことに対する行政の対 応であった。非熟練労働者の賃金は月14ドルであったのに対し、医師や歯科医の賃金はわずか月19ドルであった。 多くの人々は宗教に慰めを見出し、キリスト教と仏教の礼拝が定期的に行われた。また、アメリカ文化やアメリカ史、政治から秘書や簿記の職業訓練、生け花や 茶道などの文化コースまで、さまざまな成人向けクラスを受講して趣味に没頭したり、自己啓発に励む人もいた。若者たちは余暇の時間を娯楽に費やした。収容 所の新聞には、スポーツ、演劇、ダンスのニュースが紙面を埋め尽くしている。[5]: 70-71 居住スペースは最小限だった。家族は、壁が天井まで届いていないことが多い「アパート」に仕切られた軍隊式の兵舎に住んでいた。これらの「アパート」は、 最大でも6.1m×7.3m(20フィート×24フィート)の広さで、6人家族が暮らすことを想定していた。1943年4月、トパーズ収容所の1人当たり の平均面積は10.6m2(114平方フィート)(約1.8m×5.8m(6フィート×19フィート))であった。 収容者たちは、ブロックごとに割り当てられたいくつかの共同食堂のうちの1つで食事をとった。反体制派やその他の「問題児」を収容する陸軍運営の収容所で は、1人あたりの食費は1日あたり38.19セント(現在の価値に換算すると7ドル[9])と見積もられていた。WRAは、収容者への「甘やかし」という 噂を打ち消すため、1人当たりの費用を1日50セント(現在の価値で9ドル)に抑えたが、ほとんどの人はキャンプ内で栽培された食料で食事を補うことがで きた[7][5]:67 WRAは日系アメリカ人に自治組織を設立することを許可し、収容所の運営を助けるために、被収容者から選出された指導者が行政監督者の下で働くことになっ た。これにより被収容者は忙しく働くことができ、日々の生活についてある程度の意見を述べることも可能となったが、これは同時に、戦後に白人社会に同化で きるよう被収容者を「アメリカ化」するというWRAの使命にも役立った。「敵国人」である一世は、役職に就くことが禁じられていた。収容者と地域社会の分 析者は、WRAが重要な問題を操り、二世の指導者たちには最も基本的な些細な決定しか任せていないと主張した。[7] |

| Community Analysis Section In February 1943, the WRA established the Community Analysis Section (under the umbrella of the Community Management Division) in order to collect information on the lives of incarcerated Japanese Americans in all ten camps. Employing over twenty cultural anthropologists and social scientists—including John Embree, Marvin and Morris Opler, Margaret Lantis, Edward Spicer, and Weston La Barre—the CAS produced reports on education, community-building and assimilation efforts in the camps, taking data from observations of and interviews with camp residents.[10] While some community analysts viewed the Japanese American inmates merely as research subjects, others opposed the incarceration and some of the WRA's policies in their reports, although very few made these criticisms public. Restricted by federal censors and WRA lawyers from publishing their full research from the camps, most of the (relatively few) reports produced by the CAS did not contradict the WRA's official stance that Japanese Americans remained, for the most part, happy behind the barbed wire. Morris Opler did, however, provide a prominent exception, writing two legal briefs challenging the exclusion for the Supreme Court cases of Gordon Hirabayashi and Fred Korematsu.[10] |

コミュニティ分析課 1943年2月、WRAは全10の収容所における収容された日系アメリカ人の生活に関する情報を収集するために、コミュニティ管理部門傘下のコミュニティ分析課を設置した。ジョン・エンブリー、 マーヴィンとモリス・オプラー、マーガレット・ランティス、エドワード・スピサー、ウェストン・ラ・バールなど20人以上の文化人類学者や社会科学者を雇 用したCASは、収容所の教育、コミュニティ形成、同化政策に関する報告書をまとめ、収容所住民の観察やインタビューから得たデータを基に作成した。 コミュニティ分析者の一部は、日系アメリカ人収容者を単なる研究対象として見ていたが、他の人々は、収容やWRAの政策の一部に反対する意見を報告書に記 した。ただし、こうした批判を公にした者はほとんどいなかった。連邦検閲官やWRAの弁護士から収容所での調査結果の公表を制限されていたため、CASが 作成した(比較的少数の)報告書のほとんどは、日系アメリカ人の大半は有刺鉄線の向こう側で幸せに暮らしているというWRAの公式見解に反するものではな かった。しかし、モリス・オプレルは著名な例外であり、ゴードン・ヒラバヤシとフレッド・コレマツの最高裁判例における排除に異議を唱える2つの法的意見 書を執筆した。[10] |

| Resettlement program Concerned that Japanese Americans would become more dependent on the government the longer they remained in camp, Director Dillon Myer led the WRA in efforts to push inmates to leave camp and reintegrate into outside communities. Even before the establishment of the "relocation centers," agricultural laborers had been issued temporary work furloughs by the WCCA, and the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council had been placing Nisei in outside colleges since the spring of 1942. The WRA had initiated its own "leave permit" system in July 1942, although few took the trouble to go through the bureaucratic and cumbersome application process until it was streamlined over the following months.[7] (By the end of 1942, only 884 had volunteered for resettlement.)[11] The need for a more easily navigable system, in addition to external pressure from pro-incarceration politicians and the general public to restrict who could exit the camps, led to a revision of the application process in 1943. Initially, applicants were required to find an outside sponsor, provide proof of employment or school enrollment, and pass an FBI background check. In the new system, inmates had only complete a registration form and pass a streamlined FBI check. (The "loyalty questionnaire," as the form came to be known after it was made mandatory for all adults regardless of their eligibility for resettlement, would later spark protests across all ten camps.)[11] At this point, the WRA began to shift its focus from managing the camps to overseeing resettlement. Field offices were established in Chicago, Salt Lake City and other hubs that had attracted Japanese American resettlers. Administrators worked with housing, employment and education sponsors in addition to social service agencies to provide assistance. Following Myer's directive to "assimilate" Japanese Americans into mainstream society, this network of WRA officials (and the propaganda they circulated in camp) steered resettlers toward cities that lacked large Japanese American populations and warned against sticking out by spending too much time among other Nikkei, speaking Japanese or otherwise clinging to cultural ties.[7] By the end of 1944, close to 35,000 had left camp, mostly Nisei.[11] |

再定住プログラム 日系人が収容所に留まるほど政府への依存度が高まることを懸念したディロン・マイヤー所長は、WRAを率いて収容者たちに収容所を出て地域社会に再び溶け 込むよう促した。「再定住センター」が設立される前から、農業労働者にはWCCAから一時的な就労休暇が発行されていた。また、全米日系人学生再定住協議 会は1942年春から、二世を地域の大学に入学させていた。WRAは1942年7月に独自の「外出許可」制度を開始したが、その後の数ヶ月間に手続きが簡 素化されるまで、わずかな人々しか煩雑な申請手続きを行おうとしなかった。[7](1942年末までに再定住に志願したのは884名のみだった。) [11] 収容所からの退去を制限しようとする、収容推進派の政治家や一般市民からの外圧に加え、より利用しやすいシステムの必要性が生じたため、1943年に申請 手続きが改定された。当初、申請者は外部のスポンサーを見つけ、雇用証明または在学証明を提出し、FBIの身元調査に合格することが求められた。新しいシ ステムでは、収容者は登録用紙に記入し、簡素化されたFBIのチェックを受けるだけでよかった。(この登録用紙は、再定住の適格性に関係なく、すべての成 人に義務付けられたため、「忠誠心調査票」と呼ばれるようになり、後に10の収容所すべてで抗議運動が起こった。)[11] この時点で、WRAは収容所の管理から再定住の監督へと重点を移し始めた。シカゴ、ソルトレークシティ、および日系アメリカ人の再定住者が集まった他の拠 点に現地事務所が設置された。 行政官は、社会福祉機関に加え、住宅、雇用、教育のスポンサーと協力して支援を行った。 マイヤーの「同化」という指示に従い、WRAの役人たちのネットワーク(および収容所内で流布されたプロパガンダ)は、日系アメリカ人の人口が少ない都市 に再定住者を導き、 日系人同士で過ごす時間を長くしたり、日本語を話したり、その他の方法で文化的つながりを保ったりすることは控えるよう警告した。[7] 1944年末までに、3万5000人近くが収容所を離れ、そのほとんどは二世であった。[11] |

| Resistance to WRA policies The WRA's "Americanization" efforts were not limited to the Nisei resettlers. Dillon Myer and other high-level officials believed that accepting the values and customs of white Americans was the best way for Japanese Americans to succeed both in and out of camp. Administrators sponsored patriotic activities and clubs, organized English classes for the Issei, encouraged young men to volunteer for the U.S. Army, and touted inmate self-government as an example of American democracy. "Good" inmates who toed the WRA line were rewarded, while "troublemakers" who protested their confinement and Issei elders who had been leaders in their prewar communities but found themselves stripped of this sway in camp were treated as a security threat. Resentment over poor working conditions and low wages, inadequate housing, and rumors of guards stealing food from inmates exacerbated tensions and created pro- and anti-administration factions. Labor strikes occurred at Poston,[12] Tule Lake[13] and Jerome,[14] and in two violent incidents at Poston and Manzanar in November and December 1942, individuals suspected of colluding with the WRA were beaten by other inmates. External opposition to the WRA came to a head following these events, in two congressional investigations by the House Un-American Activities Committee and another led by Senator Albert Chandler.[7] The leave clearance registration process, dubbed the "loyalty questionnaire" by inmates, was another significant source of discontent among incarcerated Japanese Americans. Originally drafted as a War Department recruiting tool, the 28 questions were hastily, and poorly, revised for their new purpose of assessing inmate loyalty. The form was largely devoted to determining whether the respondent was a "real" American — baseball or judo, Boy Scouts or Japanese school — but most of the ire was directed at two questions that asked inmates to volunteer for combat duty and forswear their allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. Many were offended at being asked to risk their lives for a country that had imprisoned them, and believed the question of allegiance was an implicit accusation that they had been disloyal to the United States. Although most answered in the affirmative to both, 15 percent of the total inmate population refused to fill out the questionnaire or answered "no" to one or both questions. Under pressure from War Department officials, Myer reluctantly converted Tule Lake into a maximum security segregation center for the "no-nos" who flunked the loyalty test, in July 1943.[7] Approximately 12,000 were transferred to Tule Lake, but of the previous residents cleared as loyal, only 6,500 accepted the WRA offer to move to another camp. The resulting overpopulation (almost 19,000 in a camp designed for 15,000 by the end of 1944) fueled existing resentment and morale problems.[13] Conditions worsened after another labor strike and an anti-WRA demonstration that attracted a crowd of 5,000 to 10,000[15] and ended with several inmates being badly beaten. The entire camp was placed under martial law on November 14, 1943. Military control lasted for two months, and during this time 200[16] to 350[13] men were imprisoned in an overcrowded stockade (held under charges such as "general troublemaker" and "too well educated for his own good"), while the general population was subject to curfews, unannounced searches, and restrictions on work and recreational activities.[16] Angry young men joined the Hoshi-dan and its auxiliary, the Hokoku-dan, a militaristic nationalist group aimed at preparing its members for a new life in Japan. This pro-Japan faction ran military drills, demonstrated against the WRA, and made threats against inmates seen as administration sympathizers.[17] When the Renunciation Act was passed in July 1944, 5,589 (over 97 percent of them Tule Lake inmates) expressed their resentment by giving up their U.S. citizenship and applying for "repatriation" to Japan.[15][18] |

WRAの方針に対する抵抗 WRAの「アメリカ化」政策は、二世の再定住者に限定されたものではなかった。ディロン・マイヤーや他の高官たちは、白人アメリカ人の価値観や習慣を受け 入れることが、日系アメリカ人が収容所内外で成功を収めるための最善の方法であると考えていた。当局者は愛国的な活動やクラブを後援し、一世のために英語 クラスを組織し、若い男性たちに米国陸軍への志願を勧め、収容者の自治をアメリカ民主主義の模範として喧伝した。WRAの方針に従う「模範囚」には褒美が 与えられ、収容に抗議する「問題児」や戦前の地域社会で指導的立場にあった一世の年長者で、収容所ではその影響力を失った人々は、治安上の脅威として扱わ れた。劣悪な労働条件や低賃金、不十分な住居、看守が収容者から食料を盗んでいるという噂などに対する不満が緊張をさらに高め、WRAを支持する派閥と反 対する派閥を生み出した。ポストン[12]、トゥールレイク[13]、ジェローム[14]では労働争議が発生し、1942年11月と12月にはポストンと マンザナーで2件の暴力的な事件が発生し、WRAと結託していると疑われた人物が他の収容者によって暴行された。WRAに対する外部からの反対は、これら の事件の後、下院非米活動委員会による2つの議会調査と、アルバート・チャンドラー上院議員による別の調査によって頂点に達した。 収容者たちから「忠誠心調査票」と呼ばれた休暇許可登録手続きも、収容中の日系アメリカ人の不満の大きな原因となった。もともと陸軍省の勧誘手段として作 成された28の質問は、収容者の忠誠心を評価するという新たな目的のために、急いで、しかも粗雑に改訂された。この用紙は、回答者が「真の」アメリカ人で あるかどうかを判断することに大半が割かれており、野球や柔道、ボーイスカウトや日本語学校などに関する質問が含まれていたが、収容者の怒りの大半は、戦 闘任務への志願と日本の天皇への忠誠を放棄するよう求める2つの質問に向けられた。収容した国のために命を危険にさらすことを求められたことに多くの人が 憤慨し、忠誠の誓いを問う質問は、米国に対して不誠実であったという暗黙の非難であると受け取られた。 ほとんどの人が両方の質問に「はい」と答えたが、収容者全体の15パーセントは、質問票への記入を拒否したり、質問のどちらか一方または両方に「いいえ」 と答えた。陸軍省高官からの圧力により、マイヤーは1943年7月、忠誠心テストに不合格となった「ノー」の人々を収容する最高警備の隔離センターとし て、トゥールレイクを渋々転用した。 約12,000人がトゥールレイクに移されたが、忠誠心が認められた以前の居住者のうち、WRAの申し出に応じて別のキャンプに移ったのは6,500人に 過ぎなかった。その結果、過剰人口(1944年末には15,000人収容可能なキャンプに19,000人近くが収容されていた)により、既存の不満と士気 の低下に拍車がかかった。[13] 労働争議とWRAに反対するデモが起こり、5,000人から10,000人の群衆が集まった後、状況は悪化した。[15] デモは収容者数名がひどく殴られたことで幕を閉じた。1943年11月14日、収容所全体が戒厳令下に置かれた。軍の管理は2か月間続き、その間、200 人[16]から350人[13]の男性が過密状態の兵営に収監された(「一般のトラブルメーカー」や「本人のためにならないほど教育を受けすぎている」な どの容疑で収監された)。その間、一般の収容者たちは 外出禁止令、抜き打ちの捜索、労働や娯楽活動の制限の対象となった。[16] 怒れる若者たちは、日本での新しい生活に備えることを目的とした軍国主義的愛国主義団体である星団とその補助団体である報国団に参加した。この親日派グ ループは軍事訓練を行い、WRAに抗議デモを行い、当局に同調していると見られる収容者に対して脅迫を行った。[17] 1944年7月に放棄法が可決されると、5,589人(そのうち97パーセント以上がトゥールレイク収容者)が米国籍を放棄し、日本への「送還」を申請す ることで、その憤りを示した。[15][18] |

| End of the camps The West Coast was reopened to Japanese Americans on January 2, 1945 (delayed against the wishes of Dillon Myer and others until after the November 1944 election, so as not to impede Roosevelt's reelection campaign).[19] On July 13, 1945, Myer announced that all of the camps were to be closed between October 15 and December 15 of that year, except for Tule Lake, which held "renunciants" slated for deportation to Japan. (The vast majority of those who had renounced their U.S. citizenship later regretted the decision and fought to remain in the United States, with the help of civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins. The camp remained open until the 4,262 petitions were resolved.)[15] Despite wide-scale protests from inmates who had nothing to return to and felt unprepared to relocate yet again, the WRA began to eliminate all but the most basic services until those remaining were forcibly removed from camp and sent back to the West Coast.[7] Tule Lake closed on March 20, 1946, and Executive Order 9742, signed by President Harry S. Truman on June 26, 1946, officially terminated the WRA's mission.[20] |

収容所の閉鎖 西海岸は1945年1月2日に日系アメリカ人に再開された(ディロン・マイヤーや他の人々の反対により、ルーズベルト大統領の再選キャンペーンを妨げない よう、1944年11月の選挙後まで延期された)[19] 1945年7月13日、マイヤーは、日本への強制送還が予定されている「離反者」を収容するツーレレイク収容所を除き、その年の10月15日から12月 15日の間にすべての収容所を閉鎖すると発表した。(米国籍を放棄した者の大半は後にこの決定を後悔し、公民権弁護士ウェイン・M・コリンズの助力を得て 米国への残留を求めて戦った。4,262件の請願がすべて処理されるまで、収容所は開かれたままであった)[15] 戻る場所もなく、また移住する準備もできていないという理由で、収容者から大規模な抗議があったにもかかわらず、WRAは、残された人々を収容所から強制 退去させ、西海岸に戻すまで、最も基本的なサービス以外はすべて廃止し始めた。 1946年3月20日、トゥールレイクは閉鎖され、1946年6月26日にハリー・S・トルーマン大統領が署名した大統領令9742により、WRAの任務は正式に終了した。[20] |

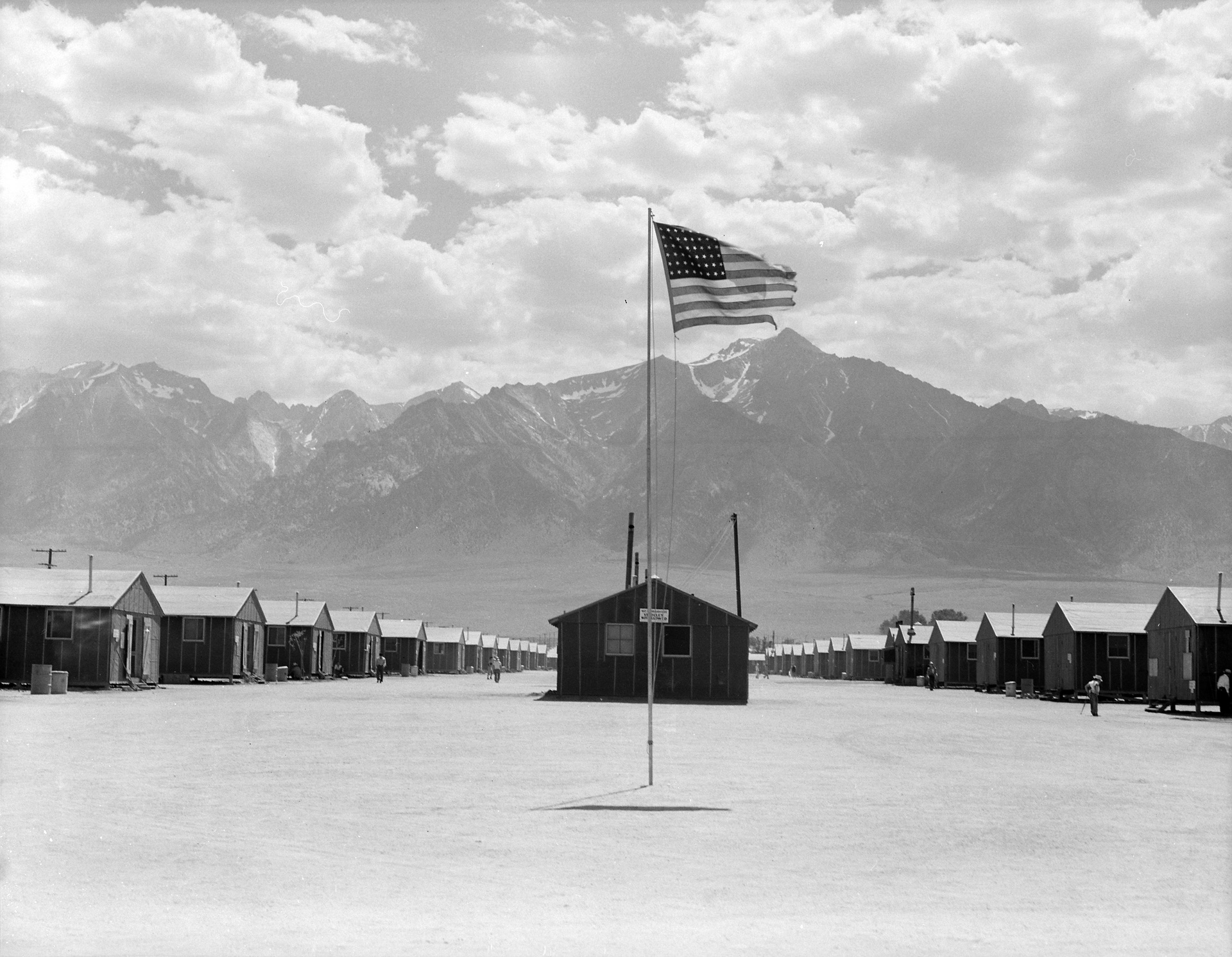

Relocation centers Dust storm at the Manzanar War Relocation Center Gila River War Relocation Center Granada War Relocation Center Heart Mountain War Relocation Center Jerome War Relocation Center Manzanar War Relocation Center Minidoka War Relocation Center Poston War Relocation Center Topaz War Relocation Center Tule Lake War Relocation Center Rohwer War Relocation Center |

移住センター マンザナール強制収容所での砂嵐 ギラ・リバー強制収容所 グラナダ強制収容所 ハートマウンテン強制収容所 ジェローム強制収容所 マンザナール強制収容所 ミニドカ強制収容所 ポストン強制収容所 トパーズ強制収容所 トゥールレイク強制収容所 ローワー強制収容所 |

| Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project Executive Order 9066 German American internment Italian American internment Japanese American internment New village Bantustan |

Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project 大統領令9066 ドイツ系アメリカ人の強制収容 イタリア系アメリカ人の強制収容 日系アメリカ人の強制収容 ニュー・ヴィレッジ バンツー・スタン |

| Beito,

David T. (2023). The New Deal's War on the Bill of Rights: The Untold

Story of FDR's Concentration Camps, Censorship, and Mass Surveillance

(First ed.). Oakland: Independent Institute. pp. 4–7. ISBN

978-1598133561. Myer, Dillon S. Uprooted Americans; the Japanese Americans and the War Relocation Authority During World War II. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1971. Riley, Karen Lea. Schools Behind Barbed Wire : the Untold Story of Wartime Internment and the Children of Arrested Enemy Aliens. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002. Tyson, Thomas N; Fleischman, Richard K. (June 2006). "Accounting for interned Japanese-American civilians during World War II: Creating incentives and establishing controls for captive workers". Accounting Historians Journal. 33 (1). Thomson Gale: 167. doi:10.2308/0148-4184.33.1.167. "The Evacuation of the Japanese." Population Index 8.3 (July 1942): 166–8. "The War Relocation Authority & the Incarceration of Japanese-Americans in World War II," Truman Presidential Museum & Library. 10 Feb. 2007 "War Relocation Authority," Greg Robinson, Densho Encyclopedia (9 Oct 2013). |

ベイトー、デビッド・T. (2023). 『ニューディールの権利章典戦争:語られなかったFDRの強制収容所、検閲、大規模監視の物語』(初版)。オークランド:インディペンデント研究所。4-7ページ。ISBN 978-1598133561。 マイヤー、ディロン S. 『根こそぎ奪われたアメリカ人:第二次世界大戦中の日系アメリカ人と戦時転住局』。ツーソン:アリゾナ大学出版、1971年。 ライリー、カレン・リー。『有刺鉄線の向こうの学校:語られなかった戦時中の抑留と逮捕された敵国人外国人(en)の子供たちの物語』。メリーランド州ランハム:ロウマン&リトルフィールド、2002年。 タイソン、トーマス・N、リチャード・K・フリッシュマン(2006年6月)。「第二次世界大戦中の抑留された日系アメリカ人民間人:捕虜となった労働者 に対するインセンティブの創出と統制の確立」。『会計史家ジャーナル』33(1)。トムソン・ゲイル:167。doi:10.2308/0148- 4184.33.1.167. 「日本人の避難」『Population Index』8.3(1942年7月):166-8。 「第二次世界大戦中の戦時転住局と日系アメリカ人の強制収容」トルーマン大統領図書館・博物館。2007年2月10日 「戦時転住局」グレッグ・ロビンソン、Densho Encyclopedia(2013年10月9日)。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_Relocation_Authority |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆