フルトヴェングラー指揮・ヘルベルト・グラーフ演出の『ドン・ジョヴァンニ』論

Wilhelm Furtwängler's Don Giovanni, 1954

W.

A. モーツァルト:ドン・ジョヴァンニ (フルトヴェングラー, 1954年)【全曲・日本語字幕】[YouTube]

| This opera was already posted on Youtube, but with Spanish subtitles. Here is now with English subtitles. Production - Herbert Graf Don Giovanni - Cesare Siepi Leporello - Otto Edelmann Donna Anna - Elisabeth Grümmer Don Ottavio - Anton Dermota Donna Elvira - Lisa della Casa Zerlina - Erna Berger Masetto - Walter Berry Il commendatore - Dezső Ernster Conductor - Wilhelm Furtwängler |

指揮:ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー ウィーン・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団 演出:ヘルベルト・グラーフ(Herbert Graf ) ドン・ジョヴァンニ:チェーザレ・シエピ 騎士長:デジェー・エルンシュテル ドンナ・アンナ:エリーザベト・グリュンマー ドン・オッターヴィオ:アントン・デルモータ ドンナ・エルヴィラ:リーザ・デラ・カーザ レポレロ:オットー・エーデルマン マゼット:ヴァルター・ベリー ツェルリーナ:エルナ・ベルガー ウィーン国立歌劇場合唱団 |

| Don Giovanni, Furtwängler, Salzburg 1954 (English subtitles) Don Giovanni K527 (1991 Remastered Version) , Atto secondo, Scena prima: Deh! vieni alla... |

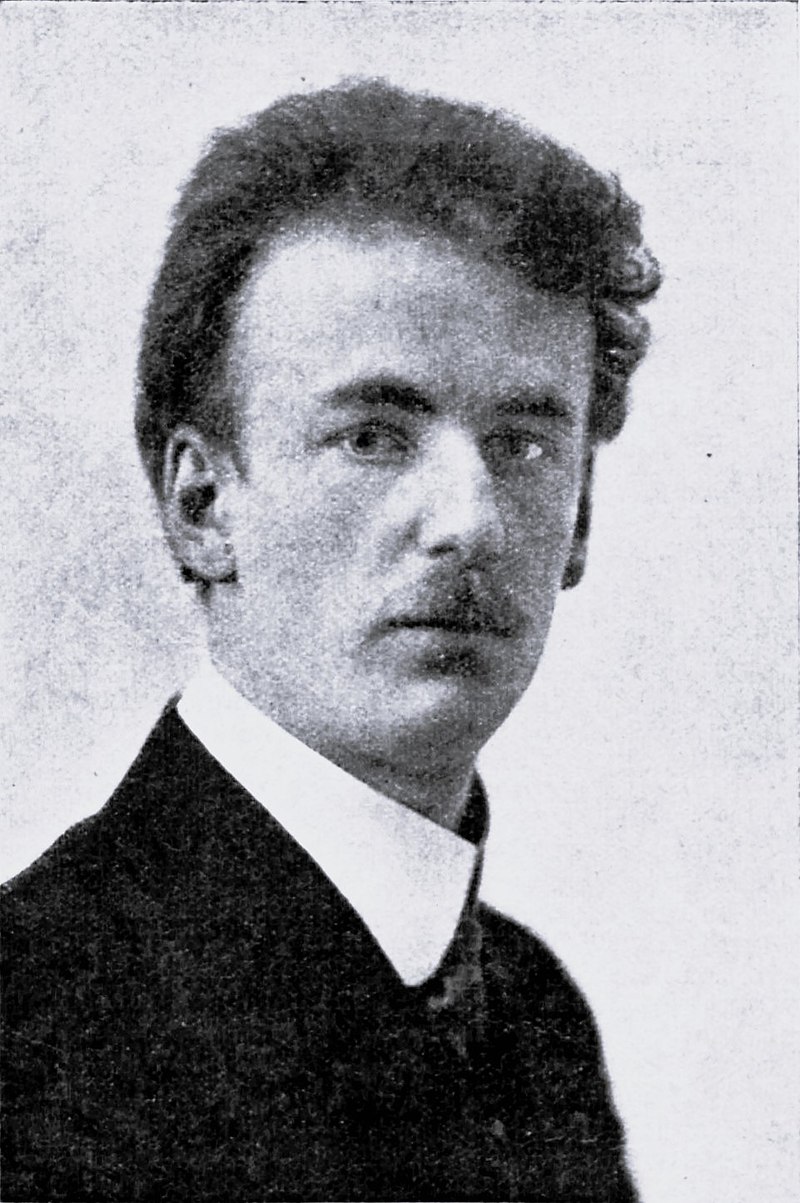

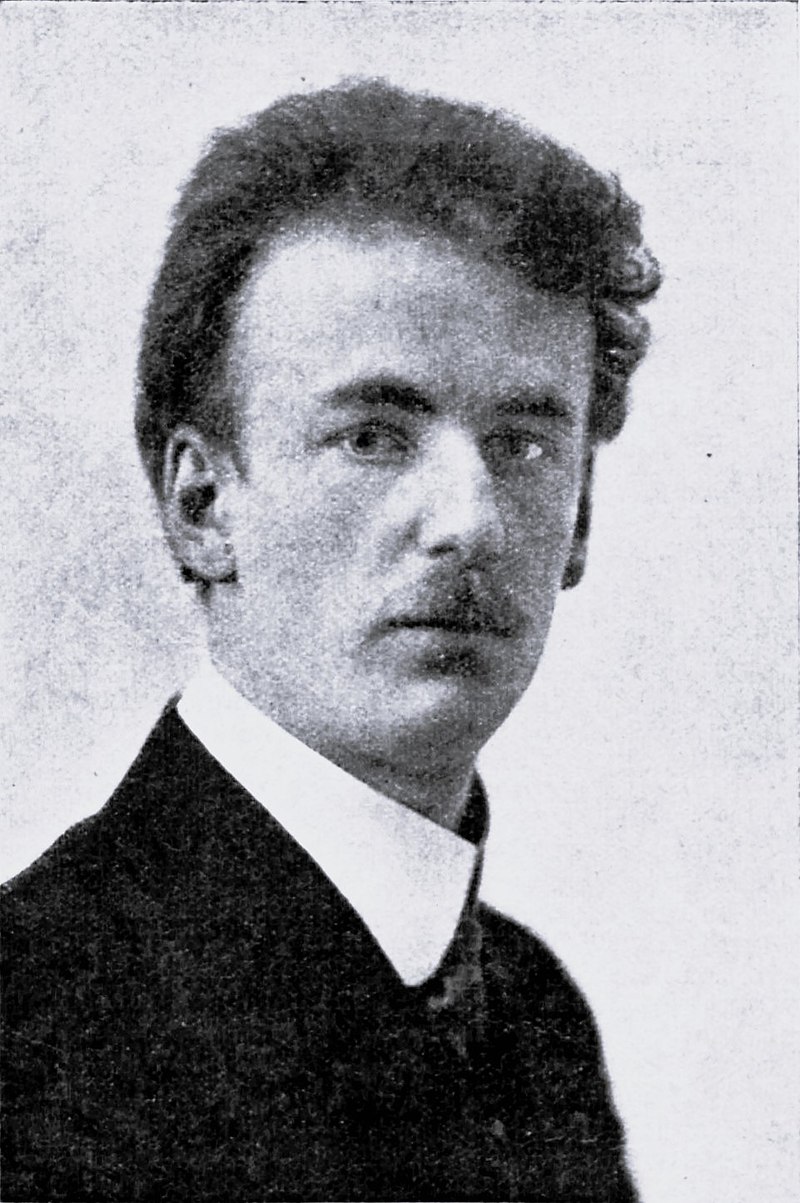

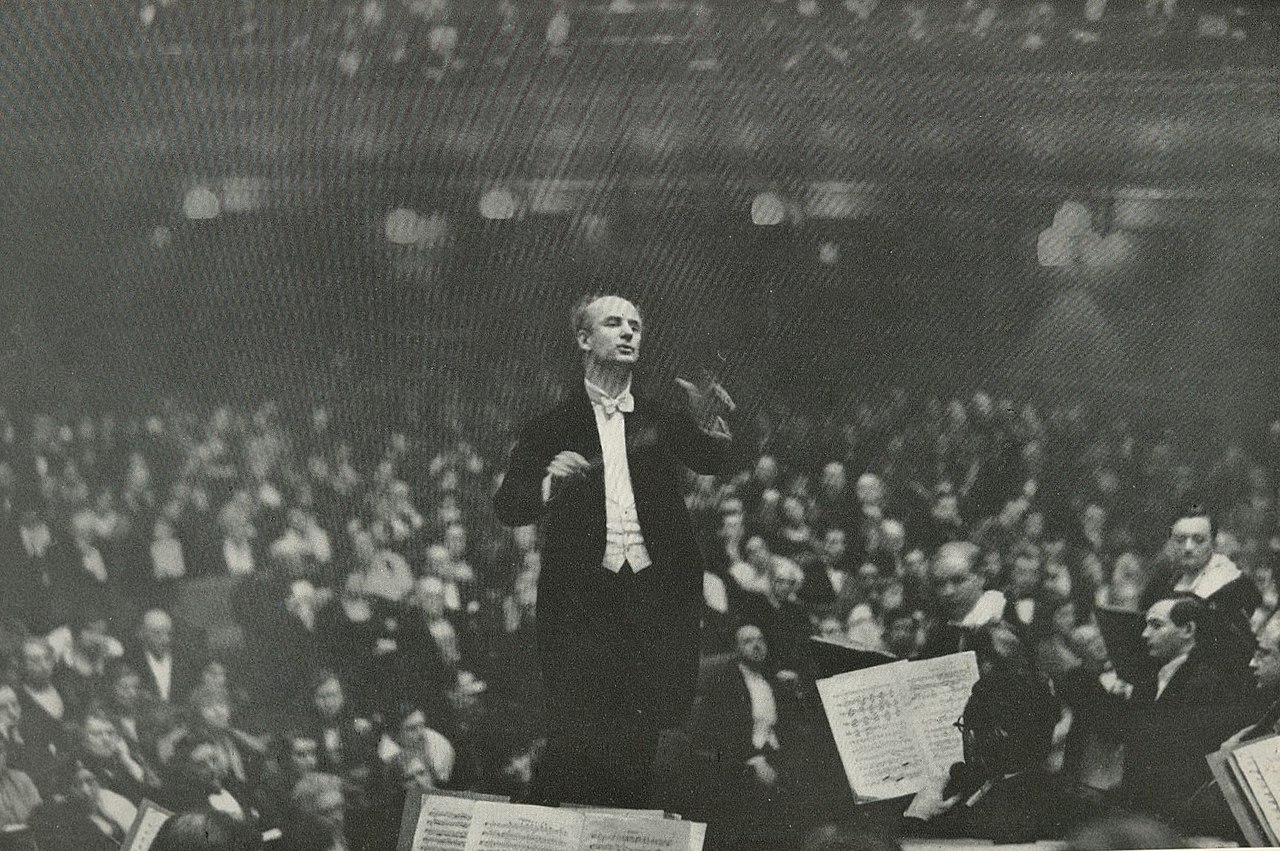

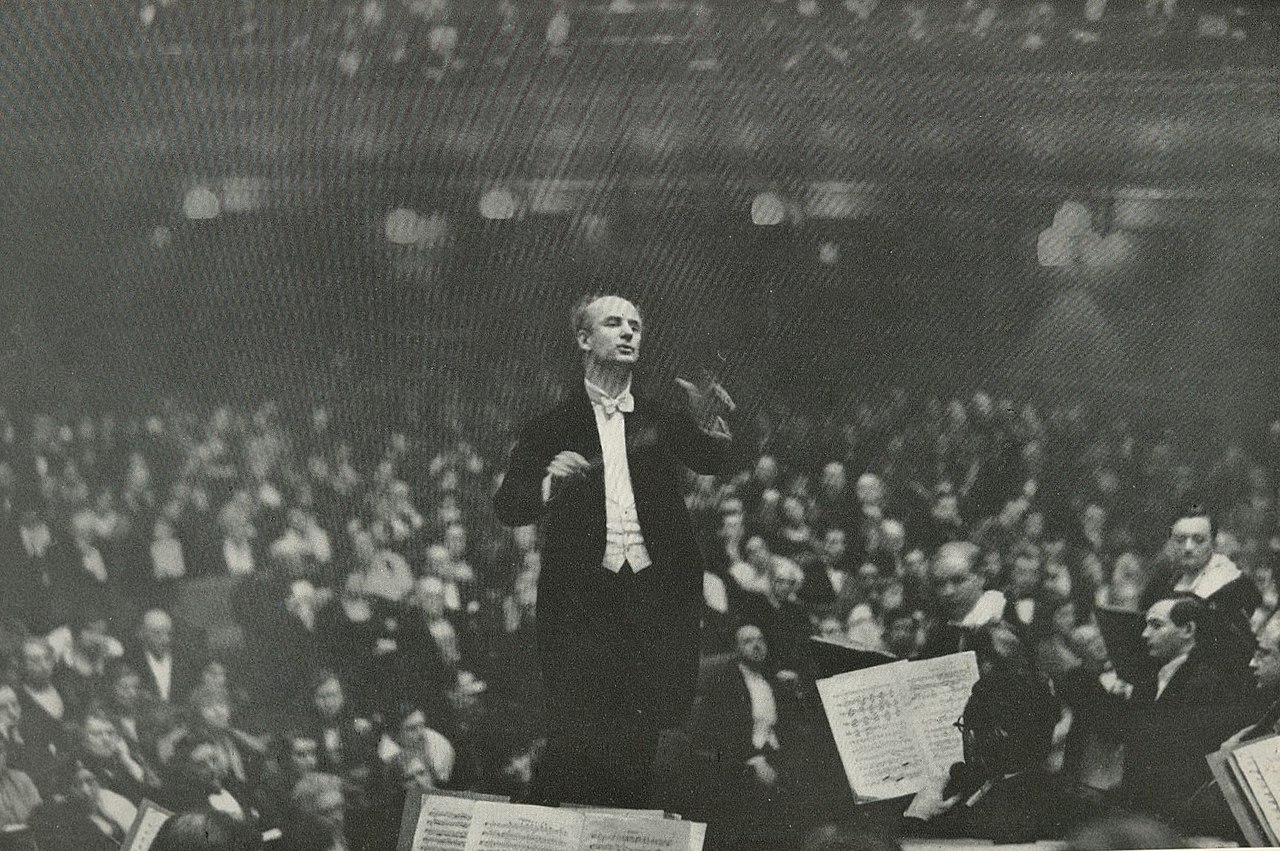

☆ グスタフ・ハインリヒ・エルンスト・マルティン・ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー(Gustav Heinrich Ernst Martin Wilhelm Furtwängler1886年 1月25 日inSchöneberg; †1954年 11月30日 inEbersteinburgnearBaden-Baden)は、ドイツの指揮者、作曲家。20世紀を代表する指揮者の一人である。

エ ミール・オルリックによるウィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラーの肖像、エッチング、1928年

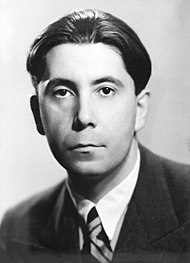

★ ヘルベルト・グラフ(1903年4月10日 - 1973年4月5日)は、オーストリア系アメリカ人のオペラ・プロデューサーである。1903年、マックス・グラフ(1873-1958)とオルガ・ヘー ニッヒの息子としてウィーンに生まれる。父はオーストリアの作家、批評家、音楽学者で、ジークムント・フロイトの仲間でもあった。ヘルベルト・グラフは、 フロイトの1909年の研究書『5歳児の恐怖症の分析』で論じられているリトル・ハンスである。

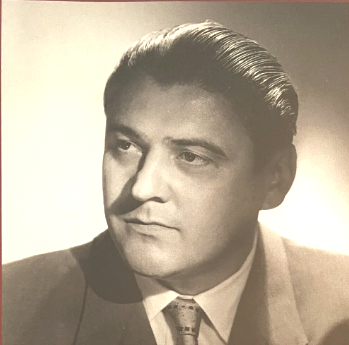

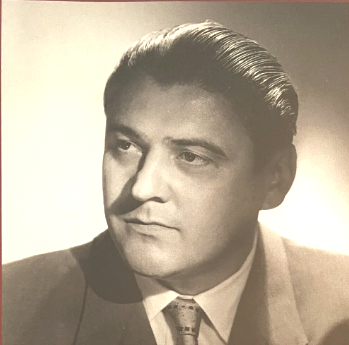

ヘ

ルベルト・グラーフ Photo from the 1930s by Wilhelm Willinger(写真家ウィルヘルム・ウィリンガー)

| Herbert Graf (10

April 1903 – 5 April 1973) was an Austrian-American opera producer.

Born in Vienna in 1903, he was the son of Max Graf

(1873–1958), and Olga Hönig. His father was an Austrian author, critic,

musicologist and member of Sigmund Freud's circle of friends. Herbert

Graf was the Little Hans discussed in Freud's 1909 study Analysis of a

Phobia in a Five-year-old Boy.[1] |

ヘルベルト・グラフ(1903年4月10日 -

1973年4月5日)は、オーストリア系アメリカ人のオペラ・プロデューサーである。1903年、マックス・グラフ(1873-1958)とオ

ルガ・ヘーニッヒの息子としてウィーンに生まれる。父はオーストリアの作家、批評家、音楽学者で、ジークムント・フロイトの仲間でもあった。ヘルベルト・

グラフは、フロイトの1909年の研究書『5歳児の恐怖症の分析』で論じられているリトル・ハンスである[1]。 |

| 'Little Hans' This was one of just a few case studies which Freud published. In his introduction to the case, he had in the years before the case been encouraging his friends and associates, including Graf's parents, to collect observations on the sexual life of children in order to help him develop his theory of infantile sexuality.[2]: 4 Thus Max Graf had been sending notes about his child's development to Freud before Herbert's fear of horses emerged. As "Little Hans", he was the subject of Freud's early but extensive study of castration anxiety and the Oedipus complex. Freud saw Herbert only once and did not analyze the child, but rather supervised the child's father, who carried out the analysis and sent extensive notes to Freud. In the published version, Herbert's father's account is abridged and punctuated by Freud's comments. When he was four years old, Herbert was witness to a frightening event when he was at the local park in the company of the family's maid. A cart horse pulling a heavy load collapsed. Herbert became fearful of going out into the street, with his fear focused on horses and heavily loaded vehicles, which he was afraid would fall over. This fear was interpreted as a neurosis (equinophobia). Herbert's father initially attributes the neurosis to "sexual over-excitement caused by his mother's caresses"[2]: 18 and fear caused by the large penises of horses. While not rejecting these explanations, Freud gradually encourages the father also to understand Herbert's disorder in terms of the anxiety caused by the arrival of his younger sister and an inadequately satisfied curiosity as to the origin of babies. Although a number of sexual and excretal fantasies and anxieties (such as Oedipal wishes and castration anxiety) are explored during the case history, Freud does not ultimately explain the case in terms of these factors, and on occasion reproaches Herbert's father for sticking too dogmatically to a rigidly Oedipal understanding of his son's anxiety.[2]: 34 Freud also regrets the parents' unwillingness to tell Herbert the truth about coition.[2]: 117 Freud wrote a summary analysis of "Little Hans", in 1909, in a paper titled Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-year-old Boy. The information gathered from the father included reports of Herbert's dreams, his behavior, and his answers to the father's questions. Freud believed that what he learned from Herbert's situation backed up his ideas about infantile sexuality as outlined in his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality in 1905. Herbert's fear was thought to be the result of several factors, including the birth of a little sister, his desire to replace his father as his mother's sexual mate, emotional conflicts over masturbation, and others. The anxiety was seen as stemming from the incomplete repression and other defense mechanisms being used to combat the impulses involved in his sexual development. Herbert's behavior and emotional state improved after he was provided with sexual information by his father, and the two became closer. Herbert's analysis falls into two distinct stages, the first concerning the fear of horses themselves, and the second of the boxes and containers that they transported around Vienna. In the first phase, Herbert is afraid that a white horse will bite him or come into his room, or will collapse and fall over. Freud interprets this as a fear of the father, fear that the father will punish him for his desires over the mother and to act aggressively towards the father. Because Herbert's father was acting as analyst, Freud conjectures that this fear is impeding the progress of the treatment, something which he resolved by inviting Herbert to see him (Freud) personally and explaining this fear to him: With this explanation I vanquished the most powerful resistance in Herbert to conscious recognition of his unconscious thoughts, since it was his own father who was taking the role of his physician. From this moment on we had conquered the summit of his condition, the material flowed abundantly, the young patient showed courage in communicating the details of his phobia and soon intervened independently in the course of the analysis. [2]: 101, 102 Following this, Herbert becomes pre-occupied with excrement, which Freud and Herbert's father help him to associate with the birth of babies. The carts and omnibuses are associated with the boxes which, according to the theory of reproduction that Herbert has been given, storks use to bring new babies. Herbert fears the arrival of more babies as this will further reduce the attention he receives from his mother, and expresses the wish that his baby sister should die. He also expresses the wish to have children of his own (with his mother) with his father elevated to the role of grandfather. Herbert's treatment is taken to be complete when he expresses two new fantasies: one which shows that he has overcome his castration anxiety, and one which consciously acknowledges his desire to be married to his mother. These fantasies coincide with the disappearance of his phobia. Freud follows the case history with a 40-page assessment of the case in which he links it to his theory of sexuality. He claims that he has learned nothing from this case that he already had not deduced from his analysis of adults, but he is nonetheless "tempted to claim a typical and exemplary importance" for the case in view of the direct and immediate proof of his theories that it appears to provide.[2]: 4, 118 In 1922, Freud wrote a short postscript to the case study, in which he reported that "Little Hans" had appeared in his office as a "strapping youth of nineteen", who "was perfectly well and suffered from no troubles or inhibitions". Minor revisions and additions to the case material were made in 1923–1924.[3] The conclusions drawn by Freud were strongly criticized by Joseph Wolpe and Stanley Rachman in the essay "A Little Child Shall Lead Them" published first as "Psychoanalytic Evidence: A Critique Based on Freud's Case of Little Hans." in Critical Essays on Psychoanalysis, edited by Stanley Rachman, Macmillan (1963) which maintains that most of the material provided by Herbert was planted in his mind by Freud and Herbert's father.[4] |

リトル・ハンス「小さなハンス」[編集]。 これは、フロイトが発表した数少ない事例研究の一つである。フロイトは、この事例を紹介する中で、この事例の数年前から、グラフの両親を含む友人や仲間 に、幼児性愛の理論を発展させるために、子どもの性生活に関する観察を集めるように勧めていた[2]: 4このように、マックス・グラフは、ハーバートの 馬に対する恐怖心が現れる前から、子どもの発達に関するメモをフロイトに送っていた。彼は「小さなハンス」として、去勢不安と エディプス・コンプレックスに関するフロイトの初期の、しかし広範な研究の対象となった。フロイトはハーバートを一度だけ診察し、その子を分析したのでは なく、むしろその子の父親を監督し、父親が分析を実施し、フロイトに膨大なメモを送った。出版された版では、ハーバートの父親の証言は要約され、フロイト のコメントが添えられている。 ハーバートが4歳のとき、家政婦に連れられて地元の公園に行ったとき、ハーバートは恐ろしい出来事を目撃した。重い荷物を引いた荷車の馬が倒れたのだ。 ハーバートは通りに出るのを怖がるようになり、馬や重い荷物を積んだ車が倒れるのを恐れるようになった。この恐怖は神経症(馬恐怖症)と解釈された。ハー バートの父親は当初、このノイローゼの原因を「母親の愛撫による性的興奮過多」[2]であるとしていた: 18と 馬の大きなペニスによる恐怖であった。これらの説明を否定するわけではないが、フロイトは次第に父親にも、妹の誕生による不安や、赤ん坊の起源に対する好 奇心が十分に満たされていないという観点から、ハーバートの障害を理解するように促す。症例経過の中で、多くの性的・排泄的空想や不安(エディプス願望や 去勢不安など)が探求されるが、フロイトは最終的にこれらの要因から症例を説明することはなく、時折、ハーバートの父親が息子の不安について厳格にエディ プス的理解に固執しすぎていることを非難する[2]: 34フロイトはまた、両親がハーバートに交尾についての真実を伝えようとしなかったことを悔やんで いる[2]: 117 フロイトは1909年、『5歳の少年の恐怖症の分析』と題する論文の中で、「小さなハンス」の要約分析を書いている。父親から集めた情報には、ハーバート の夢の報告、彼の行動、父親の質問に対する彼の答えが含まれていた。フロイトは、ハーバートの状況から学んだことが、1905年に発表した『セクシュアリ ティの理論に関する3つのエッセイ』で概説した、幼児のセクシュアリティに関する彼の考えを裏付けるものであると考えた。ハーバートの恐怖は、妹の誕生、 母親の性的伴侶として父親に取って代わりたいという願望、自慰行為をめぐる感情的葛藤など、いくつかの要因の結果であると考えられた。不安は、不完全な抑 圧や、性的発達に関わる衝動に対抗するための防衛機制から生じていると考えられた。ハーバートの行動と感情状態は、父親から性的情報を提供された後に改善 し、2人はより親密になった。 ハーバートの分析は、馬そのものに対する恐怖と、馬がウィーンのあちこちに運ぶ箱やコンテナに対する恐怖の2つの段階に分かれる。第一段階では、ヘルベル トは白馬が自分を噛んだり、部屋に入ってきたり、倒れて倒れたりすることを恐れている。フロイトはこれを、父親に対する恐怖、母親に対する欲望を父親が罰 するのではないかという恐怖、父親に対する攻撃的な行動と解釈している。フロイトは、ハーバートの父親が分析官として働いていることから、この恐怖が治療 の進行を妨げていると推測し、ハーバートを個人的に自分(フロイト)に会わせ、この恐怖を説明することで解決した: この説明によって、私はハーバートが無意識の思考を意識的に認識することに対する最も強力な抵抗を打ち消した。この瞬間から、私たちは彼の状態の頂点を征 服し、材料は豊富に流れ込み、若い患者は自分の恐怖症の詳細を伝えることに勇気を示し、すぐに分析の過程に独自に介入するようになった。 [2]: 101, 102 この後、ハーバートは排泄物に夢中になり、フロイトとハーバートの父親は、排泄物から赤ん坊の誕生を連想するように仕向ける。カートとオムニバスは、ハー バートに与えられた生殖理論によれば、コウノトリが新しい赤ん坊を運んでくるために使う箱と関連している。ハーバートは、赤ちゃんが増えることで母親から 構ってもらえなくなることを恐れ、妹に死んでほしいと願う。また、父親を祖父の役割に引き上げた上で、(母親との間に)自分の子供を持ちたいという願望も 表明している。 1つは去勢不安を克服したことを示すもので、もう1つは母親と結婚したいという願望を意識的に認めるものである。これらの空想は、恐怖症の消失と一致して いる。 フロイトは、この症例史に続いて、40ページにわたる症例の評価を行い、その中で、この症例を自分の性愛理論と結びつけている。彼はこの症例から、成人に 対する分析からすでに推論していないようなことは何も学んでいないと主張するが、それにもかかわらず、この症例が自分の理論の直接的かつ直接的な証明とな ることから、この症例について「典型的かつ模範的な重要性を主張したくなる」のである[2]: 4, 118 1922年、フロイトは症例研究に短い追記を書き、その中で「小さなハンス」が「19歳のたくましい青年」として彼のオフィスに現れたことを報告し、彼は 「完全に元気で、悩みや抑制に苦しんでいなかった」と述べている。1923年から1924年にかけて、症例資料の若干の修正と追加が行われた[3]。 フロイトによって引き出された結論は、ジョセフ・ウォルプと スタンリー・ラックマンによって、「精神分析的証拠」として最初に出版されたエッセイ "A Little Child Shall Lead Them "の中で強く批判された: A Critique Based on Freud's Case of Little Hans." inCritical Essays on Psychoanalysis,edited by Stanley Rachman, Macmillan (1963) では、ハーバートによって提供された資料のほとんどは、フロイトとハーバートの父親によって彼の心に植え付けられたものであると主張している[4]。 |

| Career in opera In 1930, in Frankfurt, Herbert Graf directed the world premiere of Arnold Schoenberg's Von heute auf morgen. In 1936, after holding operatic posts in Münster, Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland), Frankfurt (where he was director of the Opera School at the Hoch Conservatory, 1930–1933; when the Nazis came to power he was released from his duties) and Salzburg, the 33-year-old Graf emigrated to the United States, where he became a successful and popular opera producer at New York's Metropolitan Opera (1936–1960, debuting with Samson and Delilah). He staged new famous productions in the French (The Tales of Hoffmann 1937), Italian (Otello 1937, La forza del destino 1943), then German (Der Ring des Nibelungen 1947, Der Rosenkavalier 1949), repertoires. Graf had a strong sense of tradition and encouraged young operatic talent. In the late 1950s, he returned to Europe, where he produced opera at London's Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, (1958–1959). After another year in New York, Graf settled in Switzerland, working at the Zürich Opera (1960–1963), and Geneva's Grand Théâtre (1965–1973). Graf staged several operas for the Salzburg Festival: Otello (1951, with Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting, 1952 with Mario Rossi conducting; both times with Ramón Vinay as Otello), The Marriage of Figaro (1952, with Rudolf Moralt conducting, with Erich Kunz, George London, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Irmgard Seefried, Hilde Gueden; 1953 revival conducted by Furtwängler and Paul Schöffler replacing London), a legendary Don Giovanni conducted by Furtwängler and designed by Clemens Holzmeister (1953, with Cesare Siepi, Elisabeth Grümmer, Anton Dermota, Schwarzkopf, Otto Edelmann, Walter Berry, Raffaele Arié, Erna Berger; revival 1954, with Dezsö Ernster replacing Arié; 1956 with Dimitri Mitropoulos conducting), Gottlob Frick replacing Ernster, Léopold Simoneau replacing Dermota, Lisa Della Casa replacing Schwarzkopf, Fernando Corena replacing Edelmann, Rita Streich replacing Berger) an equally legendary The Magic Flute conducted by Georg Solti and designed by Oskar Kokoschka (1955, cast included Gottlob Frick, Dermota, Schöffler, Kunz, Grümmer, Erika Köth, Peter Klein; revival in 1956 with Berry replacing Kunz); Elektra (1957, conducted by Mitropoulos, with Inge Borkh, Della Casa, Jean Madeira, Max Lorenz, Kurt Böhme), Simon Boccanegra (1961, with Gianandrea Gavazzeni conducting, with Tito Gobbi, Leyla Gencer, Giorgio Tozzi, Rolando Panerai), and finally La rappresentazione di anima e di corpo by Emilio de' Cavalieri (the production premiered in 1968 and was shown each year until 1973). Graf staged Maria Callas in Les vêpres siciliennes (at the Florence May Festival and La Scala, 1951), Mefistofele (at the Verona Arena, in which Callas alternated with Magda Olivero, 1954), and Poliuto (at La Scala, 1960, also with Franco Corelli and Ettore Bastianini). For the Arena di Verona Festival, Graf directed several productions of Aida (1954, revival in 1955; 1958; and 1966). |

オペラ界でのキャリア 1930年、ヘルベルト・グラフはフランクフルトで、アルノルト・シェーンベルクの『Von heute auf morgen』の世界初演を演出した。1936年、ミュンスター、ブレスラウ(現ポーランド・ヴロツワフ)、フランクフルト(1930-1933年、ホッ ホ音楽院でオペラ学校のディレクターを務めたが、ナチスが政権を握ると解任された)、ザルツブルクでオペラのポストを歴任した後、33歳のグラーフはアメ リカに移住し、ニューヨークのメトロポリタン歌劇場(1936-1960年、『サムソンとデリラ』でデビュー)のオペラ・プロデューサーとして成功を収 め、人気を博した。彼は、フランス(『ホフマン物語』1937年)、イタリア(『オテロ』1937年、『運命の力』1943年)、そしてドイツ(『ニーベ ルングの指環』1947年、『ばらの騎士』1949年)のレパートリーで新たな名作を上演した。グラーフは伝統を重んじ、若い才能を奨励した。1950年 代後半にはヨーロッパに戻り、ロンドンのコヴェント・ガーデン 王立歌劇場でオペラをプロデュースした(1958-1959年)。さらに1年間ニューヨークに滞在した後、スイスに定住し、チューリッヒ歌劇場(1960 -1963)とジュネーブのグラン・テアトル(1965-1973)で働いた。 ザルツブルグ音楽祭では、いくつかのオペラを上演した: オテロ 』(1951年、ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー指揮、1952年、マリオ・ロッシ指揮; 1953年、フルトヴェングラー指揮、クレメンス・ホルツマイスター設計による伝説的な「ドン・ジョヴァンニ」(チェーザレ・シーピ、エリザベート・グ リュンマー、アントン・デルモータ、シュヴァルツコップ、オットー・エーデルマン、ワルター・ベリー、ラファエレ・アリエ、エルナ・ベルガーと共演; 1956年はディミトリ・ミトロプーロス指揮)、エルンスターの代わりにゴットロフ・フリック、デルモータの代わりにレオポルド・シモノー、シュヴァルツ コップの代わりにリサ・デッラ・カーザ、エデルマンの代わりにフェルナンド・コレーナ、ベルガーの代わりにリタ・シュトライヒ)、同じく伝説的なゲオル ク・ショルティ指揮、オスカー・ココシュカ設計の『魔笛』(1955年、出演はゴットロフ・フリック、デルモータ、シェフラー、クンツ、グリュマー、エリ カ・ケート、ペーター・クライン; 1956年、クンツに代わってベリーが出演); エレクトラ』(1957年、ミトロプーロス指揮、インゲ・ボルク、デッラ・カーザ、ジャン・マデイラ、マックス・ローレンツ、クルト・ベーメ共演)、『シ モン・ボッカネグラ』(1961年、ジャンンドレア・ガヴァッツェーニ指揮、ティト・ゴッビ、レイラ・ジェンサー、ジョルジョ・トッツィ、ロランド・パネ ライ共演)、そして最後にエミリオ・デ・カヴァリエーリ作『La rappresentazione di anima e di corpo』(この作品は1968年に初演され、1973年まで毎年上演された)である。 グラフは、マリア・カラスを『レ・ヴェプレ・シシリエンヌ』(1951年、フィレンツェ五月音楽祭および スカラ座)、『メフィストーフェレ』(1954年、ヴェローナ・アレーナ、カラスはマグダ・オリヴェーロと交互に出演)、『ポリウト』(1960年、スカ ラ座、フランコ・コレッリ、エットーレ・バスティアニーニとも共演)などで演出した。 アレーナ・ディ・ヴェローナ音楽祭では、『アイーダ』(1954年、1955年再演、1958年、1966年)を指揮している。 |

| Publications Among the books written by Herbert Graf were The Opera and Its Future in America (New York, W. W. Norton, 1941), Opera for the People (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1951), and Producing Opera for America (Zurich and New York, Atlantis Books, 1961). |

出版物[編集] ハーバート・グラーフの著書に、『The Opera and Its Future in America』(ニューヨーク、W.W.ノートン、1941年)、『Opera for the People』(ミネアポリス、ミネソタ大学出版局、1951年)、『Producing Opera for America』(チューリッヒ、ニューヨーク、アトランティス・ブックス、1961年)などがある。 |

| Videography Mozart: Don Giovanni (Grümmer, della Casa, Berger, Dermota, Siepi, Edelmann; Furtwängler, 1954) [live] Deutsche Grammophon Verdi: Falstaff (Carteri, Moffo, Barbieri, Alva, Taddei, Colombo; Serafin, 1956) VAI Verdi: Aïda (Gencer, Cossotto, Bergonzi, Colzani, Giaiotti; Capuana, 1966) [live] Bel Canto Society Strauss: Elektra (Nilsson, Rysanek, M.Dunn, Nagy, McIntyre; Levine, 1980) [live] Paramount |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Graf |

|

Max Graf (1 October 1873 – 24 June 1958) was an Austrian

music historian and critic. Max Graf (1 October 1873 – 24 June 1958) was an Austrian

music historian and critic.He was born in Vienna, the son of Josef and Regine (Lederer) Graf.[1][2] His father was a political writer and editor.[3] Max was described as the "dean of music critics in Vienna" in the first part of the 20th century.[4] Career He is also notable for his role in the history of psychoanalysis as the father of Little Hans, whose treatment was described by Sigmund Freud.[5] Max's first wife and Little Hans' mother, Olga Hönig, was one of Freud's patients.[6] Graf's book Composer and Critic is noted for its amicable style with M. A. Schubart of the New York Times stating, "Dr. Graf has written a charming, comprehensive, intelligent treatise on music criticism, drawing generously on his own large supply of knowledge and experience.... The only major issue which I cannot reach agreement with Dr. Graf is his manner. He is much too polite. No subject in the world deserves more rudeness than music criticism." Countering this impression, Graf published a deeply critical review of a Metropolitan Opera production produced by his son in 1946.[7] In the introduction to Composer and Critic, Graf details his original interest in music criticism as having stemmed from attending the lectures of Anton Bruckner in Vienna. Max was Jewish and fled Vienna for the United States in 1938, where he taught at the New School for Social Research in New York City until 1947, when he returned to Vienna. He died there in 1958.[8] Works Wagner-Probleme, und andere Studien, 1900 Die Musik im Zeitalter der Renaissance, 1905 Die innere Werkstatt des Musikers, 1910 Richard Wagner im "Fliegenden Holländer": ein Beitrag zur Psychologie künstlerischen Schaffens, 1911 Legend of a musical city, 1945 Composer and critic: Two hundred years of musical criticism, 1946 Modern music: Composers and music of our time, 1946 From Beethoven to Shostakovich: The psychology of the composing process, 1947 Geschichte und Geist der modernen Musik, 1953 Die Wiener Oper, 1955 |

マックス・グラフ(Max Graf、1873年10月1日 -

1958年6月24日)はオーストリアの音楽史家、評論家である。 マックス・グラフ(Max Graf、1873年10月1日 -

1958年6月24日)はオーストリアの音楽史家、評論家である。父は政治評論家・編集者であった[3]。 マックスは20世紀前半のウィーンにおける「音楽批評家の長」と評された[4]。 キャリア[編集]。 マックスの最初の妻であり、リトル・ハンスの母親であるオルガ・ヘニッヒはフロイトの患者の一人であった[6]。 グラフの著書『作曲家と批評家』は、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のM.A.シューバートが「グラフ博士は、魅力的で、包括的で、知的な音楽批評の論文を書い ており、彼自身の豊富な知識と経験を惜しみなく活用している。私がグラフ博士と合意できない唯一の大きな問題は、彼の態度である。彼はあまりにも礼儀正し すぎる。音楽批評ほど無礼に値する題材はない」。このような印象を打ち消すように、グラフは1946年に息子がプロデュースしたメトロポリタン歌劇場の公 演について、深く批判的な批評を発表している[7]。 『作曲家と批評家』の序文でグラフは、音楽批評に興味を持つようになったきっかけが、ウィーンでアントン・ブルックナーの講義を聴いたことだったと詳述し ている。 マックスはユダヤ人であり、1938年にウィーンを逃れてアメリカに渡り、1947年にウィーンに戻るまでニューヨークのニュー・スクール・フォー・ソー シャル・リサーチで教鞭をとっていた。1958年に同地で死去した[8]。 作品[編集] ワーグナー問題、その他の研究、1900年 ルネサンスの時代における音楽』1905年 リヒャルト・ワーグナーの『飛翔』、1910年 リヒャルト・ワーグナーの『飛翔するオランダ人』:芸術家精神心理学への一試論』1911年 ある音楽都市の伝説, 1945 作曲家と批評家: 音楽批評の200年, 1946 現代音楽: 現代の作曲家と音楽、1946年 ベートーヴェンからショスタコーヴィチまで:作曲過程の心理学, 1947 現代音楽の歴史と精神、1953年 ウィーン・オペラ』1955年 |

++

Gustav

Heinrich Ernst Martin Wilhelm Furtwängler (* 25. Januar 1886 in

Schöneberg; † 30. November 1954 in Ebersteinburg bei Baden-Baden) war

ein deutscher Dirigent und Komponist. Er gilt als einer der

bedeutendsten Dirigenten des 20. Jahrhunderts. Wilhelm Furtwängler, 1931 Foto: Erich Salomon  Wilhelm Furtwängler, um 1912, Fotopostkarte zum Brahmsfest, Foto: Franz Löwy |

グスタフ・ハインリヒ・エルンスト・マルティン・ヴィルヘルム・フルト

ヴェングラー(*1886年 1月25 日inSchöneberg; †1954年 11月30日

inEbersteinburgnearBaden-Baden)は、ドイツの指揮者、作曲家。20世紀を代表する指揮者の一人である。 ウィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー、1931年 写真:エーリッヒ・サロモン  ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー、1912年頃、ブラームス・フェスティバルの写真葉書、撮影:フランツ・レーヴィ |

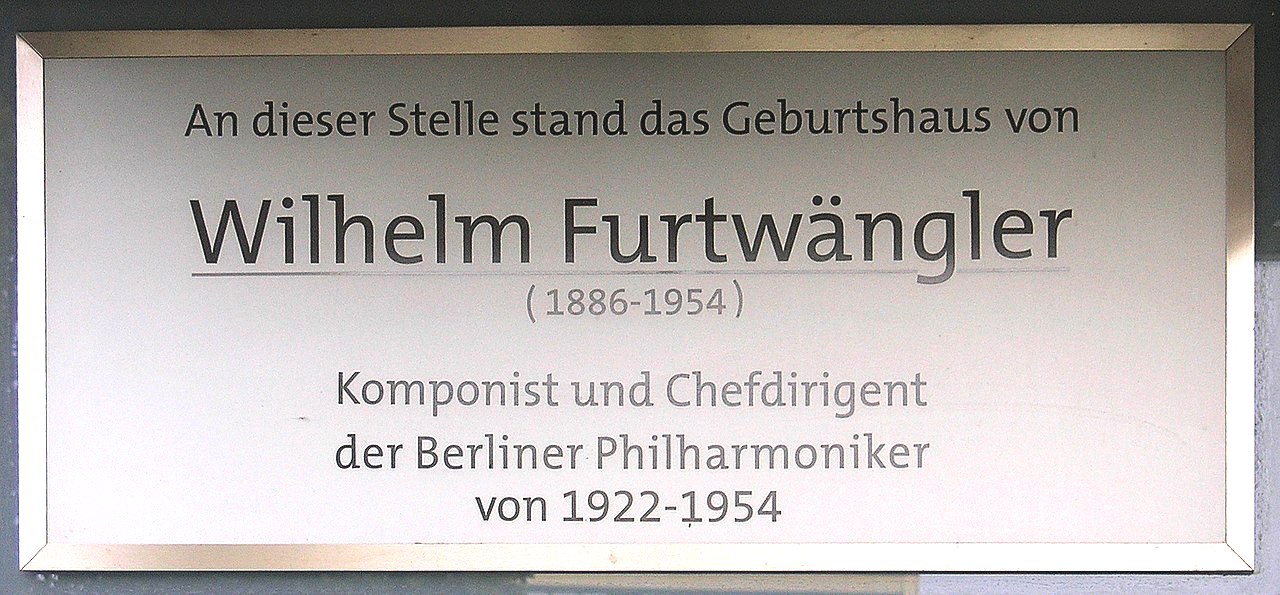

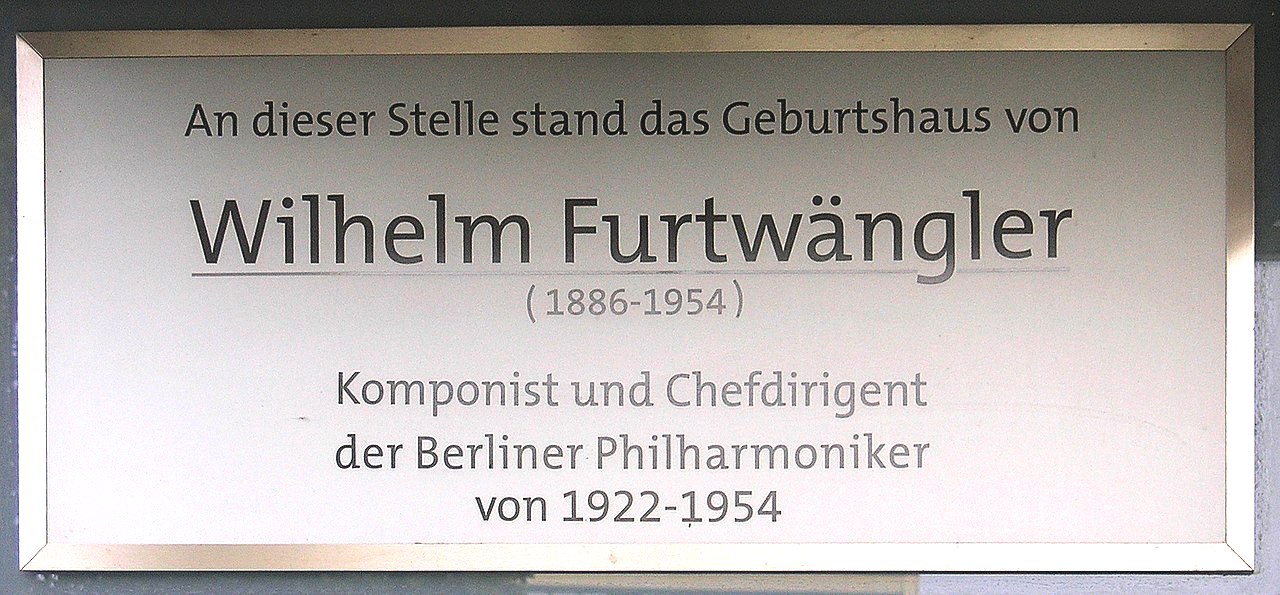

Leben Gedenktafel am Haus Nollendorfplatz 8, in Berlin-Schöneberg Wilhelm Furtwängler wurde 1886 als Sohn des Professors für Klassische Archäologie Adolf Furtwängler und dessen Frau Adelheid (geborene Wendt, Tochter von Gustav Wendt) am Nollendorfplatz in Schöneberg geboren, das erst 1920 Berlin angegliedert wurde. Jugendzeit Er verbrachte seine Jugend in München, wo sein Vater an der Universität lehrte, und besuchte ein humanistisches Gymnasium. Frühzeitig begeisterte er sich für Musik. Ab 1899 erhielt er Privatunterricht in Tonsatz, Komposition und Klavier. Seine Ausbildung zum Pianisten übernahmen Joseph Rheinberger, Max von Schillings und Conrad Ansorge. 1900 führte, wie Karl Alexander von Müller berichtet, der Münchner Orchesterverein ein Klavierquartett und eine Ouvertüre des jungen Furtwängler auf, wobei er letztere selbst dirigierte. Im Jahr darauf wurde im Haus des Bildhauers Adolf von Hildebrand ein Streichsextett aus seiner Feder gespielt, das „wahrhaftig Schuberts würdig“ gewesen sein soll.[1] Karriere als Dirigent (1906–1933)  Wilhelm Furtwängler (1911)  Porträt von Emil Orlik, Radierung, 1928 Seine ersten Engagements führten ihn 1906 als 2. Repetitor nach Berlin, 1907 über Breslau als Chorleiter nach Zürich und anschließend wieder nach München. 1910 engagierte ihn Hans Pfitzner als 3. Kapellmeister nach Straßburg. 1911 ging er als Nachfolger von Hermann Abendroth nach Lübeck[2] und dirigierte dort das Orchester des Vereins der Musikfreunde.[3] Als Träger des der Oper zur Verfügung gestellten Konzertorchesters setzte der Verein bereits durch, dass der Direktor des Theaters Hermann Abendroth auch als dessen Dirigenten zu beschäftigen hatte. Die ständige lübeckische Kritik, Intrigen, vielerlei Hickhack und das defizitäre Theater griffen die Gesundheit derart an, dass der Direktor nach drei Jahren zurücktrat und kurz darauf verstarb. Als Stanislaus Fuchs als sein Nachfolger ins Amt berufen wurde, behielt man diese Praktik bei. Furtwängler, der nahezu zeitgleich Abendroths Nachfolger im Verein wurde, war als Dirigent der Oper des ohne ihn schon defizitären Theaters zu beschäftigen.  Igor Strawinsky (links) und Furtwängler, 1930[4] Bereits 1915 verließ Furtwängler die Stadt, in der er seine erste Chefposition erhielt, und wurde Operndirektor am Nationaltheater Mannheim, von 1919 bis 1921 fungierte er als Chefdirigent des Wiener Tonkünstler-Orchesters, 1920 übernahm er als Nachfolger von Richard Strauss die Konzerte der Berliner Staatsoper. Von 1921 bis 1927 hatte er (gemeinsam mit Leopold Reichwein) die Stelle des Konzertdirektors der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien inne und dirigierte in dieser Funktion das 1921 neu konstituierte Wiener Sinfonieorchester (seit 1933: Wiener Symphoniker). Ab 1922 arbeitete er als Chefdirigent des Berliner Philharmonischen Orchesters und dirigierte außerdem bis 1928 das Gewandhausorchester in Leipzig als Gewandhauskapellmeister. Für das Jahr 1931 hatte er die Gesamtleitung der Richard-Wagner-Festspiele in Bayreuth. Furtwängler in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus Die Nationalsozialisten hofierten Furtwängler wegen seiner internationalen Reputation als kulturelles Aushängeschild. Für 1933 ist nachgewiesen, dass er sich für einige Juden[5] (wie seinen Konzertmeister Szymon Goldberg) einsetzte. Der Ministerialdirektor im Kultusministerium, Georg Gerullis, hielt am 20. Juli 1933 in einem Dienstschreiben an Reichskulturverwalter Hans Hinkel diesbezüglich verärgert fest: „Können Sie mir einen Juden nennen, für den Furtwängler nicht eintritt?“[6] Im Vorfeld eines gemeinsamen Konzerts mit den Berliner Philharmonikern im April 1933 in Mannheim kam es zu Protesten gegen die Mitwirkung jüdischer Musiker. Furtwängler sagte das Konzert daraufhin kurzerhand ab und kündigte an, in dieser Stadt nicht mehr zu gastieren, solange „bei Ihnen solche Gesinnung herrscht“.[7] In einem offenen Brief an Joseph Goebbels kritisierte Furtwängler am 11. April 1933 die Diskriminierung jüdischer Musiker: „Nur einen Trennungsstrich erkenne ich letzten Endes an: den zwischen guter und schlechter Kunst.“ Wohl habe der Kampf Berechtigung gegen jene, die „wurzellos und destruktiv, durch Kitsch und trockene Könnerschaft“ zu wirken suchten. Wenn sich dieser Kampf jedoch gegen wirkliche Künstler richte, so sei das nicht im Interesse des Kulturlebens. Es müsse klar ausgesprochen werden, dass Männer wie Walter, Klemperer und Reinhardt auch in Zukunft mit ihrer Kunst in Deutschland zu Wort kommen müssten. Der Reichsminister für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda antwortete umgehend: „Lediglich eine Kunst, die aus dem vollen Volkstum selbst schöpft, kann am Ende gut sein und dem Volke, für das sie geschaffen wird, etwas bedeuten […] Gut muß die Kunst sein; darüber hinaus aber auch verantwortungsbewußt, gekonnt, volksnahe und kämpferisch.“[8] Der Briefwechsel zwischen Furtwängler und Goebbels erschien im Berliner Tageblatt am 11. und 12. April 1933; liberal und sozialdemokratisch geprägte Blätter des Auslands (Neue Freie Presse, Prager Tagblatt) druckten den Protest auf der Titelseite. Letztlich konnte Furtwängler erreichen, dass der „Arierparagraph“ auf die Berliner Philharmoniker zunächst nicht angewandt wurde. Er lud auch jüdische Solisten ein (die dann allerdings absagten). Im Juni 1933 wurde er von Göring zum Ersten Kapellmeister, im Januar 1934 zum Direktor der Berliner Staatsoper ernannt. Nebenbei gastierte er am Deutschen Opernhaus Berlin-Charlottenburg. Im Juli 1933 ernannte Göring ihn zum Preußischen Staatsrat. Furtwängler kam den neuen Machthabern im Herbst 1933 insoweit entgegen, als er sich dazu bereitfand, sich zum Vizepräsidenten der Reichsmusikkammer ernennen zu lassen, die Goebbels’ Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda unterstand.[9] Furtwängler war, laut seinen Einlassungen nach 1945, dem NS-Regime gegenüber jedoch ablehnend eingestellt. Er habe sich von dieser Position erhofft, im Sinne einer taktischen Zusammenarbeit auf das kulturpolitische Geschehen Einfluss nehmen und damit das Schlimmste verhindern,[10] „die Kunst von allem ‚Niederen‘ freihalten“ zu können.[11] Einer anderen Einschätzung zufolge habe er zusammen mit Richard Strauss, dem Präsidenten der Reichsmusikkammer, den Ausschluss der meisten Juden und sogenannter „Kulturbolschewisten“ aus der Kammer bewirkt, was einem Berufs- und Aufführungsverbot gleichkam.[12] Gleichwohl führte er im Februar 1934 drei Stücke aus dem „Sommernachtstraum“ des bereits geächteten Mendelssohn auf und ehrte diesen somit demonstrativ zu dessen 125. Geburtstag. Am 11. und 12. März desselben Jahres dirigierte er die Uraufführung der Sinfonie „Mathis der Maler“ des später als „entartet“ verpönten Komponisten Paul Hindemith.[13] Obwohl diese Sinfonie ein überwältigender Publikumserfolg war und weitere Aufführungen und Rundfunksendungen erlebte, genehmigte Hitler im Herbst nicht die geplante Aufführung der gleichnamigen Oper. Furtwängler, der durch seine Unterschrift unter den Aufruf der Kulturschaffenden vom 19. August 1934 öffentlich bekundet hatte, dass er zu des Führers Gefolgschaft gehörte,[14] drohte daraufhin mit Rücktritt und setzte sich in einem aufsehenerregenden Zeitungsbeitrag für Hindemith ein.[15] Da das erhoffte Einlenken der NS-Führung ausblieb und sie ihn vor die Alternative Rücktritt oder Entlassung stellte, sah er sich am 4. Dezember 1934 genötigt, seine Ämter als Staatsoperndirektor, Leiter des Berliner Philharmonischen Orchesters und Vizepräsident der Reichsmusikkammer aufzugeben.[16] Daraufhin wurde ihm der Pass abgenommen, damit er keine Angebote aus dem Ausland annehmen konnte.[17]  Furtwängler dirigiert ein KdF-Konzert im Berliner AEG-Werk, 1942 Am 28. Februar 1935 ließ er sich allerdings von Goebbels empfangen und erklärte, es habe ihm völlig ferngelegen, mit dem Hindemith-Artikel „in die Leitung der Reichskunstpolitik einzugreifen“; diese werde „auch nach seiner Auffassung selbstverständlich allein vom Führer und Reichskanzler und dem von ihm beauftragten Fachminister bestimmt“.[18] So konnte er – nach weiteren Gesprächen mit Rosenberg und Hitler[19] – seine öffentliche Tätigkeit im April 1935 wiederaufnehmen, allerdings nur beim Berliner Philharmonischen Orchester,[20] weil für die Staatsoper bereits Clemens Krauss vorgesehen war. Er dirigierte 1935 und 1938 am Vorabend der Reichsparteitage in Nürnberg, war 1936, 1937 und 1943 Hauptdirigent der propagandistisch genutzten Bayreuther Festspiele und repräsentierte Deutschland 1937 bei der Pariser Weltausstellung.[21] Er ließ sich 1935 in Goebbels’ Reichskultursenat berufen und unterstützte Wahlaufrufe zur Reichstagswahl 1936 und zur Volksabstimmung über den „Anschluss“ Österreichs.[22] Im Juni 1939 wurde er mit der Leitung der Wiener Philharmoniker betraut und im Dezember desselben Jahres von Gauleiter Josef Bürckel zum Bevollmächtigten für das gesamte Musikwesen der Stadt Wien ernannt.[23] Neben Konzerten zu Hitlers Geburtstag und Weihnachtsempfang, für Goebbels’ Propagandaministerium und für die Hitlerjugend dirigierte er in Prag im November 1940 ein Konzert zur Neueröffnung des „Deutschen Theaters“ und erneut im März 1944 zum fünften Jahrestag des Protektorats Böhmen und Mähren.[24] 1936 bot sich Furtwängler die Gelegenheit, Deutschland zu verlassen und als Nachfolger Toscaninis ohne anderweitiges festes Engagement die New Yorker Philharmoniker zu übernehmen. Doch er zog es vor, mit Göring einen Vertrag abzuschließen, wonach er in der Spielzeit 1936/1937 mindestens zehn Gastdirigate an der Berliner Staatsoper geben sollte. Das führte zu Missverständnissen und zur Absage an New York.[25] Seit 1944 wohnte er mit Billigung des NS-Regimes überwiegend in Luzern (Schweiz), drei Monate vor der Besetzung Berlins durch sowjetische Truppen floh er endgültig dorthin. Von der Teilnahme am Kriegseinsatz wurde er verschont, da er nicht nur auf der Gottbegnadeten-Liste, sondern auch auf der Sonderliste der drei wichtigsten Musiker der Gottbegnadeten-Liste stand.[26] Furtwänglers Verhalten während der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus wird unterschiedlich beurteilt. Während Fred K. Prieberg und Herbert Haffner ihn als rein künstlerisch Interessierten eher zu entlasten suchen, stellt ihn unter anderen Eberhard Straub als ausgeprägten Opportunisten dar.[27] Nachkriegszeit 1945 erhielt Furtwängler von den amerikanischen Besatzungsbehörden zunächst Dirigierverbot. Verheerender noch war für ihn seine internationale Ächtung und seine Brandmarkung als Sündenbock: Man titulierte ihn als „Hitlers gehätschelten Maestro“, „musikalischen Handlanger der nazistischen Blutjustiz“ und „eine der verhängnisvollsten Figuren des Nazireiches“.[28] Die emigrierten Künstler hingegen verübelten Furtwängler vor allem seine Prominenz im Dritten Reich. Dabei wurde vergessen, dass er bereits zu Zeiten der Weimarer Republik ein Stardirigent war. Fred K. Prieberg vermutet denn auch, dass die Ablehnung, die Furtwängler aus Emigrantenkreisen entgegenschlug, sich letztlich auf die Enttäuschung gründete, dass er nicht emigriert war: „Er war ein Symbol. Er verkörperte – vor der großen Öffentlichkeit, ja in den Schlagzeilen der Weltpresse – wie kein anderer deutscher Musiker die deutsche Tonkunst. Er hatte, nicht erst seit 1933, sondern schon während der Republik, eine so fest etablierte Machtstellung, daß in der öffentlichen Meinung Aufgabe und Person verschmolzen: Furtwängler, Begriff für genialische Kunstübung, Symbol der treibenden Kraft im Musikbetrieb des Reiches. Welche Herausforderung für Emigranten! Da lebte ein unvergleichlicher Künstler in Deutschland unter der Herrschaft der Nationalsozialisten, und er weigerte sich, sie – die Emigranten – dadurch in ihrer Rolle zu bestätigen, oder wenigstens ihr erzwungenes Los zu teilen, daß er der Barbarei den Rücken kehrte.“[6] Wenn Furtwängler Kollaboration mit und Propaganda für den NS-Staat vorgeworfen wurde, so unterschätzte man dabei nicht zuletzt auch eklatant die Zwänge, denen man auch als Prominenter „in einem Terrorregime wie diesem, dessen Grausamkeit doch auch sonst jeglicher Vergleichbarkeit entzogen wird, ausgesetzt war“.[29] Ronald Harwood schrieb 1995 das Bühnenstück „Taking Sides“, das von István Szabó im Jahre 2001 unter demselben Titel (deutscher Untertitel: Der Fall Furtwängler) verfilmt wurde. Furtwängler verdankte es der Fürsprache der „entarteten“ Musiker Paul Hindemith, Yehudi Menuhin, Szymon Goldberg sowie seiner langjährigen jüdischen Sekretärin Berta Geissmar, dass er 1947 freigesprochen wurde. Am 25. Mai 1947 dirigierte er erstmals wieder in einem öffentlichen Konzert die Berliner Philharmoniker.[30] Es dauerte jedoch noch weitere fünf Jahre, bis er 1952 wieder zum Chefdirigenten der Berliner Philharmoniker ernannt wurde, diesmal auf Lebenszeit. Privates Furtwängler, Mitglied der weitverzweigten Familie Furtwängler, war zweimal verheiratet. 1923 heiratete er die Dänin Zitla Lund. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt hatte er bereits vier außereheliche Kinder. Die Ehe selbst blieb kinderlos. 1931 erfolgte die offizielle Trennung des Paars, die Scheidung jedoch erst 1943. Im selben Jahr heiratete er Elisabeth Ackermann (* 20. Dezember 1910; † 5. März 2013), geborene Albert, deren erster Mann, Hans Ackermann, im Zweiten Weltkrieg gefallen war. Aus dieser Ehe ging der einzige eheliche Sohn, der spätere Archäologe Andreas E. Furtwängler (* 11. November 1944), hervor. Befreundet war er mit der Geigerin Melanie Michaelis. Furtwängler war Stiefvater der Schauspielerin Kathrin Ackermann, die mit Bernhard Furtwängler verheiratet war, einem Sohn von Wilhelms Bruder Walter Furtwängler. Deren Tochter Maria Furtwängler ist ebenfalls als Schauspielerin bekannt. Sein Grab auf dem Heidelberger Bergfriedhof wird von einer Steinplatte mit dem Vers aus 1. Kor. 13,13 bedeckt: Nun aber bleibt Glaube, Liebe, Hoffnung, diese drei. Aber die Liebe ist die Größte unter ihnen. Neben ihm ruhen seine Mutter und seine Schwester Märit Furtwängler-Scheler, die von 1912 bis 1924 mit Max Scheler verheiratet war. |

人生 ベルリン・シェーネベルクの ノレンドルフ広場8番地にある家の記念プレート ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラーは、1886年、古典考古学の教授アドルフ・フルトヴェングラーと妻アーデルハイト(旧姓ヴェント、グスタフ・ヴェント の娘)の息子として、1920年にベルリンの一部となったばかりのシェーネベルクのノレンドルフ広場に生まれた。 青年期 [編集|原文ママ] 父が大学で教えていたミュンヘンで少年時代を過ごし、人文主義の文法学校に通った。早くから音楽に興味を持つ。1899年から作曲と ピアノの個人レッスンを受ける。ヨーゼフ・ラインベルガー、マックス・フォン・シリングス、コンラート・アンゾルゲが彼のピアニストとしての訓練を引き継 いだ。1900年、カール・アレクサンダー・フォン・ミュラーが報告しているように、ミュンヘン管弦楽団は若きフルトヴェングラーのピアノ四重奏曲と序曲 を演奏し、後者は彼自身が指揮した。翌年には、彫刻家アドルフ・フォン・ヒルデブラントの家で、彼のペンによる弦楽六重奏曲が演奏され、「まさにシューベ ルトにふさわしい」と評された。 指揮者としてのキャリア(1906年~1933年)  ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー(1911年)  エミール・オルリックの肖像、エッチング、1928年 フルトヴェングラーの最初の仕事は、1906年に第2レペティトゥールとしてベルリンへ、1907年には合唱指揮者としてブレスラウを経由してチューリヒ へ、そして再びミュンヘンへと続いた。1910年、ハンス・プフィッツナーが ストラスブールの第3カペルマイスターとして彼を起用した。1911年、リューベック[2]でヘルマン・アベンドロトの後任として、楽友協会[3]のオー ケストラを指揮した。 同協会は、オペラのためのコンサート・オーケストラのスポンサーとして、劇場のディレクターにもヘルマン・アベンドロトを指揮者として起用するよう、すで に主張していた。リューベックからの絶え間ない批判、陰謀、様々な災難、そして赤字の劇場は、彼の健康に大きな打撃を与え、監督は3年後に辞任し、まもな く亡くなった。スタニスラウス・フックスが後任に指名されたときも、このやり方は維持された。ほぼ同時期にアベントロートの後任となったフルトヴェング ラーは、同劇場でオペラの指揮者として起用されたが、フルトヴェングラー抜きではすでに赤字だった。  イーゴリ・ストラヴィンスキー(左)とフルトヴェングラー、1930年[4]。 フルトヴェングラーは、1915年には最初の首席指揮者の座を与えられたこの街を離れ、マンハイム国立劇場のオペラ監督となり、1919年から1921年 まではウィーン・トーンキュンストラー管弦楽団の首席指揮者を務め、1920年にはリヒャルト・シュトラウスの後任としてベルリン国立歌劇場の指揮者と なった。1921年から1927年まで、レオポルド・ライヒヴァインとともにウィーン楽友協会のコンサート・ディレクターを務め、1921年に新設された ウィーン交響楽団(1933年以降、ウィーン交響楽団)を指揮した。1922年からはベルリン・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団の首席指揮者を務め、1928年 まではゲヴァントハウス管弦楽団の首席指揮者としてライプツィヒの ゲヴァントハウス管弦楽団を指揮した。1931年には、バイロイトの リヒャルト・ワーグナー音楽祭の総指揮を務めた。 国家社会主義時代のフルトヴェングラー 国家社会主義者たちは、フルトヴェングラーの文化人としての国際的な名声のため、フルトヴェングラーに求愛した。1933年、彼は一部のユダヤ人[5] (コンサートマスターのシモン・ゴールドベルクなど)のために立ち上がったという証拠がある。1933年7月20日、文化省長官ゲオルク・ゲルリスは、帝 国文化行政長官ハンス・ヒンケルに宛てた公式書簡の中で、「フルトヴェングラーが擁護しないユダヤ人の名前を挙げられますか」と怒りを露わにしている [6]。 1933年4月、マンハイムでのベルリン・フィルとのジョイント・コンサートを前に、ユダヤ人音楽家の参加に対する抗議が起こった。フルトヴェングラー は、1933年4月11日にヨーゼフ・ゲッベルスに宛てた公開書簡の中で、ユダヤ人音楽家に対する差別を批判した。キッチュでドライな専門知識によって、 根も葉もない破壊的な」印象を与えようとする人々との戦いは、確かに正当なものだった。しかし、この戦いが本物の芸術家に向けられるのであれば、それは文 化的な生活のためにはならない。ヴァルター、クレンペラー、ラインハルトのような人物もまた、将来ドイツで自分の芸術について発言する必要があることを明 確に表明しなければならなかった。民衆啓蒙・宣伝担当大臣は即座にこう答えた。「民衆の全存在そのものから引き出された芸術だけが、最終的に善良であり、 それが創作された民衆にとって意味を持つことができる。 フルトヴェングラーとゲッペルスとの往復書簡は、1933年4月11日と12日の『ベルリン・ターゲブラット』紙に掲載され、海外の自由主義・社会民主主 義系の新聞(『ノイエ・フライ・プレス』紙、『プラーガー・ターゲブラット』紙)はこの抗議を一面に掲載した。結局、フルトヴェングラーは「アーリア人条 項」がベルリン・フィルに適用されないようにした。彼はまた、ユダヤ人のソリストを招聘した(その後、彼らはキャンセルした)。 1933年6月、彼はゲーリングによって第一カペルマイスターに任命され、1934年1月にはベルリン国立歌劇場の監督に就任した。また、ベルリン・ シャーロッテンブルク・ドイツ・オーパーハウスにも客演した。1933年7月、ゲーリングは彼をプロイセン国家顧問に任命した。1933年秋、フルトヴェ ングラーは、ゲッペルス率いる帝国大衆啓蒙宣伝省の下にある帝国音楽会議所の副会長に任命されることに同意し、新しい支配者に便宜を図った[9]。しか し、1945年以降の彼の発言によれば、フルトヴェングラーはナチス政権に反対していた。彼はこの立場によって、戦術的な協力という意味で文化政策に影響 を及ぼし、それによって最悪の事態を防ぐこと、つまり「芸術をあらゆる『低俗なもの』から解放すること」[10]を望んでいた。別の評価によれば、彼は帝 国音楽会議所の総裁であったリヒャルト・シュトラウスとともに、ほとんどのユダヤ人といわゆる「文化的ボリシェヴィスト」を音楽会議所から追放することを もたらし、それは職業と演奏の禁止に等しいものであったという[12]。 それでも、1934年2月には、すでに追放されていたメンデルスゾーンの「真夏の夜の夢」から3曲を演奏し、125歳の誕生日を迎えたメンデルスゾーンを 誇示した。同年3月11日と12日には、後に「退廃的」と蔑まれた作曲家パウル・ヒンデミットの交響曲《マティス・デア・マーラー》の世界初演を指揮した [13]。この交響曲は聴衆の圧倒的な支持を得て大成功を収め、その後も上演やラジオ放送が行われたが、ヒトラーは秋に予定されていた同名のオペラの上演 を認めなかった。フルトヴェングラーは、1934年8月19日のアピールに署名することで、自分が総統の信奉者の一人であることを公言していたが [14]、辞任すると脅し、センセーショナルな新聞記事でヒンデミットを支持する発言をした。 [15]ナチス指導部からの譲歩が期待されたが実現せず、辞任か解雇かの選択を迫られたフルトヴェングラーは、1934年12月4日、国立歌劇場監督、ベ ルリン・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団監督、帝国音楽会議所副会長の職を辞任せざるを得なくなった[16]。  1942年、ベルリンのAEG工場で KdFのコンサートを指揮するフルトヴェングラー。 しかし1935年2月28日、彼はゲッペルスに面会し、ヒンデミットの論文について「帝国の芸術政策の管理に介入する」ことは完全に問題外であり、彼の意 見では、これは「総統と帝国首相、そして彼に任命された大臣によってのみ決定される」ものであると宣言した。 [18]ローゼンベルクとヒトラーとのさらなる話し合いの後[19]、彼は1935年4月に公的な活動を再開することができたが、すでにクレメンス・クラ ウスが国立歌劇場に任命されていたため、ベルリン・フィルのみであった[20]。1935年と1938年にはニュルンベルクでの帝国党員集会の前夜に指揮 をし、1936年、1937年、1943年にはバイロイト音楽祭の首席指揮者を務め、プロパガンダに利用され、1937年にはパリ万国博覧会にドイツ代表 として参加した[21]。 [1939年6月にはウィーン・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団の指揮を任され、同年12月にはヨーゼフ・ビュルケル管区長からウィーン市の音楽システム全体の 全権大使に任命された[23]。ヒトラーの誕生日やクリスマス・レセプション、ゲッベルスの宣伝省、ヒトラー・ユースのためのコンサートに加え、1940 年11月にはプラハで「ドイツ劇場」再開記念コンサートを、1944年3月にはボヘミア・モラヴィア保護領5周年記念コンサートを指揮した[24]。 1936年、フルトヴェングラーはドイツを離れ、トスカニーニの後任としてニューヨーク・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団を指揮する機会を得た。しかしフルト ヴェングラーは、1936/1937年のシーズン中に少なくとも10回はベルリン国立歌劇場で客演指揮をするというゲーリングとの契約を優先した。 1944年からは、ナチス政権の承認を得て、主にルツェルン(スイス)で生活し、ソ連軍によるベルリン占領の3ヶ月前に逃亡した。彼はゴットベーグナー デーテンリストに載っていただけでなく、ゴットベーグナーデーテンリストの中で最も重要な3人の音楽家の特別リストにも載っていたため、戦争への参加は免 れた[26]。 国家社会主義時代におけるフルトヴェングラーの行動については、異なる評価がなされている。Fred K. PriebergとHerbert Haffnerは、彼を純粋に芸術的関心を持った人物として免責する傾向があるが、Eberhard Straubなどは、彼を顕著な日和見主義者として描いている[27]。 戦後 [ソース・テキストを編集する] 1945年、フルトヴェングラーは当初アメリカの占領当局によって指揮活動を禁止された。ヒトラーの甘やかされたマエストロ」、「ナチスの血の正義の音楽 的子分」、「ナチス帝国の最も悲惨な人物の一人」と呼ばれた[28]。 一方、移住してきた芸術家たちは、なによりもフルトヴェングラーが第三帝国において突出した存在であったことを恨んだ。彼らは、彼がワイマール共和国時代 にすでにスター指揮者であったことを忘れていた。フレッド・K・プリーベルクも、フルトヴェングラーが移民界から拒絶されたのは、結局のところ、彼が移民 しなかったことへの失望に基づくものだったと推測している: 「彼は象徴だった。彼は、他のどのドイツ人音楽家よりも、ドイツの音楽芸術を象徴していた。フルトヴェングラーは、独創的な芸術活動の言葉であり、帝国の 音楽ビジネスにおける原動力の象徴でもあった。フルトヴェングラーは、独創的な芸術活動という言葉であり、帝国の音楽ビジネスにおける原動力の象徴であっ た!国家社会主義者の支配下にあるドイツに、比類なき芸術家が住んでいたのだ。そして彼は、彼ら--移民--の役割を確認することを拒否し、少なくとも、 野蛮主義に背を向けることで、強制された運命を共にすることを拒否した」[6]。 フルトヴェングラーがナチス国家に協力し、そのプロパガンダを行ったと非難されたとすれば、それは少なくとも、「このような恐怖の体制において、その残酷 さは比較にならない」[29]有名人としてさらされる制約をあからさまに過小評価していたことに他ならない。 フルトヴェングラーが1947年に無罪放免となったのは、「退廃的な」音楽家パウル・ヒンデミット、ユーディ・メニューイン、シモン・ゴールドベルク、そ して長年秘書を務めていたユダヤ人ベルタ・ガイスマールの仲介のおかげだった。しかし、1952年に再びベルリン・フィルの首席指揮者に任命されるまでに は、さらに5年の歳月を要した。 私生活 [編集|原文ママ] フルトヴェングラー一族の一員であるフルトヴェングラーは、2度結婚している。 1923年、デンマーク出身のツィトラ・ルンドと結婚。この時すでに4人の子供がいた。結婚自体には子供がいなかった。同年、最初の夫ハンス・アッカーマ ンが第二次世界大戦中に戦死したエリザベート・アッカーマン(* 1910年12月20日、† 2013年3月5日)と結婚した。この結婚により、後に考古学者となるアンドレアス・E・フルトヴェングラー(* 1944年11月11日)の一人息子が生まれた。彼はヴァイオリニストのメラニー・ミヒャエリスと親交があった。 フルトヴェングラーは、ヴィルヘルムの弟ヴァルター・フルトヴェングラーの息子ベルンハルト・フルトヴェングラーと結婚した女優カトリーン・アッカーマン の継父でもあった。娘のマリア・フルトヴェングラーも女優として知られている。 ハイデルベルクの丘の上の墓地にある彼の墓には、第1コリント13:13の一節が刻まれた石板が置かれている: しかし、信仰、愛、希望、この三つは今なお存続している。しかし、愛はこれらのうちで最も偉大なものである。彼の隣には、彼の母と、1912年から 1924年までマックス・シェーラーと結婚していた妹のメーリット・フルトヴェングラー=シェーラーが眠っている。 |

| Werk Furtwänglers Werk als Dirigent  Wilhelm Furtwängler in der Queen’s Hall, London, 1931 Foto: Erich Salomon Furtwängler war ein Dirigent, dessen Selbstverständnis der Mythos von der Erlösungsfunktion der Musik ist. Seine Subjektivität äußerte sich in einer Dirigierhaltung, die häufig als unerschöpfliches Sich-Hineinsteigern in Formen und Elemente der Musik gedeutet wurde, die dabei aber auch, gerade was Accelerandi und Temporückungen betrifft, in hohem Maße kalkuliert war. Diese Haltung und Interpretationsweise hat ihren Ursprung im 19. Jahrhundert. Ebenso wie viele Musiker sehen auch Kommentatoren und Kritiker, wie beispielsweise Joachim Kaiser, Furtwängler als größten Dirigenten der Geschichte.[31][32][33] Furtwänglers Dirigierkunst wird als Synthese und Gipfelpunkt der sogenannten „Germanischen Schule des Dirigierens“ angesehen,[34][35] die von Richard Wagner initiiert wurde. Im Gegensatz zu Mendelssohns Dirigierstil zur selben Zeit, der „charakterisiert war durch schnelle, gleichmäßige Tempi und angefüllt war mit dem, was viele als vorbildliche Logik und Präzision ansahen“, war „Wagners Art […] breit, hyperromantisch und umfasste die Vorstellung von Tempo-Modulation“.[36] Wagner betrachtete eine Interpretation als eine Neuschöpfung und betonte mehr Phrase als Takt.[37] Das Tempo zu variieren war nichts Neues, denn nachgewiesenermaßen interpretierte Beethoven selbst seine eigene Musik sehr freizügig. Beethoven schrieb in einigen seiner Briefe: „Meine Tempi gelten nur für die ersten Takte, da Gefühl und Ausdruck ihr eigenes Tempo benötigen“, oder „Weshalb ärgern sie mich, indem sie nach meinen Tempi fragen? Entweder sind sie gute Musiker und sollten wissen wie meine Musik gespielt werden sollte, oder sie sind schlechte Musiker und in dem Fall wären meine Hinweise nutzlos“.[38] Beethovens Schüler, wie etwa Anton Schindler, bezeugten, dass der Komponist kontinuierlich das Tempo variierte, wenn er seine Werke dirigierte.[39] Es waren die ersten beiden festangestellten Dirigenten der Berliner Philharmoniker,[40] die Wagners Tradition folgten. Hans von Bülow unterstrich mehr die einheitliche Struktur der symphonischen Werke, während Arthur Nikisch mehr die Großartigkeit der Töne betonte. Die Stile dieser beiden Dirigenten wurden von Furtwängler zusammengeführt.[41] Furtwängler war der Schüler von Felix Mottl, einem Schüler von Wagner, als Furtwängler 1907–1909 in München weilte.[42] Darüber hinaus sah Furtwängler stets Arthur Nikisch als sein Vorbild an.[43] Wie John Ardoin darlegte, führte der subjektive Dirigierstil von Wagner zu Furtwängler, der objektive Dirigierstil von Mendelssohn zu Toscanini.[44] Zusätzlich wurde Furtwänglers Kunst stark durch den Musiktheoretiker Heinrich Schenker beeinflusst, mit dem er von 1920 bis zu Schenkers Tod 1935 zusammenarbeitete. Schenker war der Begründer der Musikanalyse und betonte darunterliegende weitreichende harmonische Spannungen und Auflösungen eines Musikstücks.[45][46] Furtwängler las 1911 Schenkers Monographie über Beethovens 9. Sinfonie. Seitdem versuchte er, alle seine Bücher aufzufinden und zu lesen.[47] Er traf Schenker erstmals 1920, und seitdem arbeiteten sie kontinuierlich gemeinsam an den musikalischen Werken, die Furtwängler dirigierte. Da seine Ideen zu modern für ihre Zeit waren, konnte Schenker nie in eine akademische Position in Österreich und Deutschland gelangen, trotz Furtwänglers Bemühungen, ihn dabei zu unterstützen.[48] Schenker lebte dank einiger Mäzene einschließlich Furtwängler. Furtwänglers zweite Ehefrau bestätigte viel später, dass Schenker einen immensen Einfluss auf ihren Mann hatte.[49] Schenker sah Furtwängler als den größten Dirigenten der Welt an und als den „einzigen Dirigenten, der Beethoven wirklich verstand“.[50] Furtwängler modifizierte die sogenannte Amerikanische Orchesteraufstellung, indem er die Bratschen rechts außen setzte (erste und zweite Geigen links, Violoncelli halbrechts und Bratschen rechts, Bässe rechts). Jedoch soll Serge Kussewitzky diese Aufstellung fast zeitgleich und angeblich unabhängig von Furtwängler praktiziert haben – mit der Variante, dass die Bässe links blieben. Allerdings sind viele Bilddokumente zu sehen, bei denen Furtwängler auch die alte deutsche Aufstellung dirigiert (zweite Geige rechts, Bässe links). Seine Orchesteraufstellung erfreut sich – als Kompromiss zwischen Amerikanischer und Deutscher Aufstellung – großer Beliebtheit. Furtwänglers Aufnahmen sind auch durch einen „außergewöhnlichen Klangreichtum“ charakterisiert,[41] mit besonderer Betonung auf Celli,[41] Kontrabässen, Schlagzeug und Holzblasinstrumenten.[51] Furtwängler zufolge lernte er von Arthur Nikisch, wie dieser Klang zu erreichen sei. Dieser Klangreichtum rührt teilweise von seinem „vagen“ Takt her, der häufig sein „fließender Takt“ genannt wird.[52] Dieser fließende Takt erzeugte eine geringfügige Taktverschiebung zwischen den Musikern, was dem Zuhörer erlaubte, alle Orchesterinstrumente klar zu unterscheiden, sogar in den Tutti.[53] Deshalb sagte Vladimir Ashkenazy einst: „Ich hörte niemals solch schöne Fortissimi wie bei Furtwängler.“[54] Yehudi Menuhin erklärte bei vielen Gelegenheiten, dass Furtwänglers fließender Takt schwieriger, jedoch Toscaninis sehr präzisem Takt überlegen gewesen sei.[55] Außerdem versuchte Furtwängler im Gegensatz zu Otto Klemperer nicht, Emotionen zu unterdrücken, die seinen Interpretationen einen hyperromantischen Aspekt gaben,[56] deren emotionale Intensität in den Aufnahmen aus der Zeit des Zweiten Weltkriegs an die Grenzen künstlerischer Erlebnisfähigkeit gehen. Die Interpretation der 9. Sinfonie von Beethoven im März 1942 mit den Berliner Philharmonikern wird von manchen seiner Bewunderer als „Jahrtausendinterpretation“ angesehen. Joachim Kaiser schreibt dazu: „Die nach wie vor gewaltigste und tiefgründigste Deutung der Symphonie Nr. 9 [von Beethoven] stammt von Wilhelm Furtwängler. Es ist der Mitschnitt eines Konzerts mit den Berliner Philharmonikern aus dem Jahr 1942.“[57] Dieser Interpretation steht eine Interpretation der großen C-Dur Symphonie von Schubert im Dezember des gleichen Jahres in nichts nach. Joachim Kaiser äußerte sich wie folgt (wenn auch nicht auf diese spezielle Aufnahme bezogen): „Wilhelm Furtwängler – darüber gibt es unter den Schubertianern der Alten und Neuen Welt wohl keinen Zweifel mehr – hat Schuberts ‚große‘ C-Dur-Symphonie faszinierender, glühender und visionärer zu dirigieren vermocht als jeder andere.“[58] Furtwängler wollte stets einen Aspekt von Improvisation und Unerwartetem in seinen Konzerten bewahren, so dass sich jede Interpretation als Neuschöpfung entwarf, wie bei Richard Wagner.[41] Jedoch gingen bei Furtwängler weder die melodische Linie noch die globale Einheit jemals verloren, nicht einmal in den dramatischsten Interpretationen, zum Teil durch den Einfluss von Heinrich Schenker, und weil Furtwängler auch Komponist war, der lebenslang Komposition studiert hatte.[59] Zu den Musikern, die die höchste Meinung über Furtwängler zum Ausdruck brachten, gehören einige der prominentesten des 20. Jahrhunderts, wie Arnold Schönberg,[60] Paul Hindemith[61] oder Arthur Honegger.[62] Solisten wie Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau,[63][64] Yehudi Menuhin[65] und Elisabeth Schwarzkopf,[66] die mit fast allen großen Dirigenten des 20. Jahrhunderts musizierten, erklärten bei mehreren Gelegenheiten, dass für sie Furtwängler der wichtigste war. John Ardoin berichtete die folgende Diskussion, die er mit Maria Callas im August 1968 hatte, nachdem sie Beethovens Achte mit dem Cleveland Orchestra unter George Szell angehört hatten: „‚Nun‘, seufzte sie, ‚Sie sehen, worauf wir reduziert wurden. Wir leben jetzt in einer Zeit, in der Szell als Meister angesehen wird. Wie klein er war neben Furtwängler.‘ Fassungslos – nicht wegen ihres Urteils, mit dem ich übereinstimmte, aber wegen dessen ungeschminkter Schärfe – stammelte ich: ‚Aber wie sehr kennen Sie Furtwängler? Sie haben nie mit ihm gesungen.‘ ‚Was glauben Sie?‘ Sie starrte mich gleichermaßen fassungslos an. ‚Er begann nach dem Krieg seine Karriere in Italien [ab 1947]. Ich hörte dort Dutzende seiner Konzerte. Für mich war er Beethoven.‘“[67] Furtwänglers Werk als Komponist Weniger bekannt ist, dass Furtwängler auch komponierte. Er sah sich selbst sogar primär als Komponist an und litt daher zeitlebens unter dem Spannungsverhältnis, dass er zwar als Dirigent bewundert wurde, aber in seiner Rolle als Komponist viel zu wenig Beachtung fand. So schrieb er beispielsweise zu Beginn seiner Dirigentenkarriere: „Morgen gehe ich in meine Verbannung als Kapellmeister nach Straßburg. Ich kann mir nicht helfen. Ich habe dabei die Empfindung, als ob ich mir untreu würde damit.“[68] Eine ähnliche Äußerung lautete wie folgt: „Ich weiß es selber am besten, daß das Leben, das ich führe, nicht mein Leben ist; daß ich sozusagen im Begriff stehe, meine Erstgeburt, meine Seele, um ein Linsengericht zu verkaufen. Aber es wird nicht geschehen. Je mehr äußere Erfolge ich heute habe, desto früher kann ich den großen Schritt machen, den ich machen muß.“[68] An seinen Privatlehrer Ludwig Curtius schrieb er: „Ich will komponieren und eigentlich nichts als komponieren. Daß meine Produktion nicht Ausfluß irgendeines Spieltriebs oder einer Eitelkeit, auch nicht irgendeiner Selbsteinbildung, sondern für mich die ernsthafte und entscheidendste Sache im Leben sei, ist mir seit langem klar. Meine Dirigentenkarriere ist ernsthafter Erwähnung nicht wert. In Wirklichkeit war das Dirigieren das Dach unter das ich mich im Leben geflüchtet habe, weil ich im Begriff war als Komponist zu Grunde zu gehen.“[68] Seine zweite Frau Elisabeth erzählte, dass sie einmal zu Furtwängler gesagt habe, dass es doch eigentlich schade sei, dass sein Vater gar nicht erlebt habe, dass er Dirigent der Berliner Philharmoniker geworden sei. Darauf habe Furtwängler geantwortet, dass sein Vater darüber sehr enttäuscht gewesen wäre, denn dieser habe gewusst, dass er Komponist sei.[68] Gegen Ende seines Lebens konnte der Komponist Furtwängler mit dem Dirigenten Furtwängler insofern wenigstens ansatzweise versöhnt werden, als es ihm vergönnt war, seine 2. Sinfonie in e-Moll bei zahlreichen Gelegenheiten aufzuführen. Seine bedeutendsten Werke, so auch die zweite Sinfonie, schrieb er nach 1935. Das meiste, was er davor komponiert hatte, stammt aus den Jahren bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg. In den zwei Jahrzehnten dazwischen konzentrierte er sich fast ausschließlich auf seine Dirigentenkarriere und vollendete kein einziges Werk. Furtwänglers schmales Œuvre umfasst drei Sinfonien (frühe Werke teilweise verschollen), einige Orchesterstücke, ein Klavierkonzert, etwas Kammermusik, Chorstücke (sämtlich Jugendwerke) und frühe Klavierkompositionen sowie Lieder. Die zweite Sinfonie ist das am meisten aufgeführte und daher auch bekannteste unter seinen Werken. Die Sätze seiner dritten Sinfonie in cis-Moll, an der er bis zu seinem Tode arbeitete, sind mit den folgenden programmatischen Bezeichnungen versehen: 1. „Das Verhängnis“, 2. „Im Zwang zum Leben“, 3. „Jenseits“, 4. „Der Kampf geht weiter“. Unter seiner Kammermusik ragt besonders die 2. Violinsonate in D-Dur mit ihrem elegisch-meditativen langsamen Satz hervor. Die reifen Kompositionen zeichnen sich besonders durch riesenhafte Ausmaße (sein dreisätziges Klavierquintett dauert 80 Minuten) sowie ein hohes Maß an motivisch-thematischer Arbeit aus. Im Großen und Ganzen ist sein Stil dem Erbe Anton Bruckners, Johannes Brahms’ und Max Regers verpflichtet, allerdings führt Furtwängler deren Traditionen auf originelle Weise weiter, sodass man den Komponisten nicht als Epigonen verurteilen darf, was oft geschieht. Zu sehr hat Furtwängler seine eigene, persönliche Tonsprache entwickelt. Die Stimmung seiner Werke lässt sich oft als grüblerisch oder tragisch bezeichnen. Dazu erschwert der hohe intellektuelle Anspruch seiner Musik das Verständnis, was zusammen mit den enormen spieltechnischen Ansprüchen wohl der Grund dafür ist, dass sie sich bisher nicht im Konzertbetrieb etablieren konnte. In jüngerer Zeit haben sich vor allem die Dirigenten Wolfgang Sawallisch, George Alexander Albrecht und Daniel Barenboim um eine Pflege der Musik Furtwänglers bemüht. Eine Gesamtausgabe der Werke und der Direktionen des Komponisten ist 2011 bei Documents erschienen. Furtwängler als Autor Der Musiker und sein Publikum[69] ist das Manuskript für einen Vortrag, der in der Bayerischen Akademie der Schönen Künste gehalten werden sollte, aber durch die Erkrankung und den Tod Furtwänglers nicht zustande kam. Furtwängler hatte dem Verleger Martin Hürlimann gegenüber vorab einer Veröffentlichung zugestimmt. Der Autor ergreift darin leidenschaftlich Partei für eine Kompositionsweise, bei der die Musik das Publikum, auch das laienhafte („Menschen des einfachen, klaren Lebens“), unmittelbar anspricht. Im Gegensatz dazu sieht er Musik, die in erster Linie für Theoretiker, Fachleute und Kritiker geschrieben werde und eines ideologischen Unterbaus bedürfe. Als Beispiel nennt er die Zwölftonmusik Arnold Schönbergs. Gespräche über Musik[70] umfasst die Mitschriften von sechs Gesprächen zwischen dem Dirigenten und dem Herausgeber Walter Abendroth, einen von Furtwängler verfassten Text („Siebentes Gespräch“) sowie ein ebenfalls von ihm stammendes Nachwort. Auch in diesen Texten verwendet er sich intensiv für die klassische, tonale Musik, insbesondere für die Werke Beethovens. |

仕事 [編集|原文ママ] フルトヴェングラーの指揮者としての仕事  ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー(1931年、ロンドン、クイーンズ・ホールにて) 写真:エーリッヒ・サロモン フルトヴェングラーは、音楽の救済機能の神話を自己像とする指揮者だった。彼の主体性は、音楽の形式や要素に無尽蔵に没入すると解釈されがちだが、特にア クセルランディやテンポの変化に関しては高度に計算された指揮法にも表れていた。このような解釈の姿勢と方法は、19世紀に起源を持つ。 多くの音楽家と同様、ヨアヒム・カイザーなどの解説者や批評家も、フルトヴェングラーを歴史上最も偉大な指揮者と見なしている[31][32][33]。 フルトヴェングラーの指揮術は、リヒャルト・ワーグナーによって始められた、いわゆる「ゲルマン流指揮術」の総合であり、集大成であると見なされている [34][35]。同時代のメンデルスゾーンの指揮スタイルが「速く、均整のとれたテンポを特徴とし、多くの人が模範的な論理と正確さとみなすもので満た されていた」のとは対照的に、ワーグナーの「スタイル[...]は幅広く、超ロマンティックで、テンポ変調の概念を取り入れていた」[36]。ベートー ヴェンは手紙の中で、「私のテンポは最初の数小節にしか適用されない。ベートーヴェンの弟子であるアントン・シンドラーなどは、作曲家が自分の作品を指揮 する際にテンポを絶えず変化させていたと証言している[39]。 彼らはベルリン・フィルの最初の常任指揮者であり[40]、ワーグナーの伝統に従った。ハンス・フォン・ビューローは交響曲の統一された構造をより強調 し、アルトゥール・ニキシュは音の壮大さをより強調した。フルトヴェングラーは、1907年から1909年にかけてミュンヘンに滞在していたとき、ワーグ ナーの弟子であったフェリックス・モットルの弟子であった[42]。さらに、フルトヴェングラーは常にアルトゥール・ニキシュを手本としていた[43]。 ジョン・アルドインが指摘したように、ワーグナーの主観的な指揮スタイルがフルトヴェングラーに、メンデルスゾーンの客観的な指揮スタイルがトスカニーニ につながった[44]。 フルトヴェングラーの芸術は、1920年から1935年にシェンカーが亡くなるまで共に活動した音楽理論家ハインリヒ・シェンカーの影響も強く受けてい る。シェンカーは音楽分析の創始者であり、楽曲の根底にある遠大な和声的緊張と解決を強調していた[45][46]。フルトヴェングラーは1911年に ベートーヴェンの交響曲第9番に関するシェンカーのモノグラフを読んだ。1920年に初めてシェンカーと出会い、それ以来、フルトヴェングラーが指揮する 音楽作品において継続的に共同作業を行った。フルトヴェングラーの努力にもかかわらず、シェンカーはオーストリアやドイツでアカデミックな地位を得ること はできなかった[48]。シェンカーはフルトヴェングラーを世界で最も偉大な指揮者であり、「ベートーヴェンを本当に理解している唯一の指揮者」と評価し ていた[50]。 フルトヴェングラーは、ヴィオラを右端に配置する(第1、第2ヴァイオリンが左、チェロが半右、ヴィオラが右、バスが右)という、いわゆるアメリカン・ オーケストラの配置を修正した。しかし、セルゲイ・クーセヴィツキーは、フルトヴェングラーとほぼ同時期に、またフルトヴェングラーとは無関係に、この配 置を実践したと言われている。しかし、フルトヴェングラーがドイツの古い配置(セカンド・ヴァイオリンが右、バスが左)で指揮している写真資料も多い。ア メリカ式とドイツ式の折衷案として、フルトヴェングラーのオーケストラ編成は大きな人気を博した。 フルトヴェングラーの録音はまた、チェロ、[41]コントラバス、打楽器、木管楽器に特に重点を置いた「並外れた豊かな響き」[51]を特徴としている。 フルトヴェングラーによれば、彼はこの響きを実現する方法をアルトゥール・ニキシュから学んだという。この豊かな響きは、しばしば「流れるようなビート」 と呼ばれる、彼の「曖昧な」拍子に由来している[52]。この流れるようなビートは、演奏者間にわずかな時間のずれを生じさせ、聴き手はトゥッティでさえ もすべての管弦楽器をはっきりと聞き分けることができる[53]。ウラディーミル・アシュケナージがかつて「フルトヴェングラーの音楽ほど美しいフォル ティッシミを聴いたことはない」と語ったのはこのためである。 「さらに、オットー・クレンペラーとは異なり、フルトヴェングラーは感情を抑制しようとしなかったため、彼の解釈には超ロマンティックな側面があった [56]。 1942年3月にベルリン・フィルと行ったベートーヴェンの交響曲第9番の解釈は、彼を敬愛する人々の間では「ミレニアム解釈」とみなされている。ヨアヒ ム・カイザーは、「(ベートーヴェンの)交響曲第9番に対する最も力強く深遠な解釈は、ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラーのものである。それは1942年 のベルリン・フィルとの演奏会の録音である」[57]。この解釈は、同じ年の12月に行われたシューベルトの偉大なハ長調交響曲の解釈に決して劣るもので はない。ヨアヒム・カイザーは次のようにコメントしている(この特定の録音に言及したわけではないが): ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー--新旧両世界のシューベルトファンの間では、もはやこのことに疑いの余地はないだろう--は、シューベルトの『偉大 な』ハ長調交響曲を、他の誰よりも魅力的に、より熱烈に、より先見的に指揮することができた」[58]。 フルトヴェングラーは、協奏曲において常に即興性と意外性を保持することを望み、リヒャルト・ワーグナーのように、それぞれの解釈が新たな創造として設計 されるようにした[41]。しかし、フルトヴェングラーでは、ハインリヒ・シェンカーの影響もあり、またフルトヴェングラーが生涯作曲を学んだ作曲家でも あったため、最も劇的な解釈であっても、旋律線や全体的な統一性が失われることはなかった[59]。 フルトヴェングラーを高く評価した音楽家の中には、アーノルド・シェーンベルク[60]、パウル・ヒンデミット[61]、アルトゥール・オネゲル[62] といった20世紀を代表する音楽家がいた。ディートリヒ・フィッシャー=ディースカウ[63][64]、ユーディ・メニューイン[65]、エリザベート・ シュヴァルツコップ[66]といったソリストは、20世紀の偉大な指揮者のほとんどすべてと共演しているが、彼らにとってフルトヴェングラーが最も重要で あったと何度か述べている。ジョン・アルドインは、1968年8月、ジョージ・セル指揮クリーヴランド管弦楽団とベートーヴェンの第8番を聴いた後、マリ ア・カラスと次のような話をしたと報告している: 「彼女はため息をついた。私たちは今、セルが巨匠とみなされる時代に生きている。フルトヴェングラーに比べたら、彼はなんてちっぽけなんだろう」。私は唖 然とした--彼女の判断に同意したのではなく、その率直な鋭さに--口ごもった。でも、フルトヴェングラーのことをどれくらい知っているの?彼女は同じよ うに唖然として私を見つめた。彼は戦後(1947年から)イタリアでキャリアをスタートさせた。そこで彼のコンサートを何十回も聴いた。私にとって、彼は ベートーヴェンだった」[67]。 作曲家としてのフルトヴェングラーの仕事 [編集|原文ママ] フルトヴェングラーが作曲もしていたことはあまり知られていない。彼は自分自身を主に作曲家として見ていたため、指揮者としては賞賛されるものの、作曲家 としての役割ではあまりにも注目されないという緊張感に生涯苦しんでいたほどである。例えば、指揮者としてのキャリアをスタートさせたばかりの頃、彼はこ う書いている。自分ではどうすることもできない。まるで自分に対して不誠実であるかのように感じる」[68] 同じような文章に次のようなものがある: 「自分のしている人生が自分の人生ではないこと、自分の長男、いわば魂をレンズ豆のために売ろうとしていることは、自分自身が一番よく知っている。しか し、そうはならない。今日、外面的な成功が多ければ多いほど、私は早く大きな一歩を踏み出すことができる」[68]。 彼は私的な師であるルートヴィヒ・クルティウスに手紙を書いた: 「私は作曲をしたいし、実際には作曲以外のことはしたくない。私の作曲は、遊び半分の本能や虚栄心の結果でも、自惚れの結果でもなく、私の人生において最 も深刻で決定的なものであることは、ずっと以前から明らかだった。私の指揮者としてのキャリアは、深刻な言及に値しない。実際のところ、指揮は、私が作曲 家として滅びようとしていたときに避難した屋根だった」[68]。 彼の2番目の妻エリザベートは、フルトヴェングラーに、彼がベルリン・フィルの指揮者になるのを父親が生きて見られなかったのは残念だと言ったことがある と語っている。フルトヴェングラーは、自分が作曲家であることを知っていたのだから、父親はさぞかし失望しただろうと答えた[68]。晩年、作曲家フルト ヴェングラーは、彼の交響曲第2番ホ短調を何度も演奏する栄誉を与えられたという点で、指揮者フルトヴェングラーと少なくとも部分的には和解していた。 交響曲第2番を含む彼の最も重要な作品は1935年以降に作曲されたが、それ以前の作品のほとんどは第一次世界大戦までの数年間に作曲されたものである。 その間の20年間は、ほとんど指揮活動に専念し、1曲も作品を完成させていない。フルトヴェングラーの小さな作品は、3つの交響曲(初期の作品はいくつか 失われている)、いくつかの管弦楽曲、ピアノ協奏曲、いくつかの室内楽曲、合唱曲(すべて若い頃の作品)、初期のピアノ曲、そしてリートから成る。交響曲 第2番は最も頻繁に演奏されるため、彼の作品の中で最もよく知られている。交響曲第3番嬰ハ短調の各楽章には、1)「破滅」、2)「生きることを余儀なく される」、3)「彼方へ」、4)「闘いは続く」というプログラム・タイトルが付けられている。 室内楽曲では、エレジーで瞑想的な緩徐楽章を持つヴァイオリン・ソナタ第2番ニ長調が特に際立っている。壮年期の作品は、特に巨大なサイズ(3楽章からな るピアノ五重奏曲は80分にも及ぶ)と、高度な動機づけと主題づけが特徴である。全体として、彼の作風はアントン・ブルックナー、ヨハネス・ブラームス、 マックス・レーガーの遺産に負っているが、フルトヴェングラーはそれらの伝統を独自の方法で継承している。フルトヴェングラーは個人的な調性言語を発展さ せすぎた。彼の作品の雰囲気は、しばしば陰鬱、あるいは悲劇的と表現される。加えて、彼の音楽は知的要求が高いため理解が難しく、演奏上の技術的要求が大 きいことも、演奏会のレパートリーとして定着していない理由だろう。最近では、特にヴォルフガング・サヴァリッシュ、ジョージ・アレクサンダー・アルブレ ヒト、ダニエル・バレンボイムといった指揮者たちが、フルトヴェングラーの音楽の育成に努めている。2011年には、フルトヴェングラーの作品と指揮者の 全集がドキュメンツ社から出版された。 著者としてのフルトヴェングラー [編集|原文]. Der Musiker und sein Publikum』[69]は、バイエルン芸術アカデミーで開催される予定であったが、フルトヴェングラーの病死により実現しなかった講演会の原稿であ る。フルトヴェングラーは出版社のマルティン・ヒュリマンと事前に出版に合意していた。その中で著者は、音楽が一般大衆(「単純明快な生活を送る人々」) を含む聴衆に直接語りかける作曲スタイルを熱烈に支持している。これとは対照的に、理論家や専門家、批評家のために書かれ、イデオロギー的な基盤を必要と する音楽を主に見ている。彼はその例として、アーノルド・シェーンベルクの 十二音音楽を挙げている。 音楽についての会話』[70]は、指揮者と編集者ヴァルター・アベンドロスとの6つの会話の記録、フルトヴェングラーが書いた文章(「第7の会話」)、そ して同じく彼が書いたエピローグで構成されている。これらの文章でも、彼は古典的な調性音楽、特にベートーヴェンの作品を強く支持している。 |

Ehrungen Briefmarke der Bundespost Berlin 1955 zum ersten Todestag  Grabanlage von Wilhelm Furtwängler auf dem Heidelberger Bergfriedhof in der Abt. R 1927: Ehrendoktorwürde der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg 1929: Ehrenbürger der Stadt Mannheim 1929: Pour le mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste 1933: Preußischer Staatsrat 1935: gemeinsam mit Hermann Abendroth die Denkmünze der lübeckischen Gesellschaft zur Beförderung gemeinnütziger Tätigkeit in Gold 1939: Orden der französischen Ehrenlegion (Annahme von Hitler verboten) 1952: Mozartmedaille durch die Mozartgemeinde Wien[71] 1952: Großes Verdienstkreuz mit Stern der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Ehrengrab der Stadt Heidelberg im Bergfriedhof 1955: In Berlin ist eine Straße nach dem Dirigenten benannt, die Furtwänglerstraße in Berlin-Wilmersdorf 1955: In Wien ist ein Platz nach dem Dirigenten benannt, der Furtwänglerplatz in Wien-Hietzing In Salzburg am Großen Festspielhaus ist eine Anlage nach dem Dirigenten benannt, der Wilhelm-Furtwängler-Garten Berlin-Grunewald, München-Nymphenburg, Stuttgart-Botnang, Bayreuth, Heidelberg-Handschuhsheim, Freiburg i. Br.-Littenweiler und Bielefeld widmeten ihm jeweils eine Furtwänglerstraße. |

栄誉 1955年ベルリン連邦郵便局の没後一周年記念切手  ハイデルベルク・ベルクフリートホーフのR区画にあるヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラーの墓 1927年:ハイデルベルクのルプレヒト・カールス大学から名誉博士号を授与される。 1929年:マンハイム市の名誉市民となる。 1929年:科学と芸術のための賞(Pour le mérite)を授与される。 1933: プロイセン国家評議員 1935年:ヘルマン・アベンドロスとともにリューベック慈善協会よりゴールドメダルを授与される。 1939年:フランス・レジオン・ドヌール勲章(ヒトラーにより受章を禁じられる) 1952:ウィーンのモーツァルト共同体からモーツァルト・メダルを授与される[71]。 1952年:ドイツ連邦共和国より星付き功労大十字勲章を授与される。 ハイデルベルク市名誉の墓(ベルクフリートホーフ墓地内 1955年:ベルリンの通りに指揮者の名前が付けられる(ベルリン・ヴィルマースドルフの フルトヴェングラー通り)。 1955年:ウィーンの広場が指揮者の名前にちなんでフルトヴェングラー広場と命名される(ウィーン・ヒーツィング)。 ザルツブルグでは、グローセス・フェストシュピールハウスの庭園に指揮者の名前にちなんでヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー・ガルテン(Wilhelm- Furtwängler-Garten)と命名された。 ベルリン=グルネヴァルト、ミュンヘン=ニンフェンブルク、シュトゥットガルト=ボットナング、バイロイト、ハイデルベルク=ハンスチュースハイム、フラ イブルク=リッテンヴァイラー、ビーレフェルトには、それぞれフルトヴェングラー通りがある。 |

| Wilhelm-Furtwängler-Preis Seit 1990 wurde im Rahmen der Veranstaltung „Gala d’Europe Baden-Baden“ in unregelmäßigem Turnus der Wilhelm-Furtwängler-Preis zur Auszeichnung international renommierter Sängerinnen, Sänger und Dirigenten für besonders herausragende Leistungen auf dem Gebiet der klassischen Musik vergeben. Initiiert wurde der Preis von Elisabeth Furtwängler, der Ehefrau Wilhelm Furtwänglers, und Ermano Sens-Grosholz.[72] Erstmals wurde der Preis an Plácido Domingo verliehen. Seit 2008 wird er während des Beethovenfestes in Bonn an herausragende Solisten, Orchester, Dirigenten und Ensembles des klassischen Musiklebens verliehen.[73] https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm_Furtw%C3%A4ngler |

ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー賞 [ソーステキストを編集する] 1990年以来、ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー賞は、「ガラ・ド・ヨーロッパ・バーデン・バーデン」の一環として不定期に授与されている。この賞は、 ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラーの妻であるエリザベート・フルトヴェングラーとエルマーノ・センス=グロショルツによって創設された[72]。 この賞は、プラシド・ドミンゴに初めて授与された。2008年からは、ボンで開催されるベートーヴェンフェストの期間中に、クラシック音楽の優れたソリス ト、オーケストラ、指揮者、アンサンブルに授与されている[73]。 |

| Aufnahmen als Dirigent https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm_Furtw%C3%A4ngler |

|

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm_Furtw%C3%A4ngler |

|

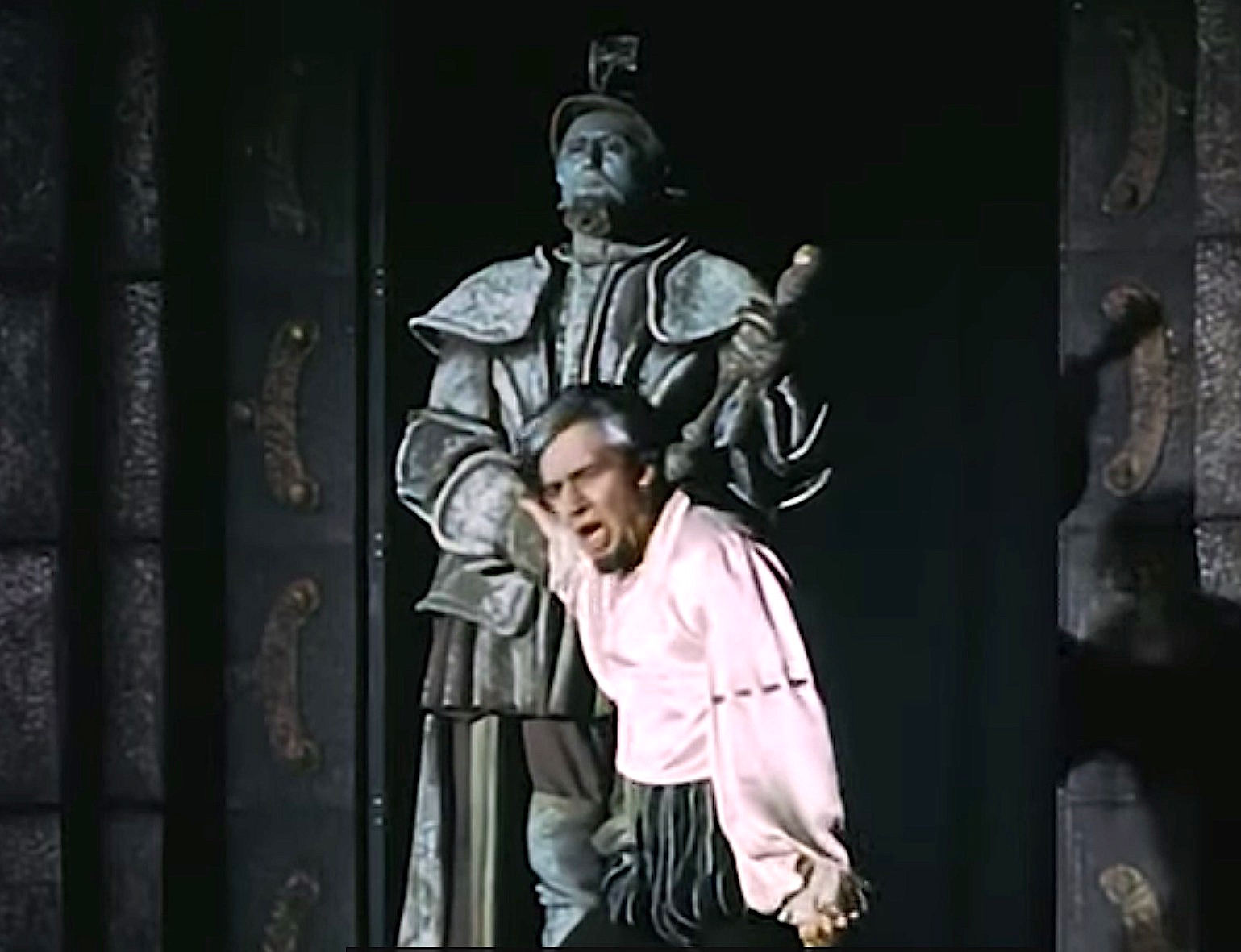

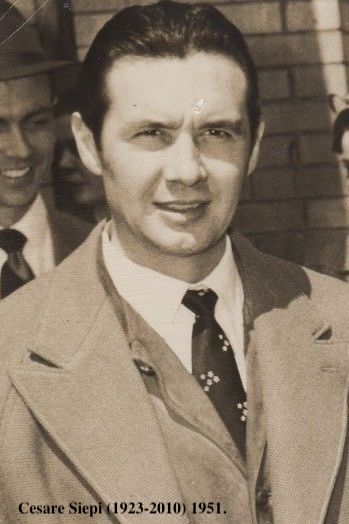

Cesare Siepi

(10 February 1923 – 5 July 2010[1]) was an Italian opera singer,

generally considered to have been one of the finest basses of the

post-war period. His voice was characterised by a deep, warm timbre, a

full, resonant, wide-ranging lower register with relaxed vibrato, and a

ringing, vibrant upper register. Although renowned as a Verdian bass,

his tall, striking presence and the elegance of phrasing made him a

natural for the role of Don Giovanni. He can be seen in that role on

Paul Czinner's 1954 film of the opera made during an edition of the

Salzburg Festival under the baton of Wilhelm Furtwängler. Cesare Siepi

(10 February 1923 – 5 July 2010[1]) was an Italian opera singer,

generally considered to have been one of the finest basses of the

post-war period. His voice was characterised by a deep, warm timbre, a

full, resonant, wide-ranging lower register with relaxed vibrato, and a

ringing, vibrant upper register. Although renowned as a Verdian bass,

his tall, striking presence and the elegance of phrasing made him a

natural for the role of Don Giovanni. He can be seen in that role on

Paul Czinner's 1954 film of the opera made during an edition of the

Salzburg Festival under the baton of Wilhelm Furtwängler.Early career Born in Milan (his year of birth is debated between 1919 and 1923, though 1923 is given as official), he began singing as a member of a madrigal group. He often claimed to have been largely self-taught, having attended the music conservatory in his home city for just a short time. His operatic career was interrupted by World War II. After his debut in 1941 (in Schio, near Vicenza, as Sparafucile in Rigoletto), Siepi, an opponent of the fascist regime, fled to Switzerland. After the end of the war his career immediately took off. Success as Zaccaria in Nabucco at La Fenice in Venice was followed by the first of many engagements at La Scala, Milan. His early engagements there were in the Verdi bass roles, the title role in Boito's Mefistofele under Arturo Toscanini, as Colline in La bohème, and in La Gioconda, La favorite, and I puritani. International success Siepi debuted abroad in 1947, at the Liceu in Barcelona in Donizetti's Anna Bolena, but his international reputation was established in 1950, when Sir Rudolf Bing brought him to the Metropolitan Opera in New York to open the 1950 season as King Philip II in Don Carlos. He was to remain principal bass at the Met until 1974, adding roles such as Boris Godunov (in English) and Gurnemanz in Parsifal (in German), and singing all the major roles of the bass repertoire. His debut at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, was in 1950, and he appeared there regularly until the mid-1970s. In 1953, Siepi debuted at the Salzburg Festival with a legendary production of Don Giovanni conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler, staged by Herbert Graf, and designed by Clemens Holzmeister. He made an immediate impact in the title role of the opera, which became perhaps his best known role, as it had been for the most famous Italian bass of the generation before, Ezio Pinza. This performance has been released on CD, and a 1954 mounting of this production was filmed in color and released in 1955. Siepi was a frequent guest at the Vienna State Opera. In 43 performances he sang Don Giovanni, more often than any other singer in modern times except for Eberhard Wächter. In 1967 Siepi was Don Giovanni in a controversially received production staged by Otto Schenk and designed by Luciano Damiani that showed Mozart's masterpiece in the light of the commedia dell'arte, emphasizing the comic and ironic elements of this opera (conductor Josef Krips strongly opposed this production's concept). In Vienna he also sang Basilio (Il barbiere di Siviglia), Colline (La bohème), Fiesco (Simon Boccanegra), Figaro (Le nozze di Figaro), Padre Guardiano (La forza del destino 1974 in a new production conducted by Riccardo Muti), Gurnemanz (Parsifal), Méphistophélès (Faust), Filippo II (Don Carlos), and Ramphis (Aida). His final performance at Vienna was in Norma (Oroveso) at the Austria Center Vienna in 1994. He was a particularly fine recital artist, especially in Community Concerts under Columbia Artist Management, and a sensitive interpreter of German Lieder. He married Met ballerina Louellen Sibley and they had two children. Siepi enjoyed a long career, and performed regularly until the 1980s, including lead roles in the ill-fated Broadway musicals Bravo Giovanni and Carmelina. In addition to his studio recordings, there are also many live recordings of performances of his major roles. Siepi's formal farewell to the operatic stage occurred at the Teatro Carani in Sassuolo on 21 April 1989. Indeed, Capon's List shows live recordings made as late as 1988. Siepi's last studio recording was as the old King Archibaldo in RCA's 1976 taping of Italo Montemezzi's L'amore dei tre re, with Anna Moffo and Plácido Domingo in the cast. Siepi died at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia on 5 July 2010 after suffering a stroke more than a week earlier. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cesare_Siepi |

チェー

ザレ・シエピ(シーピ)(1923年2月10日 -

2010年7月5日[1])はイタリアのオペラ歌手であり、一般的には戦後最も優れたバスの一人であったと考えられている。彼の声の特徴は、深く温かみの

ある音色、ゆったりとしたヴィブラートを伴うふくよかで響きのある広い低音域、鳴り響くような躍動感のある高音域である。ヴェルディのバスとして有名で

あったが、長身で印象的な存在感と優雅なフレージングは、ドン・ジョヴァンニ役にうってつけであった。1954年、ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラーの指

揮でザルツブルク音楽祭に出演した際に撮影されたポール・ツィナー監督の映像では、彼がこの役を演じている姿を見ることができる。 チェー

ザレ・シエピ(シーピ)(1923年2月10日 -

2010年7月5日[1])はイタリアのオペラ歌手であり、一般的には戦後最も優れたバスの一人であったと考えられている。彼の声の特徴は、深く温かみの

ある音色、ゆったりとしたヴィブラートを伴うふくよかで響きのある広い低音域、鳴り響くような躍動感のある高音域である。ヴェルディのバスとして有名で

あったが、長身で印象的な存在感と優雅なフレージングは、ドン・ジョヴァンニ役にうってつけであった。1954年、ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラーの指

揮でザルツブルク音楽祭に出演した際に撮影されたポール・ツィナー監督の映像では、彼がこの役を演じている姿を見ることができる。初期のキャリア[編集] ミラノで生まれ(生年は1919年から1923年の間で議論されているが、1923年が正式)、マドリガルグループのメンバーとして歌い始める。故郷の音 楽院に短期間通っただけで、ほとんど独学で学んだとしばしば主張している。オペラ歌手としてのキャリアは、第二次世界大戦によって中断された。1941年 にヴィチェンツァ近郊のスキオで『リゴレット』のスパラフチーレ役でデビューした後、ファシスト政権に反対していたシーピはスイスに亡命した。 終戦後、彼のキャリアはすぐに飛躍した。ヴェネチアのフェニーチェ劇場で『ナブッコ』のザッカリア役で成功を収めると、ミラノ・スカラ座でも多くの仕事を こなした。ミラノ・スカラ座での初期の仕事は、ヴェルディのバス役、アルトゥーロ・トスカニーニ指揮ボイトの『メフィストフェレ』のタイトルロール、 『ラ・ボエーム』のコリーネ役、『ラ・ジョコンダ』、『ラ・フェイヴァリット』、『イ・プリターニ』などであった。 国際的な成功 1947年、バルセロナの リセウ劇場でドニゼッティの『アンナ・ボレーナ』で海外デビューしたシエピは、1950年、ルドルフ・ビング卿によってニューヨークのメトロポリタン歌劇 場に招かれ、『ドン・カルロス』のフィリップ2世役で1950年シーズンのオープニングを飾ったことで、国際的な名声を確立した。その後、1974年まで メトロポリタン歌劇場の首席バスを務め、『ボリス・ゴドゥノフ』(英語)や『パルジファル』(ドイツ語)のグルネマンツなど、バスのレパートリーの主要な 役をすべて歌った。 コヴェント・ガーデン 王立歌劇場でのデビューは1950年で、1970年代半ばまで定期的に出演した。 1953年、ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー指揮、ヘルベルト・グ ラーフ演出、クレメンス・ホルツマイスター設計の伝説的な『ドン・ジョヴァンニ』でザルツブルク音楽祭にデビューした。彼はこのオペラのタイトルロールで 即座に衝撃を与え、その前の世代で最も有名なイタリア人バス、エツィオ・ピンツァと同様、おそらく彼の最もよく知られた役となった。この公演はCD化され ており、1954年に上演されたものはカラーで撮影され、1955年に発売された。 シーピはウィーン国立歌劇場に頻繁に客演した。43回の公演でドン・ジョヴァンニを歌ったが、これはエバーハルト・ヴェヒターを除けば、近代のどの歌手よりも多い回数であった。1967 年、オットー・シェンクの演出、ルチアーノ・ダミアーニのデザインで、このオペラのコミカルで皮肉な要素を強調し、モーツァルトの傑作をコメディア・デラ ルテに照らし合わせた演出でドン・ジョヴァンニを歌い、物議をかもした(指揮者のヨーゼフ・クリップスは、この演出のコンセプトに強く反対した)。 ウィーンでは、バジリオ(『シヴィリアのバービア』)、コリーネ(『ラ・ボエーム』)、フィエスコ(『シモン・ボッカネグラ』)、フィガロ(『フィガロの 結婚』)、グアルディアーノ神父(リッカルド・ムーティ指揮の新演出『運命の力』)、グルネマンツ(『パルジファル』)、メフィストフェレス(『ファウス ト』)、フィリッポ2世(『ドン・カルロス』)、ランフィス(『アイーダ』)などを歌った。ウィーンでの最後の公演は、1994年のオーストリア・セン ター・ウィーンでの『ノルマ』(オロヴェソ)である。 リサイタルでは、特にコロンビア・アーティスト・マネジメントのコミュニティ・コンサートでの活躍が目覚ましく、ドイツ・リートの繊細な解釈にも定評があった。メット・バレリーナのルーレン・シブリーと結婚し、2人の子供をもうけた。 シーピは長いキャリアを誇り、1980年代まで定期的に公演を行い、不遇のブロードウェイ・ミュージカル『ブラヴォー・ジョヴァンニ』や『カルメリーナ』では主役を演じた。彼のスタジオ録音に加え、主要な役柄を演じたライブ録音も数多く残されている。 1989年4月21日、サッスオーロのテアトロ・カラーニで、シーピはオペラの舞台に正式に別れを告げた。実際、カポンのリストには、1988年末のライブ録音が掲載されている。 シエピの最後のスタジオ録音は、RCAが1976年に録音したイタロ・モンテメッツィの『L'amore dei tre re』の老王アルキバルド役で、アンナ・モッフォと プラシド・ドミンゴが出演していた。 2010年7月5日、ジョージア州 アトランタのピードモント病院で死去した。 |

Otto Edelmann (5 February 1917 – 14 May 2003) was an Austrian operatic bass. Otto Edelmann (5 February 1917 – 14 May 2003) was an Austrian operatic bass.Life Edelmann was born in Vienna and studied singing with Gunnar Graarud.[1][2] His debut was at Gera as Figaro in Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro.[1] He later sang the Vienna State Opera,[3] the Edinburgh International Festival and the Metropolitan Opera.[4] He sang at the Bayreuth Festival immediately after its reopening in 1951 after World War II, performing the role of Hans Sachs in Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. (He also recorded as Veit Pogner the goldsmith in the same work in one of Hans Knappertsbusch's early recorded performances.) He also sang Ochs in Richard Strauss's Der Rosenkavalier[5][4] at the first performances in the new Salzburg Festspielhaus in 1960. In 1957, he recorded the role of Wotan opposite Kirsten Flagstad in Georg Solti's recording of Act III of Wagner's Die Walküre (an album made prior to the later famous complete set of Der Ring des Nibelungen). In 1982, he received a professorship for vocal pedagogy at the Vienna Music Academy.[5] He died in Vienna at the age of 86.[6] Personal life He is the father of the Austrian baritones Peter Edelmann and Paul Armin Edelmann. Voice His powerful, dark voice has proven itself in Wagner roles as well as in tasks from the Buffo subject.[5] Recordings CDs Edelmann sang Ochs in Paul Czinner's classic recording of Der Rosenkavalier conducted by Herbert von Karajan with Elizabeth Schwarzkopf and Christa Ludwig.[7][8] Videos Videos are available of him as Baron Ochs (with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf) and Leporello (with Cesare Siepi).[9][10][11] Awards 1960 Kammersänger[1] 1971 Max Reinhardt Medal[1] Honorary member of the Wiener Staatsoper[1] 1994 Lieber Augustin[1] Golden Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria[1] |

オットー・エーデルマン(Otto Edelmann、1917年2月5日 - 2003年5月14日)は、オーストリアのオペラ歌手である。 オットー・エーデルマン(Otto Edelmann、1917年2月5日 - 2003年5月14日)は、オーストリアのオペラ歌手である。生涯[編集] その後、ウィーン国立歌劇場、[3] エジンバラ国際音楽祭、メトロポリタン歌劇場などで歌った[4]。(また、ハンス・クナッパーツブッシュの初期の録音では、同作品の金細工師ヴァイト・ポ グナー役を歌っている)。また、1960年にザルツブルク音楽堂で上演されたリヒャルト・シュトラウスの『薔薇の騎士』のオックス役[5][4]も歌って いる。1957年には、ゲオルク・ショルティによるワーグナーの『ワルキューレ』第3幕の録音で、キルステン・フラグスタッドの相手役としてヴォータン役 を歌った(このアルバムは、後に有名な『ニーベルングの指環』全曲セットに先駆けて制作された)。1982年、ウィーン音楽アカデミーの声楽教育学の教授 に就任した[5]。 私生活[編集]。 オーストリアのバリトン歌手ペーター・エーデルマンと パウル・アルミン・エーデルマンの父である。 声楽[編集] 彼のパワフルでダークな声は、ワーグナーの役やブッフォの課題曲で証明されている[5]。 録音[編集] CD[編集] エーデルマンは、ヘルベルト・フォン・カラヤン指揮、エリザベス・シュヴァルツコップ、クリスタ・ルートヴィヒ共演による『薔薇の騎士』のパウル・ツィナーによる名録音でオックスを歌っている[7][8]。 ビデオ[編集] オックス男爵役(エリザベート・シュヴァルツコップとの共演)とレポレッロ役(チェーザレ・シーピとの共演)のビデオがある[9][10][11]。 受賞歴[編集] 1960年カンマーゼンゲル[1] 1971年 マックス・ラインハルト・メダル[1] ウィーン国立歌劇場名誉会員[1] 1994年 リーバー・アウグスティン[1] オーストリア共和国名誉黄金勲章[1] |

Elisabeth

Grümmer (née Schilz; 31 March 1911 – 6 November 1986) was a German

soprano. She has been described as "a singer blessed with elegant

musicality, warm-hearted sincerity, and a voice of exceptional

beauty".[1] Elisabeth

Grümmer (née Schilz; 31 March 1911 – 6 November 1986) was a German

soprano. She has been described as "a singer blessed with elegant

musicality, warm-hearted sincerity, and a voice of exceptional

beauty".[1]Life Elisabeth Schilz was born in Niederjeutz [now Yutz, near Diedenhofen (Thionville), Alsace-Lorraine] to German parents. In 1918, her family was expelled from Lorraine, and they settled in Meiningen, where she studied theater and made her stage debut as Klärchen in Goethe's Egmont. She married the concertmaster of the theater orchestra, Detlev Grümmer, and became a mother. The family moved to Aachen, where they met Herbert von Karajan under whose encouragement she made her operatic debut in 1940, in the role of First Flowermaiden in a 1940 performance of Wagner's Parsifal.[2] She went on from Aachen to perform in Duisburg and Prague. Her husband was killed in their house during the bombing of Aachen in 1944. After the war, she settled in Berlin, singing at the Städtische Oper Berlin. She performed in the major opera houses in Europe and the United States, restricting herself to a small number of roles, primarily sung in German. She was also active in song recitals and concert performances, particularly of Brahms' German Requiem. The Kammersängerin became a professor at the Berlin Musikhochschule. Among her students are Astrid Schirmer, Gillian Rae-Walker, and Janis Kelly.[3] Grümmer died in Warendorf, Westphalia on 6 November 1986.[2] Work and critical reception Grümmer was acclaimed both as an opera singer and as a lieder interpreter. The book, The Grove Book of Opera Singers, referred to her "beautiful voice, clarity of diction and innate musicianship" evidenced by her legacy on record.[2] She appeared in two videotaped performances as Donna Anna in Don Giovanni, one conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler and the other in German translation conducted by Ferenc Fricsay. |

エリザベート・グリュンマー(旧姓シルツ、1911年3月31日 - 1986年11月6日)は、ドイツのソプラノ歌手である。エレガントな音楽性、温かみのある誠実さ、類まれな美声に恵まれた歌手」と評されている[1]。 エリザベート・グリュンマー(旧姓シルツ、1911年3月31日 - 1986年11月6日)は、ドイツのソプラノ歌手である。エレガントな音楽性、温かみのある誠実さ、類まれな美声に恵まれた歌手」と評されている[1]。生涯[編集] エリザベート・シルツは、ドイツ人の両親のもと、ニーダーヨッツ[現在のユッツ、アルザス・ロレーヌ地方のディーデンホーフェン(ティオンヴィル)近郊] で生まれた。1918年、一家はロレーヌ地方から追放され、マイニンゲンに定住。そこで演劇を学び、ゲーテの『エグモント』のクレルヒェン役でデビューし た。 劇場オーケストラのコンサートマスター、デトレフ・グリュンマーと結婚し、母となった。一家はアーヘンに移り、そこでヘルベルト・フォン・カラヤンと出会い、カラヤンの勧めで1940年にワーグナーの『パルジファル』の第一花乙女役でオペラ・デビューを果たす[2]。 1944年、アーヘン爆撃の際、夫は自宅で死亡した。戦後はベルリンに定住し、ベルリン国立歌劇場で歌った。ヨーロッパとアメリカの主要な歌劇場に出演 し、主にドイツ語で歌われる少数の役柄にとどまった。また、歌曲のリサイタルやコンサート、特にブラームスのドイツ・レクイエムの演奏にも積極的に参加し た。 カンマーゼンガリンは ベルリン音楽大学の教授となった。彼女の教え子には、アストリッド・シルマー、ジリアン・レー=ウォーカー、ジャニス・ケリーなどがいる[3]。 1986年11月6日、ヴェストファーレン州ヴァレンドルフで死去した[2]。 作品と批評家の評価[編集] グリュンマーは、オペラ歌手としてもリート解釈者としても高く評価された。The Grove Book of Opera Singers(グローブ・ブック・オブ・オペラ・シンガー)』という本では、彼女の「美しい声、明瞭なディクション、生来の音楽性」がレコードで証明さ れていると紹介されている[2]。 ドン・ジョヴァンニ』のドンナ・アンナ役で、ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラーの指揮によるものと、フェレンツ・フリクサイの指揮によるドイツ語訳の2つのビデオに出演している。 |

Kammersänger Anton Dermota (June 4, 1910 – June 22, 1989) was a Slovene lyric tenor. Kammersänger Anton Dermota (June 4, 1910 – June 22, 1989) was a Slovene lyric tenor.Early life He was born in a poor family in the Upper Carniolan village of Kropa in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire (and is now in Slovenia). He went to the Ljubljana Conservatory with the intention of studying composition and organ, but in 1934 he received a scholarship which sent him to Vienna. There, he devoted himself exclusively to vocal study with Marie Radó. Career Dermota made his debut at the opera in Cluj in 1934, and was promptly invited by Bruno Walter to perform at the Vienna State Opera. Here he made his début as "First Man in Armor" in Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's The Magic Flute in 1936 and got a contract immediately. His first leading role was Alfredo in Giuseppe Verdi's La traviata, which he sang in 1937. In the same year Dermota made his début at the Salzburg Festival in a production of Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, conducted by Arturo Toscanini. Dermota quickly became a favorite of the Viennese audience and remained with the State Opera's company for more than forty years. He was a witness (and helped to save parts of the furniture) when the opera house burned down after an Allied air raid on March 13, 1945. After the war he stayed with the company in its provisional lodgings at Theater an der Wien, and was one of the stars of the reopening of the original house in 1955 (as Florestan in Beethoven's Fidelio). As early as 1946 Dermota was honoured for his loyalty with the title of Kammersänger. Anton Dermota sang as a tenor as Alfred in Die Fledermaus in the 1950 London Gramophone recording LLP 305. For 20 years, Dermota sang at the Salzburg Festival almost every summer. As guest he gave acclaimed performances at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden London, in Palais Garnier and Teatro dell'Opera di Roma, at Teatro di San Carlo in Naples, Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, in Australia, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Dermota was best known for his Mozart roles, especially his Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni. But he sang a good deal of the lyric tenor repertory during his career, including more modern parts, such as Oedipus in Igor Stravinsky's Oedipus rex, the title role of Hans Pfitzner's Palestrina and Flamand in Richard Strauss's Capriccio. Later in life he ventured into heldentenor territory, essaying parts such as the title role in Smetana's Dalibor and Florestan. All told, his repertoire included some 80 roles. Duration: 3 minutes and 7 seconds.3:07 Anton Dermota singing the lied "The Monk" by Benjamin Ipavec, accompanied on piano by his wife Hilde An accomplished Lieder singer, he gave many recitals accompanied by his wife, the pianist Hilde Berger-Weyerwald. He began a second career as a singing coach at the Wiener Musikhochschule in 1966. To celebrate his 70th birthday, Dermota sang Tamino in The Magic Flute at the Vienna State Opera. A popular anecdote states that when he spoke the line "Ist's Phantasie, dass ich noch lebe?" ("Is it a fantasy that I am still alive?") the audience broke into spontaneous applause. A year later he sang the Shepherd in Carlos Kleiber's famous recording of Richard Wagner's Tristan und Isolde, sounding astonishingly young. Death He died in Vienna less than a month after his 79th birthday. Decorations and awards 1959: Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, 1st class[1] 1977: Grand Silver Medal for Services to the Republic of Austria[2] |