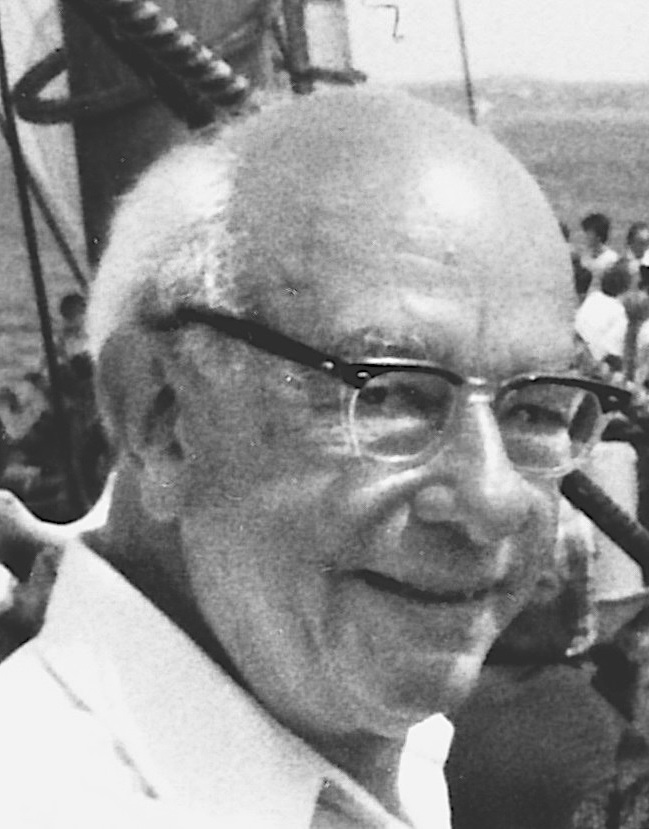

ウィラード・クワイン

Willard Van Orman

Quine,

1908-2000

☆ ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン[Willard Van Orman Quine] (/kwaɪn/ クウェイン;友人からは「ヴァン」と呼ばれた[3];1908年6月25日 - 2000年12月25日)は、分析哲学の伝統に属するアメリカの哲学者・論理学者であり、「20世紀で最も影響力のある哲学者の一人」と認められている。 [4] 1956年から1978年までハーバード大学のエドガー・ピアース記念哲学教授を務めた。 クワインは論理学と集合論の教師であった。一階論理こそが論理学と呼ぶに値する唯一の論理であるという立場で有名であり、ニューファウンデーションズとし て知られる独自の数学・集合論体系を構築した。数学哲学においては、ハーバード大学の同僚ヒラリー・パトナムと共に、数学的実体の実在性を主張するクワイ ン=パトナムの不可欠性論証を展開した[5]。彼は「哲学は概念分析ではなく、科学と連続したものである」という見解の主要な提唱者であり、哲学は経験科 学の抽象的分科であると主張した。これが「科学哲学は哲学として十分である」という彼の有名な皮肉につながった。[6] 彼は「科学そのものの資源から科学を理解しようとする体系的な試み」[7] を主導し、「貧弱な感覚入力に基づいて我々が如何にして精巧な科学理論を発展させたか」についての「改良された科学的説明」を提供しようとする影響力ある 自然化された認識論を発展させた。[7] また、デュエム=クワイン命題として知られる科学における全体論を提唱した。 主な著作には、バートランド・ラッセルの記述理論を解明した論文『存在するものについて』(1948年)がある。この論文にはクワインの有名な「存在論的 拘束」の命題が含まれている。「存在とは変数の値であることである」という有名な格言を含む。また「経験主義の二つのドグマ」(1951年)では、伝統的な 分析的・総合的区別と還元主義を批判し、当時流行していた論理的実証主義を弱体化させ、代わりに意味論的全体論と存在論的相対性の一形態を提唱した。ま た、一種の整合主義を提唱した『信念の網』(1970年)、これらの立場をさらに発展させ、クワインの有名な「翻訳の不確定性命題」を導入し、行動主義的 な意味論を主張した『言葉と対象』(1960年)といった著作も含まれる。

| Willard Van Orman

Quine (/kwaɪn/ KWYNE; known to his friends as "Van";[3] June 25, 1908 –

December 25, 2000) was an American philosopher and logician in the

analytic tradition, recognized as "one of the most influential

philosophers of the twentieth century".[4] He was the Edgar Pierce

Chair of Philosophy at Harvard University from 1956 to 1978. Quine was a teacher of logic and set theory. He was famous for his position that first-order logic is the only kind worthy of the name, and developed his own system of mathematics and set theory, known as New Foundations. In the philosophy of mathematics, he and his Harvard colleague Hilary Putnam developed the Quine–Putnam indispensability argument, an argument for the reality of mathematical entities.[5] He was the main proponent of the view that philosophy is not conceptual analysis, but continuous with science; it is the abstract branch of the empirical sciences. This led to his famous quip that "philosophy of science is philosophy enough".[6] He led a "systematic attempt to understand science from within the resources of science itself"[7] and developed an influential naturalized epistemology that tried to provide "an improved scientific explanation of how we have developed elaborate scientific theories on the basis of meager sensory input".[7] He also advocated holism in science, known as the Duhem–Quine thesis. His major writings include the papers "On What There Is" (1948), which elucidated Bertrand Russell's theory of descriptions and contains Quine's famous dictum of ontological commitment, "To be is to be the value of a variable", and "Two Dogmas of Empiricism" (1951), which attacked the traditional analytic-synthetic distinction and reductionism, undermining the then-popular logical positivism, advocating instead a form of semantic holism and ontological relativity. They also include the books The Web of Belief (1970), which advocates a kind of coherentism, and Word and Object (1960), which further developed these positions and introduced Quine's famous indeterminacy of translation thesis, advocating a behaviorist theory of meaning. |

ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン(/kwaɪn/

クウェイン;友人からは「ヴァン」と呼ばれた[3];1908年6月25日 -

2000年12月25日)は、分析哲学の伝統に属するアメリカの哲学者・論理学者であり、「20世紀で最も影響力のある哲学者の一人」と認められている。

[4] 1956年から1978年までハーバード大学のエドガー・ピアース記念哲学教授を務めた。 クワインは論理学と集合論の教師であった。一階論理こそが論理学と呼ぶに値する唯一の論理であるという立場で有名であり、ニューファウンデーションズとし て知られる独自の数学・集合論体系を構築した。数学哲学においては、ハーバード大学の同僚ヒラリー・パトナムと共に、数学的実体の実在性を主張するクワイ ン=パトナムの不可欠性論証を展開した[5]。彼は「哲学は概念分析ではなく、科学と連続したものである」という見解の主要な提唱者であり、哲学は経験科 学の抽象的分科であると主張した。これが「科学哲学は哲学として十分である」という彼の有名な皮肉につながった。[6] 彼は「科学そのものの資源から科学を理解しようとする体系的な試み」[7] を主導し、「貧弱な感覚入力に基づいて我々が如何にして精巧な科学理論を発展させたか」についての「改良された科学的説明」を提供しようとする影響力ある 自然化された認識論を発展させた。[7] また、デュエム=クワイン命題として知られる科学における全体論を提唱した。 主な著作には、バートランド・ラッセルの記述理論を解明した論文『存在するものについて』(1948年)がある。この論文にはクワインの有名な「存在論的 拘束」の命題が含まれている。「存在とは変数の値であることである」という有名な格言を含む。また「経験主義の二つのドグマ」(1951年)では、伝統的な 分析的・総合的区別と還元主義を批判し、当時流行していた論理的実証主義を弱体化させ、代わりに意味論的全体論と存在論的相対性の一形態を提唱した。ま た、一種の整合主義を提唱した『信念の網』(1970年)、これらの立場をさらに発展させ、クワインの有名な「翻訳の不確定性命題」を導入し、行動主義的 な意味論を主張した『言葉と対象』(1960年)といった著作も含まれる。 |

| Biography Quine's parents were Robert Cloyd Quine and Harriet Ellis Van Orman. Quine grew up in Akron, Ohio, where he lived with his parents and older brother Robert Cloyd. His father was a manufacturing entrepreneur (founder of the Akron Equipment Company, which produced tire molds) and his mother was a schoolteacher and housewife.[8][3] Quine became an atheist around the age of 9[9] and remained one for the rest of his life.[10] Education Quine received his B.A., summa cum laude, in mathematics from Oberlin College in 1930, and his Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard University in 1932. His thesis supervisor was Alfred North Whitehead. He was then appointed a Harvard Junior Fellow, which excused him from having to teach for four years. During the academic year 1932–33, he travelled in Europe thanks to a Sheldon Fellowship, meeting Polish logicians (including Jan Łukasiewicz, Stanislaw Lesniewski and Alfred Tarski) and members of the Vienna Circle (including Rudolf Carnap), as well as the logical positivist A. J. Ayer.[3] It was in Prague that Quine developed a passion for philosophy, thanks to Carnap, whom he called his "true and only maître à penser".[11] World War II Quine arranged for Tarski to be invited to the September 1939 Unity of Science Congress in Cambridge, for which the Jewish Tarski sailed on the last ship to leave Danzig before Nazi Germany invaded Poland and triggered World War II. Tarski survived the war and worked another 44 years in the US. During the war, Quine lectured on logic in Brazil, in Portuguese, and served in the United States Navy in a military intelligence role, deciphering messages from German submarines, and reaching the rank of lieutenant commander.[3] Quine could lecture in French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish as well as his native English. Personal He had four children by two marriages.[3] Guitarist Robert Quine was his nephew. Quine was politically conservative, but the bulk of his writing was in technical areas of philosophy removed from direct political issues.[12] He did, however, write in defense of several conservative positions: for example, he wrote in defense of moral censorship;[13] while, in his autobiography, he made some criticisms of American postwar academics.[14][15] Harvard At Harvard, Quine helped supervise the Harvard graduate theses of, among others, David Lewis, Gilbert Harman, Dagfinn Føllesdal, Hao Wang, Hugues LeBlanc, Henry Hiz and George Myro. For the academic year 1964–1965, Quine was a fellow on the faculty in the Center for Advanced Studies at Wesleyan University.[16] In 1980 Quine received an honorary doctorate from the Faculty of Humanities at Uppsala University, Sweden.[17] Quine's student Dagfinn Føllesdal noted that Quine suffered from memory loss towards his final years. The deterioration of his short-term memory was so severe that he struggled to continue following arguments. Quine also had considerable difficulty in his project to make the desired revisions to Word and Object. Before dying, Quine noted to Morton White: "I do not remember what my illness is called, Althusser or Alzheimer, but since I cannot remember it, it must be Alzheimer." He died from the illness on Christmas Day in 2000.[18][19] |

伝記 クワインの両親はロバート・クロイド・クワインとハリエット・エリス・ヴァン・オーマンであった。クワインはオハイオ州アクロンで育ち、両親と兄のロバー ト・クロイドと共に暮らした。父親は製造業の起業家(タイヤ金型を製造するアクロン・イクイップメント社の創業者)であり、母親は教師兼主婦であった。 [8][3] クワインは9歳頃に無神論者となり[9]、その後生涯を通じてその立場を貫いた。[10] 学歴 クワインは1930年にオベリン大学で数学の学士号を最優等で取得し、1932年にはハーバード大学で哲学の博士号を取得した。博士論文の指導教官はアル フレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドであった。その後ハーバード大学ジュニアフェローに任命され、4年間教職を免除された。1932-33年度にはシェルド ン奨学金を得てヨーロッパを旅行し、ポーランドの論理学者(ヤン・ウカシェヴィチ、スタニスワフ・レスニェフスキ、アルフレッド・タルスキら)、ウィーン 学派のメンバー(ルドルフ・カルナップら)、論理実証主義者のA・J・エアヤーらと交流した。[3] クワインが哲学への情熱を育んだのはプラハであった。彼自身が「真の唯一の師」と呼んだカルナップの影響によるものである。[11] 第二次世界大戦 クワインは1939年9月にケンブリッジで開催された「科学の統一」会議へタルスキを招待するよう手配した。ユダヤ人であるタルスキは、ナチス・ドイツが ポーランド侵攻を開始し第二次世界大戦を引き起こす直前、ダンツィヒを出航した最後の船で渡航した。タルスキは戦争を生き延び、その後44年間アメリカで 研究を続けた。戦争中、クワインはブラジルでポルトガル語による論理学講義を行い、アメリカ海軍では軍事諜報担当としてドイツ潜水艦の暗号解読に従事し、 中佐の階級に達した[3]。クワインは母国語である英語に加え、フランス語、ドイツ語、イタリア語、ポルトガル語、スペイン語でも講義できた。 彼は 2 回の結婚で 4 人の子供を持っていた。ギタリストのロバート・クワインは彼の甥である。 クワインは政治的には保守的だったが、彼の著作の大部分は、直接的な政治問題から離れた哲学の技術的な分野に関するものだった。しかし、彼はいくつかの保 守的な立場を擁護する文章も書いた。例えば、道徳的検閲を擁護する文章を書いた。一方、自伝では、アメリカの戦後の学者たちを批判している。 [14][15] ハーバード ハーバード大学では、クワインは、とりわけ、デイヴィッド・ルイス、ギルバート・ハーマン、ダグフィン・フォレスダル、ハオ・ワン、ヒュー・ルブラン、ヘ ンリー・ヒズ、ジョージ・マイロらのハーバード大学の卒業論文の指導を監督した。1964年から1965年の学年度、クワインはウェズリーアン大学高等研 究センターの教員フェローを務めた。[16] 1980年、クワインはスウェーデン、ウプサラ大学人文科学部から名誉博士号を授与された。[17] クワインの学生だったダグフィン・フォレスダルは、クワインが晩年に記憶喪失の苦悩に悩まされていたと記している。彼の短期記憶の衰えはひどく、議論につ いていくのに苦労していた。クワインはまた、『言葉と対象』の改訂作業にもかなりの困難を抱えていた。死の前に、クワインはモートン・ホワイトにこう語っ た。「自分の病気がアルチュセールかアルツハイマーか、その名称は覚えていない。しかし、覚えていないということは、アルツハイマーに違いない」。彼は 2000年のクリスマスにこの病気で亡くなった。 |

| Work Quine's Ph.D. thesis and early publications were on formal logic and set theory. Only after World War II did he, by virtue of seminal papers on ontology, epistemology and language, emerge as a major philosopher. By the 1960s, he had worked out his "naturalized epistemology" whose aim was to answer all substantive questions of knowledge and meaning using the methods and tools of the natural sciences. Quine roundly rejected the notion that there should be a "first philosophy," a theoretical standpoint somehow prior to natural science and capable of justifying it. These views are intrinsic to his naturalism. Like the majority of analytic philosophers, who were mostly interested in systematic thinking, Quine evinced little interest in the philosophical canon: only once did he teach a course in the history of philosophy, on David Hume, in 1946.[20][clarification needed] Logic Over the course of his career, Quine published numerous technical and expository papers on formal logic, some of which are reprinted in his Selected Logic Papers and in The Ways of Paradox. His most well-known collection of papers is From A Logical Point of View. Quine confined logic to classical bivalent first-order logic, hence to truth and falsity under any (nonempty) universe of discourse. Hence the following were not logic for Quine: Higher-order logic and set theory. He referred to higher-order logic as "set theory in disguise"; Much of what Principia Mathematica included in logic was not logic for Quine. Formal systems involving intensional notions, especially modality. Quine was especially hostile to modal logic with quantification, a battle he largely lost when Saul Kripke's relational semantics became canonical for modal logics. Quine wrote three undergraduate texts on formal logic: Elementary Logic. While teaching an introductory course in 1940, Quine discovered that extant texts for philosophy students did not do justice to quantification theory or first-order predicate logic. Quine wrote this book in 6 weeks as an ad hoc solution to his teaching needs. Methods of Logic. The four editions of this book resulted from a more advanced undergraduate course in logic Quine taught from the end of World War II until his 1978 retirement. Philosophy of Logic. A concise and witty undergraduate treatment of a number of Quinian themes, such as the prevalence of use-mention confusions, the dubiousness of quantified modal logic, and the non-logical character of higher-order logic. Mathematical Logic is based on Quine's graduate teaching during the 1930s and 1940s. It shows that much of what Principia Mathematica took more than 1000 pages to say can be said in 250 pages. The proofs are concise, even cryptic. The last chapter, on Gödel's incompleteness theorem and Tarski's indefinability theorem, along with the article Quine (1946), became a launching point for Raymond Smullyan's later lucid exposition of these and related results. Quine's work in logic gradually became dated in some respects. Techniques he did not teach and discuss include analytic tableaux, recursive functions, and model theory. His treatment of metalogic left something to be desired. For example, Mathematical Logic does not include any proofs of soundness and completeness. Early in his career, the notation of his writings on logic was often idiosyncratic. His later writings nearly always employed the now-dated notation of Principia Mathematica. Set against all this are the simplicity of his preferred method (as exposited in his Methods of Logic) for determining the satisfiability of quantified formulas, the richness of his philosophical and linguistic insights, and the fine prose in which he expressed them. Most of Quine's original work in formal logic from 1960 onwards was on variants of his predicate functor logic, one of several ways that have been proposed for doing logic without quantifiers. For a comprehensive treatment of predicate functor logic and its history, see Quine (1976). For an introduction, see ch. 45 of his Methods of Logic. Quine was very warm to the possibility that formal logic would eventually be applied outside of philosophy and mathematics. He wrote several papers on the sort of Boolean algebra employed in electrical engineering, and with Edward J. McCluskey, devised the Quine–McCluskey algorithm of reducing Boolean equations to a minimum covering sum of prime implicants. |

仕事 クワインの博士論文と初期の著作は形式論理学と集合論に関するものだった。第二次世界大戦後になって初めて、彼は存在論・認識論・言語論に関する画期的な 論文によって主要な哲学者の一人として頭角を現した。1960年代までに、彼は「自然化された認識論」を確立した。その目的は、自然科学の方法と道具を用 いて、知識と意味に関するあらゆる本質的な問いに答えることだった。クワインは「第一哲学」という概念、すなわち自然科学に何らかの形で先行し、それを正 当化できる理論的立場が存在すべきだという考えを徹底的に否定した。これらの見解は彼の自然主義に内在するものである。 体系的な思考に主に興味を持っていた分析哲学者の大多数と同様に、クワインは哲学の古典に対してほとんど関心を示さなかった。彼が哲学史の講義を行ったの は、1946年にデイヴィッド・ヒュームについて行った一度きりである。[20][clarification needed] 論理学 クワインはキャリアを通じて、形式論理学に関する数多くの技術的・解説的論文を発表した。その一部は『選集:論理論文集』および『パラドクスの諸相』に再 録されている。彼の最も有名な論文集は『論理的観点から』である。クワインは論理を古典的二値一階論理、すなわち(空でない)言説の領域における真偽に限 定した。したがって以下はクワインにとって論理ではなかった: 高階論理と集合論。彼は高階論理を「変装した集合論」と呼んだ。 『プリンキピア・マテマティカ』が論理学として扱った内容の多くは、クワインにとって論理学ではなかった。 内包的概念、特に様態論理を含む形式体系。クワインは特に量化を伴う様態論理に敵対的だったが、ソール・クリプキの関係的意味論が様態論理の標準的解釈となると、この戦いはほぼ敗北した。 クワインは形式論理学に関する学部生向け教科書を三冊執筆した: 初等論理学。1940年に入門講座を教える際、クワインは哲学学生向けの既存教科書が量化理論や一階述語論理を適切に扱っていないことに気づいた。この本は6週間で執筆され、教鞭を執る上での即席の解決策となった。 論理学の方法。この本の四版は、第二次世界大戦終結から1978年の引退までクワインが教えた上級学部生向け論理学講座から生まれた。 『論理哲学』。使用と言及の混同の蔓延、量化モダロジックの疑わしさ、高階論理の非論理的性格など、クワインの諸テーマを簡潔かつ機知に富んだ学部生向け解説で扱う。 『数学的論理学』は1930~40年代のクワインの大学院講義に基づく。本書は『プリンキピア・マテマティカ』が1000ページ以上かけて述べた内容の多 くが、250ページで表現可能であることを示している。証明は簡潔で、時に暗号的だ。最終章で扱うゲーデルの不完全性定理とタルスキの不定性定理は、クワ イン(1946)の論文と共に、レイモンド・スマリアンが後にこれらの結果を明快に解説する出発点となった。 クワインの論理学における業績は、いくつかの点で次第に時代遅れとなった。彼が教えず議論しなかった手法には、解析的表、再帰関数、モデル理論が含まれ る。メタ論理の扱いにも不十分な点があった。例えば『数学的論理学』には、妥当性と完全性の証明が一切含まれていない。キャリア初期の論理学著作における 記法はしばしば特異であった。後期の著作ではほぼ例外なく『プリンキピア・マテマティカ』の現在では時代遅れとなった記法が用いられた。これらに対比され るのは、量化定式を満たすか否かを判定する彼の好んだ方法(『論理学の方法』で展開された)の簡潔さ、彼の哲学的・言語学的洞察の豊かさ、そしてそれらを 表現した優れた文章力である。 1960年以降のクワインの形式論理学における独創的な研究の大半は、述語ファンクター論理の変種に関するものであった。これは量化子を用いずに論理を構 築する複数の手法の一つである。述語ファンクター論理とその歴史に関する包括的な考察はクワイン(1976)を参照のこと。入門編としては『論理の方法』 第45章を参照されたい。 クワインは、形式論理学が最終的に哲学や数学の領域外で応用される可能性を非常に温かく迎えた。電気工学で用いられるブール代数に関する論文を数本執筆 し、エドワード・J・マクラスキーと共に、ブール方程式を最小のプライムインプリカントの和に還元するクワイン=マクラスキーアルゴリズムを考案した。 |

| Set theory While his contributions to logic include elegant expositions and a number of technical results, it is in set theory that Quine was most innovative. He always maintained that mathematics required set theory and that set theory was quite distinct from logic. He flirted with Nelson Goodman's nominalism for a while[21] but backed away when he failed to find a nominalist grounding of mathematics.[22] Over the course of his career, Quine proposed three axiomatic set theories. New Foundations, NF, creates and manipulates sets using a single axiom schema for set admissibility, namely an axiom schema of stratified comprehension, whereby all individuals satisfying a stratified formula compose a set. A stratified formula is one that type theory would allow, were the ontology to include types. However, Quine's set theory does not feature types. The metamathematics of NF are curious. NF allows many "large" sets the now-canonical ZFC set theory does not allow, even sets for which the axiom of choice does not hold. Since the axiom of choice holds for all finite sets, the failure of this axiom in NF proves that NF includes infinite sets. The consistency of NF relative to other formal systems adequate for mathematics is an open question, albeit that a number of candidate proofs are current in the NF community suggesting that NF is equiconsistent with Zermelo set theory without Choice. A modification of NF, NFU, due to R. B. Jensen and admitting urelements (entities that can be members of sets but that lack elements), turns out to be consistent relative to Peano arithmetic, thus vindicating the intuition behind NF. NF and NFU are the only Quinean set theories with a following. For a derivation of foundational mathematics in NF, see Rosser (1952); The set theory of Mathematical Logic is NF augmented by the proper classes of von Neumann–Bernays–Gödel set theory, except axiomatized in a much simpler way; The set theory of Set Theory and Its Logic does away with stratification and is almost entirely derived from a single axiom schema. Quine derived the foundations of mathematics once again. This book includes the definitive exposition of Quine's theory of virtual sets and relations, and surveyed axiomatic set theory as it stood circa 1960. All three set theories admit a universal class, but since they are free of any hierarchy of types, they have no need for a distinct universal class at each type level. Quine's set theory and its background logic were driven by a desire to minimize posits; each innovation is pushed as far as it can be pushed before further innovations are introduced. For Quine, there is but one connective, the Sheffer stroke, and one quantifier, the universal quantifier. All polyadic predicates can be reduced to one dyadic predicate, interpretable as set membership. His rules of proof were limited to modus ponens and substitution. He preferred conjunction to either disjunction or the conditional, because conjunction has the least semantic ambiguity. He was delighted to discover early in his career that all of first order logic and set theory could be grounded in a mere two primitive notions: abstraction and inclusion. For an elegant introduction to the parsimony of Quine's approach to logic, see his "New Foundations for Mathematical Logic", ch. 5 in his From a Logical Point of View. |

集合論 論理学への貢献としては、優雅な解説や数多くの技術的な成果があるが、クワインが最も革新的な成果を上げたのは集合論の分野である。彼は、数学には集合論 が必要であり、集合論は論理学とはまったく別物であると常に主張していた。彼は、ネルソン・グッドマンの唯名論にしばらく傾倒したが[21]、数学の唯名 論的基礎を見出せなかったため、その考えから距離を置いた[22]。 クワインは、そのキャリアの中で、3つの公理的集合論を提案した。 新基礎論(NF)は、集合の許容性について単一の公理スキーマ、すなわち層別理解の公理スキーマを用いて集合を作成および操作する。これにより、層別定式 を満たすすべての個体が集合を構成する。階層化された定式とは、存在論に型が含まれている場合、型理論が許容する定式である。しかし、クワインの集合論は 型を特徴としていない。NF のメタ数学は興味深い。NF は、現在標準的な ZFC 集合論では許容されない多くの「大きな」集合、選択公理が成立しない集合さえも許容する。選択公理は有限集合に対しては成立する。ゆえにNFにおけるこの 公理の不成立は、NFが無限集合を含むことを証明する。数学に適した他の形式体系に対するNFの一貫性は未解決問題である。とはいえ、NFコミュニティで は現在、NFが選択公理を伴わないツェルメロ集合論と同等の一貫性を持つことを示唆する複数の候補証明が存在する。R. B. ジェンセンによるNFの修正形NFUは、集合の要素となり得るがそれ自体を要素としない「ウレメント」を認める。このNFUはペアーノ算術に対して整合的 であることが判明し、NFの背後にある直観を正当化した。NFとNFUは、支持者を持つ唯一のクワイン的集合論である。NFにおける基礎数学の導出につい ては、ロッサー(1952)を参照のこと。 『数学的論理の集合論』は、フォン・ノイマン=ベルナイス=ゲーデル集合論の真類を付加したNFであるが、公理化の方法がはるかに簡素化されている。 『集合論とその論理』の集合論は層化を廃し、ほぼ単一の公理化スキマから導出される。クワインは再び数学の基礎を導出したのである。本書はクワインの仮想集合と関係に関する決定的な解説を含み、1960年頃の公理的集合論の現状を概観している。 これら三つの集合論はいずれも普遍クラスを認めるが、型階層を一切持たないため、各型レベルごとに個別の普遍クラスを必要としない。 クワインの集合論とその背景にある論理は、仮定を最小限に抑えたいという願望によって推進された。各革新は、さらなる革新が導入される前に可能な限り推し 進められる。クワインにとって、接続詞はシェファーのストローク(∧)一つ、量化詞は全称量化詞一つだけである。すべての多項述語は、集合の所属関係とし て解釈可能な二項述語一つに還元できる。彼の証明規則は、モダスポネン(帰納法)と置換に限定されていた。彼は、意味論的曖昧性が最も少ないという理由 で、選択や条件文よりも接続を好んだ。キャリアの早い段階で、一階論理と集合論の全てが、抽象化と包含という二つの原始概念のみで基盤づけられることを発 見し、彼は大いに喜んだ。クワインの論理へのアプローチの簡潔さについて、洗練された入門として、彼の『論理的観点から』第5章「数学的論理学の新基礎」 を参照されたい。 |

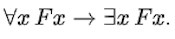

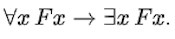

| Metaphysics Quine has had numerous influences on contemporary metaphysics. He coined the term "abstract object".[23] In his famous essay "On What There Is", he connected each of the three main metaphysical ontological positions—realism/conceptualism/nominalism—with one of three dominant schools in the modern philosophy of mathematics: logicism, intuitionism, and formalism respectively. In the same work, he coined the term "Plato's beard" to refer to the problem of empty names: Suppose now that two philosophers, McX and I, differ over ontology. Suppose McX maintains there is something which I maintain there is not. McX can, quite consistently with his own point of view, describe our difference of opinion by saying that I refuse to recognize certain entities ... When I try to formulate our difference of opinion, on the other hand, I seem to be in a predicament. I cannot admit that there are some things which McX countenances and I do not, for in admitting that there are such things I should be contradicting my own rejection of them ... This is the old Platonic riddle of nonbeing. Nonbeing must in some sense be, otherwise what is it that there is not? This tangled doctrine might be nicknamed Plato's beard; historically it has proved tough, frequently dulling the edge of Occam’s razor.[24][25] Quine was unsympathetic, however, to the claim that saying 'X does not exist' is a tacit acceptance of X's existence and, thus, a contradiction. Appealing to Bertrand Russell and his theory of "singular descriptions", Quine explains how Russell was able to make sense of "complex descriptive names" ('the present King of France', 'the author of Waverly', etc.) by thinking about them as merely "fragments of the whole sentences". For example, 'The author of Waverly was a poet' becomes 'some thing is such that it is the author of Waverly and was a poet, and nothing else is such that it is the author of Waverly'.[26] Using this sort of analysis with the word 'Pegasus' (that which Quine is wanting to assert does not exist), he turns Pegasus into a description. Turning the word 'Pegasus' into a description is to turn 'Pegasus' into a predicate, to use a term of First-order logic: i.e. a property. As such, when we say 'Pegasus', we are really saying 'the thing that is Pegasus' or 'the thing that Pegasizes'. This introduces, to use another term from logic, bound variables (ex: 'everything', 'something,' etc.) As Quine explains, bound variables, "far from purporting to be names specifically...do not purport to be names at all: they refer to entities generally, with a kind of studied ambiguity peculiar to themselves."[27] Putting it another way, to say 'I hate everything' is a very different statement than saying 'I hate Bertrand Russell', because the words 'Bertrand Russell' are a proper name that refer to a very specific person. Whereas the word 'everything' is a placeholder. It does not refer to a specific entity or entities. Quine is able, therefore, to make a meaningful claim about Pegasus' nonexistence for the simple reason that the placeholder (a thing) happens to be empty. It just so happens that the world does not contain a thing that is such that it is winged and it is a horse. Rejection of the analytic–synthetic distinction See also: Two Dogmas of Empiricism In the 1930s and 40s, discussions with Rudolf Carnap, Nelson Goodman and Alfred Tarski, among others, led Quine to doubt the tenability of the distinction between "analytic" statements[28]—those true simply by the meanings of their words, such as "No bachelor is married"— and "synthetic" statements, those true or false by virtue of facts about the world, such as "There is a cat on the mat."[29] This distinction was central to logical positivism. Although Quine is not normally associated with verificationism, some philosophers believe the tenet is not incompatible with his general philosophy of language, citing his Harvard colleague B. F. Skinner and his analysis of language in Verbal Behavior.[30] But Quine believes, with all due respect to his "great friend"[31] Skinner, that the ultimate reason is to be found in neurology and not in behavior. For him, behavioral criteria establish only the terms of the problem, the solution of which, however, lies in neurology.[31] Like other analytic philosophers before him, Quine accepted the definition of "analytic" as "true in virtue of meaning alone." Unlike them, however, he concluded that ultimately the definition was circular. In other words, Quine accepted that analytic statements are those that are true by definition, then argued that the notion of truth by definition was unsatisfactory. Quine's chief objection to analyticity is with the notion of cognitive synonymy (sameness of meaning). He argues that analytical sentences are typically divided into two kinds; sentences that are clearly logically true (e.g. "no unmarried man is married") and the more dubious ones; sentences like "no bachelor is married." Previously it was thought that if you can prove that there is synonymity between "unmarried man" and "bachelor," you have proved that both sentences are logically true and therefore self evident. Quine however gives several arguments for why this is not possible, for instance that "bachelor" in some contexts means a Bachelor of Arts, not an unmarried man.[32] Confirmation holism and ontological relativity Colleague Hilary Putnam called Quine's indeterminacy of translation thesis "the most fascinating and the most discussed philosophical argument since Kant's Transcendental Deduction of the Categories".[33] The central theses underlying it are ontological relativity and the related doctrine of confirmation holism. The premise of confirmation holism is that all theories (and the propositions derived from them) are under-determined by empirical data (data, sensory-data, evidence); although some theories are not justifiable, failing to fit with the data or being unworkably complex, there are many equally justifiable alternatives. While the Greeks' assumption that (unobservable) Homeric gods exist is false and our supposition of (unobservable) electromagnetic waves is true, both are to be justified solely by their ability to explain our observations. The gavagai thought experiment tells about a linguist, who tries to find out, what the expression gavagai means, when uttered by a speaker of a yet unknown, native language upon seeing a rabbit. At first glance, it seems that gavagai simply translates with rabbit. Now, Quine points out that the background language and its referring devices might fool the linguist here, because he is misled in a sense that he always makes direct comparisons between the foreign language and his own. However, when shouting gavagai, and pointing at a rabbit, the natives could as well refer to something like undetached rabbit-parts, or rabbit-tropes and it would not make any observable difference. The behavioural data the linguist could collect from the native speaker would be the same in every case, or to reword it, several translation hypotheses could be built on the same sensoric stimuli. Quine concluded his "Two Dogmas of Empiricism" as follows: As an empiricist I continue to think of the conceptual scheme of science as a tool, ultimately, for predicting future experience in the light of past experience. Physical objects are conceptually imported into the situation as convenient intermediaries not by definition in terms of experience, but simply as irreducible posits comparable, epistemologically, to the gods of Homer …. For my part I do, qua lay physicist, believe in physical objects and not in Homer's gods; and I consider it a scientific error to believe otherwise. But in point of epistemological footing, the physical objects and the gods differ only in degree and not in kind. Both sorts of entities enter our conceptions only as cultural posits. Quine's ontological relativism (evident in the passage above) led him to agree with Pierre Duhem that for any collection of empirical evidence, there would always be many theories able to account for it, known as the Duhem–Quine thesis. However, Duhem's holism is much more restricted and limited than Quine's. For Duhem, underdetermination applies only to physics or possibly to natural science, while for Quine it applies to all of human knowledge. Thus, while it is possible to verify or falsify whole theories, it is not possible to verify or falsify individual statements. Almost any particular statement can be saved, given sufficiently radical modifications of the containing theory. For Quine, scientific thought forms a coherent web in which any part could be altered in the light of empirical evidence, and in which no empirical evidence could force the revision of a given part. Existence and its contrary The problem of non-referring names is an old puzzle in philosophy, which Quine captured when he wrote, A curious thing about the ontological problem is its simplicity. It can be put into three Anglo-Saxon monosyllables: 'What is there?' It can be answered, moreover, in a word—'Everything'—and everyone will accept this answer as true.[24] More directly, the controversy goes: How can we talk about Pegasus? To what does the word 'Pegasus' refer? If our answer is, 'Something', then we seem to believe in mystical entities; if our answer is, 'nothing', then we seem to talk about nothing and what sense can be made of this? Certainly when we said that Pegasus was a mythological winged horse we make sense, and moreover we speak the truth! If we speak the truth, this must be truth about something. So we cannot be speaking of nothing. Quine resists the temptation to say that non-referring terms are meaningless for reasons made clear above. Instead he tells us that we must first determine whether our terms refer or not before we know the proper way to understand them. However, Czesław Lejewski criticizes this belief for reducing the matter to empirical discovery when it seems we should have a formal distinction between referring and non-referring terms or elements of our domain. Lejewski writes further: This state of affairs does not seem to be very satisfactory. The idea that some of our rules of inference should depend on empirical information, which may not be forthcoming, is so foreign to the character of logical inquiry that a thorough re-examination of the two inferences [existential generalization and universal instantiation] may prove worth our while. Lejewski then goes on to offer a description of free logic, which he claims accommodates an answer to the problem. Lejewski also points out that free logic additionally can handle the problem of the empty set for statements like  Quine had considered the problem of the empty set unrealistic, which left Lejewski unsatisfied.[34] |

形而上学 クワインは現代形而上学に多大な影響を与えた。彼は「抽象的対象」という用語を提唱した。[23] 彼の有名な論文「存在するものについて」では、三つの主要な形而上学的実在論的立場——実在論/概念論/唯名論——を、それぞれ現代数学哲学における三つ の主要学派——論理主義、直観主義、形式主義——と結びつけた。同じ著作で、彼は「プラトンのひげ」という用語を空虚な名称の問題を指すために造語した: さて、二人の哲学者、マクXと私が存在論で異なる意見を持っているとしよう。マクXは私が存在しないと主張する何かが存在すると主張しているとしよう。マ クXは、自らの立場と全く矛盾することなく、私たちの意見の相違を「私が特定の存在を認めようとしない」と述べることで説明できる... 一方、私が意見の相違を表現しようとすると、困難に直面する。マクエックスが認めていて私が認めない何かが存在すると認めることはできない。なぜなら、そ のようなものが存在すると認めることは、私がそれらを拒否しているという自らの立場と矛盾するからだ…これはプラトン的な非存在の古い難問である。非存在 はある意味で存在しなければならない。さもなければ、存在しないとは一体何を指すのか?この複雑な教義は「プラトンの顎鬚」と揶揄されることもある。歴史 的に見て、この教義は頑強であり、しばしばオッカムの剃刀の切れ味を鈍らせてきた。[24][25] しかしクワインは、「Xは存在しない」と言うことがXの存在を暗黙裡に認めることになり、したがって矛盾であるという主張には同調しなかった。クワインは バートランド・ラッセルとその「単数記述」理論に言及し、ラッセルが「複合記述名」(『現在のフランス国王』、『ウェイヴァリーの著者』など)を単なる 「文全体の断片」として考えることで、それらに意味を持たせることができたと説明する。例えば、「『ウェイバリー』の著者は詩人であった」という文は、 「あるものが『ウェイバリー』の著者であり詩人であったという性質を持ち、他のいかなるものも『ウェイバリー』の著者であるという性質を持たない」という 文に分解される。[26] クワインが存在しないと主張したい「ペガサス」という語に対しても、この種の分析を適用することで、彼はペガサスを記述に変換する。「ペガサス」という語 を記述に変えるとは、一階論理の用語で言えば「ペガサス」を述語、すなわち性質に変えることだ。したがって「ペガサス」と言うとき、我々は実際には「ペガ サスであるもの」あるいは「ペガサス化するもの」と言っていることになる。これは論理学の別の用語で言えば、束縛変数(例:「あらゆるもの」、「何か」な ど)を導入する。クワインが説明するように、束縛変数は「特定の名前を装うどころか…名前を装うことすらない。それらは一般に実体を指し示すが、それ自体 に特有の、ある種の意図的な曖昧さをもって指し示すのである」[27]。 言い換えれば、「俺は全てが嫌いだ」と言うことと「俺はバートランド・ラッセルが嫌いだ」と言うことは全く異なる主張だ。なぜなら「バートランド・ラッセ ル」という語は特定の人格を指す固有名詞だからだ。一方「全て」という語は単なる置き換え表現である。特定の存在を指すわけではない。したがって、クワイ ンは、その代用記号(物)がたまたま空である、という単純な理由から、ペガサスの非存在について意味のある主張をすることができる。たまたま、世界には、 翼があり、かつ馬であるようなものは存在しないのだ。 分析的・総合的区別の否定 参照:経験主義の二つの教義 1930年代から40年代にかけて、ルドルフ・カルナップ、ネルソン・グッドマン、アルフレッド・タルスキらとの議論を通じて、クワインは「分析的」命題 [28](例えば「独身者は結婚していない」など、その言葉の意味によって単に真となるもの)と「総合的」命題(例えば「マットの上に猫がいる」など、世 界に関する事実によって真または偽となるもの)の区別の妥当性に疑問を抱くようになった。この区別は、論理実証主義の中心的な考え方であった。クワインは 通常、検証主義とは関連付けられないが、ハーバード大学の同僚である B. F. スキナーと、その著書『言語行動』における言語分析を引用し、この教義はクワインの一般的な言語哲学と矛盾しないとする哲学者もいる。[30] しかしクワインは、敬愛する「偉大な友人」[31] スキナーへの敬意を払いつつ、究極の理由は行動学ではなく神経学に求められると考える。彼にとって行動基準は問題の枠組みを定めるに過ぎず、その解決は神 経学にこそある。[31] クワインは、彼以前の他の分析哲学者たちと同様に、「分析的」を「意味のみによって真である」と定義することを受け入れた。しかし彼らとは異なり、彼は最 終的にこの定義が循環的であると結論づけた。つまりクワインは、分析的命題とは定義によって真であるものだと認めつつ、定義による真という概念自体が不十 分だと主張したのである。 クワインが分析性に対して主に異議を唱えるのは、認知的同義性(意味の同一性)という概念である。彼は分析的文は典型的に二種類に分けられると論じる。一 つは明らかに論理的に真である文(「未婚の男性は結婚していない」など)、もう一つはより疑わしい文(「独身者は結婚していない」など)である。従来は、 「未婚の男性」と「独身者」の間に同義性が存在することを証明できれば、両文が論理的に真であり自明であることを証明したと考えられていた。しかしクワイ ンは、例えば「独身者」が文脈によっては学士号(Bachelor of Arts)を意味し未婚の男性を意味しないことなど、これが不可能である理由を幾つか論じた。[32] 確認の全体論と存在論的相対性 同僚のヒラリー・パトナムは、クワインの翻訳不確定性命題を「カントの『超越論的範疇演繹』以来、最も魅力的で最も議論された哲学的議論」と呼んだ。 [33] その根底にある中心的な命題は、存在論的相対性と関連する確認の全体論である。確認の全体論の前提は、全ての理論(およびそこから導かれる命題)が経験的 データ(データ、感覚データ、証拠)によって決定不足であるということだ。一部の理論はデータと合致しない、あるいは実用的に複雑すぎて正当化できない が、同様に正当化可能な代替案は多数存在する。ギリシャ人が(観察不可能な)ホメロスの神々の存在を仮定したことは誤りであり、我々が(観察不可能な)電 磁波の存在を仮定することは正しいが、どちらも単に我々の観察を説明できる能力によってのみ正当化される。 ガヴァガイ思考実験は、未知の土着語を話す者がウサギを見て発した「ガヴァガイ」という表現の意味を解明しようとする言語学者を描く。一見すると「ガヴァ ガイ」は単に「ウサギ」と訳されるように思える。ここでクワインは、背景言語とその参照装置が言語学者を欺く可能性を指摘する。なぜなら彼は常に外国語と 自国語を直接比較するという誤った方向へ導かれるからだ。しかし、ガヴァガイと叫びながらウサギを指さす時、原住民は「分離されていないウサギの部位」や 「ウサギのトロープ」のようなものを指している可能性もあり、観察可能な差異は生じない。言語学者が原住民から収集できる行動データは、いずれの場合も同 一となる。言い換えれば、同一の感覚刺激に対して複数の翻訳仮説が構築可能なのである。 クワインは「経験主義の二つの教条」を次のように結んだ: 経験主義者として、私は科学の概念体系を、究極的には過去の経験に照らして未来の経験を予測するための道具と捉え続けている。物理的対象は、経験に基づく 定義によってではなく、単に還元不可能な仮定として、認識論的にはホメロスの神々に匹敵する便利な仲介者として状況に概念的に導入されるのだ…。私個人と しては、素人の物理学者として、ホメロスの神々ではなく物理的実体を信じている。そうでないことを信じるのは科学的誤りだと考える。しかし認識論的立場に おいて、物理的実体と神々の違いは程度の問題であって本質的な差異ではない。両者の実体は、文化的な仮定としてのみ我々の概念に入り込むのだ。 クワインの存在論的相対主義(上記の文章に明らかである)は、彼をピエール・デュエムに同意させるに至った。すなわち、いかなる経験的証拠の集合に対して も、それを説明しうる理論は常に複数存在するという、デュエム=クワインの命題として知られる主張である。しかしデュエムの全体論は、クワインのそれより もはるかに限定的かつ制約されている。デュエムにとって、決定不足は物理学あるいはおそらく自然科学にのみ適用される。一方クワインにとっては、それは人 間の知識全体に適用される。したがって、理論全体を検証したり反証したりすることは可能だが、個々の命題を検証したり反証したりすることは不可能である。 包含理論を十分に根本的に修正すれば、ほぼあらゆる個別の命題は救済可能だ。クワインによれば、科学的思考は一貫した網の目を形成しており、そのどの部分 も経験的証拠に基づいて変更可能であり、またどの経験的証拠も特定の部分の修正を強制することはできない。 存在とその否定 非参照名の問題は哲学における古い難問であり、クワインは次のように記述してこれを捉えた。 存在論的問題の奇妙な点は、その単純さにある。それは三つの単音節の英語で表せる:「何があるか?」さらに一言で答えられる——「全て」——そして誰もがこの答えを真実として受け入れるだろう。[24] より直接的に言えば、論争はこう展開する: ペガサスについてどう語れるのか?「ペガサス」という言葉は何を指すのか?もし答えが「何か」なら、我々は神秘的な実体を信じているように見える。もし答 えが「何もない」なら、我々は無について語っているように見え、これはどういう意味を持つのか?確かに、ペガサスが神話の翼のある馬だと言う時、我々の言 葉は意味を成し、さらに真実を語っているのだ!真実を語っているなら、それは何かについての真実でなければならない。だから我々は無について語っているわ けにはいかない。 クワインは、上述の理由から、非参照用語は無意味だと言う誘惑に抵抗する。代わりに彼は、用語が参照するか否かをまず確定しなければ、その正しい理解方法 を知り得ないと説く。しかしチェスワフ・レジェフスキは、参照用語と非参照用語(あるいは対象領域の要素)を形式的に区別すべきなのに、この考えが問題を 経験的発見に還元すると批判する。レジェフスキはさらにこう記す: この状況はあまり満足のいくものではない。推論規則の一部が、入手困難な経験的情報に依存すべきだという考えは、論理的探究の本質にあまりにも反するため、二つの推論[存在一般化と全称具体化]を徹底的に再検討する価値があるかもしれない。 その後、レジェフスキは自由論理の説明を提示し、これが問題への解答を可能にすると主張する。 レジェフスキはさらに、自由論理が空集合の問題も扱えると指摘する。例えば次のような命題について:  のような文における空集合の問題も扱えると主張する。クワインは空集合の問題を非現実的と考えていたが、これはレジェフスキを満足させなかった。[34] |

| Ontological commitment The notion of ontological commitment plays a central role in Quine's contributions to ontology.[35][36] A theory is ontologically committed to an entity if that entity must exist in order for the theory to be true.[37] Quine proposed that the best way to determine this is by translating the theory in question into first-order predicate logic. Of special interest in this translation are the logical constants known as existential quantifiers ('∃'), whose meaning corresponds to expressions like "there exists..." or "for some...". They are used to bind the variables in the expression following the quantifier.[38] The ontological commitments of the theory then correspond to the variables bound by existential quantifiers.[39] For example, the sentence "There are electrons" could be translated as "∃x Electron(x)", in which the bound variable x ranges over electrons, resulting in an ontological commitment to electrons.[37] This approach is summed up by Quine's famous dictum that "[t]o be is to be the value of a variable".[40] Quine applied this method to various traditional disputes in ontology. For example, he reasoned from the sentence "There are prime numbers between 1000 and 1010" to an ontological commitment to the existence of numbers, i.e. realism about numbers.[40] This method by itself is not sufficient for ontology since it depends on a theory in order to result in ontological commitments. Quine proposed that we should base our ontology on our best scientific theory.[37] Various followers of Quine's method chose to apply it to different fields, for example to "everyday conceptions expressed in natural language".[41][42] Indispensability argument for mathematical realism In philosophy of mathematics, he and his Harvard colleague Hilary Putnam developed the Quine–Putnam indispensability thesis, an argument for the reality of mathematical entities.[5] The form of the argument is as follows. 1. One must have ontological commitments to all entities that are indispensable to the best scientific theories, and to those entities only (commonly referred to as "all and only"). 2. Mathematical entities are indispensable to the best scientific theories. Therefore, 3. One must have ontological commitments to mathematical entities.[43] The justification for the first premise is the most controversial. Both Putnam and Quine invoke naturalism to justify the exclusion of all non-scientific entities, and hence to defend the "only" part of "all and only". The assertion that "all" entities postulated in scientific theories, including numbers, should be accepted as real is justified by confirmation holism. Since theories are not confirmed in a piecemeal fashion, but as a whole, there is no justification for excluding any of the entities referred to in well-confirmed theories. This puts the nominalist who wishes to exclude the existence of sets and non-Euclidean geometry, but to include the existence of quarks and other undetectable entities of physics, for example, in a difficult position.[43] |

存在論的拘束 存在論的拘束の概念は、クワインの存在論への貢献において中心的な役割を果たす。[35][36] ある理論が実体に対して存在論的に拘束されているとは、その理論が真であるためにはその実体が存在しなければならないことを意味する。[37] クワインは、これを決定する最良の方法は、問題の理論を一階述語論理に翻訳することだと提案した。この翻訳において特に注目されるのは、存在量化子 (『∃』)として知られる論理定数である。その意味は「存在する...」や「ある...に対して」といった表現に対応する。これらは量化子の後に続く表現 内の変数を束縛するために用いられる。[38] 理論の存在論的拘束は、存在量化子によって束縛された変数に対応する。[39] 例えば「電子は存在する」という文は「∃x Electron(x)」と翻訳できる。ここで束縛変数xは電子全体を走査し、電子の存在に対する存在論的拘束を生む。[37] この手法はクワインの有名な格言「存在とは変数の値であること」に集約される。[40] クワインはこの方法を存在論における様々な伝統的論争に応用した。例えば「1000から1010の間に素数がある」という文から、彼は数の存在に対する存 在論的コミットメント、すなわち数に関する実在論を導き出した[40]。この方法自体は存在論にとって十分ではない。なぜなら存在論的コミットメントを得 るには理論に依存するからだ。クワインは我々の存在論を最良の科学的理論に基盤すべきだと提案した[37]。クワインの方法論の様々な継承者たちは、これ を異なる分野、例えば「自然言語で表現される日常的概念」に適用することを選んだ。[41][42] 数学的実在論のための不可欠性論証 数学哲学において、クワインとハーバード大学の同僚ヒラリー・パトナムは、数学的実体の現実性を主張する「クワイン=パトナムの不可欠性命題」を発展させた。[5] この論証の形式は以下の通りである。 1. 最良の科学的理論にとって不可欠な実体すべてに対して、そしてそれらの実体のみに対して(一般に「すべてかつただそれのみ」と呼ばれる)、存在論的コミットメントを持たねばならない。 2. 数学的実体は最良の科学的理論にとって不可欠である。したがって、 3. 数学的実体に対して存在論的コミットメントを持たねばならない。[43] 第一前提の正当化が最も議論を呼んでいる。パトナムもクワインも、非科学的実体の排除を正当化し「全てかつ唯一」の「唯一」部分を擁護するために自然主義 を援用する。科学理論で仮定される「全ての」実体(数を含む)を実在として受け入れるべきだという主張は、確認全体論によって正当化される。理論は断片的 にではなく全体として確認されるため、十分に確認された理論で言及される実体を排除する正当性はない。これは、例えば集合や非ユークリッド幾何学の存在を 排除しつつ、クォークや物理学の他の検出不能な実体の存在は包含しようとする名目論者を困難な立場に置く。[43] |

| Epistemology Just as he challenged the dominant analytic–synthetic distinction, Quine also took aim at traditional normative epistemology. According to Quine, traditional epistemology tried to justify the sciences, but this effort (as exemplified by Rudolf Carnap) failed, and so we should replace traditional epistemology with an empirical study of what sensory inputs produce what theoretical outputs:[44] Epistemology, or something like it, simply falls into place as a chapter of psychology and hence of natural science. It studies a natural phenomenon, viz., a physical human subject. This human subject is accorded a certain experimentally controlled input—certain patterns of irradiation in assorted frequencies, for instance—and in the fullness of time the subject delivers as output a description of the three-dimensional external world and its history. The relation between the meager input and the torrential output is a relation that we are prompted to study for somewhat the same reasons that always prompted epistemology: namely, in order to see how evidence relates to theory, and in what ways one's theory of nature transcends any available evidence... But a conspicuous difference between old epistemology and the epistemological enterprise in this new psychological setting is that we can now make free use of empirical psychology.[45] As previously reported, in other occasions Quine used the term "neurology" instead of "empirical psychology".[31] Quine's proposal is controversial among contemporary philosophers and has several critics, with Jaegwon Kim the most prominent among them.[46] |

認識論 クワインは支配的な分析的・総合的区別に異議を唱えたのと同様に、伝統的な規範的認識論にも矛先を向けた。クワインによれば、伝統的認識論は科学を正当化 しようとしたが、この試み(ルドルフ・カルナップが示すように)は失敗した。したがって我々は、感覚的入力がどのような理論的出力を生み出すかを実証的に 研究する手法で、伝統的認識論に取って代わるべきだ: [44] 認識論、あるいはそれに類するものは、心理学の一章として、ひいては自然科学の一章として、単純に位置づけられる。それは自然現象、すなわち物理的人間主 体を研究する。この人間主体には、ある実験的に制御された入力——例えば様々な周波数における特定の放射パターン——が与えられ、やがて主体は出力として 三次元外部世界とその歴史の記述を提示する。貧弱な入力と氾濫する出力の関係は、我々が研究を促される関係である。その理由は、常に認識論を促してきたも のとほぼ同じだ。すなわち、証拠が理論とどう関連するか、そして自然に関する理論が利用可能な証拠をどのように超越するかを見るためである...しかし、 古い認識論とこの新しい心理学的枠組みにおける認識論的営みの顕著な違いは、今や我々が経験的心理学を自由に利用できる点にある。[45] 前述の通り、クワインは他の場面では「経験的心理学」の代わりに「神経学」という用語を用いている。[31] クワインの提案は現代の哲学者の間で議論を呼び、いくつかの批判がある。中でもジェイグウォン・キムの批判が最も顕著である。[46] |

| In popular culture A computer program whose output is its own source code is called a "quine" after Quine. This usage was introduced by Douglas Hofstadter in his 1979 book, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. Quine was selected for inclusion in the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry's "Pantheon of Skeptics", which celebrates contributors to the cause of scientific skepticism.[47] |

ポピュラー・カルチャーにおいて 自身のソースコードを出力するコンピュータプログラムは、クワインにちなんで「クワイン」と呼ばれる。この用法はダグラス・ホフスタッターが1979年の著書『ゲーデル、エッシャー、バッハ:永遠の黄金の結び目』で導入したものである。 クワインは、科学的懐疑主義の推進に貢献した人物を称える「懐疑主義者の殿堂」に選出された。これは懐疑的調査委員会の選定によるものである。[47] |

| Bibliography Selected books 1934 A System of Logistic. Harvard Univ. Press.[48] 1951 (1940). Mathematical Logic. Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0-674-55451-5. 1980 (1941). Elementary Logic. Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0-674-24451-6. 1982 (1950). Methods of Logic. Harvard Univ. Press. 1980 (1953). From a Logical Point of View. Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0-674-32351-3. Contains "Two dogmas of Empiricism." 1960 Word and Object. MIT Press; ISBN 0-262-67001-1. The closest thing Quine wrote to a philosophical treatise. Ch. 2 sets out the indeterminacy of translation thesis. 1969 (1963). Set Theory and Its Logic. Harvard Univ. Press. 1966. Selected Logic Papers. New York: Random House. 1976 (1966). The Ways of Paradox. Harvard Univ. Press. 1969 Ontological Relativity and Other Essays. Columbia Univ. Press. ISBN 0-231-08357-2. Contains chapters on ontological relativity, naturalized epistemology, and natural kinds. 1970 (2nd ed., 1978). With J. S. Ullian. The Web of Belief. New York: Random House. 1986 (1970). The Philosophy of Logic. Harvard Univ. Press. 1974 (1971). The Roots of Reference. Open Court Publishing Company ISBN 0-8126-9101-6 (developed from Quine's Carus Lectures). 1981. Theories and Things. Harvard Univ. Press. 1985. The Time of My Life: An Autobiography. Cambridge, The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-17003-5. 1987. Quiddities: An Intermittently Philosophical Dictionary. Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0-14-012522-1. A work of essays, many subtly humorous, for lay readers, very revealing of the breadth of his interests. 1992 (1990). Pursuit of Truth. Harvard Univ. Press. A short, lively synthesis of his thought for advanced students and general readers not fooled by its simplicity. ISBN 0-674-73951-5. 1995. From Stimulus to Science. Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0-674-32635-0. 2004. Quintessence: Basic Readings from the Philosophy of W V Quine. Harvard Univ. Press. 2008. Confessions of a Confirmed Extensionalist and Other Essays. Harvard Univ. Press. Important articles 1946, "Concatenation as a basis for arithmetic". Reprinted in his Selected Logic Papers. Harvard Univ. Press. 1948, "On What There Is", Review of Metaphysics 2(5) (JSTOR). Reprinted in his 1953 From a Logical Point of View. Harvard University Press. 1951, "Two Dogmas of Empiricism", The Philosophical Review 60: 20–43. Reprinted in his 1953 From a Logical Point of View. Harvard University Press. 1956, "Quantifiers and Propositional Attitudes", Journal of Philosophy 53. Reprinted in his 1976 Ways of Paradox. Harvard Univ. Press: 185–196. 1969, "Epistemology Naturalized" in Ontological Relativity and Other Essays. New York: Columbia University Press: 69–90. "Truth by Convention", first published in 1936. Reprinted in the book, Readings in Philosophical Analysis, edited by Herbert Feigl and Wilfrid Sellars, pp. 250–273, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1949. Filmography Bryan Magee (host), Men of Ideas: "The Ideas of Quine", BBC, 1978. Rudolf Fara (host), In Conversation: W. V. Quine (7 videocassettes), Philosophy International, Centre for Philosophy of the Natural and Social Sciences, London School of Economics, 1994. |

参考文献 主な著作 1934 『論理体系』ハーバード大学出版局。[48] 1951 (1940). 『数学的論理学』ハーバード大学出版局. ISBN 0-674-55451-5. 1980 (1941). 『初等論理学』ハーバード大学出版局. ISBN 0-674-24451-6. 1982 (1950). 『論理学の方法』. ハーバード大学出版局. 1980 (1953). 『論理的観点から』. ハーバード大学出版局. ISBN 0-674-32351-3. 「経験主義の二つの教条」を含む。 1960年 『言葉と対象』 MIT出版局; ISBN 0-262-67001-1。クワインが書いた哲学論文に最も近いもの。第2章で翻訳の不確定性命題を提示。 1969年 (1963年)。『集合論とその論理』 ハーバード大学出版局。 1966年 『論理論文選集』 ニューヨーク: ランダムハウス。 1976 (1966). 『パラドクスの諸相』. ハーバード大学出版局. 1969 『存在論的相対性その他の論考』. コロンビア大学出版局. ISBN 0-231-08357-2. 存在論的相対性、自然化された認識論、自然種に関する章を含む。 1970 (第2版, 1978). J・S・ウリアンとの共著。信念の網。ニューヨーク:ランダムハウス。 1986年(初版1970年)。論理学の哲学。ハーバード大学出版局。 1974年(初版1971年)。参照の根源。オープンコート出版 ISBN 0-8126-9101-6(クワインのカーラス講義を発展させたもの)。 1981. 『理論と事物』ハーバード大学出版局。 1985. 『我が人生の時:自伝』ケンブリッジ、MIT出版局。ISBN 0-262-17003-5。 1987. 『クィディティーズ:断続的哲学辞典』ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 0-14-012522-1。一般読者を対象とした随筆集で、多くの作品に微妙なユーモアが込められており、彼の関心の広さがよく表れている。 1992 (1990). 『真実の探求』. ハーバード大学出版局. 彼の思想を簡潔にまとめた小冊子で、その簡潔さに騙されない上級学生や一般読者向けである。ISBN 0-674-73951-5. 1995年。『刺激から科学へ』。ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 0-674-32635-0。 2004年。『クワイン哲学基本読本』。ハーバード大学出版局。 2008年。『確固たる外延論者の告白とその他のエッセイ』。ハーバード大学出版局。 重要な論文 1946年、「算術の基礎としての連結」。『選集論理論文集』に再録。ハーバード大学出版局。 1948年、「存在するものについて」、『形而上学評論』2巻5号(JSTOR)。1953年『論理的観点から』に再録。ハーバード大学出版局。 1951年、「経験主義の二つの教条」、『哲学評論』60: 20–43。1953年『論理的観点から』に再録。ハーバード大学出版局。 1956年、「量化詞と命題的態度」、『哲学ジャーナル』53号。1976年刊行『パラドクスの諸相』(ハーバード大学出版局)185–196頁に再録。 1969年、「自然化された認識論」、『存在論的相対性その他の論考』(ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版局)69–90頁に収録。 「慣習による真理」初出1936年。ハーバート・ファイグルとウィルフリッド・セラース編『哲学分析読本』に再録、pp.250–273、アップルトン・センチュリー・クロフツ社、1949 年。 フィルモグラフィー ブライアン・マギー(司会)、『思想家たち:クワインの思想』、BBC、1978年。 ルドルフ・ファラ(司会)、『対話:W・V・クワイン』(7巻ビデオカセット)、フィロソフィー・インターナショナル、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス自然社会科学哲学センター、1994年。 |

| Definitions of philosophy List of American philosophers |

哲学の定義 アメリカの哲学者一覧 |

| Notes 1. Quine, Willard Van Orman (1983). "Ontology and ideology revisited". Confessions of a Confirmed Extensionalist: And Other Essays. Harvard University Press. pp. 315 ff. ISBN 0-674-03084-2. 2. Hunter, Bruce (2021). "Clarence Irving Lewis". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 3. O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (October 2003), "Willard Van Orman Quine", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews 4. Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (December 29, 2000). "W. V. Quine, Philosopher Who Analyzed Language and Reality, Dies at 92". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2023. 5. Colyvan, Mark, "Indispensability Arguments in the Philosophy of Mathematics", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2004 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). 6. Quine, W. V. (August 28, 2023). "Mr. Strawson on Logical Theory". Mind. 62 (248): 433–451. JSTOR 2251091. 7. "Quine, Willard Van Orman: Philosophy of Science". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2009. 8. Gibson, Jr, Roger F., ed. (March 29, 2004). The Cambridge Companion to Quine. Cambridge Companions to Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. doi:10.1017/ccol0521630568. ISBN 978-0-521-63056-6. 9. The Time of My Life: An Autobiography, p. 14. 10. Quine, Willard Van Orman; Hahn, Lewis Edwin (1986). The Philosophy of W.V. Quine. Open Court. p. 6. ISBN 978-0812690101. In my third year of high school I walked often with my new Jamaican friends, Fred and Harold Cassidy, trying to convert them from their Episcopalian faith to atheism. 11. Borradori, Giovanna (1994). The American Philosopher: Conversations with Quine, Davidson, Putnam, Nozick, Danto, Rorty, Cavell, MacIntyre, Kuhn. University of Chicago Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-0-226-06647-9. 12. The Wall Street Journal, obituary for W. V. Quine – January 4, 2001 13. Quiddities: An Intermittently Philosophical Dictionary, entry for Tolerance (pp. 206–208). 14. "Paradoxes of Plenty" in Theories and Things, p. 197. 15. The Time of My Life: An Autobiography, pp. 352–353. 16. "Guide to the Center for Advanced Studies Records, 1958–1969" Archived March 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Weselyan University. Wesleyan.edu. Accessed March 8, 2010. 17. "Honorary doctorates – Uppsala University, Sweden". June 9, 2023. 18. Quine, Willard Van Orman (2013). Word and Object. The MIT Press. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9636.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-262-31279-0. 19. "Willard van Orman Quine; Renowned Philosopher". Los Angeles Times. December 31, 2000. 20. Pakaluk, Michael (1989). "Quine's 1946 Lectures on Hume". Journal of the History of Philosophy. 27 (3): 445–459. doi:10.1353/hph.1989.0050. S2CID 171052872. 21. Nelson Goodman and W. V. O. Quine, "Steps Toward a Constructive Nominalism", Journal of Symbolic Logic, 12 (1947): 105–122. 22. Bueno, Otávio (2020). "Nominalism in the Philosophy of Mathematics". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 23. Armstrong, D. M. (2010). Sketch for a systematic metaphysics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780199655915. 24. W. V. O. Quine, "On What There Is", The Review of Metaphysics 2(5), 1948. 25. van Inwagen, Peter; Zimmerman, Dean W. (2008). Metaphysics: the big questions (2. rev. and expanded ed.). Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. p. 28-29. ISBN 978-1-4051-2586-4. 26. van Inwagen, Peter; Zimmerman, Dean W. (2008). Metaphysics: the big questions (2. rev. and expanded ed.). Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4051-2586-4. 27. van Inwagen, Peter; Zimmerman, Dean W. (2008). Metaphysics: the big questions (2. rev. and expanded ed.). Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. p. 31-32. ISBN 978-1-4051-2586-4. 28. Frost-Arnold, Greg (2013). Carnap, Tarski, and Quine at Harvard: Conversations on Logic, Mathematics, and Science. Chicago: Open Court. p. 89. ISBN 9780812698374. 29. Quine, W. V. (1980) [1961]. From a Logical Point of View: Nine Logico-Philosophical Essays, Second Revised Edition. Harper torchbooks. Harvard University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-674-32351-3. 30. Prawitz, Dag (1994). "Quine and verificationism". Inquiry. 37 (4): 487–494. doi:10.1080/00201749408602369. ISSN 0020-174X. 31. Borradori, Giovanna (1994). The American Philosopher: Conversations with Quine, Davidson, Putnam, Nozick, Danto, Rorty, Cavell, MacIntyre, Kuhn. University of Chicago Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-226-06647-9. 32. Quine, W. V. (1980) [1961]. From a Logical Point of View: Nine Logico-Philosophical Essays, Second Revised Edition. Harper torchbooks. Harvard University Press. pp. 22–23, 28. ISBN 978-0-674-32351-3. 33. Putnam, Hilary (March 1974). "The refutation of conventionalism". Noûs. 8 (1): 25–40. doi:10.2307/2214643. JSTOR 2214643. Reprinted in Putnam, Hilary (1979). "Chapter 9: The refutation of conventionalism". Philosophical Papers; Volume 2: Mind, Language and Reality. Cambridge University Press. pp. 153–191. ISBN 0521295513. Quote on p. 159. 34. Czeslaw Lejewski, "Logic and Existence". British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, Vol. 5 (1954–1955), pp. 104–119. 35. Craig, Edward (1996). "Ontological commitment". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. 36. Simons, Peter M. "Ontology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved December 13, 2020. 37. Bricker, Phillip (2016). "Ontological Commitment". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved December 13, 2020. 38. Magnus, P. D.; Ichikawa, Jonathan Jenkins (2020). "V. First-order logic". Forall X (UBC ed.). Creative Commons: Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. 39. Schaffer, Jonathan (2009). "On What Grounds What". Metametaphysics: New Essays on the Foundations of Ontology. Oxford University Press. pp. 347–383. 40. Quine, Willard Van Orman (1948). "On What There Is". Review of Metaphysics. 2 (5): 21–38. 41. Inwagen, Peter van (2004). "A Theory of Properties". Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, Volume 1. Clarendon Press. pp. 107–138. 42. Kapelner, Zsolt-kristof (2015). "3. Quinean Metaontology". Reconciling Quinean and neo-Aristotelian Metaontology (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 14, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2020. 43. Putnam, H. Mathematics, Matter and Method. Philosophical Papers, vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975. 2nd. ed., 1985. 44. "Naturalism in Epistemology". Naturalized Epistemology. stanford.edu. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2017. 45. Quine, Willard Van Orman (1969). Ontological Relativity and Other Essays. Columbia University Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 0-231-08357-2. 46. "Naturalized Epistemology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Plato.stanford.edu. July 5, 2001. Accessed March 8, 2010. 47. "The Pantheon of Skeptics". CSI. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2017. 48. Church, Alonzo (1935). "Review: A System of Logistic by Willard Van Orman Quine" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 41 (9): 598–603. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1935-06146-4. |

注 1. クワイン、ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン (1983). 「存在論とイデオロギーの再考」. 『確固たる外延論者の告白:その他の論文』. ハーバード大学出版局. pp. 315 ff. ISBN 0-674-03084-2. 2. ハンター、ブルース (2021). 「クラレンス・アーヴィング・ルイス」. 『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』 (2021年春版). スタンフォード大学形而上学研究所. 3. オコナー、ジョン・J.; ロバートソン、エドマンド・F. (2003年10月), 「ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン」, MacTutor 数学史アーカイブ, セント・アンドリュース大学 4. レーマン・ハウプト、クリストファー(2000年12月29日)。「言語と現実を分析した哲学者、W・V・クワインが92歳で死去」。ニューヨーク・タイムズ。ISSN 0362-4331。2023年11月21日取得。 5. コーリバン、マーク、「数学哲学における不可欠性論争」、スタンフォード哲学百科事典(2004年秋版)、エドワード・N・ザルタ(編)。 6. クワイン、W. V. (2023年8月28日)。「論理理論に関するストローソン氏」。マインド。62 (248): 433–451頁。JSTOR 2251091。 7. 「クワイン、ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン:科学哲学」。インターネット哲学百科事典。2009年。 8. ギブソン・ジュニア、ロジャー・F. 編(2004年3月29日)。『クワインのケンブリッジ・コンパニオン』。ケンブリッジ哲学コンパニオンシリーズ。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。p. 1. doi:10.1017/ccol0521630568. ISBN 978-0-521-63056-6. 9. 『我が人生の時:自伝』, p. 14. 10. クワイン, ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン; ハーン, ルイス・エドウィン (1986). 『W.V.クワインの哲学』. オープンコート. p. 6. ISBN 978-0812690101. 高校三年の頃、ジャマイカ人の新しい友人フレッドとハロルド・キャシディとよく歩き、彼らの聖公会信仰を無神論に改宗させようとした。 11. ジョヴァンナ・ボラドーリ(1994年)。『アメリカの哲学者たち:クワイン、デイヴィッドソン、パトナム、ノジック、ダント、ロートリー、キャヴェル、 マッキンタイア、クーンとの対話』。シカゴ大学出版局。30-31頁。ISBN 978-0-226-06647-9。 12. 『ウォール・ストリート・ジャーナル』紙、W・V・クワインの訃報記事 – 2001年1月4日 13. 『クィディティーズ:断続的哲学辞典』、「寛容」の項目(pp. 206–208)。 14. 『理論と事物』所収「豊かさというパラドックス」、p. 197。 15. 『我が人生の時:自伝』352–353頁。 16. 「高等研究センター記録ガイド、1958–1969年」 2017年3月14日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ。ウェズリアン大学。Weselyan.edu。2010年3月8日閲覧。 17. 「名誉博士号 – スウェーデン、ウプサラ大学」。2023年6月9日。 18. クワイン、ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン (2013). 『言葉と対象』. MITプレス. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9636.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-262-31279-0. 19. 「ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン、著名な哲学者」。ロサンゼルス・タイムズ。2000年12月31日。 20. パカルク、マイケル (1989)。「クワインの 1946 年のヒュームに関する講義」。哲学史ジャーナル。27 (3): 445–459。doi:10.1353/hph.1989.0050. S2CID 171052872. 21. ネルソン・グッドマンと W. V. O. クワイン、「建設的唯名論への歩み」、Journal of Symbolic Logic、12 (1947): 105–122。 22. ブエノ、オタヴィオ (2020). 「数学哲学における唯名論」. スタンフォード哲学百科事典 (2020年秋版). スタンフォード大学形而上学研究所. 23. アームストロング、D. M. (2010). 体系的な形而上学のスケッチ. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. p. 2. ISBN 9780199655915。 24. W. V. O. Quine, 「On What There Is」, The Review of Metaphysics 2(5), 1948. 25. van Inwagen, Peter; Zimmerman, Dean W. (2008). Metaphysics: the big questions (2. rev. and expanded ed.). マサチューセッツ州マルデン:ブラックウェル。p. 28-29。ISBN 978-1-4051-2586-4。 26. ヴァン・インワーゲン、ピーター;ジマーマン、ディーン W. (2008). 『形而上学:大きな問い』(第2版、改訂・増補版)。マサチューセッツ州マルデン:ブラックウェル。p. 31。ISBN 978-1-4051-2586-4。 27. ヴァン・インワーゲン, ピーター; ジマーマン, ディーン・W. (2008). 『形而上学:大きな問い』(第2版 改訂・増補版). マサチューセッツ州マルデン:ブラックウェル. p. 31-32. ISBN 978-1-4051-2586-4. 28. フロスト=アーノルド, グレッグ (2013). 『ハーバードのカルナップ、タルスキ、クワイン:論理学、数学、科学をめぐる対話』. シカゴ: オープンコート. p. 89. ISBN 9780812698374. 29. クワイン, W. V. (1980) [1961]. 『論理的観点から: 論理哲学的随筆九篇』, 第二改訂版. ハーパー・トーチブックス. ハーバード大学出版局. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-674-32351-3. 30. プラウィッツ, ダグ (1994). 「クワインと検証主義」. 『インクイリー』. 37 (4): 487–494. doi:10.1080/00201749408602369. ISSN 0020-174X. 31. ボラドーリ, ジョヴァンナ (1994). 『アメリカの哲学者たち:クワイン、デイヴィッドソン、パトナム、ノジック、ダント、ロートリー、キャヴェル、マッキンタイア、クーンとの対話』. シカゴ大学出版局. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-226-06647-9. 32. クワイン, W. V. (1980) [1961]. 論理的観点から:九つの論理哲学的エッセイ、第二改訂版。ハーパー・トーチブックス。ハーバード大学出版局。pp. 22–23, 28。ISBN 978-0-674-32351-3。 33. パットナム、ヒラリー(1974年3月)。「慣習主義の反駁」。ヌーース。8(1): 25–40頁。doi:10.2307/2214643。JSTOR 2214643。再版:パットナム、ヒラリー(1979)。「第9章:慣習主義の反駁」。『哲学論文集 第2巻:精神、言語、現実』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。pp. 153–191. ISBN 0521295513. 引用箇所はp. 159. 34. Czeslaw Lejewski, 「Logic and Existence」. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, Vol. 5 (1954–1955), pp. 104–119. 35. クレイグ、エドワード (1996). 「存在論的コミットメント」. ラウトレッジ哲学百科事典. ラウトレッジ. 36. サイモンズ、ピーター M. 「存在論」. ブリタニカ百科事典. 2020年12月13日取得. 37. ブリッカー、フィリップ (2016). 「存在論的コミットメント」. スタンフォード哲学百科事典. スタンフォード大学形而上学研究所。2020年12月13日取得。 38. マグナス、P. D.、市川、ジョナサン・ジェンキンズ(2020)。「V. 一階論理」。Forall X(UBC編)。クリエイティブ・コモンズ:表示-継承 3.0。 39. シェイファー、ジョナサン(2009)。「何が何を根拠とするか」。『メタ形而上学:存在論の基礎に関する新しいエッセイ』。オックスフォード大学出版局。347-383 ページ。 40. クワイン、ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン (1948)。「存在するものについて」。『形而上学のレビュー』。2 (5): 21-38。 41. インワーゲン、ピーター・ヴァン (2004). 「A Theory of Properties」. 『オックスフォード形而上学研究』第1巻. クラレンドン・プレス. pp. 107–138. 42. Kapelner, Zsolt-kristof (2015). 「3. Quinean Metaontology」. 『クワイン的メタ存在論と新アリストテレス的メタ存在論の調和』 (PDF). 2021年4月14日時点のオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。2020年12月14日閲覧。 43. パットナム, H. 『数学、物質、方法』. 哲学論文集, 第1巻. ケンブリッジ: ケンブリッジ大学出版局, 1975. 第2版, 1985. 44. 「認識論における自然主義」. 自然化された認識論. stanford.edu. スタンフォード大学形而上学研究所. 2017年. 45. クワイン, ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン (1969). 『存在論的相対性その他の論文』. コロンビア大学出版局. pp. 82–83. ISBN 0-231-08357-2. 46. 「自然化された認識論」. スタンフォード哲学百科事典. Plato.stanford.edu. 2001年7月5日. 2010年3月8日閲覧. 47. 「懐疑主義者の殿堂」. CSI. 懐疑的調査委員会. 2017年1月31日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2017年4月30日閲覧. 48. チャーチ、アロンゾ (1935). 「書評:ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン著『論理学体系』」 (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 41 (9): 598–603. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1935-06146-4. |

| Further reading Borradori, Giovanna (2008). The American Philosopher : Conversations with Quine, Davidson, Putnam, Nozick, Danto, Rorty, Cavell, MacIntyre, Kuhn. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226066493. Gibson, Roger F., ed. (2004). The Cambridge companion to Quine. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521639492. Gibson, Roger F. (1988). The Philosophy of W. V. Quine: An Expository Essay. Tampa: University of South Florida. Gibson, Roger F. (1988). Enlightened Empiricism: An Examination of W. V. Quine's Theory of Knowledge. Tampa: University of South Florida. Gibson, Roger F. (2004). Quintessence: Basic Readings from the Philosophy of W. V. Quine. Harvard University Press. Gibson, Roger F.; Barrett, R., eds. (1990). Perspectives on Quine. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. Gochet, Paul, 1978. Quine en perspective, Paris, Flammarion. Godfrey-Smith, Peter, 2003. Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. Grattan-Guinness, Ivor, 2000. The Search for Mathematical Roots 1870–1940. Princeton University Press. Grice, Paul and Peter Strawson. "In Defense of a Dogma". The Philosophical Review 65 (1965). Hahn, L. E., and Schilpp, P. A., eds., 1986. The Philosophy of W. V. O. Quine (The Library of Living Philosophers). Open Court. Janssen-Lauret, Frederique (2020) Quine, Structure, and Ontology, Oxford University Press Köhler, Dieter, 1999/2003. Sinnesreize, Sprache und Erfahrung: eine Studie zur Quineschen Erkenntnistheorie. Ph.D. thesis, Univ. of Heidelberg. MacFarlane, Alistair (March–April 2013). "W. V. O. Quine (1908-2000)". Philosophy Now. 95: 35–36. Murray Murphey, The Development of Quine's Philosophy (Heidelberg, Springer, 2012) (Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 291). Orenstein, Alex (2002). W.V. Quine. Princeton University Press. Putnam, Hilary. "The Greatest Logical Positivist". Reprinted in Realism with a Human Face, ed. James Conant. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990. Rosser, John Barkley, "The axiom of infinity in Quine's new foundations", Journal of Symbolic Logic 17 (4):238–242, 1952. Verhaeg, Sander (2018). Working from Within: The Nature and Development of Quine's Naturalism. Oxford University Press. |

追加文献(さらに読む) ボラドーリ、ジョヴァンナ(2008)。『アメリカの哲学者たち:クワイン、デイヴィッドソン、パトナム、ノジック、ダント、ロートリー、キャヴェル、マッキンタイア、クーンとの対話』。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 9780226066493。 ギブソン、ロジャー・F編(2004)。『クワインのケンブリッジ・コンパニオン』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0521639492。 ギブソン、ロジャー・F(1988)。『W・V・クワインの哲学:解説的エッセイ』。タンパ:サウスフロリダ大学。 ギブソン、ロジャー・F(1988)。啓蒙された経験主義:W. V. クワインの知識論の検証。タンパ:南フロリダ大学。 ギブソン、ロジャー F. (2004)。『真髄:W. V. クワインの哲学からの基本読本』。ハーバード大学出版局。 ギブソン、ロジャー F.、バレット、R. 編 (1990)。『クワインに関する視点』。オックスフォード:ブラックウェル出版。 ゴシェ、ポール、1978年。『クワインの視点』パリ、フラマリオン。 ゴッドフリー=スミス、ピーター、2003年。『理論と現実:科学哲学入門』。 グラッタン=ギネス、アイヴァー、2000年。『数学のルーツを求めて 1870-1940』プリンストン大学出版局。 グライス、ポールとピーター・ストローソン。「教条の擁護」。『哲学評論』65号(1965年)。 ハーン、L. E.、およびシルップ、P. A.、編、1986年。『W. V. O. クワインの哲学』(生ける哲学者の書庫)。オープン・コート。 ヤンセン=ロレ、フレデリック(2020)『クワイン、構造、そして存在論』オックスフォード大学出版局 ケーラー、ディーター、1999/2003年。『感覚刺激、言語、経験:クワイン認識論に関する研究』博士論文、ハイデルベルク大学。 マクファーレン、アリステア(2013年3月–4月) 「W・V・O・クワイン(1908-2000)」。『フィロソフィー・ナウ』95号:35-36頁。 マレー・マーフィー『クワイン哲学の発展』(ハイデルベルク、シュプリンガー、2012年)(ボストン科学哲学研究叢書291)。 オーレンスタイン、アレックス(2002)。『W.V.クワイン』。プリンストン大学出版局。 パトナム、ヒラリー。「偉大なる論理的実証主義者」。『人間的な顔を持つ実在論』に再録、ジェームズ・コナント編。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局、1990年。 ロサー、ジョン・バークレー、「クワインの新基礎における無限公理」、『記号論理学ジャーナル』17巻4号:238–242頁、1952年。 フェルヘーグ、サンダー(2018)。『内側から働く:クワインの自然主義の性質と発展』。オックスフォード大学出版局。 |

| WVQuine.org Willard Van Orman Quine at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fieser, James; Dowden, Bradley (eds.). "Quine's Rejection of the Analytic/Synthetic Distinction". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002. OCLC 37741658. "Quine's Philosophy of Science" at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Quine's New Foundations at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Willard Van Orman Quine at the Mathematics Genealogy Project Obituary from The Guardian Summary and Explanation of "On What There Is" "Two Dogmas of Empiricism" "On Simple Theories Of A Complex World" |

WVQuine.org スタンフォード哲学百科事典のウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン ファイザー、ジェームズ、ダウデン、ブラッドリー(編)。「クワインの分析的/総合的区別の拒絶」。インターネット哲学百科事典。ISSN 2161-0002。OCLC 37741658。 インターネット哲学百科事典「クワインの科学哲学」 スタンフォード哲学百科事典「クワインの新しい基礎」 数学系譜プロジェクト「ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン」 ガーディアン紙「訃報」 「存在するものについて」の要約と解説 「経験主義の二つの教義」 「複雑な世界に関する単純な理論について」 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willard_Van_Orman_Quine |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099