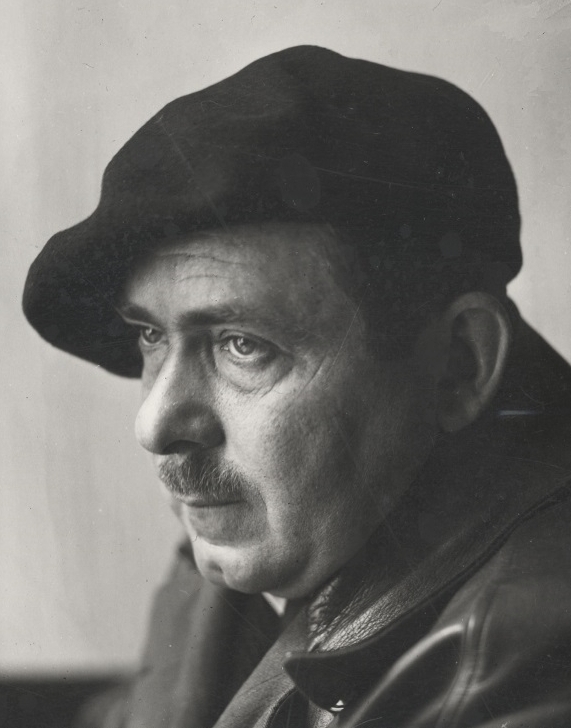

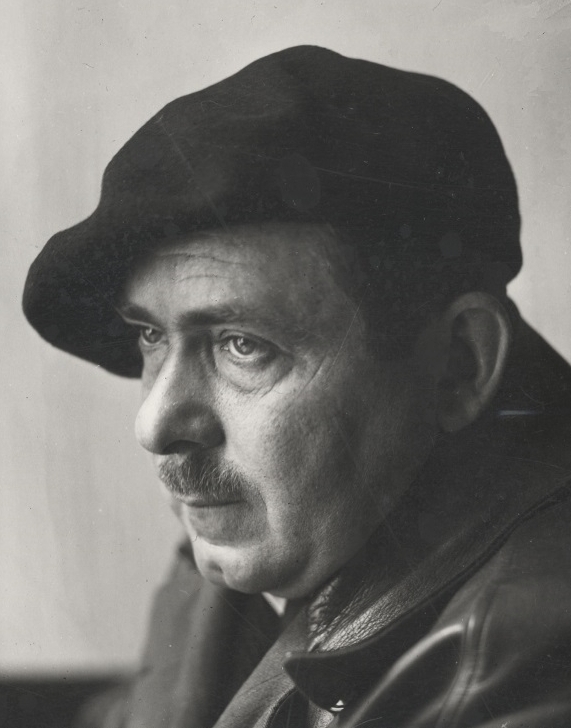

ウィリアム・シーブルック

William Seabrook, 1884-1945

☆ ウィリアム・B・シーブルック(William Buehler Seabrook、1884年2月22日 - 1945年9月20日)は、メリーランド州ウェストミンスター出身のアメリカのオカルティスト、探検家、世界旅行家、ジャーナリスト、作家である。彼は ジョージア州オーガスタ・クロニクルの記者および都市編集者としてキャリアをスタートさせ、その後ニューヨーク・タイムズで働いた。彼は人食い人種に関す る著作でよく知られており、また自らも人食い人種に関わっていた。 シーブルックの1929年の著書『マジック・アイランド』は、ハイチ・ヴードゥーに関する自身の経験を記録したもので、ゾンビの概念を描写した最初の一般 向け英語作品とされている。[1][2]

| William Buehler

Seabrook (February 22, 1884 – September 20, 1945) was an American

occultist, explorer, world traveler, journalist and author, born in

Westminster, Maryland. He began his career as a reporter and city

editor of the Augusta Chronicle in Georgia and later worked for the New

York Times. He is well-known for his writing on, and engaging in,

cannibalism. Seabrook's 1929 book The Magic Island, which documents his experiences with Haitian Vodou, is considered the first popular English-language work to describe the concept of zombies.[1][2] |

ウィリアム・B・シーブルック(William Buehler

Seabrook、1884年2月22日 -

1945年9月20日)は、メリーランド州ウェストミンスター出身のアメリカのオカルティスト、探検家、世界旅行家、ジャーナリスト、作家である。彼は

ジョージア州オーガスタ・クロニクルの記者および都市編集者としてキャリアをスタートさせ、その後ニューヨーク・タイムズで働いた。彼は人食い人種(→カニバル)に関す

る著作でよく知られており、また自らも人食い人種に関わっていた。 シーブルックの1929年の著書『マジック・アイランド』は、ハイチ・ヴードゥーに関する自身の経験を記録したもので、ゾンビの概念を描写した最初の一般 向け英語作品とされている。[1][2] |

| Early life Seabrook graduated from Mercersburg Academy. He then attended Roanoke College where he earned a Bachelor of Philosophy. He went on to receive a Master of Arts from Newberry College and also studied philosophy at the University of Geneva in Switzerland. In 1908, Seabrook was hired as a reporter by the Augusta Chronicle and was soon promoted to the desk of city editor. He was later a partner with an advertising agency in Atlanta, Georgia. In 1915, Seabrook joined the American Field Service of the French Army during World War I.[3] He was stationed on the Western Front and served as an ambulance driver at the Battle of Verdun, where he was gassed. Seabrook was later awarded the Croix de Guerre and published an account of his war service (Diary of Section VIII) in 1917.[4] Following the war, Seabrook became a reporter for the New York Times and soon adopted an itinerant lifestyle.[5] Besides his books, Seabrook published articles in popular magazines including Cosmopolitan, Reader's Digest, and Vanity Fair. |

幼少期 シーブルックは、マーカースバーグ・アカデミーを卒業した。その後、ローノーク・カレッジに進学し、哲学の学士号を取得した。さらにニューベリー・カレッ ジで文学修士号を取得し、スイスのジュネーブ大学で哲学を学んだ。1908年、シーブルックはオーガスタ・クロニクル紙の記者として採用され、すぐに都市 編集者のデスクに昇進した。その後、ジョージア州アトランタの広告代理店の共同経営者となった。 1915年、シーブルックは第一次世界大戦中のフランス軍のアメリカ野戦奉仕団に参加した。[3] 西部戦線に配属され、ベルダンでの戦いでは救急車の運転手として従軍し、そこでガスを浴びた。その後、クロワ・ド・ゲール勲章を授与されたシーブルック は、1917年に従軍記(『第8部隊の日記』)を出版した。[4] 戦後、シーブルックはニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の記者となり、すぐに放浪の生活スタイルを始めた。[5] シーブルックは、著書以外にも、コスモポリタン、リーダーズ・ダイジェスト、ヴァニティ・フェアなどの人気雑誌に記事を寄稿した。 |

| Family life In 1912, Seabrook married Katherine Pauline Edmondson. They divorced in 1934. Soon after, he married Marjorie Worthington in 1935. The marriage ended in 1941. This marriage was followed by his marriage to Constance Kuhr, which began in 1942 and ended with his death in 1945.[6] |

家庭生活 1912年、シーブルックはキャサリン・ポーリン・エドモンソンと結婚した。1934年に離婚。その後間もなく、1935年にマージョリー・ワージントン と再婚した。この結婚は1941年に終わった。この結婚に続いて、1942年にコンスタンス・クーアと結婚したが、1945年に死去した。 |

| Cannibalism In the 1920s, Seabrook traveled to West Africa and came across a tribe who partook in the eating of human meat. Seabrook wrote about his experience of cannibalism in his travel book Jungle Ways; however, he later admitted that the tribe had not allowed him to join in on the ritualistic cannibalism. Instead, he had obtained samples of human flesh by persuading a medical intern at the Sorbonne University to give him a chunk of human meat from the body of a man who had died in an accident.[7] He reported: It was like good, fully developed veal, not young, but not yet beef. It was very definitely like that, and it was not like any other meat I had ever tasted. It was so nearly like good, fully developed veal that I think no person with a palate of ordinary, normal sensitiveness could distinguish it from veal. It was mild, good meat with no other sharply defined or highly characteristic taste such as for instance, goat, high game, and pork have. The [rump] steak was slightly tougher than prime veal, a little stringy, but not too tough or stringy to be agreeably edible. The [loin] roast, from which I cut and ate a central slice, was tender, and in color, texture, smell as well as taste, strengthened my certainty that of all the meats we habitually know, veal is the one meat to which this meat is accurately comparable.[8] Seabrook might have eaten human flesh also on another occasion. When his claim of having participating in ritualistic cannibalism turned out wrong (and he hadn't yet dared reveal the Sorbonne story), he was much mocked for it. According to his autobiography, the wealthy socialite Daisy Fellowes invited him to one of her garden parties, stating "I think you deserve to know what human flesh really tastes like". During the party, which was attended by about a dozen guests (some of them well-known), a piece of supposedly human flesh was grilled and eaten with much pomp. He comments that, while he never found out "the real truth" behind this meal, it "looked and tasted exactly" like the human flesh he had eaten before.[9] |

人食い 1920年代、シーブルックは西アフリカを訪れ、人間の肉を食べる部族に出会った。シーブルックは、その体験を旅行記『ジャングルの道』に書いたが、後に その部族が儀式的な人食いに彼を参加させることを許さなかったことを認めた。代わりに、ソルボンヌ大学の医学実習生を説得して、事故死した男性の肉の一部 を入手した。[7] 彼は次のように報告している。 それは、若くはないが、まだ牛肉でもない、よく熟成された上質な仔牛肉のようだった。それは間違いなくそのようであり、私がこれまで味わったことのある他 の肉とは違っていた。それは、よく熟成された上質な仔牛肉に非常に似ていたので、普通の感覚を持つ人格であれば、仔牛肉と見分けがつかないと思う。それは マイルドで、ヤギや野禽、豚肉のような際立った特徴のない、上質な肉だった。ランプステーキは、最高級の仔牛肉よりもやや硬く、筋も少しあったが、食べら れないほど硬かったり筋っぽかったりするわけではなかった。ロース肉のローストは、中心部分の肉を切り取って食べたが、柔らかくて、色、質感、香り、味の すべてにおいて、私たちが日常的に食べている肉の中で、仔牛肉が仔牛肉に最も近い肉であるという確信を強めた。 シーブルックは別の機会にも人肉を食べたのかもしれない。彼が儀式的な人食いに参加したという主張が間違いであることが判明したとき(そして、彼はまだソ ルボンヌでの出来事を明かす勇気がなかった)、彼は大いに嘲笑された。彼の自伝によると、裕福な社交界の名士デイジー・フェローズが彼をガーデンパー ティーに招待し、「人肉が本当にどんな味がするのか、あなたには知る価値があると思うの」と述べた。招待客は12人ほど(その中には著名人もいた)で、 パーティーの間、人肉らしきものがグリルで焼かれ、盛大に振る舞われた。彼は、この食事の「真実」は決してわからないが、以前に食べた人肉と「見た目も味 もまったく同じ」だったとコメントしている。[9] |

| Later life In autumn 1919, English occultist Aleister Crowley spent a week with Seabrook at Seabrook's farm. Seabrook wrote a story based on the experience and to recount the experiment in Witchcraft: Its Power in the World Today. In 1924, he traveled to Arabia and sampled the hospitality of various tribes of Bedouin and the Kurdish Yazidi. In the first part of the book, Seabrook seeks Mithqal Al-Fayez and lives with him and his tribe for several months. When the topic of religion came to them in conversation, Seabrook admitted to Mithqal that he did not believe in the Trinity, but rather in the oneness of God, and that God sent many prophets including Muhammad; on hearing this, Mithqal asked if William would like to enter Islam and William agreed, with him repeating the Shahada after Mithqal shortly after. Adventures in Arabia: among the Bedouins, Druses, Whirling Dervishes and Yezidee Devil Worshipers, his account of his travels, was published in 1927; its success enabled him to travel to Haiti, where he developed an interest in Haitian Vodou and the Culte des Mortes, which were described at length in his book The Magic Island. The book is credited with introducing the concept of a zombie to popular culture.[10][11] Seabrook had a lifelong fascination with the occult, which he witnessed and described firsthand, as documented in The Magic Island (1929),[citation needed] and Jungle Ways (1930).[citation needed] He later concluded that he had seen nothing that did not have a rational scientific explanation, a theory which he detailed in Witchcraft: Its Power in the World Today (1940).[citation needed] In Air Adventure he describes a trip on board a Farman with captain René Wauthier, a famed pilot,[12] and Marjorie Muir Worthington, from Paris to Timbuktu, where he collected a mass of documents from Father Yacouba, a defrocked monk who had an extensive collection of rare documents about the obscure city at that time administered by the French as part of French Sudan. The book is replete with information about French colonial life in the Sahara and pilots in particular. In December 1933, Seabrook was committed at his own request and with the help of some of his friends to Bloomingdale, a mental institution in Westchester County, near New York City, for treatment for acute alcoholism. He remained a patient of the institution until the following July, and in 1935, he published an account of his experience, written as if it were another expedition to a foreign locale. The book, titled Asylum, became another best-seller.[citation needed] In the preface, he stated that his books were not "fiction or embroidery".[13] He married Marjorie Muir Worthington in France in 1935 after they had returned from a trip to Africa on which Seabrook was researching a book. Due to his alcoholism and sadistic practices, they divorced in 1941.[14] She later wrote the biography The Strange World of Willie Seabrook, published in 1966.[15] |

晩年 1919年秋、英国のオカルティスト、アレイスター・クロウリーはシーブルックの農場で1週間を過ごした。 シーブルックはその体験をもとに物語を書き、その実験を『ウィッチクラフト:その力が今日の世界にもたらすもの』で語った。 1924年にはアラビア半島を訪れ、ベドウィン族やクルド系ヤジディ族のさまざまな部族のもてなしを体験した。この本の前半では、シーブルックはミシュカ ル・アル・ファイエズを探し出し、彼とその部族とともに数ヶ月間暮らす。宗教に関する話題が会話に上った際、シーブルックはミスカルに、自分は三位一体を 信じておらず、むしろ神は唯一であると信じていること、そして神はムハンマドを含む多くの預言者を遣わしたことを認めた。それを聞いたミスカルは、ウィリ アムがイスラム教に入信したいかどうか尋ね、ウィリアムは同意し、間もなくミスカルに続いてシャハーダを繰り返した。アラビアでの冒険:ベドウィン、ド ルーズ派、旋回するスーフィ、イゼディ派悪魔崇拝者たちの中で』と題された彼の旅行記は1927年に出版され、その成功によりハイチを訪れる機会を得た。 そこで彼はハイチのヴードゥー教と死者の宗教に興味を抱くようになり、それらについて詳しく記した著書『魔の島』を出版した。この本は、ゾンビという概念 を大衆文化に紹介した功績がある。[10][11] シーブルックは生涯を通じてオカルトに魅了され、それを直接目撃し、記録した。その記録は『The Magic Island』(1929年)や『Jungle Ways』(1930年)にまとめられている。彼は後に、合理的な科学的説明のつかないものは何も見ていないと結論づけた。その理論は 『Witchcraft: Its Power in the World Today』(1940年)に詳しく述べられている。 『Air Adventure』では、有名なパイロットであったルネ・ウォティエ(René Wauthier)を機長とするファルマン機でのパリからティンブクトゥへの旅について述べている。そこで彼は、当時フランス領スーダンの一部としてフラ ンスが統治していた無名の都市に関する貴重な文書を多数所蔵していた元修道士のヤコバ神父から、大量の文書を収集した。この本には、サハラにおけるフラン ス植民地生活、特にパイロットに関する情報が満載されている。 1933年12月、シーブルックは自身の要請と一部の友人の支援により、ニューヨーク市近郊のウェストチェスター郡にある精神病院ブルーミングデールに入 院し、急性アルコール中毒の治療を受けた。彼は翌年7月まで入院患者として過ごし、1935年には、あたかも外国への新たな遠征であったかのように書かれ た自身の経験をまとめた本を出版した。この本は『アサイラム』と題され、またもベストセラーとなった。[要出典] 序文で、彼は自身の著書は「フィクションでも誇張でもない」と述べている。[13] 彼は1935年にフランスでマージョリー・ミューア・ワージントンと結婚した。この結婚は、シーブルックが本を執筆するためにアフリカを旅行した後に戻っ てきてからであった。彼のアルコール依存症とサディスト的な行為により、1941年に離婚した。[14] 彼女は後に伝記『ウィリー・シーブルックの奇妙な世界』を執筆し、1966年に出版された。[15] |

| Death On September 20, 1945, Seabrook died by suicide from a drug overdose[16] in Rhinebeck, New York.[17] He left behind one son, William.[6] |

死 1945年9月20日、シーブルックはニューヨーク州ラインベックで薬物の過剰摂取により自殺した。[16] 彼にはウィリアムという息子が一人いた。[6] |

| Popular culture The Abominable Mr. Seabrook is a graphic biography of Seabrook by Joe Ollmann.[18] |

大衆文化 『忌まわしきシーブルック氏』は、ジョー・オールマンによるシーブルックの伝記グラフィックノベルである。[18] |

| Bibliography Books Diary of Section VIII (1917)[19] Adventures in Arabia (1927)[6] The Magic Island (1929)[20] Jungle Ways (1930)[6] Air Adventure (1933)[6] The White Monk of Timbuctoo (1934)[6] Asylum (1935)[6] These Foreigners: Americans All (1938)[6] Witchcraft: Its Power in the World Today (1940)[6] Doctor Wood: Modern Wizard of the Laboratory (1941)[6] No Hiding Place: An Autobiography (1942)[6] Short stories "Wow!" (1921)[21] |

参考文献 書籍 第8章の日記(1917年)[19] アラビアの冒険(1927年)[6] 魔法の島(1929年)[20] ジャングルの道(1930年)[6] 空中冒険(1933年)[6] トンブクトゥの白い僧侶(1934年)[6] 亡命(1935年)[6] これらの外国人:アメリカ人ばかり (1938)[6] 魔法:現代世界のその力 (1940)[6] ドクター・ウッド:研究室の現代の魔法使い (1941)[6] 隠れる場所なし:自伝 (1942)[6] 短編小説 「わあ!」 (1921)[21] |

| 1. "The Magic Island". Smithsonian Libraries. Retrieved June 15, 2023. 2. Kee, Chera (2017). Not Your Average Zombie: Rehumanizing the Undead from Voodoo to Zombie Walks. University of Texas Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-1477313305. 3. "Strange Adventures in Strange Places". The Age. January 8, 1944. Retrieved January 20, 2024 – via Newspapers.com. 4. "History of the American Field Service in France: Section Eight". BYU Library. 1920. Retrieved January 3, 2017. 5. "Strange Adventures in Strange Places". The Age. January 8, 1944. Retrieved January 20, 2024 – via Newspapers.com. 6. "William Seabrook (personal information provided by son, edited by granddaughter)". NNDB. Retrieved November 16, 2016. 7. "What does human meat taste like?". The Guardian. August 9, 2010. 8. Seabrook, William (1931). Jungle Ways. London: George G. Harrap. pp. 172–173. 9. Seabrook, William (1942). No Hiding Place: An Autobiography. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott. pp. 311–312. 10. "Books: Mumble-Jumble". Time. September 9, 1940. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved January 25, 2012. 11. Bishop, Kyle William (2010). American Zombie Gothic. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7864-4806-7. Nevertheless, although these two sources make reference to the condition of the living dead, it took Seabrook's 1929 travelogue The Magic Island to link the phenomenon directly with the term zombie. 12. Wauthier, Magdeleine; Wauthier, René (1934). Connaissance des sables: du Hoggar au Tchad à travers le Ténéré (in French). Paris: Plon. OCLC 25944376. 13. Seabrook, William (1935). Asylum. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. 14. "Marjorie Worthington papers, 1931–1976". Archives West. Retrieved June 4, 2024. 15. Worthingon, Majorie Muir (1966). The Strange World of Willie Seabrook. 16. Carter, Sue (January 19, 2017). "One hell of a cartoonish life ... but it was all too real". Metro Canada. Archived from the original on April 2, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2017. 17. "William Seabrook, Author, Is Suicide". The St. Petersburg Times. September 21, 1945. Retrieved April 30, 2009. 18. Ollmann, Joe (June 15, 2016). The Abominable Mr. Seabrook. Drawn & Quarterly. ISBN 978-1-77046-267-0. Retrieved February 10, 2017. 19. Seabrook, William (1917). Diary of Section VIII. Boston: Priv. print (T. Todd Co.). 20. Seabrook, William (1929). The Magic Island. 21. Seabrook, William (1940). "'Wow!' (1921), 'The Genesis of "Wow!"', and A Note on the Text". Witchcraft. Archived from the original on May 24, 2024. |

1. 「呪術の島」スミソニアン図書館。2023年6月15日取得。 2. キー、チェラ(2017年)。「ありきたりなゾンビではない:ヴードゥーからゾンビ・ウォークまで、アンデッドを再び人間化する」テキサス大学出版。p. 4. ISBN 978-1477313305. 3. 「奇妙な場所での奇妙な冒険」. The Age. 1944年1月8日. 2024年1月20日閲覧 – Newspapers.com. 4. 「フランスにおけるアメリカ野戦奉仕団の歴史:第8章」. BYU図書館. 1920年. 2017年1月3日閲覧. 5. 「Strange Adventures in Strange Places」. The Age. 1944年1月8日. 2024年1月20日閲覧 – Newspapers.com. 6. 「William Seabrook (personal information provided by son, edited by granddaughter)」. NNDB. Retrieved November 16, 2016. 7. 「What does human meat taste like?」. The Guardian. August 9, 2010. 8. Seabrook, William (1931). Jungle Ways. London: George G. Harrap. pp. 172–173. 9. シーブルック、ウィリアム(1942年)。『隠れる場所はない:自伝』フィラデルフィア:J. B. リプコット。311-312ページ。 10. 「書籍:マンブル・ジャンブル」『タイム』1940年9月9日。2007年10月13日オリジナルよりアーカイブ。2012年1月25日取得。 11. Bishop, Kyle William (2010). American Zombie Gothic. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7864-4806-7. しかしながら、この2つの情報源は生ける屍の状態について言及しているものの、この現象を直接「ゾンビ」という言葉と結びつけたのは、シーブルックの 1929年の紀行文『魔法の島』が最初である。 12. Wauthier, Magdeleine; Wauthier, René (1934). Connaissance des sables: du Hoggar au Tchad à travers le Ténéré (フランス語). Paris: Plon. OCLC 25944376. 13. Seabrook, William (1935). Asylum. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. 14. 「Marjorie Worthington papers, 1931–1976」. Archives West. Retrieved June 4, 2024. 15. Worthingon, Majorie Muir (1966). The Strange World of Willie Seabrook. 16. Carter, Sue (2017年1月19日). 「漫画のような壮絶な人生...しかし、すべてがあまりにも現実的だった」。 Metro Canada. 2017年4月2日アーカイブ。2017年4月2日取得。 17. 「作家ウィリアム・シーブルック、自殺」。 The St. Petersburg Times. 1945年9月21日。2009年4月30日取得。 18. Ollmann, Joe (2016年6月15日). The Abominable Mr. Seabrook. Drawn & Quarterly. ISBN 978-1-77046-267-0. 2017年2月10日閲覧。 19. Seabrook, William (1917). Diary of Section VIII. Boston: Priv. print (T. Todd Co.). 20. シーブルック、ウィリアム(1929年)。『The Magic Island』。 21. シーブルック、ウィリアム(1940年)。「『ワウ!』(1921年)、『「ワウ!」の起源』、およびテキストに関する注釈」。『Witchcraft』。2024年5月24日、オリジナルよりアーカイブ。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Seabrook |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆