オッカムのウィリアム

William of Ockham, 1287-1347

☆ オッカムのウィリアムまたはオッカムOFM(William of Ockham or Occam OFM, 1287年頃 - 1347年4月10日)は、イギリスのフランシスコ会修道士、スコラ哲学者、弁証主義者、カトリック神学者。 中世思想の主要人物の一人とされ、14世紀の主要な知的・政治的論争の中心にいた。オッカムの剃刀は彼の名を冠した方法原理であり、論理学、物理 学、神学に関する重要な著作もある。ウィリアムは英国国教会では4月10日に記念式典が行われ、偲ばれている.

| William of Ockham or

Occam OFM (/ˈɒkəm/ OK-əm; Latin: Gulielmus Occamus;[9][10] c. 1287 – 10

April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher,

apologist, and Catholic theologian, who is believed to have been born

in Ockham, a small village in Surrey.[11] He is considered to be one of

the major figures of medieval thought and was at the centre of the

major intellectual and political controversies of the 14th century. He

is commonly known for Occam's razor, the methodological principle that

bears his name, and also produced significant works on logic, physics

and theology. William is remembered in the Church of England with a

commemoration on the 10th of April.[12] |

オッカムのウィリアムまたはオッカムOFM(William of Ockham or

Occam OFM, 1287年頃 -

1347年4月10日)は、イギリスのフランシスコ会修道士、スコラ哲学者、弁証主義者、カトリック神学者。

[11]中世思想の主要人物の一人とされ、14世紀の主要な知的・政治的論争の中心にいた。オッカムの剃刀は彼の名を冠した方法原理であり、論理学、物理

学、神学に関する重要な著作もある。ウィリアムは英国国教会では4月10日に記念式典が行われ、偲ばれている[12]。 |

| Life William of Ockham was born in Ockham, Surrey, in 1287.[13] He received his elementary education in the London House of the Greyfriars.[14] It is believed that he then studied theology at the University of Oxford[7][8] from 1309 to 1321,[15] but while he completed all the requirements for a master's degree in theology, he was never made a regent master.[16] Because of this he acquired the honorific title Venerabilis Inceptor, or "Venerable Beginner" (an inceptor was a student formally admitted to the ranks of teachers by the university authorities).[17] During the Middle Ages, theologian Peter Lombard's Sentences (1150) had become a standard work of theology, and many ambitious theological scholars wrote commentaries on it.[18] William of Ockham was among these scholarly commentators. However, William's commentary was not well received by his colleagues, or by the Church authorities.[19] In 1324, his commentary was condemned as unorthodox by a synod of bishops,[citation needed] and he was ordered to Avignon, France, to defend himself before a papal court.[18] An alternative understanding, recently proposed by George Knysh, suggests that he was initially appointed in Avignon as a professor of philosophy in the Franciscan school, and that his disciplinary difficulties did not begin until 1327.[20] It is generally believed that these charges were levied by Oxford chancellor John Lutterell.[21][22] The Franciscan Minister General, Michael of Cesena, had been summoned to Avignon, to answer charges of heresy. A theological commission had been asked to review his Commentary on the Sentences, and it was during this that William of Ockham found himself involved in a different debate. Michael of Cesena had asked William to review arguments surrounding Apostolic poverty. The Franciscans believed that Jesus and his apostles owned no property either individually or in common, and the Rule of Saint Francis commanded members of the order to follow this practice.[23] This brought them into conflict with Pope John XXII. Because of the pope's attack on the Rule of Saint Francis, William of Ockham, Michael of Cesena and other leading Franciscans fled Avignon on 26 May 1328, and eventually took refuge in the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Louis IV of Bavaria, who was also engaged in dispute with the papacy, and became William's patron.[18] After studying the works of John XXII and previous papal statements, William agreed with the Minister General. In return for protection and patronage William wrote treatises that argued for Emperor Louis to have supreme control over church and state in the Holy Roman Empire.[18] "On June 6, 1328, William was officially excommunicated for leaving Avignon without permission",[16] and William argued that John XXII was a heretic for attacking the doctrine of Apostolic poverty and the Rule of Saint Francis, which had been endorsed by previous popes.[16] William of Ockham's philosophy was never officially condemned as heretical.[16] He spent much of the remainder of his life writing about political issues, including the relative authority and rights of the spiritual and temporal powers. After Michael of Cesena's death in 1342, William became the leader of the small band of Franciscan dissidents living in exile with Louis IV. William of Ockham died (prior to the outbreak of the plague) on 9 April 1347.[24] |

生涯 オッカムのウィリアムは、1287年にサリー州オッカムで生まれた[13]。 その後、1309年から1321年までオックスフォード大学[7][8]で神学を学んだとされるが[15]、神学の修士号取得に必要な条件をすべて満たし たものの、摂政になることはなかった。 [このため、彼はヴェネラビリス・インセプター(Venerabilis Inceptor)、すなわち「由緒ある初心者」(インセプターとは、大学当局によって正式に教師の階級に認められた学生のこと)という敬称を得た [17]。 中世には、神学者ピーター・ロンバルトの『文』(1150年)が神学の標準的な著作となり、多くの野心的な神学者がその注釈書を書いた。しかし、ウィリア ムの注釈書は彼の同僚たちや教会当局からは評判が良くなかった[19]。1324年、彼の注釈書は司教会議によって非正統的なものとして非難され[要出 典]、彼は教皇庁の法廷で弁明するためにフランスのアヴィニョンに行くよう命じられた[18]。 最近ジョージ・クニーシュによって提唱された別の理解では、彼は当初フランシスコ会学派の哲学教授としてアヴィニョンに赴任しており、彼の懲戒上の困難は 1327年まで始まらなかったとされている[20]。 一般的には、これらの告発はオックスフォード大学総長ジョン・ルッテレルによってなされたと考えられている[21][22]。 フランシスコ会総長チェゼーナのミカエルは、異端の告発に答えるためにアヴィニョンに召喚されていた。神学委員会は彼の『文章注解』を見直すよう依頼され ており、オッカムのウィリアムはその最中に別の議論に巻き込まれることになる。チェゼーナのミカエルは、使徒的清貧をめぐる論争を見直すようウィリアムに 依頼した。フランシスコ会は、イエスとその使徒たちは個人的にも共同体としても財産を所有していないと信じており、『聖フランシスコの規則』はこの実践に 従うことを会員に命じていた[23]。 教皇が「聖フランシスコの規則」を攻撃したため、オッカムのウィリアム、チェゼーナのミカエル、その他の主要なフランシスコ会士は、1328年5月26日 にアヴィニョンから逃亡し、最終的に同じく教皇庁と対立していた神聖ローマ皇帝バイエルンのルイ4世の宮廷に避難し、ウィリアムの後援者となった [18]。ウィリアムは、保護と庇護の見返りとして、神聖ローマ帝国の教会と国家をルイ皇帝が最高管理することを主張する論文を執筆した。 [18]「1328年6月6日、ウィリアムは許可なくアヴィニョンを離れたことで公式に破門された」[16]。ウィリアムは、歴代の教皇が支持してきた使 徒的清貧の教義と聖フランチェスコの規則を攻撃したヨハネ22世が異端であると主張した[16]。オッカムのウィリアムの哲学が異端として公式に非難され ることはなかった[16]。 彼は余生の大半を、霊的権力と時間的権力の相対的な権威と権利など、政治的問題について執筆することに費やした。1342年にチェゼーナのミカエルが亡く なると、ウィリアムはルイ4世とともに亡命生活を送るフランシスコ会の反体制派の小集団のリーダーとなった。1347年4月9日、オッカムのウィリアムは ペストの流行前に死去した[24]。 |

| Philosophical thought In scholasticism, William of Ockham advocated reform in both method and content, the aim of which was simplification. William incorporated much of the work of some previous theologians, especially Duns Scotus. From Duns Scotus, William of Ockham derived his view of divine omnipotence, his view of grace and justification, much of his epistemology[citation needed] and ethical convictions.[25] However, he also reacted to and against Scotus in the areas of predestination, penance, his understanding of universals, his formal distinction ex parte rei (that is, "as applied to created things"), and his view of parsimony which became known as Occam's razor. Faith and reason William of Ockham espoused fideism, stating that "only faith gives us access to theological truths. The ways of God are not open to reason, for God has freely chosen to create a world and establish a way of salvation within it apart from any necessary laws that human logic or rationality can uncover."[26] He believed that science was a matter of discovery and saw God as the only ontological necessity.[16] His importance is as a theologian with a strongly developed interest in logical method, and whose approach was critical rather than system building.[27] Nominalism William of Ockham was a pioneer of nominalism, and some consider him the father of modern epistemology, because of his strongly argued position that only individuals exist, rather than supra-individual universals, essences, or forms, and that universals are the products of abstraction from individuals by the human mind and have no extra-mental existence.[28] He denied the real existence of metaphysical universals and advocated the reduction of ontology. William of Ockham is sometimes considered an advocate of conceptualism rather than nominalism, for whereas nominalists held that universals were merely names, i.e. words rather than extant realities, conceptualists held that they were mental concepts, i.e. the names were names of concepts, which do exist, although only in the mind. Therefore, the universal concept has for its object, not a reality existing in the world outside us, but an internal representation which is a product of the understanding itself and which "supposes" in the mind the things to which the mind attributes it; that is, it holds, for the time being, the place of the things which it represents. It is the term of the reflective act of the mind. Hence the universal is not a mere word, as Roscelin taught, nor a sermo, as Peter Abelard held, namely the word as used in the sentence, but the mental substitute for real things, and the term of the reflective process. For this reason William has sometimes also been called a "Terminist", to distinguish him from a nominalist or a conceptualist.[29] William of Ockham was a theological voluntarist who believed that if God had wanted to, he could have become incarnate as a donkey or an ox, or even as both a donkey and a man at the same time. He was criticized for this belief by his fellow theologians and philosophers.[30] Efficient reasoning One important contribution that he made to modern science and modern intellectual culture was efficient reasoning with the principle of parsimony in explanation and theory building that came to be known as Occam's razor. This maxim, as interpreted by Bertrand Russell,[31] states that if one can explain a phenomenon without assuming this or that hypothetical entity, there is no ground for assuming it, i.e. that one should always opt for an explanation in terms of the fewest possible causes, factors, or variables. He turned this into a concern for ontological parsimony; the principle says that one should not multiply entities beyond necessity—Entia non sunt multiplicanda sine necessitate—although this well-known formulation of the principle is not to be found in any of William's extant writings.[32] He formulates it as: "For nothing ought to be posited without a reason given, unless it is self-evident (literally, known through itself) or known by experience or proved by the authority of Sacred Scripture."[33] For William of Ockham, the only truly necessary entity is God; everything else is contingent. He thus does not accept the principle of sufficient reason, rejects the distinction between essence and existence, and opposes the Thomistic doctrine of active and passive intellect. His scepticism to which his ontological parsimony request leads appears in his doctrine that human reason can prove neither the immortality of the soul; nor the existence, unity, and infinity of God. These truths, he teaches, are known to us by revelation alone.[29] Natural philosophy William wrote a great deal on natural philosophy, including a long commentary on Aristotle's Physics.[34] According to the principle of ontological parsimony, he holds that we do not need to allow entities in all ten of Aristotle's categories; we thus do not need the category of quantity, as the mathematical entities are not "real". Mathematics must be applied to other categories, such as the categories of substance or qualities, thus anticipating modern scientific renaissance while violating Aristotelian prohibition of metabasis. Theory of knowledge  Depiction of William of Ockham In the theory of knowledge, William rejected the scholastic theory of species, as unnecessary and not supported by experience, in favour of a theory of abstraction. This was an important development in late medieval epistemology. He also distinguished between intuitive and abstract cognition; intuitive cognition depends on the existence or non-existence of the object, whereas abstractive cognition "abstracts" the object from the existence predicate. Interpreters are, as yet, undecided about the roles of these two types of cognitive activities.[35] Political theory William of Ockham is also increasingly being recognized as an important contributor to the development of Western constitutional ideas, especially those of government with limited responsibility.[36] He was one of the first medieval authors to advocate a form of church/state separation,[36] and was important for the early development of the notion of property rights. His political ideas are regarded as "natural" or "secular", holding for a secular absolutism.[36] The views on monarchical accountability espoused in his Dialogus (written between 1332 and 1347)[37] greatly influenced the Conciliar movement and assisted in the emergence of democratic ideologies.[citation needed] William argued for complete separation of spiritual rule and earthly rule.[38] He thought that the pope and churchmen have no right or grounds at all for secular rule like having property, citing 2 Timothy 2:4. That belongs solely to earthly rulers, who may also accuse the pope of crimes, if need be.[39] After the Fall God had given men, including non-Christians, two powers: private ownership and the right to set their rulers, who should serve the interest of the people, not some special interests. Thus he preceded Thomas Hobbes in formulating social contract theory along with earlier scholars.[39] William of Ockham said that the Franciscans avoided both private and common ownership by using commodities, including food and clothes, without any rights, with mere usus facti, the ownership still belonging to the donor of the item or to the pope. Their opponents such as Pope John XXII wrote that use without any ownership cannot be justified: "It is impossible that an external deed could be just if the person has no right to do it."[39] Thus the disputes on the heresy of Franciscans led William of Ockham and others to formulate some fundamentals of economic theory and the theory of ownership.[39] Logic In logic, William of Ockham wrote down in words the formulae that would later be called De Morgan's laws,[40] and he pondered ternary logic, that is, a logical system with three truth values; a concept that would be taken up again in the mathematical logic of the 19th and 20th centuries. His contributions to semantics, especially to the maturing theory of supposition, are still studied by logicians.[41][42] William of Ockham was probably the first logician to treat empty terms in Aristotelian syllogistic effectively; he devised an empty term semantics that exactly fit the syllogistic. Specifically, an argument is valid according to William's semantics if and only if it is valid according to Prior Analytics.[43] |

哲学思想 スコラ学では、オッカムのウィリアムが方法と内容の両面における改革を提唱し、その目的は単純化であった。ウィリアムは、以前の神学者、特にドゥンス・ス コトゥスの研究の多くを取り入れた。オッカムのウィリアムは、ドゥンス・スコトゥスから、神の全能の見解、恩寵と義認の見解、認識論[要出典]と倫理的確 信の多くを得た[25]。しかし、彼はまた、定命、懺悔、普遍の理解、ex parte rei(すなわち「創造されたものに適用される」)の形式的区別、オッカムの剃刀として知られるようになったパーシモン(parsimony)の見解の分 野において、スコトゥスに反発し、反対した。 信仰と理性 オッカムのウィリアムは、「神学的真理にアクセスできるのは信仰だけである。神の道は理性には開かれていない。神は、人間の論理や合理性が明らかにするこ とのできるいかなる必要な法則からも離れて、世界を創造し、その中に救いの道を確立することを自由に選択されたからである」[26]と述べていた。 彼は科学は発見の問題であると信じており、神を唯一の存在論的必然であると見なしていた[16]。 唯名論 オッカムのウィリアムは唯名論の先駆者であり、超個的な普遍、本質、形式よりもむしろ個体のみが存在し、普遍は人間の心によって個体から抽象化された産物 であり、精神外の存在を持たないという彼の強く主張された立場から、彼を近代認識論の父とみなす者もいる[28]。 オッカムのウィリアムは唯名論よりも概念論の擁護者と見なされることがある。唯名論者が普遍は単なる名前、すなわち現存する実在ではなく言葉であるとした のに対して、概念論者は普遍は心的概念であるとした。したがって、普遍的概念はその対象として、われわれの外の世界に存在する現実ではなく、理解そのもの の産物であり、心がそれを帰属させる事物を心の中で「仮定する」内的表象を持つ。それは、心の反省的行為の用語である。それゆえ、普遍的なものは、ロセリ ンが説いたような単なる言葉でもなく、ピーター・アベラールが説いたようなセルモでもない。この理由からウィリアムは、唯名論者や概念論者と区別するため に、「ターミニスト」とも呼ばれることがある[29]。 オッカムのウィリアムは神学的自発主義者であり、神が望めばロバや牛として、あるいはロバと人間の両方として同時に受肉することもできたと信じていた。彼 はこの信念を仲間の神学者や哲学者から批判された[30]。 効率的な推論 彼が近代科学と近代的な知的文化にもたらした重要な貢献のひとつは、オッカムの剃刀として知られるようになった、説明と理論構築における簡潔性の原則を用 いた効率的な推論であった。バートランド・ラッセルによって解釈されたこの格言[31]は、もしあれこれ仮定的な実体を仮定することなく現象を説明できる のであれば、それを仮定する根拠はない、すなわち可能な限り少ない原因、要因、変数の観点からの説明を常に選ぶべきであるというものである。この原則は、 必要以上に実体を増殖させるべきではないというものである-Entia non sunt multiplicanda sine necessitate-しかし、このよく知られた原則の定式化はウィリアムの現存する著作のいずれにも見られない[32]: 「オッカムのウィリアムにとって、真に必要な唯一の存在は神であり、他のすべては偶発的である。したがって、彼は十分理性の原理を受け入れず、本質と存在 の区別を拒否し、能動的知性と受動的知性のトミズム的教義に反対する。彼の存在論的偏狭の要求が導く懐疑主義は、人間の理性では魂の不滅も、神の存在、統 一、無限性も証明できないという教義に現れている。これらの真理は啓示のみによって私たちに知らされると彼は教えている[29]。 自然哲学 ウィリアムはアリストテレスの『物理学』の長い注釈を含む自然哲学について多くの著作を残している[34]。存在論的並存性の原則に従って、彼はアリスト テレスの10個のカテゴリーのすべてに実体を認める必要はないと考えている。数学は他の範疇、例えば物質や性質の範疇に適用されるべきであり、アリストテ レス的なメタバシスの禁止に違反しながらも、近代科学ルネサンスを先取りしている。 知識論  オッカムのウィリアムの描写 知識の理論において、ウィリアムはスコラ哲学的な種の理論を、経験によって支持されない不必要なものとして否定し、抽象の理論を支持した。これは中世後期 の認識論における重要な発展であった。彼はまた、直観的認識と抽象的認識を区別した。直観的認識は対象の存在または非存在に依存するのに対し、抽象的認識 は存在述語から対象を「抽象化」する。解釈者たちは、この2つのタイプの認知活動の役割についてはまだ定まっていない[35]。 政治理論 オッカムのウィリアムは、西洋の憲法思想、特に限定的な責任を持つ政府の思想の発展への重要な貢献者としても認識されつつある[36]。彼は、政教分離の 形態を提唱した最初の中世の著者の一人であり[36]、財産権の概念の初期の発展にとって重要であった。彼の政治思想は「自然的」あるいは「世俗的」とみ なされ、世俗的絶対主義を支持した[36]。 彼の『対話』(1332年から1347年にかけて書かれたもの)[37]で主張された君主の説明責任に関する見解は、コンカリア運動に大きな影響を与え、 民主主義イデオロギーの出現を助けた[要出典]。 ウィリアムは、霊的支配と地上的支配の完全な分離を主張した[38]。彼は、テモテへの手紙第二2章4節を引用して、教皇と教会人は財産を持つような世俗 的支配をする権利も根拠もまったくないと考えた。それはあくまでも地上の支配者に属するものであり、必要であれば教皇の罪を告発することもできる [39]。 堕落の後、神は非キリスト教徒を含む人間に、私的所有権と、一部の特別な利益ではなく人々の利益に奉仕すべき支配者を定める権利という2つの権力を与え た。こうして彼はトマス・ホッブズに先駆けて、それ以前の学者たちとともに社会契約説を打ち立てた[39]。 オッカムのウィリアムは、フランシスコ会士たちは、食料品や衣料品などの日用品を、いかなる権利も持たず、単なるusus facti、つまり所有権は依然として品物の寄贈者または教皇に属するものとして使用することで、私的所有と共有の所有の両方を避けたと述べている。教皇 ヨハネ22世のような反対派は、所有権のない使用は正当化できないと書いた: 「その人がそれを行う権利を持たないのであれば、外的な行為が正当化されることはありえない」[39]。 こうして、フランシスコ会の異端に関する論争が、オッカムのウィリアムと他の者たちに、経済理論と所有権の理論のいくつかの基礎を形成させた[39]。 論理学 論理学において、オッカムのウィリアムは後にド・モルガンの法則と呼ばれることになる公式を言葉で書き記し[40]、三元論理学、すなわち3つの真理値を 持つ論理体系について考察した。オッカムのウィリアムはおそらくアリストテレスのシロジスティックにおける空項を効果的に扱った最初の論理学者であり、シ ロジスティックに正確に適合する空項意味論を考案した。具体的には、ウィリアムの意味論によれば、ある論証が有効であるのは、それが先行分析学によれば有 効である場合に限られる[43]。 |

| Theological thought Church authority William of Ockham denied papal infallibility and often went into conflict with the pope.[44] As a result, some theologians have viewed him as a proto-Protestant.[45] However, despite his conflicts with the papacy he did not renounce the Roman Catholic Church.[46] Ockham also held that councils of the Church were fallible, he held that any individual could err on matters of faith, and councils being composed of multiple fallible individuals could err.[47] He thus foreshadowed some elements of Luther's view of sola scriptura.[48][49][50] Church and State Ockham taught the separation of church and state, believing that the pope and emperor should be separate.[46] Apostolic poverty Ockham advocated for voluntary poverty.[51] Soul Ockham opposed Pope John XXII on the question of the Beatific Vision. John had proposed that the souls of Christians did not instantly get to enjoy the vision of God, rather such vision would be postponed until the last judgement.[52] |

神学思想 教会の権威 オッカムのウィリアムはローマ教皇の無謬性を否定し、しばしばローマ教皇と対立した[44]。 [46]オッカムはまた教会の公会議が誤りを犯す可能性があるとし、いかなる個人も信仰の問題に関して誤りを犯す可能性があり、複数の誤りを犯しうる個人 によって構成される公会議も誤りを犯す可能性があるとした[47]。したがって彼はルターのソラ・スクリプトゥラに対する見解のいくつかの要素を予見して いた[48][49][50]。 教会と国家 オッカムは教皇と皇帝は分離されるべきであると考え、政教分離を説いた[46]。 使徒的清貧 オッカムは自発的な清貧を提唱した[51]。 魂 オッカムは教皇ヨハネ22世と受光の問題で対立した。ヨハネは、キリスト教徒の魂は神の幻視を即座に享受することはできず、むしろそのような幻視は最後の 審判まで延期されると提案していた[52]。 |

| Literary Ockhamism/nominalism William of Ockham and his works have been discussed as a possible influence on several late medieval literary figures and works, especially Geoffrey Chaucer, but also Jean Molinet, the Gawain poet, François Rabelais, John Skelton, Julian of Norwich, the York and Townely Plays, and Renaissance romances. Only in very few of these cases is it possible to demonstrate direct links to William of Ockham or his texts. Correspondences between Ockhamist and Nominalist philosophy/theology and literary texts from medieval to postmodern times have been discussed within the scholarly paradigm of literary nominalism.[53] Erasmus, in his Praise of Folly, criticized him together with Duns Scotus as fuelling unnecessary controversies inside the Church. |

文学的オッカム主義/ノミナリズム オッカムのウィリアムとその著作は、中世後期の文学者や作品、特にジェフリー・チョーサーをはじめ、ジャン・モリネ、ガウェイン詩人、フランソワ・ラブ レー、ジョン・スケルトン、ジュリアン・オブ・ノーウィッチ、ヨーク劇、タウンリー劇、ルネサンス・ロマンスなどに影響を与えた可能性があると論じられて きた。これらのうち、ウィリアム・オブ・オッカムや彼のテキストとの直接的なつながりを示すことができるのはごくわずかである。中世からポストモダンにか けてのオッカム主義やノミナリズムの哲学・神学と文学テクストとの対応関係は、文学的ノミナリズムという学問的パラダイムの中で議論されてきた[53]。 |

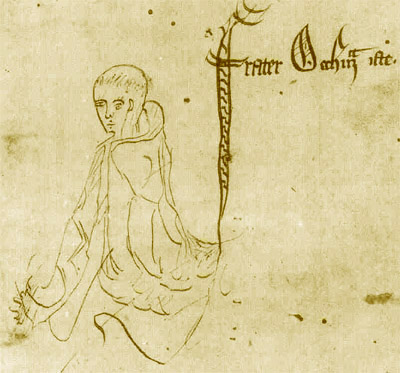

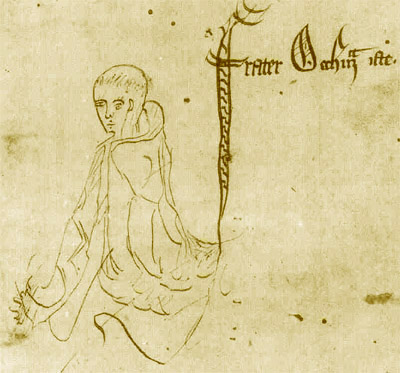

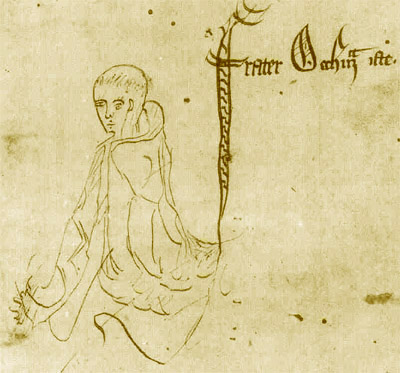

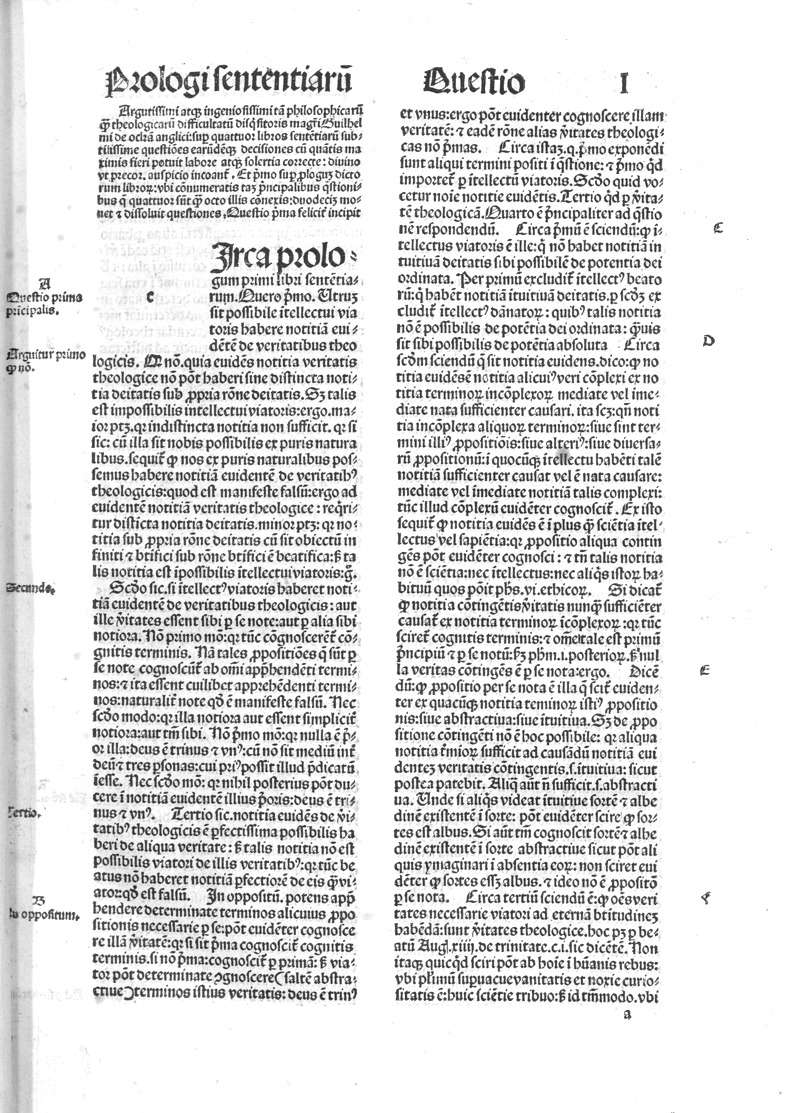

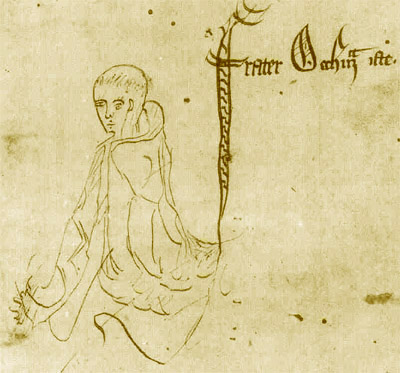

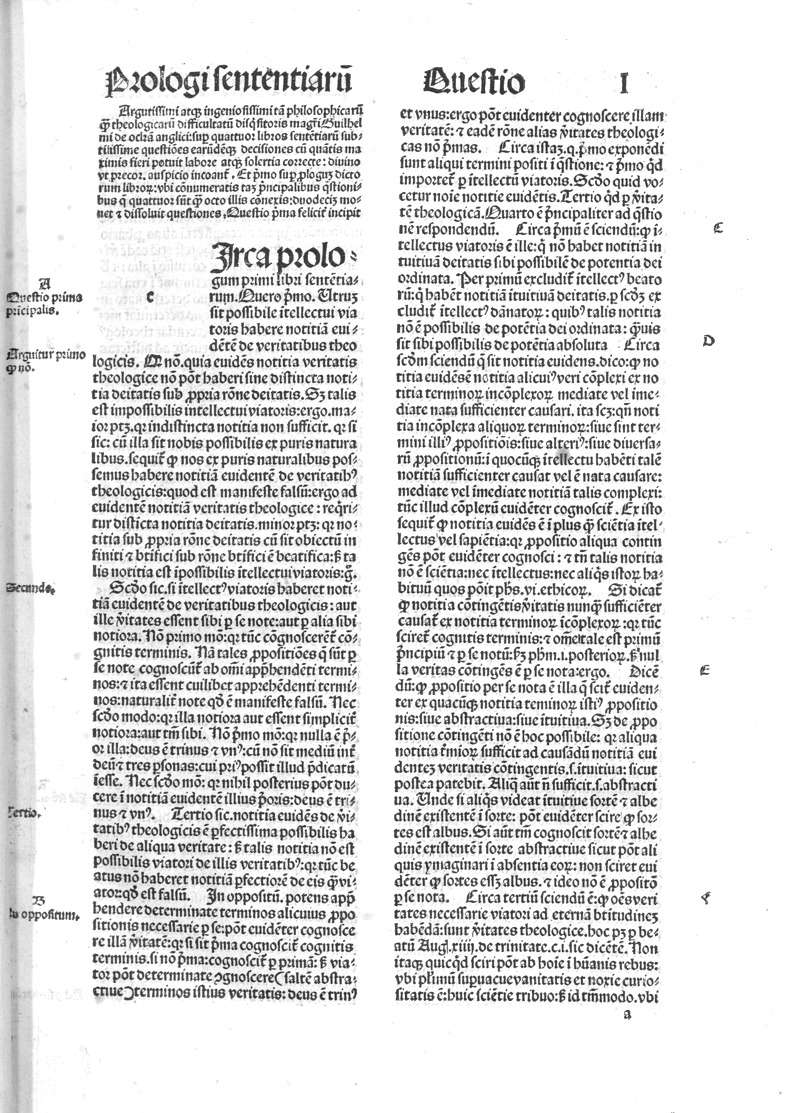

Works Sketch labelled "frater Occham iste", from a manuscript of Ockham's Summa Logicae, 1341  Quaestiones in quattuor libros sententiarum The standard edition of the philosophical and theological works is: William of Ockham: Opera philosophica et theologica, Gedeon Gál, et al., eds. 17 vols. St. Bonaventure, New York: The Franciscan Institute, 1967–1988. The seventh volume of the Opera Philosophica contains the doubtful and spurious works. The political works, all but the Dialogus, have been edited in H. S. Offler, et al., eds. Guilelmi de Ockham Opera Politica, 4 vols., 1940–1997, Manchester: Manchester University Press [vols. 1–3]; Oxford: Oxford University Press [vol. 4]. Abbreviations: OT = Opera Theologica vol. 1–10; OP = Opera Philosophica vol. 1–7. Philosophical writings Summa logicae (Sum of Logic) (c. 1323, OP 1). Expositionis in Libros artis logicae prooemium, 1321–1324, OP 2). Expositio in librum Porphyrii de Praedicabilibus, 1321–1324, OP 2). Expositio in librum Praedicamentorum Aristotelis, 1321–1324, OP 2). Expositio in librum in librum Perihermenias Aristotelis, 1321–1324, OP 2). Tractatus de praedestinatione et de prescientia dei respectu futurorum contingentium (Treatise on Predestination and God's Foreknowledge with respect to Future Contingents, 1322–1324, OP 2). Expositio super libros Elenchorum (Exposition of Aristotle's Sophistic refutations, 1322–1324, OP 3). Expositio in libros Physicorum Aristotelis. Prologus et Libri I–III (Exposition of Aristotle's Physics) (1322–1324, OP 4). Expositio in libros Physicorum Aristotelis. Prologus et Libri IV–VIII (Exposition of Aristotle's Physics) (1322–1324, OP 5). Brevis summa libri Physicorum (Brief Summa of the Physics, 1322–23, OP 6). Summula philosophiae naturalis (Little Summa of Natural Philosophy, 1319–1321, OP 6). Quaestiones in libros Physicorum Aristotelis (Questions on Aristotle's Books of the Physics, before 1324, OP 6). Theological writings In libros Sententiarum (Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard). Book I (Ordinatio) completed shortly after July 1318 (OT 1–4). Books II–IV (Reportatio) 1317–18 (transcription of the lectures; OT 5–7). Quaestiones variae (OT 8). Quodlibeta septem (before 1327) (OT 9). Tractatus de quantitate (1323–24. OT 10). Tractatus de corpore Christi (1323–24, OT 10). Political writings Opus nonaginta dierum (1332–1334). Epistola ad fratres minores (1334). Dialogus (before 1335). Tractatus contra Johannem [XXII] (1335). Tractatus contra Benedictum [XII] (1337–38). Octo quaestiones de potestate papae (1340–41). Consultatio de causa matrimoniali (1341–42). Breviloquium (1341–42). De imperatorum et pontificum potestate [also known as Defensorium] (1346–47). Doubtful writings Tractatus minor logicae (Lesser Treatise on logic) (1340–1347?, OP 7). Elementarium logicae (Primer of logic) (1340–1347?, OP 7). Spurious writings Tractatus de praedicamentis (OP 7). Quaestio de relatione (OP 7). Centiloquium (OP 7). Tractatus de principiis theologiae (OP 7). Translations Philosophical works Philosophical Writings, tr. P. Boehner, rev. S. Brown (Indianapolis, Indiana, 1990) Ockham's Theory of Terms: Part I of the Summa logicae, translated by Michael J. Loux (Notre Dame; London: University of Notre Dame Press, 1974) [translation of Summa logicae, part 1] Ockham's Theory of Propositions: Part II of the Summa logicae, translated by Alfred J. Freddoso and Henry Schuurman (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1980) [translation of Summa logicae, part 2] Demonstration and Scientific Knowledge in William of Ockham: a Translation of Summa logicae III-II, De syllogismo demonstrativo, and Selections from the Prologue to the Ordinatio, translated by John Lee Longeway (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame, 2007) Ockham on Aristotle's Physics: A Translation of Ockham's Brevis Summa Libri Physicorum, translated by Julian Davies (St. Bonaventure, New York: The Franciscan Institute, 1989) Kluge, Eike-Henner W., "William of Ockham's Commentary on Porphyry: Introduction and English Translation", Franciscan Studies 33, pp. 171–254, JSTOR 41974891, and 34, pp. 306–382, JSTOR 44080318 (1973–74) Predestination, God's Foreknowledge, and Future Contingents, translated by Marilyn McCord Adams and Norman Kretzmann (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1969) [translation of Tractatus de praedestinatione et de praescientia Dei et de futuris contigentibus] Quodlibetal Questions, translated by Alfred J. Freddoso and Francis E. Kelley, 2 vols (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1991) (translation of Quodlibeta septem) Paul Spade, Five Texts on the Mediaeval Problem of Universals: Porphyry, Boethius, Abelard, Duns Scotus, Ockham (Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett, 1994) [Five questions on Universals from His Ordinatio d. 2 qq. 4–8] Theological works The De sacramento altaris of William of Ockham, translated by T. Bruce Birch (Burlington, Iowa: Lutheran Literary Board, 1930) [translation of Treatise on Quantity and On the Body of Christ] Political works An princeps pro suo uccursu, scilicet guerrae, possit recipere bona ecclesiarum, etiam invito papa, translated Cary J. Nederman, in Political thought in early fourteenth-century England: treatises by Walter of Milemete, William of Pagula, and William of Ockham (Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2002) A translation of William of Ockham's Work of Ninety Days, translated by John Kilcullen and John Scott (Lewiston, New York: E. Mellen Press, 2001) [translation of Opus nonaginta dierum] Tractatus de principiis theologiae, translated in A compendium of Ockham's teachings: a translation of the Tractatus de principiis theologiae, translated by Julian Davies (St. Bonaventure, New York: Franciscan Institute, St. Bonaventure University, 1998) On the Power of Emperors and Popes, translated by Annabel S. Brett (Bristol, 1998) Rega Wood, Ockham on the Virtues (West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, 1997) [includes translation of On the Connection of the Virtues] A Letter to the Friars Minor, and Other Writings, translated by John Kilcullen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995) [includes translation of Epistola ad Fratres Minores] A Short Discourse on the Tyrannical Government, translated by John Kilcullen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992) [translation of Breviloquium de principatu tyrannico] William of Ockham, [Question One of] Eight Questions on the Power of the Pope, translated by Jonathan Robinson[54] |

作品 frater Occham iste」と書かれたスケッチ(オッカムの『Summa Logicae』写本より、1341年  四大文献における問答 哲学的・神学的著作の標準版は以下の通り: William of Ockham: Opera philosophica et theologica, Gedeon Gál, et al. St. Bonaventure, New York: The Franciscan Institute, 1967-1988. オペラ・フィロソフィカの第7巻には、疑わしい偽作が収められている。 対話篇を除く政治的著作は、H. S. Offler, et al. Guilelmi de Ockham Opera Politica, 4 vols., 1940-1997, Manchester: Manchester University Press [vols. 1-3]; Oxford: Oxford University Press [vol. 4]. 略号 OT = Opera Theologica 1-10巻、OP = Opera Philosophica 1-7巻。 哲学著作 Summa logicae(論理の要約)(1323年頃、OP 1)。 Expositionis in Libros artis logicae prooemium(1321-1324, OP 2)。 Expositio in librum Porphyrii de Praedicabilibus, 1321-1324, OP 2). Praedicamentorum Aristotelis』所収、1321-1324年、OP 2)。 Praedicamentorum Aristotelis, 1321-1324, OP 2). Tractatus de praedestinatione et de prescientia dei respectu futurorum contingentium(将来の偶発事象に関する宿命と神の予知に関する論考、1322-1324、OP 2)。 Expositio super libros Elenchorum(アリストテレスの詭弁的反論の解説、1322-1324、OP 3)。 Expositio in libros Physicorum Aristotelis. Prologus et Libri I-III (Exposition of Aristotle's Physics) (1322-1324, OP 4). Expositio in libros Physicorum Aristotelis. Prologus et Libri IV-VIII(アリストテレス物理学の解説)(1322-1324、OP 5)。 Brevis summa libri Physicorum(物理学の簡潔な要約、1322-23、OP 6)。 Summula philosophiae naturalis(自然哲学の小スマーマ、1319-1321、OP 6)。 Quaestiones in libros Physicorum Aristotelis(アリストテレスの物理学書に関する質問、1324年以前、OP 6)。 神学著作 In libros Sentiarum(ペーテル・ロンバールの文章注解)。 第1巻(Ordinatio)は1318年7月直後に完成(OT 1-4)。 II-IV巻(Reportatio)1317-18年(講義の書き写し;OT 5-7)。 Quaestiones variae(OT 8)。 Quodlibeta septem(1327年以前)(OT 9)。 Tractatus de quantitate (1323-24. OT 10). Tractatus de corpore Christi (1323-24, OT 10). 政治的著作 Opus nonaginta dierum (1332-1334). Epistola ad fratres minores(1334年)。 対話(1335年以前)。 対ヨハネ論[XXII](1335)。 ベネディクトゥムとの論争[XII](1337-38)。 教皇職に関する10問(1340-41年)。 婚姻原因に関する諮問(1341-42)。 ブレヴィロキウム(1341-42)。 De imperatorum et pontificum potestate [Defensorium としても知られる] (1346-47). 疑わしい著作 小論理書(Tractatus minor logicae)(1340-1347?) 論理学の入門書(Elementarium logicae)(1340-1347?) 偽書 Tractatus de praedicamentis(OP 7). Quaestio de relatione(OP 7)。 百人一首(OP 7)。 Tractatus de principiis theologiae(OP 7). 翻訳 哲学著作 Philosophical Writings, P. Boehner, rev. S. Brown (インディアナポリス). S. Brown (Indianapolis, Indiana, 1990) オッカムの用語論: マイケル・J・ルークス訳『Summa logicae』第1部(ノートルダム;ロンドン:ノートルダム大学出版局、1974年)[『Summa logicae』第1部の翻訳] オッカムの命題論: オッカムの命題論:アルフレッド・J・フレドソ、ヘンリー・シュールマン訳『Summa logicae』第二部(ノートルダム:ノートルダム大学出版局、1980年)[『Summa logicae』第二部の翻訳] オッカムのウィリアムにおける実証と科学的知識:Summa logicae III-II, De syllogismo demonstrativo, and Selections from the Prologue to the Ordinatio, translated by John Lee Longeway (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame, 2007) アリストテレスの物理学についてのオッカム: オッカム『ブレビス・スンマ・リブリ・フィジコルム』ジュリアン・デイヴィス訳(セント・ボナヴェントゥア、ニューヨーク:フランシスカン研究所、 1989年) Kluge, Eike-Henner W., "William of Ockham's Commentary on Porphyry: 序論と英訳」『フランシスカン研究』33号、171-254頁、JSTOR 41974891、34号、306-382頁、JSTOR 44080318 (1973-74) Predestination, God's Foreknowledge, and Future Contingents, Marilyn McCord Adams and Norman Kretzmann, translated (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1969) [Tractatus de praedestinatione et de praescientia Dei et de futuris contigentibus の翻訳]。 アルフレッド・J・フレドソ、フランシス・E・ケリー訳『クオドリベタル・クエスチョンズ』全2巻(ニューヘイブン;ロンドン:イェール大学出版部、 1991年)(『クオドリベタ・セプテム』の翻訳) Paul Spade, Five Texts on the Mediaeval Problem of Universals: Porphyry, Boethius, Abelard, Duns Scotus, Ockham (Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett, 1994) [His Ordinatio d. 2 qq. 4-8 から普遍に関する5つの質問]。 神学著作 オッカムのウィリアムのDe sacramento altaris, T. Bruce Birch訳 (Burlington, Iowa: Lutheran Literary Board, 1930) [数量論とキリストの体についての翻訳] 政治的著作 An princeps pro suo uccursu, scilicet guerrae, possit recipere bona ecclesiarum, etiam invito papa, Cary J. Nederman訳『14世紀初頭イングランドの政治思想:ミレメテのウォルター、パグラのウィリアム、オッカムのウィリアムによる論考』(アリゾナ州テ ンピ:アリゾナ中世・ルネサンス研究センター、2002年) ウィリアム・オブ・オッカム『九十日の仕事』ジョン・キルカレン、ジョン・スコット訳(Lewiston, New York: E. Mellen Press, 2001)[Opus nonaginta dierumの翻訳] Tractatus de principiis theologiae, translated in A compendium of Ockham's teachings: a translation of the Tractatus de principiis theologiae, translated by Julian Davies (St. Bonaventure, New York: 聖ボナヴェンチュール大学フランシスカン研究所、1998年) アナベル・S・ブレット訳『皇帝と教皇の権力について』(ブリストル、1998年) リーガ・ウッド『徳についてのオッカム』(インディアナ州ウェスト・ラファイエット:パデュー大学出版、1997年)[『徳のつながりについて』の翻訳を 含む] ジョン・キルカレン訳『小さき修道士への手紙、およびその他の著作』(ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1995年)[『小さき修道士への手紙』 (Epistola ad Fratres Minores)の翻訳を含む。 ジョン・キルカレン訳『専制政治に関する短い講話』(ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1992年)[Breviloquium de principatu tyrannicoの翻訳を含む] ウィリアム・オブ・オッカム『教皇の権力に関する八つの質問の[第一問]』ジョナサン・ロビンソン訳[54] |

| In fiction William of Occam served as an inspiration for the creation of William of Baskerville, the main character of Umberto Eco's novel The Name of the Rose, and is the main character of La Abadía del Crimen (The Abbey of Crime), a video game based upon said novel. |

フィクション オッカムのウィリアムは、ウンベルト・エーコの小説『薔薇の名前』の主人公であるバスカヴィルのウィリアムの創作のインスピレーションとなり、同小説を原 作としたビデオゲーム『La Abadía del Crimen(犯罪の修道院)』の主人公でもある。 |

| Gabriel Biel Philotheus Boehner History of science#Middle Ages List of Catholic clergy scientists List of scholastic philosophers Ernest Addison Moody occam (programming language) Ockham algebra Oxford Franciscan school Rule according to higher law Terminism |

ガブリエル・ビール フィロテウス・ベーナー 科学史#中世 カトリック聖職者の科学者リスト スコラ哲学者リスト アーネスト・アディソン・ムーディ オッカム オッカム代数 オックスフォード・フランシスコ派 高次の法則による支配 ターミナリズム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_of_Ockham |

|

| That Spanish woman who lived three hundred

years ago, was certainly not the last of her

kind. Many Theresas have been born who found

for themselves no epic life wherein there was a

constant unfolding of far - resonant action; perhaps

only a life of mistakes, the offspring of a

certain spiritual grandeur ill-matched with the

meanness of opportunity ; perhaps a tragic failure

which found· no sacred poet and sank unwept

into oblivion. With dim lights and tangled circumstance

they tried to shape their thought and

deed in noble agreement~ but after all, to common

eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency

and formlessness; for these later - born Theresas

were helped by no coherent social faith and order

which could perform the function of knowledge

for the ardently willing soul. Their ardour alternated

between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood ; so that the one was

disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned

as a lapse.

Some have felt that these blundering lives are due to the inconvenient indefiniteness with which the Supreme Power has fashioned the natures of women : if there were one level of feminine incompetence as strict as the ability to count three and no more, the social lot of women might be treated with scientific certitude. Meanwhile the indefiniteness remains, and the limits of variation are really much wider than any one would imagine from the sameness of women's coiffue and the favourite love-stories in prose and verse. Here and there a cygnet is reared uneasy among the ducklings in the brown pond, and never finds the living stream in fellowship with its own oary - footed kind. Here and there is born a Saint Theresa, foundress of nothing, whose loving heart-beats and sobs after an unattained goodness tremble off and are dispersed among hindrances, instead of centering in some long - recognisable deed. George Eliot, Middlemarch, a studynof provincial life. |

300

年前に生きたスペイン人女性は、確かにその種の最後の一人ではなかった。多くのテレーザが生まれたが、彼女自身は、遥かに共鳴する行動が絶え間なく展開さ

れるような叙事詩のような人生を送ることはなかった。おそらくは、ある種の精神的な壮大さと機会の卑しさとが不釣り合いであったために生まれた失敗の人生

であり、おそらくは、神聖な詩人も見つからず、忘却の彼方へと沈んでいった悲劇的な失敗の人生であっただろう。しかし、結局のところ、一般の人々の目に

は、彼らの苦闘は単なる矛盾と形のないものにしか映らなかったのである。彼らの熱意は、漠然とした理想と女性としての一般的な憧れの間で交互に繰り返さ

れ、一方は贅沢として否定され、他方は怠惰として非難された。 もし、女性の無能さを、3つ数える能力と同じくらい厳密なもので、それ以上には数えられないとしたら、女性の社会的地位は科学的な確証をもって扱われるか もしれない。しかし、その一方で不定性は依然として残っており、その変化の限界は、女性の髪形や、散文や詩で好まれているラブストーリーの類似性から想像 されるよりもずっと広い。あちこちの茶色い池のアヒルの子たちに混じって不安そうに育てられているシグネットは、自分たちのウーパールーパーのような種類 と交わりながら、生きている小川を見つけることはない。あちらこちらで聖テレジアが生まれるが、その聖テレジアの愛の鼓動と嗚咽は、達成されなかった善を 求めるあまり、震え上がり、妨げとなるものの中に分散してしまう。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆