女性

Woman

Left:

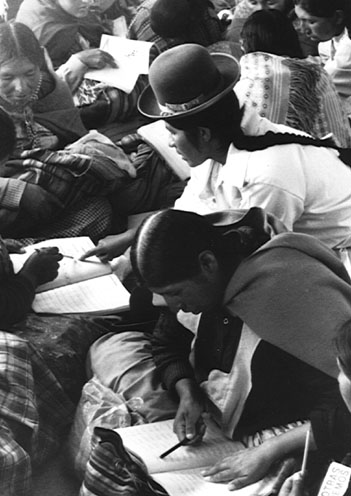

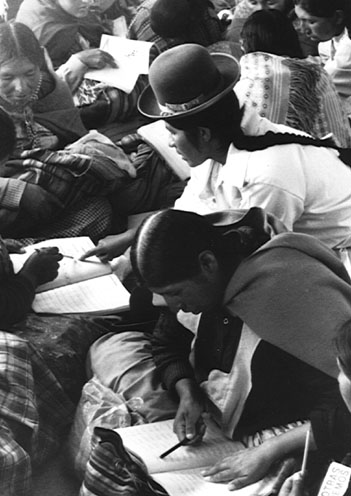

The

women's liberation movement featured political activities such as a

march demanding legal equality for women in the United States (26

August 1970)

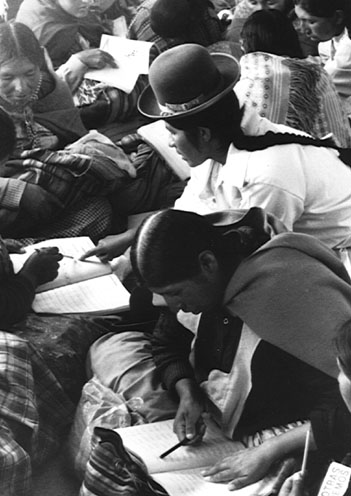

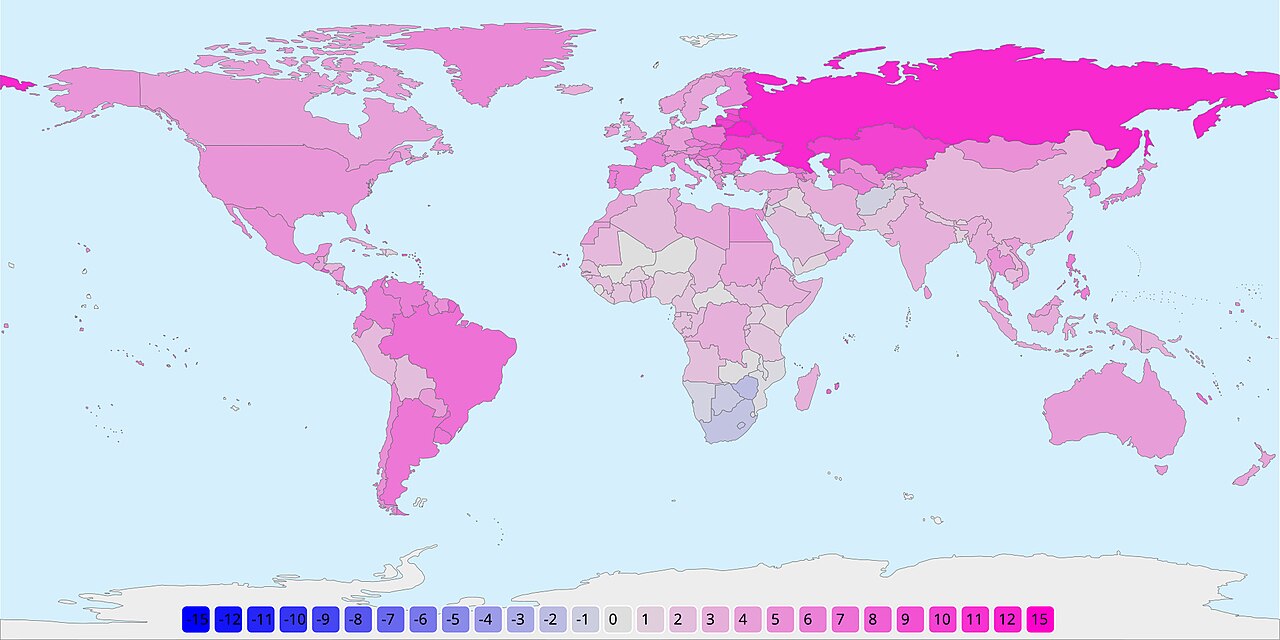

Right: Women attending an adult literacy class in the El Alto section of La Paz, Bolivia

☆

★ 女性(woman)とはなにか?女性は成人した 女性人間である。[a][2][3] 成人する前の女性の子どもや思春期女性は「女の子」と呼ばれる(→「女性解放運動」)。

| A woman is an adult

female human.[a][2][3] Before adulthood, a female child or adolescent

is referred to as a girl.[4] Typically, women are of the female sex and inherit a pair of X chromosomes, one from each parent, and women with functional uteruses are capable of pregnancy and giving birth from puberty until menopause. More generally, sex differentiation of the female fetus is governed by the lack of a present, or functioning, SRY gene on either one of the respective sex chromosomes.[5] Female anatomy is distinguished from male anatomy by the female reproductive system, which includes the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, vagina, and vulva. An adult woman generally has a wider pelvis, broader hips, and larger breasts than an adult man. These characteristics facilitate childbirth and breastfeeding. Women typically have less facial and other body hair, have a higher body fat composition, and are on average shorter and less muscular than men. Throughout human history, traditional gender roles within patriarchal societies have often defined and limited women's activities and opportunities, resulting in gender inequality; many religious doctrines and legal systems stipulate certain rules for women. With restrictions loosening during the 20th century in many societies, women have gained wider access to careers and the ability to pursue higher education. Violence against women, whether within families or in communities, has a long history and is primarily committed by men. Some women are denied reproductive rights. The movements and ideologies of feminism have a shared goal of achieving gender equality. Some women are transgender, meaning they were assigned male at birth,[6][7] while some women are intersex, meaning they have sex characteristics that do not fit typical notions of female biology.[8][9] |

女性は成人した女性人間である。[a][2][3]

成人する前の女性の子どもや思春期女性は「女の子」と呼ばれる。[4] 通常、女性は女性性であり、両親からそれぞれ1つずつX染色体を1対受け継いでおり、機能的な子宮を持つ女性は、思春期から閉経まで妊娠して出産すること ができる。より一般的には、女性胎児の性分化は、それぞれの性染色体にSRY遺伝子が存在しない、または機能していないことによって決定される。[5] 女性解剖学は、卵巣、卵管、子宮、膣、外陰部を含む女性生殖器系によって男性解剖学と区別される。成人女性は、成人男性に比べて骨盤が広く、臀部が広く、 乳房が大きい。これらの特徴は出産と授乳を容易にする。女性は一般的に顔や他の部位の体毛が少なく、体脂肪率が高く、平均的に男性よりも身長が低く、筋肉 量が少ない。 人類の歴史を通じて、父権制社会における伝統的な性別役割は、女性の活動と機会を定義し制限し、性別不平等をもたらしてきました。多くの宗教的教義や法体 系は、女性に対する特定の規則を定めています。20世紀に多くの社会で制限が緩和されるにつれ、女性は職業へのアクセスが拡大し、高等教育を受ける能力を 獲得してきました。家族内やコミュニティにおける女性に対する暴力は長い歴史があり、主に男性によって行われている。一部の女性は生殖権を否定されてい る。フェミニズムの運動や思想は、性別平等を実現することを共通の目標としている。 一部の女性はトランスジェンダーであり、出生時に男性と割り当てられた[6][7]一方、一部の女性はインターセックスであり、女性の生物学的特徴に典型 的な概念に当てはまらない性的な特徴を持っている[8][9]。 |

| Etymology See also: Man (word) The spelling of woman in English has progressed over the past millennium from wīfmann[10] to wīmmann to wumman, and finally, the modern spelling woman.[11] In Old English, mann had the gender-neutral meaning of 'human', akin to the Modern 'person' or 'someone'. The word for 'woman' was wīf or wīfmann (lit. 'woman-person') whereas 'man' was wer or wǣpnedmann (from wǣpn 'weapon; penis'). However, following the Norman Conquest, man began to mean 'male human', and by the late 13th century it had largely replaced wer.[12] The consonants /f/ and /m/ in wīfmann coalesced into the modern woman, while wīf narrowed to specifically mean a married woman ('wife'). It is a popular misconception that the term "woman" is etymologically connected to "womb".[13] "Womb" derives from the Old English word wamb meaning 'belly, uterus'[14] (cognate to the modern German colloquial term "Wamme" from Old High German wamba for 'belly, paunch, lap').[15][16] |

語源 「男 (単語)」も参照。 英語での「女性」の綴りは、過去 1000 年の間に wīfmann[10] から wīmmann、wumman、そして最終的には現代の woman に変化した[11]。古英語では、mann は「人間」という性別を区別しない意味を持ち、現代の「人」や「誰か」に類似していた。「女性」を表す単語は wīf または wīfmann(文字通り「女性の人」)でしたが、「男性」は wer または wǣpnedmann(wǣpn「武器、陰茎」から)でした。しかし、ノーマン征服後、man は「男性の人間」を意味するようになり、13 世紀後半には wer をほぼ置き換えていました。[12] wīfmann の子音 /f/ と /m/ は現代英語の woman に融合し、wīf は特に「既婚女性(妻)」という意味に狭まった。 「woman」という用語は「子宮」と語源的に関連しているという誤解が広くあります。[13] 「子宮」は、古英語「wamb」から派生し、「腹、子宮」を意味します[14](現代ドイツ語の口語用語「Wamme」は、古高ドイツ語の「wamba」 (「腹、お腹、膝の上」)に由来します)。[15][16] |

| Terminology Further information: girl, virgin, mother, wife, daughter, goodwife, godmother, lady, maid, maiden, and widow "Young Woman" redirects here. For the painting by Isabel Bishop, see Young Woman (painting). Three generations: an older woman, her daughter, and her granddaughter. The word woman can be used generally, to mean any female human, or specifically, to mean an adult female human as contrasted with girl. The word girl originally meant "young person of either sex" in English;[17] it was only around the beginning of the 16th century that it came to mean specifically a female child.[18] The term girl is sometimes used colloquially to refer to a young or unmarried woman; however, during the early 1970s, feminists challenged such use because the use of the word to refer to a fully grown woman may cause offense. In particular, previously common terms such as office girl are no longer widely used. Conversely, in certain cultures which link family honor with female virginity, the word girl (or its equivalent in other languages) is still used to refer to a never-married woman; in this sense it is used in a fashion roughly analogous to the more-or-less obsolete English maid or maiden. The social sciences' views on what it means to be a woman have changed significantly since the early 20th century as women gained more rights and greater representation in the workforce, with scholarship in the 1970s moving toward a focus on the sex–gender distinction and social construction of gender.[19][20] There are various words used to refer to the quality of being a woman. The term "womanhood" merely means the state of being a woman; "femininity" is used to refer to a set of typical female qualities associated with a certain attitude to gender roles; "womanliness" is like "femininity", but is usually associated with a different view of gender roles.[citation needed] Different countries have different laws, but age 18 is frequently considered the age of majority (the age at which a person is legally considered an adult).[21] Menarche, the onset of menstruation, occurs on average at age 12–13. Many cultures have rites of passage to symbolize a girl's coming of age, such as confirmation in some branches of Christianity,[22] bat mitzvah in Judaism, or a custom of a special celebration for a certain birthday (generally between 12 and 21), like the quinceañera of Latin America. |

用語 詳細情報:少女、処女、母親、妻、娘、良妻、名付け親、女性、メイド、乙女、未亡人 「若い女性」はここにリダイレクトされます。イザベル・ビショップの絵画については、「若い女性 (絵画)」をご覧ください。 3世代:年配の女性、その娘、そして孫娘。 「女性」という言葉は、一般的に、女性の人間全般を指す場合、あるいは「少女」と対比して、成人の女性を指す場合にも使用される。「少女」という言葉は、 もともと英語では「男女を問わず若い人」を意味していた[17]。16世紀初頭になって、初めて「特に女性の子供」を意味するようになった。[18] 「少女」という用語は、若い女性や未婚の女性を指す口語的な表現として使用されることがある。しかし、1970年代初頭、フェミニストたちは、この用語を 成人女性を指すために使用することは不快であるとして、その使用に異議を唱えた。特に、以前は一般的だった「オフィスガール」などの用語は、もはや広く使 用されなくなった。一方、家族の名誉と女性の処女性が結びついている一部の文化では、「girl」(または他の言語での同義語)は未婚の女性を指す言葉と して今も使われている。この意味では、ほぼ廃れた英語の「maid」や「maiden」と類似した用法だ。 20世紀初頭以降、女性がより多くの権利を獲得し、労働力における代表性が高まるにつれ、社会科学における「女性であること」の意味は大きく変化した。 1970年代の学術研究は、性(sex)と性別(gender)の区別と、性別の社会的構築に焦点を当てる方向へ移行した。[19][20] 女性であるという性質を表す言葉にはさまざまなものがある。「女性らしさ」という用語は、単に女性であるという状態を指す。「女性性」は、性別役割に対す る特定の態度に関連する一連の典型的な女性の性質を指す。「女性らしさ」は「女性性」と似ているが、通常、性別役割に関する異なる見方に関連している。 [要出典] 国によって法律は異なるが、18 歳が成年の年齢(人格として法的に成人とみなされる年齢)とみなされる場合が多い。[21] 月経の開始である初潮は、平均して 12~13 歳で起こる。多くの文化には、少女の成人を象徴する通過儀礼がある。例えば、キリスト教の一部では確認式[22]、ユダヤ教ではバト・ミツバ、または特定 の誕生日(通常12歳から21歳の間)を祝う特別な習慣(ラテンアメリカにおけるクインセアニェラなど)がある。 |

| Biology Photograph of an adult female human, with an adult male for comparison. The pubic hair of both models is removed. Photograph of an adult female human, with an adult male for comparison. The pubic hair of both models is removed. Main article: Sex differences in humans Male and female bodies have some differences. Some differences, such as the external sex organs, are visible, while other differences, such as internal anatomy and genetic characteristics, are not visible. Genetic characteristics Main article: Sexual differentiation in humans A multi-colored sphere, and a set of chromosomes listed in a data table Spectral karyotype of a human female Typically, the cells of female humans contain two X chromosomes, while the cells of male humans have an X and a Y chromosome.[23] During early fetal development, all embryos have phenotypically female genitalia up until week 6 or 7, when a male embryo's gonads differentiate into testes due to the action of the SRY gene on the Y chromosome.[24] Sex differentiation proceeds in female humans in a way that is independent of gonadal hormones.[24] Because humans inherit mitochondrial DNA only from the mother's ovum, genealogical researchers can trace maternal lineage far back in time. Hormonal characteristics, menstruation and menopause Main articles: Menstrual cycle and Menstruation Female puberty triggers bodily changes that enable sexual reproduction via fertilization. In response to chemical signals from the pituitary gland, the ovaries secrete hormones that stimulate maturation of the body, including increased height and weight, body hair growth, breast development and menarche (the onset of menstruation).[25] nude woman in the middle of pregnancy A pregnant woman Most girls go through menarche between ages 12–13,[26][27] and are then capable of becoming pregnant and bearing children. Pregnancy generally requires internal fertilization of the eggs with sperm, via either sexual intercourse or artificial insemination, though in vitro fertilization allows fertilization to occur outside the human body.[28] Humans are similar to other large mammals in that they usually give birth to a single offspring per pregnancy, but are unusual in being altricial compared to most other large mammals, meaning young are undeveloped at time of birth and require the aid of their parents or guardians to fully mature.[29] Sometimes humans have multiple births, most commonly twins.[30] Usually between ages 49–52, a woman reaches menopause, the time when menstrual periods stop permanently, and they are no longer able to bear children.[31][32][33] Unlike most other mammals, the human lifespan usually extends many years after menopause.[34] Many women become grandmothers and contribute to the care of grandchildren and other family members.[35] Many biologists believe that the extended human lifespan is evolutionarily driven by kin selection, though other theories have also been proposed.[36][37][38][39] |

生物学 成人の女性と、比較のために成人の男性を撮影した写真。両モデルの陰毛は除去されている。 成人の女性と、比較のために成人の男性を撮影した写真。両モデルの陰毛は除去されている。 主な記事:人間の性差 男性と女性の身体にはいくつかの違いがある。外性器などの一部の相違は目に見えるが、内臓の構造や遺伝的特徴などの相違は目に見えない。 遺伝的特徴 主な記事:人間の性分化 多色の球体と、データ表にリストアップされた染色体セット 人間の女性のスペクトル核型 通常、女性の人間の細胞には2つのX染色体が含まれており、男性の人間の細胞にはX染色体とY染色体が含まれている。[23] 胎児の発達初期段階では、すべての胚は6週目または7週目まで外見上女性的な性器を有しているが、Y染色体上のSRY遺伝子の作用により、男性胚の性腺が 精巣に分化します。[24] 女性の性分化は、性腺ホルモンに依存しない方法で進行する。[24] 人間はミトコンドリアDNAを母親の卵子からしか受け継がないため、系図研究者は母系を遥か昔まで遡ることができる。 ホルモン特性、月経、更年期 主な記事:月経周期、月経 女性の思春期は、受精による性生殖を可能にする身体の変化を引き起こす。下垂体からの化学信号に応答して、卵巣は身体の成熟を刺激するホルモンを分泌し、 身長や体重の増加、体毛の成長、乳房の発達、初潮(月経の開始)などが起こる。[25] 妊娠中の裸の女性 妊娠中の女性 ほとんどの少女は 12~13 歳で初潮を迎え[26][27]、その後妊娠して子供を出産することができるようになる。妊娠には通常、性交または人工授精による卵子と精子の体内受精が 必要だけど、体外受精では体外で受精を行うことも可能だ。[28] 人間は他の大型哺乳類と同様に、通常は1回の妊娠で1頭の子供を出産するが、他の大型哺乳類と比べて「無力児」である点が特徴的だ。つまり、出生時は未発 達で、親や保護者の援助を必要として完全に成熟する。[29] 人間は多胎出産をすることもあり、最も一般的なのは双子だ。[30] 通常、49歳から52歳にかけて、女性は閉経を迎え、月経が永久に止まり、子供を産むことができなくなる。[31][32][33] 他のほとんどの哺乳類とは異なり、人間の寿命は更年期後も多くの年数に及ぶ。[34] 多くの女性は祖母となり、孫や他の家族の手伝いをする。[35] 多くの生物学者は、人間の寿命の延長は親族選択による進化的な要因によるものだと考えているが、他の理論も提唱されている。[36][37][38] [39] |

| Morphological and physiological

characteristics diagram of internal anatomy The human female reproductive system Main articles: Sex differences in human physiology and Female body shape In terms of biology, the female sex organs are involved in the reproductive system, whereas the secondary sex characteristics are involved in breastfeeding children and attracting a mate.[40] Humans are placental mammals, which means the mother carries the fetus in the uterus and the placenta facilitates the exchange of nutrients and waste between the mother and fetus.[41][42] smiling mother holds baby to breastfeed A mother breastfeeding her baby The internal female genitalia consist of the ovaries, gonads that produce female gametes called ova, the fallopian tubes, tubular structures that transport the egg cells, the uterus, an organ with tissue to protect and nurture the developing fetus and its cervix to expel it, the accessory glands (Bartholin's and Skene's), two pairs of glands that help lubricate during intercourse, and the vagina, an organ used in copulating and birthing. The vulva (external female genitalia)[43] consists of the clitoris, labia majora, labia minora and vestibule. The vestibule is where the vaginal and urethral openings are located. The mammary glands are hypothesized to have evolved from apocrine-like glands to produce milk, a nutritious secretion that is the most distinctive characteristic of mammals, along with live birth.[44] In mature women, the breast is generally more prominent than in most other mammals; this prominence, not necessary for milk production, is thought to be at least partially the result of sexual selection.[40] Estrogens, which are primary female sex hormones, have a significant impact on a female's body shape. They are produced in both men and women, but their levels are significantly higher in women, especially in those of reproductive age. Besides other functions, estrogens promote the development of female secondary sexual characteristics, such as breasts and hips.[45][46][47] As a result of estrogens, during puberty, girls develop breasts and their hips widen. Working against estrogen, the presence of testosterone in a pubescent female inhibits breast development and promotes muscle and facial hair development.[48] Circulatory system Women have lower hematocrit (the volume percentage of red blood cells in blood) than men; this is due to lower testosterone, which stimulates the production of erythropoietin by the kidney. The normal hematocrit level for a woman is 36% to 48% (for men, 41% to 50%). The normal level of hemoglobin (an oxygen-transport protein found in red blood cells) for women is 12.0 to 15.5 g/dL (for men, 13.5 to 17.5 g/dL).[49][50][51] Women's hearts have finer-grained textures in the muscle compared to men's hearts, and the heart muscle's overall shape and surface area also differs to men's when controlling for body size and age.[52][53] In addition, women's hearts age more slowly compared to men's hearts.[54] Sex distribution Main article: Life expectancy § Sex differences Girls are born slightly less frequently than boys (the ratio is around 1:1.05). Out of the total human population in 2015, there were 1018 men for every 1000 women.[55] Intersex women Main article: Intersex Intersex women have an intersex condition, usually defined as those born with ambiguous genitalia. Most individuals with ambiguous genitalia are assigned female at birth, and most intersex women are cisgender. The medical practices to assign binary female to intersex youth is often controversial.[56] Some intersex conditions are associated with typical rates of female gender identity, while others are associated with substantially higher rates of identifying as LGBT compared to the general population.[57][58][59][60] |

形態学的および生理学的特徴 内部解剖図 人間の女性の生殖器系 主な記事:人間の生理機能の性差、女性の体型 生物学的には、女性の生殖器官は生殖器系に関与し、第二次性徴は授乳や異性への魅力に関与している[40]。人間は胎盤を持つ哺乳類であり、母親は子宮で 胎児を妊娠し、胎盤が母親と胎児の間で栄養分や老廃物の交換を行う[41][42]。 授乳する母親 授乳する母親 女性の内部生殖器は、卵子と呼ばれる女性の生殖細胞を産生する卵巣、卵管(卵子を運ぶ管状の構造)、子宮(胎児を保護し養育する組織を有する器官とその子 宮口)、付属腺(バルトリン腺とスキーン腺)、 性交時に潤滑を助ける2対の腺、および交尾と出産に使用される器官である膣から成る。 外性器(外陰部)[43] は、クリトリス、大陰唇、小陰唇、および前庭から成る。前庭には、膣と尿道の開口部がある。 乳腺は、哺乳類の最も特徴的な特徴である栄養豊富な分泌物である乳を産生するために、アポクリン様腺から進化したと考えられています[44]。成熟した女 性では、乳房は他のほとんどの哺乳類よりも目立ちます。この目立ち方は、乳の産生には必要ないため、少なくとも一部は性的選択の結果であると考えられてい ます。[40] エストロゲンは、女性の主要な性ホルモンであり、女性の体型に大きな影響を与える。エストロゲンは男性と女性の両方で生成されるが、そのレベルは女性、特 に生殖年齢の女性で著しく高い。エストロゲンは、他の機能に加えて、乳房や腰などの女性の第二次性徴の発達を促進する。[45][46][47] エストロゲンの作用により、思春期に女の子は乳房が発達し、骨盤が広くなります。エストロゲンに逆行する作用として、思春期の女性におけるテストステロン の存在は乳房の発達を抑制し、筋肉や顔の毛の発達を促進します。[48] 循環器系 女性は男性よりもヘマトクリット値(血液中の赤血球の体積割合)が低い。これは、腎臓によるエリスロポエチンの産生を刺激するテストステロンの値が低いこ とが原因だ。女性の正常なヘマトクリット値は 36% から 48% (男性は 41% から 50%)だ。ヘモグロビン(赤血球中に存在する酸素輸送タンパク質)の正常値は、女性で12.0~15.5 g/dL(男性は13.5~17.5 g/dL)です。[49][50][51] 女性の心臓は、男性に比べて筋肉の組織が細かく、体サイズや年齢を調整した場合、心臓の筋肉の全体的な形状や表面積も男性とは異なっている。[52] [53] さらに、女性の心臓は男性に比べて老化が遅い。[54] 性別分布 主な記事:平均余命 § 性差 女の子は男の子よりもやや少ない割合で生まれる(比率は約1:1.05)。2015年の人口総数では、女性1,000人に対し男性は1,018人だった。 [55] インターセックス女性 メイン記事:インターセックス インターセックス女性は、通常、曖昧な外性器を持って生まれるインターセックスの状態で、 曖昧な外性器を持つ個人の大多数は出生時に女性と割り当てられ、インターセックス女性の多くはシスジェンダーです。インターセックスの若者に二元的な女性 性を割り当てる医療実践は、しばしば議論の的となっています。[56] 一部のインターセックス状態は、女性としての性別同一性の典型的な率と関連していますが、他の状態は、一般人口と比較してLGBTとして自己認識する率が 著しく高いことと関連しています。[57][58][59][60] |

| Sexuality and gender Further information: Human female sexuality and Trans woman Most women are heterosexual (sexually attracted to men) and cisgender (were assigned female at birth and have a female gender identity). The Birth of Venus (1486, Uffizi) is a classic representation of femininity painted by Sandro Botticelli.[61][62] Venus was a Roman goddess principally associated with love, beauty and fertility. Sexual orientation Female sexuality and attraction are variable, and a woman's sexual behavior can be affected by many factors, including evolved predispositions, personality, upbringing, and culture. While most women are heterosexual, significant minorities are lesbian or bisexual.[63] Most cultures use a gender binary by which women are of one of two genders, the others being men; other cultures have a third gender.[64][65][66] Femininity (also called womanliness or girlishness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles generally associated with women and girls. Although femininity is socially constructed,[67] some behaviors considered feminine are biologically influenced.[67][68][69][70] The extent to which femininity is biologically or socially influenced is subject to debate.[69][68][70] It is distinct from the definition of the biological female sex,[71][72] as both men and women can exhibit feminine traits. Gender Most women are cisgender, meaning their female sex assignment at birth corresponds with their female gender identity. Some women are transgender, meaning they were assigned male at birth.[7] Trans women may experience gender dysphoria, the distress brought upon by the discrepancy between a person's gender identity and their sex assigned at birth.[73] Gender dysphoria may be treated with gender-affirming care, which may include social or medical transition. Social transition may involve changes such as adopting a new name, hairstyle, clothing, and pronoun associated with the individual's affirmed female gender identity.[74] A major component of medical transition for trans women is feminizing hormone therapy, which causes the development of female secondary sex characteristics (such as breasts, redistribution of body fat, and lower waist–hip ratio). Medical transition may also involve gender-affirming surgery, and a trans woman may undergo one or more feminizing procedures which result in anatomy that is typically gendered female.[75][76] Like cisgender women, trans women may have any sexual orientation. |

セクシュアリティと性別 詳細情報:人間の女性のセクシュアリティ、トランス女性 ほとんどの女性は異性愛者(男性に性的魅力を感じる)であり、シスジェンダー(出生時に女性として割り当てられ、女性の性自認を持つ)です。 「ヴィーナスの誕生」(1486年、ウフィツィ美術館)は、サンドロ・ボッティチェッリが描いた、女性らしさを表現した古典的な絵画です。[61] [62] ヴィーナスは、主に愛、美、豊穣を司るローマ神話の女神です。 性的指向 女性のセクシュアリティや性的魅力はさまざまであり、女性の性的行動は、進化した素因、性格、生育環境、文化など、さまざまな要因の影響を受ける可能性が あります。ほとんどの女性は異性愛者だけど、かなりの少数派はレズビアンやバイセクシュアルだ。[63] ほとんどの文化は、女性は2つの性別のうちの1つであり、もう一方は男性であるとする性別二元制を採用している。他の文化では、3つ目の性別がある。 [64][65][66] 女性らしさ(女性性、女らしさとも呼ばれる)は、一般的に女性や少女に関連付けられる一連の属性、行動、役割のことだ。女性らしさは社会的に構築されたも のだけど[67]、女性らしいとされる行動の一部は生物学的な影響を受けている[67][68][69][70]。女性らしさが生物学的に影響を受けてい るか、社会的に影響を受けているかの程度については議論がある[69][68][70]。これは、男性も女性も女性的な特徴を示すことがあるため、生物学 的女性性の定義とは区別される[71][72]。 性別 ほとんどの女性はシスジェンダーであり、出生時に割り当てられた女性の性別が、女性の性同一性に対応している。一部の女性はトランスジェンダーであり、出 生時に男性として割り当てられた。[7] トランスジェンダーの女性は、性同一性障害、つまり、自分の性同一性と出生時に割り当てられた性別との不一致によって生じる苦痛を経験する場合がある。 [73] 性同一性障害は、社会的または医学的な移行を含む、性別を確認するケアによって治療することができる。社会的移行には、個人の確認された女性としての性別 アイデンティティに合った新しい名前、髪型、服装、代名詞の採用などが含まれる。[74] トランス女性の医療的移行の主要な要素は、女性化ホルモン療法で、これは女性二次性徴(乳房の発達、体脂肪の再配分、腰臀比の低下など)を引き起こす。医 療的移行には性別肯定手術も含まれる場合があり、トランス女性は、女性的な解剖学的特徴を得るための1つまたは複数の女性化手術を受けることがあります。 [75][76] シスジェンダーの女性と同様に、トランス女性はあらゆる性的指向を持つ可能性があります。 |

| Health Further information: Women's health and Reproductive health Factors that specifically affect the health of women in comparison with men are most evident in those related to reproduction, but sex differences have been identified from the molecular to the behavioral scale. Some of these differences are subtle and difficult to explain, partly due to the fact that it is difficult to separate the health effects of inherent biological factors from the effects of the surrounding environment they exist in. Sex chromosomes and hormones, as well as sex-specific lifestyles, metabolism, immune system function, and sensitivity to environmental factors are believed to contribute to sex differences in health at the levels of physiology, perception, and cognition. Women can have distinct responses to drugs and thresholds for diagnostic parameters.[77][page needed] Some diseases primarily affect or are exclusively found in women, such as lupus, breast cancer, cervical cancer, or ovarian cancer.[78] The medical practice dealing with female reproduction and reproductive organs is called gynaecology ("science of women").[79][80] Maternal mortality Main article: Maternal mortality Maternal mortality or maternal death is defined by WHO as "the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes."[81] In 2008, noting that each year more than 500,000 women die of complications of pregnancy and childbirth and at least seven million experience serious health problems while 50 million more have adverse health consequences after childbirth, the World Health Organization urged midwife training to strengthen maternal and newborn health services. To support the upgrading of midwifery skills the WHO established a midwife training program, Action for Safe Motherhood.[82] In 2017, 94% of maternal deaths occur in low and lower middle-income countries. Approximately 86% of maternal deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for around 66% and Southern Asia accounting for around 20%. The main causes of maternal mortality include pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, unsafe abortion, pregnancy complications from malaria and HIV/AIDS, and severe bleeding and infections following childbirth.[83] Most European countries, Australia, Japan, and Singapore are very safe in regard to childbirth.[84][improper synthesis][better source needed] |

保健 詳細情報:女性の健康およびリプロダクティブ・ヘルス 男性と比較して女性の健康に特に影響を与える要因は、生殖に関連する要因で最も顕著ですが、分子レベルから行動レベルまで、さまざまな面で性差が見られま す。これらの違いの一部は微妙で説明が難しいものもありますが、その理由の一部は、固有の生物学的要因と、その要因が存在する周囲の環境の影響を区別する ことが難しいことにあります。性染色体やホルモン、性別特有のライフスタイル、代謝、免疫機能、環境要因に対する感受性などが、生理、知覚、認知のレベル における健康の性差に関与していると考えられている。女性は、薬に対する反応や診断パラメータの閾値に明確な違いがある。[77][ページが必要] 一部の疾患は主に女性に影響を及ぼすか、女性のみに発症する疾患です。例えば、ループス、乳がん、子宮頸がん、卵巣がんなどです。[78] 女性生殖器と生殖機能に関する医療は、婦人科(女性の科学)と呼ばれます。[79][80] 妊産婦の死亡 主な記事:妊産婦の死亡 妊産婦の死亡または妊産婦の死亡は、WHO によって「妊娠中、または妊娠終了から 42 日以内に、妊娠の期間や場所に関係なく、妊娠またはその管理に起因または悪化による原因で、偶発的または付随的な原因によるものではない、女性の死亡」と 定義されている。[81] 2008 年、世界保健機関(WHO)は、毎年 50 万人以上の女性が妊娠および出産の合併症で死亡し、少なくとも 700 万人以上が深刻な健康問題を抱え、さらに 5,000 万人以上が出産後に健康上の悪影響を受けていることを指摘し、妊産婦と新生児の保健サービスを強化するための助産師研修を要請した。助産師の技能向上を支 援するため、WHO は助産師研修プログラム「安全な出産のための行動」を設立した。[82] 2017 年、妊産婦の死亡の 94% は低所得国および低中所得国で発生している。妊産婦の死亡の約 86% はサハラ以南のアフリカと南アジアで発生しており、そのうちの約 66% はサハラ以南のアフリカ、約 20% は南アジアで発生している。妊産婦の死亡の主な原因としては、子癇前症および子癇、危険な中絶、マラリアや HIV/AIDS による妊娠合併症、出産後の重度の出血や感染症などが挙げられる。[83] ほとんどのヨーロッパ諸国、オーストラリア、日本、シンガポールは、出産に関して非常に安全だ。[84][不適切な要約][より良い情報源が必要] |

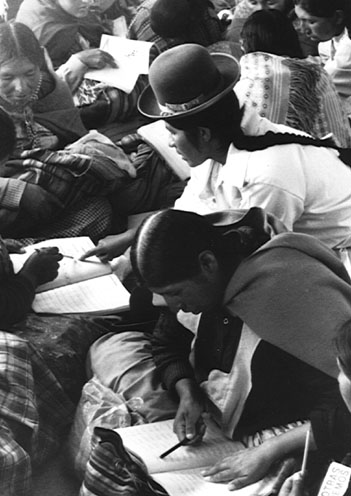

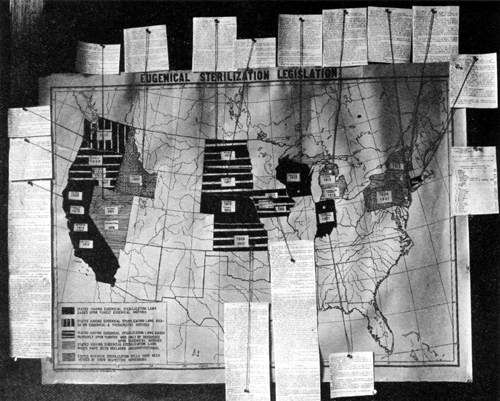

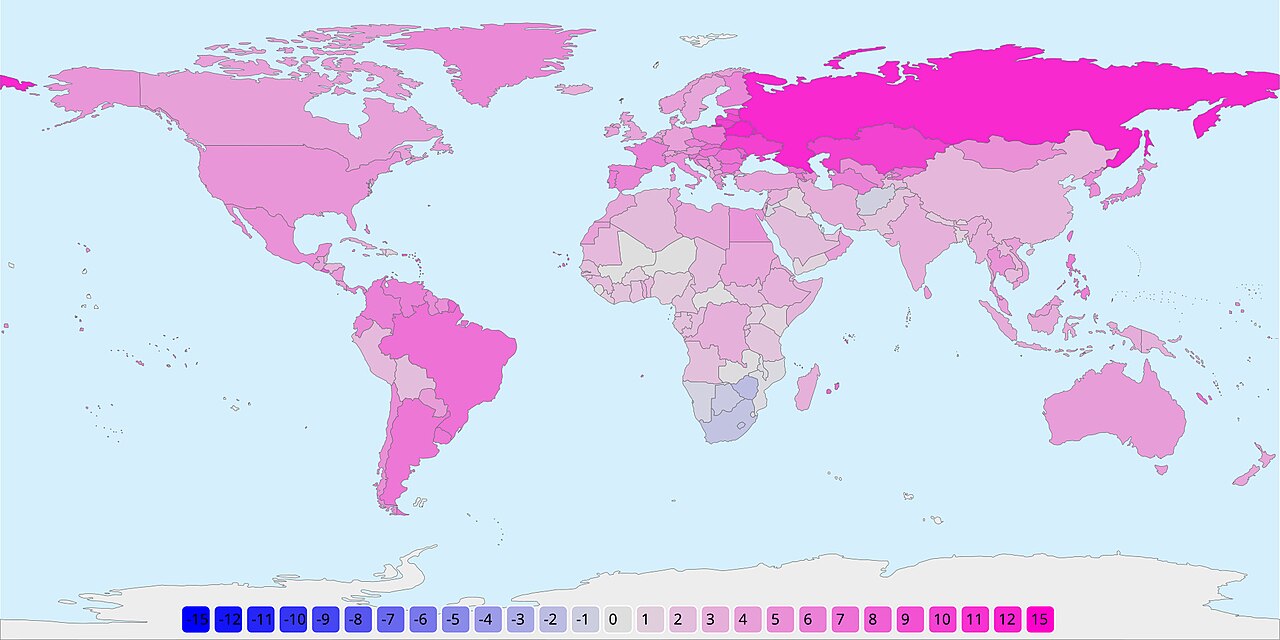

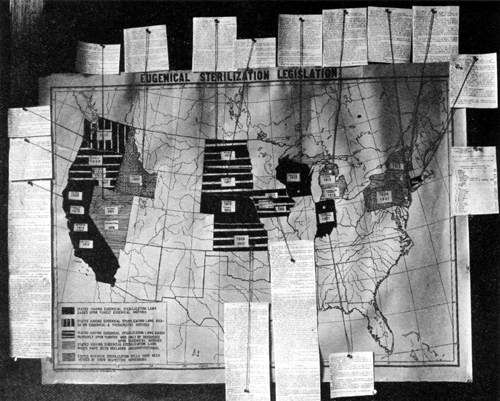

| Life expectancy Main article: Life expectancy § Sex differences  Pink: Countries where female life expectancy at birth is higher than males. Blue: A few countries in southern Africa where females have shorter lives due to AIDS.[85] The life expectancy for women is generally longer than men's. This advantage begins from birth, with newborn girls more likely to survive the first year than boys. Worldwide, women live six to eight years longer than men.[86] However, this varies by place and situation. For example, discrimination against women has lowered female life expectancy in some parts of Asia so that men there live longer than women.[86] The difference in life expectancy are believed to be partly due to biological advantages and partly due to gendered behavioral differences between men and women.[86][87] For example, women are less likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors like smoking and reckless driving, and consequently have fewer preventable premature deaths from such causes.[86] In some developed countries, the life expectancy is evening out. This is believed to caused both by worse health behaviors among women, especially an increased rate of smoking tobacco by women, and improved health among men, such as less cardiovascular disease.[86] The World Health Organization (WHO) writes that it is "important to note that the extra years of life for women are not always lived in good health."[86] Reproductive rights Main article: Reproductive rights  Monochrome photo of a map titled "Eugenical Sterilization Legislation"; with notes on each state; refer to caption A poster from a 1921 eugenics conference displays the U.S. states that had implemented sterilization legislation. Reproductive rights are legal rights and freedoms relating to reproduction and reproductive health. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics has stated that:[88] ... the human rights of women include their right to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. Equal relationships between women and men in matters of sexual relations and reproduction, including full respect for the integrity of the person, require mutual respect, consent and shared responsibility for sexual behavior and its consequences. The World Health Organization reports that based on data from 2010 to 2014, 56 million induced abortions occurred worldwide each year (25% of all pregnancies). Of those, about 25 million were considered as unsafe. The WHO reports that in developed regions about 30 women die for every 100,000 unsafe abortions and that number rises to 220 deaths per 100,000 unsafe abortions in developing regions and 520 deaths per 100,000 unsafe abortions in sub-Saharan Africa. The WHO ascribes these deaths to: restrictive laws poor availability of services high cost stigma conscientious objection of health-care providers unnecessary requirements, such as mandatory waiting periods, mandatory counseling, provision of misleading information, third-party authorization, and medically unnecessary tests that delay care.[89] |

平均寿命 主な記事:平均寿命 § 性差  ピンク:出生時の女性の平均寿命が男性よりも長い国。青:エイズにより女性の平均寿命が短いアフリカ南部のいくつかの国。[85] 女性の平均寿命は一般的に男性よりも長い。この差は出生時から始まり、新生児は女の子の方が男の子よりも1年目を生き残る確率が高い。世界全体では、女性 は男性よりも6年から8年長く生きる。[86] ただし、これは場所や状況によって異なる。例えば、アジアの一部の地域では、女性に対する差別により女性の平均寿命が低下し、男性の方が女性よりも長生き している。[86] 平均寿命の差は、生物学的優位性と、男性と女性の行動の違いによるものと考えられている。[86][87] 例えば、女性は喫煙や無謀運転などの不健康な行動をとる傾向が少なく、その結果、そのような原因による予防可能な早死が少ない。[86] 一部の先進国では、平均寿命は均等に近づきつつある。これは、女性の健康行動の悪化、特に女性の喫煙率の増加と、心血管疾患の減少など男性の健康の改善の 両方が原因であると考えられている[86]。世界保健機関(WHO)は、「女性の余命が必ずしも健康で過ごせるわけではないことに留意することが重要」と 記している[86]。 生殖に関する権利 主な記事:生殖に関する権利  「優生不妊手術法」と題された地図のモノクロ写真。各州に注釈が付いている。キャプションを参照のこと。 1921年の優生学会議のポスターには、不妊手術法を施行した米国の州が掲載されている。 生殖に関する権利とは、生殖および生殖に関する健康に関する法的権利および自由のことだ。国際産婦人科連合は、次のように述べている。[88] ... 女性の権利には、性的および生殖に関する健康を含む、自分のセクシュアリティに関する事項について、強制、差別、暴力にさらされることなく、自由に、かつ 責任を持って決定する権利が含まれる。性的関係および生殖に関する事項において、人格の完全性を完全に尊重することを含む、女性と男性の平等な関係には、 相互の尊重、同意、および性的行動とその結果に対する共同の責任が必要だ。 世界保健機関(WHO)は、2010 年から 2014 年のデータに基づき、世界中で毎年 5,600 万件(全妊娠の 25%)の人工妊娠中絶が行われていると報告している。そのうち、約 2,500 万件は危険な中絶とみなされている。WHOは、先進地域では不安全な人工妊娠中絶10万件あたり約30人の女性が死亡し、開発途上地域では220人、サハ ラ以南のアフリカでは520人に上ると報告している。WHO は、これらの死亡の原因を次のように挙げている。 制限的な法律 サービスの利用が困難 費用が高い 偏見 医療従事者の良心的反対 強制的な待機期間、強制的なカウンセリング、誤解を招く情報の提供、第三者による承認、医療上不必要な検査など、不必要な要件により、治療が遅れること。 |

| History The earliest women whose names are known include: Neithhotep (c. 3200 BCE), the wife of Narmer and the first queen of ancient Egypt.[90][91] Merneith (c. 3000 BCE), consort and regent of ancient Egypt during the first dynasty. She may have been ruler of Egypt in her own right.[92][93] Peseshet (c. 2600 BCE), a physician in Ancient Egypt.[94][95] Puabi (c. 2600 BCE), or Shubad – queen of Ur whose tomb was discovered with many expensive artifacts. Other known pre-Sargonic queens of Ur (royal wives) include Ashusikildigir, Ninbanda, and Gansamannu.[96] Kugbau (circa 2,500 BCE), a taverness from Kish chosen by the Nippur priesthood to become hegemonic ruler of Sumer, and in later ages deified as "Kubaba". Tashlultum (c. 2400 BCE), Akkadian queen, wife of Sargon of Akkad and mother of Enheduanna.[97][98] Baranamtarra (c. 2384 BCE), prominent and influential queen of Lugalanda of Lagash. Other known pre-Sargonic queens of the first Lagash dynasty include Menbara-abzu, Ashume'eren, Ninkhilisug, Dimtur, and Shagshag, and the names of several princesses are also known. Enheduanna (c. 2285 BCE),[99][100] the high priestess of the temple of the Moon God in the Sumerian city-state of Ur and possibly the first known poet and first named author of either gender.[101] Shibtu (c. 1775 BCE), king Zimrilim's consort and queen of the Syrian city-state of Mari. During her husband's absence, she ruled as regent of Mari and enjoyed extensive administrative powers as queen.[102] The glyph (♀) for the planet and Roman goddess Venus, or Aphrodite in Greek, is the symbol used to represent the female sex.[103][104][105] In ancient alchemy, the Venus symbol stood for copper and was associated with femininity.[105] |

歴史 名前が残っている最古の女性には、次のような人物がいる。 ネイトホテプ(紀元前3200年頃)、ナメル王の妻であり、古代エジプトの最初の女王。[90][91] メルネイト(紀元前3000年頃)、第一王朝時代の古代エジプトの王妃および摂政。彼女は、自らエジプトの支配者であった可能性がある。[92][93] ペセシェト(紀元前2600年頃)、古代エジプトの医師。[94][95] プアビ(紀元前2600年頃)、またはシュバド – 多くの高価な遺物が発見された墓を持つウル女王。サルゴン以前のウル女王(王妃)として知られている他の女性には、アシュシキルディギル、ニンバンダ、ガ ンサマンヌなどがいる。[96] クグバウ(紀元前2500年頃)、キシュ出身の酒場の女将で、ニップルの僧侶たちによってシュメールの覇権者となり、後に「クババ」として神格化された。 タシュルトゥム(紀元前2400年頃)は、アッカドの女王で、アッカドのサルゴン王の妻であり、エンヘドゥアンナの母。[97][98] バラナムタラ(紀元前2384年頃)は、ラガシュのルガランダ王の著名で影響力のある女王。サルゴン以前のラガシュ第1王朝の他の知られている女王には、 メンバラ・アブズ、アシュメ・エレン、ニンキリシスグ、ディムトゥル、シャグシャグがおり、いくつかの王女の名前も知られている。 エンヘドゥアンナ(紀元前2285年頃)、[99][100] シュメール都市国家ウルにある月神の寺院の高僧であり、おそらくは最初の詩人であり、性別を問わず最初の名前のある作家である。[101] シブトゥ(紀元前1775年頃)、マリの王ジムリリムの妃であり、女王。夫の不在中、彼女はマリの摂政として統治し、女王として広範な行政権限を握ってい た。[102] 惑星とローマ神話の女神ヴィーナス、またはギリシャ神話のアフロディーテを表す文字(♀)は、女性の性を表す記号として使用されている。[103] [104][105] 古代錬金術では、ヴィーナスの記号は銅を表し、女性性と関連付けられていた。[105] |

| Culture and gender roles Main article: Gender role See also: Women in the workforce and Women in the military In recent history, gender roles have changed greatly. At some earlier points in history, children's occupational aspirations starting at a young age differed according to gender.[106] Traditionally, middle class women were involved in domestic tasks emphasizing child care. For poorer women, economic necessity compelled them to seek employment outside the home even if individual poor women may have preferred domestic tasks. Many of the occupations that were available to them were lower in pay than those available to men.[107]  woman wearing a headscarf prepares to cut a man's hair An Egyptian Muslim woman who works as a men's hairdresser to "confront the customs and traditions of her society and conquer their criticism."  Two women patrolling As changes in the labor market for women came about, availability of employment changed from only "dirty", long hour factory jobs to "cleaner", more respectable office jobs where more education was demanded. Married women's participation in the U.S. labor force rose from 5.6–6% in 1900 to 23.8% in 1923.[108][109] These shifts in the labor force led to changes in the attitudes towards women at work, allowing for the revolution which resulted in women becoming career and education oriented.[citation needed] In the 1970s, many female academics, including scientists, avoided having children. Throughout the 1980s, institutions tried to equalize conditions for men and women in the workplace. Even so, the inequalities at home hampered women's opportunities: professional women were still generally considered responsible for domestic labor and child care, which limited the time and energy they could devote to their careers. Until the early 20th century, U.S. women's colleges required their women faculty members to remain single, on the grounds that a woman could not carry on two full-time professions at once. According to Schiebinger, "Being a scientist and a wife and a mother is a burden in society that expects women more often than men to put family ahead of career." (p. 93).[110] Movements advocate equality of opportunity for both sexes and equal rights irrespective of gender. Through a combination of economic changes and the efforts of the feminist movement, in recent decades women in many societies have gained access to careers beyond the traditional homemaker. Despite these advances, modern women in Western society still face challenges in the workplace as well as with the topics of education, violence, health care, politics, and motherhood, and others. Sexism can be a main concern and barrier for women almost anywhere, though its forms, perception, and gravity vary between societies and social classes. The Gender Parity Index in school enrollment varies by country.[111] The gender gaps in mathematics and reading show girls tend to have higher reading skills. The gender pay gap varies between countries and age groups.[112] |

文化と性別役割 主な記事:性別役割 関連項目:労働力における女性、軍隊における女性 最近の歴史において、性別役割は大きく変化した。歴史の初期には、幼い頃から子供たちの職業志向は性別によって異なっていた[106]。伝統的に、中流階 級の女性は育児を重視した家事に関わっていた。貧困層の女性たちは、経済的な必要から、個々の女性が家事労働を好んだとしても、家庭外での就労を余儀なく された。彼女たちに開かれていた職業の多くは、男性が就ける職業よりも給与が低かった。[107]  頭巾を被った女性が男性の髪を切る準備をしている エジプトのムスリム女性で、男性の理容師として働く女性。「社会の慣習と伝統に挑み、批判を克服するため」にこの職業を選んだ。  パトロールする2人の女性 女性の労働市場の変化に伴い、雇用機会は「汚い」長時間労働の工場仕事から、「清潔で」より尊敬される、より高い教育が求められるオフィス仕事へと変化し た。結婚した女性の米国労働力参加率は、1900年の5.6~6%から1923年には23.8%に上昇した。[108][109] 労働力構成の変化は、職場における女性への態度変化をもたらし、女性がキャリアと教育を重視する革命をもたらした。[出典必要] 1970年代、多くの女性学者(科学者を含む)は子供を持つことを避けた。1980年代を通じて、機関は職場における男女の条件の平等化を試みた。それで も、家庭内の不平等は女性の機会を妨げた:職業女性はいまだに家事や子育ての責任を負うものと見なされ、これが彼女たちがキャリアに費やす時間とエネル ギーを制限した。20世紀初頭まで、アメリカの女子大学は女性教職員に独身であることを義務付けていた。その理由は、女性が同時に2つの職業を全うするこ とは不可能だと考えられていたからだ。シュライビンガーによると、「科学者であり、妻であり、母親であることは、社会が女性に対して男性よりも頻繁に家族 をキャリアよりも優先することを期待する中で、女性にとっての負担となっている」。(p. 93)[110] この運動は、男女間の機会均等と、性別による権利の平等を提唱している。経済の変化とフェミニズム運動の努力により、ここ数十年の間に、多くの社会で女性 は、従来の主婦という役割以外のキャリアにアクセスできるようになった。こうした進歩にもかかわらず、西洋社会の現代女性は、職場や教育、暴力、保健、政 治、母性などの問題において、依然として課題に直面している。性差別は、その形態、認識、深刻度は社会や社会階級によって異なるものの、ほぼあらゆる場所 で女性にとって主要な懸念事項および障壁となっている。 学校就学率のジェンダー平等指数は国によって異なる。[111] 数学と読解力のジェンダー格差は、女子の方が読解力が高い傾向がある。男女間の賃金格差は、国や年齢層によって異なる。[112] |

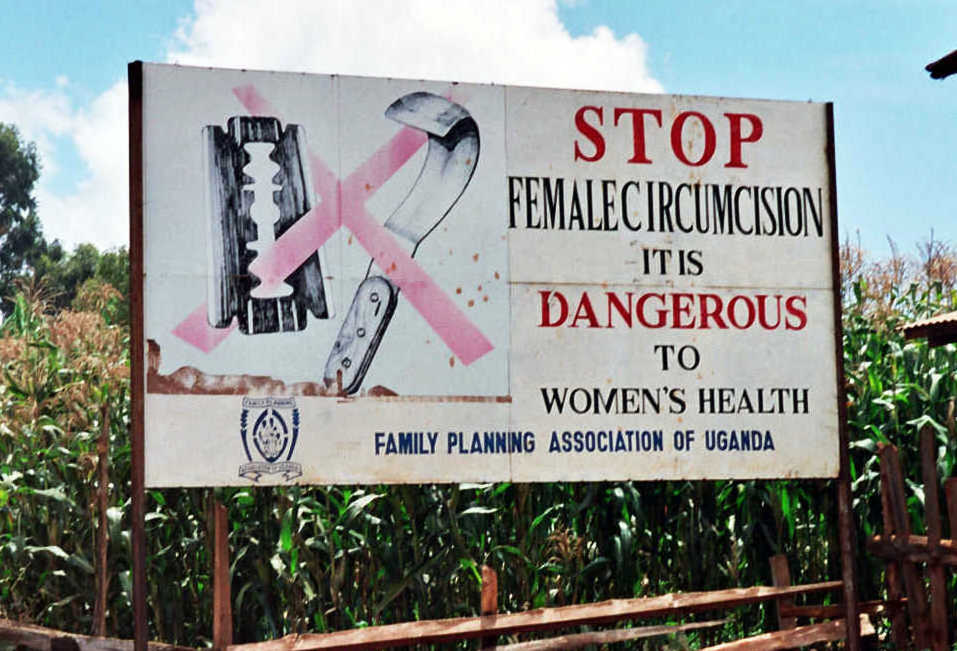

| Religion Further information: Women in Buddhism, Women in Christianity, Women in Hinduism, Women in Islam, Women in Judaism, Women in Mormonism, Women in Shinto, Women in Sikhism, and Women in Zoroastrianism Particular religious doctrines have specific stipulations relating to gender roles, the spiritual authority of women, social and private interaction between the sexes, appropriate dressing attire for women, and various other issues affecting women and their position in society. In many countries, these religious teachings influence the criminal law, or the family law of those jurisdictions (see Sharia law, for example). The relation between religion, law and gender equality has been discussed by international organizations.[113] Violence against women Main article: Violence against women  Roadside billboard saying "Stop female circumcision. It's dangerous to Women's health. Family Planning Association of Uganda." Displaying a crossed out razorblade and knife on the left. A campaign against female genital mutilation – a road sign near Kapchorwa, Uganda The UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women defines "violence against women" as:[114] ...any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life. It identifies three forms of such violence: that which occurs in the family, that which occurs within the general community, and that which is perpetrated or condoned by the State. It also states that "violence against women is a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women".[115] Violence against women remains a widespread problem, fueled, especially outside the West, by patriarchal social values, lack of adequate laws, and lack of enforcement of existing laws. Social norms that exist in many parts of the world hinder progress towards protecting women from violence. For example, according to surveys by UNICEF, the percentage of women aged 15–49 who think that a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife under certain circumstances is as high as 90% in Afghanistan and Jordan, 87% in Mali, 86% in Guinea and Timor-Leste, 81% in Laos, and 80% in the Central African Republic.[116] A 2010 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center found that stoning as a punishment for adultery was supported by 82% of respondents in Egypt and Pakistan, 70% in Jordan, 56% Nigeria, and 42% in Indonesia.[117] Specific forms of violence that affect women include female genital mutilation, sex trafficking, forced prostitution, forced marriage, rape, sexual harassment, honor killings, acid throwing, and dowry related violence. Laws and policies on violence against women vary by jurisdiction. In the European Union, sexual harassment and human trafficking are subject to directives.[118][119] Governments can be complicit in violence against women, such as when stoning is used as a legal punishment, mostly for women accused of adultery.[120] There have also been many forms of violence against women which have been prevalent historically, notably the burning of witches, the sacrifice of widows (such as sati) and foot binding. The prosecution of women accused of witchcraft has a long tradition; for example, during the early modern period (between the 15th and 18th centuries), witch trials were common in Europe and in the European colonies in North America. Today, there remain regions of the world (such as parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, rural North India, and Papua New Guinea) where belief in witchcraft is held by many people, and women accused of being witches are subjected to serious violence.[121][122][123] In addition, there are also countries which have criminal legislation against the practice of witchcraft. In Saudi Arabia, witchcraft remains a crime punishable by death, and in 2011 the country beheaded a woman for 'witchcraft and sorcery'.[124][125] It is also the case that certain forms of violence against women have been recognized as criminal offences only during recent decades, and are not universally prohibited, in that many countries continue to allow them. This is especially the case with marital rape.[126][127] In the Western World, there has been a trend towards ensuring gender equality within marriage and prosecuting domestic violence, but in many parts of the world women still lose significant legal rights when entering a marriage.[128] Sexual violence against women greatly increases during times of war and armed conflict, during military occupation, or ethnic conflicts; most often in the form of war rape and sexual slavery. Contemporary examples of sexual violence during war include rape during the Armenian Genocide, rape during the Bangladesh Liberation War, rape in the Bosnian War, rape during the Rwandan genocide, and rape during Second Congo War. In Colombia, the armed conflict has also resulted in increased sexual violence against women.[129] The most recent case was the sexual jihad done by ISIL where 5000–7000 Yazidi and Christian girls and children were sold into sexual slavery during the genocide and rape of Yazidi and Christian women, some of whom jumped to their death from Mount Sinjar, as described in a witness statement.[130] |

宗教 詳細情報:仏教における女性、キリスト教における女性、ヒンドゥー教における女性、イスラム教における女性、ユダヤ教における女性、モルモン教における女 性、神道における女性、シーク教における女性、ゾロアスター教における女性 特定の宗教の教義には、性別役割、女性の精神的権威、男女間の社会的および私的な交流、女性のための適切な服装、その他女性や女性の社会的な地位に影響を 与えるさまざまな問題に関して、具体的な規定がある。 多くの国では、これらの宗教的教えが、その国の刑法や家族法に影響を与えている(例えば、シャリーア法を参照)。 宗教、法律、男女平等との関係については、国際機関でも議論されている[113]。 女性に対する暴力 主な記事:女性に対する暴力  「女性割礼を止めよう。女性の保健に危険だ」と書かれた道路脇の看板。ウガンダ家族計画協会」と書かれた道路脇の看板。左側には、×印の付いたカミソリの 刃とナイフが描かれている。 女性器切除反対キャンペーン – ウガンダ、カプチョルワ近郊の道路標識 国連「女性に対する暴力撤廃宣言」は、「女性に対する暴力」を次のように定義している[114]。 ...公の場で、あるいは私的な生活の中で、女性に対して、身体的、性的、あるいは精神的な危害や苦悩をもたらす、あるいはその可能性のある、性別に基づ くあらゆる暴力行為。 この宣言では、そのような暴力には 3 つの形態があるとしている。すなわち、家族内で発生する暴力、地域社会内で発生する暴力、そして国家によって行われ、あるいは容認される暴力だ。また、 「女性に対する暴力は、歴史的に不平等な男女間の力関係の結果である」とも述べている。[115] 女性に対する暴力は、特に欧米以外では、家父長的な社会価値観、適切な法律の欠如、および既存の法律の施行の欠如によって助長され、依然として広範な問題 となっている。世界の多くの地域で存在する社会規範は、女性に対する暴力からの保護の進展を妨げている。例えば、ユニセフの調査によると、15~49歳の 女性のうち、特定の状況下で夫が妻を殴るまたは暴力を振るうことが正当だと考える女性の割合は、アフガニスタンとヨルダンで90%、マリで87%、ギニア とティモール・レステで86%、ラオスで81%、中央アフリカ共和国で80%に達している。[116] 2010年にピュー・リサーチ・センターが実施した調査では、不倫に対する刑罰として石打ちを支持する回答者は、エジプトとパキスタンで82%、ヨルダン で70%、ナイジェリアで56%、インドネシアで42%に上った。[117] 女性に対する暴力には、女性器切除、性的人身売買、強制売春、強制結婚、レイプ、セクシャルハラスメント、名誉殺人、酸の投げかけ、嫁入り道具に関する暴 力など、特定の形態のものがある。女性に対する暴力に関する法律や政策は、管轄区域によって異なる。欧州連合では、セクシャルハラスメントと人身売買は指 令の対象となっている[118][119]。政府は、主に姦通の罪で告発された女性に対して石打ち刑を合法的な刑罰として用いている場合など、女性に対す る暴力に加担している場合もある。[120] また、歴史的に、女性に対する暴力には、妖術師の火刑、未亡人の生贄(サティなど)、足縛りなど、さまざまな形態が広く見られた。妖術師と非難された女性 の起訴は、長い伝統がある。例えば、近世(15 世紀から 18 世紀)には、ヨーロッパおよび北アメリカのヨーロッパ植民地では、魔女裁判が広く行われていた。今日でも、世界には、妖術を信じる人々が数多く存在し、妖 術師と非難された女性が深刻な暴力を受ける地域(サハラ砂漠以南のアフリカの一部、インド北部の農村部、パプアニューギニアなど)が残っている[121] [122][123]。さらに、妖術の行為を犯罪とする刑法がある国もある。サウジアラビアでは、妖術は依然として死刑に処せられる犯罪であり、2011 年には「妖術と邪術」の罪で女性が斬首された。[124][125] また、女性に対する特定の形態の暴力は、近年になってようやく犯罪として認識されるようになったものの、普遍的に禁止されているわけではなく、多くの国で 依然として容認されている。特に婚姻内強姦がこれに該当する。[126][127] 西洋諸国では、婚姻内での性別平等を確保し、家庭内暴力の起訴を推進する傾向があるが、世界の大部分では、女性が婚姻を結ぶ際に重要な法的権利を失う状況 が続いている。[128] 女性に対する性的暴力は、戦争や武力紛争、軍事占領、民族紛争の際に大幅に増加する。その多くは、戦争によるレイプや性奴隷という形をとっている。現代に おける戦争中の性的暴力の例としては、アルメニア人虐殺におけるレイプ、バングラデシュ独立戦争におけるレイプ、ボスニア戦争におけるレイプ、ルワンダ虐 殺におけるレイプ、第二次コンゴ戦争におけるレイプなどが挙げられる。コロンビアでは、武力紛争により女性に対する性暴力が増加している。[129] 最も最近の事例は、ISILによる「性的なジハード」で、ヤジディ教徒とキリスト教徒の女性5,000~7,000人がジェノサイドと強姦の過程で性奴隷 として売られ、その一部はシンスjar山から飛び降りて死亡した。これは証言書で記述されている。[130] |

| Clothing, fashion and dress codes Women's traditional clothing varies across cultures. From left to right: Afghan model wearing traditional Afghan dress and Japanese women wearing kimono. Women in different parts of the world dress in different ways, with their choices of clothing being influenced by local culture, religious tenets, traditions, social norms, and fashion trends, among other factors. Different societies have different ideas about modesty. In many jurisdictions, laws limit what women may or may not wear. This is especially the case in regard to Islamic dress. While certain jurisdictions legally mandate such clothing (the wearing of the headscarf), other countries forbid or restrict the wearing of certain hijab attire (such as burqa/covering the face) in public places (one such country is France – see French ban on face covering). These laws – both those mandating and those prohibiting certain articles of dress – are highly controversial.[131] |

衣類、ファッション、服装規定 女性の伝統的な服装は文化によって異なる。左から右へ:アフガニスタンの伝統的な衣装を着たアフガニスタンのモデルと、着物を着た日本人女性。 世界のさまざまな地域では、女性はさまざまな服装をしており、その選択は、地域の文化、宗教的信条、伝統、社会的規範、ファッションの流行などの要因に影 響されている。社会によって、謙虚さについての考え方は異なる。 多くの法域では、女性が着用できる服装を法律で制限している。これは、イスラム教の服装に特に当てはまる。一部の地域では、特定の服装(ヘッドスカーフの 着用)を法律で義務付けている一方、他の国では、公共の場で特定のヒジャブ服装(ブルカ/顔の覆いなど)の着用を禁止または制限している(そのような国の 例としてフランスがある – フランスの顔覆い禁止法参照)。これらの法律 – 特定の服装を義務付けるものも、禁止するものも – は、非常に議論の的となっている。[131] |

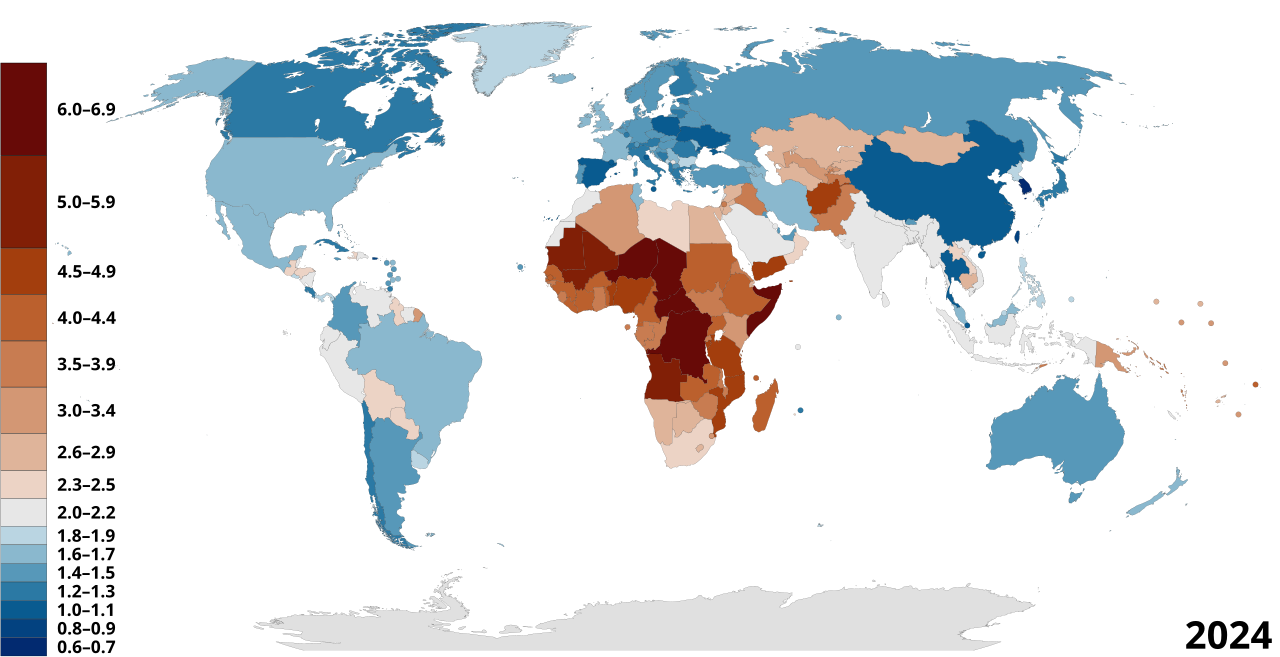

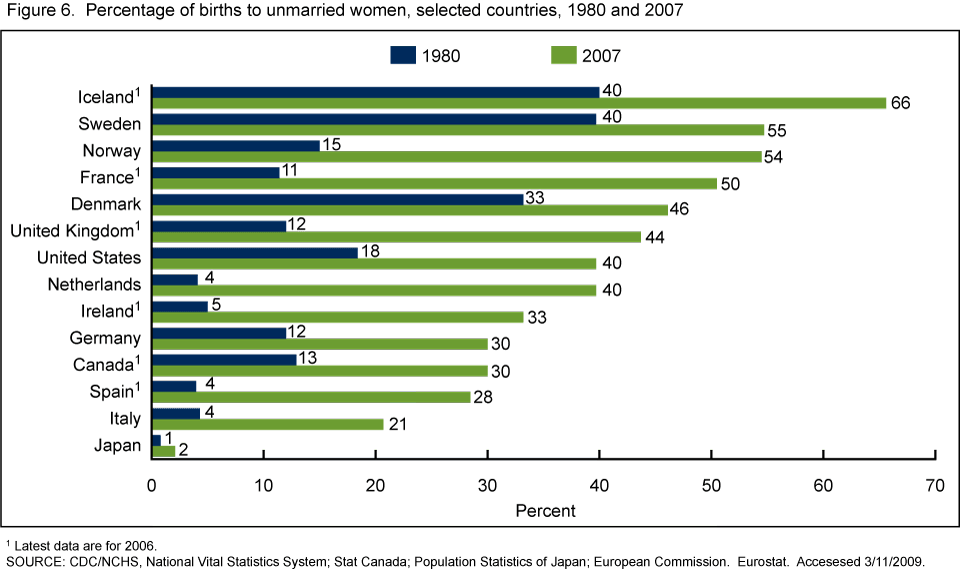

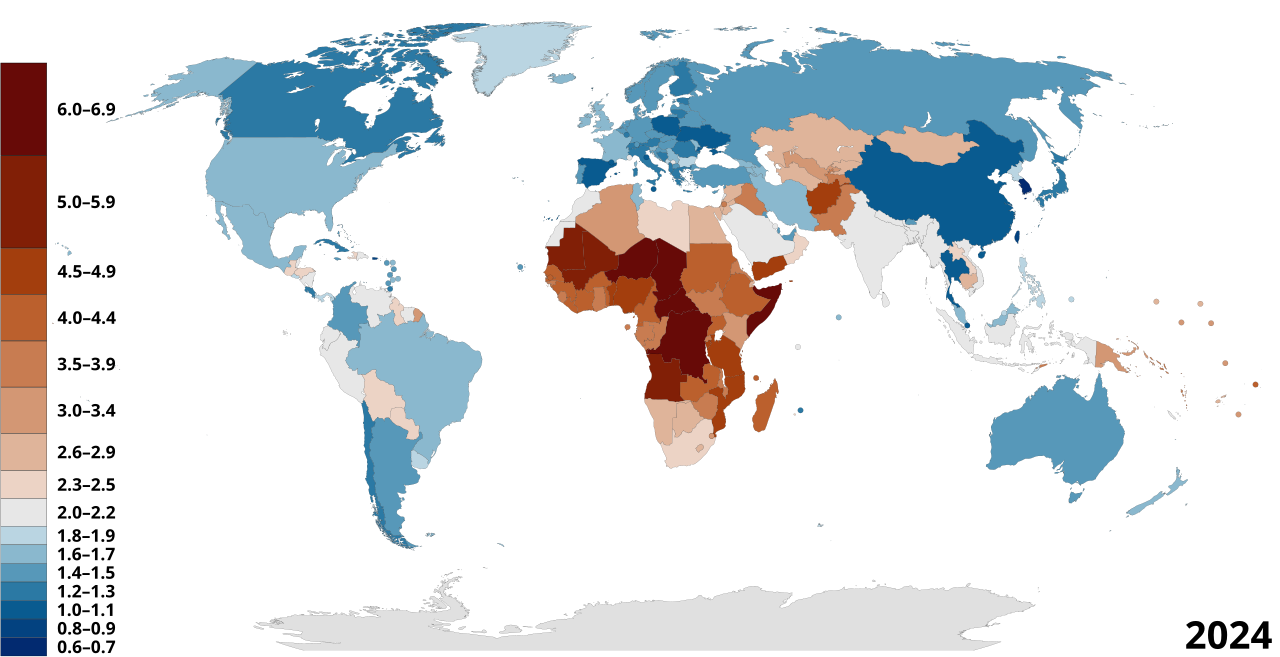

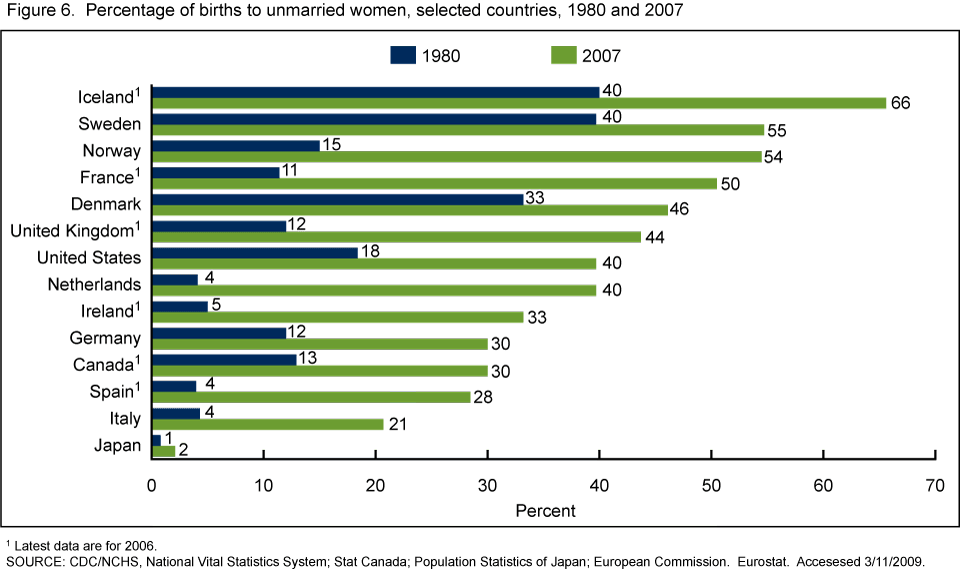

| Fertility and family life Further information: Mother  Map of countries by fertility rate (2020), according to the Population Reference Bureau  Percentage of births to unmarried women, selected countries, 1980 and 2007[132] The total fertility rate (TFR) – the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime – differs significantly between different regions of the world. In 2016, the highest estimated TFR was in Niger (6.62 children born per woman) and the lowest in Singapore (0.82 children/woman).[133] While most Sub-Saharan African countries have a high TFR, which creates problems due to lack of resources and contributes to overpopulation, most Western countries currently experience a sub replacement fertility rate which may lead to population ageing and population decline. In many parts of the world, there has been a change in family structure over the past few decades. For instance, in the West, there has been a trend of moving away from living arrangements that include the extended family to those which only consist of the nuclear family. There has also been a trend to move from marital fertility to non-marital fertility. Children born outside marriage may be born to cohabiting couples or to single women. While births outside marriage are common and fully accepted in some parts of the world, in other places they are highly stigmatized, with unmarried mothers facing ostracism, including violence from family members, and in extreme cases even honor killings.[134][135] In addition, sex outside marriage remains illegal in many countries (such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan,[136] Afghanistan,[137][138] Iran,[138] Kuwait,[139] Maldives,[140] Morocco,[141] Oman,[142] Mauritania,[143] United Arab Emirates,[144][145] Sudan,[146] and Yemen[147]). The social role of the mother differs between cultures. In many parts of the world, women with dependent children are expected to stay at home and dedicate all their energy to child raising, while in other places mothers most often return to paid work (see working mother and stay-at-home mother). |

出生率と家族生活 詳細情報:母親  人口参考局による出生率別国別地図(2020年  未婚女性による出生の割合、一部の国、1980年および2007年[132] 合計特殊出生率(TFR)は、女性が一生の間に産む平均子供数で、世界の地域によって大きく異なる。2016年、最も高いTFRはニジェール(女性1人あ たり6.62人)で、最も低いのはシンガポール(女性1人あたり0.82人)でした。[133] サハラ以南のアフリカ諸国の多くは高いTFRを有しており、資源不足による問題や過密人口の要因となっています。一方、西欧諸国では現在、人口減少や高齢 化を招く可能性がある置換水準以下の出生率が続いています。 世界多くの地域で、過去数十年で家族構造の変化が見られています。例えば、西洋では、拡大家族を含む生活形態から核家族のみの生活形態への移行傾向が見ら れます。また、婚姻内出生から婚姻外出生への移行傾向もみられます。婚姻外で生まれた子供は、同棲カップルや独身女性から生まれる場合があります。婚姻外 出生は、世界の一部地域では一般的で完全に受け入れられていますが、他の地域では強く非難され、未婚の母親は家族からの暴力を含む排除に直面し、極端な ケースでは名誉殺人さえ発生しています。[134][135] さらに、婚姻外の性行為は多くの国(サウジアラビア、パキスタン、[136] アフガニスタン[137][138]、イラン[138]、クウェート[139]、モルディブ[140]、モロッコ[141]、オマーン[142]、モーリ タニア[143]、アラブ首長国連邦[144][145]、スーダン[146]、イエメン[147]など)。 母親の社会的役割は文化によって異なる。世界の多くの地域では、扶養する子供がいる女性は、家庭に留まり、子育てに全力を尽くすことが期待されているが、 他の地域では、母親は多くの場合、有償の仕事に復帰する(働く母親および専業主婦を参照)。 |

| Education Main article: Female education  Women attending an adult literacy class in the El Alto section of La Paz, Bolivia Single-sex education has traditionally been dominant and is still highly relevant. Universal education, meaning state-provided primary and secondary education independent of gender, is not yet a global norm, even if it is assumed in most developed countries. In some Western countries, women have surpassed men at many levels of education. For example, in the United States in 2005/2006, women earned 62% of associate degrees, 58% of bachelor's degrees, 60% of master's degrees, and 50% of doctorates.[148][149] In 2020, 87% of the world's women were literate, compared to 90% of men; at the same time, only 59% of women in sub-Saharan Africa were literate.[150] The educational gender gap in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries has been reduced over the last 30 years. Younger women today are far more likely to have completed a tertiary qualification: in 19 of the 30 OECD countries, more than twice as many women aged 25 to 34 have completed tertiary education than have women aged 55 to 64. In 21 of 27 OECD countries with comparable data, the number of women graduating from university-level programmes is equal to or exceeds that of men. 15-year-old girls tend to show much higher expectations for their careers than boys of the same age.[151] While women account for more than half of university graduates in several OECD countries, they receive only 30% of tertiary degrees granted in science and engineering fields, and women account for only 25% to 35% of researchers in most OECD countries.[152] Research shows that while women are studying at prestigious universities at the same rate as men they are not being given the same chance to join the faculty. Sociologist Harriet Zuckerman has observed that the more prestigious an institute is, the more difficult and time-consuming it will be for women to obtain a faculty position there. In 1989, Harvard University tenured its first woman in chemistry, Cynthia Friend, and in 1992 its first woman in physics, Melissa Franklin. She also observed that women were more likely to hold their first professional positions as instructors and lecturers while men are more likely to work first in tenure positions. According to Smith and Tang, as of 1989, 65% of men and only 40% of women held tenured positions and only 29% of all scientists and engineers employed as assistant professors in four-year colleges and universities were women.[153] In the Soviet Union, 40% of chemistry PhDs went to women in the 1960s.[154] In 1992, women earned 9% of the PhDs awarded in engineering, but only one percent of those women became professors. In 1995, 11% of professors in science and engineering were women. In relation, only 311 deans of engineering schools were women, which is less than 1% of the total. Even in psychology, a degree in which women earn the majority of PhDs, they hold a significant amount of fewer tenured positions, roughly 19% in 1994.[155] |

教育 主な記事:女性の教育  ボリビア、ラパス郊外のエル・アルト地区で成人識字教室に通う女性たち 伝統的に、単性教育が主流であり、現在もその傾向が強い。性別に関係なく、国家が提供する初等教育および中等教育を意味する「普遍的教育」は、ほとんどの 先進国では当然のこととみなされているものの、まだ世界的な標準とはなっていない。一部の欧米諸国では、女性は多くの教育レベルで男性を上回っている。例 えば、2005/2006年のアメリカ合衆国では、女性は準学士号の62%、学士号の58%、修士号の60%、博士号の50%を取得していた。[148] [149] 2020年時点で、世界の女性の87%が識字率を有していたのに対し、男性は90%だった。一方、サハラ以南のアフリカでは、女性の識字率は59%に留 まっている。[150] 経済協力開発機構(OECD)加盟国における教育の性別格差は、過去30年間で縮小されてきた。現在の若い女性は、高等教育を修了する可能性がはるかに高 いです。OECD加盟30カ国中19カ国では、25歳から34歳の女性の高等教育修了率が、55歳から64歳の女性の修了率の2倍を超えています。比較可 能なデータがある27のOECD加盟国中21カ国では、大学レベルのプログラムを卒業する女性の数は男性と同等かそれ以上だ。15歳の少女は、同年代の少 年よりもキャリアに対する期待がはるかに高い傾向にある。[151] いくつかのOECD諸国では、大学卒業者の過半数を女性が占めているにもかかわらず、科学・工学分野の高等教育修了者の30%しか女性が占めておらず、 OECD諸国の大多数では研究者の25%から35%しか女性が占めていない。[152] 調査によると、女性は男性と同率で名門大学に進学しているにもかかわらず、教職員になる機会は男性と同じではない。社会学者ハリエット・ザッカーマン氏 は、教育機関の権威が高いほど、女性が教職員になることは難しく、時間がかかる傾向があると指摘している。1989 年、ハーバード大学は化学分野で初の女性教職員、シンシア・フレンド氏を、1992 年には物理学分野で初の女性教職員、メリッサ・フランクリン氏を常勤教職員に採用した。また、女性は最初の職として講師や助教に就く傾向が強く、一方、男 性はテニュア職に就く傾向が強いことも指摘している。スミスとタンによると、1989 年の時点で、テニュア職に就いているのは男性が 65%、女性は 40% に留まり、4 年制大学に助教授として採用されている科学者や技術者のうち、女性が占める割合は 29% に過ぎなかった。[153] ソビエト連邦では、1960年代に化学の博士号を取得した人の40%が女性だった[154]。 1992年には、工学の博士号を取得した人の9%が女性だったが、そのうちの1%しか教授にはならなかった。1995年には、科学と工学の教授の11%が 女性だった。これに対し、工学部の学部長は311人で、全体の1%未満だった。心理学のように、女性が博士号の過半数を占める分野でも、1994年には終 身在職権を持つ職に就いている女性は19%程度と、大幅に少なかった。[155] |

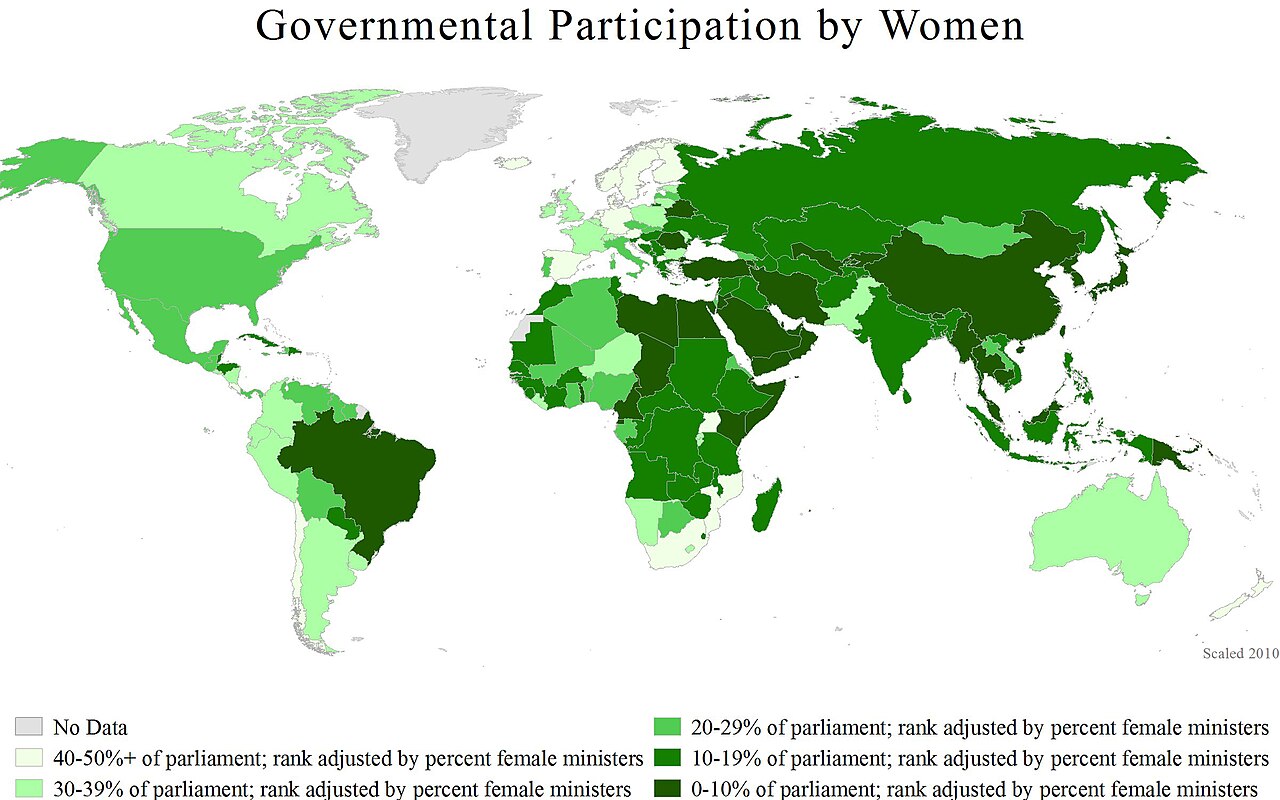

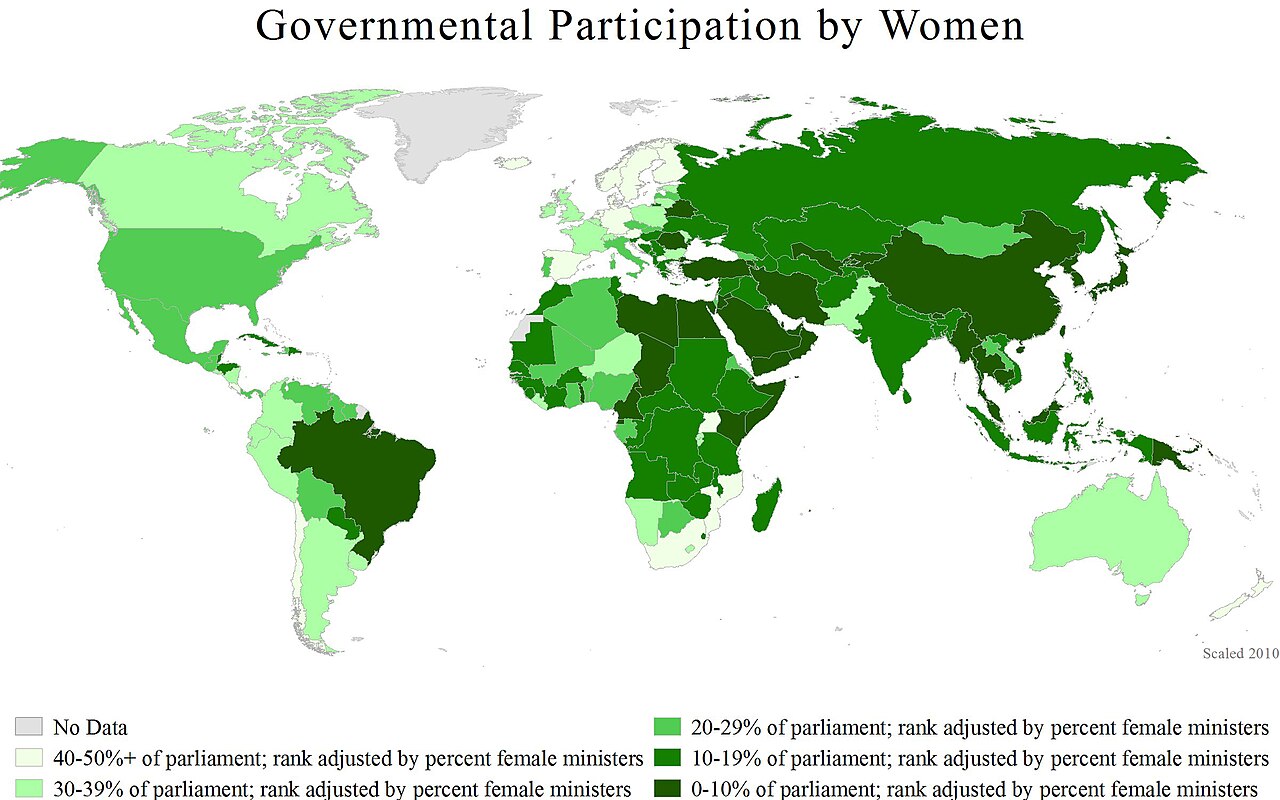

| Government and politics Main articles: Timeline of women's suffrage and List of elected and appointed female heads of state and government  A world map showing female governmental participation by country, 2010. A world map showing female governmental participation by country, 2010 Women are underrepresented in government in most countries. In January 2019, the global average of women in national assemblies was 24.3%.[156]  Sirimavo Bandaranaike was the first female prime minister; she was democratically elected in Sri Lanka in 1960. Suffrage is the civil right to vote, and women's suffrage movements have a long historic timeline. For example, women's suffrage in the United States was achieved gradually, first at state and local levels in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, then in 1920 when women in the US received universal suffrage with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Some Western countries were slow to allow women to vote, notably Switzerland, where women gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971, and in the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden women were granted the right to vote on local issues only in 1991, when the canton was forced to do so by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland;[157][158] and Liechtenstein, in 1984, through a women's suffrage referendum. |

政府と政治 主な記事:女性参政権の年表、選出された女性国家元首および政府首脳の一覧  2010年の各国における女性の政府参加率を示す世界地図。 2010年の各国における女性の政府参加率を示す世界地図 ほとんどの国の政府では、女性の割合が過小評価されている。2019年1月、各国議会における女性の割合の世界平均は24.3%だった[156]。  シリマヴォ・バンダラナイケは、1960年にスリランカで民主的に選出された、世界初の女性首相だ。 選挙権は投票する市民権であり、女性の選挙権運動は長い歴史を有している。例えば、アメリカ合衆国における女性の選挙権は段階的に実現され、19世紀末か ら20世紀初頭にかけて州や地方レベルで認められ、1920年にアメリカ合衆国憲法第19修正案が可決され、女性全員が選挙権を獲得した。一部の西欧諸国 では女性の投票権付与が遅れ、特にスイスでは1971年に連邦選挙での投票権が認められ、アッペンツェル・インナーローデン州では1991年にスイス連邦 最高裁の判決により、地方問題に関する投票権がようやく付与された。[157][158] また、リヒテンシュタインでは1984年に女性参政権に関する住民投票により実現した。 |

| Science, literature and art Main articles: Women in science, Women artists, and Women writers Science and medicine Marie Curie was the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize.[159] One area where women have been permitted most access historically was that of obstetrics and gynecology (prior to the 18th century, caring for pregnant women in Europe was undertaken by women; from the mid-18th century onwards, medical monitoring of pregnant women started to require rigorous formal education, to which women did not generally have access, and thus the practice was largely transferred to men).[160][161] Literature Writing was generally also considered acceptable for upper-class women, although achieving success as a female writer in a male-dominated world could be very difficult; as a result of several women writers adopted a male pen name (e.g. George Sand, George Eliot).[162] Music Women have been composers, songwriters, instrumental performers, singers, conductors, music scholars, music educators, music critics/music journalists and other musical professions. There are music movements,[clarification needed] events and genres related to women, women's issues and feminism.[citation needed] In the 2010s, while women comprise a significant proportion of popular music and classical music singers, and a significant proportion of songwriters (many of them being singer-songwriters), there are few women record producers, rock critics and rock instrumentalists. Although there have been a huge number of women composers in classical music, from the Medieval period to the present day, women composers are significantly underrepresented in the commonly performed classical music repertoire, music history textbooks and music encyclopedias; for example, in the Concise Oxford History of Music, Clara Schumann is one of the only female composers who is mentioned. Women comprise a significant proportion of instrumental soloists in classical music and the percentage of women in orchestras is increasing. A 2015 article on concerto soloists in major Canadian orchestras, however, indicated that 84% of the soloists with the Montreal Symphony Orchestra were men. In 2012, women still made up just 6% of the top-ranked Vienna Philharmonic orchestra. Women are less common as instrumental players in popular music genres such as rock and heavy metal, although there have been a number of notable female instrumentalists and all-female bands. Women are particularly underrepresented in extreme metal genres.[163] Women are also underrepresented in orchestral conducting, music criticism/music journalism, music producing, and sound engineering. While women were discouraged from composing in the 19th century, and there are few women musicologists, women became involved in music education "... to such a degree that women dominated [this field] during the later half of the 19th century and well into the 20th century."[164] a woman with a cello Women musicians may sing, write music, play instruments, conduct orchestras, teach music, and more. According to Jessica Duchen, a music writer for London's The Independent, women musicians in classical music are "... too often judged for their appearances, rather than their talent" and they face pressure "... to look sexy onstage and in photos."[165] Duchen states that while "[t]here are women musicians who refuse to play on their looks, ... the ones who do tend to be more materially successful."[165] According to the UK's Radio 3 editor, Edwina Wolstencroft, the classical music industry has long been open to having women in performance or entertainment roles, but women are much less likely to have positions of authority, such as being the leader of an orchestra.[166] In popular music, while there are many women singers recording songs, there are very few women behind the audio console acting as music producers, the individuals who direct and manage the recording process.[167] |

科学、文学、芸術 主な記事:科学分野の女性、女性芸術家、女性作家 科学と医学 マリー・キュリーは、ノーベル賞を受賞した最初の女性です。[159] 歴史的に女性が最もアクセスを許可されてきた分野の一つは、産科と婦人科だった(18世紀以前は、ヨーロッパでは妊娠中の女性のケアは女性が担当してい た。18世紀半ば以降、妊娠中の女性の医療監視には厳格な正式な教育が必要となり、女性は一般的にその教育を受けることができなかったため、この業務は主 に男性に移管された)。[160][161] 文学 執筆も、一般的に上流階級の女性には許容されていたが、男性優位の社会で女性作家として成功することは非常に困難だった。その結果、多くの女性作家は男性 名(ジョージ・サンド、ジョージ・エリオットなど)をペンネームとして採用した。[162] 音楽 女性は、作曲家、作詞家、楽器演奏者、歌手、指揮者、音楽学者、音楽教育者、音楽評論家、音楽ジャーナリスト、その他の音楽関連職業に従事してきた。女 性、女性の問題、フェミニズムに関連する音楽運動[明確化が必要]、イベント、ジャンルがある[出典が必要]。2010年代には、女性はいわゆるポピュ ラー音楽やクラシック音楽の歌手、作詞家(その多くはシンガーソングライター)の相当な割合を占めているが、女性レコードプロデューサー、ロック批評家、 ロック楽器演奏者は少ない。中世から現在に至るまで、クラシック音楽には数多くの女性作曲家が存在していますが、一般的に演奏されるクラシック音楽のレ パートリー、音楽史の教科書、音楽事典では、女性作曲家の存在は著しく過小評価されています。例えば、『コンサイス・オックスフォード音楽史』では、クラ ラ・シューマンが唯一の女性作曲家として紹介されています。 クラシック音楽の楽器ソロ奏者には女性が一定割合を占めており、オーケストラにおける女性の割合も増加傾向にある。しかし、2015年のカナダ主要オーケ ストラのコンチェルトソロ奏者に関する記事では、モントリオール交響楽団のソロ奏者の84%が男性だった。2012年時点でも、ウィーン・フィルハーモ ニー管弦楽団のトップランク奏者のうち女性はわずか6%だった。ロックやヘビーメタルなどのポピュラー音楽ジャンルでは、女性楽器演奏者はあまり多くない が、著名な女性楽器演奏者や女性だけのバンドもいくつか存在する。特に、エクストリームメタルジャンルでは、女性の割合が著しく低い。[163] 女性はオーケストラの指揮、音楽批評/音楽ジャーナリズム、音楽プロデュース、サウンドエンジニアリングでも少数派だ。19世紀には女性が作曲を奨励され なかったため、女性音楽学者は少ないが、女性は音楽教育に深く関与し、「19世紀後半から20世紀前半にかけて、この分野を支配するほどになった」 [164]。 チェロを弾く女性 女性音楽家は、歌を歌ったり、音楽を作曲したり、楽器を演奏したり、オーケストラを指揮したり、音楽を教えたりするなど、多様な活動を行っている。 ロンドン『インディペンデント』の音楽ライター、ジェシカ・デュチェンによると、クラシック音楽の女性音楽家は「才能ではなく外見で判断されることが多す ぎる」と指摘し、彼女たちは「ステージや写真でセクシーに見せなければならない」というプレッシャーに直面している。[165] デュチェンは、「外見で演奏することを拒否する女性音楽家もいるが、そうする人たちは物質的に成功している傾向がある」と述べてる。[165] 英国のラジオ 3 の編集者、エドウィナ・ウォルステンクロフト氏によると、クラシック音楽業界は、演奏やエンターテイメントの分野では長い間、女性を受け入れてきたが、 オーケストラのリーダーなどの権威のある地位に就く女性は、はるかに少ないという。[166] ポピュラー音楽では、歌手を務める女性は多いものの、録音の指揮や管理を行う音楽プロデューサーとして、オーディオコンソールを担当する女性はごくわずか だ。[167] |

| General Lists of women UN Women Sociological: Women's studies Dynamics: Feminization (sociology) Matriarchy Medical: Feminine psychology Other: Womyn / Womxn |

一般 女性のリスト 国連女性機関 社会学 女性学 ダイナミクス 女性化(社会学 母系社会 医学 女性心理学 その他 Womyn / Womxn |

| Chafe, William H. Archived

2009-01-13 at the Wayback Machine, The American Woman: Her Changing

Social, Economic, And Political Roles, 1920–1970, Oxford University

Press, 1972. ISBN 0-19-501785-4 Rosalie Maggio, ed. (1996). The New Beacon Book of Quotations by Women. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-6783-0. Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women, 4 vls., ed. by Cheris Kramarae and Dale Spender, Routledge 2000 Women in World History : a biographical encyclopedia, 17 vls., ed. by Anne Commire, Waterford, Conn. [etc.] : Yorkin Publ. [etc.], 1999–2002 Woman In all ages and in all countries in 10 volumes. Illustrated edition deluxe limited to 1,000 numbered copies with an index by Rénald Lévesque |

チャフェ、ウィリアム H.

2009年1月13日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ、『アメリカの女性:その社会的、経済的、政治的役割の変化、1920年~1970年』、オックス

フォード大学出版局、1972年。ISBN 0-19-501785-4 ロザリー・マッジョ編(1996)。『女性による引用集』ボストン:ビーコン・プレス。ISBN 0-8070-6783-0。 『女性に関する国際百科事典』4巻、チェリス・クラマレーとデール・スペンダー編、ラウトレッジ、2000年 世界史の女性たち:伝記事典、17巻、アン・コミア編、コネチカット州ウォーターフォード [ほか]:ヨークイン出版 [ほか]、1999–2002 『すべての時代、すべての国の女性たち』全10巻。レナルド・レヴェスクによる索引付き、1,000部限定豪華版。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woman |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆