女性解放運動は Womens_liberation_movement.html に移転しています

The we-page on Women's liberation movement is now moved to Womens_liberation_movement.html

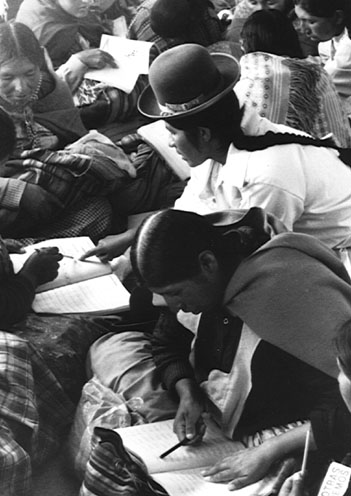

Left: The women's liberation movement featured political activities such as a march demanding legal equality for women in the United States (26 August 1970)

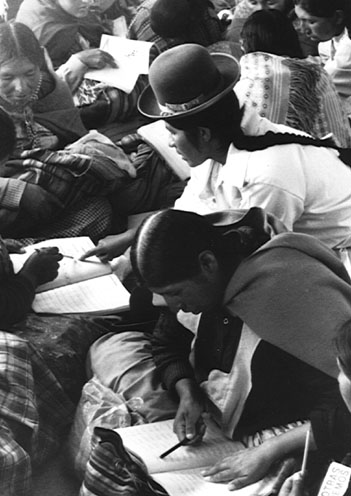

Right: Women attending an adult literacy class in the El Alto section of La Paz, Bolivia