ショロトゥル

Xolotl

A

drawing of Xolotl, one of the deities described in the Codex Borgia

☆ アステカ神話では、ショロトゥルあるいはショロトル(ナワトル語発音: [ˈolot͡ɬ] ⓘ)は火と稲妻の神であった。双子、怪物、死、不幸、病気、奇形の神でもあった。キソロトルはケツァルコアトルの犬の兄弟であり双子である[3]。彼は宵 の明星である金星の暗黒の擬人化であり、天の火と関連していた。アクソロトルの名は彼の名にちなむ。

| In Aztec mythology,

Xolotl (Nahuatl pronunciation: [ˈʃolot͡ɬ] ⓘ) was a god of fire and

lightning. He was commonly depicted as a dog-headed man and was a

soul-guide for the dead.[2] He was also god of twins, monsters, death,

misfortune, sickness, and deformities. Xolotl is the canine brother and

twin of Quetzalcoatl,[3] the pair being sons of the virgin Chimalma. He

is the dark personification of Venus, the evening star, and was

associated with heavenly fire. The axolotl is named after him. |

ア

ステカ神話では、ショロトル(ナワトル語発音: [ˈolot͡ɬ]

ⓘ)は火と稲妻の神であった。双子、怪物、死、不幸、病気、奇形の神でもあった。ショロトルはケツァルコアトルの犬の兄弟であり双子である[3]。彼は宵

の明星である金星の暗黒の擬人化であり、天の火と関連していた。アクソロトルの名は彼の名にちなむ。 |

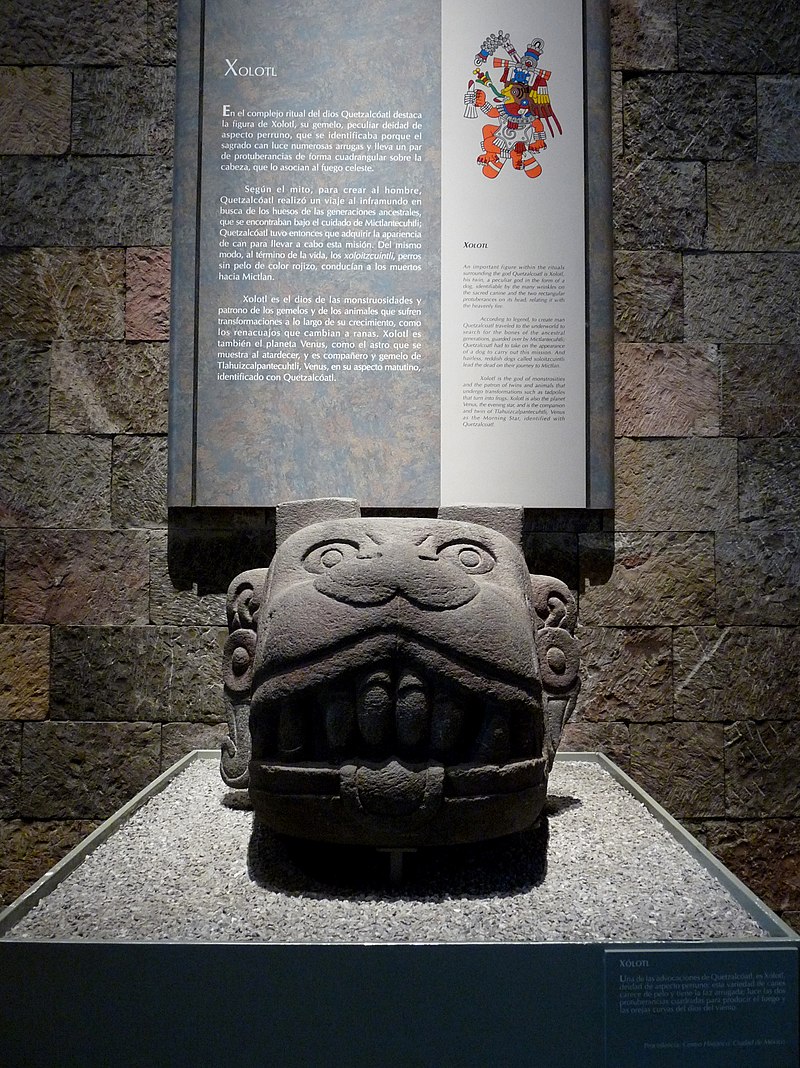

Myths and functions Xolotl statue displayed at the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City.  Codex Borbonicus (p. 16) Xolotl is depicted as a companion of the Setting Sun.[4] He is pictured with a knife in his mouth, a symbol of death.[5] Xolotl was the sinister god of monstrosities who wears the spirally-twisted wind jewel and the ear ornaments of Quetzalcoatl.[6] His job was to protect the sun from the dangers of the underworld. As a double of Quetzalcoatl, he carries his conch-like ehecailacacozcatl or wind jewel. Xolotl accompanied Quetzalcoatl to Mictlan, the land of the dead, or the underworld, to retrieve the bones from those who inhabited the previous world (Nahui Atl) to create new life for the present world, Nahui Ollin, the sun of movement. In a sense, this re-creation of life is reenacted every night when Xolotl guides the sun through the underworld. In the tonalpohualli, Xolotl rules over day Ollin (movement) and over trecena 1-Cozcacuauhtli (vulture).[7] His empty eye sockets are explained in the legend of Teotihuacan, in which the gods decided to sacrifice themselves for the newly created sun. Xolotl withdrew from this sacrifice and wept so much his eyes fell out of their sockets.[8] According to the creation recounted in the Florentine Codex, after the Fifth Sun was initially created, it did not move. Ehecatl ("God of Wind") consequently began slaying all other gods to induce the newly created Sun into movement. Xolotl, however, was unwilling to die in order to give movement to the new Sun. Xolotl transformed himself into a young maize plant with two stalks (xolotl), a doubled maguey plant (mexolotl), and an amphibious animal (axolotl). Xolotl is thus a master transformer. In the end, Ehecatl succeeded in finding and killing Xolotl.[9] In art, Xolotl was typically depicted as a dog-headed man, a skeleton, or a deformed monster with reversed feet. An incense burner in the form of a skeletal canine depicts Xolotl.[10] As a psychopomp, Xolotl would guide the dead on their journey to Mictlan the afterlife in myths. His two spirit animal forms are the Xoloitzcuintli dog and the water salamander species known as the Axolotl.[11] Xolos served as companions to the Aztecs in this life and also in the after-life, as many dog remains and dog sculptures have been found in Aztec burials, including some at the main temple in Tenochtitlan. Dogs were often subject to ritual sacrifice so that they could accompany their master on his voyage through Mictlan, the underworld.[12] Their main duty was to help their owners cross a deep river. It is possible that dog sculptures also found in burials were also intended to help people on this journey. Xoloitzcuintli is the official name of the Mexican Hairless Dog (also known as perro pelón mexicano in Mexican Spanish), a pre-Columbian canine breed from Mesoamerica dating back to over 3,500 years ago.[13] This is one of many native dog breeds in the Americas and it is often confused with the Peruvian Hairless Dog. The name "Xoloitzcuintli" references Xolotl because this dog's mission was to accompany the souls of the dead in their journey into eternity. The name "Axolotl" comes from Nahuatl, the Aztec language. One translation of the name connects the Axolotl to Xolotl. The most common translation is "water-dog" . "Atl" for water and "Xolotl" for dog.[14] In the Aztec calendar, the ruler of the day, Itzcuintli ("Dog"), is Mictlantecuhtli, the god of death and lord of Mictlan, the afterlife.[15] |

神話と機能 メキシコシティの国立人類学博物館に展示されているショロトル像。  Codex Borbonicus (p. 16) ショロトルは、沈む太陽の仲間として描かれている[4]。死の象徴であるナイフを口にくわえて描かれている[5]。 ショロトルは怪物の不吉な神で、ケツァルコアトルの螺旋状にねじれた風の宝石と耳の飾りをつけている[6]。彼の仕事は冥界の危険から太陽を守ることだっ た。ケツァルコアトルの替え玉として、法螺貝のようなエヘカイラカコスカトル(風の宝石)を携えている。ショロトルはケツァルコアトルに同行して死者の国 ミクトラン、つまり冥界に赴き、前世界(ナホイアトル)に住んでいた人々の骨を回収し、現世界(ナホイオリン、移動の太陽)のために新たな生命を創造し た。ある意味、この生命の再創造は、ショロトルが冥界で太陽を導くときに毎晩再現される。トナルポワリでは、ショロトルは昼のオーリン(動き)とトレセナ 1-コズカクアウトリ(ハゲワシ)を支配している[7]。 彼の空の眼窩はテオティワカンの伝説で説明されており、神々は新しく創造された太陽のために自らを犠牲にすることを決めた。ショロトルはこの生け贄を辞退 し、涙を流して眼窩から目を落とした[8]。フィレンツェ写本で語られる創造によれば、5番目の太陽が最初に創造された後、それは動かなかった。エヘカト ル(「風の神」)はその結果、新しく創造された太陽を動かすために他のすべての神々を殺し始めた。しかしショロトルは、新しい太陽に動きを与えるために死 ぬことを望まなかった。ショロトルは、2本の茎を持つ若いトウモロコシの植物(ショロトル)、二重になったマゲイの植物(メキソロトル)、水陸両用の動物 (アクソロトル)に姿を変えた。ショロトルは変身の達人なのだ。結局、エヘカトルはショロトルを見つけて殺すことに成功した[9]。 美術では、ショロトルは通常、犬の頭をした男、骸骨、または逆足を持つ異形の怪物として描かれた。サイコポンとして、ショロトルは神話において死者を死後 の世界であるミクトランへと導く。Xoloitzcuintli犬とAxolotlとして知られている水のサンショウウオの種である[11] Xolosは現世でも死後の世界でもアステカ人の仲間であった。犬は、主人が冥界であるミクトランを航海する際に同行できるよう、しばしば儀式の生贄にさ れた[12]。犬の主な任務は、飼い主が深い川を渡るのを助けることだった。埋葬品から発見された犬の彫刻もまた、この旅を助けるためのものであった可能 性がある。Xoloitzcuintliは、メキシコヘアレスドッグ(メキシコのスペイン語ではperro pelón mexicanoとも呼ばれる)の正式名称であり、3500年以上前にさかのぼるメソアメリカの先コロンビア時代の犬種である[13]。これはアメリカ大 陸に数多く存在する土着の犬種のひとつであり、しばしばペルーヘアレスドッグと混同される。ショロイツクイントリ」という名前はショロトルにちなんだもの で、この犬の使命は死者の魂が永遠へと旅立つのに同行することだったからである。アクソロトル」という名前はアステカ語のナワトル語に由来する。ある翻訳 では、アクソロトルとショロトルを結びつけている。最も一般的な訳は「水犬」である。「Atl 「は水、」ショロトル "は犬を意味する[14]。 アステカの暦では、この日の支配者であるイツクイントリ(「犬」)は、死の神であり死後の世界であるミクトランの主であるミクトランテクートリである[15]。 |

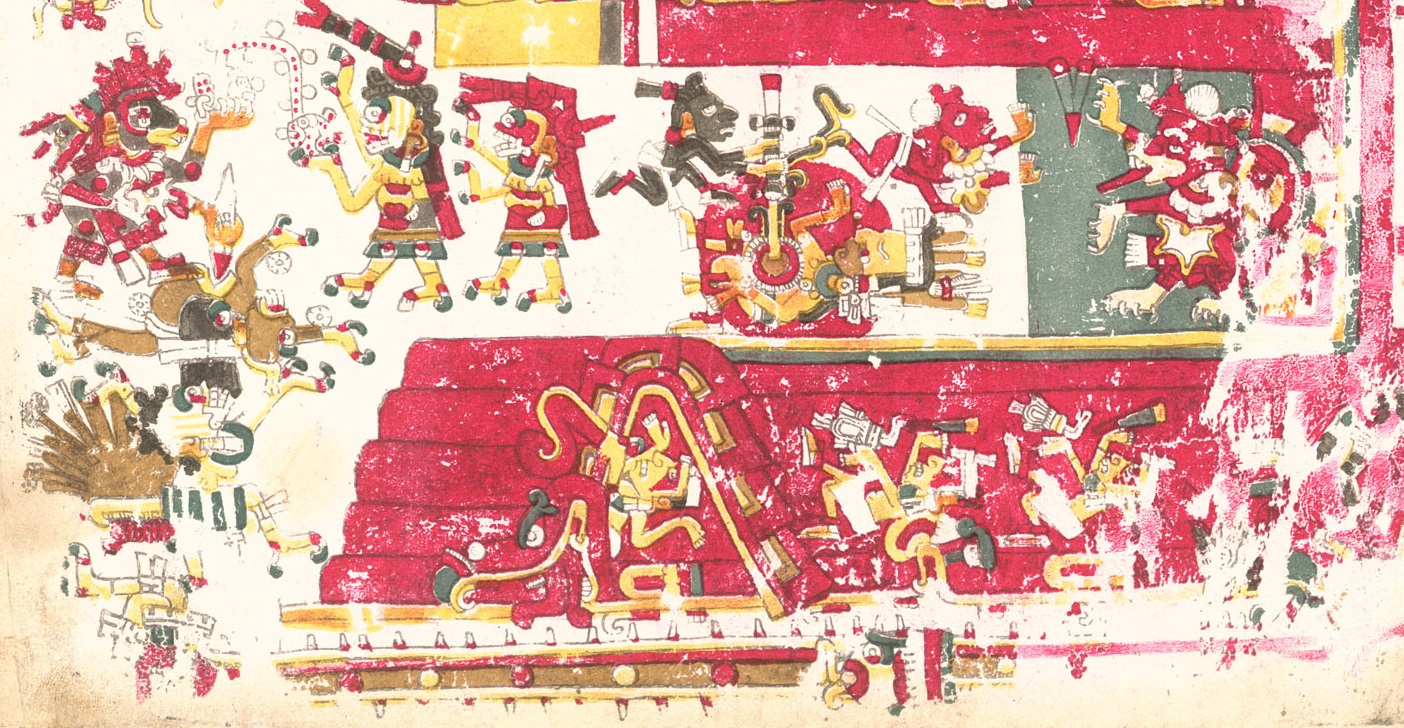

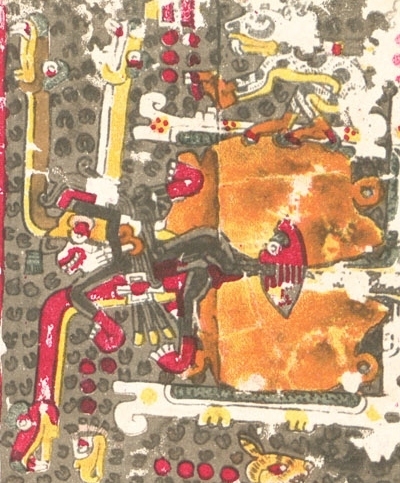

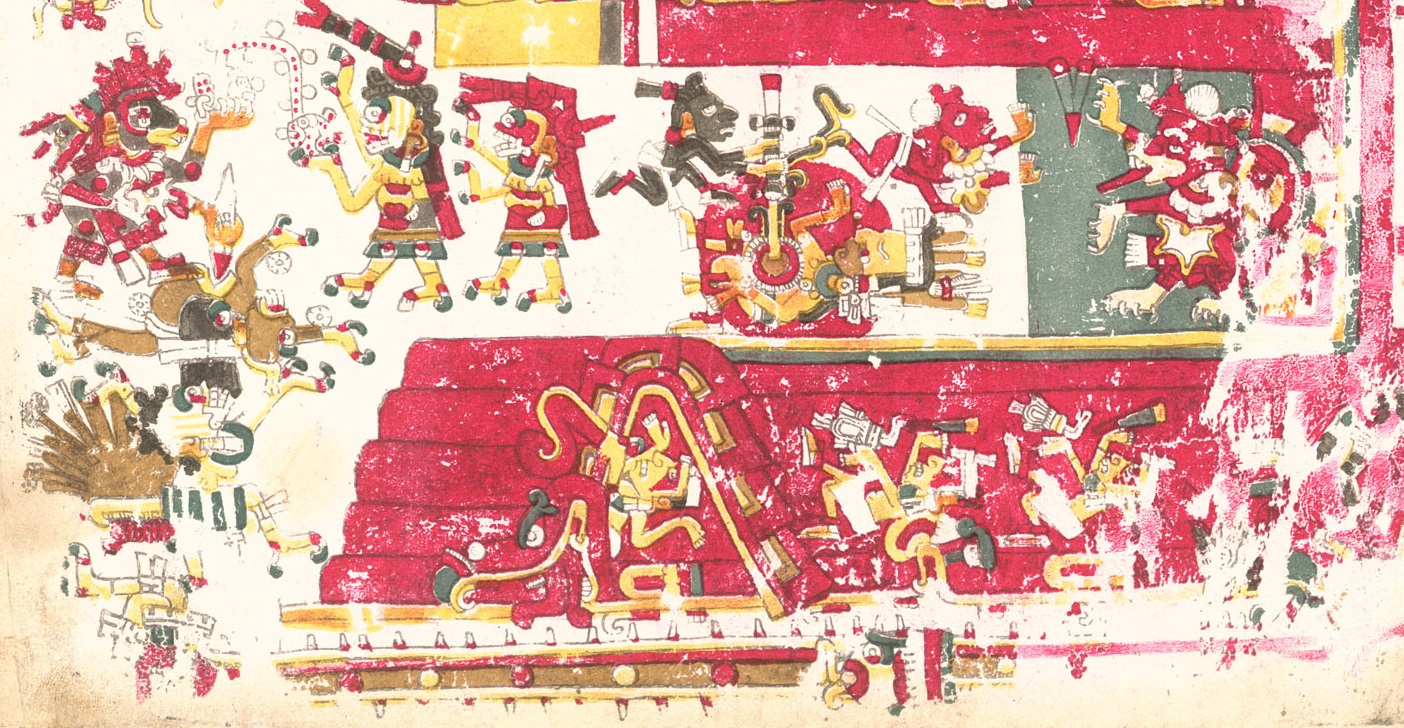

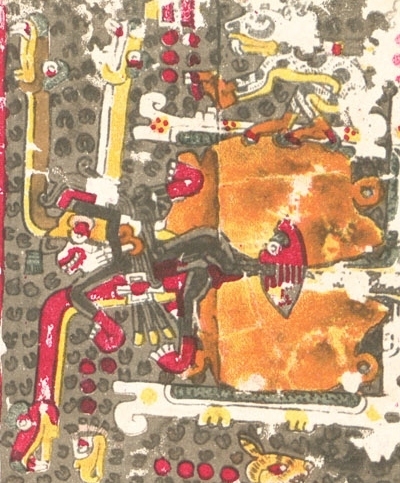

Origin Codex Borgia (p. 38) Xolotl with Xiuhcoatl "Fire Serpent" Xolotl is sometimes depicted carrying a torch in the surviving Maya codices, which reference the Maya tradition that the dog brought fire to mankind.[16] In the Mayan codices, the dog is conspicuously associated with the god of death, storm, and lightning.[17] Xolotl appears to have affinities with the Zapotec and Maya lightning-dog, and may represent the lightning which descends from the thundercloud, the flash, the reflection of which arouses the misconceived belief that lightning is "double", and leads them to suppose a connection between lightning and twins.[18] Xolotl originated in the southern regions, and may represent fire rushing down from the heavens or light flaming up in the heavens.[19] Xolotl was originally the name for lightning beast of the Maya tribe, often taking the form of a dog.[8] The dog plays an important role in Maya manuscripts. He is the lightning beast, who darts from heaven with a torch in his hand.[20] Xolotl is represented directly as a dog, and is distinguished as the deity of air and of the four directions of the wind by Quetzalcoatl's breast ornament. Xolotl is to be considered equivalent to the beast darting from heaven of the Maya manuscript.[21] The dog is the animal of the dead and therefore of the Place of Shadows.[18]  Dresden Codex Dog (p. 7)-p.6と説明 Dresden Codex Dog (p. 7)  Dog (p. 39)-p.68との説明 Dog (p. 39)  Dog (p. 40)-p.69と説明 Dog (p. 40) |

起源 ボルジア写本 (p. 38) 「火の蛇 」シュフコアトルとショロトル 現存するマヤの写本では、ショロトルは松明を持っているように描かれていることがあるが、これは犬が人類に火をもたらしたというマヤの伝承を参照している [16]。マヤの写本では、犬は死、嵐、稲妻の神との関連が際立っている。 [17]ショロトルはサポテカやマヤの稲妻犬と親和性があり、雷雲から降り注ぐ稲妻を表しているのかもしれない。 ショロトルはもともとマヤ族の雷獣の名前であり、しばしば犬の形をしていた[8]。彼は松明を手に天から飛び出す稲妻の獣である[20]。ショロトルは直 接的に犬として表され、ケツァルコアトルの胸飾りによって空気と風の四方の神として区別される。ショロトルは、マヤ写本の天から飛び出す獣に相当すると考 えられる[21]。犬は死者の動物であり、それゆえ影の場所の動物である[18]。  ドレスデン写本の犬 (p. 7)-p.6と説明 ドレスデン写本の犬 (p. 7)  犬 (p. 39)-p.68との説明 犬(39頁)  犬 (p. 40)-p.69と説明 犬 (p. 40) |

Ollin and Xolotl Stone sculpture representing the head of the Aztec god Xolotl. "An important figure within the rituals surrounding the god Quetzalcoatl is Xolotl, his twin, a peculiar god in the form of a dog, identifiable by the many wrinkles on the sacred canine and the two rectangular protuberances on its head, relating it with the heavenly fire."  Day symbol Ollin in Codex Borgia (p.10) Eduard Seler associates Xolotl's portrayal as a dog with the belief that dogs accompany the souls of the dead to Mictlan. He finds further evidence of the association between Xolotl, dogs, death, and Mictlan in the fact that Mesoamericans viewed twins as unnatural monstrosities and consequently commonly killed one of the two twins shortly after birth. Seler speculates that Xolotl represents the murdered twin who dwells in the darkness of Mictlan, while Quetzalcoatl ("The Precious Twin") represents the surviving twin who dwells in the light of the sun.[9] In manuscripts the setting sun, devoured by the earth, is opposite Xolotl's image.[22] Quetzalcoatl and Xolotl constitute the twin phases of Venus as the morning and evening star, respectively. Quetzalcoatl as the morning star acts as the harbinger of the Sun's rising (rebirth) every dawn, Xolotl as the evening star acts as the harbinger of the Sun's setting (death) every dusk. In this way they divide the single life-death process of cyclical transformation into its two phases: one leading from birth to death, the other from death to birth.[9] Xolotl was the patron of the Mesoamerican ballgame. Some scholars argue the ballgame symbolizes the Sun's perilous and uncertain nighttime journey through the underworld.[9] Xolotl is able to help in the Sun's rebirth since he possesses the power to enter and exit the underworld.[9] In several of the manuscripts Xolotl is depicted striving at this game against other gods. For example, in the Codex Mendoza we see him playing with the moon-god, and can recognize him by the sign ollin which accompanies him, and by the gouged-out eye in which that symbol ends. Seler thinks "that the root of the name ollin suggested to Mexicans the motion of the rubber ball olli and, as a consequence, ball-playing."[23] Ollin is pulsating, oscillating, and centering motion-change. It is typified by bouncing balls, pulsating hearts, labor contractions, earthquakes, flapping butterfly wings, the undulating motion of weft activities in weaving, and the oscillating path of the Fifth Sun over and under the surface of the earth. Ollin is the motion-change of cyclical completion.[24] A jade statue of a skeletal Xolotl carrying a solar disc bearing an image of the Sun on his back[25][26] (called "the Night Traveler") succinctly portrays Xolotl's role in assisting the Sun through the process of death, gestation, and rebirth. Xolotl's association with ollin motion-change suggests proper completions and gestations must instantiate ollin motion-change. Ollin-shaped decomposition and integration (i.e., death) promote ollin-shaped composition and integration (i.e., rebirth and renewal).[9] |

オリンとショロトル アステカの神ショロトルの頭部を表す石の彫刻。「ケツァルコアトル神を取り巻く儀式の中で重要な人物は、ショロトルである。ショロトルは犬の形をした特異 な神で、神聖なイヌに刻まれた多くのしわと、頭にある2つの長方形の突起によって識別することができ、天の火と関連している。」  ボルジア写本(p.10)の日のシンボル、オリン エドゥアルド・セラー(Eduard Seler)は、ショロトルが犬として描かれていることを、犬が死者の魂をミクトランに運ぶという信仰と結びつけている。彼は、メソアメリカ人が双子を不 自然な怪物とみなし、その結果、双子の片方を生後すぐに殺すのが一般的であったという事実に、ショロトル、犬、死、ミクトランの関連を示すさらなる証拠を 見出した。セラーは、ショロトルはミクトランの闇に住む殺された双子を表し、ケツァルコアトル(「大切な双子」)は太陽の光に住む生き残った双子を表して いると推測している[9]。 写本では、地球に食い尽くされた夕日がショロトルの像の反対側にある[22]。ケツァルコアトルとショロトルは、それぞれ朝星と宵星としての金星の双相を 構成している。朝の星としてのケツァルコアトルは、夜明けごとに太陽の上昇(再生)の前触れとして働き、宵の星としてのショロトルは、夕暮れごとに太陽の 沈没(死)の前触れとして働く。このように、彼らは周期的な変容という生と死の一つのプロセスを、誕生から死へ、死から誕生へと導く二つの段階に分けてい る[9]。 ショロトルはメソアメリカの球技の守護神であった。ショロトルは冥界に出入りする力を持っているため、太陽の再生を助けることができる。例えば、メンドー サ写本では、彼が月の神と遊んでいる様子が描かれており、彼に付随するオリンという記号と、その記号の最後にある抉られた目によって、彼を見分けることが できる。セラーは、「オリンという名前の語源が、メキシコ人にゴムボールであるオリの動きと、その結果としてボール遊びを示唆した」と考えている [23]。 オーリンは脈動し、振動し、中心をなす運動変化である。それは、弾むボール、脈打つ心臓、労働収縮、地震、蝶の羽ばたき、機織りにおける緯糸のうねるよう な動き、地球の表面とその下を行き来する第五の太陽の振動する経路に代表される。オーリンは周期的な完成の運動変化である[24]。 骸骨のショロトルが太陽のイメージを背負った太陽盤を背負っている翡翠の彫像[25][26](「夜の旅人」と呼ばれる)は、死、妊娠、再生のプロセスを 通じて太陽を支援するショロトルの役割を簡潔に描写している。ショロトルとオーリンの運動変化との関連は、適切な完了と妊娠がオーリンの運動変化をインス タンス化しなければならないことを示唆している。オーリン型の分解と統合(すなわち死)は、オーリン型の構成と統合(すなわち再生と更新)を促進する [9]。 |

Nanahuatzin and Xolotl Codex Borgia (p. 34) Xolotl sacrifices the rain god. Within the sanctuary of the Red Temple, the Sun is finally born. Against the background of a solid red disk, a warrior drills a fire on the chest of a figure lying down. From the smoke emerges a red solar deity with the wind jewel. Immediately to the right, the deity is enthroned in the temple. He now has canine claws, a canine mouth mask, the wind jewel, and a distended eye that identify him as the red Xolotl, he also carries the Sun on his back.[27] Codex Borgia (p. 47) a dog Xolotl accompanies an anthropomorphic avatar of Xolotl.[28]  A close relationship between Xolotl and Nanahuatzin exists.[29] Xolotl is probably identical with Nanahuatl (Nanahuatzin).[30] Seler characterizes Nanahuatzin ("Little Pustule Covered One"), who is deformed by syphilis, as an aspect of Xolotl in his capacity as god of monsters, deforming diseases, and deformities.[9] The syphilitic god Nanahuatzin is an avatar of Xolotl.[31]  Nanahuatzin |

ナナワツィンとショロトル ボルジア写本 (p. 34) ショロトルは雨の神を生贄に捧げる。赤い神殿の聖域で、ついに太陽が誕生する。赤い円盤を背景に、戦士が横たわる人物の胸に火を放つ。煙の中から風の宝玉 を持った赤い太陽神が現れる。すぐ右には、神殿に鎮座する神。彼は今、イヌの爪、イヌの口のマスク、風の宝石、そして赤いショロトルであることを示す膨張 した目を持っており、彼はまた太陽を背負っている[27]。 ボルジア写本(p.47)には、犬のショロトルがショロトルの擬人化されたアバターを従えている[28]。  ゾロトルとナナワツィンの間には密 接な関係が存在する[29]。ゾロトルはおそらくナナワトル(ナナワツィン)と同一である[30]。セラーは梅毒によって奇形化したナナワツィン(「小さ な膿疱に覆われた者」)を、怪物、奇形病、奇形の神としての立場におけるゾロトルの一側面として特徴づけている[9]。梅毒の神ナナワツィンはショロトルのアバターである[31]。  ナナワツィン(Nanahuatzin) |

| Anubis Dogs in Mesoamerican folklore and myth List of death deities Nagual Black dog (folklore) Codex Xolotl King Xolotl, grandfather of king Tezozomoc Xocotl (Aztec god) |

アヌビス メソアメリカの民間伝承と神話における犬 死神のリスト ナグアル 黒い犬(民間伝承) ショロトル写本——以下で説明 テゾゾモック王の祖父、ショロトル王 Xocotl(アステカの神) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xolotl | |

| Xocotl

("Plum" in Nahuatl) is the Aztec god of the planet Venus and of fire.

He is probably related to Xolotl, the god of lightning and death. |

Xocotl[ショコトル](ナワトル語で 「プラム」)は、アステカの金星と火の神である。おそらく雷と死の神ショロトルと関係がある。 |

The Aztec king Chimalpopoca in Huitzilopochtli costume, from the Codex Xolotl. |

ショロトル写本に描かれた、フイツィロポクトリに扮したアステカのチマルポポカ王。 |

| The Codex Xolotl (also

known as Códice Xolotl) is a postconquest cartographic Aztec codex,

thought to have originated before 1542.[1] It is annotated in Nahuatl

and details the preconquest history of the Valley of Mexico, and

Texcoco in particular, from the arrival of the Chichimeca under the

king Xolotl in the year 5 Flint (1224) to the Tepanec War in 1427.[2][3] The codex describes Xolotl's and the Chichimeca's entry to the then unpopulated valley as peaceful. Although this picture is confirmed by the Texcocan historian Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl (1568 or 1580–1648), there is other evidence that suggests that the area was inhabited by the Toltecs.[4] Ixtlilxochitl, a direct descendant of Ixtlilxochitl I and Ixtlilxochitl II, based much of his writings on the documents[5] which he most probably obtained from relatives in Texcoco or Teotihuacan.[6] The codex was first brought to Europe in 1840 by the French scientist Joseph Marius Alexis Aubin [fr], and is currently held by the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.[7] The manuscript consists of six amatl boards measuring 42 cm × 48 cm (17 in × 19 in), with ten pages and three fragments from one or more pages.[8] While it is unknown who did the binding of the manuscript, it is cast like a European book back to back.[8] The Codex Xolotl has been an important source in giving detailed information on material, social, political and cultural changes in the region during the period.[9] It is one of the few still surviving cartographic histories from the Valley of Mexico and one of the earliest of its type.[10] |

ショ

ロトル写本(Códice

Xolotl)は、1542年以前に作成されたと考えられている、征服後のアステカの地図写本である[1]。ナワトル語で注釈が付されており、5年フリン

ト(1224年)のショロトル王の下でのチチメカの到着から1427年のテパネカ戦争まで、メキシコの谷、特にテスココの征服前の歴史が詳述されている

[2][3]。 この写本では、ショロトルとチチメカが当時未開の地であったこの谷に入ったことは平和的であったと記述されている。この図式はテスコカ人の歴史家フェルナ ンド・デ・アルバ・コルテス・イクスチリルソチトル(1568年または1580年~1648年)によって確認されているが、この地域にトルテカ人が居住し ていたことを示唆する証拠が他にもある[4]。 イクストリルキソチトルは、イクストリルキソチトル1世とイクストリルキソチトル2世の直系の子孫であり、著作の多くをこの文書に基づいている[5]。 写本は42cm×48cm(17インチ×19インチ)の6枚のアマトル板から成り、10ページと1ページ以上の断片が3つある[8]。誰が製本したかは不 明だが、ヨーロッパの書物のように背中合わせに鋳造されている。 [8]ショロトル写本は、この時代のこの地域の物質的、社会的、政治的、文化的変化に関する詳細な情報を提供する重要な資料となっている[9]。 メキシコの谷の地図帳として現存する数少ない写本の一つであり、このタイプの写本としては最も初期のものである[10]。 |

| Historical significance The Codex Xolotl is an example of material culture. This means that the codex can be used as an object to understand the culture of the Aztecs. The object itself shows the Aztec understanding of the history of Texcoco.[11] It is also a document that includes an early instance of Nahuatl writings referencing specific dates.[12] There is some ongoing debate regarding how many writers were involved in creating the codex itself.[13] This can propose discrepancy about how much personal influence was involved in creating the document. Controversy There are some debates that question how valid the codex is from an archaeological perspective. This debate roots itself in the work of Jeffrey Parsons in 1970s, with his book detailing the archaeology of the Texcoco region.[14] One side of this debate states that the codex itself is not supported by the archaeological evidence of the region.[15] Another argument claims that within the discrepancies, some historical facts can be separated from the mythology.[11] An alternate response to Parsons' argument uses a hypothesis regarding a conflict between the Tula and Cholula regions to support Parsons' position.[16] |

歴史的意義 ショロトル写本は物質文化の一例である。つまり、この写本はアステカの文化を理解するための対象として使うことができる。また、この写本は、特定の日付に 言及したナワトル語文献の初期の例を含む文書でもある[12]。この写本の作成に何人の執筆者が関わったかについては、現在も議論が続いている[13]。 論争 この写本が考古学的にどの程度有効なのか、疑問視する議論もある。この論争のルーツは、1970年代にジェフリー・パーソンズがテスココ地域の考古学を詳 述した著書である[14]。この論争の一方は、写本そのものがこの地域の考古学的証拠によって裏付けられていないとするものである[15]。 パーソンズの議論に対する別の反論は、トゥーラ地方とチョルーラ地方の対立に関する仮説を用いてパーソンズの立場を支持している[16]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex_Xolotl |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Maya death god "A" way as a hunter, Classic period

☆

☆

☆