醜さ

bruttezza, fealdad, ugliness

The Ugly Duchess (painting by Quentin Matsys, c. 1513)/世界で一番著名な「醜い貴婦人」(クエンティン・マサイス)

ウンベルト・エーコ編著『醜の歴史(Storia della bruttezza)』川野美也子訳、東洋書林, 2009年:「現代の「知の巨人」エーコが、絵画や彫刻、映画、文学など諸芸術における暗黒、怪奇、魔物、逸脱、異形といった、恐ろしくぞっとするものを 徹底的に探究。本書は、世界的に好評を博した『美の歴史』の手法により、「醜」の多様性と傾向を明らかにする。なぜ我々は死、病、欠陥を恐れるのだろう か?はたまた醜さが持つ磁石のような魅力はいったい何に由来するのだろう。ミルトンのサタンから、ゲーテのメフィストフェレスまで、魔術と中世の拷問か ら、殉教、隠者まで、神話上の怪物から、夢魔、食人鬼、デカダンス、あるいはキャンプ、キッチュ、パンク、さらには現代美術まで、実に興味深い構成とト ピックにより議論が展開される」BOOK database)

| 古典世界の醜 |

|

| 受難、死、殉教 |

|

| 黙示録、地獄、悪魔 |

|

| モンスター(怪物)とポルテント(予兆) |

|

| 醜悪なもの、滑稽なもの、猥褻なもの |

|

| 古代からバロック時代までの女性の醜さ |

|

| 近代世界の悪魔 |

|

| 魔女信仰、悪魔崇拝、サディズム |

|

| フィジカ・クリオーサ(肉体への好奇心) |

|

| ロマン主義による醜の解放 |

|

| 不気味なもの |

|

| 鉄の塔と象牙の塔 |

|

| アヴァンギャルドと醜の勝利 |

|

| 他者の醜、キッチェ、 |

|

| キャンプ |

|

| 現代の醜 |

|

| Unattractiveness

or ugliness is the degree to which a person's physical features are

considered aesthetically unfavorable. Terminology Ugliness is a property of a person or thing that is unpleasant to look upon and results in a highly unfavorable evaluation. The point of ugliness is to be aesthetically unattractive, unpleasing, repulsive, or offensive.[1] There are many terms associated with visually unappealing or aesthetically undesirable people, including hideousness and unsightliness, more informal terms such as turn-offs.[citation needed] History Jean-Paul Sartre had strabismus and a bloated, asymmetrical face, and he attributed many of his philosophical ideas to his lifelong struggle to come to terms with his self-described ugliness.[2] Socrates also used his ugliness as a philosophical touch point, concluding that philosophy can save a person from their outward ugliness.[2] Famous in his own time for his perceived ugliness, Abraham Lincoln[3] was described by a contemporary: "to say that he is ugly is nothing; to add that his figure is grotesque, is to convey no adequate impression." However, his looks proved to be an asset in his personal and political relationships, as his law partner William Herndon wrote, "He was not a pretty man by any means, nor was he an ugly one; he was a homely man, careless of his looks, plain-looking and plain-acting. He had no pomp, display, or dignity, so-called. He appeared simple in his carriage and bearing. He was a sad-looking man; his melancholy dripped from him as he walked. His apparent gloom impressed his friends, and created sympathy for him—one means of his great success."[4] The problem of ugliness also has a history within theology and Christian thought, where it has often been associated with dangerous stereotypes.[5] Prejudice Main article: Lookism Discrimination or prejudice against unattractive people is sometimes referred to as lookism, cacophobia, or aschemophobia,[6] and if it is a result of one's disfigurement, ableism.[7] Teratophobia is an aversion or fear of people who appear monstrous, have blemishes or are disfigured. When such an aversion is coupled with prejudice or discrimination, it may be viewed as a form of bullying.[8] With the dating world or courtship, judging others purely based on their outward appearance is acknowledged as an attitude that does transpire, yet is often viewed as an approach that is superficial and shallow.[9] Some research indicates a sentencing disparity where unattractive people are "more likely to be recommended psychiatric care" than attractive people.[10] Prejudice against ugliness is complex: Gretchen Henderson suggests that there is, paradoxically, a cultural suspicion towards both beauty and ugliness. [11] Legality There are some jurisdictions that already make it illegal to discriminate on the basis of immutable forms of aesthetic appearance, including the Australian state of Victoria, wherein lookism was made illegal in 1995.[12] In the United States, several states and major cities' jurisdictions have legislation prohibiting appearance-related discrimination.[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unattractiveness |

魅力のなさまたは醜さとは、人の身体的特徴が審美的に好ましくないとみ

なされる度合いのことである。 用語解説 醜さとは、見るに堪えない、非常に好ましくない評価をもたらす人や物の性質のことである。醜さのポイントは、審美的に魅力的でない、不快である、嫌悪感を 抱かせる、または不快であることである[1]。hideousnessやunsightliness、turn-offsなどのより非公式な用語を含め、 視覚的に魅力的でない、または審美的に望ましくない人に関連する多くの用語がある[要出典]。 歴史 ジャン=ポール・サルトルは斜視と肥大した左右非対称の顔を持っており、彼の哲学的思想の多くは、自称醜さと折り合いをつけるために生涯闘い続けたことに 起因している[2]。 ソクラテスもまた、哲学的な接点として彼の醜さを利用し、哲学は人を外見的な醜さから救うことができると結論づけた[2]: 「彼が醜いと言っても何の意味もない。彼の姿がグロテスクだと付け加えても、適切な印象は伝わらない。しかし、彼のルックスは、彼の個人的、政治的な関係 において財産となったことが証明され、彼の法律上のパートナーであったウィリアム・ハーンドンは、「彼は決して美男ではなく、また醜男でもなかった。いわ ゆる華やかさも、誇示も、威厳もなかった。身なりも立ち居振る舞いも質素だった。悲しげな表情で、歩くたびに憂鬱な表情が滲み出ていた。醜さの問題は神学 やキリスト教思想の中にも歴史があり、そこではしばしば危険なステレオタイプと結びつけられてきた[5]。 偏見 主な記事 ルックス主義 魅力的でない人に対する差別や偏見は、ルックス主義、カコフォビア、アスケモフォビアと呼ばれることもあり[6]、醜形が原因であれば、アビリティズムと 呼ばれることもある[7]。テラトフォビアは、怪物のように見えたり、傷があったり、醜い人に対する嫌悪や恐怖である。このような嫌悪が偏見や差別と結び ついた場合、それはいじめの一形態とみなされることがある[8]。デートの世界や求愛において、純粋に外見に基づいて他人を判断することは、実際に起こる 態度として認められているが、表面的で浅はかなアプローチとみなされることが多い。 [醜さに対する偏見は複雑である。グレッチェン・ヘンダーソンは、逆説的ではあるが、美しさと醜さの両方に対する文化的猜疑心が存在することを示唆してい る[11]。[11] 合法性 オーストラリアのビクトリア州では1995年にルックイズムが違法とされた[12]。米国では、いくつかの州や主要都市の管轄区域で外見に関連した差別を 禁止する法律が制定されている[13]。 |

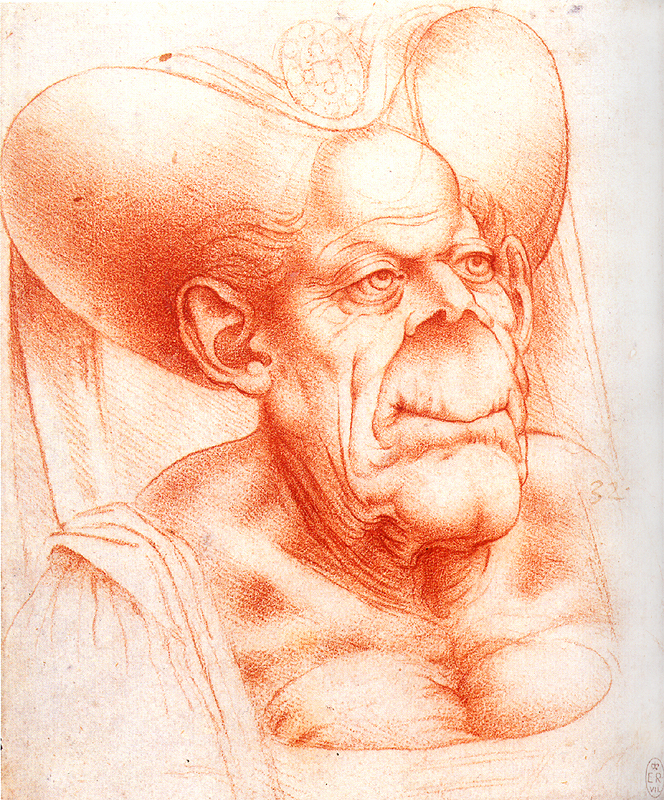

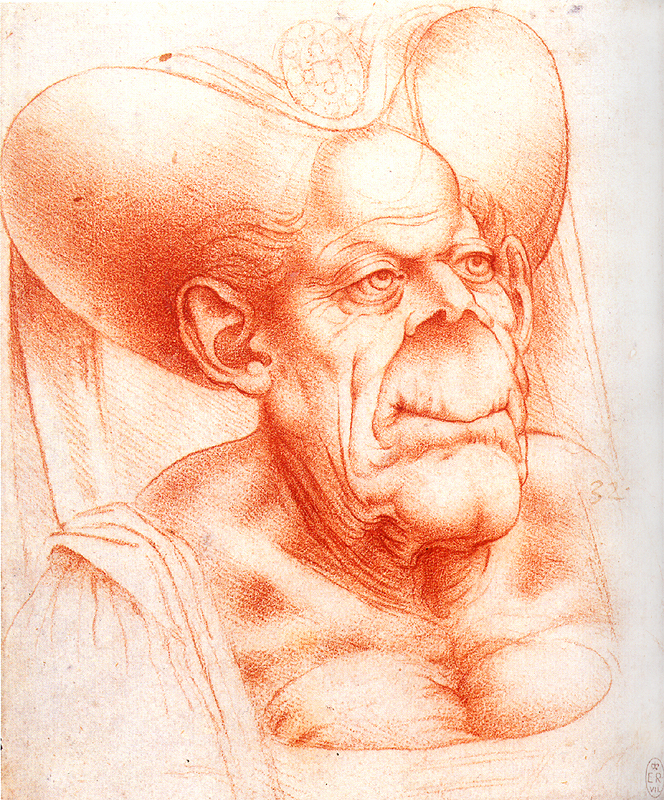

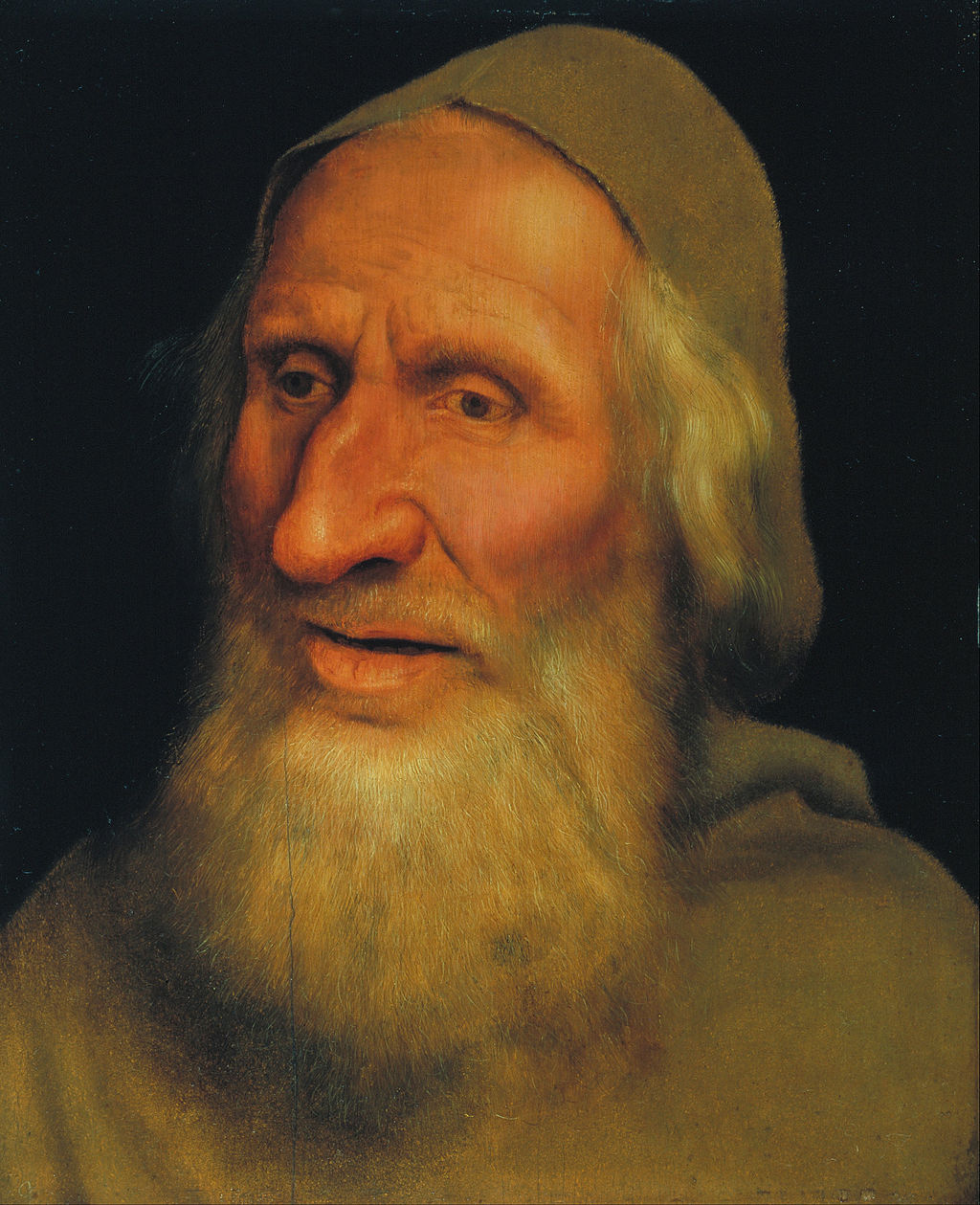

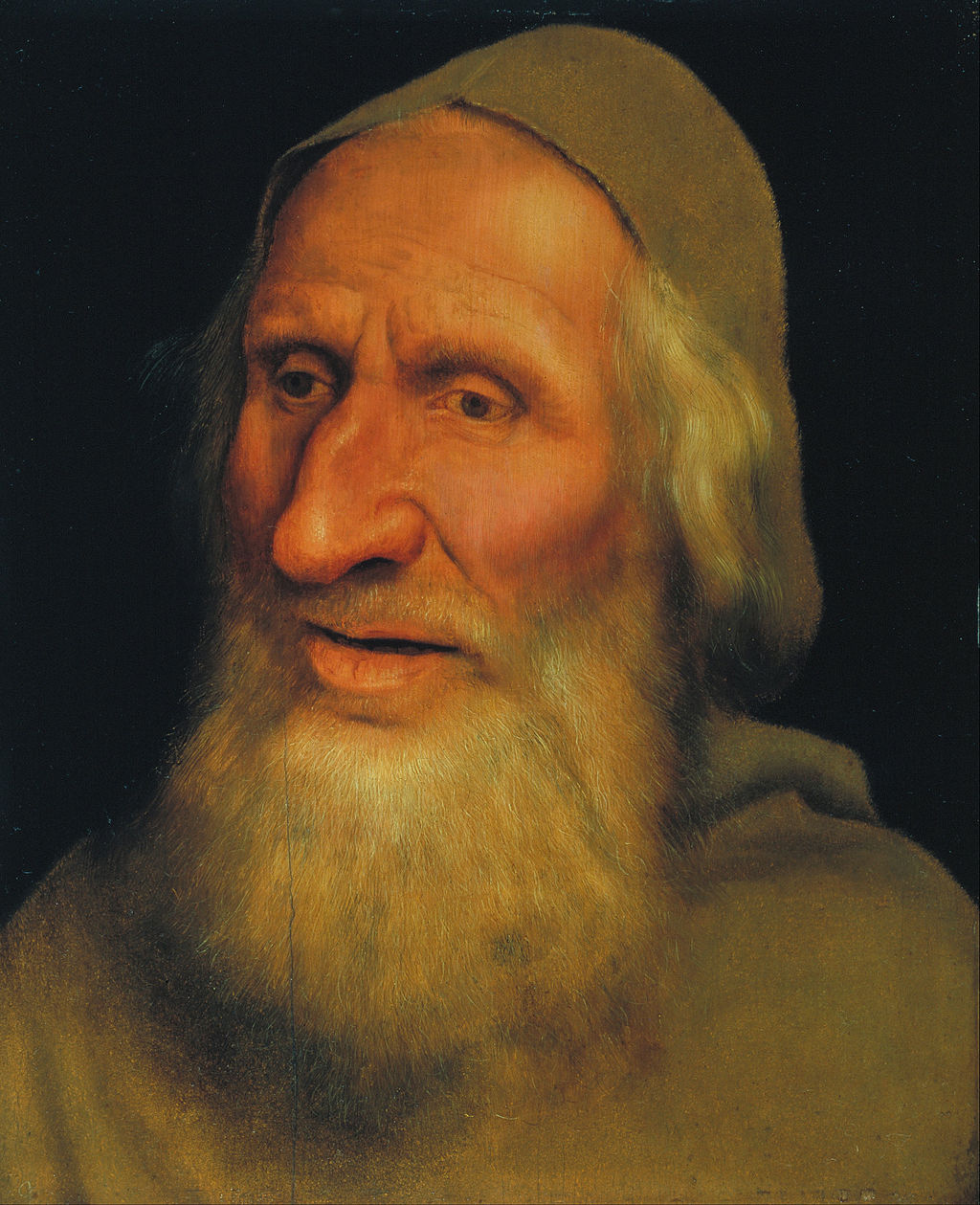

The Ugly Duchess

(also known as A Grotesque Old Woman) is a satirical portrait

painted by the Flemish artist Quentin Matsys around 1513. The painting is in oil on an oak panel, measuring 62.4 by 45.5 cm.[1] It shows an old woman with wrinkled skin and withered breasts. She wears the aristocratic horned headdress (escoffion) of her youth, out of fashion by the time of the painting, and holds in her right hand a red flower, then a symbol of engagement, indicating that she is trying to attract a suitor. However, it has been described as a bud that will 'likely never blossom'. The work is Matsys' best-known painting.[2] The painting was long thought to have been derived from a putative lost work by Leonardo da Vinci, on the basis of its striking resemblance to two caricature drawings of heads commonly attributed to the Italian artist. However the caricatures are now thought to be based on the work of Matsys, who is known to have exchanged drawings with Leonardo.[3] A possible literary influence is Erasmus's essay In Praise of Folly (1511), which satirizes women who "still play the coquette", "cannot tear themselves away from their mirrors" and "do not hesitate to exhibit their repulsive withered breasts".[2] The woman has been often identified as Margaret, Countess of Tyrol, claimed by her enemies to be ugly;[4] however, she had died 150 years earlier. The painting is in the collection of the National Gallery in London, to which it was bequeathed by Jenny Louisa Roberta Blaker in 1947.[1] It was originally half of a diptych, with a Portrait of an Old Man, in the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, which was lent to the National Gallery in 2008 for an exhibition in which the two paintings were hung side by side.[3] The portrait is thought to be a source for John Tenniel's 1865 illustrations of the Duchess in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.[5] A 1989 article published in the British Medical Journal speculated that the subject might have suffered from Paget's disease,[6] in which the victim's bones enlarge and become deformed. A similar suggestion was made by Michael Baum, emeritus professor of surgery at University College London.[3] Description The painting is in oil on an oak panel, measures 62.4 by 45.5 cm.[7] It shows an old woman depicted with exaggerated features. She has a short nose with upturned flared nostrils. Her upper lip is elongated and her mouth appears thin and pinched. The skin of her cheeks, neck and jaw hang loose on her face. The rest of her skin is wrinkled and pocked, and she has a wart on the right side of her face. Her thinning hair, concealed by an escoffion or horned headdress, is swept behind protruding ears. Despite her seemingly "ugly" visage, she wears aristocratic fashion that is more relevant to her youth rather than her advanced age. Her clothing is an adaptation of traditional Burgundian fashion, popular between 1400 and 1500. By the time Matsys completed this work, in 1513, this style of dress was already out of fashion. Her dress, with tightly laced corseted front, pushes her wrinkled breasts up beyond propriety standards for the period. Her shoulders are covered by a white veil, that falls from her escoffion headdress. It is decorated in roses and ornamented by a large gold and pearl brooch. Her fine, but out of fashion, clothing suggests she was a wealthy woman. Additionally, she holds a red flower in her right hand. At one time a red flower symbolized engagement, or courting.[7] With her ugly features and advanced age, this red flower only adds to the satirical nature of Matsys's work. Technical analysis  Detailed close-up of the ornamental brooch featured in Matsys's work, The Ugly Duchess. Shows the fine brushwork and layered colorwork. The painting technique reflects Matsys himself and is similar to his other work. The paint is worked in many places wet-in-wet and has been dragged and feathered. Matsys popularly used feathering to soften and blend transitions of tone.[8] The hair near the Duchess's right ear and the embroidery on her right cuff are rendered in sgraffito, a technique done by scratching through a layer of wet paint to show the underlying layers.[9] Matsys achieved the uneven appearance of her flesh by layering the basic pink with red and white dots in sporadic dashes and blotches. Matsys displays finer attention to detail through his brushwork when looking at the ornamental brooch. In the brooch are at least five shades of brown, orange, pink and yellow to achieve its golden hue.[7]  Detailed close-up of the horned headdress in Matsys's work, The Ugly Duchess. Produced using the sgraffito method. Infrared analysis of the painting shows that the face was carefully done, whereas the clothes and other elements were freer and more sketchy. For the face, Matsys may have carefully followed a preliminary drawing but made several changes. He drew the eyes twice, moving them slightly higher and to the right. He then decreased the final appearance of the chin, neck and right ear, visible by comparing the paint to the under drawing. Another change between the under drawing and paint are the right shoulder and both hands, which were shifted and differently posed.[7] Matsys painted the two horns of the headdress by different methods. On the right, the horn's stripes were made by sgraffito. He removed the red, white and blue to reveal the black layer underneath. The horn on the left, Matsys used the reverse method. He applied black paint on top of a multicolored layer. Though the work is largely attributed to Quentin Matsys, he did have a collection of assistants assisting him. The inconsistencies and changes in method could be attributed to the work of different assistants, or perhaps reflect a change in method from Matsys himself.[7][10] Interpretation Satire The woman depicted is dressed in the finest clothes, and holds a red flower that symbolizes engagement. She is fit to represent youth, but her grotesque appearance makes that impossible. Scholars today consider this a satire on material culture, especially preying on the elderly or those obsessed with maintaining an youthful appearance. Her appearance prompts the audience to consider the relationship between internal and external beauty. Externally, based on her exquisite dress, jeweled accessories, and budding flower, this woman was theoretically beautiful. However, her internal beauty is reflected in her exaggerated and displeasing physical appearance.[11] Refer also to Erasmus's essay In Praise of Folly (1511), which satirizes women who "still play the coquette", "cannot tear themselves away from their mirrors" and "do not hesitate to exhibit their repulsive withered breasts".[12][13] With the completion date estimated to be 1513 for The Ugly Duchess it is highly likely that Erasmus's essay influenced Matsys's production. Paget's disease In 1877 Sir James Paget observed a medical disorder where the bones became inflamed and malformed. He formally coined the condition osteitis deformans, but by the end of the century it became known as Paget's disease.[14] Though formal identification of the disease did not exist until 1877, there are accounts that suggest it's been around for far longer. Scholars now are using The Ugly Duchess to show that the disease existed as early as the 16th century. A 1989 article published in the British Medical Journal and emeritus professor of surgery at University College London, Michael Baum also offer speculation on the Duchess's diagnosis with Paget's.[15] While much of the discussion concerning Paget's disease focuses on the physical representation of the condition, scholar Sarah Newman suggests that the portrait also provides cultural insight into how disability was viewed in the sixteenth century. She argues that the portrait reflects a cultural transition from an earlier model of disability, where it was typically depicted exclusively as extreme or abnormal, to a more familiar model, one which depicts individuals engaged in daily commercial or personal activities that do not strike the viewer as exceptionally abnormal.[16] Newman's study contributes to understanding Matsys and the broader Dutch allegorical and portraiture traditions, and shows the value of historic representations in the broader study of disability. Historian Gretchen E. Henderson's book Ugliness: A Cultural History follows a similar line of discussion, but focuses on the interpretation of disability in artwork. Henderson presents the idea that, with focus on disability, the interpretation of The Ugly Duchess becomes more sympathetic rather than a study in satire.[17] As a sufferer of Paget's disease, the woman no longer appears the fool holding a red blossom that will never bloom, but a victim of unfortunate circumstances. These alternative interpretations rely on the assumption that Matsys used a live model for this portrait. While many possible identities have been suggested for the woman, none are convincing. Crossdresser theory Art curator Emma Capron has theorized that the subject is actually a man dressed as a woman, in the context of a carnival tradition- the moresca- which often involved a crossdressed man comically playing the role of a sought-after young woman. Capron noted Matsys's interest in carnivals and disagreed that the painting represented any disease. Furthermore, she also notes that the old man in the other half of the diptych may be raising his hand so as to reject "her" romance, since he realizes his companion is a crossdressed man.[18][19] Influence Quentin Matsys and Leonardo Da Vinci  Grotesque Head, Leonardo da Vinci. Red chalk on paper, 17.2 × 14.3 cm In 1490, Leonardo da Vinci created a series of sketches he called Grotesque Heads. Included in that series was a sketch that looked remarkably similar to Matsys's Ugly Duchess. With the earlier creation date there is some debate as to who the original creator is. It is well known that Matsys and da Vinci corresponded and shared work during their careers. When the Duchess was completed, many attributed its influence to the work of da Vinci since he already had a collection of caricature heads. However, when considering the under drawing and primary sketches beneath the paint, scholars now believe that Matsys had created the Duchess long before the portrait's completion. The now popular theory is that Matsys sent da Vinci an early sketch that then inspired the Italian artist to copy the exaggerated form of the woman's grotesque features.[15] John Tenniel's illustration in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland  John Tenniel's illustration of the Duchess from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, 1865 Many scholars today believe that Matsys influenced John Tenniel's illustration of the Duchess in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Author Lewis Carroll did not explicitly describe the Duchess's face in his book. Carroll described the character in chapter nine, stating "Alice did not much like keeping so close to her: first, because the Duchess was very ugly; and secondly, because she was exactly the right height to rest her chin upon Alice’s shoulder, and it was an uncomfortably sharp chin."[20] Rather than finding inspiration in Carroll's writing, Tenniel turned to the portrait of The Ugly Duchess. There are differences, Tenniel softened some of the harshness found in Matsys's work. Tenniel's Duchess has a lower headdress, and the large ears, leathery neck and breasts prominent in the original portrait, are concealed. Tenniel presents an ugly woman, but not a frightening one. She will upset children, much like the one she is holding in the illustration and the girl (Alice) who is looking at her and also talking to her, but she will not scare them like her predecessor.[21] Provenance Completed in 1513 as half of a diptych, with a Portrait of an Old Man. The portraits were at one point separated and fell into private collections. In 1920 The Ugly Duchess appeared at auction in New York City, New York.[17] Later, in 1947, Jenny Louisa Roberta Blaker bequeathed the portrait to The National Gallery in London where it remains today.[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ugly_Duchess |

『醜い公爵夫人』(『グロテスクな老婦人』とも)は、フランドルの画家

クエンティン・マサイスが1513年頃に描いた風刺的な肖像画である。 オーク材のパネルに油彩で描かれ、大きさは62.4×45.5cm[1]。彼女は、この絵が描かれた時代には流行遅れとなっていた、若い頃の貴族の角の生 えた頭飾り(エスコフィオン)をかぶり、右手には当時は婚約の象徴であった赤い花を持っており、求婚者を引き寄せようとしていることを示している。しか し、この花は「決して咲くことはないだろう」つぼみと表現されている。この作品はマツィスの最もよく知られた絵画である[2]。 この絵は、レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチが描いたとされる失われた作品に由来していると長い間考えられていた。しかし、現在では、この風刺画は、レオナルドと デッサンを交換したことで知られるマサイスの作品に基づいていると考えられている[3]。 文学的な影響として考えられるのは、エラスムスのエッセイ『愚行礼賛』(1511年)で、「いまだにコケットを演じ」、「鏡から自分を引き離すことができ ず」、「反吐が出るような枯れた乳房を見せることをためらわない」女性を風刺している[2]。 この絵画は、1947年にジェニー・ルイザ・ロベルタ・ブレイカーによって遺贈されたロンドンのナショナル・ギャラリーに所蔵されている[1]。元々は、 パリのジャックマール・アンドレ美術館に所蔵されていた『老人の肖像』との二部作の半分であったが、2008年にナショナル・ギャラリーに貸し出され、2 つの絵画が並んで展示された[3]。 この肖像画は、ジョン・テニエルが1865年に描いた『不思議の国のアリス』の公爵夫人の挿絵の元になったと考えられている[5]。 1989年に『British Medical Journal』誌に掲載された論文では、被害者の骨が肥大して変形するパジェット病[6]に罹患していたのではないかと推測されている。同様の示唆は、 ユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンの外科名誉教授であるマイケル・ボームによってなされた[3]。 描写 この絵はオーク材のパネルに油彩で描かれており、大きさは62.4×45.5cm[7]。老婆の鼻は短く、鼻の穴は上向きになっている。上唇は細長く、口 は細く、つまったように見える。頬、首、顎の皮膚は緩んで垂れ下がっている。顔の右側にはイボがある。エスコフィオンや角のある頭飾りで隠された薄毛の髪 は、突き出た耳の後ろに流されている。一見 "醜い "外見にもかかわらず、彼女は高齢というよりむしろ若さにふさわしい貴族的なファッションを身にまとっている。彼女の服装は、1400年から1500年に かけて流行したブルゴーニュの伝統的なファッションをアレンジしたものだ。マサイスがこの作品を完成させた1513年には、このスタイルの服はすでに廃れ ていた。彼女のドレスは、前身頃がコルセットできつく締められ、皺の寄った胸が当時の礼儀の基準を超えて押し上げられている。肩は白いベールで覆われ、エ スコフィオンの頭飾りから落ちている。バラで飾られ、金と真珠の大きなブローチで飾られている。上質だが流行遅れの服装は、彼女が裕福な女性であったこと を示唆している。さらに、彼女は右手に赤い花を持っている。かつて赤い花は婚約や求愛を象徴していた[7]。彼女の醜い顔立ちと老齢によって、この赤い花 はマティスの作品の風刺的な性質をさらに高めている。 技術的分析  マサイスの作品『醜い公爵夫人』に描かれた装飾ブローチの詳細なクローズアップ。繊細な筆使いと重層的な色使いがわかる。 絵画技法はマサイス自身を反映しており、彼の他の作品と似ている。絵の具はウェット・イン・ウェットでところどころに塗られ、ドラッグとフェザリングが施 されている。公爵夫人の右耳付近の髪と右袖口の刺繍は、スグラフィート(濡れた絵具の層を引っ掻くことで下層を見せる技法)で描かれている[9]。マティ スは、基本的なピンクに赤と白の点を散発的なダッシュや滲みで重ねることで、彼女の肉体の凹凸を表現している。装飾的なブローチを見ると、マサイスは筆致 を通して細部へのこだわりを見せる。ブローチには、少なくとも5色の茶色、オレンジ、ピンク、黄色が使われ、黄金色に輝いている[7]。  マツィスの作品『醜い公爵夫人』の角のある頭飾りの詳細なクローズアップ。スグラフィート技法で制作された。 赤外線分析によると、顔は入念に描かれているのに対し、衣服やその他の要素はより自由で大ざっぱに描かれている。顔については、マサイスは慎重に下絵に 従ったと思われるが、何度か変更を加えている。目を2度描き、少し上と右に移動させた。顎、首、右耳は、下絵と絵の具を比較することで最終的な見た目を小 さくした。下絵と絵の具の間のもう一つの変化は、右肩と両手で、それらは移動され、異なるポーズをとっている[7]。 マサイスは頭飾りの2本の角を異なる方法で描いている。右側の角の縞模様はスグラフィトで描かれている。彼は赤、白、青を取り除き、その下の黒い層を見せ た。左の角は、マサイスは逆の方法で作った。色とりどりの層の上に黒い絵の具を塗ったのだ。この作品の大部分はクエンティン・マサイスによるものとされて いるが、マサイスにはアシスタントの集団がいた。手法の矛盾や変化は、異なる助手の仕事によるものかもしれないし、マサイス自身の手法の変化を反映してい るのかもしれない[7][10]。 解釈 風刺 描かれている女性は最高級の服に身を包み、婚約を象徴する赤い花を持っている。彼女は若さを表すのにふさわしいが、彼女のグロテスクな外見がそれを不可能 にしている。今日の学者たちは、これは物質文化に対する風刺であり、特に高齢者や若々しさを保つことに執着する人々を食い物にしていると考えている。彼女 の外見は、観客に内面と外面の美の関係を考えさせる。外見的には、彼女の精緻なドレス、宝石をちりばめたアクセサリー、つぼみの花から、この女性は理論的 には美しい。しかし、彼女の内面的な美しさは、誇張された不愉快な外見に反映されている[11]。エラスムスのエッセイ『愚行礼讃』(1511年)も参照 され、「いまだにコケットを演じ」、「鏡から自分を引き離すことができず」、「反吐が出るような枯れた乳房を見せることをためらわない」女性を風刺してい る[12][13]。『醜い公爵夫人』の完成が1513年と推定されていることから、エラスムスのエッセイがマツィスの制作に影響を与えた可能性が高い。 パジェット病 1877年、ジェームズ・パジェット卿は、骨が炎症を起こして変形する医学的障害を観察した。彼は正式に変形性骨炎という病名を作ったが、世紀末にはパ ジェット病として知られるようになった。現在、学者たちは『醜い公爵夫人』を用いて、この病気が16世紀には存在していたことを示そうとしている。 1989年に『British Medical Journal』に掲載された論文と、ロンドン大学外科の名誉教授であるマイケル・ボームも、公爵夫人がパジェット病と診断されたことについて推測を述べ ている[15]。 パジェット病に関する議論の多くは、その病態の身体的表現に焦点を当てているが、学者のサラ・ニューマンは、この肖像画は、16世紀に障害がどのように見 られていたかについての文化的洞察も提供していると示唆している。彼女は、この肖像画が、一般的に極端で異常なものとしてのみ描かれていた以前の障害モデ ルから、より身近なモデル、つまり、見る者に特別な異常さを感じさせない日常的な商業活動や個人的な活動に従事する個人を描いたモデルへの文化的変遷を反 映していると論じている[16]。 ニューマンの研究は、マツィスや、より広範なオランダの寓意画や肖像画の伝統の理解に貢献し、障害に関するより広範な研究における歴史的表象の価値を示し ている。 歴史家グレッチェン・E・ヘンダーソンの著書『Ugliness: A Cultural History』(邦題『醜さ:文化史』)でも同様の議論が展開されているが、芸術作品における障害の解釈に焦点が当てられている。ヘンダーソンは、障害 に焦点を当てることで、『醜い公爵夫人』の解釈が風刺の研究ではなく、より同情的になるという考えを提示している[17]。パジェット病の患者であるこの 女性は、もはや決して咲くことのない赤い花を抱えている愚か者ではなく、不幸な境遇の犠牲者に見える。これらの別の解釈は、マティスがこの肖像画に生きた モデルを使ったという仮定に依拠している。この女性の身元については多くの可能性が指摘されているが、どれも説得力がない。 女装説 アート・キュレーターのエマ・カプロンは、カーニバルの伝統であるモレスカ(女装した男性がコミカルに若い女性の役を演じること)の文脈から、この肖像画 の主題は実際には女装した男性であるという説を唱えている。カプロンは、マティスがカーニバルに関心を持っていたことを指摘し、この絵が病気を表している ことには同意しなかった。さらに彼女は、二部作のもう半分に描かれている老人は、自分の連れが女装した男性であることに気づいているので、「彼女」のロマ ンスを拒絶するために手を挙げているのかもしれないとも指摘している[18][19]。 影響 クエンティン・マサイスとレオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチ  グロテスクな頭部、レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチ。紙に赤チョーク、17.2 × 14.3 cm 1490年、レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチはグロテスク・ヘッドと呼ばれる一連のスケッチを描いた。そのシリーズの中に、マツィスの『醜い公爵夫人』に酷似し たスケッチが含まれていた。制作年代が早いため、原作者が誰であるかについては議論がある。マサイスとダ・ヴィンチがそのキャリアの中で文通し、作品を共 有していたことはよく知られている。公爵夫人が完成したとき、ダ・ヴィンチはすでに風刺画の頭部をコレクションしていたため、その影響はダ・ヴィンチの作 品にあると多くの人が考えた。しかし、絵の具の下に描かれた下絵や一次スケッチを考慮すると、マサイスは肖像画が完成するずっと前に公爵夫人を制作してい たと、現在では学者たちは考えている。現在有力な説は、マサイスがダ・ヴィンチに初期のスケッチを送り、それに触発されたイタリアの画家が、この女性のグ ロテスクな特徴の誇張された形を模写したというものである[15]。 ジョン・テニエルの『不思議の国のアリス』の挿絵  ジョン・テニエルの『不思議の国のアリス』の公爵夫人の挿絵、1865年 今日、多くの学者が、マサイスがジョン・テニエルの『不思議の国のアリス』の公爵夫人の挿絵に影響を与えたと考えている。作者のルイス・キャロルは自著の 中で公爵夫人の顔を明確に描写していない。キャロルは第9章で、「アリスは公爵夫人の近くにいるのがあまり好きではなかった。第一に、公爵夫人はとても醜 かったからであり、第二に、公爵夫人はアリスの肩に顎を乗せるのにちょうどいい高さで、不快なほど鋭い顎だったからである」と述べている[20]。違いは あるが、テニエルはマツィスの作品に見られる辛辣さをいくらか和らげた。テニエルの公爵夫人は頭飾りが低く、元の肖像画に顕著だった大きな耳、皮のような 首、胸は隠されている。テニエルは醜い女性を描いているが、恐ろしい女性ではない。彼女は、挿絵の中で抱いている少女や、彼女を見ていて話しかけている少 女(アリス)のように、子供たちを動揺させるだろうが、前任者のように怖がらせることはない[21]。 由緒 1513年、「老人の肖像」と二部作の半分として完成。この肖像画は一時期分離され、個人のコレクションになった。1920年、『醜い公爵夫人』はニュー ヨークのオークションに出品された[17]。その後、1947年、ジェニー・ルイザ・ロベルタ・ブレイカーがこの肖像画をロンドンのナショナル・ギャラ リーに遺贈し、現在に至っている[7]。 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ugly_Duchess |

The Ugly Duchess aka "A Grotesque old Woman", 1513 64.2 × 45.5 cm. National Gallery, London |

Portrait of an Old Man, c. 1517. Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris |

King and Queen of Tunis, Wenzel Hollar (1607–1677) |

John Tenniel's illustration of the Duchess from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, 1865 |

Quentin Matsys[1]

(Dutch: Quinten Matsijs) (1466–1530) was a Flemish painter in the Early

Netherlandish tradition. He was born in Leuven. There is a tradition

alleging that he was trained as an ironsmith before becoming a painter.

Matsys was active in Antwerp for over 20 years, creating numerous works

with religious roots and satirical tendencies. He is regarded as the

founder of the Antwerp school of painting, which became the leading

school of painting in Flanders in the 16th century. He introduced new

techniques and motifs as well as moralising subjects without completely

breaking with the tradition.[2] Quentin Matsys[1]

(Dutch: Quinten Matsijs) (1466–1530) was a Flemish painter in the Early

Netherlandish tradition. He was born in Leuven. There is a tradition

alleging that he was trained as an ironsmith before becoming a painter.

Matsys was active in Antwerp for over 20 years, creating numerous works

with religious roots and satirical tendencies. He is regarded as the

founder of the Antwerp school of painting, which became the leading

school of painting in Flanders in the 16th century. He introduced new

techniques and motifs as well as moralising subjects without completely

breaking with the tradition.[2]Early life Most early accounts of Matsys' life are composed primarily of legend and very little contemporary accounts exist of the nature of his activities or character. According to J. Molanus' Historiae Lovaniensium Matsys is known to be a native of Leuven with humble beginnings as an ironsmith. One of four children, Massys was born to Joost Matsys (d. 1483) and Catherine van Kincken sometime between 4 April and 10 September 1466. Legend states that Matsys abandoned his career as a blacksmith to woo his wife, who found painting to be a more romantic profession, though Karel van Mander claimed this to be false, and the real reason was a sickness during which he was too weak to work at the smithy and instead decorated prints for the carnival celebrations.[3] +++++++++++++++++++++++++++  Head of an Old Man Documented donations and possessions of Joost Matsys indicate that the family had a respectable income and that financial need was most likely not the reason Matsys turned to painting. During the period in which Matsys was active in Antwerp he took only four apprentices: a certain Ariaen whom certain art historians believe to be Adriaen van Overbeke (master in 1508),[2] Willem Muelenbroec (registered in 1501), Eduart Portugalois (registered in 1504, master in 1506), and Hennen Boeckmakere (registered in 1510). It is widely believed that Joachim Patinir studied with Matsys at some point during his career and contributed to several of his landscapes (such as The Temptation of St. Anthony at the Prado Museum in Madrid).[4] Lack of guild records during this time leaves Matsys' travels to Italy and other parts of the Low Countries as part of his training open to question. For the most part, foreign influences on Matsys are inferred from his paintings and are considered to be a large portion of the artist's training during the 16th century. Work in Leuven  Detail of a c. 1500 Calendar Clock Face which shows the artist with his 'brothers' Joost the clockmaker and Jan During the greater part of the 15th century, the centres in which the painters of the Low Countries most congregated were Tournai, Bruges, Ghent and Brussels. Leuven gained prominence toward the close of this period, employing workmen from all of the crafts including Matsys. Not until the beginning of the 16th century did Antwerp take the lead which it afterward maintained against Bruges, Ghent, Brussels, Mechelen and Leuven.[5] Because no guild records were kept prior to 1494 in Leuven there is no concrete proof that Matsys attained his master's status there; however, historians generally accept this to be the location of his early training because he had not been previously registered in Antwerp as an apprentice. As a member of Antwerp's Guild of Saint Luke, Matsys is considered to be one of its first notable artists. Existing records of guild laws and regulations from the 16th century indicate that it is highly unlikely that Matsys was self-taught, despite accounts in Carel van Mander's Schilderboeck (1604) stating that Matsys studied under no artist.[6] Style Although the roots of Matsys' training are unknown, his style reflects the artistic qualities of Dirk Bouts, who brought to Leuven the influence of Hans Memling and Rogier Van der Weyden. When Matsys settled at Antwerp at the age of twenty-five, his own style contributed importantly to reviving Flemish art along the lines of Van Eyck and Van der Weyden.[5] Matsys departed from Leuven in 1491 when he became a master in the guild of painters at Antwerp. His most well known satirical works include A Portrait of an Elderly Man (1513), and The Money Changer and His Wife (1514), all of which provide commentary on human feeling and society in general. He also painted religious altarpieces and triptych panels, the most famous of which was built for the Church of Saint Peter in Leuven.  The Money Changer and His Wife (1514) Oil on panel, 71 × 68 cm Louvre Abu Dhabi Matsys work is considered to contain strong religious feeling—characteristic of traditional Flemish works—and is accompanied by a realism that often favored the grotesque. Matsys' firmness of outline, clear modelling and thorough finish of detail stem from Van Der Weyden's influence; from the Van Eycks and Memling by way of Dirck Bouts, the glowing richness of transparent pigments. Matsys' works generally reflect earnestness in expression, minutely detailed renderings, and subdued effects in light and shade. Like most Flemish artists of the time he paid a great deal of attention to jewelry, edging of garments, and ornamentation in general.[5]  The Virgin and Child Enthroned, with Four Angels (1513) Oil on panel, 62.2 × 43.2 cm National Gallery, London Most of the emphasis in his works lies not upon atmosphere, which is in fact given very little attention, but to the literalness of caricature: emphasizing the melancholy refinement of saints, the brutal gestures and grimaces of gaolers and executioners. Strenuous effort is devoted to the expression of individual character. A satirical tendency may be seen in the pictures of merchant bankers (Louvre and Windsor), revealing their greed and avarice. His other impulse, dwelling on the feelings of tenderness, may be noted in two replicas of the Virgin and Child at Berlin and Amsterdam, where the ecstatic kiss of the mother seems rather awkward. An expression of acute despair may be seen in a Lucretia in the museum at Vienna. The remarkable glow of the colour in these works, however, makes the Mannerist exaggerations palatable.[5] Matsys had considerable skill as a portrait painter. His Ægidius (Peter Gilles) which drew from Thomas More a eulogy in Latin verse, is but one of many, to which one may add the portrait of Maximilian of Austria in the gallery in Amsterdam. In this branch of his practice, Matsys was greatly influenced by his fellow countryman Jan Mabuse.[5] Matsys' portraiture exhibits highly personal and individual emotional characteristics that reflect his adherence to realism as a technique. Influences  Temptation of St. Anthony, Joachim Patinir and Quentin Matsys, 1520-1524. Prado Museum, Madrid. In comparison to other Northern Renaissance artists such as Holbein and Dürer Matsys shies away from refined and subtle detailing. Because there are numerous connections between him and these masters, however, it can be concluded that his departure in techniques was deliberate and not an act of ignorance. He most likely met Holbein more than once on his way to England, and Dürer is believed to have visited his house at Antwerp in 1520.[5] Matsys also became the guardian of Joachim Patinir's children after the death of that painter. His Virgin and Christ, Ecce Homo and Mater Dolorosa (London and Antwerp) are known for their serene and dignified mastery, gaining in delicacy and nuance in the works of his maturity. It is believed that he had known the work of Leonardo da Vinci in the form of prints made and circulated among northern artists (his Madonna and Child with the Lamb, inspired by The Virgin and Child with St. Anne, reflects da Vinci's influences).[7] This is largely regarded as proof that Matsys was greatly influenced by Italian Renaissance artists and that he most likely travelled to Italy for at least a brief period. Death Memorial on Antwerp Cathedral. The artist Luc Tuymans created a modern mosaic at the Museum aan de Stroom based on this skull plaque.  Matsys died at Antwerp in 1530. He was a religious devotee, despite several of his relatives dying as a result of their faith. His sister Catherine and her husband suffered at Leuven in 1543 for what was then the capital offence of reading the Bible: he being decapitated, she allegedly buried alive in the square before the church. In 1629 the first centennial of Matsys' death was marked by a ceremony and erection of a relief plaque with an accompanying inscription on the facade of the Antwerp Cathedral. Benefactor Cornelius van der Geest is said to be responsible for the wording, stating: "in his time a smith and afterwards a famous painter", keeping in accordance with the legends surrounding Matsys' humble beginnings. Legacy  A Grotesque Old Woman Oil on wood, 64 × 45,5 cm National Gallery, London Matsys' works include A Portrait of an Elderly Man (1513), Christ presented to the People (1518-1520)[8] (Prado), and A Grotesque Old Woman (or The Ugly Duchess), which is perhaps the best-known of his works. It served as a basis for John Tenniel's depiction of the Duchess in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. It is likely a depiction of a real person with Paget's disease,[9] though it is sometimes said to be a metaphorical portrait of the Margaret, Countess of Tyrol, who was known as Maultasch, which, though literally translated "satchel mouth", was used to mean "ugly woman" or "whore" (because of her marital scandals). His two large triptych altarpieces The Holy Kinship or Saint Anne Altarpiece (1507–1509) and The Entombment of the Lord (1508–1511) are also highly celebrated. Commissioned for the Church of Saint Peter in Leuven, they reflect strong religious feeling and precise detailing characteristic to the majority of his works.  Portrait of a woman, 1520 Matsys also painted part of the altarpiece of the Convento da Madre de Deus, in Lisbon. The altar is a primitive invocation of the Seven Sorrows of Mary, with boards still evocative of "Our Lady of Sorrows","Jesus among the Doctors", "on the path to Calvary", "Calvary", "Lamentation" (all at the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga) and "Flight into Egypt" (Worcester Art Museum). Since the convent was founded by D. Leonor, Queen Dowager of King John II of Portugal and sister of King Manuel of Portugal, in 1509, it appeared that the order of this set has been performed once, with some authors (Firedlander) pointing as the date of making the frames years prior to 1511.[10] His Christ as the Man of Sorrows is in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.[11] Quentin's son, Jan Matsys, inherited the art but did not seek to expand upon his father's legacy. The earliest of his works, a St Jerome dated 1537, in the gallery of Vienna, as well as the latest, a Healing of Tobias of 1564, in the museum of Antwerp, are evidence of his tendency to substitute imitation for originality.[5] Another son, Cornelis Matsys, was also a painter. Jan's son, Quentin Metsys the Younger, was an artist of the Tudor court, and painted the Sieve Portrait of Elizabeth I of England. Near the front of the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp is a wrought-iron well, known as the "Matsys Well", which according to tradition was made by the painter-to-be. Matsys was a cult figure during the 17th century in Antwerp [clarification needed] in addition to being one of the founders of the local school of painting (which climaxed with the career of Peter Paul Rubens). A penny serial by the British author Pierce Egan the Younger entitled Quintin Matsys was published in 1839. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quentin_Matsys |

ク

エンティン・マサイス[1](オランダ語:Quinten

Matsijs)(1466-1530)は、初期ネーデルラントの伝統を受け継ぐフランドルの画家。ルーヴェン生まれ。画家になる前は鉄鍛冶の修行をして

いたという伝承がある。マティスはアントワープで20年以上活動し、宗教的なルーツや風刺的な傾向を持つ作品を数多く制作した。彼は、16世紀にフランド

ル地方を代表する絵画派となったアントワープ派の創始者とされている。伝統を完全に壊すことなく、新しい技法やモチーフ、道徳的な主題を取り入れた

[2]。 ク

エンティン・マサイス[1](オランダ語:Quinten

Matsijs)(1466-1530)は、初期ネーデルラントの伝統を受け継ぐフランドルの画家。ルーヴェン生まれ。画家になる前は鉄鍛冶の修行をして

いたという伝承がある。マティスはアントワープで20年以上活動し、宗教的なルーツや風刺的な傾向を持つ作品を数多く制作した。彼は、16世紀にフランド

ル地方を代表する絵画派となったアントワープ派の創始者とされている。伝統を完全に壊すことなく、新しい技法やモチーフ、道徳的な主題を取り入れた

[2]。生い立ち マサイスの生涯に関する初期の記述のほとんどは、主に伝説によって構成されており、彼の活動や性格に関する同時代の記述はほとんど存在しない。J.モラヌ スの『Historiae Lovaniensium』によると、マサイスはルーヴェン出身で、鉄鍛冶職人として質素な生活を送っていた。4人兄弟の一人であるマツィスは、1466 年4月4日から9月10日の間にヨースト・マツィス(1483年没)とカトリーヌ・ファン・キンケンとの間に生まれた。伝説によると、マサイスは妻を口説 くために鍛冶職人を辞めたが、妻は絵描きの方がロマンチックな職業だと思ったという。しかし、カレル・ファン・マンダーは、これは嘘であり、本当の理由は 病気で鍛冶屋で働けず、代わりにカーニバルの祝典のために版画を飾ったからだと主張している[3]。 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++  老人の頭部 ヨースト・マサイスの寄付金や所持品が記録されていることから、一家にはそれなりの収入があり、経済的な困窮がマツィスが画家を志した理由ではなかった可 能性が高い。マサイスがアントワープで活動していた期間、彼が弟子入りしたのは、ある美術史家がアドリアーン・ファン・オーヴァーベケ(1508年に師 事)と考えているアリアーン、[2] ウィレム・ミューレンブロック(1501年に登録)、エドゥアルト・ポルトゥガロワ(1504年に登録、1506年に師事)、ヘネン・ベックマケール (1510年に登録)の4人だけであった。ヨアヒム・パティニールは、マツィスのもとで学び、マツィスのいくつかの風景画(マドリードのプラド美術館にあ る『聖アントニウスの誘惑』など)に貢献したと広く信じられている[4]。この時期のギルドの記録がないため、マツィスが修行の一環としてイタリアやその 他の低地諸国を旅行したことには疑問が残る。ほとんどの場合、マツィスに対する外国からの影響は、彼の絵画から推測され、16世紀における画家の修行の大 部分であったと考えられている。 ルーヴェンでの作品  1500年頃のカレンダー時計の文字盤のディテール。兄弟である時計職人ヨーストとヤンと共に描かれている。 15世紀の大部分、低地地方の画家たちが最も集まっていたのは、トゥルネー、ブルージュ、ゲント、ブリュッセルだった。ルーヴェンはこの時期の終わりごろ から脚光を浴びるようになり、マサイスを含むすべての工芸職人を雇うようになった。5]。1494年以前のルーヴェンにはギルドの記録が残っていないた め、マサイスがそこで親方の地位を得たという具体的な証拠はないが、マサイスがアントワープで見習いとして登録されていなかったことから、歴史家たちは一 般に、マサイスが初期に修業を積んだのはここであると受け入れている。アントワープの聖ルカ・ギルドのメンバーとして、マサイスはアントワープで最初に注 目された画家の一人と考えられている。カレル・ファン・マンデルの『Schilderboeck』(1604年)には、マサイスはどの画家にも師事しな かったと記されているにもかかわらず、16世紀のギルドの法律や規則に関する現存する記録によれば、マサイスが独学で学んだ可能性は極めて低い[6]。 様式 マサイスの修行のルーツは不明であるが、彼の作風は、ハンス・メムリングやロジェ・ファン・デル・ウェイデンの影響をルーヴェンにもたらしたディルク・ボ ウツの芸術的資質を反映している。25歳でアントワープに居を構えたマサイスは、独自の画風でファン・アイクやファン・デル・ウェイデンの流れを汲むフラ ンドル美術の復興に大きく貢献した[5]。風刺的な作品としては、『老人の肖像』(1513年)、『両替商とその妻』(1514年)などがよく知られてお り、いずれも人情や社会一般を揶揄したものである。また、宗教的な祭壇画や三幅対のパネルも描いており、最も有名なものはルーヴェンのサン・ピエトロ教会 のために制作されたものである。  両替商とその妻 (1514) 油彩、パネル、71×68cm ルーヴル・アブダビ マサイスの作品には、伝統的なフランドル絵画の特徴である強い宗教的感情が含まれており、しばしばグロテスクを好む写実主義が伴っていると考えられてい る。マサイスのしっかりとした輪郭線、明瞭なモデリング、細部の徹底的な仕上げは、ヴァン・デル・ウェイデンの影響からきており、ヴァン・エイクやメムリ ングからディルク・バウトを経て、透明な顔料の輝くような豊かさがもたらされている。マサイスの作品には一般的に、表現における真摯さ、細密な描写、光と 影の控えめな効果が反映されている。当時のフランドルの画家たちの多くがそうであったように、彼は宝飾品や衣服の縁取り、装飾全般に多大な注意を払ってい た[5]。  聖母子と4人の天使 (1513) パネルに油彩、62.2 × 43.2 cm ナショナル・ギャラリー、ロンドン 彼の作品において強調されているのは、雰囲気ではなく、文字通りの戯画である。個人の個性を表現することに力を注いでいる。風刺的な傾向は、商人の銀行家 (ルーヴル美術館とウィンザー美術館)の絵に見られる。ベルリンとアムステルダムの2つの聖母子像(レプリカ)には、彼のもうひとつの衝動である優しさの 感情が表れている。ウィーンの美術館に所蔵されているルクレチアには、激しい絶望の表情が見られる。しかし、これらの作品の色彩の驚くべき輝きは、マニエ リスムの誇張を納得させるものである[5]。 マティスは肖像画家としてかなりの技量を持っていた。トマス・モアからラテン語の詩による賛辞を引き出した彼の《イージディウス(ピーター・ジル)》は、 多くの作品のひとつであり、アムステルダムのギャラリーにあるオーストリアのマクシミリアンの肖像画もそのひとつである。マサイスの肖像画は、非常に個人 的で個性的な感情的特徴を示しており、写実主義という技法への固執を反映している[5]。 影響を受けた作品  聖アントニウスの誘惑、ヨアヒム・パティニールとクエンティン・マサイス、1520-1524年。マドリード、プラド美術館。 ホルバインやデューラーといった他の北方ルネサンスの画家と比較すると、マサイスは洗練された繊細なディテール表現から遠ざかっている。しかし、彼とこれ らの巨匠との間には多くの接点があるため、彼の技法離脱は意図的なものであり、無知によるものではないと結論づけることができる。マティスはまた、ヨアヒ ム・パティニールの死後、その子供たちの後見人となった。 《 聖母とキリスト》、《エッケ・ホモ》、《マーテル・ドローローサ》(ロンドンとアントワープ)は、静謐で威厳のある傑作として知られ、円熟期の作品では繊 細さとニュアンスを増している。マティスは、レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチの作品を、北方の芸術家たちの間で制作され流通していた版画の形で知っていたと考え られている(《聖アンナと聖母子》に触発された《子羊を抱く聖母子》は、ダ・ヴィンチの影響を反映している)[7]。 このことは、マティスがイタリア・ルネサンスの芸術家たちから大きな影響を受けていたこと、また、少なくとも短期間はイタリアを旅していた可能性が高いこ との証左とされている[8]。 死  アントワープ大聖堂の記念碑。画家のリュック・タイマンスは、この骸骨の盾をもとに、アン・デ・シュトルーム美術館でモダンなモザイク画を制作した。 マティスは1530年にアントワープで亡くなった。マサイスは信仰心の篤い信徒であったが、信仰のために亡くなった親族が何人もいた。妹のカトリーヌとそ の夫は、1543年にルーヴェンで、当時は重罪であった聖書の朗読のために苦しみを味わった。1629年、マサイスの没後100年を記念する式典が行わ れ、アントワープ大聖堂の正面に碑文が刻まれた浮き彫りのプレートが建てられた。碑文の文言は、篤志家コルネリウス・ファン・デル・ゲストが考案したと言 われている: 「彼の時代には鍛冶職人であり、後には有名な画家となった」という文言は、マサイスの謙虚な始まりにまつわる伝説に従ったものである。 遺産  グロテスクな老女 木に油彩、64×45.5cm ナショナル・ギャラリー、ロンドン マサイスの作品には、『老人の肖像』(1513年)、『民衆に捧げられたキリスト』(1518-1520年)[8](プラド)、『グロテスクな老女』(ま たは『醜い公爵夫人』)などがある。この作品は、ジョン・テニエルが『不思議の国のアリス』で公爵夫人を描いた際の下敷きとなった。パジェット病の実在の 人物を描いたものである可能性が高いが[9]、チロル伯爵夫人マーガレットの比喩的な肖像画であると言われることもある。マウルタシュは、直訳すると「か ばんの口」だが、「醜女」や「娼婦」(彼女の結婚スキャンダルのため)という意味で使われていた。彼の2つの大きな三連祭壇画『聖なる親族または聖アンナ 祭壇画』(1507-1509)と『主の埋葬』(1508-1511)も高く評価されている。ルーヴェンのサン・ピエトロ教会のために制作されたこれらの 作品には、彼の作品の多くに見られる強い宗教的感情と精密な細部描写が反映されている。  女性の肖像 1520年 マサイスは、リスボンのマドレ・デ・デウス修道院の祭壇画の一部も描いている。この祭壇は、マリアの7つの悲しみを呼び起こす原始的なもので、「悲しみの 聖母」、「博士たちの中のイエス」、「カルヴァリへの道」、「カルヴァリ」、「哀歌」(いずれも国立アンティガ美術館所蔵)、「エジプトへの逃走」(ウス ター美術館所蔵)を想起させる板が残っている。この修道院は、1509年にポルトガル国王マヌエルの妹であり、ポルトガル国王ヨハネ2世の王太后であった D.レオノールによって設立されたため、このセットの注文は一度だけ行われたようであり、一部の著者(Firedlander)は、額縁の制作時期を 1511年より何年も前であると指摘している[10]。 クエンティンの息子、ヤン・マサイスは美術品を受け継いだが、父の遺産を拡張しようとはしなかった。彼の最も古い作品である、ウィーンのギャラリーにある 1537年の聖ジェローム像や、アントワープの美術館にある1564年のトビアスの治癒像は、彼が独創性を模倣に置き換える傾向があったことの証拠である [5]。ヤンの息子、クェンティン・メツィス(Quentin Metsys the Younger)は、チューダー朝の宮廷画家で、イギリスのエリザベス1世のふるい肖像画を描いた。 アントワープの聖母大聖堂の正面近くには、「マサイスの井戸」として知られる錬鉄製の井戸があり、伝統によれば、この井戸は画家マサイスによって作られた ものである。 マサイスは、17世紀のアントワープでカルト的な人気を誇った人物であり[要出典]、また、地元の絵画学校(ペーター・パウル・ルーベンスによってクライ マックスを迎えた)の創設者の一人でもあった。 1839年には、イギリスの作家ピアース・イーガン・ザ・ヤンガーによる『クインティン・マサイス』というペニー連載小説が出版された。 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quentin_Matsys |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099