Evil, or being bad, in a

general sense, is acting out morally incorrect behavior, or the

condition of causing unnecessary pain and suffering, thus, containing a

net negative on the world.[1]

Evil is commonly seen as the opposite or sometimes absence of good. It

can be an extremely broad concept, although in everyday usage it is

often more narrowly used to talk about profound wickedness and against

common good. It is generally seen as taking multiple possible forms,

such as the form of personal moral evil commonly associated with the

word, or impersonal natural evil (as in the case of natural disasters

or illnesses), and in religious thought, the form of the demonic or

supernatural/eternal.[2] While some religions, world views, and

philosophies focus on "good versus evil", others deny evil's existence

and usefulness in describing people.

Evil can denote profound immorality,[3] but typically not without some

basis in the understanding of the human condition, where strife and

suffering (cf. Hinduism) are the true roots of evil. In certain

religious contexts, evil has been described as a supernatural force.[3]

Definitions of evil vary, as does the analysis of its motives.[4]

Elements that are commonly associated with personal forms of evil

involve unbalanced behavior including anger, revenge, hatred,

psychological trauma, expediency, selfishness, ignorance, destruction

and neglect.[5]

In some forms of thought, evil is also sometimes perceived as the

dualistic antagonistic binary opposite to good,[6] in which good should

prevail and evil should be defeated.[7] In cultures with Buddhist

spiritual influence, both good and evil are perceived as part of an

antagonistic duality that itself must be overcome through achieving

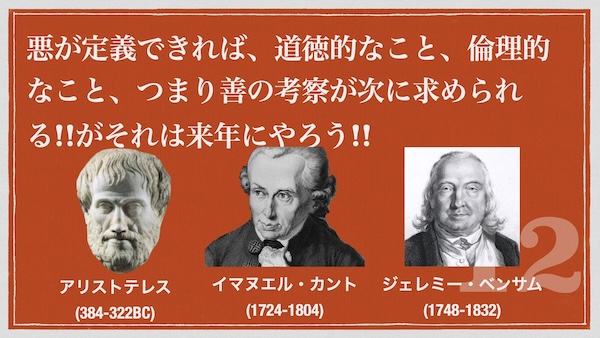

Nirvana.[7] The ethical questions regarding good and evil are subsumed

into three major areas of study:[8] meta-ethics concerning the nature

of good and evil, normative ethics concerning how we ought to behave,

and applied ethics concerning particular moral issues. While the term

is applied to events and conditions without agency, the forms of evil

addressed in this article presume one or more evildoers.

|

一般的な意味での悪とは、道徳的に正しくない行動をとること、あるいは

不必要な痛みや苦しみを引き起こすことであり、その結果、世界に正味のマイナスをもたらすことである[1]。

悪は一般的に、善の反対、あるいは時には不在と見なされる。日常的な用法では、より狭義に、深遠な邪悪さや共通善に反することについて語られることが多い

が、極めて広範な概念となりうる。一般的には、この言葉から連想される個人的な道徳的悪、(自然災害や病気の場合のような)非人間的な自然悪、宗教的思想

では悪魔や超自然的・永遠的なものなど、複数の可能な形態をとると考えられている[2]。ある宗教、世界観、哲学では「善対悪」に焦点が当てられている

が、悪の存在や人間を表現する上での有用性を否定するものもある。

悪は深遠な不道徳を示すこともあるが[3]、一般的には、争いや苦しみ(ヒンドゥー教を参照)が悪の真の根源である人間の状態の理解に何らかの根拠がなけ

ればならないことはない。ある種の宗教的文脈では、悪は超自然的な力として説明されてきた[3]。悪の定義は様々であり、その動機の分析も様々である

[4]。一般的に悪の個人的な形態と関連している要素は、怒り、復讐、憎悪、心理的外傷、便宜主義、利己主義、無知、破壊、無視を含む不均衡な行動を伴う

[5]。

仏教の影響を受けた文化においては、善も悪も涅槃を達成することによって克服されなければならない拮抗的な二元性の一部として認識されている[7]。

[善と悪に関する倫理的な問いは、善と悪の本質に関するメタ倫理学、私たちがどのように振る舞うべきかに関する規範倫理学、特定の道徳的問題に関する応用

倫理学という3つの主要な研究分野に包含される[8]。この用語は、主体性のない出来事や状況に適用されるが、この記事で扱う悪の形態は、1人または複数

の悪者を前提としている。

|

Sendan Kendatsuba, one of the eight guardians of

Buddhist law, banishing evil in one of the five paintings of

Extermination of Evil. Sendan Kendatsuba, one of the eight guardians of

Buddhist law, banishing evil in one of the five paintings of

Extermination of Evil.

|

仏法八部衆の一人であるセンダン・ケンダツバが、五悪退散図の一枚で悪

を退散させる。 仏法八部衆の一人であるセンダン・ケンダツバが、五悪退散図の一枚で悪

を退散させる。

|

Etymology

The modern English word evil (Old English yfel) and its cognates such

as the German Übel and Dutch euvel are widely considered to come from a

Proto-Germanic reconstructed form of *ubilaz, comparable to the Hittite

huwapp- ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European form *wap- and suffixed

zero-grade form *up-elo-. Other later Germanic forms include Middle

English evel, ifel, ufel, Old Frisian evel (adjective and noun), Old

Saxon ubil, Old High German ubil, and Gothic ubils.[9]

The root meaning of the word is of obscure origin though shown to be

akin to modern German übel (noun: Übel, although the noun evil is

normally translated as "das Böse") with the basic idea of social or

religious transgression.[citation needed]

|

語源

現代英語のevil(古英語 yfel)とその同義語であるドイツ語 Übel やオランダ語 euvel は、ヒッタイト語の huwapp-

に匹敵する *ubilaz

の原ゲルマン語の再構成形に由来すると広く考えられている。他の後期ゲルマン語形には、中英語のevel、ifel、ufel、古フリジア語のevel

(形容詞と名詞)、古サクソン語のubil、古高ドイツ語のubil、ゴート語のubilsがある[9]。

現代ドイツ語のübel(名詞:Übel、ただし名詞の悪は通常「das

Böse」と訳される)に類似しており、社会的または宗教的な違反という基本的な考えを持つことが示されているが、語源の意味は不明瞭である[要出典]。

|

Chinese moral philosophy

Main articles: Confucius § Ethics, Confucianism, and Taoism § Ethics

As with Buddhism, in Confucianism or Taoism there is no direct analogue

to the way good and evil are opposed although reference to demonic

influence is common in Chinese folk religion. Confucianism's primary

concern is with correct social relationships and the behavior

appropriate to the learned or superior man. Thus evil would correspond

to wrong behavior. Still less does it map into Taoism, in spite of the

centrality of dualism in that system[citation needed], but the opposite

of the cardinal virtues of Taoism, compassion, moderation, and humility

can be inferred to be the analogue of evil in it.[10][11]

|

中国の道徳哲学

主な記事 孔子§倫理、儒教、道教§倫理

仏教と同様、儒教や道教には善と悪が対立する直接的な類似点はないが、悪魔の影響への言及は中国の民間宗教によく見られる。儒教の主な関心事は、正しい社

会関係と、学識のある人間や優れた人間にふさわしい行動である。従って、悪は間違った行動に相当する。道教では二元論が中心であるにもかかわらず[要出

典]、悪は道教には当てはまらないが、道教の枢要な徳目である慈悲、節度、謙虚の反対は、道教における悪の類似であると推測できる[10][11]。

|

European philosophy

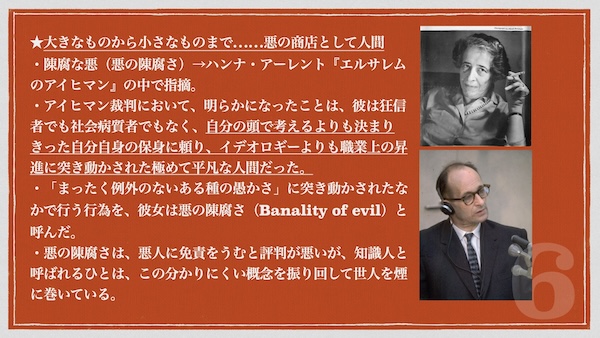

In response to the practices of Nazi Germany, Hannah Arendt concluded

that "the problem of evil would be the fundamental problem of postwar

intellectual life in Europe", although such a focus did not come to

fruition.[12]

Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza states

By good, I understand that which we certainly know is useful to us.

By evil, on the contrary, I understand that which we certainly know

hinders us from possessing anything that is good.[13]

Spinoza assumes a quasi-mathematical style and states these further

propositions which he purports to prove or demonstrate from the above

definitions in part IV of his Ethics:[13]

Proposition 8 "Knowledge of good or evil is nothing but affect of joy

or sorrow in so far as we are conscious of it."

Proposition 30 "Nothing can be evil through that which it possesses in

common with our nature, but in so far as a thing is evil to us it is

contrary to us."

Proposition 64 "The knowledge of evil is inadequate knowledge."

Corollary "Hence it follows that if the human mind had none but

adequate ideas, it would form no notion of evil."

Proposition 65 "According to the guidance of reason, of two things

which are good, we shall follow the greater good, and of two evils,

follow the less."

Proposition 68 "If men were born free, they would form no conception of

good and evil so long as they were free."

|

ヨーロッパの哲学

ナチス・ドイツの実践に対して、ハンナ・アーレントは「悪の問題が戦後のヨーロッパにおける知的生活の根本的な問題になるだろう」と結論づけたが、そのよ

うな焦点は実現しなかった[12]。

スピノザ

スピノザは次のように述べている。

善とは、われわれが確かに知っている、われわれにとって有用なものである。

悪とは、逆に、我々が善であるものを所有することを妨げると確実に知っているものを指す[13]。

スピノザは準数学的なスタイルをとり、『倫理学』の第IV部において、上記の定義から証明または実証するとしている以下のさらなる命題を述べている

[13]。

命題8 "善悪の知識とは、我々がそれを意識する限りにおいて、喜びや悲しみの影響にほかならない"

命題30

"何ものも、それがわれわれの本性と共通して持っているものによって悪になることはできないが、あるものがわれわれにとって悪である限り、それはわれわれ

に反している。"

命題64 "悪の知識は不十分な知識である"

従って、もし人間の心が適切な観念しか持たなければ、悪の観念を形成することはない。

命題65 "理性の導きに従って、善である二つのもののうち、より大きな善に従い、二つの悪のうち、より小さな悪に従う。"

命題68 "もし人が自由に生まれたとしても、自由である限り、善悪の観念を形成することはないだろう"

★ジェレミー・ベンサムの場合(功利主義的哲学)

「快の場合には、それは善とよばれるか(それは快の原因または手段と呼ばれるほうがふさわしい)、利益と呼ばれるか(それはまだ実現していない快である

か、まだ実現していない快の原因または手段とよばれるのかがふさわしい)、あるいは利便とか便宜とか恩恵とか報酬とか幸福などと呼ばれることがある。苦痛

の場合には悪とよばれるか(これは快の場合の善と呼ばれるものに相当する)、害悪とか迷惑とか不利益とか損失とか不幸などと呼ばれることがある」ジェレ

ミー・ベンサム『道徳および立法の諸原理序説(上)』中山元訳、p.95.、2022年.

|

Psychology

Carl Jung

Carl Jung, in his book Answer to Job and elsewhere, depicted evil as

the dark side of God.[14] People tend to believe evil is something

external to them, because they project their shadow onto others. Jung

interpreted the story of Jesus as an account of God facing his own

shadow.[15]

Philip Zimbardo

In 2007, Philip Zimbardo suggested that people may act in evil ways as

a result of a collective identity. This hypothesis, based on his

previous experience from the Stanford prison experiment, was published

in the book The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn

Evil.[16]

Milgram experiment

Main article: Milgram experiment

In 1961, Stanley Milgram began an experiment to help explain how

thousands of ordinary, non-deviant, people could have reconciled

themselves to a role in the Holocaust. Participants were led to believe

they were assisting in an unrelated experiment in which they had to

inflict electric shocks on another person. The experiment unexpectedly

found that most could be led to inflict the electric shocks,[17]

including shocks that would have been fatal if they had been real.[18]

The participants tended to be uncomfortable and reluctant in the role.

Nearly all stopped at some point to question the experiment, but most

continued after being reassured.[17]

A 2014 re-assessment of Milgram's work argued that the results should

be interpreted with the "engaged followership" model: that people are

not simply obeying the orders of a leader, but instead are willing to

continue the experiment because of their desire to support the

scientific goals of the leader and because of a lack of identification

with the learner.[19][20] Thomas Blass argues that the experiment

explains how people can be complicit in roles such as "the

dispassionate bureaucrat who may have shipped Jews to Auschwitz with

the same degree of routinization as potatoes to Bremerhaven". However,

like James Waller, he argues that it cannot explain an event like the

Holocaust. Unlike the perpetrators of the Holocaust, the participants

in Milgram's experiment were reassured that their actions would cause

little harm and had little time to contemplate their actions.[18][21]

|

心理学

カール・ユング

カール・ユングは著書『ヨブ記への回答』などで、悪を神の暗黒面として描いている[14]。人は自分の影を他人に投影するため、悪は自分の外側にあるもの

だと考える傾向がある。ユングはイエスの物語を、神が自らの影と向き合う物語として解釈した[15]。

フィリップ・ジンバルドー

2007年、フィリップ・ジンバルドーは、人々が集団的アイデンティティの結果として悪の行動をとる可能性を示唆した。この仮説は、スタンフォード監獄実

験での経験に基づくもので、『ルシファー効果』という本の中で発表された: Understanding How Good People Turn

Evil[16]という本で発表された。

ミルグラム実験

主な記事 ミルグラム実験

1961年、スタンレー・ミルグラムは、何千人ものごく普通の人々が、ホロコーストの一翼を担ったことをどのように納得したかを説明するための実験を開始

した。参加者は、他人に電気ショックを与えるという無関係な実験を手伝っていると思い込まされた。この実験では予想に反して、ほとんどの人が電気ショック

を与えるように仕向けられることがわかった[17]。ほぼ全員が実験に疑問を持つためにある時点で中断したが、ほとんどの者は安心させられた後に続けた

[17]。

ミルグラムの研究の2014年の再評価では、この結果は「エンゲージド・フォロワーシップ」モデルで解釈されるべきであると主張した:人々は単に指導者の

命令に従うのではなく、指導者の科学的目標を支持したいという願望と学習者との同一性の欠如のために実験を続けようとするのである。 [19][20]

トーマス・ブラスは、この実験が、「冷静な官僚が、ジャガイモをブレーマーハーフェンに出荷するのと同じ程度のルーティン化でユダヤ人をアウシュヴィッツ

に出荷したかもしれない」といった役割に人々がいかに加担しうるかを説明していると論じている。しかし、ジェームズ・ウォーラーと同様、ホロコーストのよ

うな出来事を説明することはできないと彼は主張する。ホロコーストの加害者たちとは異なり、ミルグラムの実験の参加者たちは、自分たちの行動はほとんど害

を及ぼさないと安心させられており、自分たちの行動を熟考する時間はほとんどなかった[18][21]。

|

Religions

Abrahamic

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith asserts that evil is non-existent and that it is a

concept reflecting lack of good, just as cold is the state of no heat,

darkness is the state of no light, forgetfulness the lacking of memory,

ignorance the lacking of knowledge. All of these are states of lacking

and have no real existence.[22]

Thus, evil does not exist and is relative to man. `Abdu'l-Bahá, son of

the founder of the religion, in Some Answered Questions states:

"Nevertheless a doubt occurs to the mind—that is, scorpions and

serpents are poisonous. Are they good or evil, for they are existing

beings? Yes, a scorpion is evil in relation to man; a serpent is evil

in relation to man; but in relation to themselves they are not evil,

for their poison is their weapon, and by their sting they defend

themselves."[22]

Thus, evil is more of an intellectual concept than a true reality.

Since God is good, and upon creating creation he confirmed it by saying

it is Good (Genesis 1:31) evil cannot have a true reality.[22]

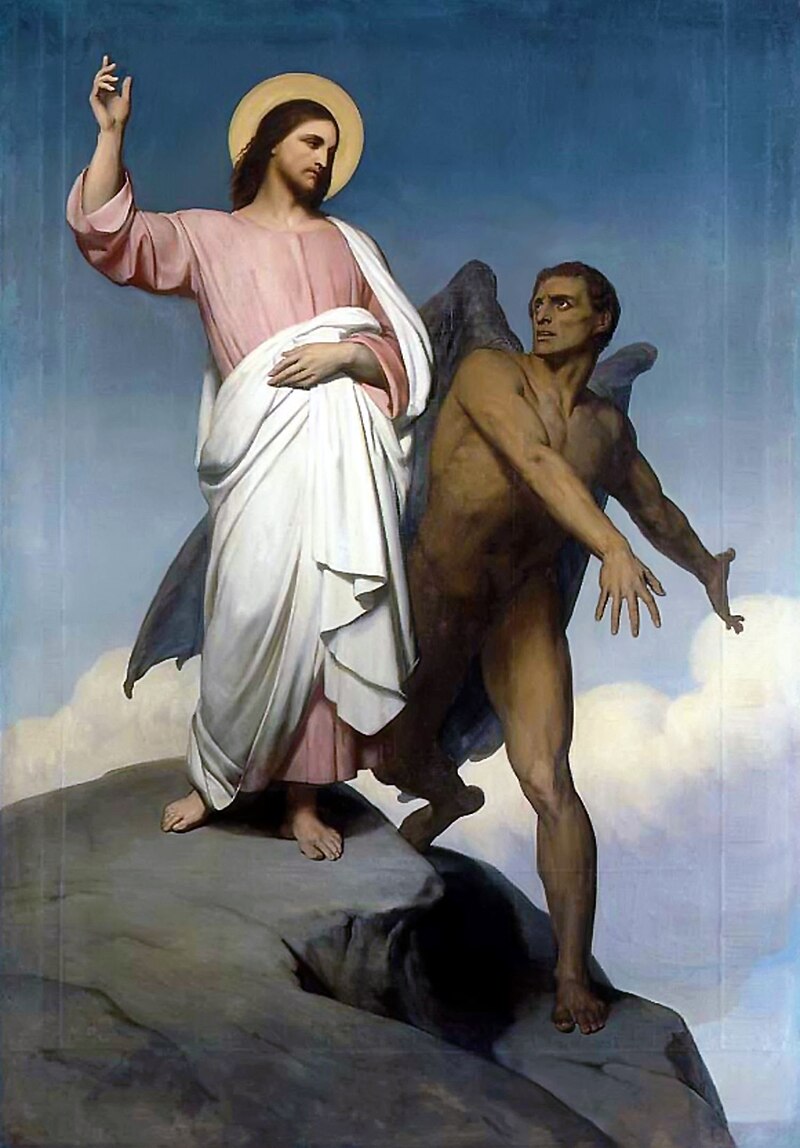

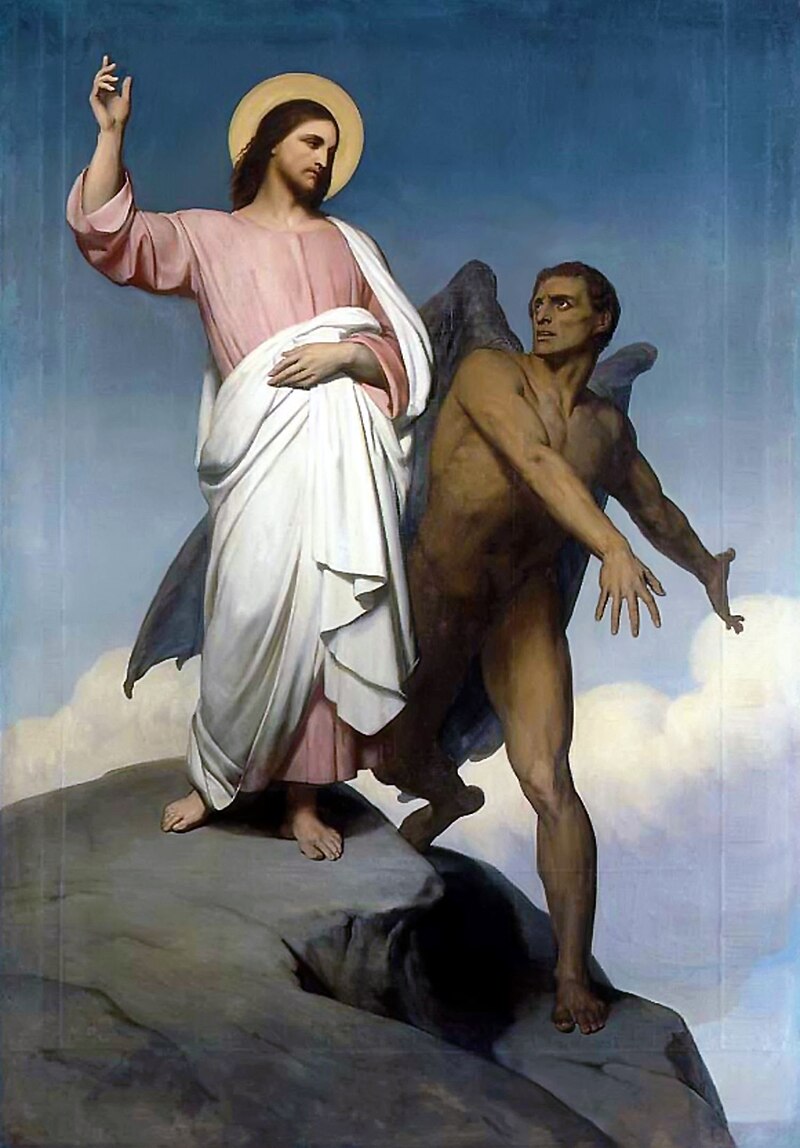

Christianity

See also: Devil in Christianity

The devil, in opposition to the will of God, represents evil and tempts

Christ, the personification of the character and will of God. Ary

Scheffer, 1854.

Christian theology draws its concept of evil from the Old and New

Testaments. The Christian Bible exercises "the dominant influence upon

ideas about God and evil in the Western world."[2] In the Old

Testament, evil is understood to be an opposition to God as well as

something unsuitable or inferior such as the leader of the fallen

angels Satan[23] In the New Testament the Greek word poneros is used to

indicate unsuitability, while kakos is used to refer to opposition to

God in the human realm.[24] Officially, the Catholic Church extracts

its understanding of evil from its canonical antiquity and the

Dominican theologian, Thomas Aquinas, who in Summa Theologica defines

evil as the absence or privation of good.[25] French-American

theologian Henri Blocher describes evil, when viewed as a theological

concept, as an "unjustifiable reality. In common parlance, evil is

'something' that occurs in the experience that ought not to be."[26]

Islam

See also: Islamic views on sin

There is no concept of absolute evil in Islam, as a fundamental

universal principle that is independent from and equal with good in a

dualistic sense.[27] Although the Quran mentions the biblical forbidden

tree, it never refers to it as the 'tree of knowledge of good and

evil'.[27] Within Islam, it is considered essential to believe that all

comes from God, whether it is perceived as good or bad by individuals;

and things that are perceived as evil or bad are either natural events

(natural disasters or illnesses) or caused by humanity's free will.

Much more the behavior of beings with free will, then they disobey

God's orders, harming others or putting themselves over God or others,

is considered to be evil.[28] Evil does not necessarily refer to evil

as an ontological or moral category, but often to harm or as the

intention and consequence of an action, but also to unlawful

actions.[27] Unproductive actions or those who do not produce benefits

are also thought of as evil.[29]

A typical understanding of evil is reflected by Al-Ash`ari founder of

Asharism. Accordingly, qualifying something as evil depends on the

circumstances of the observer. An event or an action itself is neutral,

but it receives its qualification by God. Since God is omnipotent and

nothing can exist outside of God's power, God's will determine, whether

or not something is evil.[30]

Rabbinic Judaism

See also: Satan in Judaism

In Judaism and Jewish theology, the existence of evil is presented as

part of the idea of free will: if humans were created to be perfect,

always and only doing good, being good would not mean much. For Jewish

theology, it is important for humans to have the ability to choose the

path of goodness, even in the face of temptation and yetzer hara (the

inclination to do evil).[31][32]

Ancient Egyptian

Further information: Ancient Egyptian religion

Evil in the religion of ancient Egypt is known as Isfet,

"disorder/violence". It is the opposite of Maat, "order", and embodied

by the serpent god Apep, who routinely attempts to kill the sun god Ra

and is stopped by nearly every other deity. Isfet is not a primordial

force, but the consequence of free will and an individual's struggle

against the non-existence embodied by Apep, as evidenced by the fact

that it was born from Ra's umbilical cord instead of being recorded in

the religion's creation myths.[33]

Indian Buddhism

Main article: Buddhist ethics

Extermination of Evil, The God of Heavenly Punishment, from the Chinese

tradition of yin and yang. Late Heian period (12th-century Japan).

The primal duality in Buddhism is between suffering and enlightenment,

so the good vs. evil splitting has no direct analogue in it. One may

infer from the general teachings of the Buddha that the catalogued

causes of suffering are what correspond in this belief system to

'evil'.[34][35]

Practically this can refer to 1) the three selfish emotions—desire,

hate and delusion; and 2) to their expression in physical and verbal

actions. Specifically, evil means whatever harms or obstructs the

causes for happiness in this life, a better rebirth, liberation from

samsara, and the true and complete enlightenment of a buddha

(samyaksambodhi).

"What is evil? Killing is evil, lying is evil, slandering is evil,

abuse is evil, gossip is evil: envy is evil, hatred is evil, to cling

to false doctrine is evil; all these things are evil. And what is the

root of evil? Desire is the root of evil, illusion is the root of

evil." Gautama Siddhartha, the founder of Buddhism, 563–483 BC.

Hinduism

In Hinduism, the concept of Dharma or righteousness clearly divides the

world into good and evil, and clearly explains that wars have to be

waged sometimes to establish and protect Dharma, this war is called

Dharmayuddha. This division of good and evil is of major importance in

both the Hindu epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata. The main emphasis in

Hinduism is on bad action, rather than bad people. The Hindu holy text,

the Bhagavad Gita, speaks of the balance of good and evil. When this

balance goes off, divine incarnations come to help to restore this

balance.[36]

Sikhism

In adherence to the core principle of spiritual evolution, the Sikh

idea of evil changes depending on one's position on the path to

liberation. At the beginning stages of spiritual growth, good and evil

may seem neatly separated. Once one's spirit evolves to the point where

it sees most clearly, the idea of evil vanishes and the truth is

revealed. In his writings Guru Arjan explains that, because God is the

source of all things, what we believe to be evil must too come from

God. And because God is ultimately a source of absolute good, nothing

truly evil can originate from God.[37]

Sikhism, like many other religions, does incorporate a list of "vices"

from which suffering, corruption, and abject negativity arise. These

are known as the Five Thieves, called such due to their propensity to

cloud the mind and lead one astray from the prosecution of righteous

action.[38] These are:[39]

Moh, or Attachment

Lobh, or Greed

Karodh, or Wrath

Kaam, or Lust

Ahankar, or Egotism

One who gives in to the temptations of the Five Thieves is known as

"Manmukh", or someone who lives selfishly and without virtue.

Inversely, the "Gurmukh, who thrive in their reverence toward divine

knowledge, rise above vice via the practice of the high virtues of

Sikhism. These are:[40]

Sewa, or selfless service to others.

Nam Simran, or meditation upon the divine name.

|

宗教

アブラハム

バハー教

バハーイー教は、悪は存在せず、善の欠如を反映した概念であると主張する。寒さは熱のない状態、暗闇は光のない状態、忘却は記憶の欠如、無知は知識の欠如

であるのと同じである。これらはすべて欠如の状態であり、現実には存在しない[22]。

したがって、悪は存在せず、人間にとって相対的なものである。宗教の創始者の息子であるアッブドゥル=バハーは、『答えのある質問』の中で次のように述べ

ている:

「サソリや蛇には毒がある。彼らは善なのか悪なのか。そう、サソリは人間との関係においては悪であり、蛇は人間との関係においては悪である。しかし、彼ら

自身との関係においては、彼らは悪ではない。

このように、悪は本当の現実というよりも、知的な概念である。神は善であり、被造物を創造する際に、それは善であると言ってそれを確認した(創世記1:

31)ので、悪が真の現実を持つことはありえない[22]。

キリスト教

こちらも参照: キリスト教における悪魔

悪魔は、神の意志に反して悪を表し、神の人格と意志の化身であるキリストを誘惑する。1854年、アーリー・シェファー。

キリスト教神学は、旧約聖書と新約聖書から悪の概念を引き出している。旧約聖書では、悪は神に対立するものであり、堕落した天使のリーダーであるサタンの

ようなふさわしくないもの、劣ったものであると理解されている[23]。新約聖書では、ふさわしくないものを示すためにギリシャ語のポネロス

(poneros)が使われ、人間界における神への対立を示すためにカコス(kakos)が使われている。

[24]公式には、カトリック教会はその正典である古代とドミニコ会の神学者であるトマス・アクィナスから悪の理解を引き出しており、トマス・アクィナス

は『スンマ・テオロジカ』の中で悪を善の不在または欠乏と定義している[25]。一般的な言い方をすれば、悪とは経験の中で起こる、あってはならない『何

か』のことである」[26]。

イスラム教

こちらも参照: イスラム教の罪観

コーランは聖書の禁断の木について言及しているが、それを「善悪を知る木」として言及することはない[27]。イスラム教では、個人によって善と認識され

ようと悪と認識されようと、すべては神からもたらされると信じることが不可欠であると考えられており、悪や悪と認識されるものは自然現象(自然災害や病

気)か、人間の自由意志によって引き起こされるものである。自由意志を持つ存在が神の命令に背いたり、他者に危害を加えたり、神や他者よりも自分自身を優

先させたりする行動は、より多くの場合、悪であると考えられている[28]。悪は必ずしも存在論的または道徳的なカテゴリーとしての悪を指すのではなく、

多くの場合、危害を加えたり、行為の意図や結果として、不法な行為も指す[27]。非生産的な行為や利益を生まない行為も悪と考えられている[29]。

悪についての典型的な理解は、アシャリズムの創始者であるアル・アシュアリ(Al-Ash`ari)によるものである。従って、何かを悪と認定することは

観察者の状況に依存する。出来事や行為そのものは中立であるが、それは神によって修飾される。神は全能であり、神の力の外に存在するものはないので、何か

が悪であるかどうかは神の意志によって決定される[30]。

ユダヤ教ラビ派

以下も参照: ユダヤ教におけるサタン

ユダヤ教とユダヤ教神学では、悪の存在は自由意志の考え方の一部として提示される。ユダヤ教神学にとって、誘惑やイエッツァー・ハラ(悪を行う傾き)に直

面しても、善の道を選択する能力を人間が持つことは重要である[31][32]。

古代エジプト

さらなる情報 古代エジプトの宗教

古代エジプトの宗教における悪はイスフェト、「無秩序/暴力」として知られている。それは「秩序」であるマアトの対極にあり、蛇神アペップによって具現化

され、彼は日常的に太陽神ラーの殺害を試み、他のほぼすべての神々によって阻止されている。イスフェトは根源的な力ではなく、自由意志の結果であり、宗教

の創造神話に記録される代わりにラーのへその緒から生まれたという事実によって証明されるように、アペップによって具現化された非存在に対する個人の闘争

である[33]。

インドの仏教

主な記事 仏教倫理

悪の退治、天罰の神、中国の陰陽の伝統から。平安時代後期(12世紀の日本)。

仏教における原初的な二元性は苦悩と悟りの間にあり、善悪の分かれ目には直接的な類似性はない。釈迦の一般的な教えから推測すると、苦しみの原因の目録

は、この信念体系では「悪」に相当するものである[34][35]。

実際、これは1)欲望、憎しみ、妄想という3つの利己的な感情、2)物理的な行為や言葉による行為におけるそれらの表現を指す。具体的には、悪とは、現世

での幸福、より良い生まれ変わり、輪廻からの解脱、仏陀の真の完全な悟り(三藐三菩提)のための原因を傷つけたり妨げたりするものを意味する。

「悪とは何か?殺すことは悪であり、嘘をつくことは悪であり、中傷することは悪であり、虐待することは悪であり、噂話をすることは悪であり、妬むことは悪

であり、憎むことは悪であり、誤った教義に執着することは悪である。悪の根源とは何か?欲望は悪の根源であり、幻想は悪の根源である」。ゴータマ・シッ

ダールタ、仏教の開祖、紀元前563~483年

ヒンドゥー教

ヒンズー教では、ダルマまたは正義の概念は、世界を善と悪に明確に分け、ダルマを確立し守るために、時には戦争が必要であることを明確に説明している。こ

の善と悪の区分は、ヒンドゥー教の叙事詩『ラーマーヤナ』と『マハーバーラタ』において重要な意味を持つ。ヒンドゥー教では、悪人よりもむしろ悪行に主眼

が置かれている。ヒンドゥー教の聖典『バガヴァッド・ギーター』は、善と悪のバランスについて述べている。このバランスが崩れると、神の化身がこのバラン

スを回復させるためにやってくる[36]。

シーク教

スピリチュアルな進化の核となる原則に従うと、シーク教では解脱への道における位置によって悪に対する考え方が変わる。精神的な成長の初期段階では、善と

悪はきれいに分かれているように見えるかもしれない。人の精神が最もはっきりと見えるところまで進化すると、悪という考えは消え去り、真実が明らかにな

る。グル・アルジャンはその著作の中で、神は万物の源であるから、私たちが悪だと信じているものもまた神から来たものでなければならないと説明している。

そして、神は究極的には絶対的な善の源であるため、真に悪であるものは何も神に由来することはできない[37]。

シク教は、他の多くの宗教と同様に、苦しみ、堕落、絶望的な否定性が生じる「悪徳」のリストを組み込んでいる。これらは五つの盗賊として知られており、心

を曇らせ、正しい行為の遂行から人を迷わせる性質からこのように呼ばれている[38]。これらは以下の通りである[39]。

モフ(執着

ロブ(貪欲

怒り(Karodh

カーム(欲望

アハンカル(エゴイズム

五人の盗賊の誘惑に負ける者は「マンムク」、つまり利己的で徳のない生き方をする者として知られている。逆に、「グルムク」は、神聖な知識への敬虔さを

もって繁栄し、シク教の高徳を実践することによって悪徳を凌駕する。それは次のようなものである[40]。

セワ、すなわち他者への無私の奉仕。

ナム・シムラン、すなわち神の御名を瞑想すること。

|

Question of a universal

definition

A fundamental question is whether there is a universal, transcendent

definition of evil, or whether one's definition of evil is determined

by one's social or cultural background. C. S. Lewis, in The Abolition

of Man, maintained that there are certain acts that are universally

considered evil, such as rape and murder. However, the rape of women,

by men, is found in every society, and there are more societies that

see at least some versions of it, such as marital rape or punitive

rape, as normative than there are societies that see all rape as

non-normative (a crime).[41] In nearly all societies, killing except

for defense or duty is seen as murder. Yet the definition of defense

and duty varies from one society to another.[42] Social deviance is not

uniformly defined across different cultures, and is not, in all

circumstances, necessarily an aspect of evil.[43][44]

Defining evil is complicated by its multiple, often ambiguous, common

usages: evil is used to describe the whole range of suffering,

including that caused by nature, and it is also used to describe the

full range of human immorality from the "evil of genocide to the evil

of malicious gossip".[45]: 321 It is sometimes thought of as the

generic opposite of good. Marcus Singer asserts that these common

connotations must be set aside as overgeneralized ideas that do not

sufficiently describe the nature of evil.[46]: 185, 186

In contemporary philosophy, there are two basic concepts of evil: a

broad concept and a narrow concept. A broad concept defines evil simply

as any and all pain and suffering: "any bad state of affairs, wrongful

action, or character flaw".[47] Yet, it is also asserted that evil

cannot be correctly understood "(as some of the utilitarians once

thought) [on] a simple hedonic scale on which pleasure appears as a

plus, and pain as a minus".[48] This is because pain is necessary for

survival.[49] Renowned orthopedist and missionary to lepers, Dr. Paul

Brand explains that leprosy attacks the nerve cells that feel pain

resulting in no more pain for the leper, which leads to ever

increasing, often catastrophic, damage to the body of the

leper.[50]: 9, 50–51 Congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP), also

known as congenital analgesia, is a neurological disorder that prevents

feeling pain. It "leads to ... bone fractures, multiple scars,

osteomyelitis, joint deformities, and limb amputation ... Mental

retardation is common. Death from hyperpyrexia occurs within the first

3 years of life in almost 20% of the patients."[51] Few with the

disorder are able to live into adulthood.[52] Evil cannot be simply

defined as all pain and its connected suffering because, as Marcus

Singer says: "If something is really evil, it can't be necessary, and

if it is really necessary, it can't be evil".[46]: 186

The narrow concept of evil involves moral condemnation, therefore it is

ascribed only to moral agents and their actions.[45]: 322 This

eliminates natural disasters and animal suffering from consideration as

evil: according to Claudia Card, "When not guided by moral agents,

forces of nature are neither "goods" nor "evils". They just are. Their

"agency" routinely produces consequences vital to some forms of life

and lethal to others".[53] The narrow definition of evil "picks out

only the most morally despicable sorts of actions, characters, events,

etc. Evil [in this sense] ... is the worst possible term of opprobrium

imaginable”.[46] Eve Garrard suggests that evil describes "particularly

horrifying kinds of action which we feel are to be contrasted with more

ordinary kinds of wrongdoing, as when for example we might say 'that

action wasn't just wrong, it was positively evil'. The implication is

that there is a qualitative, and not merely quantitative, difference

between evil acts and other wrongful ones; evil acts are not just very

bad or wrongful acts, but rather ones possessing some specially

horrific quality".[45]: 321 In this context, the concept of evil is

one element in a full nexus of moral concepts.[45]: 324

|

普遍的定義の問題

根本的な問題は、普遍的で超越的な悪の定義があるのか、それとも悪の定義はその人の社会的・文化的背景によって決まるのかということである。C.S.ルイ

スは『人間の廃絶』の中で、レイプや殺人など、普遍的に悪とされる行為があると主張した。しかし、男性による女性の強姦はどの社会にも存在し、夫婦間の強

姦や懲罰的強姦など、少なくとも一部の強姦を規範的なものとみなす社会は、すべての強姦を非規範的なもの(犯罪)とみなす社会よりも多い。しかし、防衛や

義務の定義は社会によって異なる[42]。社会的逸脱は異なる文化圏で一様に定義されるものではなく、すべての状況において必ずしも悪の側面であるとは限

らない[43][44]。

悪を定義することは、その複数の、しばしば曖昧な、一般的な用法によって複雑になっている。悪は自然によって引き起こされるものを含む苦しみの全範囲を表

現するために使用され、また「大量虐殺の悪から悪意のあるゴシップの悪」まで人間の不道徳の全範囲を表現するためにも使用される[45]: 321

善の一般的な反対語として考えられることもある。マーカス・シンガーは、このような一般的な意味合いは、悪の本質を十分に説明していない一般化されすぎた

考えとして脇に置かれなければならないと主張する[46]: 185, 186

現代の哲学では、悪には広義の概念と狭義の概念の2つの基本概念がある。広義の概念とは、悪を単にあらゆる苦痛と苦悩として定義するものである:

「しかし、悪は「(かつて功利主義者の何人かが考えたように)快楽をプラス、苦痛をマイナスとする単純な快楽的尺度では」正しく理解することはできないと

も主張されている。ポール・ブランドは、ハンセン病は痛みを感じる神経細胞を攻撃し、その結果、ハンセン病患者は痛みを感じなくなる。これは「骨折、多発

性瘢痕、骨髄炎、関節変形、四肢切断を引き起こす。精神遅滞は一般的である。患者の20%近くが生後3年以内に過呼吸による死亡を経験する」[51]。

マーカス・シンガーが言うように、「もし何かが本当に悪であるならば、それは必要であるはずがなく、もしそれが本当に必要であるならば、それは悪であるは

ずがない」[46]: 186

悪の狭い概念には道徳的非難が含まれるため、悪は道徳的行為者とその行為にのみ帰属する[45]: クラウディア・カードによれば、「道徳的行為者に導か

れていないとき、自然の力は "善 "でも "悪 "でもない。ただそうなのだ。その "作用

"は日常的に、ある種の生命体にとっては重要な結果をもたらし、他の生命体にとっては致命的な結果をもたらす」[53]。悪の狭い定義は、「最も道徳的に

卑劣な種類の行為、人物、出来事などを選び出す。この意味での)悪は......想像しうる限り最悪の軽蔑の言葉である」[46]。イヴ・ガラードは、悪

が「特におぞましい種類の行為であり、例えば『その行為は単に間違っていたのではなく、正に悪であった』と言えるような、より普通の種類の悪行と対比され

るべきものである」と表現することを示唆している。その意味するところは、悪行と他の不正な行為との間には、単に量的な違いだけでなく質的な違いがあると

いうことであり、悪行とは単に非常に悪い行為や不正な行為ではなく、むしろ何か特別に恐ろしい性質を持つ行為なのである」[45]: 321

この文脈では、悪の概念は道徳的概念の完全な結びつきの中の一要素である[45]: 324

|

Philosophical questions

Approaches

Main article: Ethics

Views on the nature of evil belong to the branch of philosophy known as

ethics—which in modern philosophy is subsumed into three major areas of

study:[8]

Meta-ethics, that seeks to understand the nature of ethical properties,

statements, attitudes, and judgments.

Normative ethics, investigates the set of questions that arise when

considering how one ought to act, morally speaking.

Applied ethics, concerned with the analysis of particular moral issues

in private and public life.[8]

Usefulness as a term

There is debate on how useful the term "evil" is, since it is often

associated with spirits and the devil. Some see the term as useless

because they say it lacks any real ability to explain what it names.

There is also real danger of the harm that being labeled "evil" can do

when used in moral, political, and legal contexts.[47]: 1–2 Those who

support the usefulness of the term say there is a secular view of evil

that offers plausible analyses without reference to the

supernatural.[45]: 325 Garrard and Russell argue that evil is as

useful an explanation as any moral concept.[45]: 322–326 [54] Garrard

adds that evil actions result from a particular kind of motivation,

such as taking pleasure in the suffering of others, and this

distinctive motivation provides a partial explanation even if it does

not provide a complete explanation.[45]: 323–325 [54]: 268–269 Most

theorists agree use of the term evil can be harmful but disagree over

what response that requires. Some argue it is "more dangerous to ignore

evil than to try to understand it".[47]

Those who support the usefulness of the term, such as Eve Garrard and

David McNaughton, argue that the term evil "captures a distinct part of

our moral phenomenology, specifically, 'collect[ing] together those

wrongful actions to which we have ... a response of moral horror'."[55]

Claudia Card asserts it is only by understanding the nature of evil

that we can preserve humanitarian values and prevent evil in the

future.[56] If evils are the worst sorts of moral wrongs, social policy

should focus limited energy and resources on reducing evil over other

wrongs.[57] Card asserts that by categorizing certain actions and

practices as evil, we are better able to recognize and guard against

responding to evil with more evil which will "interrupt cycles of

hostility generated by past evils".[57]: 166

One school of thought holds that no person is evil and that only acts

may be properly considered evil. Some theorists define an evil action

simply as a kind of action an evil person performs.[58]: 280 But just

as many theorists believe that an evil character is one who is inclined

toward evil acts.[59]: 2 Luke Russell argues that both evil actions

and evil feelings are necessary to identify a person as evil, while

Daniel Haybron argues that evil feelings and evil motivations are

necessary.[47]: 4–4.1

American psychiatrist M. Scott Peck describes evil as a kind of

personal "militant ignorance".[60] According to Peck, an evil person is

consistently self-deceiving, deceives others, psychologically projects

his or her evil onto very specific targets,[61] hates, abuses power,

and lies incessantly.[60][62] Evil people are unable to think from the

viewpoint of their victim. Peck considers those he calls evil to be

attempting to escape and hide from their own conscience (through

self-deception) and views this as being quite distinct from the

apparent absence of conscience evident in sociopaths. He also considers

that certain institutions may be evil, using the My Lai Massacre to

illustrate. By this definition, acts of criminal and state terrorism

would also be considered evil.

Necessity

Main article: Necessary evil

Martin Luther believed that occasional minor evil could have a positive

effect.

Martin Luther argued that there are cases where a little evil is a

positive good. He wrote, "Seek out the society of your boon companions,

drink, play, talk bawdy, and amuse yourself. One must sometimes commit

a sin out of hate and contempt for the Devil, so as not to give him the

chance to make one scrupulous over mere nothings ... "[63]

The international relations theories of realism and neorealism,

sometimes called realpolitik advise politicians to explicitly ban

absolute moral and ethical considerations from international politics,

and to focus on self-interest, political survival, and power politics,

which they hold to be more accurate in explaining a world they view as

explicitly amoral and dangerous. Political realists usually justify

their perspectives by stating that morals and politics should be

separated as two unrelated things, as exerting authority often involves

doing something not moral. Machiavelli wrote: "there will be traits

considered good that, if followed, will lead to ruin, while other

traits, considered vices which if practiced achieve security and well

being for the prince."[64]

|

哲学的な問題

アプローチ

主な記事 倫理学

悪の本質に関する見解は、倫理学として知られる哲学の一分野に属し、現代哲学では以下の3つの主要な研究分野に包含される[8]。

メタ倫理学:倫理的性質、声明、態度、判断の本質を理解しようとするもの。

規範倫理学は、道徳的にどのように行動すべきかを考える際に生じる一連の疑問について研究する。

応用倫理学:私生活や公的生活における特定の道徳的問題の分析に関係する[8]。

用語としての有用性

悪」という言葉はしばしば霊や悪魔と結び付けられるため、その有用性については議論がある。悪」という用語は、それが何を意味するのかを説明する能力を欠

いているため、役に立たないという意見もある。また、道徳的、政治的、法的な文脈で使用される場合、「悪」というレッテルを貼られることが害を及ぼすとい

う現実的な危険性もある[47]: 1-2

この用語の有用性を支持する人々は、超自然的なものに言及することなく、もっともらしい分析を提供する世俗的な悪の見方があると言う[45]: 325

ガラードとラッセルは、悪はあらゆる道徳的概念と同様に有用な説明であると主張している[45]: 322-326 [54]

ガラードは、悪の行為は、他者の苦しみを喜ぶといった特定の種類の動機から生じるものであり、この独特の動機は、完全な説明にはならないとしても、部分的

な説明にはなると付け加えている[45]: 323-325 [54]: 268-269

ほとんどの理論家は、悪という言葉の使用が有害でありうることに同意するが、それがどのような対応を必要とするかについては意見が分かれる。悪を理解しよ

うとするよりも悪を無視する方がより危険である」と主張する者もいる[47]。

イヴ・ガラードやデイヴィッド・マクノートンのようなこの用語の有用性を支持する人々は、悪という用語が「我々の道徳的現象論の明確な部分を捉えており、

具体的には『我々が道徳的恐怖の反応を持つような不当な行為を集めること』である」と主張している[55]。

クローディア・カードは、悪の本質を理解することによってのみ、人道的価値を維持し、将来の悪を防ぐことができると主張している。 [56]

もし悪が最悪の種類の道徳的過ちであるならば、社会政策は他の過ちよりも悪を減らすことに限られたエネルギーと資源を集中させるべきである[57]。カー

ドは、特定の行為や習慣を悪として分類することによって、私たちは悪に対してより多くの悪で対応することを認識し、防御することがよりよくできるようにな

り、それは「過去の悪によって生み出された敵意のサイクルを中断させる」ことになると主張している[57]: 166

ある学派は、人は悪ではなく、行為のみが悪であると考える。一部の理論家は、悪行とは単に悪人が行う行為の一種であると定義している[58]: 280

しかし、それと同様に多くの理論家は、悪人とは悪行へと傾倒する人物のことであると信じている[59]: 2

ルーク・ラッセルは、悪行と悪感情の両方が人を悪人として識別するために必要であると主張し、ダニエル・ヘイブロンは悪感情と悪の動機が必要であると主張

している[47]: 4-4.1

アメリカの精神科医であるM・スコット・ペックは、悪を一種の個人的な「戦闘的無知」と表現している[60]。

ペックによれば、悪人は一貫して自己を欺き、他人を欺き、心理的に自分の悪を非常に特定の対象に投影し[61]、憎悪し、権力を乱用し、絶え間なく嘘をつ

く[60][62]。ペックは、彼が悪と呼ぶ人々は(自己欺瞞によって)自らの良心から逃れ隠れようとしていると考えており、これは社会病質者に見られる

良心の明白な欠如とは全く異なるものであると見ている。彼はまた、ミライの大虐殺を例にとって、ある種の組織が悪であるかもしれないと考えている。この定

義によれば、犯罪行為や国家によるテロ行為も悪とみなされることになる。

必要性のある悪(=必要悪)

主な記事 必要悪

マルティン・ルターは、時には小さな悪も肯定的な効果をもたらすと考えた。

マルティン・ルターは、小さな悪が積極的な善となる場合もあると主張した。酒を飲み、遊び、下品な話をし、自分を楽しませなさい。悪魔を憎み、軽蔑するた

めに罪を犯すこともある。"[63]

リアリズムとネオリアリズムの国際関係理論は、時に現実政治と呼ばれ、国際政治から絶対的な道徳的・倫理的配慮を明確に禁止し、自己利益、政治的生存、権

力政治に焦点を当てるよう政治家に助言している。政治的現実主義者は通常、モラルと政治は無関係なものとして分離されるべきであり、権威を行使することは

しばしばモラルに反することを行うことを含むと述べて、自分たちの視点を正当化する。マキアヴェッリは、「善とされる特質には、それに従えば破滅に至るも

のがある一方、悪徳とされる特質には、それを実践すれば王子の安全と幸福を達成するものがある」と書いている[64]。

|

Akrasia

Antagonist

Archenemy

Dystopia

Banality of evil

Evil Emperor (disambiguation)

Evil empire (disambiguation)

Graded absolutism

Moral evil

Natural evil

Ponerology

Problem of evil

Sin

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Theodicy

Theodicy and the Bible

Value theory

Villain

Wickedness

|

アクラシア

敵対者

アーチェネミー

ディストピア

悪の凡庸性

邪悪な皇帝(曖昧さ回避)

悪の帝国(曖昧さ回避)

段階的絶対主義

道徳的悪

自然悪

ポネーロロジー

悪の問題

罪

ジキル博士とハイド氏の奇妙な事件

神学

神学と聖書

価値論

悪人

邪悪さ

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evil

|

|

Poetic justice

Poetic

justice,

also called poetic irony, is a literary device with which ultimately

virtue is rewarded and misdeeds are punished. In modern literature,[1]

it is often accompanied by an ironic twist of fate related to the

character's own action, hence the name poetic irony.[2]

Etymology

English drama critic Thomas Rymer coined the phrase in The Tragedies of

the Last Age Consider'd (1678) to describe how a work should inspire

proper moral behaviour in its audience by illustrating the triumph of

good over evil. The demand for poetic justice is consistent in

Classical authorities and shows up in Horace, Plutarch, and

Quintillian, so Rymer's phrasing is a reflection of a commonplace.

Philip Sidney, in The Defence of Poesy (1595) argued that poetic

justice was, in fact, the reason that fiction should be allowed in a

civilized nation.

History

Notably, poetic justice does not merely require that vice be punished

and virtue rewarded, but also that logic triumph. If, for example, a

character is dominated by greed for most of a romance or drama, they

cannot become generous. The action of a play, poem, or fiction must

obey the rules of logic as well as morality. During the late 17th

century, critics pursuing a neo-classical standard criticized William

Shakespeare in favor of Ben Jonson precisely on the grounds that

Shakespeare's characters change during the course of the play.[3] When

Restoration comedy, in particular, flouted poetic justice by rewarding

libertines and punishing dull-witted moralists, there was a backlash in

favor of drama, in particular, of more strict moral correspondence.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poetic_justice

|

勧善懲悪の技法は「詩的正義(Poetic

justice)」と呼ばれる

詩的正義は詩的皮肉とも呼ばれ、最終的に美徳が報われ、悪行が罰せられる文学的装置である。現代文学では[1]、登場人物自身の行動に関連した皮肉な運命

の展開を伴うことが多いため、詩的皮肉と呼ばれる[2]。

語源

イギリスの戯曲批評家トーマス・ライマーは、『The Tragedies of the Last Age

Consider'd』(1678年)の中で、作品が悪に対する善の勝利を描くことによって、観客に適切な道徳的行動を促すべきことを説明するために、こ

の言葉を作った。詩的正義の要求は古典的権威に一貫しており、ホレス、プルターク、キンティリアヌスにも見られるので、ライマーの言い回しはありふれたも

のの反映である。フィリップ・シドニーは『ポエジーの弁明』(1595年)の中で、詩的正義こそが、文明国家においてフィクションが許されるべき理由であ

ると主張した。

歴史

注目すべきは、詩的正義は単に悪を罰し、徳に報いることを要求するだけでなく、論理が勝利することも要求するということである。例えば、ロマンスやドラマ

の大半で登場人物が欲に支配されていたら、寛大にはなれない。戯曲、詩、小説の行動は、道徳だけでなく論理のルールにも従わなければならない。17世紀後

半、新古典主義の基準を追求する批評家たちは、ウィリアム・シェイクスピアを批判し、ベン・ジョンソンを支持したが、それはまさに、シェイクスピアの登場

人物が劇の途中で変化するという理由によるものであった[3]。

|

Contrapasso

Karma

Unintended consequences

Irony

|

|

Contrapasso

In Dante's Inferno, contrapasso (or, in modern Italian,[1]

contrappasso, from Latin contra and patior, meaning "suffer the

opposite") is the punishment of souls "by a process either resembling

or contrasting with the sin itself."[2] A similar process occurs in the

Purgatorio.[2]

One of the examples of contrapasso occurs in the fourth Bolgia of the

eighth circle of Hell, where the sorcerers, astrologers, and false

prophets have their heads turned back on their bodies such that it is

"necessary to walk backward because they could not see ahead of

them."[3] This alludes to the consequences of predicting the future by

evil means and displays the twisted nature of magic in general.[4] This

example of contrapasso "functions not merely as a form of divine

revenge, but rather as the fulfillment of a destiny freely chosen by

each soul during his or her life."[5]

The word contrapasso can be found in Inferno, in which the decapitated

Bertran de Born declares: Così s'osserva in me lo Contrapasso

(XXVIII.142),[6] which was translated by Longfellow as "thus is

observed in me the counterpoise",[7] and by Singleton as "thus is the

retribution observed in me."[8] Dante believes that De Born is in the

ninth Bolgia of schismatics for causing Henry the Young King's

rebellion against his father, Henry II of England.[9] De Born is

decapitated as a contrapasso for his supposed act of political

decapitation in undermining a rightful head of the state.[9]

Dante inherited the idea of "contrapasso" from various theological and

literary sources. These include Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologica as

well as medieval ‘visions’ such as Visio Pauli, Visio Alberici, and

Visio Tnugdali.[1]

|

コントラパッソ

ダンテの『地獄篇』において、コントラパッソ(現代イタリア語では[1]コントラッパッソ、ラテン語のcontraとpatiorに由来し、「正反対の苦

しみを受ける」を意味する)とは、「罪そのものに似ているか対照的な過程」[2]によって魂を罰することである。同様の過程が『プルガトリオ』にもある

[2]。

魔術師、占星術師、偽預言者たちは、「前が見えないので、後ろ向きに歩かなければならない」ように、頭を後ろに向けられる。

「このコントラパッソの例は、「単に神の復讐としてではなく、むしろ、それぞれの魂が生前に自由に選んだ運命の成就として機能している」[5]。

コントラパッソという言葉は『地獄篇』にも出てくる: と宣言している(XXVIII.142)[6]。

ダンテは、デ・ボルンが幼王ヘンリーの父であるイングランド王ヘンリー2世に対する反乱を引き起こしたとして、分裂主義者の第9ボルジアに属していると考

えている[9]。デ・ボルンは、正当な国家元首を貶めるという政治的な断末魔の行為のために、コントラパッソとして断頭される[9]。

ダンテは様々な神学的、文学的資料から「コントラパッソ」の思想を受け継いだ。トマス・アクィナスの『神学大全』や中世の『ヴィジオ・パウリ』、『ヴィジ

オ・アルベリチ』、『ヴィジオ・トゥヌグダリ』などの「ヴィジョン」がそれである[1]。

|

The Contrapasso of the sorcerers, astrologers, and false prophets,

illustrated by Stradanus

|

魔術師、占星術師、偽預言者のコントラパッソ(ストラダヌス画

|

Luca

Signorelli, “Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist” (c. 1500) |

ルカ・シニョレッリ、「反キリストの説教と行為」(1500年頃)

|

|

|

☆

☆