退廃芸術

Degenerate art, Entartete Kunst

☆ 退廃芸術(ドイツ語:Entartete

Kunst)とは、1920年代にドイツのナチ党が近代芸術を表現するために採用した言葉である。アドルフ・ヒトラーの独裁政権下のナチス・ドイツでは、

国際的に著名な芸術家の作品を含むドイツのモダニズム芸術は、「ドイツ感情への侮辱」「非ドイツ的」「フリーメーソン的」「ユダヤ的」「共産主義的」とい

う理由で、国有の美術館から撤去され、禁止された。退廃芸術家と認定された者は、教職を解かれ、展示や販売を禁じられ、場合によっては芸術作品の制作を禁

じられるなどの制裁を受けた。退廃芸術はまた、1937年にナチスがミュンヘンで開催した展覧会のタイトルでもあり、ナチスが美術館から持ち出した650点のモダニズム芸術作品を、芸

術や芸術家を嘲笑する落書きや文字のラベルとともに粗末に吊るしたものであった。モダニズムに対する世論を煽るために企画されたこの展覧会は、その

後ドイツとオーストリアの他のいくつかの都市にも巡回した。近

代的なスタイルの芸術が禁止される一方で、ナチスは伝統的な作風で、人種的純潔、軍国主義、服従といった「血と土」の価値観を称揚する絵画や彫刻を奨励し

た。音楽にも同様の制限が設けられ、調性でジャズの影響を受けないことが求められた。映画や演劇も検閲された(写真:1937年ベルリンで開催された「退

廃芸術」展を視察するヨーゼフ・ゲッベルス)。

☆ 退廃芸術(ドイツ語:Entartete

Kunst)とは、1920年代にドイツのナチ党が近代芸術を表現するために採用した言葉である。アドルフ・ヒトラーの独裁政権下のナチス・ドイツでは、

国際的に著名な芸術家の作品を含むドイツのモダニズム芸術は、「ドイツ感情への侮辱」「非ドイツ的」「フリーメーソン的」「ユダヤ的」「共産主義的」とい

う理由で、国有の美術館から撤去され、禁止された。退廃芸術家と認定された者は、教職を解かれ、展示や販売を禁じられ、場合によっては芸術作品の制作を禁

じられるなどの制裁を受けた。退廃芸術はまた、1937年にナチスがミュンヘンで開催した展覧会のタイトルでもあり、ナチスが美術館から持ち出した650点のモダニズム芸術作品を、芸

術や芸術家を嘲笑する落書きや文字のラベルとともに粗末に吊るしたものであった。モダニズムに対する世論を煽るために企画されたこの展覧会は、その

後ドイツとオーストリアの他のいくつかの都市にも巡回した。近

代的なスタイルの芸術が禁止される一方で、ナチスは伝統的な作風で、人種的純潔、軍国主義、服従といった「血と土」の価値観を称揚する絵画や彫刻を奨励し

た。音楽にも同様の制限が設けられ、調性でジャズの影響を受けないことが求められた。映画や演劇も検閲された(写真:1937年ベルリンで開催された「退

廃芸術」展を視察するヨーゼフ・ゲッベルス)。

| Degenerate

art (German: Entartete Kunst) was a term adopted in the 1920s by the

Nazi Party in Germany to describe modern art. During the dictatorship

of Adolf Hitler, German modernist art, including many works of

internationally renowned artists, was removed from state-owned museums

and banned in Nazi Germany on the grounds that such art was an "insult

to German feeling", un-German, Freemasonic, Jewish, or Communist in

nature. Those identified as degenerate artists were subjected to

sanctions that included being dismissed from teaching positions, being

forbidden to exhibit or to sell their art, and in some cases being

forbidden to produce art. Degenerate Art also was the title of a 1937 exhibition held by the Nazis in Munich, consisting of 650 modernist artworks that the Nazis had taken from museums, that were poorly hung alongside graffiti and text labels mocking the art and the artists.[1] Designed to inflame public opinion against modernism, the exhibition subsequently traveled to several other cities in Germany and Austria. While modern styles of art were prohibited, the Nazis promoted paintings and sculptures that were traditional in manner and that exalted the "blood and soil" values of racial purity, militarism, and obedience. Similar restrictions were placed upon music, which was expected to be tonal and free of any jazz influences; disapproved music was termed degenerate music. Films and plays were also censored.[2] |

退

廃芸術(ドイツ語:Entartete

Kunst)とは、1920年代にドイツのナチ党が近代芸術を表現するために採用した言葉である。アドルフ・ヒトラーの独裁政権下のナチス・ドイツでは、

国際的に著名な芸術家の作品を含むドイツのモダニズム芸術は、「ドイツ感情への侮辱」「非ドイツ的」「フリーメーソン的」「ユダヤ的」「共産主義的」とい

う理由で、国有の美術館から撤去され、禁止された。退廃芸術家と認定された者は、教職を解かれ、展示や販売を禁じられ、場合によっては芸術作品の制作を禁

じられるなどの制裁を受けた。 退廃芸術はまた、1937年にナチスがミュンヘンで開催した展覧会のタイトルでもあり、ナチスが美術館から持ち出した650点のモダニズム芸術作品を、芸 術や芸術家を嘲笑する落書きや文字のラベルとともに粗末に吊るしたものであった[1]。モダニズムに対する世論を煽るために企画されたこの展覧会は、その 後ドイツとオーストリアの他のいくつかの都市にも巡回した。 近代的なスタイルの芸術が禁止される一方で、ナチスは伝統的な作風で、人種的純潔、軍国主義、服従といった「血と土(Blut-und-Boden)」の価値観を称揚する絵画や彫刻を奨励した。音楽にも同様の制限が設けられ、調性でジャズの影響を受けないことが求められた。映画や演劇も検閲された[2]。 |

Theories of degeneracy Das Magdeburger Ehrenmal (the Magdeburg cenotaph), by Ernst Barlach was declared to be degenerate art due to the "deformity" and emaciation of the figures—corresponding to Nordau's theorized connection between "mental and physical degeneration". The term Entartung (or "degeneracy") had gained currency in Germany by the late 19th century when the critic and author Max Nordau devised the theory presented in his 1892 book Entartung.[3] Nordau drew upon the writings of the criminologist Cesare Lombroso, whose The Criminal Man, published in 1876, attempted to prove that there were "born criminals" whose atavistic personality traits could be detected by scientifically measuring abnormal physical characteristics. Nordau developed from this premise a critique of modern art, explained as the work of those so corrupted and enfeebled by modern life that they have lost the self-control needed to produce coherent works. He attacked Aestheticism in English literature and described the mysticism of the Symbolist movement in French literature as a product of mental pathology. Explaining the painterliness of Impressionism as the sign of a diseased visual cortex, he decried modern degeneracy while praising traditional German culture. Despite the fact that Nordau was Jewish and a key figure in the Zionist movement (Lombroso was also Jewish), his theory of artistic degeneracy would be seized upon by German Nazis during the Weimar Republic as a rallying point for their antisemitic and racist demand for Aryan purity in art. Belief in a Germanic spirit—defined as mystical, rural, moral, bearing ancient wisdom, and noble in the face of a tragic destiny—existed long before the rise of the Nazis; the composer Richard Wagner celebrated such ideas in his writings.[4][5] Beginning before World War I, the well-known German architect and painter Paul Schultze-Naumburg's influential writings, which invoked racial theories in condemning modern art and architecture, supplied much of the basis for Adolf Hitler's belief that classical Greece and the Middle Ages were the true sources of Aryan art.[6] Schultze-Naumburg subsequently wrote such books as Die Kunst der Deutschen. Ihr Wesen und ihre Werke (The art of the Germans. Its nature and its works) and Kunst und Rasse (Art and Race), the latter published in 1928, in which he argued that only racially pure artists could produce a healthy art which upheld timeless ideals of classical beauty, while racially mixed modern artists produced disordered artworks and monstrous depictions of the human form. By reproducing examples of modern art next to photographs of people with deformities and diseases, he graphically reinforced the idea of modernism as a sickness.[7] Alfred Rosenberg developed this theory in Der Mythos des 20. Jahrhunderts (Myth of the Twentieth Century), published in 1933, which became a best-seller in Germany and made Rosenberg the Party's leading ideological spokesman.[8] |

退廃芸術論 エルンスト・バルラッハの《マグデブルクの慰霊碑》は、人物の「奇形」とやせ衰えによって退廃芸術であると宣言された。 ノルダウは、1876年に出版された犯罪学者チェーザレ・ロンブローゾの著作『犯罪的人間』(The Criminal Man)を参考に、異常な身体的特徴を科学的に測定することで、生まれつきの性格的特徴を発見できる「生まれながらの犯罪者」が存在することを証明しよう とした。ノルダウはこの前提から、近代芸術批判を展開し、近代生活によって堕落し、衰弱し、首尾一貫した作品を生み出すのに必要な自制心を失った人々の作 品であると説明した。彼はイギリス文学における耽美主義を攻撃し、フランス文学における象徴主義運動の神秘主義を精神的病理の産物であると評した。また、 印象派の絵画性を視覚野の病的な兆候と説明し、伝統的なドイツ文化を賞賛しながらも、近代の退廃を批判した。ノルダウはユダヤ人であり、シオニスト運動の 中心人物であったにもかかわらず(ロンブローゾもユダヤ人であった)、彼の芸術退廃論は、ワイマール共和国時代のドイツ・ナチスによって、芸術における アーリア人の純粋性を求める反ユダヤ主義的、人種差別主義的要求の結集点として利用されることになる。 ゲルマン精神とは、神秘的で、田園的で、道徳的で、古代の知恵を持ち、悲劇的な運命に直面しても気高いものであると定義されており、ナチスが台頭するずっ と以前から存在していた。 [第一次世界大戦前から、ドイツの著名な建築家であり画家であったパウル・シュルツェ=ナウムブルクの影響力のある著作は、近代美術や建築を非難する際に 人種論を持ち出しており、古典ギリシャや中世こそがアーリア芸術の真の源泉であるというアドルフ・ヒトラーの信念の根拠となった。Ihr Wesen und ihre Werke(ドイツ人の芸術、その本質と作品)』や『Kunst und Rasse(芸術と人種)』(後者は1928年に出版)を著し、人種的に純粋な芸術家だけが時代を超えた古典的な美の理想を支持する健全な芸術を生み出す ことができるが、人種的に混血した近代芸術家は無秩序な芸術作品や怪物のような人間の形を描いた作品を生み出すと主張した。アルフレッド・ローゼンバーグ は、『20世紀の神話』(Der Mythos des 20. 1933年に出版された『20世紀の神話』はドイツでベストセラーとなり、ローゼンベルクは党を代表するイデオロギー・スポークスマンとなった[8]。 |

Weimar reactionism A still from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari See also: Secession (art), Decadent movement, and Jugendstil The early 20th century was a period of wrenching changes in the arts. The development of modern art at the beginning of the 20th century, albeit with roots going back to the 1860s, denoted a revolutionary divergence from traditional artistic values to ones based on the personal perceptions and feelings of the artists. Under the Weimar government of the 1920s, Germany emerged as a leading center of the avant-garde. It was the birthplace of Expressionism in painting and sculpture, of the atonal musical compositions of Arnold Schoenberg, and the jazz-influenced work of Paul Hindemith and Kurt Weill. Films such as Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1922) brought Expressionism to cinema. In the visual arts, such innovations as Fauvism, Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism—following Symbolism and Post-Impressionism—were not universally appreciated. The majority of people in Germany, as elsewhere, did not care for the new art, which many resented as elitist, morally suspect, and too often incomprehensible.[9] Artistic rejection of traditional authority, intimately linked to the Industrial Revolution, the individualistic values of the Age of Enlightenment and the advance of democracy as the preferred form of government, was exhilarating to some. However, it proved extremely threatening to others, as it took away the security they felt under the older way of things.[10] Wilhelm II, who took an active interest in regulating art in Germany, criticized Impressionism as "gutter painting" (Gossenmalerei)[11] and forbade Käthe Kollwitz from being awarded a medal for her print series A Weavers' Revolt when it was displayed in the Berlin Grand Exhibition of the Arts in 1898.[12] In 1913, the Prussian house of representatives passed a resolution "against degeneracy in art".[11] The Nazis viewed the culture of the Weimar period with disgust. Their response stemmed partly from a conservative aesthetic taste and partly from their determination to use culture as a propaganda tool.[13] On both counts, a painting such as Otto Dix's War Cripples (1920) was anathema to them. It unsparingly depicts four badly disfigured veterans of the First World War, then a familiar sight on Berlin's streets, rendered in caricatured style. (In 1937, it would be displayed in the Degenerate Art exhibition next to a label accusing Dix—himself a volunteer in World War I[14]—of "an insult to the German heroes of the Great War".[15]) Art historian Henry Grosshans says that Hitler "saw Greek and Roman art as uncontaminated by Jewish influences. Modern art was [seen as] an act of aesthetic violence by the Jews against the German spirit. Such was true to Hitler even though only Liebermann, Meidner, Freundlich, and Marc Chagall, among those who made significant contributions to the German modernist movement, were Jewish. But Hitler ... took upon himself the responsibility of deciding who, in matters of culture, thought and acted like a Jew."[16] The supposedly "Jewish" nature of all art that was indecipherable, distorted, or that represented "depraved" subject matter was explained through the concept of degeneracy, which held that distorted and corrupted art was a symptom of an inferior race. By propagating the theory of degeneracy, the Nazis combined their antisemitism with their drive to control the culture, thus consolidating public support for both campaigns.[17] |

ワイマールの反動主義 カリガリ博士の内閣』のスチール写真 以下も参照: 分離派(美術)、デカダンス運動、ユーゲントシュティール 20世紀初頭は、芸術が大きく変化した時代であった。20世紀初頭の近代美術の発展は、そのルーツは1860年代にまで遡るものの、伝統的な芸術的価値観 から、芸術家の個人的な認識や感情に基づくものへの革命的な分岐を示していた。1920年代のワイマール政権下、ドイツは前衛芸術の中心地として台頭し た。絵画や彫刻における表現主義、アルノルト・シェーンベルクの無調音楽の作曲、パウル・ヒンデミットやクルト・ヴァイルのジャズの影響を受けた作品の発 祥地である。ロバート・ウィーネ監督の『カリガリ博士の内閣』(1920年)やF・W・ムルナウ監督の『ノスフェラトゥ』(1922年)といった映画は、 表現主義を映画にもたらした。 視覚芸術の分野では、象徴主義、ポスト印象主義に続くフォーヴィスム、キュビスム、ダダ、シュルレアリスムなどの革新は、普遍的に評価されるものではな かった。産業革命、啓蒙時代の個人主義的価値観、望ましい政治形態としての民主主義の進展と密接に結びついた、伝統的権威に対する芸術的拒絶は、一部の人 々にとっては爽快なものであった。しかし、他の人々にとっては、旧態依然としたやり方で感じていた安心感が奪われ、非常に脅威となった[10]。 ドイツにおける芸術の規制に積極的な関心を寄せていたヴィルヘルム2世は、印象派を「汚れた絵画」(Gossenmalerei)と批判し[11]、ケー テ・コルヴィッツが1898年のベルリン大芸術展に出品した版画シリーズ『機織り工たちの反乱』でメダルを授与されることを禁じた[12]。 1913年、プロイセン下院は「芸術の退廃に反対する」決議を可決した[11]。 ナチスはワイマール時代の文化に嫌悪感を抱いていた。彼らの反応は、保守的な美的嗜好と、文化をプロパガンダの道具として使おうとする決意からくるもので あった[13]。この絵は、当時ベルリンの街角で見慣れた光景であった、第一次世界大戦でひどく醜くなった4人の退役軍人を、戯画的なスタイルで惜しげも なく描いている。(1937年、この作品は、ディックス自身第一次世界大戦の志願兵[14]であり、「第一次世界大戦のドイツの英雄に対する侮辱」 [15]だと非難するラベルが貼られた隣で、退廃芸術展に展示されることになる)。 美術史家のヘンリー・グロシャンは、ヒトラーは「ギリシャ・ローマ美術はユダヤ人の影響に汚染されていないと見ていた。現代美術は、ユダヤ人によるドイツ 精神に対する美的暴力行為と見なされた。ドイツ・モダニズム運動に多大な貢献をした人々のうち、リーバーマン、マイドナー、フロイントリッヒ、マルク・ シャガールだけがユダヤ人であったにもかかわらず、ヒトラーにとってはそうであった。しかしヒトラーは......文化的な問題において、誰がユダヤ人の ように考え、行動するかを決定する責任を自らに負わせた」[16]。解読不可能で、歪曲され、「堕落した」主題を表現するすべての芸術が「ユダヤ人」的で あるとされたことは、歪曲され堕落した芸術は劣等民族の徴候であるとする退廃の概念によって説明された。堕落論を広めることで、ナチスは反ユダヤ主義と文 化支配の推進を結びつけ、両運動に対する大衆の支持を固めた[17]。 |

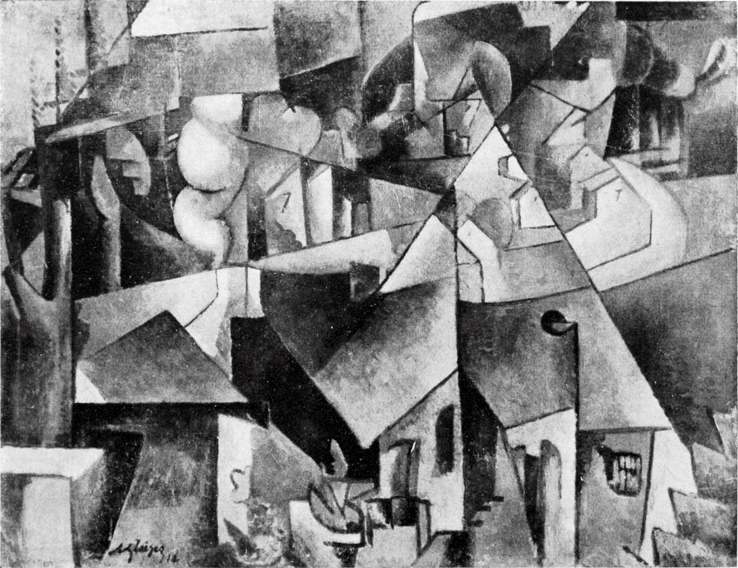

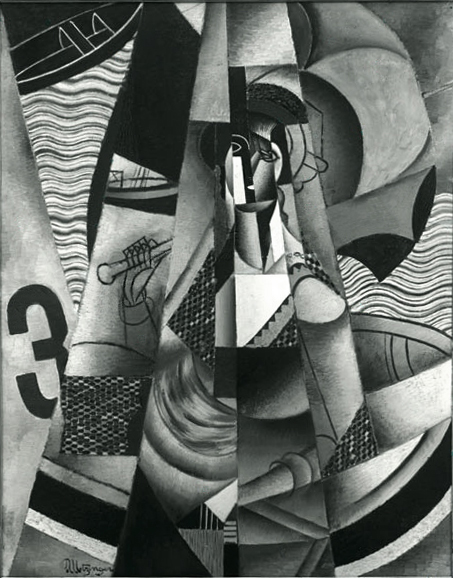

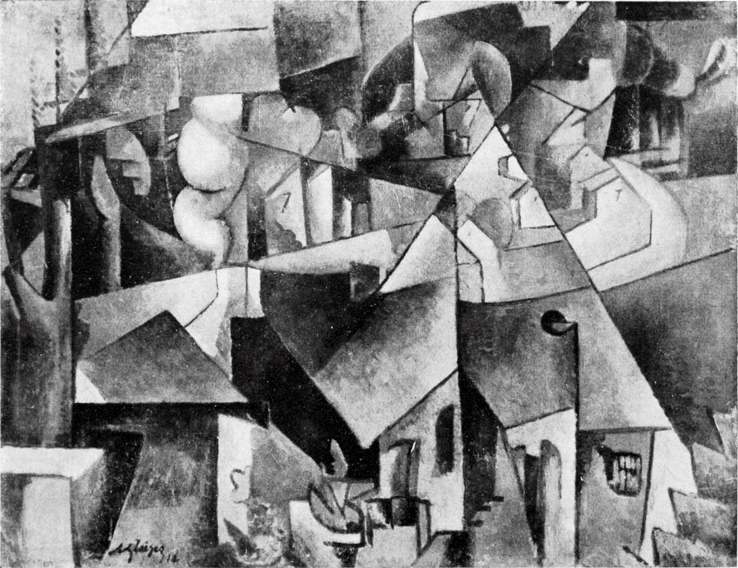

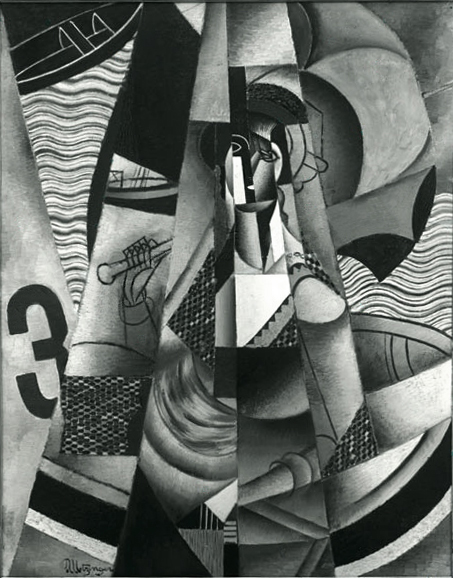

| Nazi purge Once in control of the government, the Nazis moved to suppress modern art styles and to promote art with national and racial themes.[18] Various Weimar-era art personalities, including Renner, Huelsenbeck, and the Bauhaus designers, were marginalized. In 1930 Wilhelm Frick, a Nazi, became Minister for Culture and Education in the state of Thuringia.[19] By his order, 70 mostly Expressionist paintings were removed from the permanent exhibition of the Weimar Schlossmuseum in 1930, and the director of the König Albert Museum in Zwickau, Hildebrand Gurlitt, was dismissed for displaying modern art.[11]  Albert Gleizes, 1912, Landschaft bei Paris, Paysage près de Paris, Paysage de Courbevoie, missing from Hannover since 1937[20][21]  Jean Metzinger, 1913, En Canot (Im Boot), oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm, confiscated by the Nazis c.1936 and displayed at the Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich. The painting has been missing ever since.[22][23] Hitler's rise to power on 31 January 1933, was quickly followed by actions intended to cleanse the culture of degeneracy: book burnings were organized, artists and musicians were dismissed from teaching positions, and curators who had shown a partiality for modern art were replaced by Party members.[24] In September 1933, the Reichskulturkammer (Reich Culture Chamber) was established, with Joseph Goebbels, Hitler's Reichsminister für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda (Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda) in charge. Sub-chambers within the Culture Chamber, representing the individual arts (music, film, literature, architecture, and the visual arts) were created; these were membership groups consisting of "racially pure" artists supportive of the Party, or willing to be compliant. Goebbels made it clear: "In future only those who are members of a chamber are allowed to be productive in our cultural life. Membership is open only to those who fulfill the entrance condition. In this way all unwanted and damaging elements have been excluded."[25] By 1935 the Reich Culture Chamber had 100,000 members.[25] As dictator, Hitler gave his personal taste in art the force of law to a degree never before seen. Only in Stalin's Soviet Union, where Socialist Realism was the mandatory style, had a modern state shown such concern with regulation of the arts.[26] In the case of Germany, the model was to be classical Greek and Roman art, regarded by Hitler as an art whose exterior form embodied an inner racial ideal.[27] Nonetheless, during 1933–1934 there was some confusion within the Party on the question of Expressionism. Goebbels and some others believed that the forceful works of such artists as Emil Nolde, Ernst Barlach and Erich Heckel exemplified the Nordic spirit; as Goebbels explained, "We National Socialists are not unmodern; we are the carrier of a new modernity, not only in politics and in social matters, but also in art and intellectual matters."[28] However, a faction led by Alfred Rosenberg despised the Expressionists, and the result was a bitter ideological dispute, which was settled only in September 1934, when Hitler declared that there would be no place for modernist experimentation in the Reich.[29] This edict left many artists initially uncertain as to their status. The work of the Expressionist painter Emil Nolde, a committed member of the Nazi party, continued to be debated even after he was ordered to cease artistic activity in 1936.[30] For many modernist artists, such as Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Oskar Schlemmer, it was not until June 1937 that they surrendered any hope that their work would be tolerated by the authorities.[31] Although books by Franz Kafka could no longer be bought by 1939, works by ideologically suspect authors such as Hermann Hesse and Hans Fallada were widely read.[32] Mass culture was less stringently regulated than high culture, possibly because the authorities feared the consequences of too heavy-handed interference in popular entertainment.[33] Thus, until the outbreak of the war, most Hollywood films could be screened, including It Happened One Night, San Francisco, and Gone with the Wind. While performance of atonal music was banned, the prohibition of jazz was less strictly enforced. Benny Goodman and Django Reinhardt were popular, and leading British and American jazz bands continued to perform in major cities until the war; thereafter, dance bands officially played "swing" rather than the banned jazz.[34] |

ナチスの粛清 政府を掌握すると、ナチスは近代芸術の様式を抑圧し、国家や人種をテーマにした芸術の振興に動いた[18]。レンナー、ヒュルゼンベック、バウハウスのデザイナーなど、ワイマール時代の様々な芸術家たちは疎外された。 1930年、ナチス党員であったヴィルヘルム・フリックがテューリンゲン州の文化・教育大臣に就任し[19]、彼の命により、1930年にヴァイマール・ シュロス美術館の常設展示から70点の表現主義絵画のほとんどが撤去され、ツヴィッカウのケーニヒ・アルバート美術館の館長ヒルデブラント・グルリットは 現代美術を展示したことで解任された[11]。  アルベール・グライツ、1912年、《パリの町》、《パリの近郊》、《クールベヴォワの近郊》、1937年以降ハノーファーで行方不明[20][21]。  Jean Metzinger, 1913, En Canot (Im Boot), oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm, 1936年頃ナチスに没収され、ミュンヘンの退廃芸術展に展示された。それ以来、この絵は行方不明になっている[22][23]。 1933年1月31日にヒトラーが政権を握ると、すぐに退廃的な文化を一掃するための行動が始まった。書籍の焚書が組織され、芸術家や音楽家が教職から解 任され、現代美術に偏愛を示した学芸員が党員と交代させられた[24]。文化会議所の中に、各芸術(音楽、映画、文学、建築、視覚芸術)を代表する小会議 所が作られた。これらは、党に協力的な、あるいは協力する意思のある「人種的に純粋な」芸術家たちで構成される会員制グループであった。ゲッペルスはこう 明言した。「将来、文化的生活において生産的であることを許されるのは、会議所のメンバーだけである。入会条件を満たした者だけが入会できる。このように して、すべての望まれない有害な要素は排除された」[25]。1935年までに帝国文化会議所の会員は10万人に達した[25]。 独裁者であるヒトラーは、芸術における個人的嗜好に、かつてないほどの法の力を与えた。社会主義リアリズムが必須様式であったスターリンのソビエト連邦においてのみ、近代国家が芸術の規制にこれほどの関心を示した[26]。 それにもかかわらず、1933年から1934年にかけて、党内では表現主義の問題に関して混乱が生じた。ゲッベルスや他の何人かは、エミール・ノルデ、エ ルンスト・バルラッハ、エーリッヒ・ヘッケルといった芸術家の力強い作品が北欧の精神を体現していると信じていた。ゲッベルスが説明したように、「われわ れ国家社会主義者は非近代的な存在ではない。 「しかし、アルフレッド・ローゼンベルク率いる一派は表現主義者を軽蔑し、その結果、イデオロギー論争が激化した。ナチ党の熱心な党員であった表現主義の 画家エミール・ノルデの作品は、彼が1936年に芸術活動の停止を命じられた後も議論され続けた[30]。マックス・ベックマン、エルンスト・ルートヴィ ヒ・キルヒナー、オスカー・シュレンマーといった多くのモダニズムの芸術家たちにとって、彼らの作品が当局によって容認されるという希望を捨てたのは 1937年6月のことであった[31]。 フランツ・カフカの本は1939年までに買うことができなくなったが、ヘルマン・ヘッセやハンス・ファラーダのようなイデオロギー的に疑わしい作家の作品 は広く読まれていた[32]。大衆文化はハイカルチャーよりも厳しく規制されなかったが、それはおそらく当局が大衆娯楽への強引すぎる干渉の結果を恐れた からであろう[33]。 したがって、戦争が始まるまでは、『ある夜の出来事』、『サンフランシスコ』、『風と共に去りぬ』など、ほとんどのハリウッド映画は上映することができ た。無調音楽の演奏は禁止されたが、ジャズの禁止はそれほど厳しくなかった。ベニー・グッドマンとジャンゴ・ラインハルトは人気があり、イギリスとアメリ カの一流のジャズバンドは戦争が終わるまで主要都市で演奏し続けた。その後、ダンスバンドは禁止されたジャズではなく「スウィング」を公式に演奏するよう になった[34]。 |

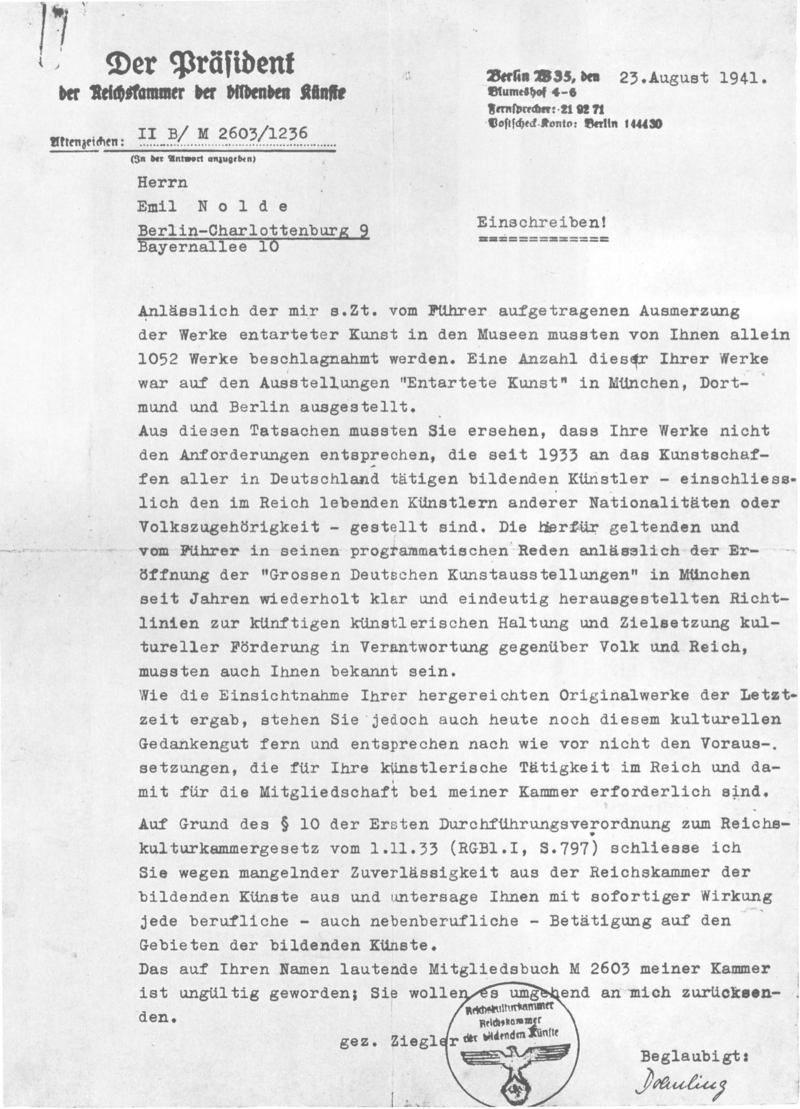

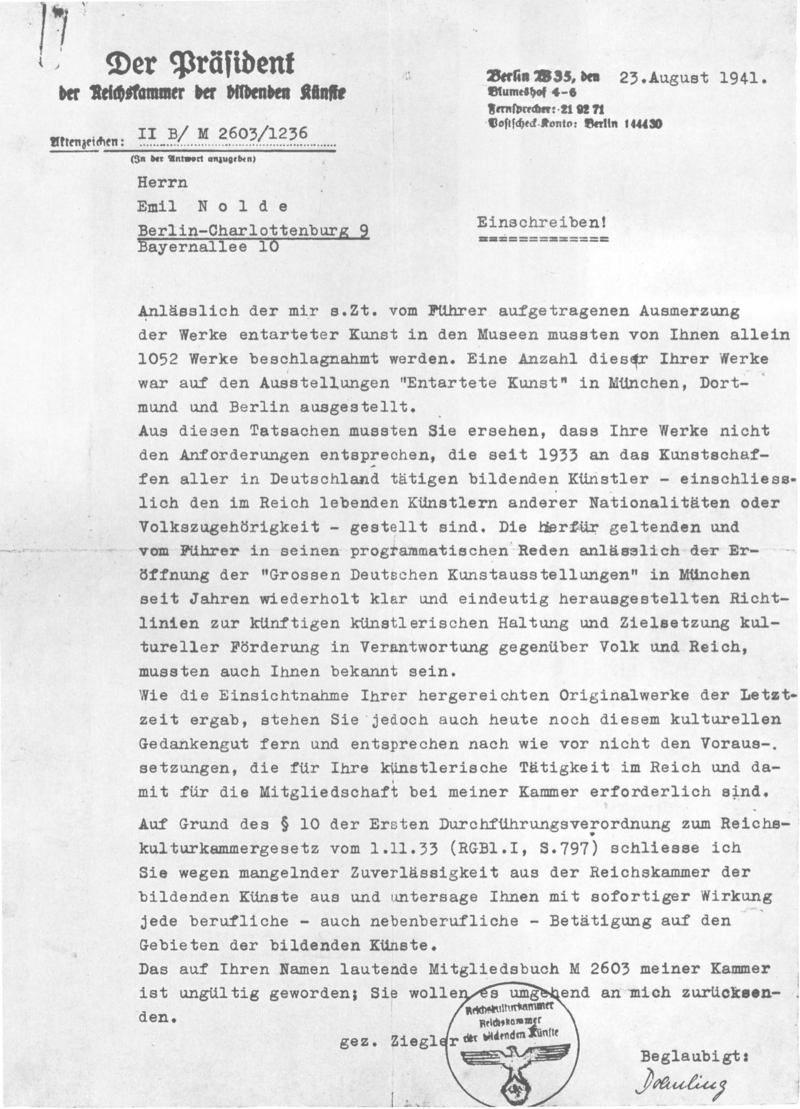

| Entartete Kunst exhibit Main article: Degenerate Art Exhibition  Entartete Kunst poster, Berlin, 1938  Letter to Emil Nolde in 1941 from Adolf Ziegler, who declares that Nolde's art is degenerate art, and forbids him to paint. By 1937, the concept of degeneracy was firmly entrenched in Nazi policy. On 30 June of that year Goebbels put Adolf Ziegler, the head of Reichskammer der Bildenden Künste (Reich Chamber of Visual Art), in charge of a six-man commission authorized to confiscate from museums and art collections throughout the Reich, any remaining art deemed modern, degenerate, or subversive. These works were then to be presented to the public in an exhibit intended to incite further revulsion against the "perverse Jewish spirit" penetrating German culture.[35][36] Over 5000 works were seized, including 1052 by Nolde, 759 by Heckel, 639 by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and 508 by Max Beckmann, as well as smaller numbers of works by such artists as Alexander Archipenko, Marc Chagall, James Ensor, Albert Gleizes, Henri Matisse, Jean Metzinger, Pablo Picasso, and Vincent van Gogh.[37] The Entartete Kunst exhibit, featuring over 650 paintings, sculptures, prints, and books from the collections of 32 German museums, premiered in Munich on 19 July 1937, and remained on view until 30 November, before traveling to 11 other cities in Germany and Austria. The exhibit was held on the second floor of a building formerly occupied by the Institute of Archaeology. Viewers had to reach the exhibit by means of a narrow staircase. The first sculpture was an oversized, theatrical portrait of Jesus, which purposely intimidated viewers as they literally bumped into it in order to enter. The rooms were made of temporary partitions and deliberately chaotic and overfilled. Pictures were crowded together, sometimes unframed, usually hung by cord. The first three rooms were grouped thematically. The first room contained works considered demeaning of religion; the second featured works by Jewish artists in particular; the third contained works deemed insulting to the women, soldiers and farmers of Germany. The rest of the exhibit had no particular theme. There were slogans painted on the walls. For example: Insolent mockery of the Divine under Centrist rule Revelation of the Jewish racial soul An insult to German womanhood The ideal—cretin and whore Deliberate sabotage of national defense German farmers—a Yiddish view The Jewish longing for the wilderness reveals itself—in Germany the Negro becomes the racial ideal of a degenerate art Madness becomes method Nature as seen by sick minds Even museum bigwigs called this the "art of the German people"[38] Speeches of Nazi party leaders contrasted with artist manifestos from various art movements, such as Dada and Surrealism. Next to many paintings were labels indicating how much money a museum spent to acquire the artwork. In the case of paintings acquired during the post-war Weimar hyperinflation of the early 1920s, when the cost of a kilogram loaf of bread reached 233 billion German marks,[39] the prices of the paintings were of course greatly exaggerated. The exhibit was designed to promote the idea that modernism was a conspiracy by people who hated German decency, frequently identified as Jewish-Bolshevist, although only 6 of the 112 artists included in the exhibition were in fact Jewish.[40] The exhibition program contained photographs of modern artworks accompanied by defamatory text.[41] The cover featured the exhibition title—with the word "Kunst", meaning art, in scare quotes—superimposed on an image of Otto Freundlich's sculpture Der Neue Mensch. A few weeks after the opening of the exhibition, Goebbels ordered a second and more thorough scouring of German art collections; inventory lists indicate that the artworks seized in this second round, combined with those gathered prior to the exhibition, amounted to 16,558 works.[42][43] Coinciding with the Entartete Kunst exhibition, the Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German art exhibition) made its premiere amid much pageantry. This exhibition, held at the palatial Haus der deutschen Kunst (House of German Art), displayed the work of officially approved artists such as Arno Breker and Adolf Wissel. At the end of four months Entartete Kunst had attracted over two million visitors, nearly three and a half times the number that visited the nearby Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung.[44] |

退廃芸術(Entartete Kunst)展 主な記事 退廃芸術展  Entartete Kunstのポスター、ベルリン、1938年  1941年、アドルフ・ツィーグラーからエミール・ノルデに届いた手紙。ノルデの芸術は退廃芸術であると宣言し、彼に絵を描くことを禁じた。 1937年までには、退廃の概念はナチスの政策にしっかりと定着していた。ゲッペルスは同年6月30日、帝国美術会議所(Reichskammer der Bildenden Künste)の責任者アドルフ・ツィーグラー(Adolf Ziegler)を6人の委員会の責任者に任命し、帝国全土の美術館や美術品コレクションから、近代的、退廃的、破壊的とみなされる残りの美術品を没収す る権限を与えた。そしてこれらの作品は、ドイツ文化に浸透している「倒錯したユダヤ人の精神」に対する反発をさらに煽ることを意図した展示で一般に公開さ れることになっていた[35][36]。 ノルデの1052点、ヘッケルの759点、エルンスト・ルートヴィヒ・キルヒナーの639点、マックス・ベックマンの508点、さらにアレクサンダー・ア ルキペンコ、マルク・シャガール、ジェームズ・アンソール、アルベルト・グライツ、アンリ・マティス、ジャン・メッツィンガー、パブロ・ピカソ、フィンセ ント・ファン・ゴッホなどの少数の作品を含む5000点以上の作品が押収された。 [37] ドイツの32の美術館のコレクションから650点以上の絵画、彫刻、版画、書籍が展示されたEntartete Kunstは、1937年7月19日にミュンヘンで初公開され、11月30日まで開催された後、ドイツとオーストリアの他の11都市を巡回した。 展示は、かつて考古学研究所が使用していた建物の2階で行われた。観客は狭い階段を使って展示室にたどり着かなければならなかった。最初の彫刻は特大の芝 居がかったイエスの肖像画で、文字通りぶつかって入るため、鑑賞者をわざと威圧した。部屋は仮設のパーティションで作られ、意図的に混沌として埋め尽くさ れていた。絵は所狭しと飾られ、時には額装されず、通常は紐で吊るされていた。 最初の3つの部屋はテーマごとにグループ分けされていた。最初の部屋には宗教を卑下した作品が、2番目の部屋には特にユダヤ人芸術家の作品が、3番目の部屋にはドイツの女性、兵士、農民を侮辱した作品が展示されていた。それ以外の展示室には特にテーマはなかった。 壁にはスローガンが描かれていた。例えばこうだ: 中道主義支配下の神への不埒な嘲笑 ユダヤ人の人種的魂の啓示 ドイツ女性への侮辱 理想的なクレチンと売春婦 意図的な国防妨害 ドイツ農民のイディッシュ的見解 ユダヤ人の荒野への憧れが姿を現す-ドイツでは黒人が退化した芸術の人種的理想となる 狂気は方法となる 病んだ心が見る自然 美術館のお偉方でさえ、これを「ドイツ人の芸術」と呼んだ[38]。 ナチス党首の演説は、ダダやシュルレアリスムなどさまざまな芸術運動の芸術家のマニフェストと対照的だった。多くの絵画の横には、美術館がその作品を取得 するために費やした金額を示すラベルが貼られていた。1キログラムのパンの値段が2330億ドイツマルクに達した、1920年代初頭の戦後ワイマールのハ イパーインフレの最中に入手された絵画の場合[39]、もちろん絵画の値段は大幅に誇張されていた。この展覧会は、モダニズムはドイツの良識を憎む人々に よる陰謀であるという考えを広めるために企画されたもので、しばしばユダヤ人=ボリシェヴィストと認定されたが、展覧会に出品された112人のアーティス トのうち、実際にユダヤ人だったのは6人だけだった[40]。 展覧会プログラムには、中傷的な文章が添えられた近代美術作品の写真が掲載されていた[41]。 表紙には、展覧会のタイトル、つまり芸術を意味する「クンスト」という言葉が、オットー・フロイントリッヒの彫刻作品「Der Neue Mensch」の画像に重ねて引用されていた。 展覧会の開幕から数週間後、ゲッペルスはドイツの美術コレクションのより徹底的な再調査を命じた。目録によれば、この第二次調査で押収された美術品は、展覧会前に集められたものと合わせて16,558点にのぼった[42][43]。 Entartete Kunst展と同時に、Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung(大ドイツ美術展)が華やかな初開催を迎えた。この展覧会は宮殿のようなHaus der deutschen Kunst(ドイツ芸術の家)で開催され、アルノ・ブレーカーやアドルフ・ヴィッセルといった公認芸術家の作品が展示された。Entartete Kunstは、4ヶ月間で200万人以上の来場者を集め、近隣のGroße Deutsche Kunstausstellungの約3.5倍を記録した[44]。 |

Fate of the artists and their work Self-portrait by Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler, who was murdered at Sonnenstein Euthanasia Centre in 1940. Avant-garde German artists were branded both enemies of the state and a threat to German culture. Many went into exile. Max Beckmann fled to Amsterdam on the opening day of the Entartete Kunst exhibit.[45] Max Ernst emigrated to America with the assistance of Peggy Guggenheim. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner committed suicide in Switzerland in 1938. Paul Klee spent his years in exile in Switzerland, yet was unable to obtain Swiss citizenship because of his status as a degenerate artist. A leading German dealer, Alfred Flechtheim, died penniless in exile in London in 1937. Other artists remained in internal exile. Otto Dix retreated to the countryside to paint unpeopled landscapes in a meticulous style that would not provoke the authorities.[46] The Reichskulturkammer forbade artists such as Edgar Ende and Emil Nolde from purchasing painting materials. Those who remained in Germany were forbidden to work at universities and were subject to surprise raids by the Gestapo in order to ensure that they were not violating the ban on producing artwork; Nolde secretly carried on painting, but using only watercolors (so as not to be betrayed by the telltale odor of oil paint).[47] Although officially no artists were put to death because of their work, those of Jewish descent who did not escape from Germany in time were sent to concentration camps.[48] Others were murdered in the Action T4 (see, for example, Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler). After the exhibit, only the most valuable paintings were sorted out to be included in the auction held by Galerie Theodor Fischer (auctioneer) in Luzern, Switzerland, on 30 June 1939 at the Grand Hotel National. The sale consisted of artworks seized from German public museums; some pieces from the sale were acquired by museums, others by private collectors such as Maurice Wertheim who acquired the 1888 self-portrait by Vincent van Gogh that was seized from the Neue Staatsgalerie in Munich belonging to today's Bavarian State Painting Collections.[2] Nazi officials took many for their private use: for example, Hermann Göring took 14 valuable pieces, including a Van Gogh and a Cézanne. In March 1939, the Berlin Fire Brigade burned about 4000 paintings, drawings and prints that had apparently little value on the international market. This was an act of unprecedented vandalism, although the Nazis were well used to book burnings on a large scale.[49][50] A large amount of "degenerate art" by Picasso, Dalí, Ernst, Klee, Léger and Miró was destroyed in a bonfire on the night of 27 July 1942, in the gardens of the Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume in Paris.[51] Whereas it was forbidden to export "degenerate art" to Germany, it was still possible to buy and sell artworks of "degenerate artists" in occupied France. The Nazis considered indeed that they should not be concerned by Frenchmen's mental health.[52] As a consequence, many works made by these artists were sold at the main French auction house during the occupation.[53] The couple Sophie and Emanuel Fohn, who exchanged the works for harmless works of art from their own possession and kept them in safe custody throughout the National Socialist era, saved about 250 works by ostracized artists. The collection survived in South Tyrol from 1943 and was handed over to the Bavarian State Painting Collections in 1964.[54] After the collapse of Nazi Germany and the invasion of Berlin by the Red Army, some artwork from the exhibit was found buried underground. It is unclear how many of these then reappeared in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, where they still remain. In 2010, as work began to extend an underground line from Alexanderplatz through the historic city centre to the Brandenburg Gate, a number of sculptures from the degenerate art exhibition were unearthed in the cellar of a private house close to the "Rote Rathaus". These included, for example, the bronze cubist-style statue of a female dancer by the artist Marg Moll, and are on display at the Neues Museum.[55][56][57] |

芸術家と作品の運命 1940年、ゾンネンシュタイン安楽死センターで殺害されたエルフリーデ・ローゼ=ヴェヒトラーの自画像。 前衛的なドイツの芸術家たちは、国家の敵であり、ドイツ文化への脅威であるという烙印を押された。多くの芸術家が亡命した。マックス・ベックマンは 「Entartete Kunst」展の初日にアムステルダムに逃亡した[45]。マックス・エルンストはペギー・グッゲンハイムの援助でアメリカに移住。エルンスト・ルート ヴィヒ・キルヒナーは1938年にスイスで自殺。パウル・クレーはスイスで亡命生活を送ったが、退廃的な芸術家という理由でスイス国籍を取得できなかっ た。ドイツを代表する画商アルフレッヒトハイムは、1937年に無一文でロンドンに亡命した。 他の芸術家たちも亡命した。オットー・ディクスは田舎に引きこもり、当局を刺激しないような緻密な作風で人気のない風景を描いた[46]。ドイツ文化局 は、エドガー・エンデやエミール・ノルデといった画家たちが画材を購入することを禁じた。ノルデは密かに絵を描き続けたが、(油絵の具の臭いで裏切られな いように)水彩絵の具しか使わなかった。 [公式には作品が原因で死刑になった芸術家はいなかったが、ドイツからの脱出が間に合わなかったユダヤ系の芸術家は強制収容所に送られた[48]。 1939年6月30日、スイスのルツェルンにあるグランド・ホテル・ナショナルで開催されたオークションに出品されたのは、最も価値のある絵画のみであっ た。売りに出された作品はドイツの公立美術館から押収されたもので、美術館が購入したものもあれば、今日のバイエルン州立絵画コレクションに属するミュン ヘンのノイエ・シュターツギャラリーから押収されたフィンセント・ファン・ゴッホの自画像(1888年)を手に入れたモーリス・ヴェルトハイムのような個 人コレクターもいた[2]。1939年3月、ベルリン消防隊は、国際市場ではほとんど価値のないことが明らかな約4000点の絵画、素描、版画を焼却し た。ナチスは大規模な焚書には慣れていたが、これは前代未聞の破壊行為であった[49][50]。 ピカソ、ダリ、エルンスト、クレー、レジェ、ミロによる大量の「退廃芸術」は、1942年7月27日の夜、パリの国立ジュ・ド・ポーム美術館の庭園で焚き 火に焼かれた[51]。退廃芸術」をドイツに輸出することは禁じられていたが、占領下のフランスで「退廃芸術家」の作品を売買することは可能であった。ナ チスは、フランス人の精神衛生に関心を持つべきではないと考えていたのである[52]。その結果、占領下のフランスの主要なオークションハウスで、これら の芸術家の作品の多くが売却された[53]。 ソフィーとエマニュエル・フォーン夫妻は、自分たちが所有していた無害な芸術作品と交換し、国家社会主義時代を通して安全に保管し、追放された芸術家たち の作品約250点を保存した。コレクションは1943年から南チロルに存続し、1964年にバイエルン州立絵画コレクションに引き渡された[54]。 ナチス・ドイツの崩壊と赤軍によるベルリン侵攻の後、展示作品の一部が地下に埋もれているのが発見された。その後、どれだけの作品がサンクトペテルブルクのエルミタージュ美術館に再び収蔵されたのかは不明である。 2010年、アレクサンダー広場からブランデンブルク門までの地下線延伸工事が始まったとき、「ローテ・ラートハウス」に近い民家の地下室から、退廃芸術 展の彫刻の数々が発掘された。これらには、例えば、芸術家マルグ・モルによるキュビズム風の女性ダンサーのブロンズ像が含まれ、ノイエスミュージアムに展 示されている[55][56][57]。 |

| Artists in the 1937 Munich show Jankel Adler Hans Baluschek Ernst Barlach Rudolf Bauer Philipp Bauknecht Otto Baum [de] Willi Baumeister Herbert Bayer Max Beckmann Rudolf Belling Paul Bindel Theodor Brün [de] Max Burchartz Fritz Burger-Mühlfeld [de] Paul Camenisch Heinrich Campendonk Karl Caspar Maria Caspar-Filser Pol Cassel Marc Chagall Lovis Corinth Heinrich Maria Davringhausen Walter Dexel Johannes Diesner Otto Dix Pranas Domšaitis Hans Christoph Drexel Johannes Driesch Heinrich Eberhard Max Ernst Hans Feibusch Lyonel Feininger Conrad Felixmüller Otto Freundlich Xaver Fuhr [de] Ludwig Gies Werner Gilles Otto Gleichmann Rudolf Großmann George Grosz Hans Grundig Rudolf Haizmann Raoul Hausmann Guido Hebert [cs] Erich Heckel Wilhelm Heckrott [de] Jacoba van Heemskerck Hans Siebert von Heister [no] Oswald Herzog [de] Werner Heuser Heinrich Hoerle Karl Hofer Eugen Hoffmann Johannes Itten Alexej von Jawlensky Eric Johansson [de] Hans Jürgen Kallmann Wassily Kandinsky Hanns Katz Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Paul Klee Cesar Klein Paul Kleinschmidt Oskar Kokoschka Otto Lange Wilhelm Lehmbruck Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler El Lissitzky Oskar Lüthy Franz Marc Gerhard Marcks Ewald Mataré Ludwig Meidner Jean Metzinger Constantin von Mitschke-Collande [de] László Moholy-Nagy Marg Moll Oskar Moll Johannes Molzahn Piet Mondrian Georg Muche Otto Mueller Magda Nachman Acharya Erich Nagel Heinrich Nauen Ernst Wilhelm Nay Karel Niestrath [de] Emil Nolde Otto Pankok Max Pechstein Max Peiffer Watenphul Hans Purrmann Max Rauh [no] Hans Richter Emy Roeder Christian Rohlfs Edwin Scharff Oskar Schlemmer Rudolf Schlichter Karl Schmidt-Rottluff Werner Scholz Lothar Schreyer Otto Schubert Kurt Schwitters Lasar Segall Fritz Skade [de] Heinrich Stegemann Fritz Stuckenberg Paul Thalheimer Johannes Tietz [no] Arnold Topp [de] Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart Karl Völker Christoph Voll William Wauer Gert Heinrich Wollheim Artistic movements condemned as degenerate Bauhaus Cubism Dada Expressionism Fauvism Impressionism Post-Impressionism New Objectivity Surrealism |

|

| Listing The Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda (Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda) compiled a 479-page, two-volume typewritten listing of the works confiscated as "degenerate" from Germany's public institutions in 1937–38. In 1996 the Victoria and Albert Museum in London acquired the only known surviving copy of the complete listing. The document was donated to the V&A's National Art Library by Elfriede Fischer, the widow of the art dealer Heinrich Robert ("Harry") Fischer. Copies were made available to other libraries and research organisations at the time, and much of the information was subsequently incorporated into a database maintained by the Freie Universität Berlin.[58][59] A digital reproduction of the entire inventory was published on the Victoria and Albert Museum's website in January 2014. The V&A's publication consists of two PDFs, one for each of the original volumes. Both PDFs also include an introduction in English and German.[60] An online version of the inventory was made available on the V&A's website in November 2019, with additional features. The new edition uses IIIF page-turning software and incorporates an interactive index arranged by city and museum. The earlier PDF edition remains available too.[61] The V&A's copy of the full inventory is thought to have been compiled in 1941 or 1942, after the sales and disposals were completed.[62] Two copies of an earlier version of Volume 1 (A–G) also survive in the German Federal Archives in Berlin, and one of these is annotated to show the fate of individual artworks. Until the V&A obtained the complete inventory in 1996, all versions of Volume 2 (G–Z) were thought to have been destroyed.[63] The listings are arranged alphabetically by city, museum and artist. Details include artist surname, inventory number, title and medium, followed by a code indicating the fate of the artwork, then the surname of the buyer or art dealer (if any) and any price paid.[63] The entries also include abbreviations to indicate whether the work was included in any of the various Entartete Kunst exhibitions (see Degenerate Art Exhibition) or Der ewige Jude (see The Eternal Jew (art exhibition)).[64] The main dealers mentioned are Bernhard A. Böhmer (or Boehmer), Karl Buchholz, Hildebrand Gurlitt, and Ferdinand Möller. The manuscript also contains entries for many artworks acquired by the artist Emanuel Fohn, in exchange for other works.[65] |

リスト 帝国啓蒙宣伝省(Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda)は、1937年から38年にかけてドイツの公的機関から「退廃的」として没収された作品のリストを、479ページ、2巻のタイプラ イターにまとめた。1996年、ロンドンのヴィクトリア・アンド・アルバート博物館が、現存する唯一の完全なリストを入手した。この文書は、美術商ハイン リッヒ・ロベルト(「ハリー」)・フィッシャーの未亡人であるエルフリーデ・フィッシャーによって、V&Aの国立美術図書館に寄贈された。コピー は当時、他の図書館や研究機関にも提供され、情報の多くはその後、ベルリン自由大学が管理するデータベースに組み込まれた[58][59]。 目録全体のデジタル複製は、2014年1月にヴィクトリア・アンド・アルバート博物館のウェブサイトで公開された。V&Aの出版物は2つのPDF で構成されており、1つはオリジナルの各巻についてである。両PDFには英語とドイツ語の序文も含まれている[60]。2019年11月、目録のオンライ ン版がV&Aのウェブサイトで利用可能になり、機能が追加された。新版はIIIFのページめくりソフトウェアを使用し、都市や美術館ごとに配列さ れたインタラクティブな索引が組み込まれている。以前のPDF版も引き続き利用可能である[61]。 V&Aの完全な目録のコピーは、売却と処分が完了した後の1941年または1942年に編集されたと考えられている[62]。ベルリンのドイツ連 邦公文書館にも第1巻(A-G)の旧版のコピーが2部残っており、そのうちの1部には個々の美術品の運命を示す注釈が付されている。1996年に V&Aが目録全体を入手するまでは、第2巻(G-Z)のすべてのバージョンは破棄されたと考えられていた[63]。詳細には、アーティストの姓、 目録番号、タイトル、メディウム、作品の運命を示すコードが続き、買い手または画商の姓(もしあれば)、支払われた価格が含まれる[63]。項目には、作 品が様々なEntartete Kunst展(退廃芸術展を参照)またはDer ewige Jude展(永遠のユダヤ人(美術展)を参照)のいずれかに含まれていたかどうかを示す略語も含まれる[64]。 言及されている主なディーラーは、ベルンハルト・A・ベーメル(またはベーメル)、カール・ブッフホルツ、ヒルデブラント・グルリット、フェルディナン ト・メラーである。手稿には、画家エマニュエル・フォーンが他の作品と引き換えに入手した多くの作品の記載もある[65]。 |

| 21st-century reactions Neil Levi, writing in The Chronicle of Higher Education, suggested that the branding of art as "degenerate" was only partly an aesthetic aim of the Nazis. Another was the confiscation of valuable artwork, a deliberate means to enrich the regime.[66] In popular culture A Picasso, a play by Jeffrey Hatcher based loosely on actual events, is set in Paris 1941 and sees Picasso being asked to authenticate three works for inclusion in an upcoming exhibition of degenerate art.[67][68] In the 1964 film The Train, a German Army colonel attempts to steal hundreds of "degenerate" paintings from Paris before it is liberated during World War II.[69] |

21世紀の反応 ニール・レヴィは『クロニクル・オブ・ハイヤー・エデュケーション』誌に寄稿し、芸術を「退廃的なもの」と決めつけることは、ナチスの美的目的の一部に過ぎなかったと指摘した。もうひとつは、貴重な美術品の没収であり、政権を富ませるための意図的な手段であった[66]。 大衆文化 1941年のパリを舞台にしたジェフリー・ハッチャーによる劇『ピカソ』では、ピカソが近々開催される退廃芸術展に出品する3つの作品の鑑定を依頼される[67][68]。 1964年の映画『The Train』では、ドイツ軍の大佐が、第二次世界大戦中にパリが解放される前に、パリから何百もの「退廃的な」絵画を盗み出そうとする[69]。 |

| Gurlitt Collection Karl Buchholz (art dealer) Art of the Third Reich Low culture Nazi plunder |

グルリット・コレクション カール・ブッフホルツ(美術商) 第三帝国の芸術 低俗文化 ナチスの略奪 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Degenerate_art |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆