暴 力

Definition

of violence

★暴力とは、人間に関わる「破壊的な強制 力のこと」である

暴 力とは、人間に関わる「破壊的な強制力のこと」である。人間がなぜ暴力を使うのか、それは殺傷行為を含めて相手をある状態(=生殺与奪の権 限)従 属させることであり、暴力とは〈従属させる強制力〉にほかならない。〈従属させる強制力〉すなわち〈暴力〉の帰結とは、動産の破壊、人間や 動物の殺傷などがある。このために、人は暴力の被害が被らないように、命乞いのように懇願したり、(因果関係の認識として)謝る必要のない謝罪を口にす る。

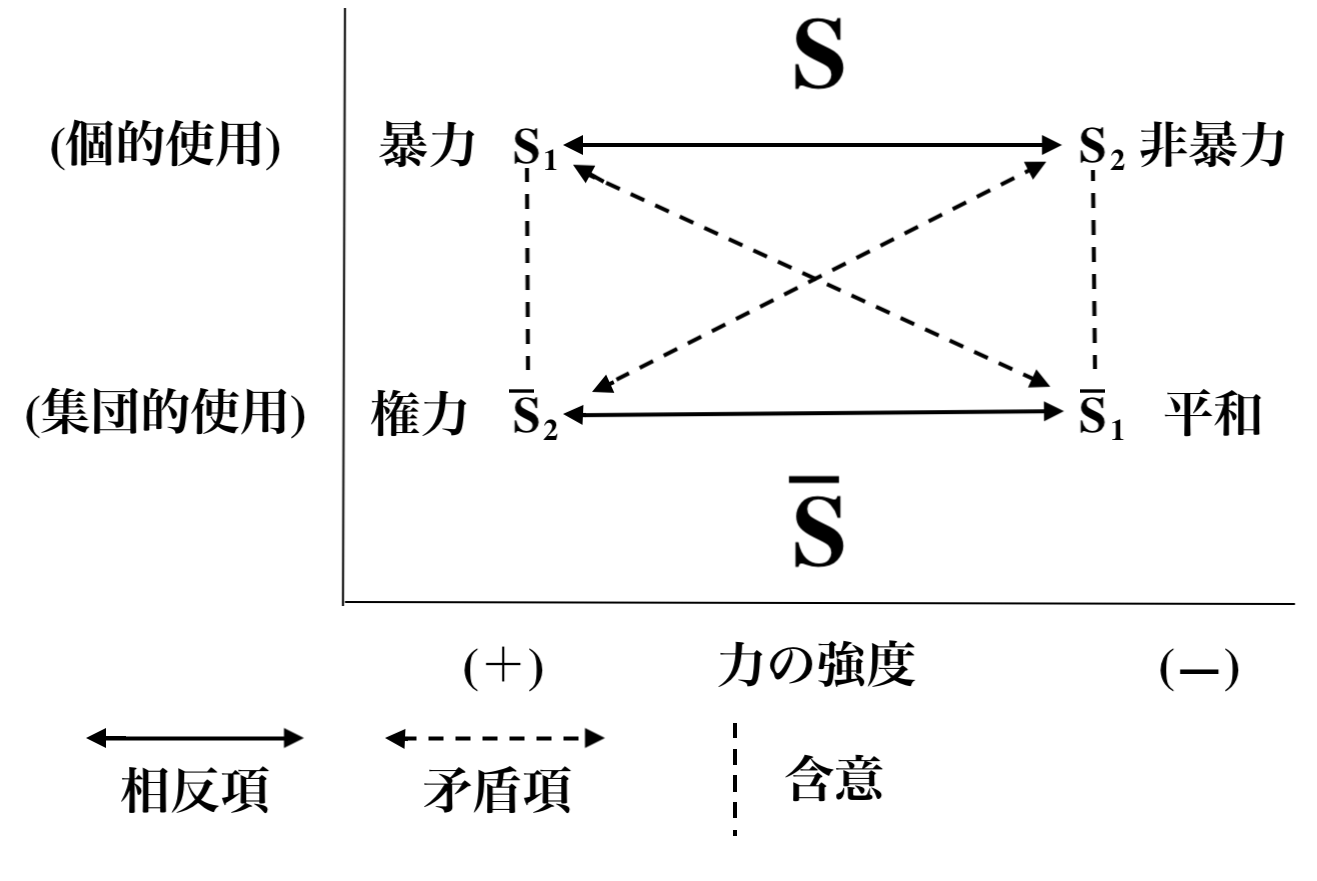

通 常は、暴力概念は権力の発露として捉えることができるが(→「ソレルの暴力論」 を参照)、以下の、ハンナ・アーレントの暴力概念は、そのように捉えない特異的な解釈なので、注意が必要である。暴力の反対語は、ある意味空間(A)にお いては、非暴力であり、非暴力が含意するものは、誰でも想像がつくように「平和」である——下図2.「近代国家における暴力装置概念」の図を参照せよ。他 方、「人を従属させる非破壊的な強制力」としての「権威」を暴力に対峙するもの、つまり反対語/反対概念とみなす立場もある。それが、ハンナ・アーレントの暴力概念であり、この概念は、アーレントが影響を受けた夫 ハインリッヒ・ブリュッヒャーとヴァルター・ベンヤミンの影響を受けているものと、私(池田)は考えている——下図1.「アーレントの暴力概念」を参照の こと。。

★常識的な暴力の定義

(1) 意味の四角形をとおして理解する、我々の常識的理解にもとづく「暴力」——《暴力と平和の「意味の四角形」》

近

代国家や平和学における「暴力」に対立する概念は「非暴力」である。そして、非暴力のコノテーションこそが「平和」ないしは「平和的状態」で

ある。従って、これをグレマスの意味の四角形に議論に落とし込む

と、暴力の矛盾項は「平和」であり、暴力が存在する平和な状態は存在しない、という我々

が日常で抱く常識的な概念のマッチングができあがる。ここから導かれるのが権力(パワー)であり、それは権威が管理する暴力装置、例えば警察や(治安出動

を目的とする)軍隊とコノテートすることで、暴力装置に正当性が与えられる。これが我々の考える、暴力——権力による暴力装置——非暴力——平和という4

つの項目の関係性である。(→応用問題としてガルトゥングの「構造的暴力」

を考えてみよ!)

★アンオーソドックスなハンナ・アーレン

トの暴力概念

(2) 《暴力と権威は共存しないというハンナ・アーレントの「意味の四角形」》——K・シュミットとは異なる「暴力を手中にする」方法について

上 記の暴力と平和の「意味の四角形」という我々の常識に疑問符を付すのがハンナ・アーレントの暴力論である。アーレントにとって、暴力の反対概 念は、権威である。つまり、彼女によると、権威のあるところに暴力は存在しない。この権威は、グラムシのいうヘゲモニー概念にある種近いものかもしれない。権威とコノテートするのが権威である。 この点は、我々と承服するところだろう。というか、権威と権力の合致こそがヘゲモニーの確立を意味するからだ。このような意味の導出は、暴力と権力を矛盾 項の関係として定義する。権力はしばしば、抑圧的権力を権力そのものであると感じる人はまさに暴力の権化のようだ。しかし、権威が確立しているところに権 力は機能しているという(我々が具有する)スタティックな社会観を経由すると、それは確かに、権力は(暴力を独占しているがゆえに、暴力の自由な発露(= 「万人の万人に対する闘争」)を禁止する。したがって、彼女の指摘は、異様なものではなく、近代啓蒙主義の始祖の一人にも数えられるホッブス(→さまざまな国家論)の権力行使論と齟齬をきたさない。そして、さらに隠された第四項には、 革命が存在する。これによると革命と暴力はコノテーション関係であり、これも歴史的事実としては理解可能である。そして革命は権力と相反するわけだから、 革命は、既存の権力を否定する意味で相反なものであり、革命後には権威による支配が確立するが、革命という現在進行形の状態は権力掌握を通して権威を希求 するものであり、権威と革命は矛盾項の関係にある。

革

命的暴力は「神的暴力」になるべきだという考え方はこれに由来する(→「ジョル

ジュ・ソレルの暴力論」「ヴァルター・ベンヤ ミンの暴力批判論」)

こ れらの関係についてのより詳しい関係は次のページにある:池田光穂「政治的暴力の概念」

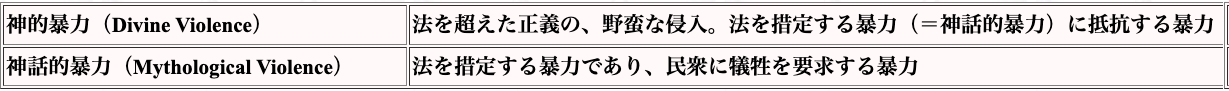

★ヴァルター・ベンヤミンの暴力の概念

(3)神的暴力と神話的暴力(→より詳し くは「ヴァルター・ベンヤミン「暴力批判論(1920/1921)」ノー ト」)

神 的暴力と神話的暴力とは、ヴァルター・ベンヤミンによる特有の暴力概念の区別である。つまり、神的暴力とは、法を超えた正義の、野蛮な侵入の ことをさす。つまり、法を措定する暴力(=神話的暴力)に抵抗する暴力のことである。したがって、神話的暴力とは、法を措定する暴力であり、民衆に犠牲を 要求する暴力である。

︎▶ヴァルター・ベンヤミン「暴力批判論(1920/1921)」ノート︎▶︎︎神的暴力と神話的暴力▶︎神

的暴力▶暴力について考える(シラバス)︎︎▶︎暴力について考える(対話術F)▶︎︎ジジェク『暴力:6つの考察』▶︎残虐行為論▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

★パターナリズムと暴力の関係について

日本語に明るくない学習者の方に,裏書とは「物事が確実であることを別の面から証明すること」という意味です.すなわち「パターナリズムは

暴力により裏書きされる」と僕が言う時パターナリズムを「社会学的に」認定する時にそこに暴力あるいは暴力の痕跡を探し出せということです。

★暴力(Violence)——ウィキペディア英語

| Violence

is characterized as the use of physical force by humans to cause harm

to other living beings, such as pain, injury, disablement, death,

damage and destruction. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines

violence as "the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened

or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or

community, which either results in or has a high likelihood of

resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or

deprivation";[1] it recognizes the need to include violence not

resulting in injury or death.[2] |

暴力とは、人間が他の生き物に対して、痛み、負傷、障害、死、損害、破

壊といった危害を加えるために物理的な力を用いる行為を指す。世界保健機関(WHO)は暴力を「自分自身、他人格、あるいは集団やコミュニティに対して、

脅威または実際に物理的な力や権力を意図的に行使し、その結果として、あるいは高い確率で、負傷、死亡、心理的損傷、発達障害、または剥奪をもたらす行

為」と定義している[1]。また、負傷や死亡に至らない暴力も含める必要性を認めている[2]。 |

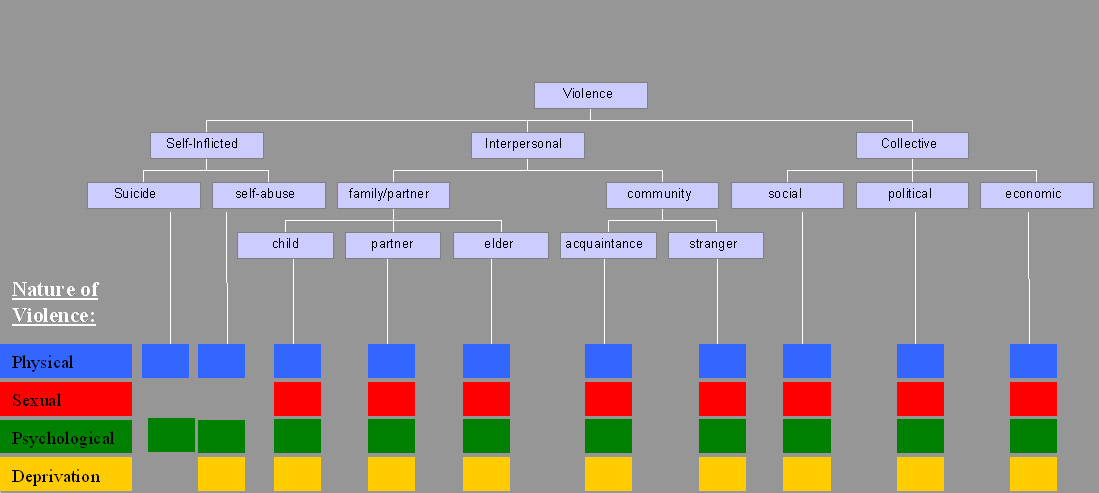

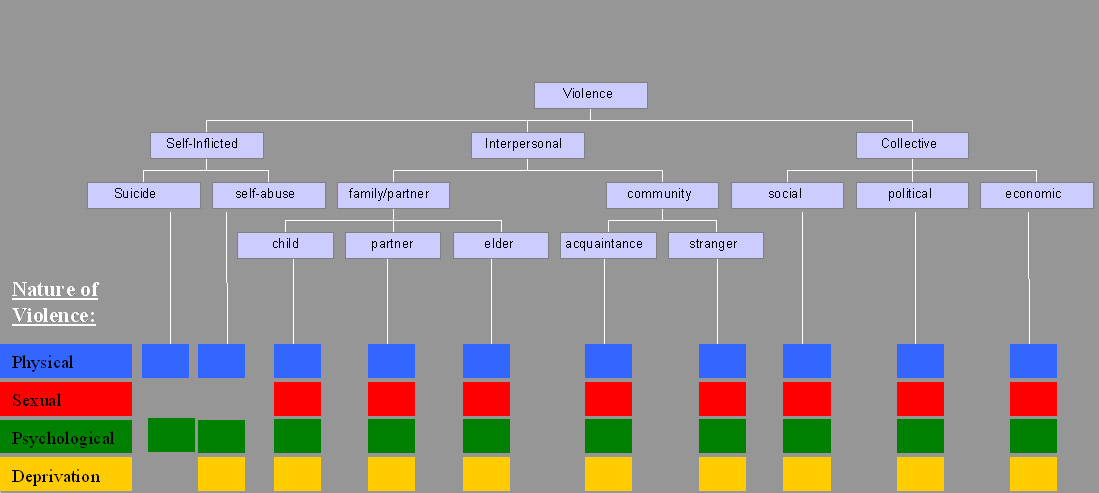

Categories Typology of violence[3] The World Health Organization (WHO) divides violence into three broad categories: self-directed, interpersonal, and collective.[3] This categorization differentiates between violence inflicted to and by oneself, by another individual or a small group, and by larger groups such as states. Alternatively, violence can primarily be classified as either instrumental or hostile.[4] |

カテゴリー 暴力の類型[3] 世界保健機関(WHO)は暴力を大きく三つのカテゴリーに分類する:自己指向型、対人型、集団型である[3]。この分類は、自身に対して加えられる暴力と 自身によって加えられる暴力、個人または小集団によって加えられる暴力、国家などの大規模集団によって加えられる暴力を区別するものである。あるいは、暴 力は主に手段的暴力と敵対的暴力のいずれかに分類することもできる[4]。 |

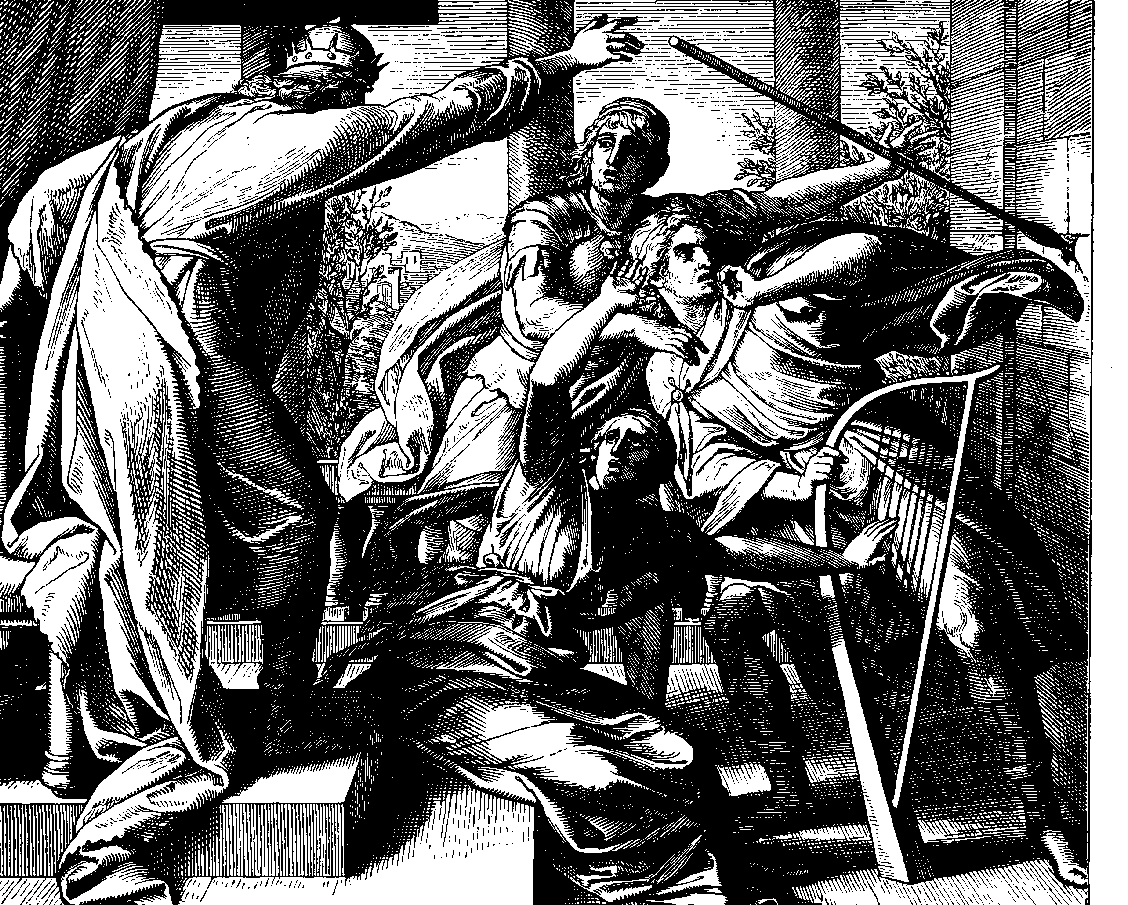

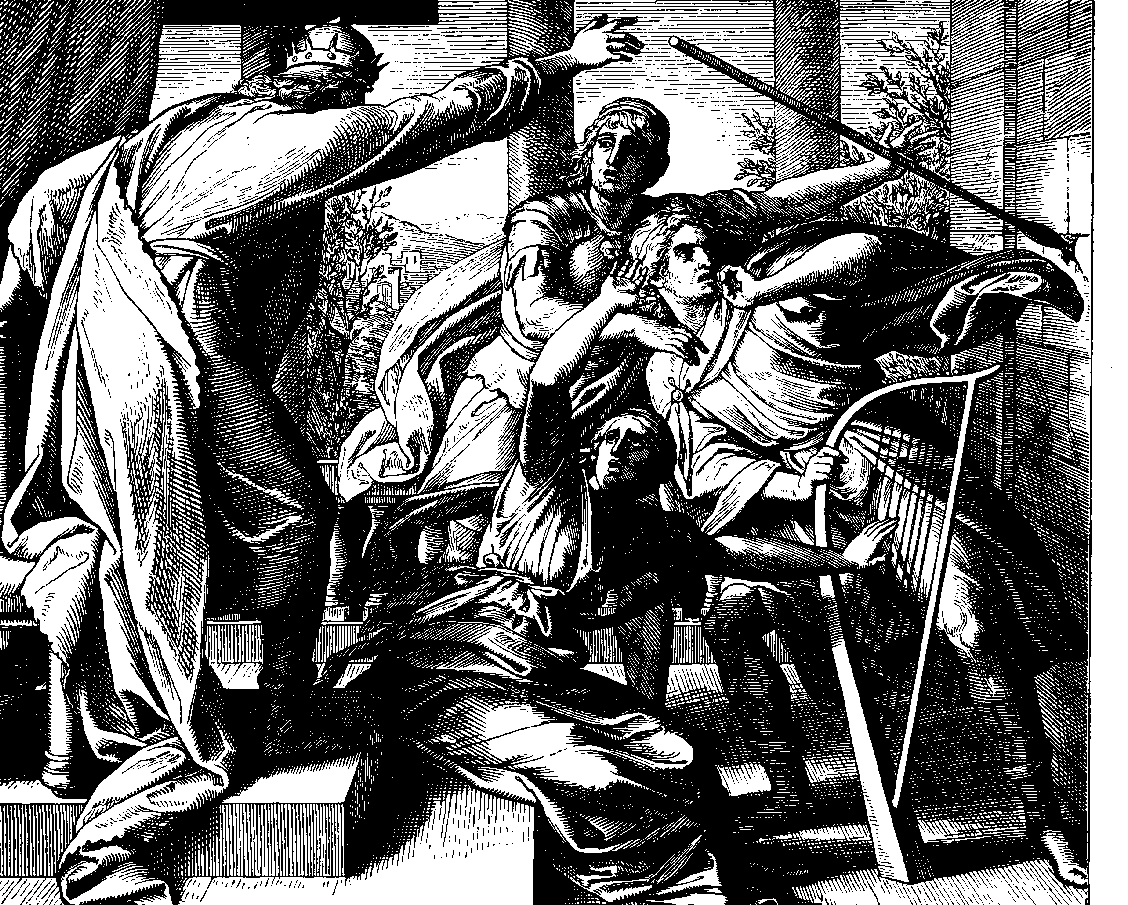

| Self-inflicted Self-inflicted violence comes in two forms. The first is suicidal behaviour, which includes suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts. The second is self-harm, which includes acts such as self-mutilation.  Cain slaying Abel, by Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1600 |

自傷行為 自傷行為には二つの形態がある。一つは自殺行為であり、自殺念慮や自殺企図を含む。もう一つは自傷行為であり、自傷行為には自傷行為などが含まれる。  カインがアベルを殺す、ピーター・パウル・ルーベンス作、約1600年 |

| Collective See also: Economic violence, Political violence, Slow violence, and Structural violence  Massacre of Polish civilians during Nazi Germany's occupation of Poland, December 1939 According to WHO, collective violence refers to "the instrumental use of violence by people who identify themselves as members of a group – whether this group is transitory or has a more permanent identity – against another group or set of individuals in order to achieve political, economic or social objectives".[5]: 82 Collective violence may be "targeted"[6][7][8][9][10][11] or stochastic. Political violence includes conflicts led by communities, by states, and by other kinds of groups. The most extreme form of collective violence is when conflicts are prolonged, large-scale, and political: war.[12] Explaining wars requires multi-factorial analysis.[13] Economic violence includes attacks motivated by economic gain—such as attacks carried out with the purpose of disrupting economic activity, denying access to essential services, or creating economic division and fragmentation. Slow violence is often invisible, gradual, and structural; it obtains through degradation, attrition, and pollution.[14] Structural violence is a form of violence wherein some social structure or social institution may harm people by preventing them from meeting their basic needs or rights. |

集団的 関連項目:経済的暴力、政治的暴力、スロー・バイオレンス、構造的暴力  ナチス・ドイツによるポーランド占領下でのポーランド民間人虐殺、1939年12月 WHOによれば、集団的暴力とは「政治的、経済的、社会的目標を達成するために、自らをグループの一員と認識する人々(そのグループが一時的なものであ れ、より恒久的なアイデンティティを持つものであれ)が、別のグループまたは個人集団に対して意図的に暴力を行使すること」を指す[5]: 82 。集団 的暴力は「標的型」[6][7][8][9][10][11] あるいは確率的である。 政治的暴力には、共同体、国家、その他の集団が主導する紛争が含まれる。集団的暴力の最も極端な形態は、紛争が長期化し、大規模で、政治的なものとなる場合、すなわち戦争である。[12] 戦争を説明するには多因子分析が必要である。[13] 経済的暴力には、経済的利益を動機とする攻撃が含まれる。例えば、経済活動を妨害する目的で実行される攻撃、必須サービスへのアクセスを拒否する攻撃、あるいは経済的分断や断片化を生み出す攻撃などである。 スロー暴力は往々にして目に見えず、漸進的で、構造的である。それは劣化、消耗、汚染を通じて達成される。[14] 構造的暴力とは、ある社会構造や社会制度が、人々の基本的ニーズや権利を満たすことを妨げることで害を及ぼす暴力形態である。 |

Interpersonal Saul attacks David (who had been playing music to help Saul feel better), 1860 woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld Interpersonal violence can be subdivided in many ways: types of abuse (physical, emotional, etc); locations where it occurs (home, work, etc); age disparity between the persons in the relationship (child, elder). It can affect the victims' other relationships in the short- and long-terms.[15] Location See also: Domestic violence, Workplace violence, School violence, and Prison violence Intimate partner violence (or domestic violence) involves physical, sexual and emotional violence by an intimate partner or ex-partner. Although males can also be victims, intimate partner violence disproportionately affects females. It commonly occurs against girls within child marriages and early/forced marriages. Among romantically involved but unmarried adolescents it is sometimes called “dating violence”.[16] A recent theory named "The Criminal Spin" suggests a mutual flywheel effect between partners that is manifested by an escalation in the violence.[17] A violent spin may occur in any other forms of violence, but in Intimate partner violence the added value is the mutual spin, based on the unique situation and characteristics of intimate relationship. The primary prevention strategy with the best evidence for effectiveness for intimate partner violence is school-based programming for adolescents to prevent violence within dating relationships.[18] Evidence is emerging for the effectiveness of several other primary prevention strategies—those that: combine microfinance with gender equality training;[19] promote communication and relationship skills within communities; reduce access to, and the harmful use of alcohol; and change cultural gender norms.[20] |

対人関係 サウルがダビデを襲う(ダビデはサウルを慰めるために音楽を奏でていた)。1860年、ユリウス・シュノール・フォン・カロルスフェルトによる木版画 対人暴力は様々な方法で分類できる:虐待の種類(身体的、精神的など)、発生場所(家庭、職場など)、関係者の年齢差(子供、高齢者)。被害者の他の関係性にも短期的・長期的に影響を及ぼすことがある。[15] 発生場所 関連項目:家庭内暴力、職場暴力、学校暴力、刑務所内暴力 親密なパートナー間暴力(または家庭内暴力)とは、親密なパートナーまたは元パートナーによる身体的・性的・精神的暴力を指す。男性も被害者となり得る が、この暴力は女性に特に多く見られる。児童婚や早期・強制結婚における少女への暴力が典型的である。恋愛関係にある未婚の青少年間では「デート暴力」と 呼ばれることもある。[16] 「犯罪的スパイラル」と呼ばれる最近の理論は、暴力のエスカレーションとして現れるパートナー間の相互的な増幅効果を示唆している。[17] 暴力的なスパイラルは他のあらゆる形態の暴力でも発生しうるが、親密なパートナー間暴力における付加価値は、親密な関係という特有の状況と特性に基づく相 互的なスパイラルにある。 親密なパートナー間暴力に対する最も効果的な一次予防戦略は、デート関係内での暴力を防止するための青少年向け学校プログラムである。[18] その他の効果的な一次予防戦略として、以下の取り組みが明らかになりつつある:マイクロファイナンスとジェンダー平等教育の組み合わせ[19]、地域社会 内でのコミュニケーション能力・関係構築スキルの促進、アルコールへのアクセス制限と有害使用の削減、文化的ジェンダー規範の変革である。[20] |

| Age disparity See also: Child abuse and Elder abuse Violence against children includes all forms of violence against people under 18 years old, whether perpetrated by parents or other caregivers, peers, romantic partners, or strangers.[16] Maltreatment (including violent punishment) involves physical, sexual and psychological/emotional violence; and neglect of infants, children and adolescents by parents, caregivers and other authority figures, most often in the home but also in settings such as schools and orphanages. It includes all types of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligence and commercial or other child exploitation, which results in actual or potential harm to the child's health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust, or power. Exposure to intimate partner violence is also sometimes included as a form of child maltreatment.[21] There are no reliable global estimates for the prevalence of child maltreatment. Data for many countries, especially low- and middle-income countries, are lacking. Current estimates vary widely depending on the country and the method of research used. Approximately 20% of women and 5–10% of men report being sexually abused as children, while 25–50% of all children report being physically abused.[3][22] Exposure to any form of trauma, particularly in childhood, can increase the risk of mental illness and suicide; smoking, alcohol and substance abuse; chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes and cancer; and social problems such as poverty, crime and violence.[23] Child maltreatment is a global problem with serious lifelong consequences.[24] It is complex and difficult to study.[24] Consequences of child maltreatment include impaired lifelong physical and mental health, and social and occupational functioning (e.g. school, job, and relationship difficulties). These can ultimately slow a country's economic and social development.[25][26] Preventing child maltreatment before it starts is possible and requires a multisectoral approach. Effective prevention programmes support parents and teach positive parenting skills. Ongoing care of children and families can reduce the risk of maltreatment reoccurring and can minimize its consequences.[27][28] Elder maltreatment is a single or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust which causes harm or distress to an older person. While there is little information regarding the extent of maltreatment in elderly populations, especially in developing countries, it is estimated that 4–6% of elderly people in high-income countries have experienced some form of maltreatment at home[29][30] However, older people are often afraid to report cases of maltreatment to family, friends, or to the authorities. Data on the extent of the problem in institutions such as hospitals, nursing homes and other long-term care facilities are scarce. Elder maltreatment can lead to serious physical injuries and long-term psychological consequences. Elder maltreatment is predicted to increase as many countries are experiencing rapidly ageing populations. |

年齢格差 関連項目:児童虐待・高齢者虐待 児童に対する暴力とは、18歳未満の人々に対するあらゆる形態の暴力を指す。加害者が親やその他の養育者、同輩、恋愛相手、見知らぬ人であるかを問わな い。[16] 虐待(暴力的懲罰を含む)には、身体的・性的・心理的/情緒的暴力、ならびに親・養育者・その他の権威者による乳幼児・児童・青少年のネグレクトが含まれ る。これらは主に家庭内で発生するが、学校や孤児院などの環境でも見られる。これには、責任・信頼・権力関係において、児童の健康・生存・発達・尊厳に実 際的または潜在的な危害をもたらす、あらゆる形態の身体的・精神的虐待、性的虐待、ネグレクト、怠慢、商業的その他の児童搾取が含まれる。親密なパート ナー間暴力への曝露も、児童虐待の一形態として扱われることがある。[21] 児童虐待の発生率に関する信頼できる世界的な推計値は存在しない。多くの国々、特に低・中所得国ではデータが不足している。現在の推計値は国や研究方法に よって大きく異なる。女性の約20%、男性の5~10%が児童期の性的虐待を報告している一方、全児童の25~50%が身体的虐待を報告している。[3] [22] あらゆる形態のトラウマ体験、特に幼少期のものは、精神疾患や自殺のリスク増加、喫煙・アルコール・薬物乱用、心臓病・糖尿病・がんなどの慢性疾患、貧 困・犯罪・暴力といった社会問題のリスクを高める。[23] 児童虐待は深刻な生涯にわたる影響を伴う世界的課題である。[24] その研究は複雑で困難である。[24] 児童虐待の結果には、生涯にわたる身体的・精神的健康の障害、社会的・職業的機能(例:学校、仕事、人間関係の問題)の障害が含まれる。これらは最終的に 国の経済的・社会的発展を遅らせる可能性がある。[25][26] 児童虐待は発生前に予防可能であり、多部門的なアプローチが必要である。効果的な予防プログラムは、親を支援し、積極的な子育てスキルを教えるものであ る。子どもと家族への継続的なケアは、虐待の再発リスクを減らし、その結果を最小限に抑えることができる。[27][28] 高齢者虐待とは、信頼関係が期待されるあらゆる関係性において発生する、単発または反復的な行為、あるいは適切な行動の欠如であり、高齢者に危害や苦痛を もたらすものである。特に発展途上国における高齢者虐待の実態に関する情報は乏しいが、高所得国では高齢者の4~6%が何らかの家庭内虐待を経験している と推定されている[29][30] しかし高齢者は、虐待事例を家族や友人、当局に報告することを恐れることが多い。病院、介護施設、その他の長期療養施設などにおける問題の規模に関する データは乏しい。高齢者虐待は深刻な身体的損傷や長期的な心理的影響を招く可能性がある。多くの国で急速な高齢化が進む中、高齢者虐待は増加すると予測さ れている。 |

| Types of abuse See also: Psychological abuse, Sexual violence, and Verbal abuse  Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall (JBM-HH) roundtable addressing digital stalking, ties to intimate partner violence Psychological (or emotional) violence includes restricting a person's movements, denigration, ridicule, threats and intimidation, discrimination, rejection and other non-physical forms of hostile treatment.[16]  Meeting of victims of sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sexual violence is any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed against a person's sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting. It includes rape, defined as the physically forced or otherwise coerced penetration of the vulva or anus with a penis, other body part or object.[31] An anthropological concept,"everyday violence" may refer to the incorporation of different forms of violence (mainly political violence) into daily practices.[32][33] Sexual violence has serious short- and long-term consequences on physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health for victims and for their children as described in the section on intimate partner violence. If perpetrated during childhood, sexual violence can lead to increased smoking,[34] drug and alcohol misuse, and risky sexual behaviors in later life. It is also associated with perpetration of violence and being a victim of violence. Many of the risk factors for sexual violence are the same as for domestic violence. Risk factors specific to sexual violence perpetration include beliefs in family honor and sexual purity, ideologies of male sexual entitlement and weak legal sanctions for sexual violence. Few interventions to prevent sexual violence have been demonstrated to be effective. School-based programmes to prevent child sexual abuse by teaching children to recognize and avoid potentially sexually abusive situations are run in many parts of the world and appear promising, but require further research. To achieve lasting change, it is important to enact legislation and develop policies that protect women; address discrimination against women and promote gender equality; and help to move the culture away from violence.[20] |

虐待の種類 関連項目:心理的虐待、性的暴力、言葉による虐待  マイヤー・ヘンダーソン・ホール統合基地(JBM-HH)におけるデジタルストーキングと親密なパートナー間暴力の関連性を議論する円卓会議 心理的(または感情的)暴力には、人格の行動制限、貶め、嘲笑、脅迫と威嚇、差別、拒絶、その他の非物理的な敵対的扱いが含まれる。[16]  コンゴ民主共和国における性暴力被害者の集会。 性的暴力とは、いかなる性的行為、性的行為の要求、望まない性的発言や行為、人身売買行為、あるいは強制を用いて人格の性に対して向けられる行為を指す。 加害者と被害者の関係や場所を問わない。これにはレイプが含まれ、陰茎、その他の身体部位、または物体による膣または肛門への物理的強制またはその他の強 制的な挿入と定義される。[31] 人類学的概念である「日常的暴力」は、異なる形態の暴力(主に政治的暴力)が日常的実践に組み込まれることを指す場合がある。[32][33] 性的暴力は、親密なパートナーによる暴力の項で述べたように、被害者とその子供たちの身体的・精神的・性的・生殖の健康に深刻な短期的・長期的な影響を及 ぼす。児童期に性的暴力を受けた場合、成人後の喫煙率上昇[34]、薬物・アルコール乱用、危険な性行動につながる可能性がある。また、暴力の加害者とな ること、および暴力の被害者となることとも関連している。 性的暴力のリスク要因の多くは、家庭内暴力と共通している。性的暴力の加害に特化したリスク要因には、家族の名誉や性的純潔への信念、男性の性的権利を主張するイデオロギー、性的暴力に対する法的制裁の弱さなどが含まれる。 性暴力防止に効果的と証明された介入策はほとんどない。児童に性的虐待の可能性のある状況を認識・回避させる学校プログラムは世界中で実施され有望だが、 さらなる研究が必要だ。持続的な変化を実現するには、女性を保護する法律の制定と政策の策定、女性差別への対処と男女平等の推進、暴力から離れた文化への 転換が重要である[20]。 |

Impact A sculpture in Petah Tikva, Israel of a padlock on the warped barrel of a semi-automatic pistol, with the inscription "stop violence!" in (Hebrew: !די לאלימות) The Institute for Economics and Peace, estimated that the economic impact of violence and conflict on the global economy, the total economic impact of violence on the world economy in 2024 was estimated to be $17.5 trillion.[35] The incidence of violence can lead to adverse health effects. Mental health issues include depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicide. Physical health issues include cardiovascular diseases and premature mortality. Health effects can be cumulative.[36] Intimate partner and sexual violence have serious short- and long-term physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health problems for victims and for their children, and lead to high social and economic costs. These include both fatal and non-fatal injuries, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.[37] |

影響 イスラエルのペタ・ティクヴァにある彫刻。半自動拳銃の歪んだ銃身に南京錠がかけられ、「暴力を止めろ!」(ヘブライ語: !די לאלימות)と刻まれている。 経済平和研究所の推計によれば、暴力と紛争が世界経済に与える経済的影響は、2024年時点で総額17.5兆ドルと試算されている。[35] 暴力の発生は健康への悪影響を招く。精神健康問題にはうつ病、不安障害、心的外傷後ストレス障害、自殺が含まれる。身体健康問題には心血管疾患や早期死亡がある。健康への影響は累積的である。[36] 親密なパートナーによる暴力や性的暴力は、被害者とその子供たちに深刻な短期的・長期的な身体的、精神的、性的、生殖に関する健康問題をもたらし、高い社 会的・経済的コストを招く。これには致死的な負傷と非致死的な負傷、うつ病や心的外傷後ストレス障害、意図しない妊娠、HIVを含む性感染が含まれる。 [37] |

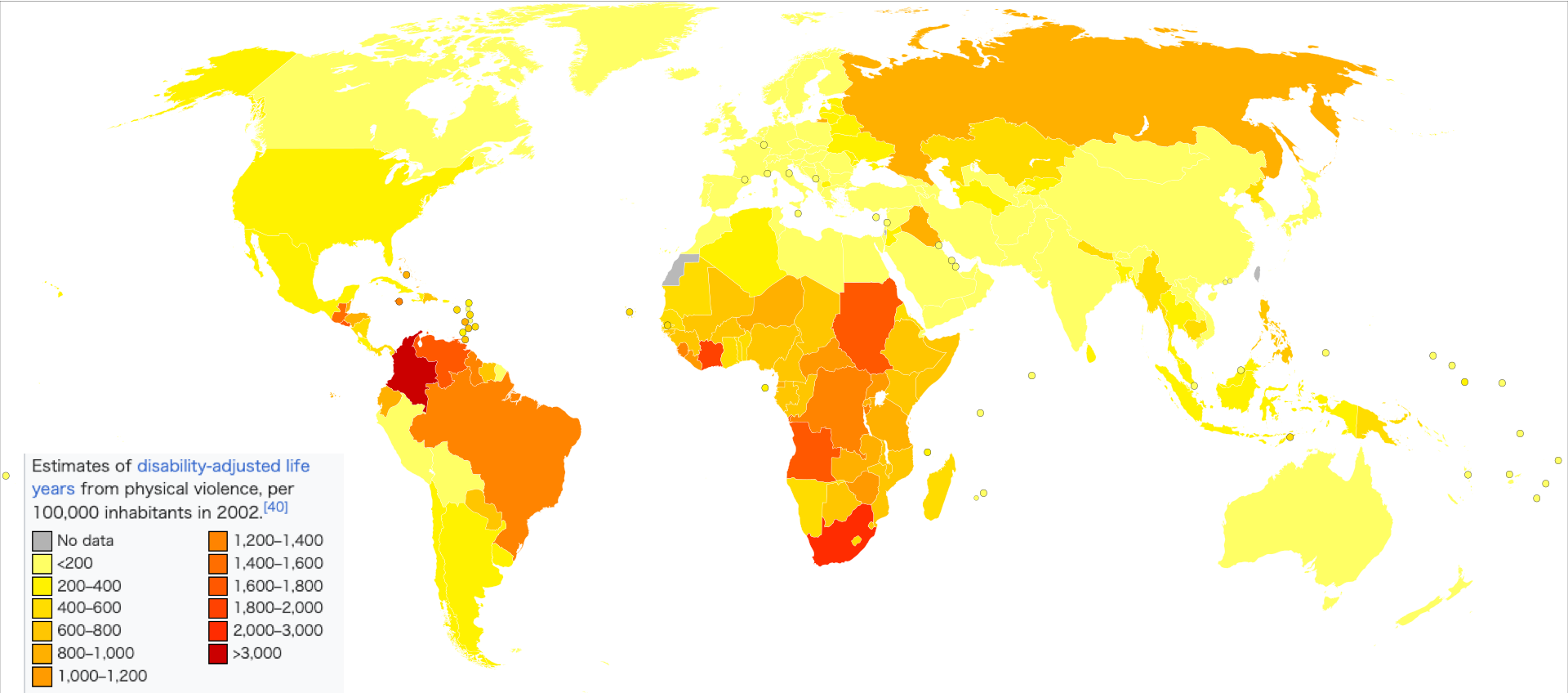

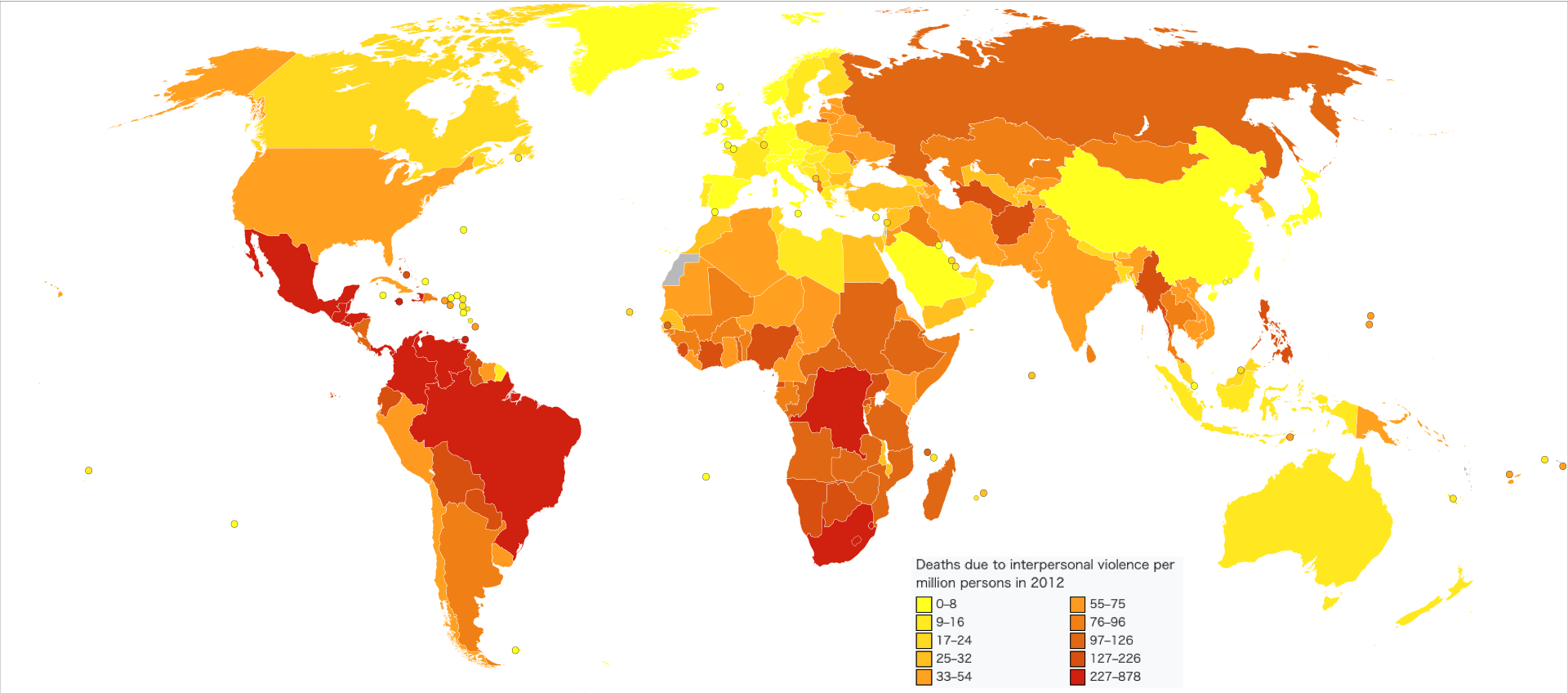

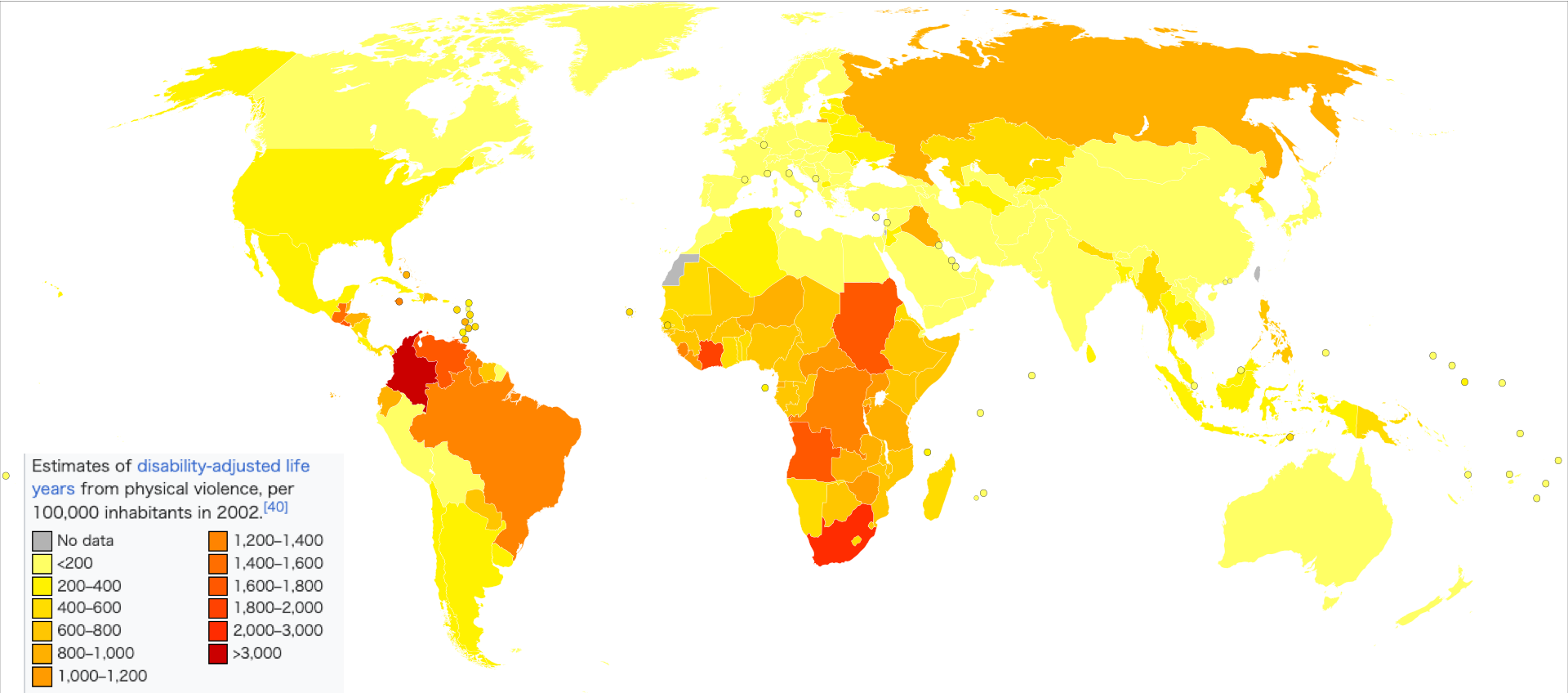

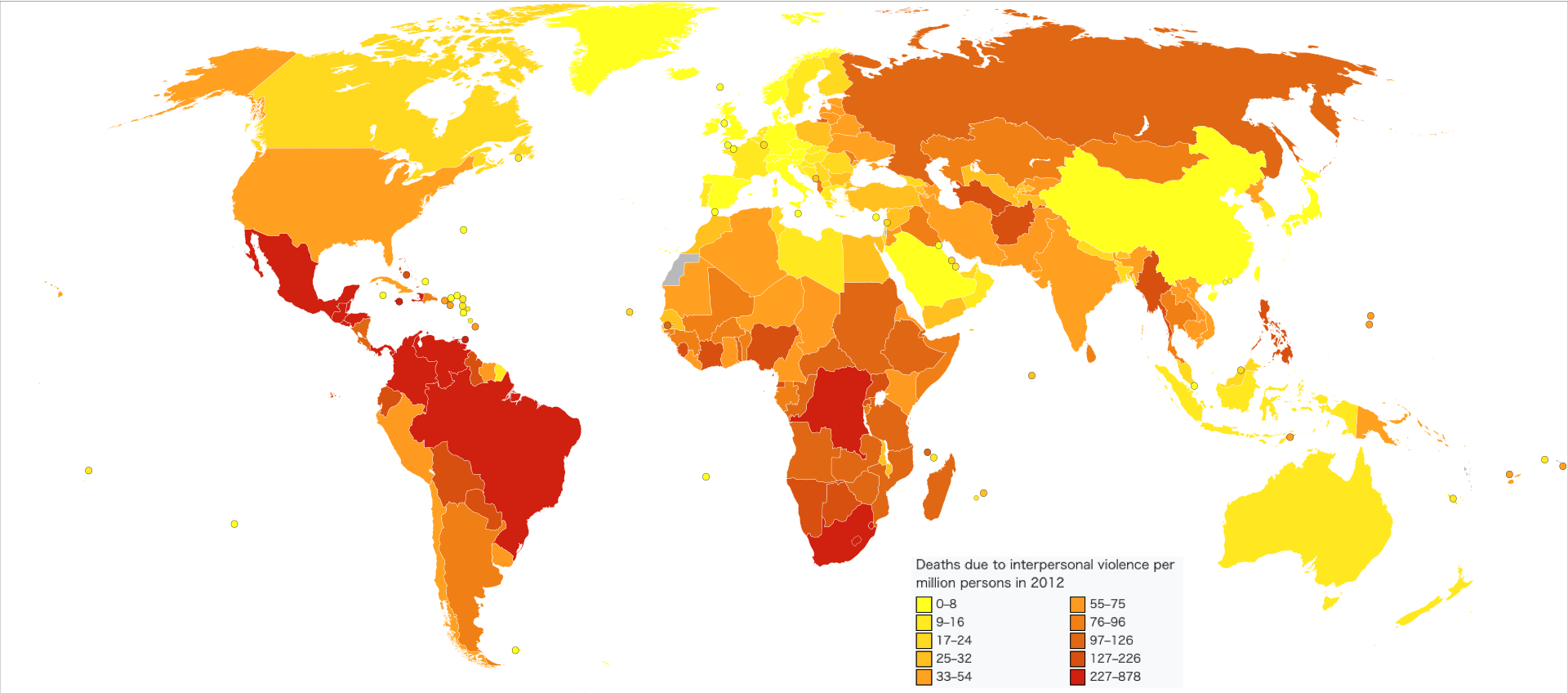

| Prevalence Injuries and violence are a significant cause of death and burden of disease in all countries; however, they are not evenly distributed across or within countries.[23] Violence-related injuries kill 1.25 million people every year, as of 2024.[23] This is relatively similar to 2014 (1.3 million people or 2.5% of global mortality), 2013 (1.28 million people) and 1990 (1.13 million people).[5]: 2 [38] For people aged 15–44 years, violence is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide, as of 2014.[5]: 2 Between 1990 and 2013, age-standardised death rates fell for self-harm and interpersonal violence.[38]: 139 Of the deaths in 2013, roughly 842,000 were attributed to suicide, 405,000 to interpersonal violence, and 31,000 to collective violence and legal intervention.[38] For each single death due to violence, there are dozens of hospitalizations, hundreds of emergency department visits, and thousands of doctors' appointments.[39] Furthermore, violence often has lifelong consequences for physical and mental health and social functioning and can slow economic and social development. It's particularly the case if it happened in childhood.[23] In 2013, of the estimated 405,000 deaths due to interpersonal violence globally, assault by firearm was the cause in 180,000 deaths, assault by sharp object was the cause in 114,000 deaths, and the remaining 110,000 deaths from other causes.[38]  Estimates of disability-adjusted life years from physical violence, per 100,000 inhabitants in 2002.[40] No data <200 200–400 400–600 600–800 800–1,000 1,000–1,200 1,200–1,400 1,400–1,600 1,600–1,800 1,800–2,000 2,000–3,000 >3,000  Deaths due to interpersonal violence per million persons in 2012 0–8 9–16 17–24 25–32 33–54 55–75 76–96 97–126 127–226 227–878 As of 2010, all forms of violence resulted in about 1.34 million deaths up from about 1 million in 1990.[41] Suicide accounts for about 883,000, interpersonal violence for 456,000 and collective violence for 18,000.[41] Deaths due to collective violence have decreased from 64,000 in 1990.[41] By way of comparison, the 1.5 millions deaths a year due to violence is greater than the number of deaths due to tuberculosis (1.34 million), road traffic injuries (1.21 million), and malaria (830'000), but slightly less than the number of people who die from HIV/AIDS (1.77 million).[42] For every death due to violence, there are numerous nonfatal injuries. In 2008, over 16 million cases of non-fatal violence-related injuries were severe enough to require medical attention. Beyond deaths and injuries, forms of violence such as child maltreatment, intimate partner violence, and elder maltreatment have been found to be highly prevalent. In the last 45 years, suicide rates have increased by 60% worldwide.[43] Suicide is among the three leading causes of death among those aged 15–44 years in some countries, and the second leading cause of death in the 10–24 years age group.[44] These figures do not include suicide attempts which are up to 20 times more frequent than suicide.[43] Suicide was the 16th leading cause of death worldwide in 2004 and is projected to increase to the 12th in 2030.[45] Although suicide rates have traditionally been highest among the male elderly, rates among young people have been increasing to such an extent that they are now the group at highest risk in a third of countries, in both developed and developing countries.[46] Rates and patterns of violent death vary by country and region. In recent years, homicide rates have been highest in developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean and lowest in East Asia, the western Pacific, and some countries in northern Africa.[47] Studies show a strong, inverse relationship between homicide rates and both economic development and economic equality. Poorer countries, especially those with large gaps between the rich and the poor, tend to have higher rates of homicide than wealthier countries. Homicide rates differ markedly by age and sex. Gender differences are least marked for children. For the 15 to 29 age group, male rates were nearly six times those for female rates; for the remaining age groups, male rates were from two to four times those for females.[48] Studies in a number of countries show that, for every homicide among young people age 10 to 24, 20 to 40 other young people receive hospital treatment for a violent injury.[3] Forms of violence such as child maltreatment and intimate partner violence are highly prevalent. Approximately 20% of women and 5–10% of men report being sexually abused as children, while 25–50% of all children report being physically abused.[49] A WHO multi-country study found that between 15 and 71% of women reported experiencing physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner at some point in their lives.[50] Wars grab headlines, but the individual risk of dying violently in an armed conflict is today relatively low—much lower than the risk of violent death in many countries that are not suffering from an armed conflict. For example, between 1976 and 2008, African Americans were victims of 329,825 homicides.[51][52] Although there is a widespread perception that war is the most dangerous form of armed violence in the world, the average person living in a conflict-affected country had a risk of dying violently in the conflict of about 2.0 per 100,000 population between 2004 and 2007. This can be compared to the average world homicide rate of 7.6 per 100,000 people. This illustration highlights the value of accounting for all forms of armed violence rather than an exclusive focus on conflict related violence. Certainly, there are huge variations in the risk of dying from armed conflict at the national and subnational level, and the risk of dying violently in a conflict in specific countries remains extremely high. In Iraq, for example, the direct conflict death rate for 2004–07 was 65 per 100,000 people per year and, in Somalia, 24 per 100,000 people. This rate even reached peaks of 91 per 100,000 in Iraq in 2006 and 74 per 100,000 in Somalia in 2007.[53] Population-level surveys based on reports from victims estimate that between 0.3 and 11.5% of women reported experiencing sexual violence.[54] |

有病率 傷害と暴力は、全ての国において死亡と疾病負担の重要な原因である。しかし、それらは国全体や国内で均等に分布しているわけではない。[23] 暴力関連の傷害は、2024年時点で毎年125万人の人民を奪っている。[23] この数値は2014年(130万人、世界の死亡原因の2.5%)、2013年(128万人)、1990年(113万人)と比較的類似している。[5]: 2 [38] 2014年時点で、15~44歳の年齢層において、暴力は世界第4位の死因である。[5]: 2 1990年から2013年の間に、自殺行為および対人暴力による年齢調整死亡率は低下した。[38]: 139 2013年の死亡者数において、約84万2千人が自殺、40万5千人が対人暴力、3万1千人が集団的暴力及び法的介入に起因すると推定される。[38] 暴力による死亡1件につき、数十件の入院、数百件の救急外来受診、数千件の医師診察が発生する。[39] さらに暴力は、身体的・精神的健康や社会機能に生涯にわたる影響を及ぼし、経済的・社会的発展を阻害する。特に幼少期に被害を受けた場合、その傾向が強 い。[23] 2013年、世界で推定40万5千件の人間関係暴力による死亡のうち、銃器による暴行が18万件、鋭利な物による暴行が11万4千件、その他の原因による死亡が残り11万件を占めた。[38]  2002年における身体的暴力による障害調整生存年(DALY)の推計値(10万人あたり)。[40] データなし 200未満 200~400 400~600 600~800 800~1,000 1,000~1,200 1,200–1,400 1,400–1,600 1,600–1,800 1,800–2,000 2,000–3,000 >3,000  2012年における対人暴力による死亡者数(100万人格あたり) 0–8 9~16 17~24 25~32 33~54 55~75 76~96 97~126 127~226 227~878 2010年時点で、あらゆる形態の暴力による死亡者数は約134万人に達し、1990年の約100万人から増加した。[41] 自殺による死亡は約88万3000人、対人暴力による死亡は45万6000人、集団的暴力による死亡は1万8000人である。[41] 集団的暴力による死亡は1990年の6万4000人から減少している。[41] 比較すると、暴力による年間150万人の死亡数は、結核(134万人)、交通事故(121万人)、マラリア(83万人)による死亡数を上回るが、HIV/エイズ(177万人)による死亡者数にはわずかに及ばない。[42] 暴力による死亡者1人につき、多数の非致死的負傷者が存在する。2008年には、医療処置を必要とする重度の非致死的暴力関連負傷が1600万件以上発生 した。死亡や負傷に加え、児童虐待、配偶者間暴力、高齢者虐待といった形態の暴力も極めて広く蔓延していることが判明している。 過去45年間で、世界の自殺率は60%増加した。[43] 一部の国では、自殺は15~44歳の死因トップ3に入り、10~24歳の年齢層では死因第2位となっている。[44] これらの数値には自殺未遂は含まれておらず、自殺未遂は自殺の最大20倍の頻度で発生している。[43] 2004年には自殺は世界第16位の死因だったが、2030年には第12位に上昇すると予測されている。[45] 従来は高齢男性で自殺率が最も高かったが、若年層の自殺率が著しく上昇し、現在では先進国・発展途上国を問わず、3分の1の国で若年層が最も高いリスクグ ループとなっている。[46] 暴力による死亡の発生率とパターンは国や地域によって異なる。近年、殺人発生率が最も高いのはサハラ以南アフリカ、ラテンアメリカ・カリブ海地域の途上国 であり、最も低いのは東アジア、西太平洋地域、および北アフリカの一部諸国である。[47] 研究によれば、殺人発生率と経済発展度、経済的平等度の間には強い逆相関関係が認められる。貧しい国々、特に富裕層と貧困層の格差が大きい国では、豊かな 国に比べて殺人率が高い傾向にある。殺人率は年齢と性別によって著しく異なる。子どもの場合、性差は最も小さい。15歳から29歳の年齢層では、男性の殺 人率は女性の約6倍であった。その他の年齢層では、男性の殺人率は女性の2倍から4倍であった。[48] 複数の国での研究によれば、10歳から24歳の若年層における殺人事件1件につき、20人から40人の若者が暴力による負傷で入院治療を受けている。[3] 児童虐待や配偶者間暴力といった形態の暴力は極めて蔓延している。約20%の女性と5~10%の男性が児童期の性的虐待を報告し、全児童の25~50%が 身体的虐待を報告している。[49] WHOの多国間調査では、15~71%の女性が人生のどこかで配偶者による身体的・性的暴力を経験したと報告した。[50] 戦争はニュースの見出しを飾るが、武力紛争下で暴力的に死亡する個人のリスクは今日では比較的低い。武力紛争に苦悩していない多くの国々における暴力死の リスクよりもはるかに低い。例えば、1976年から2008年の間に、アフリカ系アメリカ人は329,825件の殺人事件の被害者となった。[51] [52] 戦争が世界で最も危険な武力暴力形態だという認識が広まっているが、紛争影響国に住む平均的な人格が2004年から2007年の間に紛争で暴力的な死を遂 げるリスクは、人口10万人あたり約2.0人であった。これは世界の平均殺人率(10万人あたり7.6人)と比較できる。この例は、紛争関連の暴力だけに 焦点を当てるのではなく、あらゆる形態の武力暴力を考慮することの重要性を浮き彫りにしている。確かに、武力紛争による死亡リスクは国民レベルや地方レベ ルで大きく異なり、特定の国々では紛争下での暴力による死亡リスクが依然として極めて高い。例えばイラクでは2004年から2007年の直接的な紛争死亡 率が年間10万人あたり65人、ソマリアでは24人であった。この死亡率は、2006年にはイラクで10万人あたり91人、2007年にはソマリアで10 万人あたり74人とピークに達した[53]。 被害者からの報告に基づく人口レベル調査では、女性の0.3~11.5%が性的暴力を経験したと報告している[54]。 |

| Factors Violence can be attributed to protective and risk factors.[55] The social ecological model divides factors into four levels: individual, relational, communal, and social.[56] Individual Individual risk factors include poor behavioral control, high emotional stress, low IQ, and antisocial beliefs or attitudes.[57] Individual protective factors include an intolerance towards deviance, higher IQ and GPA, elevated popularity and social skills, as well as religious beliefs.[57] Family protective factors include a connectedness and ability to discuss issues with family members or adults, parent/family use of constructive coping strategies, and consistent parental presence during at least one of the following: when awakening, when arriving home from school, at dinner time, or when going to bed.[57] Social protective factors include quality school relationships, close relationships with non-deviant peers, involvement in prosocial activities, and exposure to school climates that are: well supervised, use clear behavior rules and disciplinary approaches, and engage parents with teachers.[57] Relational Relational risk factors include authoritarian childrearing attitudes, inconsistent disciplinary practices, low emotional attachment to parents or caregivers, and low parental income and involvement.[57] A number of longitudinal studies suggest that the experience of physical punishment has a direct causal effect on later aggressive behaviors.[58] Cross-cultural studies have shown that greater prevalence of corporal punishment of children tends to predict higher levels of violence in societies. For instance, a 2005 analysis of 186 pre-industrial societies found that corporal punishment was more prevalent in societies which also had higher rates of homicide, assault, and war.[59] In the United States, domestic corporal punishment has been linked to later violent acts against family members and spouses.[60] The American family violence researcher Murray A. Straus believes that disciplinary spanking forms "the most prevalent and important form of violence in American families", whose effects contribute to several major societal problems, including later domestic violence and crime.[61] Communal Community risk factors include poverty, low community participation, and diminished economic opportunities.[57] Since violence is a matter of perception as well as a measurable phenomenon, psychologists have found variability in whether people perceive certain physical acts as "violent". For example, in a state where execution is a legalized punishment we do not typically perceive the executioner as "violent", though we may talk, in a more metaphorical way, of the state acting violently. Likewise, understandings of violence are linked to a perceived aggressor-victim relationship: hence psychologists have shown that people may not recognise defensive use of force as violent, even in cases where the amount of force used is significantly greater than in the original aggression.[62] The concept of violence normalization is known as socially sanctioned, or structural violence and is a topic of increasing interest to researchers trying to understand violent behavior.[63][64] medical anthropology,[65][66] psychology,[67] psychiatry,[68] philosophy,[69] and bioarchaeology.[70][71] An environment of great inequalities between people may cause those at the bottom to use more violence in attempts to gain status.[72] Social Social risk factors include social rejection, poor academic performance and commitment to school, and gang involvement or association with delinquent peers.[57] Research into the media and violence examines whether links between consuming media violence and subsequent aggressive and violent behaviour exists. Although some scholars had claimed media violence may increase aggression,[73] this view is coming increasingly in doubt both in the scholarly community[74] and was rejected by the US Supreme Court in the Brown v EMA case, as well as in a review of video game violence by the Australian Government (2010) which concluded evidence for harmful effects were inconclusive at best and the rhetoric of some scholars was not matched by good data. |

要因 暴力は保護要因と危険要因に帰せられる。[55] 社会生態学的モデルは要因を四つのレベルに分類する:個人、関係性、共同体、社会。[56] 個人 個人の危険要因には、行動制御の欠如、高い情緒的ストレス、低いIQ、反社会的信念や態度が含まれる。[57] 個人の保護的要因には、逸脱行為への不寛容、高いIQとGPA、高い人気と社会的スキル、宗教的信念が含まれる。[57] 家族の保護的要因には、家族や大人とのつながりと問題について話し合う能力、親/家族による建設的な対処戦略の使用、以下のいずれかの時間帯における親の 継続的な存在(起床時、学校からの帰宅時、夕食時、就寝時)が含まれる。[57] 社会的保護要因には、質の高い学校関係、逸脱行動のない仲間との親密な関係、利他的活動への参加、そして以下のような学校環境への接触が含まれる:十分な 監督が行われている、明確な行動規範と懲戒方針を用いている、保護者と教師が連携している。[57] 関係性 関係性リスク要因には、権威主義的な子育て態度、一貫性のない懲戒方法、保護者や養育者への感情的結びつきの弱さ、低い親の収入と関与が含まれる。 [57] 複数の縦断研究は、体罰の経験が後の攻撃的行動に直接的な因果関係を持つことを示唆している。[58] 異文化研究では、児童への体罰の普及率が高い社会ほど暴力水準も高い傾向が確認されている。例えば2005年の186の前工業化社会分析では、体罰がより 普及している社会ほど殺人、暴行、戦争の発生率も高いことが判明した。[59] 米国では、家庭内体罰が後の家族・配偶者に対する暴力行為と関連している。[60] 米国の家庭内暴力研究者マレー・A・ストラウスは、懲罰的スパンキングが「米国家庭で最も普遍的かつ重要な暴力形態」を形成し、その影響が後の家庭内暴力 や犯罪を含む複数の重大な社会問題に寄与すると主張している。[61] 共同体 地域社会のリスク要因には、貧困、地域参加の低さ、経済機会の減少が含まれる。[57] 暴力は測定可能な現象であると同時に認識の問題でもあるため、特定の身体的行為を「暴力的」と認識するか否かには個人差があると心理学者は指摘している。 例えば、死刑が合法的な刑罰である州では、通常、死刑執行人を「暴力的」とは認識しない。ただし、より隠喩的な意味で、州が暴力的に行動していると表現す ることはあり得る。同様に、暴力の理解は加害者と被害者の関係認識と結びついている。したがって、心理学者は、たとえ使用された力の量が最初の攻撃よりも 著しく大きい場合でも、人民が防衛的な力の行使を暴力として認識しない可能性があることを示している。[62] 暴力の正常化という概念は、社会的に容認された、あるいは構造的暴力として知られており、暴力的な行動を理解しようとする研究者たちの関心が高まっている テーマである。[63][64] 医療人類学[65][66]、心理学[67]、精神医学[68]、哲学[69]、生物考古学[70][71]。人々の間に大きな不平等が存在する環境で は、最下層の人々が地位獲得のために暴力を使う傾向が強まる。[72] 社会的 社会的危険因子には、社会的拒絶、学業不振や学校への関与不足、ギャングへの関与や非行仲間との交流が含まれる。[57] メディアと暴力に関する研究は、メディア暴力を消費することと、その後の攻撃的・暴力的な行動との間に因果関係が存在するかを検証している。一部の学者は メディア暴力が攻撃性を増大させると主張してきたが[73]、この見解は学術界において次第に疑問視されるようになっており[74]、米国最高裁のブラウ ン対EMA訴訟でも退けられた。またオーストラリア政府によるビデオゲーム暴力の検証(2010年)でも、有害な影響の証拠はせいぜい決定的とは言えず、 一部の学者の主張は確かなデータに裏付けられていないと結論づけられている。 |

| Prevention Scientific evidence about the effectiveness of interventions to prevent collective violence is lacking.[3] However, policies that facilitate reductions in poverty, that make decision-making more accountable, that reduce inequalities between groups, as well as policies that reduce access to biological, chemical, nuclear and other weapons have been recommended. When planning responses to violent conflicts, recommended approaches include assessing at an early stage who is most vulnerable and what their needs are, co-ordination of activities between various players and working towards global, national and local capabilities so as to deliver effective health services during the various stages of an emergency.[3] The criminal justice approach sees its main task as enforcing laws that proscribe violence and ensuring that "justice is done". The notions of individual blame, responsibility, guilt, and culpability are central to criminal justice's approach to violence and one of the criminal justice system's main tasks is to "do justice", i.e. to ensure that offenders are properly identified, that the degree of their guilt is as accurately ascertained as possible, and that they are punished appropriately. To prevent and respond to violence, the criminal justice approach relies primarily on deterrence, incarceration and the punishment and rehabilitation of perpetrators.[75] Criminal justice  A sign that calls to stop violence The threat and enforcement of physical punishment has been a tried and tested method of preventing some violence since civilisation began.[76] It is used in various degrees in most countries. The criminal justice approach, beyond justice and punishment, has traditionally emphasized indicated interventions, aimed at those who have already been involved in violence, either as victims or as perpetrators. One of the main reasons offenders are arrested, prosecuted, and convicted is to prevent further crimes—through deterrence (threatening potential offenders with criminal sanctions if they commit crimes), incapacitation (physically preventing offenders from committing further crimes by locking them up) and through rehabilitation (using time spent under state supervision to develop skills or change one's psychological make-up to reduce the likelihood of future offences).[77] In recent decades in many countries in the world, the criminal justice system has taken an increasing interest in preventing violence before it occurs. For instance, much of community and problem-oriented policing aims to reduce crime and violence by altering the conditions that foster it—and not to increase the number of arrests. Indeed, some police leaders have gone so far as to say the police should primarily be a crime prevention agency.[78] Juvenile justice systems—an important component of criminal justice systems—are largely based on the belief in rehabilitation and prevention. In the US, the criminal justice system has, for instance, funded school- and community-based initiatives to reduce children's access to guns and teach conflict resolution. Despite this, force is used routinely against juveniles by police.[79] In 1974, the US Department of Justice assumed primary responsibility for delinquency prevention programmes and created the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, which has supported the "Blueprints for violence prevention" programme at the University of Colorado Boulder.[80] |

予防 集団的暴力の予防策の有効性に関する科学的根拠は不足している。[3] しかし、貧困削減を促進する政策、意思決定の責任性を高める政策、集団間の不平等を減らす政策、そして生物兵器・化学兵器・核兵器その他の兵器へのアクセスを制限する政策が推奨されている。 暴力紛争への対応を計画する際、推奨されるアプローチには、早期段階で最も脆弱な立場にある者とそのニーズを評価すること、様々な関係者間の活動を調整す ること、そして緊急事態の各段階で効果的な健康サービスを提供できるよう、グローバル、国民、地域の能力構築に取り組むことが含まれる。[3] 刑事司法アプローチは、その主な任務を、暴力を禁じる法律の執行と「正義が実現される」ことの確保と見なしている。個人の非難、責任、有罪、および有責性 の概念は、暴力に対する刑事司法のアプローチの中核を成す。刑事司法制度の主要な任務の一つは「正義を実行する」こと、すなわち、犯罪者を適切に特定し、 その有罪の程度を可能な限り正確に確認し、適切な処罰を与えることを保証することである。暴力の予防と対応において、刑事司法アプローチは主に抑止力、収 監、加害者の処罰と更生に依存している。[75] 刑事司法  暴力停止を求める標識 身体的処罰の脅威と執行は、文明が始まって以来、一部の暴力を防止する実証済みの方法である。[76] ほとんどの国で様々な程度で使用されている。刑事司法のアプローチは、正義と処罰を超えて、伝統的に、被害者または加害者として既に暴力に関与した者を対 象とした、示された介入を重視してきた。犯罪者が逮捕・起訴・有罪判決を受ける主な理由の一つは、抑止(犯罪を犯せば刑事制裁を受けると潜在的な犯罪者に 警告すること)、隔離(犯罪者を拘禁することで物理的に再犯を防止すること)、更生(国家の監督下で過ごす時間を活用し、技能を習得したり心理的構造を変 えたりして将来の犯罪発生確率を低下させること)を通じて、さらなる犯罪を防ぐためである。[77] 近年、世界の多くの国々で刑事司法制度は、暴力が発生する前にそれを防ぐことにますます関心を寄せるようになった。例えば、地域警察活動や問題解決型警察 活動の多くは、逮捕件数を増やすことではなく、犯罪や暴力を助長する条件を変えることでそれらを減らすことを目指している。実際、警察の指導者の中には、 警察は主に犯罪予防機関であるべきだとまで主張する者もいる。[78] 刑事司法制度の重要な構成要素である少年司法制度は、更生と予防への信念に大きく基づいている。例えば米国では、刑事司法制度が学校や地域を基盤とした取 り組みに資金を提供し、子供たちの銃へのアクセスを減らし、紛争解決を教えるよう支援してきた。それにもかかわらず、警察は日常的に青少年に対して武力を 行使している[79]。1974年、米国司法省は非行防止プログラムの主要な責任を引き受け、青少年司法・非行防止局を設立した。同局はコロラド大学ボル ダー校の「暴力防止青写真」プログラムを支援している[80]。 |

| Public health In 1949, Gordon called for injury prevention efforts to be based on the understanding of causes, in a similar way to prevention efforts for communicable and other diseases.[81] In 1962, Gomez, referring to the WHO definition of health, stated that it is obvious that violence does not contribute to "extending life" or to a "complete state of well-being". He defined violence as an issue that public health experts needed to address and stated that it should not be the primary domain of lawyers, military personnel, or politicians.[82] Public health has begun to address violence only 30 years later, and only in the last 15 has it done so at the global level.[83] In 1996, the World Health Assembly adopted Resolution WHA49.25[84] which declared violence "a leading worldwide public health problem" and requested that the World Health Organization (WHO) initiate public health activities to (1) document and characterize the burden of violence, (2) assess the effectiveness of programmes, with particular attention to women and children and community-based initiatives, and (3) promote activities to tackle the problem at the international and national levels. The World Health Organization's initial response to this resolution was to create the Department of Violence and Injury Prevention and Disability and to publish the World report on violence and health (2002).[3] The case for the public health sector addressing interpersonal violence rests on four main arguments.[85] First, the significant amount of time health care professionals dedicate to caring for victims and perpetrators of violence has made them familiar with the problem and has led many, particularly in emergency departments, to mobilize to address it. The information, resources, and infrastructures the health care sector has at its disposal are an important asset for research and prevention work. Second, the magnitude of the problem and its potentially severe lifelong consequences and high costs to individuals and wider society call for population-level interventions typical of the public health approach. Third, the criminal justice approach, the other main approach to addressing violence (link to entry above), has traditionally been more geared towards violence that occurs between male youths and adults in the street and other public places—which makes up the bulk of homicides in most countries—than towards violence occurring in private settings such as child maltreatment, intimate partner violence and elder abuse—which makes up the largest share of non-fatal violence. Fourth, evidence is beginning to accumulate that a science-based public health approach is effective at preventing interpersonal violence. The World Health Organization has identified seven strategies to prevent violence supported by evidence:[86] 1. Developing safe, stable and nurturing relationships between children and their parents and caregivers; 2. Developing life skills in children and adolescents; 3. Reducing the availability and harmful use of alcohol; 4. Reducing access to guns, knives and pesticides; 5. Promoting gender equality to prevent violence against women; 6. Changing cultural and social norms that support violence; 7. Victim identification, care and support programmes. There is a strong relationship between levels of violence and modifiable factors in a country such as concentrated (regional) poverty, income and gender inequality, the harmful use of alcohol, and the absence of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships between children and parents. Evaluation studies are beginning to support community interventions that aim to prevent violence against women by promoting gender equality. For instance, evidence suggests that programmes that combine microfinance with gender equity training can reduce intimate partner violence.[87][88] School-based programmes such as Safe Dates programme in the United States of America[89][90] and the Youth Relationship Project in Canada[91] have been found to be effective for reducing dating violence. Rules or expectations of behaviour – norms – within a cultural or social group can encourage violence. Interventions that challenge cultural and social norms supportive of violence can prevent acts of violence and have been widely used, but the evidence base for their effectiveness is currently weak. The effectiveness of interventions addressing dating violence and sexual abuse among teenagers and young adults by challenging social and cultural norms related to gender is supported by some evidence.[92][93] Interventions to identify victims of interpersonal violence and provide effective care and support are critical for protecting health and breaking cycles of violence from one generation to the next. Examples for which evidence of effectiveness is emerging includes: screening tools to identify victims of intimate partner violence and refer them to appropriate services;[94] psychosocial interventions—such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy—to reduce mental health problems associated with violence, including post-traumatic stress disorder;[95] and protection orders, which prohibit a perpetrator from contacting the victim,[96][97] to reduce repeat victimization among victims of intim |

公衆健康 1949 年、ゴードンは、伝染病やその他の疾病の予防努力と同様に、傷害予防の取り組みは原因の理解に基づくべきだと訴えた。[81] 1962 年、ゴメスはWHOの健康定義に言及し、暴力は「寿命の延長」や「完全な幸福状態」に寄与しないことは明らかだと述べた。彼は暴力を公衆健康の専門家が取 り組むべき課題と定義し、弁護士や軍人、政治家の主要な領域であってはならないと述べた[82]。公衆健康が暴力問題に取り組み始めたのはそれから30年 後であり、世界的なレベルで取り組むようになったのはさらに15年後のことである。[83] 1996年、世界保健総会(WHA)は決議WHA49.25[84]を採択した。この決議は暴力を「世界的な公衆健康上の主要問題」と宣言し、世界保健機 関(WHO)に対し以下の公衆健康活動を開始するよう要請した:(1)暴力の負担を文書化し特徴づけること、 (2) 特に女性と子ども、地域社会に基づく取り組みに焦点を当てたプログラムの効果を評価すること、(3) 国際的・国民レベルで問題に取り組む活動を促進すること。WHOはこの決議への最初の対応として、暴力・傷害予防・障害部門を設置し、『暴力と健康に関す る世界報告(2002年)』を公表した。[3] 健康分野が対人暴力に取り組むべき根拠は、主に四つの論点に立脚する。[85] 第一に、医療従事者が暴力の被害者と加害者のケアに費やす多大な時間は、彼らにこの問題への理解を深めさせ、特に救急部門では多くの者がこの問題に対処す るために動員されるようになった。健康分野が有する情報、資源、インフラは、研究と予防活動にとって重要な資産である。第二に、問題の規模と、個人および 社会全体に及ぼす深刻な生涯にわたる影響や高コストは、公衆健康アプローチに典型的な集団レベルでの介入を必要とする。第三に、暴力対策のもう一つの主要 なアプローチである刑事司法アプローチ(上記項目へのリンク)は、伝統的に、路上やその他の公共の場における男性青少年と成人間の暴力(ほとんどの国で殺 人事件の大部分を占める)に向けられてきた。これに対し、児童虐待、配偶者間暴力、高齢者虐待といった私的空間で発生する暴力(非致死的な暴力の大部分を 占める)への対応は不十分である。第四に、科学的根拠に基づく公衆健康アプローチが対人暴力の予防に有効であるという証拠が蓄積され始めている。 世界保健機関(WHO)は、証拠に裏付けられた暴力予防のための7つの戦略を特定している[86]: 1. 子どもと親・養育者との間で安全で安定した養育関係を発展させること 2. 子どもと青少年の生活スキルを育成すること 3. アルコールの入手可能性と有害な使用を減らすこと 4. 銃器、刃物、農薬へのアクセスを減らすこと 5. 女性に対する暴力を防止するためのジェンダー平等を推進すること 6. 暴力を助長する文化的・社会的規範を変えること 7. 被害者特定、ケア、支援プログラムを実施すること 暴力の発生率と、各国の変更可能な要因(地域的な貧困の集中、所得・ジェンダーの不平等、アルコールの有害な使用、子どもと親の間に安全で安定し、養育的な関係が欠如していることなど)の間には強い相関関係がある。 ジェンダー平等を促進することで女性に対する暴力を防止する地域介入策を支持する評価研究が始まっている。例えば、マイクロファイナンスとジェンダー平等 研修を組み合わせたプログラムが親密なパートナー間暴力を減少させるとの証拠がある[87][88]。アメリカ合衆国の「セーフ・デーツ」プログラム [89][90]やカナダの「ユース・リレーションシップ・プロジェクト」[91]といった学校ベースのプログラムは、デート暴力を減少させるのに有効で あることが確認されている。 文化的・社会的集団内の行動規範(ルールや期待)は暴力を助長しうる。暴力支持的な文化的・社会的規範に異議を唱える介入は暴力行為を防止し得るため広く 用いられてきたが、その有効性に関する証拠基盤は現時点で弱い。性別に関連する社会的・文化的規範に異議を唱えることで、10代から若年成人層における デート暴力や性的虐待に対処する介入の有効性は、一部の証拠によって裏付けられている[92]。[93] 対人暴力の被害者を特定し、効果的なケアと支援を提供する介入は、健康を守り、世代を超えた暴力の連鎖を断ち切るために極めて重要である。有効性の証拠が 明らかになりつつある例としては、以下が挙げられる:親密なパートナーによる暴力の被害者を特定し適切なサービスへ紹介するためのスクリーニングツール [94]、暴力に関連する精神健康上の問題を軽減するための心理社会的介入(トラウマに焦点を当てた認知行動療法など)[95]、加害者が被害者に接触す ることを禁止する保護命令[96][97](これにより親密なパートナーによる暴力の被害者における再被害を減少させる)。 |

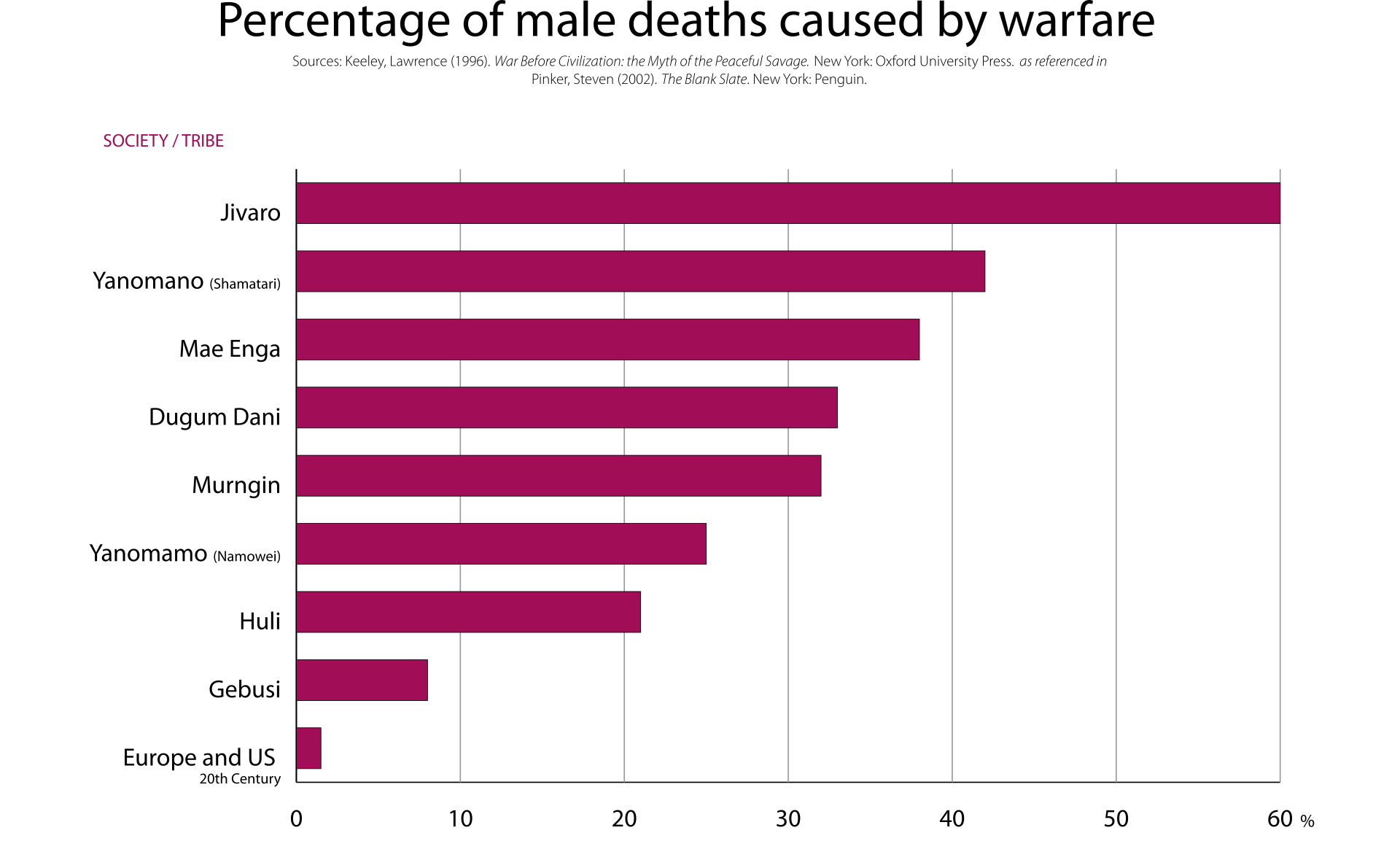

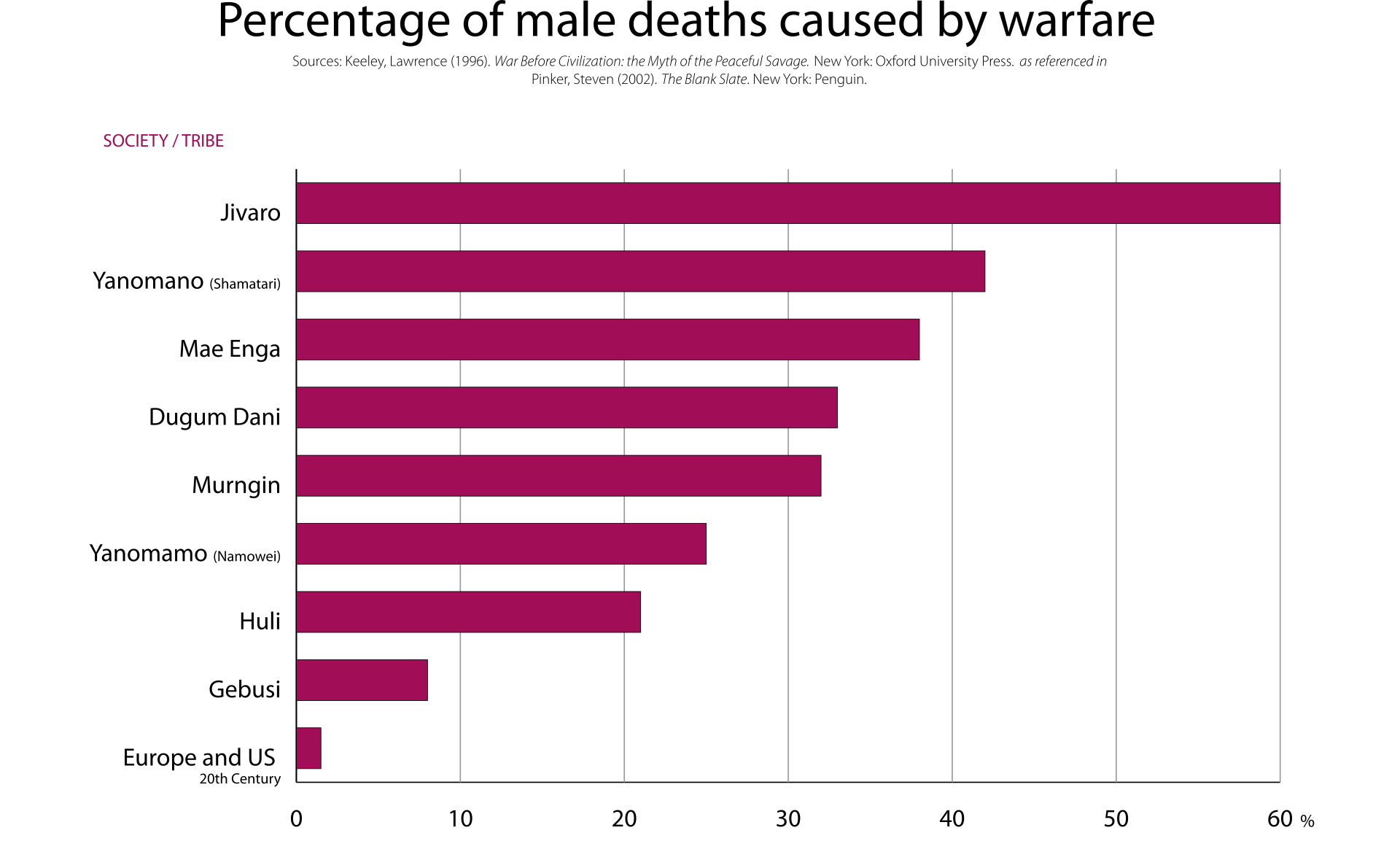

Bahrain's pro-democracy protesters killed by military, February 2011 Perspectives Historical "History of violence" redirects here. For other uses, see History of violence (disambiguation). Scientific evidence for warfare has come from settled, sedentary communities.[98] Some studies argue humans have a predisposition for violence (chimpanzees, also great apes, have been known to kill members of competing groups for resources like food).[99] A comparison across mammal species found that humans have a Paleolithic adult homicide rate of about 2%. This would be lower than some other animals, but still high.[100] However, this study took into account the infanticide rate by some other animals such as meerkats, but not of humans, where estimates of children killed by infanticide in the Mesolithic and Neolithic eras vary from 15 to 50 percent.[101] Other evidence suggests that organized, large-scale, militaristic, or regular human-on-human violence was absent for the vast majority of the human timeline,[102][103][104] and is first documented to have started only relatively recently in the Holocene, an epoch that began about 11,700 years ago, probably with the advent of higher population densities due to sedentism.[103] Social anthropologist Douglas P. Fry writes that scholars are divided on the origins of possible increase of violence—in other words, war-like behavior: There are basically two schools of thought on this issue. One holds that warfare... goes back at least to the time of the first thoroughly modern humans and even before then to the primate ancestors of the hominid lineage. The second positions on the origins of warfare sees war as much less common in the cultural and biological evolution of humans. Here, warfare is a latecomer on the cultural horizon, only arising in very specific material circumstances and being quite rare in human history until the development of agriculture in the past 10,000 years.[105] Jared Diamond in his books Guns, Germs and Steel and The Third Chimpanzee posits that the rise of large-scale warfare is the result of advances in technology and city-states. For instance, the rise of agriculture provided a significant increase in the number of individuals that a region could sustain over hunter-gatherer societies, allowing for development of specialized classes such as soldiers, or weapons manufacturers.  The percentages of men killed in war in eight tribal societies. (Lawrence H. Keeley, Archeologist, War Before Civilization) In academia, the idea of the peaceful pre-history and non-violent tribal societies gained popularity with the post-colonial perspective. The trend, starting in archaeology and spreading to anthropology reached its height in the late half of the 20th century.[106] However, some newer research in archaeology and bioarchaeology may provide evidence that violence within and among groups is not a recent phenomenon.[107] According to the book "The Bioarchaeology of Violence" violence is a behavior that is found throughout human history.[108] Lawrence H. Keeley at the University of Illinois writes in War Before Civilization that 87% of tribal societies were at war more than once per year, and that 65% of them were fighting continuously. He writes that the attrition rate of numerous close-quarter clashes, which characterize endemic warfare, produces casualty rates of up to 60%, compared to 1% of the combatants as is typical in modern warfare. "Primitive Warfare" of these small groups or tribes was driven by the basic need for sustenance and violent competition.[109] Fry explores Keeley's argument in depth and counters that such sources erroneously focus on the ethnography of hunters and gatherers in the present, whose culture and values have been infiltrated externally by modern civilization, rather than the actual archaeological record spanning some two million years of human existence. Fry determines that all present ethnographically studied tribal societies, "by the very fact of having been described and published by anthropologists, have been irrevocably impacted by history and modern colonial nation states" and that "many have been affected by state societies for at least 5000 years."[110] The relatively peaceful period since World War II is known as the Long Peace. Steven Pinker's 2011 book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, argued that modern society is less violent than in periods of the past, whether on the short scale of decades or long scale of centuries or millennia. He argues for a paleolithic homicide rate of 15%.[111] Pinker's analyses have also been criticized, concerning the statistical question of how to measure violence and whether it is in fact declining.[112][113][114] Pinker's observation of the decline in interpersonal violence echoes the work of Norbert Elias, who attributes the decline to a "civilizing process", in which the state's monopolization of violence, the maintenance of socioeconomic interdependencies or "figurations", and the maintenance of behavioural codes in culture all contribute to the development of individual sensibilities, which increase the repugnance of individuals towards violent acts.[115] According to a 2010 study, non-lethal violence, such as assaults or bullying appear to be declining as well.[116] Some scholars disagree with the argument that all violence is decreasing arguing that not all types of violent behaviour are lower now than in the past. They suggest that research typically focuses on lethal violence, often looks at homicide rates of death due to warfare, but ignore the less obvious forms of violence.[117] |

2011年2月、バーレーンで民主化を求める抗議者が軍によって殺害された 視点 歴史的 「暴力の歴史」はここへ転送される。その他の用法については「暴力の歴史 (曖昧さ回避)」を参照のこと。 戦争の科学的証拠は定住型社会から得られている[98]。一部の研究では、人類には暴力への素因があると主張されている(チンパンジーや他の大型類人猿 も、食料などの資源をめぐって敵対集団の成員を殺害することが知られている)[99]。哺乳類種間比較では、人類の旧石器時代における成人殺人率は約2% と判明した。これは他の動物より低いものの、依然として高い数値である[100]。ただしこの研究ではミーアキャットなど他動物の幼児殺害率を考慮した一 方、人類のそれは除外されている。中石器時代・新石器時代における幼児殺害の推定値は15~50%と幅がある。[101] 他の証拠によれば、組織化された大規模な軍事的、あるいは定期的な人間同士の暴力は、人類の歴史の大部分において存在しなかった[102][103] [104]。そして、そのような暴力の始まりが初めて記録されたのは、約11,700年前に始まった完新世において、おそらく定住生活による人口密度の増 加がきっかけとなった比較的最近のことである。[103] 社会人類学者ダグラス・P・フライは、暴力の増加(すなわち戦争的行動)の起源について学者の見解が分かれていると記している: この問題には基本的に二つの学説がある。一つは、戦争は少なくとも最初の完全な現代人類の時代まで遡り、さらに遡ればヒト科の祖先である霊長類にまで及ぶ とする立場だ。もう一方の学派は、戦争の起源を人間の文化的・生物学的進化においてはるかに稀な現象と位置づける。ここでは戦争は文化的地平線における後 発者であり、ごく特定の物質的状況下でのみ発生し、過去1万年の農業発展までは人類史上極めて稀であったと見る。[105] ジャレド・ダイアモンドは著書『銃・病原菌・鉄』および『第三のチンパンジー』において、大規模戦争の台頭は技術と都市国家の発展の結果であると主張して いる。例えば農業の出現は、狩猟採集社会に比べて地域が維持できる人口を大幅に増加させ、兵士や武器製造者といった専門職階層の出現を可能にした。  八つの部族社会における戦争で死亡した男性の割合(ローレンス・H・キーリー、考古学者『文明以前の戦争』より) 学界では、平和な先史時代や非暴力的な部族社会という考え方が、ポストコロニアルの視点と共に広まった。この傾向は考古学から始まり人類学へ広がり、20 世紀後半に頂点に達した[106]。しかし考古学や生物考古学における新たな研究は、集団内・集団間の暴力行為が近年の現象ではない可能性を示す証拠を提 供している[107]。『暴力の生物考古学』によれば、暴力は人類史を通じて見られる行動である[108]。 イリノイ大学のローレンス・H・キーリーは『文明以前の戦争』において、部族社会の87%が年に1回以上戦争状態にあり、65%が継続的に戦闘を繰り広げ ていたと記している。彼は、常態化した戦争の特徴である数多くの接近戦による消耗率が、最大60%の死傷率を生むと指摘する。これは現代戦争における戦闘 員の死傷率1%とは対照的である。こうした小集団や部族による「原始戦争」は、生存のための基本的欲求と暴力的な競争によって駆動されていた[109]。 フライはキーリーの主張を深く検証し、こうした資料が誤って現代の狩猟採集民の民族誌に焦点を当てていると反論する。彼らの文化や価値観は現代文明によっ て外部から浸透しており、人類の200万年にわたる存在を網羅する実際の考古学的記録ではないのだ。フライは、現在民族誌的に研究されている全ての部族社 会について、「人類学者によって記述され出版されたという事実そのものが、歴史と近代的な植民地国民国家によって取り返しのつかない影響を受けている」と 断じ、「多くの社会は少なくとも5000年にわたり国家社会の影響を受けてきた」と結論づけている。[110] 第二次世界大戦以降の比較的平和な時代は「ロング・ピース(長期平和)」として知られる。 スティーブン・ピンカーの2011年の著書『人間の本性における善の天使たち』は、現代社会は過去の数十年という短期間から数世紀・数千年という長期に至 るまで、いかなる時代よりも暴力的ではないと主張した。彼は旧石器時代の殺人率が15%であったと論じている[111]。ピンカーの分析は、暴力をどのよ うに測定するか、また実際に減少しているのかという統計上の問題に関して批判も受けている。[112][113][114] ピンカーが指摘する対人暴力の減少傾向は、ノルベルト・エリアスの研究と通じる。エリアスは、国家による暴力の独占、社会経済的相互依存関係(フィゲラシ オン)の維持、文化における行動規範の維持といった「文明化プロセス」が個人の感性を発達させ、暴力行為への嫌悪感を増大させたと説明する。[115] 2010年の研究によれば、暴行やいじめといった非致死的な暴力も同様に減少傾向にあるようだ。[116] 全ての暴力行為が減少しているという主張に異議を唱える学者もいる。彼らは、あらゆる種類の暴力行為が過去より減少しているわけではないと指摘する。研究 は通常、致死的な暴力、特に戦争による死亡率や殺人率に焦点を当てがちだが、より目立たない形態の暴力は無視されがちだというのである。[117] |

| Philosophical Max Weber stated that the state claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of force to cause harm practised within the confines of a specific territory. Law enforcement is the main means of regulating nonmilitary violence in society. Governments regulate the use of violence through legal systems governing individuals and political authorities, including the police and military. Civil societies authorize some amount of violence, exercised through the police power, to maintain the status quo and enforce laws. Hannah Arendt noted: "Violence can be justifiable, but it never will be legitimate [...] Its justification loses in plausibility the farther its intended end recedes into the future. No one questions the use of violence in self-defence, because the danger is not only clear but also present, and the end justifying the means is immediate".[118] Arendt made a clear distinction between violence and power. Most political theorists regarded violence as an extreme manifestation of power whereas Arendt regarded the two concepts as opposites.[119] Some philosophers have argued that any interpretation of reality is intrinsically violent.[120] Slavoj Žižek, in his book Violence, stated that "something violent is the very symbolization of a thing."[121] Johanna Oskala argues that while "the ontological violence of language does, in significant ways, sustain, enable, and encourage physical violence, it is a serious mistake to conflate them [...] Violence is understood to be ineliminable in the first sense, and this leads to its being treated as a fundamental in the second sense, too."[120] Both Foucault and Arendt considered the relationship between power and violence but concluded that while related they are distinct.[120]: 46 [clarification needed] In feminist philosophy, epistemic violence is the act of causing harm by an inability to understand the conversation of others due to ignorance. Some philosophers think this will harm marginalized groups.[122][123] Brad Evans states that violence "represents a violation in the very conditions constituting what it means to be human as such", "is always an attack upon a person's dignity, their sense of selfhood, and their future", and "is both an ontological crime ... and a form of political ruination".[124] Robert L. Holmes argues that however elusive its general definition may be, violence entails a moral wrong, insofar as "it is presumptively wrong to do violence to innocent persons."[125] He further argues that at least one necessary condition for the formulation of any potential moral alternative to violence in all its manifistations is the exploration of a philosophy of nonviolence which places a concern for the lives and the well being of individual persons at its moral center.[126][127] |

哲学的 マックス・ウェーバーは、国家が特定の領域内で危害を加えるための合法的な暴力行使の独占権を主張すると述べた。法執行は、社会における非軍事的暴力を規 制する主要な手段である。政府は、警察や軍を含む個人や政治権力を統制する法制度を通じて暴力行使を規制する。市民社会は現状維持と法執行のために、警察 権力を通じて行使される一定の暴力を認めている。 ハンナ・アーレントはこう指摘した。「暴力は正当化され得るが、決して合法化されることはない[…]その正当性は、意図された目的が未来へ遠ざかるほど説 得力を失う。自己防衛における暴力行使に疑問を呈する者はいない。危険が明白であるだけでなく差し迫っており、目的が手段を正当化する結果が即時的だから だ」[118]。アーレントは暴力と権力を明確に区別した。ほとんどの政治理論家は暴力を権力の極端な現れと見なしたが、アーレントは両概念を対極のもの と捉えた[119]。一部の哲学者は、現実のいかなる解釈も本質的に暴力的だと主張している[120]。スラヴォイ・ジジェクは著書『暴力』で「暴力的な ものは、まさに物事の象徴化そのものである」と述べている。[121] ヨハンナ・オスカラは「言語の存在論的暴力は確かに重要な形で物理的暴力を支え、可能にし、助長するが、両者を混同するのは重大な誤りである [...] 暴力は第一の意味において排除不可能と理解され、これが第二の意味においても根本的なものとして扱われる結果を招く」と論じている。[120] フーコーもアレントも権力と暴力の関係を考察したが、関連性は認めつつも両者は別物だと結論づけた。[120]: 46 [説明が必要] フェミニスト哲学において、認識論的暴力とは無知ゆえに他者の会話を理解できず害を及ぼす行為を指す。一部の哲学者はこれが境界化された集団を傷つけると考える。[122][123] ブラッド・エヴァンスは、暴力とは「人間であることの本質を構成する条件そのものへの侵害」であり、「常に人格の尊厳、自己意識、未来への攻撃」であり、「存在論的犯罪であると同時に政治的破滅の一形態」だと述べている。[124] ロバート・L・ホームズは、その一般的な定義がどれほど捉えどころのないものであれ、暴力は道徳的過ちを伴うと論じる。なぜなら「無実の人格に暴力を振る うことは、推定上間違っている」からだ[125]。彼はさらに、あらゆる形態の暴力に対する潜在的な道徳的代替案を構築するための少なくとも一つの必要条 件は、個人の生命と幸福を道徳的中心に据える非暴力の哲学を探求することだと主張する。[126][127] |

Religious Taliban beating woman in public  The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of French Protestants, 1572 These paragraphs are an excerpt from Religious violence.[edit] Religious violence, like all forms of violence, is a cultural process which is context-dependent and highly complex.[128] Thus, oversimplifications of religion and violence often lead to misguided understandings of the causes for acts of violence, as well as oversight of their rarity.[128] Violence is perpetrated for a wide variety of ideological reasons, and religion is generally only one of many contributing social and political factors that may foment it. For example, studies of supposed cases of religious violence often conclude that the violence was driven more by ethnic animosities than by religious worldviews.[129] Historical circumstances in conflicts often are not linear, but socially and politically complex.[130][131][132] Due to the complex nature of religion, violence, and the relationship between them, it is often difficult to discern whether religion is a significant cause of violence from all other factors.[133][130] Indeed, the link between religious belief and behavior is not linear. Decades of anthropological, sociological, and psychological research have all concluded that behaviors do not directly follow from religious beliefs and values because people's religious ideas tend to be fragmented, loosely connected, and context-dependent, just like other domains of culture and life.[134] Religions, ethical systems, and societies rarely promote violence as an end in of itself.[135] At the same time, there is often tension between a desire to avoid violence and the acceptance of justifiable uses of violence to prevent a perceived greater evil that permeates a culture.[135] |

宗教 タリバンが公衆の面前で女性を殴打  1572年、フランス・プロテスタントに対する聖バルトロメオの虐殺 これらの段落は宗教的暴力からの抜粋である。[編集] 宗教的暴力は、あらゆる形態の暴力と同様に、文脈に依存し極めて複雑な文化的プロセスである[128]。したがって、宗教と暴力の単純化は、暴力行為の原 因に対する誤った理解を招き、その稀少性を見落とすことにつながりやすい[128]。暴力は多様なイデオロギー的理由で行われ、宗教は一般的に、それを煽 る多くの社会的・政治的要因の一つに過ぎない。例えば、宗教的暴力とされる事例の研究では、暴力の背景には宗教的世界観よりも民族間の敵意が強く作用して いたと結論づけられることが多い。[129] 紛争における歴史的状況は直線的ではなく、社会的・政治的に複雑である。[130][131][132] 宗教と暴力、そして両者の関係性は複雑な性質を持つため、他のあらゆる要因から宗教が暴力の主要な原因であるかどうかを判断することは往々にして困難であ る。[133][130] 実際、宗教的信念と行動の関連性は直線的ではない。数十年にわたる人類学的・社会学的・心理学的研究はいずれも、人民の宗教的観念は他の文化的領域や生活 領域と同様に断片的で緩やかに結びつき、文脈依存的であるため、行動が宗教的信念や価値観から直接的に生じるわけではないと結論づけている。[134] 宗教、倫理体系、社会が、暴力そのものを目的として推奨することは稀である。[135] 同時に、暴力回避の願望と、文化に浸透するより大きな悪を防ぐための正当な暴力行使の受容との間には、しばしば緊張関係が存在する。[135] |

| Ahimsa De-escalation Fight-or-flight response Harm principle Hunting Legislative violence Non Violent Resistance (psychological intervention) Road rage Violence begets violence Violence in art |

非暴力 エスカレーションの回避 闘争・逃走反応 危害の原則 狩猟 立法による暴力 非暴力抵抗(心理的介入) ロードレイジ 暴力は暴力を生む 芸術における暴力 |

| Barzilai, Gad (2003).

Communities and Law: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities. Ann

Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472113151. Benjamin, Walter, Critique of Violence Flannery, D.J., Vazsonyi, A.T. & Waldman, I.D. (Eds.) (2007). The Cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052160785X. James, Paul; Sharma, RR (2006). Globalization and Violence, Vol. 4: Transnational Conflict. London: Sage Publications. Malešević, Siniša The Sociology of War and Violence. Cambridge University Press; 2010 [cited October 17, 2011]. ISBN 978-0521731690. Nazaretyan, A.P. (2007). Violence and Non-Violence at Different Stages of World History: A view from the hypothesis of techno-humanitarian balance. In: History & Mathematics. Moscow: KomKniga/URSS. pp. 127–48. ISBN 978-5484010011. States, United (1918). "U.S. Compiled Statutes, 1918: Embracing the Statutes of the United States of a General and Permanent Nature in Force July 16, 1918, with an Appendix Covering Acts June 14 to July 16, 1918". Making of Modern Law: Primary Sources, 1763–1970: 1716. |

バルザライ、ガド(2003)。『共同体と法:法的アイデンティティの政治と文化』。アナーバー:ミシガン大学出版局。ISBN 0472113151。 ベンヤミン、ヴァルター『暴力批判論』 フラナリー、D.J.、ヴァズソニ、A.T.、ウォルドマン、I.D.(編)(2007)。『ケンブリッジ暴力行動と攻撃性ハンドブック』ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 052160785X。 ジェームズ、ポール;シャルマ、RR(2006)。『グローバリゼーションと暴力 第4巻:越境的紛争』。ロンドン:セージ出版。 マレシェヴィッチ、シニシャ『戦争と暴力の社会学』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局;2010年[2011年10月17日引用]。ISBN 978-0521731690。 ナザレティアン、A.P.(2007)。『世界史の異なる段階における暴力と非暴力:技術と人道性の均衡仮説からの視点』。In: 『歴史と数学』。モスクワ:コムニガ/URSS。pp. 127–48。ISBN 978-5484010011。 アメリカ合衆国(1918)。「合衆国編纂法令集、1918年版:1918年7月16日時点で効力を有する合衆国の一般的かつ恒久的な性質の法令を収録、 付録として1918年6月14日から7月16日までの法令を掲載」。『近代法の形成:一次資料、1763–1970年』: 1716頁。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Violence |

リンク

・Naumann, Bernd. 1966. Auschwitz. New York: Frederick A. Praeger. のアーレントの序文より 「アウシュヴィッツでは、だれもが善になるか悪になるかを自分で決めることができたということである……。そしてこの決定は、ユダヤ人であるかポーランド 人であるかドイツ人であるかにけっして関わりがなかった。またSS の隊員であることにすら関わりがなかった」引用は(ヤング=ブルーエル 1999:490)[→出 典]

・Naumann, Bernd. 1966. Auschwitz. New York: Frederick A. Praeger. のアーレントの序文より

「被告が臨床的に正常であるにもかかわらず、アウシュヴィッツでの最大の人間的要素はサディズムであった。そしてサディズムは基本的に性的 である。……アウシュヴィッツの人間的要素に関するかぎり、二番目に重要なものは、おそらくまったくの気まぐれであったにちがいない。……彼等の絶えず変 る気分は、すべての実体的中身を——善いか悪いか、優しいか残忍か、「理想主義的」阿呆か皮肉屋の性的倒錯者かというような個人のアイデンティティの堅固 な外面を——破壊してしまったかのようであった。もっとも重い判決の一つ——終身プラス八年——を当然に受けた同じ人物が、ときには子供にソーセージを分 け与えることもあった。ベナレクは、囚人たちを踏みつけて殺すという特技をやった後、部屋へ戻って祈った。それは彼がそのときは正常な気分だ/ったからで ある。何万人もを死に送り込んだ同じ医務官が、彼の母校で学んだ、それゆえ彼の青春時代を思い出させた一人の女性を助けたこともあった。翌日にはガスで殺 されることになっていたが子供を生んだ母親に、花とチョコレートが贈られることもあり得た。……死はアウシュヴィッツでの最高の支配者であった。しかし、 死と並んで収容者たちの運命を決定していたのは、偶然——死の下僕どもの移ろいやすい気まぐれと一体となったもっとも非道で気まぐれな偶然であった」(ヤ ング=ブルーエル 1999:490-491)[→出典]

関連情報は→「アーレ ント暴力論:まとめ」に続きます。

リンク(授業関連)

リンク(アーレント関連)

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099