擬似科学・ニセ科学

Pseudoscience; Giji-Kagaku,

Nise-kagaku

☆ 疑似科学とは、科学的かつ事実であると主張しながら、科学的方法とは相容れない記述、信念、実践のことである。 疑似科学はしばしば、矛盾した、誇張された、あるいは反証不可能な主張、厳密な反駁の試みよりもむしろ確証バイアスへの依存、他の専門家による評 価への開放性の欠如、仮説を立てる際の体系的な実践の欠如、疑似科学的仮説が実験的に否定された後も長期間固執し続けること、といった特徴を持つ(→「科学」)。

| Pseudoscience

consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both

scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific

method.[Note 1] Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory,

exaggerated or unfalsifiable claims; reliance on confirmation bias

rather than rigorous attempts at refutation; lack of openness to

evaluation by other experts; absence of systematic practices when

developing hypotheses; and continued adherence long after the

pseudoscientific hypotheses have been experimentally discredited.[4] It

is not the same as junk science.[7] The demarcation between science and pseudoscience has scientific, philosophical, and political implications.[8] Philosophers debate the nature of science and the general criteria for drawing the line between scientific theories and pseudoscientific beliefs, but there is widespread agreement "that creationism, astrology, homeopathy, Kirlian photography, dowsing, ufology, ancient astronaut theory, Holocaust denialism, Velikovskian catastrophism, and climate change denialism are pseudosciences."[9] There are implications for health care, the use of expert testimony, and weighing environmental policies.[9] Addressing pseudoscience is part of science education and developing scientific literacy.[10][11] Pseudoscience can have dangerous effects. For example, pseudoscientific anti-vaccine activism and promotion of homeopathic remedies as alternative disease treatments can result in people forgoing important medical treatments with demonstrable health benefits, leading to deaths and ill-health.[12][13][14] Furthermore, people who refuse legitimate medical treatments for contagious diseases may put others at risk. Pseudoscientific theories about racial and ethnic classifications have led to racism and genocide. The term pseudoscience is often considered pejorative, particularly by purveyors of it, because it suggests something is being presented as science inaccurately or even deceptively. Therefore, those practicing or advocating pseudoscience frequently dispute the characterization.[4][15 |

疑

似科学とは、科学的かつ事実であると主張しながら、科学的方法とは相容れない記述、信念、実践のことである。

[注1]疑似科学はしばしば、矛盾した、誇張された、あるいは反証不可能な主張、厳密な反駁の試みよりもむしろ確証バイアスへの依存、他の専門家による評

価への開放性の欠如、仮説を立てる際の体系的な実践の欠如、疑似科学的仮説が実験的に否定された後も長期間固執し続けること、といった特徴を持つ[4]。 科学と疑似科学の境界線は、科学的、哲学的、政治的な意味合いを持っている[8]。哲学者たちは、科学の本質や、科学的理論と疑似科学的信念の境界線を引 くための一般的な基準について議論しているが、「創造論、占星術、ホメオパシー、キルリアン写真、ダウジング、UFO学、古代宇宙飛行士理論、ホロコース ト否定論、ヴェリコフスキー的破局論、気候変動否定論は疑似科学である」という点では広く一致している。 「疑似科学に取り組むことは、科学教育の一環であり、科学リテラシーを育成することである。 疑似科学は危険な影響を及ぼすことがある。例えば、偽科学的な反ワクチン活動や代替疾患治療としてのホメオパシー療法の宣伝は、人々が健康上の利点が実証 されている重要な医学的治療を見送り、死亡や不健康につながる可能性がある[12][13][14]。さらに、伝染病に対する正当な医学的治療を拒否する 人々は、他の人々を危険にさらす可能性がある。人種や民族の分類に関する疑似科学理論は、人種差別や大量虐殺につながっている。 疑似科学という用語は、不正確あるいは欺瞞的にさえ科学として提示されていることを示唆するため、特にそれを提唱する人々からは侮蔑的な用語とみなされる ことが多い。そのため、疑似科学を実践したり提唱したりしている人々は、この特徴づけにしばしば異議を唱えている[4][15]。 |

| Etymology The word pseudoscience is derived from the Greek root pseudo meaning "false"[16][17] and the English word science, from the Latin word scientia, meaning "knowledge". Although the term has been in use since at least the late 18th century (e.g., in 1796 by James Pettit Andrews in reference to alchemy[18][19]), the concept of pseudoscience as distinct from real or proper science seems to have become more widespread during the mid-19th century. Among the earliest uses of "pseudo-science" was in an 1844 article in the Northern Journal of Medicine, issue 387: That opposite kind of innovation which pronounces what has been recognized as a branch of science, to have been a pseudo-science, composed merely of so-called facts, connected together by misapprehensions under the disguise of principles. An earlier use of the term was in 1843 by the French physiologist François Magendie, that refers to phrenology as "a pseudo-science of the present day".[3][20][21] During the 20th century, the word was used pejoratively to describe explanations of phenomena which were claimed to be scientific, but which were not in fact supported by reliable experimental evidence. Dismissing the separate issue of intentional fraud – such as the Fox sisters' "rappings" in the 1850s[22] – the pejorative label pseudoscience distinguishes the scientific 'us', at one extreme, from the pseudo-scientific 'them', at the other, and asserts that 'our' beliefs, practices, theories, etc., by contrast with that of 'the others', are scientific. There are four criteria: (a) the 'pseudoscientific' group asserts that its beliefs, practices, theories, etc., are 'scientific'; (b) the 'pseudoscientific' group claims that its allegedly established facts are justified true beliefs; (c) the 'pseudoscientific' group asserts that its 'established facts' have been justified by genuine, rigorous, scientific method; and (d) this assertion is false or deceptive: "it is not simply that subsequent evidence overturns established conclusions, but rather that the conclusions were never warranted in the first place"[Note 2] From time to time, however, the usage of the word occurred in a more formal, technical manner in response to a perceived threat to individual and institutional security in a social and cultural setting.[24] |

語源 疑似科学(pseudoscience)という言葉は、「偽の」を意味するギリシャ語の語源pseudo[16][17]と、「知識」を意味するラテン語 scientiaに由来する英語のscienceに由来する。この用語は少なくとも18世紀後半から使われていたが(例えば、1796年にジェイムズ・ペ ティット・アンドリューズが錬金術について言及した[18][19])、真の科学または適切な科学とは異なる疑似科学という概念は、19世紀半ばにより広 まったようである。疑似科学」の最も古い用法のひとつは、1844年のNorthern Journal of Medicine誌387号の記事である: 科学の一分野として認識されてきたものを、原理を装って誤解によって結びつけられた、いわゆる事実だけで構成された疑似科学であったと宣告する、その反対の種類の革新。 20世紀には、この言葉は、科学的であると主張されているが、実際には信頼できる実験的証拠によって裏付けられていない現象の説明を表現するために侮蔑的に使用された[3][20][21]。 1850年代のフォックス姉妹の「レイプ」[22]のような、意図的な不正行為という別個の問題を除外して、侮蔑的なレッテルである疑似科学は、一方では 科学的な「我々」を、他方では疑似科学的な「彼ら」と区別し、「我々」の信念、実践、理論などが、「彼ら」のそれとは対照的に科学的であると主張する。基 準は4つある: (a)「疑似科学的」グループは、自分たちの信念、実践、理論などが「科学的」であると主張する; (b)「疑似科学的」グループは、その確立されたとされる事実が、正当化され た真の信念であると主張している; (c)「疑似科学的」グループは、その「確立された事実」が、本物の、厳密な、科学的方法によって正当化されたと主張する。 (d)この主張が虚偽であるか、欺瞞的であること:「後発の証拠が確立された結論を覆すというだけでなく、結論がそもそも正当化されなかったということである」[注釈 2]。 しかし時折、社会的・文化的環境における個人や組織の安全に対する脅威の認識に応じて、この言葉はより形式的で技術的な方法で使用されることがあった[24]。 |

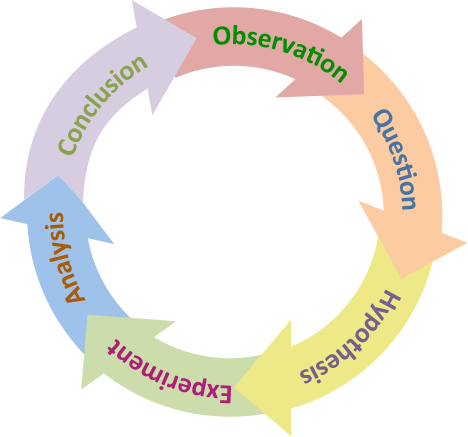

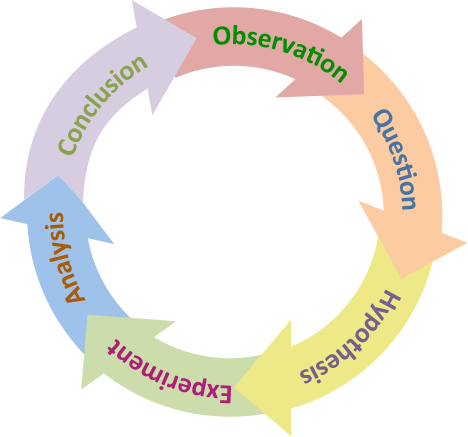

| Relationship to science Pseudoscience is differentiated from science because – although it usually claims to be science – pseudoscience does not adhere to scientific standards, such as the scientific method, falsifiability of claims, and Mertonian norms. Scientific method Main article: Scientific method  The scientific method is a continuous cycle of observation, questioning, hypothesis, experimentation, analysis and conclusion. A number of basic principles are accepted by scientists as standards for determining whether a body of knowledge, method, or practice is scientific. Experimental results should be reproducible and verified by other researchers.[25] These principles are intended to ensure experiments can be reproduced measurably given the same conditions, allowing further investigation to determine whether a hypothesis or theory related to given phenomena is valid and reliable. Standards require the scientific method to be applied throughout, and bias to be controlled for or eliminated through randomization, fair sampling procedures, blinding of studies, and other methods. All gathered data, including the experimental or environmental conditions, are expected to be documented for scrutiny and made available for peer review, allowing further experiments or studies to be conducted to confirm or falsify results. Statistical quantification of significance, confidence, and error[26] are also important tools for the scientific method. Falsifiability Main article: Falsifiability During the mid-20th century, the philosopher Karl Popper emphasized the criterion of falsifiability to distinguish science from non-science.[27] Statements, hypotheses, or theories have falsifiability or refutability if there is the inherent possibility that they can be proven false, that is, if it is possible to conceive of an observation or an argument that negates them. Popper used astrology and psychoanalysis as examples of pseudoscience and Einstein's theory of relativity as an example of science. He subdivided non-science into philosophical, mathematical, mythological, religious and metaphysical formulations on one hand, and pseudoscientific formulations on the other.[28] Another example which shows the distinct need for a claim to be falsifiable was stated in Carl Sagan's publication The Demon-Haunted World when he discusses an invisible dragon that he has in his garage. The point is made that there is no physical test to refute the claim of the presence of this dragon. Whatever test one thinks can be devised, there is a reason why it does not apply to the invisible dragon, so one can never prove that the initial claim is wrong. Sagan concludes; "Now, what's the difference between an invisible, incorporeal, floating dragon who spits heatless fire and no dragon at all?". He states that "your inability to invalidate my hypothesis is not at all the same thing as proving it true",[29] once again explaining that even if such a claim were true, it would be outside the realm of scientific inquiry. Mertonian norms Main article: Mertonian norms During 1942, Robert K. Merton identified a set of five "norms" which characterize real science. If any of the norms were violated, Merton considered the enterprise to be non-science. These are not broadly accepted by the scientific community. His norms were: Originality: The tests and research done must present something new to the scientific community. Detachment: The scientists' reasons for practicing this science must be simply for the expansion of their knowledge. The scientists should not have personal reasons to expect certain results. Universality: No person should be able to more easily obtain the information of a test than another person. Social class, religion, ethnicity, or any other personal factors should not be factors in someone's ability to receive or perform a type of science. Skepticism: Scientific facts must not be based on faith. One should always question every case and argument and constantly check for errors or invalid claims. Public accessibility: Any scientific knowledge one obtains should be made available to everyone. The results of any research should be published and shared with the scientific community.[30] Refusal to acknowledge problems In 1978, Paul Thagard proposed that pseudoscience is primarily distinguishable from science when it is less progressive than alternative theories over a long period of time, and its proponents fail to acknowledge or address problems with the theory.[31] In 1983, Mario Bunge suggested the categories of "belief fields" and "research fields" to help distinguish between pseudoscience and science, where the former is primarily personal and subjective and the latter involves a certain systematic method.[32] The 2018 book about scientific skepticism by Steven Novella, et al. The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe lists hostility to criticism as one of the major features of pseudoscience.[33] Criticism of the term Larry Laudan has suggested pseudoscience has no scientific meaning and is mostly used to describe human emotions: "If we would stand up and be counted on the side of reason, we ought to drop terms like 'pseudo-science' and 'unscientific' from our vocabulary; they are just hollow phrases which do only emotive work for us".[34] Likewise, Richard McNally states, "The term 'pseudoscience' has become little more than an inflammatory buzzword for quickly dismissing one's opponents in media sound-bites" and "When therapeutic entrepreneurs make claims on behalf of their interventions, we should not waste our time trying to determine whether their interventions qualify as pseudoscientific. Rather, we should ask them: How do you know that your intervention works? What is your evidence?"[35] Alternative definition For philosophers Silvio Funtowicz and Jerome R. Ravetz "pseudo-science may be defined as one where the uncertainty of its inputs must be suppressed, lest they render its outputs totally indeterminate". The definition, in the book Uncertainty and Quality in Science for Policy,[36] alludes to the loss of craft skills in handling quantitative information, and to the bad practice of achieving precision in prediction (inference) only at the expenses of ignoring uncertainty in the input which was used to formulate the prediction. This use of the term is common among practitioners of post-normal science. Understood in this way, pseudoscience can be fought using good practices to assess uncertainty in quantitative information, such as NUSAP and – in the case of mathematical modelling – sensitivity auditing. |

科学との関係 疑似科学が科学と区別されるのは、疑似科学は科学的方法、主張の反証可能性、マートン規範などの科学的基準を遵守していないからである。 科学的方法 主な記事 科学的方法  科学的方法とは、観察、質問、仮説、実験、分析、結論の連続的なサイクルである。 ある知識、方法、実践が科学的であるかどうかを判断する基準として、多くの基本原則が科学者に受け入れられている。実験結果は再現可能であり、他の研究者 によって検証されるべきである。[25]これらの原則は、実験が同じ条件下で測定可能に再現されることを保証し、与えられた現象に関連する仮説や理論が妥 当で信頼できるかどうかを判断するためのさらなる調査を可能にすることを意図している。基準では、科学的方法が全体を通して適用され、無作為化、公正なサ ンプリング手順、研究の盲検化、およびその他の方法によってバイアスが制御または除去されることが要求される。実験条件や環境条件を含め、収集されたすべ てのデータは、精査のために文書化され、査読に供されることが期待され、結果を確認または改ざんするためにさらなる実験や研究が実施されることを可能にす る。有意性、信頼性、誤差の統計的定量化[26]も科学的手法の重要な手段である。 反証可能性 主な記事 反証可能性 20世紀半ば、哲学者のカール・ポパーは、科学と非科学を区別するために、反証可能性という基準を強調した[27]。声明、仮説、理論に反証可能性がある のは、それらが誤りであることが証明される可能性が内在している場合、つまり、それらを否定する観察や議論を思いつくことが可能な場合である。ポパーは、 占星術と精神分析を疑似科学の例として、アインシュタインの相対性理論を科学の例として用いた。彼は非科学を、一方では哲学的、数学的、神話的、宗教的、 形而上学的な定式化に、他方では疑似科学的な定式化に細分化した[28]。 主張が反証可能であることの明確な必要性を示すもう一つの例は、カール・セーガンが出版した『The Demon-Haunted World(悪魔に取り憑かれた世界)』で、彼がガレージで飼っている目に見えないドラゴンについて論じているときに述べられている。このドラゴンの存在 を否定する物理的なテストは存在しないという指摘である。どのようなテストを考え出したとしても、目に見えないドラゴンには適用できない理由がある。さ て、熱のない炎を吐く、目に見えず、実体のない、浮遊するドラゴンと、まったく存在しないドラゴンの違いは何だろうか?私の仮説を無効にできないことは、 それが真実であることを証明することとはまったく同じではない」[29]と述べ、たとえそのような主張が真実であったとしても、それは科学的探究の範囲外 であると再び説明している。 マートン的規範 主な記事 マートン規範 1942年、ロバート・K・マートンは、現実の科学を特徴づける5つの「規範」を明らかにした。この規範のいずれかに違反した場合、マートンはその事業を非科学とみなした。これらは科学界では広く受け入れられていない。彼の規範は以下の通りである: 独創性: 実験や研究は、科学界に何か新しいものを提示するものでなければならない。 離隔: 科学者がこの科学を実践する理由は、単に知識を広げるためでなければならない。科学者は、ある結果を期待する個人的な理由を持ってはならない。 普遍性: いかなる人も、他の人よりも簡単にテストの情報を得るべきではない。社会階級、宗教、民族性、その他の個人的な要因が、ある種の科学を受けたり実行したりする能力の要因になってはならない。 懐疑主義: 科学的事実は信仰に基づいてはならない。あらゆる事例や議論に常に疑問を持ち、誤りや無効な主張がないか常にチェックすべきである。 一般への公開: 得られた科学的知識は、誰もが利用できるようにすべきである。あらゆる研究結果は公表され、科学コミュニティと共有されるべきである[30]。 問題を認めないこと 1978年、ポール・タガードは、疑似科学が科学と区別されるのは、それが長期間にわたって代替理論よりも進歩的でなく、その理論の支持者がその理論の問 題点を認めず、対処しない場合であると提唱した[31]。 [31] 1983年、マリオ・ブンゲは疑似科学と科学を区別するために「信念分野」と「研究分野」というカテゴリーを提案した。前者は主に個人的で主観的なもので あり、後者は一定の体系的な方法を伴うものである[32] スティーヴン・ノヴェッラらによる科学的懐疑主義に関する2018年の著書『The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe』は、疑似科学の大きな特徴の一つとして批判に対する敵意を挙げている[33]。 この用語に対する批判 ラリー・ローダン(Larry Laudan)は、疑似科学には科学的な意味はなく、ほとんどが人間の感情を表現するために使われていると指摘している: もし我々が理性の側に立ち、数えられるのであれば、"疑似科学 "や "非科学的 "といった用語を我々の語彙から取り除くべきである。 [34] 同様に、リチャード・マクナリーは、「『疑似科学』という用語は、メディアのサウンドバイトで自分の反対者を素早く退けるための、扇情的な流行語に過ぎな くなっている」、「治療企業家が彼らの介入を代表して主張するとき、私たちは彼らの介入が疑似科学的であるかどうかを見極めようとして時間を浪費すべきで はない。むしろ、彼らに尋ねるべきだ: あなたの介入が効くとどうしてわかるのですか?その証拠は何ですか? 別の定義 哲学者のシルヴィオ・フントヴィッチとジェローム・R・ラヴェッツにとって、「疑似科学とは、その入力の不確実性が、その出力を完全に不確定なものにしな いように、抑制しなければならないもの」と定義することができる。この定義は、『Uncertainty and Quality in Science for Policy(政策のための科学における不確実性と品質)』[36]という本の中で、定量的な情報を扱う技術の喪失や、予測を立てるために使われた入力の 不確実性を無視する代償としてのみ予測(推論)の精度を達成するという悪しき慣習を暗示している。この用語の使い方は、ポスト・ノーマル・サイエンスの実 践者の間では一般的である。このように理解すれば、疑似科学は、NUSAPや、数学的モデリングの場合は感度監査など、定量的情報の不確実性を評価するた めの優れた手法を使って戦うことができる。 |

A typical 19th-century phrenology chart: During the 1820s, phrenologists claimed the mind was located in areas of the brain, and were attacked for doubting that mind came from the nonmaterial soul. Their idea of reading "bumps" in the skull to predict personality traits was later discredited.[1][2] Phrenology was first termed a pseudoscience in 1843 and continues to be considered so.[3] |

19世紀の典型的な骨相図: 1820年代、骨相学者は、心は脳の領域にあると主張し、心は非物質的な魂から来るものであることを疑って攻撃された。骨相学は1843年に初めて疑似科学と呼ばれ、現在もそうみなされている[3]。 |

| History Main article: History of pseudoscience  The astrological signs of the zodiac The history of pseudoscience is the study of pseudoscientific theories over time. A pseudoscience is a set of ideas that presents itself as science, while it does not meet the criteria to be properly called such.[37][38] Distinguishing between proper science and pseudoscience is sometimes difficult.[39] One proposal for demarcation between the two is the falsification criterion, attributed most notably to the philosopher Karl Popper.[40] In the history of science and the history of pseudoscience it can be especially difficult to separate the two, because some sciences developed from pseudosciences. An example of this transformation is the science of chemistry, which traces its origins to the pseudoscientific or pre-scientific study of alchemy. The vast diversity in pseudosciences further complicates the history of science. Some modern pseudosciences, such as astrology and acupuncture, originated before the scientific era. Others developed as part of an ideology, such as Lysenkoism, or as a response to perceived threats to an ideology. Examples of this ideological process are creation science and intelligent design, which were developed in response to the scientific theory of evolution.[41] |

沿革 主な記事 疑似科学の歴史  占星術の星座 疑似科学の歴史とは、時代における疑似科学理論の研究のことである。疑似科学とは、科学と正しく呼ばれる基準を満たしていないにもかかわらず、科学であるかのように見せかけた一連の考え方のことである[37][38]。 適切な科学と疑似科学を区別することは時に困難である[39]。両者を区分するための一つの提案は、哲学者カール・ポパーに最も顕著に帰せられる反証基準 である[40]。科学の歴史と疑似科学の歴史においては、疑似科学から発展した科学もあるため、両者を区分することは特に困難である。この変容の一例が化 学であり、その起源は錬金術の疑似科学的あるいは前科学的研究にまで遡る。 疑似科学の多様性は、科学の歴史をさらに複雑にしている。占星術や鍼治療など、現代の疑似科学の中には科学時代以前に生まれたものもある。また、リセンコ 主義のようなイデオロギーの一部として、あるいはイデオロギーに対する脅威に対する反応として発展したものもある。このようなイデオロギー的なプロセスの 例としては、創造科学やインテリジェント・デザインがあり、これらは科学的な進化論に対抗して発展したものである[41]。 |

| Indicators of possible pseudoscience See also: List of topics characterized as pseudoscience  Homeopathic preparation Rhus toxicodendron, derived from poison ivy A topic, practice, or body of knowledge might reasonably be termed pseudoscientific when it is presented as consistent with the norms of scientific research, but it demonstrably fails to meet these norms.[42][43] Use of vague, exaggerated or untestable claims Assertion of scientific claims that are vague rather than precise, and that lack specific measurements.[44] Assertion of a claim with little or no explanatory power.[45] Failure to make use of operational definitions (i.e., publicly accessible definitions of the variables, terms, or objects of interest so that persons other than the definer can measure or test them independently)[Note 3] (See also: Reproducibility). Failure to make reasonable use of the principle of parsimony, i.e., failing to seek an explanation that requires the fewest possible additional assumptions when multiple viable explanations are possible (See: Occam's razor).[47] Lack of boundary conditions: Most well-supported scientific theories possess well-articulated limitations under which the predicted phenomena do and do not apply.[48] Lack of effective controls, such as placebo and double-blind, in experimental design. Lack of understanding of basic and established principles of physics and engineering.[49] Improper collection of evidence Assertions that do not allow the logical possibility that they can be shown to be false by observation or physical experiment (See also: Falsifiability).[27][50] Assertion of claims that a theory predicts something that it has not been shown to predict.[51][44] Scientific claims that do not confer any predictive power are considered at best "conjectures", or at worst "pseudoscience" (e.g., ignoratio elenchi).[52] Assertion that claims which have not been proven false must therefore be true, and vice versa (See: Argument from ignorance).[53] Over-reliance on testimonial, anecdotal evidence, or personal experience: This evidence may be useful for the context of discovery (i.e., hypothesis generation), but should not be used in the context of justification (e.g., statistical hypothesis testing).[54] Use of myths and religious texts as if they were fact, or basing evidence on readings of such texts.[55] Use of concepts and scenarios from science fiction as if they were fact. This technique appeals to the familiarity that many people already have with science fiction tropes through the popular media.[56] Presentation of data that seems to support claims while suppressing or refusing to consider data that conflict with those claims.[57] This is an example of selection bias or cherry picking, a distortion of evidence or data that arises from the way that the data are collected. It is sometimes referred to as the selection effect. Repeating excessive or untested claims that have been previously published elsewhere, and promoting those claims as if they were facts; an accumulation of such uncritical secondary reports, which do not otherwise contribute their own empirical investigation, is called the Woozle effect.[58] Reversed burden of proof: science places the burden of proof on those making a claim, not on the critic. "Pseudoscientific" arguments may neglect this principle and demand that skeptics demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt that a claim (e.g., an assertion regarding the efficacy of a novel therapeutic technique) is false. It is essentially impossible to prove a universal negative, so this tactic incorrectly places the burden of proof on the skeptic rather than on the claimant.[59] Appeals to holism as opposed to reductionism to dismiss negative findings: proponents of pseudoscientific claims, especially in organic medicine, alternative medicine, naturopathy and mental health, often resort to the "mantra of holism" .[60] Lack of openness to testing by other experts Evasion of peer review before publicizing results (termed "science by press conference"):[59][61][Note 4] Some proponents of ideas that contradict accepted scientific theories avoid subjecting their ideas to peer review, sometimes on the grounds that peer review is biased towards established paradigms, and sometimes on the grounds that assertions cannot be evaluated adequately using standard scientific methods. By remaining insulated from the peer review process, these proponents forgo the opportunity of corrective feedback from informed colleagues.[60] Some agencies, institutions, and publications that fund scientific research require authors to share data so others can evaluate a paper independently. Failure to provide adequate information for other researchers to reproduce the claims contributes to a lack of openness.[62] Appealing to the need for secrecy or proprietary knowledge when an independent review of data or methodology is requested.[62] Substantive debate on the evidence by knowledgeable proponents of all viewpoints is not encouraged.[63] Absence of progress Failure to progress towards additional evidence of its claims.[50][Note 5] Terence Hines has identified astrology as a subject that has changed very little in the past two millennia.[31][48] Lack of self-correction: scientific research programmes make mistakes, but they tend to reduce these errors over time.[64] By contrast, ideas may be regarded as pseudoscientific because they have remained unaltered despite contradictory evidence. The work Scientists Confront Velikovsky (1976) Cornell University, also delves into these features in some detail, as does the work of Thomas Kuhn, e.g., The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) which also discusses some of the items on the list of characteristics of pseudoscience. Statistical significance of supporting experimental results does not improve over time and are usually close to the cutoff for statistical significance. Normally, experimental techniques improve or the experiments are repeated, and this gives ever stronger evidence. If statistical significance does not improve, this typically shows the experiments have just been repeated until a success occurs due to chance variations. Personalization of issues Tight social groups and authoritarian personality, suppression of dissent and groupthink can enhance the adoption of beliefs that have no rational basis. In attempting to confirm their beliefs, the group tends to identify their critics as enemies.[65] Assertion of a conspiracy on the part of the mainstream scientific community, government, or educational facilities to suppress pseudoscientific information. People who make these accusations often compare themselves to Galileo Galilei and his persecution by the Roman Catholic Church; this comparison is commonly known as the Galileo gambit.[66] Attacking the motives, character, morality, or competence of critics (See Ad hominem fallacy).[65][67] Use of misleading language Creating scientific-sounding terms to persuade non-experts to believe statements that may be false or meaningless: for example, a long-standing hoax refers to water by the rarely used formal name "dihydrogen monoxide" and describes it as the main constituent in most poisonous solutions to show how easily the general public can be misled. Using established terms in idiosyncratic ways, thereby demonstrating unfamiliarity with mainstream work in the discipline. |

疑似科学の可能性を示す指標 こちらも参照: 疑似科学とされるトピックの一覧  ウルシ由来のホメオパシー製剤Rhus toxicodendron トピック、実践、または知識体系が、科学的研究の規範に合致しているように提示されているが、明らかにこれらの規範に合致していない場合、疑似科学と呼ばれる可能性がある[42][43]。 漠然とした、誇張された、あるいは検証不可能な主張の使用 正確でなく曖昧で、具体的な測定値を欠く科学的主張の主張[44]。 ほとんど、あるいは全く説明力のない主張の主張[45]。 操作上の定義(定義者以外の人が独自に測定・検定できるように、関心のある変数、用語、対象について公にアクセス可能な定義)を利用しないこと[注釈 3](再現性も参照)。 パーシモンの原則を合理的に利用しないこと、すなわち、複数の実行可能な説明が可能である場合に、可能な限り少ない追加的前提を必要とする説明を求めないこと(参照:オッカムの剃刀)[47]。 境界条件の欠如: 支持の厚い科学理論のほとんどは、予測される現象が適用されたり適用されなかったりする、よく明示された限界を持っている[48]。 実験計画におけるプラセボや二重盲検などの効果的な対照の欠如。 物理学や工学の基本的かつ確立された原理に対する理解の欠如[49]。 不適切な証拠収集 観察や物理的実験によって誤りであることが示される論理的可能性を認めない主張(「反証可能性」も参照)[27][50]。 ある理論が予測することが示されていない何かを予測するという主張[51][44]。予測力を与えない科学的主張は、よくても「推測」、悪くても「疑似科学」(例:ignoratio elenchi)とみなされる[52]。 虚偽であることが証明されていない主張は真でなければならず、その逆もまた真でなければならないという主張(参照:無知からの議論)[53]。 証言、逸話的証拠、個人的経験に過度に依存すること: このような証拠は発見(すなわち仮説生成)の文脈では有用かもしれないが、正当化(例えば統計的仮説検定)の文脈では使うべきではない[54]。 神話や宗教的文章をあたかも事実であるかのように使用すること、またはそのような文章の読解に証拠を基づかせること[55]。 SFの概念やシナリオを事実であるかのように使用する。この手法は、大衆メディアを通じて多くの人々がすでにSFの題材に慣れ親しんでいることにアピールするものである[56]。 主張の裏付けとなるようなデータを提示する一方で、その主張と相反するデータを抑圧したり、考察を拒否したりすること。選択効果と呼ばれることもある。 以前に別の場所で発表された過度な、または検証されていない主張を繰り返し、それらの主張をあたかも事実であるかのように宣伝すること。そのような無批判な二次報告の蓄積は、それ以外の独自の実証的調査に貢献することはなく、ウーズル効果と呼ばれる[58]。 立証責任の逆転:科学は、批判の側ではなく、主張を行う側に立証責任を負わせる。「疑似科学的な」議論はこの原則を無視し、懐疑論者に対して、ある主張 (例えば、新しい治療技術の有効性に関する主張)が誤りであることを合理的な疑いを超えて証明するよう要求することがある。普遍的な否定を証明することは 本質的に不可能であるため、この戦術は主張者ではなく懐疑論者に証明責任を誤って負わせることになる[59]。 否定的な知見を棄却するための還元主義とは対照的な全体主義へのアピール:特に有機医学、代替医療、自然療法、メンタルヘルスにおける疑似科学的主張の支持者は、しばしば「全体主義のマントラ」に頼る[60]。 他の専門家によるテストに対する開放性の欠如 結果を公表する前の査読の回避(「記者会見による科学」と呼ばれる):[59][61][注釈 4] 受け入れられている科学的理論と矛盾するアイデアの支持者の中には、査読が確立されたパラダイムに偏っているという理由で、また時には、主張が標準的な科 学的手法では適切に評価できないという理由で、自分のアイデアを査読にかけることを避ける者もいる。査読プロセスから遮断されたままであることで、これら の支持者は、情報に精通した同僚からの是正的なフィードバックの機会を逃している[60]。 科学研究に資金を提供する機関、機関、出版物の中には、他の人が論文を独自に評価できるように、著者がデータを共有することを要求するものがある。他の研究者が主張を再現するために十分な情報を提供しないことは、公開性の欠如につながる[62]。 データや方法論の独立したレビューが要求された場合に、秘密や独自の知識の必要性を訴えること[62]。 あらゆる見解の知識ある支持者による証拠に関する実質的な議論が奨励されない[63]。 進歩の欠如 テレンス・ハインズは、占星術は過去2千年の間にほとんど変化していないテーマであると指摘している[31][48]。 自己修正の欠如:科学的研究プログラムは間違いを犯すが、時間の経過とともにその間違いを減らす傾向がある[64]。対照的に、考えは矛盾する証拠にもか かわらず変更されずに残っているため、疑似科学的とみなされることがある。科学者たちはヴェリコフスキーと対決する』(1976年、コーネル大学)という 著作も、こうした特徴を少し詳しく掘り下げており、トーマス・クーンの著作、例えば『科学革命の構造』(1962年)でも、疑似科学の特徴のリストのいく つかの項目について論じている。 裏付けとなる実験結果の統計的有意性は、時間の経過とともに改善されることはなく、通常は統計的有意性のカットオフに近い。通常、実験技術が向上したり、 実験が繰り返されたりすることで、より強力な証拠が得られる。統計的有意性が向上しない場合、これは通常、偶然の変動により成功するまで実験が繰り返され ただけであることを示している。 問題や課題の個人化 窮屈な社会集団と権威主義的性格、反対意見の抑圧、集団思考は、合理的根拠のない信念の採用を促進する可能性がある。自分たちの信念を確かめようとするあまり、集団は批判者を敵 とみなす傾向がある[65]。 偽科学的情報を抑圧しようとする主流科学界、政府、教育施設 の側の陰謀を主張する。このような非難をする人々は、しばしば自分たちをガリレオ・ガリレイとローマ・カトリック教会による迫害になぞらえる。この比較は一般にガリレオ・ガンビットとして知られている[66]。 批判者の動機、性格、道徳、能力を攻撃する(Ad hominem fallacyを参照)[65][67]。 誤解を招く言葉の使用 科学的に聞こえる用語を作り出し、専門家でない人々に、嘘かもしれない、あるいは無意味かもしれない発言を信じさせること。例えば、長年にわたるデマで は、一般大衆がいかに簡単に惑わされるかを示すために、ほとんど使われない「一酸化二水素」という正式名称で水を指し、ほとんどの毒液の主成分であると説 明している。 確立された用語を特異な方法で使用することで、その学問分野における主流の研究に精通していないことを示す。 |

| Prevalence of pseudoscientific beliefs Countries The Ministry of AYUSH in the Government of India is purposed with developing education, research and propagation of indigenous alternative medicine systems in India. The ministry has faced significant criticism for funding systems that lack biological plausibility and are either untested or conclusively proven as ineffective. Quality of research has been poor, and drugs have been launched without any rigorous pharmacological studies and meaningful clinical trials on Ayurveda or other alternative healthcare systems.[68][69] There is no credible efficacy or scientific basis of any of these forms of treatment.[70] In his book The Demon-Haunted World, Carl Sagan discusses the government of China and the Chinese Communist Party's concern about Western pseudoscience developments and certain ancient Chinese practices in China. He sees pseudoscience occurring in the United States as part of a worldwide trend and suggests its causes, dangers, diagnosis and treatment may be universal.[71] A large percentage of the United States population lacks scientific literacy, not adequately understanding scientific principles and method.[Note 6][Note 7][74][Note 8] In the Journal of College Science Teaching, Art Hobson writes, "Pseudoscientific beliefs are surprisingly widespread in our culture even among public school science teachers and newspaper editors, and are closely related to scientific illiteracy."[76] However, a 10,000-student study in the same journal concluded there was no strong correlation between science knowledge and belief in pseudoscience.[77] During 2006, the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) issued an executive summary of a paper on science and engineering which briefly discussed the prevalence of pseudoscience in modern times. It said, "belief in pseudoscience is widespread" and, referencing a Gallup Poll,[78][79] stated that belief in the 10 commonly believed examples of paranormal phenomena listed in the poll were "pseudoscientific beliefs".[80] The items were "extrasensory perception (ESP), that houses can be haunted, ghosts, telepathy, clairvoyance, astrology, that people can communicate mentally with someone who has died, witches, reincarnation, and channelling".[80] Such beliefs in pseudoscience represent a lack of knowledge of how science works. The scientific community may attempt to communicate information about science out of concern for the public's susceptibility to unproven claims.[80] The NSF stated that pseudoscientific beliefs in the U.S. became more widespread during the 1990s, peaked about 2001, and then decreased slightly since with pseudoscientific beliefs remaining common. According to the NSF report, there is a lack of knowledge of pseudoscientific issues in society and pseudoscientific practices are commonly followed.[81] Surveys indicate about a third of adult Americans consider astrology to be scientific.[82][83][84] In Russia, in the late 20th and early 21st century, significant budgetary funds were spent on programs for the experimental study of "torsion fields",[85] the extraction of energy from granite,[86] the study of "cold nuclear fusion", and astrological and extrasensory "research" by the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Emergency Situations, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the State Duma[85] (see Military Unit 10003). In 2006, Deputy Chairman of the Security Council of the Russian Federation Nikolai Spassky published an article in Rossiyskaya Gazeta, where among the priority areas for the development of the Russian energy sector, the task of extracting energy from a vacuum was in the first place.[87] The Clean Water project was adopted as a United Russia party project; in the version submitted to the government, the program budget for 2010–2017 exceeded $14 billion.[88][87] Racism There have been many connections between pseudoscientific writers and researchers and their anti-semitic, racist and neo-Nazi backgrounds. They often use pseudoscience to reinforce their beliefs. One of the most predominant pseudoscientific writers is Frank Collin, a self-proclaimed Nazi who goes by Frank Joseph in his writings.[89] The majority of his works include the topics of Atlantis, extraterrestrial encounters, and Lemuria as well as other ancient civilizations, often with white supremacist undertones. For example, he posited that European peoples migrated to North America before Columbus, and that all Native American civilizations were initiated by descendants of white people.[90] The Alt-Right using pseudoscience to base their ideologies on is not a new issue. The entire foundation of anti-semitism is based on pseudoscience, or scientific racism. In an article from Newsweek by Sander Gilman, Gilman describes the pseudoscience community's anti-semitic views. "Jews as they appear in this world of pseudoscience are an invented group of ill, stupid or stupidly smart people who use science to their own nefarious ends. Other groups, too, are painted similarly in 'race science', as it used to call itself: African-Americans, the Irish, the Chinese and, well, any and all groups that you want to prove inferior to yourself".[91] Neo-Nazis and white supremacist often try to support their claims with studies that "prove" that their claims are more than just harmful stereotypes. For example Bret Stephens published a column in The New York Times where he claimed that Ashkenazi Jews had the highest IQ among any ethnic group.[92] However, the scientific methodology and conclusions reached by the article Stephens cited has been called into question repeatedly since its publication. It has been found that at least one of that study's authors has been identified by the Southern Poverty Law Center as a white nationalist.[93] The journal Nature has published a number of editorials in the last few years warning researchers about extremists looking to abuse their work, particularly population geneticists and those working with ancient DNA. One article in Nature, titled "Racism in Science: The Taint That Lingers" notes that early-twentieth-century eugenic pseudoscience has been used to influence public policy, such as the Immigration Act of 1924 in the United States, which sought to prevent immigration from Asia and parts of Europe. Research has repeatedly shown that race is not a scientifically valid concept, yet some scientists continue to look for measurable biological differences between 'races'.[94] |

疑似科学信仰の普及率 各国 インド政府のAYUSH省は、インド固有の代替医療システムの教育、研究、普及を目的としている。同省は、生物学的な妥当性を欠き、未検証であるか、効果 がないことが決定的に証明された代替医療に資金を提供しているとして、大きな批判にさらされている。研究の質は低く、アーユルヴェーダや他の代替医療シス テムに関する厳密な薬理学的研究や意味のある臨床試験も行われないまま、医薬品が発売されている[68][69]。これらの治療法には、信頼できる有効性 や科学的根拠がない[70]。 カール・セーガンは、その著書『The Demon-Haunted World』の中で、中国政府と中国共産党が、中国における西洋の疑似科学の発展と特定の古代中国の慣習に懸念を抱いていることについて論じている。彼 は、米国で発生している疑似科学は世界的な傾向の一部であると見ており、その原因、危険性、診断、治療が世界共通である可能性を示唆している[71]。 注6][注7][74][注8] Journal of College Science Teaching誌において、アート・ホブソンは「疑似科学的信念は、公立学校の科学教師や新聞編集者の間でさえも、我々の文化に驚くほど広まっており、 科学的無教養と密接な関係がある」と書いている[76]。 2006年、アメリカ国立科学財団(NSF)は、科学と工学に関する論文の要旨を発表し、現代における疑似科学の蔓延について簡潔に論じた。その論文で は、「疑似科学への信仰は広まっている」と述べ、ギャラップ世論調査[78][79]を参照しながら、世論調査で挙げられた超常現象のうち一般的に信じら れている10の例に対する信仰は「疑似科学的信念」であると述べている。 [その項目とは、「超感覚的知覚(ESP)、家に幽霊が出ること、幽霊、テレパシー、千里眼、占星術、人が死んだ人と精神的に交信できること、魔女、輪廻 転生、チャネリング」であった。NSFは、米国における疑似科学信仰は1990年代に広まり、2001年頃にピークに達し、その後わずかに減少したが、疑 似科学信仰は依然として一般的であると述べている[80]。NSFの報告書によれば、社会には疑似科学的な問題に関する知識が不足しており、疑似科学的な 慣習が一般的に行われている[81]。 調査によれば、成人アメリカ人の約3分の1が占星術を科学的であると考えている[82][83][84]。 ロシアでは20世紀後半から21世紀初頭にかけて、防衛省、非常事態省、内務省、国家議会による「ねじれ場」の実験的研究[85]、花崗岩からのエネル ギーの抽出[86]、「冷核融合」の研究、占星術や超感覚的な「研究」のためのプログラムに多額の予算が費やされた[85](軍事部隊10003を参 照)。2006年、ロシア連邦安全保障理事会のニコライ・スパスキー副議長はロシースカヤ・ガゼータ紙に記事を発表し、ロシアのエネルギー部門の発展にお ける優先分野の中で、真空からエネルギーを抽出する課題が第1位に挙げられていた[87]。 クリーン・ウォーター・プロジェクトは統一ロシア党のプロジェクトとして採択され、政府に提出されたバージョンでは、2010年から2017年のプログラ ム予算は140億ドルを超えていた[88][87]。 人種主義 疑似科学作家や研究者と反ユダヤ主義者、人種差別主義者、ネオナチの背景には多くのつながりがある。彼らはしばしば、自分たちの信念を補強するために疑似 科学を利用する。彼の著作の大部分は、アトランティス、地球外生命体との遭遇、レムリア、その他の古代文明をテーマにしており、白人至上主義的なニュアン スを含んでいることが多い。例えば、ヨーロッパ人はコロンブス以前に北アメリカに移住しており、アメリカ先住民の文明はすべて白人の子孫によって始まった と仮定している[90]。 オルト・ライトが自分たちのイデオロギーの基礎に疑似科学を用いることは、新しい問題ではない。反ユダヤ主義の基盤はすべて疑似科学、つまり科学的人種差 別に基づいている。サンダー・ギルマンによる『ニューズウィーク』誌の記事の中で、ギルマンは疑似科学コミュニティーの反ユダヤ主義的見解を述べている。 「この疑似科学の世界に登場するユダヤ人は、自分たちの邪悪な目的のために科学を利用する、病気で愚かな、あるいは愚かなほど賢い、作り出された集団であ る。他のグループも、かつてそう呼ばれていたように、『人種科学』では同じように描かれている: アフリカ系アメリカ人、アイルランド人、中国人、そしてまあ、自分より劣っていると証明したいあらゆる集団だ」[91]。ネオナチや白人至上主義者はしば しば、自分たちの主張が有害なステレオタイプ以上のものであることを「証明」する研究で、自分たちの主張を支えようとする。例えば、ブレット・スティーブ ンスは『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙にコラムを掲載し、アシュケナージ・ユダヤ人はあらゆる民族の中で最もIQが高いと主張した[92]。しかし、ス ティーブンスが引用した論文で得られた科学的方法論と結論は、その発表以来何度も疑問視されてきた。その研究の著者の少なくとも一人は、南部貧困法律セン ターによって白人ナショナリストと認定されていることが判明している[93]。 学術誌『ネイチャー』はここ数年、特に集団遺伝学者や古代のDNAを扱う研究者に対し、自分たちの研究を悪用しようとする過激派について警告する論説を数 多く発表している。科学における人種差別: 20世紀初頭の優生学的疑似科学が、アジアやヨーロッパの一部からの移民を阻止しようとしたアメリカの1924年の移民法などの公共政策に影響を与えるた めに利用されてきたことを指摘している。人種が科学的に妥当な概念ではないことは研究によって繰り返し示されているが、一部の科学者は「人種」間の測定可 能な生物学的差異を探し続けている[94]。 |

| Explanations In a 1981 report Singer and Benassi wrote that pseudoscientific beliefs have their origin from at least four sources.[95] Common cognitive errors from personal experience. Erroneous sensationalistic mass media coverage. Sociocultural factors. Poor or erroneous science education. A 1990 study by Eve and Dunn supported the findings of Singer and Benassi and found pseudoscientific belief being promoted by high school life science and biology teachers.[96] Psychology The psychology of pseudoscience attempts to explore and analyze pseudoscientific thinking by means of thorough clarification on making the distinction of what is considered scientific vs. pseudoscientific. The human proclivity for seeking confirmation rather than refutation (confirmation bias),[97] the tendency to hold comforting beliefs, and the tendency to overgeneralize have been proposed as reasons for pseudoscientific thinking. According to Beyerstein, humans are prone to associations based on resemblances only, and often prone to misattribution in cause-effect thinking.[98] Michael Shermer's theory of belief-dependent realism is driven by the belief that the brain is essentially a "belief engine" which scans data perceived by the senses and looks for patterns and meaning. There is also the tendency for the brain to create cognitive biases, as a result of inferences and assumptions made without logic and based on instinct – usually resulting in patterns in cognition. These tendencies of patternicity and agenticity are also driven "by a meta-bias called the bias blind spot, or the tendency to recognize the power of cognitive biases in other people but to be blind to their influence on our own beliefs".[99] Lindeman states that social motives (i.e., "to comprehend self and the world, to have a sense of control over outcomes, to belong, to find the world benevolent and to maintain one's self-esteem") are often "more easily" fulfilled by pseudoscience than by scientific information. Furthermore, pseudoscientific explanations are generally not analyzed rationally, but instead experientially. Operating within a different set of rules compared to rational thinking, experiential thinking regards an explanation as valid if the explanation is "personally functional, satisfying and sufficient", offering a description of the world that may be more personal than can be provided by science and reducing the amount of potential work involved in understanding complex events and outcomes.[100] Anyone searching for psychological help that is based in science should seek a licensed therapist whose techniques are not based in pseudoscience. Hupp and Santa Maria provide a complete explanation of what that person should look for.[101] Education and scientific literacy There is a trend to believe in pseudoscience more than scientific evidence.[102] Some people believe the prevalence of pseudoscientific beliefs is due to widespread scientific illiteracy.[103] Individuals lacking scientific literacy are more susceptible to wishful thinking, since they are likely to turn to immediate gratification powered by System 1, our default operating system which requires little to no effort. This system encourages one to accept the conclusions they believe, and reject the ones they do not. Further analysis of complex pseudoscientific phenomena require System 2, which follows rules, compares objects along multiple dimensions and weighs options. These two systems have several other differences which are further discussed in the dual-process theory.[104] The scientific and secular systems of morality and meaning are generally unsatisfying to most people. Humans are, by nature, a forward-minded species pursuing greater avenues of happiness and satisfaction, but we are all too frequently willing to grasp at unrealistic promises of a better life.[105] Psychology has much to discuss about pseudoscience thinking, as it is the illusory perceptions of causality and effectiveness of numerous individuals that needs to be illuminated. Research suggests that illusionary thinking happens in most people when exposed to certain circumstances such as reading a book, an advertisement or the testimony of others are the basis of pseudoscience beliefs. It is assumed that illusions are not unusual, and given the right conditions, illusions are able to occur systematically even in normal emotional situations. One of the things pseudoscience believers quibble most about is that academic science usually treats them as fools. Minimizing these illusions in the real world is not simple.[106] To this aim, designing evidence-based educational programs can be effective to help people identify and reduce their own illusions.[106] |

説明 シンガーとベナッシは1981年の報告書の中で、疑似科学的な信念は少な くとも4つの原因から生じていると書いている[95]。 個人的な経験からくる一般的な認知の誤り。 誤ったセンセーショナルなマスメディア報道。 社会文化的要因。 不十分な、あるいは誤った科学教育。 EveとDunnによる1990年の研究は、SingerとBenassiの所見を支持し、高校の生活科学と生物学の教師によって偽科学的信念が助長されていることを発見した[96]。 心理学 疑似科学の心理学は、何が科学的か疑似科学的かを区別することを徹底的に明らかにすることによって、疑似科学的思考を探求し分析しようとするものである。 疑似科学的思考の理由として、反論よりも確証を求める人間の性癖(確証バイアス)[97]、慰めになる信念を抱きがちな傾向、一般化しすぎる傾向が提唱さ れている。ベイヤースタインによると、人間は類似性だけに基づく連想をしやすく、因果関係思考においてしばしば誤帰属を起こしやすい[98]。 マイケル・シャーマーの信念依存的実在論の理論は、脳は本質的に「信念エ ンジン」であり、感覚によって知覚されたデータをスキャンし、パターンと意 味を探すという信念に基づいている。また、脳は論理に基づかず、本能に基づいて推論や仮定を行った結果、認知の偏りを生み出す傾向がある。このようなパ ターン性と主体性の傾向は、「バイアスの盲点と呼ばれるメタ・バイアス、つまり他人の認知バイアスの力を認識しながらも、それが自分の信念に及ぼす影響に は盲目的になる傾向」によっても引き起こされる[99]。 リンデマンは、社会的動機(すなわち「自己と世界を理解すること、結果をコントロールする感覚を持つこと、所属すること、世界を善良なものと見なすこと、 自尊心を維持すること」)は、科学的情報よりも疑似科学によって「より容易に」満たされることが多いと述べている。さらに、疑似科学的な説明は一般的に合 理的に分析されるのではなく、経験的に分析される。合理的思考とは異なる一連のルールの中で行動する経験的思考は、説明が「個人的に機能的で、満足でき、 十分である」場合に、その説明が有効であると見なし、科学によって提供されるよりも個人的な世界の説明を提供し、複雑な出来事や結果を理解することに伴う 潜在的な作業量を減らす。 科学に基づく心理的な助けを求める人は、疑似科学に基づかない技法を持つ、免許を持ったセラピストを探すべきである。HuppとSanta Mariaは、そのような人が何を探すべきかについて完全な説明を提供している[101]。 教育と科学リテラシー 科学的証拠よりも疑似科学を信じる傾向がある[102]。疑似科学的信念が蔓延しているのは、科学的リテラシーの低さが原因だと考える人もいる [103]。科学的リテラシーの低い人は、ほとんど努力を必要としないデフォルトのオペレーティングシステムであるシステム1によってもたらされる即効性 のある満足感に目を向ける可能性が高いため、希望的観測に陥りやすい。このシステムは、自分が信じる結論を受け入れ、そうでない結論を拒否するよう促す。 複雑な疑似科学的現象をさらに分析するには、ルールに従い、複数の次元で対象を比較し、選択肢を吟味するシステム2が必要だ。この2つのシステムには他に もいくつかの違いがあり、それは二重プロセス理論でさらに議論されている[104]。科学的で世俗的な道徳や意味のシステムは、一般的にほとんどの人に とって満足のいくものではない。人間は本来、より大きな幸福と満足の道を追求する前向きな種であるが、より良い人生という非現実的な約束に喜んで手を出す ことがあまりにも多い[105]。 心理学には疑似科学的思考について論じるべきことがたくさんある。研究によると、本を読んだり、広告を読んだり、他人の証言を聞いたりするなどの特定の状 況にさらされたときに、ほとんどの人に錯覚的思考が起こることが、疑似科学的信念の基礎となっている。錯覚は珍しいことではなく、適切な条件が与えられれ ば、正常な感情の状況でも錯覚は組織的に起こりうるとされている。疑似科学信者が最も屁理屈をこねることのひとつは、学術的な科学が通常自分たちを愚か者 扱いすることである。現実の世界でこうした錯覚を最小化するのは簡単なことではない。この目的のためには、エビデンスに基づいた教育プログラムを設計する ことが、人々が自分自身の錯覚を識別し、減らすのを助けるのに有効である[106]。 |

| Boundaries with science Classification Philosophers classify types of knowledge. In English, the word science is used to indicate specifically the natural sciences and related fields, which are called the social sciences.[107] Different philosophers of science may disagree on the exact limits – for example, is mathematics a formal science that is closer to the empirical ones, or is pure mathematics closer to the philosophical study of logic and therefore not a science?[108] – but all agree that all of the ideas that are not scientific are non-scientific. The large category of non-science includes all matters outside the natural and social sciences, such as the study of history, metaphysics, religion, art, and the humanities.[107] Dividing the category again, unscientific claims are a subset of the large category of non-scientific claims. This category specifically includes all matters that are directly opposed to good science.[107] Un-science includes both "bad science" (such as an error made in a good-faith attempt at learning something about the natural world) and pseudoscience.[107] Thus pseudoscience is a subset of un-science, and un-science, in turn, is subset of non-science. Science is also distinguishable from revelation, theology, or spirituality in that it offers insight into the physical world obtained by empirical research and testing.[109][110] The most notable disputes concern the evolution of living organisms, the idea of common descent, the geologic history of the Earth, the formation of the Solar System, and the origin of the universe.[111] Systems of belief that derive from divine or inspired knowledge are not considered pseudoscience if they do not claim either to be scientific or to overturn well-established science. Moreover, some specific religious claims, such as the power of intercessory prayer to heal the sick, although they may be based on untestable beliefs, can be tested by the scientific method. Some statements and common beliefs of popular science may not meet the criteria of science. "Pop" science may blur the divide between science and pseudoscience among the general public, and may also involve science fiction.[112] Indeed, pop science is disseminated to, and can also easily emanate from, persons not accountable to scientific methodology and expert peer review. If claims of a given field can be tested experimentally and standards are upheld, it is not pseudoscience, regardless of how odd, astonishing, or counterintuitive those claims are. If claims made are inconsistent with existing experimental results or established theory, but the method is sound, caution should be used, since science consists of testing hypotheses which may turn out to be false. In such a case, the work may be better described as ideas that are "not yet generally accepted". Protoscience is a term sometimes used to describe a hypothesis that has not yet been tested adequately by the scientific method, but which is otherwise consistent with existing science or which, where inconsistent, offers reasonable account of the inconsistency. It may also describe the transition from a body of practical knowledge into a scientific field.[27] Philosophy Main article: Demarcation problem Karl Popper stated it is insufficient to distinguish science from pseudoscience, or from metaphysics (such as the philosophical question of what existence means), by the criterion of rigorous adherence to the empirical method, which is essentially inductive, based on observation or experimentation.[45] He proposed a method to distinguish between genuine empirical, nonempirical or even pseudoempirical methods. The latter case was exemplified by astrology, which appeals to observation and experimentation. While it had empirical evidence based on observation, on horoscopes and biographies, it crucially failed to use acceptable scientific standards.[45] Popper proposed falsifiability as an important criterion in distinguishing science from pseudoscience. To demonstrate this point, Popper[45] gave two cases of human behavior and typical explanations from Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler's theories: "that of a man who pushes a child into the water with the intention of drowning it; and that of a man who sacrifices his life in an attempt to save the child."[45] From Freud's perspective, the first man would have suffered from psychological repression, probably originating from an Oedipus complex, whereas the second man had attained sublimation. From Adler's perspective, the first and second man suffered from feelings of inferiority and had to prove himself, which drove him to commit the crime or, in the second case, drove him to rescue the child. Popper was not able to find any counterexamples of human behavior in which the behavior could not be explained in the terms of Adler's or Freud's theory. Popper argued[45] it was that the observation always fitted or confirmed the theory which, rather than being its strength, was actually its weakness. In contrast, Popper[45] gave the example of Einstein's gravitational theory, which predicted "light must be attracted by heavy bodies (such as the Sun), precisely as material bodies were attracted."[45] Following from this, stars closer to the Sun would appear to have moved a small distance away from the Sun, and away from each other. This prediction was particularly striking to Popper because it involved considerable risk. The brightness of the Sun prevented this effect from being observed under normal circumstances, so photographs had to be taken during an eclipse and compared to photographs taken at night. Popper states, "If observation shows that the predicted effect is definitely absent, then the theory is simply refuted."[45] Popper summed up his criterion for the scientific status of a theory as depending on its falsifiability, refutability, or testability. Paul R. Thagard used astrology as a case study to distinguish science from pseudoscience and proposed principles and criteria to delineate them.[113] First, astrology has not progressed in that it has not been updated nor added any explanatory power since Ptolemy. Second, it has ignored outstanding problems such as the precession of equinoxes in astronomy. Third, alternative theories of personality and behavior have grown progressively to encompass explanations of phenomena which astrology statically attributes to heavenly forces. Fourth, astrologers have remained uninterested in furthering the theory to deal with outstanding problems or in critically evaluating the theory in relation to other theories. Thagard intended this criterion to be extended to areas other than astrology. He believed it would delineate as pseudoscientific such practices as witchcraft and pyramidology, while leaving physics, chemistry, astronomy, geoscience, biology, and archaeology in the realm of science.[113] In the philosophy and history of science, Imre Lakatos stresses the social and political importance of the demarcation problem, the normative methodological problem of distinguishing between science and pseudoscience. His distinctive historical analysis of scientific methodology based on research programmes suggests: "scientists regard the successful theoretical prediction of stunning novel facts – such as the return of Halley's comet or the gravitational bending of light rays – as what demarcates good scientific theories from pseudo-scientific and degenerate theories, and in spite of all scientific theories being forever confronted by 'an ocean of counterexamples'".[8] Lakatos offers a "novel fallibilist analysis of the development of Newton's celestial dynamics, [his] favourite historical example of his methodology" and argues in light of this historical turn, that his account answers for certain inadequacies in those of Karl Popper and Thomas Kuhn.[8] "Nonetheless, Lakatos did recognize the force of Kuhn's historical criticism of Popper – all important theories have been surrounded by an 'ocean of anomalies', which on a falsificationist view would require the rejection of the theory outright...Lakatos sought to reconcile the rationalism of Popperian falsificationism with what seemed to be its own refutation by history".[114] Many philosophers have tried to solve the problem of demarcation in the following terms: a statement constitutes knowledge if sufficiently many people believe it sufficiently strongly. But the history of thought shows us that many people were totally committed to absurd beliefs. If the strengths of beliefs were a hallmark of knowledge, we should have to rank some tales about demons, angels, devils, and of heaven and hell as knowledge. Scientists, on the other hand, are very sceptical even of their best theories. Newton's is the most powerful theory science has yet produced, but Newton himself never believed that bodies attract each other at a distance. So no degree of commitment to beliefs makes them knowledge. Indeed, the hallmark of scientific behaviour is a certain scepticism even towards one's most cherished theories. Blind commitment to a theory is not an intellectual virtue: it is an intellectual crime. Thus a statement may be pseudoscientific even if it is eminently 'plausible' and everybody believes in it, and it may be scientifically valuable even if it is unbelievable and nobody believes in it. A theory may even be of supreme scientific value even if no one understands it, let alone believes in it.[8] — Imre Lakatos, Science and Pseudoscience The boundary between science and pseudoscience is disputed and difficult to determine analytically, even after more than a century of study by philosophers of science and scientists, and despite some basic agreements on the fundamentals of the scientific method.[42][115][116] The concept of pseudoscience rests on an understanding that the scientific method has been misrepresented or misapplied with respect to a given theory, but many philosophers of science maintain that different kinds of methods are held as appropriate across different fields and different eras of human history. According to Lakatos, the typical descriptive unit of great scientific achievements is not an isolated hypothesis but "a powerful problem-solving machinery, which, with the help of sophisticated mathematical techniques, digests anomalies and even turns them into positive evidence".[8] To Popper, pseudoscience uses induction to generate theories, and only performs experiments to seek to verify them. To Popper, falsifiability is what determines the scientific status of a theory. Taking a historical approach, Kuhn observed that scientists did not follow Popper's rule, and might ignore falsifying data, unless overwhelming. To Kuhn, puzzle-solving within a paradigm is science. Lakatos attempted to resolve this debate, by suggesting history shows that science occurs in research programmes, competing according to how progressive they are. The leading idea of a programme could evolve, driven by its heuristic to make predictions that can be supported by evidence. Feyerabend claimed that Lakatos was selective in his examples, and the whole history of science shows there is no universal rule of scientific method, and imposing one on the scientific community impedes progress.[117] — David Newbold and Julia Roberts, "An analysis of the demarcation problem in science and its application to therapeutic touch theory" in International Journal of Nursing Practice, Vol. 13 Laudan maintained that the demarcation between science and non-science was a pseudo-problem, preferring to focus on the more general distinction between reliable and unreliable knowledge.[118] [Feyerabend] regards Lakatos's view as being closet anarchism disguised as methodological rationalism. Feyerabend's claim was not that standard methodological rules should never be obeyed, but rather that sometimes progress is made by abandoning them. In the absence of a generally accepted rule, there is a need for alternative methods of persuasion. According to Feyerabend, Galileo employed stylistic and rhetorical techniques to convince his reader, while he also wrote in Italian rather than Latin and directed his arguments to those already temperamentally inclined to accept them.[114] — Alexander Bird, "The Historical Turn in the Philosophy of Science" in Routledge Companion to the Philosophy of Science |

科学との境界 分類 哲学者は知識の種類を分類する。例えば、数学は経験的なものに近い形式科学なのか、それとも純粋数学は論理学の哲学的研究に近いので科学ではないのか [108]など、科学哲学者によって正確な境界については意見が分かれるかもしれないが、科学的でない考え方はすべて非科学的であるという点では一致して いる。非科学的という大きなカテゴリーには、歴史学、形而上学、宗教、芸術、人文科学など、自然科学や社会科学以外のすべての事柄が含まれる[107]。 このカテゴリーをもう一度分けると、非科学的な主張は非科学的という大きなカテゴリーのサブセットである。非科学には、「悪い科学」(自然界について何か を学ぼうとする善意の試みにおける誤りなど)と疑似科学の両方が含まれる[107]。したがって疑似科学は非科学の部分集合であり、非科学は非科学の部分 集合である。 科学はまた、経験的な研究とテストによって得られる物理的世界についての洞察を提供するという点で、啓示、神学、霊性とは区別される[109] [110]。最も顕著な論争は、生物の進化、共通降臨の考え方、地球の地質学的歴史、太陽系の形成、宇宙の起源に関するものである[111]。神や霊感に よる知識に由来する信念の体系は、科学的であると主張したり、確立された科学を覆すと主張したりしなければ、疑似科学とは見なされない。さらに、病人を癒 す執り成しの祈りの力など、特定の宗教的主張は、検証不可能な信念に基づいているかもしれないが、科学的方法で検証することができる。 ポピュラーサイエンスの声明や通説の中には、科学の基準を満たさないものもある。「ポップ」な科学は、一般大衆の間で科学と疑似科学との境界を曖昧にし、 SFを含むこともある[112]。実際、ポップサイエンスは、科学的方法論や専門家による査読に責任を持たない人々に流布され、またそのような人々から容 易に発信されることもある。 ある分野の主張が実験的に検証され、その基準が支持されるのであれば、その主張がいかに奇妙で、驚くべきもので、直感に反するものであっても、それは疑似 科学ではない。主張が既存の実験結果や確立された理論と矛盾しているが、その方法が健全である場合、科学は仮説を検証するものであるため、注意が必要であ る。このような場合、その研究は「まだ一般に受け入れられていない」アイデアと表現した方がいいかもしれない。プロトサイエンス (Protoscience)とは、科学的手法ではまだ十分に検証されていないが、それ以外の点では既存の科学と矛盾していない、あるいは矛盾していても その矛盾を合理的に説明できる仮説を表す言葉として使われることがある。また、実用的な知識の体系から科学的な分野への移行を表すこともある[27]。 哲学 主な記事 分界問題 カール・ポパーは、科学と疑似科学、あるいは形而上学(存在とは何かという哲学的問題など)を、観察や実験に基づく本質的に帰納的な経験的手法の厳格な遵 守という基準で区別するには不十分であると述べている[45]。後者の場合、観察と実験に訴える占星術がその例であった。ポパーは、科学と疑似科学を区別 するための重要な基準として、反証可能性を提唱した[45]。 この点を実証するために、ポパー[45]はジークムント・フロイトとアルフレッド・アドラーの理論から、人間の行動と典型的な説明の2つの事例を挙げた: 「溺れさせるつもりで子供を水に突き落とした男の場合と、子供を救うために自分の命を犠牲にした男の場合である。アドラーの視点に立てば、最初の男と二番 目の男は劣等感に苦しみ、自分自身を証明しなければならなかった。ポパーは、アドラーやフロイトの理論で説明できない人間の行動の反例を見つけることがで きなかった。ポパーは、観察が常に理論に適合していたり、理論を裏付けていたりすることが、むしろその長所であるどころか、実際にはその短所であると主張 した[45]。対照的に、ポパー[45]はアインシュタインの重力理論の例を挙げ、「光は(太陽のような)重い物体に引き寄せられ、物質体が引き寄せられ るのと同じように正確に引き寄せられるに違いない」と予測した[45]。この予測は、かなりのリスクを伴うものであったため、ポパーにとって特に印象的で あった。太陽の明るさによって、この効果は通常では観測できないため、日食中に写真を撮り、夜に撮った写真と比較する必要があった。ポパーは、「観測に よって、予測された効果が確実に存在しないことが示されれば、その理論は単純に反証される」と述べている。 ポール・R・タガードは、科学と疑似科学を区別するために占星術をケーススタディとして使用し、それらを区別するための原則と基準を提案した[113]。 第一に、占星術はプトレマイオス以来、更新も説明力の追加もされていないという点で進歩していない。第二に、天文学における歳差運動などの未解決の問題を 無視してきた。第三に、人格と行動に関する代替理論が次第に発展し、占星術が静的に天の力によるとする現象の説明を包含するようになった。第四に、占星術 師たちは、未解決の問題に対処するために理論をさらに発展させたり、他の理論との関連で理論を批判的に評価したりすることに無関心なままである。タガード はこの基準を占星術以外の分野にも適用することを意図していた。彼は、物理学、化学、天文学、地球科学、生物学、考古学を科学の領域に残す一方で、魔術や ピラミッド学のような実践を偽科学的なものとして区別することができると考えていた[113]。 科学哲学と科学史において、イムレ・ラカトスは、科学と疑似科学を区別する規範的な方法論的問題である分界問題の社会的・政治的重要性を強調している。研 究プログラムに基づく科学的方法論に関する彼の独特な歴史的分析は、次のように示唆している: 「科学者は、ハレー彗星の回帰や光線の重力の屈曲など、目を見張るような新事実を理論的に予測することに成功することが、優れた科学理論を疑似科学的な理 論や退化した理論から区別することだと考えている。 [8]ラカトスは、「ニュートンの天動説の発展についての斬新な可謬主義的分析、彼の方法論の歴史的な好例」を提供し、この歴史的転回に照らして、彼の説 明がカール・ポパーやトマス・クーンの説明のある種の不十分さに答えていると論じている。 [8]「それにもかかわらず、ラカトスはポパーに対するクーンの歴史的批判の力を認識していた-すべての重要な理論は「異常の海」に囲まれており、それは 改竄主義者の見解では理論の全面的な否定を必要とするものであった。 多くの哲学者が、次のような言葉で分界の問題を解決しようとしてきた:十分に多くの人々がそれを十分に強く信じるならば、ある声明は知識を構成する。しか し思想の歴史は、多くの人々が不合理な信念に完全に傾倒していたこと を示している。信念の強さが知識の特徴であるとすれば、悪魔、天使、悪魔、天国と地獄にまつわるいくつかの物語を知識として位置づけなければならないはず だ。一方、科学者たちは、最高の理論に対しても非常に懐疑的である。ニュートンの理論は科学が生み出した最も強力な理論だが、ニュートン自身は物体が遠く で引き合うとは信じていなかった。つまり、信念にどれだけ傾倒しても、それが知識にはならないのである。実際、科学的な行動の特徴は、自分が最も大切にし ている理論にさえ懐疑的であることだ。ある理論に盲目的にコミットすることは、知的美徳ではなく、知的犯罪なのである。 このように、ある声明が極めて「もっともらしい」ものであり、誰もがそれを信じていたとしても、それは疑似科学的なものであるかもしれないし、ある声明が 信じられないものであり、誰もそれを信じていなかったとしても、それは科学的に価値のあるものであるかもしれない。たとえ誰も理解できず、ましてや信じて いなくても、ある理論が最高の科学的価値を持つことだってある[8]。 - イムレ・ラカトス『科学と疑似科学 科学と疑似科学の境界は、科学哲学者や科学者によって1世紀以上研究された後でも、また科学的手法の基本に関するいくつかの基本的合意にもかかわらず、論 争があり、分析的に決定することは困難である[42][115][116]。疑似科学の概念は、ある理論に関して科学的手法が誤って説明された、あるいは 誤って適用されたという理解に基づいているが、多くの科学哲学者は、異なる分野や人類史の異なる時代において異なる種類の手法が適切であると主張してい る。ラカトスによれば、偉大な科学的成果の典型的な記述単位は、孤立した仮説ではなく、「高度な数学的技術の助けを借りて、異常を消化し、さらにはそれを 肯定的な証拠に変える強力な問題解決機械」である[8]。 ポパーに言わせれば、疑似科学は理論を生み出すために帰納法を使い、それを検証するために実験を行うだけである。ポパーにとって、反証可能性こそが理論の 科学的地位を決定するものである。クーンは歴史的なアプローチから、科学者はポパーのルールに従わず、圧倒的なデータがない限り、反証データを無視するこ とがあると観察した。クーンにとって、パラダイムの中でパズルを解くことが科学なのである。ラカトスはこの論争を解決するために、科学は研究プログラムの 中で発生し、それがいかに進歩的であるかによって競われることを歴史が示していると示唆した。ある研究プログラムの主導的な考え方は、証拠によって支持さ れる予測を行うというヒューリスティックな原理によって進化する可能性がある。ファイヤアーベントは、ラカトスはその例において選択的であり、科学の歴史 全体が示しているように、科学的方法には普遍的なルールは存在せず、科学コミュニティに普遍的なルールを押し付けることは進歩を妨げると主張している [117]。 - デイヴィッド・ニューボルドとジュリア・ロバーツ「科学における分界問題の分析と治療的接触理論への応用」(『国際看護実践ジャーナル』第13号 ラウダンは科学と非科学の間の境界は疑似問題であると主張し、信頼できる知識と信頼できない知識の間のより一般的な区別に焦点を当てることを好んだ[118]。 [ファイヤーラベンドは、ラカトスの見解を方法論的合理主義を装ったクローゼット・アナーキズムであるとみなしている。ファイヤーラベンドの主張は、標準 的な方法論的ルールは決して遵守されるべきではないということではなく、むしろそれを放棄することによって進歩がもたらされることもあるということであっ た。一般的に受け入れられているルールがない場合、別の説得方法が必要となる。ファイヤーラベンドによれば、ガリレオは読者を説得するために文体や修辞の テクニックを用い、またラテン語ではなくイタリア語で執筆し、すでに気質的にそれを受け入れる傾向のある人々に向けて議論を展開した[114]。 - Alexander Bird, "The Historical Turn in the Philosophy of Science" in Routledge Companion to the Philosophy of Science |

| Politics, health, and education Political implications The demarcation problem between science and pseudoscience brings up debate in the realms of science, philosophy and politics. Imre Lakatos, for instance, points out that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at one point declared that Mendelian genetics was pseudoscientific and had its advocates, including well-established scientists such as Nikolai Vavilov, sent to a Gulag and that the "liberal Establishment of the West" denies freedom of speech to topics it regards as pseudoscience, particularly where they run up against social mores.[8] Something becomes pseudoscientific when science cannot be separated from ideology, scientists misrepresent scientific findings to promote or draw attention for publicity, when politicians, journalists and a nation's intellectual elite distort the facts of science for short-term political gain, or when powerful individuals of the public conflate causation and cofactors by clever wordplay. These ideas reduce the authority, value, integrity and independence of science in society.[119] Health and education implications Distinguishing science from pseudoscience has practical implications in the case of health care, expert testimony, environmental policies, and science education. Treatments with a patina of scientific authority which have not actually been subjected to actual scientific testing may be ineffective, expensive and dangerous to patients and confuse health providers, insurers, government decision makers and the public as to what treatments are appropriate. Claims advanced by pseudoscience may result in government officials and educators making bad decisions in selecting curricula.[Note 9] The extent to which students acquire a range of social and cognitive thinking skills related to the proper usage of science and technology determines whether they are scientifically literate. Education in the sciences encounters new dimensions with the changing landscape of science and technology, a fast-changing culture and a knowledge-driven era. A reinvention of the school science curriculum is one that shapes students to contend with its changing influence on human welfare. Scientific literacy, which allows a person to distinguish science from pseudosciences such as astrology, is among the attributes that enable students to adapt to the changing world. Its characteristics are embedded in a curriculum where students are engaged in resolving problems, conducting investigations, or developing projects.[10] Alan J. Friedman mentions why most scientists avoid educating about pseudoscience, including that paying undue attention to pseudoscience could dignify it.[120] On the other hand, Robert L. Park emphasizes how pseudoscience can be a threat to society and considers that scientists have a responsibility to teach how to distinguish science from pseudoscience.[121] Pseudosciences such as homeopathy, even if generally benign, are used by charlatans. This poses a serious issue because it enables incompetent practitioners to administer health care. True-believing zealots may pose a more serious threat than typical con men because of their delusion to homeopathy's ideology. Irrational health care is not harmless and it is careless to create patient confidence in pseudomedicine.[122] On 8 December 2016, journalist Michael V. LeVine pointed out the dangers posed by the Natural News website: "Snake-oil salesmen have pushed false cures since the dawn of medicine, and now websites like Natural News flood social media with dangerous anti-pharmaceutical, anti-vaccination and anti-GMO pseudoscience that puts millions at risk of contracting preventable illnesses."[123] The anti-vaccine movement has persuaded large numbers of parents not to vaccinate their children, citing pseudoscientific research that links childhood vaccines with the onset of autism.[124] These include the study by Andrew Wakefield, which claimed that a combination of gastrointestinal disease and developmental regression, which are often seen in children with ASD, occurred within two weeks of receiving vaccines.[125][126] The study was eventually retracted by its publisher, and Wakefield was stripped of his license to practice medicine.[124] Alkaline water is water that has a pH of higher than 7, purported to host numerous health benefits, with no empirical backing. A practitioner known as Robert O. Young who promoted alkaline water and an "Alkaline diet" was sent to jail for 3 years in 2017 for practicing medicine without a license.[127] |

政治、健康、教育 政治的意味合い 科学と疑似科学の境界線問題は、科学、哲学、政治の領域で議論を呼び起こす。例えば、イムレ・ラカトスは、ソビエト連邦の共産党が一時期、メンデル遺伝学 は疑似科学であると宣言し、ニコライ・ヴァヴィロフのような著名な科学者を含むその提唱者を収容所送りにしたことや、「西側のリベラルなエスタブリッシュ メント」が、疑似科学とみなすテーマ、特に社会的モラルに反するテーマに対して言論の自由を否定していることを指摘している[8]。 科学がイデオロギーから切り離せないとき、科学者が宣伝のために科学的知見を誤魔化したり注目を集めたりするとき、政治家、ジャーナリスト、国家の知的エ リートが短期的な政治的利益のために科学の事実を歪曲するとき、あるいは一般大衆の有力者が巧みな言葉遊びによって因果関係と因子を混同するとき、何かが 疑似科学的になる。こうした考え方は、社会における科学の権威、価値、完全性、独立性を低下させる[119]。 健康と教育への影響 科学と疑似科学を区別することは、医療、専門家による証言、環境政策、科学教育の場合に実際的な意味を持つ。実際の科学的検証を受けていない科学的権威を 装った治療法は、患者にとって効果がなく、高価で、危険である可能性があり、医療提供者、保険者、政府の意思決定者、一般市民を、どのような治療法が適切 なのか混乱させる。疑似科学が主張することは、政府関係者や教育者がカリキュラムを選択する際に誤った判断を下すことになりかねない[注 9]。 生徒が科学技術の適切な使用に関連する様々な社会的・認知的思考スキルをどの程度習得しているかによって、科学的リテラシーがあるかどうかが決まる。科学 教育は、科学技術の変化、めまぐるしく変化する文化、知識主導の時代とともに、新たな局面に遭遇している。学校の科学カリキュラムの再発明とは、人類の福 祉に対する科学技術の影響力の変化に対応できる生徒を育てることである。科学リテラシーとは、科学と占星術のような疑似科学とを区別できるようにするもの で、生徒が変化する世界に適応できるようにするものである。その特性は、生徒が問題の解決、調査の実施、プロジェクトの開発に従事するカリキュラムに組み 込まれている[10]。 アラン・J・フリードマンは、ほとんどの科学者が疑似科学についての教育を避ける理由について、疑似科学に過度な注意を払うことは、それを威張ることになりかねないことを含めて言及している[120]。 他方、ロバート・L・パークは、疑似科学がいかに社会にとって脅威となりうるかを強調し、科学者には科学と疑似科学を区別する方法を教える責任があると考察している[121]。 ホメオパシーのような疑似科学は、たとえ一般的に良性であったとしても、チャラタンに利用されている。このことは、無能な開業医が医療を行うことを可能に するため、深刻な問題を提起している。真に信じる狂信者は、ホメオパシーのイデオロギーに妄信しているため、典型的な詐欺師よりも深刻な脅威をもたらすか もしれない。不合理な医療は無害ではなく、偽医療に対する患者の信頼を作り出すことは不注意である[122]。 2016年12月8日、ジャーナリストのマイケル・V・ルヴァインは、ナチュラル・ニュースのウェブサイトがもたらす危険性を指摘した: 「スネークオイル・セールスマンは、医学の黎明期から偽の治療法を押し付けてきたが、今やナチュラル・ニュースのようなウェブサイトは、危険な反医薬品、 反ワクチン接種、反遺伝子組み換えの疑似科学でソーシャルメディアを氾濫させ、何百万人もの人々を予防可能な病気にかかる危険にさらしている」 [123]。 反ワクチン運動は、小児期のワクチンと自閉症の発症を関連づける疑似科学的研究を引き合いに出して、子どもにワクチンを接種しないよう多数の親を説得して きた[124]。 アンドリュー・ウェイクフィールドによる研究を含め、ASDの子どもによく見られる胃腸疾患と発達退行の組み合わせが、ワクチンを接種してから2週間以内 に起こると主張した[125][126]。この研究は最終的に出版社によって撤回され、ウェイクフィールドは医師免許を剥奪された[124]。 アルカリイオン水とは、pHが7より高い水のことで、経験的な裏付けはないが、多くの健康上の利点をもたらすとされている。アルカリイオン水と「アルカリ ダイエット」を推進したロバート・O・ヤングとして知られる実践者は、無免許で医療行為を行ったとして、2017年に3年間刑務所に送られた[127]。 |

| Antiscience Credulity Factoid Fringe theory List of topics characterized as pseudoscience Magical thinking Not even wrong Normative science Pseudo-scholarship Pseudolaw Pseudomathematics |

反科学 信憑性 ファクト フリンジ理論 疑似科学とされるトピックのリスト 魔術的思考 間違ってさえいない 規範的科学 疑似科学 疑似法律 疑似数学 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pseudoscience |

|

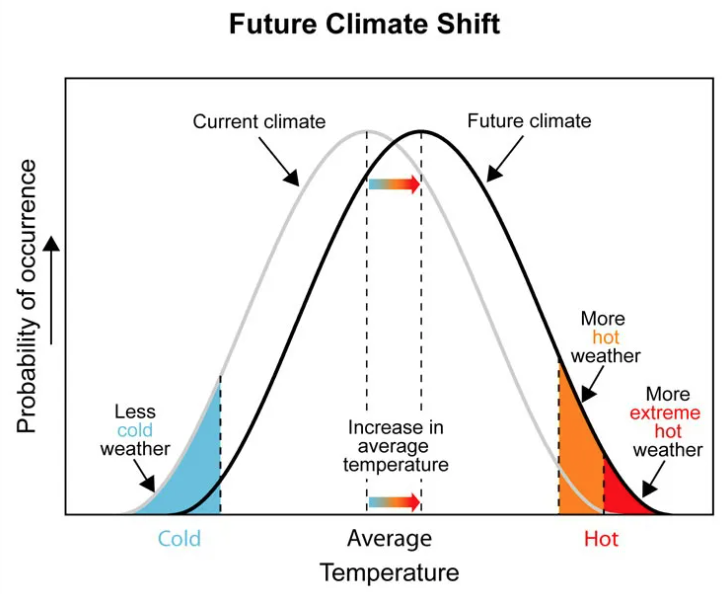

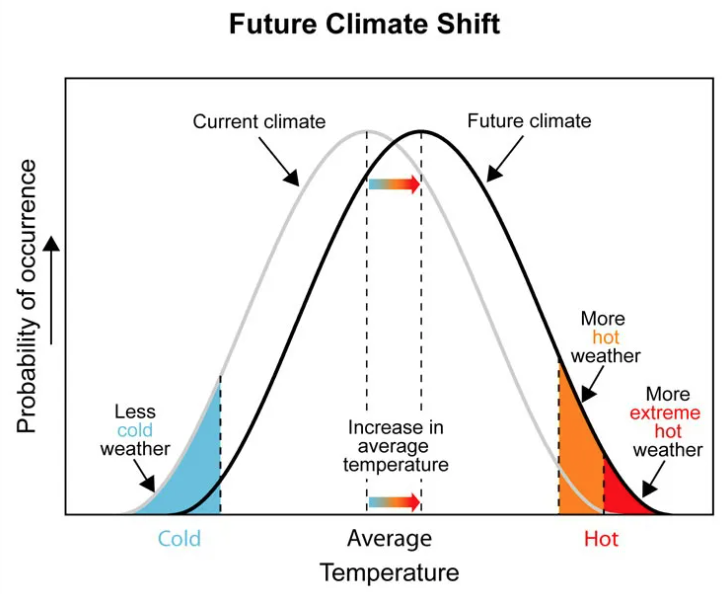

An important thing to note, however, is that small average differences can have big impacts on outliers. Many people, for example, struggle intuitively to understand why a 3- or 4-degrees Celsius increase in average global temperatures could be catastrophic given that temperatures swing by that much all the time. The reason, as shown here, is that even a small rightward shift of a bell curve leads to a wildly disproportionate increase in the number of extreme climate events. That’s a chart about climate change specifically, but the same logic applies broadly to all kinds of domains. A difference in average intelligence levels that is not particularly large or noteworthy could lead to a drastic difference in the share of the group that is capable of doing Nobel-level work. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/12/30/21042733/bret-stephens-jewish-iq-new-york-times |

しかし、注意すべき重要な点は、平均気温のわずかな差が異常値に大きな影響を与える可能性があるということである。例えば、世界の平均気温が3~4℃上昇すると、なぜ壊滅的な打撃を受けるのか、多くの人々は直感的に理解できない。 しかし、注意すべき重要な点は、平均気温のわずかな差が異常値に大きな影響を与える可能性があるということである。例えば、世界の平均気温が3~4℃上昇すると、なぜ壊滅的な打撃を受けるのか、多くの人々は直感的に理解できない。その理由は、ここに示されているように、ベルカーブが少し右にずれるだけで、極端な気候現象の数が不釣り合いに増加するからである。 これは気候変動に特化したグラフだが、同じ論理があらゆる分野に広く当てはまる。平均的な知能水準に特に大きな差や特筆すべき差がなくても、ノーベル賞級の仕事ができる集団の割合に劇的な差が生じる可能性がある。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆